BEN LILLY H ALAMO FRAUDS H ‘BEAR RIVER TOM’ SMITH H MACKENZIE’S RAID INTO MEXICO H MURDER AT THE NEW YORK BAR HISTORYNET.COM WILD WEST SPRING 2023 VOL. 35, NO. 4 SPRING 2023 HISTORYNET.COM WIWP-230400-COVER-DIGITAL.indd 1 1/26/23 8:27 AM

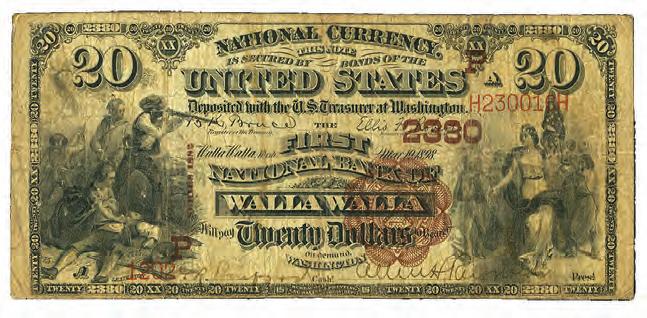

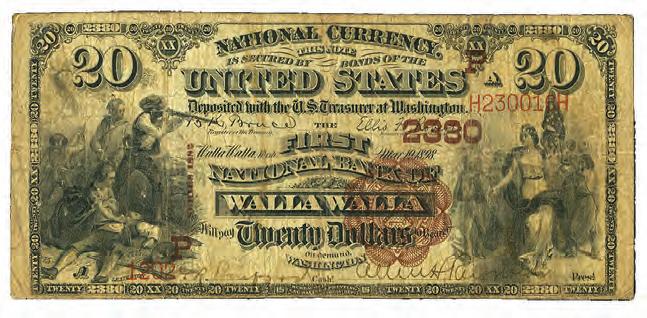

Maybe you knew that the Morgan Silver Dollar is the most widely collected and traded Silver Dollar ever minted by the United States—in part because of its iconic design, and in part because it was the hard currency found in the saddlebags of cowboys and ranchers, and of course outlaws. It was the coin that helped build the Old West.

Morgan Silver Dollars—All-American Coins

It’s also popular because it’s a 90% Silver Dollar with an American design that was first minted in 1878, from American silver that came from the Comstock Lode in Nevada. It was last minted in 1921 for circulation—which is why 2021 marked the coin’s 100th anniversary.

It’s a Wonder Any Morgans Still Exist Today

Coin experts estimate that fewer than 15% of all the Morgan Silver Dollars ever minted still exist today. At one point, the Pittman Act authorized the melting of 259,121,554 Silver Dollars to send to Great Britain to help that country during World War I—nearly half of the entire mintage of Morgans up to that time!

A First Year Morgan Silver Dollar—Guaranteed!

You’re guaranteed to receive a first-year Morgan Silver Dollar from 1878. The coins here come from a recently discovered hoard of around 500 1878 Morgans, just now available to the public. Depending on what you want to spend, you have your choice of three quality grades— Fine to Very Fine, About Uncirculated and Brilliant Uncirculated (see coin condition grid to the right). But—immediately call the toll-free number below because these first-year, 1878 Morgan Silver Dollars won’t last.

1878 Morgan Silver Dollars

Fine-Very Fine $79.95 +s/h

About Uncirculated $129 +s/h

Brilliant Uncirculated $229 + FREE SHIPPING

FREE SHIPPING: Limited time only. Product total over $149 before taxes (if any). Standard domestic shipping only. Not valid on previous purchases.

GovMint.com® is a retail distributor of coin and currency issues and is not affiliated with the U.S. government. The collectible coin market is unregulated, highly speculative and involves risk. GovMint.com reserves the right to decline to consummate any sale, within its discretion, including due to pricing errors. Prices, facts, figures and populations deemed accurate as of the date of publication but may change significantly over time. All purchases are expressly conditioned upon your acceptance of GovMint.com’s Terms and Conditions (www.govmint.com/terms-conditions or call 1-800-721-0320); to decline, return your purchase pursuant to GovMint.com’s Return Policy. © 2022 GovMint.com. All rights reserved. SPECIAL CALL-IN ONLY OFFER Get an 1878, First-Year Morgan Silver Dollar! e Silver Dollar that Helped Build the Old West! GovMint.com • 1300 Corporate Center Curve, Dept. FMD155-01, Eagan, MN 55121 1-800-517-6468 Offer Code FMD155-01 Please mention this code when you call. A+ First-Year 1878 COIN CONDITIONS Fine-Very Fine: Clear elements showing some to good detail, with moderate, even wear. Sold elsewhere for $134 About Uncirculated: Sharp elements and backgrounds with a trace of wear and some mint luster. Sold elsewhere for $176 Brilliant Uncirculated: Has never been circulated and still retains its original mint luster. Sold elsewhere for $323 Morgan Silver Dollar! From a Just Discovered Collector’s Hoard! Your Choice of Three Quality Grades! is 38.1 mm GUARANTEED! 1878 FIRST YEAR OF ISSUE WIWP-230221-005 GovMint 1st Year Issue 1878 Morgan Silver Dollar.indd 1 1/5/2023 2:45:55 PM

WIWP-230221-011 Stephen Ambrose Tours.indd 1 1/5/2023 3:21:17 PM

LILLY OF THE FIELD

By

THE FORGETTABLE ALAMO FRAUDS

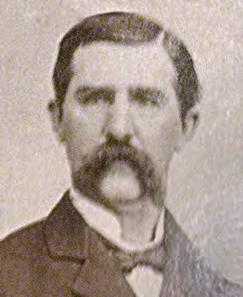

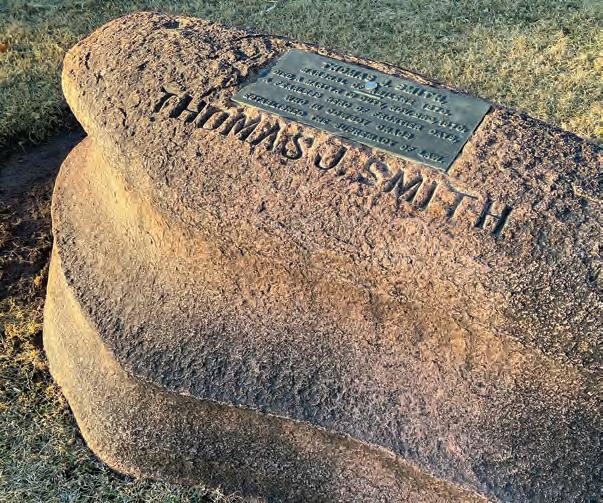

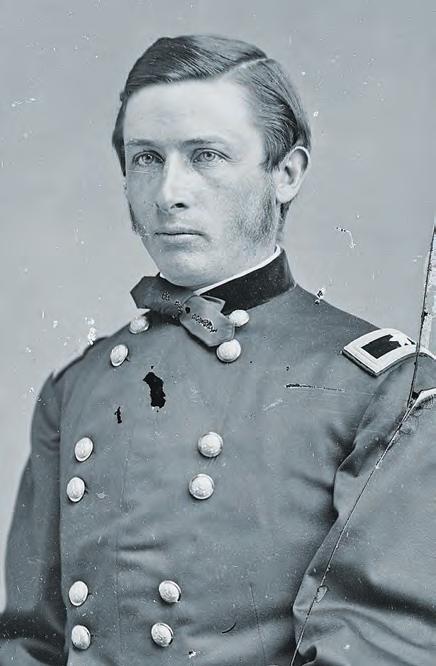

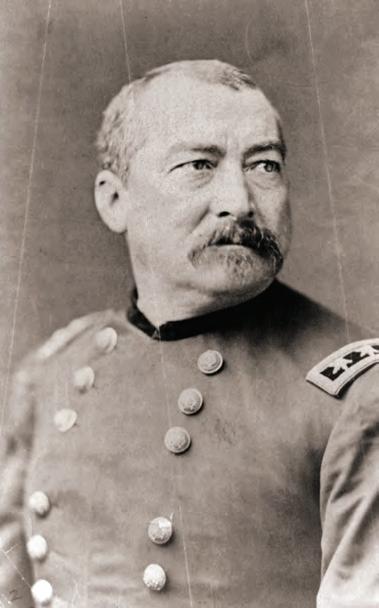

ABILENE’S ABLE BUT SHORT-LIVED LAWMAN

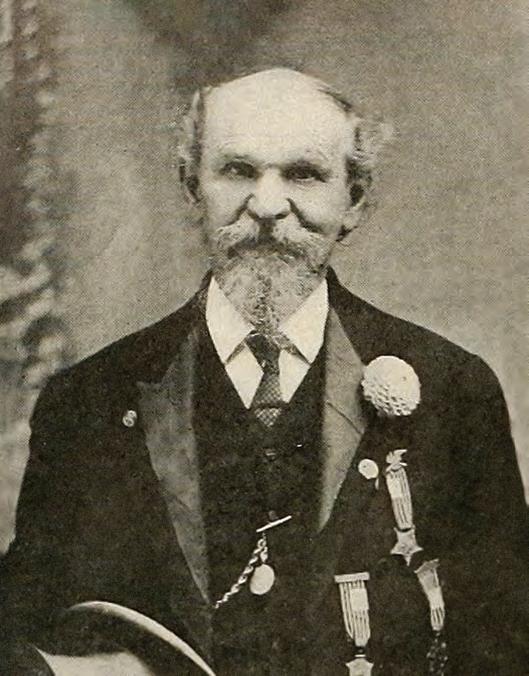

By Roger Myers

By Roger Myers

Aaron Robert Woodard

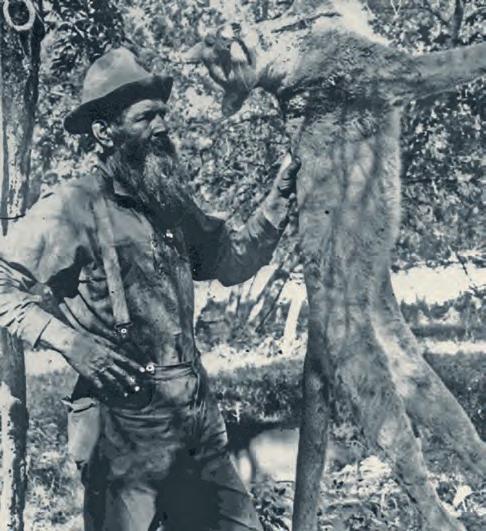

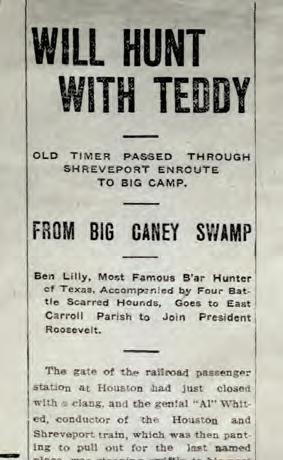

Tireless hunter Ben Lilly guided famous clients and stalked predators for bounties

By Ron J. Jackson Jr.

‘Uncle Jimmy’ Cannon and Louis Schilling slighted the remembrance of martyrs

Aaron Robert Woodard

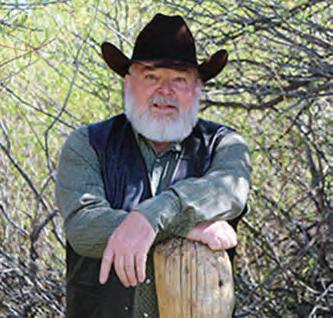

Tireless hunter Ben Lilly guided famous clients and stalked predators for bounties

By Ron J. Jackson Jr.

‘Uncle Jimmy’ Cannon and Louis Schilling slighted the remembrance of martyrs

38 46 32 WIWP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 2 1/26/23 8:28 AM

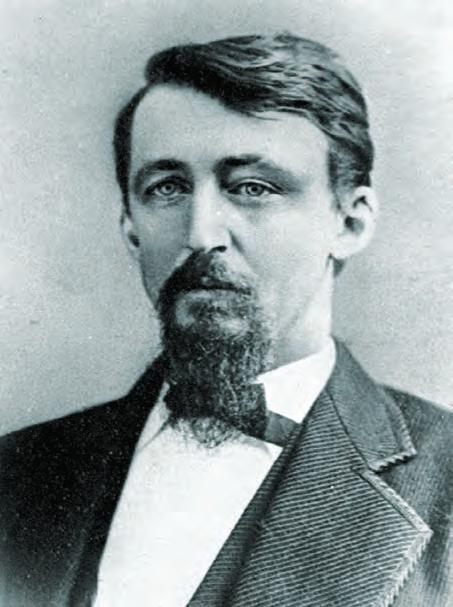

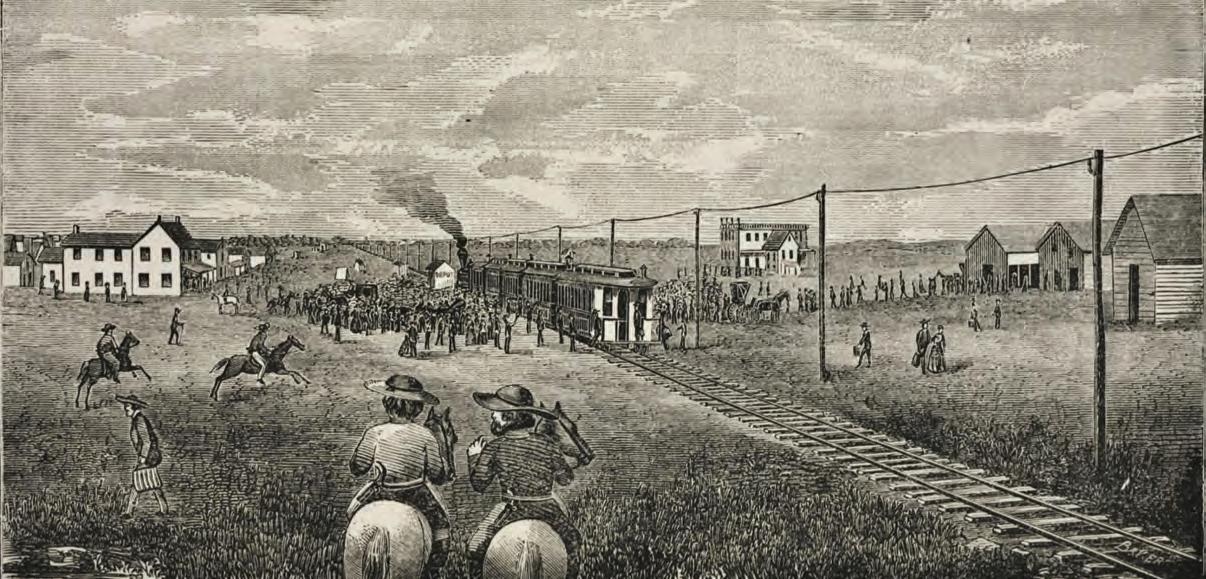

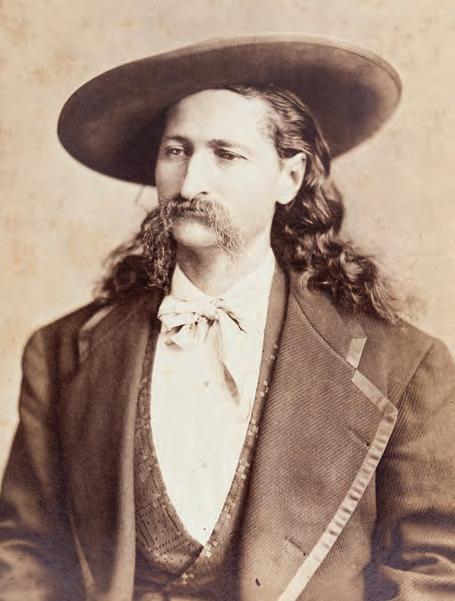

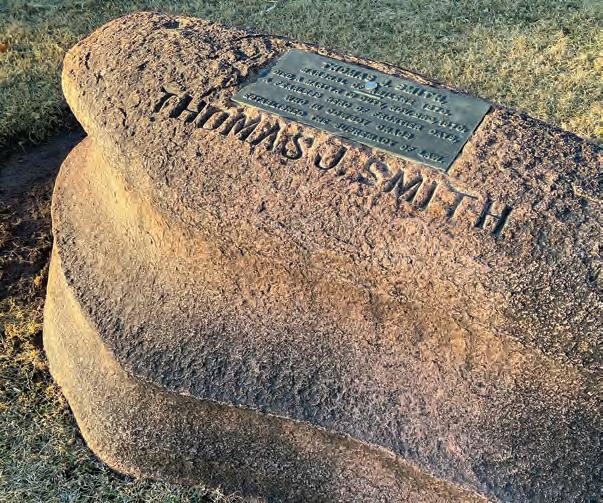

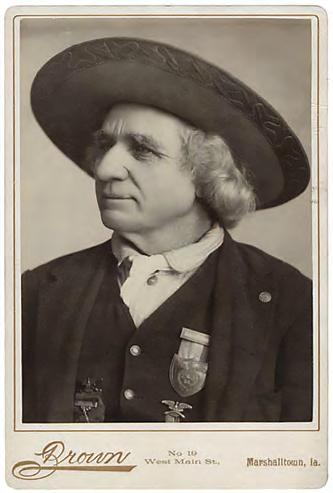

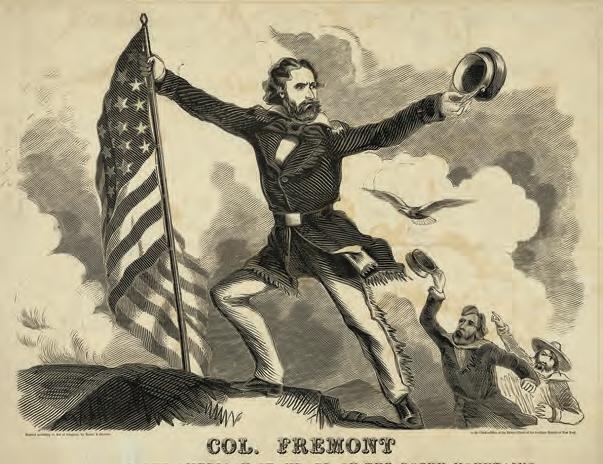

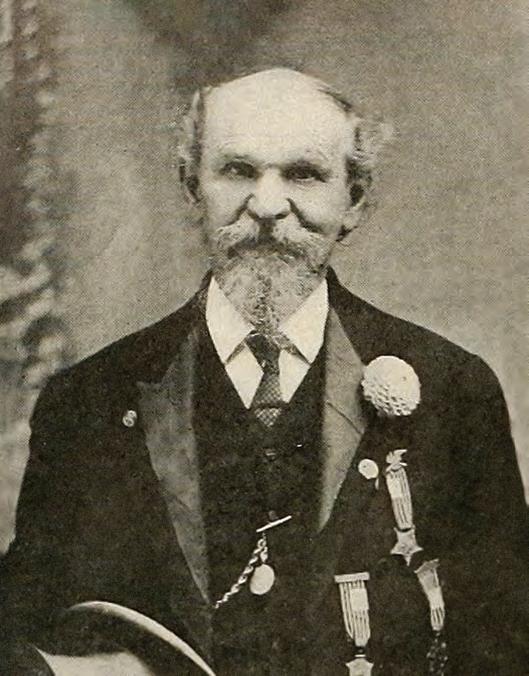

‘Bear River Tom’ Smith policed the Kansas cow town before Wild Bill Hickok

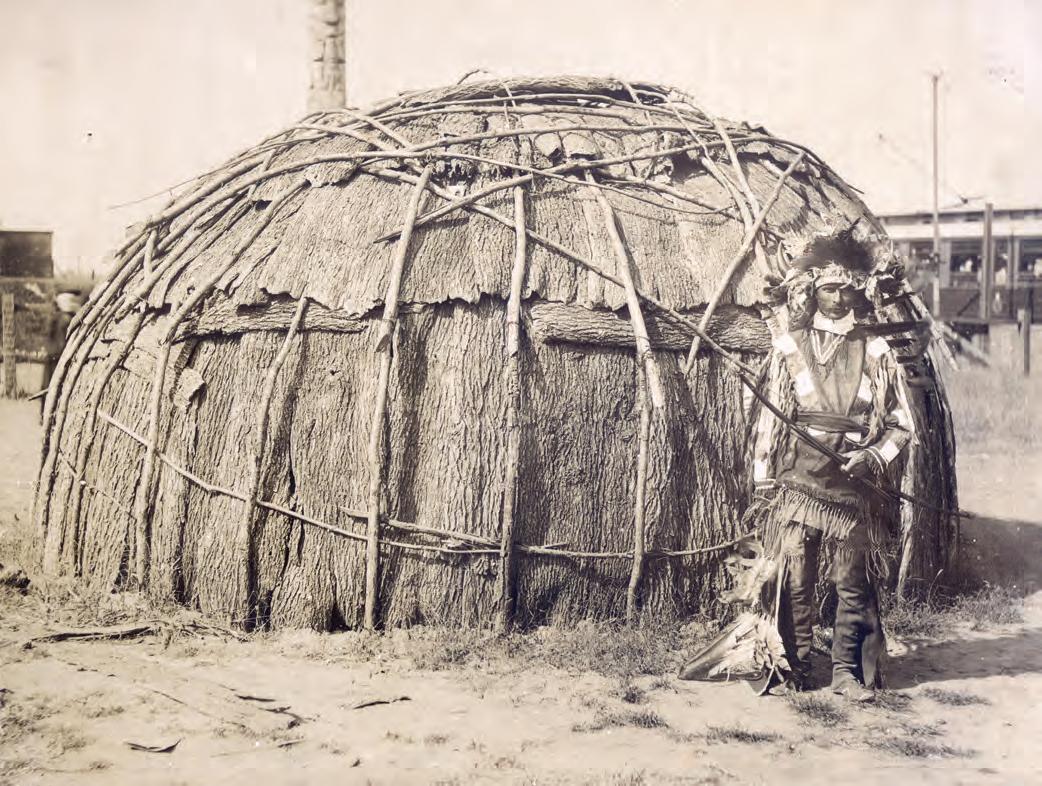

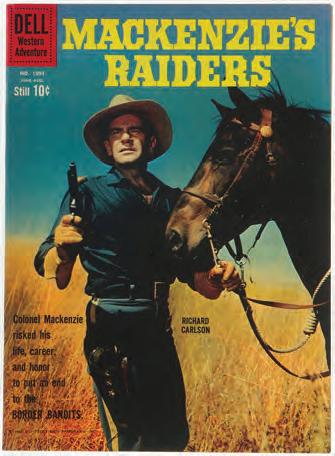

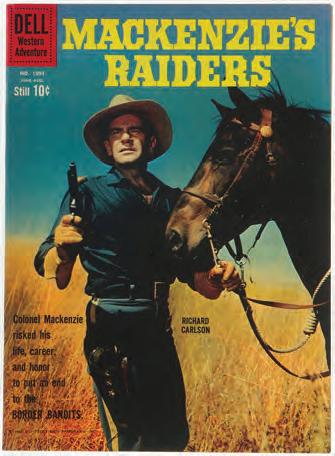

MACKENZIE’S RAID INTO MEXICO

By Allen Lee Hamilton

In 1873 Colonel Ranald Mackenzie risked war to stop cross-border Indian attacks

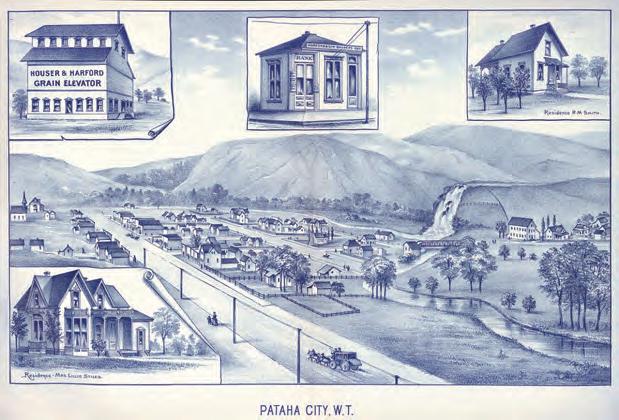

A SENSELESS MURDER AT NEW YORK BAR

By Kevin Carson

Who killed the shipping station agent on Washington Territory’s Snake River?

