MERCEDES AZPILICUETA

Cuerpos Pájaros

MUSEO DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES

8

MUSEO DE ARTE M ODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES 2018

AUTORIDADES GOBIERNO DE LA CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES

HORACIO RODRÍGUEZ LARRETA

Jefe de Gobierno

FELIPE MIGUEL

Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros

ENRIQUE AVOGADRO

Ministro de Cultura

VIVIANA CANTONI

Subsecretaria de Gestión Cultural

JUAN VACAS

Director General de Patrimonio, Museos y Casco Histórico

VICTORIA NOORTHOORN

Directora

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

MERCEDES AZPILICUETA

Cuerpos Pájaros

Autores

Mercedes Azpilicueta

Mariano Blatt

Virginie Bobin

Laura Hakel

Noorthoorn, Victoria

Mercedes Azpilicueta: cuerpos pájaros / Victoria Noorthoorn; Laura Hakel; Mariano Blatt; editado por Gabriela Comte. - 1a edición bilingüe - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2018. 136 p. ; 24 x 20 cm.

ISBN 978-987-1358-57-1

1. Artes Visuales. I. Hakel, Laura II. Blatt, Mariano III. Comte, Gabriela, ed. IV. Título. CDD 708.982

Este libro fue publicado en ocasión de la exposición Mercedes Azpilicueta. Cuerpos Pájaros, inaugurada en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires en noviembre de 2018

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Av. San Juan 350

(1147) Buenos Aires

Impreso en Argentina

Printed in Argentina

Akian Gráfica Editora

Clay 2972

Buenos Aires, Argentina

www.akiangrafica.com

Diseño

Eduardo Rey

Créditos de las imágenes / image credits:

Azul De Monte: pp. 43, 47, 48, 51.

Aratxa Boyero/Centro de Arte 2 de Mayo: p. 53.

Aad Hoogendoorn / TENT, Rotterdam: p. 54.

Juan Agustín Rojas / SlyZmud: pp. 56, 57.

Ohad Ben Shimon: pp. 58-59, 6061, 94-95, 96-97, 99.

Gert-Jan van Rooij / Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten: pp. 63, 64-65, 66, 67.

Mathilde Assier: pp. 81, 83, 120-121.

Mercedes Azpilicueta y Alan Segal:

pp. 98, 100, 101, 103, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110-111.

El resto de las imágenes y stills de video fueron tomados por [the remaining images and video stills belong to] Mercedes Azpilicueta.

CONTENIDOS

9. Agradecimientos / Acknowledgments

Victoria Noorthoorn

13. Yo hablo mi cuerpo / I speak my body

Laura Hakel

23. A nuestros solos deseos / To Our Sole Desires

Virginie Bobin

38. Cuerpo de obra

113. Las doscientas cosas que te dije / The two hundred things I told you

Mariano Blatt

123. Biografías / Biographies

127. Lista de obras / Exhibition checklist

8

Agradecimientos

Por Victoria Noorthoorn

Es una gran satisfacción para el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presentar la primera exposición de la artista argentina Mercedes Azpilicueta en un museo de nuestro país. En esta exposición, titulada Cuerpos Pájaros, hemos reunido una decena de trabajos realizados durante los últimos ocho años por la joven artista residente en Europa, a los que se suma la video-instalación de grandes dimensiones que le da el título a la muestra, un nuevo proyecto producido especialmente por el Moderno para esta ocasión.

Una de las preocupaciones centrales que guía nuestra gestión en esta casa del arte ha sido dar espacio y visibilidad a los artistas argentinos jóvenes y de mediana generación que desarrollan un trabajo potente tanto en la Argentina como en el exterior. En esta ocasión, desde el equipo curatorial del Museo, venimos siguiendo de cerca los pasos y la trayectoria de Azpilicueta, y nos enorgullece ser la primera institución argentina en presentar orgullosamente lo mejor de su trabajo para el público de Buenos Aires. Estamos impactados por la fuerza con que investiga las características afectivas, sociales y políticas de la voz y el cuerpo, que se despliegan en una obra performática visceral y experimental. Agradecemos enormemente la pasión y la dedicación con la que Mercedes se ha entregado a este proyecto, que incluye muchas obras nunca vistas en la Argentina. Esta exposición busca poner de relieve la enorme calidad estética y la radicalidad de su investigación artística, que consideramos un gran aporte a la historia del arte argentino y a nuestra escena contemporánea. También agradecemos a Laura Hakel, curadora del Moderno y de esta exposición, por su compromiso con el trabajo junto a Mercedes durante todo este tiempo.

Ha sido un enorme desafío pensar una publicación que no solo registrara el trabajo realizado en la exposición sino que también nos acercara al universo de una propuesta performática tan radical como la de Azpilicueta. Este libro ha buscado abrir el diálogo y generar nuevos sentidos, para lo cual, además de a la curadora, hemos invitado a dos jóvenes autores a participar: la escritora y curadora francesa Virginie Bobin, que aportó un osado texto

9

teatral en el que se sumerge en los múltiples temas, referencias e influencias del mundo de Azpilicueta, y el poeta y editor argentino Mariano Blatt, que escribió un texto literario en el que su propia escritura y estilo exponen en un juego lingüístico marcas de la oralidad, la época y las sensibilidades que también son algunos de los materiales de trabajo cruciales de la artista en su obra. A ambos les agradecemos su generosa escritura.

En el equipo del Moderno, deseo agradecer a Micaela Bendersky y Miriam Carbia Nagashima por su comprometido trabajo en el Departamento de Exposiciones. Desde el Departamento de Producción, Iván Rösler condujo el exquisito diseño de la exposición, junto con un gran equipo en el que se destacan Marina Gurman por su dedicada tarea como productora y por poner generosamente a disposición su enorme conocimiento técnico de video, y a Celina Eceiza y Gonzalo Silva por su dedicación en la asistencia de producción.

Deseo destacar el trabajo del Departamento Editorial, tanto el diseño de Eduardo Rey como la edición de Gabriela Comte, Martín Lojo y Julia Benseñor, las traducciones de Marcos Mayer y Daniel Tunnard, y el profesionalismo técnico de Guillermo Miguens y Daniel Maldonado, quienes con pasión por su tarea han hecho posible este libro.

Agradezco el importantísimo y generoso apoyo de Eloisa Haudenschild así como el apoyo a la exposición y a este libro de la institución holandesa Mondriaan Fonds, que por segunda vez acompaña al museo con un importante respaldo.

Por su incondicional y constante apoyo al Museo de Arte Moderno, a sus exposiciones y publicaciones, quiero agradecer muy especialmente al Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires: a Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Jefe de Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, a Felipe Miguel, Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros, a Enrique Avogadro, Ministro de Cultura, a Viviana Cantoni, Subsecretaria de Patrimonio Cultural, así como a sus respectivos equipos, por su renovado y cuidadoso seguimiento de la gestión pública del Moderno que garantiza que cada uno de nuestros proyectos llegue a buen puerto siguiendo los estándares de excelencia de esta casa del arte argentino.

Vaya también mi agradecimiento a las empresas y personas que nos acompañan a cada paso; especialmente al Banco Supervielle —nuestro aliado estratégico anual— y a sus directivos, que con entusiasmo nos alientan en cada acción.

Y, por último, agradezco la pasión y curiosidad de cada uno de nuestros visitantes y de cada uno de nuestros lectores. Ahora los invito a recorrer estas páginas.

10

Aknowledgments

By Victoria Noorthoorn

It is an enormous satisfaction for the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires to present Argentine artist Mercedes Azpilicueta’s first exhibition in an Argentine museum. Titled Cuerpos Pájaros [Body-Birds], the exhibition brings together a dozen of the works produced in the last eight years by this young artist resident in Europe, with the addition of the large-scale video installation whose title lends the exhibition its name, a new project produced especially for the Moderno exhibition.

One of our priorities in running this art museum is that we should give space and visibility to young Argentine artists and those of the middle generation producing powerful work both in Argentina and abroad. In this case, we in the Museum’s curatorial team have been closely following Azpilicueta’s career and we are proud to be the first Argentine institution to present the best of her work for a Buenos Aires audience. We are overwhelmed by the force with which she researches the affective, social and political characteristics of the voice and the body, all very much in evidence in this visceral, experimental performative work. We are enormously thankful to Mercedes for the passion and dedication she has given this project, which includes works never before seen in Argentina. This exhibition seeks to show the enormous aesthetic quality and the radicalization of her artistic research, which we consider a great contribution to the history of Argentine art and the contemporary scene. Thank you also to Laura Hakel, curator at the Moderno including this exhibition, for her commitment to her work with Mercedes during all this time.

It was a huge challenge to come up with a publication that would not only put down on paper the work produced at the exhibition but would also bring us closer to the universe of a performative approach as radical as Azpilicueta’s. This book seeks to open up a dialogue and generate new meanings. For this, Hakel was joined by two young authors: the French writer and curator Virginie Bobin, who contributed a daring theatrical text, immersing herself in the multiple themes, references and influences of Azpilicueta’s world; and the Argentine poet and publisher Mariano Blatt, who wrote a literary text in which his writing and style play linguistically with the orality, period and sensibilities crucial to Azpilicueta’s work. We are grateful to both for their generous writing.

On the Modern team, I wish to thank Micaela Bendersky and Miriam Carbia Nagashima for their committed work in the Exhibitions Department. Iván Rösler in the Production Department led the exquisite exhibition design, along with a great team featuring Marina Gurman, who worked devotedly as producer, sharing her enormous theoretical video knowledge, and Celina Eceiza and Gonzalo Silva, who gave dedicated production assistance.

I would like to highlight the work of the Editorial Department, including Eduardo Rey’s design and editing by Gabriela Comte, Martín Lojo and Julia Benseñor, the translations of Marcos Mayer and Daniel Tunnard, and the technical professionalism of Guillermo Miguens and Daniel Maldonado, whose passion for their work made this book possible.

11

Thank you to the extremely important and generous support of Eloisa Haudenschild, and the Dutch institution Mondriaan Fonds’s support for the exhibition and this book, giving the museum their vital backing for a second time.

For its unconditional and constant support for the Museo de Arte Moderno, its exhibitions and its publications, I would especially like to thank the Government of the City of Buenos Aires: Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Mayor of Buenos Aires, Felipe Miguel, Cabinet Chief, Enrique Avogadro, Minister of Culture, Viviana Cantoni, Sub-secretary of Cultural Heritage, and their respective teams, for their constant and careful monitoring of

the public management of the Moderno, ensuring that every one of our projects is produced according to the standards of excellence of this Argentine house of art.

My thanks also to the companies and individuals who are with us every step of the way: especially Banco Supervielle—our annual strategic ally—and its directors, who enthusiastically encourage our every action. And, finally, I am grateful for the passion and curiosity of each one of our visitors and every one of our readers, whom I now invite to explore these pages.

12

Yo hablo mi cuerpo

Por Laura Hakel

J. A. Jiménez

I.

Cuando Mercedes Azpilicueta se mudó a Holanda, en el año 2011, algo cambió en su producción. Como si la distancia transoceánica de la Argentina hubiera afinado su oído y dado una nueva urgencia al habla, abandonó la poca materialidad que quedaba en su obra (en Buenos Aires ya había estado anteponiendo la escritura y las sesiones de lectura de poesía a la pintura y el trabajo de taller) y fijó su interés en el lenguaje: principalmente en la oralidad, las faltas de ortografía, los errores de traducción, las palabras inventadas y todo lo “sucio” de la comunicación. Esa parte blanda, sonora, viva y usada de lo que decimos, que escapa a la normatividad de cómo “debemos” decirlo y que refleja maneras personales y locales de expresarse.

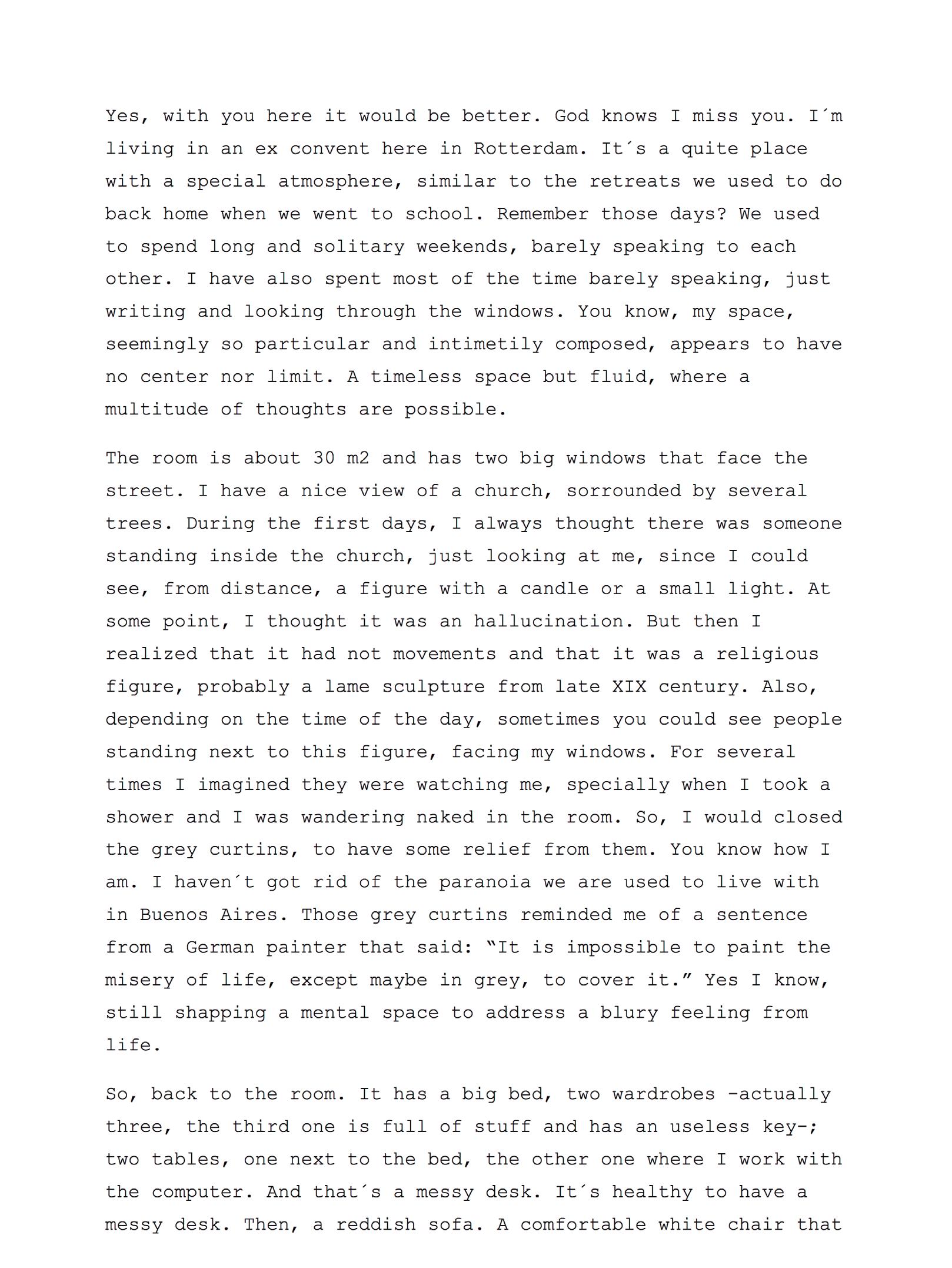

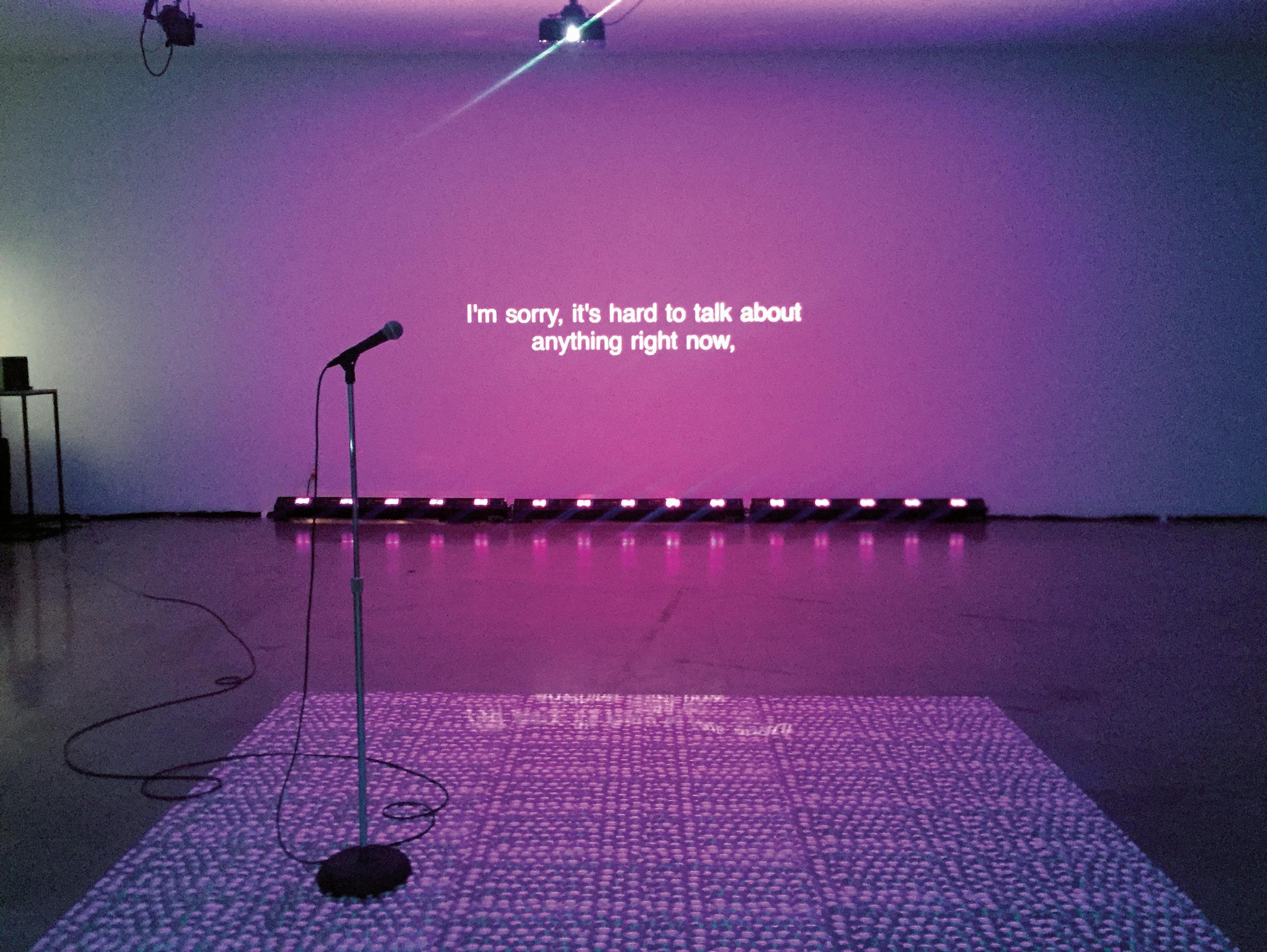

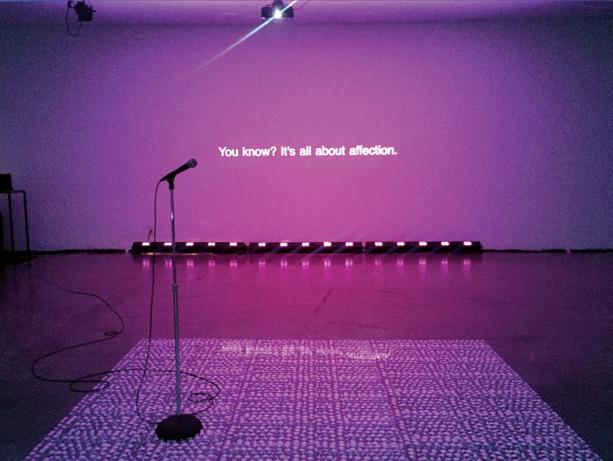

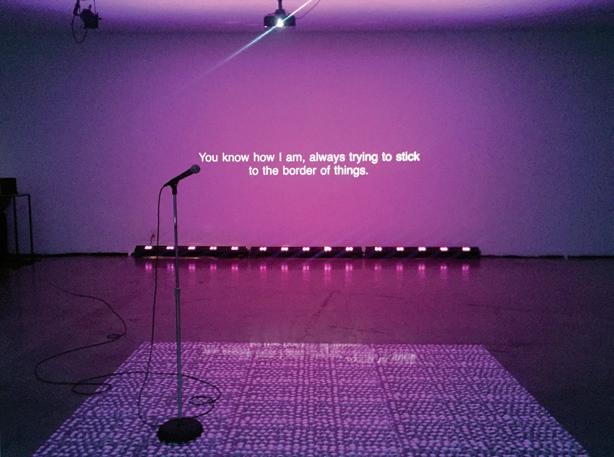

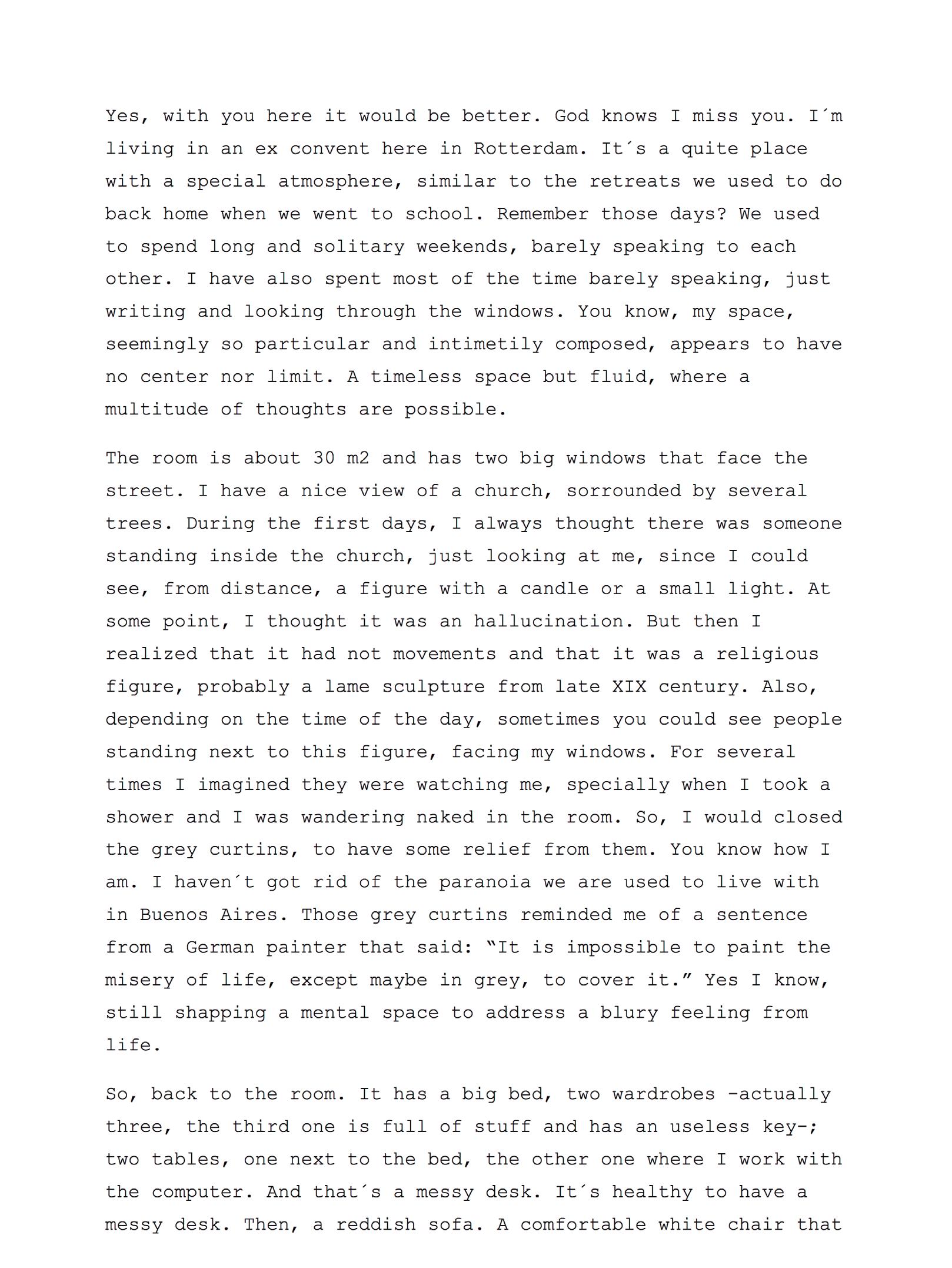

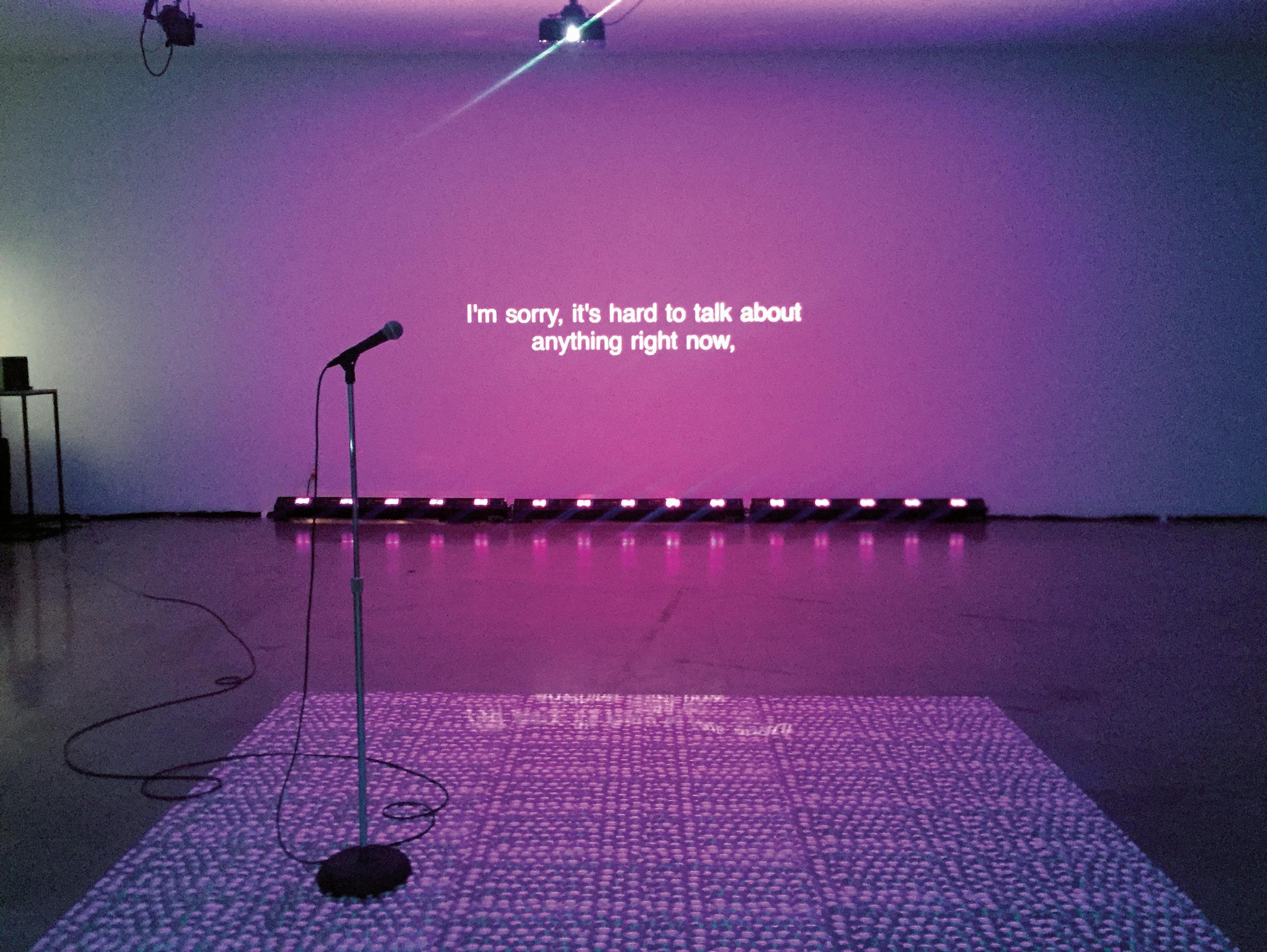

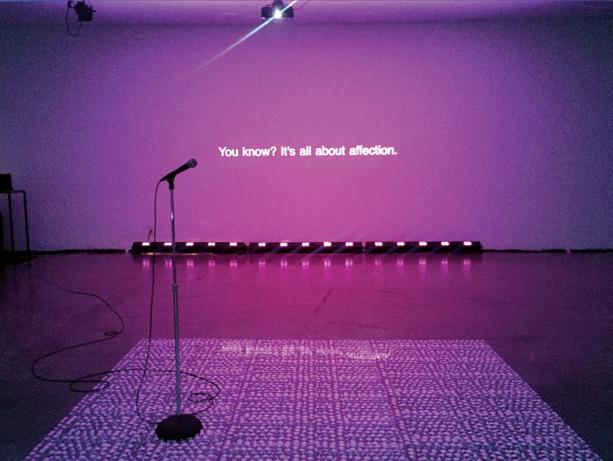

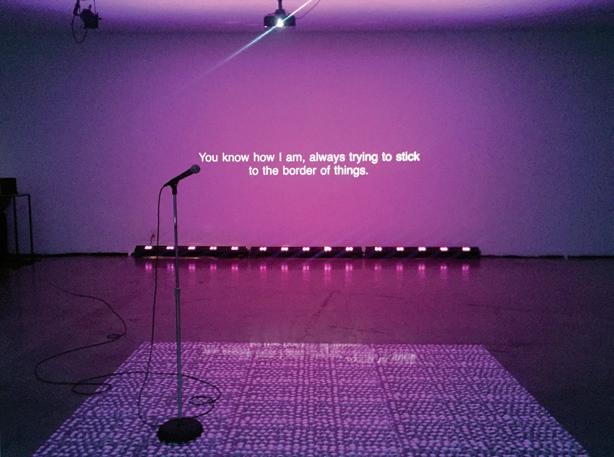

“You know? It’s all about affection”, le escribió a su hermana en la carta Dear Sister (2011), una de las primeras obras que Azpilicueta realizó al llegar a Rotterdam y que se presenta en el Museo de

