Public Health

Chronic Diseases in 2024:

Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention

www.delamed.org | www.delawarepha.org Volume 10 | Issue 1 March 2024

A publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association

Delaware Journal of

Delaware Academy of Medicine OFFICERS

Lynn Jones, L.F.A.C.H.E. President

Stephen C. Eppes, M.D. President Elect

Ann Painter, M.S.N., R.N. Secretary

Jeffrey M. Cole, D.D.S., M.B.A. Treasurer

S. John Swanson, M.D.

Immediate Past President

Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Executive Director

DIRECTORS

David M. Bercaw, M.D.

Saundra DeLauder, Ph.D.

Eric T. Johnson, M.D.

Erin M. Kavanaugh, M.D.

Joseph Kelly, D.D.S.

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S.

Brian W. Little, M.D., Ph.D.

Daniel J. Meara, M.D., D.M.D.

John P. Piper, D.O.

Megan L. Werner, M.D., M.P.H.

Charmaine Wright, M.D., M.S.H.P.

EMERITUS

Barry S. Kayne, D.D.S.

Joseph F. Kestner, Jr., M.D.

Delaware Public Health Association

ADVISORY COUNCIL

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Chair

Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Executive Director

COUNCIL MEMBERS

Alfred Bacon, III, M.D.

Louis E. Bartoshesky, M.D., M.P.H.

Gerard Gallucci, M.D., M.S.H.

Allison Karpyn, Ph.D.

Erin K. Knight, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Melissa K. Melby, Ph.D.

Mia A. Papas, Ph.D.

Karyl T. Rattay, M.D., M.S.

William Swiatek, MA, A.I.C.P.

Delaware Journal of Public Health

Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Publisher

Omar Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Angela Herman, D.N.P., R.N. Guest Editors

Suzanne Fields Image Director

ISSN 2639-6378

Public Health

3 | In This Issue

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S.; Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H.

4 | Guest Editors:

Training the Next Generation of Public Health Leaders to Tackle Chronic Disease in Delaware: Examples and Opportunities

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Angela Herman, D.N.P., R.N.

8 | Chronic Disease Risk of Family Child Care Professionals: Results of a Statewide Survey of Health and Wellbeing Indicators

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Rena Hallam, Ph.D.

12 | A Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lung Cancer in Delaware

Brian Nam, M.D., F.A.C.S.; Yeonjoo Yi, Ph.D.; Kevin Ndura, M.B.A.; Krishna Vasireddy, Pharm.D., M.S.; Claudine Jurkovitz, M.D., M.P.H.; Kiran Kattepogu, M.B.B.S., M.P.H.

26 | Social Workers, Burnout, and Self-Care: A Public Health Issue

Michelle Ratcliff, D.M.F.T., L.S.W.

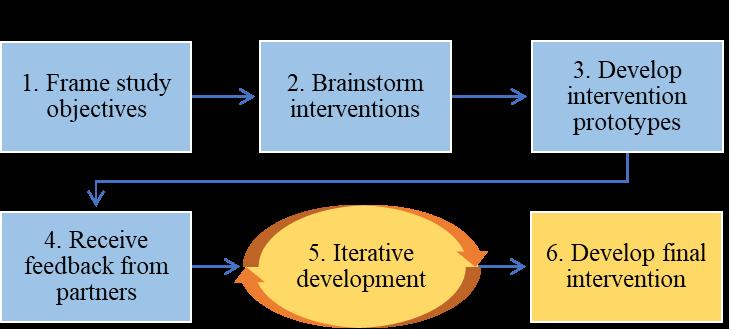

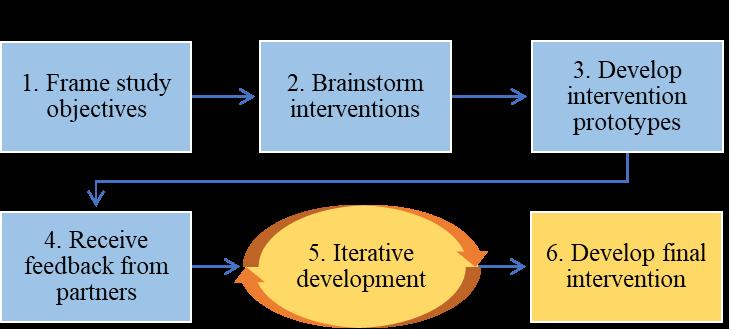

30 | Community Partnership to Co-Develop an Intervention to Promote Equitable Uptake of the COVID-19 Vaccine Among Pediatric Populations

Paul T. Enlow, Ph.D.; Courtney Thomas, M.S.; Angel Munoz Osorio, B.S.; Marshala Lee, MD, M.P.H.; Jonathan M. Miller, M.D.; Lavisha Pelaez, M.P.H.; Anne E. Kazak, Ph.D., A.B.P.P.; Thao-Ly T. Phan, M.D., M.P.H.

44 | Pediatric Dentists: Frontline Public Health Providers Leading the Way in Identifying and Preventing Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

Bari Levine, D.M.D., M.P.H.; Freda Patterson, Ph.D.; Lauren Covington, Ph.D., R.N

46 | “We Are All There to Make Sure the Baby Comes Out Healthy”: A Qualitative Study of Doulas’ and Licensed Providers’ Views on Doula Care

Erin K. Knight, Ph.D., M.P.H.; Rebecca Rich, Ph.D., C.H.E.S.

62 | Global Health Matters Newsletter

January - February 2024

Fogarty International Center

74 | Paving the Way to Active Living for People with Disabilities: Evaluating Park and Playground Accessibility and Usability in Delaware

Cora J. Firkin; Lauren Rechner; Iva Obrusnikova, Ph.D., M.Sc.

86 | How Interprofessional Community Mobile Healthcare and Service-Learning Work Together to Identify and Address Chronic Health Disparities

EmmaMathias;PeytonFree;AbbyStorm,M.S.;

HeatherMilea,M.S.N.,F.N.P.-B.C.,A.G.A.C.N.P.-B.C.;ChristineSowinskiM.S.M.;

JenniferA.Horney,Ph.D.

90|A6-WeekVirtualExercise/DanceProgramImpacts Fitness Levels for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: A DNP Project

Melanie Ayers, D.N.P., R.N., C.N.E.

98 | Navigating Risk: Understanding Chronic Disease Factors in Delaware’s College Population

AmyGootee-Ash,Ph.D.,M.S.W.,M.S.;MeganRothermel,Ed.D.,M.S.; AdamKuperavage,Ph.D.

102| ImplementingaSuccessfulInfluenzaandUpdated COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign Among Healthcare Workers in a Delaware Healthcare Facility

Lija Gireesh, D.N.P., M.B.A., F.N.P.-B.C., N.E.A.-B.C., C.O.H.N.-S.; Tabe Mase, F.N.P.-B.C., M.J., C.H.C., C.O.H.N.-S.; Marci Drees, M.D., M.S., D.T.M.H., F.A.C.P., F.I.D.S.A., F.S.H.E.A.

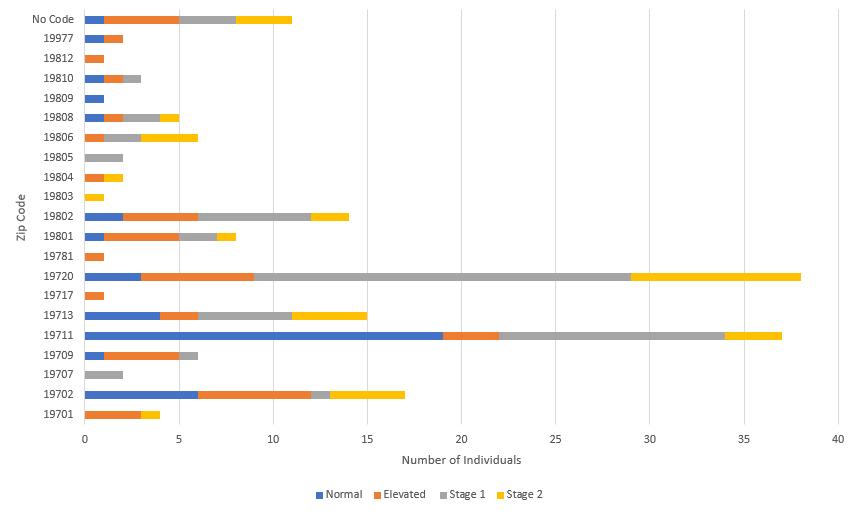

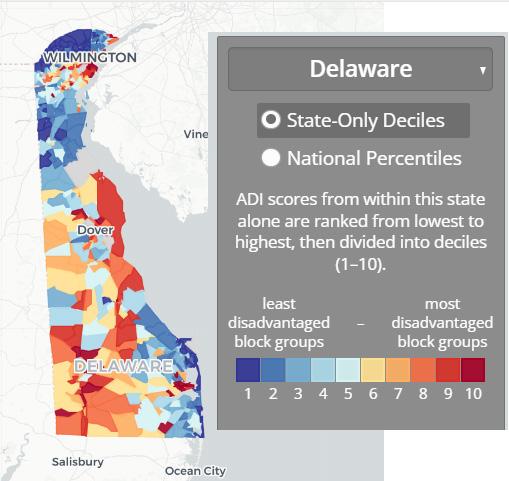

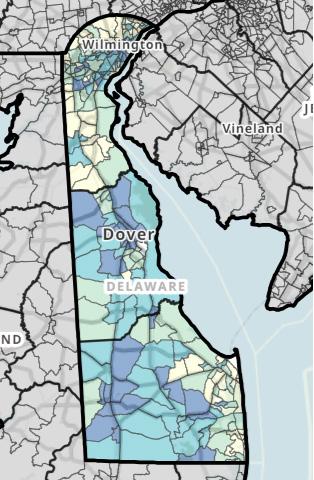

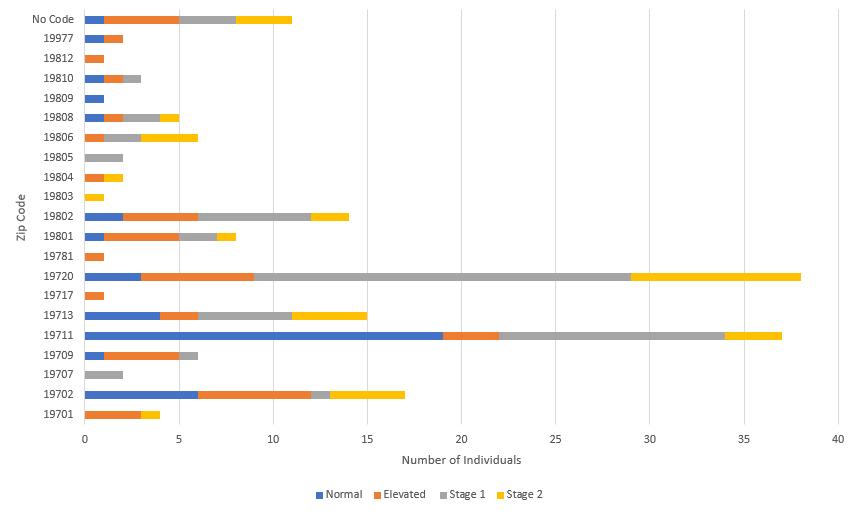

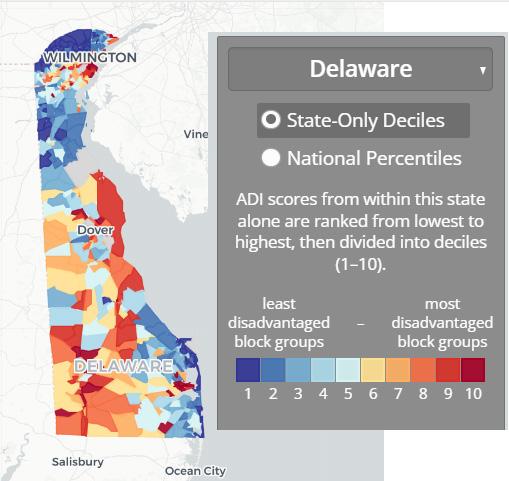

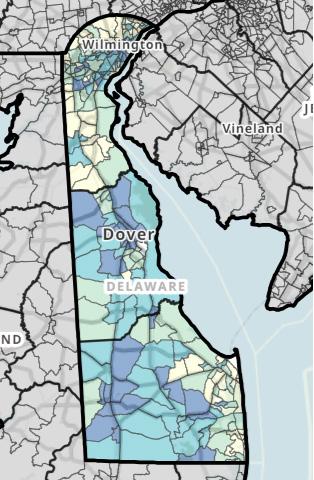

106 | Mapping Health Disparities: Leveraging Area-Based Deprivation Indices for Targeted Chronic Disease Intervention

Darrell Dow, M.S.

