Perhaps you may remember our previous Special Issue, which was created in collaboration with our partners at Certified Origins. In that issue, we aimed to provide retailers with a guide for sourcing EVOO. In this issue, our goal is to emphasize the importance of Origin.

Authenticity and traceability have been prominent topics in the grocery industry for several years, and for good reason. Retailers have discovered that these issues are important to their customers, who are increasingly concerned about the health of their families and the planet. This concern is especially strong among younger consumers, who have high expectations for these qualities in the products they purchase.

In reality, you can only be certain of a product’s authenticity and traceability if you know its origin. Origin applies not only to where the product comes from, but also to its history, including the land from which it came, the people involved in every aspect of its production, and the adherence to the rules and guidelines that are vital to maintain its heritage.

Before reading the articles that follow, my insight and understanding of origin was admittedly limited. I had a basic understanding of geographic rules and regulations. I knew that you couldn’t “produce” “Prosciutto San Daniele” in Cleveland, Ohio - or anywhere outside of San Daniele, Italy. I was aware that authentic San Marzano tomatoes had to be “grown” in San Marzano, etc.

But my understanding ended there.

After reading this issue I now understand that “origin” refers to more than just a location; it also encompasses the historical context and the circumstances in which something was first produced. This includes factors such as the land, climate, labor, and many other elements that become evident upon further exploration.

Origin defines a product and process. More substantially, it can protect it so that it can sustain the land and people who rely on it. So origin is not only about taste and providence, it is a reminder that people can sustain themselves and their planet. It just takes a little bit of ingenuity. You’ll find plenty of it in this issue, beginning with our partner, Giovanni Quaratesi’s feature on the Evolution of Modern Retail on page 8.

I’d like to thank our authors for lending their knowledge and passion to this issue and for the work they do, Giovanni Quaratesi and his colleagues Miljana Tosic, Madeleine Côté for their collaboration and diligence and Melissa Subatch for pulling it all together.

Enjoy the issue and kind regards,

Phillip Russo Founder / Editor phillip@globalretailmag.com

Nurturing Sustainability

Protecting Growers of Sustainable Foods

Back to the Roots to Move Forward

The Artisanal Food Renaissance

30 Prosciutto: A Celebration of Italian Tradition 34 Acorn Fed Iberico Ham

40 Extra Virgin Olive Oil 46 Single Origin EVOO

52 The Global Impact of Avocados

56 Tequila, a Rich Heritage of Mexico 60 Saffron from la Mancha

Authentic Experiences: Good Business for Independent Grocers 68 Preserving Authenticity and Embracing Healthier Choices 72 PR’s Role in Promoting Italian Foods’ Provenance

76 Waste Not, Package Smart

80 Protection and Promotion of Origin-linked Products as Geographical Indications 84 Quality Departments’ Role in Improving Food Safety and Authenticity

88 Blockchain in Agrifood: Transparency and Security for the Food Supply Chain

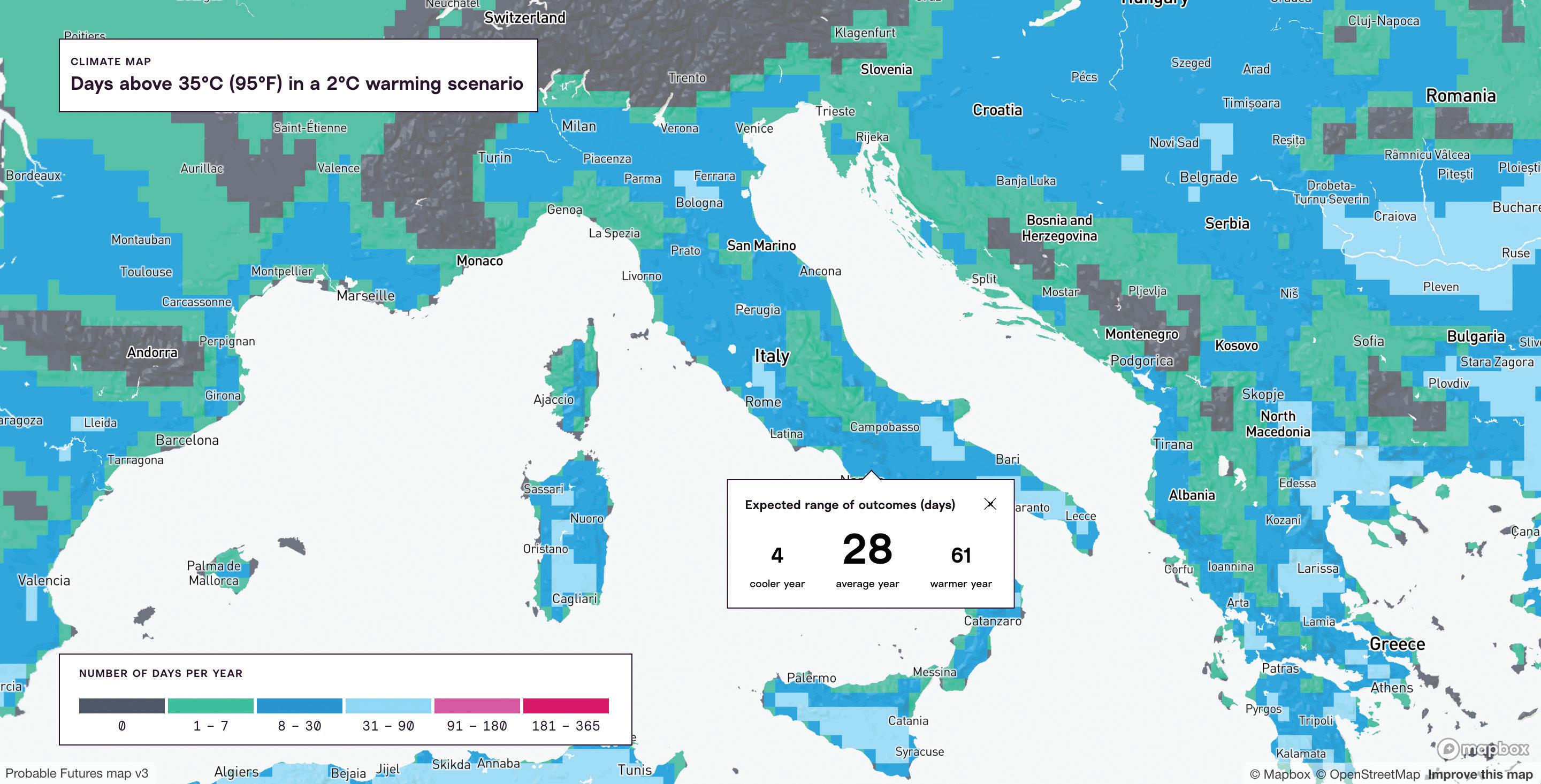

92 It’s from the Soil that Sustainable Food Systems Must Sprout 96 Supply Chain Traceability Certifications 100 Resolute Resilience for a Warming World

GIANNI BALDINI

Gianni Baldini is a Food Sector Manager at Bureau Veritas Italia - Certification division. He has been working in the agri-food sector for over 30 years as an expert in food safety and management of animal and vegetable supply chains. Since 2004, he has been a consultant and auditor for all voluntary certifications related to the sector.In 2012, he joined the Bureau Veritas Italia Group, where he has been responsible for the food certification sector since 2015.

ALMUDENA PIZA BARROSO

Almudena Piza Barroso is a food scholar and writer who specializes in the history and development of the avocado industry in Mexico and the United States. She holds a Master’s degree in Food Studies from NYU Steinhardt, a Bachelor’s degree in Applied Food Studies, and an Associate’s Degree in Culinary Arts from The Culinary Institute of America. She currently resides in Mexico working on agricultural trade research.

GIORGIO BERTOLINI

Giorgio Bertolini is a manager and entrepreneur active in the sustainability and food tech industry. He is Managing Director of ClimatePartner Italia a growing organization that supports companies achieve net zero emissions and to contribute to preserve and restore nature through certified projects.

ANDREA BIAGIANTI

Andrea Biagianti is the IT Manager at Certified Origins Italia. Born in Grosseto in 1978, Andrea has harbored a deep passion for computer science since childhood, which led him to pursue technical studies in his hometown and refine his expertise in Rome. During his academic journey, he developed an application for information protocol and document archiving for technical studies aiming for ISO 9001 certification.

