In the blockbuster film, when a strapping Australian crocodile hunter and a lovely American journalist were getting robbed at knife point by a couple of young thugs in New York, the tough Aussie pulls out his dagger and says “That’s not a knife, THIS is a knife!” Of course, the thugs scattered and he continued on to win the reporter’s heart.

Our Aussie friend would approve of our rendition of his “knife.” Forged of high grade 420 surgical stainless steel, this knife is an impressive 16" from pommel to point. And, the blade is full tang, meaning it runs the entirety of the knife, even though part of it is under wraps in the natural bone

wood handle.

Secured in a tooled leather sheath, this

equally impressive price.

one impressive

Stauer® 8x21

with

price tag out in the marketplace. In fact, we found full tang, stainless steel

This fusion of substance and

blades with bone

of $2,000.

have mastered the hunt for the best deal,

turn

that won’t cut it

the spoils on to

But we don’t stop there. While

last, we’ll include a pair of $99, 8x21 power

binoculars, and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Down Under Bowie Knife.

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the impeccable craftsmanship. If you don’t feel like we cut you a fair deal, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price.

Limited Reserves. A deal like this won’t last long. We have only 1120 Down Under Bowie Knives for this ad only. Don’t let this beauty slip through your fingers at a price that won’t drag you under.

Down

Your

What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives

“This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN

“The feel of this knife is unbelievable...this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO

•Etched

The U.S. Air Force, Navy and Marines attacked North Vietnam almost daily over an 11-night period in December 1972.

By Carl O. SchusterAfter an American bomb drop on Dec. 27, 1972, Hanoi’s Kham Thien Street lies in ruins.

By Jon Guttman

By Jon Guttman

CHUCK SPRINGSTON EDITOR

ZITA BALLINGER FLETCHER SENIOR EDITOR

JERRY MORELOCK SENIOR EDITOR

JON GUTTMAN RESEARCH DIRECTOR

DAVID T. ZABECKI EDITOR EMERITUS

HARRY SUMMERS JR. FOUNDING EDITOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY JON C. BOCK ART DIRECTOR GUY ACETO PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF MANAGING EDITOR, PRINT MICHAEL Y. PARK MANAGING EDITOR, DIGITAL CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

ROBERT H. LARSON, BARRY M c CAFFREY, CARL O. SCHUSTER, EARL H. TILFORD JR., SPENCER C. TUCKER, ERIK VILLARD, JAMES H. WILLBANKS

KELLY

MATT

ROB WILKINS

JAMIE

In the Autumn 2022 issue’s “What’s Your Favorite Song?” (Homefront, with a photo of soldiers gathered around a radio), you characterize troops as listening to tunes. In actuality, this is Team 11 of E Company, 75th Ranger Regiment, on the chopper pad waiting to be inserted on a long-range reconnaissance patrol/Ranger mission. The photo was taken by AP combat photographer Oliver Noonan. The team was listening to Neil Armstrong’s walk on the moon [July 20, 1969]. It was a staged photo by Noonan to highlight the contrast between missions. I was the leader of Team 11 and am in the picture wearing the PRC-25 [field communications radio] on my back. This pic was in the center section of Stars and Stripes beside Armstrong on the moon. It also appeared in many newspapers in the U.S.

Norm Breece Dakota City, NebraskaRegarding the article “Vital Support” (April 2022), a photo package show casing support units crucial to the success of combat operations: I was as signed to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 10th Combat Avia tion Battalion, Dong Ba Thin, South Vietnam,1966-67. My assignment was personnel, officers section, processing officers inbound and outbound, mostly aviators, both helicopters and fixed wing. Like them I was serving in a war zone. My job was equally important. I went to sleep at night with the knowledge that I was a member of the U.S. Army in a foreign country sub ject to hostilities. Inside or outside a tent, we worked together to accom plish our missions.

Paul J. Gomez Rancho Cucamonga, California

Regarding “A Healing Force,” by Tom Edwards (Autumn 2022): Mr. Edwards’ excellent article on military nurses serving in Vietnam made no men tion of Lynda Van Devanter, an Army nurse sta tioned at the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleiku 1969-70. Lynda wrote a best-selling memoir, Home Before Morning: The Story of an Army Nurse in Vietnam, published in 1983. It is a harrowing account of her year in-country as well as her struggle with PTSD and inspired the popular ABC television series China Beach. Lynda died at age 55 of systemic vascular disease exacerbated by her exposure to Agent Orange while in Vietnam.

Scott Wallace Leesburg, VirginiaThe article on nurses in the Autumn 2022 issue of Vietnam was both interesting and well written. There is a minor error: The Repose [hospital ship], not the Sanctuary, was stationed off Hue/ Phu Bai in 1966. I was a medical officer aboard the Sanctuary

Don R. Goffinet Stanford, California

Regarding “New Base Names Honor Vietnam Service Members” (Intel, Autumn 2022): Each of the men named in the article deserve the honor of having their name attached to significant military history, but not at the expense of eliminating the names those bases are currently named after.

Doug Andrews Canton, Georgia

Doug Andrews Canton, Georgia

I complained for years about naming forts after Confederates whose claim to fame was slaughter ing American soldiers. Do Germans name their forts for Nazi or East German generals? So it is wonderful to see forts renamed. It was also deeply inspiring to learn about the great Americans the forts will be named for. One problem: When bor ing others with stories of my very modest military career, do I still refer to old Fort Polk, new Fort Johnson [after William Henry Johnson, a Black Medal of Honor recipient in World War I] or just use the Beetle Bailey term “Camp Swampy”?

Raymond Paul Opeka Grand Rapids, Michigan

Email your feedback on Vietnam magazine to Vietnam@historynet.com, subject line: Feedback. Please include city and state of residence.

@VietnamMag

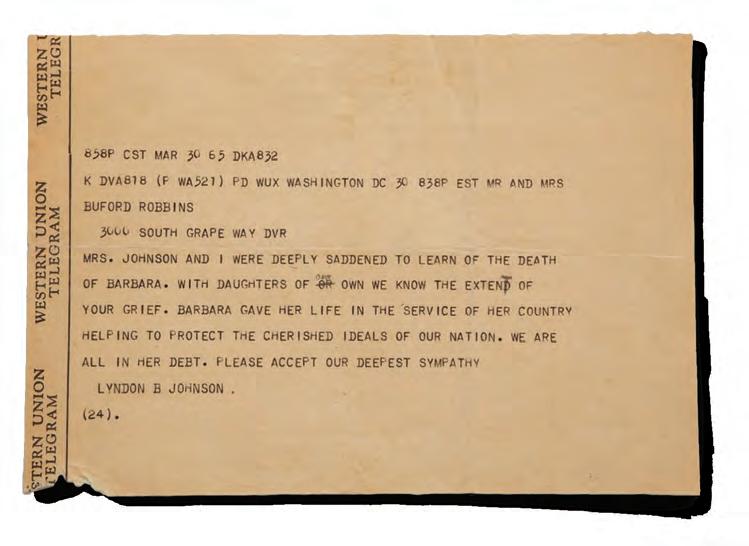

There is now a face for every name inscribed on the Vietnam Veter ans Memorial in Washington, D.C., thanks to volunteer researchers.

The Wall of Faces gallery, a webpage that profiles members of the military who died as a result of their service in Vietnam or remain missing, is complete after more than two decades of research, according to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, the organization that built The Wall.

Working on the project since 2001, researchers have collected at least one photograph for each of the 58,281 service members whose names are in scribed on The Wall.

The quest for photos was intended “to ensure that visitors to The Wall understand that behind each name is a face—a person with a story of a family and friends who were forever changed by their loss,” Jim Knotts, president and CEO of the memorial organization said in a news release.

Researcher Janna Hoehn, interviewed by Vietnam magazine in March 2022, spearheaded an effort to collect the last 18 names needed for the Wall of Faces.“I am thrilled beyond words that the project is completed,” she said in the news release. “I am grateful for each and every volunteer, each news paper that agreed to do a story for a little lady from Hawaii. I am proud of my work with this project and will never forget this time in my life.”

Other volunteers who played a key role include Andrew Johnson, a Wis consin newspaper publisher; David Hine, who learned of the project through the memorial organization’s newsletter; and Herb Reckinger, who began searching for Minnesotans on the Wall in 2014 and expanded to other states.

The Wall of Faces was initiated under the premise that even a simple image of a human face not only preserves the memory of the dead but touches the lives of people today.

While at an event that displayed “The Wall That Heals,” a smaller replica of the D.C. Wall that trav els to communities across the country, Reckinger was approached by a local veteran who wanted help finding a friend’s name on The Wall. “I asked if he wanted to see his picture,” Reckinger re counted in the news release. “After looking at his friend on the Wall of Faces, he had one sentence for me: ‘I forgot what he looked like.’”

