12 minute read

Thick-Envelope Thiago Maso

International Travelling in Times of the Pandemic

Worth the Retelling?

Advertisement

I. The Airport

After taking the longest nonstop commercial flight for 19 hours, I landed in JFK airport on January 23, 2021. I passed through the Customs Counter – which used to be full of snaky queues of foreigners – in about 10 minutes, picked up my luggage and hopped on a taxi to my apartment. During the pandemic, empty customs lobbies became a norm at every metropolitan airport. Singapore Changi International Airport was handling very few flights too, when I arrived two weeks ago on January 8. The pandemic also made unusual traveling purposes sound acceptable. When the Singaporean Customs Officer asked me about the purpose of my stay in Singapore, I answered, “I want to enter the US in 14 days.” The Officer nodded silently at my answer, which would sound weird in a pre-pandemic world. Later, I overheard a student-looking young man answering in a similar fashion to another officer. When I told my friends in the United States of my selfimposed refuge in Singapore, it bewildered them. A year ago, President Trump issued a travel ban restricting travelers who had been to mainland China in the last 14 days from entering the United States. To circumvent the restriction and arrive in the US, mainland travelers like myself resorted to staying for 14 days in a third country which not only welcomed travelers from China, but also posed little risk to the US. Excluded from the US restriction, Singapore was a viable option for Chinese travelers. On November 6, 2020, Singapore began to receive Chinese passport holders, after mainland China reported a COVID local incidence rate of 0.00009 per 100,000 people over the past 28 days (Channel News Asia, 2020). In the same month, case numbers in the US were climbing, with 371.08 per 100,000 people, the highest 7-day average 40

case rate in November (CDC, 2021). Based on the data, Washington’s insistence on banning Chinese travelers seemed more political than practical. At both JFK and Changi, the experience as a flight passenger was smooth, but there were some differences. After I picked up my bags in Singapore, I followed instructions directing me to a testing center located inside the arrivals hall. Having prepaid before departure, I got tested immediately and was instructed to stay in my booked room at one of the quarantine hotels to await my test result. The hotel workers sent me to a designated floor reserved for quarantine guests and told me that food and deliveries would be dropped at my door. The result came out fast. In 7 hours, I received a negative indication via email and was freed from my quarantine room. If you read about the quarantine experience in Singapore on English news media, the tone may have been less delighted. Travelers flying from European countries and the US are subject to 14 days of mandatory quarantine, regardless of test results at the airport. A Columbia Journalism affiliate who quarantined in a hotel shared that she was given a single-use room key, which was only valid for 20 minutes after check-in (Low, 2020). Breaching quarantine law meant severe punishments, including heavy fines, imprisonment and even losing Permanent Resident status for foreigners. Because I had flown from China, I was able to enjoy the rest of my stay as a true tourist. The mandatory quarantine regulation, which has been strictly enforced in Singapore and China, had been carried out weekly in the US. In New York, quarantine rule breakers were seldom punished and the state depended heavily on the travelers’ integrity for observing quarantine rules (Dorn, 2020). Flying from Singapore, a low risk country determined by New York State, I was neither required to quarantine, nor given a test upon landing.

Shen Xin M.S. UP

II. The Streets

As I explored the city, Singaporean streets looked almost no different from a pre-pandemic world, with the exception that every person wore a mask. On a weekend afternoon, visitors were sometimes shoulder to shoulder at the malls on Orchard Road, the most popular shopping district in the city. Later that night, I went to a semi-outdoor food court at Bugis – a hip, local neighborhood where restaurants selling street foods were packed with customers. The vibrant street scene did not surprise me because my hometown Beijing had also recovered well from the pandemic. When I took the subway to work in Beijing, the compartment was so crowded during rush-hour that people had to wait for a second train. Yet, the bustling street scene stood in sharp contrast to New York City where I now live. Last week a friend commented that Midtown Manhattan, where every tourist used to go, was “dead.” I felt the same when I was on campus, reminiscent of College Walk so populated with students. The recovery in Asia was not achieved without “sacrifice.” Prior to my departure to Singapore, I had to show airline employees at the check-in counter in Shanghai Pudong International Airport that I had installed and activated the TraceTogether application on my phone. The app uses bluetooth to track other TraceTogether devices within six feet distance from the user, and the installation and activation of the app are mandatory for all travelers prior to their departure to Singapore. Whenever people entered an indoor public space in Singapore, they scanned a Safe Entry QR code which registered their visitation. The same registration system was also applied in China, using built-in features in multiple popular apps such as Wechat and Alipay. In Asian countries, people seem to be more comfortable with disclosing their personal data to disease control agencies. At first, when I was told to register at every shopping mall and restaurant I wanted to visit, I was reluctant. But I succumbed, noting that data privacy was not on the agenda of discussion in Chinese society, and complied when I desperately wanted to hang out with friends at my favorite bar. The Asian governments were successful in cultivating a consensus that sharing personal data was in the public’s best interest. By building trust, public agencies could then deploy this personal data for the public good.

