24 minute read

Collective Learning Hasbrouck Miller, Stella Ioannidou, & Ryan Leifield

MR: I wonder, however, what is the incentive to employ someone when one could be using gig platforms and outsourcing labor to other countries.

PD: I think it’s a smart observation. The firm owner’s choice becomes, why should I pay for health benefits when I can make everybody a contract worker? But my feeling is that those displaced workers, who used to have a salary and now forced to be contract workers, will themselves organize. I’m optimistic that they’ll recognize the injustice of this and I think we have greater awareness of how to organize against these unjust, unsustainable, and anti-worker neo-liberal practices. It might be how deprofessionalization happens. First the thesis: salary work in a supposedly prestigious profession; then antithesis: independent contractor just like other less prestigious workers; synthesis: a workerforward discipline that understands its worth. The profession’s gone, but being organized, we are economically astute and socially relevant. MR: What could be the mechanisms that we could use to organize across borders while our realities are so different?

Advertisement

PD: It’s such a good question. That is one that I do wonder about. In my work on different countries’ architectural professional organizations, and recognizing how nationally bound they are, how radically different they are, and how difficult it is to import positive workerforward initiatives from one country to another - it just makes me wonder why there’s not an organization that organizes internationally. There is the Union of International Architects, but its main concern is the portability of licensure from one country to the next. If you have a license in Portugal, does it equal a license in France? The organization’s purpose is totally for firm owners and how they can get as much work as possible without evaluating the conditions or relevance of that work.

MR: I wanted to talk more about authorship and creativity and the terms that architects use to describe themselves in the context of labor, as many are fascinated with the idea of immaterial labor and how it has shifted over the years.

PD: I think the concept of immaterial labor is very productive. It’s helpful to get architects to think that they’re working within the economy, that their immaterial labor is part of capitalism, and has come through economic paradigms of manufacturing, then service, and now knowledge work; it’s helpful in that historical context. There’s a lot of controversy around the idea of immaterial labor: immaterial labor is still material - some insist; or what we call ‘knowledge’, more broadly, isn’t actually new. My feeling is that it is good to keep alive the particularity of immaterial labor in terms of its workerist, autonomous origin which embraces a huge spectrum of workers - domestic, technical, managerial, etc – that in its radical rhizomatic nature makes it so powerful. It resists the division of labor, resists the division of status, makes one conscious of our sisterhood with caregivers, to doctors, and engineers. While I recognize that the term is controversial, I think it is very useful. MR: How can university, as a place, and as an entity can help us understand changes in the economy and organization of labor? PD: The Architecture Lobby is offering a summer school that is trying to address the question. It’s supposed to be a beta test of what the model of an ideal education is. And part of that is putting the role of the economy and understanding architecture as a profession on the table; we would be unlearning capitalism, rethinking what design is, and relocating architecture in that unlearning.

Mariana Riobom is an architect originally from Portugal and a graduate of the Yale School of Architecture. She is based in New York and is involved in teaching, writing and research projects. She has also practiced architecture in France, Italy and Japan.

Collective Learning

Networks of Labor and Care in Architecture

What does an architecture centered around a theory and an ethics of care look like? Is it possible for architecture as a professional discipline—born of a market-oriented, colonial logic—to restructure itself according to the values of repair, maintenance, and other forms of reproductive labor? Can the architect serve as caregiver?

In the first weeks of 2020, the three of us were invited to participate in the 2020 Venice Biennale under the theme of “Talking Trees”. The beginning of the endeavor found all of us employed in full time jobs in architecture, urban design, and museum work, embedded in the existing, rigid system of production and trying to survive within the softer enclosures of the socio-economic neoliberal apparatus. Our conversations were shaped by the disappointment and dissent we felt toward the exploitative models of work we chafed against in our professional lives. Our research was driven by our need to engage with alternative modes of working, knowing, and existing. We began by reading widely.

“Until quite recently no one seriously explored the possibility that plants might ‘speak’ to one another…. There is now compelling evidence that our elders were right—the trees are talking to one another…. There is something like a mycorrhizal network that unites us, an unseen connection of history and family and responsibility to both our ancestors and our children.” (Kimmerer, 2013)

There were innumerable, branching possibilities that the theme “talking trees” offered, but one direction resonated with us most: considering the tree as a member of an interconnected and interrelated network. We found that over the past few decades in the West, ecologists demonstrated that older trees within a forest will often transfer water and nutrients through root systems to neighboring younger trees, even to those of different species; that leaf canopies sometimes form microclimates to protect saplings; or that chemical secretions from one tree warding off disease or predators can warn other trees to defend themselves (Simard, et. al., 2012; Wohlleben, 2016). More resilient, healthier forests tend to be those that encourage communication and cooperation. Pushback to these findings, which has been considerable in certain academic fields, seems to be rooted in a worldview that demands that organisms be considered discrete and self-interested actors within an unforgivingly competitive universe.

