Urgent: Special Summer Driving Notice

To some, sunglasses are a fashion accessory…

To some, sunglasses are a fashion accessory…

Drivers’ Alert: Driving can expose you to more dangerous glare than any sunny day at the beach can… do you know how to protect yourself?

Thesun rises and sets at peak travel periods, during the early morning and afternoon rush hours and many drivers find themselves temporarily blinded while driving directly into the glare of the sun. Deadly accidents are regularly caused by such blinding glare with danger arising from reflected light off another vehicle, the pavement, or even from waxed and oily windshields that can make matters worse. Early morning dew can exacerbate this situation. Yet, motorists struggle on despite being blinded by the sun’s glare that can cause countless accidents every year. Not all sunglasses are created equal. Protecting your eyes is serious business. With all the fancy fashion frames out there it can be easy to overlook what really matters––the lenses. So we did our research and looked to the very best in optic innovation and technology. Sometimes it does take a rocket scientist. A NASA rocket scientist. Some ordinary sunglasses can obscure your vision by exposing your eyes to harmful UV rays, blue light, and reflective glare. They can also darken useful vision-enhancing light. But now, independent research conducted by scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has brought forth ground-breaking technology to help protect human eyesight from the harmful effects of solar radiation

light. This superior lens technology was first discovered when NASA scientists looked to nature for a means to superior eye protection— specifically, by studying the eyes of eagles, known for their extreme visual acuity. This discovery resulted in what is now known as Eagle Eyes

The Only Sunglass Technology Certified by the Space Foundation for UV and Blue-Light Eye Protection. features the most advanced eye protection technology ever created. The TriLenium Lens Technology offers triple-filter polarization to block 99.9% UVA and UVB— plus the added benefit of blue-light eye protection. Eagle Eyes® is the only optic technology that has earned official recognition from the Space Certification Program for this remarkable technology. Now, that’s proven science-based protection. The finest optics: And buy one, get one FREE! Eagle Eyes® has the highest customer satisfaction of any item in our 20 year history. We are so excited for you to try the Eagle Eyes® breakthrough technology that we will give you a second pair of Eagle Eyes® Navigator™ Sunglasses FREE––a $59.95 value!

That’s two pairs to protect your eyes with the best technology available for less than the price of one pair of traditional sunglasses. You get a pair of Navigators with stainless steel black frames and the other with stainless steel gold, plus one hard zipper case and one micro-fiber drawstring cleaning pouch are included. Keep one pair in your pocket and one in your car.

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed.

Studies by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) show that most (74%) of the crashes occurred on clear, sunny days

Navigator™ Black Stainless Steel Sunglasses

Receive the Navigator™ Gold Sunglasses (a $59.95 value) FREE! just for trying the Navigator™ Black

Navigator™ Gold Stainless Steel Sunglasses

was developed from original NASA Optic technology and was recently inducted into the Space Foundation Technology Hall of Fame.

Fit-ons available for $39 +S&H Black or Tortoise-Shell design

with absolute confidence, knowing your eyes are protected with technology that was born in space for the human race.

Two Pairs of Eagle Eyes® Navigator™ Sunglasses $119.90†

Offer Code Price $49 + S&P Save $70.90

Offer includes one pair each Navigator™ Black and Navigator™ Gold Sunglasses

1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: EEN923-06

more vivid and sharp. You’ll immediately notice that your eyes are more comfortable and relaxed and you’ll feel no need to squint. The scientifically designed sunglasses are not just fashion accessories—they are necessary to protect your eyes from those harmful rays produced by the sun during peak driving times.

If you are not astounded with the Eagle Eyes® technology, enjoying clearer, sharper and more glare-free vision, simply return one pair within 30 days for a full refund of the purchase price. The other pair is yours to keep. No one else has such confidence in their optic technology. Don’t leave your eyes in the hands of fashion designers, entrust them to the best scientific minds on earth. Wear your Eagle Eyes® Navigators

You must use this insider offer code to get our special price.

Stauer ®

Rating of A+

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. EEN923-06 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com

† Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code.

Smart Luxuries—Surprising Prices ™

a pair of Eagle Eyes® and everything instantly appears

Where does hunting fit in the modern world? To many, it can seem outdated or even cruel, but as On Hunting affirms, hunting is holistic, honest, and continually relevant. Authors Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, Linda K. Miller, and Capt. Keith A. Cunningham dive deep into the ancient past of hunting and examine its position today, demonstrating that we cannot understand humanity without first understanding hunting.

Readers will…

• discover how hunting formed us,

• examine hunting ethics and their adaptation to modernity,

• understand the challenges, traditions, and reverence of today’s hunter,

• identify hunting skills and their many applications outside the field,

• learn why hunting is critical to ecological restoration and preservation, and

• gain inspiration to share hunting with others.

Drawing from ecology, philosophy, and anthropology and sprinkled with campfire stories, this wide-ranging examination has rich depths for both nonhunters and hunters alike.

On Hunting shows that we need hunting still—and so does the wild earth we inhabit.

“All true hunters ‘feel’ the truth, but few are able to ‘articulate’ that truth. Now, thankfully, we have On Hunting to be our champion of the wild!”

—JIM SHOCKEY, Naturalist, Outfitter, TV Producer and HostFEATURES

26 DESTINATION: SWEDEN

American aircrews who couldn’t make it back to England in World War II had a Scandinavian option.

BY GARY G. YERKEY

BY GARY G. YERKEY

34 THE DOLE DISASTER

Participants in a 1927 air race learned the hard way that Hawaii is a long way from California.

BY STEPHAN WILKINSON44 A SUNDAY WITH LILIENTHAL

One week before a pioneering aviator’s tragic death, an American watched him at work.

BY STEVE WARTENBERG

BY STEVE WARTENBERG

52 IGO ETRICH’S DOVES

These once-ubiquitous airplanes may have looked like birds, but they were based on a seed.

BY JON GUTTMAN SUMMER 2023 26 18

60 COMPROMISED ARROW

What did the Soviets know about Canada’s new interceptor, and when did they know it?

70

ON THE COVER: In an illustration by Jack Fellows, a Swedish Reggiane Re.2000 escorts the damaged Boeing B-17 Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby to a landing in Sweden.

70

ON THE COVER: In an illustration by Jack Fellows, a Swedish Reggiane Re.2000 escorts the damaged Boeing B-17 Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby to a landing in Sweden.

Historically, gold has proved to be a reliable hedge against inflation and economic uncertainty. Plus, gold bars are a convenient and popular way to invest in gold. PAMP® gold bars are one of the most trusted gold investment products on the planet.

In a nutshell, PAMP Suisse is the world’s leading independent Precious Metals refiner. An acronym, “PAMP” stands for Produits Artistiques Métaux Précieux (“artistic precious metals products,” in French). The company is completely independent of any government, and provides more than half of all the gold bars under 50 grams sold around “the world. They are so well respected in the gold industry, they are assigned as an ‘Approved Good delivery Referee’ to determine the quality of products by the London Bullion Market Association. Located in the southern part of Switzerland in Castel San Pietro, the company was founded in 1977.

PAMP Suisse Minted Gold Bars are certified, assayed, guaranteed, and struck in 999.9% pure gold! These gold bars feature an obverse design portraying Fortuna, the Roman Goddess of fortune and the personification of luck in Roman religions. PAMP Suisse’s exclusive Veriscan® technology uses the metal’s microscopic topography, similar to a fingerprint, to identify any registered product, aiding in the detection of counterfeits. The tamper-evident assay card makes it easy to tell if the bar has been questionably handled, while guaranteeing the gold weight and purity.

Add gold to your portfolio. PAMP Suisse Minted Gold Bars are available here in a wide variety of sizes—from one gram to one ounce—at competitive prices. PLUS, you’ll receive FREE Shipping on your order over $149. Call right now to get your PAMP Suisse Minted Gold Bars shipped to your door!

PAMP Suisse Minted Gold Bars

1 gm Gold Bar $109 $95 + s/h

2.5 gm Gold Bar $249 $219 + FREE SHIPPING

5 gm Gold Bar $449 $399 + FREE SHIPPING

10 gm Gold Bar $849 $749 + FREE SHIPPING

1 oz Gold Bar $2,399 $2,149 + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING! Limited time only. Product total over $149 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases.

