Volume 3, March–April 2023 Magazine of the Bartók Spring International Arts Weeks

mupa.hu

Müpa Budapest is supported by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation

EXPERIENCE! In

Corporate partner:

every respect.

DEAR FESTIVAL AUDIENCE!

As a conservatory student, I had the chance to attend many events in Vienna spotlighting the music of György Ligeti. I also remember well a conversation focusing on the composer’s interest in African music. Although honoured as a hero of new music, Ligeti believed it important to exceed expectations and put our firmly held convictions to the test. It was a formative experience to hear that, to Ligeti, ideas were more important than ideology. He was an explorer who knew no fear, advancing on his own path and conquering fresh territories with each new work. Can there be any more noble pursuit in contemporary music?

As for Klangforum Wien’s relationship with Ligeti, we are proud to own a photograph of the maestro rehearsing with our orchestra in the 1980s. It is no secret that initially the musicians feared him, doubting if they could meet his expectations. Ligeti was critical and demanded extraordinary efforts from the orchestra, but after the concerts he never failed to make his satisfaction known. We could tell a similar story about György Kurtág, and this is hardly a coincidence given that both emerged from the same cultural background, and both always strived to bring the most out of musicians.

In January, we launched a series of concerts with Klangforum Wien based around the work of Ligeti, who was born 100 years ago. We are in the privileged position of being able to present to a broad audience the radical, creative activity that Ligeti pursued in new music in the second half of the 20th century. It is important to us for audiences to understand that, in terms of quality, these are compositions of the same standard as the classic works of music history. The variety of Ligeti’s œuvre is also a defining trait, as performing his works gives every one of Klangforum Wien’s twenty-four soloists the opportunity to showcase their skills.

The Ligeti 100 concert at Bartók Spring has been made possible through the collaboration of Müpa Budapest and the Heidelberg Spring music festival. The production comes to Budapest two days after its debut in Germany, presenting four concertos by Ligeti featuring Hungarian soloists under the exceptional composer and conductor Péter Eötvös, who also assembled the concert programme. As a creative personality in his own right, Eötvös has unequivocally marked out new directions in music. Klangforum Wien last performed in Budapest in 2019. We are close both literally and figuratively, being very similar in our Central European cultural roots and our approach to music at the same time. We look forward to this fresh encounter and its reception by the Hungarian audience!

Peter Paul Kainrath, Artistic director of Klangforum Wien

Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo

Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo

Songs at the Edge of the Snow Line A conversation with Benjamin Appl 06 Greetings by Peter Paul Kainrath, Klangforum Wien 01 The Distantly Familiar György Ligeti 100th anniversary of the composer behind 2001: A Space Odyssey 12 The Editor Recommends 18 04 The War and Peace of the Worlds Bartók and Stravinsky through each other’s eyes I Doubt, Therefore I Am Luciferian dilemmas, from Richard Strauss to Levente Gyöngyösi 16 Embracing the World Beyond Sara Baras: Alma (Soul) 10

Village Tunes in Budapest Style Fifty years of Muzsikás 26 The Editor Recommends 32 Light at the End of the Tunnel Mark Oliver Everett’s survival story: Eels 30 The Good, the Bad, the Ugly and the Beautiful Modern folk revelations with Damien Rice 24 What You Haven’t Seen Before World music and music films at Budapest Ritmo 34 Tales to Arm Us for a Lifetime Classic tales and the misconceptions related to them 36 Alpine Inspiration Béla Bartók’s Swiss connections 20

THE WAR AND PEACE OF THE WORLDS

BARTÓK AND STRAVINSKY THROUGH EACH OTHER’S EYES

There are truths we accept without a second thought. Among lovers of 20th century classical music, the appearance of the names of Bartók and Stravinsky side by side on a concert programme or recording is no cause for uproar. But what would the two giants themselves have made of it? B

y Tamás Jászay

The question is of course rhetorical, and many perhaps know the answer only too well, for while Béla Bartók was long a devoted follower of Igor Stravinsky’s revolutionary music, the Russian-born composer spoke of his Hungarian contemporary with cold detachment at best. (We should regard his remark on hearing of Bartók’s death that he never really liked his music as one that was hastily and somewhat unfortunately expressed.)

For his part, Bartók wrote in the daily Brassói Lapok in 1924: ‘In my view, among composers living abroad today, only two are geniuses, Stravinsky and Schoenberg. I am closer to Stravinsky, if we think of The Rite of Spring, which I believe to be the most colossal musical opus of the last thirty

years.’ At the time they had already met in person, though in Parisian music circles Stravinsky initially took Bartók for a violinist. The Hungarian composer told his wife of their acquaintance matter-of-factly: ‘Not exactly modest – but an interesting person who I think cuts and belittles with his words just as he does with his music…’

A MEETING OF TITANS

The emerging parallel between the two men nevertheless holds its own in a historical context. A critic in the periodical Pester Lloyd in 1917 identified Bartók’s place for readers with the following: ‘His music, comprehensible even to the lay listener, could best be charac terised

4

Igor Stravinsky | Photo: Bain News Service

by kinship to the music of Igor Stravinsky, whose works have already been performed here on several occasions. This kinship lies partly in the fertilisation of both men’s art by the new French [composers], and partly in their deep roots in folk song.’

And this is where the problems begin, as while Bartók proudly claimed folk song and music as a great source of inspiration throughout his life, Stravinsky – having left Russia – viewed any enthusiasm for the genre with incomprehension. In a series of conversations with Robert Craft, he said of Bartók: ‘I never could share his lifelong gusto for his native folklore. This devotion was certainly real and touching, but I couldn’t help regretting it in the great musician.’

Naturally, while it is not our intention to declare a winner between two rival equals, one must perceive behind this summary judgement from 1959 the backdrop of the Cold War, at the time already a decade and a half in progress. As a Russian émigré living in America, Stravinsky put his faith not in national values, but in the universality of twelve-tone technique, which did not lend itself to any political interpretation.

FOLK MUSIC ON THE BALLET STAGE

From the very beginning, however, Stravinsky was greatly indebted to Russian folklore: we need only think of the wonderful music he wrote for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris. His method of blending folk motifs with modernism served as a model for many, Bartók among them. We know the Hungarian composer closely followed the music of many nations and thus would have been certain that Stravinsky drew on folk sources in his music and that this was precisely what lent authenticity to the Russian composer’s modernism.

This notion recurs across decades in Bartók’s letters and interviews, of which we cite only a few here. In 1920, he writes of Stravinsky and Zoltán Kodály: ‘[T]he work of both springs so much from the pure folk music of their homeland that it is almost its apotheosis.’ In 1931, writing of Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla, he notes that although neither collected peasant music, they most likely studied it live as its imprint can be heard so vividly in their works.

In 1943 – four years after a similar commission for Stravinsky – Bartók gave a series of lectures at Harvard where he highlighted the folk motifs in ballet music, particularly in The Rite of Spring. And though Stravinsky denied it until his death, today it is widely acknowledged that certain elements of this work truly derive from collections of Russian folk music.

repulsive. In spite of, or perhaps because of this, it gave him defining impulses and some believe that only Kodály exerted a greater influence.

Thanks to Bartók’s first wife, Márta Ziegler, we know that in 1918 he constantly carried around the score for The Rite of Spring, attempting – unsuccessfully – to bring it to the intention of Miklós Bánffy, the intendant of the Hungarian Royal Opera House. In 1920, Bartók was still pronouncing enthusiastically on the few Stravinsky works known to him, although within a few months this had already given way to disappointment: ‘I had expected something of true grandness, of real development; and I am truly very sad for not finding at all what I imagined.’ By 1928, Bartók was characterising Stravinsky as one who had suddenly turned his back on tradition, while Kodály’s method of summarising previous knowledge was far more to his liking.

TOGETHER AND APART

A key event in this contradictory, multifaceted relationship was a concert in Budapest on 15 March 1926 that featured not only performances of Stravinsky’s works, but the master himself as piano soloist – as if provoking Bartók on his home turf. The latter still gave a positive assessment of the concert, observing that the coldness felt on first reading evaporated in the concert hall. A letter from his second wife, Ditta Pásztory to her mother gives an explanation, however, when she writes that if Bartók had produced such ‘machine music’ they could have nothing more to do with each other.