Hasbrouck Miller (M.Phil), Stella Ioannidou (M.Arch), & Ryan Leifield (M.Arch)

We are not forestry experts, yet we choose to believe that trees, like humans, do not stand alone. Unsurprisingly, strands of this basic idea have existed within the collective knowledge of various Indigenous American cultures for generations, where they serve as an explanation or observation of how the natural world works and, therefore, as a normative proposition for how humans ought to act within the world. Extrapolating from the behavior of arboreal networks might then provide a model protocol for the exchange of information and resources among humans — one that is predicated on the embrace of gift economies, communalism, and social responsibility.

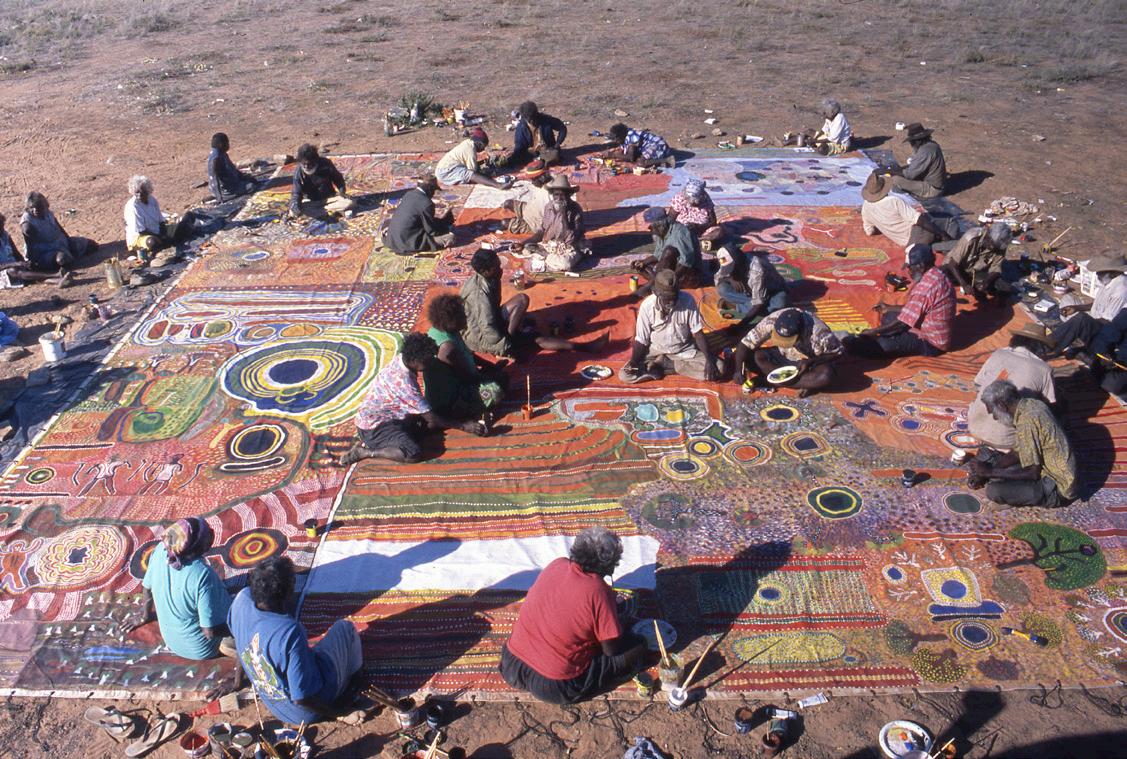

The Ngurrara Canvas II, painted by Ngurrara artists of Australia, was created to serve as evidence of historical land tenure in Australian court. The painting depicts communal water holes across the landscape. K. Dayman (Ngurrara Artists and Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency), Adrian Lahoud, 1997.

“The currency of a gift economy is, at its root, reciprocity. In Western thinking, private land is understood to be a “bundle of rights,” whereas in a gift economy property has a “bundle of responsibilities” attached.” (Kimmerer, 2013)

The pandemic arrived and our working method remained the same: individualized research with periodic video check-ins. Yet as the pandemic unceasingly unfolded and the fabric of our daily lives stretched and frayed, we began to rely on these virtual meetings for comfort, airing anxieties, and making observations on the inadequate support structures in our social and professional lives. The calls evolved into episodes of collective learning, inextricable from the personal support they provided, and in searching for the form this protocol could take within an architectural space, we saw that it existed already among young architects and students. In order The pandemic arrived and our working method remained the same: individualized research with periodic video check-ins. Yet as the pandemic unceasingly unfolded and the fabric of our daily lives stretched and frayed, we began to rely on these virtual meetings for comfort, airing anxieties, and making observations on the inadequate support structures in our social and professional lives.

