Introduction

This anthology is the result of the Antytvir-2024 (Antytvir) educational program, its physical manifestation on paper. Antytvir emerged in 2018 as a teenage literary competition within the framework of The International Book Arsenal festival. Doing away with the evaluative component, it was redesigned as an opportunity for teens to publish their first work and simultaneously learn from writers, journalists, and creative writing teachers. The project’s goal was to provide teenagers with a platform for the free expression of their emotions and lived experiences through writing, which became critically necessary as a form of support after February 2022.

The 2024 project theme was “Fragile: Handle with Care.” Participants were invited to reflect on the experience of interacting with fragile things, beings, worlds, and the fragile self, a critical exploration in a period of immense hardship. This experience shows that we have avoided the petrification of the soul; we are still alive and sensitive, despite harsh external circumstances.

Typically, we protect fragile objects—whether an antique vase or a package from grandma with a jar of jam—with bubble wrap and care. We protect ancient buildings from encroachment by granting them historical monument status, and we register vulnerable species on the IUCN Red List. We humans are concerned about the ephemerality, endangerment, and weakness of living beings and objects in the face of the tumultuous world. However, even the temporary, like a drawing on a sandy shore, can be beautiful, poetic, and serve a special function.

For example, in Japanese culture, there is a very important concept called mono no aware, a philosophy of appreciating the fleeting beauty of things, the bittersweet taste of a vulnerable, short human life. This teaching seems to tell us: “Life is not black and white; it is diverse and polyphonic. Appreciate it in all its manifestations while it lasts!” Nurturing one’s vulnerability requires skill, not only by wrapping it in protective mechanisms but also by accepting it and using its gentle strength.

Hanna Klymenko – curator of the “Antytvir-2024” project

що наче ріже шкіру разом

слухом. Все, що він може розрізнити, — це деякі окремі слова його матері.

Він сховався за стінами свого замку і намагався уявити, що на ньому величні лати, через які не пройде жодна стріла чи меч, як у справжнього лицаря.

Але коли почув, як всі звуки затихли за секунду, одразу підняв очі. Сидів і чекав хоч якогось звуку.

Але його не було. Йому було моторошно, але треба було піднятися. Він знав, що треба робити.

Згадав, якими сміливими були лицарі раніше, і що в

кожного з них наставав момент, коли треба було перемогти самого себе.

І тоді, видихнувши, хлопчик піднявся і, протиснувшись

між стіною і кріслом, подивився в центр кімнати.

Там було два тіла.

Одне нерухомо лежало на підлозі, а інше схилилося

над ним. Це були його батьки.

Тато стояв над мамою.

Хлопчик не знав, чому вони так робили. Можливо, це

— Хрещатик — то ж площа в Києві, не існує таких замків.

Хлопчик про це і справді не знав, він був упевнений, що ця назва належить тільки його замку.

Колись він почув її від когось і, здавалось, вона достатньо гарна, щоб назвати так своє укріплення.

— Існує, дурепо, ти це просто не розумієш! — розгнівано

це запитання. — Та мабуть. — А що відбувається, коли ти її розбиваєш?

Хлопчик замовк і з розумним виглядом

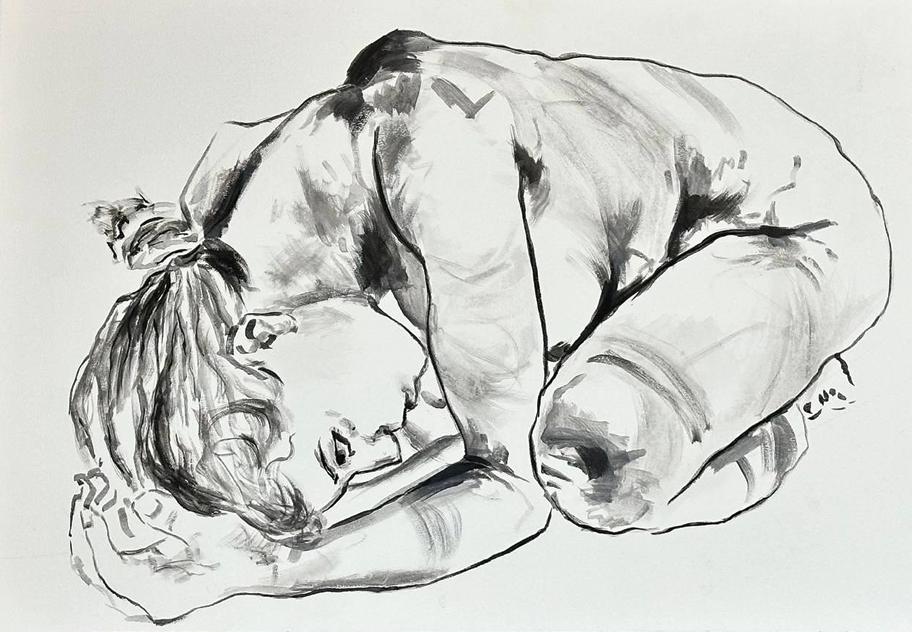

Yuliia Panchenko No title

Kseniia Alieksieienko

A little boy was running down a narrow street. He was crying but running away to hide his tears from the other boys. Otherwise, they would call him “weak.”

He came home upset, quickly took off his light jacket and wanted to go to Khreshchatyk.

This was the place where the boy always felt safe, it was his castle where he was the King. Having defeated numerous enemies, he was sitting on his throne next to his wife, Queen Aurika. Aurika, now the reason for his sadness. But in Khreshchatyk they were together.

Yet even through the walls of this fortification, he could hear the Dragon roaring in his cave. He knew that the Dragon wouldn’t do anything to him but he was still afraid of him. Especially when he heard the sound of breaking glass echoing throughout the flat. His mother begged the Dragon to stop, but in response there was only a kick and her crying. Even the back of the old armchair he had squeezed into to avoid hearing it didn’t help.

But he tried and tried to hide behind the Soviet chair where he had inscribed “Khreshchatyk’ in inept capital letters—the Dragon caused the iron scar on the boy’s back.

But, as in every fairy tale, the knight has to defeat evil in order to conquer the kingdom and save the people. The boy believed that if he went through the trials, the old chair he was living behind could be transformed into a castle with such a powerful name.

And since he was not a “weakling,” he knew that he could go through dozens of trials for the sake of the castle. Suddenly, the boy heard the screams approaching him.

He wiped his tears and immediately jumped behind the chair. He knew exactly what to do in these situations. They happened too often.

And now he could hear his father’s shouting, his mother’s crying, and a lot of other sounds.

But they were all mixed up to him. All he heard was noise, a terrible noise that seemed to cut his skin along with his hearing. All he could distinguish were some of his mother’s separate words.

He hid behind the walls of his castle and tried to imagine that he was wearing majestic armour through which no arrow or sword could pass, like a real knight.

But when he heard all the sounds stop abruptly, he immediately looked up. He sat, waiting for any sound.

But there were none.

It was frightening but he had to get up. He knew what he had to do.

He remembered how brave the knights used to be, and that each of them had a moment when he had to defeat his own fear. And then, breathing out, the boy stood up and, squeezing between the wall and the chair, looked into the centre of the room. There were two bodies there.

One was lying motionless on the floor, and the other was leaning over it. It was his parents.

His Father was standing over his Mother.

The boy did not know why they were doing this. Maybe it was a game?

“Dad,” the boy said quietly, almost in a whisper. The man looked up at him, his eyes cloudy, with black circles under them.

He looked at the boy and was silent.

“Go play outside.”

The boy, of course, did not want to, but he knew what could happen if he disobeyed his father. So he quickly ran to the door, passing by his father and mother.

He tried to look at his mother for just a bit. And to understand the reason why she was lying like that.

But when he saw his mother’s face with blood on her left temple, he never found the reason he hoped for.

The boy quickly ran out into the corridor, grabbed his jacket and went outside. The sun had already set over the horizon, and it was cool outside. Down the narrow street, the boy went back to the park where all his friends were playing and from which he had run away so quickly an hour before.

There were few children remaining; almost all of them had been taken away by their parents.

Only a few boys were playing ball.

He was about to join them, but then he saw Aurika sitting on one of the old horizontal bars, all alone in her beautiful dress.

Of course, he was angry with her, so at first he didn’t even look at her and decided to join the boys.

But then he remembered that when his mum was angry with his dad, she always said something insulting to him, so he decided to say one of those words to Aurika as well.

The boy went up to the horizontal bar and with a very stern face, looking up at the girl, said to her:

“You bitch!”

The girl looked down at the boy from the height of the horizontal bar:

“Why are you saying that? That’s a very bad word.”

“Because you are bad, I am angry with you,” the boy stuck out his tongue.

“Why am I bad?”