In the arts just as in science, many hesitate to ask the question ‘what if’. In closing, however, let us indulge in speculation. In 1945, Nathaniel Shilkret invited the leading composers of the day to collaborate on a seven-movement work based on the biblical Book of Genesis. Apart from Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Milhaud, the original roster featured Bartók, but the request came too late. Could the two geniuses have reconciled their differences in the Genesis Suite?

31 March | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

SEMYON BYCHKOV AND THE CZECH PHILHARMONIC

The opening concert of the Bartók Spring

Bartók: The Miraculous Mandarin – suite

ATTRACTION AND REPULSION

In an extensive study, Bartók scholar David Schneider analyses in detail the Hungarian composer’s highly complex relationship with Stravinsky. In his view, throughout his career as a whole Bartók found the Russian composer’s music at once irresistible and

Thierry Escaich: Études symphoniques –Hungarian premiere

Stravinsky: Petrushka (1946 revised version)

Featuring: Seong-Jin Cho – piano, Czech Philharmonic

Conductor: Semyon Bychkov

5

SONGS AT THE EDGE OF THE SNOW LINE

A CONVERSATION WITH BENJAMIN APPL

Few can say they have enjoyed the patronage of a living legend at the very start of their career. As the last pupil of the epoch-defining singer Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, German-British baritone Benjamin Appl is one who can stake such a claim. Abandoning a highly promising career in finance, the Bavarian-born artist burst onto the international music scene in the 2015/16 season when he took part in the Rising Stars concert tour as the nominee of London’s Barbican Centre, before going on to winning an award for ‘Young Artist of the Year’ at the Gramophone Awards 2016. We spoke with the 40-year-old singer about Bach and the Romantic song culture, his work with György Kurtág, his connections to both the artistic and business circles and his recording of Schubert’s Winterreise in the Swiss Alps. B y Péter Merényi

Photo: Gábor Valuska / Müpa Budapest

Photo: Gábor Valuska / Müpa Budapest

In recent years, you’ve brought out two records featuring vocal works by the Bach family, primarily Johann Sebastian Bach. What is the important of these works for you? When I sang in the Regensburg boys’ choir as a child, we performed a great number of Bach motets. Subsequently, I often sang the passions and the Christmas Oratorio series of cantatas. So Bach was always an important composer for me. I believe the most important thing in his work is its well thought-out musical structure, his analytical way of thinking as a composer and the art of counterpoint; at the same time, behind the well-structured fabric of the music, a rich horizon of feelings and emotions is revealed.

We first had the chance to hear you at Müpa Budapest in 2016 as part of the Rising Stars international concert series and you later performed at the Bridging Europe festival presenting German culture in 2021. But this is the first time you’re giving a concert at the Liszt Academy.

What’s more, this is the first time I’ll be performing with the Gabetta Consort! Our concert falls on Holy Saturday, which played a very important role in the life of a composer as deeply religious as Bach. We begin the programme with two perfectly tailored secular compositions which display a little-known, more rarely heard side of Bach. The rest of the programme is based on the ecclesiastical period of Easter, including arias from the timeless St Matthew Passion, as well as orchestral works and pieces that call for a solo singer, where the ideas are defined by contemporary notions of death and the fervent belief in the existence of afterlife. I’m interested in the attitude of people of that time to life and death: the solo cantata that begins with Ich habe genug, especially the closing aria that contrasts the approach of death with a nonetheless cheerful mood, is a great example of this – and it’s no coincidence that it also marks the conclusion of the programme. These pieces present a major challenge, but at the same time it’s also a great experience if I can successfully deliver a convincing performance for the audience.

You’ve sung numerous operatic roles at many of the world’s opera houses. How do these experiences help you – even at the coming concert in Budapest – when you sing Bach’s cantatas?

Opera is a complex genre: director, conductor and répétiteur together inspire the singer, enriching their palette with a variety of colours, emotions and characters. I can profit from this knowledge at song recitals and in performing oratorical works.

The culture of German Romantic song also plays a key role in your work. The Lied, the German song genre, is very close to my heart. For almost four years, I had the chance to work with the outstanding German lyric baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who passed away in 2012. I have been deeply moved by Winterreise since I was a teenager. In this song cycle, Schubert never shows off or entertains and instead the music is sincere and from the heart. Wherever I go in the world, I try to make young people fall in love with German song culture.

Winterreise is also the subject of a special concert film you recorded with the bbc at the Julier Pass in the Swiss Alps, surrounded by snow at a height of almost 2,300 metres, which was first screened last year. We shot the film in harsh conditions – in minus 16 °C weather and 60 centimetres of snow –so the work was a big challenge even though I’d already performed Winterreise more than a hundred times before. The visuals of the film were magnificent, that’s how important the popularisation of German song culture is to the British public service broadcaster!

I’ve read that you’re a dual German-British citizen, but spent most of your life in Germany. I grew up in the Bavarian town of Regensburg where, as I mentioned before, I sang in the boys’ choir of St Peter’s Cathedral. I never dreamed that I’d be a musician. I couldn’t imagine living the lifestyle I have today and that I’d be travelling the world with a suitcase and living off my vocal cords. I always thought that it didn’t pay to be a musician. I graduated in finance and accounting and went to work at a bank. But later on, I felt a strong drive to explore my inner self and realised that self-reflection of this kind might find fulfilment in an artistic profession.

7

How does your business training help you manage your career?

It’s good that I’m ready to negotiate with bank officials about my new mortgage! [laughs] All joking aside, a business diploma and analytical skills are a big help. I use my knowledge of negotiating technique in my life as an artist as well – particularly when I have discussions with sponsors or clients from the business world, since I know their way of thinking and motivations.

Now that you’ve raised the issue of the relationship between the world of business and the arts, there’s a much stronger tradition of artistic sponsorship in the English-speaking countries than in Europe. There are advantages to both systems. In Germany, culture is mainly supported by the state. This is great because it has a stimulating effect on projects with an experimental nature; for example, promoting the performance of contemporary music in concerts, so it’s not completely at the mercy of ticket revenues. On the other hand, the primarily market-based financing of the arts – as in Canada, for example –has the benefit of making financial support for culture something to be expected among the wealthiest sections of society.

A few years ago you began a close collaboration with György Kurtág. You’re considered a specialist in his Hölderlin-Gesänge for baritone, the six songs of which are performed by the singer almost without instrumental accompaniment, except for some brass in the third song.

The Konzerthaus Dortmund dedicated its Zeitinsel (Time Island) festival in February 2020 to the works of Kurtág, ahead of which the concert hall’s artistic director asked for the composer’s advice about the programme. Kurtág enthusiastically suggested the Hölderlin-Gesänge, which he saw as one of his most successful works in terms of the integration of text and music. A suitable singer was chosen through a lengthy four-round casting process. Ten baritones were auditioned from all over the world – including me – and the recordings were sent to Kurtág, who shortlisted five names. In the next round, we had to sing a short excerpt from the Hölderlin-Gesänge, after which three of us remained. Kurtág then asked for recordings of the singers in a lower register, and finally I won the commission.

How was your encounter with the composer?

I was already aware – as I’d heard from a number of colleagues – that Kurtág is an extremely demanding composer who concerns himself with even the smallest details. At the first rehearsal, the aforementioned artistic director in Dortmund and representatives of Kurtág’s publisher [UMP Editio Musica Budapest – Ed.] were present, along with a film crew, as director Dénes Nagy is making a documentary on the composer which is scheduled for release in 2024. I clearly remember the moment when the composer’s wife Márta Kurtág [who passed away in autumn of 2019 – Ed.] said to me after half an hour, ‘You’re our man!’

8

Photo: Gábor Valuska / Müpa Budapest

Do you visit Budapest regularly to work with him in person?

We’re mainly occupied with Schubert’s songs and of course the Hölderlin-Gesänge. We’ve been working on it for years and it’s quite a Sisyphean task as on several occasions we’ve gone through all the details of the work again and again from the beginning.

[The preparations are documented in 18 hours of film –Ed.] Kurtág has an extraordinary knowledge of music, music history and other composers, but he’s also at home in the fields of philosophy, literature and fine art. This is refreshing for me, since these days the music profession is often about money and business.

I understand you’re working on a new album with the composer.