Thanks to Hoehn’s research, James Vaughn of Quincy, Massachusetts, was able to obtain a post er-size photo of his friend Robert “Bobby” Phil lips to display at a public memorial ceremony. Phillips has been missing since June 1970 and is officially listed as “Unaccounted For” by the U.S. government. “People were going up after the cer emony taking their pictures with Bob [next to the poster],” Vaughn said in an interview with Viet nam magazine. “That made me feel good—that he was so well-remembered in town.”

Although the Wall of Faces now has a photo for each name, the memorial organization wants better images for slideshows. Banners at the bot tom of existing photos on the Wall of Faces indi cate whether higher-quality pictures are needed.

—Zita Ballinger FletcherNo. This myth appears to have originated from a blog written by prolific conspiracy theorist Wayne Madsen more than 40 years after the incident. The blog post claimed that McCain, then a U.S. Navy A-4E Skyhawk pilot aboard aircraft carrier USS Forrestal, was responsible for causing the devastating fire that killed 134 sailors and wounded 161 others. Madsen’s the ory falls apart under scrutiny. It is contradicted by dozens of eyewitnesses and the Navy’s of ficial investigation report.

Shortly before 11 a.m. on July 29, 1967, the Forrestal was cruising in the South China Sea as its crew prepared for an other bombing mission over North Vietnam. Forty strike air craft crowded the flight deck, attended by several hundred sailors making last-minute checks before the airplanes launched. Suddenly, a Mark-32 Zuni rocket mounted on an F-4B Phantom II roared across the deck and struck the exter nal fuel tank of an A-4E Skyhawk some 100 feet away on the rear end of the flight deck. Hundreds of gallons of burning jet fuel spread beneath the neighboring aircraft, one of which in cluded McCain’s Skyhawk. The future senator made it to safe ty. His wingman did not.

lessly claimed that the resulting plume of flame from the rear of McCain’s Skyhawk reached across the deck and ignited the Zuni rocket. That assertion is patently false.

The Navy’s investigation, completed on Sept. 26, 1967, found that the accidental firing of the Zuni rocket was caused by an electrical power surge on the Phantom aircraft that car ried it. All the documentary evidence and eyewitness ac counts agree that McCain’s plane was parked with its tail pointed outward, toward the ocean and not down the flight deck toward other aircraft.

After Madsen published his blog post in May 2008, some of McCain’s political opponents used the story to discredit the senator, who was running for president. Since then, Madsen’s claim has been resurrected at times to smear McCain. However, historical facts prove that McCain was blameless in the fire that devastated the Forrestal in 1967.

Dr. Erik Villard is a Vietnam War specialist at the U.S. Army Center of Military History at Fort McNair in Washington D.C.

Firefighters had just begun to battle the inferno when a bomb ex ploded. Seven more 1,000-pound bombs detonated in the next five minutes, ripping deep into the hull and showering the foredeck with bodies and debris. The Forrestal’s crew made a heroic effort to save the ship, finally extinguishing the last part of the fire at 4 a.m. the next morning. Besides the sailors killed and wounded, 21 of the Forrestal’s 73 aircraft were destroyed and an ad ditional 40 damaged. The carrier re turned home for repairs, arriving at Norfolk, Virginia, on Sept. 14, 1967.

Madsen alleged that McCain had caused the conflagration by making a “wet start” in his Skyhawk, deliber ately flooding his engine’s combus tion chamber with extra fuel before hitting the ignition switch. He base

Marine Lance Cpl. Ralph McWilliams, 3rd Military Police Battalion, 1st Marine Division, and his scout dog Major scan the horizon in November 1967. Major “saved my life several times,” McWilliams, of Cresco, Pennsylvania, said in a newspaper interview during the war. Accompanying a reconnaissance patrol one day, the corporal and Major came under fire. Major was wounded by shrapnel in the right foreleg. The limping dog was slowing the patrol. A decision was made to destroy him. “I just couldn’t destroy him,” McWilliams said in the article. He picked up the wounded 90-pound dog and carried him 2 miles to a helicopter pickup. “I figured I owed him a chance to live.”

“I have been among the officers who have said that a large land war in Asia is the last thing we should undertake. Most of us, when we use that term, are thinking about getting into a land war against Red China. That’s the only power in Asia which would require us to use forces in very large numbers.

I was slow in joining with those who recommended the introduction of ground forces in South Vietnam. But it became perfectly clear that because of the rate of infiltration from North Vietnam to South Vietnam something had to be done.”

—Retired Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor (chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff 1962-64, ambassador to South Vietnam 1964-65), interview, “Top Authority Looks at Vietnam War and Its Future,” U.S. News & World Report, Feb. 21, 1966

Tim Page, a photojournalist acclaimed for his work during the Vietnam War, died Aug. 24, 2022, at age 78 in New South Wales, Australia. Page, born in Turnbridge Wells, England, on May 25, 1944, left the United Kingdom in 1962 and traveled through Europe, the Middle East and Asia, where he be came a freelance photographer during a 1965 coup attempt in Laos. Page then moved to Saigon and began covering the Vietnam War, accompanying U.S. troops on missions, often in dangerous loca tions. He worked on assignment for major media organizations, including AP, UPI and Paris Match magazine. Known for his flamboyant personality, Page embraced the counterculture and drug use of the 1960s and 1970s. He was wounded four times in Vietnam. In 1966, Page was badly injured in a grenade explosion. After an exploding land mine sent a fragment into his brain in 1969, he was pro nounced dead but revived and eventually recov ered. After the war, he covered rock music and the drug culture. Page also photographed the 1967 Arab-Israeli “Six Day War,” sandwiched between his Vietnam trips, and the wars in Bosnia and Af ghanistan. He later became an adjunct professor of photojournalism in Brisbane, Australia.

—Zita Ballinger Fletcher

—Zita Ballinger Fletcher

Ronald Glasser, author of the acclaimed Vietnam War memoir 365 Days, died at age 83 in a Minneapolis veterans hospital on Aug. 26, 2022. Glasser, a Chicago native born May 31, 1939, earned a medical degree from Johns Hopkins University in 1965 and specialized in pediatric medicine. Glasser was drafted in August 1968, commissioned as a captain and sent to a military hospital in Zama, Japan, where he initially worked as a pediatrician for military families. Glasser soon was also treating servicemen suffering from severe wounds and trauma. After he returned home, Glasser drew upon his experiences with the wounded for 365 Days, the title a reference to the number of days Army troops had to serve in Vietnam before they could go home. The book, published in 1971, documents the emotions and experiences of young soldiers dealing with terrible injuries. It was a finalist for the National Book Award. After his military service, Glasser continued his career as a pediatrician and wrote other medical-related books.

—Zita Ballinger Fletcher

—Zita Ballinger Fletcher

Fidel V. Ramos, president of the Philippines 1992-98, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and the leader of a Philippine contingent in Vietnam, died July 31, 2022, in Manila at age 94. Ramos, born March 18, 1928, graduated from West Point in 1950 and was deployed to Korea, where he served with the Philippine Expeditionary Force. In the Vietnam War, Ramos was a major commanding the Philippine Civic Action Group of military engineers and medical troops assisting the South Vietnamese. Back in the Philippines, Ramos served as commander of the Philippine Constabulary, a military force with policing functions, under President Ferdinand Marcos, who declared martial law in 1972. Ramos joined in a 1986 peaceful rebellion that ousted Marcos and elected Corazon Aquino president, who made Ramos a four-star general. He succeeded her in the presidency.

No matter your service allegiance, now you can show your support in big, bold style, with our “ Military Pride” Men’s Hoodie —an exclusive design available in four military branches. Crafted in tan easy-care cotton blend knit, it features a large official branch emblem on the back and bold branch name on the front. The letters on the front are individual appliqués designed with a unique gradient technique. Detailing continues throughout this apparel exclusive, like a flag patch on the left sleeve, complementary cream sherpa lining in the hood, kangaroo pockets, knit cuffs and hem, a full front zipper, and even chrome-look metal

tippets on the hood drawstrings. And it’s available in 5 sizes, medium to XXXL. Imported.

The “Military Pride” Men’s Hoodie can be yours now for $99.95* (sizes XXL-XXXL, add $10), payable in 3 convenient installments of just $33.32 each, and backed by our 30-day, money-back guarantee. To reserve yours, send no money now; just return your Priority Reservation. But don’t delay! This custom hoodie is only available from The Bradford Exchange, and this is a limited-time offer. So order today!

In the spring of 1969, I arrived in Vietnam as a sergeant in the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) after completing a small unit leadership training pro gram at Fort Benning, Georgia. Even though I was an untested infantry squad leader, I was put in charge of a dozen men who had been in-country four, five or six months.