Actual sizes are 11.5 x 19 to 24 x 41 mm

GovMint.com® is

SUMMER 2023 / VOL. 33, NO. 3

TOM HUNTINGTON EDITOR LARRY PORGES SENIOR EDITOR JON GUTTMAN RESEARCH DIRECTOR

STEPHAN WILKINSON CONTRIBUTING EDITOR ARTHUR H. SANFELICI EDITOR EMERITUS

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY GUY ACETO PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES MGreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER TJenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

© 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com

Aviation History (ISSN 1076-8858) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC

901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Tysons, Va., and additional mailing offices. Postmaster, send address changes to Aviation History, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc.; 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

What a superb issue [Spring 2023]! It is really hard to pick a favorite article—but Stephan Wilkinson’s “Second Best” sure stands out to me with its fresh perspective on the Boeing 247. The depth of history in only 10 pages is terrific. It even has an ad for the ill-fated UAL 247 NC13304, blown out of the sky by a bomb over Chesterton, Indiana.

John D. Bybee, Vermont, IllinoisWe plan to include more about the mysterious bombing of the UAL Boeing 247. Stay tuned.

In his article about the Boeing 247, author Stephen Wilkinson is in error when he states, “By 1929, Boeing had acquired a number of aviation-industry companies” to form the United Aircraft and Transport Corporation. In fact, William Boeing and Frederick Rentschler merged their companies to form the corporation. It was a merger of equals to create a vertically integrated aviation holding company. The companies it owned were those noted by Wilkinson. In 1934, the government stepped in and forced a breakup. Boeing kept everything west of the Mississippi and Rentschler kept everything east, forming United Aircraft, which later became United Technologies and now is called Raytheon Technologies, while United Airlines became an independent company.

Herb Reutter, Escondido, CaliforniaIt’s great to see E. Royce Williams getting the recognition he deserves for an amazing feat of airmanship [“The Secret Dogfight,” Winter 2023]. I’ve discussed this mission several times with Royce and according to Royce, there was weather down south, but the aerial combat in which he downed four MiGs was clear (contrary to the way this event is shown in most depictions). He did head south and dive into the clouds to avoid the MiG that accosted him from behind after the downings. I’ve included a picture of me with Royce at Tailhook 2021 (with a first preliminary sketch of art I was developing).

Hank Caruso, California, MarylandOn January 18, 2023, I awoke to a story about Royce Williams, the Navy pilot who shot down four MiG-15s on November 18, 1952, but could not talk about it because of the tensions of the Cold War. I wasn’t only happy to hear he would receive credit and the Navy Cross but felt I got the “inside scoop” by reading your article. Sometimes these articles and books help people receive credit for their accomplishments. I wonder how many other people out there still can’t talk about their stories because of security issues. I hope one day we will find out.

Michael Ariano, Clayton, North Carolina

Michael Ariano, Clayton, North Carolina

In December 2022, Royce Williams was approved for an upgrade from the Silver Star to the Navy Cross. He received it in a ceremony at the San Diego Air & Space Museum on January 20, 2023.

I just wanted to point out that in the great article “The Secret Dogfight,” the image caption on page 56 showing a Grumman Panther states it is taking off, but the location and height suggest that the image is either of a missed approach or a planned fly-by. During the Korean War F9Fs were usually catapulted off the forward end. The height above the deck of this Panther makes a take-off image rather unlikely.

Jerry O’Neill, Cheshire, ConnecticutI can identify well with 2nd Lt. Carter Harman’s “jumping off” a Sikorsky YR-4B in the Burmese jungle at high temps, as described by Steve Wartenberg in “Send the Eggbeater to Taro” [Spring 2023]. On April 12, 1957, I flew a similar rescue mission in an Army OH-23C Raven to rescue a hiker who had set out to walk a trail in Panama. An Army Ranger unit found him exhausted and severely dehydrated. A helicopter rescue was necessary. There was enough room at the pickup point to get both skids on the ground, but I kept the engine running because I didn’t want to risk a no-start. Everything went well until the hiker wanted to bring his pack along. The ship was already heavy, so I told him to leave the pack with the Rangers. He refused. I relented and let him stow his pack. The humidity and altitude were so bad, I could not bring the Raven to a hover.

Normal engine operating RPM was 3,200. I revved it to 3,400, jumped it off and dived down into the valley below, desperately trying to reach flying speed before ending up in the trees. Luckily, my airspeed built up enough to get into level flight without sharing the cockpit with tree branches. Slowly I began climbing out of the valley. Needless to say, the engine overspeed did not make it into the flight record that day.

John Ottley Jr., Alpharetta, Georgia

As of late March 2023, the Dakota Territory Air Museum, in Minot, North Dakota, is preparing for the first flight of its impeccably restored Republic P-47D-23 Thunderbolt. It is encouraging to see any P-47 restoration, much less one as compulsively complete and airworthy as this one. The chubby fighter was recovered from Papua New Guinea, where it had been abandoned by the Army Air Forces in September 1944 as worn out and obsolescent. AirCorps Aviation of Bemidji, Minnesota, started the restoration in 2015. The tape-like stripes visible on the airframe in the photo above are the brushed-on evidence of acid wash in preparation for spot welding, a 1940s technique that AirCorps Aviation revived for authenticity. The restorers also reproduced the assembly-line workers’ hidden scribblings inside the structure—none of them important but all of them original. The airplane will eventually be repainted in a color scheme that is yet to be determined.

When it’s done, this will be the only Republic-built Razorback that still flies. The earliest D models were Razorbacks, but later ones had bubble canopies. The bubble canopies offered better visibility, but the straight dorsal fairing—the “razorback”—behind the cockpit created less drag and provided more longitudinal stability. This would have made the Razorback a slightly better gun platform.

And the P-47 was an effective gun platform. In fact, you can make the case that the Pratt & Whitney propelled Thunderbolt was the most effective fighter, Allied or Axis, of World War II. It had eight guns, carried 65 percent more ammunition than its smaller Merlin-engined mates, and could lift more than a ton of bombs. The P-47N was faster and had a longer range than the North American P-51 Mustang. The Thunderbolt’s feats as a low-level fighter-bomber were never equaled,

and at 30,000 feet, with its dishwasher-size turbocharger wailing, there simply was no other 2,000-boosted-horsepower single-engine fighter flying. The P-47 owned the sky.

Back then, there was an adage, “If you want to impress the girls back home, fly a Mustang. If you want to see them again, fly a P-47.” In the words of the warbird website Hush-Kit, “Its biggest asset was its survivability, which meant the most important weapon the Air Force had—its experienced pilots—were kept alive.” Every single P-47 ace survived the war, something that cannot be said of any other fighter, friendly or foreign. Now another P-47 will not only survive but remain flying. —Stephan

WilkinsonRead more about the P-47 at historynet.com/ p47-thunderbolt

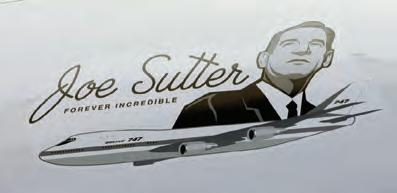

An era of aviation history truly ended on December 6, 2022, when the last Boeing 747 jumbo jet to be manufactured rolled out of the Boeing factory in Everett, Washington. The airplane, a 747-8, was the last 747 of 1,574 the company had built since the first one emerged from the same factory in 1968.

“For more than half a century, tens of thousands of dedicated Boeing employees have designed and built this magnificent airplane that has truly changed the world,” Kim Smith, the vice president and general manager of the 747 and 767 programs, said in a press release. “We are proud that this plane will continue to fly across the globe for years to come.” A freighter (not a passenger plane), the last 747 was delivered to its owner, Atlas Air Worldwide Holdings, on January 31 of this year.

Designed under the direction of Boeing’s Joe Sutter, the 747 was, noted author Simon Winchester, “the most remarkable aircraft of its time” and “the largest financial and technological gamble in the history of aviation.” Committing to it brought huge risks—to Boeing, which would be designing an unprecedentedly large and expensive airliner; to Pan American World Airways, whose president, Juan Trippe, ensured the 747 would happen by pre-ordering 25 of them; and to Pratt & Whitney, which took on the challenging task of creating engines to power the jumbo jet.

