Houston: Extreme Weather, Environmental Justice, and the Energy Transition

Houston, Texas, has been called the “prophetic city.” It is a city that is reflective of America’s past, with its celebration of individualism and economic opportunity combined with legacies of extraction and racial disparities. As a testament to its continued dynamism, it is also a city that is rapidly changing, driven by its increasingly diverse and growing population. In Houston, the drivers of the twentieth-century city—cars and fossil fuels—will have to give way to those of the twenty-first century: extreme weather, environmental justice, and the energy transition.

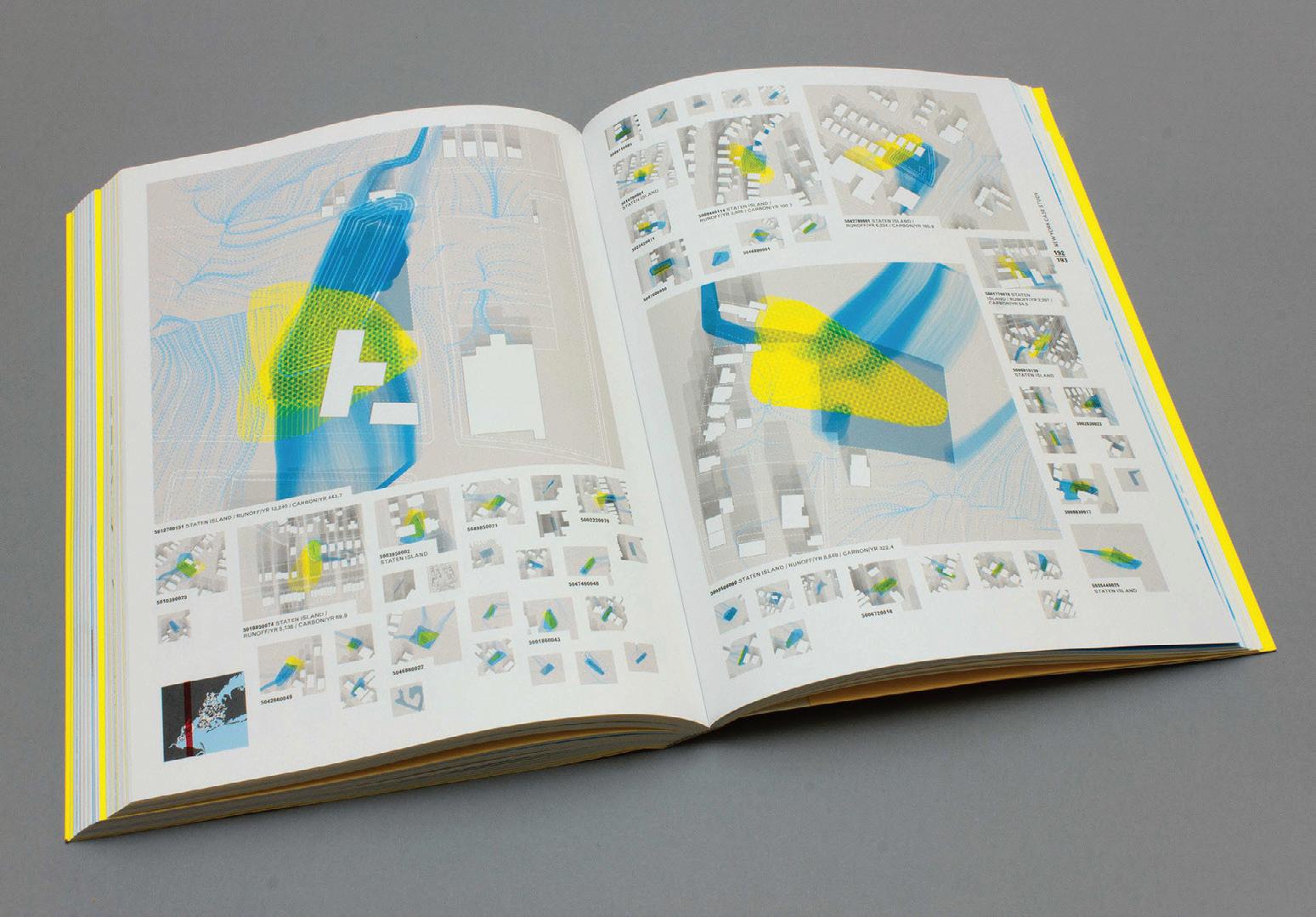

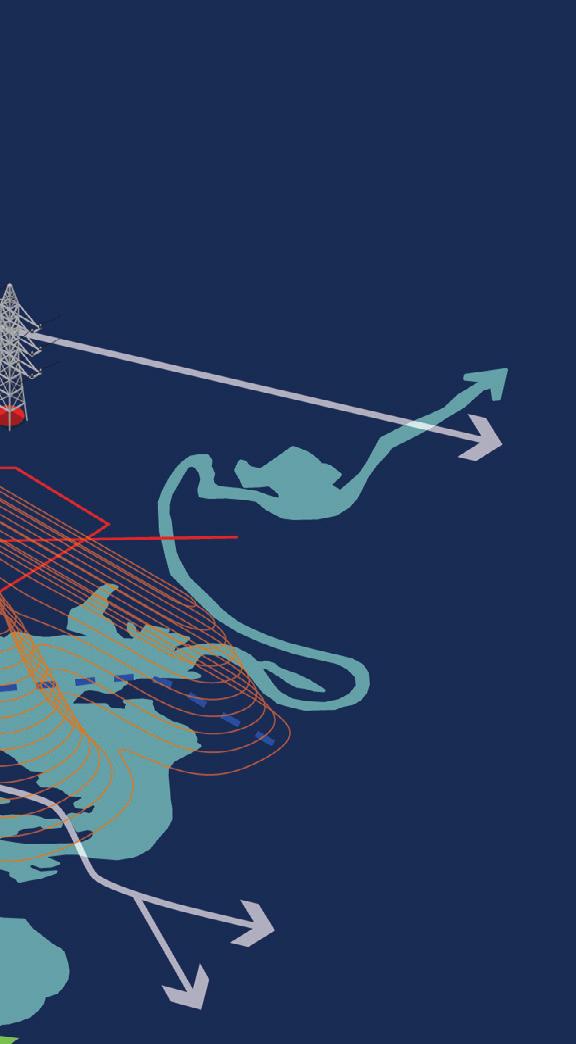

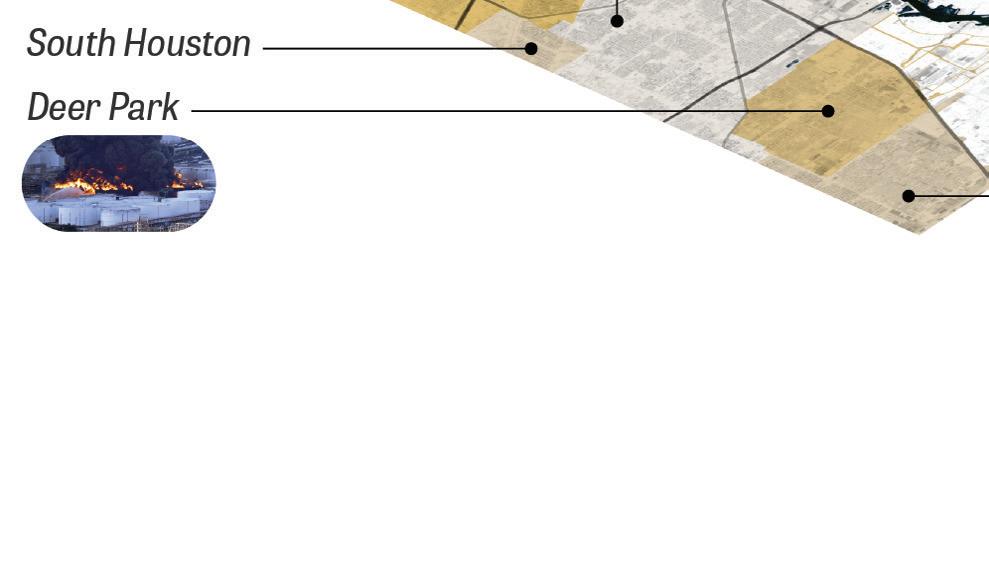

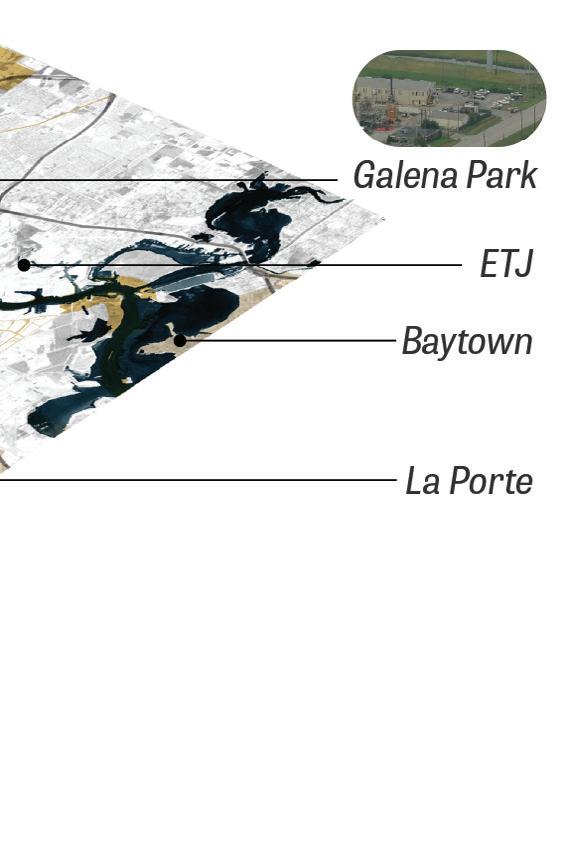

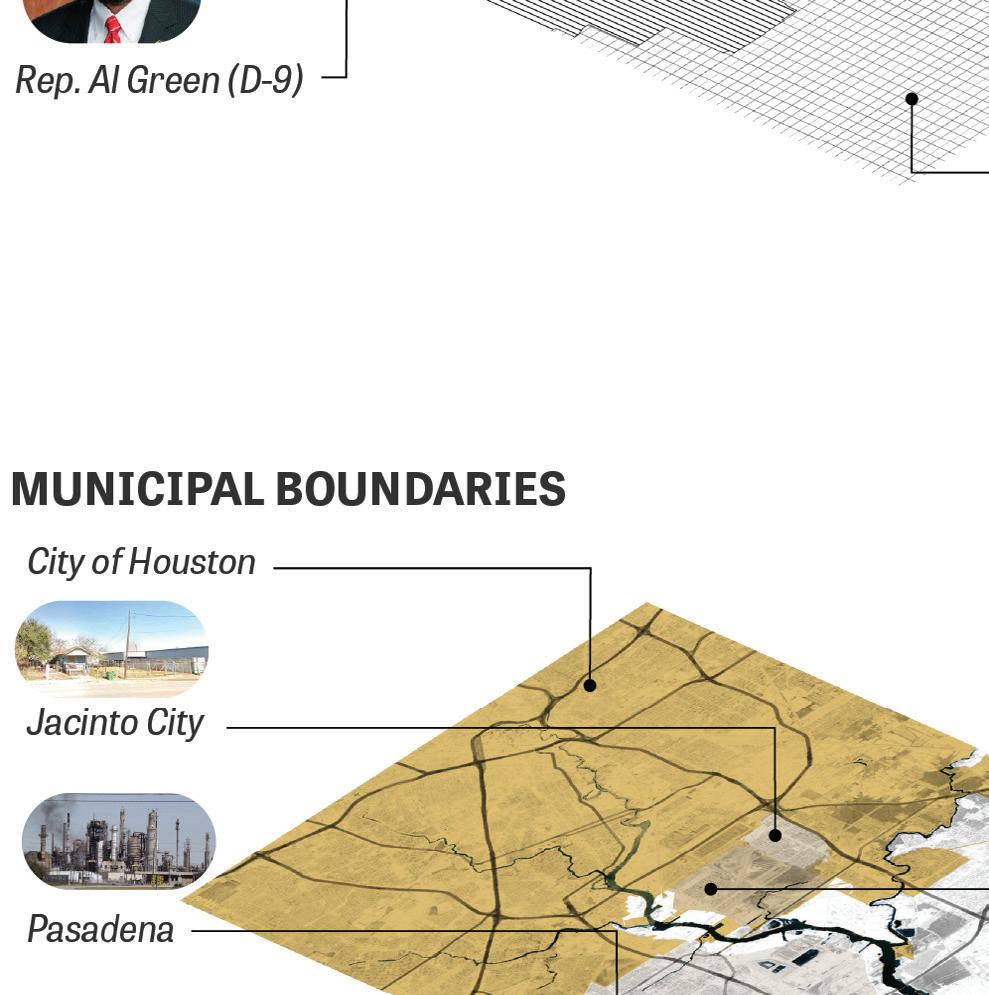

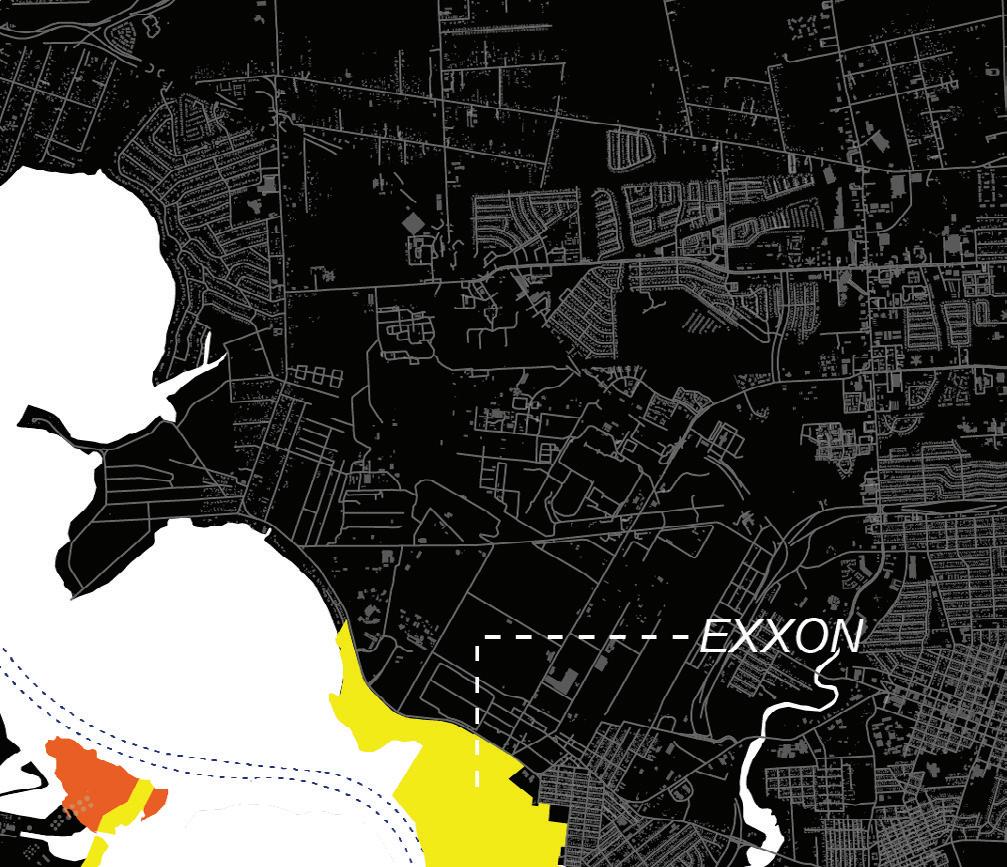

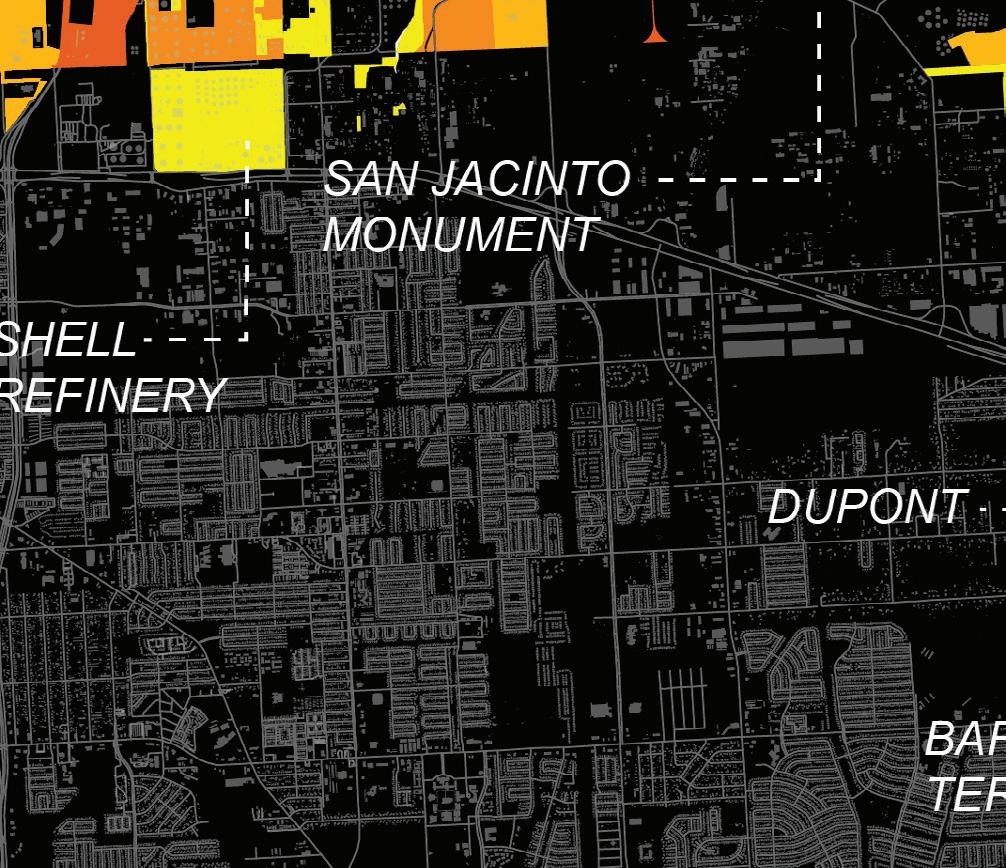

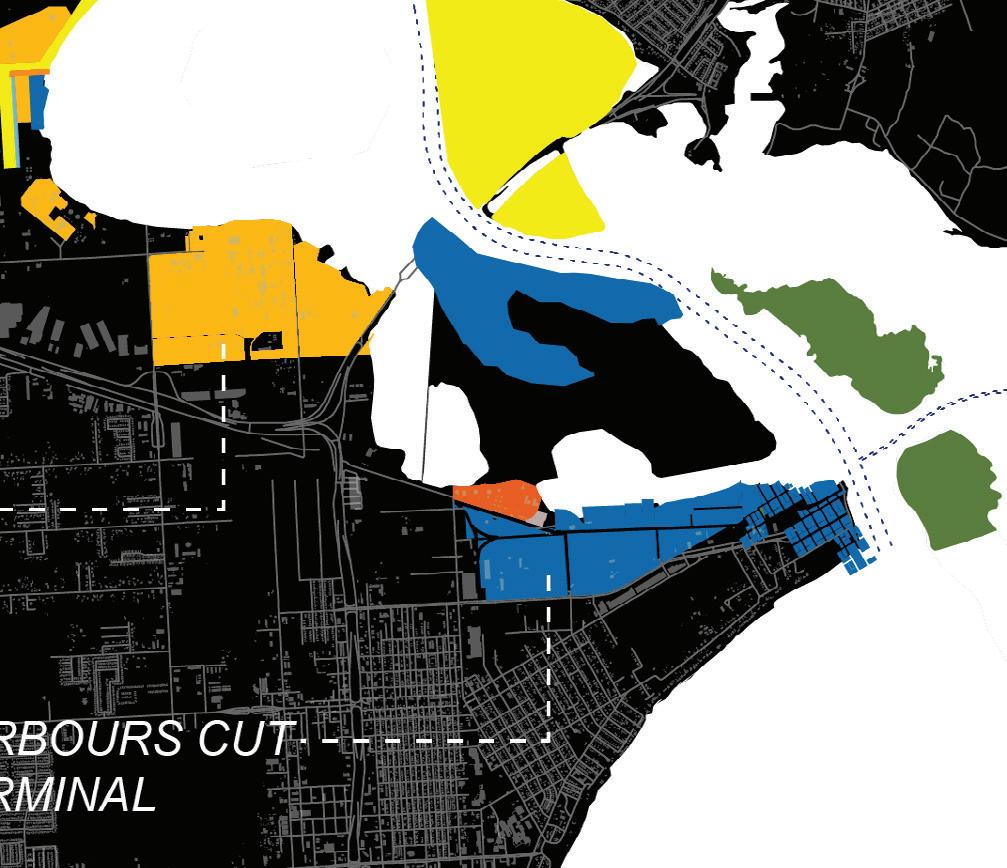

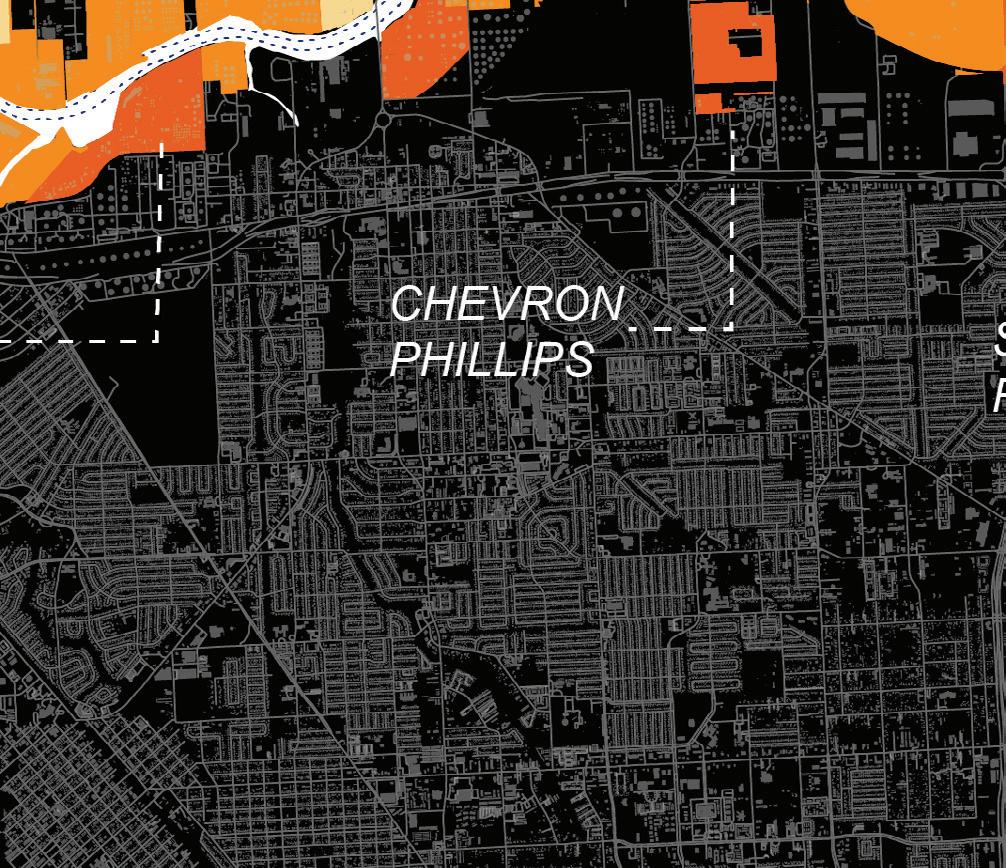

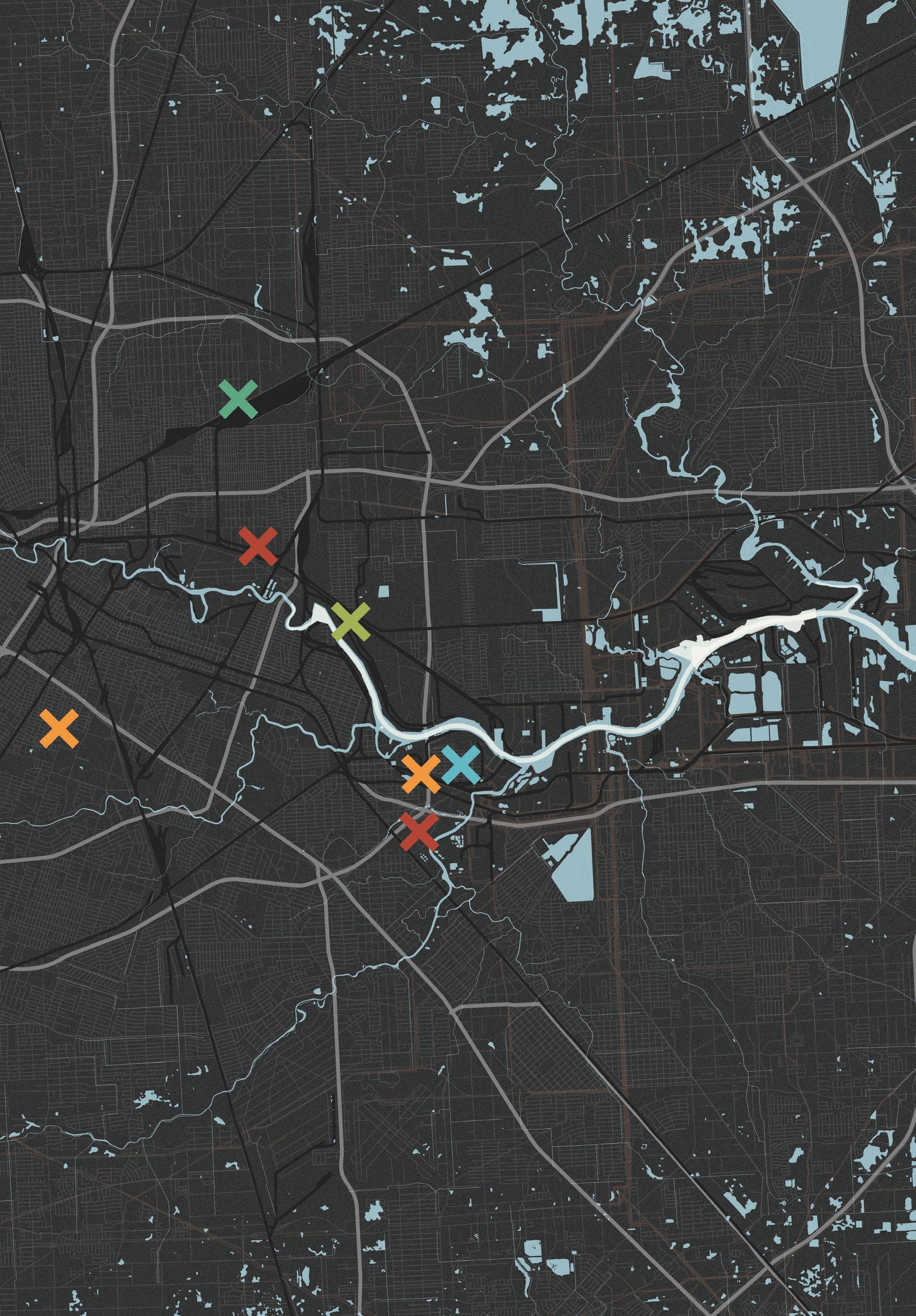

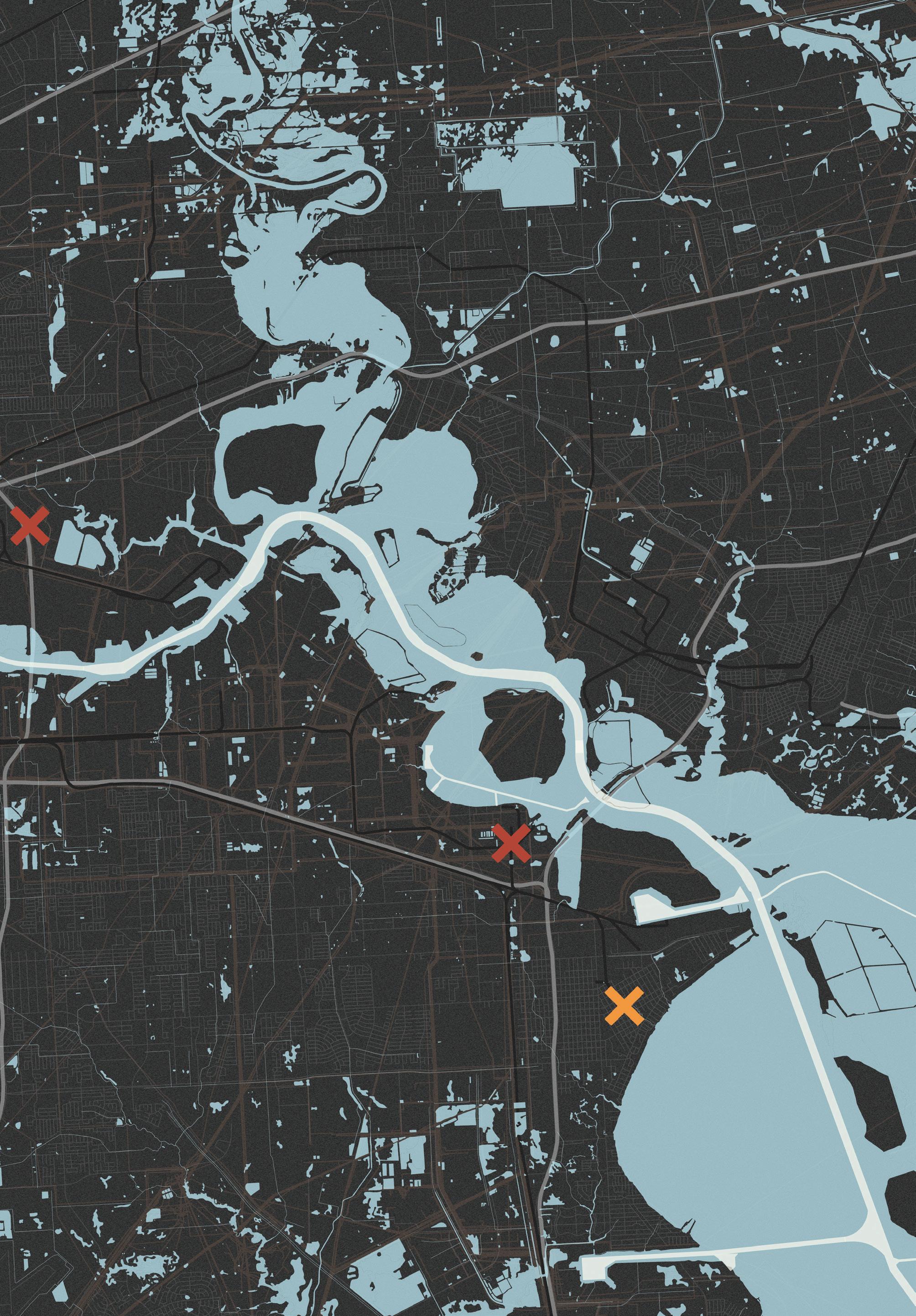

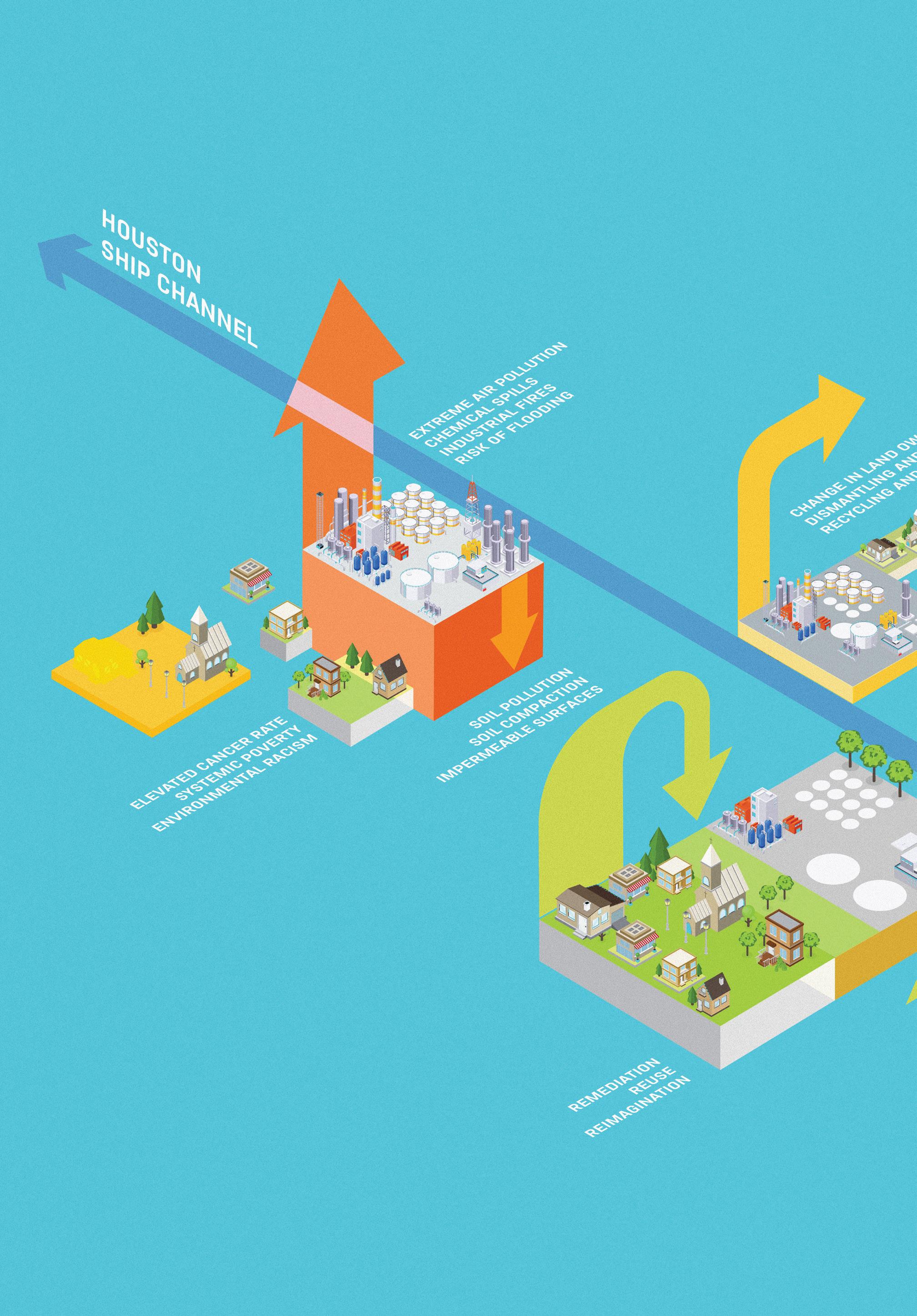

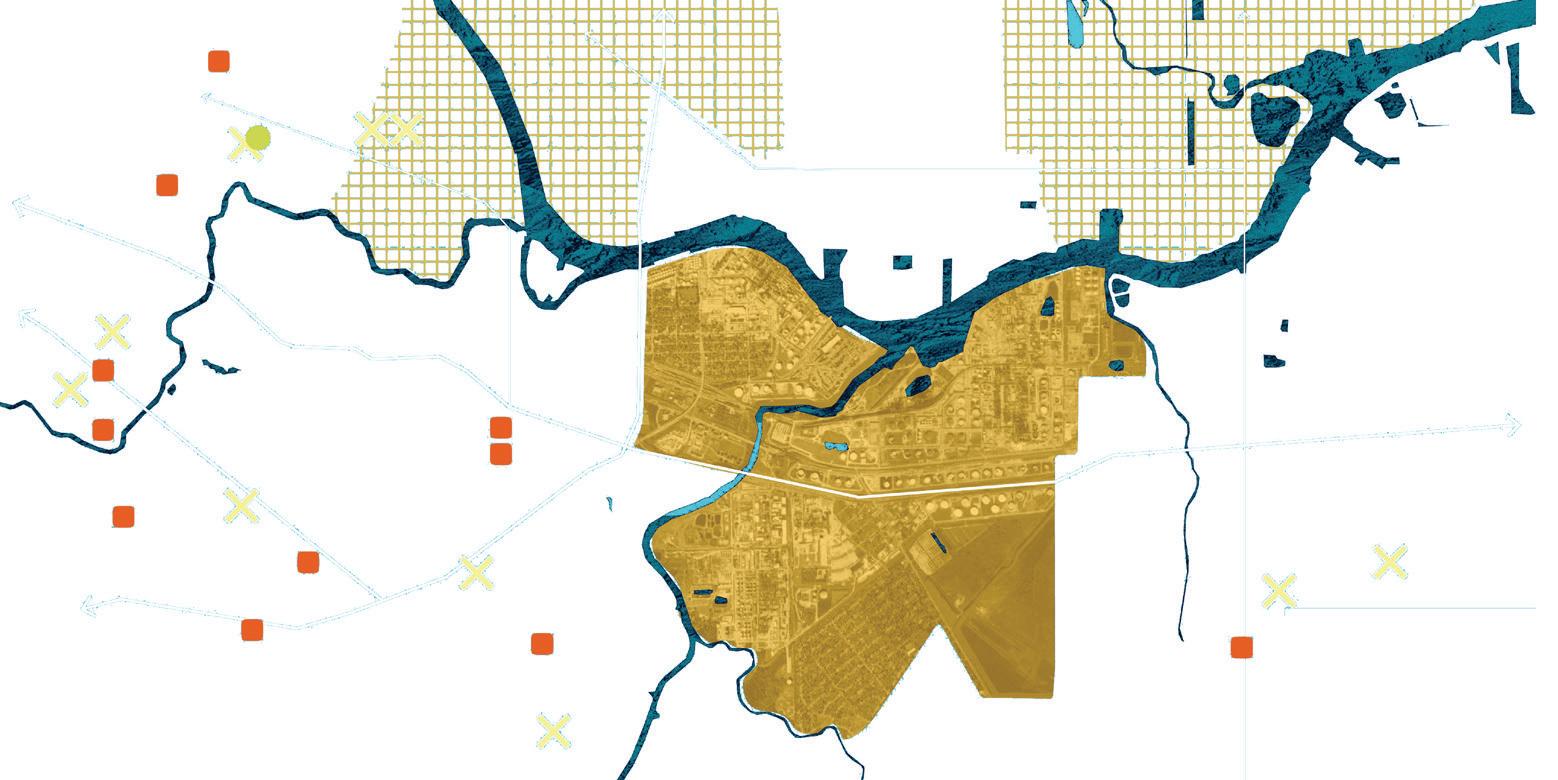

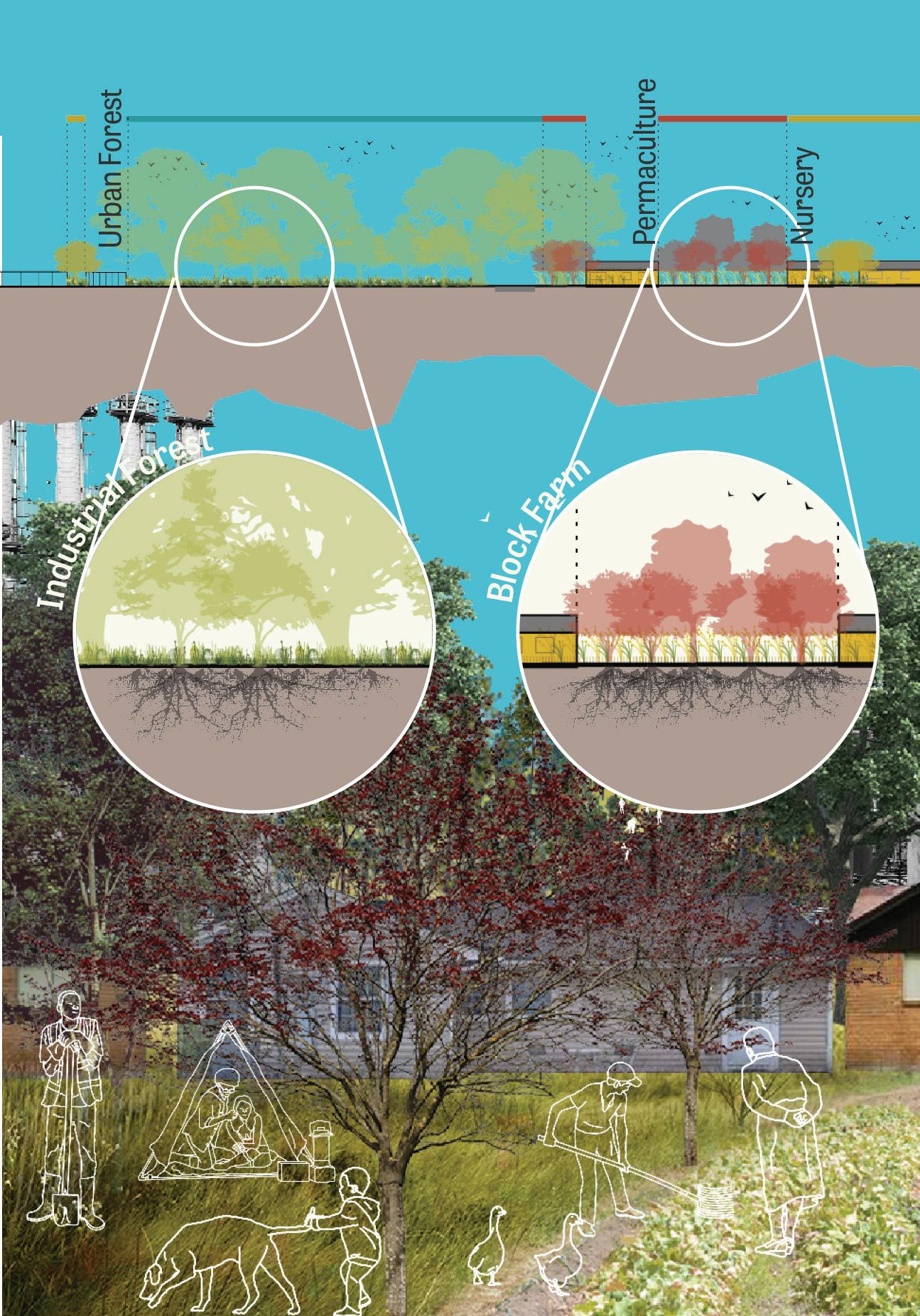

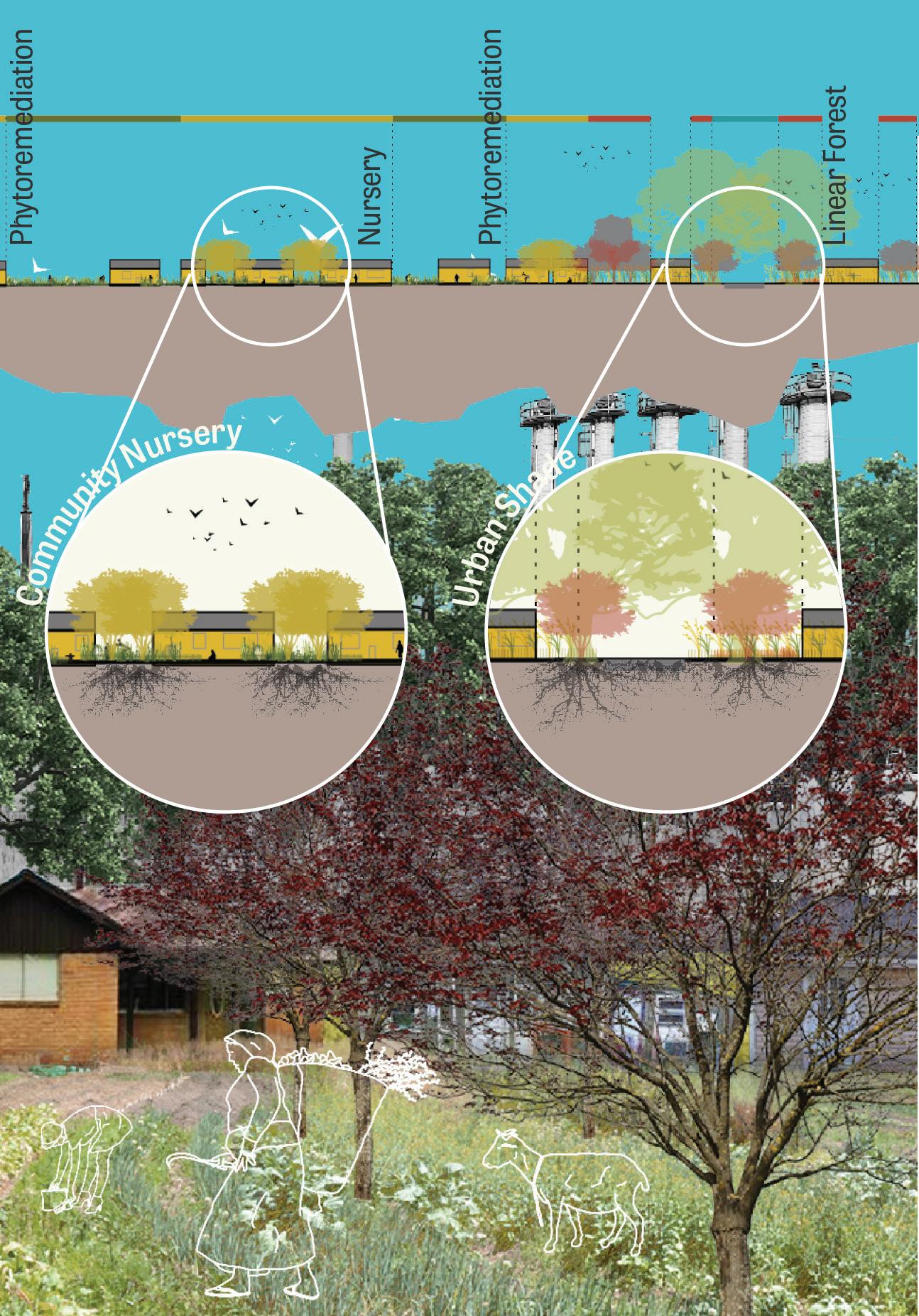

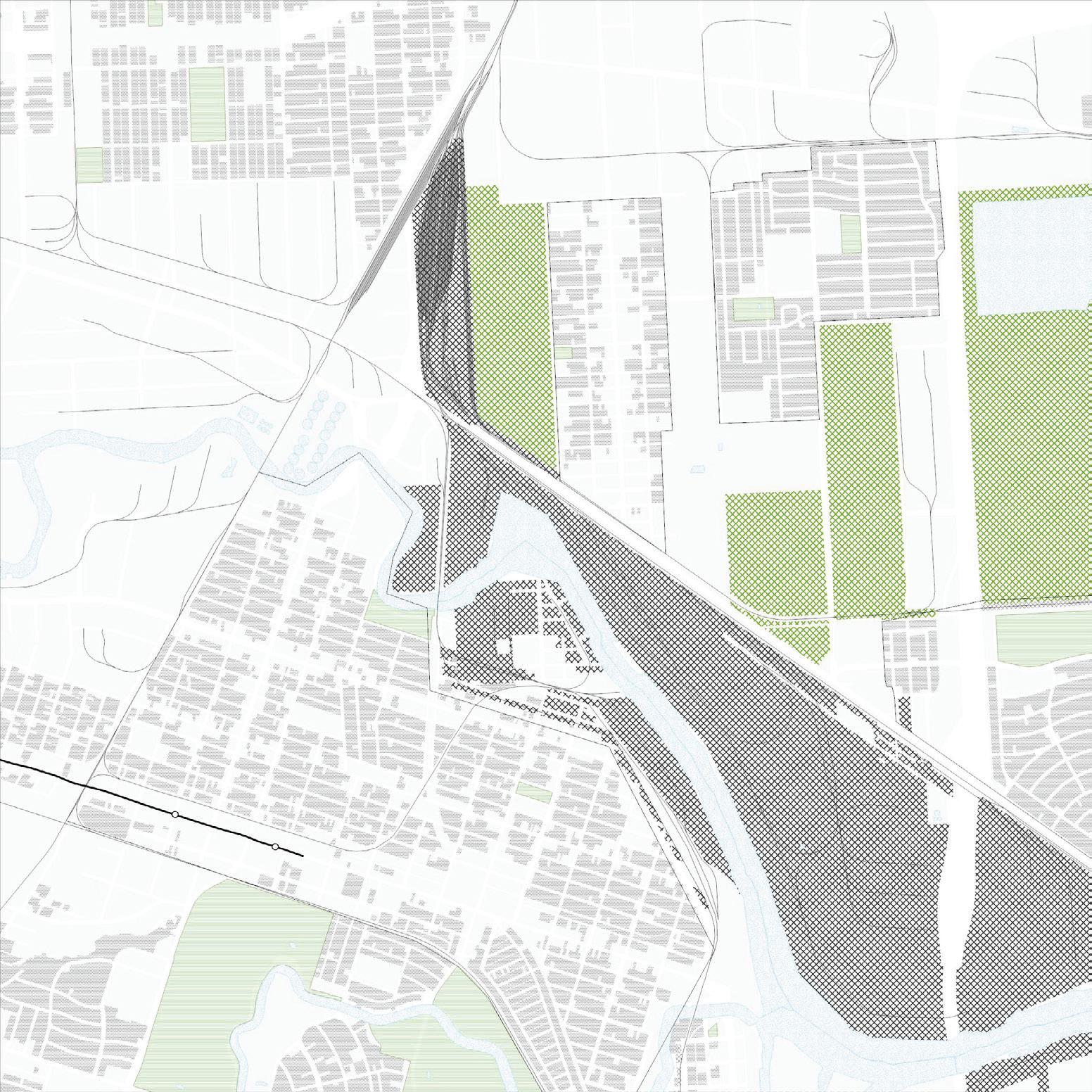

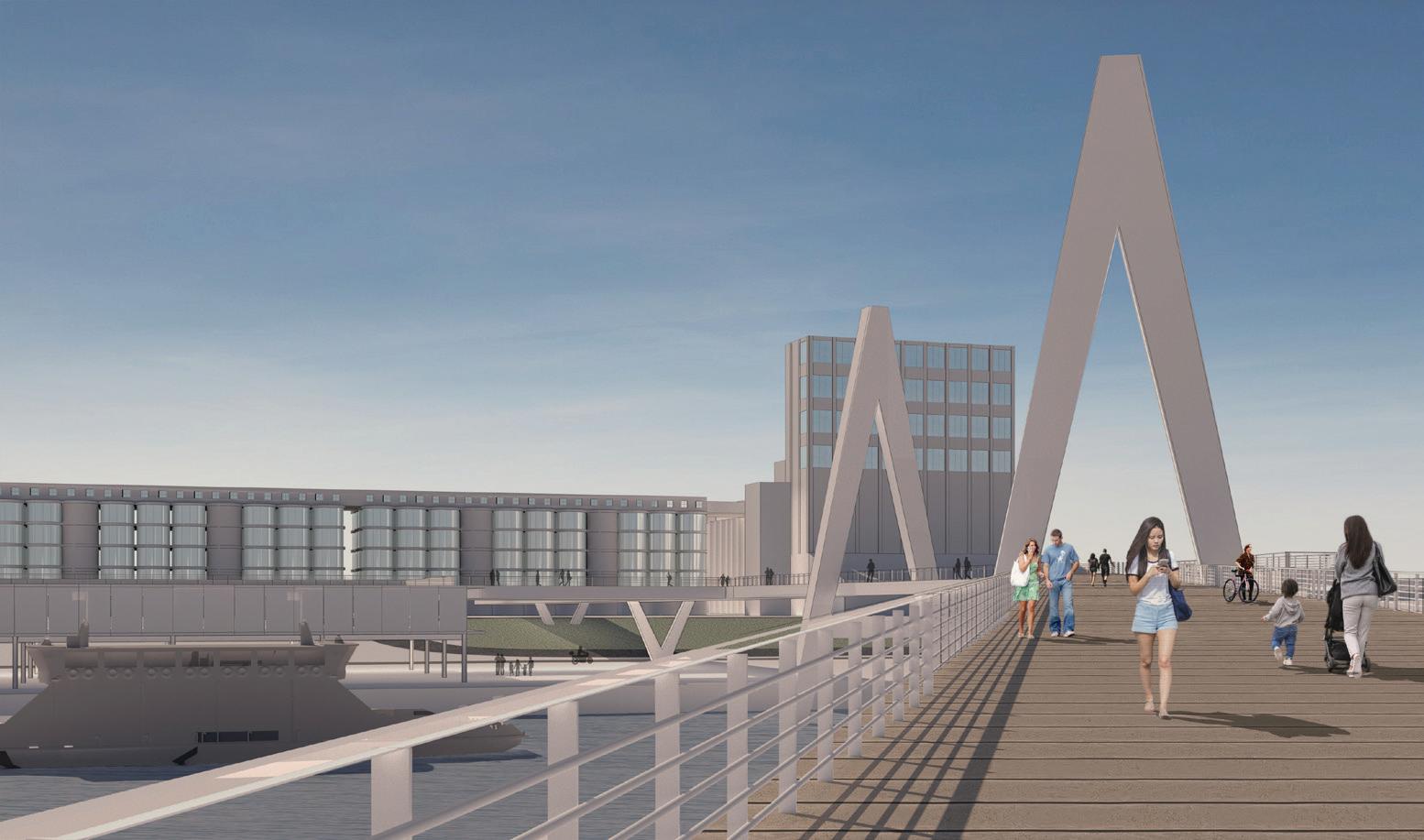

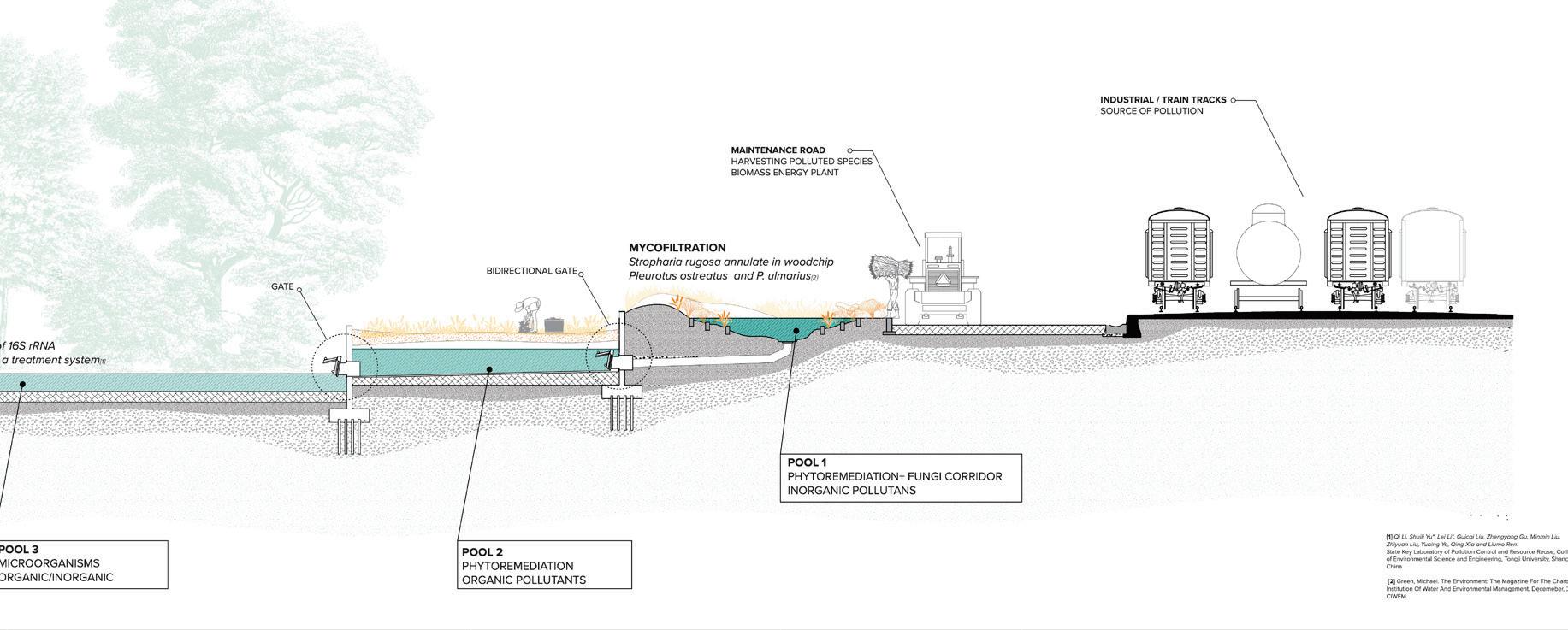

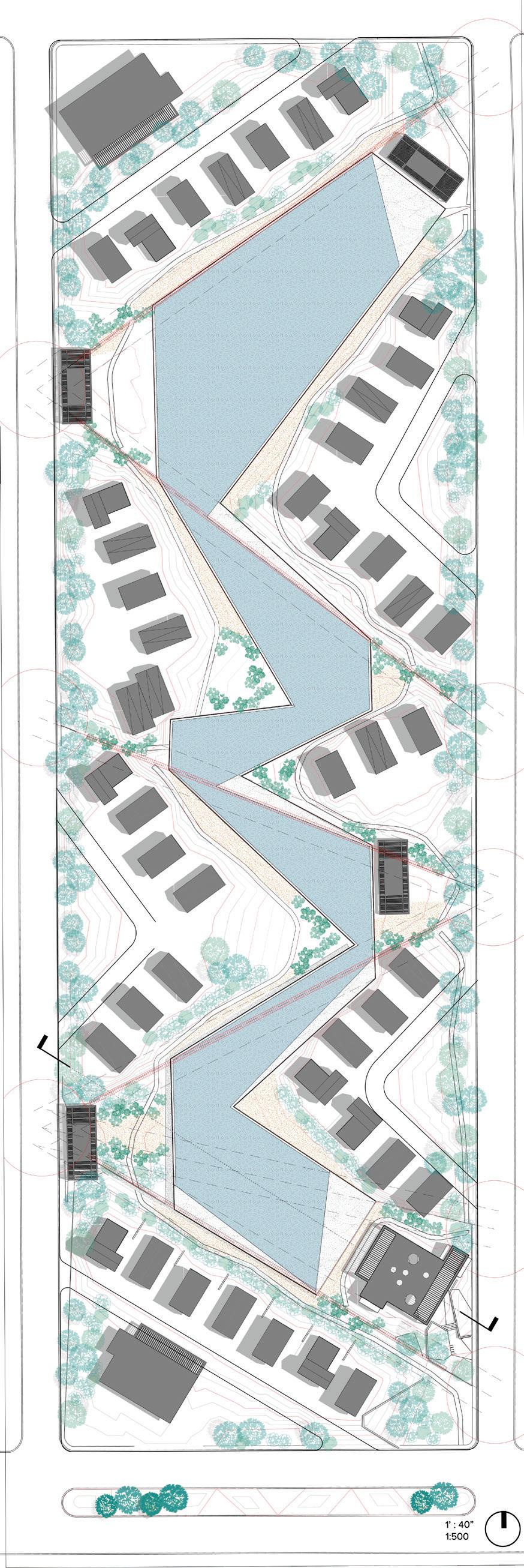

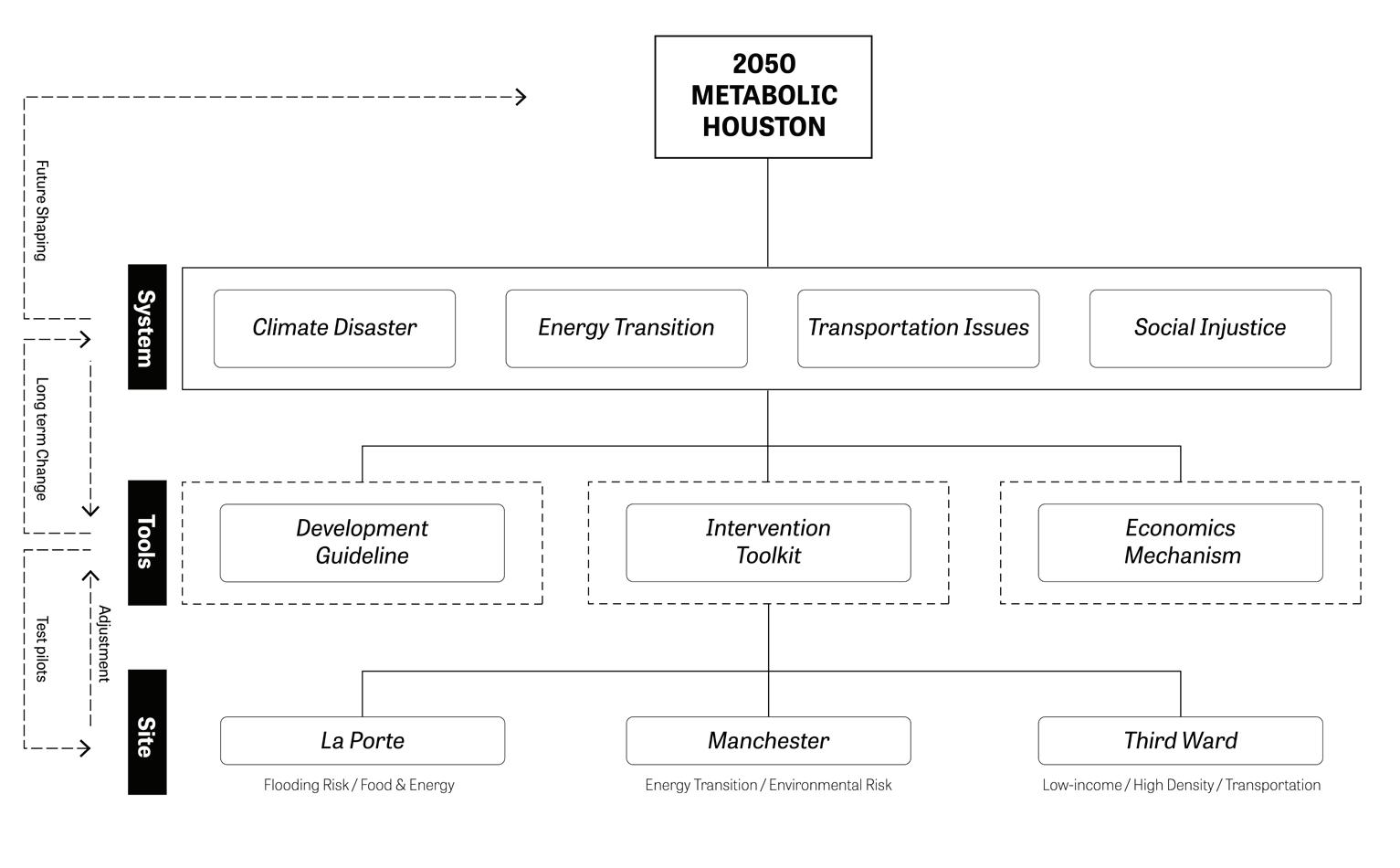

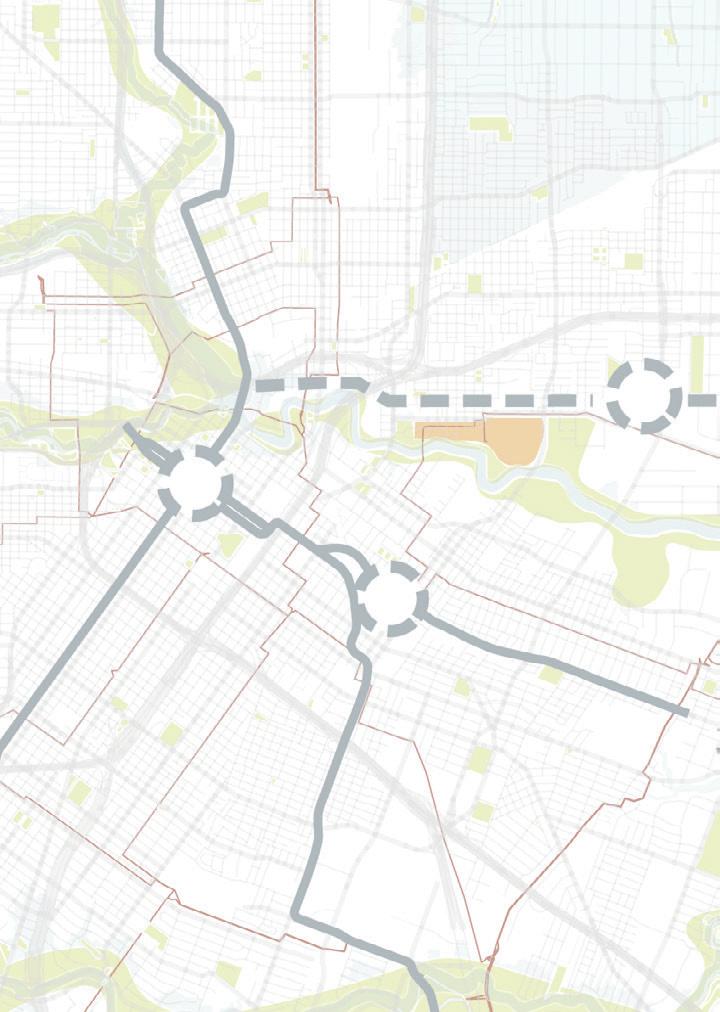

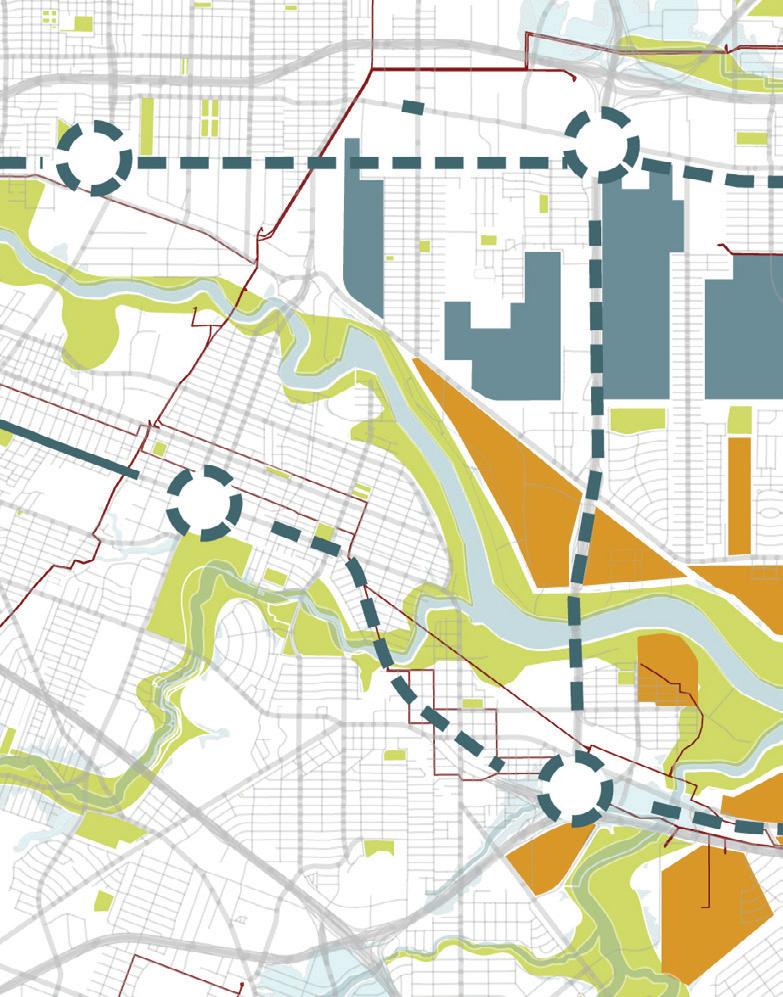

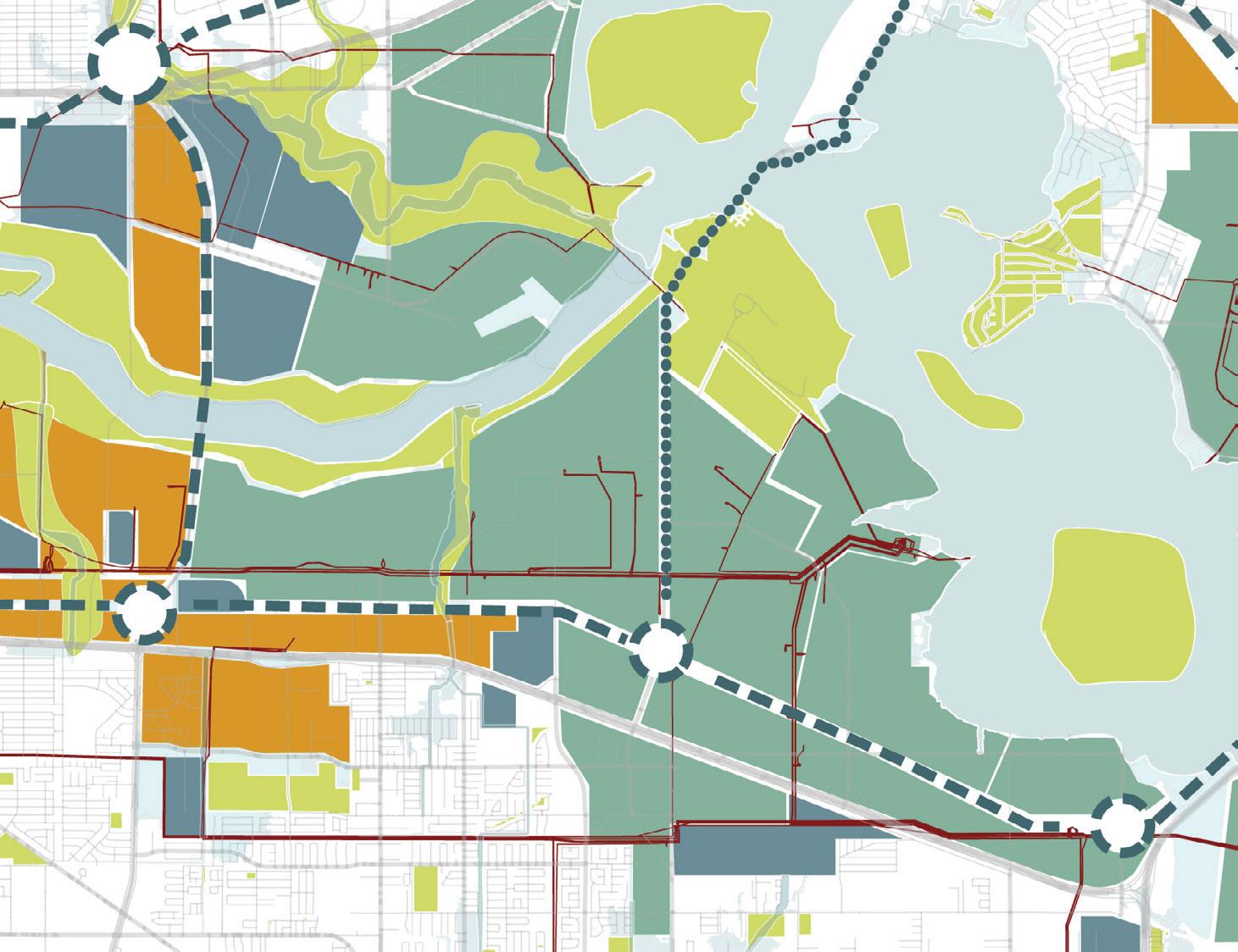

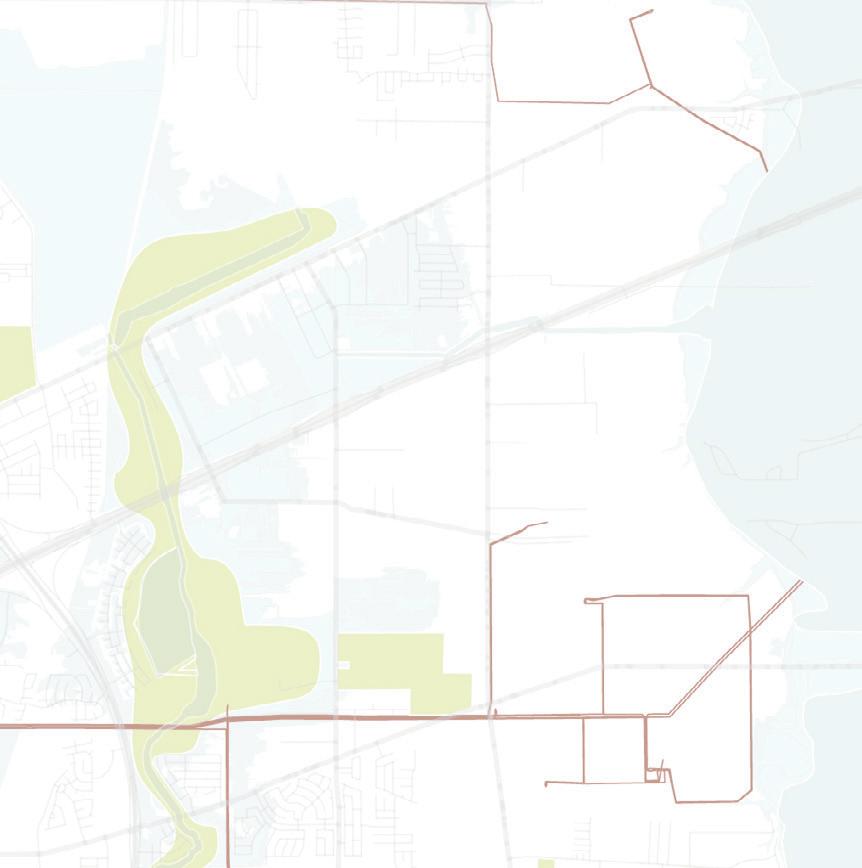

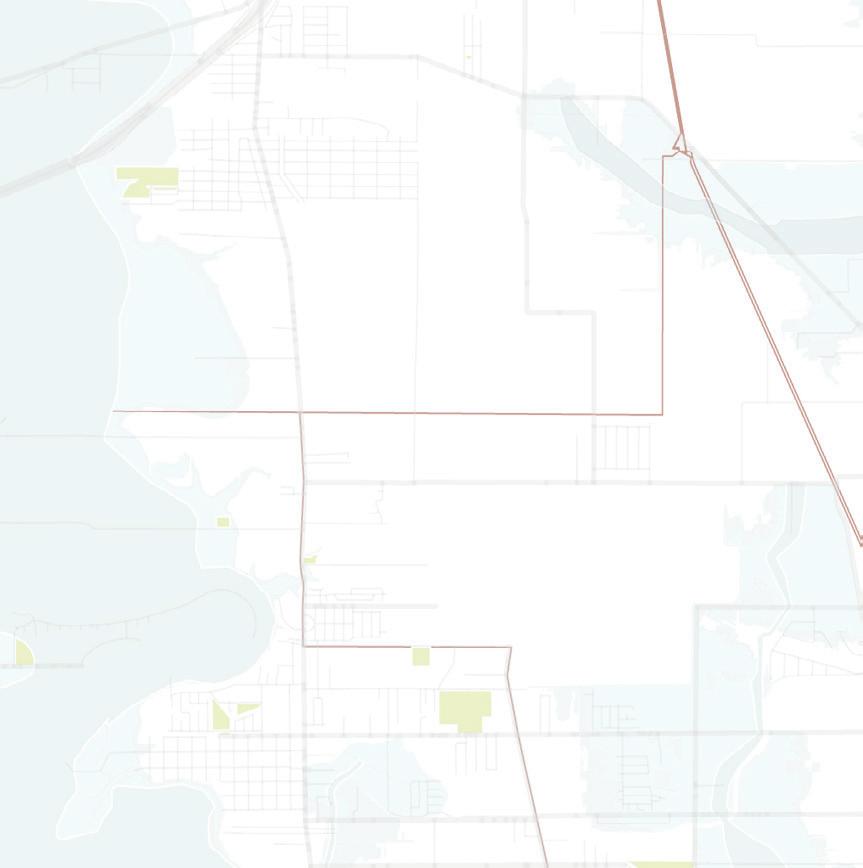

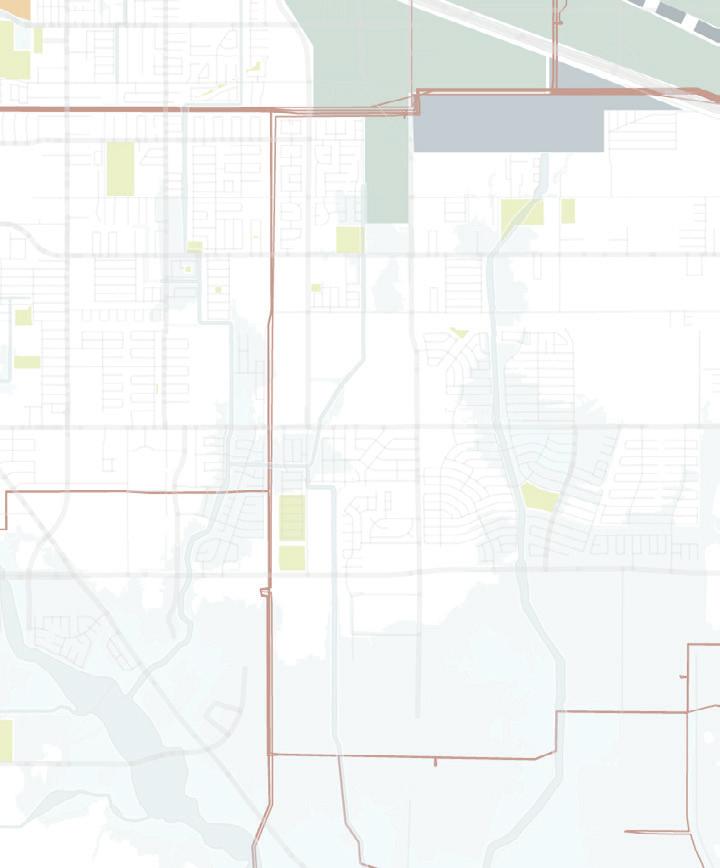

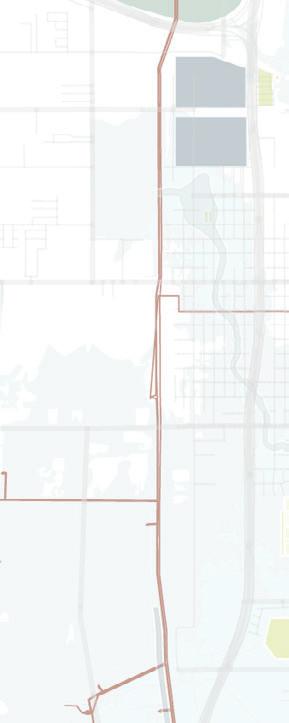

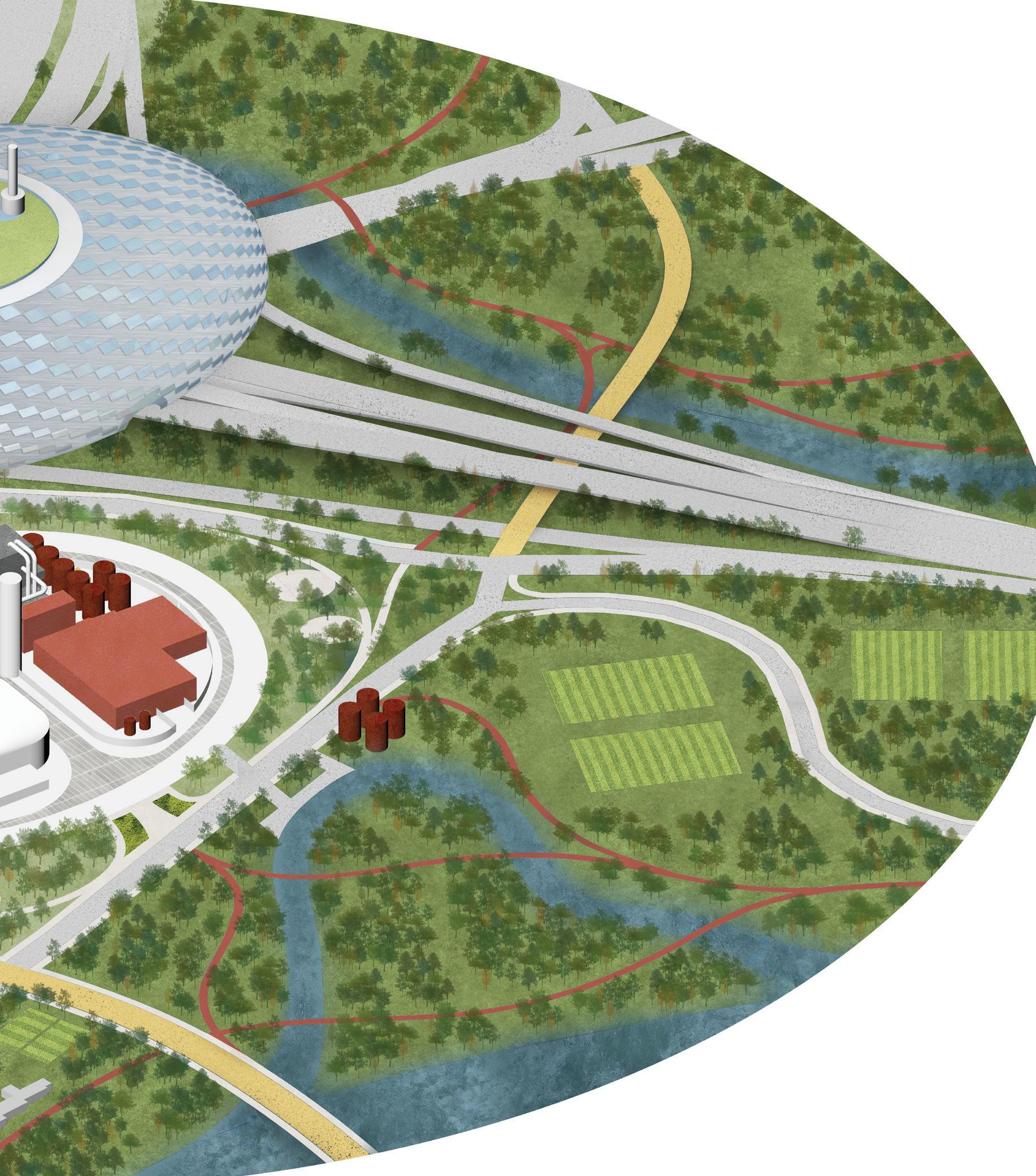

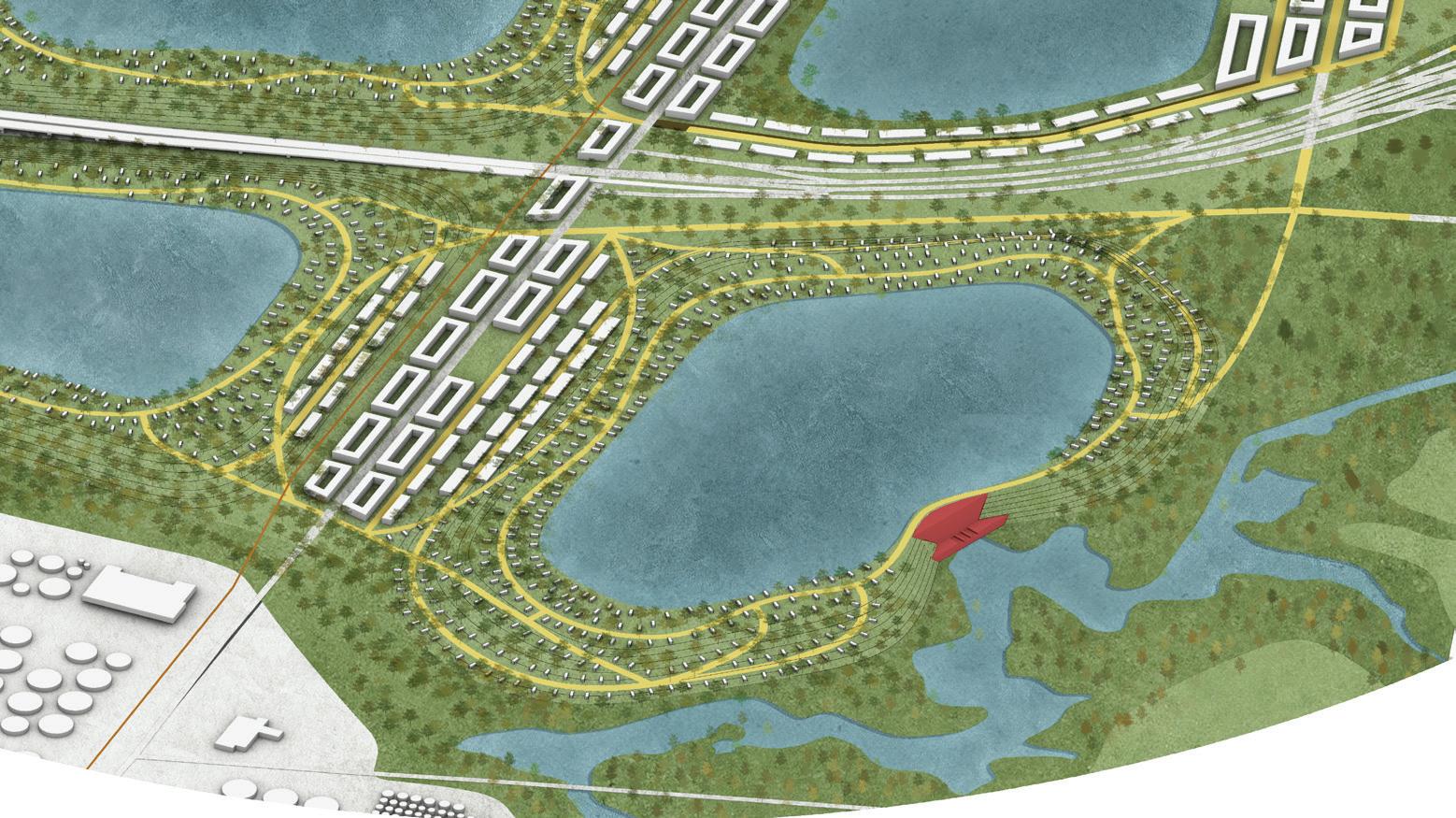

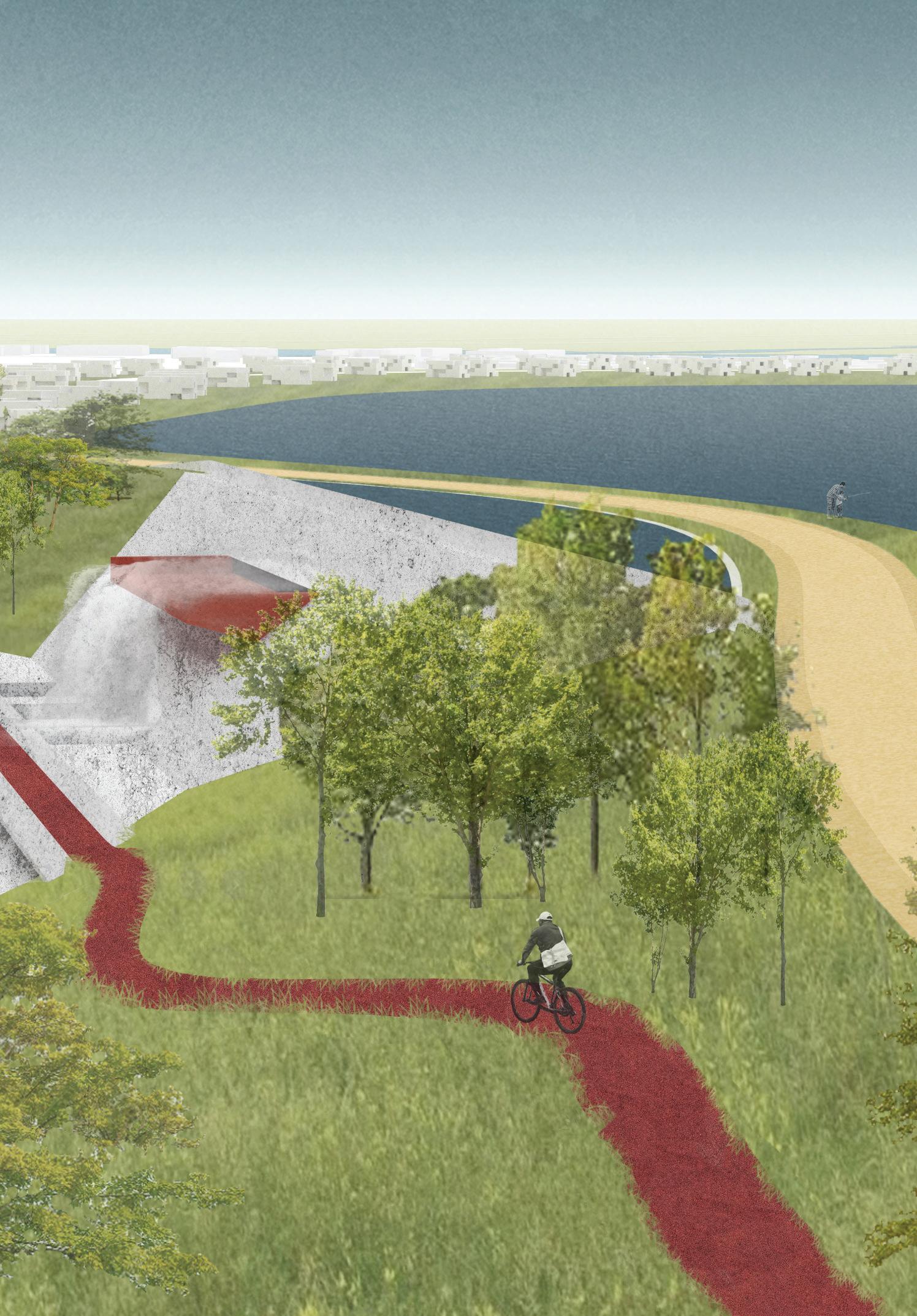

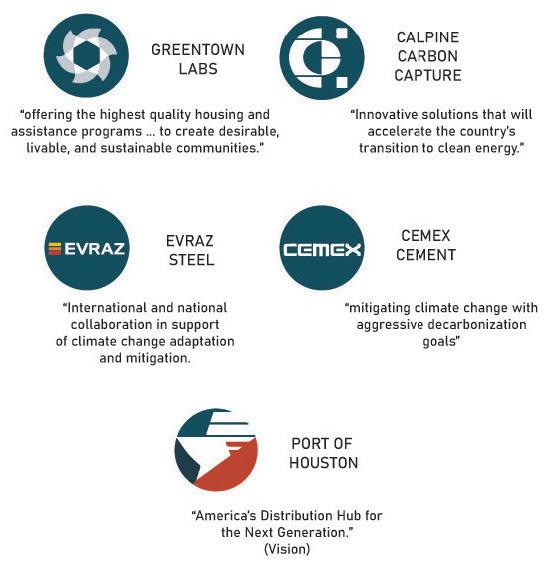

