8 minute read

The Gig Economy & Architecture Mariana Riobom

‘gender’ was mostly confined to grammatical categories. However, the term was co-opted in the 1950s by psychologist and sexologist John Money as a tool to reconstruct the sex binary and avoid the outright acceptance of the existence of intersexual babies, or babies of sexual organs that could not be immediately identified as male or female (Preciado, 2017). This definition took on a more modern form in 1968, when psychologist and author of “Sex and Gender” Robert Stoller used the term ‘sex’ to pick out biological traits and ‘gender’ to define the amount of femininity and masculinity a person exhibited, beginning to explain the identity of trans individuals, in which the sexual and gender identities of an individual do not align (Mikkola, 2019). This distinction between sex and gender and trans identity has emerged as the basis of the latest debate over the separation of public restrooms. In March 2016, as a response to a non-discrimination city ordinance passed in Charlotte, North Carolina that allowed the right to access the bathroom best matching ones gender identity, North Carolina drafted House Bill 2 requiring, among other provisions, people to use public toilets that correspond with the sex stated on their birth certificate (H.B.2, p. 2). By restricting trans individuals from using the bathroom that matched their gender identity, House Bill 2 alienated their rights and threw them into the center of a national culture war. While a compromise was eventually reached in North Carolina, the mark of House Bill 2 remains as the repeal did nothing to advance the rights of LGBTQ individuals within public space. The outstanding conflict between the opposing sides of this litigation, and the national discussion that continues today, is a direct consequence of the sex-separation of public restrooms dating back to the discriminatory “Separate Spheres” ideology of the nineteenth century. Still, in crafting their opposing litigation strategies, all parties accepted the existing model architectural configuration of the sex-separated public restroom as a given, unaware or unwilling to reckon with the role of architecture in the organization of bodies, and therefore sexuality and gender, within space. By advocating for individuals to use one of the two options of public restrooms that most closely align with ones gender identity, adhering to the longstanding codified division of public restrooms into two, normative sex-separated spaces, the sexgender binaries are reaffirmed, leaving large groups of non-conforming trans individuals unprotected (Kogan, 2017, pp. 1222-27). As such, the key to this debate returns to the code. If multi-user public restrooms in the future become all-gender, the central debate raised over the criterion for restroom usage in the North Carolina House Bill 2 would dissolve. Intersectional bathroom equity groups such as “Stalled!” have worked to reimagine the public bathroom as a space not only to liberate trans individuals, but everyone — from those with medical issues, to parents with young children of a different gender identity, to people needing a space to practice religious rites, or people with a physical disability not accounted for in the American Disabilities Act. In 2018, thanks to the work of “Stalled!” among

other advocates, the International Plumbing Code was amended to not only require that single-user toilet facilities no longer be designated by gender markers, but to also allow for the adoption of all-gender multiuser restrooms in public buildings (Luckel, 2019). While the changes will officially take effect in 2021, state jurisdictions are typically slow to adopt new releases until they add their own provisions, so widespread implementation may not be seen for years. Further, governing bodies at the city and state level could purposefully choose to ignore the particular update and continue to design public restrooms based on their nineteenth century precedents and current implementation of the code (Mars, 2020,

