TODAY IN HISTORY

JANUARY 16, 2001

THEODORE ROOSEVELT BECAME THE ONLY U.S. PRESIDENT EVER TO RECEIVE THE MEDAL OF HONOR. PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON AWARDED THE MEDAL TO ROOSEVELT POSTHUMOUSLY FOR HIS SAN JUAN HILL BATTLE HEROICS. THEODORE ROOSEVELT JR. ALSO RECEIVED THE MEDAL OF HONOR AS THE OLDEST MAN AND ONLY GENERAL TO BE AMONG THE FIRST WAVE OF TROOPS THAT STORMED NORMANDY’S UTAH BEACH.

For more, visit HISTORYNET.COM/ TODAY-IN-HISTORY

Relive Civil War history! Walk This Hallowed Ground at Manassas/Bull Run, Gettysburg and Appomattox to experience the beginning and end of the Civil War. Visit Memphis, Shiloh, Vicksburg and New Orleans on our Mississippi River Campaign Tour, to study “the key to the Confederacy.” Explore the rivers, ridges and the battles that raged from Atlanta to Chattanooga to Nashville on our Civil War on the Rivers, Rails and Mountains Tour Our Civil War, American History and WWII tours are unrivaled in their historical accuracy!

CIVIL WAR TIMES SPRING 2023

ON THE COVER: What motivated Civil War soldiers to fight: money or patriotism?

28

Rich Man’s War, Poor Man’s Fight?

By Caroline E. JanneyDid the poor fight, while the wealthy stayed home? The answer is complicated.

36 Battle’s Hard Aftermath

By Steven CowieThe Army of the Potomac spread disease and devastation across the Sharpsburg, Md., region.

46

The Trouble With Tanglefoot

Liquor played an integral role in the daily life of both armies, as a medicine and as an escape.

54 ‘Nothing of the Kind Ever Took Place’

By Marc Storch and Kevin HamptonA young Union officer likely fabricated an attack by Confederate guerrillas along the Potomac River.

Whiskey-Fueled Warrior

By Rick BrittonWeapons

The

EDITORIAL

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF

CHRIS K. HOWLAND SENIOR EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

AUSTIN STAHL ASSOCIATE DESIGN DIRECTOR

CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

ADVISORY BOARD

Gabor Boritt, Catherine Clinton, Thomas G. Clemens, William C. Davis, Gary W. Gallagher, Lesley Gordon, D. Scott Hartwig, John Hennessy, Harold Holzer, Caroline E. Janney, Robert K. Krick, James M. McPherson, Ethan S. Rafuse, Phil Spaugy, Megan Kate Nelson, Susannah J. Ural

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP Advertising Sales mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS Regional Sales Manager tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

NANCY FORMAN MEDIA PEOPLE

nforman@mediapeople.com

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION

800-435-0715 and SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM

© 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

Civil War Times (ISSN 1546-9980) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER, send address changes to:

Civil War Times, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519, Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC

GENIUS.

KEY DETAILS

ALL-NEW RELEASE: New coin inspired by the enduring impact of one of the Civil War’s greatest military minds.

EXCLUSIVE DESIGN: Intended as a collectors’ item, this exclusive coin is offered in Proof condition. Richly plated with 99.9% silver, the reverse showcases the Great Civil War General, Robert E. Lee. The obverse bears a Civil War-era cannon and crossed flags of the United States and the Confederacy.

LIMITED RELEASE: Strictly limited presentation. Due to the extremely low quantity available, only the earliest responders will successfully secure this commemorative Proof coin.

SECURED AND PROTECTED: Your Proof arrives sealed in a crystal-clear capsule for enduring protection.

The Greatest Leader of America’s Civil War

When South Carolina seceded from the Union, the first person offered the job of commanding the Union forces to return the rebel state to the fold was Robert E. Lee. But when his home state voted to join the Confederacy, he resigned his commission in the Union Army and took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. What he did then is legend and he remains the most admired general on either side of the conflict for his superb strategy and ability to find success in the face of far superior numbers. Now, his military achievements inspire The Robert E. Lee Proof Coin from the Bradford Exchange Mint. Magnificently plated in 99.9% silver, this exclusive coin’s reverse showcases the historic Great Civil War General surrounded by a wreath inspired by the 1863 Indian Head Penny, carried by soldiers on both sides of the conflict and backed by crossed Springfield rifles. His name appears above and a golden privy mark reads C.S.A. declaring his side of the conflict. The obverse features a Civil War era cannon backed by crossed United States and Confederate battle flags. American Civil War appears above and the years of battle below. Proof quality coining dies create your nonmonetary coin’s polished, mirror-like fields and raised, frosted imagery. It arrives secured in a crystal-clear capsule.

limited AVAILABLILITY ... Claim it now!

Act now to reserve this brilliant salute to military genius as well as each edition to come in The Greatest Civil War Generals Proof Coin Collection The Robert E. Lee Proof Coin can be yours for just $49.99*, payable in two convenient installments of $24.99 each. Your purchase is risk free, backed by our unconditional, 365-day guarantee. You need send no money now, and you will be billed with shipment. Just return the coupon below. Supplies are strictly limited. Coins will be sent about once a month at the same price. You may cancel at any time simply by notifying us. But hurry — high expected demand is likely to impact availability, so claim yours now!

PLEASE RESPOND PROMPTLY SEND NO MONEY NOW

YES. Please send me the Robert E. Lee Poof Coin for my review as described in this announcement. I need send no money now. I will be billed with shipment. I am under no obligation. I understand that I can return my item free of charge. Limit: one per customer.

*Plus a total of $6.99 shipping and service per coin; see bradfordexchange.com. Please allow 4-8 weeks for delivery of your first coin. All sales are subject to product availability and request acceptance. By accepting this offer you will be enrolled in The Greatest Civil War Generals Proof Coin Collection with the opportunity, never the obligation, to collect future issues.

910899-E39002

DIGITAL WATCH

Civil War Times is now on TikTok. Check us out at tiktok.com/@civilwartimesmagazine for video features like Civil War Stuff on My Desk, Hidden Gettysburg, and a new series: the Civil War in Miniature. We’ll be bringing you sneak peeks from the battlefields and upcoming issues, and more! Don’t miss a thing. Follow us now!

HARPERS FERRY GRATITUDE

#HumpDayHistory runs every Wednesday on our Facebook page (facebook.com/CivilWarTimes) with vignettes about the war and its era. In our last #HumpDayHistory post of 2022 we shared the story of Harpers Ferry’s Camp Hill. Regiments on both sides encamped there during the war before its rebirth as a launching pad for Civil Rights. You had a lot to say!

Working as a ranger there was one of the best years of my career.

—Historian Jared FrederickNever forgotten. —Dan Dry Lived not far from Harpers Ferry.... Visited few times...before National Park Service took over....Also remains of Stoner College....GG Grandfather was one of military captured John Brown... Buried in family plot in Petersville, MD.

—Robert HempVery nice research which made for a good story. —Lester

AdamsI’ve never seen those older illustrations or the photo. —Mark

MinterFROM THE ARCHIVES

When we posted our February 2020 cover story “Selling Stonewall” about how the sites of Stonewall Jackson’s wounding and death became tourist attractions, we received lots of comments from readers who have visited the spots and many who want to go.

Great article, I’ve visited the sites before myself.

—Candy Massey FairclothGreat Story! —Scott Saunders

I stood beside that a few years ago. Actually he died in a house a few miles away several days after he was shot. —Gary

St ClairI remember stopping off at Jackson’s Shrine after seeing the sign on Interstate 95 whilst traveling through Virginia back in September 2017. It was a gorgeous, sunny day and we had the best one on one tour there. Our teenage daughters enjoyed it, too, and appreciated the stretch of the legs after the drive from Washington, D.C.

—Rob RyanMade It Out Alive

It was a perfect late autumn day in the northern Rockies. Not a cloud in the sky, and just enough cool in the air to stir up nostalgic memories of my trip into the backwoods. is year, though, was di erent. I was going it solo. My two buddies, pleading work responsibilities, backed out at the last minute. So, armed with my trusty knife, I set out for adventure.