In this studio, we explored the challenges and opportunities that come with this transformation along these three drivers and designed responses on various scales, with a focus on the areas around the Ship Channel, which runs from downtown Houston to Galveston Bay.

The climate crisis has manifested itself in Houston from repeated five-hundred-year flood events to cold snaps and subsequent grid failure. As in most places, such events disproportionately impact the city’s marginalized populations. In response, Houston has developed an ambitious resilience strategy and climate action plan supported by billions of dollars in funding. Climate adaptation, however, is challenging given the city’s geography and the state of its infrastructure. Climate mitigation might even be more difficult due to the dominance of the car and the petrochemical industry.

Houston’s lack of zoning, its history of structural racism, and its role as a center for distribution, logistics, and petrochemical industries have resulted in massive disparities in health outcomes, educational attainment, and economic opportunity—especially for the communities of color that have been bisected by highways or that are adjacent to the industrial areas of the Ship Channel. How can legacies of pollution be remediated, and how can these injustices be remedied?

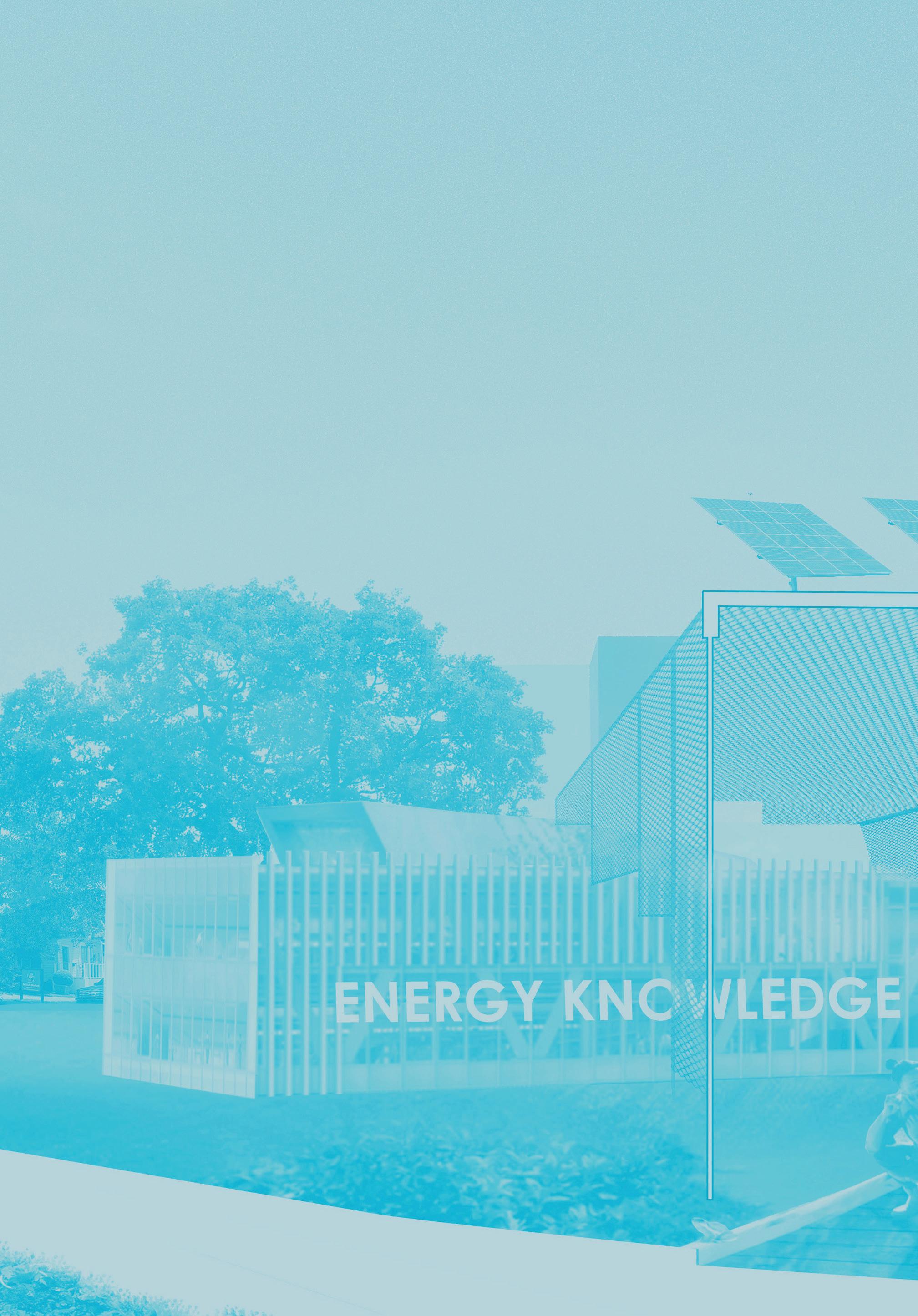

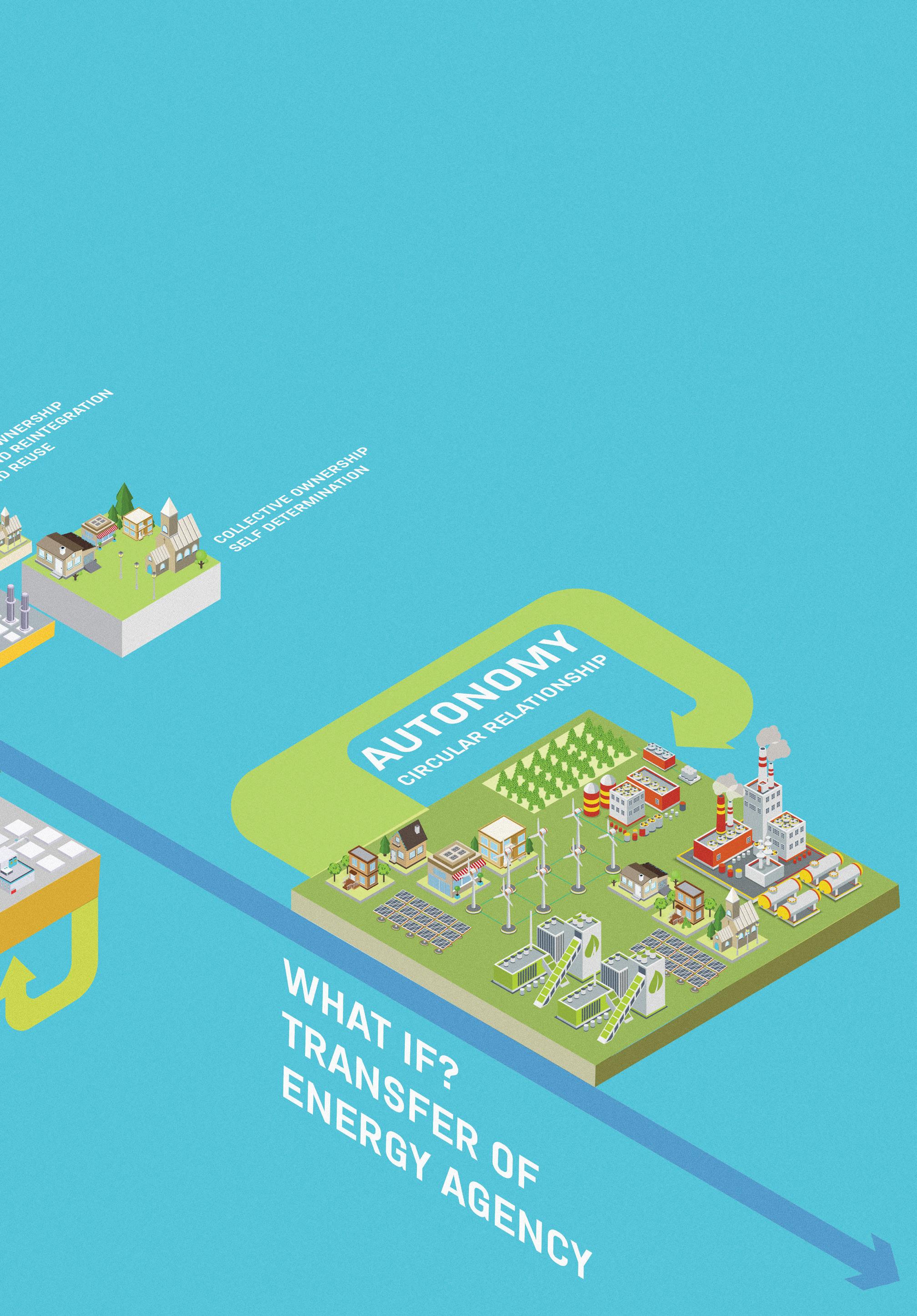

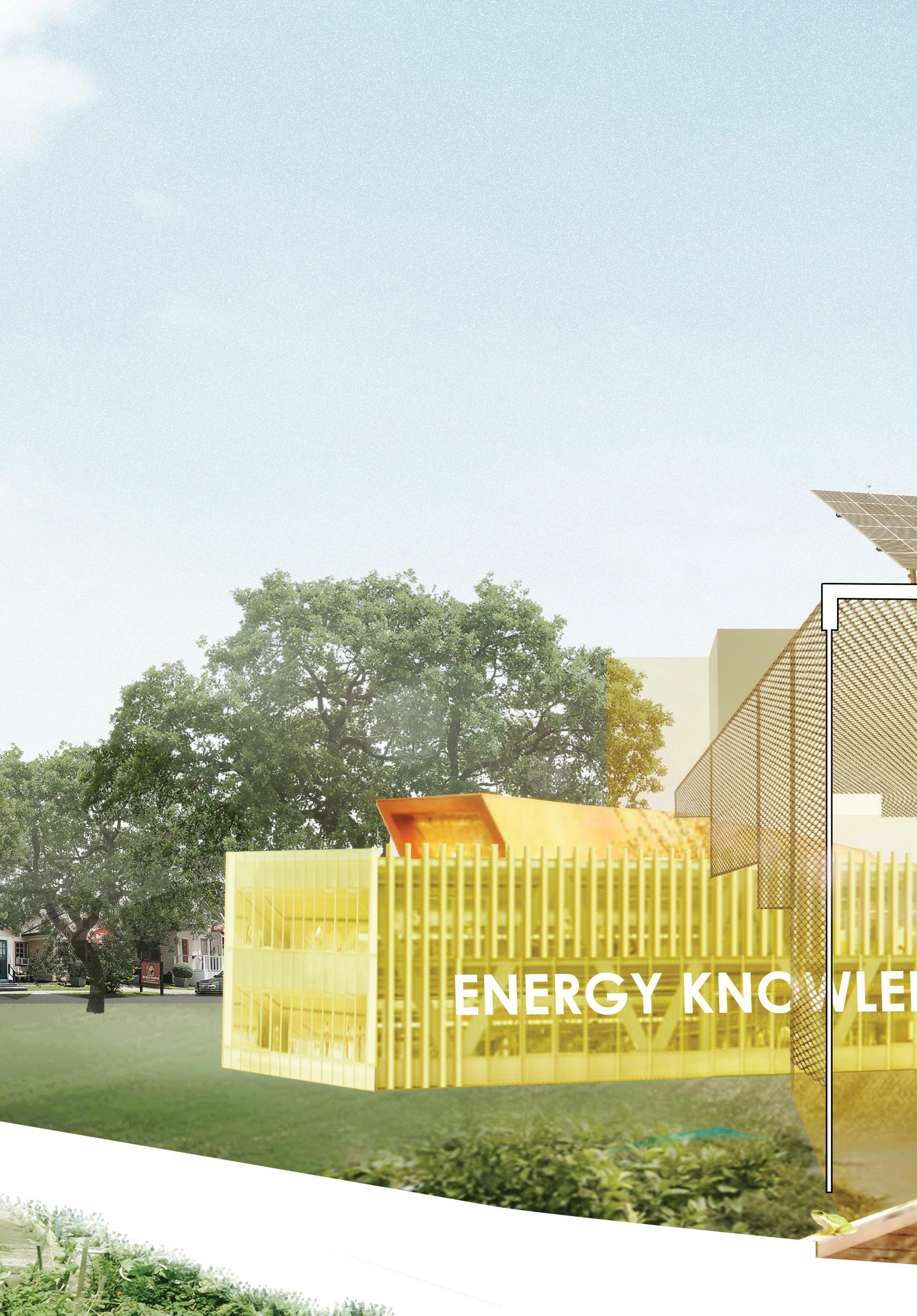

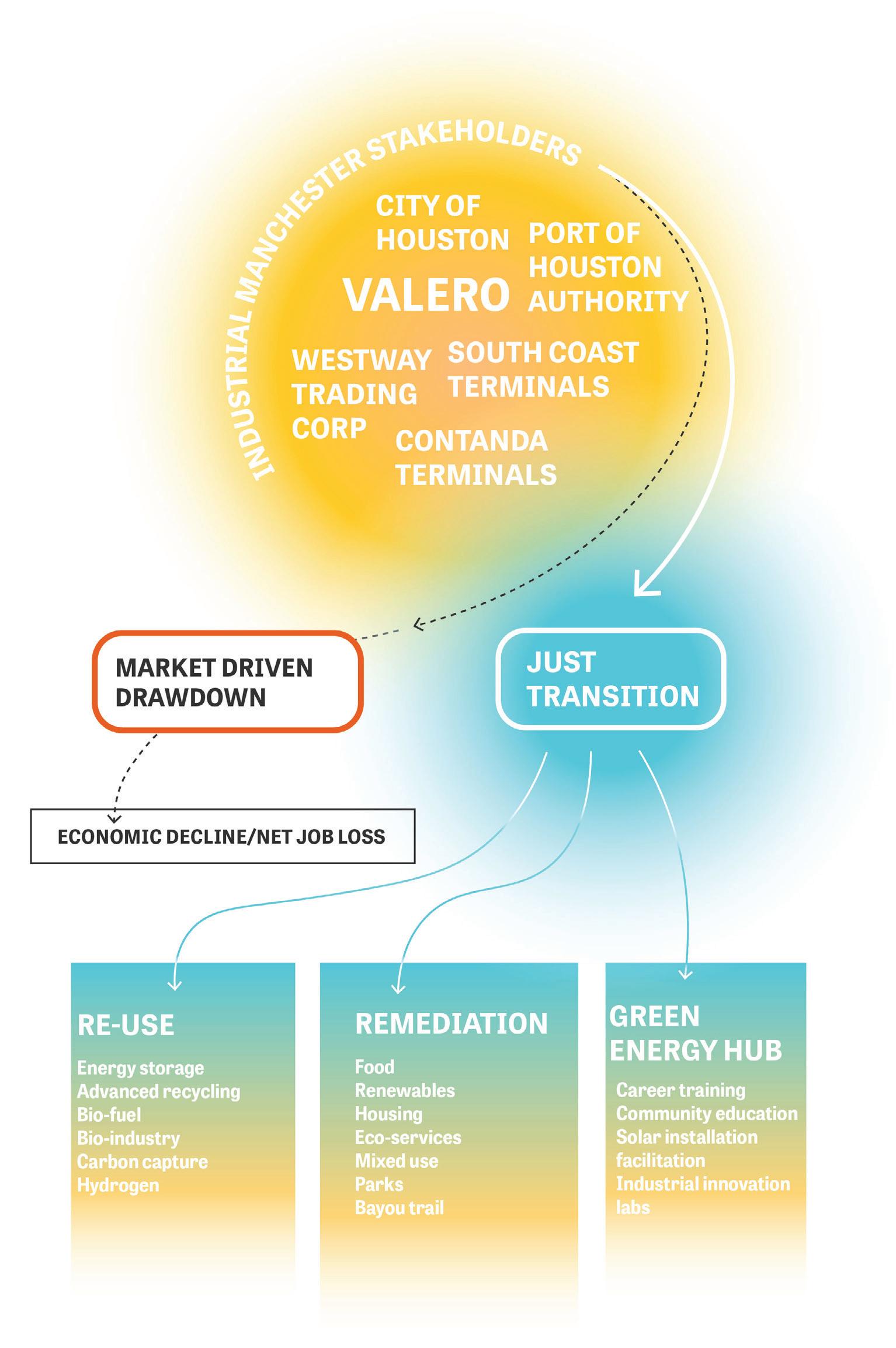

The City of Houston, and even industry organizations such as the Greater Houston Partnership, acknowledge the need to transition away from fossil fuels. For a city shaped by the energy industry, especially around the Ship Channel, this will provide opportunities to reimagine large swaths of its urban area. Questions about this transition, however, abound. How can it unroll, and will it be fast enough? Who will drive this transition, and who will benefit? What are the spatial interventions that can trigger innovation?

