Prairies

An MKSK field guide for communities and developers with goals to restore habitats and combat climate change by sequestering carbon out of the atmosphere.

LAB FOR CLIMATE & BIODIVERSITY RESILIENCE

An MKSK field guide for communities and developers with goals to restore habitats and combat climate change by sequestering carbon out of the atmosphere.

LAB FOR CLIMATE & BIODIVERSITY RESILIENCE

Planting and restoring prairies is a technique for carbon sequestration. A large amount of fixed carbon is stored in plant roots. When the plant dies some of the root remains in the soil for hundreds of years as organic carbon. Prairie soil acts as a “carbon sink”.

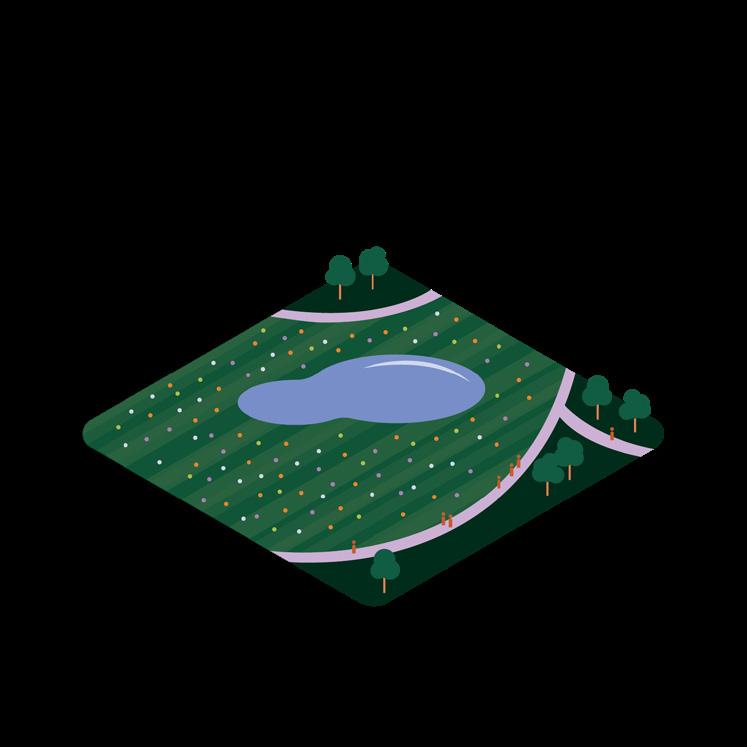

Prairie landscapes are a beautiful natural alternative to lawns. They are recreations of the native wildflower and grass carpets that once covered the central US - the Midwest south into Mexico. They require low energy, labor, and resource input, and cost less to install and maintain than lawn.

