AIRPORT ROAD www.electrastreet.net/airportroad NYU Abu Dhabi 19 Washington Square North New York, NY 10003 Send inquiries to: Cyrus R. K. Patell Publisher Airport Road NYU Abu Dhabi PO Box 903 New York, NY 10276-0903 nyuad.electrastreet@nyu.edu

© 2020 Electra Street

Front and Back Cover Design by Rayna Li

CO-EDITORS

EDITORIAL BOARD

DIGITAL EDITOR EXECUTIVE EDITOR PUBLISHER

Emily Broad Nur’aishah Shafiq Abdi Ambari Emília Vieira Branco Fiona Lin Joseph Hong Karno Dasgupta Emily Broad Deborah Lindsay Williams Cyrus R. K. Patell

Issue 11 Summer 2020

… an unholy loop in history, where one event leads to …

… in a seemingly eternal disaster, because otherwise it will crumble … … people rushing for answers, in a place where fear drives …

… it doesn’t affect me, is the only way to take comfort, saying …

… it is all over, then the cycle repeats again, until it is declared … … again …

Ouroboros

Eddie Electra Han

CONTENTS Emily Broad and Nur’aishah Shafiq, Introduction.........................................9 PROSE Aathma Nirmala Dious, Susan Writes to Papa............................................18 Emily Broad, Gulf Heritage..........................................................................29 Nur’aishah Shafiq, Void..............................................................................34

Jamie Uy, Oxtail .........................................................................................48 Ivy Akinyi, The Whispers of Niyamgiri..........................................................64 Nur’aishah Shafiq, The Apostate................................................................88 Jamie Uy, The Aubergine Autobiographies..................................................99

Jamie Uy, Moth Killing for Beginners.........................................................111

POETRY Eddie Electra Han, Ouroboros......................................................................5 Vamika Sinha, alternate love letter...............................................................15 Nur’aishah Shafiq, dark magic...................................................................17 Emily Broad, Archiving the Climate Age......................................................43 Smrithi Nair, house.....................................................................................52 Tusshara Nalakumar Srilatha, On Earth: a meditation from a mouth...........56

Vongai Christine Mlambo, Tears That Wet The Ground..............................60

Grace Shieh, Wanderer...............................................................................69 Chiran Raj Pandey, Snowpiercer.................................................................71 Athena Thomas, An Ode to Garbage..........................................................74 Cassandra Mitchell, And The Sun Hung.....................................................78 Maria Jose Alonso, Monarcas on Migration................................................84

Sara Pan Algarra, displaced body a letter to God.......................................85

Sreerag JR, ballBuilding..............................................................................96 Mary Collins, What can you do for the earth.............................................108 Nur’aishah Shafiq, CPR...........................................................................114

Grace Shieh, Lost Child, Red...................................................................117

Nur’aishah Shafiq, In Memoriam...............................................................121 VISUAL Achrakat El Fitory, Manking Facing Uncertainty..........................................14

Emily Broad, Black Earth............................................................................16 Vamika Sinha, the sun is a pistol.................................................................28 Noor Altunaiji, Camels Don’t Swim............................................................ 31

Valeriya Golovina, Afternoons at the edge of the coast..............................32 Vamika Sinha, isolation...............................................................................33 Boby Liu Chihling, You Can’t See Me With Your Eyes Closed........... .........42 Vamika Sinha, the errors of hands..............................................................46

Achrakat El Fitory, Revenge of the Earth.....................................................47 Sara Pan Algarra, Airport Road 11 Cover Competition Submission #1.......51 Emily Broad, Jazeerat Al Hamra.................................................................55

Michelle Hughes, looking in or out, toward or away....................................59 Vamika Sinha, sunken.................................................................................63 Achrakat El Fitory, Mourning of the Forest Nymph......................................67 Emily Broad, Infestation..............................................................................68 Rayna Li, personal <-- protection --> Earth.................................................72 Athena Thomas, Trashy Nights & Snowy Days...........................................73

Emily Broad, Factory...................................................................................76 Michelle Hughes, untitled...........................................................................77

Achrakat El Fitory, Where Do We Go Now..................................................82 Al Reem Al Hosani, Airport Road 11 Cover Competition Submission #2....85 Rayna Li, Untitled (Homage to Filippino Lippi).............................................87

Emily Broad, Manmade.............................................................................98

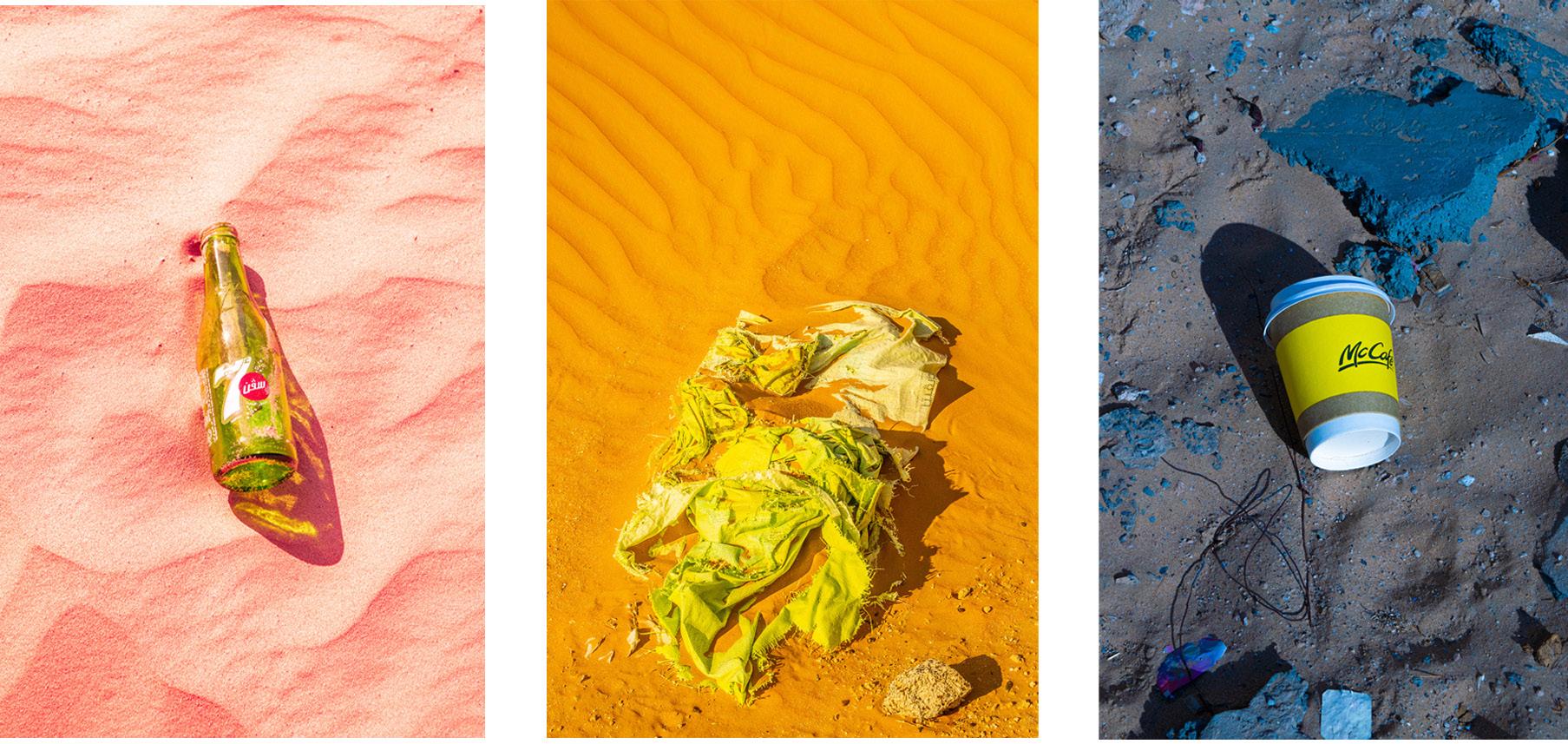

Valeriya Golovina, Kekeno........................................................................107 Emily Broad, Trash Triptych.......................................................................110 Aya Afaneh, Masked.................................................................................116 Sreerag JR, This is How the World Moves................................................119

Rayna Li, Untitled......................................................................................120

INTRODUCTION For many, this year has been and continues to be a lesson in uncertainty. The pandemic reminds us that human endeavors can be easily

disrupted and that safety is conditional in the wake of such disruption. No phenomenon embodies this precariousness more than the climate

emergency, which threatens to render any semblance of stability a thing of the past.