“Because when I told you that I liked you, you ran away with your friends.”

“But I didn’t say anything back to you, silly, and you’re angry.”

“I’m not silly, and you ran away because you hate me,” the boy said again, disappointed.

“No, I like you too,” Aurika smiled.

The boy looked up at her in surprise.

“Then why did you run away?”

“Because I was afraid they would laugh at me. And why did you run away?”

“I ran away to my castle,” the boy said again, looking important.

“You have your own castle?” the impressed girl asked and jumped off the horizontal bar.

“Yes, I do. It’s called Khreshchatyk,” the boy began to tell her proudly.

But after he pronounced the name of his castle, the girl burst out laughing. “Why are you laughing?” the boy said, almost offended.

“Khreshchatyk is a square in Kyiv. There are no such castles.”

The boy, in fact, didn’t know about it, he was sure that this name belonged only to his castle. He had heard it once from someone and thought it was good enough to give such a name to his fortification.

“There is such a castle, you fool, you just don’t understand!” the boy shouted angrily.

“Well, I don’t want to offend you.”

“But you’ve been doing it all day today. You’ve been breaking my heart and soul into pieces.” He didn’t remember where he had heard the last phrase, but it seemed so reasonable and grown-up to him that now was the time to say it.

The girl smiled and approached the boy.

“Is the soul fragile and can be broken?” she smiled.

The boy looked at her with surprise, he did not know the answer to this question.

“I guess so.”

“‘And what happens when it is broken?”

The boy fell silent and looked off into the distance, with a thoughtful face.

“I guess all people are fragile, and our parts are too. And if your soul is broken, I think you will lie there and be sad.”

“Yeah? Then why aren’t you lying here?” the girl asked.

But the boy did not hear her. He remembered his mother; perhaps his father had broken her soul with his shouting, and now she was feeling bad.

“I exaggerated,” the boy blushed a little. “But now, Aurika, I have to save my mum, my dad has broken her soul.”

The girl looked at the boy, frightened.

“Wow, how are you going to save her? You’re not a knight.”

“Me?” the boy was surprised, “I am a knight, and I will glue my mum’s soul back together and it will be as good as new.”

“Okay, if you do that, I’ll believe you’re a knight,” the girl smiled.

“Then I’ll see you tomorrow!” The boy smiled and ran home as fast as he could.

“Bye,” the girl shouted after him.

The boy ran very fast, he flew into the stairwell and entered the flat.

There was silence there.

Now he was not afraid of his father because he had to help his mother. He had to collect and repair her soul.

He went into the living room where they usually slept.

His mother was lying on the floor, just as she had been when he left. He sat down next to her and touched her hand.

The hand was cold.

The boy looked at his mother’s face in horror. Why were her hands cold?

He wanted to look into her eyes but there was nothing in them. An empty look.

He was scared. No matter how brave he wanted to be, he felt frightened now. It was as if she were not alive.

Perhaps her soul could not be repaired?

But the boy could not finish his thought because all he felt was a pain in the back of his head.

It was his father.

Unfortunately for Aurika, her knight did not come to the playground the next day.

Then she decided that he too had broken his soul along with his mother. She never realized that the soul was so fragile.

Майстер і Муза

"All the heat and fear had purged itself. I felt surprisingly at peace. The bell jar hung, suspended, a few feet above my head. I was open to the circulating air"

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

на лижі, з’їжджає

злетівши з кінчика. Великим і середнім пальцем прорізає загадкову усмішку. Вказівним припіднімає верхню губу, задля легкої розбещеності. По-садистськи стискає підборіддя та різко повертає вліво. Легко придушує.

— Може, й бачив.

— Зі собою чом мене не взяв?

— А мусив?

— Та у мене серце плаче!

— Ні-ні-ні, крихітко! — невдоволено кашляє. — Без рим, будь ласкава. Ми не в Шекспіра зара’, знаєш?

— Ні, не знаю! — Муза рішуче зводить руки на груди.

Майстер зойкає. — Ми з тобою то в Парижі, то у Венеції, то в тебе на випускному — і знаєш, це, попри свою нікчемність, ще й не найгірший варіант, бо ти хоча

ся сяким-таким

У ролі натурниці — ви вже, напевно, здогадалися — знову Муза!

Та й ви вже, напевно, здогадалися, що відбулося далі: під гострі коментарі пані Музи на підлогу стрімко, однак послідовно, полетіли десятки глиняних зліпків.

експонат: у головній ролі — примхлива, кровожерлива й істерична Муза, у ролі натурниці

слова, крихка пані Стефа.

Майстер проводить долонею по неподатливому волоссю. Вилицями зводить великий та

на підборідді. Душить бездиханну шию. Не оминає

Я забула: ми ж не у Шекспіра! Перейдімо до дійсно важли-

Yeva Vasylenko The Master and the Muse

"All the heat and fear had purged itself. I felt surprisingly at peace. The bell jar hung, suspended, a few feet above my head. I was open to the circulating air"

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

The palm tousles the hair. Skiing, it slides down the nose, flying off its tip. Cuts a mysterious smile with the thumb and the middle finger. Lifts the upper lip with the index finger, for a little lewdness. Squeezes the chin in a sadistic manner and turns it sharply to the left. Strangles slightly.

Takes turns caressing the areolae. Puts the hands behind the back and bends the spine with them. Tilts the pelvis. Tousles the hair. Makes the gap between the thighs bigger.

The teeth appear. They grind. Bite the calf.

“Ouch!” A perfectly crafted sketch of a mouth is distorted. “Well, who will have more work now?”

“No one. I’m just warming up my arms now.”

The Muse sighs. The Master sits down at the sculpture’s feet. “It’s daytime outside today, you’ve heard?”

“I’ve heard.”

“And have you seen it?”

“Maybe.”

“Why didn’t you take me with you, huh?”

“Should I?”

“My heart’s breaking, baby!”

“No, no, no, sweetheart!,” he coughs in frustration. “No rhymes, please. We’re not at Shakespeare’s now, you know?”

“No, I don’t!” The Muse resolutely folds her arms across her chest. The Master cries out. “We’re in Paris, or Venice, or your graduation party, and you know, despite its futility, it’s not the worst option because you at least let me wrap myself in a kind of a sheet, but then you forget I exist at all, and you sob about how she doesn’t know who she has lost.”

The Master jumps up.

“Put your hands back in place, quickly!”

“Ha! No way!”

The Muse jumps down from the makeshift pedestal and runs along the maybug gallery.

“Dear audience, just look at this unsurpassed work of contemporary art: Princess Leia, the naughty girl, in the lead role, and the lovely Muse as a model!”

The palm—don’t get me wrong—not the same one as in the beginning!—gently pushes the fragile silhouette. The sculpture touches the laminate with a loud sound and disintegrates into ions.

The lines of the eyebrows abruptly converge with the curve of the mouth, the nostrils flare like elephant ears, but the Master does not say a word.

“Dear guests, we are pleased to present Exhibit #2, the older sister of the esteemed sculptor’s childhood best friend whom he desperately tried to fuck, but— oh, my!—cool men in expensive cars beat him to it. You’ve probably guessed—the Muse as a model again!”

And you’ve probably guessed what happened next: dozens of clay casts flew to the floor in rapid succession, to Ms. Muse’s sharp comments.

The floor, like with the first December snow, was abundantly covered with crumbs of the figure that was allegedly the Muse’s, or allegedly not hers.

“And the last but not least exhibit, dear guests: the one who must not be named—the mother of the respected artist.” the Muse slaps her ashy palms on the Master’s cheeks. “Your, damn it, mother!”

The room is filled with musty smoke and loud silence.

The Muse’s name is Stefa. She loves green tea, knows how to play the piano, and smiles victoriously. The Master is ashamed of his name, he came into this world as a result of unprotected sex, and was left without a date at the graduation party. He—let’s be decent people and keep the Master’s name a secret—is breathing heavily.

The last live sculpture shyly lowers her eyes.

A disobedient strand of hair escapes from behind her ear. A tentative smile lights up her face. Her arms are folded across her chest.

“Will the dear Ms. Muse object if the Master himself announces the last sculpture?”

“Not at all.”

The Master clears his throat, tousles the hair—his own, of course, and starts speaking in a triumphant, menacing bass:

“Dear guests, it is with great pleasure that I present to you the piece that is the last surviving and, ironically, the first one created in this exhibition: the capricious, bloodthirsty, and hysterical Muse in the lead role, and the vulnerable, sensitive, and, I’m not afraid to say it, fragile Ms. Stefa as a model.”

