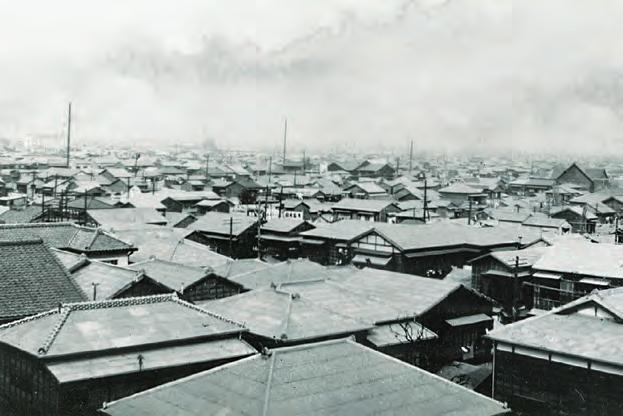

H H H HISTORYNET.COM TURNING THE TABLES ON GERMANY’S U-BOATS TH E DAY THE ENGLISH CHANNEL CAUGHT FIRE AM ERICA’S FORGOTTEN POW MASSACRE Plus FIRESTORM “If we lose,” LeMay confided in an aide, “we’ll be tried as war criminals.” GENERAL CURTIS LEMAY’S BRUTAL BOMBING STRATEGY SET JAPAN ABLAZE WINTER 2023 WW2P-230100-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 9/29/22 6:37 AM

Every once in a while a timepiece comes along that’s so incredibly good looking, masterfully equipped and jaw-droppingly priced, that it stops us stone cold. A watch that can take you seamlessly from the 18th hole to the board room. A watch that blurs the line betweens sports watch and dress watch. We’re talking the Blue Stone Chronograph, and it sits at the top of the discerning gentleman’s watch list.

Striking in appearance and fully equipped with features, this is a watch of substance. The Blue Stone merges the durability of steel with the precision of crystal movement that’s accurate to 0.2 seconds a day. Both an analog and digital watch, the Blue Stone keeps time with pinpoint accuracy in two time zones.

The watch’s handsome steel blue dial seamlessly blends an analog watch face with a stylish digital display. It’s a stopwatch, calendar, and alarm. Plus, the Blue Stone resists water up to 30 meters, making it up for water adventures.

A watch with these features would easily cost you thousands if you shopped big names. But overcharging to justify an inflated brand name makes us blue in the face. Which is why we make superior looking and performing timepieces priced to please. Decades of experience in engineering enables Stauer to put quality on your wrist and keep your money in your pocket.

satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Experience the Blue Stone

If you’re not convinced you got excellence for less, send it back for a refund of the item price.

is running out. Originally priced at $395, the Blue

• Precision movement • Digital and analog timekeeping • LED subdials • Stainless steel crown, caseback & bracelet • Dual time zone feature • Stopwatch • Alarm feature • Calendar: month, day, & date • Water resistant to 3 ATM • Fits wrists 7" to 9" St auer… Affo rd the Extraord ina ry.™ “Blue face watches are on the discerning gentleman’s ‘watch list’.” –watchtime.com

Your

Chronograph for 30 days.

Time

Stone Chronograph was already generating buzz among watch connoisseurs, but with the price slashed to $69, we can’t guarantee this limited-edition timepiece will last. So, call today! 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. BSW396-01 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer Blue Stone Chronograph non-offer code price $395† Offer Code Price $69 + S&P Save $326 You must use the offer code to get our special price. 1-800-333-2045 Your Offer Code: BSW396-01 Please use this code when you order to receive your discount. Rating of A+ Stauer ® † Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. TAKE 83% OFF INSTANTLY! When you use your OFFER CODE “The quality of their watches is equal to many that can go for ten times the price or more.” — Jeff from McKinney, TX Stone Cold Fox So good-looking...heads will turn. So unbelievably-priced...jaws will drop. WW2-221108-010 Stauer Blue Stone Watch.indd 1 10/1/22 1:32 PM

D-DAY TO THE RHINE : A TOUR YOU WON’T FORGET STEPHEN AMBROSE HISTORICAL TOURS PRESENTS Travel with us June 1-13, July 21-August 2, or September 1-13, 2023 Follow along the path where America’s best and brightest fought in WWII as you travel from England to Normandy to the Ardennes on our D-Day to the Rhine Tour. Pay homage to the fallen in Europe and the Pacific on our Operation Overlord, Original Band of Brothers, Iwo Jima, Battle of Britain, Battle of the Bulge, Ghost Army, In Patton’s Footsteps, Italian Campaign, Manhattan Project, Normandy Campaign and Poland and Germany tours. Our WWII, Civil War and American History tours are unrivaled in their historical accuracy! EXPLORE NOW AT STEPHENAMBROSETOURS.COM 1.888.903.3329 The best way to understand history is to study the places it was made. DR. STEPHEN AMBROSE WW2-221108-005 Stephen Ambrose.indd 1 10/1/22 1:40 PM