Arte Moderno, dentro del conjunto de obras que componen su primera exposición panorámica, como una instalación de video donde las palabras aparecen, como en un karaoke mudo, para que el espectador reproduzca la voz en su mente. Con complicidad y nostalgia, la artista relata a su hermana situaciones banales de su nueva vida cotidiana —la disposición de su cuarto, la vista de su ventana, la sensación profunda de soledad, pero también la de estar siendo observada—, mezcladas con reflexiones y recuerdos de ambas en Buenos Aires (“Remember when we went to the delta?”). Es un relato íntimo que explora la subjetividad del “yo” como lugar de enunciación y la distancia inherente al género epistolar. En la carta, la voz íntima funde la memoria personal y la compartida, y construye un espacio de conexión entre las dos ciudades y las dos hermanas. El texto también es una forma de habitar otra lengua. Paradójicamente escrito en inglés, en él la artista valora los errores de ortografía como si fuesen la puerta a una nueva acepción de las palabras, menos correcta pero más subjetiva y significativa.

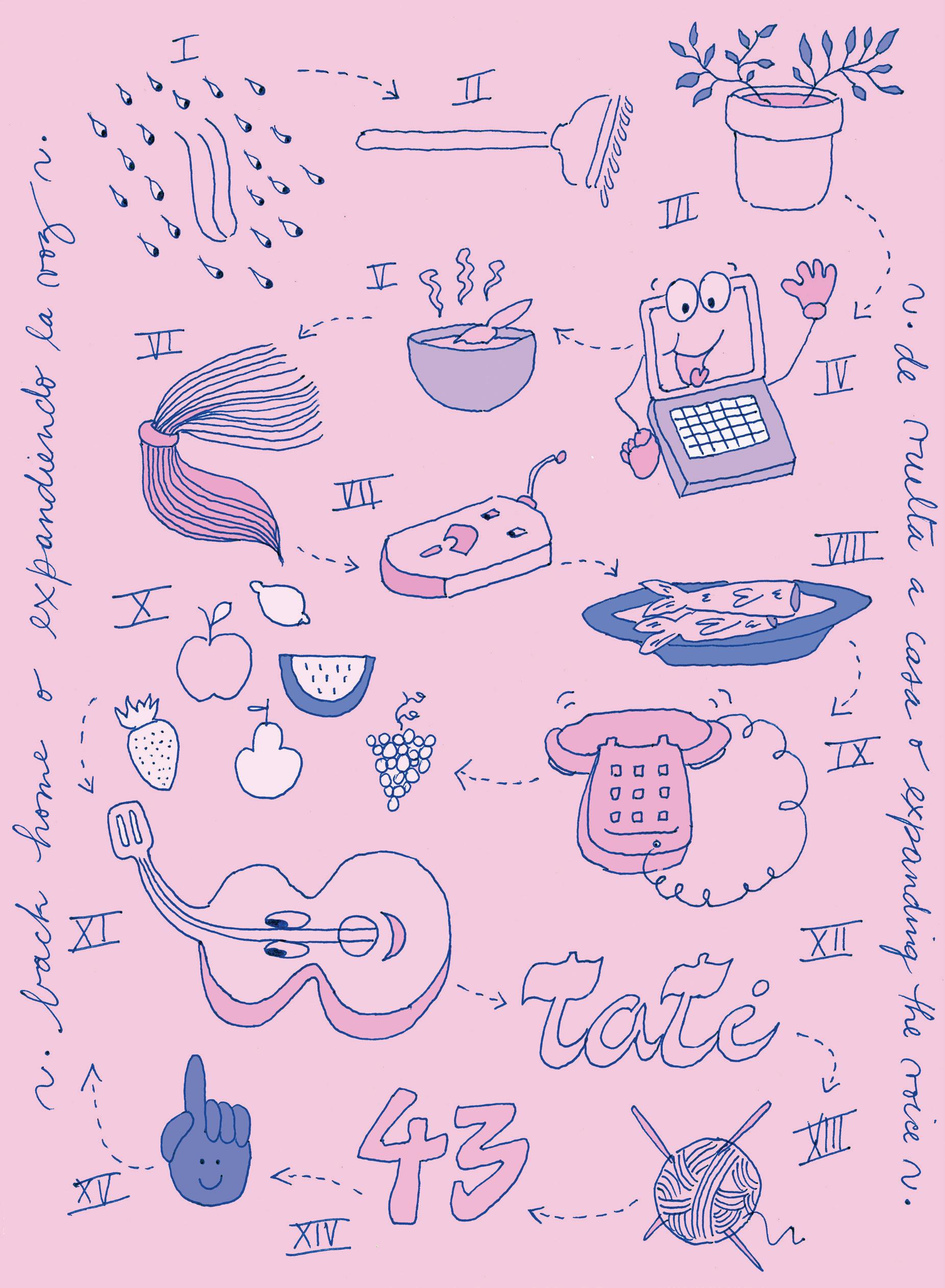

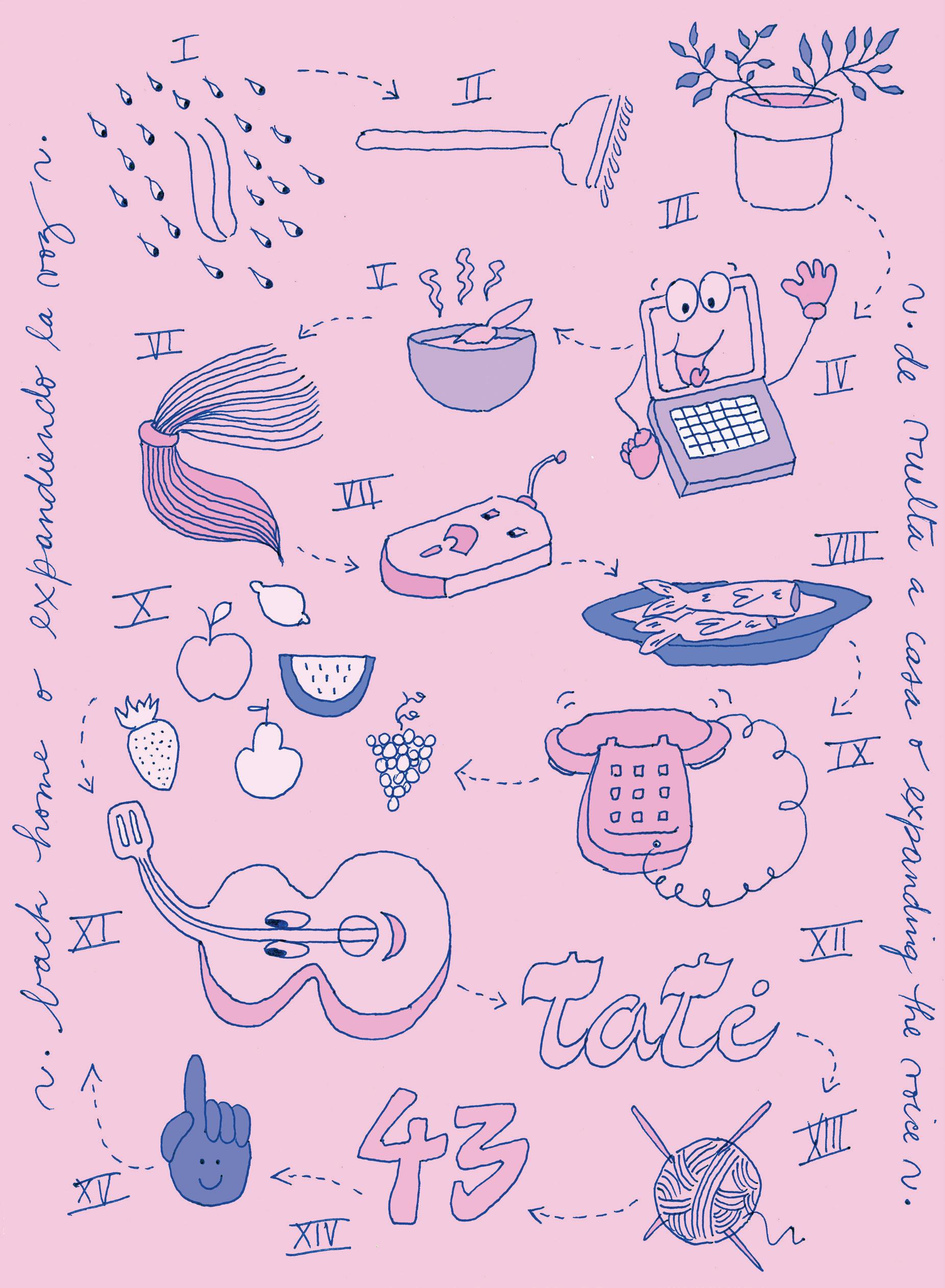

La afectividad que es capaz de transmitir la palabra también es una clave en Volver a casa expandiendo la voz (2012). Se trata de una de las primeras piezas performáticas realizadas por la artista, en la que

13

Si te acuerdas de mí No me menciones Porque vas a sentir Amor del bueno.

recita un guión creado a partir de los mensajes de texto acumulados en su celular a lo largo de un año, combinados con poemas: “te quiero Chau/ ¿cómo estás Pum?/ ¿recuperada?/ si están por la zona/ estoy en el cafecito de pasteur y corrientes/ besos cuchufru/ Pum me llamó gato/ diluvia y no vuelve”. El discurso se compone de momentos de encuentro y desencuentro con el otro que nos llevan desde la sensación de una enorme cercanía hasta la imposibilidad de comunicarse: ese momento en que el lenguaje gira en falso, convertido en una máquina casi automática y frustrante de saludos y monólogos.

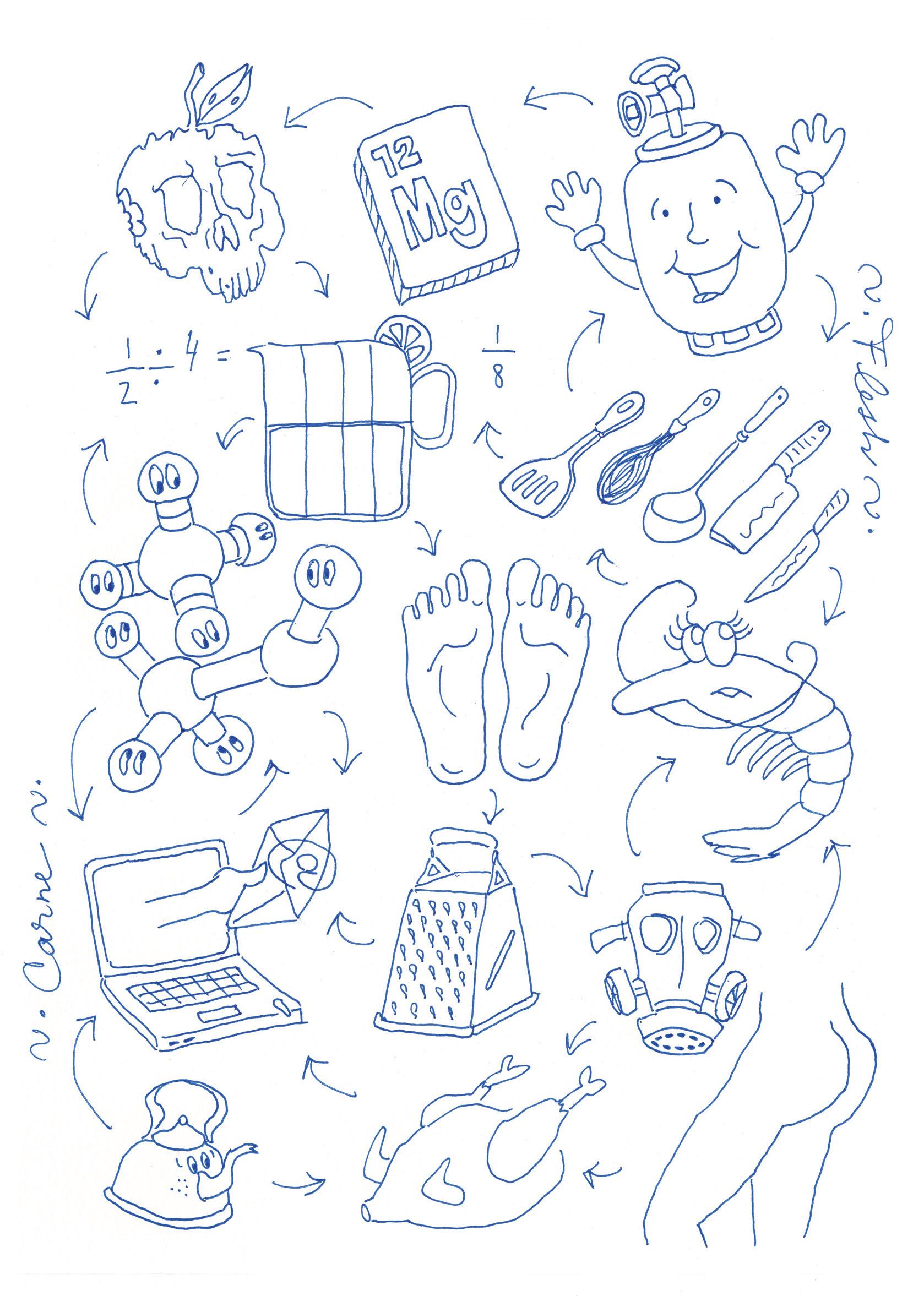

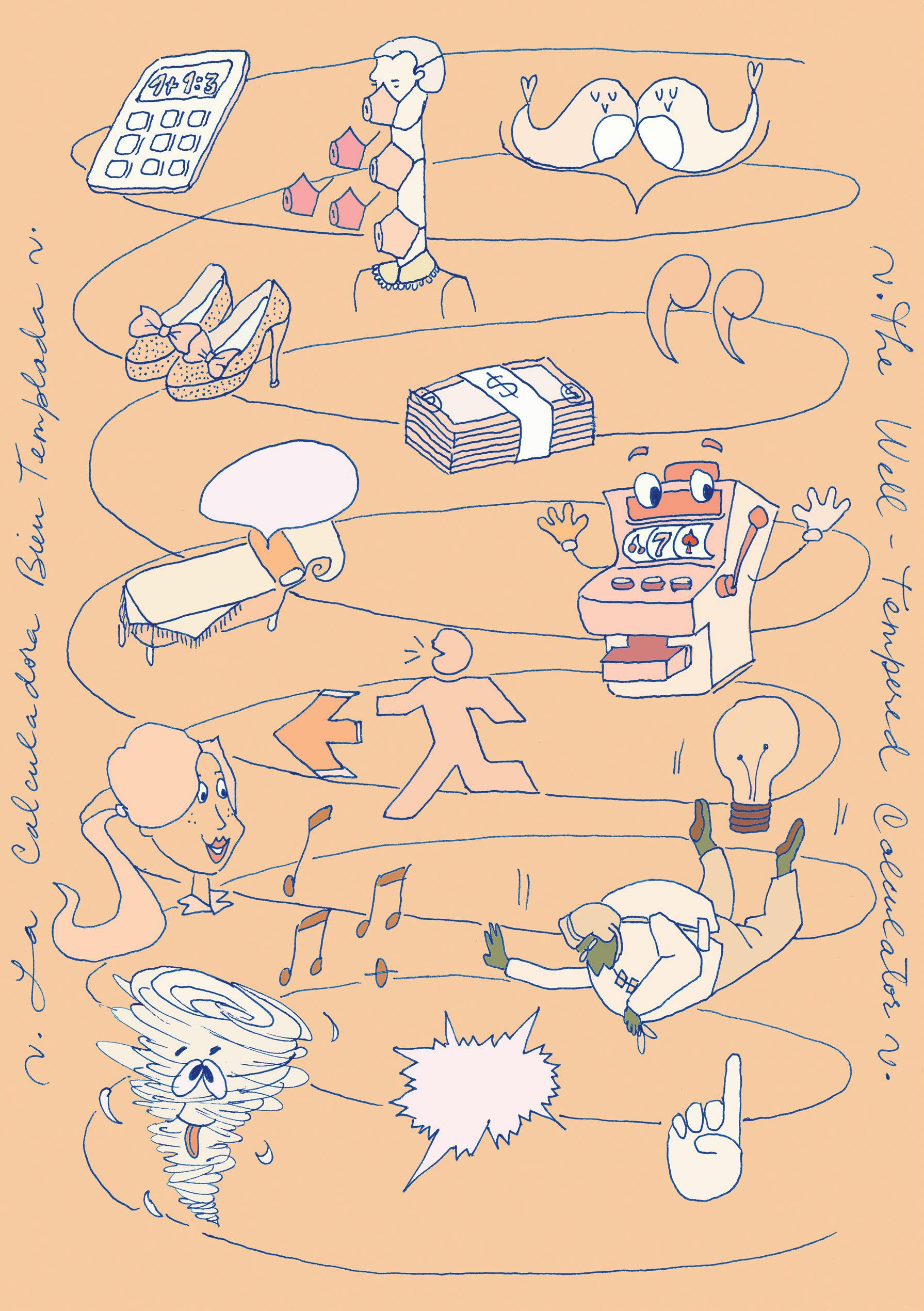

En sus siguientes obras, Azpilicueta comenzó a pedir prestadas voces ajenas. Para construir los guiones de las performances La Calculadora Bien Templada (2013), CARNE (2013) y POW! (2014) se apropió, entre otras, de las frases de una madre obsesiva, una profesora de yoga autoritaria, un rematador de obras de arte y un profesor en un examen de idioma.

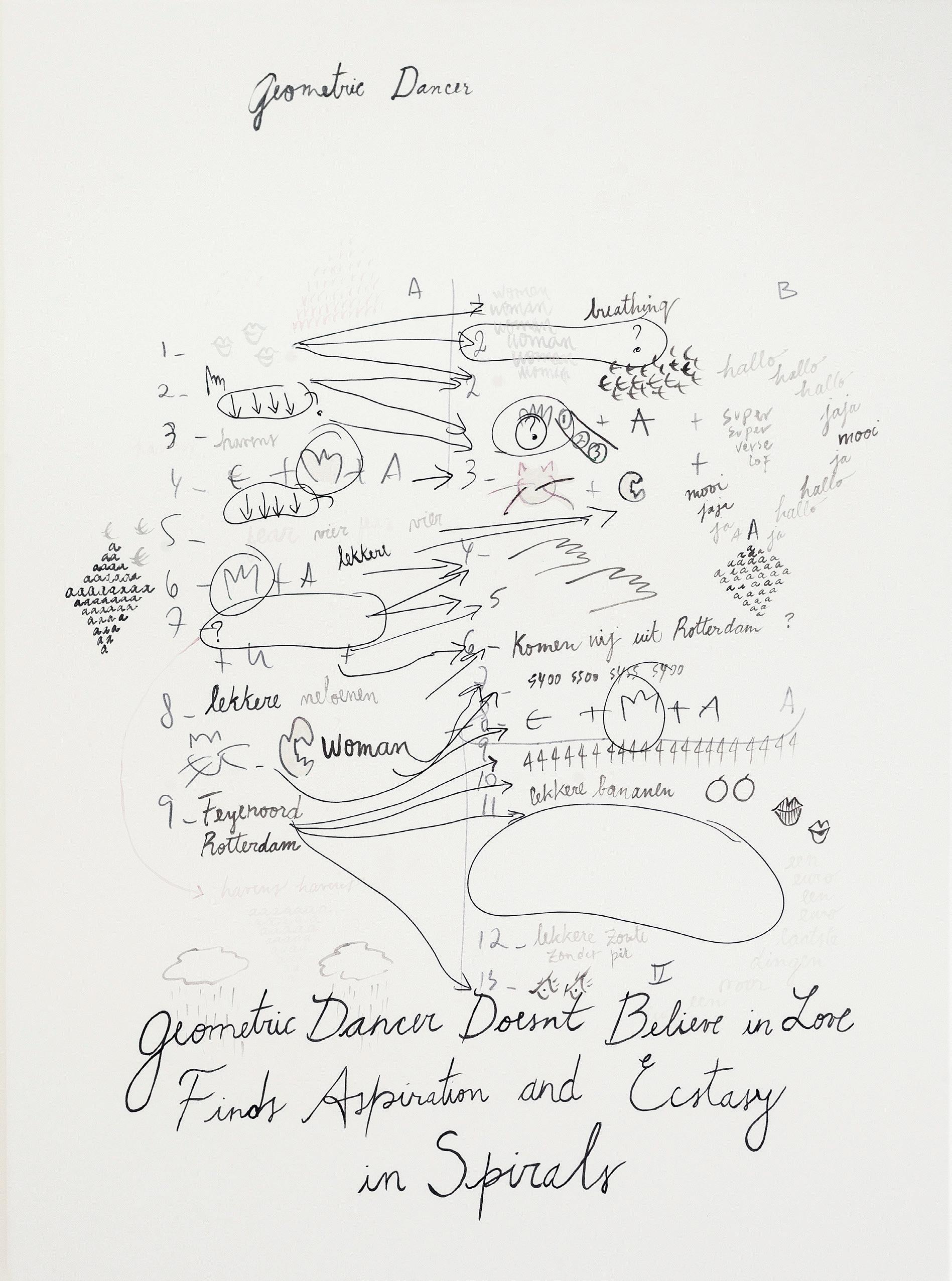

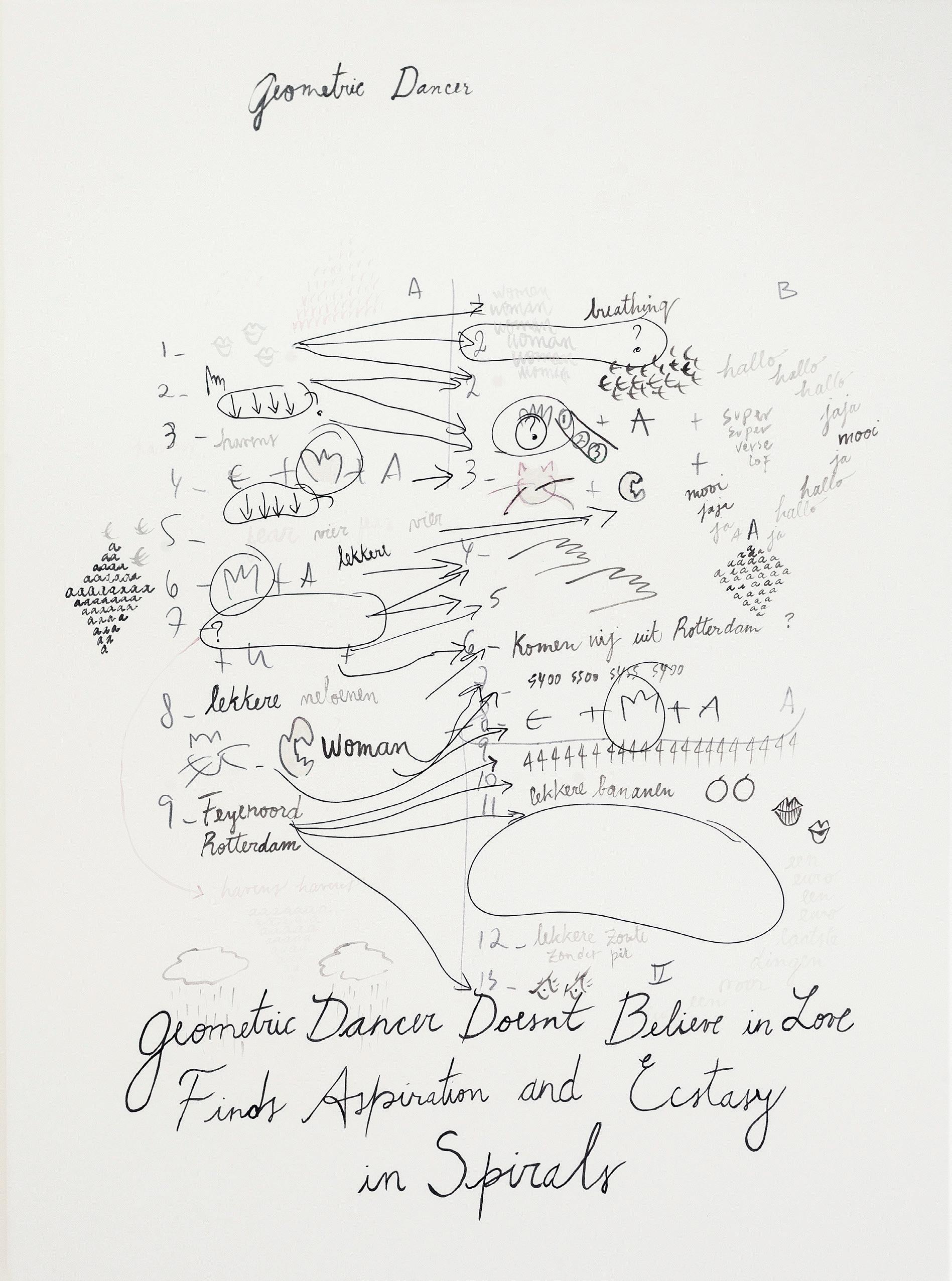

Pascal Quignard dice que, a diferencia de lo que ocurre con la vista y los párpados, en los oídos no hay nada que limite la información del exterior.1 Lo que oímos, voluntaria o involuntariamente, nos une a los demás y al lugar en el que estamos. En la videoinstalación Bailarina Geométrica No Cree en el Amor, Encuentra Aspiración y Éxtasis en Espirales (2015), la artista transformó su voz en un colectivo social y en un territorio. Reconstruyó con su voz el paisaje sonoro de Rotterdam, poniendo en carne propia lo que se escucha en los mercados, en el puerto y en la calle. Sentada, de piernas cruzadas en posición de flor de loto, como si fuese una pitonisa o una médium en trance, reproduce las ofertas de los vendedores ambulantes al grito de “eeen eurroooo, een euroo”,

