SPITEFUL: LAST OF THE LEGENDARY SPITFIRES WWI’S NIEUPORT 28 AN AIRPLANE THE AMERICANS DIDN’T WANT (BUT GOT ANYWAY) THE CRASH THAT KILLED WILL ROGERS AND WILEY POST WHAT’S SO GREAT ABOUT THE BOEING 247? PLUS AIRLINE POSTERS FROM TRAVEL’S GOLDEN AGE SPRING 2023 HISTORYNET.COM AVHP-230400-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 12/18/22 7:07 PM

SUPERMARINE

A watch that revolutionized timekeeping at a price equally as radical.

In the history of timepieces, few moments are more important than the creation of the world’s first Piezo timepiece. First released to the public in 1969, the watch turned the entire industry on its head, ushering in a new era of timekeeping. It’s this legacy that we’re honoring with the Timemaster Watch, available only through Stauer at a price only we can offer.

Prior to Piezo watches, gravity-driven Swiss watches were the standard bearer of precision timekeeping. But all that changed when the first commercially available Piezo watch came onto the market.

The result of ten years of research and development by some of the world’s top engineers, they discovered that when you squeeze a certain type of crystal, it generates a tiny electric current. And, if you pass electricity through the crystal, it vibrates at a precise frequency–exactly 32,768 times each second. When it came on the market, the Piezo watch was the most dependable timepiece available, accurate to 0.2 seconds per day. Today, it’s still considered a spectacular advance in electrical engineering.

“[Piezo timepieces]...it would shake the Swiss watch industry to its very foundations.”

Foundation For Economic Education

With the Timemaster we’ve set one of the world’s most important mechanical advances inside a decidedly masculine case. A handsome prodigy in rich leather and gold-finished stainless steel. The simplicity of the watch’s case belies an ornately detailed dial, which reflects the prestige of this timepiece.

Call today to secure your own marvel of timekeeping history. Because we work directly with our own craftsman we’re able to offer the Timemaster at a fraction of the price that many Piezo watches cost. But a watch like this doesn’t come along every day. Call today before time runs out and they’re gone.

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Spend some time with this engineering masterpiece for one month. If you’re not convinced you got excellence for less, simply send it back within 30 days for a refund of the item price. But we’re betting this timekeeping pioneer is a keeper.

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ®

WatchThat Shook

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. TPW350-04 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer ® Timemaster Piezo Watch $299* Offer Code Price Only $29 + S&P Save $270 Rating of A+ 1-800-333-2045 Your Insider Offer Code: TPW350-04 You must use the insider offer code to get our special price. *Discount is only for customers who use the offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price. TAKE 90% OFF INSTANTLY! When you use your INSIDER OFFER CODE • Precision Piezo electric movement • Stainless steel caseback and crown • Cotswold® mineral crystal • Crocodile embossed leather strap fits wrists 6 ½"–8 ½" • Date window display • Water resistant to 3 ATM [ Wear it today for only $29 AVHP-230123-005 Stauer Timemaster Watch.indd 1 12/11/22 3:44 PM

Meetthe

UpSwitzerland

The B-17 Aircraft Flies Before Your Eyes!

The historical B-17 Flying Fortress was an important symbol of America’s strength and resilience. Now this trailblazing aircraft inspires a uniquely levitating collectible that conveys its power in flight! The sculpture is authentically crafted and features innovative technology with hidden electro magnets, so the airplane levitates above the base. The aircraft literally flies in mid-air! It’s hand-painted and features a wood-finished base with a silvery title plaque and trim.

Strictly Limited. Order Today!

Strong demand is expected for this impressive levitating plane inspired by the B-17, and it is released in a strictly limited edition. You can order yours now at the excellent price of $149.99*, payable in four convenient installments of just $37.49, the first due before shipment. Your purchase is fully backed by our unconditional, 365-day money-back guarantee. So don’t miss out! You need send no money now. Simply complete and return the Reservation Application today.

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 10, 7x10 Magazine Master, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical updated 11/2013 Price Logo Address Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service

Striking Tribute to History and Victory B-17 FLYING FORTRESS LEVITATING SCULPTURE Iconic Aircraft FLIES IN MID-AIR above the base! Shown larger than actual size: Plane is about 7" W; Base is about 6½" diam Innovative technology and hidden electro magnets suspend the aircraft above the base Fully dimensional plane is intricately crafted and individually hand-painted for authentic details

A

ORDER TODAY AT BRADFORDEXCHANGE.COM/36927 Levitation technology in this product has been licensed from Levitation Arts Inc. under U.S. and international patents. See www.levitationarts.com/patent-notice YES. Reserve the B-17 Flying Fortress Levitating Sculpture for me as described in this announcement. Please Order Promptly RESERVATION APPLICATION SEND NO MONEY NOW *Plus a total of $20.99 shipping and service; see bradfordexchange.com. Limited-edition presentation restricted to 295 casting days. Please allow 4-6 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales are subject to product availability and order acceptance. Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email (optional) 01-36927-001-E13901 Where Passion Becomes Art The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Avenue · Niles, IL 60714-1393 ©2022 BGE 01-36927-001-BIR AVHP-230123-008 Bradford Exchange B-17 Flying Fortress Plane.indd 1 12/11/22 3:31 PM

SECOND

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

36 AN AIRPLANE FOR THE YANKS

BY JON GUTTMAN

BY JON GUTTMAN

44 THE DAY WILEY POST KILLED WILL ROGERS (AND HIMSELF)

BY ROBERT O. HARDER

BY BARRY LEVINE

BY STEVE WARTENBERG

ON THE COVER: Daniel Karlsson photographed the Collings Foundation’s restored Nieuport 28 in the skies over Sweden.

26

BEST Boeing’s 247 was everything a modern airliner could be—so why wasn’t it successful?

When American pilots in World War I got the Nieuport 28, they learned that you can’t always get what you want.

News of the accident shocked the world, but the crash could have been avoided.

SNATCHING INTELLIGENCE FROM THE SKY Taking surveillance photos by satellite wasn’t easy. Neither was getting them

to Earth.

52

back

60 “SEND THE EGGBEATER TO TARO” The helicopter proved its worth on a rescue mission in Burma during World War II.

SPRING 2023 36 FEATURES 5 MAILBAG 6 BRIEFING 10 AVIATORS 14 FLIGHT LOG 16 EXTREMES 18 PORTFOLIO 24 FROM THE COCKPIT 66 REVIEWS 70 FLIGHT TEST 72 FINAL APPROACH DEPARTMENTS 44 26 18 AVIATION HISTORY PHOTOS FROM TOP: ©DANIEL KARLSSON; SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM; LIBRARY OF CONGRESS (LEFT); COURTESY CHARLES DORIGAN (RIGHT); KEYSTONE-FRANCE/GAMMA-KEYSTONE VIA GETTY IMAGES 52 AVHP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 2 12/20/22 9:14 AM

This Historic World War II Coin, Note and Stamp Collection Can Be Yours!

is is an extensive 23-Pc. Collection of superb World War II memorabilia, spanning the United States, the Paci c and Europe. Each piece was issued by or for their respective nation during the World War II era, and this is the rst time ever that we’ve seen them assembled in one great set. is collection includes: U.S. and Foreign Coins—including U.S. “emergency” coins struck in uncommon metals to help with the war e ort, including a silver U.S. War Nickel, a steel 1943 Cent, and a Cent struck from copper recycled from shell cases—along with German “propaganda” coins featuring the Nazi swastika, and an Italian Lira displaying symbols of its own fascist regime; plus coins from Canada and Great Britain, two of our closest allies.

Japanese Invasion Notes—including Japanese guerilla and invasion notes printed for the Philippines and Burma which were controlled by Japan during the war, all in uncirculated condition.

U.S., Japanese and German Nazi Stamps—patriotic U.S. stamps—like the 3¢ Win the War stamp, occupational Japanese stamps and Nazi stamps are all here!

These Remarkable WWII Collection Are Going Fast—HURRY!

is incredible collection of World War II Memorabilia of authentic coins, notes and stamps, beautifully housed in a custom-designed album, will amplify any World War II collection perfectly—and what a wonderful, unique, muchappreciated gi !

Dept. HCC121-01, Eagan, MN 55121

U.S.

U.S. 1943

Germany 1939-45 Reichspfennig

Great Britain 1939-45 Half Penny

Canada 1944-45 “V” Five Cents

Italy 1939-43 Lira

Historic Japanese Guerilla and Invasion Notes

Philippines 1943 1 Peso Japanese Invasion Note

Philippines 1943 5 Peso Japanese Invasion Note

Philippines 1942-44 25 Centavos Guerilla Note

Burma 1942 1 Rupee Japanese Invasion Note

Burma 1942 5 Rupees Japanese Invasion Note

Burma 1942-44 10 Rupees Japanese Invasion Note

Burma 1944 100 Rupees Japanese Invasion Note

Patriotic and Significant U.S. and Foreign Stamps

U.S. 1940 2¢ National Defense Stamp

U.S. 1943 2¢ Allied Nations Stamp

U.S. 1942 3¢ Win the War Stamp

U.S. 1946 3¢ WW II Veterans Stamp

U.S. 1946 3¢ Iwo Jima Stamp

Germany 1941-44 12 Pfenning Hitler Head Stamp Germany 1941-44 25 Pfenning Hitler Head Stamp Philippines 1942-44 2 Centavos Japanese Occupation Stamp Philippines 1942-44 5 Centavos Japanese Occupation Stamp

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible

involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations

accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www. govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s

Return

SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER A+ Don’t wait—to get your hands on this amazing collection you need to immediately call the toll-free number below. Supplies are limited and you don’t want to miss out! World War II 23-Pc. Historic Coin, Note and Stamp Collection $59.95 + $9.95 s/h SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER $49.95 + $4.95 limited time shipping/handling FREE SHIPPING on 3 or More! Limited time only. Product total over $149 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases. Call now toll-free for fastest service 1-800-517-6468 Offer Code HCC121-01 Please mention this code when you call. STUNNING COLLECTION OF HISTORIC WWII MONEY & STAMPS!

coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and

deemed

Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve,

and Foreign Coins

Lincoln Steel Cent

U.S. 1942-45 Jefferson Silver Nickel

U.S. 1944-45 Lincoln Shell Case Cent

23-Pc. Collection! SAVE $15 or more! AVHP-230123-004 GovMint 23 Pieces WWII Collection.indd 1 12/11/22 3:35 PM

Thunderbolts for Brazil

SPRING 2023 / VOL. 33, NO. 2

TOM HUNTINGTON EDITOR

LARRY PORGES SENIOR EDITOR JON GUTTMAN RESEARCH DIRECTOR

STEPHAN WILKINSON CONTRIBUTING EDITOR ARTHUR H. SANFELICI EDITOR EMERITUS

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY GUY ACETO PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION MEL GRAY PRINT PRODUCTION COORDINATOR ADVERTISING MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES MGreenberg@mco.com TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER TJenkins@historynet.com

41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The

in part without the written consent of

LLC PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com © 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com Aviation History (ISSN 1076-8858) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC 901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Tysons, Va., and additional mailing offices. Postmaster, send address changes to Aviation History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc.; 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com Canada Publications Mail Agreement No.

contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or

HistoryNet,

& PUBLISHER VISIT HISTORYNET.COM Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at: historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday— or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen—every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way.

