InfinitaMente Exhibition

88

No lugares Non-places

TEXT

De lugares, paseos, recuerdos y ruinas Of places, walks, memories and ruins

La espiropapa The spiralised potato Jorge de CasCante

DOSSIER

EDITORIAL 4. 6. 18. 30. 38. 46. 58. 68. 78. 84. 92. 100.

Branislav Kropilak La imagen inhóspita The inhospitable image

Raúl Belinchón Ciudades subterráneas Underground cities

Lukas Korschan Could be any place…

Nigel Shafran Escaleras mecánicas y supermercados Escalators and supermarkets

Lynne Cohen Políticas de lo vulgar The politics of the vulgar

Xavier Ribas Lugares imprevistos Unexpected places

Wojciech Karlinski Train Station in Poland

Benjamin Price

“¡Circulen! No hay nada que mirar” “Move along! There’s nothing to see here!”

Peter Fischli & David Weiss

El viaje como no lugar Travel as a non-place

Xavier Aragonès

Veintiséis gasolineras catalanas abandonadas Twentysix Catalan Abandoned Gasoline Stations

Portfolio

110. 116. 122. 128. 134.

Juan Brenner

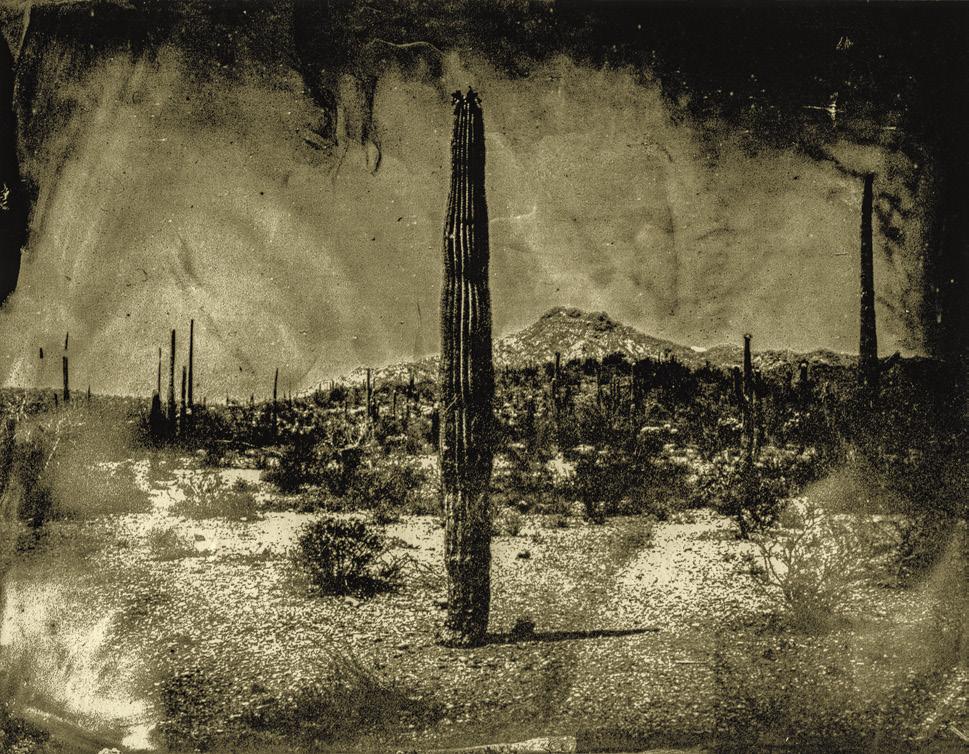

Marcus DeSieno

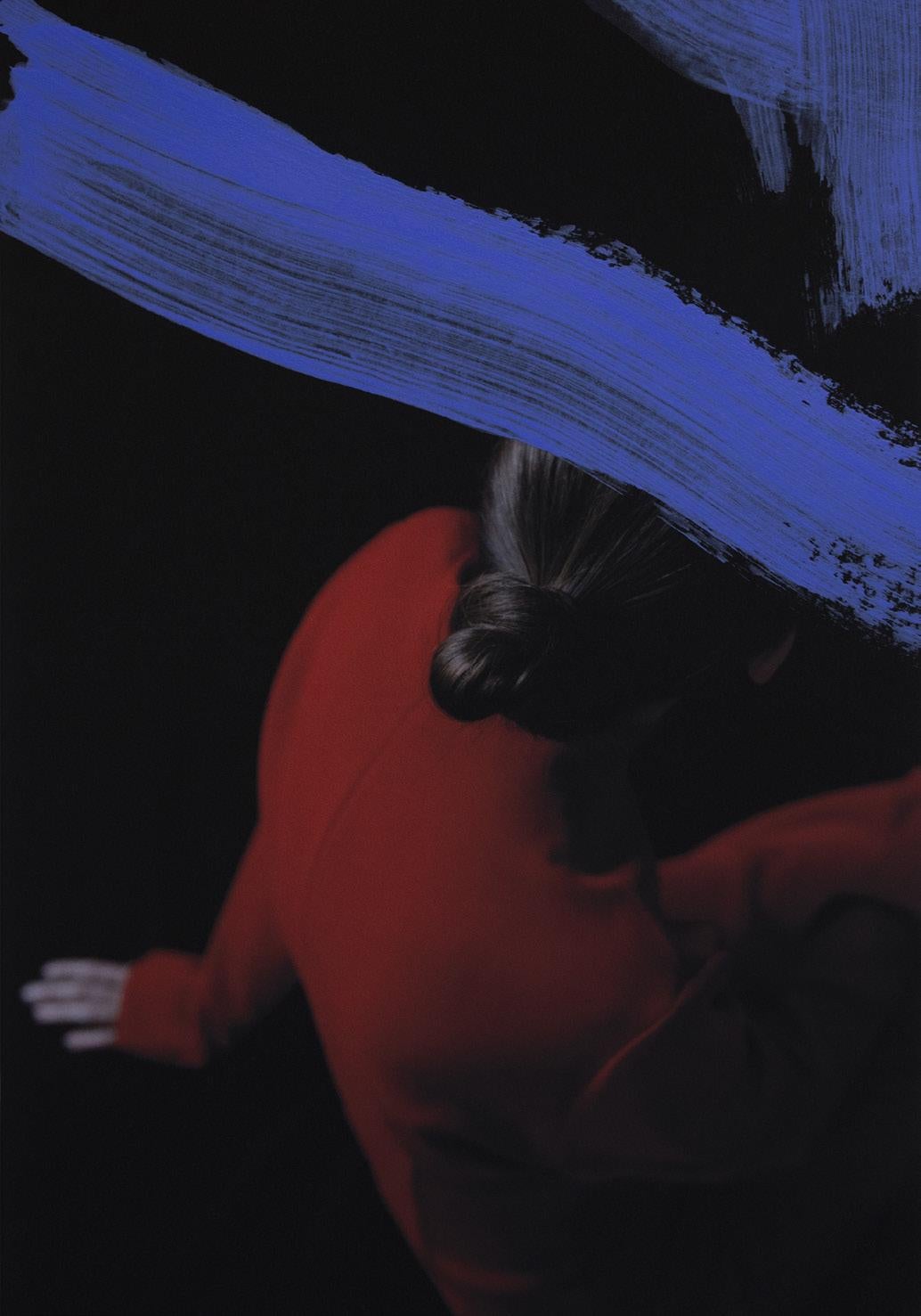

Andrea Torres Balaguer Sander Vos Stephanie Syjuco

EXIT ImagEn y CulTura es una publicación trimestral de Producciones de Arte y Pensamiento, S. L.

EXIT ImagE & CulTurE is published quarterly by Producciones de Arte y Pensamiento, S. L.

EdITado por / publIshEd by Producciones de Arte y Pensamiento SL

EdITor fundador / foundEr EdITor Rosa Olivares / editor@exitmedia.net

EdITora / EdITor Clara López / logistica@exitmedia.net

EdITora adJunTa / assoCIaTE EdITor Marta Sesé / edicion@exitmedia.net

EquIpo asEsor / advIsory CommITTEE Jens Friis, Gerardo Montiel Klint, Sergio Rubira, Laura Terré, Willem van Zoetendaal, Paul Wombell rEdaCCIÓn / EdITorIal sTaff Manuel Padín Fernández

TraduCCIÓn / TranslaTIon James Calder, Paula Zumalacárregui Martínez dIsEño y maquETaCIÓn / dEsIgn and layouT José María Balguerías (estudioblg.com)

publICIdad / advErTIsIng publi@exitmedia.net / logistica@exitmedia.net T. +34 914 049 740 susCrIpCIonEs / subsCrIpTIons suscripciones@exitmedia.net

admInIsTraCIÓn / aCCounTIng ad@exitmedia.net

ofICInas / maIn offICEs España: Juan de Iziar, 5 28017 Madrid T. +34 914 049 740 edicion@exitmedia.net www.exitmedia.net dIsTrIbuCIÓn / dIsTrIbuTIon España: Distribution Art Books T. +34 881 879 662 info@distributionartbooks.com

Producciones de Arte y Pensamiento T. +34 914 049 740 circulacion@exitmedia.net

Internacional: México: EXIT La Librería Río Pánuco, 138 Colonia Cuauhtémoc 06500 Ciudad de México T. +52 (55) 5207 7868 libreria@exitlalibreria.com www.exitlalibreria.com

Exit ha sido galardonada con los siguientes premios Exit has won the following awards

Lucie Awards 2015

Mejor revista de fotografía del año Photography Magazine of the Year

Kraszna-Krausz Foundation 2003

Mejor publicación de fotografía entre 2000 y 2003 Best Photography’s Publication 2000-03

Todos los derechos reservados. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida o transmitida por ningún medio sin el permiso escrito del editor.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means without written permission from the publisher.

© of the edition: Producciones de Arte y Pensamiento, S.L. © of the images: its authors © of texts: its authors © of translations: its authors © of authorised reproductions: VEGAP. Madrid, 2022.