III. The Metropolitan

Having lived most of my life in metropolitan areas such as Beijing and New York City, I was used to picturing rural issues as remote from my personal life. When the pandemic broke out in Wuhan and other major cities in the globe, I thought of public health as a huge challenge that densely populated cities would face. However, this January, I realized that it has been a misconception that cities are more vulnerable to infectious disease than rural areas. A couple of days after I left my hometown Beijing, I heard from my family that the municipal authorities were tightening up pandemic controls due to the discovery of several clusters of cases in the nearby rural areas. Streets became quiet again; people were advised not to travel for family reunion during the Spring Festival; mass testing was initiated in affected neighborhoods. My family canceled plans for vacation. Local news described that the populous, rural area with inadequate health care service had been a loophole in the country’s containment effort (The Strait Times, 2021). Authorities attributed the spread to a combination of the 41

rural residents’ low health awareness and an ill-prepared rural clinic system loosely incorporated into the national epidemic monitoring mechanism (The Strait Times, 2021; China Daily, 2021). Research also indicated that rural communities received little government aid of any sort and suffered a number of consequences such as high unemployment rates and reduced household income (Wang et al., 2021). The local news report also called it a “misconception” that the risk of infection is higher in urban areas than in rural areas (The Strait Times, 2021).

In the US, rural infection rates surpassed those in metropolitan areas in August 2020 (Marema, 2020). The spread of COVID on farms, meatpacking plants, prisons, and nursing homes created substantial impacts on marginalized and vulnerable communities in the countryside, where rural residents lack accessibility to quality healthcare and are excluded from fiscal relief (Ajilore, 2020). In comparison, Singapore’s disease control was a largely urban story. Unlike the US and China, which faced issues of containing the infectious disease in their vast rural lands, Singapore was able to swiftly mobilize its resources majorly located in a highly urbanized physical environment. Although urban density has been seen as a disadvantage to containing the spread of disease, cities such as Singapore enjoy advantages of advanced amenities and well-managed disease response systems.

IV. Moving On

On a Sunday morning this March, I joined a group at Union Square for a rally for Black and Asian Solidarity. I saw people holding #StopAsianHate signs and I heard passionate speakers voicing their support for racial justice and social equity. Standing in the far back of a very large crowd, I caught limited words that flew to me. The punchline which got me into deep thinking was the description of the American society as “a system which emphasizes our differences over our similarities.” 42

I do not know how American society could embrace Asian Americans, especially Chinese Americans, in a more friendly way, when political leaders in this country have been antagonizing their voters against China. As I write this essay, travel bans on Chinese nationals are still in place. The US-China trade war is dragging on, with US geopolitical interests evermore intertwined with its economic goals. When the US created indefinite barriers for Chinese international students to arrive at the campuses of American universities, I feared the severance of conversations between Americans and Chinese nationals in a relatively safe space for cultural exchange, such as universities, would breed ignorance and bias, harming Chinese Americans as well. I do not know how our streets could be safer for Asian Americans, especially Chinese Americans, when the previous administration has spread so much false information on the disease and called the coronavirus “China-virus.” Chinese Americans and Chinese nationals have different histories, but their cultural ties also make it impossible for them to be completely separated. I learned from watching the last two elections with my American friends that this country has been very divided, not only along color lines, but also along geographical lines between urbanity and rurality. I started to wonder, if we, as planners, could build

Shen Xin is an Urban Planning student, traveler and diary writer. Her latest hobby is watching movies by herself.