SPRING 2023

4 EDITOR’S LETTER

8 LETTERS

10 ROUNDUP

16 INTERVIEW

BY CANDY MOULTON

Mark Miller’s biography of Wyoming outlaw George Parott digs up all the dirt

18 WESTERNERS

Italian-born dancer Giuseppina Morlacchi once co-starred with Buffalo Bill Cody

20 GUNFIGHTERS &

LAWMEN

BY TERRY HALDEN

In 1920 a trio of bunglers robbed a train in Alberta, prompting a series of killings

22 PIONEERS & SETTLERS

BY CHUCK LYONS

Texan Sarah Hubbard witnessed loved ones’ deaths and survived Indian captivity

24 WESTERN

ENTERPRISE

BY DAVID MCCORMICK

In 1902 Harry Buckwalter teamed up with William Selig to film early Westerns

26

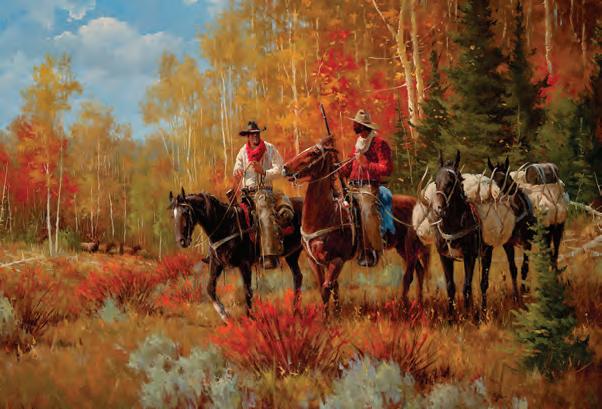

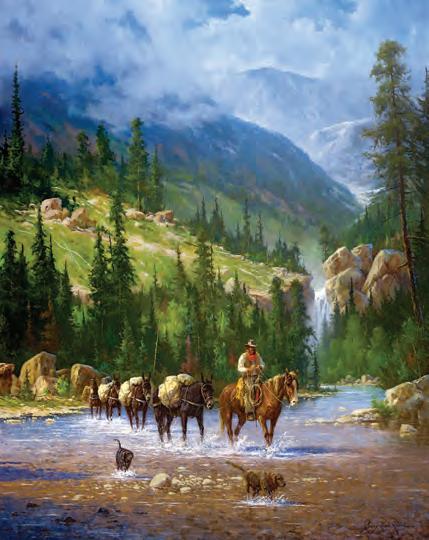

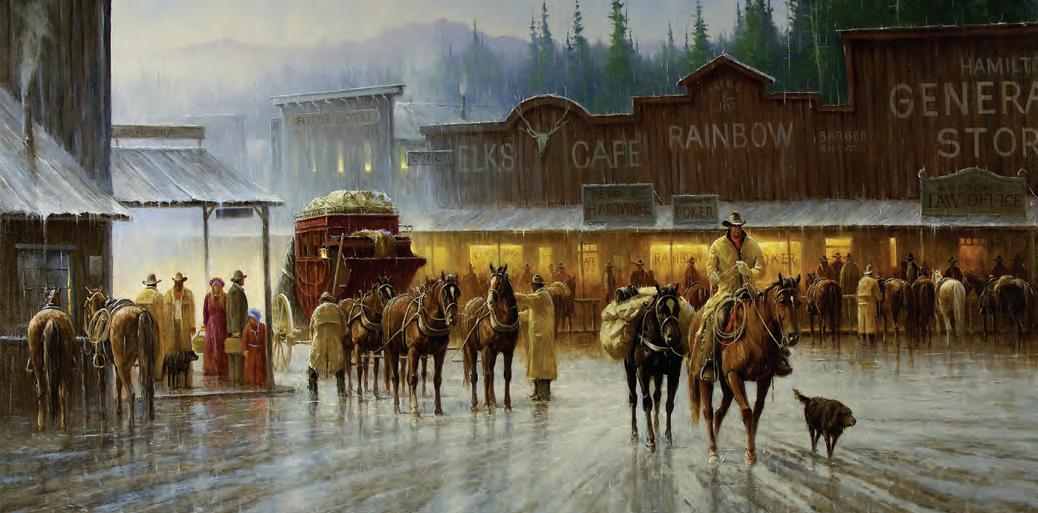

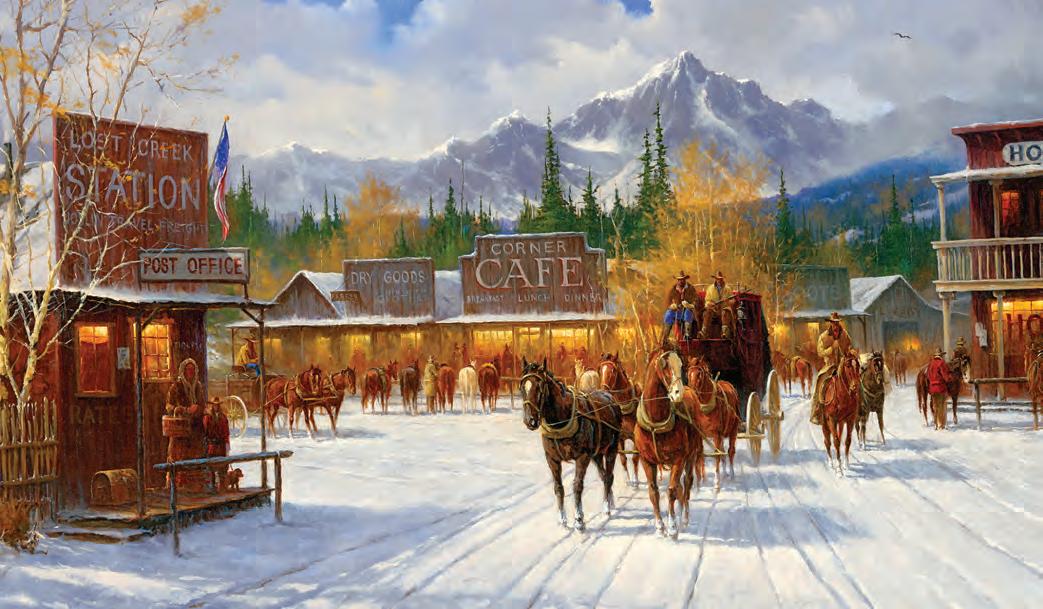

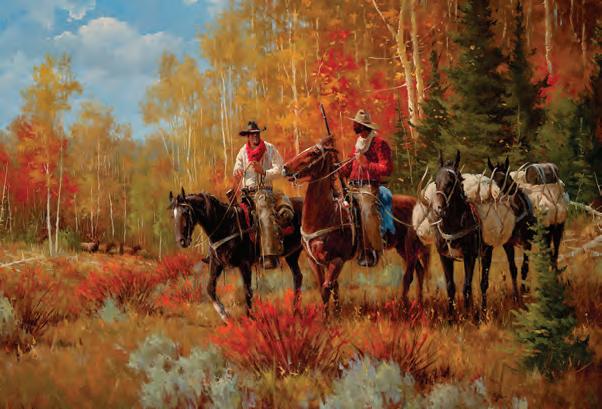

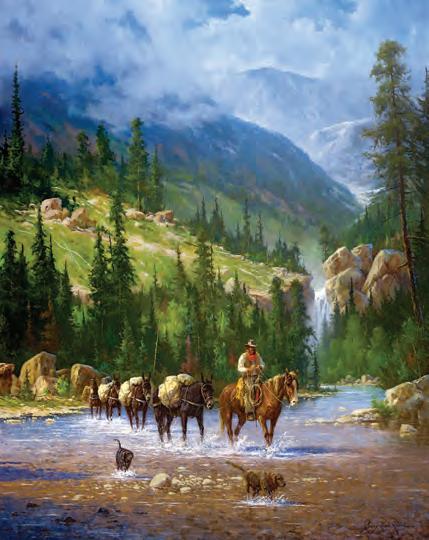

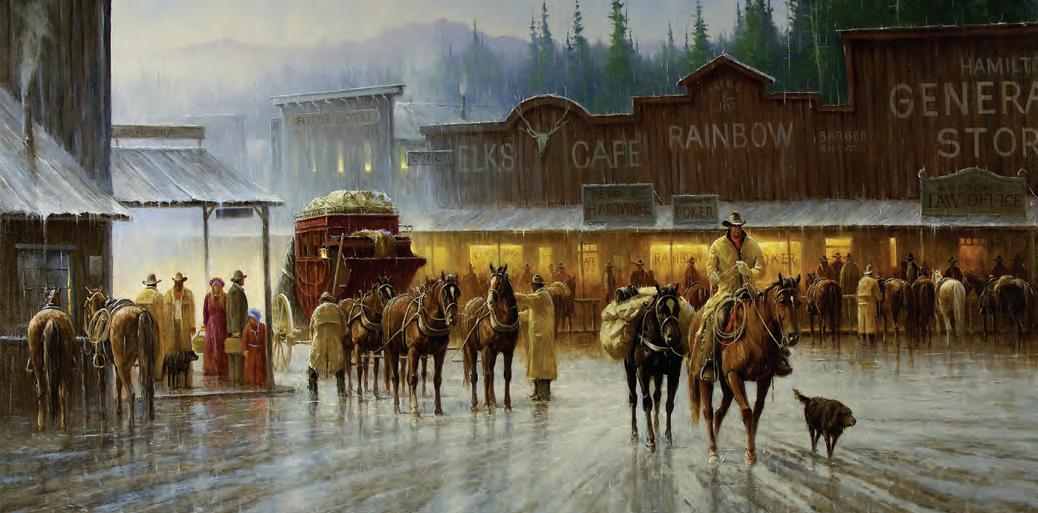

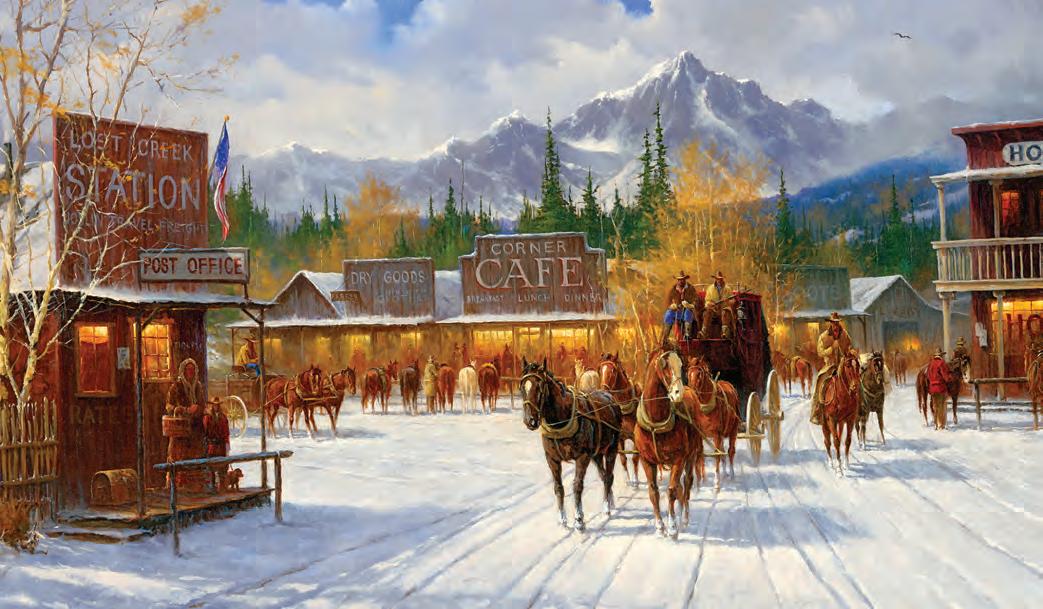

ART OF THE WEST

BY JOHNNY D. BOGGS

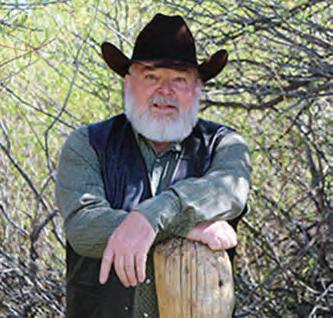

Painter Gary Lynn Roberts takes inspiration from his parents and Charlie Russell

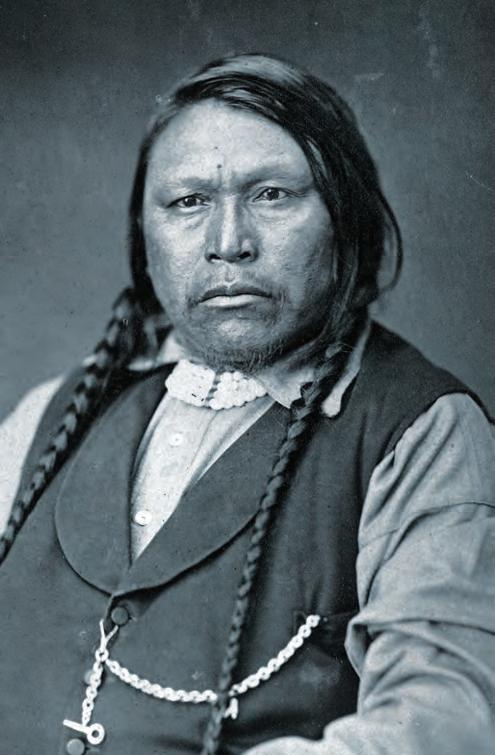

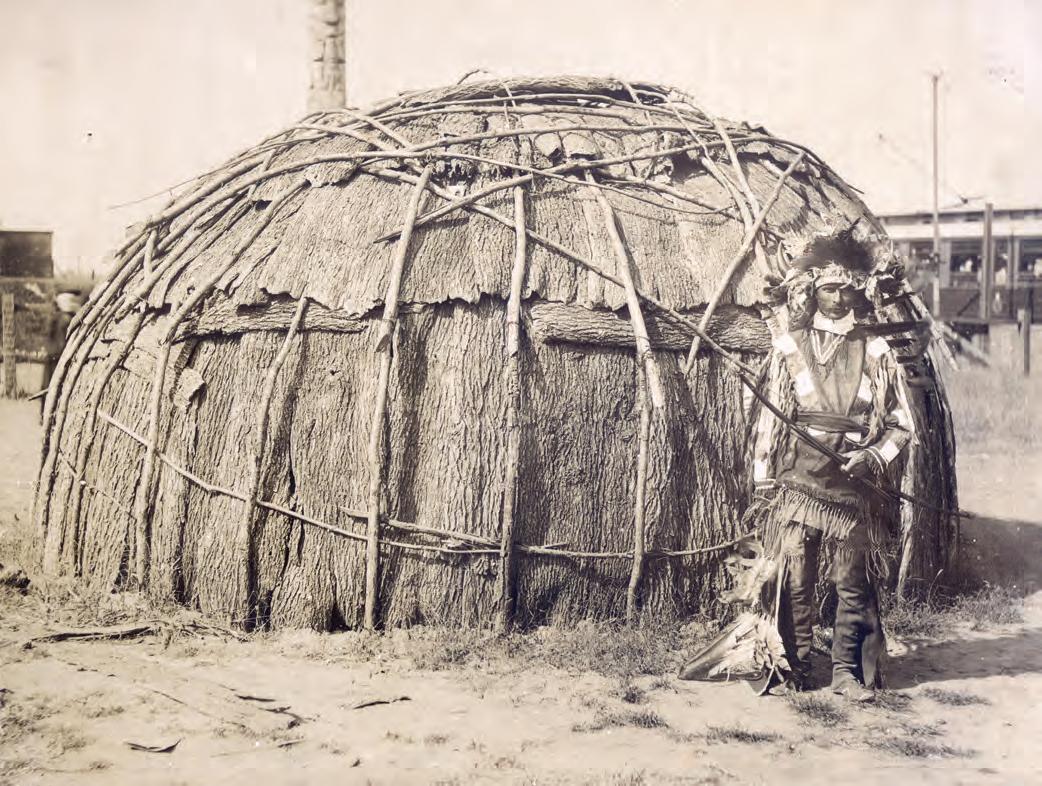

30 INDIAN LIFE

BY DAVID MCCORMICK

That Cheyennes love horses is no secret, but how did horses transform the tribe?

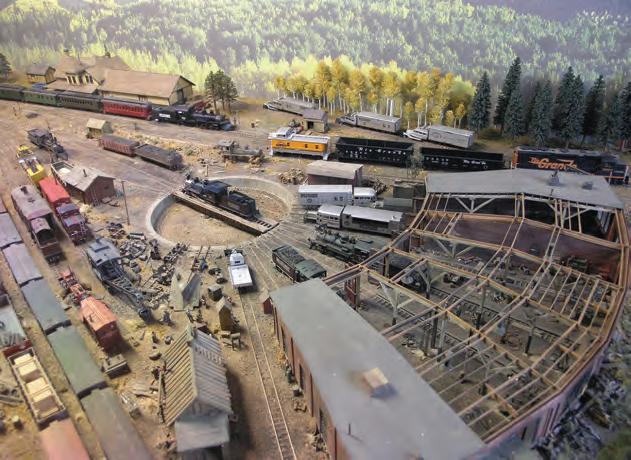

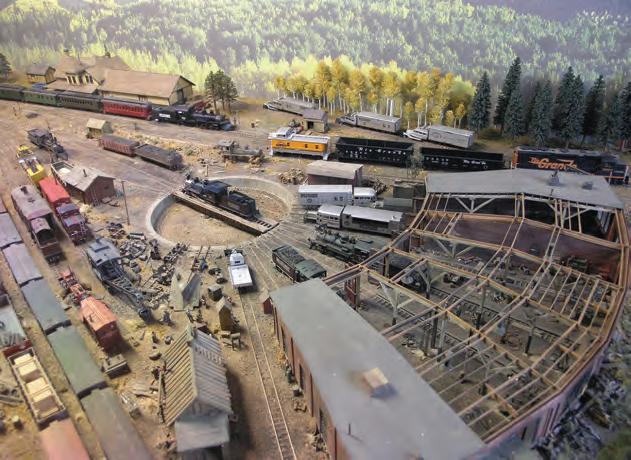

68 COLLECTIONS

BY LINDA WOMMACK

Ride and learn about trains at southwest Colorado’s Ridgway Railroad Museum

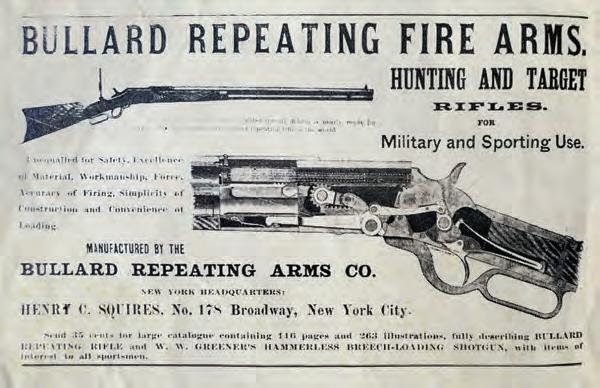

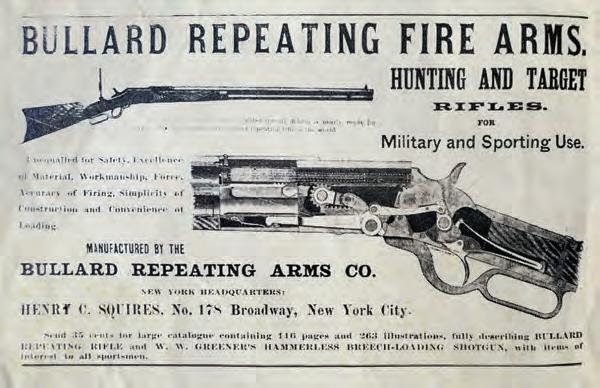

70 GUNS OF THE WEST

BY GEORGE LAYMAN

James H. Bullard made fine single-shot and repeating rifles—but not fast enough

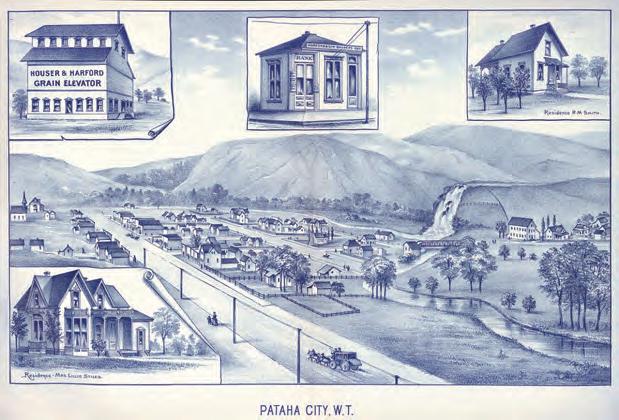

72 GHOST TOWNS

BY TERRY HALDEN

Keystone, Mont., went by several names on its journey through boom and bust

74 REVIEWS

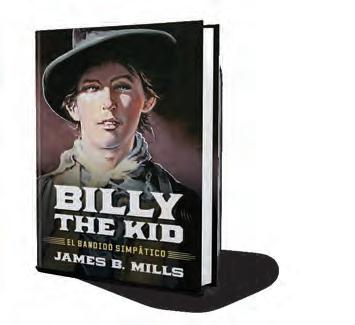

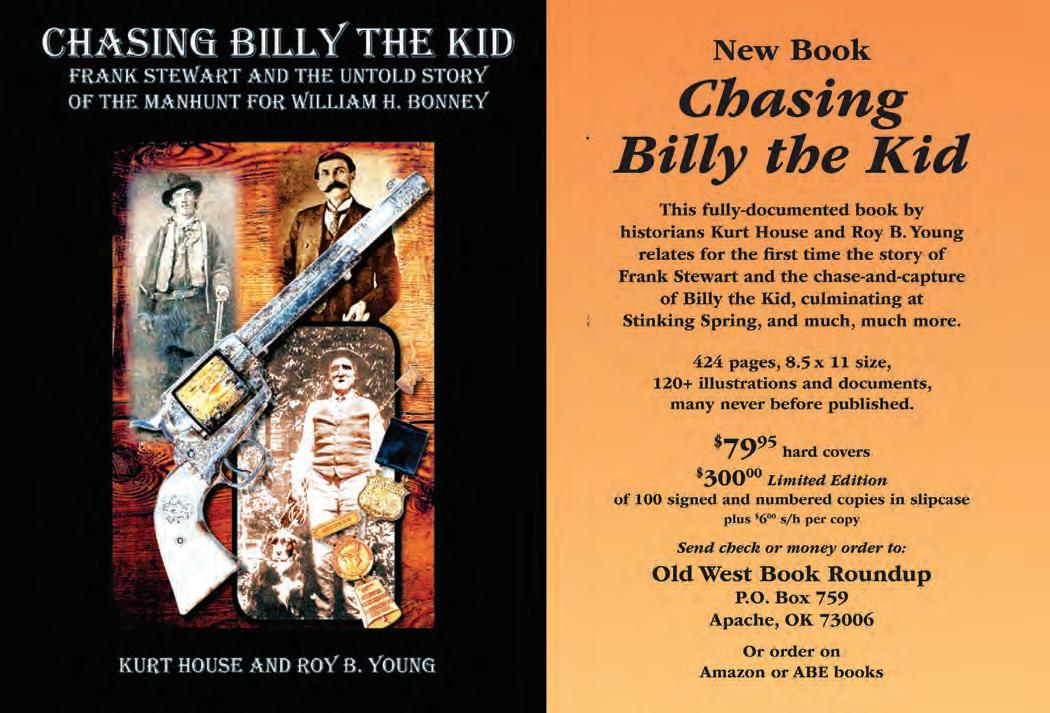

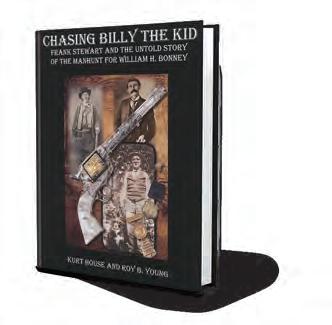

Author Linda Wommack suggests top books and films about her native Colorado. Plus reviews of books about Billy the Kid, Wild Bill, Buffalo Bill and others

