Україна

в огні Ukraine ablaze Mystetskyi Arsenal. Kyiv, 2023 Мистецький арсенал. Київ, 2023

*Назва видання відсилає до однойменної кіноповісті Олександра Довженка «Україна в огні» (1966 р.)

*The title of this publication refers to the film essay of the same name, «Ukraine in Flames» (1966), by Oleksandr Dovzhenko

СПІЛЬНОТИ ОБ’ЄДНУЮТЬСЯ, ЩОБ ЗАХИСТИТИ

КУЛЬТУРНУ СПАДЩИНУ

зміст Передмова НАТАША ЧИЧАСОВА Розмова про присутність НАТАША ЧИЧАСОВА І АСЯ ЦІСАР

з

Просторові діалоги»

Таймлайн виставок «Одне

одним.

ПРАЦІВНИКИ МИСТЕЦТВА НА ВІЙНІ: ЯК УКРАЇНСЬКІ АРТ

ПОЛІНА БАЙЦИМ 8-11 14-33 34-71 74-85

Форми присутності ЯК ВІДЧУВАЄТЬСЯ ПРОСТІР В ЧАСИ ВІЙНИ? МАТЕРІАЛЬНІСТЬ І МИСТЕЦТВО ПИТАННЯ ДО СЕБЕ Проживаючи російську війну в Україні: про втрати й мистецтво КАТЕРИНА ЯКОВЛЕНКО Архівування мистецтва в часи війни. Навіщо ми це робимо? ПокаЖчик архівів 212-243 244-251 252-259 88-209

Foreword

NATASHA CHYCHASOVA

A CONVERSATION ABOUT PRESENCE

NATASHA CHYCHASOVA AND ASIA TSISAR

Timeline of the «One with the other. Spatial Dialogues» exhibitions

Art Workers at War: How the Ukrainian Art world Has Rallied to Protect Cultural Heritage

POLINA BAITSYM

34-71

CONTENTS 8-11 14-33

74-85

Forms of presence HOW DOES SPACE FEEL DURING WARTIME? MATERIALITY AND ART QUESTIONS TO YOURSELF Eyewitness the Russian War in Ukraine: The Matter of Loss and Arts KATERYNA IAKOVLENKO ARCHIVING ART DURING WARTIME. WHY ARE WE DOING THIS? Index of archives 212-243 244-251 252-259 88-209

Передмова

У цьому виданні ми спробували зібрати думки про різні події й тексти, що складаються в проєкт «Україна в огні». Він почався як онлайн-платформа для закордонного поширення творів українських художників і художниць, які у своїх практиках осмислюють війну, а далі розрісся, немов виноградна лоза.

На початку ми не уявляли, чим він буде і як ми рухатимемося далі, а просто робили свою роботу, яка давала внутрішній спокій і допомагала налагодити зв’язок із собою і реальністю. Що більше робіт ми знаходили й завантажували на сайт проєкту, то чіткіше розуміли, що в швидкозмінній реальності просто поширювати і збирати мистецькі твори вже недостатньо. Ми довго обговорювали всередині команди Мистецького арсеналу, чим іще може бути наша платформа, що ще можна зробити (і чи треба це робити), й нарешті знайшли рішення, яке видавалось природним: почати говорити зі спільнотою.

Говорити про досвіди, практики і зміни, нові страшні відкриття і про те, де ми тепер.

Ми запрошували до розмови учасників і учасниць проєкту, вони, своєю чергою, друзів та подруг, колег і колежанок, про яких хочеш дізнатися більше й просто поговорити. Через ці діалоги довколишній світ починав увиразнюватись, а з ним увиразнювалися

8

й ми самі, наші почуття і думки. Пригадуючи кожен етап проєкту, ніби поступово проживаєш стани з початку повномасштабного вторгнення: розгубленість і швидкі рішення, злість, пошуки можливостей бути корисною і допомагати, думки про несвоєчасність виставок в Україні, безкінечний серфінг в інтернеті й потоки повідомлень, повернення додому, перший несміливий лист до художниці («вибач що турбую, сподіваюсь, у тебе все добре і ви з близькими у безпеці. ми хочемо зробити виставку. чи хотіла би ти взяти участь?») і таке бажане «так, давай зідзвонимось». Усі ці парості почуттів і подій так чи інакше говорять про наш колективний досвід проживання війни, де всі голоси важливі. Саме вони стали підґрунтям для виставкової програми Лабораторії сучасного мистецтва «Мала Галерея Мистецького арсеналу», а пізніше й виставки «Форми присутності».

За час роботи ми ще сильніше впевнилися, що дрібниць не існує, а важливість турбуватись

одне про одного є базовою потребою. Саме тому ми досі продовжуємо запитувати «як ти спав сьогодні вночі?», співчувати болю і втратам інших, злитися і плакати разом, працювати всупереч, обіймати тих, хто поруч і дуже далеко, пам’ятати тих, хто пішов, і не давати їм розчинитися в небутті.

Безмежно вдячні кожному й кожній за довіру, любов і те, що були і лишаєтєся поруч.

Наташа Чичасова

9

In this publication, we tried to collect thoughts on various events and texts that comprise the «Ukraine Ablaze» project. It began as an online platform for the international distribution of the works of Ukrainian artists who were making sense of the war in their practices, and later it grew like a vine.

Initially, we couldn’t imagine what it would be like and how we would move forward. We did our work, which brought inner peace and helped establish a connection between ourselves and reality. The more artistic works we found and uploaded to the project website, the more clearly we understood that in a rapidly changing reality, simply distributing and collecting works of art was no longer enough. We discussed extensively within Mystetskyi Arsenal team what else our platform could be, what more could be done (and whether it was necessary to do it), and finally found a natural solution: to start engaging with the community by talking about experiences, practices and changes, new horrifying discoveries, and where we are now.

We invited project participants, and they, in turn, invited their friends, colleagues, and acquaintances about whom they were eager to learn more and have a conversation. Through these dialogues, the surrounding world began to take shape, and along with it, we became more defined – our feelings and thoughts became more evident. Recalling each stage of the project, it’s as if you gradually

10

Foreword

relive the states from the beginning of the fullscale invasion: confusion and quick decisions, anger, searching for opportunities to be useful and helpful, thoughts about the appropriateness of exhibitions in Ukraine, endless internet surfing and streams of messages, returning home, the first timid letter to the artist («I apologise for disturbing you. Hope you and your loved ones are safe. We want to organise an exhibition. Would you like to participate?») and receiving the desired response, «Yes, let’s have a call». All these sprouts of feelings and events somehow tell about our collective experience of living through the war, where all voices are critical. They became the basis for the exhibition programme of the Laboratory of Contemporary Art « Mala Gallery of the Mystetskyi Arsenal», and later the exhibition «Forms of Presence».

During our work, we became even more convinced that there are no trivial things, and that caring for each other is a fundamental need. That’s why we continue to ask, «How did you sleep last night?» to express sympathy for each other’s pain and losses, to be angry and cry together, to work despite the challenges, to hug those who are near and very far, to remember those who have passed away, and to not let them dissolve into oblivion.

