Indice

The MedWays Open Atlas

Mosè Ricci Water 29 City networks. Geometries of development Alberto Clementi, Ester Zazzero 35 Constructing Mediterranean Trajectories Elena Longhin 45 East Med Landscapes Francesco Alberti 57

EChOWAYS

Maddalena Ferretti, Antonio Barone, Sara Ferrar, Elisabetta Baldassari, Gianluigi Mondaini

Giulianathewhale Silvana Kühtz, Ina Macaione, Silvia Parentini, Chiara Rizzi

Internet of Ecologies Mathilde Marengo, Iacopo Neri, Chiara Farinea

93 Mediterranean. Waterpower Amalfi Coast Luigi Centola 99 Mediterranean Vito Cappiello 107

The Mediterranean ways of marine biodiversity Stefano Acunto 119 Mĕdĭterrānĕa Thermae Sara Favargiotti, Margherita Pasquali, Chiara Chioni 129

Mediterranea Viviana Panaccia, Mauro Canali

Med MPAs in the net Romina D’Ascanio, Stefano Magaudda, Serena Muccitelli, Anna Laura Palazzo

Only by water

Paola Cannavò, Pierfrancesco Celani, Donatella Cristiano, Antonella Pelaggi, Massimo Zupi

Reviving Barada`s River in Damascus city

Ghada Bilal

8

71

83

137

147

159

165

A section of the landscapes of the Mediterranean along the route of a thread of water

Carles Llop, Josep Maldonado, Gemma Milà, Ramón Sisó, Artur Tudela

Land 183

Allegories of the Downshifting

Fabrizia Berlingieri, Lucia La Giusa

195

The breath of the city

Pepe Barbieri, Angela Fiorelli, Alessandro Lanzetta

207

Build on the margin Alessio Battistella 219

Catalunya – Land Grid(S) Manuel Gausa

239

Finding Romulea

Adelina Picone, Giovanni Luigi Panzetta, Maria Barrasso, Marina Giangrieco, Andrea Lo Conte, Antonio Sena

251

Focus on Disaster

Francesco Gangemi, Rossana Torlontano, Valentina Valerio

265

Food Street

Gianluca Burgio, Antonio Cal Marco Graziano, Deborah Giunta, Paolo Rosario Pagano, Pere Fuertes Pérez

275

The Mediterranean invented Antonio Pizza, Arianna Iampieri 287 Mediterranean Sections Alessia Allegri, Caterina Anastasia 299 Mediterranean walls Maria Gelvi

311

Three miradores Cherubino Gambardella

319

The Trasversale Sicula Renzo Lecardane

Coast 333 Adriatic Inner Sea

Chiara Ravagnan, Domenico D’Uva, Chiara Amato, Giulia Bevilacqua, Ozgun Gunaydin

347

‘Along the line’ between Noto and Pachino Gero Marzullo

359

Beyond the Port City Beatrice Moretti 373

Condomini overlooking the Gulf Chiara Ingrosso 385 Corinth Project Lucio Zazzara

397

The design of the pergolas of the Gulf of Naples

Simona Ottieri

407

Mare Monstrum: a land between the seas

Consuelo Nava, Irene Curulli, Giuseppe Mangano, Alessia Leuzzo, Domenico Lucanto, Alessia Rita Palermiti

421

SubLimen landscapes

Carmen Mariano, Marsia Marino

429

Transitional Memories

Emanuele Sommariva, Nicola Valentino Canessa 441

Upstate Rome

Lina Malfona, Monica Manicone, Andrea Crudeli

Route 455 Balkan Narratives

Lorenzo Pignatti, Federico di Lallo, Claudia Di Girolamo, Stefania Gruosso, Andrea Di Cinzio, Maria Catamo, Lorenzo Morelli, Ilde Manuela Paulucci

