www.delamed.org | www.djph.org Volume 9 | Issue 2 June 2023 A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association

Delaware Journal of

Public Health

Delaware Academy of Medicine

OFFICERS

S. John Swanson, M.D. President Killingsworth

Lynn Jones, FACHE

President-Elect

Professor Rita Landgraf (Co-Chair) Vice President

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A. Treasurer

Stephen C. Eppes, M.D. Secretary

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. (Co-Chair) Immediate Past President

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director, Ex-officio

DIRECTORS

David M. Bercaw, M.D.

Lee P. Dresser, M.D.

Eric T. Johnson, M.D.

Erin M. Kavanaugh, M.D.

Joseph Kelly, D.D.S.

Joseph F. Kestner, Jr., M.D.

Brian W. Little, M.D., Ph.D.

Arun V. Malhotra, M.D.

Daniel J. Meara, M.D., D.M.D.

Ann Painter, M.S.N., R.N.

John P. Piper, M.D.

Charmaine Wright, M.D., M.S.H.P. EMERITUS

Robert B. Flinn, M.D.

Barry S. Kayne, D.D.S.

Delaware Public Health Association

Advisory Council:

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Chair

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H. Executive Director

Louis E. Bartoshesky, M.D., M.P.H.

Gerard Gallucci, M.D., M.H.S.

Melissa K. Melby, Ph.D.

Mia A. Papas, Ph.D.

Karyl T. Rattay, M.D., M.S.

William J. Swiatek, M.A., A.I.C.P.

Delaware Journal of Public Health

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

Publisher

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief

Stephen Metraux, Ph.D., Roger Hesketh, Sean O’Neill, M.C.P., Mimi Rayl, M.R.P.

Guest Editors

Liz Healy, M.P.H.

Managing Editor

Kate Smith, M.D., M.P.H.

Copy Editor

Suzanne Fields

Image Director

Public Health Delaware Journal of

A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association

3 | In This Issue

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S.; Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H.

4 | Guest Editor

StephenMetraux,Ph.D.;RogerHesketh;SeanO’Neill, M.C.P.; MimiRayl,M.R.P

6|HomelessnessInDelaware:AnAssessment

StephenMetraux,Ph.D.;StevenW.Peuquet,Ph.D.

14|DemographicsofthePopulationExperiencing Homelessness and Receiving Publicly Funded Substance Use and Mental Health Treatment Services in Delaware

David Borton, M.A.; Rachel Ryding, Ph.D.; Meisje J. Scales, M.P.H., C.P.S.; Kris Fraser, M.P.H., P.M.P.

18 | Health & Housing in Delaware: Matching Medicaid Claims and Encounters and the Community Management Information System databases

Erin Nescott, M.S.; Stephen Metraux, Ph.D.; Mary Joan McDuffie, M.A.; Elizabeth Brown, MD, M.S.H.P.

24 | Evaluating Approaches to Linking Evictions Records: Assessing the Feasibility of Research with Integrated Data

J. J. Cutuli, Ph.D.; Mary Joan McDuffie, M.A.; Erin Nescott, M.S.

30 | Housing in Delaware for the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Population

Jody A. Roberts, Ph.D.; Ankita Mohan

34 | Homelessness Among Persons on Delaware’s Sex Offender Registry

Stephen Metraux, Ph.D.; Alexander C. Modeas, M.A.

44 | An Overview of Poverty in Delaware

Erin Nescott, M.S., Janice Barlow, M.P.A.; Miranda Perez-Rivera

50 | Considering the Benefits Cliff Embedded in the Relationship between Housing and Health

Dorothy Dillard, Ph.D.; Bianca Mers, M.C.R.P.

54 | Gauging and Responding to the Need for Home Repair Assistance in Delaware

Katharine Millard, M.S.P.P.M.; Stephen Metraux, Ph.D.

60 | The Perilous Intersection of Housing Precarity and Climate Change in Delaware

Victor W. Perez, Ph.D.; William Swiatek, M.A., A.I.C.P

62 | Global Health Matters

Fogarty International Center

74 | Solving Homelessness in Delaware Requires Resolving the Disparities That Cause It

Sequoia Rent, B.A.

80 | LGBTQ+ Youth Homelessness in Delaware: Building a Case for Targeted Surveillance and Assessment of LGBTQ+ Youth Needs and Experiences

Mary Louise Mitsdarffer, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Rebecca McColl, M.A.; Erin Nescott, M.S.; Jim Bianchetta; Eric K. Layland, Ph.D.; Tibor Tóth, Ph.D.

88 | Delaware’s Domestic Violence Housing Crisis

Monica Beard, D.Phil., Esq.

94 | Providing a Home for Good

Eugene R. Young, Jr.

96 | Homelessness, Housing and Health: The Secrets ALICE Will Not Tell You

Michelle A. Taylor, Ed.D.

100 | Fire on My Tongue

Michael Kalmbach, M.F.A.

102 | Sunday Breakfast Mission: A Christian Non-Medical Model Toward Addiction Homelessness Rehabilitation

Reverend Tom Laymon

104 | Housing, Poverty, and Health Outcomes

Kim Blanch, R.N., B.S.N..

110 | A Vision for Community, Connection and Reinvestment

Amanda August, M.A

116 | Leveraging Delaware’s Public Health Resources to Mitigate Spread of Communicable Diseases in Congregate Settings

Laura A. Strmel, M.P.A.; Diane Hainsworth, B.S.N./B.A; Muriel Gillespie; Sydney Kappers, B.S.; Mollee Dworkin, M.S.

122 | Social Capital from Online Social Media is Associated with Visiting a Healthcare Practitioner at Least Once a Year Among College Students

Joshua Fogel, Ph.D.; Ashaney Ewen, B.S., B.B.A.

130 | Ensuring Access to Opioid Treatment Program Services Among Delawareans Vulnerable to Flooding

Jennifer A. Horney, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Sarah Elizabeth Scales, M.P.H.; Urkarsh Gangwal; Shangjia Dong, Ph.D.

134 | Postpartum Contraceptive Use, Pregnancy Intentions in Women With and Without a Delivery of a NAS-Affected Infant in Delaware, 2012-2018

Khaleel Hussaini, Ph.D.; George Yocher, M.S.

142 | Lexicon & Resources

144 | Index of Advertisers

The Delaware Journal of Public Health (DJPH), first published in 2015, is the official journal of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA).

Submissions: Contributions of original unpublished research, social science analysis, scholarly essays, critical commentaries, departments, and letters to the editor are welcome. Questions?

Write ehealy@delamed.org or call Liz Healy at 302-733-3989

Advertising: Please write to ehealy@delamed.org or call 302-733-3989 for other advertising opportunities. Ask about special exhibit packages and sponsorships. Acceptance of advertising by the Journal does not imply endorsement of products.

Copyright © 2023 by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association. Opinions expressed by authors of articles summarized, quoted, or published in full in this journal represent only the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Delaware Public Health Association or the institution with which the author(s) is (are) affiliated, unless so specified.

Any report, article, or paper prepared by employees of the U.S. government as part of their official duties is, under Copyright Act, a “work of United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the U.S. Code is not available. However, the journal format is copyrighted and pages June not be photocopied, except in limited quantities, or posted online, without permission of the Academy/DPHA.Copying done for other than personal or internal reference use-such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale- without the expressed permission of the Academy/DPHA is prohibited. Requests for special permission should be sent to ehealy@delamed.org

ISSN 2639-6378

June 2023 Volume 9 | Issue 2

The issue of homelessness, poverty, and substandard housing is a significant public health concern that affects millions of individuals worldwide. Homelessness is the state of lacking a permanent, safe, and adequate dwelling, while substandard housing refers to conditions that do not meet basic health and safety standards. These issues have far-reaching implications for public health, as they contribute to the spread of communicable diseases, exposure to environmental hazards, and the exacerbation of physical and mental health problems.