The Boeing 747 has been forced to step down as “queen of the skies” in favor of newer and more cost-efficient jets, but 747s will continue to fly for years to come, mainly as cargo haulers (only a handful of the jumbo jets still fly passengers). But the rollout of the final specimen means that no one will every again experience that “new 747 smell.” —Tom

Huntington

Huntington

There’s a lot more about the 747 at historynet. com/jumbo-boeing-747

In other 747 news, NASA’s flying telescope, a converted Boeing 747 called the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), departed Palmdale, California, on December 13, 2022, on its final flight. It landed at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, before being moved to its new home at the Pima Air & Space Museum next to the base. SOFIA was towed to the museum in January and NASA technicians completed a “save list” of items that can be repurposed before the observatory goes on public display, probably in May.

SOFIA began life as Pan Am’s Clipper Lindbergh, making its first flight on April 25, 1977. Charles Lindbergh’s widow, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, christened the jetliner on May 20, 1977, the 50th anniversary of her husband’s solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. United Air Lines purchased Pan Am’s Pacific fleet in 1986, and NASA acquired the airplane in October 1997. NASA had the jetliner modified in Waco, Texas, and SOFIA made its first post-modification flight on April 26, 2007, and its first science flight on December 1, 2010.

An international astrophysics collaboration between NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), SOFIA carried a telescope with a 106-inch (2.7 meter) diameter telescope and a suite of six instruments to study the universe at mid- and far-infrared wavelengths. Its observations focused on planets, planetary nebulae, astrochemistry, comets, supernovae, star formation and the galactic center. Science missions lasted 10 hours and were flown at altitudes between 38,000 and 45,000 feet to avoid interference from the atmosphere. The airborne observatory became noted for its discovery of helium hydride, thought to be the first type of molecule to form after the Big Bang. Its observations also revealed that the nearby planetary system surrounding the star Epsilon Eridani is very similar to our solar system, and it studied the role magnetic fields play in the behavior of black holes. You can find a top 10 list of SOFIA’s most influential discoveries on the NASA.gov website. And now you can visit SOFIA for yourself in Arizona.

—Nicholas A. VeronicoIn January, Mecum Auctions put rocker Elvis Presley’s 1962 Lockheed 1329 JetStar on the block. The winning bid was $260,000, but when the bidder backed out, businessman/ entrepreneur James “Jimmy” Webb stepped in and made the purchase for $234,000. Webb, who operates the YouTube site Jimmy’s World, had the airplane disassembled and trucked to Florida, where he has plans for the jet’s next incarnation. “The short version is I’m going to convert the fuselage into an RV so it can travel around the country for the rest of the world to enjoy,” he says. Webb’s analysis indicated it could cost nearly $6 million to get the JetStar airworthy again.

The King of Rock and Roll had purchased the four-engine craft in December 1976 for $840,000 and sold it shortly before this death on August 16, 1977. Its last owner was a Saudi Arabian company. The plane had suffered from weathering during the nearly four decades it spent parked outside at the Roswell International Air Center in Roswell, New Mexico, and its engines and some of its cockpit instrumentation had been removed. It still boasted some unique features, including a red velvet interior and a working cassette deck and VCR player. Also included in the sale was a copy of the airplane’s aircraft security agreement, signed by Presley and his father, Vernon.

The swept-wing JetStar made its first flight in 1957 and entered service in 1961, establishing itself as one of the world’s premier business jets. The earlier versions were powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT-12 engines, with two each in pods mounted at the rear of the fuselage. (Later versions acquired quieter Garrett TFE731 turbofans.) Presley actually owned two of the airplanes. He purchased the first, a 1960 version, in 1975, the same year he bought a Convair 880 that he named Lisa Marie after his daughter. Both those airplanes are on display at Graceland, Presley’s home in Memphis, Tennessee.

Webb estimates it will take about a year to convert the fuselage into an

RV. In the meantime, he plans to take metal from the wings and other parts of the airplane and fashion it into memorabilia that he will sell to fund the project, and he will donate any surplus revenue to two of Elvis’s favorite charities, St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital and the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor. “We’re trying to do everything we can to keep his legacy alive and to do what he would have wanted done,” Webb says. In the meantime, he will post about his progress on the Jimmy’s World YouTube channel. —Tom Huntington

You can see our interview with Jimmy Webb at historynet.com/elvis-jetstar

Not much remains of the Avro Arrow, the Canadian supersonic interceptor that was intended to counter the threat of Soviet bombers at the height of the Cold War (see the feature that starts on page 60). When Canada canceled the program in 1959, all five of the completed jets were ordered destroyed, along with engines and parts. Today the largest piece of the Arrow in existence is this nose section, which is on display at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. The nose had been removed so it could be used as a pressure chamber by the Royal Canadian Air Force Institute of Aviation Medicine in Toronto; the institute donated it to the museum in 1965. The museum has a few other Arrow components, including an Iroquois engine, the Canadian-built powerplant that was intended to propel the Arrow through the sky, but never got the opportunity.

As World War II ground to a close, the Allied-occupied German capital of Berlin became a flashpoint for the simmering rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States. The two powers cooperated well enough at first, as American and Red Army troops, along with the British and French, withdrew to four pre-assigned city sectors agreed upon before the end of hostilities. Since Berlin was isolated 100 miles deep inside the larger Soviet zone of occupation, further negotiations afforded the U.S. the use of one rail line, one highway and three air corridors 20 miles wide to supply American troops in the city.

As the Iron Curtain began to descend, the Soviets started reneging on the right of access. By the end of June 1948, niggling Soviet restrictions turned into a full-on blockade as the Russians tried to starve the city and its two million inhabitants. The U.S., Britain and France remained determined to keep Berlin out of Soviet hands and launched an all-out aerial resupply campaign that became known as the Berlin Airlift.

The operation, run by U.S. Maj. Gen. William H. Tunner, a veteran of Hump missions to China, called into service more than 100 Douglas C-47 Skytrains, each with a three-ton cargo capacity, and two larger C-54 Skymasters, which could haul ten tons of goods each, along with several British aircraft types. Over the next 15 months, Allied aircraft delivered more than 2.3 million tons of supplies to the beleaguered city. American aircrews conducted about three-quarters of the missions—more than 189,000 flights that logged 92 million miles—and, at the Airlift’s peak, a plane landed with supplies in Berlin every three minutes. Thirty American servicemen and one civilian lost their lives in 12 crashes, a remarkably low number given the wide-ranging scope of the operation.

While Gail Halvorsen, the Candy Bomber, captured popular imagination with his airborne delivery of sweets for Berlin’s children, critical life-sustaining cargo like coal and potatoes was more the norm.

The Soviets agreed to lift their blockade on May 12, 1949, but the Airlift continued through September, as the Allies continued to stock the city with supplies. Western suspicion of the Soviets paved the way for the formation of NATO that same year.

The program was a huge public relations triumph for the Allies and made many Berliners forever grateful. As Wolfgang Samuel, a 13-yearold German who later immigrated to America, joined the Air Force and rose to the rank of colonel, said, “You inspired at least one German boy to want to be just like you when he grew up.”

It all began 75 years ago this summer. —Larry Porges

Learn more about the Berlin Airlift at historynet.com/the-berlin-airlift

No one can realize how substantial the air is, until he feels its supporting power beneath him. It inspires confidence at once.

—OTTO LILIENTHAL, LATE 19TH CENTURY

BY DENNIS K. JOHNSON

BY DENNIS K. JOHNSON

Many Hollywood actors promote causes—social justice, animal welfare and so forth—but Robert “Bob” Cummings was a popular film and television star who used his celebrity to endorse general aviation.

Cummings played aviators in many of his productions and flew his own airplanes to shooting locations and while touring to promote his films. He was often photographed alongside his airplanes, all of which he named Spinach , although no one seems to know why.

Charles Clarence Robert Orville Cummings was born June 9, 1910, in Joplin, Missouri, and learned to fly while in high school, soloing in March 1927. Cummings studied aeronautical engineering at the

Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh but was forced to withdraw from school when his family’s finances were severely reduced by the stock market crash of 1929. He had become interested in acting while still at Carnegie and landed his first roles on Broadway and found work as a Hollywood extra during the early 1930s, sometimes working under different stage names. After signing a contract with Universal Pictures, he began to appear in better films, including It Started with Eve and The Devil and Miss Jones (both 1941) and Kings Row and Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (both 1942).

Cummings joined the Civil Air Patrol after the attack on Pearl Harbor, flying search and rescue missions, courier flights and border patrols with the Glendale, California, squadron. He used his own airplane, the first Spinach , a 1936 Porterfield. Later he owned a Cessna Airmaster, which he named Spinach II. In 1942, Cummings was inducted into the U.S. Army Air Forces as a flight instructor.