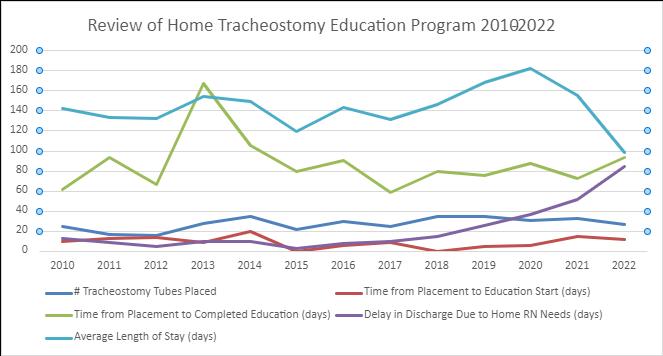

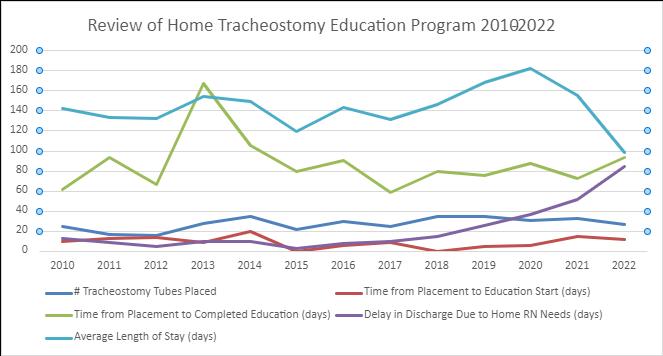

112 | Review of Pediatric Tracheostomy Training Program for Home Discharge Patients

Katlyn L. Burr, M.S.M., R.R.T.-N.P.S., A.E.-C.; Erin Nilson-Italia, R.R.T.-N.P.S.; Michael Treut, R.R.T.-N.P.S., A.E.-C.; Kimberly McMahon, M.D.; Kelly Massa, B.H.S., R.R.T.N.P.S.

116 | Lieutenant Governor’s Challenge: Motivating and Honoring Delawareans to Improve Their Health and Well-Being

Helen Arthur, M.H.A.; Lauren Butscher, C.H.E.S.; Lisa Moore, M.P.A.; Keith Warren

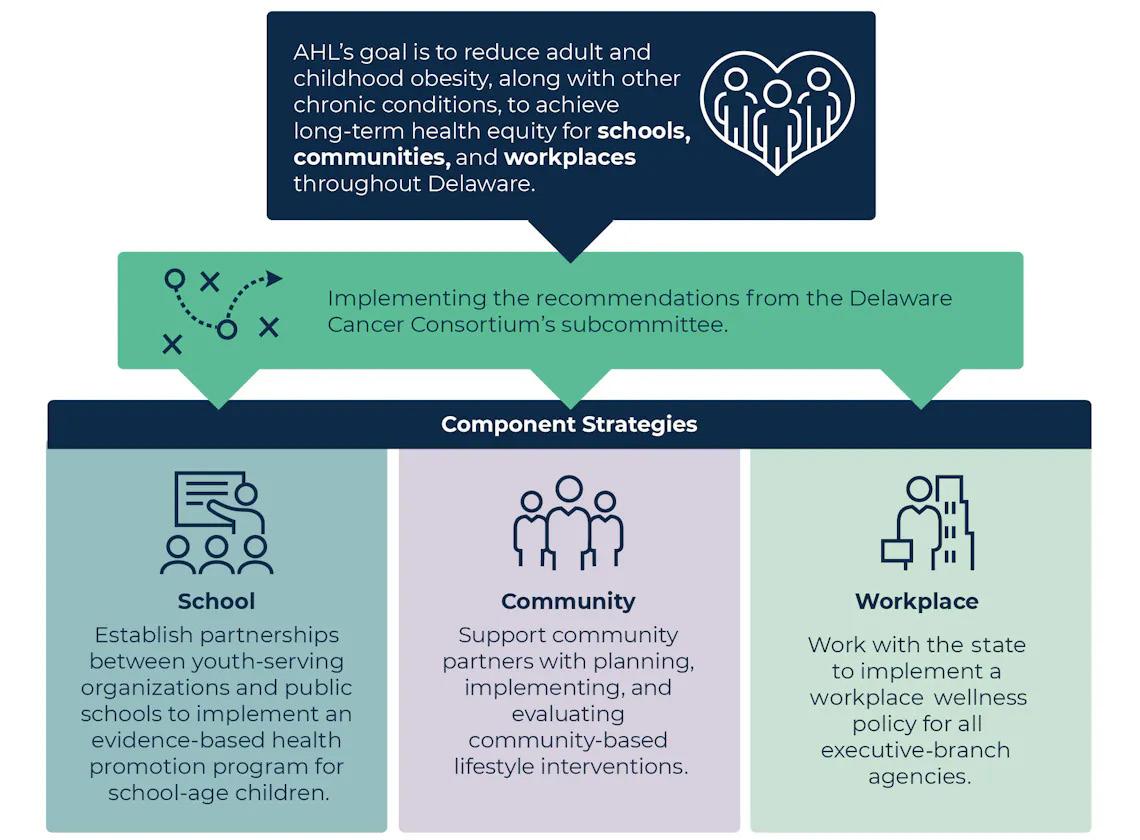

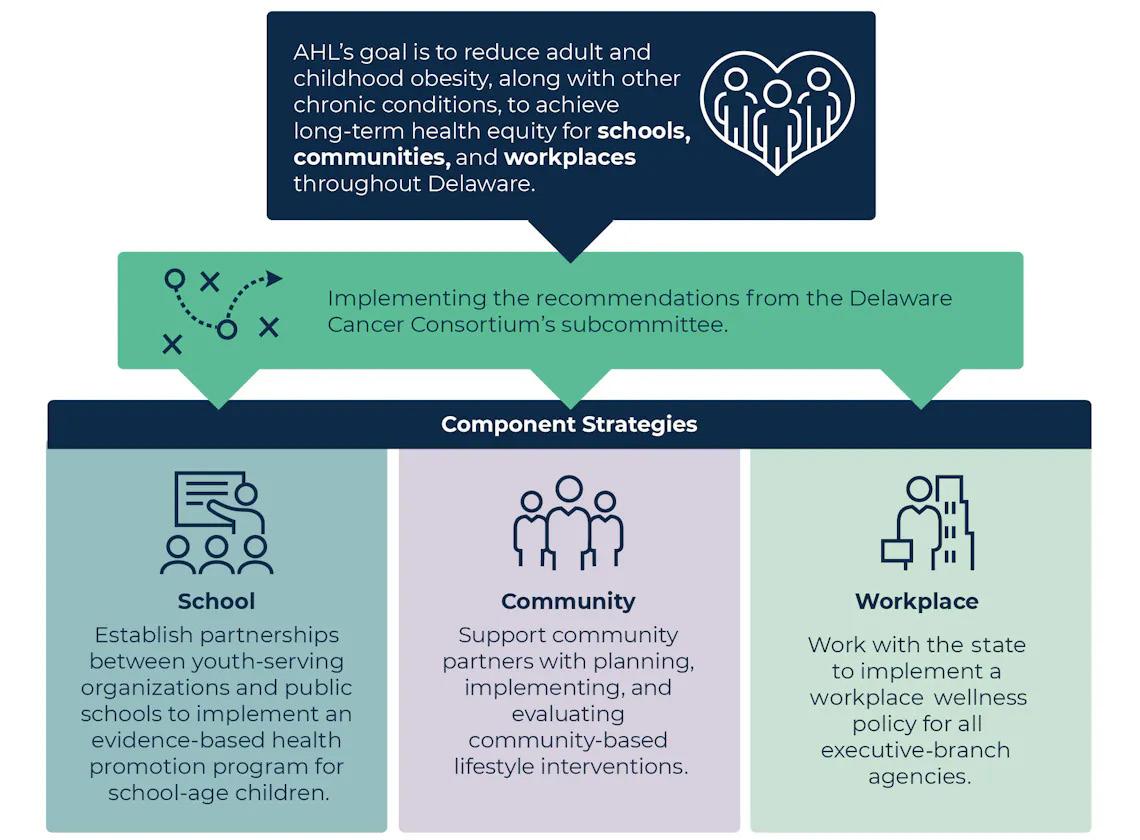

122 | Advancing Healthy Lifestyles: A Multicomponent Initiative to Reduce the Burden of Obesity In Delaware

Helen Arthur, M.H.A.; Lauren Butscher, C.H.E.S.; Lisa Moore, M.P.A.

