Teachers with impact effect

Every student learns by design, not by chance

Ana Moreno Salvo Director of Impuls Educació

Ana Moreno Salvo Director of Impuls Educació

Dear reader,

In the latest macro study on what factors positively impact student learning and education, John Hattie concludes that: “teachers should focus more on the impact of their teaching than on the quality of that teaching,... schools should give visibility to the teachers with the greatest impact and their methods for achieving it”. And, as the author of the bestseller "Visible Learning" repeats, quality teaching is found in almost all schools, so most schools have acceptable average results, or even good or very good ones. But that does not mean that all of their teachers or educational leaders are doing a good job. It does mean that they have some teachers who are doing a really great job and sustain good results year after year. If we add a favourable learning environment in the family, it is even better. However, this does not mean that all students benefit from that quality. For this to happen, we should also measure whether each student at a school is progressing in their education and learning over one year in proportion to what they should learn for a year of school work. That is when we should really be proud of our school.

But how do we achieve this progress? According to Doug Lemov, the creator of the “Teach like a Champion” method of teaching excellence, we achieve it with top-quality continuing professional development for teachers. We do it with training to ensure that teachers know how to create a classroom culture that is conducive to learning and know how to be the best teacher for each of their students, creating a positive relationship with them that boosts their interest in learning on a daily basis.

However, that is not all. In “Well-Being in Schools”, Andy Hargreaves further encourages educational systems to take into account the development of students as human beings, in all their dimensions and as a whole, to ensure that the system itself is a safe place to be happy and learn without the threat of failure or exclusion. In Hargreaves' opinion, we have to overcome the limited focus on socioemotional factors and instead create healthy environments specially designed to meet human beings' basic needs, especially in terms of their expectations and integral development.

We have dedicated this new issue of "Diàlegs" magazine to the teaching profession because we believe--and this is corroborated by evidence--that teachers are the key to quality education. We wanted to draw from prominent experts from all over the world, from Australia to Canada, from England to the United States, from Colombia and, of course, Spain. Guy Claxton speaks about the importance of changing the paradigm of learning, Miquel Àngel Prats about the role of technology and digital competency in teaching, Mercè Gisbert and Joan Anton Sánchez about teacher training, Stephen Harris about how to design and implement an innovative educational model, jettisoning any dead weight from the past thanks to a new model of school and, of course, of teachers.

This time, our tribute goes to Robert Swartz, a dear friend who left us last October after heroically dedicating his life to improving education.

I hope you enjoy it.

project

INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN HARRIS AND LETICIA LIPP

6

INTERVIEW WITH GUY CLAXTON

24

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN HATTIE

Every student learns by design, not by chance

14

2

EDITORIAL BOARD

Management and interviews

Ana Moreno

Publications

Jordi Viladrosa

Original Design

Guillem Batchellí

Design and Communication

Maria Font

Illustrations

Maria Yuling Martorell

Editorial department and subscriptions

Impuls Educació

Avda. Montserrat Roig, 3 08195 Sant Cugat del Vallès revista@impulseducacio.org

https://impulseducacio.org/

ISSN 2938-2122

DL B7336-2023

The heroism of giving one's life until one's last breath to help people think better

Stephen Harris is co-founder and director of Learnlife in Barcelona. In 2005, he founded the Sydney Centre for Innovation in Learning (SCIL). His vision is to integrate innovation in schools by leveraging the passion and experience of the teams that have worked with him. He has in-depth knowledge of leadership, innovation and culture. He is a 2017 recipient of the prestigious John Laing Award from the Principals Australia Institute (PAI), given to exceptional school leaders.

Leticia Lipp is one of the founding members of Learnlife. She has been head and leader of the Human Resources and Culture teams since Learnlife was founded. Her current mission is to grow Learnlife's partner schools towards innovation. She also acts as a head-hunter searching for talent such as principals, pedagogical leaders, teachers and learning experience designers.

In 2023, Learnlife was chosen by hundrED as one of the 100 educational innovation initiatives with the greatest future impact on educational transformation. Can you tell us the keys to the Learnlife transformation project and what makes it different from other innovation projects?

Stephen Harris (SH): I found it interesting that only two of the 100 innovation programmes recognised by hundrED were truly school-based. It was encouraging to see that what we were doing was on a larger scale.

What are the keys to transformation?

We have managed to define a framework and simply carry it out. We have been aware that in order to create a different model, it is essential

to identify what can limit creativity and thinking. Learnlife has engaged in an evolutionary process towards what we really think is at the core of good learning, that is, what a teacher should be able to understand. Therefore, we can take this model to any context. You have to be able to effect the transformation. Change needs to be actionable at the classroom, school or system level, if needed. The most important thing in learning is for the learner

What is important in learning is for the learner to experience a world of functional relationships

to experience a world of functional relationships.

If you enter a community and feel threatened, or if there is a power imbalance, that will limit your learning. The bottom line is to make positive relationships central to everything else. Once that is achieved, you can begin to build trust and a culture of learning in the direction you want to go. I guess the key to our project is understanding where we are starting from with a very clear sense of purpose for each child, each student and each adult. And all this takes place within a mutually positive relational experience.

Learnlife is a very young project, founded in 2017. You had to choose and train teachers in a

brief period of time. How would you describe the role of a Learnlife School teacher?

SH: What makes the difference to us is that, if we get rid of the idea that there is only one way to go, any school or community can get students to do well on a test at age 18.

But, five years after finishing school, the most important thing is: Has that student gone on to learn? Has he or she started to make an impact somewhere in the world, on how to address some of the world's major problems? If there is no evidence of this, then the country's educational system has to be questioned.

I have worked in Rwanda, in central Africa, and the fact is that they manage to get 97% of their children into school, a much higher rate than other African countries. But, despite being in school for twelve years, the unemployment rate is still 85%, as if they had never been to school. The problem lies in what happens at school. The teacher thinks that his or her only purpose is to convey information and knowledge to the children. That is the problem.

How do we select and train our teachers in this brief time? First of all, we have understood that there is urgency. If we look at what has happened in the world of education in the last six months, it seems that AI, the main language models, ChatGPT and so on have suddenly come to schools. But they have actually been in existence for ten years. The world of artificial intelligence did not arrive in November 2022. It's been here for a while, but schools haven't caught on. That's because the systems that train teachers are still focused on very

Five years after finishing school, has that student continued to learn?

narrow goals, such as “your kids have to take this test so they can get into this university”. It's a transactional world. For us, a teacher is a person capable of guiding, orienting, training, adapting and being agile according to students' needs. All of these things are part of a teacher's role, and we have sought out the right people.

I don't know if you've heard of Alvin Toffler, the writer. In 1979, he wrote that the twenty-first century was going to be the century of learning, unlearning and relearning. It's a very simple but incredibly insightful statement, because until the advent of the Internet, knowledge was a sort of defined commodity that you got from books or people. Now it's universal. We have teachers coming into our system burdened with an old school concept and the expectation that their job is to keep the kids quiet and the inspector happy or to get the kids to pass the test. We want to get rid of all this because it limits children's opportunities. For us, a teacher is a learning guide.