After the war, Cummings took on numerous roles, beginning with You Came Along, in which he portrayed a U.S. Army Air Forces officer during World War II. He starred in his first TV

series, the comedy My Hero, from 1952 to 1953, and in 1954 he won an Emmy award for his performance in “Twelve Angry Men” on the Westinghouse Studio One show. In 1954, Cummings starred alongside Ray Milland and Grace Kelly in Hitchcock’s film Dial M for Murder. From 1955 to 1959, he starred in his own TV sitcom, The Bob Cummings Show. He played Bob Collins (the same name he had in You Came Along), a former World War II pilot who becomes a Hollywood photographer. The New Bob Cummings Show began airing in 1961, with Cummings playing Bob Carson, a charter pilot and amateur detective who owned two airplanes, a 1960 Taylor Aerocar and a twin-engine Beech Super 18. The Aerocar, introduced in 1949 by designer Moulton Taylor, was a vehicle that could fly like an airplane or drive like an automobile. Cummings’s Aerocar was one of only six ever built and it could be seen taking off in the show’s opening credits. That wasn’t enough to save the show, which lasted for only 22 episodes.

Cummings also appeared in “King Nine Will Not Return,” a 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone in which he played the captain of a North American B-25 Mitchell bomber that crashed in the North African desert.

Throughout his life, Cummings was an avid pilot and enthusiastic supporter of general aviation. He also told some stories about his connections with aviation history that don’t withstand close scrutiny. For instance, he said that his father, a doctor, once treated Orville Wright and as a result gave his son the middle name Orville. The story appeared in a March 1960 article in Flying magazine, which said, “His father, the late Dr. Charles C. Cummings, a physician and surgeon, had treated Orville Wright for barber’s itch, a facial fungus which the pioneer airman picked up in a Kansas City tonsorial parlor while enroute to Joplin with brother Wilbur. One of the first practitioners to employ ultraviolet rays in treating skin diseases, Dr. Cummings quickly cured Orville’s infection and the two men became good friends.” Nonetheless, no known historical records mention a visit by the Wrights to Joplin or anything about Orville’s “barber’s itch” or treatment by Dr. Cummings. At other times Cummings apparently claimed that Orville Wright was his godfather and had taught him how to fly, although he told Flying that his teacher was a plumber named Cooper. One of the actor’s middle names was Orville, but it’s most likely that Cummings—or his publicist— invented the stories about a connection with Orville Wright.

Another story Cummings told is that when the government began licensing flight instructors, Cummings received certificate number one, making him the first official flight instructor in the United States. The Flying article said that “in 1938 the CAA [Civil Aeronautics Authority], aware that many people who could fly were actually incapable of teaching the art, created the rating of flight instructor. Bob applied for the rating even before Washington had prepared an examination. As a result, the Los Angeles CAA inspector, Gene Scroggy, drafted a tough 10-hour written, which Bob passed. After a thorough flight test, he qualified for Flight Instructor Certificate number ‘one’ by virtue of the fact he had been the first pilot in the country to apply!”

The Flying article also noted that “to Bob Cummings flying is an indispensable ‘way of life.’” That, at least, seems indisputable.

Cummings appeared in many other shows and movies throughout the years—his Internet Movie Database listing includes 105 appearances as an actor—before his death on December 2, 1990, at the age of 80. He was interred at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California. His Aerocar, owned by Ed Sweeney, had been on display at the Kissimmee Air Museum in Florida until the museum closed in 2021.

BY DOUGLAS G. ADLER

BY DOUGLAS G. ADLER

The Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk, known to the world as the “Stealth Fighter,” entered operational service in 1989 with a limited role in the invasion of Panama, but the public became more aware of the aircraft when it saw widespread use in combat during the first Gulf War in 199091. The airplane employed faceted angles across its entire surface and consequently had a remarkably small radar cross section, making it extremely difficult to detect while in flight. The F-117 was also coated in plates lined with radar-absorbing material (RAM) held in place with a special adhesive. Details about the composition of the F-117’s RAM remain classified to this day, but analysts believe it is made of ferromagnetic particles embedded in neoprene sheets, which absorbs radar energy.

Until recently, the public had, essentially, no way to view an F-117 up close. That’s been changing as a small number of F-117s have been released to museums for the first time since Congress passed legislation in 2017 ending a requirement that the aircraft “be maintained in a condition that would allow recall of those aircraft to future service.”

Hill Aerospace Museum near Ogden, Utah, received its F-117 in August 2020, and the aircraft is currently nearing completion of an extensive restoration. The museum’s Nighthawk, serial number 82-0799, rolled off the assembly line in 1982 at Lockheed’s fabrication plant in Burbank, California. It first flew in combat during Operation Desert Storm and eventually amassed 54 combat sorties across Operations Desert Storm, Allied Force and Iraqi Freedom. Over its operational lifetime, 82-0799 flew as part of the 4450th Tactical Group and was based out of Tonopah Test Range in Nevada. The 4450th was the de facto home to the first F-117 squadrons and where much of the developmental work on the aircraft and the training of its pilots took place. It is worth noting that all F-117 flights out of Nevada took place at night to keep the secret craft out of sight of Soviet spy satellites. Aircraft 82-0799 also flew out of Holloman Air Force base in New Mexico as part of the 49th Fighter Wing when that unit handled F-117 operations.

The museum at Hill was chosen to receive its Nighthawk because of its institutional knowledge of the airplane. In December of 1998, Hill Air Force Base’s Air Logistics Center became responsible for repairing battle and crash damage to F-117s through the 649th Combat Logistics Support Squadron. This role required teams of Hill personnel to deploy around the world as needed to work on F-117s. The 649th performed this mission until 2008, when the F-117 retired from operational service. All of this translated to a deep familiarity with the care and handling of F-117s among personnel associated with Hill AFB.

THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING OFFICIALLY OPENS. IN ITS FIRST YEAR ONLY 23% OF THE AVAILABLE SPACE WAS SOLD. THE LACK OF TENANTS LED NEW YORKERS TO DISMISS THE BUILDING AS THE “EMPTY STATE BUILDING.” IN YEAR ONE THE OBSERVATION DECK HAULED IN APPROXIMATELY $2 MILLION IN REVENUE, EQUAL TO WHAT ITS OWNERS COLLECTED IN RENT. THE BUILDING FIRST TURNED A PROFIT IN THE 1950s.

For more, visit

HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

Top and center: When the F-117 reached Hill Aerospace Museum, it had been stripped of its top-secret outer coating and radar-absorbing material (RAM). The airplane did retain its full cockpit, however. Above: Today the F-117 sits back-to-back with a Lockheed SR-71 at the museum as its restoration nears completion.

The restoration team, including restoration lead Brandon Hedges and key team members Tim Randolph, George Burkey, Brandon Neagle and Dave Mitchell, have devoted an enormous number of man-hours to the restoration.

Randolph, who was an F-117 crew chief during Desert Storm, recalled that the Nighthawk was a “tricky airplane” from a maintenance point of view, as it included parts from various other aircraft, including the main landing gear from the A-10, heads-up display from the F-15, ejection seat from the F-15/16, engines from the F/A-18 (minus the afterburner) and avionics and fly-bywire system from the F-16.

The aircraft arrived at the museum in a bare-

bones condition, stripped clean and with wings and tail removed. The plane was also lacking all fluids and both engines. Still, the restoration team received a few lucky breaks: 82-0799 arrived with a complete cockpit and, perhaps more importantly, a full tail assembly. The tail had been removed, but the museum had not expected it at all and believed it would need to be fabricated. Nonetheless, 82-0799 has tested the restoration team’s skills. Fully deprived of its classified outer coating, RAM and all of its leading edges, the aircraft on arrival looked very little like the F-117s that the public has come to know. The team had to replicate the appearance of a fully functional F-117 using only off-theshelf materials.

The restoration has been accomplished on an extremely limited budget, made possible by the hard work of a dedicated (and unpaid) team that make use of a significant amount of donated material. Per Hedges, the entire restoration has only cost $4,000, a staggeringly small number compared to the typical investment required for most aircraft restorations; paint alone can often cost more than $10,000 for fighter aircraft restorations and far more for bombers.