We are infinitely grateful to everyone for their trust and love and for being there, both in the past and continuing to stand by our side.

Natasha Chychasova

Natasha Chychasova

11

РОЗМОВА ПРО ПРИСУТНІСТЬ

Записано у червні 2023 року

Ася Цісар: Я б хотіла почати з автоетнографії

чи з наголошення суб’єктивної позиції та проговорювання витоків цієї суб’єктивності.

Тому розкажи — що для тебе «Україна в огні»?

Наташа Чичасова: «Україна в огні» з’явилася на початку повномасштабного вторгнення як певна автотерапія, обсесивне збиральництво. Коли все розвалюється і ти не знаєш, де будеш завтра, не знаєш, чи будеш завтра і що від тебе залишиться, виникає необхідність усе зібрати. Тоді цей проєкт став певним поверненням до мистецтва, до того, чим ми з колегами й колежанками займалися перед повномасштабним вторгненням. Це був шлях робити те, що вмієш, тоді, коли твої навички і здібності здаються привілеєм і чимось непотрібним.

А.Ц.: Розкажи трошки більше про цей механізм — чому, коли все розвалюється і немає певності, що навіть твоя країна завтра існуватиме, вибираєш пам’ятати, запам’ятовувати, архівувати?

Н.Ч.: На першому етапі це було радше про говорити

й популяризувати. На початку вторгнення до нас зверталися закордонні колеги та колежанки

14

НАТАША ЧИЧАСОВА І АСЯ ЦІСАР

із запитом на підтримку українських митців, але вони не знали імен. І мені здається, це була дуже показова історія про видимість українського мистецтва. Ми хотіли не лише збирати роботи, які б говорили про війну, а й дати уявлення про різні практики художників

та художниць і можливість із ними зв’язатися.

Ми збирали базу даних. Тодішнє мистецтво було дуже прямим. Воно досить влучно фіксувало перебіг війни, і тому, власне, в нас з’явилась

ідея його збирати. Спочатку це була приватна

ініціатива, якою я зайнялася зі своїми колегами й колежанками. Все будувалося через дружні зв’язки — я оголосила open call у соцмережах, ми отримали якусь шалену кількість робіт, і дружня платформа надала нам ресурс, щоб їх публікувати. Згодом проєкт став частиною Мистецького арсеналу і ліг в основу роботи Лабораторії сучасного мистецтва Мала Галерея. Десь у травні ми запустили свій сайт. Тобто

проєкт з’явився як відповідь на певну потребу

і трансформувався разом із нею.

Працюючи над сайтом, ми почали звертати велику

увагу на зміст робіт, аналізували їх, думали,

що ми хочемо включити в цей архів і які там

15

мають бути проєкти. Для нас стало принципово додавати роботи з 2014 року, а не лише з 2022го.

А.Ц.: Але ти кажеш, що тобі незручно називати «Україну в огні» архівом. Чому?

Н.Ч.: Мені все ще важко називати «Україну в огні» архівом, тому я її називаю радше кураторською добіркою. Я розумію, що це дуже особиста добірка дуже обмеженого кола людей. Наші критерії суб’єктивні — як і саме мистецтво. Вибираючи роботи, ми думали про наповнення цього проєкту, про сенси, які ми туди закладаємо. Переважно ми працюємо з художниками й художницями, чию практику знаємо, і тому розуміємо, наскільки, на нашу суб’єктивну думку, та чи інша робота органічна

і важлива для певної людини й для контексту історії українського мистецтва. Ми весь час намагаємося повертатися назад, думати, наприклад, у якому стані були, коли вибирали

саме ці роботи, з якої причини це зробили, і рефлексувати процеси, які відбувалися з нами й навколо нас.

Це дослідження всередині спільноти — як ми змінилися, як змінилося мистецтво, якими темами послуговуються художники та художниці, що вони змінили у своїх практиках. Нам цікаво архівувати ці процеси. Так постала ідея діалогів, де ми пропонуємо митцям і мисткиням вибрати собі пару до розмови і поговорити про те, що їх хвилює у практиках одне одного. Архів, на мою думку, — це база, яку ми намагаємося

проблематизувати і ставити під сумнів, запитувати, як і чому там опинилися певні речі й чого там нема. А питання, чого там нема, дуже часто може вивести на ще цікавіші думки та дослідження.

А.Ц.: Тобто ви архівуєте зміну. Тем, думок, художніх практик, самих людей — від початку війни й поки вона триває?

16

Н.Ч.: Так. Важливо, що цей архів, роботи, які в

ньому є, стають певними точками на відрізку.

А.Ц.: Тоді розкажи мені, як змінився погляд між 2014-м і 2022-м. Якою війна постає в роботах після 2014 року, і що змінилося після 24 лютого?

Н.Ч.: Ну, наприклад, зображення військового

2014-му не було настільки популярним мотивом, як зараз. І це, на мою думку, пов’язано з нинішньою масовістю військового досвіду в Україні. Тепер ми бачимо військових у медіа, серед своїх друзів і знайомих. У 2014 році

до війни були причетні все ж менше людей, тому цей образ не став патерном. З іншого боку, мені здається, що митці й мисткині вже з 2014-го так чи інакше говорили про війну чи втрачений дім, зокрема ті з них, хто походить

з Донбасу і Криму.