#StopAsianHate

Thick-Envelope

Thiago Maso M.S. AAD

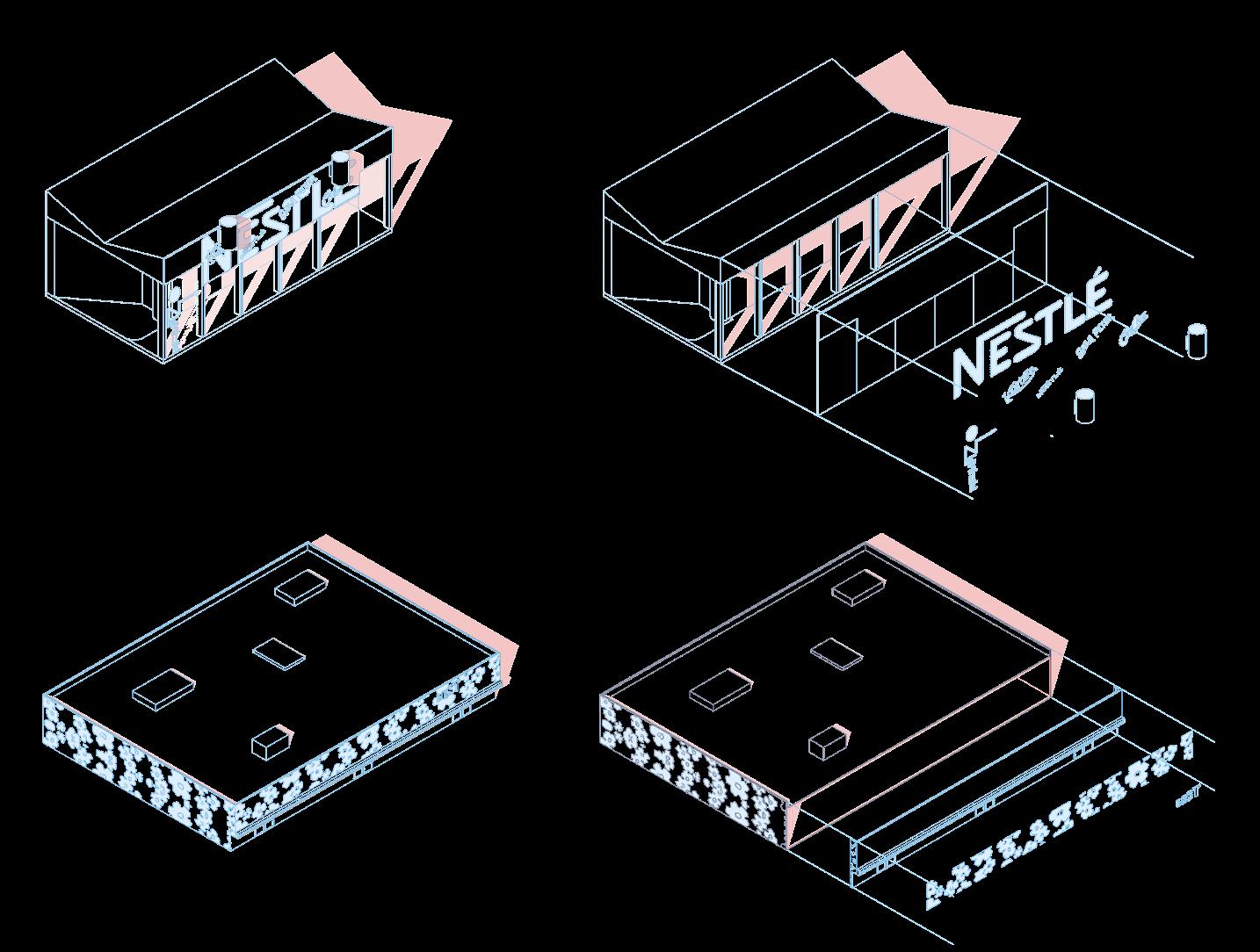

Nestlé Pavilion, Le Corbusier and BEST Store, V&SB. Decorated shed.

Why are we still talking about buildings or cities as if they are separated only by a thin wall?

On a not-so-famous project, Le Corbusier called for an idea that would reappear about forty years later. In his Nestle Pavilion from 1928, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret applied a superficial treatment, on the outside-skin of a shed, as decoration to convey meaning. All the virtues of a semi-generic form, decorated as a commercial device intended as a billboard were printed into a thin, metal-sheet façade. Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, his most famous detractors did the same in 1978, painting their trademark pop-inspired flowers and colors into enamel panels enclosing a big-box retail shed. This example shows that reading contemporary 44