Over the last few days [the interview was conducted in December 2022 – Ed.], I’ve spoken with him about the pieces on the album. I hope the record will come out soon, on which Kurtág himself accompanies me on piano. We’ve put together an album of a personal nature, presenting the collaboration of a singer with one of the greatest living composers today. With that in mind, we’re also publishing background documents on its creation, so the listener can familiarize Kurtág’s teaching approach and what’s important for him. The album will be released on the Alpha Classics label, which I record for exclusively.

I’ve read that you also collaborated with another Hungarian, writer and Holocaust survivor Éva Fahidi, for which you requested no payment. Éva is an extraordinary person. After we got to know each other a few years ago, the idea of a joint production arose: she spoke about her life, while I sang German songs that held particular significance for her. As a young woman before the Shoah, Éva had trained as a classical musician and pianist. At the performance, I sang songs from Schubert, Schumann, Wagner and Brahms, as well as from composers who wrote in the concentration camps, such as the Czech Hans Krása. We performed the programme in Germany and England: understandably, it had a completely different effect on audiences in the two countries, but was none the less moving in both.

Classical music for all ages in the heart of Budapest!

8 April | 7.30pm Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

BENJAMIN APPL AND THE GABETTA CONSORT

Works by Bach and Pachelbel

Featuring: Benjamin Appl – baritone, Gabetta Consort

Conductor and featured on the violin: Andrés Gabetta

EMBRACING THE WORLD BEYOND

‘Increasingly in flamenco, it’s the women who wear the trousers, literally and metaphorically’, reflected a reviewer for The Guardian on the performance of Sara Baras and her company at Sadler’s Wells in London, opening the 2019 international flamenco festival. Hailing from San Fernando in southwest Spain, the dancer and choreographer is currently a living legend of the genre whose performances sell out in record time. Could her secret be the raw, primal power that emanates from every movement and draws the eye like a magnet? Or is it the boldness with which she blends various dance, musical and visual genres on stage: classical and contemporary, ruffled skirts and figure-hugging trousers? Bartók Spring features the company’s latest production, Alma (Soul). B y Zsófia Hacsek

ANDALUSIAN TREASURES OF MUSIC AND DANCE

Sara Baras was born in 1971 and threw herself into dancing from childhood: she was initially taught by her mother, Concha Baras, a dancer herself who also headed a dance school. Two musicians had a huge influence on her early career. One of these was the Roma flamenco singer Camarón de la Isla, a great figure of the genre who lived in the same neighbourhood where young Sara grew up. Years later, Baras would still refer to Camarón as her ‘artistic

godfather’, evoking the memory of the legend – who passed away in 1992 – in many of her performances. Her other role model is flamenco guitarist Manuel Morao who led the Gitanos de Jerez company which Baras herself joined at the age of twenty-four. Morao’s stated intention was to introduce the whole world to the flamenco talents of the Cádiz province and they toured extensively with this goal in mind. So it was that Baras found global fame. After appearing with Gitanos de Jerez in Paris in 1991,

10

Sara Baras: Alma | Photo: Sofia Wittert

the following year she travelled to Japan, where she and dance partner Javier Barón took their show to a multitude of venues over six months.

Gitanos de Jerez also appeared at the 1992 Seville Expo while Baras’ popularity soared. In 1993, she won the Madroño Flamenco Prize as the most outstanding flamenco artist of the year, so it was no surprise when a growing number of leading figures in Spanish flamenco sought her out, including the singer Enrique Morente and dancer-choreographers Merche Esmeralda and Antonio Canales.

After years of guest starring for various companies and performing at festivals solo or with a partner, in 1997 Baras decided to finally stand on her own two feet. A year later, she debuted at the head of her own company with the show Sensaciones. The company presented 13 shows over the past quarter-century, all of which were choreographed by Baras; its popularity is clearly proven by the fact that it has remained on the bill for years in London, Madrid, Barcelona and Paris. It has also conquered stages beyond Europe, including shows from Thailand to Mexico and Shanghai to San Francisco. There have now been over 4,000 performances and the company’s enthusiastic and talented members never fail to realise their leader’s ideas, which – as the performance of Alma in Budapest will surely demonstrate – promise a range of surprises for the audience.

A SPINNING, PULSATING SOUL

The creation of Alma was inspired by Baras’s father, Cayetano Pereira – although he was not a devotee of flamenco (and ‘had a hard time differentiating a seguiriya from a soleá or a taranto’), he was still fond of the more melancholic bolero. In the piece, Baras evokes every musical and dance genre that her father held dear. In light of this, it’s particularly heartbreaking that he can no longer see the performance, as he passed away one month after the premiere in December 2021. Yet this also opens the way to another interpretation: namely, do the messages we send to our loved ones after their passing eventually reach them? And as Baras asks, are there any better means than art, catharsis and language beyond words for calling out to our departed while simultaneously reconciling us, deep down, with the fact they are no longer physically with us?

The performance is literally colourful, with a riot of different shades appearing on stage. Sometimes Baras dances in a classic ruffled black flamenco dress, with the crimson light around her evoking the colour most often associated with the genre. On other occasions, she and her partners wear figure-hugging polka dot dresses and don trouser suits (as mentioned before, also worn by the female dancers) or evening dresses, as a succession of solos, duets and group dances appear on stage. The entire show is a gigantic fusion – or, as Baras puts is, a vast embrace – in which flamenco and bolero melt together into a variety of styles, forms, colours and sensual experiences.

THE DIZZYING CLATTER OF HEELS

‘In Alma, the rhythm and beat, emotion-fuelled movement and dizzying, almost surreal clatter of heels streams from every pore, filling the entire auditorium with energy’, gushed a Spanish critic on the Diariocrítico portal. An Australian reviewer, having seen the piece in Sydney Opera House, praised the unusual costumes, well-composed sequence of dances (allowing the story to unfold slowly) and harmony between musicians and dancers. The review on the Theatre Travels website relates how Baras ‘mesmerised us with her body movement and remarkable footwork’, adding that ‘It was absolutely insane to see how the drummer was trying his best to keep up with Baras during her solo routines as the audience cheered her on.’ The choreographer herself says, ‘[L]ife sometimes takes us to madness and only love, the miracle, an embrace or the shelter of skin can save us.… [T]here is no need to tell you that I would give my life to dance with you, there is no need to tell you that my flamenco heart has a bolero soul.’ One can scarcely imagine a more moving artistic creed from a dancer. What more can we do than join Baras in hoping that amidst the plethora of costumes, lights and sounds, the embrace of Alma will reach the man who inspired the performance’s creation, her beloved father, in the world beyond.

10 and 11 April | 7pm

Müpa Budapest – Festival Theatre

SARA BARAS: ALMA (SOUL)

Performed by: Sara Baras, Chula García, Charo Pedraja, Daniel Saltares, Cristina Aldón, Noelia Vilches, Marta de Troya – dance, Rubio de Pruna, Matías López ”El Mati” – voice, Keko Baldomero, Andrés Martínez – guitar, Diego Villegas – saxophone, accordion, flute, Antón Suárez, Manuel Muñoz “El Pájaro” – percussion

Featuring: Juana la del Pipa, Israel Fernández, Rancapino Chico – voice, Alex Romero – piano, José Manuel Posada “Popo” – double bass

Written by: Sara Baras

Lyrics: Santana de Yepes

Music: Keko Baldomero

Set: Peroni, Garriets

Costumes: Luis F. Dos Santos

Lighting: Antonio Serrano, Chiqui Ruiz

Choreographer, director: Sara Baras

11

THE DISTANTLY FAMILIAR GYÖRGY LIGETI

‘Music is not an island to me but rather part of a complex continuum of life and experience’, wrote György Ligeti. On another occasion, he firmly rejected striving for purity in music, explaining that his works are ‘contaminated by an insane number of associations, because I think in a highly synaesthetic way’. This Bartók Spring concert marking the 100th anniversary of Ligeti’s birth features notable concertos by the world-renowned Hungarian composer. B y Máté Csabai

Photo: Peter Andersen

Photo: Peter Andersen

Ligeti was a brave, immensely resolute individual who was constantly drawn to centuriesold traditions. His countless interests ranged from linguistics through politics to history and his works at once resembled everything and nothing at all. Yet he was not fit for any kind of messianic role and he would not commit himself to any single tendency. What could characterise a composer who created an imaginary land and language as a child, and who later – driven by the desire to explore – left the state socialist system behind and almost proudly proclaimed, as a cosmopolitan artist, that he was not at home anywhere? As he declared, ‘I am a Transylvanian-born Hungarian of Jewish descent and a citizen originally of Romania, then of Hungary and finally of Austria. I belong to no place: I belong to European intelligentsia and culture.’