An industrial supplier of automobile paint donated appropriate overlay material. In addition to paint, the restoration team further simulated RAM with Platinum Patch compound purchased in bulk at home improvement retailers. Perhaps the greatest challenge was recreating all the various leading edges of the entire airframe from scratch. The restoration team tried many different materials and construction methods to find a solution that looked just right. They ended up constructing most of the leading edges from a mixture of sheet metal and fiberglass panels. As of this writing, the restoration is approximately 85% complete and the aircraft is currently on display even as work continues.

Up close, and even though incomplete, 82-0799 is still a wonder to behold. Perched next to an SR-71C Blackbird (its spiritual forerunner), the F-117 appears much larger in person than it looks in photographs; in fact, it is actually about the same size as an F-15. The interior of the port bomb bay door is, surprisingly, graced by a handmade painting of the comic book character the Silver Surfer perched atop an F-117, a nod to the airplane’s nickname of “Midnight Rider.” Visitors to the museum now have the opportunity to see, up close and in person, an aircraft previously protected from public view that changed the history of military aviation in a lasting and meaningful way.

It was a perfect late autumn day in the northern Rockies. Not a cloud in the sky, and just enough cool in the air to stir up nostalgic memories of my trip into the backwoods. is year, though, was di erent. I was going it solo. My two buddies, pleading work responsibilities, backed out at the last minute. So, armed with my trusty knife, I set out for adventure.

Well, what I found was a whole lot of trouble. As in 8 feet and 800-pounds of trouble in the form of a grizzly bear. Seems this grumpy fella was out looking for some adventure too. Mr. Grizzly saw me, stood up to his entire 8 feet of ferocity and let out a roar that made my blood turn to ice and my hair stand up. Unsnapping my leather sheath, I felt for my hefty, trusty knife and felt emboldened. I then showed the massive grizzly over 6 inches of 420 surgical grade stainless steel, raised my hands and yelled, “Whoa bear! Whoa bear!” I must have made my point, as he gave me an almost admiring grunt before turning tail and heading back into the woods.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars FREE when you purchase the Grizzly Hunting Knife.

Make sure to act quickly. The Grizzly Hunting Knife has been such a hit that we’re having trouble keeping it in stock. Our first release of more than 1,200 SOLD OUT in TWO DAYS! After months of waiting on our artisans, we've finally gotten some knives back in stock. Only 1,337 are available at this price, and half of them have already sold!

Knife Speci cations:

• Stick tang 420 surgical stainless steel blade; 7 ¼" blade; 12" overall

• Hand carved natural brown and yellow bone handle

• Brass hand guard, spacers and end cap

• FREE genuine tooled leather sheath included (a $49 value!)

I was pretty shaken, but otherwise ne. Once the adrenaline high subsided, I decided I had some work to do back home too. at was more than enough adventure for one day.

Our Grizzly Hunting Knife pays tribute to the call of the wild. Featuring stick-tang construction, you can feel con dent in the strength and durability of this knife. And the hand carved, natural bone handle ensures you won’t lose your grip even in the most dire of circumstances. I also made certain to give it a great price. After all, you should be able to get your point across without getting stuck with a high price.

The Grizzly Hunting Knife $249 $79* + S&P Save $170

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. *Special price only for customers using the offer code. 1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: GHK236-02

When World War II ended, many aircraft manufacturers anticipated an increased demand for new commercial airliners. The Beech Aircraft Company of Wichita, Kansas, was no exception. Walter Beech, the company’s co-founder and president, had been producing outstanding aircraft since 1925 when he, along with Lloyd Stearman and Clyde Cessna, founded the Travel Air Manufacturing Company. Travel Air proved so successful that the Curtiss-Wright Corporation merged with it in 1930. Relegated to a desk job, Beech resigned two years later to start his own company with his wife, Olive Ann. In the years before WWII, it produced two outstanding Beechcraft airplanes, the Model 17 “Staggerwing” cabin biplane and a small twin-engine airliner, the Model 18. During the war the company produced thousands of light transports and trainers.

With the war over, Beech turned his attention toward two new projects. One was a small single-engine cabin monoplane to succeed the prewar Staggerwing; the other a 14- to 20-seat airliner, larger than the pre-war Model 18, that would be suitable for short-haul feeder services. The result of that dual effort ended up 50 percent successful. The small cabin monoplane became the famous V-tailed Beechcraft Model 35 Bonanza, one of the most popular general aviation craft of all time. On the other hand, the prospective airliner, known as the Model 34 Twin Quad, never advanced beyond a single prototype.

Like the Bonanza, the Model 34 sported the distinctive Beechcraft V-tail configuration. It also featured a strengthened fuselage underside that included integral landing skids to protect the occupants in case of

Top: Although an innovative design, the Twin Quad never advanced beyond the prototype stage. Above: The man behind the airplane was Walter Beech, shown here in 1925. Beech had started his own airplane business in 1932 after a stint at the Travel Air Manufacturing Company.

a forced landing. The Model 34 was originally built for 14 passengers in “coach seats,” but the cabin interior was later redesigned to hold 20, with the option of folding up the seats to accommodate cargo that could be loaded via a hatch behind the pilot’s compartment. The new airplane’s most unique feature, however, was the

arrangement of its power plants.

Although the Model 34 looked like a conventional twin-engine, high-winged monoplane, it actually had four engines. Two 380-hp Lycoming GSO-580 air-cooled flat-8 piston engines were buried sideways within the leading edge of each wing, facing each other. A system of clutches and bevel gears linked their drive shafts to a single tractor propeller—hence the “GSO” designator, which stood for “geared, supercharged and opposed.” The system was designed so that in the event of an engine failure the dead engine could automatically de-clutch and the other engine could keep powering the propeller. Because of the airplane’s unusual power system, Beechcraft painted “Twin Quad” on the nose.

The Beechcraft Model 34 had a wingspan of 70 feet and was 53 feet long and 17 feet high. With a gross weight of 19,500 pounds, it had a maximum speed of 230 mph, a range of 1,450 miles and a ceiling of 23,000 feet.

Beechcraft’s chief test pilot, Vern L. Carstens, flew the Twin Quad’s first and totally uneventful flight on October 1, 1947. Carstens summed up his impression by declaring, “We have another outstanding Beechcraft.” The prototype went on to accumulate more than 200 hours of flight time by the time disaster struck on January 17, 1949. The airplane experienced an electrical fire in flight, a situation exacerbated when a crewman cut off an emergency master switch while fighting the blaze. The resulting wheels-up landing killed the copilot and injured the pilot and the two engineer-observers who were onboard.

The incident did prove the value of the aircraft’s reinforced belly, but otherwise everything went wrong for the Twin Quad after that.

The U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board delayed licensing, but even worse was the fact that the feeder airliner business, which didn’t require cutting-edge performance like intercontinental airliners did, had little need for a new, innovative air transport when there were so many war-surplus Douglas DC-3s, C-47s and Beech 18s available at rock-bottom prices. Consequently, Beechcraft never completed the two other Twin Quads under construction (one of which was just for ground testing) and canceled the whole project. Walter Beech died on November 29, 1950, but his wife continued to run the company.

It is a shame that the Model 34 has been all but forgotten. It was a unique and intriguing design that deserves to be better remembered, even if it proved to be the wrong innovation at the wrong time.

Center: The Model 35 included a strengthened belly, which proved its worth when a fire led to a crash of the prototype on January 17, 1949. The copilot was killed and the pilot injured. Above: The Twin Quad’s nickname was derived from the two linked 380-hp Lycoming engines that made up each of the airplane’s dual powerplants. The idea was that if one of the engines in the pair quit, the other one could de-clutch and continue running.

During World War II, 6.5 million American women entered the workforce, filling jobs that opened when men joined the military. Women workers were essential as America ramped up to become the arsenal of democracy, cranking out munitions, ships, tanks, landing craft—and airplanes.

Some women started working out of patriotism, others for economic reasons and some from a combination of both. “Suddenly, the standard idea of seeing women as fragile creatures, ill-suited for work outside the home, much less for hard labor, seemed like a peacetime luxury,” wrote Emily Yellin in her 2004 book, Our Mothers’ War: American Women at Home and at the Front During World War II. “Like never before America asked women to take up the slack—to join in producing the vital machinery of war.” In the aircraft industry, around 40% of the workforce was women.

The enduring symbol of these women is Rosie the Riveter, a character from a song made iconic on a Saturday Evening Post cover by Norman Rockwell and in the government-issued “We Can Do It!” poster. One government agency charged with encouraging women to work was the Office of War Information. Among its ranks was photographer Alfred Palmer, who took the images here.