Well, what I found was a whole lot of trouble. As in 8 feet and 800-pounds of trouble in the form of a grizzly bear. Seems this grumpy fella was out looking for some adventure too. Mr. Grizzly saw me, stood up to his entire 8 feet of ferocity and let out a roar that made my blood turn to ice and my hair stand up. Unsnapping my leather sheath, I felt for my hefty, trusty knife and felt emboldened. I then showed the massive grizzly over 6 inches of 420 surgical grade stainless steel, raised my hands and yelled, “Whoa bear! Whoa bear!” I must have made my point, as he gave me an almost admiring grunt before turning tail and heading back into the woods.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars FREE when you purchase the Grizzly Hunting Knife.

Make sure to act quickly. The Grizzly Hunting Knife has been such a hit that we’re having trouble keeping it in stock. Our first release of more than 1,200 SOLD OUT in TWO DAYS! After months of waiting on our artisans, we've finally gotten some knives back in stock. Only 1,337 are available at this price, and half of them have already sold!

Knife Speci cations:

• Stick tang 420 surgical stainless steel blade; 7 ¼" blade; 12" overall

• Hand carved natural brown and yellow bone handle

• Brass hand guard, spacers and end cap

• FREE genuine tooled leather sheath included (a $49 value!)

I was pretty shaken, but otherwise ne. Once the adrenaline high subsided, I decided I had some work to do back home too. at was more than enough adventure for one day.

Our Grizzly Hunting Knife pays tribute to the call of the wild. Featuring stick-tang construction, you can feel con dent in the strength and durability of this knife. And the hand carved, natural bone handle ensures you won’t lose your grip even in the most dire of circumstances. I also made certain to give it a great price. After all, you should be able to get your point across without getting stuck with a high price.

The Grizzly Hunting Knife $249 $79* + S&P Save $170

California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. *Special price only for customers using the offer code. 1-800-333-2045

Your Insider Offer Code: GHK217-02

BEYOND THE BATTLE

For years, the Adams County Historical Society has been housed in a cramped Victorian house on Seminary Ridge, unable to display its rich horde of artifacts or offer access to researchers. But this April, the ACHS will open a new 29,000-square-foot complex just north of the Gettysburg battlefield. The expansive building will feature 12 galleries of immersive exhibits that showcase the county’s deep history.

No matter how much has been written, displayed, or filmed about the Civil War’s largest engagement, the appetite for more information about the Battle of Gettysburg remains insatiable. The ACHS will help satisfy that hunger with its revolutionary Beyond the Battle Museum, featuring some of Gettysburg’s rarest artifacts and using media and special effects technology to take visitors on a journey through time.

“Beyond the Battle will push the boundaries of a traditional museum experience to deliver a new perspective of the fight,” says Andrew Dalton, ACHS’ energetic executive director. “What was it like to live through the battle? To hear Abraham Lincoln’s immortal words? These questions and more

will be answered and help visitors expand their knowledge of this remarkable town and its people.”

Caught in the Crossfire, a 360-degree re-creation of a home trapped between Union and Confederate lines, will be a unique feature of the museum. This immersive experience uses light projections, surround-sound speakers, and special effects to transport visitors back to the battle. Guests will enter a family’s home shortly after their rush to safety in the cellar below, hear their hushed conversations, split-second decisions, and life-or-death encounters with Union and Confederate troops. Visitors will hear the whizzing of bullets through the home, the hiss of shells overhead, the shaking of floorboards and furniture, and the family’s frightened reaction from below.

UNDER ONE ROOF

The ACHS’ new complex will house its entire library and archives. The museum’s 12 galleries will showcase many of its collection highlights.

The new museum will also include a spacious library and archives where visitors can access rare archival holdings, including civilian accounts from the Battle of Gettysburg and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

To learn more, visit achs-pa.org or follow the ACHS on Facebook and YouTube. Advanced tickets will go on sale starting March 1, 2023.

FOR OLD ABE

IN NOVEMBER, The Lincoln Forum hosted its 27th annual symposium at Gettysburg. This year’s event featured two cable news stars: John Avlon, who spoke on “How Lincoln Helped Win the Peace After World War II,” and Jon Meacham, who delivered an address on Lincoln as a moral leader.

Three biographers discussed their recent books: Walter Stahr on Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, Elizabeth D. Leonard on Union general Benjamin F. Butler, and John Rhodehamel on John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln assassination.

Jonathan W. White delivered a lecture on his two recent books about Lincoln and African Americans; Roger Lowenstein and Frank J. Williams had a conversation about how the North financed the Civil War, and Christopher Oakley received a standing ovation for showing how historic photographs and computer technology could be used to pinpoint the location of the platform from where Lincoln delivered his epochal “Gettysburg Address.”

Attendees at the symposium enjoyed the all-author book signing, a battlefield tour by Carol Reardon, a concert of Civil War music featuring Jari Villanueva and the Federal City Brass

IN LINCOLN’S HONOR

From left: Lincoln Group President David J. Kent accepts the Wendy Allen Award from Wendy Allen, Jonathan White, and Harold Holzer.

Band, and breakout sessions and panels featuring Forum favorites such as Harold Holzer, John Marszalek, Craig Symonds, Edna Green Medford, Christian McWhirter, Edward Steers, J. Matthew Gallman, Michael Green, and Andrew F. Lang.

The Forum’s 2022 Richard N. Current Award of Achievement went to Jon Meacham; the Harold Holzer Book Award went to Roger Lowenstein; and the Wendy Allen Award went to the Lincoln Group of the District of Columbia.

For more information or to join, visit www.thelincolnforum.org.

WA R F R AME

SOME SOLDIERS had a bit more flair when it came to having their images taken than others. This unidentified Union bon vivant is showing off his “camp hat.” Patterns for such hats were available in ladies’ magazines of the era, and it’s possible a loved one made this and sent it to the soldier to help keep him warm during winter camp. He’s added some drama to the sixth-plate tintype by opening the top buttons on his overcoat and brandishing an Allen & Wheelock revolver and a rifle with a gnarly looking sword bayonet. Those weapons might be photographer props. He spent a little extra to have the photo tinted with color, which makes the decoration on the hat pop and even more interesting.

REGIMENTAL NEWSPAPER

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS recently acquired a rare surviving copy of the complete run of the Civil War regimental newspaper, the Soldier’s Letter of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry. More than 100 regiments on both sides of the conflict printed at least one edition of a camp newspaper, but few survive and a complete run of one paper is even harder to find. The 2nd Colorado Cavalry’s four-page Soldier’s Letter was staunchly against slavery and the Confederacy. It ran for 50 editions between 1864 until after the war ended in 1865.

“The rebels have taken to smuggling in bacon past the blockage,” a short item noted in one edition near the end of the war. “The evidences multiply that they are on their last legs.”

Three pages in each edition were devoted to a narrative history of the regiment, war news, local gossip, rumors, and jokes.

The fourth was left blank for soldiers to write letters or notes to family and then mail home. Each copy cost 10 cents. The paper’s editor, Oliver Wallace, was a private in the 2nd Colorado Cavalry.

More than 200 regimental papers in at least 32 states printed at least one edition, according to

historian Earle Lutz, but they had mostly vanished by the time he surveyed the nation’s libraries, museums, and major private collections in the early 1950s.

“I was struck by its uniqueness: a complete run of an American Civil War regimental newspaper and a specially collected set presented to the regimental commander,” says Georgia Higley, head of the Physical Collections Services in the Serial and Government Publications Division, who recommended the acquisition of the paper.

“Researchers and Civil War enthusiasts value regimental newspapers for the honesty expressed by the men and their descriptions of life on the front lines—both at times at odds with mainstream newspapers.”

EXTRA! EXTRA!

Each copy of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry’s regimental newspaper the Soldier’s Letter cost 10 cents. The full run, recently acquired by the Library of Congress, ran 50 editions between 1864 and after the war ended in 1865.

CALL FOR

VOLUNTEERS

ENLIST NOW! Join the volunteer army transcribing the papers and correspondence of notable figures in the collections of the Library of Congress. Launched in 2018, the Library’s “By the People” crowdsourcing campaign has several active projects in progress. Volunteers are helping transcribe, review, and tag digitized pages in the collections of Walt Whitman, Clara Barton, James Garfield, Theodore Roosevelt, and more.

As of December 2022, the Library has released more than 831,000 pages for transcription, and about 591,000 have been transcribed. For more information visit: https://crowd.loc.gov.

A New Charge

The American Battlefield Trust is raising funds to acquire and raze General Pickett’s Buffet in Gettysburg and “restore the area to its wartime appearance.” The eatery, on Steinwehr Avenue, is visible from much of the area where the climactic Pickett’s Charge occurred on July 3, 1863.