EXIT is member of the Asociación de Revistas Culturales de España, ARCE, and the Centro Español de Derechos Reprográficos, CEDRO.

Printed in Spain / Printed by Escritorio Digital, Madrid. D.L.: M–4001–2012 ISSN: 1577–272–1 Versión digital ISSN-e: 2605-3497

Esta revista ha recibido una ayuda a la edición del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte

PORTADA / COVER Xavier Ribas. Untitled (table with views), from Domingos series, 1996. Courtesy of the artist.

CONTRAPORTADA / BACK COVER

Branislav Kropilak. Garages, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

agradECImIEnTos / aCknowlEdgEmEnTs

Aileen Mangan, Catharine Clark Gallery, Lucas Zenk, Allison Parssi, Stephen Daiter Gallery, Erica Gibble, Matthew Marks Gallery, Marina Chao, Higher Pictures Generation.

Y a todos los artistas y autores que han participado en este número. And all the artists and authours that have contributed to this issue.

De lugares, paseos, recuerdos y ruinas Of places, walks, memories and ruins

Las cosas cambian continuamente. También cambian las palabras y, con ellas, cambia el sentido de lo que nombran. Los lugares cambian, pero sobre todo cambiamos nosotros, los que vivimos y pasamos por tantos sitios a lo largo de nuestras vidas, y cambiamos la realidad a partir de nuestra memoria tan olvidadiza. Cambiamos en nuestra cabeza —en nuestros recuerdos— como fueron realmente las cosas. ¿Realmente fueron alguna vez de una sola e inequívoca manera?

Los filósofos, los lingüistas, los historiadores se fuerzan siglo tras siglo intentando dejar todo claro, poniéndole nombres a las cosas y a las ideas, a los sentimientos, al aire que respiramos, a las cosas que nunca decimos, incluso a lo que ocultamos en lo más profundo de nuestro olvido. Esos nombres son parte de una cultura que se transforma cada vez más rápidamente. Y con la llegada de la reproductibilidad de la imagen, con la llegada de unas sociedades urbanas cada vez más convulsas e híbridas, muchas de esas definiciones han perdido su sentido. Desde luego no para todos, pero sí posiblemente para los más jóvenes que ven el mundo, la ciudad, de formas contradictorias. En este número 88 de EXIT tratamos, como si fuera un doble oxímoron, la idea de “no lugar”, ese concepto terriblemente acertado, aunque voluble, con el que Marc Augé definiría algo que muchos veíamos sin saber acotar claramente: “Si un lugar puede definirse como lugar de identidad, relacional e histórico, un espacio que no puede definirse ni como espacio de identidad ni como relacional ni como histórico, definirá un no lugar”1. Esos lugares que nombrábamos como vulgares, anónimos, periféricos, sin identidad ni características propias. Recientes e intercambiables. Lugares de tránsito, intercambiables entre sí como los túneles de los metros de cualquier gran ciudad, homogeneizados por la suciedad, la soledad, la prisa. Lugares imprescindibles tal vez, al menos algunos, en la vida moderna; inevitables, pero nunca agradables ni queridos; lugares de los que no quedaba memoria en nosotros después de pasar

1. Augé, Marc: Los no lugares. Espacios del anonimato Ed. Gedisa, 2005. p. 83.

Things change all the time. Words change too, and with them the meaning of the things they name. Places change, but most of all we change, the people who live in and pass through so many places during the course of our lives, and we change reality from our memory, which is so forgetful. We change how things really were in our head and in our memories. Is it really the case that things were just one single, unequivocal way only?

For centuries now, philosophers, linguists and historians have striven to make everything clear, putting names on things, ideas, feelings, the air that we breathe, the things we never say, and even what we hide away in the deepest recesses of our forgetfulness. These names are part of a culture that is changing at an everincreasing pace. And with the advent of the reproducibility of the image, with the advent of increasingly convulsive and hybrid urban societies, many of these definitions have lost their meaning; not for everyone, of course, but quite possibly for the youngest, who see the world and the city in contradictory ways. In this, issue 88 of EXIT, we look at, as if it were a double oxymoron, the idea of the “non-place”, that terribly accurate yet unstable concept that Marc Augé used to define something that many of us could see without being able to envision its boundaries: “If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.”1 We call these places vulgar, anonymous, peripheral, devoid of identity, characterless, recent and interchangeable. They are places of transit, as interchangeable with each other as metro tunnels in any major city, made uniform by dirt, solitude, haste;

1. Augé, Marc: Los no lugares. Espacios del anonimato (Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthology of Supermodernity) Ed. Gedisa, 2005. p. 83.

por ellos… o al menos eso creíamos. Especial importancia tenía, al menos para los que estamos en el mundo del arte, la afirmación de que el futuro de estos lugares no sería el monumento sino la ruina. El monumento nos habla de un pasado honorable, importante, de una historia, de que hubo algo y desapareció, suponiendo una gran pérdida (“...esas ruinas que hoy ves, ayer fueron Itálica gloriosa”2);sin embargo el futuro verá los restos de todos estos no lugares sin recordar un pasado glorioso, sin memoria, borrada su existencia por el viento del tiempo. Sin embargo, tampoco hoy las nuevas generaciones saben nada de Itálica ni de su gloria hoy perdida, pero sin duda recuerdan esos subterráneos donde vivieron sus primeras experiencias de iniciación, de libertad. Tal vez su Itálica gloriosa sea una estación de metro, o un prado entre dos solares en construcción. Un famoso tango de Gardel, Barrio, nos puede ampliar el concepto de lugar alejado de la gloria, pero envuelto en los recuerdos; asfixiado por la nostalgia, el cantante recuerda su infancia, su barrio, un vulgar villorrio de Buenos Aires, sin más pena ni gloria que ser el lugar de su infancia, y canta: “Barrio, que tenés el alma inquieta de un gorrión sentimental”. Gardel nos recuerda lo más simple, los lugares que tienen su espacio en nuestra memoria, en ese territorio en el que siguen viviendo los mejores recuerdos; un lugar que, posiblemente, nunca existió y que fue por tanto el más auténtico de los no lugares, aquellos que nunca mueren.

El mismo Augé desarrollaría los conceptos de lugar como continuación del no lugar, como la continuación de una misma idea que se transforma sin fin ni principio: “el primero (el lugar) no queda nunca completamente borrado y el segundo (el no lugar) no se cumple totalmente”3. Los conceptos de identidad y de pertenencia varían con los cambios sociales. Los lugares viven otras vidas en nuestras memorias, y sirven para reconstruir recuerdos de algo que no fue. Esa es tal vez su gloria más perdurable.

Esa memoria, esa nostalgia, está en el origen de algunas de las fotografías que conforman esta revista que en estos momentos empieza a leer. Esos lugares que vivimos de una forma y recordamos de otra. Pero también la necesidad de la que hablábamos al principio; la necesidad de poner nombre a las cosas, de clasificar y de enumerar. La necesidad de que el archivo sea de insectos, de libros o de recuerdos. Túneles, gasolineras, aeropuertos, antesalas, vestíbulos, escaleras mecánicas, barriadas periféricas, estacionamientos… Muchos de ellos tienen relación con nuestros movimientos, con nuestros viajes, con esa nueva sociedad que redefine el paisaje y convierte la naturaleza en un jardín vertical. Todos intercambiables entre sí, sin identidad ni nada especial. Simplemente lugares que todos nosotros cruzamos, que habitamos y casi siempre olvidamos. Solo la mirada del fotógrafo, las imágenes que reconstruyen otra realidad, permanecerán tal vez como monumentos, tal vez solamente como ruinas. ¶

2. Canción a las ruinas de Itálica, Rodrigo Caro (1595 primera versión)

3. Augé, Marc: op. cit. p. 84.

essential places perhaps, at least some of which are unavoidable in modern life, but never pleasant or loved; places we no longer remember after having passed through them, or at least that is what we believed. The assertion that the future of these places is not as monuments but as ruins was especially important, at least for those of us in the art world. The monument talks to us of an honourable and important past, of a history, of something that was there and has disappeared, representing a major loss [“...These ruins that you see today were glorious Italica yesterday”2]. The future, however, will see the remains of all these non-places without remembering a glorious past, without a memory, their existence erased by the winds of time. Yet even today our new generations know nothing of Italica or its long-lost glory, though they no doubt remember those underground spaces where they lived out their first experiences of initiation, of freedom. Their glorious Italica is perhaps a metro station or a meadow between two building sites.

Melodía de Arrabal, a famous tango written by Carlos Gardel, broadens our view of a place far removed from glory but shrouded in memories. Overcome with nostalgia, the singer remembers his childhood, his neighbourhood, an insalubrious corner of Buenos Aires with nothing more to commend it than the fact it was where he grew up. He sings: “Barrio, que tenés el alma inquieta de un gorrión sentimental” (“Neighbourhood, you have the restless soul of a sentimental sparrow”). Gardel reminds us of the simplest things, the places that occupy a space in our memory, in that area where the happiest memories continue to be lived out, a place that possibly never even existed and which was, therefore, the most authentic of the non-places, the places that never die.

Augé himself would develop the concept of place as a continuation of the non-place, as a continuation of a single idea that is transformed without end or beginning: “… the first [the place] is never completely erased, the second [the non-place] never totally completed.”3 The concepts of identity and belonging vary according to social changes. Places lead other lives in our memories and serve to rebuild memories of something that was not. That is perhaps their most enduring glory.