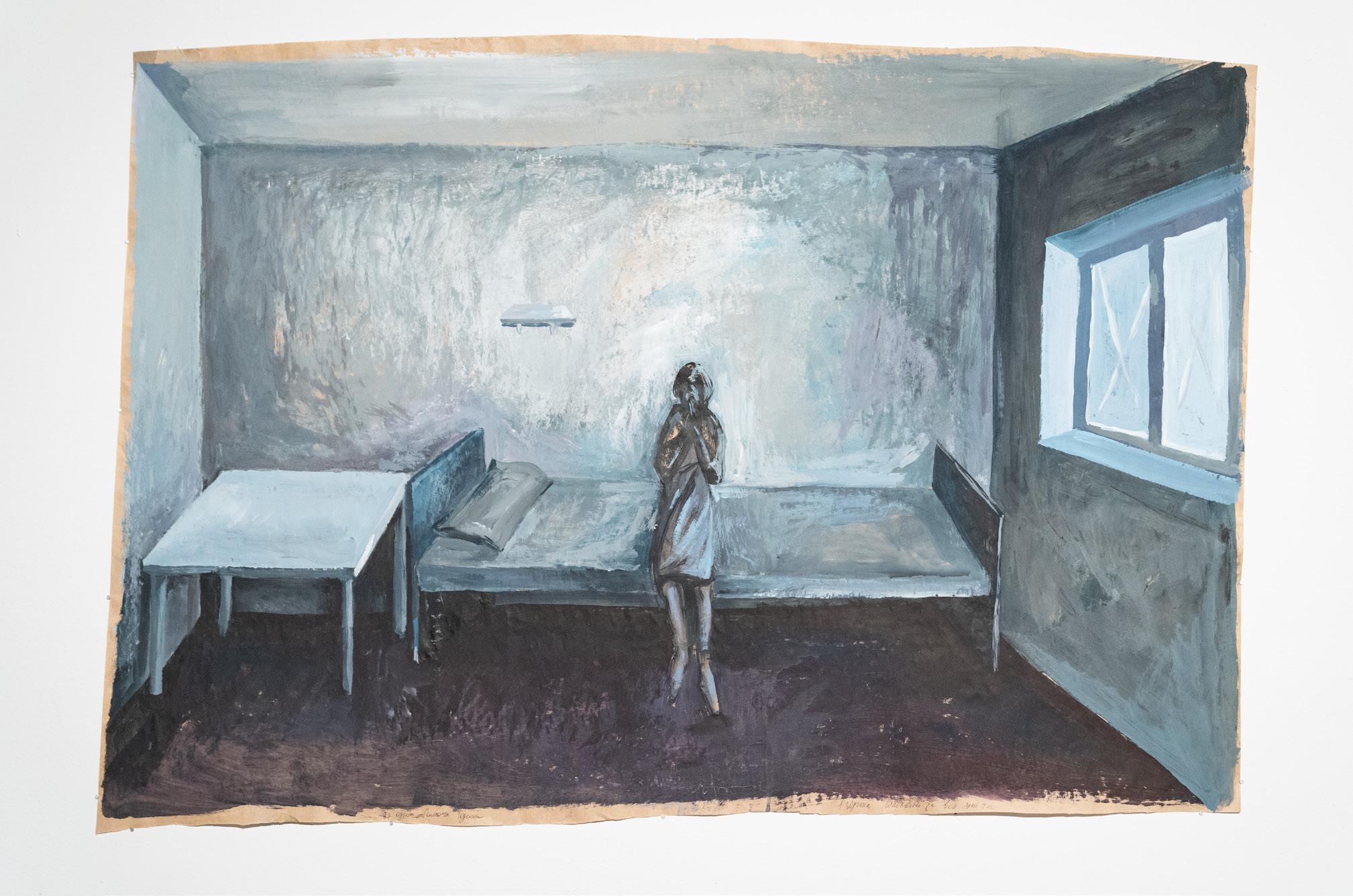

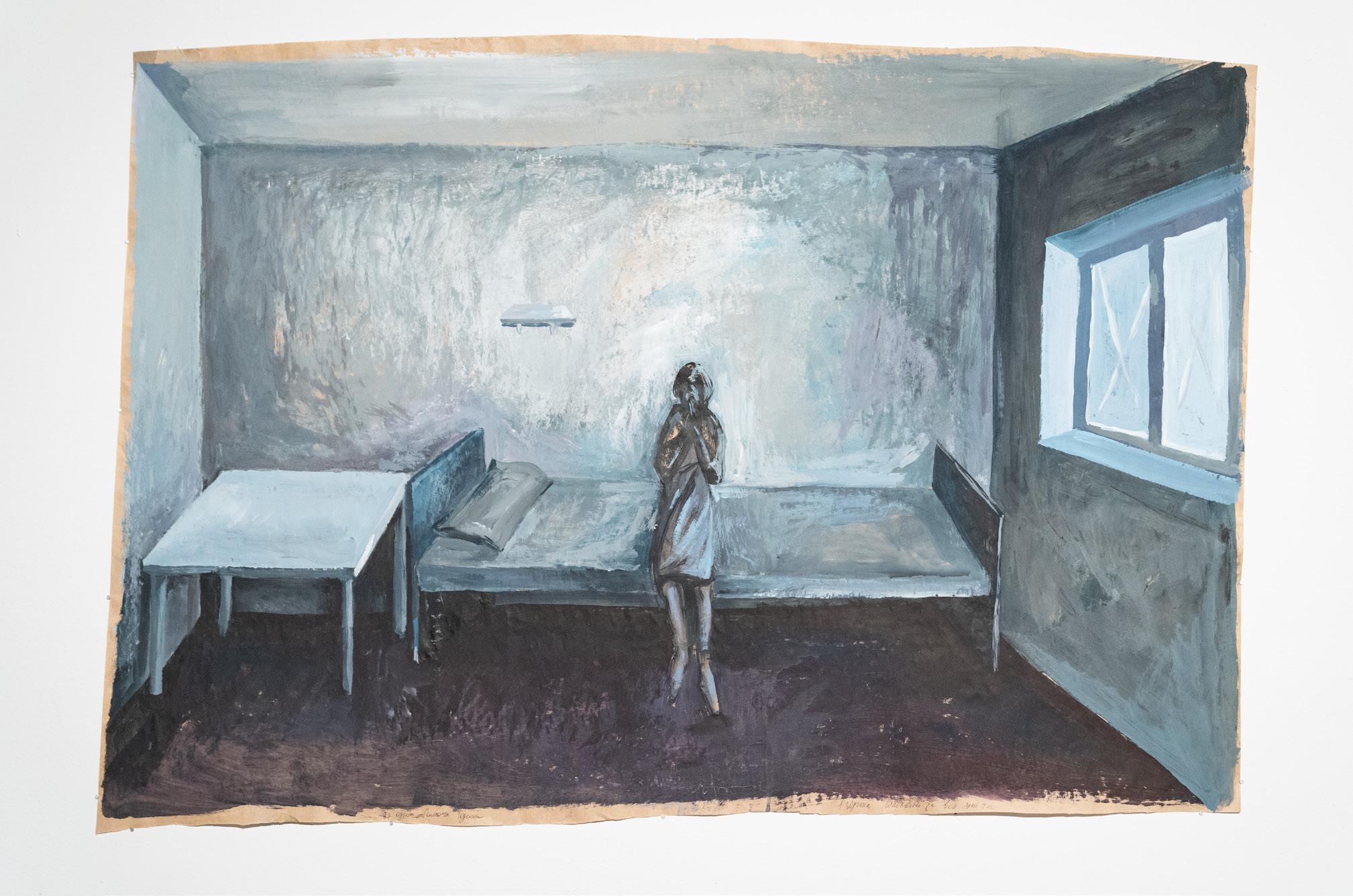

Тут я б хотіла згадати прекрасну роботу Катерини Єрмолаєвої «Блокада спогадів» (2015), де вона реконструювала свою кімнату, вручну відмалювавши кожну річ, яка залишилася

в її донецькому домі. Наступні, кого варто згадати, — Лія Достлєва і Андрій Достлєв. Вони рефлексують про війну в багатьох роботах, одна

з них — проєкт «Зализуючи рани війни» (20162021), протягом якого митці облизували соляну лампу у формі танка, придбану в Бахмуті. Вони сподівались, що коли зникне лампа, закінчиться й війна. Натомість із нами сталося 24 лютого, а Соледар і Бахмут зазнали страшних руйнувань… Так само проєкт Алевтини Кахідзе про її маму Клубніку Андріївну… Це все дуже особисті історії, які тепер стають частиною спільного досвіду. Я маю на увазі ситуацію, коли твої родичі, твоя мама й бабуся залишились на окупованій території. Мені здавалося, що ці проєкти великою мірою мали на меті пояснити людський досвід, а ще показати, що Донбас лишається українським. І оце розповідання про

17

у

свою ідентичність, про себе як частину України було дуже важливим. Наступний вартий згадки проєкт — «Пліт Крим» (2016) Марії Куліковської.