Following a $1.5 million campaign to cover acquisition and subsequent restoration costs, the Trust plans “to take down the current structure, remove the asphalt parking lot, and restore the landscape, preparing the property for an interpretation and visitor experience that will attract heritage tourists for years to come.” Buffet owner Gary Ozenbaugh is moving the buffet to a larger site about four miles southwest of Gettysburg. He approached the ABT about preservation options for the half-acre site when making the decision to move it. Ozenbaugh “made a proactive and profound choice,” says ABT President David Duncan. In addition to funds already committed, including a contribution from the Gettysburg Foundation, the trust must raise an additional $550,000 to complete the transaction.

See You in Court

Residents in Virginia’s Prince William County have filed a lawsuit against the county’s supervisors over the recent decision to allow more than 25 million square feet of data centers to be developed near Manassas National Battlefield Park. In November, officials voted in favor of changing the area’s comprehensive plan, which paves the way for the data center development under a project known as the PW Digital Gateway. The lawsuit, filed in December, argues that the board “failed to consider” the proposal’s impact on the environment and

nearby Manassas National Battlefield Park or the effects of noise, traffic, and “visual blight” on the surrounding community. It aims to reverse the comprehensive plan amendment and prevent future changes to the plan. No hearings have been scheduled and the county had not submitted a response at press time. A coalition of groups, including the Manassas Battlefield Trust, the National Parks Conservation Association, the Prince William Conservation Alliance, Piedmont Environmental Council, and the American Battlefield Trust have been advocating for alternative plans. “We see industrial development of this location, historically part of the battlefield and teaming with wildlife, as the worst possible fate for this largely pristine landscape,” the ABT said in a statement released last year. More information about this new fight at Manassas can be found at growsmartpw.org.

Campus Crossroads

On October 7, 2022, George Mason University dedicated a Civil War redoubt on its Fairfax campus as a Virginia historic site. The redoubt, an earthen fortification, was one of three constructed by Confederate troops along Braddock Road in 1861. The nearby intersection of Braddock and Route 123 dates back to the 1700s. The redoubt was built in the strategic location known as Farr’s Cross Roads, because it provided views of both Braddock Road, which was used to travel from the port in Alexandria into the Shenandoah Valley, and Route 123, a major thoroughfare. The redoubt changed hands many times between Union and Confederate forces during the Civil War. The preservation and interpretation of the site is the result of a partnership between Mason and the Bull Run Civil War Roundtable, which began in 2016.

MISCELLANY WORTH A MOVE

REAL ESTATE WITH CIVIL WAR CONNECTIONS

as soon as he was the least startled…”), or bemoaning command decisions (“Jeff Davis did hate to put Joe Johnston at the head” of what was left of the Army of Tennessee, “For a day of Albert Sidney Johnston, out West! And Stonewall, could he come back to use here!!!”), her opinions provide a page-turning chronicle of the rebellion’s rise and fall.

You can own the Columbia, S.C., home the Chesnuts lived in for periods during the war, and where she wrote a part of her diary. The six-bedroom house was built in the 1850s, and survived the February 1865 fires that swept the South Carolina capital after William T. Sherman’s men occupied the town.

There are hundreds of published primary sources of soldiers, civilians, and politicians, but the massive diary kept by South Carolinian Mary Chesnut (1823-1886), published as Mary Chesnut’s Civil War in 1981, remains a classic must-read of its genre. Mary, the wife of South Carolina politician and officer James Chesnut, knew and interacted with the Confederacy’s elite.

Whether expressing disgust at the contradictions of slavery (“our men live all in one house with their wives and their concubines, and the mulattoes one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children….”), describing a general’s appearance (Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson “had an odd habit of falling into a state of incessant winking

Offered at $950,000 and located on Hampton Street in the historic district, the house has operated as a bed & breakfast and is still zoned for such use. Or it can serve as a private residence. Buy it and walk to the Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, or swing by the old capitol building and see where the scars remain from Union shellfire. Upon returning, you might want to sit down and record your own thoughts of the war that so intrigues us.

ANSWER TO LAST ISSUE’S QUIZ CLOSE UP!

WHAT PARTICULAR TYPE of object is pictured here? Send your answer to dshoaf@historynet.com, subject heading “Boom!”

CLOSE UP

CONGRATULATIONS to Ashley Healy of Olympia, Wash., who identified the stone tenant house on the Thomas Farm on the Monocacy Battlefield near Frederick, Md.

When 1982 rolled around, the U.S. Mint hadn’t produced a commemorative half dollar for nearly three decades. So, to celebrate George Washington’s 250th birthday, the tradition was revived. The Mint struck 90% silver half dollars in both Brilliant Uncirculated (BU) and Proof condition. These milestone Washington coins represented the first-ever modern U.S. commemoratives, and today are still the only modern commemorative half dollars struck in 90% silver!

Iconic Designs of the Father of Our Country

These spectacular coins feature our first President and the Father of Our Country regally astride a horse on the front, while the back design shows Washington’s home at Mount Vernon. Here’s your chance to get both versions of the coin in one remarkable, 40-year-old, 2-Pc. Set—a gleaming Proof version with frosted details rising over mirrored fields struck at the San Francisco Mint, and a dazzling Brilliant Uncirculated coin with crisp details struck at the Denver Mint. Or you can get either coin individually.

Very Limited. Sold Out at the Mint!

No collection of modern U.S. coins is complete without these first-ever, one-year-only Silver Half Dollars—which effectively sold out at the mint since all unsold coins were

melted down. Don’t miss out on adding this pair of coveted firsts, each struck in 90% fine silver, to your collection! Call to secure yours now. Don’t miss out. Call right now!

1982 George Washington Silver Half Dollars

GOOD — Uncirculated Minted in Denver

2,210,458 struck Just $29.95 ea. +s/h

Sold Elsewhere for $43—SAVE $13.05

BETTER — Proof Minted in San Francisco

4,894,044 struck Just $29.95 ea. +s/h

Sold Elsewhere for $44.50—SAVE $14.55

BEST — Buy Both and Save!

2-Pc. Set (Proof and BU) Just $49.95/set

SAVE $9.95 off the individual prices

Set sold elsewhere for $87.50—SAVE $37.55

FREE SHIPPING on $49 or More! Limited time only. Product total over $49 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases.

1-800-517-6468

Offer Code GWH134-01

Please mention this code when you call.

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not affiliated with the U.S.

KEEN EYES, STEADY HANDS

EVEN SIMPLE IMAGES can tell interesting stories. At a quick glance, this sixth-plate tintype simply appears to be of three unidentified Union soldiers. But a closer look uncovers interesting hat badges on two of the men and unique, non-military issue rifles. Those clues reveal that these men are members of Vermont’s Company E of the 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, one of two regiments of sure shots raised by Hiram Berdan, an enterprising inventor and marksman from New York. The regiments were nicknamed “Berdan’s Sharpshooters” and earned acclaim on many battlefields. By 1864, both regiments were combined into one: the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters. Unlike most volunteer units, the men in the Sharpshooters came from many different states: Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Wisconsin. It was not easy to get into the Sharpshooters. To do so, a man had to place 10 consecutive shots in a 10-inch circle from 200 yards away while resting his weapon, then repeat the feat while hitting a target 100 yards away and firing offhand, or without resting his weapon on a stabilizing device. Recruits tried out with their own weapons brought from home, similar to those carried by the three men here—one of the clues to whom they served with. —D.B.S.

1. The forage caps of the left and right soldiers provide other important clues. They bear the hat brass figures “E” and “2” arranged horizontally or vertically within a wreath. “E” stands for Company E, and “2” indicates the 2nd regiment. The wreath is key, in that placing company letters and regimental numerals within a wreath was unique to Berdan’s men.

2. Sharpshooters wore dark green frock coats, which appeared no different than the more typical blue in Civil War photography. This trio wears an early version of the green uniform produced by Martin Bros. of New York City. The photographer tinted the brass buttons. Later in the war, the Sharpshooters were issued coats that used non-reflective, black hard-rubber buttons. The man in the middle also has a painted rain cover on his forage cap.

3. Each man shoulders his personal small-caliber civilian rifle. These were no doubt used in the shooting trial that qualified them to join Berdan’s Sharpshooters. All test shooting was done with open sights, no scopes.

Civil War Times would like to thank Brian White for the use of this image and for his expertise on Sharpshooter clothing and equipment.