That memory, that nostalgia, provides the source for some of the photographs that appear in this magazine that you’re just about to read, the places that we experience in one way and remember in another. Then there is the need that we spoke about at the start, the need to give names to things, to classify and enumerate, the need to archive things, whether they are insects, books or memories. Tunnels, petrol stations, airports, waiting rooms, lobbies, escalators, neighbourhoods on the outskirts of town, car parks… many of these places are linked to our movements, to travel, to that new society that redefines the landscape and turns nature into a vertical garden. They are all interchangeable with each other, lacking in identity or any special feature. They are merely places through which we all pass, in which we live and almost always forget. Only the photographer’s gaze, the images that reconstruct another reality, will perhaps endure as monuments, perhaps only as ruins. ¶

2. Song to the Ruins of Italica, Rodrigo Caro (1595, first version)

3. Augé, Marc: op. cit. p. 84.

La espiropapa The spiralised potato

Tu hermana me regaló el patinete eléctrico, dijo que ya no te gustaba. Ahora lo uso siempre para ir y volver de la correduría, funciona perfecto. Me han dicho que no puedes recibir cartas en el hospital, pero bueno, la Sandra te acercará esta hojita en Navidad. Querría haberte escrito antes, he tardado porque se me ha ido haciendo bola. Sabiendo cómo te fue a ti con el patinete solo me queda rezar para que no esté maldito (es broma).

¿Te acuerdas del túnel que conectaba la acera de tu casa con la acera de la mía? Lo han cerrado, las dos entradas tapiadas, ya no se puede cruzar. Estará todo oscuro ahí dentro. Hay un paso de cebra nuevo en la avenida, lo cruzo subido al patinete como si nada. Mejor así, porque me da el viento en la cara y es más sano, pero echo de menos atravesar el túnel y ver los mensajes que escribimos y los chicles de hierbabuena que pegamos en las paredes hace quince o veinte años. Es como si nada le importase a nadie, no hay respeto desde que acabó la pandemia.

Sigo yendo al VIPS de la calle Don Pancracio, me siento en donde siempre, aunque ahora estoy solo. Siempre estoy solo en el VIPS. Voy a desayunar, sobre todo. Estamos de habituales una señora mayor y yo, y las camareras. Una camarera tiene un parche en un ojo y en el parche tiene cosido el logo del conejito de Playboy; es genial. La señora mayor me habló una vez y me preguntó si había visto a su iguana, le dije que no y dijo que esa iguana era su vida entera. Pero yo no la he visto nunca, a la iguana. Cuando íbamos al VIPS con el Migue y el Loren era otra cosa, una vez el hijo de puta del Migue me

Wojciech Karlinski. Kłodzko Miasto, from Train Station in Poland series, 2022. Courtesy of the artist.

@wojciech.karlinski

Your sister gave me the electric scooter. She said you didn’t like it anymore me. I always use it to go to the brokerage and back, and it goes just great. They told me you can’t receive letters in hospital, but I’ll get Sandra to bring this little page to you at Christmas. I wanted to write to you before but I just couldn’t get round to it. Knowing how you got on with the scooter, I can only pray it’s not cursed (I’m joking!).

You remember the tunnel that ran between the pavement outside your house to the pavement outside mine? They’ve closed it. They bricked up the two entrances and now you can’t go through it. It’ll be all dark in there. There’s a new zebra crossing on the avenue. I cross it on the scooter as if it were the easiest thing. It’s better because I get the wind in my face and it’s healthier, but I miss walking through the tunnel and seeing the messages we wrote and the blobs of mint chewing gum we stuck on the walls 15 or 20 years ago. It’s as if no one cares about anything. There’s been no respect since the pandemic was over.

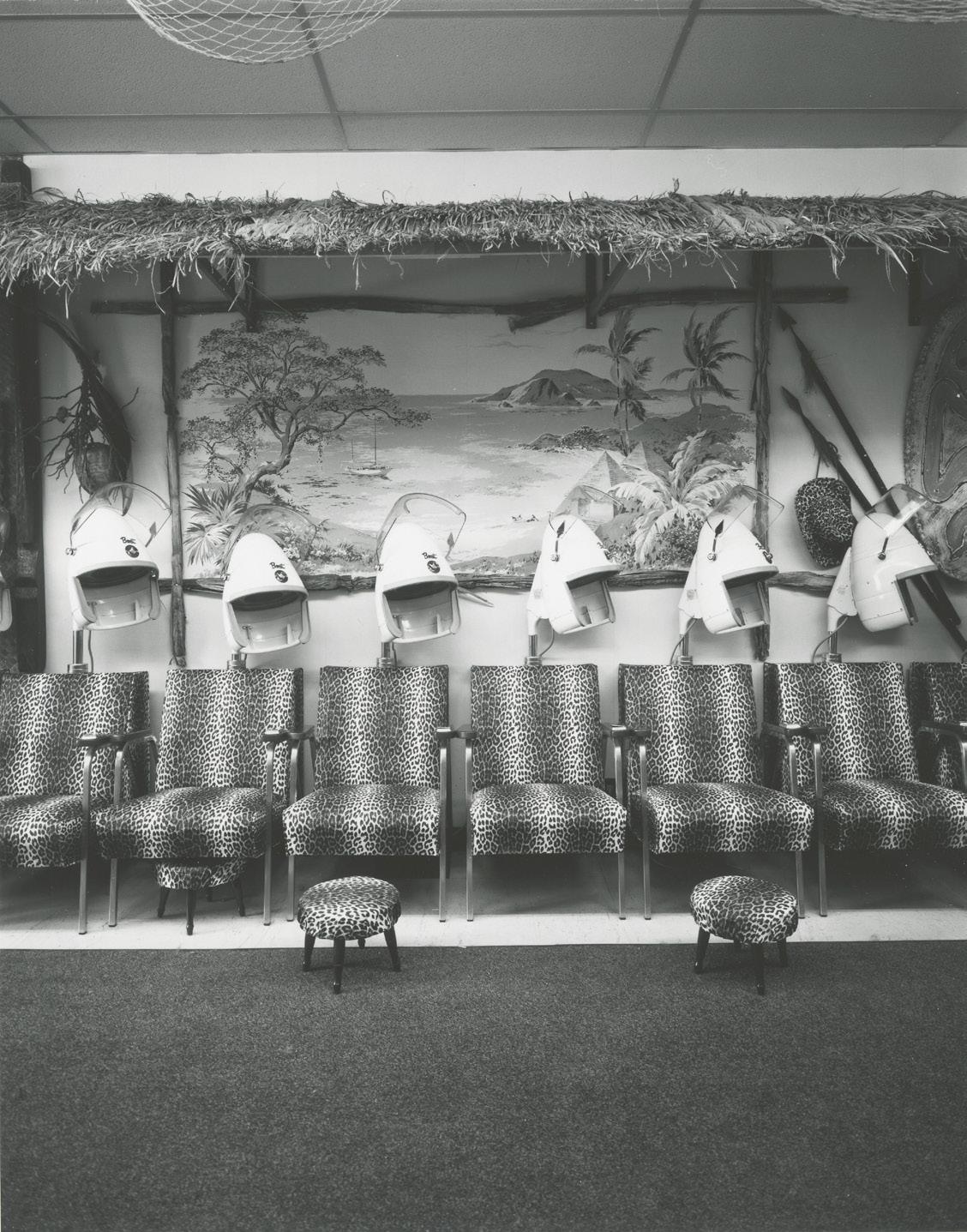

Lynne Cohen. Phileas Fogg Cafeteria, Ottawa, 1978. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

I still go to the VIPS fast food restaurant on Don Pancracio Street. I sit in my usual place, but I’m on my own now. I’m always on my own at VIPS. I go for breakfast more than anything else. It’s usually me, an old lady and the waitresses, one of whom wears an eyepatch with the Playboy bunny stitched onto it. It’s great. The old lady spoke to me once and asked me if I’d seen her iguana. I said I hadn’t. She told me the iguana meant the world to her, but I’ve never seen it, the iguana. When we used to go to VIPS with Migue and Loren it was something else. That son of a bitch Migue stuck a fork in my shoulder once and we had to go to A&E. I’m laughing so hard I’m pissing myself, but you won’t remember.

clavó un tenedor en un hombro y tuvimos que ir a Urgencias; me da la risa que es que me meo encima, tú ya ni te acordarás.

En agosto me crucé con tu padre en el bar “Los Amigos” y me dijo que el hombre no es como la mujer, que el hombre es dos mujeres o tres, porque la mujer viene de la costilla del hombre y de la costilla de un hombre se pueden sacar incluso más mujeres todavía, sobre todo en caso de que ese hombre en concreto sea maricón. Dijo tu padre que hace falta ser muy hombre para ser maricón, mientras me agarraba de la cintura, y luego dijo que el hombre no viene del mono, que viene del búfalo. Añadió: “yo no vengo del mono, mira estos brazos”. Tiene los brazos como dos fideos mojados. Yo creo que tu padre no ha visto un búfalo ni por la tele. Al final cerró el discurso diciendo que si el hombre viniera del mono tendría que venir de un mono muy listo, porque el hombre ha construido mucho y ha pensado incluso más. Que todas las ciudades las ha construido el hombre. Al parecer no hay ciudades hechas por perros ni por ardillas. Te lo cuento porque sé que te hará gracia, a pesar de todo.

Pronto me mudaré, he aceptado el traslado a Zaragoza. Espero volver pronto, quizá por Semana Santa, a ver si con suerte ya estás en casa con los tuyos. Venga, cabrón, que en nada sales.

Tengo en la mesilla la bola de cristal que me regalaste con el tiranosaurio con sombrero de cowboy dentro que si la agitas le cae la nieve por encima. Si mañana me toca el Euromillón me compro un chalecito y lo lleno de cosas: raquetas, peines, zapatos, naranjas de las caras, tele nueva, un loro de cincuenta años, entrenador personal para no estar gordo, mesas de madera y un altarcito para la bola de cristal, mi bien más preciado. Pensarás que exagero, pero no. Esa bola es mi bien más preciado, en serio. Me encanta mirarla. También guardo los cromos de monstruos y el triceratops de peluche.

I bumped into your father at Los Amigos bar in August and he said men are not like women, that men are twice or three times what women are, because women are made from a man’s rib and you can get even more women from a man’s rib, especially if the man in question is a faggot. Your father grabbed hold of me by the waist and said you have to be a real man to be a faggot, and then he said that man wasn’t descended from monkeys but from buffaloes. He added: “I’m not descended from a monkey. Look at these arms!” His arms are like two wet noodles. I don’t think your dad has ever seen a buffalo, even on TV. I wrapped up our chat by saying that if man were descended from monkeys, they’d have to be very clever monkeys because man has built lots of things and has thought about even more. Man has built every city. Apparently, no cities have been built by dogs or squirrels. I’m telling you this because I know you’ll find it funny, in spite of everything.