At other times, he rejected even this and spoke of exotic or dreamlike, physical or metaphysical influences. For Ligeti, art was both the wasteland of T. S. Eliot and the wonderland of Lewis Carroll, where anything can happen. This does not imply a carefree attitude on his part, since he would gladly dwell on details with journalists and fellow professionals alike. He also described himself as an ‘anti-ideologue’ though perhaps knowing that it is difficult for such a thing to exist; at best, only when an artist resists all allures of conformity.

Ligeti’s music cannot be separated from his life, nor his musical inspirations from those derived from mathematics, painting, poetry or science as he himself always refused to set boundaries. According to an oft-quoted comment from fellow composer György Kurtág, Ligeti’s art leads one to suspect that ‘there are connections in art, in the sciences, in the cosmos, which he is aware of’. Exactly what these are will become clearer at the concert of four Ligeti concertos to be conducted by Péter Eötvös with Klangforum Wien on 6 April. Let us see what we can say about Ligeti in light of his works.

THE PRISON OF TRADITIONS

To the cursory observer, it may seem that when the avant-garde composers of the 20th century violated the musical rules and broke with the traditions of earlier centuries, they no longer needed to bother with tonality, the sonata form, familiar instrumental combinations or the symphonic genre, all of which were previously featured in the composer’s ‘toolbox’. In reality, the exact opposite often occurred: these tools would remain very much present – either because the modernists embraced them or because they rejected them. Throughout his life, Ligeti diligently and avidly studied the scores of his predecessors – Gesualdo, Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Debussy and Bartók – and it appears there was no line of music that would not generate three new ideas. Most of his works trigger associations with a dozen composers, two or three continents and a few scientific findings as well: Atmosphères, famed for its use in 2001: A Space Odyssey, would not exist without Debussy’s impressionistic sonic palette; the spatial effects of Lontano without similar attempts by Mahler and his String Quartet No. 2 without the works of Bartók or Alban Berg in the same genre.

When speaking about his own works, Ligeti often defined them in comparison or in contrast to something: he dubbed his stage work Le Grand Macabre an ‘anti-anti-opera’, while he likened his creation of micropolyphonic textures to Bach or Palestrina – even though there are at least as many discernible differences as there are similarities. All this would be but an irrelevant aside were it not that it greatly aids our understanding of Ligeti’s work. While those with sensitive ears may sometimes perceive it, it is precisely when we listen to Ligeti’s music as if listening to, for example, the similarly revolutionary works of Beethoven in his own time that its greatness can be grasped.

CHALLENGING CONCERTOS

The first note of Ligeti’s 1966 Cello Concerto, the pianississimo emerging from silence and steadily gaining in volume over the next two minutes or so, may immediately evoke another notable musical moment, the opening bars of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, conjuring the biblical image of the ‘face of the deep’ and the act of creation from the void. For Ligeti, however, the universe is far richer and more chaotic than to merely have a single joyful ode sung in this created world: around it is the teeming universe itself, the attraction and repulsion of elementary particles heard amid a somehow indescribable sense of order.

13

Three years later, Ligeti wrote the Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, in which he rediscovers melody – albeit only for fleeting moments. While a composer writing a melody might seem a humorous revelation, in Ligeti’s case it amounts to a discovery of a more philosophical nature. It relates to the question in æsthetics of whether beauty exists that is not artificial or affected, or for the poet whether there is an authentic mode of communication.

From the early 1980s, Ligeti’s style became more classical and this may once again direct our attention to the composer’s relationship with his illustrious predecessors. For years, he struggled with his Piano Concerto – five years for the first page alone to take proper shape – and by his own admission, the work has little to do with Schoenberg, Berg or the Second Viennese School and even less with the avant-garde circles of Darmstadt. It is inspired more by the unusual approaches of Debussy, Stravinsky and Ives and by African, Indonesian and Melanesian rhythms. ‘If this music is played correctly … it will after a time “take off” like an airplane’, wrote the maestro in an accompanying text for the world premiere. A beautiful idea from the same source may help us grasp many of Ligeti’s other works, ‘I prefer musical forms that have a more object-like than processional character. Music as “frozen” time, as an object in imaginary space evoked by music in our imagination, as a creation that truly develops

in time, but in imagination it exists simultaneously in all its moments. The spell of time, enduring its passing, encapsulating it in a moment of the present is my main intention as a composer.’ It is no coincidence that we find the mathematical Mandelbrot and Julia sets among Ligeti’s inspirations; needless to say, this is a concerto that imposes superhuman difficulties upon the soloist.

MUSIC OF THE PAST AND FUTURE

Debuting in 1993, the five-movement Violin Concerto is one of Ligeti’s most popular, complex and multifaceted pieces. Before setting out, the composer studied the violin repertoire methodically from Bach to Prokofiev, but he also utilised a folkloreinfluenced movement from his youth. He was drawn to the elegance of Mendelssohn’s popular Violin Concerto, while the influence of Paganini in the music’s broad, extravagant gestures is impossible to ignore. At this time it was increasingly clear even to Ligeti himself that he sought an alternative to the 12-tone technique building on perfect intervals, the overtones of tempered scales: a compositional method simultaneously pointing to the past and future. ‘I imagined a kind of “super-Gesualdo” sound’, wrote Ligeti and if this is hard to explain without score samples and technical jargon, we need only ask the reader to imagine what the music

14

of a 16–17th century Italian composer might have meant in their own time and what perspectives we might hear 400 years later. Ligeti sought these same perspectives when he composed, once noting, ‘I am in a prison: one wall is the avant-garde, the other wall is the past, and I want to escape.’

Ligeti’s œuvre is among the most exciting, but also most liberal of the second half of the 20th century, with a variety that may baffle even familiar audiences. On the one hand, this is the music of the great unknown, the big Other, which is perhaps symbolised by the famous monolith of Space Odyssey. On the other hand, the listener well-versed in music history is filled with a sense of distant familiarity when hearing some of his works. While Stockhausen, Boulez or Xenakis relied on reusable models as the basis for their compositions, Ligeti reinvented himself with each successive work. ‘I am like a blind man in a labyrinth, feeling his way around and constantly finding new doorways and entering rooms that he did not even know existed’, Ligeti once said of himself. Ligeti injected his music with chaos, the fractal structure of the world, Renaissance vocal polyphony and polyrhythms heard from indigenous peoples. He was a composer who did not create a school, but whose music leaves more or less no one untouched. In Eckhard Roelcke’s book of interviews, published in 2003, Ligeti recalls how he once jokingly mentioned to a friend in Budapest: ‘Let me express my wish: nothing should be named after me, but if they insist, let them call it “the György Ligeti Wrong Way”.’ He was right in that the path he showed was not clearly defined; the possibilities he saw, however, lay in all directions of the wide world.

6 April | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

PÉTER EÖTVÖS AND THE KLANGFORUM WIEN

Ligeti 100

Ligeti: Chamber Concerto

Violin Concerto

Cello Concerto

Piano Concerto

Conductor: Péter Eötvös

15

Featuring: Barnabás Kelemen – violin, László Fenyő – cello, Zoltán Fejérvári – piano, Klangforum Wien

Péter Eötvös, György Ligeti and György Kurtág at the International Bartók Seminar and Festival in Szombathely, 1990

Photo: Kálmán Garas

I DOUBT, THEREFORE I AM LUCIFERIAN

DILEMMAS, FROM RICHARD

STRAUSS TO LEVENTE GYÖNGYÖSI

What is the meaning of life? What is the nature of the universe? Is there salvation and eternal truth?

Is there such as a thing as human development, or is civilisation simply treading water? These are questions that have occupied thinkers since the drawn of humanity, including the likes of scientists, philosophers, writers and composers. Yet what has this got to do with a concert at Bartók Spring? The Sceptical Spirit, the concert of the Budafok Dohnanyi Orchestra, promises similarly philosophical depths, with an exciting programme based on questions of this nature. By

Endre Tóth

WHAT WOULD THE SUN’S HAPPINESS AMOUNT TO IF IT HAD NO ONE TO SHINE ON?