The gadgetry of war—new and old— effective, and not-so effective.

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN

Weapons & Gear

Master Sergeant Robson Saldanha was a Brazilian who flew P-47Ds for the nation’s 1st Fighter Group in northern Italy during World War II. historynet.com/brazilian-p47

TRENDING NOW SMITHSONIAN’S NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM AVHP-230400-MASTHEAD.indd 4 12/18/22 6:35 PM

GRAVE MATTERS

MAILBAG

The article on the aerial adventures of Merian Cooper in the Autumn 2022 issue was very interesting. A few years ago, I visited Lwow (now Lviv), Ukraine, and went to the Lychakiv Cemetery, which includes the Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwow. I was surprised to discover the memorial to the American pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron, with the graves of T.V. McCallum, Arthur Kelly and Edmund Graves. It appears that the entire military cemetery fell into a degree of disrepair under Soviet rule, but since Ukraine gained its independence, the Polish military cemetery was restored in 2005.

Rene BeBeau, Alexandria, Virginia

THE WRONG STUFF

In his editorial in the Winter 2023 issue, Tom Huntington stated that Orville Wright “never piloted an airplane again after he nearly died in a crash in 1908.” That is not correct. Just one year later, Orville did all the flying to complete the test trials for the Army contract for the first U.S. military airplane. The next year, Orville’s many flights included taking his brother Wilbur up for their only flight together. In 1911 he returned to Kitty Hawk where he set soaring records that lasted many years, and in 1913 he piloted pioneering seaplane flights.

Al Stettner, Fairfax, Virginia

Al Stettner, Fairfax, Virginia

FOUR TOO FEW

I always love your magazine, but to quibble: the Saunders-Roe Princess [“Flight Test,” Winter 2023] had 10 turbines, not six. The four inboard nacelles had two turbines each, driving contra-rotating props. The outboards had single turbines driving single props. The Princess was the victim of early innovation—the use of efficient/reliable/lightweight turbines on an anachronistic hull. There were plenty of adequate airports after the war, so water landings were no longer necessary.

Joe Deck, Buffalo, New York

LOSE SOME WEIGHT

Having worked for many years on the Space Shuttle program, I enjoyed the article by Douglas G. Adler about the Shuttle Training Aircraft [“Sticking the Landing,” Autumn 2022]. There is a significant error in the quoted weight of the orbiter, however. As bad as the glide ratio was for the orbiter, it would have been much worse at 4 million pounds. In reality, the heaviest landing ever, STS-83, was 235,421 pounds. The Space Transportation System liftoff weight was about 4.5 million pounds.

Douglas Dobbin, Anthony, New Mexico

STUCK

In “Sticking the Landing,” the photo reminded me of my times flying as copilot on Northwest Airlines’ DC-7Cs, because with that aircraft the pilot could lower the main landing gear but not the nose gear when needing to get the plane down faster, and then lower the nose gear when appropriate. The article “The Ten Worst Fighters of World War II” in that issue gave me everything I’ve ever wanted to

know about the CW-21 Demon, which is a beautiful design. Thanks for a fine magazine.

Paul A. Ludwig, Seattle, Washington

CORRECTIONS

In the Winter 2023 “Milestones” entry, you wrote that “the action on the invasion’s first day marked the first time in history that Americanbuilt airplanes squared off against each other in war.” I’m afraid this is not correct. There were several previous instances in which this unfortu

prior to the Allied invasion of North Africa was during the so-called “Leticia Affair” involving Peru and Colombia in 1932, in which Curtiss, Douglas and Vought aircraft engaged each other rather significantly. I detail this in my book The Forgotten American Volunteer Group Then, on page 43 of Steve Wartenberg’s otherwise excellent account of the adventures of Cal Rodgers, the photo is not of the plane Robert Fowler used to make the first aerial crossing of the Isthmus of Panama but actually shows Major Walter W. Wynne of the 7th Aero Squadron after he made the first airmail flight from the Atlantic to the Pacific side of the Canal in 1919. He was the squadron commander at the time, having been preceded by a young Henry H. “Hap” Arnold.

Dan Hagedorn, Fairfax, Virginia

We know better than to contradict Mr. Hagedorn, Curator Emeritus of the Museum of Flight at Boeing Field. We do regret the errors and include here the photo of Fowler’s airplane that we should have used.

SEND LETTERS TO: aviationhistory@historynet.com (Letters may be edited for publication)

5 SPRING 2023

HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

@AVIATIONHISTMAG @AVIATIONHISTORY

AVHP-230400-MAILBAG.indd 5 12/18/22 6:36 PM

Robert Fowler and his 1913 airplane

HOMEBUILT SPITFIRE CLEARED FOR FLIGHT

wanted a Spitfire ever since I was eight years old and I saw Reach for the Sky,” said Steve Markham of Odiham, Hampshire. That was a common inspiration among English boys who saw the 1956 film about the Royal Air Force’s legless Spitfire ace, Douglas Bader. Few, however, made the fantasy come true.

BRIEFING

In 2006 the retired engineer and his wife Kay—also a licensed pilot— bought a kit for an 80-percent-scale “Mark 26” Supermarine Spitfire airframe plus engine parts, propellers and other components, and began assembling a replica of an unarmed photoreconnaissance version. They based their airplane on one with the registration number PL793, which had operated from Hampshire. “If you want to buy a World War II original Spitfire, it now costs between two and four million pounds,” Markham

It

explained. This is a much less expensive way of doing it.”

After 11,250 hours of work, Markham completed the Spitfire in 2017, but it needed evaluation for a full flight permit from Britain’s Civil Aviation Authority. It was finally cleared for flight in October. Markham could then fulfill another longstanding dream—flying to the Isle of Wight for ice cream. Future destinations include Scotland and Rome. “It feels fantastic, it’s gorgeous,” Markham said, echoing the feelings of just about everyone who ever piloted a Spitfire. “It’s something special.” —Jon Guttman

AIR QUOTE

—WILL

MAY 22, 1927

6 SPRING 2023

TOP: DAVID CLARKE/SOLENT NEWS SERVICE; BOTTOM: BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: ©BOEING/COURTESY OF THE AIR AND SPACE FORCES ASSOCIATION; TY GREENLEES/NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE; AIRFIX/HORNBY HOBBIES, UK

“Of all things that Lindbergh’s great feat demonstrated, the greatest was to show us that a person could still get the entire front page without murdering anybody.”

ROGERS,

AVHP-230400-BRIEFING.indd 6 12/18/22 6:41 PM

took a lot of work, but this replica Spitfire became a dream come true for Englishman Steve Markham.

“I

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress first flew in 1952, more than 70 years ago. Since then, it has provided the backbone for the U.S. Air Force’s bomber fleet and is expected to continue its prominent role until around 2050—when the venerable aircraft will be pushing 100.

It cannot do that without upgrading, though, and in October the Air Force unveiled an artist’s conception (above) of what the B-52 of the future will look like. The B-52K or J will be powered by eight Rolls-Royce

NOT YOUR FATHER’S B-52

SPITFIRE RETURNS TO PRODUCTION IN THE U.K.

n other Spitfire news, the English model company Airfix has released its new Spitfire Mk.IXc model, a top-of-the-line 1/24th scale kit. The model company will manufacture them on “home soil” at a factory in Sussex, in southeast England. “For various business rationale, Airfix models have been manufactured overseas, predominately in China, India and France since the mid-90s,” said Airfix’s Dale Luckhurst. “However, when we decided to produce this new Supermarine Spitfire Mk.IXc, it just felt right to move the production of such a British icon back to the UK.” This marks the first time “Spitfires” have been manufactured in England since 1948.

Airfix released its first model airplane in 1955, and it was a basic 1/72 scale version of the Spitfire. The new kit will build into a bigger airplane, more than 15 inches long and with a wingspan of 18.5 inches.

Follow Aviation History on Historynet.com and Facebook for an exclusive review of the kit online and follow along with our “Modeling Minute” on Facebook, TikTok and Instagram. —Guy Aceto

F-130 engines instead of the Pratt & Whitney TF-33 engines that Stratofortresses have been using since 1962. The airplane will also sport an updated cockpit, new radar systems and various other additions for the twenty-first century. The Air Force expects the new, improved B-52s to enter service in 2028.

AIR FORCE MUSEUM DEBUTS SKYRAIDER

In November, the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio, unveiled its latest acquisition, a Douglas A-1H Skyraider for the museum’s Southeast Asia War Gallery. The airplane flew for South Vietnam from 1965 to 1975, but during 18 months of work it was restored to look like the Proud American, a Skyraider flown over Vietnam by Air Force Capt. Ron Smith. The propeller-driven Skyraiders often flew search-and-rescue missions, where their firepower and range let them secure territory until rescue helicopters arrived. Smith received the Air Force Cross for once such mission he flew in the Proud American to rescue an American shot down over North Vietnam. Lt. Col. William A. Jones III received the Medal of Honor for a rescue mission he flew in the same airplane in 1968. The original Proud American was shot down in September 1972, the last Skyraider lost during the Vietnam War.