This year alone, we saw Australia burning. Jakarta inundated. The Bay of Bengal ravaged as super cyclone Amphan made landfall. The list of disasters and potential disasters predates 2020 and will continue to

devastate populations with greater frequency and intensity. First to suffer are the vulnerable and marginalized, easily and often obscured. But all strata of society must eventually reckon with ecological breakdown.

The 11th issue of Airport Road became an invitation for student artists within NYUAD to reflect on these existential anxieties, and for us as editors to wrestle with art’s role in an increasingly insecure world.

“Solutions” to the climate emergency have typically been the province of the sciences, both natural and social. Many factions turn to economics and engineering for much needed transformations, or to international politics and climate science for the innovations that might pave the

way to a green sustainable future. Our intention is not to diminish the

importance of such fields, but to make the case that change—lasting,

radical, transformative—requires a shift in values. An introduction of new perspectives or a revision of old ones. And that is where art comes in.

The stories we tell, the images we see, can instigate or critique, reinforce or oppose actions that are taken in other disciplines. Thus, consider

9

Airport Road: To Extinction an offering to such ends: a recognition that a change in priorities must accompany and even at times precede

legislation and societal restructuring. Without such a holistic approach, we risk preserving the mechanisms of power we seek to undo.

The work featured in this issue considers extinctions of various kinds.

Not merely that of our own and other forms of life, but also the extinction of ideas: what are the ways of living and thinking that must come to an

end if we are determined to avoid further loss of life, and honor the lives

that have been lost. What is there to learn and possibly gain amidst such absolute erasure?

As editors, we organized the work into Collapse and Rise, guiding a

journey through various forms of loss and possible ways to continue living despite it all. In doing so, we do not foreclose alternative readings of Airport Road: To Extinction, merely to offer ours.

Although the age of climate change is one of uncertainty, destructive actions are already apparent. In Collapse, one sees the evidence of dystopia in our lives, from the ubiquitous waste we produce to the

annihilation of entire cities. Artists grapple with both present devastation and imagined apocalypse as they confront the paradox that is humanity —to be killing and dying at the same time. Many pieces confront the

struggle families undergo in the wake of this duality, the pain of loving when insufficient care is given to human and non-human life. Against

such insecurity, what does “home” even mean? What is living when so much is collapsing—is death preferable to survival?

Pieces within Collapse also investigate the tension between civilization and the natural world, with some artists attempting to reconcile this

contrast and others deeming it an insurmountable conflict. Elemental

10

motifs of snow and forest and sea are at odds with the human structures of oil rig, satellite dish, and museum. Contestations over space speak

towards processes of change, asking what endures and what is lost. It is a temporal question as much a physical one, as Collapse ends with the recognition that a changing world is no longer an abstract vision on the horizon, but here nowâ&#x20AC;&#x201D;and one we must face without denial.

In Rise, art explores life amid or post-collapse, wrangling with ways to cope and heal. The opening pieces of this section address particular realities of displacement, not just of humans, but other species on

Earth. The lack of security can challenge the conviction in oneâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s faith,

be it in religious entities or more human enterprises. Such questioning demonstrates the capacity for ecological breakdown to destabilize all

that one once believed in. But Rise also seeks answers, other guiding

experiences within such confusion. What new environmentalism is there

to amend the flaws of the current one? Can the wild and the constructed co-exist in mutually benefiting relationships? Can something abhorrent

like waste be beautiful, and what are the implications for consumption?

Rise contends that there is still unexpected knowledge and beauty to be found within a seemingly dying world.

And yet, not everything is immediately fixed. Mistakes are made. Hands

that seek to heal can still hurt. But effort is made to try again, with greater care and attention, always seeking to bring about a kinder future. And

that is how Airport Road: To Extinction ends, as it begins, with the cyclical nature of human history. But in asking how we can break this cyclicity, we do not resign ourselves to fatalism, but commit ourselves to action. To vision and reimagination. To art.

A love letter to our failures and triumphs, Airport Road: To Extinction

contains musings on how to forward as we commit to certain extinctions,

11

whatever they may be. Although there is pain and anger within these pages, thereâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s optimism too, touches of hope that keep us from completely caving to defeat.

We thus invite you now, dear reader, to face the myriad endings and

beginnings to be found in the climate emergency. The journey may be

discomforting, even harrowing. But we ask you to persist, to converse

and imagine. For there are many stories yet to tell, including your own. Emily Broad and Nurâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;aishah Shafiq

12

Part I Collapse

13

Manking Facing Uncertainty Achrakat El Fitory

14

alternate love letter Vamika Sinha

dear ____________,

with you i have learned love

is utopia & dystopia at the same time. so basically, love is Earth

& we are highly skilled to kill

it. like damn, what did you think? all the god in the gold

chains round our necks

could make us beautiful, & holy & not human? we are just bodies, drums

of water & chemicals & constructions, paper -skinned. little marbles of World rubbing

against each other, how

acid leaks from a cloudâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s

cheek more than rain. all this, to say: we are ending.

15

Black Earth Emily Broad

16

dark magic

Nurâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;aishah Shafiq I walk through the city of claws, bleeding.

black fountains erupt at my feet along rivulets of ichor, golden in the half-light of a fading sun. I bleed.

everywhere, there are wounds, vomiting earthsblood

and lifesbane. claws dig into me, taking, taking, taking

the ancient sunlight within, and from these liquid offerings

coaxing darkness. can you taste it. the skies black. burning ether. planetary poison that molds all things living. the monster city stops its labor for the day. I lie down on my metal bed, wet with my dying. ghosts disrupt my respite, empty bodies save for hungry hearts in calcium cages and tumors speckling lungs like stars, cannibalistic stars.

the graveyard shift. after all, killing is a round-the-clock enterprise. my sons, I cry out. in answer, they drag me to my altar. killing is a silent enterprise. more gather. blades lift and fall. the clawed city sleeps. its work does not. killing is a communal enterprise,

but so is dying. my wounds are theirs, so I laugh,

and spit, as flesh peels, carbon leaking at the seams: you are no sorcerer-kings. only elemental.

17

Susan Writes to Papa Aathma Nirmala Dious

Susan has only known her Papa as a myth, growing up on folktales of his presence, the genre changing, ranging from cautionary tale to success

story, depending which tongue of the people of Maruthadi it came from.

Ammama, his mother, described him as a sensitive boy who daydreamed of lands beyond the sea outside their house. Amma described him with a silence, which was more accurate. However the end of all the stories

were all the same. He was not here. He was in the Gulf, fathering a new

set of buildings or pulling oil from the sand, sending money as the dutiful breadwinner should.

Papa left because money lenders searching for the money that is now

Kochamma’s dowry came knocking with threats of taking the roof away. Papa prayed to God, Mother Mary, and Eshopa all in that precise order for help. In a dream, a pathemari came upon the shore of Maruthadi.

Papa stepped on, confused and a thunderous voice that he guessed was the sea, Kadalamma herself, woke him in a sweat. When the sun rose,

Papa heard the call from a pathemari that lulled men with the promise of

dreams made of jewels and gold. In exchange, he would help build a new oasis for Arabis, made of concrete and glass from liquid gold in the Gulf, the new name for Persia.

A dream for a dream after all. A fair exchange. Papa believed this Gulf that Ammama calls Persia is where he can change the future. The night before, Amma cried, putting his hand on her round belly.

“Swear on our child,” she told Papa, “that you won’t drown in their

18

quicksand promises or follow fool’s gold that you will come back to father them–”

He nodded solemnly. Susan’s Papa stepped upon the pathemari the

next day, its belly pregnant with men with carbon copy contract dreams, carrying memorabilia of the family they left and Gods who they hoped would stay with them in foreign lands.

Two months after, neat envelopes of money came every month and the money lenders stopped trying to break down the door.

Susan looks at her dark wrist, adorned with a gold bracelet her Papa put on her toddler hand when he first came back, luggage now filled with gifts. There was a pretty green sari for Kochamma, a gold bangle for

Ammama, a small bottle of whisky for Amma’s Papa, Pappachan (Arabis

drink? No, they don’t, according to Amma, but the Vellakaran bosses from Britain do and Papa secretly got it from the same place). Amma got a

gold ring and her little brother, baptized Jose but nicknamed Unnikuttan, although he came 9 months after that visit. When the sun glinted off the

gold, Susan would stare at the bracelet, till she recalled a soft lullaby and a silhouette of a man by the door. Leaving or coming? Who knows? Was that even Papa? Who knows?