LA GUERRE CIVILE

FROM FRANCE AND FROM A FRIEND

ONE OF THE GREAT BENEFITS of working in the field of Civil War history derives from the generosity of other scholars. Their sense of shared exploration promotes the circulation of materials that otherwise would remain unknown. More than 25 years ago, I met Donald E. Witt, a scholar of French literature with a deep interest in the American conflict. He had spent years translating the French newspaper Le Temps (The Times) for the period 1860-65. Because historians had frequently quoted the British press but paid relatively little attention to French newspapers, the materials he showed me seemed especially fresh. Happy to know someone else shared his enthusiasm for the project, he gave me seven thick binders containing more than 3,500 pages of translations.

A perusal of Le Temps revealed a rich body of descriptive and analytical evidence. The newspaper’s correspondents pursued an expansive approach to the American war that addressed politics, military affairs, swings of national morale, diplomatic

maneuverings, and other topics. Political and military leaders figured prominently in the articles, which suggests Parisians exhibited a desire for such news.

Fourteen newspapers served Paris in 1861. Napoleon III’s government sponsored Moniteur and received largely favorable treatment from several other papers deemed “semi-official press.” Le Temps, which would become one of the important French dailies, supported the house of Orleans. With a pro-Union, antislavery editorial slant, it stood at odds with a pro-Confederate imperial press. In October 1861, Le Temps made a distinction regarding slavery’s role in the American crisis. “Yes, slavery is at the root of the war,” read the piece, “since it is the institution of slavery that, in the North and in the South, has made two nations, has created hostile interests between them...that has determined for her (the South) the rupture of the pact...” But it was not a war to kill slavery because “the abolitionist opinion has ever been, in the North, only that of an intimate minority.”

Le Temps allocated considerable attention to the Emancipation Proclamation. Noting that President Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation of September 22, 1862, finally “placed the debate between the North and the South on its true terrain,” the editors labeled it a military expedient forced on Lincoln by Rebel victories in the Eastern Theater. The paper found it “regrettable that the President hesitated for so long a time” and quoted from his letter to Horace Greeley dated August 22, 1862, concluding that “[t]his policy has only one aim, the re-establishment of the Union.” The newspaper responded to the final proclamation, which it termed “very important news from America,” on January 15, 1863. “This proclamation,” read the perceptive article, “...can hardly have any immediate effect; but it is not any less one of these utterances destined to have repercussions in history, to be converted into acts, and to become definitive.”

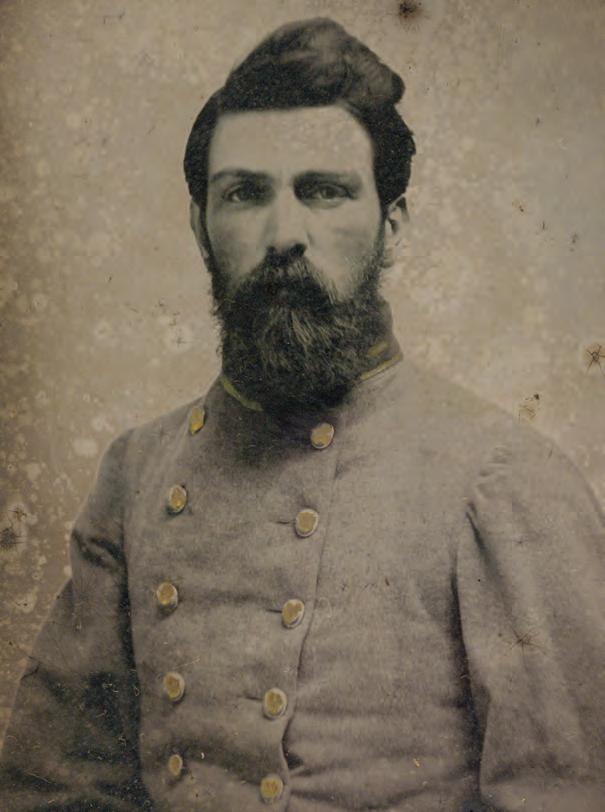

The prospective dual between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee in 1864 generated sustained coverage in Le Temps that praised both commanders. “General Grant has acquired in his western campaigns habits of vigor” that would allow him “to lead the Army of the Potomac to victory,” while Lee, a general of “remarkable talent,” had won victories that showcased “the courage and energy of the Confederate troops.” Le Temps initially predicted Union triumph, largely because of faith in “the militar y capacity, but especially in the tenacity and the character of Grant.”

After the Battle of the Crater, the editors adopted a more ambivalent stance. “Whatever will be the denouement of this campaign in Virginia,” observed a piece treating Lee and Grant as equals, “it will remain a testimony of the indomitable tenacity of the two armies and the two generals who resist each other for so long...without any perceptible advantage on either side.”

Grinding operations in Virginia between early May and August 1864 set up a long piece in early September.

Analyzing the two societies at war, a correspondent explored the combatants’

NEWS FROM AMERICA

The January 15, 1863, edition of Le Temps discusses the Battle of Murfreesboro, fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863, as well as the Emancipation Proclamation.

national morale and chances for victory. Confederates had faced “bankruptcy, despotism, famine” and “no longer have anything to hope for except independence; they no longer have anything to lose except their life.” The author admired “the courage that they deploy in this long resistance” and resoluteness in “this obstinacy of a common people who, for two years, block[ad]ed, invaded, decimated, found resources, [and] faced immense forces from the Union.” The Confederate economy lay in ruins “from top to bottom; all able men from fifteen to fifty-five are under arms....One no longer sees but women in the families and Negroes in the fields.” Yet Confederates manifested discipline born of “a unity of will” and still “held on, and no one can say when they will succumb.”

The United States presented a vastly different picture. It “has not renounced its richness,” asserted the author, “the war has interrupted neither its industry, nor its commerce.” Daily life progressed essentially as in peacetime, and Northerners shrank from “extreme measures, acting little and spending a lot, placing

mercenaries opposite seasoned men, wasting immense resources without breaking down a poor enemy.”

The Union effort lacked the sense of collective direction evident in the Confederacy. Writing before the full impact of Sherman’s capture of Atlanta had become evident (travel across the Atlantic took 10 days or more), this writer perceived a possibly disastrous lack of will above the Potomac: “The North can yield to fatigue; then the war would have served only to substitute a national hate for a political rivalry; and to ruin more profoundly the Union.”

Four months later, on January 2, 1865, the paper had changed its tone. It celebrated the “re-election of Mr. Lincoln, and the manner in which it was accomplished” as “the gage of an indestructible liberty, and will remain in history as an imperishable testimony of political and moral grandeur.” The editors accurately predicted the difficult road that remained ahead: “[If] it is no longer hardly possible to doubt the re-establishment of the Union, the final success, and especially the final pacification do not appear still less a rather lengthy operation.”

Whenever I see the seven binders on the bookcase in my library, I think of Donald Witt’s great generosity and the trove of French evidence he made available to me. ✯

ACHOO!

COLORFUL REPRODUCTION HANDKERCHIEFS

IN HIS SPRAWLING HOUSE on the outskirts of Murfreesboro, Tenn., Chris Utley shows me his second-floor office—the nerve center of his business for 19th-century reproduction clothing. Atop a bookcase rest 150-plus year-old boots and shoes. To our left stands a display of original U.S. Christian Commission ephemera. To our right, in a closet, hang some of the repro clothing Utley sells.

But I’m not here for the old-style vests and overshirts or the denim and linen jackets. I’m here to learn about handkerchiefs. Utley, a 47-year-old healthcare investigator, is the only person I know who collects original hankies from the Civil War. Of the 14 in his collection, seven belonged to identified soldiers. For nearly a decade, Utley has reproduced and sold copies of original Civil War hankies—a business that spawned his reproduction clothing business called South Union Mills.

The war has enthralled Utley since he first read Bruce Catton’s books as a kid. As he grew older, the Kentucky native caught the reenacting bug. In 1998, Utley and hundreds of his reenacting pards—including Robert Lee Hodge of Confederates in the Attic fame—re-created Stonewall Jackson’s famous Flank March on the very ground where the general’s soldiers advanced at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863.

Utley owns roughly 20 books on “Old Jack,” whom he admires for his devout Christian beliefs. In the back yard of his 10-acre spread, Utley raises chickens, just as Jackson did at his farm outside Lexington, Va., when he served as a

PERSONAL EFFECT

Chris Utley and one of his prized original cotton handkerchiefs. Norman Hastings of the 45th Massachusetts stenciled his name, company, and regiment on the colorful hanky.

professor at Virginia Military Institute.