This studio sought to begin to answer some of these questions. Taken together, these designs form a catalog of responses that can stimulate conversation about Houston’s transformation to a climate-resilient and “just city” in a post-carbon world.

Studio Instructor

Matthijs Bouw

Teaching Assistant

Youngsoo Yang

Students

Christopher Ball

Cristian Bas

Dylan Culp

Yijia Duan

Grant Fahlgren

Kai Guo

Percy Long

Wanjiku Ngare

TR Radhakrishnan

Skyler Smith

Tian Wei Li

Youngsoo Yang

Mid-Review Critics

Amna Ansari

Janice Barnes

Sean Chiao

Steven Duong

Dalia Munenzon

Albert Pope

Margaret Wallace Brown

Final Review Critics

Lauren Alexander Augustine

Janice Barnes

Sean Chiao

Gonzalo Cruz

Steven Duong

Gina Ford

Cleo Glenn Johnson-McLaughlin

Nancy Lin

James McLaughlin

Dalia Munenzon

Sarah Whiting

Ross Wimer

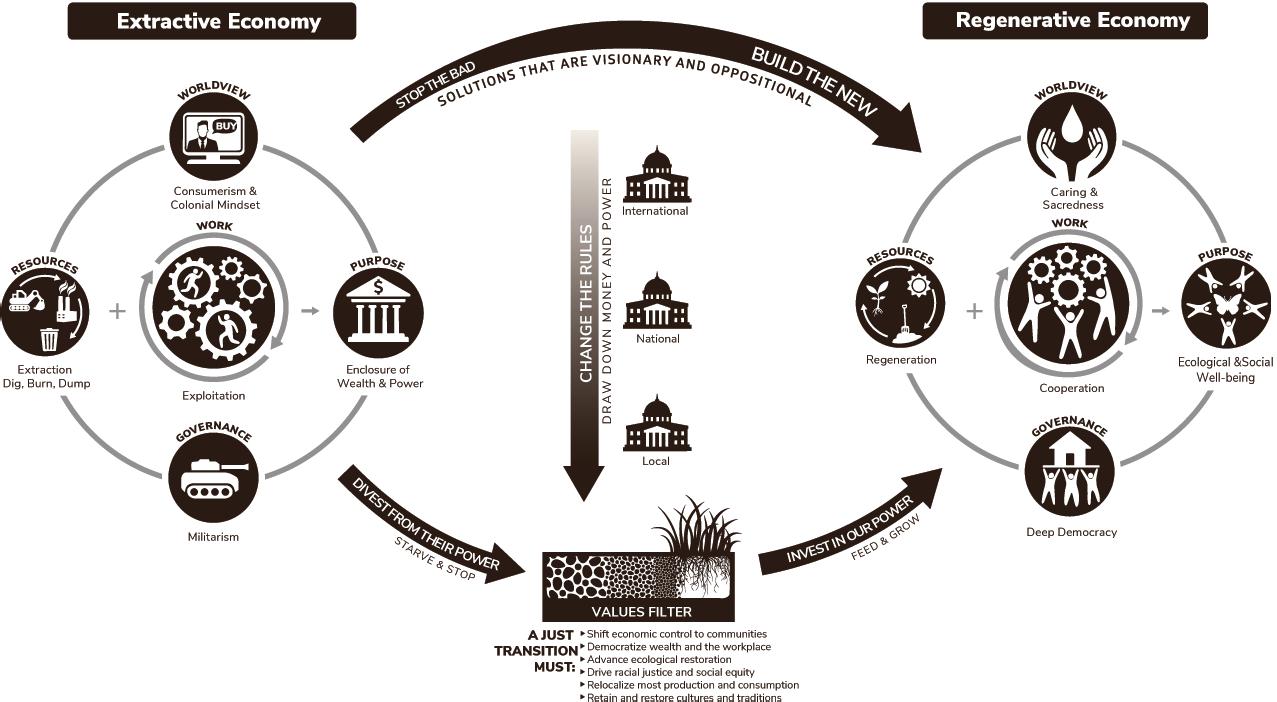

78 Economy

Yijia Duan, Skyler Smith, Youngsoo Yang

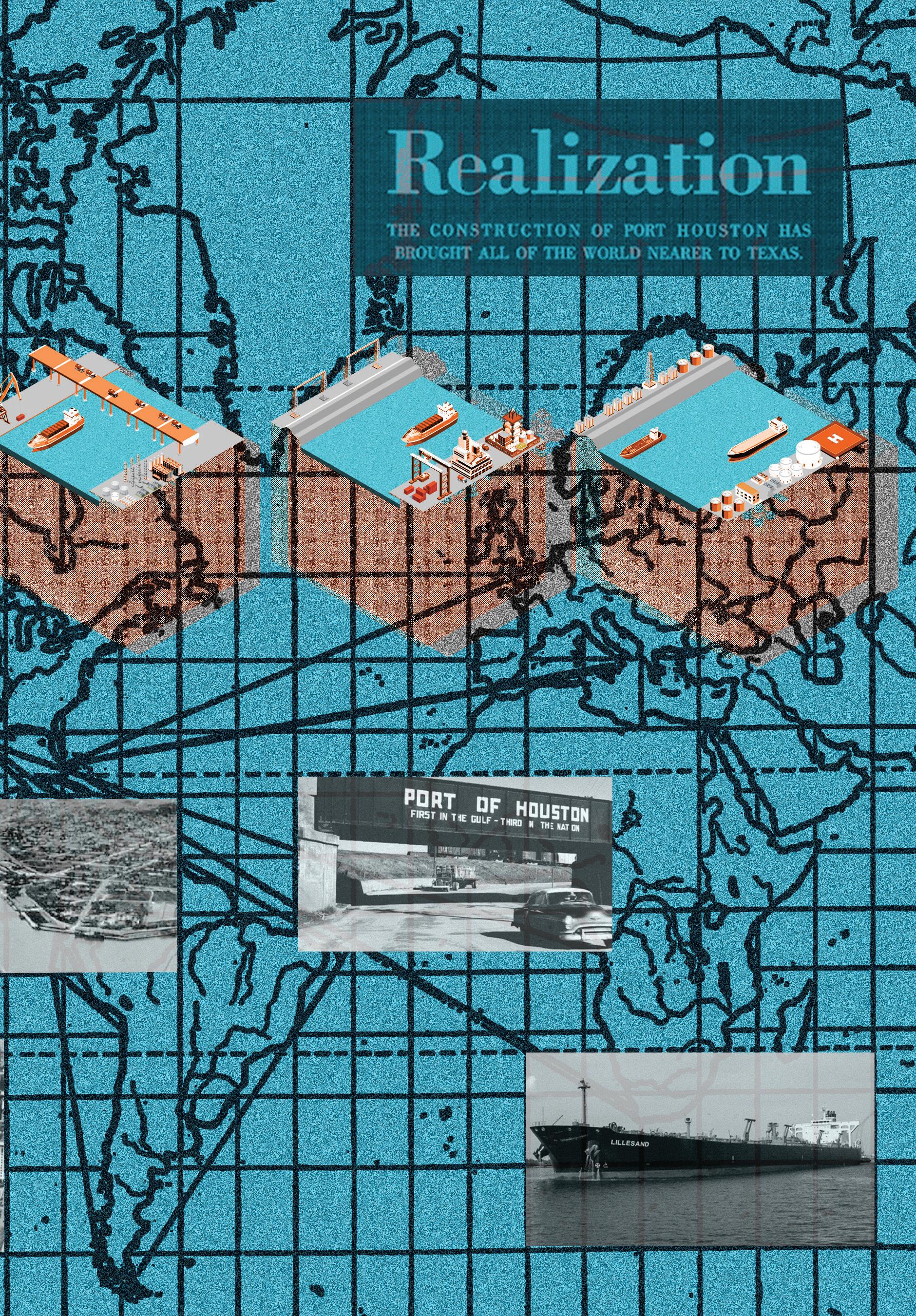

What If? Scenarios

86 Propositions

Projects

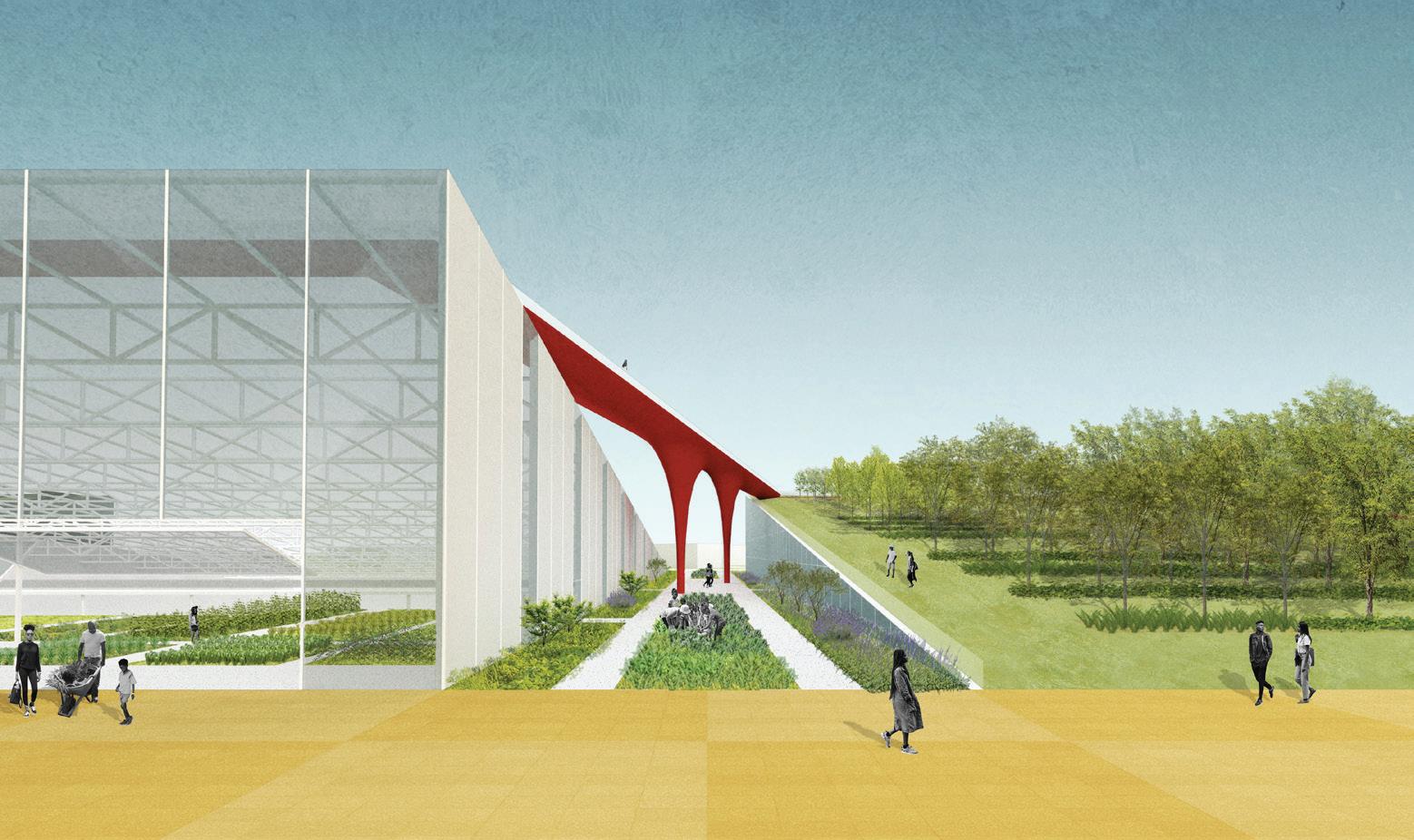

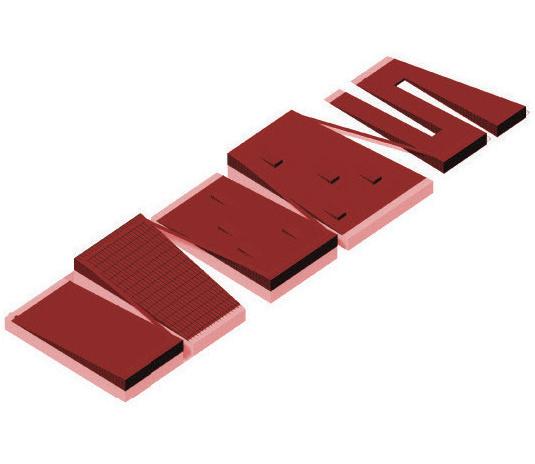

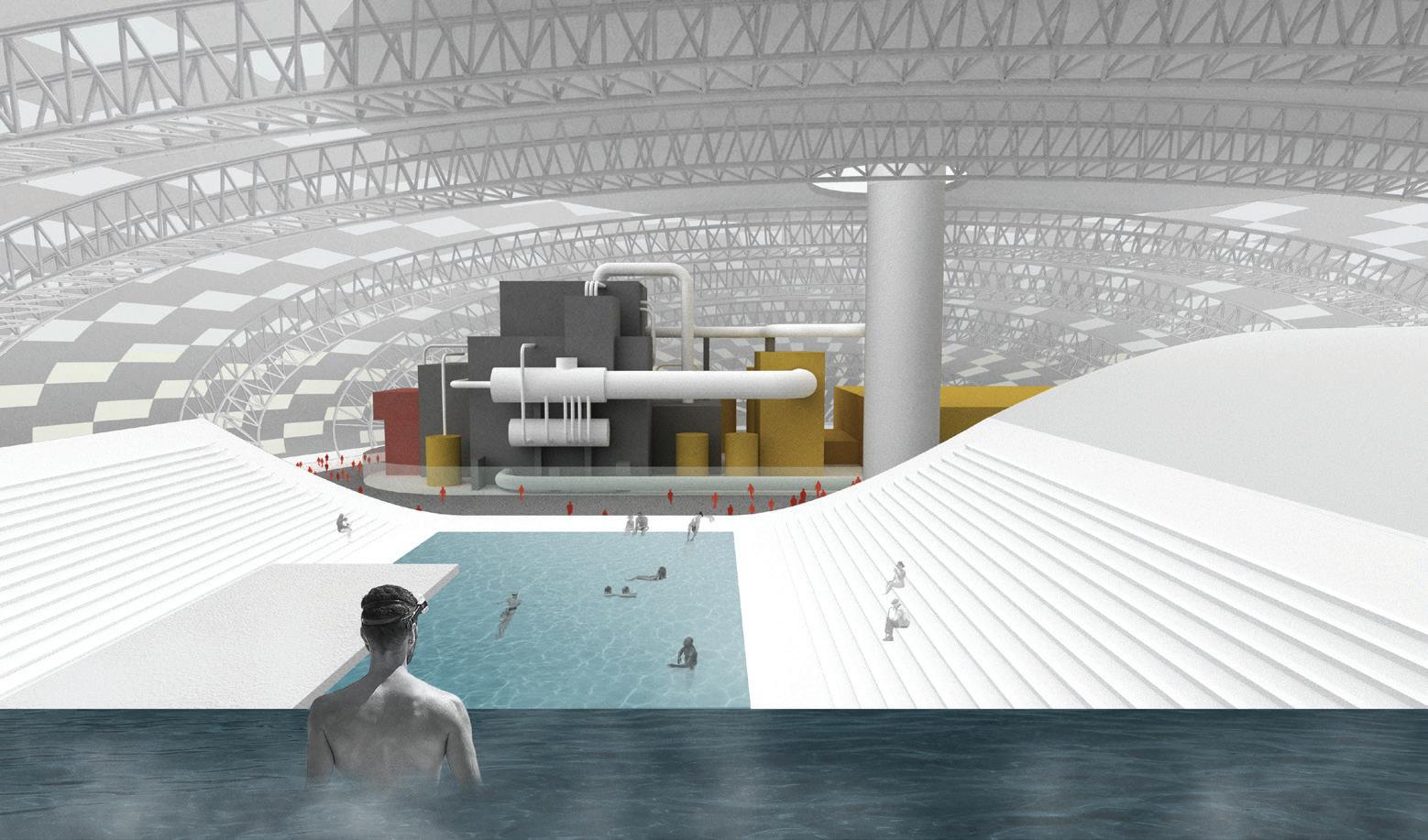

98 Activism by Design

Tian Wei Li, TR Radhakrishnan, Skyler Smith

126 Reuse by Design

Dylan Culp, Youngsoo Yang

138 Resilience by Design

Cristian Bas, Wanjiku Ngare

160 Adaptation by Design

Yijia Duan, Kai Guo, Percy Long

Christopher Ball, Grant

Houston. It was the first word heard on the moon (Houston, Tranquility Base Here. The Eagle Has Landed, proclaimed Neil Armstrong in 1969). The word continues to resonate with otherworldliness today. While Houston boasted the first electric streetcar system in 1891, the city now sprawls across 665 square miles and is associated with endless highways rather than public transit. Seemingly dominating its subtropical climate with air conditioning, Houston expanded with astonishing rapidity across the second half of the twentieth century as it took on the role of energy capital of the world.

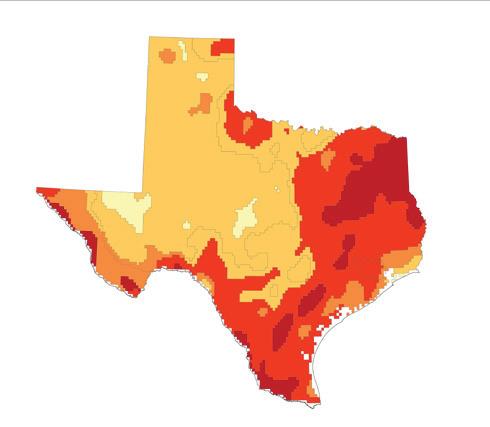

Today, however, Houston’s sprawl and hermetically sealed towers have become visible emblems of how not to design for a planet in peril. An alarming rise in extreme weather events, combined with rapidly increasing temperatures (Houston averages temperatures that are already three degrees higher than they were at the end of the twentieth century) and numerous social and spatial inequities, make it urgently necessary to imagine alternative futures for the city.

These are the kinds of challenges that we love to sink our teeth (and brains) into as a design school, but it is an especially daunting enterprise to take on a challenge of Houston’s complexity in a fourteen-week studio. I want to thank our visiting design critic Matthijs Bouw for organizing a remarkable studio that used design strategies of adaptation, mitigation, and justice to envision how to reconfigure the Houston Ship Channel — the busiest waterway in the U.S. — as it transitions from hosting the biggest petrochemical complex of its kind to sites for clean energy, logistics, and natural systems. The studio additionally explored ways of addressing the appalling social, environmental, and economic inequities long experienced by the neighborhoods abutting the Channel.

Part of this ambitious semester was devoted to research, conducted in groups and resulting very quickly in an important shared resource. Experts joined the studio at points to expose the students to strategies of geological sciences, urban development, data science, and community engagement, among others. Our partnership with AECOM, which made this studio possible, afforded us access to still further information, expertise, and assistance.

The results were group projects, each devoted to one large component of this immense urban challenge: activism, reuse, resilience, adaptation, and culture. The studio results have to be appreciated in combination. While the projects displayed within this Studio Report are innovative and interesting individually, the studio was itself a deep dive into synthetic design: the collaborative work started with the research and continued with the projects and even with this book, each iteration grouping different members of the studio. By the end, every student had learned that for design to succeed in tackling the greatest and most urgent challenges of the day, it has to be approached synthetically, connecting disciplines, connecting expertise, connecting topics, and connecting individual designers.

Union Pacific Englewood Yard, looking toward downtown Houston.

Union Pacific Englewood Yard, looking toward downtown Houston.

Bouw Studio Instructor

Bouw Studio Instructor

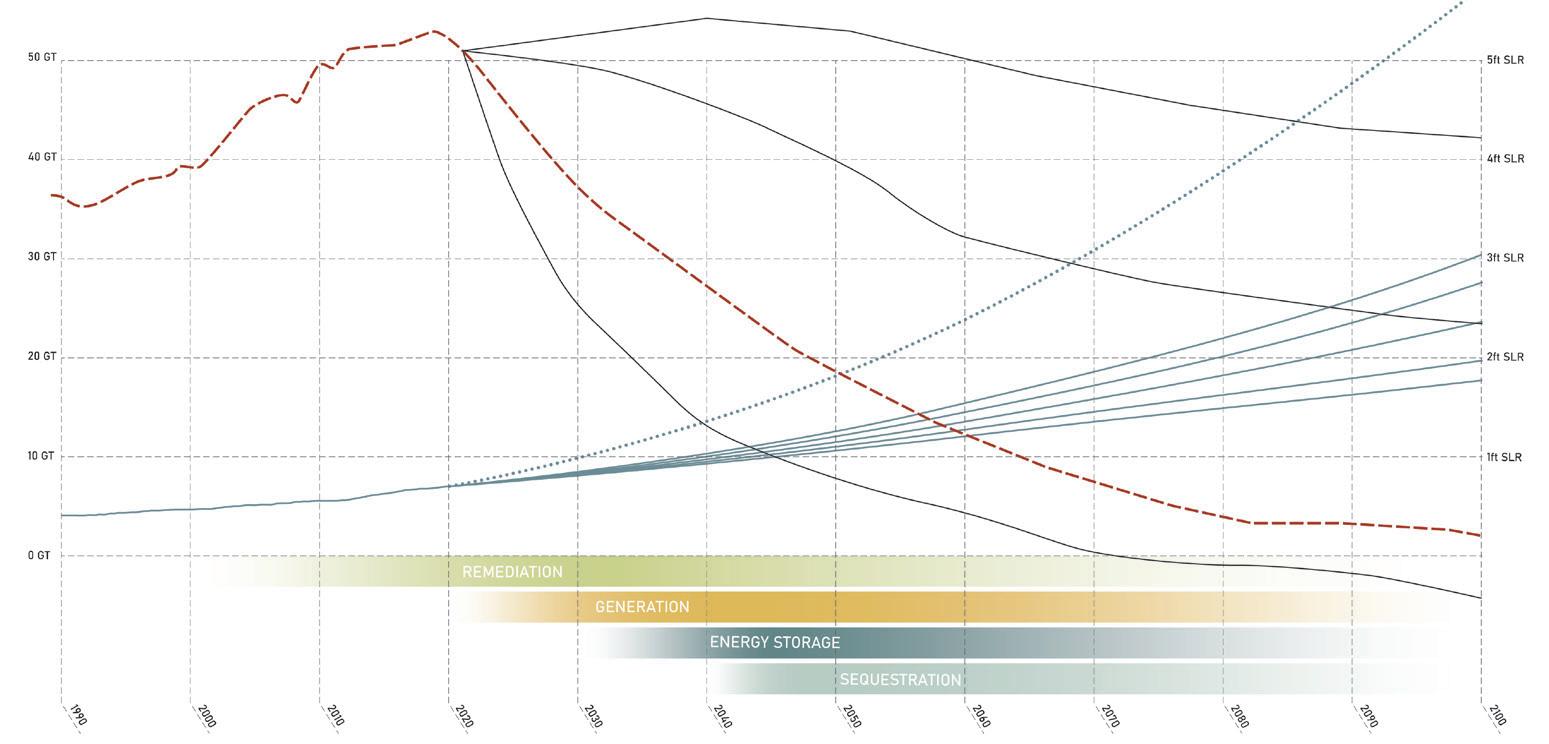

The climate crisis is not only changing what we design, but also how we design. Without stable environmental conditions, we must now design for constant change. Whatever we design now will have to perform, later in its useful life, in radically different climate conditions. What these conditions will be, and when certain conditions will be reached, we do not know. The pace and impact of a changing climate will depend largely on society’s ability to mitigate emissions and on often yet unknown feedback mechanisms in the Earth’s climatic system. Given that uncertainty, and the high costs of investing in worst-case adaptation scenarios, the buildings and infrastructures we design should not be designed for a final state, but rather as part of a succession of iterations in which any project becomes part of a process of constant change.

The uncertainty and unpredictability that characterizes the climate crisis makes it even more important to engage both the near term and the long term simultaneously. We need to understand how what we design can adapt, and how what we design (or decide not to design) can mitigate the climate crisis, which, in this complex system, also impacts the need for adaptation. Nowhere is that clearer than in Houston, where adaptation and mitigation are locked into a macabre dance.

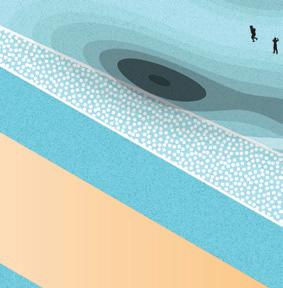

The Houston Ship Channel at the Sidney Sherman I-610 Bridge, Harrisburg-Manchester.

The Houston Ship Channel at the Sidney Sherman I-610 Bridge, Harrisburg-Manchester.

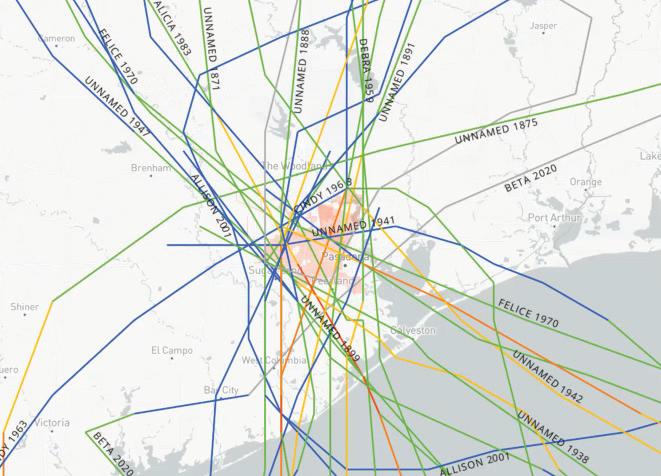

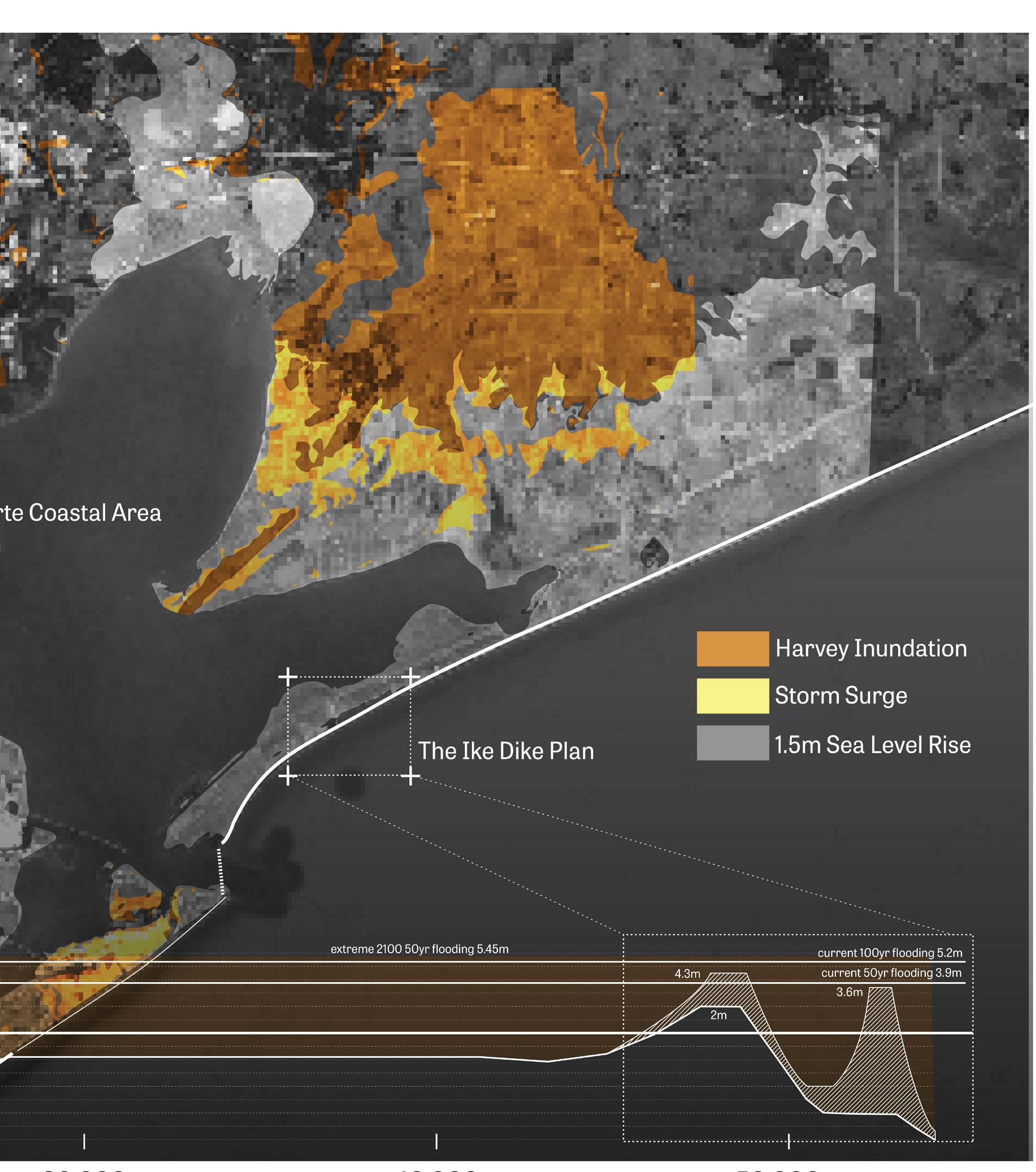

Houston is one of the US cities most impacted by the climate crisis. In the 2010s, a number of onethousand-year storms hit the area, including the Tax Day Floods and Hurricane Harvey. Harvey unleashed up to fifty inches of rain on the city, and the Harvey-related costs attributed to the climate crisis are estimated to be as much as $67 billion USD. In 2021, Winter Storm Uri resulted in the collapse of the energy system. And while 2008’s Hurricane Ike had limited impacts on Houston proper, sea level rise and increased

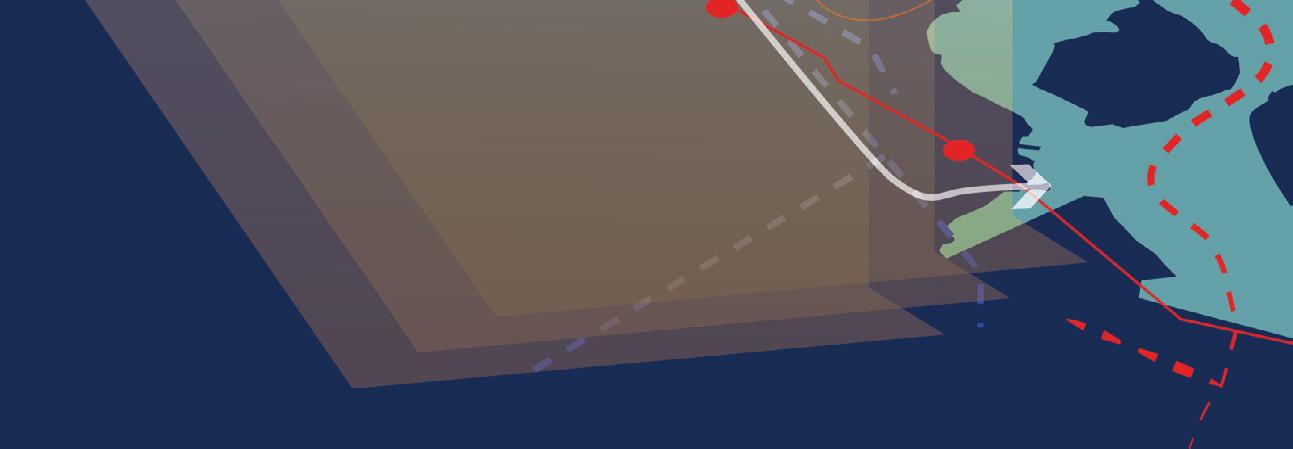

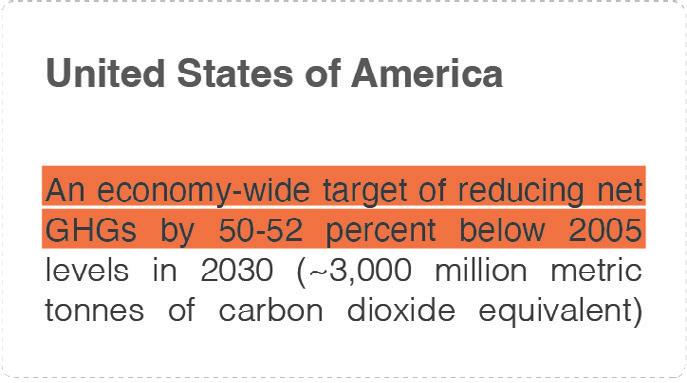

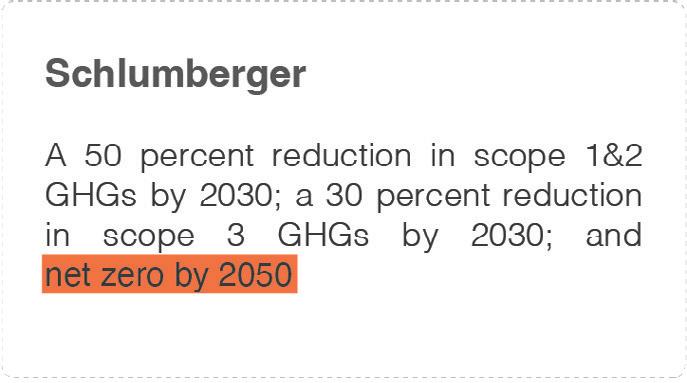

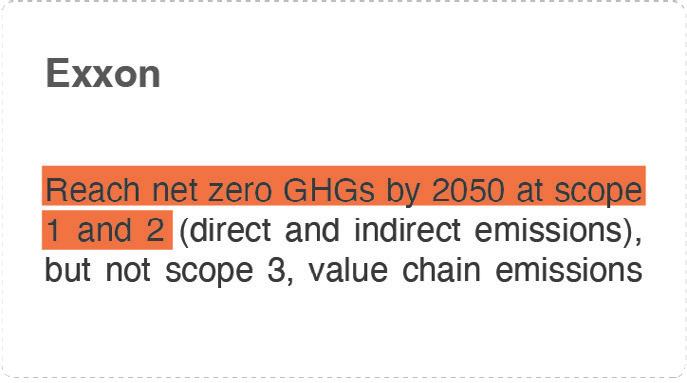

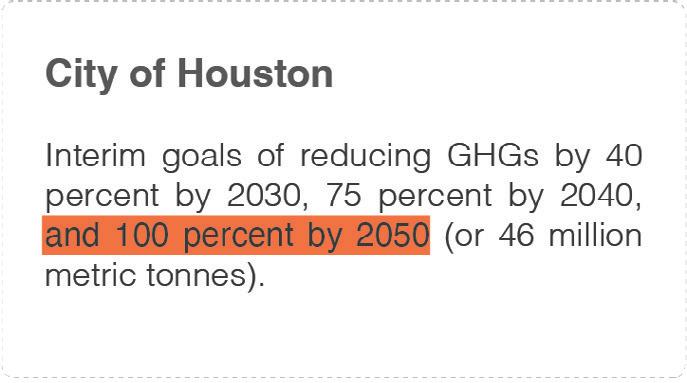

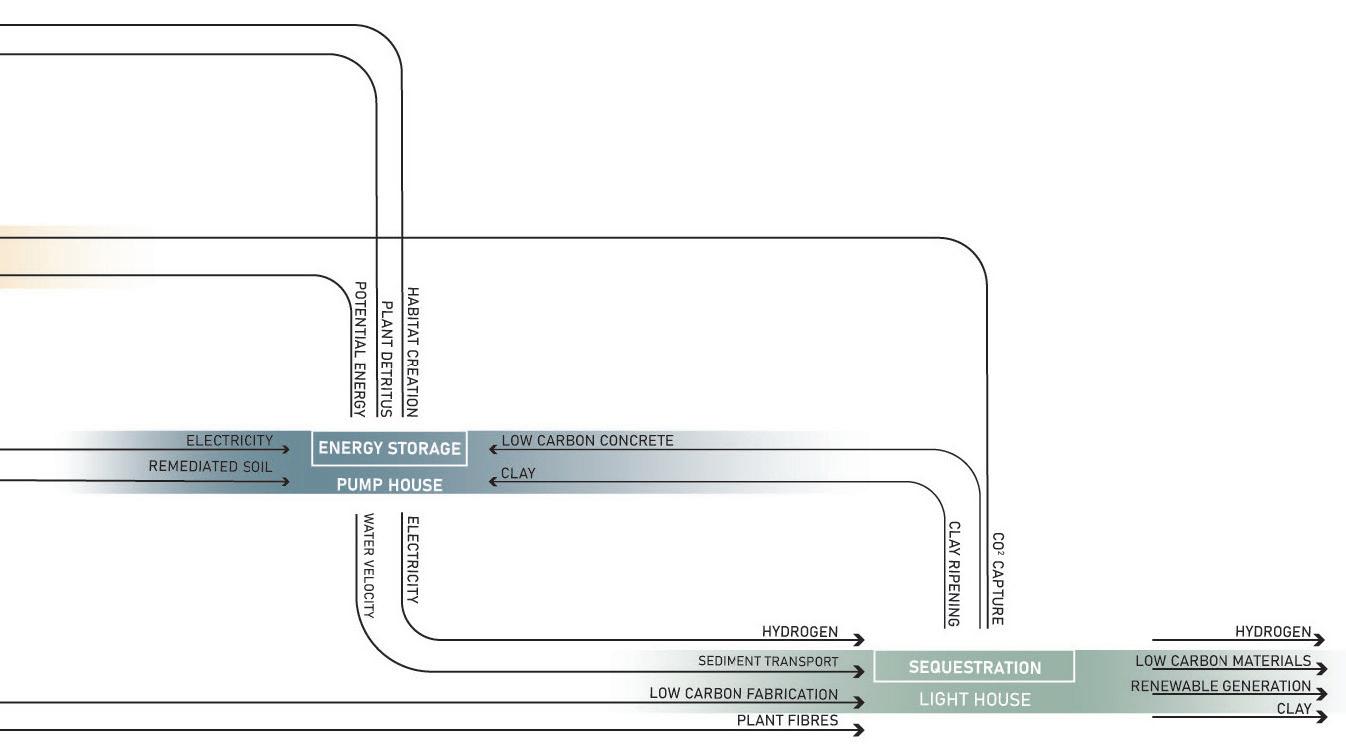

Climate Action Plan sets ambitious goals in four focus areas: transportation, the energy transition, building optimization, and materials management.1 Resilient Houston, a resilience strategy initiated after Hurricane Harvey, looks holistically at the various shocks and stresses that can befall the city and formulates its vision in five themes: “a healthy place to live, an equitable, inclusive, and affordable city, a leader in climate adaptation, a city that grows up, not out,” and “a transformative economy that builds forward.”2 The strategy was supported by a large donation from Shell Oil. Houston’s business community, through the Greater Houston Partnership, has developed more plans to help Houston adapt to the climate crisis. Its Regional Energy Transition Initiative (HETI) from 2021, for instance, proposes to invest in “carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS), hydrogen production and application, the circular economy (specifically plastics recycling), and energy storage solutions” and uses as an example ExxonMobil’s proposal for a $100 billion carbon-capture innovation zone along the Ship Channel.3

storm intensity have increased the risk to such an extent that the US Army Corps of Engineers is preparing a $34 billion Texas Coastal Project to protect the region.

Houston effectively represents both the impacts and causes of the climate crisis. The Ship Channel is home to the largest petrochemical industrial complex in the world. It is a city whose growth and urban form have been driven by the car and the air conditioner. The size of Houston’s fossil-fuel-generated wealth, its highways, and its monuments are testament to what we now see as the hubris of the twentieth-century city, with the climate crisis coming back to bite it.

To thrive in the twenty-first century, with climate change rapidly accelerating, the city will need to lead decarbonization efforts, build resilience, and rebalance its urban and natural systems.

In order to facilitate that process, Houston has made some ambitious plans. Its 2020

Such a proposal could be funded, in part, through private investment and, in part, through the federal government, which has allocated significant funding for carbon capture and removal in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Critics, however, say the proposal is part of Big Oil’s tactics to delay the energy transition because it would allow the continued use of fossil fuels. Such massive projects are filled with uncertainty and take a long time to realize while locking in continued investment in fossil fuels, making the rapid drawdown of their use, as demanded by science and international agreements, much more challenging.

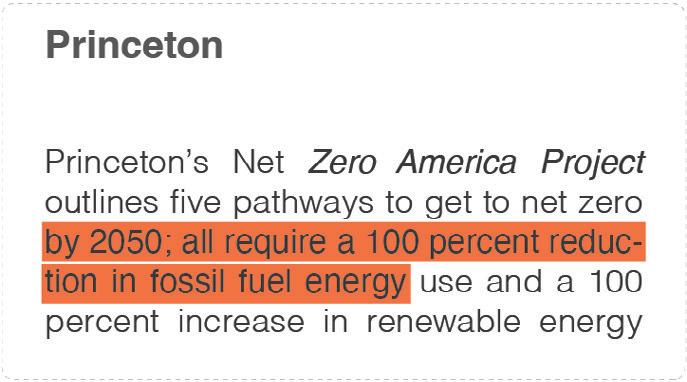

Other scenarios for the energy transition suggest that government subsidies are best directed away from what these same critics call historically unreliable corporations and toward more decentralized and local initiatives for renewable energy production and reduced energy use, such as rooftop or community solar, home weatherization and batteries, and changes in transportation and manufacturing. When combined with the significant deployment of solar and wind, such scenarios would suggest more rapid and drastic changes to the industry in the Ship Channel than are currently envisioned by the petrochemical industry itself.

Manchester’s Valero Refinery surrounds a residential community.

Manchester’s Valero Refinery surrounds a residential community.

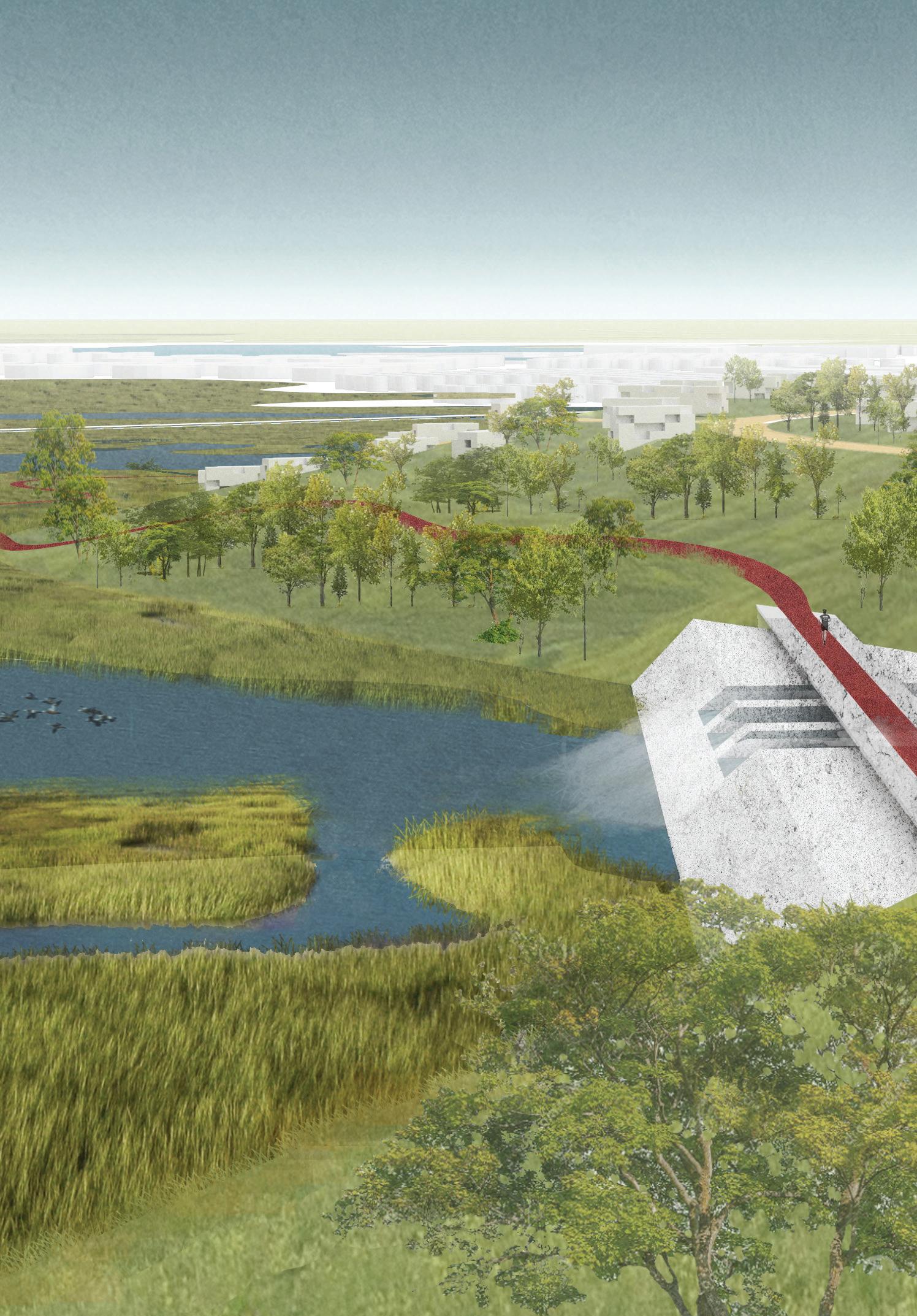

Wildlife returns as Hunting Bayou is renaturalized.

Wildlife returns as Hunting Bayou is renaturalized.