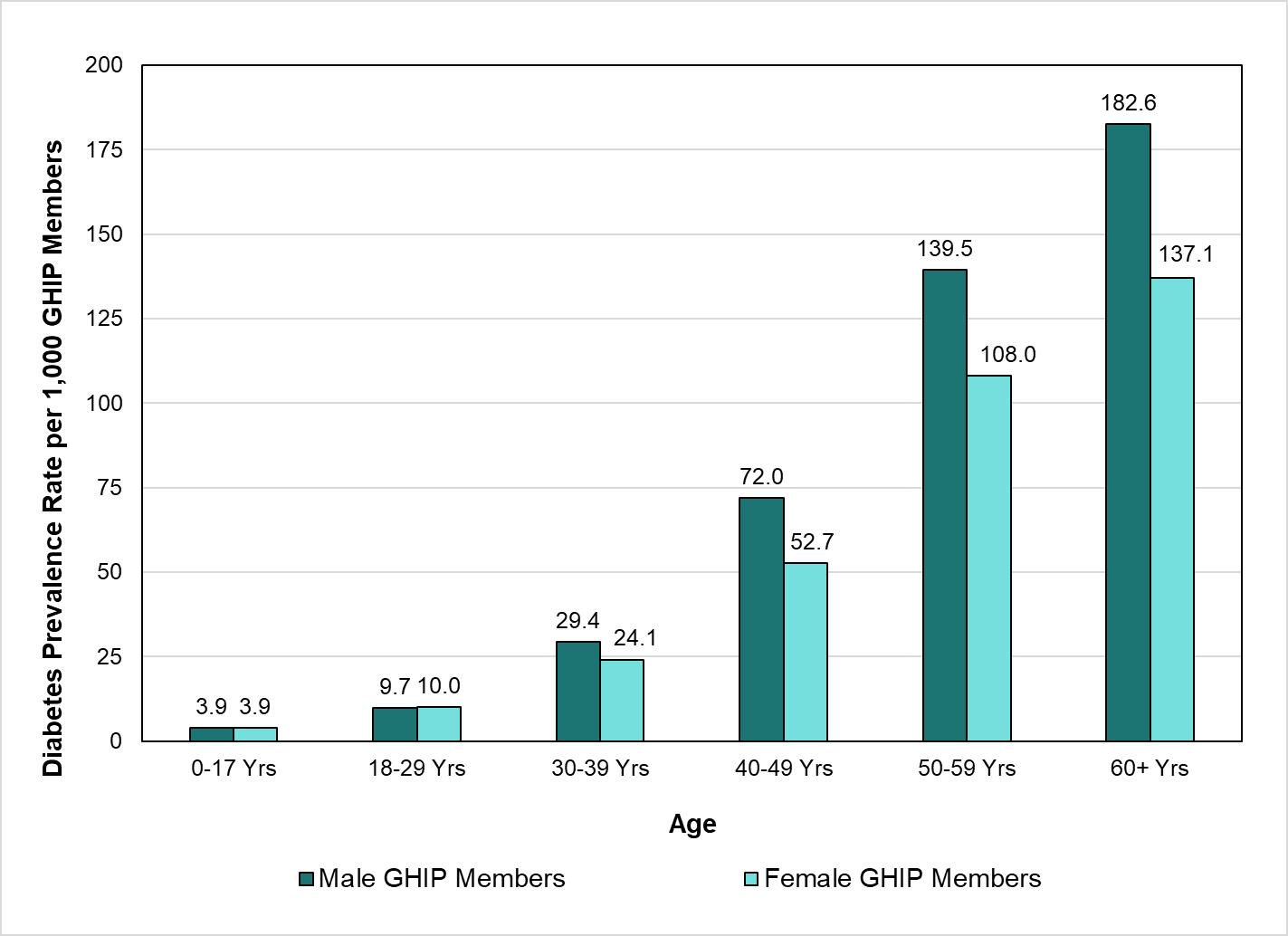

130 | The Impact of Diabetes in Delaware 2023

Delaware Department of Health and Social Services Division of Public Health

152 | Lexicon & Resources

156 | Index of Advertisers

158 | Delaware Journal of Public Health Submission Guidelines

The Delaware Journal of Public Health (DJPH), first published in 2015, is the official journal of the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association (Academy/DPHA).

Submissions: Contributions of original unpublished research, social science analysis, scholarly essays, critical commentaries, departments, and letters to the editor are welcome.

Questions? Contact managingeditor@djph.org

Advertising: Please contact ksmith@delamed.org for other advertising opportunities. Ask about special exhibit packages and sponsorships. Acceptance of advertising by the Journal does not imply endorsement of products.

Copyright © 2023 by the Delaware Academy of Medicine / Delaware Public Health Association. Opinions expressed by authors of articles summarized, quoted, or published in full in this journal represent only the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Delaware Public Health Association or the institution with which the author(s) is (are) affiliated, unless so specified.

Any report, article, or paper prepared by employees of the U.S. government as part of their official duties is, under Copyright Act, a “work of United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the U.S. Code is not available. However, the journal format is copyrighted and pages June not be photocopied, except in limited quantities, or posted online, without permission of the Academy/DPHA.Copying done for other than personal or internal reference use-such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale- without the expressed permission of the Academy/DPHA is prohibited. Requests for special permission should be sent to managingeditor@djph.org

Delaware Journal of

publication of the Delaware Academy of Medicine

Association March 2024 Volume 10 | Issue 1

A

/ Delaware Public Health

Chronic Disease

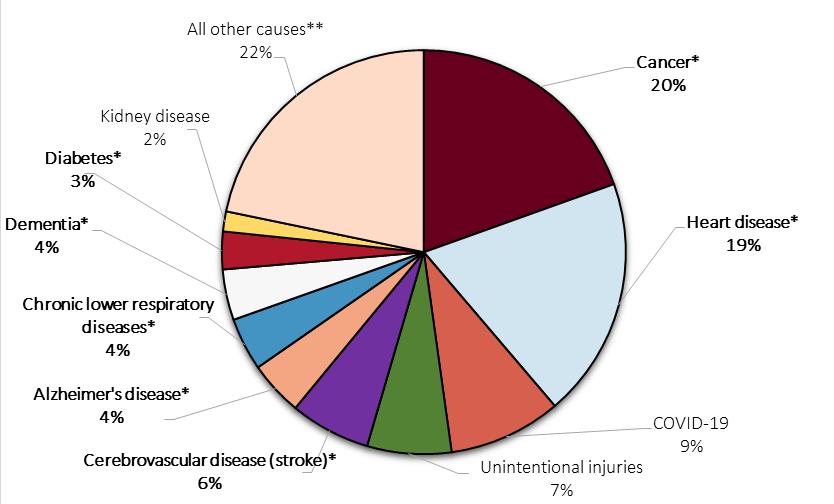

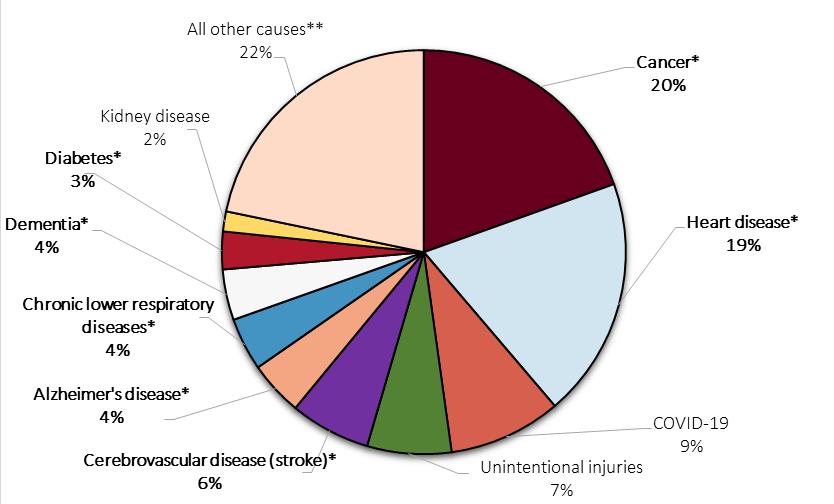

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, six in ten Americans live with at least one chronic disease.1 Many live with more than one. These diseases (heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, etc.) have significant health and economic costs, and interventions to prevent, treat, and manage these diseases can make up a large portion of our national and local health care expenditures.

These chronic diseases affect the lives of Delawareans in many ways, and also offer the potential for improvement. Often, improving one area (such as diabetes) requires a comprehensive approach uniting medicine and public health. This approach can thus positively impact many other areas of chronic diseases as well.

Prevention. Preventing these diseases is the best way to keep health care costs down. Some of the best ways to prevent chronic disease are to quit smoking; eat a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and low-fat dairy; get regular physical activity; limit alcohol; keep up to date on preventative screenings; take care of your teeth; and get enough sleep.2

Treatment & Management. According to Delaware’s Division of Public Health, cardiovascular disease (including heart disease and stroke) is the leading cause of death in the First State, followed by cancer, lung disease, and diabetes – all diseases of a chronic nature.3 This is the DJPH’s third issue devoted to chronic disease; the first two issues were published back-to-back in 2017, and looked at statewide initiatives working in the prevention, treatment, and management spheres.

In this issue, we welcome Dr. Laura Lessard and Dr. Angela Herman, researchers and educators from the University of Delaware and Wilmington University, respectively, and experts in the field of chronic disease. The articles within take a look at how COVID-19 fits into the chronic disease world, at how some of our frontline providers are working to prevent chronic disease in special populations, and at some of the programs offered for those groups of people living with chronic disease in the state.

As always, we welcome your feedback! We also take the opportunity to remind you to register for our Annual Dinner Meeting on May 1, 2024. This is a very special annual event and we cover many of the costs involved to make it accessible to the maximum number of attendees. Details are available on our website, at https://delamed.org

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, May). National center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, Oct). How you can prevent chronic diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/prevent/index.htm

3. Delaware Division of Public Health. (n.d.). Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention. https://dhss.delaware.gov/dph/dpc/bcd.html

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Omar A. Khan, M.D., M.H.S. Editor-in-Chief, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Publisher, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Katherine Smith, M.D., M.P.H. Publisher, Delaware Journal of Public Health

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2024.03.01

IN THIS ISSUE

3

Training the Next Generation of Public Health Leaders to Tackle Chronic Disease in Delaware: Examples and Opportunities

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Department of Health Behavior and Nutrition Sciences, University of Delaware

Angela Herman, D.N.P., R.N. College of Health Professions and Natural Sciences, Wilmington University

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases are the number one cause of death in Delaware and across the United States, accounting for four of the five top leading causes of death each year.1 In a previous issue of the Delaware Journal of Public Health (December 2022), data on the geographic distribution of chronic illness in the state was presented, illustrating patterns of disease and their relationship to demographic patterns. Of note, the authors posit that, “an aging population [in Delaware] is more likely to develop chronic disease as a natural result of the aging process.”2 Indeed, medical treatment advancements have extended the lifespan and quality of life for many living with chronic diseases, resulting in an increased need for disease management and support. The realm of chronic diseases and public health is continually broadening, incorporating innovative approaches for both preventing and managing these conditions. As educators helping to train and support the next generation of public health professionals, we recognize that preparing our students to meet this reality takes a multi-level approach. In this paper, we present examples from our institutions of the ways that chronic disease is taught in our curricula with the hopes of both shining this light on this work but also identifying opportunities for collaboration, expansion and growth.

CHRONIC DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGY

At a fundamental level, it is imperative that public health professionals understand the epidemiology of chronic disease, including its distribution and determinants. This can take the form of learning about sources of epidemiological data, ways to collect valid and reliable data and identifying trends in data over time.

At Wilmington University, Epidemiology for the Health Professions is a course shared by graduate students in both Nursing and Health Science majors to promote interdisciplinary communications and teamwork. Students are introduced to the principles and methods of epidemiologic investigation, data and the use of classical statistical approaches to describe the health of populations. A final project presentation provides the opportunity for them to do a thorough discussion of a specific chronic health condition from an epidemiologic focus - including the natural history of the disease, pathophysiology and transmission as

well as screening recommendations and current policy issues related to the condition. WilmU’s Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) program also includes a course in Epidemiology which provides an advanced evaluation and analysis of the principles of epidemiology. Students become familiar with epidemiologic approaches to causation and the use of analytic epidemiology. Assignments provide students with methods to discern measures of disease burden in the community.

At the University of Delaware (UD), our introductory epidemiology course taught to undergraduate students teaches students about the prevalence, incidence and risk factors for chronic disease like diabetes and heart disease. Course assignments frequently use chronic disease examples, showing students how data sources such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Notifiable Diseases Registry can be used to understand both the current status and trends over time in chronic disease diagnoses in Delaware and how those compare to other jurisdictions. In the graduate Epidemiology of Aging course, part of the MPH curriculum at UD, students conduct research culminating in a presentation of aging, demographics, epidemiology of aging-related disorders and current issues related to aging for a particular jurisdiction of choice (country or state). Class discussion examines the similarities and differences across jurisdictions.

CHRONIC DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

As the incidence of chronic disease increases, the population of individuals who could benefit from primary, secondary and tertiary prevention as well as treatment also expands. Students need to understand both the mechanisms and opportunities for prevention along with the current state of treatment for chronic diseases. These topics are integrated in a variety of learning experiences appropriate for student level and program.

At UD, for example, the Graduate Certificate in Health Coaching provides training to become a Nationally Board Certified Health and Wellness Coach (NBC-HWC). The curriculum teaches students the skills needed to support clients with their individualized health goals, including those to reduce chronic disease risk such as increasing physical activity, reducing stress and improving diet. Students in the program learn both the theory and practice of health behavior change and have ample practice coaching clients during their training.

