9 minute read

The Ladies’ Room Alek Tomich

Architecture as a Tool for Justice

Long-standing societal norms dictate that men are responsible for working, securing their families’ survival, while women are responsible for taking care of children. This idea originated from the division of labor in old times when productivity was significantly low and labor forces generated resources through farming and hunting. Due to the labor-intensive nature of this work, males had more advantages in securing jobs. This logic unfortunately has had a lasting influence on today’s labor mentality. Meanwhile, in modern society, many jobs are carried out in contemporary workplace settings, where women have demonstrated an equal working capacity to their male counterparts. This begs the question: Would gender disparity eventually fade because men no longer have any ‘advantages’ over women? If so, what should be done to accelerate this phase?

Advertisement

Today, regardless of what kind of house a family is living in; the dwelling unit is almost always arranged around the same collection of spaces: a kitchen, dining room, living room, bedrooms, garage, or parking area – whether located in a suburban, exurban, or inner-city neighborhood, whether the dwelling is a split-level house, a contemporary masterpiece of concrete and glass, or an old brick townhouse. These spaces provide an everyday necessity for someone, typically a female, doing unpaid labor by carrying out private cooking, washing, childcare, and usually using personal transportation. A standard dwelling unit is typically physically separated from common community spaces due to residential zoning restrictions. For instance, no industrial, community daycare facilities or laundry facilities are likely to be part of a dwelling’s spatial scope (Hayden, 1980). How can justice for women be implemented economically and environmentally through Architecture in Housing projects? How can a conventional home serve an employed woman and her family? A house provides women the basic set of elements when they are required to carry all the household work with or without participation from their partners. Women work outside the home to be financially secure, achieve their career goals, and contribute to society. Further, progressive nations encourage women to be educated and economically independent. Yet, the patriarchal expectations of what women’s responsibilities should be never changed. Despite this, women continue to prove their ability to balance their work and responsibilities at home. Adding to the struggle of being both a working wife and/or a mother, men still enjoy advantages over women. Employed mothers are usually expected to spend more time in private housework and child care than employed men. Architecture is a major contributing factor to this injustice. Justice for women calls upon architects to be more socially conscious free-independent thinkers (Fitz, Krasny, & Wien, 2019). Dwellings, districts, and towns are constructed to limit women physically, socially, and economically. When women resist these restrictions to spend all or part of their workday in the paid labor force, intense resentment arises. Hayden (1980) argues that creating a new model for the house, the community, and the city is the only solution to this issue. For instance, a good neighborhood is typically identified based on shopping centers, schools, and perhaps public transportation, instead of additional working parent community services, such as

