How the Archaeology of Mystetskyi Arsenal was Researched

Olena Onohda

не лише на одні

з наймасштабніших розкопок у столиці, а й на величезний шмат роботи, обсяг якої ми досі

не вповні зрозуміли та використали. Знакові

київські розкопки, як-от під час будівництва

метрополітену на Подолі у 1970-х чи на території Михайлівського Золотоверхого монастиря у 1990-х, дають змогу усвідомити, що таких унікальних можливостей для фахівців стає дедалі менше, а шансів віднайти непорушений цілісний комплекс

Насамперед ідеться про комплекс Києво-Печерського монастиря, передбачувано багатий на культурну спадщину середньовічної та ранньомодерної доби. До того ж під час різноманітних будівельних робіт дослідники фіксували археологічні об’єкти й по вул. Цитадельній, на площі Слави, на території церкви Феодосія Печерського тощо. Усе це свідчило про значний археологічний потенціал арсенальської ділянки. Про територію Старого арсеналу, яка до

середини 2000-х була закритим військовим

об’єктом, бракувало об’єктивної інформації і щодо стану культурного шару за даними історичних джерел2. Відомим був факт існування тут Вознесенського дівочого монастиря. Перша

письмова згадка про

Доступ пересічних громадян сюди став

обмеженим, і жодних наукових досліджень аж до початку ХХІ ст. тут не проводилось. Нога професійного археолога вперше ступила за паркан військової частини № 2161 (на той

момент — Київського ремонтного заводу) у 2005

році. Саме тоді, після розв’язання юридичних

питань щодо передавання мілітарного комп-

лексу задля створення культурної інституції3 та

початку реконструкції комплексу на території

Старого арсеналу, тут розпочала роботу коман-

да співробітників Архітектурно-археологічної

експедиції Інституту археології НАН України під керівництвом Гліба Івакіна. Влітку 2005 року ми з колегами із подивом роздивлялися територію військового містечка, що доживало свої останні дні. Ще

Основна частина археологічних досліджень тривала з 2005 до 2009 року — водночас із зовнішніми будівельними роботами з реконструкції пам’ятки. Згодом, після відкриття першої виставки у 2009 році та з початком повноцінного функціонування Мистецького арсеналу як культурно-мистецького та музейного

Археологи опинились

царстві розкиданих заводських меблів, залишків гасел цілком радянського стилю та важкої будівельної техніки. Залишитися мала тільки будівля Старого арсеналу, очищена від усіх пізніх

нашарувань. Оскільки спеціальних приміщень на території не було, команда експедиції облаштовувала кімнати для роботи в колишніх кабінетах військової частини. В пригоді стали столи, стільці, коробки та шухляди від старих шаф, у які було зручно складати нововиявлені артефак-

будівлі, наступним — простір всередині Старого арсеналу

комплексу. Внутрішнє подвір’я площею 8769 м2 дослідили переважно впродовж літа — пізньої осені 2005 року4 Деякі ділянки, прилеглі до стін будівлі, опрацьовували як окремі «прирізки» в міру просування будівельних робіт упродовж 2006–2009 років. Тут команда археологів майже одразу почала фіксувати перші знахідки. Для зручності та системності величезний простір умовно поділили на 4 частини, кожна з яких (так звані розкопи 1–4) надалі вивчалася окремими групами фахівців та мала власну нумерацію виявлених об’єктів. Усього археологи виявили тут

та кілька поховань. З

вої цінності, фрагментарність об’єктів корпусу цілком компенсується хронологічним розмаїттям знахідок — від кераміки ХІV ст. до пізнього посуду та предметів зброї ХVІІІ ст. На території комплексу зовні будівлі археологічні дослідження здійснювалися переважно

методом наукового нагляду й тривали впродовж

усіх років роботи Архітектурно-археологічної

експедиції6. Культурний шар зберігся довкола

Старого арсеналу незначною мірою. Тут вда-

зафіксувати поодинокі залишки людської

зокрема

цювали одночасно з роботою важкої будівельної техніки, а в найінтенсивніші 2005–2006 роки —

впродовж майже всього світлового дня, включно з холодними місяцями року. Майже одразу, влітку 2005 року, розпочалася і камеральна

обробка матеріалів, що тривала доволі інтенсивно до 2010 року. Вона традиційно включала

очищення знахідок від поверхневих забруднень, склеювання фрагментованих предметів, їхнє маркування та складання польових описів, первинну реставрацію, підготовку графічних зображень знахідок, аналіз антропологічних решток, тощо. До списків первинного обліку за період з 2005 до 2010 років. було внесено

4

Г. Ю., Козубовський Г. А., Балакін С. А. та ін. 2006. Дослідження на території Старого Арсеналу в Києві. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2004–2005, С. 175–177; Івакін Г. Ю., Балакін С. А., Відейко М. М. та ін. 2007. Археологічні дослідження 2006 р. території дівочого Вознесенського монастиря в Києві. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2005–2007, С. 178–180; Івакін Г. Ю., Козубовський Г. А., Чекановський А. А. та ін. 2008. Археологічні дослідження на внутрішньому подвір’ї Старого Арсеналу 2007 р. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2006–2007, С. 119–121.

5 Івакін Г. Ю., Балакін С. А., Баранов В. І., Оногда О. В. 2007. Археологічні дослідження в корпусі Старого Арсеналу в 2006 р. Археологічні

2005–2007, С. 175–178; Івакін Г. Ю., Балакін С. А., Баранов В. І., Оногда О. В. 2008. Архітектурно-археологічні дослідження у підвалі корпусу Старого Арсеналу та навколо нього. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2006–2007, С. 115–118.

6 Івакін Г. Ю., Балакін С. А., Баранов В. І., Оногда О. В. 2008. Архітектурно-археологічні дослідження у підвалі корпусу Старого Арсеналу та навколо нього. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2006–2007, С. 115–118; Івакін Г. Ю., Баранов В. І., Оногда О. В. 2009. Архітектурно-археологічні дослідження на території Старого київського арсеналу. Археологічні дослідження в Україні 2008, С. 84–87.

7 Івакін Г. Ю., Козубовський Г. А., Балакін, С. А. 2005. Підземні скарби Старого Арсеналу (попередня інформація). Відлуння віків, 2 (04), С. 52–56; Івакін Г. Ю., Козубовський Г. А., Балакін, С. А. 2005. Археологічні дослідження на території київського Арсеналу 2005 р. (попередня інформація). Праці центру пам’яткознавства, 8, С. 119–145; Ивакин Г. Ю., Балакин С. А. 2006. Предварительные итоги археологических исследований 2005 г. на территории киевского Арсенала. Материалы III Судакской междунар. научной конф., І, С. 159–168; Івакін Г. Ю., Балакін С. А. 2007. Підземні скарби київського Арсеналу (результати досліджень та перспективи музеєфікації). Відлуння віків, 1 (7), С. 26–32.

черська фортеця та київський Арсенал: нові

дослідження», до якого увійшли 6 публікацій за матеріалами археологічних досліджень та історичні розвідки8. Інтенсивність опрацювання

матеріалів з 2010-х років знизилася внаслідок

активізації інших рятівних досліджень у Киє-

ві та об’єктивної нестачі ресурсу. Матеріали розкопок досі потребують узагальнювального ґрунтовного дослідження та видання повного

каталогу знахідок. Попри певну фрагментарність публікацій, отримані висновки, здобуті

дані та колекція

артефактів дають

змогу оцінити

пам’ятку як уні-

кальне археоло-

гічне джерело.

Науковці ви-

значили, що територія Старого арсеналу пройшла три основні хронологічні етапи

розвитку: 1. Доба, що

передує першій

ділянки. До нього зараховано близько 130 різноманітних

іншого призначення, продуктових та сміттєвих ям, монастирського колодязя, поховань тощо. Домінанта археологічного комплексу — залишки Вознесенського храму, зведеного

письмовій згадці про Вознесенський монастир. Деякі поодинокі знахідки належать до давньоруського часу, проте ділянка тоді ще залишалася незаселеною й перебувала на периферії

будівництв Києво-Печерського монастиря. Уламки плінфи та шиферу, кубики смальти та

ня монастиря). Єдине ідентифіковане поховання — могила київського цивільного губернатора, генерал-майора Семена Івановича Сукіна (помер у 1740 році), із декорованим кам’яним надгробком та написом-присвятою. Вивчення кістяка Семена Сукіна

Archaeological

рештками. Переважно це сліди діяльності артилерійського двору та зброярських майстерень. Особливу увагу археологів привернули непересічні знахідки скляних ручних гранат11 та кніпелів

(антикорабельного боєприпасу). Археологи простежили деякі конструктивні особливості

земляних укріплень Печерської фортеці, зокрема — цегляну потерну-сортію ХVІІІ ст. Артефактів у цій підземній галереї не виявили, хоча зафіксували трохи кумедне свідчення подальшої експлуатації пам’ятки в радянський час — рисунок простим олівцем на стіні, на

9

XVII–XVIII століття. Лаврський альманах, 19, С. 17–26.

10 Козак О. Д. 2008. Деякі остеобіографічні риси до портрета київського губернатора. Лаврський альманах, 21, С. 50–63.

11 Староверов Д. А. 2007. Стеклянные гренады из киевского Арсенала. Археологічні відкриття в Україні 2005–2007, С. 347–349; Староверов Д. А. 2007. Стеклянные гранаты XVIII в. из раскопок на территории киевского Арсенала // Нові дослідження пам’яток козацької доби в Україні, 16, С. 147–150. 12 Зажигалов О. В. 2012. Комплекс керамічних світильників ХVІІ ст. з розкопок Старого Арсеналу в Києві. Лаврський альманах, 26, С. 8–10; Оногда О. В. 2008. Керамічні комплекси ХІV–ХVІ століть

розкопок на території Старого Арсеналу. Лаврський альманах, 21, С. 24–31; Оногда О. В. 2014. Гончарний

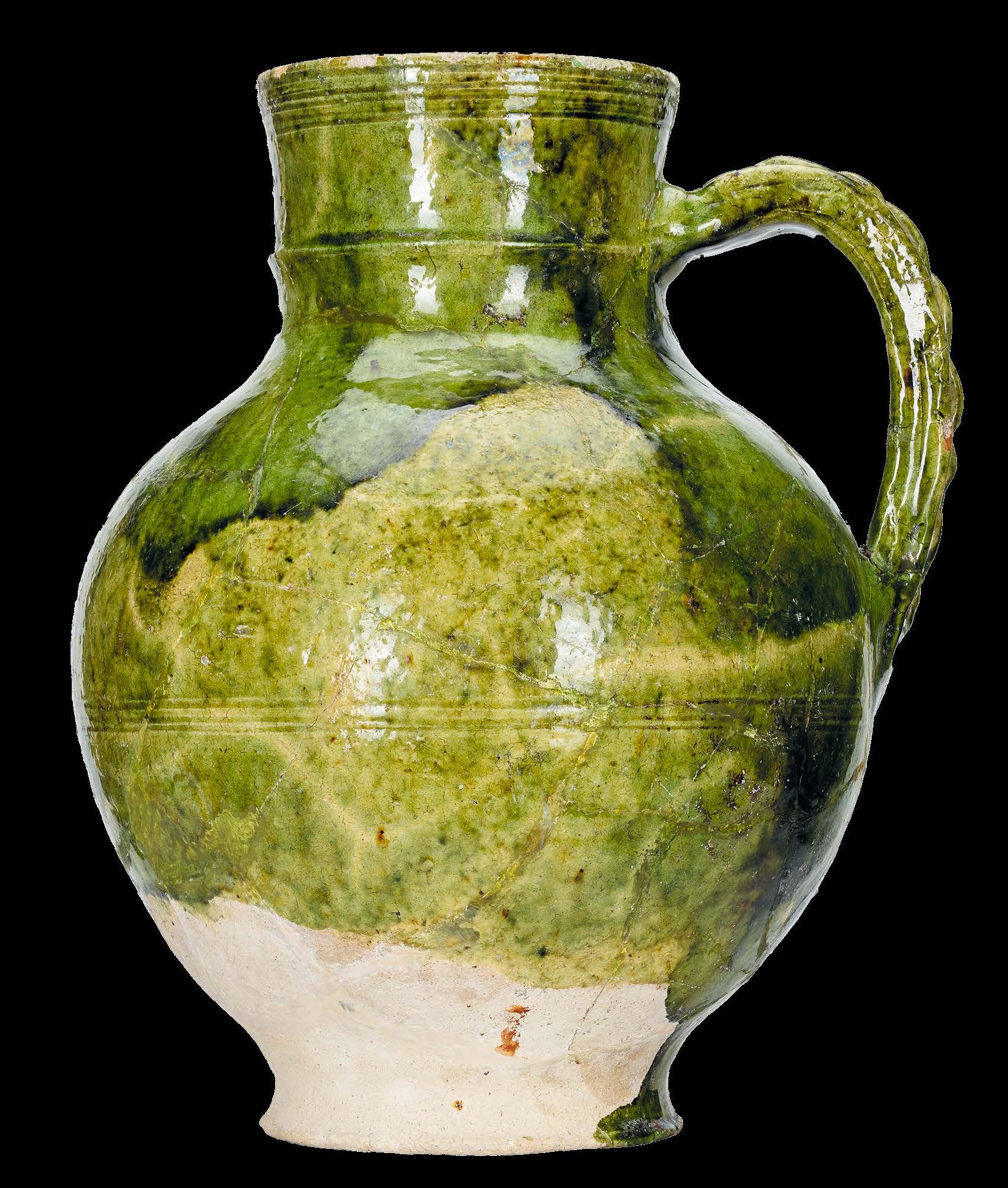

поповнилося знання про українську матеріальну культуру ХІV–ХVІІІ ст.12 Численні артефакти, здобуті в процесі розкопок, представлено значною колекцією гончарних виробів: кухонного, столового посуду, кахлів. Є тут і зразки тарного

посуду та мініатюрні посудини-іграшки. Частина столового посуду — із художнім декором (рослинні орнаменти, квіткові композиції, абстрактні зображення), або імпортного походження (наприклад, глек із так званої рейнської кам’яної маси), що свідчить про високий соціальний статус та економічні спроможності обителі.

Болховітіновський щорічник 2013/2014, С. 137–152; Оногда О. В. 2018. Комплекс із полив’яною керамікою другої половини ХV — першої половини ХVІ ст. (за матеріалами розкопок Старого арсеналу в Києві). Археологія і давня історія України, 4 (29), С. 246–253; Чміль Л. В. 2007. Керамічні тарілки з Арсеналу. Попередні підсумки. Нові дослідження пам’яток козацької доби в Україні, 17, С. 111–119; Чміль Л. В. 2007. Ужиткова кераміка ХVІІ ст. з розкопок Вознесенського жіночого монастиря в Києві. Лаврський альманах, 17, С. 164–170; Чміль Л. В. 2008. Кераміка Вознесенського монастиря. Лаврський альманах, 21, С. 32–42; Чміль Л. В. 2009. Імпортна кераміка з розкопок Старого Арсеналу в Києві. Нові дослідження пам’яток козацької доби в Україні, 18, С. 68–72.