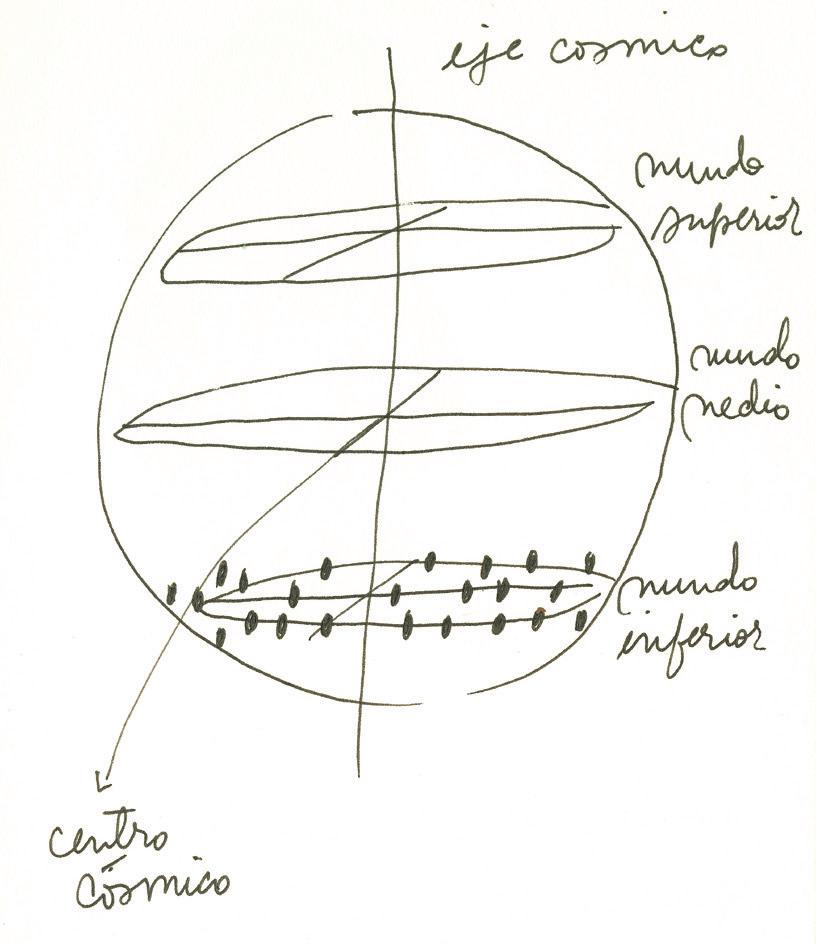

los cantos de los estadios deportivos y toda la trama sonora socio-económica, popular y precaria de la ciudad, que circula a través de ella en un idioma que no necesariamente entiende. El título de la obra evoca la figura de la poetisa italiana Valentine de Saint-Point, autora del Manifiesto de la mujer futurista A partir de ella, la artista imagina la conversión en energía femenina de la decadencia y la virilidad de esta ciudad reconstruida luego de la guerra; al igual que la poesía convierte las palabras y su sonoridad en una nueva energía. El poeta entrerriano Juan L. Ortiz afirmaba que en el paisaje veía "todas las dimensiones de lo que trasciende”, la vida secreta que lo abisma.2 Mercedes Azpilicueta transmuta la cotidianeidad urbana en algo sustancial, una trascendencia encarnada en un coro pronunciado por una sola voz.

De este conjunto de obras se desprende su interés por la afectividad que vehiculiza el lenguaje, pero también por el control y la violencia ejercidos a través de él. Utilizando su oído como un gran radar, la artista investigó lo que se trasmite en lo que decimos y escuchamos, y que transporta, como una cadena invisible de ADN, nuestra identidad. Todo lo que oyó lo exorcizó en sus performances. Se valió de la elasticidad de la palabra utilizando en sus guiones recursos poéticos de Marguerite Duras, Clarice Lispector, Susana Thénon y Alejandra Pizarnik —de quien toma su nombre este texto: Yo hablo mi cuerpo—, y de la capacidad del tono y el timbre de la voz para desbordar el sentido del lenguaje.

II.

A la voz como canal de encuentro entre el adentro y el afuera, le siguió la pregunta sobre el lugar del cuerpo en este circuito recalentado de comunicación.

En el 2015, si alguien entraba en su taller de la Rijksakademie en Ámsterdam podía encontrarla