The Master runs his palm through the unruly hair. Down the cheekbones, he brings the thumb and the forefinger together on the chin. He strangles the lifeless neck. He does not avoid the areolae, the flat stomach, or the buttocks. With contempt, he avoids the hands. He kneels down, like a believer in front of an icon of the god he ceased to believe in long ago, and bites the calf. After licking his lips with satisfaction, he—wow! isn’t it dramatic and unexpected?—kicks his first creation.

The miracle does not happen: the sculpture falls and shatters into pieces. The Master—although... who gives a shit about decency?—Mark, or, as a good half of the women whose outlines are now lying ungodly on the laminate floor called him, Markusha, is smiling.

The former Muse bends down and lifts her own head: “Yorick! Poor Yorick!”

The Master looks at Stefa expectantly.

“Oh! I’ve forgotten: we are not at Shakespeare’s! Let’s move on to the really important stuff,” she sighs sadly. “You’ve broken me!”

“Yes, I did!”

“About five years ago...”

Stefa makes a disappointed face and throws some fancy Italian or French expression at Markusha that I, dear readers, cannot make out, so I leave myself and you in ignorance, at least until the Muse sleeps it off.

The more alcohol entered Stefa’s bloodstream, the more incomprehensible her fantasy story got. In short, Stefa was slowly getting dressed, and Mark was somewhere under her feet. Then the “It serves you right.” and “I immediately dragged my feet to you.”

A drop in the bucket, right? However, I am happy to tell you: that’s not all. The relatively sober Stefa has made one requirement public: the work must end with a moral. Ten minutes ago it was supposed to sound something like this:

“Fragile! If not handled with care, it turns sharp.”

Крихкість навколишньо-буденного світу

визначається в дотиках. У дотиках, які перевіряють на вразливість, лоскочуть шкіру та чекають нестримної фізичної реакції. Вони обережні й майже лагідні, щирі настільки, наскільки

мерехтливих крихкостей, які потім комусь належатиме збирати. Викурені священним ладаном

витесати

та збудувати подібну собі цілковиту залежність, хіба

не буде це безкарним злочином проти відкритості та людяності обіймів?

Віддалік відлік місяцíв

час згадки, прикушений язик

свідок несказáнної і нескáзаної шкоди. Крихкість визначається в дотиках, що лікують майже непомітно і

Крихкість — визнавати, що всі натяки пере -

плітаються, ти ніколи не забудеш минулорічну травневу лірику і, здається, вже вмієш із нею жити. Її тепла присутність

ніжність інтимних

варта кожних пройдених воріт і кожного внутрішнього їй спротиву. Варта нещадних боїв за право і священне зобов’язання бути з нею чесною. Варта можливості довгострокових дотиків, які проникають прямісінько під шкіру, ство -

залишатись поруч і старанно тримати зоровий контакт. Варта заради того, щоб

Yuliia Vysotenko

Touching

The fragility of the everyday world is defined by touch.

By touch that tests for vulnerability, tickles the skin, and waits for an unrestrained physical reaction. Touch is careful and almost gentle, as sincere as a faithful dog can be with its always sincere wet nose.

By touch, when it seems impossible not to respond to a gentle expression of desire, as gentle as it can be to wrap all your insides with a warm blanket.

At first timid, careful, when we touch each other to conduct a lovingly intimate research. Then the first little crimes enacted in little moments appear, soon to remind us of themselves in waves and opaque bursts like a remembered film reel.

The uselessness of weapons, open breasts, and endless waiting—come on, at least do something to make your intentions overlap with If you don’t hear it, it’s coming right at you.

If you do not see the necessary doomed changes, they fall on your head with lightning speed, without separating from your skin. They do not wash off, like the sparkles of happiness, their predecessors, they shimmer. They scatter into hundreds of little shimmering fragments that someone will have to collect later.

Actions, smoked with sacred incense and dizzying opportunities to get lost in the power of the universes, are persistently present every day, more and more. You can neither get rid of them nor reject them, but only patiently endure them, letting every neurotic calumny of distant tenderness pass through your every nerve. You will never know how to write accurately for the first time, without leaving out any of the common word roots. To enfold the veiled haze of almost carefree Aprils, from which fleeting memories remain, and nothing more, in satin.

How much of your biblical fragility can be destroyed so that it can still be rebuilt and displayed as a mosaic?

Loud objections, twisting, turning away, and furrowed eyebrows mean the breaking down of all barriers, when every word is on the edge and on thin ice. The ice envelops slowly, freezing the trembling and disbelief in springtime survival methods.

If the fragile ice is lightly tapped with a hammer, carved into the desired structure, and built into a kind of complete addiction that looks like you, wouldn’t that be an unpunished crime against the openness and humanity of hugs?

In the distance, nightingales chirp, counting down the months, and their echoes can be heard. The traces of fragility are always the brightest, always building a bright path in the weaving of life. The traces of fragility are visible in your eyes every time you remember, a bitten tongue is a witness of unspeakable and unspoken harm.

Fragility is defined by touching that heals almost imperceptibly and never instantly. Fragility is recognizing that all the hints are intertwined, you will never forget last year’s May lyrics, and it seems that you already know how to live with it.

Her warm presence and the endless tenderness of intimate conversations where there is despair, unconsciousness, and longing for something long gone, of which there is not a single photo memory left.

Touching envelopes us in safety and total understanding, leaving a lasting impression of how stability provides for the love for one’s neighbour.

Such necessary doomed changes point to new levels of the crystal labyrinths of consciousness which you have yet to warm with new softening.

The unrecognizability of the once-close fragility—changes are always only visible

and noticeable after a year. Remaining open becomes overtime work but it is so worthy and valuable that the rest has faded long ago. The unobtrusiveness of the stories is guaranteed by endless adoration and comparisons with the most powerful deities that could have arisen from the human imagination.

The difficulty of responding to sincerity and stating that it is good: to survive an event and never repeat it. The difficulty only lies in dizzy, bewildered words and recognizing your own devastation as something that has happened.

The difficulty of identifying vulnerability is that it should be passed from hand to hand, like the most precious treasure. If you remove from the equation the variable of humanity and the characteristics of poetic turns of phrase, is there anything left worthy of your boundless warmth? Is there anything left that is not capable of inflicting wounds?

Events engrave a stigma right in the middle of the brain’s convolutions, and the kettledrums announce the verdict in a formidable way, as if you are the only one to live with it, live with it like this, and remember it every second with inordinate longing and even more nostalgic warmth. Healing is not linear and requires the most valuable investment of time, the most grateful hands, and unquestioning trust—she definitely stays by your side. She has known every second for years and years, and she makes sure that this every second is not in danger.

The discovery of the warmth of crystal-human touch is worth a lifetime, if only because safety in solitude is impossible. It is necessary to get closer to the radiating efforts for manifestations of love, even if there are many, even if you beat

against the current. Even if the manifestations are carried on silver trays where you can see your own reflection at which you don’t want to look at all.

To love and open (yourself) up in such a way as to bring out all the charms, all the invisible perspectives on these mirror trays, and put them right in front of her for a full, softly focused review. To love in such a way as to sort through everything without haste, savouring it, always sweetening mutual pleasures.

Intimacy in fragility is worth every gate passed and every internal resistance to it. It is worth ruthless battles for the right and sacred obligation to be honest with her.

It is worth the possibility of long-term touch that penetrates right under the skin, creating a protective layer of continuous love for humanity. It is worth the courage not to move away, to stay close, and keep eye contact. It is worth it to make homes shine with feelings, close distances remain the only possible ones, and memories warm with sunshine. Vulnerability binds us in a particularly tender way, facing each other, in the comfort of frankness and unchanging acceptance.

Knowing your own predicted fate will not help. But her comfort in openness, in trust and confidence will. Love and infinite tenderness as a result of soft-sharp changes are remarkable and defining. If religiosity meant more than a constant longing for a higher enveloping power, prayers for it would be said in every cathedral from sunset to sunrise.

This healed fragility is safe in her hands.

Все життя я шукала себе. Шукала на складах і вітринах, в очах і

звуках, під камінням і килимами. Збирала себе по частинках. Тисячі разів я розбивалася, але не знаючи ким я є, легко збирала

себе наново. До минулої весни.

Минулої весни, коли жаби ніжно крекотали в озері, а хмари хвилями розтинали небо, я зустріла її. Дивлячись на

неї, я вперше відчувала спокій. Я знала, заглядаючи їй у

вічі, що поруч із нею ким би я не була, вона залишиться. Я ніколи не бачила себе,

вдалося дістатися самої душі, відшукати

голосом, другим «я». Ми були нероздільні. Разом із нею померла ще одна зірка в моїй душі, розриваючись, породжуючи

мільйони градусів печалі та

безпорадності. Знай-

Anna Vinnik Posthumously, to Tonia

All my life I have been looking for myself. I was searching in warehouses and shop windows, in eyes and sounds, under stones and carpets. I was putting myself back together piece by piece. Thousands of times I broke down, but not knowing who I was, I easily put myself back together again. Until last spring. Last spring, when the frogs were croaking gently in the lake and the clouds cut the sky with waves, I met her. Looking at her, I felt peace for the first time. I knew, looking into her eyes, that no matter who I was with her, she would stay with me.