Since my men had previous combat experience and I had none, the pressure I faced when taking control was enormous.

I did not have to wait long for the opportunity to prove myself because my company had just been ordered to take part in the famous battle for Hamburger Hill, May 10-20 in the A Shau Valley of northern South Viet nam. Upon entering the assault staging area, we were instructed to leave all nonessential gear behind and to only take weapons, ammunition and a sin gle canteen of water. However, I decided to bring along a small C-ration can of sliced peaches in case I got hungry along the way.

As we slowly moved into our assault position, the formidable jungle terrain and thick vegetation caused significant delays. Other U.S. military units ran into the same problem, causing the assault to be postponed until the next day. That meant we had to spend the night at the base of the contested mountain.

When morning arrived, everyone was hungry. It had been nearly 24 hours since we last

Troops from the 101st Airborne Division run a wounded soldier to medical help on May 18,1969, during the Battle of Hamburger Hill, where Sgt. Arthur Wiknik Jr., inset, went from selfish to selfless.

I n the early 1930s watch manufacturers took a clue from Henry Ford’s favorite quote concerning his automobiles, “You can have any color as long as it is black.” Black dialed watches became the rage especially with pilots and race drivers. Of course, since the black dial went well with a black tuxedo, the adventurer’s black dial watch easily moved from the airplane hangar to dancing at the nightclub. Now, Stauer brings back the “Noire”, a design based on an elegant timepiece built in 1936. Black dialed, complex automatics from the 1930s have recently hit new heights at auction. One was sold for in excess of $600,000. We thought that you might like to have an affordable version that will be much more accurate than the original. Basic black with a twist. Not only are the dial, hands and face vintage, but we used a 27-jeweled automatic movement. This is the kind of engineering desired by fine watch collectors world wide. But since we design this classic movement on state of the art computer-controlled Swiss built machines, the accuracy is excellent. Three interior dials display day, month and date. We have priced the luxurious Stauer Noire at a price to keep you in the black… only 3 payments of $33. So slip into the back of your black limousine, savor some rich tasting black coffee and look at your wrist knowing that you have some great times on your hands.

offer that will make you dig out your old tux. The

ate. Assuming my fellow soldiers had also brought food, I casually opened my can of peaches and started eating. Immediately, some of the guys began staring at me. They all wanted peaches. Since the tiny can could not realis tically feed a dozen men, I decided to get it over with and quickly ate the rest of the fruit.

No one said anything, but their cold stares confirmed that I had made a mistake. Instead of acting like a leader, I had disappointed them by only thinking of myself.

A short time later, we were given the order to assault the mountain. The moment we moved into the battle area we immediately came under heavy fire. As enemy bullets pinned down our skirmish line, I looked for a way to escape. To my left was a small ridge that had enough vegetation to provide cover.

I immediately leapt to my feet and ran to the ridge yelling to my squad: “Follow me! We’re going up this way!” I charged up that ridge like a madman, push ing branches aside, jumping over abandoned enemy positions and ignoring bullets nipping at my feet. When I reached the crest of the hill, I realized it was the perfect location to set up a defensive position.

But when I turned around to inform my squad, I was alone! They had let me run up the hill by myself.

ers, maybe we would be able to get more free items. I secretly sifted through discarded con tainers from other soldiers’ care packages for ad ditional supplier addresses and began sending requests at two-week intervals.

It did not take long for the goodies to start roll ing in. In the coming months I received large quantities of peanuts, pretzels, fruit nectar, canned berries, sardines, steak sauce and more. As a joke, I even asked a tobacco distributor for cigar prices, and I was sent a free box. My letter writing campaign was working so well that I had to maintain a chart to keep from contacting a company a second time.

My squad members began calling me “Opera tor” because I reminded them of the “Sgt. J.J. Sef ton” character portrayed by William Holden (who won a best actor Oscar for the role) in the 1953 movie Stalag 17

Before an assault up Hamburger Hill, Wiknik ate a can of peaches while the sergeant’s men looked at him disappointedly.

About 30 minutes later the fighting subsided. My guys finally made their way to my position. As they gathered, I scolded them: “Why the hell didn’t you guys follow me?! That ridge had plenty of cover! If we all came up together, we might’ve made a differ ence!”

No one answered. The men sheepishly looked at each other, knowing full well that they should never have let a fellow soldier charge the enemy alone. Then one of the men broke the silence. “We didn’t follow you because you didn’t share your peaches.”

Everyone burst out laughing, including me.

I learned an important lesson that day. In a dangerous place like a com bat zone, refusing to share something as simple as peaches can get a guy killed. To prevent that from happening again, I needed to find a way to atone for my selfishness.

Before long, I found the solution. One of the most welcome diversions from the Vietnam War came in “care packages” from home filled with cookies, fruitcakes, seasonings, powdered juices and a variety of canned goods. One package from my mother contained a 7-ounce can of apple juice from a New Hampshire cannery. It was the first real thirst quencher I had in over two months. It was so refreshing that I wrote a thank-you letter to the company.

In the letter, I briefly described how miserable infantry life in Vietnam was, explaining how the juice was such a welcome change from drinking water out of rice paddies and rubber bladders. I also wrote that I wanted to purchase a case of the apple juice to share with my squad.

About two weeks later, I received a complimentary carton of 20 4-ounce cans with a letter from the cannery stating that the gift was its way of show ing support for the troops. What a fantastic surprise!

Infantrymen often feel unappreciated in wartime, so something as sim ple as a free can of apple juice was a real treat. It not only revitalized our taste buds but also restored our long-lost faith in the folks back home.

Then I got an idea. If I write the same kind of letter to other food suppli

However, unlike Sefton, who as a prisoner of war was somehow able to live comfortably while his POW comrades suffered, I shared everything that came my way to help make the situation a little more bearable for all of us.

Naturally, my squad was curious about how I obtained cases of hard-to-get provisions. I simply told them I had an uncle who worked in a food distribution warehouse. I was afraid that if the guys knew the truth they might try the same thing and the suppliers would catch on and stop sending the freebies!

Later, I wondered if I had taken advantage of some very generous people, but I quickly dis missed such thoughts. The combat infantryman suffered under so many unforgiving conditions that we were basically at the bottom of the food chain. One of a soldier’s biggest fears is to be for gotten. I should not have had to go to such trou ble to remind so many people that there was a war going on. However, in doing so, the free food was a huge benefit because it not only lifted our spirits but also taught me a valuable lesson in sharing. V

Arthur Wiknik Jr. is the author of Nam Sense: Surviving Vietnam with the 101st Airborne Division. Wiknik has appeared on the History Channel show Vietnam in HD and was a featured guest on the Military Channel (now American Heroes Channel) show An Officer and a Movie He lives in Higganum, Connecticut.

Do you have reflections on the war you would like to share?

Email your idea or article to Vietnam@historynet.com, subject line: Reflections

The locations of the antennas enabled the EB-66 to provide all-around coverage of North Vietnamese radars.

The EB-66 replaced the rear gun mount of the B-66 bomber with powerful radar jammers.

The EB-66B had 36 VHF/UHF fiberglass antennas. The later EB-66E also had 36 antennas, but they were more refined.

The B-66 Destroyer, originally powered with two Allison J71-A-11 engines, was upgraded with more reliable J71-A-13 turbojets.

At 8:05 a.m. on July 24, 1965, four F-4C Phantom II aircraft from the Air Force’s 47th Tactical Fighter Squadron were patrolling for MiGs that could threaten U.S. bombers southwest of Hanoi when two EB-66C Destroyer electronic warfare reconnaissance planes warned the F-4s about a surface-to-air missile launch. Seconds later three SAMs downed one of the Phantom IIs and damaged the others. That attack finally awakened the Pentagon to the SAM threat and the need for tactical aircraft with electronic countermeasures.

The Air Force EB-66, installed with those electronics, derived from the Navy’s A-3D-1 Skywarrior, designed in 1949 to carry a 5-ton nuclear weapon out to 2,300 miles. The Air Force wanted to purchase the Navy planes to replace its B-26 Invader bomber and RB-26 reconnaissance aircraft, but the required modifications delayed production until 1957. The new bomber became the B-66 Destroyer. The reconnaissance version was the RB-66.

Equipped with electronic sensors and photographic equipment, the first RB-66s arrived in South Vietnam on April 9, 1965. The aircraft was designated the EB-66 in 1966. Its variants—the EB-66B and EB-66C—worked in tandem. The EB-66C detected and identified enemy radars for the EB-66B to jam.

The EB-66 aircraft often worked in concert with Marine EF-10B Skyknight and Navy EKA-3B Skywarrior planes that accompanied attack aircraft to blind enemy defenders along the route. They also guided “Wild Weasel” fighter-bombers hauling missiles targeting SAM sites. The EB-66E with specialized communications intercept and jamming equipment joined the war in 1967.