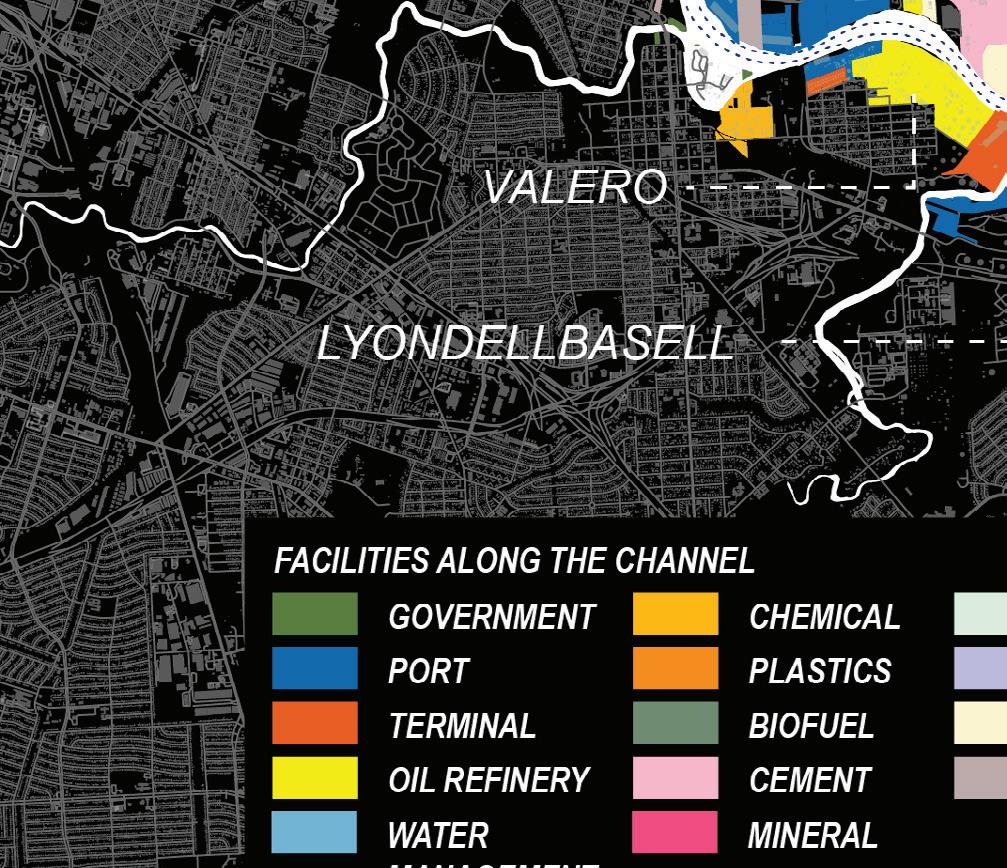

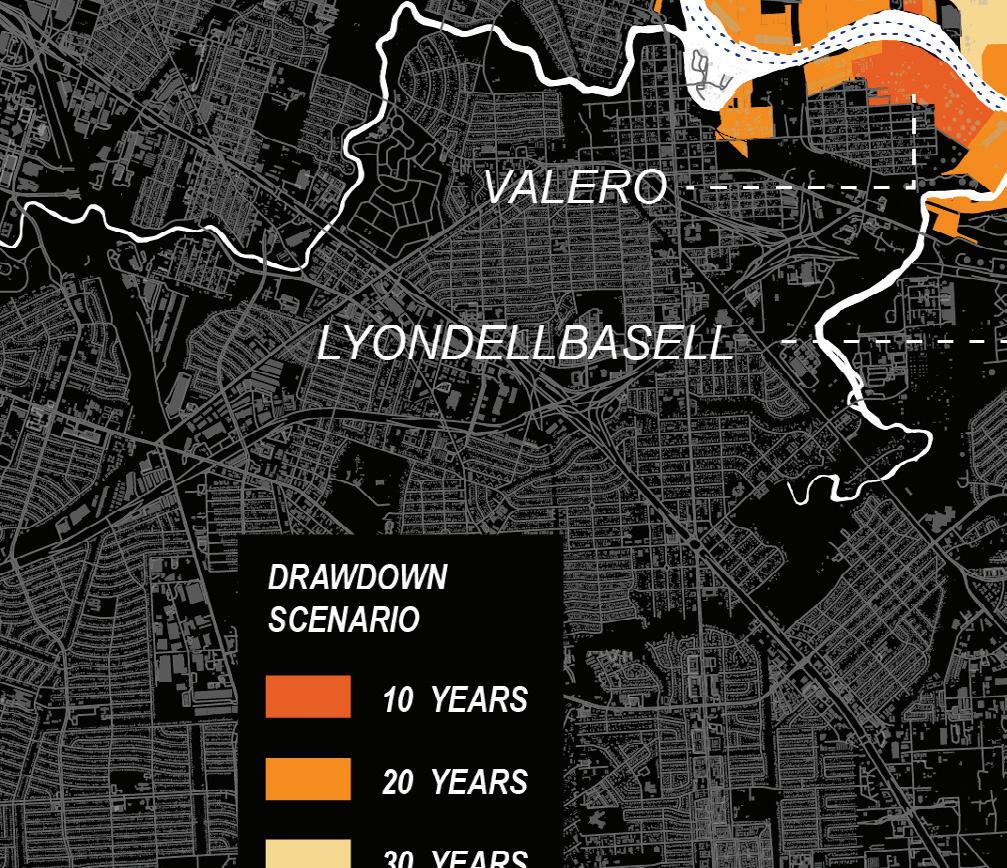

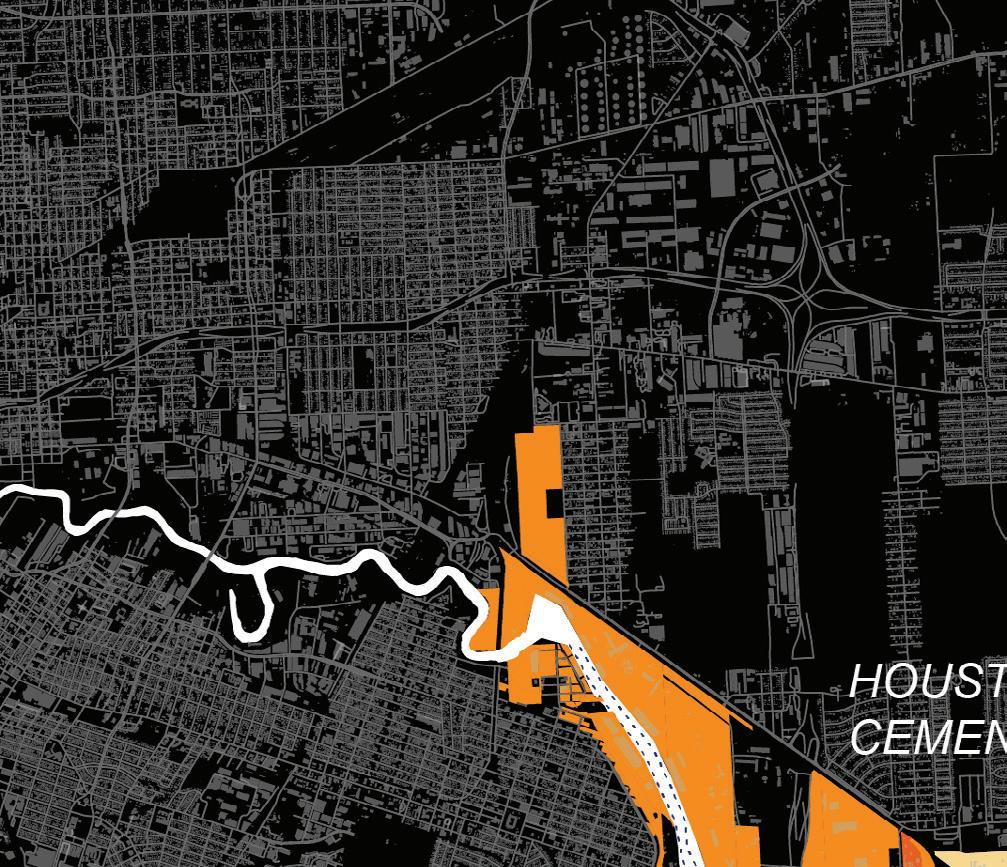

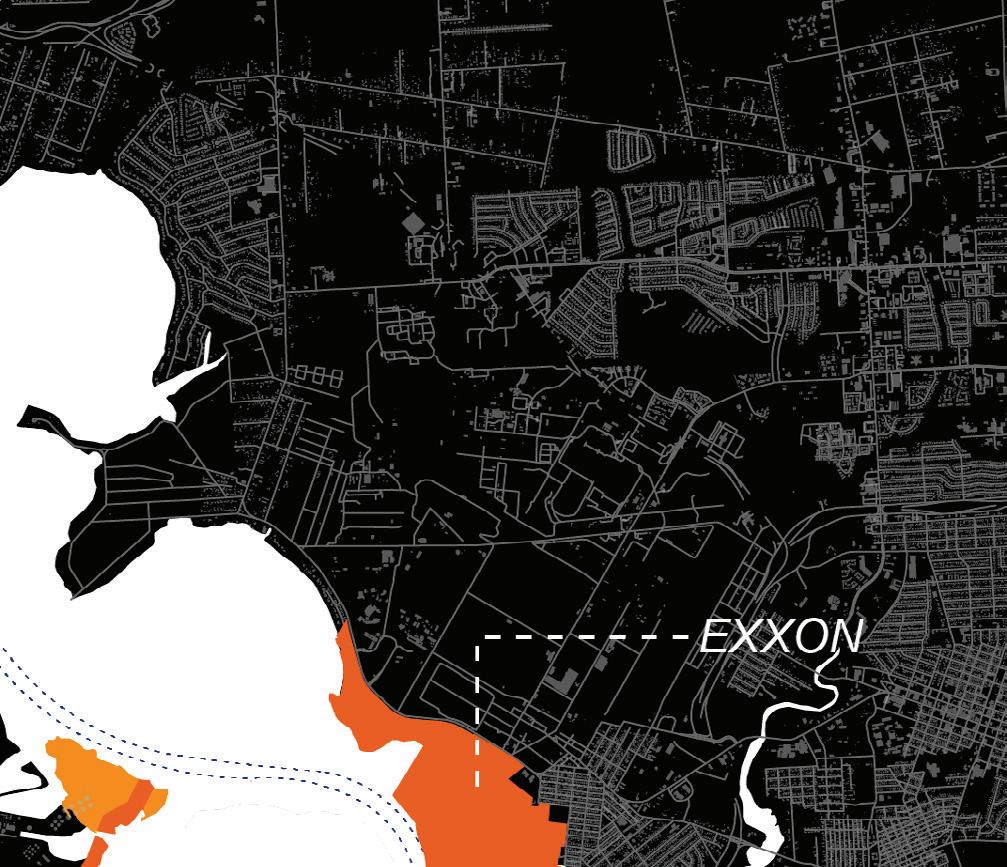

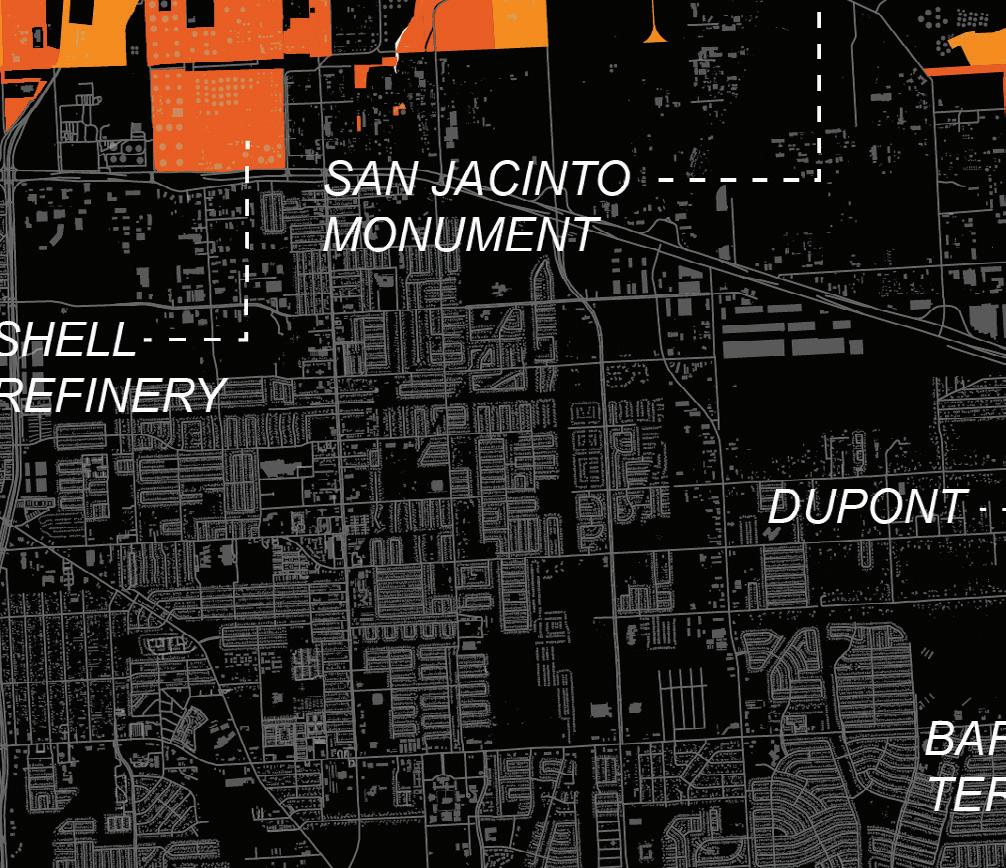

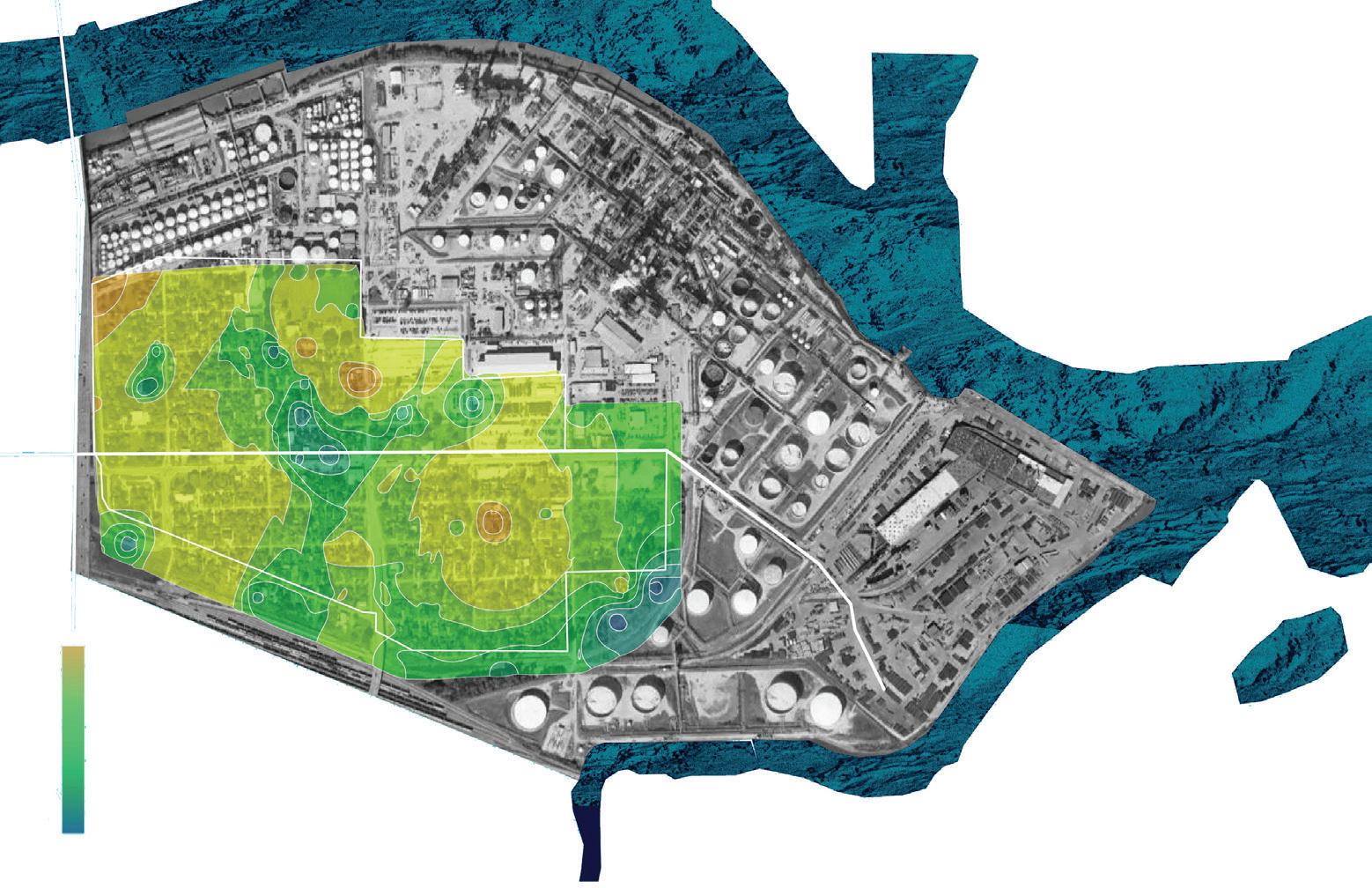

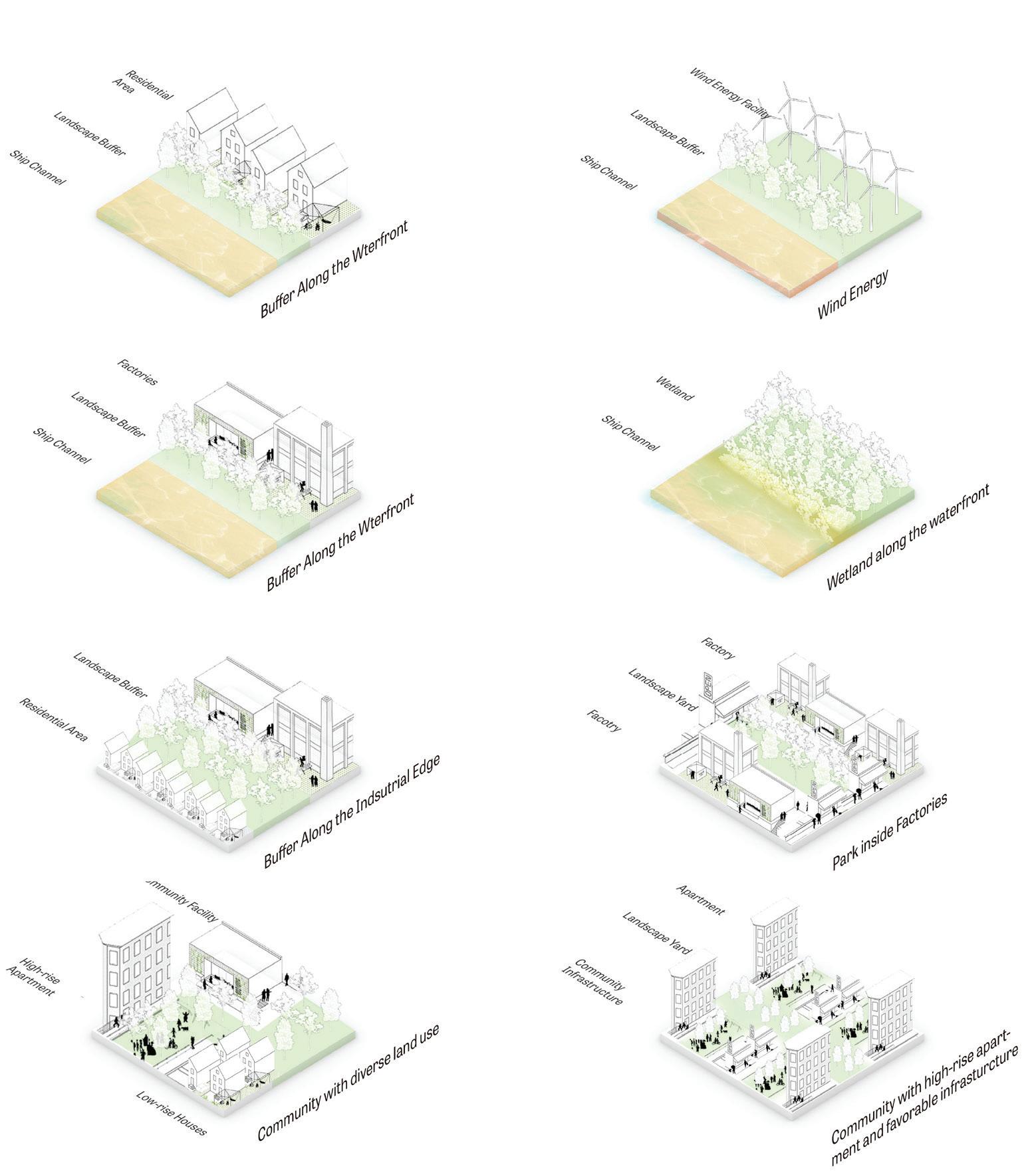

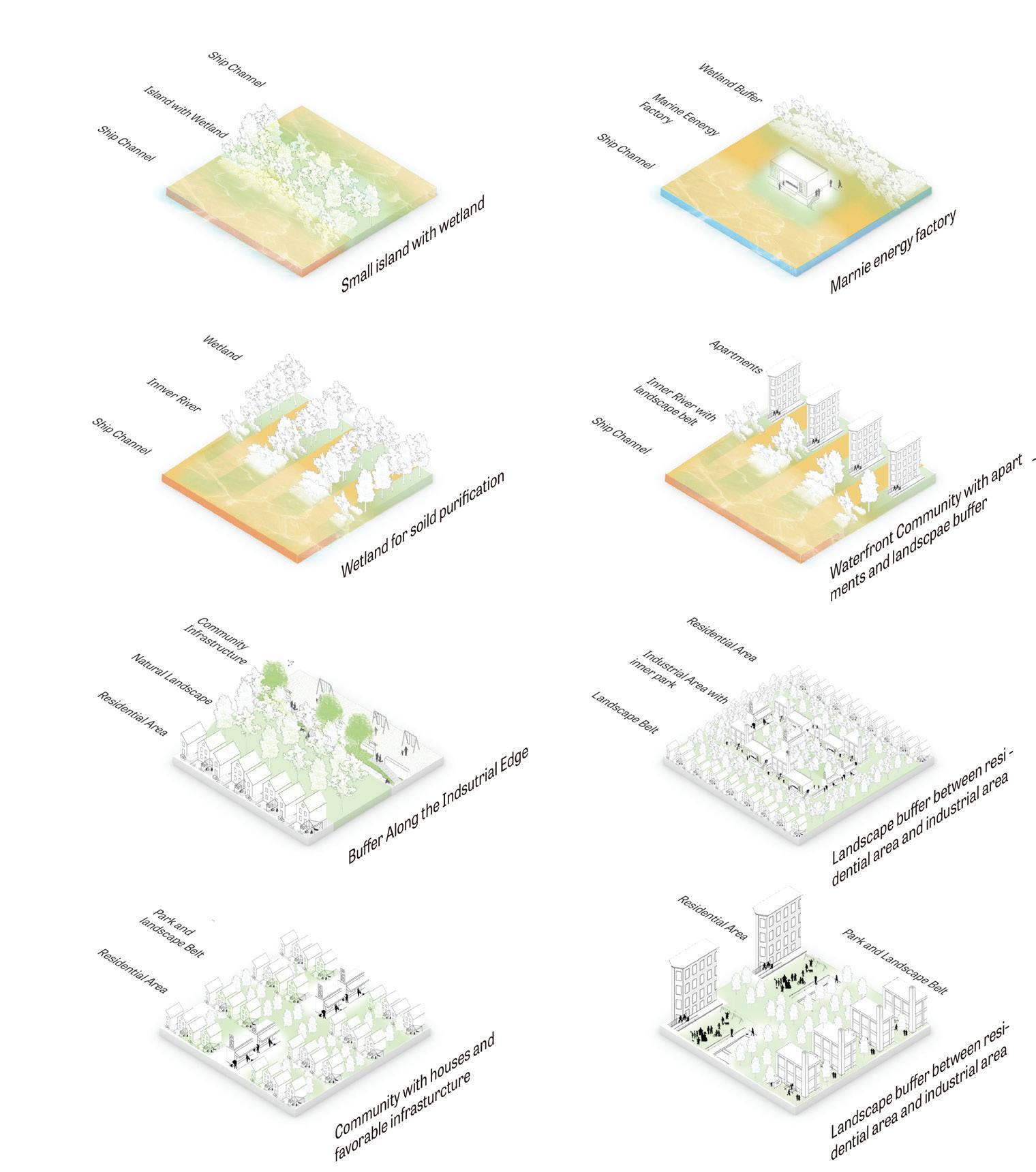

While we do not know how the energy transition will play out in the Ship Channel, we do know that the spatial impacts will be significant. The chemical giant Lyondell Basell’s announcement that its seven-hundred-acre Houston refinery would be shut down in 2023 seems a likely precursor to many land use changes to come.4 Such sites can be reused for clean energy or for functions that are ill-suited elsewhere. The drawdown of contaminating industries will also

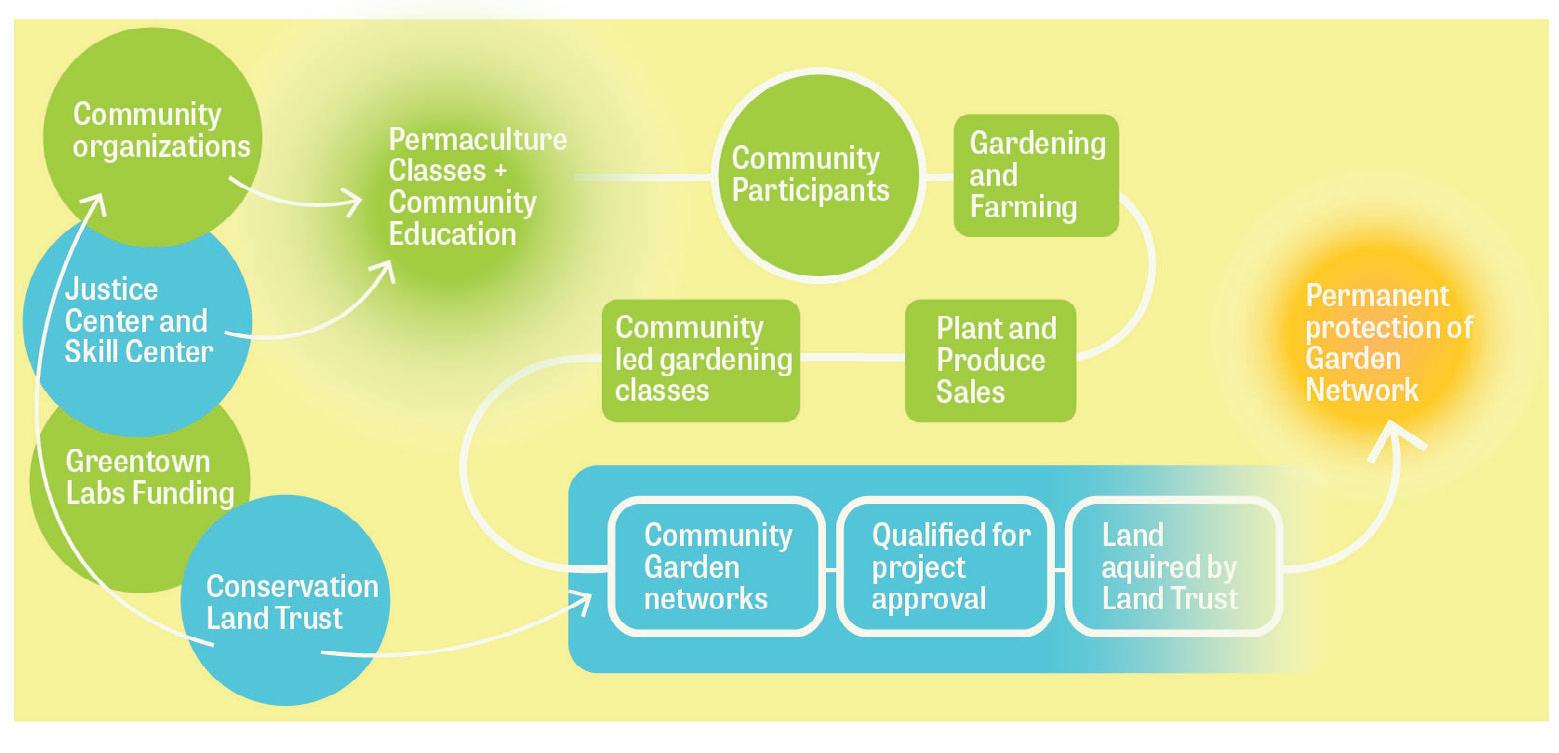

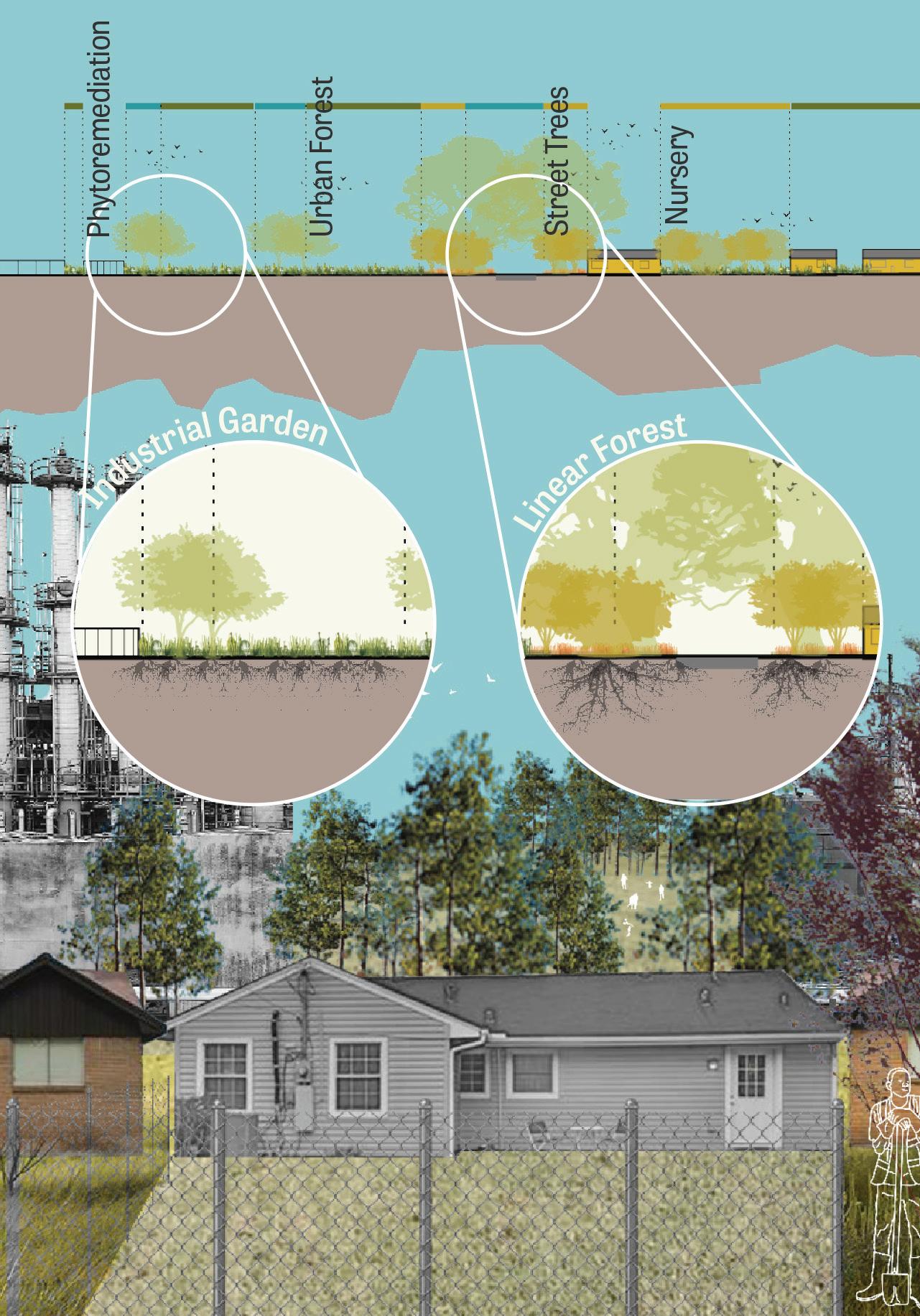

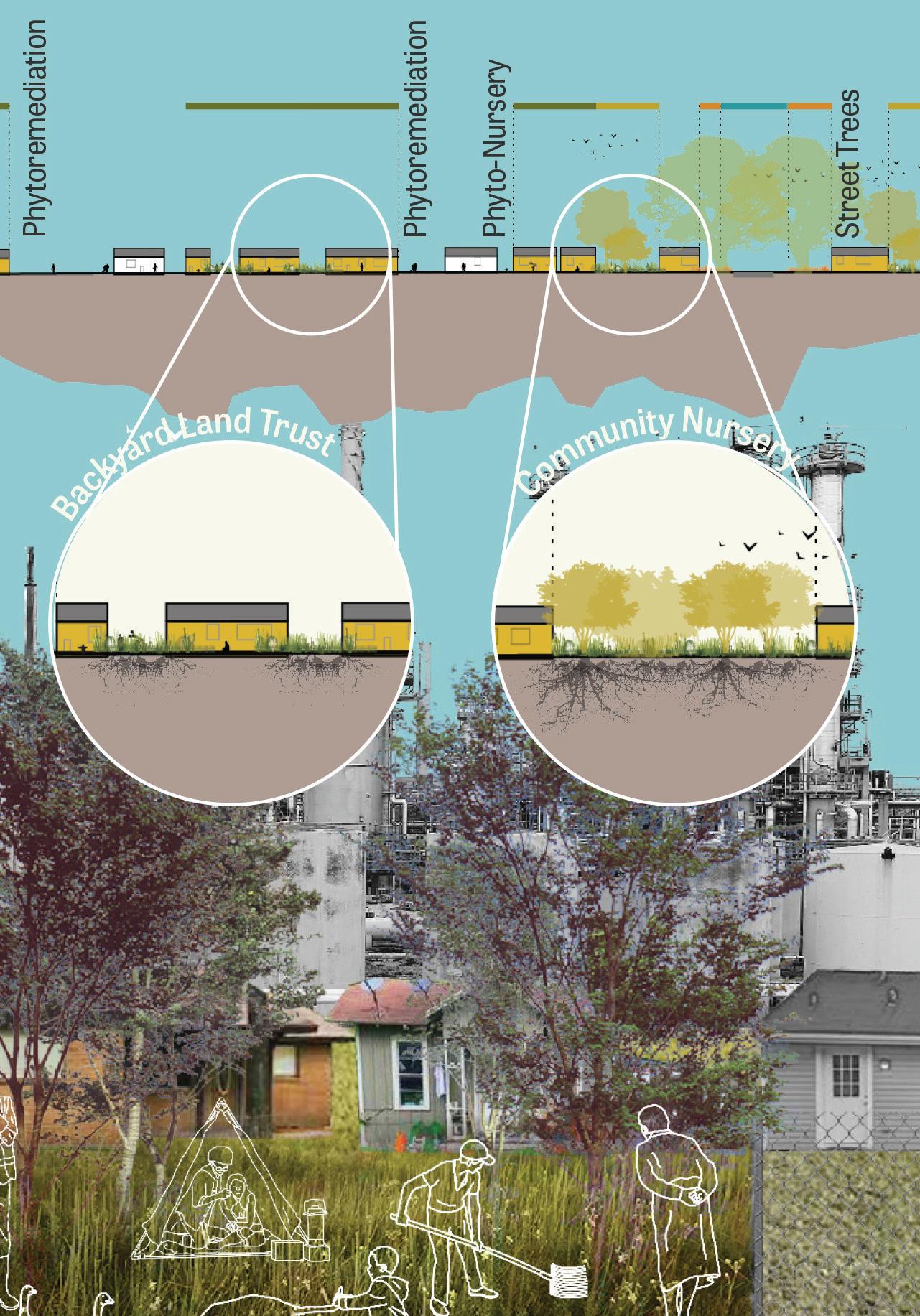

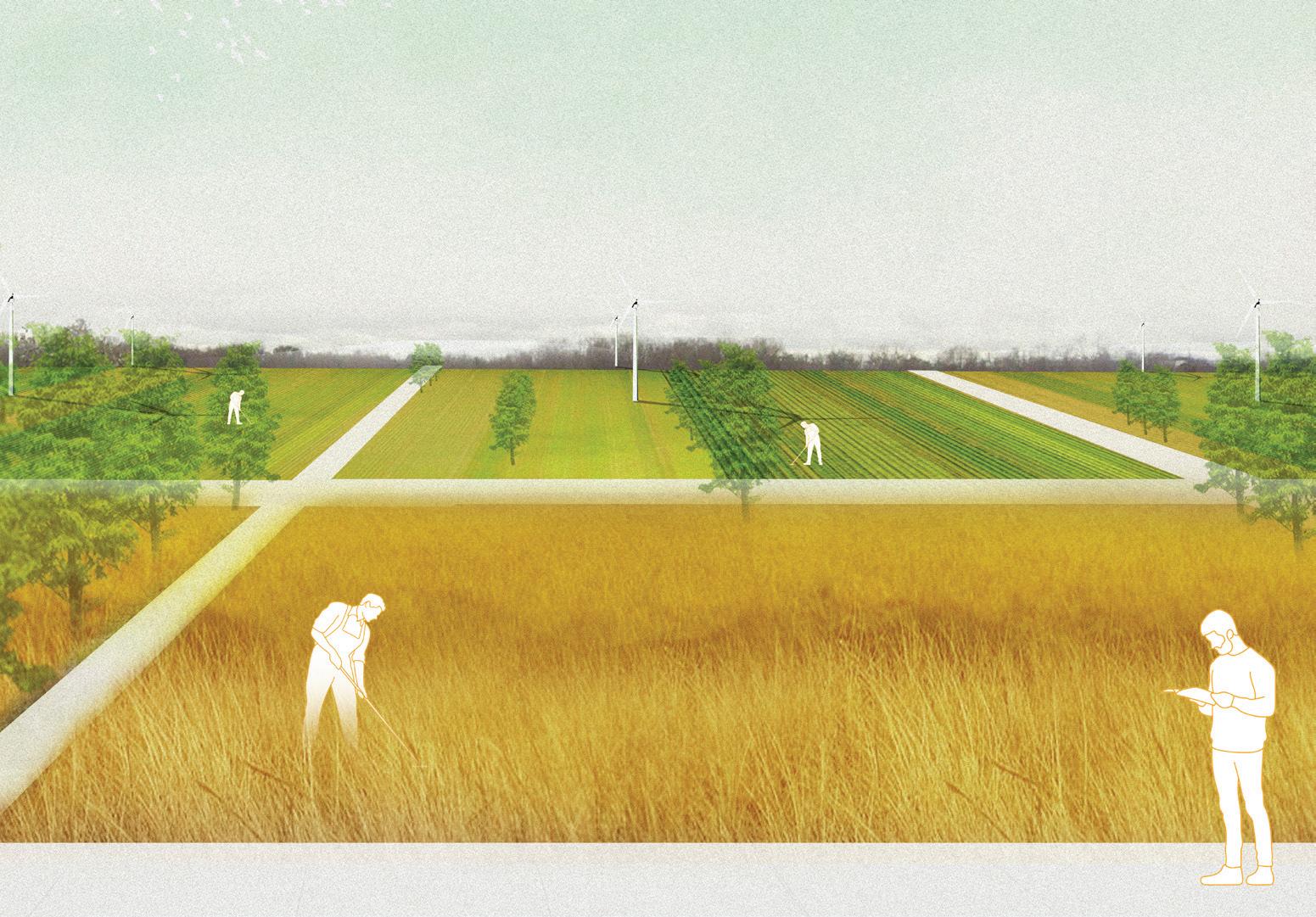

help the frontline communities, many of whom have been negatively impacted by industrial pollution affecting their soil, water, and air quality. The energy transition brings significant opportunities to these historically marginalized communities. Land use changes in the Ship Channel area can enable its isolated neighborhoods to better connect with one another, pursue economic opportunities, and adapt to climate change. Nature-based solutions to protect from floods and store water can be combined with recreational amenities and ecological restoration to increase biodiversity. Because they can capture carbon, these efforts would support the Port of Houston’s goal, as stated in April 2022, to be carbon neutral by 2050.5 And, in a more decentralized energy transition scenario, significant local investments, such as the Sunnyside Solar Project, might make the Ship Channel’s communities more livable and resilient while creating local jobs.

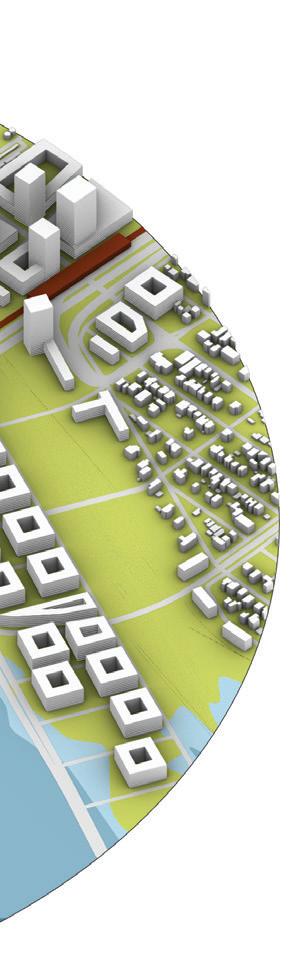

The studio Houston: Extreme Weather, Environmental Justice, Energy Transition was organized to help understand these changes and, by extension, the intersections between the three drivers of extreme weather, environmental justice and the energy transition. But its main aim is to explore desirable futures. As the studio brief formulates, architecture, landscape architecture, and planning students (most with a specialization in urban design) worked from “the hypothesis that these three drivers can result in a wholesale reconfiguration of the Ship Channel area, where sites left empty by the drawdown of fossil-fuel industries can be reimagined as sites for clean energy, logistics and natural systems. This process creates the opportunity for the communities near the downtown end of the channel to reconnect, remediate and regenerate.” The Dutch political scientist Maarten Hajer used his inaugural lecture as Distinguished Professor of Urban Futures at Utrecht University to describe the idea of “techniques of futuring,” which he defines as “practices bringing together actors around one or more imagined futures and through which actors come to share particular orientations for action.” Design is one such practice. Design helps us make the interdependencies within complex systems concrete by positioning its components in territory, space, and time, thus ground-truthing developments, claims, and ideas. It helps show where different ways of tackling problems can be optimized and integrated into widely beneficial solutions and inclusive visions. And through all that, because of its ability to visualize and make things concrete, it becomes a tool for social sharing, helping stakeholders understand issues and positions, and build the coalitions necessary for a way forward.

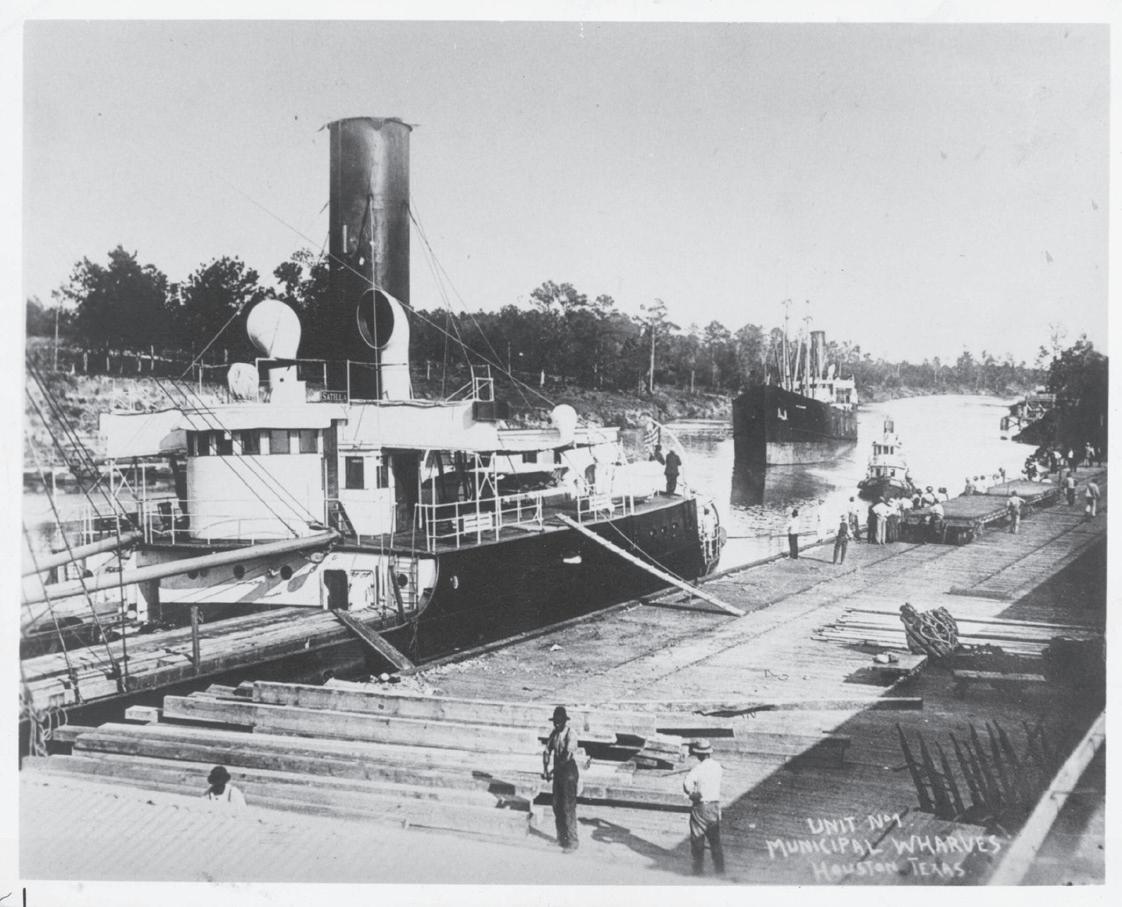

The Houston Ship Channel is the busiest waterway in the United States.

The Houston Ship Channel is the busiest waterway in the United States.

In this book, we share the results of the Houston studio. As the reader will appreciate, many of the considerations above have shaped the studio’s format and final outcomes.

It began with group-wide, collaborative research in which multi-disciplinary teams worked on a range of topics (Place, Environment, Economy and Capacity), capped off with a two-week “research by design” phase that used scenarios to jump-start the design process.

The future of the Ship Channel area is uncertain and exciting. As a global hub for energy, Houston’s transition will be driven by factors playing out at a worldwide scale. At the same time, because of this connectedness, innovations in Houston’s energy ecosystem can teach and inspire others, in turn driving up the speed of the transition globally. The ability to reduce emissions on this global scale will, in turn, impact the tempo and scale of the necessary adaptation to extreme weather events and other impacts of global warming. Houston’s success will therefore benefit both the world and the city itself. Playing out these uncertainties and interdependencies through a series of “what if” exercises in the studio allowed the students to appreciate the factor of time in their work.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, the seemingly binary choice between an energy transition driven by big business or by local actors is overly limiting. A look at recently-passed federal acts show that the kitchen sink is being thrown at the problem. By refusing to follow just one path, we have been able to hold inclusive conversations with guests from government, business, and local communities that joined the studio and its reviews. In the process, the studio learned about the site’s history, the relationships between industrial and residential areas, and the opportunities offered by the energy transition. We began to understand the ways that the energy transition can be used to drive a just transition that works against legacies of environmental racism while preparing for a radically changed climate.

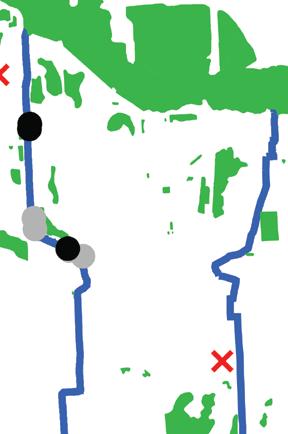

The inevitable drawdown of fossil fuel infrastructure and the accompanying changes in land use and infrastructure can allow for large-scale environmental restoration, including the use of nature-based solutions for remediation and flood control. While analyzing the geological, hydrological, and ecological history of the area and learning about different ways to “build with nature,” students began to envision ways to rebalance the built and natural environments by incorporating natural infrastructure at all scales.

The focus on communities and localized strategies for adaptation and mitigation put another issue forward. While a long-term vision for a post-fossil-fuel Houston is important, it is equally critical to develop ideas about what to do in the near future. This is not only because Houston is still vulnerable to climate shocks and stresses; it is also because change in the neighborhood—and the city—needs to be tangible and address ongoing community concerns in order to build trust and capacity for large-scale, long-term transformation. For this reason, the studio developed projects, in addition to a series of initial “what if” scenarios, that propose nearand medium-term steps as well as a theory and program of long-term change.

Working at various scales and timescales simultaneously while grappling with gray, green, and blue techniques, social and physical systems, and a keen understanding of uncertainty is difficult. That is why teamwork has been so critical to this studio. It is not just to cover the broad scope of knowledge necessary, but also to make use of the disciplinary diversity within the group of students. Navigating the complex and messy problems of this world requires new pedagogies and new attitudes from designers: we need to be more collaborative, more focused on the process and the conversation than on the siloed product. In this studio, the open environment produced a series of visions that helped spur productive conversations about what a thriving, resilient, sustainable and just Houston can look like in the future. We hope these vital conversations will continue beyond the studio, its guests, and its community partners.

1. Houston Climate Action Plan. 2020. Houston, TX: City of Houston.

2. Resilient Houston. 2020. Houston, TX: City of Houston Mayor’s Office.

3. Perspective on the Energy Transition Capital of the World: Houston’s Opportunity to Win by Catalyzing Capital Formation. 2022. Houston, TX: Houston Energy Transition Initiative, Greater Houston Partnership.

4. LyondellBasell Announces Plans to Exit Refining Business. 2022. LyondellBasell. April 21, 2022. https://www.lyondellbasell.com/en/news-events/ corporate--financial-news/lyondellbasell-announces-plans-to-exit-refining-business/.

5. Port Houston Commits to Carbon Neutrality by 2050. Port Houston. April 4, 2022. https:// www.porthouston.com/news-media-press/ press-releases/.

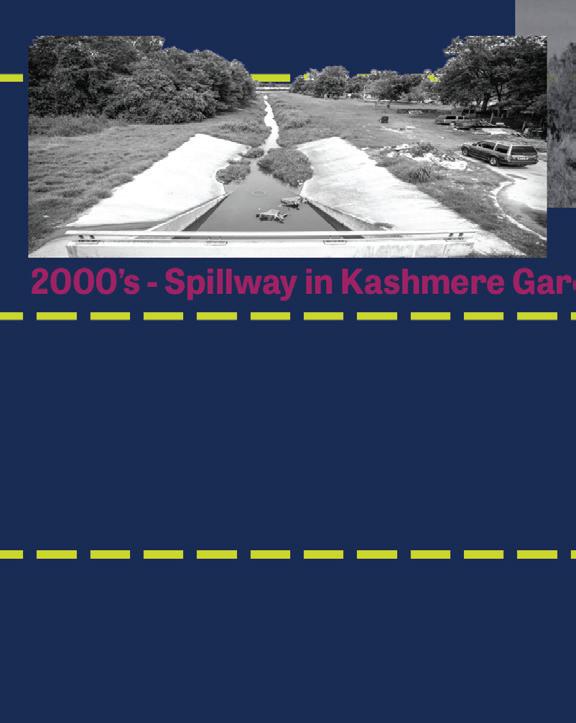

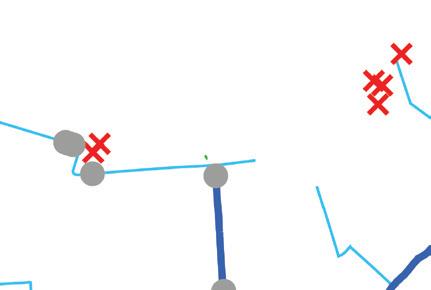

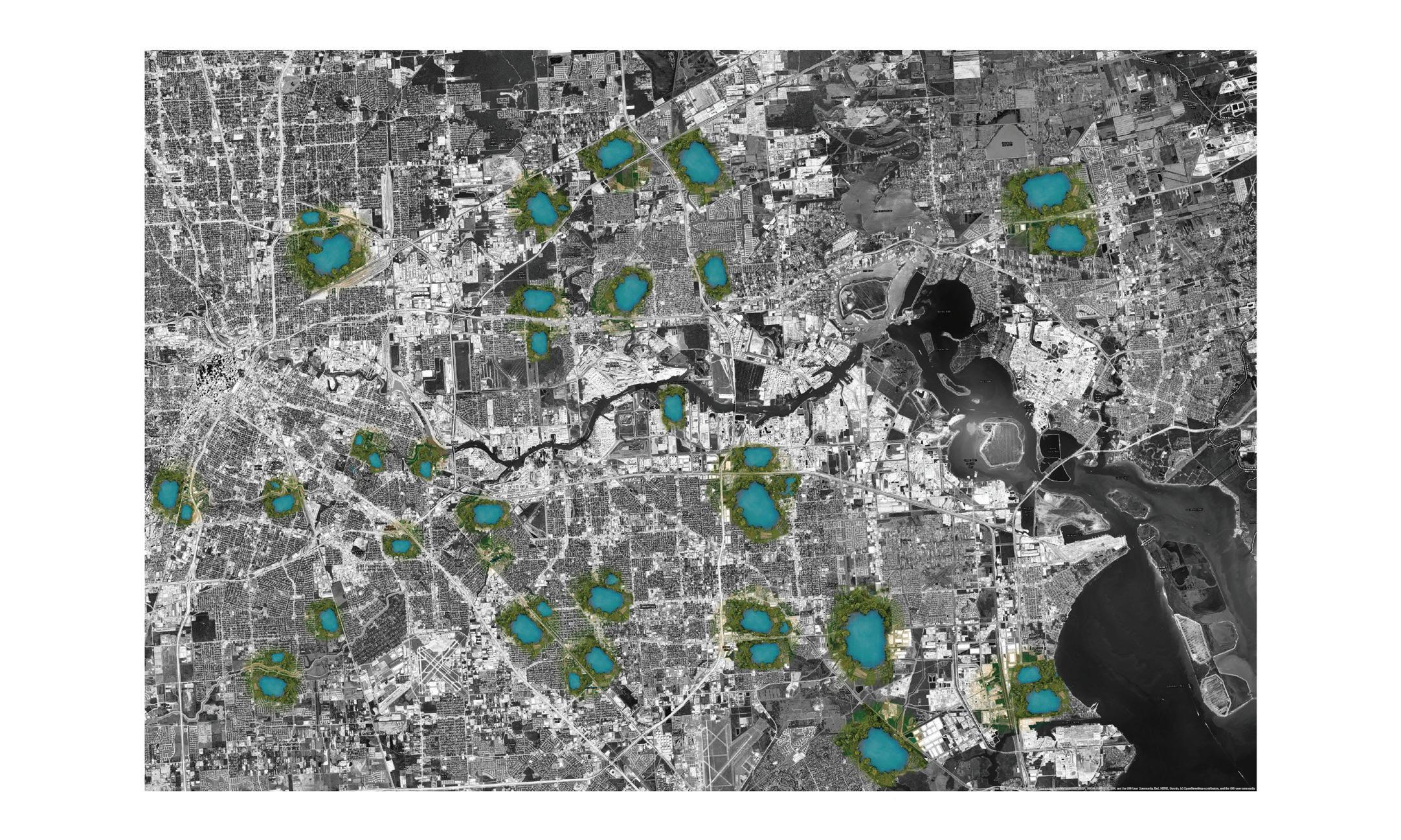

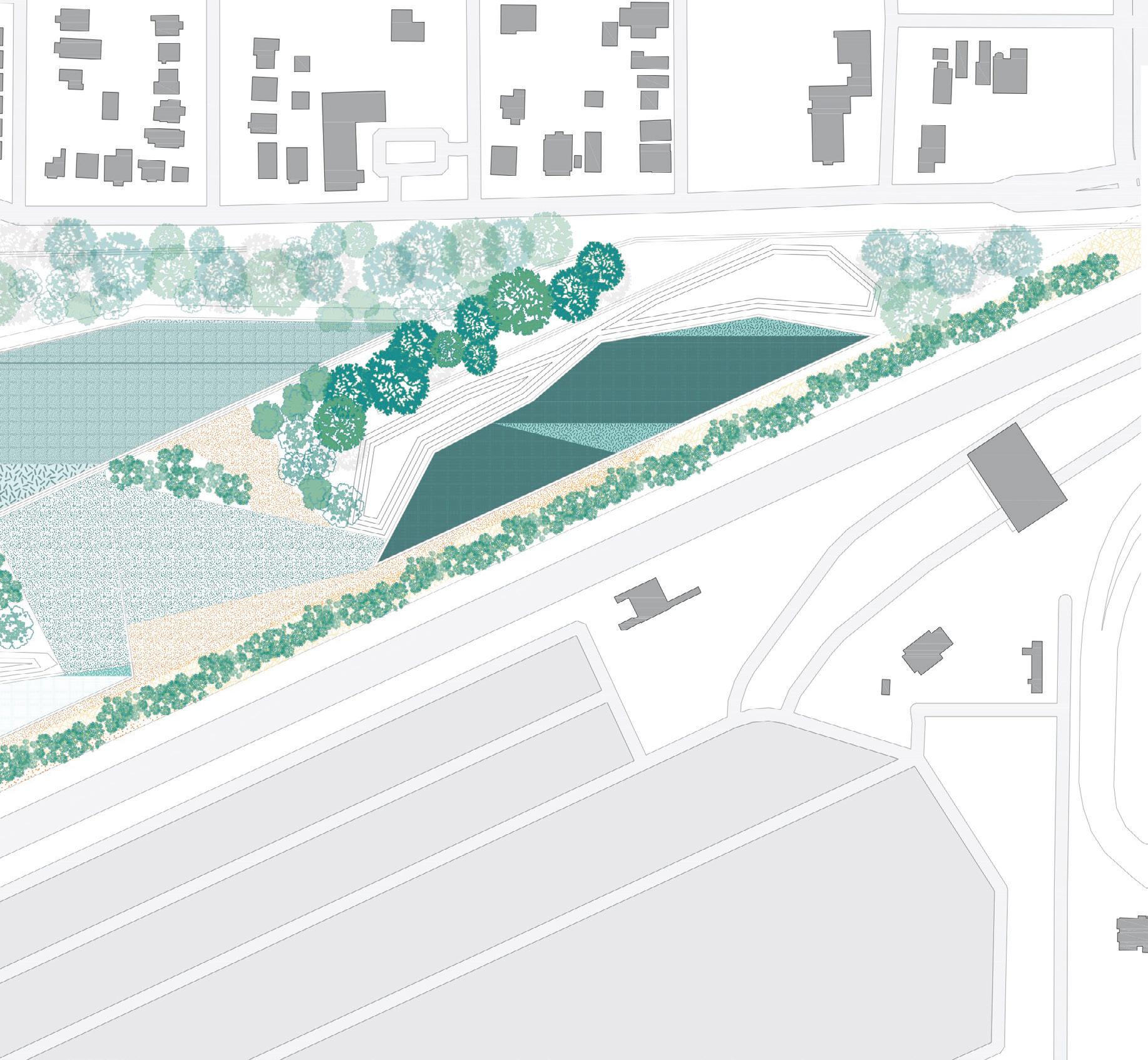

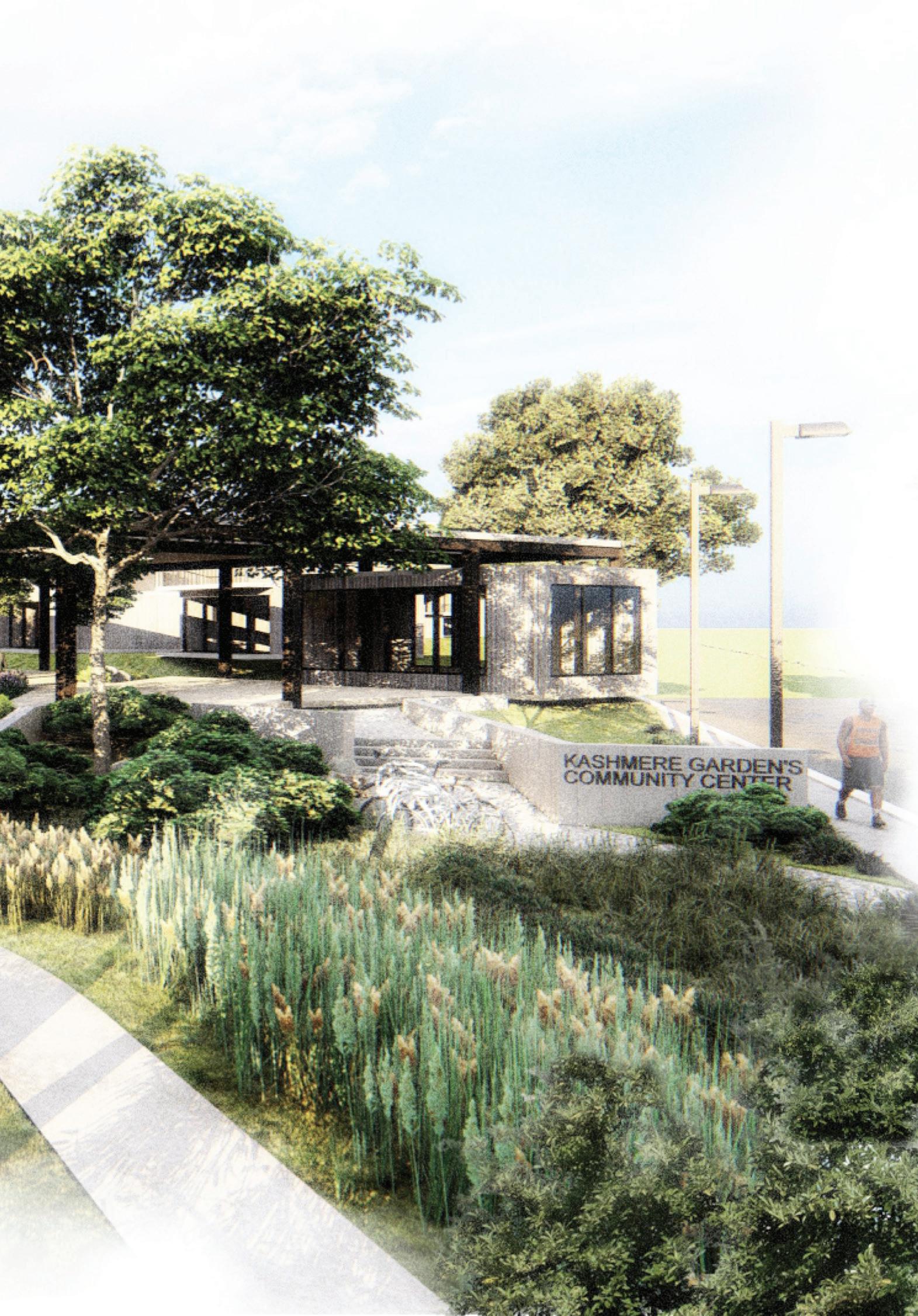

Detention ponds and rainwater infrastructure in Kashmere Gardens.