467

Circular Territories

Jörg Schröder, Riccarda Cappeller, Alissa Diesch, Federica Scaffidi

479

Crossing Borders

Marco Scarpinato, Fanny Bouquerel, Lucia Pierro

493

Cultural routes and trails

Massimo Crotti, Paolo Mellano 501 A first report Gentucca Canella, Paolo Mellano

513

From Constantinople to Rome along the via militaris

Alessandro Camiz 519 Invisible Routes Margherita Pasquali 533

Itineraries in landscape Massimo Angrilli, Valentina Ciuffreda 543

Landscapes of (im)mobilities

Alessandro Raffa 555 MED@Tunnel

Maria Maccarrone, Francesco Finocchiaro

571

The MedWay of the Due Principati

Felice De Silva, Pasquale Persico, Roberto Vanacore 581

Migration in the Mediterranean Anna-Maria Lioga

593

The Paths of Magic Simonetta Bassi 611

The ports of the Mediterranean Rosario Pavia 619

The Silk Road 5.0 Francesca Moraci, Maurizio Francesco Errigo, Dora Bellamacina, Celestina Fazia

629

Synchronic nodes and Mediterranean thought Giorgia De Pasquale 639

The VENTO Cycleroute Rossella Moscarelli, Paolo Pileri 651

Vitruvio return to Rome Valentina Radi 665

The way of flowers Giorgia Tucci 673

Uniform Circular Motion Raffaele Cutillo, Egidio Cutillo, Giovanni Izzo

Legacy 681 Accessibility and storytelling

Bruna Di Palma, Lucia Alberti

693

AFAL, a meridian story Elisabetta De Lucia

703

The archaeological MedWay of the Gulf of Naples

Manuela Antoniciello, Felice De Silva 715

Beyond the borders

Pino Scaglione, Rosanna Algieri, Isabella Capalbo, Yuan Wang

725

Complex representation and integrated risks management

Carmine Gambardella, Rosaria Parente, Alessandro Ciambrone

749

Historic paths of Abruzzo Caterina Palestini, Alessandro Basso, Francesca Marzetti

761

Houses made of Sun Concetta Tavoletta

779

How cultures of the Mediterranean persist Kay Bea Jones

793

Lustre ceramics in the Mediterranean basin

Brunetto Giovanni Brunetti, Claudio Seccaroni, Antonio Sgamellotti

811

Malaga through the eyes of the barrio of El Molinillo

Alona Martinez Perez

819

Mediterranean Ways Fabrizia Ippolito, Ilenia Mariarosaria Esposito

833

Postcards from the underworld

Caterina Padoa Schioppa

839

Taranto, a female enterprise path from the sea

Daniela Cavallo

847

Tessere Arianna Papale

857

Via Egnatia

Florian Nepravishta, Xhejsi Baruti, Benida Kraja, Fiona Nepravishta

871

"U IARDINU"

Alberto Tempi, Elena Barthel

Island

879

Aἰγαῖον

Silvia Mannocci

887

About the Perfect City Francesca Rossi

897

Aegean emotional landscapes

Lucia Alberti, Bruna Di Palma

909

Favignana Quarry Island

Giuseppe Marsala, Pasquale Mei

921

Inhabiting the Apocalypse

Alessandro Franchetti Pardo

937

Ischia and the Path of Consumer Tourism

Gioconda Cafiero, Viviana Saitto

951

Lampedusa: the central Mediterranean route of migration

MariaLuisa Palumbo 957

Seven Mediterranean Islands

Pablo Pérez-Ramos, Duarte Santo, Stefania Staniscia

967

Shallow WatersHidden land

Eli Janja Stojanović 975

A stone house in Malta Mario Pisani 981

Temple of Biodiversity of Skadar Lake

Ajša Đukić 989

T(h)RACE

Irene Poli 999

Venice Sylva Sara Marini

πέλαγος

The

by Mosè Ricci

I. Atlas

This book is an open and potentially infinite interdisciplinary atlas of the Mediterranean Ways (MedWays/MW). Where ways is in the multiple meaning of paths or routes and ways of behaving, ways of living. It is an Atlas of narratives rath er than descriptions. The web is full of descriptions and the Mediterranean is the place of narratives. The Atlas is imagined to receive contributions (narratives) from multiple authors from different disciplines and collects the final con tents and results of the Le Vie del Mediterraneo (MedWays) research project awarded by the Centro Linceo Interdisciplin are Beniamino Segre of the Accademia dei Lincei, the Italian National Academy of Sciences. The MedWays are those systems of material or immaterial relations that somehow leave a trace in the Mediterranean landscape. The research intends to put them under obser vation through narrative devices that capture their meaning. The narratives may be true, false or verisimilar to explore the sense, nature and indeed the myths of the Mediterranean. As Aristotle explains in the Poetics1 , there is no substantial dif ference between the story and the tale, both deal not with the true but with the verisimilar. The verisimilar is more useful than the true because it has characters of universality and re petitiveness. It does not discover the past as it was exactly, it puts us in tune with tomorrow, because the verisimilitude re peats itself. The exact description of true – assuming we can know it – like Borges’ map of the empire would be unique, unrepeatable in different times and useless2