Ancient myths and legends, even religions themselves, were born out of the need to find answers to the pressing questions of who we are, where we came from, why we’re here and what is our purpose and task. The brilliant thinker, René Descartes held that thought is a prerequisite for cognisance and that one of the fundamental expressions of thought is doubt – or, as the French philosopher called it, ‘methodic doubt’. Based on these premises, Descartes saw God’s existence as proven, his conclusion in its entirety reading ‘I doubt, therefore I think; I think, therefore I am; I am, therefore God exists.’

A salient example of the relationship between philosophy and music is Also sprach Zarathustra, one of Richard Strauss’s most famous symphonic poems; its eponymous character (Zoroaster in the Greek version) was a Persian prophet who founded a religion in pre-Christian times. Having studied his teachings, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote one of the best-known philosophical works of all time, and its language – which is filled to the brim with musicality – captured Strauss’s creative imagination. In Nietzsche’s work, Zarathustra is the eternal denier whose response to every notion is to underline its futility. Leaving his home, he moves into the mountains, where he spends his days in contemplation for ten

16

years. Eventually, however, his heart yearns for something more and one morning he steps into the Sun and declares, ‘Thou great star! What would be thy happiness if thou hadst not those for whom thou shinest!’ Strauss launches his symphonic poem with the introduction of the musical nature motif (C–G–C’), radiating eternal, universal order.

Just as in Descartes’ philosophy, Zarathustra is a doubting, critical thinker, but his doubts lead to destructiveness: in the course of his allegorical journey, he dismisses religion, morality, science, desires, joys and passions and, in the words of music historian András Batta, ‘melts away happily and alone in the harmony of the universe’. Back to nature, one might say. The C major theme representing the universe, which continually rears its head throughout Strauss’s symphonic poem, is irreconcilable and incompatible with the B tonality of the mortal world that seems so near, and yet is still so distant.

LUCIFER, THE ANCIENT SPIRIT OF DENIAL

It is doubt that drives Lucifer in John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost. In the work originally published in 1667, Milton portrays the fallen angel as an ambitious, proud creature who is not afraid to confront God, and consequently the view understandably arose in later times that the author was actually siding with Satan in his writing. The first part of Milton’s work describes Lucifer’s battle with God, while the second relates Adam and Eve’s fall into sin and their regret after tasting the fruit of the tree of knowledge – as a result of Adam’s imaginary journey. After their expulsion from the Garden of Eden, an angel tells the first human couple they may also find Paradise within themselves and that they may remain in touch with God. Just as Nietzsche did at the end of the 19th century, Milton was already questioning numerous articles of faith in the 17th century, contrasting predestination with free will.

The idea of human development is also a familiar motif in Hungarian literature, expressed in Imre Madách’s dramatic poem The Tragedy of Man, with Lucifer, the ‘ancient spirit of denial’, again appearing as one of its driving forces. Therefore Levente Gyöngyösi was faced with no small task when he decided to write an opera brimming with oratorical elements based on Madách’s worldrenowned work. Apart from the familiar characters from Madách’s story, one of the winners of Müpa’s 2020 Composition Competition, Tragœdia temporis features a new protagonist, the Child, a figure Gyöngyösi derived from a messianic image portrayed in the Book of Proverbs.

Equally rich in tone as the composer’s previous opera, The Master and Margarita, the first act of the work presented here deals with events up to the expulsion from Paradise. The divine and supernatural episodes draw on the traditions of classical music, while the human scenes are inspired by popular

musical genres. The duality of the musical world of Also sprach Zarathustra thus assumes a different form in Gyöngyösi’s piece.

HOPE INSTEAD OF DOUBT

‘The logic of the Child is self-evidently childish. And yet we can say that the Child has a deep and mature knowledge of the world, in the sense we no longer possess. At the same time, in reality, the Child has still seen very little of the world. This dichotomy makes the Child a cosmic character’, explains Gyöngyösi. Like Zarathustra, the Child withdraws from the world. ‘According to Madách, doubt and critical thinking move the world forward. However, in itself, doubt is not productive. It’s precisely for this reason that to me, Lucifer is a humourless, monomaniacal, obsessive figure’, adds the composer.

The conclusion of the four-act Tragœdia temporis will also depart from Madách’s pessimistic admonition (‘I told you, man: fight, trust and be full of hope!’), instead ending with a thought from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount, ‘Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth.’ For Gyöngyösi, this is a far more radical assertion in our age. Though we may be embittered at the world around us, we can withdraw into ourselves – after Milton, and even Comenius, freely: we can find Paradise in our hearts. As long as we have friends and we’re surrounded by like-minded people, there is hope. What we make of this opportunity is up to us.

Gustave Doré: ’O, Earth, how like to Heaven, if not preferred more justly’ (detail). | Source: John Milton: Paradise Lost. Illustrated by Gustave Doré. New York – London – Paris, 1866, Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co.

12 April | 7.30pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

THE SCEPTICAL SPIRIT

Gábor Hollerung and the Budafok Dohnanyi Orchestra

R. Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra

Milton: Paradise Lost – excerpt

Levente Gyöngyösi: Tragœdia Temporis I – based on Imre Madách’s dramatic poem, The Tragedy of Man – world premiere

Featuring: Gabriella Balga, Zoltán Megyesi, Eszter Zemlényi, Csaba Sándor, Krisztián Cser – voice, Eszter Ónodi – prose

Featuring: Budafok Dohnanyi Orchestra, Cantemus Choral Institute Nyíregyháza

(choirmaster: Soma Szabó), Pro Musica Girls’

Choir (choirmaster: Dénes Szabó)

Conductor: Gábor Hollerung

Host: Sándor Lukács

Libretto: Judit Ágnes Kiss

Concept, dramaturgy: András Visky

17

31 MARCH | 1PM

Ludwig Museum –Museum of Contemporary Art

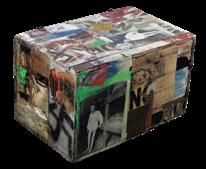

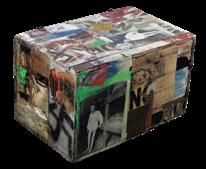

BORIS LURIE & WOLF VOSTELL: ART AFTER THE SHOAH

PLAYING WITH THE UNSPEAKABLE Confrontational and unsettling, confusing and thought-provoking, an important new exhibition at the Ludwig Museum offers a wholly unique perspective on one of Western culture’s greatest catastrophes, the Shoah. American Boris Lurie and German Wolf Vostell both began working on radical Holocaust-related projects from the end of the 1950s, the primary goal of which was to both remember and remind. Both artists felt that broad layers of society did not appropriately handle and process all the horrors that had essentially taken place before their eyes for years. Born in Leningrad, Lurie experienced concentration camps first hand, and would go on to combine terrible images of war with photos of advertising dominating everyday life, in a harsh critique of the self-protecting reflexes of contemporary society in processing problems and trauma. Having fled the Nazis to Czech lands, Vostell considered it his sole mission on returning to Germany after the war to remind German society of the sins committed during the global conflagration, which in his eyes had been inadequately processed. The exhibition of works from these two artists can be seen in Hungary for the first time in this form. The effect of these raw and bold works has been likened by some to shock therapy, directing the attention of the viewer to both the continuity of violence and the importance of humanist values.

The exhibition is on view between 1 April and 30 July.

14 APRIL | 10AM Museum of Fine Arts

CSONTVÁRY 170

CSONTVÁRY, THE ALCHEMIST OF THE CANVAS

He was born 170 years ago, in 1853, the same year as Vincent van Gogh – and though we bow our heads to van Gogh’s sunflowers, the hearts of Hungarians beat a little faster for Csontváry’s lonely cedar, and of course for the other wonders imagined and painted by the artist. He was over fourty before he swapped his trade as a pharmacist for paintbrushes: on seeing his sketch of a cart on the back of a prescription paper, his superior told him he was born to be a painter. Happily clutching his first drawing, Csontváry heard a voice behind him say ‘You will be the greatest sunway-painter in the world, greater than Raphael.’

And yet the imaginary voice did not lie, for he remains one of the few artists whose distinctive works we recognise at once even if we’ve never seen them before. Confronted with the extraordinary cavalcade of colour, the dazzling yellows, burning reds, greying pinks and piercing blues, we can only concur with Pablo Picasso, who with an excited exclamation declared Csontváry to be the century’s other painter genius. He was a legendary figure who worked tirelessly on promoting his own myth, an integral part of which was the extensive and dangerous travel he undertook from Taormina to Athens and from Gibraltar to Bethlehem and beyond, all captured in his paintings.