Advertisement

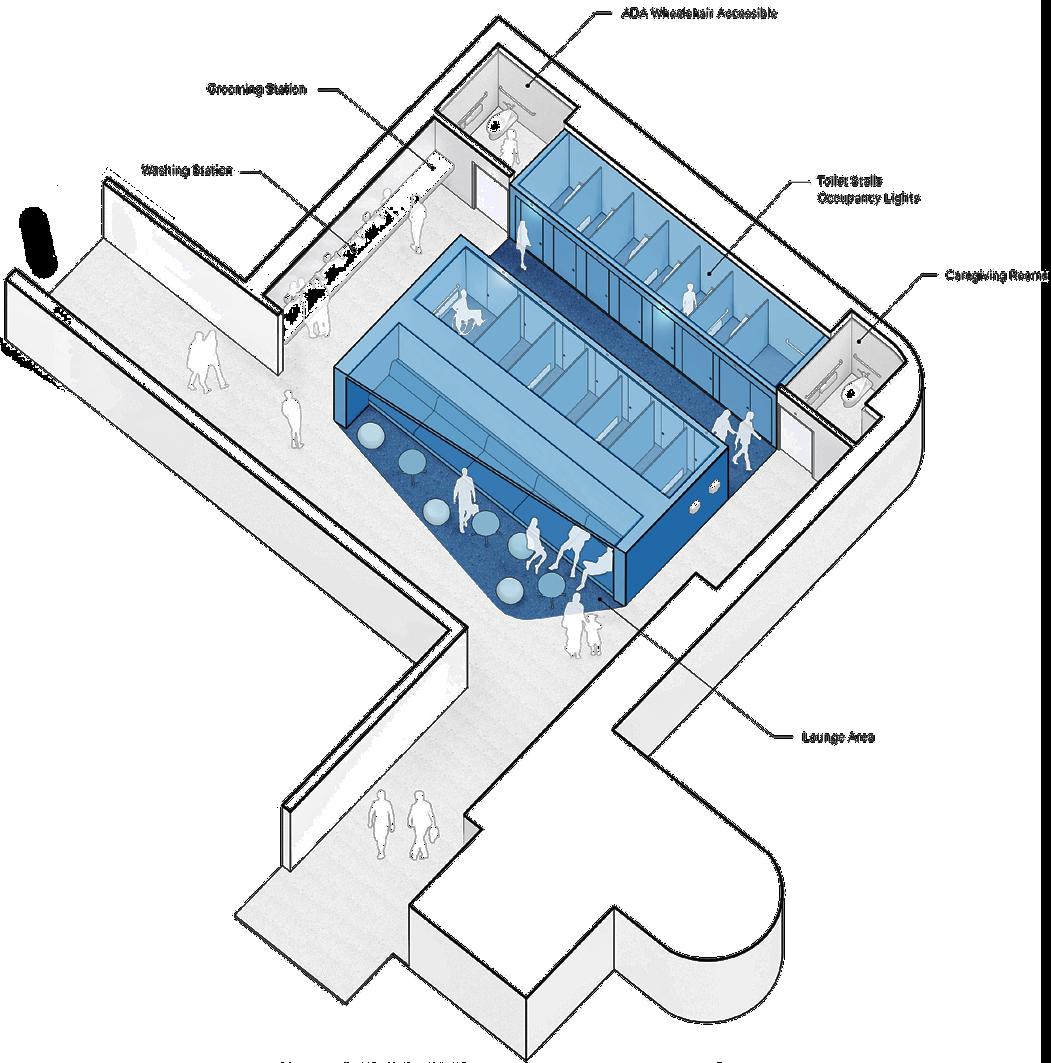

An inclusive multi-user restroom prototype design for Gallaudet University Source: Stalled! 1:00:27). Thus, it is left to the architects to advocate for the social, and potentially economic, benefits of the combination and designation of all-gender multi-user restrooms in the public buildings of the future. By rejecting the binary definition of spaces, the argument surrounding trans individuals accessing public restrooms can be reframed. In accordance with the new building code, architects have the opportunity to create shared public bathroom spaces that incorporate the needs of historically overlooked populations, while simultaneously safeguarding other marginalized groups from facing future discrimination in the public sphere. In doing so, rather than creating overly specific spaces that segregate and isolate bodies according to their differences, the public restroom could be a shared space that accommodates, welcomes, and refuses to frame the occupant as they interact within public space.

Alek Tomich is an architecture student in his final year with the M.Arch program at Columbia University GSAPP. He is a designer and maker interested in materials, visualization, perspective, equity, and the environment.