7 SPRING 2023

TOP: DAVID CLARKE/SOLENT NEWS SERVICE; BOTTOM: BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: ©BOEING/COURTESY OF THE AIR AND SPACE FORCES ASSOCIATION; TY GREENLEES/NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE; AIRFIX/HORNBY HOBBIES,

UK I

AVHP-230400-BRIEFING.indd 7 12/18/22 6:41 PM

CAREER CHANGE

CAT HOUSE

The Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star is a trainer version of the P-80— the U.S. Air Force’s first operational jet. Given a stretched fuselage to accommodate a second seat, the T-33 first flew in 1948; Bolivia was still using it as late as 2017. During the T-33’s long career, more than 40 nations used it for everything from target towing to combat missions. Until recently, however, the T-33 was never used to raise kittens.

That changed in October thanks to a discovery by a volunteer at the Hickory Aviation Museum in Hickory, North Carolina. When Bill Falls investigated noises coming from the facility’s T-33, which was on display outdoors, he discovered that a cat had crawled into the airplane to give birth to a litter. “I saw this furry little head pop up,” Falls told the Washington Post. “And suddenly there was another, then another and another.” There were five kittens in all, and the mother turned out to be a feral cat named Phantom that had made the museum grounds her home.

The museum staff decided to leave the cats alone in the T-33. Later that

month, when the kittens were old enough, the Humane Society of Catawba County captured them so they could be offered for adoption. The humane society also gave the kittens airplane-related names: Prowler, Hornet, Mohawk, Corsair and Falcon.

By the time production ended in 1959, Lockheed had built 5,691 T-33s. The museum’s airplane is a T-33A with the tail number 529 that is on loan from the National Museum of the United States Air Force. Now free of cats, it remains on display on the museum grounds.

AERO ARTIFACT

LIGHT MY FIRE

French-born Gervais Raoul Lufbery (who makes an appearance in the feature about the Nieuport 28 that starts on page 36) lived a peripatetic life before World War I. At 19 he relocated to the United States, where his father had moved when Raoul was young. He joined the U.S. Army (and earned his U.S. citizenship) and was posted to the Philippines. As an aviation mechanic he barnstormed around Asia, Africa and Europe. After World War I began, Lufbery flew for the French and later joined the American volunteers of the Lafayette Escadrille, where he continued racking up victories (his final official tally was 16). “He had broad shoulders, a perpetual scowl, crude speech, and apparently no emotions of any kind,” wrote historian Arch Whitehouse. Once America entered the war, Lufbery joined the 94th Aero Squadron.

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force has several items related to Lufbery on display, including this cigarette lighter made out of a spark plug from the Nieuport 28 in which he made his final flight. Ironically, contemporaries said that one thing that obsessed the flier was a fear of fire in the air. On May 19, 1918, Lufbery was pursuing a German observation plane when an incendiary bullet set his Nieuport ablaze. Rather than burn to death, Lufbery jumped from his cockpit from a height of about 200 feet and was impaled on a fence. He was 33 years old. —Tom Huntington

8 SPRING 2023

TOP: WILLIAM FALLS (BOTH); BOTTOM: BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES; INSET: TY GREENLEES/NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE TOP: COURTESY CHRISTIAN ARZBERGER; BOTTOM: UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI LIBRARY/CUBAN HERITAGE COLLECTION AVHP-230400-BRIEFING.indd 8 12/19/22 6:51 PM

Left: A kitten occupies the rear seat. Right: The mother, Phantom, peers out from the wheel well.

MONUMENT MAN

Christian Arzberger is an automotive engineer by trade, but his passion is researching Allied bombers that crashed during World War II in his home province of Styria in eastern Austria. He has been a driving force in the effort to commemorate the crewmen and mark the crash sites of their aircraft. He has six monuments to his credit so far.

THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND MILESTONES

Fidel Castro’s Communist takeover of Cuba ushered in a period of conflict and tension with the United States that has lasted ever since the 1959 revolution. Tucked amid the saber-rattling was the Freedom Flight program of 1965-73, a rare example of cooperation between the two belligerent states. After coming to power in Cuba, Castro began aligning himself with the Soviet Union and its repressive version of Communism, prompting many well-off Cubans to leave the island. As Castro seized more private property, the middle class began leaving, too. At first, Castro welcomed ridding the island of those opposed to his political philosophy. In September 1965, he announced that Cubans wishing to join their families in the U.S. (except males of military age) could leave by boat, kicking off the mas-

An estimated 553 American and 31 Royal Air Force aircraft went down in Austria as they flew north from their Italian bases to hit targets in Germany or Austria. When he was ten, Arzberger learned that seven American flyers were buried in the cemetery in his hometown, Sankt Jakob im Walde. They were from two B-17 crews of the 301st Bombardment Group who crashed nearby on July 26, 1944. Fascinated, Arzberger gathered information and interviewed locals to find out what they remembered. Later, after completing college and working as an automotive engineer in nearby Graz, Arzberger resumed his research. In 2009, he oversaw the dedication of his first memorial, to honor the B-17 crewmembers buried in Sankt Jakob im Walde. He arranged to have the memorial unveiled by 87-year-old Bill Brainard, who had been radio operator on one of the fortresses that had gone down.

Christian Arzberger has created six monuments to Allied aircrews who crashed in Austria during the Second World War.

Organizing the other memorials followed the same pattern as the first. After researching the crash sites, Arzberger briefed officials in the closest towns, oversaw the creation of memorials and plaques and organized dedications. To date he’s also created monuments in Wenigzell (2010), Fischbach (2012), Ratten (2013), Strallegg (2015), and Bad Wimsbach-Neydharting (2017), and in 2022 his first memorial in Sankt Jakob im Walde was updated, enlarged and relocated. Arzberger also provides research support for memorial projects in other Austrian locales, such as one in Upper Austria.

Arzberger continues his investigations and research. He is at work on his next memorial, to be placed at Rettenegg to honor eight crewmembers killed when a Consolidated B-24 Liberator crashed there on May 10, 1944. He has also conducted research on an additional 20 crash sites and done preliminary research on many more. His work serves as a testimony to a spirit of peace and reconciliation between two formerly enemy nations. —Fred Allison

sive Camarioca Boatlift and, along with it, a humanitarian crisis. That led to the Freedom Flight program, for which Pan American World Airways was commissioned to fly two flights a day, five days a week to bring eligible Cubans to the United States. The first flight lifted off from Varadero Airport, near Matanzas, on December 1, 1965.

The program proved extremely popular in Cuba, with waitlists of up to two years—despite Castro’s pointed attempts to harass and shame those who wanted to leave. As it became apparent that Freedom Flights were exacerbating a Cuban brain drain, Castro grew wary. He suspended flights for six months in 1972 before halting the program altogether in 1973. By then nearly 300,000 Cubans had escaped the island for American shores. The last Freedom Flight touched down in Miami on April 6, 1973—50 years ago this spring. —Larry Porges

9 SPRING 2023

TOP: WILLIAM FALLS (BOTH); BOTTOM: BETTMANN/GETTY IMAGES; INSET: TY GREENLEES/NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE TOP: COURTESY CHRISTIAN ARZBERGER; BOTTOM: UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI LIBRARY/CUBAN HERITAGE COLLECTION AVHP-230400-BRIEFING.indd 9 12/19/22 6:51 PM

Cuban refugees depart a Freedom Flight airplane in Florida. The program started in 1965 and ended in 1973.

MADE IN FRANCE

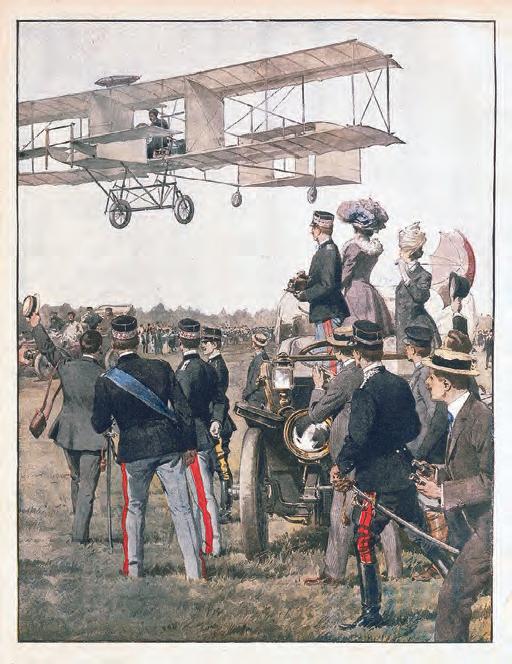

ONCE LÉON DELAGRANGE TOOK UP FLYING, HE NEVER LOOKED BACK

BY W. M. TARRANT

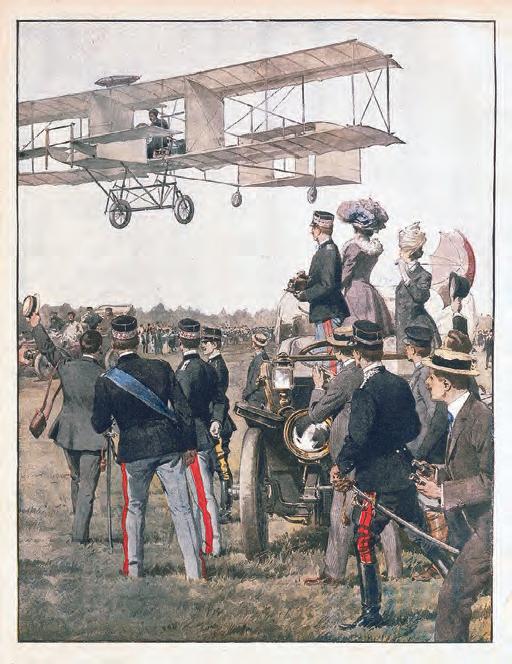

“Contagious enthusiasm.” That phrase describes early French aviator Léon Delagrange, who helped spread the gospel of pow ered heavier-than-air flight through Europe during the first decade of the twentieth century.

AVIATORS

Ferdinand Léon Delagrange was born into a well-to-do family on March 13, 1872, in Orléans, France, his father being the owner of a textile factory. Young Delagrange studied art at École des Beaux-Arts and became a respected sculptor before heavier-than-air flying machines grabbed his attention in 1907. Then he totally immersed himself in aviation, joining the Aéro-Club de France and getting elected president. He earned French pilot license number 3. “I believe that the aeroplane is destined to become the bicycle of the airs in tomorrow’s world,” he predicted.