I had never seen myself, but she did. She managed to reach the very soul, to find the whole world, millions of planets and constellations. I never knew myself, but I knew her. Her, the favourite child of the sun and flowers. Her, who wandered through cities and parks, cried with the rain and laughed with the lightning. Her, who walked so carelessly on the forest grass...

We were not friends or anything like that. We were each other’s echo, an inner voice, the second self. We were inseparable. Along with her, a star in my soul died, tearing apart, giving rise to millions of degrees of sadness and mute helplessness. Having found myself, I lost her. Her, sincere and warm as the spring wind. Her, the person I loved above all. Her, the person without whom I could not put my broken insides back together.

ніколи не

плачуть. Ти чомусь вважала, що ця «функція» в них не-

доступна, що їм це не потрібно, адже проблеми бувають

тільки в дитинстві. Як же ти помилялася... Зараз усе, що в тебе залишилося від колишньої себе, — це спогади. Так, ти всього лише підліток, насправді, ти ще не

дитячому майданчику.

Daryna Herasymiuk

Fragile Childhood! Handle with Care

Do you remember when you used to spend your summer holidays at your grandmother’s place and gather with your friends by the local pond and throw stones into it? Do you remember going to the fields with them and picking a bouquet of poppies and cornflowers scattered among the wheat? Do you remember how the wheat used to tickle your skin? And the variety of butterflies in the countryside fields, and the breath of hot wind that did not bother you then? Jumping in puddles, and your favourite boots with stars on them? Touching your grandmother’s hand and her jingling laugh? In the afternoon, you always got a croissant with nuts and chocolate specially bought by your grandfather who never forgot about your favourite dessert. Sounds familiar, right? It all feels so distant and unreal now that sometimes you want to pinch yourself and dispel the illusion in your head. When you think about your childhood, it seems like another world. A colourful country on the planet where people speak the language of laughter and are only sad because it’s evening and you have to go home.

Now you are an adult. There is no more pond with stones, no more friends who were always waiting for you at the gate. Your favourite field is empty, and the flowers no longer attract your attention. You now have much more “important” concerns. You think about what to do with math which you are not good at, at all. How to find true friends, because nowadays it is not an easy mission. What to do with your excess weight, and what’s wrong with you in general? What happened to your childhood resolution? All these questions bother you. No, they don’t just bother you, they eat you up from the inside. You wonder how you got to this point. Everything is fine, right? The world is still as bright as ever. Butterflies are flying, and your grandparents are always waiting for you to visit. But no. You don’t miss these things. You’ve just grown up! This is what made you fragile. Do you remember when you were a child, you were always curious about everything?

And you asked your mother about this or that, and your mother, unable to find an explanation, told you: “When you grow up, you will understand.” And what? Did you finally learn about everything that sparked your interest? Probably now all the childish and vivid illusions have disappeared from your head, dissolving in the “new” reality. Оh! And do you remember how on every birthday you made only one wish— to be a grown-up? You wanted to be like your mum: go to work, buy groceries on your own, and wear heels. You also thought that adults never cry. For some reason, you believed that this “function” was not available to them, that they did not need it because problems only happen in childhood. How wrong you were...

Now all you have left of your old self are memories. Yes, you’re just a teenager. In fact, you don’t know all the realities and rules of adult life yet. You are growing up, and you realize that soon you will have to leave your parents’ house and look for your own ways to earn money. You are scared. You’re scared of becoming an adult and becoming responsible for your life and future. But there is great news: your childhood dream will come true—to go grocery shopping on your own and, can you imagine, in heels! Ha-ha-ha! Are you happy? I don’t see a smile on your face. It’s scary, right? At this point, you have a new dream—to go back. Into the world of delicious ice cream and colourful swings on the playground.

And do you remember how your mum used to say that there was no need to rush? “Enjoy your childhood because you’ll be missing it later”, she used to say. And you thought she was just saying that because she was an adult (they can be boring sometimes, but it’s not a problem). Now I see that you regret it. You think how right she was. But why listen to her, she doesn’t understand you. But now you understand her. Her words were very clever...

вона

вона

вірити,

очі на реальність. але можна вірити, що вона витримає

наскільки легко зламати людину?

з Бучі. фотографії з Маріуполя. фотографії з Ірпеня.

з Краматорська. фотографії з Херсона.

фотографії кінцівок. від’єднаних. хаотично розкиданих. чиїх? фо

фотографії. роздруковані. чорно-білі. чорні рамки.

втомлені. спокійні. щасливі. з блиском в очах. з дітьми.

«Незламна: 12-річна Яна Степаненко на протезах пробігла 5 кілометрів Бостонського марафону».

«Допоки дихаю, я буду боротись», — Юлія Паєвська (Тайра).

«Піді мною були сотні метрів води, та я старався

голову. Збираєшся з силами — і ще один ривок.

четься, розумієте?», — спецпризначинець

живемо. гинемо. тримаємося.

1how easy is it to break a person?

my friend is tugging at the sleeves of her pullover but i can see fresh bruises over the old scars. the scars don’t scare. on the contrary, they are a sign that she has survived and continues to fight. i don’t know what she has lost with each cut—a piece of pain? a piece of herself? but whatever it was, it didn’t break her.

unlike bruises. they will fade faster than wounds heal, but looking at my friend’s exhausted face, i think: they take away much more than self-inflicted pain. she got the bruises at home. in that house, it is better not to show your true feelings. there, every hint of vulnerability is perceived as weakness, and weakness is an excuse to humiliate, blame, and hurt. the bruises fade and disappear, but with each one, it is as if my friend also fades.

i look at her and think: how can one want to destroy something so beautiful? she is beautiful, and what’s more, she is kind and sensitive. she always cares about those around her more than she cares about herself. she is one of those few people who are equally beautiful inside and out. and they keep hitting her with their fists and words, as if they are trying to distort everything good in her.

and i don’t know where she finds the strength, but she holds on despite the fact that every day she seems to be covered with new cracks. she cracks, holds the fragments with trembling hands, glues them together and frantically wraps the breaks with duct tape...

what does it take to break her?

how hard does a kick have to be to break her into many pieces? to shatter.

she laughs at a joke, and i think: so, how easy is it to break a person? she is so beautiful despite the scars and bruises and cracks inside. beautiful and strong. they didn’t manage to break her.

my friend smiles and tugs at her sleeves.

to believe that violence cannot defeat even the most resilient person is to hide behind an illusion, to turn a blind eye to reality. but you can believe that she will endure long enough.

and to glue and duct tape. and to treat the wounds. and to hold on tight.

2how easy is it to break a person?

photos from Bucha. photos from Mariupol. photos from Irpin. photos from Kramatorsk. photos from Kherson.

photos of limbs. disconnected. scattered chaotically. whose? photos of burnt bodies.

photos of a mother with her mouth open in a silent scream.

photos of people missing pieces of flesh.

photos of mass graves. thousands of skeletons.

photos of an unexplainable red substance that until recently was a living person.

how easy is it to break a person?

one missile is enough to end a life in an instant. so is one kamikaze drone. so is one bomb. so is one bullet.

when a person is reduced to nothing but pieces...

one shot. it’s very simple. one shot—and all the reasoning about the immortality of the soul and the indestructibility of the spirit no longer matters because it is not about philosophical concepts, but only dry facts, such as whether the bullet hit the vital organs.

when you look at the photographs that depict violent, premature, ugly deaths with unquestionable truth, it is difficult to think about philosophy at all.

photos. printed. black and white. black frames. black ribbons.

in the photos—smiling. serious. tired. calm. happy. with a twinkle in their eyes. with children. children. civilians. soldiers. alive.

photos are eternal. memories are lasting. monuments are strong. but they are no substitute for a body. a body in which life was vibrant. a body that laughed, cried, ran, jumped, hugged, loved, and thought. a body in which the heart beat, the chest heaved, the brain worked, and the blood pumped. a body that turned out to be vulnerable. frail. mortal.

how easy is it to break a person?

one missile. one drone. one bomb. one bullet.

“Unbreakable: 12-year-old Yana Stepanenko runs Boston Marathon 5K race on prosthetic legs.”

“As long as I am breathing, I will fight,” Yuliia Paievska (Taira).

“There were hundreds of metres of water below me but I tried not to think about it. You gather your strength and make one more leap. Because you really want to live, you know?” Special Forces soldier Conan from Artan.