14

1 Pascal Quignard, El odio a la música, Buenos Aires, El cuenco de plata, 2012, p. 67.

2 AA. VV., Una poesía del futuro: conversaciones con Juan L. Ortiz, Buenos Aires, Mansalva, 2008, p. 21.

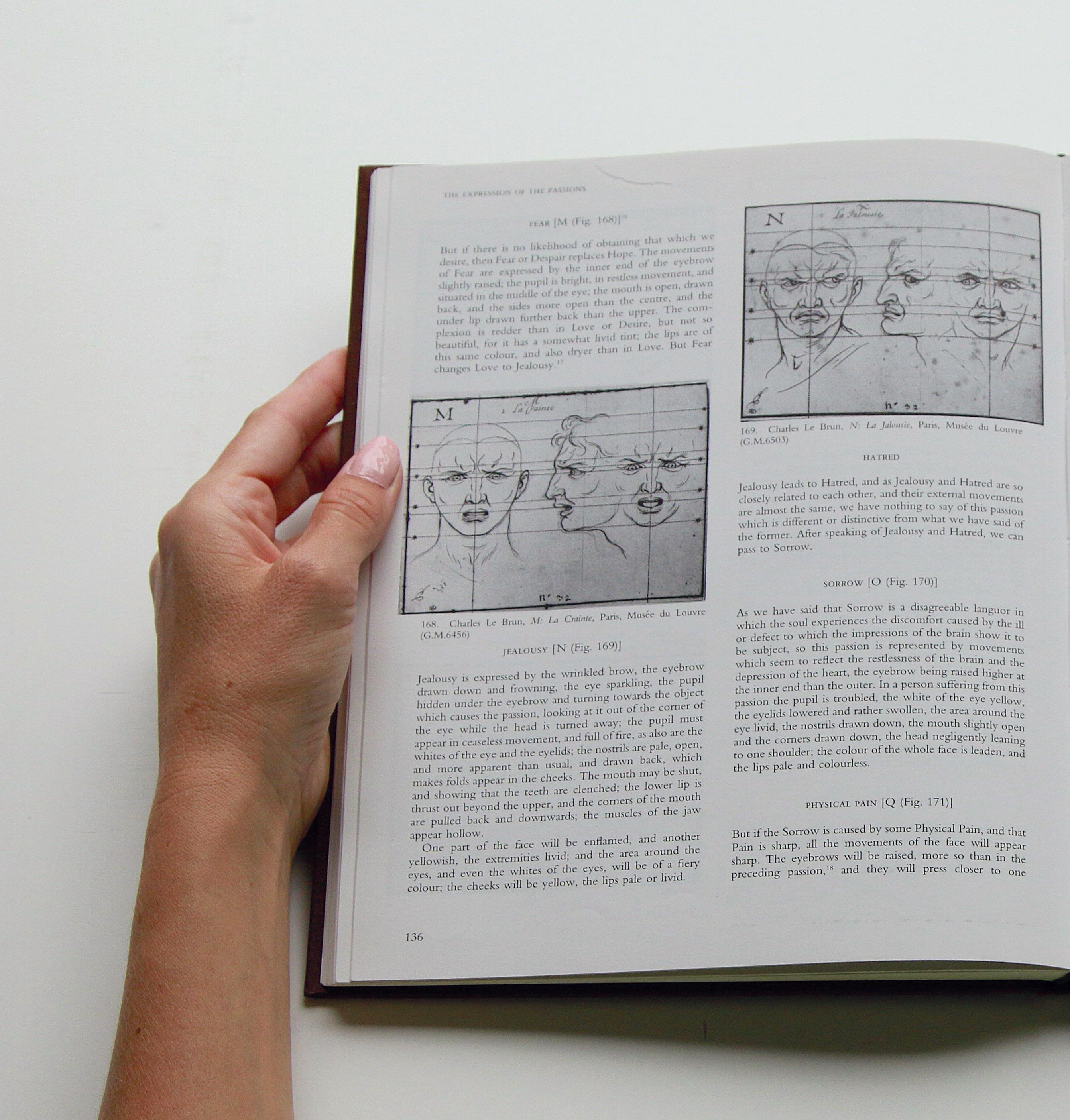

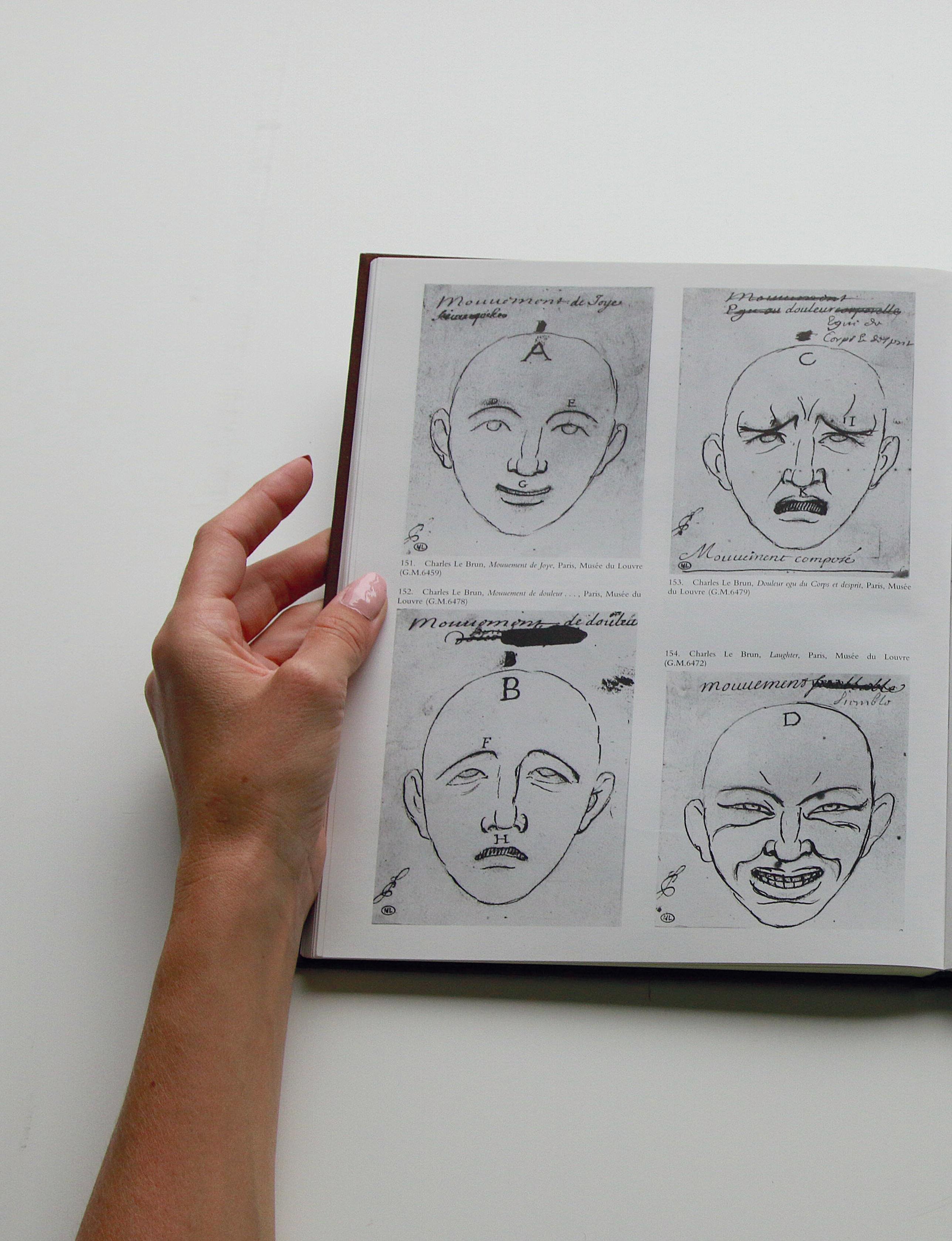

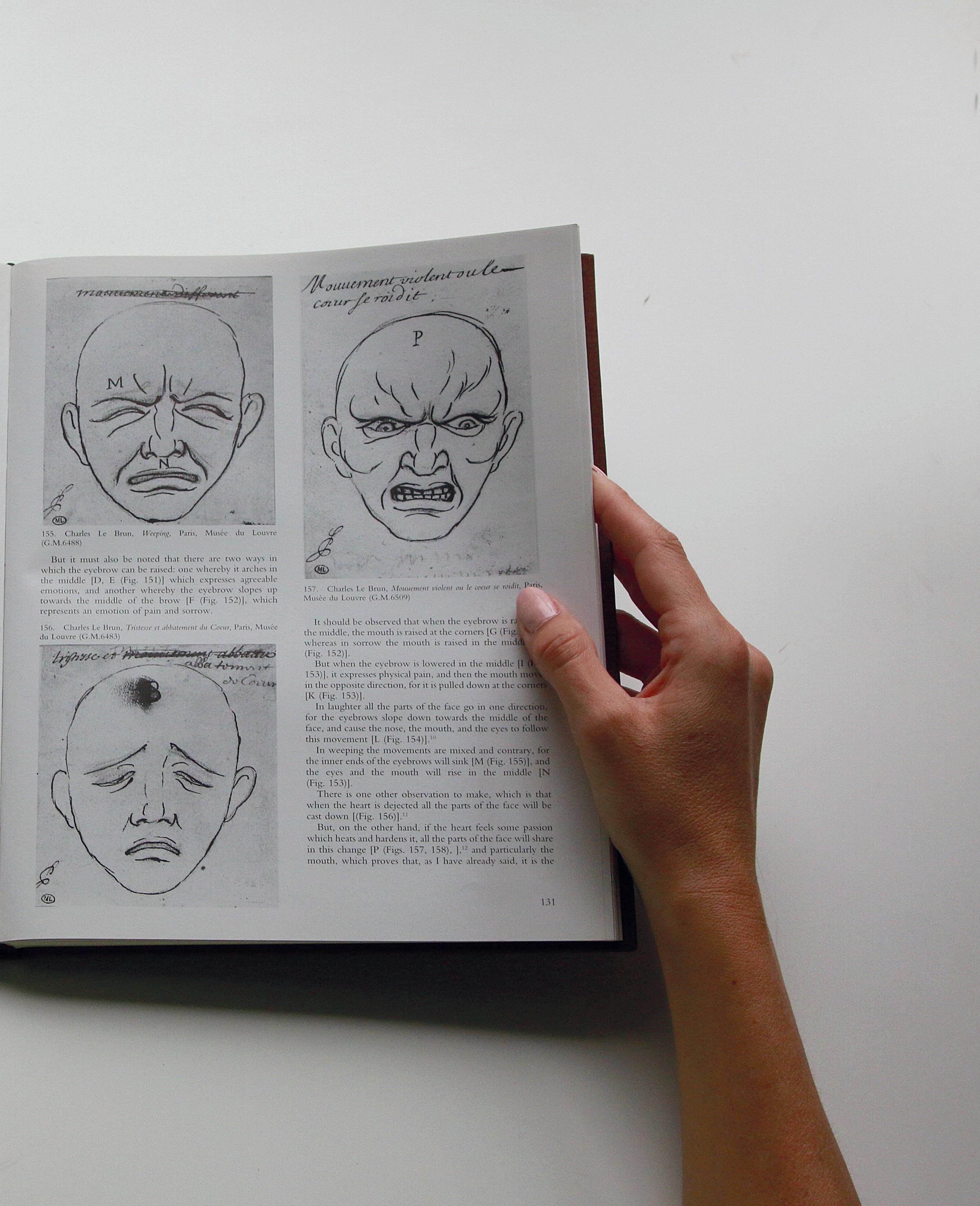

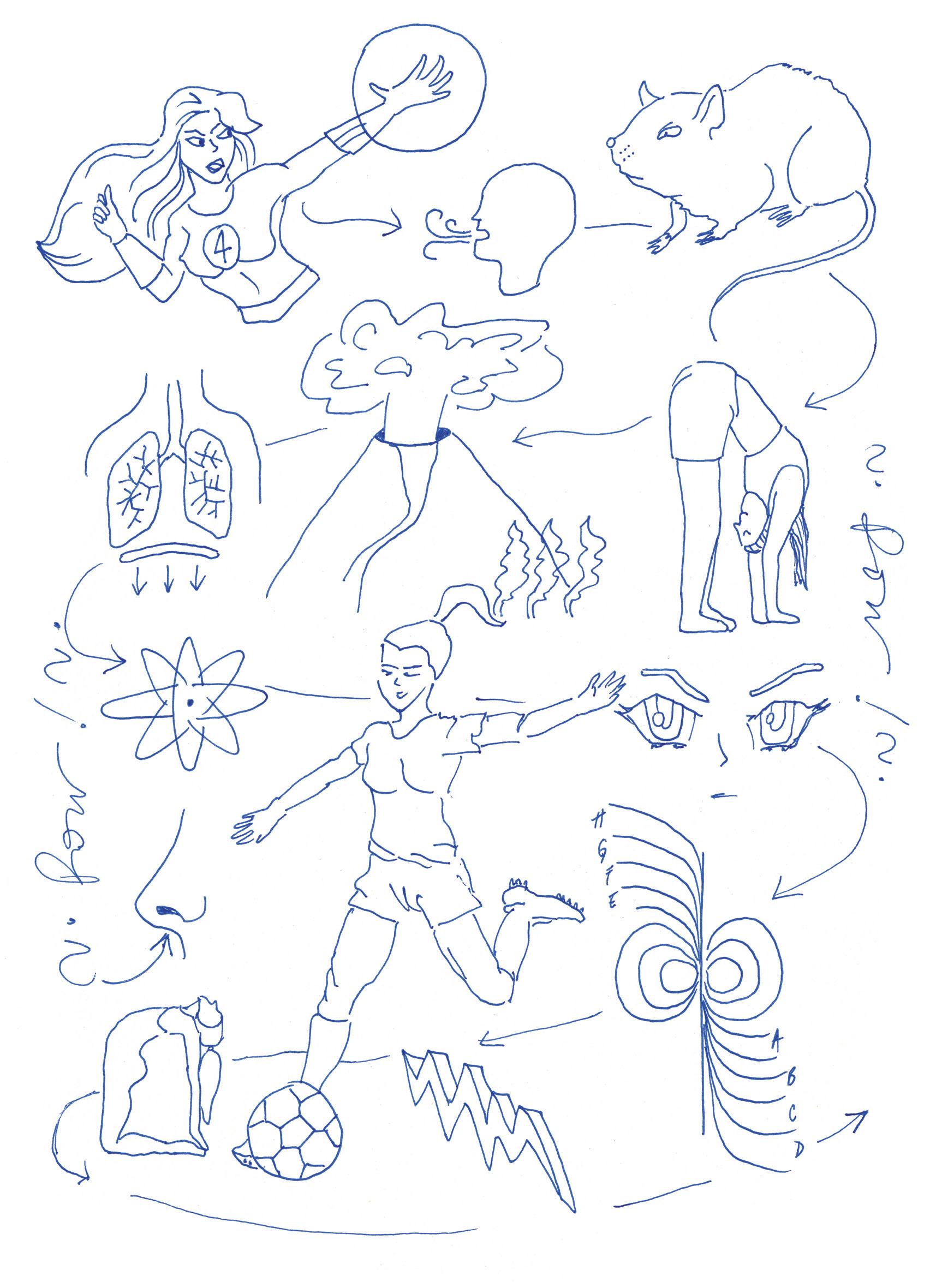

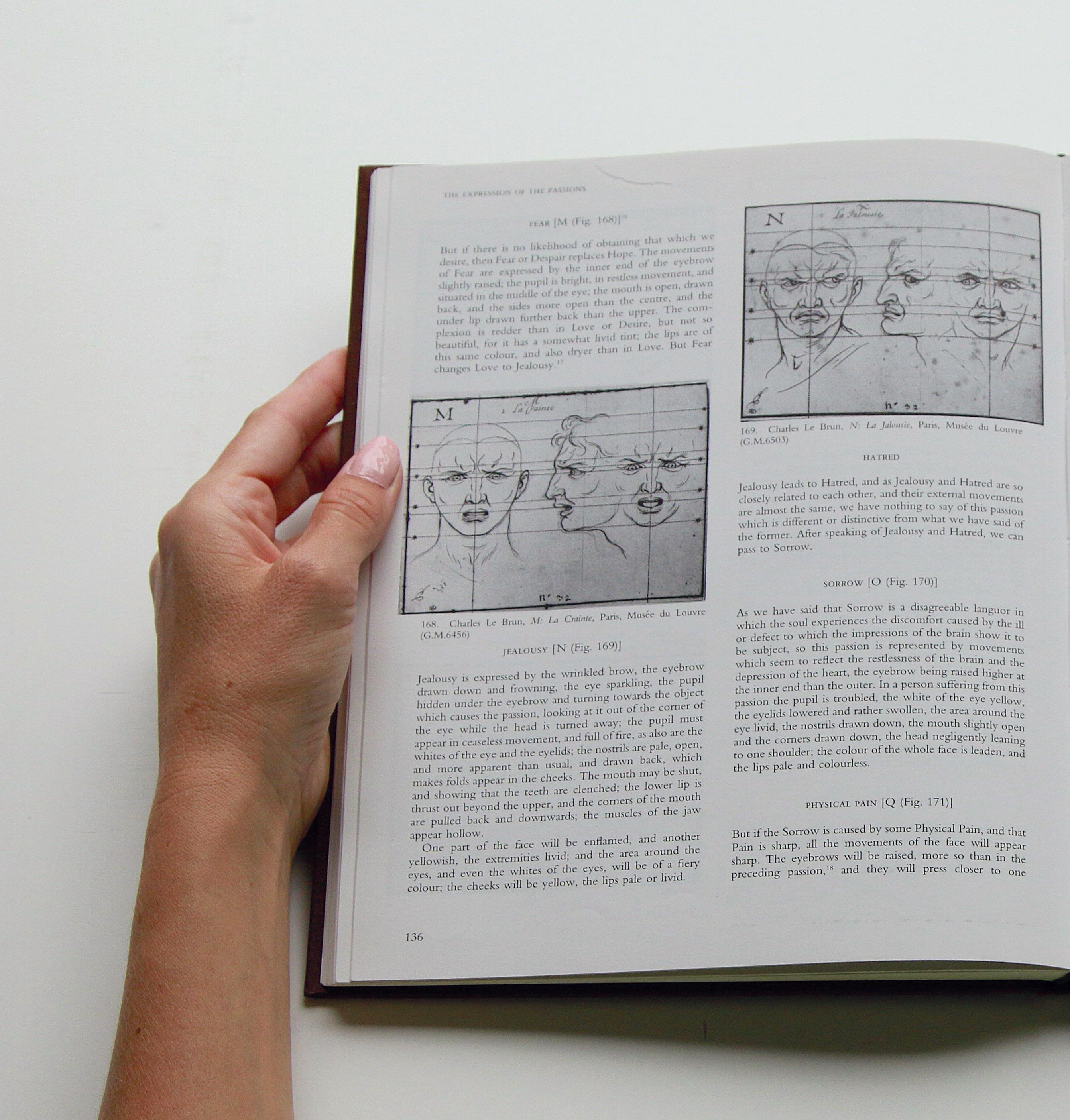

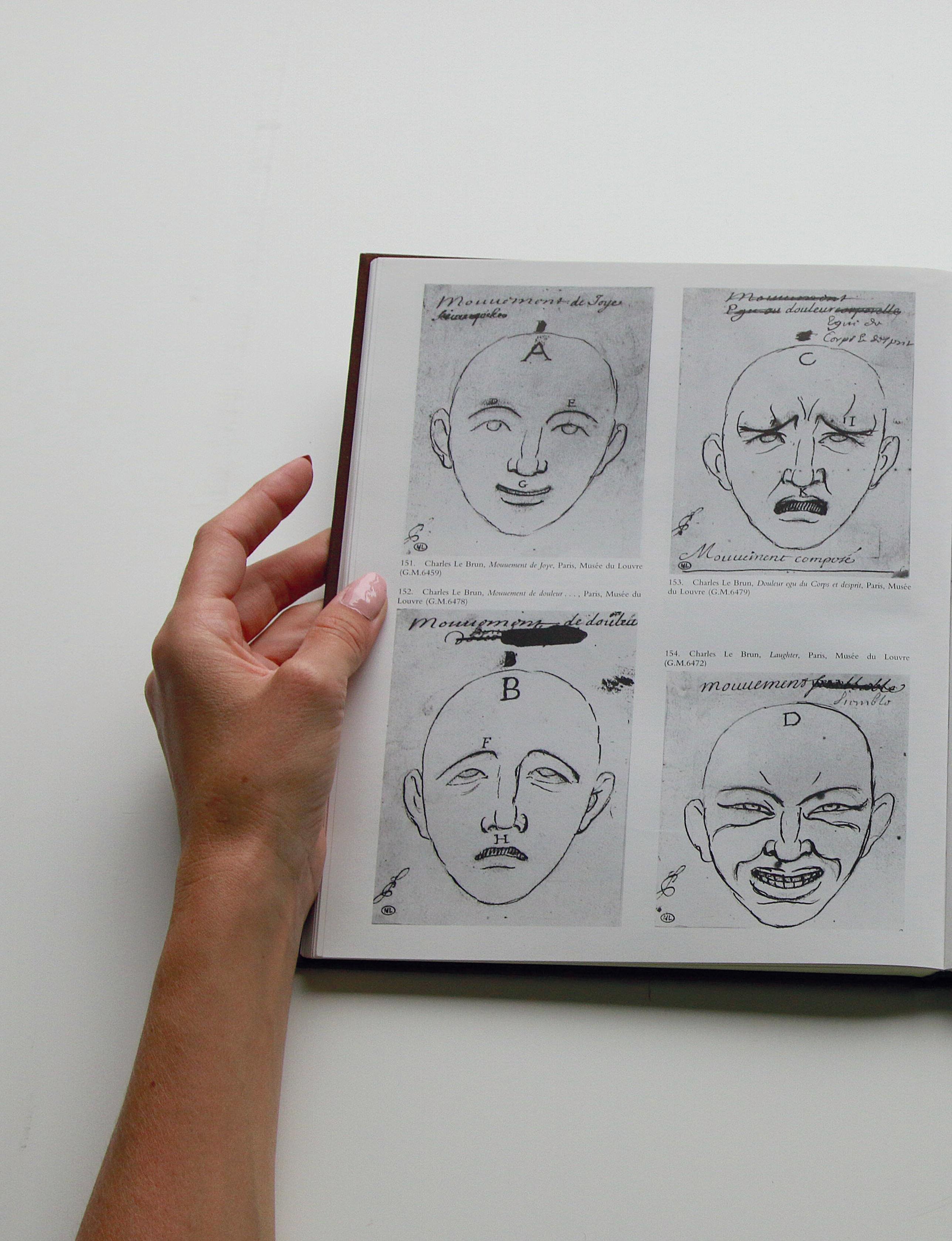

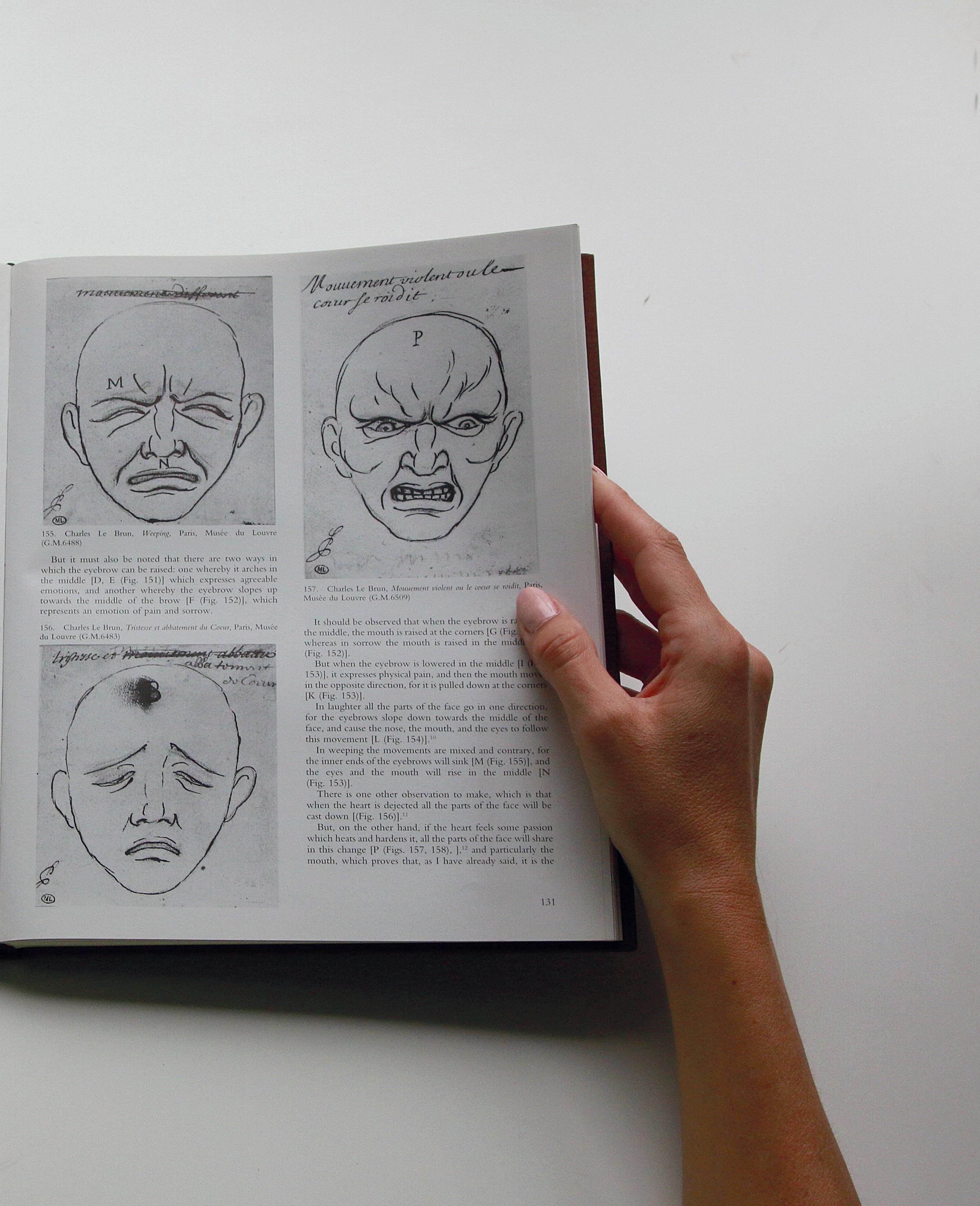

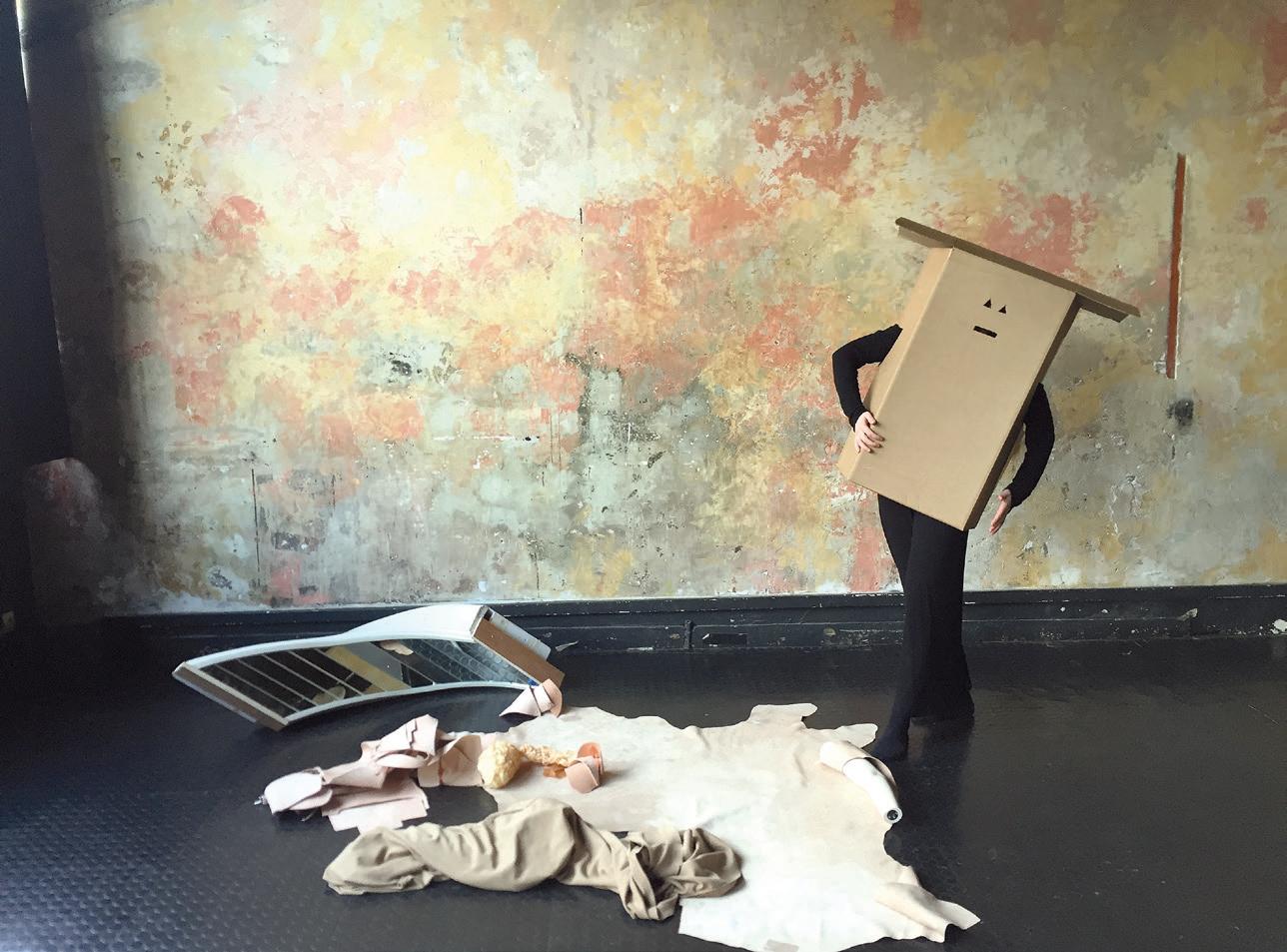

imitando, hasta la deformación facial, el estudio de expresiones y emociones de Charles Le Brun con el libro abierto,3 pronunciando palabras como mantras y sonidos guturales. Un Mundo Raro es el resultado de esta experimentación, que unió la mirada holística de cuerpo y alma de Spinoza, referente de performances históricas de artistas como Bruce Nauman, Lygia Pape y Lygia Clark, y el despecho emocional de un bolero de la mexicana Chavela Vargas. Enfundada en una armadura Adidas, Azpilicueta se retuerce, gesticula, habla sola, canta y explora todas las formas sonoras físicamente posibles de su voz. Investiga la caja de resonancia que es el cuerpo y busca expandirla con respiraciones exigentes del yoga y ejercicios físicos, para que pueda albergar más; como una carpa que se infla en un festival para que entre una multitud. En la antigua Grecia, el atletismo era un culto al cuerpo y, a través de él, a la belleza y a la verdad. En Un Mundo Raro, Azpilicueta es una atleta que en el acto de expandir su cuerpo imagina que podríamos ser más flexibles para escuchar quiénes somos y cómo somos con los otros.

En El género en disputa, 4 Judith Butler propone pensar el habla como un acto performático, donde se unen el cuerpo y el lenguaje, y donde operan convenciones y normativas que determinan nuestro modo de ser y nuestro comportamiento. Desde esta óptica, la performance en la obra de la artista es un motor en vivo de investigación: una herramienta de deconstrucción de estructuras significantes y comportamientos corporales heredados a través del lenguaje.

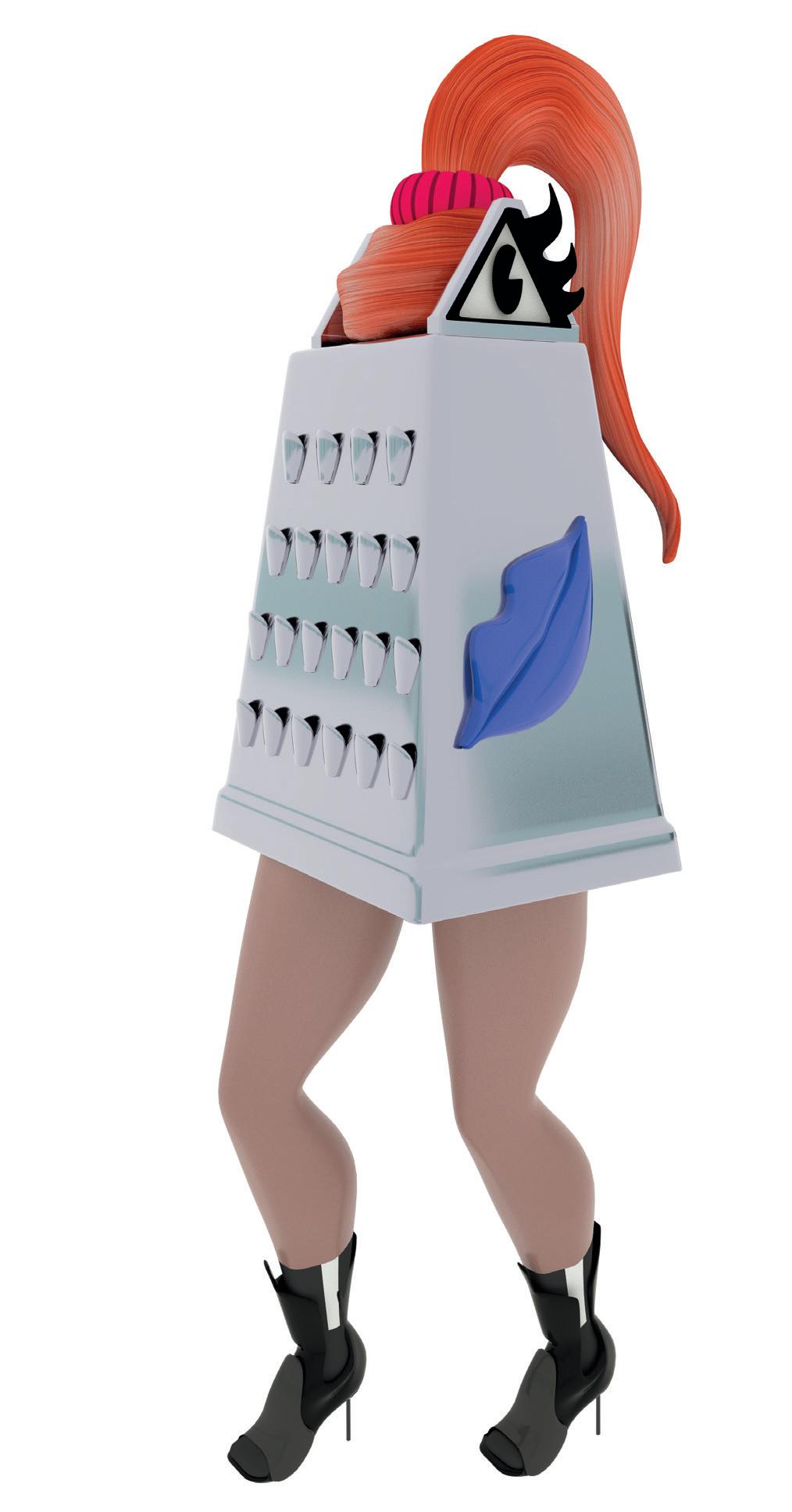

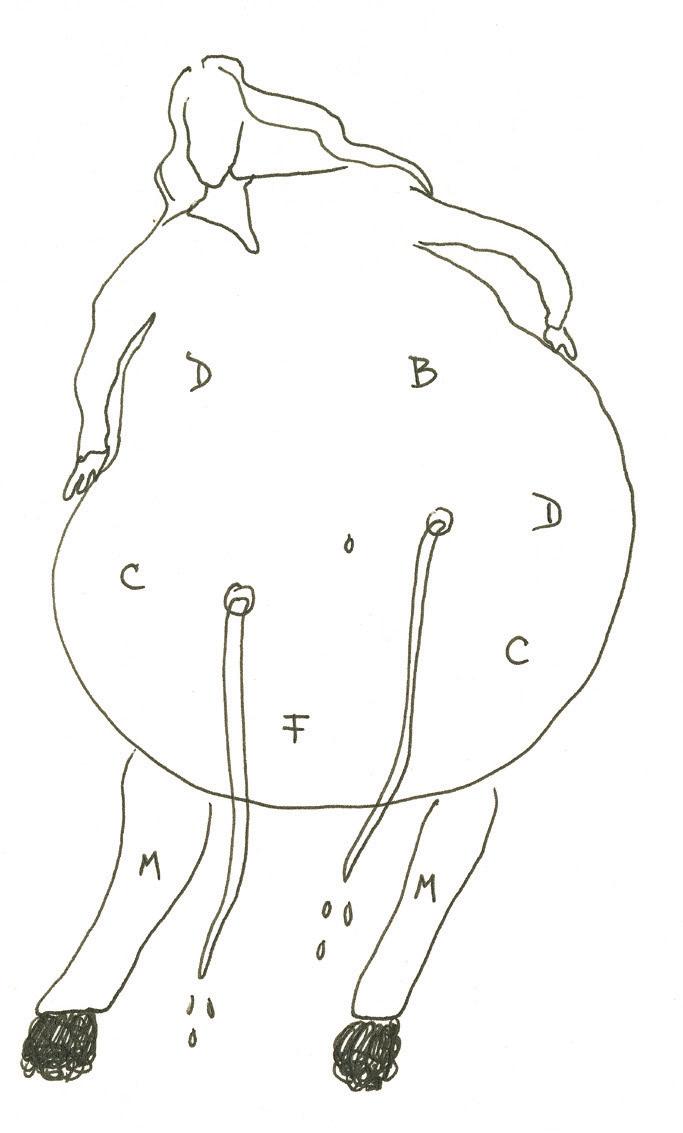

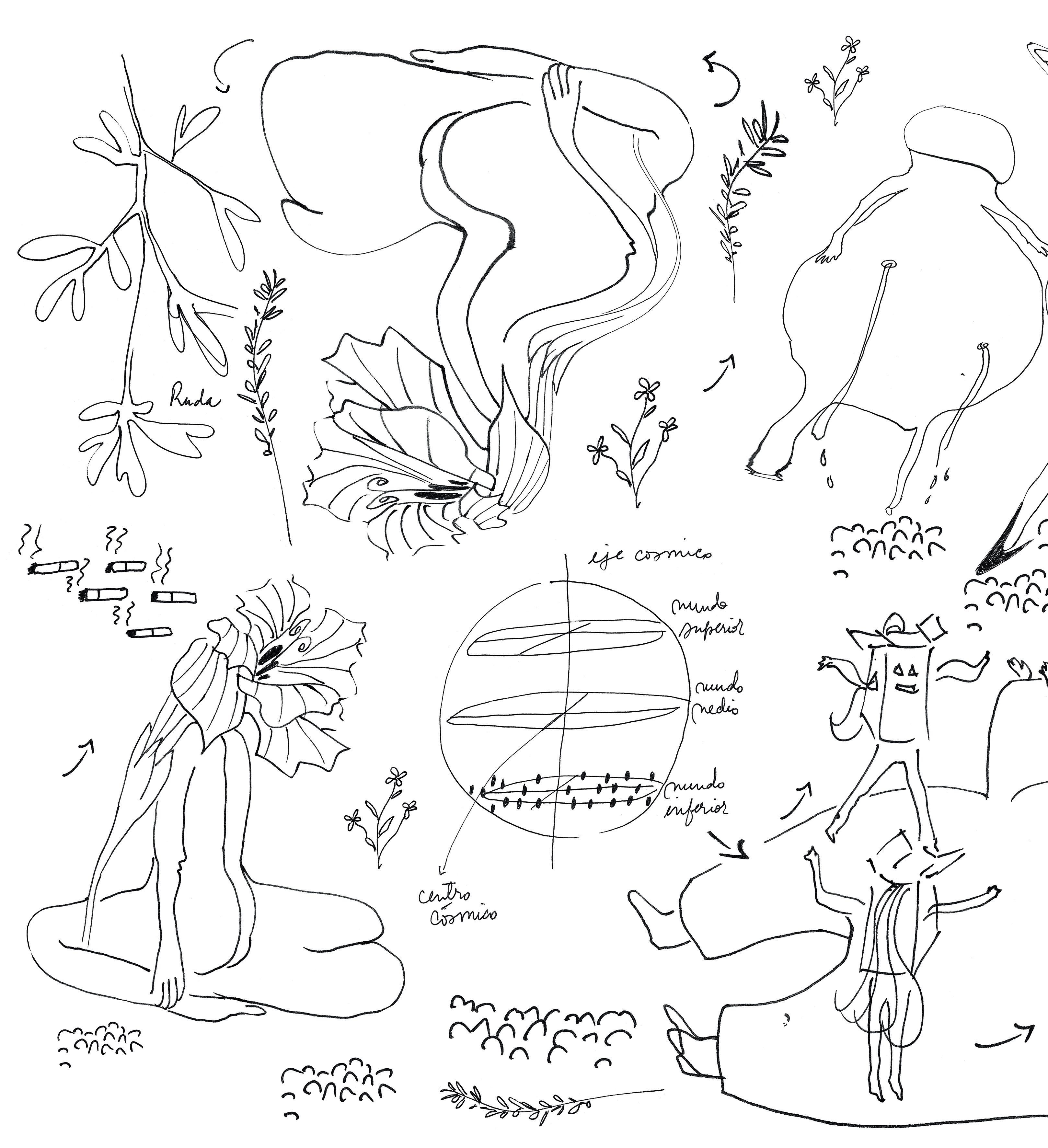

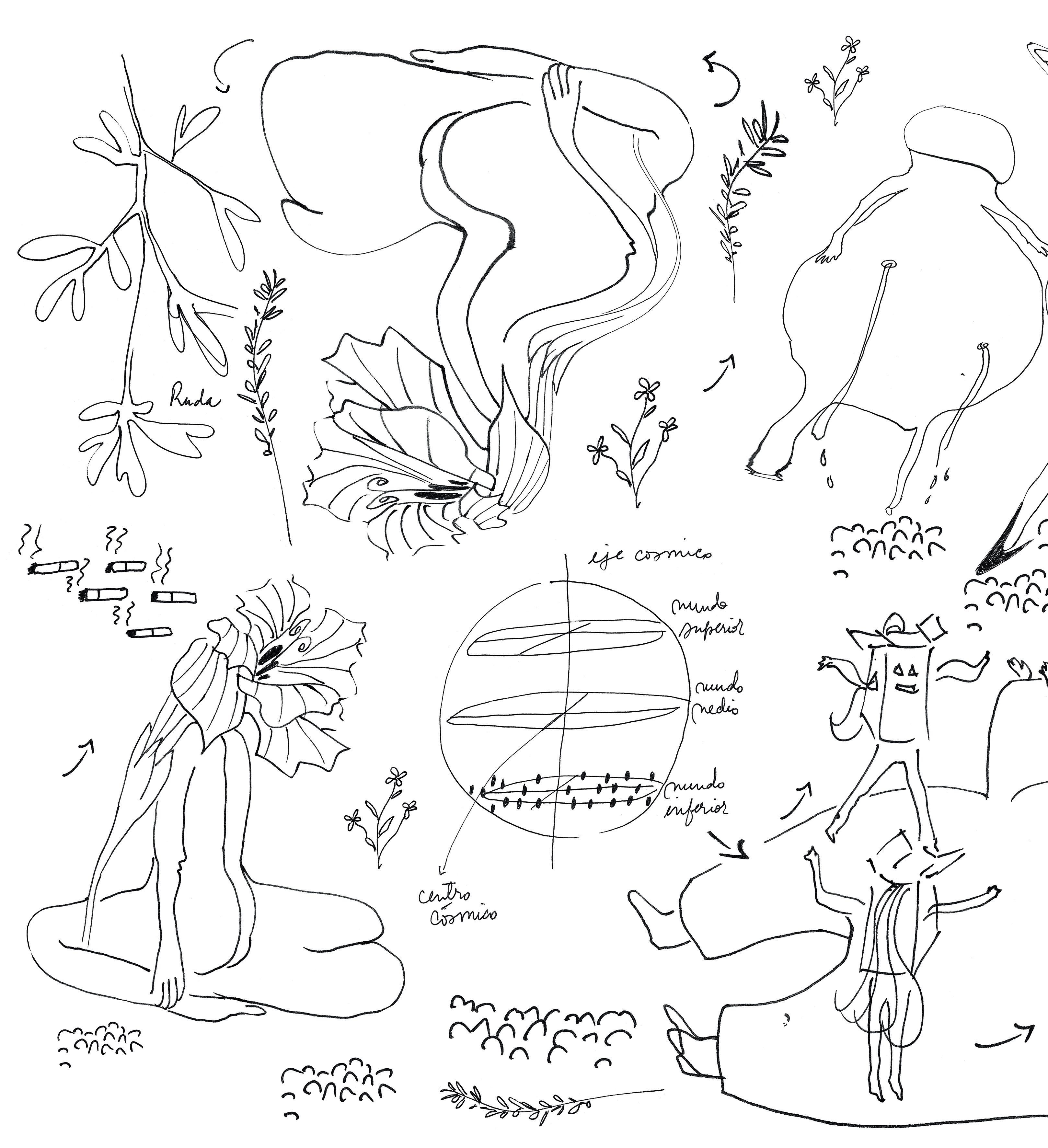

En este sentido, Molecular Love [Amor molecular] (2016) es un proyecto guiado por el interés de incluir en la práctica artística otro tipo de conocimiento a través de la performance, algo que Marie Bardet llama pensar con mover,5 un conocimiento no necesariamente racional, sino cercano a lo instintivo. Molecular Love es el resultado de un trabajo experimental en el que Azpilicueta convocó a coreógrafas y bailarinas de distintas disciplinas de danza y teatro para interpretar un guión de acciones, ideas, frases y movimientos propuestos por la artista, pero que mutaban al absorber el trabajo del grupo. La obra, constituida como un organismo vivo, se compone de una performance —que en su primera presentación duró ocho horas— una serie de dibujos, el video Molecular Love (2016) y mnemónicas visuales, apuntes escritos en un código personal que combina palabras y dibujos utilizados para memorizar y ensayar sus performances. El foco de la obra está puesto en pensar el deseo femenino como el centro del acto creativo y artístico. Propone un ritmo de trabajo desacelerado y no conclusivo, con resultados no necesariamente visuales ni objetuales. Es un ensayo sobre la información que se encuentra en el cuerpo y sobre la posibilidad de discutir el dominio de la materialidad y de la mirada por sobre el resto de los sentidos, tanto en el arte como en la vida (en su Manifiesto de la mujer futurista, Valentine de SaintPoint decía: “Mujeres, durante demasiado tiempo pervertidas por la moral y los prejuicios, volved a vuestro sublime instinto”).6 En la performance, dos cuerpos femeninos se corresponden en un diálogo no verbal. Es una relación en la que hay algo de hermandad y de aprendizaje por medio de la reversión de movimientos y, sobre todo, del reconocimiento del cuerpo propio a través del otro. La palabra aparece como un juego de cantitos, a veces algo inocentes o

15

3 Jennifer Montagu, The Expression of the Passions: The Origin and Influence of Charles Le Brun`s “Conference sur l`expression generale et particuliere”, Yale University Press, 1a edición, 1994.