балтійсько-шведської чеканки, меншою мірою — російської. До унікальних знахідок

належать чотири кістяні шахові фігурки ХV–

ХVІ ст. (пішак, слон, тура, та, ймовірно, ферзь) та пізніша двостороння іконка на металевому овальному медальйоні.

Отже, головний результат археологічних пошуків на території Старого арсеналу — фіксація багатошарової історико-культурної пам’ятки, що віддзеркалює всі хронологічні етапи історичного розвитку цієї частини Печерська, осердям якої був жіночий Вознесенський монастир ХVІІ ст. З огляду на комплексність вивчення ділянки, що раніше ніколи не досліджувалася, зазначені розкопки можна вважати безпрецедентними для Києва. Усе це акцентує актуальність музеєфікації

вав підземні споруди, Юрій

нив архітектурні обміри та склав точний план залишків фундаментів Вознесенського храму, археозоолог Олег Журавльов підготував аналіз решток кісток тварин, антропологиня Олександра Козак дослідила значний масив людських решток Вознесенського некрополя. Матеріали розкопок сприяли науковим пошукам на той час молодого

Архітектурно-археологічної експедиції за різними напрямами. Серед них

14 , історія керамічного

17

та провідного спеціаліста з української пізньо-середньовічної археології. Саме завдяки його попереднім дослідженням змінилися уявлення про розвиток Наддніпрянщини після Батиєвої навали та подолано стереотипи про запустіння деяких частин

Києва аж до ХVІІ ст. Розкопки Старого арсеналу додатково продемонстрували тяглість історич-

дослідження.

До польових робіт у різний час долучалося багато фахівців з археології різних періодів. Серед них — випускники новоствореної магістерської програми «Археологія» Національного університету «Києво-Могилянська академія»: Ірина Карашевич, Тарас Коростильов, Андрій Олійник, Антон Смірнов. Тривалий час тут працювали Ольга Абишкіна, Микола Беленко, В’ячеслав Гайдук, Павло Комаренко, В’ячеслав Крижановський, Андрій Кротенко, Дмитро Старовєров, Микола Тарасенко, Андрій Сидорчук. Камеральною обробкою опікувалися Марія Відейко, Наталія Воловоденко, Оксана Вотякова, Любов Шумакова.

імені Тараса Шевченка.

Окрім науковців, неможливо оминути увагою постать Президента Віктора Ющенка. З його ініціативи було розпочато реконструкцію

комплексу та створено Мистецький арсенал як

державну інституцію. Під час візитів на робочі наради Віктор Андрійович жваво цікавився

перебігом археологічних робіт і як очільник

держави, і як щирий аматор історичних дослі-

джень.

Історія розкопок Старого арсеналу хоч і

завершилася, проте формування археологічної колекції Мистецького арсеналу триває. 2018 року на сусідній ділянці через дорогу від

археології

Цитадельна. Вони передували спорудженню

офісу Ґете-Інституту (нині — територія за адресою вул. Лаврська, 16-Л). Керував розкопками фахівець з історії середньовічної культури, науковий співробітник відділу археології Києва

Андрій Оленич.

Цю частину колишнього Печерського містечка люди почали заселяти з XIV ст. — одночасно з ділянкою майбутнього Вознесенського монастиря. Археологи віднайшли тут артефакти від

13

14 Мельник О. 2017. Археологічні

ст. Eminak, № 1 (17), т. 4, С. 16–21.

15 Оногда О. В. 2011. Прийоми формування денець горщиків другої половини ХІІІ–ХV ст. як ознака технологічного прогресу гончарного виробництва. Могилянські читання 2010, С. 400–403; Оногда О. В. 2012. Кераміка

ст.: автореф. дис. канд. іст. наук. Київ; Оногда О. В. 2013. Керамічний посуд із защипами з розкопок монастирських комплексів ХV — першої половини ХVІ ст. на території Києва. Церква–наука–суспільство: питання взаємодії, С. 29–31; Починок Е. Ю. 2008. Скляний столовий посуд з території Старого Арсеналу. Лаврський альманах, 21, С. 43-49; Фінадоріна Д. 2011. Художньо-декоративні різновиди комплексу пічної кахлі ХVІІ ст. з розкопок київського Арсеналу. Болховітіновський щорічник 2010, С. 135–143.

16 Абишкіна О. А. 2007. Натільна іконка з Вознесенського монастиря. Могилянські читання 2006, ч. 1, С. 289–292.

17 Балакін С. А., Оногда О. В. 2010. Культурно-хронологічний горизонт ХІV–ХVІ ст. Києво-Печерської лаври та її околиць. Актуальні проблеми археології, С. 110–111; Оногда О. В., Чміль Л. В. 2008. До питання про технологію виробництва київської кераміки другої

— початку ХVІ ст. Праці центру пам’яткознавства, 14, С. 104–132; Оногда О. В. 2009. До питання про стан збереженості культурного горизонту другої

ХІІІ–ХVІ ст. у Києві. Могилянські читання 2008, С. 343–349; Оногда О. В., Чекановський А. А., Чміль Л. В. 2010. Підсумки, проблеми і перспективи вивчення кераміки Середньої Наддніпрянщини ІІ-ї половини ХІІІ–ХVІІІ ст. Археологія і давня історія України, 1, С. 446–453; Чміль Л. В. 2010. Керамічний посуд Середньої Наддніпрянщини XVI–XVIII ст.: автореф. дис. канд. іст. наук. Київ; Чміль Л. В. 2013. Значення археологічних досліджень київських храмів та монастирів для датування артефактів. Церква–наука–суспільство: питання взаємодії, с. 54–56.

18 Крайня О. О. 2008. Нові матеріали до історії Вознесенського Печерського монастиря. Лаврський альманах, 21, C. 66–111; Крайня О. О. 2012. Києво-Печерський жіночий монастир ХVІ — початку ХVІІ ст. і доля його пам’яток. Київ: Національний Києво-Печерський

оптимістичною сторінкою в історії вивчення давнього Києва. Нині Мистецький арсенал як культурна інституція, спрямована в майбутнє, водночас оперує свідченнями про своє безпосереднє минуле, видобуте з-під землі

збережене для нащадків.

1 The term “Old Arsenal” will be used hereinafter to refer to the historical and architectural monument located on the protected territory of the Old Kyiv-Pechersk Fortress at 12 Lavrska Street. Despite the established simplified short version of “Arsenal,” we use this word combination in order to avoid confusion with the New Arsenal, also a historical and architectural building, but from a later time (19th century), located at the intersection of the current Kniaziv Ostrozkykh Street and Mazepy Street.

2 Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A. 2008. Rozkopky na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho Arsenalu 2005–2007 rokiv. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21. S. 9–23.

3 Legal basis for research: Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 1343 dated 15.12.2000 “On measures to mark Ukraine's entry into the third millennium;” Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 49-p “On Founding the Art and Culture Museum Complex "Mystetskyi Arsenal” dated March 3, 2005. The excavations were carried out according to an open letter and permission of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Ukraine, issued in the name of H. Yu. Ivakin.

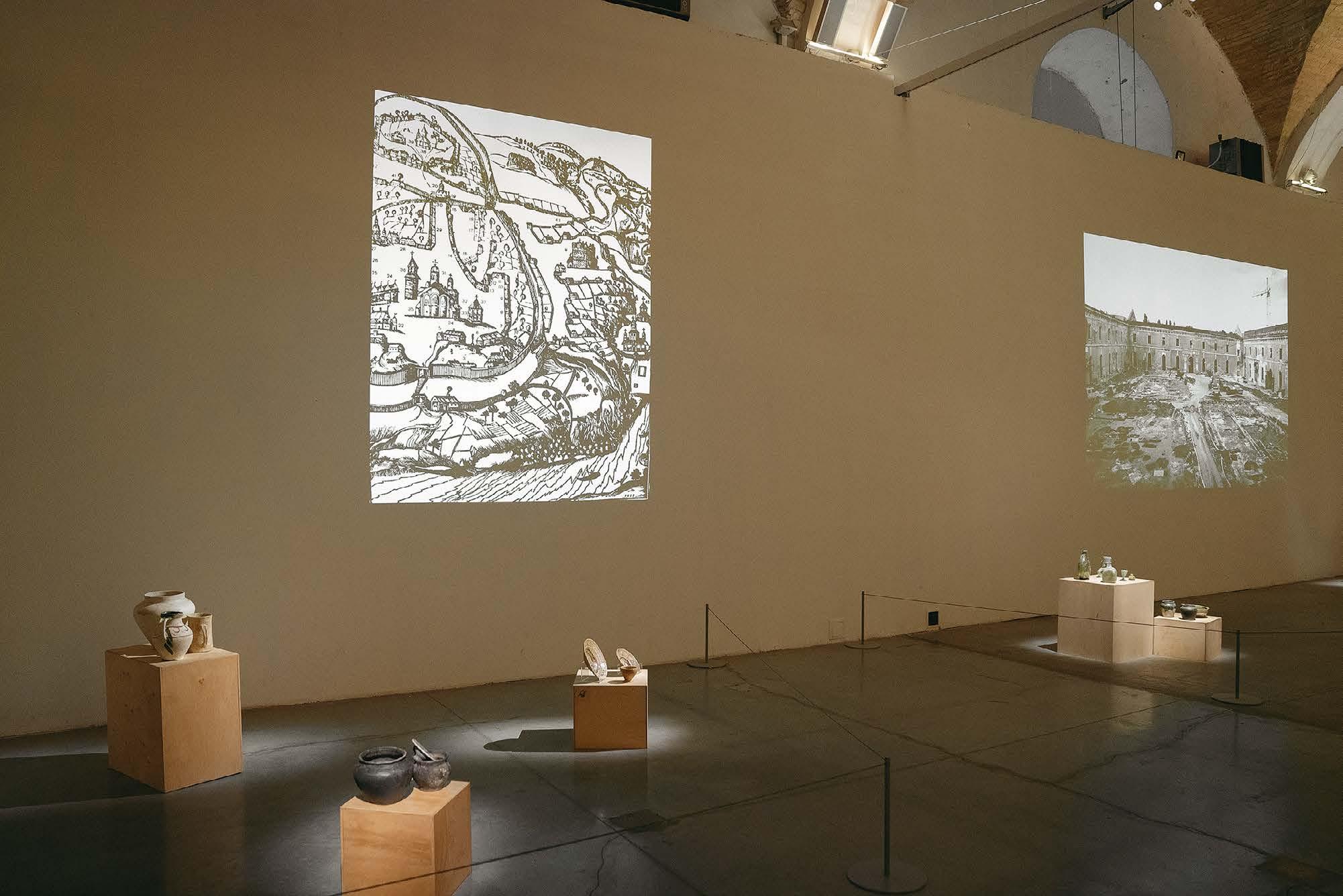

The location of Mystetskyi Arsenal could be called an ‘archaeologist's dream.’ On the one hand, it is located in the heart of the historic district of Pechersk, a district with an ancient and turbulent history. On the other hand, this area was lucky to not be so destroyed by the intensive re-building of Kyiv, the merciless vices of which razed more than one site of antiquity. The main stage of archaeological research in the territory of the Old Arsenal1 fell between 2005–2009. The realization of the ‘dream’ turned into not only one of the largest excavations in the capital but also a huge amount of work, the extent of which we have not yet fully understood or completed. Iconic excavations in Kyiv, such as during the construction of the subway in the Podil district in the 1970s or in the territory of the St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in the 1990s, make it possible to realize that such unique opportunities for specialists are becoming fewer, and there are almost no chances of finding an intact and integral complex in the capital. The research on the Old Arsenal covered an area of about 30,200 square meters and became another bright chapter in Kyiv archaeology.

Before the start of excavations, researchers were aware of numerous archaeological sites around the territory of the Old Arsenal. Firstly, this includes the complex of the Kyiv-Pechersk Monastery, which is supposedly rich in the cultural heritage of the medieval and early modern era. Secondly, during various construction works, researchers recorded archaeological objects along Tsytadelna Street, on Slavy Square, in the territory of St. Theodosius Pecherskyi Church, etc. All this testified to the significant archaeological potential of the Arsenal site.

There was a lack of objective information—

↑

both regarding the current state of the cultural layer and according to historical sources2—about the territory of the Old Arsenal, which was a closed military facility until the mid-2000s. One of the few known details was the existence of the Voznesenskyi Monastery at this site. The first written mention of the monastery dates back to 1619, a significant period in its history when Mariia Mahdalyna, Ivan Mazepa's mother, was the monastery’s abbess. The monastery was mentioned by Guillaume de Beauplan in his “Description of Ukraine” and Paul of Aleppo in his travel notes from the middle of the 17th century. Its architectural blueprint and location was recorded on the oldest plans of the city by Athanasius Kalnofoiskyi (1638) and Ivan Ushakov (1695). All this created the expectation of a unique site of archeology for researchers to engage with, a site which existed for a relatively short time. At the beginning of the construction of the Pechersk Fortress, the monastery (as an institution) was moved to Podil, and the cathedral continued to exist for some time as a parish church of the Pechersk district. Since the end of the 18th century, when the construction of the Old Arsenal began, the site functioned as a military facility, and the material remains of the monastery were preserved under the layers of new military life. Access to this area for ordinary citizens became limited, and no scientific research was conducted until the beginning of the 21st century.