I’ll be moving soon. I’ve agreed to go to Zaragoza. I hope to be back soon, maybe for Easter. Hopefully, you’ll be back home with your family. Come on, you bastard! You’ll be out of there in no time.

I’ve got that snow globe you gave me on my bedside table, the one with the tyrannosaurus wearing a cowboy’s hat. If I win Euromillions tomorrow. I’m going to buy a nice little chalet and fill it up with things: racquets, combs, shoes, expensive oranges, a new TV, a 50-year-old parrot, a fitness coach to keep me in shape, wooden tables and a little altar for the snow globe, my most treasured possession. You’ll think I’m going over the top, but I’m not. I’m not kidding when I say that globe is the most

Y el cómic que hicimos en COU... “Antonio y Carlos: Detectives del Mesozoico”. Me muero de la vergüenza (aunque reconozco que me encanta).

Tengo el cuarto de estar lleno de recuerdos. Muchos objetos a mi alrededor. Las personas proyectan sobre ti su angustia, pero en los objetos te proyectas tú y te quedas tranquilo, es mejor así, nadie sale herido, no dependes de nadie, no eres un esclavo, estás con tus cosas, tan pancho. No sé si las personas dan la felicidad. Cuanta más gente cerca menos feliz eres porque la gente es como si se llevase tu alegría, ¿no? Se la llevan al respirar igual que se llevan el aire. Supongo que hay personas que no son así, pero es raro encontrarlas y cuando las encuentras a menudo las pierdes, qué te voy a contar. A veces me siento como un muñeco de fieltro recortado por un niño de dos años.

Hoy tomaría una copa contigo, una copita de cava o un champán; eres muy guapo, siempre lo has sido. Si tu madre me pilla escribiendo esto me mata, pero me da igual porque me gusta el peligro, es trepidante, me hace sentir que no he muerto, ¿quién sabe lo que puede pasar?, es un enigma... un misterio internacional. Tú y yo juntos en una playa blanca, todos los días a las dos antes de comer, luego a lavarnos los dientes, pim pam, y Listerine para tapar el sabor del Biofrutas Mediterráneo Pascual que me bebo a media mañana en el descanso del trabajo para fumar (que ya no fumo, palabra). Cuando hace frío te echo de menos intensamente, como en una novela buena. Me olvido de los apellidos y de las caras de las personas que conocía, cada año es peor. Estaba enamorado de todos mis amigos y ahora si me los cruzo por la calle ya no sé ni quiénes son. Cada mes pasa más deprisa que el anterior, Antonio, pero de ti no me olvido. Necesito dar un giro a todo esto, comer más acelgas, más pescado azul, hacer más cardio, pesa rusa arriba y abajo. Si lo piensas, España está llena de oportunidades. Restoranes, discobares, oficinas de Correos, bailes que no acaban, patinetes eléctricos, mucho sol. El amor es como si me pegasen con él en la cara. Cuando eres joven te crees que todo es de una única forma, que vas a durar toda la eternidad, pero nadie dura tanto, lo normal es que las cosas duren poco, las fabrican con esa idea en mente.

treasured thing I own. I love looking at it. I’ve also kept the monster stickers, the triceratops cuddly toy, and the comic we made on our pre-uni course: “Antonio and Carlos: The Mesozoic Detectives”. How embarrassing! I do love it, though.

The living room is full of mementoes. I’ve got a lot of things around me. People project their anguish on you, but with objects you project yourself on them and it keeps you nice and calm. It’s better that

way. No one gets hurt, you don’t depend on anyone and you’re not a slave. You’re there with your things and that’s just fine. I don’t know if people can make you happy. The more people you have close to you the less happy you are because it’s almost as if people take your happiness away, isn’t it?. They just suck it in like they suck in the air when they’re breathing. I suppose some people aren’t like that but they are few and far between and when you do find them you often lose them. You don’t need me to tell you that. Sometimes I feel like a felt doll fashioned by a two-year-old.

I’d have a drink with you today, a glass of cava or champagne. You’re very handsome. You always have been. If your mother found me writing this, I’d die, but I don’t care because I like danger. It’s all very daring. It makes me feel like I haven’t died. Who knows what might happen? It’s an enigma, an international mystery. You and I together on a white, sandy beach, every day at 2, before lunch. Then we’d go and brush our teeth, just like that, and a drop of Listerine to cover the taste of the Biofrutas Mediterráneo Pascual I drink when I take my mid-morning cigarette break at work (I’ve given up smoking, honest!). When it’s cold, I miss you intensely, like in a good novel. I forget the surnames and the faces of the people I knew. It gets worse every year. I was in love with all my friends, but if I see them in the street now I don’t know who they are. The months go by faster and faster, Antonio, but I don’t forget you. I need to turn all this around, eat more chard, more blue fish, do more cardio training, do kettlebells. If you think about it, Spain is full of opportunities – restaurants, night clubs, post offices, endless dances, electric scooters, so much sun. Love is like being hit in the face with it. When you’re young you think everything is just one way, that you’re going to last forever. Nobody lasts for so long, though. More often than not things don’t last long. They’re made with that idea in mind.

Xavier Ribas. Untitled (zodiacs), from Domingos series, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

@xavierribas_

¿Te acuerdas del Hotel Agamenón, en Denia? Tremendo viaje de fin de curso. No me lo he pasado mejor jamás. Una noche soñé que volvía a estar allí, contigo. Era todo idéntico, nos estábamos pajeando viendo la gala de José Luis Moreno, pero la habitación se inundaba de agua de mar y de repente aparecía un mosasaurio que nos quería comer vivos. Desperté y estaba sudando. ¿Tiene sentido esto que te cuento? No soy un intelectual como tú, sin ánimo de ofender. Quisiera estar explicándome bien.

Tú y yo nos hemos reído hasta que nos ha hecho ñaca la tripa. Quiero creer que podemos volver a ser un algo. Cuando me dijiste aquello no me lo esperaba y no supe responder como es debido. No es que no te quiera. Sabes que te quiero de verdad. ¿Es que no lo ves? Te quiero de verdad. Te echo mucho de menos, pero ¿qué puedo hacer? No sé qué decir, Antonio. Es como si en Madrid ya no quedaran personas que no se hubieran muerto. Computadoras, aparcamientos, casetes, colegios abandonados, radios, canchas de baloncesto, energía nuclear, fotocopiadoras, una correduría de seguros, dos corredurías de seguros, ropa comprada en Desigual, faxes, árboles bonitos, escaparates vacíos y el teleférico; todo eso queda. Pero no estás tú. Para vivir en una ciudad llena de muertos prefiero mudarme a Zaragoza, que allí también tienen VIPS (tienen tres, menos mal, dios mío), aunque hace más frío, no sé. Tu belleza, para mí, era una hoguera en el centro de la noche.

Do you remember the Hotel Agamenón, in Denia? What an end-of-year trip that was. I had the best time ever. One night I dreamed I was back there with you. The place was just how it was. We were jerking off watching the José Luis Moreno gala on TV when the room suddenly flooded with sea water and a mosasaur appeared and tried to eat us alive. I woke up, covered in sweat. Does this make sense to you? No offence, but I’m not an intellectual like you. I wish I was making myself clear.

You and I have laughed until our sides hurt. I want to believe that we can be something again. When you said that thing to me I wasn’t expecting it and I didn’t respond in the way that I should. It’s not that I don’t love you. You know that I really love you. Can’t you see it? I really love you. I miss you so much but what can I do? I don’t know what to say, Antonio. It’s as if there was no one left in Madrid who wasn’t dead. Computers, car parks, cassettes, deserted schools, radios, basketball courts, nuclear power, photocopiers, an insurance brokers, two insurance brokers, clothes bought in Desigual, faxes, beautiful trees, empty shop windows and the cable car – that’s all there still. But you’re not. If I’m going to live in a city full of dead people, I’d rather move to Zaragoza. They’ve got VIPS there too (three in fact, which is just as well, my God). It’s colder there, though. I don’t know. To me your beauty is like a bonfire in the middle of the night.

Yesterday, I went down to the neighbourhood festival for a while and bumped into Loren and Sandra. When you see her, the little clever clogs, ask her to explain what happened with the mechanical bull because I can’t. They should have sent a poet. Incredible! Then, I came back from the loo and saw a rat stealing a spiralised potato. I’m cracking up. They’re potatoes cut into a spiral and they come on a wooden stick. They didn’t do them before and I don’t know if you’ve ever had one. I didn’t have time to get my mobile out and film

Branislav Kropilak. Lobbies series, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Branislav Kropilak. Lobbies series, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Ayer bajé un rato a las fiestas del barrio, coincidí con el Loren y la Sandra. Cuando la veas a la muy lista dile que te explique la movida que pasó con el toro mecánico, yo no me veo capaz, tendrían que haber enviado a un poeta, increíble. Aparte de eso, una vez que volvía de hacer pis vi a una rata robando una espiropapa, me parto. Una espiropapa es una patata de esas cortadas en espiral y pinchadas en un palito de madera; antes no las hacían, no sé si te habrás comido alguna. No me dio tiempo a sacar el móvil para grabar la escena. La muy sinvergüenza subió a un puesto y se llevó la espiropapa, visto y no visto. El hombre del puesto salió corriendo detrás de la rata, pero no pudo alcanzarla. La rata se coló entre los tablones de la entrada del túnel de la avenida y desapareció para siempre. Me habría gustado hacer como ella: huir de todo y regresar al túnel que conectaba tu acera y la mía, con el tentempié entre los dientes. Las ratas y yo podemos ver en la oscuridad, no sé si lo sabías. Quisiera pisar ese suelo por última vez, leer nuestros mensajes escritos con Edding de color rojo. “Amavisca selección. Mamadas gratis. OTAN no, bases fuera. Toño x Charly para siempre”. Pasar una mano por las paredes, la otra mano agarrando la espiropapa. Todos los días yendo y viniendo contigo, atravesando ese túnel con la mochila en la espalda. Yo es que de lo importante no me olvido nunca.

