1

2

ALIADO ESTRATÉGICO

CON LA COLABORACIÓN DE

MEDIOS ASOCIADOS SPONSOR APOYO

AUTORIDADES DEL GOBIERNO DE LA CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES

Ing. Mauricio Macri Jefe de Gobierno

Lic. Horacio Rodríguez Larreta Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros

Ing. Hernán Lombardi Ministro de Cultura

María Victoria Alcaraz Subsecretaria de Patrimonio Cultural

Pedro Aparicio Director General de Museos

Lic. Victoria Noorthoorn Directora del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

3

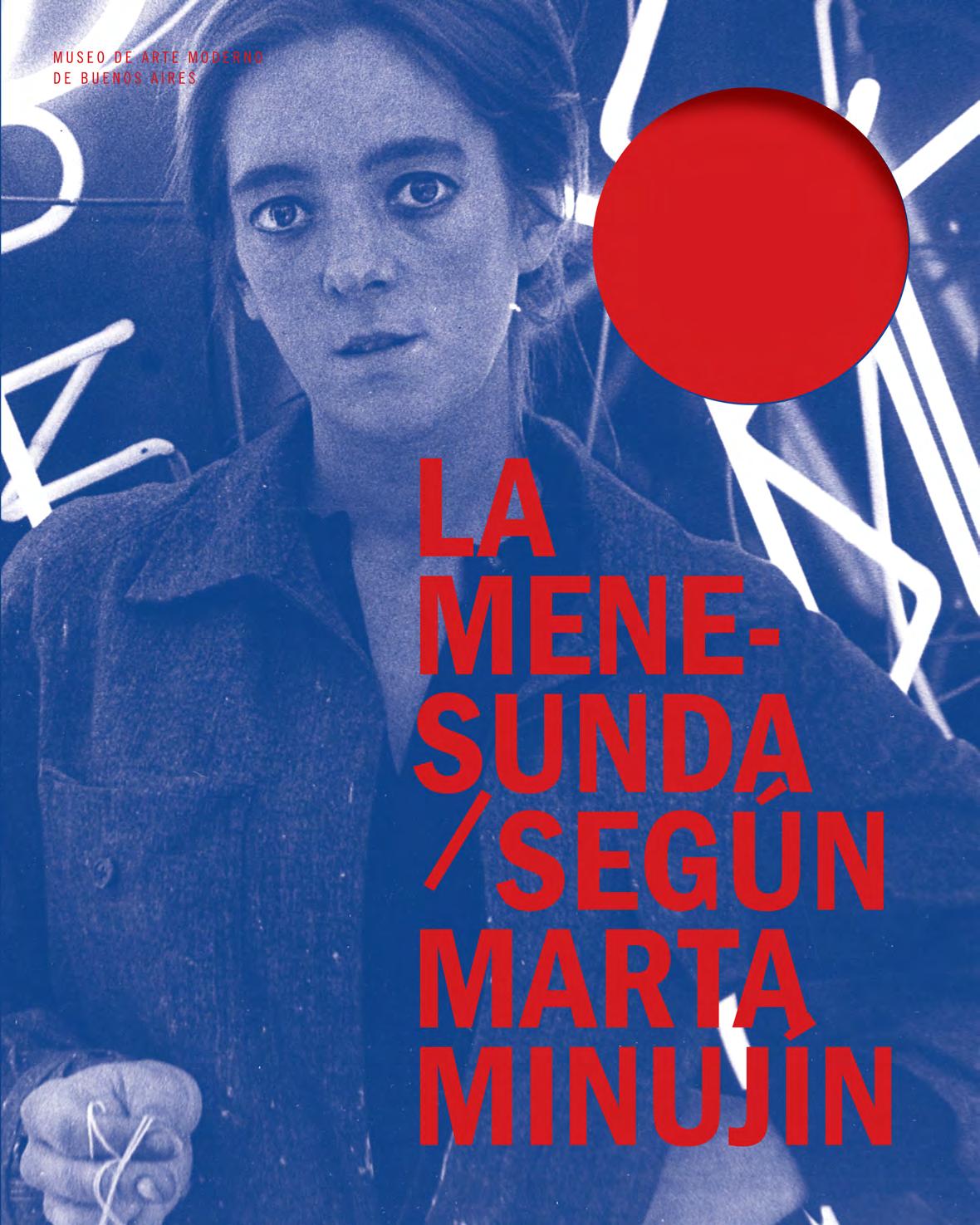

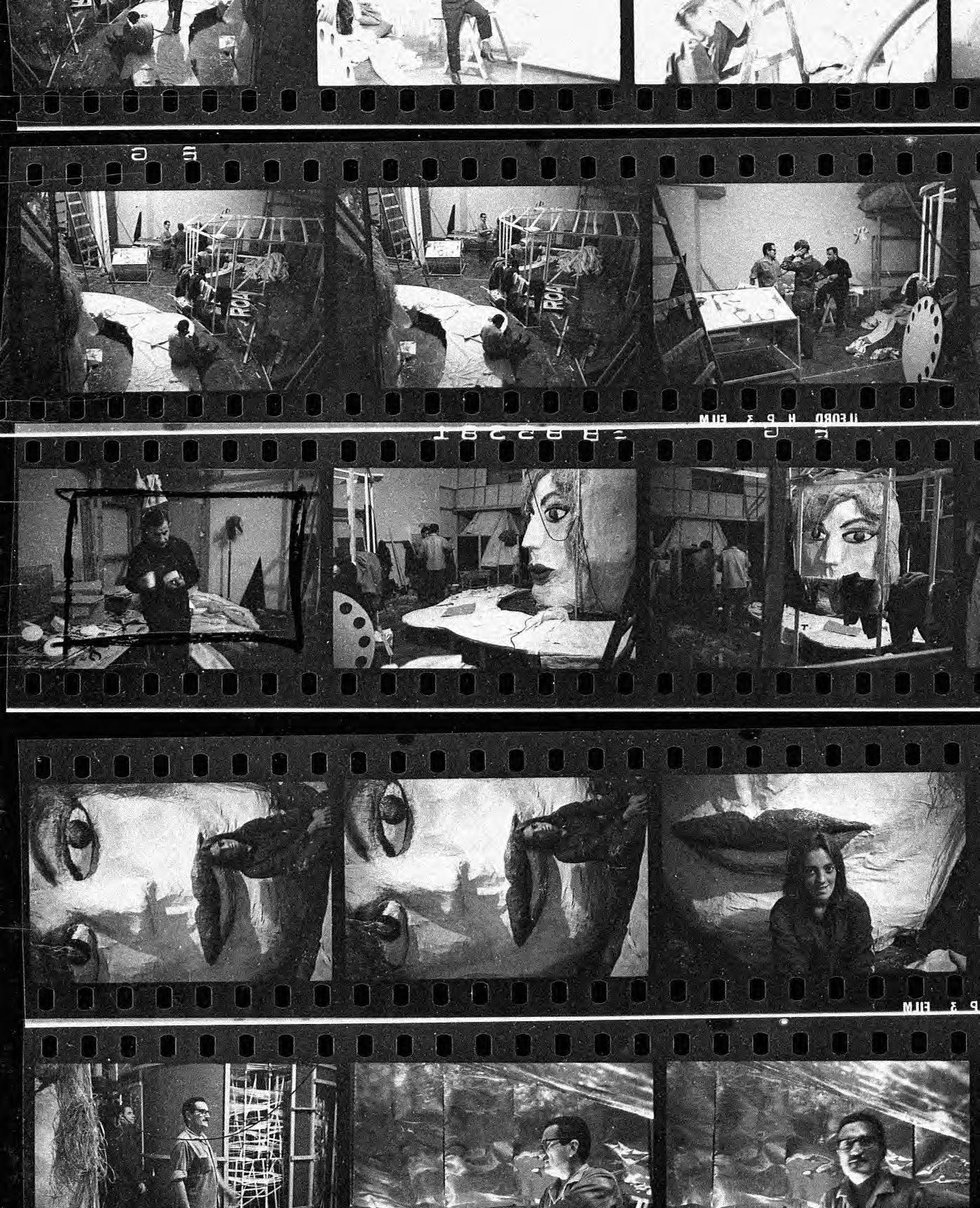

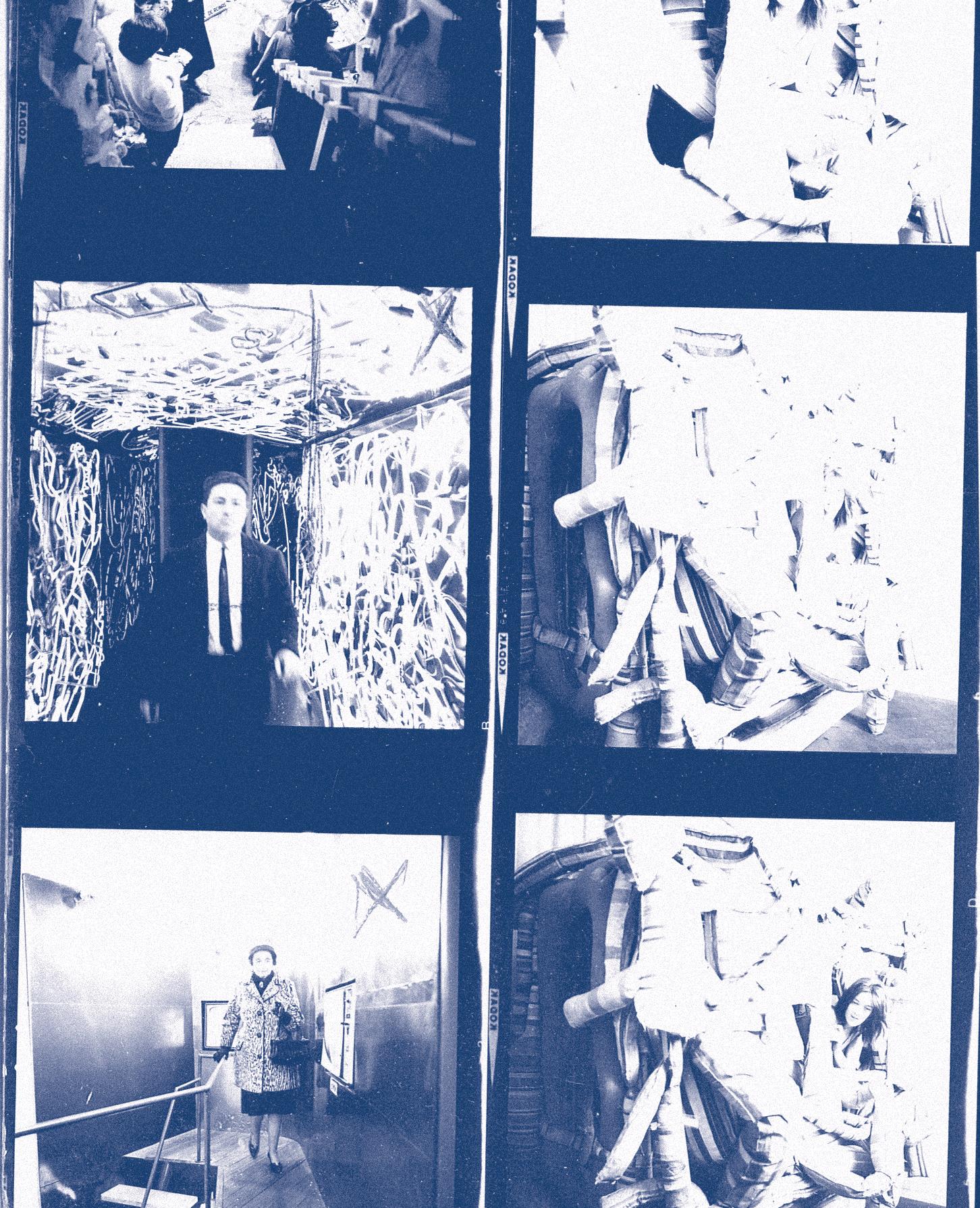

Contactos La Menesunda, 1965

Del 8 de octubre de 2015 al 28 de febrero de 2016

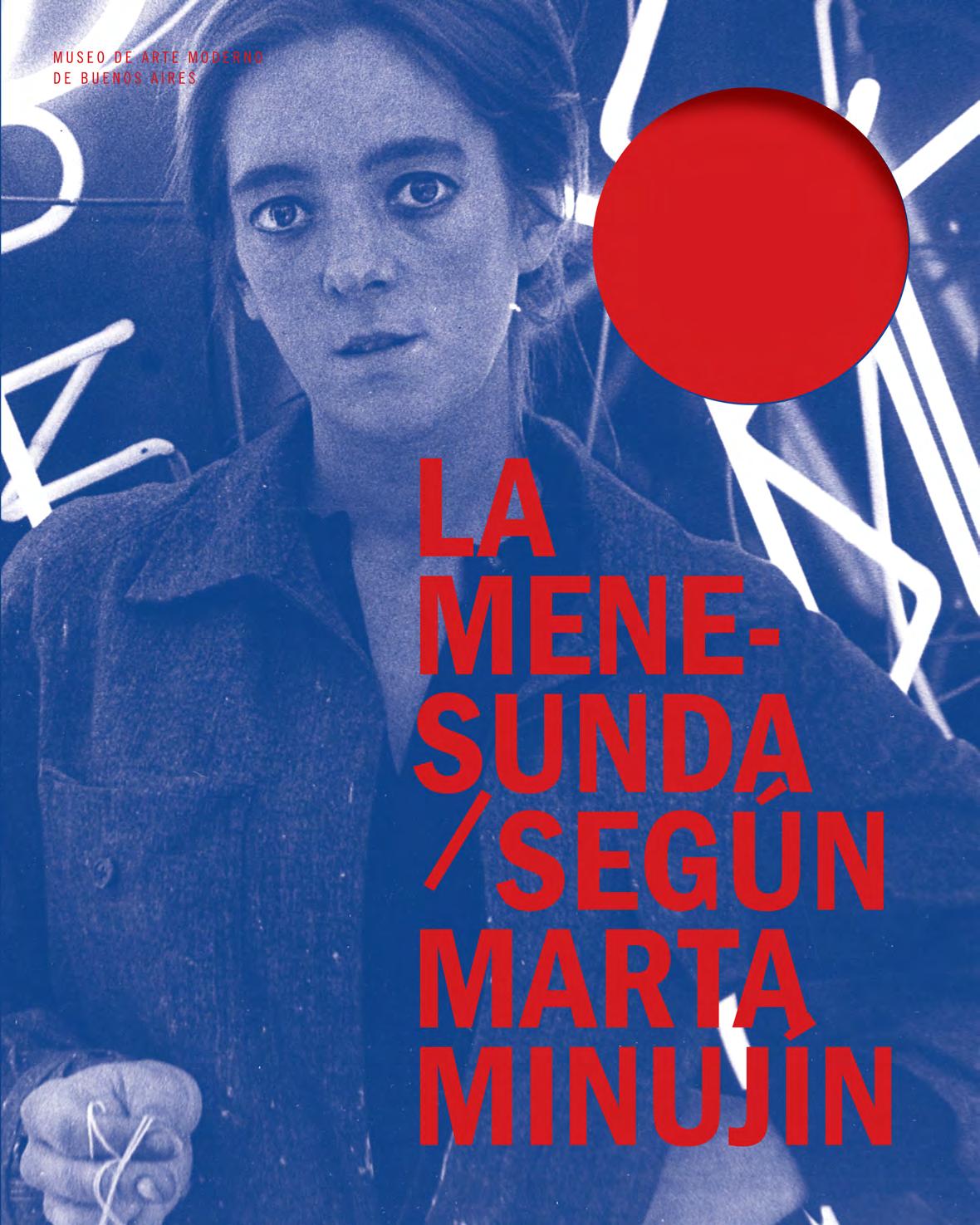

LA SEGÚNMENESUNDA MINUJÍNMARTA

DE ARTE MODERNO DE BUENOS AIRES

MUSEO

Este libro fue publicado en ocasión de La Mesesunda según Marta Minujín, presentada en el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires desde el 08 de octubre de 2015 al 28 de febrero de 2016

© Imágenes reproducidas: Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, 2015

Noorthoorn, Victoria

La Menesunda según Marta Minujín / Victoria Noorthoorn.1a ed. edición bilingüe. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires.

Dirección General de Museos, 2015.

220 p. ; 25 x 20 cm.

ISBN 978-987-1358-40-3

1. Arte Argenitno. I. Título.

CDD 709

Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires

Av. San Juan 350 (1147) Buenos Aires

Impreso en Argentina

Akian Gráfica Editora Clay 2972 Buenos Aires, Argentina www.akiangrafica.com

6

ÍNDICE INDEX

p.08 Agradecimientos Por Victoria Noorthoorn

p.21 La Menesunda Por Sofía Dourron

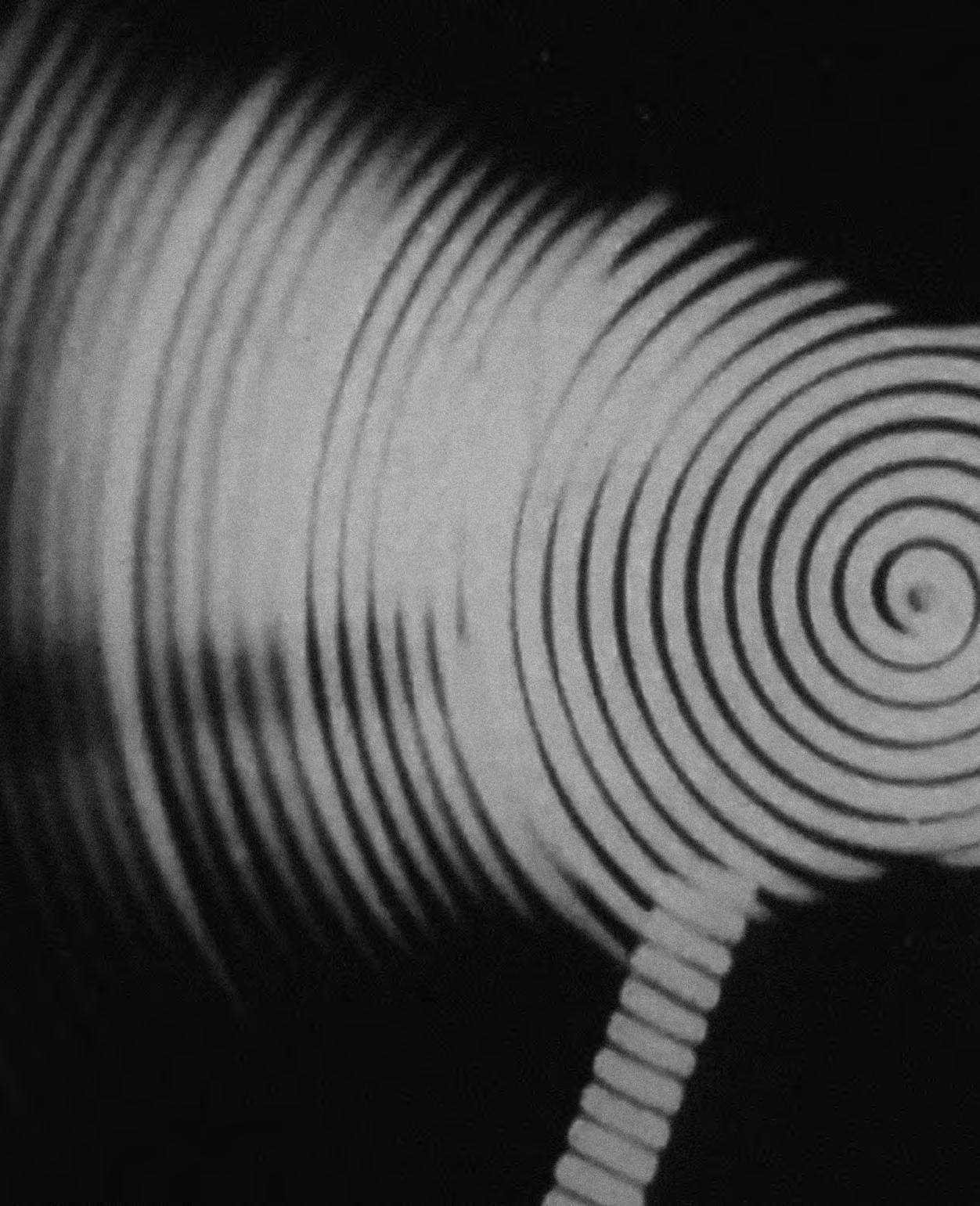

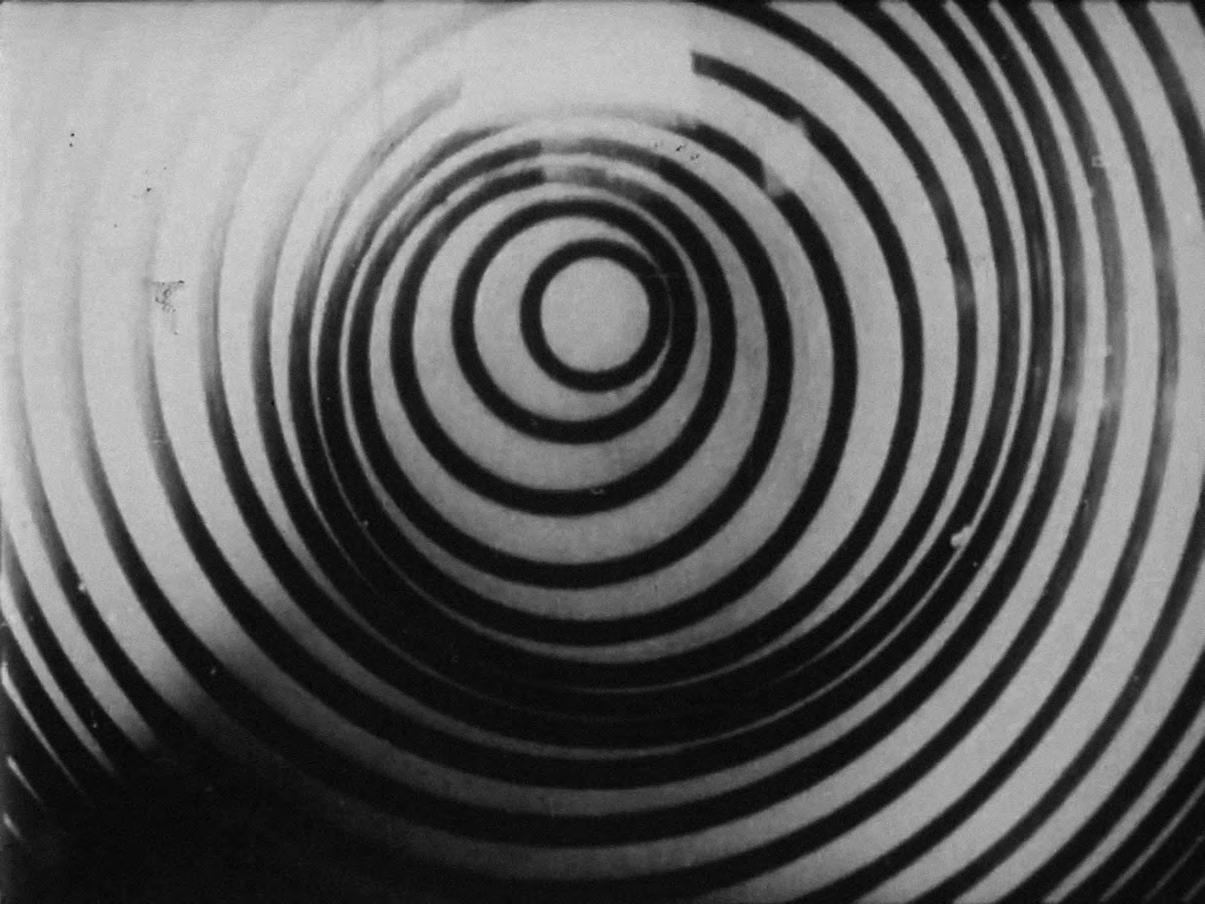

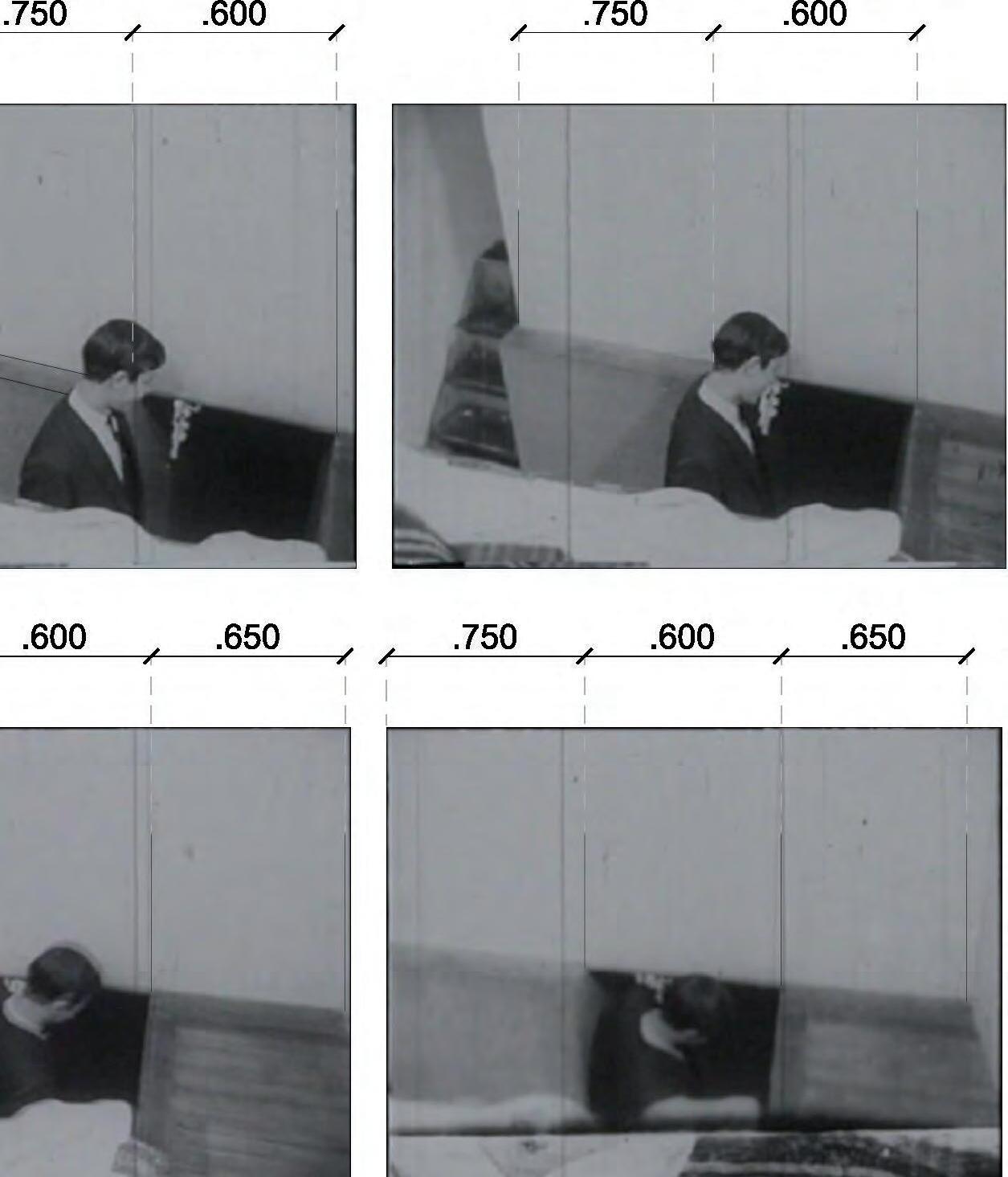

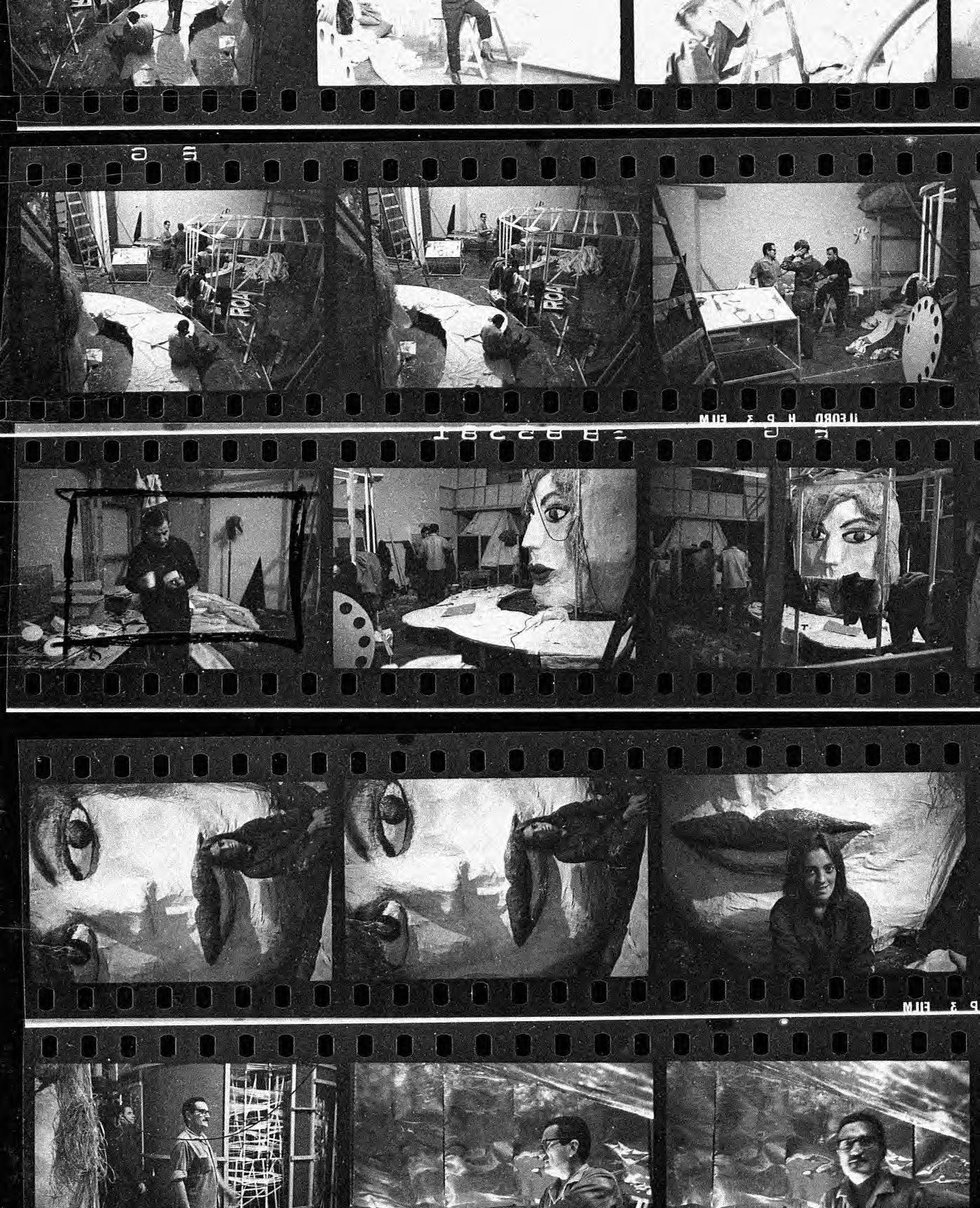

p.57 Film Stills de La Menesunda (1965) por Leopoldo Maler

p.157 La reconstrucción de La Menesunda

Por Sofía Dourron, Iván Rösler, Almendra Vilela, Javier Villa y Agustina Vizcarra