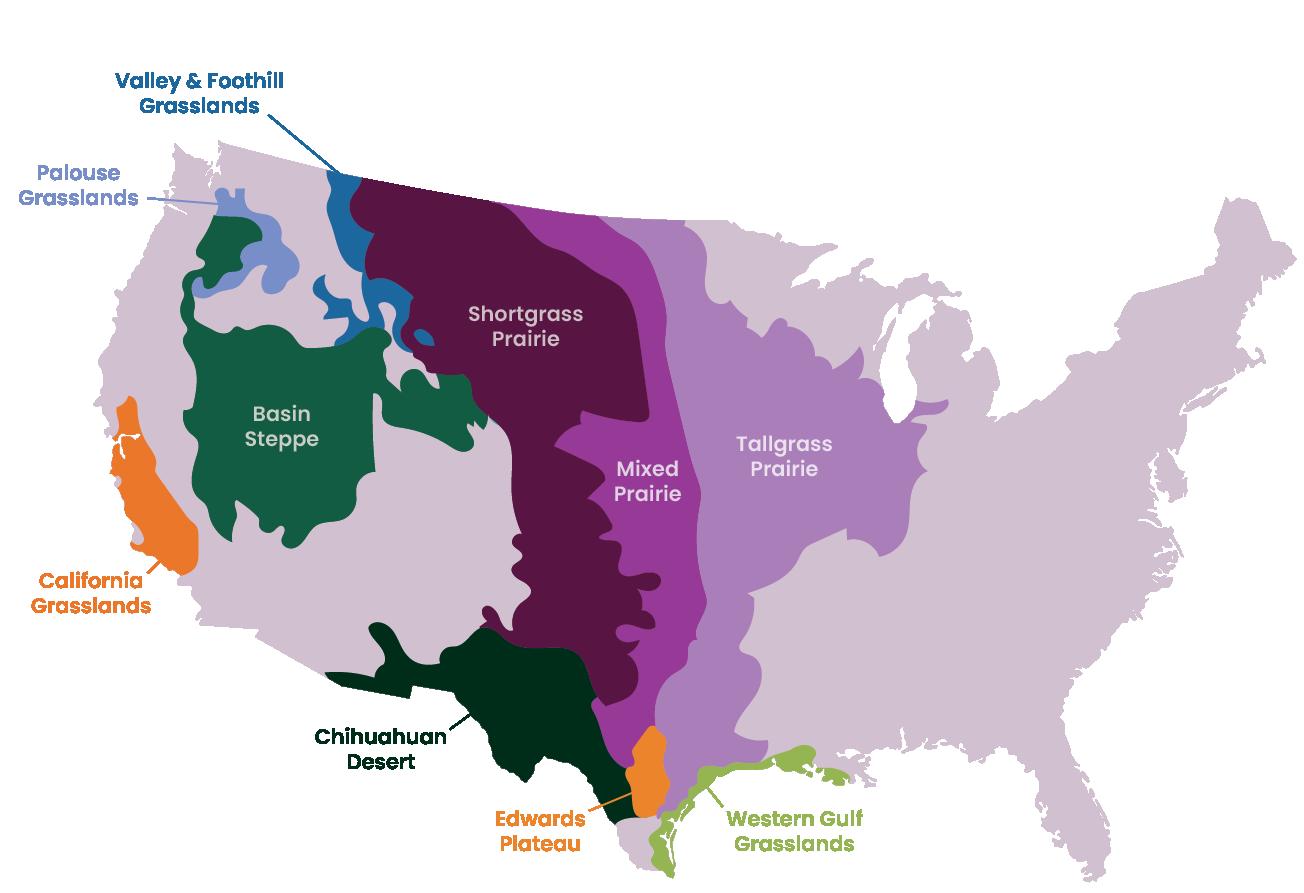

Prairies are a type of grassland unique to central North America. Grasslands are habitats where trees and shrubs are naturally excluded by limiting environmental factors. In the case of prairies, low precipitation and constant dry westerly winds keep woody plants at bay, so that grasses and wildflowers dominate. Our central plains have particularly rich, deep, silty soils, known as loess, that comes from weathered rock powder blown off of the Rocky Mountains over many millions of years. The result is a very dense and resilient plant community with deep roots, high biomass, and high diversity.

Prairies are generally composed of a few dozen varieties of grasses - about 80% - with the remaining 20% made up of hundreds of species of wildflowers. Prairies vary across their biome, from cool to hot along the north to south axis, and taller to short from the moister east to the drier base of the Rocky Mountains. This variation creates a patchwork of prairies types, each with a signature character in various regions.

By the 1920’s nearly all wild prairies had been broken up by the plow, and much of their natural thatch and soil richness was lost. Prairies today are either preserves or restorations, but once established, prairie landscapes begin to function like wild prairies, accumulating soil carbon and attracting

Select Site: Select the location for the prairie, taking tractor/mower access into account. Leave room at the edges for mown turf walks.

Soil Report: A standard soil test is needed, such as from a university extension service, to determine what grasses and wildflowers will perform best.

Existing Plants Inventory: Carefully inventory the existing plants on the site, especially invasive weeds. Controlling competition is the most significant maintenance issue for prairie landscapes. If invasives are present, they should be removed at the outset of the project. Early spring into mid-summer is the best time to inventory existing plants. A visit from a local extension specialist can help.

Choose Prep Method: There are two ways of realizing a prairie planting: working with the existing plants or clearing the whole area and starting fresh. The first method is faster and costs less, but comes with more risk of weed invasion. The second is more predictable, but costs more and takes longer to establish. Conditions found on the site should inform this decision.

Choose Seed Mix: The seed mix selected should reflect the native plant community of the project location and contain a balance of perennials grasses and wildflowers that will thrive in a variety of sun, soil, and water conditions. Specialist prairie seed suppliers offer trial-anderror tested mixes, usually with color and seasonal interest options.

Monitoring: Prairies require much less maintenance than lawns but are more knowledge and monitoring intensive. Watch prairies for weed invasions, die back areas, and waterlogging.

Initial Mowing: During their first two years, mow plants to a height of 4” before they start to bloom, to eliminate most annual weeds and woody plants, favoring perennial grasses and wildflowers.

Ongoing Maintenance: Starting in year three, mow close to the ground and rake in early spring to allow the sun to warm the soil. This clears the prairie of last year’s stalks, as spring wildfires do in Nature. Do not water or fertilize.

Prescribed Burning: Fire is part of the natural cycle of prairies. Mowing takes the place of burning for most prairie maintenance needs, but carefully controlled burning can be done by specialized services.

Periodic Renewal: From time to time, parts of prairie landscapes are overwhelmed by weeds or their species composition becomes unbalanced. These areas can be overseeded or dug up, sheet mulched, and reseeded. Acting quickly minimizes the problem.

Carbon sequestration: Prairie grasses and wildflowers are mostly hidden underground, with fibrous root systems that can grow to a depth of 12’. These roots die back each year, leaving root tissue to decompose, adding soil carbon every season for hundreds of years. On average, prairies sequester 1 ton of carbon/acre each year - a significant carbon sink.

Low maintenance input: Prairies thrive without irrigation, fertilizers, or pesticides. They require mowing once or twice per year, once established, about 1/20th of the mowing demanded by conventional lawns. Considering that single stroke engines in most mowers are among the dirtiest polluters, this is a significant benefit.

Stormwater mitigation and cooling: The thick foliage of prairies breaks the momentum of raindrops and slows surface runoff, decreasing erosion and allowing nitrogen and phosphorus to be absorbed by grasses and wildflowers. Deep roots create pathways through the soil for percolation, replenishing ground water. This deep moisture keeps the prairie alive between rainfalls, cools the soil and air, and contributes moisture that builds clouds, further cooling the earth

Biodiversity and habitat: The diversity of the prairie plant community attracts many insects, birds and other wildlife, and its density provides them with critically important cover. Grassland birds are now the fastest declining type of wild birds in North America.

MKSK is committed to designing the change our world needs, discovering new solutions and building new ways of working. Every project is an opportunity to address climate change and loss of biodiversity in the design and planning of communities, landscapes, and cities. MKSK can assist in the design and planning of prairies, and other habitat restoration and carbon sequestering landscapes, to help fulfill the environmental stewardship goals of our commercial, institutional,

LAB FOR CLIMATE & BIODIVERSITY RESILIENCE