torytelling S uite S M esélo

S

lakosztályok

Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest

STORYTELLING SUITES

Five stories inspired by paintings and sculptures of the Corvinus Art Collection Suites

MESÉLŐ LAKOSZTÁLYOK

Öt novella, amelyeket a Corvinus Art Collection Lakosztályok műalkotásai ihlettek

Published by / Kiadó: Stephan Interthal / Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest

Texts / Szövegek: BARTÓK Imre, HALÁSZ Rita, MÉCS Anna, TERÉK Anna, TOTTH Benedek

Translated by / Fordító: DÁNYI Dániel

Photo / Fotó: RÁCMOLNÁR Milán, SAJÓ Dóra, FARKASINSZKI Bence

Portrait photos / Portré fotók: BOGDÁN Réka, BEZZEG Gyula, KISS Tibor Noé, BACH Máté (prae), MÁTÉ Péter (Jelenkor Kiadó)

Design / Grafikai terv: SZABÓ Ferenc

Copy editor / Olvasószerkesztő: DUDÁS Ildikó

Edited by / Szerkesztő: KOSINSKY Richárd

kempinski.com/budapest September 2022 / 2002 szeptember

Cover / Borítón:

Péter Ujházi: Árki maple, 2017, Kempinski Art Collection

Ujházi Péter: Árki juhar, 2017, Kempinski Műgyűjtemény

Five stories inspired by paintings and sculptures of the Corvinus Art Collection Suites

Öt novella, amelyeket a Corvinus Art Collection Lakosztályok műalkotásai ihlettek

S torytelling S uite S M esélo lakosztályok 730 860 960 830 930

Kosinsky Richárd Art historian, art director at Kovács Gábor Art Foundation, Curator of Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest Art Collection

művészettörténész, a Kovács Gábor Művészeti Alapítvány művészeti igazgatója, a Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest Műgyűjteményének kezelője

Introduction

To travel is always an adventure. Whether for business or leisure, every journey bears the promise of new experience, or a visit to safe and cozy places with a feeling of arrival. To experience travel is a true privilege. Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest has been host to this experience for some 30 years now.

Come to think of it, what is it we remember about a hotel? The atmosphere, the scents, that feeling you get when you enter the room, the padded silence of the halls. These, and the whole milieu composed of countless little details. This hotel has always been keen on detail. As curator of Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest, I am very familiar with the premises. As I step out of the elevator, I know exactly which sculpture or painting I’ll see on the halls of each floor. Right now, there’s a woman dressed in gray writing her text message in The Living Room, while every few months there’s a new exhibition to greet me on the Promenade, and the spa and event level abounds with paintings and sculptures.

The suites are serenely ready and waiting, their own separate section within the hotel is a sort of inner sanctum. Each suite offers a different environment, but all have the same ultimate aim: to make me feel this is my space, my castle, and - if only temporarily - my home. The idea is to create a timeless space, so we may sit in a room without any sense of urgency or obligations.

Bevezető

Utazni mindig kaland. Legyen az üzleti vagy szabadidős, minden utazás új élményeket ígér vagy olyan biztonságos és komfortos helyek meglátogatását, ahol azt érezzük: megérkeztünk. Az utazást megélni kiváltság. A Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest immár 30 éve ezt az élményt nyújtja.

Mire is emlékszünk egy hotelből, ha belegondolunk? A hangulatára, az illatokra, az érzésre, amely a szobában elfog, a folyosók süppedős csendjére. Arra a milieu-re, amely számtalan észrevehetetlen apró részletből áll össze. Ez a szálloda mindig is nagy hangsúlyt fektetett a részletekre. A Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest kurátoraként jól ismerem az egész épületet. Ma már minden emeleten, a liftből kilépve tudom, hogy mely szobor fog köszönteni, mely grafikák díszítik a folyosót. A The Living Roomban most is sms-ét írja a szürke kosztümös női alak; a promenádon pár havonta új kiállítás fogad; a spa- és a rendezvényszinten járva folyamatosan feltűnik mellettem egy-egy festmény vagy szobor.

A lakosztályok mindig rendíthetetlen nyugalommal várnak, a szállodán belül is külön egységet képezve, mintegy belső szentélyként. Mindegyik lakosztály mást kínál, de ugyanarra törekszik: hogy azt érezzem, ez az én terem, az én bástyám és – ha csak arra a rövid időre is –, az én otthonom. A cél valójában pont az időtlenség megteremtése, hogy kényelemmel időzzünk a szobákban, ne érezzünk semmilyen sürgetést, a teendők felelősségét.

2 s torytelling s uites

This has always been art’s aim and essence: to elevate the viewer from their everydays into the world created by the artist. To be transported into an imaginary reality, which has the power to change our perception. This is the message behind the five Corvinus Art Collection Suites, the same experience and journey presented in these five short stories written for us by some of the best contemporary authors in Hungarian literature. We invited these authors to spend some time and make themselves at home in these suites, and now we extend this invitation to you, the reader, to come on a very special journey, take a look behind the doors, immerse yourself in the stories and destinies unfolding from these works of art.

A good work of art will stay with us long after we are no longer physically in its presence. A painting, drawing or sculpture can become a focal point defining all the other experiences of a singular journey. This is why the practice of patronship and collection that Kempinski Hotel Corvinus has represented from its first opening in Budapest is so vital today. With over 1500 pieces of art in its collection, it has ventured well beyond the purpose of decorating its halls and walls. Besides active patronship of local artists, Kempinski has gone the extra mile beyond a hotel service, presenting the best pieces of its collection in a unique experience — framed.

Richárd Kosinsky

Art historian, art director at Kovács Gábor Art Foundation Curator of Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest Art Collection

A művészet célja és esszenciája is mindig ez volt: kiemelni a hétköznapiból és bevonni a nézőt abba a világba, amelyet a művész felmutat. Átlépni egy elképzelt valóságba, amely a mi percepciónkat is megváltoztathatja. Az öt Corvinus Art Collection Lakosztály is ezt az üzenetet közvetíti. Ezt az élményt, ezt az utazást kínálják e kötet novellái, amelyek neves magyar kortárs írók tollából születtek. Ahogy az írókat meghívtuk, hogy egy időre leljenek otthonra ezekben a lakosztályokban, úgy most Önt, az olvasót is egy különleges utazásra invitáljuk: pillantson be a zárt ajtók mögé, merüljön el a műalkotásokból kibontakozó történetekben, sorsokban. Egy jó műalkotás akkor is velünk marad, miután már fizikailag nem vagyunk vele egy térben. Egy festmény, grafika vagy szobor így válhat fókuszponttá, amely köré az utazás többi élménye is szerveződik. Ezért nagyon fontos és példamutató az a mecénás és gyűjtői praxis, amelyet a Kempinski Hotel Corvinus megnyitása óta képvisel Budapesten. Közel 1500 darabos gyűjteménye túlmutat a szobák és a folyosók dekorációs igényén. A helyi képzőművészeti kultúra célzatos támogatása mellett, a szállodai szolgáltatásokat felülmúlva, a Kempinski műgyűjteményével és annak legszebb darabjainak bemutatásával élményt kínál –keretbe foglalva.

Kosinsky Richárd művészettörténész, a Kovács Gábor Művészeti Alapítvány művészeti igazgatója a Kempinski Hotel Corvinus Budapest Műgyűjteményének kezelője

3 M esélo lakosztályok

730

6 S torytelling S uite S

Ervin Tamás: Spring I Tavasz

BENEDEK TOTTH

Where It Is Always Spring

She’s standing at the window of a seventh-story suite. The din of the outside world filters in faintly, as if it were transmitting from another world. White hot gondola lights from the Ferris wheel illuminate the room. Her shadow on the wall like a black monochrome. She watches the rain-soaked silent city, her first time here in many long years. Once it had been her home, but all that remains is a feeling. It had been spring when she was last here. It is spring now. The time between the two spring seasons feels like an eternity, and a single fleeting moment. She had never talked to anyone about it. The words are there, but she can’t voice them.

The wind picks up, and raindrops streak the windows in choppy diagonals, like breath on a very cold day. Yet there’s bustle in the square below, muted people laughing, muted cars gliding, trees swinging mutely in the breeze. A soft, comforting quiet.

Her eyes follow a yellow taxi cab. It pulls up to park before the hotel. A man gets out from the back seat. As the cab drives away, he looks up at the building. His gaze seems to pierce the window. It makes her shudder, even knowing that the seamless windows only show a giant Ferris wheel’s reflection. She wasn’t yet eighteen when she first modeled for a portrait, and still she’s not comfortable with men’s intrusive gazes.

Her feet sink into the pile carpeting, fleece popping up between her toes. She holds her palms against the cold windowpane. Wanting to touch the city, the rain clouds, the dome of the Basilica. She goes to fetch the thick white bathrobe, and puts it on. The smooth feel of the fabric calms her down, makes her feel safe.

TOTTH BENEDEK

Ahol mindig tavasz van

A hetedik emeleti lakosztály ablakában áll. A külvilág zajai tompán szűrődnek be, mintha a hangok egy másik, távoli világból érkeznének. Az óriáskerék fehér fénnyel lángoló fülkéi megvilágítják a szobát. Az árnyéka a falon, mint egy fekete festmény. Az esőáztatta, néma várost nézi, hosszú évek óta először jár itt. Egykor ez volt az otthona, de mostanra már csak egy érzés maradt. Tavasz volt, amikor utoljára itt járt. Most is tavasz van. A két tavasz között eltelt idő egyszerre tűnik örökkévalóságnak és egy pillanatnak. Erről még sosem beszélt senkinek. A szavak megvannak, csak hangja nincs hozzá.

Feltámad a szél, az ablakon átlósan csorognak le az esőcseppek, szaggatott vonalat rajzolnak, mint a lélegzet a nagy hidegben. A tér mégsem kihalt, hangtalanul nevető emberek, hangtalanul suhanó autók, a szélben hangtalanul billegő fák. Megnyugtató ez a tompa csend.

Egy sárga taxit követ a szemével. A jármű a szállodával szemben parkol le. Egy férfi száll ki a hátsó ülésről. Ahogy a taxi elhajt, a férfi felnéz az épületre. Mintha a tekintete áthatolna az ablakon. Megborzong, hiába tudja, hogy kintről csak az óriáskerék tükörképe látszik az összefüggő ablakokban. Nem töltötte még be a tizennyolcat, amikor először modellt állt egy festményhez, mégsem tudott hozzászokni a férfiak fürkésző tekintetéhez.

7 M esélo lakosztályok

She’d left everything behind to leap into the unknown, with no idea what lay beyond. Then it seemed that happiness awaited her on the far side of the world. Everything worked out for her, as they say. Yet something was lost when she left here. Sometimes it felt comforting to think it was the right decision after all, because had she stayed, she would have missed out on all that luck.

It was her husband’s idea to travel. He said it wouldn’t do to see her so sad. So it wasn’t such a secret sadness after all. When he first talked about the trip, she got upset and resisted, perhaps too intensely. She ended up settling for spending Easter here together.

Her real reason for being sad was one she kept to herself. But now for the first time, she felt strong enough to face that man and look him in the eye. Only then can she put the past behind her.

Softly, the door opens. Her husband enters the room, wearing a white bathrobe, arriving from the sauna. He flashes her a kind smile. For a moment that stretches awfully long, she can’t bear to return the smile. She just looks at her husband, wishing she could tell him to stop worrying, that it’ll all be fine. But she can’t speak. Then he steps up and puts his arms around her.

„How was it,” she asks.

„You should try it,” he says.

„When I get back,” she smiles at him.

„Alright,” he says, „I’ll be right here.”

Talpa a padlószőnyegbe süpped, a bolyhok az ujjai közé furakodnak. Tenyerét a hideg ablakra teszi. Meg akarja érinteni a várost, az esőfelhőket, a Bazilika kupoláját. Fázni kezd. A fürdőszobába megy, felveszi a vastag, fehér fürdőköpenyt. Megnyugtatja a testére simuló puha szövet, biztonságban érzi magát.

Itt hagyott mindent, beleugrott az ismeretlenbe, nem tudta, mi vár rá. Aztán úgy tűnt, hogy a világ túlsó felén sikerül megtalálnia a boldogságot. Minden összejött neki, ahogy mondani szokás. Valami mégis elveszett, amikor elment innen. Néha azzal próbálja nyugtatni magát, hogy jól döntött, mert ha itt marad, nem alakult volna ilyen szerencsésen az élete.

Az utazás a férje ötlete volt. Azt mondta, nem akarja ilyen szomorúnak látni. Pedig ő azt hitte, sikerült eltitkolnia a szomorúságát. Amikor a férje először szóba hozta az utazást, ideges lett, és ellenkezett, talán túl hevesen. Végül mégis elfogadta az ajánlatot, hogy töltsék itt a Húsvétot.

Sosem árulta el senkinek a szomorúsága valódi okát. De most elég erősnek érzi magát, hogy megkeresse azt az embert, és a szemébe nézzen. Csak így zárhatja le a múltat.

Halkan nyílik az ajtó. A férje lép be, a fehér fürdőköpeny van rajta, szaunázni volt. Kedvesen rámosolyog. Egy végtelennek tűnő pillanatig nem bír visszamosolyogni rá. A férjét nézi, szeretné elmondani neki, hogy ne aggódjon, minden rendben lesz. De nem tud megszólalni. Aztán a férfi odalép hozzá, és megöleli.

8 S torytelling S uite S

– Milyen volt? – kérdezi.

– Ki kellene próbálnod – feleli a férfi.

– Ha visszajövök – mosolyog rá a nő.

– Rendben van – mondja a férfi. – Itt várlak.

Aztán a nő felöltözik, kisminkeli magát, és elindul. A kezét a kilincsre teszi, de hirtelen megtorpan, visszafordul. A férfi nem veszi észre, a menüsort böngészi, rendelni akar valamit, farkaséhes. A nő elmosolyodik, aztán kilép a folyosóra, és óvatosan behúzza maga mögött az ajtót. Beszáll a liftbe. A tükrökben megsokszorozódik és a végtelenbe veszik az alakja. A földszinten kilép a fülkéből. A recepciós a szálloda előtt várakozó taxihoz kíséri. Ahogy elhajtanak, az óriáskereket nézi, és megszédül.