En fin, termino ya, perdón por la sábana. Espero que te guste mi carta y que te estén tratando bien en el hospital. Siempre te han gustado los hospitales, en el fondo estarás en tu salsa. Pronto te pondrás bueno, eres muy fuerte. No importa lo que diga la gente, yo creo en ti. Pienso seguir usando tu patinete (que ahora es mío), no tengo ningún miedo a las maldiciones. Soy agnóstico y del Real Madrid.

A ver qué tal me va en Zaragoza, espero que bien, te iré contando; se supone que en esa sucursal tienen máquina de Nespresso. Hace un rato estaba con las maletas y toda la pesca y tuve que envolver la bola de cristal en papel de ese de burbujitas. Me da pánico que se rompa con tanto vaivén y perder la nieve que hay dentro. Si se rompiese la bola yo no sé qué haría. Sé que hay cosas peores. O sea, te pueden pasar cosas peores y tal. Lo que pasa es que ahora no se me ocurre ninguna. ¶

it. The cheeky little thing climbed up one of the stands and just took the potato, in a flash. The man at the stand chased after the rat but couldn’t catch it. The rat snuck between boards at the entrance to the tunnel on the avenue and disappeared forever. I wish I could have done what it did – escape from everything and return to the tunnel that connected your pavement and mine, with the snack between my teeth. Rats and I can see in the dark. I don’t know if you knew that. I’d like to walk that ground one last time and read the messages we wrote with a red Edding pen – Amavisca for Spain! Free blow jobs! No to NATO! Shut the bases! Toño and Charly forever! – run a hand over the walls, the other clutching the spiralised potato. Going back and forth with you every day, walking through that tunnel with a rucksack on my back. I never forget the important stuff.

Well, that’s all from me. Sorry about the sheet. I hope you like my letter and that they’re treating you well in hospital. You’ve always liked hospitals, and deep down you’ll be in your element. You’ll be right as rain soon enough. You’re very strong. It doesn’t matter what people say; I believe in you. I think I’ll keep on using your scooter, which is mine now. I’m not scared of curses. I’m an agnostic and a Real Madrid fan after all.

Let’s see how things go for me in Zaragoza. Well, I hope. I’ll keep you posted. The branch is supposed to have a Nespresso machine. I’ve just been packing my bags and all the fishing gear and I had to wrap the snow globe in bubble wrap. I’m scared it’ll break with all the coming and going and lose the snow inside it. I don’t know what I’d do if it broke. I know there are worse things, that there are worse things that can happen. I just can’t think of any right now. ¶

Manuel

Branislav Kropilak

Branislav Kropilak. Garages no. 05, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

La imagen inhóspita. Garajes, gasolineras y vestíbulos

Ante nuestra mirada inquieta, las fotografías de Branislav Kropilak testimonian una realidad distante, superficial, deshumanizada. Las imágenes se suceden en serie bajo una misma temática, una tras otra. En todas ellas, aparecen superficies brillantes, coloridas, planas, artificiales. Después de largo rato de contemplación, nuestra mirada se agota, se exaspera, desiste en su ansiosa búsqueda por hallar un resquicio de vida, un cobijo, una morada. Allí donde cabría esperar algún signo de presencia humana —el trajín, el ruido, la circulación irrefrenable de los coches, el intercambio de las miradas, la velocidad de los cuerpos—, no queda ni un hálito de vida. “¿Hay alguien?”, preguntamos con voz temerosa. No encontramos respuesta alguna, solo el eco de nuestra propia voz que golpea contra las paredes de un garaje infinito. Todos se han ido a otra parte, a otro lugar. Allí por donde habitualmente pasamos sin pausa, sin miramientos, ya nada pasa, nadie pasa. Todo queda a la vista y, sin embargo, da la sensación de que algo o alguien se esconde en algún sitio. “¿Dónde está todo el mundo?”, “¿y el fotógrafo?”, susurramos mientras nos tiembla la voz.

Las series fotográficas del autor eslovaco Branislav Kropilak, Garages, Gas Pumps y Lobbies, están dedicadas a capturar no-lugares, es decir, espacios inhabitados e inhabitables marcados por el ir y venir, el entrar y salir de gente —jamás por el quedarse, el hacer hogar, el hacer lugar—. Sin embargo, ninguno de estos no-lugares cumple con su función, tampoco con nuestras expectativas. En el parking no hay coches, en el vestíbulo no hay tránsito y en la gasolinera nadie echa gasolina. Kropilak registra espacios al desnudo, sin ningún tipo de huella humana —de algún paseante extraviado o de un niño que juega a la pelota—, tampoco del propio artista, que toma distancia y no se involucra afectivamente con el entorno, que

no se deja ver en la imagen. Su trabajo fotográfico consiste así en un ejercicio aséptico de distanciamiento. El resultado que nos ofrece consiste en un cúmulo de fotografías que parecieran instantáneas realizadas por un ojo maquínico: testimonios de un robot que se posiciona frente a espacios y objetos ante los cuales el ciudadano no detiene la mirada ni su caminar.

Este tipo de fotografía, que elimina cualquier forma de presencia humana en la imagen fotográfica, encuentra su legado en el trabajo artístico de los Becher (Bernd y Hilla Becher), promotores de la escuela de Düsseldorf, quienes documentaron la arquitectura industrial de Europa y Estados Unidos durante los años cincuenta y sesenta. Este vaciamiento radical de lo humano devuelve al espectador una planitud pulcra e inquietante, escenarios que contemplamos como si se tratasen de decorados, como puro artificio. Nos recuerdan, estas imágenes, a las del artista alemán Thomas Demand, quien construye modelos a tamaño real de arquitecturas para recrear así fotografías de prensa. En un afán de simulacro, esculpe espacios reales que nunca cuentan con la presencia humana. Estas imágenes artificiosas permiten al espectador reconstruir la historia, la escena y los personajes ausentes. Por el contrario, las fotografías de Kropilak no lamentan la pérdida del humano que ya no está, o indagan en su condición extinta, tampoco tratan de evidenciar su huella, de manifestar su ausencia a través del rastro o la sombra, sino que enfatizan el brillo de las superficies, la pulcritud de los espacios, la entidad autónoma de las arquitecturas y la inutilidad de sus equipamientos. Esta vacuidad higiénica nos desvela un espaciotiempo inhóspito, desquiciado; allí donde ni tan siquiera se manifiesta el tránsito, el devenir; allí donde solo se puede constatar la huida absoluta de cualquier seña de humanidad.

Si bien, durante los comienzos de la historia de la fotografía, los largos tiempos de exposición de las cámaras fotográficas daban como resultado escenas fantasmales donde ningún cuerpo estaba presente (imágenes de calles vacías), en este caso la vacuidad y artificialidad es premeditada. Si bien, antiguamente, la cámara se volvía forzosamente ciega al devenir de la gente por el espacio urbano, ahora la cámara de Kropilak busca de forma firme y esforzada el momento de mayor ausencia en los espacios de mayor tránsito. No existe ya posibilidad alguna de imaginar la presencia humana, de ahí el colapso de la mirada. Una cierta sensación de incertidumbre, de duda, nos invade a causa de este total desalojo de la huella y mirada humanas. Nos situamos como testigos de la extinción, como espectadores maquínicos y no dejamos de ver pasar ante nuestros ojos imágenes de un mundo sin nosotros.

The inhospitable image: garages, gas pumps and lobbies

When we cast our restless gaze on the photographs of Branislav Kropilak we see a distant, superficial, dehumanised reality. Covering the same theme, the images appear in series, one after the other, all of them showing surfaces that are bright, colourful, flat, artificial. Our eyes eventually tire of looking at them. They lose patience and give up their anxious search for the merest sign of life, a shelter, a dwelling place. Expecting to find some sign of a human presence – hustle and bustle, noise, ceaseless traffic, exchanged glances, the speed of bodies on the move – we see no trace of life. “Is anyone there?” we ask fearfully, receiving no answer, only the echo of our voice bouncing off the walls of a garage that goes on forever. Everyone has gone somewhere else, to another place. The place where we usually walk without stopping, without looking, is now a place where nothing happens, nobody passes through Though everything is in plain sight, we get the feeling that something or someone is hiding somewhere. “Where is everyone? What about the photographer?” we whisper, our voice shaking.

Garages, Gas Pumps and Lobbies, three series by the Slovakian photographer Branislav Kropilak, capture non-places, those uninhabited and un-

inhabitable spaces where people come and go, where they enter and leave but never stay, make a home, make a place The fact is, however, that none of these non-places fulfils its function or meets our expectations. There are no cars in the car park, no one moving through the lobby and no one filling up at the gas station. Kropilak records spaces that are left bare, devoid of any human trace, of any passers-by who have lost their way or children playing with a ball. The artist is not even there. Positioned at a distance, he does not emotionally engage with his surroundings and does not allow himself to be seen. His photographic work is thus an aseptic exercise in distancing. The result is a host of photographs that seem to have been taken by a machine-like eye, the visual testimonies of a robot that takes up position in front of spaces and objects that a person would not even look at, let alone stop to contemplate them.

This type of photography, which removes any form of human presence from the image, takes its cues from the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, the de facto founders of the Dusseldorf School, who documented the industrial architecture of Europe and the USA in the 1950s and 60s. This radical removal of the human from the scene brings the

viewer face to face with a meticulous and worrying flatness, with scenes we look upon as if they were sets, as pure artifice. These images remind us of those of the German artist Thomas Demand, who builds life-size models of buildings in recreating press photographs. In a desire for simulation, he sculpts real spaces in which there is a never a human presence. Skilfully created, the images allow the viewer to rebuild the story, the scene and the missing characters. In contrast, Kropilak’s images do not lament the loss of the human who is no longer there or contemplate their extinction. Nor do they attempt to make any remnant of them visible, to manifest their absence through a trace or a shadow. What they do is emphasise the brightness of the surfaces, the neatness of the spaces, the autonomous entity of the buildings and the uselessness of the equipment they contain. This hygienic hollowness reveals a space and time that is inhos-

pitable, unhinged. It is a place where transit, movement, is not even shown, where all that can be seen is the flight of all signs of humanity.

