September 2022

Keeping Mum: Leaving calves on cows

Global dairy: Aussie dairy exodus

Sentience: Positive and negative emotions

Learn, grow, excel

FMD: Are you ready for Foot and Mouth Disease?

Keeping Mum: Leaving calves on cows

Global dairy: Aussie dairy exodus

Sentience: Positive and negative emotions

FMD: Are you ready for Foot and Mouth Disease?

Moving ahead means making changes. And that usually comes with a few risks along the way. But with us as your partner, you can progress with more confidence. That’s because FMG offers the kind of specialised advice and knowledge that only comes from working alongside rural New Zealand for generations. To find out more, ask around about us. Better still, give us a call on 0800 366 466 or go to fmg.co.nz. FMG, your partners in progress.

22 Milking on Faroe islands a vital industry

25 Foot and Mouth: Farmers urged to be vigilant

27 Relationships: When it all goes pear-shaped

29 Scientist urges caution on treated urea

30 Budgets: Staying in control

SYSTEMS

32 Opinion: Exclusion of exotics from ETS are back in the mix

34 Kicking the nitrogen habit

Use Bovilis BVD for 12 months of proven foetal protection1. The longest coverage available.

Exposure to BVD could mean your unborn calves become Persistently Infected (PI’s) - spreading BVD amongst your herd. It is estimated that up to 40% of dairy herds are actively infected with the BVD virus at any given time. The convenience of the longest coverage available along with flexible dosing intervals2 means you can protect this season’s calves no matter when they are conceived.

Avoid an outbreak. Ask your vet about vaccinating with Bovilis BVD or visit bovilis.co.nz

Page

62 Sexed semen key to veal trade

64

65 Here comes the sun(flowers)

86 Loving the science of soil

RESEARCH WRAP

90 Ashley Dene on a health mission

WELLBEING

92 Addressing grief and trauma

DAIRY 101

94 Risk: Gamblers and ramblers

SOLUTIONS

96 Nutrition that stacks up

97 Nutrition’s big five

OUR STORY

50 ENVIRONMENT 66

Page

STOCK

76

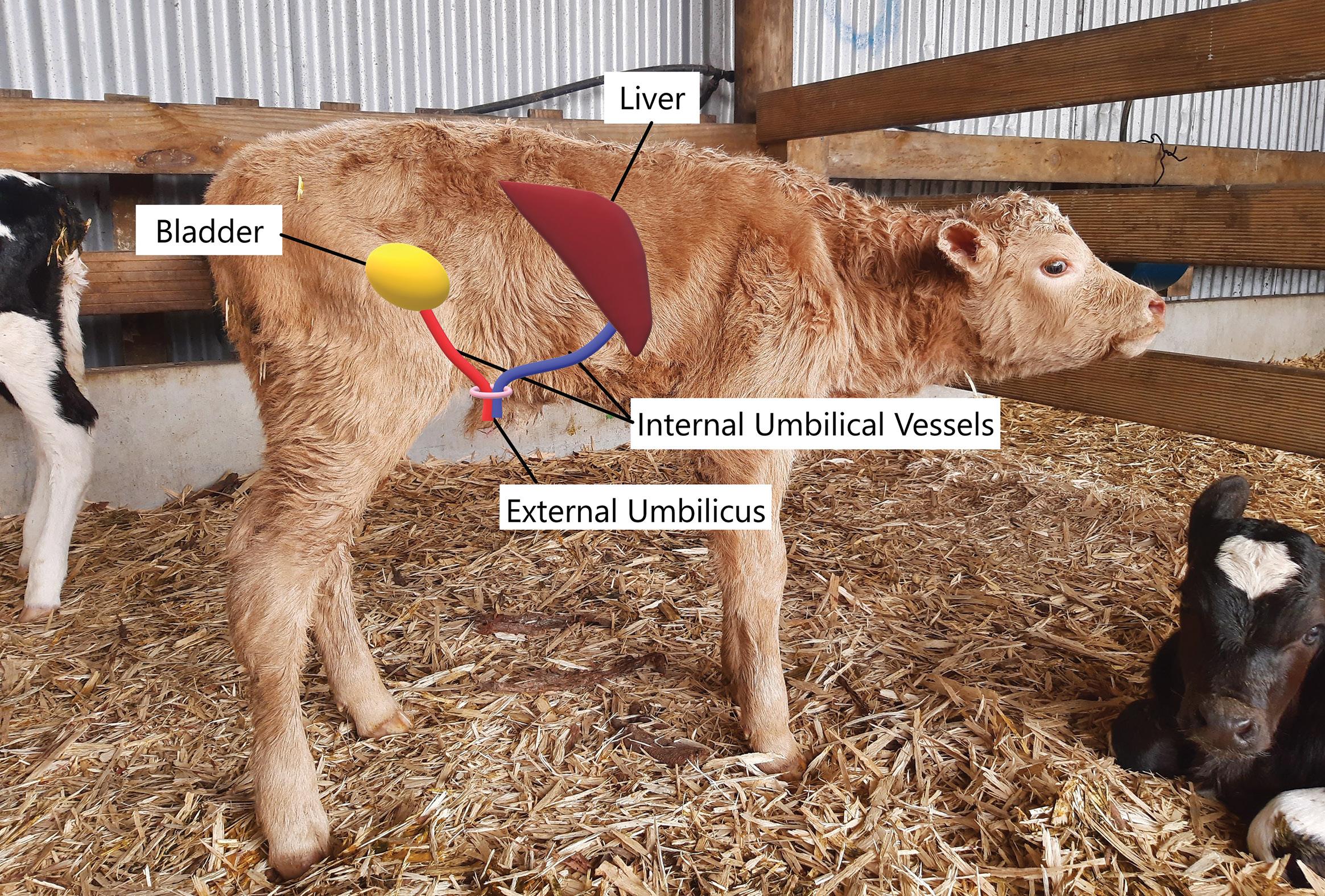

Vet Voice: Navel care for calves

September 27 – A Pasture Summit Field Day in Taranaki is being held on Nathan and Courtney Joyce’s Manaia Road farm. The field days are hosted by farmers for farmers, with input from dairy sector specialists, sharing ideas and developments on achieving profitable food production from grass and how they are adapting to change. More? visit www.pasturesummit.co.nz

September 27-28 – DigitalAg 2022 is at the Distinction Hotel in Rotorua. The formerly MobileTECH Ag brings together technology leaders, agritech developers, early adopters and the next generation of primary industry operators. To find out more and to register, go to agritechnz.org.nz/event/ digitalag

September 28 – Lincoln University Dairy Farm focus day with a focus on mating, managing costs and inflation. The day begins at 10.30am. Visit www.ludf.org.nz/events.

October 1 – Entries open for the 2023 Dairy Industry Awards. Visit www.dairyindustryawards.co.nz

October 6-7 – The New Zealand Landcare Trust is hosting the National Catchments Forum at Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. It looks at water reforms, integrated farm and catchment planning, and how

catchment groups are addressing the climate challenge. For more, visit www.landcare.org.nz/event-item/ national-catchments-forum

October 14-15 - AgFest returns to the West Coast. The event recognises the importance of the agriculture sector to the Coast and includes the latest in farming vehicles, stock care, health and wellbeing, entertainment, fashion and more. The event is being held at the Greymouth Aerodrome. To find out more visit www.agfest.co.nz

October 19 – A Pasture Summit Field Day in Southland is being held on Daniel and Emily Woolsey’s Gorge Road farm. Hosted by farmers for farmers, with input from dairy sector specialists, sharing ideas and developments on achieving profitable food production from grass and how they are adapting to change. For more information visit www.pasturesummit.co.nz

October 30 – Applications close for the first 2023 Kellogg Rural Leadership Programme at Lincoln. To apply, visit ruralleaders.co.nz/kellogg

November 3 – Reprogram – Charge the Brain is a webinar run by ASB in partnership with Dairy Women’s Network. It looks at the neuroscience of attention, memory and energy to help

with busy lives and increasing change. To register go to register.gotowebinar. com/register/1687105359498338318

November 9 – New Zealand Agricultural Show at Canterbury Agricultural Park in Christchurch. Visit www.theshow.co.nz

November 15-17 – The NZ Grassland Association’s annual conference takes place in Invercargill in conjunction with both the Agronomy Society and the NZ Society of Animal Production. A highlight of the conference is a tour to the Southern Dairy Hub. For more information and to register, visit www.grassland.org.nz

November 17 – Owl Farm is holding a focus day where it will present seasonal results to date. For more information about the Waikato demonstration farm, go to owlfarm.nz

November 18 – The supreme winner of the NZI Rural Women NZ Business Awards will be presented in Wellington. For more about the awards go to ruralwomennz.nz/nzi-rural-women-nzbusiness-awards-2022

November 30 – December 3 –Fieldays is a summer event this year at the Mystery Creek Events Centre near Hamilton. For details visit www.fieldays.co.nz

When everyone around you is zigging, should you zag?

Staying strong onfarm portrays an innovative programme run by Reporoa dairy farmer and cancer survivor Sarah Martelli, who helps other women find their balance and build strength and wellbeing to be the best they can be.