Professional archaeologists first set foot behind the fence of military unit No. 2161 (at that time, the Kyiv Repair Plant) in 2005. After the resolution of legal issues regarding the transfer of the military complex into a cultural institution3 and at the beginning of the reconstruction of the complex in the territory of the Old Arsenal, a team

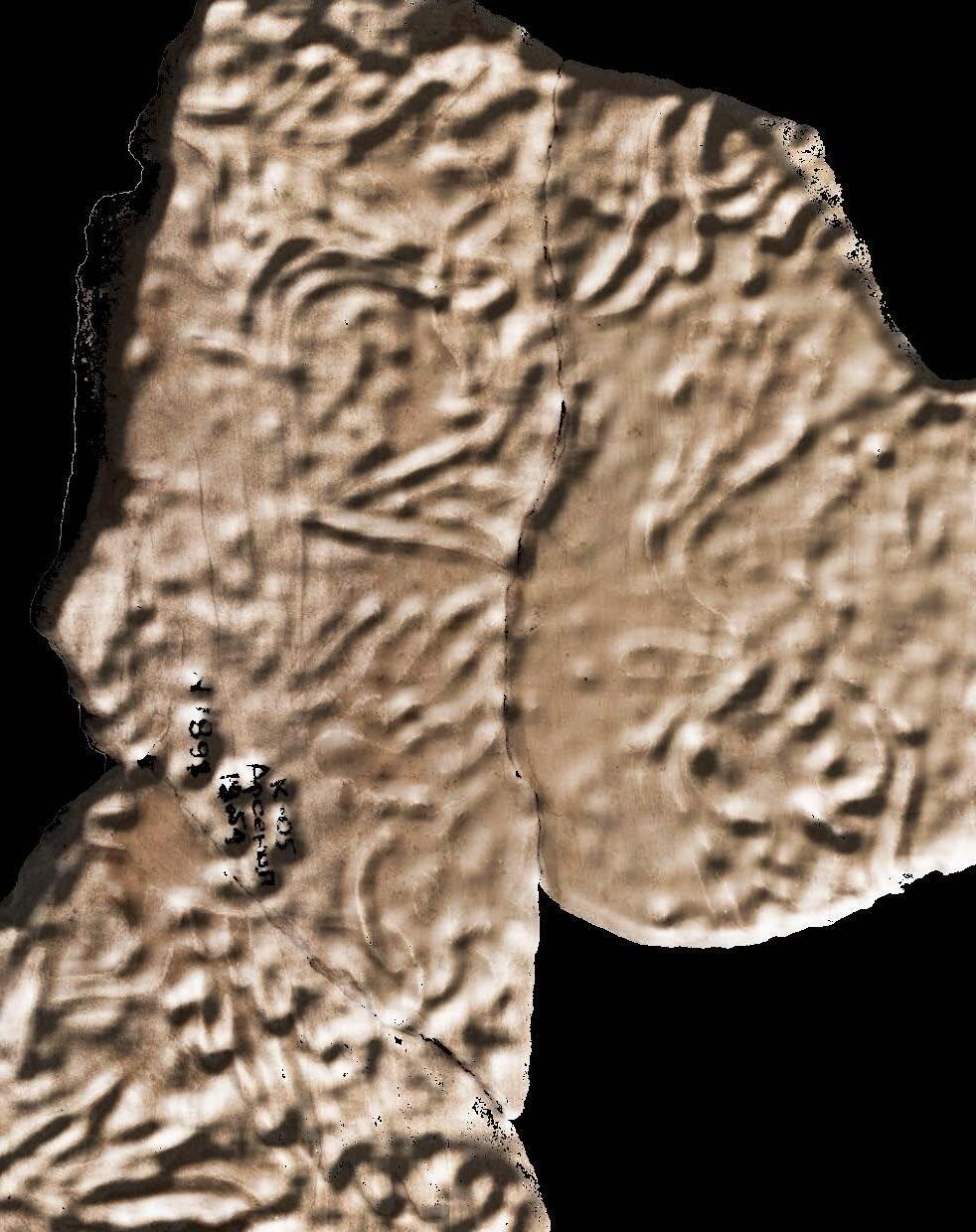

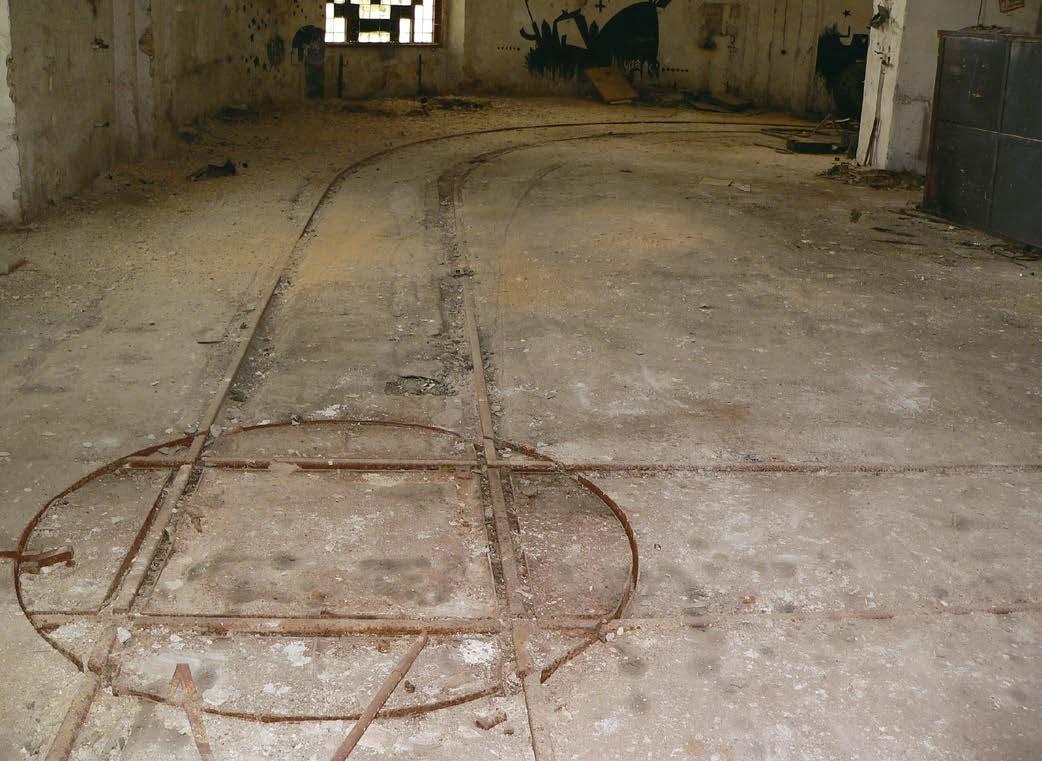

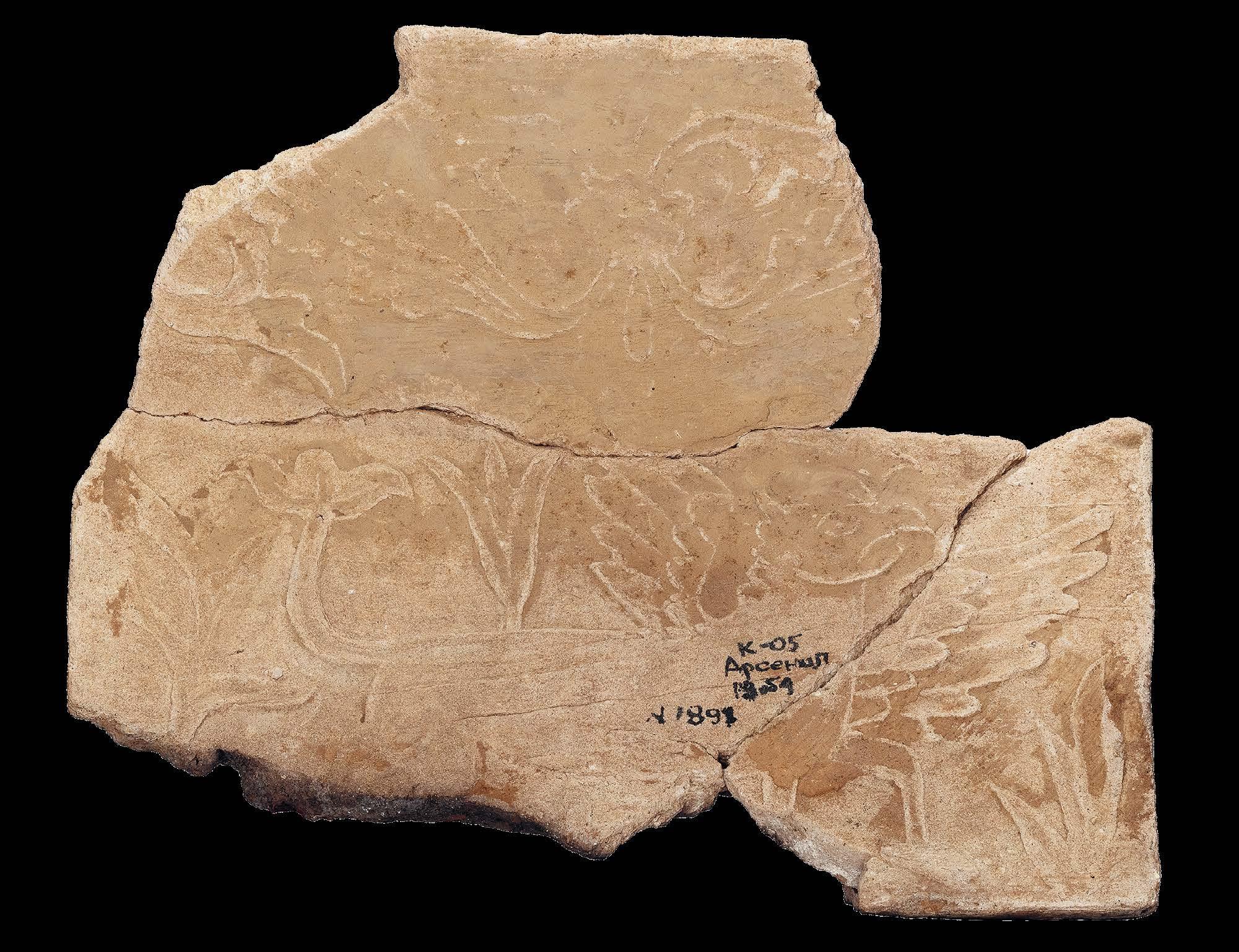

Postern from the 18th century found in the fortifications of the Old Pechersk Fortress. 2008

of employees of the Architectural and Archaeological Expedition of the Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine under the leadership of Hlib Ivakin began their work here. In the summer of 2005, my colleagues and I looked in amazement at the territory of the military town, which was living out its last days. Until recently, this was an active facility full of life, many traces of which looked rather anachronistic. At the time of our visit, a military employee was on duty at the entrance checking documents with the lists of authorized access. A significant part of the military equipment and materials had already been taken out, and the process of purging the less necessary and obsolete items was in full swing. Archaeologists found themselves in the realm of scattered factory furniture, remnants of completely Soviet-style slogans, and heavy construction equipment. Only the building of the Old Arsenal, cleared of all later layers, was to remain. Since there were no special premises in the territory, the expedition team arranged rooms for work in the former offices of the military unit. Tables, chairs, boxes, and drawers from old wardrobes came in handy—convenient places to store newly discovered artifacts. It made our cameral labs look a little archaic and romantic. While walking around the territory during lunch breaks, we came across various wonders, such as a full set of vintage government-issue telephones or white urinals. One day, the builders pulled out a set of foam-gilded figures representing the muses from the basement. Human-sized, they were the remains of the stage props of a local amateur group.

Archaeological excavations started from the middle of the inner courtyard of the Old Arsenal. Until recently, it was completely paved, and surrounded by old poplars on the perimeter. The walls of the building were tightly entwined with various plumbing and electrical pipes, like so much industrial ivy. The building looked like an old living organism. With the help of heavy machinery, the removal of the top layer of asphalt and construction fill began. Since then, in the deeper layer of the soil, the picture of the material history of the site recorded in the remains of ancient buildings, burials, and numerous artifacts began to unfold before the researchers.

The main archaeological research efforts took place from 2005 to 2009, at the same time as the external construction work of rebuilding the site. Subsequently, after the opening of the first exhibition in 2009 and with the beginning of the fully

functioning of Mystetskyi Arsenal as a cultural, art, and museum complex, scientific archaeological supervision was carried out situationally. The sequence of archaeological excavations depended on the stage of reconstruction of the complex and, if possible, was coordinated with the builders. This is exactly how urban archeology works, which, unfortunately, leaves no time for measured methodological development or peaceful dig sites one might find in rural places. The research was carried out in several segments: the first was the area of the inner courtyard of the building, the next was the space inside the Old Arsenal, and, finally, the adjacent areas and the rest of the territory of the complex.

The inner courtyard with an area of 8,769 square meters was investigated mainly during the summer and late autumn of 2005.4 Some areas adjacent to the walls of the building were developed as separate excavation sites as construction work progressed between 2006–2009. In these areas, a team of archaeologists began recording the first finds almost immediately. For convenience and organization, the huge space was conditionally divided into 4 parts, each of which (so-called excavation sites 1–4) was later studied by separate groups of specialists and had its own numbering of the discovered objects. In total, archaeologists discovered more than 150 objects here of various purposes (remains of dwellings, storage buildings, and pits), more than 250 burials, and traces of the main monastic building—Voznesenskyi Monastery. The objects inside the inner courtyard were more intact in comparison to other parts of the studied territory due to the smaller number of construction interventions during the 18th–20th centuries. Areas inside the building were mostly damaged by its construction. Archaeological work continued here between 2006–2007.5 These excavations covered almost the entire rectangle of the building except for the eastern part, under which the historical basements are located. In the working systematization, the discovered materials were denoted by the conventional name ‘building’ (in contrast to excavations 1–4). Scientists investigated about 80 archaeological sites and several burials inside the building. In terms of research value, the fragmentary nature of the objects in the building is fully compensated by the chronological variety of finds, from ceramics of the 14th century to late dishes and weapons of the 18th century.

In the territory of the complex outside the building, archaeological research was carried

out mainly through scientific supervision and continued throughout the years with the work of the Architectural and Archaeological Expedition.6 The cultural layer around the Old Arsenal was preserved to a small extent. Here it was possible to record isolated remains of human activity from the 19th century and some constructive features of the earthen fortifications of the Pechersk Fortress, including the brick underground postern from the 18th century.

Almost the entire volume of fieldwork—research on archaeological objects, recording of planigraphy and stratigraphy, photography, and architectural measurements—was carried out in the traditional conditions of urban archaeology. Archaeologists worked alongside active, heavy construction equipment, and during the most intensive years of 2005–2006 were working from dawn until dusk even in the winter. The cameral processing of the materials began almost immediately in the summer of 2005, which continued quite intensively until 2010. It traditionally included cleaning the finds from surface contamination, gluing fragmented objects, labeling them, compiling field descriptions, primary restoration, preparation of graphic images of the finds, and analysis of anthropological remains. More than 23,500 finds were added to the lists of primary records in the period from 2005 to 2010. Some of these objects, which have exhibition or scientific significance, were later transferred to the collection of Mystetskyi Arsenal and thus accounted for as part of the State Museum Fund of Ukraine. The remaining fragments of artifacts, though not individually catalogued, are kept as an auxiliary research and study resource for the institution.

The entire complex of archaeological artifacts was characterized by high intensity and significant volumes, considering the number of recorded objects and discovered materials. The team of researchers began to publish the results of the primary analysis in scientific publications almost immediately. Even during the fieldwork, the evident development of a significant collection was such that first generalizations were made and a series of special studies7 was initiated. Perhaps the most complete among them is the special edition of the ”Lavrskyi Almanac: Pechersk Fortress and Kyiv Arsenal: New Studies,” which includes 6 publications based on the materials of archaeological research and historical research.8 The intensity of material processing has decreased since the 2010s due to the intensification of other pressing archae-

4 Ivakin H. Yu., Kozubovskyi H. A., Balakin S. A. ta in. 2006. Doslidzhennia na terytorii Staroho Arsenalu v Kyievi. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2004–2005, S. 175–177; Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A., Videiko M. M. ta in. 2007. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia 2006 r. terytorii divochoho Voznesenskoho monastyria v Kyievi. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2005–2007, S. 178–180; Ivakin H. Yu., Kozubovskyi H. A., Chekanovskyi A. A. ta in. 2008. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia na vnutrishnomu podviri Staroho Arsenalu 2007 r. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2006–2007, S. 119–121.