***

When Susan went to school for the first time, Ammama braided her black curls with new red ribbons, bought with gulf money. Amma tugged at her blue pinafore. “Listen, you should work hard. Papa wanted you to study. He said he’ll send over a doll if you study well.”

Ammama whispered just after Amma went to take her bag for her, that she should try becoming the doctor Amma wanted to be. It was years

after when Susan learned Amma was married to Papa before she could

19

even try– Amma’s Papa, Susan’s Pappachan discovered an unread love letter between her 12th standard Malayalam textbook, slipped into her

bag by Susan’s teacher George during class. Kuncheria, Pappachan, first

trashed her to put the fear of God in her because a woman of God should not love but obey. Amma had no Amma to defend her. A month after

she finished school, Papachan commanded that she would be married to Papa. On the wedding day in the church, Amma imagined the gold

chains decorating her getting tighter and tighter around her. She wanted

a stethoscope around her, not this! Pappachan’s quiet glare kept her from running into the sea, back to Kadalamma.

Papa did not know about George’s letter until three months after they

married, when Kochamma heard it from Rosakutty, whose husband drank with Pappachan and then told Ammama. Papa came from his meeting with a gulf recruiter to see Ammama throwing clothes upon Amma,

who was lying on the floor and weeping. He calmly picked her up, told Ammama to stop and took Amma to the safety of the bedroom. “He

asked me and I told him. He actually did not care and then said we should not mention it again.” Amma ended the story with that.

Lucky, They all told Amma, all the time. Papa does not hit you. Papa is a

man from a good Christian family, planning to go to the Gulf soon. He will bring Gold for you.

What they forgot to tell in the stories was how the Gulf, like Kadalamma

on a bad day punishing the fishermen, swallowed men whole and did not return them.

***

“Why did Amma marry Papa?” Susan asked one night, lying next to

Amma on the mat. The only thing Maruthadi’s tales did not have was a love story.

20

Amma turned to stare at her. Susan was still on her mat, expecting the usual silence.

“He had kind eyes, unlike the stone-blank ones the man that got me

married did, and ears that actually listened.” Susan almost sat up if it was not for Amma’s hand on her belly, pressing her down. “Usually a man’s

ego falls as easily and hurts as much as a ripe coconut falling on your foot after you kick the tree. Your Papa never had that. I never understood how. He said it was because he did not want to be like his Papa.”

She paused, stroking Susan’s hair. “He just yearned to give your

Ammama a feast and a house that did not flood from the monsoons.

However he mostly wanted to escape from his Papa, your Appapan, who loved the spirits more than the holy spirit he preached of.” Susan looked at Amma’s face and she could see a tear slowly play with the edge of

Amma’s brown jaw. “That’s why he used to pray to God in Church and

ask Kadalamma by the sea as he sat on the shore to take him and your Ammama somewhere far, somewhere safe. Your Appapan went to God

too soon, just before I met him. I guess we both knew the pain fathers can inflict.”

Later, when only the moon was awake, Susan slowly slipped out and from her door looked at the sea, where her father was last seen. She wondered if fathers can inflict pain even if they were not here. ***

At the wise age of 8 years old, Susan would say yes. Some of the other girls whispered that her Papa is not there and more

bad whispers mimicking the evening talks of their families. She would see their Papas, Appas, Achas and Uppas pick the other girls and boys up

after school, taking their bags, hoisting them on cycles and walking them

21

back. It’s okay. Susan just stared at the board when the girls whispered.

Susan liked studying and learning about rhymes and letters and numbers. Laxmi Teacher always gave her three out of three stars drawn in her

notebook. One month later, Amma came with a doll with white hair and

ghostly blue eyes. “Papa is happy you are studying. I told him about the stars in your notebook.”

Unnikuttan whined about wanting a doll and Amma distracted him with

a box of Quality Street chocolate. Susan smiled at the mention of Papa’s pride. Who cares what the other girls say–her Papa was real. The doll,

now named Mary, sat beside her as she slowly made her way through a

nursery rhyme. She will get more stars and maybe with enough stars, she can bring Papa back.

She whispered a silent wish for Papa to Kadalamma every time she

walked on the beach to school, the sea calm in the morning fog. Fatima, her best friend walked with her but would only stand by because her

Umma would not be happy at her asking anyone else but Allah for her

Uppa, also in the Gulf. Hussain Ikka, older and more impatient than his

little sister Fatima, would keep yelling their names till they started walking again.

***

When Susan’s writing got better, Amma suggested that she write a line in the letter about to be sent to Papa. She painstakingly drew the curls

of her Malayalam to ask if he was okay and when he would come so she

can show him her notebook and eat Unniyappam with him by the beach. Amma added more words of her own, folded the white paper covered in

Camel Ink into a brown envelope and put a stamp with some old man on it.

In a month, with the envelope of money, came Papa’s reply. “Hello

Susankutty. You write so well! Keep studying, okay? Papa will come when

22

the rains start. I am working hard so I can bring chocolates and more

gifts for you. When I come, we will take your Amma and Unnikuttan with

us to the beach, look at the stars above while we eat both the chocolate and unniyappam!”

Susan slowly read it out with the help of Amma. Later, Susan took her

notebook out and slowly copied each letter out again and again in her

notebook, exactly how Papa wrote it. Amma’s eyes watered and blinked a lot when she showed her the notebook. Did she not write it properly? She kept the letter next to her that night.

“I want Papa.”

***

“Unnikuttan.” “I WANT PAPA!” Susan stood by Ammama, watching her Amma fumble at Unnikutttan’s request. Unnikuttan also goes to school now so now Susan walks with

Fatima, Unnikuttan and Ikka. Fatima’s Uppa came today. Everyone saw Hussain Ikka yelling in joy and Fatima smiling as their Uppa took their

bags. Susan and Unnikuttan waved goodbye to them and then stood in silence in front of the school, till Ammama came.

“Unnikuttan, please. I said I will come tomorrow to pick you up. Susan chechi and Fatima chechi and Hussain chetan all walk with you too.” “Their Uppa came back. I want Papa.” “Papa will come soon, Unni—”

23

“YOU ALWAYS SAY THAT. I HAVE NEVER SEEN HIM!” Unnikuttan

stomped around Amma. “I WANT PAPA OR IS HE A GHOST LIKE THE BOYS SAY?”

“What? Who said that? Susan, did you hear this?” All eyes on her now. Amma’s angered ones, Unnikuttan’s teary ones, and Ammama’s curious ones. Susan nodded. “They always say it to me and

Fatima too.” She doubted they would say it about Fatima anymore. It was just her now.

Ammama sighed. “It must be that Rosakutty. She has a nose longer than what the Lord gave her.”

“Mummy, stop. I have to talk to the teacher about this. They cannot keep

parroting their parents,” Amma snapped before slowly kneeling in front of Unnikuttan. “Now, Papa said he will come when the rains start–”

“That’s what he said last time too and he did not come last monsoon,”

Susan blurted out. The letter, among many other similar letters, sat by her notebooks and Mary Doll, that now had brown hair from the dirt.

Unnikuttan turned back on Amma, glaring at her before bursting into tears and running out.

“Unnikuttan!” Amma ran after and caught him just before he left the new gate. “Come in! Now! There’s a storm coming–”

Looking up, Susan saw the dark clouds gather, then looked down at her

brother struggle in her Amma’s arms, screaming for Papa. She could see

24

some of the neighbors pop their heads over the wall between the houses and their doors. houses and their doors. It was just her and her Amma, Ammama and Unnikuttan, and no Papa. Never Papa. The sea’s waves were getting higher. She ran. “Susankutty!” Ammama shouted but unlike Amma, she was slow due to her age and hurting knees.

Susan heard the wind whistle in her ears as her legs carried her to the beach. After a few heavy gasps of air, Susan poked her finger into the fine beige sand. She heard Thoma and Krishna say that if you wrote Kadalamma’s name in the sand, the sea will come to wash it away.

Her finger moved with practice to the letters, more fluent to her now from

rewriting Papa’s letters and school. She stepped back to look at the word and waited. Thoma and Krishna, known pranksters, were lying for sure.

Why would Kadalamma, the sea itself, listen to a child’s words in sand? But before she could formulate an answer, water splashed her out of her

thoughts and before she could move, the water went back and the letters were gone. Susan’s mouth dropped.

Not caring about her only school uniform, Susan knelt down, the wet

sand grains scrapping her legs and dug her index finger back into the

sand to write. Ka-da-l-A-mm-a, bri-ng Pa-pa ba-ck. She had to listen.