Strong Woman is an online community for women to work on their fitness with a workout to do at home, find quick and easy healthy recipes, goal planners and to connect with other women on the same journey.

Her philosophy is to help women create healthy, sustainable habits around moving and feeding their bodies and their families.

If women can prioritise their own health and fitness, they can inspire their partners, their children and their community around them, Sarah says (p82).

(p42). We also cover the Heald family of Norsewood (p52) who have transitioned to organics, OAD philosophies and are enjoying the less intensive more resilient system they have moved to, along improved profitability.

She is an inspirational woman creating a moment of lift for many women.

You might wonder at the sense of thinking of diversifications on your farm at a time of record high milk price, but on the other hand, maybe now is the best time to do it.

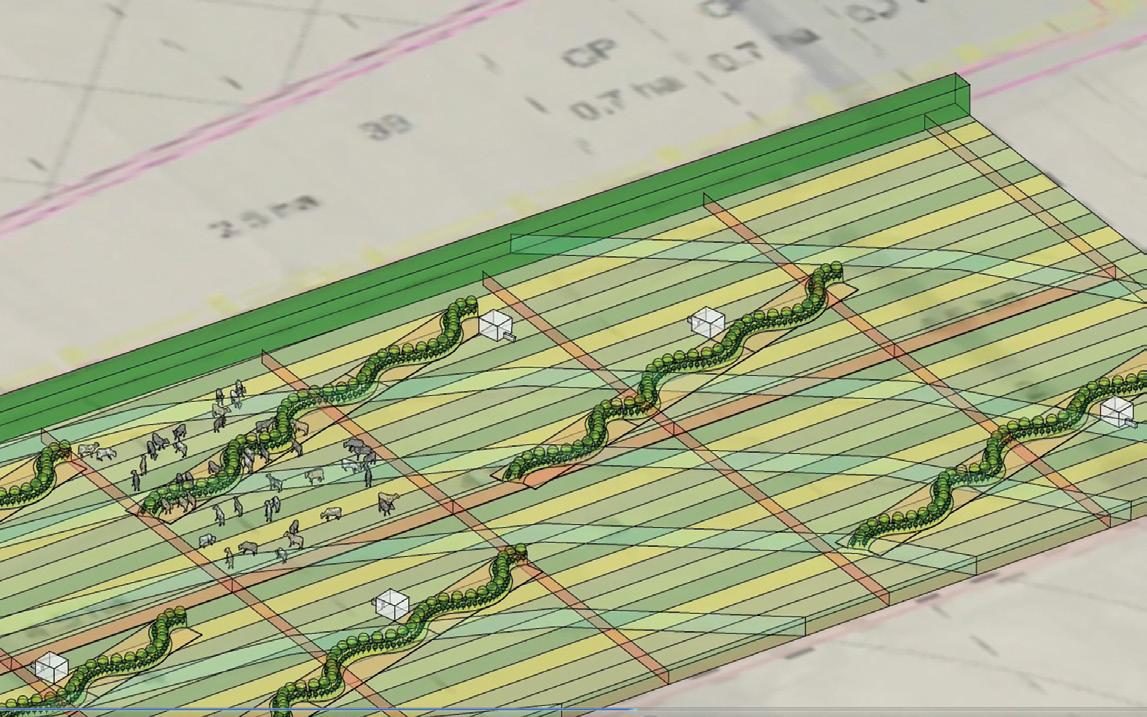

In this issue we take a look at the regenerative agri journey some NZ farmers are already on, and that the government has signalled they want others to join in on, in our Special Report.

At a time of good income you have good cashflow to invest in a diverse income stream and the headspace to think strategically about how it might help in the future, when the milk price has its next inevitable cyclical downturn.

And for out-ofthe-box thinking, Canterbury company Leaft has come up with a diverse income stream from plant protein that would also produce a low N food source for stock.

There is more research to be done in the NZ system context, says MPI’s chief scientist John figure out what will and won’t work, but he encourages farmers to engage and learn more, and to embrace regenerative as a verb - saying all farmers could be more regenerative, more resilient, lowering and building carbon storage.

The regen debate has divided the farming community in a big way - many scientists are affronted that NZ would need regenerative methods from overseas countries with highly degraded soils - would that then infer that our conventional methods were degenerative?

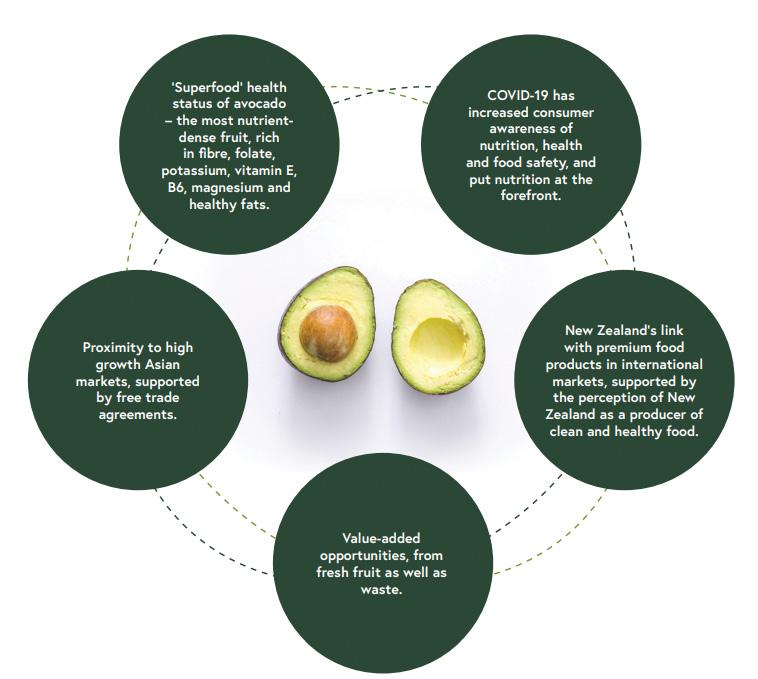

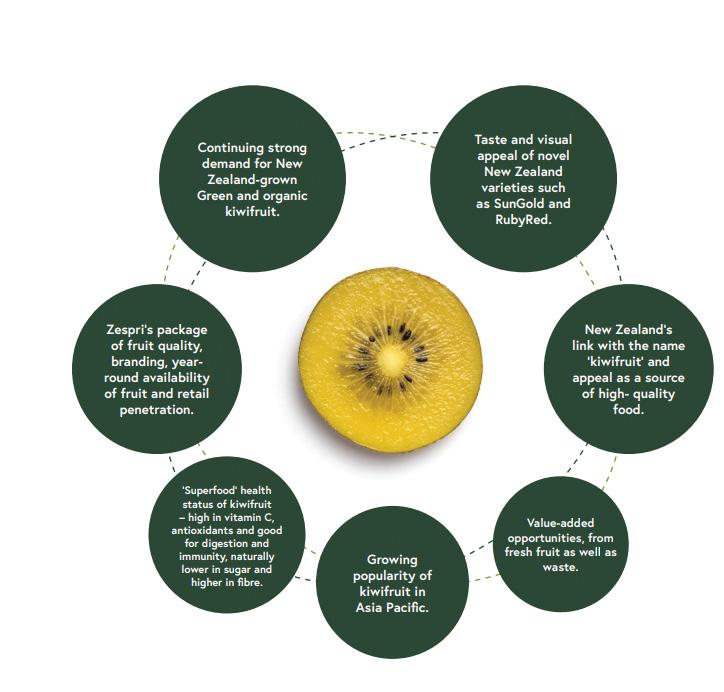

Of course many of the onfarm side hustles we have uncovered in our Special Report this month were established not just for reasons of having a diverse income stream. The subtropical fruits being investigated in the sunny Northland have come about because the climate has changed so much that these products are now viable, same with the investigations into growing avocados and kiwifruit, along with other innovative plants in Taranaki.

They say the methods won't work, and that research has already shown that, and also our farmers are already following regenerative practices. Others say that the methods are not prescribed and each farmer can take out of it what they want. It has been called a social movement rather than a science and the claimed benefits of improved soil and stock health and building soil carbon through diverse species, use of biological fertilisers and laxer and less frequent grazing practices along with less nitrogen is something that resounds emotionally with many.

Sheep dairy is touted as having a much smaller environmental footprint, and the grain crops being grown on Southland dairy country both make farmers more self contained and work to mop up excess N from the soils at critical times of the year (Pg48).

We ran out of room to tell of all the onfarm diversifications there are out there - I would love to hear of any more you have so we can keep the conversation going. A cabin on a hill? A glamping site by the river down the back? Native tree nursery? Truffles under a grove of hazelnut trees? Or a back paddock of walnut trees? The opportunities are endless. Sentience is a word that many farmers may not have heard, but now it’s been combined into the overhaul of the animal welfare regulations you need to be aware that it’s the ability to experience feelings and sensationslike pain and sadness. Accepting that animals feel pain and discomfort means we need to actively treat them to minimise those feelings (Pg76).