PETER CROCE

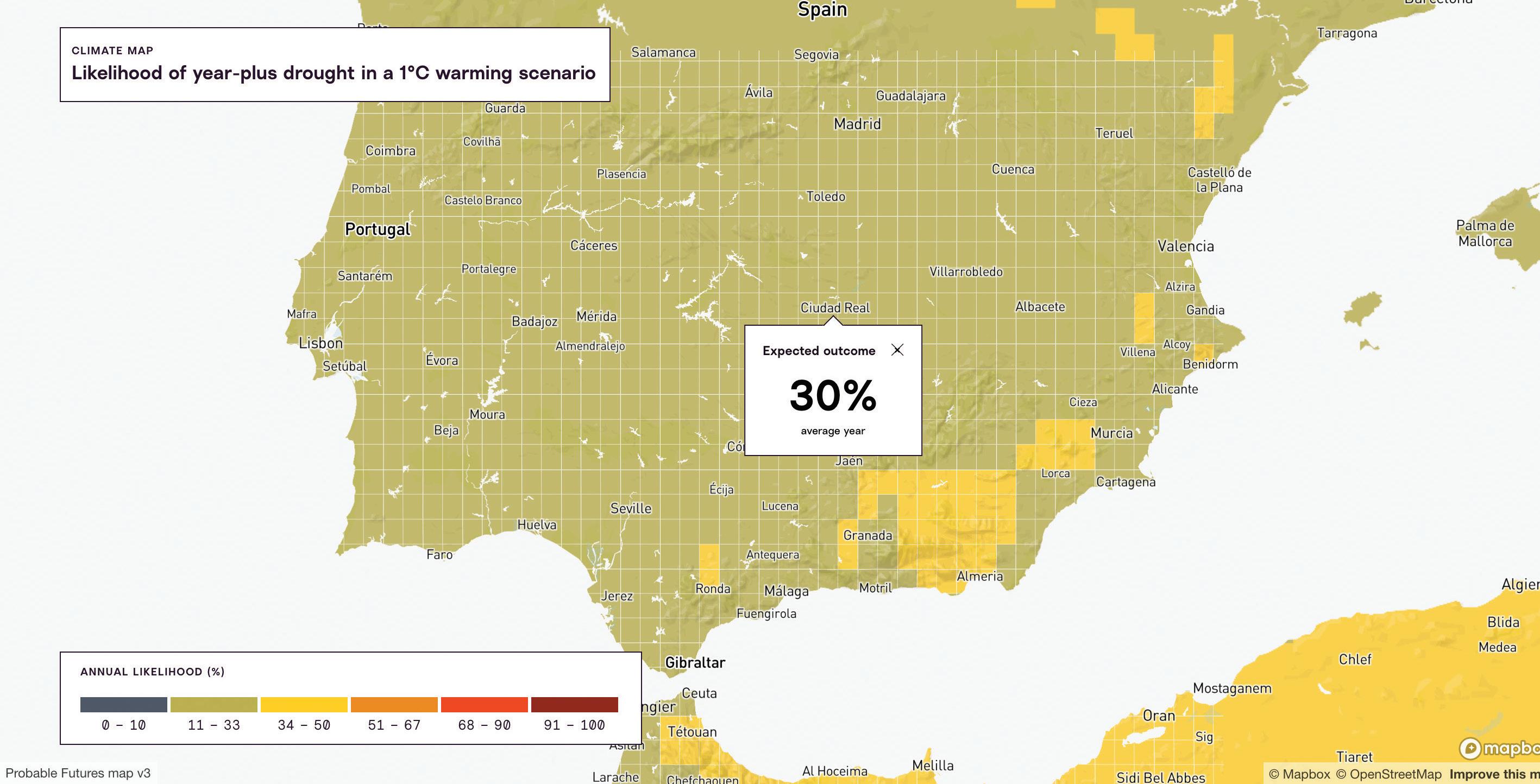

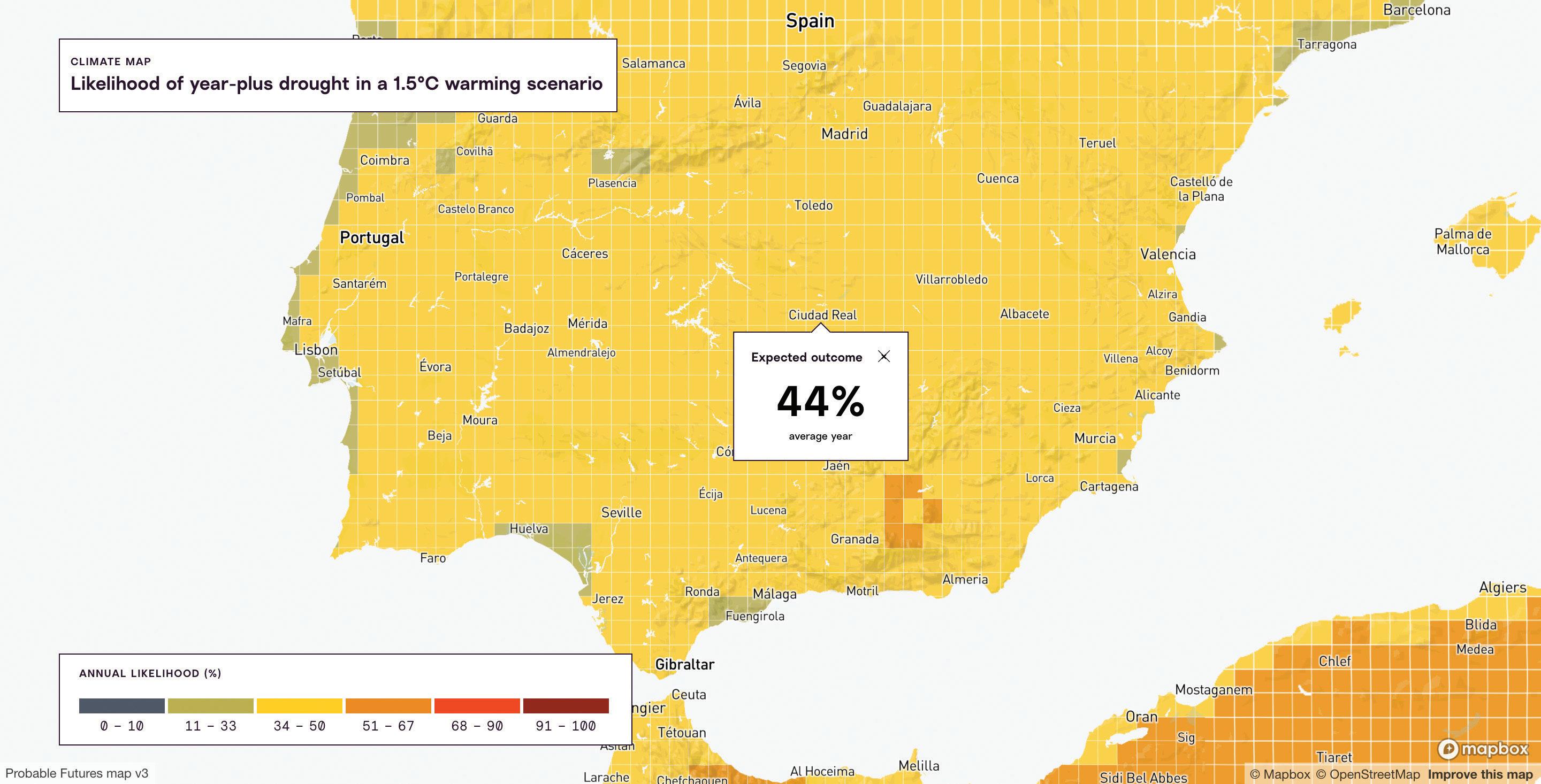

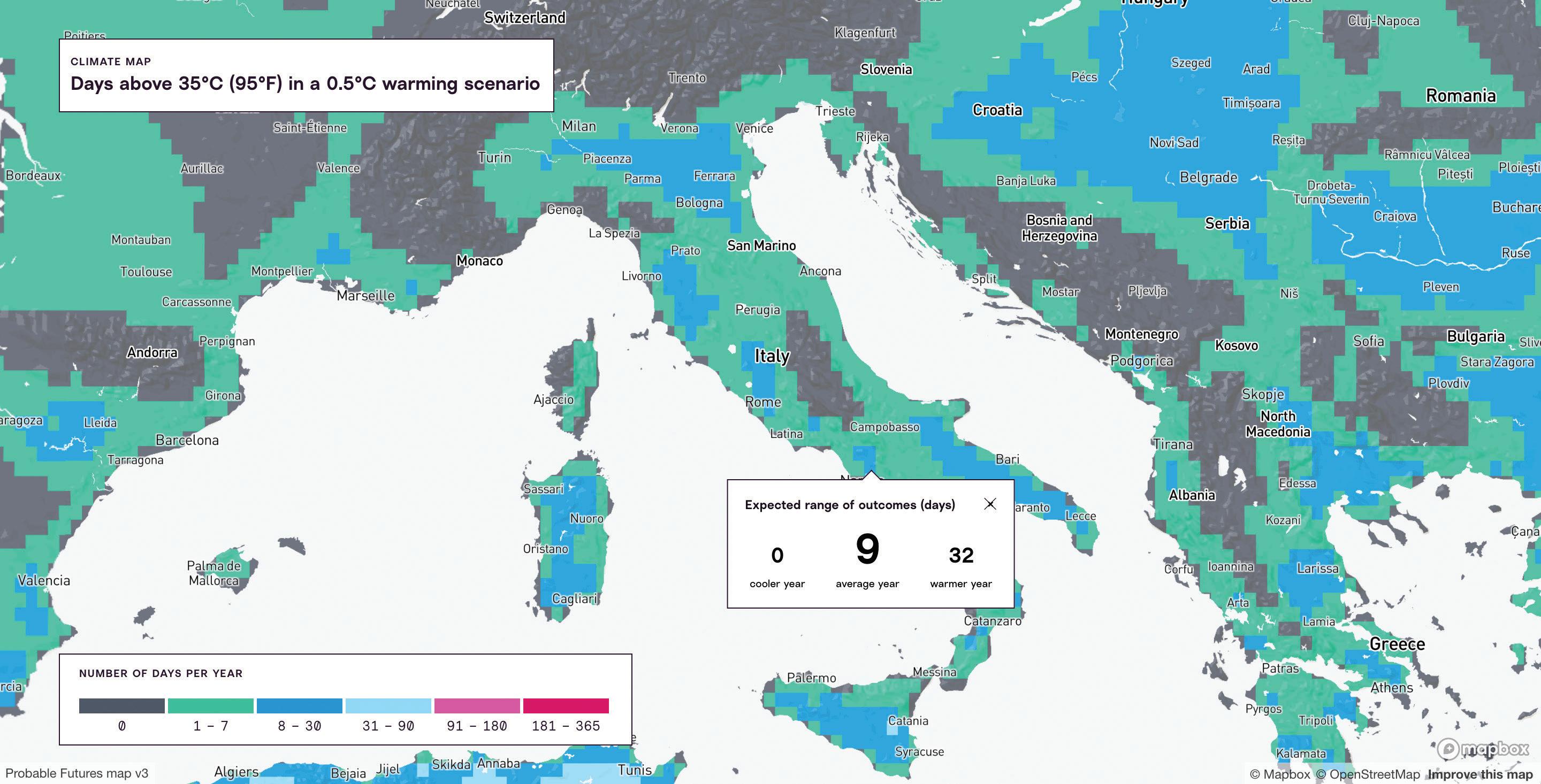

Peter Croce leads the digital product team at Probable Futures, speaks to public audiences, and builds partnerships to help people live well and act with confidence in our changing world. Probable Futures makes climate literacy resources and climate maps available online for everyone, everywhere. To begin exploring, visit probablefutures. org. The maps included in the article, and many more, are available at probablefutures.org/maps.