With the evidence of these narratives defining landscapes, the overall aim of the Open Atlas is to mitigate the risk of their erasure. Furthermore, it is also important to understand why a place in the world where everything seems to be arranged, where the management of the Public Realm is often entrusted to random facts and interpersonal contacts, where apparently nothing works well, where tremendous conflicts have always been experienced ... is the most desired place to experience a journey, a season or even life. In other words, what is the hidden meaning of the Mediterranean that produces an irre sistible attraction and develops imaginaries of beauty and happiness? The research aims to realize a choral scientific enterprise with several coordinated and autonomous voices. Everyone develops its own narrative, its own page of the Atlas

8 MedWays-Open Atlas Ricci

MedWays Open Atlas

MEDITERRANEAN

Main Sea | αρχι πέλαγος

Everyone with their own narrative (a text, a series of images, a project, an installation...) can tell, define and improve the MW Open Atlas as a system of physical or immaterial relations that define a way of being or an idea of the Mediterranean. The Open Atlas of the Mediterranean Ways is not meant to be another authorial essay on the Mediterranean. Because these books are already there, and it would be really difficult to add new words, new interpretations to the frescoes of the Medi terranean by Fernand Braudel, Pedrag Matvejevic, David Abu lafia, Giorgio Jeranò, Jean-Claude Izzo, Paolo Rumiz, George Simenon, Claudio Magris, Orhan Pamuk, to name a few3. More direct bibliographical reference can rather be found in the Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1927). It consisted of 40 wood en panels covered with black cloth, on which were pinned nearly 1,000 pictures from books, magazines, newspaper and other daily life sources. These pictures were arranged according to different themes. There were no captions and only a few texts in the atlas. “Warburg certainly hoped that the beholder would respond with the same intensity to the images of passion or of suffering, of mental confusion or of serenity, as he had done in his work”4 Mnemosyne Atlas was dedicated to preserving the classical heritage of Western cul ture and it was left unfinished when Warburg died in 1929. The MedWays Atlas is intentionally designed as an open and unfinished manuscript. It includes 86 Mediterranean Ways and 176 narrating scholars, singly or in groups. There could have been many more or fewer, but mainly many more MW could be narrated and added to these to make the Atlas always more complete and, indeed, open. But the Med WAys collected here are already significant in investigating the meaning and role that the Mediterranean has always had and can play today for those who inhabit its landscapes and want to continue to enhance them. But the Atlas is open even in the sense of having an interdisciplinary and opensource structure where different authors can address the final result like in the Net. As in the Odyssey, perhaps the first Atlas of the Mediterranean Ways, this book is a random journey across the Mediterranean, a collection of meanings, landscapes and social facts that explore the significance of the Middle Sea Finally, the aim of the Atlas is to recognize and keep alive the Mediterranean Ways (in the double sense of routes and habits) and to reinforce their meaning as slow, material or intangible cultural infrastructures that give sense to Mediter ranean habitats and lifestyles. Narratives have always been a powerful engine of cultural development and social emancipation in the Mediterranean. In Abruzzo, for example, where between the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the last century a remote, peripheral region became the hub of a system of international

9MedWays Open Atlas

Land

Landscape Transect Fragile Territories Topology Design Allegories Downshifting Fabrizia Berlingieri*, Lucia La Giusa** * Politecnico di Milano | DAStU, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies ** Architect, PhD in Architecture and Urban Design Allegories of the Downshifting The Isthmic way Sybaris-Laos, a topological atlas

land

Lateral contexts

The Mediterranean is a privileged stage where history exer cises the inflexible cycle of risings and downfalls. The corpus of settlement cultures that populate it gives evidence of an alternative paradigm to the predominant model addressing urban-centric imageries. Looking today at this historical and cultural basin requires clarifying a lateral position.