Вона без їжі та речей спускалася на плоті по Дніпру й виживала завдяки допомозі небайдужих людей, які траплялися на шляху. Мені здається, ми в якийсь момент усі були на цьому плоті й виживали, бо допомагали одне одному. Після 24 лютого ми відчули цей досвід на власній шкірі.

А.Ц.: Можливо, ти відслідковувала за публічними дискусіями, реакціями глядачів чи професійної спільноти, як змінилося сприйняття цих проєктів

з 2014 року до сьогодні та яким воно стало

після 24 лютого?

Н.Ч.: Я пам’ятаю, мені казали, що це пророчі роботи, хоча вони нічого не пророчили, вони просто фіксували дійсність, якою вона була.

А.Ц.: Я спитала про це, бо згадала, що вперше дізналася про цю роботу Маші з якоїсь розмови за келихом на черговому відкритті. Уся тамтешня дискусія будувалася на тому, що цей проєкт

вторинний за своєю художньою формою і через це не аж такий важливий. У сенсі — хто тільки на плотах не сплавлявся, від японських авангардистів до Open Group. Зараз така розмова неможлива, але вона була можливою тоді, й, мені здається, про це варто пам’ятати. Якщо ми зараз почнемо свідомо копатися в тому, що говорили митці з Донбасу і Криму у 2014—16-му, ми зможемо, по-перше, зробити ревізію власних відчуттів і критичніше поставитися до себе, а по-друге, переоцінити значення цих проєктів у контексті українського мистецтва. Бо те, що тоді здавалося абстракцією, тепер стало нашим особистим досвідом.

Н.Ч.: Це правда, для мене багато робіт зараз іще актуальніші. А ще мені здається, що з 2014 року ще були можливі аналітичні роботи, емоційно дистанційовані, такі, що мають

18

простір абстрагуватися в образ. Хочеться

згадати «Труднощі профанації» (2015) Нікіти Кадана на Венеційській бієнале. Він створив

парник, де речі з зони бойових дій, наповнені

сенсами та емоціями, проростали рослинами. І

це важливий образ, що дає зрозуміти: рано чи

пізно все зникне, і щоб цього не сталося, нам треба пам’ятати, пригадувати, працювати.

Тимчасова окупація Донецька і Луганська

зробили цей регіон центром уваги багатьох

художників і художниць, які, по суті, вперше

відкривали його для себе. Вони намагалися

поставити питання «що таке Донбас?», дізнатися

про нього більше, зрозуміти, що там сталося.

Я не можу собі зараз уявити таку історію, наприклад, у Херсонській області. Не тільки

через бойові дії. Мені здається, наша травма

ще настільки жива, що ми не маємо сил від неї абстрагуватися. У нас просто ще немає

дистанції для критичного погляду, для створення аналітичних робіт. Напевно, вони з’являться з часом, але зараз ми ще не готові.

А.Ц.: А може, ми просто помінялися місцями? Коли ти говорила, мені подумалося, що ми зараз дуже схожі на тих хлопців і дівчат із Криму й Донбасу, які 2014-го намагалися щось пояснити решті українців. Але оскільки їхній біль був дуже безпосередній, а наш погляд — надзвичайно дистанційований, ми не могли почути одне одного. А після 24 лютого вся Україна стала Донбасом, і тепер у нас є цілий світ, є якась умовна Європа, якій ми намагаємося пояснити те, що переживаємо. Але дистанції знову різні. Як у 2014-му ми почали цікавитися Донецьком та Луганськом, досліджувати, намагатися зрозуміти, що це таке, так само 24 лютого європейці раптово відкрили для себе, що Україна існує, спробували дізнаватися про неї більше, щось читати, якось із нею взаємодіяти, виставляти українських художників та художниць. Але парадокс повторюється. Як ми тоді не могли

19

прочитати і зрозуміти, про що насправді були роботи художників із Донбасу та Криму, так зараз європейці не можуть зрозуміти, про що

говоримо ми.

Н.Ч.: 100%, так і є. Щобільше, мені здається, що безпосередній досвід переживання війни дає тобі

якийсь неймовірний регістр чуттєвості. У Каті Лисовенко є цитата, яку я часто повторюю: «Я кладовище, що рухається». Всі репресії, про які ти читала, Голодомор, війни у твоїй країні, війни цілого світу, Перша, Друга світова, Боснія, — всі вони стають не абстрактними, а дуже конкретними. Навіть якщо вони ставались на іншому боці земної

кулі. Бо всі їх тепер можна зіставити зі своїм безпосереднім досвідом.

А.Ц.: Але це також питання самої можливості переповідання досвідів. Ти згадала про Боснію, а я згадала, якими неймовірними були боснійці.

Як багато зробили, через що пройшли, і як захоплювався ними світ. Утім, їхній досвід нікого не врятував і нічого не навчив. Чи ти не боїшся, що «Україна в огні» й узагалі

все, що ми зараз пишемо, робимо, збираємо, переповідаємо та виставляємо, за 10-15-20 років стане просто черговою поличкою в якомусь онлайн- чи офлайн-архіві, буде там укриватися пилом до наступної великої війни в Європі? Н.Ч.: Я б сказала, що ми все одно більшою мірою робимо це для себе, ніж для закордонних колег. Нам важливо пам’ятати, осмислювати, щоб змінюватися. Сьогодні ми вже однією

ногою в майбутньому, тому важливо, що ми в це майбутнє заберемо. Треба зберігати пам’ять про ці події, щоб вона жила і спонукала українське суспільство до позитивних змін. І вже з цієї точки проробленої внутрішньої роботи ми, агенти змін, можемо йти назовні і там щось робити. Плюс, у нас досі немає музею сучасного мистецтва, який би цей архів війни збирав, але є багато ініціатив, які це

20

роблять самотужки. І дуже хочеться вірити, що коли музей з’явиться, такі проєкти стануть підґрунтям, із якого він зможе зібрати цілісну історію.

А.Ц.: Що ти сама хотіла б розказати про «Україну в огні»?

Н.Ч.: Я б хотіла розказати про виставки. За два тижні до повномасштабного вторгнення ми відкрили в Малій Галереї виставку Тараса Бичка «Близько». Це був проєкт про переживання хвороби, про стани, з якими стикається

людина, коли дізнається про онкологічний

діагноз. Це була дуже особиста виставка, і замість кураторського тексту я просто питала Тараса про те, через що він проходив під час лікування, — що давало йому сили, в який момент у нього з’явилась надія, що допомогло

це пережити, що він відчував. 24 лютого ми прибрали роботи в сховище. В галереї залишилась тільки велика фотографія обгорілого дерева і тексти з його відповідями. У травні 22-го здавалося, що виставки не на часі, але все ж ми вирішили відкривати Малу Галерею. Першу виставку запропонували Інзі Леві й Тамарі Турлюн. Вони прийшли дивитися простір — і

ми відкрили галерею вперше після 24 лютого.