p.186 Biografía Marta Minujín

p.202 Biografía Rubén Santantonín

p.211 Bibliografía

7

p.08 p.21 p.57 p.159 p187 p.203 p.211

Agradecimientos

Por Victoria Noorthoorn

8

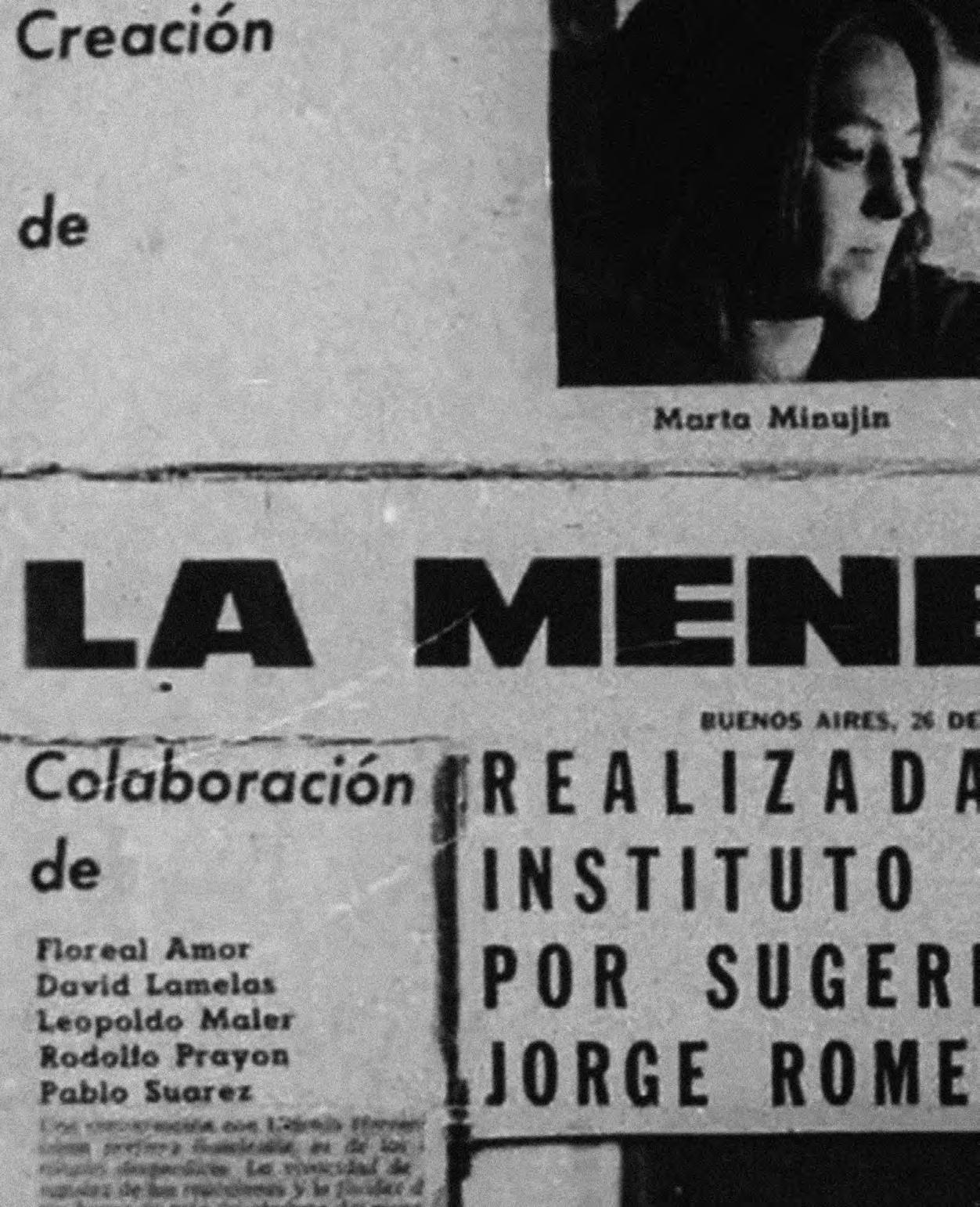

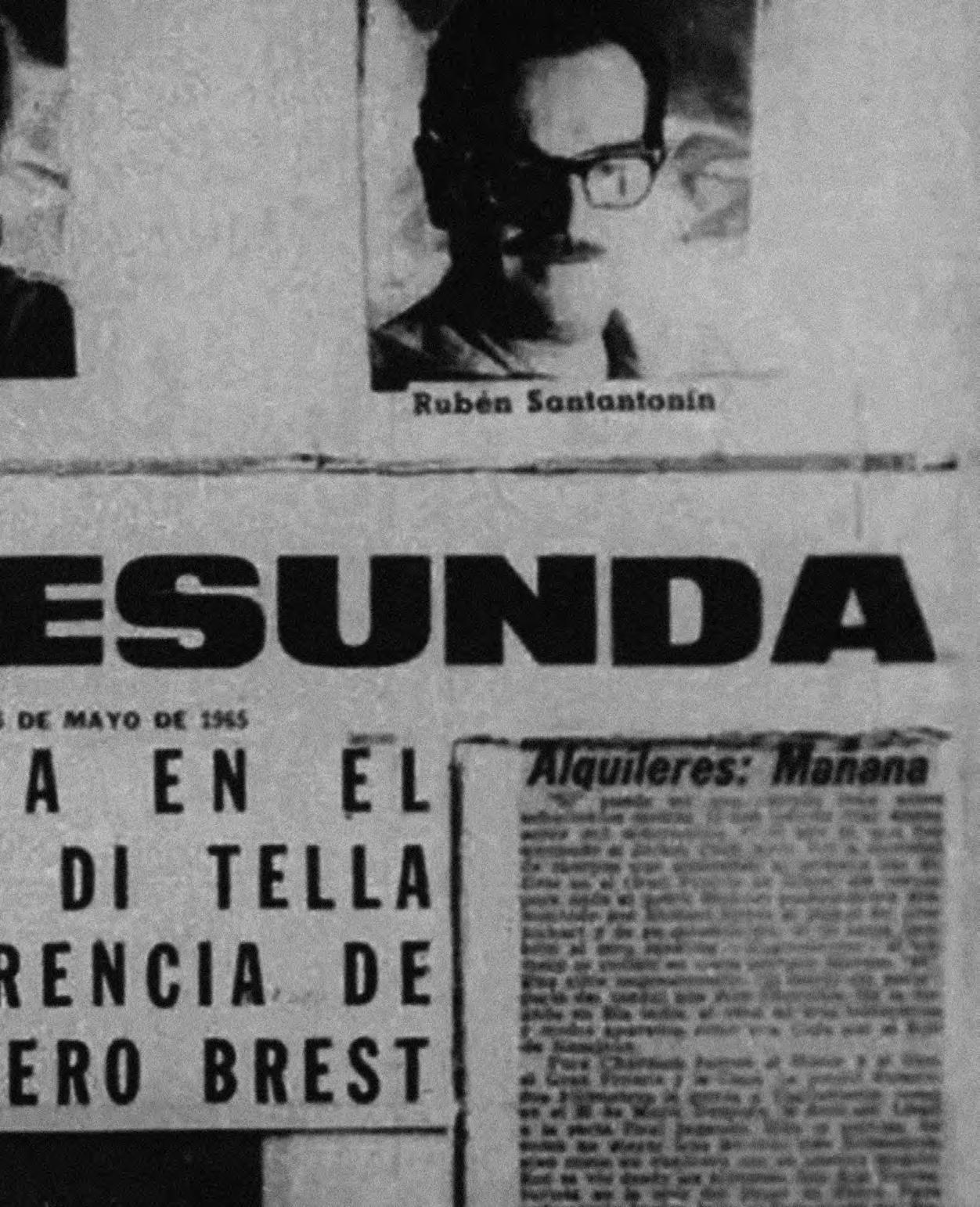

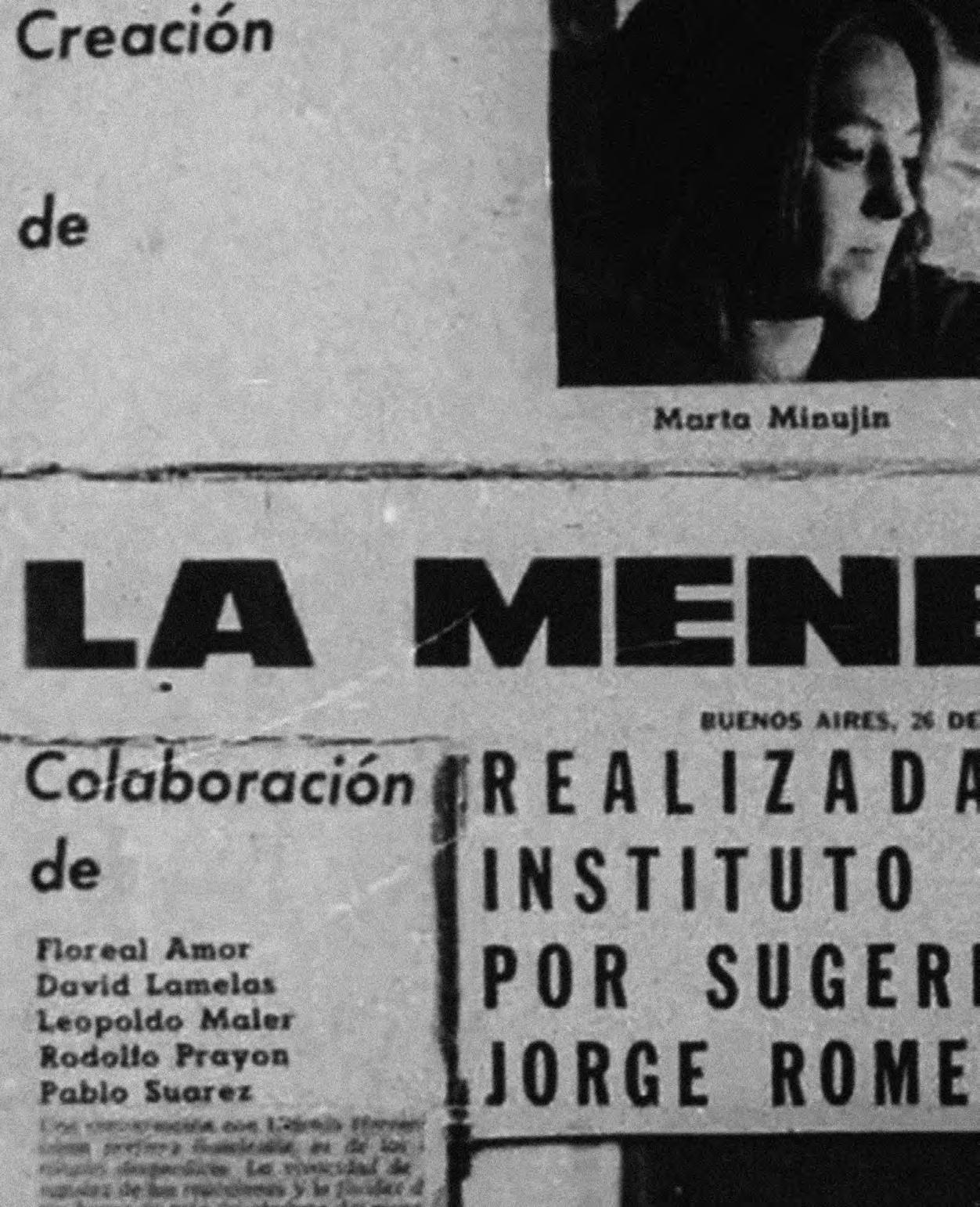

El Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires tiene el privilegio de presentar la reconstrucción de La Menesunda (1965), la obra emblemática realizada por Marta Minujín y Rubén Santantonín por encargo de Jorge Romero Brest, Director del Centro de Artes Visuales del Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, y que contó con la importante colaboración de Floreal Amor, David Lamelas, Leopoldo Maler, Rodolfo Prayón y Pablo Suárez. Esta reconstrucción, es, sin dudas, un momento de inflexión en la gestión del Museo por los inmensos desafíos que implica poner en escena esta obra compleja, que permanece como un mito en la memoria de tantos profesionales del arte y artistas argentinos.

La Menesunda buscaba provocar al espectador e instarlo a la acción: movilizarlo, agitarlo y ofrecerle una nueva experiencia estética, donde lo culto y lo popular se confundiesen en un espacio en el que habrían de confluir lo más sofisticado del arte contemporáneo del momento y una enorme cantidad de elementos de la experiencia estética de la vida cotidiana, en un tiempo en que el consumo y la nueva cultura de masas estaban cambiando el paisaje de la ciudad y los hogares de la clase media argentina. En La Menesunda, la calle y los lenguajes de vanguardia se combinaban a través de una sucesión de estímulos multisensoriales, estéticos y éticos. Entre el folclore y el espectáculo mediático, la “confusión” a la que apelaba la obra quedó registrada en la prensa de la época como memoria de un tiempo de profundos cambios en los modos de entender y experimentar el arte: marcó un punto de quiebre, un antes y un después. En La Menesunda confluyen dos artistas que, cada uno por separado, revolucionó el arte argentino tensionando hasta el extremo las posibilidades de la vanguardia del momento.

Reconstruir La Menesunda implicó sortear múltiples desafíos. En primer lugar, abordar la reconstrucción sin Rubén Santantonín presente. De allí la importancia del título del proyecto en el Moderno: La Menesunda “según Marta Minujín”, que pone de relevancia el rol fundamental de Marta Minujín en la posibilidad misma de llevar adelante este ambicioso proyecto originalmente ideado y dirigido por sus dos autores. Con esta cláusula en el título del proyecto, el Museo de Arte Moderno asume las limitaciones que pueda presentar este emprendimiento y que bien podrían deberse a la falta de interlocución con Rubén Santantonín.

En segundo lugar, encarar cincuenta años después la reconstrucción de uno de los grandes mitos de la cultura artística y visual, en un contexto de recepción en el que la noción de lo monumental ha cambiado radicalmente. Aquello que sorprendía en 1965 apenas sorprenderá hoy. Apostamos, entonces, por afirmarnos en 1965 desde el comienzo mismo de la obra, y recuperar aquella experiencia de escala 1:1, de escala humana, en la cual la experiencia artística se medía por la puesta en acción del propio cuerpo del espectador.