The effects of an uncontrolled growth based on limited re sources initially set out in the Meadow Report1 (Meadows et al., 1972) still are at the core of several reflections on eco-sys temic balance, climate change, and sustainable development, themes which appear, albeit differently, in the thesis of de growth2. The latter constitutes a critical revision of Modernist positions regarding linear and infinite progress, large-scale planning, and anthropic hegemony on natural systems. De growth does not amount to negative growth or even less to the simple reduction of human impact on the planet. It envi sions a different social and economic model restoring an idea of the limit (Latouche, 2007) to rethink our societies in a radi cal alternative and reverse the increasingly selective develop ment dynamics in favour of social solidarity3. In this complex and contested debate, architecture also has a role to play, considering its statutory vocation to anticipate the future:

«Instead of falling victim to the economic structures that gov ern our lives, architecture needs to redefine the value it contrib utes to society and promote degrowth» (Harper & Smith, 2020).

In 2019, the Oslo Architecture Triennale presented itself to the public with the title Enough: The Architecture of Degrowth, an investigation into alternative paradigms of sharing economy in an era of climate emergency and social inequality. The four curators – Maria Smith, Matthew Dalziel, Cecilie Sachs Olsen, and Phineas Harper – explored the theme through possible and distant futures. They addressed the architectural prac tice as an agent of social change, rather than reiterating the status quo, or worse, a set of guidelines for short-term and implementable solutions — a harsh criticism of the architec ture and the current panorama of its production.

«Architecture is no exception. The promise of a meaningful life’s work harnessing the transformative power of design to mix beauty and social justice is deeply felt. Yet for many, our daily practice looks very different to the work we aspired to. The majority of urban practitioners are not the agents of social change they might have been, but cogs in a vast val ue-producing machine whose hunger for expansion is never abated» (Dalziel, Harper, Olsen, Smith, 2019).

Even in the recent Italian debate, the theme emerges in a dominant way (Cacciari, 2006; De Rossi, 2020; Cersosimo & Donzelli, 2020; Coppola et al., 2021), supporting possible territorial rebalancing actions that, however, struggle to show