80 GO WEST

Once a hunting ground, Yellowstone’s Lamar Valley is where the buffalo roam

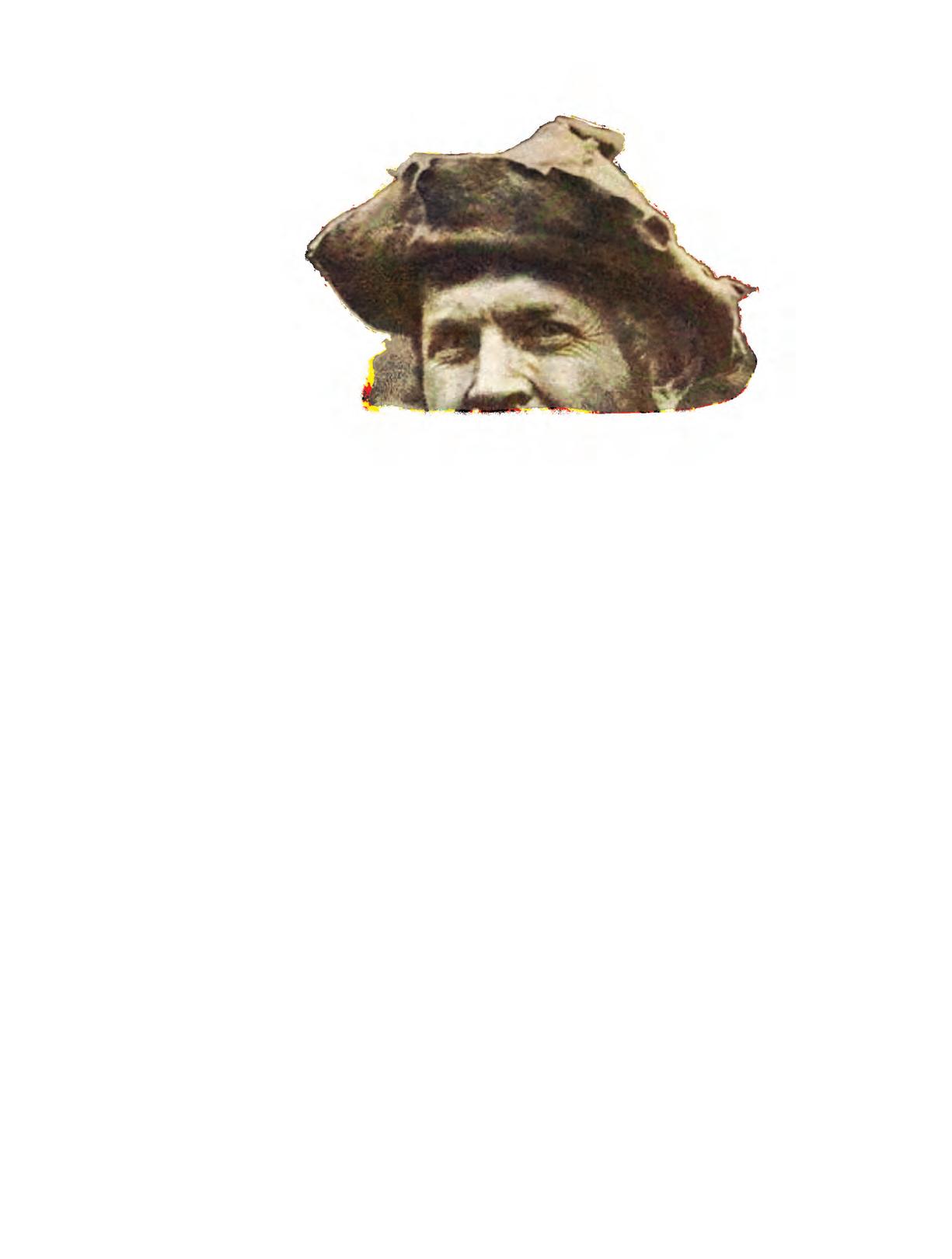

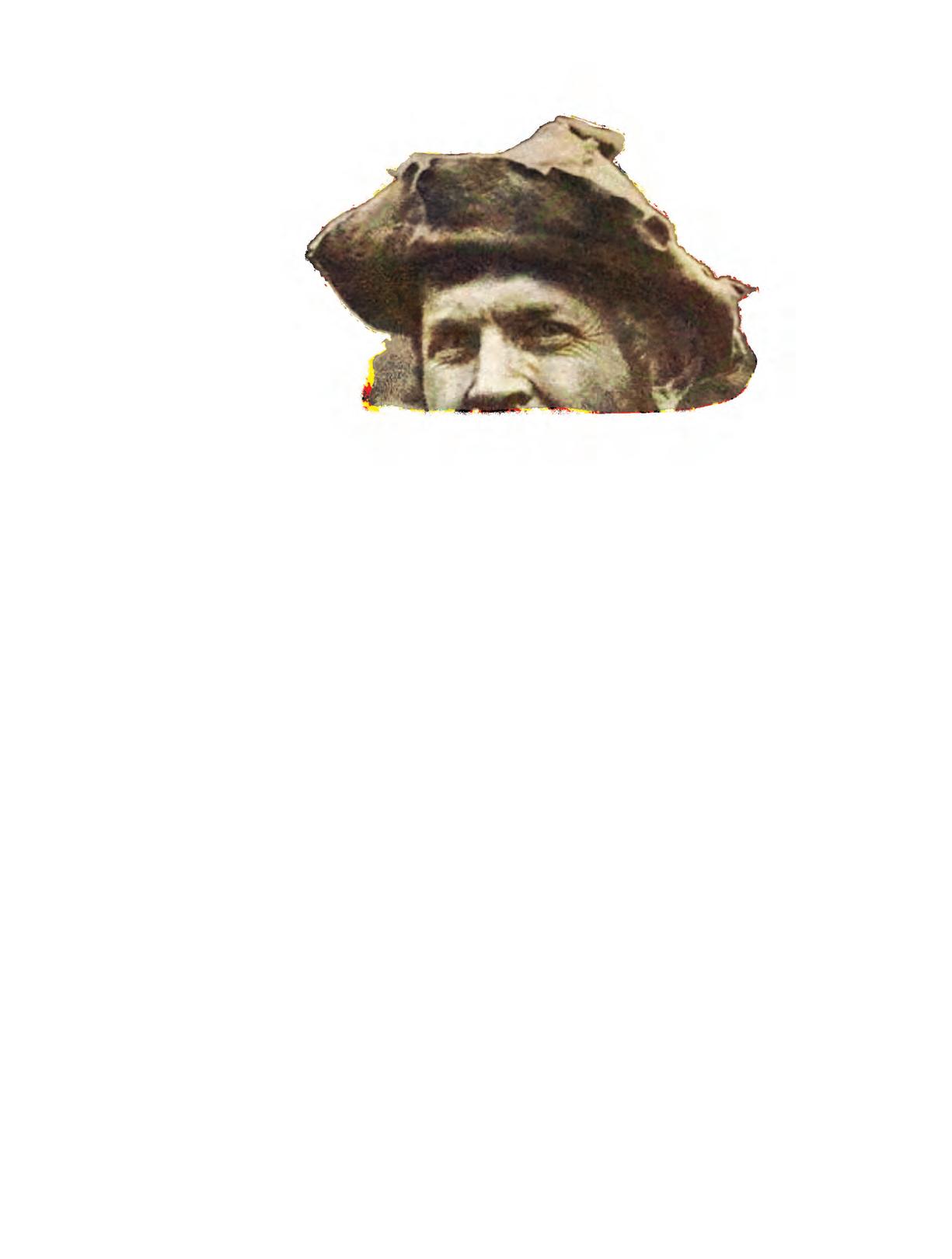

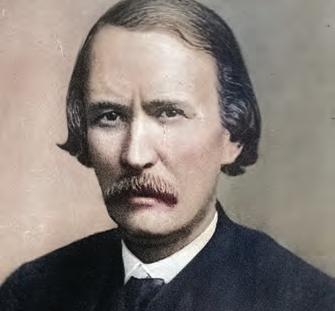

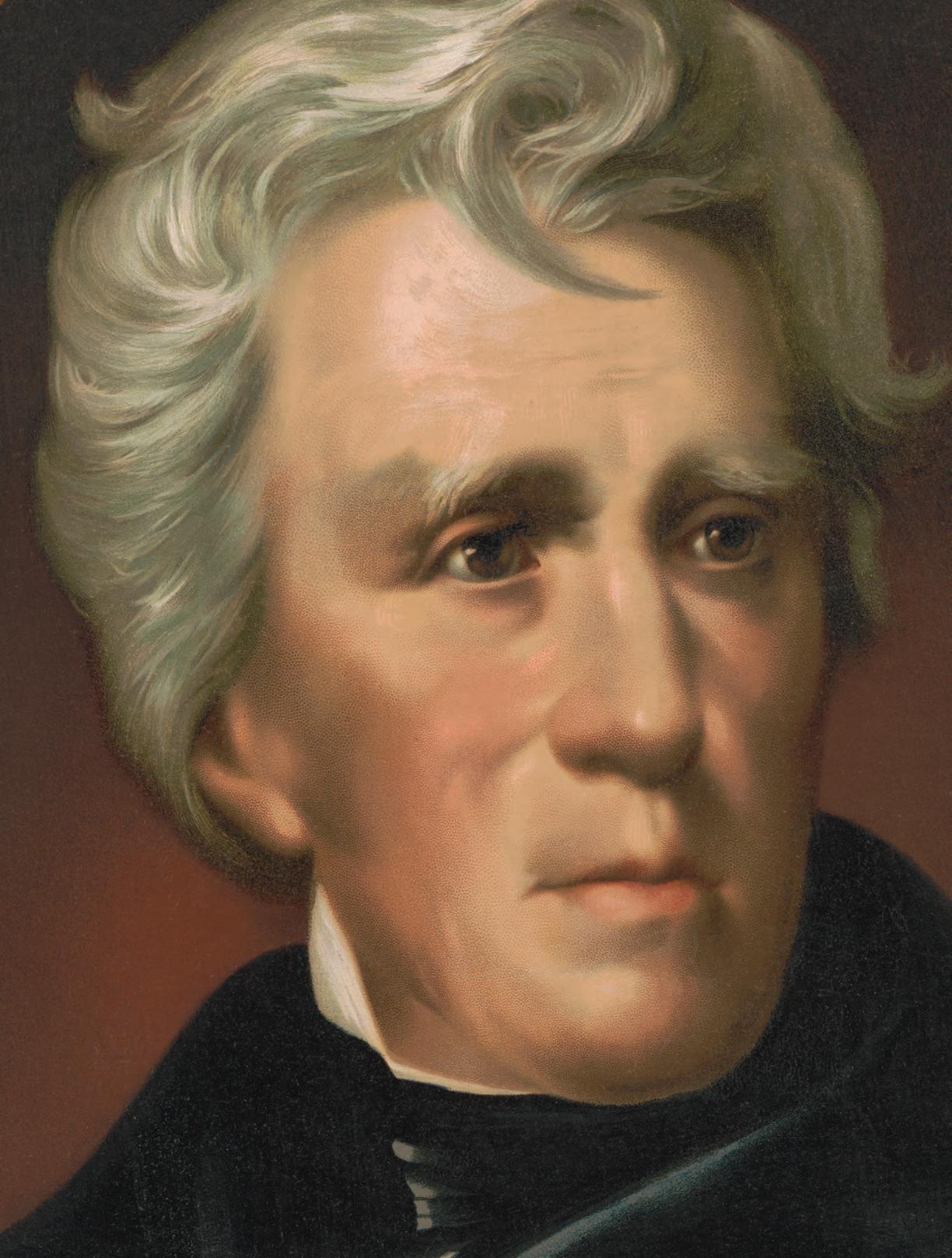

ON THE COVER

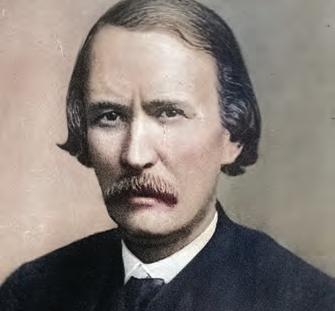

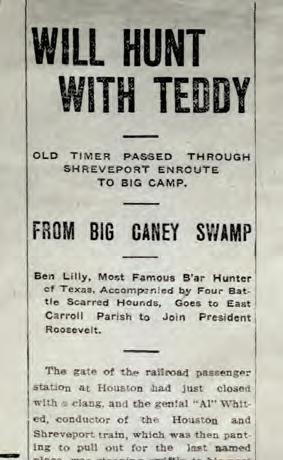

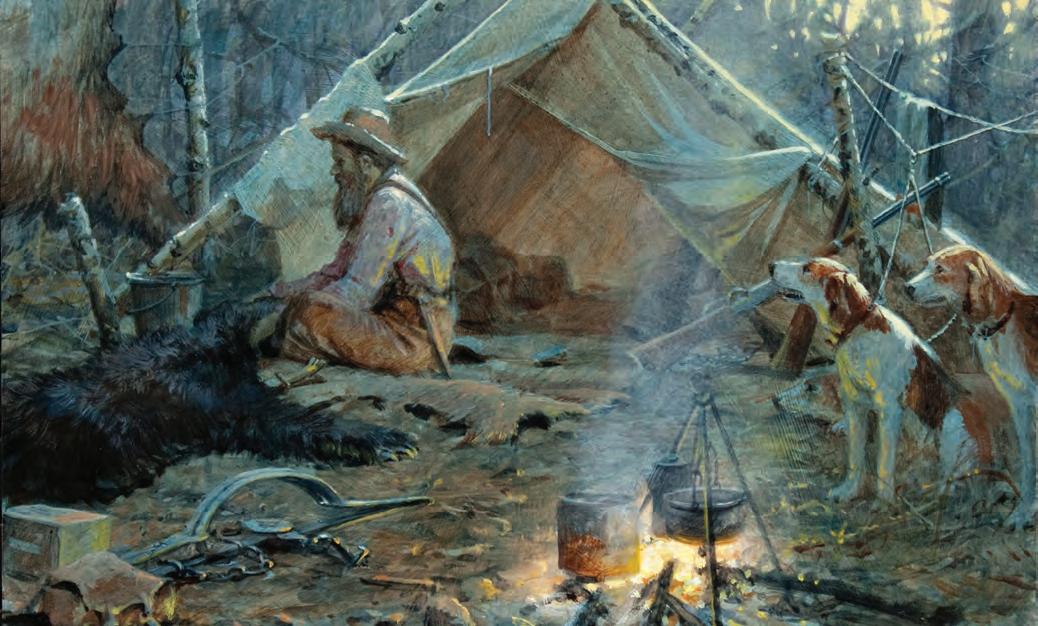

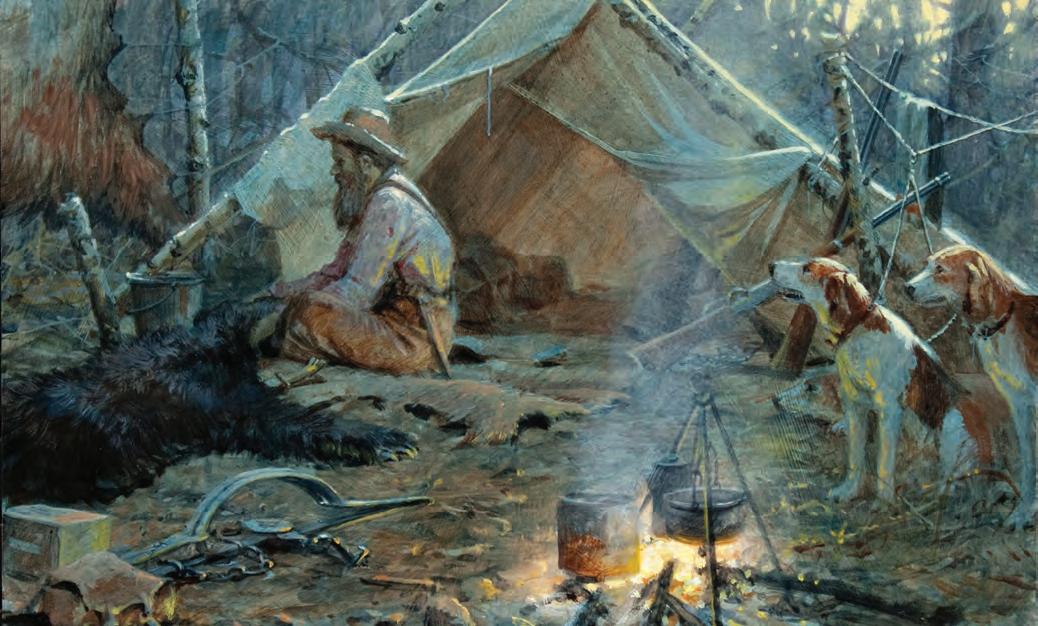

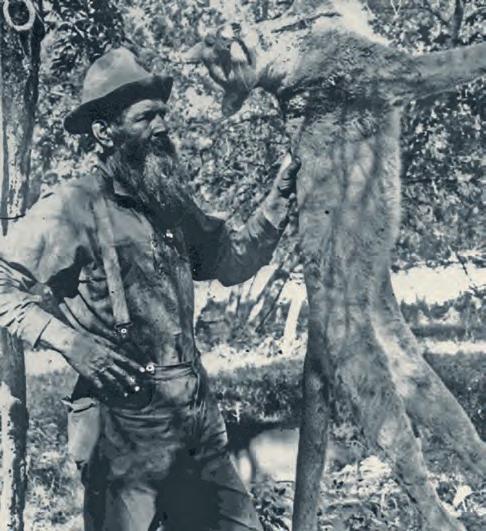

Big-game hunter Ben Lilly was as hard as nails. Drawn to wilderness rambles as a young man, he made his living collecting federal bounties on bears, mountain lions and other apex predators and guiding hunts for such notables as President Theodore Roosevelt. “He seemed to relish reducing himself almost to the level of the animals he pursued,” Aaron Robert Woodard remarks of Lilly in the cover story. Indeed, Lilly proved as tireless as the pack of hounds he raised and trained. Not until late in life did his exertions begin to tell, claiming his life days shy of his 80th birthday.

(Silver City Museum, N.M.; photo illustration by Brian Walker)

54

62 WIWP-230400-CONTENTS.indd 3 2/1/23 4:51 PM

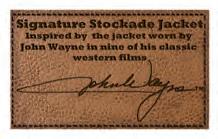

A New Sheriff in Town

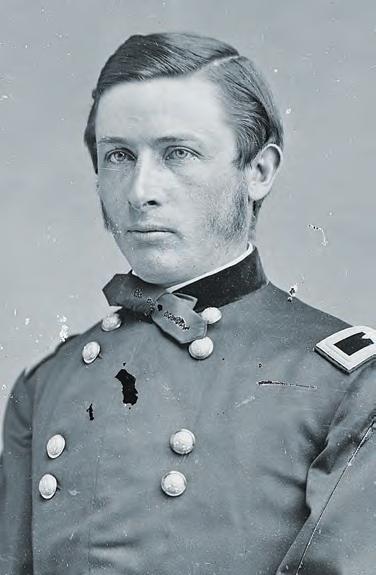

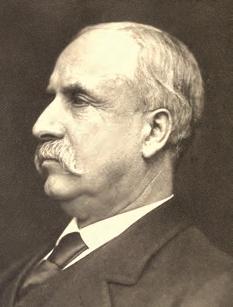

This year marks 35 years Wild West has been “Chronicling the American Frontier,” as it once read on the cover. It was back in June 1988 that editor Bill Vogt steered the premiere issue into print, and from Vogt’s untimely death in 1995 to 2022 editor Greg Lalire rode herd over the magazine. Over that span the pair of them published the works of a stellar lineup of Western writers as dedicated to sharing history as we are.

I am humbled to succeed Vogt and Lalire as editor of Wild West

Over that same 35 years I’ve pursued a career in publishing that has led me and my wife from Doc Holliday’s home state of Georgia to California and back East with detours in between. A modern-day explorer, I’ve crisscrossed the West on big roads, little ones and countless trails, albeit not poling upriver or straddling the back of an ornery mule. Prior to joining the HistoryNet magazine group, I wrote and edited travel guides for the likes of National Geographic, Lonely Planet and Rough Guides.

When a newfound friend asks what I do for a living, I answer, “I get paid to learn.” Boy howdy, how true that is! As managing editor of Wild West from 2008 to 2022 I edited and factchecked everything we sent to the printer. In the 100 issues we published over that time, that tallies around 3 million words read, weighed and, yes, unwillingly cut to fit writers’ wonderful stories of the Old West between the covers of the magazine.

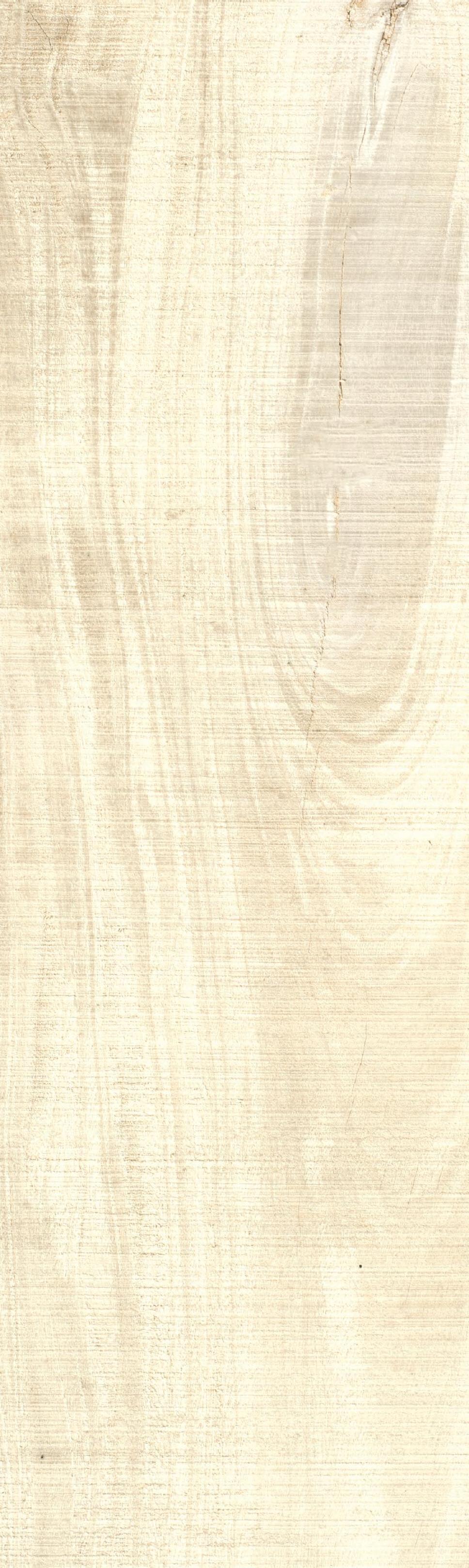

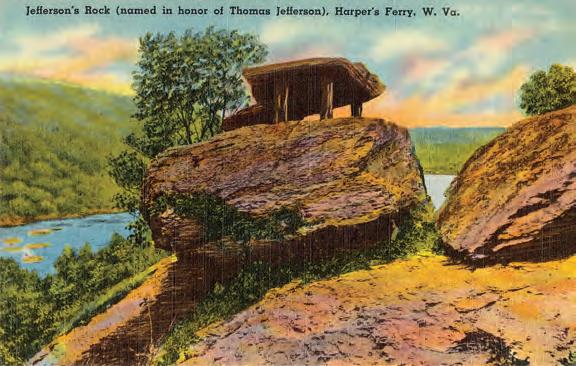

I now work from a home office in our westward-facing cabin in Harpers Ferry, W.Va., midway up a mountain between the Appalachian Trail and Shenandoah River and overlooking 40 miles of valley. Thus my gaze is inexorably drawn to the West. Minutes downriver from our cabin is Jefferson Rock. It was there on Oct. 25, 1783, Thomas Jefferson stood and contemplated the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, gateway to the “undiscovered country” that lay beyond. “For the mountains being cloven asunder,” he wrote, “she presents to your eye, through the cleft, a small catch of smooth blue horizon, at an infinite distance in that plain country, inviting you, as it were, from the riot and tumult roaring around you to pass through the breach and participate in the calm below.”