Detention ponds and rainwater infrastructure in Kashmere Gardens.

Loop 610 and La Porte Freeway interchange.

Loop 610 and La Porte Freeway interchange.

“Mama and daddy, let’s go! We’re gonna run late and we won’t make it to the market or Zydeco Fest 2040!” said Alicía.

“Alrighty, darling, I’m moving faster! Malcolm, after Alicía’s swim lesson, I have a board meeting. We’ll see you at the market with James and Camila?” asked Lupita.

“Yes, my love—I’m done with classes at the Power House at 2 p.m. I’ll take the train to the market with Alicía’s favorite auntie and uncle, Camila and James. Plus, you know Uncle Larry’s band is playing today. He’s reminded me so many times, you’d think they’re reincarnating the Chenier Brothers and all the other zydeco greats!” replied Malcolm.

On her way out, Alicía dashed back into the living room, screaming, “Bye, Grandma! I’ll see you at the market today, right?”

She replied, “Of course you will, Suga! Save your grandmama a dance!”

Grandma Adélaïde was no stranger to the complexity of being Houstonian. From the creativity and ingenuity born of the fusion of cultures and ideas to the generational trauma caused by Bayou City storms. Her people had migrated to Houston from Louisiana in 1927 after the Great Mississippi River flood. Like many Creole families, they settled in Frenchtown, one of the few places they could live in segregated Houston. Her childhood was filled with stories about the migration and the community’s resiliency in building their own joyful and communal spaces like Our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church. Even so, the storms would play a major role in how they understood themselves. She heard stories about Hurricane Carla from her parents; lived through Alicia, Allison, and Rita; and raised children during Ike, Harvey, and the worst of them all—Ernesto, the great storm of 2024.

The way Grandma Adélaïde told it to Alicía, after Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Houston was in shock from the devastation, but nothing could prepare them for what was to come. Promises were made about this time being different, but the city wasn’t ready when a thousand-year storm hit. It was a combination of a rain and coastal storm more destructive than Harvey. Lives were lost and forever changed as the bayous overflowed and found space wherever they could, destroying entire neighborhoods. The biggest industries—

Their goal was to have the city’s policies and actions treat flooding and other natural disasters as public concerns as opposed to individual burdens that only the wealthy had the resources to weather. Camila was part of an organizing collective that grew from West Street Recovery, a disaster recovery nonprofit formed during Harvey. It was comprised of several neighborhoods: Fifth Ward, Kashmere Gardens, and Manchester, among others. They preferred a futurist methodology—a mix of protests, com-

shipping and petrochemicals—were brought to a standstill. Ernesto surged up the Ship Channel, destroyed infrastructure, and spread harmful chemicals throughout Houston. Very little made sense in the aftermath, but one thing was clear: Bayou City had no choice but for things to be different this time.

In 2022, America’s first big climate bill passed, the Inflation Reduction Act. Houston would become the catalyst for national transformations in environmental justice models and the renewable energy and resilience technologies teed up by the bill. Alicía’s family had been part of it—protesting after the storm, organizing their communities for seats at the rebuilding table, and leading innovation and implementation of bold solutions.

Alicía’s Auntie Camila cut her teeth organizing low-income and Black and Brown communities after Ernesto to ensure resiliency and adaptation efforts centered their needs.

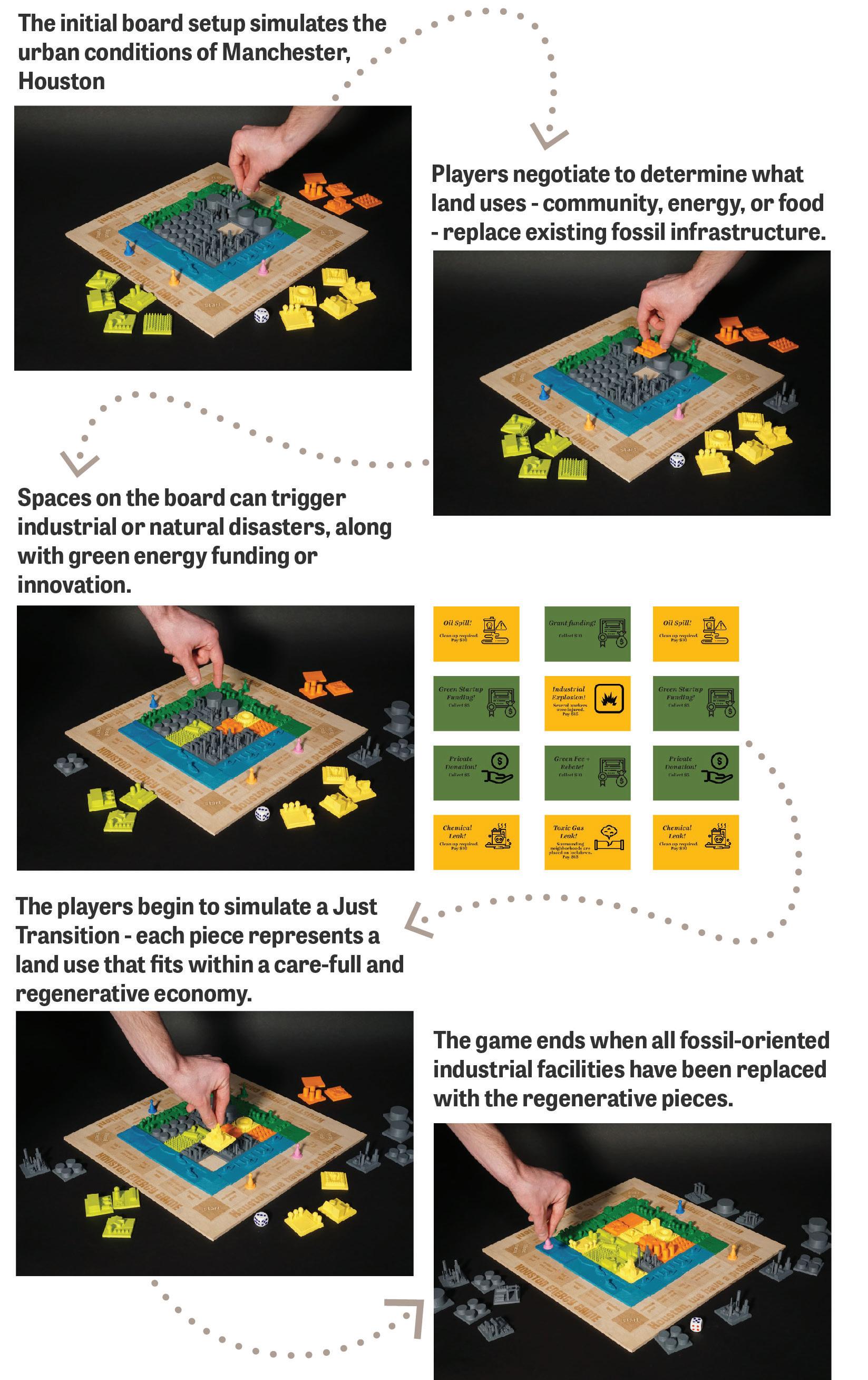

munity meetings, storytelling, and games. The collective created The Houston Energy Games to facilitate community-based articulation of the fossil-fuel-free and sustainable futures they imagined for themselves. But they knew imagining was just the beginning. Their organizing values included truth, reconciliation, and accountability between marginalized communities and powerful entities whose activities played a major role in climate change.

The Manchester neighborhood was the collective’s first major victory. It was so contaminated after Ernesto that the EPA declared it as a Superfund site. The entire community was relocated to Fifth Ward as agencies undertook clean-up and regenerative processes to mimic nature’s own energy and material sources—from urban forests to solar energy. The collective worked with relocated residents to outline their demands and envision a just rebuilding process and outcome. They also negotiated reparations

Local pride runs strong in Houston.

Local pride runs strong in Houston.

A family takes a tour down the Ship Channel.

A family takes a tour down the Ship Channel.

Lunch at POST Houston.

Lunch at POST Houston.

funded by the government and companies whose operations intensified the contamination. It became a model for communities harmed by the convergence of extreme weather, highly polluting industries, and climate change.

As a city resilience and adaptation officer, Lupita was at the forefront of these transformational models. She started college in the aftermath of Ernesto and went to protests and organizing meetings with her older sister, Camila. She often wondered how to make the visions and demands she heard from community members real. Lupita knew the costs would be out of reach for the city. So she got her degree in finance, focusing on resiliency and redistributive models.

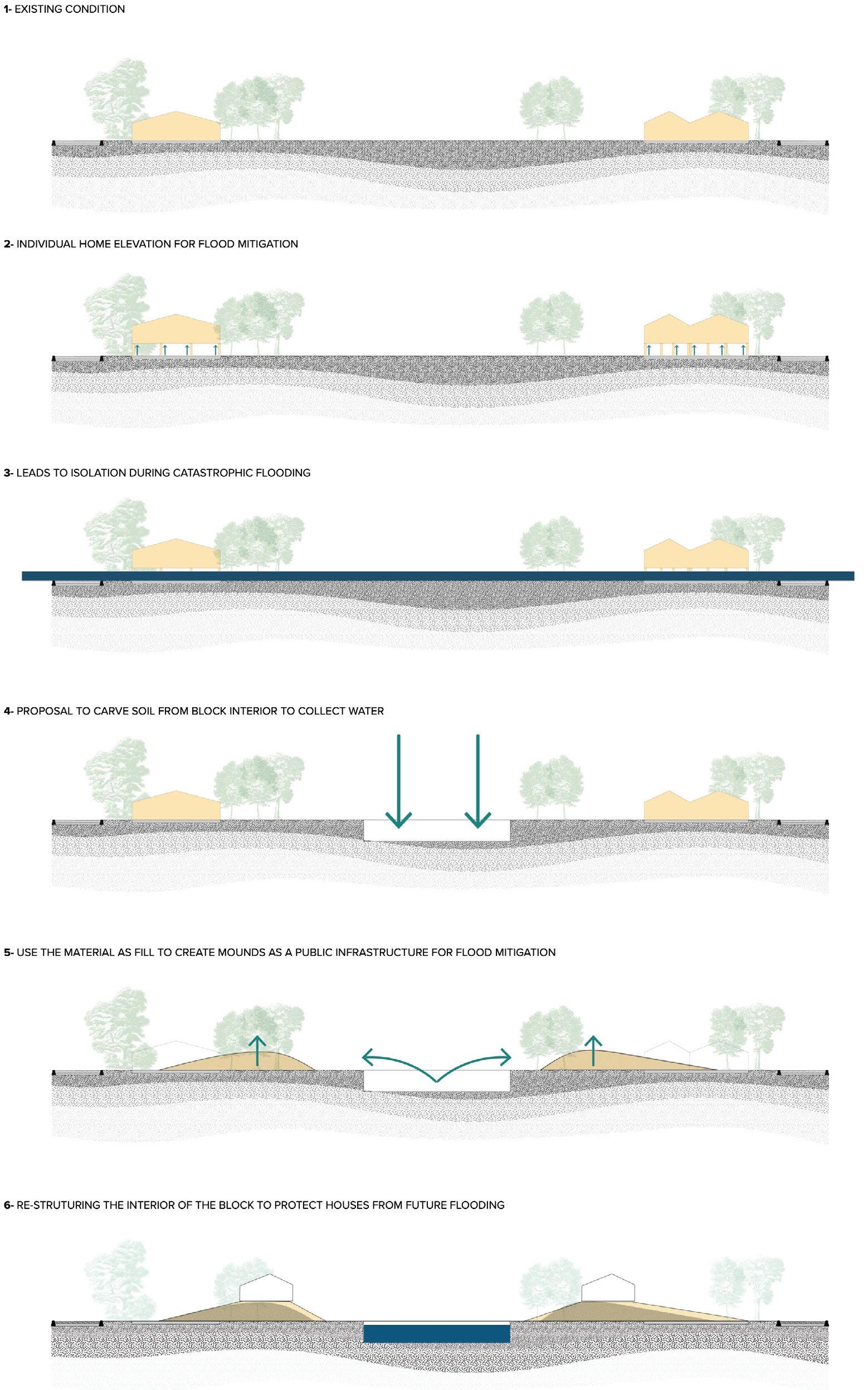

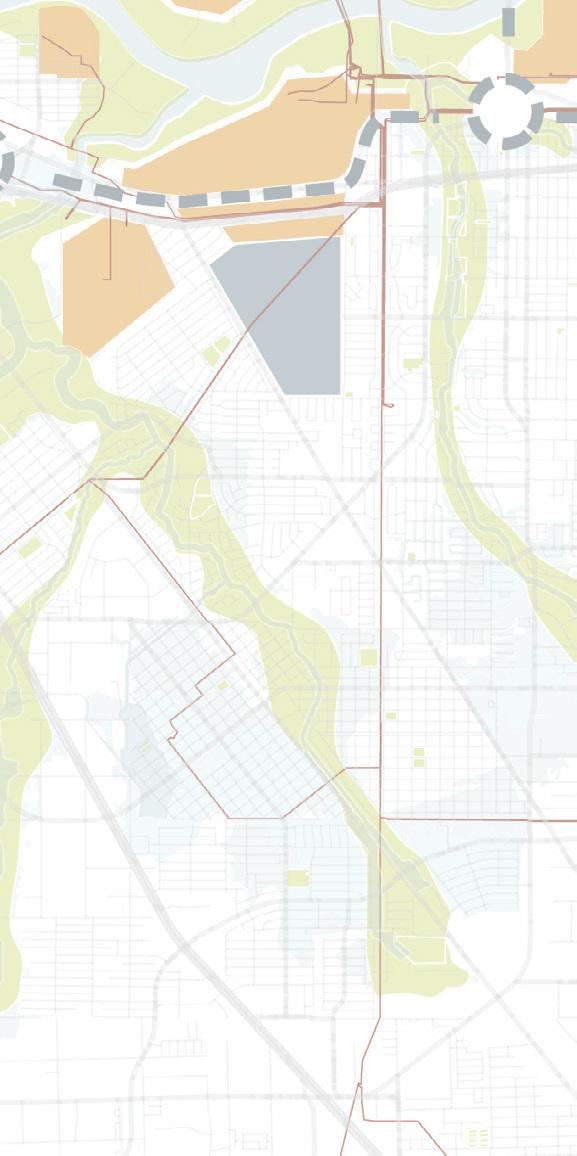

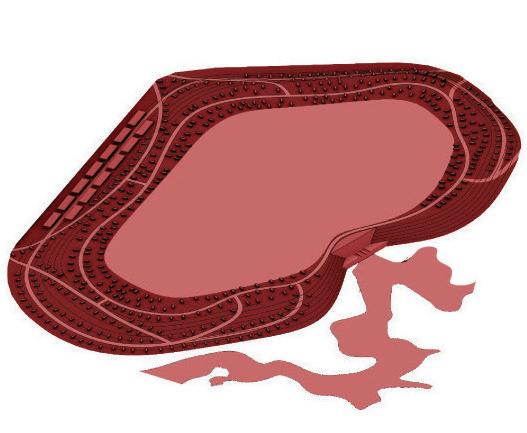

She interned with the city’s Resilience by Design program. Their mandate was to meld innovative planning and finance tools with regenerative and restorative design practices. Her biggest contribution was designing the redistributive finance and governance tools, including reparations for direct harm like the cancer clusters in Fifth Ward and Manchester. She also helped develop newer tools like environmental, resilience, and social-impact bonds. Communities would have a stake in resilience and adaptation investments and receive dividends if they were successful in mitigating flooding and reducing contamination, thereby reducing recovery and insurance costs for the city. A local committee managed the proceeds from these investments in the equivalent of a neighborhood sovereign wealth fund housed at the post office bank. Years later, Lupita became a board member for her neighborhood’s fund— that of Kashmere Gardens, redesigned after it was overwhelmed by Harvey and devastated by Ernesto. New design features included elevated blocks and homes, small detention ponds, and green buffers and other nature-based methods of cleaning contaminated water. The most beautiful part was the rewilded park near Alicía’s school, Kashmere Gardens Fine Arts Magnet Elementary. She and her friends spent hours there during class and recess!

Alicía’s father, Malcolm, was a biomass technician. His field assignment was the Kashmere Gardens micro-grid, which provided power to their neighborhood. He was especially affected by the 2021 Texas Freeze, when nearly 250 people died; his own family struggled without heat and water for days. He was proud to be a small part of the reason Houston had not suffered a power crisis since. But his dream job was to become a transmission line engineer. The second iteration of the climate bill passed in

2025, focused on funding upgrades and catalyzing the innovation needed in the transmission network, so jobs in the sector were booming. Since Malcolm was Alicía’s primary caregiver, he worked part-time and took classes on weekends at Houston’s central biomass plant, the Power House in Manchester. That next step in his career would have to wait until Alicía was a little older. Until then, he relished the memories he got to make with his daughter in an H-town that was remaking itself, bit by bit.

James was a transplant from San Francisco with a passion for nature. After college, he moved to Houston in 2024 to work for a petrochemical company. James was drawn to the protests and would sometimes attend those near his office downtown. Camila noticed him and invited him to an organizing meeting to see where the real work happened. Having grown up in the Bay Area, he was no stranger to natural disasters made worse by human indecision. He watched as officials in communities ravaged by wildfires finally heeded the fire-management practices of Native communities who had been there for thousands of years. James wondered what working with nature might look like in Houston. He switched careers, becoming a designer focused on embracing Bayou City’s natural inclination for water.

Adélaïde, Malcolm, Lupita, Camila, and James knew better than to miss the monthly farmers’ market and zydeco concert at the Green House in Fifth Ward. It was home to the city’s largest plant nursery and a beautiful plaza for the festivities. For Malcolm and Lupita, it was one of the precious moments that threaded their Houston childhood with that of their daughter. For Adélaïde, it was a symbol of a promise finally kept after the traumatic storms she’d lived through. For Camila and James, it was a reason to keep building and fighting for the worlds they imagined.

It wasn’t lost on any of them that raising their families in Houston was a miracle made real in no small part by the collective power of Houstonians. They were grateful for it. Like so many others, their little girl, Alicía Adélaïde Francois, inherited the legacy of the Bayou City that learned to embrace and honor its waters. The storms didn’t stop coming, but Houston was readier than ever.

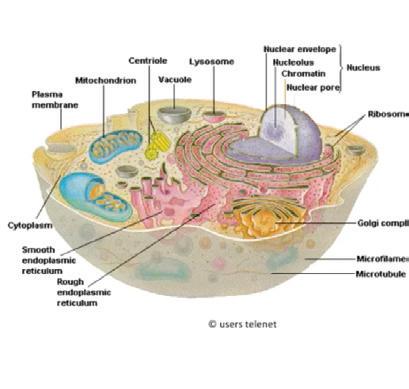

The studio began with a series of lectures by experts in hydrology, environmental pollution, infrastructure, urban design, and data visualization. The lectures initiated the studio’s research on these topics as they related to Houston. The lectures included Antonia Sebastian, Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences at UNCChapel Hill, on Houston’s hydrology; Han Meyer, Professor Emeritus of Urban Design at TU Delft, on delta urbanism; Danielle Getsinger, co-founder and CEO of Community Lattice, on overcoming barriers to community revitalization through data science; Rod McCrary, Tony Loyd, and Chris Levitz of AECOM Houston, on the Port of Houston’s infrastructure and resiliency. Additional lectures were delivered by studio instructor Matthijs Bouw on “Hackable Cities” and by data visualization designers Daniel Gross and Joris Maltha of Netherlands-based Catalogtree.

Antonia Sebastian

Antonia Sebastian is an Assistant Professor at UNC-Chapel Hill in the Department of Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences. She has a Ph.D. in Civil and Environmental Engineering from Rice University and was a Netherlands American Foundation (NAF)/Fulbright Flood Management fellow at TU Delft. She has been studying Houston and flooding for over ten years.

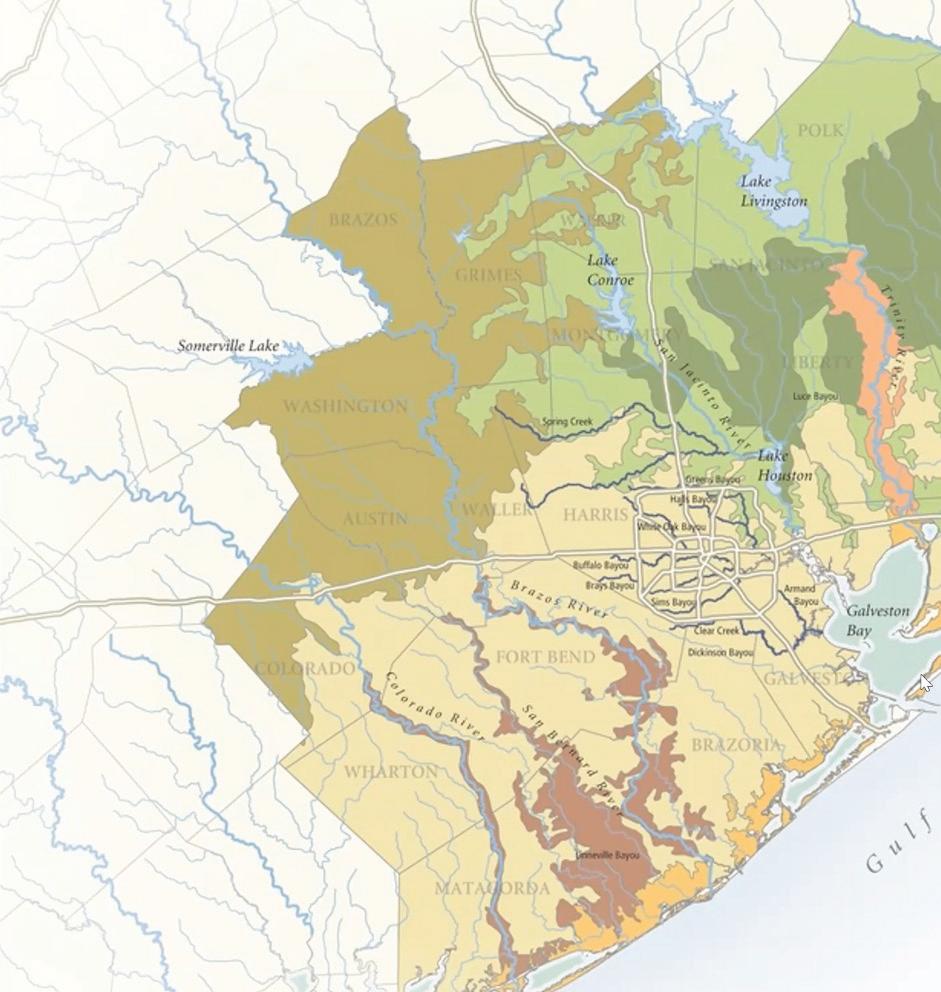

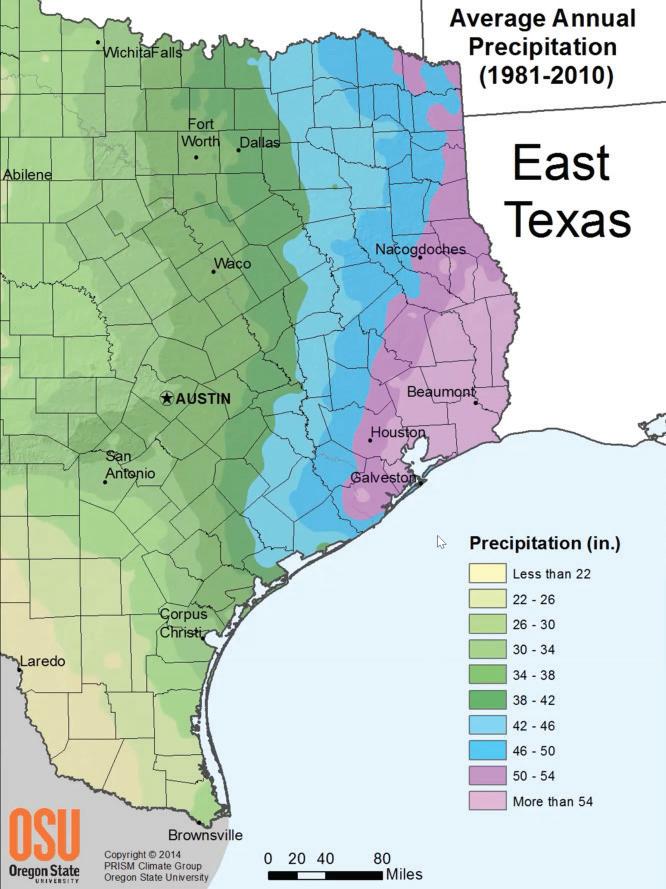

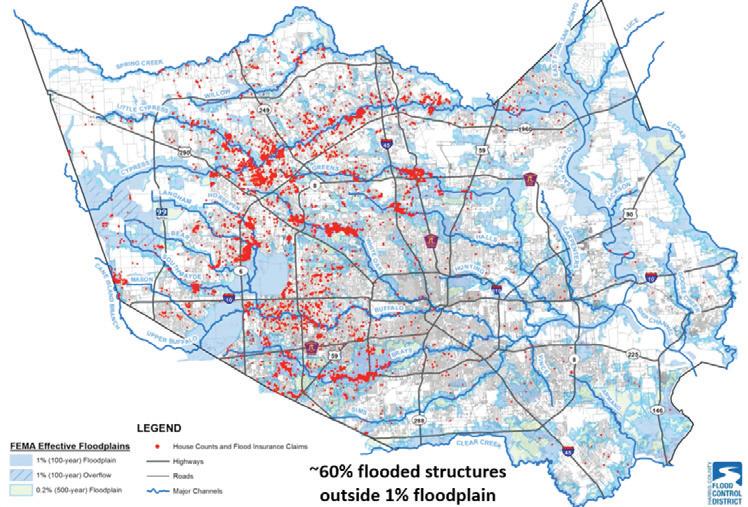

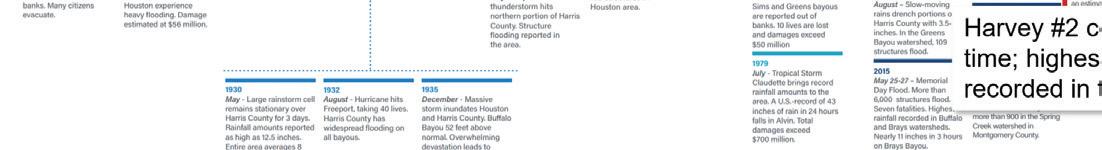

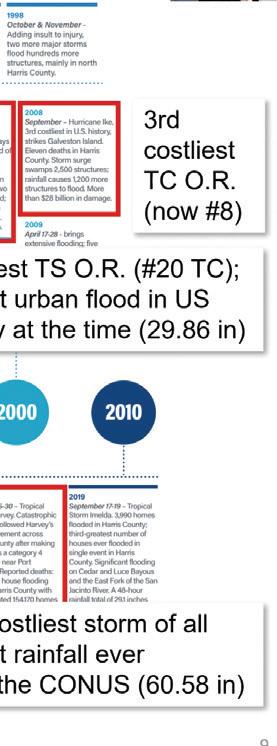

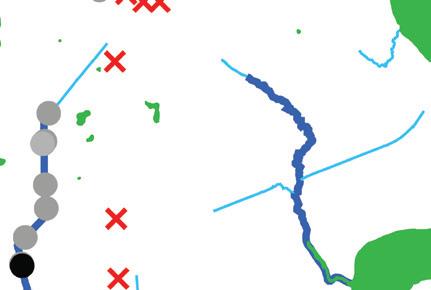

An expert in Houston hydrology, Antonia Sebastian started off the lecture series by focusing on the ways that Houston’s urban form, hydrology, and historical development patterns have contributed to flood disasters since the city’s inception. Sebastian began by outlining Houston’s geographical context and hydrology. Located on Galveston Bay along Buffalo Bayou and its watershed, Houston sits on a flat coastal plain. There are twenty-one bayous (and their watersheds) that intersect the current boundaries of the city. Additionally, over the last one hundred years of settlement, large amounts of water and oil have been extracted from the ground beneath the city, causing increasingly severe subsidence in portions of the city. According to Sebastian, while Houston does see intense rainfall (primarily during the

spring and throughout the hurricane season) and the area does have a geological history of flooding, it is land subsidence, urban development, botched flood management, and climate change that have turned these events into disasters. As Sebastian states, “flood disasters are created by

Houston to become a major metropolis.

Sebastian next reminded us that this growth would not have been possible without widespread flood mitigation projects. In response to repeat major flood events in 1930, 1932, and 1935, the Addicks and Barker reservoirs were established to the west of the city. In the 1960s, the Texas City levee was constructed and most bayous were channelized (with the exception of Buffalo Bayou). The reservoirs and levee allowed for westward and southern expansion, respectively, while the channelization of the bayou system allowed water to be quickly and efficiently redirected from the city and to the bay to minimize flooding.

human decisions and the placement of people and infrastructure in harm’s way.”

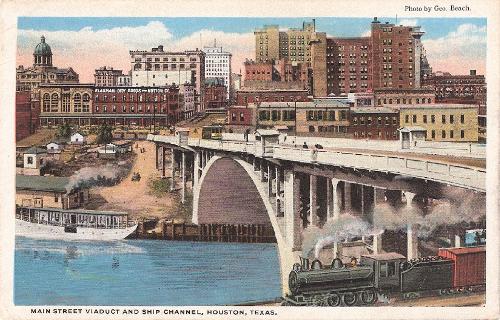

According to Sebastian, the emergence of Houston as a major American cityindeed, the largest in the southern United Statesis tied directly to this history of flooding and recovery. In the early twentieth century, a series of hurricanes hit Galveston, Houston’s neighbor to the southeast, and devastated the city. The “1900 Storm” remains the deadliest natural disaster in US history. Galveston, known at the time as the “Wall Street of the South,” was nearly wiped out. This event, and another major hurricane in 1915, provided inland Houston with the opportunity to emerge as the economic powerhouse and major port of southeastern Texas. However, in order for Buffalo Bayouinitially only three to six feet deepto become navigable, it had to be dredged and widened extensively and connected to the Gulf of Mexico. Today portions of the channel are upwards of fifty feet deep and over three hundred feet wide. The dredging of the Bayou into what would become the Ship Channel and its subsequent emergence as the engine of economic growth for the region have allowed

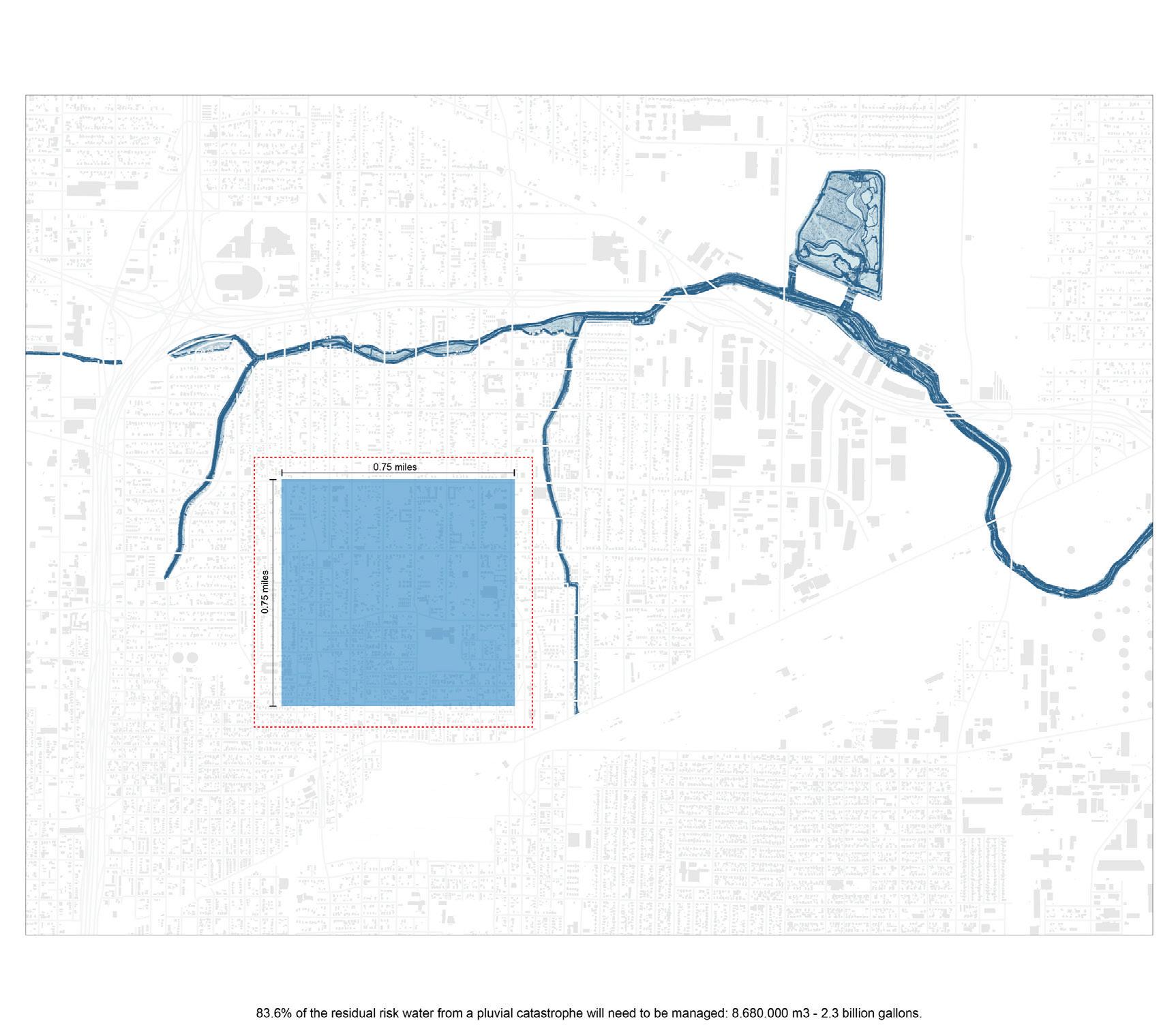

These interventions haven’t been enough, however, as the increase in flooding events over the last twenty years makes clear. Sebastian detailed different types of flooding and how their effects and impacts can differ. Fluvial (riverine) flooding results when the water level in the channel exceeds the elevation of the banks. Pluvial (street) flooding results when overland runoff overwhelms the capacity of the storm sewer network and ponds in the streets. Surge (coastal) flooding results when high wind events push water onshore. Compound flooding is a combination of two or more of those above. Recent storms have caused varying types of flooding: Tropical Storm Allison (2001) caused major fluvial flooding in the Texas Medical Center. Hurricane Ike in 2008 had a large storm surge, while the “Memorial Day flood” of 2015 and the “Tax Day” flood of 2016 were cases of intense pluvial flooding. Hurricane Harvey (2017) caused some of the worst pluvial flooding ever recorded.

Why has storm water discharge increased so dramatically in Houston? Sebastian highlighted three main reasons. First is increased urban runoff due to the nature of Houston’s sprawling development patterns. Second are (failed) historical flood management practices, such as

channelization and reservoir/pond construction, many of which are still considered “best practices” today. The third is climate change, a “threat multiplier” that will continue to worsen over the next century. Ultimately, these urban pattern shifts in Houston have reduced its ability to cope with climate-change-related disasters.

The studio asked Sebastian a number of follow-up questions on the topics presented.

Q: What bayou de-channelization efforts are underway?

A: Currently, projects are underway to de-channelize Brays, Sims, and the Lower WhiteOak Bayou, via the Interstate 45 expansion.

Q: Are there efforts to contain Houston’s sprawl?

A: Unfortunately, no, but onsite retention requirements for developers have increased.

Q: What are the risks for the petrochemical complexes along the Channel?

A: Each tank usually has a levee designed to prevent flooding. Therefore, most facilities can withstand some level of flooding unless the storm hits the Channel directly.

Q: What complications arise with coastal flooding and sea level rise?

A: While existing models that combine the two are limited, sea level rise will likely impede drainage from the bayou system.

Q: What are your thoughts on the Ike Dike?

A: Currently the Ike Dike cost-benefit doesn’t make sense, especially because it leaves major portions of the region at risk and the timeline for construction is too. Much of the vulnerability dynamics in the region could change over this period, and the hazards are also increasing. It will soon become outdated.

Q: Finally, absent political or financial constraints, what would your recommendations be for the City of Houston?

A: The City should adapt structures that are at risk for riverine flooding, avoid building new structures in flood hazard areas, and densify other areas that are not at risk. They should also re-envision where the dense urban centers are presently. Finally, Houston will flood no matter what. Whatever is built should be able to live with water.

Han Meyer is Professor Emeritus of Urban Design at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), where he taught until 2019. While there, he was the leader of the research program “Delta Urbanism.” Previously, he worked at the Project Organization Urban Renewal of the City of Rotterdam for ten years. He currently conducts research on urban development in delta areas, giving lectures and publishing articles in and outside of the Netherlands.

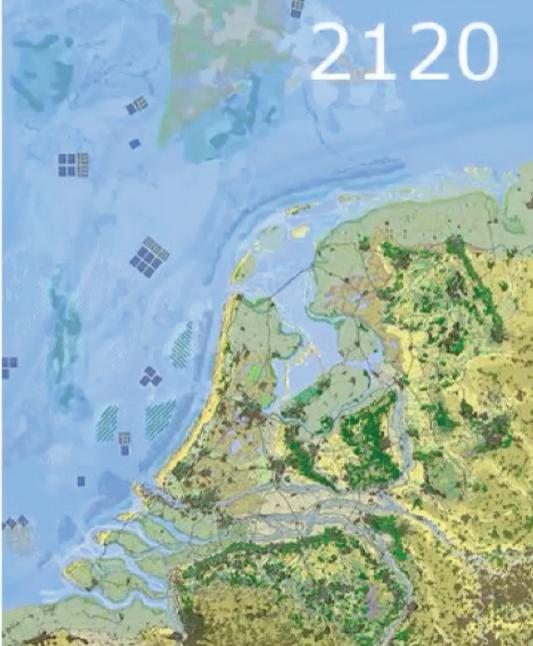

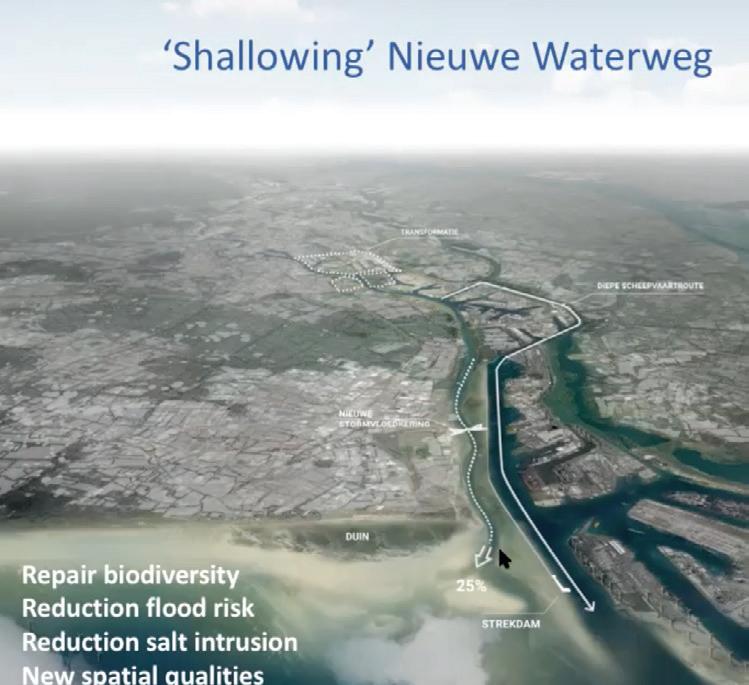

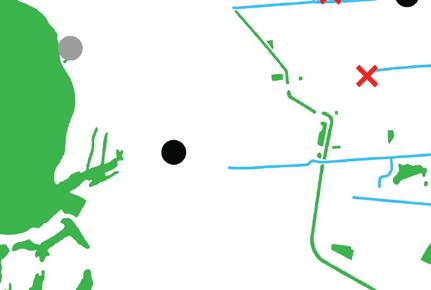

Han Meyer is a leader in research and design work on the topic of “delta urbanism,” or the relationship between cities, ports, and urbanized river deltas. He spoke to the studio about his role in reimagining the port-city relationship in Rotterdam to cultivate an energy transition that also takes natural systems into account, thereby bringing the health of the regional ecosystem and waterways to the forefront of the process.

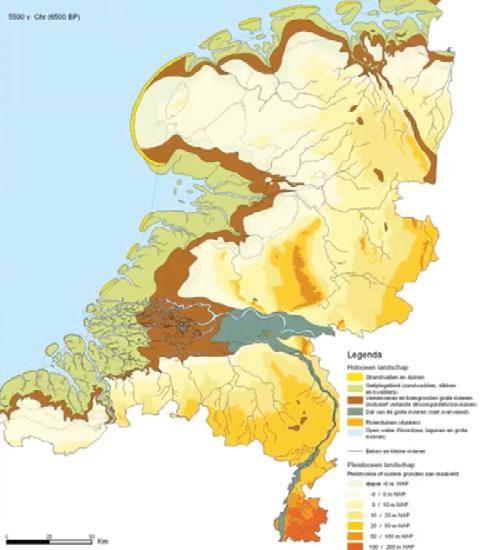

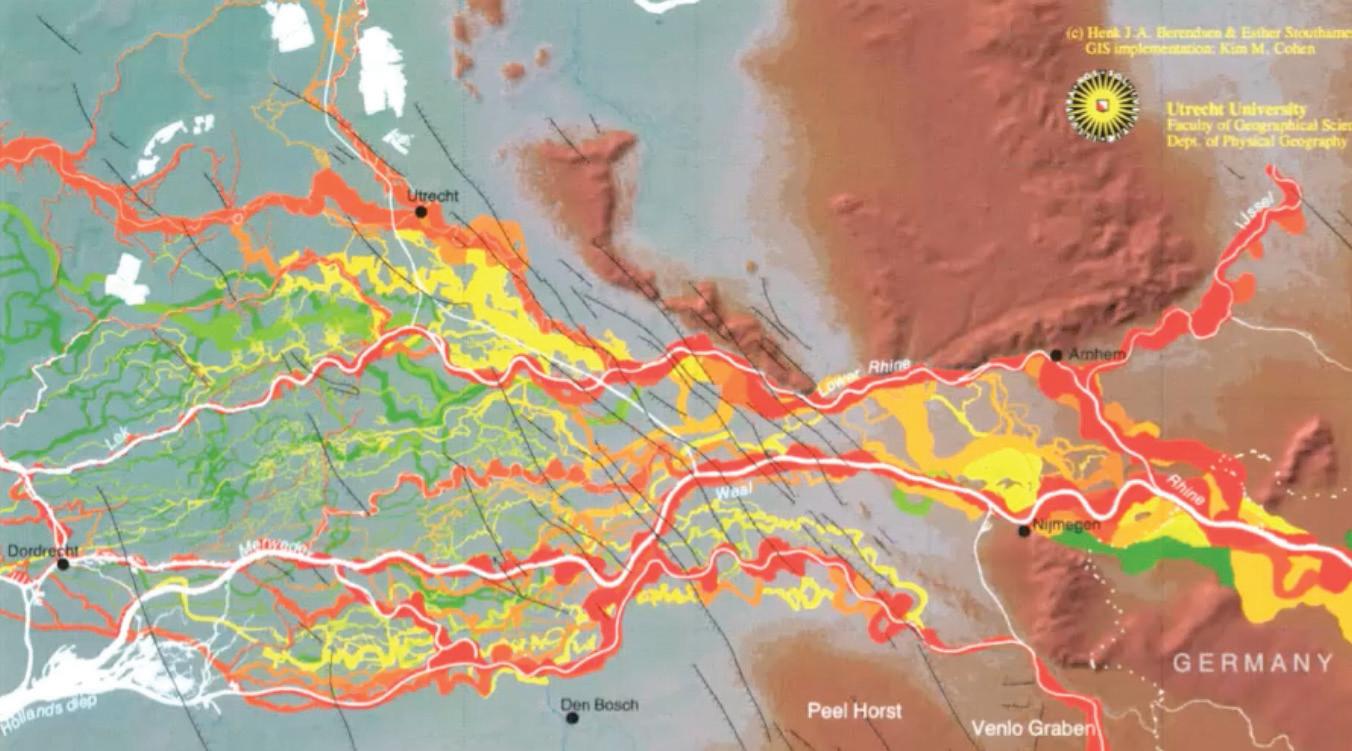

Meyer started by detailing the ways that cities located on deltas and coastal areas, such as Rotterdam and Houston, inhabit emergent and ever-changing landscapes that only first appeared since the retreat of the glaciers around ten thousand years ago. Because of this reality, it is vital to take a holistic approach to understanding ports and cities embedded in delta systems. This approach includes planning for biodiversity, preparing for the energy transition, reducing flood risk, ensuring freshwater supply, and prioritizing spatial quality. He referred to a report from the University of Utrecht that asks: “What does the river itself want?”1

Meyer described the Rotterdam delta region as “an enormous armor of interventions” that have allowed for massive economic growth but have also had adverse ecological

consequences. This process of “machination,” along with a long-term ignorance of the natural hydro-morphological system, has led to a “critical phase in the evolution of the Rhine-Meuse delta” that requires an immediate response.

In the face of these challenges, Meyer and his team asked, “what does the river actually want?” Their response was a long-term, naturebased framework that would address the major water issues facing the territory: saline intrusion, flooding, loss of biodiversity, and a lack of a spatial relationship to the water. By shallowing (un-deepening) the channel and reducing outflow to the “New Waterway” (a highly engineered portion of the Rhine completed in the early twentieth century), the need for dredging would decrease, biodiversity could flourish, saline intrusion would diminish, and flooding would be less frequent and intense.

Meyer then noted several cities around the globe, such as Venice, London, Shanghai, and Houston, that are negotiating new relationships with their ports and deltas. He found Houston to be a “fantastic challenge” because nearly eighty percent of its bayous and streams have been lost to human development. He implored the group to ask, “what does this landscape want?” He speculated that the answers should include an understanding of hydrological and geomorphological systems and “solid blue-green frameworks” to ultimately discover what role the Houston Ship Channel can play in post-carbon Houston.

The studio asked Meyer a number of follow-up questions related to the topics presented.

Q: What is happening to Rotterdam’s petrochemical industry as it begins to wind down?

A: The industry is evolving toward greenhouse gas storage and hydrogen, but it still exists.

Q: How do people in Rotterdam feel about the energy transition?

A: I can’t speak for everyone, but the port presently struggles to keep employees. Those who live near it don’t like the pollution. A shift toward green energy could allow the port to retain employees and build a better image.

Q: Finally, what suggestions do you have for how to manage stormwater in Houston?

A: I suggest thinking of the Ship Channel as an open door to the sea and assessing how that relationship can evolve for better outcomes.

The twentieth century’s mechanical view on the city will have to make way for the twentyfirst century’s organic view on the city.

Asking, “what does the river actually want?” Meyer and his team proposed a naturebased framework for the Rhine delta.

Danielle Getsinger

Danielle Getsinger is the co-founder and CEO of Community Lattice, a consulting firm specializing in using data science to overcome environmental barriers to community revitalization. Getsinger is a licensed professional geologist and MBA recipient with over fifteen years of experience working on complex environmental issues ranging from technical assessment and cleanup of brownfields to community-wide strategies for addressing environmental injustice, climate adaptation, and resiliency. Getsinger also serves on various economic development committees and nonprofit boards, giving her a unique perspective on how to align grassroots interests with government strategies and funding opportunities.

Danielle Getsinger has over fifteen years of experience in environmental consulting. She has worked with a wide array of clients across the country to cultivate equitable solutions to environmental justice issues. She spoke with the studio to discuss her work in Houston as part of Community Lattice, an environmental consulting services group that she founded with Shannon Loomis in 2019. Community Lattice helps communities find simple solutions to complex environmental issues by leveraging publicly available data to visualize toxic sites across communities and helping to identify funding resources.