When men returned from the war, women began leaving work. Some left voluntarily; others were forced out. But things were different. In her book, Yellin quotes a worker named Katherine O’Grady, who said, “After the war, things changed, because women found out they could go out and they could survive. They could really do it on their own.”

At the Douglas Aircraft Company in Long Beach, California, in October 1942, women work on the tail section of a Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress. Women became an essential part of the war effort, especially in the aircraft industry. Left: Photographer Alfred Palmer created indelible images like these of real-life “Rosies” while working for the U.S. Office of War Information.

A B-25 Mitchell medium bombers were built at the North American Aviation factory in Inglewood, California. Here a worker puts some finishing touches to part of the cowling for one of a B-25’s twin engines.

B Another worker for North American Aviation labors over an engine.

C At North American’s control surface department, an employee uses a hand drill to assemble a section of the leading edge of a horizontal stabilizer.

D An assembly-line worker gets a well-earned lunch break at the Douglas Aircraft Company plant in Long Beach. Behind her are parts of bomber nacelles. This Douglas facility assembled Boeing’s B-17 heavy bomber as well as Douglas’s own A-20 Havoc assault bomber and C-47 Skytrain transport airplane.

E This Palmer photograph was used for a poster promoting the need for more women in the work force. The woman in the image, described as the “girl in a glass house,” is a Douglas employee working on the plexiglass nose of a Flying Fortress.

F Wartime demands provided opportunities for African American women as well. Here a woman at the Vultee Aircraft plant in Nashville, Tennessee, uses a hand drill on a Vultee A-35 Vengeance dive bomber. The plant also assembled Lockheed P-38 Lightings and the Stinson 0-49 observation airplane.

G Douglas employee Annette del Sur publicizes a salvage campaign at the company’s plant in Long Beach. She is looking over lathe turnings in the metal salvage pile, while sporting a tiara made out of the scrap. Scrap metal as fashion accessory did not really catch on.

H Inspectors at the Douglas factory check wing sections that will be assembled for C-47s. Despite their indispensable contributions to the war effort, women workers could not avoid sexist labeling. The original caption for this image described these employees as “girl inspectors.” G H

Find more of Alfred Palmer's wartime photographs at historynet.com/womenat-work

BY TOM HUNTINGTON

BY TOM HUNTINGTON

Last issue we ran a feature by Barry Levine about the C-119s that snatched spy satellite photos from the sky back in the early 1960s. That feature included a sidebar about how the United States attached cameras to balloons that were set adrift over the Iron Curtain to photograph things that the Soviets wanted to keep hidden. When we were preparing that sidebar, using balloons seemed like a pretty quaint way to collect intelligence.

And then spy balloons re-entered the news on January 28, 2023, when one launched by China was detected drifting over the United States. Amid much international uproar, the lighter-than-air interloper was shot down by U.S. Air Force F-22s Raptors off the South Carolina coast on February 4. I guess there is nothing new under the sun (or above the earth).

The pilot of an Air Force U-2S spyplane captured the selfie shown here as he soared above the balloon before the Raptors swept in to do their job. Like balloon spies, U-2s are nothing new: the long-winged Lockheed jets have been making their high-altitude flights (and doing some spying of their own) since the first U-2 took to the skies in 1955. Cover stories get recycled too: The Chinese government claimed their spy-in-the-sky was just a weather balloon that had been blown off course. The Eisenhower administration said that about the U.S. balloon spies, too, and after the U-2 piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the USSR on May 1, 1960, the U.S. claimed

that Powers had been studying the weather when he strayed into Soviet airspace.

It’s pretty amazing to realize that the U-2 has been flying for almost 70 years now, although the type has been consistently updated (the U-2S is the latest version) and the Air Force is talking about phasing it out by 2026. In 1955 the U-2 was on the cutting edge of technology. Created by Kelly Johnson and the legendary Lockheed Skunk Works, it could fly higher than 70,000 feet, above the ceiling of potential interceptors, and take pictures with its specially designed cameras. Richard Bissell, who oversaw the project for the CIA, was giddy when the first photos arrived. “From seventy thousand feet you could not only count the airplanes lined up on the ramps, but tell what they were without a magnifying glass,” he said. “We were astounded. We had finally pried open the oyster shell of Russian secrecy and discovered a giant pearl.”

That’s what spies do—pry open the oysters of secrecy. That’s what the Soviets were doing in Canada in the 1950s as the Canadians were developing their own supersonic interceptor, the Avro Arrow. You can read about that in this issue.

Spies! They’re everywhere!

BY GARY G. YERKEY

BY GARY G. YERKEY

Osce V. Jones, a 26-year-old first lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Forces, was a war-tested pilot by the summer of 1943. Born in the small Georgia town of Camilla on August 6, 1916, Jones attended Louisiana State University and enlisted in the U.S. Army National Guard in the fall of 1940. He entered flight school a few months later, graduating in early December 1942, and was assigned as the pilot of a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. The next May he and his crew flew their airplane from Dow Army Airfield in Maine to RAF Ridgewell airfield in southeastern England, the eventual home of the Eighth Air Force’s 381st Bombardment Group. After they arrived, the crew named their bomber, tail number 42-3217, Georgia Rebel.

Jones had completed five missions over Europe, but his luck ran out on July 24, 1943. On that day, Georgia Rebel was one of the 324 bombers that Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, commanding general of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, sent out on what was the Eighth’s first operation against targets in Nazioccupied Norway. Georgia Rebel ’s target was an aluminum, nitrate and magnesium manufacturing complex at Herøya, just south of Oslo.

After releasing its bombs, the aircraft was hit by a barrage of antiaircraft fire at 2:18 p.m. and was last seen by its group as it left the formation. One engine was smoking, another was out of commission, and fuel was leaking through a hole in the port wing. Jones and his navigator, 2nd Lt. Arthur L. Guertin, agreed that a safe return to England was unlikely, so the young pilot swung the crippled aircraft northeast from Herøya toward neutral Sweden. Once over the Swedish town of Årjäng, Jones turned north and flew low over rolling, wooded hills for about 15 miles until he saw a long, open field just south of the village of Vännacka. Local residents looked up as the plane passed over the field and circled back to make a perfect belly-landing.

Among the first to reach the plane was farmer Olof Persson. “I understood immediately that it was a British or American bomber because it said ‘Georgia Rebel’ on the fuselage, and I saw a five-pointed star and the colors of the flag,” Persson told a reporter from the Swedish newspaper, Aftonbladet . “So I hurried to the bog where the plane had crashed.” Persson greeted the pilot in English. “Well, how do you do?” he said.

By the time Persson reached the B-17, the Swedish military had also arrived and began to surround the wreck. “I asked the pilot if anybody had been injured,” Persson recalled. “[The pilot] said that he and his nine buddies were [safe and] happy to have landed in Sweden…and he asked me to tell the Swedish military that they had machine guns on board and that they were all loaded, but there were no bombs. They had been released over Norway.”

Jones and his men were the first American aircrew to land in Sweden during the war. They were not the last.

As a neutral country, Sweden was required by the Hague Convention of 1907 to intern any military personnel from belligerent nations who arrived within its borders. Sweden ended up accommodating many Americans. By war’s end, more than 150 crippled American warplanes followed the Georgia Rebel to land or crash land in Sweden, leading to the internment of 1,218 airmen, including Jones and his crew. The vast majority of the internees reached Sweden during a hectic 48-hour period in mid-June 1944 when no fewer than 34 B-17s and B-24 Liberators landed safely or crashed on Swedish soil. A Swedish newspaper, Trelleborgs Allehanda, reported that on June 20—after the Eighth Air Force had deployed 1,965 “heavies” across Europe in one of the largest such opera-

A Consolidated B-24 Liberator passes over the Swedish city of Malmö on its way to a landing at the Bulltofta airfield on June 20, 1944. This was the busiest day for emergency landings in Sweden, with a total of 21 bombers arriving.