4 Judith Butler, El género en disputa, Buenos Aires, Paidós, 2018.

5 Marie Bardet, Pensar con mover. Un encuentro entre danza y filosofía, Buenos Aires, Cactus, 2012.

6 Valentine de Saint-Point, Manifiesto de la mujer futurista, 1912.

ingenuos (“Beeso, beso besito, besooo, besito...” o “Renata trabaja todala, todala semana Renata”), que componen momentos corales a lo largo de la obra.

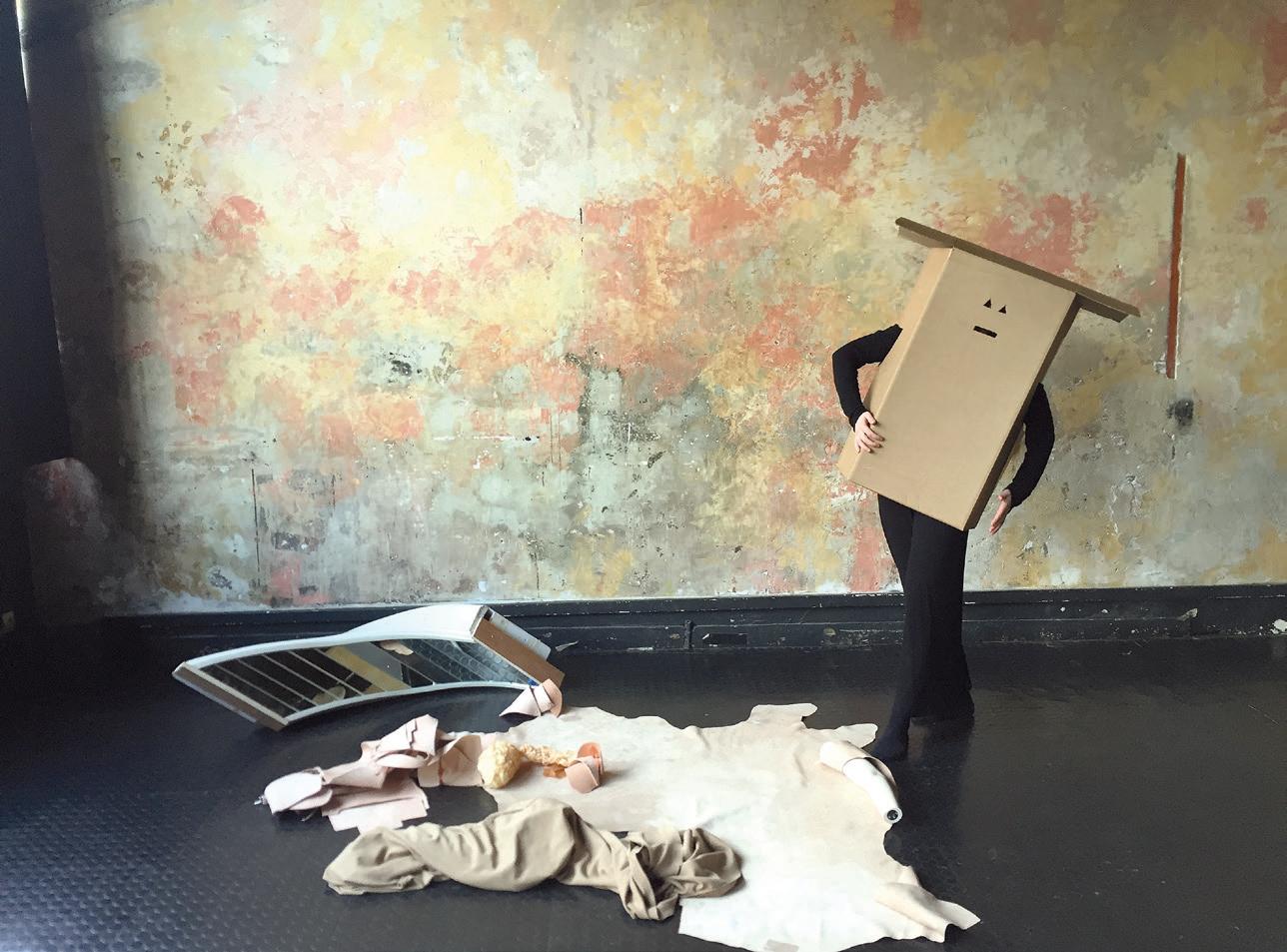

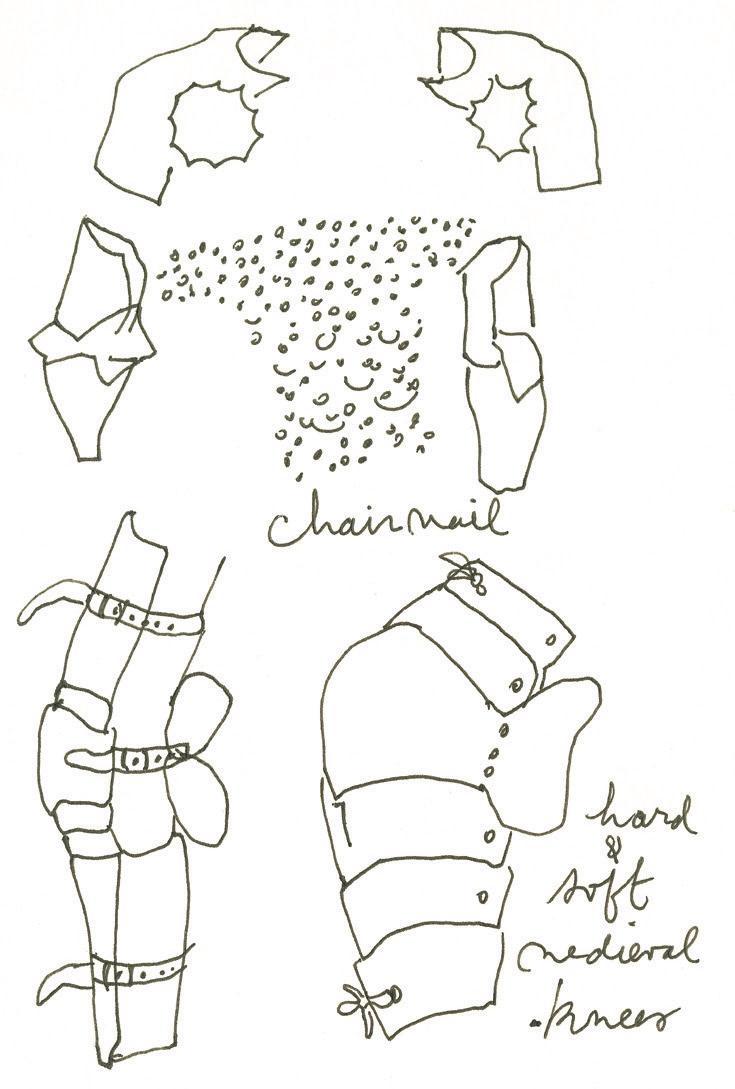

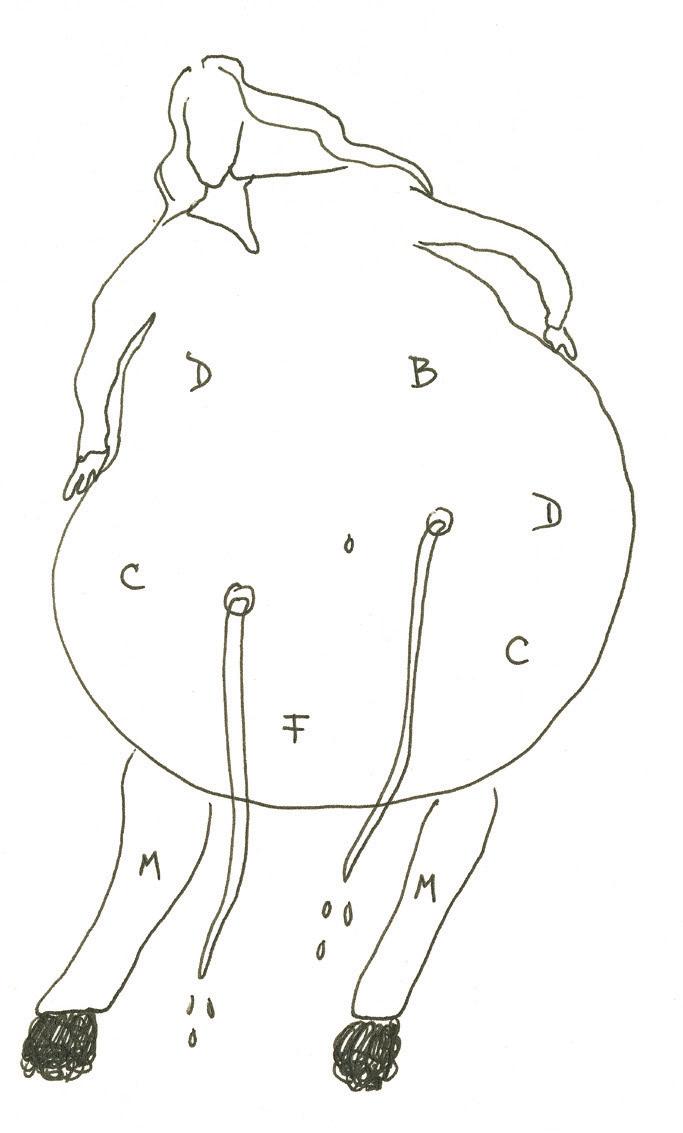

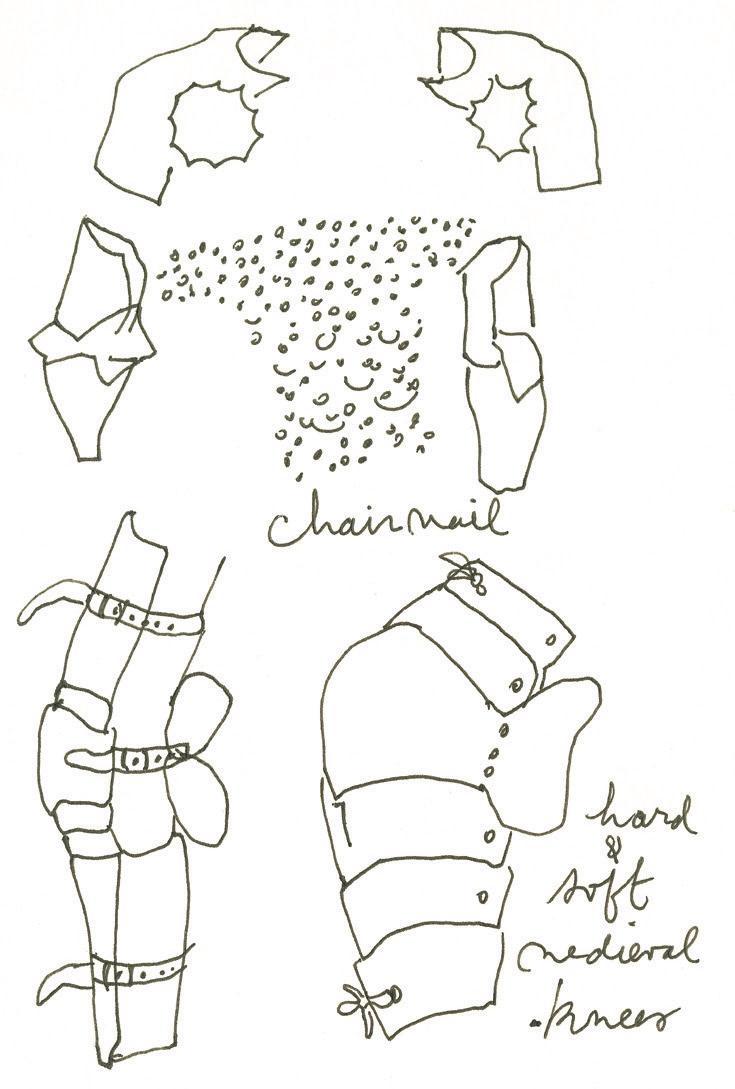

Pero, a diferencia de un coro formal, donde la composición y la normativa a seguir son necesarias para conformar esa sola “voz” que no debe evadirse, en las obras de Mercedes Azpilicueta lo polifónico y lo corporal responden más a la idea de intoxicación Así se expresa en su diario de viaje a París: “i feel intoxicated. we feel intoxicated. our bodies feel intoxicated”,7 para describir la reacción en cadena de escalofríos que siente al escuchar a un cantante callejero en un subte parisino; y también: “i also feel touched. suddenly we all feel touched. we understand we might have very little in common. still, at least we are feeling something together. for sure this music is making sensible something that is real in all our bodies”.8 El texto forma parte de la obra Bestiario de Lengüitas, un proyecto iniciado en 2017 en la residencia Villa Vassillief, en París, que reflexiona, entre otras cosas, sobre la intoxicación como algo tan positivo como inevitable. La obra, de carácter procesual y concebida como una investigación en el largo plazo, está compuesta de distintas partes, entre ellas un manual de ejercicios de supervivencia con Armaduras suaves, realizadas en materiales orgánicos, porosos y reciclados que cuidan a la multitud de cuerpos blandos y migrantes que somos.

La polifonía de voces también comenzó a transformarse en una polifonía de referencias. Con los años se conformó una corriente subterránea de obras,

7 “me siento intoxicada, nos sentimos intoxicadxs, nuestros cuerpos se sienten intoxicados”. Mercedes Azpilicueta, about hell, smells & shame, París, 2017-18.

8 “también me conmueve. de repente, todxs estamos conmovidxs. entendemos que tal vez tengamos muy poco en común. aunque aun así, al menos estamos sintiendo algo juntxs. esta música seguro está haciendo sensible algo que es real en todos nuestros cuerpos». Idem.

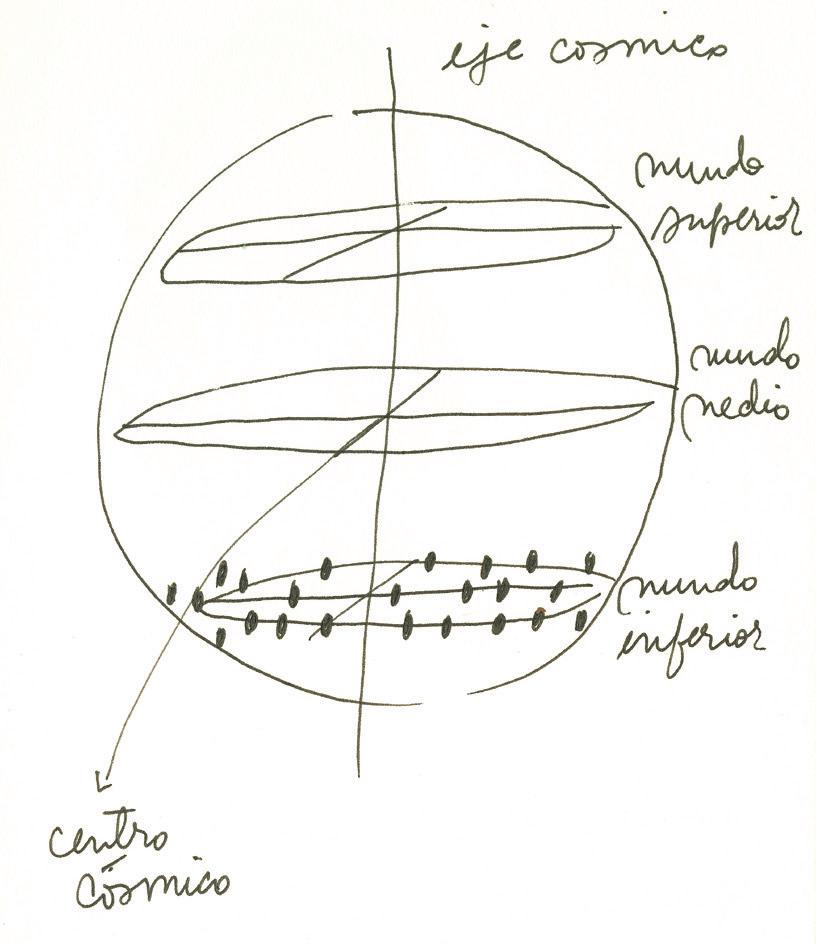

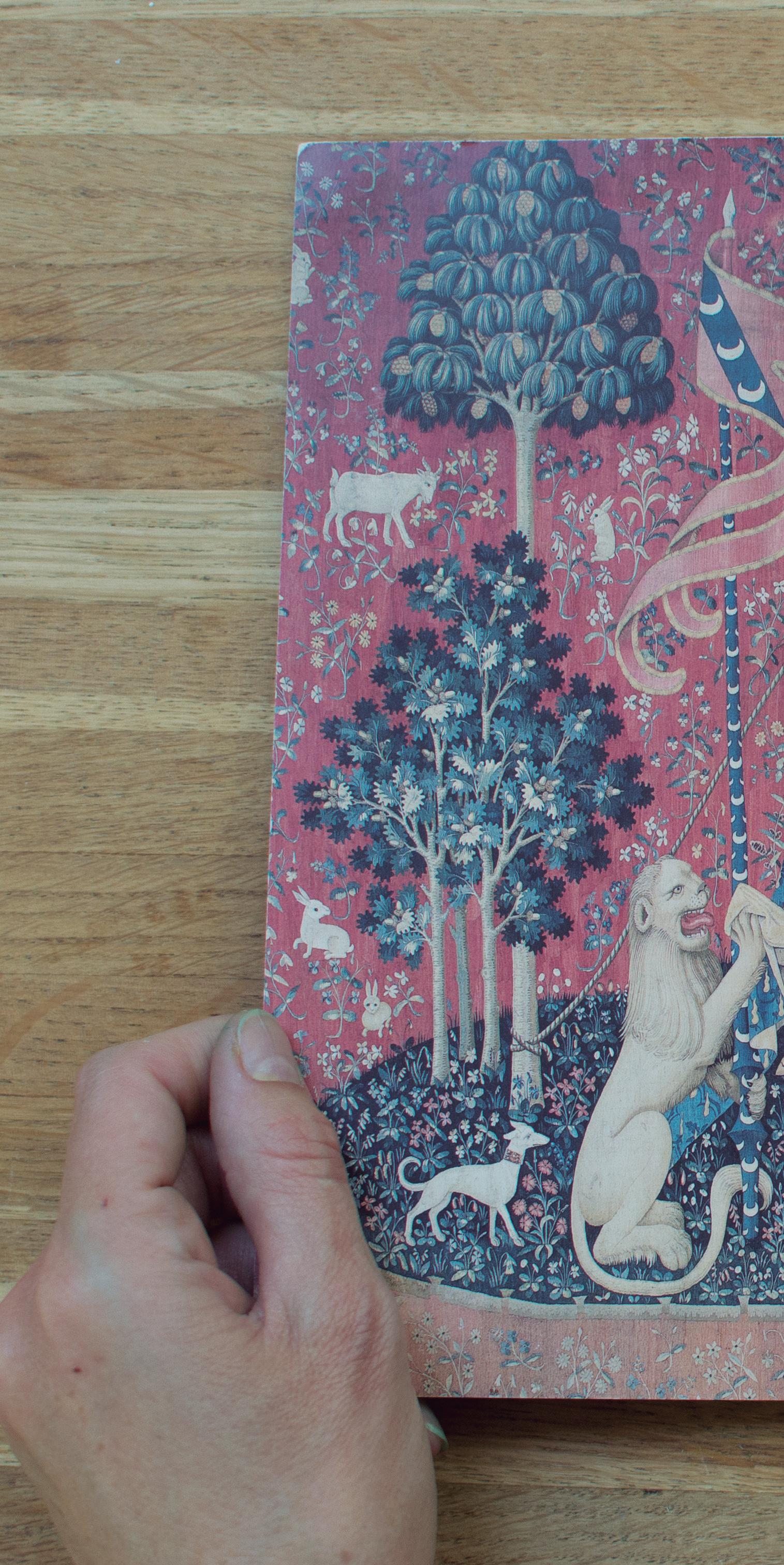

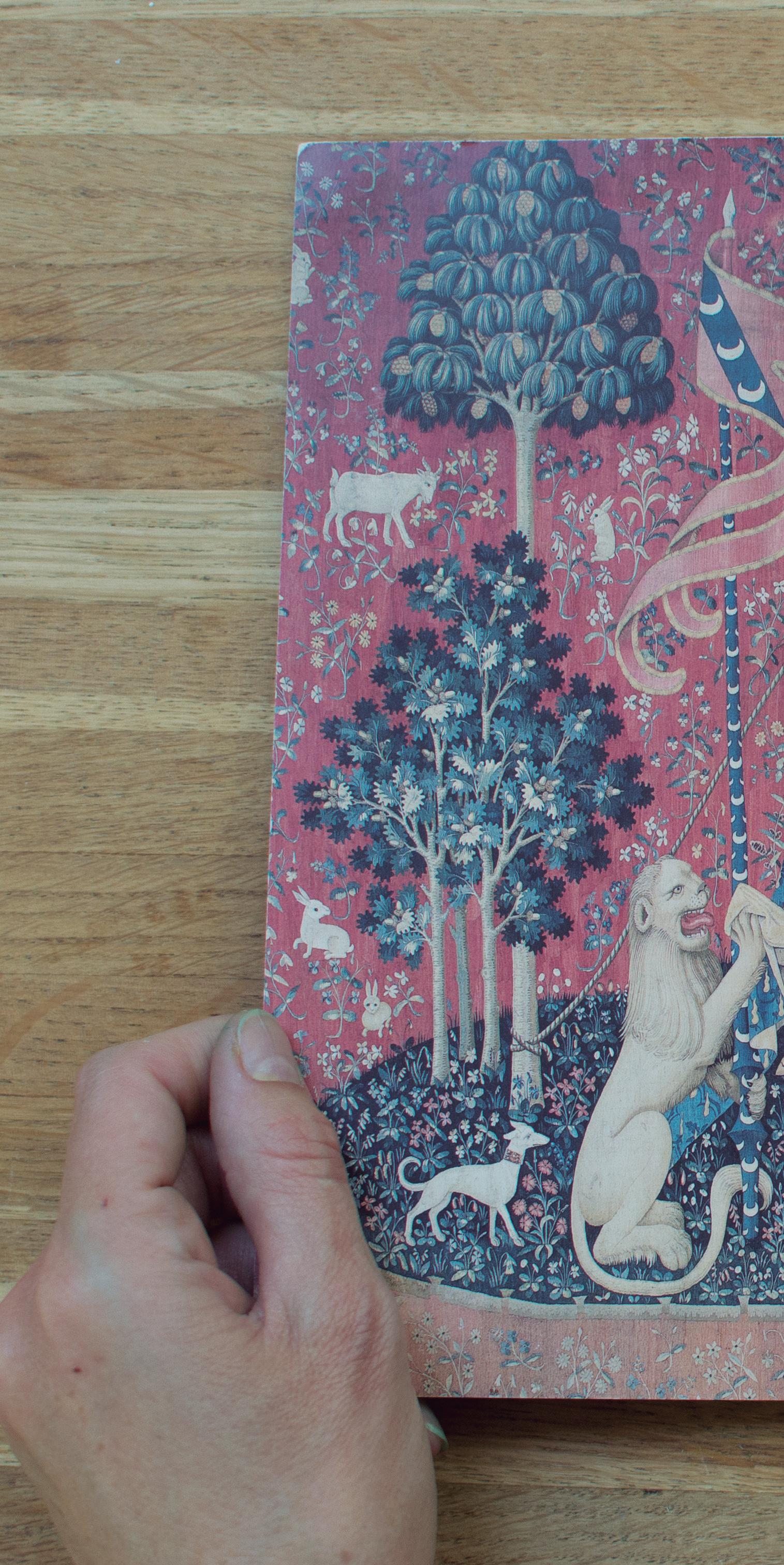

artistas y escritores, contemporáneos e históricos, que atraviesan sus proyectos y que confluyen en una manera de realizar investigaciones artísticas transversal y a contrapelo de las convenciones. “Investigaciones deshonestas”, como las llama. En Bestiario de Lengüitas (2017-en curso), más que filiaciones conceptuales o vínculos históricos, Azpilicueta imagina afinidades afectivas entre Lea Lublin, la artista argentina feminista radicada en París en los años sesenta, la poesía “neobarrosa porteña” de Néstor Perlongher, el reguetón chileno de Tomasa del Real y el tapiz medieval La dama y el unicorno, un conjunto enigmático de seis piezas dedicadas a los sentidos donde, en la última, la dama sostiene un cofre bajo la leyenda A mon seul désir, que para Azpilicueta permite pensar en el deseo femenino, algo ausente y negado históricamente, como un tesoro. La “investigación deshonesta” de la artista es un modo de hacer que revuelve la historia del arte canónica y patriarcal, planteando vínculos no ortodoxos y transhistóricos que reescriben el pasado y nuestro presente.