Allegories of the Downshifting

183

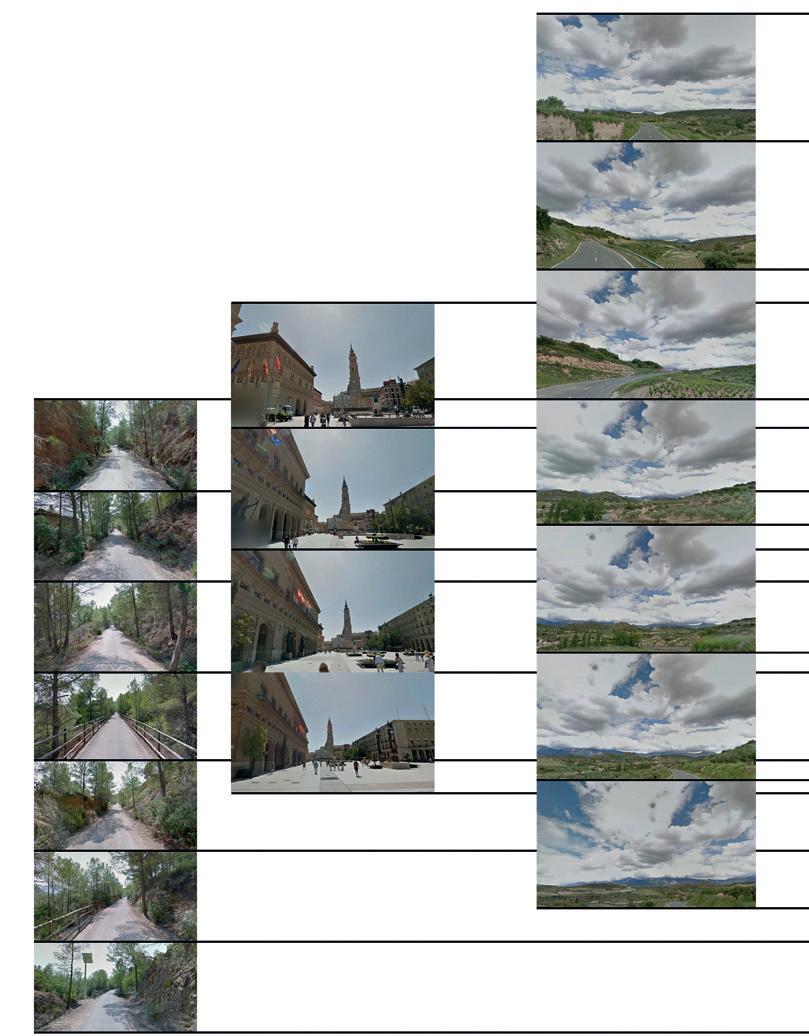

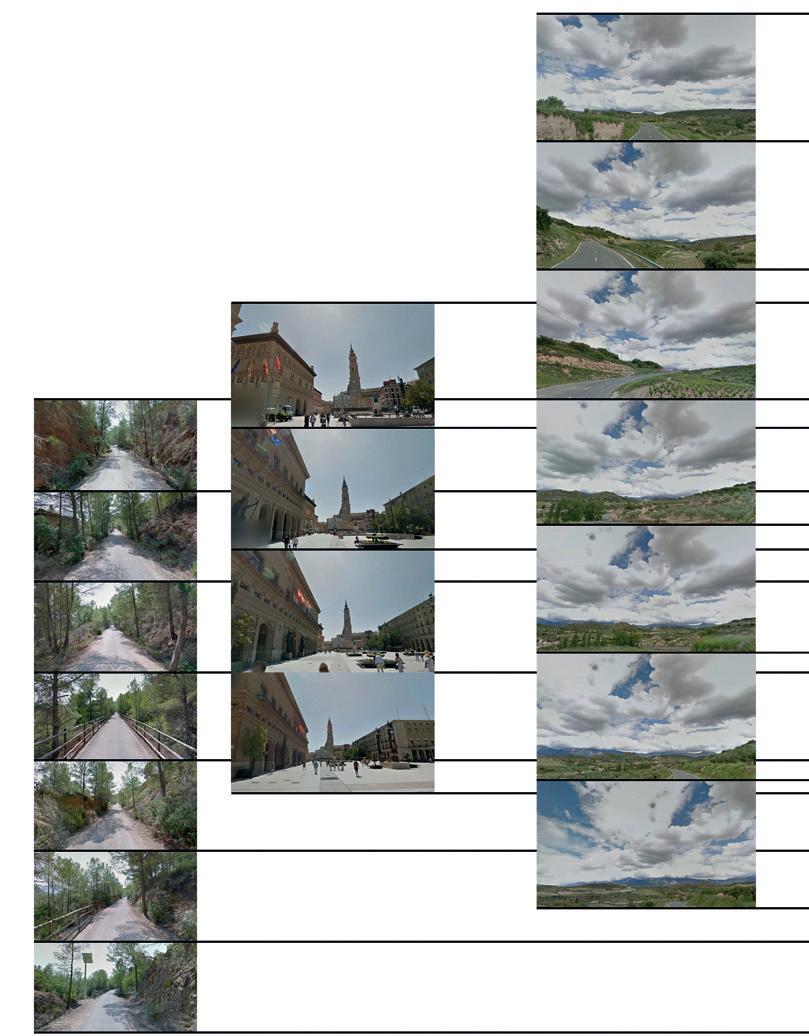

Fig. 8 | Photosections of the Ebro River Valley; from source to mouth. Source: authors’ elaboration.

294 MedWays-Open Atlas

Allegri, Anastasia

295 land

Fig. 9 | Photosections of the Ebro River Valley; from source to mouth. Source: authors’ elaboration.

Mediterranean sections

Legacy

Bruna Di Palma*, Lucia Alberti** * University of Naples Federico II | CNR – National Research Council of Italy | DiARC – Department of Architecture; ISPC – Institute of Heritage Science ** CNR – National Research Council of Italy | ISPC – Institute of Heritage Science the Doclea archaeological site as a cultural hub between the Adriatic Sea and the Inner Balkans Accessibility and storytelling Doclea in Montenegro Route Networks Roman Infrastructures Archaeological Landscape Accessibility Architectural Design For Archaeological Landscape