Все було так само – порожні стіни, Тарасові тексти і його фотографія, — але сприймалося це зовсім по-іншому.

Інга і Тамара сказали, що дуже відчули все написане в тих текстах, бо вони буквально про збирання себе наново, про пошук надії, — і ми вирішили їх залишити. Так з’явилась ідея діалогів, у яких, окрім розмови між двома людьми, відбувається розмова з простором

і попередньою художньою роботою. Щось із попередньої виставки залишається в новому

проєкті й переходить у довший діалог.

Глибше цю ідею мені допоміг усвідомити проєкт

Ярослава Футимського та Антона Саєнка. Ярослав

21

колись у розмові сказав фразу, що мистецтво – це мова, і, переживаючи досвід спільних катастроф, ми всі говоримо про одне. В роботах інших художників і художниць він пізнає себе. Вони допомагають краще зрозуміти, про що його робота, що він зараз відчуває, переживає. І це залишання однієї роботи — воно про спільний досвід. Про те, що ми беремо одне від одного, як протягуємо ідеї й предмети крізь простір і час, як розділяємо відчуття між собою. А ще про швидкі зміни, про втрачання.

До Ярослава та Антона в нас була виставка Вікторії Розенцвейг та Асі Гармаш, де Віка показувала свою серію «Нова Каховка окупована» (2022). Це її рідне місто. І от зараз її хроніка закінчилася на тому, що Нова Каховка спустошена.

А.Ц.: Наступне моє питання прозвучить особливо

жорстоко. Воно не стосується конкретної роботи чи трагедії, але я часто ставлю його самій собі. Чим іще можуть бути роботи про війну, крім як документуванням часу?

Чи не інструменталізуємо ми мистецтво, щоб розказувати історії?

Н.Ч.: Я б сказала, що для багатьох художників і художниць, особливо тих, хто працює з образом, після 24-го лютого постала дуже сильна проблема: візуальність реальності

стала настільки потужною, що художня мова виявилася німою. Її треба було винаходити наново. Все почало працювати по-іншому.

Наприклад, з’явилося багато живопису, але причини цього «живописного повороту» зовсім не ті, що були, скажімо, в 90-х. Зараз живопис –це про повернення собі того, що ти вмієш, якісь дуже базові, мануальні, майже медитативні речі. Ця тотальність реальності залишилася з нами, але вона почала проростати образами, як у роботах Каріни Синиці проростають руїни, і

22

з’явилась можливість, що на їхнє місце прийде

щось інше, прийде відбудова. Так само в роботах Олени Курзель є надія, що в ці порожні

будинки повернуться люди. А з приводу твого

питання… Так, це, безперечно, документ часу, але мені тут важливо думати не тільки про те, що зображено, але й про матеріальність, про те, з чого створено ці роботи, з яких практик

вони постали, бо це теж говорить про час, про те, що нового ми дізналися про себе, як змінилися ми й наші цінності.

Самоорганізація, солідарність, емпатія, ще якісь штуки. Мені здається, що мистецтво

на війні говорить і про ці речі, щоб ми не просто про них пам’ятали, а зробили їх сталими практиками свого життя.

23

A CONVERSATION ABOUT PRESENCE

NATASHA CHYCHASOVA AND ASIA TSISAR

Recorded in June 2023

Asia Tsisar: I’d like to start with autoethnography, or emphasising the subjective position and talking about the origins of this subjectivity. So, tell me — what does the «Ukraine Ablaze» project mean to you?

Natasha Chychasova: «Ukraine Ablaze» appeared at the beginning of the full-scale invasion as a kind of autotherapy, obsessive collecting. When everything falls apart, and you don't know where you will be tomorrow, you don't know whether you will be here tomorrow and what will be left of you, there is a need to collect everything. The project then became a certain return to art, to what my colleagues did before the full-scale invasion. It was a way of sticking with what you were competent in when your skills and abilities appeared to be a privilege and something useless.

A.Ts.: Tell us a little more about this kind of mechanism—when everything is falling apart, and there is no certainty that even your country will exist tomorrow, why do you choose to remember, retain, and archive?

24

N.Ch.: Initially, it was more about discussing and popularising. At the beginning of the invasion, foreign colleagues approached us with a request to support Ukrainian artists, but they needed to learn their names. And it was a pretty illustrative story regarding the visibility of Ukrainian art, in my opinion. We wanted not only to collect works that discussed the conflict, but also to provide an overview of the various practises of artists as well as a means of contacting them. We were creating a database.

The art of that time was very direct. It quite accurately recorded the course of the war, and actually, that’s how we came up with the idea to collect it. At first, it was a private initiative that I took up with my colleagues and co-workers. Everything was built around friendships—I announced an open call on social media, we received a crazy number of works, and a friendly platform provided us with a resource to publish them. Subsequently, the project became part of Mystetskyi Arsenal and formed the basis for the work of the Laboratory of Contemporary Art «Mala Gallery

25

of the Mystetskyi Arsenal». We launched our website in May. All this is to say, the project appeared to respond to a particular need and was transformed along with it.

While working on the website, we began to pay great attention to the content of the artworks, analysed them, and thought about what we wanted to include in this sort of archive, and what projects should be there. It became vital to us to include works created since 2014 rather than just 2022.

A.Ts.: But you state that calling «Ukraine Ablaze» an archive is uncomfortable for you. Why?

N.Ch.: I still find it difficult to call «Ukraine Ablaze» an archive, so I call it rather a curatorial selection. I understand this is a very personal selection of a very limited group. Our criteria are subjective, just like art itself. When selecting works, we considered the project’s content and the meanings we placed there. We mostly work with artists whose practises we are familiar with, and thus we understand to what extent, in our subjective opinion, this or that work is organic and meaningful for a particular person and in the framework of Ukrainian art history. We constantly try to recall and analyse, for example, what state we were in when we chose these works and why we did it, and reflect on the processes that happened to us and around us. This is a study within the community—how we have changed, how art has changed, what themes artists use, and what they have changed in their practices. We are interested in archiving these processes.

This is how the idea of dialogues came about: we proposed that the artists pick a partner for a conversation and discuss what worries

26

them about each other’s practices. In my opinion, the archive is a base that we try to examine and question, to ask how and why certain items ended up there and what is lacking. And the question of what it lacks can typically lead to even more interesting thoughts and research.

A.Ts.: So you’re archiving the change of topics, thoughts, artistic practices, and in the people themselves since the beginning of the war, and for as long as it lasts, aren’t you?

N.Ch.: Yes. This archive and its works must become specific points in this period.

A.Ts.: Then tell me how perception changed between 2014 and 2022. How does war appear in works since 2014, and what changed after February 24th?