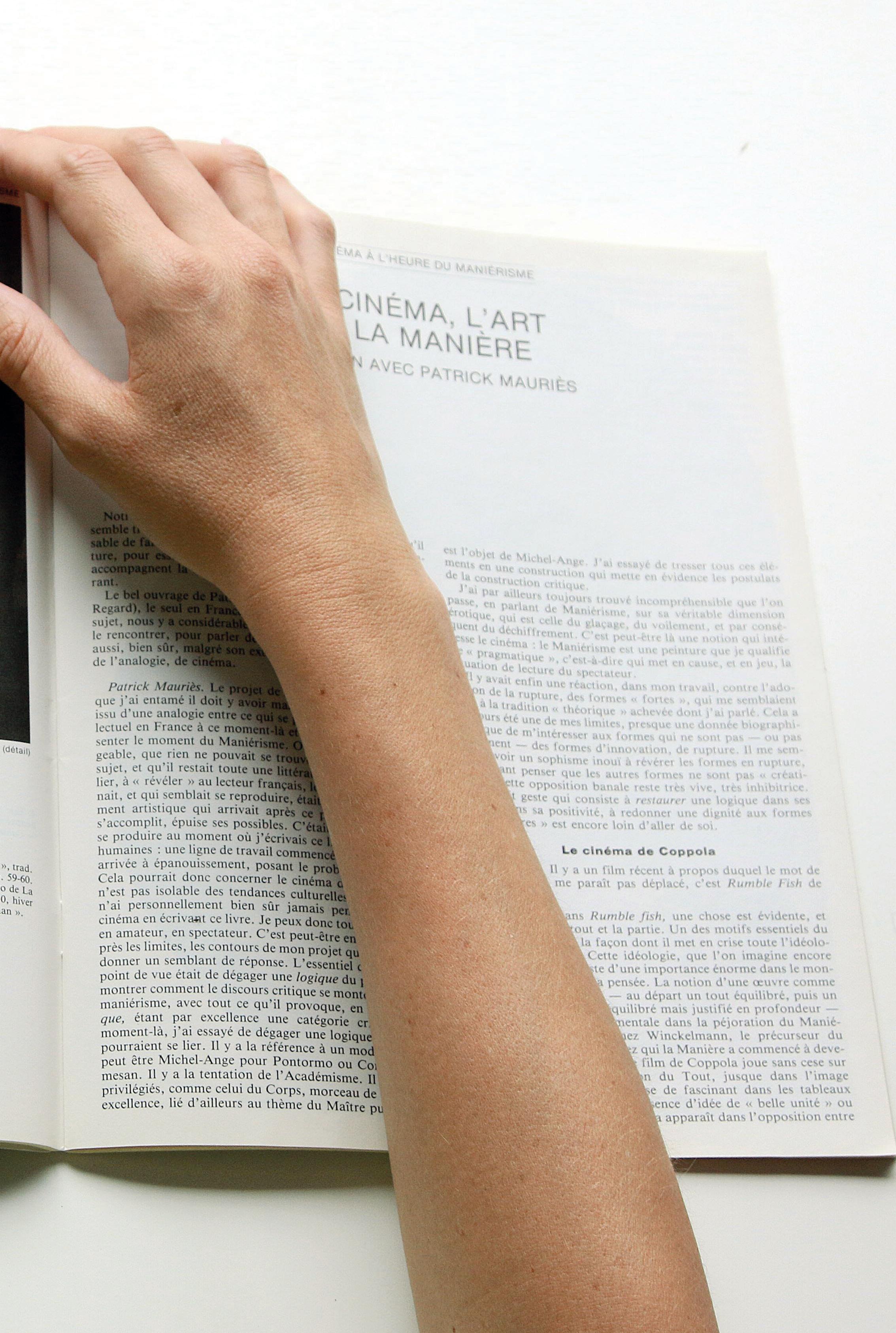

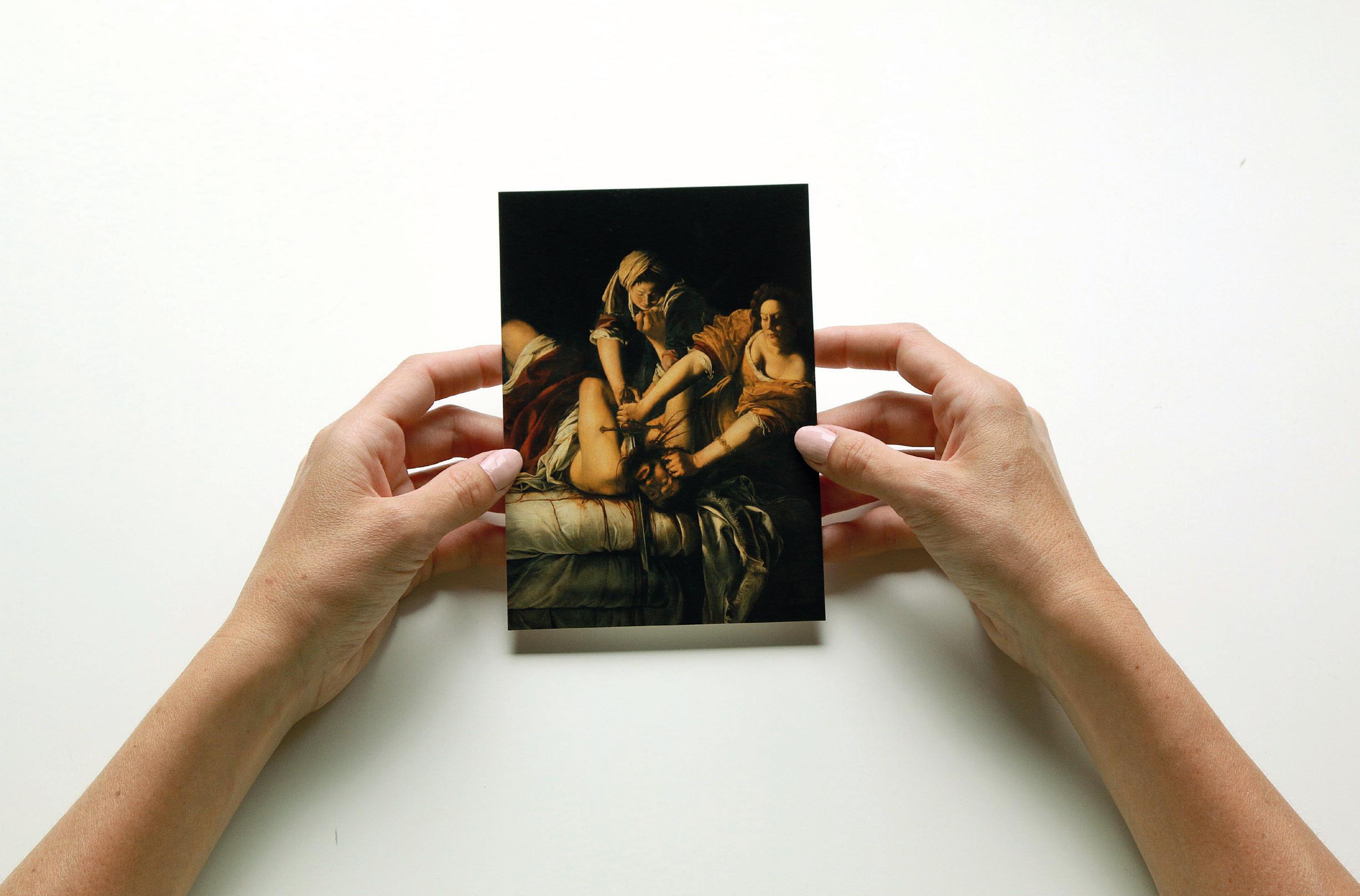

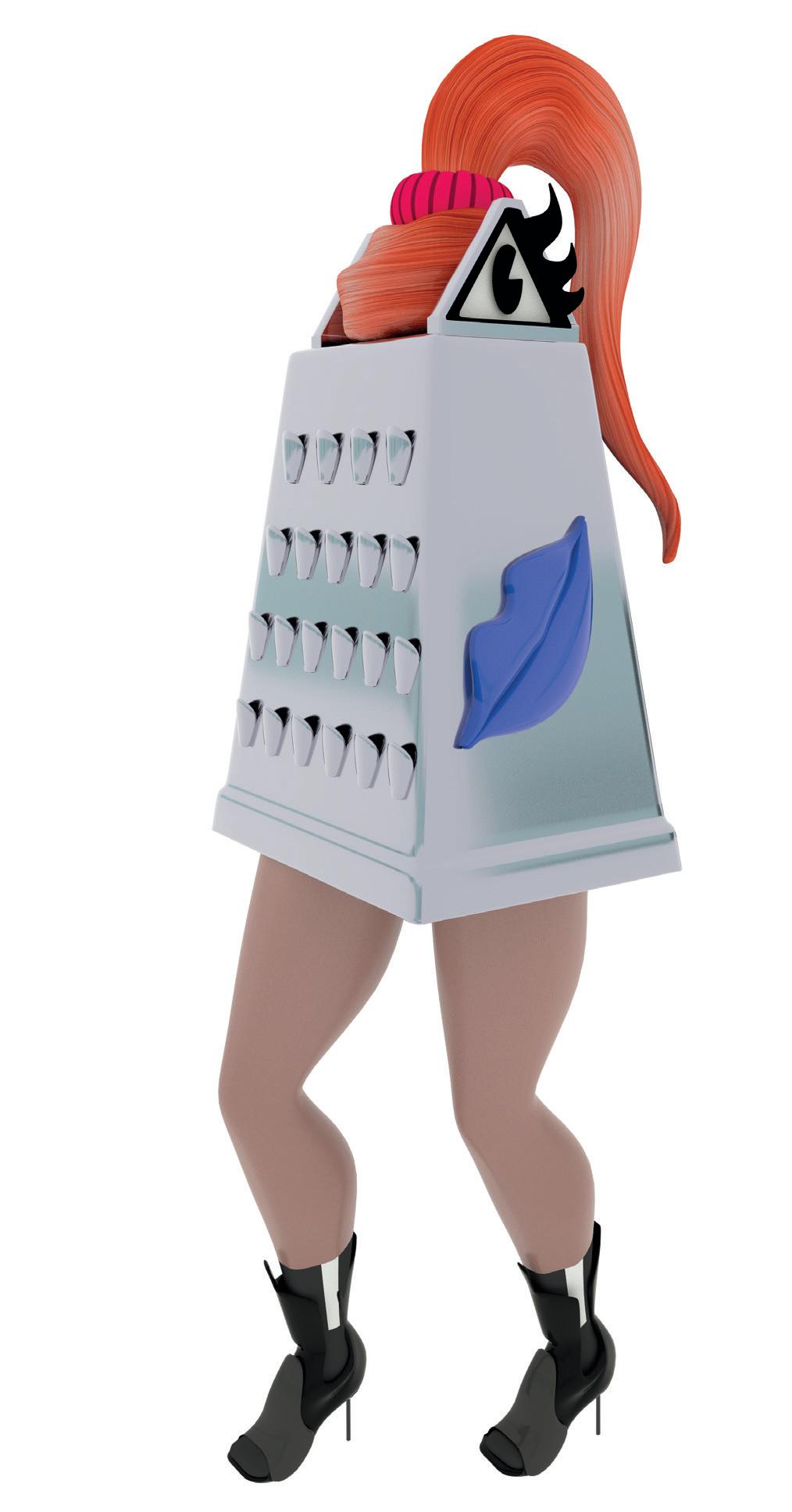

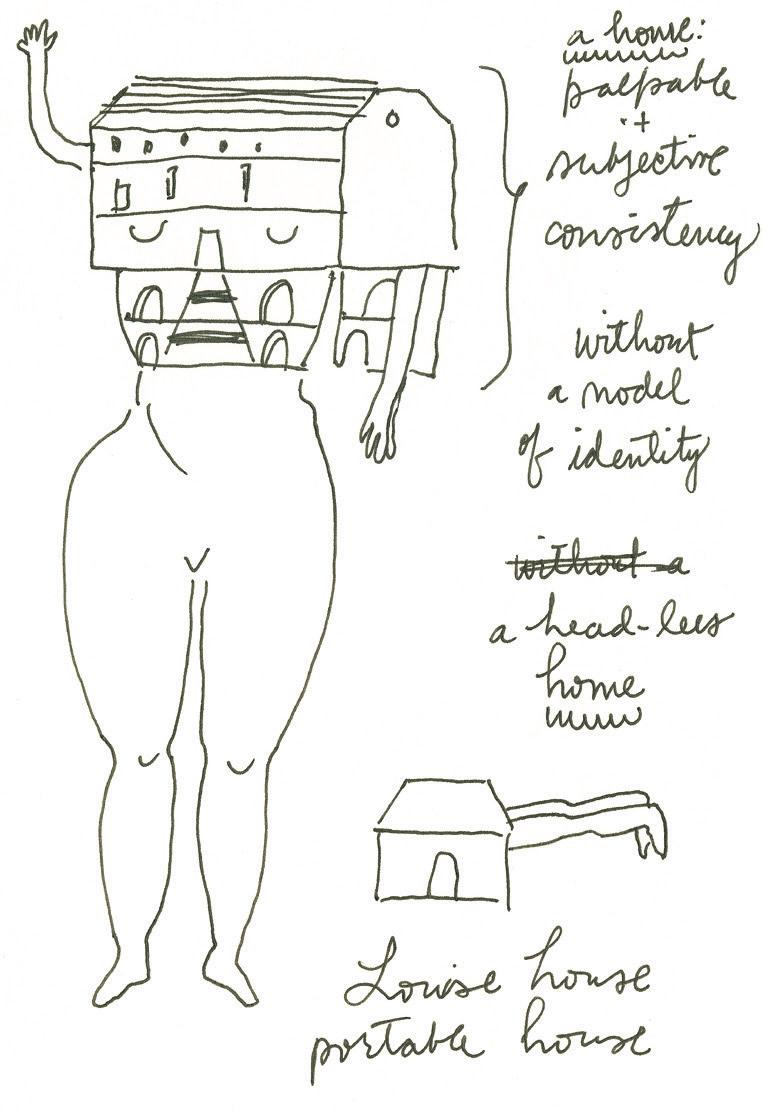

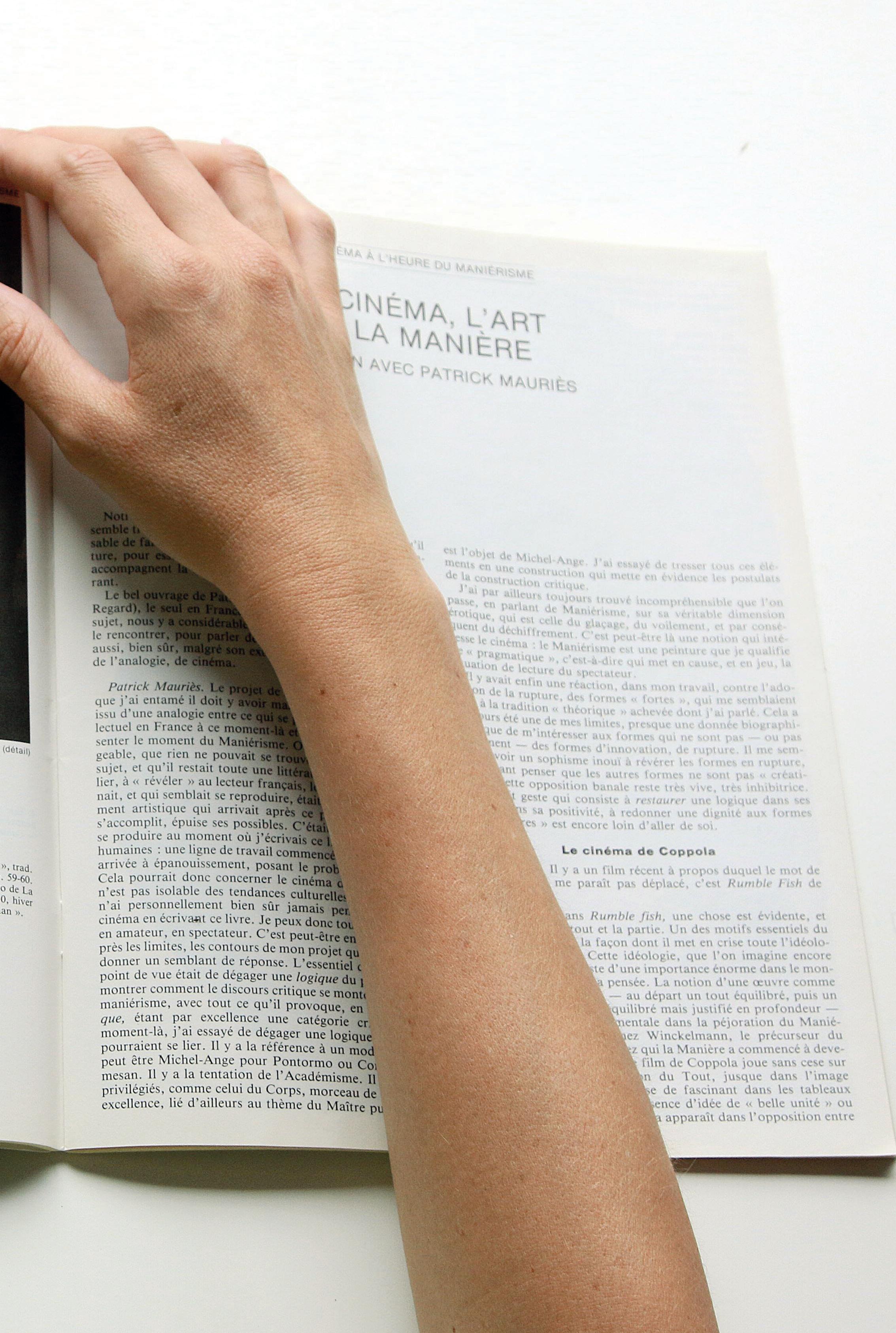

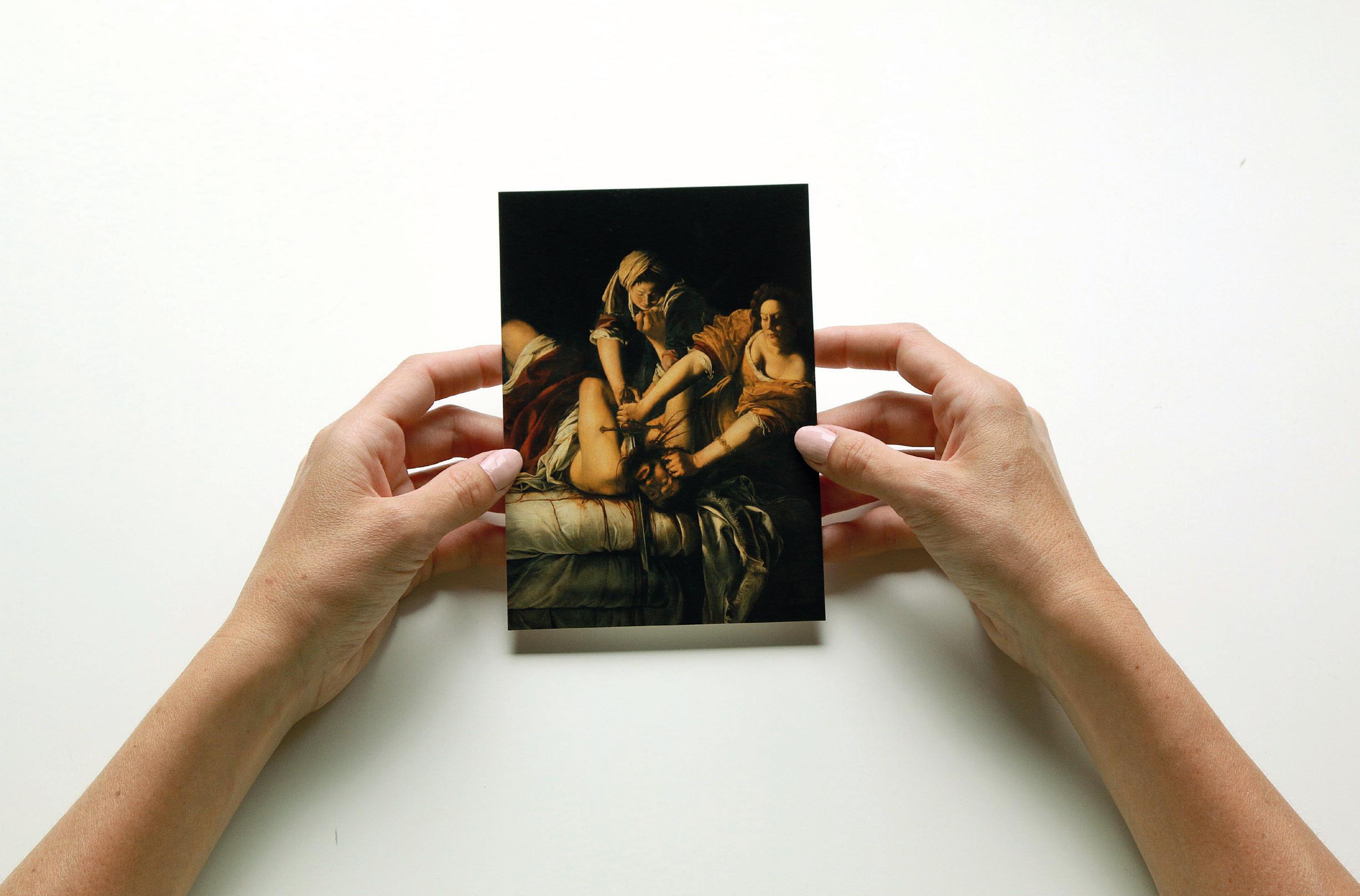

Su último proyecto, Cuerpos Pájaros (2018), producido especialmente para esta exposición, plantea la pregunta sobre dónde comienza y dónde termina el cuerpo, este cuerpo intoxicado que imagina como colectivo. Un cuerpo formado por muchas partes, diverso y desmitificado; más guarro y afectado que ideal y convencionalmente atractivo o domesticado, sujeto a normas de belleza tradicionales y represivas. La obra es una instalación de video con un guion que se compone de tres voces o discursos (uno personal, uno histórico y uno teórico) que entretejen reflexiones sobre la escritura y la descripción como un acto emancipador, sobre las deformaciones de la figura humana en el arte manierista, y relatan las impresiones de una espectadora frente a la gestualidad de la obra barroca Judith decapitando a Holofernes, de Artemisa Gentileschi. Estas narrativas,

16

combinadas con un sonido de bajos profundos que atraviesan al espectador, se superponen sobre una colección de planos cortos de imágenes recolectadas por la artista en largas recorridas por Buenos Aires durante el verano de 2018, que muestran detalles de rodillas, cuellos, torsos, pelos, labios y brazos. Son fragmentos que, en lugar de reducirse a abstracciones o mostrar el cuerpo como un objeto, presentan rasgos, gestos y poses personales imposibles de adaptar al corsé normativo de un “ideal” físico.

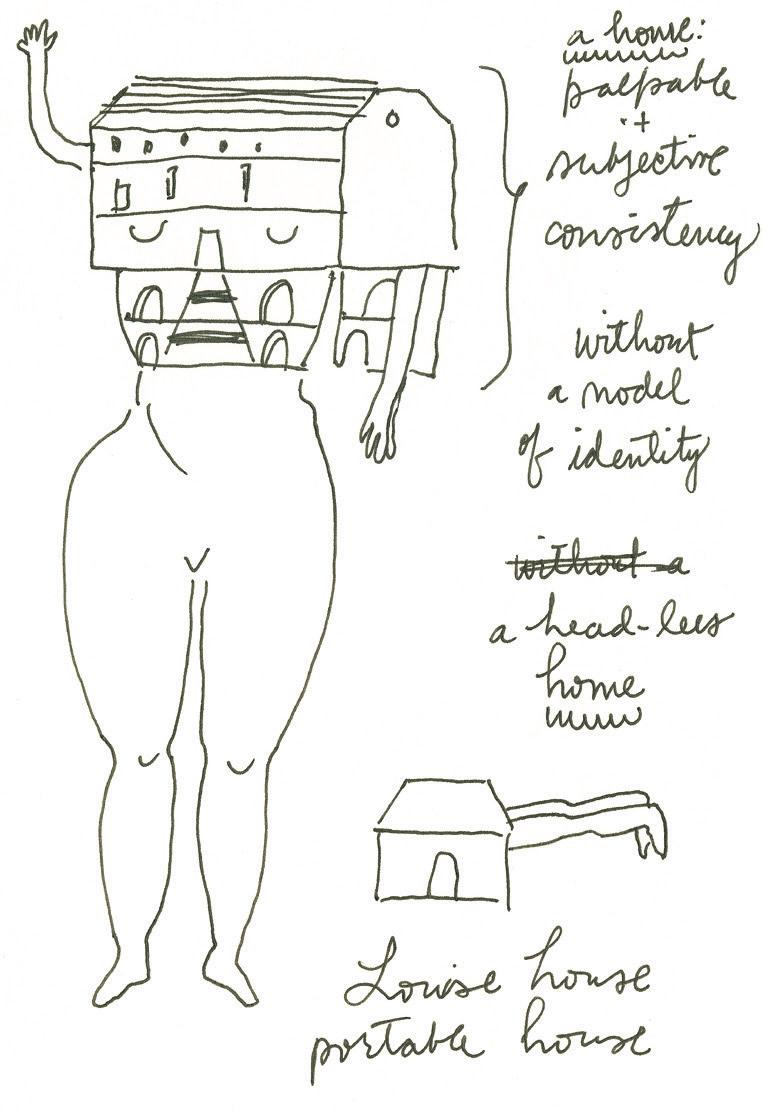

La escritura de guiones y la producción de mnemónicas visuales son actividades importantes en la obra de Azpilicueta. En sus primeros proyectos, las mnemónicas eran pequeños papeles que entraban en su mano y que podía transportar de un lado a otro. Con el tiempo, comenzó a realizar con ellos grandes telas bordadas y patchworks trabajados a mano, recuperando la factura manual y las tradicionales prácticas artísticas catalogadas como femeninas. Las mnemónicas forman parte de su proceso de trabajo y de pensamiento sobre la performance. Son objetos que llevan condensada la acción, que le otorgan materialidad a la memoria de la obra y que articulan y dividen el espacio de la sala guiando los movimientos del visitante.