Like so many great artists, Csontváry was treated unfairly in his own time: despite having several exhibitions in Budapest in the 1900s, ‘eccentric’ was only the mildest epithet attached to him by uncomprehending critics, and he was unable to sell a single painting during his lifetime. Contemporaries viewed his habits with suspicion: it was common knowledge that he was mainly a vegetarian, while his plan for a grand-scale silkworm breeding project was not an unqualified success either. The sins of a narrow-minded era are today offset by the large number of museum visitors, as the Museum of Fine Arts pays tribute with a major exhibition marking the anniversary of his birth. Finally we get to see the symbol-creating ‘sunway-painter’ and lover of colour in a new light.

18

The exhibition is on view between 14 April and 16 July.

1 AND 5 APRIL | 7.30PM

Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

DÉNES VÁRJON AND THE CONCERTO BUDAPEST

PARALLELS BETWEEN BACH, BARTÓK AND BEETHOVEN

Bartók Spring offers us again a chance to hear the Concerto Budapest ensemble led by András Keller: on this occasion, they continue their Bartók series began last year, building on novel spiritual and musical connections. Two concerts with the Kossuth Prize–winning pianist Dénes Várjon provide a glimpse into the historical musical roots of Bartók’s music, through the works of Bach and Beethoven.

The working relationship and friendship between orchestra and pianist is not new. The series began in 2022 with a performance of Bartók’s Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, while this year they perform his Piano Concerto No. 1 and two early works, the Scherzo and the Rhapsody. ‘I’m very attracted to early Bartók, his search for a path, his incredible courage’, revealed Várjon in an interview with Papageno magazine this year. ‘His own language is already there, but the influence of his predecessors Franz Liszt and Richard Strauss can also still be felt, it’s fantastic!’ The pianist will personally perform the solo parts of the two early works for the first time on stage.

The second concert closes with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 from 1808, which nearly suffered an unfortunate fate after it debuted together with the hugely successful Symphony No. 5. Rich in images from nature, this bold programme music would only subsequently become the frequently heard work familiar to Bartók.

4 APRIL | 7.30PM

Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

BENJAMIN EREDICS: CASTLES, WARRIORS, FRONTIERS – PREMIERE

LOVE IN A TIME OF OTTOMAN RULE

Castles, Warriors, Frontiers, incidental music for dance theatre by Benjamin Eredics, was a category winner at the Müpa 2020 Composition Competition and the music material will be heard in its entirety for the first time at Bartók Spring. Eredics calls the Grand Hall of the Liszt Academy his home, having taught tambura at the Folk Music Department for years. Together with his brothers, he is also a member of the Szentendre-based Söndörgő, a group specialising in Southern Slavic music that is regularly featured at the top of world music charts, touring throughout the world several times over the years.

Eredics’s work is based on István Fekete’s novel The Testament of the Agha of Koppány and the film of the same title, evoking the world of the 16th century Turkish occupation in Hungary and combining love and intrigue, Spahis and Giaours. The composer’s diverse experience guarantees the seamless integration of folk instruments and symphony orchestra, along with past and current students of the Liszt Academy who, under the guidance of Gergely Ménesi, provide the musical accompaniment to the historical story. Géza Hegedűs D., who took part in a radio adaptation of The Testament of the Agha of Koppány in 1978, assumes the role of the narrator.

19

Boris Lurie: Immigrant’s NO! box, 1963 © Boris Lurie Art Foundation Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka: Ruins of the Ancient Greek Theatre at Taormina, 1904–1905 © Museum of Fine Arts – Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest

Dénes Várjon | Photo: Andrea Felvégi / Müpa Budapest Benjamin Eredics | Photo: Áron Eredics

ALPINE INSPIRATION

BÉLA BARTÓK’S SWISS CONNECTIONS

Béla Bartók first visited Switzerland in 1908, at the time of his development as a mature artist. Over thirty years later, in October 1940, he travelled through the Alpine country on his final journey to the United States. These two facts illustrate the important role in Bartók’s life played by the Swiss Confederation, where he returned almost annually from 1923 to 1940. Not only did Swiss friends and patrons contribute to the creation of significant works by Bartók, but they also arranged for his manuscripts to be sent to the West, and played a key part in preparations for the composer and his wife to depart for America. By

Zsombor Németh

Bartók came into contact with the Swiss music scene even before he set foot in the country itself. At a concert in Budapest on 13 January 1904, which included the premiere of his symphonic poem Kossuth, the French violinist Henri Marteau also appeared. The charismatic playing of Marteau, who was then also active as a teacher at the Geneva Conservatory, was undoubtedly engraved in Bartók’s memory. In spring 1908, when he came to realise that Stefi Geyer would not perform the violin concerto he had dedicated to her, he turned to Marteau with the idea of presenting the work. (Marteau’s engagements eventually prevented him from including the concerto in his programme, along with the String Quartet No. 1, which was also offered for him to play.)

At this time, Bartók saw great opportunities on the music scene of the Alpine country and, in the hope of a performance, sent freshly composed orchestral pieces to several Swiss conductors – among them Volkmar Andreae, who headed the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich. Bartók’s efforts resulted in the premiere of the Rhapsody, Op. 1 for piano and orchestra in the spring of 1910 with the composer playing the solo part.

FAR FROM THE NOISY CITIES

Bartók first visited Switzerland in the summer of 1908: on his journey to the Mediterranean, he stopped in Zürich, Lucerne and Vierwaldstättersee, before travelling on through Geneva. With his first wife Márta Ziegler he twice visited Zermatt and its environs: in summer of 1911 with his composer friend Zoltán Kodály and his wife, and in 1913 to rest on the way home from his field trip to North Africa. In 1927, he spent several months in Davos for the medical treatment of his second wife Ditta Pásztory, and the couple would often choose Switzerland subsequently as a holiday destination.

Surprisingly, however, we read in Bartók’s letters to friends and relatives even on his first trip that he did not feel comfortable in Swiss cities, finding them ‘touristy’, to use today’s parlance. He found peace in pure nature and longed for silence in Alpine villages far from the traffic, and so endeavoured from then on to find smaller places and to stay in simple inns. Excursions and mountain climbing filled him with so much energy that he often began to sketch out new works on these trips. The Swiss mountains inspired both String Quartets No. 3 and No. 4 and the choral work Cantata Profana, while the orchestration of Bluebeard’s Castle was partly completed in the vicinity of the Matterhorn.

MULTIPLYING VISITS TO SWITZERLAND

Bartók’s first performance in Switzerland took place on 26 May 1910 in Zürich, where he debuted as soloist with his Rhapsody, Op. 1. He most often performed his Piano Concerto No. 2 in the Alpine country, on six occasions between 1934 and 1939 in Winterthur, Zürich, Basel, Schaffhausen, Lausanne and Geneva, under such distinguished conductors as Hermann Scherchen and Ernest Ansermet.

Among Bartók’s concerts in Switzerland, an honoured place was reserved for the chamber evenings where he performed with musical partners for whom he once nurtured especially tender feelings. At the Geneva Conservatory at the end of 1923, Bartók gave a joint concert with the Arányi sisters Adila and Jelly (he wrote both of his sonatas for violin and piano for the latter), while in 1929 and 1930 he appeared with the aforementioned Stefi Geyer in Zürich, Winterthur and Bern. In 1920, Geyer married the Swiss composer, conductor and concert agent Walter Schulthess, who from 1929 emerged as one of the main organisers of Bartók’s concerts in Switzerland.

Folk music also had a role in Bartók’s relationship with Switzerland. In 1933, for example, he published two series of articles in the periodical of the Swiss Workers’ Singing Association, abundantly illustrated with sheet music samples. One year earlier, Three Transylvanian Folk Songs for male choir – an early version of Székely Folk Songs – had appeared in the same publication. In 1938, he gave two lectures for the Musikforschende Gesellschaft in Basel. It is also a mark of Bartók’s reputation in scholarly circles (and public life) that in the summer of 1931 he was the only Hungarian invited to participate in the standing committee on literature and the arts of the League of Nations, based in Geneva.