Refan M. Abed M.S. AAD

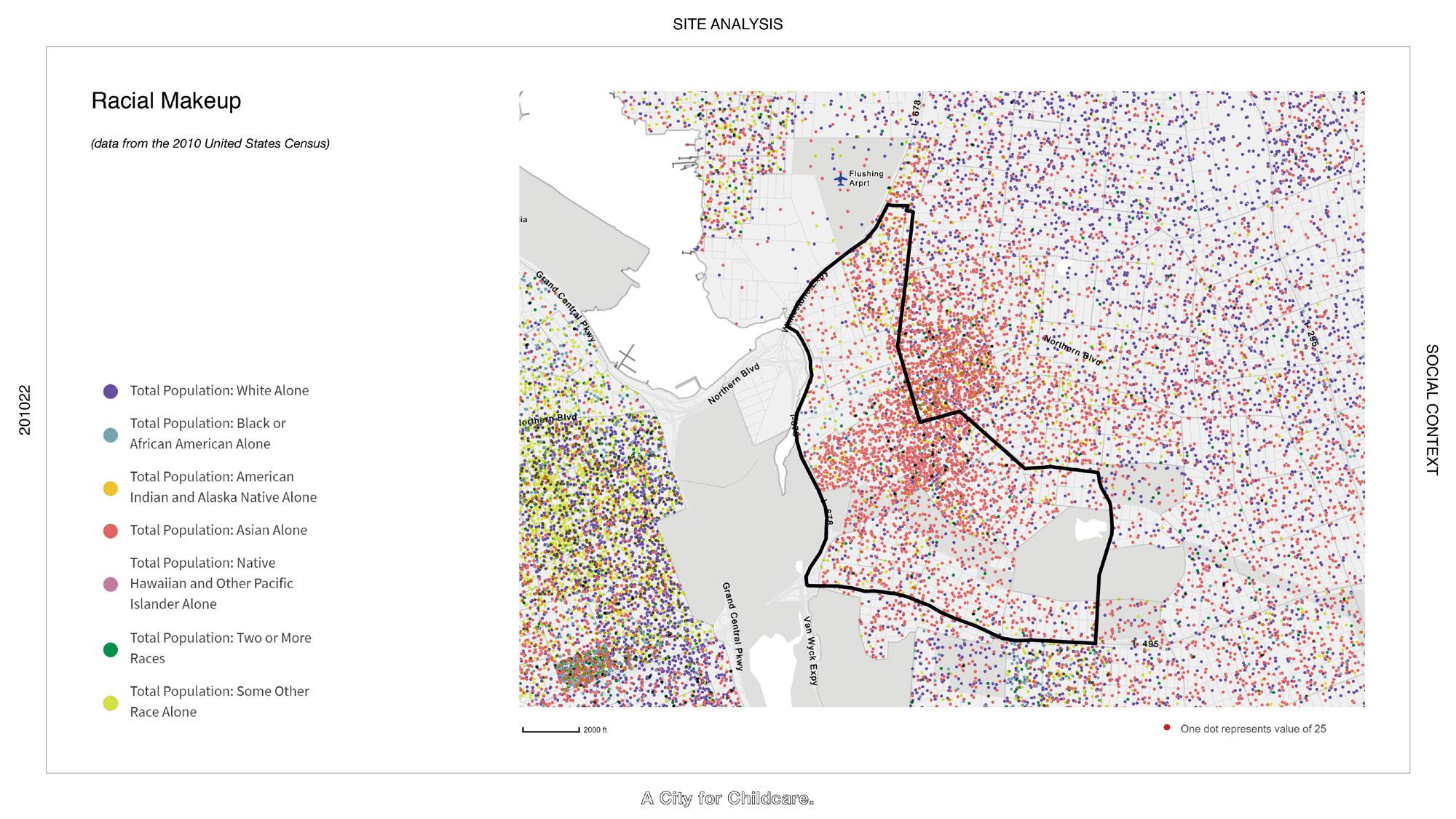

nursery or overnight clinics. This leads to questioning how architects, urban designers, and landscape architects could unite with governmental programs and supportive agencies to bring justice to women in a broader sense and ensure them a better life to achieve the Ideological, inclusive, and gender-free city. During the Advanced V studio on Childcare, I had two questions: “How can architecture offer access for a healthful and equal lifestyle considering children, working parents, and care workers?” and “How can architecture organize different scales of community engagement over different demographics?” These questions served as my starting point for The City for Childcare project proposal located in Flushing, Queens, a neighborhood with significant forms of racial and gender variety. The proposed design merges various prototypes that are seamlessly incorporated into what is called a community unit. The concept seeks multiple design alternatives for daycares that respond to every children’s age group, including home nurseries, a co-working space attached to it, and a co-living area (a more affordable living option). My goal was creating an architecture that gives residents the care they need, embraces their abilities, and acknowledges their differences, by providing job opportunities, affordable housing options, and of course, childcare facilities.