The Gig Economy & Architecture:

an Interview with Peggy Deamer

Mariana Riobom YSOA, M.Arch

Peggy Deamer is professor emeritus of architecture at Yale University and has spent years researching and writing about the relationship between subjectivity, design and labor. She is the founding member of The Architecture Lobby, a group that advocates for the value of architectural design and work. I recently asked her to speak with me about how gig work—a genre of labor organization typically characterized by short-term recruitment of workers through digital platforms—could map on to architecture. The speed, scope and pervasiveness of computation and digital media is remaking the organization of labor for designers across the globe. Architects are now also programmers, digital engineers, robotic-manufacturing experts and, in some cases, managers of outsourced workers, all of which blurs the distinctions around authorship and architectural creativity. Professor Deamer and I spoke in February about these issues, including the current state of labor discourse in architecture. Here is our interview, slightly edited and condensed for clarity. Mariana Riobom: I wanted to start with your activism and work with The Architecture Lobby. You often have described architects as precarious workers. How do you think gig work fits into your thesis? Peggy Deamer: Small architectural offices – which are the majority of architectural offices – have always been part of the gig economy, as in, be your own entrepreneur. Make it on your own. Compete against other people. Self-employment is in some way what the gig economy is, so we’ve suffered under that rubric for a long time. So, it’s interesting and good that gig work and the criticisms that come with it are coming to the fore; it brings a certain selfconsciousness that we’ve lacked. And, obviously, I think we’re all precarious workers in that larger tradition of gig work. Your overarching thoughts on outsourcing architectural work enters into the conditions surrounding large firms and the rubric of rote work people in large offices often do versus creative work they aspire to. Or, at a more general scale, the type of work many firms in the US feels is properly their domain – being problem solvers, being talented designers, being form givers, being creative – versus those that don’t necessarily have those skills, just merely expected to follow instructions, implement working drawings, or do renderings. That general division – being creative vs. being merely technical or rote – is problematic. I think eradicating that mental division would be helpful in not encouraging the farming out of responsibility.

MR: Some of the models you’ve written about— workers cooperatives, and even national professional architectural associations—are quite local and limited to particular geographic or national areas. As digital technology allows for outsourcing and these shortterm labor interactions that can be fulfilled by anyone anywhere on the globe, is there a need to rethink organizing strategies? PD: I don’t think it is the case that cooperatives work only at the local level. There are many examples outside of architecture of cooperatives that work across state lines, and work internationally. And certainly, digital technologies allow those forms of communications at the non-physical, or non-institute level. The same overall technology that allows for people in different locations to organize their documents, to organize their finances together, work as well for cooperatives as they do for farming out of labor. MR: As work gets optimized and removed from central workplaces and people work short term on contracts, do you think that architects should stop placing our work in rarified air but instead seek solidarity with all workers, gig and otherwise? PD: Your original question about the platforms that allow the division of labor and outsourcing to cheap labor, is very much related to this question. I think part of what I was trying to suggest in that problematic mental division between the techies and the real designers can be alleviated if we deprofessionalize. I think the need to describe what you do if you’re not put into that label of “architect,” if you’re not held within a system of licensure that dictates doing certain things and not others or associating with certain people and not others, clients will begin to ask the serious questions” What expertise do you bring to the table? Who do you have in your firm? Who might you associate with? MR: Due to the pandemic, many architects have been able to work from anywhere. What do you think will be the consequences for office organization? And do you think that this scenario will lead architecture employees being increasingly gig and freelance workers? PD: I’m optimistic about what distance work does, and what we’re discovering about how well it works. I tend to think that distance work is equalizing the labor force. Firm owners have to give workers a certain amount of trust and tasks that really carry responsibility; I’ve seen it as working against the traditional division of labor. It’s offered workers the opportunity to be more in control of their schedule more which comes with labor, leisure, and family time awareness. And then I think that a lot of workers in firms where they feel that they’ve been forced to go back to work too earlier and in unsafe conditions, have developed a labor consciousness that wouldn’t have been there if they hadn’t had this opportunity to get out of the 9 to 5 norm that works for the boss but doesn’t work for the laborer.