Individuals facing homelessness and those living in substandard housing are at an increased risk of exposure to environmental and infectious diseases due to poor living conditions and limited access to healthcare. They may also lack access to clean water, sanitation facilities, and basic hygiene necessities, further increasing their vulnerability to illness. Moreover, these individuals often face barriers to healthcare, including limited access to medical care, lack of health insurance, and difficulties accessing medication.

In addition to physical health concerns, homelessness and substandard housing have a significant impact on mental health. The stress of living in unstable and unsafe environments, coupled with the lack of support networks, can lead to anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns. Individuals facing homelessness also face a greater risk to their personal safety, and of substance abuse and addiction

Addressing the connection between homelessness, substandard housing, and public health requires a multi-sectoral approach that involves collaboration between healthcare, housing, and social services. Efforts to improve access to affordable housing, healthcare, and social support networks can help address the root causes of these issues and improve public health outcomes for vulnerable populations.

We were privileged to be interviewed on this topic by the University of Delaware’s First State Insights online radio show. Our comments amplify this brief summary and we encourage you to take a listen for free: Housing, Place, and Health Outcomes by First State Insights (soundcloud.com)

Homelessness and substandard housing are significant public health concerns that require urgent attention, and we hope this issue helps explicate these areas for the reader. This issue, we welcome guest editors from the University of Delaware: Dr. Stephen Metraux, Roger Hesketh, and Mimi Rayl from the Center for Community Research and Service, and Sean O’Neill from the Institute for Public Administration; they have gathered a number of excellent articles. As always, we look forward to hearing from you with your feedback on this issue, and suggestions for future issues of the Delaware Journal of Public Health.

IN THIS ISSUE

Timothy E. Gibbs, M.P.H Publisher, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.06.001

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief, Delaware Journal of Public Health

3

An Introduction to the Homelessness, Housing & Poverty Issue

Stephen Metraux, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, Biden School of Public Policy and Administration, Director, Center for Community Research and Service, University of Delaware

Roger Hesketh

Assistant Policy Scientist, Center for Community Research and Service, University of Delaware

Sean O’Neill, M.C.P Policy Scientist, Institute for Public Administration, University of Delaware

Mimi Rayl, M.R.P.

Ph.D. Student, Housing Initiatives Coordinator, Center for Community Research and Service, University of Delaware

We are pleased to present this special issue of the Delaware Journal of Public Health, with a focus on homelessness, housing and poverty. These three topics are tightly intertwined with each other, and with public health. Briefly put, as both poverty and access to affordable housing become more acute, homelessness becomes more widespread and entrenched. Poverty and housing are both elemental in their roles as social determinants of health; as deprivation of income and housing impacts both individual and population health in numerous ways. When economic and housing conditions lead to homelessness, this confluence produces a multiplier effect, as existing health conditions become exacerbated and vulnerabilities to a range of new health risks abound.

This issue features an unprecedented collection of studies on these three intertwined topics as they manifest in a Delaware context. While homelessness, housing and poverty are all prominent problems in Delaware, most of our understanding about the dynamics of these topics comes from other places and do not factor in Delaware’s unique constellation of political, services and socioeconomic structures. As such, these studies start to define how broader dynamics around public health and services provision play out in this unique setting.

We present these studies in three sections. In the first section, six studies use different empirical data sources to show how homelessness plays out in Delaware in specific populations and circumstances.

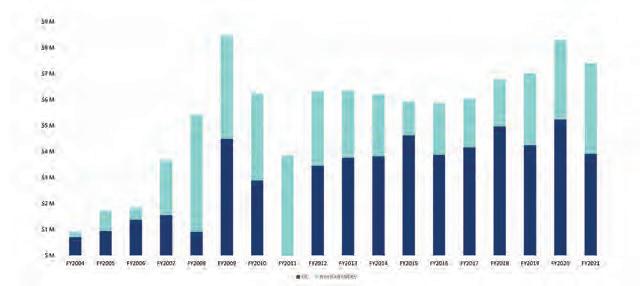

•Metraux (one of the issue editors) and Peuquet use almost two decades worth of counts of people experiencing homelessness and beds that shelter them to show how, perversely, homelessness in Delaware is at unprecedented levels while the supply of temporary housing available to shelter them has seen substantial cutbacks.

•Two studies, Borton et al. and Metraux and Modeas, apply data from state systems to document alarmingly high levels of homelessness among people in known risk groups: those who receive behavioral health treatment services and those who are on the state’s sex offender registry, respectively.

•Roberts and Mohan use data collected from interviewing services providers to document the extreme vulnerability to homelessness and housing insecurity experienced by individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are served by the state’s Division of Developmental Disabilities Services in the midst of the current housing crisis.

•Nescott et al. demonstrate a hidden cost of homelessness, estimating that, in 2019, experiencing homelessness was associated with excess Medicaid costs of $4,611 (non-chronic homelessness) to $5,218 (chronic homelessness) per person.

•Cutuli et al. develop an approach that matches homeless, Medicaid, and eviction court data and show the feasibility of such an approach to identify adults and children who are at risk for health complications associated with their housing instability.

4 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023 Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.06.002

These studies are noteworthy in their compelling documentations of how housing need specifically impacts vulnerable populations, and the urgency for housing-specific responses to be part of the mix of services that most of those in the populations studied receive from healthcare, social services and criminal justice systems in Delaware. Beyond this, the studies collectively bring to bear, in a manner unprecedented in Delaware, the power of data to inform policy and services on homelessness in Delaware. These studies lay a foundation for an empirically grounded research agenda and additional innovative uses of available data.

The second section of this issue features seven analyses of special topics within the realm where homelessness, housing and poverty intersect. Nescott et al. provide an overview of poverty in Delaware, the first such assessment to incorporate the years following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dillard and Mers take a deeper dive into a specific aspect of poverty with her focus on the “benefits cliff” faced by extremely low- and low-income families when they attempt to gain economic self-sufficiency. Other analyses show how homelessness, housing and poverty exacerbate preexisting disparities in a range of health and social outcomes (Rent); magnify the impact of climate change (Perez & Swiatek); and represent burdens borne disproportionately by sexual minority groups (Mitsdarffer et al.) and domestic violence survivors (Beard). Finally, Millard et al. demonstrate the need for housing repair assistance, and how modest help with home repairs and modifications act to both preserve housing stock and enable healthier lives. Each of these studies opens a door into a specific facet of the topics covered in this special issue, and situate it in Delaware, thereby giving it dimensions that are at once more familiar and more difficult to ignore.

The third section provides seven views from providers who bear witness to the quotidian manifestations of homelessness, housing scarcity, and poverty and simultaneously labor to ameliorate the concomitant deprivations. Taylor and Young each report from their vantage points as heads of the United Way of Delaware and the Delaware State Housing Authority, respectively, on assistance for housing development (Taylor) and homeless services (Young). Kalmbach and Laymon each describe their programs; the former an art-inspired day center and the latter a Christian-oriented shelter and transitional housing facility, and put forth two very different approaches to addressing homelessness, a problem that both acknowledge, for different reasons, is getting worse.

Rounding out these dispatches are ones from:

•Blanch on how Beebe Health System has been expanding its commitment to identifying and responding to the social determinants of health of its patient population and support connection to appropriate resources.

•August on Jefferson Street Center, a community development corporation, and its efforts at revitalization and community-building in Northeast Wilmington.

•Strmel on how Delaware’s Division of Public Health implemented COVID-19 prevention and mitigation strategies in Delaware’s homeless shelters.

These provider perspectives complement those provided by the empirical research studies in the first section and the analyses in the second section.

Taken together, the studies in this issue show the many ways in which homelessness, housing and poverty manifest themselves in Delaware. The reader will get a good idea of not only the challenges faced by those involved with these topics, but also the work that is being done. It promises to give the reader a solid point of departure from which to continue the critical work of addressing these issues.

