INTRODUZIONE INTRODUCTION

Lo scaffale del premio Bruno Zevi, nella sua rinnovata veste editoriale, si arricchisce di un nuovo titolo che ci guida alla riscoper ta dei Paesi Nordici, un ambito molto caro a Zevi fin dagli anni giovanili. Il saggio di Giovanni Bellucci che qui presentiamo ha il pregio di riportare l’attenzione su due protagonisti dell’architettura svedese del Novecento – Sven Backström e Leif Reinius – tanto apprezza ti e influenti nel dopoguerra quanto presto dimenticati.

Il tema scelto, quello dei modelli abitativi, è centrale e di piena attualità ed è parte di una ricerca più ampia che mira a indagare tempi e forme della ricerca di un delicato equilibrio fra tradizione e modernità, fra tecnologia e uma nesimo che ha a lungo distinto il mondo scan dinavo e nordico. Il ritratto dei due protagonisti – a partire dagli anni della formazione, in cui assume uno spazio significativo l’incontro con la cultura mediterranea, e attraverso le pri me sperimentazioni del progetto della residen za collettiva – è preciso e appassionato e chia ma in causa figure chiave come il costruttore Olle Engkvist o l’architetto paesaggista Sven Hermelin e il designer Oscar Nilsson. La ricostruzione della collaborazione professionale

The Bruno Zevi Award bookshelf, in its new editorial guise, has been further enriched with a new title that leads us to a rediscovery of the Nordic lands, a region so dear to Zevi from his youthful years. Giovanni Bellucci’s essay, which we are presenting here, has the merit of drawing attention to two leaders of 20th-century Swedish architecture – Sven Backström and Leif Reinius – who were esteemed and influential in the post-war period but quickly forgotten.

The chosen theme, housing models, is a central and highly topical area and forms part of a broader field of research that sets out to investigate the times and the forms taken in the quest to strike a delicate balance between tradition and modernity, technology and hu manism, that has long been a hallmark of the Scandinavian and Nordic world. The portrait of these two protagonists – from the beginning of their formative years, when their encounter with Mediterranean culture took on a signifi cant role, through their early experiments with the collective residence project – is here clear ly and passionately depicted, introducing key figures as the builder Olle Engkvist, the landscape architect Sven Hermelin and the designer Oscar Nilsson. This reconstruction of the

6 Antonello Alici

tra Backström e Reinius si amplia al contesto sociale e politico di un Paese guida nella mes sa a punto di un modello di equilibrio sociale che dà prova di sensibilità ai bisogni dell’uomo e dà spazio alle fasce più svantaggiate, si apre all’indagine del mondo della costruzione che unisce le novità tecniche alla flessibilità delle soluzioni. Bellucci propone coerentemente una rassegna dell’edilizia residenziale dei due autori dagli anni trenta alla metà degli anni cinquanta del Novecento segnando le principali tappe di una sperimentazione che si sposta program maticamente da un funzionalismo canonico e da rigidi schemi compositivi alla ricerca di soluzioni in sintonia con il contesto che sug geriscono nuovi schemi aggregativi, come le celebri case-torre (punkthusets) di Danvikslippan o le case-stellari di Gröndal fino alle case a gradoni (terrasshusets) di Galjonsbilden, che trovano piena risonanza nelle riviste italiane e hanno avuto una rilevante influenza etica e po litica nel panorama italiano della ricostruzione postbellica.

professional partnership between Backström and Reinius moves outwards to examine the social and political context of a leader country in the design of a model of social equilibrium that demonstrated sensitivity to human needs offering a space for the most disadvan taged groups, reaching out to investigate the world of construction, combining technical innovations with flexible solutions. Bellucci offers a consistent overview of the two authors' residential buildings from the 1930s to the mid-1950s, marking out the main stages of an experimental approach designed to shift away from the canonical functionalism and rigid compositional models, in the quest for solu tions that were in tune with an environment that gave rise to new combinatory models, such as Danvikslippan's famous tower-hous es (punkthusets) or Gröndal's star-houses, and even Galjonsbilden's terraced houses (ter rasshusets), which were so eagerly taken up by Italy’s journals and which brought huge ethical and political influence to bear on Italian postwar reconstruction development.