How many wishes has Susan said to the horizon? How many stars has

she gotten for her writing? He had to come, he had to come, he had to— As soon as she finished the letters, a wave came. Susan did not see the

wave. It did not just come to the words. Before she could process it, the

25

wave crashed onto her and the force flung her off her knees and salt water entered into her mouth.

Susan does not remember what happened after. She woke up coughing

on her mat, with her Amma shaking her while screaming at her for going to the beach during a storm. Ammama started thanking the cross on the wall. Unnikuttan jumped on her, talking fast about how she had

disappeared and how they found her on the shore, eyes closed, finger in the sand, the rain falling on her.

*** Kadalamma was so angry that night, she flooded all the houses and

toppled all the boats, swallowing people left, right and center. For once,

even the new house Susan’s Papa worked so hard in the Gulf for, did not stop the water from coming. The four of them did not sleep the whole night, trying to pick things off the watery floor.

Susan picked up her bag to put into the cupboard and one of Papa’s

letters fell into the water. She pushed the bag in and scrambled for the letter. She was late. The water covered the letter, smearing the neat malayalam words her father wrote during his nights in the Gulf.

Her tears came in spite of all the blinking, and soon the teardrops joined the sea around Susan’s feet, the letter scrunched in her hand. *** A man with a grey mustache in khaki pants and a blue shirt stood by the gate. It was three days after the storm. Susan was holding Unnikuttan’s hand, having just come back from school.

26

“Ah, you must be Susan and Jose.” Unnikuttan looks at Susan. “Chechi, Who’s Jose?” “It’s you, potta.” Susan slapped the back of his bald head before turning to the man. “Sorry, Uncle. We always call him Unnikuttan.”

The man smiled, but a sadness overcast it, confusing Susan. “Is your Amma home, Susankutty?”

Amma came out, answering his question, and shooed Susan and Unni back into the house.

Just as Susan removed her shoes, a shrill scream made her fall. She got up and turned to her Amma, falling to the ground, still screaming. The man stood, with a look Susan did not have the words to call.

Susan learned later the word for it was “guilt.” Kadalamma or God or

neither of them sent him to deliver Papa’s last letter, which asked her to keep looking for stars. On the day Kadalamma raged at the shores of

Maruthadi, Papa was swallowed into the Arabian sea at the shores of

the Gulf, while in the pursuit of the oil that promised too much, like these letters. He will always remain a myth and no more stars would bring him back.

27

the sun is a pistol Vamika Sinha

28

Gulf Heritage Emily Broad

Al Mirfa’s hotel has white stucco walls and reflective windows. The roof

curves in waves, and its facade is a mixture of classical Islamic and 70’s American architecture. It’s almost brutalist.

Inside, a bellhop assists you to your room. The hotel is vacant. It’s 115 degrees, you feel a feverish delirium. The stained-glass ceiling in the

lobby appears as a kaleidoscope. You miss the city. As you enter the elevator, you expect blood to pour across the marble floors.

As he holds your hand, the bellhop tells you secrets of Mirfan Emiratis binging on alcohol. Here, everyone knows each other’s cars. There’s no hiding addiction, the women talk. Surely, this’ll change with

modernization. You were sent here to develop a city plan for 2050. You

imagine the town turning to dust. You remind yourself: Heritage depends on alteration for survival.

You can’t say why, but the bellhop breaks off the door handle and hands

it to you. You pack it away, it’ll serve as a relic. He leaves the room, when you notice a bottle. Once intoxicated, you begin collecting bits of the

room–bars of soap, toilet water, linen slices. You scrape the wall, grabbing some plaster. Now, you shatter the kaleidoscope ceiling.

You leave the hotel and find yourself on the grounded dhow that overlooks the town. The air is a hazy, dark orange. Holographic

skyscrapers litter the horizon; the ones your company will build. Sweat trickles onto the boat, and your skin falls away from bone.

29

Time passes. From the distance, fish heads emerge from the local market, and begin tracing the landscape. They harass you with their eyes while climbing

the megalithic buildings. The performance ends as they vomit waves of seawater, and the buildings come crumbling down.

30

Camels Donâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t Swim Noor Altunaiji

31

Afternoons at the Edge of the Coast Valeriya Golovina

32

isolation

Vamika Sinha

33

Void

Nur’aishah Shafiq

She’s supposed to be in class. Rebuilding Cultural Heritages. The irony is not lost on Amal as she lingers in the entrance hall of the Institute. Seemingly endless crowds stream past her, some people brushing

her aside, others shoving not quite as gently—a river parting around a

rock. School field trips, tour groups, scientists, businessmen, TV hosts, journalists—ticket sales haven’t yet stopped skyrocketing, despite the Institute’s opening almost a year ago now. Why would they? Nothing

beats the glamour of a place promising the return of a bygone age. Even if that bygone age is just a few years dead and the Institute’s promise a hollow thing.

It’s been a while since Amal last skived, back when the stifling warmth of

this many people in one place stoked a zeal in her until she nearly burned. She hesitates, but walks inside anyway, bathed immediately in the blue

glow of chlorinated water behind walls of plexiglass. The contents of her stomach start churning uncomfortably.

Amal wanders, ghostlike. Halls lead into antechambers down into viewing rooms up into smaller halls, bigger halls, more chambers. An infinite labyrinth of aquariums stretching from wall to ceiling, display boxes

for the ocean’s wealth, from the coastal shorelines to the high seas.

Fluorescent jellyfish adorn whole showcases, next to a tank of sharks bearing scars not from each other. An entire gallery recreates the lost

corals of the world—the Great Barrier Reef, Coral Triangle, Fiji’s Rainbow. Only one hall is devoid of aquariums, its walls bearing instead plaque

upon plaque of extinct marine fauna—dugongs and albatrosses and polar bears and zooplankton and, and, and. This hall is entirely empty.

34

Amal hovers before one exhibit, becoming ice as she stares at the

paraphernalia from Operation Burning Water. Light glints off sharpened

metal and serrated edges. Teenage Amal, warrior Amal would have driven her fist through the glass and proceeded to splatter mud and oil and fake blood all over the mess. The press would’ve eaten it up. That girl is gone though. Amal walks away from the display, leaving the glass intact. The crowd’s murmur grows when she reaches a narrow corridor

surrounded by ghostly dolphins, all limp tails and blanched skin. An

Institute tour group is ahead, gathering at the entrance of yet another chamber.

“Our finest specimen, ladies and gentlemen,” someone is announcing.

“The pride of our institution! You won’t find anything else like it anywhere else in the country.”

The air is electric with anticipation. Amal shoulders her way through, the urgency pulling her forward a resurrected thing. Some lost part of her

awakens, the heart of sun and sky that she thought drowned with the land, a pinprick of warmth amidst the gaping coldness inside of her. She stumbles to the front of the crowd, breath catching somewhere

between her lungs and throat. The tour guide continues her spiel, but

Amal registers only fragments. Her gaze is fixed on the aquarium, on the other it contains.

Boxed by a paltry enclosure, 10 by 10 feet, she slumps against a side

wall, a hulking meaty crescent twice the length and width of a grown man, squished against the front viewing panel. A shroud of diaphanous dark

hair swirls languidly around her body, billowing through the water to splay against the plexiglass.

35

“… native to the Polynesian Triangle, but all our specimens were collected from the depths of the Pacific … many weren’t salvageable, and some that were didn’t survive the extraction process …”

She is utterly still. Eyes closed. Her face the only part of her untouched.

The rest of her body is home to blatant violence, visible through the ebb and flow of her hair.

“… when land-water border skirmishes escalated into open war … the

coastal tribes rallied with the deepwater tribes … tried to hoard the fuel sources … the operation lasted 100 days … exterminate the threat …”

Ridges chart a course of abuse across her flesh. A patchwork of scars

criss-crosses her midriff, etching deep in the shadow of a net, webbing arms atrophying in the chemically treated water. Worse still are the

gouges scattered between these longer marks, amid the missing scales

of her tail. So visceral are these poorly healed wounds that Amal need not have stopped at the earlier exhibit to imagine the giant hooks that had

found purchase within the other, latching onto sinew and muscle, tearing through her body as lines snapped taut with a ship’s engine.

“our experts here are dedicated to rescue and rehabilitation … awardwinning center for conservation research—”

The tour guide’s performance is effectively halted when Amal falls to her knees and empties the contents of her stomach all over the floor. She

dry-heaves when there is nothing left within her, feeling arms taking her by the shoulder, stroking her hair back in an attempt at comfort. More disembodied voices filter through but Amal looks up to the aquarium, hugging herself desperately, face pained, pleading.