5

Homelessness In Delaware: An Assessment

Stephen Metraux, Ph.D. & Steven W. Peuquet, Ph.D. Center for Community Research & Service, Joseph R. Biden, Jr. School of Public Policy & Administration, University of Delaware

ABSTRACT

The authors provide an assessment of trends and dynamics of homelessness in Delaware since 2007, when the last systematic study of this topic was released. Using population data on homelessness in the state, the authors present evidence that, after a period of apparent stability, homelessness in Delaware is currently at levels that are unprecedentedly high, while providers of homeless services have not adapted to this change. As a first step to addressing this alarming trend, the authors call for stakeholders to regroup and develop a coordinated, statewide approach to address this problem.

INTRODUCTION

The number of people in Delaware who were counted as homeless on a given night doubled between 2020 and 2022.1 Housing Alliance Delaware (HAD), who organizes the annual counts of Delaware’s homeless population, announced it without much fanfare. Media outlets dutifully reported this unprecedented surge. Beyond that there was little response, and assistance for emergency housing was actually cut later in the year. In this essay, we frame this moment, when the response to homelessness in Delaware appears incommensurate to the extent of need, in an historical context that goes back to 2007, when the last systematic assessment of homelessness in Delaware was undertaken. Such an analysis provides insight on how homelessness in Delaware got to this present situation, as well as a basis for how to proceed.

Sixteen years ago, in 2007, University of Delaware’s Center for Community Research and Service (CCRS) released a report titled Homelessness in Delaware: Twenty Years of Data Collection and Research. 2 The study looked back to 1987, when CCRS conducted the first study of the extent and nature of homelessness in Delaware. Based upon that and subsequent counts of the state’s homeless population, the CCRS report found there to have been an initial decade of marked increase (from 1986 to 1995), followed by a decade during which the size of the homeless population first dipped and then remained constant. This assessment was a milestone, both because it was the first longitudinal analysis of homelessness in the state, and because, for the first time, data was available to support such an empirically grounded retrospective.

The CCRS report presented a picture of cautious optimism. Homelessness was not getting worse, and, after adjusting for general population growth, was lower than the national rate. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and national advocacy groups, through strategies that targeted “chronically homeless” individuals and called for services enriched permanent housing to supplant shelters, offered means by which to reduce and even eliminate homelessness.3 Finally, local initiatives were falling into place for collecting data, both from comprehensive, single-night counts and from compiling administrative records on shelter and other homeless services, as a means to monitor progress in efforts to reduce homelessness.

After the 2007 CCRS report came a pair of successive reports from the Delaware Interagency Coalition on Homelessness (DICH). DICH was launched in 2005 by Governor Ruth Ann Minner’s executive order, and consisted of representatives from state agencies and key community stakeholders. The reports that DICH issued were plans, ambitiously titled Breaking the Cycle: Delaware’s Ten-Year Plan to End Chronic Homelessness and Reduce Long-Term Homelessness4 (2007) and Delaware’s Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness5 (2013), that built on the belief that homelessness was a problem that could be solved. Both DICH plans laid out roadmaps, but there has been no subsequent examination of how (or even whether) these plans were implemented, or of any impact these plans may have had. Homelessness in Delaware has clearly grown to a scale far greater than what was envisioned by these plans. But beyond that we know little about the interplay between dynamics of the homeless population and the availability of services to house them, both temporarily and permanently.

ASSESSING HOMELESSNESS IN DELAWARE

The 2006 count of Delaware’s homeless population, examined in detail in the 2007 CCRS report, was the first of what has become an annual series of Point in Time (PIT) counts of the homeless population, both in Delaware and nationwide, that continue to this day. The core of the PIT count involves volunteers and outreach workers going to interim housing facilities and to other, non-shelter locations to count people experiencing homelessness. PIT counts are conducted in late January, and results are reported to (and standardized by) HUD.6 For the past 17 years, HUD has issued an Annual Homeless Assessment Report to the US Congress based upon these data and has made these reports and the underlying PIT data available online.7 PIT counts are the means by which the magnitude of homelessness is most commonly assessed, analogous to what the unemployment rate is to labor and the consumer price index is to inflation: imperfect but ubiquitous.

Figure 1 shows the annual size of the homeless population from Delaware’s PIT counts for the years 2006 through 2022.8 We see this series of counts as consisting of two segments. The first segment, starting with the 2006 count of 1,089 homeless people,

6 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023 Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.06.003

shows little evidence of sustained increases or decreases for the next 13 years. While the rise in 2009 coincides with the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, overall population changes look to be minor fluctuations more than any clear evidence of sustained increases or decreases. These fluctuations may also have more to do with inconsistencies in the counting process, which is sensitive to weather, numbers of volunteers, and other intangibles unrelated to the actual population size, than to actual changes in the homeless population.

While Delaware’s PIT count remained largely unchanged, Delaware’s overall population between 2006 and 2018 increased from 864,764 to 973,764, a 12.6 percent increase.9 This means that Delaware’s rate of homelessness, which was 12 per 10,000 people in 2007, dropped to 9.6 per 10,000 in 2019.7 So, while the homeless population size was relatively unchanged, homelessness as a proportion of the overall population declined by about 25 percent over this time. However, homelessness in the US also declined over this period, from 22 to 17 per 10,000.7 This amounted to a 23 percent rate of decline nationally, comparable to Delaware’s rate of decline.

Taken together, in 2019 (as in 2006) Delaware’s level of homelessness remained at the low end of what is “typical” for rates in other US states. Such a consistently low rate more likely reflects Delaware’s relative lack of highly urbanized areas and relatively low housing costs, than how Delaware has responded to homelessness. There is no evidence in Delaware’s homeless population counts that specific programmatic initiatives—like the DICH reports—were linked to systematic decreases in the homeless population.

In abrupt contrast, the second segment of annual Delaware PIT counts shows three consecutive and substantial year-to-year increases. This started with a count of 1,165 in 2020, a 26.5 percent increase and, at the time, Delaware’s highest PIT count ever. This rate of increase was also the highest that year of any state. By comparison, the national PIT count only increased by two percent.10 A closer look shows that Delaware’s increase was across the board – among families and individuals, sheltered and unsheltered, and those newly homeless and with long-term, “chronic” homelessness patterns.11 All this indicates a real increase in Delaware’s homeless population, rather than minor yearly fluctuations.

The 2020 count, conducted in January, preceded the COVID pandemic shutdown, and thus the increase could not be blamed on the pandemic. But additional alarming increases followed into the pandemic, with a 35 percent increase in 2021 and then a 50 percent increase in 2022. The 2022 count was ultimately more than double that of the then-record 2020 count, and in 2022 the homeless rate stood at 23.6 per 10,000. This was now substantially higher than the national rate of 18,12 and more than wiped out the population-adjusted decline that occurred over the thirteen years in the first segment.

INTERIM HOUSING CAPACITY (SHELTER, TRANSITIONAL HOUSING, AND MOTEL VOUCHERS)

The increases in the PIT counts in 2021 and 2022 reflected major changes in the way that interim housing was provided in Delaware following the pandemic lockdown. This underscores

how the PIT count is influenced not only by the size of the homeless population, but also by the supply of accommodations available to this population.

Interim housing is a term we use to include emergency shelter (EH), transitional housing (TH), seasonal shelter, and hotel/motel vouchers. All are used, in various circumstances, as temporary accommodations for homeless households (both individuals and families). HAD reports data on interim housing capacity to HUD annually in the Housing Inventory Count.13 Up through early 2020, ES and TH were the predominant forms of interim housing in Delaware. After the onset of COVID the majority of households received interim housing through hotel and motel vouchers. This reflects a stunning transformation of service delivery and provides key insights to the homeless population dynamics in the state.