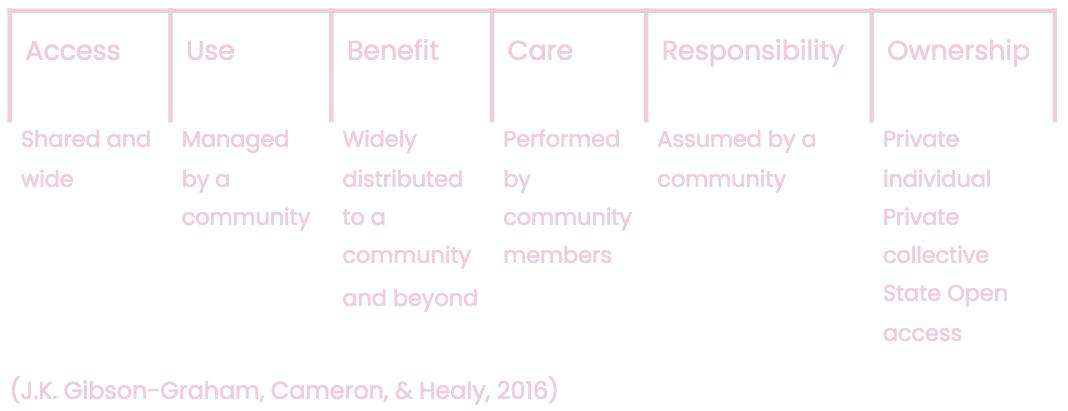

We characterise commoning as a relational process— or more often a struggle—of negotiating access, use, benefit, care and responsibility (see Figure 12.1). Commoning thus involves establishing rules or protocols for access and use, taking care of and accepting responsibility for a resource, and distributing the benefits in ways that take into account the wellbeing

Commoning enclosed resources

A model for collective learning began to emerge:

Collective learning is commoning. We create a community that builds knowledge by interrogating the manifold limitations imposed by existing systems of oppression and inequality. Learning becomes an inextricable part of the practice of commoning and a form of sustenance that bonds us together.

As our weekly video calls became open forums for discussions of equitable work practices, we inevitably interwove comparisons of our own experiences with speculative ideals. We acknowledged the ways in which academic programs glorify a “no breaks’’ lifestyle and condition students to accept overexertion and exploitation for the sake of pursuing their creative passion, while marginalizing and undervaluing the structures of care required to sustain this ethic. We recognized an ethos of terminal individualism that pervades our discipline--the unrestrained genius, siloed in their obsession with realizing a singular, uncompromising vision.

“Historically, architecture, as we have seen, was at the very center of forming the independent genius-subject. This clearly posited the architect and his work outside of care. Care thinks of subjects “through connectedness with others,” on the ontological level as much as on the political one. [...] While independence, both as a philosophico-political concept and an economicmaterial reality, has defined the subject position of the architect, the philosophico-political idea of interdependence and the economic-material reality of dependence have shaped the subject positions of care workers.” (Krasny, 2019)

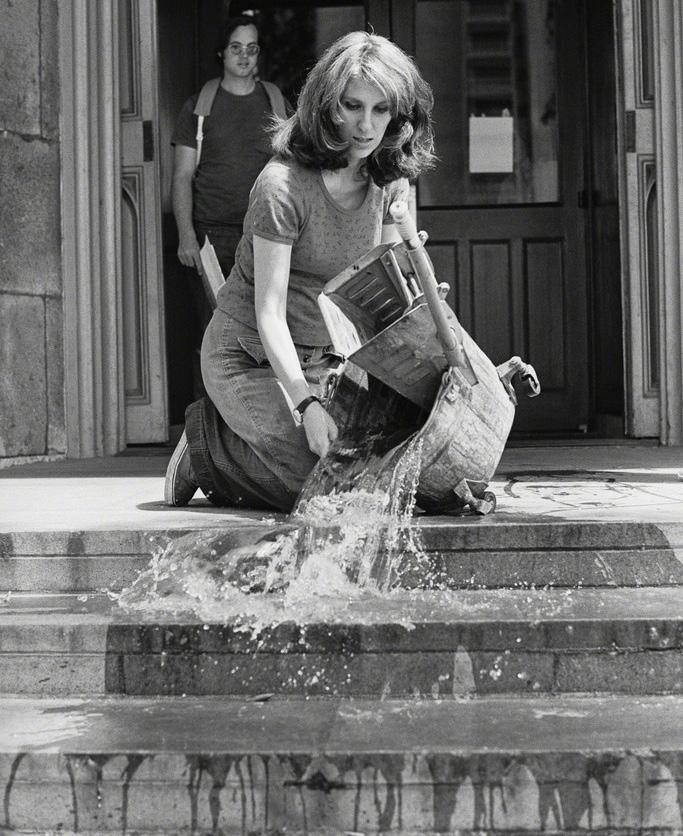

On the left: Still from Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, in which the artist methodically cleans the Wadsworth Atheneum as a performance. Ukeles’ work draws attention to the feminized maintenance infrastructure invisibly supporting the contemporary art industry. Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, 1973.