7 Introduzione / Introduction

THE HOUSING MODELS OF BACKSTRÖM AND REINIUS BETWEEN THIRTIES AND FIFTIES An alternative to Scandinavian functionalism GIOVANNI BELLUCCI I MODELLI ABITATIVI DI BACKSTRÖM E REINIUS TRA GLI ANNI TRENTA E GLI ANNI CINQUANTA Un’alternativa al funzionalismo scandinavo

«Guardando indietro all’architettura degli anni trenta, scopriamo che forse non era perfetta come avrebbe potuto essere. Il funzionalismo ha svolto un compito pionieristico e ha mostrato la strada a nuovi metodi di lavoro che, se correttamente compresi, costituiscono una base eccellente per tutti i futuri sviluppi archi tettonici, ma mancano alcune caratteristiche essenziali che a volte si trovano nell’architet tura più antica. Penso principalmente a quei fattori psicologici e irrazionali che contribuiscono a rendere gradevole la vita e in questi può rientrare la bellezza. L’uomo è un essere complicato e dovremmo fare tutto il possibile per scoprire ciò che è essenziale per lui e quindi costruire le nostre case e le nostre città di conseguenza. […] Produrre case ben differenziate, conservando allo stesso tempo tutto ciò che c’è di meglio nel funzionalismo, deve essere consi derato l’obiettivo proprio di una comunità de mocratica che vuole che i suoi cittadini siano esseri indipendenti»1.

Con queste parole Sven Backström nel 1950 introduce il volume monografico, curato insie me a Stig Ålund, dedicato all’edilizia residen ziale svedese degli anni quaranta. Quello del social housing, o più in generale dell’abitare, è un tema centrale in Svezia sin dai primi decenni del Novecento. I risultati ottenuti, in particolare negli anni in cui nel resto d’Europa a

«Looking back at the architecture of the thir ties, we find that it was perhaps not as perfect as it might have been. Functionalism performed a pioneer task and showed the way to new working methods which, when correctly understood, constitute an excellent basis for all future architectural developments, but we miss certain essential features sometimes found in older architecture. I am thinking mainly of those psychological and irrational factors which help to make life agreeable and in these may be included beauty. Man is a complicated being, and we should do all we can to find out what is essential for him and then construct our houses and towns accordingly […] To pro duce homes that are well differentiated, while at the same time retaining all that is best in functionalism, must be regarded as the proper goal of a democratic community that wants its citizens to be independent beings»1.

These were the words used by Sven Backström in 1950 to introduce the monographic book he edited with Stig Ålund on Swedish housing in the 1940s. Social housing or housing in gen eral has been a central theme in Sweden since the early decades of the twentieth century. The results achieved, particularly in the years when building activity in the rest of Europe came to an almost complete standstill due to the Second World War, quickly went beyond Sweden’s

9

anche per gli appartamenti che si affacciano sul giardino privato; questi si differenziano per avere una superficie leggermente maggiore (30 contro 23 metri quadrati) rispetto a quelli sulla strada pubblica per compensare la mancanza di vista. In entrambi i casi comunque la notevole quantità di luce diretta e diffusa che entra nelle stanze dà la sensazione di trovarsi in uno spazio più ampio del reale e inoltre, per la particolare conformazione pieghettata dei bow-window, gli appartamenti lato strada hanno di fatto la possibilità di godere di un doppio affaccio23. Se la visione esterna dell’immobile in qual che modo ci lascia pensare a un’architettura di chiara matrice contemporanea, nell’arredo e nella sistemazione dei monolocali sembra di compiere un salto all’indietro nel tempo a causa delle scelte stilistiche operate dal designer Oscar Nilsson. Così il mobilio dal design clas sico, i pesanti tappeti e le tende con decori e colori sobri alle finestre rendono il piccolo spa zio privato confortevole e accogliente ma allo stesso tempo evidenziano la distanza stilistica rispetto al progetto architettonico. Viceversa negli ambienti comuni prevale un design con temporaneo, a tratti quasi futurista, se si con sidera ad esempio la bellissima consolle presen te all’ingresso con gli scomparti utilizzati per contenere gli avvisi per le residenti e, a fianco, la modernissima cabina telefonica [6B]. La parte impiantistica comprende il sistema di ventilazione, raffreddamento e riscaldamento progettato dallo studio di ingegneria Theorells e dall’ingegnere Robert Wahlström mentre la parte strutturale in calcestruzzo armato è stata messa a punto dall’ingegnere e professore della Chalmers University of Technology di Göteborg Hjalmar Granholm (1900-1972), che per molti anni ha lavorato con Leif Reinius alla re dazione di «Byggmästaren» quale responsabile