5 Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A., Baranov V. I., Onohda O. V. 2007. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v korpusi Staroho Arsenalu v 2006 r. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2005–2007, S. 175–178; Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A., Baranov V. I., Onohda O. V. 2008. Arkhitekturno-arkheolohichni doslidzhennia u pidvali korpusu Staroho Arsenalu ta navkolo noho. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2006–2007, S. 115–118.

6 Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A., Baranov V. I., Onohda O. V. 2008. Arkhitekturno-arkheolohichni doslidzhennia u pidvali korpusu Staroho Arsenalu ta navkolo noho. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2006–2007, S. 115–118; Ivakin H. Yu., Baranov V. I., Onohda O. V. 2009. Arkhitekturno-arkheolohichni doslidzhennia na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho arsenalu. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2008, S. 84–87.

7 Ivakin H. Yu., Kozubovskyi H. A., Balakin, S. A. 2005. Pidzemni skarby Staroho Arsenalu (poperednia informatsiia). Vidlunnia vikiv, 2 (04), S. 52–56; Ivakin H. Yu., Kozubovskyi H. A., Balakin, S. A. 2005. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia na terytorii kyivskoho Arsenalu 2005 r. (poperednia informatsiia). Pratsi tsentru pamiatkoznavstva, 8, S. 119–145; Ivakin H. Yu., Balakin S. A. 2007. Predvaritelnie itogi arkheologicheskikh issledovanii 2005 g. na territorii kievskogo Arsenala. Materiali III Sudakskoi mezhdunar. nauchnoi konf., І, S. 159–168; Іvakіn G. Yu., Balakіn S. A. 2007. Pidzemni skarby kyivskoho Arsenalu (rezultaty doslidzhen ta perspektyvy muzeiefikatsii). Vidlunnia vikiv, 1 (7), S. 26–32

8 Lavrskyi almanakh: Kyievo-Pecherska lavra v kontekstі ukrainskoi іstorii ta kultury. Zb. nauk. prats. 2008. Vip. 21, spetsvypusk 8: Pecherska fortetsya ta Kyivskyi arsenal: novі doslіdzhennia. Kyiv: Fenіks, NKPІKZ.

chapter 2 ✳ provenance

ological rescue research in Kyiv and the objective lack of resources. Excavated materials still need summarizing and description thorough research and publication of a complete catalog of finds. Despite the somewhat fragmented nature of the existing publications, the conclusions obtained, the data obtained, and the collection of artifacts make it possible to evaluate the site as a unique archaeological resource.

Scientists determined that the territory of the Old Arsenal underwent three main chronological stages of development, pre-monastic, monastic, and military:

1) The period preceding the first written mention of the Voznesenskyi Monastery. Some isolated finds belong to the Old Rus period, but the site was still uninhabited and was on the periphery of the buildings of the Kyiv-Pechersk Monastery. Plinth and slate fragments, smalt cubes, and part of a 12th-century pot found themselves in the territory of the complex, apparently by accident. The permanent development of the site began in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, as evidenced by the remains of several objects. During the 15th and 16th centuries, life intensified, and the number of inhabitants increased. In total, archaeologists discovered about 20 objects from the 14th–16th centuries. At that time, Pechersk district played the role of one of the centers of life in Kyiv and finds from the territory of the Old Arsenal corroborate this. Unfortunately, archaeological materials do not provide an answer to the question of when the objects became part of the Voznesenskyi Monastery. However, the fact of quite intensive life activity in the studied territory is indisputable.

2) The complex of the Voznesenskyi Monastery from the 17th—early 18th centuries reflects the “monastic” stage of development of the site. It is represented with almost 130 different objects: the remains of underground portions of houses or other structures, food and garbage pits, the monastery well, burials, etc. The dominant feature of the archaeological complex—the remains of the Voznesenskyi Monastery, built in 1705—was located in the central part of the inner courtyard of the Old Arsenal. After the demolition of the Monastery between 1797–1798, only the backfilling of the foundation trenches remained from the triapsal structure measuring about 23×34 m. Voznesenskyi Necropolis had more than 250 burials.9 This was one of the largest burial sites in Kyiv in the early modern period, which went through two stages of development: active monastic and

parish (after the monastery was abolished). The only identified burial is the grave of the civilian governor of Kyiv, Major General Semen Ivanovych Sukin (d. 1740), with a decorated tombstone and a dedicatory inscription. The study of Semen Sukin's skeleton made it possible to discover interesting facts about his life, starting from the conditions in which he grew up as a child and ending with venereal disease.10 Syphilis was very widespread in the military at that time, and the general could easily have been infected in his youth, leading a mobile military lifestyle. It is worth mentioning that upon completion of this and other studies of the anthropological materials of the necropolis, conducted by Oleksandra Kozak, the human remains were reburied. This happened on the initiative of the then director of Mystetskyi Arsenal Nataliia Zabolotna at the end of 2012. The skeletons were reburied at the Florivskyi Monastery, which at one time was joined by the congregation of the closed Voznesenskyi Monastery.

3) The “military” period of operation of the site took place from the 18th–20th centuries. Materials of this time were found sporadically in the cultural layer, and represented by few remains. These are mainly traces of the activities of the artillery yard and gunsmith workshops. Extraordinary finds of glass hand grenades and naval anti-ship ammunition attracted the special attention of archaeologists.11 Archaeologists have traced some structural features of the earthen fortifications of the Pechersk Fortress, including the 18th-century brick postern. Artifacts were not found in this underground gallery, although the research team recorded humorous and unexpected evidence of further exploitation of the site in Soviet times: a simple pencil drawing on the wall depicting a naked woman. Some particular items of military life in the 20th century did not make their way underground and therefore did not become archaeological objects. But careful scientists also paid attention to such above-ground curiosities and collected a small grouping of items from the time of the military unit's stay here, such as a political map of the world during the Cold War left on the wall of the office.

Thanks to this archaeological research, the knowledge of Ukrainian material culture from the 14th–18th centuries12 has increased both in aesthetic understanding and object function. Numerous artifacts obtained during excavations resulted in a significant collection of pottery: kitchenware, tableware, and tiles. There are also samples of

tableware and miniature toy vessels. Some of the tableware is decorated artistically in styles consistent with Ukrainian motifs of the period (plant ornamentation, floral compositions, and abstract images) while other pieces appear to be of imported origin (for example, a jar made of the so-called Rhine stone mass), which indicates high social status and economic resources of the owners. One of the 16th century pots had grain marks on the bottom. Some of the oven tiles are decorated with rare images of griffins or tailed lions, heraldic ornaments, and even letter inscriptions. Among the more enigmatic pieces is a pot with three rounded holes in the bottom part, the purpose of which there is still no consensus.

The Old Arsenal complexes from the second half of the 17th century—through the 18th century contained a wealth of handicrafts: drinking jars, containers for storing liquids, glass panes, etc. Metal products mainly concern everyday implements: knives, nails, and metal shoe soles. Numismatic finds date from the end of the 15th to the 18th century; these are mainly coins of Lithuanian-Polish and Baltic-Swedish minting, and russian to a lesser extent Unique finds include four bone chess figures from the 15th–16th centuries (pawn, bishop, rook, and probably queen) and a later two-sided icon on a metal oval medallion.

The main result of archaeological excavations in the territory of the Old Arsenal is the recording of a multi-layered historical and cultural site that reflects all the chronological stages of the historical development of this part of Pechersk, the heart of which was the 17th century Voznesenskyi Monastery. Taking into account the complexity of the study of the site, which had never been explored before, these excavations can be considered unprecedented for Kyiv. All this emphasizes the relevance of the museification of the collection from excavations as a logical continuation of scientific research.13

Large-scale research was carried out by the hundreds of people who joined the excavations and cameral works at various stages of the study of the Old Arsenal. Among the researchers, the outstanding archaeologist Hlib Ivakin—the head of the expedition and a leading specialist in Ukrainian late-medieval archeology—should be mentioned first. His previous research changed ideas about the development of the Dnipro region after the Batu invasion, and in turn overcame stereotypes about the desolation of some parts of Kyiv until the 17th century. Excavations of the

9 Іvakіn G. Yu., Balakіn, S. A. 2007. Pokhovannya v sklepakh ta na tseglyanikh vimostkakh Voznesenskogo nekropolya XVII–XVIII stolіttia. Lavrskyi almanakh, 19, S. 17–26.

10 10 Kozak O. D. 2008. Deiakі osteobіografіchnі rysy do portreta kyivskogo gubernatora. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 50–63.

11 Staroverov D. A. 2007. Stekliannie grenadi iz kievskogo Arsenala. Arkheolohichni vidkryttia v Ukraini 20052007, S. 347–349; Staroverov D. A. 2007. Stekliannie granaty XVIII v. iz raskopok na territorii kievskogo Arsenala // Novi doslidzhennia pamiatok kozatskoi doby v Ukraini, 16, S. 147–150.

12 Zazhyhalov O. V. 2012. Kompleks keramichnykh svitylnykiv XVII st. z rozkopok Staroho Arsenalu v Kyievi. Lavrskyi almanakh, 26, S. 8–10; Onohda O. V. 2008. Keramichni kompleksy XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho Arsenalu. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 24–31; Onohda O. V. 2014. Honcharnyi posud XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho arsenalu. Tserkva–nauka–suspilstvo: pytannia vzaiemodii, S. 31–33; Onohda O. V. 2015. Honcharnyi posud XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho arsenalu. Bolkhovitinovskyi shchorichnyk 2013/2014, S. 137–152; Onohda O. V. 2018. Kompleks iz polyvianoiu keramikoiu druhoi polovyny XV—pershoi polovyny XVI stolit. (za materialamy rozkopok Staroho arsenalu v Kyievi). Arkheolohiia i davnia istoriia Ukraiiny, 4 (29), S. 246–253; Chmil L. V. 2007. Keramichni tarilky z Arsenalu. Poperedni pidsumky. Novi doslidzhennia pamiatok kozatskoi doby v Ukraini, 17, S. 111–119; Chmil L. V. 2007. Uzhytkova keramika XVII st. z rozkopok Voznesenskoho zhinochoho monastyria v Kyievi. Lavrskyi almanakh, 17, S. 164–170; Chmil L. V. 2008. Keramika Voznesenskoho monastyria. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 32–42; Chmil L. V. 2009. Importna keramika z rozkopok Staroho Arsenalu v Kyievi. Novi doslidzhennia pamiatok kozatskoii doby v Ukraini, 18, S. 68–72. Zazhyhalov O. V. 2012. Kompleks keramichnykh svitylnykiv XVII st. z rozkopok Staroho Arsenalu v Kyievi. Lavrskyi almanakh, 26, S. 8–10; Onohda O. V. 2008. Keramichni kompleksy XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho Arsenalu. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 24–31; Onohda O. V. 2014. Honcharnyi posud XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho arsenalu. Tserkva–nauka–suspilstvo: pytannia vzaiemodii, S. 31–33; Onohda O. V. 2015. Honcharnyi posud XIV–XVI stolit z rozkopok na terytorii Staroho kyivskoho arsenalu. Bolkhovitinovskyi shchorichnyk 2013/2014, S. 137–152;

13 Balakin S. A., Onohda, O. V. 2011. Kyivskyi «Mystetskyi Arsenal»: pidsumky arkheolohichnykh doslidzhen ta problemy muzeiefikatsii. Tserkva–nauka–suspilstvo: pytannia vzaiemodii, S. 42–45.

Contours of the foundations of the Ascension Cathedral revealed during archaeological excavations in the inner courtyard of the Old Arsenal. 2005

Old Arsenal additionally demonstrated Pechersk's historical development. All fieldwork at the site was carried out under permits in the name of Hlib Ivakin; under his leadership, the first summary materials were prepared based on the results of the excavations. Analytical publications were also prepared by other members of the team on the archaeological study of the Old Arsenal: Heorhii Kozubovskyi, a researcher of medieval numismatics and head of fieldwork in the inner courtyard of the building; Serhii Balakin, a specialist in Pechersk archeology and researcher of Voznesenskyi Necropolis; Lesia Chmil, a specialist in early modern ceramic production and head of work on excavation sites III and IV; and Olena Onohda, author of this article, a researcher of late medieval ceramics who was responsible for work on excavation site II. Viacheslav Baranov began his Kyiv stage of scientific research here, joining the organization of scientific supervision in the building and in the areas adjacent to the building. At different stages, certain aspects of the history of the site were studied by particular specialists: speleo-archaeologist Tymur Bobrovskyi examined underground structures, Yurii Lukomskyi carried out architectural measurements and drew up an accurate plan of the remains of the foundations of the Voznesenskyi Monastery, archaeozoologist Oleh Zhuravliov prepared an analysis of the remains of animal bones, and anthropologist Oleksandra Kozak examined a significant array of human remains of the Voznesenskyi Necropolis.