21

The Matterhorn during autumn sunrise | Photo: Rudolf Balasko

COMMISSIONS FROM A PATRON IN BASEL

From Bartók’s correspondence, we know that from the 1930s onwards his relationship with his Swiss friends may have been as valuable to him as the physical and mental stimulation he gained from his Alpine sojourns. Among these friends, perhaps the most important was the conductor Paul Sacher, whom Bartók had met at a concert in 1929. Three of Bartók’s most popular and most performed works would emerge as a result of this acquaintance.

In early summer of 1936, Bartók was first commissioned to write an orchestral work by Sacher after the latter had come into considerable wealth through marriage. Barely three months later he completed the masterpiece Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, which premiered on 21 January 1937 at a concert marking the tenth anniversary of the Basler Kammerorchester.

A few months after the well-received premiere of this work, Sacher ordered another piece from Bartók, this time for a small ensemble, for the Basel section of the International Society for Contemporary Music. The composer proposed a quartet for two pianos and two percussion groups. Doubting whether two percussionists would suffice for the performance of a work placing considerable rhythmic demands upon its performers, he modified the originally planned title to Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. The highly successful premiere took place on 16 January 1938 in Basel, performed by Bartók and Ditta Pásztory, with percussionists Fritz Schiesser and Philipp Rühlig.

Sacher also commissioned a piece for string orchestra from Bartók, inviting the composer to

Saanen to facilitate its writing. Bartók spent three and a half weeks in August 1939 in a peasant cottage provided to him for this purpose, devoting this time to his music in complete peace. The result was his Divertimento, with some remaining time to complete initial drafts of the String Quartet No. 6. However, the winds of the approaching world war would put an end to this idyll, and Bartók interrupted his stay on 25 August, eleven days earlier than planned, and returned to Budapest before the invasion of Poland. The Divertimento premiered in Basel on 11 June 1940, but the composer was unable to participate.

SURROUNDED BY A DISTRESSING IDEOLOGY

Bartók had other important allies in Basel besides Sacher. On several occasions in the 1930s he was a guest of the Müller-Widmanns, married physicians and patrons of the arts, who regularly hosted concerts of his works in their home. The composer would develop a close friendship with Annie Müller-Widmann. As the clouds gathered on the political horizon following the Anschluss in 1938, Müller-Widmann voiced concern over the potential consequences of the rise of Nazism in Bartók’s life, and actively participated in transporting the composer’s manuscripts to the West (as initiated by Bartók himself).

While Bartók enjoyed increasing recognition in the years prior to the outbreak of war, he became more and more occupied with the idea of moving to the United States. His final decision came only with the death of his beloved mother in December 1939, and he promptly wrote to his three most valued friends in Switzerland to inform them in detail

22

of his itinerary. Bartók also requested that they cooperate to secure train tickets for him and his wife for the route from Switzerland through Spain to Portugal, as these were no longer avail able in Budapest. In October 1940, after a laborious journey through Yugoslavia and Italy, the Bartóks arrived in Switzerland. Stefi Geyer accompanied them as far as Geneva, from where they continued by bus through France and Spain to Lisbon. Bartók would see the shores of Europe for the last time from the deck of the SS Excalibur as it sailed from the Portuguese capital on 20 October.

SWISS LEGACY

Many of Bartók’s masterworks – including the three important pieces commissioned in Switzerland –found an appreciative audience among the Swiss the most quickly. This is partly due to the receptiveness of Swiss music-lovers to Bartók’s novel musical language. Luckily, the Swiss connection would not be broken with the composer’s passing. His early violin concerto – the score of which lingered unperformed for half a century, to be passed by Stefi Geyer to Paul Sacher not long before her death – was eventually presented at a celebration of Bartók’s music in Basel in 1958 by Sacher and the Basler Kammerorchester, with Hansheinz Schneeberger as soloist. The material took flight to America, which for a time rested in the New York Bartók Archives, before being transferred to the private possession of Péter Bartók (the composers’s second child who passed away in 2020); the work was then passed to and is currently held by the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel.

The pianist and composer Nik Bärtsch, a Swiss citizen himself, who first experienced classical music through Bartók, went on to compose a number of works reflecting Bartók’s influence: Rofu and Manta Mantra, for example, a pair of works created in 2012 for two pianos and percussion. His performance at Bartók Spring also pays homage to the Hungarian composer as he and his musical partners present a concert.

5 April | 8pm

House of Music Hungary – Concert Hall

NIK BÄRTSCH REFLECTING BARTÓK

Music historian and research fellow at the Bartók Archives, Institute for Musicology of the Research Centre for the Humanities.

Featuring: Petra Várallyay, Eszter Krulik –violin, Andor Jobbágy – viola, Tamás Zétényi –cello, János Palojtay – celesta, Dániel Janca –percussion

Conrad Beck, Béla Bartók and Paul Sacher in Schönenberg, Pratteln, Switzerland, 1937 | Unidentified photographer © Paul Sacher Stiftung (Basel), Paul Sacher Collection

Music historian and research fellow at the Bartók Archives, Institute for Musicology of the Research Centre for the Humanities.

Featuring: Petra Várallyay, Eszter Krulik –violin, Andor Jobbágy – viola, Tamás Zétényi –cello, János Palojtay – celesta, Dániel Janca –percussion

Conrad Beck, Béla Bartók and Paul Sacher in Schönenberg, Pratteln, Switzerland, 1937 | Unidentified photographer © Paul Sacher Stiftung (Basel), Paul Sacher Collection

THE GOOD, THE BAD, THE UGLY AND THE BEAUTIFUL

MODERN FOLK REVELATIONS WITH DAMIEN RICE

Damien Rice is one of the most successful and also most unusual figures in modern folk music. Trends leave him cold, and although he has only issued three solo albums over two decades, his songs are already part of the contemporary folk canon. His compositions have an outstanding sense of drama, from moments of fragile vulnerability to cathartic heights, while his melodies have the feel of music that is long familiar. Here we take a look at the Irish multi-instrumentalist and singer, who retired for years while his records sold millions, before once again permitting us an unsettlingly deep insight into his life. We can soon experience his music live at Bartók Spring.

By András Rónai

Damien Rice was born in Dublin in 1973, and formed the rock band Juniper with his friends at the age of eighteen. The group signed a six-album deal with Polygram, but after two successful singles Rice found the limits imposed by the label on his artistic freedom intolerable, quitting in 1998. In spring of the following year he went as far as Tuscany, working as a farmer for six months. In the meantime he began writing songs again, which by his return to Dublin at the end of the year he had come to regard as his second chance at a music career. Thanks to his second

cousin

SHACKLED BY FAME

Rice intended to release one album’s worth of his songs on his own label, but the success of the 2002 album O surpassed all expectations in the uk , and the record then found its way to the United States.

24

Photo: Blair Alexander

David Arnold (who has written scores for five James Bond films), he acquired a mobile studio, enabling him to record songs at various locations, even in the homes of his friends.

The initial low level of confidence about the album is illustrated by a story Rice told in an interview with Hot Press in 2009. Asking his musical partners if they would prefer a share of revenues from the album or a one-off payment of £100 a song, the session bass guitarist, Shane Fitzsimons, chose the latter as the safer option. (Rice would later grant him the share of profits preferred by the others.)

While initially Rice managed the affairs of his record label, success inevitably made it necessary to involve a bigger label – and the singer once again faced the expectations attached to an established performer. ‘[My] artistic side was kicking up a storm inside, saying, “You’re only doing this because you’re giving in to other people’s desires to have you sell more records”’, he recalled in an interview with The Guardian in connection with a request when he was asked to remix his song for radio.

Rice toured with the album for almost three years, but on returning home he felt huge pressure bearing down on him as the label expected a follow-up. He reluctantly conceded, but the result was a bitter pill. His second album was released to a mixed critical reception under the title 9, the studio work which he later described to The Guardian as ‘hell’, though adding, ‘Here’s something I’ve gotten very clear about: I made it hell.’

FOR WHOM HE’D GIVE EVERYTHING

During recordings for the album and the subsequent tour, disagreements became frequent between Rice and the singer Lisa Hannigan, whose friendship and professional relationship had developed over the years into a romantic one. Eventually in 2007, in the heat of an argument immediately before a concert in Munich, Rice lost his head and fired Hannigan, who embarked on a solo career that same year. In the aforementioned interview with Hot Press, he spoke about how this was his greatest regret in life, ‘I would give away all of the music success, all the songs, and the whole experience to still have Lisa in my life.’ (Their work together is so emblematic – as on their duet on Volcano – that a possible reconciliation remains a hot topic in the music press to this day.)