“The Death Instinct (“separation, individuality, Avantegarde par excellence, to follow one’s own path to death, do your own thing, dynamic change”) and the Life Instinct (unification, the eternal return, the perpetuation and MAINTENANCE of the species, survival systems and operations, equilibrium”).” (Ukeles, 1969)

Our work is grounded in care and imagination. We acknowledge the systems of support and care that — despite being rendered invisible under a capitalism-promoted ideology of independence — are necessary both for the production of life and the production of knowledge. We allow these systems to surface; we strategize with care and mobilize with imagination, working toward a practice that envisions radical and sustainable alternate futures.

It is unsurprising that this mentality is perpetuated in the professional world, both in the labor practices and in the wages paid. Young employees, who often graduate with exorbitant amounts of debt, expect to be overworked and underpaid and they begrudgingly or proudly accept their precarious work conditions. Advocating for higher pay and a 40 hour work week is antithetical to the ethos of practicing architecture, where the balance of adequate remuneration and the societal benefit of the work is often posited as a zero-sum proposition.

“Architecture isn’t a career, it is a calling!’ What? How had we fallen into the same ideology that Christianity used to make the poor feel blessed for their poverty? How could architecture have become so completely deaf to the labor discourse that it could so unselfconsciously subscribe to the honor of labor exploitation?” (Deamer, 2015)

A practice that is equitable and horizontal. Rather than reproducing structural inequalities and hierarchies that pervade our current socio-economic and academic system, we seek to distribute power horizontally, share knowledge and perform in collectivity, by forming reciprocal relations of rights and responsibilities. The horizontal distribution of power allows for equal access to participation and decision-making, but it extends beyond the limits of the group, to the humans and other-than-humans to whom we are bound and connected.

Architectural work outside of professional firms operates within this logic as well. The international biennale circuit is an extension of the dominant pedagogical and professional system undergirded by free labor, which values result over process and innovation over wellbeing. Maintaining the invisibility of labor permits the continued fetishization of the architectural object whose meaning and agency is fixed upon an arbitrary market value. An architecture that is predicated on subjugation and exploitation will only perpetuate those values in its output. Instead, reproductive labor (from housework and childcare to infrastructure maintenance and repair) needs to be recognized as central to the production and reproduction of the commons.

Members of The Architecture Lobby read the organization’s manifesto advocating for equitable labor practices in architecture and a reconsideration of the value system underpinning the discipline. (www. architecture-lobby.org)

“All activities, including those that we think of as political, involve a caring dimension because in addition to acting we need to sustain ourselves as actors.’’ (Tronto & Fisher, 1990)

“No common is possible unless we refuse to base our life and our reproduction on the suffering of others, unless we refuse to see ourselves as separate from them.” (Federici, 2019)

As we reflect on our role within the structures of professionalized architecture, we inevitably also question the ramifications of our work within the biennale economy. Does sustaining a system that depends on our free labor further undermine its value and the possibility of building equitable work structures in the future?

It is because of questions like these that we have described the contours and direction of our collaboration over the past year. In doing so we attempt to claim our own framework and agency by exposing the process of mutual care and collective learning that took place between us. The collaborative educational process that we have inhabited over the past year is a distillation of the ways in which all learning takes place, in which objectives and priorities are constantly shifting, in which the idea of “completion” is rarely sought or achieved, and in which moments of levity, anxiety, and insight arrive unexpectedly, occasionally in sudden flashes and, at other times, slowly and furtively.

We work to do away with the current structuring of practice and learning around the manufactured scarcity of material wealth and we re-imagine an architectural environment centered on an ethics of care, where collaboration becomes a form of meaningful sustenance, of bonding and connecting to others. We work to sustain a space for recognizing each other, becoming recognizable and, through acts of experimentation, arriving at a common vernacular. We iterate on this vernacular by gathering, reading, making connections, arranging and rearranging, on our pathway to find a collective voice and to construct meaning together.

Stella Ioannidou, Ryan Leifield, and Hasbrouck Miller are recent graduates of Columbia University working in the fields of architecture, urban design, and museum work. They were recently invited to participate in a methodological experiment as part of the Korean Pavilion’s Future School program for the upcoming Venice Biennale centered around the theme of “Trees”. They are currently based in Athens, Los Angeles, and New York.