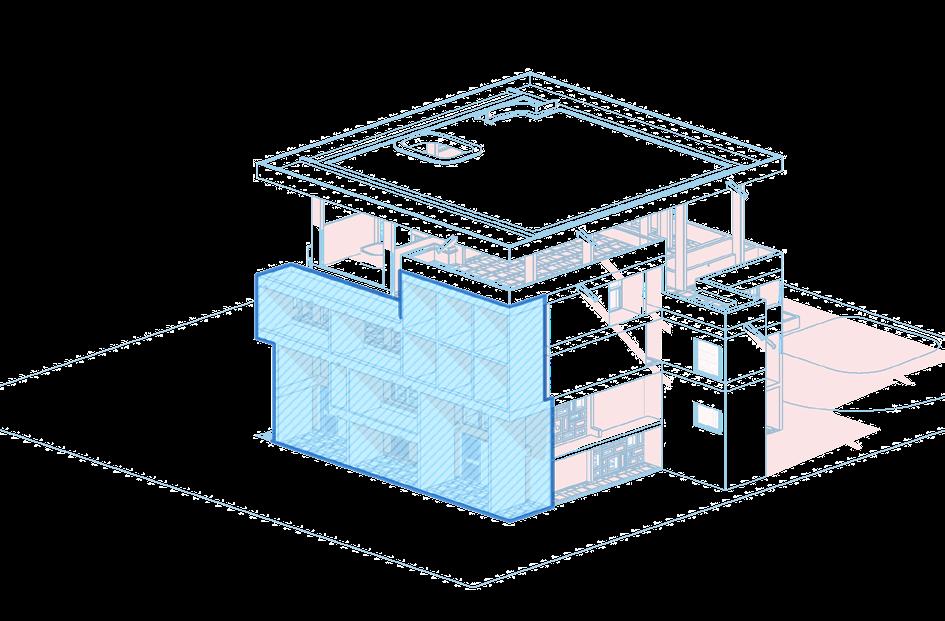

theory as a play on façades is too superficial, and we shall look deeper into the definition of the façade by researching not its decoration or composition, but the relationship between façade and its thickness. Historically, we could insinuate the façade is an assemblage of symbols attached to the external face of a (generic) wall — the urban portion of the limits of a building — and comprehend this double relationship, building and city form (and the subsequent lobotomy), as a signifier to the city. This ambiguity between the interiorexterior representation is what Venturi (1966) calls the difficult whole, or the complexity and contradiction in the element of the façade that synthesizes the forces existing between the interiority and exteriority of the building.

With the increased complexity of contemporary designs, especially since the 1990s, the limits between the façade, the floor, and the ceiling become fluid, complicating the separation into discrete elements, turning the classical definition of the façade no longer operational. It then becomes necessary to introduce a new concept, that of the envelope and “its series of attachments” (ZaeraPolo, 2008). Still, this maintains a superficial vision of the façade’s role in contemporary terms, that ZaeraPolo even identifies, but does not provide an answer to when he says that the envelope “has been relegated to a mere ‘representational’ or ‘symbolic’ function. The reasons for such a restricted political agency may lie in the understanding of the envelope as a surface, rather than as a complex assemblage of the materiality of the surface technology and its geometrical determination.” By considering thickness of space rather than the material of the façade, we finally realize “the hierarchies of interface become more complex: the envelope has become a field where identity, security and environmental performances intersect” (Zaera-Polo, 2008, p.199).

Politics: the urban vs the architectural building

To Pier Vittorio Aureli (2011):

“If one were to summarize life in a city and life in a building in one gesture, it would have to be that of passing through borders. Every moment of our existence is a continuous movement through space defined by walls.” (p.46)

By questioning the thickness of the envelope, and its consequential multiplicity of walls and borders, we could argue that architecture confuses itself with the city. This dual identity of the edifice as city and as an object, from the urban building versus the architectural building in the search to be “within its own boundaries and to have an effect outside”, an urban-architectural fantasy that “implies the reduction of the physical-spatial reality of the city to the status of the architectural building: the city as an object of architectural desire is the city as building” (Gandelsonas, 1998).

If we analyze a building’s façade in this ambiguous role, we note the limits get confused when this imaginary line of separation possesses not only a few inches of material but reaches a spatial order of magnitude. In other words, (Leatherbarrow, 2001, p.57) “by instituting an inhabitable space in the thickness of the window wall, making an experiential threshold between street and room”, this border is not only hermeneutically re-signified as is its political agency – from the “capacity to re-articulate the affinity between the fragments of reality already existing we could detect and mobilize”(Jaque, 2019). By observing contemporary buildings in a critical analysis of thick-envelopes and towards an expansion of the definition, we provide new meaning to the façade and its political role in the contemporary city, with its implications both for the interior space, belonging to the building, and for the public space of the city.