Silvia D’Alesio is a food and packaging expert as well as an international scouter on food innovation, leading several projects regarding developing new food and beverage products and businesses. She has earned a BSc. in Food Sciences and Technology along with an International MSc. in Food Innovation and Product Design. Her work includes research projects and scientific direction for Digital Food Ecosystem and FoodTech European Events; assistant professor at the University of Milan Department of Nutrition and Environment; and Professor of Futures Studies and Brand Packaging Design at NABA, Milan.

GREG FERRARA

Greg Ferrara is president and CEO of the National Grocers Association, the national trade association representing the retail, wholesale and supplier companies of the independent sector of the supermarket industry. With NGA since 2005, Ferrara brings a wealth of experience in the grocery industry, having managed his family’s century-old supermarket in New Orleans before the store was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

PIER PAOLO GHELFI

Pier Paolo Ghelfi, a dedicated Export Manager at Ferrarini, has been with the company since 1985, celebrating his 40th anniversary next year. After initially focusing on commercial development in Italy, Pier moved to Madrid in 1992 to establish Ferrarini’s presence in the Spanish market. Pier’s unwavering goal has been to position Ferrarini as the benchmark for uncompromising quality in Italian cured meats, particularly through its flagship product, il “Prosciutto Cotto Ferrarini,” which pioneeredin Italy - the production of the first cooked ham without added polyphosphates.

JORDI JARDI

Jordi Jardi Serres is a Technical Specialist in Hospitality and Tourism, specializing in Kitchen Specialty at INS Escola Hospitality and Tourism in Cambrils. With over three decades of experience, he has served as a Teacher of cooking and gastronomy and held various leadership roles including Director and Head of Studies. His culinary career spans roles as a cook at notable establishments in Catalonia, including Restaurant Eugènia and Fonda Turú. He also co-owns Restaurant Casal de Miravet and hascontributed to gastronomic innovation projects with Griffith Foods.

PEDRO MANUEL PÉREZ JUAN

Pedro Manuel Pérez Juan obtained a Doctorate in Chemical Sciences from the University of Córdoba, in Spain. He is a consultant and trainer in the agri-food sector, specializing in food quality and safety. He managed the La Mancha Saffron PDO from December 2013 to February 2023.

KAMI KENNA

Kami Kenna completed a master’s degree in Food Studies from New York University where her focus was on the traditional beveragesof Latin America, Kami Kenna has lived in Latin America for work since 2015. She is the Senior Tour Coordinator for Experience Agave, a boutique agave-spirits tour company in Mexico, an owning-partner of the women-owned Peruvian pisco brand, PiscoLogía, and a Pan-American beverage industry consultant with clients in Peru, Mexico, and Brooklyn.

CLAUDIA LARICCHIA

Professor Claudia Laricchia, CEO of Smily Academy,leads initiatives that bridge traditions and innovation. A G7 Advisor for gender equality (W7), anda Professor at the European Institute of Innovationfor Sustainability, she champions the harmonious coexistence between nature and human innovation. Learn more about Smily Academy’s transformative journey at: www.smilyacademy.org

ALBERTO MARRASSINI

Alberto Marrassini has been part of the Coop Italia group for over 20 years. Since 2019, he has been the CEO of Coop Italian Food North America and Italian Food Canada. Prior to this role, Alberto led the Asian global sourcing team Coop Far East, with over ten years of assignment in China, Hong Kong, and Vietnam, in the development of Coop Non-Food private label products. Earlier in his career, he held several positions in purchasing and sales across the Non-Food spectrum.

LUCIA MAZZI

Lucia Mazzi holds a degree in Technologies and Analysis of Ecotoxicological Impacts from the University of Siena, Italy. In 2010, she obtained an academic scholarship for a Doctorate in Medical Biotechnology, completed her PhD in 2015, and passed the state exam for Biologists in 2014, enrolling in the Professional Register the following year. During her career, she had the opportunity to broaden and share her knowledge through positions at various analysis laboratories and by teaching scientific subjects in schools. Since 2016, she has worked with Certified Origins Italia Srl, becoming a global quality and food chemistry specialist and leader in her field, collaborating with Universities and various institutions.

DANIELLE NIERENBERG

Danielle Nierenberg is a world-renowned researcher, speaker, and advocate on all issues relating to our food system and agriculture. In 2013, Danielle Nierenberg co-founded Food Tank (foodtank.com) with Bernard Pollack, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization focused on building a global community for safe, healthy, nourished eaters. Danielle has an M.S. in Agriculture, Food, and Environment from the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and spent two years volunteering for the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic. Danielle is the recipient of the 2020 Julia Child Award.

JUAN VICENTE OLMOS

Juan Vicente Olmos Llorente is a General Manager of Grupo Monte Nevado. Belonging to the 4th generation of Monte Nevado, and being veterinarian by training, he is a tireless researcher of the world of ham. He is wellacquainted with numerous ham facilities across Spain and has experience working in several in Italy, Germany, Belgium, Portugal, and the USA. Additionally, he has written three books on ham and the Iberian pig.

FABIO PARASECOLI

Fabio Parasecoli is Professor of Food Studies in the Nutrition and Food Studies Department at New York University. His research explores the cultural politics of food, particularly in media, design, and heritage. Recent books includeKnowing Where It Comes From: LabelingTraditional Foods to Compete in a Global Market (2017), Food (2019), Global Brooklyn: Designing Food Experiences in World Cities (2021, coedited with Mateusz Halawa), Gastronativism: Food, Identity, Politics (2022), and Practicing Food Studies (2024, coedited with Amy Bentley and Krishnendu Ray).

STEPHANE PASSERI

Stephane Passeri is a French expert in Geographical Indication (GI). He currently leads regional GI projects for the FAO in Asia and the Pacific from Bangkok, Thailand. With over 25 years of experience, he has significantly shaped Intellectual Property Rights and GI frameworks across numerous Asiancountries. Since 2013, he has managed several FAO projects to promote rural development through GIs in the region. In 2017, he was awarded the Knight of the Order of Agricultural Merit by the French Government for his contributions to agriculture. Mr.Passeri holds advanced degrees in Economics and Finance from the Universityof Nice-Sophia Antipolis.

EMILY PAYNE

Emily Payne has served as editor of the global sustainable food nonprofit Food Tank since 2015. Her writing covers the intersection of food, agriculture, climate, and health and has appeared in GreenBiz, Edible Magazines, The Counter, Mad Agriculture Journal, AgFunder News, FoodUnfolded, Thomson Reuters Foundation, Inter Press Service, the New York City Food Policy Center, and more. She is based in Denver, Colorado.

JOSEPH R. PROFACI

Joseph R. Profaci has served as Executive Director of the North American Olive Oil Association since October 2017. He is an experienced food products attorney and business manager, with almost 30 years of experience in the olive oil category. Previously, he served as general counsel for Colavita USA, LLC, a leading importer and distributor of Italian specialty foods. He was an active representative for Colavita to the NAOOA, serving on the board for 4 years, including serving as the NAOOA chair from June 2015 - June 2017. Mr. Profaci is a graduate of Harvard College and New York University School of Law.

GIULIA PEROVICH

Giulia Perovich is the passionate founder of Arnald NYC, a PR and communications boutique agency fueled by her EmiliaRomagna roots and lifelong love of hospitality. Named after her favorite childhood eatery, Arnald NYC embodies Giulia’s commitment to crafting client experiences through targeted messaging, strategic networking, media planning, and storytelling across multiple platforms. Among her current clients are Acetaia Giusti, Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano, Giadzy by Giada De Laurentiis, Ferrarini, and Palazzo di Varignana. www.arnaldnyc.

GIOVANNI QUARATESI

Giovanni Quaratesi is the Head of Corporate Global Affairs at Certified Origins, leading the company’s communication strategies and public relations. His mission is to be an ambassador for good food and to empower others to create positive change in the food system.

SARA ROVERSI

Sara Roversi is an experienced entrepreneur and thought leader in the food ecosystem. As a seasoned growth expert, she works with globally recognized high-profile think tanks on setting the agenda for the sustainable food industry. With her Future Food, founded in 2014, she is the Focal Point of the UNESCO Emblematic Community for Mediterranean Diet, Pollica (Cilento). She is the co-founder of goodaftercovid19.org, Ambassador of the Agrifood Tech & Wellbeing (Federated Innovation project @MIND), President of the Scientific Committee of Fondazione Italia Digitale, member of the Google Food Lab, and partner of the Food For Climate League.

BY GIOVANNI QUARATESI

The history of grocery stores in the United States dates back to the early colonial period when European settlers relied on local markets, general stores, trading spots, and small farms to obtain provisions they could not produce or source independently. Over the years, some family-owned stores have maintained their original spirit while others have evolved into complex institutions with a wide range of local and imported products, services, and sales strategies as we know and experience them today.