In the early days of photography, the long exposure times of the first cameras yielded ghostly scenes of empty streets and the like, scenes in which no one is present. In this case, however, the emptiness and artificiality is premeditated. Whereas in the past the camera was necessarily blind to people moving through the urban space, Kropilak’s camera decisively and effortlessly searches for the moment of greatest absence in spaces that are transited the most. The human presence can no longer be imagined in any way, which means we have nothing to look at. This complete removal of the human trace and gaze causes uncertainty and doubt in us. We are witnesses of extinction, machine-like spectators, and we see images of a world without us continually flash before our eyes.

no.

Branislav Kropilak. Garages no. 18, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

La cámara de Kropilak busca de forma firme y esforzada el momento de mayor ausencia en los espacios de mayor tránsito.

Kropilak’s camera decisively and effortlessly searches for the moment of greatest absence in spaces that are transited the most.

Branislav Kropilak.

Lobbies no. 30, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Pages 26-27, Branislav Kropilak.

Garages no. 12, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

Branislav Kropilak. Lobbies no. 01, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Raúl Belinchón Ciudades subterráneas Underground cities

En las primeras líneas del ensayo No lugares: Espacios del anonimato, del filósofo y antropólogo Marc Augé, un personaje llamado Juan Pérez recorre un aeropuerto.

En 2022, el nieto de Juan Pérez es mi personaje. En honor a su abuelo le he dado el mismo nombre. Juan espera sentado en uno de los bancos del metro —que es considerado, al igual que el aeropuerto, un no lugar por el filósofo—, cuya línea amarilla recorrerá el centro de la ciudad para llevarle a la parada final, Argüelles, donde otro grupo de adolescentes le esperan sentados en las escaleras de salida.

Juan queda casi todos los viernes en las mismas escaleras. En aquellas ocasiones en que llega antes, escucha con atención cantar a una chica de largo pelo rubio y ojos melancólicos que mira el suelo con frecuencia mientras versiona, con una

Written by the philosopher and anthropologist Marc Augé, the essay

Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity opens with a character called Pierre Dupont walking through an airport.

Fast forward to 2022 and my character is the grandson of Pierre Dupont. In honour of his grandfather, I have given him the same name. Pierre sits waiting on a bench in the metro – a place, like the airport, regarded as a non-place by the philosopher – the yellow line of which runs through the city centre

Raúl Belinchón.

Oxford Circus, Londres, 2003.

Courtesy of the artist.

Waterloo, Londres, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

Monument, Londres, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

guitarra española, los éxitos que suenan en la radio. Cuando ella no está en su lugar de siempre, la echa de menos. Hasta la llegada de algún amigo, suele entretenerse con el móvil u observa a la gente pasar. Si se siente animado, a veces recorre el espacio con grandes auriculares y, con las manos en los bolsillos, lee las cartelas de los cuadros expuestos en el hall o en los interminables pasillos del metro.

En su ensayo, Marc Augé diferencia claramente los lugares antropológicos de los no lugares. Los primeros son espacios geográficamente bien definidos y que poseen fundamentalmente tres características: son identitarios porque tienen sentido de unidad para aquellos que los habitan, definen a un grupo o cultura, compartiendo unas características y unos rasgos con los que se identifican. Son, además, relacionales porque implican un desarrollo grupal que no es estático, que se sostiene en base a un discurso y a un lenguaje peculiar que dinamiza formas de hacer, de actuar y de reunirse y, por último, son lugares históricos ya que por ellos transcurre el tiempo; suelen ser antiguos y tener la capacidad de añorar tiempos pasados. Los no lugares, en contraposición, son espacios despojados de las expresiones de los lugares antropológicos, es decir, carecen de identidad, de relaciones y de historia. Lo que solo se transita y no se habita es un no lugar para Augé. En base

to take him to its final stop, Argüelles, where another group of teenagers sit waiting for him on the stairs leading to the exit.

Pierre sits on the same stairs virtually every Friday. On the occasions when he gets there first, he listens attentively to a young woman singing. She has long blonde hair and sad eyes that frequently fall to the floor as she sings hits from the radio on a Spanish guitar. He misses her when she is not there. As he waits for his friends to arrive, he passes the time on his phone or watching people go by. Sometimes, he walks around the concourse or endless walkways reading the posters, hands in pockets and large headphones wrapped around his ears.

In his essay, Augé clearly differentiates “anthropological places” from “non-places”. The former are geographically well-defined spaces that essentially have three characteristics. Firstly, they are self-defining because they have a sense of unity for those who live there and they define a group or culture, sharing the characteristics and traits they identify with. Secondly, they are relational because they involve a group development that is not static, and they are founded on a distinctive discourse and language that energise ways of doing, acting and meeting. And thirdly, they are historic places, as time passes through them, they are usually old, and they have the ability to yearn for days gone by. In contrast, non-places lack the expressiveness of anthropological places. In other words, they lack identity, relations and history. In Augé’s view, a place that is merely transited and not inhabited is not a place. On the basis of these characteristics, Pierre defines the metro as a place of identity,

Raúl Belinchón. Lubyanka Station, Moscow, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

Raúl Belinchón. Lubyanka Station, Moscow, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

a estas características, Juan definiría el metro como un lugar identitario, relacional e histórico, al menos para su generación, pero a la vez es también como un no lugar.

Para la época que le ha tocado vivir a Juan, el filósofo acuña el neologismo de sobremodernidad. Sin embargo, Augé se olvida de nombrar en su ensayo la palabra que mejor la define: el nihilismo. La palabra nihilismo, que significa sin doctrina, sin creencia, o lo que es lo mismo, la pérdida de la moral es, en su esencia más pura, la ruptura del hilo que nos une a la vida. Ni-hilo-ismo, es decir sin hilo a la vida como condición de estar vivo. Una vida que se transita, pero no se habita.

Si la expresión material de la vida sería el cuerpo, al igual que el espacio físico es la expresión del lugar y el no lugar, en el 2022 el cuerpo no se vincula a nada, ni siquiera a sí mismo. Este, ni es reconocido ni aceptado, sino transformado y utilizado. El cuerpo no es capaz de ocupar ni siquiera el mismo lugar por mucho tiempo. Como escribía Pascal: “Todas las desgracias del hombre se derivan del hecho de no ser capaz de estar tranquilamente sentado y solo en una habitación.” En la sobremodernidad de Augé, uno ha roto el hilo con la expresión material de la vida, su propio cuerpo. Un cuerpo que nunca se habita del todo y al que por lo tanto le es imposible habitar ningún lugar.

Como bien escribía el propio Augé en su ensayo: “El lugar y el no lugar son más bien polaridades falsas: el primero no queda nunca completamente borrado y el segundo no se cumple nunca totalmente”. Es así como el metro se convierte, para la generación de Juan, en un lugar antropológico y a la vez en un no lugar. Como en mis fotografías, su cuerpo se transforma en un infinito túnel de subidas y bajadas donde aún consciente de sus brillos y sombras, de sus colores, de sus formas, de su belleza o fealdad, de la temperatura o de su olor, lo recorre cada día, sin abandonarlo nunca, sin habitarlo jamás.

Raúl Belinchón. Duomo, Milán, 2004. Courtesy of the artist.

Southwark, Londres, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

Gare Saint Lazare, París, 2003. Courtesy of the artist.

relations and history, for his generation at least, though also as a non-place.

The philosopher coins the neologism “supermodernity” to define the times Pierre lives in. In his essay, however, Augé neglects to use the word that best describes it: nihilism. The word “nihilism”, which means the rejection of all doctrine and beliefs – in other words the loss of all moral values – is, in its purest form, the snapping of the thread (“hilo” in Spanish) that connects us to life. Nihil-ism is the removal of that thread as a condition of being alive. It is a life that is transited but not inhabited.

If the material expression of life is the body, just as the physical space is the expression of the place and the nonplace, in 2022 the body is not linked to anything, not even itself. It is not recognised or accepted but transformed and used. The body is not even capable of occupying the same space for much time, as Pascal wrote: “All man’s misfortunes stem from his inability to sit quietly on his own in a room.” In Augé’s supermodernity we have snapped the thread that links us to the material expression of life, to our own body, a body that is never fully inhabited, thus making it is impossible to inhabit any place.

“El lugar y el no lugar son más bien polaridades falsas: el primero no queda nunca completamente borrado y el segundo no se cumple nunca totalmente”

“Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased; the second never totally completed”

As Augé wrote in his essay: “Place and non-place are rather like opposed polarities: the first is never completely erased; the second never totally completed.” For Pierre’s generation the metro is thus an “anthropological place” rather than a “non-place”. As in my photographs, his body becomes an endless tunnel of inclines and descents where, still conscious of its brightness and shadows, its colours, shapes, beauty and ugliness, temperature and smell, he travels every day, without ever leaving it but without ever inhabiting it.

Lukas Korschan

Could be any place…

Could be any place…, de Lukas Korschan, es una investigación visual sobre las actuales esferas mundanas de soledad y conformismo en todo el mundo —tanto físicas como de naturaleza digital— y una búsqueda de los destellos de romanticismo, belleza y poesía que albergan. La constante persecución de la mariposa.

Lukas indaga en el carácter intercambiable de los aeropuertos, hoteles o centros comerciales y en lo que significan tanto a nivel particular como social. Vemos viajeros atareados camino del trabajo delante del fondo gráfico de un aeropuerto desconocido. La silueta de Nueva York, las flores de Perú, las coloridas telas de Uganda… El fotógrafo enmarca momentos que, aun pudiendo tener lugar en cualquier parte del mundo, marcan las pautas de la identidad moderna: lo que nos une es que, aferrados a nuestros smartphones, recibimos comunicación optimizada y publicidad dirigida mientras esperamos un mensaje de texto de algún ser querido que nos devuelva a la realidad.