We have taken a snapshot of thinking by scientists in MPI and DairyNZ (p46) and portrayed what farmers using the practices are finding, including ongoing coverage of the comparative trial work by Align Group in Canterbury

If you are interested in getting into farm ownership getting out but retaining an interest, read about Moss’ innovative idea for a speed-dating weekend potential partners (p11). We think it could be

@YoungDairyED

@DairyExporterNZ

@nzdairyexporter

JULY 2021 ISSUE

In the next issue: October 2022

• Special Report: Farming/business investment – if you are starting out or bowing out.

The glimpse at veal farming in Denmark shows how strategic mating and clever marketing into established world markets for veal could turn an undervalued bobby calf resource into a profitable beef farming venture (Pg62).

Others have planted areas of their dairy operations in trees, for amenity, carbon and production timber and others have harnessed the abundant local water resource into hydro power to mitigate rising electricity prices and sell back to the grid.

The Lincoln University study comparing three methods of calf rearing, including leaving them on mum for six weeks and a wean time of 10 weeks, is not looking at sentience - but the more practical aspects of growth rates, passive immunity, rumen development and lifetime performance alongside monitoring the mums for differences in a range of production and health measures. (pg82).

There is always interesting research going on, enjoy the read,

• Milking it - looking at all the milks.

• Wildlife onfarm

• Ahuwhenua winners

• Going organic to get to Carbon Zero

• Sheep milking conference coverage

- Tongariro farm.

• New programmes at Dairy Trust Taranaki.

New Zealand Dairy Exporter’s online presence is an added dimension to your magazine. Through digital media, we share a selection of stories and photographs from the magazine. Here we share a selection of just some of what you can enjoy. Read more at www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Young Country is pleased to announce that episode three of From the Ground Up is now live on all of your favourite podcast providers.

NZ Dairy Exporter is published by NZ Farm Life Media PO Box 218, Feilding 4740, Toll free 0800 224 782, www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Editor

Jackie Harrigan P: 06 280 3165, M: 027 359 7781 jackie.harrigan@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Deputy Editor Sheryl Haitana M: 021 239 1633 sheryl.haitana@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Sub-editor:

Andy Maciver, P: 06 280 3166 andy.maciver@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Reporters

Anne Hardie, P: 027 540 3635 verbatim@xtra.co.nz

Pareka farm has gone through a significant change in farm systems this season with the aim of cutting N losses and methane emissions, paving the way and creating learning opportunities for others.

Take a look:

https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=SV9t9tqB3Kc

- Succession Series Podcast

Episode 3: The Mangamarie Sunflower Field, established by farmer, photographer and mum, turned sunflower entrepreneur extraordinaire, Abbe Hoare, is turning heads for all the right reasons.

Episode 2: Amanda King founder of By The Horns. They say you should never work with children or animals, but By the Horns photographer Amanda King has carved out a niche for herself doing exactly that.

Episode 1: Delwyn Tuanui from The Chatham Island Food Co about how he chased his dreams from the ground up.

We love highlighting positive stories of young agri-innovators chasing their dreams Listen to From the Ground Up: nzfarmlife.co.nz/podcasts-2 or scan QR code

Anne Lee, P: 021 413 346 anne.lee@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Karen Trebilcock, P: 021 146 4512 ak.trebilcock@xtra.co.nz

Delwyn Dickey, P: 022 572 5270 delwyn.d@xtra.co.nz

Phil Edmonds phil.edmonds@gmail.com

Elaine Fisher, P: 021 061 0847 elainefisher@xtra.co.nz

Claire Ashton P: 021 263 0956 claireashton7@gmail.com

Design and production:

Lead designer: Jo Hannam P: 06 280 3168 jo.hannam@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Emily Rees emily.rees@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Partnerships Managers: Janine Aish

Auckland, Waikato, Bay of Plenty P: 027 890 0015 janine.aish@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Welcome to the ASB Rural Insights

- Succession Series podcast, where we’re talking about farm ownership transition from all sides. Thanks to the ASB Rural team for partnering NZ Farm Life Media on this four-part series. Each week Angus Kebbell will be profiling farming families, talking to experts from the advisory sector and investigating new opportunities for farmers thinking about diversifying their farming business. When it comes to ‘what’s next’ for the farm, there’s a lot to think about, so we aim to share success stories, provide useful tips and help you understand more about the many facets of succession planning in the food and fibre sector today.

To listen:

https://nzfarmlife.co.nz/podcasts-2/

CONNECT WITH US ONLINE:

www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

NZ Dairy Exporter @DairyExporterNZ

NZ Dairy Exporter @nzdairyexporter

Sign up to our weekly e-newsletter: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz

Tony Leggett, International P: 027 474 6093 tony.leggett@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Angus Kebbell, South Island, Lower North Island, Livestock P: 022 052 3268 angus.kebbell@nzfarmlife.co.nz

Subscriptions: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz subs@nzfarmlife.co.nz

P: 0800 2AG SUB (224 782)

Printing & Distribution:

Printers: Ovato New Zealand

Single issue purchases: www.nzfarmlife.co.nz/shop

ISSN 2230-2697 (Print)

ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

One thing we love about dairy farming is the amazing rural community that backs it. You would be hard-pressed to find any other sector that has such a cohesive and strong network of support behind it.

Here in the Waikato, it has been a hard slog - five months of drought, autumn skipped, and straight into winter and floods. Things haven’t really improved since our last article. Pasture is something we are still squinting to find. Rather than dust it’s now mud, inflation is worsening, interest rates keep rising, and expenses are still out of control. Milk production is also down despite our best efforts.

But the light behind this has been our rural community. And getting support during these hard times is important. Our rural community has been amazing, and we want to acknowledge them.

We have been grateful to the gestures of our rural providers who have turned up with food in hand and forced us to have a breather over a coffee.

We are grateful to the relationships that go beyond the farm gate.

To those in our rural network who take the view that a problem shared is a problem halved.

To our rural suppliers – namely PGG Wrightson in our case – who bend over backwards to get us the right product when we need it and take the time to understand our farming business.

To LIC, who gave us the chance to have a day and night away from the farm and get an understanding of how they are moving our agriculture industry forward.

To our rural consultants – namely DairyNZ and BakerAgwho are on hand to provide resources when we need them and an impartial view of how the business is running.

To our business partner and farm owner, who gets that things are hard going for us as sharemilkers at the moment and is willing to be flexible on our contractual agreements. The big one was allowing us to bring our yearlings home to graze due to a feed shortage at the block they were at.

To our farming peers – that unspoken agreement that we are all in this together and they are going through it also. Watching out for each other is something you would struggle to find in any other sector. While we have our individual goals, we have the same collective goal to see each other succeed.

So, while things are likely to get worse before they get better, reach out to your rural network. They are on hand to support you. You are not alone.

Keep your finger on the pulse with your financial budgets. While it is easier to put your head in the sand, in the long run keeping abreast of your financials will give you the time to make good decisions.

We are constantly reviewing our budgets and identifying where the fat is that will ultimately be trimmed out if we must. We feel at times we are taking one step forward and two steps back; the most recent has been breaking a twoyear hiatus and contracting palm kernel while we wait for the pasture to come back on board. That’s farming – unpredictable as ever. But we have a great community backing us and we are proud to be part of it.

Kirsty and Nic Verhoek give credit where it’s due to the people of their local network.Cosy calves in their Thermoo covers from Antahi. A lesson in puncture repairs.

Getting support during these hard times is important. Our rural community has been amazing, and we want to acknowledge them.

Dairy Exporter’s ‘50 years ago’ feature has John Milne reminiscing about the way things were done.

This industry is definitely evolving year on year. We have our first year of N reporting completed for our N Cap for the regional council, our GHG (greenhouse gas) number has been calculated through Overseer.

Where this information takes our farming operation is yet to be decided and determined.

’50 Years Ago’ on the back page of the NZ Dairy Exporter, it is one part of the magazine I am always interested in. One of the articles back in the July issue was regarding the ‘Induction Trials’. It just shows how things come and things go.

Obviously we weren’t farming when they started things 50 years ago, but I can remember using ‘The jab’. It started in 1989 for me, while going through one of the toughest springs in ’88, many had seen and probably not seen since then.

I can’t remember how much rain we had on the family farm that season, but clearly remember it just never seemed to stop. Calving came around in August ‘89 and we had an extremely stretched-out calving like we had never seen before.

‘The jab’. A couple of seasons before we stopped, we had to increase the percentage of replacements we kept.

Culling began and in the first couple of years it was amazing to see how many had been kept in the herd that probably shouldn’t have been.

Three years later and the culling had settled down for that reason, our next target was non-cyclers. It was a tougher decision than stopping ‘The jab’, it was a good five years till that decision settled down. Sticking to our guns on the direction we had taken, it was and is tough to watch some good cows go off to greener pastures, but as I said: you have to stick to your plan.

‘Genermate’ was another system we stuck with for a number of seasons as well, ‘Syncro’ the heifers for the readers who haven’t heard of this before.

The idea was to get the high BW calves from the highest genetic animals in your herd, in a condensed calving spread. We had quite good success with this and achieved what it was set out to do. The downside was with a slightly longer calving spread for the animals that did not hold to the ‘Syncro’. That has all been stopped now as we have gone to a less-intensive system and only pick yearlings for AI if required.

So ‘The jab’ began for a genuine reason. From then on it became common practice. Year on year, a similar percentage each year, only small numbers but we thought it was beneficial. In the background we had unwittingly started a problem.