Ten years later President Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore and map the newly acquired territory of Louisiana, up the Missouri to the Rockies and down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. Corps of Discovery leader Lewis first stopped by the federal armory in Harpers Ferry for firearms, knives and other equipment, including a collapsible iron-framed boat. My backyard is steeped in history.

Storytelling—the sharing of anecdotes common to human experience—is a cultural tradition that spans time and place. Only the means of sharing it has changed—dramatically so in

recent decades. Wild West has kept up with the changing times, and in coming months we’ll further update and make changes to our print and online editions. What won’t change is our commitment to relate entertaining, authoritative stories of the people, places and events of the American West.

Our small, hardworking outfit includes senior editor Jon Guttman, art director Austin Stahl, photo editor Alex Griffith and a few dedicated special contributors. Lalire joins that list of contributors as editor emeritus. Our remuda of talented writers includes members of Western Writers of America (WWA), the Wild West History Association (WWHA), historians, scholars and a host of mavericks who just plain love the history of the American West. We strive to continue a tradition of excellence that has garnered our writers numerous awards, including several Six-Shooter Awards from WWHA, five Spur Awards from WWA and a half dozen bronze Wranglers from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. We’re proud of their accomplishments. They, and ever curious readers like you, are the reason for our longevity.

Toward that end we invite your feedback. By voicing your opinion, you’ll help craft the content you enjoy each issue. Write us at WildWest@HistoryNet.com.

Now, saddle up—we’re burning daylight!

Wild West editor David Lauterborn is a published writer, author and photographer with two books and hundreds of magazine articles to his credit. A hopelessly addicted traveler to and onetime resident of the American West, he lives in historic Harpers Ferry, W.Va.

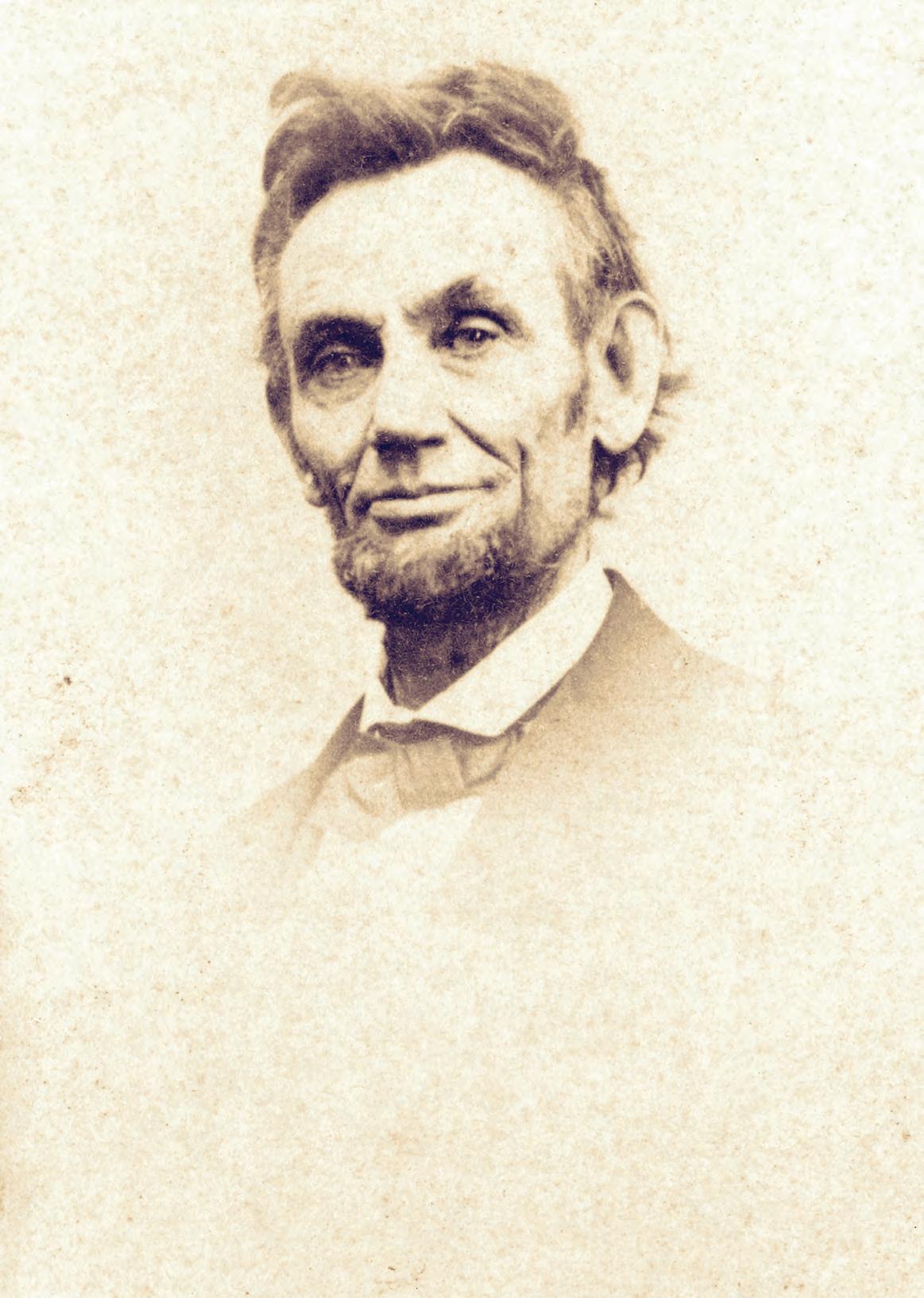

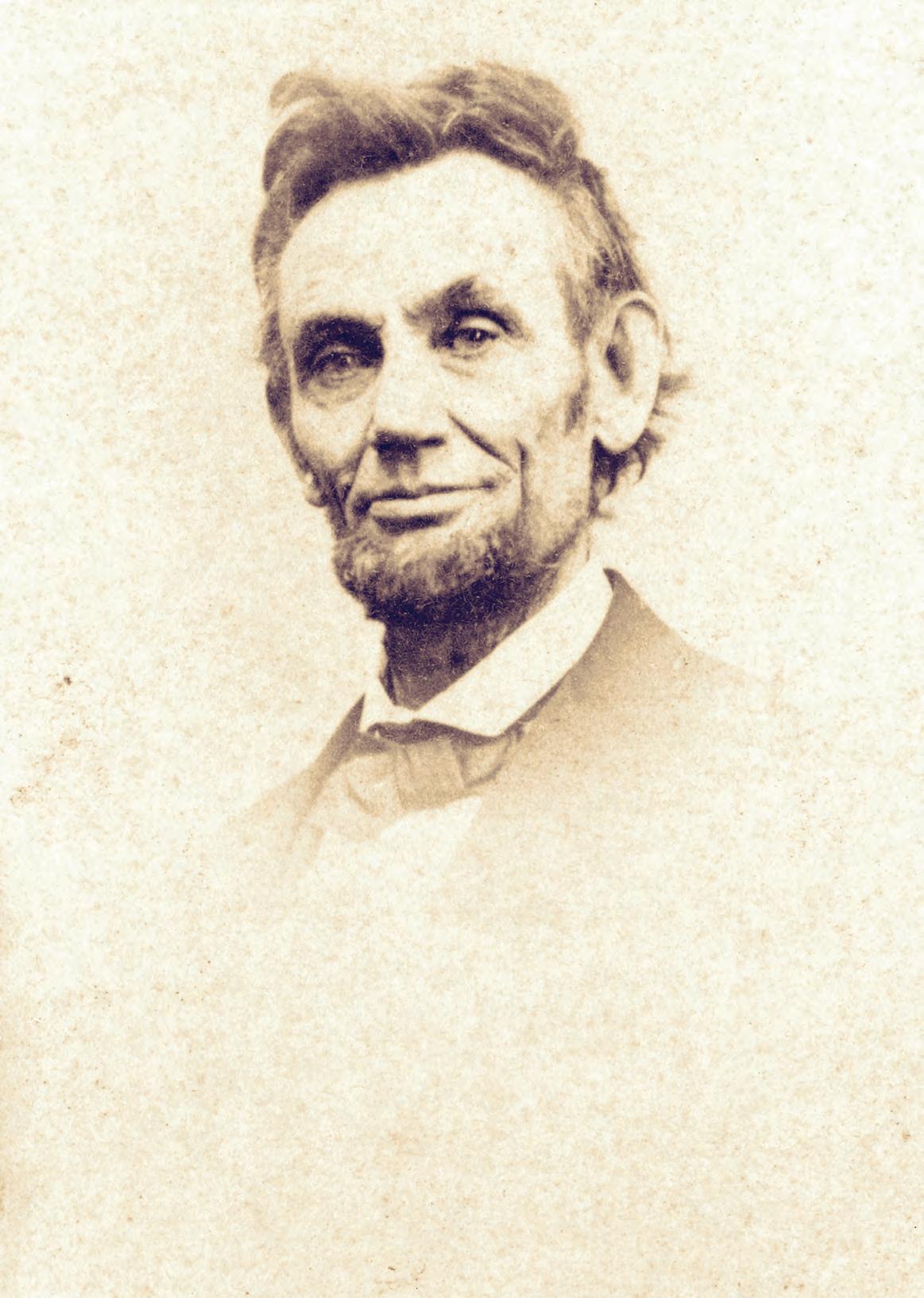

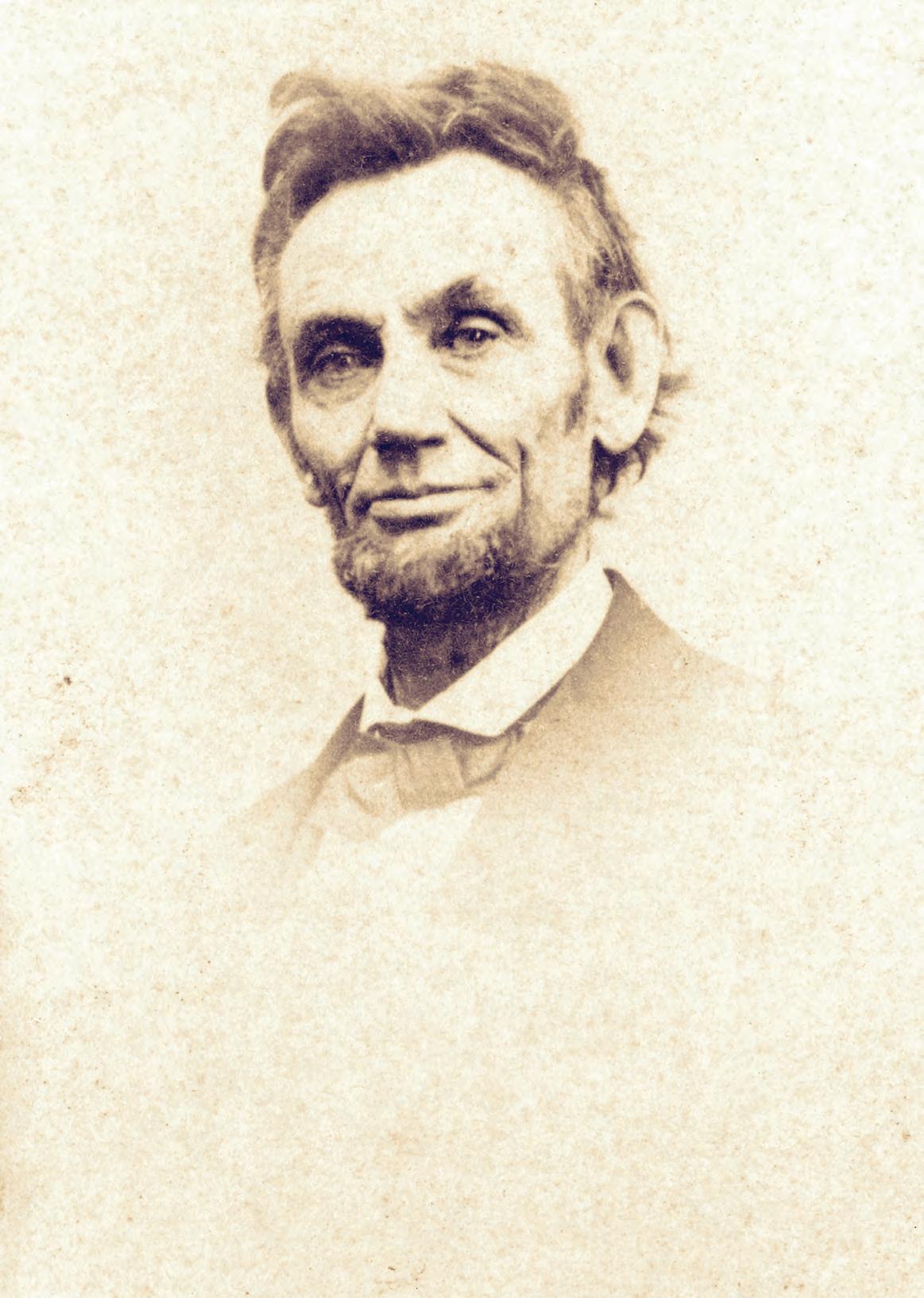

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 4 EDITOR’S LETTER DIGITAL COMMONWEALTH, BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY

WIWP-230400-EDITORS-LETTER.indd 4 1/26/23 8:29 AM

In 1783 Thomas Jefferson stood on this rock at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers to contemplate the “undiscovered country” to the west. Little could he imagine the history to be made.

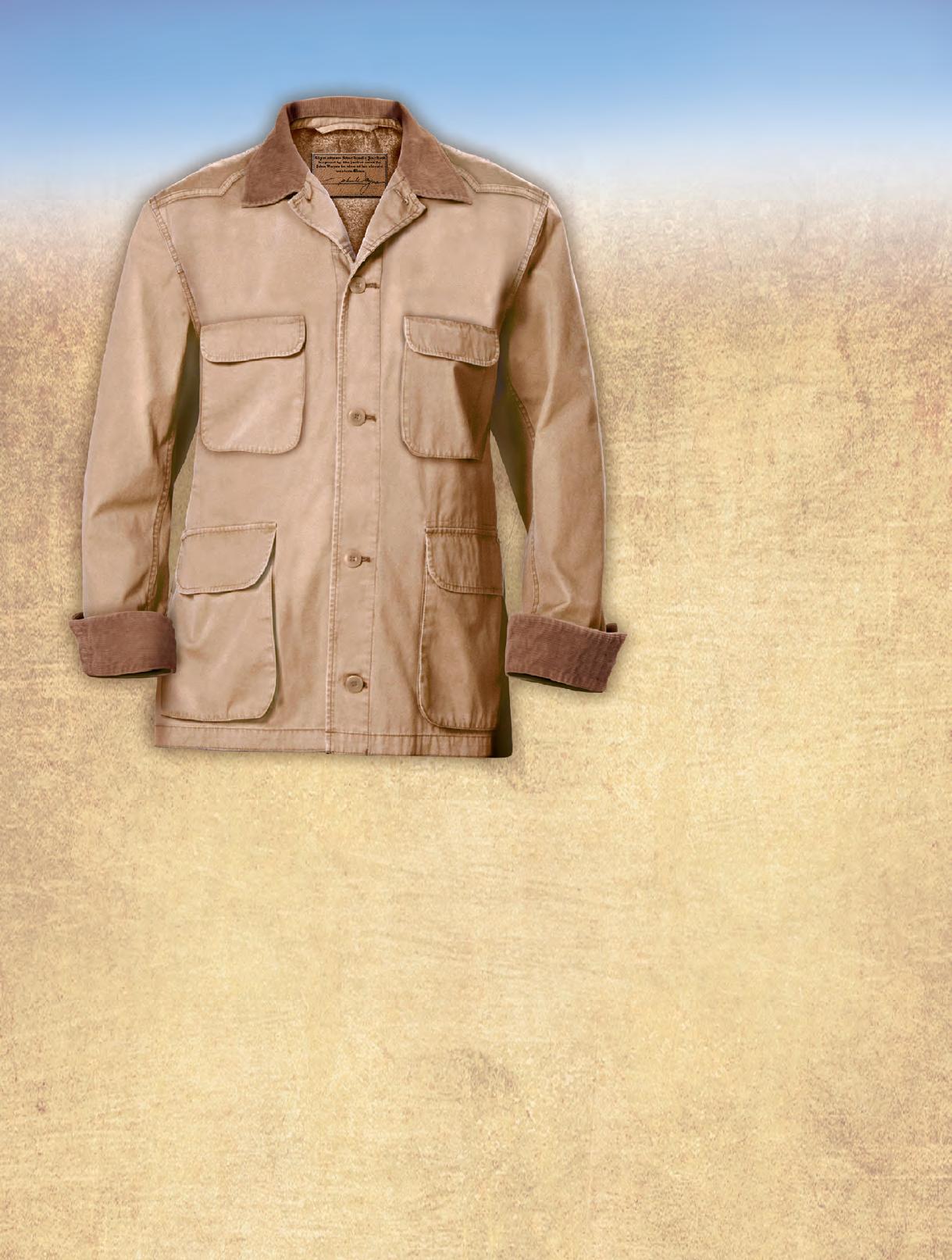

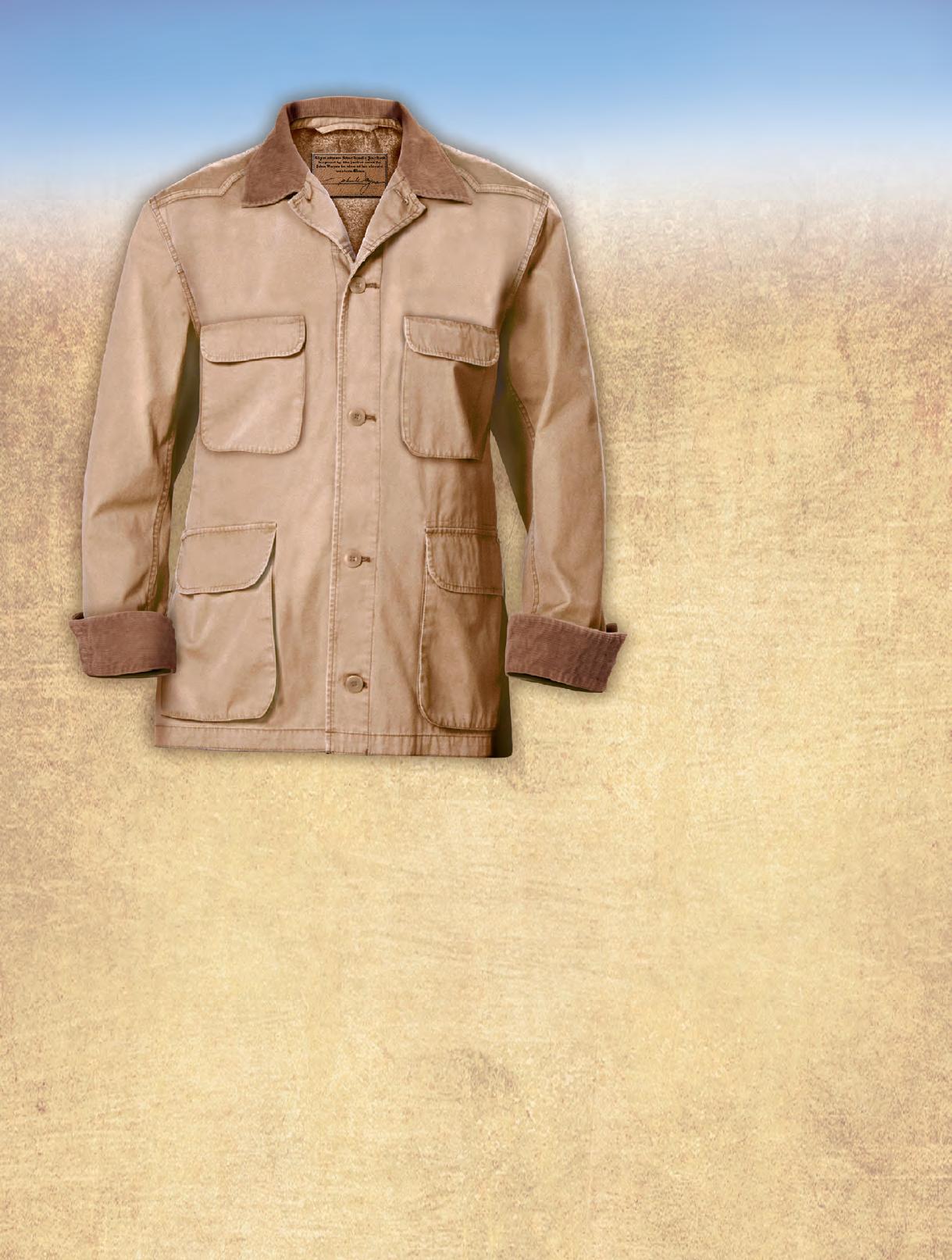

Signature John Wayne Stockade Jacket

Inspired by the Jacket John Wayne Wore in Many of His Classic Western Films!

Expertly Crafted of Tan Cotton Canvas with Flannel Lined Interior

Corduroy Collar and Cuff Accents

Faux Leather Patch Embossed with John Wayne’s Signature Sewn in at the Neck

A Custom Apparel Design Available Only from The Bradford Exchange

Own the West… Just Like “DUKE”

With a legendary career as a noble hero, along with a much-admired striking presence, nobody embodies classic Western movies like John Wayne. Now you can wear a fitting tribute to this iconic star of the silver screen with our rugged yet handsome Signature John Wayne Stockade Jacket

Available only from The Bradford Exchange, this casual jacket was inspired by the same jacket John Wayne wore in many of his classic western films! Masterfully crafted of desert tan cotton canvas with flannel lining, this comfortable jacket is designed for rugged good looks and classic western style. The rough and tough jacket also features a corduroy collar and cuff accents, and a classic 5 button front closure. A faux leather patch embossed with John Wayne’s signature is sewn in at the neck, so you can show you’re a fan wherever the trail may take you! The jacket has a roomy fit, and 4 front

flap pockets on the chest and waistline. It’s a wonderful way to honor the enduring spirit of a true American icon!