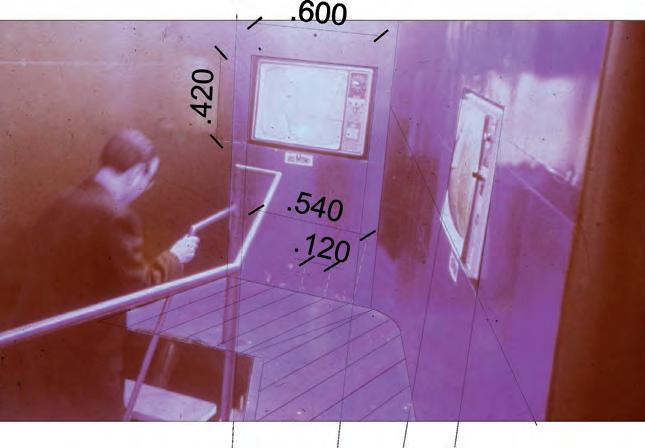

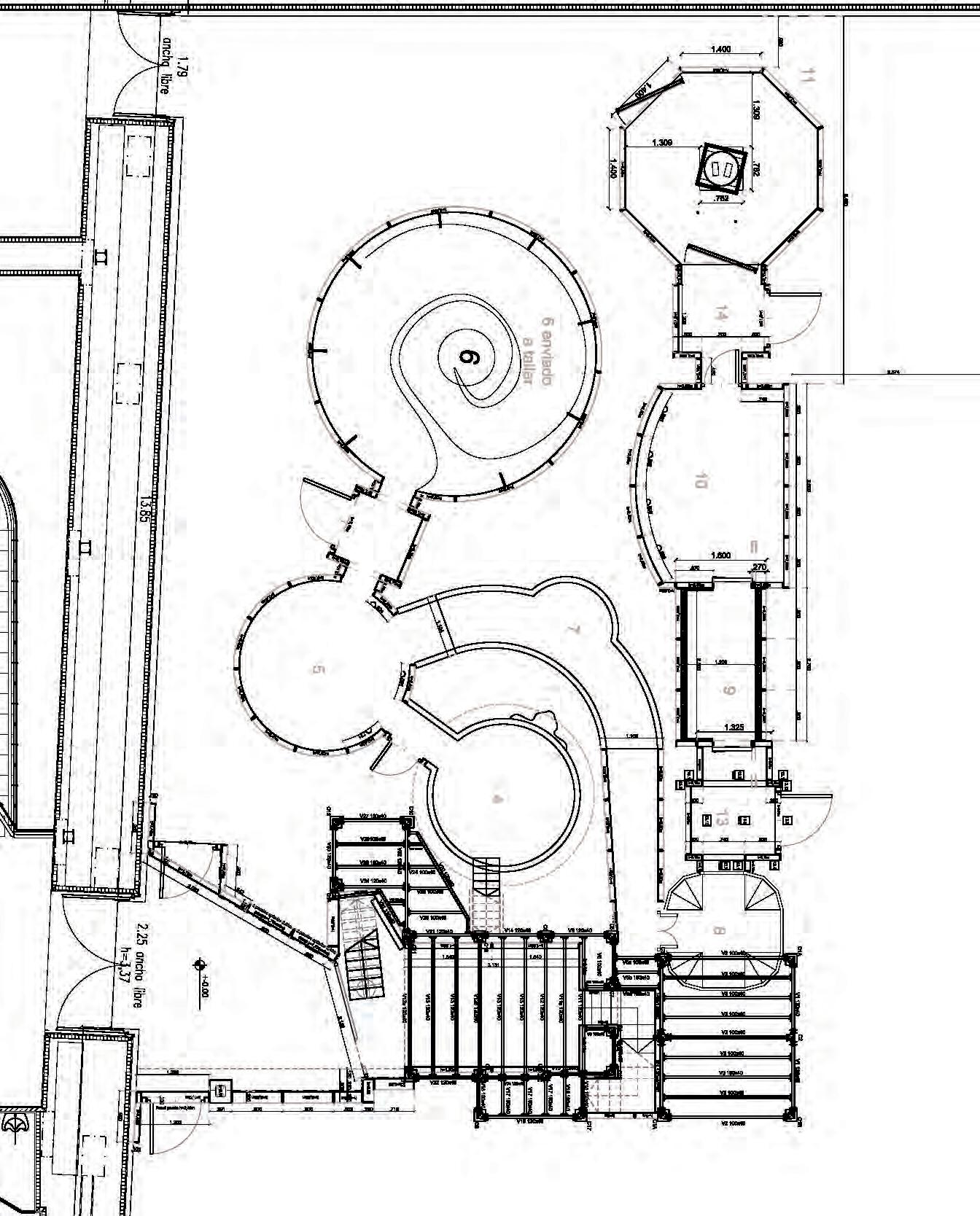

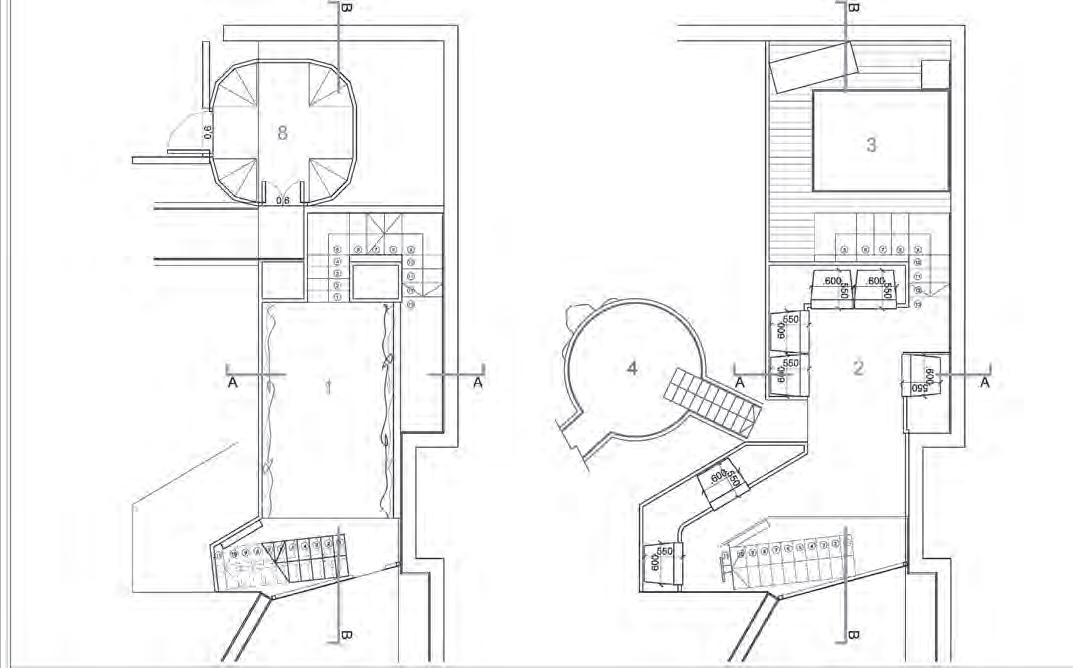

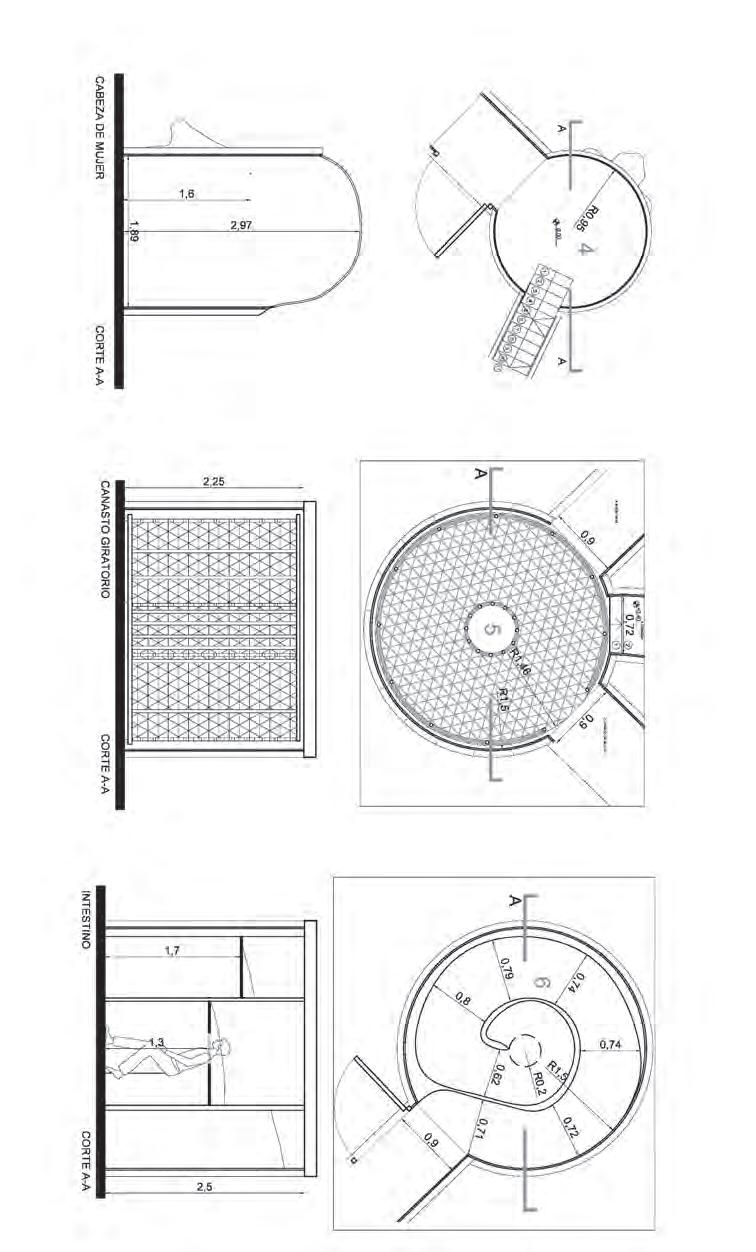

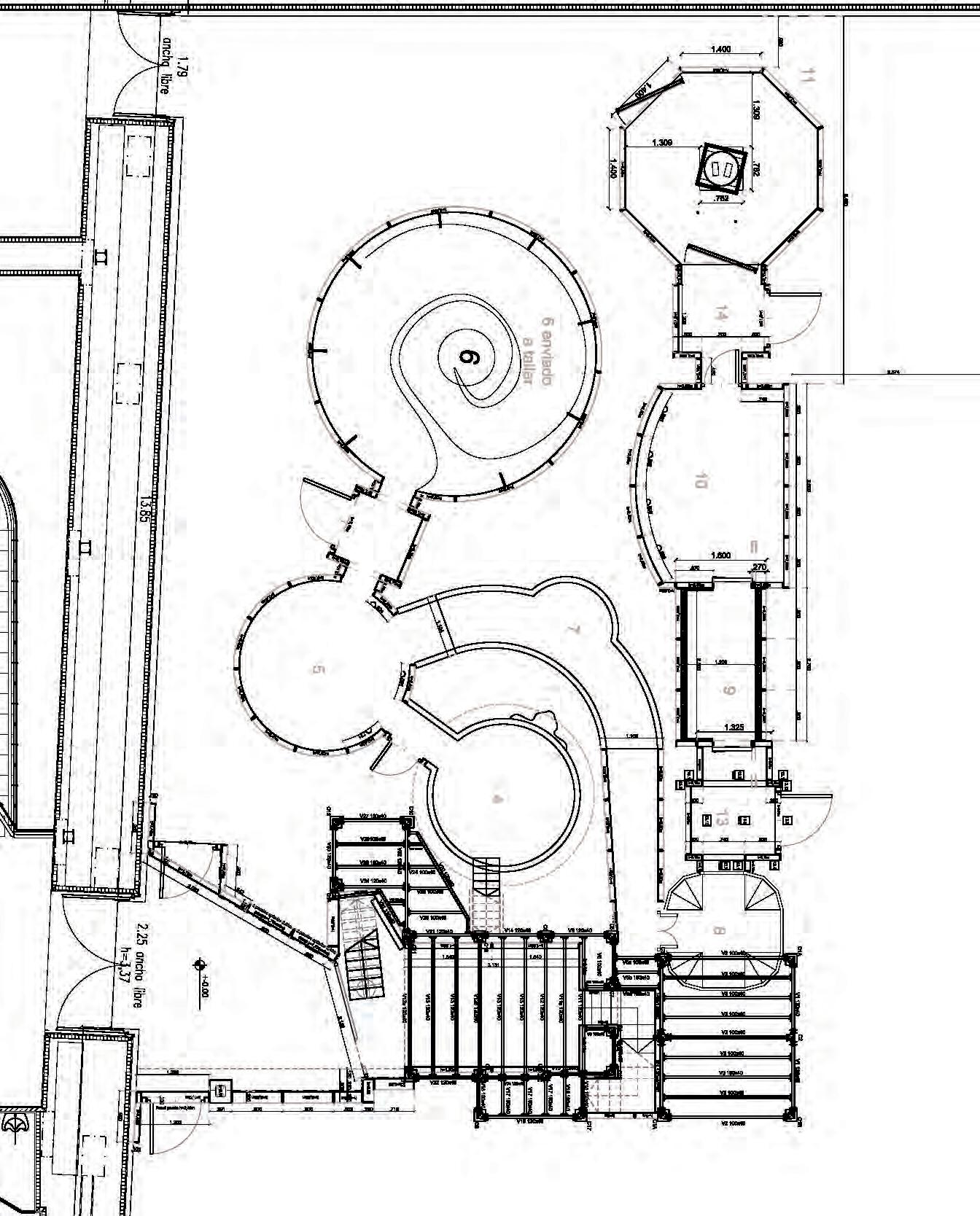

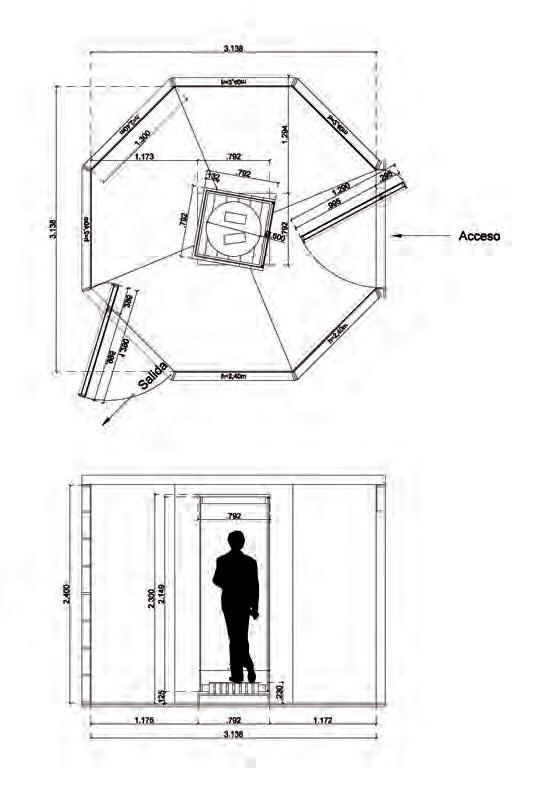

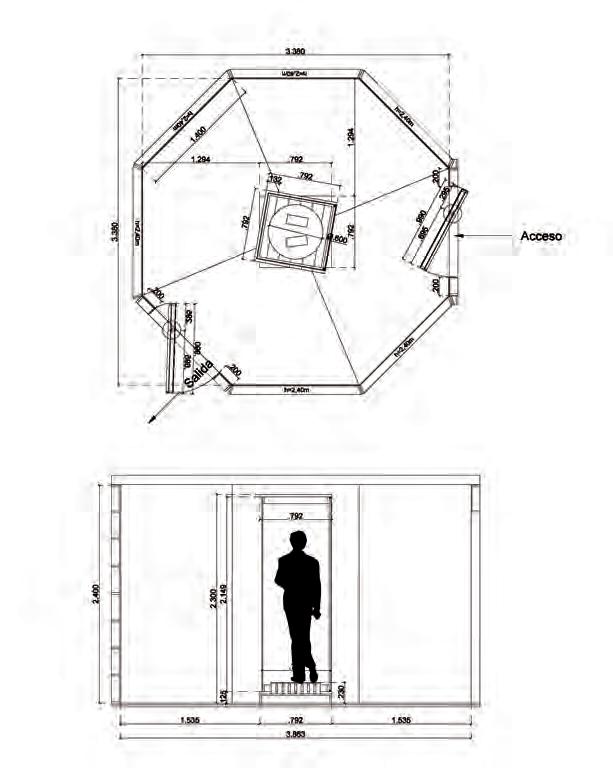

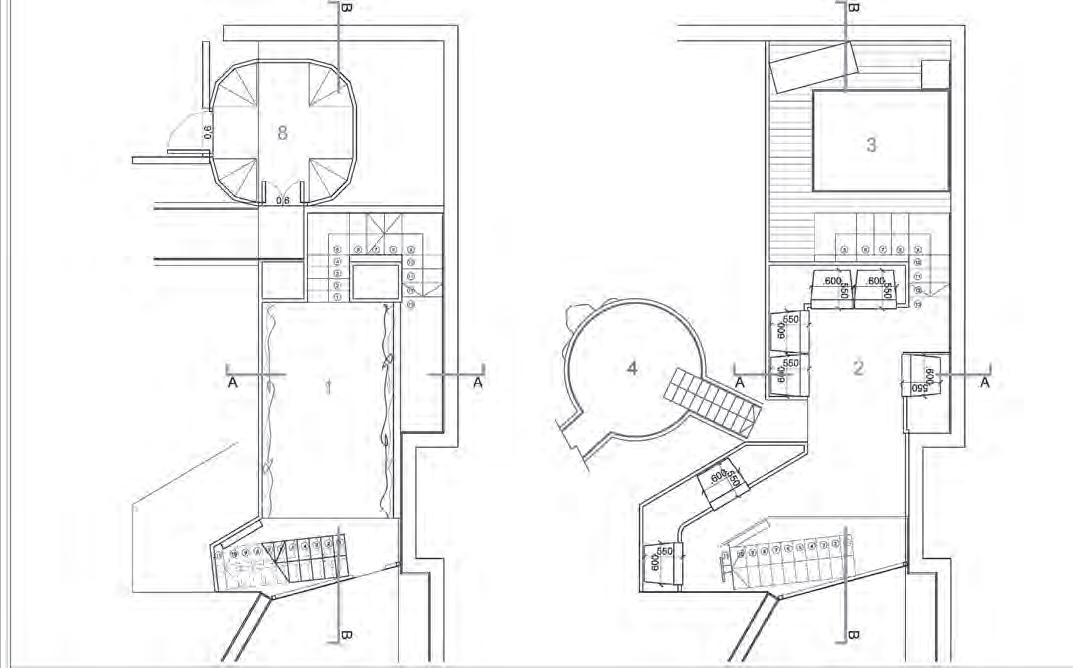

Por último, el desafío de lanzarse a reconstruir La Menesunda sin contar con los planos originales. A partir de una nueva investigación, los equipos técnicos estructuraron los once ambientes que componían el recorrido y sus

9

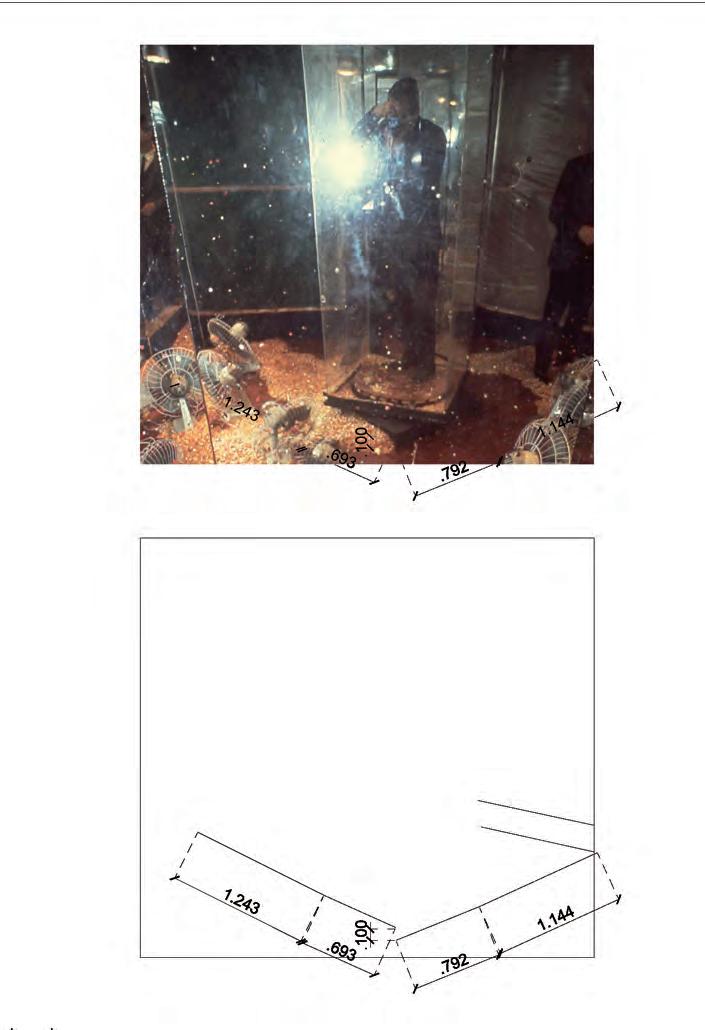

espacios de transición basándose en un análisis pormenorizado de las fuentes documentales (fotografías, artículos de prensa, correspondencia, y registros audiovisuales, incluido el film de Leopoldo Maler), en los relatos de la propia Minujín —cuya memoria, hemos constatado, es realmente prodigiosa— y de otros protagonistas de la época que la recorrieron.

Una obra de reconstrucción de estas características sólo es posible gracias al trabajo de un enorme equipo de profesionales y empresas y pone a prueba los conocimientos técnicos y la estructura del Museo, como sucede con todas las obras que tensionan su tiempo expandiendo sus límites, e incluso poniendo en crisis el orden de lo aceptable.

La Menesunda según Marta Minujín ha contado con el apoyo incondicional y la activa participación del Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, a través del Régimen de Promoción Cultural, de los equipos técnicos del Museo, de Marta Minujín y de nuestros generosos sponsors.

Dentro del Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, agradecemos muy especialmente el apoyo a la gestión del Museo que recibimos constantemente de Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros, Hernán Lombardi, Ministro de Cultura, María Victoria Alcaraz, Subsecretaria de Patrimonio Cultural, Pedro Aparicio, Director General de Museos, y Alejandro Capato, Director General Técnico, Administrativo y Legal del Ministerio de Cultura, y sus respectivos equipos. Vaya también nuestro agradecimiento a Franco Moccia, Subsecretario de Planeamiento y Control de Gestión, y a Juan Pablo Fasanella, Director General de Evaluación del Gasto, por su constante atención a este gran museo de la ciudad, que busca posicionarse como referente líder en arte argentino en nuestra ciudad y en el mundo.

Asimismo, agradecemos al Consejo de Promoción Cultural por apoyar muy especialmente este gran proyecto, que permite que los ciudadanos del mundo puedan reencontrarse con una de las obras históricas más importantes de la cultura visual de la Argentina. A Juan Manuel Beati Vindel, Presidente del Consejo, y a sus miembros: Carlos Ernesto Gutiérrez, Carlos Ángel Porroni, Maria Anahí Cordero, Astrid Obonaga y Celso Alberto Silvestrini; a los Consejeros Alternos en Artes Visuales: María Silvia Corcuera, Marion Eppinger y Ataúlfo Pérez Aznar, nuestra especial gratitud.

Deseo expresar nuestro más profundo agradecimiento al Banco Supervielle, aliado estratégico del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires que hace posible nuestra actividad durante los 365 días del año. Le agradecemos por recibir con tanto entusiasmo nuestra propuesta de apoyar la presentación de La Menesunda según Marta Minujín en el Moderno, una obra cuyos desafíos son tan importantes que sería imposible llevarla a cabo sin un apoyo estratégico tan contundente.

Asimismo, extiendo mi agradecimiento personal a nuestra Asociación

10

Amigos y a su flamante Comisión Directiva que se entusiasma a cada paso con los proyectos que proponemos todos los días para hacer de este Museo una institución de excelencia del siglo XXI, como también a nuestros sponsors que acompañan cada una de nuestras iniciativas: Alba Artística, Grupo Clarín, Durlock, Gancia, Plavicon, Fundación Andreani e Interior Forma Knoll, quienes contribuyeron activamente al proceso de construcción del proyecto.

Dentro del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, agradezco a Javier Villa, Curador de Arte Contemporáneo del Museo, y a Sofía Dourron, Asistente Curatorial del Museo, por su seguimiento curatorial de este proyecto, que requirió tanta atención en tan diversas instancias. Recién llegada al Museo, Sofía abrazó este proyecto con extremo rigor y valentía y produjo gran parte de los textos que se publican hoy en este catálogo, que nos enorgullece. Por su interlocución a lo largo de este proceso, que se desprende de su trabajo de investigación sobre la obra de Marta Minujín, agradezco asimismo a Jimena Ferreiro, Coordinadora de Curaduría y Curadora Asistente, quien también colaboró en la producción de esta importante publicación.

Ahora bien, más allá del fundamental seguimiento curatorial, este proyecto sólo puede materializarse con un impecable y obsesivo equipo de Producción. Mi agradecimiento especialísimo, entonces, a Iván Rösler, Jefe de Diseño y Producción de Exposiciones, que aceptó el desafío de dirigir este proyecto a pesar de su escala y complejidad, y cuyo desempeño estuvo a la altura de todas las exigencias de excelencia que nos propusimos. Dentro de su equipo, Almendra Vilela, Coordinadora de Producción, lideró el proyecto con el mayor profesionalismo, atendiendo a la necesidad de lograr en todo momento —tanto en su estructura como en los detalles— fidelidad absoluta al proyecto original. Por su generosidad, dedicación, calma y sabiduría, le agradezco el enorme esfuerzo y trabajo dedicado a este gran proyecto. Por su parte, Agustina Vizcarra asumió como propios los desafíos de La Menesunda según Marta Minujín y también contribuyó a que el proyecto viera la luz con una fidelidad al original y una exigencia pocas veces vista. Vaya mi agradecimiento a Pino Monkes, Jefe de Conservación del Museo, por su importantísima interlocución a lo largo de todo este proceso.

Dentro del equipo de Marta Minujín, mi agradecimiento al Arquitecto Fernando Manzone, quien trabajó en los planos de La Menesunda, y a Gerardo Peña, el constructor que asumió el desafío no sólo de encarar el proyecto de la construcción de estructuras, sino de comprender las múltiples necesidades de perfección que un proyecto como éste exige a cada paso.

Este proyecto demandó, como pocos, el enorme compromiso y trabajo de nuestro equipo de Desarrollo de Fondos. Agradezco el inmenso trabajo puesto en conseguir el necesario apoyo para La Menesunda según Marta Minujín de María Florencia Munaretto, nuestra siempre creativa Jefa de Desarrollo de Fondos, de Silvia Braun, Coordinadora de Desarrollo de Fondos, por su tenacidad para conseguir apoyos a cada paso, de Isabel Palandjoglou, por su

11

capacidad para liderar los procesos relativos a la Ley de Mecenazgo que hacen posible este proyecto y de Verena Schobinger, quien día a día contribuye a llevar a este Museo a otros horizontes a través de sus siempre entusiastas gestiones a cargo de la Cooperación Internacional.

Asimismo, la publicación que usted tiene en sus manos forma parte del programa editorial que hemos lanzado hace dos años. Al frente de este libro han estado María Sibolich, en calidad de Diseñadora Gráfica Senior, y Ailin Staicos, en calidad de Coordinadora de Comunicación. Ambas han hecho posible que lleguemos a buen puerto con este libro, en tiempo y forma. Les agradezco muy especialmente su pasión a cada momento y ante cada proyecto a ellas y a sus colegas en el equipo de Comunicación, Francisco Capuzzi y Lucía Ladreche, Diseñadores Gráficos, Victoria Onassis y Mercedes Ezquiaga, responsables de Prensa, Mariel Breuer, a cargo de las redes sociales, y Josefina Tommasi, a cargo de la Fotografía. Juntos logran transmitir la pasión de este Museo por todos los proyectos que han surgido a partir de La Menesunda. Les agradezco muy especialmente su dedicación y compromiso, la belleza de este ejemplar, de todas las piezas gráficas y los productos desarrollados, así como el desafío que asumen para acercar las exposiciones y los proyectos de este Museo a cada persona de nuestra sociedad. Agradezco, también, las múltiples gestiones de Ruben Mira, quien con tanto compromiso se dedicó a soñar las posibilidades de este Museo más allá de sus muros.

Agradezco finalmente a Joaquín Rodríguez, Coordinador de Dirección, y a María José Oliva Vélez, Coordinadora de Exposiciones, que colaboraron en la coordinación general del proyecto, así como a cada uno de los integrantes del equipo del Museo que colaboró activamente con el ambicioso proceso de la exposición y de esta publicación.

Por último, para Marta Minujín sólo tengo palabras de admiración, profundo reconocimiento y especial agradecimiento por haber confiado en los equipos del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires para presentar este gran proyecto. Le agradecemos no sólo su confianza, sino su dedicación para acercarse paso a paso y cada vez más a La Menesunda original contrastando su propia memoria y la de sus colegas con las fuentes documentales y los materiales que le fuimos aportando. Ha sido un verdadero placer y un gran honor para este Museo trabajar con una persona excepcional, la artista que ha desafiado en la Argentina a la institucionalidad desde los años 60 hasta la actualidad, con un sentido crítico poco reconocido por el público general. Así, el Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires se complace en presentar al público de la Argentina y del mundo la obra que Marta Minujín ideó junto a Rubén Santantonín en su juventud y que hoy permanece desafiante, provocadora e irrefutablemente contemporánea.

12

Acknowledgements

Por Victoria Noorthoorn

The Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires has the great privilege of presenting a reconstruction of La Menesunda (1965), the iconic artwork by Marta Minujín and Rubén Santantonín commissioned by Jorge Romero Brest, Director of the Centro de Artes Visuales at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, in collaboration with Floreal Amor, David Lamelas, Leopoldo Maler, Rodolfo Prayón and Pablo Suárez. This reconstruction undoubtedly marks a watershed for the Museo due to the immense challenges involved in reconstructing a legendary piece in the memory of Argentine artists and art professionals.

La Menesunda sought to provoke the spectator and spur them into action, offering them a new aesthetic experience in which both high and low culture would merge in a space that brought together some of the most sophisticated and thought-provoking proposals of contemporary art at the time and so many elements drawn from the aesthetic experience of daily life, during a period when consumer culture and mass media were changing the landscape of the city. In La Menesunda, the street and the languages of the avantgarde combined in a complex and invigorating succession of multisensory, aesthetic and ethical stimuli. On the cusp between folklore and a society of the spectacle, the ‘confusion’ the artwork sought to create was recorded in the contemporary press as a memory of a period of profound change in the ways that art was understood and experienced: it marked a new departure, a before and after. In La Menesunda, two artists who revolutionized Argentine art in very different ways came together to stretch the potential of avant- garde art of the time to breaking point.

Reconstructing La Menesunda meant overcoming many different challenges. Firstly, we had to take it on without the presence of Rubén Santantonín. This is why it was crucial to entitle the project at the Moderno: La Menesunda “according to Marta Minujín”, to highlight Marta Minujín’s fundamental role in an ambitious project that was originally conceived and directed by two central authors. With the extra clause in the project title, the Museo de Arte Moderno acknowledges the limitations of the enterprise and the possible flaws that may very well have occurred as a result of Rubén Santantonín’s absence.

Secondly, we were undertaking the reconstruction of one of the great legends of visual and artistic culture in Argentina fifty years after the fact, when perceptions of what is monumental have changed radically. What was

13

surprising in 1965, would barely raise an eyebrow today. So, right from the start of the project we thought in 1965 terms, aiming to reconstruct the experience on a 1:1, human scale, in which the artistic experience is measured by the degree of action that has been stimulated in the spectator’s body.

The final challenge was to rebuild La Menesunda without the original plans. The technical team carried out painstaking research, rebuilding the eleven environments included in the work and their transition spaces based on a detailed analysis of documentary sources (photographs, press articles, correspondence and audio-visual records, including a film by Leopoldo Maler), the accounts of Minujín herself —we confirmed once again in the process that she has a prodigious memory— and other people who experienced the piece at the time.

A reconstruction project like this is only possible with an enormous team of professionals and companies, and puts to the test the technical expertise and structure of the Museo, as is appropriate for any work that pushed the boundaries in its time and even subverted the limits of what was seen as acceptable.

La Menesunda según Marta Minujín has benefitted from the unconditional support of the Government of the City of Buenos Aires, via its Ley de Mecenazgo (Regime for Cultural Promotion), and our generous sponsors, and from the hard work, enthusiasm, and strong commitment of the technical teams at the Museo and of course, Marta Minujín herself.

At the Government of the City of Buenos Aires, we are especially grateful for the constant support that the Museo’s administration has received from Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, Head of the Cabinet of Ministers, Hernán Lombardi, Minister of Culture, María Victoria Alcaraz, Undersecretary for Cultural Patrimony, Pedro Aparicio, Director General of Museums and Alejandro Capato, Director General of Technical, Administrative and Legal Affairs at the Ministry of Culture and their respective teams. Our thanks also go out to Franco Moccia, Undersecretary of Planning and Administration Control, and Juan Pablo Fasanella, Director General of Spending Evaluation, for their attention to this museum, which is seeking to position itself as the leading institution in Argentine art in our city and across the world.

We would also like to thank the Council of Cultural Promotion for supporting La Menesunda según Marta Minujín, allowing the citizens of the world to rediscover one of the most important works in the history of visual culture in Argentina. Our special and sincere thanks go to Juan Manuel Beati Vindel, President of the Council, and its members: Carlos Ernesto Gutiérrez, Carlos Ángel Porroni, Maria Anahí Cordero, Astrid Obonaga and Celso Alberto Silvestrini; and to the Alternate Council in Visual Arts: María Silvia Corcuera, Marion Eppinger and Ataúlfo Pérez Aznar.

14

I wish to express my deep gratitude to Banco Supervielle, the strategic ally of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires that makes our activities possible, for receiving our proposal to support the presentation of La Menesunda según Marta Minujín at the Moderno so enthusiastically— a work whose challenges were so big that its reconstruction would have been impossible without such a firm strategic support.

In addition, I extend my personal thanks to our Asociación Amigos and its new Board of Directors who welcome the projects we propose to help this institution achieve the necessary excellence, as well as the sponsors who participate in every one of our initiatives: Alba Artística, Grupo Clarín, Durlock, Gancia, Plavicon, Fundación Andreani and Interior Forma Knoll, all of which have actively contributed in the construction of the project.

At the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, I thank Javier Villa, Curator of Contemporary Art, and Sofía Dourron, Curatorial Assistant, for their careful and committed curatorial supervision of the project which required so much attention for such an extended period of time; recently arrived at the Museo, Sofía has embraced this project with extreme rigour and courage and has produced most of the texts in this catalogue, in which we take so much pride. For her valuable contribution throughout this process, a natural extension of her previous research project on the work of Marta Minujín, I thank Jimena Ferreiro, Coordinator of the Curatorial Department and Assistant Curator, who has also played an active role in this important publication.

Now, this project could only have come about with an impeccable and obsessive Production team. My very special thanks go, then, to Iván Rösler, Head of Exhibition Design and Production, who took on the challenge of directing this project in spite of its scale and complexity and who met every hurdle with the level of excellence required to get past it. In his team, Almendra Vilela, Production Coordinator, led the project with the greatest professionalism, answering the need of achieving at all times —both in the structure and in every detail— fidelity to the original project. For their generosity, dedication, calm and wisdom, I thank them for the enormous effort and work they put into this great project. Agustina Vizcarra, Production Assistant, also took the challenges of La Menesunda según Marta Minujín to heart, and with an attention to detail rarely seen, she contributed hugely to achieving outstanding quality and the desired degree of fidelity to the original. I am further grateful to Pino Monkes, Head of Museum Conservation, for his extremely important involvement throughout the process.

Within Marta Minujín’s team, I am thankful to architect Fernando Manzone, who worked on the floorplans for La Menesunda, and Gerardo Peña, the builder who did not just take on the challenge of the construction project but also understood the multiple requirements of perfection that such an ambitious endeavour demands at every stage.

15

This project required an unprecedented degree of commitment and work from our Development Department. I am grateful for the immense amount of work put into garnering the necessary support for La Menesunda según Marta Minujín from María Florencia Munaretto, our always creative Head of Fundraising, and Silvia Braun, Fundraising Coordinator, for managing to earn support at every stage. I thank, as well, Isabel Palandjoglou, for her ability to take the lead in all the processes related to the Ley de Mecenazgo which made this project possible and Verena Schobinger, who every day helps to expand the Museo’s horizons with her always enthusiastic administration of International Cooperation.

The publication that you have in your hands is part of the Editorial Programme we launched two years ago. Taking the lead in this book were María Sibolich, in her role as Senior Graphic Designer, and Ailin Staicos, in her role as Communications Coordinator. It is thanks to their orchestrated efforts that we have managed to deliver this book on schedule. I thank them especially for their passion at every turn and during each project that they and their colleagues in the Communications team, Francisco Capuzzi and Lucía Ladreche, Graphic Designers, Victoria Onassis and Mercedes Ezquiaga in the Press Department, Mariel Breuer, Head of Social Media and Josefina Tommasi, Photographer, produce every day. Together they manage to transmit the excitement of this Museo for all the projects that we have developed for and around La Menesunda. I thank them very especially for their dedication and commitment, the beauty of this publication, and for assuming the challenge of bringing the Museo’s projects and exhibitions to our society. I am also grateful to Ruben Mira, who has been so committed to the dream of this museum’s potential beyond its own walls.

I extend my gratitude, as well, to Joaquín Rodríguez, in the Director´s Office, and María José Oliva Vélez, Exhibition Coordinator, who contributed actively to the general coordination of this project as well as every member of the Museo’s team who worked actively on the ambitious process of the exhibition and the publication.

Lastly, for Marta Minujín I have only words of admiration, profound respect and sincere gratitude for having trusted the teams of the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires to present this unique project. We thank her not just for her faith, but for her dedication in accompanying the project step by step, as we got ever closer to the original La Menesunda, contrasting her own memories and those of her colleagues with the documentary sources and materials we supplied to her. It has been a true pleasure and genuine honour for this Museo to work with such an exceptional person, the artist who has challenged artistic institutions in Argentina from the 60s to the present day with a critical sensibility for which she is rarely given credit by society at large. It is therefore with huge pride that the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires presents to the public of Argentina and the world the work that Marta Minujín created together with Rubén Santantonín in their youth and that today remains challenging, provocative and irrefutably contemporary.