Éjfél után ér vissza a szállodához. A barna csomagolópapírral beburkolt festménnyel a hóna alatt belép a hallba. A hetedik emeletre megy a lifttel, nesztelenül surran be a lakosztályba. A falhoz megy és felakasztja a képet, aztán befekszik a férje mellé az ágyba. A férfi békésen szuszog, a mellkasa egyenletesen süllyed és emelkedik. A nő odabújik hozzá, testében szétárad a boldogság. Évek óta nem érezte magát ilyen könnyűnek. Tudja, hogy most már minden rendben lesz. Álmodik, hosszú idő óta először. Álmában belép a festménybe, és levetkőzik. Most már mindig ott marad a hetedik emeleti lakosztály falán, ahol mindig tavasz van.

9 M esélo lakosztályok

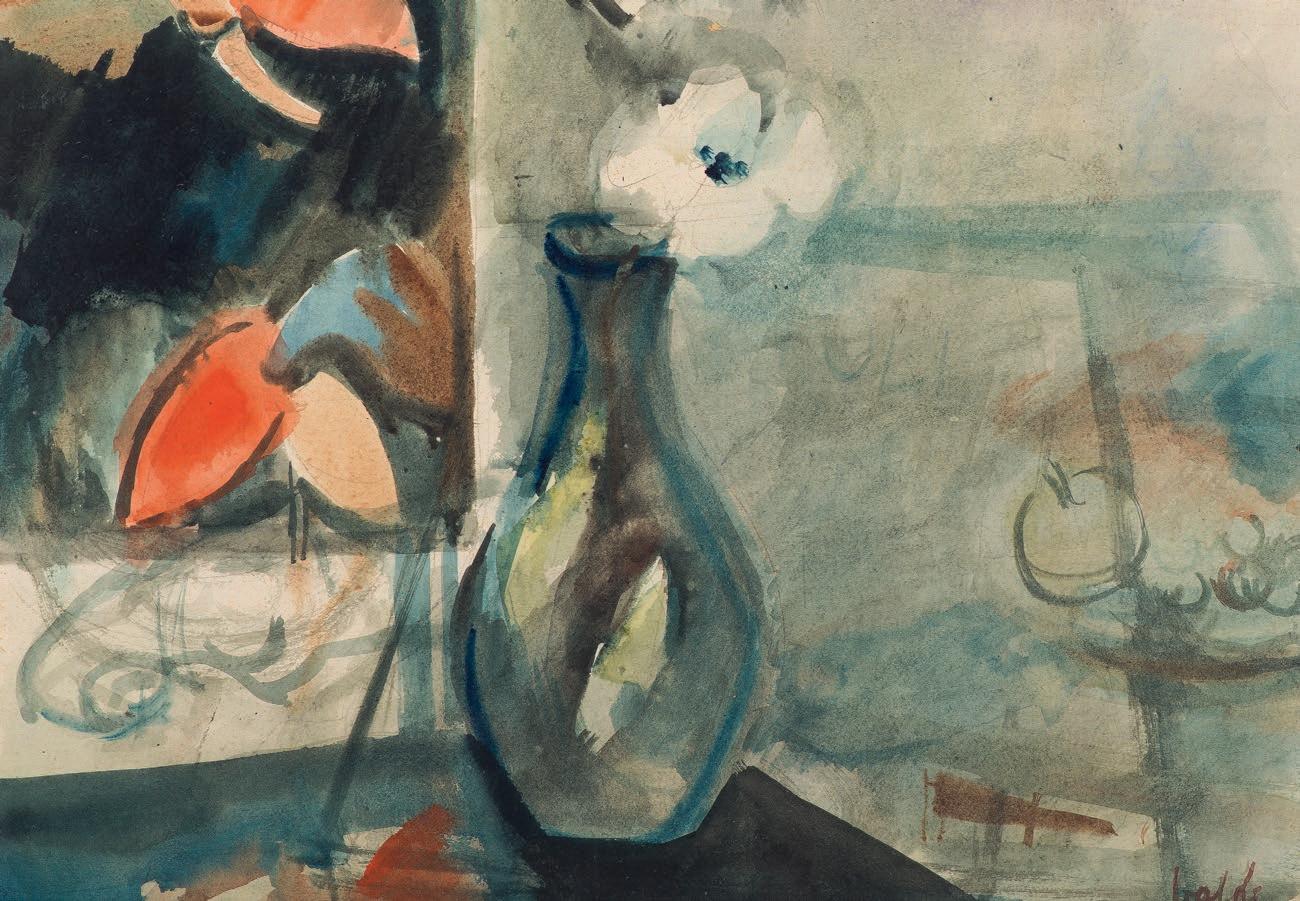

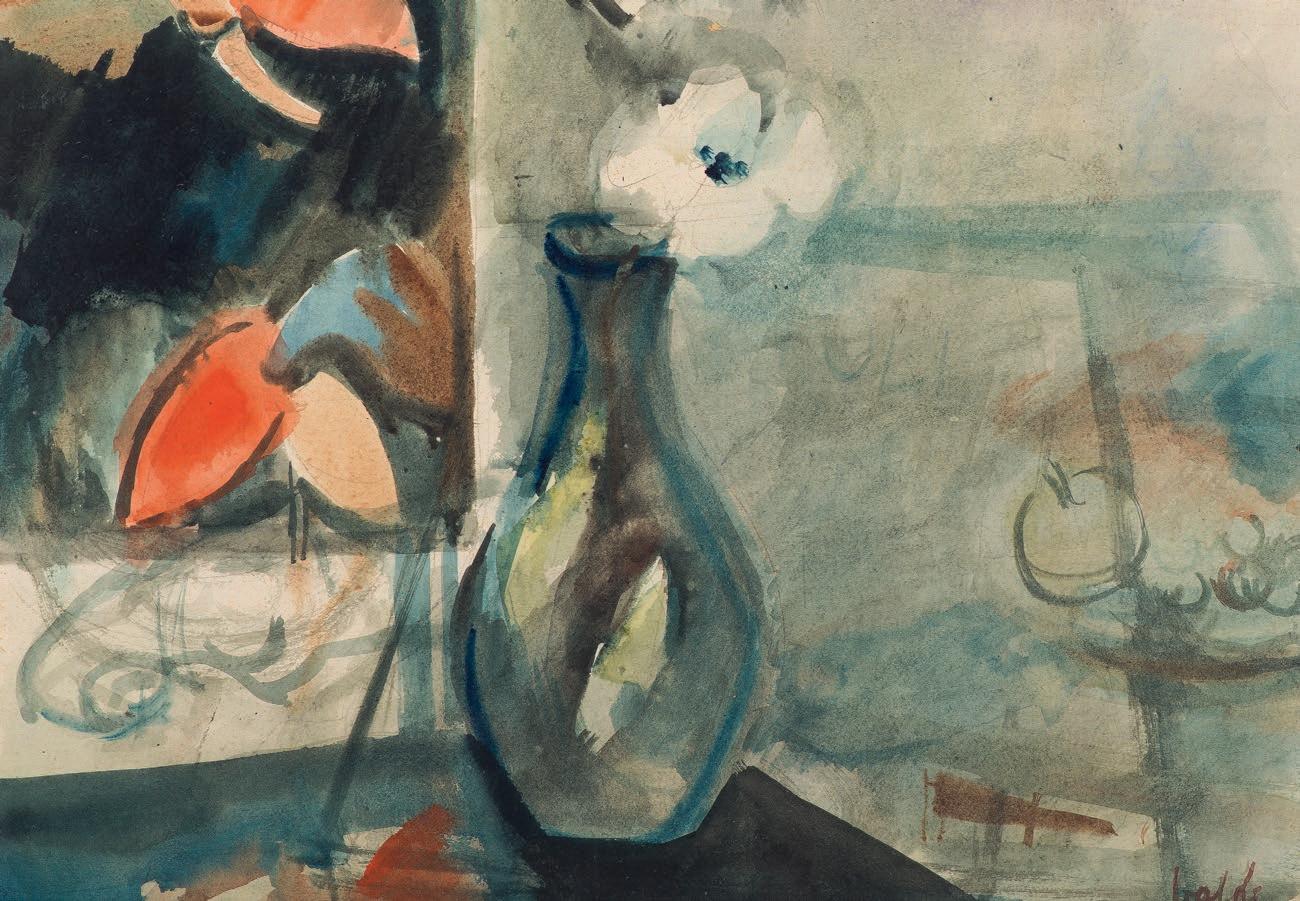

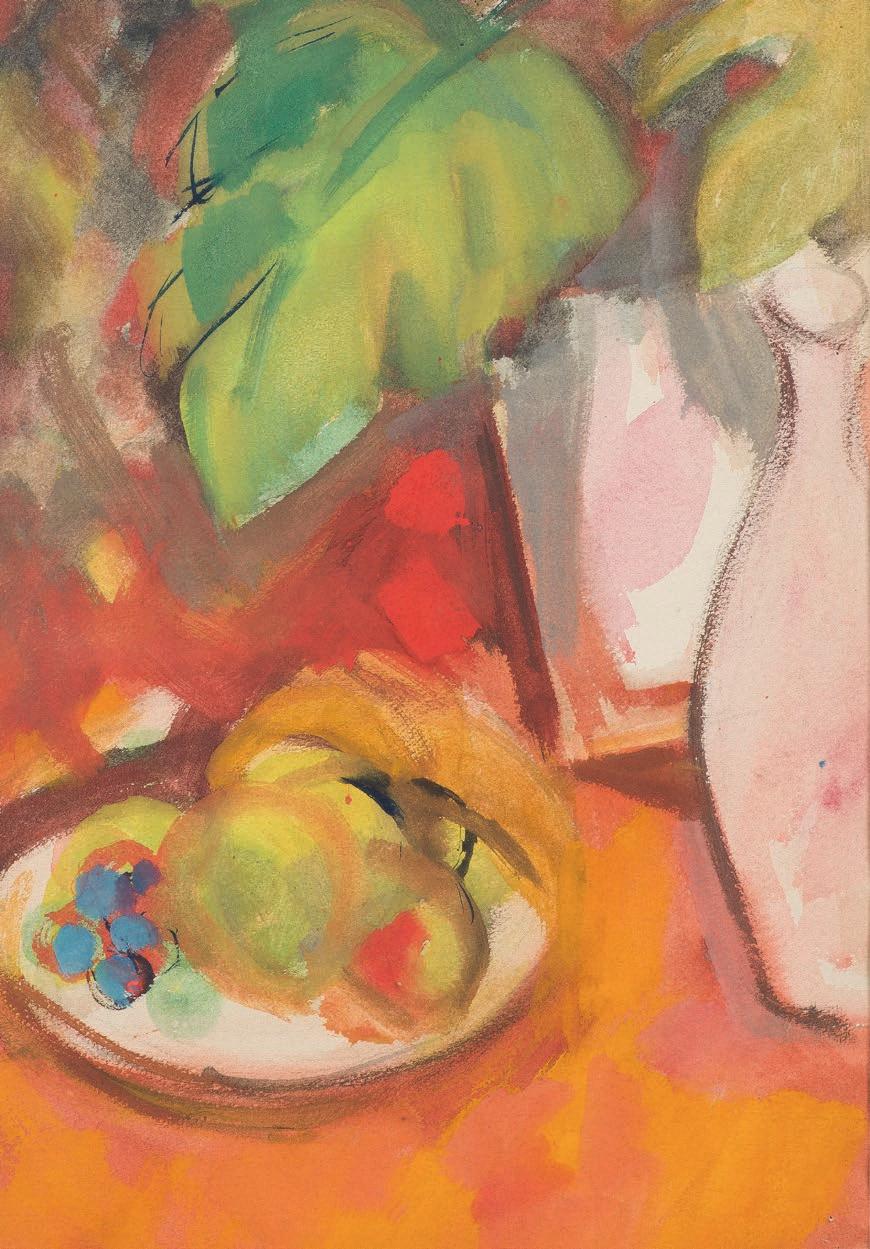

László Viski Balás: Still life | Csendélet

Then she gets dressed, puts on make-up, and turns to leave. Her hand’s on the door handle when she suddenly stops and turns back. The man doesn’t notice, he’s absorbed in the menu, about to order room service, famished. She smiles, then heads out into the hall, quietly pulling the door closed behind her. She takes the elevator. In the mirror, her figure is multiplied in infinite reflections. She gets out in the lobby. The receptionist shows her to the taxi waiting out front. As they drive off, she looks up at the giant Ferris wheel, feeling giddy.

It’s past midnight when she gets back to the hotel. Carrying a painting wrapped in brown paper, she breezes through the lobby. The elevator takes her to the seventh floor, where she sneaks into the suite without a sound. She takes the painting and hangs it on the wall, then gets into bed beside her husband. He’s snoozing peacefully, chest rising and falling steadily. She snuggles up to him, and feels happiness engulf her. It’s been years since she felt so light. Certain that everything’s going to be okay.

Then she dreams, a first in a long time. In her dream, she steps inside the painting and undresses. She will stay there forever on the wall of that seventh-story suite, where it is always spring.