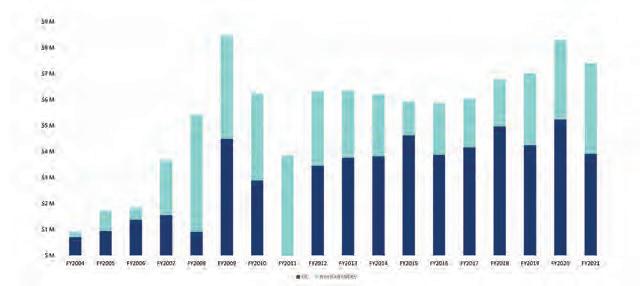

Figure 2 is a time series of Delaware’s combined ES and TH capacity, broken down by family or individual household (i.e., 1-person household). For comparison, Figure 2 also shows the numbers of family and individual households that stayed in interim housing on the night of that year’s PIT count.8 This latter count reflects upwards of 90 percent of those enumerated in the PIT count, as relatively few people are typically counted in unsheltered locations in this count (more on this below). Up through 2019 the supply of ES/TH beds stayed flat for families and declined slightly for individuals, mirroring patterns for the PIT counts of family and individual households, respectively.

Figure 2’s pairing of homeless households and available ES/TH accommodations show that when there is a decline in the ES/ TH supply, there is a corresponding decrease in the number sheltered. The clearest example of this is in 2019, when the closure of the SafeSpace Delaware (formerly the Rick Van Story Resource Center), following its loss of state funding,14 was mirrored by a drop in the number of individuals in the PIT count. Having fewer shelter beds does not mean that more people resolved their homelessness. It means that there are less beds available for those experiencing homelessness, and those who are unable to get a bed are less likely to be included in the PIT count. Conversely, as happened in 2016, when the interim housing supply expands, those who occupy these additional beds are almost certain to be included in the PIT count.

The gap in most years in which the ES/TH capacity exceeds the occupancy numbers, both in family and individual households, creates the impression that there was no need to expand existing interim housing capacity. In other words, ES/TH supply seemingly stayed flat because no further capacity was needed. The view on the ground was different, however. The vacancies indicated in Figure 2 do not line up with the types of households seeking interim housing for various reasons. For example, vacancies in TH facilities designed for veterans, elderly, or persons with psychiatric disabilities will be unsuitable for those outside of these subpopulations. Thus, the Delaware Center for Homeless Veterans does not accommodate non-veterans, even if they have a vacancy. Geography is also a factor; people in southern Delaware may not be able to travel to northern Delaware, even if there are vacancies. These and other supply and demand mismatches explain why Delaware’s Centralized Intake system, a “one stop” source since 2013 for arranging shelter assignments to most of Delaware’s ES/TH facilities, reported fielding more than 1,100

7

8 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023

Figure 1. Total Homeless Population in Delaware8

Figure 2. Homeless Individuals and Families and Corresponding Emergency Shelter and Transitional Housing Capacities in Delaware8,13

inquiries in July 2022 from households who were homeless or were having a housing crisis, and were only able to make 213 referrals to available homeless assistance resources.1

A final aspect that warrants further examination concerns 2021 and 2022, when the number of people staying in interim housing vastly exceeded the ES/TH supply. This overflow represents the numbers of households receiving hotel/motel vouchers, a form of interim housing not included in the ES/TH numbers in Figure 2. In Delaware, a limited supply of hotel/motel vouchers have traditionally been available to pay for short term stays when there are no other places for households to stay. The only regular provider of these vouchers is the state’s Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS), which had traditionally provided assistance for up to 50 homeless households at a time who were receiving other state-administered assistance. But with the onset of the COVID pandemic, that changed.

The COVID pandemic wreaked havoc on the provision of interim housing. Most ES and TH facilities, in Delaware and elsewhere, were in congregate settings. This means that, in some facilities, people slept with other individuals and families in large rooms, and, in most facilities, they ate and otherwise spent time with others in common areas. Such arrangements were not conducive to COVID quarantine, thus public health guidelines necessitated that congregate ES/TH facilities cut back on the number of people they accommodated and that they take other measures to limit transmission of COVID. In some cases, facilities had to close outright. Even with these precautions, many were fearful of staying at these facilities and exposing their households to COVID. In response, federal assistance provided funding to states for using hotels and motels, which had rooms sitting empty due to lockdown restrictions, to accommodate households who would otherwise have been faced with going to ES or TH facilities. In Delaware, DHSS administered this hotel/ motel voucher assistance.15

This created a situation wherein interim housing suddenly became more desirable and easier to come by. Households that were homeless and/or precariously housed, who otherwise could not or would not have stayed in ES or TH facilities, now applied for and received the DHSS vouchers. As a result, DHSS’s voucher program quickly transformed from its small-scale, short-term pre-pandemic incarnation to administering a voucher program for hundreds of households, both families and individuals, for indefinite periods of time. In 2021, DHSS provided vouchers for 839 people on the night of the PIT count, and in 2022, this number increased further to 1,056.16 At this point, DHSS was Delaware’s largest supplier of interim housing, providing emergency accommodations for more than all the ES and TH facilities combined. Then, in early fall 2022, DHSS scaled back the voucher program to pre-pandemic levels after federal support for this program was no longer available.

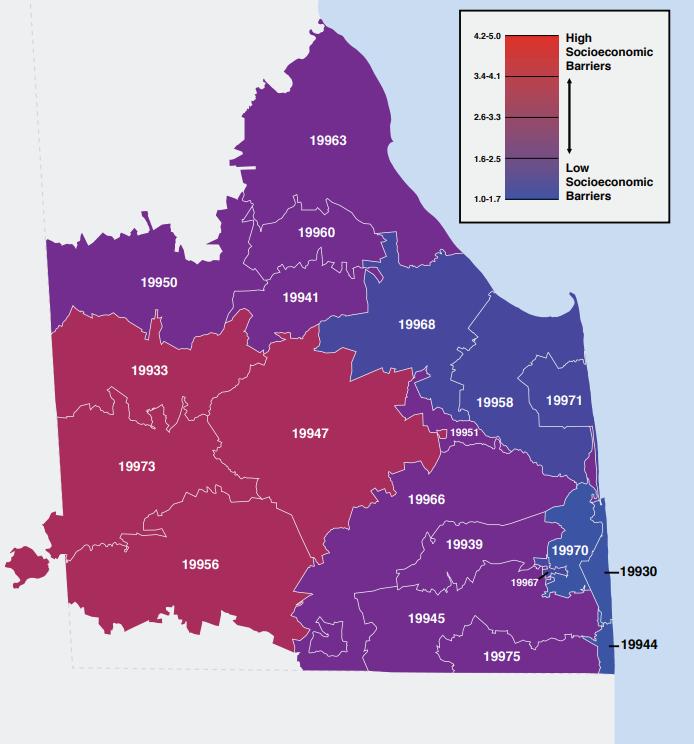

The 2021 and 2022 PIT count numbers provide a window into the actual demand for interim housing in Delaware. HAD called it “a crisis laid bare,”11 as it revealed the presence of hundreds of additional individuals and families who were homeless but who otherwise would have been invisible in the PIT count. DHHS data indicated, for example, that the majority of voucher holding families came from Sussex County, the southernmost of Delaware’s three counties that contains a

quarter of Delaware’s population and was the most underserved in terms of interim housing until vouchers became available.17 As mentioned earlier, indications are that Delaware’s homeless population was on the increase even before the pandemic due to a tightening supply of affordable housing, and this trend also likely contributed to people receiving DHSS vouchers. However, while the COVID pandemic led to less available EH and TH beds, there is no evidence that it directly led to increased levels of homelessness.

With interim housing capacity and occupancy expanding in tandem to twice its pre-pandemic levels in just two years, Delaware’s interim housing system now lacks the capacity to absorb the actual demand for interim housing in the wake of DHSS’s voucher program rollback. Little is known as to what people, facing homelessness and who otherwise would have applied for vouchers, are now doing. Presumably, they will retreat into a world of makeshift housing arrangements that include sleeping outdoors, in cars, in exploitative or abusive situations, “doubled up” with friends or relatives, or in substandard housing, where only a sliver of them will get included in the PIT count.