16

17

20

21

Por Sofía Dourron

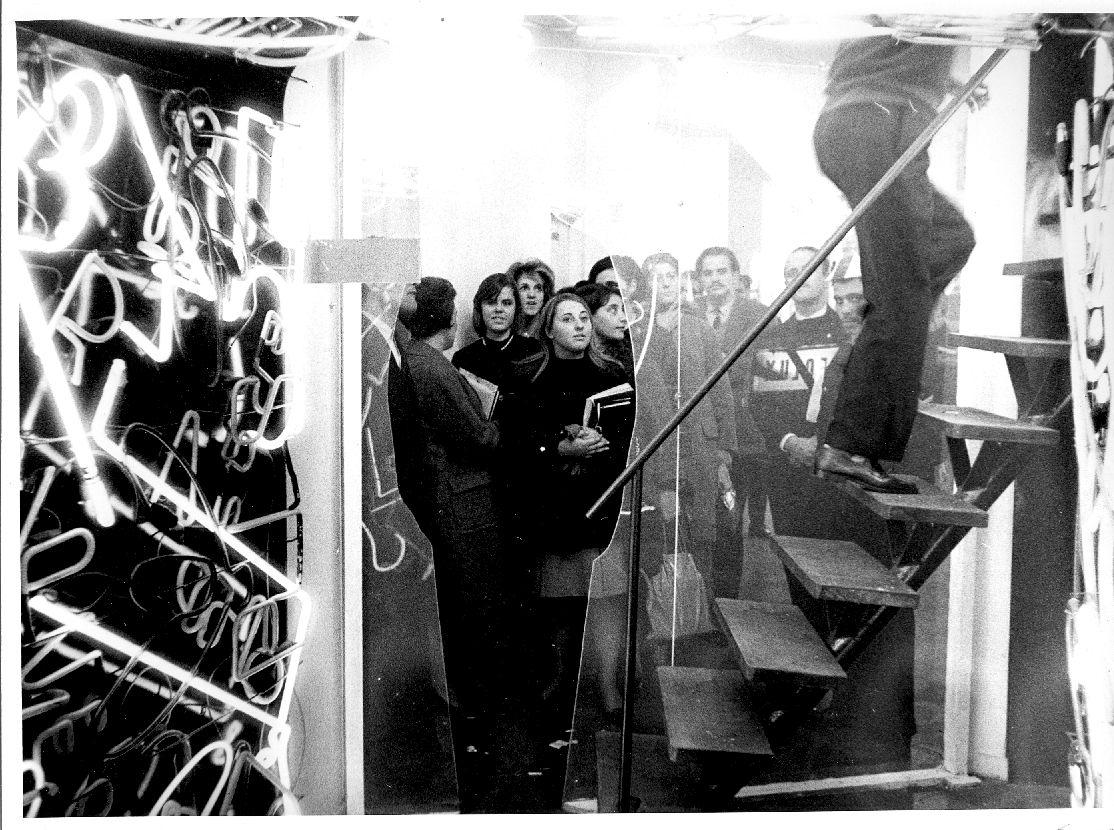

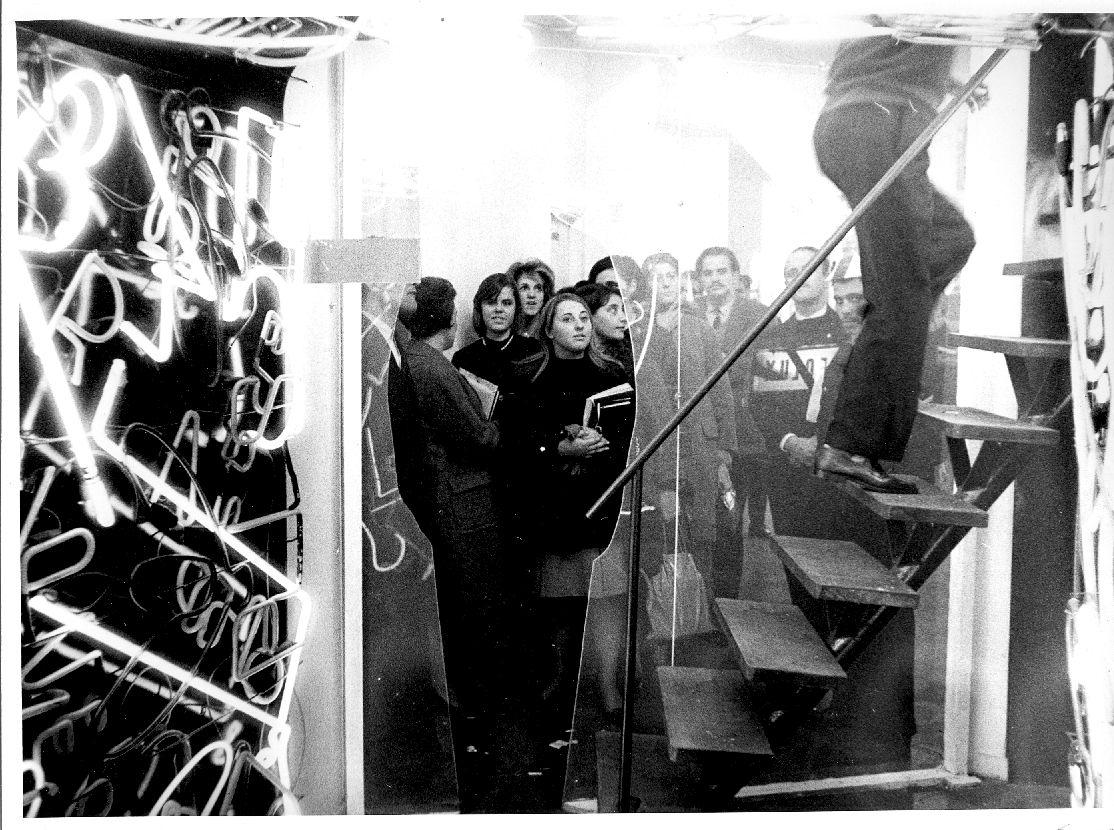

22 La Menesunda , 1965 Vista general del Túnel de neón Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín La Menesunda , 1965 General view of The Neon Tunnel Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

La Menesunda

Por Sofía Dourron

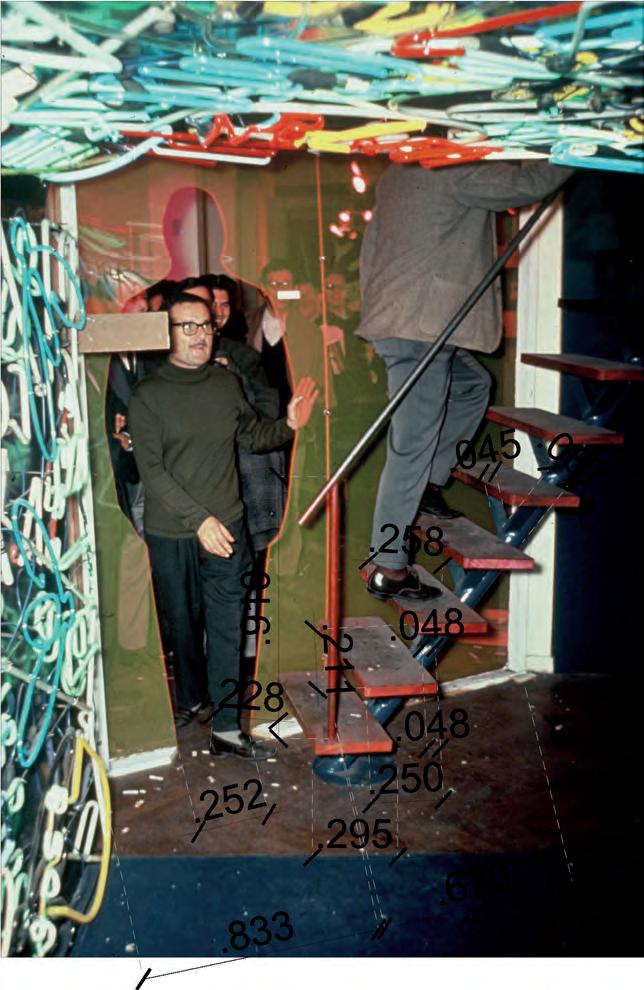

A mediados de mayo de 1965, cientos de porteños se agolpaban en la calle Florida haciendo cola a la intemperie durante horas, bloqueando las entradas de las boutiques y provocando miradas y cuchicheos entre los transeúntes. Aguardaban, pacientes, para ingresar de a uno por vez a La Menesunda , la mítica obra que Marta Minujín y Rubén Santantonín construyeron dentro del Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. Bajo la premisa “Más acá de dioses e ideas / sentimientos / mandatos y deseos”, 1 el enrevesado laberinto confrontaba, incomodaba, sorprendía y zarandeaba a todo aquel que osara traspasar su umbral. Sacudiendo al espectador de su habitual pasividad y sumergiéndolo en un agitado revoltijo, la obra confundía la cotidianeidad doméstica con el bullicio de las calles del centro y el más reciente de los lenguajes de la vanguardia, todo en una misma sala. Uno tras otro, los visitantes eran impulsados a través de estrechos pasillos que los conducían de un insólito ambiente a otro, en medio de una sucesión de estímulos multisensoriales, estéticos y éticos ideados para impactar sus sentidos y su sensibilidad, incluso la de los más escépticos, desconfiados y temerosos. La Menesunda , dijeron sus creadores, no era obra ni happening , tampoco espectáculo. Entre rito folclórico porteño y espectáculo mediático, La Menesunda , con su desfachatez, espíritu revulsivo e histrionismo, era pura experiencia y provocación. Un proyecto de una magnitud descomunal que se convertiría en el escándalo del año, pero también en uno de los grandes hitos de la historia del arte argentino.

23

1-Marta Minujín, Rubén Santantonín, La Menesunda, Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, 1965, folleto

El gran despliegue que organizaron Minujín y Santantonín, junto con los artistas Floreal Amor, David Lamelas, Leopoldo Maler, Rodolfo Prayón y Pablo Suárez, sólo fue posible como parte de la culminación del proceso de modernización del arte y la cultura que, iniciado diez años antes, hacia 1965 parecía estar consolidado. El derrocamiento del peronismo en 1955 había instalado la convicción de que se estaba saliendo de años de aislamiento cultural y que se presentaba la gran oportunidad para que el arte se renovara y se pusiera a tono con el resto del mundo. Hacia mediados de los años cincuenta, apareció la noción de “arte nuevo” y se planteó con urgencia la necesidad de fundar estilos locales de alcance internacional, pero que, bajo ningún punto de vista, emularan las tendencias foráneas. Se trató de un corte radical con las estéticas del pasado. Desde finales de la década anterior, con el raudo ascenso de la pintura informalista, gestual y matérica, que buscaba despegarse de la tradición pictórica local, los artistas comenzaron a asumir una nueva actitud rupturista, con Kenneth Kemble (1923-1998) y Alberto Greco (1931-1965) a la cabeza, decididos a abandonar los antiguos cánones, sus formatos y materiales, para explorar nuevos caminos que acompañarían los virulentos quiebres con los lenguajes tradicionales del arte. Se investigaron los materiales más insólitos: brea, arena, trapos, chapas, cartones, una miscelánea de objetos de la cultura de masas y desperdicios que se adherían a los lienzos. La conmoción estética no sólo alteró los métodos de producción y los materiales, sino que también se elaboraron nuevas estrategias para la circulación y legitimación de las producciones contemporáneas. Se conformó un incipiente marco institucional que impulsó políticas culturales que se retroalimentaban del nuevo desarrollo económico. Se fundaron el Museo de Arte Moderno (1956) y el Fondo Nacional de las Artes (1958), a la vez que el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes reabrió sus puertas en 1956. Finalmente, en 1960, inició sus actividades el catalizador por excelencia de los movimientos de vanguardia de la cultura argentina: el Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. El Centro de Artes Visuales del Instituto se lanzó en 1963, bajo la potestad del calvo e ilustrado Jorge Romero Brest, un

influyente crítico de arte, fundador de la revista Ver y Estimar y Director del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes entre 1955 y 1963. Su espíritu de progreso, insuflado por la voluntad de modernización e internacionalización que rigió el país durante el período desarrollista, permitió fomentar la experimentación en el arte, inyectarle recursos y promoverla mediáticamente de una manera hasta entonces inusitada en el ámbito argentino. En 1964, las palabras del pope del arte dan clara cuenta de esta operación: “Los jóvenes no sólo rompen moldes, tarea que hicieron ya los de las generaciones anteriores, sino que adoptan actitudes más libres, y esto se logra únicamente actuando en campo total. La diferencia podrá ser excesivamente sutil [...] pero existe: es base de nuestro optimismo, nutrido además por el juicio coincidente de todos los críticos extranjeros que nos han visitado en los últimos años...”.2

Promediando la década del sesenta, muchos de los artistas que se nuclearon en torno al Di Tella habían realizado ya sus respectivos viajes transatlánticos de exploración y autodescubrimiento, con París como principal destino, luego reemplazada por Nueva York, nuevo centro neurálgico del arte moderno. Estos jóvenes exultantes y cargados de ideas volvían a Buenos Aires para desplegar y complejizar las experiencias vividas y las lecciones aprendidas en el exterior. El Di Tella les ofreció el espacio y la contención que necesitaban para tender sus redes y hacer avanzar el arte argentino hacia una nueva era. Durante algunos años, vanguardia e institución caminaron felices de la mano, y el Instituto logró condensar en su programación gran parte del afán de ruptura que reinaba entre los artistas. Se trató de un matrimonio que generó múltiples beneficios para ambas partes, pero que comenzó a resquebrajarse hacia fines de la década debido a las previsibles tensiones entre los artistas y la institución, que se fueron generando a partir de las divergencias de intereses y la distancia ideológica entre unos y otros. El Instituto finalmente mostró su hilacha conservadora ante el avance de la politización y radicalización de los artistas, que opusieron una fuerte resistencia a los intentos institucionales de edulcorar sus producciones y hacerlas aptas al ambiente institucional.

24

2- Romero Brest, Jorge. “Introducción.” En: New Art of Argentina. Cat. Exhib., Buenos Aires: Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, 1964.

Lo hicieron a través de diversas acciones, muchas de las cuales afloraron en torno al Premio Ver y Estimar, presentado en el Museo de Arte Moderno; a la exposición Experiencias 68, en el Di Tella, y al Premio Braque, auspiciado por la Embajada de Francia y presentado en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.3

Sin embargo, durante los años de dicha institucional, los artistas explotaron la oportunidad y dieron rienda suelta a sus investigaciones en torno a una serie de estrategias que buscaron quebrar los límites de las categorías artísticas de rutina. Las aventuras del Pop, el happening , las ambientaciones, la desmaterialización de los objetos y los cruces disciplinarios se convirtieron en moneda corriente entre aquellos que circulaban por los alrededores de “La Manzana Loca”, mote cariñoso con el que se conocía la zona del Di Tella. Estas prácticas también fueron vehículo para una preocupación creciente por la contemporaneidad, por la rápida transformación del tiempo presente y la horda de dilemas culturales, políticos, económicos y sociales que ésta acarreaba. En este contexto de prueba y error, el problema del arte como experiencia y su potencial crítico se fue presentando cada vez con mayor vigor hasta que, a mediados de 1964, para indignación de la prensa y de los detractores de la vanguardia, el Instituto Di Tella otorgó su Premio Nacional a Minujín por sus obras ¡Revuélquese y Viva! , un habitáculo de colchones multicolor que invitaba al visitante a desatar su hedonismo y, literalmente, a revolcarse en la suavidad de la pieza, y Eróticos en Technicolor (1964). Asimismo, otorgaron una mención especial a Emilio Renart por Integralismo. Bio-Cosmos N°3 (1964), una instalación recorrible compuesta por esculturas y pinturas de diversos materiales que representaban inmensas y titilantes vaginas. El Premio no sólo legitimó y abrazó las prácticas de estos jóvenes artistas, sino que institucionalizó una serie de

problemáticas vinculadas a la intimidad, la sexualidad y el compromiso forzoso del cuerpo del espectador con la obra, empujando los límites de la moral y la decencia de la época, a lo que se sumó una explícita y estridente voluntad escandalizadora. Este es el año en que la palabra happening comenzó a aparecer en los medios masivos y el Di Tella se convirtió en objeto de polémica y discusión en los medios.

En la década del sesenta se abrió en el arte un espacio para la transgresión, para quebrar las barreras de aquello sobre lo que durante mucho tiempo no se había podido hablar, de aquello sobre lo cual apenas se había podido pensar, un portal a una nueva dimensión. Así surgen las preocupaciones políticas y sociales que atormentaban a la sociedad argentina en obras como Introducción a la esperanza (1963), de Luis Felipe Noé, que hizo estallar los límites de la pintura con la pura fuerza de la historia argentina, y los Vivo-Dito (1962-1965) del agitador de agitadores, Alberto Greco: acciones mediante las cuales el artista señalaba todo tipo de personajes encerrándolos en un círculo de tiza para luego firmarlos, como si fueran una escultura o una pintura, desacralizando el objeto artístico y utilizando el cuerpo ajeno como único soporte. Aparecen el azar y el humor en la obra de Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos, que en 1964 presenta en la Galería Witcomb unas pinturas tan inmensas que no se pudieron colgar y cuya gran cantidad de materia comenzó a deslizarse por el lienzo hasta llegar al piso de la galería, que se cubrió de pintura, rompiendo así con el rictus de la tradición artística. Peralta Ramos llegó incluso a serruchar una pintura que no pasaba por la puerta.

Tras un largo período de estricta tutela militar, inaugurado en 1955 por la Revolución Libertadora y extendido a los gobiernos de los radicales Arturo Frondizi y José María Guido, la frágil institucionalidad política que a duras penas había

3- En 1968, el medio artístico llegó a su punto de mayor tensión. En la inauguración del Premio Ver y Estimar, Eduardo Ruano lanzó un ladrillo contra su obra, un afiche de John F. Kennedy en una vitrina, al grito de “¡Fuera yanquis de Vietnam!” En mayo se realizó la exhibición Experiencias 68, que originariamente era el Premio Nacional Di Tella, y tomó el título de Experiencias a partir de 1967. Durante la inauguración, Pablo Suárez distribuyó su “Carta de renuncia”, dirigida a Romero Brest, en la puerta del Instituto, en la que manifestaba su disconformidad con la institución y su decisión de no seguir exhibiendo sus obras en ese contexto. Pocos días después, la policía clausuró la exhibición a raíz de las manifestaciones espontáneas del público contra el régimen de Onganía en la obra de Roberto Plate. Ante la clausura, los artistas retiraron sus obras del Instituto y las trasladaron a la calle Florida, donde las destruyeron. Algunos de los artistas fueron arrestados. En junio, el Premio Braque anunció un nuevo requisito: debía presentarse una descripción de los textos que se incluirían en las obras y los organizadores se reservarían el derecho de modificar las obras si lo consideraban necesario. Los artistas respondieron con cartas y manifiestos: primero Margarita Paksa, luego Plate y, finalmente, un grupo de artistas rosarinos liderado por Juan Pablo Renzi escribió y distribuyó el texto “Siempre es tiempo de no ser cómplices”. Durante la entrega de premios, otro grupo de artistas irrumpió en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes arrojando objetos y vociferando su propio discurso. Nuevamente, varios de los artistas fueron arrestados.

25

26

27 La Menesunda, 1965 Vista del Túnel de televisores Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín View of The TV Tunnel Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

logrado establecer el Dr. Illia generó, entre 1963 y 1966, una sensación de posibilidad que resultaba imperativo aprovechar. Sin embargo, el próximo golpe militar estaba a la vuelta de la esquina, y los grupos militares y económicos más poderosos del país respiraban en la nuca del doctor. La Guerra Fría sacudía al mundo entero, y la famosa “doctrina de seguridad nacional”, impulsada por Estados Unidos, infestaba a toda América Latina. Es el fin de la era de Kennedy, y el inicio del recrudecimiento de la lucha militarizada contra el comunismo y cualquier tipo de subversión que se atreviera a manifestarse contra los valores esenciales: los occidentales y cristianos. Es la guerra de Vietnam, la ocupación de la República Dominicana y la invasión de Bahía de Cochinos, es la guerrilla, la contra-cultura, el hippismo y la lucha por los derechos humanos. Para la Argentina, el período inaugurado por la Revolución Libertadora fue turbulento, políticamente convulsionado y económicamente inestable, interrumpido solamente por breves respiros de bonanza económica y alivio pseudo-democrático. Los artistas no permanecieron indiferentes.

El mismo año en que, al interior del paréntesis de aire fresco que era el Instituto, Renart y Minujín fueron galardonados por los ilustres jurados del Premio Nacional Di Tella —Romero Brest, Pierre Restany y Clement Greenberg—, también Julio Le Parc recibió una mención especial en la sección internacional del certamen. La obra Inestabilidad. Proposición arquitectural estaba compuesta por una serie de placas de aluminio curvas que, conectadas a un motor que provocaba su movimiento, permitía el paso intermitente de luces rasantes emitidas desde uno de los lados de la estructura. La pieza, en línea con las investigaciones del GRAV ( Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel ), del cual Le Parc formaba parte en París, se proponía como un lugar para la activación del visitante, abriéndose a los matices de su percepción y reclamando su cuota de participación.

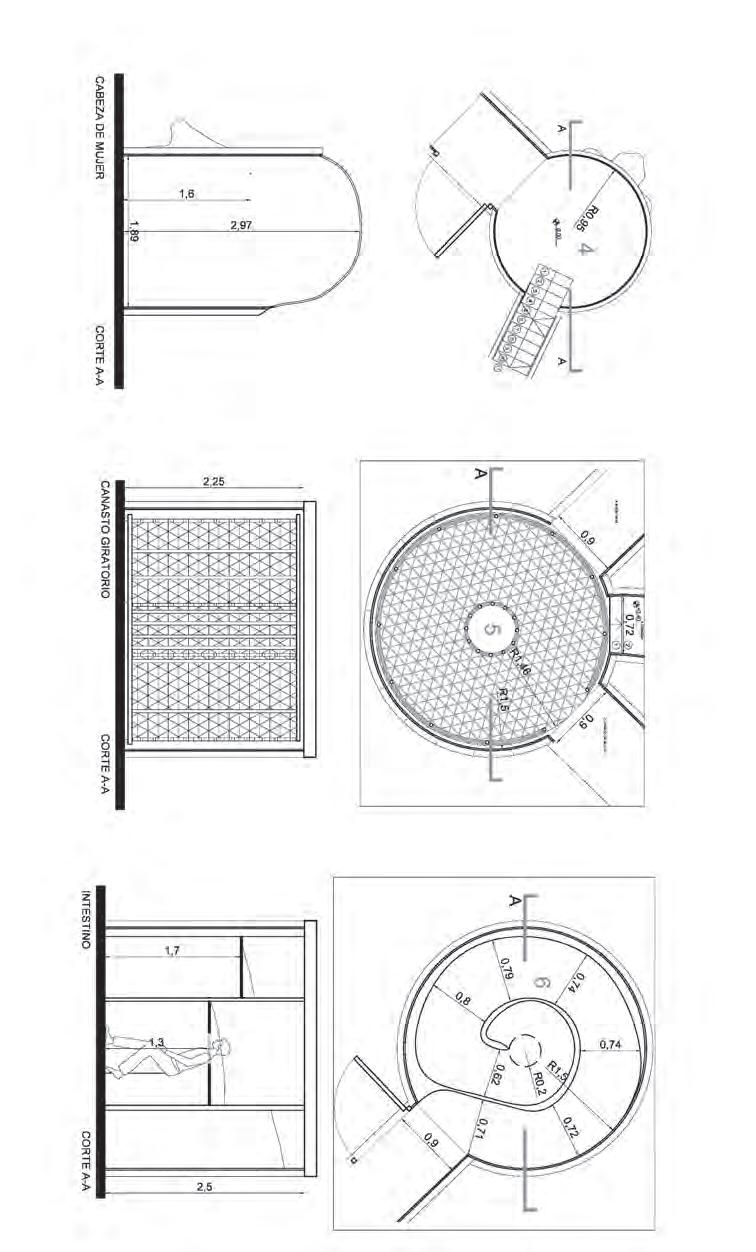

Para fines de 1964, hacía tiempo que una serie de proyectos estructurados en torno a estos planteos que

esperaban ser realizados zumbaban como abejas en los oídos de Romero. Entre ellos, deambulaba por el Instituto un proyecto en forma de maqueta, producto de reuniones que por esos días mantenían Santantonín y Minujín con Renart, Kemble y Pablo Suárez, el germen de lo que poco después se convertiría en La Menesunda . 4 Desde 1963 circulaba también en las oficinas del Di Tella el proyecto Arte-cosa rodante de Santantonín. Una iniciativa que buscaba materializar sus ideas sobre el rol del espectador/participante/ mirón —como Santantonín definió al no-contemplador de su trabajo 5— en la obra de arte. De acuerdo con sus escritos, se trataba de una “especie de informe de superficie rojiza y seca extendido sobre una tarima arrastrada por un jeep [...] que se pasearía por la ciudad atrayendo por su semejanza con los monstruos populares de Bolivia, México o Perú. Una vez estacionado en una plaza se apelaría al público, invitando a la gente a penetrar en su interior. Una vez adentro, el espectador dejaría de serlo para participar directamente en este mundo mágico y distinto del cual él mismo crearía buena parte. Entraría en el vientre de una inmensa forma donde se encontraría moviendo y componiendo formas”.6 Arte-cosa rodante constituía el extremo mismo de “la cosa”, concepto acuñado en 1961 por Santantonín para nombrar a sus obras y que le ganó un lugar junto a Luis Wells en el panteón de “los malditos de Argentina” de Kenneth Kemble, 7 que los consideraba artistas incomprendidos por su innovación y que, anticipándose al futuro, se arriesgaban a ser ignorados.

Las claras manifestaciones de los artistas acerca de su contemporaneidad, en las que cuestionaban los términos de la participación del espectador en los procesos de creación y exposición de las obras, los límites cada vez más lábiles del lenguaje estético y su posibilidad de disrupción parecen haber inspirado a Romero Brest, también a instancias del acoso que le propiciaron los artistas y muy especialmente la infatigable Minujín, para finalmente comisionar la realización de un audaz proyecto. Así es que, a fines de 1964, se dio inicio

28

4- Este proyecto es mencionado en: Laura Buccelato, Greco Santantonín, Fundación San Telmo, 1987, catálogo de exposición; y en Marcelo Pacheco, “De lo moderno a lo contemporáneo. Tránsitos del arte argentino 1958-1965”. En Inés Katzenstein (ed), Escritos de vanguardia. Arte argentino de los años ´60, Fundación Espigas, Buenos Aires, 2007.

5- Rubén Santantonín, Hoy a mis mirones, Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, 1961, folleto.

6- Rubén Santantonín, archivo personal.

7- Kenneth Kemble, “Argentina’s Band of the Damned”, Buenos Aires Herald, 25 de septiembre de 1961.