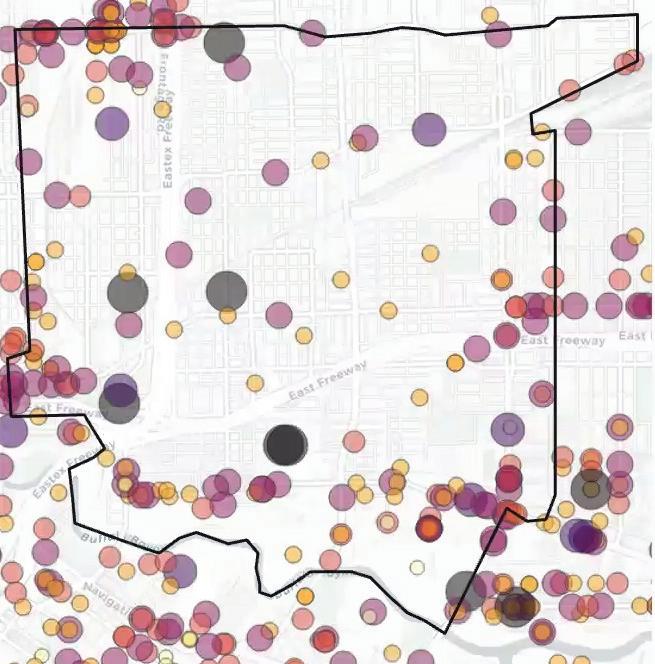

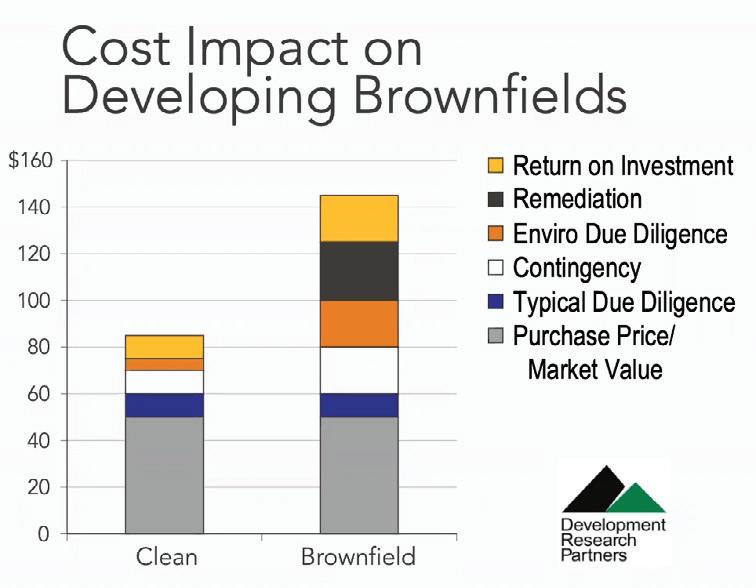

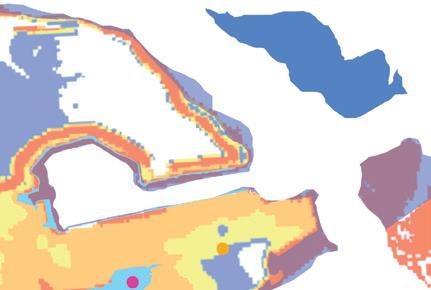

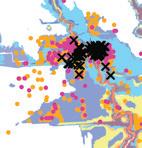

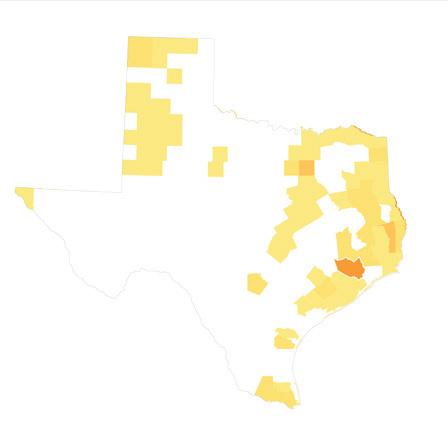

Getsinger began her lecture by noting that it is an interesting time to be working in Houston. By her telling, the City is realizing that “they have dirty soil” and that brownfield sites must be dealt with as Houston densifies and reclaims old industrial sites. Brownfields, as defined by the EPA, are “a property,

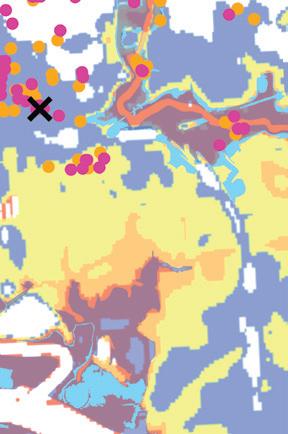

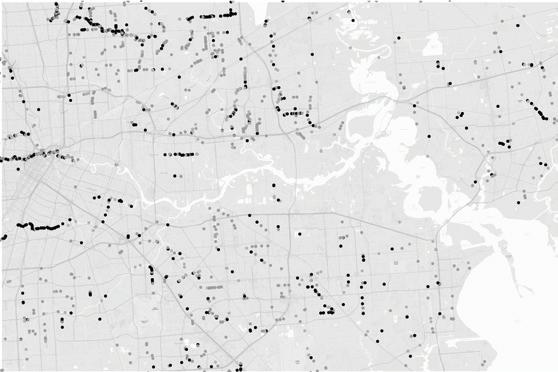

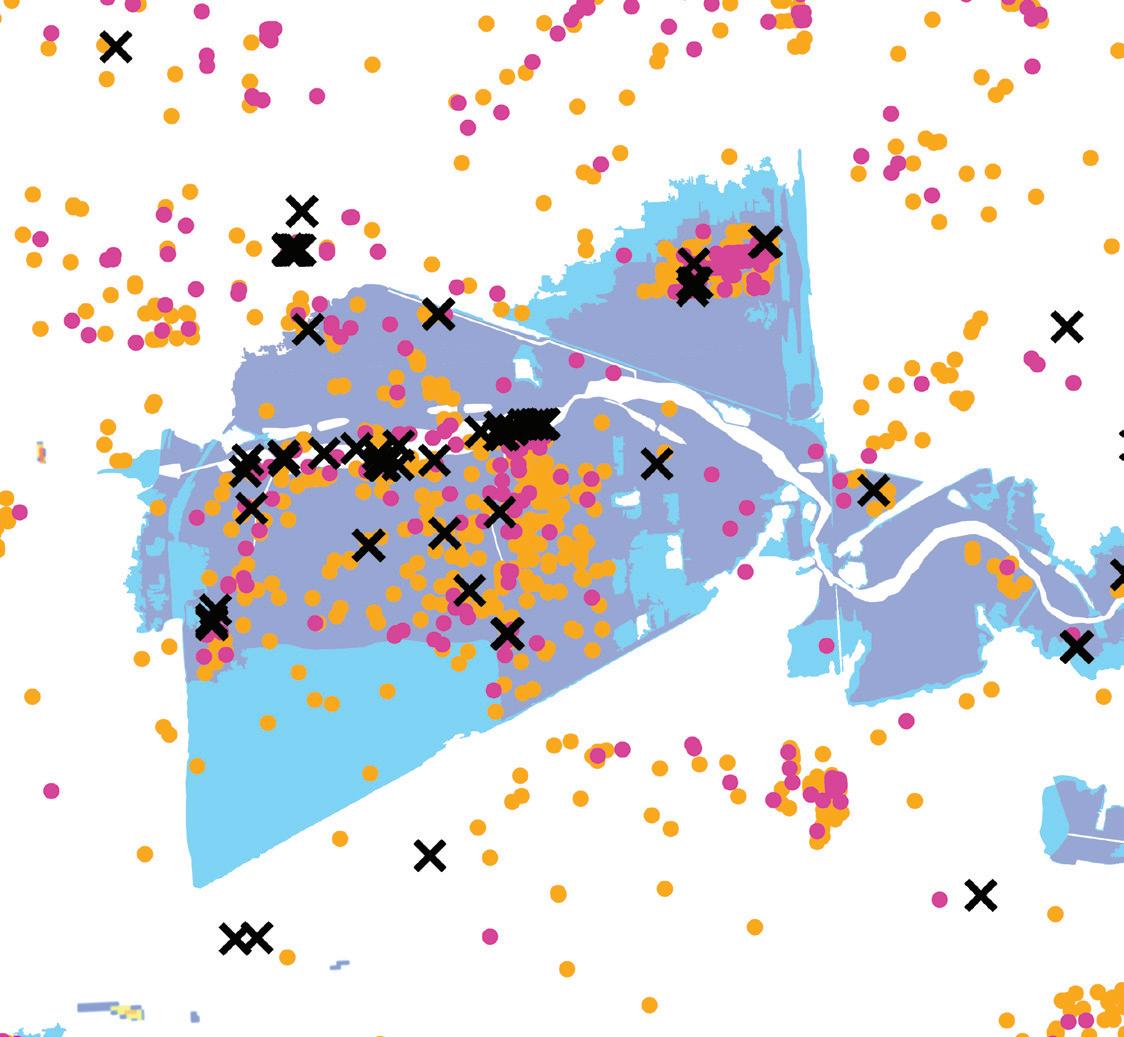

In Houston’s vulnerable Fifth Ward neighborhood, the EPA’s map of officially recognized brownfield sites (left) contrasts sharply with brownfield sites as recognized in Community Lattice’s database

the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.”1 Given such a broad definition, many properties can qualify as brownfields. This complicates the development process in a number of ways and lowers land values significantly. To remedy this, the EPA has incentivized the redevelopment of polluted sites through the Brownfields Redevelopment Program. This program gives grants to municipalities, non-profits, and state and local governments. Community Lattice helps their clients understand how they can leverage these grants. Recently, they put together a Brownfields Strategic Plan for the City of Houston.

Getsinger gave some examples of relevant projects in Houston, such as the Fifth Ward Cultural Arts District, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, the Brownfields to Parks Initiative, and Sunnyside Landfill. All of these projects required

EPA funding to study and manage potential pollution on those sites. As such, there are thousands of brownfield sites out there that aren’t recognized by the EPA simply because they have not received EPA funds. This is similar to how Superfund sites are differentiated from brownfields. Superfund sites are designated for cleanup by the EPA and receive funding from the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). In contrast, brownfields are any site where environmental contamination is present. To remedy this lack of visibility, Community Lattice has built a comprehensive tool for identifying brownfield sites, which they built over several years by compiling data on historic polluting land uses and then rating them on a scale of high to low potential for chemical/pollutant releases. The tool is called Platform For Exploring Environmental Records, or PEER, and is available online at https://lattice.shinyapps.io/peer/

Q: What is a developer required to do in order to develop a polluted brownfield site?

A: There are a lot of regulations around developing polluted sites. But essentially a developer, if they want to use EPA funds, must go through a Liability Protection Review and must adhere to American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) standards when undergoing cleanup. The review protects the developer from liability if pollutants are found on the site after the fact. But if the review finds any contamination, the developer must remedy it, which can be very costly.

Brownfield sites often face significant remediation costs which serves as a barrier to redevelopment, particularly in already disinvested neighborhoods.

difficult and long-term organizing to identify and address each site’s particular pollution issues. She noted that much of the work that needs to be done is related to awareness. Brownfields, as noted above, can be ambiguous to define and therefore hard to make visible. In addition, Superfund sites, which are specifically designated by the EPA for cleanup, can be confused easily with brownfields.

Getsinger next answered several questions from the studio.

Q: Your visualizations, surprisingly, did not show a lot of brownfield sites in EPA GIS data along the Ship Channel. Why is this the case?

A: The brownfield data provided by the EPA only documents sites that have received

Q: What is the best way to balance economic benefits versus the health impacts of living near contaminated land (i.e. workers living close to industrial jobs)?

A: There are a lot of environmental justice organizations working on issues around this question, like Air Alliance Houston and TEJAS. In Houston, the biggest threats of living near industrial sites are air pollution and industrial explosions. However, there is a lot of community pride in the industry, so navigating this balance is difficult.

1. Smart Growth, Brownfields, and Infill Development. n.d. Epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://www.epa.gov/ smartgrowth/smart-growth-brownfields-and-infill-development.

Rod McCrary, PE, is a Vice President at AECOM and oversees the company’s work with the Port of Houston on the Houston Ship Channel. Tony Loyd, PE, was Vice President at AECOM and Head of the Houston Office until 2022. Chris Levitz, PE, CFM is a Project Manager at AECOM and works on the firm’s Gulf Coast projects, specializing in coastal engineering, planning and resiliency.

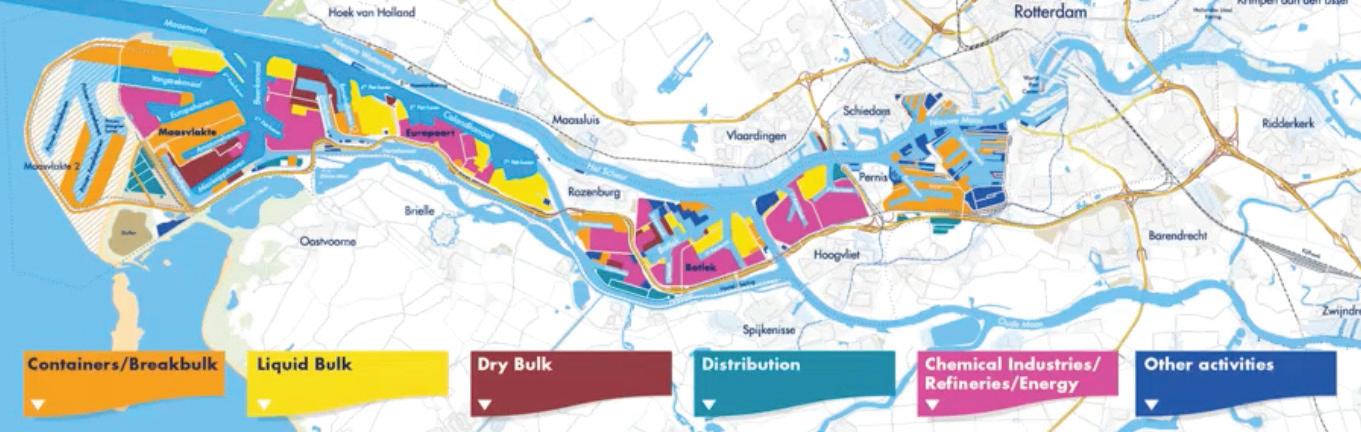

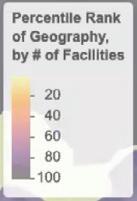

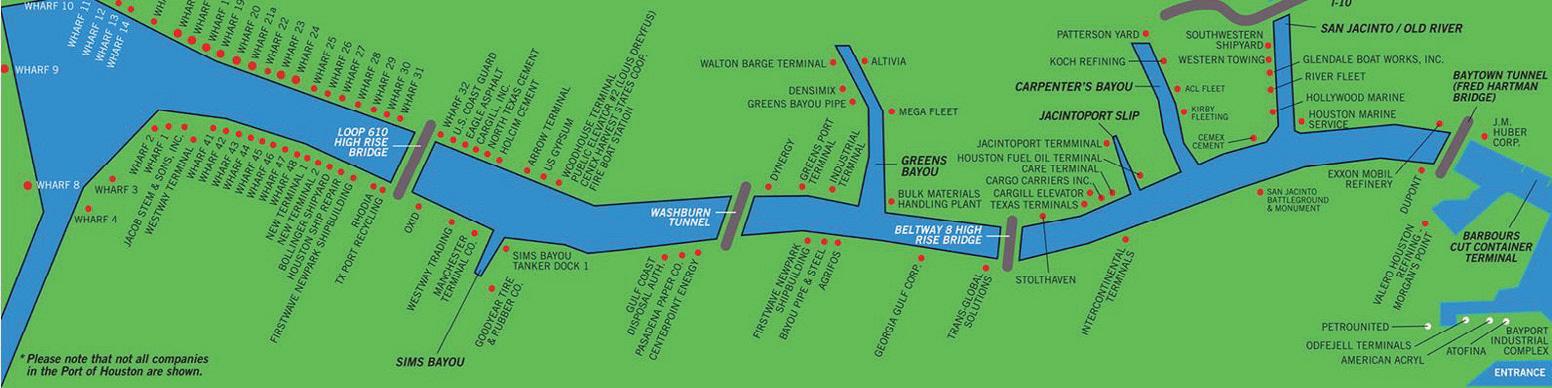

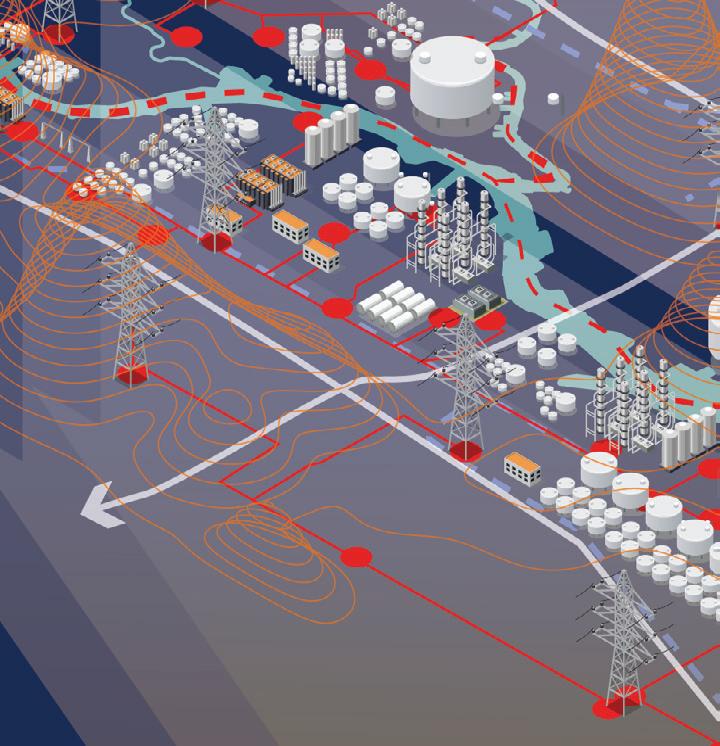

Rod McCrary, Tony Loyd and Chris Levitz of AECOM Houston led the studio through a series of presentations about the infrastructure and resiliency of the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel. AECOM Houston is a major design partner of the Port of Houston and has been intimately involved with design and construction efforts related to the Ship Channel’s various expansion and infrastructure projects over the last several decades. The Port of Houston Authority is a quasi-public authority, shared between the state of Texas and Harris County, and is responsible for the entire fifty-two miles of the Ship Channel. Since 2010, the Port of Houston has been planning Project 11, the eleventh major expansion of the Ship Channel, working with Congress, the Army Corps of Engineers, AECOM, and other design partners.

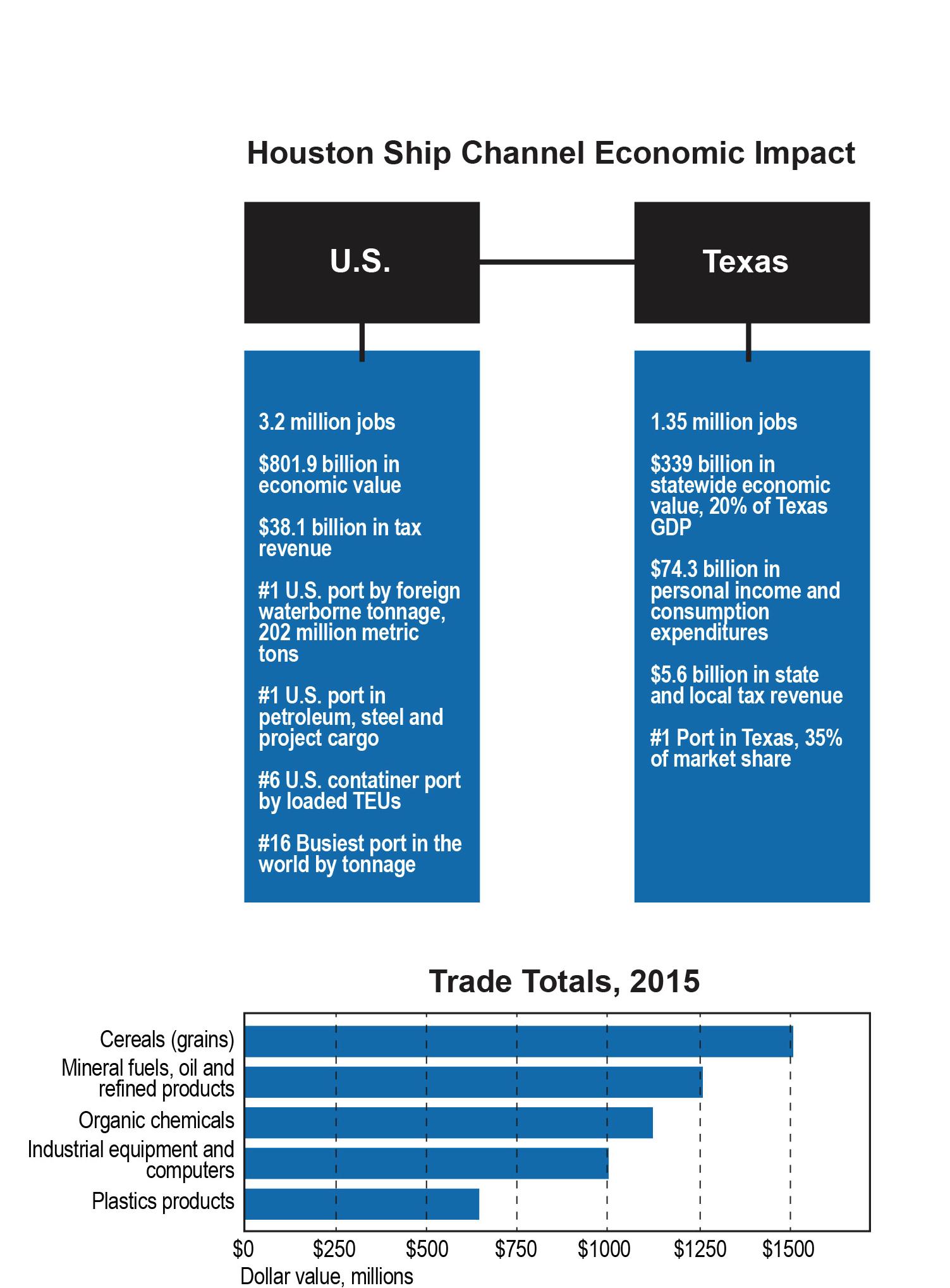

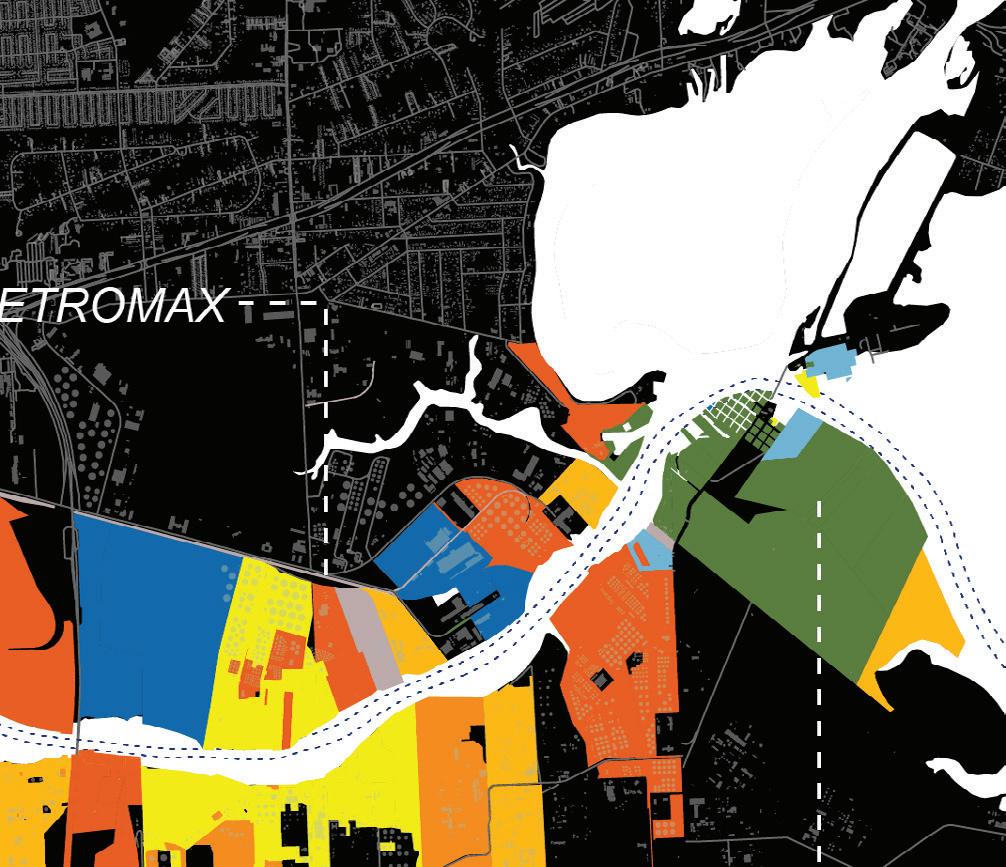

The presentation began with some background on the industries that the Port of Houston and the Ship Channel support. Seventy percent Ship Channel cargo is “liquid bulk,” including gasoline, diesel, gasoil, residual fuel oil, or other similar kinds of liquid cargo, making the Port of Houston the largest petrochemical complex in the world. Twenty percent of cargo (and growing) is containerized cargo, three percent is project cargo, four percent dry bulk, and the remaining three percent is general cargo. Altogether, this makes Houston the first-ranked US port in foreign waterborne tonnage, with 193.8 million short tons in 2021. Ships arrive from all over the world, with thirty-seven percent from East Asia (increasing due to Panama Canal improvements); twenty-six percent from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMA), twenty-one percent from Latin America; twelve percent from the Indian subcontinent; and four percent from all other regions. The Ship Channel has an

enormous economic influence as a “national treasure,” impacting 1.35 million jobs in Texas and 3.2 million jobs nationwide while contributing $339 billion in value to the Texas economy and $802 billion in value across the US.1

The Channel has seen significant changes, having been repeatedly deepened in five-foot increments over its one-hundred-year history. A containerized cargo boom since 1957 has driven one of the fastest-growing segments of the port. However, its chief export remains chemical resins that are made into plastic products. Today there are half again more imports than exports, but imports and exports were equal as recently as twenty years ago. Because of this tremendous growth, the Port and Army Corps are already looking past Project 11 and toward a Project 12 expansion. Presently, the Ship Channel vessel size is limited to eleven hundred feet long due to bends in the channel, but Project 11 includes necessary widening to accommodate twelvehundred-foot Post-Panamax vessels (a standard size) and two-way traffic, both necessary for the present volume. Project 12 would look to deepen the channel up to fifty-five feet. Project 11 is estimated to cost $1 billion, while Project 12 would run at least $1 billion or more due to the dredging of the continental shelf, which would be required to allow deeper-draught vessels to continue out to the Gulf of Mexico over twenty miles offshore.

The Houston Ship Channel (HSC) is federally owned, so any changes must be done in conjunction with the Army Corps of Engineers. As such, for Project 11 fifty percent of the cost is

shared by the federal government. The first step towards completing the project was a feasibility study that AECOM completed between 2015 and 2020. The Channel gets narrower further inland, down to three to four hundred feet wide instead of over five hundred feet wide. It has been dredged about as deeply as it can be with existing constraints, but future plans would deepen the Channel from 41.5 feet in the upper reaches to 46.5 feet for the remaining length.

As a result of a partnership among the Port of Houston, US Army Corps of Engineers, and the Beneficial Users Group (or BUG, which includes the Environmental Protection Agency, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Resource Conservation Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, the Texas General Land Office, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service), all dredged material from maintaining and upgrading the Channel is used to create artificial bird islands and salt water marshes in Galveston Bay. Today, these islands are home to nearly ten thousand nests, several bird species (including great blue herons, great egrets, snowy egrets, tricolored herons, and brown pelicans) and the largest gathering of nesting bird pairs in the entire Galveston Bay system. There has been a net loss of saltwater marsh across the years, but Project 11 will result in 300 acres of additional bird islands and oyster reefs made from clay core and rock, including three bird islands. As channel widening typically disrupts oyster growth, which occurs on the sides of the waterway, Project 11 will also include the creation of eighteen twenty-acre oyster reefs at Dollar Point and San Leon.

The Ship Channel has a number of private terminals serving petrochemical facilities.

Dredge material from Project 11’s expansion of the Ship Channel will be used to supplement and build new bird islands and environmental habitat in Galveston Bay. Oyster reefs are also proposed.

The Port aims to proceed with Project 11 using a compressed construction schedule. The Federal Water Resources Development Act (WRDA) ensures that projects with benefit to cost ratio above 1:1 are more likely to receive funding and appropriations, so pursuing a compressed schedule would be likely to use more local funds. Doing so, however, could cut up to five years from the project. Targeting improvements for Post-Panamax vessels and other improvements are beyond present federal commitments.

National and global competition drives these dredging and expansion projects; otherwise, private industry would move to competing ports such as Corpus Christi, New Orleans, Savannah, or Los Angeles. Ships are continuing to get bigger to drive down costs, a process accelerated by widening of Panama Canal. This, in turn, forces ports to expand their capacity.

The Port of Houston is financed by tolls and fees for its use, as well as leasing of facilities. It uses debt financing, revenue bonds, and private industry investment for construction. Port ES2G is the Port’s Environment, Social, Safety and Governance program. Since 2016, the Port’s carbon footprint is down by fifty-five percent. In April of 2022, the Port of Houston committed to carbon neutrality by 2050.2 Port officials plan to achieve a net-zero GHG footprint by 2050 by upgrading technology, improving infrastructure and equipment, and using alternative fuels and clean energy sources.

The presentation continued with an overview of the resiliency projects, both planned and underway, around the Galveston Bay and Port of Houston. One major such project is the Texas Coastal Study, also known as the “Ike Dike,” a $26 billion storm-surge protection proposal to build a dike at the mouth of the Galveston Bay to combat hurricane storm surge risk. Every year, hurricanes shut down the Ship Channel for several days, and Hurricane Harvey caused severe siltation, restricting the draught of the Channel and requiring it to be dredged at major expense. Much of the criticism of the “Ike Dike” proposal comes from its enormous price tag in addition to the fact that it does not protect Houston from storm surge originating within Galveston Bay itself. As a result, a team from Rice University has proposed the Galveston Parks Plan in addition to the Ike Dike, pairing a system of artificial island parks as a storm protection system. The plan proposes a ten-thousand-acre public park, event venues, marinas, and destination sailing, going beyond disaster planning to balance an array of civic needs. By using a consensus resilience planning approach instead of just an

engineering solution, the plan would engage both community and ecology. Hydrological challenges remain outstanding, however, and it would require significant effort to de-engineer the Ship Channel. The planning study was funded by the city, county, and developers, but the federal government has already completed a separate study and concluded that the Ike Dike remains the preferred alternative (PA). Since the Rice University project is only preferred locally, a series of hurdles remain to prove its viability to the federal government.

The session concluded with questions regarding the future of energy in Houston.

Q: How is the decarbonization conversation playing out in Houston?

A: There has been a pullback in offshore drilling as well as some investment in carbon capture. Shell is studying refinery plant consolidation by considering plant hibernation, but not yet phasing them out. Additionally, ExxonMobil, headquartered in the Houston area, has proposed an Innovation Zone along Ship Channel with a $100 billion carbon capture and storage plant. Some plants are already being phased out; for example, LyondellBasell recently announced that they will be closing their Ship Channel refinery due to market factors. Carbon markets are coming to Texas, with a big focus on “blue carbon” investments including financial incentives to maintaining coastal wetlands, prairies, etc. The Port of Corpus Christi wants to become the leading green port in the country by leveraging Texas’s success with wind energy to create more capacity to serve that market. Because of state-level Texas politics, you will never see Port of Houston talking about these things in the same way as in Los Angeles or the Pacific Northwest. However, we see the energy transition happening quickly because of a quickening regulatory environment and culture.

1. “Port Statistics.” n.d. Port Houston. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://www.porthouston. com/about/our-port/statistics/.

2. Port Houston Commits to Carbon Neutrality by 2050. 2022. Porthouston.com. Port Houston. April 4, 2022. https://www.porthouston.com/ news-media-press/press-releases/.

Matthijs Bouw

Matthijs Bouw is a Dutch architect, urbanist and founder of ONE Architecture and Urbanism. Established in 1995, ONE is an award-winning design and planning firm focused on the use of design for climate adaptation and mitigation. Bouw is Professor of Practice at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design and lectures and teaches internationally. His latest book, co-authored with Jonathan Barnett, Managing the Climate Crisis: Designing and Building for Floods, Heat, Drought, and Wildfire was published in 2022 by Island Press.

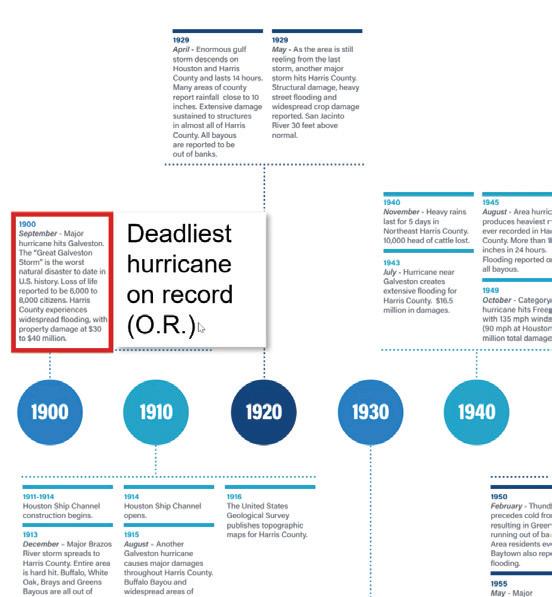

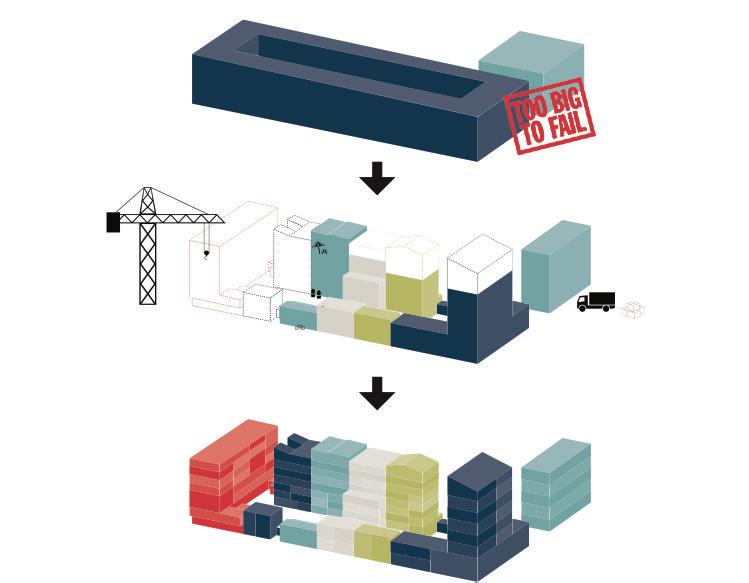

After the “Research” and “What If” phases of the studio, Matthijs Bouw, studio instructor and founder of ONE Architecture and Urbanism, gave a lecture about the work ONE has done designing within circular economic models in Amsterdam. The presentation focused on the “Hackable City,” a joint research initiative that studied circular economies, community-driven coalitions, and development patterns to combine top-down smart-city tech with bottom-up “smart-citizen” initiatives. This work served as a model for the students as they embarked on the studio’s project development phase.

Buiksloterham, a post-industrial neighborhood in Amsterdam, has been undergoing redevelopment and transition for the last two and a half decades. The area was built on

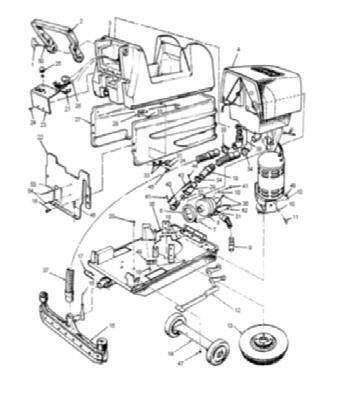

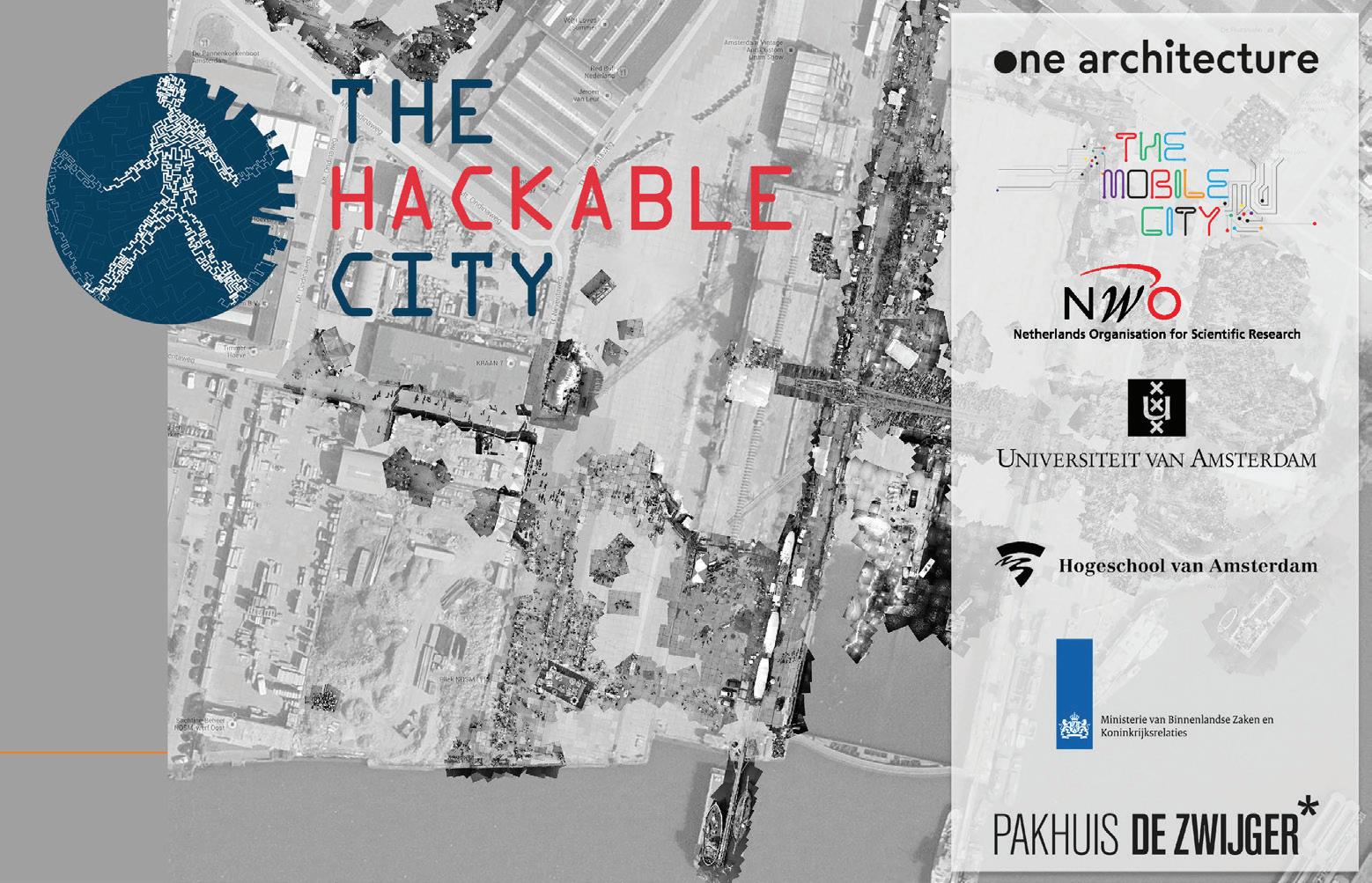

Step 1: The abandoned and polluted site lies underutilized. Step 2: A remedial wetland is constructed to clean polluted soil. Step 3: Secondhand houseboats are refurbished and put in the park. Step 4: A raised boardwalk connects the houseboats. Step 5: Events are organized, pollution is reduced, and a new community forms. Step 6: After ten years, the houseboats move to a new location and the soil is given back to the city, cleaner than before.

residents lived in a self-built neighborhood of secondhand houseboats above.

Step 1

Step 4

Step 2

Step 5

Step 3

Step 6

residents lived in a self-built neighborhood of secondhand houseboats above.

Step 1

Step 4

Step 2

Step 5

Step 3

Step 6

fill during the 1950s and was initially the site of industrial facilities and an airport. This legacy left significant environmental pollution and required intense clean-up measures to make it suitable for residential use. The original redevelopment plan was proposed in 2005 but never came to fruition due to the 2008 real estate market crash. As a result, the first redevelopment initiative to move forward was small-scale and a bit unusual: a group of regular citizens came together and built a temporary “floating” development on De Ceuvel, a heavily polluted parcel of land. Made up of secondhand houseboats connected by a network of boardwalks, the neighborhood blossomed while a constructed remedial wetland below worked to remove pollutants and restore the soil. This community created, in short, a circular environmental infrastructure model that included greywater remediation (via the wetlands) in addition to sewage and organic waste processing for fertilizer and biogas. They also grew their own food enough to supply a café and restaurant that soon became a local hotspot, putting the neighborhood “on the map” and demonstrating the feasibility of small-scale circular models of development.

Drawing from the success of the De Ceuvel community, the City of Amsterdam began to sell plots of land in Buiksloterham individually instead of pursuing a top-down, master planned development. This created a culture of social innovation that prioritized creativity and spontaneity. Neighborhood pioneers built their own houses, experimenting with form and materials while cultivating a distinct spirit of community. In one example, a resident built their house entirely from secondhand materials sourced from eBay and bankrupt building suppliers. These nascent communities began to self-organize and advocate for a park system and infrastructure improvements.

Within this community-driven context, ONE Architecture and Urbanism was brought in as a design consultant (without involving a conventional developer). Using a bottom-up approach, including a robust lineup of community engagement tools such as “serious gaming,” ONE designed a flexible apartment building plan that accommodated a wide range of users and uses. During the design process, community stakeholders collaborated to create efficiencies such as shared geothermal power, pile foundations, joint workspaces, and shared guest

apartments for visitors between the apartment building and its nearby contexts. This reduced construction costs and conserved water and electricity. After construction, the apartment building was recognized as among the most energy-efficient in Amsterdam.

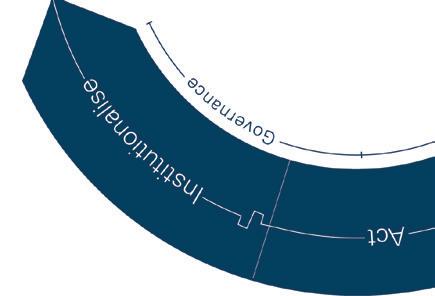

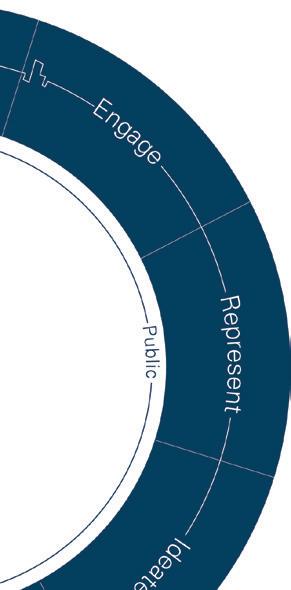

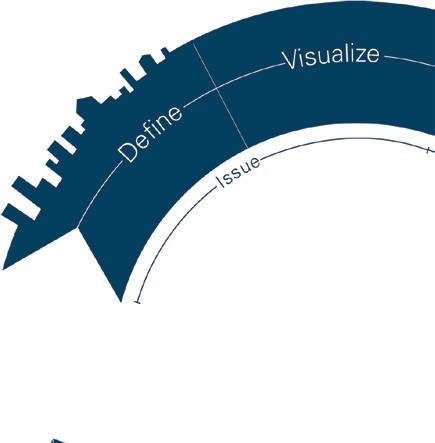

These first development projects in Buiksloterham generated significant interest in this unusual form of city-making. Citizens even set up temporary homes to wait in line for plots to open for sale. To study these emergent phenomena, ONE, in conjunction with The Mobile City, an organization focused on technology and cities, received funding to begin the “Hackable City” project, a research initiative to explore the dynamics between citizens, design professionals, institutions, and digital technologies and new media. This research culminated in “The Hackable City Research Manifesto and Design Toolkit,” a publication that took a close look at how digital tools are improving the built environment in areas such as urban farming, social dynamics, borrowing services, and sustainable water use. The study documented an emerging network of shared economies that were changing the way cities were governed by creating spaces for improvement, implementation, and institutionalization. This sharing economy created feedback loops that led to continuous city-making at a community level: individuals organize into collectives, collectives organize to enact communal benefit, and communal benefit leads to fundamental change, transcending its small-scale beginnings. Ultimately, this research showed that sharing knowledge (sharing economies) are sustainable, affordable, flexible, andperhaps most importantlynot reliant on global capital.

The unfolding city-making in Buiksloterham is an important case study for designers. It demonstrates that their role should move beyond designing physical environments to include researching and designing community-driven city-making processes. Designers should find synergistic roles, such as the inventor, lobbyist, communicator, organizer, or planner, to stage bottom-up interventions.

The session concluded with questions about the project and its processes for community-driven development.

Q: From the lessons learned in this project, do you think such a model is replicable outside of the context of Amsterdam?

A: We do, and we think about this question a lot. The answer should be yes; the possibilities for this framework in places like Houston and New York are great because real estate in these

cities is often so valuable. If you do it smartly perhaps in land with no intrinsic value (like the polluted De Ceuvel site) social processes can be organized to create value, and that value can be returned back to the local contexts. Take, for example, the Triboro Line study for New York City (now the Interborough Express) organized by the Regional Plan Association (RPA) for the city’s Fourth Regional Plan in 2017, which ONE collaborated on. This proposal used similar tools and ideas to organize and connect development sites in the outer boroughs, where there is less real estate activity, via an underutilized rail corridor. These locally-oriented models allow for community-driven densification and decrease carbon emissions while creating community-building capacity and well-being. The study also used several American typologies, like community land trusts, to ensure value generation stays local.

Q: What was it like to work with the municipality to change its preference for top-down development?

A: It was a complex process. When money was tight, most of the development was smaller-scale anyway. But when money came back, they started selling larger plots again to developers. Community groups fought against this quite a bit and had some successes and failures. But many people bought into the idea and now the municipality dedicates eighty percent of its sites to this type of bottom-up development.

ONE’s design and engagement process involves a series of steps to engage, refine ideas, and build institutional capacity with communities.

The mixed-income neighborhood that resulted in Buiksloterham is an important case study for designers by demonstrating how their role can move beyond just designing physical environments to designing community-driven development models.

Catalogtree

Catalogtree, based in Arnhem, The Netherlands, is an interdisciplinary design studio founded in 2001 by Joris Maltha and Daniel Gross. They work on commissioned and self-initiated projects centered on self-organizing systems using the framework “form equals behavior.” Maltha and Gross have lectured and taught widely. Their work is in the collection of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Museum of Design, The Archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut, and the Museum of Design Zurich.

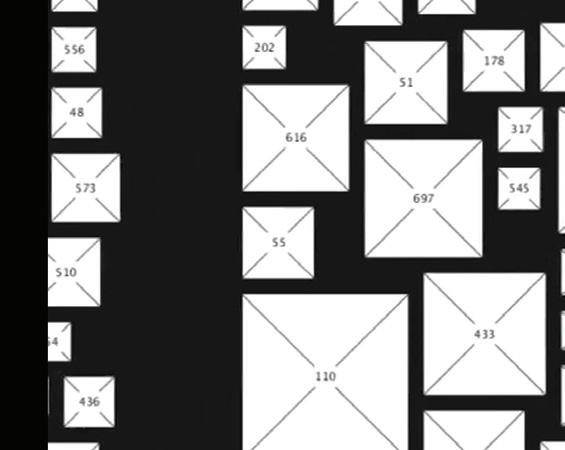

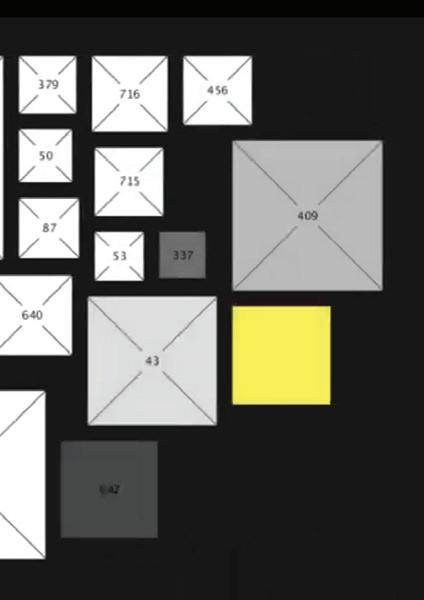

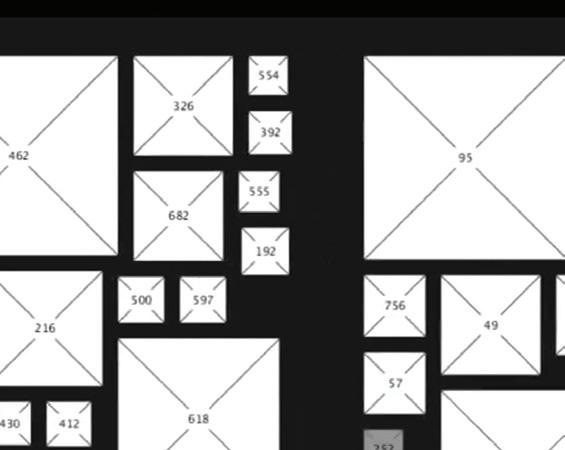

Catalogtree is a multidisciplinary design studio founded by Joris Maltha and Daniel Gross and based in Arnhem, The Netherlands. The studio is focused on experimental toolmaking, programming, typography, and the visualization of quantitative data. Joris and Daniel virtually visited the GSD to give an overview of their work and provide critiques of and support for data visualization and graphic clarity in the students’ projects. In their lecture, Catalogtree told a story of a project they worked on to build an algorithm to detect helipads in Sao Paolo, Brazil. The algorithm didn’t work as expected: tasked with identifying blue helipads, it picked up tennis courts, swimming pools, and other things that were irrelevant to their work. It also

turned out that not all helipads in the city were blue, as they initially expected. Their algorithm ended up locating over one thousand blue objects in the City of Sao Paolo. While it returned a lot of data points, in the end, there was not much they could do with that information. They gave another example of their work, the design of the book Local Code: 3,659 Proposals About Data, Design, and the Nature of Cities by Nicholas de Monchaux. The book highlights thousands of vacant lots in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Venice, all of which were identified using GIS data analysis. To organize these sites, Catalogtree sorted them by price. Lower-priced sites were assigned a larger size in the layouts while more higher-priced sites were smaller on a descending scale. They recommended using systems like this: simple organizational principles to make layouts that define hierarchies on a page. The last example that they gave was the story of an intoxicated driver that, while under the false impression that they are being chased by the police, drove erratically through a cornfield for half an hour. Catalogtree showed an aerial image of the car tracks looping through the field, tracing the driver’s looping path. They used this to say that it is a complex undertaking to draw good diagrams based on vague, bad, or incomplete data.

Their lesson to the studio: data is never purely objective; it requires smart decisions to make sense of it.

Catalogtree developed an algorithm to identify helipads in the city of Sao Paulo. While it generated thousands of data points, flaws in their underlying assumptions meant the database was unusable.

The example of the case of an intoxicated driver who was under the impression he was being pursued through a cornfield playfully demonstrates how it is difficult to draw proper conclusions if the input data is faulty.

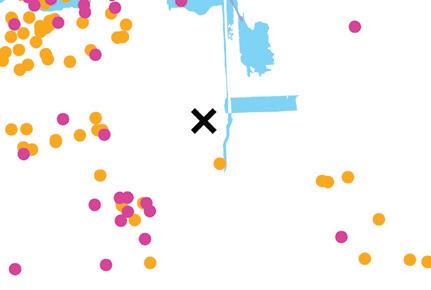

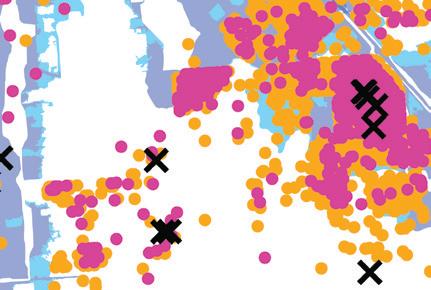

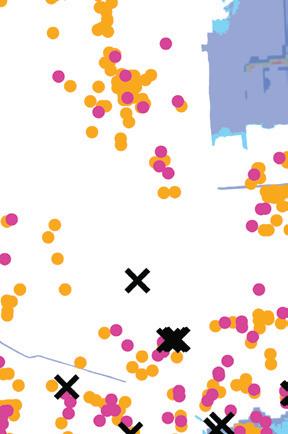

One of the aims of the studio was not only to teach students about resilience, but also to emulate critical components of designing for resilience: working through scales and systems, collaborating with different disciplines, and innovation through design. Students worked in interdisciplinary teams of three across urban design, landscape architecture, and urban planning to research a theme on Houston and communicate the resulting analyses in a way that could be used by the entire studio. The four themes were place, capacity, environment, and economy.