The materials of the excavations contributed to the scientific research by the then-young generation of the Architectural and Archaeological Expedition in various directions. Topics that emerged included necropolistics (Olena Melnyk),14 the history of ceramic and glass production (Olena Onohda, Elvira Pochynok, and Dariia Finadorina),15 and applied art (Olha Abyshkina).16 The publication of archaeological materials became an impetus for the activation of new research.17 Among the historical works, it is worth mentioning the thorough investigations of Olha Krainia on the history of the Kyiv-Pechersk Convent (Voznesenskyi Monastery) in the 16th-early 18th centuries, when the monastery first became the object of comprehensive research.18

Many specialists in the archaeology of different periods joined the fieldwork at different times. Among them were graduates of the newly created master's program in Archaeology at the

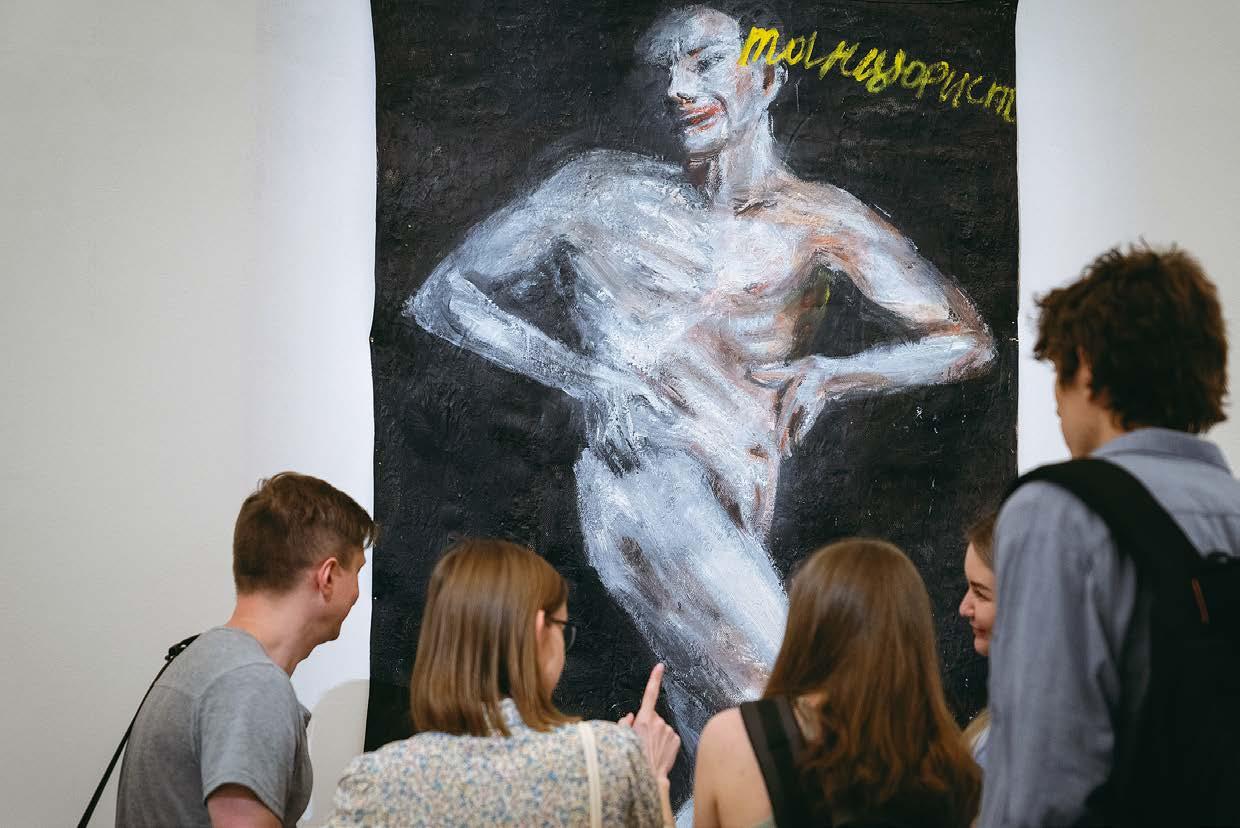

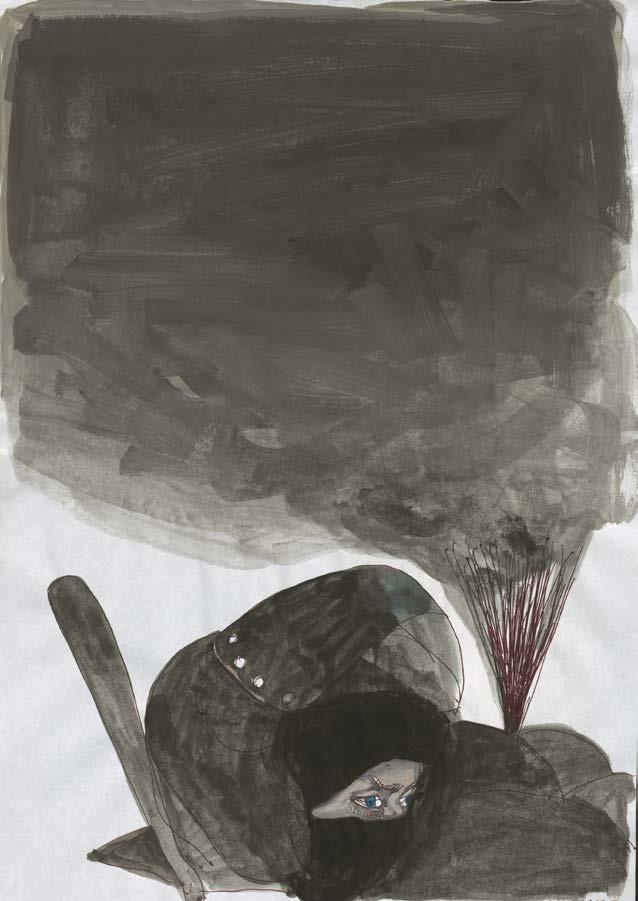

← Fragment of the pop-up exhibition “New Old Arsenal.” Mystetskyi Arsenal. 2022

14 Melnyk O. 2017. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia pokhovan Kyieva XVI–XVIII st. Eminak, № 1 (17), t. 4, S. 16–21.

15 Onohda O. V. 2011. Pryiomy formuvannia denets horshchykiv druhoi polovyny XIII–XV stolit yak oznaka tekhnolohichnoho prohresu honcharnoho vyrobnytstva. Mohylianski chytannia 2010, S. 400–403; Onohda O. V. 2012. Keramika Serednoi Naddniprianshchyny druhoi polovyny XIII–XV st.: avtoref. dys. kand. ist. nauk. Kyiv; Onohda O. V. 2013. Keramichnyi posud iz zashchypamy z rozkopok monastyrskykh kompleksiv XV—pershoi polovyny KhVI st. na terytorii Kyieva. Tserkva–nauka–suspilstvo: pytannia vzaiemodii, S. 29–31; Pochynok E. Yu. 2008. Sklianyi stolovyi posud z terytorii Staroho Arsenalu. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 43-49; Finadorina D. 2011. Khudozhno-dekoratyvni riznovydy kompleksu pichnoi kakhli XVII st. z rozkopok kyivskoho Arsenalu. Bolkhovitinovskyi shchorichnyk 2010, S. 135–143.

16 Abyshkina O. A. 2007. Natilna ikonka z Voznesenskoho monastyria. Mohylianski chytannia 2006, ch. 1, S. 289–292.

17 Balakin S. A., Onohda O. V. 2010. Kulturnokhronolohichnyi horyzont XIV–XVI st. Kyievo-Pecherskoi lavry ta ii okolyts. Aktualni problemy arkheolohii, S. 110–111; Onohda O. V., Chmil L. V. 2008. Do pytannia pro tekhnolohiiu vyrobnytstva kyivskoi keramiky druhoi polovyny XIII—pochatku XVI st. Pratsi tsentru pamiatkoznavstva, 14, S. 104–132; Onohda O. V. 2009. Do pytannia pro stan zberezhenosti kulturnoho horyzontu druhoi polovyny XIII–XVI st. u Kyievi. Mohylianski chytannia 2008, S. 343–349; Onohda O. V., Chekanovskyi A. A., Chmil L. V. 2010. Pidsumky, problemy i perspektyvy vyvchennia keramiky Serednoi Naddniprianshchyny II-i polovyny XIII–XVIII st. Arkheolohiia i davnia istoriia Ukrainy, 1, S. 446–453; Chmil L. V. 2010. Keramichnyi posud Serednoi Naddniprianshchyny XVI–XVIII st.: avtoref. dys. kand. ist. nauk. Kyiv; Chmil L. V. 2013. Znachennia arkheolohichnykh doslidzhen kyivskykh khramiv ta monastyriv dlia datuvannia artefaktiv. Tserkva–nauka–suspilstvo: pytannia vzaiemodii, s. 54–56.

18 Krainia O. O. 2008. Novi materialy do istorii Voznesenskoho Pecherskoho monastyria. Lavrskyi almanakh, 21, S. 66–111; Krainia O. O. 2012. Kyievo-Pecherskyi zhinochyi monastyr XVI—pochatku XVII st. i dolia yoho pamiatok. Kyiv: Natsionalnyi Kyievo-Pecherskyi istoryko-kulturnyi zapovidnyk.

chapter 2 ✳ provenance

National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy: Iryna Karashevych, Taras Korostylov, Andrii Oliinyk, Anton Smirnov. Olha Abyshkina, Mykola Belenko, Viacheslav Haiduk, Pavlo Komarenko, Viacheslav Kryzhanovskyi, Andrii Krotenko, Dmytro Staroverov, Mykola Tarasenko, and Andrii Sydorchuk spent significant time working at the site. Cameral processing was handled by Mariia Videiko, Nataliia Volovodenko, Oksana Votiakova, Liubov Shumakova, while Andrii Chekanovskyi and Oleksii Zazhyhalov took photographs of the research areas and found materials.19 For some of these people, the excavations of the Old Arsenal became the basis for further scientific work, while others changed the direction of their work and never returned to archaeological research.

Traditionally, for large-scale archaeological projects, students of specialized universities participated in excavations for summer internships. Several groups from the Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University, the National University of Culture and Arts, the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture, and the Taras Shevchenko Luhansk National University worked at the Arsenal.

In addition to the scientists, it is impossible to ignore the figure of President Viktor Yushchenko. Through his initiative, the reconstruction of the complex was started and Mystetskyi Arsenal was founded as a state institution. During his visits to working meetings, President Yushchenko was keenly interested in the course of archaeological work both as the head of the state and as a sincere amateur of historical research.

Although the history of excavations of the Old Arsenal has come to an end, the formation of the archaeological collection of Mystetskyi Arsenal continues. In 2018, the Institute of Archeology carried out new rescue excavations on the adjacent site across the road from the southern wing of the Old Arsenal.20 This area was abandoned for a long time. At one time, the workers of the Architectural and Archaeological Expedition walked along the green fence, hoping that there might be interesting finds at this site of a former shoe factory, synchronous with those found in the Arsenal. Archaeological excavations covered an area of about 600 square meters close to Tsytadelna Street. They preceded the construction of the office of the Goethe Institute (now the territory at 16-Л Lavrska Str.). Andrii Olenych, a specialist in the history of medieval culture and a researcher at the Department of Archeology of Kyiv, supervised the excavations.

People began to settle in this part of the former Pechersk town in the 14th century, in the same period as settlements at the site of the future Voznesenskyi Monastery. Archaeologists found artifacts from the 16th–18th centuries: various household utensils, a cross, coins, cradles, chairs, and shoe covers. There were also children's toys, for example, a molded clay figure of a rider in a military uniform. The finds in this complex are largely consistent with the finds from the Arsenal territory, but there are also differences. Future research to develop not only a generalization study but also a comparative analysis with materials from the territory of the Old Arsenal would be useful. Given the geographical proximity of the site and the obvious historical richness of the territory, it was decided to transfer these materials to the collection of Mystetskyi Arsenal in 2020.

The history of archaeological excavations in the territory of the current Mystetskyi Arsenal had several stages, and in terms of scientific conclusions, it still cannot be considered complete. The published results and the subsequent transfer of the acquired collection to the institution now residing on the territory where these objects were found showcase a unique and rather optimistic page in the history of the study of ancient Kyiv. Currently, Mystetskyi Arsenal (as a future-oriented cultural institution) also operates with evidence of its immediate past, extracted from the ground and preserved for posterity.

19 This list of employees involved in the excavations is not exhaustive due to staff turnover.

20 Ivakin H. Yu. (†), Ivakin V. H., Baranov V. I., Olenych A. M. 2020. Doslidzhennia Arkhitekturno-arkheolohichnoi ekspedytsii IA NANU na vul. Tsytadelna, 3. Arkheolohichni doslidzhennia v Ukraini 2018, S. 52–54.

недовгу, хоча й бурхли-

історію інституції, створення

якої у 2005 році виглядало на

початку радше як гучний політичний маніфест щодо національного культурного надбання.

й стратегічного бачення щодо її формування. Складові її власної назви ніби конкурували між собою. Що є визначальним — «мистецький» чи «арсенал», візуальні практики чи історія?

У переліку реалізованих виставкових про-

єктів, попри доволі широке тематичне

силя Єрмилова, Казимира Малевича, Вадима

Меллера, Оксани Павленко, Віктора Пальмова, Анатоля Петрицького, Марії Синякової, Олександра Хвостенко-Хвостова, Ісаака

Олександра Тишлера, що характеризують твор-

Малевича. Твори Богомазова «В’язниця на Кавказі»2, «Композиція», «Портрет», «Портрет жінки» та інші роботи 1915–1916 років, що зберігаються зараз у Мистецькому

Art Section of the Collection

Ihor Oksametnyi

An installation of Hamlet Zinkivskyi “Load” on the “Instant Time” exhibition. Mystetskyi Arsenal. 2018

й стратегічного бачення щодо її формування. Складові її власної назви ніби конкурували між собою. Що є визначальним — «мистецький» чи «арсенал», візуальні практики чи історія?

У переліку реалізованих виставкових про-

єктів, попри доволі широке тематичне

різноманіття виставкової діяльності Мистецького арсеналу, простежуються дві лі-

нії, які виглядають як пілотні, стратегічні

напрацювання на майбутнє інституції.

Перша зорієнтована на висвітлення різних

аспектів історії українського мистецтва

першої третини ХХ ст., тих явищ, які об’єднуються поняттям український авангард,

друга — на фіксацію сучасного культурно-

го ландшафту, на висвітлення актуального художнього процесу. Ці лінії поступово визначили тенденцію у формуванні мистець-

кої складової колекції.

Добірка «історичного мистецтва» є доволі суб’єктивною, адже вона сформована вподобаннями та смаками відомого колекціонера й