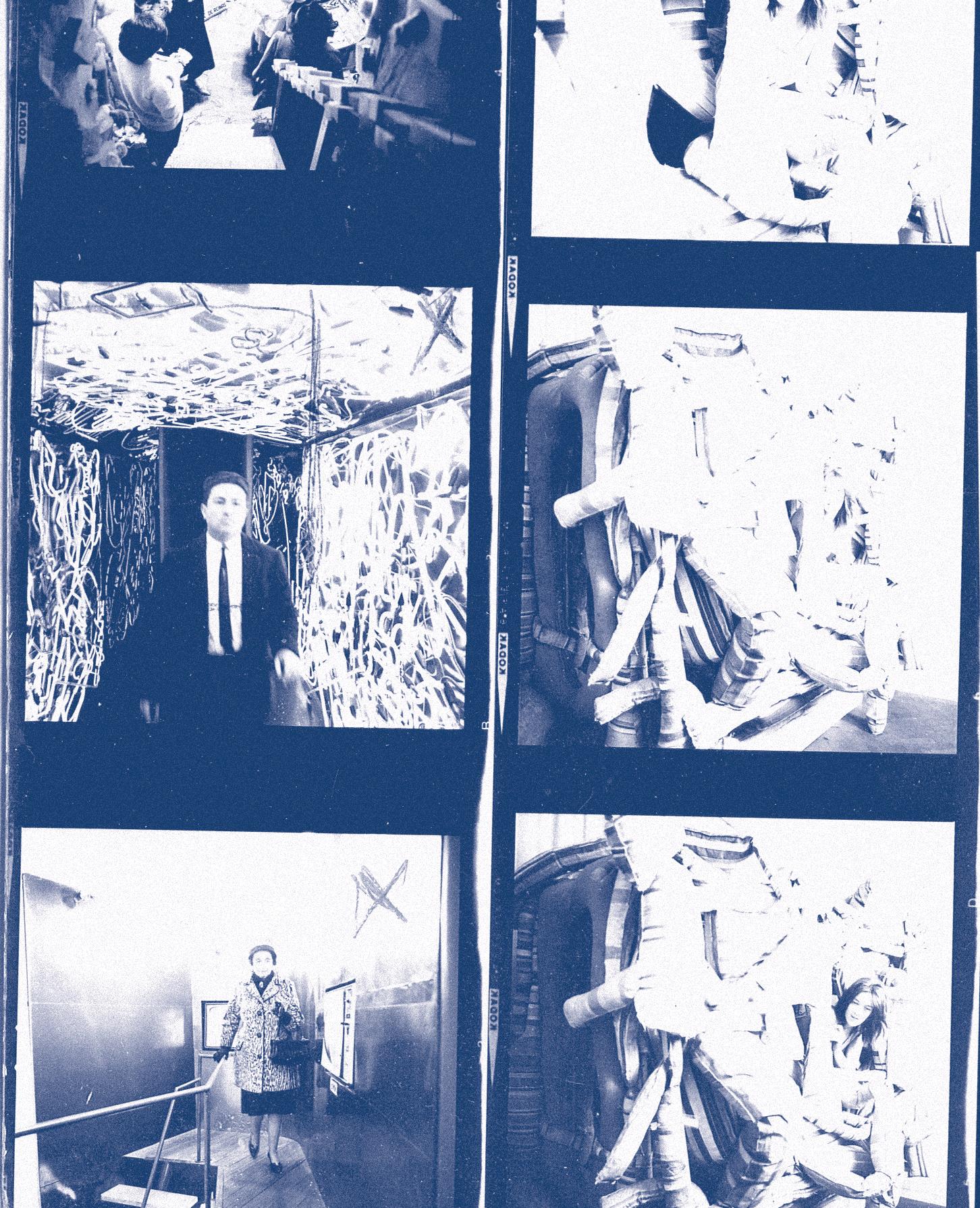

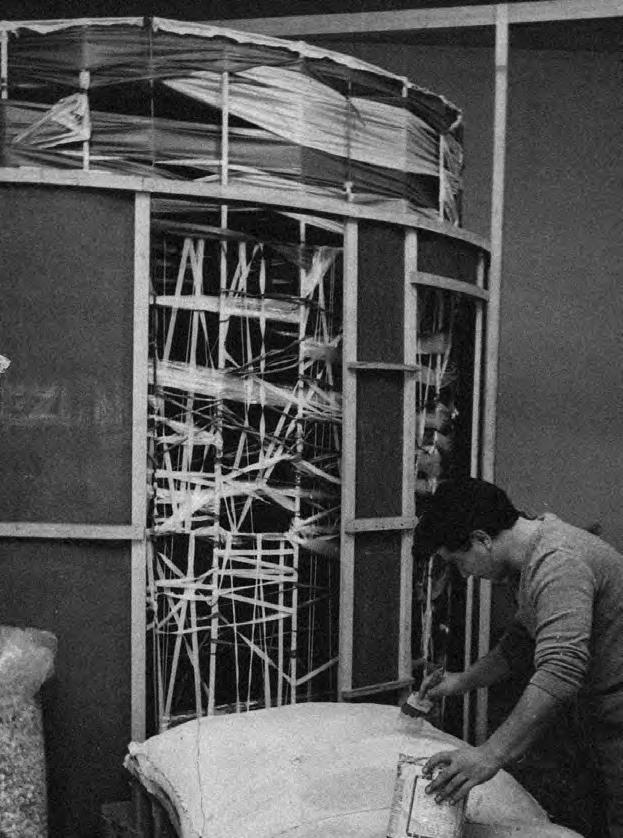

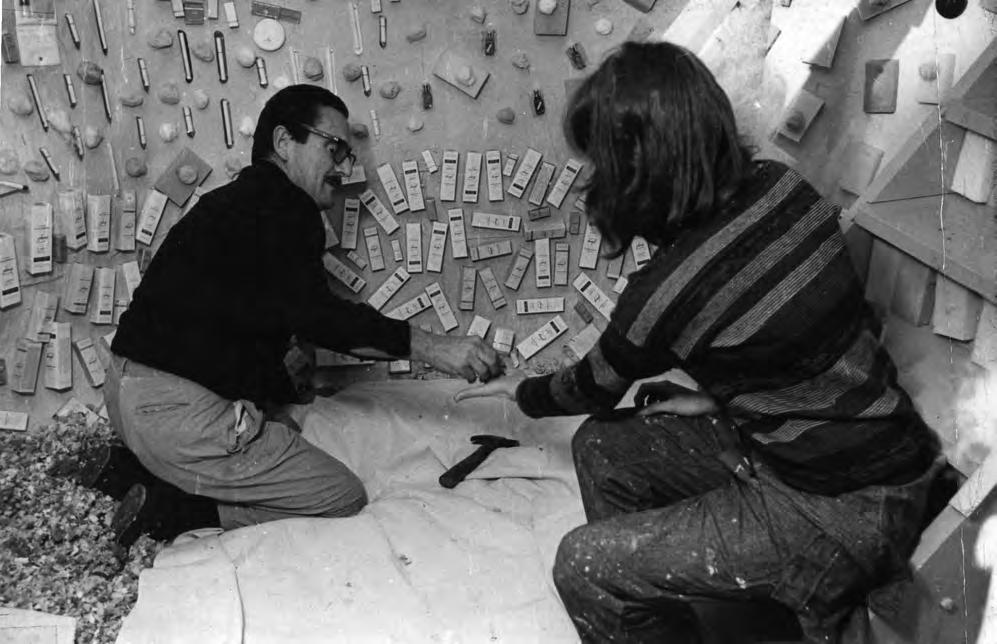

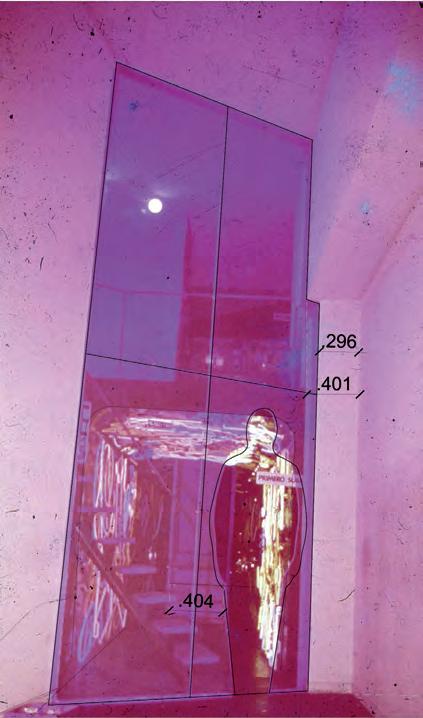

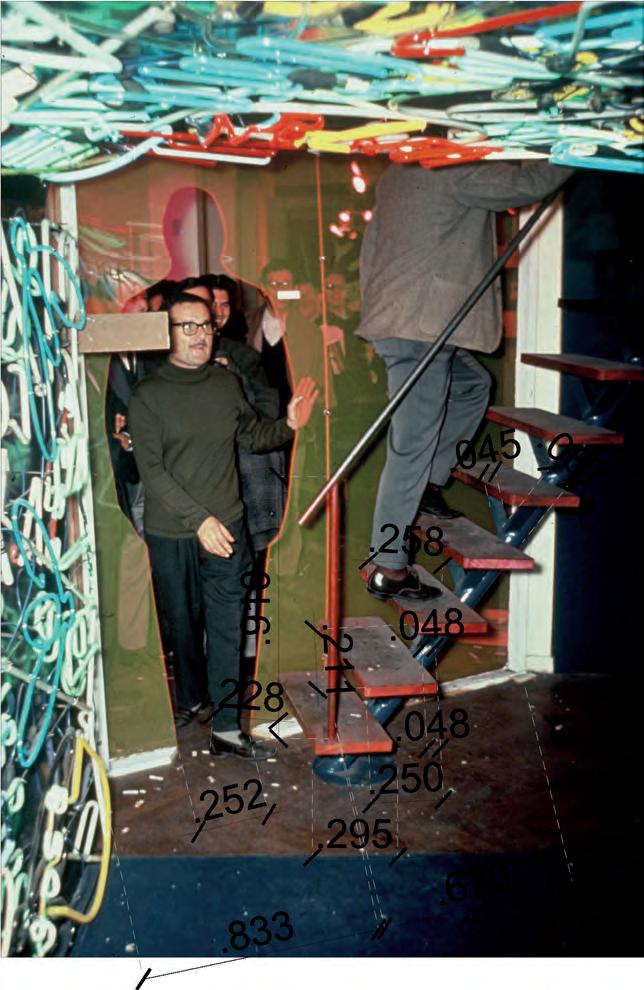

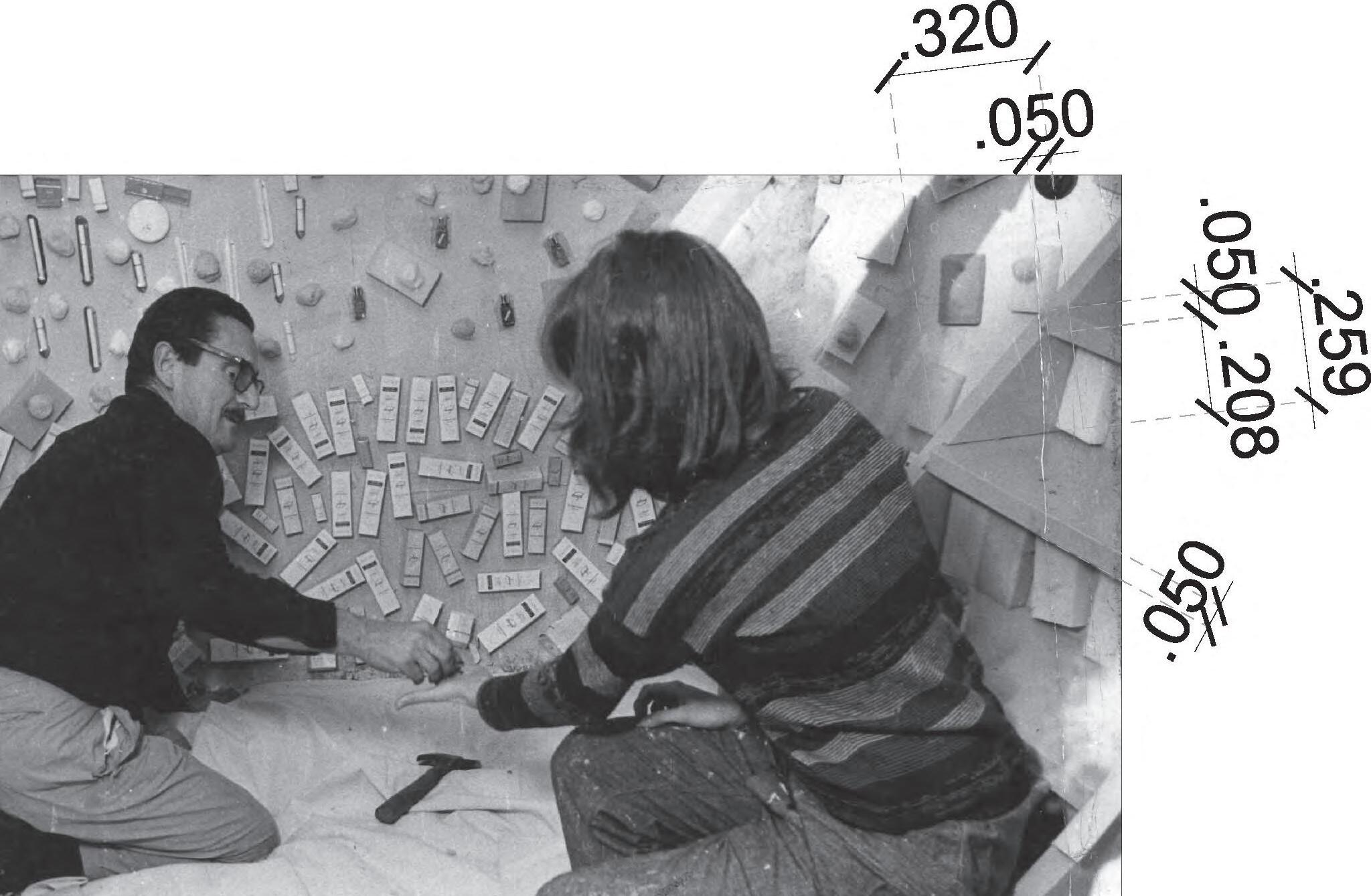

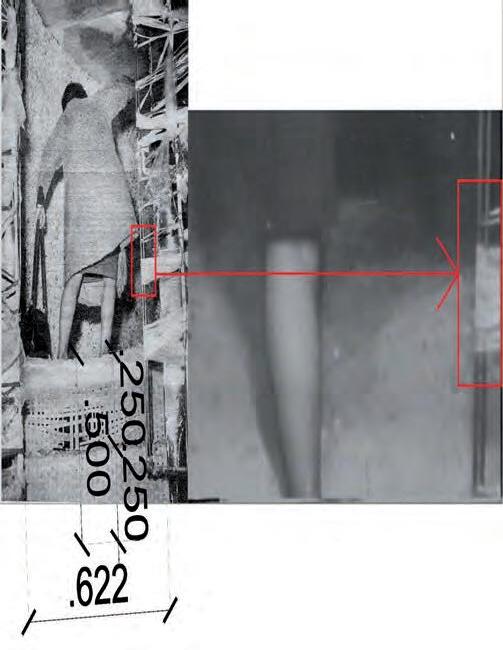

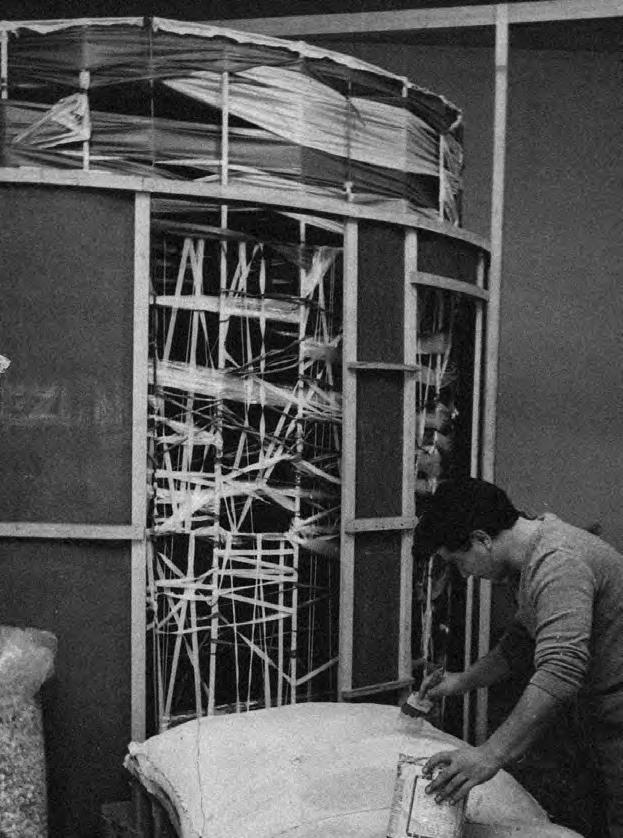

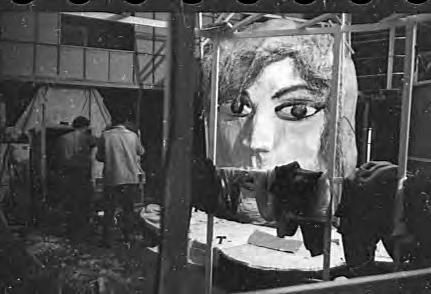

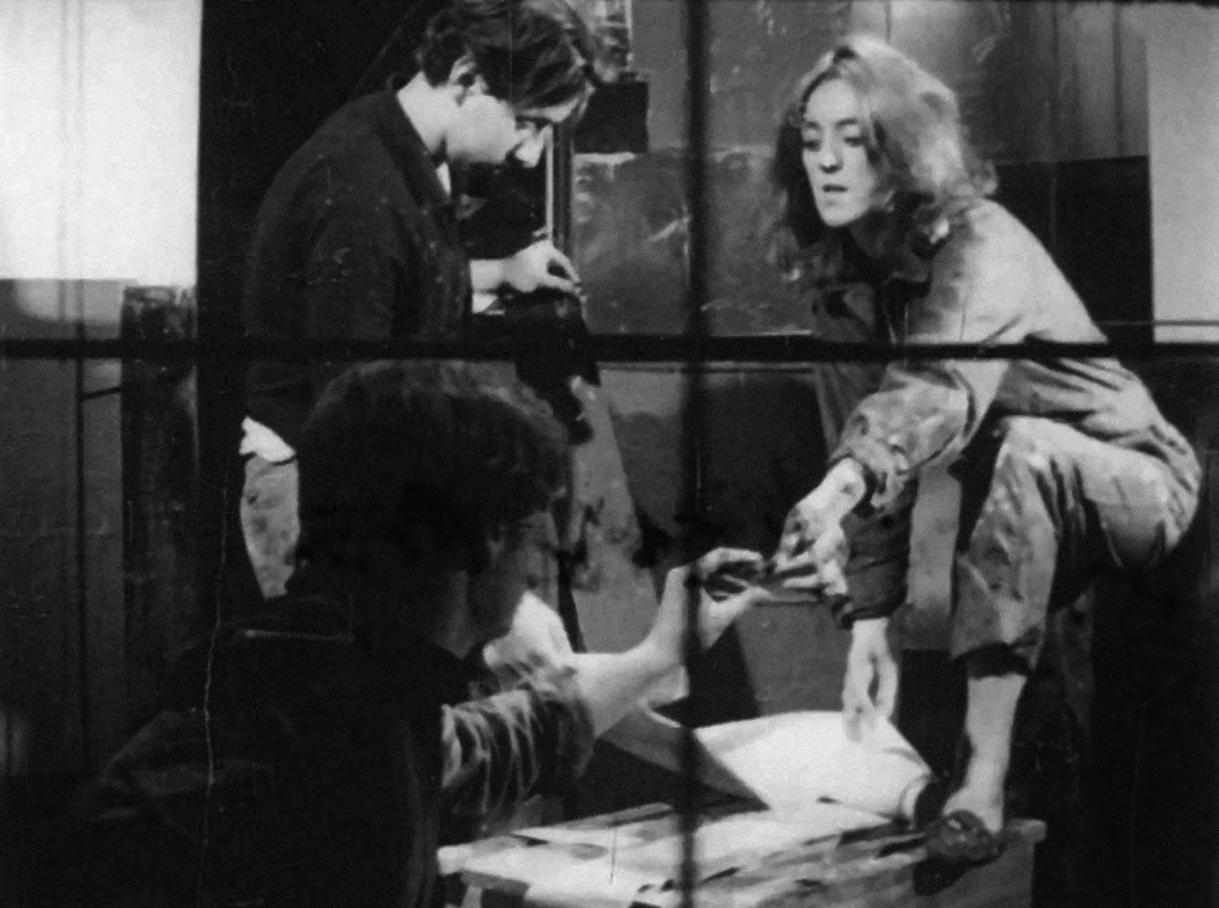

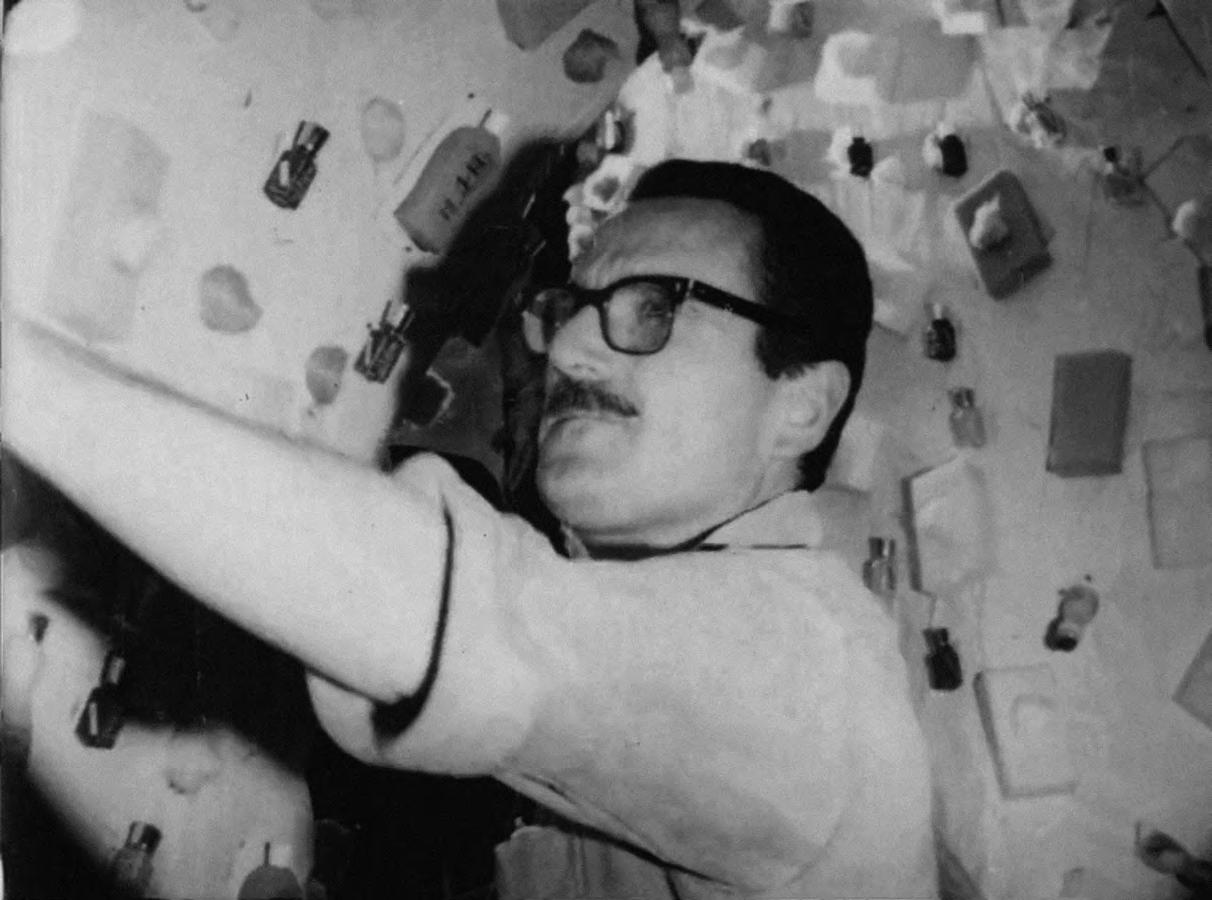

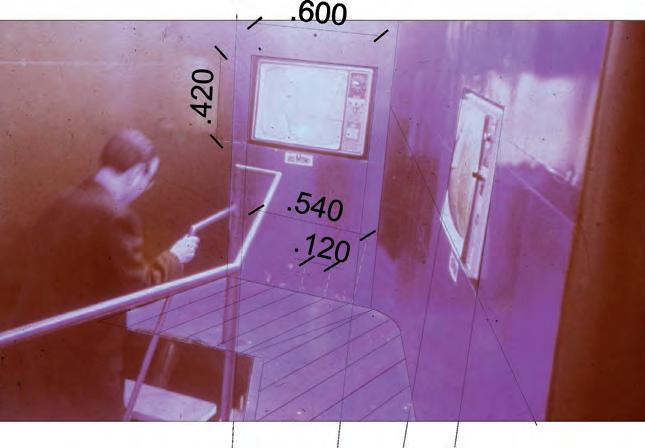

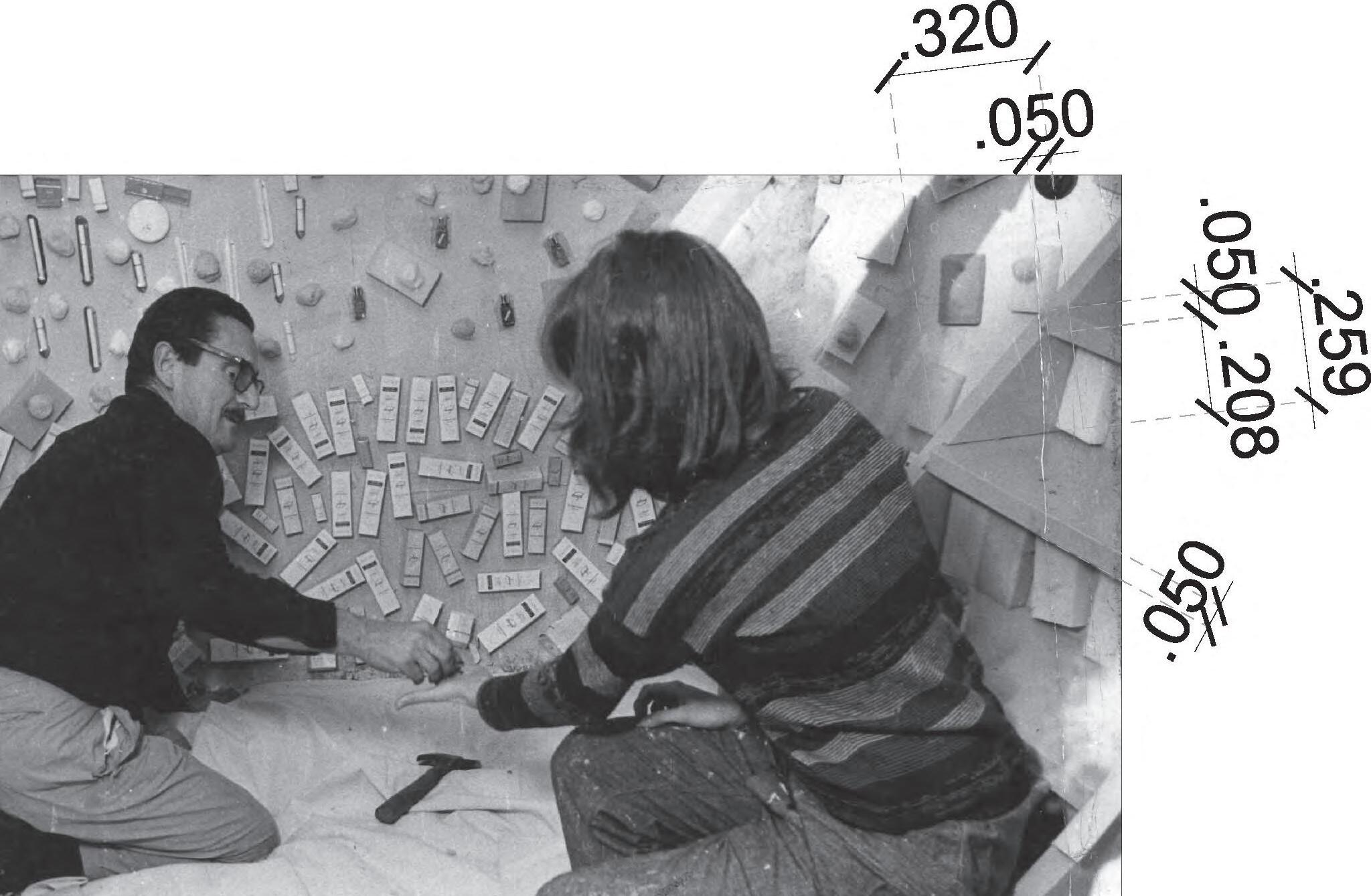

La Menesunda, 1965 Vistas de la construcción Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín Installation views Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

La Menesunda, 1965 Vista del Túnel de televisores Cortesía Archivo Centro de Artes Visuales, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

View of The TV Tunnel Courtesy Centro de Artes Visuales Archive, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

La Menesunda, 1965 Vista general del Túnel de neón Cortesía Archivo Centro de Artes Visuales, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

View of The Neon Tunnel Courtesy Centro de Artes Visuales Archive, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

30

al titánico proyecto de La Menesunda , liderado por Minujín y Santantonín, quienes con la complicidad de Floreal Amor, Lamelas, Suárez, Prayón y Maler y un maestro mayor de obras cuyo nombre ha sido olvidado, se embarcaron en la creación de un laberinto de compartimentos contenedores de situaciones cuyo propósito era —según reza el folleto de la exhibición— “intensificar el existir”.

Esta obra, con sus once ambientaciones, laberíntica y confusa, como su nombre en lunfardo lo indica, producía un entramado visual y sensorial anclado en la vida moderna de la ciudad, una vida que para 1965 tenía en Buenos Aires una corta pero intensa existencia, con sus ritos colectivos, culturales y folclóricos, con itinerarios y preocupaciones establecidos, reconocibles a lo largo del recorrido. Tras una larga espera en la calle Florida y luego, entre las pinturas del moderno pintor Jean Dubuffet, la expectante audiencia ingresaba finalmente a la exposición de la que todos los medios hablaban. La prensa retrataba la escena con minucia: “Llegamos al Instituto Torcuato Di Tella (Florida 936) y nos encontramos con una larga fila de gente esperando entrar en La Menesunda. Hombres y mujeres. Escépticos unos. Sonrientes otros. Observaban ansiosos los rostros de los que salían. Querían saber de qué se trataba. Qué era lo que iban a ver. Qué les iba a pasar allí adentro…” 8

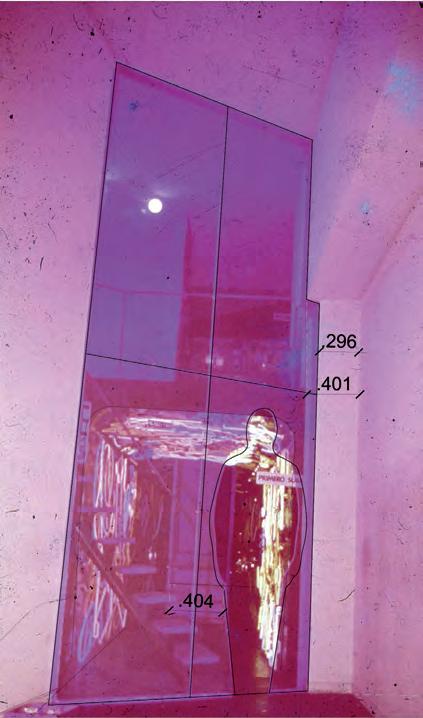

El primer paso consistía en atravesar un portal de acrílico rosa, a través de una alargada figura humana, donde un guardia recibía a los visitantes y los instruía acerca del uso de la obra. En el mismo tono, un cartelito indicaba que el visitante debía primero subir una empinada y precaria escalera que impedía el paso hacia un túnel de neones que emulaba las luces y el frenesí de las calles del centro. El visitante debía aventurarse escaleras arriba para encontrarse con el primero de los ambientes: una especie de cubierta de barco equipada con siete televisores, de los cuales dos reproducían la imagen del visitante en circuito cerrado y los cinco restantes emitían imágenes de programas de televisión abierta, desde el noticiero hasta el Club del Clan. Este pequeño espacio

resumía la naturaleza del resto del recorrido. La presencia de los aparatos de T.V., incipientes miembros de la gran familia argentina, y la posibilidad para muchos de ver aparecer su imagen por primera vez en una pantalla plantean una serie de cuestiones que aparecerán, a partir de aquí, en forma recurrente: el avance desaforado y el uso doméstico de la tecnología y de los medios de comunicación, la invasión del cuerpo y la privacidad del espectador y la absoluta inmersión en una estructura tan precaria como espectacular que impide que el espectador la evada o, lo que en este caso es igual, se evada a sí mismo. La Menesunda era, decididamente, una provocación; su objetivo, sacar a la gente del estupor de la vida cotidiana y obligarla a enfrentarse a esa cotidianeidad representada por objetos en extremo familiares, para abrir nuevas lecturas en oposición. ¿Será la televisión un nuevo y mejorado entretenimiento o un medio masivo de distracción y disputas de poder?