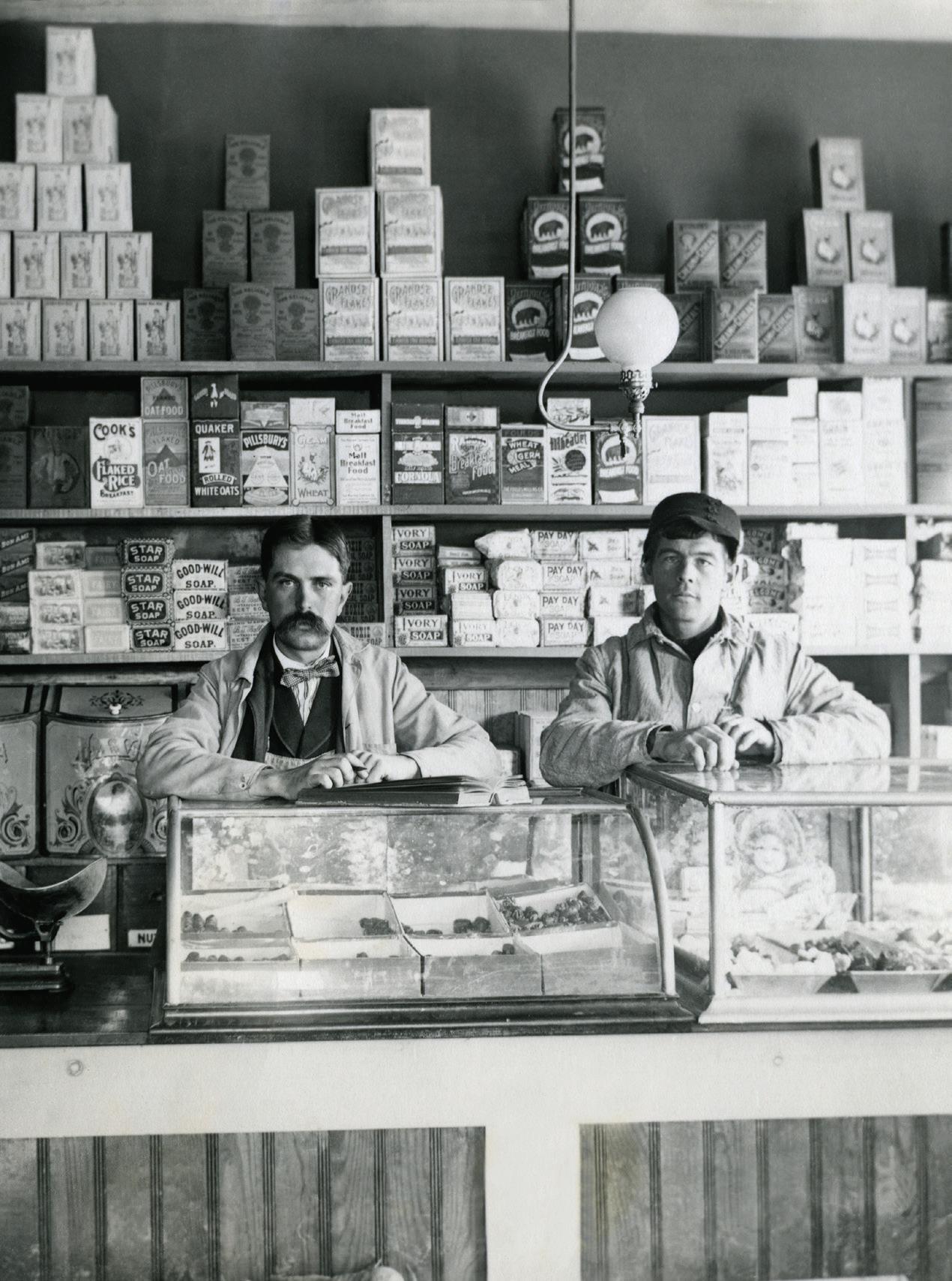

American retail began with small, local stores offering a limited product range. Shoppers would communicate with one or more clerks, separated by a counter, to inquire about products and convey their preferences. The store owner or their staff would be the sole trustworthy source of information about the origin, nature, and price of the goods, and they would be responsible for displaying, weighing, portioning, and packaging the loose goods. Social factors such as religion, race, gender, and social status would likely influence and shape the interactions between the store staff and the customers.

As the country evolved in its cultural diversity and global outreach, and entered its industrialized phase, there was a growing opportunity for new and more efficient shopping experiences. The early 20th century saw the introduction of a wide range of pre-packaged, shelf-stable, refrigerated, and frozen foods. This significantly transformed how Americans shopped and their relationship with food, contributing to the modern retail landscape.

“The

growth of large-scale retail has also led to an increase in the distance from which food is sourced, which has diluted our understanding of the origins of our groceries.”

The first supermarket, Piggly Wiggly, opened in Memphis, Tennessee in 1916. This store, founded by Clarence Saunders, introduced and patented the concept of self-service shopping, offering mostly pre-sized and packaged food, eliminating the need to interact with others to get what you need. Customers could browse through aisles, select their desired products, and bring them to a checkout counter. This innovation sped up the shopping process and gave customers a new sense of autonomy and satisfaction.

Following the success of Piggly Wiggly, other supermarkets quickly adopted and expanded upon Saunders’ innovation. The 1930s saw the emergence of chain supermarkets like Safeway and A&P, which capitalized on economies of scale to offer lower prices and a wider variety of products. These stores introduced new practices such as shelf price labeling, product advertising, and shopping carts, further enhancing the customer experience.

In the post-World War II era, supermarkets continued to evolve, incorporating technological advancements to streamline operations and improve customer service. The introduction of computerized

inventory management, barcode scanning, and electronic payment systems in the latter half of the 20th century revolutionized retail efficiency and accuracy. These innovations allowed supermarkets to manage more extensive inventories, reduce costs, and offer a broader selection of goods.

Modern retail has brought many benefits to the American population, such as convenience, variety, and affordability. As of 2021, the U.S. food and grocery retail industry employed 2.89 million workers and generated $880 billion in sales, with major players like Walmart, Amazon, Costco, and Kroger leading the market. The sector boasts over 63,000 stores nationwide, reflecting its extensive reach and importance.

The growth of large-scale retail has also led to an increase in the distance from which food is sourced, which has diluted our understanding of the origins of our food. As a result, it has become increasingly challenging for the average person to find clear answers to fundamental questions such as who created it, its geographical origin, the production process, and the philosophy behind it.

Today, the average grocery store carries over 39,000 items, and the median size of a U.S. grocery store is almost the size of a football field. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of online grocery sales, which now account for over 10% of food grocery sales. While this shift has improved convenience and access in underserved areas, it has also created a greater disconnect between consumers and their food source.

The evolution from local markets to modern supermarkets has prioritized efficiency and cost reduction, often at the expense of supply chain transparency and education.

In this special edition of Global Retail Brands magazine produced by Certified Origins, with the invaluable support and contribution from a number of world-class food experts, we will explore the importance of understanding where our food comes from and how reconnecting with the origins of our nutrition can lead to better choices, a more sustainable future, and resilient economies.

Join us in understanding more about the history, the present, and the future of food and uncovering the stories behind the ingredients that fuel our health and happiness.

Giovanni Quaratesi is the Head of Corporate Global Affairs at Certified Origins, leading the company’s communication strategies and public relations. His mission is to be an ambassador for good food and to empower others to create positive change in the food system.

BY CLAUDIA LARICCHIA

In a world where choices reverberate globally, understanding the intricate tapestry of food origins becomes paramount.

Guardians of biodiversity and climate, particularly Indigenous Peoples, play a pivotal role in safeguarding our planet’s delicate balance. At 5 years and less than 100 hundred days marked by the climate clock as deadline for the climate collapse, humanity needs to merge traditional Indigenous wisdom with innovative solutions, acknowledging the need for harmonious coexistence between nature and human endeavors. These ingredients must be aimed to invest in the next generations for a regenerative future.

As we transition from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the Agenda 2030, the Indigenous Factor becomes integral to sustainability’s 4th dimension - the inner dimension, meaning the consciousness transformation process that allow humanity (including entrepreneurs) to reconnect with themselves at first, for changing mindset and afterwords rapidly design new sustainable and regenerative development models. This further dimension is now crucial for training a new class of ecopreneurs as the current tools, kpi and methodologies are simply not enough anymore for tackling such a severe anthropocentric climate emergency.

Indigenous Peoples, meaning 5% worldwide population, protect 85% of biodiversity at a global level, extending their crucial custodianship beyond ecological preservation to the heart of our food systems. Excluding these custodians undermines any sustainability effort, emphasizing the profound interconnection between food, climate, and Indigenous communities.

Their wisdom is invaluable in terms of humanity and nature balance and it must be rapidly integrated while being in charge of sustainability at all levels, including economic and industrial ones.

Involving Indigenous communities also means elevating their voices, sharing wisdom, and fostering peer-to-peer knowledge exchange. Integrating Indigenous People’s spiritual and regenerative mindset into our food systems challenges existing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), urging a transformative shift towards sustainability rooted in Indigenous wisdom.

A systemic thinking approach reveals the interconnectedness between consumers, farmers, and the sources of nutrition. Through an Indigenous lens, this connection is deepened, fostering an appreciation for the symbiotic relationship with the origins of sustenance. Prioritizing diverse voices, rooted in science, data, and facts, aims to inspire informed choices that resonate globally.

While the Western world brings technology and economic sustainability, Indigenous populations contribute biodiversity and nature. Co-creating innovative ecobusinesses requires a holistic approach, incorporating systemic thinking, interconnectedness, indigenous factors, diversity, and science-driven principles. Technology tools, such as blockchain, RFID, QR Codes, AI, and more, become meaningful within this framework, designed to protect food origins transparently. This bridge between two different worlds must be solid for next generations to lead the future.

Recognizing the urgency before the predicted climate collapse, these tools must integrate the Indigenous factor for effective design and customer utilization. The concrete example of the Smily Academy, a unique initiative founded in collaboration with The Forest Man of India and implemented by his NGO - Indigenous People’s Climate Justice Forum - symbolizes the synergy between tradition and innovation for a regenerative future.

“Integrating

Indigenous People’s spiritual and regenerative mindset into our food systems challenges existing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), urging a transformative shift towards sustainability rooted in Indigenous wisdom.”

Professor Claudia Laricchia, CEO of Smily Academy, leads initiatives that bridge traditions and innovation. A G7 Advisor for gender equality (W7), and a Professor at the European Institute of Innovation for Sustainability, she champions the harmonious coexistence between nature and human innovation. Learn more about Smily Academy’s transformative journey at: www.smilyacademy.org

BY DANIELLE NIERENBERG AND EMILY PAYNE

Global agriculture and food systems cannot be truly sustainable without protecting the workers who produce our food. Now, the private industry has a powerful role to play in driving change.

“Our agricultural industry was built on slave labor,” says Rosalinda Guillen, Founder of Community to Community (C2C), a U.S.-based grassroots organization dedicated to food sovereignty and immigrant rights. “A powerful industry was built, and an infrastructure created at every level that would focus on profit, not the rights or benefits for the workers at every level.”