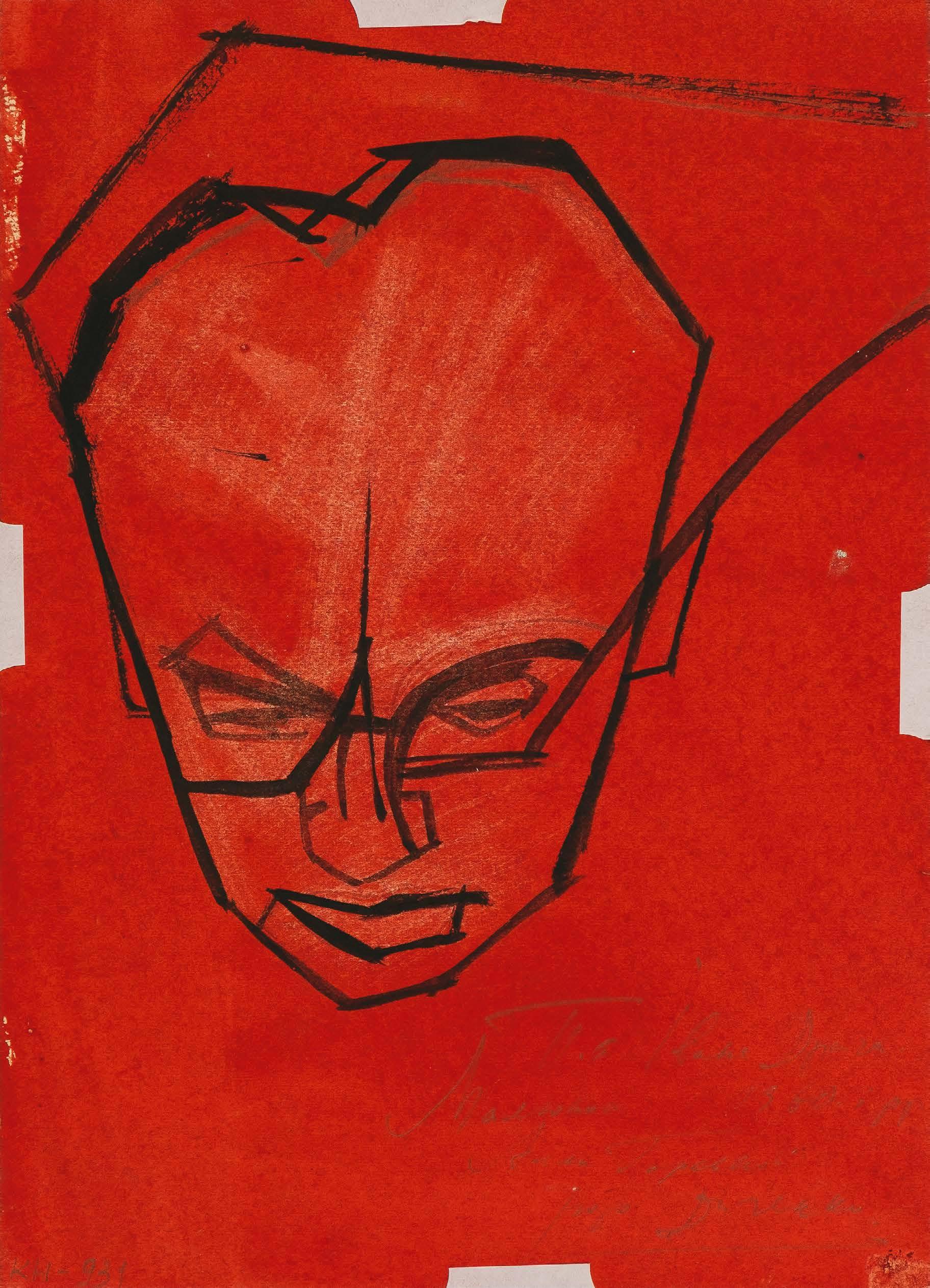

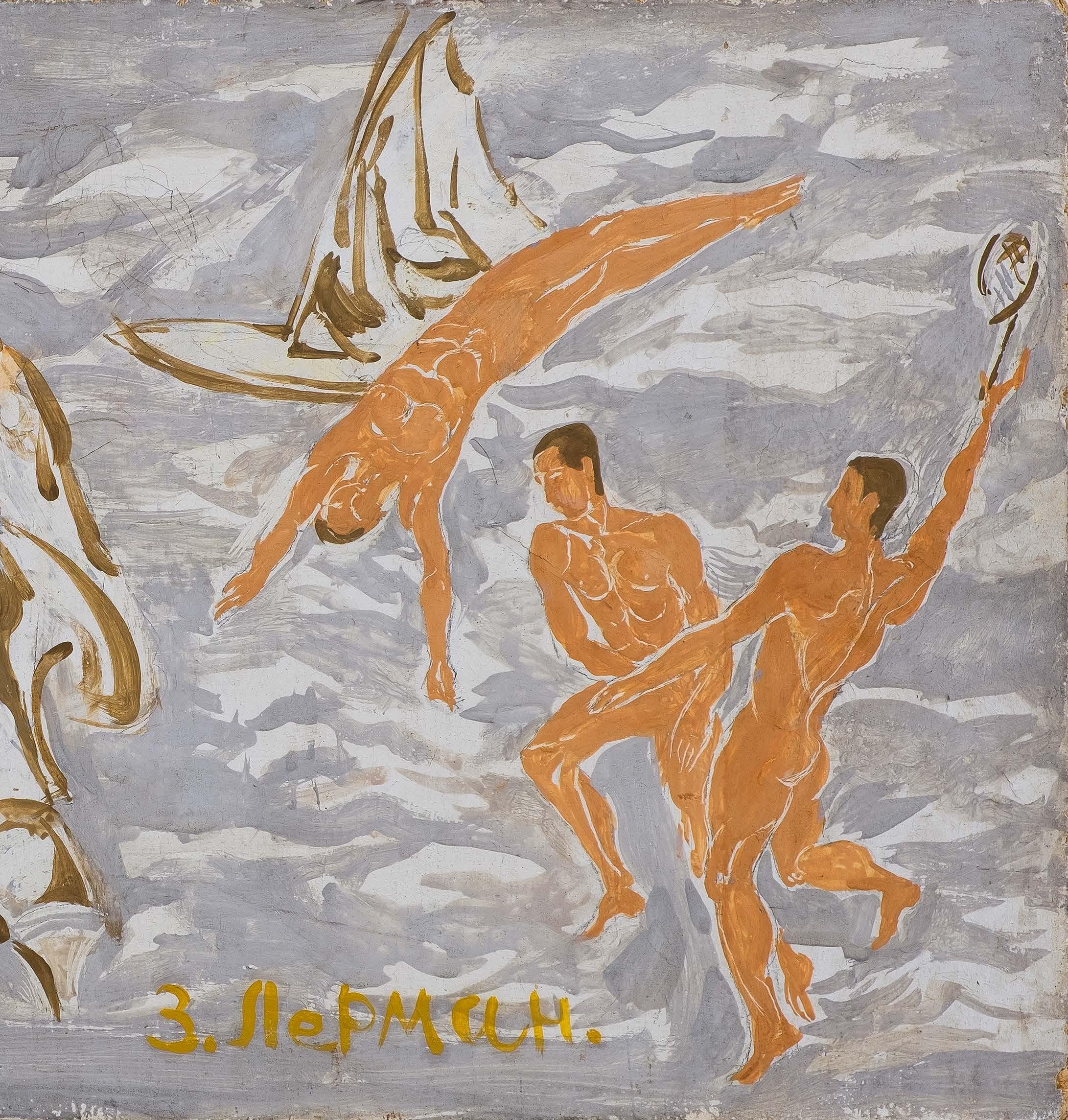

мистецтвознавця Ігоря Диченка1. До неї ми зараховуємо насамперед твори 1910–1930-х років Олександра Богомазова, Михайла Бойчука, Василя Єрмилова, Казимира Малевича, Вадима Меллера, Оксани Павленко, Віктора Пальмова, Анатоля Петрицького, Марії Синякової, Олександра Хвостенко-Хвостова, Ісаака Рабиновича, Олександра Тишлера, що характеризують твор-

того часу — «Про духовне

(1912), «Точка і лінія на площині» (1918–1919) Василя Кандинського, «Супрематизм» (1920) Казимира Малевича. Твори Богомазова «В’язниця на Кавказі»2, «Композиція», «Портрет», «Портрет жінки» та інші роботи 1915–1916 років, що зберігаються зараз у Мистецькому арсеналі, крім, безумовно, самодостатньої цінності, можуть розглядатися також як практичне втілення ідей

з’являється його цикл живописних робіт, у

яких художник намагався оперувати новими засобами виразності, де колір є головним, а сюжет просто слідує за ним. Його

формальні пошуки втілились у своєрідну

концепцію «кольоропису», яку він виклав

на сторінках часопису «Нова генерація».

Кількісно спадщина Віктора Пальмова є

відносно невеликою, тому кожна робота

має неабияку культурну цінність. У чотирьох творах різних років, які пощастило

придбати Ігорю Диченку, простежується чи не весь творчий шлях художника, який

внаслідок невдалої операції помер, у 1929 році, у самий розпал творчої та педагогічної

діяльності. Ось «Варіація на тему Гогена» початку 1920-х років — кубофутуристична

інтерпретація гогеновської теми — таїтянський позачасовий рай. Тільки замість

спокою і умиротворення — тривожна

напруга, замість безтурботних красунь —

якийсь чоловік із лопатою, що порається

в землі на передньому плані. У цей період

було написано й картину «Українське село

взимку» — враження від українського по-

селення у Приамур’ї, куди художника

занесла доля разом із його товаришем Да-

видом Бурлюком. Робота експонувалася на

великій виставці авангардистів, яку друзі

організували в Японії і за яку він отримав

золоту медаль. Тут уже простежуються особливості того пальмовського живописного стилю, який остаточно сформувався у київський період і яскравим відображенням якого є «Пляж» 1926-го року. Спонтан-

На жаль, ми не маємо жодного документального підтвердження

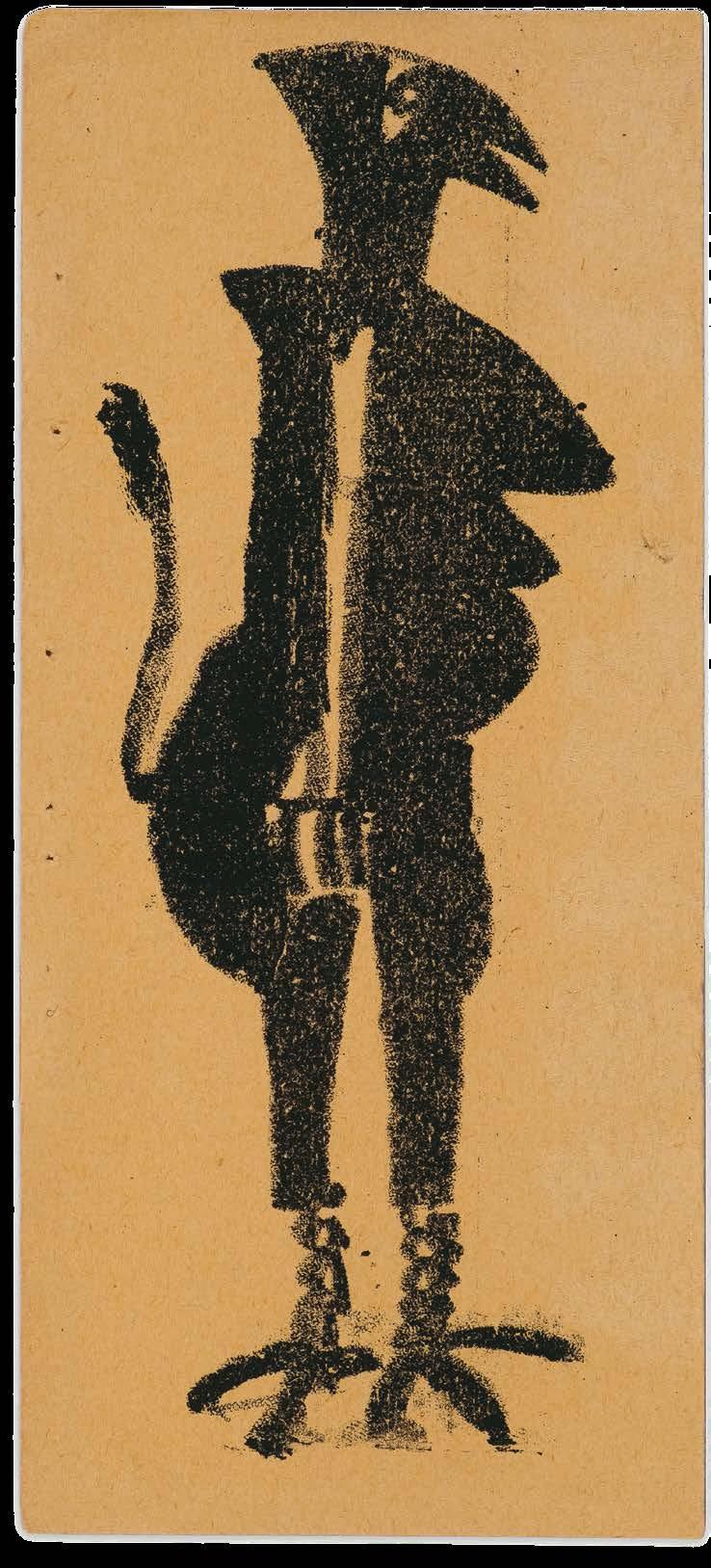

от щодо іншого твору — літографічної ілюстрації до поеми 1914-го року Олексія Кручених та Велимира Хлєбникова «Гра в пеклі» — сумнівів немає. Заняття літографією в Малевича збіглися з кубістичним періодом у його творчості. Точніше, періоду повороту від кубізму до супрематизму. У 1914 році вийшло друге видання поеми, до якого Малевич виконав обкладинку, два малюнки та сторінкову композицію із зображенням двох чортів, які розпилюють грішницю. Є версія, що постать чорта, зображена

Олександр Хвостенко-Хвостов, Ісаак Рабинович.

Ці митці вже у 1920–1930-ті роки були всесвітньо відомими майстрами, їхні роботи — макети, ескізи, декорації, костюми — експонувалися на міжнародних виставках. Наприклад, Меллер у 1925 році брав участь в епохальній виставці Art Deco у

Парижі, яка дала назву цьому стилю. Там Меллера було нагороджено золотою медаллю за його

сценічне оформлення вистави театру «Березіль» за твором Леруа Скотта «Секретар профспілки».

Того ж таки року його твори експонувалися на міжнародній театральній виставці

«Інваліди» (1924) була представлена на Венеційській бієнале 1930 року, отримала там надзвичайно високу оцінку і потім кілька років подорожувала містами Європи й Америки у складі

міжнародної виставки, про яку багато писала світова преса. Цих митців знали як реформаторів-сценографів, які не лише

сценічним формам експресії, об’ємності та руху, а й змінили підхід до організації сценічного простору. Водночас театр був хоч і важливою, але не єдиною сферою їхньої діяльності. Долі цих митців, на відміну

від багатьох діячів того часу, склалися відносно

вдало. Вир великого терору їх не торкнувся, хоча

їхні відносини з владою були непростими. Вони

прожили довге творче життя, залишивши після

себе різноманітний спадок, який ще й сьогодні

не до кінця досліджено.