N.Ch.: Well, for example, the image of the military in 2014 was not as popular a motif as it is now. In my opinion, this is due to Ukraine’s current wealth of military experience. Now we see the military in the media, and among our friends and acquaintances. In 2014, fewer people were involved in the war, so this image did not become a pattern. On the other hand, it seems that artists have been discussing war or lost homes in their works since 2014, particularly those who are originally from Donbas and Crimea. Here I’d like to mention Kateryna Yermolayeva’s «Blockade of Memories» (2015), in which she recreated her room manually, painting everything that remained in her house in Donetsk.

The next ones worth mentioning are Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev. They reflect on the war in many works, one of which is the project «Licking War Wounds» (2016-2021), where these artists licked a tank-shaped salt lamp,

27

which was bought in Bakhmut. After the end of a project, the artists hoped that the war would also come to an end soon. Instead, February 24th came, and the towns of Soledar and Bakhmut are horribly ruined... Also, Alevtyna Kakhidze’s story about her mother, Strawberry Andriivna... These are personal stories that are now becoming part of a shared experience. I mean, the situation when your relatives, your mother and grandmother, remained in the occupied territory. It seemed that these projects were intended mainly to explain the human experience and show that the Donbas region remains Ukrainian. And such stories about one’s identity, about oneself as a part of Ukraine, were significant. The next project worth mentioning is «Raft CrimeA» (2016) by Maria Kulikovska. She went down the Dnipro River on a raft without food or belongings and survived thanks to the help of caring people along the way. It feels as if we were all on this raft at some point, and survived because we helped each other. We experienced this on our own after February 24th.

A.Ts.: Have you been following the public discussions, the reactions of the audience or the professional community, and how the perception of these initiatives has changed since 2014 and after February 24th?

N.Ch.: I remember being told that these were prophetic works; although they did not prophesy anything, they simply recorded reality as it was.

A.Ts.: I asked about this since I remembered hearing about Maria’s art during a talk over a drink at another occasion. The entire conversation centred around the idea that this project is secondary in its artistic form and, thus, less important. Everyone has been rafting, starting with Japanese avant-garde artists

28

and all the way up to the Open Group. Now such a conversation is impossible, but it was possible then, and I think it is worth remembering. Suppose we begin consciously delving into what artists from Donbas and Crimea said in 2014–2016. In that case, we will be able to, first, review our feelings and adopt a more critical approach towards ourselves, and, second, reevaluate these initiatives in the context of Ukrainian art. Because what appeared to be abstraction at the time is now our personal experience.

N.Ch.: True, many works have become even more important to me. Besides, it appears that in 2014 and later, analytical, unemotional works were possible, and there was space to abstract something into an image. I want to mention Nikita Kadan’s «Difficulties of Profanation» (2015) at the Venice Biennale. He built a greenhouse where things from the war zone, full of value and emotion, sprouted with plants. And here is an important image that illustrates the point: eventually, everything will disappear, and to avoid this, we must remember, recall, and work.

The temporary occupation of Donetsk and Luhansk made this region the centre of attention of many artists who, actually, discovered it for themselves for the first time. They tried to ask, «What is Donbas?» to learn more about it and to understand what happened there. I can’t imagine such a situation now, for example, in the Kherson region. It’s not just because of the hostilities. I feel like our trauma is still so fresh in our minds that we lack the strength to go on. We do not yet have the distance for a critical view to create analytical works. They will probably appear over time, but now we are not yet ready.

29

A.Ts.: Or did we just exchange places? When you spoke, I thought about how we are now very similar to those boys and girls from Crimea and Donbas who tried to explain something to the rest of the Ukrainians in 2014. But we couldn’t hear each other because their pain was so intense, and our perception was so distant. And after February 24th, the whole of Ukraine came into Donbas. And now there’s the whole world, or let’s say, Europe, to which we are trying to explain what we are going through. The distances are different again. Just as in 2014, we began to take an interest in Donetsk and Luhansk, to research, and to attempt to understand what they are, so on February 24th, Europeans suddenly discovered that Ukraine exists, tried to learn more about it, to read something, to somehow interact with it, to exhibit Ukrainian artists. But the paradox keeps happening. Just as we could not read and understand what the works of artists from Donbas and Crimea were actually about, Europeans now cannot understand what we are talking about.

N.Ch.: That’s it, 100%. At most, the direct experience of war seems to give you some incredible register of sensibility. Katya Lysovenko has a quote I often repeat, «I am a moving cemetery». All the repressions you read about, the Holodomor, the wars in your country, the wars of the whole world, the First World War, the Second World War, Bosnia, all of them become not abstract but very concrete. Even if they were on the other side of the world. Because all of them you can now compare with your own experience.

A.Ts.: But there’s also a matter of the very possibility of retelling experiences. You mentioned Bosnia, and I recall how incredible the Bosnians were. How much they did, what they went through, and how much the world admired

30

them. However, their experience did not save anyone and did not teach the world anything. Aren’t you afraid that «Ukraine Ablaze» and, in general, everything we are now recording, doing, collecting, retelling and exhibiting will become just another shelf in some online or offline archive in 10,15,20 years, and will be covered with dust until the next great war in Europe?

N.Ch.: I’d say that we still do it more for ourselves than for foreign colleagues. We need to remember, to comprehend, to change. Today, we already have one foot in the future, so what we’ll bring there is important. It is necessary to preserve the memory of these events so that it lives on and encourages Ukrainian society towards positive changes. And right from this point of the internal work done, we, the agents of change, can go outside and do something there. Additionally, we still need the establishment of a museum of contemporary art in Ukraine, one that would be able to include this archive of war in its collection, but many initiatives do it on their own. I really want to believe that when the museum appears, such projects will become the basis from which it will be able to collect a holistic history.

A.Ts.: What would you like to tell us about «Ukraine Ablaze»?

N.Ch.: I’d like to tell you about our exhibitions. Two weeks before the full-scale invasion, we opened Taras Bychko’s exhibition «Close» in the Mala Gallery. It was a project about the experience of disease, about the conditions a person faces when they learn about an oncological diagnosis. It was a very personal exhibition, and instead of a curatorial text, I just asked Taras about what he went through during treatment— what gave him strength, at what moment he had hope, what helped him survive, and what he felt. On February 24th, we moved his works to stor-

31

age. Only a large photo of a burnt tree and texts with his answers remained in the gallery. In May 2022, it still didn’t seem like the right time for exhibitions, but we decided to open the Mala Gallery anyway. The first exhibition was offered to Inga Levi and Tamara Turliun. We opened the gallery for the first time since February 24th when they came to look at the space. Everything was the same–empty walls, Taras’s texts and his photo—but we perceived it in an entirely different way. Inga and Tamara said that they really felt everything written in those texts because they were literally about reassembling the selves, about finding hope— and we decided to leave them. This is how the idea of dialogues appeared—dialogues in which, in addition to a conversation between two people, there is a conversation with the space and the previous artistic work. Something from the previous exhibition remains in the new project and goes into a more extended dialogue. The project of Yaroslav Futymskyi and Anton Saienko helped me to understand this idea more deeply.