36

She’s dying. Even so, the mermaid is beautiful, but of a ruinous kind that stirs both awe and fear. Like an ocean in the throes of a storm. Her eyes are open now. Her face tilted to the sea of humans beyond the cage, to the young woman kneeling before her. Do you see me? Amal wants to cry. I’m not like them, believe me. In answer, the mermaid looks away, unforgiving.

*** Amal returns the next day. She’s missing class again—Post-Anthropocene Poetics this time—another echo of the countless Fridays she had skived in her adolescence. The crowd has thinned, and she notices the row of

empty tanks on either side of the one occupied. There’s no need to even speculate as to the whereabouts of their residents.

The mermaid has not moved since yesterday. Perhaps she has not

stirred at all since whoever it was put her here. In the recent past, this

hall would’ve struggled to contain all the youth and labor activists and

indigenous people who’d come to occupy for the right of all life to life. But the old movements are dead, and Amal is the only one sitting in today, a meager remnant of that hopeful time. She feels silly coming here, but all such intentions seem that way these days.

Amal is now a foot away from the glass, far closer than any visitor would

venture, who all keep their distance despite an abject fascination towards the other being. This close, the mermaid towers over her. This close, one cannot escape the scars. A familiar nausea begins its crawl up Amal’s throat, but she swallows it.

“I wish it were me in there.”

37

The confession is quiet. Barely audible even to someone on the same

side of the glass. Amal reaches out a hand, pressing her palm against the tank wall. Beyond, an emaciated abdomen stiffens, as if registering the

touch. Amal withdraws her hand slightly but raises her palms before her in a symbol of placation, of peace.

“I’m sorry we hurt you,” she continues in a half-whisper, but sighs right after; the words are empty even to her.

She’s tired of emptiness, of the nothingness everywhere. In the oceans, in the ranches and flat fields that have replaced the forests. In the

abandoned homes of those who flee flood and famine. In the eyes of her peers who had raged through the streets like a rising tide when the air

was still charged with possibility. In herself, when before there was only a

devotion to her home and all other islands of the world. She’s tired. Of the years sitting on her ass, screaming words, carrying signs, only to watch

the absence spread, until there’s nothing left of the beautiful wild places in

the world. Until there’s nothing left of the beautiful wild places in her heart. The mermaid does not move. Amal sighs, stands and leaves. *** But returns the next day. And the next, and the day after that. Every day,

Amal resumes her seat on this side of the glass. Sometimes speaking her quiet confessions, sometimes staying silent. Often with her palm pressed gently against the aquarium.

On the days of confession, she remembers. The taste of almost-victory

years ago, when the streets had swelled with millions demanding change. The defeat that followed, profit trumping all else, launched a thousand

38

ships on a crusade for the last of black gold, that most coveted treasure.

Most of all, she remembers home. Running through the waves beneath a sky that was yet to be blackened, splashing through water still untainted by blood.

On the days of silence, she mourns. On one such day—the twenty-seventh? twenty-ninth?—a hand on her

shoulder jolts Amal from the haze of her thoughts. She looks up into the blurry face of a little girl who stares down at her unabashedly. “Why are you crying?” Amal blinks. The barefaced innocence in the question, the girl’s wide

luminous eyes, has Amal haphazardly swiping at her face but she stops herself midway. Turning back, she sees the mermaid still lying there, as

motionless as the first time Amal had seen her, but not completely without change. With each new day, her skin grows ever translucent, drawing tighter against the edges of her bones. The luster of her dark hair has

paled, the corrupting flesh around her wounds spread. The least Amal can do is let the tears fall, unhidden and unashamed. “What’s your name, sweetheart?” The girl smiles. “Emma.” “Well, Emma,” Amal starts carefully, face still shining. “I’m crying because I’m sad. About a lot of things, but mostly I’m sad that she’s in there.” At this, the girl’s gaze lifts up to the mermaid, and she chews her lip thoughtfully. After a moment, her eyes brighten with revelation.

39

“Maybe if you leave then you won’t be sad. If you leave, you won’t be reminded that she’s here. Then you don’t have to cry anymore.”

Amal’s eyes widen. “I don’t think that’s gonna work, sweetheart.” “Why not?” “Because I can’t leave her.” Emma’s frown deepens. Amal sighs, struggling to gather the words that’ll make the other understand. “She’s all alone here. No one really comes to

see her. They look at her once, see something we conquered so we could keep building our cities and driving our cars, and then they leave. I won’t though.” Amal isn’t sure how much sense she’s making to the child, so she concludes simply. “Because she’s a living being too. And no living being deserves this. Even if she isn’t like us.” “Is she going to die, Miss?” “Yes,” Amal whispers. “But I won’t let her die alone.” Emma says nothing, and Amal goes back to her silent vigil. The mermaid is ethereal in her stillness, more wraith than flesh. Amal feels a sudden urge to find an emergency escape hammer and shatter the glass that

separates them so the other need not die in a cage. But to die out of the

water seems a crueler fate. So she places her palm against the aquarium, over the mermaid’s shoulder, and hangs her head, clenching her eyes

against the pain. A soft nudge on her hand makes Amal look up. Emma’s palm is pressed against the glass too.

40

They stay like that for a while, two humans watching over the dying mermaid, reaching out the only way they know how.

“Can you help me find my mommy?” the girl asks abruptly. Amal huffs a tired laugh. She stands and takes Emma’s hand. “The poor woman must be worried sick. Let’s head back.”

As they leave, Amal glances one last time towards the aquarium. A

webbed palm is pressed against the glass, hovering against the memory of human touch.

*** Amal returns the next day, feeling warmer than she has in a long time. But when she arrives, she’s met only with an empty hall bearing only a row of empty tanks.

41

You Canâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t See Me With Your Eyes Closed Boby Liu Chihling

42

Archiving the Climate Age Emily Broad

Ref 214: From the top left clockwise: buildings in Damascus, a street

scene, and the Minaret of the Bride (Madhanat al-Arus) at the Umayyad Mosque.

Google Search,

Umayyad Mosque, destruction

See: Syria clashes destroy ancient Aleppo minaret See: Umayyad Mosque destroyed In pictures.

Ref 918: An aerial landscape of the Citadel of Aleppo. Google Search,

Citadel of Aleppo,

See: Destruction of Aleppo then now

In pictures. Somewhere, a photograph Someone adjacent to Fire in Australia California Amazon

Home at risk,

Cling to photographs

43

Singed edges of their father, Burnt hole in their daughter

Viewers feel the encroaching fire,

Embers bouncing off the subjectâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s face

Obsidian trees are ash puddles in the Foreground, where you and I Double tap

For sympathy

2500 lost homes

1.25 billion dead animals Corpses of ecosystems

In the early nineteenth century,

Daguerre invented photography As an exercise for

memory replacement. Photographers, scientists Capture the world as is,

Display nature in glass boxes Through imagery

Photography as a replacement for memory The birth of photography leads to: Photojournalism Photo Archive Photograph

Permanence

44

Ref 412: A girl in Bangladesh sits on top of her father’s car as her house floods due to

As this is written, another relic is lost to See forest fires, See flooding,

See global warming, See landfill Photofill,

Treasure trove for humanity’s lost items A photograph of my grandmother Fishing off the coast of Mexico,

But the water isn’t cobalt blue anymore It’s tainted with the streets of men, And the sea is at my abdomen.

In the end, objects destroyed in Wars and conflicts

Or by climate change

Heritage burning, lost What does it mean to work as an archivist in the twenty-first century? When preserving a photograph, Means codifying history, But how is this possible

When the earth is reclaiming it.

45

the errors of hands Vamika Sinha

46

Revenge of the Earth Achrakat El Fitory

47

Oxtail

Jamie Uy When she slept she dreamt of mornings. Her mother frying banana fritters her brothers bicycling across rice terraces her cheek on cool bamboo

floors. Day greening like a crab apple ready to pick off the tree. Houses

on stilts farmers plowing their fields grandmothers weavelooming scarves grandfathers chewing betel nuts paper kites like dragonflies peach

blossoms molded out of glutinous rice. In the dream she was eating

salted fish with chili paste warming herself near the fire. When she awoke her mouth was dry she was shivering only her motherâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s black sarong

covering her no brothers no food. She got up slowly. She wanted to pray

to the ancestors to her mother but she had no coin to throw nothing white to wear no pig no fruit to place at the altar. Gelid air. Each day colder than the last. The girl dreamed often of her mother as she trudged through valley after valley. Strained her ear for bombs. She cursed every god

every animal every ghost every flower every holything. Until her tongue

felt dead dumb desiccated. Moonchipped mountains sneaklaughing at

her. She was sure there were fat catfish somewhere if only. She could find a river. She longed for a frog to eat but there were none.