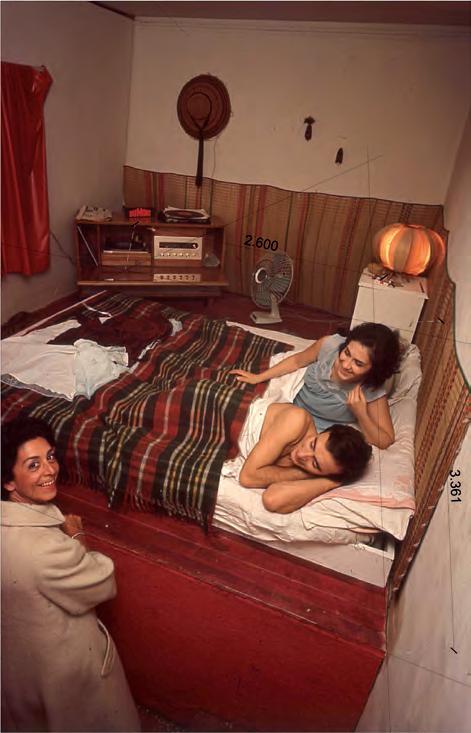

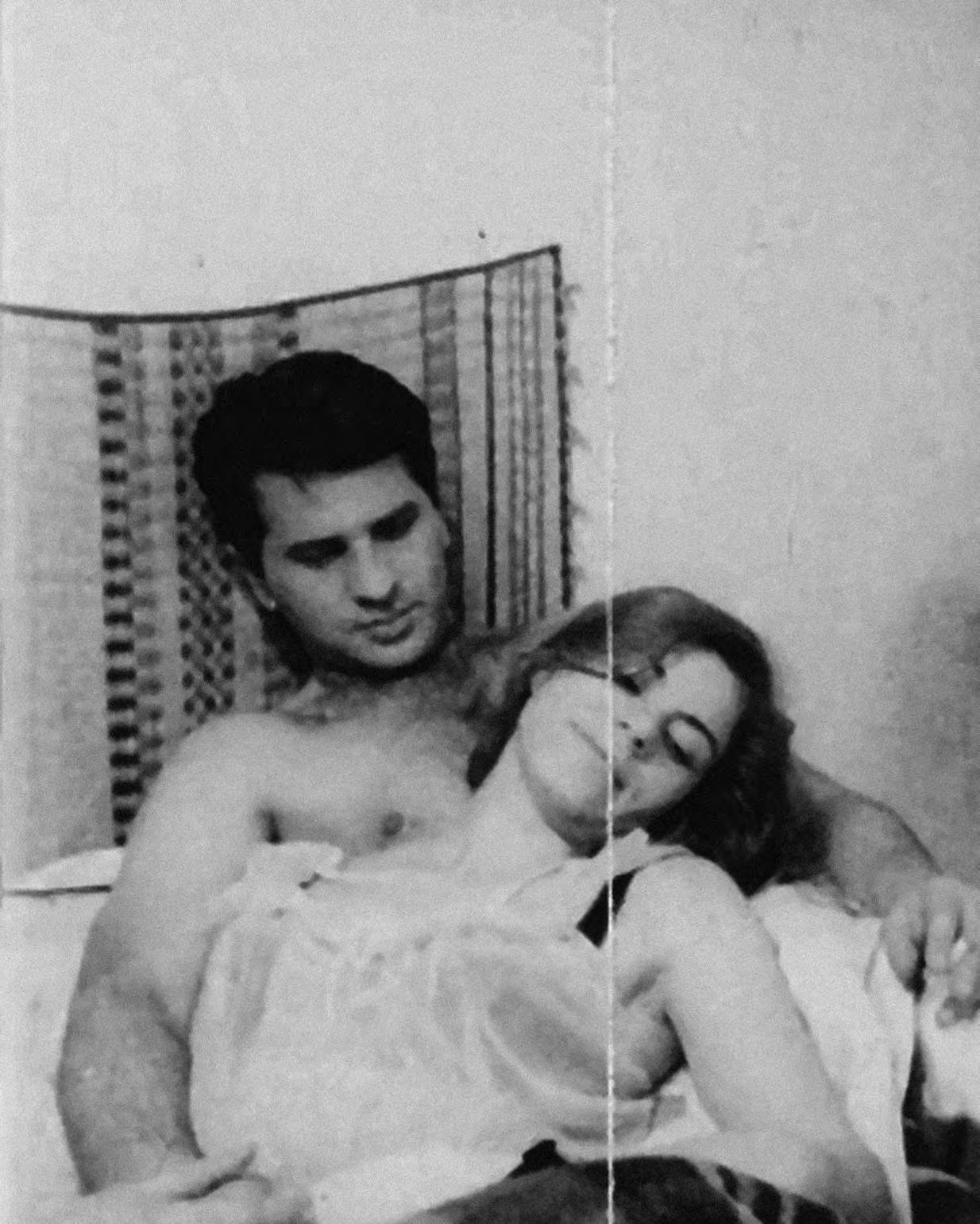

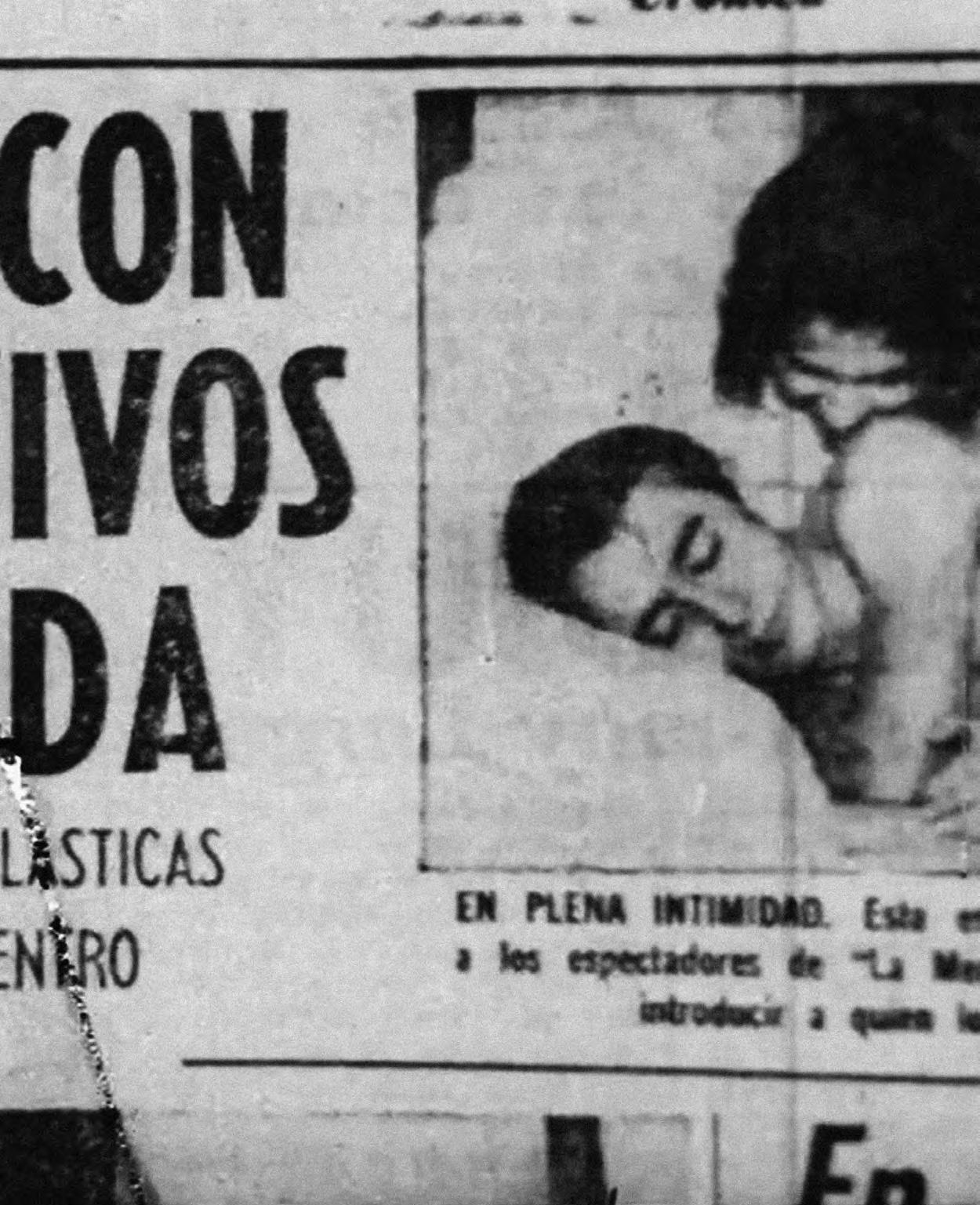

Luego de verse impactado por su propia imagen en una pantalla, el visitante debía optar por bajar hacia un túnel de neón que emulaba las luces de la Avenida Corrientes, o bien continuar rumbo al siguiente espacio, donde nuevamente se veía impactado por una imagen, esta vez la de una pareja que reposaba en paños menores en una cama.9 Los actores —una pareja que tras la larga estadía en la obra terminó por separarse y otra que apenas se conocía—10 pasaban el día fumando, tejiendo y escuchando a Los Beatles, mientras la gente circulaba por el costado de la cama, algunos increpándolos con preguntas, con miradas de desaprobación, y otros esbozando sonrisitas cómplices de asentimiento y aceptación. La desnudez y un lecho matrimonial expuestos a la luz del día: una afrenta a la moral, un cruce descarado de lo privado hacia lo público; en pocas palabras, un escándalo supino, o bien un golpe de liberación propinado por una juventud sofocada a una sociedad pacata que entronizaba la virtud cristiana. Esta imagen se reprodujo en varios medios y se convirtió en ícono de la obra y sinónimo de provocación. Sólo esto era suficiente para amedrentar a los visitantes, que tras golpearse la frente con el vano de la pequeña puerta de salida,

8- “‘Algo’ para locos o tarados”, Careo, 2 de junio de 1965.

9- Según los relatos de algunos de los artistas que colaboraron en la construcción de la obra, fue el lecho matrimonial y la actuación de sus performers lo que disparó el interés de los medios y el consiguiente aluvión de público curioso. Conversaciones de la autora con Leopoldo Maler y Rodolfo Prayón, mayo 2015.

10- Según el relato de Leopoldo Maler, mayo 2015.

31

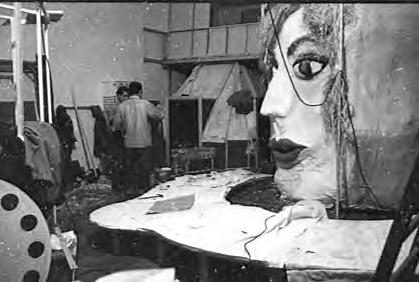

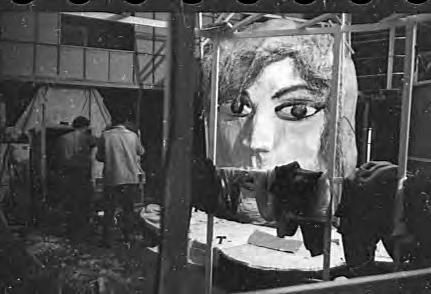

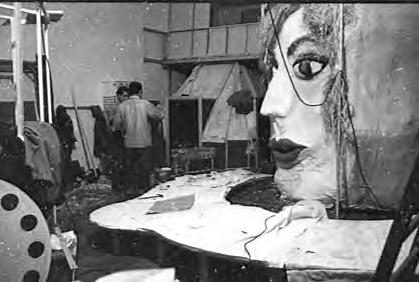

debía continuar su camino a través de otra estrecha escalera hacia lo que luego sabría era el interior de una enorme cabeza de mujer, cuyo exterior había sido pintado por Pablo Suárez,11 y su interior, revestido con productos de belleza. Allí, una maquilladora profesional y una masajista ofrecían, solícitas, sus servicios a quien quisiera recibirlos. En un artículo, Minujín y Santantonín explicaban: “Con eso quisimos significar que el espectador se halla dentro del cerebro de una mujer de nuestra generación…,”12 a lo cual la prensa respondió con quejas y polémicas, alegando que era un agravio a las mujeres cuyos intereses no se centraban exclusivamente en el maquillaje y los tratamientos de belleza, sin admitirlo como una posible reflexión acerca del cambiante rol de la mujer y sus nuevas obligaciones y posibilidades en una sociedad en plena transformación.

El paso siguiente consistía en el dificultoso ingreso a un canasto de hierro giratorio recubierto por tiras de plástico de colores, que daba paso a otros dos espacios. El primero, un angosto pasillo de paredes recubiertas por enormes “intestinos” de polietileno, tenía un techo que se hacía más bajo a medida que el espectador avanzaba, hasta desembocar en un orificio, probablemente anal, por el cual podía asomarse y contemplar una serie de apacibles escenas de paisajes tomadas de películas del sueco Ingmar Bergman, figura con gran influencia sobre el nuevo cine argentino que atacaba la tradicional cinematografía de comedias burguesas y aventuras gauchescas.

La trama de referencias cultas y populares que se revela aquí da cuenta de la complejidad de una obra atenta a su entorno y sus transformaciones, así como de las posibilidades de vinculaciones que desbordan todos los ámbitos de la cultura y se encuentran reunidas y desjerarquizadas en un solo ambiente. El juego de oposiciones entre la sofisticación y densidad bergmanianas y la cultura de masas de la televisión argentina o sus productos de belleza tensiona de manera crítica la bases de la construcción de la contemporaneidad en la ciudad de Buenos Aires, donde convivían en constante negociación el Club del Clan y

Los Gatos, Rodolfo Walsh y Palito Ortega, Rodolfo Kuhn y Carlitos Balá, Los Beatles y el folclore nacional. Estos matices, sin embargo, se disiparon en el barullo de las acusaciones e insultos propiciados por la prensa; claro que semejante barullo era de esperarse con la irrupción de una propuesta de estas características en un foro público, plagado de innumerables contradicciones internas, que enfrentaba a una sociedad en plena modernización cultural con el avance de los militares y la imposición de sus valores anquilosados.

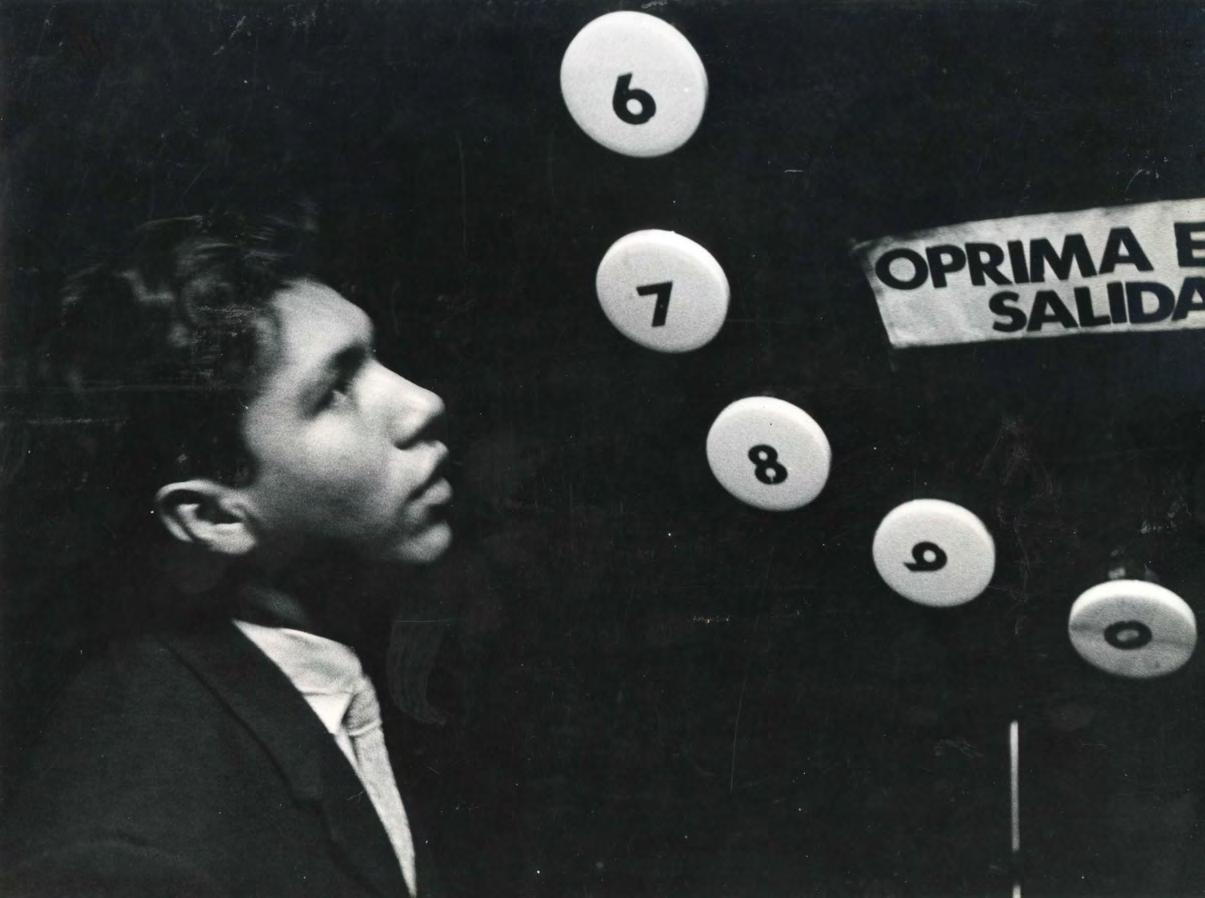

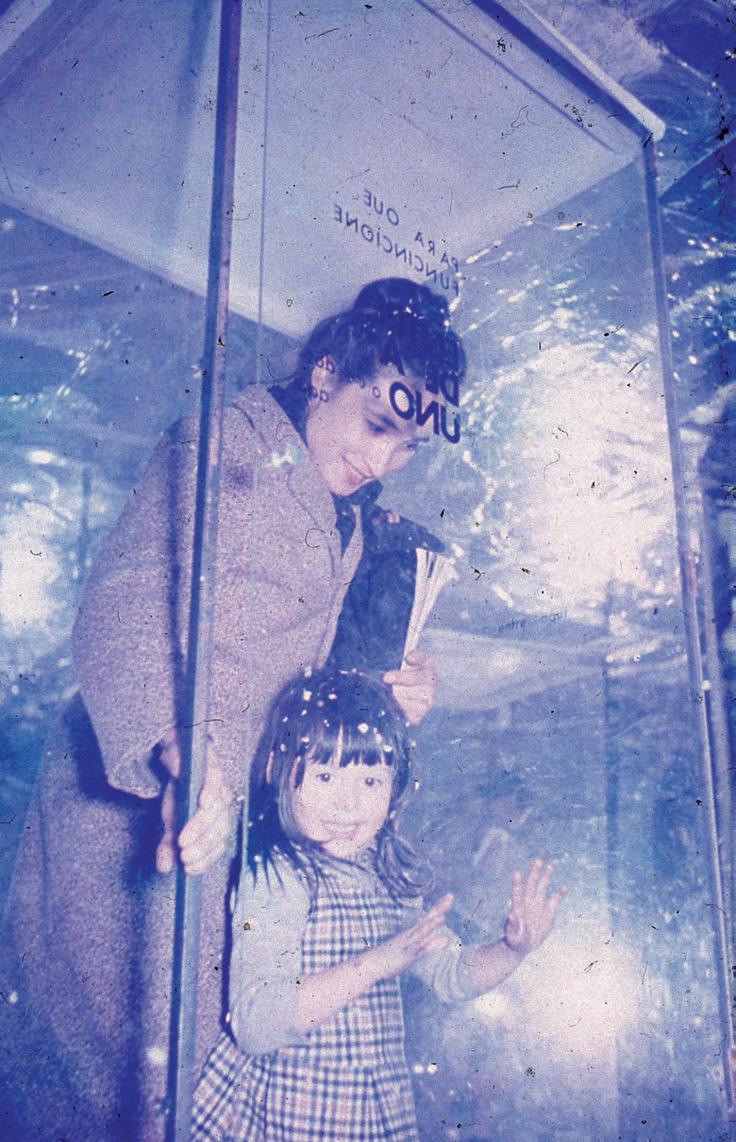

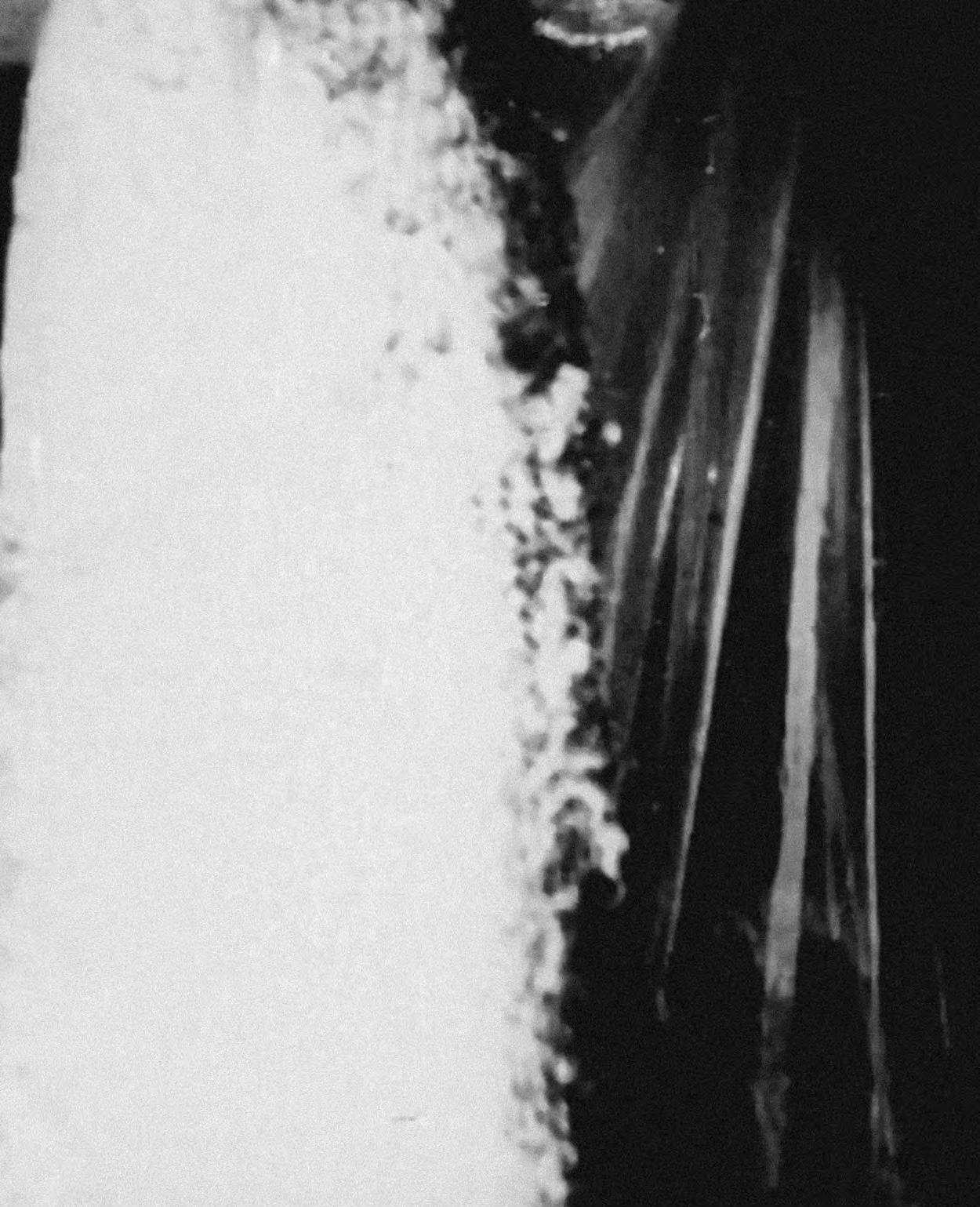

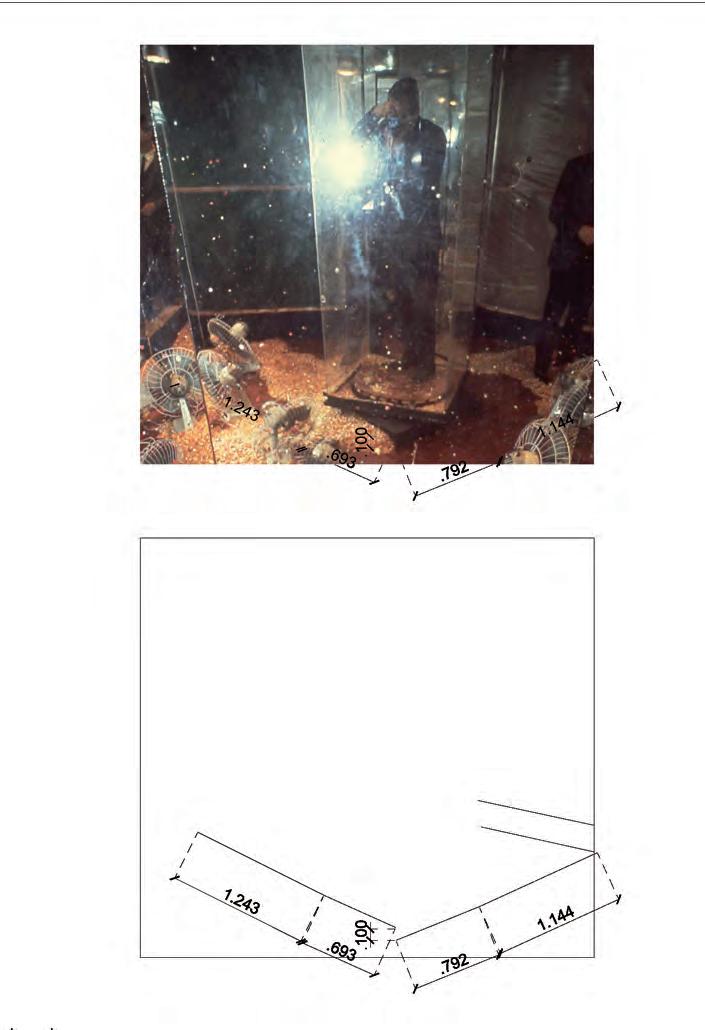

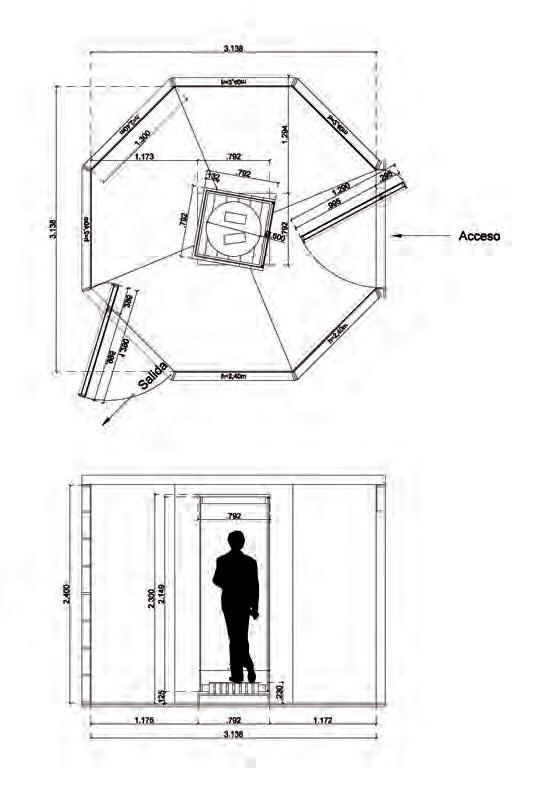

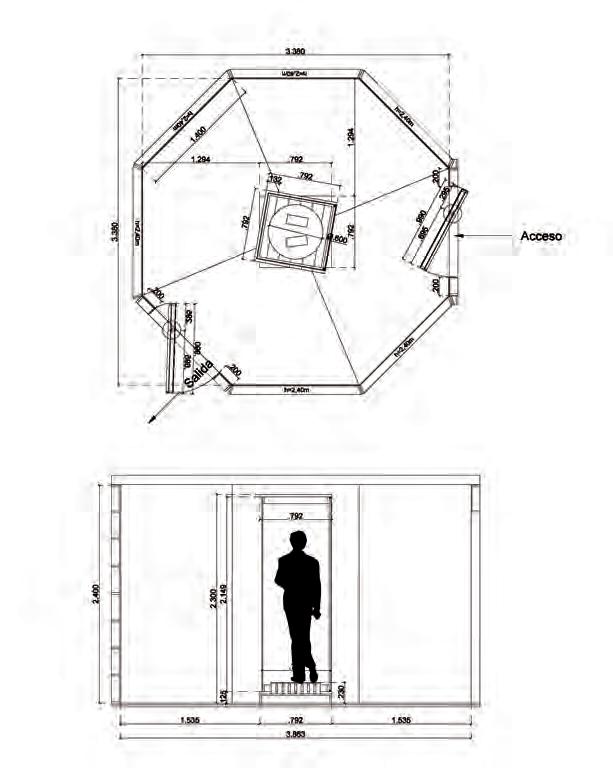

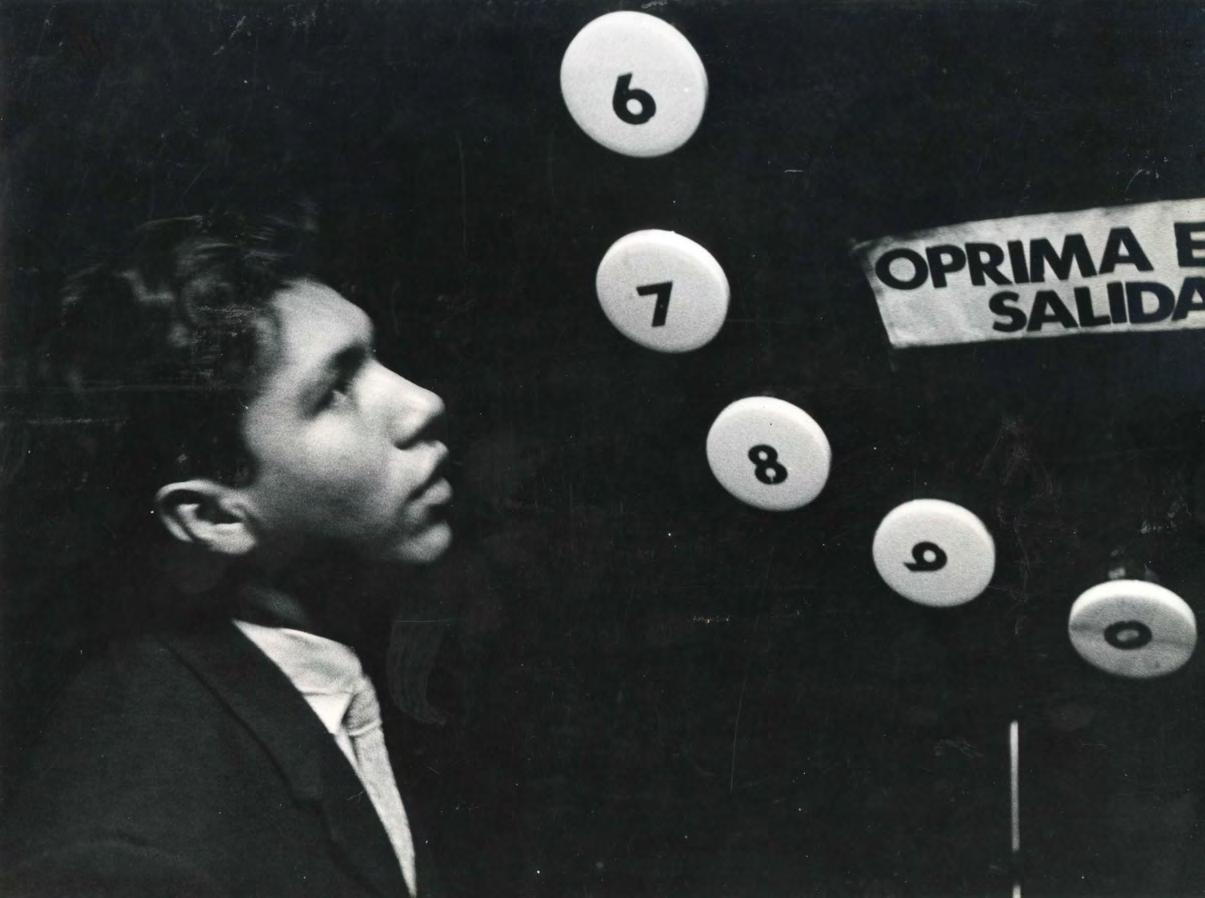

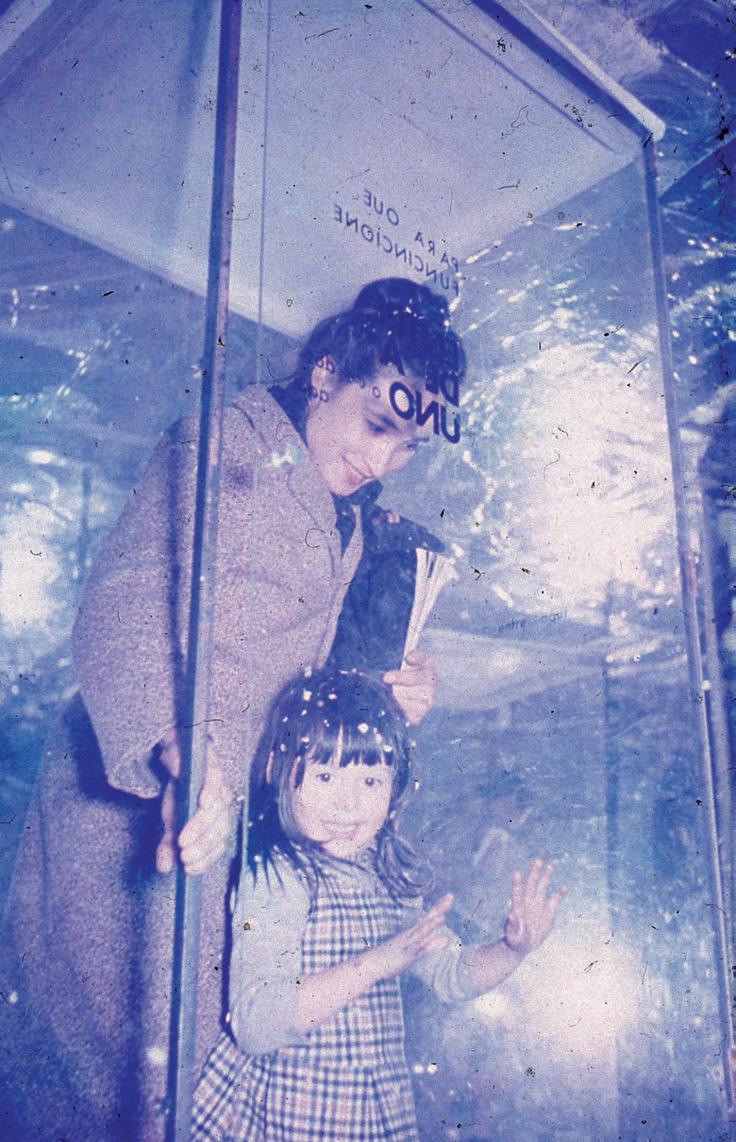

Tras el breve lapsus fílmico, el visitante debía retornar al canasto e ingresar a lo que los autores llamaron “La Ciénaga”, un pasillo mullido, tanto que se entorpecía el avance y las paredes desprendían pedacitos de goma espuma que iban cubriendo poco a poco el piso. A continuación, se ingresaba a una pequeña y oscura habitación, con un intenso olor a dentista potencialmente provocadora de ataques de claustrofobia, coronada por un inmenso dial de teléfono y una única instrucción: apriete el botón para abrir la puerta. 13 Un breve tránsito por una heladera con temperaturas bajo cero conducía a un pasillo ocupado por diversas formas y texturas, suaves y ásperas, placenteras e irritantes, que los transeúntes no tenían manera de evitar. Finalmente se llegaba a una habitación octogonal con paredes de espejos y olor a fritura, ese olor que en Buenos Aires se encuentra en la Avenida Corrientes entre la pizza de “Güerrin” y las milanesas del “Palacio de la papa frita”, en cuyo centro se ubicaba una cabina de acrílico transparente, desde la cual se activaban luces negras y ventiladores que provocaban un torbellino de papel picado que acompañaría a los visitantes durante todo el trayecto de vuelta a su hogar. Se trata del golpe final: un caos de papel picado volando por el aire, luces negras de boite bailable al mejor estilo Mau Mau, 14 paredes de espejos cual laberinto de parque de diversiones o casa del horror. Para algunos, suficiente material para varias sesiones de psicoanálisis. En esta habitación octogonal, la mirada no tenía adónde escapar, el reflejo la seguía a todas partes: era la confrontación final con la vanguardia, con la brutal transformación del arte y con

11- Conversaciones de la autora con Leopoldo Maler y Rodolfo Prayón, mayo 2015.