“A lot of the ways he led his life, I lead mine,” says Utley, a devout Christian himself.

In 2013, the idea to reproduce and sell Civil War handkerchiefs came to Utley while he was taking a lunch break at his cubicle at work.

“What is something I can do that nobody else can do?” the former patrol officer thought. “I want to find a niche that’s mine.”

At the time, Utley didn’t know anything about textiles and little about Civil War-era handkerchiefs. Reenactors used handkerchiefs as an added touch of authenticity for their uniforms. But no one, as far as Utley could tell, made versions that were true to the period.

“The big thing for me is I wanted to be as authentic as possible,” he says.

In 2014, Utley bought his first original Civil War handkerchief from a Virginia antiques/relics dealer. The 18- by 16-inch cotton hanky belonged to Lieutenant S. Millet Thompson of the 13th New Hampshire. On the handkerchief —which features black, red, and tan patterns—the officer had stenciled his name and regiment. Thompson survived the war, including a wound at the siege of Petersburg. He died in 1911.

Over the years, Utley purchased other handkerchiefs on eBay and from Civil War dealers from $500 to $1,000. In an online auction, Utley spotted a handkerchief carried by U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield at Gettysburg, but he dropped out of the bidding when it soared to several thousand dollars.

All Utley’s originals belonged to U.S. Army soldiers except for one. When new, most featured vibrant colors, now dulled by time. Some have intricate patterns. All are made of either cotton or silk. A soldier paid about $1.50 for a silk hanky, less for cotton. Utley’s reproductions sell for $15 to $30 apiece.

One of Utley’s originals was carried by Lincoln Ripley Stone, a surgeon in the 54th Massachusetts, the most famous Black regiment of the war. The Harvard Medical School graduate served with Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, who was killed in the 54th Mas-

A GLORY-IOUS HANKY

Surgeon Lincoln Ripley Stone began the war with the 2nd Massachusetts, and was briefly held prisoner in 1862 at Winchester, Va. He later became the 54th Massachusetts’ surgeon.

sachusetts’ epic night attack at Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863.

Corporal Cyrus Dennis of the 1st Maryland “Potomac Home Brigade” Cavalry (U.S.) carried another. Utley owns his wartime Bible, too. Another belonged to Private Reuben Sweet of the 5th Wisconsin, who served under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman during his March to the Sea.

The only non-soldier handkerchief in Utley’s collection was carried by a Philadelphia man named George Johnson, a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Escaped slaves used the network of clandestine routes and safe houses to escape to free states and freedom.

The first original soldier handkerchief Utley re-created for sale came from the collection of an Idaho doctor. That hanky is named the “Galloway” after the collector’s surname.

For a nominal fee, Utley has purchased the reproduction rights of other soldier handkerchiefs from the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Va.; the Adams County (Pa.) Historical Society in Gettysburg; the Ohio Historical Society; the Oshkosh (Wis.) Public Museum, and elsewhere.

After receiving photos of handkerchiefs from Utley, a designer in Europe re-creates the hankies in digital form in their original, striking colors.

“My aim was to make them look like new,” Utley says.

An overseas mill makes the cotton or silk handkerchiefs for Utley, who sells them on his website and at Civil War shows. They’re also available at the Chickamauga battlefield in Georgia and at two outlets in Gettysburg.

Besides living historians, Utley says the handkerchiefs are popular with attorneys and cowboy action shooters who participate in Old West target competitions.

Hollywood likes Utley’s hankies and reproduction clothing, too. He has spotted his goods in movies such as The Free State of Jones, Nightmare Alley, and Jane Got a Gun.

“It’s gotten to be so common that I no longer make a mental note of it,” he says. In a display case on a bottom shelf in the nerve center, I stare at one of Utley’s original handkerchiefs—probably his favorite, he tells me. “Norman Hastings,” reads the name stenciled on the handkerchief in neat, block letters. “Co. C 45th Reg. Mass. V.”

In mid-September 1862, the 29-yearold married farmer enlisted as a private in the 45th Massachusetts, a ninemonth regiment. On November 5, 1862, his regiment departed from Boston on the steamship Mississippi, bound for North Carolina to reinforce U.S.

RAMBLING

WITH JOHN BANKSArmy occupation forces.

In North Carolina, 45th Massachusetts soldiers suffered from yellow fever, typhoid, and dysentery. As the weather turned brutally hot—a “fiery furnace,” a 45th Massachusetts veteran recalled— the already debilitating conditions turned worse.

“The sickness increased daily, and some poor fellows passed on to their resting-place above, when almost in reach of that earthly home towards which their thoughts and dreams had so long been directed,” a regimental historian wrote.

On June 24, 1863, Hastings and his bedraggled 45th Massachusetts comrades jammed aboard the steamer S.R. Spaulding, bound for Boston and their families.

“Forlorn and weary,” an observer described the soldiers.

On the journey from Fort Monroe, a stop in Virginia en route to Massachusetts, Hastings and another 45th Massachusetts man died from disease, probably dysentery. They were only several days’ travel from home.

“Their bodies will be forwarded to their friends,” a contemporaneous newspaper account noted. On Hastings’ “Casualty Sheet,” a clerk wrote: “Effects sent [to] wife.” Hastings’ cotton hand-

LOST TO DISEASE

While Norman Hastings’ handkerchief survived the war (previous spread), he did not. Disease killed him in 1863 while he was returning home.

kerchief probably was among them.

On the shelf near the Hastings hanky, another display case catches my eye. It contains two handkerchiefs—one plain white with a pattern along the edges and another featuring a maroon design—as well as a small tobacco box and an old metal chain, perhaps for a watch.

The relics belonged to Ira Lindsay, a

38-year-old machinist and shoemaker from Worcester, Mass. In 1857, he married a woman named Mary Estabrook, who bore him three children: Ellen, Kate, and Joseph Jr. On March 17, 1864, their father enlisted in the 25th Massachusetts as a private.

In early June 1864, Lindsay and his comrades found themselves at Cold Harbor, a dusty hamlet 10 miles northeast of Richmond. On June 3, in Ulysses Grant’s infamous, poorly coordinated charge, the 25th Massachusetts was among the Army of the Potomac regiments cut to pieces.

“[Our] lines were broken [and] the flying iron crushed bones like glass, and men and officers seemed to be staggered,” a 25th Massachusetts soldier recalled.

In the assault, Lindsay and 74 other soldiers in his regiment suffered mortal wounds. He may have bled on the chain in the display case. An old tag with it reads: “Blood was never washed off” and “Chain worn by father in the army.”

I wonder about those handkerchiefs.

Did Lindsay use them to wipe away tears after he received a letter from his wife, Mary?

Did he wrap one of them around a tintype of his children? Joseph Jr. was only nine months old when he lost his father.

Did Lindsay or someone else use them to stanch his wounds as he lay dying at Cold Harbor?

Who sent the relics home to Lindsay’s family?

I ask Utley if he visits his handkerchiefs late at night, as I probably would, perhaps to commune with the spirit of their owners.

“I think about what these have seen and whose pockets they were in,” he tells me. Then he pauses.

“Sometimes,” he says, “it just seems surreal that I own them.” ✯

SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE

John Banks, author of two Civil War books, has another one coming in late-spring 2023. Check out A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime (Gettysburg Publishing). Banks’ home base is Nashville, Tenn.

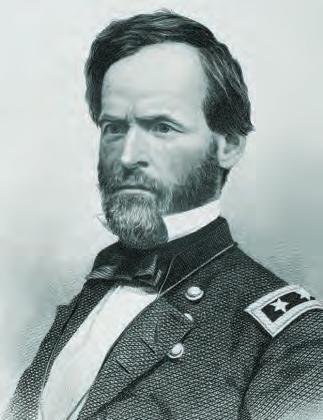

PYRRHIC TRIUMPH

Sherman’s 15th Corps took part in the January 1863 fight at Arkansas Post. Despite the victory, it marked another blip in a poor start for “Cump” and his men.