She had no clothes except for the sarong. Watermelonskirt with stripes.

The last time she ate watermelon was two days before the uniformed men came. Her mother reserved the sarong for festivals wore silver jewelry

and a greenmango belt. She knotted the cotton frayed scorched around her chest. Before she had breasts small hills now the little peaks had

collapsed. During nights she wondered if she might have married the

boy. He had smiled when she held his hand during the xoedance. The branches of her body thin. If she survived how would she ever bear a child. She thought if this is living no one should ever be born.

48

She walked through gorges so steep she thought the rock swallowed

the sky. Her chest a cave. Her legs so thin. Fog made her forget what her limbs looked like. She saw dead shrimp fully translucent floating

down a stream shrivelled ravaged trunks of forests that once were. She was too afraid to eat because they had poisoned the land. She did not

wash herself. You were not supposed to bathe until after the funeral was

complete besides she had no water. Even if she found a wateringhole she would freeze to death after. And they would have to lightcorpse her too. Until she was just ash. All that was left. The girl remembered distantly another village another tribe in the mountains seven days journey.

Famous for red plums size of your palm. More planes overhead. She got

lucky. Landmine exploded on the third day abandoned rice field. Didn’t hit

her. But she hallucinated. She began to doubt if there was a village if there ever was a tribe. If there were others.

The girl found the uniformed men on the sixth day. Rib of a girl. She

wanted to cry at least taste the salt of her teartracks but couldn’t. The

fog had eaten the moon. Her mother her father her brothers her village. Maybe they didn’t see her because she was already dead. They lit

firewood and roasted cans of pork beans. She was just thinking to wait for them to leave and lick what was leftover. When she saw the water

buffalo. In another world sacrificehouses greengrass fine coats of hair rolled in the mud. The buffalo was emaciated. The girl once lived in a

house with a buffalohorn roof and corn wine. She remembered her mother smoking buffalo meat for the festival. Thick corpulent slabs ginger spiced. She salivated. One of the men pushed food to the buffalo like an offering. Stupid. Buffalos eat bamboo fern moss grass waterlilies.

When the man shot the buffalo the first time she meant to run.

49

But she was tired. And the eyes of the buffalo so big. The man shot two three four five six seven eight nine ten eleven twelve thirteen fourteen

fifteen sixteen times. Her mother her father her brothers her village. Her

mother by the man one two three four five times. Naked trembling told her to go take her sarong no time. Eyes watching. All that was left.

The girl ashamed wished they would leave the baby buffalo. For her to eat. She didn’t care how filthy. But the men threw the carcass into the well. Long silence ringing aftermath of artillery too still. Then they left.

Unseeing boots crunching bruising the earth. The girl kept hearing faint

bleating bubbling. Toothless baby buffalos slaughtered carved on hooks. When she hefted herself onto the brick she did not recognize her own

haggard face pupils shiny black and dumb in the reflection of turgid water. Contaminated. She lowered herself into the well. Fumbled with shaking hands a piece of an ear mouth twitching mouth. The head or what was

left of it the skull. At last she found it. The oxtail. Ravenous the girl tore off flesh glistening raw sucked on marrow imagined her mother’s cooking.

She ate of the holyanimal. Fighter jets bombers overhead. Somewhere a massacre.

Once there were blessings. Her mother’s singing basketfuls of rice

wooden flutes sundrying silk hot wintermelon soup picking tamarind her

brothers kicking rubber balls stuffed pheasants ebony flowers frangipani trees tortoiseshell shamans pickled jackfruit embroidered quilts harvest

season. Life the white membrane of a perfect egg. Kitchenspirits dancing in the alpine air. She chewed two three four five six seven eight nine ten

eleven twelve thirteen fourteen fifteen sixteen times. Her mother her father her brothers her village. Once there were blessings and lush mountains that reached gods.

Image on facing page by Sara Pan Algarra

50

51

house

Smrithi Nair it’s made of wood and stones and history all things a house dreams to be I guess

it’s nice

but it’s a little big for me from a distance

the house looks fragile

dollhouse

but we’re real people humans

my heart must know

when lightning strikes

because that’s the thing

lightning’s not in the habit

of striking the places of fake power in a made-up system it is all fake unnatural

we are just playing house

but when we played house, we were

mothers and fathers and kids and sisters and brothers and aunts and uncles and friends and neighbors we were not dead bodies.

how do I appeal to your humanity when you are playing god and we are playing house

52

chechi tells me that our house has security guards donâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t be scared

they donâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t let anything bad in but chechi

how do guards keep the lightning out? the fake gods?

how do guards keep being human?

but chechi who protects the guards? who protects you?

when you walk home at night, down the hill, outside the forest to take the route that goes by the temple

who do you pray to? who listens?

the house will outlast us all

and i fear for the people within and without because i only have words the gods have more. i am scared we are not infallible

when the earth gives way we will all go

and that is comforting because

we did everything wrong

how can we be forgiven?

53

when the earth gives way

we will all go but the earth will stay

and when it gets new lives i hope they do better

i hope they are not human and that is comforting

the gates tremble slightly tonight

i wish the house the flowers the history the guards goodnight please be fine safe okay please be alive

54

Jazeerat Al Hamra Emily Broad

55

On Earth: a meditation from a mouth Tusshara Nalakumar Srilatha Krishna says “Ahh,”

Yashoda peeks into His mouth. He has a cavity,

and it’s a big one. Inside, she sees the

churning cosmos and spies planet Earth

nestled into a left molar. “Wider,” she commands, and Krishna obliges. There, at the cusp,

is Earth turning rot, green going limp, blue going sour.

Yashoda leans closer

and loses her balance. She falls into His mouth, into the universe,

bounces off His gums,

and lands on His tongue.

56

Perching so, she feels apart from herself,

enveloped by the expanse of alltimeandallspace. The planets hum to

their choreography of orbit as light skims darkness in practiced rhythms. But there,

was Earth ailing.

Wheezing and labored, inharmonious.

Its wounds look tender. Scorched land,

heaving waters,

air cloyed corrupt. Humans look about

to cave into themselves. And combust all together.

The decay goes deeper

than Yashoda had imagined.

57

Down to the gum, into the pulp, infected soft tissue.

Sticky tears

sweep Yashoda

back to the feeling of her own body.

To think her child

was in so much pain.

The very nerve that nourished Earth, diseased. Yashoda leaps

out of His mouth

and pulls Him to her chest. He is her baby.

Before all His splendor

and grace, He is her baby. She wants to take away the pain and soothe.

58

looking in or out, toward or away

Michelle Hughes

59

Tears That Wet The Ground Vongai Mlambo

Dive into the river snaking across gogo’s yard Water molding my arms and legs

A tender hug plunging me into its depths Releasing control, I choose to sink

Emerging only to realize it is a puddle

And I am sullied by the filth of promises unkept Lies like plastic beads Weigh down my lungs

Each cough a dust of coal Blackening my hands They tell me

Drills piercing fragile soil is “development”

And with an economy like mine, I should be grateful for it Each time they strip the landscape dry My people cry

Your black gold is worthless We have no use for it

Climate change meetings are a popularity contest

Secret societies where the password is “developed nation” Men in black smog suits Debate till they are blue Say nothing of equity.

The problem is not climate change It is the ability of privileged

To hold rain clouds hostage

Leaving the cracked ground cowering at its knees

60

If climate action affects capitalism, forget it. Who will police the powerful? They cannot be restrained.

I jump on their shoulders, cover their eyes Hoping that if they can’t see, they will feel The broken rhythm of my bleeding heart

They send their journalists here to capture the moment A tragic story for the Sunday Times

That kisses the memory too softly to be remembered Do those images convince you?

My gogo posed for a photographer once, Yielding to his passion to portray tragedy

He trained his black box on her dying garden “What a shame”

He thought my gogo’s plantation a hobby

Not a battle to feed herself in the ruined environment That distributed justice on its own, Misfired at the broken ones

The ones already wearing bullet holes We have all sinned, but why must she pay? When she uses less than 10 liters a day, Rations meat to once a year

Uses the heavily veined sticks in her torso As her primary mode of transport

She knew sustainability before it was popular Practiced and embodied it,

without expecting a tax break

Or a reputation as an environmental savior

61

She just wanted to be a proud farmer. My gogoâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s homestead is my childhood, But its borders are getting so tight, I am afraid to claim it as my own

So I hide in the urban centers of my adulthood Determined to honor her Not to betray her

Feigning joy when she calls But silently crying,

I would give it all to come home.