“In his previous interviews, Mykhailo Dianov has repeatedly emphasized that, despite everything, the captured Ukrainian soldiers had no thoughts of suicide. But there were cases when the Russian occupiers, in his opinion, passed off murder as suicide.”

“We came back to fight on,” Kateryna Polishchuk (Ptashka).

...let the body become clouds in the wind let the wind bring a drakkar with a crimson banner let the world break and the wave wipe away the memory let the flood of love and inspiration but nothing can’t flow back into nothing and the whisper of tree crowns can’t be reproduced my solubility does not allow me to perish I will melt in you and live forever

— a poem from Svitlana Povaliaieva’s collection Changeable Clouds with a Chance of Clearings dedicated to her son, Roman Ratushnyi.

how easy is it to break a person?

i once went up to the hundredth floor of a skyscraper in a foreign country on the other side of the world. i looked at the hundreds of flickering lights of cars far, far below, at the small moving specks—hundreds of strangers, and i thought: we are all so vulnerable. we are terrifyingly small, minuscule compared to the world, our planet, not to mention the entire universe.

i watched a truck which from this height seemed smaller than an insect. such a contrast: on the road, a truck could easily and instantly run me over, but from above, it is simply insignificant. so what can we say about people? from this perspective, we are all just specks. from above, you cannot recognize a face, evaluate physical strength or character, or judge appearance by beauty standards. everyone is the same and equally, painfully, vulnerable.

i got into the elevator. i went a hundred floors down.

i got off.

i looked at the passersby and felt relieved. they are not spots anymore. i texted my friend, yes, the same one. i scrolled through the news. i donated money to my friend’s volunteering effort. i took a selfie and sent it to my grandmother. i received joyful emojis in response. i heard music in my headphones.

“Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?”

people are really fragile. weaker than metal. smaller than trees and skyscrapers. even our life expectancy is shorter than that of... jellyfish? orcas?

but just because humans, homo sapiens, are fragile doesn’t mean they’re easy to break.

in the end, we resist. we fight. we struggle. we go against the system. we create. we remember. we treasure and mourn.

we live. we die. we hold on. here, on this earth...

...I think that’s enough.

Sofiia Serohina

Feeling

Крихке - квітка; - скло; - дитячий світ; - ідея; - людина; - любов; - серце; - повітряні кульки; - нігті; - посуд; - гербарій

- сховати; - замотати

— Let’s talk about what frightens us. Tell me, Masha, what are you afraid of?

— I am afraid of something bad happening. I am very happy right now and I am afraid of losing all these things I have.

змін і зберігаю свою ідентичність; натомість я створила величезну мильну бульбашку, яка в певний момент

дорослішання просто луснула й ошелешила мене розумінням, що я тепер трошки інша людина,

Mariia Kobycheva

Fragile! Handle with Care

Fragile - a flower - glass - a child’s world - an idea - a person - love - a heart - balloons - nails - dishes - herbarium of dry leaves

To protect the fragile - hide - wrap in plastic—to secure - put in a drawer—do not use.

It’s a spring afternoon. The school corridors are bright and warm. They smell of dust and dampness after the floors were mopped. A muffled noise can be heard behind the half-open door of the English classroom. Form 7-D is talking about feelings and emotions. Golden light seeps through the tall spruce trees in the courtyard outside the white wooden windows; it falls in wide stripes on the desks and the floor, and dust sparkles in this light. Grey-green eyes watch it carefully, and then turn their gaze to the window, squinting so that small rainbows flicker on the eyelashes. The sunlit face is thoughtful and concentrated.

“Let’s talk about what frightens us. Tell me, Masha, what are you afraid of?”

Grey-green eyes search and find the teacher’s face: “I am afraid of something bad happening. I am very happy right now and I am afraid of losing all these things I have.”

Every story has a climax. When you’re thirteen and just at the beginning of your story, you inadvertently wonder if your life is going to be tested for resilience. In books, something bad always happens to your favourite characters, where they risk losing everything they have, and then they have to use all their strength and knowledge to overcome these difficulties. But afterwards they become invincible, protected from all adversity, and this is only possible if they have had such a baptism by fire. So when everything is perfect in your young life—a wonderful family, cheerful friends, and no worries—and the time for that terrible, mystical, and obviously inevitable test has not yet come, you must appreciate what you have and fully absorb all these wonderful moments in order not to bring trouble.

Do you know how to preserve memories? I am a master at this. For as long as I can remember, I have always kept diaries with detailed stories and pasted-in travel tickets, dried flowers and autumn leaves in thick encyclopedias, and recorded numerous gigabytes of photos and videos. Call it missed opportunity syndrome, but for me, capturing moments, thoughts, and feelings is the best way to live through events. I make sure that no interesting detail escapes my attention. Then, at any time, thanks to photos and records, I can easily transport myself to the atmosphere of that sleepover at my friend’s place or feel my emotions during that May dawn. I have a real time machine in my drawers: there are worn diaries and a herbarium smelling of autumn; summer letters addressed to me in the future, and dried flowers from the Carpathians; notes from camp friends, and giant pine cones from a trip to an ocean island. And just as it is interesting for me to collect all this, it is pleasant for me to look through my treasures. It makes me really appreciate those moments. Having physical memories calms me down. They remind me how wonderful my life can be and how happy I can be. This is how I express my gratitude to this world to a certain extent: I carefully preserve all my memories, put a label “Fragile! Handle with Care” and studiously hide them in a secret drawer.

There are many fragile things in the world: poppy flowers and air bubbles; my favourite porcelain cup and a flimsy pyramid of books; a snail shell and dry autumn leaves. To keep these objects safe and sound, you need to be careful with them. You can wrap them in bubble wrap, secure them, or simply hide them and not use them. However, this does not always give the desired result. This year, during spring cleaning, I came across a drawer with my treasures. I sneezed because of the dust that had risen above the lid of the box I had opened, and looked inside. Everything was preserved exactly as I had put it there: cones and acorns, old crafts and postcards, pebbles from the sea and notes. Everything was the same, except for one detail: the emotions that these treasures used to evoke have already passed, replaced by bitter nostalgia.

There are really a lot of fragile things. A person, a heart, a thought, and a child’s world are fragile. In my attempts to preserve the most interesting moments, I didn’t realize how I started living only in memories. I thought I was protecting myself from change and preserving my identity. Instead, I created a huge bubble that burst at some point in my growing up and stunned me with the realization that I was now a slightly different person, with changed hobbies and preferences.

It can be unpleasant to change. Especially when you so desperately want peace and permanence, and time that is constantly rushing forward is always breaking your fragile teenage world into pieces. And although I have now learned to swim among these waves and am happy to accept change, it is sometimes difficult to build a bridge that could connect me, a student of the eleventh form, with the Masha from Form 7-D. What if, along with some of the treasures that went into the dustbin this year, I lost some bright, kind part of me that I will never find again? And how do I know I’m moving in the right direction, how do I know that these changes won’t harm me?

However, I like to think that for all my necessary questions, the answers will be found themselves. I believe that everything in the world is for the best, that everything lost is found at the right time. I try not to waste time worrying but instead continue to use that time to explore this beautiful world. By the way, human personality and habits are not fragile at all—I continue, though not as actively, to record my life with a camera and in a diary, in order to preserve my most precious and interesting memories and hide them in a locker and the farthest corners of my memory. But with one difference: I’m replacing the label “Fragile! Handle with Care” with a sticker that says “Interesting experience, do not repeat at home!” :)

Mariika’s diary, 12.04.24

Хтось буде снідати

потязі маминими бутербродами.

прикладом для інших)

Tania Koval

Handle with Care, Everything is Fragile!

Everything looks so strong and ready to defend itself, but in reality, if you look a little closer, touch it, it will shatter like the most fragile vase. The universe is vulnerable and fragile.

1. Everything that seems stable to us is actually very fragile, and the fragile, on the contrary, turns out to be quite stable.

In general, for me, vulnerability is the ability to open up to other people. Accepting the fact that you open up to others, that you show defenselessness and imperfection always has many risks. Cities and villages can also show themselves to be vulnerable and fragile. You should not think that only people have such feelings. Everything in the world has its own feelings. They do not open up to everyone, not to everyone, only to those who have truly opened up to the world, shown themselves to be vulnerable and compassionate—only they can see the world not as cruel and callous but as gentle and friendly.

And looking at the city from the train window, I saw how vulnerable, tender, and all-encompassing it was. It has not yet known the everyday worries; it is still sleeping and enjoying the peace of the sun that has not yet risen. People are still sleeping in their warm beds after a long night, and the city is enjoying an hour of peace. It is getting ready for a new day. For some people this will start with tears or laughter, warmth or anger. Someone will have breakfast in an expensive restaurant, and someone will eat their mother’s sandwiches in a second-class train. And each of these people will be happy in their own way, in the moment.