16 56 WW2P-230100-CONTENTS.indd 2 9/30/22 5:00 PM

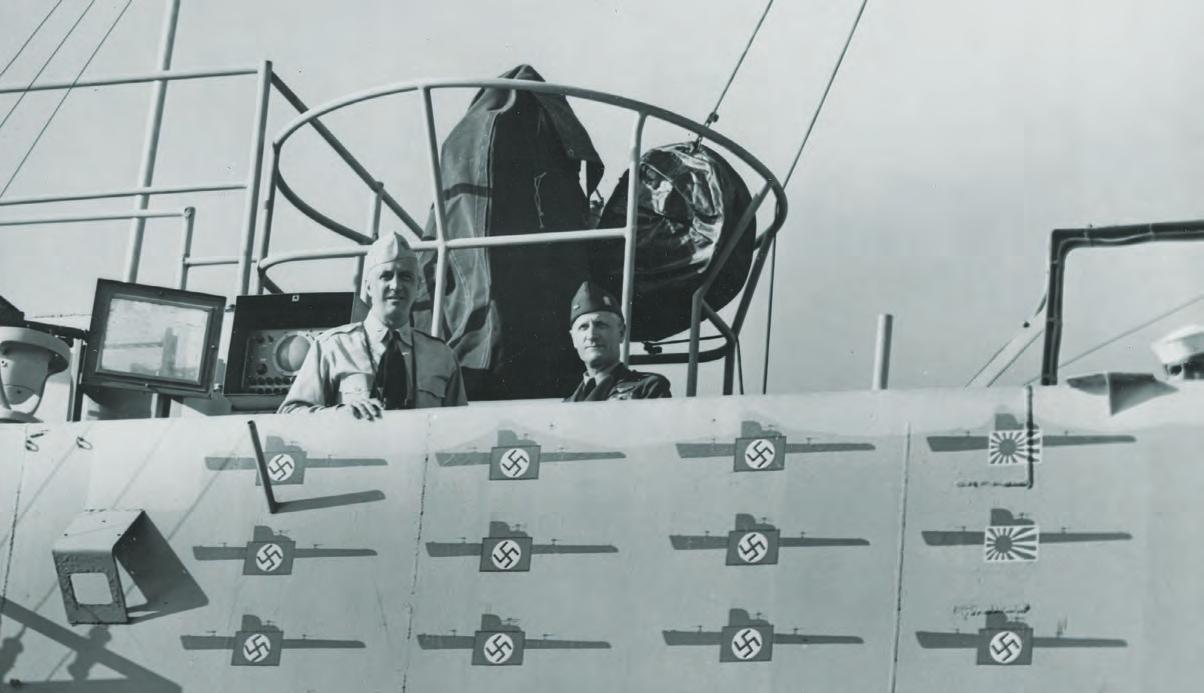

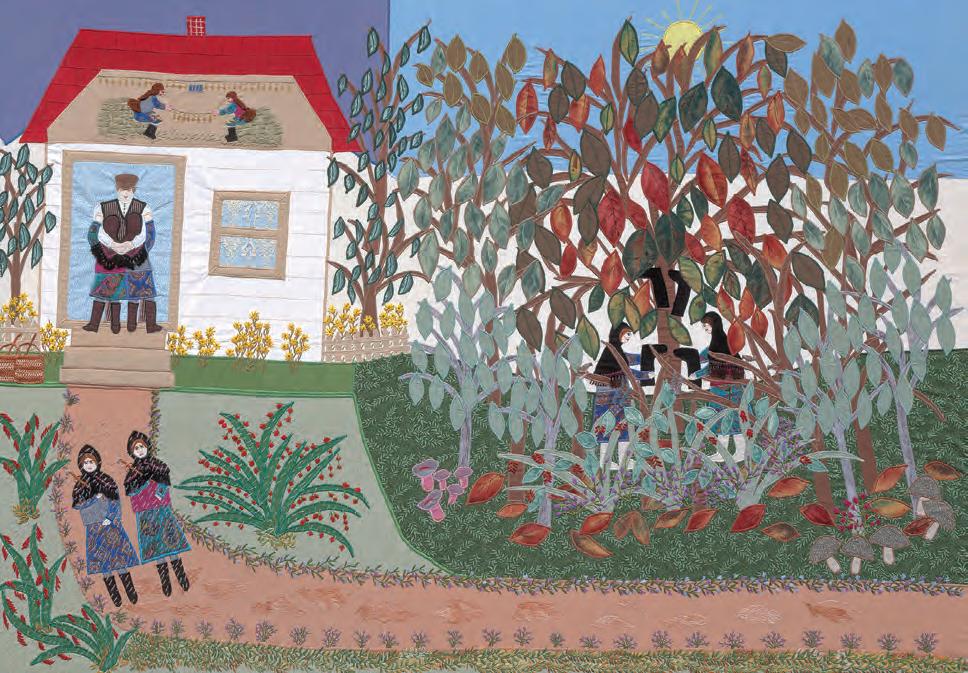

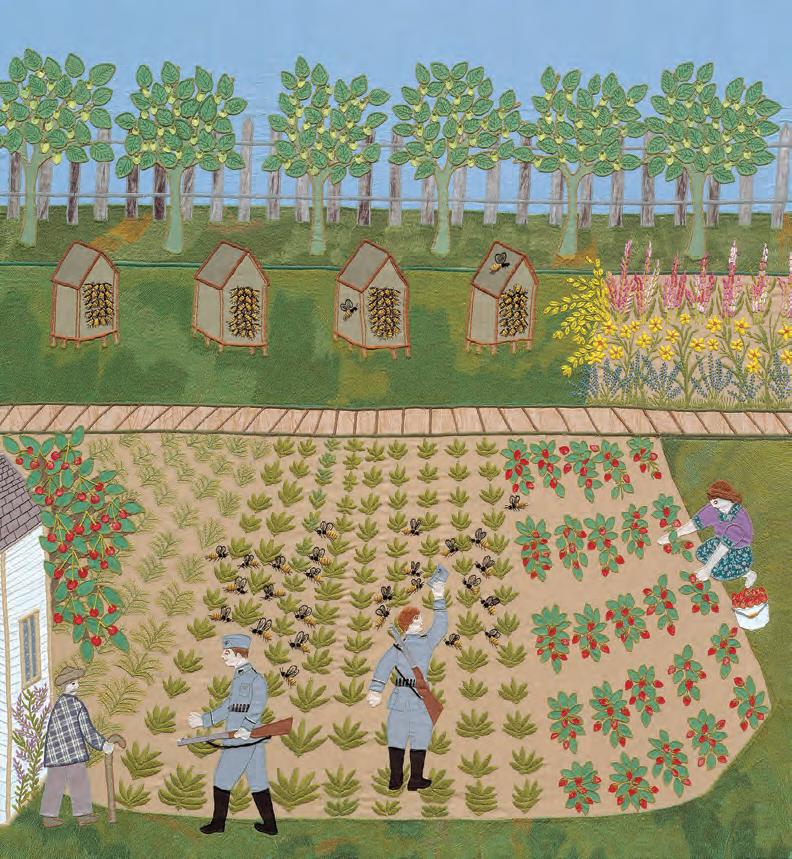

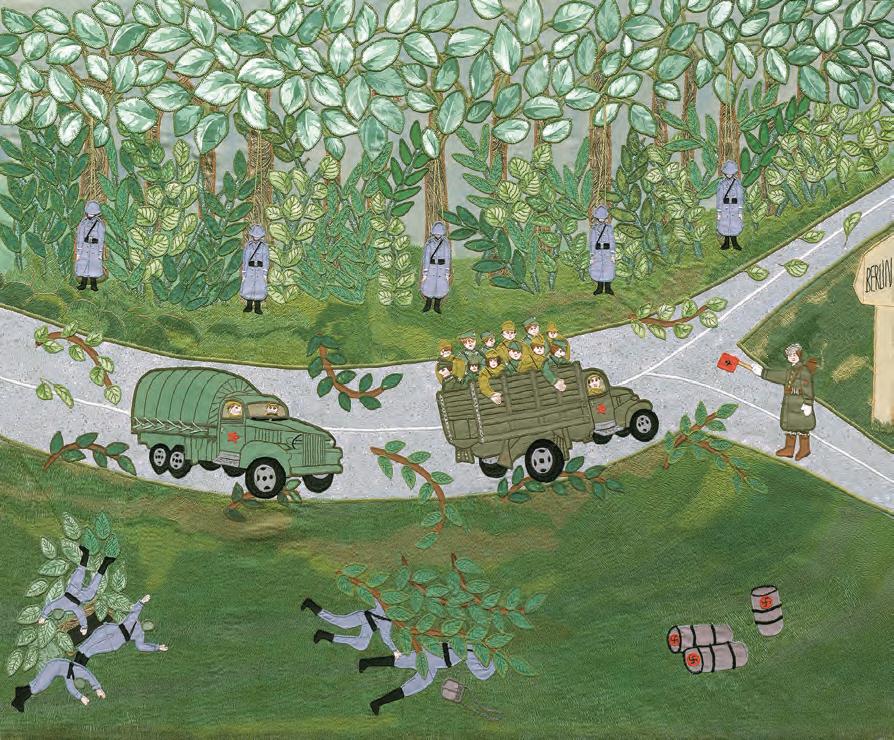

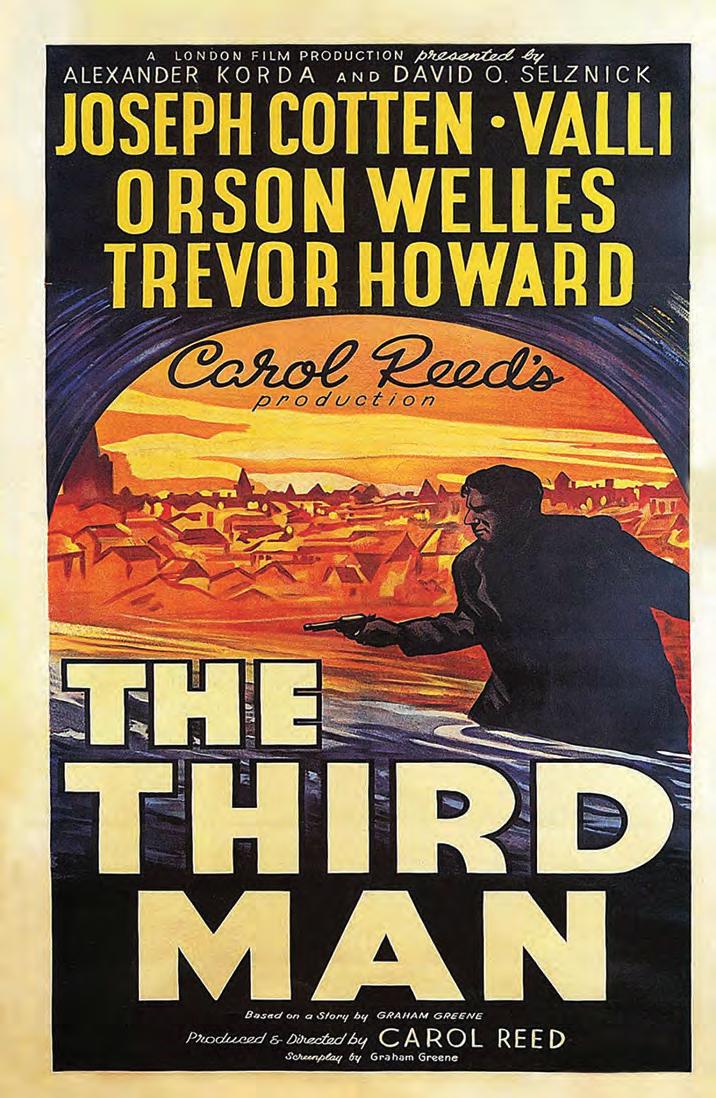

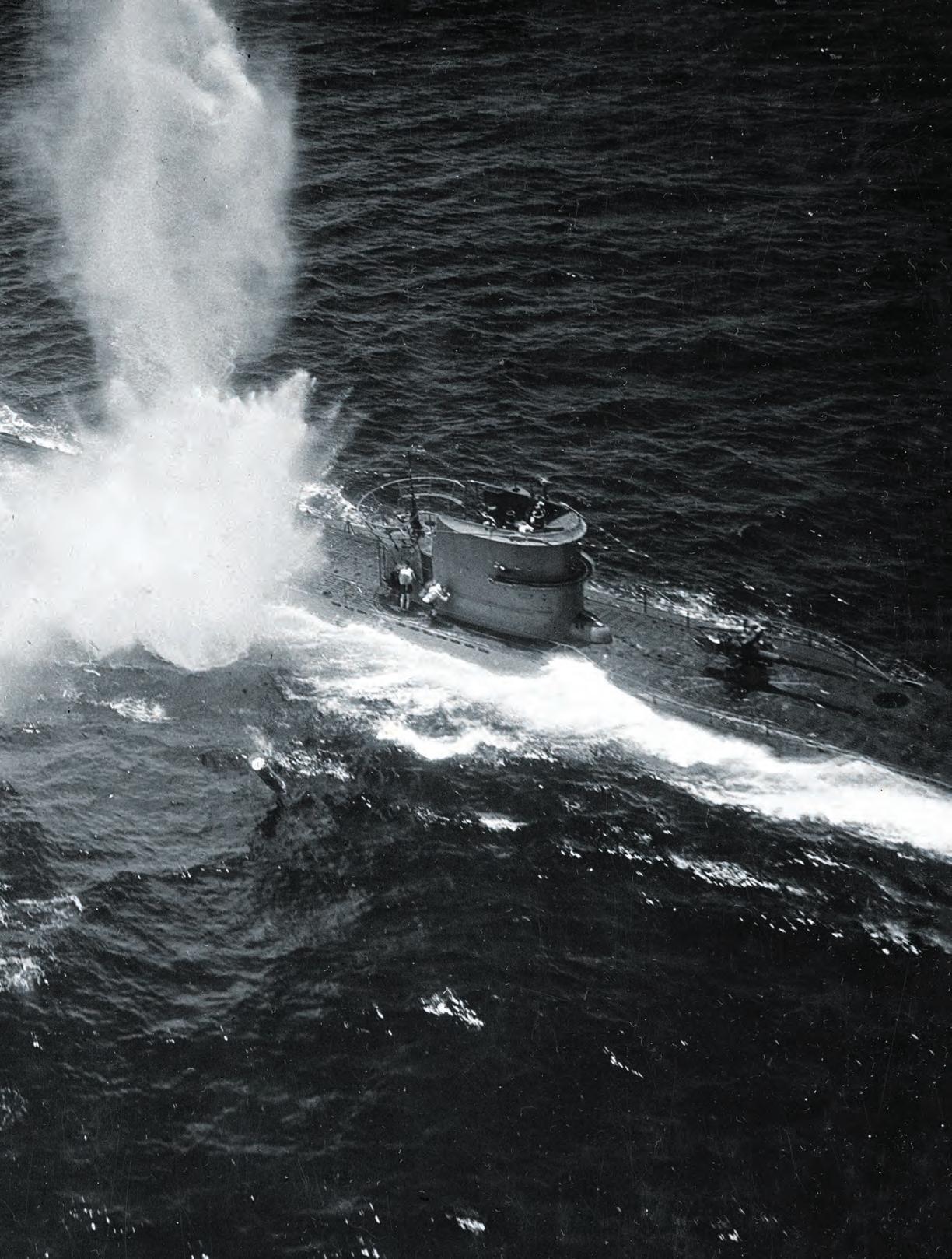

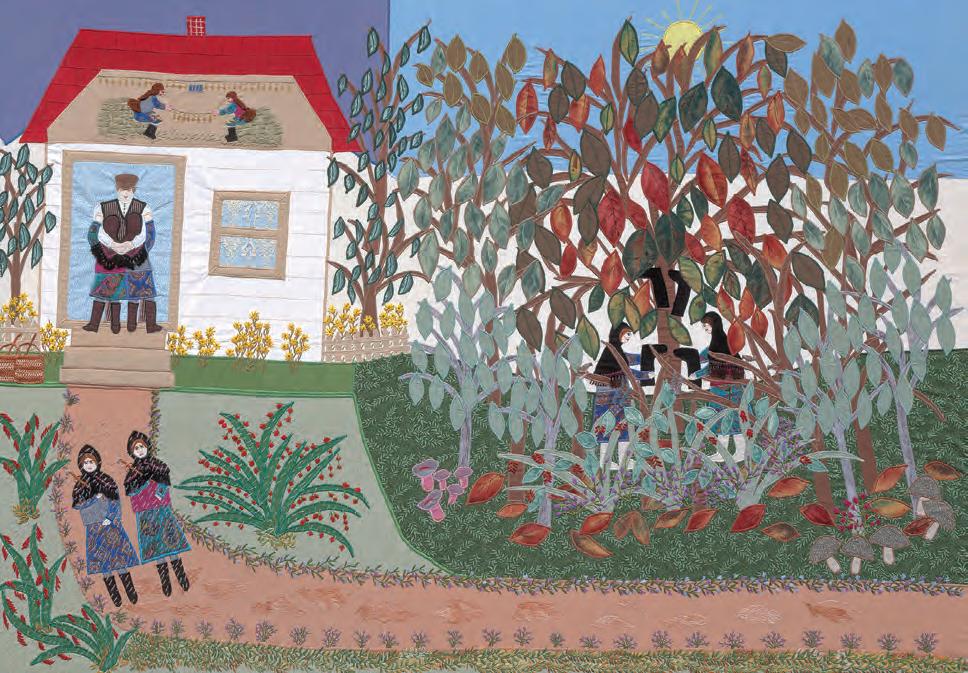

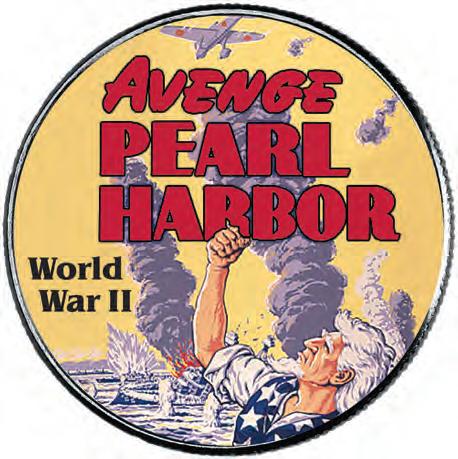

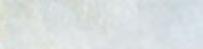

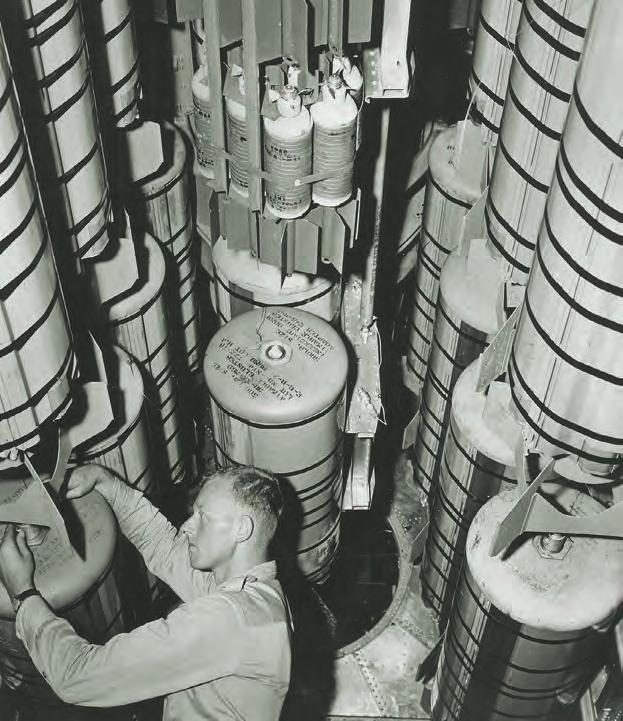

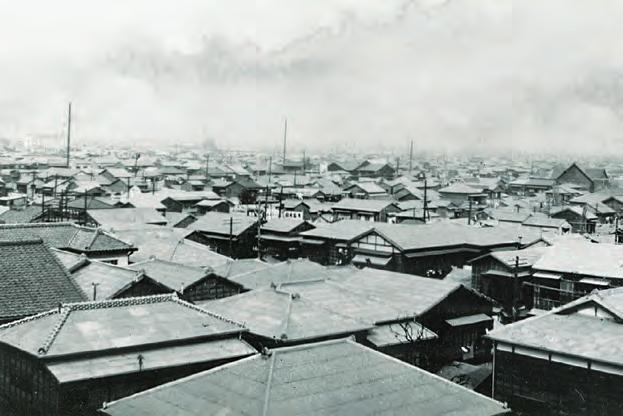

WINTER 2023 3 WINTER 2023 ENDORSED BY THE NATIONAL WORLD WAR II MUSEUM, INC. 12 FEATURES COVER STORY 30 NIGHT TERRORS General Curtis LeMay’s brutal but effective firebombing of Japan changed the course of the war JAMES M. SCOTT 38 BRAIN POWER Decrypted messages and razor-sharp wits helped British and American intel teams win the Battle of the Atlantic DAVID SEARS WEAPONS MANUAL 46 DUCK AND COVER America’s DUKW amphibious truck 48 THE DAY THE SEA CAUGHT FIRE The British relied on flame-based weapons—and a “Big Lie”— to deter a German invasion STEVEN TRENT SMITH PORTFOLIO 56 ON PINS AND NEEDLES A Holocaust survivor recalled the war’s dark days in Poland— a story she told via fabric and thread 62 GOLDEN GIRL Wealthy socialite Mary Jayne Gold bucked first impressions and saved desperate refugees in Vichy France GAVIN MORTIMER DEPARTMENTS 8 MAIL 10 WORLD WAR II TODAY 18 CONVERSATION He survived a deadly kamikaze attack on the USS Bunker Hill 22 FROM THE FOOTLOCKER 24 NEED TO KNOW 26 TRAVEL Memories linger of a G.I.’s massacre of German POWs in Utah 70 REVIEWS The Mosquito Bowl; Ken Burns’s latest; Team America; and more 76 BATTLE FILMS The Third Man delivers an uncomfortable message 79 CHALLENGE 80 FAMILIAR FACE 18 The USS Bunker Hill burns after a kamikaze attack on May 11, 1945, at the Battle of Okinawa. NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND COVER: INCENDIARY BOMBS HIT OSAKA, JAPAN, ON JUNE 1, 1945; NATIONAL ARCHIVES 22 WW2P-230100-CONTENTS.indd 3 9/30/22 5:01 PM

Larry

Kirstin

T.

Brian Walker

A.

Dana B.

Y.

John C.

DESIGN

HERITAGE AUCTIONS

Porges SENIOR EDITOR

Fawcett ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jerry Morelock, Jon Guttman HISTORIANS David

Zabecki CHIEF MILITARY HISTORIAN Paul Wiseman NEWS EDITOR

GROUP

DIRECTOR Melissa

Winn DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Guy Aceto PHOTO EDITOR

Shoaf MANAGING EDITOR, PRINT Michael

Park MANAGING EDITOR, DIGITAL Claire Barrett NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR ADVISORY BOARD Ed Drea, David Glantz, Keith Huxen,

McManus, Williamson Murray CORPORATE Kelly Facer SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS Matt Gross VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES Rob Wilkins DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING Jamie Elliott PRODUCTION DIRECTOR ADVERTISING Morton Greenberg SVP ADVERTISING SALES MGreenberg@mco.com Terry Jenkins REGIONAL SALES MANAGER TJenkins@historynet.com DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING Nancy Forman / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com © 2022 HistoryNet, LLC Subscription Information 800-435-0715 or shop.historynet.com LIST RENTAL INQUIRIES: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. / 914-925-2406 / belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com World War II (ISSN 0898-4204) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 N. Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Vienna, VA and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: send address changes to World War II, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900 Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519 Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001 The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC. PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA VOL. 37, NO. 3 WINTER 2023

Michael A. Reinstein CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at: historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET VISIT HISTORYNET.COM PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday— or any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen—every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way. Weapons & Gear The gadgetry of war—new and old— effective, and not-so effective. If poetic license isn’t something you’re looking for in movies about World War II, here are some top films that tell it like it was. By Mark DePue historynet.com/accurate-ww2-movies