UNSHELTERED HOMELESSNESS

In the 2006 PIT count, outreach workers and volunteers fanned out across the state to count people who were homeless and sleeping in unsheltered locations. They counted 213 persons, with the acknowledgement that this count was far from comprehensive. This was the most people that were ever counted in Delaware PIT count. Subsequent unsheltered counts have been as low as 22 (2011-2012), 10 (2013), and 37 (2014-2015). In 2020 and 2022 the unsheltered counts were at 150 and 154 people,8 respectively, the highest tallies since 2007.

There is no evidence that fluctuations in the unsheltered PIT counts reflect changes in the actual numbers of persons experiencing unsheltered homelessness. A more likely explanation is that resources and conditions particular to individual PIT counts can better explain the drops in unsheltered counts in the early 2010s, and the fluctuations in numbers in other years. Even when the numbers went back up to 150, which paralleled the increases in the overall PIT counts discussed previously, these were likely still substantial undercounts.

The unsheltered portion of the PIT count, in general, is notorious for its methodological limitations.18 Even in a state as small as Delaware, the resources needed to adequately canvas the state far exceed what is available. Even then, the unsheltered homeless population seeks, by default, to be unnoticed, unobtrusive and hidden, often staying in locations that would only be found if their whereabouts were known beforehand. In two tragic illustrations of this, in 2019, four people died from carbon monoxide poisoning while sleeping in a tent with a faulty heater,19 and in 2020 a man, 64 years old, a veteran, and diagnosed with severe mental illness, died of exposure, literally on Main Street, in Newark.20 None of these people were receiving services, and none were included in the PIT count.

Two other counts of homeless subpopulations indicate the magnitude of the Delaware PIT’s undercount of those experiencing homelessness in circumstances other than interim housing. One is a study, included in this issue, of homelessness among people on Delaware’s sex offender registry (SOR).21 People

9

on the SOR are required to report their residence regularly to state police and must check in monthly when they are experiencing homelessness. Their homeless status is noted on their SOR record, which is publicly available online.22 On a night in November 2021, 121 people on the SOR reported homelessness; on a night in February 2023, that number rose to 140. Less than 10 people in each of these counts reported staying in interim housing; indeed, most homeless facilities are off limits to people on the SOR. Thus, the number of people who are homeless (presumably unsheltered) and on the SOR is almost as many as were counted as unsheltered on the 2022 PIT (n=154). Assuming that people on the SOR would constitute, at most, only a modest minority of the unsheltered population, the actual size of the overall unsheltered homeless population in Delaware could easily exceed 400 or 500. The second count covers a very different population: children and youth enrolled in Delaware’s 19 public school districts who were identified as “homeless” in reports to the US Department of Education (DOE). Over the course of the 2018-2019 academic year, the DOE count had 3,539 students as homeless, with only 122 of these students staying in interim housing. The large majority lived doubled up (2,604) and, by definition, not covered by the PIT count. As the PIT counts increased in subsequent years, the DOE counts dropped to 2,709 (2019-2020) and 2,576 (2020-2021). These decreases were attributed to the added difficulties in identifying homeless students during the COVID pandemic.23 While the PIT counts and the DOE counts are not directly comparable, the DOE count provides a window into how large numbers of homeless and precariously housed families are missed by the PIT count. Presumably, these households who were among those who “appeared” in the 2021 and 2022 PIT counts when hotel/motel vouchers were more available, and will again be uncounted in the PIT count now that these vouchers are scarcer.

CHRONIC HOMELESSNESS AND PERMANENT SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

Among the first goals to reducing Delaware’s homeless population was “to adopt and oversee the implementation of a plan to reduce homelessness and end chronic homelessness in Delaware.” DICH’s 2007 plan, Breaking the Cycle, laid out the process to do just that, with the key element consisting of adding 409 new units of permanent supportive housing (PSH) to the existing supply of 277 units.4

PSH, simply put, is the provision of housing that is both affordable and coupled with support services that provide whatever is needed to let the tenant maintain this housing. This housing targets the most difficult to serve among the homeless population, and consistently shows retention rates of around 85 percent.24 This housing is often targeted to people designated as “chronically homeless,” meaning households in which a person has a disabling condition and who has either been continually homeless for a year or more or has had at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three years. In a typical homeless population, less than 20 percent meet the chronic threshold, yet this subpopulation typically consumes upwards of 80 percent of homeless services. Thus, the DICH report asserted that not only would such a near-tripling of Delaware’s PSH supply disproportionately reduce the need for homeless services, but it would also lead to substantial collateral reductions in this group’s use of inpatient hospital, criminal justice and emergency health care services.4

Tracking the progress to attaining the twin goals of an increased statewide PSH supply and a reduced number of people in the homeless population meeting chronic criteria are both possible using HIC data from Delaware that is reported to HUD.11 The benchmark used in the 2007 DICH plan was 297 chronically homeless persons,4 with the goal being to reach zero in ten years by, in part, having 686 PSH units in the state. This housing target was surpassed in 2019, with 724 PSH units dedicated to housing people who had experienced chronic homelessness,11 but there remained 168 people counted in the 2019 PIT count who were considered chronically homeless.8

Following the attainment of this benchmark, the number of PSH units started to decline. By 2022, the number of dedicated units had dwindled back to 420 units.11 Meanwhile, in a manner that reinforces the inverse relationship between PSH supply and numbers of people considered chronically homeless, in 2022 the PIT count enumerated 223 people as chronically homeless, sliding back toward the number cited in 2007.1 This decline in PSH is not a deliberate policy, rather it is partially due to existing projects converting PSH units to more conventional housing, as well as there being difficulty in attracting organizations to develop and manage new PSH housing in Delaware.25

Additionally, the goal in the 2007 DICH report may have been too modest, and an updated assessment is needed to determine the number of PSH units in which the annual turnover in tenants matches the demand for housing from people newly identified as chronically homeless.

DATA COLLECTION

The 2007 CCRS report and the 2007 DICH plan both drew heavily on the body of data on Delaware homelessness that was emerging at the time. The CCRS report notes the substantial progress made in two fundamental areas of data collection to guide efforts to reduce homelessness.2 One was establishing the PIT count. The second was the creation of a homeless management information system (DE-HMIS) that systematically collects administrative data compiled by homeless service providers in the state during the course of providing shelter and other services. The DICH plan endorsed the DE-HMIS, and went a step further in stating that “State Departments and Divisions should become users of DE-HMIS, both as the recipients and the providers of data.”4

Seventeen years later, we now have annual PIT count data available for studies, such as this one, which can use it, despite its clear flaws, as a basis for sketching a broader picture of the state of homelessness in Delaware. Getting accurate assessments of the nature and extent of the homeless population is a key first step for better determining the levels and types of resources needed to reduce, and ultimately solve homelessness.

The DE-HMIS, now known as the Community Management Information System (CMIS), also is well-established as a central data repository for administrative records on services provided by homeless service organizations, including shelters, transitional housing programs, PSH providers, outreach programs, and others. As described in the CCRS report, this web-based information system is a powerful means for making the collection of homelessness-related data systematic, accurate and inexpensive.2 Recent studies have combined CMIS data with other data sources to examine connections between homelessness and eviction,26 as well as (in this issue) the costs

10 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023

that homelessness adds to Medicaid expenditures.27

However, the usefulness of the CMIS database is severely restricted by large gaps in the data it collects. One major data hole comes from the refusal of Delaware’s second largest provider of interim housing to share data on their services. A second and larger data hole is the inability of the State of Delaware and HAD, the organization that maintains CMIS, to develop a mechanism by which the State will share with CMIS their data on hotel/motel vouchers. In the wake of the recent expansion of the DHSS voucher program, this has led to a situation where data on homeless services reside in two isolated and incomplete databases, neither of which can be used to draw comprehensive conclusions about homelessness in Delaware at a point when comprehensive data is needed more than ever to address this crisis.17

2023 AND LOOKING AHEAD

As this article was going to press, preliminary 2023 PIT count and HIC results became available.28 Overall, the number of people counted as homeless in Delaware on the night of the count was 1,245 people. This number is substantially lower than the overall numbers from the last two PIT counts (see Figure 1), but is still higher than any of the pre-pandemic PIT counts, dating back to the first PIT count in 2006. Similarly, the preliminary 2023 HIC reported a substantial drop in the statewide supply of interim housing (emergency shelter, transitional housing, and hotel/ motel vouchers), largely driven by the rollbacks the State made in is hotel/motel voucher program, from 1,056 vouchers on a given night in 2022 to 98 vouchers in 2023.