One airplane interned in Sweden eventually made its way back to the United States. A Boeing B-17G Flying Fortress named after a song by the Andrews Sisters, Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby landed safely in Sweden after suffering multiple engine failures over Poland on May 29, 1944, during its 24th and last bombing mission. After the war the B-17 flew as a passenger plane in Sweden before being sold to a Danish airline. Following later stints in the Danish army and navy, the airplane was purchased by a French aerial mapping company that used it until 1961. In 1972 France gave the airplane to the United States and it was disassembled and flown to Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, for restoration. The restored B-17 was flown to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in 1988 and put on display. The well-traveled Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby is currently in storage prior to an eventual transfer to the National Air and Space Museum.

tions to date—there was “literally a queue” of American bombers waiting to land at Bulltofta airfield in Malmö. A total of 21 bombers made forced landings in Sweden that day, by far the largest single-day influx of American aircraft in the country since the beginning of the war.

After the planes were on the ground at Bulltofta, according to Trelleborgs Allehanda, “it was hard to find an empty spot” at the airfield. “What’s going to happen during the next few days if a similar invasion continues?” the paper asked. But the invasion continued the next day, June 21, with another 13 American bombers arriving.

One American airplane to reach Sweden that June was a Consolidated B-24 Liberator with the tail number 42-51125 piloted by 1st Lt. Leander Page Jr. Page had been interned in Sweden once before, after his B-24 Queen of Peace had landed there on January 4, 1944. Page was released and he returned to combat, and his plane was hit by flak over Pölitz, Germany, on June 20, damaging the right stabilizer, the rear bomb bay, the fuselage and the two engines on the right wing. “After being hit…the ship dived straight down,” a U.S. intelligence officer later reported after interviewing the copilot, 2nd Lt.

Collier’s magazine ran a feature about the Americans in Sweden in its August 26, 1944, issue. Such coverage did not please Hap Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces. He ordered an investigation into the “stopovers.”

F. Leroy Qualey. “The manual controls were found to be inoperative, so the pilot turned the auto-pilot on. The plane went on its back, then recovered. They flew for about twenty minutes more, and No. 2 engine failed. A few minutes later the auto-pilot ceased to work, and they went into a tight spin.

The order for bail-out was given.” By this time the airplane was over Swedish territory. Qualey said that after bailing out he landed on a greenhouse and sustained cuts and bruises, while pilot Page hit the side of the bomb bay as he bailed out but suffered only minor injuries.

The unmanned airplane crash-landed in a field near the village of Röstånga and burned for some time. Eight of the 10 crew members were safe, although shaken and slightly injured. The body of Tech Sgt. Robert B. Kellerman, the engineer, was found some distance from the aircraft. According to reports, the body of the tail gunner, Sergeant Glenn A. Deck, was found either in the wreck or nearby. Page said later that both men had been “paralyzed with fear.” Another survivor said that Kellerman may have bailed out too late for his parachute to open fully and that Deck was too frightened to bail out and may have waited too long to make the attempt, or he may have been prevented from exciting by the overwhelming centrifugal force. Page said that his own escape from the aircraft had been due to “great luck,” explaining that he had been literally thrown from the plane when it inverted and went into a spin. Page became the only American airman to be interned in Sweden twice.

After landing, the surviving members of the crew were taken to a local inn and served a hot meal before being sent the next day to an internment camp at Fornäs, near Falun. On July 3, the remains of Kellerman and Deck were interred at a cemetery in Malmö. Copilot Qualey attended the funeral on behalf of the surviving members of the crew, along with representatives of the Swedish government, the U.S. Army and the U.S. Army Air Forces.

Some of the airplanes heading for Sweden never made it. On May 24, 1944, a B-17 with the tail number 42-107178 plunged into the sea off the southern coast of Sweden following a bombing raid on Berlin. According to the ball turret gunner, Tech Sgt. Leonard A. Bielawski, the airplane’s pilot, 1st Lt. William F. Nee, along with two other crew members, 2nd Lt. Reginald Aragona, the copilot, and Tech Sgt. Gaetano A. Scida, the top turret gunner, bailed out after the plane was hit by enemy aircraft fire or flak over Berlin. Apparently, the other members of the crew did not hear the order to exit the plane because the wiring on the back of the pilot’s seat had caught fire, cutting off inter-aircraft communications.

Frederic T. Neel, the 2nd lieutenant who was serving as navigator, managed to extinguish the fire and jumped into the pilot’s seat, telling Tech Sgt. Donald E. Spaulding, the tail gunner, to fly as copilot. Close to the Swedish coast near the village of Örnahusen, the rest of the crew, except for Neel, bailed out. Sgt. Robert Heimbach, the waist gunner, went out first and drowned. Spaulding was killed when he hit the water.

Bielawski and Tech Sgt. Philip J. Branner, the radio operator, both landed uninjured. The bombardier, 2nd Lt. Richard Markley, landed in the water and was rescued by Swedish fishermen. As for Neel, he “went down with the ship,” according to Bielawski, who spoke with investigators after the

Top: These internees were able to roam while in Sweden. Above: Two Americans clearly enjoy Swedish hospitality during their internment. Perhaps surprisingly, most men surveyed said they were ready to return to war before too long.

incident. On July 1, several months later, Neel’s body was recovered near the coastal village of Gislöv, about three miles from where the plane had crashed.

The survivors of Nee’s B-17 joined the growing population of internees in Sweden. The numbers continued to rise, particularly in the first six months of 1944, until there were about 900 by the end of June. As the numbers swelled, so did concerns that some the airmen had diverted to Sweden simply to avoid further combat. In May 1944 The New York Times wrote that the interned airmen were being held in “one of Sweden’s most picturesque regions”—the province of Dalecarlia— and that they were playing “all sorts of games,” reading and enjoying “great freedom of movement.” In August, a multi-page photo essay in Collier’s magazine showed U.S. airmen in tuxedos laughing and drinking at a Stockholm restaurant surrounded by beautiful Swedish

women. Others were photographed skiing, riding bicycles and enjoying a dip in a heated indoor swimming pool.

General Henry H. Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, was not pleased by the coverage and he ordered an investigation. He even sent an uncommonly unfriendly memo to his long-time friend, Brig. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the newly formed U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSTAF), noting that an increasing number of aircraft were landing in neutral countries, like Sweden and Switzerland, “without indication of serious battle damage or mechanical failure, or shortage of fuel.” He wondered whether the landings were “intentional evasions of further combat service.”

Spaatz blew up over the implication that the crews were cowards or lacked the will to fight. “Such is a base slander against the most courageous group of fighting men in this war,” he wrote back, adding that the number of interned airmen amounted to only a small fraction of the crews dispatched.

Nevertheless, Spaatz followed up on Arnold’s concerns. Maj. Gen. David N.W. Grant, the air surgeon for the USSTAF, wrote to Brig. Gen. Malcolm C. Grow, director of medical services at

USSTAF headquarters in Washington, D.C., saying that Arnold believed— “and I agree with him”—that the “best survey” of crew morale should be carried out by flight surgeons. One flight surgeon who was selected for the task was Major John D. Young Jr., who had been a passenger on the Liberator Mistah Chick that had made a forced landing in Sweden on June 20. As a “non-combatant,” he was not interned with the crew but was attached to the American Legation in Stockholm to provide medical care to Americans. While in Sweden Young interviewed about 500 internees and concluded that the general feeling among them was one of “great thankfulness” to have survived and that they would “not like to repeat this experience.” But after a week or two, the more harrowing aspects of the experience tended to fade, Young said, and the men would begin to feel restless and want “to get back to flying again.”

There were five main internment camps in Sweden—Falun, Rättvik,

Loka Brunn, Gränna and Mullsjö—and Young visited all of them. He said that the internees were free to leave the camps and mix with Swedish civilians and that the men were able to “freely date” Swedish women. “I think it has been remarkable that they have gotten on as well as they have,” Young said.

Queried by an Air Forces intelligence officer, Lt. Col. R.E. Stone, Young said that the internees had not force-landed in Sweden to evade further military service. “There are aircraft reports to substantiate that their planes were badly damaged and that it was foolhardy to attempt to return [to England],” Young said, adding that, beyond any doubt, they had used their “good judgment” in deciding to head for Sweden.

In addition, the USSTAF’s Office of the Surgeon sent out a questionnaire to every squadron surgeon serving in the Eighth Air Force at the time, and representatives of the office made personal visits to units that were suspected of having low morale or whose personnel had made force-landings in Sweden.

At the end of the process, Grow concluded that five crews “may” have landed in Sweden “for the purpose of avoiding further combat.” But his report emphasized that the number of crews that had done so was “so low that it is not considered to be of any particular significance.”