The

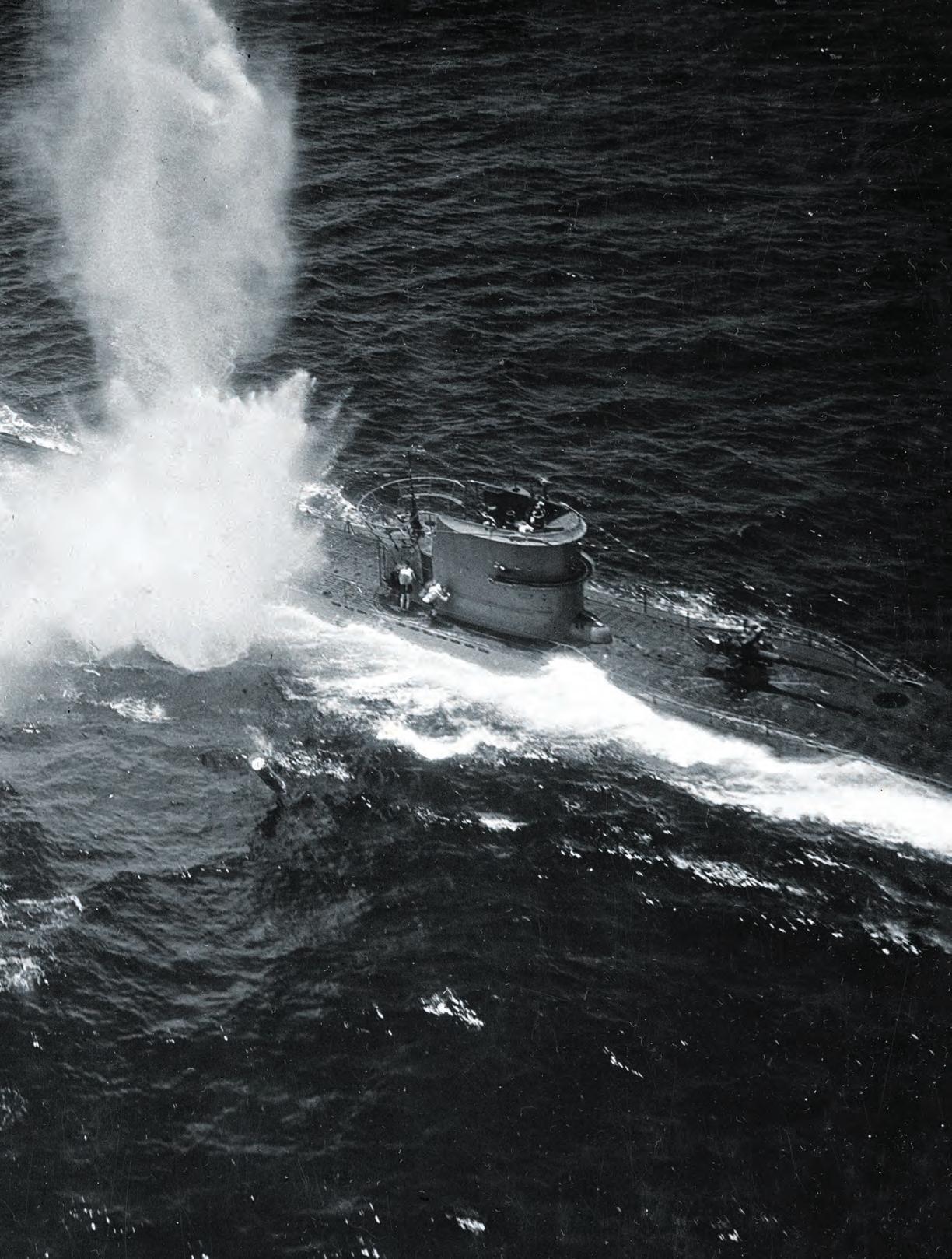

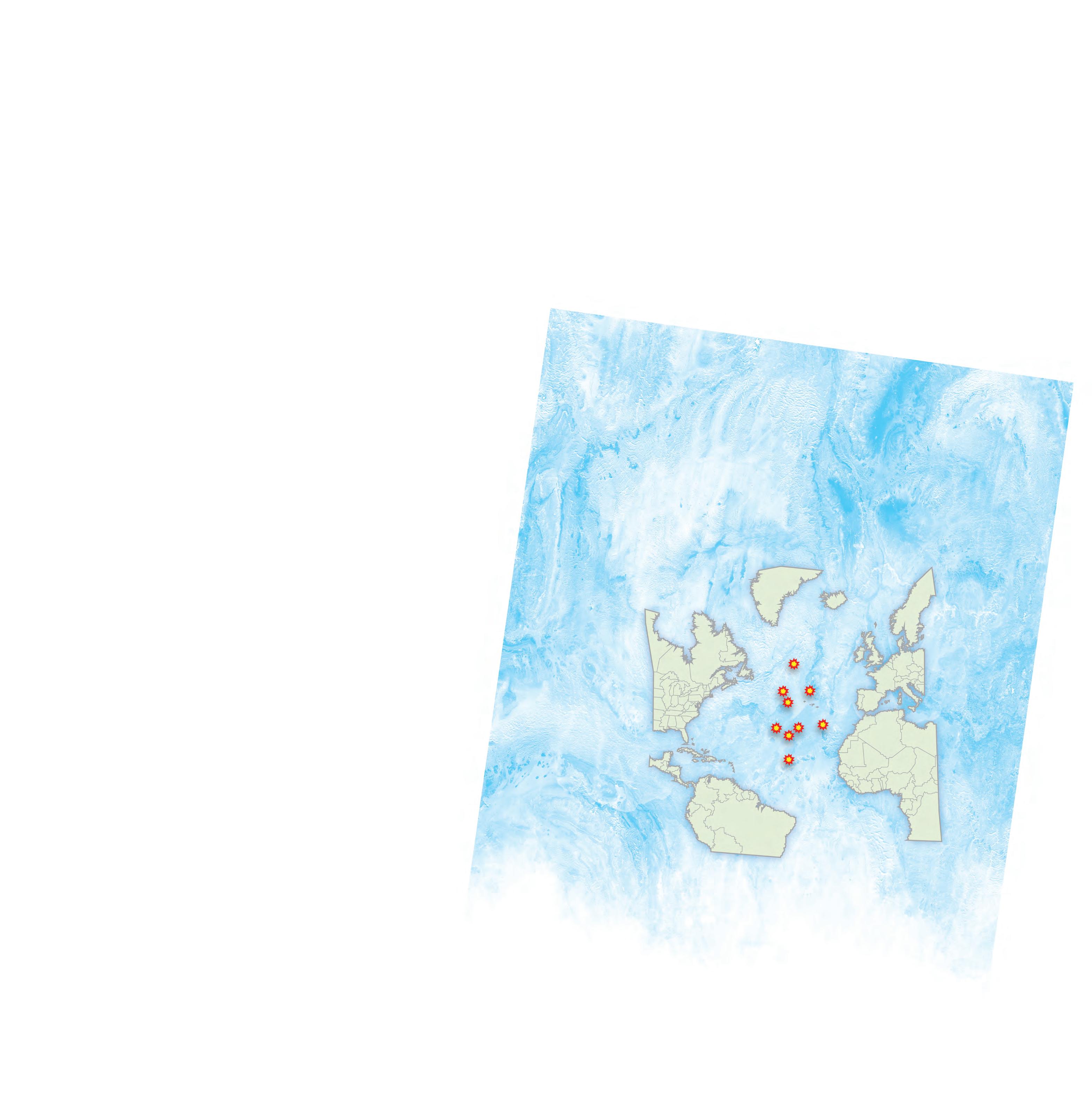

Dam Busters, 1955 10 Accurate WWII Battle Films TRENDING NOW WW2P-230100-MASTOLINE.indd 4 10/5/22 3:52 PM

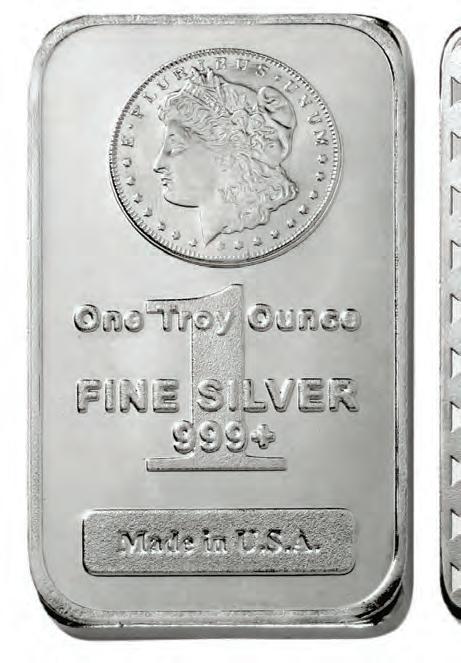

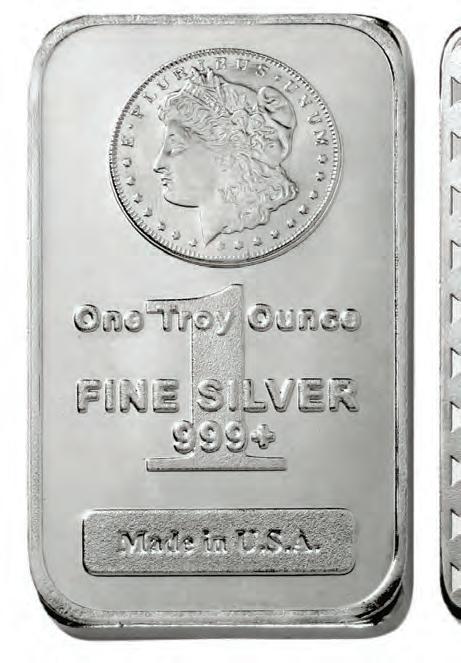

Notonly are these hefty bars one full Troy ounce of real, .999 precious silver, they’re also beautiful, featuring the crisp image of a Morgan Silver Dollar struck onto the surface. That collectible image adds interest and makes these Silver Bars even more desirable. Minted in the U.S.A. from shimmering American silver, these one-ounce 99.9% fine silver bars are a great alternative to one-ounce silver coins or rounds. Plus, they offer great savings compared to other bullion options like one-ounce sovereign silver coins. Take advantage of our special offer for new customers only and save $5.00 off our regular prices.

Morgan Silver Dollars Are Among the Most Iconic Coins in U.S. History

What makes them iconic? The Morgan Silver Dollar is the legendary coin that built the Wild West. It exemplifies the American spirit like few other coins, and was created using silver mined from the famous Comstock Lode in Nevada. In fact, when travelers approached the mountains around the boomtown of Virginia City, Nevada in the 1850s, they were startled to see the hills shining in the sunlight like a mirror. A mirage caused by weary eyes?

No, rather the effect came from tiny flecks of silver glinting in the sun.

A Special Way for You to Stock Up on Precious Silver

While no one can predict the future value of silver in an uncertain economy, many Americans are rushing to get their hands on as much silver as possible, putting it away for themselves and their loved ones. You’ll enjoy owning these Silver Bars. They’re tangible. They feel good when you hold them, You’ll relish the design and thinking about all it represents. These Morgan Design One-Ounce Bars make appreciated gifts for birthdays, anniversaries and graduations, creating a legacy sure to be cherished for a lifetime.

Order More and SAVE

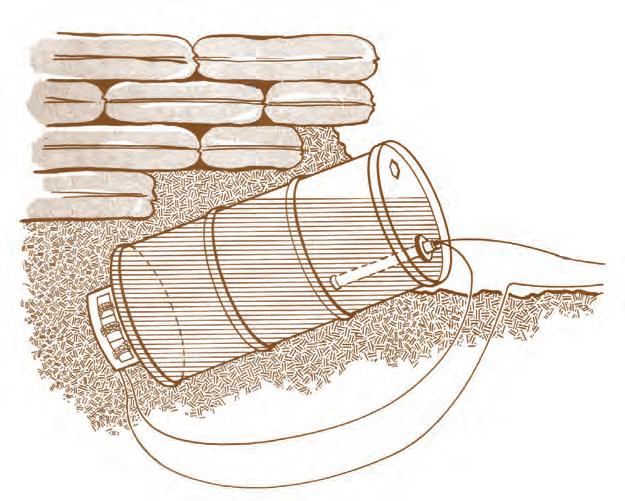

You can save $5.00 off our regular price

buy now. There is a limit of 25 Bars per customer, which means with

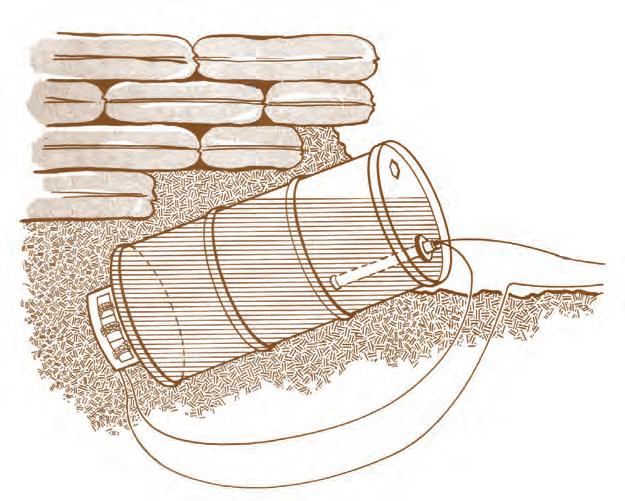

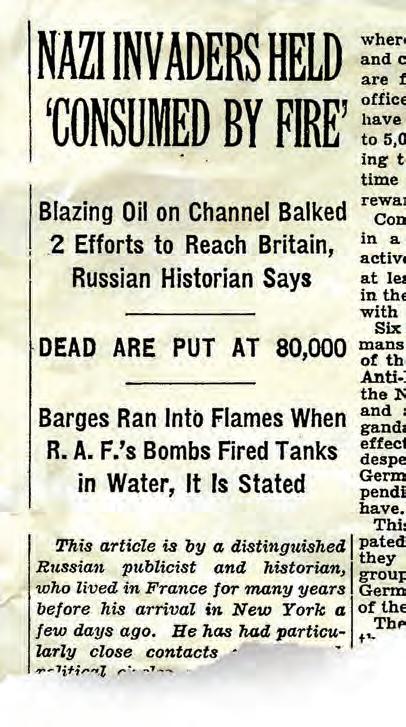

GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. MSB184-01, Eagan, MN 55121

when you

this special offer, you can save up to $125. Hurry. Secure Yours Now! Call right now to secure your .999 fine silver Morgan Design One-Ounce Silver Bars. You’ll be glad you did. One-Ounce Silver Morgan Design Bar $49.95 ea. Special o er - $44.95 ea. +s/h SAVE $5 - $125 Limit of 25 bars per customer Free Morgan Silver Dollar with every order over $499 (A $59.95 value!) FREE SHIPPING over $149! Limited time only. Product total over $149 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases. For fastest service call today toll-free 1-888-201-7144 Offer Code MSB184-01 Please mention this code when you call. SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER Fill Your Vault with Morgan Silver Bars GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not a liated with the U.S. government. e collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, gures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change signi cantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint. com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. Actual size is 30.6 x 50.4 mm 99.9% Fine Silver Bars Grab Your Piece of America’s Silver Legacy BUY MORE SAVE MORE! BUY MORE SAVE MORE! BUY MORE SAVE MORE! A+ WW2-221108-014 GovMint Morgan Silver Bars.indd 1 10/1/22 1:33 PM

MORTIMER

CONTRIBUTORS

JAMES M. SCOTT (“Night Terrors”) is a former Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, and the author most recently of Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Fire bombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb, from which our cover article is adapted. His previous books include 2018’s Rampage, which was named one of the best books of the year by editors at Amazon, Kirkus, and Military Times; and Target Tokyo, a 2016 Pulitzer Prize finalist in history. Other works include The War Below (2013) and The Attack on the Liberty (2009), which won the Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Excellence in Naval Literature. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina, with his wife and two children.

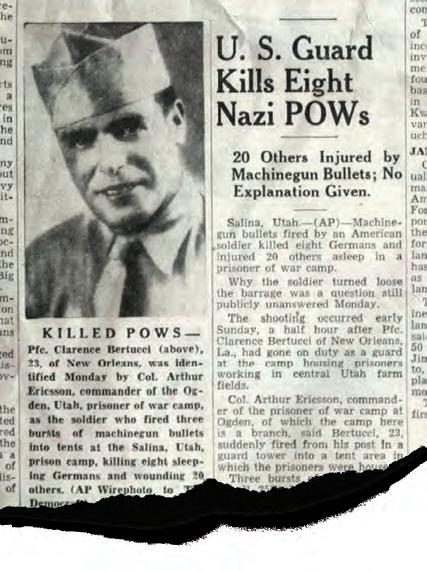

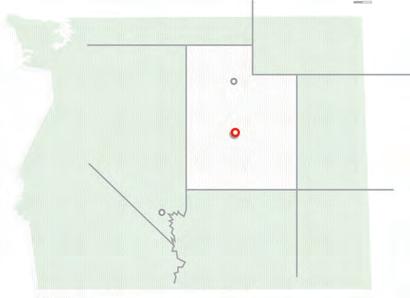

JESSICA WAMBACH BROWN (“A Tragic Night in Utah”) travels across the nation from her home base in northwest Montana to write about the unusual wartime histories of home-front communities. Searching for an excuse to cycle in southern Utah, she happened upon this issue’s “Travel” destination, the city of Salina, where a rogue guard opened fire on a camp of sleeping German prisoners two months after the war in Europe’s end.

GAVIN MORTIMER (“Golden Girl”), a British writer who lives in Paris, is the author of more than 25 books. While researching the history of the British Army’s elite Special Air Service Regiment, he learned of SAS member and gangster Raymond Couraud; his girl friend, the enigmatic American heiress Mary Jayne Gold; and their wartime adventures in Vichy France.

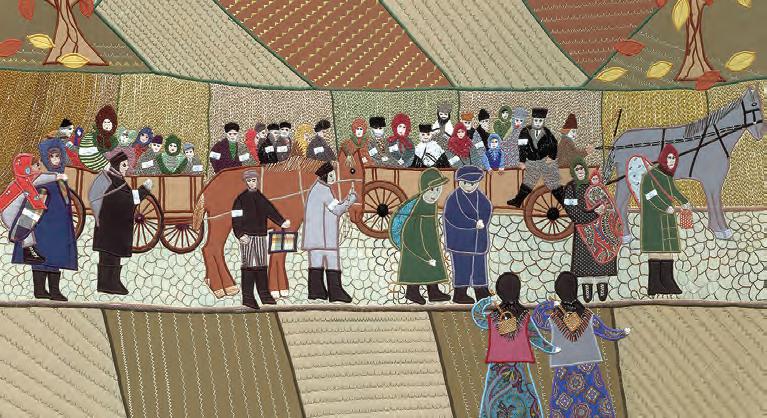

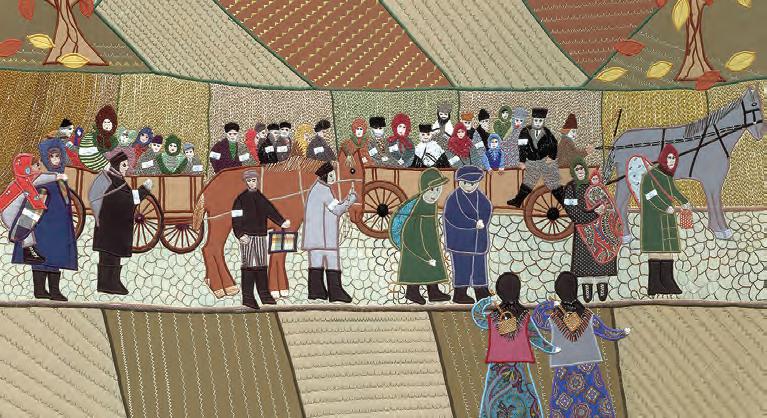

DAVID SEARS (“Brain Power”) is a New Jersey-based military history writer and frequent World War II contributor. His latest book, Duel in the Deep, about a U.S. Navy destroyer in the Battle of the Atlantic, is slated for publication in August 2023; for this issue he remained on theme, writing about the British and American intelligence teams whose combined efforts helped vanquish the Kriegsmarine.

STEVEN TRENT SMITH (“The Day the Sea Caught Fire”) is a five-time Emmy Award-winning TV photo journalist. He became inspired to learn more about Britain’s fire-based weapons after watching the BBC documentary series Coast, which looked at the devel opment of World War II’s flame barrage system. Smith is the author of two books, The Rescue (2001) and Wolf Pack (2003), both about the submarine war in the Pacific. He lives in northwest Montana, in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains.