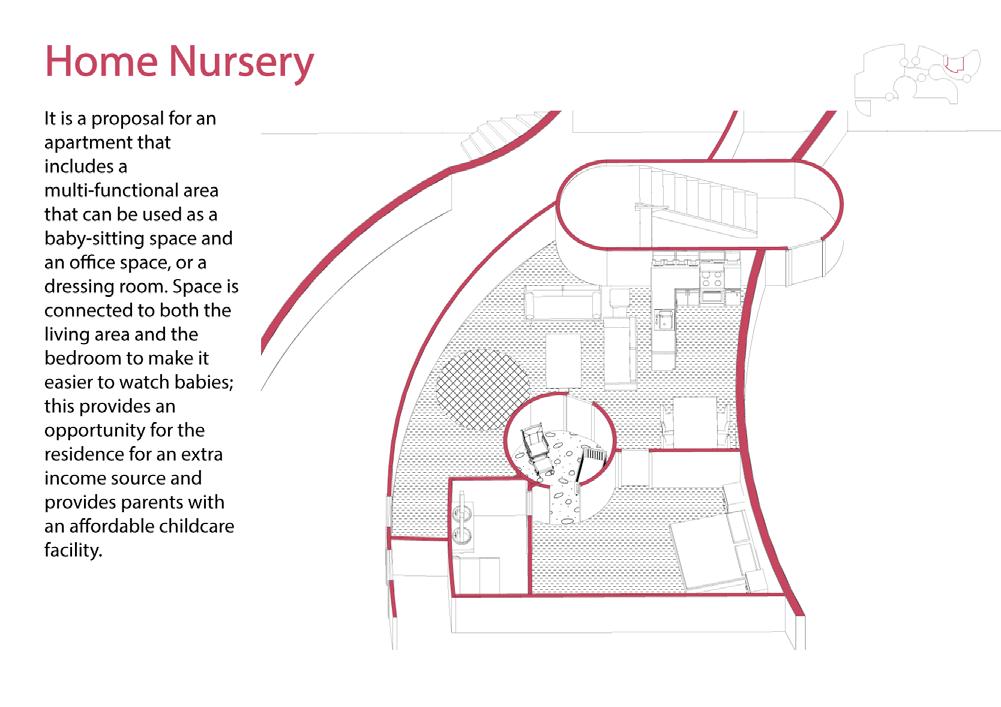

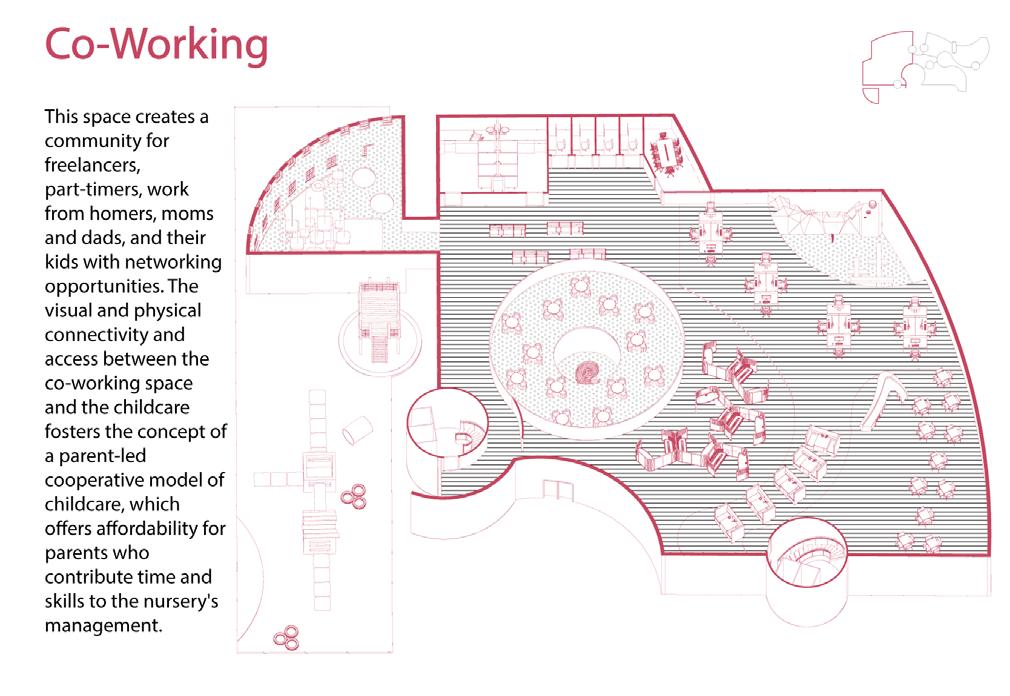

The Home Nursery is for an apartment that includes a multi-functional area that can be used as a babysitting space, office space, or dressing room. The space is connected to both the living area and the bedroom to make it easier to watch babies. This provides an opportunity for residents as a source for extra income, and provides parents with an affordable childcare facility. The Co-Working Space hosts a community of freelancers, part-timers, work from homers, moms and dads, and their kids, providing them with networking opportunities. The visual and physical connectivity and access between the co-working space and the childcare area fosters the concept of a parent-led cooperative model of childcare, which offers affordability for parents who contribute time and skills to the nursery’s management.