Our challenge is to focus on finding the right person with the right mindset, because we don't have time to change people's mindsets. Then we can work with them easily because we can show them that things can be different. The problem is that it causes thousands of young teachers to leave teaching after five years, and there is no need for this to happen if their experience is positive and not stressful, as it is in many countries.

Leticia Lipp (LL): “Learning guides', the name we call teachers at Learnlife, are people who promote passion and put the responsibility for learning back on the children. It's not about controlling classroom behaviour and trying to differentiate” it's about establishing a positive relationship and accountability. The student's responsibility is the student's, not the teacher's. That is an essential difference. Students should not have the attitude of “I have to follow the rules', “I don't want to get

Learning guides are people who promote passion and put the responsibility for learning back on the child

kicked out of class', “I have to behave”, “I have to get good grades to make my parents happy”. This still happens far too often. Children don't do it for themselves, they do it for their parents or their teachers. And that is what changes with learners and the relationship between the teacher and the learner in guided learning.

Learnlife schools are called Hubs (Urban Hub, ECO Hub). Why did you choose this name? How would you describe the learning environment you are trying to build?

SH: To get people out of their previous thinking about schools, like “classroom”, “hallway”, “bell”, “schedule” and everything else, we wanted to create a different universe of words so that kids would see what was happening in a very different way. So we decided to stop using the word “school” because for many children it is loaded with negative connotations. Interestingly, when we started, the word “maths' was the most negative word for children. “School” was the second and “teacher” the third. In contrast, the word “hub” is just a word used in business. You have business hubs, which can be an entire city, part of a city or even a small community. So, basically, we chose the name because it was different, it was simple and it shows that this place is a specific community.

The Urban Hub is a community of teenage students attending a programme in the centre of Barcelona. And the Eco Hub is a community of younger students attending a more nature-based

programme in Castelldefels. How would we describe the learning environment? Well, we want to create a community where the learning culture is very strong. If we take into account the world in which children live, we know that social media have an impact on them. Is screen time limited? Are cell phones limited? Some countries prohibit ChatGPT. What we would say is that we don't want children to feel that their culture, their parents' culture, their ethnic culture, their love of soccer, sports, surfing or shopping is wrong or not valued. What we want, however, is a stronger culture that they adopt subliminally, without thinking, when they enter the hub, so that when they arrive they get the sense that they are here to learn.

That is what we are trying to

establish: an environment where the learning culture is strong and unconscious. It is there, and it drives the individual in their choices and behaviours and desire to participate in the programmes.

Why design a new age-based learning pathway for students unlike the usual one: adventurers, discoverers, pioneers in primary school and explorers, creators, changemakers in secondary school? Can you briefly explain the role of the teacher in guiding students along these pathways?

SH: When we talk about the students' pathway being different from the usual one, it actually isn't. If you look at virtually every country in the world and check their curricular documents, they are all based on step-by-step

learning. In the vast majority of documents, one stage covers two calendar years. In other words, six and seven years old is one stage, eight and nine years old is another. What we have done, again, is change the word. We have removed “Stage One”, which means nothing, and called it “Adventurers'. It's a much more interesting word to get kids to join the programme. I think about the number of schools that have the names one, two, three, four, five, six or just completely meaningless

What we want is a strong learning culture that they adopt when they enter the school© Estudio Alejos

If a child has a problem, first look at the system, because it may be the cause of the problem

bureaucratic names on the classroom doors.

I prefer to get kids into an Eco Hub as “Adventurers' to stimulate their thinking. So our “Adventurers' are usually six and seven, “Discoverers' eight and nine, “Pioneers' ten and eleven or so in elementary school, and then in secondary school our “Explorers' are twelve and thirteen, “Makers' fourteen and fifteen and “Changemakers' sixteen or older. All we have done is say why should a child who can speak six languages and is very good at intuiting scientific concepts sit in Adventurers when she is clearly capable of so much more? We are not rigid in saying “just because you are seven years old, you have to be sitting in this room”. We have a set of competencies that must be visible and measurable for a child to move from one programme to the next. So if we look at Creators who are going to become Changemakers, we ask: Do they know how to make a public presentation? Can they write? What projects have they been working on? What is the evidence of their learning? Is it enough for them to move up to the next programme? Are there any projects they are passionate about? Have they been successful or have they encountered any difficulties? It is good for someone to make an effort as long as they recognise what the struggle is all about. These criteria for passing are the guide to what the kids need to demonstrate to us so we know they are ready to move on to the next programme.

The teacher's role is to intervene when necessary. If you have a child who has difficulty engaging, you don't just tell them to sit down, shut up

and look straight ahead. You need to find out what is blocking their engagement. What can we change as adults to unleash a love of learning? To me, that's a fundamental change that any school and any teacher can make. If there is an obvious problem with a child, don't blame the child. First look at the system, because it may be the cause of the problem.

What are the key aspects of training to become better teachers, or “learning guides', as you call them?

SH: Trust is the most fundamental aspect. If there is no trust in the community, teachers are going to have difficulties. There are many areas where it is very easy to lose trust. And if you don't have trust, you're not going to move forward. Teachers around the world are told they have to teach a new generation to collaborate, but the reality is that probably 95% of teachers are awful collaborators because they have never been taught.

In order for a teacher to be the best “learning guide”, we need to focus on the problems that may prevent them from getting there. We have to make sure that they have a psychologically safe environment in which there is trust. We have to make sure they understand where they're going and why things are a little different, because otherwise it's very tempting to just go back to where they were. They have to understand what works. John Hattie's research clearly shows that timely feedback is one of the most powerful determinants of learning growth. How many schools keep a child's project or essay for three or four weeks before returning it to them? You have to have a system where you have that relationship and those conversations that allow you to give immediate feedback, because that is the powerful change. That's how trust grows. The impact of trust is that you can move from cooperation to

collaboration. The impact of positive relationships is that you can feel safe enough with me to raise any difficult issue because I'm not going to question your loyalty or anything else. I will try to help you grow in that context.

Faced with a project as innovative as Learnlife, what is the process of creating a teaching team that works effectively?

LL: At Learnlife we had the luxury of building the team from scratch. We were very thorough in the way we recruited and chose people. Typically, an interview with a group of experts or discussions with adults are held. In our case, it all started with a conversation, but we wanted to see people in action with the children in an assessment context and a team context, because we were looking for people who had the right “why”. That is, they personally wanted to innovate and change education for themselves as a kind of intrinsic motivation. We wanted them to have the ability to be good collaborators and build positive relationships with the children. In this way, we make decisions with the children about who their learning guides and team should be in the future.

It was an inclusive form of teambuilding. Genuine trust is essential. As Stephen was saying, having a culture that creates a safe space or even a brave environment for people to say when things are difficult for them is essential in that hiring process.

SH: As leaders, as recruiters, we have to have the skills to know how to manage a team. There are many school principals who have never been taught that skill. There is a

The impact of trust is that you can move from cooperation to collaboration

fundamental problem if a school leader does not know how to listen, create a safe space or build a team.

Once on the team, everyone needs to grow and feel that they contribute to the mission. Could you tell us the keys to getting each person in the right “seat”, given their profile and aspirations?