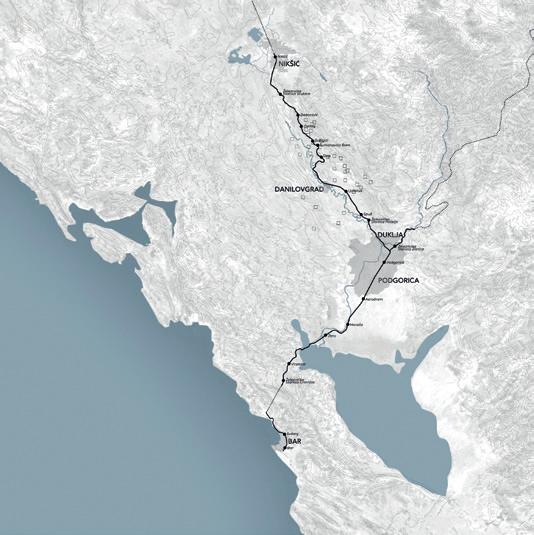

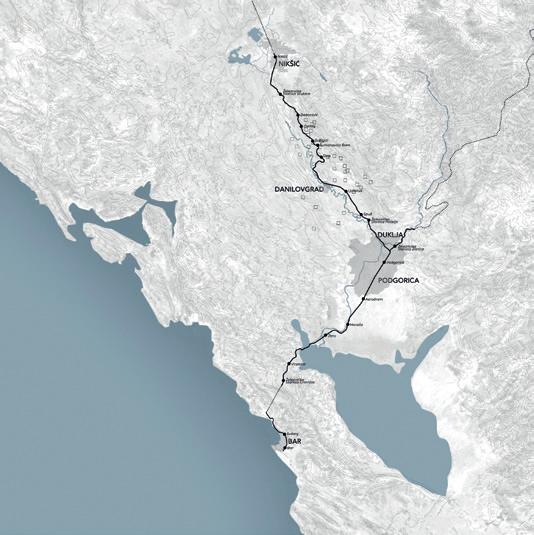

An interconnected land Dominated by mountains of considerable height (up to 2,500 metres), Montenegro possesses a thin flat and somewhat hilly strip of land only in the south, in the area between the Shkodra Lake and the sea. To the north the Montenegrin coast is deeply marked by the Boka Kotorska Bay, the only existing fjord in the Mediterranean Sea, where the sea worms its way into the mountains, eventually creating a sort of inland lake; for centuries this was an impregnable bulwark of the Republic of Venice. Further inland, there are the great moun tain ranges, which give their name to the country, crossed by rivers with a substantial water flow, which have carved up the landscape and created significant valleys (Fig. 1).

Since antiquity that portion of the Mediterranean Sea we call the Adriatic has proved no obstacle to communication, but rather an opportunity, a kind of lake connecting both eastwest and north-south the lands bordering it. But in the 19th century the coastal area of Montenegro seemed somehow to have become disconnected from its hinterland. Earlier the Romans, to overcome this apparent break, created Roman provinces and municipia, and built road infrastructures that had improved both internal communications and those with the Adriatic area. A similar history of infrastructure construc tion was repeated at the beginning of the 20th century, when the Italian Kingdom, directly or through private companies, built ports, railways and stations.

681 legacy Accessibility and storytelling

Fig. 1 | The itinerary from the Adriatic coast to the inner Montenegro (elaboration by Marianna Sergio).

When tracing ancient and more recent itineraries that lead from the Adriatic Sea to inland Montenegro, the Roman city of Doclea, a municipium founded in the 1st century AD at the gates of the capital Podgorica, emerges as the nodal point of arrival and departure of these road networks. Thus, it has become the hub of a contemporary project for a new accessibility to the archaeological landscape of Montenegro (Alberti, 2019).