An Outstanding Value… Satisfaction Guaranteed

This custom jacket is a remarkable value at $169.95*, and you can pay for it in 4 easy installments of $42.49. Sizes XXL-XXXL, add $10. To order yours, in 5 men’s sizes from M-XXXL, backed by our unconditional 30-day guarantee, you need send no money now... just fill out and mail in your Priority Reservation today!

JOHN WAYNE, , DUKE and THE DUKE are the exclusive trademarks of, and the John Wayne name, image, likeness and voice, and all other related indicia are the intellectual property of, John Wayne Enterprises, LLC. ©2022. All rights reserved. www.johnwayne.com.

©2022 The Bradford Exchange 01-22289-001-BIBR6

B_I_V = Live Area: 7 x 9.75, 1 Page, Installment, Vertical Price Logo Address Code Tracking Code Yellow Snipe Shipping Service NOT AVAILABLE IN STORES

Order Today at bradfordexchange.com/STOCKADEJACKET Connect with Us! RESERVATION APPLICATION SEND NO MONEY NOW YES. Please reserve the Signature John Wayne Stockade Jacket in the size checked below for me as described in this announcement. Please Respond Promptly ❑ Medium (38-40) 01-22289-011 ❑ Large (42-44) 01-22289-012 ❑ XL (46-48) 01-22289-013 ❑ XXL (50-52) 01-22289-014 ❑ XXXL (54-56) 01-22289-015 The Bradford Exchange 9345 Milwaukee Avenue · Niles, IL 60714-1393 *Plus a total of $18.99 shipping and service (see bradfordexchange.com). Please allow 2-4 weeks after initial payment for shipment. Sales subject to product availability and order acceptance. Signature Mrs. Mr. Ms. Name (Please Print Clearly) Address City State Zip Email E56302 Where Passion Becomes Art WIWP-230221-004 Bradford Exchange John Wayne Stockade.indd 1 1/5/2023 2:41:05 PM

MICHAEL A. REINSTEIN CHAIRMAN & PUBLISHER

Codemakers: History of the Navajo Code Talkers

By William R.

By William R.

DAVID LAUTERBORN EDITOR

JON GUTTMAN SENIOR EDITOR

GREGORY J. LALIRE EDITOR EMERITUS

JOHNNY D. BOGGS SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

JOHN KOSTER SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

JOHN BOESSENECKER SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

BRIAN WALKER GROUP DESIGN DIRECTOR

MELISSA A. WINN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

AUSTIN STAHL ASSOCIATE DESIGN DIRECTOR

ALEX GRIFFITH PHOTO EDITOR

DANA B. SHOAF EDITOR IN CHIEF

CLAIRE BARRETT NEWS AND SOCIAL EDITOR

CORPORATE

KELLY FACER SVP REVENUE OPERATIONS

MATT GROSS VP DIGITAL INITIATIVES

ROB WILKINS DIRECTOR OF PARTNERSHIP MARKETING

JAMIE ELLIOTT SENIOR DIRECTOR, PRODUCTION

ADVERTISING

MORTON GREENBERG SVP ADVERTISING SALES mgreenberg@mco.com

TERRY JENKINS REGIONAL SALES MANAGER tjenkins@historynet.com

DIRECT RESPONSE ADVERTISING

NANCY FORMAN / MEDIA PEOPLE nforman@mediapeople.com

© 2023 HISTORYNET, LLC

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: 800-435-0715 OR SHOP.HISTORYNET.COM

WILD WEST (ISSN 1046-4638) is published quarterly by HistoryNet, LLC, 901 North Glebe Road, 5th Floor, Arlington, VA 22203 Periodical postage paid at Tysons, Va., and additional mailing offices. postmaster, send address changes to WILD WEST, P.O. Box 900, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0900

List Rental Inquiries: Belkys Reyes, Lake Group Media, Inc. 914-925-2406; belkys.reyes@lakegroupmedia.com

Canada Publications Mail Agreement No. 41342519

Canadian GST No. 821371408RT0001

The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of HistoryNet, LLC

PROUDLY MADE IN THE USA

NATIONAL ARCHIVES VISIT HISTORYNET.COM Sign up for our FREE weekly e-newsletter at historynet.com/newsletters HISTORYNET PLUS! Today in History What happened today, yesterday or on any day you care to search. Daily Quiz Test your historical acumen every day! What If? Consider the fallout of historical events had they gone the ‘other’ way. Weapons & Gear The gadgetry of war—new and old, effective and not so effective. TRENDING NOW

SPRING 2023 / VOL. 35, NO. 4

THE AMERICAN FRONTIER

Vexed by Japanese cryptographers during World War II, the Americans succeeded by developing a secret code based on the language of the Navajos.

Wilson historynet.com/wwii-navajo-code-talkers

WIWP-230400-MASTHEAD.indd 6 1/20/23 1:44 PM

History. Heritage. Craft CULTURE. The Great Outdoors. The Nature of the West. 1.1

million acres of pristine wildland in the Bighorn National Forest, encompassing 1,200 miles of trails, 30 campgrounds, 10 picnic areas, 6 mountain lodges, legendary dude ranches, and hundreds of miles of waterways. The Bighorns offer limitless outdoor recreation opportunities.

101

restaurants, bars, food trucks, lounges, breweries, distilleries, tap rooms, saloons, and holes in the wall are spread across Sheridan County. That’s 101 different ways to apres adventure in the craft capital of Wyoming. We are also home to more than 40 hotels, motels, RV parks, and B&Bs.

seasons in which to get WYO’d. If you’re a skijoring savant, you’ll want to check out the Winter Rodeo in February 2022. July features the 92nd edition of the beloved WYO Rodeo. Spring and fall are the perfect time to chase cool mountain streams or epic backcountry lines.

Sheridan features a thriving, historic downtown district, with western allure, hospitality and good graces to spare; a vibrant arts scene; bombastic craft culture; a robust festival and events calendar; and living history from one corner of the county to the next.

4

∞ WIWP-230221-003 Sheridan Tourism.indd 1 1/10/2023 10:00:45 AM

Print the Legends

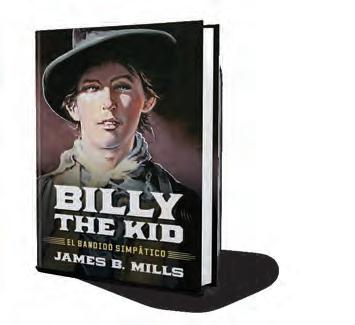

WHO’S KIDDING WHO?

I was grateful the cover of your Autumn 2022 Wild West labeled part of your magazine’s contents as “Tales of Billy the Kid.” The issue’s assortment of articles about and around the character of Billy the Kid contained a delicious stewpot of facts, assertions, suppositions and conjectures that stimulated my imagination but confused my cognitive digestive tract about just what was clearly known and not known about one William H. McCarty, aka William H. Bonney, a 19th-century resident of New Mexico Territory. The articles were well-written and laid out artfully on the pages of your glossy magazine, which makes it all the more dyspeptic that the combination of the articles’ ingredients made it very difficult to sort verifiable information from educated guesses. Of course, several of the authors were conscientious about qualifying their speculations, but others were not. I suppose in the free market of ideas the consumer is well advised to check out the authenticity of any written statements themselves; your term “tales” points readers in that scrutinizing direction.

Jeff Schwehn Las Cruces, N.M.

Editor responds: “Recollections of the Kid” author Mark Iacampo notes clearly in his article how these tales told in later years about the Kid are questionable. As for the other articles, they are written by authors who have done thorough research. No matter what qualifications an author has, however, information in any article about Billy is due further scrutiny, as there remain plenty of uncertainties in the story of his life and career.

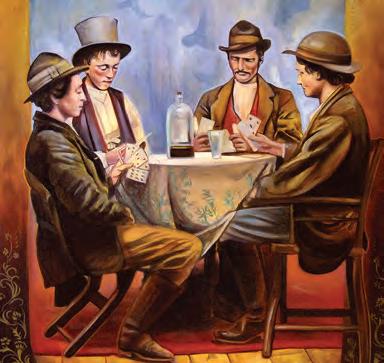

I’m disappointed to see that a painting [see above] based on a thoroughly discredited photo alleging to show Billy the Kid was used in Mark Iacampo’s article “Recollections of the Kid.” The tintype this painting depicts went up for auction in 2019 and went unsold. For just one example of the many reasons it went unsold: While the owner claimed a provenance (without documentation) that connected the tintype to a friend of Billy’s when it went up for auction in 2019, in 2016 he admitted there was no provenance when he tried selling it on eBay. Publishing depictions of a debunked photo gives it an air of legitimacy and can lead readers to believe there’s a strong chance it could be Billy (there’s not). I expect better from Wild West as a respected Western history publication.

Corey Recko Hudson, Ohio

Editor responds: We share your concern for historical accuracy, but our use of the depiction of the Kid playing poker surely adds no legitimacy to the debunked photo from which it was taken. After all, we ran the painting in an article presenting recollections of people who had met the Kid or said they had. As author Iacampo stated, such tales should be taken with a large grain of salt. Thus, the painting seemed fitting for the article. Yes, it was based on a photo someone misrepresented as showing Billy—though few people in the know recognize it as such. There wasn’t room in the caption to get into all that, but Wild West has repeatedly stated there is only one authenticated photo of the Kid—and he isn’t playing poker in that one.

WAYNE’S WORLD

[Re. “John Wayne, Big As Life,” Collections, by Linda Wommack, Autumn 2022:] Everything’s bigger in Texas, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that larger-than-life John Wayne has found a home there in the new museum John Wayne: An American Experience. This museum lies deep in the heart of Texas at the Fort Worth Stockyards, in America’s cowboy capital—a perfect venue for the legendary individual who played cowboys in such classics as Red River and The Cowboys. A rugged John Wayne at 6-foot-4, together with his “Feo, fuerte y formal” (“Ugly, strong and dignified”) credo, and his incorruptible virtues and principles of hard work, discipline, integrity, fairness, loyalty, courage and patriotism ( otherwise known as the “Cowboy Code”) capture the epitome of a cowboy. This beautiful museum not only honors and celebrates Duke’s huge film legacy, but also pays tribute to the same strong American values for which Wayne proudly stood.

Paul Hoylen Deming, N.M.

Send letters by email to wildwest@historynet.com Please include your name and hometown @WildWestMagazine

Editor responds: Any museum that spurs further interest in the West and history, not to mention Western film history, is always welcome. The Autumn 2022 issue also featured editor David Lauterborn’s interview with Ethan Wayne [historynet.com/ ethan-wayne-interview], who succeeded his brother Michael as president of the family-run John Wayne Enterprises and director of the John Wayne Cancer Foundation. It was Ethan who spearheaded efforts to create the Fort Worth museum, and his father’s positive influence continues under his able direction.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 8 LETTERS SARA BLOODWOLF

Sara Bloodwolf based her oil on canvas Regulators on a debunked photo of the Kid and cohorts, thus it suited writer Mark Iacampo’s collection of “Kid tales” to a T.

WIWP-230400-LETTERS.indd 8 1/26/23 8:29 AM

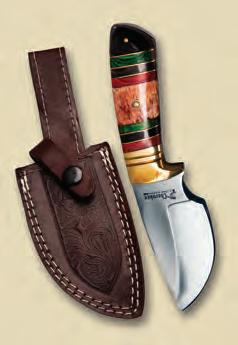

Survival of the Sharpest

That first crack of thunder sounded like a bomb just fell on Ramshorn Peak. Black clouds rolled in and the wind shook the trees. I had ventured off the trail on my own, gambled with the weather and now I was trapped in the forest. Miles from camp. Surrounded by wilderness and watching eyes. I knew that if I was going to make it through the night I needed to find shelter and build a fire... fast. As the first raindrops fell, I reached for my Stag Hunter Knife

Forget about smartphones and GPS, because when it comes to taking on Mother Nature, there’s only one tool you really need. Our stunning Stag Hunter the ultimate sidekick for surviving and thriving in the great outdoors. Priced at $149, the Stag Hunter can be yours today for an unbelievable $79! Call now and we’ll include a bonus leather sheath!

A legend in steel. The talented knifemakers of Trophy Stag Cutlery have done it again by crafting a fixedblade beauty that’s sharp in every sense of the word. The Stag Hunter sports an impressive 5⅓" tempered German stainless steel blade with a genuine deer stag horn and stained Pakkawood™ handle, brass hand guard and polished pommel. You get the best in 21st-century construction with a classic look inspired by legendary American pioneers.

But we don’t stop there. While supplies last, we’ll include a pair of $99 8x21 power compact binoculars and a genuine leather sheath FREE when you purchase the Stag Hunter Knife.

Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Feel the knife in your hands, wear it on your hip, inspect the craftsmanship. If you’re not completely impressed, send it back within 30 days for a complete refund of the item price. But we believe that once you wrap your fingers around the Stag Hunter’s handle, you’ll be ready to carve your own niche into the wild frontier.

Stag Hunter Knife $149*

Offer Code Price Only $79 + S&P Save $70

Your Insider Offer Code: SHK352-09

You must use the insider offer code to get our special price.

14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. SHK352-09 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337

• 5 1/3" fixed German stainless steel blade (9 3/4" total length) • Stag horn and Pakkawood™ handle • Includes leather sheath Stauer ®

of

www.stauer.com

Rating

A+ 1-800-333-2045

is only for

who

the

Not shown actual size.

*Discount

customers

use

offer code versus the listed original Stauer.com price.

When it’s you against nature, there’s only one tool you need: the tempered steel Stag Hunter from Stauer—now ONLY $79!

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary . ® TAKE 47% OFF INSTANTLY! When you use your INSIDER OFFER CODE “This knife is beautiful!” — J., La Crescent, MN

feel of

knife is unbelievable... this an incredibly fine instrument.” — H., Arvada, CO EXCLUSIVE FREE Stauer 8x21 Compact Binoculars -a $99 valuewith your purchase BONUS! Call today and you’ll also receive this genuine leather sheath! WIWP-230221-008 Stauer Stag Hunter Knife.indd 1 1/5/2023 3:17:02 PM

“The

this

10 Interesting Westerners With Ties to Colorado

1 Bent Brothers William and Charles Bent partnered with Ceran St. Vrain in the best known trading post west of the Mississippi. Established in 1833 on the Santa Fe Trail in what today is southeastern Colorado, Bent’s Fort was a gathering spot for travelers, trappers and traders. The Bent brothers forged lasting relationships with the Cheyennes and Arapahos.

2 Kit Carson Christopher “Kit” Carson began his career trapping beaver in the Colorado Rockies and hiring on as a hunter at Bent’s Fort. In the 1850s he served as an Indian agent, working for peace on behalf of his friend Ute Chief Ouray. Late in his career he commanded Fort Garland before taking up ranching in the San Luis Valley. Carson died at Fort Lyon on May 23, 1868, and was initially buried beside wife Josefa at their home in Boggsville.

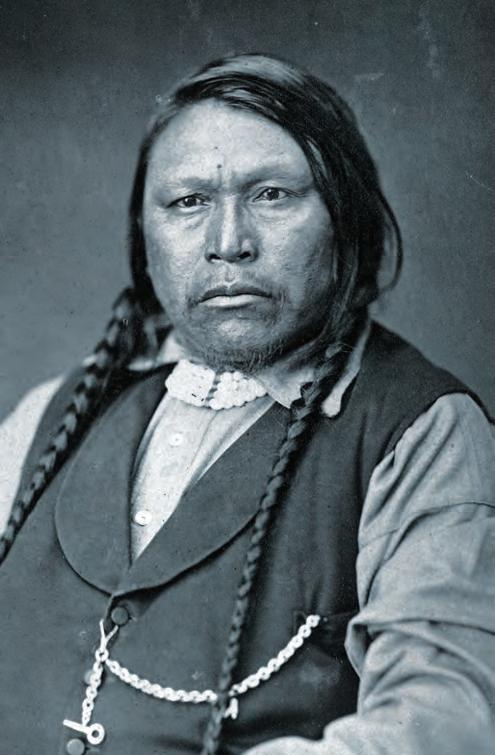

3 Chief Ouray Born in 1833, the year of the shooting stars in tribal lore, the Ute chief sought peace with the U.S. government and preservation of his tribe’s hereditary lands at the height of the Indian wars. By life’s end he and wife Chipeta lived in a six-room house on a 300-acre farm

along the Uncompahgre River near Montrose. Following his death on Aug. 24, 1880, despite Ouray’s best efforts, the government relocated the Utes to reservations in Utah.

4 Buffalo Bill Cody William Frederick Cody earned his reputation as an Army scout, his nickname as a buffalo hunter for the railroads and fame for touring worldwide with the best known Wild West show in American history. At age 13, however, he’d reportedly earned little during the 1859 gold rush to what would become Colorado. In later life he repeatedly visited his sister in Denver, where he died on Jan. 10, 1917. Cody is buried atop Lookout Mountain near Golden.

5 Doc Holliday Tubercular dentist turned professional gambler and gunman John Henry Holliday came West for his health. After risking his life in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, backing the Earp brothers in the O.K. Corral fight and aftermath, Holliday made his way to Colorado, where he gambled in Trinidad, Pueblo and Leadville. The reputedly curative waters of Glenwood Springs failed to remedy his tuberculosis, and he died there on Nov. 8, 1887.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 10 DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY (5) FROM TOP: ROBERT G. MCCUBBIN COLLECTION; RENELIBRARY, CC BY-SA 4.0; ALAMO TRUST

ROUNDUP

Chief Ouray

Buffalo Bill Cody

Ann Bassett

Baby Doe Tabor

WIWP-230400-ROUNDUP.indd 10 1/26/23 8:30 AM

Kit Carson

6

Baby Doe Tabor

The beautiful Elizabeth Bonduel McCourt divorced her worthless first husband in 1880, moved to Leadville and met silver magnate Horace Austin Warner “Haw” Tabor, who left his wife of 25 years to marry Baby Doe. Alas, Horace died destitute in 1899, leaving the widowed Baby Doe penniless once again. Her body was found frozen to her cabin floor in 1935.

A Better Remembrance

7 Alferd Packer

Self-proclaimed wilderness guide Packer and five fellow travelers suffered in the San Juan Mountains during the harsh winter of 1874. The only one to emerge alive, Packer later confessed to cannibalism. Though he denied having killed the others, evidence suggested otherwise. Convicted of manslaughter, he served 18 years before being paroled in 1901. Packer died on April 23, 1907, in Deer Creek and is buried in Littleton Cemetery, a stone’s throw from this writer’s house.

8 Margaret Brown A celebrated survivor of the 1912 sinking of RMS Titanic, this Colorado socialite, activist and philanthropist is best remembered as the “Unsinkable Molly Brown.” Known to family and friends as “Maggie,” she married mining engineer James Joseph Brown in Leadville in 1886, and in 1894 the successful couple bought a Victorian mansion in Denver preserved today as the Molly Brown House Museum. Maggie died in her sleep on Oct. 26, 1932.

9 Tom Horn He served at times as a scout, soldier, range detective and Pinkerton agent, but Horn became notorious as a paid-for-hire killer. In 1900, while working for the Swan Land & Cattle Co. in northwest Colorado, he gunned down suspected rustlers Mat Rash and Isom Dart. In 1902 Horn was convicted of having murdered 14-year-old rancher’s son Willie Nickell near Iron Mountain, Wyo., and on Nov. 20, 1903, he was hanged in Cheyenne. His brother brought Tom’s body to Boulder for burial.

On March 3, 2023, amid anniversary observations for the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, the historic site in San Antonio will open a two-story exhibition hall and collections building—the first building of an ongoing redevelopment plan and the newest since the 1950s. The new building (see artist’s sketch below photo of Alamo facade) will occupy the corner of the compound directly behind the iconic chapel. Its 10,000 square feet of gallery space will center on the 430-item collection of Alamo and Texana artifacts donated by British rock star Phil Collins and the recently purchased collection of Spanish colonial artifacts from acclaimed Alamo artist Don Yena and wife Louise. The latter includes more than 400 items used by

WEST WORDS

‘Shake that [Alexander] McSween outfit up till it shells out and squares up and then shake it out of Lincoln. I will aid to punish the scoundrels all I can. Get the people with you.…Have good men about to aid [Sheriff William] Brady and be assured I shall help you all I can, for I believe that there was never found a more scoundrely set than that outfit’

10

Ann Bassett The first white child born in Browns Park, an isolated northwest Colorado valley notorious for rustling and illegal land grabs, Ann Marie Bassett was in the thick of the action for much of her life. After Tom Horn’s 1900 killing of Mat Rash, her fiancé, Bassett sought vengeance against Horn’s employer, cattle baron Ora Haley. Tried twice for cattle rustling, she was found not guilty both times. In an interview given just before her death on May 8, 1956, Bassett said, “I did everything they said I did and a helluva lot more.”

—Linda Wommack

settlers and indigenous peoples of the Southwest, everything from swords and cannons to kitchen utensils, farming implements and ranching gear. Yena also donated six of his large paintings depicting Spanish Texas and the battle, including the 36-by-60-inch oil First Light, Gunsmoke, Bayonets and Texas History (see historynet.com/don-yena).

The ongoing $388 million overhaul of Alamo Plaza —a partnership between the city, Texas’ General Land Office and the Alamo Trust—will include a new visitor center and museum in which the collections will ultimately be housed. “When people leave the Alamo,” said trust executive director Kate Rogers, “We don’t want them to say, ‘Is that it?’”

—In a letter from Las Cruces, New Mexico Territory, on Feb. 14, 1878, district attorney William L. Rynerson wrote this to James Dolan and John Riley, members (with Lawrence Murphy and others) of a competing economic and political faction in Lincoln, just four days before the killing of McSween associate John Tunstall triggered the Lincoln County War.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 11 DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY (5)

FROM

TOP: ROBERT G. MCCUBBIN COLLECTION; RENELIBRARY, CC BY-SA 4.0; ALAMO TRUST

WIWP-230400-ROUNDUP.indd 11 1/26/23 8:30 AM

Wounded Knee Relics

The Founders Museum in Barre, Mass., recently returned some 150 culturally significant artifacts, several with reported ties to the 1890 Wounded Knee battle turned massacre, to Oglala Sioux and Cheyenne representatives of South Dakota’s Pine Ridge and Cheyenne River Indian reservations, respectively. Upward of 200 Lakotas and 31 U.S. soldiers were killed at Wounded Knee. The museum obtained the artifacts more than a century ago from salesman and circus impresario Frank Root, who donated the items after having used them in a traveling show. The 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act calls on federally funded institutions to return such artifacts. As a private institution, the Founders Museum isn’t bound by the act, but its association considered repatriation the respectful thing to do. For years the Wounded Knee Survivors Association has pressed a Scottish museum to return beaded moccasins, a war necklace and a child’s bonnet collected in the aftermath of the 1890 tragedy. Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum acquired its artifacts in 1891 from former soldier and Lakota interpreter George Crager, who had traveled to Scotland with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West. In 1998 the museum repatriated a Ghost Dance shirt (intended to protect its wearer from bullets) to the tribe, but the association had not then requested the return of the other three items.

FAMOUS LAST WORDS

And the Wister Goes to…

Western Writers of America has chosen prolific Oglala/Sicangu Lakota writer Joseph M. Marshall III as its 2023 Owen Wister Award honoree for lifetime contributions to Western literature. It will present him with the award—a bronze bison by artist Robert Duffie—at WWA’s annual convention, June 21–24 in Rapid City, S.D. He will also be inducted into the Western Writers Hall of Fame at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West

and such nonfiction titles as The Day the World Ended at Little Bighorn (2007) and The Journey of Crazy Horse (2004). Born in 1945, he was raised on South Dakota’s Rosebud Indian Reservation. Lakota is his first language, and many of his books relate tribal history, customs and beliefs. “ Lila pilamayaya pelo—I thank you very much,” Marshall said on hearing the news. “[This] is an affirmation for me that I pursued the right dream.” Previous Owen Wister honorees include historians Robert M. Utley and Eve Ball and Pulitzer Prize–winning Kiowa writer and poet N. Scott Momaday.