While this drop in the PIT count will likely be framed as a reduction in the homeless population, our analysis here indicates that cuts in the availability of interim housing better explains this reduced count. In the absence of any signs that poverty has eased or that housing has gotten either more available or less costly over the previous year, a more likely explanation is that, were hotel and motel vouchers as available in 2023 as they were in 2022, there would be no reason to expect any reduction in this year’s PIT count.

Furthermore, in the wake of the reduction in hotel/motel voucher supply, one would expect that more people who otherwise might have received vouchers would be without any housing. The PIT count supports this assumption. Despite the overall drop in the PIT count, the count of the unsheltered homeless subpopulation increased in 2023, from 154 in 2022 to 198. This increase occurred despite a cold, pouring rain that fell on the night of the PIT count, as well as the dismantling of the Milford29 and Georgetown encampments30 earlier that January. In 2022, as many as 100 people lived in unsheltered circumstances in these two sites; places where they could readily be counted last year but stood empty just before this year’s count. That, in spite of these factors, there was such an increase in the unsheltered count this year indicates that actual homelessness has increased while the PIT count has dropped.

Ironically, these contemporary, heightened levels of homelessness coincide with the tenth anniversary of DICH’s ten-year plan to “prevent and end homelessness.”5 More than that, many of the problems called out by the previous reports from DICH and CCRS remain. Instead of visions of chronic homelessness being

diminished through an expanded availability of housing for this population, a declining supply of this housing has ushered in the same levels of chronic homelessness seen in 2007. Instead of being at the threshold of a coordinated and comprehensive data collection system, Delaware is still left without the basic tools for getting a systematic accounting of the nature and extent of its homeless population. And, based upon the fragmented data we present here, the size of the unsheltered homeless population conceivably exceeds that of those staying in interim housing. There have been no statewide initiatives that have addressed homelessness in Delaware since the PIT counts started increasing in 2020. Governor John Carney’s administration has not made any policy pronouncements on homelessness over this period. After using federal funding to massively increase access to hotel/motel vouchers, the State has scaled the program back to pre-COVID levels after federal funding ended. Beyond that, Governor Carney, in his most recent budget address, promoted increased state investments in affordable housing, but asserted that homelessness is “a very different problem” from the housing initiatives he has proposed to fund.31

Delaware’s nonprofit homeless services providers, when faced with the doubling of the homeless population, have stewarded a services system that is largely unchanged from its pre-pandemic structure. Part of this is dictated by the levels of available funding, but there has also been a lack of any stated vision or blueprint about how the homeless services system could better respond to homelessness at its current magnitude. The last time that the Delaware Continuum of Care (CoC), the collective of Delaware’s homeless services providers, assessed the state of homelessness was in 2017 with an action plan called Ending Homelessness in Delaware. 32 This action plan laid out specific, systemwide objectives and measures for responding to homelessness, along with a call for the CoC to report back two years later on the progress made toward implementing these objectives and measures. This follow up is now three years past due.

Finally, Delaware lacks an active grassroots advocacy structure focused on homelessness. The recent doubling of the homeless population and subsequent scaling back of services has been met with a conspicuous lack of protest, resistance, or calls for action coming from outside of the homeless services delivery systems. The one piece of legislation in front of the Delaware State Legislature that calls for a substantially different approach to addressing homelessness, the Homeless Bill of Rights (HB 55),33 has a limited backing and little prospect for passage. While Shyanne Miller, an advocate with the H.O.M.E.S. Campaign, acknowledges a need for radical action to end homelessness in Delaware and to fully realize housing as a human right, she also acknowledges the “pervasive silence amongst advocates serving people experiencing homelessness. There’s not enough community outcry and public rejection of austere policies that reduce resources and criminalize people experiencing homelessness.”34

In the absence of a statewide response, the most substantial activities in addressing Delaware’s homelessness are happening on local levels. In 2021, New Castle County, for example, purchased and repurposed a Sheraton hotel into what is now the Hope Center, the largest homeless facility in the state.35 In Georgetown, a partnership between the municipal government and the nonprofit Springboard Collaborative was instrumental in creating

11

a pallet shelter village to provide interim housing to Georgetown’s burgeoning unsheltered homeless population.30 These initiatives both leveraged federal COVID funding to launch these initiatives. In Kent County, the nonprofit organizations Dover Interfaith Housing and Code Purple Kent County are each in initial steps of building new interim housing capacity. While such expansions of capacity are badly needed, they are also ad hoc and not part of a more coordinated response.

A coordinated, statewide response is a critical first step toward addressing what are, based on the data presented here, unprecedented levels of homelessness for Delaware, even after the reductions in the 2023 PIT count results. In 2005, Governor Minner convened DICH to spearhead an effort to end homelessness. In 2007, CCRS’s report set the stage for a very well-attended statewide conference to further assess and act upon homelessness in Delaware. Sixteen years later, a similar convening is again needed to reinvigorate its approach, create an updated plan, and provide a collaborative framework for addressing homelessness. While unity and direction are prerequisite, such a first step will be followed by challenges related to implementation and assessment, given their historical absence in the wake of the plans reviewed here.

In summary, the pandemic has not so much induced waves of new homelessness as exposed deficiencies in how homelessness is being addressed. However, it also presents an opportunity for proceeding in a new manner. Putting these dynamics together creates a situation in which taking action commensurate to the current magnitude of the homelessness problem is critical, lest the problem become even larger and more intractable in the future.

Dr. Metraux may be contacted at metraux@udel.edu.

REFERENCES

1. Housing Alliance Delaware. (2022). Housing and homelessness in Delaware: 2022. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from:

https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ ugd/9b0471_322d16c2158c4ab09743a897dc12aa6d.pdf

2. Peuquet, S. W., Robinson, C. B., & Kotz, R. (2007). Homelessness in Delaware: Twenty years of data collection and research. University of Delaware Center for Community Research and Service and the Homeless Planning Council of Delaware. Retrieved from: https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/2c5d57a8-cad4495a-bc4a-54fbc9bc6c02/content

3. Burt, M. R., Hedderson, J., Zweig, J., Ortiz, M. J., & Aron-Turnham, L. (2004). Strategies for reducjng chronic street homelessness. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/publications/pdf/chronicstrthomeless.pdf

4. Delaware Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2007). Breaking the cycle: Delaware’s ten-year plan to end chronic homelessness and reduce long-term homelessness. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/FormsAndInformation/Publications/ delaware_ten_yr_plan.pdf

5. Delaware Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2013). Delaware’s plan to prevent and end homelessness. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/FormsAndInformation/Publications/ plan_end_homeless.pdf

6. Exchange, H. U. D. (2015). Point-in-time count methodology guide. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/4036/point-in-time-countmethodology-guide/

7. Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). AHAR Reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/ahar/#2022-reports

8. Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). CoC homeless populations and subpopulations reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-homelesspopulations-and-subpopulations-reports/

9. The Disaster Center. (2020). Delaware crime rates: 1960-2019. The Disaster Center. Retrieved from: https://www.disastercenter.com/crime/decrime.htm

10. Henry, M., de Sousa, T., Roddey, C., Gayen, S., & Bednar, T. J. (2021). The 2020 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. Retrieved from:

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

11. Housing Alliance Delaware. (2020). Housing and homelessness in Delaware: A crisis laid bare. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ ugd/9b0471_8c4b0aad6a664d309794565c70e8ff42.pdf

12. de Sousa, T., Andrichik, A., Cuellar, M., Marson, J., Prestera, E., & Rush, K. (2022). The 2022 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. Retrieved from:

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2022-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

13. Exchange, H. U. D. (2023). CoC housing inventory count reports. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from:

https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-housing-inventorycount-reports/