A causa de la pandemia se quedaron desiertos los no-lugares del hipercapitalismo (Marc Augé) que Lukas había documentado en sus numerosos viajes. Durante el confinamiento, en Ámsterdam, el artista dio la vuelta al concepto y adoptó un enfoque fotográfico más estático. Retrató a personas que pasaban a toda velocidad junto al objetivo y con el resultado creó una composición dinámica. Esta serie ilustra un mundo ajetreado incapaz de detenerse.

Lukas Korschan. Bus, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Could be any place… by Lukas Korschan is a visual research on today’s mundane spheres of solitude and conformity across the world – physical as well as of digital nature – and a quest for the glimpses of romance, beauty and poetry within. An ongoing chase for the butterfly Lukas enquires the exchangeability of airports, hotels or shopping malls and their meaning to both the individual and society. We see busy travelers commuting in front of graphic backdrops of an unknown airport. The skyline of New York, flowers in Peru, colorful fabrics in Uganda. He is framing moments that can possibly take place anywhere in the world and yet set the tone of modern identity: Holding on to our smartphones as the one thing we have in common, we receive streamlined communication and targeted advertising – hoping for that one text message from your loved one that brings you back to reality.

During the pandemic, the non-places of hyper capitalism (Marc Augé) that Lukas had documented on his extensive travels remained deserted. Being locked down at home in Amsterdam, the artist thus flipped the concept and went for a more static approach to photography. He captured people flashing by the lens and assembled the outcome to a dynamic composition. This series illustrates a busy world that is just not meant to stop moving.

Lukas Korschan. Metal Gate, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Lukas Korschan. Cruise Ship, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Lukas Korschan. Airport, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Lukas indaga en el carácter intercambiable de los aeropuertos, hoteles o centros comerciales y en lo que significan tanto a nivel particular como social.

Lukas enquires the exchangeability of airports, hotels or shopping malls and their meaning to both the individual and society.

Lukas Korschan. Escalator, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Lukas Korschan. Train Station, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. @lukaskorschan

Las escaleras mecánicas y los supermercados de Nigel Shafran1

1.

El fotógrafo Nigel Shafran vive en una casita victoriana que forma parte de una pequeña hilera de casas adosadas apartada de Harrow Road, una vía principal del oeste de Londres, en cuyas inmediaciones se halla el majestuoso y melancólico cementerio de Kensal Green. Bajo la casa de Shafran —tan cerca que la estructura vibra en armonía con los sonidos y movimientos que se producen debajo— se encuentran los profundos pozos y túneles de la red ferroviaria londinense por la que circulan a toda velocidad los trenes con origen o destino en Birmingham y donde se escucha a todas horas el pesado traqueteo de los de la línea Bakerloo. Un poco más allá, al otro lado de las lápidas y los monumentos del cementerio, gime en armonía el eco de la Great Western Railway de Brunel.

La casa, construida en 1864, parece vinculada de una forma tremendamente tangible a la inmensa máquina de la ciudad y sus transformaciones históricas: forma parte de su herencia industrial, su narrativa arquitectónica, su comercio, sus esquemas de trabajo y el continuo y jadeante movimiento de su población. El acuciante peso de esas condiciones es el marco de las operaciones más delicadas del mundo particular del interior de la casa, que, aproximadamente en los últimos catorce años, ha protagonizado la obra de Shafran, tras la que siempre ha subyacido el intento de crear una vida singular, una sensación de originalidad, un cierto orden a partir del caos potencial.

Desde sus primeras fotografías, Shafran se ha guardado de la “pomposidad”, siempre atento a los hechos que tenía delante y deseoso de mantener despejados los canales de observación directa. Pero en su obra reciente esos principios han adquirido una relevancia aún mayor. Ahora es más probable que se preserven intactas, como la propia obra, las formas de la fotografía doméstica habitual a las que, igual que todos nosotros, Shafran siempre se ha dedicado, así como la “toma de notas” visual, igual de cotidiana, que quizás albergara alguna vez la germinación de una idea. Para Shafran, esto entraña una comprensión cada vez mayor de que la esencia de su obra no reside en las cualidades artísticas singulares de la imagen resultante, sino en los detalles particulares de lo que fotografía y en la idea que ello encarna, así como en la motivación para tomar la fotografía y su proceso de realización.

Shafran ha puesto el foco del revés: lo ha apartado del hogar y ha centrado su atención en la ciudad. Así pues, la impresión familiar de que su obra es, en gran medida, una respuesta fortuita y espontánea a las cosas y a las situaciones se ve reemplazada por una atención más sostenida y recurrente, que nos induce a imaginar que el fotógrafo se ha visto hipnotizado por situaciones que vinculan la actividad humana a formas de movimiento mecánico: las cintas transportadoras de las cajas de los supermercados, las escaleras mecánicas descendentes de una estación de metro y el interior de las tiendas que ven-

den equipos de movilidad y de otro tipo para personas discapacitadas. Así pues, de manera ambigua y extraña, en estas series el movimiento está ligado a diversos estados de inercia e incomodidad, una cinta de correr para el cuerpo pasivo, aquietado y abrumado. Las mujeres retratadas en las escaleras mecánicas son fundamentales para esa condición presente en el libro: muchas veces dan la impresión de sufrir incomodidad física, pues se retuercen con torpeza para ajustarse la ropa o parecen agobiadas por las cosas que llevan, como si no solo les costara mantener el equilibrio, sino también mantenerse a flote. Aparentemente empeñadas en ignorar todo ese febril desenmarañamiento, otras mujeres se quedan absortas, físicamente presentes pero sumidas en sus pensamientos, o descienden enfrascadas en sus teléfonos móviles. La sensación que transmite la ciudad en esas fotografías es la de una máquina que provoca y procesa una población distraída y envejecida de trabajadores y consumidores. Y quizás eso encierre un toque fatalista, un tirón hacia abajo de inevitabilidad.

Las primeras escaleras mecánicas se instalaron en 1911 en la estación de metro londinense de Earl’s Court. Las escaleras, desarrolladas en los Estados Unidos a partir de un modelo construido en 1895 como una innovadora atracción para Coney Island, se volvieron fundamentales para el diseño de las estaciones de ferrocarril modernas y para el concepto de los grandes almacenes, donde, al atraer a los clientes hacia arriba, fomentaban la libre circulación entre plantas y garantizaban que edificios enteros funcionaran como instrumentos mecánicos de venta. Como parte de su polifacética modernidad, las escaleras móviles también generaban experiencias cinematográficas: las vistas que ofrecían de las plantas ayudaban a dramatizar el entorno comercial e invitaban a los clientes, que se deslizaban embelesados por el espacio, a imbuirse de la cautivadora narrativa de las compras. Pero las escaleras mecánicas no solo transformaron el funcionamiento y la percepción del espacio, sino que también contribuyeron a reconfigurar las ciudades.

Aunque esta serie diarística era, en parte, una especie de lúdica antropología doméstica, representaba asimismo una forma de empoderamiento que celebraba la circulación de las elecciones aleatorias e idiosincrásicas que enriquecen los rituales particulares. En el supermercado, en el punto de venta, los montones y los desordenados surtidos de alimentos y productos sugieren lo contrario, una manifestación de sumisión; en lugar de generar energía y sugerir determinación, potencia, estas imágenes resultan agotadoras, pues introducen la sensación de fatiga y nos recuerdan las horas que perdemos deambulando aturdidos por pasillos abarrotados.

Escalators and supermarkets

by Nigel Shafran1

by Nigel Shafran1

The photographer Nigel Shafran lives in a small Victorian house that forms part of a short terrace tucked away from the main thoroughfare of west London’s Harrow Road. Nearby is the majestic and melancholy Kensal Green Cemetery. Beneath Shafran’s house, so close that its structure can be felt to vibrate in tune to the sounds and movements below, are the deep wells and tunnels of London’s underground rail system, through which trains speed to and from Birmingham and those of the Bakerloo Line lumber and rattle, day and night. And a little further away, from across the cemetery’s gravestones and monuments, the echo of Brunel’s Great Western Railway moans in harmony.

Built in 1864, the house seems very tangibly bound in this way to the vast machine of the city and its historic transformations: part of its industrial heritage, its architectural narrative, its commerce, its patterns of work and the constant, heaving motion of its population. It is the pressing weight of these conditions that frames the more delicate operations of the private world inside the house, which have, over the last fourteen years or so, been the principal subject of Shafran’s art, where the striving to create a singular life, a sense of uniqueness, some order from potential chaos, has been an underlying theme.

From his earliest photographs Shafran has been cautious about ‘pomposity’, always attentive to the facts before him and keen to keep the channels of direct observation clear. But in his recent work these principles have become even more important. Now the forms of habitual domestic photography that Shafran has, like all of us, always engaged in, and the equally routine visual ‘note-taking’ that may have once harboured the germination of an idea, are more likely to be preserved intact, as the work itself. For Shafran this amounts to a growing recognition that the essence of his work resides in the particular details of the subject, in the idea that the subject embodies and in the motive for and the process of making the picture. It is not to be found in the unique, artful qualities of the resulting image.

Shafran has turned his attention inside out, away from the home and into the city. Here the familiar impression from his work of a largely incidental, spontaneous response to things and situations is replaced by a more sustained, repeated attention, from which we might imagine the photographer has been mesmerised by situations that bind human activity to forms of mechanical movement: the conveyor belts of supermarket checkouts, the

down escalators of a tube station and the interiors of shops selling mobility and other equipment for the disabled. So, ambiguously, and strangely, in these series, movement is bound up with varying states of inertia and discomfort, a treadmill for the passive, stilled and encumbered body. The women pictured on the escalator are pivotal to this condition in the book: they often seem physically ill at ease, twisting awkwardly to adjust their clothing or appearing burdened by the things they carry, as if they are struggling to keep not just their balance but their selves together. As if determined to ignore all this feverish disentangling, other women are transfixed, physically present but lost in thought, or preoccupied by their mobile phones as they make their descent. The sense of the city in these photographs is of a machine that induces and processes a distracted and ageing population of workers and consumers. And in this, perhaps, there is something fatalistic, a downward pull of inevitability.