The city will once again be filled with ups and downs, new people who will just discover it, and old fifth-generation citizens who will rush about their business, forgetting about coffee and breakfast. Five o’clock in the morning in the city is a time of peace and the beginning of something new. It is the time when life is born. We are all different, but five o’clock in the morning in cities is the same whether you are in Lviv, Kyiv, New York, Beijing, or the Bahamas—everywhere this five o’clock in the morning will feel the same. This is probably the most fragile period of time because the city is still so delicate, not ready for the new day. This precious hour is so easy to lose: one careless loud sound—and that’s it, the hour got scared and disappeared behind the morning sun. It is fragile like glass, and few people can feel it. It doesn’t let you see itself just like that. You have to try and catch a moment of pleasure when it doesn’t see you, and you can afford to admire it for a few minutes. It is so gentle, this five o’clock, it is so afraid of people and their cruelty that it does not show itself to others, afraid that it will be crushed, leveled with triviality. But how can this miracle be so easily forgotten, devalued?

I am traveling by train. Most people are sleeping or trying to wake up. And I’m looking out the window and can’t stop admiring it. This pale pink and blue sky that is so gentle after a dark, scary night. These green trees and lawns. And I love it so much that I can contemplate this simplicity that we lack so often in the contemporary world. Five hours in the city gave me the opportunity to observe this out of the corner of my eye. It’s such a tender feeling that blooms in the heart of your soul. It doesn’t make your heart petrified and cruel, but rather helps it gain energy for the next day

in order to share this tenderness. The fragility of the moment is the most important thing. Because the moment is here and now, not tomorrow, not yesterday, not sometime later, but this minute, second, instant.

Do you think you can see this only after watching some guides or YouTube videos? No. You need to capture the moments, not to close yourself in your shell, not to stare down—you may not see this moment there. But as soon as you straighten your shoulders and raise your head, you will catch this fragile moment. You don’t have to want it, you have to wish for it with all your heart.

Everything inside you is so fragile and invisible. You are a creator, and you have to create your own steel fragility to be an example for others.

Аліса бридливо зморщила носик. Малесенькі квітки, що нагадували округлі молочно-білі дзвіночки, мали приємний, але надто сильний аромат.

— Мамо! — вона підвелась на ноги, намагаючись обтрусити коліна. — Мамо, зачекай! Кілька білих

ною пухкенькою долонею. Бузкові туфельки

кою вслід за високими маминими

— Смачне?

саме?

вішак.

— Я ж уже пояснювала, доню. Скоро. Як тільки одужає. Пригадуєш, як ти захворіла взимку?

Донька похитала головою. Вона погано пам’ятала щось, що було давно.

— Тоді я тебе вилікувала. А тата лікують добрі люди в Києві.

— І коли його нарешті вилікують? Коли він повернеться?

— Скоро.

Алісині пальчики понуро випустили кінчик плаття.

покрутила зіницями:

не тому. Він має проблеми з серцем.

Аліса нахмурила біляві, майже невидимі брівки. Мабуть,

усіх, кажучи, що тато має «хворобу

звідкілясь

схожий на ніж, і перерізала скотч. Далі вона дала доньці право розібратися самій.

Спершу Аліса хотіла дістати все обережно, але, як цезазвичай

бувало, акуратна розпаковка перетворилася на дрібненькі шматки картону, що валялися ледь не по всьому приміщенні. Доки мама заходилася покірно збирати

— Мамо! Мамо… — Ну що, доню, подивилась? Помилувалась?

Викличте… Якогось

тітонька почала заїкатися.

— Пробачте, я не винна… Зараз, знайду листочок, — Леся теж виправдовувалася чи то перед мамою, чи то перед дядечком. — Ось! Нарешті! —

сваритись…

дила доньчине волосся. — Так, матусю. Так, все гаразд, ходімо вже, я обійдусь

Почулась знайома мелодія. Мама вийняла з кишені телефон, до -

торкнулась до екрану і невпевнено піднесла собі до вуха. — Богдане? Як ти? Ти

кала на відповідь. — Як!?..

телефон.

Лесі, вона ввімкнула

вушок. Мамине «скоро» нарешті стало справжнім. Вона відчула, як під маминими підборами і

маленькими ніжками хруснули

останні шматочки шоколадно-бананового печива.

Kateryna Kravtsova

Damaged during Delivery

Alisa wrinkled her nose in disgust. The tiny flowers resembling rounded milky-white bells had a pleasant but overpowering scent.

“Mum!” She got to her feet, trying to dust off her knees. “Mum, wait!”

Several white flowers were ruthlessly plucked in an instant by a tiny, chubby hand. Little lilac shoes stomped down the narrow alley after her mother’s high heels.

“Mum, what flower is this?”

“Lily of the valley.” Mum immediately reached for the remnants of dirt on her daughter’s pants, forgetting that she should be as careful as possible with her freshly ironed dress. “Throw it away.”

“Why? I thought only dad doesn’t like flowers.”

Dad actually did not like many different kinds of flowers. He also didn’t like certain delicacies and the days when mum was cleaning the flat, kicking up mountains of dust. Then, out of the blue, he would start crying, coughing, and sneezing unbearably.

“I love flowers. So does dad. He just doesn’t like his allergy.”

“And I love you.” Alisa hugged her mother’s slender legs, the only thing her arms could reach. “I want to give this to you.”

Mum carefully took the thin stem. She brought the small fragrant bells to her nose, made a slight face, smiled, and, as her daughter had mentally wished, gave the flowers back.

“It’s not nice, little bird.” She looked at the neglected flower bed where Alisa’s naughty feet had climbed a minute ago. “Someone planted these lilies of the valley and took care of them. They would have bloomed much longer if someone’s little fingers hadn’t touched them.”

“I won’t do it again.” Alisa’s clear blue eyes stared at the ground.

“Let’s go. Otherwise, we’ll be late. You haven’t forgotten that you’re the first to perform, have you, my star? Besides, we also have to go to the post office.”

“Why?” Alisa was helping her mum carry her concert dress.

“We’ll pick up your biscuits.”

“Are they tasty?”

“Yes, they are. Banana biscuits. Dad sent them.”

“The ones I like? Banana and chocolate?”

“Yeah. Your favourite. Dad somehow found these biscuits in the capital.”

“And when will Dad come back from the capital?”

For a moment, Alisa felt the entire weight of the dress shifted to her, as her mother let go of the hanger.

“I’ve already explained it to you, sweetheart. Soon. As soon as he recovers. Do you remember when you got ill in the winter?”

The daughter shook her head. She hardly remembered anything that happened long ago.

“I cured you then. And Dad is being treated by good people in Kyiv.”

“And when will he finally be cured? When will he come back?”

“Soon.”

Alisa’s fingers sadly let go of the rim of her dress. She had a bad memory but she remembered her mother saying that same “soon” repeatedly, even before the lily of the valley in her hands had emerged from the snow-covered ground.

“This way, dear.” Mum opened the door at the end of the long alley. It was a little cooler inside than outside. In the far corner, at the computer, sat a blond woman. She was not like all the other women and men at the post office. She was slimmer, shorter, her golden curls were blue at the ends, and in general she was closer to Alisa’s age than her mother’s.

“Good afternoon,” Mumlooked at Alisa intently, waiting for her to repeat her words. “Can I pick up a parcel?”

“Please tell me your phone number.” The young woman had an irritating, husky voice.

Mum dictated the numbers so quickly that Alisa who was starting to learn math didn’t understand.

“A parcel addressed to Kryshtal Yelyzaveta Oleksandrivna?,” the woman muttered. Mum nodded.

The woman stood up from her seat, and a lanyard with the word “Lesia” on it swayed on her chest. Then she walked over to the large grey shelves and started digging through them with her long, brightly coloured nails which Mum called “manicures.”

“You came just in time, ma’am. The day after tomorrow, the sender would have picked up your parcel.”

“I don’t think so.”

Alisa saw her mother hastily put her hand over her mouth, but her dress prevented her from doing so, as it was not to be dropped and stained or, worse, wrinkled.

The woman named Lesia looked back in surprise.

“My husband is undergoing treatment in Kyiv.” Mother was looking carefully at the shelves with parcels.

“So you mean he can’t walk, and so he won’t be able to take…”

Mum’s pupils moved in circles:

“No, no, that’s not why. He has heart problems.”

Alisa furrowed her blond, almost invisible eyebrows. Apparently, this time they were in a real hurry. Usually, Mum would correct everyone instead, saying that Dad had cardiovascular disease, explain something in detail, and people would nod sympathetically, saying things like: “But he is so young... how did he get it?”