the beautiful console at the entrance with the compartments used to contain notices for res idents and, to the side, the very modern telephone booth [6B]. The technical installations include the ventilation, cooling and heating system designed by the Theorells engineering firm and engineer Robert Wahlström, while the reinforced concrete structural part was de veloped by engineer and professor at Chalmers University of Technology in Göteborg Hjalmar Granholm (1900-1972), who for many years worked with Leif Reinius on the editorial staff of Byggmästaren as the person responsible for investigating the technical (mainly structural) aspects of the buildings. Beginning in the late 1930s and continuing through the mid-1950s, Backström and Reinius worked in Stockholm and other Swedish cities24, such as Linköping, Gävle, and particu larly Sandviken, on numerous residential blocks, a compositional theme that the two architects would gradually abandon in favor of building aggregates and residential neighborhoods. It is certainly with this type of work that Backström and Reinius achieve the most brilliant results of their career because they can fully express their technical skill in both planning and detailing and, not least, let all their sensitivity and at tention to context emerge. With the design of these neighborhoods, the pair of Swedish architects definitively abandoned the model of the siedlung, creating a real relationship with the surrounding environment through the development of new aggregative schemes that in addition to the most famous tower houses (punkthus) and star houses (stijärnhusen) also provide other solutions such as that adopted for Elfvinggården. Once again, this was a pro ject designed to house women who were not totally self-sufficient, single or with children,