MANAGED MAYHEM

WILLIAM T. SHERMAN’S LEGACY probably is linked more to 15th U.S. Army Corps than any other unit or army he would command during the Civil War. Still today, more than 160 years later, Sherman and the “Diabolical 15th” continue to spur wrath in Southern hearts and minds, particularly for the carnage wreaked during the 1864 “March to the Sea” in Georgia and the subsequent Carolinas Campaign. As Eric Michael Burke reveals, however, in his captivating new tome, Sherman’s reputation as a “hard war” commander evolved as the war progressed and, contrary to popular belief, Sherman’s men likely had a greater impact on him during that evolution than he did on them. In Soldiers From Experience (LSU Press, 2022, $50 hardcover) Burke explores new ground in analyzing the rise of corps-level tactical culture within respective Civil War volunteer armies.

CWT: What inspired your research?

EB: Initially, my hope was (and still is) to develop new ways of effectively bridging the older, now occasionally maligned “drums and guns” literature focused on Civil War military operations with so much of the incredibly fascinating and vitally important ideas circulating in the less military-centric sub-fields of the war’s historiography. My time spent in and out of combat in the Army while serving in different units inspired an interest in me for understanding why different organizations, trained to conduct particular tasks in more or less identical ways, still tend to operate in distinctive fashions. I wanted to try to develop a more holistic understanding of why military units had such a timeless habit of developing unique collective personalities. Given the particularities of how volunteer regiments—and thus the

higher commands to which they were assigned—were raised and maintained in the field during the Civil War, it was a natural place to focus that research.

CWT: Were any preconceived notions you had about Sherman impacted?

EB: As a non-commissioned officer, I frankly found it hard to believe 19thcentury generals enjoyed the degree of influence over those in the ranks they likely believed they did. That said, I think that Sherman has classically been depicted as having been far more in touch with his junior subordinates than many of his peers. I was struck to find that, while this was certainly the case later in the war, Cump truly had to grow into that role. He was never inclined toward believing some kind of special wisdom was maintained within the rank and file, and he seemed to think of himself as a consummate professional among others merely masquerading as such—and there’s some truth to that, of course—but he ultimately recognized that to be successful in pursuing his objectives he had to “speak their language” and accept their “eccentricities.”

CWT: Was Sherman’s “hard war” evolution purely the product of military necessity?

EB: Sherman was a consummate conservative in just about every conceivable way. Politically, socially, tactically, the man was wracked with anxiety about radical change. Early on, few of his echelon in the Western Theater were as committed to ensuring that the conflict wouldn’t be transformed from a “kid-gloved” military prosecution of a mostly contained domestic insurrection into a “radical” social revolution in which America morphed from a slave society into something altogether different—which to conservatives like Sherman was, of course, frightening.

Unfortunately for Cump, he did not control events to that effect. He struggled to control the war’s political drift, struggled to control the libertine and destructive spirit of the volunteers he at least nominally “commanded,” and he

very much struggled to control the trajectory of the combat engagements he prosecuted. It took considerable time and what appears to have been a nervous breakdown of sorts to finally force him to embrace the fact he would—to use his phrase—have to accept that he was “riding a whirlwind unable to guide the storm.”

Like many of his peers, Sherman grew increasingly reticent about the possibility the Southern rebellion could be terminated by relatively conservative means. By the summer of 1862, he knew only harsher policy measures would bring the most ardent secession-

Believe it or not, generals are human beings, too, which means their beliefs are likewise shaped by their experiences leading particular bodies of troops that respond to events and their own orders in particular ways. Thus, there is a perpetual cycle of mutual influence whereby commanders and their men influence each other’s behavior and thoughts, besides exogenous factors like environment or enemy action.

Historians have paid far too little attention to this dynamic and instead emphasize the individual personalities of general officers in order to explain the incredibly intricate behavior of the massively complex human systems they commanded. The truth is, it is literally impossible for a single officer to have the kind of direct unmitigated influence over the behavior of an organization as large as an army corps that they often believed they enjoyed.

ists to their knees, but it was important to him that such a policy be prosecuted exclusively by officers and men kept on a tight leash by professionals who knew how to ensure that “hard war” didn’t spontaneously devolve into mass destruction, rapine, murder, and such. Tightly controlled chaos became one of his favorite strategic tools, even if it leaned too far for his liking toward the chaotic side of the spectrum.

CWT: Why do you feel Sherman’s men influenced his growth as a commander, not the other way around.

EB: As I write, the cultures of military organizations arise organically from cycles of experience, reflection, and collective meaning-making. The experiences soldiers have are of course directly shaped by the decisions and expectations of their leaders, but a wide array of factors go into shaping a soldier’s experiences and thus his or her beliefs, assumptions, ideas, norms, etc.

Granted, the unity of command principle does mean that in an ideal situation it all comes down to one individual calling the shots. But as historians, we have to parse the difference between the legal responsibility of a final military decision and the incredibly complicated network of people, ideas, culture, and other influences that lead to shaping that individual’s decision as well as the even more complex story of how that decision is or is not actually prosecuted. Attributing it all simply to a single individual’s actions or decisions is far too easy an explanation. As a historian, I am infinitely skeptical of excessive parsimony.

CWT: Chickasaw Bayou, the corps’ first true fight, was a disaster. What did Sherman do wrong there?

EB: Sherman’s expeditionary force failed foremost in its coordination between brigades and divisions. While that was mainly a product of the Yazoo bottomlands’ nightmarish terrain, it was exacerbated by the inattention Sherman and his staff paid to integrating each component command. Major delays in communications due to that terrain and Sherman’s habit of frustrating attempts by couriers to find him as

TIGHTLY CONTROLLED CHAOS BECAME ONE OF SHERMAN’S FAVORITE STRATEGIC TOOLS

he wandered the battlefield—mixed with major personality clashes among senior leaders—proved a toxic brew. Given the Union advantage in numbers, a well-coordinated offense would have left the Confederates incapable of responding to all the threats Sherman could pose simultaneously. Sherman and his lieutenants also did not learn the appropriate lessons from the debacle. Instead of taking a hard look at their own coordination failures, they sought scapegoats in the inexperienced junior officer corps, whom they charged with insufficient ardor and discipline.

CWT: Though it was a Union victory, Arkansas Post saw many of the same mistakes as at Chickasaw Bayou. Was Sherman in danger of losing his men?

EB: He was at risk of losing the confidence of his corps by the winter of 1862-63—and had already in a vast number of cases. The despondency he observed in the ranks after Arkansas Post was proof enough to him that the men of the 15th Corps were not especially happy; but, as was his habit, Sherman struggled to understand why or to what extent because he failed to empathetically observe events from their different perspective. The men lamented the loss of beloved comrades in what had been a stiff fight, but Sherman wrote off the engagement as a minor skirmish. That divergence in meaning-making in the wake of a major trauma did result in a serious deterioration of confidence between commanders and their subordinates.

CWT: Does Sherman deserve the blame he gets for the failed Union attacks at Vicksburg in May 1863?

EB: In short, yes. Sherman and Grant failed miserably in the planning and execution of both the May 19 and 22 assaults on the works at Vicksburg. Given the strategic context, it is understandable Grant opted for an “attack by open force.” Even his decision to launch a more army-wide assault on May 22 made some practical sense. But the coordination, and thus prosecution, of both assaults was abysmal.

WITH ERIC BURKEEverything from insufficient artillery preparation; complete failure to often coordinate attacks above the division level; inadequate attention to preparation for the myriad pioneering tasks involved in breaching a fortification like Stockade Redan; and a complete

compact masses against salient enemy positions without the formations deteriorating into a “cloud of skirmishers.” Broken terrain would fragment attacking commands and inspire the men to go to ground and “sharpshoot” rather than push the charges to fruition.

CWT: Sherman is generally criticized for his November 1863 effort at Chattanooga. You give him credit. Why?

UNCLE BILLY’S BOYS

disregard for the actual psychological, emotional, and physical state of the Army of the Tennessee—these top the long list of disastrous oversights at play.

CWT: You argue battlefield terrain had a greater impact on Sherman’s tactical philosophy than weapons. EB: The 15th Corps fought nearly every engagement in heavily wooded, swampy, or intractably hilly and broken terrain. With the exception of the siege at Vicksburg and perhaps the fight before Atlanta on July 22, 1864, few of its actions featured viewsheds that would have allowed soldiers to visually identify targets at the actual maximum effective range of their rifle-muskets.