Within all of our conversations, Yaroslav said that art is a language, and when we experience common disasters, we all speak about the same thing. He recognises himself in the works of other artists. They help him to better understand his work and what he now feels and is experiencing. And keeping some previous works in the gallery space is about a shared experience. It’s about what we take from each other, how we drag ideas and objects through space and time, and how we share feelings with each other. And also about rapid changes and loss. Before Yaroslav and Anton’s exhibition, we had an exhibition by Viktoriia Rosentsveih and Asya Harmash, where the former showed her series «Nova Kakhovka occupied» (2022). Nova Kakhovka is her hometown. And now her chronicle end with the fact that Nova Kakhovka is devastated.

32

A.Ts.: My next question will sound particularly harsh. It doesn’t refer to a specific work or tragedy, but I often ask it of myself. What else can works about war be, other than documenting the moment? Aren’t we instrumentalising art to tell stories?

N.Ch.: I’d say that for many artists, especially those who work with images, a solid problem arose after February 24th: the visuality of reality became so powerful that the artistic language turned out to be silent. It had to be reinvented. It all started working differently. For example, there was an important rise in painting, but the reasons for this «painting turn» differ greatly from the 1990s. Reclaiming your knowledge of some very fundamental, manual, almost contemplative things is what painting is all about today. This totality of reality remained with us, but it began to sprout with images, just as the ruins began to grow in the works of Karina Synytsia. There was a possibility that something else would take their place, and reconstruction would come. Likewise, in the works of Olena Kurzel, there is hope that people will return to these empty houses.

And regarding your question... This is undoubtedly a document of the moment, but it is important for me to consider here not only what is depicted, but also the materiality, what these works are made of, and from what practices they emerged, because this also speaks of this time, of what new things we learned about ourselves, how we and our values have changed. As well as self-organisation, solidarity, empathy, and some other stuff. It seems that art in war also speaks about these things, so that we don’t just remember them, but make them permanent practices in our lives.

33

ОДНЕ З

ОДНИМ.

ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

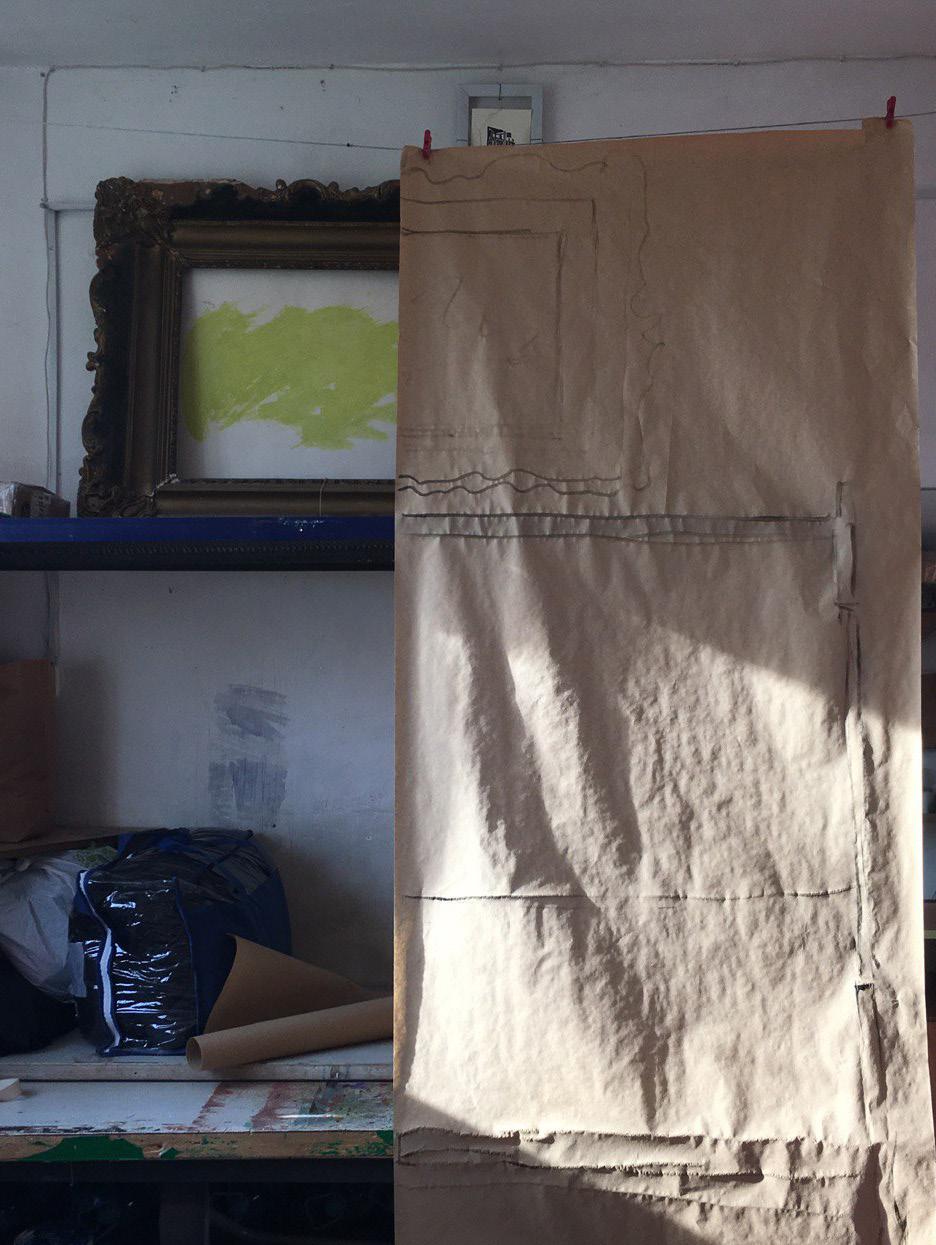

«Одне з одним. Просторові діалоги» — це процесуальний проєкт Лабораторії сучасного мистецтва «Мала Галерея Мистецького арсеналу», що став результатом і втіленням розмов і взаємодій в українській художній спільноті.

Від початку повномасштабного вторгнення Росії ми почали збирати українські мистецькі твори на воєнну й довколавоєнну тематику про війну, що виникли від 2014 року та пізніше. Будь-який архів — результат суб’єктивного впорядкування знань, але нам було важливо зробити свій архів інклюзивним і горизонтальним, давши змогу авторам і авторкам розповісти про власні творчі практики. Так виникла серія відеорозмов «Одне з одним. Розмови про художні практики».

34

Згодом ми запропонували митцям і мисткиням продовжити свої роздуми у фізичному просторі Малої Галереї

Мистецького

арсеналу.

приміщення лишалося незмінним від 24 лютого й на той момент зберігало артефакти останнього проєкту — фотовиставки Тараса Бичка «Близько». Попросивши відреагувати на твори й тексти, які залишились у просторі галереї, ми заохочували перших учасниць проєкту до переосмислення своїх мистецьких практик і впливу на них повномасштабної війни. Кожна наступна виставка проєкту розвиває попередні діалоги й ситуації, резонуючи з їхніми темами. Усі учасники й учасниці обирали для своєї експозиції певні об’єкти від попереднього проєкту, які таким чином послідовно складалися в поліфонію голосів та рефлексій.