26 Giovanni Bellucci

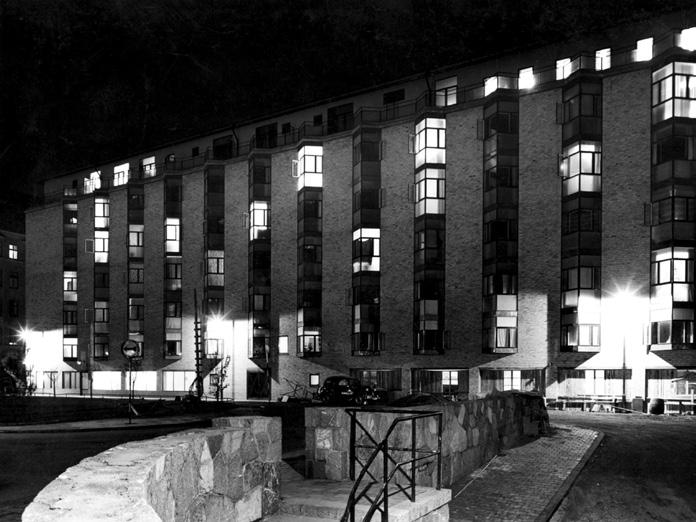

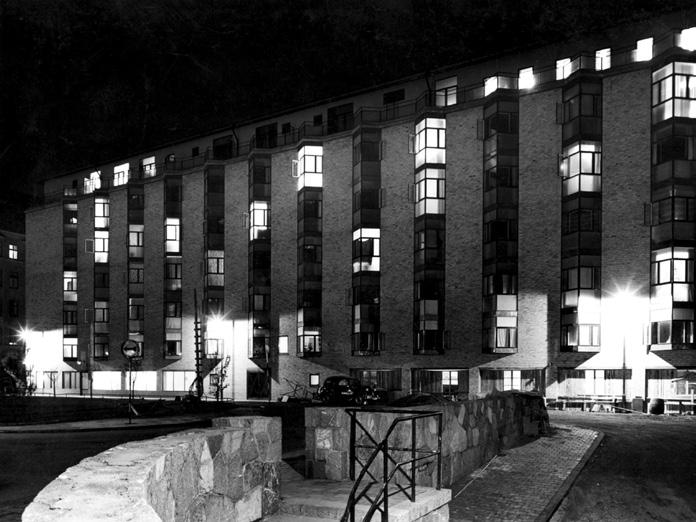

6A. Kvarteret Smaragden, Stoccolma 1937-1938.

Vista della facciata principale con i bowwindow illuminati (ArkDes, Stoccolma, ARKM.1962-101-0405).

Kvarteret Smaragden, Stockholm 1937-1938. View of the main facade with the illuminated bow windows (ArkDes, Stockholm, ARKM.1962101-0405).

6B. Kvarteret Smaragden, Stoccolma 1937-1938.

La consolle all’ingresso con la cabina telefonica (ArkDes, Stoccolma, ARKM.1962-101-0408).

Kvarteret Smaragden, Stockholm 1937-1938. The console at the entrance with the telephone booth (ArkDes, Stockholm, ARKM.1962101-0408).

I modelli abitativi di Backström e Reinius tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta / The housing models of Backström and Reinius between thirties and fifties

27

8A. Residenze per insegnanti in pensione “Björnbo”, Lidingö, Stoccolma. Planimetria (da «Byggmästaren», n. A12, 1955, p. 307). Retired teacher residences “Björnbo”, Lidingö – Stockholm. Plan (from Byggmästaren, n. A12, 1955, p. 307).

fiordo che da est si insinua per chilometri fino al centro dell’isola. Si è accennato a una serie di percorsi convergenti negli spazi comuni e in particolare nell’edificio torre: qui, a differen za di Elfvinggården dove i diversi padiglioni sono collegati alla quota del terreno, i percorsi sono prevalentemente aerei (per i residenti) o interrati (dedicati ai tecnici della manutenzione o più in generale ai servizi). Questa se parazione esprime l’attenzione alle questioni funzionali ma allo stesso tempo, pensando

Furthermore, from the point of view of construction, although the spatial needs of the res idents are not as heterogeneous as in the cases we have already seen and others we will see, since we are dealing with singles or, at most, couples, Backström and Reinius and their collaborators (the architects Sven Löfström and Börge Grahn and the engineers Carl Segergren, Nils Pettersson, Walter Bauer and Harald Wale) develop different types and sizes of flats that include 27 one-bedroom (ranging

32 Giovanni Bellucci

8B. Residenze per insegnanti in pensione “Björnbo”, Lidingö –Stoccolma. Vista dei corridoi di collegamento aerei (Tekniska Muset, Stoccolma, TEKA0019728). Retired teacher residences “Björnbo”, Lidingö – Stockholm. View of the corridors connecting airplanes (Tekniska Muset, Stockholm, TEKA0019728).

8C. Residenze per insegnanti in pensione “Björnbo”, Lidingö – Stoccolma. Vista dell’interno dei corridoi di collegamento (Tekniska Muset, Stoccolma, TEKA0019724).

Residences for retired teachers “Björnbo", Lidingö – Stockholm. View of the inside of the connecting corridors (Tekniska Muset, Stockholm, TEKA0019724).