LL: We are clear about the competencies needed to be a good learning guide. We conduct a very thorough competency assessment. The goal is to demonstrate flexibility and agility, as well as keen self-awareness and the ability to recognise emotions and to set and maintain healthy boundaries. Executive functioning, decisionmaking, collaboration, positive relationships, creativity, the ability to design learning experiences... all of

these are essential.

We do not have a set curriculum, but we do partly use the state curriculum. Our intention is for them to change it and turn it into play-based learning, challenge-based learning, nature-based learning and so on. A learning guide is a designer, but also a planner and a facilitator. Learnlife people have changed. They came in as product managers and are now learning guides.

What am I good at and how could I use these skills? For example in the primary programme we find that the different learning guides on the learning team have complementary skills, so some people are engineering- and coding-minded, others are very good with digital media and videos and others are caring. Others specialise in special needs or deal with health and

safety. We try to assemble teams that complement each other and to ensure that people change, grow and evolve. I guess this is also a reason why we don't really need a retention strategy.

Just today I read an email from a person who has been with us for five years, who came from elsewhere and now has a completely different role and is very happy to have been able to grow and evolve. This is one of the reasons people stay, as well as because from the beginning they are strongly aligned with your purpose. It is much more than a job. This is meaningful to them, and they come here to be who they are. They don't just come to work.

Leading the team of professionals at Learnlife must be a complex task. What types of leadership are

A learning guide is a designer, but also a planner and a facilitator

needed? How is this leadership structured and energised?

LL: Everyone at Learnlife has to be a leader. Self-leadership is the most essential factor because that is the only way you can lead a team or a programme. It is more about listening than talking. It is practical leadership. You are a role model. If you go into the urban school, you don't know who the founder is, who the learning guide is or who the teenage learner is, because everyone is more or less at the same level. It is a distributed leadership model. I would say that everyone can have an influence, everyone can take a decision, as long as the people affected by that decision are consulted, and experts are consulted. I guess that's also what keeps people here: the opportunity to visibly see the impact of their work and their ideas.

SH: Leaders have to learn throughout their lives. You don't get to this position to say, “I've made it, I've got an office, I've got people working for me”. Learnlife is nothing like that. There is no office. The space is shared by everyone. So I have to be able to rid myself of any perception I may have that leadership is about hierarchy, because leadership is about leading and it's about serving. If a chair needs to be moved, if there's a faucet that doesn't work, I'm not going to ask someone to fix it. I will try to solve it myself, because what we want the kids to learn are the same skills that I show in problemsolving, in challenge-based thinking, in creative thinking. If I can't do it right, how are they going to learn?

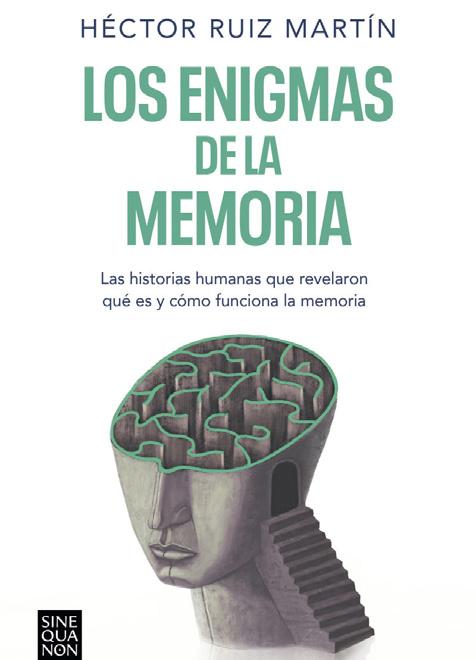

John Hattie (New Zealand, 1950) is Emeritus Professor at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education. He is also president of the Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leaders and co-director of the Hattie Family Foundation.

More than 250 million students have participated In his study, “Visible Learning”, based on evidence-informed education. He has just published "Visible Learning: The Sequel", which updates his previous book and highlights the need for teachers to consider assessing the impact of that evidence on student learning in their classrooms.

by Ana Moreno Salvo

by Ana Moreno Salvo

Teachers should focus on the impact of their teaching on learning

To what extent does the educational excellence of a school depend on the professionalism of its teachers? What does the scientific evidence tell us about the essential features of quality teaching from the teachers' vantage point?

Teachers are the ones who can have the greatest effect on a school. The main source of variation comes mainly from the students' attributes and then from teachers and school principals. This means that we need to analyse the variability of teacher impact. The greatest influence is related to the teacher's professionalism and experience. This is a very exciting finding: it shows that there is a lot of excellence in our countries' schools. Excellence is all around us. The main problem is that the variability of teacher impact is greater within schools than between schools. Thus, there is variability within the same school. The main message I want to convey is to ask school principals to have the courage to reliably identify teachers who have a high impact, form a coalition around them and invite others to join it.

What I want those great teachers

Principals should identify teachers who have a high impact, form a coalition with them and invite others to join it

to do is to think more out loud, because what the teachers do isn't important; what matters is how they think about what they do. What are the thought processes underlying these great teachers? How do they think? How do they use their evaluative thinking and make decisions on the fly? What happens, however, is that teachers get together and talk about what they do. They talk about curriculum, lessons, students and assessments. And they should talk more about the decisions they make, their interpretations. I want them to critically evaluate each other, because that is what makes all the difference in many powerful schools. What is the difference between highimpact and low-impact teachers? Frankly, as I travel the world, I hear your ideas and see a lot of excellence.

In your latest book, “Visible Learning: The Sequel”, you say, “every student should have a great teacher by design, not by chance”.

What are the keys to creating a great teacher?

The greatest effect on students is achieved when teachers are willing to work together to evaluate their impact. That has a huge effect because teachers are very good critics, in the best sense of the word. They are very good at finding multiple interpretations when they have school leaders who give them the confidence to raise teaching problems or student problems to professional learning communities without prejudices. It often comes down to this key skill: putting yourself in other teachers' shoes and understanding their point of view, and putting yourself in your students' shoes and understanding what it means to them.

We always talk about teaching, and frankly, I hardly care about teaching. What I care about is the impact of teaching. It matters to me because great teachers are “nosy” in many ways: they want to know

The greatest effect on students is achieved when teachers are willing to work together to evaluate their impact

how their students think, what their blocks are, what their barriers are. They want to know how hard they work, because learning is hard work. Learning involves a great deal of effort. Learning means making many mistakes. The fact that the teacher has created a climate not only between the teacher and the students but among the students themselves makes it safe to make mistakes, and those mistakes are seen as learning opportunities, not sources of embarrassment. Teachers who create a climate of safety to take on challenges in their classrooms, who know their students and their students' willingness to take on challenges, can listen to their students think out loud and thus track their learning process.

Learning has to do with “something”. Teachers want their students to acquire knowledge and skills, but they also want them to solve problems. Too often we ask whether we should teach explicitly or whether we should teach problemsolving. Great teachers are ambitious. They want to do both. They know when to focus on factual content and when to focus on problems. Great teachers seem to work backwards: they determine what the success criteria are for the problems they want their students to solve, as well as what skills and knowledge they need to solve those problems. And then they teach both. No child is left behind. Children are very clear about what success is and what it means to be good enough in class. They create that climate with the students. “Challenge, challenge, challenge, challenge, trial, error, error, error, deliberate practise, seek feedback”. In these classrooms, you can feel and hear everyone's passion for achieving the common goal of accelerating and

progressing, regardless of a student's performance level or background. This is happening in many, many classrooms around the world.