More often than not, the region’s broken, cluttered terrain tended to dismantle the tight cohesion of assault columns featured in most contemporary infantry commands. It was exceedingly hard, if not impossible, to send

EB: Sherman’s hesitation to launch an attack on the Rebel right at Tunnel Hill has drawn considerable fire from historians. I argue the fault belongs with Grant in failing to consider the 15th Corps’ new tactical culture in designing his operation to break out of the siege. His reticence in launching yet another failed frontal assault marks one of the first instances Sherman showed a grasp of his command’s tactical weaknesses. While some of his future actions, most notably at Kennesaw Mountain, suggest he occasionally hoped he was wrong about that conclusion, he ultimately accepted the corps was not a viable tool for frontal assaults against any but dramatically outnumbered defenders.

CWT: Will there be a second volume?

EB: I’m interested in following the corps’ story further only if, in doing so, it shines an interesting theoretical or historiographical light on what interests me most: namely, crafting maximally holistic explanations for the tactical behavior of historical military organizations. I do not want to simply write a narrative of the latter half of the war from the limited perspective of the 15th Corps. I fervently believe that operational military historians like myself have an onus to prove “drums and guns” histories need not be abandoned as fruitful scholarship topics. But doing so requires more rigorous, more interdisciplinary, and more innovative approaches to analyzing military operations; not merely re-narrating them ad infinitum. ✯

LOOKING FOR THE REAL WAR

FRESH WAR HISTORY KEEPS ON COMING

I’VE HEARD THIS A LOT, and I am sure you have, too: “What new could there possibly be to say about the Civil War?” Skeptics need look no further. I always try to get “new” stuff in Civil War Times, and I hope you’ll find this issue especially engrossing. On P. 54, we share a newly uncovered version of 2nd Wisconsin Captain William Strong’s legendary 1861 encounter with Confederate pickets along the Potomac. The findings from a clandestine investigation of his account sat buried in archives at the Wisconsin Historical Society for 161 years and are published here for the first time. In our February 2019 cover story, “Battle Scars,” Eric Michael Burke wrote about General William T. Sherman’s 15th Corps and how it developed its own, unique fighting identity—an analysis he further expounds in his new book Soldiers From Experience. In this issue’s “Interview,” P. 22, Burke discusses with CWT his fresh approach to the study of military history. In “Battle’s Hard Aftermath,” P. 36, Steven Cowie examines something that’s been in front of our eyes since 1862, but we have not seen: How the Army of the Potomac turned minuscule Sharpsburg, Md., into one of America’s largest cities for weeks after the Battle of Antietam. When Union troops finally marched away, Sharpsburg was as devastated as any hamlet that lay in the path of the March to the Sea. You all keep reading, and we will keep digging. ✯

RICH MAN’S WAR POOR MAN’S FIGHT?

STATISTICS HELP US UNDERSTAND WHO WENT TO WAR AND WHY

BY CAROLINE E. JANNEYAcommon maxim during the Civil War held that it was “a rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” Both Union and Confederate critics leveled this charge—especially in the wake of conscription. But was that the case? Did the poorer classes of Union and the Confederacy bear the burden of fighting while the rich remained at home? The answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no.

In the two principal armies in the Eastern Theater, the Union’s Army of the Potomac and Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia, precise numbers are difficult to determine. Approximately 240,000 soldiers served in General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (although the average at any given time ranged between 35,000 and 90,000).

On the Union side, approximately 350,000–375,000 men served in the Army of the Potomac (although its strength at any given time averaged 125,000). Most of the soldiers on both sides were in their teens or early twenties when the war began. Single men—those with the fewest ties to keep them at home—were the most likely to rush off to war in 1861.

FOR CAUSE OR CASH?

The average Civil War soldier stood about 5 feet 8 inches tall, weighed 143 pounds, and was 26 years old. But what do we know about their economic backgrounds, and what induced them to serve?

Unwedded men, therefore, dominated both armies. The same held true for soldiers with children. Only one in three Confederates had children at home. But Union soldiers were even less likely to be married and have children than Confederates—only one of five Army of the Potomac soldiers left a family behind. Ninety-five percent of Lee’s soldiers came from farming communities. Conversely, only 30 percent of soldiers in the Army of the Potomac were farmers or farmhands. The Army of the Potomac was instead a predominately working-class army. The largest segment were day laborers, finding any work they could. Others constructed homes and buildings, some worked as shoe or boot makers, while a handful held skilled positions such as blacksmiths.

UNWEDDED MEN DOMINATED BOTH ARMIES

The next question concerns personal wealth. It is helpful to consider not an individual soldier’s wealth, but rather that of his family, as a majority of the soldiers on both sides still resided with their parents or older siblings. Approximately half of Lee’s men still lived with their families and therefore reaped the benefits of their parents’ lifestyle and wealth. For example, in 1860, Howlit Irvin was a student and owned nothing. But his father was

the former lieutenant governor of Georgia, whose wealth was valued at $170,000—including an estate with 117 slaves—making him one of the richest men in Georgia, if not the South.

On the Union side, two of five soldiers still resided with their parents or other family members when the war began. Examining the combined personal and family wealth therefore reveals a dramatic disparity between Union and Confederate soldiers: The median wealth of most Federal soldiers was a paltry $200. Conversely, soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia enjoyed a median personal and family wealth that was 6½ times greater than their Union counterparts.

Moreover, more than half of the Union soldiers fell into the category of “poor.” In fact, historian William Marvel has shown that the men who enlisted ear liest in the Union Army proved to be some of the poorest. While popular belief has held that those who enlisted earliest did so from unbridled patriotism, Marvel finds that the desire for economic relief proved a more likely motivating factor for Union soldiers in 1861-62.

Many men still reeling from the effects of the financial panic that swept New York City in 1857 found the prospect of a steady paycheck and bounties their overriding motive for enlisting. For example, when men from the 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Infantry were captured by Confederates at Ball’s Bluff in the fall of 1861, they explained their motivations: “A great many of them gave it as their excuse for fighting that they were out of employment and had nothing else to do,” noted their North Carolinian captor.

BATTLE AWAITS

Two out of every five Union enlistees lived at home when the war began. Despite his attempt at an aggressive, warlike pose, this bluecoated volunteer can’t hide his youth.

Returning to the Army of Northern Virginia, perhaps even more telling when we consider the lament of a “poor man’s war” is that Lee’s army had, as a percentage, according to historian Joseph Glatthaar, fewer poor folks (those worth less than $800) and more wealthy men (those from families claiming more than $4,000 in property) than the Southern states at large.

There was considerable affluence among Lee’s army, and that wealth was tied to the ownership of enslaved people. As Glatthaar has explained, “slaveholding had a powerful grip on…Lee’s army.” While only 13 percent of Lee’s soldiers were slaveholders, if we look at their families— we find that 44 percent came from slaveholding households—a statistic revealing that slaveholders were far more prevalent in Lee’s army than in the Southern population at large (where only 25 percent of households owned slaves).

In the Confederacy, therefore, this was not a poor man’s fight. Slaveholders, among the richest in the South, served in disproportionally high numbers in Lee’s army. Believing that slavery

was under attack, they flocked to the cause. Those from the middle- and upper-classes in the Army of the Potomac, however, did not have the same financial interest in fighting. Even those who came from the wealthy class would not have lost a fortune had the South achieved its independence.

But that fact must be balanced with the reality that there were certainly those from more privileged backgrounds that fought for the Union. For example, approximately 1,300 men with Harvard ties fought in the Union ranks—they clearly were from the privileged class. In other words, the poor, elite, and middle classes were represented in the Union Army just as they were in the Confederate armies.

Despite these men’s service, by the spring of 1862, Confederate armies were shrinking because of battlefield casualties, sickness, and disease, but also as a result of expired enlistments and deser tion. The Confederate Congress responded to the emergency by taking one of the most momentous steps of the war: conscription (or the draft). On April 16, 1862, the first of

SO EXCITING

With bold graphics and stirring text, recruiting posters encouraged men to join the military. The Union poster at left also uses the threat of being drafted with the enticement of bounty money to fill the ranks.

three Confederate conscription acts became law and required the following:

• All able-bodied White men already serving would have their enlistments extended for two years—men who had enlisted in good faith for one year’s service

• All other White males between the ages of 18-35 would serve for three years

Two subsequent revisions to the legislation, passed in September 1862 and February 1864, changed the age limits—eventually setting the range from 17-50. In effect, if the Confederacy got a man into uniform, he never got out. The draft was unprecedented in American history. But we need to keep in mind it was as much carrot as it was stick. The potential for conscription convinced men to enlist. Men of 1861 worried that if they didn’t reenlist, they would be forced to add three years, instead of two. Others worried that if they went home and risked draft, then they would be forced to serve in units other than the ones they had joined by choice. Fear of serving with strangers drove Spencer Barnes of North Carolina to admit to his father, “I hate to be thrown into another company.”