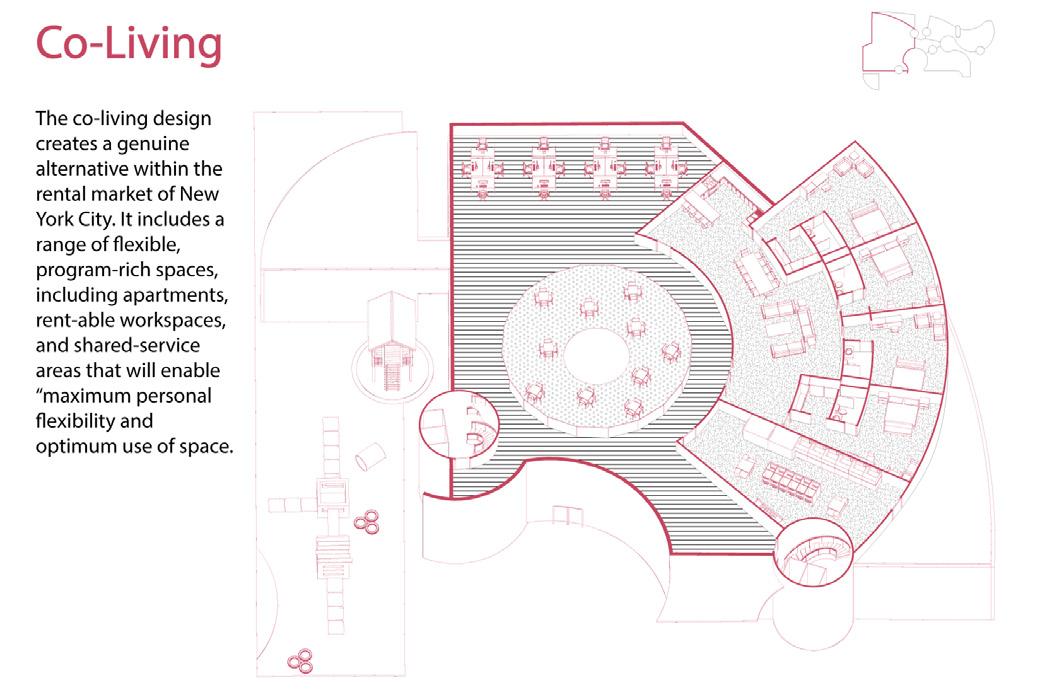

The Childcare area consciously brings in some of nature’s intriguing aspects to design thinking. Nature is by far the best learning ground for children; which encourages children to move in countless ways and helps them fully explore their physical and cognitive abilities. The Co-Living design creates a genuine alternative within the rental market of New York City. It includes a range of flexible, program-rich spaces, including apartments, rentable workspaces, and shared-service areas that will enable maximum personal flexibility and optimum use of space.

Refan is a student in the MSAAD program at GSAPP. She feels that her mission in life is to seek equality and justice. She is a multi-directional person; her passion ranges from design to storytelling.