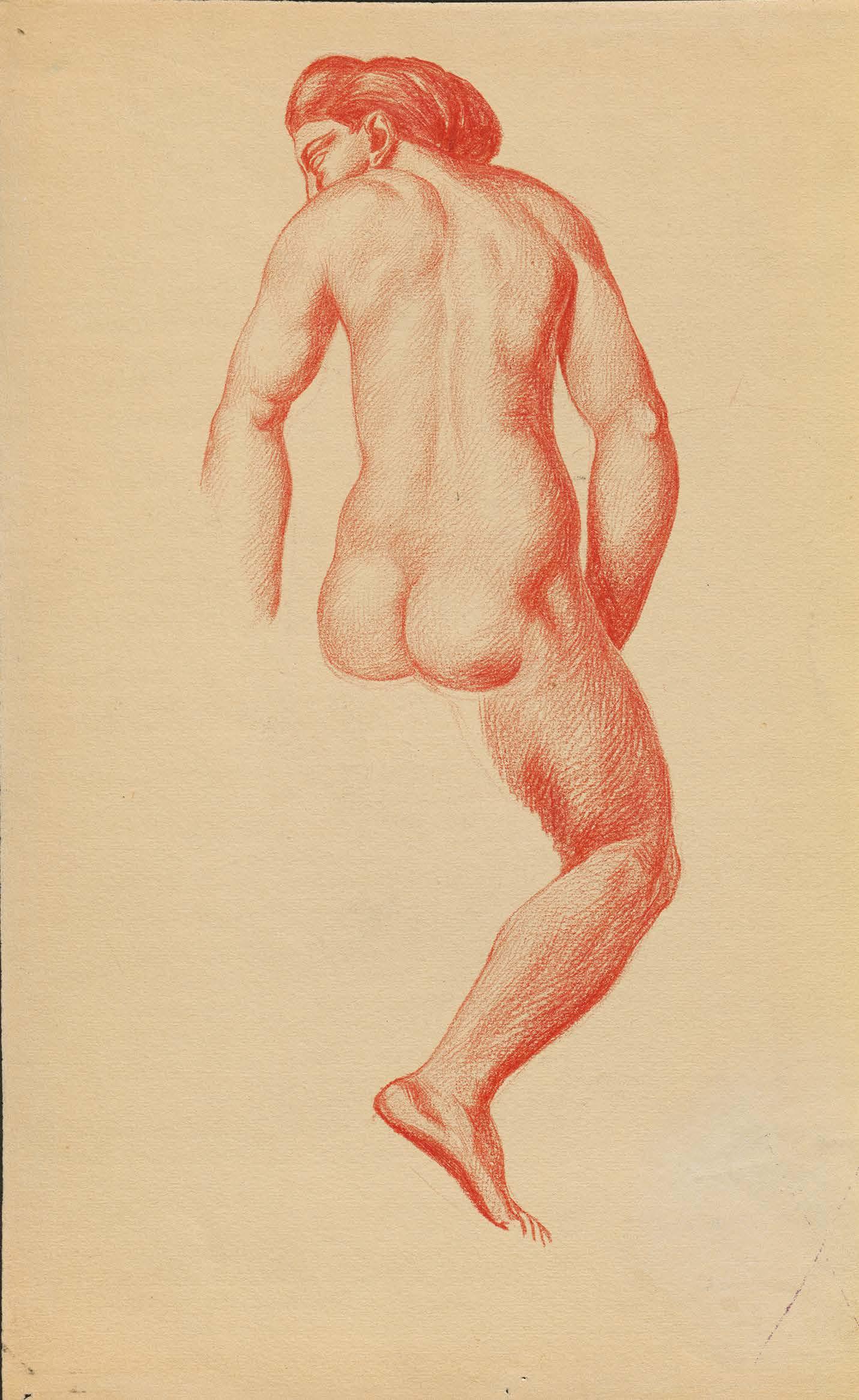

На особливу увагу заслуговують три роботи

Вадима Меллера, дві з яких — ескізи костюмів до балету «Ассирійські танці» студії

Броніслави Ніжинської, унікальні за досконалістю кубофутуристичної пластики,

«Виставка про наші відчуття». Мистецький арсенал. 2022

“Exhibition about Our Feelings.” Mystetskyi Arsenal. 2022

київському театрі Соловцова Константин Марджанов (Коте Марджанішвілі) до Першого травня 1919 року. Інша робота — ескіз костюмів купців до вистави «Ревізор» 1921 року за Миколою Гоголем. Сценографічна творчість Олександра Тишлера представлена ескізами до вистави «Король Лір» за Вільямом Шекспіром, здійсненої у 1935 році Московським державним єврейським театром та до невстановленої вистави 1930 року.

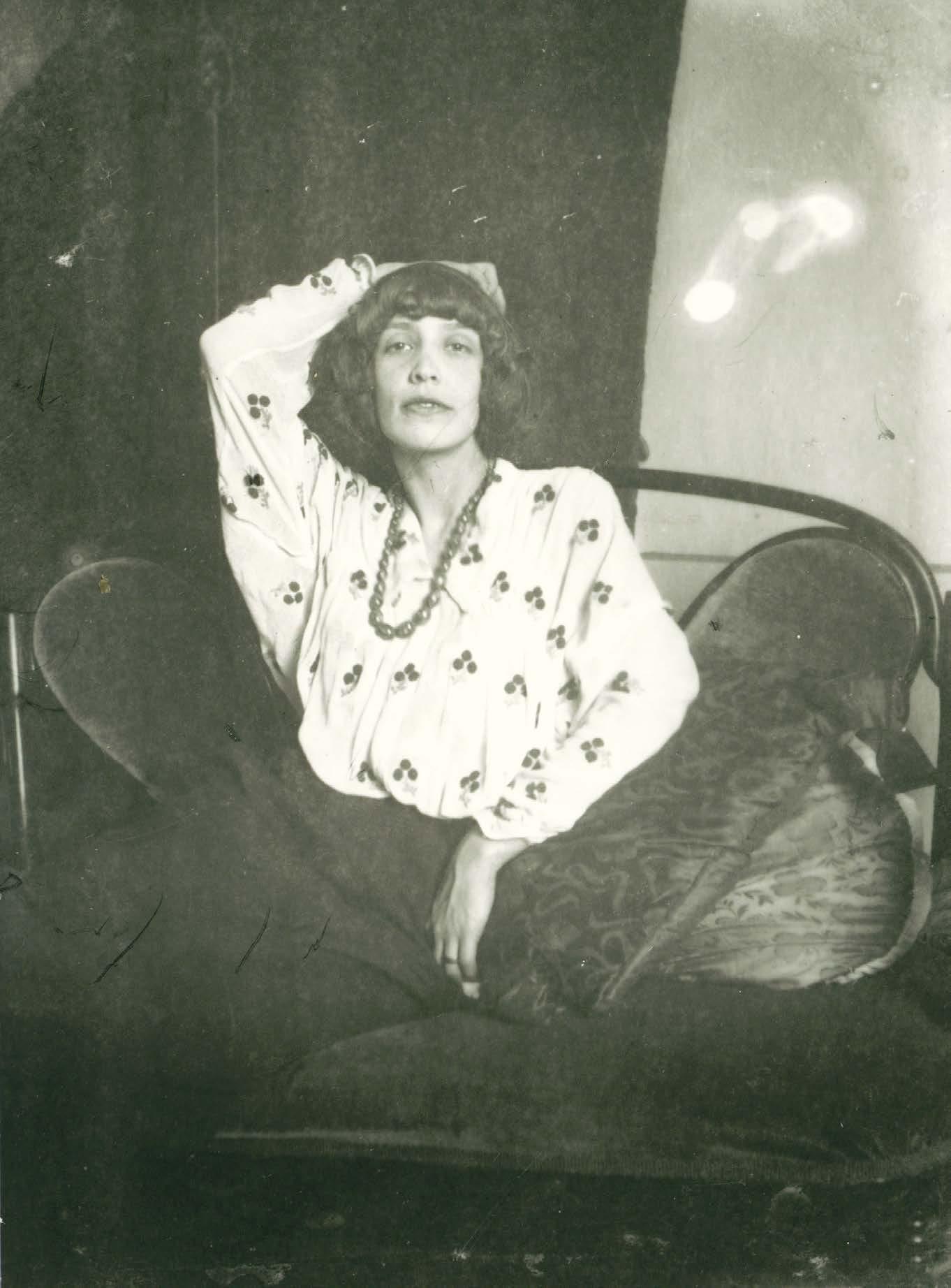

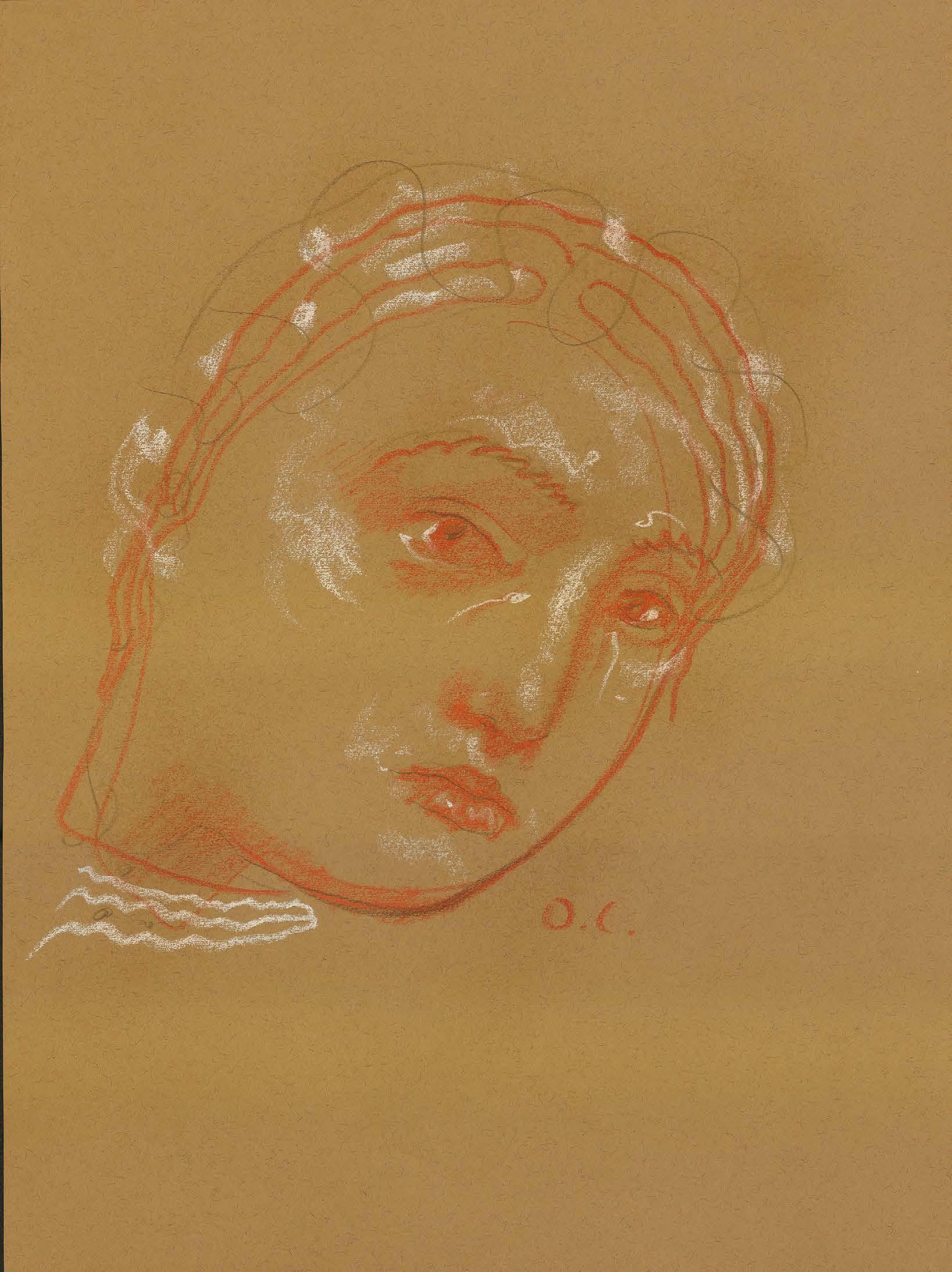

Ім’я Марії Синякової-Уречиної відсилає

до сторінки, а точніше, до цілого розділу українського та російського мистецтва, яке

отримало назву «неопримітивізм», або «народний футутризм». Це про неї писав Ве-

лимир Хлебников: «Вперед! Вперед Ватаго! Вперед! Вперед! Синголи». Це їй Маяков-

ський присвятив низку поетичних творів, зокрема поему «Синие оковы». У 1910-х ро-

ках вона експонувала свої твори в художніх

об’єднаннях «Союз молоді» та «Сім плюс

три» разом із творами Казимира Малеви-

ча, Давида Бурлюка, Наталії Гончарової,

Михайла Ларіонова й Марка Шагала, була

однією з авторів футуристичної декларації

«Труба марсіан» (Харків, 1916), входила до

числа «Голів земної кулі» — заснованого

Хлебниковим товариства. Тоді ж сформу-

валася її творча манера. «Неправильний»,

кострубатий малюнок, нечіткий «текучий

контур», орнаментальна композиція — ре-

зультат захоплення (можливо, під впливом Давида Бурлюка) народною творчістю, луб-

ком, мистецтвом Сходу. Родинний будинок на хуторі Красна

кар’єри. На початку 1920-х років майстер переходить від

рельєфу, тонованого кольором. Його пошуки того часу

в річищі загальноавангардистського тяжіння до нових форм мистецтва, відходу від станкової картини.

із такими

ми, як дерево, метал, тканина, цвяхи, шурупи. Рельєфи є одним із найяскравіших

ужиткового й

мистецтва, обстоювала перевагу монументального мистецтва над станковим. Підтвердженням інтересу Василя Єрмилова до школи Михайла Бойчука є два стилістично близькі до неї студійні рисунки 1920-х років. Школа монументального мистецтва Михайла Бойчука представлена творами самого метра, його молодшого брата Тимофія та учениць-послідовниць — Оксани Павленко й Антоніни Іванової. Ідея школи базувалася

на традиціях візантійських ікон, мистецтва Київської Русі, Проторенесансу, живопис-

ного примітивізму безіменних українських малярів минулих віків. Михайло Бойчук розглядав монументалізм як універсальний мистецький метод, принципи якого застосовуються в різних формах мистецтва. Водночас, монументалізм — це не великі за розміром твори, а особлива організованість

образу, в процесі творення якого відкидається випадкове та несуттєве. Кожен твір є узагальненим від самого початку. Кожна робота — це не зображення часткового, випадкового, а відстояне, сконцентроване поняття, узагальнений, чітко виліплений образ. Бойчукізм як метод мав охопити всі сфери повсякденного життя через син-

тез різних видів мистецтв. Це була спроба створення всеохопного національного за

духом «великого стилю», пошук «формули

вічності», як написала літературознавиця

Тетяна Огаркова. Історія цього явища— одна з найтрагічніших сторінок української культури. Твори «бойчукістів» 20–30-х років — розписи червоноармійських Луцьких казарм, оформлення Київського

колекції Мистецького арсеналу ми умовно називаємо «сучасним мистецтвом». Хронологічно — це твори від початку 1960-х, попри всю дискусійність визначення хронологічних меж цього поняття. Тут представлено твори художників, які уособлюють собою значне явище, що сьогодні визначається термінами «неофіційне мистецтво», «нонконформізм», «авангард другої хвилі», «андеґраунд». При загальній неоднозначності, різноспрямованості окремих постатей і груп, головним у цьому явищі був вільний пошук форми, аналітичний (іноді виражений на рівні теоретизування)

вого мистецтва. З доволі

творів, що підпадають під наведені визначення, відзначимо роботи художників-дисидентів — «Портрет Івана Драча» Алли Горської, «Могила Тараса Шевченка» Опанаса Заливахи, «Портрет Ігоря Диченка» Віктора Зарецького, а також дві напівфігуративні композиції донедавна ще мало відомого художника Анатолія Сумара, чия творча спадщина (вона становить кілька десятків робіт, створених переважно між 1957 і 1963 роком) є принциповою з погляду нашого сьогоднішнього уявлення про мистецтво України періоду «хрущовської відлиги».

художніх шкіл. І взагалі, в мистецькому середовищі Глущенко сприймався трохи як іноземець. Цьому сприяли і певний, на тлі іншого, радикалізм творів, і часті закордонні відрядження (мандрував Італією, Швейцарією, Францією, Бельгією тощо), і зовнішність, манери, стиль поведінки. Три його роботи, що зберігає Мистецький арсенал, — «Квітучі дерева», 1970, «Оголена в майстерні», 1967, «Оголена в інтер’єрі», 1971–1972 — є підтвердженням сказаного.