It wasn’t until the numbers and the herd records started showing that we had been fooling ourselves. So we stopped

So this season is well and truly underway. Our calving spread is pretty much the same year on year. First calvers, calving in a timely fashion, mixed age cows heading down the same constant track as usual. It matches our growth and early start to calving every year.

Whether this evolves into changes will probably depend on who’s in charge further down the track.

I can’t remember how much rain we had on the family farm that season, but clearly remember it just never seemed to stop.“More evolution. Gone are the days of dehorning. Now sedation and disbudding, checking for extra teats on calves, castration of steers all while they are sound asleep.

In the midst of a challenging season, George Moss managed to take a break and go fishing.

As I write it is p….. down with rain but mercifully it is very warm and has pulled the soil temps back up to 13-ish.

Winter has been and still is challenging with soil temps of 12C at the start of July and gradually decreased to lows of 4C about a week back due to a couple of “pearler” frosts. We grew more grass in June and July than we have for August. A period of extreme wet in late July required us to stand off cows repeatedly. Grass is very short, and cows are getting silage and palm kernel to fill the gap.

The winter project has been to paint the inside of both farm homes, new floor coverings where required and a new kitchen unit on the second farm, a DVS system at home, all of which chews through the cash, but hopefully maintains or improves the value of the dwellings.

Accounts are back from the accountant showing a big increase in costs but offset by the good milk price despite our fixed milk price positions.

the risk of tax rates increasing as well. We are comfortable with the decision. We managed to get away for four days just prior to the start of calving and I managed to get the kayak out on some gloriously still days and catch a good feed of gurnard, kahawai and a large snapper that went flip flop on my legs and left. Out on the water alone with just sea and sky and hopefully a few fish is my happy place and I yearn to be there now. Kayaks have a silence and a simplicity that is totally relaxing.

Like a great many farms, we are short staffed on the home front and yours truly has ended up back in the shed for the first few weeks. We have employed a young guy (16-yearold) drive in to assist in the shed and do the plant and yard washes. He is keen, pleasant and tries hard, but it is a lot to take in if you have not been exposed to dairying before.

With inflation running amok, we are fortunate to be growing our own leafy greens and still harvesting the odd tomatoes and have a freezer full of vegies/ fruit and meats. We are truly fortunate to be living on a farm with our own food. Hopefully, the onfarm inflation will be offset by product prices – in theory there should be a natural hedge.

Just had an interview with a couple of delightful Wintec students who are working on “circular economies” and their role in solving the “big” problems of the planet so that we have a thriving and enduring humanity.

The numbers are being entered into Dairybase as I write, and this will give us definitive indication as to our performance. The full impact of cost increases will be felt this season, with interest being the biggest mover despite significant debt reductions.

Rightly or wrongly, we have used a mixture of Farm Income Equalisation to take the spikes out of the tax bill. There is an inherent assumption that either due to costs increasing more than income or a structural change, our incomes will fall in the next three to five years. There is also

Given as a society, the paradigms are leaving us more stressed and divided. I pose the question of how do we move our value system from “standard of living” to “quality of life” and what does that look like?

Out on the water alone with just sea and sky and hopefully a few fish is my happy place.Right: The Good Life: Homegrown lettuce and tomato, from George and Sharon’s hydroponic glasshouse setup, and homemade feta cheese.

ecent regulatory moves by other countries to limit non-traditional food producers hijacking terminology associated with animal protein could soon be considered in New Zealand.

An update of the joint Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code has been proposed across the Tasman with implications for shop shelves in NZ, based on a sympathetic assessment of meat industry claims of unjust product labelling.

This might instinctively be seen as an early victory for those in the business of producing animal protein the traditional way. But when considering wider investment and government policy trends favouring the expansion of plant-based food production, not to mention consumer indifference to being ‘duped’ by vegan mince and the like, any such change in labelling laws might yet be a hollow victory for those wanting the supremacy of conventional sources of protein restored and unopposed.

Calls for bans on ‘fraudulent’ meat and dairy category branding have been made for some time now, but recent changes to labelling laws offshore is creating a precedent for others to follow. France led the way when it amended its Agriculture legislation to prohibit any product based on nonanimal ingredients from featuring traditional meat and/or dairy

The ban is scheduled to come into force in October. Elsewhere, Turkey has banned the production and sale of vegan cheese alternatives that look like traditional dairy cheese and the Belgian government, following France’s lead, has been

Internationally, regulators are tussling with the issue of labelling traditional animal-based foods and their plant-based reports.

working on guidelines that would make it more difficult for vegetarian and vegan plant-based foods to refer to animal products.

Rule changes in far-off lands might otherwise be given cursory attention but this year a Senate committee across the ditch released findings on an inquiry into the state of meat category branding. It recommended, among other things, a review of the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Food Standards Code be made to limit the use of named meat, seafood and dairy category brands. The committee shared concerns with the meat industry, which had agitated for the review, that plant-based protein manufacturers are dishonourably using terms that animal protein sectors have invested heavily in to distinguish their own products.

Wheels turn slowly in mammoth regulatory reviews, however the FSANZ Act is being modernised (the process began in 2020) and a Food Code change could

be contemplated as part of this. This could be good news for those who believe that not only have the meat and dairy industries been robbed by plant-based newcomers, but that tighter rules will reinvigorate the appeal of animal protein.

It sounds like common sense finally prevailing. But... in all cases listed above, legislators have been stymied by challenges from plant-based manufacturing interests.

In the United States, advocates of the plant-based food sector have successfully prevented new rules applying in some states, while some high-profile producers of alternative meat products (such as Tofurky) have been victorious in fighting labelling laws. In 2020 the European Union tried to ban terminology such as ‘burger’, ‘steak’ or ‘sausage’ in relation to plant-based products, however this legal amendment was not supported by the European Parliament. And in July this year,

France’s highest court halted its new law due to be enacted following a request from an alternative protein association.

All this speaks to the thorny challenge of balancing consumer interests. On one hand there is the rightful interest in protecting consumers from misleading labelling. On the other there are equally compelling arguments insisting consumers should have the freedom to access food in whatever form they demand, and that it is not obstructed by anti-competitive regulations.

The recent experience of NZ feta cheese manufacturers being told they won’t be able to label their product as such when

the NZ-EU free trade agreement is ratified comes to mind. It is worth noting there is no research in NZ that suggests consumers are feeling tricked by plant-based mishmash being labelled as vegan mince, for example. A spokesperson for the NZ Food & Grocery Council says it has previously discussed the issue with FSANZ and the Commerce Commission.

“There’s no evidence so far that consumers are being misled. A consumer purchasing an Impossible Burger is unlikely to believe it’s genuine meat. No doubt issues like these are open to debate, but words such as ‘burger’ and ‘steak’ could be seen by many as generic words now commonly used by consumers to describe plant-based and meat products.

our fledgling modern foods sector presents nearly unlimited opportunity to participate in the food revolution over the coming decades.”

And while the Australian Senate committee review referred to earlier was quite forthright in the need to bring plant-based producers to account for unfair use of animal protein terminology, in the very next breath it recommended that Australia’s Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment “support investment opportunities into the plant-based alternative product sector’s manufacturing infrastructure to foster competitiveness and market opportunities”. It also advised “the plantbased protein product sector is supported to contribute to the Ag2030 goal of achieving a $100 billion agricultural sector by 2030.”

making sure investment in the science of cellular agriculture has a focus on what the consumer wants, and this means delivering products with functionality. But it doesn’t mean the person who will fill the role will be tasked with developing a product to take to market. It’s about generating more understanding about the processes and science behind the technology.

It’s difficult to dispute the fact that new, viable food production systems have evolved and there are credible reasons to believe they will continue to grow, and in so doing, threaten the growth prospects of conventional food production.

“As far as we could see from the Australian inquiry, there is no evidence of confusion. Both countries have legislation to deal with misleading representations in the Food Acts and the Fair Trading Acts. We doubt there is the basis to develop a standard along the lines proposed.” We’ll see.

Meanwhile, the momentum in the protein debate that may or may not be edging towards the protection of animal protein interests at the level of the supermarket shelf, is not being replicated at the production investment level, nor it could be said at the level of governmental policy.

The Ministry for Primary Industriesaligned primary sector think tank Te Puna Whakaaronui, which this year pitched to reframe NZ’s food sector opportunities, insisted “continued development of our natural food system must not come at the exclusion of New Zealand’s participation in the fast and accelerating world of modern foods, defined as plant-based, fermented and lab-grown products.” It also stated “Although our natural food systems are experiencing record financial returns, this is time-limited … In contrast,

As with challenges associated with balancing consumer interests, this speaks to a difficulty in managing the arguably contradictory interests of plant-based and animal protein producers. Like Australia, that tension is visible in NZ. A recent example was seemingly conflicting messages delivered by AgResearch. At the end of June, it publicised research that showed red meat held a nutritional advantage over highly processed plantbased products, that are formulated to mimic the taste and basic nutrient composition of meat. A few weeks later, AgResearch announced it was jointly funding the first ever NZ Chair in cellular agriculture, acknowledging that biotechnologies for producing animal protein-based foods without animals has the potential to significantly disrupt the traditional animal protein industry, and that it is extremely important for NZ to develop capability in cellular agriculture and exploit commercial opportunities.