The first escalator was installed in a London Underground Station at Earls Court in 1911. Developed in the US from a model built as a novelty ride at Coney Island in 1895, escalators became integral to the design of modern rail-

way stations and also to the concept of department stores, where, drawing customers upward, they encouraged the free flow of movement between floors and ensured that entire buildings could function like mechanical instruments for selling. As part of their multi-faceted modernity moving stairways also created cinematic experiences; the views they opened up across floors helped to dramatize the retail environment and invited the customers – entranced and gliding through space – to enter the compelling narrative of shopping. But escalators not only transformed the functioning and perception of space, they also helped to reshape cities.

If this diaristic series was partly a kind of playful domestic anthropology, it also represented a form of empowerment, celebrating the flow of random, idiosyncratic choices that enrich private rituals. In the supermarket, at the point of sale, the piles and ragged assortments of food and products suggest the opposite, a form of compliance; instead of generating energy, and that sense of purpose, of momentum, these pictures seem draining, introducing the feeling of fatigue and reminding us of those lost hours wandering the overstocked aisles in a daze.

Shafran se ha visto hipnotizado por situaciones que vinculan la actividad humana a formas de movimiento mecánico.

Shafran has been mesmerised by situations that bind human activity to forms of mechanical movement.

Nigel Shafran. Paddington Escalator, London, 2009-10. Courtesy of the artist.

Nigel Shafran. Paddington Escalator, London, 2009-10. Courtesy of the artist.

Lynne Cohen. Stairwell, Bio Lab, 1982. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

La escasez o el lujo construidos de la antesala; la disposición artificial, deshumanizada, del mobiliario; la promesa, con lo cual, la construcción de expectativas sobre lo que vendrá después, cuando atravesemos la puerta y lleguemos al supuesto espacio real, el de verdad, el definitivo. Todo esto se puede vincular con las imágenes de Lynne Cohen, aquellas que, según palabras de Walker Evans, se construyen a través de estrategias basadas en una “imagen sin arte”.

Las sillas, pero especialmente los sofás en los portales, me generan una pena profunda. Apenas nadie se sienta en ellos, tienen algo de fake que me incomoda, algo de sospecha y hostilidad, algo de pose que me enrabia. Pero, sin embargo, no hay nada naif en su ubicación, no son inocentes y están ahí, precisamente, para ser vistos por todos: su cuero nos habla de

Lynne Cohen

Políticas de lo vulgar

The politics of the vulgar

The constructed sparsity or luxury of the entrance hall; the artificial, dehumanised arrangement of the furniture; the promise with which expectations are built, on what will come later, when we walk through the door and reach the supposed real space, the actual definitive space. This is what the images of Lynne Cohen bring to mind, images that, in the words of Walker Evans, are constructed through strategies based on an “artless image”.

When I walk into the entrance hall of an apartment block and see armchairs, and sofas in particular, it makes me feel very sad. Hardly anyone ever sits in them and there is something so fake about them that it makes me feel uncomfortable, something suspicious and hostile, something affected that makes me angry. There is, however, nothing unknowing about their location.

They are not innocent and there they are, positioned so they can be seen by everyone. The leather on them talks to us of class issues, in the same way that an artificial or a natural plant does in a lobby – it takes money to look after them. The arrangement of the furniture is indicative of control, and the quality of the material used to fashion the letterboxes says a lot to us about the people who live there.

Cohen started out in photography in 1971 and developed her technique and themes over the course of her career, while maintaining a firm commitment to recording places devoid of people. In her early days she took an interest in vernacular US culture, paying particular attention to domestic and public interiors and, from the 1980s onwards, focusing on images around the consumer and surveillance society. Aside from

cuestiones de clase, igual que lo hace una planta artificial o natural en un vestíbulo —sus cuidados cuestan dinero—, la disposición de los muebles nos habla de control, la calidad material de los buzones dibuja unos u otros rostros y bolsillos.

Lynne Cohen empezó a trabajar a través de la fotografía en 1971 y, a lo largo de su trayectoria, tanto su técnica como sus temas fueron evolucionando, manteniendo, eso sí, un firme compromiso con registrar el “lugar” despojado de personas. En sus inicios se interesó por la cultura vernácula estadounidense, con especial atención a interiores domésticos y públicos y, a partir de los años ochenta, el énfasis se situó en imágenes alrededor de la sociedad de consumo y vigilancia. Pero más allá del tema o el objeto fotografiado, merece mención las características formales de su fotografía. Cohen se hacía valer de una cámara de placas, aplicando exposiciones largas y poca profundidad de campo consiguiendo, como resultado, iluminaciones particularmente planas y homogéneas. En una entrevista con William A. Ewing, Vincent Lavoie, Lori Pauli y Ann Thomas publicada

Lynne Cohen. Apartment Lobby, 1979. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

the theme and the subject of the images, the formal characteristics of her work are also worthy of mention. Cohen used a plate camera with long exposures and a shallow depth of field, creating flat, homogeneous lighting as a result. In an interview with William A. Ewing, Vincent Lavoie, Lori Pauli and Ann Thomas published in 2001, Cohen said that the use of flat lighting and symmetry enhanced the illusion of neutrality, lending a cold and dispassionate touch to her photographs. They seem in some way to have been conceived immaculately, resembling the format of a postcard or a taxonomic catalogue, a strategy that allows her to camouflage the specific histories of these places, to deprive

en 2001, Cohen menciona que mediante la iluminación plana y la simetría podía aumentar la ilusión de neutralidad, aportando a sus fotografías un toque frío y desapasionado. De algún modo, la sensación es de estar concebidas inmaculadamente, acercándose al formato de postal o de catálogo taxonómico, una estrategia que le permite camuflar las historias específicas de esos lugares, despojarlas de contexto, acercarlas al “no lugar”. Y es justo a través de la repetición, de la insistencia temática, que uno puede empezar a trazar patrones, comprender el potencial político de esos lugares y atender a las complejidades que se esconden tras un sofá delante de una pared de mármol o tras una silla aislada entre dos columnas.

Y mientras escribo pienso, qué curioso, muchos lugares que identificamos, justamente, como no lugares, hemos accedido a llamarlos en inglés: hall , lobby , parking , spa . Un vocabulario global para un lugar que, a pesar de sus connotaciones políticas, también es global, intercambiable, identificable aquí y allá.

Lynne Cohen. Furniture Showroom, 1979. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

them of context, and bring them closer to the “non-place”. And it is through repetition, insistence on the theme, that we can start to identify patterns, understand the political potential of these places and look into the complexities that lie behind a sofa positioned in front of a marble wall or an armchair standing on its own between two columns.

And as I write, I think how strange it is that we have come to call many of the places that we identify as non-places by their English names: hall, lobby, parking (meaning “car park”), spa. This is a global vocabulary for a place that, in spite of its political connotations, is also global, interchangeable and identifiable both here and there.

Lynne Cohen. Lobby, Barbican, London, England, 1978. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

La iluminación plana y la simetría podía aumentar la ilusión de neutralidad, aportando a sus fotografías un toque frío y desapasionado.

The use of flat lighting and symmetry enhanced the illusion of neutrality, lending a cold and dispassionate touch to her photographs.

Lynne Cohen. Motel Lobby, Atlantic City, N.J., 1975. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Lynne Cohen. Waiting Area, Ohio Glass Store, Steubenville, Ohio, 1980. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Lynne Cohen. Salon, 1973. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Lynne Cohen. Lower Level, Ottawa, 1976. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Lynne Cohen. Lobby Engineering Buiding, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, 1980. Copyright Estate of Lynne Cohen. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago.

Xavier Ribas

Lugares imprevistos Unexpected places

El crecimiento de las ciudades se ha producido de una forma salvaje, generando, en torno a las nuevas barriadas, básicamente, edificios de apartamentos sin servicios públicos, a veces incluso sin caminos ni calles, entre ellos, sin nada que los identifique ni sugiera, realmente, una vida. Son dormitorios en colmenas, donde se va a dormir entre las diferentes jornadas de trabajo. Pero, ¿y los domingos, y los tiempos libres? ¿Cómo se vive esos tiempos muertos en los que no se trabaja en estas barriadas sin terminar de adecuar a la vida cotidiana? Estos lugares nuevos son “no lugares” ya desde los planos de los arquitectos: nacen sin identidad, son futuras ciudades periféricas pero tardaran años, generaciones, en conseguir su propia identidad, e incluso sus propios nombres; puede ser que sean fallidos y se vacíen, se conviertan en vaciaderos urbanos, en nada, ni ruinas siquiera. Como las construcciones de edificios entre la maleza del interior de Cuba, edificios de cinco alturas en medio de una selva que se los come y rodeados de animales. Si el ocio, como apunta Xavier Ribas, se ha planeado sistemáticamente para no ser pasivo, sino activo, reglado, eficaz, en lugares planificados y con reglas de uso, un espacio legislado como el de trabajo, y rentable económicamente, los domingos en las periferias salvajes son libres y alejados de normas. Las propias características no formales del lugar favorecen ese alejamiento de las normas.

Cities grow at a savage rate. Apartment buildings devoid of utilities spring up around new neighbourhoods, some with no paths or streets between them, without anything that identifies them or even points to the lives they contain. These places are beehive dormitories, where people go to sleep when not at work. But what about Sundays and free time? How do they survive the dead hours when they are not working, in a place where everyday life is not catered for? These new places are “non-places”, from the very moment they are first conceived in architects’ plans. They are born with no identity. These future cities on the periphery take years, generations even, to acquire an identity of their own and even their own names. They may fail and fall empty, become urban rubbish tips, become nothing, not even ruins, like buildings shrouded in weeds in inland Cuba, five-storey constructions surrounded by wildlife,

Xavier Ribas. Untitled (Bellvitge), from Domingos series, 1997. Courtesy of the artist.

@xavierribas_