Teachers often comment that if class sizes were smaller, performance would improve, but according to your book, the evidence shows that this is not the case. How should we interpret these data? How can this evidence help teachers understand how to improve their teaching?

There are many studies that agree that class size has a very minor effect. The premise of your question is absolutely correct: class size should improve performance. The fact that it doesn't is fascinating. I have done a lot of research to try to understand why the effect is small. The answer turns out to be that when teachers are in classes with 30 to 40 students and then go to classes with 15 to 20, they teach the same way. Not surprisingly, the effect hardly changes. If a system wants to lower class sizes, teachers have to change their teaching method to make any impact. I have never advocated class sizes, although they should not be large. If you look around, you see teachers doing brilliant work regardless of class size. However, many people argue that lowering class size lowers the workload. It turns out that this is not the case. Teachers continue to find ways to fill the time they have. The biggest problem is that some of our most challenging students are very disruptive. Suppose I give you two options: take ten students out of your class at random, or pick five of

your choice to take out. Which would you choose? Most teachers choose to eliminate five of their choice, five difficult students who take up too much of their time and disrupt the other students' learning. So it's not so much a question of size but of behaviour. Class size is usually an indicator of the impact of difficult students more than the number. The bad news is that someone has to have them. However, what teachers do inside their classrooms, regardless of size, has a dramatic effect.

One example is small group learning in a classroom. It has an impact as long as the groups are constantly changing. If you have low expectations for some children as soon as you set them up, it doesn't work and it's unfair. The goal is to establish cohesion and rapport and to make sure there is s flow and a rhythm to the class management to ensure that all students understand what is and is not allowed in class. All of this is regardless of class size. You can do that with a class of 15 or a class of 100. There are schools with 100 students in a class and three teachers. Their concept of excellence is quite different from the concept of excellence if they had 30 or 15 students. But in them you can see all those ideas of excellence in the classroom, all the notions of continuously changing to small groups, building cohesion, teaching students to work on their own and work with others. You see that gradual release of responsibility on the part of the teacher. You often don't see this in a class of 15. There's the irony. When I did a review of the qualitative research on class size, I found that in smaller classes the teacher talked more and there was less group work and less feedback. The teachers did the same as teachers with classes of 30 students.

What teachers do inside their classrooms, regardless of size, has a dramatic effect

The class size argument has not resulted in a large reduction, because we don't change our teaching, and having more teachers is expensive and ineffective. I would argue that we need to find ways to help teachers work with the usual class sizes.

At another point in your latest book you comment that “in too many schools teachers function as independent professionals who are very comfortable with their own way of teaching but share little about the impact their way of teaching has on student achievement and their ideas about educational excellence”. How does the joint work of the teaching team and the pedagogical leadership of the school administration impact

student performance?

As I mentioned earlier, one of the biggest effects is when teachers work together to evaluate their impact. We don't want schools full of independent contractors arguing that they have the autonomy to teach as they wish. These teachers have a below-average effect. They actually do not have the right to teach as they wish. Down the hall is another teacher with the same kids, the same curriculum, the same assessment and the same principal who has a much bigger impact. So we have to realise that we already have excellence and we need to boost that excellence. We need the teachers who are having that big impact to be the ones to make their voices heard in the discussions. Their thinking is

privileged, and everyone should work together. We know that the moment you embarrass a human being, much less a teacher, you've lost them. They are not going to change what they do. They are going to resist, like I do. But regardless of their position in the distribution of impact, all teachers want to improve.

How do we do it? How do we do it with the resources we have in the classrooms? I live here in Australia, and what I say to politicians when I meet them is that it must be an acknowledgement of courage that they never go to Finland, Shanghai or Singapore in their term of office. There is excellence all around them and they have to find it in school. School leaders are powerful. The word “I” should never be mentioned

in the teachers' lounge. Everything revolves around “we”. We are the keepers of all students and their progress. We have to look at others' progress because achievement comes through progress. We look at their progress at three months, at six months, at one year. We need to discuss students, both individually and collectively. We moderate each others' expectations about curriculum standards, and we do so together. It is a difficult and hard job. It takes a lot of courage, and that's probably the most missing ingredient in our system: that courage to have these open conversations and to learn.

But when I analyse what is happening in so many professional learning groups, I see them make statements like: “Well, you can't possibly understand because you weren't in my class when this happened”. And they talk about lessons, assessment and curriculum, but the discussion should be about impact. And that's what your question points out: you have the power of the school, criticism, the evaluative judgment of many of your teachers. Let's make them part of the school's collective so that all students achieve good results and all of them get at least one year of growth in exchange

We need to find ways to help teachers work with the usual class sizes

for one year of work. Many do, but I”m not saying it's easy.

According to the data on the household effect, the variable that most affects student performance is their parents' aspirations and expectations regarding their children's educational performance. Could you tell us the reason behind the impact of this factor and how can parents and the school can align it with excellent performance on the part of each student?

Let me tell you a story. I have six grandchildren. When my first grandchild arrived, I was a source of wisdom for my son by telling him how he could best raise my granddaughter. He often resisted

All students should get at least one year of growth in exchange for one year of work

and I would tell him: “But Carl, you were a good kid and now you're a great dad, so listen to me”. On time he said to me: “Dad, do you have evidence to substantiate this claim?” That hurt. I went away and found 100 meta-analyses looking at the effects of parents. So, the next time he asked me the same question, I was prepared to put evidence on the table. We later worked together on a book about visible learning for parents and the effects of parents. Parental expectations are the most powerful family variable of all.

However, let me offer a minor but important clarification. There is a big difference between the notion of parental aspirations, “What do I want my child to be?”, and expectations, “What do I think my child is going to be?” There is very little relationship with aspirations; it's all in expectations: “What do I expect?” Expectations are what drive parents' interactions and behaviours. That's what students pick up on. They may see the aspirations, but the expectations are much more real to them.

We recently completed a study in five schools in New Zealand. We interviewed all the parents whose children were starting school for the first time and asked them what expectations they had for their children at the end of the school year. Almost 90% of them said that their children would take a vocational training course or go to university to continue studying. Years later, we interviewed those same parents when their children moved up from elementary to middle school. Nearly 90% of those same parents said their children should get a job. As a school system, we had adjusted parental expectations downward. That's not very healthy. We saw that parents' expectations are particularly aligned

with teachers' expectations at school, and the expectations of what you expect from a student often drive their behaviour.

We have conducted studies in classrooms of teachers with high expectations for all students and compared them to teachers with low expectations. There are dramatic differences in the classroom, which can be felt and seen. And the same is true for parents, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Therefore, parental expectations are very powerful, and when supported by the school, they have a huge impact on accelerating student learning.