AgResearch science group manager Stefan Clerens says there is plenty of room for both traditional and modern food production systems to co-exist and there is no reason why NZ can’t be successful in facilitating advances in both. The importance is about

At the same time though, there’s enough evidence to dispel the possibility of a near-term takeover. Just last month Beyond Meat, one of the biggest US producers of plant-based meat substitutes cut its estimated revenue based on a fall in demand following some disheartening commercial trials. Among others retail food chains, McDonalds had decided not to go ahead with an immediate broader launch of Beyond Meat products. Similarly, the growth expectations of the large Swedish food company Oatly have been curbed after failing to convert more consumers from dairy to its plant-based alternative than anticipated.

The perceived reasons behind these developments are that the taste of the Beyond Meat and Oatly products aren’t quite on the mark. This undervalued factor in determining the appeal of meat and dairy alternatives is most likely the key reason holding back the march of modern foods. If NZ funding of the science of modern foods is aligned to what consumers want (tasty!), then issues around labelling might end up being neither here nor there.

CALLS FOR BANS ON ‘FRAUDULENT’ MEAT AND DAIRY CATEGORY BRANDING HAVE BEEN MADE FOR SOME TIME NOW, BUT RECENT CHANGES TO LABELLING LAWS OFFSHORE IS CREATING A PRECEDENT FOR OTHERS TO FOLLOW.

ECLIPSE® and EPRINEX® have formed the backbone to New Zealand farms over the generations for animal health. So together with these Merino Icebreaker Thermals, we’ve created the ultimate legends of the land for you and your stock this season.

Purchase qualifying cattle drench products this season and you’ll receive either an ICEBREAKER short sleeve merino tee or a long sleeve merino jersey absolutely FREE *

*Promo runs from 1st August - 30th September 2022. Ask in clinic for qualifying products. Ensure

the back of seasonal-friendly pricing.

Plenty of dairy farmers were already reviewing their system, Mumford said.

“Do we as businesses need to be milking seven days a week over 365 days, for example?” he said.

Record farmland prices made it attractive to exit farming altogether and Mumford said those keen to stay on the land could now generally make a reasonable living grazing beef cattle, which needed a fraction of the labour demanded by dairying.

“Labour is the number one issue they look at first,” he said.

“It would probably be safe to say that every farmer who employs staff is probably one labour unit short, and that’s having a huge effect on the dairy industry.

“It puts stress on businesses and it puts stress on family units.”

seeing many Australian dairy farmers quit the industry. By Marian Mac.

Breaking the $10/kg milk price barrier for the first time hasn’t been enough to stop Australian dairy farmers exiting the industry in large numbers.

Farmgate milk production fell another 3.9% to less than 8.51 billion litres in 2021/22, the lowest figure this century.

It’s not a loss-driven contraction. The National Dairy Farmer Survey (NDFS) showed 88% of Australian dairy farms expected to make a profit in 2020/21 and 90% thought they would make a profit this year, too. It’s unlikely to be a seasonal aberration, either. One in eight farms has left the industry since 2019/20, taking the total down to just 4401 dairy farm businesses by March this year. United Dairyfarmers of Victoria president Paul Mumford said dairying was no longer the only natural choice for his members.

“Dairy farmers are putting a lens over their business, thinking, ‘Are we prepared to go on in the dairy industry? Do we want

that stress and are there alternatives for our business and our lifestyle?’,” he said.

In its Situation & Outlook report, Dairy Australia said, “high beef prices and soaring land values have enticed farmers and farmland away from dairy,” and they expected the trend to continue.

It’s something Duncan Morris has seen first hand. Morris, who administers the two-year-old processor SW Dairy Ltd, is an accountant, southwest Victorian dairy farmer, and former Murray Goulburn Cooperative director.

“The number of farms exiting dairy has been absolutely massive around here, and nearly every one of them has gone to beef or sheep,” Morris said.

The solution, he said, was to adopt something of New Zealand’s seasonal, low-input model, but that needed to be matched with a suitable milk price model. That realisation was the catalyst for SW Dairy Ltd, which had grown from 8 million litres to 30 million in two years on

Mumford’s observations were backed up by the NDFS report, which highlighted three main issues: input costs, labour and climate.

Of the 700 farmers surveyed, 57% said input costs like feed, fertiliser and fuel were their top concerns.

Almost a quarter (at 23%) said they had shrunk their herds in the last 12 months in response to the labour shortage. At the same time, floods swept through South Australia, Queensland, and New South Wales, while the normally reliable northwest Tasmania suffered one of its driest summers, and Western Australia was scorched by bushfires.

The 2016 dairy crisis had also played an ongoing role in the dairy exodus, Morris said, and would continue to be felt for many years.

“It’s not going to come back easily,” he said.

“There’s a generation of kids in their later teens and early 20s who’ve gone and they’re never coming back because they got burned when mum and dad got burned.”

Sow the right chicory this spring, and you’ll be ahead of the game right from the start, with a fast-growing, nutritious summer crop that’s ready for grazing sooner than you think.

501 Chicory jumps out of the ground fast because it’s an annual, and that early start means up to one more full grazing during summer than other perennialtype chicory cultivars.

Feel like immersing yourself in two days of pasture expertise and understanding, at our expense? Your chance is coming up fast – our interactive farmer workshop Grass into Gold is back by popular demand in November.

You’ll join other farmers from all over New Zealand at our research farm in Canterbury for a first-hand look at our latest R&D, exciting new emerging technologies and the opportunity to share and learn everything pasture from outside experts as well as from each other.

You’ll also help shape our research going forward – your feedback about the future of farming is a key driver behind our efforts to create the pastures you need in years to come.

Who should apply for Grass into Gold? Anyone who wants to improve their business through growing better pastures.

You’ll learn about pasture genetics and how to help your pastures thrive, and tips on how to maximise the use of home grown pasture, because that’s where the rubber hits the road in terms of on-going

profitability and sustainability.

Golden opportunity

The programme starts mid morning on 1 November; includes field trips and visiting speakers; and concludes mid afternoon the next day, with plenty of time for open discussion and debate.

Afterwards, you’ll have the opportunity to follow up, and have us visit your farm to help get the best out of pastures for the good of your business.

We’ll pay all the expenses –flights where appropriate; meals, accommodation and transport to and from the airport. All you have to do is fill in the entry form at www. barenbrug.co.nz, and tell us briefly why you want to come to Grass into Gold and how it will benefit your farm.

Spaces are very limited, so check it out now. We look forward to seeing you November!

You can make the most of this benefit by getting well organised for sowing ahead of time – signs are summer crop plantings will be up this season, and 501 Chicory needs to go into the ground when the soil is consistently above 12oC.

So now’s the time to select paddocks, order seed and book your contractor, if you use one, to ensure you are all set to go when conditions are right.

Best results come from sowing 501 Chicory into effluent paddocks; using AGRICOTE and slug bait to protect seedlings from insect pests; drilling seed no deeper than 10 mm, and rolling before and after drilling to improve seed to soil contact.

Visit www.barenbrug.co.nz for more information.

As world economies teeter, Stuart Davison reads the tea leaves on the prospects for NZ dairy on world markets.

Peak milk approaches in little old New Zealand, global market uncertainty is still rife, central banks are dancing the monetary policy line in the face of inflation and China’s economy remains the counterbalance. Cool, so we know the headlines, what does that mean for dairy and other soft commodities?

Let’s start at the top of that list. NZ milk supplies are looking more price supportive. Expectations for NZ’s total milk production season are pointing to another year of reduction. If our tea leaves are telling the truth, two years of production declines in a row will really stir the global milk market. Such a result would turn the trend of a growing milk pool in the South Pacific on its head, and make the global market think a little harder about dairy prices. This carries some weight considering where the trajectory of European milk production is. Likewise, the United States dairy market is still growing, but only just keeping up with their population. Strike one for pricesupportive market measures.

Global market uncertainty has been a buzz word for the first two quarters of 2022, but as we head into the tail end of the year, markets seem more confident. Not enough that hedge funds or other investment funds are shouting from the rooftops, but enough for investors to price in expectations.

For equity markets, that’s moving from the bottom of the screen on the left to the top right, not the opposite, as we witnessed over the first six months of 2022. This is an insight into expectations of economies, albeit still a little blurry. Two strikes for price-supportive market measures. Global monetary policy should be accumulating a lot of your cowshed thought patterns; these policies are far reaching, and the farm isn’t out of reach. You know the story; pandemic,

quantitative easing (QE) (money printing), inflation,rate hikes, cooling of inflation. Rate hikes appear as interest rate hikes for those with debt. These control inflation by controlling spending, by burning consumers’ fingers when they buy things or by increasing interest costs so discretionary spending is limited. With these rate hikes, we know consumers will be less likely to spend on luxuries. Unfortunately, dairy is a luxury for most. Consumers in NZ alone are already spending a little less on dairy, as cheese prices soar. It has been mooted the 30% decline for whole milk powder prices, thus the 30% decline in forecast farm gate milk price in NZ, is a result of dairy procurement teams measuring the risks of inflation on consumers’ purchases.