Yellow Journalism

in Cody, Wyo. An author of fiction and nonfiction, a historical consultant and a small-screen actor, Marshall is known for his novels The Long Knives Are Crying (a 2009 Spur Award finalist about the Battle of the Little Bighorn) and Hundred in the Hand (a 2007 work about the 1866 Fetterman Fight)

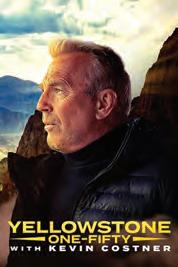

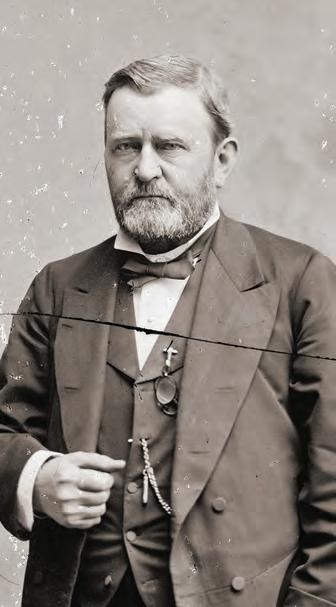

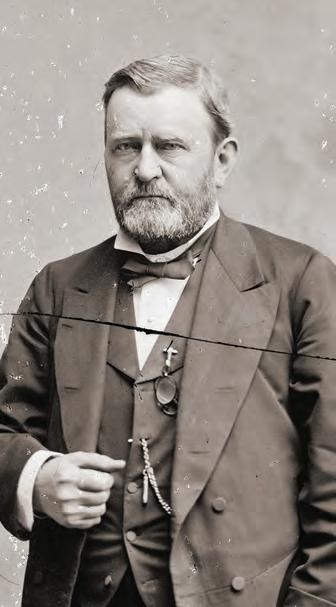

Seeking to piggyback on the success of the Paramount neo-Western TV series Yellowstone, starring Kevin Costner, the on-demand service Fox Nation hired the actor to narrate its recent fourepisode documentary Yellowstone: One-Fifty , marking the sesquicentennial of that national park. The series features spectacular footage of such highlights as Yellowstone Falls, Grand Prismatic Spring, Old Faithful and the Lamar Valley. Unfortunately, as often happens when Hollywood meets history, history suffers. Costner contends that Congress, with the complicity of big business (“powerful people who wanted the land for themselves”), sent geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden and his scientific party to the region in 1871 to “tear it to shreds in the name of progress,” and that it was Hayden who had a change of heart and lobbied for its protection. But the alleged “battle between the regular guy against the impossibly huge behemoth that is the United States government” never happened. For one, it was Congress that funded the expedition, Hayden taking his orders from the Department of the Interior. For another, investment banker Jay Cooke (financier of the Northern Pacific Railway) was among the most vocal proponents for Yellowstone’s preservation as a national park and provided the expedition with the services of artist Thomas Moran, whose monumental paintings of Yellowstone were seminal in convincing Congress to protect it. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act that created the park. At one point in Yellowstone: OneFifty inappropriately grand music accompanies the spectacle of a bison scratching itself on a tree —consider that one more reason to watch this beautiful footage with the sound turned down.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 12 TOP: PHILIP MARCELLO (ASSOCIATED PRESS); BOTTOM: JOHNNY D. BOGGS

‘Very uncomfortable necktie’

WIWP-230400-ROUNDUP.indd 12 1/26/23 9:01 AM

—Convicted of having killed a jailer during a failed April 1883 escape attempt from the Pima County jail in Tucson, Arizona Territory, Joseph Casey said these words from the gallows on April 15, 1884, as Sheriff Bob Paul cinched a noose around his neck. Moments later, just before the trap was sprung at 1:07 p.m., Casey called out, “Turn her loose—goodbye!”

explore THE HISTORY AND LORE OF THE WILD WEST

The WILD WEST HISTORY ASSOCIATION is dedicated to providing publications and forums for the enlightenment and enjoyment of anyone interested in Wild West history, facilitating and encouraging research, study, writing, presentation, and preservation of the history and lore of the people, events, and places that made the American West “wild” in the last half of the nineteenth century …the lawmen, outlaws, gunfighters, rustlers, vigilantes, feuds, shady ladies, saloons, cowtowns, and mining camps …along with recognizing and honoring those individuals and institutions that make significant contributions to the knowledge and preservation of Wild West history and lore.

Enjoy our annual ROUNDUP held somewhere in the West every July. This year’s ROUNDUP will be held in San Antonio, Texas, July 12–15, 2023, at the Menger Hotel where we’ll be celebrating the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Texas Rangers, and much, much more.

Become a member and receive our quarterly JOURNAL, containing the latest research, informative articles, authentic photographs, book reviews, and more, defining “the good, the bad, and the ugly” in the Wild West.

WILDWESTHISTORY.ORG

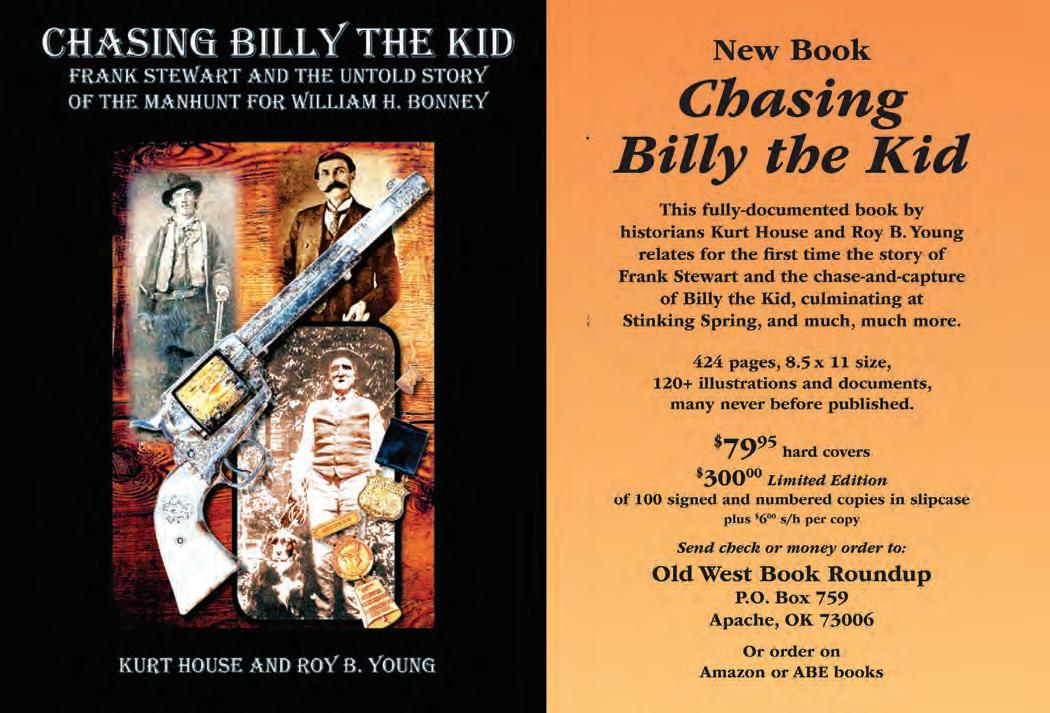

ROYYOUNG AD-01.23.indd 1 1/3/23 3:52 PM

SEE YOU LATER...

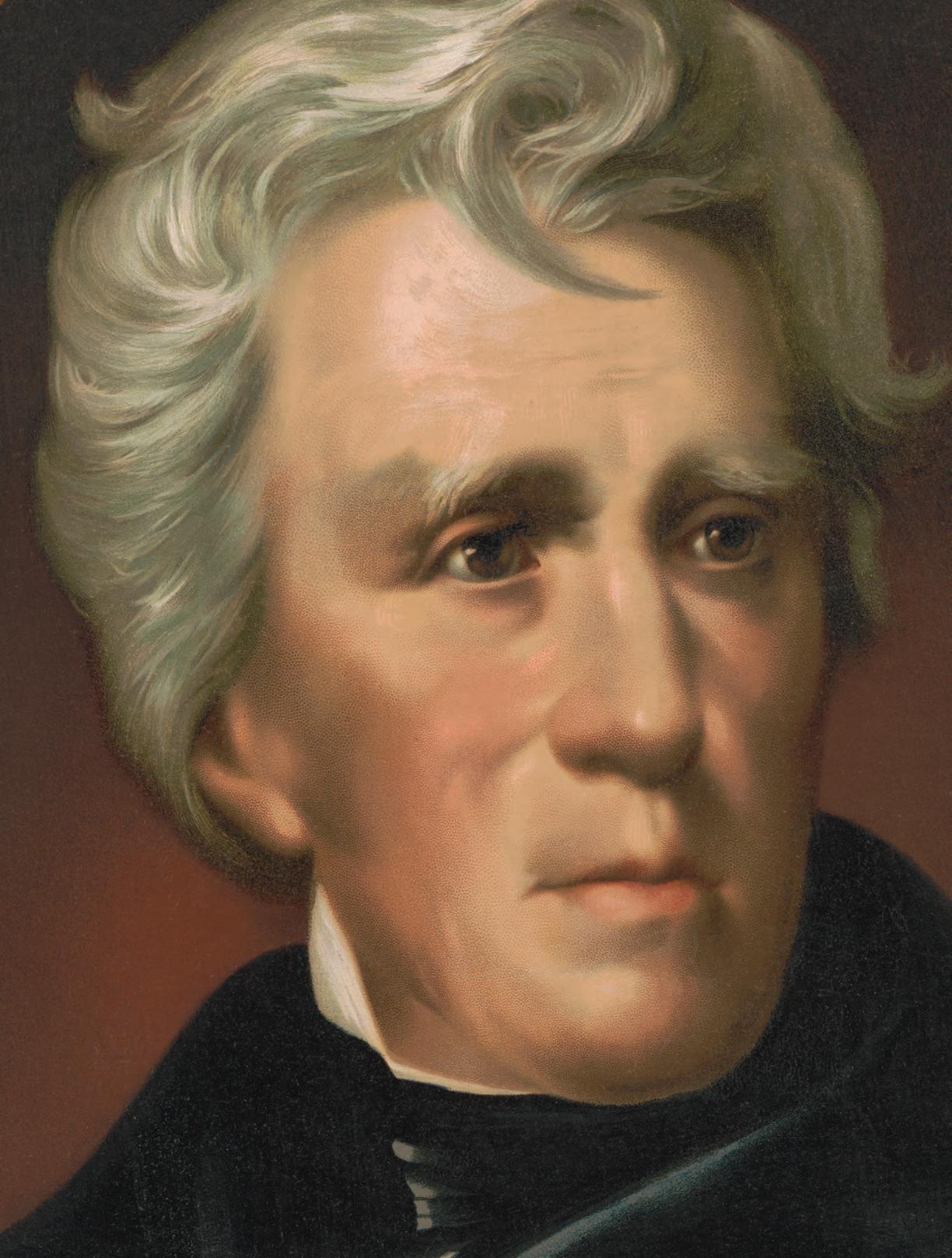

ANDREW PRINE

Actor Andrew Prine, 86, perhaps best known for portraying Lincoln County War storeowner Alexander McSween in the 1970 Western Chisum, died while visiting Paris on Oct. 31, 2022. Over his half century on the big and small screen he appeared in numerous episodes of such classic Western TV series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, The Virginian and Wagon Train and the films Bandolero! (1968) and Rooster Cogburn (1975). As host of the Encore Western Channel show Conversations With Andrew Prine he interviewed such notable Western actors as Eli Wallach, Harry Carey Jr. and Patrick Wayne, as well as Mark Rydell, who directed John Wayne in The Cowboys (1975).

MARY McCASLIN

Folk singer Mary McCaslin, 75, whose 1974 album Way Out West garnered her attention, died on Oct. 2, 2022. Though she was never a household name, lyrics from the title song of her 1974 release still resonate with fans of the Old West: My family left home when I was a child / To head out West, all open and wild / I couldn’t wait to gallop the prairie on a pony / But we passed over the plains and on down / Into the great stucco suburb forest / The people there all held my dreams in jest / Somehow I grew to spite them / Way out West.

DON EDWARDS

Cowboy singer, songwriter, guitarist and Western musicologist Don Edwards, 86, died in Hico, Texas, on Oct. 23, 2022. Two of his several albums are in the Folklore Archives of the Library of Congress, and he appeared on-screen as Smokey in Robert Redford’s The Horse Whisperer (1998). His legacy prompted none other than “Singing Cowboy”

Gene Autry to once say to Edwards, “I’m proud and honored to be riding the same trail as you.”

Pueblo Pottery

“Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery” is showing at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe through May 29, 2023, and will get plenty more exposure in years to come, including stops at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (July 13, 2023–June 4, 2024), Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts (Oct. 27, 2024–Jan. 19, 2025) and the St. Louis Art Museum (March 9–June 1, 2025). Organized by the Indian Arts Research Center of the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe and the Vilcek Foundation in New York and curated by the American Indian communities it represents, the traveling exhibition features more than 100 historic and contemporary clay Pueblo pots. “Pottery permeates the lives of Pueblo peoples,” says Elysia Poon, director of the Indian Arts Research Center. “For many, it is impossible to divorce the pieces from the people.”

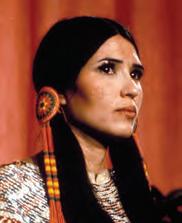

Playing Indian

Sacheen Littlefeather, 75, who died in Novato, Calif., on Oct. 2, 2022, achieved Hollywood notoriety in 1973. Claiming to be a White Mountain Apache, she attended that year’s Academy Awards ceremony on Marlon Brando’s behalf and refused his best actor Oscar for The Godfather in protest for the way American Indians had been depicted in film. Only trouble is, Littlefeather wasn’t her name, and she wasn’t an Apache but of Mexican heritage, born Maria Louise Cruz in Salinas, Calif., in 1946. On refusing Brando’s Oscar she was jeered from the stage. Two weeks before her death the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hosted an evening in Littlefeather’s honor and issued her a formal apology. “We Indians are very patient people,” she told attendees. “It’s only been 50 years!” Cruz was neither the first nor last Hollywood type to have feigned Indian ancestry. Among the most visible was Italian American actor Espera Oscar de Corti, aka Iron Eyes Cody, best known for appearing as a crying Indian chief in an early 1970s series of Keep America Beautiful TV ads decrying pollution.

Ship of Gold

On Sept. 12, 1857, the 278foot side-wheel steamship Central America sank amid a hurricane in the Atlan tic Ocean some 160 miles off the Carolinas. Lost with the ship were 425 of its 578 passengers and crew. Many of the passengers were men returning from the Califor nia Gold Rush, and Central America’s holds held a cargo of gold worth an estimated $765 million in today’s dol lars. Expeditions to the wreck between 1988 and 2014 recovered gold and artifacts, but legal wrangles kept much of the find off the auction market until recently. On Dec. 3, 2022, Holabird Western Americana Collections [holabirdamericana.com] of Reno, Nev., offered 270 artifacts from the famed “Ship of Gold,” netting nearly $1 million. Fetching the top bid was the oldest known pair of miner’s heavyduty work pants (above), which fetched $114,000 —the highest price ever paid for a pair of jeans, despite parents’ claims to the contrary.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 14

LEFT, FROM TOP: TCD/PROD.DB (ALAMY STOCK PHOTO); STUART BRININ (FLI ARTISTS); DONALD KALLAUS; TOP RIGHT: ZUMA PRESS, INC. (ALAMY); BELOW: HOLABIRD WESTERN AMERICANA COLLECTIONS; BOTTOM LEFT: MUSEUM OF INDIAN ARTS AND CULTURE, SANTA FE WIWP-230400-ROUNDUP.indd 14 1/26/23 8:30 AM

The Amazing Telikin One Touch℠ Computer The Smart, Easy Computer for Seniors !

● Easy One Touch Menu!

● Large Fonts

200% Zoom

● 100% US Support

● Large Print Keyboard

If you find computers frustrating and confusing, you are not alone. When the Personal Computer was introduced, it was simple. It has now become a complex Business Computer with thousands of programs for Accounting,Engineering, Databases etc. This makes the computer complex.

You want something easy, enjoyable, ready to go out of the box with just the programs you need. That’s why we created the Telikin One Touch computer.

Telikin is easy, just take it out of the box, plug it in and connect to the internet. Telikin will let you easily stay connected with friends and family, shop online, find the best prices on everything, get home delivery, have doctor visits, video chat with the grandkids, share pictures, find old friends and more. Telikin One Touch is completely different.

One Touch Interface - A single touch takes you to Email, Web, Video Chat, Contacts, Photos, Games and more.

Large Fonts, 200% Zoom – Easy to see easy to read.

Secure System – No one has ever downloaded a virus on Telikin

Voice Recognition - No one likes to type. Telikin has Speech to Text. You talk, it types.

Preloaded Software - All programs are pre-loaded andset up. Nothing to download.

100% US based support – Talk to a real person who wants to help. Telikin has great ratings on BBB and Google!

Secure System No Viruses!

Speech to Text You talk, It types!

Great Customer Ratings

This computer is not designed for business. It is designed for you!

"This was a great investment."

Ryan M,CopperCanyon, TX

"Thank you again for making a computer for seniors"

Megan M,Hilliard, OH

"Telikin support is truly amazing.”

NickV,Central Point, OR Call toll freeto find out more!

Mention Code 1185 for introductory pricing

60 Day money back guarantee

844-215-3127

WIWP-230221-007 Journey Health & Lifestyle WOW Computer.indd 1 1/5/2023 2:49:18 PM

Copyright Telikin 2022

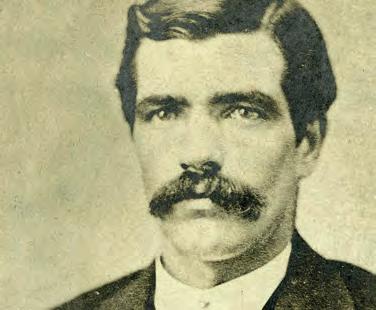

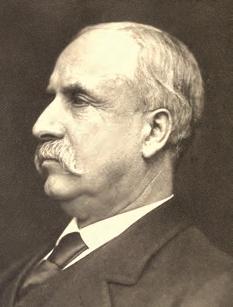

Following His Nose

IN HIS BIOGRAPHY OF ‘BIG NOSE GEORGE’ PAROTT AUTHOR MARK MILLER SEEKS TO DEMYTHOLOGIZE THE INFAMOUS WYOMING HIGHWAYMAN

BY CANDY MOULTON

On March 22, 1881, convicted murderer Big Nose George Parott, having filed the rivets off his shackles with a smuggled pocketknife, tried to escape from the Carbon County Jail in Rawlins, Wyo. After striking jailer Bob Rankin over the head, however, Parott was persuaded at gunpoint by Rankin’s wife, Rosa, to return to his cell. Parott was just a couple of weeks shy of his scheduled execution for the ambush killing of Union Pacific detective Tip Vincent and Carbon County Deputy Sheriff Bob Widdowfield after a bungled 1878 train robbery. On the night of Parott’s escape attempt an impatient mob rushed the jail, dragged him from his cell and hanged him from a telegraph pole on Front Street in Rawlins.

Former Wyoming State Archaeologist Mark Miller had heard about Parott’s misdeeds, trial and lynching from the time he was a boy, for the county sheriff at the time of the outlaw’s trial and lynching had been Miller’s great-grandfather Isaac “Ike” Miller. The younger Miller and other archaeologists later studied the relevant crime scenes, as well as Parott’s skull, for in the wake of the outlaw’s death doctors had sawn off his skullcap to examine his “criminal brain.” Doctor John Osborne went a step further, having strips of Parott’s skin made into a pair of shoes. The bad doctor even wore the shoes to his Jan. 2, 1893, inaugural as governor of Wyoming.

Miller recently spoke with Wild West about his recent biography Big Nose George: His Troublesome Trail , in which the author relates the macabre details and seeks to get at the truth about the outlaw’s life, criminal career, trial and death.

How did you establish who killed Vincent and Widdowfield?

They were first identified by their partners in crime to other outlaws and eventually to authorities under threat of lynching. The murder indictments in the Carbon County Clerk of Court records list eight murderers on each formal accusation, written down after a grand jury and sworn to by authorities. Their names came from outlaw “confessions,” and Big Nose George confirmed them during his court proceedings.

Who were the murderers?

Big Nose George Parott, Dutch Charley [Burris], Jack Campbell, Frank James, Joe (or John) Minuse, Tom Reed, Frank Tole, Sim Wan and John Wells.

How was your great-grandfather Miller involved?

Citizens of Carbon County elected my great-grandfather Isaac C. Miller as sheriff in November 1880 while George Parott sat in jail awaiting trial for murder. Once elected, Ike would be responsible to conduct the sentence of hanging Parott in April 1881.…Vigilantes hanged him in town while Ike was away on business in Sand Creek.

Why did Big Nose George return to the headlines in the 20th century?

The most significant event was the 1950 discovery of a whiskey barrel buried near Front Street in Rawlins that contained the sk eletal remains of an adult male missing the skullcap on his cranium. Lillian Heath had been a medical assistant to Dr. Thomas Maghee and Dr. John Osborne in the early 1880s, and Dr. Osborne gave her Parott’s skullcap when they studied the outlaw’s brain. She was still alive in 1950 and sent the skullcap to the barrel discovery site, where the two pieces of cranium were refit perfectly. This solid chain of custody proved the identity of the skeleton in the barrel. This discovery rekindled stories of the outlaw legend and influenced the perspective citizens hold today about the desperado.

Describe the related DNA work you engaged in as state archaeologist.

A research team consisting of myself, Dr. George Gill, graduate student Kristi McMahan and research scientist Rick Weathermon were able to assemble all the physical evidence remaining from the Big Nose George story in 1995. The Union Pacific Museum gave permission to Dr. Gill to remove a small piece of hide from Parott’s skullcap for DNA. The sample has not been run and is still in storage in case a future DNA study is called for. In addition, we measured the skull, analyzed the dental pattern, estimated age, race and sex. Weathermon studied superpositions of photographs taken of the skull, death mask and only known photo of the outlaw, showing they all were likely from the same individual. A stature estimate was impossible, because the postcranial bones had disappeared. The Wyoming State Crime Lab indicated the lighter components of a pair of Dr. John Osborne’s shoes in the Parott collection were consistent with human flesh.

To read the full interview visit historynet.com.