WORLD WAR II6 PORTRAITS BY JOHANNA GOODMAN

SEARS

COVER STORY SCOTT

BROWN

SMITH

WW2P-230100-CONTRIB.indd 6 9/30/22 5:06 PM

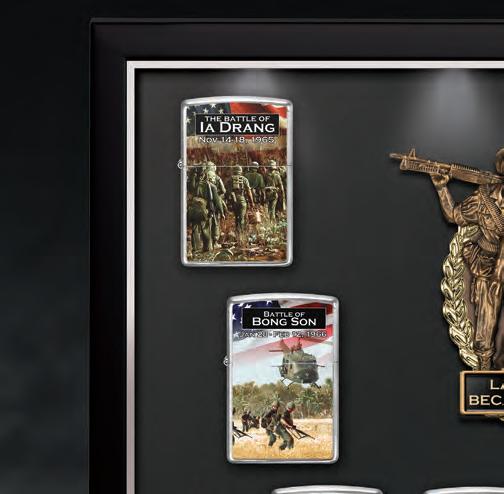

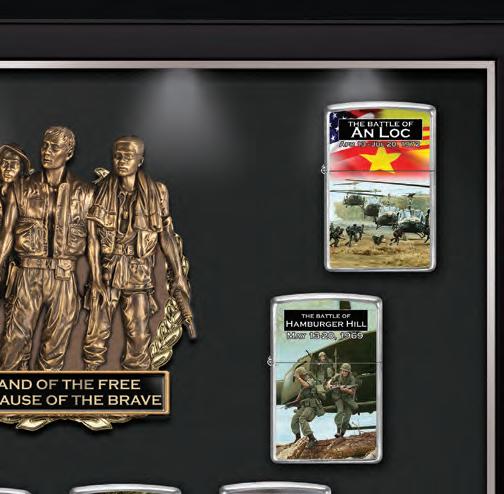

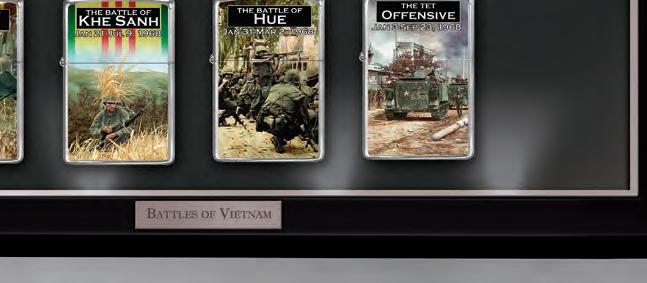

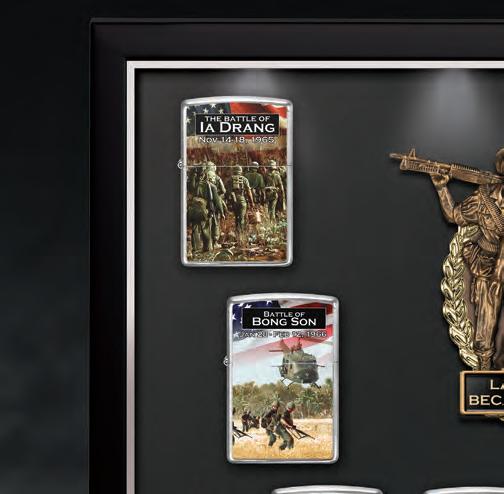

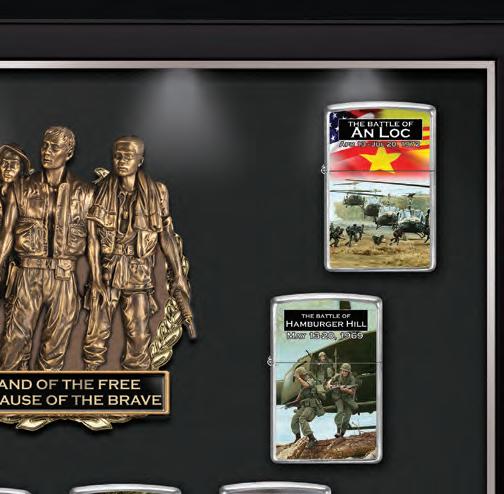

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service Greatest Battles of Vietnam Zippo® Lighter Collection Salute the exemplary men and women who served and sacrificed in Vietnam with the Greatest Battles of Vietnam Zippo® Lighter Collection. Gleaming with the Zippo Chrome finish, these genuine Zippo® windproof lighters feature different iconic images recalling critical battles in the Vietnam conflict. The collection includes a lighted display crowned with a sculptural centerpiece inspired by “The Three Servicemen” Vietnam memorial statue in Washington, D.C. A $100 value, the custom display is yours for the price of asingle lighter. Commemorating Heroism in the Foxholes ,“ZIPPO”, , and are registered trademarks in the United lighter decorations are protected by copyright. © 2022 Zippo® Manufacturing Company Actual size 13" wide x 9¾" high. Display your collection on a tabletop or wall. Mounting hardware included. Display made in China. Lighters ship unfilled; lighter fluid not included. single ORDER TODAY AT BRADFORDEXCHANGE.COM/922998 ©2022 BGE 01-34538-001-BDR Distinctive bottom stamp authenticates this collectible as a genuine Zippo® windproof lighter Premiere Edition “The Battle of Khe Sanh” begins the Greatest Battles of Vietnam Zippo® Lighter Collection and you can order it now at $49.99 per edition, payable in two installments of $24.99 (plus a total of $10.99 shipping and service each, including the $100-value display*). Send no money now. Three Servicemen statue @ 1984 F. Hart and VVMF STRICTLY LIMITED TO 5,000 COMPLETE COLLECTIONS! Risk-Free Subscription Plan. This is the convenient, risk free auto-renewal plan. You will be charged with each future shipment, about once a month, at the same low price stated above. This continues until you cancel or the collection is complete. You are under no obligation and may cancel at any time. You may also return any item free of charge for a full refund. *See bradfordexchange.com. Display will be shipped after second lighter. Limitededition presentation restricted to 5,000 complete collections. Please allow 4-6 weeks for delivery of Edition One. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. YES. Please accept my order for the Greatest Battles of Vietnam Zippo® Lighter Collection as described. I need send no money now. I will be billed with shipment. By sending this form, I accept the Risk Free Subscription Plan stated at left. Where Passion Becomes Art PLEASE RESPOND PROMPTLY SEND NO MONEY NOW The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Ave., Niles, IL 60714-1393 Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email (optional) 922998-E57391 WW2-221108-009 Bradford Vietnam Zipo Lighter CLIPPABLE.indd 1 10/1/22 12:50 PM

I READ WITH PRIDE the Autumn 2022 article “4,415 Souls and Counting” by John D. Long describing the National D-Day Memori al’s efforts to calculate how many died in the invasion. From 2012 to 2014 I served as the commander of Air Force Mortuary Affairs Oper ations at Dover Air Force Base, providing dignity, honor, and respect to our nation’s combat-fallen. In addition to supporting our nation’s present-day fallen, our operation was charged with reuniting fallen Americans from previous conflicts—from World War II to Korea to Vietnam—with their families. My time at Dover was, and remains, special to me, and we as a nation should be proud of the work being done by the National D-Day Memorial as well as the ongoing efforts to identify and reunite our nation’s fallen with their families led by the Department of Defense and our individual services.

John Devillier

John Devillier

Dayton, Ohio

FAREWELL SALUTES

Now approaching 80, I have been a serious student of World War II since the third grade. (My dad served as a staff sergeant in the 1478th Engineer Maintenance Company. We were blessed to get him back healthy and whole in 1946.) It’s a very rare occasion that I write any message to an editor, but I felt the need to reach out to Karen Jensen, who served as World War II ’s editor in chief for more than a decade and announced her retirement in the August issue. I wanted to extend my thanks for a job well done, by you and your staff, and for all your efforts in producing a superb magazine. Please let me wish you good health and happiness in your years to come, and continued success in whatever you choose to do.

Thomas S. Griffin Jr.

Darien, Conn.

AS A LONGTIME print subscriber, I wanted to tell you I appreciate HistoryNet’s recently revamped webpage, historynet.com. Thank you for the upgrade—and best wishes to Karen Jensen as she leaves her work. Much obliged for the years of great reading you provided your loyal readers, Karen.

Richard Dinges

Oregon City, Ore.

PAINFUL PROGRESS

When I read Sergeant Lafayette “War Daddy” Pool’s story (“Always Forward”) i n the Autumn 2022 issue and learned that he had had his right leg amputated. I was reminded of Ted Lawson’s loss of his left leg in China, as chronicled in his 1943 book about the Doolit tle Raid, T hirty Seconds Over Tokyo. I own sev eral editions, including the latest published in 2002 by his wife, Ellen. In it Lawson writes that the Medical Corps had ruled, after study ing his case, that there needed to be proce dural changes in leg amputations to allow the amputee’s leg stump to better adapt to a pros thesis. This deficiency was especially pro nounced in Lawson’s case because Lieutenant Dr. Thomas Robert White, who went along on the Doolittle Raid as a crewman in one of the B-25s, with the assistance of the Chinese doc tors, had had little time to accomplish the

WORLD WAR II8 U.S. AIR FORCE/JASON MINTO HISTORYNET ARCHIVES (BOTH)

MAIL

Swathed in flags, transfer cases containing combat-fallen servicemembers await transfer at Dover Air Force Base.

NUMBERING THE STARS WW2P-230100-MAIL.indd 8 10/3/22 7:17 PM

amputation as they were fleeing the Japanese.

I will bet that Sergeant Pool, and perhaps many others, benefited from Lawson’s sur gery and rehabilitation trials. Perhaps some one can shed more light on this small part of history where one man’s travails directly ben efited those who came after him.

Paul Butterworth

Paul Butterworth

Newnan, Ga.

CRACKING A MYSTERY?

I enjoyed Jessica Wambach Brown’s Autumn 2022 “Travel” article, “Bombers in the Big Sky,” on Montana’s Cut Bank Army Airfield. I may have discovered the reason for its unex plained closure in October 1943. According to Richard E. Osborne’s 1996 book World War II Sites in the United States: A Tour Guide and Directory, the airport “had a serious problem in that the runways began to deteriorate soon after construction,” as their concrete, poured during the winter, cracked amid the spring thaw. The runways were later mended, and Cut Bank Army Airfield was used as a transit base for fighters and light bombers (instead of heavy B-17s) until the war’s end, after which the site became a regional airport.

Ralph Larson

San Antonio, Tex.

HELPING HANDS

I would like to thank World War II for being one of the first national-level publications to

cover Stories Behind the Stars, the non profit initiative to collect the stories of all of America’s 421,000 World War II fallen into one common database accessible via smartphone app at any gravesite or memo rial. “World War II Today” reporter Paul Wiseman’s article on our organization in the December 2020 issue and his followup piece in December 2021 helped us attract many volunteers.

We have completed 20,000 stories, but we still have 401,000 to go. You can read any of them at fold3.com/partner/storiesbehind-the-stars.

Don Milne Louisville, Ky.

FULL CIRCLE

I am the son of G. W. Benedict, the Pacific navy officer whose wartime-era ID bracelet was discovered decades ago in Europe by infantryman Paul Balkin; his son-in-law, Henry Kliman, submitted a photo to your publication’s October 2021 “From the Footlocker” column hoping to learn more about its owner.

It is with great humility a nd gratitude that I say thanks to three very special people who ultimately helped return the bracelet to me: Kliman, who wrote to World War II knowing he had something special; editor Karen Jensen, for continuing to ask questions; and finally, writer Paul Wiseman, for assimilat ing these details into a tale of human kindness. I appreciate your efforts to tell the stories of the men and women who served their country and protected democracy for all.

Bene “Lynn” Benedict Alto, Mich.

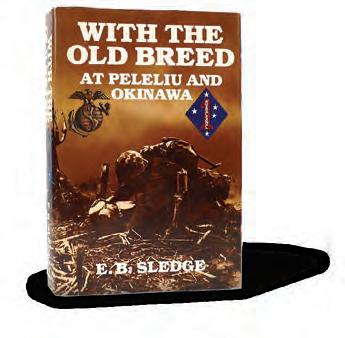

GIVING THANKS TO THE NEW BREED

I’m a retired pharmacist who was once a grunt with Patton. It was an absolute pleasure to read Henry Sledge’s Autumn 2022 article, “When Things Get Tough,” on his father Eugene Sledge’s seminal 1981 book, With the Old Breed. I own over a hundred books on World War II and have read them all. Henry, your dad’s book is at the very top of the list.

Ronald P. Gros Metairie, La.

FROM THE EDITOR

I’m writing this on the morning of the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, the princess who served as a military driver and auto mechanic during World War II…before going on to rule Britannia for seven decades.

Elizabeth’s service reminded me of the many types of people, from all walks of life, it took to win the war. In this issue we feature several: Curtis LeMay, the steel-mill work ing son of an itinerant father who went on to lead the brutal but effective bombing campaign of Japan; Mary Jayne Gold, a wealthy socialite who could have fled wartime France but instead stayed behind to aid desperate refugees; and two intelligence offi cers with serious medical issues, one in England and one in the United States, who utilized brain power over physical strength to defeat the Kriegsmarine in the Atlantic.

It takes all types. Luckily, all types answered the call.

—Larry Porges

PLEASE SEND

Please include your name, address, and daytime telephone number.

@WorldWarIImag

WINTER 2023 9 U.S. AIR FORCE/JASON MINTO HISTORYNET ARCHIVES (BOTH)

LETTERS TO: worldwar2@historynet.com

Ted Lawson

WW2P-230100-MAIL.indd 9 10/5/22 3:35 PM

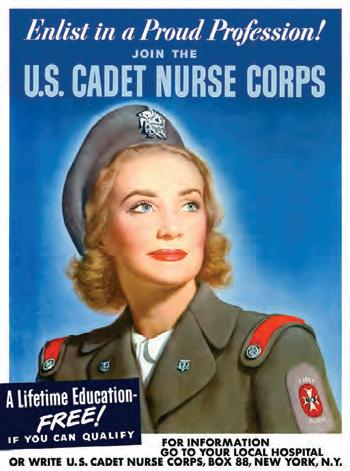

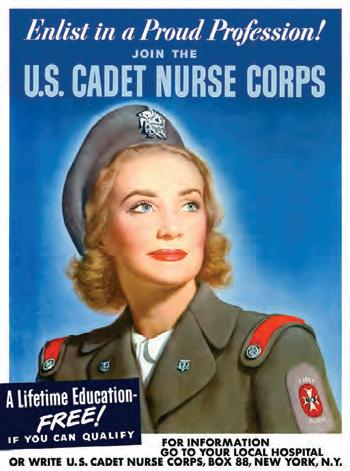

The 124,000 women who entered the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps addressed a critical wartime nursing shortage. Several in Congress are trying to belatedly

work.

THEY SIGNED UP IN DROVES because a nation at war was desperate for nurses. In 1943, Congress created the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps, promising young women a free education and a career in nursing. Two years later, they were providing 80 percent of the nursing care in American hospitals. But after the war the corps was disbanded, and the women’s contributions were largely forgotten.

“I was a nurse for 50 years, and I just found out about them in 2018,” said Barbara Poremba, professor emeritus of nursing at Salem State University in Massachusetts. “I was pretty shocked.” She was also outraged: the cadets

GENE LESTER/GETTY IMAGES; INSET: JOHN PARROT/STOCKTREK IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES COURTESY OF JEFFREY REASE WORLD WAR II10

recognize their

WWII TODAY REPORTED AND WRITTEN BY PAUL WISEMAN

PUSH APACE TO RECOGNIZE WARTIME NURSES WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 10 9/30/22 5:04 PM

received no postwar benefits and couldn’t even call themselves veterans. She formed a group, Friends of the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps WWII 1943-1948, and started a push—backed by Representative Cheri Bustos (D-Ill.), Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), and other lawmakers—to pass legislation giving the Cadets honorary vet eran status. The honor wouldn’t come with any retirement or medical perks. “They don’t want benefits,” Poremba said. “They just want recognition.”

The United States had a nursing shortage even before it joined the war. Then veteran nurses were sent to Europe and the Pacific, and hospitals on the home front scrambled for help. The government tried advertising campaigns—“They were trying to grab them before they became Rosie the Riv eter,” Poremba said—and even considered drafting nurses.

Finally, it settled for the nursing corps, which took women as young as 17: 179,000 enrolled, and 124,000 graduated from nursing training programs for domestic service. They signed up for the duration of the war and wore military-style uniforms— two sets: summer and winter—but had to provide their own mandatory white hosiery and shoes. They earned from $15 to $30 a month and received room and board.

The corps was pathbreaking: it was the first uniformed service to be integrated, accepting Black and Native American women, and even Japanese American women from wartime internment camps. It led to the standardization of nurse train ing, and its veterans formed the core of American nursing after the war. “The cadet nurses are really pioneers of modern nurs ing. They changed everything,” Poremba said, adding that during the war, “they were credited with preventing a total collapse of the hospital system.”

Still, the legislation to grant them honor ary veteran status—which would cost the government virtually nothing—has stalled in a divided Congress. Twice it was inserted into and then stripped out of massive defense spending bills. Poremba says time is running out, as the surviving cadets are in their nineties or older. She noted, “We thought it was a slam dunk like, duh: why would you deny some great-grandmothers their final wishes?”

KEEPING WWII MEMORIES ALIVE

ARMY RANGERS DESTROYED German gun emplacements at Omaha Beach on D-Day and freed hundreds of Allied prison ers from a Japanese POW camp in the Philippines. In all, 7,000 Americans served as Rangers during World War II. Only 12 survive, President Joe Biden noted on June 7, 2022, as he joined Congress in honoring the elite force with the Congressional Gold Medal.

Three weeks later, the last surviving Medal of Honor recipi ent from World War II—Hershel “Woody” Williams, who braved machine gun fire to attack Japanese pillboxes on Iwo Jima with a flamethrower—died at a veterans’ hospital in West Virginia at age 98. His remains lay in honor at the U.S. Capitol on July 14.

These separate news items provided a stark reminder that the World War II generation is vanishing. Even the youngest wartime vets are now in their nineties. The National WW2 Museum in New Orleans says that only 240,000 of 16 million veterans of the war were still alive as of September 2021 and that 234 are dying daily. “Every day,” the museum notes on its website, “memories of World War II—its sights and sounds, its terrors and triumphs—disappear.”

Volunteers are working hard to make sure the veterans are not forgotten. As a ponytailed California teenager, Rishi Sharma, the son of immigrants from India, embarked on a cam paign to record interviews with combat veterans of the war (“World War II Today,” April 2017). Now, more than five years later, his “Remember WWII” nonprofit (rememberww2.org) has completed 1,500 interviews.