Інший класик, графік Василь Касіян, теж

прожив значну частину життя за кордоном, отримав освіту в Празькій Академії

образотворчих мистецтв. Там, у Празі, він

здобув широке визнання як майстер різних

графічних технік, як автор станкових серій та ілюстрацій до літературних творів. Касіян повертається з еміграції до України,

прийнявши перед тим радянське громадянство, у 1927-му році. Тоді ж він починає свою діяльність на посаді професора Київського художнього інституту. Офорт «Скорочені» із серії «На Заході» 1925-го року, тобто ще празького періоду, характеризує

мистецтво Касіяна того часу з властивими

йому психологізмом, драматичною напру-

гою, орієнтацією на соціальні теми.

Поповнення фондів Мистецького арсеналу творами наших сучасників відбувалося впродовж усіх років його діяльності. Більшість надходжень — це

подарунки самих авторів. Передусім ідеться про митців, чия творчість охоплює період у понад пів століття, чиї імена маркують собою

An element of Mariia Kulikovska's multimedia installation “Stardust” in the courtyard of Mystetskyi Arsenal

«Мотивом

моєї творчості став біль: людина народжується в

болю, живе в болю, вмирає в болю, залишаючи по собі біль». Він був послідовним прихильником неоекспресіонізму. На початку 1970-х Соловій

почав працювати над великим проєктом під назвою «Тисяча голів». Митець вирішив намалювати тисячу голів, застосовуючи різноманітні техніки та матеріали: олію, акварель, олівець, туш,

пластику, волосся, папір… Манера, у якій створено «Голови» є абстрактною. Героями стали Ісус Христос, Ван Гог, Венера тощо. Завершити серію Юрій Соловій не встиг. У колекції Мистецького арсеналу є десять робіт із цієї серії, а також

поліптих «Розп’яття» 1969 року та картина

«Родження 1» з 1970-х. Київський глядач міг бачити їх у вже далекому 2007 році, коли саме виставкою Юрія Соловія Мала галерея

Мистецького арсеналу розпочала свою публічну

діяльність, і на недавній, 2022 року, виставці «Про наші відчуття».

У 2017 році в бюджеті Мистецького арсеналу з’явилася окрема стаття на закупівлю

мистецьких творів. Відносна скромність

наданих фінансових можливостей ніяк не

применшувала нашого ентузіазму щодо

формування мистецької колекції. Впро-

довж чотирьох років, до фінансової кризи, яка стала наслідком короновірусної пан-

демії, а потім і російської агресії, ми були

чи не єдиною державною інституцією в

країні, яка здійснювала практику закупівлі експонатів музейного значення.

Фотографії надруковано автором у Словаччині на папері для довгострокового зберігання — Hahnemühle.

До Віктора Марущенка ще за його життя закріпилась репутація невтомного пропагандиста

фотографії», в своїй творчій біографії він мав

ризонт подій» — мультимедійну інсталяцію, яка складається з двадцяти двох фото, видрукованих на ПВХ і папері, а також двох відео. Угода з автором передбачала передавання у власність Мистецькому арсеналу схем розміщення елементів інсталяції та файлів для друку великоформатних фото. У цьому творі медіахудожник застосовує характерну для його художнього методу практику апробації — використання знімків анонімних

авторів із приватних архівів. Усі вони є частинками внутрішнього, приватного, сакрального та спільного досвіду. Нещодавно фотографічна

збірка Мистецького арсеналу поповнилася роботами Владислава Краснощока з Харкова та київського фотографа Олександра Ранчукова. Владислав Краснощок сьогодні став воєнним фотографом, який фіксує на свою камеру російсько-українську війну, перебуваючи іноді в її гарячих точках. А до війни він був учасником відомої харківської

групи «Шило». Працював із документальною фотографією, анонімними архівами, використовуючи прийоми технічних маніпуляцій та ручного розфарбування, що

сформувалися в харківській фотографії ще наприкінці 1970-х років. «Негативи зберігаються» — так називається серія, яку

Краснощок створював між 2011 та 2017

роками. Три роботи з неї він передав у дар

Мистецькому арсеналу. Ідею цієї серії художник пояснював так: «Багатьом фотографіям циклу близько ста років. Ще через

24-х фотографіях, переданих Мистецькому арсеналу донькою автора, — проникливі, впізнавані й, окрім того, доволі особисті образи Києва 1980-х років. Підрозділ під умовною назвою «Художники ХХІ століття» містить понад сотню картин, графічних робіт, об’єктів, інсталяцій художників, творче становлення більшості з яких відбулось у 2000-х. Ідеться про APL (Гліба Шароглазова), Даниїла Галкіна, Сергія Григоряна, Сергія Дехтярьова, Гамлета Зіньківського, Микити Кравцова, Марії Куліковської, Лади Наконечної, Альони Науменко, Зої Орлової, Марії Павленко, Юрія Пікуля, групи «Шапка», Володимира Сая, Станіслава Сілантьєва, Марини Талюто, Інни Хасілєвої, Олега Харча, Лесі Хоменко. Їхні твори в різний час експонувалися в Мистецькому арсеналі, були частинами різних виставкових проєктів. Ми свідомо їх не систематизуємо за

техніками або

мистецьких

сукупності

втілюють живий, часом турбулентний, сучасний мистецький процес. Це те, що твориться тут і тепер, постійно зазнає змін і трансформацій. Деякі роботи створювалися спеціально на запропоновану кураторами тему. Характерним прикладом такої творчої колаборації є масштабна перформативна скульптурна інсталяція «Зоряний пил» уже добре знаної не тільки в Україні мисткині завдяки своїм гучним

відтворювала градації кольорів неба над

Керченською протокою в різний час доби.

Відео було створено способом сканування фотографій з особистого архіву художниці. На його фоні розміщувалися п’ять од-

накових скульптур (зліпок власного тіла

авторки), які було встановлено на «ґрунті»

площиною 250 квадратних метрів. «Ґрунт»

відтворював ландшафт та конфігурацію

Керченського півострова. Наприкінці 2019 року Марія Куліковська передала у влас-

ність Мистецькому арсеналу свій твір —

гіпсову модель-форму скульптур, фото- та

відеофіксацію, креслення з розмірами макету, детальний опис монтажу, сценарій освітлення, що уможливлює відтворення інсталяції в авторському варіанті. Оголені

жіночі постаті у повний зріст без рук (ті, що були частиною інсталяції, й поступове руйнування яких відповідало авторському задуму) за пропозицією Марії Куліковської

було встановлено просто неба на території

Мистецького арсеналу.

Відзначимо ще два твори з цього блоку. Твори, які є суб’єктивними рефлексіями художниць на українські революційні та воєнні події останнього часу. Це інсталяція Алевтини Кахідзе «Жданівка або історія Полуниці Андріївни» (2014–2016, вишивка, акрил, маркер, аудіо, відео) та 44 аркуші Влади Ралко із серії «Київський щоденник» (2013–2015, Папір, кулькова ручка, акварель). Аналізуючи мистецьку збірку нашої інституції, маємо зазначити, що наявні сьогодні твори

The portion of the Fund discussed in this article is the 660-piece art collection of Mystetskyi Arsenal. Of course, in terms of quantity, it cannot compete with the collections of the country’s leading museums. To some extent, it reflects the relatively short, albeit whirlwind, history of the institution. The creation of Mystetskyi Arsenal in 2005 initially felt more like a loud political manifesto regarding national cultural heritage than the founding of a museum. The new museum lacked not only the main feature of ‘museumness’—its own collection—but also a strategic vision for its formation. The components of its own name seemed to compete with each other in their very definitions: ‘art’ (‘mystetskyi’ in Ukrainian) or ‘arsenal’ (which conjures military reserves preparing for defense). But these terms reflected the deeply political act of creating such a museum—a space to build up stores of cultural heritage and artistry to celebrate a country whose existence is a form of resistance.

In the list of implemented exhibition projects, despite the rather wide thematic diversity of Mystetskyi Arsenal’s exhibition activities, two throughlines emerge. The first is focused on highlighting various aspects of the history of Ukrainian art in the first third of the 20th century. These phenomena are united by the concept of the Ukrainian avant-garde. The second is focused on addressing and representing the contemporary cultural landscape, on highlighting the current artistic process. These lines gradually determined the trends in the formation of the art segment of the collection. The selection of ‘historical art’ is quite subjective, because it is shaped by the preferences and tastes of the famous collector and art critic Ihor Dychenko1. We include primarily the works by Oleksandr Bohomazov, Mykhailo Boichuk, Vasyl Yermylov, Kazymyr Malevych, Vadym Meller, Oksana Pavlenko, Viktor Palmov, Anatol Petrytskyi, Mariia Syniakova, Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov, Isak Rabynovych,

and Oleksandr Tyshler. These works were created between 1910–1930, and characterize the creativity of these outstanding Ukrainian artists. To a certain extent, they reflect the concerns, directions, and achievements of the age, which is sometimes called “The Age of the Great Experiment.” This relates, first of all, to the seven works by Oleksandr Bohomazov, an artist whose artistic and theoretical legacy today is gradually, we hope, approaching true recognition in the context of the history of world avant-gardism. In his 1914 treatise “The Art of Painting and the Elements,” Bohomazov traced the birth of form from the movement of the first element—the point—as well as formulated the idea of rhythm, reflected on the properties of the line, and touched on the issue of the emotional aspect of color. In the 1920s, his theory of color became the subject of systematic research in the Weimar Bauhaus. He was one of the first in the art world to predict the liberation of art from material attachment to reality. Bohomazov, in fact, proposed for the new century not just a new form and a new style, but also a fundamentally new conception of painting. The artist lived most of his short life in Kyiv, with the exception of three relatively brief periods in Moscow, Finland, and the Caucasus. Bohomazov’s theoretical achievements were not destined to receive publicity during his lifetime, in part because the issues of his research largely coincided with the more famous theoretical works of that time in the world: “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” (1912), “Point and Line to Plane” (1918–1919 ) by Wassily Kandinsky, and “Suprematism” (1920) by Kazymyr Malevych. Bohomazov’s works “Prison in the Caucasus”2, “Composition”, “Portrait”, “Portrait of a Woman” and other works created between 1915–1916, are now housed in Mystetskyi Arsenal and are valuable pieces in their own right. When observed in the context of his theoretical contributions, they can be considered as a practical embodiment of the artist-theoretician’s ideas. In them, we see movement and dynamics, the rhythm of lines

1 In a separate article for this publication, Olha Melnyk describes the story of how Mystetskyi Arsenal obtained Ihor Dychenko’s collection.

2 For a long time, this work was considered one of the Kyiv-period works. There was even a legend that it depicted the Lukianivska Prison.

Recently, Bohomazov specialist Olena Kashuba-Volvach, based on the Catalogue of the 5th Spring Exhibition of Paintings. 1917, proved that the

painting “Prison” was created in 1916 in the village of Gyurasy, Nagorno-Karabakh, where the artist was working as a teacher of graphic arts.

In the current collection of Mystetskyi Arsenal, the “Suprematist Composition 1” of 1916 probably holds the greatest intrigue. According to the story told by Ihor Dychenko, this small canvas was thrillingly offered to him by Moscow collectors among other works of Malevych’s students. Later, the work was attributed by Dychenko as the work of the master himself. The conclusions of the experts in the countries where this work was exhibited seemed to coincide with Dychenko’s. Unfortunately, we do not have any documentary evidence of this. Yes, this assumption is supported by the very composition of the painting and its rhythm, which is very similar to that which can be seen in other Suprematist works of Malevych of that time. And yet, even after the restoration and technical examination carried out in 2023 at the Lviv branch of the National Scientific Restoration Center of Ukraine, which certified the correspondence about the canvas and the paint colors used to be accurate to the date of the work, and despite all the desire to have a work by the founder of Suprematism in the state collection, we still do not dare to assert his authorship. Therefore, we put a question mark under the name of the creator of “Suprematist Composition 1” of 1916, leaving the space for the possibility of its authorship to be either one of Kazymyr Malevych’s students or the man himself.

As for another work—a lithographic illustration of the 1914 poem by Oleksii Kruchenykh and Velymyr Khlebnykov, “Game in Hell”—there are no doubts. Malevych’s lithographic activities coincided with the Cubist period in his work. More precisely, his lithographs were created during the period of his turn from Cubism to Suprematism. The second edition of the poem was published in 1914, for which Malevych made a cover, two drawings, and a page composition with the image of two devils who spray a sinner. There is one theory that the figure of the Devil, depicted by Malevych on the cover, is related to the well-known sketches for the costumes of the budetliany strongmen for the futuristic opera “Victory over the Sun” by Mykhailo Matiushyn and Velymyr Khlebnykov.

Scenographic works of the 1910s and 1930s, which embodied the ideas of avant-garde (or as they said then, ‘leftist’ art) make up the

chapter 3 ✧ parts of the collection and planes, and the juxtaposition of colors, which Oleksandr Bohomazov wrote about in his treatise. Four paintings by the theoretician and teacher Viktor Palmov are true pearls of the collection. He was born in Russia, but came into his own in Kyiv, where in 1925 he was invited to teach at the Kyiv Art Institute together with Volodymyr Tatlin, Kazymyr Malevych, and Oleksandr Bohomazov. It was in Kyiv that a cycle of paintings appeared in which the artist began to operate with new means of expression, where color was the main focus and the story just followed. His formal explorations were embodied through a peculiar concept of ‘color painting,’ which he presented on the pages of the magazine “Nova Heneratiia” (New Generation). Quantitatively, Viktor Palmov’s legacy is relatively small, so each work has considerable cultural value. In the four works of different years that Ihor Dychenko was lucky enough to acquire, one can almost trace the entire creative path of the artist. Sadly, Palmov died in 1929 at the height of his creative and pedagogical activity as the result of an unsuccessful medical procedure. In Palmov’s “Variation on a Gauguin Theme” from the early 1920s, he undertakes a cubo-futurist interpretation of a classic Gauguin theme—a timeless Tahitian paradise. Only, instead of peace and tranquility, there is an anxious tension; instead of carefree beauties, there is a man with a shovel digging in the foreground. During this period, “Ukrainian Village in Winter” was also painted: an impression of the Ukrainian settlement in the Amur region, where fate brought the artist along with his friend Davyd Burliuk. The work was exhibited at a large exhibition of avant-garde artists, which his friends organized in Japan and for which he received a gold medal. The peculiarities of Palmovian painting style, which were fully formed in his Kyiv period and which are vividly reflected in the “Beach” (1926), can already be observed here: spontaneous, as if a child’s drawing, made of colored spots that only hint at the subject matter. The main ‘load’ is carried by color, which varies in intensity and shades in different areas of the canvas. It is color that manages the emotional perception of the viewer in Palmov’s works and shapes the dynamics of the canvas, leaving a feeling of direct improvisation.

2020-2021

An exhibition “Archive of Photographer Oleksandr Ranchukov” at the Mala Gallery of Mystetskyi Arsenal. 2020-2021

2017

Works by Vladyslav Krasnoshchok from the series “Negatives Are Preserved” in the exhibition “Pure Art.” Mystetskyi Arsenal. 2017