Historically, U.S. farmworkers have been excluded from many federal worker rights and benefits. Congress excluded farmworkers from the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which protects workers who join and organize labor unions. It was not until 1966 that employers were required to pay farmworkers the federal minimum wage, almost 30 years after the Fair Labor Standards Act passed these protections - and still today, federal overtime pay requirements do not cover farmworkers.

“One reason for this is the lack of farmworker-led organizations and unions that can build power in rural America and try to respond to inequitable laws and workplace rules and sometimes deadly exploitative situations,” says Guillen.

Child labor laws even have different standards for agriculture. For the majority of jobs in the U.S., children can only be legally employed for a restricted number of hours, starting at 14 years old. But in agriculture, children can work for an unlimited number of hours starting at 12 years old.

This issue is not unique to the U.S.— globally, agricultural labor is largely unregulated. The International Labour Organization reports that at least 3 in every 1,000 people in Asia-Pacific are in forced labor, with agriculture among the sectors where it is most prevalent. In Canada, black and brown farmworkers are inextricably tied to their employers, undermining their ability to organize, and making them vulnerable to exploitation.

Conditions are getting worse. Studies have shown that the health impacts of climate change on smallholder farmers— who are working outdoors in extreme conditions like flooding, wildfire smoke, and heat domes—will hamper the realization of many of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals. In 2022, the U.S. National Institute of Health reported that farmworkers are 35 times more likely to die from heat than other workers. Outdoor workers’ exposure to hazardous heat is expected to quadruple by 2065.

“Under the combined pressures of climate change and the long-term consolidation in the food system both in the U.S. and globally…farmers and workers on farms struggle to make ends meet economically and in terms of mental and physical health,” says Elizabeth Henderson, cofounder of the Agricultural Justice Project and member of the Northeast Organic Farming Association.

In recent decades, awareness about the connection between food and climate has led to a proliferation of sustainably produced food labels and the popularization of products like Certified Organic. Almost all the major global food and beverage companies have announced ambitious greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals. According to the New York University Stern Center for Sustainable Business, from 2013 to 2022, products marketed as sustainable grew twice as fast as products not marketed as sustainable.

Now, the same must be done for social sustainability and farmworkers’ rights.

“When you choose what food to buy, you can consciously contribute to the urgent shift from a system based on the cheapest possible food to a solidarity economy based on values of caring, health, and fairness,” says Henderson. “By seeking out products from local farms and small-scale processors, you can help break [long-term consolidation] up and end the death grip that consolidated mega-monsters have on our health, our communities, and the health of our planet.”

An increasing number of fair-trade labels and standards work to eliminate forced labor and child labor, improve conditions for workers, and promote gender equity in food-producing regions. Henderson cofounded the Agricultural Justice Project, in particular, which was developed with input from farmworkers and is regulated

by organizations that advocate for farmworker rights, like C2C. Experts and advocates also recommend looking for global standard certifications from Fairtrade International, Fair for Life, Equal Exchange, and The Rainforest Alliance.

Those who source food can give voice to farmworkers by increasing the prevalence of these fair-trade labels on store shelves and in school systems, hospitals, and corporate offices. The U.S. government alone spends billions of dollars per year on food, presenting a massive opportunity to require that foods be produced with basic farmworker rights. Alongside climate commitments, grocers and retailers can purchase from producers who are protecting and advancing farmworker rights and justice.

Needless to say, these commitments must be met with global policy changes.

There have been major victories in recent years. In 2021, U.S. unions like United Farmworkers and Familias Unidas por la Justicia successfully overturned the exclusion of overtime pay for farmworkers in Washington State. In 2023, the European Union’s reformed Common Agricultural Policy introduced a social pillar, tying subsidies to compliance with minimum social and labor standards. But there is still so much more work to be done.

“If we want to build a truly sustainable food system where workers and land and water are treated well, then we need to rebuild the ways we grow food and distribute our food,” says Guillen.

Protecting our global food supply means protecting those who tend the land and grow our food. Everyone has a critical role to play, especially those with the purchasing power to drive significant change by implementing procurement criteria and advocating for fair labor policies. Together, we can create the food system that future generations deserve.

“Everyone has a critical role to play, especially those with the purchasing power to drive significant change”

Danielle Nierenberg is a world-renowned researcher, speaker, and advocate on all issues relating to our food system and agriculture. In 2013, Danielle Nierenberg cofounded Food Tank (foodtank.com) with Bernard Pollack, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization focused on building a global community for safe, healthy, nourished eaters. Food Tank is a global convener, thought leadership organization, and unbiased creator of original research impacting the food system.Danielle has an M.S. in Agriculture, Food, and Environment from the Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and spent two years volunteering for the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic. Danielle is the recipient of the 2020 Julia Child Award.

Emily Payne has served as editor of the global sustainable food nonprofit Food Tank since 2015. Her writing covers the intersection of food, agriculture, climate, and health and has appeared in GreenBiz, Edible Magazines, The Counter, Mad Agriculture Journal, AgFunder News, FoodUnfolded, Thomson Reuters Foundation, Inter Press Service, the New York City Food Policy Center, and more. She is based in Denver, Colorado.

BY SARA ROVERSI

According to Copernicus’ analysis, March 2024 was the tenth consecutive warmest month ever recorded. The future outlook is even more alarming: the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) warns that there is a 98% chance that one of the next five years will be the warmest on record and estimates a 66% probability that temperatures could temporarily exceed the +1.5°C threshold above pre-industrial levels.

This scenario is significantly worsened by activities related to agriculture, forestry, and other land uses (AFOLU), which account for 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions, along with the energy, industry, transport, and building sectors, which contribute 79%. All these sectors are interconnected within the global food system— from production to transport, from processing to consumption. Yet, a tragic paradox emerges. As highlighted by the UN, the global population is expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, further increasing to 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.4 billion by 2100. This progressive demographic growth will lead to a mounting pressure on our planet’s already limited resources—a situation that, as attested by the FAO, will require increasingly careful and sustainable management.

It is clear that the foundation on which the global food system has relied so far has proven inadequate. Adopting a new approach is now more imperative than ever, and this essential change requires innovation. But what kind of innovation? Does innovation necessarily translate into artificial food production? Possibly. Or does it mean incorporating insects or novel foods into our diet? It could be. However, perhaps not, because there likely is another solution right under our feet. If we truly aim to create a paradigm shift, we must start from the roots. If our real goal is to act concretely and produce tangible results for the well-being of our planet, we must not only ask what we eat but also where it comes from. Not just what we will eat but how we will produce it. This continues to make a difference because the food we bring to our tables is the result of a process that starts from a root, and it is from the roots that we must return to begin anew.

Food is never just food; it encompasses everything that precedes it: the soil where it was grown, the hands that cultivated and harvested it; the water that irrigated it, the air surrounding it, and the processes and methods that brought it into our kitchens. Knowing the origin of our food means understanding its impact on our health; it means understanding what kind of production methods I support and whether I am benefiting or harming my planet. It means embracing the values that each food carries with it and becoming its indirect ambassador and guardian.

We must demand to recognize the origin of our food not only through a label but through its flavors. This (it is becoming increasingly

clear) is only possible when the foods result from sustainable production methods, such as those of regenerative agriculture, which respect the rhythm of the seasons, the cycle of nature, and human timings. A system that not only contributes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 50%—thanks to minimal soil tillage, permanent cover, and crop diversification—but also offers foods of superior quality. Foods that delight the palate, properly nourish our body, and support the community inherently linked to them. Returning to the roots in how we produce, and mentally, reflecting on how that food is produced, represents an act of excellent food awareness and a recovery of our historical and cultural heritage. It is a matter of safety, quality, and transparency, but it is also an exploration of the traditions at our lifestyle’s foundation.

Clearly, our focus should not be on implementing short-term strategies, but rather on promoting and adopting lifestyles or management models based on food with regenerative potential for the individual and for the planet—starting from each purchase, from each question of “where does this product come from”. Each of us has the power to make a difference, and it starts with the choices we make every day.We need to go back to the roots to move forward. This does not mean going back to the past, but going back to take a run-up, adapting yesterday’s values to today’s and tomorrow’s needs.

It is essential that every entity, particularly large organizations, re-establish a direct connection with those who produce our food. Only through this connection can we

truly value and convey to the consumer the essence of what we consume, promoting and spreading agricultural practices that respect and maintain the natural balance. It is imperative to create the conditions for a vital and sustainable ecosystem essential for the survival of the life chain, which includes our food resources and the health of our environment. The soil represents an element and the crucial foundation from which all forms of regeneration and prosperity emerge. Roots, deeply anchored in the earth, not only support trees but also offer the possibility of generating fruits that, transplanted elsewhere, can give life to new shrubs and forests. This is the true spirit of food production envisioned for the future, which questions how much food has been produced and how and where it comes from, thus perpetuating a virtuous cycle of growth and regeneration.

Sara Roversi is an experienced entrepreneur and thought leader in the food ecosystem. As a seasoned growth expert, she works with globally recognized high-profile think tanks on setting the agenda for the sustainable food industry. With her Future Food, founded in 2014, she is the Focal Point of the UNESCO Emblematic Community for Mediterranean Diet, Pollica (Cilento). She is the co-founder of goodaftercovid19.org, Ambassador of the Agrifood Tech & Wellbeing (Federated Innovation project @MIND), President of the Scientific Committee of Fondazione Italia Digitale, member of the Google Food Lab, and partner of the Food For Climate League.

BY FABIO PARASECOLI

Darjeeling tea from India, Taleggio cheese from Italy, and Baena extra virgin olive oil from Spain: over the past few decades, consumers in the Global North have shown growing interest in artisanal ingredients, traditional culinary customs, and heritage foods from all over the world.

The more obscure and less known, the better, it would seem. Knowledgeable consumers often express a desire for culinary specialties that ensure great taste, quality, but also opportunities for discovery and exploration. Ingredients, dishes, and practices that have maintained connections to places, the people that live in them, and the traditions they have developed over generations do not risk any longer to be forgotten in a global food system that is increasingly standardized. Instead, they have become objects of curiosity and, at times, passion.