14. Kuang, J. (2018, Dec). Most clients placed in temporary housing as ‘RVRC’ shelter closes for good in Wilmington. Delaware Online/Delaware News Journal. Retrieved from:

https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/local/2018/12/31/ wilmington-rvrc-homeless-shelter-safespace-delawarecloses/2449603002/

15. Kiefer, P. (2022, May). Number of people experiencing homelessness in Delaware doubled over past two years. Delaware Public Media. Retrieved from:

https://www.delawarepublic.org/show/the-green/2022-05-20/numberof-people-experiencing-homelessness-in-delaware-doubled-over-pasttwo-years

12 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023

16. Housing Alliance Delaware. (2022). Point in time count & housing inventory count: 2022 Report. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_ b4f4bc93e75c4923a891bc0d33fb4dbd.pdf

17. Metraux, S., Solge, J., & Mwangi, O. W. (2021). An overview of family homelessness in Delaware. Housing Alliance Delaware. Retrieved from: https://www.housingalliancede.org/_files/ugd/9b0471_ b09ebb113aa74d13ae09eba6677523df.pdf

18. Lee, T., Leonard, N., & Lowery, L. (2021). Enumerating homelessness: The point-in-time count and data in 2021. The National League of Cities. Retrieved from: https://www.nlc.org/article/2021/02/11/enumerating-homelessness-thepoint-in-time-count-and-data-in-2021/

19. Hughes, I., & Perez, N. (2020, Feb). ‘It’s devastating’: 4 found dead in tent at homeless camp in Stanton. Delaware Online/ Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2020/02/18/large-policepresence-along-route-7-stanton/4798286002/

20. Cassidy, J. (2021, Mar). Homeless Delaware vet honored after being found dead on a cold wintry day in Newark. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2021/03/26/communitycomes-together-honor-veteran-edgar-mack/6941492002/

21. Metraux, S., & Modeas, A. C. (in press). Homelessness among persons on delaware’s sex offender registry. Delaware Journal of Public Health.

22. Delaware State Police, State Bureau of Identification. (n.d.). Delaware sex offender central registry. State of Delaware. Retrieved from: https://sexoffender.dsp.delaware.gov/

23. National Center for Homeless Education. (2023). State Pages: Delaware. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from: https://profiles.nche.seiservices.com/StateProfile.aspx?StateID=10

24. Cunningham, M., Gourevitch, R., Pergamit, M., Gillespie, S., & Hanson, D. (2018). Denver supportive housing social impact bond initiative: housing stability outcomes. Urban Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99180/denver_ supportive_housing_social_impact_bond_initiative_3.pdf

25. Kuang, J. (2019, Nov). YMCA ends program that provides 41 beds for Wilmington’s homeless. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2019/11/11/wilmingtonlose-41-beds-homeless-ymca-plans-end-program/2510678001/

26. Metraux, S., Mwangi, O., & McGuire, J. (2022, August 31). Prior evictions among people experiencing homelessness in Delaware. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8(3), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2022.08.009

27 Nescott, E. P., Metraux, S., McDuffie, M. J., & Brown, E. (in press). Health & homelessness: Matching Medicaid claims and encounters and the community management information system databases. Delaware Journal of Public Health.

28. Personal Communication. (2023). Housing Alliance Delaware.

29 Kiefer, P. (2023, Jan). Residents Milford homeless encampment disperse ahead of final sweep. Delaware Public Media.

Retrieved from:

https://www.delawarepublic.org/politics-government/2023-01-13/ residents-milford-homeless-encampment-disperse-ahead-of-final-sweep

30. Kiefer, P. (2023, Jan). Long-awaited Georgetown pallet shelter village welcomes first residents. Delaware Public Media.

Retrieved from:

https://www.delawarepublic.org/politics-government/2023-01-30/longawaited-georgetown-pallet-shelter-village-welcomes-first-residents

31 Carney, J. (2023). Governor Carney presents FY24 budget

Retrieved from:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxCaUQLcYgo (38:35 in video).

32 Delaware Continuum of Care. (2017). Ending homelessness in Delaware: Our action plan. Delaware State Housing Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.destatehousing.com/OtherPrograms/othermedia/h4g_ action_plan_2017.pdf

33. Lynn, S. (2023). House substitute 1 for House Bill 55. Delaware General Assembly. Retrieved from: https://legis.delaware.gov/BillDetail?legislationId=130082

34 Miller, S. (2023, Apr 24). H.O.M.E.S. Campaing. Personal communication.

35 Kuang, J. (2020, Dec). ‘I’m not scared anymore’: New Castle County’s hotel-turned-homeless shelter gets underway. Delaware Online/Delaware News-Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/2020/12/23/new-castlecountys-hotel-turned-homeless-shelter-housing-73-people/3990700001/

13

Demographics of the Population Experiencing Homelessness and Receiving Publicly Funded Substance Use and Mental Health Treatment Services in Delaware

David Borton, M.A.

Center for Drug and Health Studies, University of Delaware

Rachel Ryding, Ph.D.

Center for Drug and Health Studies, University of Delaware

Meisje J. Scales, M.P.H., C.P.S. Center for Drug and Health Studies, University of Delaware

Kris Fraser, M.P.H., P.M.P.

Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, Delaware Department of Health and Social Services

ABSTRACT

Objective: To determine the prevalence of clients experiencing homelessness in publicly funded substance use and mental health services in Delaware and uncover basic patterns in the demographics and service access of said clients. Methods: We analyzed Consumer Reporting Form data for clients admitted to publicly funded substance use and mental health treatment. All clients who were admitted to services from a publicly-funded provider and completed the CRF between 2019 and 2021 were included in this analysis (n=29,495). Results: 5,717 clients (19%) reported experiencing homelessness. 20% of men reported homelessness, compared to 18% of women, and 22% of Black clients reported homelessness, compared to 19% of White clients. 48% of admissions were to substance use treatment, 29% were to mental health treatment, and 23% were to treatment for both. Conclusions: Nearly one-fifth of clients who received publicly funded treatment between 2019 and 2021 reported experiencing homelessness, a vast overrepresentation when compared against the less than 1% of the population who was counted as homeless through the annual PIT count in Delaware. Policy Implications: Homelessness can be experienced across the lifespan and impacts individuals and families of all demographic makeups. Individuals are often unable to access primary care, insurance supported services, and chronic disease management teams resulting in a disproportionately high use of emergency services and departments for acute needs.

Funding for this project has been provided by the Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

INTRODUCTION

Across the United States, the increasing prevalence of homelessness and other forms of housing insecurity present a major social justice issue. Social and economic conditions brought on during the COVID-19 pandemic have in some cases exacerbated housing issues that preceded the pandemic and have made housing less accessible and more expensive for many low-income households. Access to safe and affordable housing functions as a social determinant of health,1 making it important to examine populations experiencing homelessness from a public health lens. Conditions of homelessness can put people at greater risk for early mortality as well as for contracting infectious and chronic diseases.2

Per federal requirements, at a minimum, publicly funded substance use disorder and mental health treatment services in the United States must collect admissions and discharge data from the clients they serve. In Delaware, this data is collected using the Consumer Reporting Form (CRF) and reported by providers to

the Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health (DSAMH). This state-level data is then reported and compiled as Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS).

While there has been no recent publication of Delawarespecific data regarding clients in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment who have been or are currently homeless, there has been research using national TEDS data or data specific to other states. One study of treatment data in California found that people experiencing homelessness, when compared to clients with stable housing, have lower rates of retention and successful discharge, a greater prevalence of mental health diagnoses and unemployment, and were more likely to receive residential treatment.3 Another study, focused on national data, reported that while 12.5% of clients admitted for opioid use disorder treatment were experiencing homelessness, those who reported experiencing homelessness were less likely to receive medicationassisted treatment than clients in stable housing; those clients experiencing homelessness were also more likely to be male and admitted to a residential program.4

Because of the often-hidden nature of homelessness, it can be difficult to get a true measure of its prevalence across a population; as a result, groups experiencing homelessness are

14 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023 Doi: 10.32481/djph.2023.06.004

often understudied. The Delaware Continuum of Care (COC) is a collaborative and community-based body committed to addressing homelessness in Delaware with the goal of securing housing for all. The COC conducts a point in time (PIT) count one night a year to assess the scope of the problem of homelessness in the state. In 2022, the PIT count reported 2,369 people experiencing homelessness in Delaware, which is double the number of people experiencing homelessness measured by the 2020 PIT count just prior to the onset of the pandemic.5 In particular, they found sharpest increases in homelessness among families with children, veterans, and Black or African American people.