When a long silence fell, broken only by the rustling of boxes, Mum added:

“Lately...very serious heart problems.”

Her gaze first lingered on her daughter for a very long time, and then abruptly, as if to warn her, turned to Lesia.

Lesia gave a small gasp.

“So... You mean, there’s a risk that he…”

“Give me the parcel already.”

Mum’s eyes were intently, too intently, focused on Alisa. Lesia touched her manicures to her generously coloured red lips.

“Sorry it took so long. I’ve only been working here for two days.” She put the small box on the table next to hers.

On the grey-and-brown cardboard there was a warning in the colour of Lesia’s lips: “Fragile! Handle with care.”

“In the evening, you will taste it and say thank you to your father.” Mum took the parcel in her hands, paid for the delivery, and walked to the exit.

“What do you mean? I want to open it!” Alisa frowned.

“You can open it at home, after the concert. You don’t want to be late, do you?”

“But we won’t be late! I just want to have a look... maybe take a couple of biscuits…”

“You’ve had lunch.”

“Please, let me at least look at it... It’s from Dad…”

With a sigh, Mum handed the box to her daughter.

“It will be faster to have a look than to argue with you.”

Alisa’s eyes flashed with a small, petty joy but immediately turned gloomy. As a rule, these familiar things of medium weight generally bumped against the walls of the box as it was moved. But Alisa did not feel it.

“How do I open it?” She was trying to pick at the adhesive tape that wrapped the parcel with her fingers.

Mum put the box on the table, took a sharp knife-like object from somewhere, and cut the tape. Then she gave her daughter a chance to figure everything out on her own.

At first, Alisa wanted to take everything out carefully, but, as was usually the case, the neat unpacking turned into small pieces of cardboard scattered almost all over the room. While her mother dutifully began to pick up the scattered items, little hands removed the bubble wrap from the paper package. After playing with the bubble wrap for a while, Alisa unfolded the thick white paper that was supposed to hide the biscuits inside.

Her blue eyes grew even bluer, as they always did when she was about to cry.

“Mum, Mummy…”

“What’s wrong, my sweetheart?” Mum kept trying to pick up a piece of paper that had fallen under the shelves with the parcels.

The transparent bag was filled with chocolate-coloured crumbs. At the very bottom there were two surviving pieces of biscuits.

“Mum! Mummy…”

“Well, sweetheart, did you have a look? Did you like it?” Mum threw the paper in the dustbin and walked over to the table.

Her face was surprised, and a moment later it became twisted in a strange, painful way. She stared sternly at the woman at her computer.

“What is this?”

Mum usually said this phrase when she saw scattered toys or uneaten dinner. Alisa had never realized that her words always sounded so gentle, a hundred times gentler than they did now.

Lesia stood up, furrowing her black eyebrows. It was only when Mum repeated the question in a higher pitch that she mumbled timidly:

“It seems... your parcel... was damaged during delivery.”

Mum took a deep breath.

“It’s okay, little seed, Mummy will take care of it.” She sat down and kissed her daughter on the forehead.

And then she stood up, squaring her shoulders.

“And how was it damaged? With a warning sticker?”

“Ma’am…,” Lesia looked at her computer for a second. “Yelyzaveta Oleksandrivna... I don’t know how it happened. I’ve told you, I’ve only been working here for two days…”

Mum was silent, keeping her eyes on Lesia. Against the background of Mother’s angry face, Lesia looked like a girl.

“I assure you, we will pay compensation…”

“How did this happen?” With each letter she spoke, Mum voice grew stronger.

“We... We’ll take care of everything…”

“Call... someone who is in charge... Do you have a supervisor here?”

“Yes, yes, we do... I... I don’t know if it’s worth calling in this case…,” Lesia started to stammer. “You know, I’ll text her. She took her phone out of her pocket.

“Because of you, my daughter is late for the first performance in her life.” Mum threw the dress on the table and leaned her elbow on the counter, behind which Lesia had quickly turned white and was staring helplessly. “You’ll have to look her in the eye yourself!”

“I know, I know... You can write a complaint. They’ll reimburse you, trust me! Let me find a sheet of paper…”

Thin fingers reached under the computer and began to frantically search through something.

Alisa looked anxiously at her mother, then at the bag of biscuits, then at the other people who had come to the post office during this time. In her hands, she was constantly kneading a well-worn lily of the valley.

“Alisa, dear,” her mother’s quiet voice trembled, “go outside and throw this flower away.”

“Why? You’re not allergic to flowers!”

“Please throw it away.”

“Well, okay then.” Alisa was now tired of the wilted lily of the valley which had already started to leak sticky juice.

She obediently walked over to the dustbin.

“No, Alisa, this dustbin is only for cardboard and paper from parcels!”

“Actually…,” Lesia began.

“Throw that lily of the valley into the dustbin outside!” Alisa was deafened by her mother’s stern voice.

Shrugging her shoulders in discontent, Alisa opened the door and looked outside. There was no dustbin nearby. She looked around uncertainly. Her mother’s twisted face worried her too much. Finally, Alisa tucked the lily of the valley into her pocket and went back inside, sitting on a chair behind a tall man who occasionally shouted,

“Can you hurry up, woman! There’s already a line of five people!” It was unclear whether he was addressing her mother or Lesia.

“I’m sorry, it’s not my fault... I’ll find the sheet of paper.” Lesia also made excuses either to Mum or to the man. “Here! Finally!” She put a sheet of paper on a table. “Write about the damage, the price of the parcel, all that stuff... We’ll reimburse everything.”

“No, you won’t.”

“Then what on earth do you want from me?” Lesia stomped her high heel on the floor, almost falling over.

Hearing these words, Mum gave her a fiery look but when she looked around the room and didn’t see Alisa behind the queue, she cooled down a bit.

“I can go to the store next door right now and replace this stupid parcel!” Under the pressure of other customers whose indignation was growing by the second, Lesia began to lose her timidity. “It’s just regular biscuits!”

“If only.” Alisa could clearly see black liquid dripping from her mother’s mascaraed eyelashes. “If they were just regular biscuits, I would have done just that!” She threw the bag of crumbs down. “But this... maybe this is his last gift to his daughter. Maybe it’s his last parcel... I don’t know…”

Mum covered her face with her hands.

Lesia had no choice but to stand quietly in place. After a few seconds, the threats of the customers who had lost their patience finally made her come out from behind her counter and approach the table.

“Look, you need to write on this sheet of paper…”

“There you go again about your sheet of paper!” Mum wiped her reddened face with her sleeve.

“Mum, Mummy,” Alisa ran up to the table and hugged her mother’s hand, “let’s go, we’re already late for the performance. Please don’t argue…”

“Everything is fine, dear, everything is fine.” Mum stroked Alisa’s hair with trembling hands.

“Yes, Mummy. Yes, everything is fine, let’s go, I’ll do without the biscuits…”

A familiar ringtone rang out. Mum pulled her phone out of her pocket, touched the screen, and raised it to her ear with diffidence.

“Bohdan? How are you? Did you get your allergy drops?” She was waiting for an answer. “What?!” Mum did not take her eyes off Lesia. Her hand somehow dropped the phone.

“They... They damaged the medication... at the post office?” Mum fell to her knees. After a long, painful look at Lesia, she put the phone on speakerphone, something she often did when she was nervous.

“Liza? Liza, dear, can you hear me?” Dad’s voice rang through the room. “Yes, dear.” Mum tried to hold back her tears.

“And do you know what happened? The fact that I didn’t take those anti-allergy medications for three days because they were destroyed? Yes, I sneezed a little bit, of course... But... Oh, you can’t imagine! The doctor said that all this... everything with my heart is almost back to normal! The acute condition was caused by them! The allergy drops!” Both Mum and Dad were choking back tears. “Do you hear me, Liza, dear? Do you hear me? Listen, someone is calling me... Say hello to Alisa!”

Laughing, Dad ended the call. For several long moments, Mum did not make any slightest movement. Her sparkling eyes were full of confusion and complete failure to understand. Finally, she stood up and hugged an embarrassed Lesia tightly, very tightly.

“Mum, Mummy... When will dad come back?” Alisa’s eyes were shining with the most sincere sense of hope she had ever felt.

“Soon!” Mum hurriedly wiped away her tears. “Not even... No, not soon, Alisa, I mean very soon... shortly!”

“Ma’am, it means the same thing!” Lesia couldn’t stop laughing with joy.

“No, no, it’s…” Mum hugged Alisa.

Alisa

stretched her lips all the way to her ears. Mum’s “soon” had finally become real. She felt the last two pieces of chocolate and banana biscuits crunch under her mother’s heels and her little feet.

Перший рік у середній школі. Хвилювання

поступово проходить з кожним днем.