After meeting brothers and aircraft builders Gabriel and Charles Voisin, Delagrange bought a machine from them. Like Delagrange, Gabriel Voisin had been a student of École des Beaux-Arts before turning to aviation. He worked in partnership with Louis Blériot but the two had a falling out and Voisin established his own aircraft manufacturing business with his brother. In addition to making custom-order machines, the brothers designed a pusher biplane powered by a 50-hp Antoinette engine. With a box tail and vertical partitions between the wings, the plane resembled a giant box-kite. A canard provided attitude control and a rudder gave yaw control, both operated by a control wheel that moved fore and aft and side to side. But without ailerons or wing warping the craft lacked roll control, which resulted in uncoordinated, skidding turns. Because of this lack of turn coordination, some question whether it was truly a controllable heavier-than-air machine, which in

Top:

Above: Delagrange often flew with his friend, the artist and sculptor Thérèse Peltier, who became the first woman to pilot an airplane.

turn casts doubt on the validity of any records set in it.

Delagrange took his first tentative flight in his machine, the Voisin-Delagrange (the Voisins named their planes after the customers who bought them) on November 5, 1907. After damaging the machine in a hard landing, he ordered another, the Voisin-Delagrange II. He first flew it on January 20, 1908.

In the meantime, another Frenchman, Henri Farman, also bought a Voisin biplane. Being more mechanically inclined than Delagrange, Farman made improvements to his machine that Delagrange soon incorporated on his. The two aviators enjoyed a friendly rivalry as they each set records for distance and endurance. On March 21, 1908, Farman became the first airplane passenger when he went aloft with

10 SPRING 2023 TOP: ©MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY; BOTTOM: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF FRANCE

Pioneering aviator Léon Delagrange flies his Blériot XI at the Reims Airshow in August 1909.

AVHP-230400-AVIATORS.indd 10 12/18/22 6:43 PM

The time is right to salute the heroic men and women of the United States Air Force™, and this officially licensed wall clock honors our Airmen with commanding style and technical precision. This limited edition is available only from The Bradford Exchange.

A full-color U.S. Air Force™ Emblem is featured front and center against the Stars and Stripes. Proud Air Force™ words declare: Aim High. Because it is in sync via radio waves with the official source of U.S. time in Fort Collins, Colorado, it is completely self-setting and accurate to the second. You never need to adjust it, even for Daylight Savings. As night falls, a built-in sensor cues hidden LED lights to illuminate the glassencased face and bold Roman numerals. The 14-inch diameter copper-toned housing is crafted of weather-resistant materials, ideal for indoor or outdoor living.

Peak demand for this fine clock is expected, so don’t miss out. Make it yours now in four payments of $36.25, the first due before shipment, totaling $145*, backed by our unconditional, 365-day money-back guarantee. Send no money now—order today!

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Job Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service ILLUMINATED YES. Please reserve the U.S. Air Force™ Indoor/ Outdoor Illuminated Atomic Clock for me as described in this announcement. Please Respond Promptly *Plus a total of $19.99 shipping and service; see bradfordexchange.com. Limited-edition presentation restricted to 295 crafting days. Please allow 4-8 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. RESERVATION APPLICATION SEND NO MONEY NOW

©2022 BGE 01-35620-001 BI Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email (optional) 01-35620-001-E13901 Over a foot in diameter! Shown much smaller than actual size of about 14" diameter. Requires 1 AA and 4 D batteries, not included. ATOMIC CLOCK Where Passion Becomes Art ORDER TODAY AT BRADFORDEXCHANGE.COM/AIRFORCEATOMIC The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Avenue, Niles, IL 60714-1393 Atomic clocks are completely self-setting and accurate to the second INDOOR AND OUTDOOR U.S. AIR FORCE™ Indoor/Outdoor Illuminated Atomic Clock ™Department of the Air Force. Officially Licensed ™ Product of the Air Force www.airforce.com AVHP-230123-009 Bradford Exchange Airforce Atomic Clock.indd 1 12/11/22 3:30 PM

Delagrange. (The Wright brothers didn’t fly a passenger until May 14. Ernest Archdeacon, a French lawyer and aviation enthusiast, sometimes receives credit as the first airplane passenger in Europe after he flew with Farman on May 29, 1908.)

On March 16, 1908, Delagrange made five flights of 500 to 600 meters (1,640 to 1,969 feet), which made him the first European flier to best the longest flight the Wrights had made (852 feet) on December 17, 1903. On March 20, he flew a circle of about 700 meters (2,297 feet). On April 10, Delagrange flew 2,500 meters (8,202 feet) though his wheels did touch the ground once. The following day, he flew an official distance of 3,925 meters (12,877 feet) thus beating Farman’s distance of 2004.8 meters (6,577 feet). Delagrange’s flight unofficially was 5,575 meters (18,291 feet) but since his wheels touched the ground at the 3,925-meter mark he was not credited with the entire distance.

During the summer of 1908, Delagrange toured Italy with his airplane, flying an exhibition for King Victor Emmanuel III and setting distance and endurance records. On June 22, he flew 16 kilometers (9.94 miles) in 16 minutes and 30 seconds, setting an official distance and

endurance record. The next day, he flew 17 kilometers (10.56 miles) in 18 minutes and 30 seconds.

On July 8 in Turin, Delagrange flew with his friend and travel companion, the artist and sculptor Thérèse Peltier, who wrote articles of the flights for French newspapers. Some sources say she was the first woman to fly in a powered heavier-than-air machine, though others credit Mademoiselle P. Van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie as the first after she flew with Farman in Ghent, Belgium, on May 31, 1908. Peltier, however, did enter the record books as the first woman to pilot an airplane when she flew Delagrange’s airplane 200 meters (656 feet) in a straight line at about 2.5 meters (8 feet) altitude in Turin.

Upon returning to France, Delagrange and Farman continued their friendly rivalry. In September, Delagrange flew 25 kilometers (16 miles) and by October Farman topped his distance by flying 40 kilometers (25 miles). Peltier continued accompanying Delagrange; on September 17 she flew with him on a 30 minute and 26 second flight. Though she continued to fly she did not pursue a license.

The world’s first air meet took place on May 23, 1909, at PortAviation, about 12 miles south of Paris. The meet drew only four aviators and though none of them completed the ten 1.2-kilometer (.75 mile) laps, Delagrange managed to fly a little over halfway and was declared the winner.

The first international air meet took place August 22-29 at Reims, France, and drew 22 aviators. The meet featured the inaugural Gordon Bennett Trophy competition. Delagrange was overshadowed by other entrants, but according to one source he placed tenth for speed and eighth for distance. He fielded three Blériot monoplanes and one Voisin biplane, having recruited Hubert Le Blon, Georges Prévoteau and Léon Molon as pilots. Delagrange flew his own Voisin-Delagrange III. Delagrange also traveled to England to fly at a meet in Doncaster. Held in October 1909, the event was England’s first air meet. Delagrange’s team of fliers from Reims was there and Delagrange set a speed record of 49.9 mph, though it could not be officially approved since the meet wasn’t sanctioned by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. He also won the Nicholson Cup for the fastest five laps around the flying field.

On January 4, 1910, the airfield at Croix d’Hins, near Bordeaux, a site of early flying experiments, held an official inauguration ceremony. Delagrange agreed to demonstrate his Blériot XI, powered by a 50-hp Gnome rotary engine rather than the original 25-hp Anzani. The ceremony originally was scheduled for December, but bad weather forced a postponement. Weather remained poor on January 4 with strong gusty winds, yet Delagrange took to the sky. He completed two circuits around the field and was rounding a turn on his third circuit when the wings collapsed. Delagrange died in the crash, the first of several fatal Blériot accidents that would plague the machine. Grieving, Thérèse Peltier walked away from aviation forever. The field at Croix d’Hins eventually closed.

Delagrange’s death fueled skepticism about the new field of aviation. “The death of Léon Delagrange, crusht [sic] under the wreck of his falling aeroplane at Bordeaux last week, raises again the question whether the aeroplane is not to be classed with the tightrope and the ‘loop-the-loop,’ rather than to be considered seriously as a practical means of locomotion,” noted the January 15, 1910, issue of The Literary Digest. Despite such skepticism, flying machines advanced far beyond anything even Delagrange imagined and became much more than simply “the bicycle of the airs.”

12 SPRING 2023 ©DAE PICTURE LIBRARY/AGE FOTOSTOCK

AVHP-230400-AVIATORS.indd 12 12/18/22 6:44 PM

An illustration by Achille Beltrame depicts Delagrange flying his Voisin-Delagrange II at Milan in the summer of 1908. The aviator set numerous records during his Italian tour that year.

In the blockbuster film, when a strapping Australian crocodile hunter and a lovely American journalist were getting robbed at knife point by a couple of young thugs in New York, the tough Aussie pulls out his dagger and says “That’s not a knife, THIS is a knife!” Of course, the thugs scattered and he continued on to win the reporter’s heart.

Our Aussie friend would approve of our rendition of his “knife.”

Forged of high grade 420 surgical stainless steel, this knife is an impressive 16" from pommel to point. And, the blade is full tang, meaning it runs the entirety of the knife, even though part of it is under wraps in the natural bone and wood handle.

Secured in a tooled leather sheath, this is one impressive knife, with an equally impressive price.

This fusion of substance and style can garner a high price tag out in the marketplace. In fact, we found full tang, stainless steel

blades with bone handles in excess of $2,000. Well, that won’t cut it around here. We have mastered the hunt for the best deal, and in turn pass the spoils on to our customers. But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99, 8x21 power compact binoculars, and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Down Under Bowie Knife

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the impeccable craftsmanship. If you don’t feel like we cut you a fair deal, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

Limited Reserves. A deal like this won’t last long. We have only 1120 Down Under Bowie Knives for this ad only. Don’t let this beauty slip through your fingers at a price that won’t drag you under. Call today!

What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives

êêêêê

“This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN êêêêê

“The feel of this knife is unbelievable...this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO

•Etched

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ® BONUS! Call today and you’ll also receive this genuine leather sheath! 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. DUK352-01 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer ® *Discount is only for customers who use the offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price. California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product.

of A+

FREE

8x21

1-800-333-2045 Your Insider Offer Code:

You must use the insider offer code to get our special price.