Enter geographical indications and other products that can be clearly and reliably connected to their soil, their climate, their precise locations, the communities that inhabit them and the production method that they have developed to respond to their needs in that specific context.

In fact, the market value of products with specific and identifiable provenance has been increasing. This may come across as a paradox at a time when mass production and industrial technologies dominate our contemporary food systems, at least from a quantitative point of view. This transformation is a crucial historical development that should not be discounted, because it has allowed for increased food availability around the world, making hunger and famines less prevalent, although

unfortunately still occurring. However, issues of sustainability, labor justice, and nutrition have come to the fore with mass production; moreover, new research is pointing to the health dangers of hyper-processed foods. Due to these concerns, growing numbers of consumers are turning to purchases that provide more than just affordability and convenience.

Not only advertisers and marketers but also distributors, retailers, and restaurateurs are well aware of these dynamics and the shifting preferences of their customers. Crops, specialties, and dishes whose growth or manufacture was usually limited to small areas and were available only near the production location, can be appreciated anywhere, if their supply chains reach far enough.

Products coming from the most far-flung corners of the planet are now widely available in dining establishments and shops and have become increasingly visible in media, thanks to social networks and the active role consumers have played in their expansion. New segments of consumers with relatively high spending power are learning to appreciate the manual skills and knowhow of artisanal food producers and their historical ties with local cultures, and they are ready to pay more for products that embody those traits.

Pleasure comes from the flavors and textures of ingredients and dishes; however, the stories connected with them are also important. The value of products is often determined not only by their inherent material and sensory characteristics, including their objective and memorable qualities - but also by the promise of something else: joy, indulgence, and feeling part of something larger. For affluent consumers in postindustrial societies, preoccupations with availability and access to food are being replaced by a longing for the consumption of experiences rather than just material substances. Shopping and eating become arenas for what Joseph Pine and James Gilmore defined in the late 1990s as the “experience economy,” pointing to how production, business, and services have shifted toward providing forms of personal engagement -intellectual, emotional, and sensory-- and the memories that follow them. The value of such experiences increases proportionally with their uniqueness and intensity.

Marketing research, as well as scholarly investigations, suggest that consumption contributes to customers’ construction of their sense of self and their cultural and social identity. As purchasing choices play an increasingly important role in defining who we are as individuals and as members of communities, food has moved to the center of political issues, social dynamics, and cultural preoccupations. Far from being

perceived as embarrassing leftovers from a backward past, rural and artisanal traditions are appreciated as anchors against the globalized and seemingly unstoppable flows of goods, people, finance, and ideas. They can also become sources of inspiration and emotional sanctuary: the sense of cultural loss and a lack of direct relationship with the origins of what we eat often lead consumers to look for forms of tradition and authenticity.

This yearning is also behind the growth of culinary tourism, in which food becomes a fundamental component—if not the main motivation—for traveling. Visitors not only want to get decent meals; they want to enjoy the distinctiveness of the new location through its culinary products and gastronomic traditions. This interest in exploring different realities through food reflects the desire for a cosmopolitan lifestyle that allows individuals to consider their openness to encounters with the unfamiliar as a mark of their sophistication and cultural capital.

Probably for these reasons, similar dynamics are also emerging in developing countries of the Global South, where burgeoning middle classes are embracing food connoisseurship and access to specialty products as a relevant element of their cultural identity. Of course, these dynamics change from country to country, and at times from region to region, responding to the specific cultural contexts and historical developments that make the meanings and practices attached to traditional and local foods so varied and complex. Such localized dynamics are now the object of a growing body of study and research.

Ingredients, dishes, and practices that have maintained connections to places, the people that live in them, and the traditions they have developed over generations no longer risk being forgotten in a global food system that is increasingly standardized.

Of course, the interest in artisanal and traditional foods brings its own causes for anxiety, traceability and safety being the first ones. From this point of view, geographical indications are in general well-positioned. Concerns in terms of treatment of farmers and other laborers involved, especially in less developed countries, have acquired great relevance.

Last but not least, we need to take into consideration the environmental consequences of the growing demand for certain crops or animal breeds, as well as the impact of climate change on their agronomic and economic viability. That said, opportunities to leverage artisanal and traditional foods exist in terms of socio-economic development: it is up to the communities involved to figure out the best and fairest ways to take advantage of them.

Fabio Parasecoli is Professor of Food Studies in the Nutrition and Food Studies Department at New York University. His research explores the cultural politics of food, particularly in media, design, and heritage. Recent books include Knowing Where It Comes From: Labeling Traditional Foods to Compete in a Global Market (2017), Food (2019), Global Brooklyn: Designing Food Experiences in World Cities (2021, coedited with Mateusz Halawa), Gastronativism: Food, Identity, Politics (2022), and Practicing Food Studies (2024, coedited with Amy Bentley and Krishnendu Ray).

BY PIER PAOLO GHELFI

In our fast-paced, globalized world, many of us have lost sight of where our food comes from, leaving us disconnected from the cultures, landscapes, and practices that make up the food we eat every day.

Thankfully, a growing movement is calling for us to rediscover the origin of our food and celebrate it. As prosciutto makers, we wanted to seize this opportunity to help you understand the craft of prosciutto making and celebrate its connection to Italian culture.

At the heart of this conversation comes the concept of “terroir”. Terroir is a French term that describes the combination of soil, climate and topography that gives a food product its unique character. But terroir goes beyond the physical. It’s about the human element, about traditional practices and culture that have been passed down through generations.

If we look at Italian gastronomy, for example, prosciutto stands as an emblem of tradition and taste. This air-dried, cured ham, appreciated for its delicate flavor and tender texture, offers more than a culinary delight—it serves as a prime example when looking into the importance of origin and production methods in our global food story.

Originating from Italy, the craft of making prosciutto is an art form that has been perfected over centuries, a tradition to which we have devoted our entire lives.

Prosciutto di Parma, for instance, is produced from carefully selected breeds of pigs, fed a diet that includes the whey from Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese production. The hams are then salted and air-dried in a process that can take up to two years, a method that highlights the significance of time and tradition in crafting foods that are deeply rooted in a specific cultural and geographical landscape. The result is a product that not only is delicious, but also conveys the spirit of the region.

The special weather in the Italian regions where prosciutto is made, such as Parma and San Daniele, have a significant impact on the flavor of the ham. The air, humidity, and even the traditional practices of the area all play pivotal roles in shaping the final product.

The exploration of food origins reveals diverse culinary traditions of sustainable practices, ethical husbandry, and respect for the natural world. The best producers adhere to stringent regulations that ensure their products not only meet high standards for animal welfare, feed quality, and environmental stewardship,

but also respect ecological balance and animal well-being. This commitment to sustainability and ethical practices highlights the profound impact our food choices have on our planet. By choosing foods rooted in responsible production methods, consumers wield the power to drive change and encourage producers to adopt practices that nurture the environment and culinary tradition.

Moreover, understanding the provenance of our food offers invaluable insights into its nutritional value and health implications. Locally produced, responsibly sourced foods are more likely to retain their nutritional integrity and be free from harmful additives, ensuring freshness and reducing the need for preservatives. Transparency empowers consumers to make informed decisions regarding GMOs, pesticide use, and antibiotic resistance, promoting a healthier lifestyle and a more sustainable food system.

As we navigate the modern food landscape, the conversation about food provenance emerges, guiding us towards a more conscientious approach to living.

“By connecting with the origins of our food, we embrace a celebration of tradition, terroir, and sustainability – one that honors the land, the producer, and the culinary heritage that nourishes our world.”

This journey invites us to question the narratives behind our food, to support local and sustainable producers, and to advocate for policies that promote transparency and environmental stewardship. In doing so, we not only contribute to a more equitable and resilient food system but also ensure that the diverse flavors and stories that have delighted generations past will continue to nourish generations to come.

Pier Paolo Ghelfi, a dedicated Export Manager at Ferrarini, has been with the company since 1985, celebrating his 40th anniversary next year. After initially focusing on commercial development in Italy, Pier moved to Madrid in 1992 to establish Ferrarini’s presence in the Spanish market. Today, he also oversees the company’s operations in the United States.

Pier’s unwavering goal has been to position Ferrarini as the benchmark for uncompromising quality in Italian cured meats, particularly through its flagship product, il “Prosciutto Cotto Ferrarini,” which pioneered - in Italythe production of the first cooked ham without added polyphosphates.

About Ferrarini

Ferrarini is a family-owned company celebrated for pioneering the production of cooked ham without added polyphosphates. With a deep commitment to tradition and quality, Ferrarini has become a symbol of Italian gastronomy, offering a wide range of delicacies including Prosciutto di Parma, salami, Mortadella, and Parmigiano Reggiano PDO. In addition to its presence in Italy, Ferrarini has expanded internationally with a subsidiary in the USA. To ensure the authenticity of its sliced salumi imported directly from Italy, Ferrarini employs blockchain technology to certify the origin of its products. Embracing sustainability and innovation, Ferrarini continues to share the richness of Italian food culture with the world, rooted in family heritage and a passion for excellence.

BY JUAN VICENTE OLMOS

The history of the iberico pig and the “Montanera”

The “montanera” is the period in which the Iberian pig is fattened on acorns, grass, and natural resources of the pasture to reach its final weight before slaughter. During this timeat least 60 days - the animal must gain at least 46 kg and reach a final weight of over 138 kg.

It may be another of the many fortunate coincidences that come together to produce the wonderful Iberian acorn-fed ham, but the truth is that the weather aligns with the maturation of the acorns, which coincides with the propitious moment for the pig’s traditional slaughter. In the winter, until a few years ago before the invention of artificial refrigeration, the only viable way to safeguard the pig’s meat was to slaughter it at the beginning of winter to take advantage of the season’s cold to conserve the meat and its products.

The result is a finished animal, as they say: well fed and with all its fattening potential culminated. Its meat and bacon have also captured all the flavor of the pasture, the antioxidants of the grass, the oleic acid of the acorn, and so many other aromatic compounds that have integrated into its bouquet.