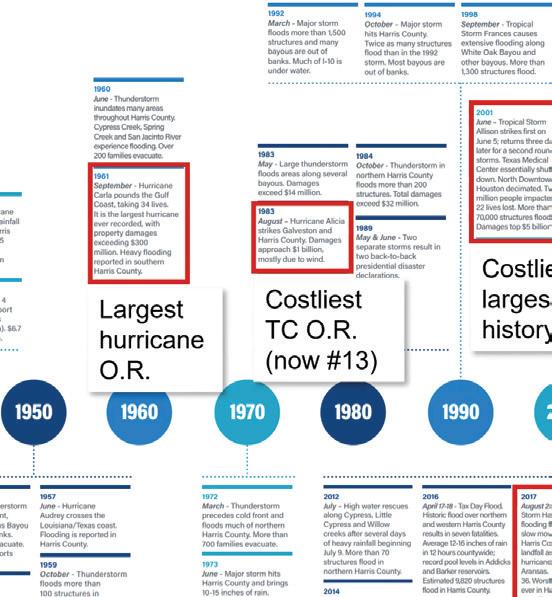

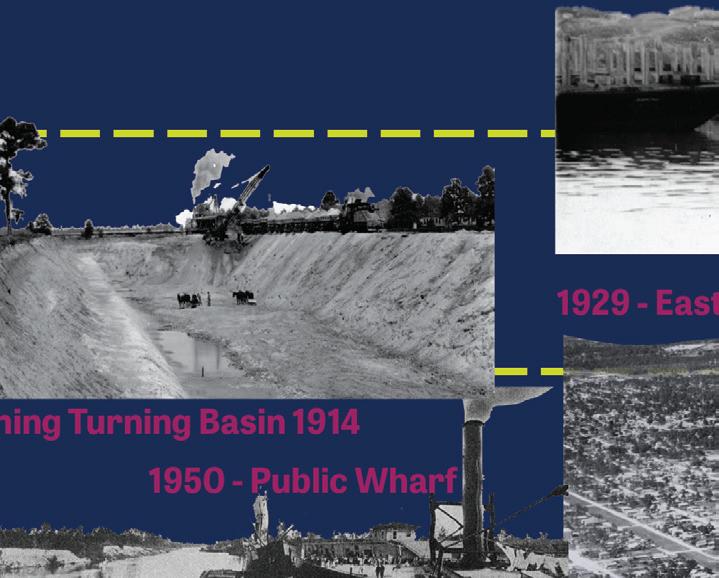

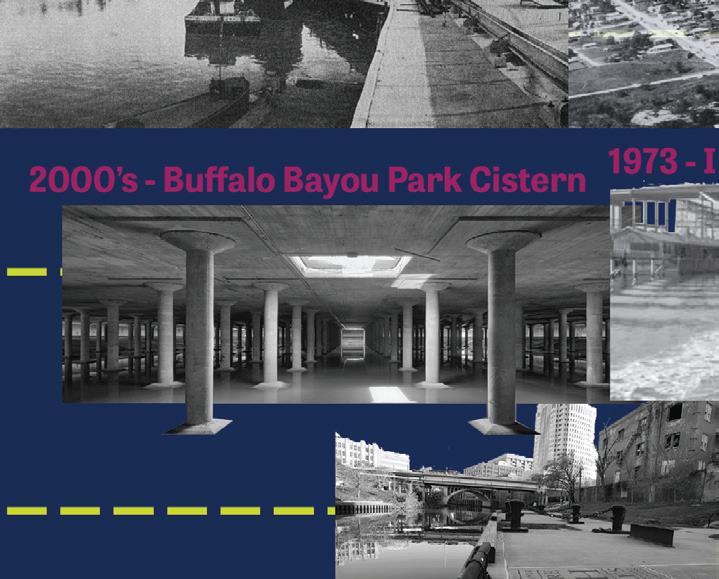

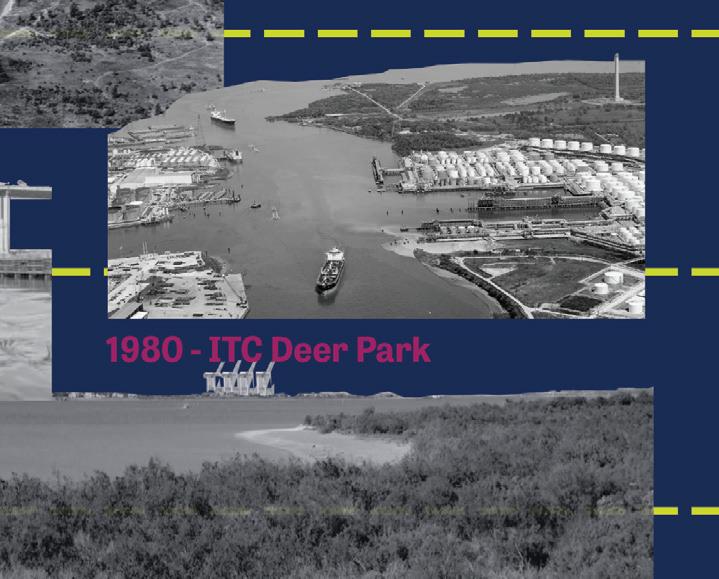

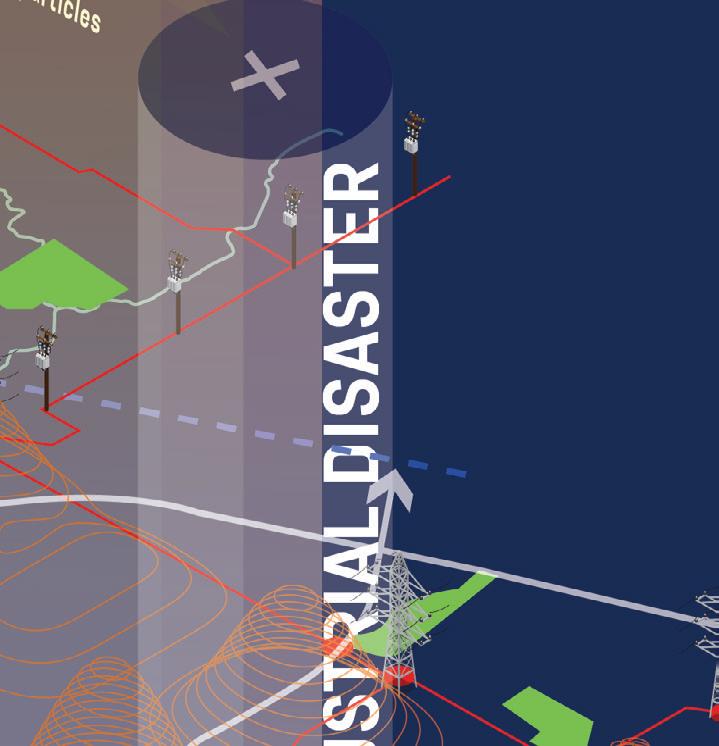

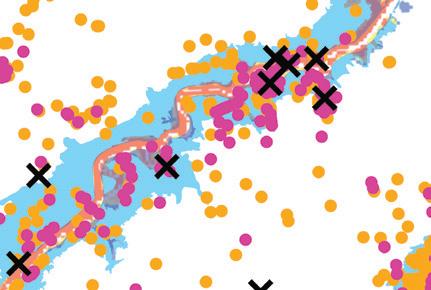

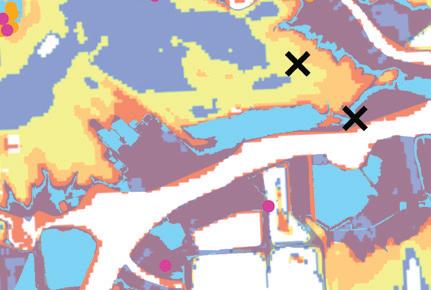

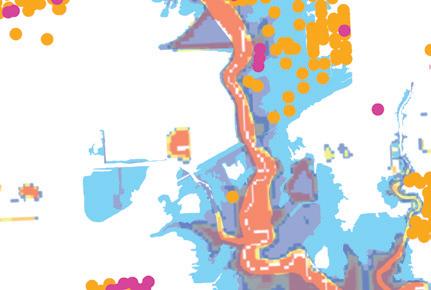

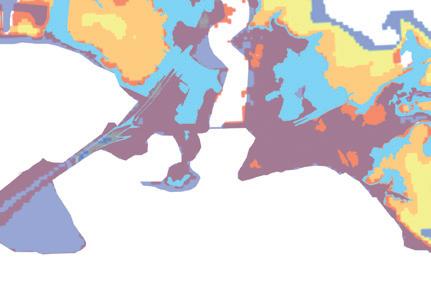

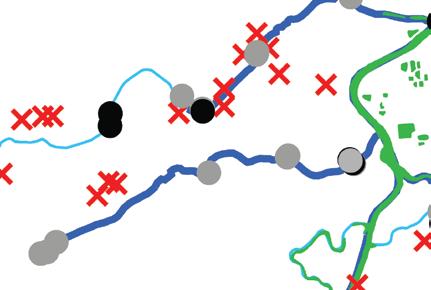

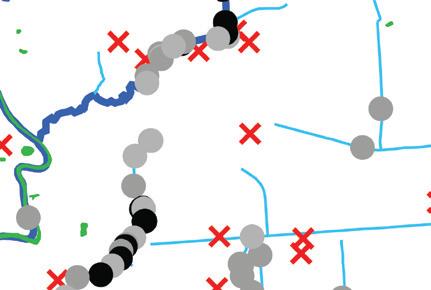

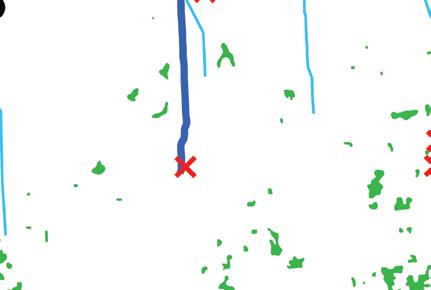

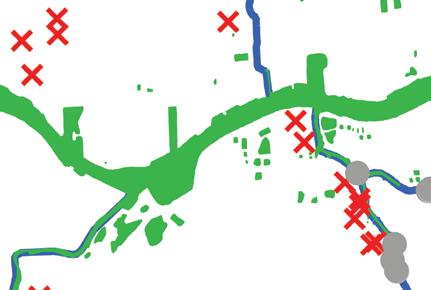

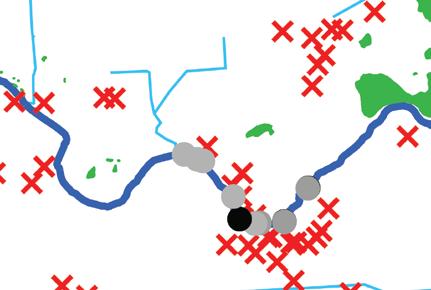

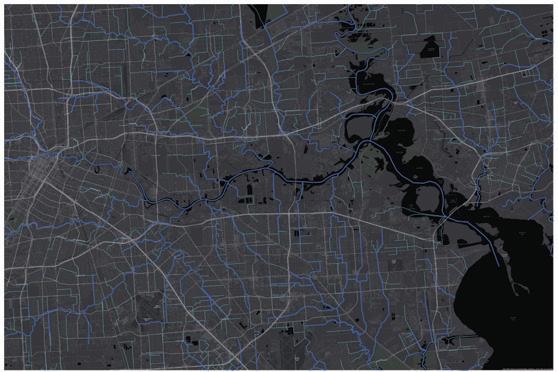

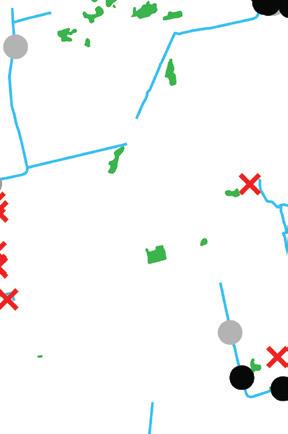

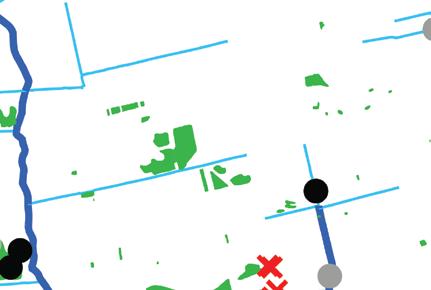

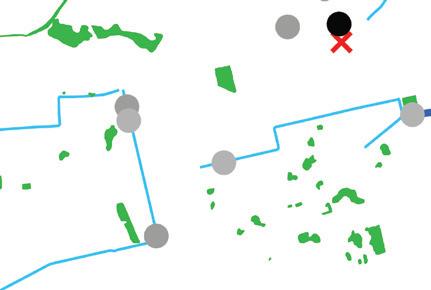

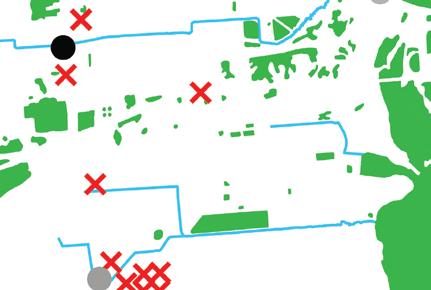

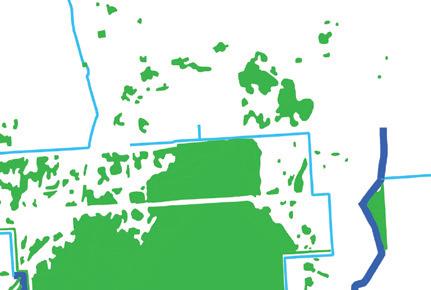

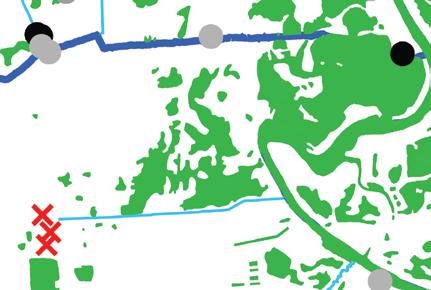

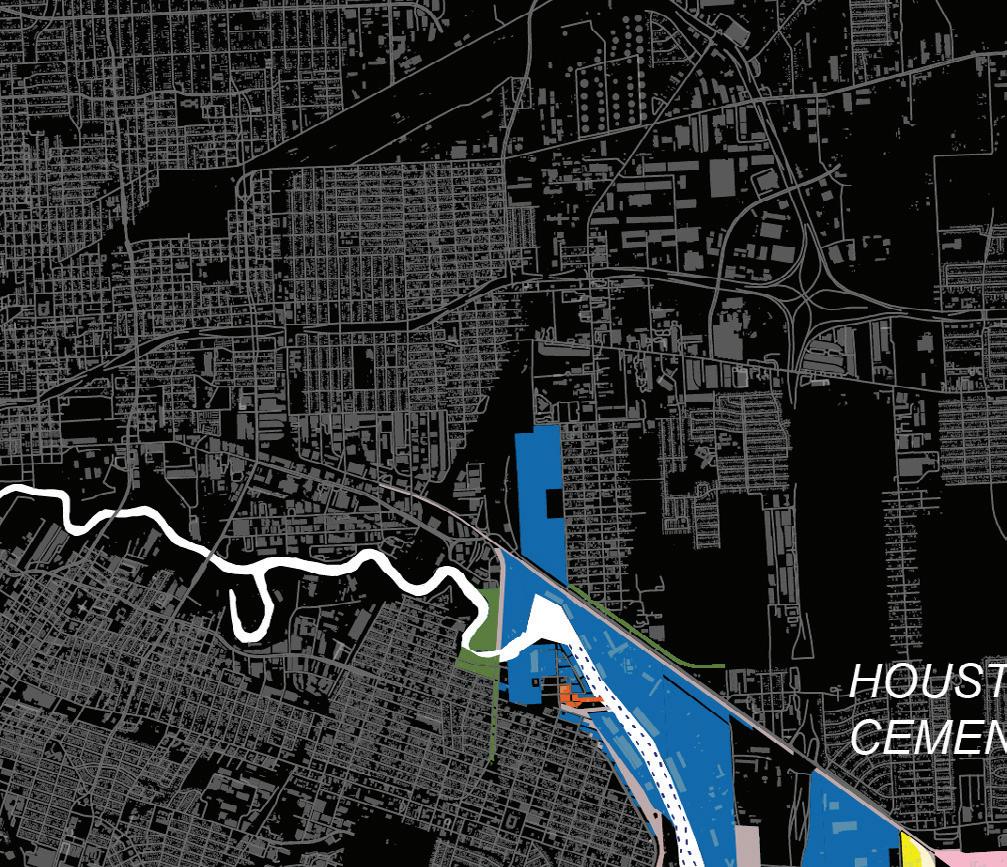

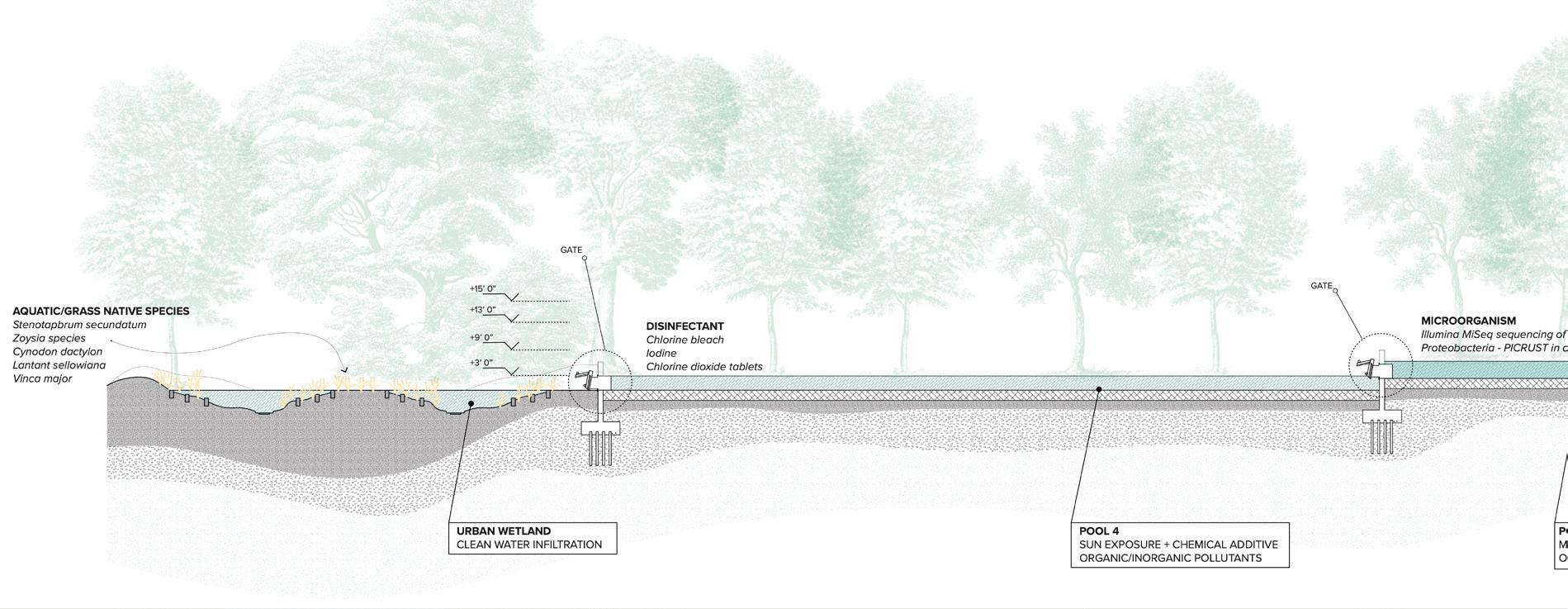

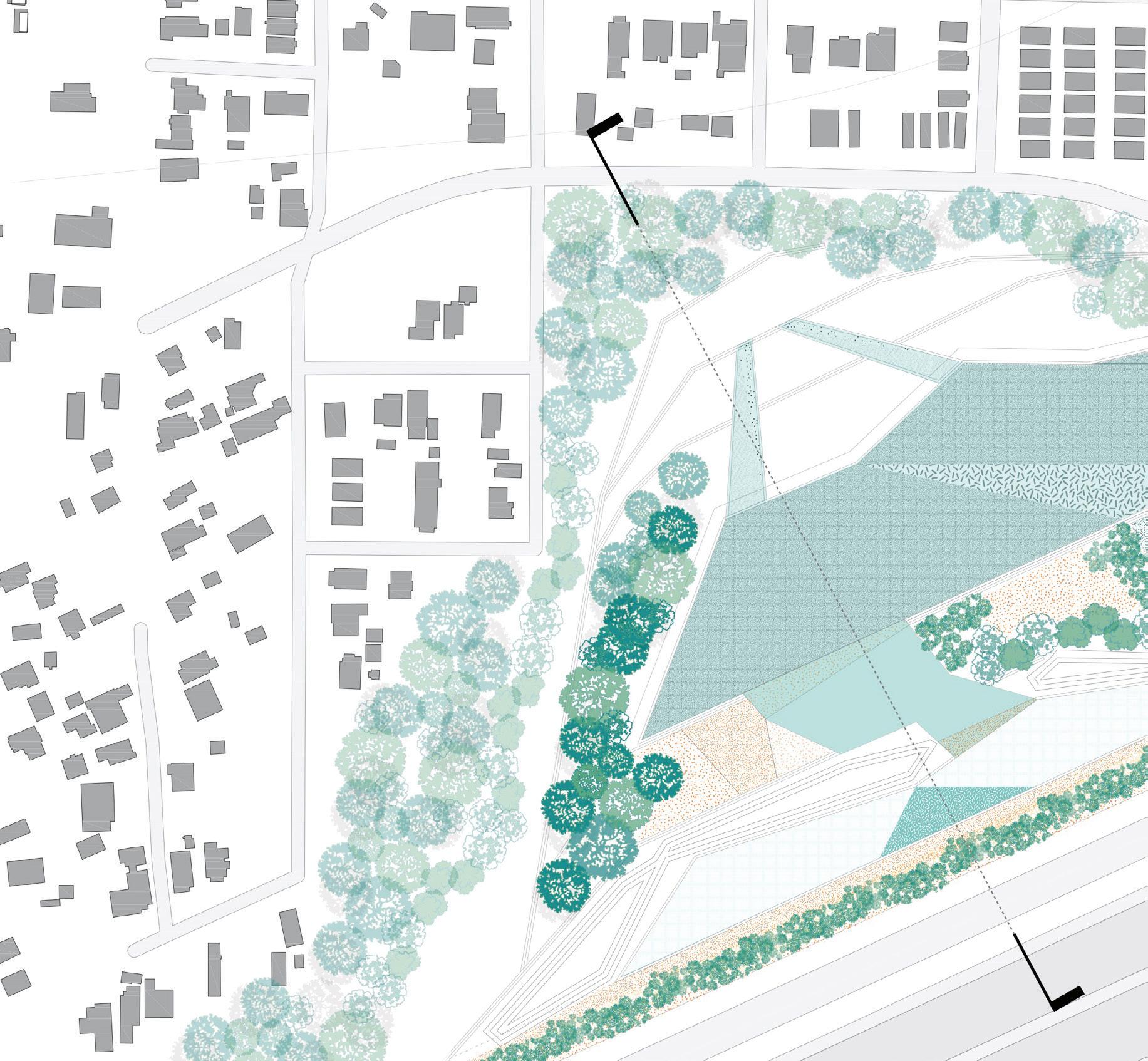

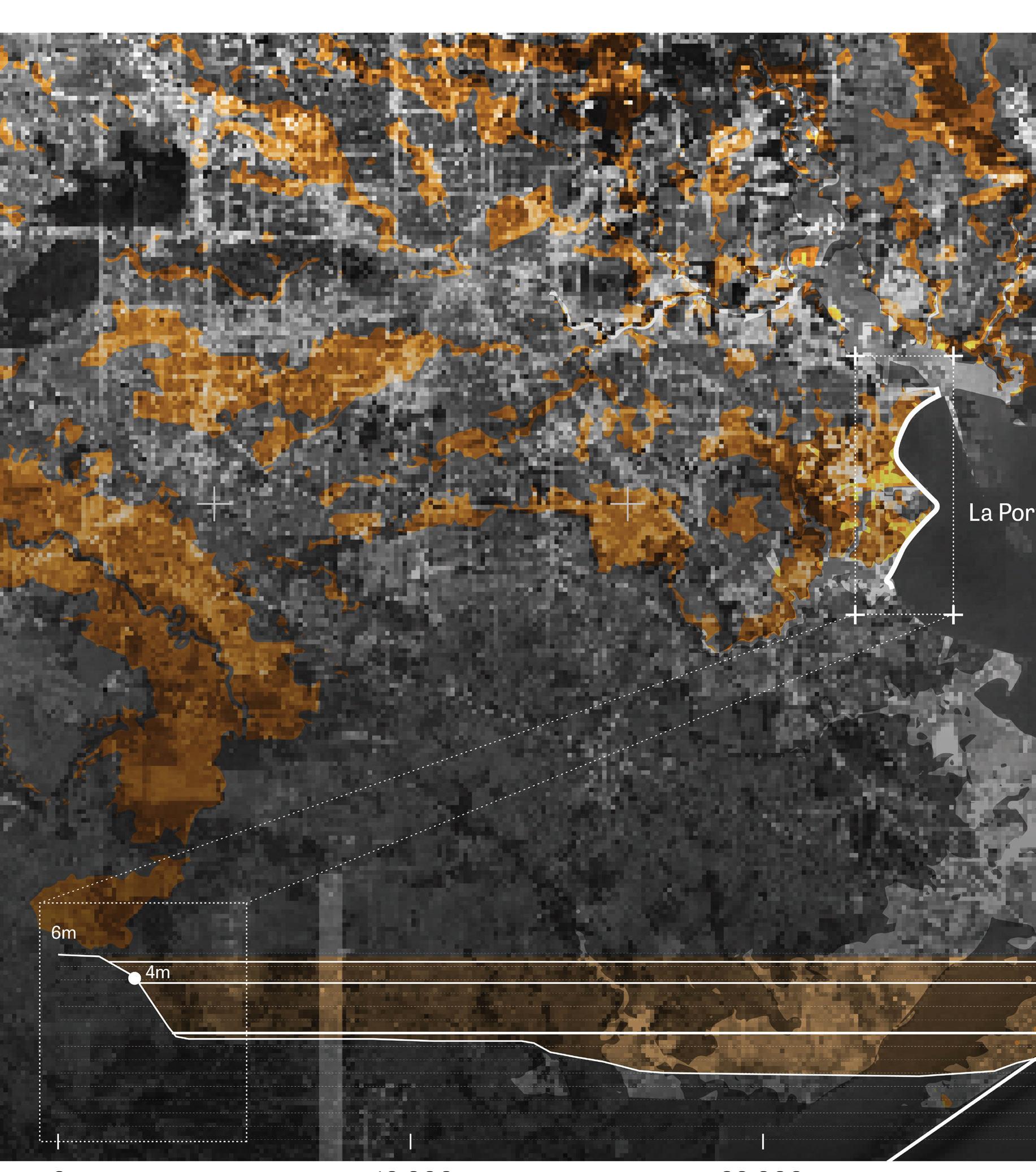

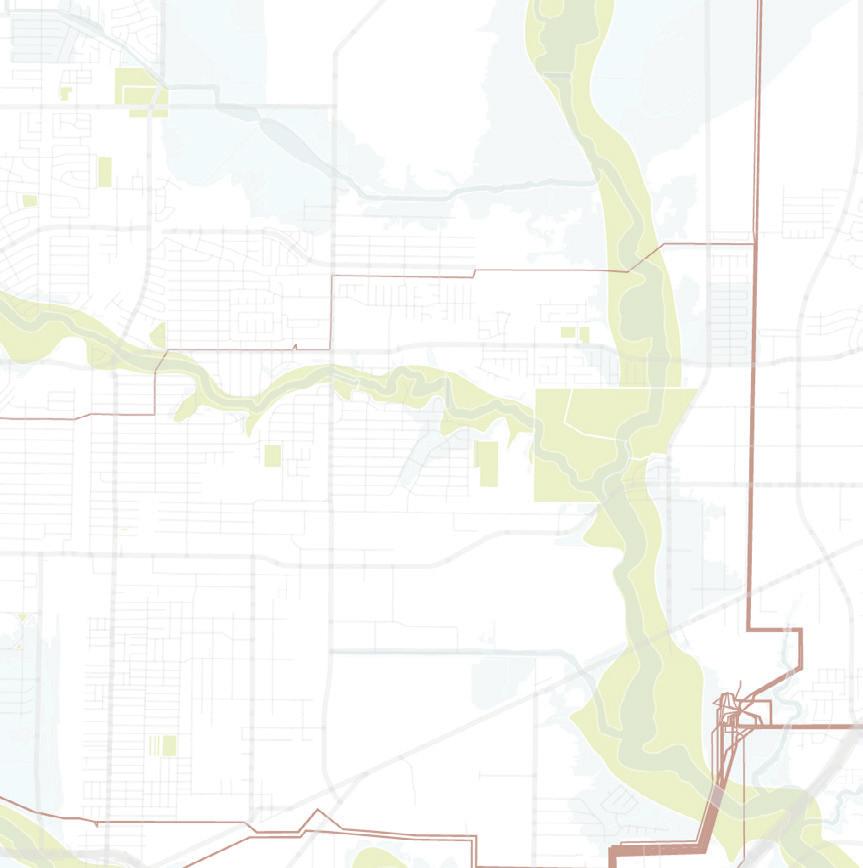

For centuries, the watershed surrounding the Ship Channel has been exploited for commerce. This has brought great wealth to the region at a significant environmental cost. The climate crisis has made it clear that we will need to rethink our urban and natural systems to find a new balance. Nature-based solutions are increasingly being used to mitigate and adapt to climate change, reduce pollution, and increase biodiversity, and such techniques will be a critical tool in renegotiating this balance. The Place team aimed to understand and map the natural and human history of the area, with a special focus on the interactions between natural and man-made systems. The group also began to identify which areas are likely to change as we transition away from fossil fuels and explored how concepts of “building with nature” might be applied. The history of the Ship Channel has made it abundantly clear that the ecological and natural environment of Buffalo Bayou has been sacrificed for the city’s economic development, transforming what was once a three- to five-foot-deep bayou into a forty-five-foot deep and over five-hundred-foot-wide industrial channel. This has propelled Houston to become one of the country’s largest metropolitan areas while simultaneously heightening risks of flooding and environmental disaster for those in and around the Channel.

The history of the Ship Channel is intertwined with that of Houston.

The history of the Ship Channel is intertwined with that of Houston.

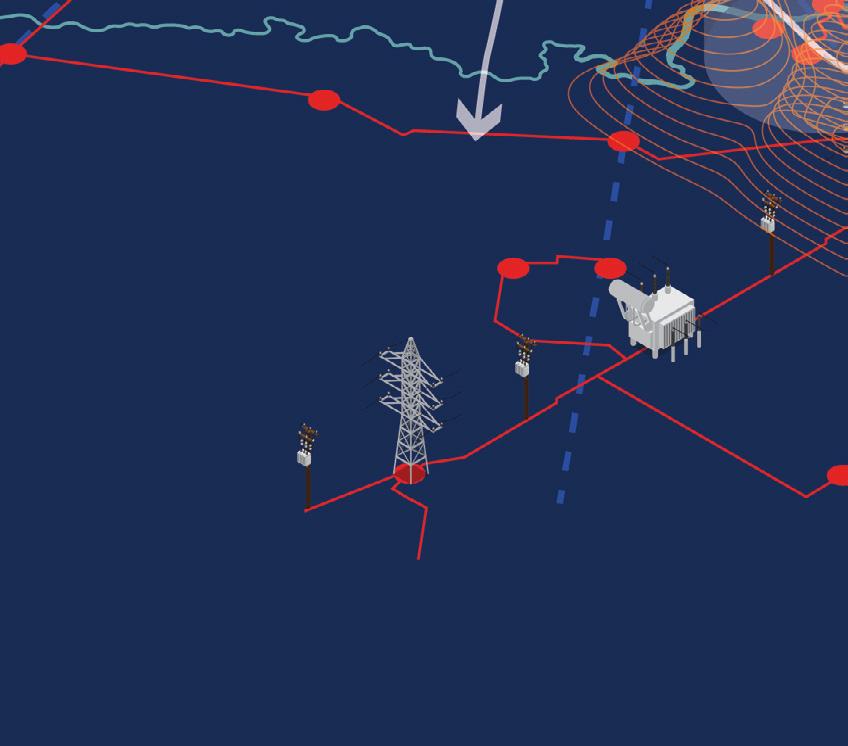

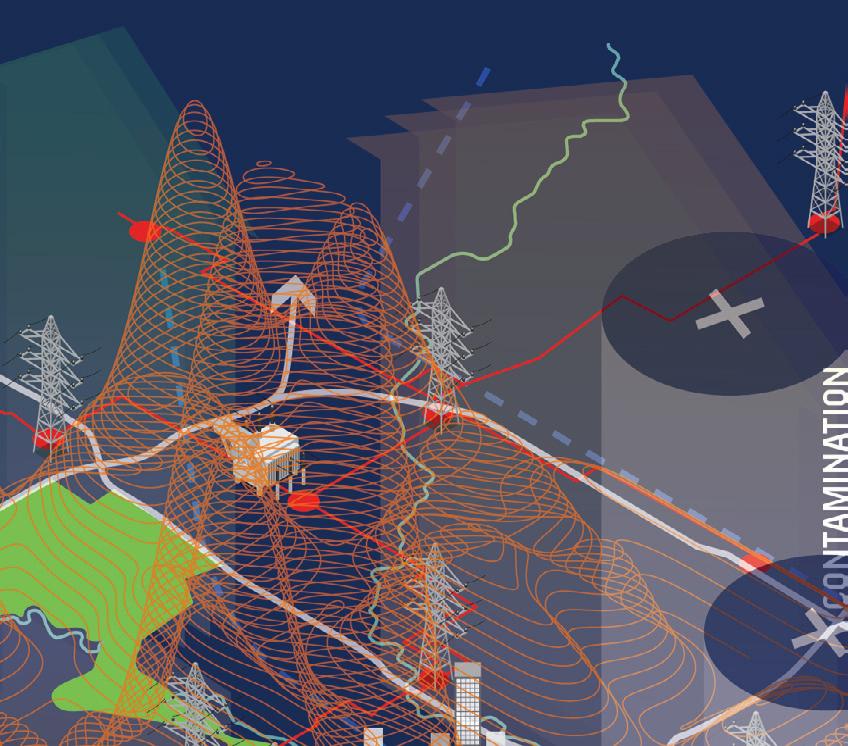

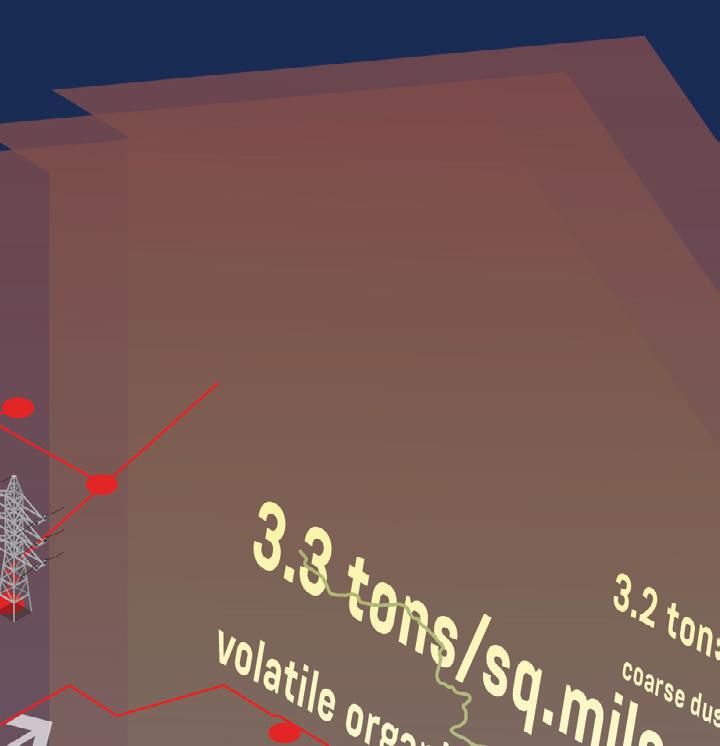

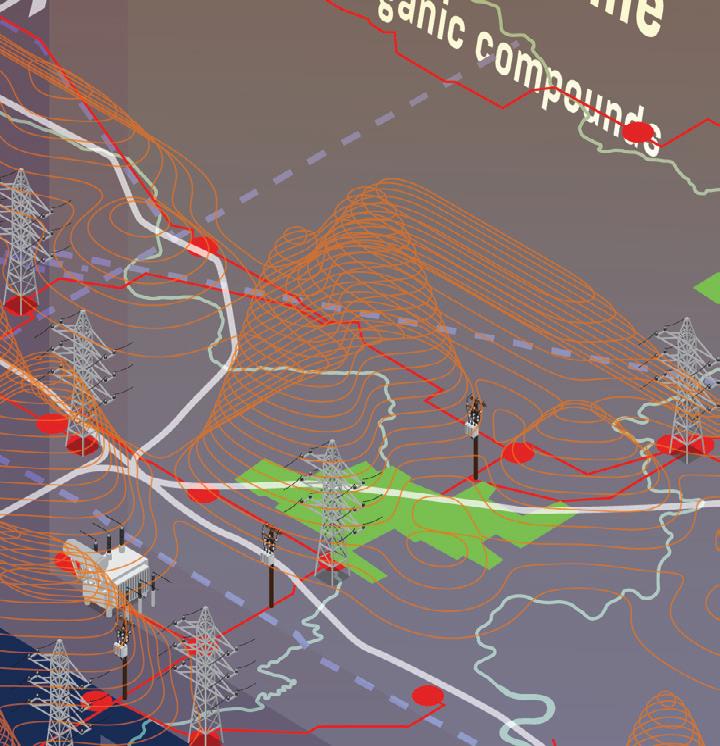

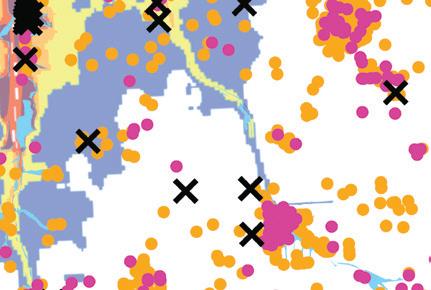

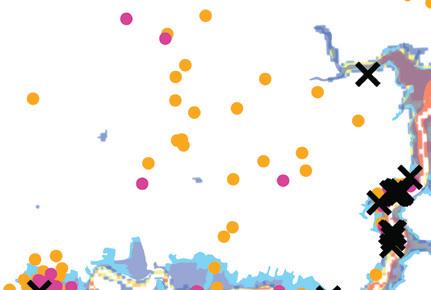

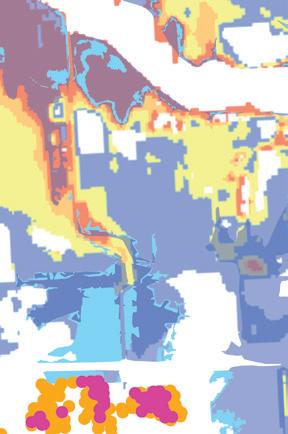

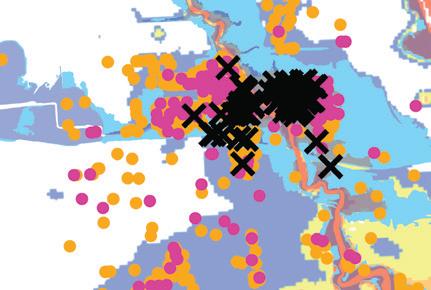

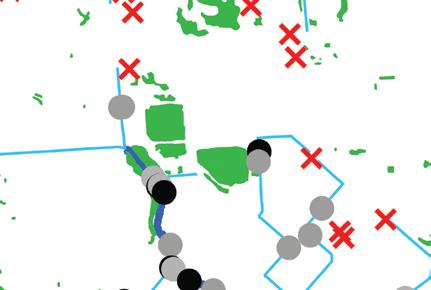

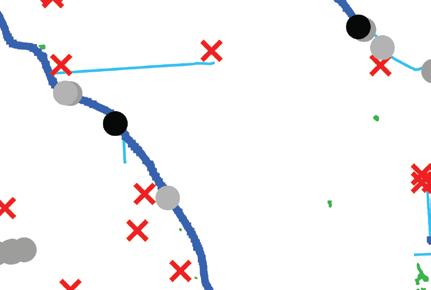

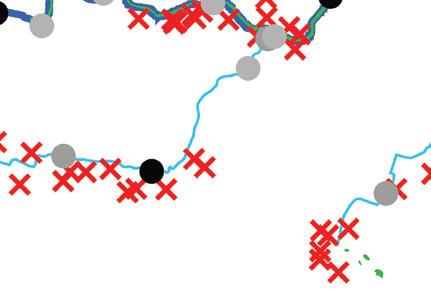

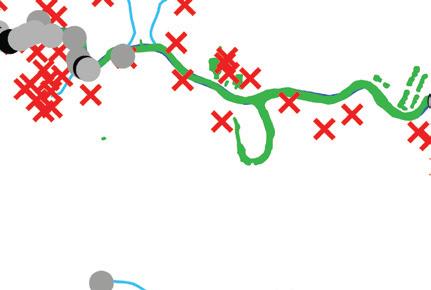

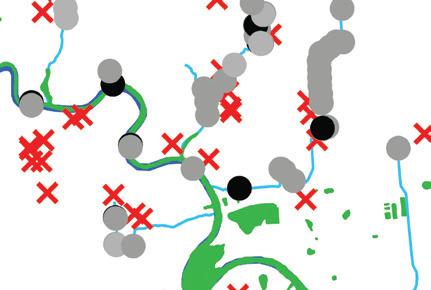

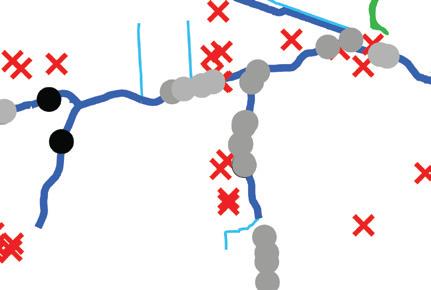

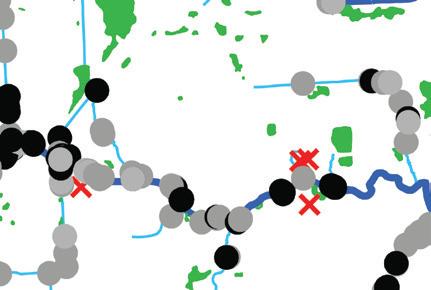

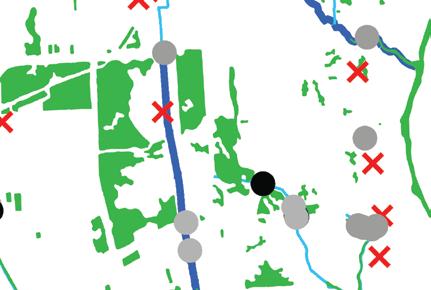

Pollution and CO2 emissions are a constant presence along the Ship Channel. The networks of infrastructure and bayous criss-cross the region providing essential services, while the risk factor for disaster is high.