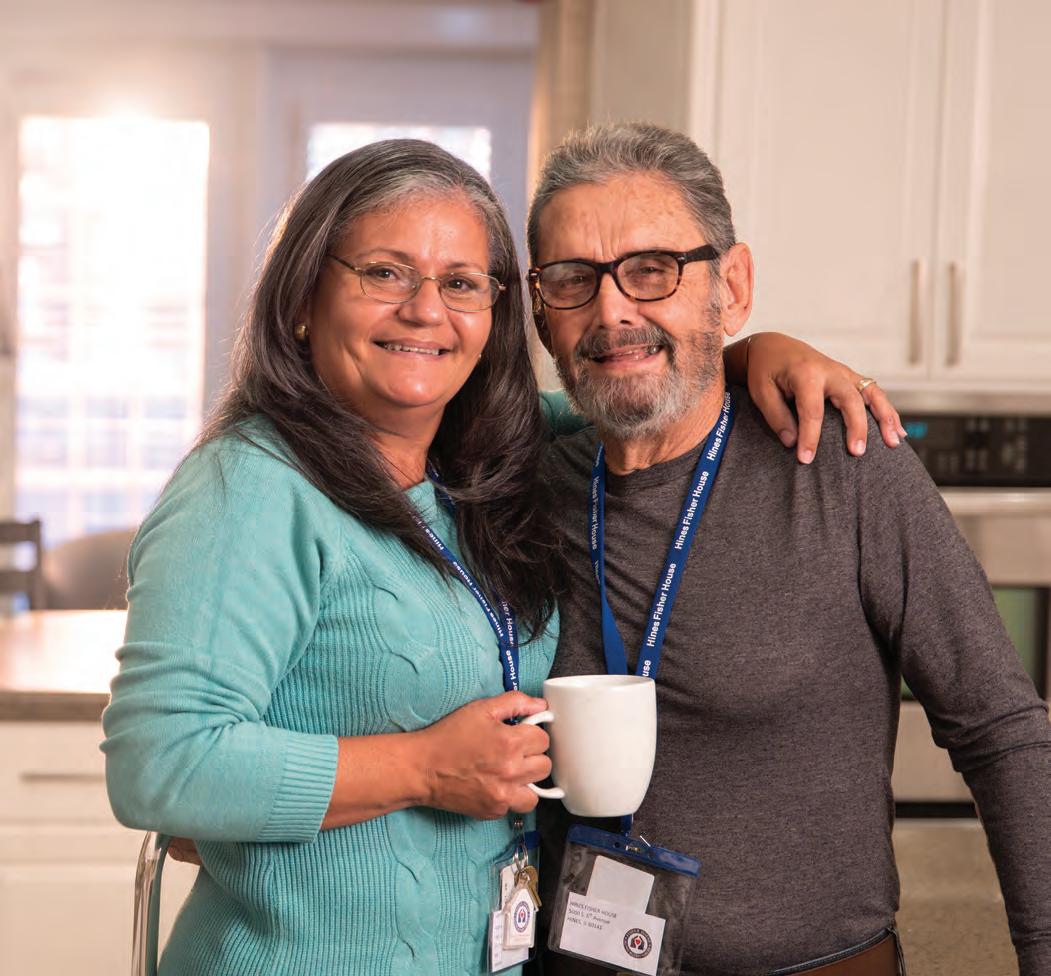

Meanwhile, Birmingham, Alabama, photographer Jeffrey Rease has made it his mission to snap portraits of as many wartime vets as possible (“World War II Today,” February 2021). His project received a boost when NBC News broadcast a feature on his efforts in August 2022, bringing in donations for travel and tips on veterans to photograph. By early September, he’d taken 292 portraits. He’s hoping to hit the road to shoot more, perhaps focusing on Midwestern states like Ohio, Illinois, and Minnesota. You can see his work and make donations at portraitsofhonor.us.

Rease knows the clock is ticking. “I won’t be able to get them all,” he told World War II. “Some will pass away. So, yeah, it’s urgent.”

GENE LESTER/GETTY IMAGES; INSET: JOHN PARROT/STOCKTREK IMAGES/GETTY IMAGES COURTESY OF JEFFREY REASE

World War II veteran Alvin Lopez sits for a portrait with photographer Jeffrey Rease.

WINTER 2023 11 WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 11 9/30/22 5:04 PM

NEW CAMPUS IN WORKS FOR NORMANDY INSTITUTE

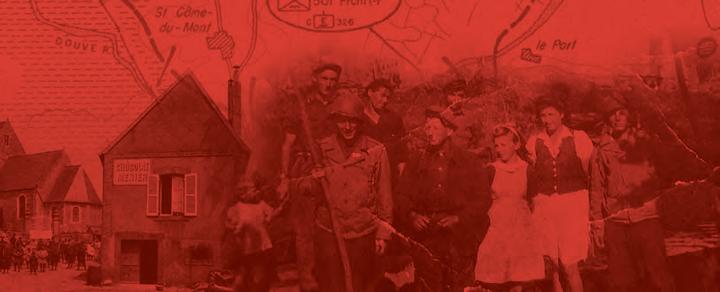

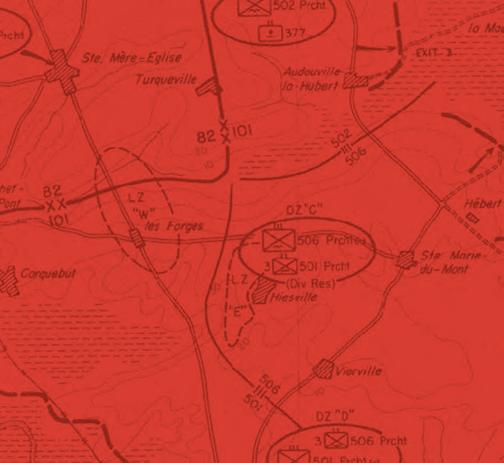

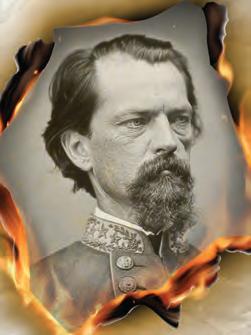

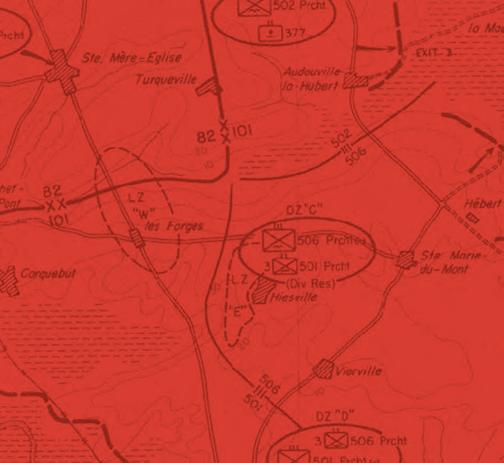

THE DESERT FOX walked its steps. German officers prepared their defense of the Normandy coast in its hallways. Paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne fought on the terrain nearby, not far from D-Day’s Utah Beach.

Now the nonprofit Normandy Institute wants to convert the Cha teau de Bernaville and its 50 surrounding acres into a nonprofit campus and conference center, where students, scholars, policy makers, and military leaders can come to bask in the French coun tryside and consider the bloody history that unfolded there and ways to prevent a recurrence.

The institute, incorporated in 2016, is raising money (normandy institute.org/support-us) for a planned $25-million makeover of the property, including the construction of a 60-room residence hall. Much of the work will involve restoring the chateau into an 11-room guesthouse, putting 30 guest rooms in the estate’s carriage house, and transforming the conservatory into a dining room and conference hall that can hold 350. A small chapel is also available for weddings and other gatherings.

Dorothea de La Houssaye, chair of the institute, says the location is perfect for conferences and educational retreats—beautiful coun tryside with a deep history. But the surrounding area is bereft of significant hotel capacity. So the Normandy Institute hopes to fill

Chateau de Bernaville (left), the former headquarters of German field marshal Erwin Rommel (center, above), is slated to become the new home of the nonprofit Normandy Institute.

the gap and attract conference goers from, say, NATO headquarters in Brussels, 360 miles to the north, to discuss military strategy and diplomacy. “We want to leave something behind that future generations can forever use and enjoy,” she said.

Occupying German forces used the chateau as a headquarters as they braced for the Allied invasion that would come on June 6, 1944; there’s a photograph of German general Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox, descending the steps of the chateau three weeks before D-Day. (Rommel wasn’t around when the fighting started, having returned to Germany for his wife’s birthday.)

The Normandy Institute has long pursued D-Day-related projects. It’s raising money for a documentary about retired U.S. Army Colo nel Keith Nightingale’s Normandy tours with D-Day veterans, and last year it released a short film about the 2005 reunion in Nor mandy, the Netherlands, and Belgium of the Band of Brothers—the men of Easy Company, 2nd Battalion of the 506th Parachute Infan try Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division, whose story was told in Stephen Ambrose’s 1992 book and HBO’s 2001 miniseries.

The Chateau de Bernaville is a three-hour drive from Paris and can be reached by train on the Paris-Cherbourg line.

WORLD WAR II12 BOTH: COURTESY OF THE NORMANDY INSTITUTE FROM TOP: GENE LESTER/GETTY IMAGES; AP PHOTO/DARKO VOJINOVIC

WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 12 9/30/22 5:04 PM

DISPATCHES

Sinking water levels in the Danube River, the consequence of a devastating European drought, in August 2022 exposed the wreckage of more than a dozen German ships scuttled during World War II. Part of the Nazi regime’s Black Sea fleet, the ships were sunk by retreat ing German forces to keep them from falling into the hands of the advancing Soviets. The hulks contain almost 10,000 pieces of unexplod ed ordnance. As the Danube dropped, the ships emerged off the port of Prahovo in what is now Serbia. The cost of clearing the explosives and moving the ships to make way for river traffic could come to $30 million.

WINTER 2023 13 BOTH: COURTESY OF THE NORMANDY INSTITUTE FROM TOP: GENE LESTER/GETTY IMAGES; AP PHOTO/DARKO VOJINOVIC

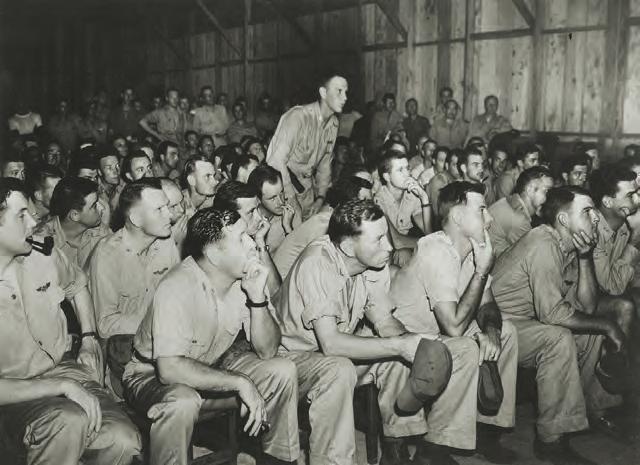

No movie screen

was big enough to contain the combined

talents

of these

celebrities, who

in spring

1942 embarked

on

a

patriotic cross-country fundraising campaign dubbed the

Hollywood Victory

Caravan. Conceived

by the

U.S.

Treasury

Department, the star-studded railroad tour brought household names such as

Desi Arnaz (fourth from left), Claudette Colbert

(fourth from right), and

Frank McHugh

(far

right)

to over a dozen cities, where they hosted variety

shows

for $11 per ticket. Collectively, the performers raised $800,000—today, more than $14.5 million—for army and navy relief funds. ON THE HOME FRONT

WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 13 10/5/22 7:42 PM

My late grandfather, Flight Officer Louis J. Cyr, served in the Pacific with the 27th Bombardment Squadron of the 30th Bombardment Group. He rarely spoke about the war, and I was wondering what you could tell me about his squadron’s service. We recently found some of his Army Air Forces papers that could provide some leads.

– Andrea Scott, Alexandria, Va.

Your grandfather’s unit, the 27th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), was established in November 1940 as the U.S. began building up its military readiness after war had broken out in Europe. Activated on January 15, 1941, the squadron—part of the 30th Bombardment Group—was first stationed at California’s March Field, training with Douglas B-18 Bolo medium bombers.

In May 1941, the 27th moved to New Orleans, where for the rest of the year it flew Lockheed A -29 Hudsons in coastal reconnais sance missions over the Gulf of Mexico in search of enemy subma rines. Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the squadron returned to California, where it joined the rest of the 30th Bomb Group patrolling West Coast waters for threats while also training aircrews in other units. It served in this role for two years until October 1943, when the group moved to Mokuleia Army Airfield in Hawaii.

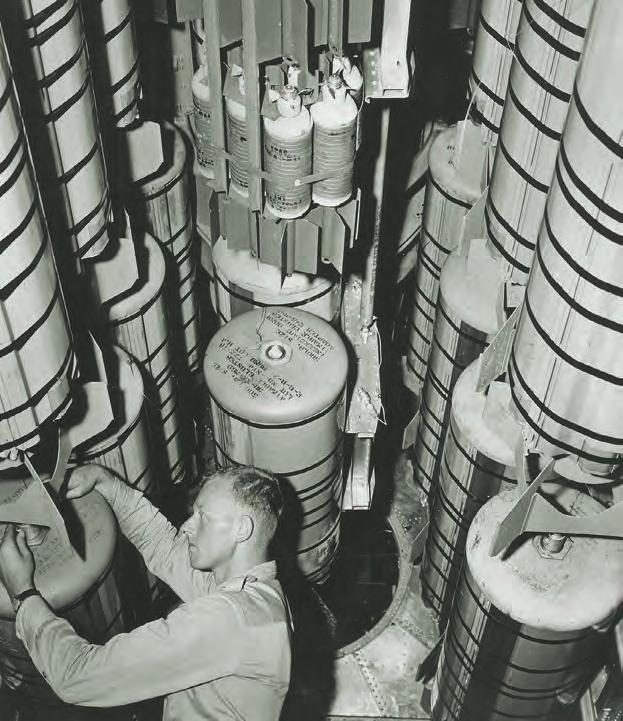

As the U.S. island-hopping campaign in the Pacific moved west, so did the 27th Bomb Squadron. In November 1943, the 30th Bomb Group—now flying B-24 Liberators—relocated from Hawaii to the Gilbert Islands. On December 23, B-24s from the 27th Squadron became the first U.S. heavy bombers to use the recently seized airfield on Tarawa, escorting reconnaissance aircraft in prepara

tion for further incursions in the Pacific.

The bloody battle for Saipan from June 15–July 15, 1944, was a critical American victory in this push toward Japan. The records you sent indicate your grandfather, Louis J. Cyr, joined the 27th Squadron at this time after rating as a navigator on July 3, 1944. In August 1944, the 27th, along with Flight Officer Cyr, moved with the rest of the 30th Bomb Group to Saipan’s hard-won East Field, from where it would operate for the rest of the war.

The Americans’ next target: Iwo Jima. From Saipan, the 27th predominantly targeted the Bonin Islands around Iwo Jima to keep the Japanese from being able to stage aircraft and fend off an invasion. Cyr flew seven mis sions in late-model B-24Ms from January 24 to February 20, 1945—including five longrange bomb strikes to soften resistance on Iwo Jima itself—all carried out to support the Marine landings on the island on February 19. T he 27th continued to bomb Japanese bases in the Marianas and the Caroline Islands until March 1945, when the 30th Bom bardment Group returned to Hawaii. The squadron flew standard patrols and continued training new crews until the 30th was inacti vated on June 25, 1946.

Do you have a relative from a World War II company, squadron, or division you’d like to hear more about?

Contact us at worldwar2@historynet.com with the following: —Your relative’s full name, date of birth, and the specific unit in which he or she served —A high-resolution wartime-era photograph —Copies of any paperwork that may help us determine the particulars of your relative’s service.

Note that we are unable to conduct independent genealogical research.

WORLD WAR II14 LEFT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES; RIGHT: COURTESY OF ANDREA SCOTT

American B-24s bomb Iwo Jima in preparation for the February 19, 1945, invasion. Flight Officer Louis J. Cyr (right), of the 27th Bombardment Squadron, flew in five missions over the island.

MY PARENTS’ WAR WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 14 9/30/22 5:05 PM

Secrets of a Billionaire Revealed

We’re going to let you in on a secret. Billionaires have billions because they know value is not increased by an in ated price.

avoid big name markups, and aren’t swayed by ashy advertising. When you look on their wrist you’ll nd a classic timepiece, not a cry for attention–– because they know true value comes from keeping more money in their pocket.

We agree with this thinking wholeheartedly. And, so do our two-and-a-half million clients. It’s time you got in on the secret too. e Jet-Setter Chronograph can go up against the best chronographs in the market, deliver more accuracy and style than the “luxury” brands, and all for far, far less. $1,150 is what the Jet-Setter Chronograph would cost you with nothing more than a di erent name on the face.