One positive for NZ dairy because of these rate hikes, is the strengthening of the US$, thus devaluing the NZ$. The devalued NZ$ meant dairy exports earned, which has somewhat cushioned farmgate price expectations from falling further. However, the strengthening of the US$ hurts our trade partners, who buy dairy in US$, termed buying power. Over the last two years, our trade partners have had significant buying power, making imports cheaper. So, rate hikes and currency movements have been two measures, but

the cumulative pressure is negative, so two strikes for negative market pressure.

China is in trouble. NZ is one of those economies tied to China; they are our biggest trading partner, and our biggest dairy trading partner. When they suffer, we suffer. Right now, the Chinese economy is stumbling; economic growth expectations have been downgraded, unemployment for Chinese in their 20s is at 20%, and the housing market is about to implode.

Added to the economic issues, China’s Communist party is due to sit for congress elections shortly, creating political tension within the country itself, as well as geopolitical issues such as Taiwan. As a result, the buying power of the Chinese yuan has been reduced.

If dairy consumption follows the trend of the last two years, imports will remain a key part of the market. So, on balance, the Chinese dairy market is somewhat neutral; economic, political and monetary policy weigh one end, but consumer demand and changed consumption levels continue to provide support to the other end of the scale.

After all of that, the market hangs in a precarious spot with pressures on both sides. Added to the global macroeconomic and monetary issues, China’s economy is acting like a duck on a pond: calm on the surface, but paddling like mad. Uncertainty is unlikely to reduce any time soon.

With just over 1140 dairy cows on 16 farms producing milk for 53,800 people, the dairy industry in the Faroe Islands is quite a vital sector.

The Faroes are in the north Atlantic Ocean, halfway between Iceland and Norway, northwest of Scotland, and cover 1400 square kilometres.

It is one of the three constituent countries that form the Kingdom of Denmark along with Denmark and Greenland.

Aside from the fishing industry, which is by far the biggest in terms of food production, dairying, sheep farming and vegetable growing are the main agricultural sectors.

Due to challenging climate, soil types and field structures, most dairy cows on the Faroes are kept indoors. One of the more modern farms is owned by business partners Roi Absalonsen, Nils Absalonsen and Esmar Sorensen, based at Vioareioi in the north of the island.

Dairying has been a traditional enterprise on this farm for hundreds of years, but as Roi explained there have been major changes there in recent years.

“We milk 120 cows that are yielding 32 litres per day on average at 4.2% butterfat and 3.45% protein,” Roi says. “The milk is sold to MBM, the only dairy processor on the Faroe Islands. Our

current price we receive for the milk is around seven Danish Krones or 94 euro cents per litre (NZ$1.50).

“The cows are being milked an average 2.8 times per day through our two DeLaval VMS300 robots, with 60 cows grouped to each robot.”

Roi’s grandfather built a new barn while running the farm in 1980. His uncle and business partner Nils took over the farm in 1987 and continued to milk cows.

However, with a restructured ownership, the trio decided to heavily invest in the farm and built a new barn for the cows in 2019.

That was not the only investment required though, as extra quota needed to be purchased to increase cow numbers.

“In total, we have about 60 hectares here on our farm and we manage to buy or rent another five hectares each year.

“Our cows are kept indoors all year long but the youngstock graze outdoors during the summer from June to September.

“Nils, Esmar and myself first drew up the plans to build a new barn in 2013. At that time Nils had 212,000 litres of quota so we bought another 320,000 litres that same year. With more

The remote Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic are almost self-sufficient in dairy produce, Chris McCullough writes.

‘THE ROBOT IS SET TO FEED THE COWS EIGHT TO 10 TIMES PER DAY. THEY ARE BEING FED GRASS AND SILAGE AS WELL AS MASH FROM THE LOCAL BREWERY, PLUS CONCENTRATED FEED.’Faroe Islands Roi and Nils Absalonsen in their new barn on their Faroe Islands farm.

quota purchased in 2019 we now have a total of 1.3 million litres to work with each year.”

Most of the cows in the herd are of the Holstein Friesian, plus there are a number of Norwegian Red cows. The team use AI across the herd to get the cows in calf each season.

The Faroe Islands have quite a mild climate, given their latitude, with temperatures only dropping to 3C or 4C in the winter. Summer days are mostly overcast with temperatures never really getting above 15C.

Heavy rain is common and the islands get 210 rainy or snowy days per year. With this in mind, dairy farmers tend to keep their cows in during the year to avoid damaging the land as they can prove to be too heavy to suit the wetter ground conditions.

Forage is transported into the cow barn all summer and silage is fed in the winter via a robotic feeding system.

“We feed the cows with a robotic TKS system which is a Norwegian system. The robot is set to feed the cows eight to 10 times per day. They are being fed grass and silage as well as mash from the local brewery, plus concentrated feed,” Roi says.

The Faroes are almost self-sufficient in dairy products, with the exception of cheese.

Over the past 10 years milk production has increased by 10%, but the number of farms that include dairy cattle has fallen from 28 in 2012 to 16 in 2021.

In 2012, the Faroe Islands produced 6.8 million litres of milk from 1138 cows. This compares to 7.5 million litres produced from 1147 cows in 2021. Due to advances in breeding the average yield has also increased from 6000 litres per cow in 2012 to 6,600 litres in 2021.

One of the main problems associated with dairy farming on the islands is the lack of a slaughterhouse, so there is nowhere to kill cull cows.

“This is a job we must take on ourselves,” Roi says. “We slaughter the older cows ourselves and sell the meat to the public, just like door-to-door selling. It’s a tedious task but it has to be done.”

Roi and his business partners plan to expand their milk production keeping a close eye on new technology.

“We have invested heavily to reduce labour in the new barn with the milking robots and the robotic feeding system. At the moment we have cattle in a barn in a different location, so in the future we would like to extend the barn so we can house all the cattle under the one roof,” he says.

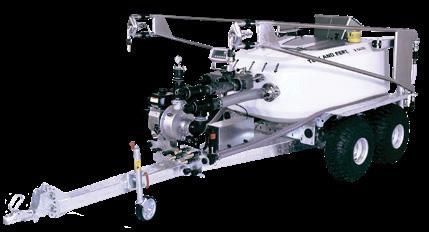

The outbreak of foot and mouth disease in Indonesia has raised alert levels in New Zealand.

By Anne Hardie.

By Anne Hardie.

Biosecurity measures at the border will hopefully continue to keep foot and mouth disease (FMD) out of New Zealand, but farmers also need to be on the front foot with their own biosecurity practices. Because sometimes, like Covid-19, the problem can be in the country and circulating before we know it.

That means keeping a diary of all visitors to the farm and if you have staff or family returning from countries that have FMD and they have been around animals, they should not have contact with animals in NZ for a week. That’s not just Indonesia which has the latest outbreak, but numerous parts of the globe including countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and South America.

An estimated 77% of the global livestock population live in countries with FMD, so

it gives some idea of its prevalence and the airways are busy again with travellers.

Ministry for Primary Industries chief veterinary officer, Dr Mary van Andel, says biosecurity practices on farms are an insurance so that if the disease gets into the country, it doesn’t spread or at least spreads slowly.

alarm to get it checked out as soon as they are suspicious. Dr van Andel acknowledges farmers will be fearful of doing that, but every day delayed is another day where farms can get infected.

“We would hope we would find the first case of FMD in New Zealand, but we could never be sure.”

It is one of the reasons farmers need to know the signs of FMD and raise the

Traceability is key and since Mycoplasma bovis there has been a marked improvement in NAIT recording on NZ farms which, she says, will be essential for tracing animals if there is a FMD outbreak. It is not perfect yet though and she says some people find it difficult to comply with the NAIT scheme, for whatever reason.

“WE DON’T NEED TO WAIT FOR RESULTS TO LOCK DOWN THAT FARM TO MAKE SURE THERE IS NO FURTHER SPREAD.”Ministry for Primary Industries chief veterinary officer, Dr Mary van Andel.

Farmers’ own biosecurity measures for a potential outbreak of FMD – or any other diseases that may slip into NZ - should start with a simple onfarm biosecurity plan that is updated regularly and familiar to all staff.

The visitor diary should record anyone coming onto the property so that should an infection arise, it is easy to trace people movements for the weeks leading up to its discovery.

Dr van Andel says every farm should have a policy all the time that no dirty boots are brought on to the farm because of the potential to introduce diseases from other properties. The same applies to equipment and machinery used on different properties and there should be a ‘clean slate’ policy between properties.

All employees should know the rules and she says everyone should be respectful to other farmers’ biosecurity when going to a property.

One of the most dangerous ways of spreading the disease is through animals and meat products imported from countries with FMD. Feeding food waste

that includes meat products (swill) to pigs, whether it is your own pigs or supplying it to someone else’s pigs, is high-risk if the disease gets here. Any food waste needs to be heated to 100C for an hour to destroy disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

If a FMD case is suspected, MPI will immediately enforce restrictions to stop all movement on and off the property. Tests take only a matter of hours to determine whether the disease has breached the border or it is a false alarm.

“We don’t need to wait for results to lock down that farm to make sure there is no further spread.”