CITATIONS

& notes

A Glimpse Into the Year Written by Elaine Hsieh Edited by Zeineb Sellami

Civic Engagement in Physical and Digital Public Space Written by Sarah Mawdsley Edited by Geon Woo Lee

Carmona, M., de Magalhães, C., & Hammond, L. (Eds.). (2008). Public space through history. In Public Space: The Management Dimension (pp. 23-42). Routledge. Chakrabarti, V., & Gladstone, B. (2017). Reimagining protest in New York City (and every city). Log, (39), 106-109. Monckton, Paul. (2020, June 2). This is why millions of people are posting black squares on Instagram. Forbes. Schwartzstein, P. (2020, June 29). How urban design can make or break a protest. The Smithsonian. Tremayne, M. (2014). Anatomy of protest in the digital era: A network analysis of Twitter and Occupy Wall Street. Social Movement Studies, 13(1), 110-126.

Solidarity can make a new world possible Written by Al Tariq Shabazz Edited by Shreya Arora

Concerning the events of June 2, 2020 Written by Hayes Buchanan Edited by Tihana Bulut

Evolution of city-organism: Fight or Flight? Written by Sneha Aiyer Edited by Shreya Arora

Bushey, Ryan, (Jan 12, 2014) How Japan’s Most Popular Messaging App Emerged From The 2011 Earthquake, Business Insider Cannon, Walter Bradford(1915). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear, and rage. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 211. Colomina, Beatriz, Wigley, Mark, (2016) Are We Human?, Lars Muller Publishers, Zurich Federici, Silvia, (2012) Revolution at point zero: housework, reproduction, and feminist struggle, Oakland, CA: PM Press; Brooklyn, NY: Common Notions: Autonomedia Federici uses this term not simply to refer to having children and raising them; it indicates all the work performed to sustain ourselves and others around us. Kisner, Jordan (2021, February 17). The Future of Work, The Lockdown Showed How the Economy Exploits Women. She Already Knew. New York Times. Retrieved on February 22, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/17/magazine/ waged-housework.html?action=click&block=more_in_recirc&impression_id=eaeec7567551-11eb-9838-37ecdfcbe4da&index=4&pgtype=Article®ion=footer Powell, Catherine, (June 4, 2020). The Color and Gender of COVID: Essential Workers, Not Disposable People, Think Global Health Retrieved on February 22, 2021, from https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/color-and-gender-covid-essential-workers-notdisposable-people

Prohibition and Appropriation: Spatial Activism During the Coronavirus Pandemic Written by Hanzhang Yang Edited by Eve Passman

Agamben, G. (2020). The state of exception provoked by an unmotivated emergency (Trans.). PositionsPolitics: Praxis. http://positionswebsite.org/giorgio-agamben-the-state-of-exceptionprovoked-by-an-unmotivated-emergency/ Agamben, G. (2020). Contagio. https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-contagio Agamben, G. (2020). Chiarimenti. https://www.quodlibet.it/giorgio-agamben-chiarimenti Baltimore, D. (2003). SAMS – Severe Acute Media Syndrome? Wall Street Journal, 2003, April 28. Borden, I. (2001). Skateboarding, space and the city: Architecture and body. Oxford: Berg. Caldeira, T. P. (2012). Imprinting and moving around: New visibilities and configurations of public space in São Paulo. Public Culture, 24(2 (67)), 385-419. Campbell, M. (2005). What tuberculosis did for modernism: the influence of a curative environment on modernist design and architecture. Medical history, 49(4), 463-488. Fan, E., X. (2003). SARS: Economic Impacts and Implications. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb. org/publications/sars-economic-impacts-and-implications Foucault, M. (1984). The Foucault reader (P. Rabinow, Ed.). New York: Pantheon Books: 276-277 Foucault, M. (1978). About the concept of the “dangerous individual” in 19th-century legal psychiatry (A. Baudot & J. Couchman, Trans.). International journal of law and psychiatry, 1(1), 1-18. Foucault, M. (1995 [1977]). Panopticism. In Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison (A. Sheridan, Trans). New York: Vintage. Kraemer, M. U., Yang, C. H., Gutierrez, B., Wu, C. H., Klein, B., Pigott, D. M., ... & Scarpino, S. V. (2020). The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science, 368(6490), 493497. Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell. Liu, Y. (2020, April 24). [During the epidemic, Internet traffic increased by 50% from the end of last year].