The other argument we make in the book is that parents are not children's first teachers. We discovered during COVID that many of our parents had no aptitude to be teachers, nor did it occur to them to act like teachers. They thought their child did a good job if he worked on an interesting task and finished it. That's not true. Sometimes you work on uninteresting tasks, finish them and then ask for more and go on to more. Parents are not the first teachers; they are the first learners. Children imitate how parents learn. If parents can't deal with mistakes, if parents can't deal with failure, if parents are always trying 100%, it shows in the students, for better and for worse. Parents can have a dramatic effect on kids' expectations, especially in terms of how they learn.

Finally, could you briefly explain to us the major lessons and discoveries from the latest research in “The Sequel”, 14 years after the first major study on

visible learning?

After publishing “Visible Learning” in 2008, I realised that I have the best critics in the world. I learned a lot from them. I seldom respond to articles written about my book “Visible Learning” because I believe it is somewhat legitimate to criticise others. A few years ago, we analysed all the reviews we could find and wrote a monograph about them.

I also learned that in the first book I did not pay enough attention to the nature of teacher quality. I didn't spend enough time understanding the essence of how teachers think. I sensed that what mattered was not what they do but how they think. We have done a lot of work on this topic over the past 15 years and have published a book on the mental frameworks of teachers, leaders, parents and students. Now we are studying the mental frameworks of the environment, how we think about these things. In the chapter on teaching in the first book, there were things that didn't make much sense to me, such as that the effects of influences were very low according to our research. In “The Sequel”, I have introduced a model called “intentional alignment”, which helps explain why they are low and how we can make them much higher.

The message is that when I talk about research in this book, I talk about likelihood. There is a chance that you will have a high impact, but it depends on how faithfully you implement it. If you apply reciprocal teaching, which is very high-impact, but you do so poorly, you're not going to get that high impact. I never paid enough attention to the students' ways of thinking. It is strange, and I admit it, that I had a book called “Visible Learning” and there was no chapter on learning. So I've

Parental expectations are the most powerful family variable of all, driving student interactions and behaviours

addressed all of that in “The Sequel”. In the second part, I spend much more time on the story behind the data. The first book was more about the data leading up to a story. Now I am talking about story and data. I also want to mention that in “The Sequel” I point out things that are going to happen in the next five years. For example, I am amazed that when I get home every night, every teacher I know is preparing the next day's classes.

There is practically no research on that subject. So I call on my colleagues in academia to engage in a rich discussion and launch a research programme that will help teachers understand not only how lessons are designed but also the impact of the lessons they design. How can we do that? We have reviewed almost 5,200 meta-analyses on technology since 1976 with very small effects. But for the last five to ten years, the use of social media is having a very positive effect. I know it has some disadvantages, but just like with most innovations we have overlooked it. So that excites me. I also believe we have a very limited research base in education on how to expand success. And in the book that Arron Hamilton, Dylan Wiliam and I just finished writing, we talk about how to get schools to stop doing things that are not efficient or effective. That's difficult.

To conclude, five years ago we published all the data on a free website called MetaX. So if you want to see all the data, all the references and the sources of all the metaanalyses, it's all there. One of the reasons I did this is that I wanted to challenge my colleagues: “Look, you don't have to spend 40 years collecting the data. I will give them to you for free. What I want is for you to propose alternative explanations. If you propose one that fits the evidence better than mine, I will be the first to support it.”

The latest news is that we are

There is a chance that you will have a high impact, but it depends on how faithfully you implement it

very close to a breakthrough in the world of research: instant coding of classroom observation. Although it has some problems and disadvantages, it's going to be exciting to combine what I do with the really rich and busy life of a classroom. So we have a lot of work ahead. If anything, I want to be known as the person who changed the questions from “what works' to “what works best” when talking about the nature and impact of teaching. To focus on “how students are receiving feedback” rather than “how teachers are giving feedback”. I think that's the most exciting part of being a researcher.

Guy Claxton (London, 1947) is a British cognitive scientist and educator. He holds degrees from Cambridge University and Oxford University. He garnered recognition by successfully rethinking schooling to better prepare all young people for a lifetime of learning with an inclusive perspective. His books include “What's the Point of School? Rediscovering the Heart of Education” (Oneworld Publications), and “The Future of Teaching: And the Myths That Hold It Back” (Routledge). His practical approach to the power of learning has influenced schools around the world.

Today we often hear the comment, “there is a lot of criticism of traditional education, but I look at many people who have gone through it and they haven't done so badly”. How would you respond to this statement?

We must be clear about what we mean by traditional education. It is content-heavy education in which everything is channelled through the teacher. Knowledge is assumed to be certain and unquestionable. Students' job is to learn it, memorise it and understand it to the point where they can use the information successfully under examination conditions. That is traditional education. Students who have an aptitude for this system for whatever reason get good marks. This

gives them access to elite universities and allows them to move into secure and well-paid professions. Many of them end up as professors, judges, neurosurgeons....

The problem with traditional education is that it works for a minority of young people who meet three characteristics: First of all, they have a certain intellectual inclination, they are capable of holding abstract discussions and they find debating

Traditional education is elitist in a particular way, selecting young people with certain characteristics

pleasurable. Secondly, they do not need much physical activity and do not mind spending time sitting. However, some people have to move to think. Some studies by my late friend Sir Ken Robinson talk a lot about the importance of bodily activity for different types of intelligence. Third, this kind of school is designed for people who want to wait for a long time before making decisions, while others want to be treated as adults by 13 or 14, want to be free to get a job, to be held responsible, to be paid for their work. They are ready to join the adult world. School is not too well suited for people who are neither intellectual nor sedentary and are impatient to leave childhood. Unfortunately, there are no alternatives for them in the

If we are interested in preparing all young people for life, we must ask ourselves what knowledge will be useful to them

traditional education system. And, if there are any, they are always treated as if they were inferior. If you are bright enough to learn Latin, English, science, maths... then you will do well. But if you are not bright enough, you have to study plumbing or carpentry, cooking or other useful things. My problem with traditional education is that it is elitist in a particular way. It selects young people who have certain characteristics and works well for a few, but not for all.

Knowledge has long been the main objective of formal education. Many of the criticisms of “progressive” or “innovative” views of education are about the huge setback entailed by not maintaining the primacy of knowledge. How do you think we should view knowledge today, and what role should it play in the schools of today and tomorrow? This ties in with my first answer. The role and nature of the knowledge taught in school essentially depends on clarity and consensus about the purpose of schooling. Is it about preparing students to be intellectuals? Is it about passing on the precious knowledge of the past? Or is it about equipping people to thrive across a wide range of different lifestyles, jobs and professions at a complicated, challenging and stressful time in human history? I am inclined to go with the third option. Education should be about learning how to think, how to learn, how to collaborate, how to converse with other people. It should be a basic

set of mental habits, dispositions or human skills that will be useful whether you are going to become a neurosurgeon or a shepherd. Education should be valuable to whatever you are going to be.

The role of knowledge depends on your underlying value system about education. If we are interested in preparing all young people for life, we have to ask ourselves what knowledge will be useful to them. My friend David Perkins at Harvard University has written a book in which he explores what he calls “lifeworthy” knowledge. What do young people need to know to be prepared for the future?