If it is a positive result, there will be a national halt to livestock movement as MPI traces movements to and from the infected farm. The length of time will depend on the spread of the disease.

One of the problems with the disease is that animals can shed the virus before they have clinical signs and it can take anywhere between three to 14 days for clinical signs to show up.

That reinforces the need to be prepared and have biosecurity measures in place on the farm – in case the worst-case scenario happens.

Make sure you:

• purchase stock from reputable suppliers

• keep a simple on-farm biosecurity plan handy and update it regularly

• consider vaccines for local diseases

• have easily identified farm animals (tagged or marked)

• minimise contact between your stock and other animals (for example, on neighbouring properties)

• record new stock entering the farm

• quarantine new stock away from existing stock until you’re sure they are healthy –at least for one week but preferably two

• check feed labels to make sure they are suitable for the stock

• manage the potential contamination of people, vehicles and equipment entering and moving throughout the farm. For example, ask visitors to clean their footwear before walking around the farm and as they leave

• follow routine best practice biosecurity measures such as disinfecting farm equipment and maintaining intact boundary fences where possible

• consider developing a detailed farm health plan with your vet.

Don’t:

• feed ruminant protein to ruminants (such as cattle, sheep, lambs, goats, deer, alpacas and llamas)

• feed pigs food that could contain (or have contacted) meat, unless it has been cooked for 1 hour at 100 degrees Celsius

• let overseas visitors near stock for a week after they were last near animals or infected places overseas

• let overseas visitors bring contaminated shoes or clothes onto your farm.

• High fever for two or three days.

• Blisters or sores around the mouth, muzzle, feet and teats

• Drooling, tooth grinding and chomping

• Lameness (limping) or a tendency to lie down (pigs may also squeal when walking)

• Shivering or raised temperature

• Lethargy or depression

• Drop in milk yield for cows

• Death of young animals.

For more advice from MPI: www.mpi.govt.nz/biosecurity/ plans-for-responding-to-seriousdisease-outbreaks/foot-andmouth-disease

Dairy Women’s Network has presented a Relationship Property webinar to give advice in case of relationship breakdown.

By Elaine Fisher.

By Elaine Fisher.

When a relationship breaks down, get professional advice early – even before leaving the relationship.

That was among the recommendations from lawyers Angela Kershaw and Nicole Gordon of Eastern Bay of Plenty law firm Hamertons Lawyers during a Dairy Women’s Network webinar on Relationship Property presented in July.

“It is important to get advice quickly. The best outcomes often result from seeking advice before you leave,” Angela said.

“It may sound awful to see a lawyer before your partner knows you are going to leave but, especially in a farming situation where everything is tied up together, a consultation can help think things through before leaving.”

Nicole said fear often stopped people getting advice early.

“We see clients who are afraid to get advice, who don’t want to rock the boat or spend the money but in fact there is

a lot of value to be had in getting legal advice early on.”

The webinar hosted by DWN outlined what relationship property is and what can happen when a relationship breaks down. It also covered intergenerational farming operations and how to protect a farm from a child’s relationship break-up.

Constructive Trusts, often used by courts to settle relationship disputes, were explained – as was why they arise in farming situations on relationship breakups so often.

What happens to the farming operation while the division of property was resolved and how to protect against adverse outcomes were also outlined.

The widely held assumption was that in relationship break ups, property and assets would be divided 50/50 but Angela and Nicole said that was not always the case.

Angela used as an example a family in which husband and wife were both accountants, but the wife left work

“Our somatic cell count was sitting at 150,000. Since installing the iSPRAY4, it’s settled at 90,000”.

Andrew Pritchard - Taranaki Milking 420 cows across 2 herds

nozzles

to raise the family while the husband continued to progress with his career. After 20 years they separated and the husband, because of his earnings and support from his wife, was financially significantly better off than his wife, who had put her career on hold.

“In such a case it would be unfair to divide the property 50/50 as clearly his life moving forward would be easier financially than hers.”

An unequal sharing of the relationship property may be ordered but could be complicated and would involve independent advice from financial advisers.

It was a mistake for a disadvantaged party to walk out thinking the only option was a 50/50 division. “They really need to take some independent advice and tell their lawyer all the circumstances. Likewise, the advantaged party should also talk to their lawyer and be realistic about what the advantages and disadvantages are within the relationship,” Angela said.

Relationship breakups among farming families were often complicated because everything was tied up in the farming operation including employment and the family home.

Consideration must also be given to who would continue to run the farm and who would remain in the home.

“If minor children are involved, who stays in the home may not be the person running the farm. There are questions too around if there is enough money from the farm to fund two separate households,” Angela said.

When it was an intergenerational farming property the situation could become even more complicated if the relationship of a child working and living on the farm broke up.

Both Angela and Nicole stressed the

importance of not leaving anything to chance. “You need to think about these issues before they happen.

“To protect against adverse outcomes number one is to have open family discussions about expectations and reach an agreement.”

It was vital parents engaged with the spouses of their child or children involved in the farm when reaching agreements.

“If they are not involved everything can become unravelled. Don’t make promises which are not followed through in documents as that can also lead to problems,” Angela said.

Dinner table promises were common, but Angela and Nicole said it was vital nothing was agreed without advice from a lawyer, and often an accountant and banker.

“I can’t emphasise enough the importance of paying market rates for services. Paying children what anyone else in their role would be paid is vital. If they put money into the farm, document that as debt back to them. Putting money in on a handshake understanding is a big mistake.”

A contract-out agreement in which the son or daughter and their partner had a clear understanding of what was expected was not a complete answer but was close to it.

“It is hard to argue against when people have gone into it with eyes wide open. Don’t leave things to chance. It is much harder to address after the fact.”

Angela said the division of relationship property came down to money.

“I know that sounds awful but realistically the division of assets and who pays what is akin to a business decision. Try to make decisions with your head rather than your heart.”

Relationship break ups were hard for both parties as they represented the loss of shared family goals, dreams, aspirations and perhaps financial security.

“It is a grieving process, even if it’s amicable. To survive it is vital to have a good support team, not just your lawyer. Lawyers are not councillors. It’s really good to see someone, a counselor or psychologist for one or two appointments to get your head around the changes so you are emotionally prepared for what is happening.”

Nicole and Angela both said – “never take legal advice from someone who is not a lawyer”.

Angela heads up the Family and Estates team at Hamertons Lawyers Ltd. She brings compassion and care to sorting out separations, dividing assets, establishing optimal familial arrangements and supporting families in times of crisis.

Nicole specialises in family and estates and has a passion for helping clients cope with emotionally challenging situations. She especially enjoys guiding clients through all of their legal options, helping identify optimal solutions.

www.hamertons.co.nz

‘It may sound awful to see a lawyer before your partner knows you are going to leave but, especially in a farming situation where everything is tied up together, a consultation can help think things through.’

Dairy Exporter published a story about coated urea (August 2022) in which it was claimed using this type of product could reduce the volatilisation of nitrogen from urea by 50%. The associated editorial asks –should all farmers switch to these types of products?

Most farmers reading this would, I think, take the message that these products are very beneficial and economic. I express great caution.

To be clear; what we are talking about is urea treated with the chemical agrotain. Both fertiliser co-ops sell this product as either SustaiN (Ballance) or N Protect (Ravensdown). Agrotain slows the conversion of urea-N to ammonium-N and thus through to nitrate-N. Both companies

claim adding agrotain to urea reduces the loss of N, via volatilisation as ammonia gas, by 50%, thus increasing N use efficiency (NUE).

Ammonia is not a green-house-gas and thus the only benefit a farmer can derive from switching from straight urea to SustaiN or N Protect is via an increase in NUE. In other words more pasture or crop growth per unit of N applied.

In a paper to the New Zealand Grasslands Association in 2011, a colleague and I reviewed all of the available trials in NZ comparing the effect of urea and agrotain-treated urea on pasture production (n = 16 trials).

The average response to agrotaintreated urea, relative to straight urea, was 4% (confidence interval 7%). We have subsequently updated this estimate by

With the extensive Massey Ferguson hay range, including Mowers, Rakes, Tedders, Conditioners and Balers.

AVAILABLE NOW

Loads of models are in stock now and ready to roll.

including trials from all around the world on both pastures and crops (n= 348). The average response was 3%.

Of particular relevance to NZ pastures, the results were rate dependent; at low rates of < 50 kg N/ha (108 kg urea/ha) the average response was 1.4% increasing to 7.5% where the rate of application was > 200 kg N/ha (434 kg urea/ha).

If, as both co-ops claim, adding agrotain to urea reduces ammonium volatilisation by 50%, then the only realistic conclusion, given the pasture and crop yield data above, is that the absolute amount of N volatilised is very small, in the range of 2-3kg N/ha, irrelevant in the overall scheme of things - 50% of a small number is a smaller number?

Rising costs are a concern for households and businesses across New Zealand – and dairy farmers are also feeling the impact of high inflation.

Many farms have had cost increases in their budgets of around $1/kg milksolids (equivalent to a 19% lift from 2020/21 average operating expenses).

Higher fertiliser, feed, wages and fuel costs are some of the key drivers of these increasing costs.