Science and Technology Daily, 4. (in Chinese) Mordant, A. (2020). Tony Manning uses a frying pan to make noise from his window Tuesday night [Online image]. New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirusapartment-applause-20200401-krgylnadfferrgqqp5tlm6vnay-story.html Poggioli, S. (2020). In Naples, Pandemic ‘Solidarity Baskets’ Help Feed The Homeless. NPR. https://www. npr.org/2020/04/07/828021259/in-naples-pandemic-solidarity-baskets-help-feed-the-homeless quarantine (n.). (2011). In Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 30, 2020, from https://www. etymonline.com/word/quarantine Rancière, J. (2020). [Viralità / Immunità. due domande per interrogare la crisi: #2 | JACQUES RANCIÈRE / ANDREA INZERILLO]. Institut français Italia. https://www.institutfrancais.it/italia/viralita-immunita (in Italian) Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: Reframing political thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Run Runner. (2020). Coronavirus - People singing the Chinese national anthem. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=cdvBkyNbhfs Tian, H., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, C. H., Chen, B., Kraemer, M. U., ... & Dye, C. (2020). An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science, 368(6491), 638642. Webster, J. G. (2011). The duality of media: A structurational theory of public attention. Communication Theory, 21(1), 43-66.

Casa de Todos (Home for all): The day when the arrival of COVID-19 in Perú brought along a new chapter of hope Written by Alex Hudtwalcker Rey Edited by Sherry Aine Te

Baez Gonzalez, J. (2021, February 05). Casa de todos, el proyecto en Perú que transformó una Plaza de toros en albergue durante la pandemia. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.aa.com.tr/es/ mundo/casa-de-todos-el-proyecto-en-per%C3%BA-que-transform%C3%B3-una-plaza-de-torosen-albergue-durante-la-pandemia-/2134520 Beneficencia de Lima. (2020). Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://beneficenciadelima.org/public/ casadetodos/

Cáceres Alvarez, L., Fuller, C., Krajnik, F., & Vidal, J. (2020). Casa de Todos. Rostros de la calle en Plaza de Acho. Lima: Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC). Available at https:// repositorioacademico.upc.edu.pe/handle/10757/653738

Advocating for Public Space in a Pandemic Written by Sharvari Raje, Tal Fuerst, Einat Lubliner, and Kunal Mokasdar Edited by Geon Woo Lee

International Traveling in Times of the Pandemic Written by Shen Xin Edited by Eve Passmani

Ajilore, O. (2020, October 8). Rural America Has Been Forgotten During the Coronavirus Crisis. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/ reports/2020/10/28/492376/rural-america-forgotten-coronavirus-crisis/ Channel News Asia. (2020, October 30). COVID-19: Singapore to lift border restrictions for visitors from mainland China and Australia’s Victoria state from Nov 6. https://www.channelnewsasia. com/news/singapore/covid-19-singapore-lift-border-restrictions-china-victoria-

nov-6-13404790

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 2). Trends in Number of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US Reported to CDC, by State/Territory. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-datatracker/#trends_totalandratecasessevendayrate China Daily. (2021, January 12). Loopholes in rural COVID-19 prevention should be plugged: Experts. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202101/12/WS5ffd5e47a31024ad0baa2190.html Dorn, S. (2020, October 17). Florida man is sole out-of-state traveler busted in NYC for breaking quarantine. NY Post. https://nypost.com/2020/10/17/florida-man-only-traveler-busted-in-nycfor-breaking-quarantine/ Low, M. (2020, April 7). Singapore Dispatch: Someone Will Notice if I Die in This Room. Columbia Journalism. https://medium.com/columbiajourn/singapore-dispatch-quarantined-in-a-hotelroom-with-no-complaints-8b4021cb77ca Marema, T. (2020, October 15). Rural Infection Rate Surpasses Metro-America’s All-Time High. Daily Yonder. https://dailyyonder.com/rural-infection-rate-surpasses-metro-americas-alltime-high/2020/10/15/ The Strait Times. (2021, January 13). China’s rural areas require better Covid-19 defences: China Daily. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/chinas-rural-areas-require-better-covid19-defenses-china-daily

Wang, H., Zhang, M., Li, R., Zhong, O., Johnstone, H., Zhou, H., Xue, H., Sylvia, S., Boswell, M., Loyalka, P., Rozelle, S. (2021). Tracking the effects of COVID-19 in rural China over time. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(35). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01369-z

Thick-Envelope Written by Thiago Maso Edited by Will Cao

Andraos, A. e Wood, D. We get there when we cross that bridge. New York: Monacelli Press, 2017. Aureli, P.V. The possibility of an absolute architecture. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2011. Gandelsonas, M., “The city as the object of architecture” in: Assemblage, n.37, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998, 128-144. Jaque, A. Mies y la gata niebla. Madrid: Puente Editores, 2019. Leatherbarrow, D. and Mostafavi, M. Surface Architecture, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2002. Sennett, R. The Open City. (2019, June 17) https://www.richardsennett.com/site/senn/ UploadedResources/The%20Open%20City.pdf, 2006.