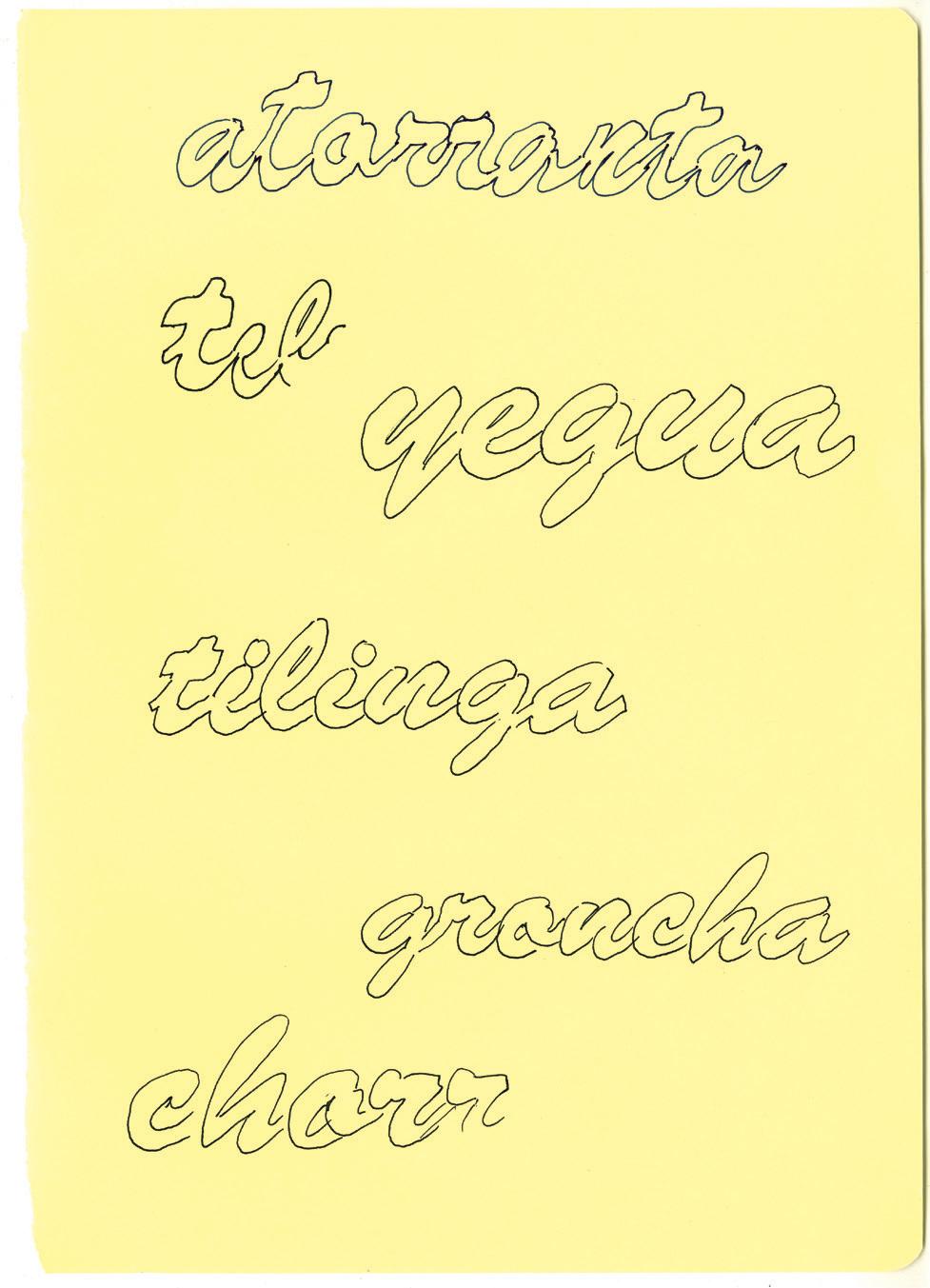

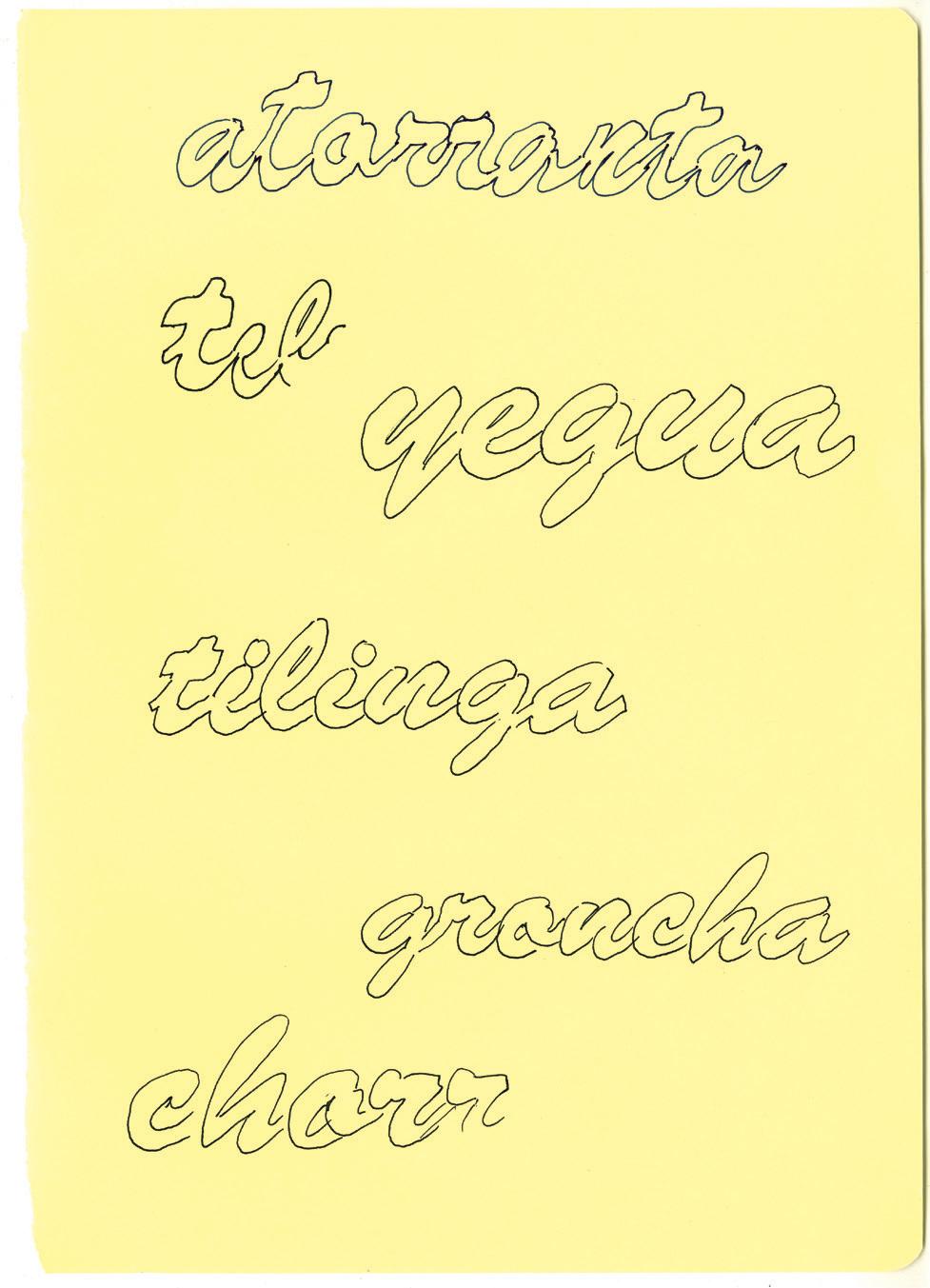

Por otro lado, existe un interés radical por lo performático, vinculado a la posibilidad de pensar la obra como un sistema abierto y procesual, con investigaciones extensivas que se enriquecen en el largo plazo. Algunos de sus trabajos tienen la lógica de una enciclopedia abierta, como es el caso de yeguayeta-yuta (iniciada en 2015), donde un listado de más de cuatrocientos insultos a mujeres en lunfardo sigue creciendo con el correr del tiempo. Otros constituyen constelaciones que reúnen un guion textual, una mnemónica, el trabajo performático y, a veces, un video realizado en base al trabajo en vivo, como

son los casos de Bailarina Geométrica... o Molecular Love. Es difícil determinar cuándo empiezan, cuándo terminan y qué partes conforman las obras de Mercedes Azpilicueta. Esta apertura se debe a su interés por no orientar la producción artística hacia la búsqueda de un resultado cerrado, sino por reinstalar el valor del proceso de la investigación, desacelerarla, derivando de cada momento piezas, repensando la materialidad de la obra y sus componentes.

III.

Las obras de Mercedes Azplicueta tienen la potencia de una carta de amor encontrada en un placard, un mensaje de texto deseado en el medio de la noche, el recuerdo añorado de las palabras de un familiar. Tratan sobre emociones personales que todos reconocemos. Un llamado a distancia, un mail que llega justo a tiempo, un corazón que late como cuando corremos el colectivo que nos espera para subir. El fade-out del reguetón del flete que arranca en un semáforo, el “mamita”, la “curita”, la “ballenita” y todos los cantitos de venta callejera. Su obra investiga en el lenguaje, en el cuerpo y en lo que oímos; aquello que tomamos de afuera y que sedimenta en nosotros convirtiéndose en algo personal, pero que nos conecta entre todos. Su voz es la que escucha atenta lo que pasó a través de nosotros en la vida cotidiana y nos asegura: “creeme, sister, esas palabras tienen un efecto, aun hoy”.9

17

9 Extracto de Dear Sister (2011)

I speak my body

By Laura Hakel

If you remember me

J. A. Jiménez

I.

When Mercedes Azpilicueta moved to the Netherlands in 2011, something changed in her work. As if the transoceanic distance from Argentina had tuned her ear and given a new urgency to her speech, she abandoned what little materiality remained in it (in Buenos Aires she had already been putting more of an emphasis on the exercise of writing and poetry reading sessions over painting and studio work) and affirmed her interest in language, primarily in orality, spelling mistakes, mistranslations, made-up words and everything that is “dirty” in communication, that soft part—sonic, living, used—of what we say, the bits that dodge the rules of how we “ought” to speak, reflecting personal and local forms of expression.

“You know? It’s all about affection,” she wrote to her sister in the letter Dear Sister (2011), one of Azpilicueta’s first works on arriving in Rotterdam, presented now at the Museo de Arte Moderno as part of the works that make up her first panoramic exhibition, as a video installation where the words appear as in a silent karaoke, so that spectators reproduce the voice in their minds. Knowingly, nostalgically, the artist tells her sister banal details of her new day-to-day—the layout of her room, the view from her window, the profound sense of loneliness, but also the sensation of bring observed, mixed with reflections and memories of them both in Buenos

Aires (“Remember when we went to the delta?”). It is an intimate account that explores the subjectivity of the self as a place of enunciation and the distance inherent in the epistolary genre. In the letter, the intimate voice merges personal and shared memory, constructing a space of connection between the two cities and the two sisters. The text is also a way of inhabiting another language. Paradoxically written in English, in the text Azpilicueta finds value in the spelling mistakes, as if they were the gateway to new meanings for the words, less correct but more subjective and significant.

That affectivity that can transmit the word is also a key part of Volver a casa expandiendo la voz [Back Home Expanding the Voice] (2012). This was one of Azpilicueta’s first performative pieces, a recital of a script created from text messages accumulated on her mobile phone over the course of a year, combined with poems: “te quiero Chau/ ¿cómo estás pum?/ ¿recuperada?/ si están por la zona/ estoy en el cafecito de pasteur y corrientes/ besos cuchufru/ pum me llamó gato/ diluvia y no vuelve” [love you Bye/how are you pum?/ feeling better?/ if you’re in the area/ I’m in the little café on Pasteur and Corrientes/ kisses cuchufru/ pum cat called me/ it’s pouring and he’s not coming back]. The discourse is made up of moments, meet-ups and missed encounters, leading us from a sensation of enormous closeness to the impossibility of communication: that moment when the language takes a false turn, becoming a near automatic, frustrating machine of greetings and monologues.

In her subsequent works, Azpilicueta began to borrow other voices. To construct the scripts of the perfor-

18

Don’t mention me

Because you’re going to feel A good kind of love.

mances La calculadora bien templada [The Well-Tempered Calculator], (2013), CARNE [Flesh] (2013) and POW! (2014) she appropriated the words of such characters as an obsessive mother, an authoritarian yoga teacher, an art auctioneer, and a teacher in a language exam.

Pascal Quignard says that unlike what happens with our sight and eyelids, in our ears there is nothing to limit the information from the outside.1 What we hear, voluntarily or involuntarily, joins us to others and the place where we are. In the video installation Bailarina Geométrica No Cree en el Amor, Encuentra Aspiración y Éxtasis en Espirales [Geometric Ballerina Doesn’t Believe in Love, Finds Aspiration and Ecstasy in Spirals] (2015), Azpilicueta transformed her voice into a social collective and a territory. She reconstructed the soundscape of Rotterdam with her voice, embodying what she heard in the markets, the port, and the street. Sitting cross-legged in the lotus position, like a fortune teller or a medium in a trance, she reproduced the offers of the street traders with the cry of “eeen eurroooo, een euro”, the chants of sport stadiums and the city’s whole socioeconomic soundscape—working-class, precarious—moving through her in a language she doesn’t necessarily understand. The title of the work evokes the figure of the French poet Valentine de Saint-Point, author of the Manifesto of Futurist Woman. Working from this, the artist imagines the decadence and virility of this city, reconstructed after the war, converted into feminine energy, just as poetry turns words and their sonority into a new energy. Entre Ríos poet Juan L. Ortiz claimed that the landscape saw “all the dimensions from which it transcends”, the secret life that casts it down.2 Mercedes Azpilicueta transmutes the urban routine into something substantial, a transcendence embodied in a chorus uttered by a single voice. One notable aspect in this group of works is Azpilicue-

ta’s interest in the affectivity that is channeled through language, but also in the control and violence exerted through it. Using her ears as a great radar, the artist investigated what is transmitted in what we say and hear, which transport our identity, like an invisible DNA chain. In her performances she exorcized all that she heard, availing herself of the elasticity of the word, using in her scripts poetic resources by Marguerite Duras, Clarice Lispector, Susana Thénon and Alejandra Pizarnik—from whom the name of this text, Yo hablo mi cuerpo [I speak my body], is taken—and the capacity of the tone and timbre of the voice to go beyond the meaning of language.

II.

The voice as a channel where inside and outside meet was followed by the question of the place of the body in this overheating circuit of communication. In 2015, if anyone entered her workshop in the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam they would find her imitating, to the point of facial deformation, the expressions and emotions of Charles Le Brun with the book open,3 uttering words like mantras and guttural sounds. Un Mundo Raro [A Rare World] is the result of that experimentation, connecting the Spinozan holistic gaze of body and soul, a point of reference for historical performances by such artists as Bruce Nauman, Lygia Pape and Lygia Clark, and the emotional spite of a bolero by the Mexican Chavela Vargas. Swathed in Adidas armor, Azpilicueta writhes, gesticulates, speaks to herself, sings and explores all the physical sound forms her voice can produce. She investigates the sounding board of the body and seeks to expand it with demanding yoga breathing and physical exercises, so that it might accommodate more, like a tent inflated at a festival to house a multitude. In Ancient Greece, athleticism was body worship and, through it, the worship of beauty and truth. In Un Mundo Raro, Azpilicueta is an athlete who in the act of

19

1 Pascal Quignard, El odio a la música, Buenos Aires, El cuenco de plata, 2012, p. 67.

2 AA. VV., Una poesía del futuro: conversaciones con Juan L. Ortiz, Buenos Aires, Mansalva, 2008, p. 21.

3 Jennifer Montagu, The Expression of the Passions: The Origin and Influence of Charles Le Brun`s “Conference sur l`expression generale et particuliere”, Yale University Press, first edition, 1994.

expanding her body imagines that we could be more flexible, to listen to who we are and how we are with others.

In Gender Trouble,4 Judith Butler proposes thinking of speech as a performative act, where body and language come together, and where conventions and norms operate that determine how we are and the way we behave. From this perspective, performance in Azpilicueta’s work is a live driving force for investigation: a tool of deconstruction of significant structures and bodily behaviours inherited through language.

In this respect, Molecular Love (2016) is a project guided by an interest in including in the artistic practice another kind of knowledge through performance, something that Marie Bardet calls thinking with moving,5 a knowledge that isn’t necessarily rational, but rather closer to instinct. Molecular Love is the result of an experimental work in which Azpilicueta brought together choreographers and dancers from different disciplines of dance and theater to perform a script of actions, ideas, phrases and movements proposed by the artist, but which mutated when absorbing the group’s work. Set up as a living organism, the work consists of a performance—lasting eight hours in the first presentation—a series of drawings, the video Molecular Love (2016) and visual mnemonics, notes written in a personal code combining words and drawings used to memorize and rehearse the performances. The focus of the work is placed on thinking of female desire as the center of the creative and artistic act. It proposes a decelerated, non-conclusive work rate, with results that are not necessarily visual or objectual. It is an essay on the information that can be found in the body, and on the possibility of discussing the authority of materiality and the gaze over the rest of the senses, both in art and in life (in her Manifesto of Futurist Woman, Valentine de Saint-

Point said: “Women, for too long perverted by morals and prejudices, return to your sublime instinct.”).6 In the performance, two female bodies communicate in a non-verbal dialogue. It is a relation in which there is something of sisterhood and learning through the reversal of movements and, above all, the recognition of one’s own body through the other. The word appears as a singing game, at times rather innocent or naïf (“Beeso, beso besito, besooo, besito...” or “Renata trabaja todala, todala semana Renata),7 forming choral moments throughout the work.

But unlike a formal chorus, where the composition and the rules to be followed are necessary to form that single “voice” that must not be strayed from, in Mercedes Azpilicueta’s works the polyphonic and the corporal respond more to the idea of intoxication. This is expressed in her Paris travel diary: “i feel intoxicated. we feel intoxicated. our bodies feel intoxicated,”8 to describe the chain reaction of shivers she feels on hearing a busker on the Paris Metro; and also “i also feel touched. suddenly we all feel touched. we understand we might have very little in common. still, at least we are feeling something together. for sure this music is making sensible something that is real in all our bodies”.9 The text is part of the work Bestiario de Lengüitas [Bestiare of Tonguelets], a project started in 2017 at the Villa Vassilieff residence in Paris, reflecting on intoxication as something as positive as it is inevitable. The work, of a procedural character and conceived as a long-term investigation, is composed of different parts, including a manual of survival exercises with Armaduras suaves [Soft Armor], made from organic, porous, recycled materials that take care of the multitude of soft, migrating bodies that we are.

9 Ibid.

20

4 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, New York, Routledge, 1990.

5 Marie Bardet, Pensar con mover. Un encuentro entre danza y filosofía, Buenos Aires, Cactus, 2012.

6 Valentine de Saint-Point, Manifesto of Futurist Woman, 1912.

7 “Kiiss, kiss kissy, kisss, kissy…” or “Renata works allthe, allthe week Renata.”

8 Mercedes Azpilicueta, about hell, smells & shame, Paris, 2017-18. (in English in the original)

The polyphony of voices has also started to turn into a polyphony of references. Over the years an underground stream has formed of works, artists and writers, contemporary and historical, running through Azpilicueta’s projects and flowing together in her way of making transversal artistic investigations, against the grain of convention. “Dishonest investigations”, as she calls them. In Bestiario de Lengüitas (2017-ongoing), more than conceptual affiliations or historical ties, Azpilicueta imagines affective affinities between Lea Lublin, the Argentine feminist artist who settled in Paris in the 1960s, the “neobarrosa porteña” poetry of Néstor Perlongher,10 the Chilean reggaeton of Tomasa del Real, and the medieval tapestry The Lady and the Unicorn—an enigmatic group of six pieces dedicated to the senses in which, in the last one, the lady holds a chest under the legend a mon seul désir, which for Azpilicueta suggests female desire, something absent and historically denied, like a treasure. Azpilicueta’s “dishonest investigation” is a way of doing that turns the canonical and patriarchal history of art on its head, suggesting unorthodox, transhistorical connections that rewrite the past and our present.

Azpilicueta’s latest project, Cuerpos Pájaros [BodyBirds] (2018), produced especially for this exhibition, asks where the body begins and ends, this intoxicated body she imagines as collective. A body made up of many parts, diverse and demystified; filthy and affected rather than ideally and conventionally attractive or domesticated, subject to traditional, repressive beauty rules. The work is a video installation with a script made up of three voices or discourses (one personal, one historical, one theoretical) that interweave reflections on writing and description as an emancipating act, on the deformations of the human figure in mannerist art, and narrate the impressions of the spectator faced with the body language of the baroque work Judith Beheading

Holofernes by Artemisa Gentileschi. These narratives, combined with a low bass sound that goes through the spectator, are superimposed on a collection of closeups of images compiled by the artist on long walks around Buenos Aires in the summer of 2018, showing details of knees, necks, torsos, hairs, lips, and arms. They are fragments that instead of reducing to abstractions or showing the body as an object, present features, gestures and personal poses impossible to adapt to the prescriptive straitjacket of a physical “ideal.”

The writing of scripts and the production of visual mnemonics are important activities in Azpilicueta’s work. In her first projects, the mnemonics were small papers that fit in her hand and which she could move from one place to another. In time, she started to make embroidered fabrics and handmade patchworks from them, recovering the manual work and artistic practices traditionally classed as female. Mnemonics are part of her work process and of her thinking about performance. They are objects that carry with them the action in condensed form, giving materiality to the memory of the work, articulating and dividing the space of the room, guiding the visitor’s movements.

Furthermore, there is a radical interest in the performative, connected to the possibility of thinking of the work as an open, evolving system, with extensive investigations that are enhanced in the long term. Some of her works have the logic of an open encyclopaedia, such is the case of yegua-yeta-yuta [mare-jinx-pig] (started in 2015), in which a list of over four hundred insults for women in lunfardo (Buenos Aires slang) continues to grow with the passing of time. Others form constellations that join together a textual script, and mnemonic, performative work and, sometimes, a video based on the live work, such as the case of Bailarina Geométrica and Molecular Love. It is hard to work out where Azpilicueta’s works begin and end and which parts make them up. This open-endedness is down to her interest in not directing artistic production towards

21

10 Neobarrosa is a pun of Perlongher’s on “neobaroque” and barro, referring to the mud of the River Plate. (TN.)

a search for a closed result, but rather reappraising the value of the research process, decelerating it, deriving pieces from each moment, rethinking the materiality of the work and its components.

III.

Mercedes Azpilicueta’s works have the potency of a love letter found in a wardrobe, a text wished for in the middle of the night, the yearning memory of a relative’s words. They deal with personal emotions familiar to us all. A long-distance call, an email that arrives just in time, a heart that beats like when we run for a bus that waits for us to catch up. The fade-out of the reggaeton of the van pulling away from the traffic light, the street

trader’s words and catchphrases and singsong calls. Her work investigates—through language, the body and what we hear—all that we take from the outside and all that settles in us, becoming something personal, but also something that connects us. Her voice is the one that listens attentively to what has passed through us in everyday life and reassures us: “trust me sister, those words have to do something, even now.” 11

22

11 Extract from Dear Sister (2011)

A nuestros solos deseos

Por Virgine Bobin

ACTO 1: A NUESTROS SOLOS DESEOS

La escena ocurre durante el verano de 2018 en el salón de té de un baño turco parisino, no lejos del Sena. ARTEMISIA G. y LEA L. están acostadas en divanes, en bata de baño, con sus largos cabellos mojados envueltos en toallas. Al momento de este encuentro, ARTEMISIA parece tener 27 años, la edad en la que pintó su segunda versión de Judith decapitando a Holofernes (1620), conservada en la Galería Uffizi de Florencia. LEA, que parece estar en los cincuenta, ya ha realizado Le Milieu du Tableau [El medio del cuadro], una serie de cuatro pinturas acompañadas de un texto, Espace perspectif et désirs interdits d’Artemisia G. [Espacio perspectivo y deseos prohibidos de Artemisia G.], que datan de 1979.

A pesar de la ligera humedad que hay en el aire, las paredes están cubiertas de un empapelado color carne, adornado con motivos dibujados a mano: cuerpos deformes, fragmentados, descompuestos, tóxicos; cuerpos antropófagos, cyborgs, protectores, húmedos, deseantes. También hay dibujos de plantas, de cigarrillos, una cofia con forma de cabeza de lobo de piel verdadera; un repertorio completo de brujas, benévolas o no, y de esos ingredientes prohibidos por las normas de seguridad internacional y que solemos ver representados con logotipos negros y rayas rojas antes de quitarnos los zapatos y colocar los dispositivos electrónicos en las bandejas de plástico del área de seguridad del aeropuerto. No hay ventanas. Un reloj asombroso, cuya aguja gira y baila en todas las direcciones, da el siglo en lugar de la hora. Se ven tres vasos de té humeantes sobre una pequeña mesa ratona para tomar café.

ARTEMISIA: Se toma su tiempo, ¿no? Sin embargo, acaba de pasar cuatro años en restauración.

LEA: Debes entenderla, todos estos viajes por Asia la han agotado. Ya no es tan joven.

ARTEMISIA: Hablando de mujeres trotamundos, ¿has visto a Mercedes recientemente?

23

LEA: Fue a visitar a mi hijo el invierno pasado. Hablaron de mí. Le pidió a un curador barbudo del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires que reactivara mi performance Dissolution dans l’eau, Point Marie [Disolución en el agua, Pont Marie]. Tengo el video, te lo enviaré.

ARTEMISIA, riéndose: ¡No le falta humor a esta niña! También vino a verme; en realidad vino a ver a Judith en la Galería Uffizi. Vi su reflejo en los ojos de Holofernes y en la hoja de la espada. Se sentó por un largo rato frente a la pintura, atónita, como una joven enamorada ante un primer y muy esperado encuentro. Yo tenía un fuerte calambre en el brazo derecho, pero logré mirarla por el rabillo del ojo. Parecía irradiar una emoción que era tanto física como intelectual...

LEA: Me gustan estos momentos de gracia, cuando de este deseo tanto sensual como cognitivo nace una nueva intensidad de conocimiento…

LA DAMA DEL UNICORNIO, con una toalla de felpa enrollada en la cabeza hace su entrada, espejo en mano, con un estruendo de oro y flores.

ARTEMISIA: ¿Y cómo va el tratamiento con plantas medievales?

LA DAMA, sentándose graciosamente en un diván: Divino. Siento que he perdido cuatro siglos. ¿Hablaban de deseo? Soy toda oídos.

LEA, acariciándole la mano como gesto de bienvenida: My Dear Sister... Estábamos hablando de la reunión entre Mercedes y Artemisia, en Florencia. ¿Sabías que llegó a ese cuadro gracias a mí?

ARTEMISIA: Sí, eso es lo que explica en la banda sonora de su próxima exposición en Buenos Aires. Me dejó leer el guion en Google Drive y me conmovió. Me gusta la forma en que comparte sus referencias, sus notas, sus obsesiones, que reaparecen de un trabajo a otro, irrigándolos. Yo también traté de reflexionar sobre el trabajo de la pintura en mis cuadros. Me refiero a pintar como trabajo, al esfuerzo de todo el cuerpo, no solo al de La Mano. Bajo el brillo de las sedas, en la vibración de la carne y en la tensión de los músculos, quiero mostrar la economía del cuerpo productivo, la potencia del cuerpo de las mujeres, de mi cuerpo de artista femenina aliada al cuerpo de la mujer sirvienta en un trabajo compartido. Creo que Mercedes logró comprenderlo. Si tuviera su edad en este siglo, yo también haría mis performances envuelta en una armadura de Adidas. Hubiera aprendido técnicas de autodefensa feminista para aplastar a Holofernes, en lugar de haberme pescado una tendinitis con esa enorme espada. Claro que habría corrido menos tinta de los intérpretes sobre el simbolismo sexual de la pintura...