Today this fattening system practically exists only in the Iberian Peninsula. Still, it has historically been the most common and

rational way of exploiting the pig’s adipogenic capacity and the natural resources to which this animal is naturally adapted. Throughout Europe, there are references to this system of grazing, in which the main fruits of the autumn trees - acorns, chestnuts, and beechnuts, for example - are used.

Deforestation in Europe has intensified in recent centuries for different reasons in each epoch: from mining and fuel needed for the extraction of metals, in Roman times and earlier; to the construction of ships for the great Spanish Armada and to everyday activities such as the construction of houses or fire for heating and cooking. In the 18th century, with the agricultural and industrial revolution, deforestation intensified as the production of grain and other crops multiplied. All these factors forced the pig farmer to take pigs out of their environment and into stables, and change the pig’s natural fattening in the forest with natural resources, for feeding in stables with cultivated food.

This paradigm shift caused important modifications in local pig breeds - and most disappeared altogether. Faced with the need to make pig breeding profitable, now that food has to be provided to pigs rather than foraged for themselves, the animal’s efficiency and speed in fattening and producing large numbers of piglets has become more important.

Thus began the formation of the new European pig breeds, with a large contribution of blood of Chinese origin that provided the crossbreeds with greater prolificacy and precocity in their maturation and consequent fattening. These animals were also more adapted to breeding in stables and would no longer have thrived in the natural conditions of the forest.

After different historical periods, in which fat production was initially prioritized but later penalized, breeds continued to evolve into what we see today: pigs capable of reaching weights over 100 kg within a few months and with hardly any fat on their bodies.

But in the Iberian Peninsula, and specifically in its southwest, there remains a small redoubt in which we still find an ancient, rustic, and extremely fatty pig: the Iberian pig, which is fattened in the dehesa, an anthropic forest characteristic of this region, one that aspires to be declared a cultural landscape by UNESCO. Its main fruit is the acorn, which has a high energy content and low protein levels, a nutrient that the animal will compensate for in part by consuming grass and other natural resources.

The survival of this type of ecosystem in our peninsula is due to various reasons including the quality of the soil, the 13th century reconquest of these lands, and the quality of the acorns produced by these trees, which are much sweeter and more appetizing than in the rest of Europe. But ultimately, it’s the quality of the meat products obtained, especially Iberian acorn-fed ham, that has allowed these unique systems to be maintained in the Iberian Peninsula

From the Iberian pork and the elements of the dehesa ecosystem, we obtain the raw material. After minimal processing and up to years of maturation and curing, this raw material gives rise to the gastronomic marvel that is Iberian acorn-fed ham. The slices boast a bright, almost crimson red color, sometimes softened by the white streaks of infiltrated fat.

At room temperature, this fat lends a shine and fluidity in the mouth, which is further intensified by the rapid salivation produced by exciting the taste buds with just the right amount of salt and a multitude of sapid molecules. The pleasant texture is consistent but not hard, with no sensation of wetness but a fluidity that becomes livelier with each bite - keeping us salivating. The powerful aromas, with tones of slightly aged, cured fat, are pleasant and intense, softened by sweet nuances of certain amino acids, slowly released during maturation. All this is wrapped in the oiliness of the oleic acid and dozens of volatiles that together give the ham that exquisite persistence in the mouth.

Juan Vicente Olmos Llorente is a General Manager of Grupo Monte Nevado. Belonging to the 4th generation of Monte Nevado, and being veterinarian by training, he is a tireless researcher of the world of ham. He is well-acquainted with numerous ham facilities across Spain and has experience working in several in Italy, Germany, Belgium, Portugal, and the USA. Additionally, he has written three books on ham and the Iberian pig.

EXTRA VIRGIN

OLIVE OIL

The highest quality grade

CHEMICAL STANDARDS

Free Acidity (%)

Peroxide Numeber (meqO2/Kg) K232

SENSORY STANDARDS

OLIVE OIL

A blend of refined olive oil with extra virgin and/or virgin olive oils

OLIVE - POMACE OIL

A blend of refined olive-pomace oil with extra virgin and/or virgin olive oils

Virgin olive oil

The olive milling process

Extra-virgin Virgin Lampante

The physical-chemical refining process

The

Pomace

extraction

The physical-chemical refining process

N.B.: Only the boxes highlighted in green are suitable for human consumption

BY JORDI JARDI SERRES

Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) is not only an essential ingredient in cooking, but also a flagbearer of sustainability and agricultural tradition.

Let’s explore its history, advances in production and impact on society and tourism, touching on the concept of kilometre-zero products and the important role played by farmers in the industry.

Mankind’s relationship with olive oil dates back to the Phoenicians and Romans, who improved and expanded its production, considering oil an essential element of their diet, medicine, and religious rituals.

Particularly noteworthy is the continued survival of ancient olive trees in regions like Catalonia which not only produce liquid gold but also represent a living cultural heritage. These witnesses of bygone eras demonstrate the continuity and adaptation of agricultural techniques over centuries, forging a symbol of culture and prosperity, just as the culinary experience has developed from home cooking to restaurants.

The longevity of these trees, often centuries old, not only pays testament to age-old cultivation techniques but also encapsulates how this biodiversity has withstood the test of time, adapting to both climate and human changes.

The modernization of olive oil extraction has made it possible to preserve the quality and purity of the product. Methods have evolved from the simple hand presses used in ancient times to today’s complex centrifugal extraction machinery, an evolution that increases yield and ensures the integrity of the oil’s flavour and nutrients.

This technologically advanced process must be managed by highly qualified farmers and technicians, whose knowledge and experience are fundamental to the final quality of the end product. Appreciating their efforts is essential to understanding the complexities and simplicities of olive oil at its finest.

Since ancient times, olive oil has been an essential element of domestic kitchens, used in cooking, preserves, and dressings. Its nutritional value and versatility make it an indispensable element of the Mediterranean diet and in homes across the globe. Savouring a slice of fresh bread soaked in freshly pressed Oli del Raig oil at home; sweet dishes like coc ràpid with olive oil, as yogurt was still not used, or the popular Clotxa are just a few of the popular culinary options that can be relished in a limited number of places with this liquid gold.

When it comes to traditional cuisine, especially in the Mediterranean, olive oil is the base for countless recipes, from simple dressings to complex stews and roasts, and is a crucial element of the Mediterranean diet.

Regarding professional cooking and haute cuisine, extra virgin olive oil is used not only as an ingredient but as an essential component that contributes to the flavor of simple or complex dishes and creations. Chefs from around the world use it for its ability to enhance natural flavors without overpowering them, rounding out all the nuances captured by the senses that chefs try to provoke, respecting its specific organoleptic qualities as an essential ingredient in culinary creations.

Oil capsules are now a feature of supermarket shelves as a result of research performed in kitchens. A gastronomic legacy to make the lives of consumers easier. It is worth noting that the use of animal fats in cooking has been significantly reduced compared to the consumption of EVOO.

Furthermore, in hospital kitchens, olive oil is recognized for its health benefits, including its ability to assist in the reduction of cholesterol and the prevention of cardiovascular disease, making it a preferred ingredient in nutritional diets.

Olive oil has had a significant impact on society beyond health and cuisine. Oleotourism, a niche tourism attraction, offers visitors the opportunity to witness the production process from harvest to bottle, taste unique varieties, and participate in cooking courses. This aligns with the “kilometre-zero” concept, promoting local products that reduce carbon footprints, ensure freshness, and support local economies. Educational initiatives, like “Has begut OLI” in DOP Siurana, aim to preserve this legacy by teaching students about the attributes of EVOO across all educational levels.

by

Extra virgin olive oil, from its historical roots in ancient olive trees to its modern role in gastronomy, oleotourism, and sustainability, has demonstrated its role as a bridge between the past and the present.

Its production, rooted in the tireless efforts of farmers and respect for the land, offers us more than just food: it serves as a lesson in cooking culture, sustainability and connection with our land.

“We don’t think twice about how much we pay for almost a liter of wine, but we question the price of a liter of extra virgin olive oil. We are simply paying for access to this ancient heritage that we can enjoy in a wholly ethereal way once we have sampled it”.

“Without a great product, great creations are impossible. In this equation, to obtain great results, we need great producers.”

Jordi Jardi Serres is a Technical Specialist in Hospitality and Tourism, specializing in Kitchen Specialty at INS Escola Hospitality and Tourism in Cambrils. With over three decades of experience, he has served as a Teacher of cooking and gastronomy and held various leadership roles including Director and Head of Studies. His culinary career spans roles as a cook at notable establishments in Catalonia, including Restaurant Eugènia and Fonda Turú. He also co-owns Restaurant Casal de Miravet and has contributed to gastronomic innovation projects with Griffith Foods. Passionate about sustainability, he actively designs Training Cycles for the hospitality sector, focusing on environmental impact.

BY JOSEPH R. PROFACI

The best olive oil is the one that suits your palate and desires. That could be a single origin oil. But it just might be a masterful blend.

Many companies striving to distinguish their brands in what has become a very crowded extra virgin olive oil market are focusing on the concept of “single origin.” Unfortunately, promoting the idea that single origin is an important guarantee of quality is misleading and confusing to consumers in multiple ways.

Origin can be important for several reasons, but not quality

No doubt, origin is important to many olive oil consumers. Some see it as an indication of traceability to a particular place with which they may associate quality, such as countries or regions that in their minds make the best olive oil. Others may look for oils from a specific origin because of their ancestry or fond memories from a travel experience. Or maybe they’re striving to be “authentic,” using an oil from the place that matches a particular ethnic dish they are preparing. More sophisticated consumers may also look to single origin oils to experience unique varietal characteristics, distinct production techniques, or the terroir (the special attributes imparted by geography, geology, climate).

For any consumer interested in origin, accurate and not misleading labeling is fundamental. “Single origin” however, doesn’t fit the bill. It is a marketing term that is not regulated by any authority and often can mean different things. The term loosely describes olive oil produced using olives from one specific location, but the origin could thus be as large as a country or as small as a single farm. This is in contrast to strictly regulated certifications like DOPs, which means a protected designation of origin, guaranteeing that the olives were grown in a specific location, or the less stringent IGPs, which means a protected geographical indication related to the location of the production process. (The California Olive Oil Council’s “COOC” certification and the Olive Oil Commission of California membership logo both function like a DOP for California-origin oils.)