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2024.03.02

4 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

At Wilmington University, Bachelor Degree students in the Health Sciences program students are prompted to consider all areas of disease and prevention through the lens of patient education, healthcare leadership, healthcare policy, evidence, public health, as well as law and ethics. The concepts of chronic care are infused through the resources and assignments as the students consider its context within their programs. In the RN to BSN program, core classes provide a thorough practice-focused learning opportunity intended to provide nurses with a deep understanding of the skills required to integrate chronic care into their nursing practices. In the Chronic and Palliative Care course nurses complete a practice-focused learning opportunity to explore the skills required to integrate chronic care into practice. Health Sciences and BSN students at Wilmington University also may incorporate a certificate in Interdisciplinary Care Management into their program. This comprehensive certification informs students about the need for care management services across all healthcare levels as the connection for patients with chronic illness to successfully navigate transitions of care using a team-based patient-centered approach. Students are provided an in-depth evaluation of the principles and strategies of care management across the healthcare continuum. The curriculum delves into a thorough analysis of value-based financial issues, healthcare quality metrics, and their impact on the provision of care for patients. Students develop skills to leverage innovative technology to optimize workflow efficiency, and foster self-care engagement strategies for patients.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS AND THEIR IMPACT ON CHRONIC DISEASE

While health behavior and genetic factors influence chronic disease risk, we know that social determinants of health are also powerful drivers of disease incidence. These determinants include conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age and are known to relate to chronic disease risk.3 Exposing students to the breadth of determinants and their potential impact on health is necessary across the curriculum.

At the University of Delaware, the Social and Environmental Determinants of Health course offered to graduate students in public health and health promotion explores income, living conditions, education and other factors that impact health and longevity. Through readings and case studies, students learn more about factors and drivers of population health.

Wilmington University’s new MS in Health Sciences includes concentrations in both Public Health and Environmental Health. Both include the Foundations of Community and Health Education course that provides a focus on trends in community health disparities and health promotion strategies and education principles to combat adverse events. Within the Population Health concentration students further delve into the issues of determinants of health and their underlying causes. Interprofessional management of complex issues in population health is emphasized within the context of healthcare policy, value-based care, and the use of data analytics. Health Science students further collaborate with the MS in Environmental Science program in a course in Human Health and the Environment. Chronic illness as it relates to and is impacted by environmental factors is examined. The MSN program includes a

Public Health concentration. Within the DNP program students also gain valuable knowledge from a Population Health course. This course incorporates experiential engagement time at a site focusing on a vulnerable population. Students collaborate with healthcare peers to develop a community based action research project to improve health outcomes and utilize a logic model to evaluate the effectiveness of the program.

POLICY INFLUENCES ON LIVING WITH CHRONIC ILLNESS

Living with and often dying from chronic disease are complex and emotional experiences. Since many of our students aim to work with patients and in the community after graduation, it is important to expose them to these realities across the curriculum. In addition, policies at the local-, state- and federal-level often influence how these diseases are identified (via screening), treated and managed, with health insurance policy and access to longterm care and support at the top of the list.

At UD, the Chronic Illness in America course is a perfect example of how students can explore these topics. This innovative course was developed in collaboration with Lori’s Hands, a local nonprofit organization that pairs students with individuals in the community that are living with chronic illness. Student volunteers provide companionship and non-medical support for their clients in the home setting, affording students the chance to see firsthand the experience of their clients and their families. The course provides a wrap-around experience for students, teaching them about topics that their clients face including identity, social determinants, the health care system and the complexity of aging. This scaffolded educational experience allows students to grapple with the intersection of the evidence around chronic illness with the day-to-day realities. The service-learning component of the course, volunteering with Lori’s Hands, along with reflection opportunities maximizes the translation of the information into future practice.

At Wilmington University, All BSN students as well as Health Sciences may choose to focus their core coursework with certificates or electives that can enhance their learning in chronic disease management. The Holistic Palliative and End-of Life Care certificate offers extensive preparation for students to deal with patients facing serious illness or death. This 5 course certificate provides 5 core classes: Topics in Palliative and End of Life Care, The Process of Dying, and Families and Crisis. Through these courses, students are led to explore concepts impacting chronically ill patients such as psychosocial adjustment, social isolation, self-management and advocacy, and quality of life. Additionally, students can choose 3 other courses in a variety of applicable topics such as health psychology or healthcare policy. All Health Sciences are required to take an interdisciplinary course in Health Policy shared with their fellow students within the Law, Policy & Political Science program.

DISCUSSION

Through these examples, we’ve shown just some of the ways that chronic disease can be embedded within the curriculum and these are just a subset of the educational opportunities that exist across the state. Even with these examples, we see several themes that rise to the top. Firstly, interprofessional education is

5

essential to exploration of chronic disease. Across our programs, we see several examples of where students from different fields come together and leverage their expertise to tackle challenges of chronic disease. This collaboration allows students to think outside of their typical training about the challenges and opportunities of diagnosing, treating and living with chronic disease. This in turn prepares them for a workforce that is equally diverse. Patient-centered care provides a focus for students to view these challenges and plan healthcare provisions to meet individual needs and goals of those with chronic illness.

Secondly, our programs value real world applications and community engagement. Across both institutions, students are afforded opportunities to learn from and with communities about the realities of chronic disease. We have found that students thrive when they are challenged to apply what they learn from lectures and readings to the real world experience of patients and communities. This helps them both understand chronic disease better but also to ask more questions about why and how we screen for, care for and support individuals with chronic disease. Lastly, our programs are committed to teaching cutting edge modern and advancements, whether in the realm of epidemiologic methods, treatments or approaches to chronic disease management. The acknowledgment for the increasing use and application of data analytics and digital health technology is evident in many areas of the curricula. This leadership is facilitated by our engagement with research on chronic disease, which spans our institutions and includes others across the state and country.

Delaware

Public Health

CONCLUSION

We present examples of public health training across our institutions that are not designed to be comprehensive, indeed there are other courses and training opportunities across the state in these areas. We encourage our colleagues to share ideas and best practices in these areas moving forward and potentially identify opportunities for cross-program and cross-institutional training on topics of mutual interest.

Dr. Lessard (llessard@udel.edu) and Dr. Herman (angela.j.herman@wilmu.edu) may be contacted at their respective e-mail addresses.

REFERENCES

1. Delaware Department of Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health. (Nov 2019). Chronic Disease in Delaware: Facts and Figures, 2019.

2. Gibbs, T., & Sabine, N. (2022, December 31). Chronic disease management and the healthcare workforce. Delaware Journal of Public Health, 8(5), 176–196.

https://doi.org/10.32481/djph.2022.12.043

3. Hill-Briggs, F., Adler, N. E., Berkowitz, S. A., Chin, M. H., Gary-Webb, T. L., Navas-Acien, A., . . . Haire-Joshu, D. (2020, November 2). Social determinants of health and diabetes: A scientific review. Diabetes Care, 44(1), 258–279.

https://doi.org/10.2337/dci20-0053

Each year, the Delaware Journal of Public Health publishes five different theme issues. Article submissions are accepted on a rolling basis, and the editorial board considers all submissions, both those connected directly to a theme issue, and non-thematic submissions. The editorial board reserves the right to include non-thematic submissions in each issue.

The working publishing calendar and thematic issues for 2024 are as follows:

If you have questions about submissions, ideas for an article, or suggestions for a future theme issue, please email Kate Smith: ksmith@delamed.org

All submissions can be submitted via the online submission portal: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/2DSQN98 Submissions guidelines can be found at: https://djph.org

Journal of Upcoming Issues Issue Submission Publication Chronic Disease February 2024 March 2024 Violence April 2024 May 2024 Cancer & the Power of Preventive Screening June 2024 July 2024 Childhood Development & Education August 2024 September 2024 After COVID - Rebuilding Public Health & Healthcare Resilience October 2024 November 2024 6 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

February - March 2024

The Nation’s Health headlines

Online-only news from The Nation’s Health newspaper

Stories of note include:

Public health girding for funding challenges in 2024

Kim Krisberg

Health care access a struggle for undocumented immigrant children

Teddi Nicolaus

Q&A with Renee Salas: Lancet Countdown brief urges US action on climate change

Minoli Ediriweera

Healthy People 2030 champions advance US health objectives

Michele Late

Report: America falling behind in global science, technology

Kim Krisberg

States using Medicaid funds for firearm violence prevention

Mark Barna

Team sports can be a home run for your child’s health

Teddi Nicolaus

Many other articles available when you purchase access

Entire Issue $12

Visit https://www.thenationshealth.org/user

HIGHLIGHTS FROM The NATION’S HEALTH A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION 7

Laura Lessard, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Chronic Disease Risk of Family Child Care Professionals: Results of a Statewide Survey of Health and Wellbeing Indicators

Department of Health Behavior and Nutrition, Delaware Institute for Excellence in Early Childhood, University of Delaware

Rena Hallam, Ph.D.

Delaware Institute for Excellence in Early Childhood, Department of Human Development and Family Sciences, University of Delaware

ABSTRACT

Objective: To document the chronic disease risk factors and prevalence rate of family child care professionals. Given that a significant number of young children spend time in family child care (FCC) settings, these environments are an important focus for efforts to improve children’s health. Methods: Data were collected in fall 2021 from a statewide survey of licensed FCC professionals in one mid-Atlantic state (N=541), using validated questionnaires to assess health status, including chronic diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes, and asthma, as well as nutrition and physical activity. Results: While a majority of respondents reported good overall health and adherence to healthy behaviors like drinking water, eating fruits and vegetables, and engaging in physical activity, a substantial proportion were overweight or have obesity (86.1%), and there were notable rates of high blood pressure (41.1%) and asthma (17.9%). The study found higher diabetes rates among FCC professionals compared to national averages for early childhood education workers, possibly reflecting demographic differences. Conclusions: The results highlight both areas needing support, such as managing chronic disease risks, and areas where FCC professionals excel, like maintaining healthy lifestyle habits. Policy Implications: There is a need for targeted support for FCC professionals to manage and prevent chronic diseases, thereby ensuring their wellbeing and enabling them to continue being positive health role models for the children in their care.

INTRODUCTION

Given that 60% of young children (ages 0-5) have at least one weekly nonparental care arrangement,1 these environments are important determinants of the health and wellbeing of children and families. While most of the child care literature is focused on center-based programs, home-based or family child care (FCC) programs are an important environment to consider. In family child care programs, a small number of mixed aged children (typically <10) are cared for in a home setting, generally with one or two adults. FCC programs are a popular choice for infants and toddlers,1 children from non-English speaking households, and those in rural areas.2

Understanding the chronic disease risk of FCC professionals is important for several reasons. A healthy professional ensures the safety and wellbeing of the children in their care, maintains consistency and reliability in caregiving, and contributes to the children’s emotional security. The emotional and mental health of the provider influences their interactions with children, impacting the quality of care. Research shows that child care providers who were more positive showed more optimism, provided higher quality of care and expressed less negative regard and more positive remarks towards the children.3

In addition, FCC professionals serve as role models for the children in their care. Research suggests that when staff do not engage in outdoor play, children engage in significantly less physical activity,4 and child care provider practices around

mealtime are associated with child dietary intake.5 It is important to identify opportunities to leverage educators’ positive health behaviors and address barriers to improving other health behaviors. Despite the importance of the health of this workforce, few studies have documented their chronic disease risk, which is needed in order to identify assets and opportunities to provide support.6 To address this gap, this study focused on FCC professionals and sought to determine their health status in relation to chronic disease.

METHODS

A statewide survey of licensed FCC professionals was conducted in the fall of 2021. The full methods are available elsewhere,7 but briefly, a series of email invitations were sent by the state’s licensing office to all licensed FCC professionals (N=541). Respondents were eligible to enter a raffle for one of fifteen $200 gift cards.

MEASURES

Survey items were drawn or adapted from existing, validated questionnaires. Demographic and health status items were drawn from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.8 To measure chronic disease status, respondents were asked to report, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse or other health professional that you have…” with options of high blood pressure, diabetes, pre-diabetes or borderline diabetes and asthma.

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2024.03.03

8 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

Nutrition items were drawn from the Food Attitudes and Beliefs Survey9 and included questions related to water consumption and frequency of fast food consumption. Physical activity was assessed using items drawn from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) survey,10 which asked about the frequency and duration of physical activity at the moderate to intense level.