ai collegamenti aerei panoramici, fa riflettere sull’inventiva e l’attenzione dei progettisti nei confronti dei residenti che in questo modo, mentre si spostano tra le varie zone del complesso, possono fermarsi a osservare il paesag gio e la stessa architettura. Per questo motivo le passerelle aeree sono completamente vetrate e arredate con sedute in modo da creare piccole aree di sosta e relax, una sorta di soggiorni comuni in cui incontrarsi e trascorrere in serenità piacevoli momenti [8B, 8C]. A grandi linee questo dettaglio si potrebbe interpretare come un’anticipazione delle “Streets-in-the-sky” che, qualche anno dopo, gli architetti Alison and Peter Smithson avrebbero largamente impiega to per qualificare le loro architetture con spazi collettivi e di aggregazione, corridoi più o meno aperti che corrono in quota, così come le più recenti passerelle di collegamento tra i grandi blocchi del Linked Hybrid building che Steven Holl ha completato a Pechino nel 2009. Dal punto di vista esecutivo inoltre, nonostante le necessità spaziali dei residenti non siano eterogenee come nei casi già visti e in altri che vedremo, in quanto si ha a che fare con single o al massimo con coppie, Backström e Rei nius e i loro collaboratori (gli architetti Sven Löfström e Börge Grahn e gli ingegneri Carl Segergren, Nils Pettersson, Walter Bauer e Harald Wale) mettono comunque in campo diversi tagli e metrature per gli appartamenti che comprendono ventisette monolocali (da 25 a 37 metri quadrati), venticinque bilocali (da 43 a 75 metri quadrati) e otto trilocali (da 63 a 71 metri quadrati) tutti dotati di bagno e cucina. Il blocco centrale ospita una cucina comune con una sala da pranzo per settanta commensali, una sala per i ricevimenti e le feste, un ne gozio di alimentari, un’infermeria, una lavan deria e alcune stanze da letto per chi lavora nel

from 25 square meters to 37 square meters), 25 two-bedroom apartments (from 43 to 75 square meters), and 8 three-bedroom apartments (from 63 to 71 square meters) all with bathrooms and kitchens. The central block houses a communal kitchen with a dining room for seventy diners, a room for receptions and parties, a grocery store, an infirmary, a laundry room, and a few bedrooms for those working in the complex including a cook, some waiters, cleaning staff, and a nurse27.

Finally, the single-family dwellings which com plete the project in two rows in the northwest

I modelli abitativi di Backström e Reinius tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta / The housing models of Backström and Reinius between thirties and fifties

33

12A. Punkthus (casetorre) Rosta, Örebro 19481952. Vista da sud (Örebro Läns Museum, Örebro, OLM-2012-8-12178). Foto di Örebro Kuriren.

Punkthus (tower-houses) Rosta, Örebro 1948-1952. View from the south (Örebro Läns Museum, Örebro, OLM-2012-812178). Photo by Örebro Kuriren.

12B. Punkthus (casetorre) Rosta, Örebro 1948-1952. Piano tipo (da «Byggmästaren», n. 24, 1951, p. 407).

Punkthus (tower-houses) Rosta, Örebro 19481952. Typical plan (from Byggmästaren, n. 24, 1951, p. 407).

una sua autonomia compositiva [12A, 12B].

Una strada intrapresa negli stessi anni anche da altri architetti, a cominciare da Mario De Renzi (1897-1967) che, a Roma, progetta le “torri stellari” per il quartiere INA-Casa Valco San Paolo e quelle per il Tuscolano II, il cui impianto ricorda rispettivamente la torre di Gröndal e quelle di Danviksklippan, per fini re, a Danys Lasdun (1914-2001), con l’edifi cio per appartamenti Bethnal Green a Londra dove, come nella torre di Örebro, è manifesta la separazione tra il collegamento verticale e la parte abitativa. Ma il quartiere popolare di Örebro, a cui Backström e Reinius lavorano tra