LA DAMA, hastiada: No me hables de eso... No todas tuvimos la oportunidad de ser visitadas por Linda Nochlin. Sin embargo, las artes del tapiz y el bordado se consideran esencialmente femeninas; ella misma lo escribe.1 Me recuerda una escena de un documental reciente sobre “el mejor artista de Sudáfrica”. Este hombre, blanco, imponente, firma tapices hechos por

24

1 Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, en ARTnews, enero de 1971

trabajadoras exclusivamente negras en el taller del que es dueño y que es dirigido por una mujer blanca. Ite, missa est... En resumen, cada vez que un nuevo aspirante a medievalista se acerca a mis tapices y mira mi mano mientras acaricia el cuerno de esta pobre bestia, mis hilos se opacan por la aprensión. Sueño con ser irrepresentable. No es porque me haya reencarnado, como tú, en novelas, pinturas, películas, y por haber recorrido los departamentos de historia del arte o los estudios de género en todo el mundo desde la invención de la universidad, borroneando las pistas, multiplicando la madeja de lecturas posibles, sembrando enigmas y juegos de espejos... Afortunadamente, los artistas de hoy, como nuestra pequeña Mercedes, se dedican a investigar y releen la historia del arte con absoluta irreverencia. Es sumamente rejuvenecedor.

LEA: “En la cuestión del cuadro, quiero hablar de la pantalla, plantear la cuestión de la pantalla de proyección, sus rastros, las imágenes que proyectan, que registran, que congelan la imagen, las imágenes que nos cuentan historias, los lugares donde se llevan a cabo las historias, que imprimen las figuras que nos paralizan. [...] Se supone que el espectador debe estar al lado de la cama de la víctima, al otro lado de un muro invisible donde se encierra la representación de la escena. Pared invisible que funciona como un espejo colocado entre el espectador y la pintura, en el lugar del viajero cómplice, que disfruta del acto representado, visto como un reflejo en un espejo al otro lado del cuadro [...]. Los deseos y los continuos procesos inconscientes desencadenados, el castigo, el complejo de castración, la culpa, el asesinato, transgreden el espacio de lo prohibido para dejar ver el transcurrir del deseo y los límites de un espacio simbólico que lo vela, que lo viola, que lo borra”.2

ARTEMISIA: Siempre me he preguntado si habría una errata en tu texto. ¿El “viajero cómplice” no sería más bien un “voyeur cómplice”?

LA DAMA: A riesgo de parecer pedante, te recuerdo que la etimología latina de la palabra deseo, de-siderare, significa “dejar de contemplar (las estrellas)”. Luego entramos en el reino de la fantasía, como tú, Lea, cuando rediseñas a Holofernes en el parto, devolviendo nuestra mirada al mismo tiempo que devuelves su cuerpo y su sexo. En las fantasías de Mercedes, somos mujeres heroicas, resistentes, madres, amantes, musas, pero especialmente amigas. Como verdaderas amigas, ignoramos el tiempo, la historia y las verdades convencionales. Tomamos cuerpo y voz a través de los cuerpos y las voces que ella convoca, dibuja, filma y con los cuales colabora. Estamos afectadas para siempre, al igual que su trabajo se ve afectado, y así contaminamos la mirada y los cuerpos de los espectadores de este siglo.

LEA: Por cierto, he invitado a Alejandra a unirse a nosotros, pero ella pasa su tiempo entre la Argentina y los Países Bajos en este momento, para aparecérsele a Mercedes en los preparativos de su exposición. Cuando supo que estábamos en el baño turco, me envió este poema:

25

2 Lea Lublin, Espace perspectif et désirs interdits d’Artemisia G., Le carnet, 1979.

L’obscurité des eaux

Escucho resonar el agua que cae en mi sueño. Las palabras caen, como el agua yo caigo. Dibujo en mis ojos la forma de mis ojos, nado en mis aguas, me digo mis silencios. Toda la noche espero que mi lenguaje logre configurarme. Y pienso en el viento que viene a mí, permanece en mí. Toda la noche he caminado bajo la lluvia desconocida. A mí me han dado un silencio pleno de formas y visiones (dices). Y corres desolada como el único pájaro en el viento.3

ARTEMISIA, levantando su vaso de té: ¡Por Alejandra!

LEA, levantando el suyo: ¡Por los cuerpos-pájaros!

LA DAMA, sonriendo: À nos seuls désirs!4

Fundido a negro.

ACTO 2: EL SUEÑO DE MERCEDES

La escena está sumida en la oscuridad. Aparece una pantalla sobre la que desfilan imágenes borrosas, temblorosas, sin que se pueda distinguir que haya una cronología clara entre ellas. Se ve la silueta con interferencias de Mercedes, de espaldas, a través de diferentes espacios, entre los cuales creemos reconocer los pasillos del metro de París, las calles de Buenos Aires, las de Rotterdam y una serie de habitaciones, ascensores y escaleras que podrían ser los de la Galería Uffizi en Florencia. Espacio de tránsito, lugares ambivalentes que se rigen por reglas explícitas o tácitas muy particulares y destinadas a facilitar la convivencia y la circulación de los cuerpos. Las imágenes pululan entre cuerpos que se aferran a sus prótesis-tabletas luminosas que los conectan con otros espacios, con otras temporalidades, a través de las cuales Mercedes salta como un pequeño personaje de videojuegos, aspirando los aromas, los sonidos, los gestos de deseo o de agresión, las posturas, las emociones que agitan a todos estos cuerpos, humanos o no. Hay cuerpos pintados en lujosos claroscuros, cuerpos fragmentados, pies encerrados en

4 Esta frase, cuya traducción constituye el título del texto y del primer acto, hace referencia a una serie de seis tapices de fines del siglo XV conocidos como La Dame à la Licorne [La dama y el unicornio], que se encuentran en el Musée National du Moyen Âge de París. Se suele considerar que los primeros cinco tapices corresponden a una representación de los cinco sentidos. La interpretación del sexto, en cambio, fue motivo de largas discusiones entre especialistas. A la dama noble, el león y el unicornio que aparecen en todas las piezas, el sexto tapiz le suma un cofre cerrado y una tienda en cuyo frontispicio puede leerse la polisémica frase à mon seul désir [a mi solo deseo]. Esa frase puede interpretarse, entre otras variantes, como una dedicatoria al ser amado o al propio deseo, e incluso como una declaración de soberanía y poder del deseo, que en ese caso podría parafrasearse como “según mi voluntad”. Este último tapiz, que aparece reproducido en la página 94, es una referencia importante en el trabajo de Mercedes Azpilicueta, como puede cotejarse en el ensayo de Laura Hakel publicado en este mismo libro. (N. del E.)

26

3 Alejandra Pizarnik, El infierno musical. Buenos Aires, Siglo XXI, 1971. El título original es en francés (L’enfer musical).

provocadores zapatos de cuero, torsos femeninos envueltos en redecillas negras, e incluso las huellas impresas de manos azules y negras en la pared de una cueva... Una extendida danza de cuerpos-multitud, cuerpos-fragmento atrapados en una red sinestésica y transhistórica. Mercedes sueña con esculturas de látex, cuero, tul, tejidos iridiscentes, donde estos cuerpos y espacios encuentran refugio, logran imprimirse, traducirse. Algunos arqueólogos afirman que las voces de los antiguos ceramistas estarían registradas en las ranuras de terracota. En este sueño, las obras de Mercedes son como pedazos de tierra, que acarrean voces llegadas de épocas y lugares de otro modo irreconciliables.

Una banda sonora también acompaña a las imágenes. Es la voz de Marguerite Duras. En el sueño de Mercedes, Marguerite habla español con acento argentino. Lee un extracto del guion de la propia Mercedes con un tono ligeramente sentencioso:

una escritora es un país extranjero donde hay historias imposibles ilegibles o prohibidas y aunque se ordene las ideas de la manera más calculada siempre surge lo incontable o lo irrepresentable

Cuando la película se termina, invade el escenario un fuerte olor a tomates, ajo y sardinas. Otra anomalía espacio-temporal. La autora de esta pieza escribe en la mesa de la cocina de una familia franco-marroquí, la víspera de Eid-el-kebir. Mercedes acaba de enviarle un mensaje por whatsapp: “¡Eid Mubarak!”

Fundido a negro.

ACTO 3: EL MONÓLOGO DE LA TUMOR

El escenario está vacío, a excepción de una gran cortina rosa brillante bordada y un micrófono de pie. Entra LA TUMOR. Lleva un traje de látex arrugado, del color de la carne descompuesta. Su cuerpo hinchado, enorme, apenas deja asomar sus brazos y piernas, la cabeza cubierta con una máscara. Sus movimientos son dificultosos; sus ojos están ciegos. Lleva una larga cola de caballo rubia hecha con cabello sintético y habla con la voz de Chavela Vargas, “the rough voice of tenderness”.5

LA TUMOR toma el micrófono y se dirige a la audiencia: No te veo, pero sé que estás aquí. No te preocupes, no te lastimaré. “Déjame contarte una historia. Porque eso es todo lo que tengo, una historia. Una historia transmitida de generación en generación, llamada Alegría. Contada

5 “la voz áspera de la ternura”, en inglés en el original (N. del T.).

27

para la alegría que le produce a la persona que la cuenta y a la persona que la escucha. La alegría inherente al proceso que consiste en contar una historia. Cualquiera que entienda esto también entiende que una historia, sin importar cuán abrumadora sea su alegría, nunca le quita nada a nadie. Recuérdenlo, se llama Alegría. Su doble, Llanto Miedo Mayor”. Estas son las primeras fases de un texto de Trinh T. Minh-ha, Grandma’s Story. ¡Sí, soy una tumor culta, además de ser maligna, ja, ja! Me gustan las citas. Me gusta reír. Me encanta contar historias que sobrevivirán a los cuerpos, o que se escaparán de ellos para unirse a otros cuerpos. ¡Historias sin pie ni cabeza, ja, ja! Es una forma de cuidar el cuerpo: perpetuar sus historias, incluso distorsionarlas, traicionarlas. Contaminan al mismo tiempo que se expanden.

Podría contarles la historia de cinco mujeres, incluida nuestra Mercedes, que se encuentran en un taller para niños, pero no llegarán niños porque el horario fue mal programado. De todos modos, deciden hacer la clase. Gritan como animales, se rascan, se menean. Cantan al unísono, con la cabeza apoyada en la espalda o en el hueco del hombro de sus acompañantes. Estallan en carcajadas. Almas errantes las observan a través de la puerta abierta, pero no les importa. Estas mujeres están aquí como Programadora, Curadora Invitada, Artista Invitada, Coreógrafa Invitada... Se espera de ellas una Contribución. Pero ahora lanzan gritos de elefante y son como monos aullando. Se escapan de la Invitación para convertirse en Alegría. Podría contarles la historia de una casa-mujer,6 cuyo vientre sería el taller. Pero Mercedes la contará mejor que yo, basta solo con mirar sus dibujos. A veces estoy cansada. No piensen que es tan fácil ser una Tumor. Primero, es mucho trabajo. Se necesita astucia, sin dudas, pero también una gran fuerza física y una enorme voluntad, una aguda comprensión del arte del mantenimiento. Es un trabajo muy íntimo también, cargado de afectos, un poco como el de una auxiliar de enfermería, una enfermera, una partera... Todas esas llamadas profesiones femeninas. Tengo problemas para separar la vida privada de la vida profesional. ¡Y no cuento mis horas, créanme! Muchos me consideran una freak, aunque me haya reconciliado con la idea desde que leí ese libro de Renate Lorenz. Por ejemplo, soy muy sensible a lo que escribe sobre el drag, pues me presento aquí frente a ustedes en atuendo de drag, no me digan que no se dieron cuenta: “el drag puede referirse a las relaciones productivas de lo natural y lo artificial, lo animado y lo inanimado, la ropa, las radios, el cabello, las piernas, aquello que tiende ante todo a generar relaciones con los otros y con las otras cosas más que ocuparse de representarlas. Lo que se hace visible en este drag no son las personas, los individuos, los sujetos o las identidades, sino conjuntos que no funcionan para ‘crear género / sexualidad / raza’, sino más bien para ‘deshacer’ estas categorías. Si ‘yo’, como escribió Judith Butler, sigo constituyéndome a través de normas que no produje, entonces el drag es una forma de entender esta constitución y reconstruirla en su propio cuerpo. Pero, al mismo tiempo, el drag es una manera de organizar un conjunto de métodos

28

6 Alusión a la obra de Louise Bourgeois (N. del E.).

efectivos, laboriosos, a medias amigables y agresivos para producir una cierta distancia en relación a estas normas [...]”. 7 Bueno, fue una cita muy larga, lo siento. Pero ya ven adónde voy, ¿verdad? Es por eso que me identifico bastante con lo que Mercedes califica como “investigador indigno”, dishonest researcher, 8 perdón por mi acento. En esta deshonestidad que ella reivindica veo una forma de drag, así como en el vestuario que usa y en la forma en la que atavía a sus colaboradores. En conclusión, me gustaría asegurarme de que se comprenda algo muy importante. Se habla mucho de “(re)dar voz”: a artistas mujeres injustamente olvidadas, por ejemplo. ¿Pero eso no sería asumir una posición de autoridad, desde arriba, como que sé de qué hablo cuando digo lo que ustedes hacen desde este escenario, ja, ja? Lo que realmente importa es aprender a es-cu-char. Debemos volver a aprender el potencial político de una escucha. Mi monólogo se compone de voces múltiples, entrelazadas con profundos silencios. Shhh... Escuchen... “

Fundido a negro.

ACTO 4: REGUETÓN EN EL METRO

ARTEMISIA, LEA y LA DAMA formaron un grupo de reguetón chileno. Cantan ilegalmente en el metro de París; un poco, por diversión; otro poco, por dinero; a veces, para crear conciencia en los usuarios:

“we feel intoxicated. our bodies feel intoxicated. our parisian bodies, tourist bodies, homeless bodies, european bodies, african bodies, foreign bodies, digital bodies, latino bodies, heteronormative bodies, old bodies, soft bodies, hard bodies, young bodies, queer bodies, worked-out bodies, fancy bodies, dirty bodies, sweaty bodies, all these different and individual bodies feel intoxicated. we start to vibrate. maybe not all of them do, but i want to imagine that all of them do. and they do. all kinds of different bodies down here are being shaken at the same time.”9

POLICÍAS DE CIVIL intentan detenerlas: ¡Sus papeles por favor!

7 Renate Lorenz, Queer Art. A Freak Theory. Citas del texto original en francés tomadas de la traducción publicada en B42, París, 2018, p. 38.

8 En inglés en el original (N. del T.).

9 “nos sentimos envenenadas, nuestros cuerpos se sienten envenenados, nuestros cuerpos parisinos, nuestros cuerpos turistas, cuerpos homeless, cuerpos europeos, cuerpos africanos, cuerpos extranjeros, cuerpos digitales, cuerpos latinos, cuerpos heteronormativos, cuerpos viejos, cuerpos amables, cuerpos tensos, cuerpos jóvenes, cuerpos queer; cuerpos trabajados, cuerpos elegantes, cuerpos sucios, cuerpos transpirados, todos esos cuerpos diferentes e individuales se sienten intoxicados. empezamos a vibrar. quizá no todos, pero quiero imaginar que todos lo hacen, y lo hacen, que todas las clases diferentes de cuerpos que se encuentran aquí se sacuden a un mismo tiempo”. Fragmento del diario de Mercedes Azpilicueta, about hells, smells and shame, París, abril de 2017. (En inglés en el original, N. del T.).

29

Pero es demasiado tarde. Todo el metro entra en una especie de trance. ARTEMISIA, LEA y LA DAMA lanzan insultos en fonética argentina: ¡ye-gua-ye-ta-yu-taaaa!

PASAJEROS: ¡ye-gua-ye-ta-yu-taaaa!

Todos los cuerpos se mezclan en un gran magma fluido. Las tres cantantes se alejan. Solo Mercedes permanece sentada en un asiento plegable. Ha grabado todo. Pero en el atelier se da cuenta de que la tarjeta de memoria estaba llena. Tendremos que creer en su palabra.

30

Agosto de 2018

To Our Sole Desires

By Virginie Bobin

ACT 1: TO OUR SOLE DESIRES

The scene takes place in the summer of 2018, in the tearoom of a Parisian hammam, close to the Seine. ARTEMISIA G. and LEA L. are lounging on divans, in dressing gowns, their long, damp hair wrapped in towels. At the time of this meeting, ARTEMISIA appears to be 27, the age at which she painted her second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620), kept in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. LEA, for her part, looks fifty-something, and has already completed Le Milieu du Tableau [The Center of the Painting], a series of four line drawings accompanied by a text, Espace perspectif et désirs interdits d’Artemisia G. [Perspectival Space and the Forbidden Desires of Artemisia G.], dated 1979.

Despite the slight moisture in the air, the walls are covered in a flesh-colored wallpaper with hand-drawn motifs: deformed, fragmented, decomposed, toxic bodies; cannibalistic bodies, cyborg bodies, protective, wet, desiring bodies. There are also drawings of plants, of cigarettes, a headdress in the form of a wolf’s head with real fur: a whole repertory of witches, benevolent or not, of those items forbidden by international security norms, which one usually sees in the shape of black signs with red lines crossing through them, before one removes one’s shoes and places one’s electronic devices in the plastic trays at airport security.

There are no windows. An astonishing clock, whose hand jumps and dances in all directions, marks the century instead of the hour. Three steaming tea glasses rest on a small coffee table.

ARTEMISIA: She takes her time, doesn’t she? And yet, she’s spent the last four years under restoration.

LEA: You have to understand, she’s exhausted from all those travels in Asia. She’s no spring chicken.

ARTEMISIA: Speaking of globetrotting women, have you seen Mercedes lately?

LEA: She went to see my son last winter. They talked about me. She asked a bearded curator at the Buenos Aires Museum of Modern Art to do a revival of my performance Dissolution dans l’eau, Point Marie [Dissolution in Water, Pont Marie]. I’ve got the video, I’ll send it to you.

ARTEMISIA, laughing: She’s got a sense of humor, this kid! She came to see me too, or rather, see Judith, at the Uffizi. I saw her reflection in Holofernes’ eyes and in the blade of the sword. She spent a long time sitting in front of the painting, blown away, like a young bashful lover on a long-awaited first date. I had a right old cramp in my right arm but I watched her out of the corner of my eye, she seemed to radiate physical and intellectual excitement…

LEA: I like these moments of grace, when a new intensity of knowledge is born from this sensual, cognitive desire…

THE LADY AND THE UNICORN, a terrycloth towel in her hair, makes her entrance in a riot of gold and flowers, a mirror in her hand.

ARTEMISIA: So, how’s the treatment with medieval plants?

THE LADY, settling gracefully on a divan: Wonderful. I feel like it’s taken four centuries off me. You were talking about desire? I’m all ears.

LEA, stroking her hand to welcome her: My Dear Sister… We were talking about the encounter between Mercedes and Artemisia, in Florence. Did you know she came across that painting thanks to me?

ARTEMISIA: Yes, she explains as much in the soundtrack to her forthcoming exhibition in Buenos Aires. She let me read the script in Google Drive, it was quite moving. I like the way she shares the source of her references, her notes, her obsessions, which reappear from

31

one work to another, irrigating them. I too have tried to embody a reflection on the painting process in my artworks. What I mean is: painting as work, the effort of the whole body, not just The Hand. Under the shimmering of the silk, in the quivering flesh and tensing muscles, I want to show the economy of the productive body, the power to act in women’s bodies, my body as a woman artist allied to the body of the servant woman in a shared labor. I believe Mercedes has grasped that. If I was her age in this century, I would do performances kitted out in Adidas armor too. I would have learned feminist self-defense techniques to kill Holofernes, instead of giving myself tendonitis with that enormous sword. Mind you, less might then have been written about the painting’s sexual symbolism.

THE LADY, blasé: Don’t say another word… We haven’t all been lucky enough to receive a visit from Linda Nochlin. Furthermore, the arts of tapestry and embroidery are considered essentially feminine, she said so herself.1 This reminds me of a scene in a recent documentary on “the greatest artist in South Africa.” This imposing white man signs tapestries made exclusively by black women workers in the workshop he owns, managed by a white woman. Ite, missa est… In short, whenever a new aspiring medievalist approaches my tapestries and leers at my hand caressing the horn of this poor animal, my threads grow pale with apprehension. I dream of becoming unrepresentable. It isn’t because I’ve been reincarnated, as you have, in novels, in paintings, in films, and having skimmed the history of art and gender studies departments around the world since the invention of the university. Covering my tracks, multiplying the skein of possible readings, sowing riddles and games of mirrors… Fortunately today’s artists, like our young Mercedes, embrace research and reread the history of art with such irreverence. It’s most rejuvenating.

LEA: “As regards the painting, I want to talk about the

screen, to raise the question of the projection screen, the traces, the images projected, inscribed, that freeze the image, the images that tell us stories, places where stories take place, which print the figures that freeze us. […]. The viewer is supposed to be at the bedside of the victim on the other side of an invisible wall that contains the stage of representation. It is an invisible wall in a oneway mirror placed between the viewer and the painting, in the place of the complicit voyager on the stage, enjoying the act performed, perceived as the reflection in the mirror on the other side of the painting […]. Desires and the rest of the unconscious processes triggered: punishment, castration complex, guilt, killing, transgressing the forbidden space, through the laying bare of a body to show the course of desire and the limits of a symbolic space that veils it, violates it, erases it.” 2

ARTEMISIA: I still wonder whether there was a misprint in your text: “Complicit voyager”, shouldn’t that actually be “complicit voyeur”?

THE LADY: At the risk of sounding pedantic, I must remind you that the Latin etymology of the word desire, de-siderare, means “to cease contemplating (the stars.)” Then we enter the realm of fantasy, like you Lea when you redraw Holofernes in childbirth, returning our attention while at the same time returning his body and his sex. In Mercedes’s fantasies, we are heroic women, resilient, mothers, lovers, muses, but above all, friends. As true friends we disregard time, history and truths. We take body and voice through the bodies and voices that she summons, draws, films or collaborates with. We are affected forever, just as her work is affected, and thus we contaminate the gaze and the bodies of this century’s viewers.

LEA: By the way, I asked Alejandra to join us, but she divides her time between Argentina and the Netherlands at the moment, to haunt Mercedes during the preparations for her exhibition. When she found out we were meeting at the hammam, she sent me this poem:

32

1 Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” ARTnews, January 1971.

2 Lea Lublin, Espace perspectif et désirs interdits d'Artemisia G., Le carnet, 1979

L’obscurité des eaux

I hear the sound of the water falling in my sleep. The words fall like water as I myself fall. I draw in my eyes the shape of my eyes, I swim in my waters, I tell myself my silences. All night I wait for my language to configure me. And I think of the wind that comes to me, that dwells in me. All night, I walked in the unknown rain. I was given a silence full of forms and visions (you say.) And you run disconsolate like the only bird in the wind. 3

ARTEMISIA, raising her glass of tea: To Alejandra!

LEA, raising her glass: To the body-birds!

THE LADY, smiling: À nos seuls désirs!4 Blackout.

ACT 2: MERCEDES’S DREAM

The stage is plunged into darkness. A screen appears, on which vague, wobbly images scroll past, with no clear chronology. We see the blurred outline of Mercedes, her back to us, moving through different spaces, among which we may recognize the corridors of the Paris Metro, the streets of Buenos Aires or Rotterdam, and a series of rooms, lifts and staircases that could be those of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Spaces of transit, ambivalent

3 Alejandra Pizarnik, in L’enfer musical, Ypsilon éditeur, 2012, p.49. Original title in French.

4 This phrase, the translation of which is the title of the text and the first act, is a reference to a series of six tapestries from the late fifteenth century known as La Dame à la Licorne [The Lady and the Unicorn] which can be found in the Musée National du Moyen Âge in Paris. It is usually considered that the first five tapestries correspond to representations of the five senses. The interpretation of the sixth, in contrast, has been cause for much debate among specialists. As well as the noble woman, the lion and the unicorn who appear in all the pieces, in the sixth tapestry there is the addition of a chest and a tent, on the frontispiece of which can be read the polysemous phrase à mon seul désir [to my sole desire]. This phrase can be interpreted, among other variants, as a dedication to a loved one or to desire itself, and even as a declaration of sovereignty and power of desire, which in that case could be paraphrased as “according to my will.” This last tapestry, reproduced on page 94, is an important reference in Mercedes Azpilicueta’s work, as can be seen in Laura Hakel’s essay published in this book. (Editor’s Note.)

places, governed by official rules or very specific unspoken ones to make it easier for bodies to live together and move together. The images swarm with bodies clinging on to their luminous tablet-prosthetics binding them to other spaces, other temporalities, through which Mercedes leaps like a little video game character, breathing in the steam, the sounds, the gestures of desire or aggression, the postures, the emotions that shake all these human or non-human bodies. There are bodies painted in luxurious chiaroscuro, fragmented bodies, feet squeezed into provocative leather pumps, female torsos larded with black fishnets, and even the memory of blue and black handprints on the walls of a cave… A great dance of crowd-bodies, piece-bodies, caught in the snares of synesthetic, trans-historical gazes. Mercedes dreams of sculptures, of latex, of leather, of tulle, of iridescent fabrics where these bodies and these spaces might find refuge, be imprinted, be translated. Certain archaeologists claim that the voices of ancient potters may be recorded in the grooves of terracotta. In this dream, Mercedes’s works are like shards of earth, carrying the promise of voices from otherwise irreconcilable eras and places. A soundtrack accompanies the images elsewhere. It is the voice of Marguerite Duras. In Mercedes’s dream, Marguerite speaks Spanish with an Argentine accent. She reads an extract from Mercedes’s own script, in a slightly sententious tone:

una escritora es un país extranjero donde hay historias imposibles ilegibles o prohibidas y aunque se ordene las ideas de la manera más calculada siempre surge lo incontable o lo irrepresentable5

Then the film goes off, a strong smell of tomatoes, garlic and sardines invades the stage. Another anomaly of space and time. The author of this play writes in fact at

5 “a writer is a foreign country/ where there are impossible stories/ illegible or forbidden/ and although the ideas are ordered/ in the most calculated manner/ there always emerges the unsayable/ or the unrepresentable.”

33

the kitchen table of a French-Moroccan family, the night before Aïd-el-kebir. On WhatsApp, Mercedes has just sent her a message: “Eid Mubarak!”

Blackout.

ACT 3: THE TUMOR’S MONOLOGUE