Further, some will also wrongly use the term “single origin” to include “monocultivar,” which means that all the olives used to make the oil are from a single variety, or “estate-produced” which means that the olives are both grown and milled on a single property. Bottom line, without regulatory guidance, consumers cannot really know what “single origin” actually means in relation to specific products.

Regardless of what “single origin” is intended to mean, it is wrong to link it with quality. Single origin oils can be and often are excellent (as can also be true with monocultivars and estate-produced oils). But it is not necessarily the case. A “single origin” olive oil that is labeled 100% from a particular region from a single olive variety could be sublime. It could also be terrible. That’s because the singularity of the origin (or the variety or the estate) is not what confers quality.

For many, quality is also associated with traceability. But contrary to what those promoting the single origin concept will have you believe; traceability also doesn’t depend on there being a single origin. Thanks to modern technology, companies can provide traceability even for oils that are blended from multiple origins (“olive oil blends”), often assisted with blockchain data and QR codes.

In the end, what determines the quality of an olive oil is not information about its origin, but the skill of the farmers who cultivated and harvested the olives and the miller who extracted the oil (and yes, sometimes even the bottler who creates a blend with different oils). Arguably, the only thing that the “single origin” designation on an EVOO label can guarantee are potential variations in flavor from year to year.

Unfortunately, falsely equating “single origin” oils with quality also implies the contrary is true: that any olive oils that are not single origin, such as blended olive oils, are poor quality. This is also false. The results of skillful

“coupage,” as the blending practice is known in the industry, can include flavor consistency (blending allows for a consistent taste yearround, regardless of variations in individual crops), balanced flavor (producers can create a well-rounded product that appeals either to a broader audience or a discerning consumer), and cost-effectiveness (it’s often more economical, allowing companies to offer quality products at competitive prices). Just like single origin oils, coupages can be and often are high quality. Indeed, it is not uncommon for coupages to win esteemed competitions like the Mario Solinas. This is no different than what we know happens in the wine industry, in which vintners blend grape varieties to achieve a desired and often award-winning flavor profiles.

Consumers-as well as the trade and the media-seeking to define quality should not hitch their wagons to “single origin.”

The quality of an olive oil does not depend on whether it comes from a single origin any more than whether it comes from a particular origin, or for that matter, where it is bottled. Indeed, many multi-origin coupages are crafted to meet exacting standards of flavor, versatility, and/or affordability to meet consumers’ demands. The practice is respected in winemaking, and it should be respected with olive oil as well.

When it comes to quality, marketing terms like “single origin”--and “first cold pressed,” for that matter--are false idols that ignore and even disrespect what is truly behind great olive oils: the skill and dedication of the passionate people who make them and bring them to market.

“Without regulatory guidance, consumers cannot really know what “single origin” actually means in relation to specific products.”

Joseph R. Profaci has served as Executive Director of the North American Olive Oil Association since October 2017. He is an experienced food products attorney and business manager, with almost 30 years of experience in the olive oil category. Previously, he served as general counsel for Colavita USA, LLC, a leading importer and distributor of Italian specialty foods. He was an active representative for Colavita to the NAOOA, serving on the board for 4 years, including serving as the NAOOA chair from June 2015 - June 2017. Mr. Profaci is a graduate of Harvard College and New York University School of Law.

BY ALMUDENA PIZA BARROSO

Avocados have transcended mere culinary status to become a cultural phenomenon deeply entrenched in American food culture. From guacamole at the Super Bowl, to the proliferation of avocado toaston brunch menus across the nation, these creamy fruits have permeatedvirtually every aspect of modern dining.

Yet, the story of avocados stretches far beyond their contemporary popularity. Avocados, now an iconic symbol of American culinary culture, trace their roots back to ancient civilizations in Mesoamerica. However, their journey to prominence took a significant turn with their introduction to California in the early 20th century, leading to a revolution in avocado cultivation and consumption. As avocados flourished in California, another region emerged as a powerhouse in avocado production: Michoacán, Mexico. This fertile land, nestled amidst the mountains, became the epicenter of avocado cultivation, supplying a significant portion of the world’s supply. From its ancient origins to its modern-day dominance, the story of avocados is a testament to the enduring appeal and global impact of this beloved fruit.

The history of avocados is deeply intertwined with the rich tapestry of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations that cultivated and revered them for their nutritional value. Mayans and Aztecs alike believed avocados symbolized fertility and abundance, and included the fruit in their diet and rituals. Early Spanish explorers were quick to recognize its culinary potential, with one 16th century description remarking: “like butter and is of marvelous flavor, so good and pleasing to the palate that it is a marvelous thing”.

“The journey of avocados, from ancient staple to modern marvel, embodies the dynamic interplay of culture, commerce, and innovation.”

While the avocados of antiquity differed from those we enjoy today, it was the ingenuity of California growers that propelled the fruit into modern prominence. In the early 20th century, avocados found their way to California, where they would undergo a transformative journey thanks to the pioneering efforts of growers like Rudolph Hass. The development of the Hass avocado variety revolutionized the industry, offering consumers a fruit with a buttery texture and resilient skin that facilitated easier transportation and extended shelf life. This innovation expanded the availability of avocados and paved the way for consumer adoption in America.

However, the path to consumption in the United States was not without its challenges. In 1915, California growers and producers created “The California Avocado Growers Exchange”, a member owned cooperative organization with the goal to grow the industry and educate consumers. The fruit formally known as “alligator pears” was largely unknown outside of California. The California Avocado Grower’s Exchange decided to lean into its cultural roots and petition for a name change to “avocado”, derived from the Aztec name “ahuacacuahatl”. In addition, early perceptions of avocados as high in fat and calories posed obstacles

to their acceptance among health-conscious consumers; but concerted efforts by industry stakeholders, aided by scientific research and savvy marketing campaigns, avocados gradually shed their negative image and emerged as a symbol of healthy eating. As that awareness spread, fueled by social media and endorsements in health publications, avocado consumption surged from 1.51 pounds to an average of 8 pounds per person by 2018 - and growing - according to the latest USDA reports.

However, despite California’s significant contribution to avocado production, demand has consistently outpaced domestic supply, leading the United States to rely heavily on imports from Mexico, the world’s largest producer. Michoacán - Mexico’s primary avocado-growing region - boasts ideal climatic conditions and sustainable farming practices that ensure year-round production. As avocado production grew in the US, importing avocados from Mexico was banned to protect their crops from possible infestation. Producers in Mexico, specifically in Michoacán, worked with the U.S. Animal Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to adapt their practices to meet standards. In 1997, the ban was partially lifted, and avocados started to flow into the US. Other Mexican states followed suit, and in 2022, Jalisco was approved to to start exportation.

Today, Michoacán stands as the epicenter of avocado production, accounting for a significant portion of Mexico’s avocado exports and supplying markets around the world. The region’s avocado orchards stretch across vast land expanses, encompassing small family-owned farms and large-scale commercial operations. From the picturesque highlands of Uruapan, to the fertile valleys of Tancítaro, avocado trees blanket the landscape, their lush green foliage a testament to Michoacán’s status as the “Avocado Capital of the World.”

Yet, Michoacán’s success in avocado production has not come without challenges. The region has had to contend with issues such as water scarcity, soil erosion, and the threat of pests and diseases. However, through innovation, investment in technology, and sustainable farming practices, Michoacán has continued to thrive, maintaining its position as a global leader in avocado production.

As we look to the future, the avocado industry is poised for further innovation and growth. From advancements in cultivation techniques, to the introduction of new, high-yielding varieties, like the Luna UCR, that enhances freshness and increases pollination efficiency.

In essence, the journey of avocados from ancient staple to modern marvel embodies the dynamic interplay of culture, commerce, and innovation. As consumers continue to embrace this fruit, its enduring appeal serves as a testament to its remarkable versatility and enduring legacy in the world of food.

Almudena Piza Barroso is a food scholar and writer who specializes in the history and development of the avocado industry in Mexico and the United States. She holds a Master’s degree in Food Studies from NYU Steinhardt, a Bachelor’s degree in Applied Food Studies, and an Associate’s Degree in Culinary Arts from The Culinary Institute of America. She currently resides in Mexico working on agricultural trade research

BY KAMI KENNA

Tequila is a formidable global spirits category.

In 2021, Mexico produced 527 million liters of tequila worth eight billion dollars (Szczech, 13). In 2022, tequila surpassed American whiskey in sales in the United States (Carruthers 2024). All spirits are agricultural products intrinsically tied to the land and the people who look after it. Maybe tequila has landed on your radar recently, but agave-based beverages go way back in Mexico’s history. In fact, Tequila’s beginnings date back to 400 hundred years but are rooted in traditions from 10,000 years ago.

Similar to Champagne or Pisco, Tequila has its roots in a specific geographic location. Meaning “place of work” or “place of tribute” in the native Nahuatl language, Tequila is the name of the dormant volcano where indigenous people collected obsidian stone to carve into tools and weapons. In due course, the surrounding valley, the town at its base, and the beverage also took the name (Szczech, 18).

Today, tequila is the most well-known regional mezcal. Spirits made from cooked agave are mezcals, from “metl” and “ixcalli”, mezcal means “oven-baked agave” in Nahuatl. The author of A Field Guide to Tequila, Clayton Szczech, affirms that “[m]ost Mexican agave spirits are known as mezcales, and tequila was born as a regional mezcal called vino mezcal de Tequila” (18). Over time the name was shortened to just Tequila. In 1974, the Mexican government established the Denominación de Origen Tequila (DOT) declaring it distinctly Mexican to ward off imitators. Tequila became Mexico’s first Geographical Indication and the first established outside of Europe. Since 1994, its norms have been enforced by the Consejo Regulador de Tequila (CRT), a nongovernmental organization funded by the tequila industry. From plants in the ground to chemical makeup to bottling, tequila is the most regulated spirit in the world.