example. Here, in fact, the plant presents a solution halfway between the two mentioned above; and if on the one hand the planimetric articulation is not exasperated as in Gröndal, on the other hand there is a clear functional evolu tion in that the residential part is separated from the vertical connection represented by the stair case and elevator group, which is emancipated and expelled from the main nucleus, acquiring its own compositional autonomy [12A, 12B]. A path undertaken in the same years also by other architects, starting with Mario De Renzi (1897-1967) who, in Rome, designed the “star towers” for the INA-Casa Valco San Paolo dis trict and those for Tuscolano II, whose layout is reminiscent of the Gröndal and Danviksklippan towers respectively, and finally, to Danys Lasdun (1914-2001), with the Bethnal Green apartment building in London where, as in the Örebro tower, the separation between the vertical connection and the residential part is evident. But the working-class neighborhood of Örebro, on which Backström and Reinius worked between 1948 and 1952, deserves attention not only for the tower but also for the different compositional strategy obtained from the aggregation of the same Y-shaped el ement used in the Swedish capital [13]. Here, in fact, a tight plan layout is not implemented as in Stockholm, but, given the characteristics of the area, which is almost completely flat, the perimeter of the entire area is defined in order to obtain two enormous free spaces in the center, delimited by a segmented sequence of multicolored residential buildings34. These central spaces present once again a meticulous green arrangement strongly desired by Örebrobostäder – the Municipal Housing Company founded in 1946 on the initiative of the City Council to cope with the lack of housing in the

42 Giovanni Bellucci

13. Stjärnhuas (case stellari) Rosta, Örebro 1948-1952. Maquette (ArkDes, Stockholm, ARKM.1962-101-1483).

Stjärnhuas (star houses) Rosta, Örebro 1948-1952. Maquette (ArkDes, Stockholm, ARKM.1962101-1483).

il 1948 e il 1952, merita attenzione oltre che per la torre anche per la diversa strategia com positiva ottenuta dall’aggregazione del me desimo elemento a Y utilizzato nella capitale svedese [13]. Qui infatti non si mette in opera un impianto planimetrico serrato come fatto a Stoccolma ma, date le caratteristiche dell’area quasi completamente pianeggiate, si procede alla perimetrazione dell’intero comprensorio in modo da ricavare al centro due enormi spazi liberi delimitati da una sequenza segmentata di edifici abitativi multicolori34. Questi spazi centrali presentano ancora una volta una meticolosa sistemazione a verde fortemente voluta dall’Örebrobostäder la Società municipale di Alloggi fondata nel 1946 per iniziativa del Consiglio comunale per far fronte alla man canza di abitazioni nella città che peraltro negli stessi anni promuove la realizzazione del Baronbackarna, un altro importante quartiere popolare firmato degli architetti Sidney White (1917-1982) e Per-Axel Ekholm (1920-2019)

city – which, moreover, in the same years promoted the realization of Baronbackarna, an other important working-class neighborhood signed by the architects Sidney White (19171982) and Per-Axel Ekholm (1920-2019) in the northern part of the city35. The Stjärnhuas Rosta of Örebro is completed with a nucleus of neighborhood services allocated in some buildings placed parallel to the main road that marks the residential area on the eastern side; among others, some stores, a nursery school, office spaces and a neighborhood center are located here36.

To introduce a final type of settlement, which once again marks Backström and Reinius’ ca reer in a positive way, we need to take a step back and mention the Kvarteret Timmerman nen project completed in 1942. The layout of this building on the island of Vaxholm opens up a new compositional typology in their already rich architectural production. Vax holm, an island north of Stockholm largely

I modelli abitativi di Backström e Reinius tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta / The housing models of Backström and Reinius between thirties and fifties

43

15A. Recupero urbano quartiere Pilens Backe, Linköping 1945-1948. Pianta di studio di uno dei nuovi edifici residenziali (ArkDes, Stoccolma, ARKM.1987-10-100).

Urban rehabilitation Pilens Backe district, Linköping 1945-1948. Study plan of one of the new residential buildings (ArkDes, Stockholm, ARKM.1987-10-100).

15B. Recupero urbano quartiere Pilens Backe, Linköping 1945-1948. Vista dei nuovi edifici (Friluftsmuseet Gamla Linköping, Linköping, ÖM.ARGU.000728).

Foto di Arne Gustafsson.

Urban rehabilitation Pilens Backe district, Linköping 1945-1948. View of the new buildings (Friluftsmuseet Gamla Linköping, Linköping, ÖM.ARGU.000728).

Photo by Arne Gustafsson.

50 Giovanni Bellucci

I modelli abitativi di Backström e Reinius tra gli anni trenta e gli anni cinquanta / The housing models of Backström and Reinius between thirties and fifties

51