Venturi, R. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1966. Zaera-Polo, A. The Politics of The Envelope. In: Log,vol.13/14, 2008., 193-207. Images

Image 01: Nestlé Pavilion and BEST Store, V&SB. Decorated Shed. Source: Author, 2019. Image 02: Villa Shodhan, Le Corbusier, inhabitable space. Source: Author, 2019. Image 03: Lerner Hall, exterior. Source: Columbia Admissions, 2010. Accessed August 08 2019, https://www.flickr.com/photos/columbia_admissions/4876292965 Image 04: Miami Garage, exterior. Source: Imagen Subliminal (Miguel de Guzmán + Rocío Romero), 2018. Courtesy of the authors.

The Relationship between Different Spellings of “Urban Planning” in Asia and the History of Urban Planning in Northeast Asia (“都市计划”与 东北亚近代城市规划史的变迁) Written by Lai Ma Edited by Eve Passman

Jun B. (1918). Modern Civilization and Urban Planning. Oriental Magazine Volume 15, No. 12, 1918 君實. 《現代文明與都市計畫》[J]. 《東方雜誌》第十五卷 第十二号(1918)(外編) Wang, J., Sun Q. and Xie H. (2004). The Capital Planning of the Early Period of the National Government. New History Studies, Volume 15, Issue 1. 王俊雄、孫全文、謝宏昌.國民政府定都南京初期的《首都計畫》[J].新史學十五卷一期.2004年3 月. Huang L. (1996). The Comparison Research of the Urban Planning Law in Taiwan, Japan, Korean and Kwantung Leased Territory: The Characteristics of “Taiwan Urban Planning Law” 1936. Journal of Architecture and Urban-Rural Studies of National Taiwan University, Volume 8. 黃蘭翔. 臺灣﹒日本﹒朝鮮﹒關東州都市計畫法令之比較研究——1936年「台灣都市計畫令」的 特徵[J]. 國立台灣大學〈建築與城鄉研究學報〉第八期. 民國八十五年六月 Hou L., Wang Y. (2015). The Greater Shanghai Metropolitan Planning: Modern Vision and Planning Practice of Metropolitan Cities in Modern China. City Planning Review, Volume 39, Issue 10. 侯 丽、王宜兵. 《大上海都市计划1946-1949》——近代中国大都市的现代化愿景与规划实践[J]. 《城市规划》2015年第39卷第10期 Zhang J., Li J. (2017). Urban and Public Green Space Construction in Shenyang during the Period of “Puppet Manchukuo”. Journal of Shenyang Architectural University (Social Science), Volume 19, Issue 3 张健、李竞翔. “伪满”统治时期沈阳的城市与公共园林绿地建设[J]. 沈阳建筑大学学报( 社会科 学版) 2017年6月 第19卷第3期 Li Y. (2002) “Du Shi Ji Hua”: From Tradition to Modernity. Hanjiang Forum 2002.3. 李芸. 都市计划: 从传统到现代[J]. 江汉论坛 2002.3 Yao C., Yu L. (2017). Comments on Japan’s First Urban Planning Law and Its Supporting Decrees. International Urban Planning, Vol.32, No.2. 姚传德、于利民. 日本第一部《都市计划法》及其配套法令评析[A]. 国际城市规划 2017 Vol.32, No.2 Sun H. (2012). Urban Development and Social Change in Modern Shenyang. Northeast Normal University. 孙鸿金. 近代沈阳城市发展与社会变迁[D]. 东北师范大学. 2012年12月 Xin W., Liao S. (2000). Development, Change and Prospect of Urban Planning System in Taiwan. Urban development research, 2000.6. 辛晚教、廖淑容. 台湾地区都市计划体制的发展变迁与展望[J]. 城市发展研究 2000.6. Chen X. (2005). The Changing Course of the Function and Characteristics of Taiwan’s Urban Detailed Planning Legal System from the Period of Japanese Rule to the Post-war Period. City and Planning, Volume 32, Issue 3, 253-275. 陈湘琴. 日治至战后时期台湾都市细部规划法制的功能与特性之变迁历程[J]. 都市与计划民国九十四年 第三十二卷 第三期:第253-275页