With over two million timepieces sold (and counting), we know a thing or two about creating watches people love. e Jet-Setter Chronograph gives you what you need to master time and keeps the super uous stu out of the equation. A classic in the looks department and a stainless steel power tool of construction, this is all the watch you need. And, then some. Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Experience the Jet-Setter Chronograph for 30 days. If you’re not convinced you got excellence for less, send it back for a refund of the item price.

Time is running out. Now that the secret’s out, we can’t guarantee this $29 chronograph will stick around long. Don’t overpay to be underwhelmed. Put a precision chronograph on your wrist for just $29 and laugh all the way to the bank. Call today!

Absolute best price for a fully-loaded chronograph with precision accuracy... ONLY $29! Absolute best price for a fully-loaded chronograph with precision accuracy... ONLY $29! • Precision crystal movement • Stainless steel case back & bracelet with deployment buckle • 24 hour military time • Chronograph minute & small second subdials; seconds hand • Water resistant to 3 ATM • Fits wrists 7" to 9" Stauer ® 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. JCW493-01, Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com † Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. Limited to the first 1900 responders to this ad only. “See a man with a functional chronograph watch on his wrist, and it communicates a spirit of precision.” — AskMen.com®

ey

CLIENTS LOVE STAUER WATCHES… êêêêê “The quality of their watches is equal to many that can go for ten times the price or more.” — Jeff from McKinney, TX Stauer…Afford the Extraordinary . ® You must use the offer code to get our special price. 1-800-333-2045 Your Offer Code: JCW493-01 Please use this code when you order to receive your discount. Rating of A+ Jet-Setter Chronograph $299† Offer Code Price $29 + S&P Save $270 TAKE 90% OFF INSTANTLY! When you use your OFFER CODE “Price is what you pay; value is what you get. Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.” — wisdom from the most successful investor of all time WW2-221108-013 Stauer Jetsetter Watch.indd 1 10/1/22 1:37 PM

En bloc clips for M1 Garands were sometimes valuable battlefield finds.

ASK WWII

Q: After big battles where huge amounts of ordnance were expended, did U.S. forces ever go back after the fighting was over to salvage ammunition clips left behind to be reloaded again for future use?

—Patrick J. Kirkland, Wylie, Texas

A: Several military historians looked into this question. Our primary source was the 1968 U.S. Army Center of Military History publication, The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront, by senior historian Lida Mayo. Several times Mayo references ordnance collecting companies that scanned the field after World War II battles to recover usable items. Most of the items recovered seem to have been spare parts or tanks that had been disabled by enemy fire. The companies were equipped with tractors and often operated at night.

T hat said, after the battle of El Guettar in April 1943, Mayo mentions that the 188th Ordnance Battalion stayed behind in Gafsa to assist in the “mammoth job of battlefield clearance. The Americans left behind them a 3,000-square-mile area that was littered with ammunition, tanks, gasoline and water cans, clothing, and all kinds of scrap. Out of the 20,544 long tons col lected, more than half was ammunition.”

While this is indeed evidence that ammunition was recov ered, we are unaware of any army policy, order, or salvage operation of any scope to recover the en bloc clips, preloaded with .30-06 caliber rounds, that were expended and ejected from M1 Garands during the war. Like brass cartridge casings, these inexpensive metal stampings were designed to be dis posable. There are some anecdotal stories where individual soldiers ran low on ammo for their Garands and, to alleviate their short supply, rounded up all the en bloc clips they could find and loaded them with scavenged .30-06 caliber ammo that was linked for machine guns—but those were more ad hoc efforts than official operations.

F. Lee Reynolds is a strategic communications officer at the U.S. Army Center of Military History

worldwar2@

WORD FOR WORD

DISPATCHES

The National Medal of Honor Museum memorializing the more than 3,500 recipients of the nation’s highest military award, including 473 from World War II—is scheduled to open in Arlington, Texas, in late 2024 after a ground breaking in March 2022. The museum will con tain 31,000 square feet of exhibition space and will include a restored Grumman F4F Wildcat, a World War II fighter flown by eight Medal of Honor recipients, in the naval aviation gallery.

WORLD WAR II16 SEND QUERIES VIA EMAIL to Ask World War II at

historynet.com

“Democracy is not dying. We know it because we have seen it revive—and grow. We know it cannot die, because it is built on the unhampered initiative of individual men and women joined together in a common enterprise— an enterprise undertaken and carried through by the free expression of a free majority.”

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s third inaugural address, delivered on January 20, 1941

LEFT: LAURENT STEMKENS; RIGHT: PHOTO12/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP VIA GETTY IMAGES WW2P-230100-TODAY-2.indd 16 9/30/22 5:05 PM

Order by Dec. 6 and you’ll receive FREE gift announcement cards that you can send out in time for the holidays! LIMITED-TIME HOLIDAY OFFER CHOOSE ANY TWO SUBSCRIPTIONS FOR ONLY $29.95 TWO-FOR-ONE SPECIAL! CALL NOW! 1.800.435.0715 PLEASE MENTION CODE HOLIDAY WHEN ORDERING SCAN HERE! OR VISIT HISTORYNET.COM/HOLIDAY Offer valid through January 8, 2023 * For each MHQ subscription add $15 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames Tulsa Race Riot: What Was Lost Colonel Sanders, One-Man Brand J. Edgar Hoover’s Vault to Fame The Zenger Trial and Free Speech Yosemite The twisted roots of a national treasure HISTORYNET.com JUL 2020 H H HISTORYNET.COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY An ammunition dump explodes during the April 1972 battle for An Loc. Defeating Enemy Stereotypes White and Black POWs bonded as cellmates The Green Berets Battles that inspired the book and movie TERROR AT AN LOC 9TH CAVALRY’S HEROIC FIGHT TO RESCUE DOWNED AIRMEN Huey Haven Old Warbirds Are Getting a New Museum HOMEFRONT Sweet success for Sammy Davis Jr. JUNE 2022 HISTORYNET.COM HNET SUB AD_HOLIDAY-2022.indd 1 8/30/22 8:34 AM

CONVERSATION WITH EVERETT LANMAN

BY DAVE KINDY

NEVER SURRENDER,NEVER SINK

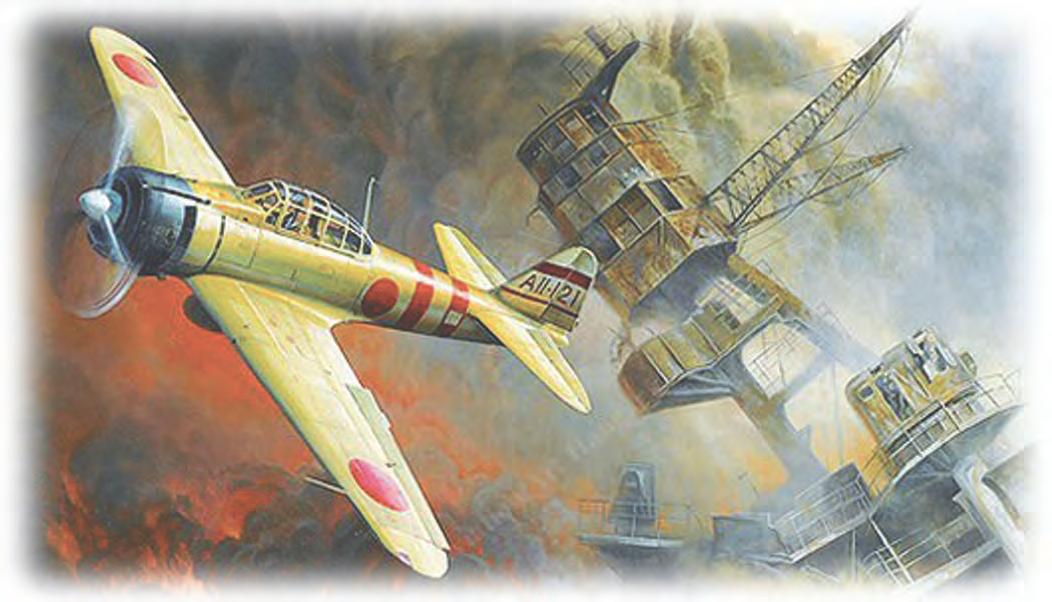

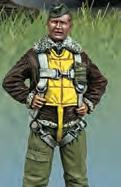

ON MAY 11, 1945, Everett “Red” Lanman of Plymouth, Massachusetts, was serving as an aviation mechanic on board the USS Bunker Hill when it was struck by two kamikazes during the Battle of Okinawa. He had been assigned to the Essex -class aircraft carrier shortly after it was launched on December 7, 1942—exactly one year after Pearl Harbor. Today, the 100-year-old is still going strong, just like the Bunker Hill ’s motto: “Never Surrender, Never Sink.” Lanman’s hair is no longer red, but the Bronze Starrecipient has a clear memory of the dramatic events of nearly 80 years ago.

Where did you first serve when you enlisted right after Pearl Harbor?

I was stationed in New York City at Pier 92, which was a receiving station. We were on guard duty there before ship ping out to the Pacific. One of my first duties was after the SS Normandie rolled over at Pier 88. It was being converted to a troopship in February 1942 when a fire broke out and it sank at dock. After that, we were assigned to the USS Bunker Hill.

One of your first stops on board the aircraft carrier was Pearl Harbor. What was that like?

When we pulled into port in October 1943, we saw the sunken ships on Battleship Row. I remember seeing the USS Utah overturned and the USS Arizona at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. It was pretty shocking, even close to two years later.

We tied up there for two days next to the Utah. Then we headed out into the Pacific and went to Rabaul on New Britain, which was a stronghold for the Japanese. Our task force made a raid on the naval base there. Later that afternoon, we were attacked by 114 Jap planes. They were sons of guns! We started firing and shot down a few of them. It was a tough battle. Then our Corsairs got into the action. Their guns were firing even as they were taking off! They were good pilots. A couple of them made ace in one day.

What other battles did you participate in?

We sailed to the Gilbert Islands for the invasion of Tarawa. We also took part in air raids at Kavieng, the Marshall Islands, Truk, and the Marianas, as well as Palau, Ulithi, and Hollandia, in support of landings on Saipan and Guam. The Bunker Hill also served at Leyte Gulf, Luzon, Formosa, Iwo Jima, and, of course, Okinawa. All in all,

the ship and crew received 11 battle stars and a Presidential Unit Citation.

One time we tied up to an island in the Solo mons, where we went ashore so we could work on the planes. There were no Japanese there. Well, they told us they didn’t want anybody wandering off into the jungle because there were big snakes in there. So I said, “You bet your ass I won’t!”

What was your job when the ship went to battle stations?

Mostly I was supposed to take cover, unless I was working on a plane. I would take cover up on the port side at a fire station, right near where they pumped out gasoline for the planes. There was a 40-millimeter gun

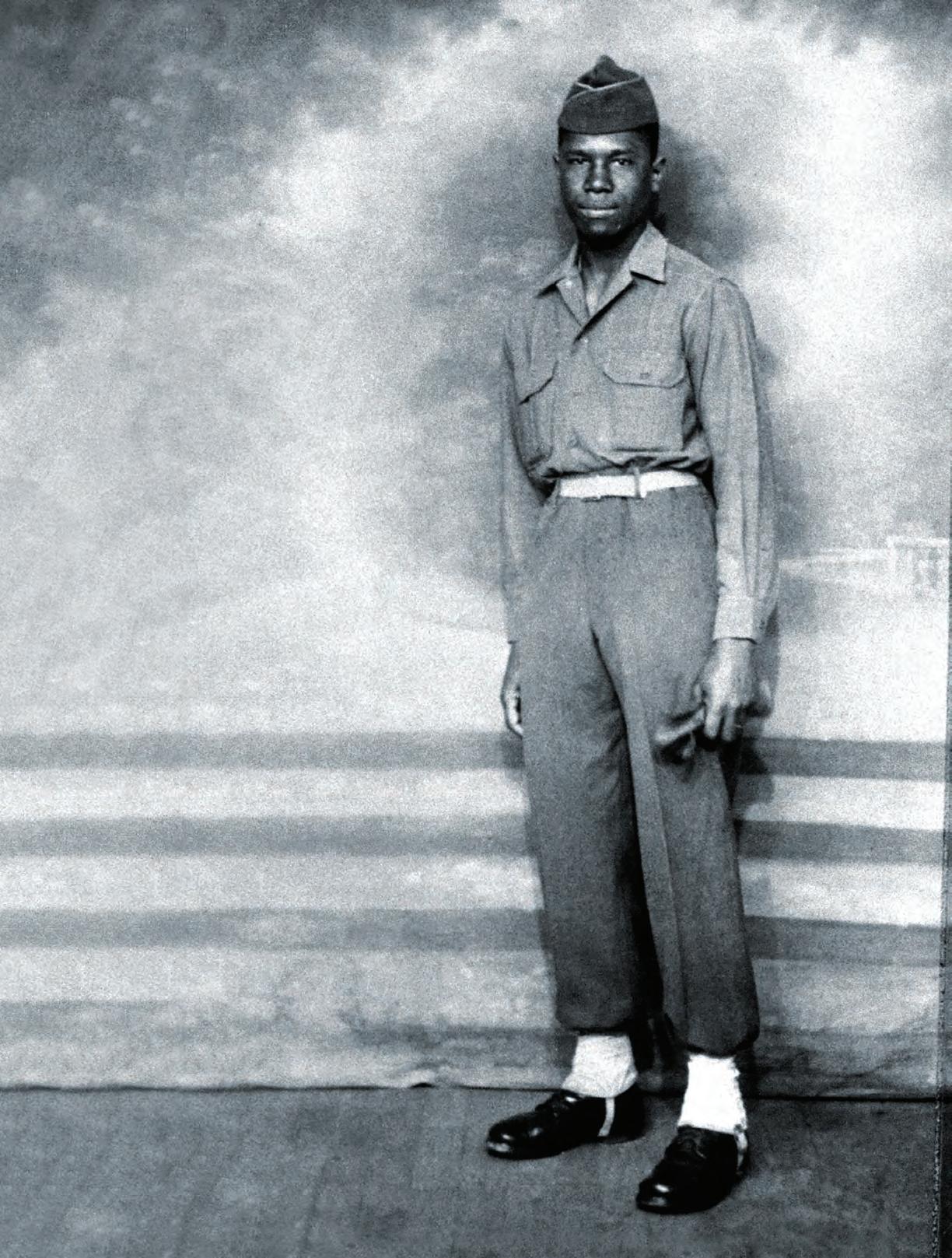

WORLD WAR II18 COURTESY OF EVERETT LANMAN DAVE KINDY

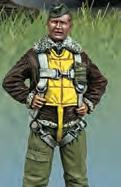

Everett “Red” Lanman in 1942, the year the aircraft mechanic joined the crew of USS Bunker Hill

WW2P-230100-CONVO-LANMAN-1.indd 18 10/3/22 2:55 PM

Lanman, at his home in Massachusetts, holds a fragment from one of the two kamikaze airplanes that struck Bunker Hill on May 11, 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa.

mount, and we passed ammunition to the guys who were firing. We did whatever we could to help, but when the bombs started to drop, we ducked.

What happened at Okinawa on May 11, 1945?

It’s hard to remember all of it. Things hap pened so fast that you don’t comprehend that much. We were working on a couple of planes on the hangar deck, right near the chow hatch. While we were putting on a flap and tighten ing down the bolts, General Quarters went off.

Then the kamikazes hit.

I was working on an F4U Corsair with this other fellow. I was just getting ready to tighten a bolt on the wing flap. All of a sudden, everything broke loose. Stuff was coming down from overhead, and a fire started in hangar deck control, where the first plane had dropped a bomb and then crashed. The

other one hit about a minute later.

This other fellow and I went over to the chow hatch. Sailors were lying on top of each other in the passageway. The wreckage was terri ble! We climbed over them, and I said to this other guy, “How the hell are we going to get out of here?” He says, “I got an idea.” So we undogged a hatch, pushed it open, and climbed up. The guys above us on the 40-millimeter gun mount pulled us up. They asked us what it looked like down there on the hangar deck, and I said, “It’s a mess!” Okinawa was a tough fight.

After the planes crashed, the USS Wilkes-Barre, a cruiser, came along our starboard side to help fight the fires and take off the wounded. We had a teak deck, and those fires burned very hot. The Wilkes-Barre got so close that the paint on its hull started to blister. We tried to help the wounded, but we couldn’t help them all.

Years later, I was at the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., for the dedication, and I met a guy with a Wilkes-Barre hat. He saw my Bunker Hill hat, and we hugged for about 10 minutes. We both had tears. He told me he thought my ship was going to roll.

How did you react to the attack?

We didn’t have time to think about it. We lost almost 400 guys. They had

WINTER 2023 19 COURTESY OF EVERETT LANMAN DAVE KINDY

WW2P-230100-CONVO-LANMAN-1.indd 19 9/27/22 3:44 PM

Bunker Hill burns in the East China Sea after the attack, which killed nearly 400 servicemen on the Essex-class carrier.

to be buried at sea. We assembled on the hangar deck and stood in formation. They put each body in a bag with a spent five-inch shell so that when it hit the water, it sank. As they brought the bodies up, they would put them on a slab of wood and then slide them off into the water. There was a service, and we played “Taps” and fired a salute.