10 S torytelling S uite S

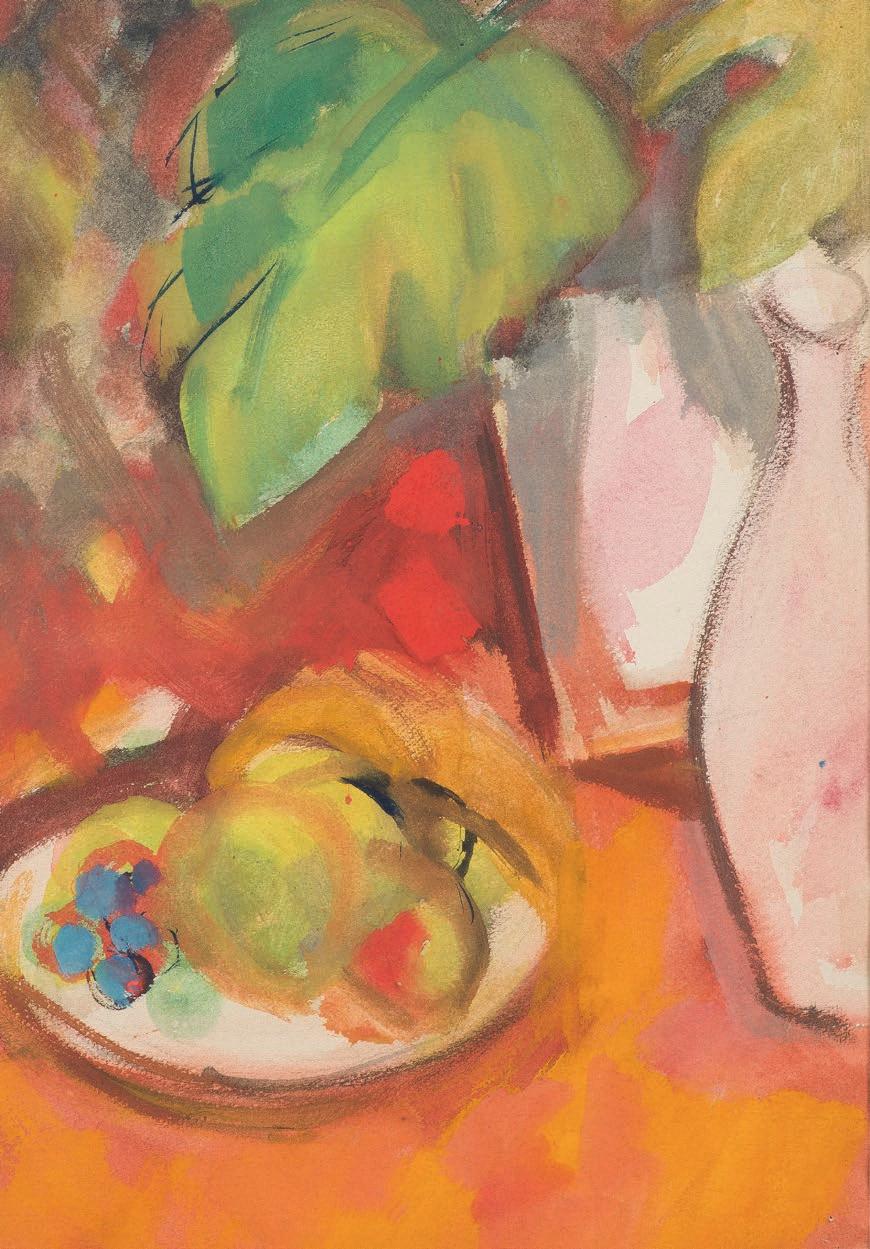

László Viski Balás: Still life with fruits and a vase | Gyümölcscsendélet vázával

Benedek Totth (Kaposvár, 1977 - ) is an author, literary translator and editor. His novel Dead Heat (Holtverseny) won Best First Novel Prize at Margó Literary Festival in 2015, and has since been published in English, French, Slovakian, and Romanian. His second book, Az utolsó utáni háború (The War After the War to End All Wars ) was published in 2017 by Magvető Publishing House.

Totth Benedek (Kaposvár, 1977 - ) író, műfordító, szerkesztő. Holtverseny című regénye 2015-ben megnyerte az elsőkönyves prózaírók Margó-díját, amely azóta megjelent angol, francia, szlovák, román nyelven is. Második könyvét, Az utolsó utáni háborút 2017-ben adta ki a Magvető Kiadó.

11 M esélo lakosztályok

860

14 S torytelling S uite S

Unknown artist | Ismeretlen művész: Woman with rose | Nő rózsával

ANNA TERÉK

Lamplight

I’m looking at his back as he turns to the window, watching evening set in and the lights of the Citadella. The street bustles below, and from our suite window it looks as if life carried on just fine without us down there, like the world or Budapest never missed us for a beat. The lights are dwindling, the last rays of sunlight slide back down the buildings’ walls onto the sidewalk. You can see all the way to the Danube, the river glistening as it washes the heart of the city from all the weekday grime.

My heart feels tranquil now, it’s Saturday, evening is all but here, and I sip my coffee on the couch, seeing his back and his profile as he watches over the town and unremittingly waits for evening. He is silent, I am silent, despite the thoughts crawling around inside me. When we settled into the room, we talked a lot: I told him about my grandparents, my mother, my father - I didn’t understand it myself, how of all things it was their stories that came into my mind. The suite smells faintly of coffee, and the light itself has a hint of latte to it. My hand’s warmed by the porcelain cup, I brew a stiff espresso, and my stomach’s relaxing into it. As I wait for the coffee to dribble from the machine, I smooth the dresser’s carved pattern over with a stray finger. It’s like you could feel out the past. As if a carving could spell out bygone times and all that the wood had lived through, before a strong hand carved these patterns into it.

There was that summer I laid down on the rug every evening and left the lights off, just watching the lights receding from the room. Everything was quiet and motionless, I laid on the rug taking deep breaths, imagining what the room was like without me in it, when I wasn’t home. The chair stood undisturbed, and the table, and on it a book, the lamp out, and the window allowing the shadows to come creeping in.

TERÉK ANNA

A lámpa fénye

Nézem a hátát. Áll az ablak felé fordulva és nézi az esteledést, nézi a várost, nézi a kivilágított Citadellát. Nyüzsög az utca, a lakosztály ablakából egészen úgy néz ki, mintha gond nélkül folyna odalenn az élet nélkülünk, mintha nem is hiányoznánk a világból, Budapestből. Fogynak a fények, a házak faláról a járdára csúsznak vissza a nap sugarai. Ellátni a Dunáig, csillog a folyó, mossa a város szívét, hordja ki belőle a hétköznapok hordalékát.

A szívem egészen nyugodt, szombat van, mindjárt este lesz, és én kávét szürcsölve a pamlagon nézem a hátát, az arcának oldalát, ahogy figyeli a várost, várja rendületlenül, hogy megérkezzen az este. Hallgat, hallgatok én is, pedig a gondolatok motoszkálnak bennem. Miután elfoglaltuk a szobát, sokat beszélgettünk, mesélni kezdtem a nagyszüleimről, anyámról, apámról, magam sem értettem, miről is jutottak eszembe pont az ő történeteik. A lakosztály kávé illatú, a fény is épp olyan, mint a tejeskávé színe. A csésze porcelánja melegíti a tenyeremet, jó erős feketét főztem, a gyomrom egészen ellazul. Miközben vártam, hogy a gépből kicsorogjon a kávé, ujjammal végigsimítottam a komód intarziáján. Mintha ki lehetne tapintani a múltat. Mintha egy intarzia kirajzolhatná az elmúlt időt és mindazt, amit végigélt a fa, melybe mintákat vágott egy erős kéz.

Volt egy olyan nyaram, amikor minden este a szőnyegre feküdtem, nem gyújtottam villanyt és csak figyeltem, hogyan fogynak el a fények a szobából. Csend volt, minden mozdulatlan volt, én a szőnyegen feküdtem, nagyokat szuszogtam és figyeltem: milyen lehet a szoba, ha nem vagyok benne, ha nem vagyok otthon. Érintetlenül áll a szék, az asztal, rajta a könyv, a lámpa alszik, az ablak pedig hagyja, hogy beszökjenek rajta az árnyékok.

15 M esélo lakosztályok

I leave the lights off now and lay down on the soft carpet to watch his back, and the side of his face, and then the room. It’s quiet. It’s quiet inside me too.

I’d spent too much time on the road these last few months. Cramming clothes into suitcases, rushing to unpack in strange hotel rooms, tossing and turning in strange beds all night, airport coffee, running to catch that transfer, always taking off, always landing, but ultimately failing to arrive anywhere. If you’re on the road enough, it turns into a perpetual in-between, without ever arriving or finding your way home.

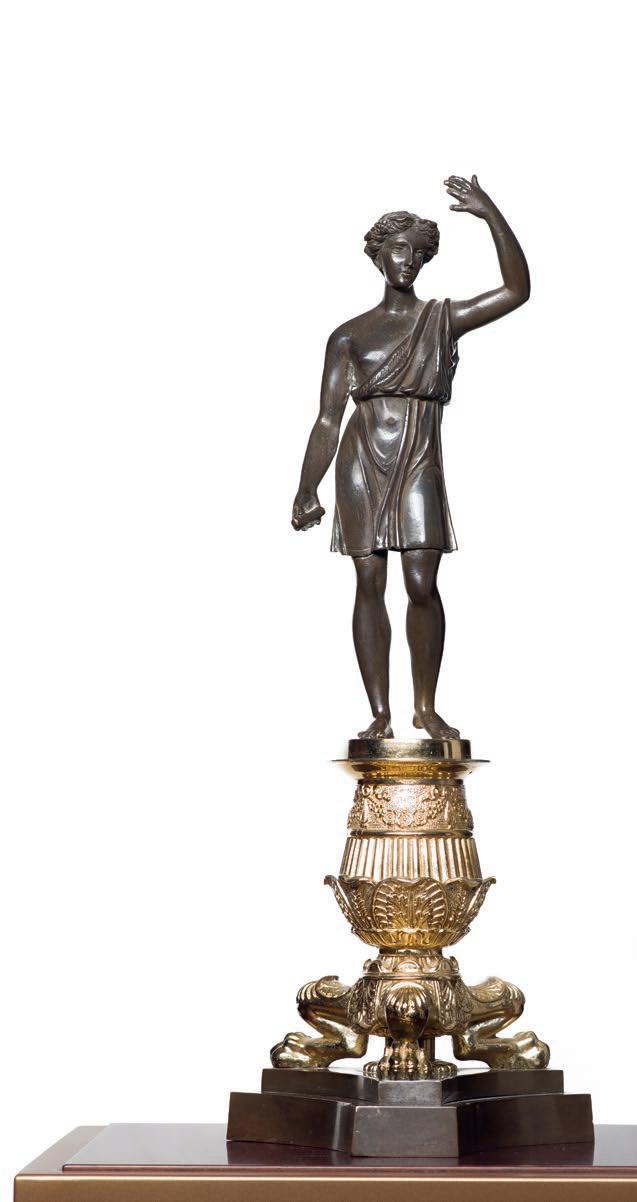

Formal dress and comfortable couch regardless, I lie on the carpet and watch the sculptures atop the carved dresser. Their metallic muscles flex, and they spill light onto the softly patterned carpet that seems to drink it right in. My eyes wander to the painting in the twilight, and I take in the distant blue mountains, her row of pearls and the faintly verdant roses in her hair and hands, and her gaze so full of tranquil anticipation, or perhaps yearning. Beside her the display cabinet is lined in proud porcelains, and they too trickle with light, attracting my eyes. I go up real close to look at the delicate porcelain butterfly, the intertwining ducks, and the saucers painted with delicate flowers. All this reminds me of my grandmother, especially the yearning look of the lady with the roses.

My grandmother was an odd person, and when I was little I often thought she was sulky, when she was merely lost in her thoughts. Her eyes, too, were always filled with yearning.

My grandmother also traveled a lot, moving house and changing city many times in her long life. She moved to the sea to follow my grandfather when they were newlyweds, and he was transferred to a medical practice in Montenegro. She got on the train all alone and arrived in a country where she didn’t even speak the language, but she ended up building a home there. Then they moved to the

Most sem kapcsolok villanyt, a puha szőnyegre fekszem és nézem a hátát, az arcának oldalát, aztán nézem a szobát. Csend van. Csend van bennem is.

Az elmúlt hónapokban túl sokat utaztam. Bőröndbe gyömöszölni a ruhákat, idegen hotelszobákban sietve kipakolni, forgolódni éjjelente az idegen ágyban, repülőtereken kávét inni, szaladni, hogy elérjem az átszállást, folyton indulni, folyton landolni, megérkezni mégsem tudtam igazán sehová. Ha sokáig van úton az ember, egy idő után úgy tűnik, mintha folyton útközben lenne, megérkezés nélkül, hazatalálás nélkül.

Hiába a csinos ruha és a kényelmes pamlag, mégis a szőnyegen fekszem és figyelem az intarziás komódon álló szobrokat. Fémes izmaik feszülnek, lecsorog róluk a fény, a mintás, puha szőnyeg mintha magába inná. Tekintetem a festményre téved, a félhomályban nézem a távoli, kék hegyeket, a nő

Miklós Barabás: Portrait of Katalin Zetk | Zetk Katalin portréja

prairie, a dusty smalltown where they had to start everything over from scratch. Everywhere she went my grandmother ended up making a home, she fought and pulled her own weight, and to what extent she contributed to changing the world or bringing it to order may be anyone’s guess. Yet wherever her home base was, she enveloped her family in love, taking care of everyone, and even if she couldn’t always find what was needed, she could still build a home for her husband and children.

My grandmother had a thing for Herendi chinaware. She had a beautiful dining set with a butterfly motif, and at big family dinners she put on, when all her kids and their kids were seated and she’d bring out the butterfly china set, plates and cups, to serve the food in. My cousins and I would help set the table, and Grandma never seemed to worry we might drop a plate and smash that intricate Herendi porcelain. I believe that’s what made those plates special to me: they had the feel of her trusting us to take care of them, because we knew they were special to her. We try to take care of the delicate moments of our lives, but it’s no use carrying them around inside our hearts everywhere we go when we don’t end up arriving anywhere.

I go to the desk and switch on the Herendi lamp, so the room suddenly floods with a glowing, cozy yellow light, which always brings to mind my grandmother’s house. We spent many nights at her place when I was a child, and whenever

gyöngysorát, a halvány, hamvas rózsákat a hajában, a kezében és a tekintetét, ami tele van nyugodt várakozással, vagy talán elvágyódással. Mellette a vitrinben büszkén állnak a porcelánok, csorog le róluk is a fény, de még így is vonzzák a tekintetemet. Egészen közel megyek hozzájuk, nézem a törékeny porcelán lepkét, az egymáshoz bújó kacsákat és a tányérra festett törékeny virágokat. Nagyanyám jut eszembe róluk. Főleg a rózsát tartó nő elvágyódó tekintetéről.

Nagyanyám különös ember volt, kiskoromban sokszor hittem, hogy mogorva, pedig csak folyton a gondolataiba mélyedt. Az ő szemében is ott volt mindig ez az elvágyódás.

Nagyanyám is sokat utazott, élete során többször is költözött, hazát váltott, várost váltott. Hol a tenger mellett lakott, hogy friss házasként kövesse nagyapámat, akit Montenegróba helyeztek át, hogy orvosként ott dolgozzon. Egyedül ült fel a vonatra, ismeretlen országba érkezett, ahol a nyelvet sem tudta, de végül ott is otthont teremtett. Aztán a síkságra költöztek, egy poros kisvárosba, ahol ismét újra kellett kezdeni mindent. Nagyanyám mindenütt otthont teremtett, küzdött és tette a dolgát, ki tudja mennyivel járult hozzá a világ változásához, vagy ahhoz, hogy rend legyen benne, mindenesetre bárhol is volt, szeretettel vette körül a családját, gondoskodott mindenkiről és ha nem is volt épp nála minden, amire szüksége lett volna, mégis otthont tudott teremteni a férjének, a gyerekeinek. Nagyanyám nagyon szerette a Herendi porcelánokat. Gyönyörű, pillangós étkészlete volt, s ha nagy családi ebédet rendezett, amin minden gyereke és unokája ott volt, akkor elővette a pillangós tányérokat, csészéket és abban tálalt. Unokatestvéreimmel segítettünk teríteni, de a nagyi sosem félt attól, hogy leejtjük a tányért, összetörjük a finom mintájú Herendi porcelánokat. Azt hiszem, pont amiatt voltak számomra különlegesek ezek a tányérok, mert miattuk éreztem nagyanyám bizalmát bennünk, hogy

17 M esélo lakosztályok

Unknown artist | Ismeretlen művész: Portrait of a woman | Női portré

I slept at her house I would watch the yellow glow of the old table lamp struggling against the darkness, splashing over the table as my gran sat darning socks at its light, or reading a book, or just watching my own light-bathed, smiling face until I fell fast asleep.

I stand at the window and we watch the city lights together while the Liberty Statue on top of the Citadella holds up the sky. It’s good standing together in the darkness. The light of the table lamp seems to be getting stronger, the desk and the painting of the lady with black hair all awash in yellow light. I finally turn a light on, and the switch I flip puts a spotlight on the painting of the lady with the roses. I step up to observe her face, its look of longing. I’m looking to find myself in her, to find my past and my grandmother’s smile, because a smile is what she has on her face, a promise of the present as well as the future, and gradually, I smile with her.

Then I draw the bedroom curtains and sit at the makeup table, observing my own face and smile before looking at his smile as I see it mirrored when he stands behind me. As I lie on the bed and close my eyes in the lamplight, I can almost smell my grandmother, and I place my pearl necklace on the nightstand, yellow light, golden evening; then I stretch out on the bed. Here at last it feels like coming home.

majd vigyázunk rá, hiszen tudjuk, hogy sokat jelentenek neki. Próbáljuk őrizni az életünk törékeny pillanatait, de hiába hurcoljuk a szívünkben mindenhová, ha nem tudunk sehová sem megérkezni.

Az asztalhoz megyek, bekapcsolom a Herendi lámpát, a szobát hirtelen elönti az otthonos, sárgás fény, amiről mindig nagyanyám lakása jut eszembe. Gyerekkoromban sok estét töltöttünk nála, s ha ott aludtam, elalvásig figyeltem az asztalon álló öreg lámpa sárga fényét, amint küzd a sötéttel, beteríti az asztalt, s a fényénél nagyanyám zoknit stoppol, könyvet olvas vagy épp csak a lámpa fényében fürdő arcomat nézi mosolyogva.

Az ablakhoz állok és együtt nézzük a város fényeit, ahogy a Citadellán a Szabadság szobor az eget tartja. Jó együtt állni a sötétedésben. Az asztalon álló lámpa fénye egyre erősebbnek tűnik, sárga színben úszik az asztal, a fekete hajú nő festménye. Lámpát gyújtok végül, találok egy olyan kapcsolót, ami a rózsát tartó nő festményét külön megvilágítja. Elé állok újra, az arcát nézem, az elvágyódását. Keresem benne magamat, keresem benne a múltamat, keresem benne nagyanyám mosolyát. Mert ott van az arcán a mosoly, a jelen és a jövő ígérete, mosolyogni kezdek lassan én is.

Aztán a hálószobában összehúzom a függönyöket, a tükrös asztalhoz ülök, nézem egy ideig a saját arcomat, a saját mosolyomat, aztán az ő mosolyát is, ahogy felbukkan az arca tükörben, mikor mögém áll. Ahogy az ágyra fekszem, a lámpafényben behúnyom a szemem, szinte érzem nagyanyám illatát, az éjjeli szekrényre teszem a gyöngysorom, sárga a fény, aranysárga az este, nagyot nyújtozok az ágyon. Itt úgy érzem, végre hazaérkeztem.

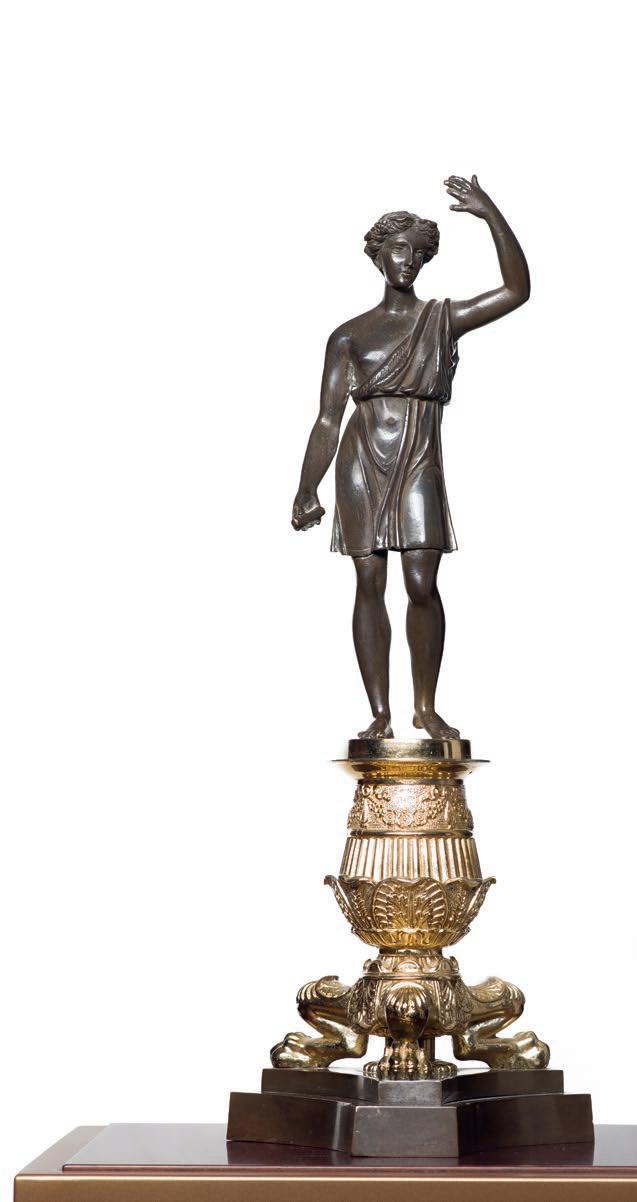

Mohos: Mythological figure | Mitológia alak

18 S torytelling S uite S

János Molnár Z.: Still life with melons | Dinnyés csendélet

Károly

Anna Terék (Topolya, 1984 - ) is a poet, dramatist and psychologist. Since 2007, she has published four volumes of poetry and one collection of dramatic works. Her poems have appeared in English, German, Spanish, Turkish, Polish and Croatian. She has won a number of literary awards. She lives and works in Budapest.

Terék Anna (Topolya, 1984 - ) költő, drámaíró, pszichológus. 2007 óta négy verseskötete és egy drámagyűjteménye jelent meg. Verseit többek között angol, német, spanyol, török, lengyel és horvát nyelvre fordították. Több irodalmi díjat nyert. Budapesten él és dolgozik.

19 M esélo lakosztályok

960

22 S torytelling S uite S

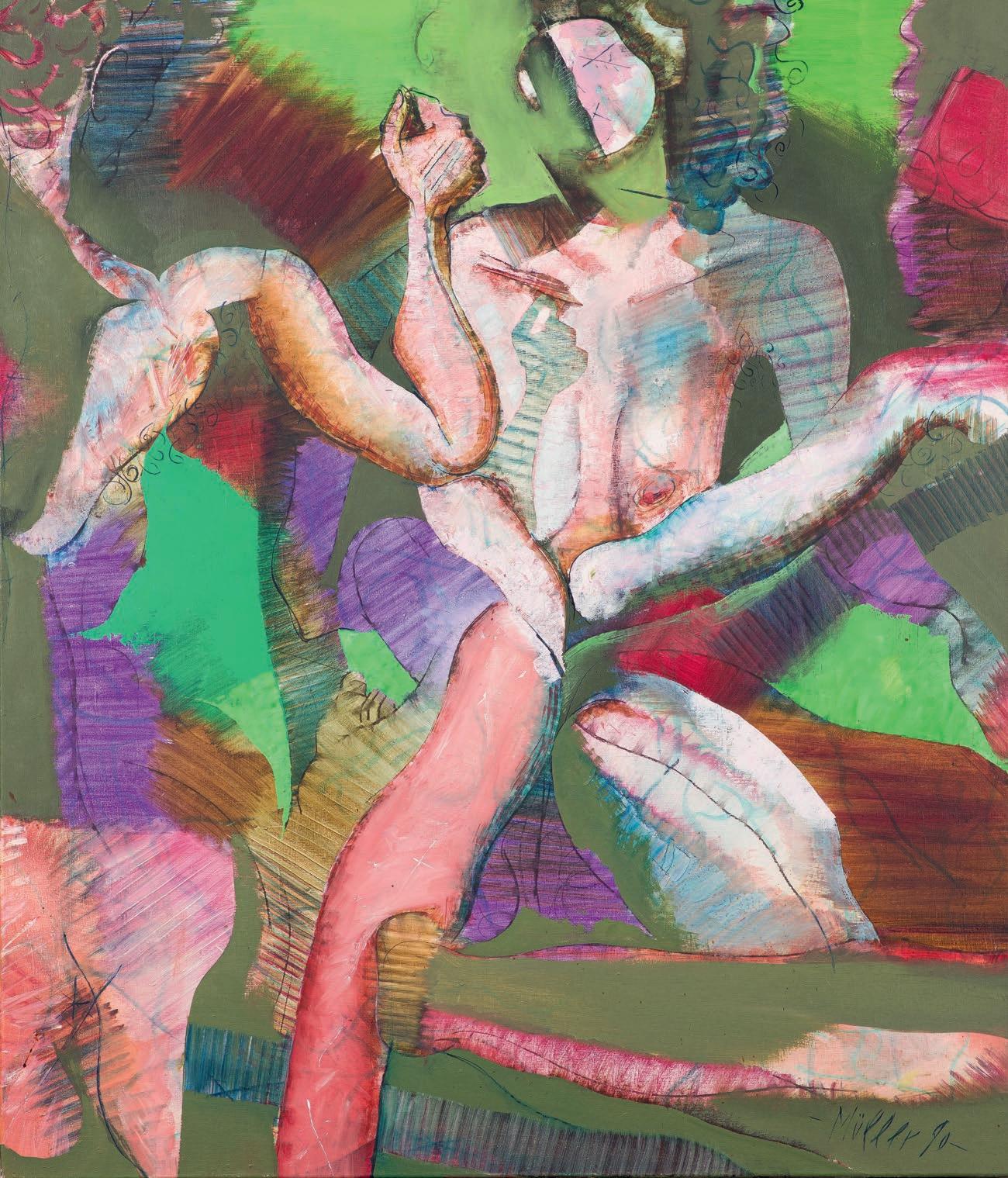

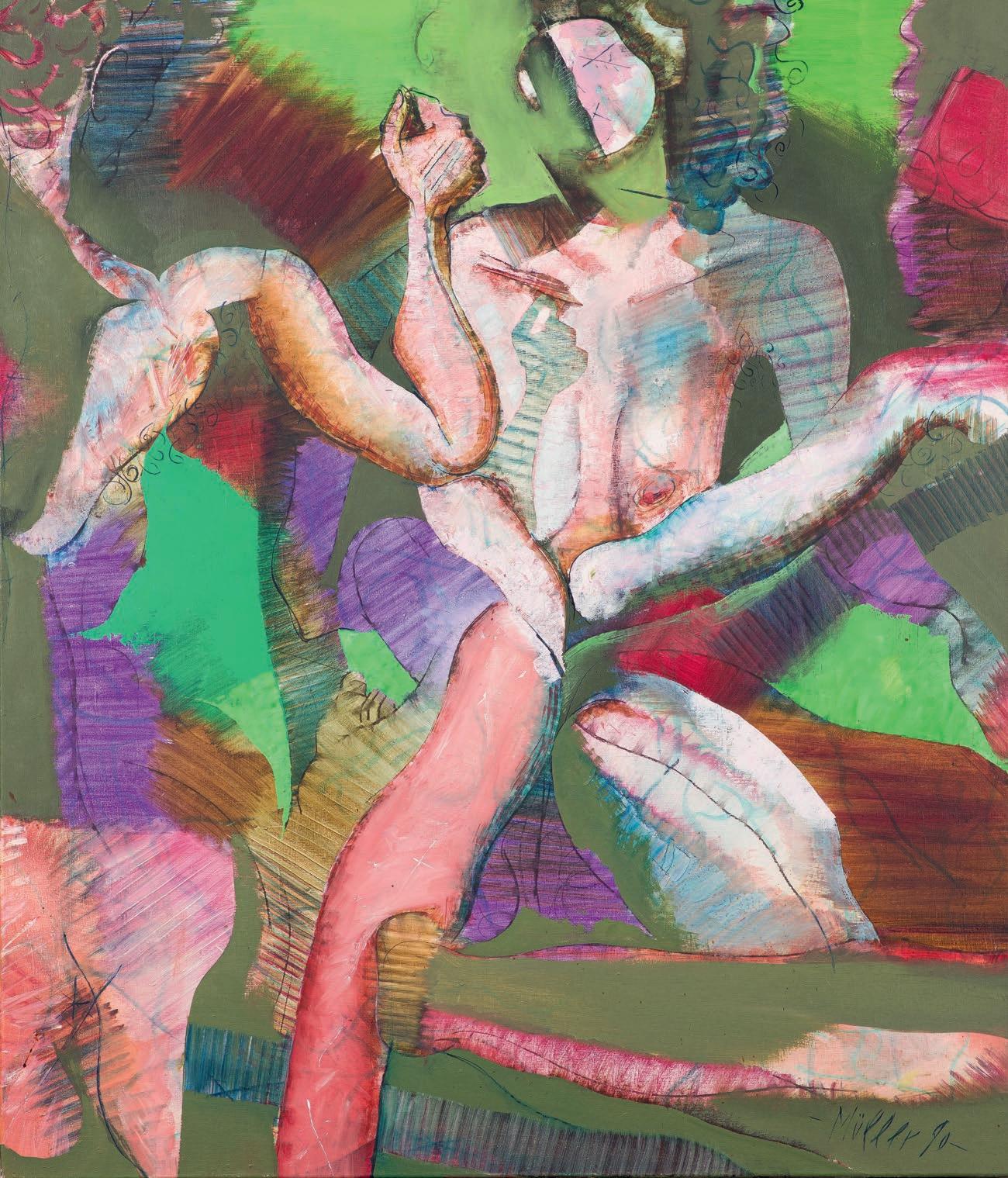

Árpád Müller: Jester | Bohóc

BARTÓK

Jester

Glad you made it here. But before you ask anything, there’s something I have to tell you. There’s nothing that I know, except perhaps the fact that I know nothing. But you look familiar, yes, I think I know your face, in fact, I can see right through you. They say my smile isn’t genuine, and I’m more of a melancholy type. They say, and I’ll admit as much, my smile is only taken at face value by children, and they’re also the only ones to believe that glee could be pictured this way, even as my mottled heart overflows with grief. What could be further from the truth? Whoever knows about forms is exempt from sorrow. Whoever knows the shapes and forms of city and body is beyond all woe. I’m not saying I know anything at all, it’s not knowledge as such, I simply became familiar with the city and myself, walking these streets, offering a curious child a rattle, ice cream to the women, and shackles to their husbands. They laugh, I smile, and everyone’s happy. My Parisian friends – not that I have friends, they’re quite imaginary -, so these friends from Paris wrote me a letter on cubism. Apparently you can slice up an image into bits. Apparently, the whole world’s a great butcherblock. They say you can split time into seconds, and space into tiny but distinct blocks, like firewood, in fact even human figures can be hacked into a multitude of mutually reflecting mirror planes. At the center of this cubist labyrinth, I duck and hope and wait for you to find me. A cute young herald stands at the labyrinth gateway, waiting, and you can even ask for a ball of yarn, a nice little bundle, trail it along and see if it helps you find a way out. All the walls are mirrors, and there I am waiting for you at the center of this maze, a mirror myself, although different from all the rest, reflecting an image of you such as you have never seen. My face is a musical rapture, remember? Childhood’s own melody echoed, a memory that never had a present tense. I know nothing, only that I know you and see your secrets. Don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone, I don’t need to, when all of it is written on my face from this point on. My face is the music of your joy, all that’s left of your bygone wonder and awe. You see it in my eyes, don’t you? We don’t know nothing, but nothing knows all about us. We came

BARTÓK IMRE Bohóc

Örülök, hogy megérkeztél. Mielőtt azonban kérdezni akarsz, tartozom egy vallomással. Semmit sem tudok, csak talán azt, hogy nem tudok semmit. Te viszont ismerős vagy, igen, azt hiszem ismerlek, sőt átlátok rajtad. Azt mondják rólam, a mosolyom nem valódi, és igazából szomorú természet vagyok. Azt mondják, nem is próbálom rejtegetni, és csak a gyerekek hisznek a mosolyomnak, csak ők gondolják, hogy így fest a vidámság, miközben tarka szívem túlcsordul a bánattól. Mi sem állhatna távolabb a valóságtól! Hiszen aki ismeri a formákat, nem lehet szomorú. Aki ismeri a város és a test formáit, túl van a bánkódáson. Nem állítom, hogy bármit is tudnék, hiszen ez nem tudás, egyszerűen csak megismertem a várost és megismertem magamat, ahogy ezeken az utcákon sétálok, ahogy csörgőt nyújtok a kíváncsi gyermek felé, fagylaltot az asszonyoknak, bilincset a férjeiknek. Ők nevetnek, én mosolygok, mindenki elégedett. A párizsi barátaim – egyébként nincsenek barátaim, csak elképzelem őket –, tehát a párizsi barátaim levelet írtak nekem a kubizmusról. Állítólag fel lehet szeletelni a látványt. Állítólag a világ egy nagy hentespult. Azt mondják, fel lehet aprózni az időt másodpercekre, a teret kicsiny, még éppen belakható kockákra, mint a tűzifát, sőt az emberi alakot is fel lehet így hasogatni egymást tükröző üveglapok sokaságára. A kubista labirintus az, amelynek a közepén én gubbasztok, remélve, hogy rám találsz. A labirintus előtt kedves kis rikkancs várakozik, aki kéri, annak még egy fonalat is ad, csinos gombolyag, húzza csak maga után, hátha segít kitalálni. Minden fal tükör, és az útvesztő, a szabályos formák kifürkészhetetlen középpontjában ott várok rád, tükör vagyok magam is, de másmilyen, mint a többi, olyannak mutatlak, ahogyan még sosem láttad magad. Arcom az öröm zenéje, emlékszel? A gyerekkor dallamának visszhangja, emlék, amelynek sosem volt jelenideje. Semmit sem tudok, csak azt, hogy ismerlek téged, látom a titkaid. Ne félj, nem árulom el senkinek, nincs is rá szükség, hiszen ettől kezdve az arcomra van írva minden. Arcom a te örömöd zenéje, mindaz, ami a régi csodálkozásból megmaradt. Látod a szemem, ugye? Semmit sem tudunk, de a semmi tud rólunk. Azért jöttünk a városba,

IMRE

23 M esélo lakosztályok

to this city to walk, and laugh, hand a kid a ball with a whisper: this is the world. I know there’s plenty you want to tell me, that’s what I’m here for, so now that you’ve found me, don’t hold back, talk. Don’t get disappointed if I’m not there for you, I can still hear your voice loud and clear. I’m not sorry, and you can’t make me sorry, no matter how hard you might try, though I might yet put a smile on your face. You know, for my Parisian friends’ sake. Look at the colors I’m wearing, it’s all for you. We haven’t even started the show and so much has happened already. You’ve come such a long way. Perhaps you might rest a while. I know nothing about you, nobody told me you’d be coming, and yet you look so familiar. I bet you have secrets. Don’t be afraid, they’ll all be safe with me. Sit down, relax. No, don’t sit down yet. Look out the window. You see that inquisitive child, that woman, her husband? They’re my family. Do you see what I see? Do I look sad to you? How could I be sad in this city, how could anyone be down when we’ve found one another? Sit down, lie back, stretch your tired limbs. Lie comfortably. Sleep, I can tell you could use some. Sleep, and dream something for me, something happy, if it’s not too much trouble.

Péter Paizs: Square | Négyzet

Péter Paizs: Square | Négyzet

hogy sétáljunk, nevessünk, labdát adjunk egy gyerek kezébe, és odasúgjuk neki: ez a világ. Tudom, mennyi mindent elmondanál nekem, ezért is vagyok itt; ha már egyszer rám találtál, ne légy rest, beszélj. Ne légy csalódott, ha épp nem figyelek oda, azért nagyon is hallom a hangod. Nem vagyok szomorú, nem tudsz szomorúvá tenni, bárhogyan is igyekszel, de én még talán mosolyt csalhatok az arcodra. Tudod, a párizsi barátok kedvéért. Nézd csak, milyen tarka a ruhám, a kedvedért vettem fel. Még el sem kezdtük az előadást, és máris mennyi minden történt. Nagy utat tettél meg. Talán pihenhetnél egy kicsit. Semmit sem tudok rólad, nem szóltak előre, hogy jönni fogsz, most mégis olyan ismerősnek tűnsz. Úgy sejtem, titkaid vannak. Ne félj, nálam biztonságban lesz mindegyik. Ülj le, és pihenj. Nem, még ne ülj le. Nézz ki az ablakon. Nézd meg a kíváncsi gyermeket, az asszonyt, a férjét. Ők az én családom. Látod, amit én látok? Ugye, hogy nem vagyok szomorú? Hogyan is lehetnénk szomorúak ebben a városban, hogyan is lehetnénk bánatosak, ha már ilyen jól egymásra találtunk. Ülj le, heverj el, nyújtóztasd ki a tagjaid. Feküdj kényelmesen. Aludj, úgy látom, rád fér. Aludj, és álmodj valamit a kedvemért, valami vidámat, ha kérhetem.

25 M esélo lakosztályok

Árpád Müller: Shower of light | Fényeső

Péter Paizs: Crystals | Kristályok

Péter Paizs: Crystals (on white) | Kristályok (fehér alapon)

26 S torytelling S uite S

Árpád Müller: In the open | Szabadban

Imre Bartók (Budapest, 1985 - ) is an author and critic who studied philosophy and aesthetics at ELTE University, and published his first novel in 2011. He is a known essayist and contributor to literary monographies. His latest novel Lovak a folyóban (Horses in the River, Jelenkor) was shortlisted for the 2022 Libri Literary Award.

Bartók Imre (Budapest, 1985 - ) író, kritikus. Filozófiát és esztétikát tanult az ELTÉ-n, első regénye 2011-ben jelent meg. Esszéistaként és irodalomtörténeti monográfiak közreműködőjeként is ismert. Legutóbbi regénye, a Lovak a folyóban (Jelenkor) 2022-ben felkerült a Libri irodalmi díj rövidlistájára.

27 M esélo lakosztályok

830

30 S torytelling S uite S

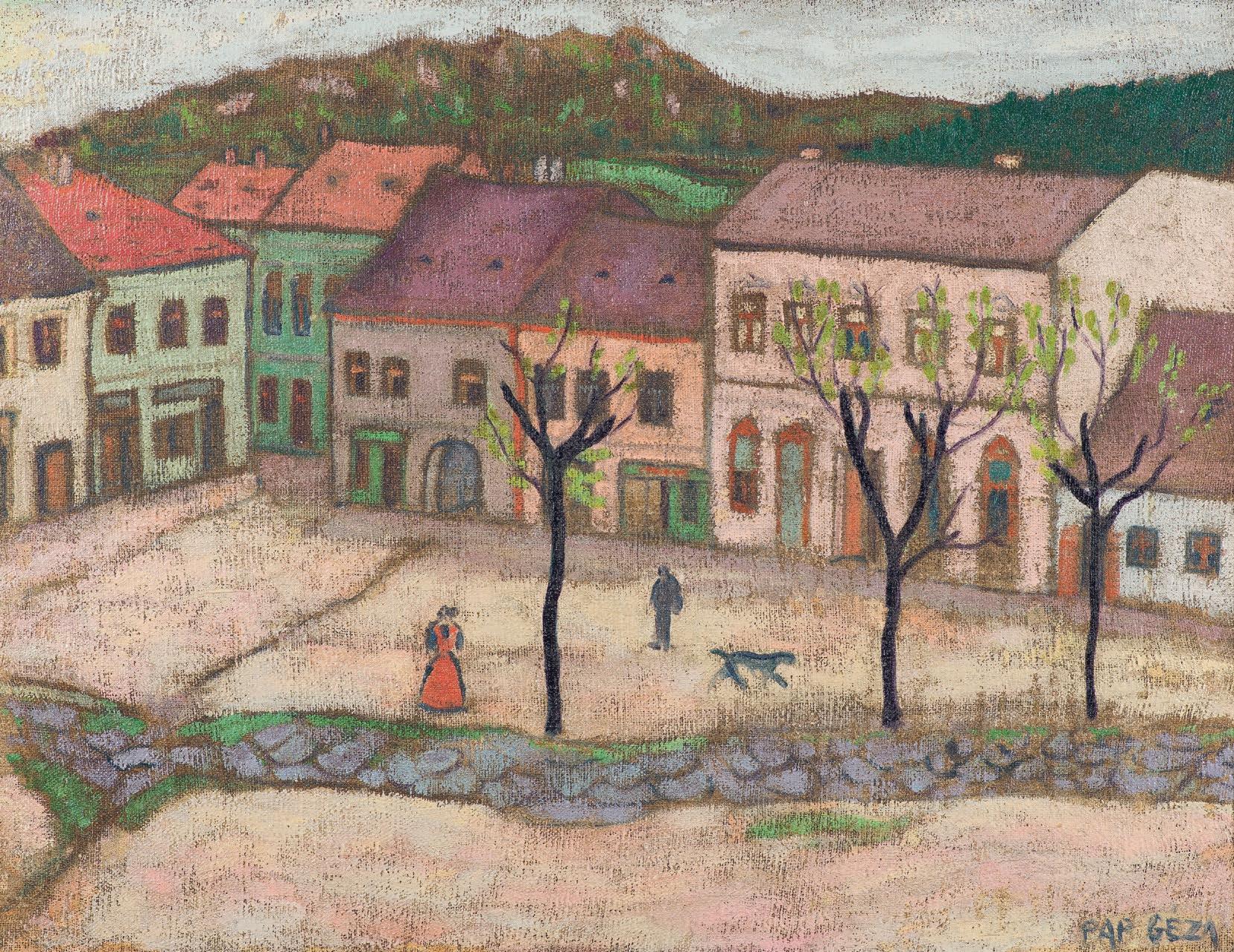

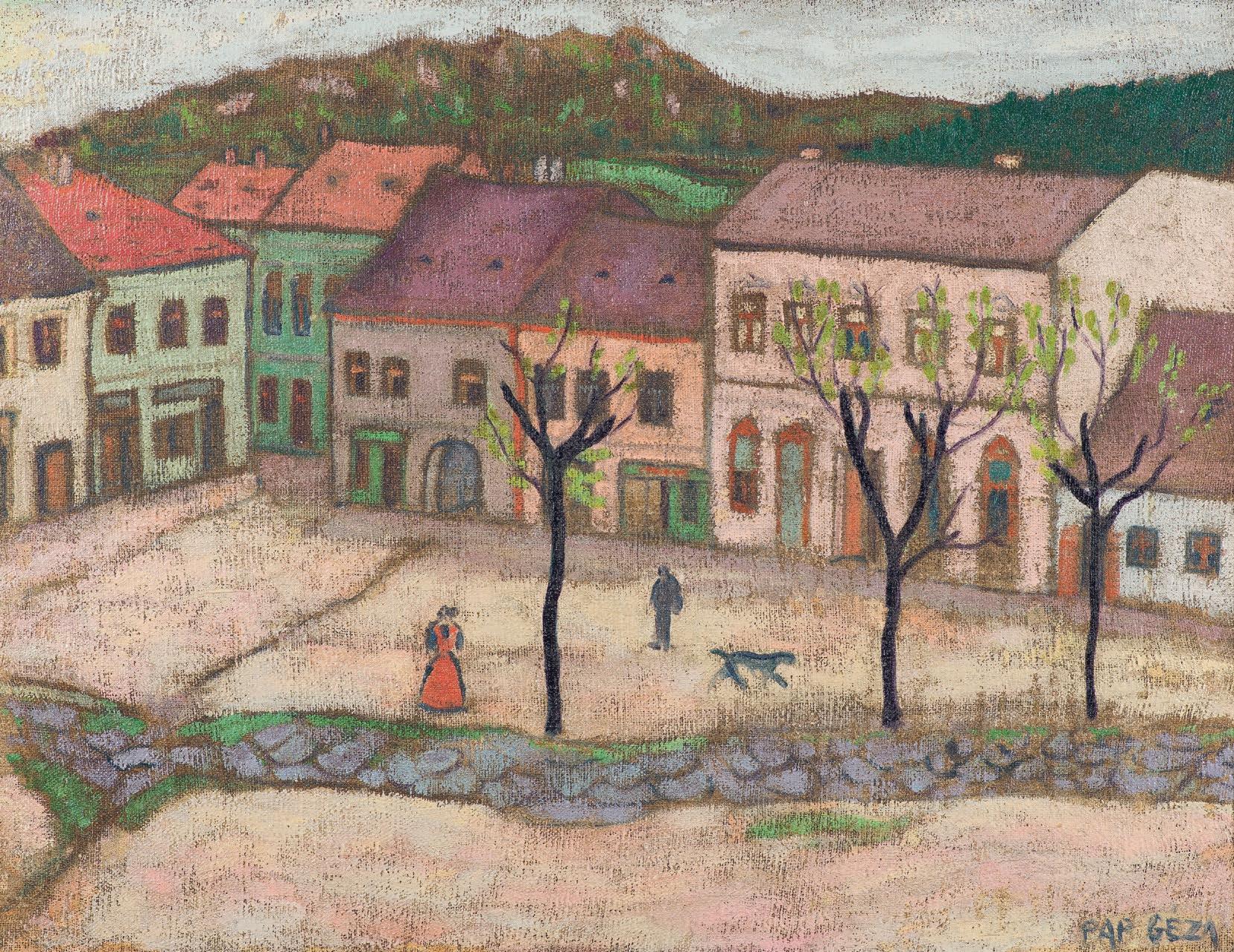

Géza Pap: Small town | Kisváros

A Walk under Intense Light

It was an unusual morning for early spring, the sun already high at dawn. He sat up in bed, bathing his face in the light that flooded through the threadbare blinds. His wife was sleeping peacefully, her dreams undisturbed by the light on her face and skin, as if her eyelids kept her safe from the outside world like gates of iron. He shuffled out softly to the living room, where Táltos sat at the front door with a pleading look. He donned his gray jacket and could only hope they’d be back before his wife woke up.

They followed the usual routine. They turned left at the old front gate, and from there he could rely on Táltos without a second thought. Passing the dentist’s office, they took a right at the shoemaker’s store. The sun didn’t budge an inch, as if time were standing still. He yawned and looked at the balding mountain tops, only now noticing they were just like the bald heads he’d watch at church of those sitting in the pew before him when the preaching got too tedious. Only rarely would he consider that he might present the same sight to anyone sitting behind him. Mountains encircled the small town, which found shelter in a valley, so that the sun was always later to rise and earlier to set. This seemed to lend an easy familiarity to the place, though all the colors were toned darker.

MÉCS ANNA

Séta erős fényben

Szokatlan volt az a kora tavaszi reggel, már hajnalban magasan járt a nap. Felült az ágyában, a redőny kopott deszkái között fürdette arcát a fényzuhatagban. Felesége békésen szuszogott, mintha szemhéja vaskos kapuként védené őt a külvilágtól, arcát és bőrét érő fény nem zavarta meg nyugodt álmát. Halkan kicsoszogott a nappaliba, ahol Táltos a bejárati ajtó előtt ült, és kérlelve nézte. Felvette szürke kabátját, és csak remélni tudta, hogy visszaér, mielőtt felesége felébredne.

A szokásos körükre indultak. Kiléptek az ódon kapun és balra fordultak, már nem is kellett figyelnie, merre megy, csak követte Táltost. Elmentek a fogorvos előtt, a cipésznél jobbra. A nap egy tapodtat sem mozdult, mint ami kimerevítette az időt. Ásított egyet, és a hegyek kopasz ormát figyelte, csak most látta meg bennük a tar fejbúbokat, amelyeket a templomban az előtte lévő sorokban figyel, ha untatja a prédikáció. Csak ritkán gondolt arra, hogy ő is így festhet a mögötte ülők szemében. Körben mindenhol hegyek vették körbe a kisvárost, egy völgyben találtak menedéket, náluk mindig később kelt a nap és hamarabb nyugodott. Mintha ettől lassabb és otthonosabb, de sötét színnel átitatott lett volna minden.

ANNA MÉCS

31 M esélo lakosztályok

He kept an eye on the cobblestones under his feet, always just the one his foot was about to land on. He remembered his wife stumbling across these stones in her dressy shoes. And he thought about their theater visits, her beautiful red dress he had fallen in love with from day one. The only shadow that fell across this adoration was that he wanted to keep the sight to himself and keep those feelings from ever welling up in anyone else. Envy, he muttered under his breath, jealousy, shaking his head, strict in self-judgement for any trace of a sinful sentiment.

Lifting his gaze from the cobblestones ever so slightly, he first caught a sight of Táltos’s behind, and only by looking further up could he elevate his line of sight to a clearer view of a square they had arrived at, one that was off their usual early morning beat. As the outlines of the little square lit up before his eyes, he found himself facing the theater building. He shook his head gently at Táltos, muttering bad dog, to which the dog sidled up and sat down at his feet. It eyed its master apologetically, then turned, and he too turned to where the dog was looking. He saw a woman in front of the theater; she had a beautiful red dress on. He looked on, enchanted, and was about to walk up to her when he saw that she was not alone, that a dark-dressed man was holding her in his arms, and she returned his embrace, so they stood cleaved to one another and motionless. They never seemed to notice that evening had dawned into a new day, and an unusually bright new dawn at that, making every dust mote and drifting idea plainly visible. He felt a lump in his throat as he watched the embracing lovers. The dog poked his limply hanging hand with its nose before setting off at a quick pace. He shook his head, but the couple just stood there stockstill. He didn’t want to intrude on them by staring like that, so he took off after Táltos when he heard the tolling of bells, bing-bong, bing-bong, his feet colliding with pavement like a bell ringing out, bing-bong, bing-bong, and as he lengthened his stride, the ground under his feet rang out louder and louder. They would usually be having breakfast with his wife when the bells sounded. He was flummoxed about what had just happened here, how long were they dawdling in that square, where had the time gone? Sweating, he arrived at the gate. Táltos stopped beside him, tongue hanging out. He ran up the stairs to

A macskaköveket figyelte a lába alatt, mindig csak azt, amelyikre éppen rálépni készült. Eszébe jutott, felesége hogyan csetlett-botlott a köveken, amikor elegánsabb cipőt húzott. A színházban tett látogatásokra gondolt, felesége gyönyörű piros ruhájára, amibe első pillanatban beleszeretett. Később csak azért keveredett csodálatába némi rossz érzés, mert csak magának akarta azt a látványt, nem akarta, hogy bárkiben fellángoljon, ami benne. Irigység, dörmögte maga elé, féltékenység, ingatta a fejét, szigorú volt magával szemben, ha bűnös érzéseket fedezett fel magában.

A macskakövekről felemelte kissé a tekintetét, először csak Táltos fenekét látta meg, majd még feljebb nézve vette észre, hogy tekintete nem ütközik akadályba, hogy egy térre értek, pedig hajnali sétájuk során nem szoktak teret érinteni. Mikor kiviláglottak számára a terecske körvonalai, akkor vette észre, hogy a színházépülettel szemben áll. Ingatta a fejét Táltos felé, rossz kutya, mormogta, a kutya pedig csak odasomfordált, és leült a lába elé. Bocsánatkérő, de határozott tekintettel nézte gazdáját, majd elfordította a fejét, így ő is követte, merre néz a kutya. Egy nőt látott meg a színház előtt, gyönyörű, piros ruhában. Megbabonázva nézte, már indult volna, hogy odalépjen, amikor észrevette, hogy nem egyedül áll. Hogy egy sötét ruhás férfit öleli őt. És a nő is öleli a férfit, szinte eggyé válnak, mozdulatlanul. Mintha észre sem vették volna, hogy az estét váltó sötét éjszaka felderengett, és hogy már hajnal van, szokatlanul fényes hajnal, ahol minden porszem és gondolat láthatóvá válik. Alig bírt nyelni, az egymásba olvadt szerelmeseket nézte. Táltos megbökte az orrával az ernyedten lógó kézfejét, és gyors léptekkel elindult. Ő megrázta a fejét, de a pár még mindig ott állt, rezzenetlenül. Nem akarta őket tovább zavarni azzal, hogy belefeledkezik a látványukba, így Táltos után eredt, amikor zengő harangozást hallott, bimmbamm, bimm-bamm, lépései, akár a harang teste, bimm-bamm, a földnek csapódtak, egyre nagyobbakat lépett, lába alatt egyre hangosabban döngött a talaj, harangozáskor már reggelizni szoktak feleségével, nem is érti, mi történhetett, vajon

32 S torytelling S uite S

33 M

esélo lakosztályok

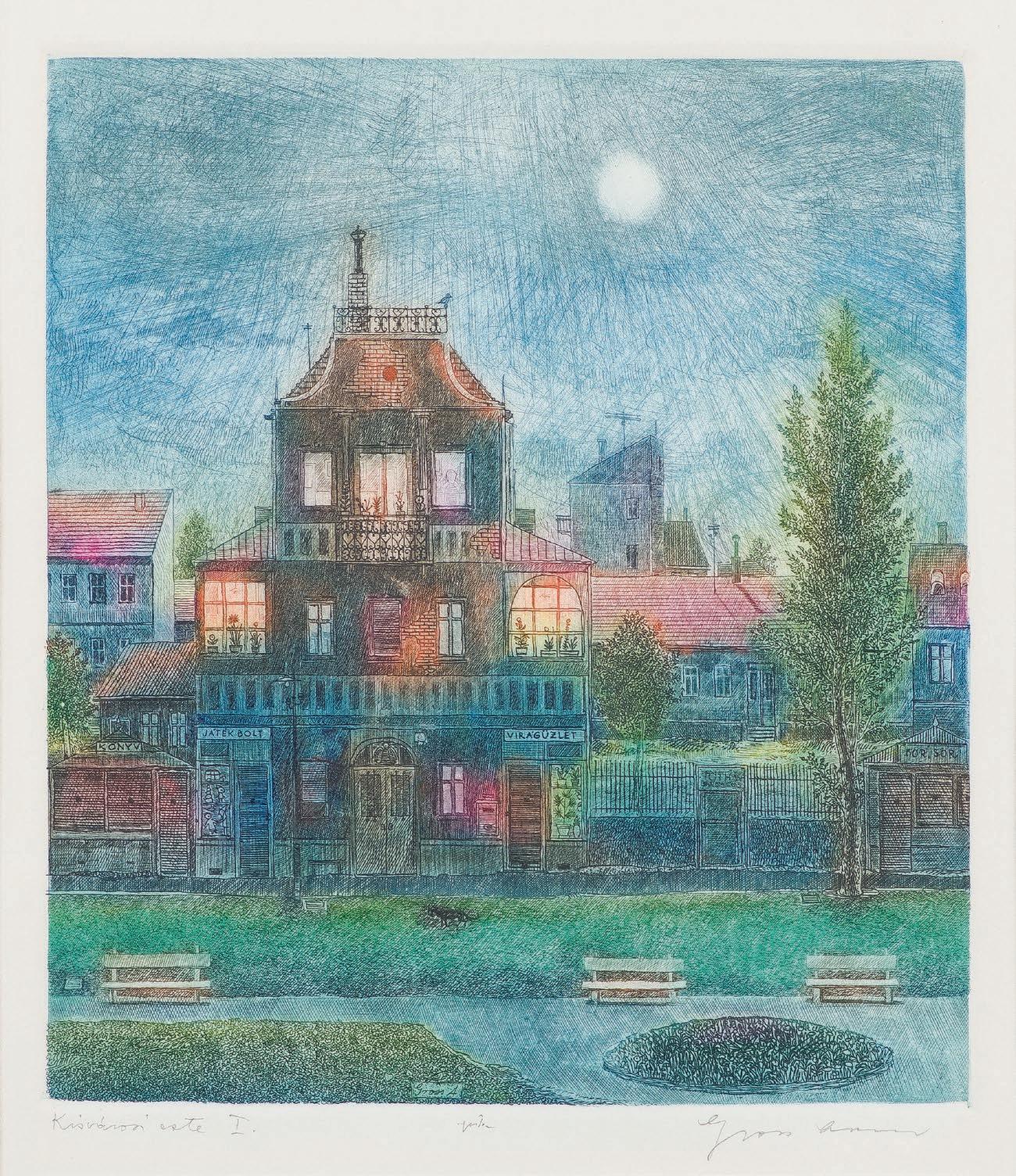

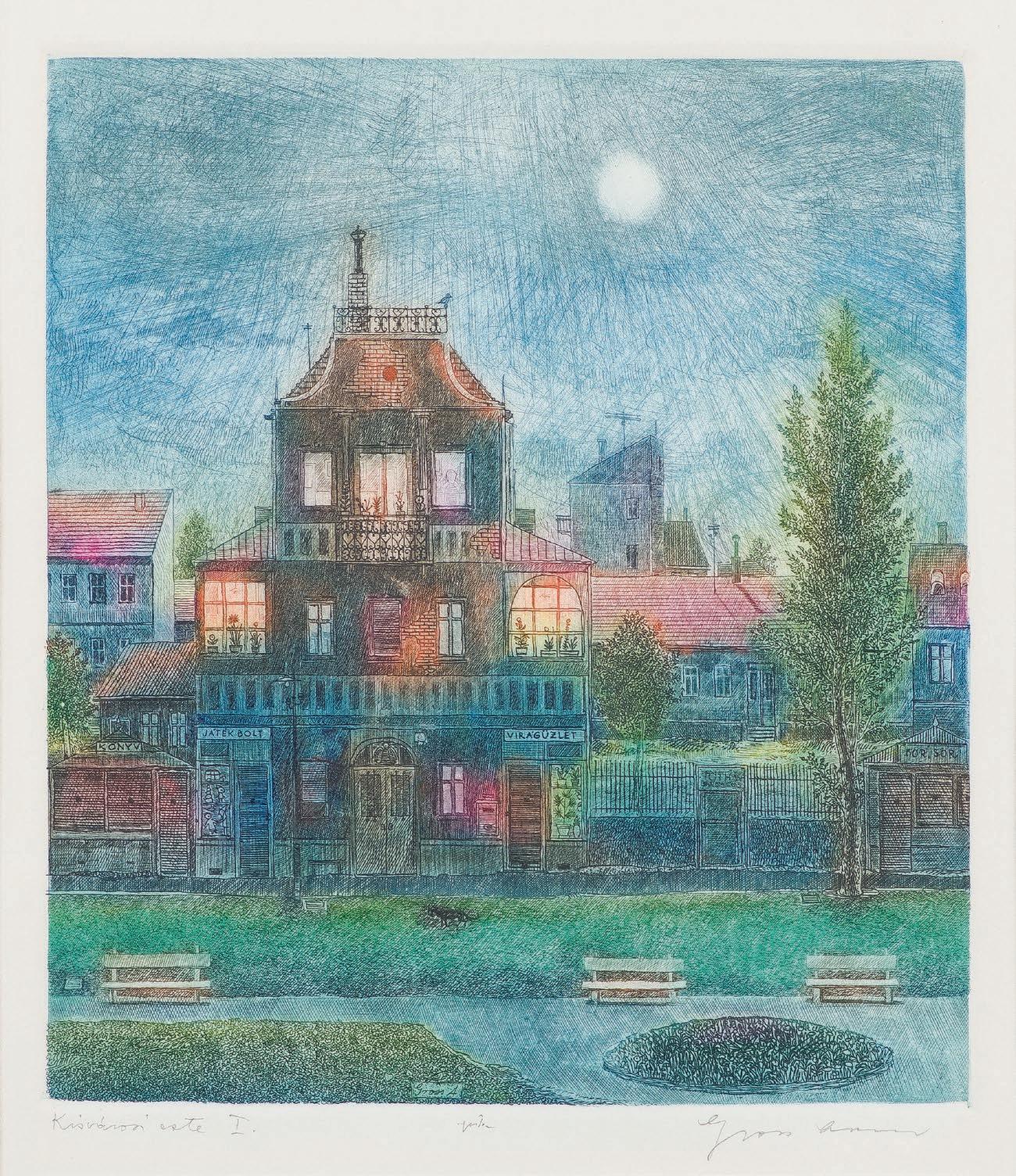

Arnold Gross: Small town evening I | Kisvárosi este I.

the first floor, knees aching, taking the steps two at a time, the dog on his heels. Even in the hallway he could tell he was already too late. His wife’s resonantly incoherent screaming. He rushed into the apartment, and took the woman in his arms, but she only screamed louder, her whole body a rigid rebuff. This prompted him to clasp her to himself even harder, It’s me, he whispered, dearest love, though he knew by now she barely understood a word. Perhaps it was his smell, or the familiar voice, perhaps even just the close proximity of another human body, the rhythm of his racing heart, but in a few more minutes she relaxed pliantly in his arms. He sat her down at the dining table and prepared breakfast.

meddig ácsorogtak a téren, hová tűnt az idő. Izzadva ért a kapualjhoz, Táltos megtorpant mellette, nyelve kint lógott. Felszaladt az első emeletre, térde fájt, de kettesével szedte a lépcsőfokokat. A kutya utána. Már a folyosón hallotta, hogy elkésett. Felesége zengve, artikulálatlanul kiabált. Berontott a lakásba, és magához ölelte az asszonyt, aki eleinte még hangosabban üvöltött, egész teste merev volt és elutasító. A férfi erre még jobban magához szorította, én vagyok, suttogta, édes szerelmem, bár tudta, az asszony már nem sokat ért belőle. Talán az illata, talán a hangja ismerőssége, de lehet, csak az emberi test közelsége, a zakatoló szíve ritmusos dobbanása tette, de az asszony pár perc múlva már ernyedten pihent karjaiban. Leültette az étkezőasztalhoz, és előkészítette a reggelit.

34 S torytelling S uite S

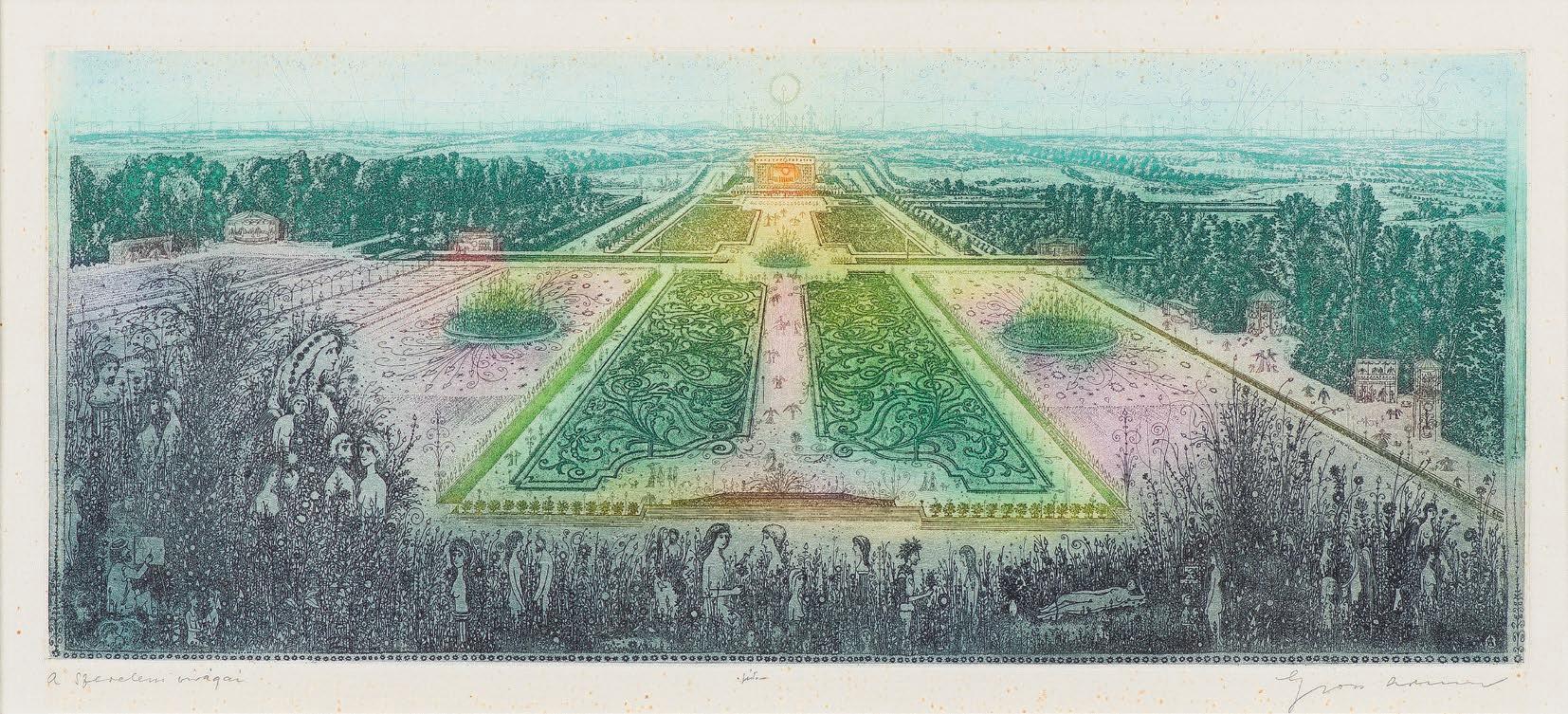

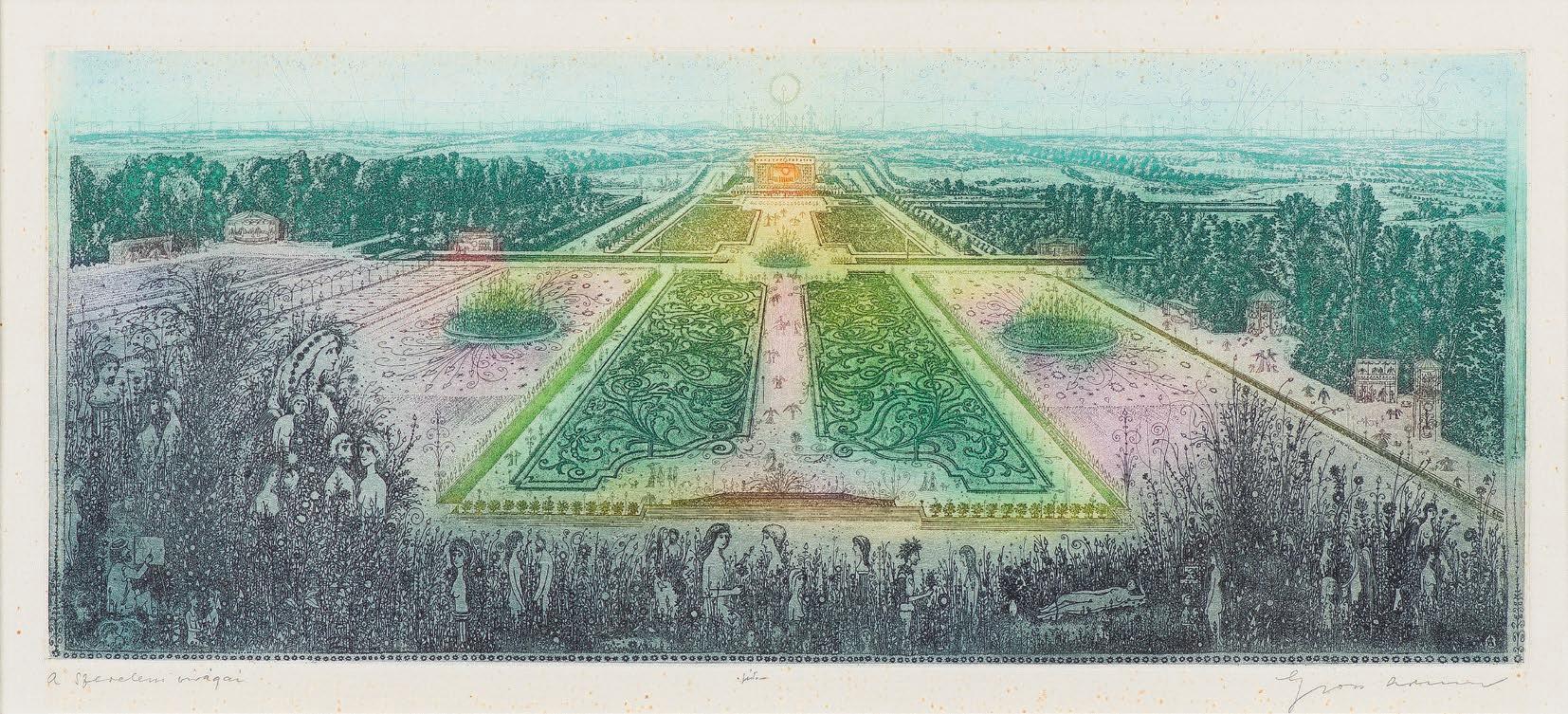

Arnold Gross: Roman holiday II | Római ünnep II.