Rice then vanished from public view again for years. ‘I did all kinds of things. Scuba diving in the brain,… I went to schools for cleaning my mind’, he recalled of this period to The Guardian. In a radio interview with kcrw in 2014, he explained how he worked to overcome his preconceptions, for example by freeing himself from the axioms carried by words like ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘ugly’ and ‘beautiful’. He also spoke about how he learned to view the world with understanding and humour. It was then that he released his third album, My Favourite Faded Fantasy, overseen by three-time Grammy Award–winning producer Rick Rubin, who asked him to come to the studio even on days when he wasn’t in the mood. Rice says Rubin’s method helped him to get over the feeling of only needing to make music when his prevailing emotions dictate it.

COMPLETE WITH CONTRADICTIONS

Catchy melodies, revealing lyrics that offer points of identification, instrumentation that seems timeless, and a powerful sense of drama: all things that have always been needed in pop music, and so Damien Rice’s huge success is hardly surprising. His first album went quadruple platinum in the uk , his second double, while the third was certified silver. His songs have been heard in Hollywood movies, and are regularly sung in talent shows. Girl group Little Mix, winners of the eighth series of the British X Factor, had their first major success in 2011 with a cover of Cannonball, the second single from Rice’s debut album – which prompted the song to eventually rose to the top of the uk and Irish singles charts almost a decade after its original release.

Since the record industry began, the freshness of performers has tended to be judged based on the frequency of their appearances, but in this sense Rice is also eccentric since he does not communicate only through the records he releases at sporadic intervals. When he has something to say, he speaks about his life in perplexingly revealing interviews. It is these apparent contradictions that make the unique figure of Damien Rice complete.

The singer’s last album came out nine years ago, and there’s no indication of when his most recent song Astronaut, included on the 2022 charity compilation The Busk Record, might be followed by new material. What we can be sure of is that the upcoming concert is a great opportunity to get to know one of the most interesting figures in 21st century folk music in a live setting.

25 3 April | 8pm Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall DAMIEN RICE

VILLAGE TUNES IN BUDAPEST STYLE

FIFTY YEARS OF MUZSIKÁS

Last year marked half a century of the táncház (dance house) method, the one-time movement among Budapest intellectual circles that grew into a practice attracting hundreds of thousands worldwide, listed on the unesco list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In 2023, the Muzsikás ensemble, one of the key pillars of the new wave of folk music in Hungary, likewise celebrates its 50th anniversary at Bartók Spring. The group takes its name from the original practitioners of peasant music (muzsikás), from whom its members endeavoured to learn the authentic playing styles previously thought impossible to master. It is thanks to Muzsikás that Hungarian folk music – in all its beauty, repute and power – has found its way into the world’s most renowned concert halls over recent decades.

By Béla Szilárd Jávorszky

By Béla Szilárd Jávorszky

26

There are numerous reasons why Muzsikás stands out from the crowd of folk music groups over the past fifty years. It had much to draw on, given the extraordinarily strong intellectual family background of its founding members; we need only to mention that one member was raised by an internationally renowned dance researcher, another as the son of a two-time Kossuth Prize–winning poet. The band’s name is associated with epochal hit folk songs such as Start Out on a Road, Falling Leaves, Cold Winds Are Blowing and I Thought It Was Raining. Besides its members’ talents, the fact that all speak several languages was another factor contributing to the band’s success, and together they proved an unstoppable force. But for Muzsikás to able to reach the heights it has over such a long period is due to the irreplaceable individual roles of each of its members. Although the musicians of Muzsikás have devoted their lives to passing on folk traditions, they first encountered Hungarian folk music in an urban setting. Growing into society in the 1960s, as teenagers they were as much excited about the new sound of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, the catchy beat and rhythm and blues tunes, as about archaic Hungarian folk music from Transylvania. But what captivated them from both these seemingly different worlds was the same: the energy and enormous freedom of the music.

BORDERS WITHIN AND BEYOND

Over the past half century it has often been the task of Muzsikás to break the ice: the dance house they launched at the Municipal Cultural Centre of Budapest in autumn 1973, with dance instruction, would set the benchmark. Muzsikás was the first in the revival movement to record an album purely of folk music. They were also largely responsible for working out how to present folk music effectively on stage, bringing it closer to the audience with introductions and short explanations. They were the first to reverse the role of musicians; rather than merely accompanying the dancers (as they did initially), entire evenings of folk dance choreography were put together from their tunes.

As the folk music revival spread, Muzsikás emerged as the movement’s most popular ensemble. From 1979, viola player Péter Éri officially joined the group, as did singer Márta Sebestyén from 1980. Adding to regular appearances in clubs and dance houses at home, they began travelling abroad more often to Western Europe and even Australia. But increasingly they also crossed or broke down boundaries in another sense. Bringing traditional folk music to the stage required not only a degree of adaptation and rearrangement, but also the matching of technically incongruous lyrics and melodies in a bold and free fashion. But, although they upended traditional instrumentation, unlike their contemporaries they never wrote music or came up with new tunes.

As the driver of these ‘adventures’, the band’s founding violinist Sándor Csoóri Jr, recalled, ‘For me the bluesy experiments absolutely fit into the spirit of Muzsikás. These two feelings for life entirely cohabit within me. I wanted us to be more, to be more special; as Ferenc Bodor [one-time documentarian of the dance house movement – Ed.] put it, to be The Rolling Stones of folk music.’

ENTER THE LEGENDARY PRODUCER

The varied and unusual soundscape developed by Muzsikás in the 1980s would eventually catch the attention of noted American producer Joe Boyd, head of Hannibal Records, which would play a defining role in the evolution of world music as a genre. The manager who had helped launch the careers of numerous world-famous musicians and groups, among them Pink Floyd, flew in person to Budapest to acquire foreign publishing rights for the 1986 Muzsikás album later issued by Hannibal under the title Prisoner’s Song, for Márta Sebestyén’s collaboration with the band originally released in 1987 (and for the second lp by the Vujicsics Ensemble). The British and American

27

Photo: Géza Barcsik

issues of both Muzsikás albums were physically released on the same day in 1987 as the group played to resounding success at the Cropredy Festival marking the 20th anniversary of the foundation of English folk-rock legends Fairport Convention. With this, the British market opened up for Muzsikás, with Joe Boyd going on to play a key role in the group’s international launch.

THE CONQUEST OF GREAT BRITAIN

Muzsikás played the Electric Cinema and Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club, and in May 1995 conquered Queen Elizabeth Hall, followed two years later by the 2,000-seat Barbican Hall, and the 2,500-seat Royal Festival Hall in November 1998. ‘Qualitatively, everything took place on a different level’, says Dániel Hamar, the group’s double bassist and spokesman, recalling their reception in England. ‘Instead of crawling around in our beat-up minibus, we travelled like lords by plane. For a single concert. We were taken from the airport straight to a fancy hotel, and the next day we had twenty people working just for us at rehearsal.’

It was Joe Boyd who wrote the sleeve notes appearing on the back of the Blues for Transylvania album Muzsikás released in March 1990 (issued in Hungary a year earlier under the title Ősz az idő ). As an illustration, he published a rough map of Transylvania, while asking the question of how Americans would feel if their country was truncated for the benefit of Mexico to an extent similar to that set down in the 1920 Treaty of Trianon. With his strongly subjective words, Boyd aimed to bring home to record-buyers across the Atlantic the emotional charge behind an album recorded in the year of the Romanian Revolution.

‘In 1988–1989, the “rural systematization program” took place in Romania, known colloquially simply as the destruction of villages, and launched with the wholly obvious political intention of breaking up blocks of the Hungarian population’, recalls Hamar. ‘I know from Boyd that the Romanian foreign mission immediately protested against the record label over the cover, but of course to no avail.’

HOMMAGE À BARTÓK

At the time of their concert at the Barbican Centre in April 1997, László Porteleki was already playing for Muzsikás, having joined after the departure of one its founders, Sándor Csoóri Jr. The new violinist proved a fortunate choice for several reasons: in contrast to urban intellectuals, he had village roots, with fourteen years spent leading the Téka ensemble as his calling card, while he was also one of the few accepted as one of their own by the Palatka Gypsy Band, a leading ensemble from Transylvania.