If we ask this question, the nature of the status of knowledge becomes as problematic as it does interesting. Should we teach psychology? Should we teach Freud? Should we teach banking? Should we teach how to detect fake news? Should we teach whether it is honest or dishonest for ChatGPT to write an essay for you? There are all sorts of things that we might consider valuable knowledge that may not be part of the traditional curriculum. I believe that trigonometry and algebra, the periodic table and some classic works of literature should have to fight harder to justify their place in a twenty-first-century curriculum.

It does not seem obvious to me that in English schools reading Charles Dickens is better preparation for life in the twenty-first century than reading J.K. Rowling. I don't know. Let's have that discussion. Let's talk about it. Are we teaching useful knowledge? Are we teaching the treasures of the past? They have

their place, but it's not necessarily a dominant place in the curriculum. Are we teaching young people knowledge that provides them with a good mental exercise to deal with something like solving simultaneous equations in mathematics? Is that a good “battery of exercises' to develop

I think trigonometry, the periodic table and some classical works of literature should have to fight harder to justify their place in the twenty-firstcentury curriculum

should it play in a kind of learning aimed at fostering the capacity for lifelong learning?

Knowledge is not stored as little bits of propositions in the brain. It is stored as changes in functional creativity

resilience, creativity, imagination... to develop useful dispositions for young people to live their lives?

Those in favour of knowledge have a responsibility to answer these questions: Why do we teach knowledge and how do we set priorities? Could accounting be taught as lifeworthy knowledge in school?

I am not against knowledge, but I think people who are very much in favour of it need to engage at a deeper and more serious level and ask themselves what kind of knowledge they want and for what purpose.

One of the most controversial issues in this regard is memory. What role does it play in knowledge acquisition? What role

We need to explore the concept of memory again. Since the time of Plato, people have sought to understand memory through different metaphors. Plato thought that memory was like a birdcage and knowledge like the birds inside it. The birds had to be caught and put in the cage. When you wanted knowledge, you had to find the right bird, go to the right compartment and make sure the bird was in the right place. What we mean by memory depends on the “hidden metaphor” used to explain it.

Since the 1960s, psychology has promoted an image of memory as a digital storehouse, like a library. A warehouse, a pantry where you store flowers, rice or different ingredients in your kitchen. It says that knowledge is things that come in through your eyes or your ears, and then somehow you have to find the right place on the shelf to store those things. In this sense, the purpose of knowledge is to find it in order to take it out and demonstrate it. This is the traditional view of education. And this brings us back to the question of knowledge. We are not only interested in filling our memory with interesting knowledge. As your question brings up, we are interested in a learning process that fosters the capacity for lifelong learning.

The conception of memory has changed a lot. Memory is not a storehouse. It's not a place where you store things. As far as we know, the only thing inside our heads is vast neural networks. Knowledge,

skill, expertise, values or interests can only be represented as changes in the functionality of those neural networks, and when we talk about declarative knowledge, things that we can assert, like “Madrid is the capital of Spain”, that is not in a special place in the brain but in some neural networks in the brain so, for example, when someone asks you the question, “What is the capital of Spain?”, you are directed to activate a small subnetwork in your brain that allows you to articulate the word “Madrid”. Thus, knowledge is not stored as little bits of propositions in the brain. It is stored as changes in functional creativity.

If we move to a more current metaphor for memory, as neural networks whose functionality continually changes, then it is much more compatible with the second part of your question aimed at fostering the capacity for lifelong learning. Part of the brain's functionality has to do with perseverance. When we encounter something we find difficult, confusing or challenging, our brain kicks into gear in a way that says: “I can figure this out. I'm going to use my intelligence and my thinking to see if I can figure it out on my own.” Memory contains values, attitudes, interests, beliefs and opinions. Memory doesn't only contain little bundles of knowledge or little parakeets flying around in Plato's birdcage. How we think about memory and knowledge depends on whether we have updated our understanding of how we register experience. As far as we know, the neural network model is

How we think about memory depends on our understanding of how we register experience

more fruitful, appropriate and positive for thinking about education than an outdated and discredited notion of memory like a computer.

You are a prominent expert on learning and the conditions for quality learning. Could you tell us a little bit about your “Building Learning Power” to help students become better learners in and out of school?

Let me first say that “Building Learning Power” was sort of an early version of my thinking about what turns young people into empowered learners. Now I now tend to talk more about the learning power approach, which is a broader term that includes my own version of building learning power but also includes the work of many other people around the planet in the US, Canada, South America, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and Spain. How do we think about education in the twenty-first century?

I keep going back to the fundamental question: “What is the purpose of education?” I believe that education must equip all young people with the knowledge, skills, dispositions and habits of mind or character strengths, also called twenty-first century competencies. There are many different ways to talk about this. We have to equip young people with all of them to enable them to thrive in the world, whatever their career or path in life may be.

We are now very familiar with teaching knowledge and teaching skills. But until very recently we were not very explicit or sophisticated in thinking about how we taught. I believe that “teaching” is the wrong

word for the development of these characteristics or attitudes. The approach of the term “Learning Power” is like an emerging coalition of the thinking from different places around the globe. I must specifically mention the Harvard Graduate School of Education and in particular the work of Howard Gardner and David Perkins in developing a set of research projects called Project Zero, which has been a global leader in creating a sound scientific and philosophical basis for thinking about education more broadly, instead of viewing education as a narrow funnel that selects people to move on to the next stage of education.

In my country, England, there is still an obsession with the school leaving qualification that decides whether people go to Oxford, Cambridge or other universities. This is not good. It is an injustice to all young people for whom going to Oxford or Cambridge is neither possible nor appropriate in terms of their wishes, values, skills, talents... Education should not be built around this funnel to select people. There are all kinds of innovations underway around the world to build “learning power”, some of them much more radical than the “learning power” approach. More democratic and unstructured changes are needed, like the Khan Academy; more liberal and online innovations so students can set their own pace of learning and have more choice and autonomy to create their own curriculum.

These models provide conceptual evidence of other forms and other ways of educating. Many of them thrive on their own and depend on charismatic leadership.

Another level of thinking about the future of education, is to ask the question: “Can we introduce small tweaks or adjustments in schools?” We can continue to teach the traditional subjects; we don't have to do away with them. We can continue with traditional exams; we are not

going to get rid of them in the near future. But we can change the value system so that it no longer consists of retaining and reproducing knowledge for its own sake.

I just did some work with a colleague from New Zealand on what we called one of our favourite films: “The Magnificent Seven”, a good old cowboy movie. We are working with what we call the “magnificent seven learning dispositions', namely curiosity, perseverance or persistence, concentration (being able to focus your attention), imagination, careful critical thinking, communication and collaboration with others, and a quality mindset, what we call “crafting to your own satisfaction”, wanting your products to be the best possible quality. The goal is to not settle for, “Is this going to get me an A on the test, teacher?” but realising that there is a kind of pride or satisfaction that comes from having worked hard and overcome obstacles, researched, revised, polished... until you have produced something that is better than anything you dreamed you were capable of. The “ethic of craftsmanship”1 is something we should help to cultivate in all young people. People have slightly different lists of these attributes, and that's what I am working on right now.