DATA ANALYSIS

After data cleaning procedures, which included removing duplicates and respondents who answered fewer than 20% of questions, data were analyzed using descriptive statistics appropriate to the measure (e.g. frequencies, means). Body Mass Index (BMI) was classified using the standard formula and established cutoffs for adults (e.g. overweight defined as a BMI of 25-29.9; obesity defined as a BMI of 30 or higher).

RESULTS

A total of 168 responses were included in the analysis (31% response rate). The majority of respondents identified as White (53.6%), with another third (34.3%) identified as Black or African-American (Table 1). Just 12 respondents (7.3%) identified as Hispanic, Latino/a or of Spanish origin. Only 10.2% of respondents (n=17) reported currently receiving SNAP benefits in the past 12 months. The mean number of hours worked per week was nearly 50 hours.

In terms of health status, the majority of respondents rated their overall health as Excellent (14.9%) or very good (47.4%) and a high proportion reported zero days in the past 30 days when their physical (73%) health was not good. Despite those reports, 86.1% of respondents are overweight or have obesity, 41.1% have diagnosed high blood pressure, and 17.9% have diagnosed asthma.

A very small proportion of respondents reported financial barriers to health care, and nearly all respondents reported having one or more people they think of as a personal doctor or health care provider. A majority of respondents reported drinking four or more cups of water per day (71.1%), eating fast food <1 time per week (77.3%), consuming five fruits and vegetables each day (77.0%), and participating in moderate to vigorous physical activity at least three days per week (56.2%).

CONCLUSIONS

This study provided a portrait of chronic disease prevalence and risk factors among FCC professionals, identifying areas of potential support and other areas to be celebrated. The diabetes rate in our sample (12.7%) was nearly double the rate found in a recent national survey of ECE workers (6.5%), which included both center-based and homebased educators.11 This increase may partially be due to the demographics of FCC educators in Delaware; 34.3% of our sample was Black or African-American, communities that have been disproportionately impacted by diabetes.12 The asthma rate in our sample (17.9%) is comparable to other national studies of ECE workers,11,13 but much higher than population-based estimates for women, and nearly 50% higher than the rate for women in the State of Delaware (12.6%). The existing research is inconclusive regarding the reason for this elevated risk, but one possible explanation includes poor indoor air quality in home and work environments due to high rates of pesticide use.14

NumberPercentage Demographics Identifies as White 8953.6 Identifies as Black or AfricanAmerican 5734.3 Identifies as Hispanic, Latino/a or of Spanish origin 12 7.3 SNAP Recipient 1710.2 Hours per week worked at child care job (mean, SD) M = 49.54SD = 16.6 Health Status Overall health rated excellent 2314.9 Overall health rated very good7347.4 Overall health rated good 5334.4 Overall health rated fair 5 3.2 In the past 30 days, zero days when physical health was not good 10873.0 Body Mass Index Classification Normal or underweight 2013.9 Overweight 6041.7 Obese 6444.4 Chronic Disease Diagnosis High blood pressure 62 41.1 Diabetes 1912.7 Pre-diabetes or borderline diabetes 2114.1 Asthma 2717.9 Health Care Access Health insurance coverage 141 87.6 One or more person they think of as a personal doctor or health care provider 141 92.8 Needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost within the past 12 months 1711.2 Health Behaviors Drink four or more cups of water per day 9671.1 Eat fast food <1 time per week 9977.3 Typically eat five or more fruits or vegetables each day 104 77.0 Three or more days per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity 7756.2

9

Table 1. Demographics and Chronic Disease Profile of Family Child Care Professionals, Delaware, 2021

In contrast, a high proportion of our respondents reported following recommended health behaviors including water drinking, fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity. The rates in our sample are higher than other studies of FCC educators which found closer to 50% of respondents reporting these healthy behaviors,15 compared to the 70-77% we found in our study. This difference may be due to timing; the previous study was conducted in 2014 and our data were collected in 2021. One limitation of our study was the relatively small sample size (n=168), however our response rate (31%) was significantly higher than several other published studies of FCC educators.15 Another limitation is that these data were collected during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and may have been influenced by pandemic-related factors such as lack of access to healthcare that influenced our respondents ability to seek care and receive chronic disease diagnosis and treatment.16

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

This study paints a picture of the chronic disease related health and behaviors of FCC professionals across the state. Future work should explore whether and how existing evidence-based chronic disease prevention and management programs, such as the National Diabetes Prevention Program and others, can be successfully implemented with FCC professionals. Additional work should also be done to explore the reasons for the elevated asthma rate found in our sample and other samples of child care professionals. Dr. Lessard may be contacted at llessard@udel.edu

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Early Childhood Program Participation: 2019 (NCES 2020-075REV), Table 1.

2. Tonyan, H. A., Paulsell, D., & Shivers, E. M. (2017). Understanding and incorporating home-based child care into early education and development systems. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 633–639.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1324243

3. de Schipper, E. J., Riksen-Walraven, J. M., Geurts, S. A. E., & Derksen, J. J. L. (2008). General mood of professional caregivers in child care centers and the quality of caregiver–child interactions. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(3), 515–526.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.07.009

4. Boyle, M. H., Olsho, L. E. W., Mendelson, M. R., Stidsen, C. M., Logan, C. W., Witt, M. B., . . . Copeland, K. A. (2022, June 1). Physical activity opportunities in US early child care programs. Pediatrics, 149(6), e2020048850.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-048850

5. Hasnin, S., Saltzman, J. A., & Dev, D. A. (2022, April 8). Correlates of children’s dietary intake in childcare settings: A systematic review. Nutrition Reviews, 80(5), 1247–1273. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab123

6. Lessard, L. M., Wilkins, K., Rose-Malm, J., & Mazzocchi, M. C. (2020, January 8). The health status of the early care and education workforce in the USA: A scoping review of the evidence and current practice. Public Health Reviews, 41, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-019-0117-z

7. Lessard, L., Hallam, R., Drain, D., & Ruggiero, L. (2022, March 19). COVID-19 vaccination status and attitudes of family child care providers in Delaware, September 2021. Vaccines, 10(3), 477.

https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030477

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

9. Erinosho, T. O., Pinard, C. A., Nebeling, L. C., Moser, R. P., Shaikh, A. R., Resnicow, K., . . . Yaroch, A. L. (2015, February 23). Development and implementation of the National Cancer Institute’s Food Attitudes and Behaviors Survey to assess correlates of fruit and vegetable intake in adults. PLoS One, 10(2), e0115017.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115017

10. Nelson, D. E., Kreps, G. L., Hesse, B. W., Croyle, R. T., Willis, G., Arora, N. K., . . . Alden, S. (2004, Sep-Oct). The health information national trends survey (HINTS): Development, design, and dissemination. Journal of Health Communication, 9(5), 443–460.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730490504233

11. Elharake, J. A., Shafiq, M., Cobanoglu, A., Malik, A. A., Klotz, M., Humphries, J. E., . . . Gilliam, W. S. (2022, September 22). Prevalence of chronic diseases, depression, and stress among US childcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventing Chronic Disease, 19, E61.

https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.220132

12. Rodríguez, J. E., & Campbell, K. M. (2017, January). Racial and ethnic disparities in prevalence and care of patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes, 35(1), 66–70.

https://doi.org/10.2337/cd15-0048

13. Kwon, K. A., Ford, T. G., Salvatore, A. L., Randall, K., Jeon, L., Malek-Lasater, A., . . . Han, M. (2020). Neglected elements of a high-quality early childhood workforce: Whole teacher well-being and working conditions. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1–12.

14. Querdibitty, C. D., Williams, B., Wetherill, M. S., Sisson, S. B., Campbell, J., Gowin, M., . . . Salvatore, A. L. (2021, August 11). Environmental health-related policies and practices of Oklahoma licensed early care and education programs: Implications for childhood asthma. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8491.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168491

15. Tovar, A., Vaughn, A. E., Grummon, A., Burney, R., Erinosho, T., Østbye, T., & Ward, D. S. (2016, November 14). Family child care home providers as role models for children: Cause for concern? Preventive Medicine Reports, 5, 308–313.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.010

16. Roy, C. M., Bollman, E. B., Carson, L. M., Northrop, A. J., Jackson, E. F., & Moresky, R. T. (2021, July 13). Assessing the indirect effects of COVID-19 on healthcare delivery, utilization and health outcomes: A scoping review. European Journal of Public Health, 31(3), 634–640.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab047

10 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

Start or Advance Your Health Care Career With Wilmington University

Tremendous opportunity awaits you in the health care industry. No matter where you are in your career, WilmU has a health sciences degree designed to fit your professional goals and your busy schedule.

Associate of Science in Health Sciences

The ever-evolving health care landscape continually creates novel roles, and individuals with foundational knowledge in health care coupled with specific, concentrated skill sets can prove increasingly marketable in these new positions. WilmU’s A.S. in Health Sciences is intended to create exactly these opportunities for entry-level career starters, as well as mid-career changers, to enter health care positions with maximal career mobility.

Bachelor of Science in Health Sciences

Our B.S. in Health Sciences program is designed for students who have an interest in health care roles that provide managerial, educational and/or clinical expert direction in a health care setting. This program can be tailored to meet specific career goals by using electives to complete a related WilmU certificate and/or through meaningful, hands-on cooperative learning experiences that build skill sets and expand professional networks.

Master of Science in Health Sciences

Prepare to improve health outcomes across the continuum of care using evidence-based practice and data-driven decision making with WilmU’s M.S. in Health Sciences. This interdisciplinary program exposes students to different viewpoints and problemsolving strategies, placing strong emphasis on health care policy and environmental influences, population-based health interventions, and a cross-cultural approach toward all individuals in the prevention of illness and promotion and management of health.

Upon graduation, students will be eligible to pursue certification as a Certified Health Education Specialist. This designation demonstrates a mastery of skill sets for multiple arenas: nonprofit, government and for-profit acute or community-based health care organizations. Graduates will be equipped to deliver education both formally and informally to individuals and populations from an environmental health or population health perspective.

Part of a Series of Accelerated, Stackable Credentials

WilmU’s Dual-Credit ADVANTAGE™ lets you accelerate from one degree to the next by applying credits from the Health Sciences associate degree to the B.S. program. Go even further by incorporating graduate-level courses into your bachelor’s in Health Sciences program. It’s a great way to save time and tuition dollars! Learn

more at: go.wilmu.edu/HealthSciences

ADVANTAGE are registered trademarks of Wilmington University. All rights reserved. © Wilmington University 2024 11

WilmU and Dual-Credit

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Lung Cancer in Delaware

Brian Nam, M.D., F.A.C.S.

Department of Thoracic Surgery, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, ChristianaCare Health Services, Inc.

Yeonjoo Yi, Ph.D.

Institute for Research on Equity and Community Health (iREACH), ChristianaCare Health Services, Inc.

Kevin Ndura, M.B.A.

Institute for Research on Equity and Community Health (iREACH), ChristianaCare Health Services, Inc.

Krishna Vasireddy, Pharm.D., M.S.

Delaware Health Information Network (DHIN)

Claudine Jurkovitz, M.D., M.P.H.

Institute for Research on Equity and Community Health (iREACH), ChristianaCare Health Services, Inc.

Kiran Kattepogu, M.B.B.S., M.P.H.

Department of Thoracic Surgery, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, ChristianaCare Health Services, Inc.