North Vietnam’s air defenders quickly understood the EB-66 planes’ importance and tried to en gage them with SAMs and MiGs, often employing radar emission tactics to draw the EB-66 within engagement range.

By 1972, the Air Force’s EB-66B, C and E’s capabilities and less restrictive rules of engagement en abled them and their Navy electronic partners to all but paralyze Hanoi’s air defenses during the Linebacker II bombing campaign Dec. 18-29, 1972. The Air Force retired the last EB-66 in 1974.

The EB-66—the Air Force’s only electronic intelligence aircraft in Southeast Asia—ensured the survival of hundreds of American air crews as it mapped and jammed Hanoi’s SAM radars. V

Crew: Three EB-66B; six to seven EB-66C and E

Engine: Two Allison J71 turbojets, with 10,000 lbs. thrust

Wingspan: 72 ft., 6 in.

Length: 75 ft., 2 in.

Max takeoff weight: 83,000 lbs.

Max speed: 630 mph

Cruising speed: 528 mph

Max. range: 2,529 miles

Mission endurance: Three hours Service ceiling: 39,400 ft.

Electronics: AN/ APR-25/26 radar homing and warning system; EB-66B and E: C-I band jammers; EB-66C: A-J band receivers; EB-66E: AN/QRC-128 communications jammer

ago, Persians, Tibetans and Mayans considered turquoise a gemstone of the heavens, believing the striking blue stones were sacred pieces of sky. Today, the rarest and most valuable turquoise is found in the American Southwest–– but the future of the blue beauty is unclear.

On a recent trip to Tucson, we spoke with fourth generation turquoise traders who explained that less than five percent of turquoise mined worldwide can be set into jewelry and only about twenty mines in the Southwest supply gem-quality turquoise. Once a thriving industry, many Southwest mines have run dry and are now closed.

We found a limited supply of turquoise from Arizona and purchased it for our Sedona Turquoise Collection . Inspired by the work of those ancient craftsmen and designed to showcase the

stabilized

blue stone,

cabochon

Bali metalwork.

The Buffalo Bills trounced the San Diego Chargers 23-0. The MVP was Bills quarterback Jack Kemp, who threw for 155 yards and one touchdown.

The Green Bay Packers beat defending champs Cleveland Browns 23-12 in the last NFL championship before the Super Bowl era. The MVP was Pack ers’ fullback Jim Taylor, who rushed for 96 yards.

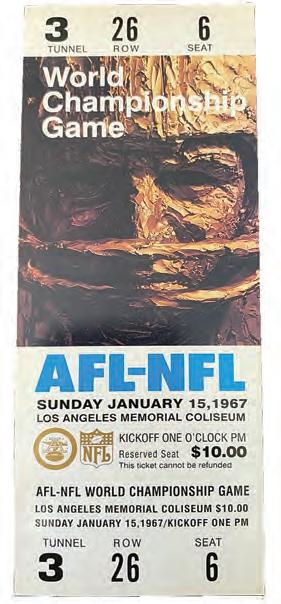

In the first battle between the AFL’s best team and the NFL’s best team at the AFLNFL World Championship Game (unofficially called the Super Bowl by the media and

others), the Green Bay Packers downed the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10. The MVP was Packers’ quarterback Bart Starr, who completed 16 passes for 250 yards and two touchdowns.

The NFL’s Green Bay Packers defeated the Oakland Raiders of the AFL 33-14 in the World Championship Game (later dubbed Super Bowl II). Quar terback Starr was again the MVP, with 13 passes for 202 yards and one touchdown.

Quarterback Joe Namath and his underdog New York Jets of the AFL beat the NFL’s Baltimore Colts 16-7 in Super Bowl III, the first official use of “Super Bowl.” Three days earlier, Namath had boasted, “We’re going to win the game. I guarantee it.” He was the MVP,

with 17 passes for 206 yards.

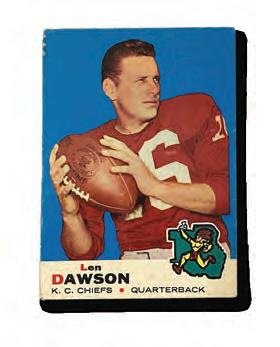

The AFL’s Kansas City Chiefs beat the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings 23-7 in Super Bowl IV.

The MVP was Chiefs quarter back Len Dawson, who threw 12 passes for 142 yards and one touchdown. This was the last Super Bowl battle between the AFL and NFL. A merger announced in June 1966 and effective with the 1970 season combined the two leagues under the NFL name and established two conferences within the NFL.

The Baltimore Colts of the NFL’s American Football Con ference edged out the National Football Conference’s Dallas Cowboys 16-13 in Super Bowl V. The MVP was Dallas

linebacker Chuck Howley, who nabbed two interceptions and became the only member of a losing team to win the award.

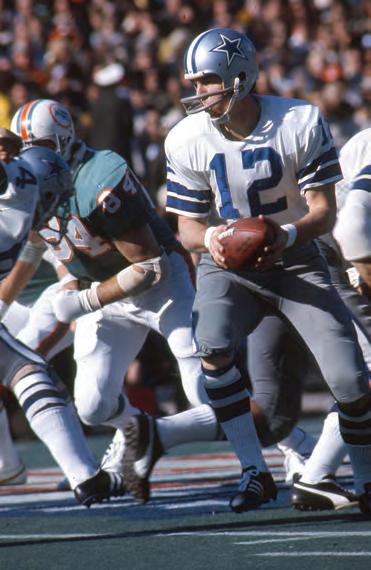

In Super Bowl VI, the NFC Dallas Cowboys crushed the AFC Miami Dolphins 24-3. Dallas quarterback Roger Staubach, a Naval Academy graduate and Vietnam veteran, was MVP. He completed 12 passes, two for touchdowns.

The Miami Dolphins beat the Washington Redskins 14-7 in Super Bowl VII. The MVP was Miami safety Jake Scott, who made two interceptions, including a crucial one in the fourth quarter. With this victory, the Dolphins became the only NFL team with an undefeated season, 17-0.

RINGS: ZUMA PRESS INC ALAMY; 1965: CHARLES AQUA VIVA/GETTY IMAGES; 1966: AP PHOTO/VERNON BIEVER; 1968: AP PHOTO/VERNON BIEVER; 1972: TONY TOMSIC VIA AP PHOTO; 1973: AP PHOTO/VERNON BIEVER; TICKET: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES; DAWSON: HISTORYNET ARCHIVES; NAMATH: AP PHOTO/VERNON BIEVER

By Carl O. Schuster

By Carl O. Schuster

At 7:30 p.m. on Dec. 18, 1972, Hanoi time, U.S. Air Force F-111 Aardvark attack aircraft initiated Operation Line backer II by striking six North Vietnamese airfields. One minute later, EB-66 Destroyer electronic warfare planes started to jam enemy radars, and F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers began laying corridors of small metal strips of chaff to confuse enemy radar and protect the first wave of B-52 Stratofortress bombers approaching Hanoi and Haiphong.

Completely surprised and blinded, Hanoi’s Air Defense Command aimed its anti-aircraft artillery fire along the routes and altitudes used by B-52s during the Linebacker I bombings of May-October 1972, conducted in response to the North’s massive ground offensive started during Easter weekend. Surface-to-air missile sites launched Soviet SA-2 Guideline SAMs based on the Linebacker I pattern, only to come under attack from F-105G Thunderchief fighters-bombers code-named “Wild Weasels,” carrying mis siles that homed in on the SAM sites.

The North Vietnamese launched MiG fighters toward the points where they had intercepted Linebacker I planes. Meanwhile, U.S. Marine Corps aircraft protected Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker aerial refueling planes while the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 77 struck coastal targets. The Vietnam War’s final bombing campaign had begun. Unlike earlier bombing opera tions, Linebacker II, Dec. 18-29, was a maximum effort to cripple if not destroy North Vietnam’s capacity to continue the war in the South.

Hanoi’s intelligence services had known since Dec. 16 that a major air operation was imminent but assumed the targets would be south of the 20th parallel, sparing Hanoi and the surrounding area, includ ing the big port at Haiphong. After bombing the Hanoi area in Linebacker

I, the U.S. had shifted its bombing strikes to tar gets below the 20th Parallel and interdiction mis sions to disrupt supply movements.

If the big bombers should come farther north, Hanoi’s leaders believed they were prepared. A study of B-52 Stratofortress operations indicated that the bombers tended to abort their missions when they knew they had been detected by the Fan Song SAM fire-control radar that tracked and targeted enemy aircraft.