Rating

EXCLUSIVE

Stauer®

Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith purchase of Down Under Knife

DUK352-01

stainless steel full tang blade ; 16” overall • Painted natural bone and wood handle • Brass hand guards, spacers & end cap • Includes genuine tooled leather sheath

is not

ONLY $99! Now, THIS is a Knife! AVHP-230123-006 Stauer Down Under Bowie Knife.indd 1 12/11/22 3:43 PM

Down Under Bowie Knife $249* Offer Code Price Only $99 + S&P Save $150 This 16" full tang stainless steel blade

for the faint of heart —now

G.I. JOE VS. THE VOLCANO

IN 1935 TWO U.S. ARMY BOMBER SQUADRONS RECEIVED UNIQUE ORDERS—TO FIGHT AN ERUPTION

BY DAVE KINDY

Christmas Day 1935 turned out to be a busy one for the 23rd and 72nd Bombardment Squadrons of the U.S. Army Air Corps in Hawaii. Stationed at Luke Field on Ford Island, inside Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, the soldiers spent the holiday preparing for an unusual mission: dropping live ordnance on an erupting volcano.

Keystone bombers like this B-3 were the last biplanes the Army Air Corps ever ordered. In December 1935 the Army used Keystone B-3s and B-6s to try to stop a volcano’s eruption in Hawaii. The results of the mission remain questionable.

LOG

On the orders of the Hawaiian Division’s intelligence officer, groundcrews made sure the 10 Keystone B-3 and B-6 biplane bombers were ready for the first-of-its-kind operation. The squadrons would fly from Oahu to the big island of Hawaii and bomb the Mauna Loa volcano to stop it from spewing lava that threatened the community of Hilo and its 20,000 residents.

This bizarre scenario began November 21, when Mauna Loa started erupting. Thomas Jaggar, founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, became concerned by what he saw on the volcano’s north face. Red-hot magma was flowing through lava tubes at the rate of about one mile per day. It wouldn’t be long before it placed Hilo in danger. Jaggar decided to approach the Army and see if the military could do something to cut off the lava flow.

Explosives had been considered before to stop the volcano. When Mauna Loa erupted in 1881, local officials discussed the idea of using dynamite to shut off the lava flow but never followed through. Jaggar was thinking the Army could send an overland expedition to set off TNT charges, but chemist Guido Giacometti suggested that Army bombers might be more effective. Jaggar traveled to the Hawaiian

District headquarters at Schofield Barracks and met with the intelligence officer there. He was Lt. Col. George S. Patton Jr., who would later gain fame as one of World War II’s most successful and controversial generals.

Patton approved the scheme and assigned the operation to the Army Air Corps’ Lt. Col. Asa N. Duncan, commander of the 5th Composite Group at Luke Field. Duncan gave orders to the 23rd and 72nd bomber squadrons, accompanied by a detachment from the 50th and 4th observation squadrons, to prepare for a unique mission.

On December 26, 10 bombers, two amphibious planes and two observation aircraft flew to Hilo Airport, where an operations base was established. The weapons and groundcrews traveled to Hilo by ship. After refueling, one of the seaplanes took Jaggar and some of the bomber pilots to identify the lava tubes he had selected as targets, located about 8,500 feet up

14 SPRING 2023 TOP: U.S. NAVY (NAC)/UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT HILO; INSET: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES U.S. AIR FORCE

FLIGHT

AVHP-230400-FLIGHTLOG.indd 14 12/18/22 7:05 PM

the northeast slope of Mauna Loa.

With the objectives clearly defined, soldiers affixed ordnance to the bombers’ wings. The aircraft were light bombers built by Pennsylvania-based Keystone Aircraft. The B-3 was a biplane powered by twin Pratt & Whitney R-1690-3 engines; the B-6 was similar, with more powerful R-1820-1 engines. (Keystone bombers, including the B-6, were the last biplanes the U.S. Army Air Corps ordered.) Each plane was fitted with 600-pound MK 1 demolition bombs, as well as 300-pound dummy bombs for aiming purposes.

The next day, the pilots flew two missions of five bombers each. They first dropped their dummy ordnance for sighting, then made final runs and released the MK 1 bombs at two locations. Ground observers reported direct hits with the 20 bombs. Lt. Col. Duncan flew in one of the observation planes to check on the results. “It was found that five bombs hit the stream itself, three in the flowing lava of the first target and two directly above the tube of molten lava of the second target,” he reported. “One of these caved in the tunnel. Three other craters were within five feet of the stream, the explosions throwing ashes into the red lava. Two others were within 20 feet of the target.” Duncan said the pilots estimated that “seven other bombs fell within 50 feet of the stream.”

The bombers had been spot-on with their attack and the magma flow began to slow. It ceased altogether within a few days, and Hilo was saved from being wiped off the map. Jaggar was pleased with the results and thanked the Army Air Corps for their efforts. “The Army, on one day’s work, has stopped a lava flow, which might have continued indefinitely and have caused incalculable damage to the forest, water resources and city,” he stated in the Air Corps News Letter of January 15, 1936.

Others, including the pilots, remained unconvinced the aerial bombings had actually made much of an effect. Scientists believed then—and still do—that the volcano likely ceased erupting on its own. Harold T. Stearns, a government geologist who flew in one of the bombers and later wrote Geology of the State of Hawaii, didn’t think the explosives had stopped the flow of lava at all. “I am sure it was a coincidence,” he wrote.

In 1942, the Army Air Forces bombed Mauna Loa again, this time to prevent Japanese vessels offshore from using the glowing lava to spot the island. Again, the results were mixed, with most volcanologists believing that the eruption stopped by itself. Unexploded ordnance from

both missions was found at the site in 2020.

To this day, the 5th Composite Group—now the 23rd Bomb Squadron of the 5th Bomb Wing, stationed at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota—is remembered for its strange encounter with Mauna Loa. In fact, the squadron’s patch, featuring bombs striking an erupting vol cano, seemingly commemorates that moment in its history.

Except it doesn’t. According to historical records, an early version of the patch showing the bombs and volcano was approved by the Secretary of War on September 20, 1931—four full years before the historic bombing mission. Instead, the artwork was intended to symbolize the unit’s proximity to Mauna Loa as well as its firepower—two things that just happened to intersect in December 1935.

1935 and its lava soon threatened the town of Hilo. Above: The 23rd Bombardment Squadron’s patch may seem to commemorate the unit’s attempt to silence the volcano with bombs, but the design actually predates the mission.

15 SPRING 2023 TOP: U.S. NAVY (NAC)/UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT HILO; INSET: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES U.S. AIR FORCE

AVHP-230400-FLIGHTLOG.indd 15 12/18/22 7:05 PM

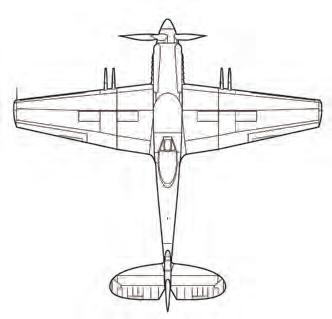

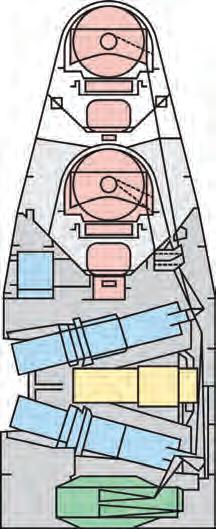

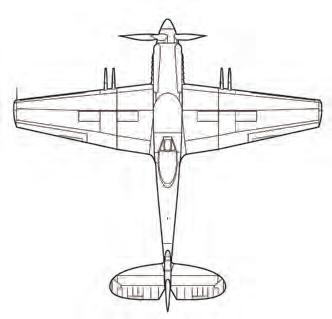

BY ROBERT GUTTMAN

The little-remembered Spiteful was the last iteration of the famous and long-lived line of Supermarine Spitfires. It was also noteworthy as the fastest British piston-engine fighter to enter production, although few were built before the project was cancelled. The Spiteful had taken too long to develop and did not reach production until World War II was over and jet-powered fighters were coming into use. Nevertheless, its protracted development did allow it to play a transitionary role in the Jet Age.

In September 1942 Britain’s Air Ministry asked Supermarine to improve the Spitfire’s flying qualities at high speeds. The latest versions were approaching the speed of sound in power dives, and the effects of compressibility—the shock waves and instability created by the air flowing over the wing or tail at such high speeds—were becoming a problem. That phenomenon soon became known as the “sound barrier,” which would not be broken until the advent of high-performance rocket

and jet-powered aircraft in the late 1940s.

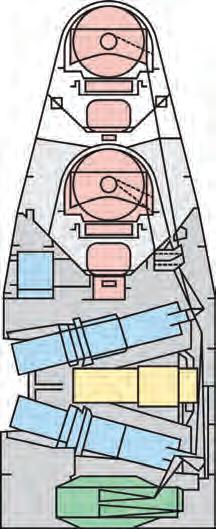

In the case of the Spitfire, the engineers determined that the best solution to the compressibility issue was to reduce drag by replacing the famous elliptical wing with a smaller one of an entirely new design. The new wing would have a shorter span and a straight-tapered planform, with the wing area reduced from 242 to 210 square feet. In addition, it had a thinner, laminar-flow section. The thickest part of the laminar-flow section was farther back on the wing’s surface than it was on a conventional wing and that moved the point of boundary layer separation—where the smoothly flowing air lifts off the wing surface—farther back as well. The result was to reduce skin-friction drag and enhance control at higher speeds. The shorter span was also expected to increase the fighter’s rate of roll. Other departures from the traditional Spitfire design included the introduction of a wide-track, inward-retracting landing gear to improve ground handling and an increased armament of four 20mm cannons. The new version of the Spitfire was deemed sufficiently different to be given a whole new name, the Spiteful.

The disadvantage of laminar-flow wings was that they required far more precise manufacturing tolerances than conventional wings. Even small imperfections of shape or finish could have a detrimental effect on performance. The

16 SPRING 2023 RAF MUSEUM, HENDON TOP AND CENTER: RAF MUSEUM, HENDON; BOTTOM: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

EXTREMES THE SUPERMARINE SPITEFUL WAS FAST, BUT IT ARRIVED TOO LATE FOR WORLD WAR II

The Supermarine Spiteful belonged to the Spitfire family but incorporated improvements intended to boost its speed and performance. In the end, it could not compete with new jet aircraft.