As the winds of war began to shift inexorably toward the Allies, the Swedes saw fit to release the internees at a relatively rapid pace— as quickly as they could be flown out of the country. By the end of November 1944, in fact, the number of internees had fallen to about 200— down from a near-high of 1,076 in mid-October. By mid-January 1945, the number was just 25.

Herschel V. Johnson, the American Minister in Stockholm, wrote to Acting Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius on November 24, 1944, expressing relief and praising the Swedes for the way they had treated the Americans. “The treatment in every respect which the Swedes have accorded our aviators has been humane and understanding to a high degree and beyond the bounds of what are their obligations under international law and custom,” Johnson said.

After their release from internment—sometimes following protracted negotiations between American and Swedish officials over, for example, the sale of North American P-51 Mustangs to the Swedish Air Force— most of the American “bomber boys” were returned to England and further combat. Some released internees were shot down a second time. Arthur Guertin, the navigator on Georgia Rebel, was killed on April 28, 1944, in Georgia Rebel II. Osce V. Jones of Georgia Rebel was also aboard Georgia Rebel II. He survived but spent the rest of the war in a Nazi prison camp.

After the war, Jones continued to serve in the Air Force and flew B-52s and KC-135 tankers as commander of the Strategic Air Command’s 4241st Strategic Wing at Seymour Johnson AFB in North Carolina. But Jones never forgot the American airmen who had lost their lives in service to their country in World War II, including the 40-plus men who were killed when their planes force-landed or crashed in neutral Sweden.

Gary G. Yerkey is an author and journalist based in Washington, D.C. He previously spent more than a decade in Europe reporting for TIME-LIFE, ABC News, the Christian Science Monitor and other U.S. news outlets. For further reading he recommends Making for Sweden: Part 2, The United States Army Air Force, The Story of the Allied Airmen Who Took Sanctuary in Neutral Sweden by Bo Widfeldt and Rolph Wegmann.

On June 20, 1959, the 15th anniversary of the crash landing in Sweden of Leander Page Jr.’s B-24, local resident Ernest Göransson erected a simple stone monument near the field where the Liberator had come down.

Göransson paid for the monument himself to honor the memory of the two American airmen who had been killed.

In 1984, on the fortieth anniversary of the incident, a number of Swedish dignitaries and officials from the U.S. Embassy in Stockholm attended a remembrance ceremony near the monument. Captain Charles A. Meyer, assistant air attaché at the embassy, addressed the audience, saying that “those courageous flyers…fought and died in a great battle against the forces of totalitarianism.

“Standing here today, forty years later, after that terrible battle, our memories of that time have begun to fade, the vision of that moment may dim,” Meyer said. “I hope that this fine ceremony, though it began as a memorial to the past, can continue to serve as a guidepost for the future. This is not a monument to the horrors of war. This is a monument to our sincere hope for peace, democracy and human dignity, for our generation and for all the generations to come.” —G.Y.

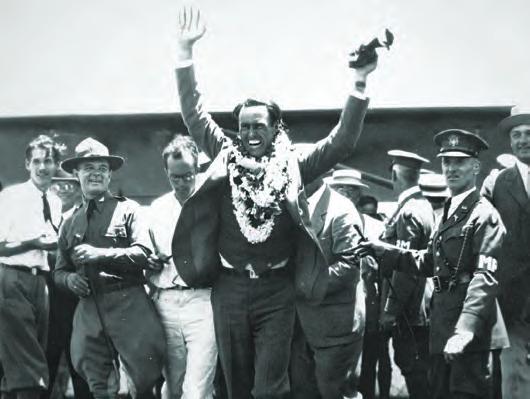

IN 1927 A PINEAPPLE MAGNATE SPONSORED AN AIR RACE TO HAWAII. IT DID NOT GO WELL BY STEPHAN WILKINSON

The Pabco Pacific Flyer, with Livingston Irving at the controls, lifts off from Oakland on August 16, 1927, at the start of the ill-fated contest known as the Dole Derby. Like most of the contestants, Irving did not reach the race’s end point in Hawaii. He crashed his specially designed Breese-Wilde 5 after a flight that traversed less than two miles. Unlike some race participants, Irving survived. So did Norman Goddard, whose wrecked El Encanto is visible in the background to the left of the photo’s center.

It is said that the first automobile race took place the moment the second car was built, but motorsport took a bit longer to appear in aviation. The first air race was flown in 1909, in France, more than five years after the Wright brothers’ first flight. There were four entrants. Two started the race and none finished. The rules had foreseen that. They specified that the winner would be the competitor who had traveled farthest.

Things hadn’t progressed much by August 1927, when the Dole Derby, a heavily promoted race between California and Hawaii, limped to an unfortunate start. Eleven racers entered the contest, six actually flew and two finished. Ten people—pilots, navigators and one unfortunate passenger—died before the race was over. Two entrants later died while searching for survivors.

Call it the Dole Disaster and blame it on the pineapple.

In 1899, 22-year-old James Dole moved to Honolulu with a Harvard degree in agriculture in his suitcase, and he began canning pineapple. In 1907, Dole set about advertising his exotic product throughout the U.S. mainland and soon had a hit on his hands. By 1922, Dole pineapples were so popular that young James bought the entire Hawaiian island of Lanai as a 20,000acre pineapple plantation.

In May 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris, and aviation suddenly became the hottest game in town. Airports and airlines sprang up everywhere; aviators set and

James Dole made a fortune in Hawaii selling canned pineapple. A pair of newspaper reporters convinced him that an air contest from the continental U.S. to Hawaii would result in a publicity bonanza for Dole’s product.

broke records weekly. The months after Lindbergh’s flight were called the Summer of Eagles, and some people were seeking a Pacific Eagle. Hollywood theater mogul Sid Grauman offered $30,000 for the first flight from Los Angeles to Tokyo. Dallas stockbroker William Easterwood put up $25,000 for anyone who could make the first flight from Dallas to Hong Kong in less than 300 hours, with no more than three refueling stops. And immediately after James Dole announced plans for what would become the infamous California-to-Hawaii Dole Derby, the San Francisco Citizen’s Flight Committee promised an additional $50,000 prize to extend the route all the way to Australia.

The idea for a Hawaii-bound air race didn’t originate with James Dole. It took a pair of Honolulu newspaper reporters, Riley Allen and Joseph Farrington, to light the fuse. Just two days after Lindbergh’s flight, they sent Dole a telegram—simultaneously printed in the Honolulu Advertiser—pointing out that the post-Lindberghian swoon made the times ripe for someone to offer a substantial prize for a nonstop flight to Hawaii. If Dole ponied up, the reporters said, his reward would be “all the press coverage he could stomach.”

Dole bit. He assumed he would be promoting the first such flight and thus a significant world record. He offered $25,000 and $10,000 (about $426,000 and $170,000 in today’s dollars) for the first- and second-place finishers in a “Derby” in which the only requirement was the aviators had to fly from the continental U.S. to the Territory of Hawaii—no specific takeoff or landing points were named, although Oakland did become the starting point—and that the race would start on August 12, 1927.

Perhaps he should have said the Dole Derby would start the next morning, for two months before the date that Dole set, two Army Air Corps lieutenants in an Atlantic-Fokker C-2 trimotor named Bird of Paradise quietly and professionally flew from Oakland, California, to Honolulu in just under 26 hours. Their airplane was a military version of the Fokker F.VIIa, built in Fokker’s Teterboro, New Jersey, factory. It had been modified for the Hawaii flight—the longest overwater flight ever attempted anywhere—with a larger wing and extra fuel tanks that gave it a range of just over 2,500 miles. Which was cutting it close, since the distance from Oakland to Hawaii was 2,418 miles.

The USAAC had been planning such a trip since 1919. One of the flight crew, MIT-degreed Lieutenant Albert Hegenberger, was a prime mover in the development of long-distance navigation for the Air Corps and had been in charge of developing the service’s radio navigation instruments and equipment. Hegenberger’s pilot was Lester Maitland, an aide to General Billy Mitchell who had spent much of his Air Service and then Air Corps career setting records and winning air races that accrued publicity for the military. He was unofficially the first American pilot to fly faster than 200 mph, and in October 1923 he set an absolute world speed record of just a bit under 245 mph, flying the Curtiss R-6 biplane racer in which he’d finished second in that year’s Pulitzer Trophy race.

Hegenberger’s radio skills turned out to be moot, since the Bird of Paradise ’s radio compass and directional receiver both failed soon after