There certainly were those that complained. Unionists were distraught at having to fight for a cause they opposed. Others complained on ideological grounds: they argued that the Confederacy had been founded to protect states’ rights—but the conscription law allowed the central government to

LOOKING FOR A LOOPHOLE

Drafted New Yorkers swarm a draft office to plead their case to an official in the hopes of claiming an exemption from military service. In 1863, only one draftee out of 30 actually entered the Union Army.

usurp states’ rights. Then there was the list of exemptions from the draft. The occupations exempted included government officials, teachers, millers, some artisans, and laborers engaged in industries such as mining, railroads, textile mills—all things necessary for the war effort. But there were two exemptions that particularly galled many Rebels. The first was the Overseer Clause—added in October 1862. This clause exempted one white male from each plantation with 20-plus slaves under the assumption that one white man was needed to manage large numbers of slaves. But non-planters and slave-less whites claimed the clause gave preferential treatment to planters and their sons.

The second exemption that triggered protests was substitution, which allowed draftees to avoid military service by finding someone exempt from the draft to replace him—this meant hiring someone who was either under or over the mandatory conscription age, someone whose trade of profession exempted him, or

BAD LUCK OF THE DRAW

An original New York City draft tumbler. The cards pulled out of drums such as this sparked the July 1863 draft riots in that city—the largest, most violent demonstration against forced service in the North.

a foreign national. Prices for substitutes in the South were said to range as high as $3,000 in specie (gold) or even higher in Confederate money—a sum that only the very wealthy could afford. Like the Overseer Clause, this provision also seemed to favor the wealthy and provoked calls of “rich man’s war,” and the Confederate Congress did ultimately abolish the practice.

But did conscripts change the composition of Lee’s army? In large part, no, because nearly all of those men volunteered. Only eight percent were drafted or served as substitutes. In fact, the vast majority of Lee’s soldiers, nearly 80 percent, volunteered before the Confederacy implemented conscription. But draftees did tend to be poorer and owned fewer slaves than their comrades who volunteered. They also tended to be older— between the ages of 26 and 40. The most glaring difference between Confederate volunteers and draftees, however, revolved around marital status and children: 70 percent of conscripts were married. And nearly every drafted married soldier left behind children. In other words, having a family and children to support made men less likely to volunteer than the younger, single enlistees.

THE VAST MAJORITY OF LEE’S SOLDIERS VOLUNTEERED BEFORE THE CONFEDERACY IMPLEMENTED CONSCRIPTION

The Union draft began a year after Confederate conscription and operated somewhat differently. Each loyal state was divided into recruiting districts, and each district had a quota to meet based on population. When the recruiting district failed to meet its quota through volunteers, soldiers would be drafted by lottery among men between the ages of 20 and 45—as well as immigrants seeking U.S. citizenship. If a man’s name was selected by the lottery—he had three options: enlist, find (and pay) a substitute to take his place, or pay a $300 commutation fee that exempted him from that round of the draft. In 1860, $300 would have been the equivalent of the annual wage of an unskilled laborer.

Unlike Confederates, the Union lawmakers allowed no occupational exemptions. But there

were some exemptions—exemptions that critics charged favored the poor. For example, the only son of a widow or of infirm parents did not have to serve if he was their primary support. And a widower with children younger than 12 was not subject to conscription. Those with more means, of course, could afford to hire a substitute (essentially bribing someone else to fight for them) or pay the commutation fee. Thousands of middle and upper-class Northerners, including John D. Rockefeller and future president Grover Cleveland escaped military service by these means.

In the first national draft levy, in 1863, only one drafted man out of every 30 went to war. In some states, this number was far higher—for example, in Connecticut only one in 63 drafted men found himself in a blue uniform. In some communities, men subject to the draft pooled

WAR RALLY

Union recruiters make a splash with a trolley. Veteran John Billings claimed that early in the war “waving banners, martial and vocal music” would drive crowds into a frenzy, and a town’s quota could be “filled up in less than an hour.” As casualty lists grew, however, so did the monetary subsidies for new troops.

DOLLAR SIGNS

The signboards posted at a Northern recruiting office accentuate cash incentives over all else. There is nary a mention of patriotic motivation. Martin Kelley, an immigrant from Ireland, volunteered late in the war, avoiding the draft and earning some money.

their money in draft insurance clubs that would hire substitutes for those selected. As Marvel pointed out, “[U]nless a man was unable to simultaneously support his family and hire a substitute or pay the commutation fee, it was easy to avoid going into the Union Army, and the overwhelming majority of those who were called to serve” avoided it. In 1864, Congress abolished the commutation provision, but not substitution.

As it had in the Confederacy, the Northern draft provoked outrage, with many arguing that it abridged their fundamental personal liberties. Both substitution and commutation produced cries of “a rich man’s war” just as the Overseer Clause had done in the South. Combined with emancipation, the draft of 1863 unleashed a storm of violent protests in the loyal North. Some provost marshals—those in the army charged with enforcing of the law—were shot, their families threatened, their property vandalized. More than 160,000 men—one-fifth of those drafted—refused to report for duty. Thousands more who did eventually deserted and others dodged the draft by going to Canada.

The draft likewise spurred protests. Democrat politicians, especially Copperheads (the name given to anti-war Democrats), inspired the most violent protests. The most notorious and deadliest rioting erupted in New York City on July 13-17, 1863. Anti-conscription sentiment spilled into four of the bloodiest days of mob violence in the city’s history—by the time the smoke cleared, at least 105 people, mostly rioters—lay dead and another 300 were severely injured. Twenty thousand armed troops marched from Gettysburg to quell the rioting.

The draft began without incident on July 11—but that evening and into the next day disgruntled draftees, including urban laborers and immigrants—many of whom were Irish—gathered and planned to disrupt the draft proceedings by attacking the provost marshal’s station and setting it on fire. The cry of a “rich man’s war” may have ignited the riot, but racial tensions and economic dislocation fanned the flames. The working poor, including the mostly unskilled Irish workers, competed with African Americans for jobs—yet African Americans were not subject to the draft. This infuriated Whites—they might be forced to serve and die in a war that was now about liberating slaves. Rioters burned the Colored Orphan Asylum and rampaged through Black neighborhoods lynching at least six African Americans on lampposts and brutally mutilating others. There were other smaller riots—in Boston, in New Hampshire, and even Wisconsin—but theses riots served as the high point of draft resistance.

DON’T DO IT

A broadside urges Northern laborers not to resist the draft and to unite against a common enemy. More than half of the Union Army was composed of “poor” men who made less than $200 per year.

The question remains: did the draft alter the composition of the Union Army? Historians have yet to answer this question regarding the Army of the Potomac as fully as they have for the Army of Northern Virginia.

What we do know is that in the Army of the Potomac, approximately three percent were drafted while another six percent were substitutes. Like the Confederate draft, the Union draft was far more crucial as a spur to local recruitment than as an end unto itself. And, as such, it likely had a similar impact—that is, draftees were probably poorer, older, and more likely to be husbands and fathers than their volunteer counterparts.

So was the Civil War a poor man’s fight?

In answering this question, we need to keep in mind the difference between reality and perception. Many people at the time believed that it was a rich man’s war and poor man’s fight. But a closer examination suggests that all classes were well represented. Indeed, as Glatthaar has explained, “on the whole, soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia were very comfortable financially, whereas the men in the Army of the Potomac were comparatively poor.”

Even though Lee’s soldiers were more likely to come from wealthy families, we should keep in mind that war placed great strain on the poor and middle classes of both sides. War always takes harder toll on those who have fewer resources. Even those of the middle class had a great deal to lose in the war. Their families had worked quite hard to achieve even moderate success—and they worried about losing all of it. Given the scale of the

mobilization on each side—the war did not belong to one class alone.

Despite what some chose to believe, it was not a poor or rich man’s fight, it was every man’s fight.

Caroline E. Janney is the John L. Nau III Professor in History of American Civil War and Director of the John L. Nau Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia. She has published seven books, including Ends of War: The Unfinished Fight of Lee’s Army after Appomattox (2021) winner of the 2022 Lincoln Prize.

FURTHER READING