LAST

AVHP-230400-EXTREMES.indd 16 12/18/22 6:46 PM

THE

SPITFIRE

Spiteful’s new wing took such a long time to design and build that the Air Ministry criticized the company for its slow progress. In addition, the Supermarine design and development staff was deeply involved with developing other improved versions of the Spitfire. As a result, the first Spiteful prototype, a Spitfire XIV fitted with the new laminar-flow Spiteful wings, did not make its first flight until June 30, 1944. The first true Spiteful prototype, which also included a new fuselage with a slightly raised cockpit to improve visibility over the long nose, did not fly until January 1945.

Like the Spitfire, the new fighter was supposed to come in two versions, one with the Rolls-Royce Merlin and the other with the Griffin engine. However, the Merlin version was cancelled by the time the wing was ready, leaving only the more powerful Griffin-engine Spiteful. The new fighter was 32 feet 11 inches long, had a wingspan of 35 feet and a gross weight of 9,950 pounds. Its 2,375-hp Griffin gave it a service ceiling of 42,000 feet and maximum speed of a blistering 483 mph. The Spiteful performed well and was generally pleasant to fly at high speeds, but the story was different at lower speeds, where the Spitfire proved noticeably superior. One problem was that the Spiteful would drop one wing without warning when it approached stall. Investigation revealed that when the Spiteful’s wing stalled, it began from the tip inward, whereas the Spitfire’s wing began to stall from the root outward, producing a gentler and more controllable stall. Supermarine introduced numerous design tweaks to resolve the Spiteful’s handling problems, including larger tail surfaces. The tweaks eventually made the Spiteful an acceptable fighter, but the modifications increased drag so much that the new aircraft did not markedly outperform existing production Spitfires. Furthermore, with the war rapidly coming to an end and jet fighters in the offing, the RAF regarded the Spiteful as redundant. As a result, on September 23, 1945, the Air Ministry cancelled its order. Supermarine delivered only 17 production Spitefuls and none ever reached operational squadrons.

In parallel with the Spiteful, Supermarine developed a carrier-based naval version of the new fighter. Called the Seafang, it differed from the Spiteful principally in having folding wings, a “sting” type tail hook, two contra-rotating propellers to reduce torque during take-off and room for reconnaissance cameras inside the fuselage. The Seafang’s development was even slower than the Spiteful’s and it was first flown

Top: This aircraft, with a longer fuselage than the Spitfire’s and with a redesigned wing, is considered the first true Spiteful prototype. It first flew in January 1945. Center: The Seafang was an attempt to create a Spiteful for the Royal Navy. It sported a pair of three-bladed, contra-rotating propellers. Above: The wings of the Spitfire (left) and Spiteful show their obvious differences.

in January 1946. The Royal Navy soon abandoned it in favor of the Hawker Sea Fury and the de Havilland Sea Hornet. The navy did order 89 examples of the Supermarine Seafire FR 47, which was similar to the Seafang and eventually saw combat during the Korean War.

The Spiteful represented the absolute apex of piston-engine fighter development. Its story might have ended differently had it entered production a year earlier, but it arrived too late. The Spitfire became legend because it was the right airplane in the right place at the right time, but the Spiteful was lost to obscurity. Nevertheless, its heritage did live on. The laminar-flow wings developed for the Spiteful were subsequently fitted to Supermarine’s first production jet fighter, the Attacker, of which 185 were manufactured.

17 SPRING 2023 RAF MUSEUM, HENDON TOP AND CENTER: RAF MUSEUM, HENDON; BOTTOM: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

AVHP-230400-EXTREMES.indd 17 12/18/22 6:46 PM

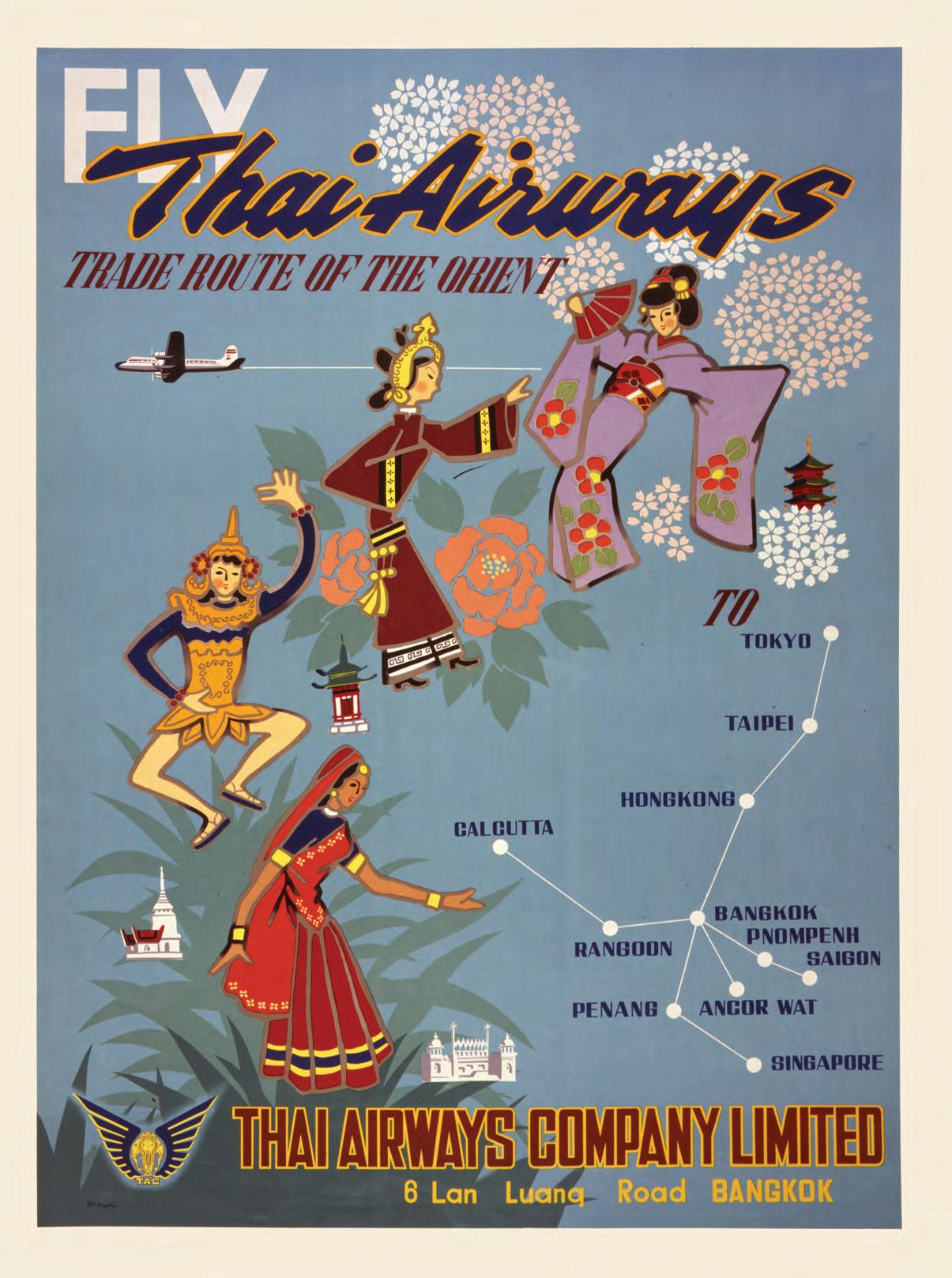

COME FLY WITH US

PORTFOLIO

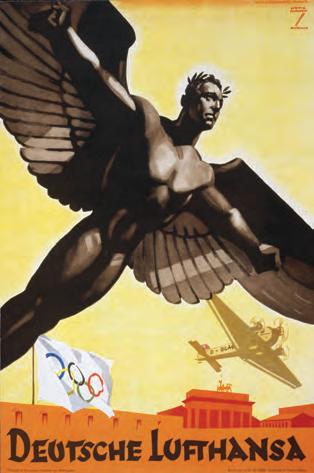

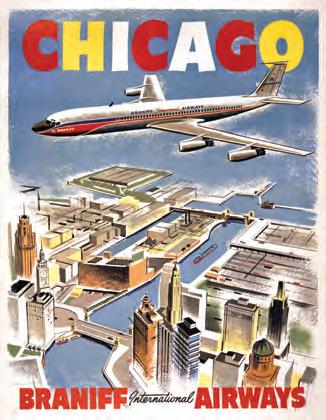

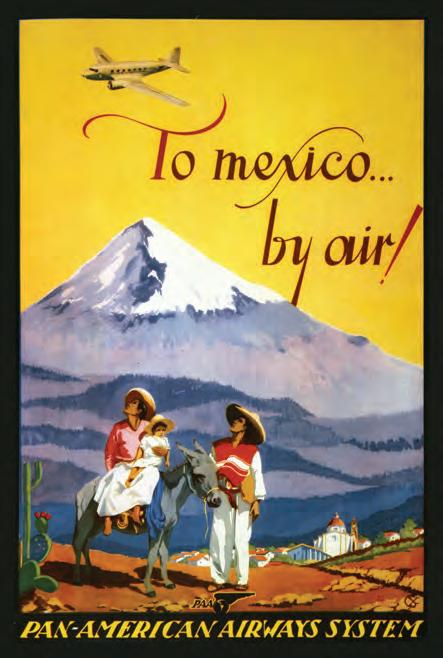

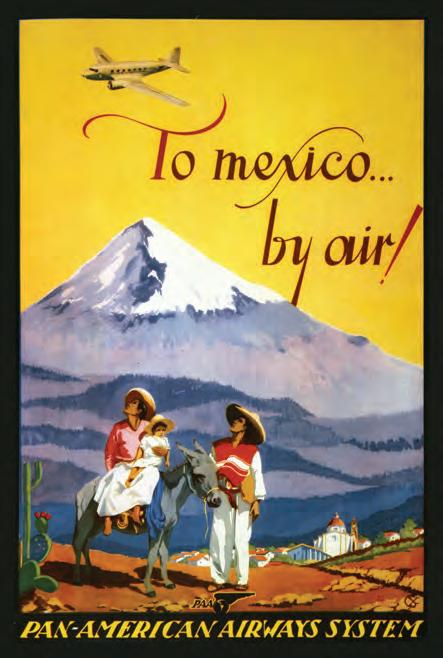

Once upon a time there was a “golden age” of air travel, when passengers wore suits and dresses to fly and airlines created colorful posters to tempt those well-dressed customers to exotic destinations like…Minnesota.

But not just Minnesota. Airlines used posters to tout the appeal of destinations all over the world—and to persuade potential customers that their carriers were the best way to get there.