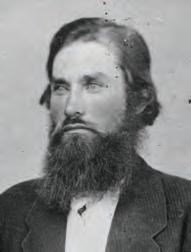

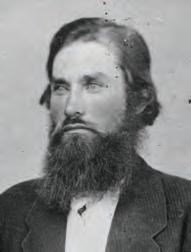

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 16 INTERVIEW MARK E. MILLER

WIWP-230400-INTERVIEW.indd 16 1/20/23 1:46 PM

Mark Miller

The Day the War Was Lost It might not be the one you think Security Breach Intercepts of U.S. radio chatter threatened lives 50 th ANNIVERSARY LINEBACKER II AMERICA’S LAST SHOT AT THE ENEMY First Woman to Die Tragic Death of CIA’s Barbara Robbins HOMEFRONT the Super Bowl era WINTER 2023 WINTER 2023 Vicksburg Chaos Former teacher tastes combat for the first time Elmer Ellsworth A fresh look at his shocking death Plus! Stalled at the Susquehanna Prelude to Gettysburg Gen. John Brown Gordon’s grand plans go up in flames MAY 2022 In 1775 the Continental Army needed weapons— and fast World War II’s Can-Do City Witness to the White War ARMS RACE THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF MILITARY HISTORY WINTER 2022 H H STOR .COM JUDGMENT COMES FOR THE BUTCHER OF BATAAN THE STAR BOXERS WHO FOUGHT A PROXY WAR BETWEEN AMERICA AND GERMANY PATTON’S EDGE THE MEN OF HIS 1ST RANGER BATTALION ENRAGED HIM UNTIL THEY SAVED THE DAY JUNE 2022 JULY 3, 1863: FIRSTHAND ACCOUNT OF CONFEDERATE ASSAULT ON CULP’S HILL H In one week, Robert E. Lee, with James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson, drove the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond. H THE WAR’S LAST WIDOW TELLS HER STORY H LEE TAKES COMMAND CRUCIAL DECISIONS OF THE 1862 SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN 16 April 2021 Ending Slavery for Seafarers Pauli Murray’s Remarkable Life Final Photos of William McKinley An Artist’s Take on Jim Crow “He was more unfortunate than criminal,” George Washington wrote of Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator. No MercyWashington’s tough call on convicted spy John André HISTORYNET.com February 2022 CHOOSE FROM NINE AWARD - WINNING TITLES Your print subscription includes access to 25,000+ stories on historynet.com—and more! Subscribe Now! HOUSE-9-SUBS AD-11.22.indd 1 12/21/22 9:34 AM

‘The Peerless’

More than a decade before sharpshooter Annie Oakley joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West, dancer Giuseppina

Morlacchi garnered headlines performing with Cody in the traveling Western stage drama Scouts of the Prairie. Dime novelist and entrepreneur Ned Buntline, who hastily wrote the three-act Western script in December 1872, had the Italian-born prima ballerina play an Indian princess named Dove Eye. The male stars of Buntline’s theatrical company were Cody and John Baker “Texas Jack” Omohundro, notable Army scouts who played themselves onstage. Landing Morlacchi was quite a coup for Buntline. Since making her U.S. debut in New York City in 1867, she had become the most sought-after dancer in the country, introduced the can-can to American audiences and earned the nickname “The Peerless.” Photo collector Tony Sapienza said that when graceful Giuseppina performed the “grand gallop can-can” on Jan. 6, 1868, in Boston, where this photograph was taken, her interpretation of the high-stepping dance left the audience breathless. In Scouts of the Prairie she not only remembered her lines better than her costars, but also found romance with one of them. On Aug. 31, 1873, she married Omohundro at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Rochester, N.Y. Morlacchi continued to perform with her dance troupe and star with her husband in Western dramas. But tragedy was to strike the young couple when 33-year-old Texas Jack died of pneumonia in Leadville, Colo., on June 28, 1880. With that Morlacchi stopped touring. A scant six years later, on July 23, 1886, she died of cancer at age 49 in Billerica, Mass. (For more on both Omohundro and Morlacchi see “‘Texas Jack’ Takes an Encore,” by Matthew Kerns, in the April 2022 Wild West.)

TONY

COLLECTION 18 WILD WEST SPRING 2023 WESTERNERS

SAPIENZA

WIWP-230400-WESTERNERS.indd 18 1/20/23 1:46 PM

“I’’ve gotten many compliments on this watch. The craftsmanship is phenomenal and the watch is simply pleasing to the eye.”

—M., Irvine, CA

“GET THIS WATCH.”

—M., Wheeling, IL 27

In the early 1930s watch manufacturers took a clue from Henry Ford’s favorite quote concerning his automobiles, “You can have any color as long as it is black.” Black dialed watches became the rage especially with pilots and race drivers. Of course, since the black dial went well with a black tuxedo, the adventurer’s black dial watch easily moved from the airplane hangar to dancing at the nightclub. Now, Stauer brings back the “Noire”, a design based on an elegant timepiece built in 1936. Black dialed, complex automatics from the 1930s have recently hit new heights at auction. One was sold for in excess of $600,000. We thought that you might like to have an affordable version that will be much more accurate than the original. Basic black with a twist. Not only are the dial, hands and face vintage, but we used a 27-jeweled automatic movement. This is the kind of engineering desired by fine watch collectors worldwide. But since we design this classic movement on state of the art computer-controlled Swiss built machines, the accuracy is excellent. Three interior dials display day, month and date. We have priced the luxurious Stauer Noire at a price to keep you in the black… only 3 payments of $33. So slip into the back of your black limousine, savor some rich tasting black coffee and look at your wrist knowing that you have some great times on your hands.

An offer that will make you dig out your old tux. The movement of the Stauer Noire wrist watch carries an extended two year warranty. But first enjoy this handsome timepiece risk-free for 30 days for the extraordinary price of only 3 payments of $33. If you are not thrilled with the quality and rare design, simply send it back for a full refund of the item price. But once you strap on the Noire you’ll want to stay in the black.

this

and handassembled parts drive

classic

Take Mine

Stauer… Afford the Extraordinary ® 27-jewel automatic movement • Month, day, date and 24-hour, sun/ moon dials • Luminous markers • Date window at 3’ o’clock • Water resistant to 5 ATM • Crocodile embossed leather strap in black fits wrists to 6½"–9" Stauer Noire Watch $399† Your Cost With Offer

$99 + S&P Save $300 OR 3 credit card payments of $33 + S&P 1-800-333-2045

Code: NWT536-06 You must use this offer code to get our special price. Stauer ® 14101 Southcross Drive W., Ste 155, Dept. NWT536-06 Burnsville, Minnesota 55337 www.stauer.com † Special price only for customers using the offer code versus the price on Stauer.com without your offer code. Rating of A+ Exclusive Offer—Not Available in Stores Back in Black: The New Face of Luxury Watches “...go black. Dark and handsome remains a classic for a reason” — Men’s Journal WIWP-230221-010 Stauer Noire Watch.indd 1 1/5/2023 3:08:48 PM

jewels

masterpiece. I’ll

Black…No Sugar

Code

Offer

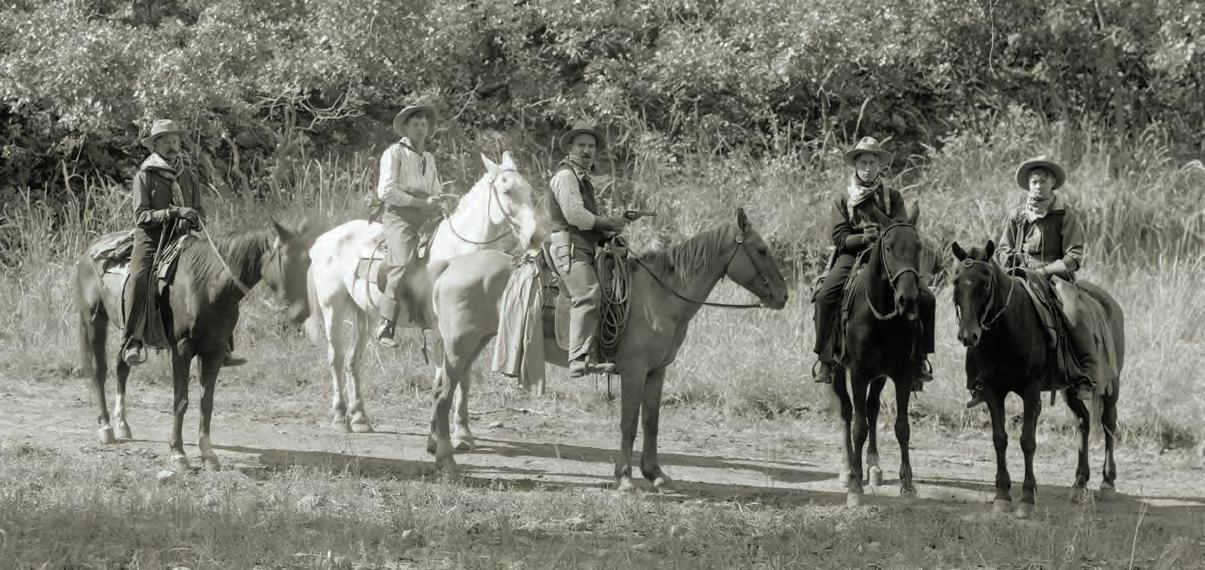

The Not-So-Great CPR Train Robbery

THE TRIO OF AMATEURISH BANDITS DIDN’T WEAR MASKS OR HAVE AN ESCAPE PLAN, AND THREE LAWMEN WERE KILLED IN THE AFTERMATH

BY TERRY HALDEN

BY TERRY HALDEN

The three Russians were acquaintances. Two were recent immigrants, while the third had been in North America for a time. Hard labor in the copper mines of Butte, Mont., had not fulfilled their idea of the “American Dream.” There had to be an easier way to make a living. They considered train robbery. As it was less common north of the border, they resolved to rob a Canadian train.

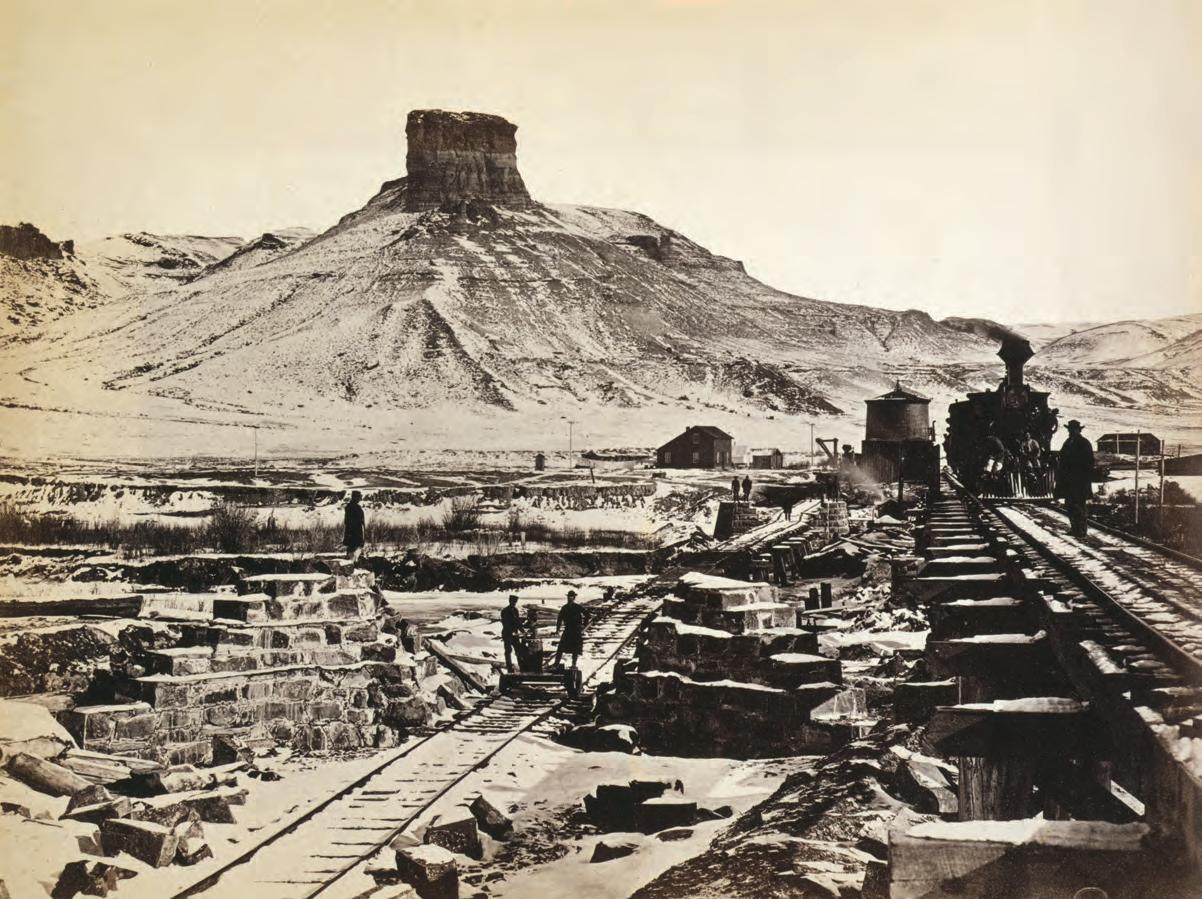

On Monday, Aug. 2, 1920, a warm summer’s day in southern Alberta, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) passenger train No. 63 chugged west. Soon entering the Rocky Mountains, it passed in turn through the neighboring towns of Bellevue, Frank, Blairmore and Coleman. Back in the baggage car Bill Staples readied freight to be unloaded at Sentinel, the next stop, at a passenger’s request.

Conductor Sam Jones checked the time on the prized gold pocket watch he’d recently purchased in Lethbridge. On returning it to his breast pocket, he found himself staring down the barrel of a semiautomatic pistol. As the gunman ushered Jones back to the baggage car to join Staples, the conductor was able to surreptitiously tug the emergency cord once. Three pulls would have called for an immediate stop, putting everyone in danger. Once signaled the train crew to stop at the next convenient place, which was Sentinel.

Meanwhile, two other robbers were relieving male passengers of their valuables, while leaving female passengers alone. On finishing their collection, the pair joined the third robber in the baggage car. As the train slowed for the stop at Sentinel, they jumped off and ran into the brush south of the tracks. The inept trio, who had ignored the safe containing several hundred dollars, made off with little more than $400 and Jones’ gold pocket watch. Authorities soon telegraphed descriptions of the suspects to Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Alberta Provincial Police (APP) stations in the area. Also joining the hunt were CPR detectives—two of them, William R. MacLeod and Albert Robine, having suffered the ignominy of being robbed. Jones informed lawmen the trio had boarded the train in Lethbridge, and police there soon identified the suspects as Tom Bassoff, George Arkoff and Ausbey Auloff, Russians from south of the border with prior arrests on minor charges.

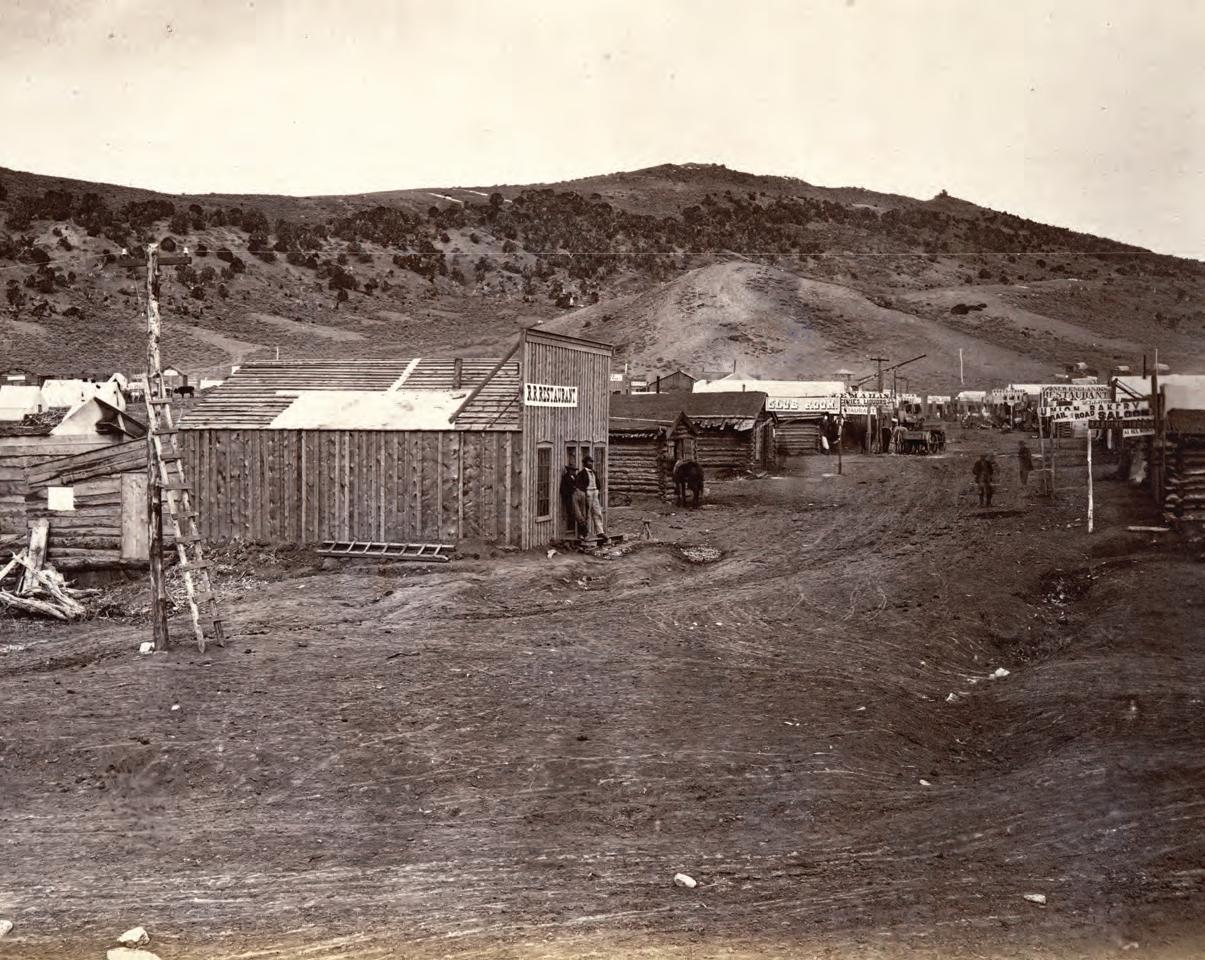

Authorities blocked all roads, stopped and searched every train, and investigated numerous sightings. The following Saturday, August 7, APP Constable James Frewin got a tip that two men answering the descriptions of the fugitives had entered a café in Bellevue. Frewin investigated with fellow Constable F.W.E. “Fred” Bailey and RCMP Corporal Ernest Usher.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 20 TOP: UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY; LEFT: GLENBOW MUSEUM, CALGARY GLENBOW MUSEUM, CALGARY

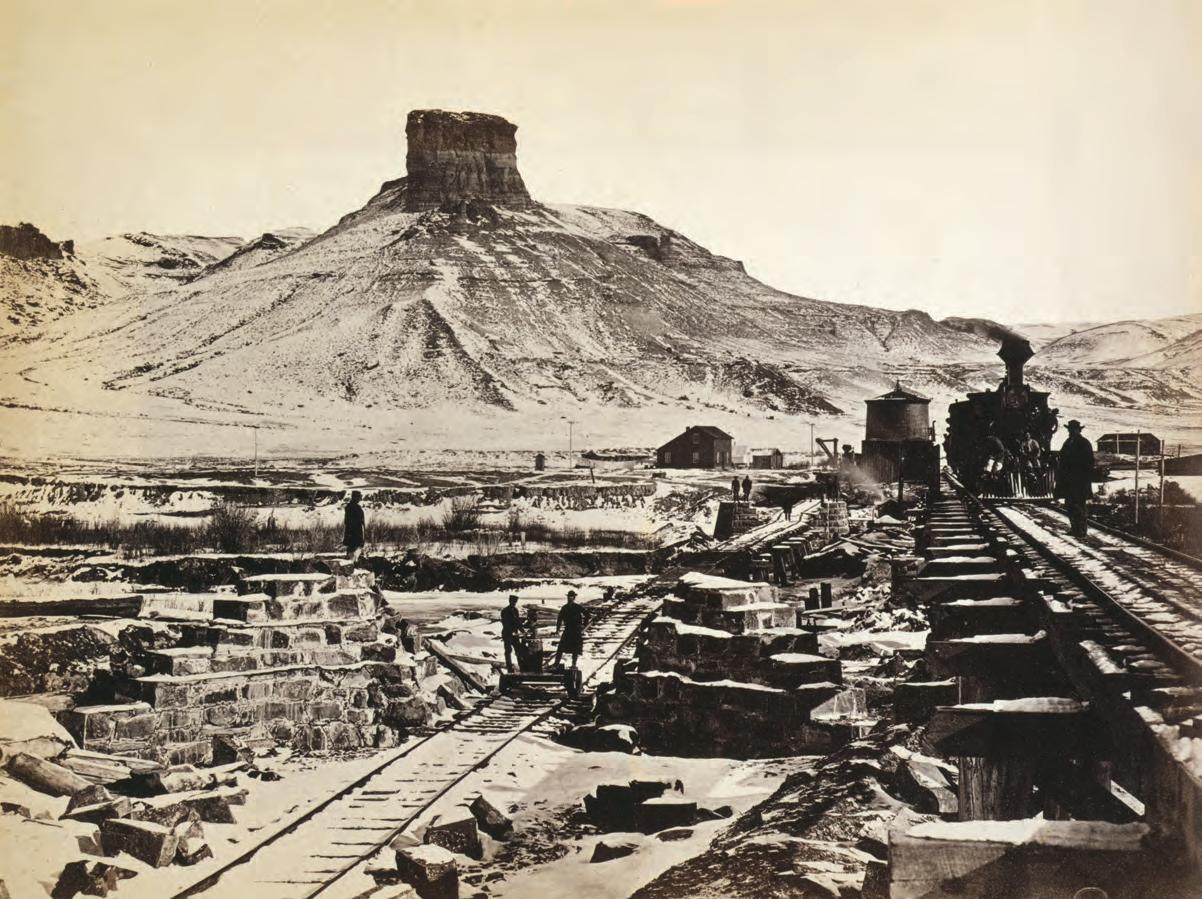

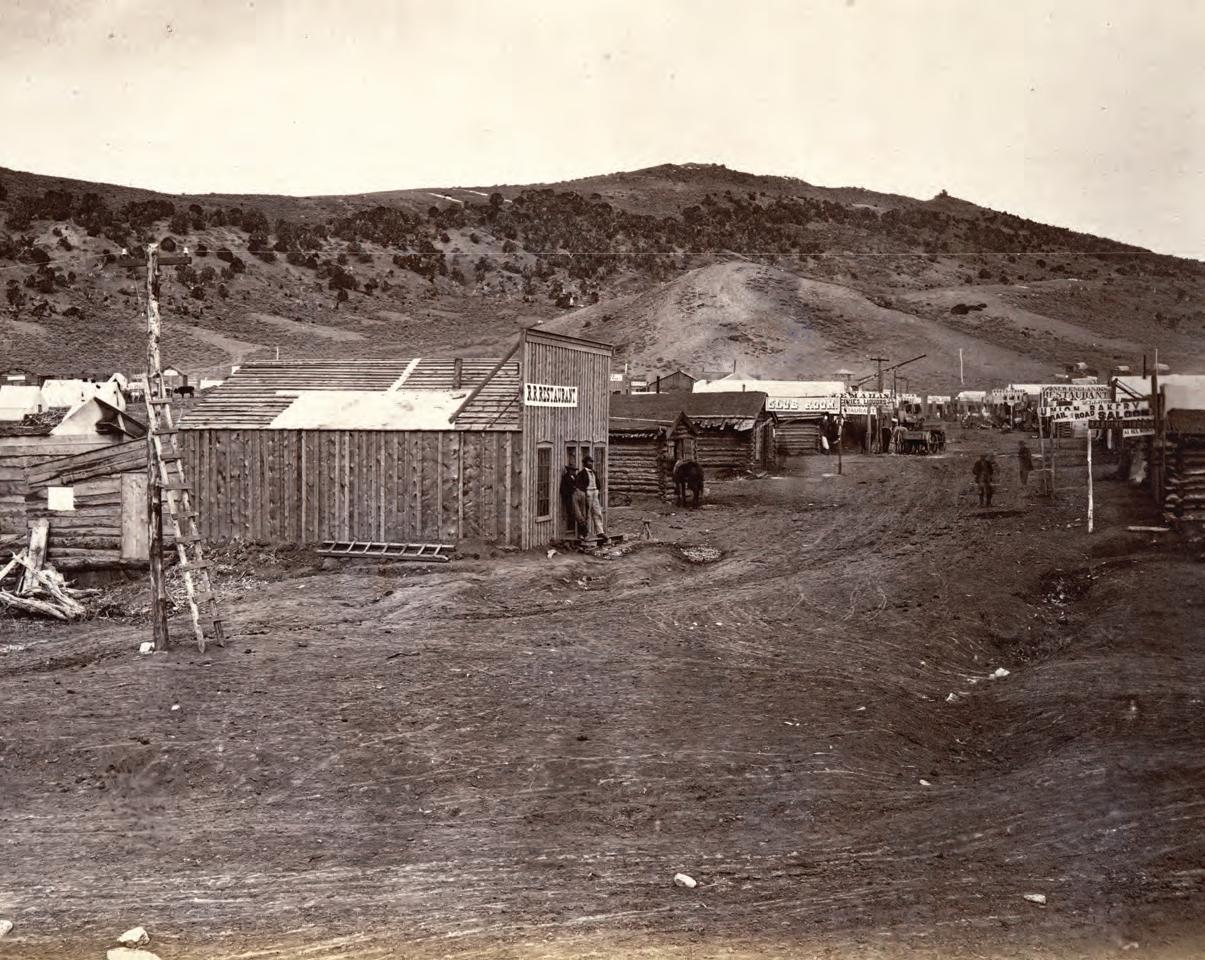

The backbone of the Canadian Rockies hemmed in the tracks south and north of the robbery site near Sentinel, Alberta, forcing the trio of fugitives to flee east or west with authorities close on their heels.