The Death and Life of Shanghai Shikumen Written by Yining Lei Edited by Will Cao

Bao, Yalan (2019). What Remains: A History of Six Lanes in Shanghai. SmartShanghai. Retrieved from https://www.smartshanghai.com/articles/shanghai-life/walking-into-thelanes-of-shanghai Goldberger, Paul (2005). Shanghai Surprise: The radical quaintness of the Xintiandi district. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/12/26/ shanghai-surprise Ruan, Y., Zhang, C., & Zhang, J. (2011). Shanghai Shikumen. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House. Tay, Sue Anne (2015). Conversations: Jie Li on “Shanghai Homes: Palimpsests of Private Life”. Shanghai STREET STORIES. Retried from http://shanghaistreetstories.com/?p=7271 UNCC SoA (2015). Chinese Puzzle: The Shifting Patterns of Shanghai’s Shikumen Architecture. The Thinking Architect. Retrieved from https://thethinkingarchitect.wordpress. com/2015/10/21/chinese-puzzle-shifting-spatial-and-social-patterns-in-shanghaishikumen-architecture/ Yang, Jian (2014). Fears for the last of city’s historic shikumen. ShanghaiDaily. Retrieved from https://archive.shine.cn/metro/society/Fears-for-the-last-of-citys-historic-shikumen/ shdaily.shtml 上海石库门首尝抽户改造:抽离部分居民释放空间. (2020, April 27). Retrieved from https://new. qq.com/omn/HSH20200/HSH2020042700117700.html 上海市国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和二〇三五年远景目标纲要. (2021, January 30). Retrieved from http://www.shanghai.gov.cn/nw12344/20210129/ ced9958c16294feab926754394d9db91.html

Architecture as a Tool for Justice Written by Refan Abed Edited by Sherry Aine Te

Fitz, A., Krasny, E., & Wien, A. (Eds.). (2019). Critical care: Architecture and urbanism for a broken planet. MIT Press. Hayden, D. (1980). What would a non-sexist city be like? Speculations on housing, urban design, and human work. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 5(S3), S170-S187.

Recent zoning fights on the commune issue have occurred in Santa Monica, Calif.; Wendy Schuman, ‘The Return of Togetherness,’ New York Times, 20 Mar. 1977, reports frequent illegal downzoning by two-family groups in one-family residences in the New York area.

The Ladies’ Room: The Role of Public Toilets as a Barrier to Marginalized Groups Entering Mainstream Society Written by Alek Tomich Edited by Will Cao

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. (1902 - 1914). Two women & man in front of outhouses; one woman getting water Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-4c94-a3d9-e040e00a18064a99 Eliot W. H. (1830) Tremont House Hotel Main Floor Plan. Annotated by Kogan T. S. for Stalled! Retrieved from https://www.stalled.online/standards-navigation Stalled! (2018). Gallaudet University’s Field House Inclusive Facilities Prototype. https://www. stalled.online/gallaudet

The Gig Economy and Architecture: an Interview with Peggy Deamer Written by Mariana Riobom Edited by Shreya Arora & Sherry Aine Te

Collective Learning: Networks of Labor and Care in Architecture Written by Hasbrouck Miller, Stella Ioannidou, and Ryan Leifield Edited by Geon Woo Lee

Akbulut, B. (2017, February 2). Carework as Commons: Towards a Feminist Degrowth Agenda. Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2017-02-02/carework-as-commons-towardsa-feminist-degrowth-agenda/ Deamer, P. (2016). Introduction. In P. Deamer (Ed.), The Architect as Worker: Immaterial Labor, the Creative Class, and the Politics of Design. Bloomsbury Academic. Federici, S. (2019). Women, Reproduction, and the Commons. The South Atlantic Quarterly, 118(4), 711-724. Gibson-Graham, J.K., Cameron, J., & Healy S. (2016). Commoning as a postcapitalist politics. In A. Amin & P. Howell (Eds.), Releasing the Commons: Rethinking the Futures of the Commons (pp. 192-212). Routledge. Gu, J. Y. (2020). Formats of Care. Log, 48, 67-74. Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions. Krasny, E. (2019). Architecture and Care. In A. Fitz & E. Krasny (Eds.), Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet (pp. 33-41). MIT Press. Simard, S. W., et. al. (2012). Mycorrhizal networks: Mechanisms, ecology and modelling. Fungal Biology Reviews, 26, 39-60. Tronto, J. (1995). Care as a Basis for Radical Political Judgments. Hypatia, 10(2), 141-149. Tronto, J. & Fisher, B. (1990). Toward a Feminist Theory of Caring. In E. Abel & M. Nelson (Eds.), Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives (pp. 35-62). SUNY Press. Ukuleles, M. L. (1969). Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Proposal for an exhibition: “CARE”. Wohlleben, P. (2016). The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World. (J. Billinghurst, Trans.). Greystone Books. (Original work published 2015)

EDITORS

Senior

Tihana Bulut Design Geon Woo Lee Content Zeineb Sellami Publishing

Junior

Shreya Arora Will Cao Eve Passman

Online

Sherry Aine Te

To see your work in the next volume of URBAN, send your written and visual work to: urban.submissions@gmail.com