7 minute read

Evolution of City-Organism Sneha Aiyer

Evolution of City-Organism

Fight or Flight?

Advertisement

Sneha Aiyer M.S. UP

I stood in shock amongst my friends on the middle school football ground on January 26, 2001, when a 7.7 magnitude earthquake, lasting over 2 minutes, destroyed many settlements and killed over 30,000 people in the Western State, Gujarat, India. Ten years later, in 2011, I researched the transformation of the city, Bhuj, India at the epicenter of the quake. We build to endure, to resist time, although we know that ultimately time will win. What previous generations erected for eternity, we demolish. Then, with similar intent, we lay stone upon stone and build again. Permanence is instinctively sought. The built environment, like all complex phenomena, artificial and natural, endures by transforming its parts.

Habraken, N.J, Structure of the Ordinary

Many beautiful dwellings, streets, monuments, and lives withered, but they picked up the pieces, adapted to the situation, and prepared themselves and their built environment to endure a future calamity. Like Bhuj, many cities are redesigned after a disaster. Consequently, we redesign how we relate culturally, socially, and even politically to the city after re-organizing it to mitigate future perilous events. The urban human finds themselves constantly updating and generating newer versions of themselves, and therefore we see a rapidly evolving society. We are not strange to these rapid changes in our social interactions owing to the current pandemic. A protein molecule permeated our biological pathways that resulted in reshaping our cultural practices of assembly and congregation, perhaps for many years to come. After almost a year of holding onto the hope that we can go back to our previous state, it is time to see this as an opportunity for urban systems to not merely create possibilities to physically distance and provide sanitary conditions, but facilitate an egalitarian society that can have a chance to thrive under any future adversities. The pandemic brought forth imparities of our society that have been ignored and, therefore, most affected as the economic landscape changed drastically in a matter of days in March 2020. With ‘shelter-in-place,’ the onus of reproductive work (Federici 2012) was thrust on women across all cultures. In the last year, 2.3 million women in the US dropped out of the workforce, often to perform child care, when schools and daycares closed. (Jordan 2021) Within this new ecosystem, a “racial justice paradox” has emerged: Blacks and Latinxs are more likely to be unemployed due to the impacts of the pandemic on the labor market, but they are also overrepresented among essential workers who must stay in their jobs, particularly lower-skilled positions, where they are at greater risk of exposure to the virus (Powell 2020). Domestic work in Indian urban homes is typically performed by migrants from remote villages that were suddenly left without jobs or support from the administration. Amidst a complete lockdown, unable to commute, helpless and jobless, many chose to return to their villages on foot. There hasn’t been a time when it was more evident that a city’s infrastructure is measured by the equity of privileges and opportunities rendered to its people. What kind of evolutionary changes within the infrastructural zone will help us prevail under these conditions?

In most living organisms, a fight or flight response to stress stimuli causes a reaction within the nervous system triggered in the amygdala secreting adrenaline. The activation of the pituitary gland causes a hormone release that triggers further reactions to boost energy

in the organism to prepare for physical action against imminent danger. From an evolutionary perspective, quick physical response to threatening stimuli provided early organisms with biological mechanisms to rapidly respond to threats and thrive under perilous conditions. Some organisms can also maintain homeostasis even under such conditions. (Canon 1915) The fascinating protocols of organism design offer possibilities for an investigation into a city-organism. Like organisms, cities are an assembly of functioning parts with protocols that describe their disposition. An arborescent metaphor for a city-organism signifies authoritarian yet accretive growth of the settlement. In contrast, Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” depicts the city as a machine powered by workers’ servitude while the overlords enjoy the expensive skyscrapers. In both cases, the metaphors of an efficient machine and an ever-expanding organism, authoritarian politics and its control over the socio-cultural environment are evident. The growth and efficiencies are controlled by a power regime to toy with the societal imparities, limiting opportunities for some while awarding privileges to a few in exchange for more power. Theocracy ordered the early medieval cities, where the central position belonged to the monarch and subsequent hierarchies were organized based on occupational specialties. Cities past the industrial era remain reminiscent of this disposition based on the socio-economy of its citizens. Technology plays a critical role in taking control of these protocols and breaking away from the city’s authoritarian structuring. Over the past 30 years, it progressively created a socio-technological environment in which a human exists as an Avatar (a representation) of themselves in media, unbound by their contextual conditions. The socio-technological environment offers its occupants a level playing field, possibly pre-empting devolution of the authoritarian politics that exacerbated the acute economic imparities during the pandemic.