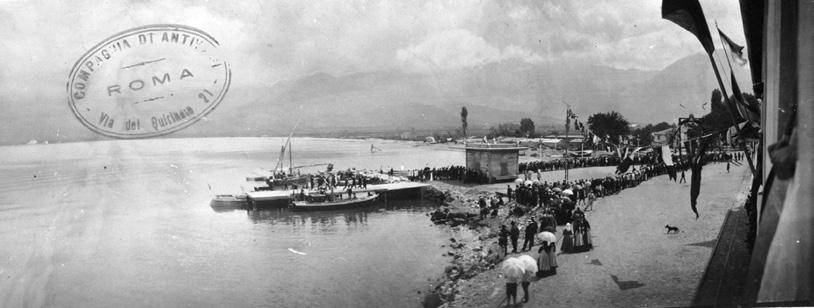

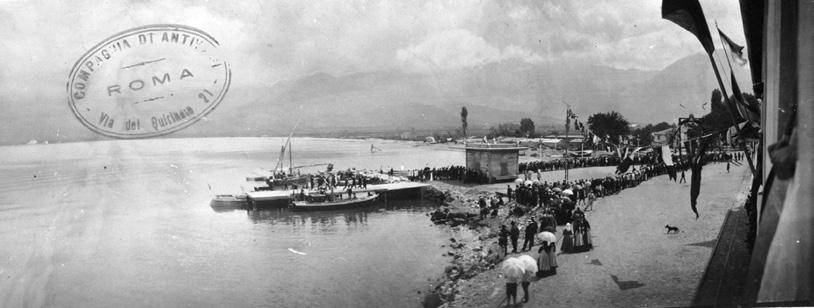

The landing and the penetration towards the interior: the port of Bar and the railway to Virpazar Called once Antivari, that is ‘in front of/opposite Bari’, Bar shows by its name the essence of its geographical position. The history of this the largest port in Montenegro saw its main development at the beginning of the 20th century: this story is closely linked to the history of relations between Italy and Mon tenegro. It was then that Bar became for the Italian Kingdom the ‘gateway to the Balkans’, a place from which to start the penetration, above all economic, but also cultural, into a region whose main point of coastal access is exactly opposite Apulia. The coast at the end of the 19th century, however, was almost uninhabited. The medieval city of Bar, located on a high hill at about 4 km from the coast, had been destroyed by the Turks in 1878-1879 and never rebuilt.

Thanks to the direct interest of Italy and the commitment of many entrepreneurs, at the beginning of the 20th century there was established the Company of Antivari. Between 1905 and 1909 this planned and financed not only the construction of the port of Bar, inaugurated in 1909, but also the building of a series of important infrastructures (Fig. 2. Burzanović, 2019).

Among these, and of great importance for the modernization of Montenegro, was the railway that led from the coast to Vir pazar on the Shkodra Lake. This was a work of high engineer ing that crossed a mountain 660 metres high and required a tunnel 1300 metres long. Started in the spring of 1906, by September 1908 it was already in operation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2 | The inauguration of the Bar port (after Burzanović 2019, fig. 12, courtesy of Slavko Burzanović).

682 MedWays-Open Atlas

Di Palma, Alberti

Fig. 3 | The first train journey of the Antivari-Virpazar railway (after Burzanović 2019, fig. 9, courtesy of Slavko Burzanović).

Other communication infrastructures put in place were the Shkodra Lake docks, a better canalization of the insufficiently deep parts of the lake, new roads between Virpazar and Cet inje, and the urban layout of the new town of Bar, with sanita tion facilities, power generators and the construction of key buildings such as the Hotel Marina. Other projects of the Italian engineers remained on paper, such as the construction of an imposing theatre designed by Adolfo Magrini in 1911, and the extension of the railway Bar-Virpazar. According to the Company of Antivari’s designs, the railway should have been the starting point of a new trans-Balkan rail way line, which was to connect with the Danube area and then southern Russia and central Europe. These projects were nev er realized, due to the deterioration of the international political situation before the outbreak of the First World War.

It is from Bar that, thanks to Guglielmo Marconi, the first radio transmission between Italy and the Balkans was realized. In 1904, on the coast of the future port there was set up the first radio-telegraph station, which corresponded to a twin one in S. Cataldo, near Bari. From here, on August 4th was sent the first radio communication that not only allowed Queen Elena of Montenegro, wife of Vittorio Emanuele III, to communicate more easily with her family, but also, strategically, allowed Montenegro to escape the control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which until then held the monopoly of the telegraph communications in the Balkans. This new transport system, which includes the port of Bar, the railway Bar-Virpazar and the navigation system of the Shkodra Lake, was intended to develop centres such as Vir pazar, Rijeka Crnojevića and Podgorica, where the Italians were particularly active.

683 legacy

Accessibility and storytelling