Managing your budget in times of high inflation isn’t easy. Any savings you can make in the season will continue into future seasons, so it’s worthwhile being proactive now, before a fall in milk prices requires action.

We’ve seen farmers prioritise paying off debt in recent years. This has left farmers better positioned to cope with tougher years. Continuing to focus on reducing debt is an excellent strategy to reduce future interest costs, so you can meet higher costs – or cope with a lower milk payout.

Benchmarking your business against similar farms can help identify opportunities to save or increase your income. Focus on making incremental gains to boost your income such as improving cow reproductive performance or ensuring you receive all the premiums your dairy company is offering.

Consider if you can increase milk production from pasture – the cheapest feed source. You can compare your current pasture use with similar farms using DairyNZ’s pasture potential tool at dairynz. co.nz/pasture-potential

There may also be opportunities to use pasture, supplements or fertiliser more efficiently. Drawing on advice from farmers, DairyNZ has information on options to reduce fertiliser use without reducing production, visit dairynz.co.nz/ nitrogen-use

You might find zero-based budgeting useful. It involves starting with a blank budget and reviewing each cost. Most farmers can find some savings using this approach.

If you’re finding it difficult to identify options to manage costs, it can be helpful to involve your farm advisor, or get in touch with your DairyNZ local team on 0800 4324 7969.

With costs rising quickly, we encourage contract milkers to run their figures for this season through DairyNZ’s contract milker premium calculator, to check you’ll

achieve a reasonable return. If contract rates are set too low, both parties should discuss the situation as a first step. Involving professional advisors can also be useful. You might identify opportunities to review contract conditions or to agree on how cost increases can be managed.

With costs changing rapidly, it’s important to set future contracts based on up-to-date figures, and ensure the contract can accommodate cost increases without penalising contract milkers.

To use the contract milker premium calculator, see dairynz.co.nz/homework.

BENCHMARKING YOUR BUSINESS AGAINST SIMILAR FARMS CAN HELP IDENTIFY OPPORTUNITIES TO SAVE OR INCREASE YOUR INCOME.

Alternatives to the exclusion of exotic forests from the Emissions Trading Scheme are back in the mix.

By Joanna Grigg.Without getting bogged down in detail, here’s a quick summary of where things are at with the Emissions Trading Scheme.

The Government has hit pause on the plan to exclude exotics from the new permanent post-1989 forest ETS category. This is a win for forestry advocates, including iwi who actively swayed Economic Development Minister Stuart Nash and Climate Change Minister James Shaw. It was an impressive campaign.

Emerging Forests managing director Mark Belton was one of the campaigners. In June, he floated an alternative scheme, to take the heat out of farmland conversions, but still allow permanent exotics in the ETS.

He suggested exotics should be allowed for permanent carbon forestry but only when integrated within farmland owned by New Zealand citizens. This should primarily be located on problem marginal LUC 6, 7 and 8 land types.

He floated the idea of landowners and the Government partnering on permanent carbon forests. They would take 50% each of the carbon credits. He believes this so-called ‘Belton-scheme’ would decelerate the carbon market price, making it rewarding but more stable. Returns per hectare to the landowner would be reduced – slowing the land price escalation problem. Will this idea be taken on board?

Will the farm sequestration choir sing as loudly and in unison, as the foresters?

In their July report, the Climate Change

Commission threw the cat among the pigeons suggesting onfarm sequestration be excluded from an agriculture emissions scheme. Instead, it should lie within the MPI-administered ETS. The reasons were that it would be too complicated to run and too costly.

Will Beef + Lamb NZ, Federated Farmers and other farmer groups, wanting inclusion of farm sequestration outside the ETS, get the same response from their advocacy? Perhaps not, unless Maori farming groups rally to the cause. The weight of the Climate Change Commission advice may tip it.

Farmer organisations have cried that it’s unfair to exclude farmland trees. Kiwis pride themselves on being fair. The beast that is the ETS, tends to see only in black and white, and onfarm indigenous blocks are seldom let through the gates. Yes, building a custom system to measure onfarm sequestration might be tricky and require building another beast to do it, but shouldn’t we try?

A possible solution is a voluntary option for farms to opt into measuring and contracting sequestration, via He Waka Eke Noa. Keep it simple and don’t try to count every shrub, scrub and stump. Build on it over time, as the science comes through. With a subsidised methane tax, increasing in cost over time, farmers may not see it making much of a difference to their bottom line initially. They may opt in later as the tax increases. Watch this space.

The Climate Change Commission made some more big calls last month. One

was the suggestion that the Government put shopping for carbon credits overseas back on the agenda. And now, not later. NZ will never meet emissions reduction targets otherwise. There are no approved overseas units in the NZ ETS. Dr Rod Carr, in his chair’s message, said it is essential the Government secure access to sources of offshore mitigation as soon as possible, and decide how this will affect the NZ ETS. This matter cannot be left until later this decade, he said.

The other was decarbonisation. Carr

“He suggested exotics should be allowed for permanent carbon forestry but only when integrated within farmland owned by New Zealand citizens.”

They want to see the stick used on emitters. The government provides some NZUs for free to firms undertaking activities that are both emissions-intensive and trade-exposed. This is called industrial

free allocation. The commission suggests the Government reduce the subsidiary businesses’ allocations on carbon liabilities. In other words, businesses have to reduce emissions, not rely on subsidiaries.

One issue has been the stockpile of credits in private ownership. There are 144 million units held in the NZ ETS as of June 1, 2022. This is about four times as many units as were surrendered for emissions released in 2021. The commission suggests reducing auction volumes, and driving down the surplus by 2030. Watch the price rise.

Auction price levers should be pulled, suggests the commission. It suggests reducing the limit on the number of units available for auction from 16m in 2023 to 10m in 2027. It also suggests raising the trigger prices for the cost containment reserve and auction reserve price. Combined, these moves set the tone for the carbon market which agriculture is being drawn into.

• First published in Country-Wide magazine September 2022.

Ballance Farm Environment Awards regional winners

Geoff and Jo Crawford are charting their own course with reduced fertiliser and water use. By Delwyn Dickey.

Farmers have got to get off the nitrogen drug,” Geoff Crawford says.

Wanting to show it is possible to be both financially and environmentally sustainable in a large-scale farming operation saw Geoff and Jo Crawford enter the 2022 Ballance Farm Environment Awards.

Here they won the Northland Regional Supreme Award, including Ballance Agri-Nutrients Soil Management Award, DairyNZ Sustainability and Stewardship Award, Hill Laboratories Agri-Science Award and WaterForce Wise with Water Award. Geoff and Jo are trialing different pasture species in their paddocks as they adapt to a warming northern climate, and finding ways to reduce both synthetic fertilizer and water use. The couple’s home looks out over the vast Hikurangi Swamp farm land, west of Whangarei.

And although they’ve farmed in the area for 30 years, with their operations covering dairy and beef, they hadn’t farmed “the swamp”.

Then seven years ago they bought three farms over several years on the swamp, and set about adapting the dairy operations to accommodate the occasional flooding. Sitting side-by-side, the farms totaling 260 hectares are run as a single operation, and run 1000 cows. Another 140ha dairy farm in the Hikurangi Hills runs a 500-cow herd. Combined they average 590,000kg of milksolids annually. The only downside of the swamp operation is the main infrastructure buildings, including the 50-bale rotary, are at one end of the farm, so it can be a bit of walk for the cows. To help counter this a second milking shed still operates for about three months of the year at the other end, for the autumn herd.

Most of the 1000 calves born on the farms each year are destined for beef production, and Geoff has built a large

barn specially for them.

The changing climate is seeing a lot more pasture growth in autumn and has seen them shift to mainly autumn calving. The 60% autumn calving will likely increase to 80% in the next couple of years, Geoff says.

When they first bought the home farm it had been set up in a way that used a lot of water – easily 70 litres per day, per cow - with their effluent pond filling up too quickly and Northland Regional Council unhappy. Cows were also injuring themselves slipping on the concrete in the milking shed.

This saw Geoff covering the concrete with rubber mats, and start scraping instead of washing down the yards. The water on the backing gate was also stopped. They may be expensive, but rubber mats are needed to do this properly, Geoff says, as the concrete gets very slippery without them. Big water washers for the cups were changed to small squirters. In the end, having installed a water meter, they say they were able to show the council they were using far less water than the average 70l/day/cow and didn’t need to get an annual $2500 resource consent for water. While flooding can be a nuisance, farmers on the Hikurangi Swamp have learned to adapt. July is the wettest month with flooding on the plains almost every year, says Jo. Covered stand-off pads for the cows are becoming more common in the area, as flooding can see some paddocks out of action for up to two months.

The Crawfords have built a covered standoff pad that can hold 600 cows.

While these floods keep farmers on their toes, Jo and Geoff use them to their advantage. The big floods only tend to happen about once a year and Jo and Geoff now use these events to significantly cut back on the amount of synthetic fertiliser they use by making compost from the animal manure deposited on the stand-off pad.

When flooding looks likely a layer of pine peelings goes on the floor of the pad, before the cows are moved in. Rather than standing for days on hard concrete this makes the cows’ stay more comfortable and they can lie down on it.

Here they are fed, watered and can be moved off to be milked, with more peelings being applied over time. When the paddocks have recovered the cows are