ABSTRACT

Background: COVID-19 has greatly impacted the U.S. health system. What is not as well-understood is how this has altered specific aspects of lung cancer care. While cancer incidence and screening have been affected, it is not known whether pre-existing racial and socioeconomic disparities worsened or if treatment standards changed. The purpose of this study is to provide a comprehensive analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on lung cancer in the state of Delaware. Methods: Health care claims were analyzed from the Delaware Health Care Claims Database for the years 2019-2020. Patients with a new lung cancer diagnosis and those who had undergone lung cancer screening were identified. Demographic and socioeconomic variables including gender, age, race, and insurance were studied. Patients were analyzed for type of treatment by CPT code. The intervention of interest in this study was the institution of restrictions at the end of March 2020. An interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) was utilized to evaluate baseline levels and overall trend changes. Results: The incidence of lung cancer diagnoses and lung cancer screenings decreased in the nine-month time period after the initiation of COVID-19 lockdowns. Demographic and socioeconomic variables including gender, race, income, and education level were not affected; however, statistical differences were seen in the most elderly subgroup. Treatment modalities including number of surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy did not change significantly. Conclusions: COVID-19 has had a significant impact on lung cancer care within the state of Delaware. Lung cancer incidence, screenings, and elderly patients were affected the most.

INTRODUCTION

The first cluster of cases of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus2 (SARS-CoV-2) was reported in Wuhan, China in December of 2019.1 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention detected the first laboratory-confirmed case in the U.S. on January 20, 2020.2 In Delaware, a State of Emergency was issued on March 12, and stay-at-home restrictions were instituted on March 23, 2020. Since then, COVID-19 has been responsible for the deaths of around 3000 Delawareans,3 and more than one million Americans.4

COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact on health care in the US and health systems needed to adapt to this new reality. Restrictions limited the spread of infection; however, access to care was impaired. Providing timely cancer care was an ongoing challenge as health systems and physicians adopted new practice models to deal with the influx of acutely sick patients. Treatment standards, along with patient perceptions towards care, may have been altered. Pre-existing disparities may have

worsened as well. The impact on cancer care delivery is not yet fully understood, and a comprehensive examination of the effects of the pandemic on lung cancer has not been performed to date. The objective of this study is to evaluate impact of COVID-19 on lung cancer care in Delaware.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Health care claims from the Delaware Health Information Network Database were collected for the years 2019-2020. Two populations were identified using ICD-10 and CPT codes: patients with a new lung cancer diagnosis (ICD- 10 code C34.9) and those who have undergone lung cancer screening (CPT code 71271). These two study populations were analyzed separately. The study population for lung cancer screening was selected according to the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, which recommends annual screening for adults aged 50 to 80 years who have a 20 pack-year smoking history and are current smokers or have quit within the past 15 years.5

Doi: 10.32481/djph.2024.03.04

12 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

From these claims, we obtained demographic information (gender, age at diagnosis or screening, race), type of cancer treatment – i.e., surgery (CPT codes: 32440, 32482, 32484, 32504, 32505, 32663, 32668, 32669, 32670, 32671), chemotherapy (CPT codes: 96401, 96402, 96409, 96411, 96413, 96415, 96416) and radiation (CPT codes: 32701, 77412, 77470) – as well as census tract information. We further linked the census tract data to the American Community Survey to obtain socio-economic information such as median income.6

Statistical Analysis

An interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) was used to evaluate the level and trend changes in lung cancer incidence and screenings from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020.7–10 Primary outcomes were defined as the weekly number of new lung cancer cases, the weekly number of screenings and the monthly number of different treatment modalities. A breakpoint in significant level changes and trends was identified corresponding to the institution of COVID restrictions at the end of March 2020.

Patient-level demographics are summarized as descriptive statistics. Median income was defined as $90,000/year based on the Pew Research Center definition for 2020.6 Continuous variables are presented as means and medians, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies. Group differences were evaluated by chi-squared and Fisher-Exact tests for categorical variables and T-test for continuous variables. All tests were 2-sided and statistical significance was set at p ≤0.05.

Segmented regression analysis used statistical models to estimate levels and trends of outcomes before the pandemic and after the institution of restrictions. The fitted model was selected using stepwise selection and AIC (Akaike information criterion). Sensitivity analyses were performed. The trend before the pandemic was added to the final model as a control variable. Segmented regression with an ordinary least-squares method was used in this analysis. Autocorrelation was assessed by examining the plot of ACF (Autocorrelation Function) and PACF (Partial Autocorrelation Function) residuals and conducting Durbin-Watson and Breusch-Godfrey tests. After detecting autocorrelations, these were adjusted for standard errors. Subgroups analyses were conducted to examine whether changes

in new lung cancer and lung cancer screening varied according to age group and insurance. Segmented regression was used to measure parameter estimates and 95% confidence interval (CI) for immediate (level) changes in the outcome as well as changes in the trend (slope). The Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare median of monthly counts of lung cancer treatments between the two time-periods. Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2 and SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

A total of 2,031 patients with a new diagnosis of lung cancer and a total of 4,285 patients who underwent lung cancer screening were identified during a two-year period from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2020.

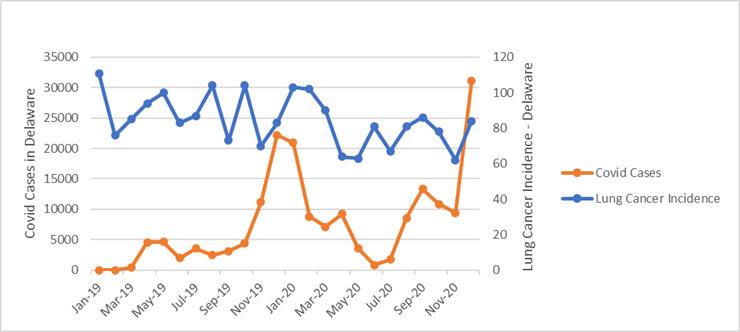

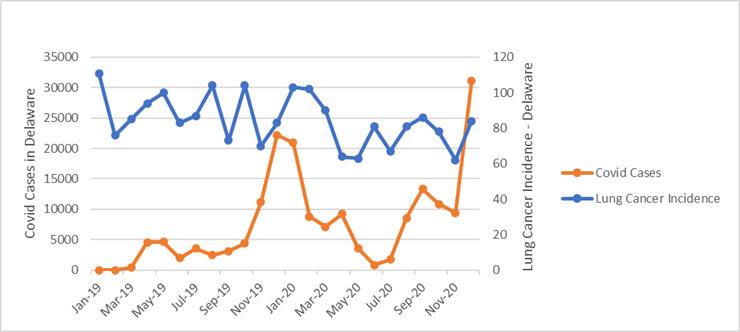

Lung Cancer Counts

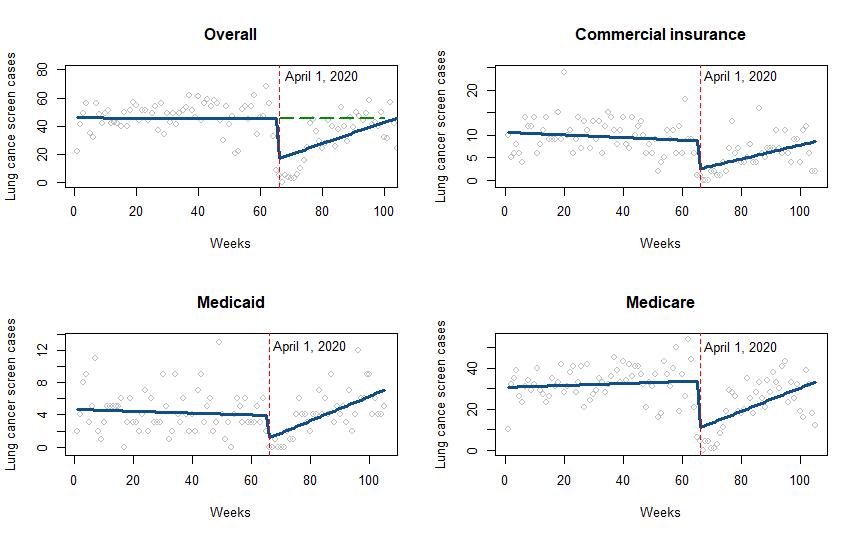

The monthly counts of newly diagnosed lung cancer cases along with the number of new COVID cases in Delaware are shown in Figure 1. Several demographic and socioeconomic groups were examined for worsening of pre-existing disparities (Table 1). No significant differences were seen between the two time-periods in mean age, gender, race, insurance, geographic county, or income level. However, a significant change was seen in the most elderly population, ages 81-90 (p=0.038) for whom the frequency of new cases of lung cancer was much lower during the COVID time-period.

Segmented regression results are provided in Table 2 Autoregressive error models were used to quantify changes over time and compare patterns before and after April 1, 2020. The Durbin-Watson statistic for the regression model of lung cancer incidence was 2.0901 (p-value for hypothesis of negative autocorrelation =0.3023, p-value for hypothesis of positive autocorrelation = 0.6977), indicating no autocorrelation. The baseline level before the COVID-19 pandemic was 20.8063 (95% CI: 18.8257 to 22.7869). The trend before the pandemic was flat (0.0026; 95% CI: -0.0481 to 0.0533). The level change (p-value=0.005) in incidence of new lung cancers decreased by 4.204 (95% CI: -7.3717 to -1.0364) or 20% immediately after the institution of restrictions after April 1, 2020. There was no evidence of significant recovery or upward trend change, even though restrictions were lifted on June 1, 2020 (Figure 2).

13

Figure 1. Monthly Lung Cancer Incidence and COVID Cases in Delaware Before and During the Pandemic

The grey circle represents the observed weekly lung cancer screening cases. The solid blue line corresponds to the fitted regression line for each of the two study intervals.

The vertical dashed red line indicates the institution of restrictions on April 1, 2020.

Results of age group sub-analyses are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. The institution of restrictions had an immediate effect on new lung cancer diagnoses for individuals of the ages 80-90 (-1.5424, 95% CI: -2.9151 to -0.1697). This represents a 37% decrease in incidence within this cohort. Changes in age groups 20-69 and 70-79 were small and not statistically significant.

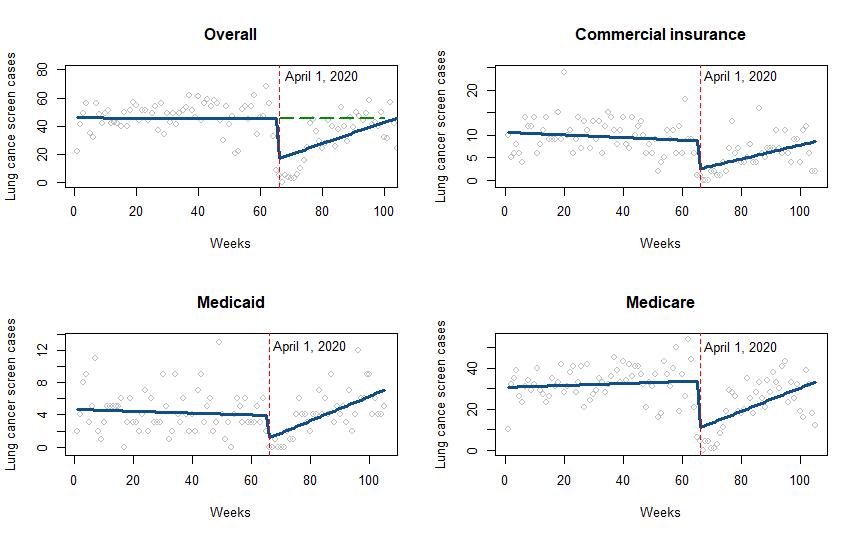

Lung Cancer Screening

Several demographic and socioeconomic groups were again examined for worsening of pre-existing disparities (Table 3). No significant differences were seen in screening frequency according to age groups, mean age, gender, race, or income level.

Compared to patients who were screened before the pandemic, those screened after April 1, 2020 were more likely to have Medicaid and less likely to have commercial insurance (p=0.0002). Differences between the two time-periods were also seen in the proportions of patients screened per county (p<0.0001).