12-“‘Algo’ para locos o tarados”, Careo, 2 de junio de 1965.

13- El número secreto, aunque no tan secreto según informa la prensa, era indicado al momento de ingresar para evitar desmayos o sensaciones de claustrofobia entre los más sensibles a la oscuridad.

32

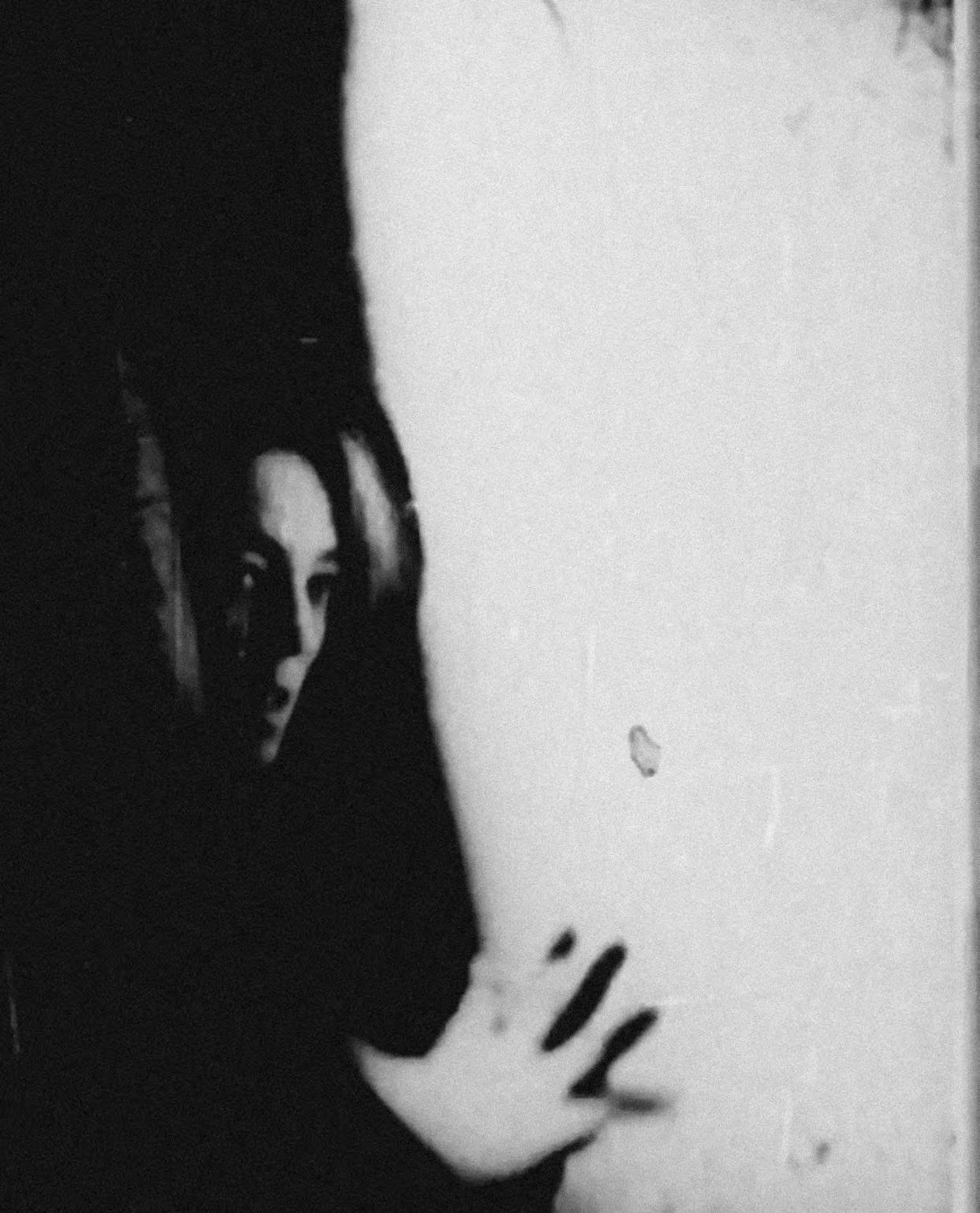

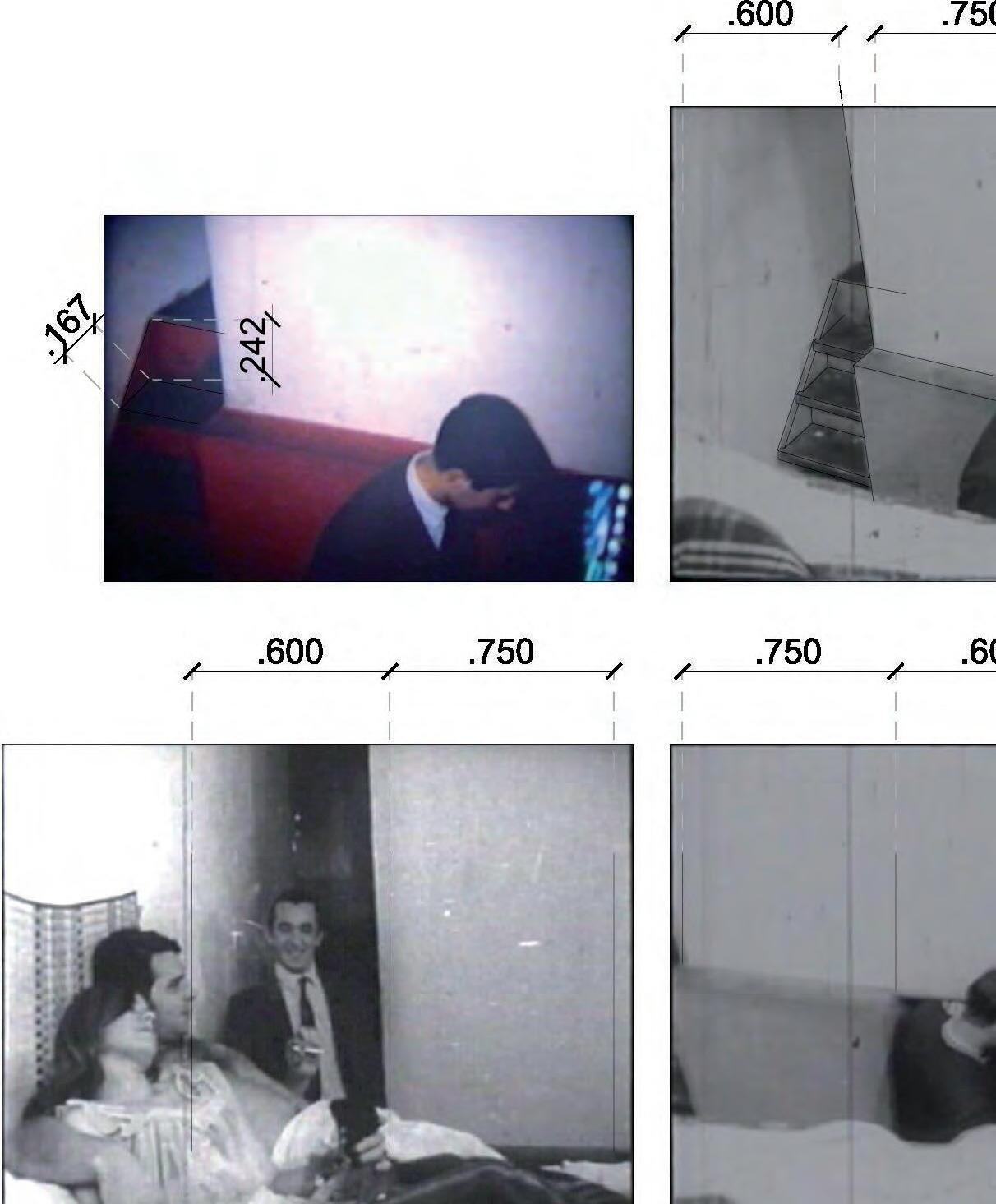

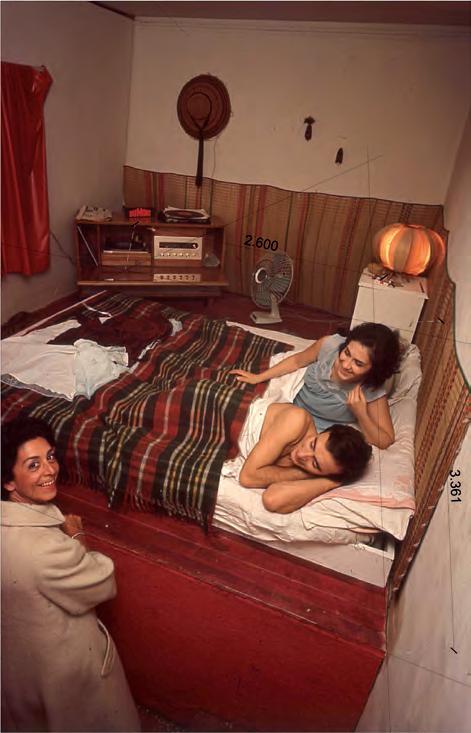

La Menesunda, 1965

Vista del espacio Dormitorio

Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín

View of The Bedroom

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

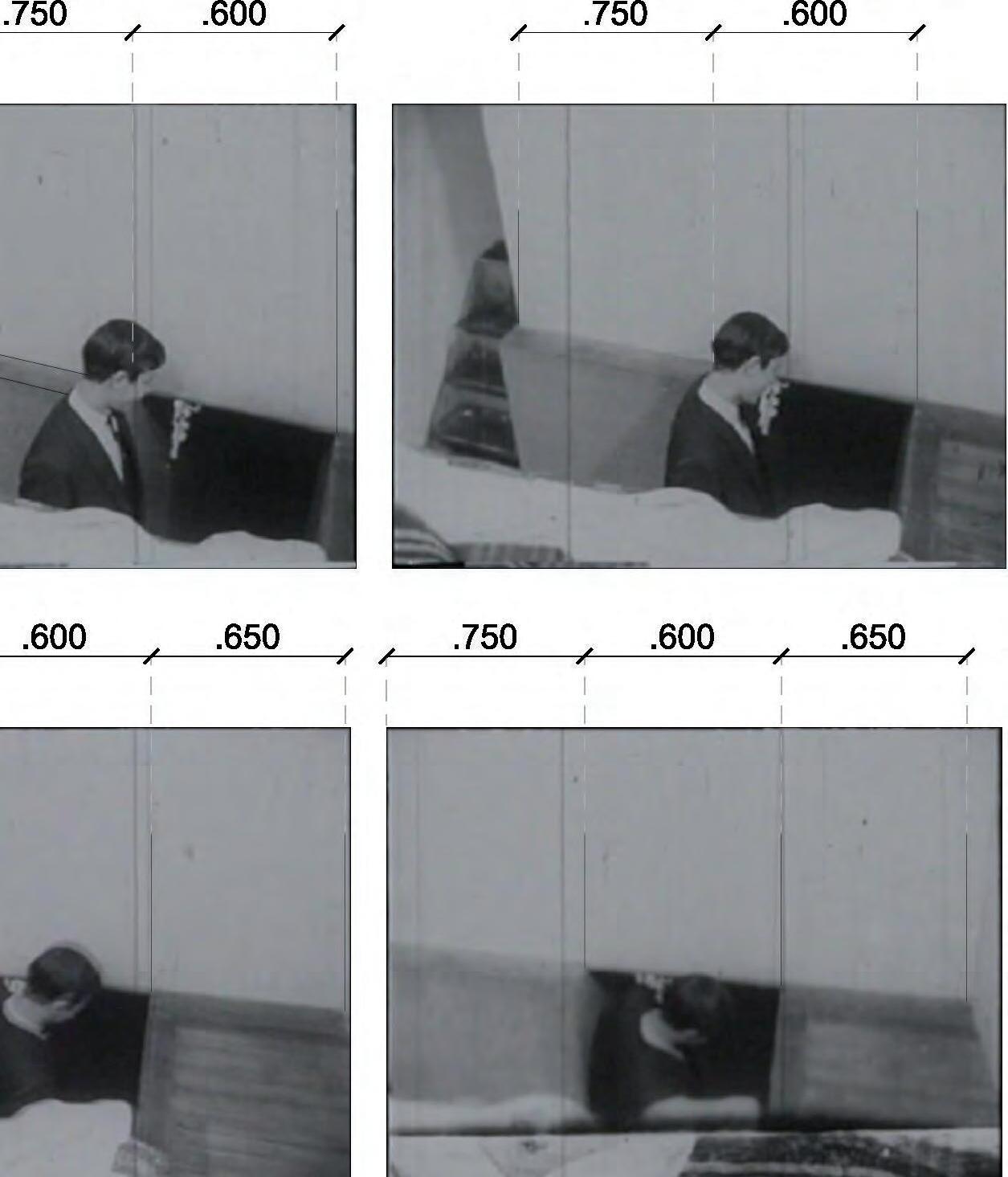

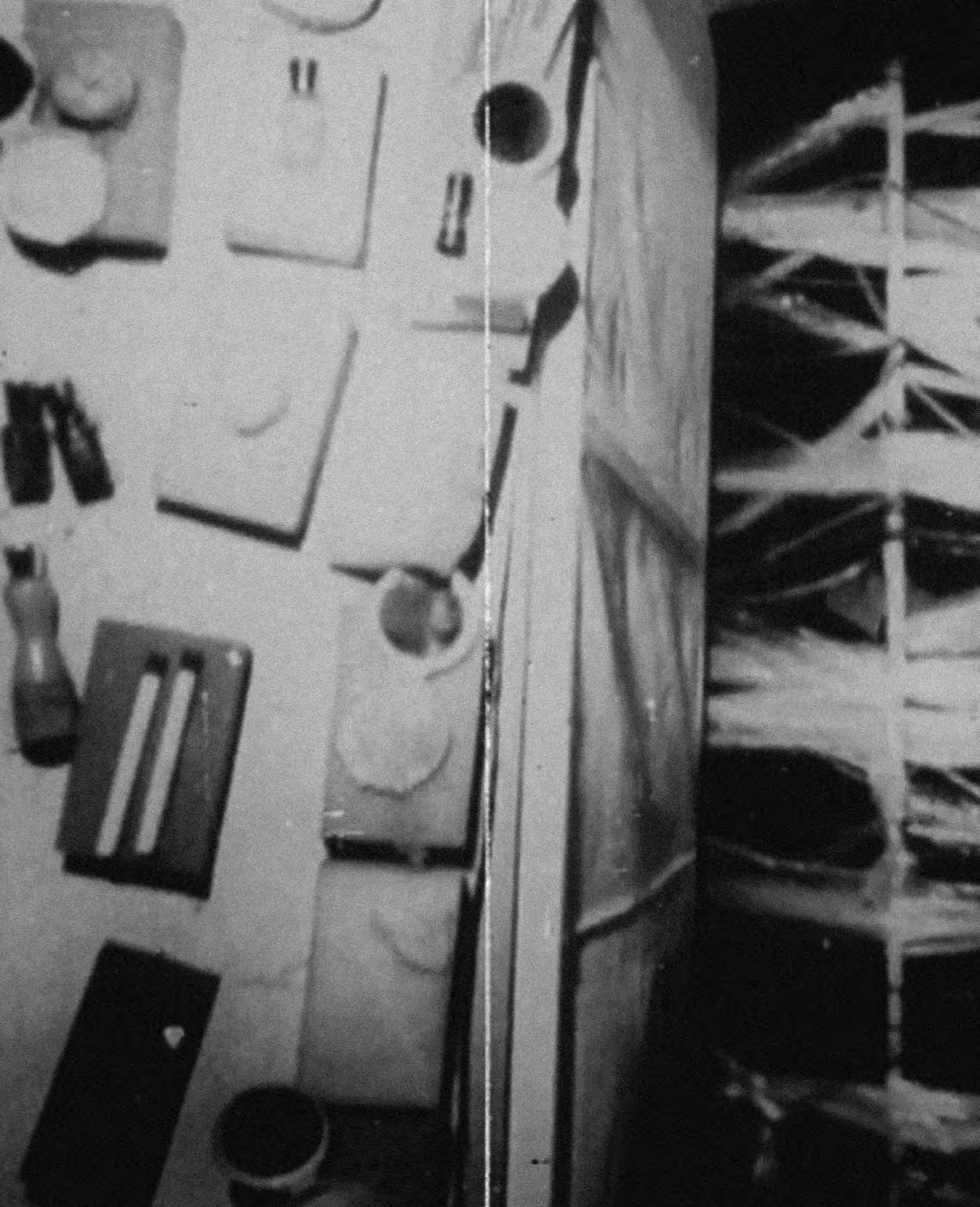

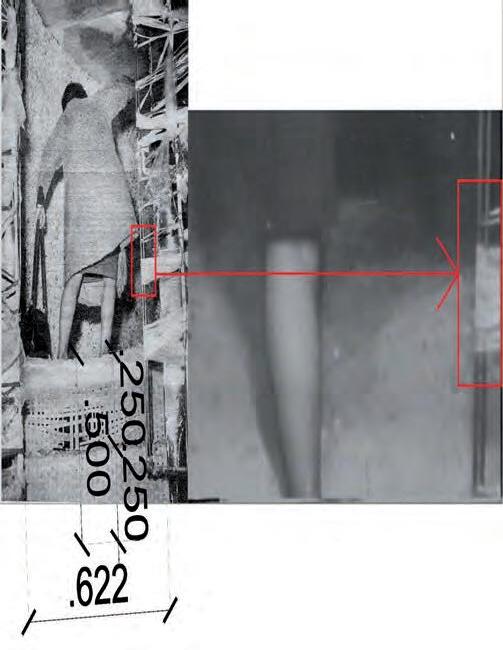

La Menesunda, 1965

Entrada al espacio Heladera

Cortesía Archivo Centro de Artes Visuales, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Entrace to The Icebox

Courtesy Centro de Artes Visuales Archive, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

La Menesunda, 1965

Rubén Santantonín y Marta Minujín

Cortesía Archivo Centro de Artes Visuales, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

Rubén Santantonín and Marta Minujín

Courtesy Centro de Artes Visuales Archive, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

33

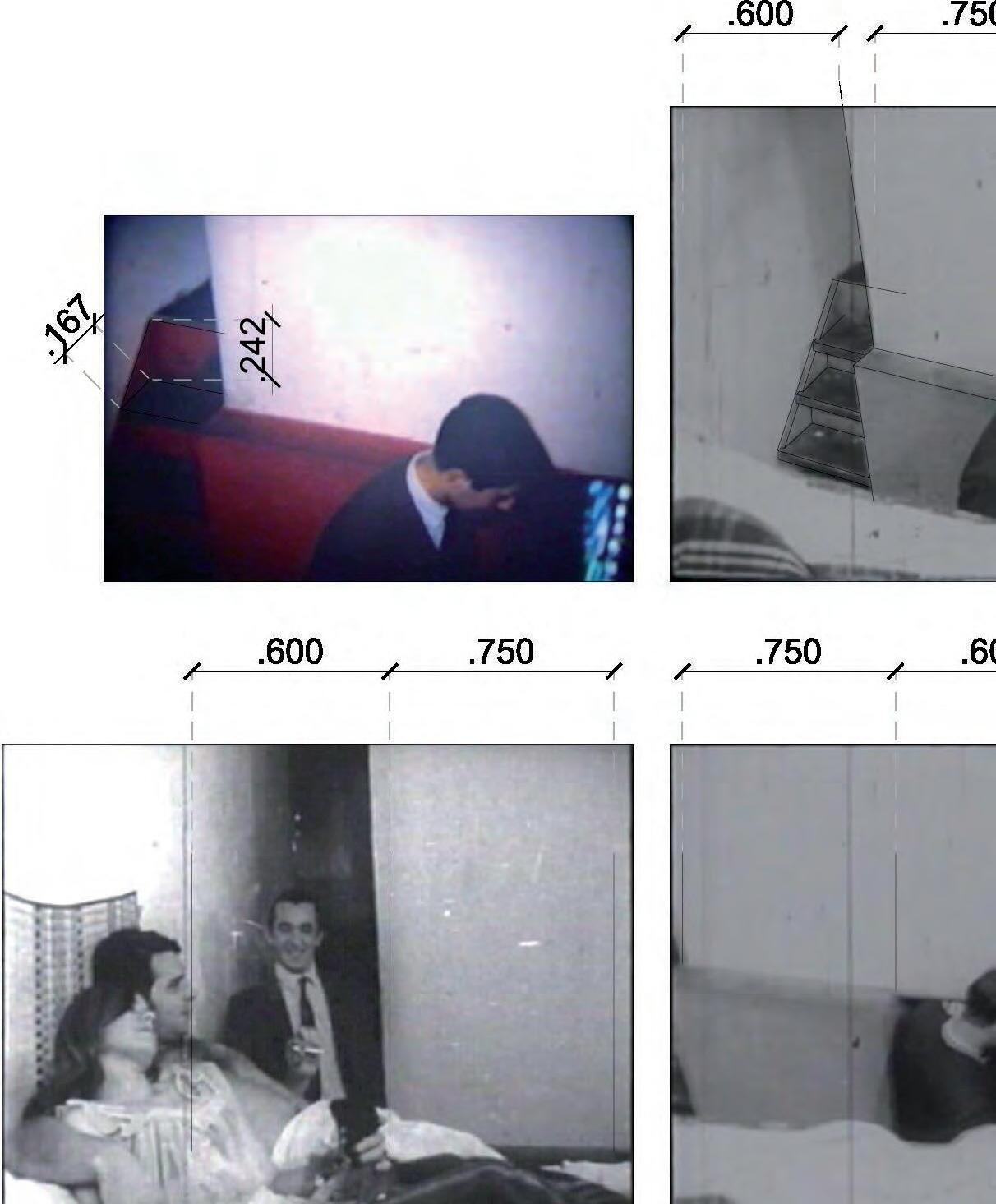

La Menesunda, 1965 Vista interior del Teléfono Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín View of The Telephone Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

el propio ego. No hay dudas de que, de ahí en adelante, ya no hubo vuelta atrás.

Además de las problemáticas inherentes a los lenguajes de la vanguardia, la participación del público, su experiencia, la cultura de masas y la colaboración como metodología de trabajo, este proyecto planteaba una dinámica que había sido inaugurada antes en iniciativas tales como la exposición de Arte Destructivo (1961), en la cual un grupo de artistas liderado por Kemble exhibió una serie de objetos encontrados y un audio realizado especialmente para la ocasión, o el famoso cartel ¿Por qué son tan geniales? (1965) que Edgardo Giménez, Charlie Squirru y Dalila Puzzovio realizaron junto a una agencia de publicidad e instalaron durante meses en la esquina de Florida y Viamonte, o las obras de la exultante dupla Delia Cancela y Pablo Mesejean, una sociedad pop que duró más de veinte años. La Menesunda no sólo abrazó la colaboración como práctica contemporánea, sino que esta producción desmesurada no habría sido posible sin ella. No solamente por su gran tamaño —el recorrido ocupaba toda la sala del Instituto—, sino por la gran complejidad constructiva y de planificación que este proyecto demandó, lo que lo convirtió en una empresa colosal que puso a prueba la voluntad, la paciencia y el compromiso de todos los participantes. Tanto fervor y entusiasmo había en este equipo que hubo incluso quienes perdieron sus trabajos en pos de La Menesunda. Lo que este tipo de asociación implicaba no era casual. No se trató sólo de una práctica diferenciada y una estrategia de visibilización y representación de la figura del artista, que se contraponía a las ansias subjetivas de reconocimiento encarnadas en artistas como Minujín y Greco, sino que expresa una clara postura que permite comenzar a releer la noción de autoría, anticipando los debates que estallarían en torno a este tema hacia finales de la década con las discusiones y escritos de Roland Barthes y Michel Foucault.15 La figura del autor comienza a perder sus contornos definidos, así como la obra de arte se escapa por los bordes de los marcos para convertirse en objeto y finalmente deshacerse en el aire. La Menesunda es, desde su más incipiente germen,

la suma de infinitas partes. Es la suma de Minujín y Santantonín, y de tantos otros cuyas influencias se filtraron por la grietas de las improvisadas paredes del laberinto. Por allí aparecen el Bio-cosmos n°1 (1962) de Renart, la Primera Exposición de Arte Vivo - Dito (1962) de Greco, Microsucesos (1965) de la compañía La Siempreviva, el espíritu libre de Federico Manuel Peralta Ramos, las Anthropométries de Yves Klein y los happenings de Allan Kaprow, Robert Whitman o Jim Dine, entre otros. Se trató de la confluencia de dos artistas que, por separado, revolucionaron el arte argentino, agitadores, cada uno a su manera, de la vanguardia artística, a través de su pensamiento crítico y su acción rotunda. Juntos forzaron la trama institucional del arte argentino de los años sesenta, para hacer entrar en ella una gigantesca y absurda obra, que tensionaría hasta el extremo las posibilidades de la vanguardia antes del estallido final del 68.