With that in mind, the defenders moved two SAM and two MiG fighter regiments to cover central and southern North Vietnam, although they retained their anti-aircraft artillery regi ments around the capital region in case the U.S. sent fighter-bombers and attack aircraft against Haiphong. They knew the effectiveness of those aircraft would be reduced by December’s heavy overcast and intense rains. Also, the Air Defense Command had spent the past two months rearm ing and repairing the air defense units depleted by Linebacker I.

The North Vietnamese did not expect Presi dent Richard Nixon to risk the political fallout of striking Hanoi. While Republican Nixon had won a landslide reelection over “peace candidate” Democrat George McGovern, the congressional elections had resulted in a majority determined

TOP: A bomb-laden B-52 gets its fuel topped off en route to North Vietnam. KC-135 tankers flew from bases in Japan and the Philippines to conduct aerial refueling missions. MIDDLE: An F-105G Thunderchief fighter-bomber of the 17th Tactical Fighter Squadron, armed with missiles that could destroy enemy radar, lands at Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base on Dec. 29, 1972, the last day of Linebacker II sorties. ABOVE: North Vietnamese haul a purported piece of a B-52, their “trophy,” to a surface-to-air missile battery.

Hanoi’s assurances that it would not reinforce its troops in South Vietnam.

Nixon’s Cabinet largely opposed a bombing campaign along the lines of Linebacker I. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and Secretary of State Wil liam Rogers argued against it. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Adm. Thomas H. Moorer only supported it if Hanoi violated a signed agreement. Kissing er was worried that it would increase the number of prisoners of war. Only one of the president’s key advisers, deputy national security adviser Alexan der Haig, supported sending the B-52s against Hanoi and Haiphong.

Nixon had met with Moorer and Laird several times in November as the peace talks foundered. He had continued the bombing south of the 20th parallel to maintain the pressure on Hanoi, but North Vietnam’s intransigence convinced him that wasn’t enough. On Dec. 6, Nixon ordered the Joint Chiefs to establish a working group to plan for strikes on Hanoi. He directed that “the plan should be so configured to produce a mass shock effect in a psychological context.”

Nixon envisioned that responsibility for the air war over North Vietnam would be given to Military Assistance Com mand, Vietnam, which controlled all land, water and air combat operations inside South Vietnam. The 7th Air Force was MACV’s air component commander and directed all land-based opera tions of fighter-bombers and attack aircraft.

The Joint Chiefs gave the Strategic Air Com mand the planning authority for the operation’s B-52 bomber missions, a decision that violated unity of command and turned mission planning over to a staff that considered the Linebacker campaign a distraction from SAC’s main mis sion: preparing for nuclear war with the Soviet Union. Nixon warned Moorer that he was giving military leaders everything they wanted and would hold the admiral “personally responsible” if the operation failed.

Today’s 8th Air Force sprang from the Army Air Forces VIII Bomber Command, activated Jan. 28, 1942, in Savannah, Georgia, and sent to England the next month.

On Feb. 22, 1944, in a reorganization of air operations,the VIII Bomber Command was christened the 8th Air Force. In June 1946, it attached to the Strategic Air Command. In 1965, the 8th Air Force’s units in the States deployed to Guam, Okinawa and Thailand. SAC in April 1970 transferred the 8th to Andersen Air Force Base in Guam where it oversaw bombing operations in Southeast Asia. On Jan. 1, 1975, the 8th Air Force moved to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana.

The president wanted a 24/7 bombing campaign to deny the North’s de fenders rest and recovery time. Nixon also demanded the bombers press on to their targets despite enemy defenses so the North Vietnamese would “feel the heat until they saw the light.”

“If we renew the bombing,” he explained to Kissinger, “it will have to be something new, and that means that we will have to make the big decisions to hit Hanoi and Haiphong with B-52s. Anything less will only make the enemy contemptuous.”

On Dec. 14, Nixon ordered the plans finalized and one day later alerted all forces to be ready for three days or more of maximum effort. He approved the final plan on Dec. 15, with the attack to start on Dec. 18, one day after Congress recessed for Christmas break. That morning Navy aircraft from Task Force 77 seeded minefields in Haiphong Harbor’s approaches.

About 4:30 p.m. North Vietnamese intelligence reported that B-52s had taken off from Guam. They intercepted a radio call at approximately 7:30 p.m. from a Navy plane patrolling ahead of the B-52s and warning them to turn south. That convinced the Air Defense Command that the B-52s were

going to strike south of the capital region. The B-52 pilots, however, ignored the “warning” and stayed the course.

Naval aircraft struck North Vietnam’s coastal radar and SAM sites, fol lowed almost immediately by Air Force F-111 Aardvarks hitting six MiG airfields. The surviving radar stations were blinded by jamming and chaff clouds. By 10 p.m., the Air Defense Command realized that Hanoi was the target area, but it was too late. North Vietnam’s defenses were quickly over whelmed. Confused, the defenders launched fighters to intercept the flight paths the B-52s used in Linebacker I, and anti-aircraft artillery fired barrag es along those same flight routes. Unfortunately for Hanoi, the B-52s were flying different routes and at 32,000-34,000 feet, rather than the 14,000 feet used in Linebacker I.

Each B-52 wave was supported by eight F-105 Wild Weasel SAM sup pression planes, 20 F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers and two chaff corri dors, about 60 miles long and 5 to 7 miles wide. The B-52s struck Radio Hanoi, two airfields, the Kinh No repair yards and the Yen Vien rail yard. The airfields and rail yards were nearly destroyed, and Radio Hanoi was heavily damaged.

Despite those successes, the results also revealed weaknesses. Aircraft targeting Hanoi’s air defense system, especially Wild Weasel SAM hunters, were spread too thin. The 7th Air Force asked SAC to reduce a four-hour separation between waves because the long interlude was forcing its aircraft to launch and sustain multiple chaff reseeding and radar jamming efforts.

Also the decision to have each wave fly the same pattern enabled the de fenders to simply fire missiles along the predicted route. Additionally, SAC required planes to use the same post-strike turn point that forced them to turn into the jet stream, decelerating an aircraft as it was about to be engaged.

A crowd gathers for funeral services at Bach Mai hospital, which was accidentally hit by bombs targeting a nearby Hanoi airfield on Dec. 22. The bomb strike killed 28 hospital staffers and an uncertain number of patients.

The 8th Air Force, which had tactical com mand of the B-52s on Guam, recommended that SAC change its tactics to keep the North’s defend ers off-balance. SAC planners rejected the rec ommendations, saying it was too late to change their plans.

Hanoi, however, had learned the Americans’ tactics and adjusted accordingly. The North’s Air Defense Command plotted the B-52 routes and repositioned its SAM sites to concentrate on turn points and the bombers’ target approach routes. Search radars fed target data to the air defense sites so the Fan Song fire control radars did not have to be activated until a few seconds before the missile launch. The defenders established SAM “engagement boxes” to fire missiles manu ally in concentrated barrages.

The 129 B-52s that flew the first night faced 174 SAMs, which shot down three bombers and damaged two. However, no B-52s were lost to MiG attacks—in fact, one B-52 tail gunner claimed a MiG-21. Anti-aircraft artillery downed an F-111. In the second day’s raid by 93 B-52s,

none were lost, convincing SAC planners their tactics were sound.

On Day Three, six B-52s were downed. Only the second of the three bomber waves returned home unscathed. Le Duan, his confidence in his air defenses restored, remained steadfast, still be lieving the Americans would fold first.

Nixon, pushing aside the poor results and criticism from the anti-war delegation in Hanoi, ordered three more days of bombings.

SAC and the Pacific Air Force Command re evaluated their tactics. B-52Gs were prohibited from flying over the North because of their less powerful electronic radar jamming equipment and smaller bomb loads. The Guam-based B-52Ds were also excluded because of the longer flight time. That resulted in smaller raids of 30 B-52Ds from U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield that were comparatively easier to protect.

Unfortunately for them, SAC did not change its flight tactics. Day Four’s raid struck three tar gets but lost two B-52Ds to SAMs. SAC shifted to Haiphong to avoid Hanoi’s denser defenses. No B-52s were lost on Day Five, Dec. 22. However, one stick of bombs overshot Hanoi’s Bach Mai Airfield and hit Bach Mai Hospital, killing 28 hospital personnel and a still-unconfirmed num ber of patients.

Meanwhile, the North’s focus on downing the B-52s benefited U.S. fighter-bomber operations. Although not thoroughly appreciated at the time, those Air Force, Navy and Marine aircraft faced lighter defenses during the day because Hanoi was resting its air defense teams to engage the B-52s. Fighter-bomber sorties exceeded 100 a day, and losses were much lower than in Rolling Thunder or Linebacker I. Bombing effectiveness also improved.

Nixon instituted a 36-hour bombing halt on Dec. 25, a pause that both sides used to reevalu ate all aspects of their operations. SAC trans ferred planning and operational authority to the 8th Air Force on Guam, tightening the opera tional structure and improving coordination.