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 3, the weekly overall count of patients undergoing lung cancer screening was constant prior to the pandemic at approximately 46 per week, with a nonsignificant decrease of 0.0073 per week. However, the restriction in services due to COVID-19 led to a sharp decrease of 29 screenings per week (95% CI: -42.6616 to -15.4949) immediately after March 31 followed by a gradual and significant increase of 0.7625 (95% CI: 0.2184 to 1.3066) lung cancer screenings per week. The estimated trend for the post-COVID pandemic was 0.7552 [95% CI: 0.2851 to 1.2251], (0.7552= trend pre (-0.0073) + changes in trend after pandemic (0.7625)).

The best-fitting model estimates for each of the insurance categories are given in Table 4. The immediate decreases in the counts of patients undergoing screening in the first week just after April 2020 were significant for the three types of insurance: -6.3933 (72.83%) for commercial insurance, -2.9467 (62.95%) for Medicaid, and -23.413 (69.40%) for Medicare.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the pandemic effect diminished over time with the number of lung cancer screenings increasing. The absolute difference and relative difference between the hypothetical number of cases on the counterfactual line and the

Jan 1, 2019 - Mar 31, 2020 (n=1365)Apr 1, 2020 - Dec 31. 2020 (n=666) P-value Age, mean (SD) 71.17 (9.69) 70.51 (9.17) 0.138 Age Groups 20 - 69 553 (40.51%) 282 (42.34%) 0.038 70 - 79 537 (39.34%) 281 (42.19%) 80 - 90 275 (20.15%) 103 (15.47%) Gender Female 685 (50.18%) 336 (50.45%) 0.910 Male 680 (49.82%) 330 (49.55%) Race AA 138 (10.11%) 66 (9.91%) 0.999 White 994 (72.82%) 474 (71.17%) Other 75 (5.49%) 36 (5.41%) # of missing 158 (11.58%) 90 (13.51%) Insurance Commercial 150 (10.99%) 69 (10.36%) 0.869 Medicaid 132 (9.67%) 62 (9.31%) Medicare 1083 (79.34%) 535 (80.33%) County Kent 252 (18.46%) 122 (18.32%) 0.137 New Castle 594 (43.52%) 262 (39.34%) Sussex 519 (38.02%) 282 (42.34%) Income < 90,000 502 (36.78%) 266 (39.94%) 0.161 >90,000 83 (6.08%) 30 (4.50%) # of missing 774 (56.70%) 365 (54.80%) 14 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

Table 1. Demographics of New Lung Cancer Patients Before and After April 1, 2020

All models are unadjusted. 95% Confidence Interval (CI) in brackets, Estimates from best-fitting segmented regression. *Statistically significant with p-value ≤ 0.05.

observed number of cases was smaller six months (10.766 and -0.239) after March 31, 2020 compared to three months (19.922 and -0.439). At three months after the pandemic, the absolute difference for the number of lung cancer screening per week was 4.18 for commercial insurance, 0.99 for Medicaid, 17.153 for Medicare compared with what the number of cases would have been if the trend observed prior to the pandemic had not been interrupted, indicating that lung cancer screening recovered faster for patients on Medicaid than for patients on commercial insurance and Medicare.

The grey circle represents the observed weekly lung cancer screening cases. The solid blue line corresponds to the fitted regression line for each of the two study intervals. The vertical dashed red line indicates the institution of restrictions on April 1, 2020. The dashed green line represents the counterfactual. If the institution of restrictions had not happened, the blue line would have continued as shown by the green line.

Figure 2. Weekly Numbers of Lung Cancer Diagnoses in Delaware from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020

Level Before Pandemic (95% CI) Trend Before Pandemic (95% CI) Absolute Changes in Levels After the Institution of Restrictions April 1, 2020 (95% CI) Overall 20.8063 (18.8257,22.7869)* 0.0026 (-0.0481,0.0533) -4.204 (-7.3717,-1.0364)* Age 20-69 8.4961 (7.4703,9.522)* 0.0001 (-0.0262,0.0264) -1.4427 (-3.0878,0.2022) Age 70-79 8.0906 (6.7995,9.3816) * 0.0033 (-0.0297,0.0363) -1.249 (-3.3138,0.8158) Age 80-90 4.2204 (3.3621,5.0787) * -0.0006 (-0.0226,0.0213) -1.5424 (-2.9151,-0.1697) *

Table 2. Interrupted Time Series Regression Analysis of Lung Cancer Incidence Overall and Per Age Group

15

All models are unadjusted. 95% Confidence Interval (CI) in brackets, Estimates from best-fitting segmented regression. *Statistically significant with p-value≤0.05.

Jan 1, 2019 - Mar 31, 2020 (n=3023)Apr 1, 2020 - Dec 31. 2020 (n=1262)P-value Age, mean (SD) 66.133 (5.732) 65.824 (5.857) 0.1106 Age 50-59 491 (16.24%) 229 (18.15%) 0.2805 60-69 1618 (53.52%) 669 (53.01%) 70-79 914 (30.23%) 364 (28.84%) Gender Female 1514 (50.08%) 645 (51.11%) 0.5401 Male 1509 (49.92%) 617 (48.89%) Race AA 213 (7.05%) 106 (8.40%) 0.0597 White 1956 (64.70%) 759 (60.14%) Other 182 (6.02%) 87 (6.89%) # of missing 672 (22.23%) 310 (24.57%) Insurance Commercial 631 (20.87%) 223 (17.67%) 0.0002 Medicaid 280 (9.26%) 164 (13%) Medicare 2112 (69.86%) 875 (69.33%) County Kent 646 (21.37%) 257 (20.36%) <.0001 New Castle 725 (23.98%) 391 (30.98%) Sussex 1652 (54.65%) 614 (48.65%) Income < 90,000 1114 (85%) 468 (37.08%) 0.8444 >90,000 119 (3.94%) 48 (3.80%) # of missing 1777 (58.78%) 739 (58.56%)

Table 3. Demographics of Patients Undergoing Lung Cancer Screening Before and After April 1, 2020

Level Before Pandemic (95% CI) Trend Before April 1, 2020 (95% CI) Immediate Change in Level (95% CI) Change in Trends After April 1, 2020 (95% CI) Overall 45.9419 (36.8882,54.9956)* -0.0073 (-0.2429,0.2283) -29.0783 (-42.6616,-15.4949)* 0.7625 (0.2184,1.3066)* Commercial 10.6625 (8.8195,12.5054)* -0.0289 (-0.0774,0.0196) -6.3933 (-9.3671,-3.4196)* 0.1843 (0.0726,0.296)* Medicaid 4.6811 (3.5419,5.8204)* -0.0114 (-0.0414,0.0185) -2.9467 (-4.7828,-1.1106)* 0.163 (0.0939,0.232)* Medicare 30.55 (24.4714,36.6286)* 0.049 (-0.1094,0.2074) -23.413 (-32.911,-13.9149)* 0.522 (0.1557,0.8883)*

Table 4. Interrupted Time Series Regression Analysis of Lung Cancer Screening Overall and Per Insurance Category

16 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

Jan 1, 2019 - Mar 31, 2020 Median Monthly (range) Apr 1, 2020 - Dec 31, 2020 Median Monthly (range) P-value Surgery (n=283) 14 (10-15) n=191 9 (8-11) n=92 0.0848 Radiation (n=482) 21 (17-23) n=317 17 (15-22) n=165 0.3848 Chemotherapy (n=340) 12 (11-17) n=196 15 (13-21) n=144 0.1023 Median

Table 5. Comparison of Treatment Methods Before and After April 1, 2020

(the first quartile, the third quartile), n=new lung cancer patients.

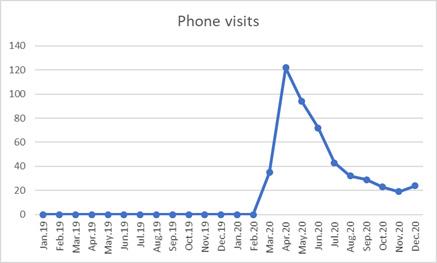

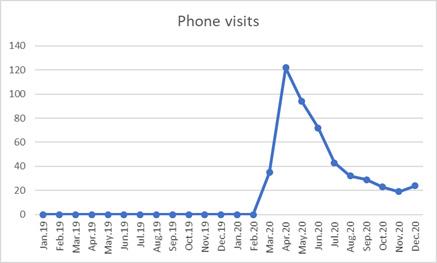

Figure 4. Monthly Phone Visits Before and After the Pandemic

Figure 3. Weekly Numbers of Lung Cancer Screening in Delaware from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020

17

Figure 5. Monthly Number of Healthcare Claims Before and After the Pandemic

Impact of COVID on the Management of Lung Cancer

The impact of the pandemic on the treatment practice of lung cancer was also examined. The median of the monthly numbers of patients receiving surgical resection decreased from 14 to 9 after the institution of restrictions and from 21 to 17 for those receiving radiation therapy, but the differences were not significant (p=0.0848, p=0.3848) (Table 5). An increase was observed for those receiving chemotherapy (median:12 vs 15, p-value = 0.1023); however, this was also not statistically significant.

Impact on Health Care Utilization

Virtual visits in the form of phone visits were a new phenomenon in the care of lung cancer patients. The usage of this modality peaked in April of 2020 and then decreased for the remainder of the year (Figure 4). The average of the monthly number of submitted health claims (Figure 5) decreased by 27% during the months of April and May of 2020 (300,137 claims/month before April 1, 2020 to 218,220)) but returned close to pre-pandemic levels for the remainder of 2020 (292,604 claims/month).

DISCUSSION

These results illustrate the impact of the pandemic on health systems and lung cancer care.

Significant decreases in lung cancer incidence and screening were observed in this analysis are in line with findings from previous studies.11,13

Interestingly, these decreases did not correlate with the course of the virus, or the number of Americans infected; but, rather, with the institution of lockdowns. Lockdowns mitigated the spread of the virus and saved lives; however, restricting access adversely affected cancer care.12 These findings suggest that alternative mitigation plans should be considered in the future.

Screening recovered to pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2020; however, lung cancer incidence did not. These effects may have led to delayed diagnoses and an upshifting of all stages although this could not be analyzed within the scope of this study. Fortunately, a worsening of pre-existing disparities in several demographic and racial/socioeconomic groups was not observed. However, one group that was significantly impacted was the most elderly population (ages 80-90). These patients were the most vulnerable to COVID-related mortality and should be kept at the forefront when developing future healthcare policies.

In the lung screening group, a decrease was observed in those with commercial insurance while those needing Medicaid insurance increased. Likely, this was secondary to employment patterns during the pandemic with patients losing employment and necessitating Medicaid for health coverage. The differences in screening at the county level were likely due to individual health systems resuming their screening programs at different rates.

Treatment paradigms for lung cancer were possibly altered during the pandemic. Fewer patients underwent surgical

resection and more underwent less invasive treatment options such as chemotherapy, although these differences were not statistically significant. Other studies have examined these trends as well14 and are important to keep in mind, so that patients continue to receive the standard of care amidst a future health crisis.

The pandemic adversely impacted total health care claims and health care revenue for the 2020 year. Federal relief funds blunted some of these deficits; however, the need for innovation led to the development of novel alternative forms of care including virtual visits. Virtual medicine persisted even as the pandemic waned and will likely become a permanent option for accessing and delivering health care.

