4 minute read

Prohibition & Appropriation Hanzhang Yang

Advertisement

Prohibition & Appropriation

Spatial Activism During the Coranavirus Pandemic

Hanzhang Yang M.S. UP

In fighting this regional, and now global COVID-19 pandemic, governments have deployed both voluntary and involuntary forms of quarantine as an essential measure to contain the spread of the disease. This piece explores how emergent medical restrictions, i.e. quarantine and social distancing, powered over regular social order, restricted daily public spaces, and affected the spread of the disease. Furthermore, this piece discusses how people in quarantine employed different spatial activism strategies to appropriate, create, and reproduce new public spaces.

Pandemic, Quarantine, and the Exercise of Power

The word “quarantine” evolved from the Italian phrase “quaranta giorni,” which means the time of forty days. These forty days of isolation originated from an ancient Venetian policy enacted in 1377 to segregate ships from plagued areas to ensure there were no cases on board (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2011). During the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine means retreating physical movement from public spaces to one’s home or hotel room. Historical lessons from contagious pandemics like the 1910 Manchurian plague and 1918 Influenza pandemic, and current examples of East Asian countries’ response to COVID-19 all proved the effectiveness of quarantine as a public health tool. Research also showed strict transmission control measures, like shutting down public transportation, entertainment venues, and gathering, will effectively mitigate the spread of the virus (Kraemer et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020).

However, exercising power during quarantine can also be discussed through Michel Foucault’s (1977, 1978) medical knowledge arguments. Focault argues the heart of modernity in European discourse relies on the idea that subjects marked as abnormal, diseased, criminal, or illicit should be isolated for their betterment and the collective good. Subjects who resist the logic of these disciplining institutions, who fight their confinement or resist enclosure and separation, simply reinforce the perception that they are dangerous, amoral actors who need and deserve segregation. Foucault (1984) further analyzed the noso-politics[biopolitics] under the topic of medical knowledge as power. He concludes that medical service once exercised surveillance functions identifying “unstable” or “troublesome” elements in the society. Moreover, in the eighteenth century, the exercise of power furthered the disposition of order, enrichment and health, through various regulations and institutions in the name of policing. Giorgio Agamben (2020c) argued the COVID-19 pandemic turns the state of exception into a normal condition of our society, and worried this sacrifice of freedom for security reasons would erode citizens’ social relationships, work, and even affections. Eventually, Agamben argues, this state of exception would turn every one to bare life (la vita nuda). Agamben (2020a)

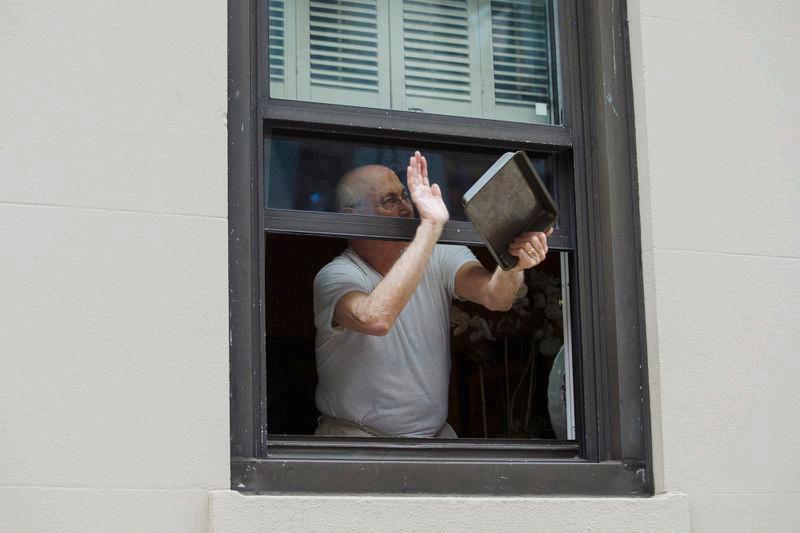

A NYC resident uses a frying pan to make noise from his window at 7 pm. Source: (Mordant, 2020).

notes the state of emergency might pose a threat to society by promoting unnecessary fear between citizens, and turn everyone into a potential source of infection, like the “untore[plague-spreader]” in the 1630s Great Plague of Milan under Manzoni’s pen (Agamben, 2020b). Fan (2003) also mentions the pronounced social impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak could be attributed to “the almost costless and rapid transmission of information due to the development of modern media and communication technologies.”

Example of Space (Re)production - Spatial Activism by Skateboarders

The COVID-19 lockdown kept citizens from their usual public space - sidewalks, streets, and plazas. Where can we find new public space during the state of exception? Maybe we can learn some lessons about spatial activism from skateboarders. Borden (2001) describes the three steps of spatial activism used by skateboarders to create territories in his enlightening book Skateboarding, Space and the City: Architecture and the Body. Skateboarders first find neglected space in the suburbia city; second, skateboarders showcase their die-hard skateboarding tricks to coin the occupation, and; third, spread the idea of skateboarding space to the larger public by documenting the activities with photography and movie clips. Through these three steps, skateboarding transforms the material realm of American suburbia into a romantic sphere of destabilized movements.

The following sections review how citizens around the world protect their public spaces through spatial activism during this state of exception brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Find and Utilize the Balcony as Public Space

Exercising social activities on balconies marks the declaration of visibility and the reclamation of public space by citizens (Caledria, 2012). Facing the street and plaza, the balcony is spatially proximate to former public spaces. Balconies are also regarded as the space between private and public, as activities on the balcony will be judged by others, despite them being performed on a private property. By exercising activities like singing, cheering, and shouting, the balcony serves as a public space in times of quarantine.