Le Duan interpreted the pause as a victory, much like earlier bombing halts. But it was actu ally a pause for the flight crews. Nixon wanted a massive attack on Hanoi starting on the night of Dec. 26 with no letting up.

Incorporating lessons from Linebacker I and suggestions from B-52 crews, the 8th Air Force de cided there would be no more long lines of bomb ers following identical routes to their targets. The bombers would fly in four waves, each compact

and coming at Hanoi from a different axis and exiting via different routes.

The Thailand-based aircraft would recover in Guam and the Guambased aircraft in Thailand. As the four waves approached their targets, they split into seven serials of varied size to attack 10 targets. Seven targets were hit simultaneously. Each wave flew a separate route at a different altitude. The compressed waves enabled the Navy and Air Force fighters and jam mers to concentrate their attacks against radar and SAM sites. F-111s joined the attacks on SAM sites. Twelve of the North’s 32 SAM sites were put out of action.

The chaff corridors were denser, and instead of 60 to 90 minutes of exposure to enemy defenses, each wave was in and out in under 15 minutes. Although two B-52s were lost on Dec. 26, the vast majority of the bombers were able to remain within the chaff corridors, and the varied routes confused the defenders. The North Vietnamese fired their SAMs along the old routes and turn points. The MiGs got lost and had to search for their targets.

The fighting consumed more than 10 percent of the SAMs, and Hanoi was worried about re supply. About 800 missiles were in storage, but they needed assembly and delivery to the SAM battalions. The storage depots were also under attack. Two were destroyed on Dec. 26. Henceforth, SAM launches were rationed and their use limited to engagements with B-52s.

Le Duan realized that Nixon wasn’t going to ease up and more bombs were likely to drop. The effectiveness of North Vietnam’s air defenses was declining rapidly. Le Duan worried about his own support within the Politburo if future raids proved equally successful. On Dec. 27, he sent a message to Nixon saying he wanted to resume negotiations on Jan. 8, 1973. Nixon told Kissinger to propose Jan. 2.

The bombing continued for three more days. North Vietnam’s last air defense success came on Dec. 28 when a SAM downed a B-52. The Dec. 29 raids reported few SAM launches and suffered no losses. Linebacker II offi cially ended at 6:59 a.m., Hanoi time on Dec. 30. Le Duan had agreed to

resume the Paris talks on Jan. 2.

In total, 2,003 strike sorties into Vietnam delivered 20,237 tons of ord nance against 59 targets in North Vietnam. B-52 bombers delivered 75 per cent of the tonnage dropped (15,237 tons) in 729 sorties, while fighter-bomber and attack aircraft garnered 25 percent (5,000 tons) in 1,274 sorties—769 Air Force and 505 Navy/Marine fighter-bombers. Half of the Navy/Marine sorties (277) were flown at night.

North Vietnam fired between 289 and 487 SAM missiles against the bombers, downing 15, damaging four beyond repair and eight later re stored to service. The losses of fighter-bombers and attack aircraft were lighter, with the Navy and Air Force each losing five and the Marines two.

In aerial combat engagements, Air Force fighters downed two MiG-21s, the Navy one and B-52 gunners one confirmed, possibly another. North Vietnam’s rail yards received half of the bomb tonnage. All of the North’s industrial facilities, rail yards and hubs, 80 percent of its electrical generat ing capacity and every major military facility had been destroyed, as had two-thirds of the SAM storage and assembly inventory.

However, the campaign revealed several command and planning short falls beyond SAC’s rigid flight schedules, which simplified the planning process but also aided enemy defenders.

For one, there was the failure to consider the North Vietnamese air de fense’s Achilles’ heel—its SAM supplies. Linebacker II planners ignored Hanoi’s SAM storage and assembly units until the final three days. Destroy ing those facilities early on would have reduced the missile threat. The 8th Air Force’s planners, when they got more authority during the Christmas pause, addressed that oversight, proving what a professionally planned air campaign can achieve.

The Paris peace talks resumed on Jan. 8, and an agreement remarkably similar to the October draft was signed on Jan. 27. It differed only in modi fying the requirements for a National Council of National Reconciliation and Concord. The October version would have brought an unidentified third party into a Saigon government consisting of Thieu and the Viet Cong.

In the final agreement, the two South Vietnamese parties were required to establish a three “segment” reconciliation council to oversee implementa tion of the agreement and national elections. “Segment” was not defined. North Vietnamese forces retained the territory they had captured up to that point and permission to resupply them via the DMZ and other means.

In Hanoi’s sarcastuc view, the bombing drove the North to sign an agree ment that contained all of America’s concessions. Even though Le Duan was the one pleading for a resumption of the talks, Nixon was in no posi tion to ring any more concessions out of the communists. Both knew that Congress was ready to prohibit further U.S. military action in Vietnam. There would be no more bombing, and absent that leverage, Le Duan had no incentive to compromise.

The 591 POWs held by North Vietnam were released and brought home by April 4, 1973.The U.S. turned over millions of dollars of military equipment to South Vietnam, but that did not include the extensive logistic support and supplies required for the South to fight as its forces had been trained.

Neither Saigon nor Hanoi conformed to the agreement. Le Duan rebuilt and deployed his forces over the next two years. He launched an offensive in January 1975, pausing after the initial advances to measure the U.S. response. Seeing none and noting the reduction in funding to resupply South Viet nam, Le Duan ordered the final drive that conquered the South on April 30, 1975. The last South Vietnamese resistance ended three days later.

AIRCRAFT

AIRCRAFT

AIRCRAFT

AIRCRAFT

Linebacker II demonstrated that a properly planned and employed strategic bombing cam paign can achieve military objectives to deliver political pressure. But it also showed that a welltrained and equipped integrated air defense force can inflict heavy losses on an inadequately pre pared or poorly employed air attacker.

The U.S. enjoyed air superiority over North Vietnam throughout the war, but at an unneces sary cost. Before Linebacker II, America’s leaders made no sustained attempt to crush North Viet nam’s air defenses. Le Duan’s memoirs show he interpreted Rolling Thunder’s bombing halts not as gestures requiring reciprocation from him but as opportunities to rebuild his forces and contin ue the war. Linebacker II changed his calcula tions. However, it came seven years too late to ensure South Vietnam’s survival as an indepen dent nation.

Carl O. Schuster is a retired Navy captain with 25 years of service. He finished his career as an intelligence officer. Schuster, who lives in Honolulu, is a teacher in Hawaii Pacific University’s Diplomacy and Military Science program.

A lieutenant leading a platoon in the 1st Marine Division makes a call during an operation in 1967. Communist forces frequently intercepted U.S. radio signals and were able to interpret sensitive information due to lax radio protocols.

A lieutenant leading a platoon in the 1st Marine Division makes a call during an operation in 1967. Communist forces frequently intercepted U.S. radio signals and were able to interpret sensitive information due to lax radio protocols.

By David M. Fiedler

By David M. Fiedler

O

f the many battles the U.S. fought in the Vietnam War none hurt more than the 1965 battle in the Ia Drang Valley and the 1968 Tet Offensive. The outcome of those clashes and hundreds of smaller ones were not the clearcut, decisive victories that senior American command ers expected. That’s because they didn’t think the “prim itive” enemy was shrewd enough and sophisticated enough to intercept radio communications, then use that information against U.S. troops. When it was conclusively proved that the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong had those capabilities, military intelligence agencies briefed Gen. Creighton Abrams, the head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in early 1970. He responded: “This is terrible. They are reading our mail, and it has to stop! Get the word out to every division and corps commander.”

The enemy radio intercepts shouldn’t have been a surprise. There had been warning signals for years. In the late 1950s the Army directed its Electronics Command at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, to develop a new “family” of single-channel tactical field radios to replace the obsolete in ventory of World War II and Korean War field radio equipment still in use. At the same time the Defense Department directed the National Security Agency to concurrently develop and field “communications security equipment,” to encrypt all tactical voice and data radio equipment devel oped by the services.

The result was a series of Army and joint ser vices security regulations and directives incorporated into the equipment specifica tions for new Army single-channel combat net work radios. The Army built a mostly transistor ized vehicular mounted 50-watt radio (VRC-46), a toughened 1.5-watt manpack radio (PRC-25) and some hand-held, low-power transmitters and receivers (PRT-4, PRR-9) intended to replace the old walkie-talkie at the squad level.

Simultaneously, the NSA developed “narrow band secure voice equipment,” or NESTOR, to secure radios produced by the Electronics Com mand. Unfortunately, there were problems in the design, integration and production of this securi ty equipment. Both technical and tactical adjust ments had to be made to meet the Army’s fielding schedule because military operations in Vietnam were ramping up.