CONCLUSIONS

COVID-19 had a significant impact on lung cancer care within the state of Delaware. Lung cancer incidence, screenings, and the most elderly patients were affected. These findings can be utilized to help shape health policies in the event of a future pandemic. Dr. Nam may be contacted at bnam@christianacare.org

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Work supported by Institutional Development Awards (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20 GM103446 (PI: Duncan) and grant number U54-GM104941 (PI: Hicks)

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. (2020). Pneumonia of unknown cause — China.

https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkowncause-china/en/

2. Holshue, M. L., DeBolt, C., Lindquist, S., Lofy, K. H., Wiesman, J., Bruce, H., . . . Pillai, S. K., & the Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. (2020, March 5). First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(10), 929–936. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

3. Delaware Health and Social Services. (2023, Feb 24). Myhealthycommunity coronavirus COVID-19 data dashboard.

https://myhealthycommunity.dhss.delaware.gov/locations/state/deaths

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, Feb 24). COVID data tracker.

https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

5. Krist, A. H., Davidson, K. W., Mangione, C. M., Barry, M. J., Cabana, M., Caughey, A. B., . . . Wong, J. B., & the US Preventive Services Task Force. (2021, March 9). Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA, 325(10), 962–970.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1117

6. Kochhar, R., & Sechopoulos, S. (2022, April 20). How the American middle class has changed in the past five decades. Pew Research Center

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/04/20/how-the-americanmiddle-class-has-changed-in-the-past-five-decades/

18 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

7. Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S., & Gasparrini, A. (2017, February 1). Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(1), 348–355.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098

8. Bernal, J. L., Cummins, S., & Gasparrini, A. (2021).

Corrigendum to: Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial.

International Journal of Epidemiology, 50(3), 1045.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa118

9. Xiao, H., Augusto, O., & Wagenaar, B. H. (2021, July 9). Reflection on modern methods: A common error in the segmented regression parameterization of interrupted timeseries analyses. International Journal of Epidemiology, 50(3), 1011–1015.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa148

10. Turner, S. L., Karahalios, A., Forbes, A. B., Taljaard, M., Grimshaw, J. M., & McKenzie, J. E. (2021, June 26).

Comparison of six statistical methods for interrupted time series studies: Empirical evaluation of 190 published series. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 21(1), 134.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01306-w

11. Fedewa, S. A., Bandi, P., Smith, R. A., Silvestri, G. A., & Jemal, A. (2022, February). Lung cancer screening rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest, 161(2), 586–589.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.030

12. Van Haren, R. M., Delman, A. M., Turner, K. M., Waits, B., Hemingway, M., Shah, S. A., & Starnes, S. L. (2021, April). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on lung cancer screening program and subsequent lung cancer. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 232(4), 600–605.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.12.002

13. Mariotto, A. B., Feuer E. J., Howlader, N., Chen, H., Negoita, S., & Cronin, K. A. (2023, September). Interpreting cancer incidence trends: challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 115(9), 1109-1111.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djad086

14. Piñeiro, F.M., & Aguado, J. F. (2021, February). Management of lung cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment. 7, 10.

https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-4722.2020.115

Even the best rider is at the mercy of other drivers. If you go too fast, they may cut you off, change lanes, or make turns before they see you coming.

SO WATCH YOUR SPEED, WATCH OUT FOR OTHER DRIVERS, AND STAY SOBER.

ArriveAliveDE.com/Respect-The-Ride

Life'stooshorttogo

19

too fast

From the Delaware Division of Public Health February 2024

New DPH leadership team announced

Delaware Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) Secretary Josette Manning announced a new leadership team at the Division of Public Health (DPH), led by Division Director Steven Blessing.

“This team has extensive experience in managing key areas at DPH,” Secretary Manning said. “They will help our nationally accredited division protect and promote health for all Delawareans.”

Director Blessing oversees over 1,000 staff and manages a $433 million budget in grant and state funding. He previously served as Interim DPH Division Director since September 2023. He was named DPH Deputy Director in October 2022.

For 29 years, Director Blessing has served DPH in various leadership positions, including Emergency Medical Services Director, Paramedic Administrator, and Executive Assistant to the Director. During his 12 years as Chief of the Emergency Medical Services and Preparedness Section, he led the development and expansion of response capacity for health and natural disasters. During the COVID-19 response, Director Blessing managed the State Health Operations Center (SHOC) and was the Incident Commander in the final phases. He also managed the SHOC during Hurricanes Sandy and Irene, the Ebola crisis, and other emergencies.

Director Blessing was elected by his peers as President of the National Association of State EMS Officials from 2008 to 2010. He participated in a number of meaningful projects at the state and national levels.

Director Blessing is a former U.S. Army officer and holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Political Science from the University of Delaware and a Master's degree in Business from Webster University.

“The Division of Public Health is a large and multifaceted agency, staffed with incredibly talented and dedicated professionals,” Director Blessing said. “It is a great honor to have this opportunity to lead at such a critical time and meet the challenges of improving

the overall health status and well-being of people in Delaware.”

Shonetesha (Tēsha) Quail, PhD, LPCMH, NCC was named Deputy Director of DPH in October 2023, providing oversight for over 1,000 employees. Previously, Dr. Quail served as DPH Associate Deputy Director since December 2022 and oversaw the Birth to Three Programs and Community Health Promotion Branch. With 25 years of organizational experience working in the private and government sectors, she ensures health equity with a continuum of care approach and continues to serve as Chief Health Equity Officer.

Dr. Quail began her DPH career in 2013 and oversaw Southern Health Services for Kent and Sussex counties. She teaches classes as an Adjunct Professor at Wilmington University in the College of Health Professions and Natural Sciences.

Dr. Quail graduated from Wilmington University with a Bachelor of Science in Human Resources Management and a Master of Science in Clinical Mental Health Counseling. She became a licensed psychotherapist in 2012 She holds a second Master’s degree in Psychology and has a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Health Psychology with a concentration in Public Health, both from Walden University. Dr. Quail is currently enrolled in the Leadership Development to Advance Equity in Health Care program at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Rebecca D. Walker, PhD, JD, MSN is the Deputy Director for Clinical Sciences. Since coming to DPH in 2020, Dr. Walker served as the Director of Nursing for two years and oversaw multiple sciencebased teams. She has over 31 years of administrative, academic, and clinical nursing experience. Her clinical background is in emergency nursing, surgical trauma, critical care transport, and pre-hospital incident response.

Continued on p. 2

Shonetesha Quail

Rebecca Walker

Shonetesha Quail

Rebecca Walker

20 Delaware Journal of Public Health - March 2024

Steven Blessing

New DPH leadership team ― from p.1

Dr. Walker has served as the President of the Delaware Board of Nursing, the Chair of the Overdose Fatality Review Commission, an Associate Professor in Academia, Director of the International Master of Laws (LLM) program at Widener Law, a health care litigator in Philadelphia, and the Chief of Operations for the Division of Forensic Sciences. She also served the State of Delaware’s 9th District as a state representative Dr. Walker led major statewide initiatives and managed budgets at the Delaware Department of Safety and Homeland Security

Dr. Walker received her foundational nursing education at Delaware Technical Community College (ADN), Wilmington University (BSN), and Wesley College (MSN). She is a 2004 graduate of Widener Law School where she received her Juris Doctor and became a member of both the Pennsylvania and New Jersey Bars. She completed her PhD in nursing research at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Awele Maduka-Ezeh, MD, MPH, PhD, CCHP was recently named Medical Director of DPH. Dr. Maduka-Ezeh is a public health physician with expertise (research and practice) in pandemic preparedness and response among vulnerable and marginalized populations, and in managing public health laboratories.

She previously worked for DPH as State Medical Director and Chief of the Infectious Disease Prevention Section; and Director of the Delaware Public Health Laboratory. Prior to her appointment, Dr. Maduka-Ezeh was the Medical Director and Health Care Epidemiologist for the Delaware Department of Correction’s Bureau of Health Care, Substance Abuse, & Mental Health since 2018.

Dr. Maduka-Ezeh earned her Medical Doctorate from the University of Ibadan in Nigeria in 2000. She received a Master of Public Health from Harvard University in 2005 and completed her Internal Medicine residency at the Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia from 2006 to 2009. In 2011, she completed an infectious diseases fellowship at the Mayo Clinic, where she was also an instructor in medicine. Dr. Maduka-Ezeh earned a PhD in Disaster Science & Management from the University of Delaware in 2020

Dr. Maduka-Ezeh is board-certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine in infectious diseases (2011-2033) and internal medicine (2009-2029).

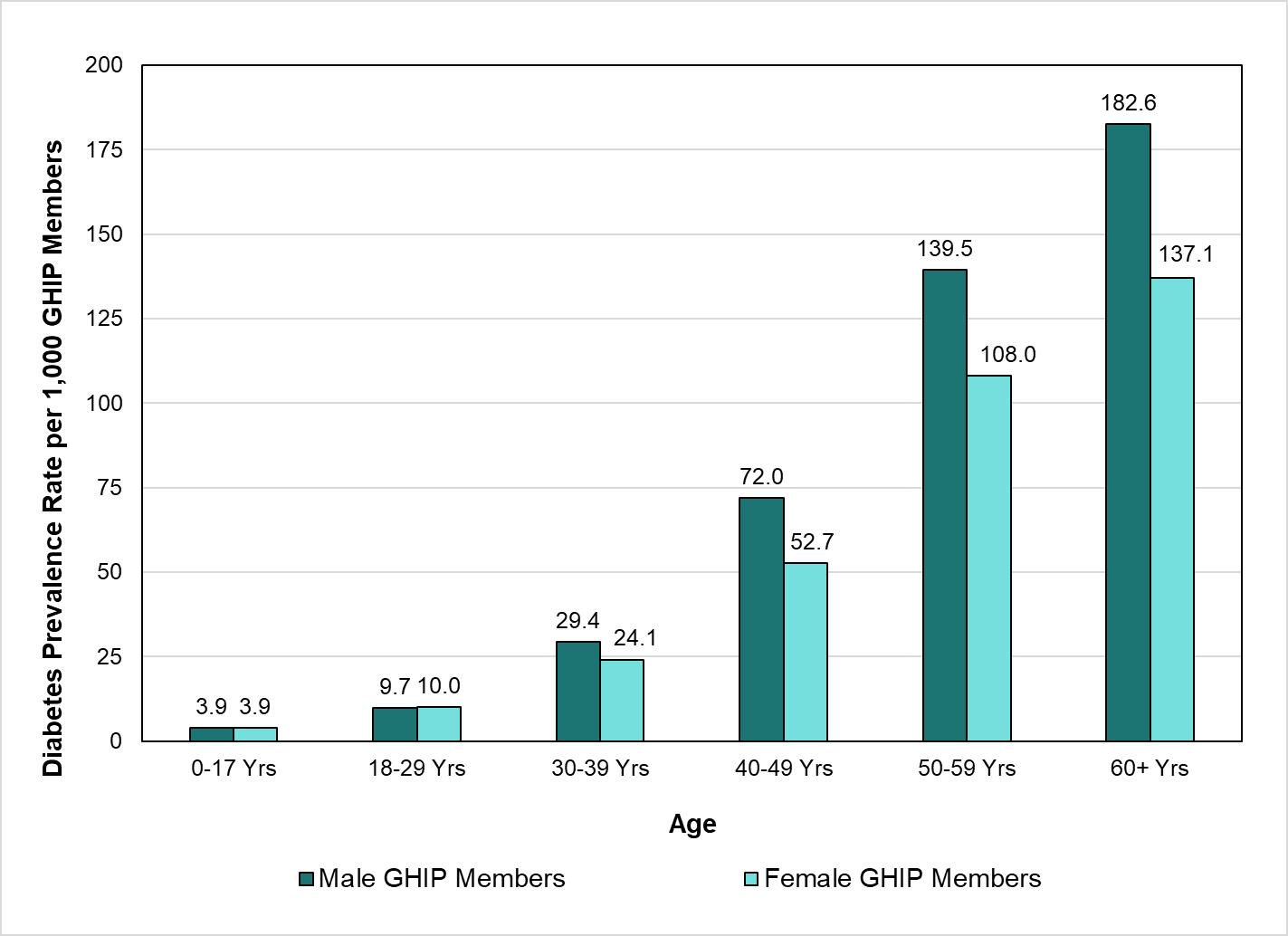

Christina (Tina) Farmer was recently named Chief of Staff of DPH. Farmer represents the Director and Deputies at meetings and hires Director’s Office staff. She coordinates with the DHSS Deputy Attorney General and oversees the Office of Communications, Contracts & Grants, and the Office of Performance Management.