This was in the days when most people planning a trip had to visit a travel agent. Perhaps an eye-catching poster, one featuring the latest airliner soaring over a scenic vista, would be just

XXXXXXXXXX ALL IMAGES: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 18 SPRING 2023

AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 18 12/18/22 6:50 PM

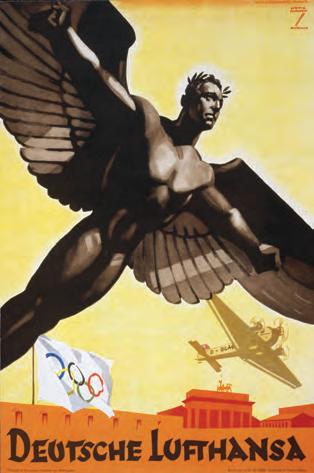

Opposite, clockwise from far left: A Canadian Pacific poster from the 1950s balances the beauty of Hawaii with the appeal of flying there in a pressurized Douglas DC-6; Deutsche Lufthansa features a Junkers Ju-52 and a winged figure flying over Berlin at the time of the 1936 Olympics; Philippine Air Lines shows potential customers in the 1950s how the company could send them flying in all directions from Manila. Left: In a 1950s offering from Northwest Airlines, New York’s Statue of Liberty remains impassive as a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser passes overhead. The big propellerdriven Boeings flew for Northwest until September 1960.

XXXXXXXXXX ALL IMAGES: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 19 12/18/22 6:50 PM

20 SPRING 2023 AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 20 12/18/22 6:50 PM

the thing to seal the deal.

In his book The Art of the Airways , Geza Szurovy traces the airline poster back to 1914, when the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line in Florida issued one to promote its “fast passenger and express service.” Early airline posters touted not just the novelty of flight, but also its safety. Once air travel became less novel after World War II, the posters stressed the destination, with the airplanes often reduced to a tiny image streaking across the top. Many of the art-

ists who did these works have retreated into anonymity but some—like David Klein, who created the TWA San Francisco poster on the opposite page—became known for their poster work. Seeing images like these may make you feel nostalgic for a time when airline travel seemed a little magical. The posters may also make you wistfully contemplate airlines that have vanished, like bird species gone extinct. What remains is the allure of travel—no matter what you’re wearing.

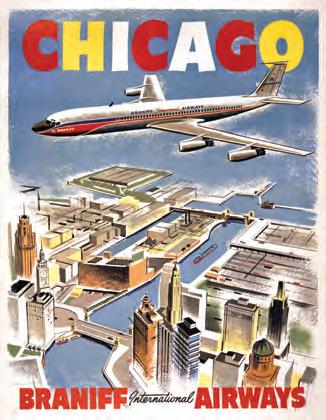

Opposite page: A United DC-6 overflies Yosemite; a TWA Boeing 707 passes the Golden Gate Bridge; an American DC-7 soars through Texas; and a TWA Constellation approaches L.A. This page: Braniff Airways became international in 1947 but also flew to U.S. destinations like Chicago (with a 707 in this case).

21 SPRING 2023

AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 21 12/18/22 6:50 PM

SPRING 2023

22

AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 22 12/18/22 6:51 PM

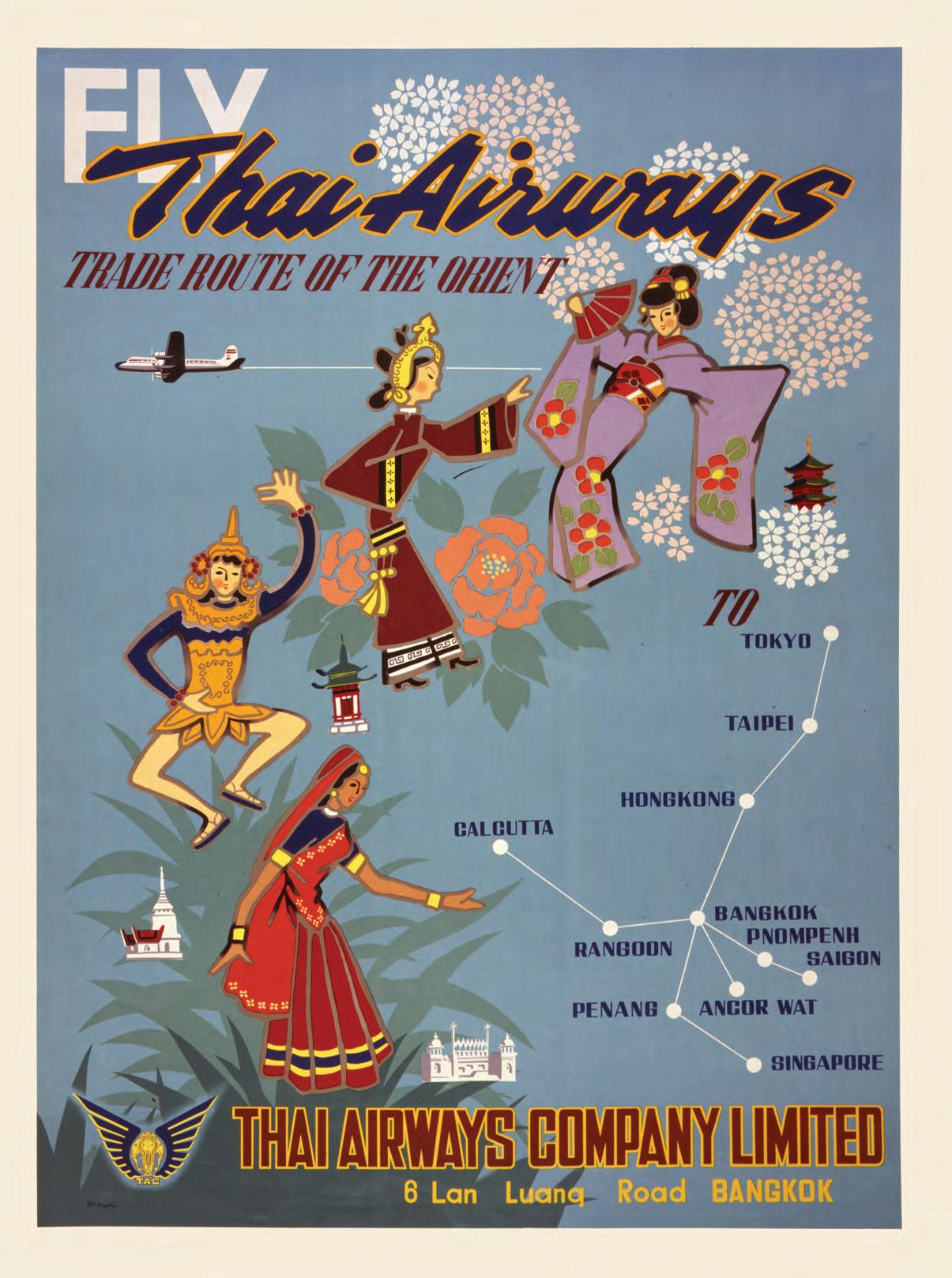

ANA boasted of its coverage, while other posters here feature Qantas’ Short S-23 Empire flying boats, Pan Am’s Boeing 314, Pan Am’s DC-2 and KLM’s wooden shoe. Opposite: Thai Airways flew airplanes, not shoes.

AVHP-230400-PORT-POSTERS.indd 23 12/18/22 6:51 PM

CLOSE ENCOUNTERS

BY TOM HUNTINGTON

It’s something like running into a celebrity.

FROM THE COCKPIT

That’s how I feel when I see in person an airplane that we have covered in Aviation History. I’ve had that experience several times recently. Last fall I visited the American Heritage Museum in Massachusetts and got a close look at the Nieuport 28 that appears on this issue’s cover. As you’ll read in the article by Jon Guttman that starts on page 36, this is the world’s only flyable example of the type and had only recently returned to the sky after a lengthy restoration in Sweden. When I saw it, the World War I biplane seemed a little out of place, sitting on the museum’s main floor surrounded by hardware from more modern wars. It had returned to the United States only about a month earlier and had been flying at an airshow the weekend before, so I guess it was still waiting for its permanent home. It would have looked great no matter the setting, as if it had just rolled out of the factory. (Keep this to yourself: When no one was looking I stepped over the ropes surrounding the airplane so I could peer into the cockpit.)

Another airplane that appears in this issue, the Boeing 247D that Roscoe Turner flew in the 1934 MacRobertson International Air Race (see the feature that starts on page 26), is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. I visited the museum in October when it reopened some of the galleries that had been closed for renovation and I saw the Boeing in the expansive America by Air Gallery, which it shares with other air transport stalwarts like the Ford Trimotor and the Douglas DC-3. I used to work in the museum building some years ago and I had always been fascinated by the 247. Squint a bit (and mentally add a couple engines) and you can

easily see its ancestral relationship to the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, which was one of my favorite airplanes growing up. Way back in 1996 I was lucky enough to fly in the world’s only flightworthy 247, which had returned to the air after restoration by the Museum of Flight in Seattle. It was quite an experience—like taking a trip in a time machine. The 247 is also a surprisingly small airplane, at least by today’s airline standards. That airplane made its final flight in 2016, so if you hope to fly in a Boeing 247 someday, you are out of luck.

I saw another airplane the magazine has covered when I visited the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in Rhinebeck, New York, on a beautiful (if a bit windy) fall day. Back in the Autumn 2022 issue’s Briefing section, Stephan Wilkinson wrote about the 1912 Etrich Taube replica that Mike Fithian finished last year. It’s now at the aerodrome and it was really something to see it lift off and float through the air, like a steampunk dragonfly.

Whenever I visit places like this, I take lots of photos and videos and post them on our Facebook page and on TikTok and other social media outlets. I love print magazines as much as anyone, but you can do things in the digital realm that just aren’t possible with ink-on-paper magazines. But then again, there was also a time when they said that if man were meant to fly, he’d have wings…

24 SPRING 2023 PHOTOS BY TOM HUNTINGTON

Left: The only flyable Nieuport 28 belongs to the American Heritage Museum. Top: This Etrich Taube replica found a home at Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome. Above: A Boeing 247D that Roscoe Turner flew is a resident of the National Air and Space Museum.