The communications security requirements for the PRT-4/PRR-9 radios were removed since the NSA could not come up with a small enough de

sign for the hand-held and helmet-mounted radi os. The elimination of the security requirement was justified tactically. The hand-held radios were intended for squad and platoon communications, and thus the radio’s power level was very low and the communications distance was very short.

The Vietnam ramp-up was bad news for secu rity systems in the PRC-25. The basic radio met all of its specifications, but a PRC-25 manpack with NESTOR security equipment was far be hind the basic radio in development. With the fight in Vietnam intensifying, the Army decided to field the basic manpack radio without a com munications security capability and wait for the NESTOR security hardware to become available. The Army planned to withdraw the PRC-25 from service when the NSA completed its NESTOR development and deploy an upgraded radio, identified as the PRC-77, with the proper com munications security equipment.

Fortunately, the vehicle part of the family had very few issues and essentially met all technical, tactical and communications security require ments early in the troop buildup. Ditto for the aircraft version.

Unfortunately, the unsecured manpack radio would become the “workhorse” of combat com munications because the preponderance of the ground fighting was done by infantry troops, in cluding airborne and helicopter airmobile units.

The vehicle VRC-12/manpack PRC-25 family of combat network radios was a great step for ward in tactical radio communications. The sys tems were extremely easy to install, operate and maintain in combat units. All the operator had to do was pick a radio frequency, a transmitter pow er level and one of two selectable noise reduction modes, then hook up an antenna and a handset, and he was operational.

That turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. Since the radios were so simple the Signal Corps changed Army doctrine and had the equipment designated as “user owned operated and maintained.” That meant radio telephone op erators with fighting units in the field were no longer Signal Corps personnel but rather combat arms soldiers (infantry, artillery, armor).

With that change, officers and non commissioned officers were taught how to operate the radios during ba sic and advanced individual training at combat arms training centers. The training received by officers and NCOs was barely above that of the unit RTOs (who mostly learned on the job), even though higher-level commanders still held them

A helmet-mounted PRR-9 receiver worked in conjunction with a PRT-4 hand-held walkie-talkie transmitter. This system was used primarily at the squad and platoon level.

responsible for all combat communications. In a glaring deficiency, the training failed to impress upon the officers and NCOs the critical role of proper antenna selection and operating frequency in radio system perfor mance, which often resulted in unnecessary communications failures at critical moments on the battlefield.

Because the initial manpack radios had no communications security ca pability, the NSA substituted paper-based RTO procedures to assure broad cast security over combat radio networks. They included changing station call signs and network radio frequencies on a periodic paper-based sched ule and the use of one-time operational codes (a random letter group sub stituted for a common military phrase) and “authentication tables” (en abling operators to identify valid stations in their radio networks). The NSA delivered pallet loads of Signal Operating Instructions, operations codes and authentication tables to Vietnam and all other commands worldwide very frequently.

The NSA-generated paper procedures, however, were cumbersome, complicated and easily lost. Units, particularly at division level and below, invented their own code systems (often based on distances from easily identi fied landmarks on military maps), seldom changed radio frequencies or station call signs and never assigned new code words to places like firebases, landing zones, base camps, command centers, medical facili ties and other important locations. Key individuals, such as commanders, were given “sexy” code names that sounded super over the radio but were easily identified by enemy forces listening to radio transmissions.

Each division had an attached field company from the Army Security Agency that monitored radio communications and reported violations to unit commanders, but they were mostly ignored by commanders, and sig

Key individuals were given “sexy” code names that sounded super but were easily identified by enemy forces.

nal officers who grew up watching World War II movies on TV and thought their homemade commu nications security systems were great. Throughout the war, many key units never addressed their radio security problems until battlefield losses forced them to do so.

The attitude of commanders at all levels was ex pressed by Col. Sidney Berry, a brigade commander in the 1st Infantry Division, who stated: “It simplifies communications for units and individuals to keep the same radio frequency and particularly call signs. Fre quent changes of call signs confuses friendly forces more effectively then enemy actions.” Unfortunately, Berry was very wrong.

Despite numerous warnings from the NSA, ASA and other intelligence sources that their radio net works were being intercepted and exploited, both U.S. Army Vietnam, a logistics and support organization, and MACV refused to believe the warnings or take any action.

Maj. Gen. Harry Kinnard, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), received a report of 11,000 communications violations during pre-deployment training moni tored by the ASA prior to the division’s departure for Vietnam.

Kinnard dismissively said: “Even if the VC/NVA could intercept our radio communications and understand English well enough to know what a mes sage meant, our actions are so immediate, and our movements so rapid that they would never be able to exploit any information ‘gleaned’ from a radio intercept.” That comment was typical.

Denial of the enemy’s radio intercept capa bilities continued from the first large de ployments in 1965 until the morning of Dec. 20, 1969. A scout from the 1st Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, discovered a long wire antenna on the old Michelin rubber plantation northwest of Saigon. The antenna was connected to a con cealed underground bunker complex packed with radio equipment. The bunker was the operations center for an NVA/VC platoon later identified as Alpha-3, part of the NVA’s 47th Tactical Recon naissance Battalion. After a short fight, 12 Alpha-3 personnel were captured along with all their equipment, training material and, most import ant, their logbooks.

The logbooks were written in perfect English (the language our senior commanders doubted the enemy could understand). This proved be yond a doubt that the communist intercept and exploitation effort been underway since the arriv al of U.S. military advisers in the early 1960s.

Writings in the logbooks revealed that the radio intercept personnel understood the exact meaning of American voice conversations. The 47th Recon naissance Battalion personnel easily deciphered locally generated unit codes and took advantage of infrequent call sign changes and radio frequency adjustments.

Of particular interest, according to the train

There are several painful examples of the impact that intercepted radio signals had on U.S. operations, but perhaps the most notable occurred in the first major encounter between American forces and the North Vietnamese. In mid-November 1965, 500 troopers in UH-1 “Huey” helicopters of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), under the command of Lt. Col. Hal Moore, were dropped into a small landing zone in the Ia Drang Valley in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The landing zone had been named LZ X-Ray. It was common practice to give landing zones identifiers and call signs, most of which didn’t change.

X-Ray was only 15 miles from Plei Me, the base camp of Moore’s parent 3rd Brigade and his source of combat support, but Plei Me was still well outside the reach of the PRC-25-manpack radio (3-7 miles) that was the combat communications heart of the 1st Battalion.

Another problem: X-Ray was near the Chu Pong massif (mountain) dominating the valley at an altitude that enabled U.S. communications during the fight to be easily monitored by both sides. The 1st Cavalry Division did not know that Chu Pong was occupied by a multibattalion North Vietnamese Army/Viet Cong force that included a radio-intercept reconnaissance organization.

Moore did not know that an Army Security Agency detachment at Ple Me would monitor more than 28,000 radio transmissions during the three-day battle that killed 234 Americans and wounded hundreds more in three 1st Cav battalions—Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry; the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry; and the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment.

ing manuals, were communications involving forward air controllers (spotter planes that di rected airstrikes), artillery forward observers (ar tillerymen embedded in infantry units to adjust the fire of artillery batteries), command and con trol leaders, and the civilian press. The press was a great source of immediate operational informa tion throughout the war, which could have easily been prevented. Press reports were not censored in Vietnam, but there could have been a time de lay until the operation was completed.

The captured material confirmed the ASA/ NSA warnings to senior commanders. Alpha-3 logs showed that from the beginning of the war

North Vietnamese personnel were intercepting, analyzing and tactically reacting to news broad casts and information disclosed over military ra dios, such as artillery targets, artillery harassment and fire schedules, ambush site locations, casual ty reports, airstrike warnings, troop positions, radio call sign and frequency changes, unit status reports, and unit plans and operations. The logs also revealed that idle radio operator chatter was a lucrative source of operational information.

The documents also included transcripts of American conversations that were copied down verbatim even though the U.S. personnel trans mitting them assumed they would be incompre

LEFT: A radio repairman with the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) tests a PRC-77 radio transmitter in December 1968. The PRC-77 was an upgrade of the PRC-25 manpack and contained more secure communications equipment.

RIGHT: Officers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade check a map at Vung Tao, near Saigon, with radio equipment visible in their vehicle in July 1965. Unlike the manpacks, vehicles had radio security equipment early in the war.

The enemy monitoring effort revealed the location of LZ X-Ray and the fact that there were only enough helicopters available to lift one company of Moore’s battalion into the landing zone at a time. With that intelligence, the enemy force attacked the first troop lift immediately after landing, isolating platoon-size units and causing heavy casualties. As the rest of the battalion flew in piecemeal, each lift was attacked in turn, resulting in the U.S. force being surrounded and nearly wiped out.