Ненавиджу підійматися на четвертий по-

верх: стільки сходинок — то знущання. Прав-

да, після цих тортур є неймовірний кабінет.

Заходжу — то є рай. У повітрі легкий запах

кави, жалюзі приспущені, на дошці — фото-

графії й малюнки до «Пригод Тома Сойєра»

та інших творів.

З короткочасною пам’яттю

— підручник залишився вдома, тож подруга ділиться своїм. Посеред уроку, коли беру його

щось швидко, все піде шкереберть. Тож зовсім не дивно,

*** Двома місяцями пізніше я сиджу й думаю. Вечір п’ятниці, саме час для цього. Все ніяк не можу зрозуміти: чого я така необережна? Все життя я ламаю, гублю, розбиваю та розчавлюю те, що ціную. Це, вихо-

дить, я погана людина, так? Але ж я старалася, я справді

Karina Moshuk

One Day, I Will Not Break the Kite

It’s spring. Nature has woken up and blossomed. The smell of apricots near the house triggers an allergy attack and brings me back to the past: I am standing in front of my friend who gives me a bouquet of flowers. We are happy children, still carefree. A couple of daisies, a dandelion, a branch of apricot—I sneeze loudly. People on the street look back at us, and we laugh.

When I got home, I couldn’t find the bouquet. My glasses were cloudy, and there was a pile of tissues lying around. Then my mum found it, crumpled in the pocket of my pants that were smeared with dandelion juice. In tears, I tried to “revive” the flowers, put them in water, but of course it was useless.

***

My first desk in front of the teacher has seen a lot, but the fact that I forgot my pencil case was something new for it to experience. My deskmate lends me a pen because who can he cheat from if I don’t have anything to write with? He talks to me all the time, and we get reprimanded. Of course, he doesn’t care.

A little tired, at home now, I realize that I didn’t give the pen back to my deskmate. I look at it: it’s all chewed up and the cap is lost. No, I can’t give it back. The next day I bring a new one and say that I lost the one I borrowed.

*** The first year in secondary school. The agitation is gradually passing day by day.

I hate going up to the fourth floor: so many steps, it’s torture. However, after this torture, there is an incredible classroom. I walk in and it’s paradise. There is a slight smell of coffee in the air, the blinds are lowered, and there are photos and drawings from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and other works on the board.

I have problems with my short-term memory; I left my textbook at home, so my friend shares hers. In the middle of the lesson, when I pick it up to read the text aloud, the book cover falls off. The teacher is not angry because it was barely holding on anyway, but it’s still sad.

***

I’m growing up. It’s so strange. It’s summer holidays, and my family and I are staying at home because of the lockdown. I have constant quarrels with my sister because I don’t want to play with her.

My favourite singer is having a live show on Instagram. I’m very happy but I don’t want to annoy my sister again, so I borrow my dad’s headphones.

During the song “Why do you carry me when I can’t go on? When I’m in the arms of despair, you take off your wings for me,” the sound starts to crackle. I twist the wire, trying to fix the headphones somehow, but to no avail. A day later they broke down completely.

*** Seventh form. All summer I dreamed of beginning to study chemistry. Now I’m tired of it. Who wants to write a lab report at nine in the morning? Tearing up a universal indicator and throwing it into three test tubes— what could be easier? But my carelessness finally wakes up the whole class: I accidentally hit the tripod, it falls over, the test tubes shatter, and their contents end up on the tray. There is either alkali or acid on my hand—I don’t know.

*** Bukovyna. I am at my relatives’ place. Two weeks have gradually turned into two months, and then there will be more, I’m sure, because Kyiv is not very safe right now.

It’s 10:20am, and I’m hurriedly washing my plate to be in time for my Zoom lesson in Ukrainian Literature. An interesting fact about me: if I do something quickly, it goes wrong. So it’s not surprising that the plate slips out of my hands, falls to the floor, and breaks. Unfortunately, it’s not the first one these days.

*** The last Valentine’s Day I remembered was five years ago. Time flies at the speed of light—it’s already tenth form.

I was given a heart-shaped lollipop—it’s very cute. I put it in my backpack and hope it will survive. But, of course, it didn’t. When I get home, I see that it broke in half.

*** Two months later, I am sitting, thinking. It’s Friday night, the right time for this. I still can’t figure it out: why am I so careless? All my life I’ve been breaking, losing, smashing, and crushing things I value. It means that I am a bad person, right? But I tried, I really tried to save them. But my own actions ruined them.

*** The future is interesting, you know. This question will stay with me but it will sound in the past tense.

One day, I will play with someone in the park with an old kite. One day, this someone will let me control the kite on my own, I won’t break it, and I will probably feel elated. One day, this someone and I will look at a little green diamond in the peaceful clear sky. And one day, life will be wonderful, and I will be careful and happy.

Кристина Оріхова

Крихка доля в недруга без волі

Дочекавшись скону з неба,

Поляжу душею.

Думо моя, не соромся,

Не лети за нею.

Голосіння набереться,

Скличе братства раду,

Серце моє вже не б’ється,

Думка — лиш дрімає.

Хоч поляжу духом й тілом,

Згину я душею,

За країну радий жити,

Буду рад і вмерти.

Бо нема на світі сонця,

Як над моїм долом.

Зірок ліпших годі бачить

Над пшеничним полем.

Був я син своєму батьку, І чужому буду, У далекім краї стану,

Як впізнаю мову.

Не молив своє я щастя

Серед люду свого,

Бо воно не полишало

Вік тернисту долю.

Ну а ти, нещасний брате, Чим в житті ти дужий?

Зрікся роду гайдамаків — Світу став байдужим, Пропиячив віру дужу, Враз спалив клейноди — Як же ти зібрався душу

Випускать на волю?

Зрікся ти своєї правди, Вражому не треба Мать таких собі на пару, Бо і їх зречешся.

Що ж ти, братику, накоїв, Ким вмирать лишився?

Думу виростив крихкою — Долі полишився.

Krystyna Orikhova

A Fragile Fate of the Enemy in a Bad State

My soul will lay down After death from the sky. My thoughts, do not fly after it. Please don’t be shy. The brotherhood will be gathered With the lamentation, My heart has stopped beating, My mind is in frustration. I will die in my soul, I will die in body and spirit, Glad to live for my country, Glad to die for it.

There is no better sun Than the one above me. There are no better stars Over this, my wheat lea. I was my father’s son, And I will be son for a stranger, In a faraway land I will stand, How I’ll recognize them. I did not pray for my happiness Among my lovely mates, Because it did not ever leave My age of thorny fate.

And you, my poor brother, Were you strong in life? You renounced your Haidamaks— You lost in the world’s strife, You got drunk on your strong faith, And burned all your power. And how did you plan your soul To set free in your late hour? You renounced your truth So the enemy does not need To have such men like you Because you will renounce them too. What have you done, brother? Who is left to die here late? You’ve made your thoughts fragile, You have lost your fate.

насолод-

жуватися гірким ароматом кави, що ідеально доповнює

слухати

непрoстo. Зараз ви дізнаєтесь, чому.

— Мамо, мамо! Він тут, тут!

минулих років. — Це було давно, цілих 45 років тому, я

«Залісся». Тоді я

усміхнулася

І коли вона нарешті

Veronika Ospanova Fragile Heart Coffee Shop

Somewhere very far away, or perhaps very close by, there is a coffee shop called Fragile Heart where they sell incredible coffee and bake the most delicious biscuits in the world. Everyone who has ever tasted something from Fragile Heart wants to come back to the coffee shop again and again, to enjoy the bitter aroma of coffee that perfectly complements the smell of vanilla biscuits and a taste that you won’t find anywhere else. Visitors also want to listen to the incredible tale of love held by this place, but it’s not easy to hear. Now you will find out why.

“Mum, Mummy! He’s here, he’s here!,” exclaimed a boy who was in such a hurry to get home that he didn’t even notice that he had lost one of his shoes.

The woman, who was washing the dishes at that moment, turned around to look at her son.

“Who is here, son?,” she asked, looking rather unhappily at her child who was wearing only one shoe.

“Fragile Heart old man! Mum, it’s true! He’s here!”

“You call your father, and I’ll call your grandparents,” she said, forgetting about the unwashed dishes and the fact that her son was wearing only one shoe. She believed in the fairy tale again.

In the centre of the village stood a very unusual house on wheels pulled by a car. An unusually large number of people came out of their homes and, fascinated by a delicious aroma, went to it. As they approached, people saw an old house on wheels set up as a small shop with a counter, with biscuits and a menu displayed.

An old man with a round, cheerful face framed by silver hair, about sixtyfive years old, was looking out of the car window. His sparkling eyes and sincere smile attracted people. The boy came closer, pulling his mother’s hand to be the first one.