Afterward, a guy on Gun Mount Five in the back aft said, “Red, did you know there was a third plane that made a dive? My battle station shot it down.”

Where were you when the war ended?

After Okinawa, we went back to Pearl Harbor for repairs. We were in Hawaii when we got the news that the war was over. Everybody was excited. Some of the guys said they knew the Japanese were licked when we dropped the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. We were surprised by how powerful those bombs were.

When did you return home after the war?

I came back by train to Plymouth. I was still in uniform when I got married to my wife, Dolores, on December 7, 1945. I was late because the train was delayed. I was at Quonset Point in Rhode Island, and a fellow came to pick me up. Right after we were married, I had to go back to my quarters. Not much of a honeymoon! But I got out of the service about a week later. Dolores is gone now. I miss her a lot.

When did you start discussing your combat experiences?

I never talked about what happened until I was interviewed for the

book Danger’s Hour: The Story of the USS Bunker Hill and the Kamikaze Pilot Who Crip pled Her by Maxwell Taylor Kennedy. I went to the book signing in 2008. I was legally blind by then, so I couldn’t read it. I got the book on tape. Couldn’t listen to the ending, though. Too emotional. I gave a book to each of my grandsons. I told them not to read the ending because it was too sad.

Did you stay in touch with your navy buddies after the war?

Yes. Every year we had a reunion. My wife and I never missed a one. We had them in a differ ent city throughout the country every year. It would be very emotional because we would remember what happened and all the sailors who never came home. It’s only been in the past 10 years that we had to stop because there were so few of us left.

I also visited some of my friends. One of my closest buddies lived up in Grand Forks, North Dakota. He ran a chocolate factory. Once he took me to the factory, put a hat on me, and I was making taffy! I miss the guys I served with. I feel very humble when I hear the names of my buddies who are gone now. H

WORLD WAR II20 NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND

The reunions were very emotional because we would remember all the sailors who never came home.

WW2P-230100-CONVO-LANMAN-1.indd 20 9/27/22 3:44 PM

On May 18, 1980, the once-slumbering Mount St. Helens erupted in the Pacific Northwest. It was the most impressive display of nature’s power in North America’s recorded history. But even more impressive is what emerged from the chaos... a spectacular new creation born of ancient minerals named Helenite. Its lush, vivid color and amazing story instantly captured the attention of jewelry connoisseurs worldwide. You can now have four carats of the world’s newest stone for an absolutely unbelievable price.

Known as America’s emerald, Helenite makes it possible to give her a stone that’s brighter and has more fire than any emerald without paying the exorbitant price. In fact, this many carats of an emerald that looks this perfect and glows this green would cost you upwards of $80,000. Your more beautiful and much more affordable option features a perfect teardrop of Helenite set in gold-covered sterling silver suspended from a chain accented with even more verdant Helenite.

Limited Reserves. As one of the largest gemstone dealers in the world, we buy more carats of Helenite than anyone, which lets us give you a great price. However, this much gorgeous green for this price won’t last long. Don’t miss out. Helenite is only found in one section of Washington State, so call today!

Romance guaranteed or your money back. Experience the scintillating beauty of the Helenite Teardrop Necklace for 30 days and if she isn’t completely in love with it send it back for a full refund of the item price. You can even keep the stud earrings as our thank you for giving us a try.

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary . ®

• 4 ¼ ctw of American Helenite and lab-created DiamondAura® • Gold-finished .925 sterling silver settings • 16" chain with 2" extender and lobster clasp Rating of A+ 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. HEN436-01, Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.comStauer ® * Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. Helenite Teardrop Necklace (4 ¼ ctw) $299* .....Only $129 +S&P Helenite Stud Earrings (1 ctw) ....................................... $129 +S&P Helenite Set (5 ¼ ctw) $428* ...... Call-in price only $129 +S&P (Set includes necklace and stud earrings) Call now and mention the offer code to receive FREE earrings. 1-800-333-2045 Offer Code HEN436-01 You must use the offer code to get our special price. Uniquely American stone ignites romance Tears From a Volcano Necklace enlarged to show luxurious color EXCLUSIVE FREE Helenite Earrings -a $129 valuewith purchase of Helenite Necklace 4 carats of shimmering Helenite Limited to the first 1600 orders from this ad only “I love these pieces... it just glowed... so beautiful!” — S.S., Salem, OR WW2-221108-012 Stauer Helenite Teardrop Necklace.indd 1 10/1/22 1:36 PM

Curators at The National World War II Museum solve readers’ artifact mysteries

An American B-24 bombardier downed over Slovakia in late 1944 brought home this one-of-a-kind German medal (above) as a souvenir. What about it makes it unique?

THE

MIX AND MATCH

My father, Robert W. Wicks, was a B-24 bombardier with the 763rd Bomb Squadron of the 460th Bomb Group, 15th Air Force, based in Spinazzola, Italy. e was shot down on his 24th combat mission in December 1944 and saved by a Slovak family who hid him on their farm for almost five months.

Shortly after my father passed away in 1996, I came across this German medal I have not been able to identify. Can you tell me its significance?

—David E. Wicks, Dansville, N.Y.

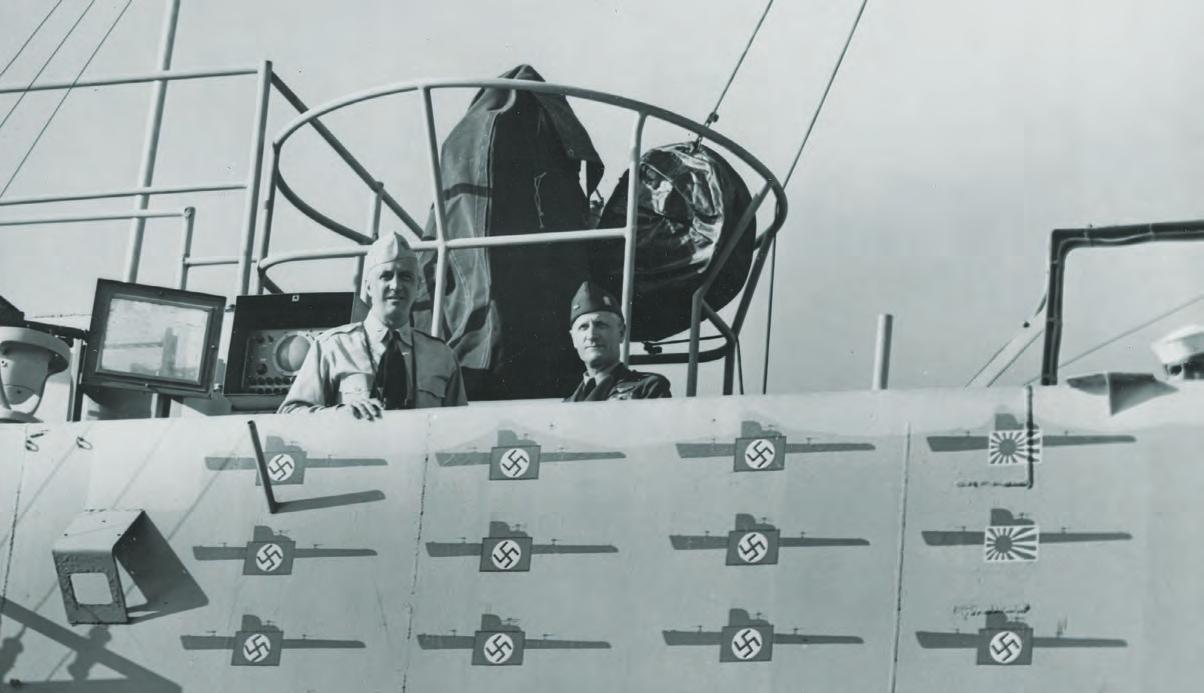

As the war entered its final year, thousands of American service men snatched up Third Reich medals and pins by the handful. They were perfect souvenirs—small and plentiful, but still bear ing the fearsome iconography of the Nazi regime.

While The National World War II Museum focuses on the American wartime experience, this institution also holds a vast and varied collection of German military and civilian ephemera, most of which came home in the sea bags and rucksacks of exhausted U.S. servicemen returning home in 1945 and 1946. A dive into our collection reveals no fewer than 15 examples of this medal, the Kriegsverdienstkreuz, or War Merit Cross, which was awarded to both soldiers and civilians for exceptional service unrelated to combat. While more than a dozen of these silver or bronze state decorations reside in our collection, I have never seen one with a ribbon apparently poached from another German military award.

The blood-red ribbon attached to this War Merit Cross, with thin black and white lines at its center, comes from an Ostmedaille, known in Western circles as the Eastern Medal, or more formally, the Winter Battle in the East 1941–42 Medal. It was awarded to German servicemen who fought in the invasion of the Soviet Union during that first terrible winter. The commendation was also given to the families of those who died, inspiring some to ghoulishly call it the “Order of the Frozen Meat.”

The owner of this unusual conglomeration of wartime memorabilia tumbles into our story from war-torn skies. First Lieutenant Robert W. Wicks bailed out of his stricken B-24 on December 11, 1944. He wasn’t supposed to be there, but at the last moment had switched to the ill-fated Liberator to give the new crew a more experienced bombardier. He parachuted into Slovakia, where he was hidden by the Pavol Macina family on their farm for months.

At the conclusion of fighting in Europe, Wicks came home. On his long road back, did he encounter a savvy entrepreneur selling souvenirs from the cast-off fragments of the now-defunct totalitarian state? Or did he assemble this unique war memento on his own? We may never know for sure. While the origin of the unusual piece is murky, the psychology of grabbing a trophy checks out. Many soldiers, sailors, and fliers, when given the chance, snatched a small fragment of the vanquished to take home. —Cory Graff, Curator

Have a World War II artifact you can’t identify?

Write to Footlocker@ historynet.com with the following:

Your connection to the object and what you know about it.

The object’s dimensions, in inches.

Several high-resolution digital photos taken close up and from varying angles.

Pictures should be in color, and at least 300 dpi. Unfortunately, we can’t respond to every query, nor can we appraise value.

WORLD WAR II22 COURTESY OF THE WICKS FAMILY

FROM

FOOTLOCKER

WW2P-230100-FTLCKR-1.indd 22 9/28/22 6:16 PM

a full front zipper, and silver-toned metal tippets on the hood drawstrings. Imported.

Remarkable Value... Available for a Limited Time

in 5 men’s sizes M-XXXL, this personalized hoodie is a remarkable value at just $99.95*, payable in 3 easy installments of $33.32, and backed by our 30-day money-back guarantee. This is a limited-time offer, so don’t delay. To acquire yours, send

just return the

Reservation

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service READY AT THE REVEILLE Military Personalized Hoodie Signature Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email E57301 YES. Please reserve the “Ready at the Reveille” Military Personalized Hoodie for me with the name, branch and size indicated below. (Personalization will be in all capital letters.) ©2022 The Bradford Exchange 01-32397-001-BIBMPOR1Connect with Us! ❑ U.S. Air Force™ 01-32398-001 Size ❑ U.S. Army® 01-32399-001 Size ______ ❑ U.S. Marines 01-32397-001 Size ❑ U.S. Navy® 01-32400-001 Size ______ Available in 5 Men’s Sizes M-XXXL Stay warm and strong in proud military style. Crafted in a charcoal gray easy-care cotton blend knit, this everyday hoodie showcases a bold design featuring your branch of choice and logo on the back. The sleeve displays your branch motto and the front is personalized with your name or nickname (max. 12 characters) in embroidery, along with the branch logo and name with established date. Custom details include expertly embroidered accents, a comfortable brushed fleece interior, a light gray thermal knit lined hood, kangaroo front pockets, knit cuffs and hem,

A

Available

no money now;

Priority

today! PRIORITY RESERVATION SEND NO MONEY NOW Where Passion Becomes Art. The Bradford Exchange 93 45 Milwaukee Avenue, Niles, Illinois 60714-1393 U.S.A. *Plus a total of $14.99 shipping and service each (see bradfordexchange.com). Please allow 2-4 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. Product subject to change. Order Today at bradfordexchange.com/militaryready U.S. ARMY ® “THIS WE’LL DEFEND” ON SLEEVE U.S. NAVY® “SEMPER FORTIS” ON SLEEVE U.S. AIR FORCE ™ “FLY. FIGHT. WIN.” ON SLEEVE U.S. Marines PERSONALIZED WITH PRIDE! FREE PERSONALIZATION Max 12 characters per hoodie M (38-40) L (42-44) XL (46-48) XXL (50-52) XXXL (54-56) Have Your Name Embroidered on the Front of the Hoodie for FREE! ®Officially Licensed by the Department of the Navy. www.airforce.com Officially Licensed Product of the Department of the Air Force. Endorsement by the Department of the Air Force is neither intended nor implied. Officially Licensed Product of the United States Marine Corps. ®Official Licensed Product of the U.S. Army. By federal law, licensing fees paid to the U.S. Army for use of its trademarks provide support to the Army Trademark Licensing Program, and net licensing revenue is devoted to U.S. Army Morale, Welfare, and Recreation programs. U.S. Army name, trademarks and logos are protected under federal law and used under license by The Bradford Exchange. WW2-221108-008 Bradford P USMC Military Grey Hoodie CLIPPABLE.indd 1 10/1/22 12:48 PM

NEED TO KNOW

BY JAMES HOLLAND

FALSE FRONT

I’VE BEEN STAYING on a small Greek island, and from the house I’ve been able to look across the wine-dark sea to the distant blue mountains of Epirus in the northwest part of mainland Greece. It’s hard not to think of Odysseus sailing these waters, but my thoughts also turn to the Greek tragedy of the war years, a dark period in the nation’s history, if ever there was one.

Epirus witnessed the Italian invasion in late October 1940, the Greek counterattack, and then the German invasion a few months later. It also saw not only guerrilla activities but civil war, between the Communist-organized ELAS and the more liberal but anti-monarchy EDES partisan movements. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed during those years, and thou sands—literally—of villages were wiped from the face of the earth.

The Allies, and the British especially, also played their part in Greece’s war: first, sending some 48,000 British troops plus a handful of Royal Air Force planes when the Germans and Bulgarians invaded in April 1941. The Germans swept all before them in a matter of weeks, the British hastily evac uated, and, thereafter, their involvement continued in the form of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

SOE agents infiltrated Greece with little understanding of what was going on internally. Guidelines from London were to incite armed resistance against the Axis, but also to promote loyalty to the exiled Greek king—even though, for all the different politics within Greece, one unifying factor was a growing desire to get rid of the monarchy.

The SOE in Greece, led by Major Eddie Myers, soon began to understand the complex and immense challenges they faced, and navigating these tricky waters swiftly led to some uncomfortable moral compromises. One of SOE’s roles was to sabotage Axis supply lines, but another, in the summer of 1943, was to persuade the Germans and Italians that Greece was the main target for an imminent Allied invasion, rather than Sicily, the real objective. That meant also persuading the ELAS and EDES partisans that Greece was about to be invaded. In other words, they had to dupe their allies into believing something they knew to be wholly false. The consequences of Operation Animals—blowing up bridges, attacking Axis troops and locomotives—were

the roundup of Greek civilians, sum mary executions, and the destruc tion of villages. Many Greeks lost their lives in an effort to make the Axis believe the Allies intended to land in Greece and not Sicily.

Much has been made of these deception measures, especially with Operation Mincemeat, the British plan to ditch a body into the Mediter ranean with incriminating papers attached that pointed to an Allied invasion first of Sardinia, then of Greece. The story has just been adapted into a film with all the hyperbole of changing the course of history one would expect from a movie release.

It’s true two German divisions were sent to Greece, but this was more in anticipation of the imminent Italian collapse: there were some 750,000 Italian troops throughout Greece and the Balkans that would need replacing should Italy drop out of the war. In truth, Hitler was convinced Greece would be the next target because he was paranoid about the Allies taking the Ploesti oil fields in Romania, and an Allied attack in Greece seemed to give them the best chance of achieving that. But Albert Kesselring, his senior com mander in the Mediterranean, and the Italian high command, Musso lini included, all assumed the Allies would attack Sicily, because it was so blindingly obvious. Only Sicily allowed the Allies fighter cover from bases in North Africa, a prerequisite for such an amphibious assault. Operations Animals and Mincemeat reinforced what Hitler already believed and dissuaded no one else that the target would be Sicily.

Fortunately today, the mountains of Epirus are altogether more peace ful, but gazing across the sea I can not help wondering about the nature of the moral crusade on which the Allies embarked during the war. For the cause of right, yes, but with a number of moral conundrums along the way, of which duping the Greeks was just but one. H

WORLD WAR II24 XXXXXXXXXXXXXILLUSTRATION BY RICHARD MIA

WW2P-NEEDTOKNOW-2.indd 24 9/26/22 5:09 PM

It was a perfect late autumn day in the northern Rockies. Not a cloud in the sky, and just enough cool in the air to stir up nostalgic memories of my trip into the backwoods. is year, though, was di erent.

I was going it solo. My two buddies, pleading work responsibilities, backed out at the last minute. So, armed with my trusty knife, I set out for adventure.

Well, what I found was a whole lot of trouble. As in 8 feet and 800-pounds of trouble in the form of a grizzly bear. Seems this grumpy fella was out looking for some adventure too.