While evidence suggests that people experiencing homelessness often have acute healthcare needs,6 there has been no recent publicized data on the prevalence of homelessness among clients receiving mental health and substance use treatment in Delaware. In this brief report, authors seek to fill this gap by using data from the CRF to analyze the prevalence of homelessness among people receiving publicly funded treatment in Delaware and key demographic characteristics of this priority population.

METHODS

We analyzed CRF data for clients admitted to publicly funded substance use and mental health treatment services in Delaware in 2019, 2020, and 2021. Clients are asked about the following: treatment and diagnosis (reported by clinician); substance use; medical status; employment; income; legal status; family; housing; and mental health. CRFs are completed at admission, discharge, and annually if the client remains in treatment longer than a year. The client’s provider interviews each client using the form, and all questions are self-reported by the client to the provider aside from diagnoses and treatment services provided which are filled out solely by the provider. All clients who were admitted to services from a publicly funded provider and completed the CRF between 2019 and 2021 were included in this analysis (n=29,495). As a part of the CRF, clients are asked for their current residential arrangement, which includes the option “None/Homeless,” as well as whether they have been homeless in the past 30 days. There is no operational definition of homeless on the CRF; as such a client’s status as homeless is determined by their own interpretation. Clients who reported past 30-day homelessness or “None/Homeless” at admission were included in the experiencing homelessness group for this analysis.

RESULTS

Between 2019 and 2021, 29,495 unique clients were admitted to publicly funded services. Of them, 5,717 clients (19%) reported experiencing homelessness at some point in that period. Table 1 summarizes rates of experiencing homelessness by demographic categories.

In this period, 20% of men reported homelessness, compared to 18% of women. When examining patterns of homelessness by race, 22% of Black clients reported homelessness, compared to 19% of White clients, 19% of mixed-race clients, and 17% of clients who reported another race. Hispanic or Latino clients had slightly lower rates of homelessness (17%) than clients who were not Hispanic or Latino (20%). Clients who did not complete high school experienced the highest rate (24%) of homelessness by education level. Similarly, clients who were unemployed had

higher rates of experiencing homelessness (29%) than any other group, followed by clients who were disabled (21%); 11% of clients who were either employed or students at admission reported experiencing homelessness. Veterans also had higher rates of homelessness (22%) than clients who were not veterans (19%).

The rate of client homelessness varied within this period. In 2019, 19% of clients experienced homelessness at some point that year (n=14,190). In 2020, the rate increased to 20% (n=12,074). In 2021, it decreased sharply to 15% (n=13,710).

Among clients experiencing homelessness in this period, 48% of admissions were for substance use diagnoses only, 29% were for mental health diagnoses only, and 23% were for co-occurring diagnoses. Table 2 shows select comparisons between the major response categories of client demographics and services accessed for both clients who experienced homelessness and those who did not during the analysis period. Withdrawal management services are short term (1-7 day) residential programs to help clients cease substance use and monitor safe withdrawal, otherwise known as detox programs. Mental health crisis services include short term (up to 30 days) admissions to residential mental health facilities. Community support services include Assertive Community Treatment, an evidence-based practice for community-based mental health treatment, DSAMH’s Community Behavioral Health Outpatient Treatment (CBHOT) Program, and case management. Outpatient includes medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) treatment, criminal justice diversion programs for substance use, and other outpatient services. Short-term residential services include recovery housing and sober living communities, as well as residency in group homes. Long-term residential services include clients who are long-term residents of psychiatric hospitals.

15

Percentage of All Clients who Experienced Homelessness (n = 29,495) Gender Men 20% Women 18% Race Black 22% White 19% Mixed Race 19% Another Race 17% Ethnicity Hispanic or Latino 17% Not Hispanic or Latino 20% Employment/Education Less than HS Education 24% Employed/Student 11% Unemployed 29% Disabled 21% Veteran 22% Non-Veteran 19%

Table 1. Rates of Experiencing Homelessness by Demographics

As the table illustrates, men were represented at a slightly higher rate among those who experienced homeless compared to those who did not (61% to 57%, respectively). Black clients were more represented among clients who experienced homelessness as well (33% compared to 29%), while the opposite was true for White clients (59% compared to 62%). A much larger percentage of clients experiencing homelessness were unemployed (50%) than that of clients who were not (29%).

Clients who experienced homelessness accessed withdrawal management services at a higher rate than clients who did not (26% compared to 11%), as well as short term residential treatment (7% compared to 2%).

DISCUSSION

Nearly one-fifth of clients who received publicly funded treatment between 2019 and 2021 reported experiencing homelessness. There is no official population level estimate for homelessness in among Delawareans during this time period. The closest approximation comes from the annual PIT count, which estimates homelessness from a single night. The 2019, 2020, and 2021 PIT counts in Delaware suggested that on a given night, between 921 and 1,579 people were currently experiencing homelessness, which represents less than 1% of the population of Delaware. While point-in-time counts from a single night are not directly comparable to a measure of homelessness over the past 30 days, these data do suggest that people experiencing homelessness may

be overrepresented among DSAMH clients receiving SUD and mental health services.

When comparing treatment modalities, homelessness was more prevalent among clients admitted to substance use treatment as opposed to mental health treatment. People experiencing homelessness and people with substance use disorders are both highly stigmatized groups; when studying the intersections of these populations it is important to acknowledge that people experiencing homelessness are not typically homeless solely because of their substance use. Because of these dual stigmas associated with homelessness and substance use disorders, people experiencing homelessness who also struggle with substance use face additional barriers in accessing evidence-based health care.7 This underscores the importance of examining the demographic characteristics of this population in DSAMH services and that are more likely to serve people experiencing homelessness. Withdrawal management and short-term residential care were both identified in this data as modalities that serve a higher proportion of homeless or housing insecure clients. There was also a substantial difference in employment status among clients who reported homelessness compared to clients who were stably housed, with approximately half of homeless or housing insecure clients reporting unemployment. This suggests a strong need for workforce development programming for these clients, as well as investment in job opportunities paying a living wage.

16 Delaware Journal of Public Health - June 2023

Percent among Clients Who Experienced Homelessness (n=5,717) Percent among Clients Who

Not Experience Homelessness (n=23,778) Gender Men 61% 57% Women 39% 43% Race Black 33% 29% White 59% 62% Ethnicity Hispanic or Latino 6% 8% Employment/Education Less than HS Education 29% 22% Employed/Student 18% 36% Unemployed 50% 29% Veteran 6% 5% Service Access Withdrawal Management 26% 11% Mental Health Crisis Services 8% 12% Community Support Services 45% 44% Outpatient Treatment 10% 16% Short Term Residential Treatment 7% 2% Long Term Residential Treatment 10% 19%

Table 2. Comparison of Clients who Did or Did Not Experience Homelessness

Did

The overall rate of homelessness among the DSAMH treatment population varied over the course of the years of available data. The rate increased from 2019 to 2020, but then decreased in 2021. While extant data sources suggest an increase in the prevalence of homelessness and housing insecurity over this time period of time in Delaware5,8 these trends are not clearly reflected in our data. Given facility closures and gaps in CRF administration, it is still difficult to fully account for the impact that the pandemic may have had on both patterns in treatment enrollment and in data collection protocols across locations. In the final section of this paper we outline general public health implications for studying this population and possible future research agendas to continue the work that started here.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS