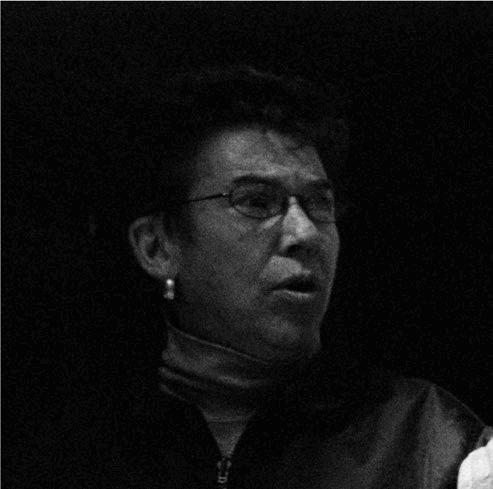

YORK HOLGER B I ERMANN

Vom Anspruch, das Chaos zu ordnen

Freddy Langer

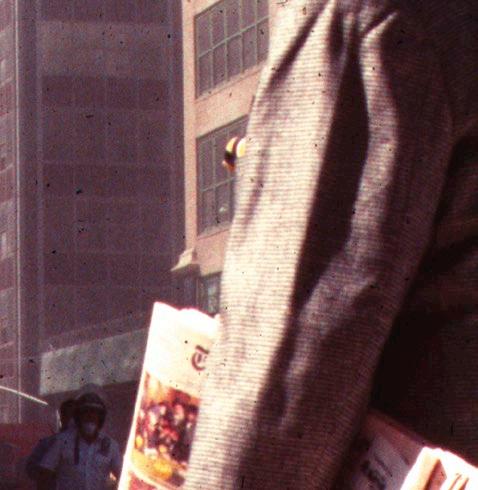

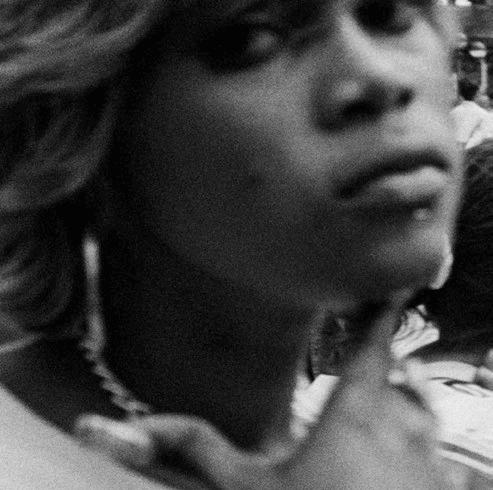

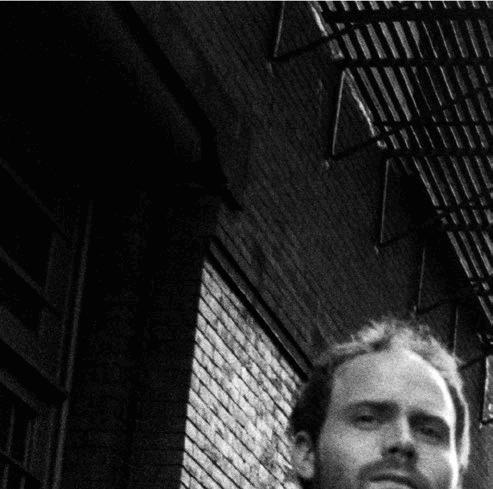

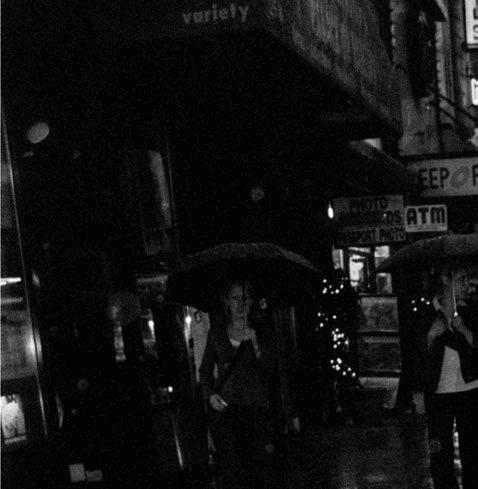

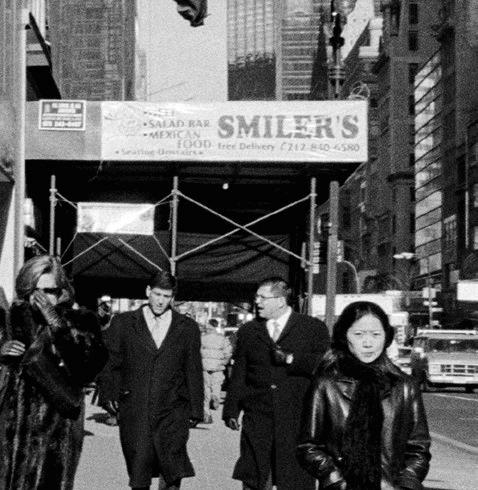

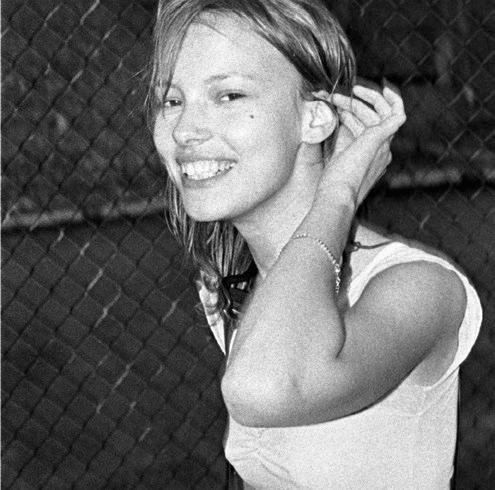

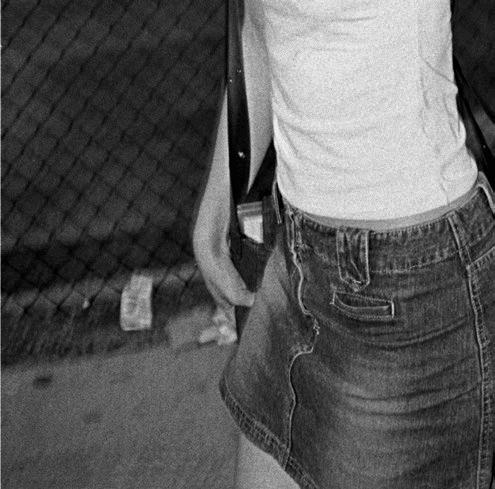

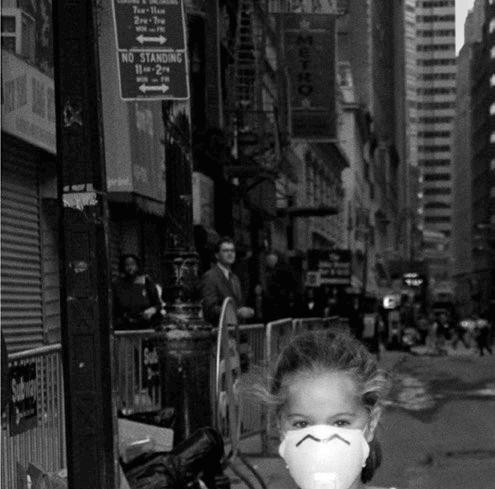

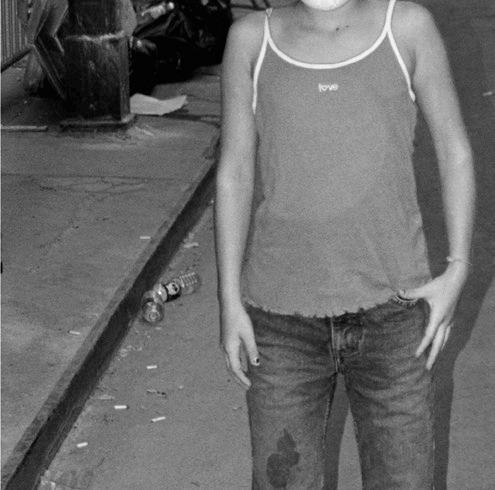

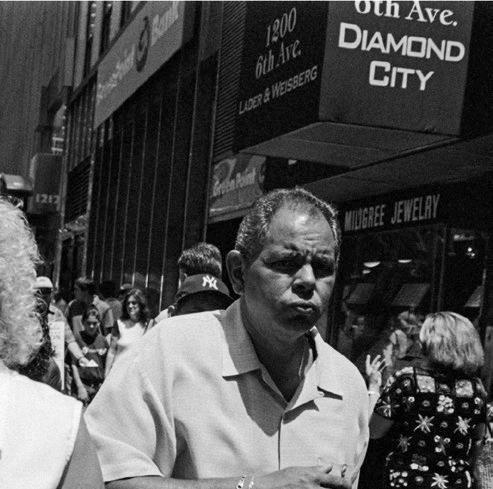

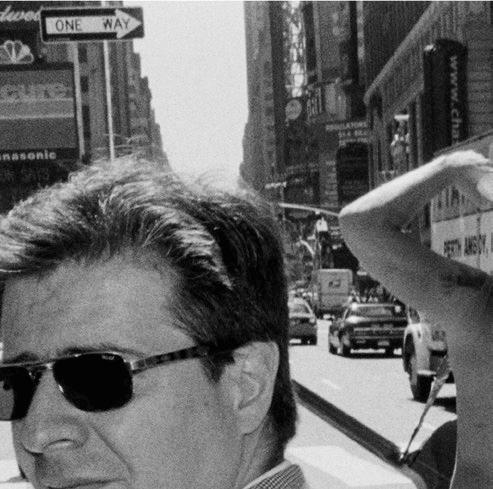

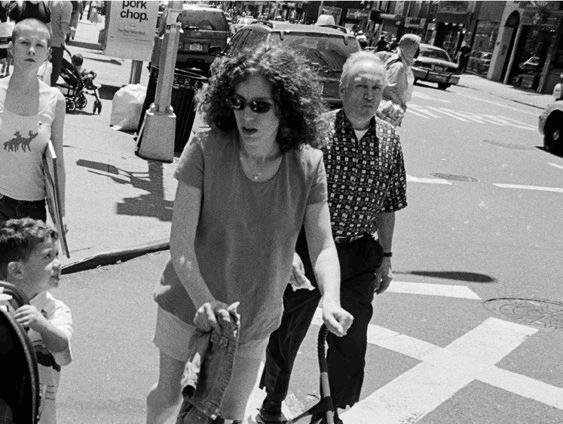

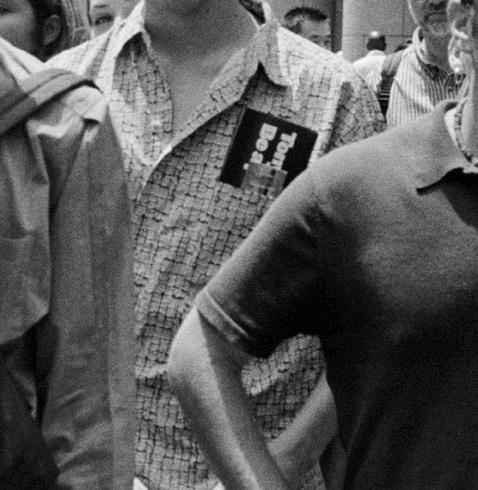

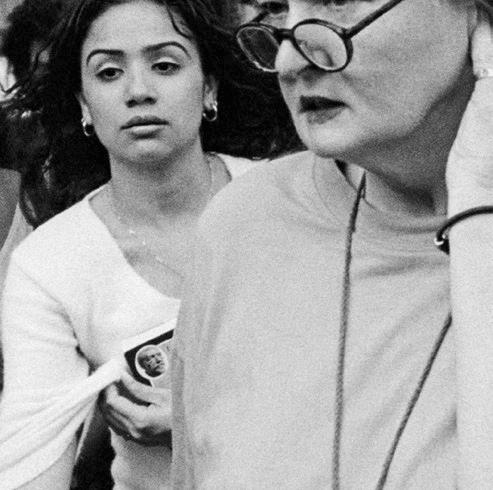

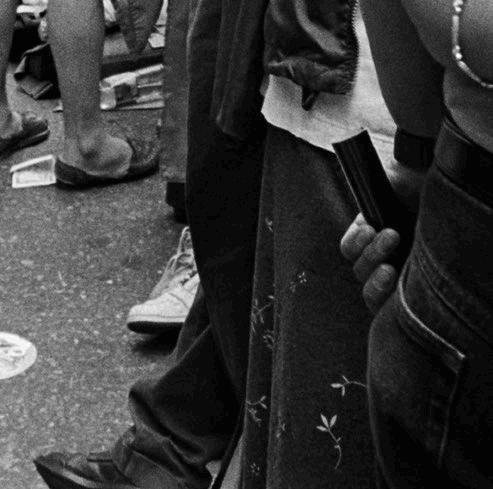

Luise sprang ihm sofort ins Auge. Blond. Jung. Frech. Gekleidet im ärmelfreien Hemdchen und einem Minirock. Über das Gesicht ein breites Strahlen, das ihn an die junge Frau mit dem Eis in der Hand erinnert haben mag, die Garry Winogrand mehr als ein halbes Jahrhundert zuvor aufgenommen hat, ebenfalls in New York. Wie man ja überhaupt in New Yorks Straßen kaum schöne Frauen betrachten kann, ohne augenblicklich an Garry Winogrand zu denken und an sein großartiges Buch « Women are Beautiful ».

Ob er sie ein paar Schritte begleiten dürfe, nur ein, zwei Blocks weit, fragte Holger Biermann, noch bevor er ihren Namen kannte und nicht ahnen konnte, dass sie nach New York gekommen war, ausgerechnet um sich bei einer Modell-Agentur vorzustellen. Mit den Augen habe er gefragt, sagt Biermann, und weil er in ihrem Blick ein charmant formuliertes Ja zu sehen meinte, nahm er das erste Foto auf. Im Gehen, ohne durch den Sucher zu schauen. Aber eben keineswegs ein zufälliger Schnappschuss. Klick. Da lachte sie noch ein wenig herzlicher, strich sie sich das Haar aus dem Gesicht, und Biermann löste noch einmal aus. Immer noch im Gehen. Klick. Es war ein herausgekitzelter Moment. Beide lachten, wechselten ein paar Sätze, beim Abschied rief sie ihm ihren Namen zu. Dann trennten sich die Wege. Und erst später, Tage später, als er die Kontaktstreifen seines SchwarzWeiß-Films mit der Lupe betrachtete und er das öffentliche Telefon bemerkte, das sich ins Bild dieses Sekundenflirts geschoben hatte, mag sich Holger Biermann geärgert haben, nicht nach ihrer Nummer gefragt zu haben.

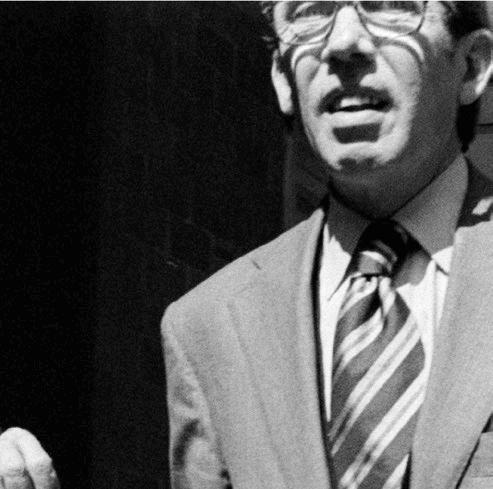

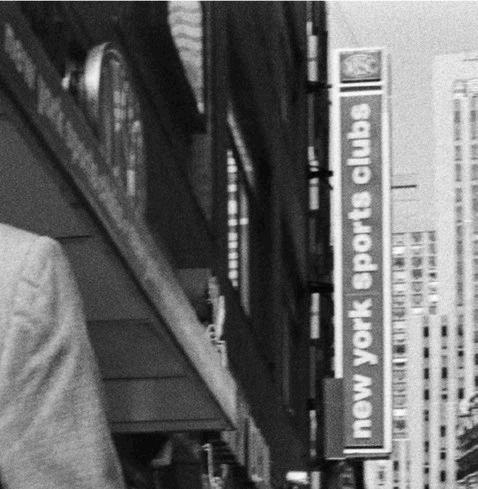

Zwanzig Jahre später ist es kaum noch vorstellbar, dass ein Straßenfotograf fremde Frauen ungestraft begleiten kann, um ein Bild aufzunehmen, und sei er noch so erfüllt von einem schamlosen Enthusiasmus; im Gegenteil. Schon vor Langem hatte ein New Yorker Bürgermeister erwägt, die Straßenfotografie in Manhattan zu verbieten. Und in Berlin musste vor einigen Jahren nach einem aufsehenerregenden Prozess das Plakat einer Ausstellung abgehängt werden, weil sich eine Passantin erkannt hatte – und nicht gefiel. Welche Motive also bleiben den Straßenfotografen, nicht nur um das Leben in all seinen Facetten zu dokumentieren, sondern, mehr noch, um den eigenen Platz in der Welt auszuloten? Denn Straßenfotografien, so hat Joel Meyerowitz, einer ihrer wichtigsten Vertreter, bei Gelegenheit erklärt, seien ja zuallererst Mittel der Selbstdarstellung. Der Fotograf versuche seine eigene Befindlichkeit in der Außenwelt gespiegelt wiederzufinden. « An einem Tag von Optimismus bestimmt, an einem anderen eher melancholisch gestimmt, suchten wir im Alltag nach Augenblicken, die unsere Gefühle wiedergaben. Streng genommen nahmen wir immer nur Selbstporträts auf. »

Es war der frühe Sommer 2002, als Holger Biermann das Bild von Luise aufgenommen hat, der jungen Frau in den trägerlosen Hemdchen und dem Minirock. Keine lustige, genaugenommen sogar eine bedrückende Zeit, wie er heute sagt. Denn noch immer stand die ganze Stadt unter Schock. Der Angriff vom 11. September auf die beiden Türme des World Trade Centers prägte nach wie vor das Denken und Fühlen. Prägte das Straßenbild im Süden Manhattans. Warum sollte sich in der Begegnung zweier junger Menschen in New York diese Spannung deshalb nicht zumindest einen Moment lang entladen. Straßenfotografie hier nicht als Selbstporträt, sondern als das in einer hundertfünfundzwanzigstel Sekunde gebannte Abbild eines Wunsches, einer Hoffnung.

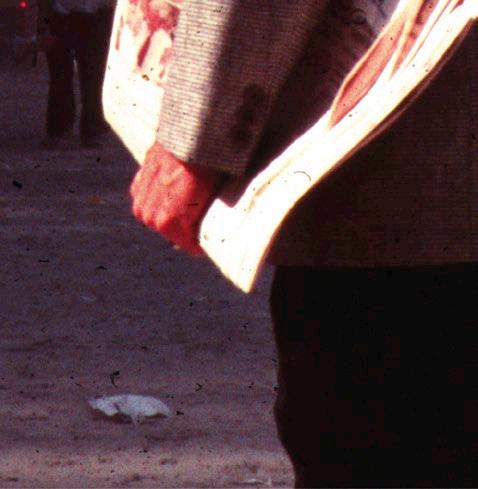

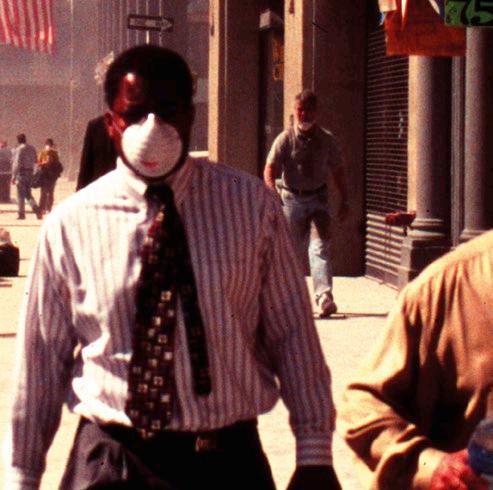

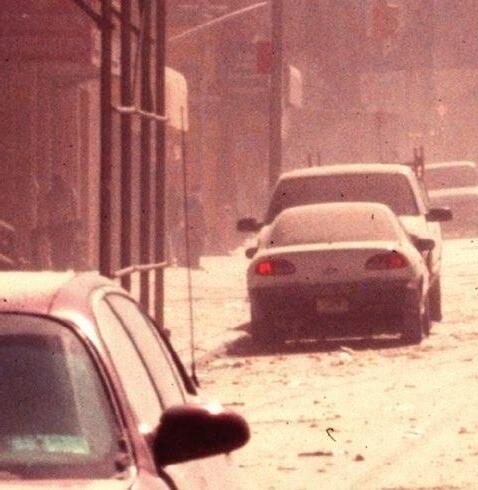

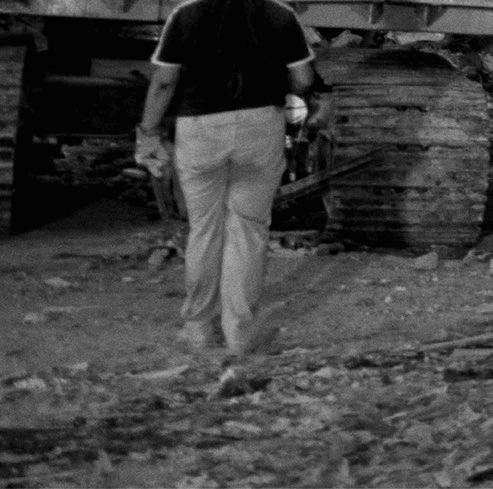

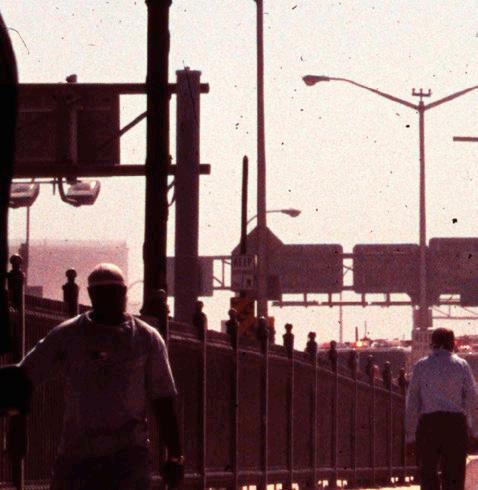

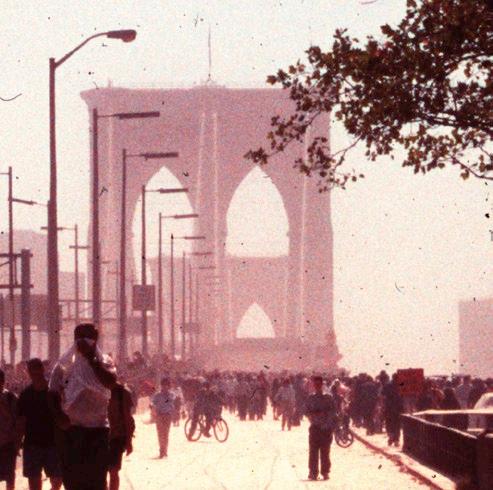

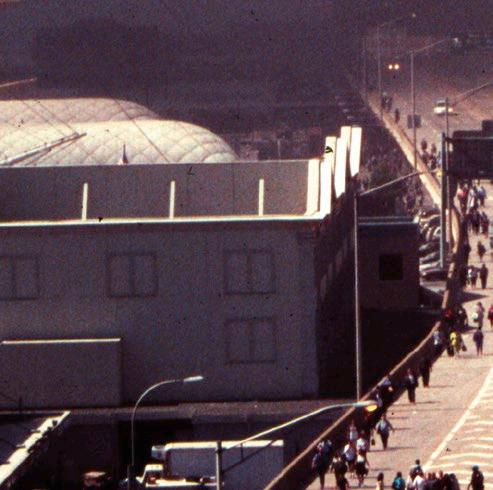

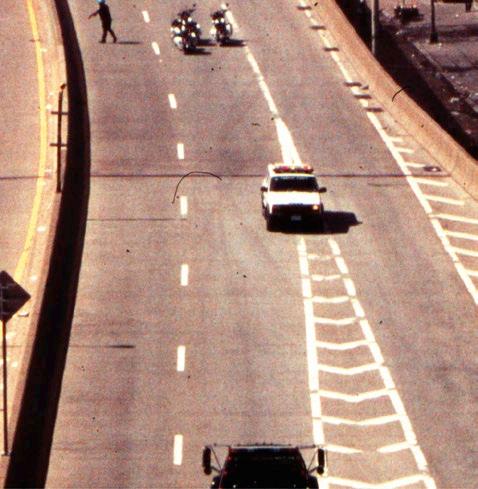

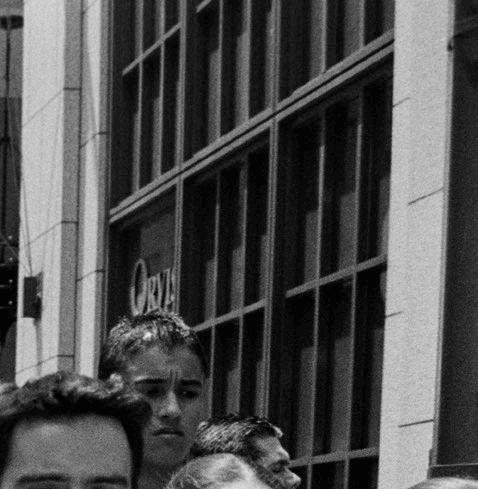

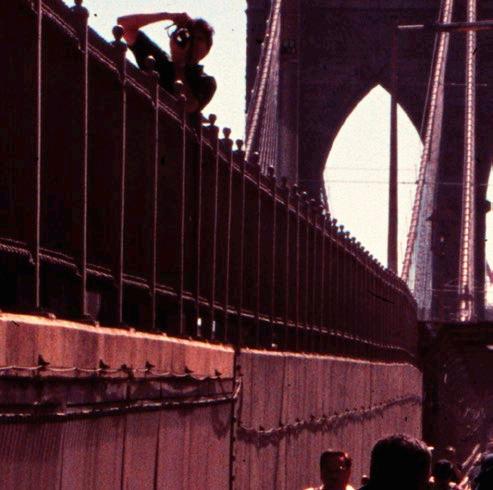

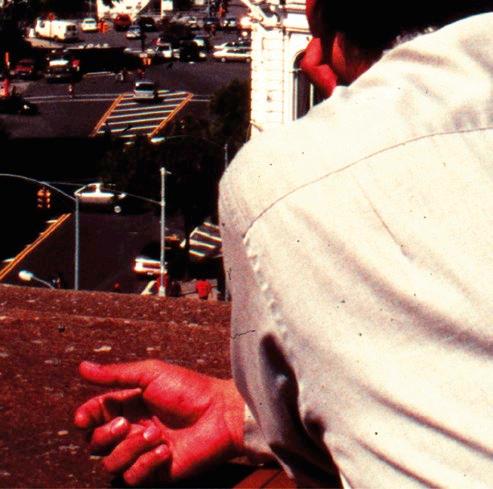

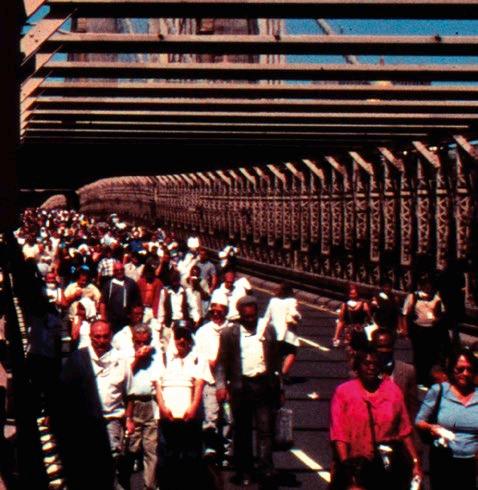

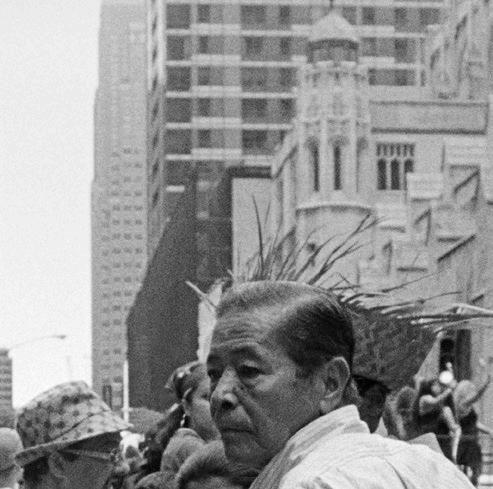

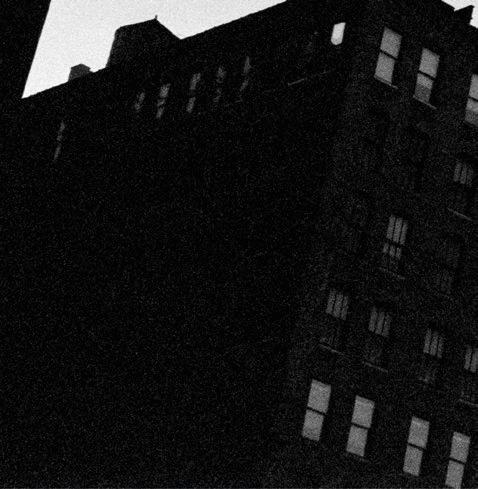

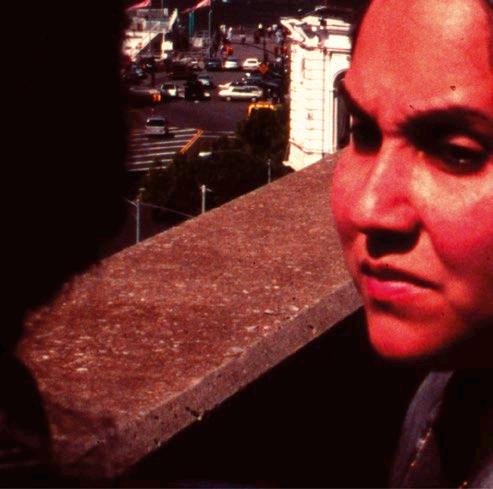

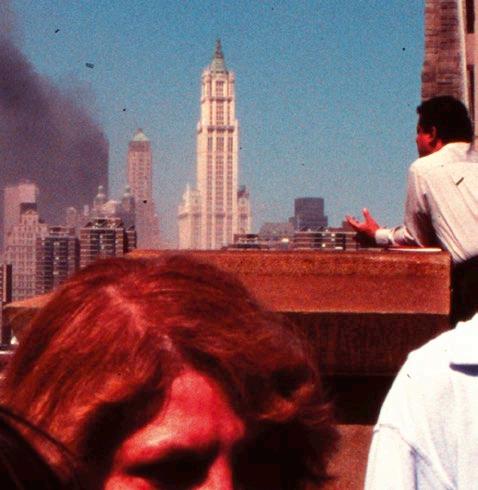

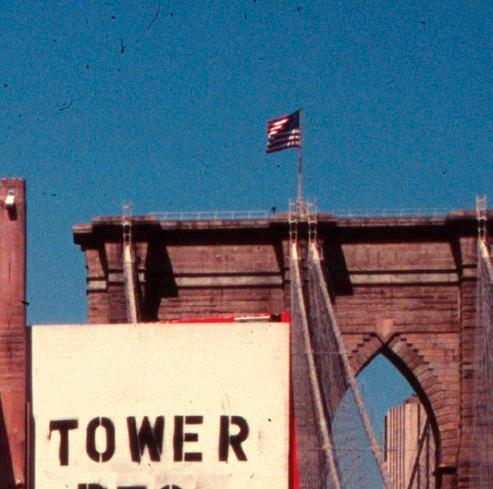

Holger Biermann war nur drei Blocks entfernt gewesen, als an dem strahlenden Spätsommermorgen zwei Flugzeuge in die mächtigen Türme rauschten, einst die höchsten Gebäude der Welt. Erst der entsetzliche Schlag, dann eine kreischende Menschenmenge, erinnert er sich, die sich vor den einstürzenden Häusern in Sicherheit brachte. Geistesgegenwärtig kaufte er im Vorübergehen in einem Convenience Store fünf Diafilme, während er mit zehntausend anderen Menschen den Stadtteil Richtung Brooklyn Bridge verließ. Immer ruhiger sei es geworden, als die Polizei begann, die Massen zu lenken, und irgendwann, sagt er, hätten alle geschwiegen, während hinter ihnen der Qualm als riesige Säule in den Himmel stieg. Holger Biermann hörte nicht mehr auf zu fotografieren und nahm Szenen auf, die mehr als nur den Alltag aus den Angeln hoben. Die Welt würde nicht mehr dieselbe sein. Und aus dem Flaneur, der stets einen Fotoapparat bei sich hatte, aber nur gelegentlich zur Kamera griff, wurde binnen eines Wimpernschlags ein Bildreporter.

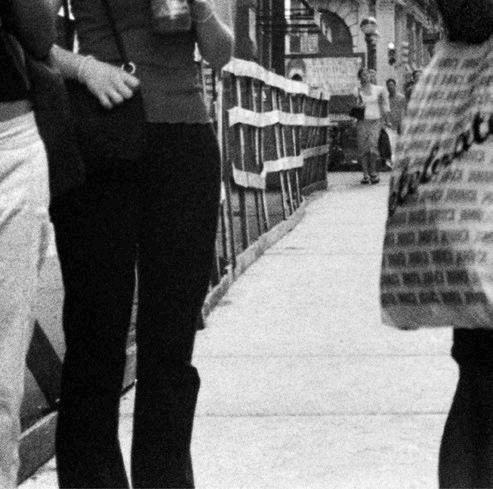

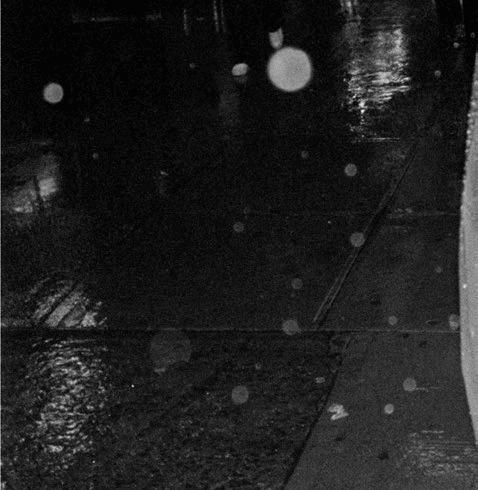

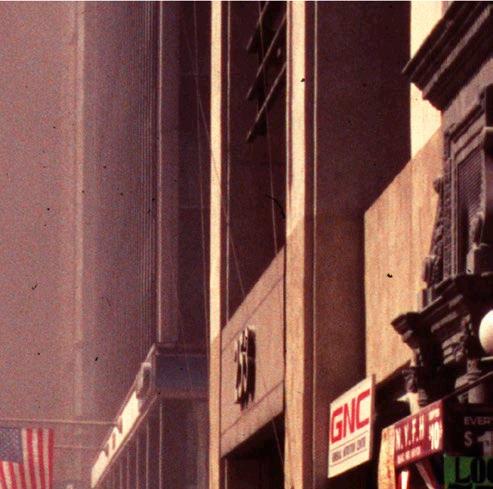

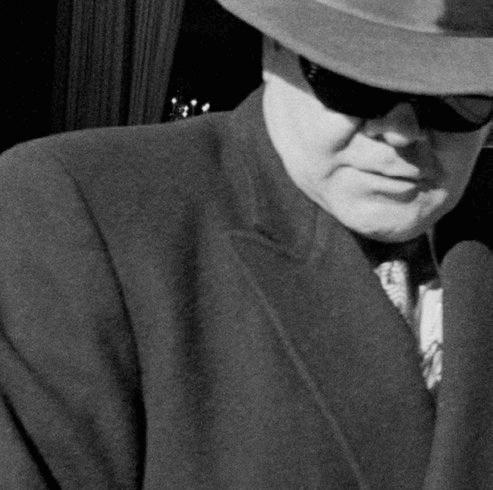

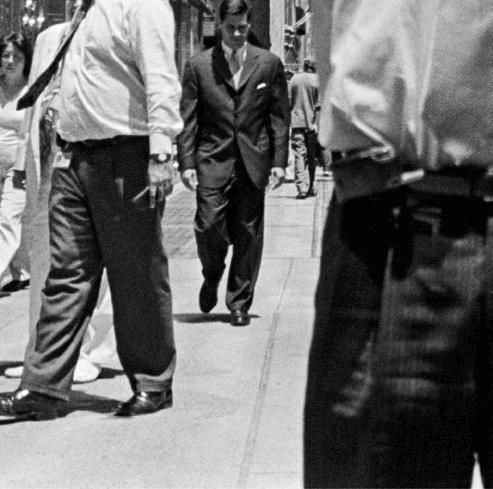

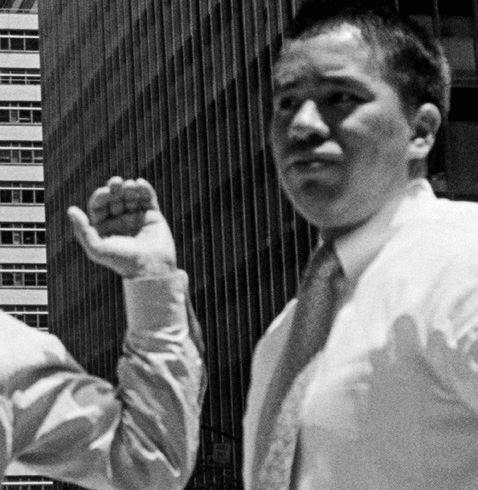

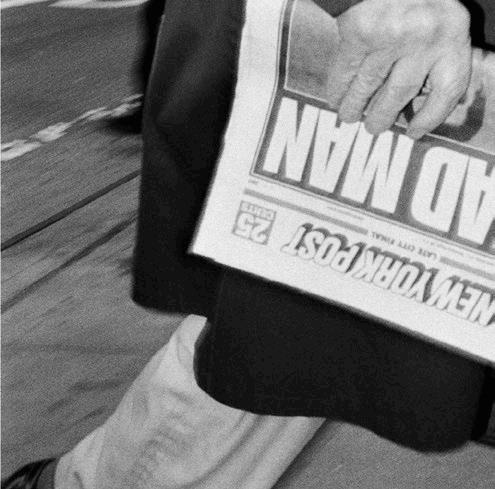

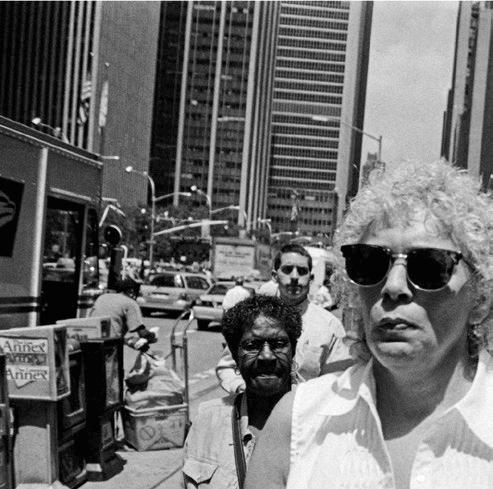

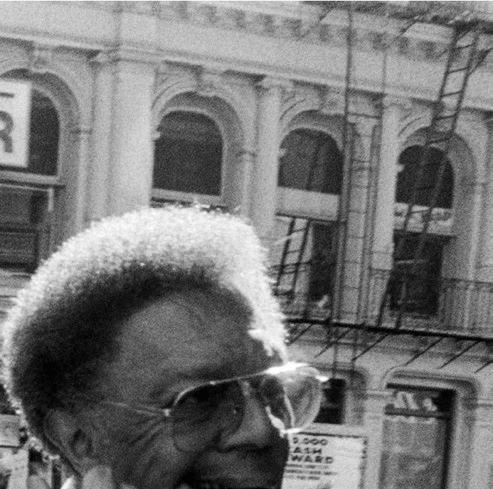

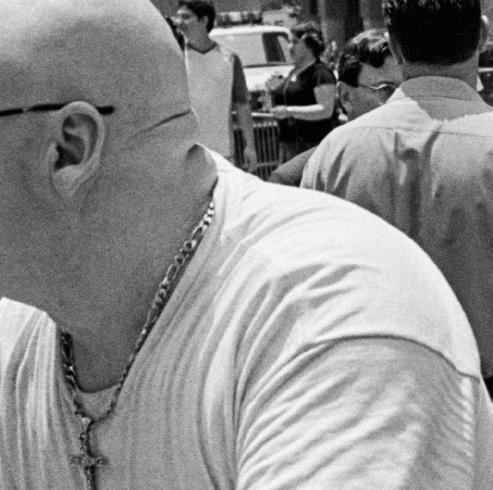

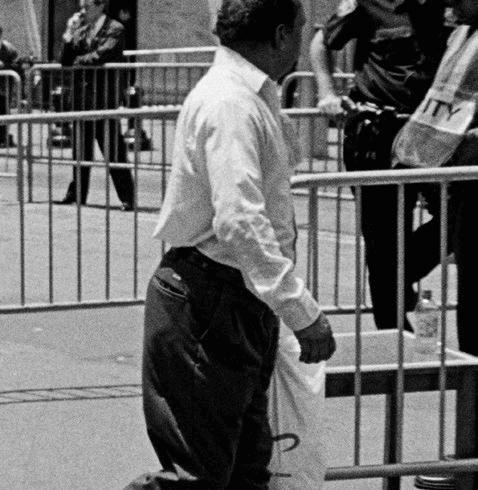

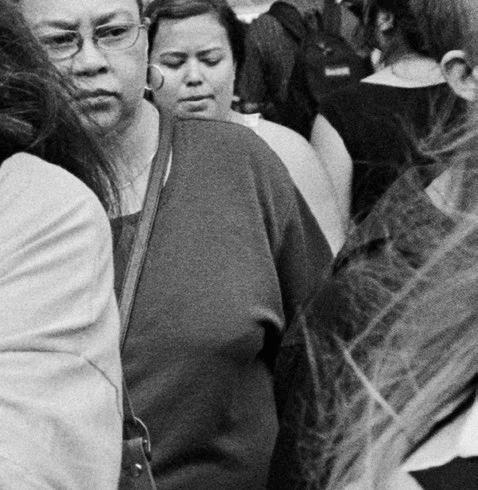

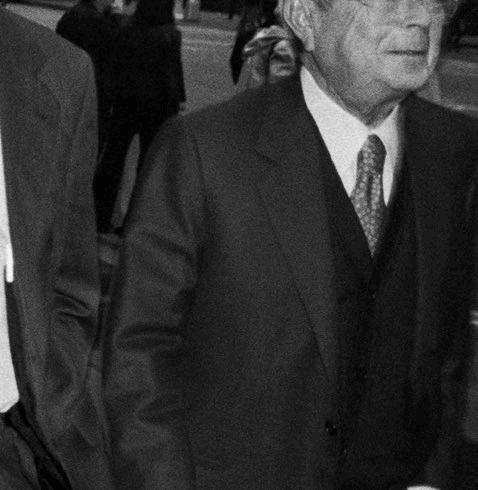

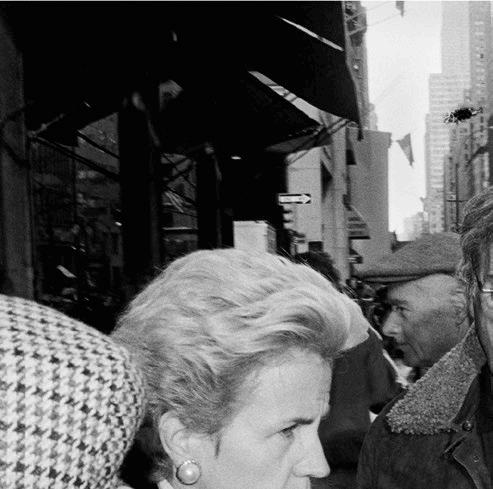

Ursprünglich war Holger Biermann als schreibender Journalist mit einem Praktikumsplatz bei einem deutschen Verlag nach New York gekommen, aber an diesem Tag begriff er, wieviel freier er sich mit dem Fotoapparat ausdrücken konnte. Und er verstand, was hinter der Redensart steckt, sich ein Bild von etwas zu machen. Der 11. September, sagt er, sei der Tag gewesen, an dem er seine Profession gefunden hatte. Statt, wie geplant, ein Jahr in New York zu verbringen, blieb er zweieinhalb Jahre dort. Tag für Tag wanderte er fortan durch die Stadt. Von der 137. Straße West, in der er wohnte, hinunter bis zur Fifth Avenue in Midtown, dort den Tag über auf und ab und abends weiter nach China Town, weil es dort das günstigste Essen gab. Was macht diese Stadt aus, fragte er sich. Wer sind diese Leute? Sind ihnen womöglich die Umwälzungen der Zeit ins Gesicht geschrieben? Dabei mangelte es Holger Biermann nicht an Chuzpe, sich ihnen in den Weg zu stellen, wenn er meinte, so tiefer hineinsteigen zu können in die Seele New Yorks.

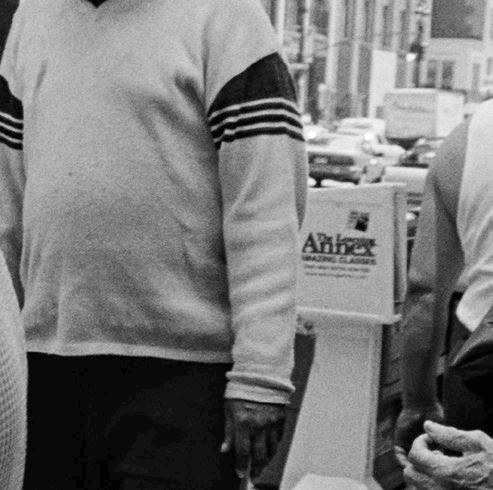

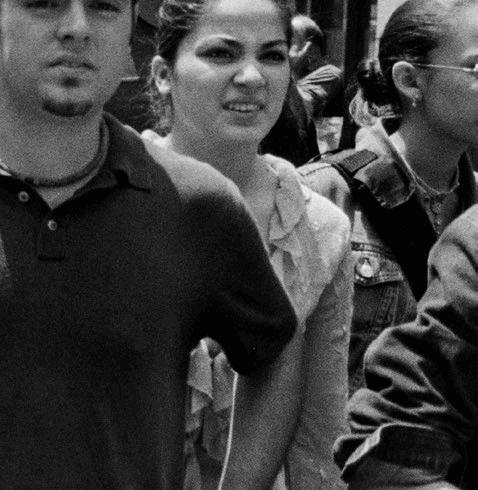

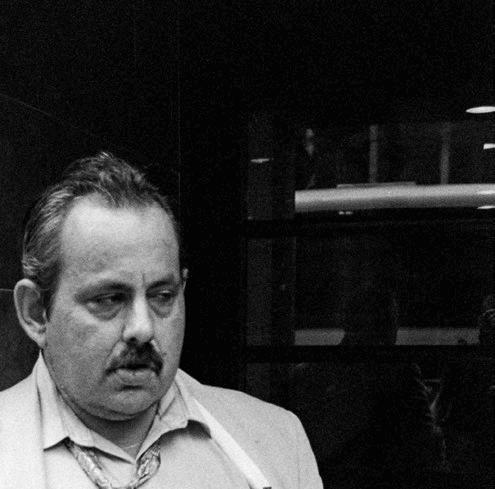

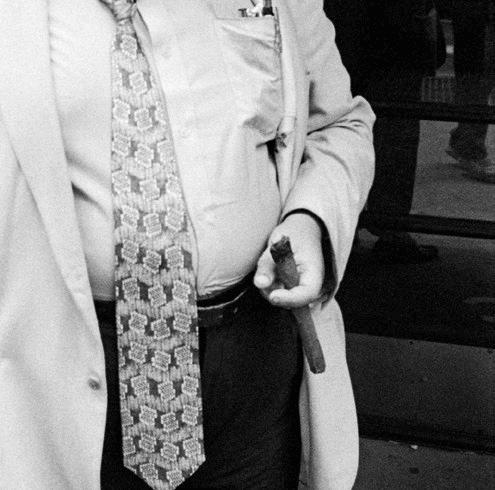

Um Sensationen war es ihm so wenig zu tun wie um ausgefallene Momente. Er suchte nach dem Gewöhnlichen und strebte dabei nach einer Klarheit im Bild, die den Alltag ein wenig verständlicher macht

und uns den Menschen einen Schritt näherbringt. Was er versuchte, war, Szenen herauszugreifen, in denen er mit einem Blick, einer Geste oder der zufälligen Begegnung zweier Passanten nicht nur das Leben einer bestimmten Straße in einer bestimmten Stadt bannt, sondern zugleich ein Sinnbild für das menschliche Verhalten schafft, also das, was gemeinhin unter dem Begriff conditio humana zusammengefasst wird.

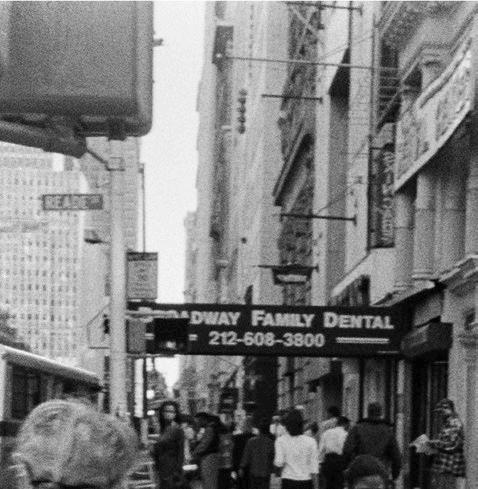

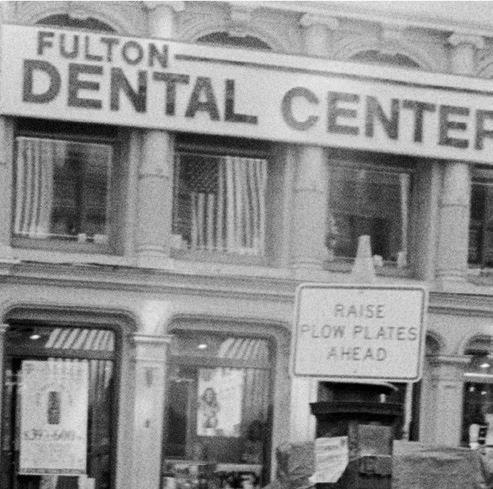

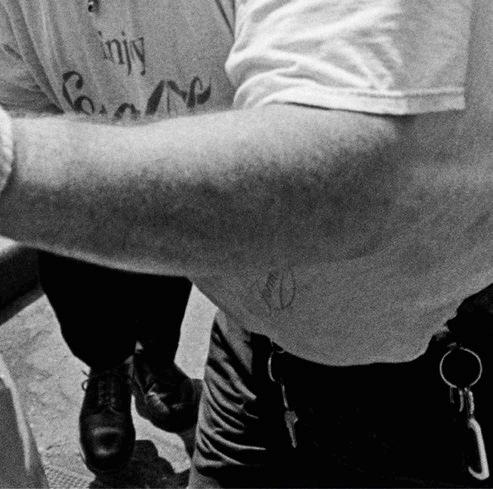

Einmal war ich dabei, als er fotografierte. Das war in Berlin. Und ich erlebte, wie er die Kamera ans Auge hob, auslöste und den Apparat am Gurt wieder nach unten fallen ließ, ohne einen Moment lang stehen zu bleiben oder wenigstens einen Schritt langsamer zu gehen. Das geschah, wie man sonst so gerne sagt, schneller, als man schauen kann. Er aber musste etwas gesehen haben, bevor er blitzschnell reagierte. Oder, wie er es formuliert: Die Welt hat ihm etwas zugeflüstert, das er in die Sprache eines Bilds übersetzt. Hier waren es drei Bauarbeiter, die in auffällig blauen Pullovern vor einem auffällig blauen Plakat den Bürgersteig der Friedrichstraße aufschachteten. Allerdings ist es gut möglich, dass Holger Biermann die Aufnahme gar nicht der Koinzidenz der Farben wegen gemacht hatte. Vielleicht interessierte ihn die Formation der drei Männer, womöglich sahen sie aus seiner Perspektive und durch die leichte Verzerrung des Weitwinkelobjektivs aus wie Tänzer auf einer Bühne, festgehalten inmitten ihrer fließenden Bewegungen. Vielleicht aber spiegelte auch irgendein Passant die Arbeiter. So wie auf seinen Bildern ja ganz oft Menschen miteinander oder mit den Objekten anderswo im Bild korrespondieren. Im besten Fall greift sich dann bei ihm ein Passant ausgerechnet vor dem Haus mit der Werbung des Fulton Dental Center in den Mund, als wolle er prüfen, ob sein Backenzahn noch ordentlich sitzt.

Natürlich steckt hinter dem Anspruch, das Chaos zu ordnen, immer auch der Wunsch, sich selbst zu sortieren. Sich selbst zu fragen, ob alles richtig sitzt. Und damit könnte sogar das neuerlich erwachte Interesse an der Straßenfotografie erklärt werden. In Magazinen mag die Gattung kaum noch eine Rolle spielen. Aber seit einigen Jahren rückt sie auf dem Kunstmarkt in den Fokus. Und auf dem Büchermarkt. Und mehr noch verbreitet sie sich über die sozialen Netzwerke. Instagram zählte noch vor kurzem unter dem Hashtag streetphotography mehr als 45 Millionen Beiträge, und aller juristischen Bedenken zum Trotz werden es täglich mehr – fast so, als könne man sich inmitten des Lebens Überfluss nur noch mit Bildern selbst vergewissern und in der Beobachtung der anderen seiner eigenen Position bewusst werden. Am Schnittpunkt von Schnappschuss, Reportage und Dokumentation wird die Straßenfotografie zu einer Art Anker. Dass unter dem Hashtag auch Tausende Selbstporträts stehen, könnte genau damit zu tun haben.

Viel Raum für Unerwartetes

Holger Biermann

Es fiel mir lange schwer, über meine Erlebnisse in New York zu schreiben. « Wer Bücher hinterläßt wird siebenmal in Folge als Esel wiedergeboren », hab ich mal gelesen. Worte und Bilder, so hieß es da, sind nur Finger, die auf den Mond zeigen. Wer auf die Finger achtet, wird den Mond, also das Wesentliche, nicht sehen. Das Wesentliche –20 Jahre nach meiner Rückkehr glaube ich zu erkennen, was das Wesentliche meiner Zeit zwischen 2001 und 2003 in New York war. Es war diese unglaubliche Positivität. Egal wohin ich kam, egal wen ich traf – fast immer begegneten mir die Menschen mit Interesse und Offenheit. « Tu, was du gerne tust », « Alles ist möglich » und « Du wirst es schaffen », erzählten mir die Bewohner an jeder Ecke und es hatte eine unglaubliche Kraft. Es war dieser Spirit, der New York für mich besonders machte.

Ich kam als schreibender Journalist in die Metropole. Ich war 27, hatte die Ausbildung gerade beendet und hoffte, nun die große weite Welt zu sehen. Ausgestattet mit einem Stipendium der Carl-Duisburg-Gesellschaft wollte ich ein Jahr bleiben und für zwei deutsche Medien die Stadt erkunden. Auf dem Weg zur Arbeit stieg ich dabei einmal versehentlich im dritten statt im vierten Stock aus dem Fahrstuhl. Unerwartet stand ich plötzlich in den Räumen von Steps, einem Tanzstudio, das hervorragende Broadway-Tänzer ausbildet. Schon im Eingangsbereich saß ein Dutzend junger Leute auf dem Boden und dehnte sich. Interessiert machte ich einen Schritt vor, schaute um die Ecke in einen Saal mit Spiegelwänden und Ballettstangen – und wurde sofort mit einem Lächeln angesprochen. Ob ich auch tanzen wolle? Das sei gar kein Problem! Und es sei sehr schön, daß ich hier sei. Ich bekam eine kleine Führung und Info-Material in die Hand gedrückt. So etwas passierte ständig in New York. Visitenkarten – ich bekam hunderte und begann sie zu sammeln.

Auch an meine Ankunft am 28. März erinnere ich mich gut. Schwer bepackt vom Flughafen kommend stand ich plötzlich verloren im schier unendlichen Tunnelsystem der U-Bahn an der 42. Straße. Ich suchte den « Local 1 train ». In der einen Hand den großen Rollkoffer, in der anderen den Laptop, dazu einen Rucksack und eine über die Schulter gehängte Reisetasche. Bewegen war schwierig in diesem Zustand und ich wußte wirklich nicht wo entlang – auch weil von allen Seiten Menschen auf mich zuströmten. Unglaublich, welch ein Durcheinander hier unten herrschte und doch wurde ich gleich erkannt und angesprochen: « Ahh, schaut euch den an: Crocodile Dundee hat sich verirrt. Sie brauchen Hilfe? » So fand ich meinen Weg.

Ich kam zur 103. Straße und Central Park, wo ich zum Auftakt für 500 Dollar einen Monat im Atelier des deutschen Malers Laurentz Thurn wohnen konnte, der gerade die Heimat besuchte. Über Freunde hatte ich von dieser Möglichkeit gehört. An der Elbe in Hamburg übergab er

mir Tage vor dem Abflug den Schlüssel am Tresen einer düsteren Raucherkneipe und trug mir auf, ihm als Geschenk eine Familienpackung mit Likör gefüllter Pralinen mitzubringen: « In New York gibt es kein Mon Chéri. » Ich verstand nicht, was er meinte, sagte aber zu und lief mit dem Schlüssel überglücklich hinunter zur Elbe, wo ich erstmal einen Glückspfennig mit der linken Hand über die rechte Schulter ins Wasser warf. Nicht, dass ich abergläubisch gewesen wäre, aber schaden konnte es auch nicht. So vorbereitet stand ich also an diesem ersten Abend in New York auf den Stufen meiner Unterkunft und probierte den Schlüssel: er paßte! Auch oben kam ich auf Anhieb ins Atelier.

Am nächsten Morgen wurde ich von gurrenden Tauben geweckt. Vor dem verhangenen Fenster schien die Sonne. Es dauerte einen kleinen Moment bis mir auf meiner Pritsche klar wurde, wo ich eigentlich war. Über mir hing ein riesiges Ölgemälde, auf dem drei « Harlem Guys » portraitiert waren. Auf dem farbverschmierten Boden standen überall Farbtöpfe, Tuben und Rahmen in verschiedensten Größen. Daneben volle Aschenbecher und Musikkassetten, Blöcke und Skizzen, und auch in den Regalen war neben den Gläsern mit Pinseln alles Mögliche zu finden. Es roch stark nach Terpentin, aber ich mochte den Kosmos dieser Bilder-Höhle und zog von hier begeistert mit der Kamera los, um New York zu entdecken. Ich ging runter zum Central Park und durchquerte ihn an diesem leuchtenden Frühlingstag abseits der Wege so frei es ging einmal komplett durch die Mitte bis hinunter zur 59. Straße. So erwanderte ich mir Manhattan über die Monate Stück für Stück, um abends erschöpft ins Bett zu fallen.

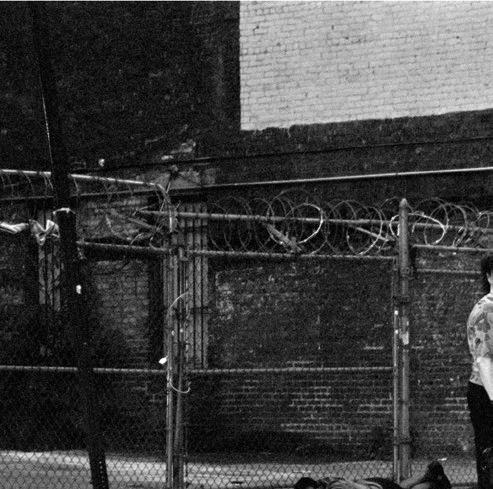

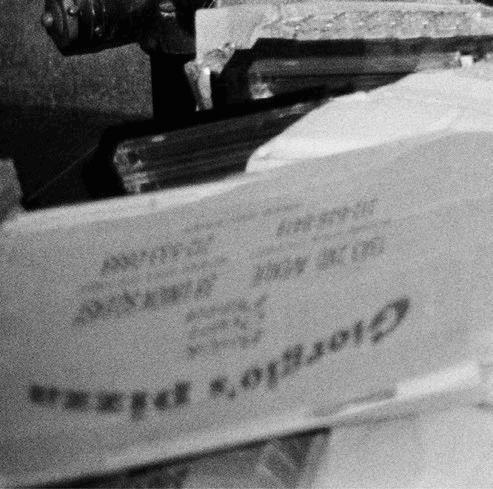

Ich hatte doch keine Ahnung. Einmal zum Beispiel bestellte ich ganz naiv eine Pizza – und bekam eine tischgroße statt nur ein Stück zum Mitnehmen. Ich aß reichlich davon, bevor ich die übrigen Zweidrittel im Pappkarton zurück in die Küche stellte. Als ich am nächsten Morgen erneut einen Blick auf den belegten Hefeteig warf war er über und über mit Kakerlaken besät. So vieles war neu. Ich erlebte talentierte Tenöre, die zur Gäste-Unterhaltung in Restaurants auftraten, besuchte eine vereinsamte Millionärin, die mich zum Lunch in ihr Penthouse lud, sah Obdachlose sich in der U-Bahn die Zähne putzten. Es gab sogar ein Lokal, wo der Wein umsonst ausgeschenkt wurde. Stets galt es Unerwartetes zu erwarten. Nur dass New York so besonders gefährlich sei, empfand ich lange nicht. Doch man hatte mich gewarnt. Für alle Fälle sollte ich immer einen Fünf-Dollar-Schein extra in die Hosentasche stecken, was ich tat und was sich auszahlte. Auf einer meiner Entdeckungstouren durch Harlem erschien plötzlich ein junger Fahrradfahrer auf meiner Höhe, begann weiterrollend ein Gespräch und hielt mir plötzlich ein Messer an die Seite. « Gib mir deine Uhr », sagte er ruhig. Ohne das Portemonaie zu zücken gab ich ihm die Fünf-Dollar-Note und weg war er.

Genauso unerwartet erlebte ich die Anschläge vom 11. September. Ich war inzwischen zweimal umgezogen – am Ende waren es sie-

ben Wohnungswechsel in 28 Monaten – und bewohnte oben in Spanish Harlem an der 137. Straße und Broadway ein winziges WG-Zimmer mit Gitterstäben vor dem Fenster. Die dafür fälligen 600 Dollar musste ich stets im Umschlag zum ersten des Monats unter einer Nachbartür durchschieben. Wer dort wohnte, wußte ich nicht. Der Zufall wollte es, daß ich am Morgen des 11. ganz früh in die Redaktion ging, um mit dem Chefredakteur in Ruhe über mögliche Geschichten zu sprechen.

Ein halbes Jahr war seit meiner Ankunft vergangen und ich wollte mich stärker einbringen. Daß irgendetwas passiert war, spürte ich schon auf dem Weg in der U-Bahn. Im Waggon war die Stimmung so ernst und die Leute tuschelten. In der Redaktion sagten sie, es habe einen Unfall am World Trade Center gegeben. Ein Flugzeug sei verunglückt. Im Juli 1945 war so etwas schon einmal passiert. Damals flog ein unbewaffneter B-25-Bomber bei dichtem Nebel versehentlich ins Empire State Building. Ich sollte mal hingehen und mir das ansehen. Also machte ich kehrt und zog wieder los.

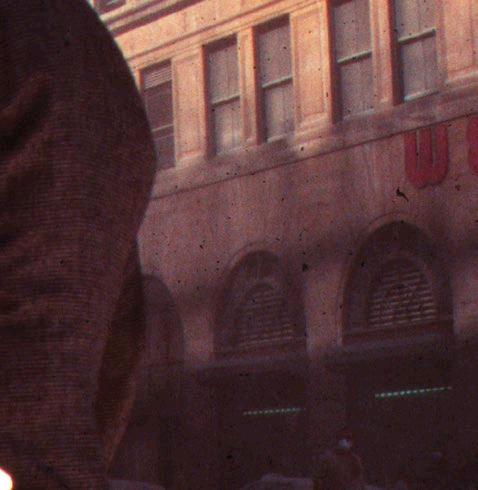

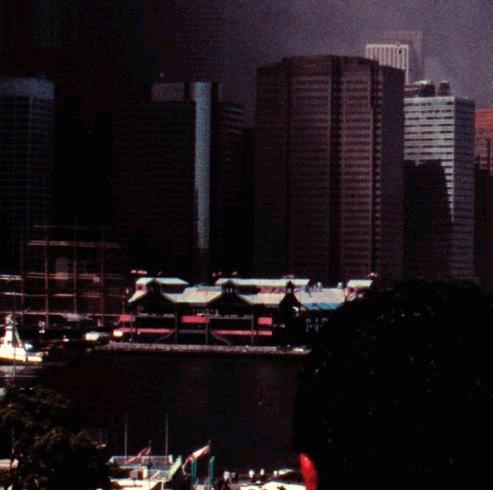

Mit der U-Bahn fuhr ich runter, bis der Zug an der 18. plötzlich stoppte. Über Lautsprecheranlage kam die Durchsage, dass der gesamte Verkehr aufgrund technischer Störungen eingestellt sei. Ich stieg die Treppen wieder hoch und lief zu Fuß gen Süden. Ich kannte die Strecke. Die Twin Towers hatte ich vor Wochen schon mal besucht. Am letzten Montag im Mai, Memorial Day, fuhr ich allein hinauf auf die Besucherterrasse im 110. Stock und schaute runter auf die Stadt bei Nacht. Ein großartiger Anblick: Ich sah die vielen Wege und Unendlichkeit in alle Richtungen. Danach nutze ich noch die Gelegenheit, um von dort einen Licht-Gruß ins All zu senden – ein Service, der umsonst angeboten wurde. Ich schrieb « Danke Sonne », da mir nichts Besseres einfiel. Und auch jetzt, als ich kurze Zeit später im Gehen das World Trade Center in der Ferne erkannte, fehlten mir die Worte. Ein Turm war gefallen, der andere brannte wie eine Fackel mit enormem Rauch. Mir war klar, daß ich eigentlich hätte umdrehen können und ich wundere mich heute, daß ich es nicht tat. Stattdessen lief ich weiter an diesem wolkenlosen Spätsommertag ohne Wind. Eine akute Gefahr meinte ich nicht zu erkennen. Was genau war überhaupt passiert?

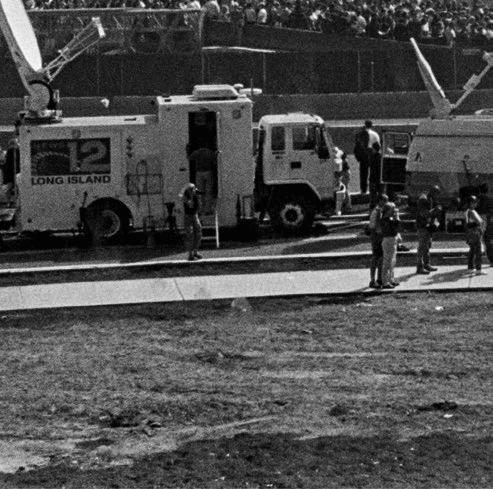

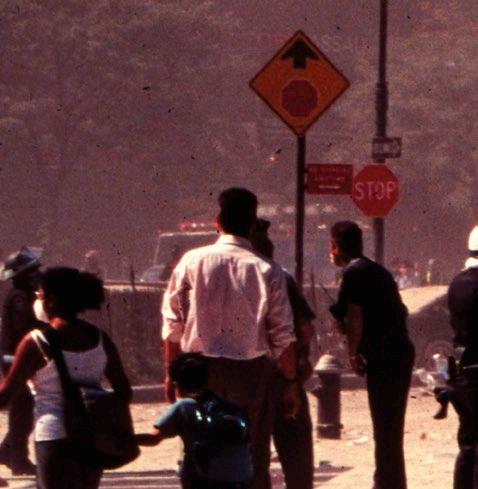

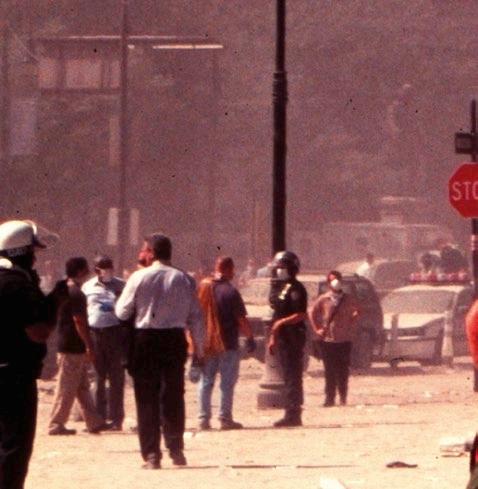

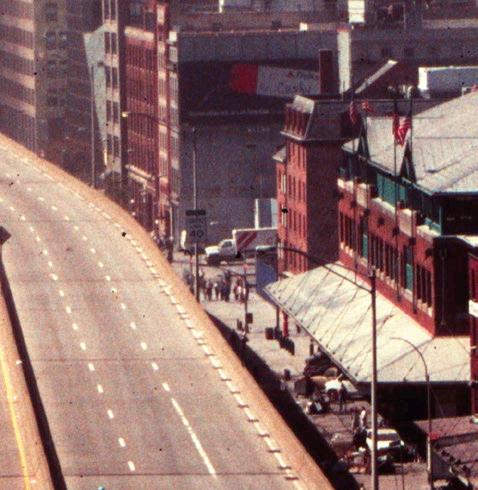

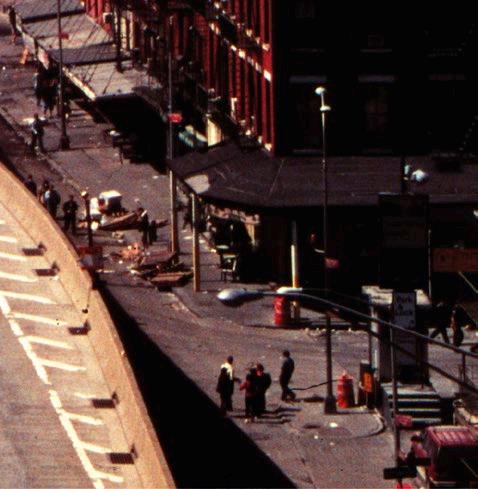

Überall standen Leute auf der Straße, fassungslos schweigend oder am Telefon. Auch Autos fuhren keine mehr, nur die Rettungswagen peitschten vorbei. Mit meinem Presseausweis kam ich weiter unten problemlos durch die Polizeisperre. Ich ging und ging bis ich – in diesem Moment zwischen zwei Blocks – das laute Aufschreien der Passanten hörte. Der zweite Turm stürzte und kurz darauf stand eine enorme Staubwolke in den Straßen von Downtown. Da erst wachte ich auf, zog mein T-Shirt über die Nase und wollte raus. Aber wie? Und wo war ich? Ich bewegte mich durch den Nebel vorbei an Polizisten, die an ihren Autos standen, vorbei an News-Fotografen, die im Laufschritt die Straße kreuzten. Ich sah völlig erschöpfte Feuerwehrleute mir entgegen kommen und dazwischen immer wieder frisch geföhnte

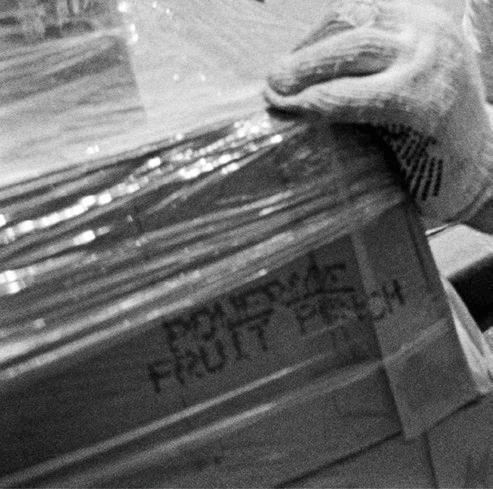

Passanten auf dem Weg zur Arbeit? Es schien so absurd – und ich merkte, daß ich zwar wie immer in New York die Kamera dabei, aber keinen Film mehr hatte. Dass ich an einem Deli an der Ecke kurz darauf wirklich fünf Rollen Farbfilm fand, empfand ich als kleines Wunder.

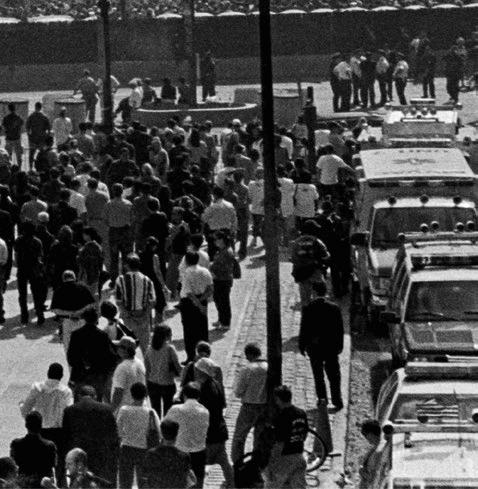

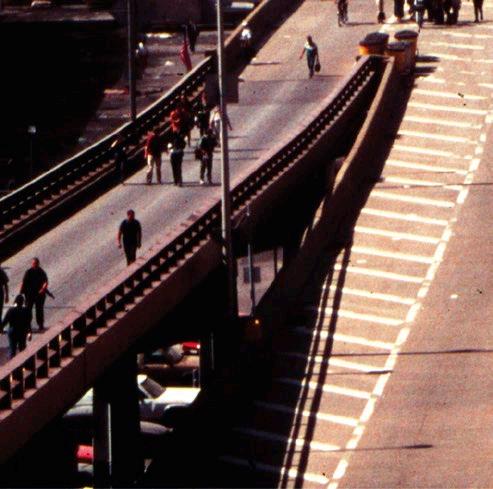

So begann ich zu fotografieren, während ich Downtown wie Zehntausend andere langsam und von Polizisten geleitet über die Brooklyn Bridge verließ. Wir gingen mehrheitlich schweigend, während hinter uns die enorme Rauchsäule stand. Hier und dort hörte ich Sätze wie « Ein Anschlag auch in Washington » oder « Das gibt Krieg ». Aber sicher wußte ich nichts wie die meisten. Das Internet war abgeschaltet und man konnte niemanden erreichen. Auch die U-Bahn stand weiter still und so entschied ich mich über die nahe gelegene Manhattan Bridge ins Zentrum zurückzulaufen. Ich kam noch einmal in die Nähe von Ground Zero und sah das Haus World Trade Center 7 in sich zusammenfallen. Dann machte ich mich auf den Weg nach oben. Ab der 14. Straße waren die Café-Terrassen voll besetzt. Es schien als sei der halbe Stadtteil auf den Beinen, um über das Unglaubliche zu reden. Am Times Square machte auch ich eine Pause und las auf den großen News-Laufbändern die Schlagzeilen. Da erst merkte ich, daß ich voller Staub war und meine Haare komplett weiß. Auweia, ging mir durch den Kopf, was habe ich eingeatmet?

Zu Hause angekommen, empfingen mich meine mexikanischen Mitbewohnerinnen mit furchtbaren Bibelstellen, die sie zitierten. Ich spürte tiefe Ängste und träumte in der Nacht von einer Atombombe, die in New York explodiert. Schweißgebadet wachte ich auf. Mitarbeiter der Redaktion waren vorübergehend sogar nach Upstate New York geflüchtet und kehrten erst Tage später nach Manhattan zurück. Auch der besondere Geruch, der nach dem Anschlag wochenlang über der Stadt lag und von Downtown bis weit über die 72. Straße zu riechen war irritierte mich immer wieder. Ebenso wie die Kampfflugzeuge, die eine Zeitlang über Manhattan patrouillierten und all die US-Flaggen, die plötzlich gehisst wurden. Der Anschlag veränderte die Stimmung. In der U-Bahn machten Halbstarke plötzlich älteren Damen Platz. Paare, die sich gerade getrennt hatten, sah man herzlich vereint. « United we stand », hieß der plakatierte Slogan der Stunde. Und wirklich rückten die New Yorker für den aufmerksamen Beobachter eine gewisse Zeitlang näher zusammen.

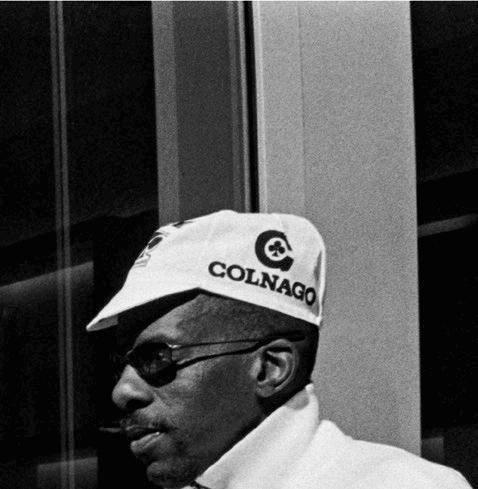

Ich fotografierte jetzt. Und je intensiver ich fotografierte, desto mehr lernte ich Fotografen und Künstler kennen, die mich ans International Center of Photography brachten. Ab dem Frühjahr 2002 arbeitete ich dort als Teacher Assistant. Ich lernte Filme entwickeln, entdeckte die Fotobücher von Garry Winogrand und Robert Frank und kam in Kontakt mit Gleichgesinnten. Ich wusste ja gar nicht, dass so etwas wie Straßenfotografie als Kunstform überhaupt existierte. Jetzt aber wollte ich so lang wie möglich bleiben und diese Zeit, die so schwierig und so frei für mich war, mit der Kamera beschreiben. Dafür gab

ich all mein Erspartes. Und New York schenkte mir perfekte Bedingungen: Das südliche Licht, die intensiven Farben, Menschen aller Kulturen auf engstem Raum vor einer über Jahrhunderte gewachsenen Kulisse. Ohne diesen Anfang wäre ich nicht Fotograf geworden. Manchmal verwandeln sich furchtbare Dinge in ungeahnte Möglichkeiten zu wachsen.

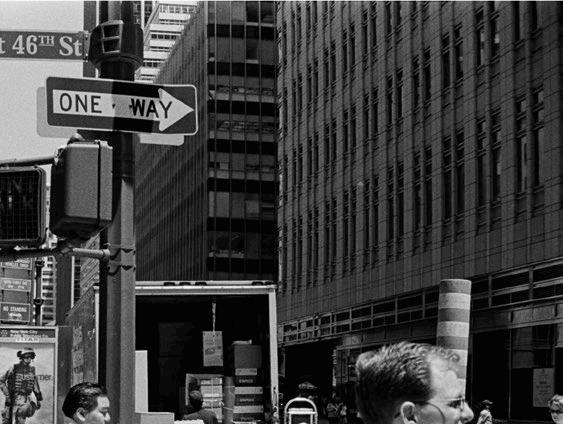

Wie ein Fisch zog ich in den nächsten Monaten den Broadway runter und wieder rauf, jagte durch die Diamantenstraße, die 47., und rüber zur Grand Central Station. Wie im Rausch stand ich oft fotografierend in der Rushhour an der 34. und immer öfter traf ich Leute wieder. Ich wurde nach dem Weg gefragt. Überraschungen warteten überall: Im März 2002 winkte mir Michael Jackson auf der 5th Avenue in die Kamera, bevor er als Trauzeuge für Liza Minnelli auftrat. Am ICP beauftragte mich eine Angestellte der Deutschen Bank Aktfotos von ihr zu machen, die sie zu Weihnachten ihrem Mann schenkte. Und eine Freundin übertrug mir sogar ihr Praktikum bei der Photoagentur Magnum, das sie aus terminlichen Gründen nicht wahrnehmen konnte. Wenn ich eine Pause oder Weite brauchte, verschwand ich einfach im nahen Central Park oder nahm den « N train » ans Meer nach Coney Island. Für Momente war es wie im Traum und ich träumte nun oft auf Englisch.

Kurz vor meinem Abschied am 17. Juli 2003 fand ich sogar noch einen Job bei einer kleinen deutschsprachigen Zeitung. Ich hätte bleiben und fünf Tage pro Woche in die Redaktion gehen können – doch ich ließ es sein. Stattdessen entschied ich mich mit Hilfe meines Freundes Patrick Becker am ICP zwei Portfolios zu drucken – eines mit Straßen-, eines mit Fashion-Bildern – und mir ein Rückflugticket zu kaufen. Als ich es hatte, saß ich auf den Stufen der Public Library und weinte. Ich verpackte alle Negative in zwei große Kartons, die ich zu meinen Eltern schickte, und verließ New York ohne Verabschiedung. Ich fotografierte bis zum Flughafen, bis zum Einstieg in den Flieger und war seither nicht mehr vor Ort. Das heißt, eigentlich bin ich noch immer dort – im Geiste. « Und für alles was im Leben passiert, kann ein Grund 20 bis 25 Jahre davor gefunden werden », hab ich mal gelesen.

Holger Biermann: Leaving Today

At 9/11 in New York

Galerie Franzkowiak Berlin

Blotto Books 2023

Grafisches Konzept und Layout: Troppo Design Berlin

Gesamtherstellung: Thomas Dehne, Nienstädt

The claim to order chaos / Introduction

Freddy Langer

Luise immediately caught his eye. Blonde. Young. Cheeky. Dressed in a sleeveless shirt and a miniskirt. Across her face a broad glow that may have reminded him of the young woman with the ice cream in her hand, photographed by Garry Winogrand more than half a century earlier, also in New York. Just as one can hardly look at beautiful women in New York’s streets without immediately thinking of Garry Winogrand and his great book « Women are Beautiful. »

Whether he could accompany her a few steps, just a block or two away, Holger Biermann asked, even before he knew her name and could not have guessed that she had come to New York, of all places, to introduce herself to a modeling agency. He asked with his eyes, Biermann says, and because he thought he saw a charmingly worded yes in her gaze, he took the first photo. While walking, without looking through the viewfinder. But it was by no means a random snapshot. Click. Then she laughed a little more heartily, stroked her hair out of her face, and Biermann took another shot. Still walking. Click. It was a tickled-out moment. They both laughed, exchanged a few sentences, and as they parted, she called out her name to him. Then they parted ways. And only later, days later, when he looked at the contact strips of his black-and-white film with a magnifying glass and he noticed the public phone that had slipped into the picture of that split-second flirtation, Holger Biermann may have been annoyed not to have asked for her number.

Twenty years later, it is hard to imagine that a street photographer can accompany strange women with impunity to take a picture. Long ago, a New York mayor had considered banning street photography in Manhattan. And in Berlin a few years ago, after a sensational trial, the poster for an exhibition had to be taken down because a passerby recognized it – and didn’t like it. So what motifs are left for street photographers, not only to document life in all its facets, but, even more, to sound out their own place in the world? For street photography, as Joel Meyerowitz, one of its most important representatives, has explained on occasion, is first and foremost a means of self-expression. The photographer tries to find his own state of mind reflected in the outside world. « On one day determined by optimism, on another more melancholy mood, we searched in everyday life for moments that reflected our feelings. Strictly speaking, we only ever took self-portraits. »

It was the early summer of 2002 when Holger Biermann took the picture of Luise, the young woman in the strapless shirts and mini skirt. Not a fun time, in fact a depressing time, as he says today. For the whole city was still in shock. The September 11 attack on the two towers of the World Trade Center still shaped the way people thought and felt. Shaped the street scene in southern Manhattan. Why should

this tension not be released, at least for a moment, in the encounter of two young people in New York? Street photography here not as a self-portrait, but as the image of a wish, a hope, captured in a hundred and twenty-fifth of a second.

Holger Biermann had been just three blocks away when, on that bright late summer morning, two planes roared into the mighty towers, once the tallest buildings in the world. First the horrific impact, then a screaming crowd of people, he recalls, scrambling to safety from the collapsing buildings. Quick-witted, he bought five slide films in a convenience store as he passed by, while he and ten thousand other people left the borough for the Brooklyn Bridge. It got quieter and quieter as the police began to direct the crowds, and at some point, he says, everyone fell silent while smoke rose into the sky as a huge column behind them. Holger Biermann never stopped photographing, capturing scenes that did more than upset everyday life. The world would no longer be the same. And the flâneur, who always had a camera with him but only occasionally reached for it, became a photo reporter in the blink of an eye.

Holger Biermann had originally come to New York as a journalist with an internship at a German publishing house, but that day he understood how much more freely he could express himself with a camera. And he understood what was behind the saying, to take a picture of something. September 11, he says, was the day he found his profession. Instead of spending a year in New York, as planned, he stayed there for two and a half years. Day after day, he wandered the city from then on. From West 137th Street, where he lived, down to Fifth Avenue in Midtown, up and down there throughout the day, and on to China Town in the evening, because that’s where the cheapest food was. What makes this city tick, he wondered. Who are these people? Is it possible that the upheavals of the times are written all over their faces? Holger Biermann did not lack the chutzpah to stand in their way if he thought he could get deeper into the soul of New York. He was as little concerned with sensations as he was with outlandish moments. He was looking for the ordinary, striving for a clarity in the image that would make everyday life a little more understandable and bring us one step closer to people. What he tried to do was to pick out scenes in which, with a glance, a gesture or the chance encounter of two passers-by, he not only captures the life of a particular street in a particular city, but at the same time creates a symbol of human behavior, that is, what is commonly summarized under the term conditio humana.

Once I was there when he was taking pictures. That was in Berlin. And I witnessed how he lifted the camera to his eye, released the shutter, and let the camera fall back down by the strap without stopping for a moment or at least slowing down a step. It happened, as they usually say, faster than you can look. But he had to have seen

something before he reacted with lightning speed. Or, as he puts it: The world whispered something to him, which he translated into the language of an image. In this case, it was three construction workers in conspicuous blue sweaters scooping up the sidewalk of Friedrichstraße in front of a conspicuous blue poster. However, it is quite possible that Holger Biermann did not take the picture at all because of the coincidence of the colors. Perhaps he was interested in the formation of the three men, perhaps from his perspective and through the slight distortion of the wide-angle lens they looked like dancers on a stage, captured in the midst of their flowing movements. Or perhaps some passerby was mirroring the workers. Just as in his pictures people often correspond with each other or with objects elsewhere in the picture. In the best case scenario, a passerby reaches into his mouth in front of the house with the Fulton Dental Center advertisement, as if to check whether his molar is still properly in place.

Of course, behind the claim to order the chaos, there is always the desire to sort oneself out. To ask oneself whether everything is in the right place. And this could even explain the renewed interest in street photography. The genre may hardly play a role in magazines anymore. But for some years now, it has been coming into focus on the art market. And on the book market. And even more so, it is spreading via social networks. Instagram recently counted more than 45 million posts under the hashtag streetphotography, and despite all legal concerns, there are more every day – almost as if, in the midst of life’s abundance, one can only reassure oneself with images and become aware of one’s own position in the observation of others. At the intersection of snapshot, reportage and documentation, street photography becomes a kind of anchor. The fact that there are also thousands of self-portraits under the hashtag could have something to do with this.

Plenty of room for the unexpected Holger Biermann

For a long time, it was difficult for me to write about my experiences in New York. « Whoever leaves books behind will be reborn seven times in a row as an ass, » I once read. Words and pictures, it said, are only fingers pointing to the moon. Who pays attention to the fingers will not see the moon, thus the substantial. The essence – 20 years after my return I think I recognize what was the essence of my time between 2001 and 2003 in New York. It was this incredible positivity. No matter where I went, no matter who I met – people almost always met me with interest and openness. « Do what you love to do, » « Anything is possible, » and « You’ll make it, » residents told me on every corner, and it had an incredible power. It was this spirit that made New York special to me.

I came to the metropolis as a journalist. I was 27, had just finished my education and hoped to see the big wide world. Equipped with a scholarship from the Carl Duisburg Society, I wanted to stay for a year and explore the city for two German media outlets. On my way to work, I accidentally got out of the elevator on the third floor instead of the fourth. Unexpectedly, I suddenly found myself in the rooms of Steps, a dance studio that trains outstanding Broadway dancers. Already in the entryway, a dozen young people sat on the floor stretching. Interested, I took a step forward, peered around the corner into a room with mirrored walls and ballet bars – and was immediately approached with a smile. Did I also want to dance? That was no problem at all! And it was very nice that I was here. I was given a small guided tour and information material. This happened all the time in New York. Business cards – I got hundreds and started to collect them.

I also remember my arrival on March 28 well. Coming heavily packed from the airport, I suddenly found myself lost in the seemingly endless tunnel system of the 42nd Street subway. I was looking for the « Local 1 train. » In one hand the large rolling suitcase, in the other the laptop, plus a backpack and a travel bag slung over my shoulder. Moving was difficult in this state and I really didn’t know where to go – also because people were streaming towards me from all sides. Unbelievable what a mess was down here and yet I was immediately recognized and addressed: « Ahh, look at him: Crocodile Dundee is lost. You need help? » So I found my way.

I came to 103rd Street and Central Park, where, as a prelude, I could live for $500 for a month in the studio of the German painter Laurentz Thurn, who was visiting home. I had heard about this opportunity through friends. On the Elbe in Hamburg, days before my departure, he handed me the key at the counter of a gloomy smokers’ bar and told me to bring him a family pack of chocolates filled with liqueur as a gift: « There’s no Mon Chéri in New York. » I didn’t understand what

he meant, but agreed and ran down to the Elbe with the key, overjoyed, where I first threw a lucky penny with my left hand over my right shoulder into the water. Not that I was superstitious, but it could not hurt. Thus prepared I stood on this first evening in New York on the steps of my accommodation and tried the key: it fit! Upstairs, too, I entered the studio at the first attempt.

The next morning I was awakened by cooing pigeons. The sun was shining outside the curtained window. It took me a moment to realize where I was on my bunk. Above me hung a huge oil painting on which three « Harlem Guys » were portrayed. On the paint-smeared floor, paint pots, tubes and frames of various sizes were everywhere. Next to them were full ashtrays and music cassettes, pads and sketches, and there was also all sorts of stuff on the shelves, along with jars of paintbrushes. It smelled strongly of turpentine, but I liked the cosmos of this picture cave and enthusiastically set off from here with my camera to discover New York. I went down to Central Park and crossed it on this bright spring day off the paths as freely as I could once completely through the middle down to 59th Street. So I hiked Manhattan over the months piece by piece to fall in the evening exhausted in bed.

I had no idea after all. Once, for example, I naively ordered a pizza –and got a table-sized one instead of just one slice to go. I ate plenty of it before putting the remaining two-thirds back in the cardboard box into the kitchen. When I took another look at the topped yeast dough the next morning, it was covered in cockroaches. So much was new. I saw talented tenors performing in restaurants to entertain guests, visited a lonely millionaire who invited me to lunch in her penthouse, saw homeless people brushing their teeth in the subway. There was even a pub where wine was served for free. The unexpected was always to be expected. Only that New York was so particularly dangerous, I did not feel for a long time. But I had been warned. Just in case, I should always put an extra five-dollar bill in my pocket, which I did and which paid off. On one of my explorations of Harlem, a young bicyclist suddenly appeared at my height, started a conversation as he rolled on, and suddenly held a knife to my side. « Give me your watch, » he said calmly. Without pulling out my wallet, I gave him the five-dollar bill and he was gone.

I experienced the September 11 attacks just as unexpectedly. In the meantime, I had moved twice – in the end, there were seven apartment changes in 28 months – and lived upstairs in Spanish Harlem at 137th Street and Broadway in a tiny shared room with bars in front of the window. I always had to slip the $600 due for it under a neighboring door in an envelope at the first of the month. Who lived there, I did not know. As chance would have it, I went to the editorial office very early that morning of the 11th to have a quiet talk with the editor-in-chief about possible stories. Half a year had passed since my arrival and I wanted to get more involved. I already sensed that

something had happened on the way in the subway. In the train car, the mood was so serious and people were whispering. In the newsroom, they said there had been an accident at the World Trade Center. An airplane had crashed. In July 1945, something like this had happened before. At that time, an unarmed B-25 bomber accidentally flew into the Empire State Building in thick fog. I should go and take a look. So I turned around and started again.

With the subway I went down until the train suddenly stopped at the 18th. Over loudspeaker system the announcement came that the entire traffic was stopped due to technical disturbances. I climbed the stairs again and walked south. I knew the route. I had visited the Twin Towers weeks ago. On the last Monday in May, Memorial Day, I went up alone to the visitors’ terrace on the 110th floor and looked down on the City at night. It was a magnificent sight: I saw the many paths and infinity in all directions. Afterwards I took the opportunity to send a light greeting into space from there – a service that was offered for free. I wrote « Thank you sun », because I could not think of anything better. And even now, when I recognized the World Trade Center in the distance while walking a short time later, words failed me. One tower had fallen, the other was burning like a torch with enormous smoke. I realized that I could have actually turned around and I wonder today that I did not. Instead, I kept walking on this cloudless late summer day with no wind. I did not see any acute danger. What exactly had happened?

Everywhere, people stood in the street, stunned in silence or on the phone. Even cars were no longer driving, only the ambulances whipped past. With my press card, I got through the police barricade further down without any problems. I walked and walked until – at that moment between two blocks – I heard the loud yelling of passers-by. The second tower collapsed and shortly thereafter there was an enormous cloud of dust in the streets of downtown. Only then I woke up, pulled my T-shirt over my nose and wanted to get out. But how? And where was I? I moved through the fog past police officers standing by their cars, past news photographers crossing the street at a run. I saw completely exhausted firefighters coming towards me, and in between, again and again, freshly blow-dried passers-by on their way to work? It seemed so absurd – and I realized that, as always in New York, I had my camera with me, but no film. That I really found five rolls of color film at a deli on the corner shortly afterwards, I felt as a small miracle.

So I began to take pictures as I slowly left downtown like ten thousand others, guided by police officers across the Brooklyn Bridge. We walked mostly in silence, while behind us stood the enormous column of smoke. Here and there I heard sentences like « An attack also in Washington » or « This means war ». But for sure I knew nothing like most. The Internet was switched off and no one could be reached. Also the subway continued to stand still and so I decided to

walk back to the center via the nearby Manhattan Bridge. I got close to Ground Zero once again and saw the World Trade Center 7 building collapse. Then I made my way up the hill. From 14th Street on, the café terraces were packed. It seemed like half the borough was on its feet talking about the unbelievable. At Times Square, I also paused to read the headlines on the big news tapes. Only then did I realize that I was covered in dust and my hair was completely white. Oh dear, I thought, what have I inhaled?

When I arrived home, my Mexican roommates welcomed me with terrible Bible passages that they quoted. I felt deep fears and dreamed in the night of a nuclear bomb exploding in New York. I woke up in a sweat. Editorial staff members had even temporarily fled to Upstate New York and returned to Manhattan days later. I was also constantly irritated by the particular smell that lingered over the city for weeks after the attack and could be smelled from downtown to well beyond 72nd Street. As did the fighter planes that patrolled over Manhattan for a while and all the U.S. flags that were suddenly hoisted. The attack changed the mood. On the subway, half-castes suddenly made way for older ladies. Couples who had just broken up were seen warmly united. « United we stand, » was the billboard slogan of the hour. And for the attentive observer, New Yorkers really did move closer together for a while.

I was now taking photographs. And the more intensively I photographed, the more I got to know photographers and artists who brought me to the International Center of Photography. Starting in the spring of 2002, I worked there as a Teacher Assistant. I learned to develop films, discovered the photo books of Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank, and came into contact with like-minded people. I didn’t even know that something like street photography existed as an art form. But now I wanted to stay as long as possible and describe this time, which was so difficult and so free for me, with the camera. I gave all my savings for that. And New York gave me perfect conditions: The southern light, the intense colors, people of all cultures in a confined space against a backdrop that had grown over centuries. Without this beginning, I would not have become a photographer. Sometimes terrible things turn into unexpected opportunities to grow.

Like a fish, I moved down Broadway and back up again over the next few months, chasing through Diamond Street, 47th, and over to Grand Central Station. As if in a frenzy, I often stood photographing at 34th during rush hour and more and more often I met people again. I was asked for directions. Surprises were waiting everywhere: In March 2002, Michael Jackson waved at me on 5th Avenue before appearing as best man for Liza Minnelli. At the ICP, a Deutsche Bank employee asked me to take nude photos of her, which she gave to her husband for Christmas. And a friend even entrusted me with her internship at the Magnum photo agency, which she was unable to fulfil for sched-

uling reasons. When I needed a break or space, I simply disappeared into nearby Central Park or took the « N train » to the ocean at Coney Island. For moments it was like being in a dream and I now often dreamed in English.

Shortly before I left on July 17, 2003, I even found a job at a small German-language newspaper. I could have stayed and worked five days a week in the editorial office – but I let it go. Instead, with the help of my friend Patrick Becker at the ICP, I decided to print two portfolios – one with street images, one with fashion images – and buy a return ticket. When I had it, I sat on the steps of the Public Library and cried. I packed all the negatives in two big boxes to send to my parents, and left New York without saying goodbye. I photographed all the way to the airport, all the way to boarding the plane, and haven’t been back since. In many ways, in spirit – I never left. « And for everything that happens in life, a reason can be found 20 to 25 years before, » I once read.