WIWP-230400-GUNFIGHTERS.indd 20 2/6/23 8:52 AM

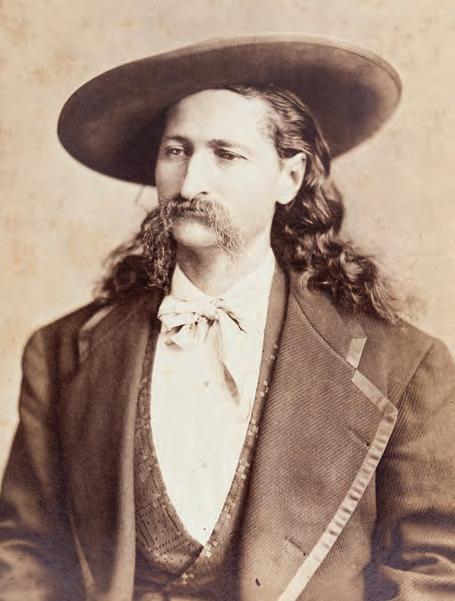

GUNFIGHTERS & LAWMEN Tom Bassoff

Bailey stood by the rear door of the restaurant while Frewin and Usher strode through the front door. The only diners were Bassoff and Arkoff, who shared a booth. Drawing their sidearms, Frewin and Usher cautiously approached. When Frewin saw Arkoff reach for his coat, which hung beside the booth with the butt of a gun sticking out, the constable opened fire, emptying his gun and then backing away to reload. Usher, who had his gun trained on Bassoff, did not fire. Responding to the shots, Bailey rushed in and over to the booth. Frewin, in a “shell-shocked” state at having shot a man for the first time, left the restaurant. It was then, police later determined, Bassoff saw an opportunity, yanked his Mauser pistol and opened fire.

Witnesses outside the restaurant said that after hearing several shots, they watched Corporal Usher back out the front door and turn to descend the step when he caught a bullet in the back. Constable Bailey followed, immediately stumbling over Usher, who lay crumpled on the ground with his head in the doorway. Next came Arkoff, who staggered up the street and collapsed, dead from his wounds. Finally, Bassoff emerged. As Bailey tried to rise, Bassoff fired once into the top of his skull. At that Usher stirred, and Bassoff emptied his gun into the wounded constable before taking off west on foot. Searchers later lost his trail.

By nightfall the manhunt had drawn more than 200 possemen, including police from as far away as Calgary. Anyone with a gun was sworn in and told to shoot on sight. This proved disastrous. On Sunday evening, August 8, Special Constable Nick Kyslik and APP Constable J. Hidson were searching a cabin near the railroad tracks when a slow-moving freight train rumbled past. Kyslik must have seen something suspicious on the train, as he leapt from a window and chased after it. In the twilight all Hidson saw was a running figure. Figuring they had flushed the suspect from the cabin, he yelled “Stop!” Kyslik, unable to hear over the train noise, kept running, so Hidson fired, killing his partner.

Not until Wednesday evening, August 11, did CPR detectives, responding to reports of a suspect limping along the tracks near Pincher Station, capture Bassoff. Despite the bullet wound to his leg, the fugitive had limped 25 miles east over four days and somehow managed to elude 200 possemen. The following Tuesday, August 17, he was arraigned in Fort Macleod before Magistrate Harold P. Burrell on charges of holding up a CPR train and murdering two police officers. The charges were held over, as that afternoon there was a massive double funeral for the slain lawmen. A local man, Bailey left a wife and two young children. Corporal Usher was a native of Ireland with no known relatives in Canada.

On October 13th, with Justice Maitland McCarthy presiding, Crown prosecutor E.J. MacDonald was ready to proceed when someone noticed there was no council for the defense. The judge duly appointed local attorney Donald J. Matheson and gave him an hour to confer with his client. Ballistic evidence revealed Usher had four bullet wounds in his right arm and one in his body from the Luger found on Arkoff, but the corporal had nine other wounds in his body, any one of which could have been fatal, from a Mauser. Bailey had one wound from a bullet that entered his skull through his peaked cap, also from a Mauser. When Bassoff was arrested, he had on his person an empty 10-shot Mauser. That evidence alone sealed his fate.

It took the jury less than an hour to bring in a guilty verdict. The judge condemned Bassoff to hang on December 22.

According to Bassoff, after the heist the trio had argued about the best escape route, and Auloff had headed west, taking Jones’ watch as his share of the loot. APP Sergeant John D. Nicholson reasoned Auloff had probably crossed the border to find work in the Western States, where Russians dominated the lumbering business. With the help of local police Nicholson visited lumber camps and dives across Oregon and Washington, but he had no luck. A break finally came in January 1924 when Portland city police wired then Assistant Superintendent Nicholson with news Jones’ stolen watch had been pawned, and they had identified a suspect. Nicholson sent detective Ernest P. Schoeppe to Portland, only to discover the suspect was not Auloff. Under questioning, the man admitted having bought the watch from an acquaintance in Butte, Mont. On a promise authorities would drop the charge against him, he took Schoeppe to the Butte home of that acquaintance. The man who answered the door was Auloff, who had returned to his old job. Schoeppe arrested the fugitive and turned him over to Butte police.

Waiving extradition, Auloff was returned to Alberta and convicted at trial of armed robbery, for which he received a seven-year sentence. On April 5, 1926, three years into his sentence, Auloff died in prison of respiratory disease brought on by his years underground. Thus what had started six years earlier as an amateurish attempt at a holdup ended up costing three lawmen and, ultimately, three bandits their lives.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 21 TOP: UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY; LEFT: GLENBOW MUSEUM, CALGARY GLENBOW MUSEUM, CALGARY

WIWP-230400-GUNFIGHTERS.indd 21 2/6/23 8:52 AM

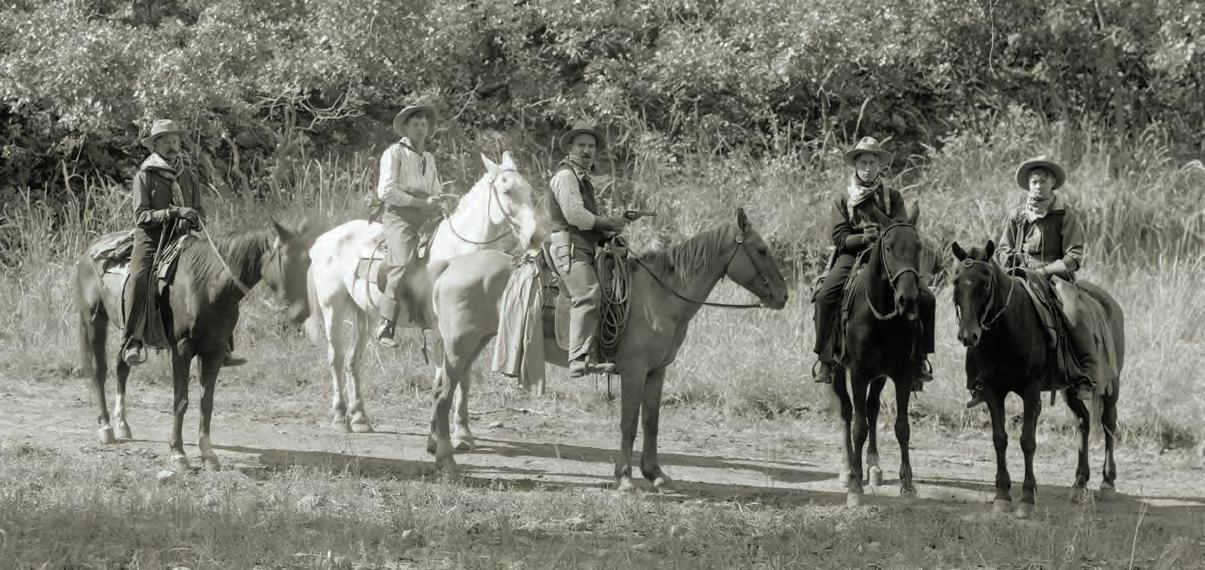

An officer reenacts the deadly Aug. 7, 1920, shooting at a café in Bellevue, east of the robbery site. When Alberta Provincial Police Constables James Frewin and Fred Bailey and Royal Canadian Mounted Police Corporal Ernest Usher confronted fugitives Tom Bassoff and George Arkoff, Bailey, Usher and Arkoff were killed, and Bassoff fled.

PIONEERS & SETTLERS Sarah

the Survivor

THIS HARDY TEXAS PIONEER WITNESSED THE DEATHS OF MANY A LOVED ONE AND ESCAPED CAPTIVITY BY COMANCHE RAIDERS

BY CHUCK LYONS

By life’s end Sarah Creath McSherry Hibbins Stinnett Howard could claim five surnames, one from her birth and one each from her four husbands. Along the way she had suffered more hardship on the Texas frontier than most pioneers, man or woman. Described in her youth as “a beautiful blonde…graceful in manner and pure of heart,” she had watched as two of her husbands, her only brother and one of her children were killed in front of her and had lost a third husband in mysterious circumstances. She herself had been captured by Comanches and escaped, making a perilous and painful journey before stumbling bruised and bleeding into a camp of Texas Rangers. But she had survived.

Originally from the vicinity of Brownsville, Ill., where she was born Sarah Creath around 1810, Sarah married John McSherry

while still a teenager. In 1828 the newlyweds moved south, settling in DeWitt’s Colony, along the Guadalupe River in south Texas, then a Mexican province. In 1829 a son was born to them. Then tragedy struck.

On an otherwise pleasant day that year, around noon, John left the cabin to fetch water from a nearby spring. Moments later Sarah heard yelling and opened the cabin door to the sight of Indians killing and scalping her husband. She quickly slammed and barred the door, locking herself and the baby inside, then grabbed John’s rifle, determined to defend herself and the baby as best she could. While she waited in the still cabin, the Indians slipped away as quietly as they had come.

Around twilight a man named John McCrabb happened by. Seeing what had happened and hearing Sarah’s story, he placed her and the baby on his horse and led them through the

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 22 SAN ANTONIO CONSERVATION SOCIETY FOUNDATION GRANGER

WIWP-230400-PIONEERS.indd 22 1/20/23 1:47 PM

Opposite: A romanticized 1858 engraving depicts a lone female captive being carried off by Comanche warriors. Real-life captive Sarah Creath McSherry Hibbins Stinnett Howard witnessed the murders of two husbands, her brother and a child by Comanches.

darkness to the home of the McSherrys’ nearest neighbors, Andrew Lockhart and family, some 10 miles upriver. Mother and child remained with the Lockharts several months until Sarah remarried, to a well-off Guadalupe Valley man named John Hibbins (also given as Hibbons or Hibben). In 1835, after having given birth to a second child, Sarah returned to Illinois with her two children to visit relatives. In early 1836 they returned to Texas by way of New Orleans, accompanied by Sarah’s only brother, George Creath. In February the four met up with John Hibbins at Columbia, Texas (present-day West Columbia) on the Brazos River, setting out from there by ox cart bound west for the Guadalupe Valley. They never made it. Fifteen miles from home, they were attacked by a band of 13 Comanches who killed Sarah’s husband and brother, took her and the children prisoner, and rode north.

“They traveled slowly up through the timbered country,” John Henry Brown wrote in his 1880 book Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, “securely tying Mrs. Hibbins at night and lying encircled around her.” The next day one warrior, weary of listening to the cries of Sarah’s infant, killed it by smashing its head against a tree as Sarah helplessly watched. Days later the party crossed the Colorado River deep in Comancheria and relaxed the security in which they held their captives.

Sarah faced a crossroads. Though she realized there was a chance to escape, she knew she could not make it away safely with her young son, so she made the heartrending decision to leave him. Wrapping him in a buffalo robe, she quietly slipped out of the Indian camp and into the darkness.

“Daylight found her but a short distance from camp, not over a mile or two,” Brown wrote, “and she secreted herself in a thicket from which she soon saw and heard the Indians in pursuit. The savages compelled the little boy to call aloud, ‘Mama! Mama!’ But she knew that her only hope for herself and child was in escape and remained silent.”

When Sarah was certain the Comanches had given up their search, she pressed on through the heavy brush and down the Colorado, eventually stumbling across a riverside cabin in which 18 Texas Rangers had just settled down to their evening meal. Though she’d walked only 10 miles, it had taken her 24 hours. “She was so torn with thorns and briars, so nearly without raiment and so bruised about the face that her condition was pitiable,” Brown wrote.

The Rangers, under the command of Captain John J. Tumlinson Jr., quickly saddled up and went after the Comanches. The next morning, after a brief but hard fight, they rescued Sarah’s child. Sarah and son next went to live among the families Harrell and Hornsby, near the site of presentday Austin, and fled with them as the Mexican army that had taken the Alamo in March moved north. They eventually found refuge with former Dewitt’s Colony neighbor Claiborne Stinnett, and in the spring of 1837 Sarah and Claiborne married. In 1838 Stinnett was elected sheriff of Gonzales County. That fall the sheriff disappeared while returning north to Gonzales from Linnville, on Lavaca Bay. He was thought to have been killed, either by Indians or, as Brown believed, by two runaway slaves. Regardless, Sarah was again a widow. By then, though still shy of 30 years old, she had been widowed three times and seen her brother, one child and two husbands killed before her eyes. On May 29, 1839, she married her fourth and final husband, Phillip Howard. In June 1840 the couple left the Guadalupe Valley and moved west to the San Juan Capistrano Mission south of San Antonio. On arrival they were subjected to an Indian raid, Sarah’s son barely escaping capture a second

time. The Howards later moved farther down the San Antonio River to southern Goliad County. There they experienced more Indian raids and again fled, this time to the vicinity of present-day Hallettsville, in Lavaca County. Finally finding peace there, Sarah gave birth to three daughters, and her husband was named a county judge. In their later years the Howards moved once more, settling in Bosque County, where Sarah died on March 28, 1870, of natural causes. She had been with Phillip for more than half of her 60 years—her reward after long years of hardship.

In 1840, after having lost family members to raids and escaped captivity in Comancheria, Sarah moved to the San Juan Capistrano Mission (above) south of San Antonio with fourth husband Phillip Howard. Further raids prompted two more moves before the couple settled in Lavaca County, Texas. The Howards lived out their days in peace in Bosque County.

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 23 SAN ANTONIO CONSERVATION SOCIETY FOUNDATION GRANGER

WIWP-230400-PIONEERS.indd 23 1/20/23 1:47 PM

One warrior, weary of listening to the cries of Sarah’s infant, killed it by smashing its head against a tree as Sarah helplessly watched

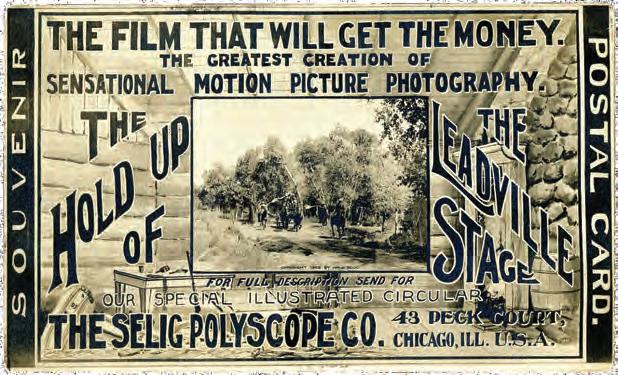

WESTERN ENTERPRISE Photographer in Motion

IN 1902 COLORADO-BASED PHOTOGRAPHER HARRY BUCKWALTER TEAMED UP WITH FILMMAKER WILLIAM SELIG TO MAKE ‘REEL’ WESTERNS

BY DAVID M c CORMICK

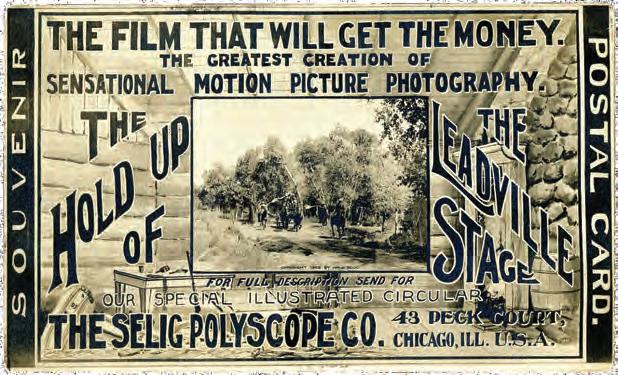

On Oct. 9, 1904, amid production on the film The Hold Up of the Leadville Stage (or Robbery of the Leadville Stage), a real shootout occurred. The crew and some two dozen cast members were filming the climactic holdup scene in the foothills of Colorado Springs, Colo., when a wagonload of Eastern tourists happened on the location. Hearing gunshots and witnessing a man falling to the ground, armed men among the tourists opened fire on the make-believe highwaymen, wounding film executive William Selig in the arm. Meanwhile, the director rushed

toward the dudes, waving his arms and beseeching them to cease fire. By the time the Easterners holstered their six-shooters, they’d fired nearly a dozen rounds. Fortunately for cast and crew, the trigger-happy tourists proved pitiable shots, otherwise the affray might have resulted in alltoo-real bullet-ridden bodies.

The director who came to the rescue was Harry H. Buckwalter. Realizing Americans had long been captivated with the lore and legends of the Old West, he was among the first to film what have since been branded Westerns. A photojournalist turned filmmaker, Buckwalter teamed up with William Selig, owner of Selig Polyscope Co., around the turn of the 20th century. Over the next decade the pair produced assorted rudimentary, histrionic narratives for rapt theatergoers. Buckwalter served as producer, director and cameraman, while Selig distributed the films. Though Buckwalter’s production career was brief, it was prolific. Between 1901 and 1913 he completed nearly 50 Western-themed films, some simple scenic panoramas, others action narratives with unpolished plots.

Born in Reading, Pa., on Nov. 1, 1867, Harry Hale Buckwalter first ventured West at age 16. Colorado’s striking vistas prompted an interest in photojournalism, leading him in turn to The Denver Republican and the Rocky Mountain News. As a photographer and roving reporter for the latter, he was soon making headlines. To highlight Buckwalter’s stories, staff artists initially reproduced his photos as wood block-illustrations.

Buckwalter was fearless. On Aug. 12, 1894, having enlisted local balloonist Ivy Baldwin, he prepared to shoot a series of aerial photographs of Denver and environs. When the weight of both men proved too much for the balloon to lift, Buckwalter made the ascent solo from Elitch Gardens. The resulting article, “Dancing in the Air,” featured his sweeping landscapes—early Western photojournalism at its best.

By 1900 Buckwalter had left the Rocky Mountain News to pursue a career as a freelance photographer. He soon found himself working on the railroads, notably the Colorado Midland (CM), taking promotional photographs of trackside scenery. That lucrative work stirred his interest in capturing objects in motion, and he experimented with various high-speed shutters. The sideline paid off, as New York–based Prosch Manufacturing Co., which made early photographic equipment, paid $100 for an enhanced shutter devel-

WILD WEST SPRING 2023 24 TOP: DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY; RIGHT: MARGARET HERRICK LIBRARY DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY

WIWP-230400-ENTERPRISE.indd 24 1/20/23 1:47 PM

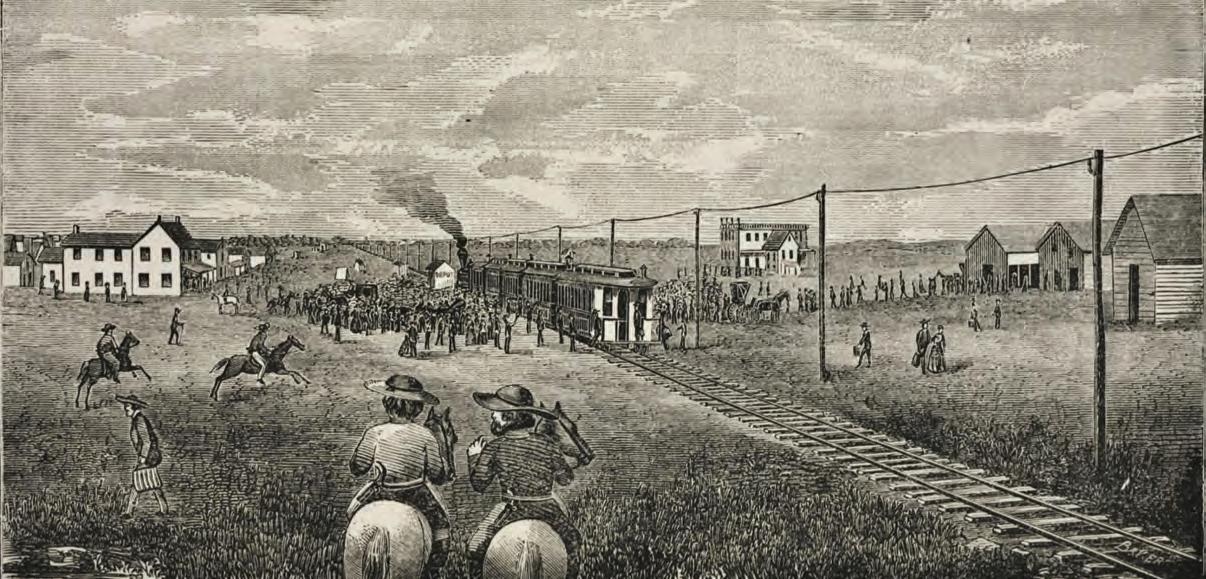

Drawn west as a teen, Buckwalter earned fame as an enterprising Colorado photojournalist who in 1894 photographed Denver and environs from the basket of a balloon. Motion pictures soon lured him away.

oped by Buckwalter. With his newly honed skill he was soon capturing still images of moving trains, rodeos and other action subjects. It was a short hop from there to motion pictures. For the well-paying CM Buckwalter filmed “travelogues,” early documentaries of spectacular Western routes.