Adding to the battalion’s troubles, the radio tele phone operators, poorly trained at combat arms schools, along with many officers and senior noncom missioned officers, were disclosing all sorts of opera tional information that the enemy intercepted. The offline, paper-based system of codes and authentica tion tables proved too time consuming to be useful and was abandoned.

The only thing that saved the 1st Battalion from destruction was artillery support from surrounding firebases, close-air support and the grit and determina tion of Moore’s troopers. Ironically, the artillery forward observers and the forward air controllers were using virtually the same radio equipment as the infantry, but they were better trained and used the

equipment well.

Thanks to the overwhelming ground and air support and reinforcements from the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, and 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, U.S. forces finally beat back the NVA/VC. They secured LZ X-Ray, though not much more than that. Moore and the battered 1st Battalion were lifted out from X-Ray, but the battle was not over.

The 1st Cavalry Division instructed the remaining battalions (over the intercepted nonsecure radio, of course) to withdraw in column to LZ Columbus a few miles away, where the 2nd Battalion, 5th Cavalry, would be lifted out. The last battalion, the 2nd Battal ion of the 7th Cavalry, would then move a few more miles to LZ Albany, where it would be extracted. All instructions, such as unit order of march, landing zone names/locations, security plans, airlift plans, artillery plans, etc. were again broadcast in the clear and again intercepted by the enemy reconnaissance unit.

The NVA/VC allowed the lift at Columbus to proceed unmolested, thus cutting the U.S. force in half, and then hit the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry, on the trail to LZ Albany so hard that it, along with the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, was out of combat for months to come.

—David M. Fiedler

Frequency range: 30-75.95 MHz

Operating bands: Low, 30-52.95 MHz; High, 5375.95 MHz

Channels: 920 with 50 kHz separation

Signal power: 1.5 watts

Normal range: 3-7 miles Long-range antenna:12-31 miles

Range limitation: line of sight Battery life: two to 20 hours Weight: 23 lbs.

hensible to enemy listeners. Next to the text, ene my analysts wrote the transmission call sign, the unit, identity of the sender, and the position of senders and their locations, along with the analy sis of what the transmission meant.

There is evidence that the 47th Reconnaissance Battalion’s personnel were educated enough to understand the tone and content of intercepted radio traffic as well as the tactics and procedures, so that they could actually predict individual unit actions.

Typical entries would say (written in English): “This is a Company Commander (call sign) telling his Battalion Commander (call sign) that there is an ambush site at (coordinates) to be occupied tonight. This unit is proba bly part of (U.S. unit) known to be op erating in this area.” There were hun dreds of similar entries in the captured logbooks. Of course, after reading this type of a log entry one wonders who ambushed whom that night.

The 47th Reconnaissance Battal ion training materials went into great detail and plainly stated that American units didn’t change call signs or radio frequencies very often. And when they did, some elements of the old network structure were of ten retained so that confused operators who lost contact could transmit the new network infor mation over the air. Knowing this, the 47th could adapt to the new network structures even before they were fully implemented.

The communist training material also ex plained that radio operators who were battalionand brigade-level officers and senior NCOs were often prone to long transmissions that invariably led to disclosure of important operational infor mation. If this was not shocking enough, the training materials showed in detail how extracted information was used against specific U.S. units in their operational area.

The 47th Reconnaissance Battalion’s targets were the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the 1st Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). Other communist reconnaissance battalions no doubt were targeting American units in other opera tional areas.

The NVA and VC managed to profile U.S. units in their area to the degree that they knew not only the U.S. unit opposing them, but also the methods of navigation being used (particularly if it was a landmark-based code) and the weapons, equip ment and modes of transportation. They were im

pressed by the UH-1 “Huey” helicopter and the M113 armored personnel carrier, but not the V-100 armored car used by military police for base and road patrols. The M151 jeep also did not im press them.

Alpha-3’s actual radio intercept hardware wasn’t particularly sophisticated. It was certainly not the product of some super-secret Chinese or Soviet communications laboratory. It consisted mostly of PRC-25 radios captured from Ameri can units and their Vietnamese partners or pur chased through a third party that acquired them in a U.S. foreign military sales program. Obvious ly, those radios were able to receive U.S. radio traf fic since they were American radios. To supplement the captured U.S. ra dios, Alpha-3 had several Chinese R-139 radio receivers and Sony and Panasonic commercial radios modi fied in the field to operate in the U.S. tactical radio frequency band.

Alpha-3 must have had some very good radio engineers in its ranks, since they not only were able to mod ify the commercial equipment but also engineered a way around the critical shortage of BA-4386 radio batteries needed by U.S. forces. Al pha-3 engineers produced the 12 volts direct current required to operate the PRC25 receiver by soldering together common flash light batteries.

The enemy engineers also designed, fabricated and deployed radio antennas that were much more efficient than the standard antennas that came with the PRC-25. This allowed them to stand long distances away from U.S. units, where it was safer. Additionally, the antennas were much more concealable, a critical factor for clandestine intercept operations.

After the capture of Alpha-3 in 1969, the U.S. lack of electronic communications security could no longer be denied. Training levels increased, but never to the point where 100 percent of U.S. radio networks were secure. The NSA did manage to get manpack NESTOR equipment to combat units to secure communications. However, the unit RTO had to then carry the radio and the NESTOR, whose combined weight came to 54 pounds, plus his weapon and personal gear, plus in most units spare batteries and maybe also other communi cations equipment like flares and smoke gre nades. Quite a load for one soldier, so the NESTOR invariably got left behind and the secu

The communist training materials showed in detail how information was used against specific U.S. units.

rity situation did not change. This far-from-ideal situation lasted until 1973 when all U.S. forces were with drawn from Vietnam. Summing it all up, Lt. Gen. Charles Myer, former com mander of the 1st Signal Brigade, the largest Signal Corps unit in Vietnam, said: “All users were more or less aware [after 1969] of their vulnerabilities to enemy intercept, analysis, and decoding and the need for authentication and encoding. The gap between this knowledge and actual practice [in combat units] was im mense and in Vietnam it was an insurmountable problem.” V

David M. Fiedler is retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps who served in Vietnam 1969-70. He graduated from the Pennsylvania Military College in 1968. Fiedler was employed for 37 years as senior Department of the Army civil ian engineer and technical manager. He was also a Reserve officer in the New Jer sey Army National Guard, serving in positions including battalion signal officer, assistant division signal officer and chief of the communications division, New Jer sey State Area Command.

1. Good communications security can save the lives of American troops, and bad communica tions security will cost lives. No one knows how many lives were lost in Vietnam due to poor communications security, but the number is not small and certainly far exceeds the much-talked-about losses due to “friendly fire” and noncom bat related deaths.

2. The U.S. learned the hard way that American forces needed a new family of combat network radios with integrated equip ment security, and in the 1980s and beyond they got them.

3. Unit commanders need better communications security training even today. In Iraq and Afghanistan there were many instances of command ers permitting the use of troop-purchased nonsecure commercial hand-held radios for combat operations.

4. The use of individual identify ing call signs is still with us and needs to be stamped out. Who among us cannot identify Maverick and Goose from Top Gun? Who doesn’t know what POTUS means? It has to stop.

5. Press conferences need to be carefully thought out even today. In Vietnam, the logbooks of the enemy’s Alpha-3 recon naissance unit make many references to information such as unit deployments, unit strengths and ongoing opera tions revealed by monitoring U.S. radio and television commercial broadcasts. President Lyndon B. Johnson himself disclosed on national TV that “today I have ordered the Air Mobile Division [1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile)] to Vietnam.” —David M. Fiedler

Although the communist capture of Saigon on April 30, 1975, is the recognized end of the war, events on other days set in motion reactions that made defeat inevitable. One of those took place in November 1963, when South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem was overthrown in a coup, shown here, and assassinated.

If asked, “When did America lose the Vietnam War?” most re spondents with some knowledge of the war would likely an swer, “April 30, 1975.” That day, North Vietnamese Army tanks crashed through the gates of the Republic of Vietnam’s Presi dential Palace in Saigon and celebrated a communist victory in the Second Indochina War (1955-1975). Certainly, that day was the end of the shooting war. But when exactly did the U.S. and its allies lose their ability to win the war? When did defeat become inevi table in America’s efforts to preserve a democratic South Vietnam in the face of North Vietnam’s relentless, ruthless aggression? The answer to that question is key—determining when America lost reveals how and why the decades-long effort failed.

If asked to pinpoint the date when the U.S. irretrievably lost the war, some historians would suggest the following “usual suspects”:

NOV. 2, 1963 – Those recognizing the importance of political leaders’ influence might single out the day when South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem was killed in a coup. President John F. Kennedy knew of prepa rations for the coup and his administration supported the overthrow of Diem, who was assassinated in the process. Diem’s murder removed the struggling democracy’s “last, best hope,” as some have called Diem, the