Anna Mécs (Budapest, 1988 - ) is an author and creative writer. She holds a master’s degree in mathematics and one in Hungarian literature. Her first collection of short stories, Gyerekzár (Child Lock), was published in 2017, and won the 2018 Margó Literary Award for Best First Prose Book. Her latest book was Kapcsolati hiba (Connection Error), published in 2020.

Mécs Anna (Budapest, 1988 - ) író, szövegíró. Matematika-magyar tanári mesterszakon végzett. Első novelláskötete, a Gyerekzár 2017-ben jelent meg, amely 2018-ban elnyerte a Margó-díjat, a legjobb első prózakötetnek járó díjat. Legutóbbi, 2020-as kötete Kapcsolati hiba címmel jelent meg.

35 M esélo lakosztályok

930

38 S torytelling S uite S

Péter Ujházi: Spring in Árki | Árki tavasz

RITA HALÁSZ

Zoom

There’s no mistaking the woman I see, it’s me, but I’m not sure what age. Only I know, full well, but I’m playing my mother’s old game here. Cut three minutes from the present. Any three minutes, anytime, it really makes no difference, any that comes to mind. Imagine watching yourself in that scene ten years before, imagine how you might interpret what you see, and what conclusions you might draw. Five years, ten years, twenty years back. Pick a time. I pretend to see myself from fifteen years ago as I’m sitting on this couch flipping through a Henri-Cartier Bresson catalog. Fifteen years back, András and I had gotten married, and were just back from our honeymoon. That’s my vantage point.

Zoom in.

Faint horizontal creases cross my forehead, and two deeper vertical lines between my eyebrows, one broader furrow beneath my eyes, and a faint one that extends outward from the lower eyelids. Not so bad. I might be thirty-five or so. My hair wound in a loose haystack bun on top, like it usually is. No earrings, but pierced holes are still visible on the lobes, not quite closed up yet. Let’s go to the back. My hair, I can see now, is dyed, only slightly exposed at the roots but you can still tell. So I’m one of those dye-job women now. I used to be all about natural looks, and ignoring public expectations. I flip through the catalog page by page, stopping to look at certain pictures, taking my phone out to shoot a pic. So we’ll have photo-phones, that’s neat, very practical. My hands, however, look older, veiny. I might be forty, perhaps even older. My boobs look bigger, tighter. Did I get those done? Me, who swore never to succumb to the knife? But then I also said I wouldn’t dye my hair.

HALÁSZ RITA

Zoom

Az biztos, hogy az a nő, akit látok, én vagyok, de nem tudom, hány éves lehetek. Persze nagyon jól tudom, mindent tudok, de most anyám játékát játszom. Ragadj ki a jelenből három percet. Bármilyen három percet, bármikor, teljesen mindegy, amikor eszedbe jut. Képzeld el, hogy tíz évvel korábban kívülről látod magad a jelenetben, képzeld el, hogy mit értenél belőle, milyen következményeket vonnál le. Öt év, tíz év, húsz év. Amit akarsz. Most azt játszom, hogy tízenöt évvel ezelőtt látom a mostani önmagamat, amint a kanapén ülök és egy Henri-Cartier Bresson katalógust lapozgatok. Tizenöt éve már megvolt az esküvőnk Andrással, most jöttünk haza a nászútról. Innen nézem magamat. Közelítsünk.

A homlokomon halvány vízszintes ráncok, a szemöldököm között két erőteljesebb függőleges vonal, a szemem alatt egy erősebb, oldalt, az alsó szemhéj meghosszabbításaként egy halványabb csík. Nem vészes. Talán harmincöt lehetek. A hajam lazán kontyba tekerve a fejem tetején, csak úgy összevissza, ahogy szoktam. Fülbevalóm nincs, de még mindig látszik a lyukasztás nyoma, nem forrt össze. Menjünk vissza. A hajam, most látom, festve van, nagyon kicsi a lenövésem, de látszik. Tehát olyan nő lettem, aki festi a haját. Pedig hogy mondtam, fő a természetesség, nem kell megfelelni a társadalmi elvárásoknak. Lapozgatom a katalógust, bizonyos képeknél megállok, előveszem a telefonomat, lefényképezem. Ezek szerint fényképezős telefonjaink lesznek, ez tetszik, praktikus. A kezem viszont öregebbnek tűnik, eres. Lehet, hogy negyvenéves

39 M esélo lakosztályok

Where am I? Let’s pull back. Elegant interior, afternoon sunlight pouring in the apartment window. No TV blare, no music. I still go for quiet. What am I doing here? Am I alone? Where’s András? Let’s see a close-up of my hand. Wedding ring still on. Good. Let’s pan full circle. Men’s bag on the couch. Must be his. It’s all too tidy looking, too clean. A hotel. Maybe a foreign business trip. András made the big time, and brought me along. Why can’t I be the success story? Maybe I brought us here, but then that would mean my dad got his way. Legal career instead of art. Pull back. Look out the window. Somewhere in Europe. This could even be Budapest, the street looks familiar, those houses, trees, vaguely homelike, except for the Ferris wheel there. But this is Budapest, I can see the Basilica from here, even the dome of the Parliament. So Budapest got a giant wheel too, like the London Eye. We took a ride on that with András on our honeymoon, that’s how we found out he’s scared of heights; he just sat real still hiding his face in his hands, I patted his back. Have we got any kids? Apparently I’m not browsing through their pictures on my phone, but that’s not much to go on. If I’m forty here, they would be teenagers. Two teenage girls, glad to have their parents out of the house, like we’re glad to take a break from their teenage angst.

Finally, I get up at last. I’m going up to the big desk, to look at the bronze statue beside the window. It’s an apple core. I gently feel out the apple’s curve, then the bite marks on its robust heart. Adam and Eve’s, a last memento of paradise lost. Will I be the kind of person reminded of original sin when I see this, or will my thoughts take an entirely different direction?

Well, how do you like it? A male voice. Not András. A man in a bathrobe emerges from the bathroom. Tall, blonde, pushing forty. Bespectacled. Is this my lover? What else could he be? I go up to him, kiss his lips, give him a hug. No passionate lipwrestling, no sex. If he’s my lover, it’s a long standing arrangement. But who knows what I might have witnessed an hour before. I’m digging this sculpture, I tell him. I didn’t mean the sculpture, he says. I know, but I really like having it here. I like your paintings a lot better, he says. So my father didn’t win after all, I’m no lawyer, I’m a painter. And this too, he fondles my

40 S torytelling S uite S

Péter Ujházi: Nadap

Péter Ujházi: Árki maple | Árki juhar

Pál Gerzson: Spring image | Tavaszi kép

is vagyok már, talán el is múltam. A cicim viszont mintha nagyobb és feszesebb lenne. Megcsináltattam volna? Én, aki azt mondtam, soha nem fekszem kés alá? Dehát azt is mondtam, hogy nem fogom festeni a hajam.

Hol vagyok? Távolítsunk. Egy elegáns lakás, kellemes délutáni fény ömlik be az ablakon. Nem szól a tévé, nincs zene. Még mindig szeretem a csöndet. Mit keresek itt? Egyedül vagyok? Hol van András? Közelítsünk a kezemre. Ott a jegygyűrű az ujjamon. Megkönnyebbülök. Pásztázzunk körbe. A kanapén egy férfi táska. Biztos az övé. Túl nagy a rend, a tisztaság. Ez egy szálloda. Talán külföld, munka ügy. András sikeres üzletember lett, és elhozott magával. Miért ne lehetnék én is sikeres? Lehet, miattam vagyunk itt, de ha miattam vagyunk itt, az azt jelenti, hogy apám győzött. Jogász lettem, nem művész. Távolítsunk. Nézzünk ki az ablakon. Valahol Európában. Budapest is lehetne, ismerős utcakép, a házak, a fák, otthonos érzésem van tőlük, csak a nagy óriáskerék idegen. Pedig Budapest, látom a Bazilikát, sőt még a Parlament kupoláját is. Tehát Budapestnek is lesz óriáskereke, mint Londonnak. A nászutunkon Andrással felszálltunk rá, akkor derült ki, hogy Andrásnak tériszonya van, végig egy helyben ült, az arcát a kezébe temette, a hátát simogattam. Vajon lettek gyerekeink? Mindenesetre nem veszem elő a telefonomat és nem nézek róluk képeket. Ez persze nem jelent semmit. Ha negyvenéves vagyok, akkor már kamaszok is lehetnek. Két kamaszlány, akik örülnek, hogy a szüleik végre nincsenek otthon, mi pedig örülünk, hogy nem kell nézni az arcukon a világfájdalmat. Végre, felálltam. A nagy íróasztalhoz lépek, az ablak mellett álló bronzszobrot nézem. Egy almacsutka. Óvatosan megsimogatom az alma sima felületét és a harapásnyomokkal tűzdelt robosztus belsőt. Ádám és Éva almája, az elveszett paradicsom utolsó emléke. Vajon olyan ember leszek, akiknek akkor is eszébe fog jutni a bűnbeesés, vagy valami teljesen másra fogok gondolni?

41 M esélo lakosztályok

belly. My belly. Now that I notice it. And the breasts. I didn’t get a boob job, I’m pregnant! But where’s András? Zoom in on the hand. That’s not my wedding band, it’s got a stone in it. We always wanted to keep everything simple with András. Wedding with just the two witnesses, white summer dress, plain wedding band. So we must be through with András, and this is my new husband, I’m dyeing my hair, there’s a stone in my wedding ring and I’m pregnant at over forty. How did all this happen?

Well come on, let’s take another look! The man, my husband and father of my unborn child, puts his arm around me as I hold my belly, and we walk over to the bedroom, stopping to look at a blue painting. Stand right there, let me take a photo, he says, and I stop beside the painting, look into the camera, turn my head slightly to the left and smile. Did I paint that? My paintings used to be all dark, figurative, unsmiling women wearing heavy makeup, lonely girls staring far into space, hints of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, dreary color palette. Is my hair okay? It’s fine. Do I need to touch it up? No really, you’re great, it’s spontaneous. What do I do with my hands? Cross your arms. Isn’t that kind of aloof? Then hold your belly. But isn’t that too pregnant? Well, but you are pregnant, aren’t you? Yeah, but I don’t have to spell it out for a painting like that. I won’t show your hands then, okay?

The scene disperses, three minutes are up. I’m eating an apple, my husband has his arm around me. We watch the night lights of Budapest.

Na, hogy tetszik? Egy férfi hang. Nem Andrásé. Egy férfi köntösben jön ki a fürdőszobából. Magas, szőke, negyvenes férfi. Szemüveges. A szeretőm? Ki más lenne? Odamegyek hozzá, megpuszilom a száját, megölelem. Nincs heves csókolózás, szex. Ha a szeretőm, akkor ez már egy régebbi kapcsolat. De lehet, egy órával ezelőtt még mást láttam volna. Bejön ez a szobor, válaszolom neki. Nem a szoborra gondoltam. Tudom, de kifejezetten tetszik, hogy itt van. Nekem a te festményeid sokkal jobban tetszenek, mondja. Akkor mégsem apám nyert, nem lett belőlem jogász, festő vagyok. Meg ez itt, mondja, és megsimogatja a hasamat. A hasam. Most látom. A mellem. Nem csináltattam meg, hanem babát várok. De hol van András? Közelítsünk a kezemre. Ez nem az a jegygyűrű, ebben kő van. Andrással mindig azt beszéltük, hogy legyen minden a legegyszerűbb. Esküvő két tanúval, fehér nyári vászonruha, sima, vékony karikagyűrű. Tehát Andrással vége lett, új férjem van, aki mellett festem a hajamat, köves karikagyűrűt hordok és negyven fölött babát várok. Vajon mi történhetett?

Na, gyere, nézzük meg megint! A férfi, a férjem, leendő gyermekem apja átkarol, én a hasamat fogom, átmegyünk a hálószobába, megállunk egy kék festmény előtt. Állj ide, lefotózlak, mondja, én pedig beállok a kép mellé, a kamerába nézek, kicsit balra fordítom a fejemet és mosolygok. Ezt én festettem? Régen sötét, figuratív képeket alkottam, pengeszájú, mosoly nélküli nőket erős sminkben, távolba meredő magányos lányokat, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner stílusában, komor színekkel. Jó a hajam? Jó. Ne igazítsam meg? Nem kell, jó volt úgy spontán. És mit csináljak a kezemmel? Foghatod keresztbe. Az nem túl távolságtartó? Akkor fogd meg a hasad. Az meg nem túl kismamás? Kismama vagy, nem? Jó, de egy ilyen képhez nem biztos, hogy meg kell mutatni. Akkor nem lesz benne a kezed, jó? A kép eltűnik, letelt a három perc. Almát eszem, a férjem átkarol. Budapest éjszakai fényeit nézzük.

42 S torytelling S uite S

43 M esélo lakosztályok

Péter Jecza: Meditation II | Meditáció II.

Rita Halász (Budapest, 1980 - ) is an author, art historian and teacher. Her first novel, Mély levegő (Deep Breath), came out in October 2020 with JelenkorPress, and won the Margó Award before being shortlisted for the Libri Literary Award. The book is being adapted as a television series. Halász is now working on her second novel.

Halász Rita (Budapest, 1980 - ) író, művészettörténész, tanár. Első regénye Mély levegő címmel 2020 októberében (Jelenkor) jelent meg, amelyért 2021-ben Margó-díjat kapott és bekerült a Libri irodalmi díj tízes listájára. A tervek szerint filmsorozat készül belőle. Jelenleg második regényén dolgozik.

44 S torytelling S uite S

Attila Rajcsók: Smokey apple core | Füstös almacsutka

45 M esélo lakosztályok

Péter Paizs: Square | Négyzet

Péter Paizs: Square | Négyzet