Minujín y Santantonín, Marta y Rubén, el día y la noche, el agua y el aceite. La joven Marta (Buenos Aires, 1943), efervescente y llena de entusiasmo, fascinada por el futuro y todo lo que éste tiene para ofrecerle, siempre ansiosa por conocer el mundo y que el mundo la conozca a ella; Rubén (Villa Ballester, 1919-1969), “pintorcosista”, 16 austero, sobrio, reflexivo y circunspecto, siempre preocupado por los males que aquejaban al hombre contemporáneo. Sus caminos ya se habían cruzado en ocasiones anteriores en exhibiciones organizadas en la Galería Lirolay (1962), en el Museo de Arte Moderno (1962) y en el Di Tella (1964). En el folleto de la exhibición El hombre antes del hombre (1962), una muestra colectiva que exploraba la creciente producción de los jóvenes artistas de la ciudad, promovida por la Galería Florida y auspiciada por el Museo de Arte Moderno su director y fundador Rafael Squirru,17 relataba que fue una conversación con ellos sobre la situación derrotista e indiferente del “ambiente” artístico contemporáneo en el país lo que lo inspiró para organizar ese proyecto. Se trata, sin embargo, de dos artistas de generaciones distintas, y temperamentos opuestos, pero que, en un momento dado de la historia, recorrieron caminos paralelos y simultáneos,

14- Famosa discoteca que funcionó en Buenos Aires entre mediados de los años sesenta y comienzos de los ochenta.

15- En 1968, Barthes publica “La muerte del autor”; al año siguiente, en 1969, Foucault publica su texto “¿Qué es un autor?”.

16- Así define Rubén Santantonín su actividad en un formulario del MAM, completado de puño y letra por el artista en 1966. Biblioteca y Archivo Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

35

que se iniciaron en la pintura informalista, oscura y existencial, de materiales precarios, para disolverse en los itinerarios de la obra de arte total y la experiencia de inmersión, transitando en distintos momentos y circunstancias por la senda de la destrucción de su propio trabajo.18

A comienzos de los años sesenta, Marta comenzaba a incorporar nuevos materiales a su ya tradicional pintura informalista. Incorporó cajas de cartón, las pintó de negro y en ocasiones hasta se metió dentro de ellas: es el comienzo de un largo camino. Poco después, en París, recolectaba colchones viejos y sucios, muchos de ellos provenientes de hospitales, con los cuales construía pequeños habitáculos, que sorprendentemente también indagaban en la posibilidad de habitar la obra. En 1963, Minujín ya estaba dejando atrás parte de su vinculación con el Nouveau Réalisme al quemar todas sus pinturas y colchones en una gran pira en el contexto de su acción conocida como La destrucción (1963). En una memoria escrita poco tiempo después, Minujín relata la acción en el Impasse Ronsin: “Sentía y afirmaba que el arte era algo mucho más importante para el ser humano que esa eternidad a la que sólo los cultos accedían, enmarcada en museos y galerías; para mí era una forma de intensificar la vida, de impactar al contemplador, sacudiéndolo, sacándolo de su inercia, ¿para qué, entonces, iba a guardar mi obra?...”.19 De esta manera, la artista se lanzó hacia la construcción de ambientes con sus colchones ahora multicolores y cosidos a mano, como La chambre d’amour (1963-1964), realizada junto a Mark Brusse: una estructura de madera recubierta de colchones, un ambiente habitable, lúdico, con guiños eróticos. De vuelta en Buenos Aires, la artista elaboró sus experiencias y realizó las obras con las que gana el ya citado Premio Di Tella. En octubre de 1964, Minujín realizó su primer happening en Buenos Aires, en el programa de televisión La campana de cristal , de Canal 7, que involucró decenas de gallinas, globos, untuosos atletas sólo cubiertos por slips, un pony que en vez de montura llevaba baldes de pintura, y a una provocativa Minujín bailando una desaforada danza Sioux.

La carrera artística de Santantonín fue veloz, tan veloz como potente y atípica. Nacido en 1919, recién en 1943, según acuerdan varias biografías de la época, se inició en la pintura de manera autodidacta, a instancia de las recomendaciones de Carlos Ripamonte, vecino de Villa Ballester. Realizó su primera exhibición individual en 1958: una serie de pinturas abstractas que rápidamente se convirtieron en informalistas y que igual de rápido se transformaron en cosas : bultos informes de telas enyesadas y materiales de descarte, papeles, cartones y tientos de cuero, que pendían del techo con alambres o hilos. Las cosas hicieron su primera aparición en público en 1961, en la exhibición Collages y cosas que Santantonín realizó junto con Luis Wells en la Galería Lirolay. Allí también presentó el texto/manifiesto que tituló Hoy a mis mirones , 20 donde declara: “Creo que hago cosas. Intuyo que comienzo a descubrir una forma de hacer que me coloca frente a la encrucijada existencial con una más intensa vibración que si reduzco mi ser, con su dilatada ansiedad, al canon de la pintura”. En 1964, las ideas del artista acerca de su propia producción y acerca del arte parecen consolidadas. En el folleto que acompañó su exhibición Cosas de 1964, explica: “La COSA como preocupación artística del problema es el acontecer del objeto. ACONTECE gracias a esa vida que le prestamos al concebirlo como COSA. Pues en tanto le quitemos la adhesión que ese préstamo implica, volverá a ser objeto irremediablemente. Entiendo a la COSA como la prevalencia de lo humano sobre los objetos, la poesía vital del objeto”.21 La cosa, lo puramente indeterminado, actúa como punto de partida, como lugar para la investigación de lo que está por ser; es también el comienzo del desplazamiento del espectador de la contemplación hacia la inmersión, el quiebre del hermetismo de la obra de arte como objeto.

Las inflexiones en las palabras de ambos artistas se hacen eco unas de otras. Desde el momento en que la pintura informalista ha quedado atrás se abren nuevos caminos para nuevas experiencias, más revulsivas y más comprometidas con su entorno y con el tiempo presente.

17- Fue Rafael Squirru quien en 1956 impulsó la creación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. Crítico de arte y poeta, Squirru fue promotor del Informalismo, el movimiento de Arte Generativo, y muchos de los jóvenes artistas que circulaban en Buenos Aires entre mediados de los años cincuenta y comienzos de los sesenta.

18- En 1963, Marta Minujín realiza una acción conocida como La destrucción, cuando quema sus obras realizadas durante su estadía en París. En una tónica completamente diferente, en 1969, poco antes de morir, Rubén Santantonín destruye casi todas sus obras en una gran quema.

19- Marta Minujín, texto dactiloscrito sobre La destrucción, Archivo Marta Minujín.

20- Santantonín, Rubén, Collage y cosas, Galería Van Riel, Buenos Aires, 18 de septiembre de 1961, folleto de exposición.

21- Rubén Santantonín, “Porque nombro ‘cosas’ a estos objetos”, en Cosas, Galería Lirolay, Buenos Aires, 1964, folleto.

36

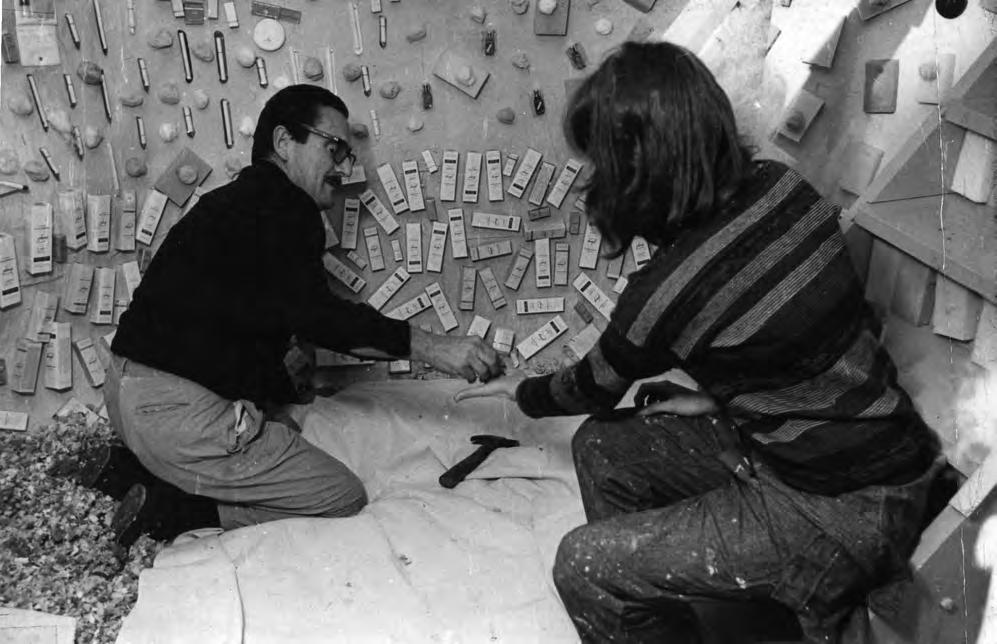

La Menesunda, 1965 Marta Minujín y Rubén Santantonín en la construcción Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín

Marta Minujín and Rubén Santantonín installing The Woman´s Head Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

37

38

La Menesunda , 1965 Interior de la Cabeza de mujer Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín View of The Woman´s Head Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

La Menesunda, 1965 V ista gener al del Túnel de TV Cortesía Archivo Marta Minujín

View of The TV Tunnel Courtesy Marta Minujín Archive

La Menesunda resume la potencia de ambos: las acciones que Minujín realiza consistente y persistentemente desde que hace su primera aparición en escena, su praxis siempre arriesgada y cuestionadora, y la muy profunda reflexión de Santantonín en torno a su propia práctica, existencial pero de cara al futuro, arraigada en el estudio y trabajo minucioso con los materiales y las formas, y cómo estos se desenvuelven en el mundo y afectan al espectador.

La Menesunda es la materialización de las preocupaciones y los interrogantes de ambos artistas sobre las posibilidades del lenguaje artístico y su capacidad de afectar y transformar al espectador, íntimamente relacionada con su tiempo y su contexto. Un tiempo de transformación cultural, efervescencia artística y tensión política que la tiñen por completo. Todos estos elementos se catalizaron a través de un conjunto de elementos, en algunos casos precarios y cotidianos —bolsas de polietileno rellenas de aserrín, papel picado y goma espuma—, en otros, tan sofisticados como un circuito de televisión cerrado, organizados a partir de una endeble lógica basada en las fantasías del grupo, una secuencia desconcertante que sometía al visitante a pasar de un estado a su opuesto subiendo o bajando unos pocos escalones, atravesando un túnel de neón o un pasillo de “intestinos” con la total convicción de estar, si no transformando, al menos torciendo el paradigma moderno del arte y abriendo las puertas de la contemporaneidad.

Si a comienzos de los años sesenta la vanguardia comenzaba a incorporar elementos hasta el momento foráneos a una obra de arte, entrelazándose de manera íntima con la cultura popular, hacia mediados de la década este proceso parece consolidado. Ya no sólo se incorporaron objetos a la pintura, o se utilizaron de manera compositiva dentro de la pintura, la escultura o las exposiciones mismas, sino que se comenzó a reproducir el tiempo y el espacio real dentro del ámbito expositivo. Se estrecharon al extremo los vínculos con la realidad, que se reprodujo sin mediación alguna o que fue simplemente apropiada. Las escurridizas imágenes de la televisión, el cine y la publicidad se infiltraban

en la cultura, impulsadas por una juventud con ansias de futuro, que ahora confiaba plenamente en lo nuevo y sospechaba de todo lo que oliera a viejo. La cultura de masas se convirtió en fuente inagotable de material para los artistas pop, que encontraron inspiración en las páginas de las revistas y las tapas de los discos de las estrellas norteamericanas. Se exaltaron los valores de los objetos de consumo, los materiales vulgares y los colores brillantes, la simulación y lo artificial, que le disputaban el lugar al buen gusto tradicional, y el hedonismo juvenil como estrategia de disrupción del orden establecido. El Pop, con el tono festivo que lo caracterizó, apareció también como un arte reflexivo y crítico desde donde hacer patentes las mediaciones de los lenguajes y las estructuras sociales en la relación del hombre con el mundo y, a la vez, un catalizador del cambio histórico en el gusto estético.22 El espíritu juguetón, sus héroes, sus ídolos, sus deseos y fantasías aparecen en el manifiesto que Delia Cancela y Pablo Mesejean escriben en 1966:

“Nosotros amamos los días de sol, las plantas, los Rolling Stones, las medias blancas, rosas, plateadas, a Sony and Cher, a Rita Tushingam y a Bob Dylan. Las pieles, Saint Laurent y el young savage look, las canciones de moda, el campo, el celeste y el rosa, las camisas a rayas, que nos saquen fotos, los pelos, Alicia en el país de las maravillas, los cuerpos tostados, las gorras color, las caras blancas y los finales felices, el mar, bailar, las revistas, el cine, la cebellina. Ringo y Antoine, las nubes, el negro, las ropas brillantes, las baby-girls, las girls-girls, los boys-girls, las girls-boys, los boys-boys.”

La Menesunda asumió este problema como propio y reprodujo distintos aspectos de la realidad, como una arqueología de su propia contemporaneidad. Recogió elementos de la ciudad, pero sobre todo de la intimidad de los hogares de clase media, sus ritos y artilugios, fundiendo a los participantes con su entorno al introducirlos al interior de una serie de electrodomésticos, como el televisor, el teléfono, la heladera. Ya no se trataba de incorporar los desechos del consumo a las obras, sino de transformar los objetos de

39

22- Oscar Masotta, Revolución en el arte. Pop-art, happenings y arte de los medios en la década del sesenta, Buenos Aires, Edhasa, 2004. [Texto original sobre arte pop: El pop art, Buenos Aires, Columba, 1967]

uso doméstico en experiencia estética, exponiendo así los mecanismos que operaban en la sociedad de consumo de los sesenta, la banalidad, las estrategias del marketing y la manipulación de los consumidores. Indudablemente es irónico que este despliegue sucediera a costas de SIAM Di Tella, una de las empresas industriales más grandes del país. La Menesunda, por su masividad única y su cualidad autodestructiva (para el final de la exposición la obra estaba prácticamente destruida), logró escapar a la objetualización y, al mismo tiempo, a cualquier atadura al pasado o a la tradición que pudiera restringirla, distinguiéndose así de su prehistoria, caracterizada por la veneración de los objetos artísticos únicos. Se trató de una obra de arte total, que interpeló todos los sentidos del participante y también su sentido moral, y que apeló de manera tenaz a su voluntad de romper los antiguos límites.

Tanto Minujín como Santantonín elaboraron, con su característica vehemencia, reflexiones sobre el arte y la posibilidad de transformación del espectador a través de la experiencia de una obra, sobre sus prácticas individuales y sobre La Menesunda. Minujín escribió: “[…] Menesunda estimula la espontaneidad, la imaginación; la creatividad no admite frenos ni razones. Menesunda no está para ser contemplada sino vivida; su significación se encuentra en la persona que la incursiona“.23 En la misma tónica se encuentran las palabras de Santontonín: “[…] Queremos que el hombre sienta la vejez de su anterior actitud ante la cosa artística, que se sienta complicado, comprometido, con su propia imagen mezclada a lo que siente, ve e intenta hacer. / Provocar en el participante una sensación inédita, tan inédita que él mismo tenga que crearle un nombre”.24

En la conferencia que Romero Brest dictó en ocasión de la exhibición, además de referirse a las falencias y desaciertos del resultado final, aludió nuevamente a la noción de experiencia: “yo creo que los artistas de nuestro tiempo están intentando ampliar el campo de la experiencia, una experiencia que no termina, una experiencia, por lo tanto, que no tiene límite...”.25 El participante se veía compelido a unirse a la obra de arte, se fundía con ella para activarla y para ser activado, para

23- Marta Minujín, texto dactiloscrito sobre La destrucción, Archivo Marta Minujín.

24- Rubén Santantonín, archivo personal.

conocer y conocerse a sí mismo en el proceso, a través de sus propias actitudes, gestos y reflexiones.

Pero La Menesunda también indicaba el camino. Instruía, confrontaba y examinaba comportamientos, investigaba conductas y contraconductas que oscilaban entre el ejercicio de la libertad y la creatividad y el itinerario normativo de un laberinto-laboratorio. Asimismo, la obra trazaba patrones de orden y conducta, materializados en una serie de instrucciones de uso comunicadas a través de carteles y guardias de seguridad, instrucciones que en cierta medida limitaban la posibilidad de libre participación del visitante. Se trataba de un itinerario previamente diseñado, que desencadenó múltiples reacciones y contrapuso la feliz idea de la participación con una avalancha de estímulos que iban desde el roce de suaves texturas a la hostilidad de un ambiente a temperaturas bajo cero, de la grata sorpresa de verse reflejado en una pantalla de televisión al encierro en una pequeña y oscura “cabina telefónica”. El juego de oposiciones generó actitudes igualmente opuestas, que se acumulaban una tras otra a lo largo del recorrido, conformando una experiencia intensa y cargada de emociones. La Menesunda puso a prueba al espectador y su capacidad para incorporarse a la corriente que la obra proponía y para subsistir en medio de la vorágine de imágenes y estímulos que se le presentaban, ejerciendo su propia subjetividad al decidir los caminos a tomar y la actitud a asumir frente a cada situación.

En el contexto de un golpe de estado al acecho y un mundo penetrado por la Guerra Fría, las protestas, la guerrilla y la defensa de los derechos humanos, la idea de participación en cualquier caso excede los términos de la experiencia y resulta mucho más compleja que el entramado de estímulos sensoriales y espectáculo sobre el cual la prensa y la historia construyeron el mito de La Menesunda. La experiencia y la participación desbordaron la obra, y desbordaron también las ideas de los artistas. Y así, sin que nadie se diera cuenta, se convirtieron en experimento sociológico que observaba los comportamientos humanos en un contexto determinado, el de un laberinto devenido obra de arte vanguardista, en la Buenos Aires de mayo de 1965.

25- Jorge Romero Brest, Arte 1965: del objeto a la ambientación, 11 de junio de 1965, mimeo, Archivo JRB, UBA.

40

Pocos años después, Minujín maduraría y profundizaría estas ideas, lejos del caos de sus happenings con gallinas y motociclistas (Suceso Plástico, Montevideo, 1965), al sondear en las conductas humanas y sus usos sociales en obras posteriores como Minucodes (1967), una “ambientación social” en formato de video-instalación, que resultó de una convocatoria a grupos sociales de diversos campos profesionales: empresarios, políticos, modelos y artistas, quienes interactuaban en el marco de un mismo espacio considerado neutral. La manipulación y acoso mediáticos reaparecieron en Simultaneidad en simultaneidad (1966), llevada a cabo en el Di Tella, donde sesenta personas famosas, seleccionadas a partir de una especie de ranking mediático, fueron grabadas, filmadas y fotografiadas de frente y perfil, mientras, en paralelo, todo lo que acontecía en la sala podía verse en circuito cerrado de televisión. Una semana después, los mismos invitados fueron convocados nuevamente a la sala del Instituto para vivir la experiencia de ver su imagen devuelta por los medios. Durante los años setenta, Minujín incluso experimentó con el secuestro (voluntario) como forma de participación del espectador en la obra Kidnappening (1973), realizada en el MoMA de Nueva York con la colaboración de Gary Glover y cuarenta performers maquillados según cuadros cubistas del recién fallecido Pablo Picasso, que realizaban movimientos y cantos combinando ópera, poesía y danza, e instaban a la audiencia a participar. Una vez finalizada esa etapa, los performers secuestraban a quince espectadores —que habían prestado su consentimiento previamente— para depositarlos en distintos lugares de Nueva York y sus alrededores para continuar con su experiencia.

Los años posteriores al peronismo fueron un período de suma complejidad política, pero también económica: el país profundizó el proceso de crecimiento y modernización iniciado pocos años antes, obstaculizado, sin embargo, por una miríada de conflictos. Esta modernización económica introdujo profundos cambios en la sociedad argentina, y tuvo como consecuencia una correlativa transformación del orden social y cultural, que permeó todos los ámbitos de la vida. La masiva audiencia que convocó el Instituto Di Tella para esta ocasión fue un evento extraordinario que puso de manifiesto no sólo el gran poder de convocatoria

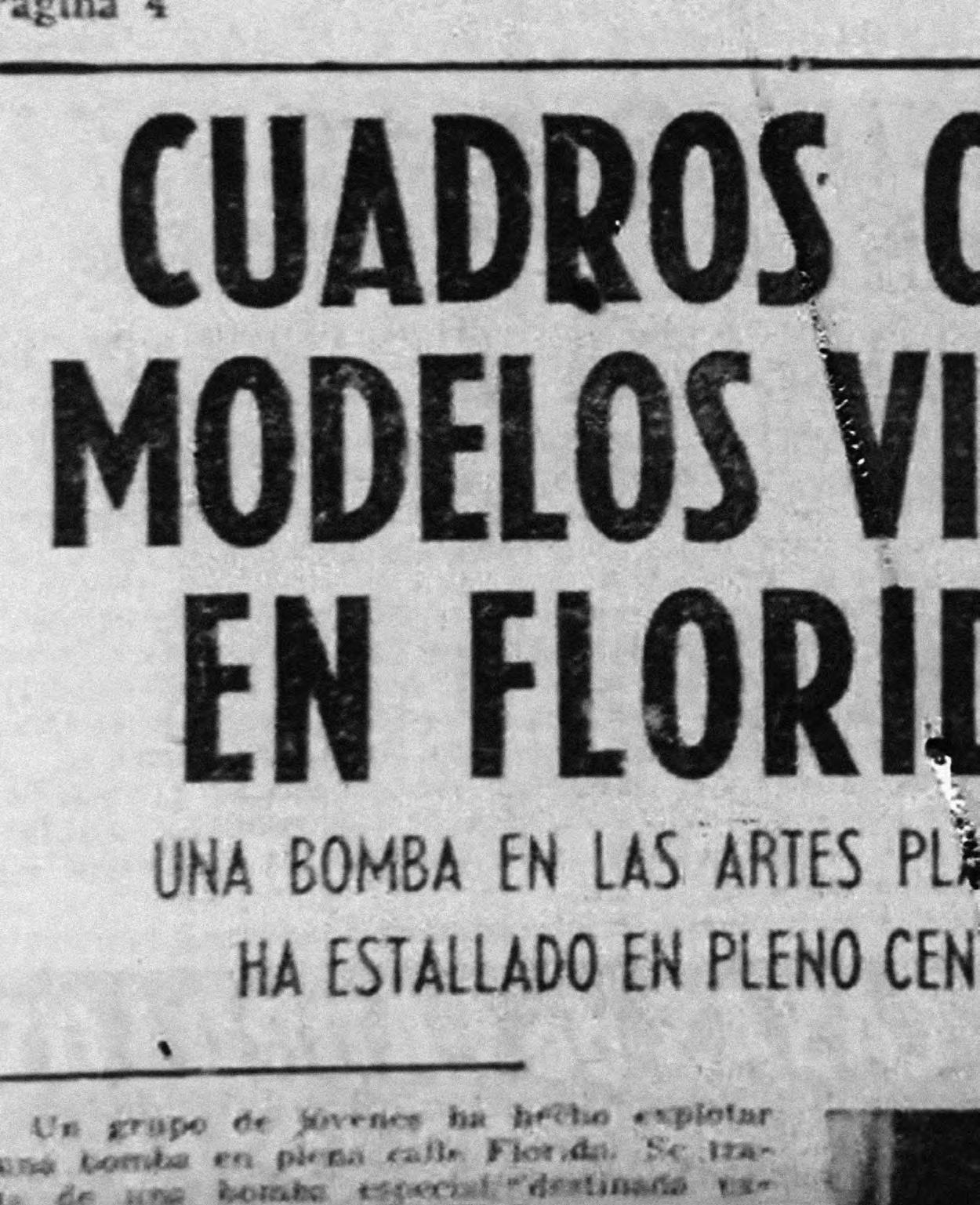

traccionado por los medios, sino también el surgimiento de un nuevo público para la cultura, conformado en gran parte por sectores profesionales de clase media, jóvenes intelectuales y estudiantes. Se trataba de un público ávido de consumos culturales y de información, una de cuyas fuentes principales fue el semanario Primera Plana, fundado en 1962 por Jacobo Timerman. Junto a Primera Plana surgieron Panorama (1963) y Confirmado (1964), tres semanarios de actualidad que fueron centrales para la difusión del ámbito político y cultural, nacional e internacional. Si bien estaban orientados a un público de clase media alta, pronto ampliaron su base de lectores a otros sectores de la sociedad. Para mayo de 1965, los problemas de las vanguardias artísticas eran ya un tema discutido en las páginas de estas publicaciones: Primera Plana se había acercado, no sin problemas, a las nuevas prácticas y movimientos, como el happening y el Pop, al cual dedicaría su portada un año más tarde. La Menesunda catalizó este interés y provocó un frenesí mediático, en medio del cual se la calificó de “un desesperado intento para espantar ‘al buen burgués’” y “una suerte de divertissement”, se la comparó con el Parque Retiro y parques de diversiones varios, pero hubo consideraciones sobre su valor de ruptura en “un medio tan pacato y provinciano (en el peor de los sentidos, el cultural)”, y sobre el riesgo que esto significaba.

Fermín Fèvre escribía: “La Menesunda implica riesgos, un verdadero acto de asumir un gran compromiso, no solamente ante la crítica o frente al destino posterior de los artistas ‘confabulados’ en esta oportunidad. Se trata de un trascendental compromiso ante el público y ante el arte”.

Las palabras del crítico condensan una atmósfera de ruptura pero también de apertura y contingencia, la aparición de un nuevo modo de acercamiento a la cultura, que afianza la experiencia como ámbito para la investigación y la práctica artística, como problema para la vanguardia y como medio para su expansión. Pierre Restany, crítico francés fundador del Nouveau Réalisme, recibe noticias de La Menesunda a través de los artistas y declara: “Menesunda est une contribution locale á la grande oeuvre commune. Elle illustre l’avènement à Buenos Aires d’une sensibilité autre,qui se pense et qui se veut à l’échelle du monde de demain”, 26

41

26- Pierre Restany, “Soyez réalistes: apprenez à conjuguer la vie au futur!”, París, mayo 1965. Documento mecanografiado, Archives de la critique d’art PREST.XSAML24/40 a 42.

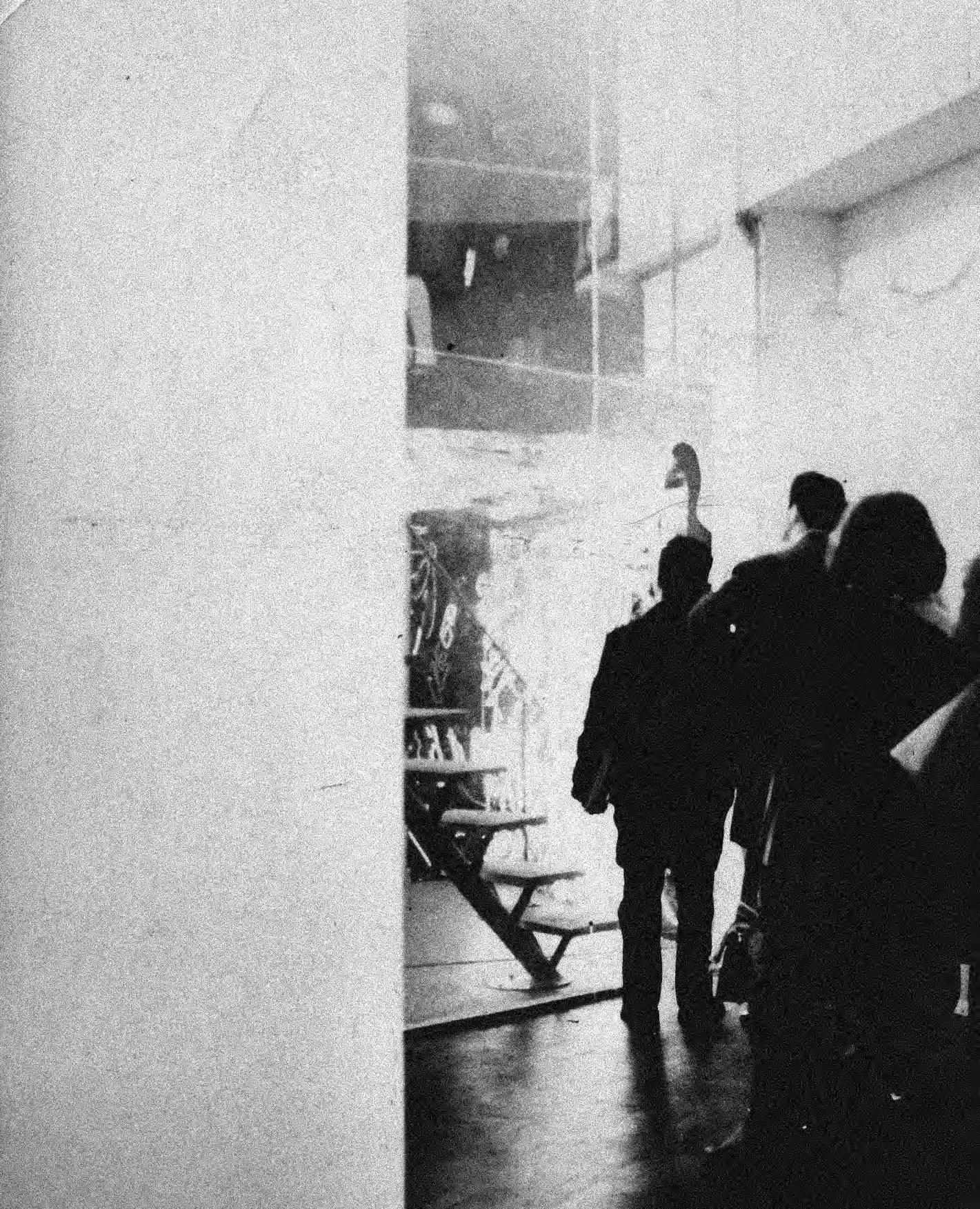

La Menesunda, 1965

Vista interior de la entrada Cortesía Archivo Centro de Artes Visuales, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

View of the entrance Courtesy Centro de Artes Visuales Archive, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella

42