62

sunken

Vamika Sinha

63

The Whispers of Niyamgiri Ivy Akinyi

She stares at me, firmly rooted by the stream crashing against the black rocks. Her dance, mild and elegant, accompanies the soft wind, as if

speaking out unknown words. Is she speaking to me? The melody of the

river crashes against a cacophony of alien insects. Her chlorophyll paints itself on my iris. The name, Niyamgiri, appears.

It’s bizarre, the power she has over me. I can see blood flowing in her

green veins. My vision pans, noticing the map they inscribe. The map of

Odisha. The place where she stands by the stream is marked with a clot of blood. Her whispers return. “She comes back to remember them.” Who? “Avani. She comes back for the ones that were murdered. She found

her sister’s head right by this rock, golden earrings still dangling on her. Most of the time, the bandits would take such valuables with them, but I suppose they did not want a reminder of her screams. Avani says her sister was only sixteen. And with child.”

I don’t know what to say. Even Niyamgiri is silent, as if waiting for my answer. I take courage in the wind, in the water, so I ask. Why did they kill her sister? “The rich ones from the factory had been asking her family to give up their farm for a long time. Naturally, they refused. And can you blame them?

This was a land ploughed, shoveled and harvested by the strength of an

entire generation in preparation for the many generations to come. It was

64

an empire of its own,” Niyamgiri smiles, “and their names were written on every mango tree enclosing it.”

Her smile fades. “But the rich ones cared little for their rights and of the mango trees. They were vicious in their determination.” What happened exactly? Niyamigiri meets my eyes. They gleam with sorrow. “On the day of the ambush, the sky was beautiful. Like ink soup coming to a boil. A hazy curtain of rain hovered in the air, a blessing as the rice paddies were

drying up fast. The family were rice farmers, so they rejoiced in the rain, laughing and humming to their songs.

“By nightfall, their blood watered my veins, their bodies and limbs strewn on the fields like scattered rice seeds. Only Avani escaped, but she

returned when the bandits were gone. Trying so hard to piece together

those she loved. She walked many miles to recover the last piece of her sister.”

I am cold with horror. What of the bandits? “Avani went to court,” she continues. “She had their IDs as proof of their existence, the title deeds that dated back generations, even rice grains from their farm. Every evidence to claim justice for her family.” “But she didn’t get it.” “No, she did not.”

65

“She comes to me sometimes,” Niyamgiri adds after a while. “Weeping. Begging for death. Telling me her story, so that I may tell it to others like you.”

The screen suddenly cuts to black. I blink as my eyes readjust to the

tungsten light slowly fading onto the dark screen. They turn into a pair of headlights from a tuk tuk. I feel vague and intense at the same time.

“Ma’am, the gallery is closing in five minutes,” the guard returns, blinding my eyes with his flashlight. Some of the light spills onto my notebook, revealing roughly jotted facts. “Ma’am?” the guard persists. With a

hard sigh, I gather what’s left and leave the gallery. I mutter the phrase,

‘Sovereign Forest’ with some reassurance. Avani’s truth, deep-rooted in a whispering sapling, will spread by the echoing wind. And I will speak out.

66

Mourning of the Forest Nymph

Achrakat El Fitory

67

Infestation

Emily Broad

68

Wanderer

Grace Shieh I carried a suitcase of pineapples to the Arctic Little pockets of sun, heat, and laughter With all my fingers I dug one open

The pines rebelled, cutting my ring finger Blood dripped down

Frozen before it reached the ground Rubies I called them

I picked up the pineapple My dowry to the arctic

And chugged all its juice Sweetness exploding

Some golden tears falling In the innermost ring I found my men

Dancing like little drunk bastards With their happiest faces In groomsmenâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s clothes Fingers pointing

At my amusing sorrowful face In this place where a wandererâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s courage fades Freedom isolation a breath away They left a piece of themselves

69

With me Suddenly I see

A slice of me left behind

In their memories and prayers An empty space in the dance Reserved for me

Now in both ends of the world We are no longer complete But doomed,

Some pineapple in the Arctic Glacier in the tropic.

70

Snowpiercer

Chiran Raj Pandey Chris Evans: hero

of the tail. Substanceless white

glow of the distant

apocalypse. Captain, America

is not the answer. Apocalypse is never an answer. We will destroy the world

before apocalypse happens. Better to die than live quietly. This is size 10 chaos. Donâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;t need no saving.

71

personal <-- protection --> Earth PVG Medical Staff (10-min live sketch at Shanghai Pudong International Airportâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;s COVID testing tent, night, March 14, 2020) Rayna Li

72

Trashy Nights & Snowy Days Athena Thomas

73

An Ode to Garbage Athena Thomas

8:37 AM: I’ve thrown away five things, a Maggi noodle wrapper from breakfast a pen that’s run out of ink a dead battery

a can from last night a wipe to sanitize

Plastic takes a thousand years to decompose; all the websites say so. 1000 years for a wrapper 500 for a pen

100 years for a battery 250 for a sprite 100 for a wipe

Exponentially growing landfill in developing country. Like me, this trash will traverse land and sea,

1000 years for a quick meal 500 to fill a few pages

100 to power my remote 250 to sip a drink

100 to clean a stain My trash, you will outlast me,

Though I can’t grasp such numbers,

74

How easy it is to commit a crime,

How sprawling and invisible the sentence, How long the consequences last, How much harder to undo. Who is to blame?

Corporations are greenwashing,

People rushing to ethical consumption. Ubiquitous names mediate our lives: NestlĂŠ noodles Laknock pens

Energizer cells

Coca-Cola cans Clorox wipes A system built to generate refuse,

Weâ&#x20AC;&#x2122;re capitalistically conditioned, falling into misinformation, Companies too big to fail.

Crinkled foil, chocolate bar, afternoon snack, open backpack, shiny black pen,

fresh can of soda, new wipes, soymilk Tetra pak Climate emergency smoking on the backburner, Time decomposes.

75

Factory

Emily Broad

76

untitled

Michelle Hughes

77

And the Sun Hung Cassandra Mitchell

I sat on the beach and the sun hung innocent above us The sky baby blue and the clouds cotton But I saw the storm far out at sea

The barest dark smudge on the horizon I turned and asked, Do you see?

But they shook their heads, smiling,

You are no prophet, child. So don’t worry. Today we are happy. So I sat on the beach and the sun hung watchful above us The clouds blackened and the waves rose I stood and yelled, DO YOU SEE?

But they turned their backs to me.

You are no prophet, child. So don’t worry. Today we are busy. So I sat back down on the beach and the sun hung drowning above us The waves closer now

Roaring and ripping at the sky Enraged

Cannibal waves

I screamed and pointed and leaped and stomped, It’s coming! It’s coming!

But they shook me scoldingly and said,

Can’t you feel the breeze? Can’t you feel the sun? You are no prophet, child. Today we are safe.

78

I see the ocean pulling away from the land The storm inhaling

Foam wave reaches the sky

And the sun hangs dead above us So I run,

Leaving them behind.

79

80

Part II rise

81

Where Do We Go Now Achrakat El Fitory

Image on facing page by Al Reem Al Hosani

82

83

1 Monarcas on Migration Monarcas on Migration 1 MaríaJosé José Alonso María Alonso

_______________________ 1

Climate change displacement day by more people are forced to leave their homes due to environmental reasons; 1 Climate change displacement day more are forcedvisit to leave homesgardens. due to environmental reasons; yearday bybyyear lesspeople Monarcas mytheir winter

84

year by year less Monarcas visit my winter gardens.

displaced body a letter to God Sara Pan Algarra God I Trust That

You Will

Guide Me

I Trust That

I Trust That

The shelter has sunk under waters of plastic

I am displaced

You Will

Help Me Follow

Believe

To

the footprint of automobiles I cannot afford

The

Earth Has

Given Me Life For

Something

85

Guide Me To

See

Why

You Do What

You Do

Why:

displacement

ozone depletion

Why he drowned crossing a border

I Know

Why they murdered her when they took her land

You Are Always

Protecting Us

I Want To

Trust You

86

But the trees we breathe are dying

And there is no compassion

Untitled (Homage to Filippino Lippi) Rayna Li

87

The Apostate

Nur’aishah Shafiq

ENDING ...