The second question is: “So, how do we do it?” We now know a lot about how to shape the culture of a classroom. How to adjust the language, the layout of the furniture, the design of the activities, the forms

The purpose of education should be to equip all young people with the knowledge and skills to enable them to thrive

There is proof that students who are more resourceful or self-sufficient perform better on tests

of assessment, the types of wall decorations, conversations among students. There are still many aspects of the conventional classroom that we can modify to prevent students from becoming passive, submissive, shy and less adventurous, as happens all too often in the traditional classroom. Now the undercurrent leads students to be more independent, adventurous, curious, self-reliant, tolerant of mistakes and understanding of the fact that it often takes several not-so-good attempts to do something important well.

We are creating a different philosophy. The brilliant thing about this work is having a very clear understanding of what any teacher in any school in Spain, Paraguay, Singapore, Poland or anywhere else could do. We have to create that change in environment that makes us gradually build, value, encourage, observe and stimulate students to become more independent. As we build their learning power, they can pour that power into the traditional curricular

subjects if they want to and become better at passing exams.

There is proof that students who are more resilient, resourceful or self-sufficient perform better on tests. So, it is not a competition between the traditional and the progressive. The terrain we are now inhabiting is a sophisticated synthesis of these traditional objectives. If people want to learn trigonometry or the periodic table or the history of Spain, fine, but they will learn it better if they install a learning propellant in their own minds and if their teachers encourage them to continually improve and update those learning skills and attitudes. I believe that the future of twenty-first century education lies in cultivating these attributes, not some kind of intelligent machine. I'm not too concerned about artificial intelligence. I am much more concerned about the expansion of embodied intelligence, the intelligence embodied in young people. But perhaps history will prove me wrong. However, this is my commitment for the time being.

I'm not too concerned about artificial intelligence; I'm much more concerned about the expansion of embodied intelligence

Finally, could you describe the future of education as you see it, as well as the role of schools and families?

We have to evolve, not revolutionise, our way of conceiving education. But we need to be very clear about

Part of our job as school principals must be to try to reshape parents' expectations

where this evolution is headed and the small steps needed to effect out. We need a model for discerning the purpose of education, pedagogy model, a curriculum model, an assessment model and a school development and leadership model. They all need to mesh well together, like a set of well-oiled gears. There is a great deal of coherence between what we teach, how we teach it, how we assess it and how we implement it in our schools. All of this is driven by real clarity about how we should prepare all young people to thrive in the twenty-first century. Much of school leaders' responsibility is to work to help parents understand this change. Many parents still think that school is pretty much the way it was when they were going, and it's not. There is a new philosophy, a new psychology, a new pedagogy.

Part of our job as school principals must be to try by all means to reshape parents' expectations. We need to help parents understand that traditional education may be precisely what is harming their children's opportunities in life, especially if they do not belong to the group of intellectually sedentary children. So we need parents on our side.

Notes

1 “Ethic of craftsmanship”: the quality of working with passion, care and attention to detail.

MERCÈ GISBERT CERVERA

Continuing education for teachers in the twenty-first century. XXI p. 34

INTERVIEW WITH MIQUEL ÀNGEL PRATS

FERNÁNDEZ

Tackling the challenges of technology and artificial intelligence is essential p. 38

JOAN-ANTON SÁNCHEZ VALERO

Pre-service teacher training p. 44

Mercè Gisbert Cervera holds a PhD in Education and is professor of Educational Technology at the University Rovira i Virgili (URV), where she has been vice-dean of the FCEP, PhD at the Institute of Educational Sciences (ICE) and vice-rector of Teaching and ICT. She is the Principal Investigator of the ARGET research group. She is coordinator of the URV's interuniversity doctoral programme in Educational Technology. She is also a visiting professor at British Columbia University, Canada, and at the Graduate School of Education at the University of California at Berkeley.

There has been talk of the importance of lifelong learning in the twenty-first century for a long time now. From this perspective, how do you see today's teachers?

Yes, if we review the publications from the last three decades we find references to the topic of lifelong learning. The concept of continuous learning is applicable to everyone. The term “lifelong learning” also implies the teaching staff.

Practising teachers have a wide range of training opportunities so they can constant upgrade their skills, and while doing so they can develop in all types of subjects, methodologies and teaching strategies. Most of this training is free and voluntary. However, not all teachers have the

same perception of the need for continuous learning. Some teachers still decide that they do not need training, although there are fewer and fewer of them.

What do you think are the keys to sustainable teacher training to

For a plan to have an impact, a training plan should be developed with a middle-term vision geared towards improving the educational process

ensure the effectiveness of schools today?

As always, for a plan to be effective and have an impact on improving the educational system, it should be able to develop a training plan with a middle-term vision that is designed around the strategic aims of education and geared towards improving the educational process. Public policy strategies are often short-term in nature. There are training strategies that start and last one or two academic years. This short duration prevents them from having an impact on the school system in terms of improvement and quality assurance.

In education, there is a deeply rooted idea that each teacher

has his or her own style and should teach as he or she sees fit. Sometimes this makes it difficult for teachers to work as a team. What is your opinion of this trend and its effect on students' academic performance?

I believe that tackling the issue of academic performance from the perspective of teachers' “academic freedom” is oversimplifying the situation today and failing to have a holistic view of education or student learning outcomes.

The issue of academic performance, which is directly related to students' development process in terms of learning, should be analysed from a 360-degree perspective and bear in mind that students learn as much or more outside the school as inside. For this reason, teaching is increasingly complex because it actually has to consider not only strictly school-related academic development but also all the inputs received in society and the family (especially the latter).

Returning to your question, I believe that more and more schools are working in teams, because the methodological changes that have been incorporated in recent years and the use of digital technologies

It is impossible to design effective continuing teacher training if when one change has begun to be implemented another one comes along

Teaching is increasingly complex. It has consider not only academic but also social and emotional inputs

have led teaching teams to have to design and carry out projects together. Determining to what extent these new directions have affected students' academic performance without evidence is very difficult, and I would not venture to say that there is a direct relationship between the two.

Sometimes we get the feeling that teachers do a lot of training, but it rarely has the effect of changing educational paradigms or the way they teach and learn in their classrooms. Why do you think this happens?

Yes, I agree that teachers are getting more and more training. The fact that nothing changes is perhaps more a vision derived from the current need for everything to change almost in real time than from the fact that teaching does not have an impact on the reality of education in terms of change and innovation.

Let me illustrate this with an example. Since the 1970 Education Act, there has been no other general law that has lasted long enough (about 17 years) to be able to be deployed in its entirety. Why is that? It is impossible

to design

effective continuing teacher training if when one change has begun to be implemented another one comes along. The effect this generates is disorientation. In addition, no evidence of the reality of education is collected to see what has changed, if anything, and it is never borne in mind that education is a kind of long-distance race, so we will never know how it has developed if we don't have the capacity to “shield” public policies in education from changes in legislatures and partisan ideologies.

What is meant by effective pedagogical leadership at a school? Why is it necessary? How can it be achieved?

When we talk about leadership, we mean the ability to design and develop projects of any kind and to integrate all the related stakeholders in order to achieve and implement them successfully.

If we apply this to a school, we can say that effective pedagogical leadership is exercised by the administrative team when it is able to design an educational project for the school that is innovative and sustainable and involves the entire educational community with a 360-degree perspective.