The Ladies’ Room:

The Role of Public Toilets as a Barrier to Marginalized Groups Entering Mainstream Society

Alek Tomich M. Arch

Throughout American history, there have been many waves of resistance to new groups of people moving into the public sphere and needing accommodation. Beginning with women in the nineteenth century, the focus of this resistance has often manifested itself spatially in the public bathroom (Mars, 2020, 1:00:27). Tacit and formalized building codes enforced sexist ideologies, ultimately leading to the separation of public toilets by sex. This pattern has repeated itself throughout history, with public restrooms becoming the epicenter of marginalized communities, most recently trans individuals, prevented from entering the public sphere freely. However, with upcoming provisions to the building code, therein arrives an opportunity to break the chain. By reframing the argument surrounding trans individuals accessing public restrooms to reject the binary definition of space as for men or for women, architects, in accordance with the new building code, have the opportunity to create shared public bathroom spaces that incorporate the needs of historically overlooked populations, while simultaneously safeguarding other marginalized groups from facing future discrimination in the public sphere. There is no evidence that indicates early American privies were sex-separated. Up until the middle of the nineteenth century, most people in the urban context, with the exception of the extremely wealthy, used outdoor singleuser toilets collectively among their neighbors (Kogan, 2007, p. 35).

Shared Single-User Toilets outside of a tenement building in New York City, 1902. Source: Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library In response to the nineteenth century “Separate Spheres” ideology that separated the social roles and spatial domains on the basis of sex and the growing role of autonomous women in society, architects began to introduce sexsegregated spaces into the public realm to protect women from the stresses and dangers of the male public sphere (Kogan, 2018). The Tremont House, designed in 1829 by Isaiah Rogers in Boston, was one of the first urban establishments to be designed to open up its public space to women. By explicitly defining programs and spaces by gender, Rogers transformed the tacit architectural code that separated the private sphere from the public sphere into one where both men and women could exist, albeit separately, in the public (Kogan, 2018). Notably, the Tremont House was the first major public building in America to incorporate indoor plumbing. However, unlike the other rooms, the eight single-user “privies” were not separated by sex, suggesting that in the first building to transcribe the “Separate Spheres” ideology into an

Shared single-user toilet stalls among sex-separated social spaces in the Tremont House Hotel, 1830. Source: Stalled!

architectural plan, there was no association between the perceived need to designate separate women’s spaces and the need to separate the toilets by gender. As the construction of luxury hotels proliferated over the middle of the nineteenth century, advances in technology increased the amount of indoor toilets allocated per building, ultimately leading to the separation of these spaces by sex, as they were attached to already gendered spaces (Kogan, 2018). There was no formal code dictating the practice until the end of the nineteenth century, when sanitarians turned to factories to regulate workplace conditions. Massachusetts adopted the first law mandating that “water closets” in factories and other workplaces be separated by sex. New York enacted a similar law two months later, and by 1920, 43 states had adopted similar legislation that limited the hours that women were allowed to work among other labor restrictions (Kogan, 2007, p. 39). These laws were symbols of a broader anxiety over women competing for jobs traditionally held by men within the public realm, discriminatory measures disguised as protection. As women entered the workforce and further into the public domain, the perceived necessity to protect them through a designated bathroom served as an obstruction to free navigation. Yet, the public restroom and its associated building codes have proved to serve as a barrier to still other marginalized groups entering mainstream American society. Jim Crow laws enacted in the South explicitly restricted Black Americans to separate restrooms among other places, while the panic associated with the emergence of openly homosexual individuals and HIV in the latter half of the twentieth century served as an implicit barrier for queer people in public toilets. The lack of comprehensive building codes created a physical barrier for the disability community up until the 1990 signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which has only scratched the surface of mandating provisions to accommodate bodies of all types safely in the public realm. While these groups have been formally accepted into public space and public restrooms through legislation or social acceptance, questions remain on the efficacy and longevity of the damage, as social stigmas and implicit segregation still endure throughout the American social context to this day. Over the last decade, the debate around public toilets has reignited around the inclusion or exclusion of trans individuals. To comprehend the issue, one must first understand the distinction, and the origins of said distinction, between sex and gender. Historically, the academic use of the word 65