There are great gashes in the world that we love with so much pain.

—Muriel Rukeyser

The room went utterly silent, save for the scratch of pen on paper and the incessant tap-tap-tap of typing. Words hung suspended in the

air, formless without voice. The suspense was straight out of a film

confrontation; you could practically see the camera panning the set,

cutting from one impassive face to the next before zeroing on a young girl

in the background, her wide eyes marring the tableau of otherwise perfect composure. I would’ve savored the drama if I weren’t so disappointed at being part of the scene.

The instigator settled back in his chair, replete at a job well done. Still,

no one spoke. I almost chewed through my cheek to stop myself from laughing hysterically, a reaction that would’ve shattered the unspoken protocol of the meeting. And we couldn’t have that. Decorum is everything at the United Nations.

The silence persisted for enough time to signal an appropriate level of

disapproval, before the facilitator noted down the offending statement for further deliberation. Deliberate when, you ask? Probably in future

negotiations the planet cannot afford. I looked around, even then waiting for someone’s interjection, an exclamation of outrage perhaps towards the words of the Russian delegate—that we shouldn’t consider human

rights and gender when implementing the Paris Agreement. Apparently,

the wellbeing of people, especially women, was an inappropriate point to

88

aise when discussing how best to avert, address and minimize the loss and damage associated with impacts of climate change.

The words were a weapon well-wielded, but only because the silence meant no one had thrown themselves forward to obstruct the bullet’s

flight. Instead, an entire room of people who claimed to care about the welfare of our planet and its inhabitants acquiesced to the violence at hand. I had come to partake in the fervour of climate action, but

rather found myself a collaborator in the killing of our commitment to

democracy and equality, for I too stayed silent. Wordlessly, I helped bury the remnants of a just political system, riddled with wounds, rendering environmentalism just another fever dream of the egalitarian spirit. And thus, my faith was broken. It had been breaking for some time. In the weeks preceding my excursion as a youth delegate to COP25, the 2019 UN conference on climate change, I moved through time in the torpor of disillusionment. The

absence of fanaticism on my part for this ‘opportunity’ was a sacrilege

even I did not yet care to acknowledge. But I had grown weary trying to compel others to care, to give a damn for once about the state of our

world and the fragility of our future. Worse still, I was tired from constantly

questioning my actions, from the dread that I was doing it all wrong. Every effort abided by the scripture of contemporary environmentalism, and yet I saw so little fruit borne from my work.

I mobilized students in sustainability initiatives, facilitated environmental education and awareness. I organized events and attended conference upon conference in order to help my fellow peers learn how the

environmental crisis was being politically addressed. And yet, those who didn’t care still preached their ignorance about how the ways we ate,

89

moved, bought, consumed, lived was threatening humanity’s continued

existence on Earth. Was exploiting countless people and ravaging nature in order to uphold our lifestyles. Those who did care remained largely

apathetic to the possibility of change, experiencing disempowerment

about their perceived smallness within the largeness of our problems. It

was this latter group that hurt my conviction the most. I remember two of the most environmentally-conscious people I know confide that they’ve given up caring about how flying on holidays spewed carbon into the

sky; they’d rather travel and experience all there is to life before it’s gone then “waste” their chances to “live” on actions that didn’t even make a difference.

And so on the brink of my pilgrimage to Madrid, where thousands of environmentalists would gather to deliberate implementing the Paris

Agreement, I wavered—my devotion to that great religion was not what it once was, when I was first converted to it in high school and initiated

in its ways upon entering college. For so long, I believed in the capacity of top-down mechanisms such as that of the UN to bring about the

large-scale radical transformations that we so clearly need. I fostered my

activism in the opportunity to attend COP whilst still at university, thinking that I would be one step closer to influencing the decisions that really

mattered in facing climate change. To break the Machine that burns fossil fuels with abandon, that prioritises economic growth over the sanctity of

human life, that treats the planet as cannon fodder for the progress of our civilisation.

Before Spain, I had been so caught up in the doing doing doing, I failed to see that the cause to which I was a devout follower was a religion of the Machine. I wanted to believe that the political elite would drive actions

that reversed the harm we had done the natural world and its countless denizens. Because they had more power than I did, had been in this

90

game longer, and knew what they were doing while I was just a rookie,

a mere acolyte. So when I got to that negotiation hall, when I heard the Russian delegate disregard that foundational ideal of equality—that all

are deserving of human rights—when all this happened, I stayed silent. I

stayed silent because everyone else did too. I cooled the rage that burned within me to join that tableau of perfect stone seen in everyone else’s reactions.

I was and still am ashamed at my complicity. My one consolation is that

in the silence I found revelation. How can an environmentalism that rubs shoulders with the powerful ever heal the gashes that such power leads to in the first place? We invest in the political game, in climate treaties,

and inter-government collaboration, seduced by promises of ‘meaningful change.’ We want so badly to believe that strategies like carbon trading and renewable energy are the answers to our problems, because they’ll preserve our current way of life and all its conveniences. All we need

to do is substitute one resource for another—oil for sunlight, plastic for biodegradables—and monetize carbon to let the free market work its

infallible magic. This way, we can still have our development, since such changes render it ‘sustainable’.

In donning shiny suit-and-tie ensembles appropriate for corporate

settings, we shed our mantle of eco-warrior to become merely cogs

colluding in the machinations of our alienating system, one that abides by a single principle—grow alone or die together. You can claim that

environmentalism is completely different than the engines of economic

growth, that it cares for the environment in a way the Machine does not. Well. Tell me then, how does environmentalism perceive the Earth?

From above. As if humans are separate from nature, as if nature is there for us to experience, for us to save. Yes, unlike the engineers of the

91

Machine, we are not lords bearing dominion over lesser beings. But we

environmentalists figure ourselves nature’s saviour, its steward, which of

course is predicated on the conviction that first we are its destroyer, and it is in need of our protection. Did there ever exist a race more arrogant? We need the natural world, this planet of ours, in a way it has never needed

us. The myth of our own self-importance is one we’re resistant in facing, a myth exemplified by us naming this historical period the Anthropocene— the age of human influence.

What if we are never able to escape our own myth? The atmosphere continues to warm, the seas expanding in their effort to kiss the sky.

Our years on this Earth grow shorter. And yet, narratives perpetuated by both environmentalist and plutocrat marry the human race to a

future that cannot exist, one where we preserve the values that underlie environmental degradation and socio-economic injustices. Values that

claim we are free to sacrifice each other and the planet’s wealth without consequence, for the sole purpose of our own comfort and pleasure.

Do you see then, the end towards which we run? When all that is left of us are the peaks of ivory towers, once the oceans finish their work of drowning and the air blazes with the sun’s fury.

... IS BEGINNING

we are all compost, not posthuman.

—Donna Haraway

The future however, is not here yet. And until it arrives, we must act on

even the slimmest chance that we have within us an ability to still affect what shape the future will take.

92

But how to act, I asked myself, when so much of what I knew fell through the cracks in my conviction. I had been an arrow once, in my singleminded commitment towards environmentalism. But an arrow is still

a weapon and the world needs more than violence. That of words, of

silence. And most of all, the violence at the heart of the Machine—the

violence of lovelessness, that commitment towards individual interests over the welfare of all others.

How, you ask, does one oppose lovelessness? I won’t claim any

expertise, but perhaps speaking of my relationship to Aiin can offer something to that end.

Aiin is my sister, born twelve years after me, through whom I have learned intimately the fear that I may never succeed in building a world in which she will always be protected. It’s a primordial being, this fear, settling

within me against that other beast, the deep-seated instinct every species possesses for their own eventual extinction.

When I first realised the existential implications of climate change and

environmental degradation, I resigned myself to the chance that I might

never be a mother. How can I possibly subject another to a life in which

the only certainty is the fragility of our existence? To the ease with which our bodies give in to the effects of both words and silence. Nor can I

bring myself to subject the world’s existing inhabitants with the burden

of supporting yet another life. Despite these considerations, I may never even reach the age wherein I’ll have to act upon them. Such are the circumstances we face.

But in Aiin, I have tasted motherhood; I have touched a shard of this

delicate far-off abstract that may never come to be but for this gift in the

93

present moment, and I have felt the sting of this touch, of knowing that my life is no longer my own. Was it ever though?

We individuals do not live in isolation from the rest of the world.

Everything we see around us, everything we experience, everything that we are, is the result of myriad organisms working in tandem with one another. Is the product of innumerable processes, spanning from the

chemical and geological laws that shape the Earth, to the human forces of politics and economic organization. From the food we eat and the air