AVHP-230400-COCKPIT.indd 24 12/18/22 6:52 PM

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

SECOND

26 SPRING 2023 AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 26 12/19/22 8:33 AM

Crewmembers of a United Air Lines Boeing 247 admire their sleek new aircraft. Modern as it was, the 247 was quickly eclipsed by the Douglas DC-3 in part because the Douglas could carry more passengers.

SECOND

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

BEST WAS THE BOEING 247 REALLY EVERYTHING IT’S SUPPOSED TO BE?

AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 27 12/19/22 8:33 AM

Top: Boeing’s Model 40A was a mail plane that utilized welded steel for its fuselage structure. Center: With its Model 80, Boeing began focusing on passengers over mail. Bottom: The all-metal Model 221 Monomail was another step forward for Boeing.

The Boeing 247 was the end result of a battle between company management and its engineers. Unfortunately, the engineers lost. Although enshrined today as “the first modern airliner”—and it certainly looked the part—the 247 was actually too small and low-powered to make it as a money-making passenger carrier. It was the wrong airplane at the right time.

That time was the early 1930s, when a series of events and innovations was transforming air transportation. Until then commercial aviation had been a cold, miserable, noisy, cramped, vibratory and often vomitous experience. Airline passengers flew aboard drafty biplanes, three-engine antiques with fixed landing gear and a shrubbery of struts and rigging. Operators offered no creature comforts, and passengers were little more than an afterthought, since carrying government-subsidized airmail paid the bills. According to Transcontinental and Western Air pilot Daniel W. Tomlinson IV, “Flying in the old Ford [Trimotors] was an ordeal…. The flight was deafening. The metal Ford shook so much that it was an uncomfortable experience. It surprised me that people would pay money to ride in the thing.”

At that time, the Boeing Aircraft Company had no experience designing passenger airplanes. It built biplane pursuits for both the Army and Navy, as well as two mail plane designs and a surprisingly modern bomber for the Army. Boeing’s first passenger airplane was the 1925 Model 40A, a single-engine, fixed-gear biplane with space for just two passengers in a pair of tiny, handsomely wood-trimmed, enclosed cabins, each with its own door, below and ahead of the pilot’s open cockpit. The original plan was that those cabins could be occupied by a riding mechanic and, if necessary, a deadheading pilot.

Boeing built only one straight Model 40, since it was powered by an oily and obsolete Liberty V-12 engine. The company replaced it with the just-introduced 410-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial. The Wasp was 200 pounds lighter than the World War I Liberty, which meant the new Model 40A could carry 200 pounds more mail. The slightly widened 40C could also accommodate four riders.

The Model 40s all made extensive use of welded steel tubing for the fuselage structure,

since Boeing had pioneered the precise fitting, beveling and electric arc-welding of thin-wall steel tubes. The company initially applied the technique to a 1923 Army contract for 22 de Havilland DH-4s, with welded steel tubing replacing the original spruce-framed fuselage. They were called DH-4Ms, the M standing for “modernized,” not “metal.” (Outmoded as they were, the DH-4Ms made at least a minor amount of history. In 1927, serving as Marine Corps Boeing O2B-1s, several carried out the first dive-bombing attacks ever flown by the U.S., against Nicaraguan rebels.)

Despite the discomfort, passenger demand soon outstripped the Model 40C’s four seats. Most of these airplanes were flying for Boeing Air Transport, which the company had formed in 1927 when it won the lucrative San Francisco-Chicago airmail route. Boeing also realized that it would be convenient to have a captive customer for its civil products. (After a variety of name changes, BAT became what we now know as United Airlines, which is still happy to fly Boeings.)

Boeing realized that it needed a bigger passenger carrier, so it intro -

28 SPRING 2023 PREVIOUS SPREAD: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; TOP: BOEING; CENTER AND BOTTOM: SAN DIEGO AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM TOP: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; BOTTOM: 504 COLLECTION/ALAMY

AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 28 12/19/22 8:34 AM

duced the Model 80, a not particularly attractive 12-passenger trimotor biplane soon lengthened to carry 18. The 80 was Boeing’s first real focus on passengers rather than mail. Boeing considered the airplane to be the Pullman of the skies—a luxurious railway coach with wings, though that was largely a PR fantasy. The 80A did have leather chairs for seats, a small amount of hot and cold running water in a tiny lavatory and a heated cabin. The 80A was also the airliner that finally convinced pilots they didn’t have to sit in open cockpits so they could feel the wind on their cheeks and keep the airplane trimmed and coordinated like human yaw strings. They also didn’t have to squint through rain and snow at the engine nacelles to read the pressure and temperature instruments. In the Boeing, those instruments were on the flight-deck panel. The Model 80A also introduced to aviation what would quickly become an airline necessity: the flight attendant, then called a stewardess. Boeing

Air Transport hired registered nurses to fly aboard its Model 80As, supposedly to cater to the possible medical needs of passengers. In fact, their presence was a goad to potential businessman passengers who still distrusted aviation. “Afraid to fly? Well, here’s a young lady braver than you.”

Boeing had been lining its mail plane cargo compartments with an aluminum alloy called Duralumin to keep metal fittings on mailbags from tearing through the fuselage fabric. Duralumin was the first metal light enough to be carried aloft en masse by the engines of the time, and Boeing chief engineer Claire Egtvedt

29 SPRING 2023 PREVIOUS SPREAD: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; TOP: BOEING; CENTER AND BOTTOM: SAN DIEGO AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM TOP: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS; BOTTOM: 504 COLLECTION/ALAMY

The Northrop Alpha sported a stressed-skin, semi-monocoque fuselage. Below: Boeing chief engineer “Monty” Monteith had written an aerodynamics textbook but took a conservative approach to new airplane designs.

AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 29 12/21/22 9:43 AM

COMMERICAL AVIATION WAS A COLD, MISERABLE, NOISY, CRAMPED, VIBRATORY AND OFTEN VOMITOUS EXPERIENCE.

247s near completion at the Boeing plant in Seattle. Left: The airplane pictured in this Boeing ad crashed in Indiana on October 10, 1933, following a midair explosion, apparently caused by an explosive device in the baggage compartment. No suspects were ever identifed.

mused that perhaps an entire stressed-skin, semi-monocoque fuselage could be formed of Duralumin. (Jack Northrop had already figured that out with the Northrop Alpha, so Boeing bought Northrop’s company, Avion.) That was a challenge to Boeing’s conservative approach, as well as the industry’s. Until then, the Ford and Fokker technique was to use corrugation to provide structural strength for metal, but it turned out that the drag of the corrugations, even though they were in line with the assumed airflow, was greater than anticipated. Egtvedt called those airplanes “flying washboards” and he intuited that a rounded fuselage would create less drag than the boxy style of the time.

Egtvedt had moved on to Boeing’s executive ranks by the time the company’s pioneering Model 200/221 Monomail emerged under the stern gaze of engineer Charles “Monty” Monteith in 1930. (Monteith was so conservative he insisted that his staff draw up just-in-case alternative biplane configurations for every Boeing design, even the 247.) The Monomail was an all-metal, semi-monocoque, retractable-gear design with a neatly cowled radial engine. The Model 200 was a pure mail plane, the 221 a six-passenger transport soon to be stretched to accommodate eight. Both variants set new

30 SPRING 2023 BOTH: BOEING HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 30 12/19/22 6:54 PM

Above:

standards for low-drag aerodynamic efficiency—so much so that the Model 200/221 outflew its powerplant. With a prop pitched for a reasonable takeoff, the airplane cruised too fast to make use of that blade angle. The airplane needed a variable-pitch propeller, which hadn’t yet been developed.

Much of what made the Monomail special was carried over to an imaginative Boeing Army bomber contender, the YB-9. Though Boeing built only seven YB-9s—it was trumped by Martin’s faster and more modern B-10—the B-9 did have one new feature that became commonplace for multi-engine aircraft. Its engines were not carried in draggy, free-standing, strutted nacelles but were faired into the leading edges of the wing. This created better prop efficiency and smoother airflow over the wings.

On March 31, 1931, a pug-nosed TWA Fokker F-10 trimotor crashed outside Bazaar, Kansas, killing the much-admired Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne. The accident happened because the Fokker’s wooden wing spar had rotted and failed, moving the Department of Commerce essentially to ban trees for airliner construction. Both Boeing and Douglas Aircraft immediately embarked upon the design of all-

metal airliners.

The Northrop Alpha, the Boeing Monomail and B-9, the Knute Rockne crash, the adoption of stressed-skin semi-monocoque construction, cantilever wings, retractable landing gear, drag reduction through streamlining…once all this came together, the time had come for Boeing to create the 247.

Initially, Boeing management wanted to build a new metal airliner the size of the 18-passenger Model 80A, but cautious Monty Monteith felt that building a fast airplane of that size would be “like flying a barn door in a Kansas windstorm.” He advocated for a smaller design. Those initial 247 proposals included a biplane trimotor and a high-wing monoplane twin before Boeing finalized the low-wing configuration.

By 1929, Boeing had acquired a number of aviation-industry companies, including Stearman, Chance Vought, Sikorsky, Pratt & Whitney and, in 1930, Jack Northrop’s Avion. It now called itself the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation, so there were a number of cooks stirring the broth that became the Boeing 247. Two of the most knowledgeable chefs were Frederick Rentschler, founder and president of

The 247’s speed allowed its users to call it the “3-Mile-A-Minute” airliner. Here United Air Lines also touted the airplane’s “warm, spacious cabins” and the “stewardess service.” None of that was enough to make the 247 competitive in the burgeoning market for airliners.

31 SPRING 2023 BOTH: BOEING HISTORYNET ARCHIVES

AVHP-230400-BOEING247D.indd 31 12/19/22 6:55 PM

Top: Three Marx Brothers (Zeppo, Harpo and Chico) clown before taking a flight on a 247. Above: Once aboard, the Marxes would have been seated in a cabin that looks cramped by today’s standards, but was considered the lap of luxury in 1933.

Pratt & Whitney, and his chief engineer, George Mead. (Mead designed many of P&W’s most powerful radials, including the ubiquitous R-2800.) But the pilots who flew for Boeing’s United Air Transport stuck their spoons in the design discussion as well.

Pratt had two engines that could power the 247: the 1,860-cubic-inch Hornet radial and the 1,340-cubic-inch Wasp. Using the Hornet would have resulted in a 16,000-pound airplane. To quote Henry Holden’s book The Boeing 247: the First Modern Commercial Airplane, “The pilots flatly refused to accept the Hornet engines, stat-