Good pedagogical leadership is necessary to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the educational process in terms of learning outcomes, school climate, innovation and integration of all responsible stakeholders.

How do you think teaching teams should work and interact with each other? Today there is a lot of talk about networking and sharing experiences, and about Edu Labs. To what extent can this practice improve teaching?

All collaborative practices in themselves are a huge contribution. Education is largely

Effective leadership is exercised by the administrative team when it is able to design an innovative and sustainable educational project

a communicative and social act. For this reason alone, teamwork is more geared to what education should be than individual work. In fact, the emergence of the Internet in the 1990s and the recent health

emergency caused by COVID-19 are clear examples. Communities, both analogue and digital, have enabled us to guarantee the development of education despite the difficulties. In both cases, networking has been a clear example of the added value of working as a group rather than individually.

Likewise, the experiences of Edu Labs, Maker spaces and all the programmes that are currently being promoted by the Department of Education, are a clear example of how the whole is more than just the sum of its parts and extends the impact of changes and innovations.

is

In

world full of machines, the role of teachers will be even more focused on providing students with personalised supportby Ana Moreno Salvo

The advancement of technology and artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming the world and the way we live. How should the education sector view or interpret this transformation?

In the first place, we have to think about the major need we teachers and educators have to become literate in everything related to data, to quantify them, value them and know exactly that we are working with machines and that behind them there

is data.

Secondly, we are faced with the huge challenge of revitalising and resignifying in-person activities. We have know what we should do in class and in the presence of these powerful technological tools. We have to ask ourselves why it is worthwhile for us to learn about and take advantage of them.

The third challenge is related to the fact that these “smart machines' or “smart technology tools' may eventually allow us to automate a

We have to question all the technology we use, we should not believe everything we see and we should ask about what media we are consuming when we use technology

whole range of tasks. We have already experienced them making our lives a little “easier”; they can help us at work, too, so we can devote ourselves to really enhancing our student support. We are facing a very interesting challenge: to ask these virtual butlers or assistants we will end up having to do jobs. This is all moving very quickly. I think that within a year we will start to have our own little artificial intelligence virtual butlers. This will make it easier for us to devote much more time to individualised student attention and therefore for teaching to be much more personalised.

The fourth challenge has much to do with the ethical aspect or critical thinking. We have to question all the technology we use, we should not believe everything we see and we

Àngel Prats Fernández is a teacher, educational psychologist and PhD in Education from the Faculty of Psychology, Education and Sport Sciences at Ramón Llull University (URL). He is the coordinator of the Master's in Educational Leadership and Innovation, a professor of Educational Technology and the researcher in charge of the eduTIC line of the PSiTIC research group (Pedagogy, Society, Innovation and ICT). In 2020 he was awarded the 30th Joan Profitós Pedagogical Essay Award for his book “10 Lliçons per a un Ús Ètic, Saludable i Responsable de les Tecnologies Digitals”.

We have to be able to be mentally flexible and have huge doses of emotional reserve to be able to learn, unlearn and relearn

should ask about what media we are consuming when we use technology. We need to become questioners of everything around us.

What do you think are the priority challenges that teachers are facing in their ongoing professional training to meet the educational needs of the digital era?

There is an aspect that has a lot to do with the bureaucratic side of filling out paperwork, applications, appeals, documentation and all that. If these tools can help us do that, it would be great.

Another challenge has to do with the emotional dimension. We teachers need to prepare ourselves emotionally for everything that lies ahead. We have to be able to be mentally flexible and have huge doses of emotional reserve to be able to learn, unlearn and relearn. Therefore, we have to be very flexible. We will have to start working on issues related to with this personal support or being tutors. And that is a very interesting task. Some teachers say, “don't bother me with that; I'm a maths teacher”, because I don't know if maths will be better explained by artificial intelligence someday. Our task will probably involve support, monitoring, individualised attention to a series of students whom we will have to assist in their growth and character. In the end, we will have “to grow by making grow” in Xavier Marcet's words.

The priority challenges have to do with soft skills: decision-making, teamwork and problem-solving. How can we help our students to have or gradually acquire the 6Cs that Michael Fullan often talks about: communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking and especially civility and citizenship,

and compassion and character? Therefore, the aim is to help these students to become self-leaders, selfregulators and self-knowledgeable. We have to be able to work with them, help them know how to interpret what is going on around them or in a given situation. Artificial intelligence will not be able to do that. I often tell students: “Hold on a minute, stop. What are you looking at? What is happening right now? How is that person feeling? What did this other one just say? Did you hear what you are saying? How should we proceed from here?” A machine won't be able to do that, and the big challenge is to know how to take advantage of this. Coming to class should be worthwhile to work on these questions and learn how to interpret the environment, oneself and others... I am not saying that knowledge is not important, but we have to find this balance. In the future, we will not have so many master classes; instead, we will have to find that balance of making them work more as a team and being able to find other strategies.

How can digital technology help teachers to improve their day-today work?

Technology harbours huge possibilities. Many of these emerging tools that have an artificial intelligence component are already beginning to appear. We even see how they can help us in our teaching, like writing exams, exercises or certain teaching materials. There is a series of resources where technology can help us a lot, such as planning and

designing our teaching action. It will allow us to work more collaboratively with other teachers and schools to create projects together.

We will have to be very creative. Ultimately, technology only puts a mirror in front of us so we are able to rethink our role in a world full of machines.

There are many teacher training models. What are the key features of effective teacher training in digital competency?

Digital competency is an issue that has a lot to do with what I often call “disconnecting to connect”, having attitudes. And when I say attitudes, I mean that we are capable of putting the brakes on it, setting limits and knowing how to regulate it.

What key features are needed for good digital competency training? The first is that it should not be completely exceptional but instead an everyday, invisible thing. We should not be afraid of it; it should become just another task that we can hybridise. Also, let's meet face-to-face; we can use personal encounters when needed.

There are different models, which means that we are probably talking about a kind of session that deals solely and exclusively with technological issues. It would be healthier, or at least complementary, for technology to be present in every single subject or project we are working on.

I would therefore advocate complementarity. First, it can be a subject of study, meaning “we study the technology itself” in terms of computational thinking or robotics. This is how we come to understand how devices work and how we learn about the technology itself. The second is learning with technology. It

Technology will allow us to work more collaboratively with other teachers and schools to create projects together

cuts across the curriculum. That is, we are doing mathematics and if needed we use a calculator, GeoGebra or any other technological tool. But, above all, making students think is what matters the most.

It is one thing to “learn about” something and another to “learn with” it. And let's not forget the more attitudinal dimension; that is, everything related to critical thinking and digital well-being: how we are using it, how many hours we are connected and if we are able to put it down. It is important to work on these aspects when teaching our students, to explore how we interact and

It would be useful and healthier for technology to be present in every single subject or project we are working on

coexist with technology. Nowadays, many of our interactions are not only personal but also technological. Therefore, we will have to spend some time reflecting on this.

Although digital devices are part of our everyday lives, there is a great deal controversy around the role they should play in schools. As an expert and author of the book “Viure en Digital” (Living Digitally),

what would you say to teachers, school principals and families in this regard?