Mr. Grizzly saw me, stood up to his entire 8 feet of ferocity and let out a roar that made my blood turn to ice and my hair stand up. Unsnapping my leather sheath, I felt for my hefty, trusty knife and felt emboldened. I then showed the massive grizzly over 6 inches of 420 surgical grade stainless steel, raised my hands and yelled, “Whoa bear! Whoa bear!” I must have made my point, as he gave me an almost admiring grunt before turning tail and heading back into the woods.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars FREE when you purchase the Grizzly Hunting Knife.

Make sure to act quickly. The Grizzly Hunting Knife has been such a hit that we’re having trouble keeping it in stock. Our first release of more than 1,200 SOLD OUT in TWO DAYS! After months of waiting on our artisans, we've finally gotten some knives back in stock. Only 1,337 are available at this price, and half of them have

Knife

• Stick tang

I was pretty shaken, but otherwise ne. Once the adrenaline high subsided, I decided I had some work to do back home too. at was more than enough adventure for one day.

Our Grizzly Hunting Knife pays tribute to the call of the wild. Featuring stick-tang construction, you can feel con dent in the strength and durability of this knife. And the hand carved, natural bone handle ensures you won’t lose your grip even in the most dire of circumstances. I also made certain to give it a great price. After all, you should be able to get your point across without getting stuck with a high price.

The

sold!

carved natural

hand

already

Speci cations:

420 surgical stainless steel blade; 7 ¼" blade; 12" overall •Hand

brown and yellow bone handle •Brass

guard, spacers and end cap •FREE genuine tooled leather sheath included (a $49 value!)

Grizzly Hunting Knife $249 $79* + S&P Save $170 California residents please call 1-800-333-2045 regarding Proposition 65 regulations before purchasing this product. *Special price only for customers using the offer code. 1-800-333-2045 Your Insider Offer Code: GHK185-02 Stauer, 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. GHK185-02, Burnsville, MN 55337 www.stauer.com Stauer® | AFFORD THE EXTRAORDINARY ® A 12-inch stainless steel knife for only $79 I ‘Bearly’ Made It Out Alive What Stauer Clients Are Saying About Our Knives “The feel of this knife is unbelievable... this is an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO “This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN 79 Stauer®Impossible Price ONLY Join more than 322,000 sharp people who collect stauer knives EXCLUSIVE FREE Stauer 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith your purchase of the Grizzly Hunting Knife WW2-221108-011 Stauer Grizzly Hunting Knife.indd 1 10/1/22 1:34 PM

TRAVEL SALINA, UTAH STORY AND PHOTOS BY JESSICA WAMBACH BROWN

A TRAGIC NIGHT IN UTAH

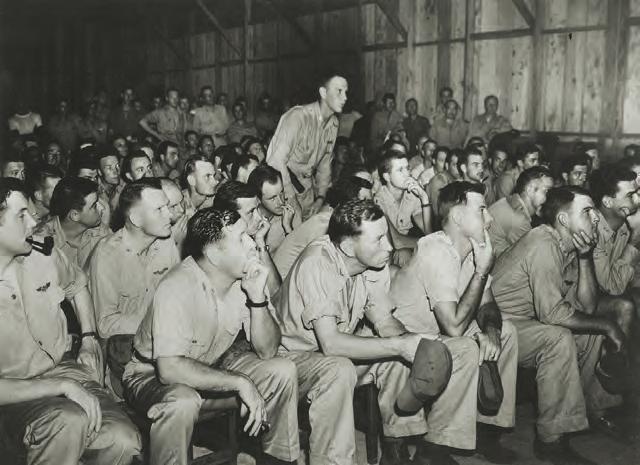

IN THE FIRST HOUR OF JULY 8, 1945, six-year-old Rodney Rasmussen was startled awake in his bed in Salina, Utah, by the unmistakable rhythm of machine gun fire a mere 300 feet away. He dressed and hustled to the front porch in time to see the flash of the .30-caliber Browning in the guard tower across the street still raining bullets into the compound where 250 German prisoners of war had been peacefully sleeping in neat rows of canvas tents.

Salina, a town of 2,600 people tucked between the Pahvant and Wasatch Mountains, where the dirt gradually brightens from beige to the signature burnt orange of southern Utah, seems an unlikely location for the largest mass murder of German prisoners on U.S. soil during World War II. The biggest hazards I encounter on my visit are the Tootsie Rolls still clinging to the sidewalks two weeks after a classic small-town, candy-tossing Fourth of July parade.

The darkest moment of Salina’s history would still be largely forgotten were it not for the homegrown effort that launched the CCC & POW Camp Salina museum in 2016. I step inside the camp’s slightly renovated and relo cated command post to meet Rasmussen, now 83, who still lives in his child hood home and caretakes the museum, which also includes a restored guard barracks and the original motor pool garage. Rasmussen extinguishes the loud fans battling the dry morning heat to walk me through Salina’s past.

In 1863, 28 Mormon families moved south from Salt Lake City to settle the north Sevier River valley. Salt, or “sal” in Spanish, became Salina’s namesake industry, later to be supplanted by farming and coal mining. The command post’s exhibits tell how in 1933 the Civilian Conservation Corps—President

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s effort to employ young men slighted by the Great Depression while also advanc ing public works—set up a camp here on the eastern end of Salina, where Main Street disappears into dusty shrub-speckled foothills. With the U.S. entry in World War II, the CCC dissolved and most of the Salina camp buildings were dismantled and moved 80 miles northwest to Delta, Utah, for use in the Topaz War Relo cation Center, one of 10 camps in the western U.S. interior where Japa nese Americans would be detained for fear of their possible sympathy toward Japan.

In 1943, the United States began to host prisoners of war captured in Europe and North Africa and launched construction of a vast net work of camps—primarily in rural inland areas—to house them. The army opened a large camp in Ogden, Utah, with nine small branch camps strategically located throughout the state to ease war-caused non-mili tary labor shortages. The remains of Salina’s CCC camp became Branch Camp No. 4. Although Germany would surrender in May 1945, it would take the United States more than a year to return the nearly 400,000 German and Italian prison ers in its care to war-ravaged Europe.

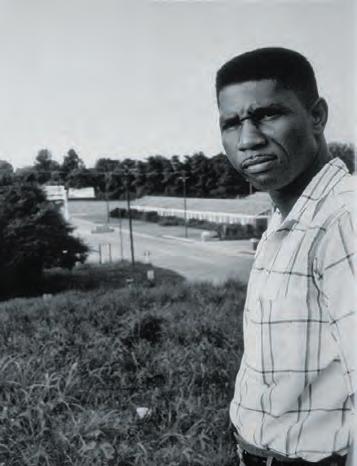

WORLD WAR II26 QUAD-CITY TIMES ARCHIVES

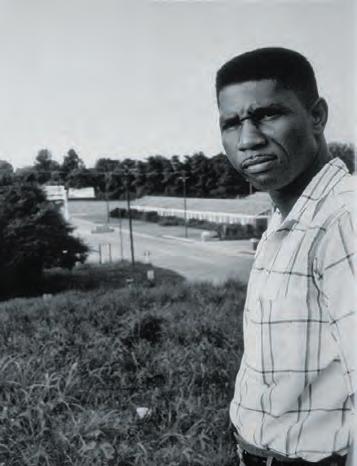

Little remains of the former POW camp in Salina, Utah, where a G.I. shot dozens of unarmed German prisoners on July 8, 1945.

WW2P-22-TRAVEL-SALINAUTAH-3.indd 26 10/5/22 3:32 PM

Meanwhile, on June 7, 1945, 250 German prisoners previously held in Arizona arrived in Salina to work on the many local farms that were producing sugar beets in a labor-intensive effort to thwart the national sugar shortage. Six days a week, trucks hauled the men in small groups to fields where they thinned and harvested beets for 5 to 10 cents per day.

Rasmussen opens the doors to the restored guard barracks to reveal an intricate scale model of the camp. Forty-three tents on wooden platforms surrounded a latrine, a kitchen where prisoners prepared meals, and a mess hall. Two layers of wire fencing enclosed the compound, with a wooden guard tower rising over each corner, save the southeast, where a natural hill provided the foundation for a small guardhouse.

I cross the road and scramble up that hill to project the museum’s model across the few acres that once housed the camp. Today, it is half-rodeo arena for the Salina Riding Club, half empty asphalt park ing lot. The only surviving camp structure still in place is the unrec ognizable mess hall. Years ago, the Riding Club tacked corrugated tin over the hall’s lath and tar paper siding and used it as their office building.

Back in the pine-sided motor pool garage, which still houses original tools soldiers used to maintain the few vehicles assigned to the camp, a plaque tells me the museum was largely the vision of the late Dee Olsen, who was a teen ager when prisoners came to work on his family farm seven miles up the road in Axtell. “His sister and mother would make chicken lunches for the prison ers,” says Olsen’s daughter, Tami Beach.

Prompted by Salina’s mayor, in 2014 Olsen, a retired engineer, recruited Beach and a few others to help raise funds and restore the salvageable build ings into a museum. Locals pitched in a variety of remnants now on display, from a box of original tent pegs to a slightly tattered prisoner uniform to a jewelry box one prisoner crafted from matchsticks and toothpicks and gifted to a farming family for whom he worked.

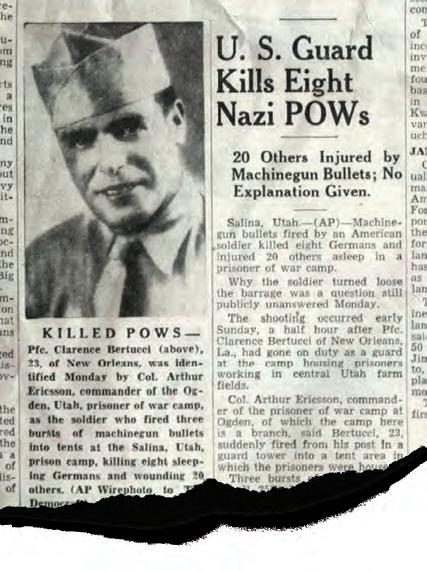

U.S. soldiers assigned to Branch Camp No. 4 had the monotonous duty of guarding compliant prisoners in the quiet fields and tents. Private Clarence V. Bertucci, a short and slight 23-year-old from New Orleans, loathed the job. In his five years of army service, he had seen no combat and had twice faced

Bertucci would later report his desire to “get his Germans someday.”

On Saturday night, July 7, Bertucci had coffee at Salina’s Mom’s Cafe, men tioned to a waitress that something exciting was about to happen, then walked the seven blocks to camp. After downing a cup or two in the still thriv ing sandy-bricked café myself, I do the same. In a single block, the awninged stucco-and-glass storefronts of down town give way to tidy single-story resi dences. A teenage boy watering hanging pots of petunias smiles at me, and I wonder whether anyone that fateful

XXXXXXXXXXXXX XXXXXXXXXXXXX AUTUMN 2022 27 QUAD-CITY TIMES ARCHIVES

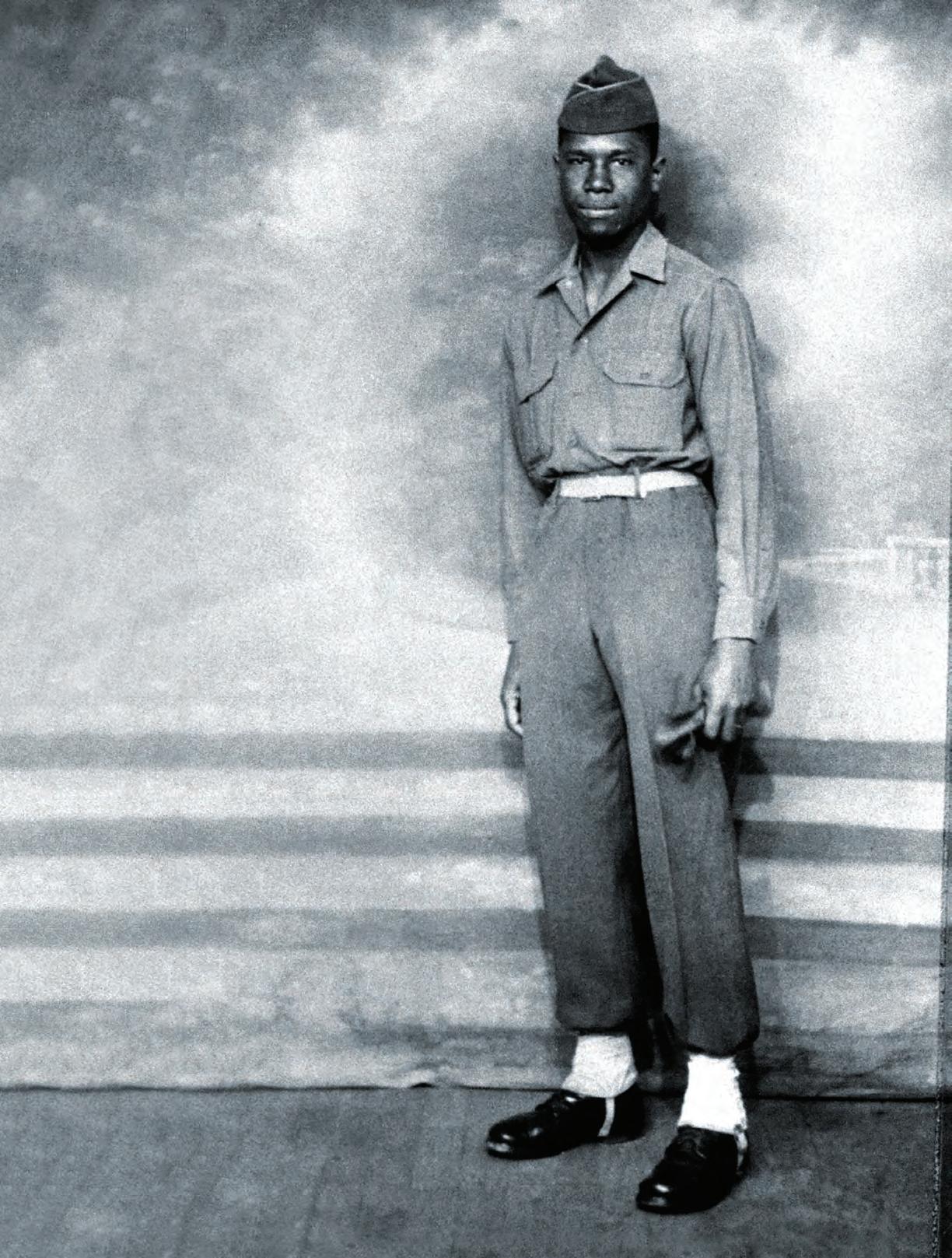

Private Clarence V. Bertucci (bottom right) had coffee at Mom’s Cafe–still a staple of downtown Salina—before walking to his guard post overlooking the POW camp to commit his crime.

WW2P-22-TRAVEL-SALINAUTAH-3.indd 27 10/6/22 10:45 AM

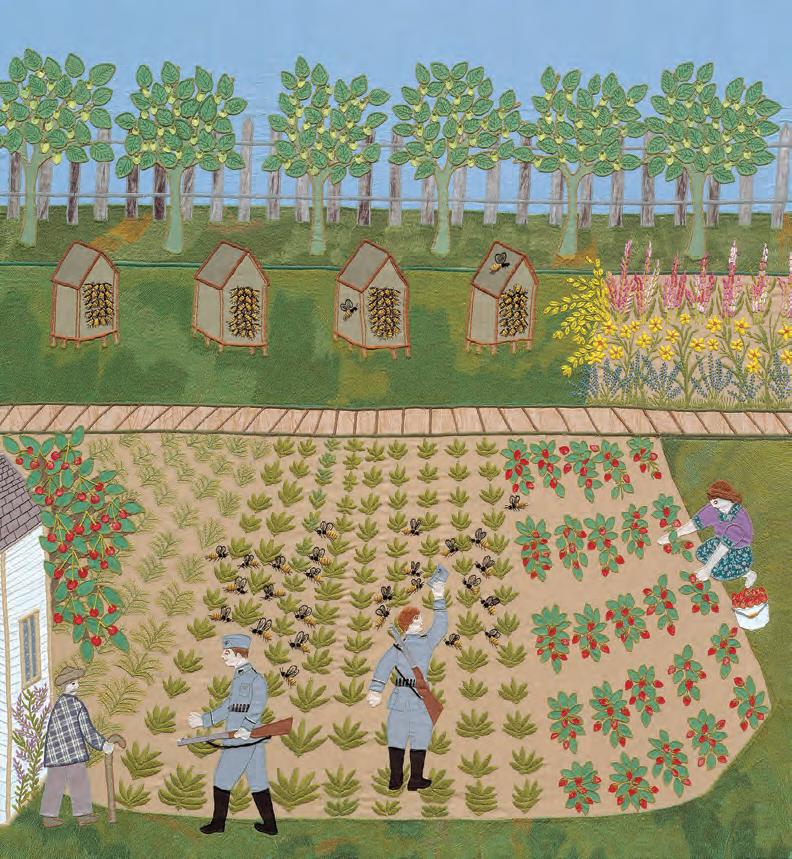

night noticed Bertucci ascending the gradual grade of Main Street.