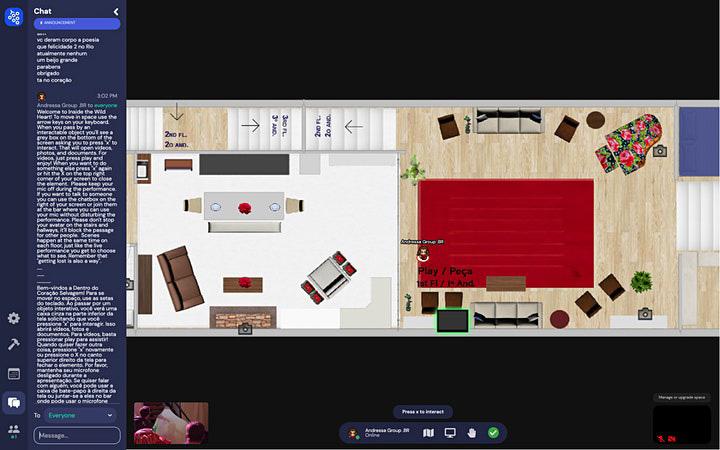

Group.BR ingeniously used the Gather.town digital platform to allow the audience to guide their avatar across various rooms and floors and interact with other viewers as they navigated through a recorded version of the multidisciplinary show about author Clarice Lispector and her writings. [source: eventbrite.com]

Under the threat of the contagious virus, our collective fight or flight response kicked in, and we locked ourselves out from the thrills of urbanity. We disabled our most tactile and present forms of communication and found media prosthetics to compensate and expand our potential under these circumstances. We accepted a life within the socio-technological environment. Platforms like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet could connect people online, recreating the infrastructure zone that facilitated their physical congregation pre-pandemic. Taking a step further, Gather.town transformed the media to emulate spatial conditions of meetings such as office environments, living rooms, schools, game rooms, speakeasy, waterfronts, and so on. Creating this media environment bore no relationship to the city or context. Instead, traveling across the globe and subverting placeness, it defined a technospatial endeavor that may be our most prominent evolutionary feature under these circumstances. Communication technologies have come to the rescue of the human network in the past. In March 2011, Japan was hit by an 8.9 magnitude earthquake that initiated a 30-foot high tsunami. The giant wave then triggered a nuclear meltdown of the Fukushima Daichi plant, killing 1800 people and completely demolishing Japan’s telecommunication systems. This distressing experience prompted employees of NHN Japan, a subsidiary of a South Korean internet company, to devise a solution for people to contact family and friends during crises. Line was launched as a messenger service for instant communication where users can text and call people from their smartphones that rely on Internet-based resources to connect (Bushey 2014). Not long ago, a group of coders built a free online tool to create child care co-ops such as Komae. “On Komae, parents swap ‘Komae Points’ with other families as a way to manage and coordinate care for their children within a trusted network. I sit for you. You sit for me. We don’t pay for sitters anymore—Huzzah!” as advertised on their website. Mutual aid networks have flourished during the pandemic. A group of people seeking services and help use something as simple as a Google Doc, where they write down what they need and provide in exchange, forming a network of symbiotic relationships. Such initiatives in response to calamities did not rely on the primary infrastructure of their cities. Communities banded together to pool and increase their resources, creating a participatory infrastructure based in a socio-technological zone. Like a network of biological protocols inherent in the organism’s design, which kick-starts a series of reactions in the neural pathways, the human network switched from a socio-cultural environment to a socio-technological environment as our physical interactions were prohibited during the pandemic. Subverting the geographical limitations, connecting across the continents, and creating an infrastructural zone independent from boundaries of authoritarian ideologies and motivations, the evolved human inches close to dissolving the accumulation of power. This is an evolutionary response of the human network under a biospatial threat. Can cities create such socio-technological infrastructures that host a participatory network providing equity of opportunity across communities?

Stepping back from morphological transformations to create adaptability within our environments, we must focus on designing protocols that establish relationships and define the actions performed within the socio-technological zone resulting in an ephemeral infrastructure. This infrastructure will be inherently adaptable, just like an organism.

Sneha Aiyer was a graduate student in the MS AAD program at GSAPP. Her projects and research investigate ephemeral and temporal aspects of built environments.