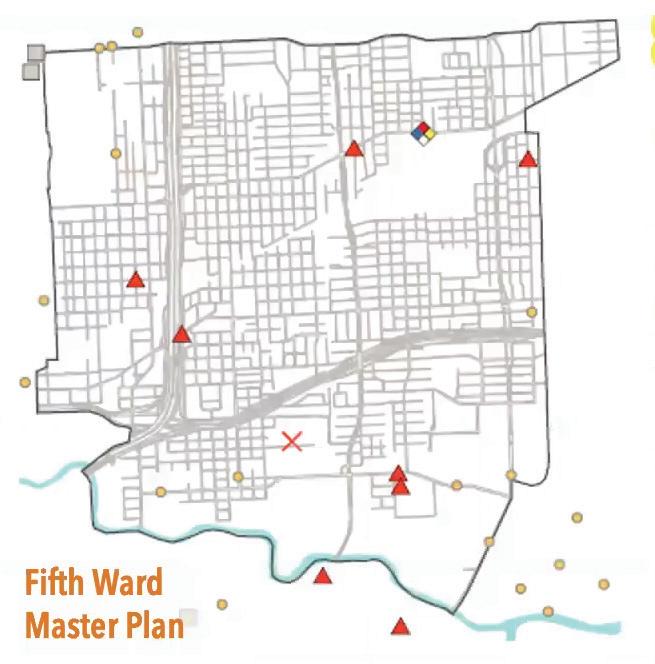

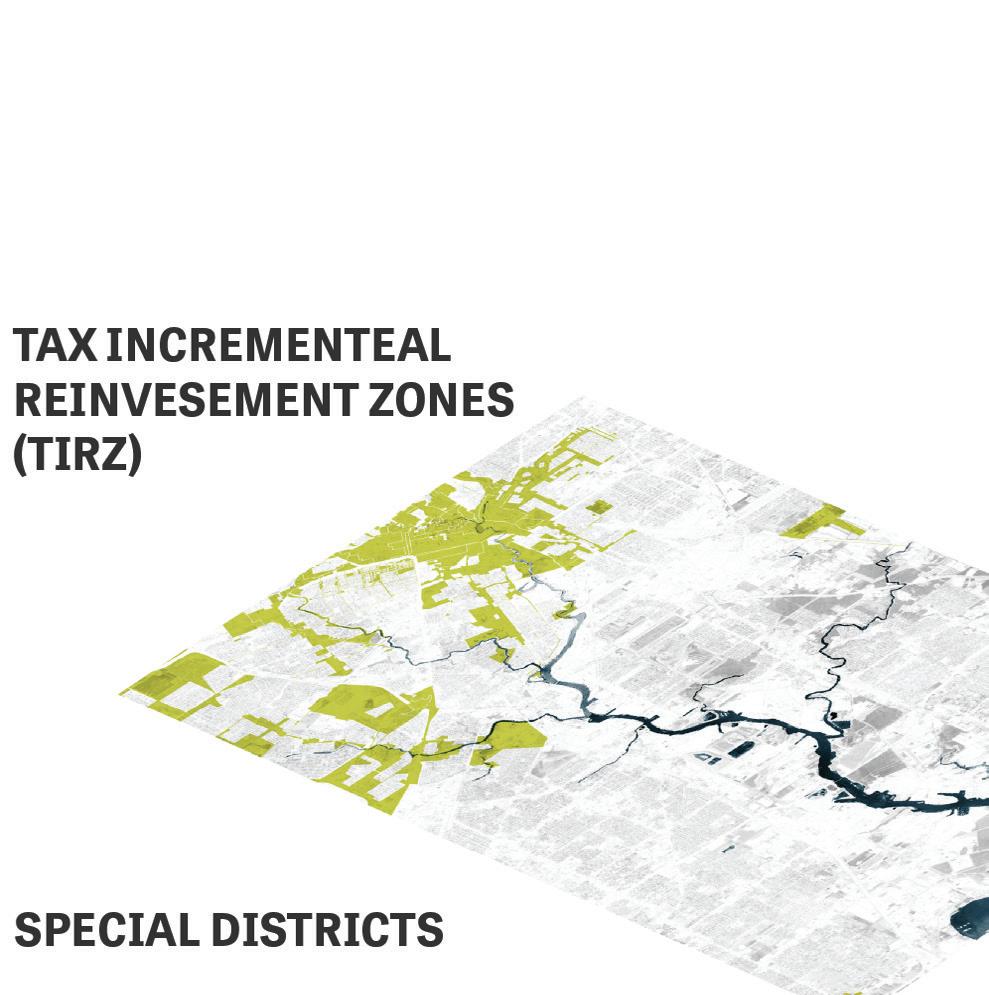

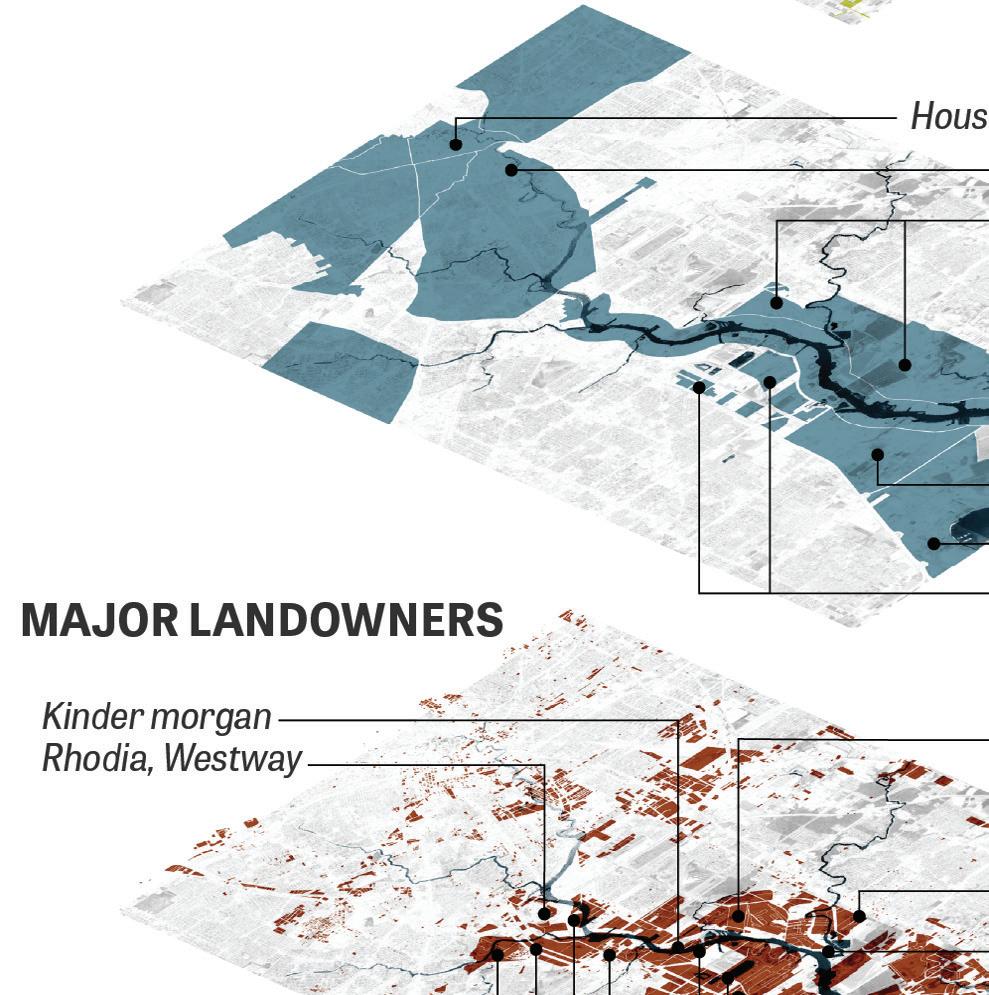

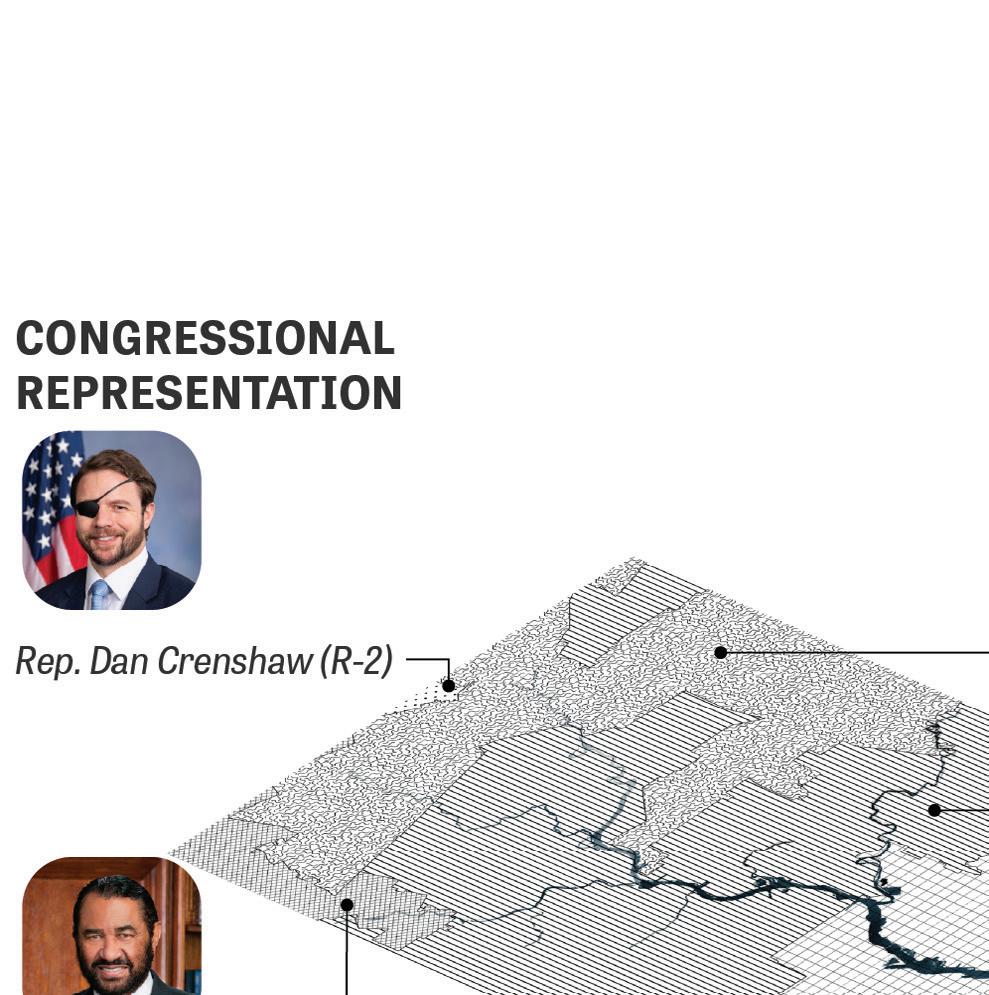

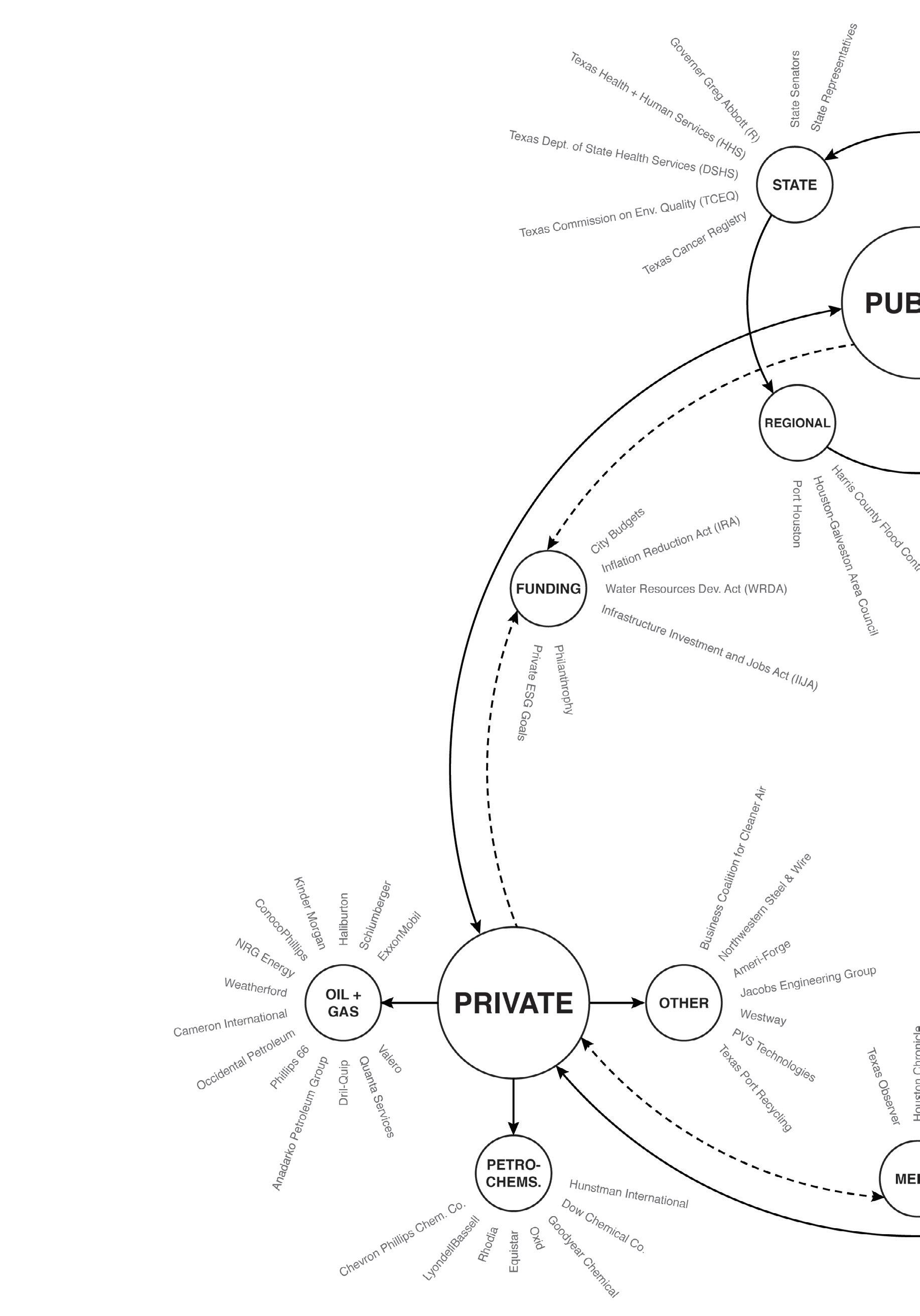

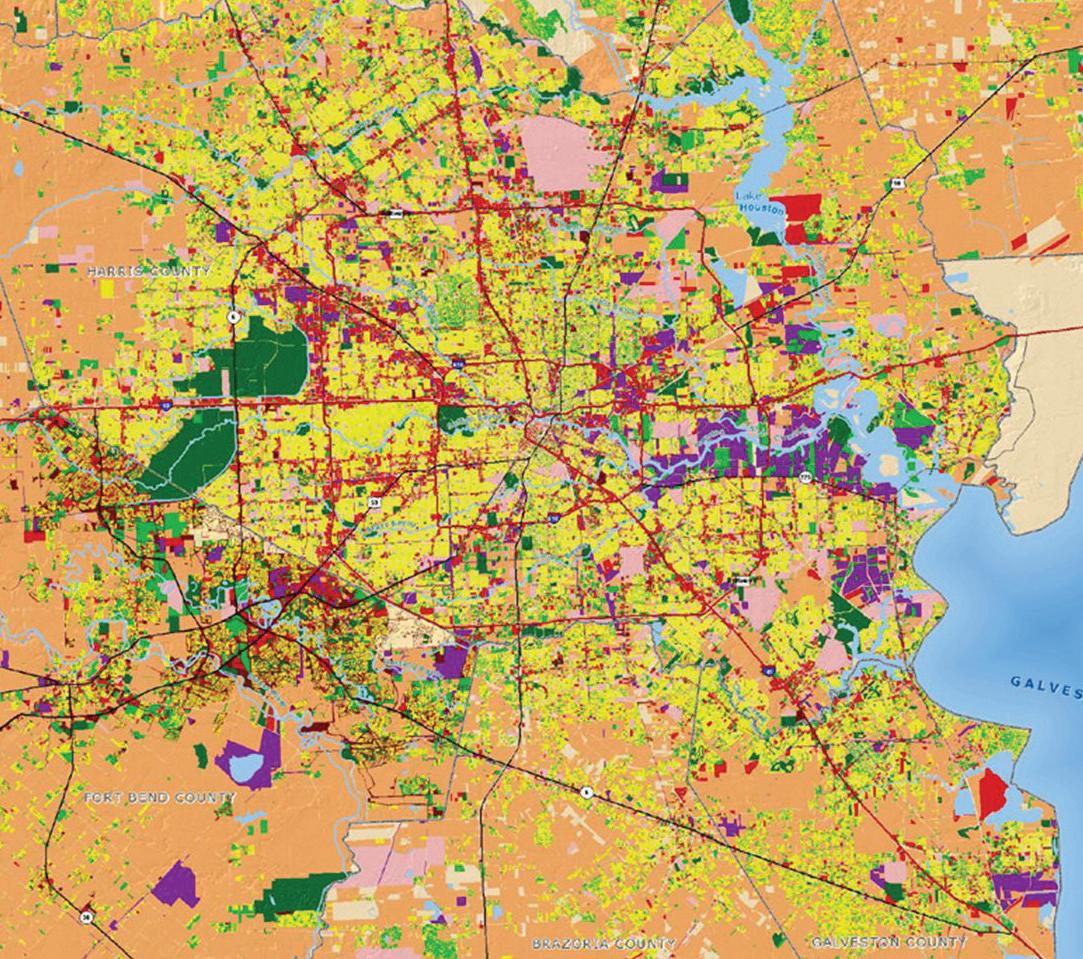

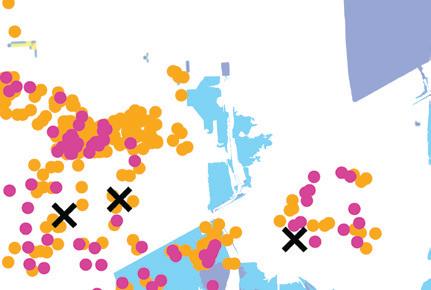

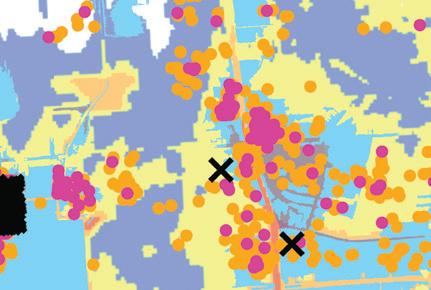

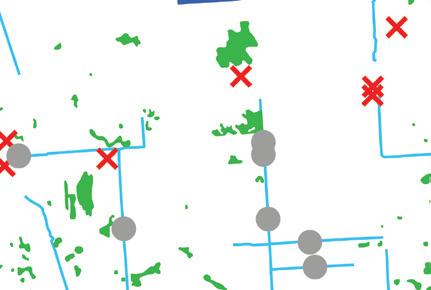

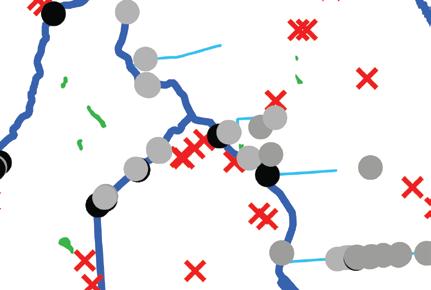

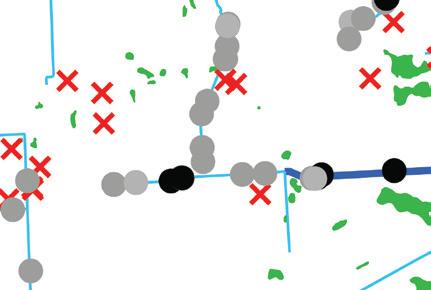

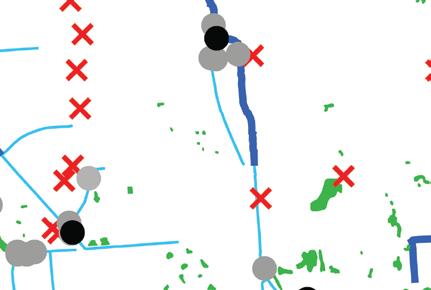

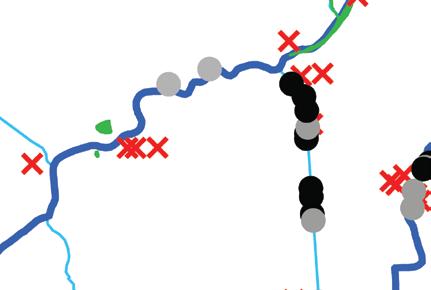

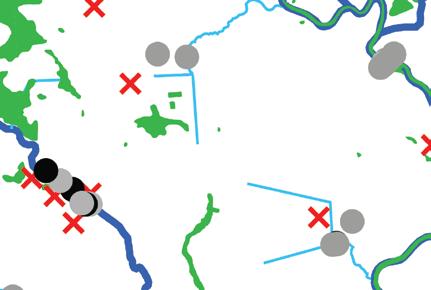

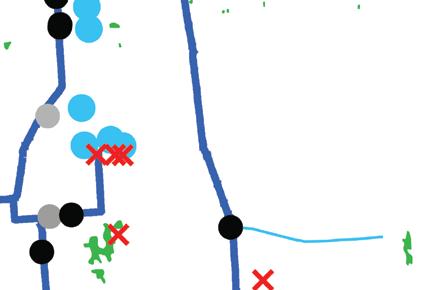

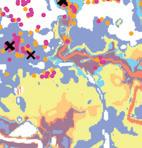

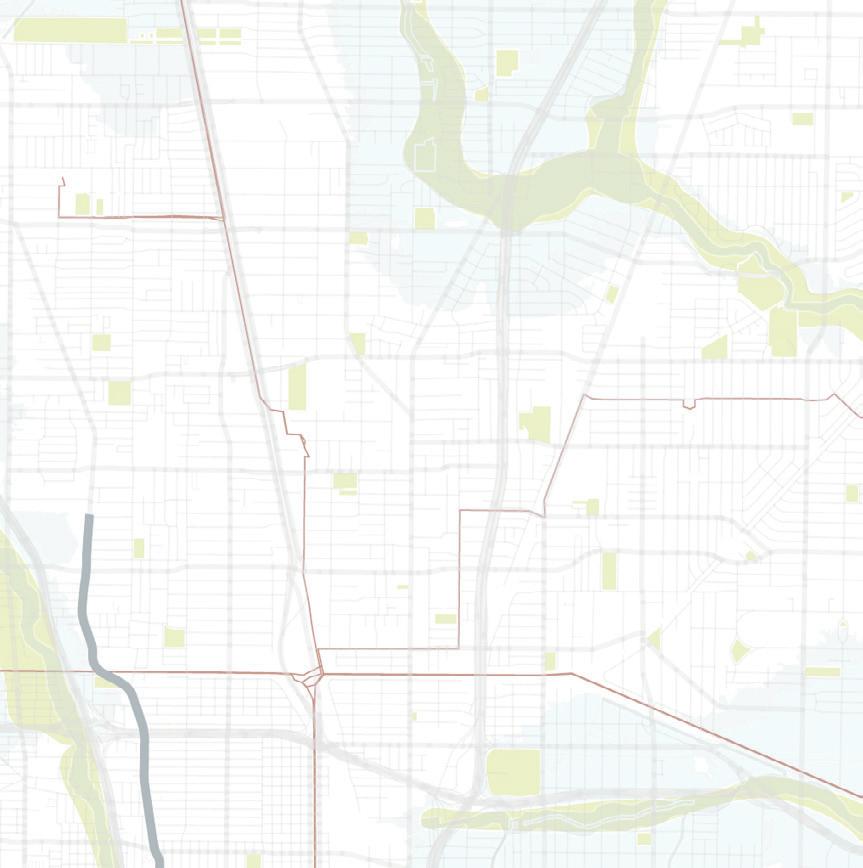

Houston is known as “the city with no zoning,” which is, according to many, a prime reason for its economic dynamism and many opportunities for minorities. It has also resulted in many problematic adjacencies and externalities. Contrary to what many people think, however, no zoning does not mean a free-for-all: there are many tools and actors that influence land use. The Capacity team analyzed Houston’s zoning, land use, and regulatory regime while exploring the different actors (communities, business associations, government institutions, and funders) that help shape the city to learn about its capacity for change.

Like many cities, Houston must attempt to balance the needs and desires of a diverse set of actors with varying degrees of influence and often competing priorities. The lack of a zoning ordinance allows for an innovative but problematic mix of land uses that can only be controlled with tools like subdivision ordinances, deed restrictions, residential buffering ordinances, airport zones, parking requirement ordinances, flood zone development restrictions, historic districts, central business districts, and tax increment financing (TIF) districts. Such tools often put decision-making power in the hands of private landowners, which, combined with a fragmented political administration, often results in market-driven urbanization. However, as the Houston Ship Channel is a federally-administered resource, there exists significant capacity for change—if there is sufficient political will to enact it.

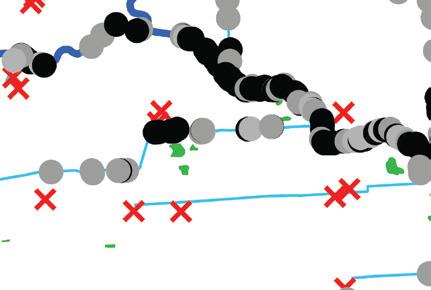

The City’s fragmented administrative structure puts much of the power in the hands of landowners, resulting in marketdriven urbanization. The Ship Channel however, as a federallyadministered resource, could be vehicle for change—if there is sufficient political will to enact it.

To drive change, Houston must attempt to balance the needs and demands of a diverse set of actors with varying degrees of influence and often-competing priorities across public, private, and non-profit sectors.

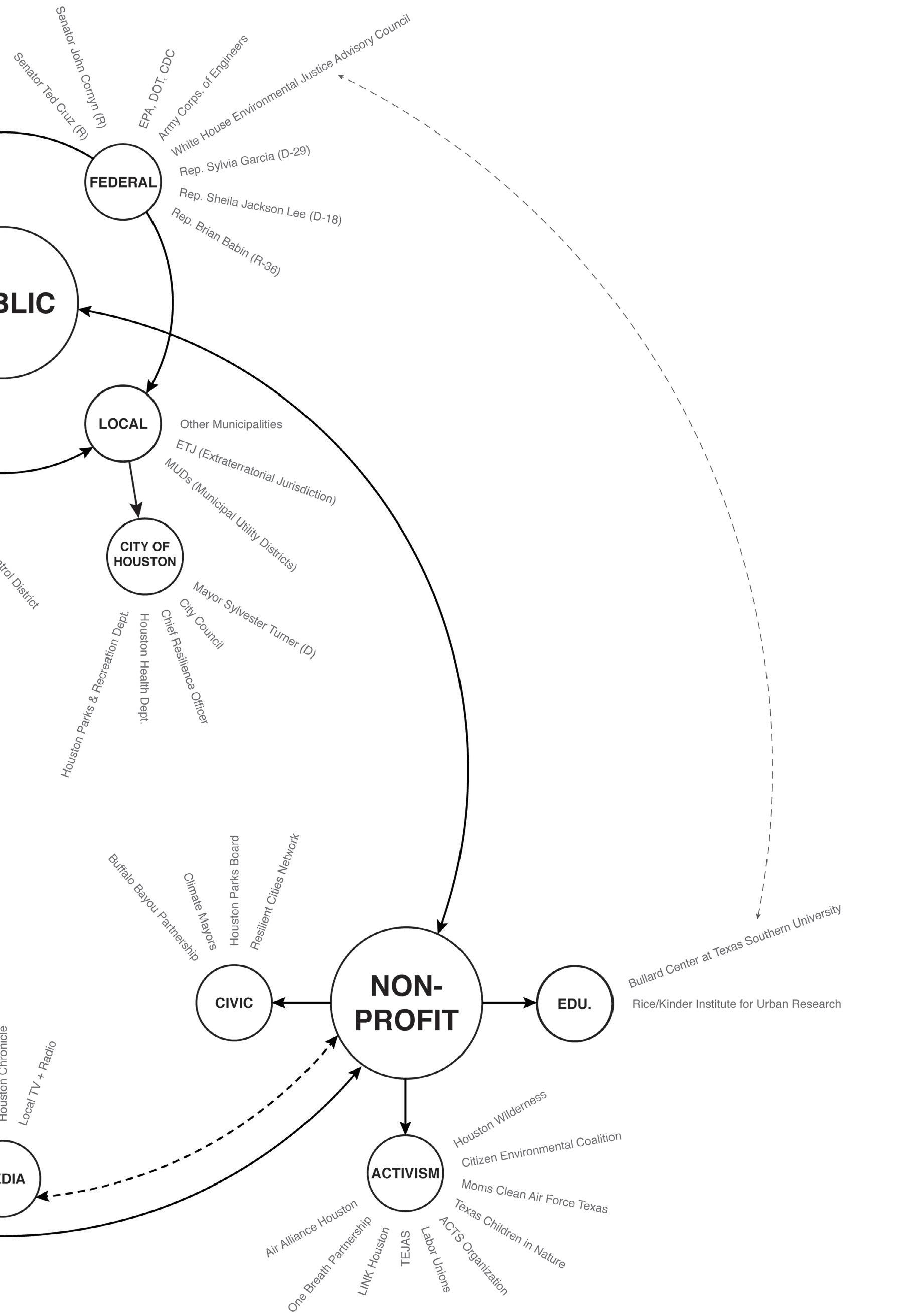

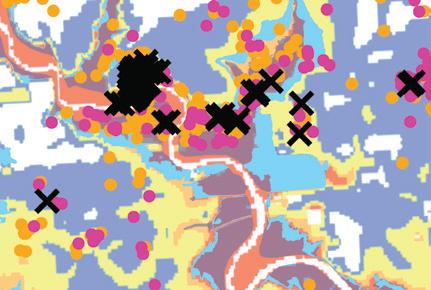

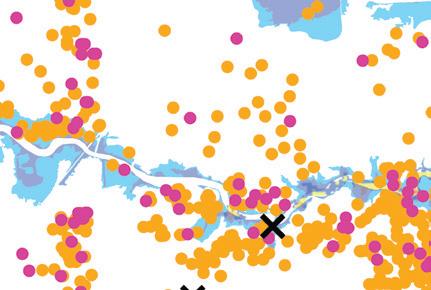

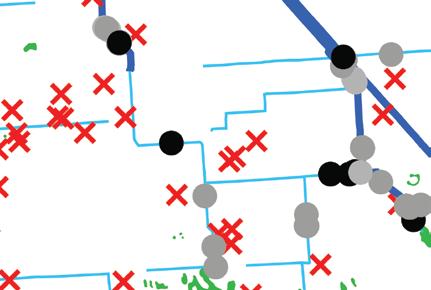

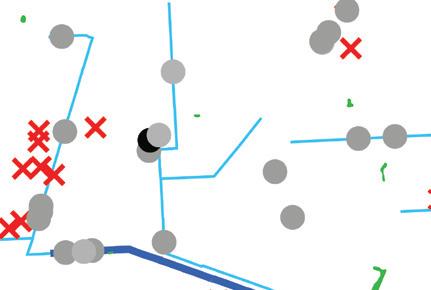

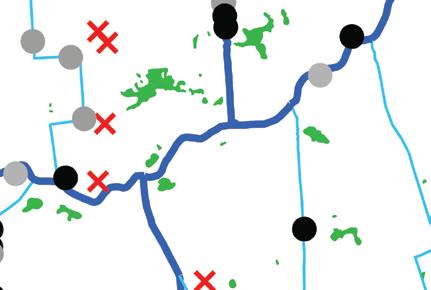

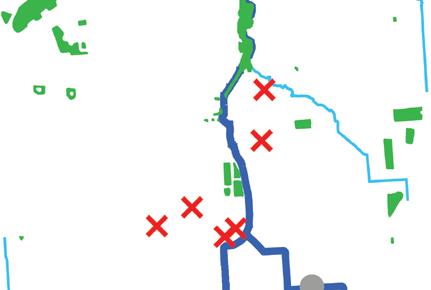

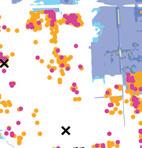

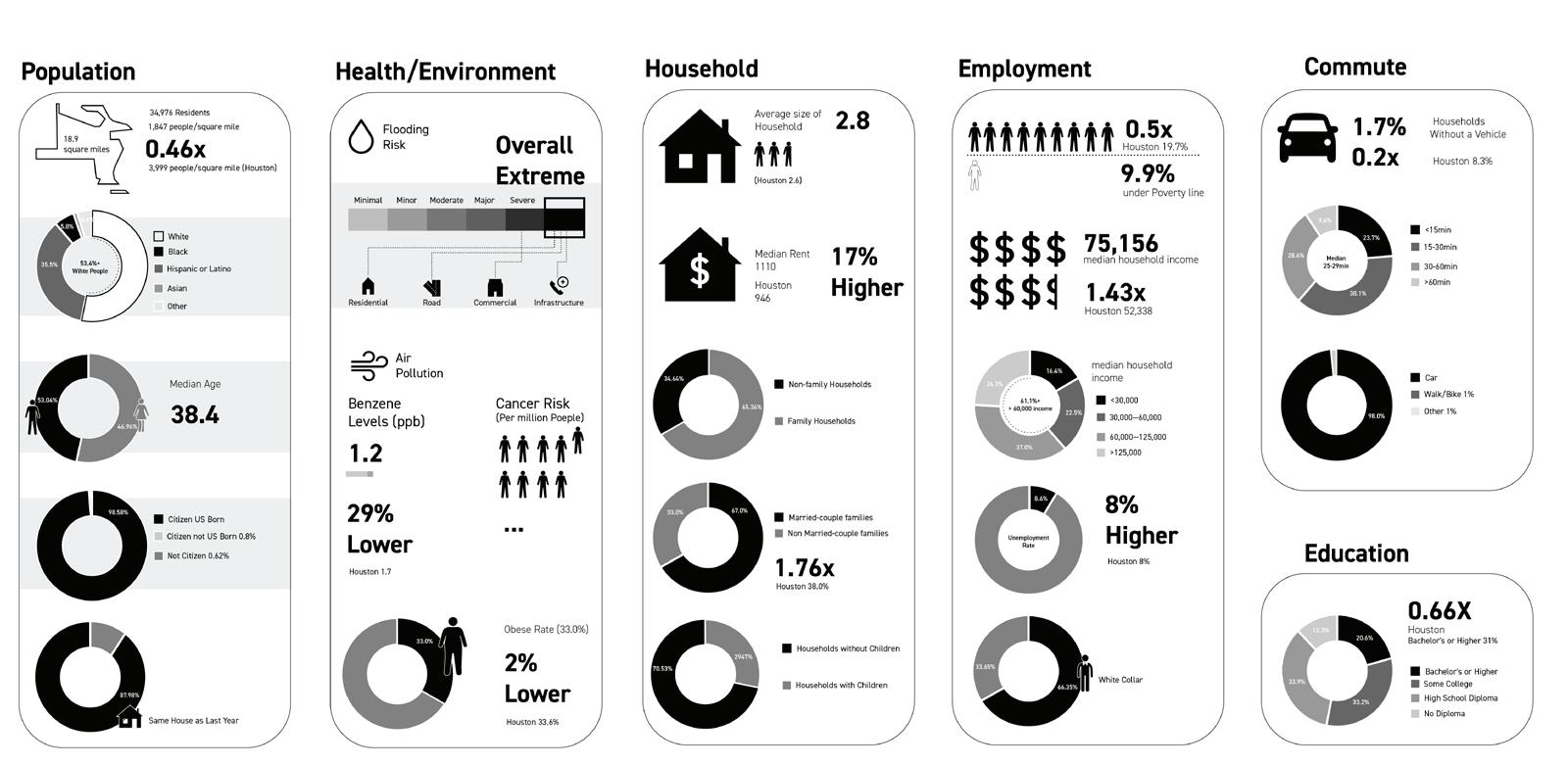

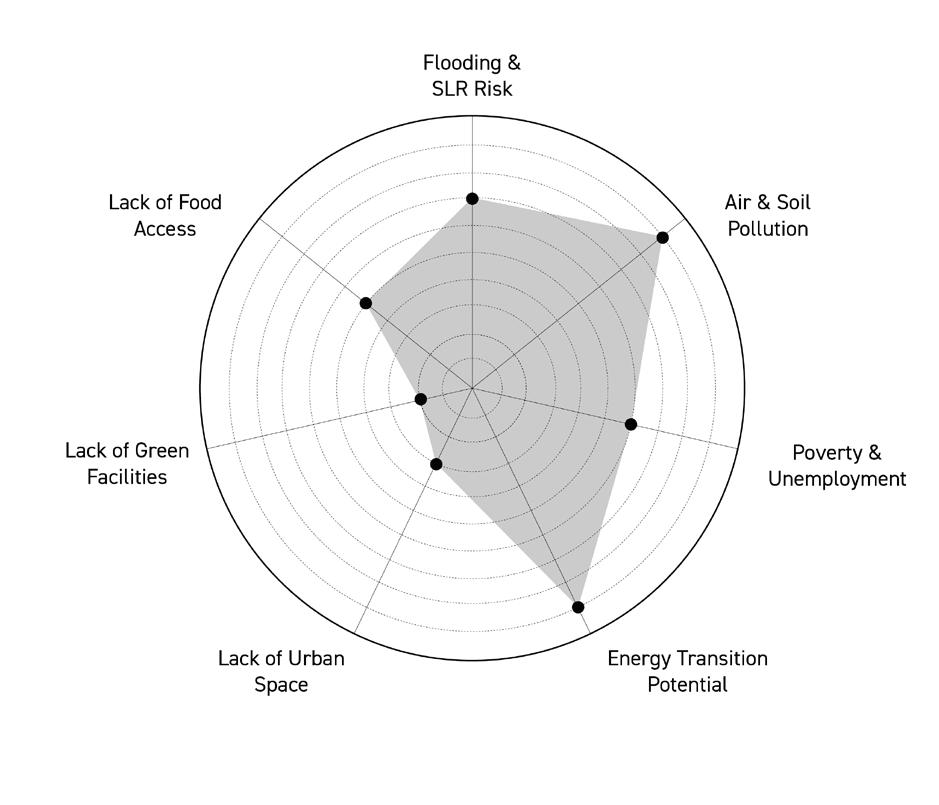

Many of Houston’s climate risks have made the national news in the past decade. The Tax Day floods and Hurricane Harvey have revealed the city’s vulnerability to stormwater flooding. The Texas cold snap of 2021 and the resulting grid failure was not as widely predicted. Many additional climate risks are not frontof-mind, including heat stress and storm surge. In addition, Houston’s population suffers from the environmental impacts of industry and transport, often in ways that exacerbate economic, social, and health inequities.

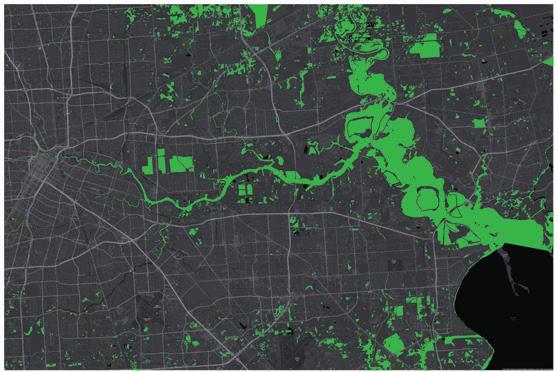

The Environment team aimed to produce a comprehensive risk analysis and explored what is and can be done to reduce these risks. Overall, Houston’s present patterns of development and sprawl are compounding risks that are already inherent in Houston’s geography. Without removing buildings from the floodplain, providing greater space for stormwater runoff, prioritizing the separation of industrial and residential uses, and remediating environmental pollution, risks to Houstonians will grow exponentially as climate change worsens extreme weather.

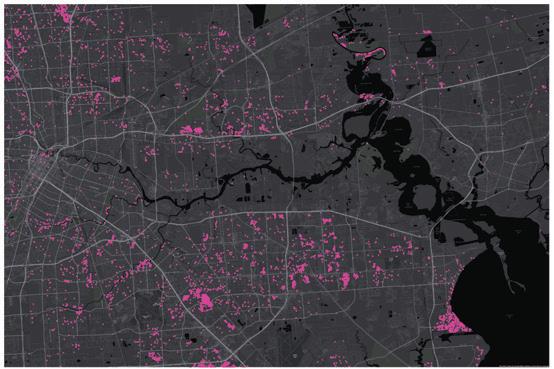

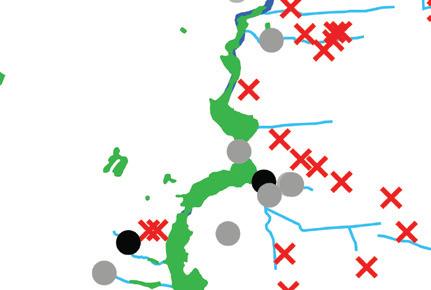

Industrial land use in Houston is concentrated primarily around the Shipping Channel

Commercial Interstates

Industrial/Utility/ROW

Residential

Farm Ranch Lands

Other land uses (e.g. schools, hospitals)

Parks, Reserves, Recreational spaces

Vacant

Undevelopable

Undetermined Land Use

State Highways

Other Roads

County Boundaries

Major Rivers & Bayous

Water

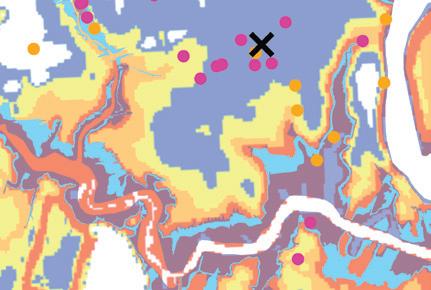

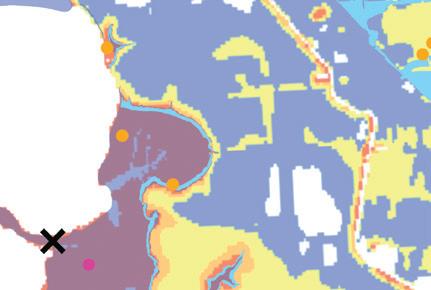

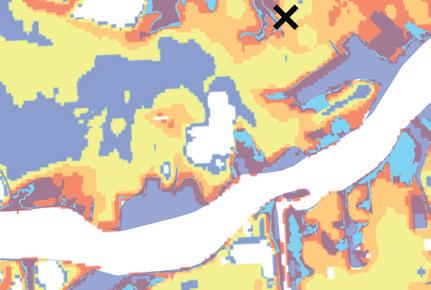

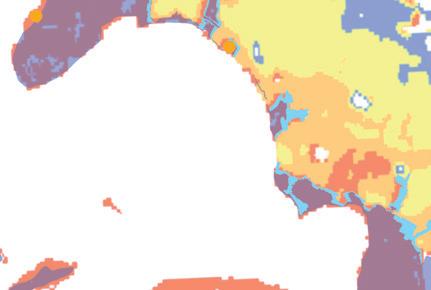

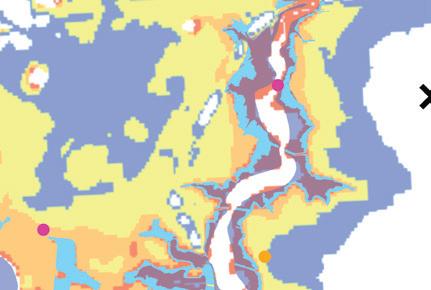

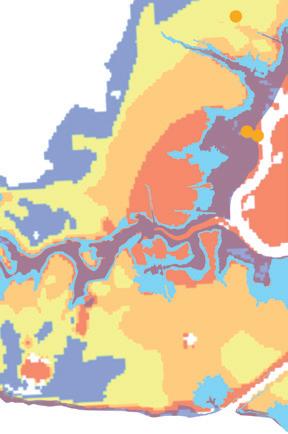

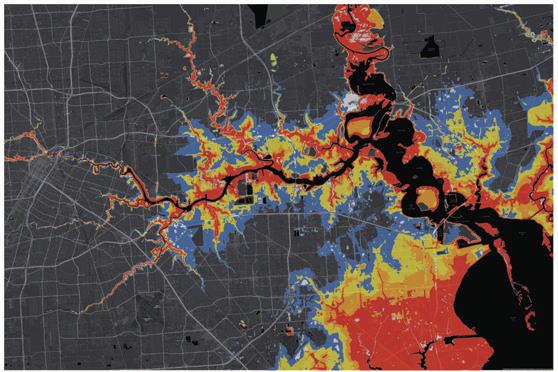

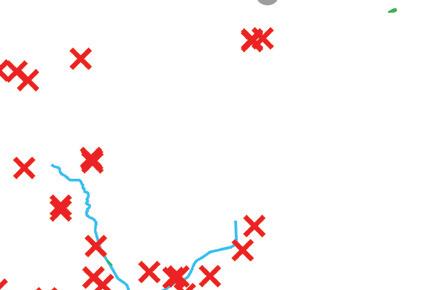

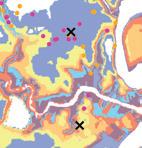

Flood Risk: Composite Map The map shows the distinct elevated risk faced by communities along the Ship Channel. Past storm events have triggered flood emergencies throughout vast areas of East Houston and Harris County, an intersectional risk that remains very high despite efforts post-Hurricane Harvey.

The map shows that risk factors are often layered and concentrated along bayous, wetlands, and waterways. These intersecting risk factors bolster the necessity for robust, maintained public drainage infrastructure.

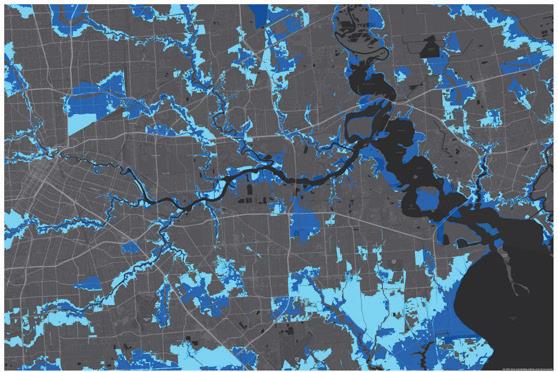

01: Existing waterways and wetlands in Harris County.

02: The list of endangered species includes 2 amphibians, 16 birds, 3 fish, 5 mammals, 7 reptiles, and 13 plants.

03: Debris and erosion after a catastrophic storm event can clog storm drains and block roads.

04: Many hazardous material sites are within high-risk areas for flooding and near wetlands.

05: Streams and bayous that are part of the stormwater runoff management and sewer system of the county.

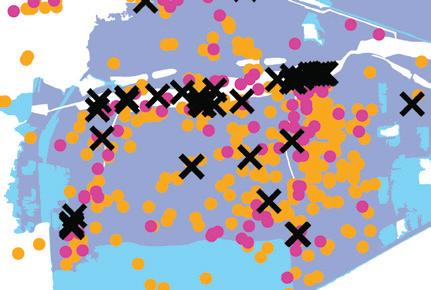

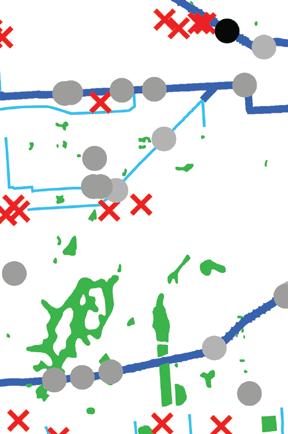

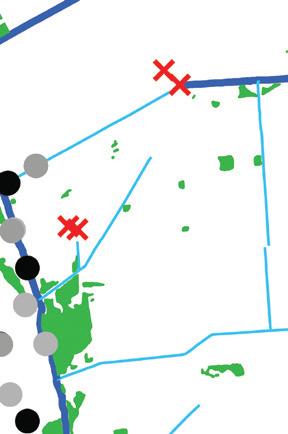

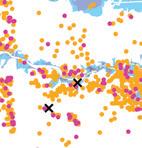

Despite its inland location, the Houston Shipping Channel has become an infrastructural behemoth thanks to massive dredging projects as well as its location near the oil fields of Texas. The Channel is now a pivotal hub in the US economy and contributes to over one million jobs in Texas alone. The Ship Channel Complex, according to the Port of Houston, is the first-ranked port in foreign and domestic waterborne tonnage, totaling over 276 million tons of imports and exports in 2020. The scale and magnitude of this industrial center is difficult to comprehend.

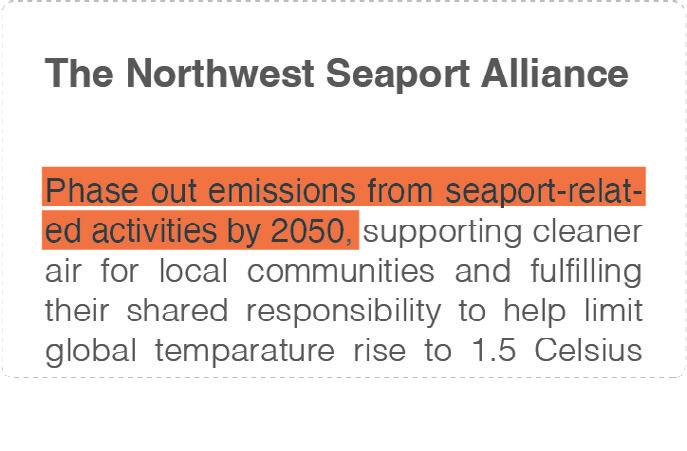

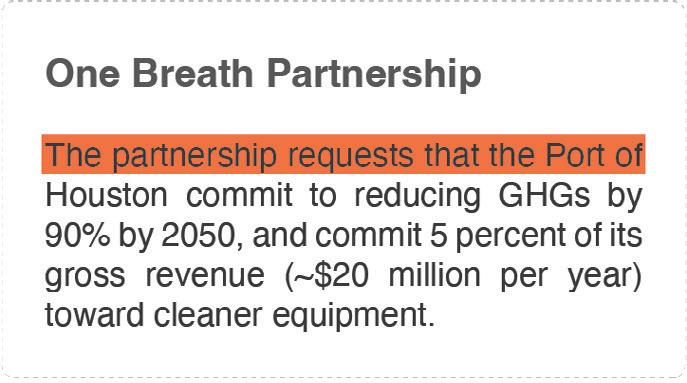

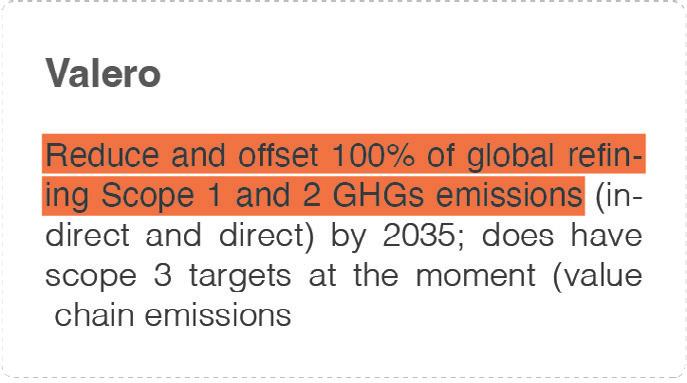

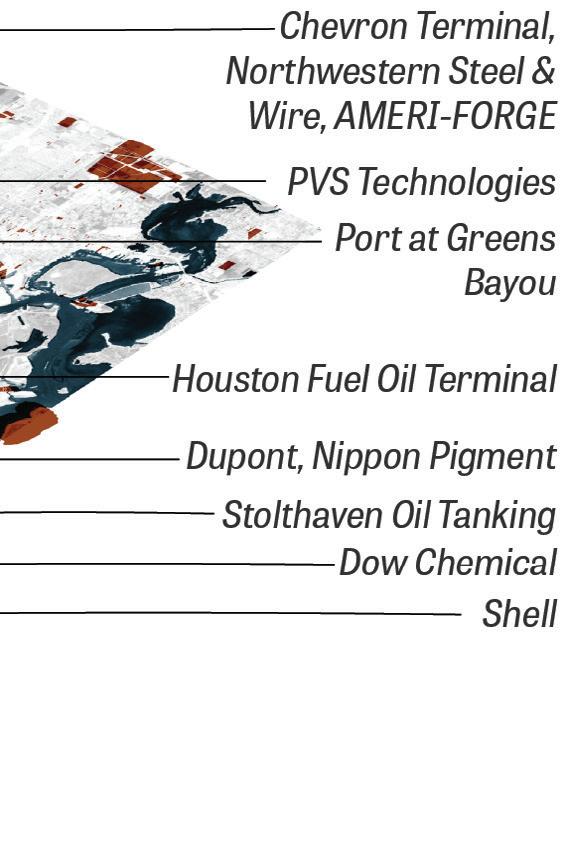

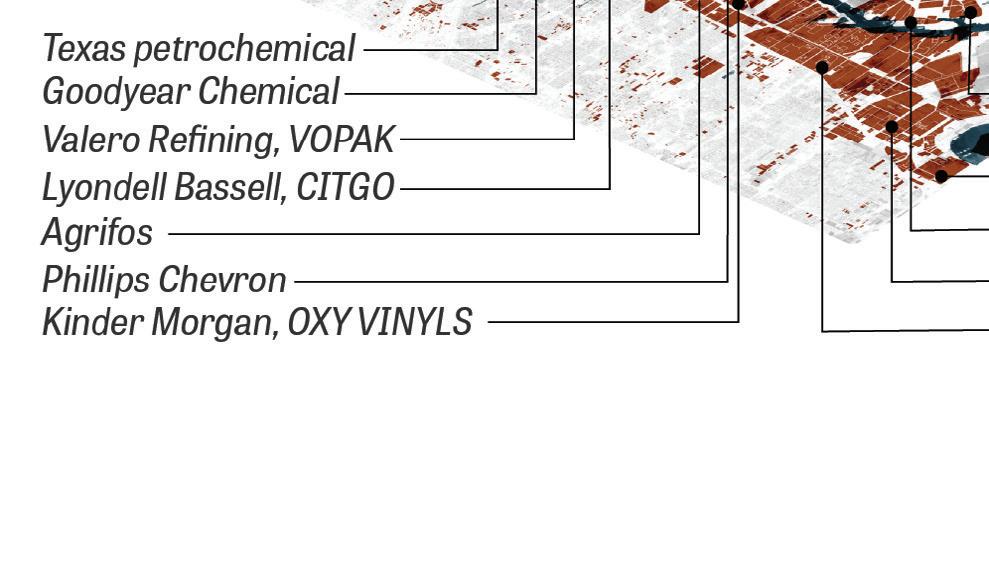

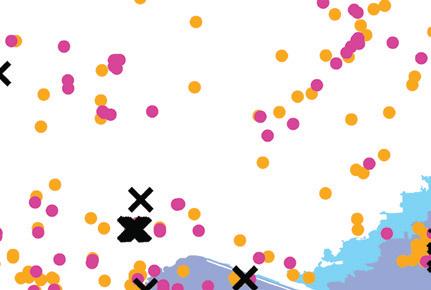

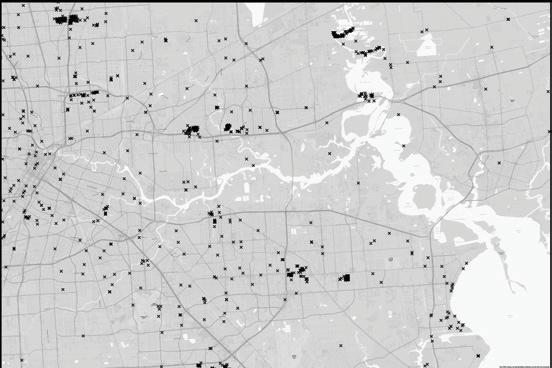

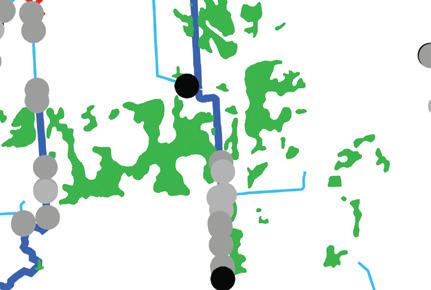

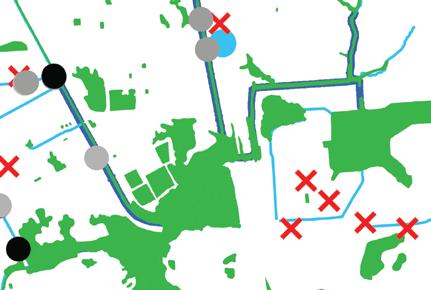

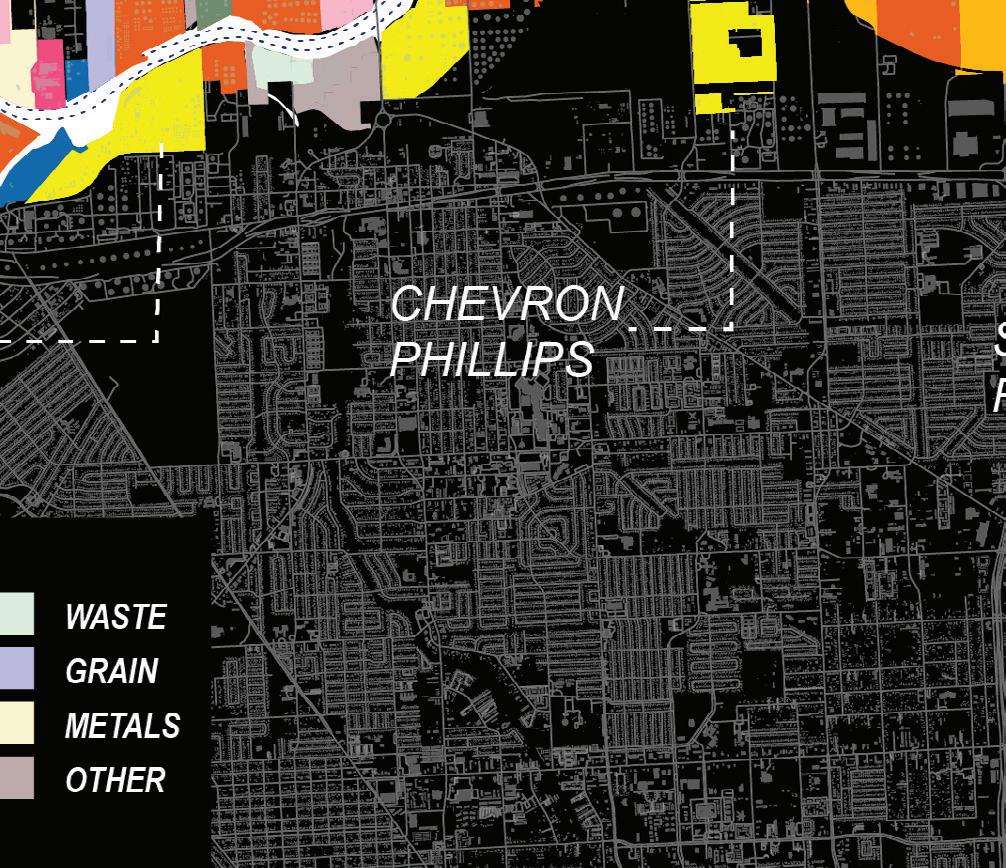

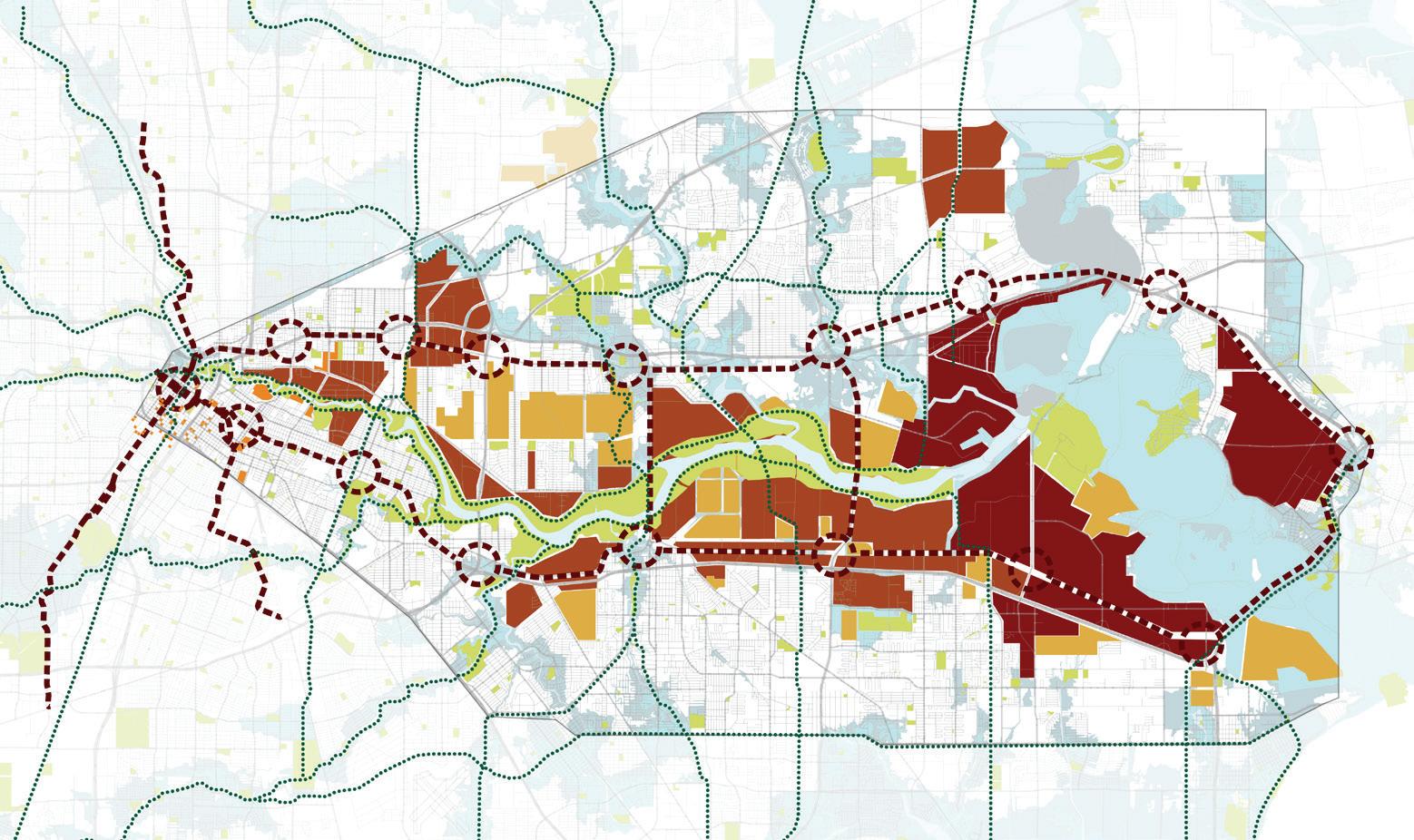

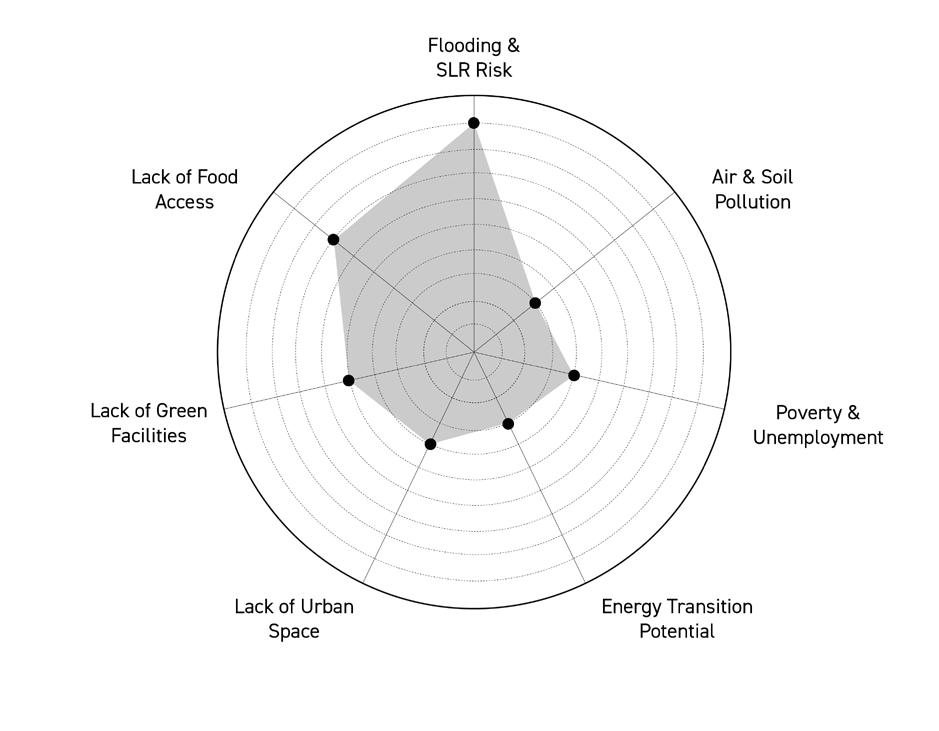

The Economy team sought to map Houston’s role in the global network of trade and transport, understand the systems that underlie the site’s current economic activities, and plan out the local spatial impacts and opportunities that come with the energy transition and the circular economy. As the global economic system shifts from fossil fuels in response to the climate crisis and towards principles of circularity, the impacts on Houston will be significant. The analysis documents the broad range of existing land uses that border the channel and then places them on a drawdown-scenario scale that predicts when and where land use changes are most likely to occur.

The industrial complex along the Ship Channel is the largest in the Americas. While oil, gas production, and refining is dominant, the Channel houses dozens of other industry types.