За перебігом проєкту можна слідкувати за QRкодом.

35

Її

ONE WITH THE OTHER. Spatial Dialogues

ONE WITH THE OTHER. Spatial Dialogues is a procedural project of the Laboratory of Contemporary Art «Mala Gallery of the Mystetskyi Arsenal», which was the result and embodiment of conversations and interactions in the Ukrainian artistic community. Here is its short summary.

Since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, we have begun collecting Ukrainian artworks about the war, and about the military topics that arose in 2014 and earlier. Any archive implies the subjective principle of constructing knowledge, and it was important for us to make it inclusive and horizontal, giving authors the opportunity to talk about each other’s creative practices. This is how the series of video conversations «One with the other. Conversations about artistic practices» came to be.

36

Subsequently, we proposed that the artists continue their reflections in the physical space of the Mala Gallery of the Mystetskyi Arsenal. The space itself had remained unchanged since February 24th and preserved artefacts from the gallery’s last exhibition project—the exhibition «Close» by photographer Taras Bychko. By proposing that artists react to the works and texts that remained in the space, we encouraged the participants of the project to rethink their artistic practices and the impact that the full-scale war has had on them. Each subsequent exhibition of the project develops on already-created dialogues and situations, and resonates with previous themes. All participants chose certain objects from the previous project for their expositions, creating a polyphony of voices and reflections.

You can follow our project's updates via the QRcode.

37

діалог: Інга Леві і Тамара Турлюн

До повномасштабного вторгнення Росії художниці планували камерну експозицію про київський спальний район Голосіїв. Узимку мав розпочатися їхній проєкт «Районна хонтологія» — про міські краєвиди і приховані в них безмовні примари. Висловлювання в Малій Галереї сформувалося довкола ідеї цієї нереалізованої виставки, довкола уламків майбутнього, яке так і не настало. Авторки проєкту намагалися проговорити свої інтимні переживання, відновити зв’язок із минулим і подолати привидів, що зазіхають на нашу внутрішню безпеку.

38

Перший

ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

3‐24 листопада 2022 року

Інга Леві — художниця, що живе і працює в Києві. Працює з темами міського простору, архітектурою та монументальним мистецтвом, з урбаністичним пейзажем. У 2021 році завершила курс Contemporary Art у Kyiv Academy of Media Arts і стала стипендіаткою програми Gaude Polonia за напрямом «Візуальне мистецтво».

Учасниця

численних резиденційних програм та групових і персональних виставок.

Тамара Турлюн — художниця родом з Черкащини. Живе і працює в Києві. Співзасновниця самоорганізованого простору depot12_59. Співзасновниця та учасниця групової виставки kein Kaffee, keine Blumen, kein Fisch, kein Fleisch. Учасниця численних

резиденційних програм та багатьох інших групових

і персональних виставок.

39

First dialogue: Inga Levi and Tamara

Turliun

3‐24 November 2022

Before the full-scale invasion of Russia, the artists planned to hold a small exposition about Holosiiv, a residential area of Kyiv. In winter, their project «District Ghostology» was supposed to take place. It was meant to tell about urban landscapes and the silent ghosts hiding beneath them. The expression in the Mala Gallery took shape around the idea of this unmade exhibition, i.e. the fragments of that future that never came to be. The authors of the project tried to talk about their intimate experiences, restore feelings of the past and overcome the ghosts that encroach upon our internal security.

40

Spatial Dialogues

Inga Levy is an artist. She lives and works in Kyiv. She works with the topics of urban space, architecture, monumental art, and urban landscape. In 2021, she finished the Contemporary Art course at the Kyiv Academy of Media Arts and became a fellow of the Gaude Polonia programme in the field of Visual Arts. She has been a participant in numerous residency programmes and both group and personal exhibitions.

Tamara Turliun is an artist from Cherkasy region. She lives and works in Kyiv. She is co-founder of the self-organized space Depot12_59 and also a co-founder and participant of the group exhibition «kein Kaffee, keine Blumen, kein Fisch, kein Fleisch». She participates in numerous residency programmes and many other group and personal exhibitions.

41

Другий діалог: Dreamscape

2‐29 грудня 2022 року

Учасники проєкту: Єлена Орап, Даша Подольцева і Олексій Шмурак

Dreamscape — метафоричне відтворення спальника чи ковдри як безпечного простору (safe space). Важливою частиною проєкту стала музикальна композиція, створена Олексієм Шмураком на основі зібраних через open call музики та звуків, які в останні дев’ять місяців допомагали людям у бомбосховищах, під час обстрілів, на чужині. Композитор перетворив ці музичні історії на цілісний звуковий ландшафт за логікою сновидіння — з неочікуваними переходами, беззмістовними повторами, дивними лакунами. Назва проєкту означає «ландшафт снів/мрій», а ще відсилає до слова escape (втеча).

Проєкт підтримано в результаті відбору на відкритому конкурсі (re)connection UA, пілотного проєкту, створеного ГО «Музей сучасного мистецтва» у партнерстві з UNESCO, та фінансується через Надзвичайний фонд спадщини UNESCO.

Даша Подольцева — графічна дизайнерка і художниця. Працює з темами публічного простору, предметним світом і «тимчасовими незручностями». Випускниця школи урбаністики Canactions Studio 1. Співзасновниця проєкту «Серія », присвяченого українським панелькам.

Єлена Орап — архітекторка, дослідниця та художниця. Народилася у Києві. Працює з такими темами: масове житло, самоідентифікація, кордони та тимчасова архітектура. Співзасновниця проєкту «Серія » , присвяченого українським панелькам.

Олексій Шмурак — композитор і саунд-артист. Народився у Києві. Працював як композитор та виконавець у класичній, сучасній класичній, експериментальній музиці та мультимедійних перформансах. Основні теми творчості: жанрові кордони, ностальгія, деконструкція й лакуни уваги. У своїх виступах часто використовує голос, духові, ударні, електроніку та простір.

45

ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

Second dialogue: Dreamscape

2‐29 December 2022

Project participants: Elena Orap, Dasha Podoltseva and Alexey Shmurak

Dreamscape is a metaphorical recreation of a sleeping bag or blanket as a safe space. An important part of the project was a musical composition created by Alexey Shmurak based on the music and sounds, collected through an open call, that, in the preceding nine months, had helped people in bomb shelters, during shelling, and in foreign lands. After receiving the materials and stories, he processed and mixed them in such a way as to create the feeling of an unconscious, dreamlike experience with unexpected changes and meaningless repetitions. The name of the project means a landscape of dreams or daydreams, but also refers to the word «escape».

The project was supported as part of the open competition (re)connection UA, a pilot project created by the NGO «Museum of Contemporary Art» in partnership with UNESCO and financed by the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund.

46

Spatial Dialogues

Dasha Podoltseva is a Ukrainian graphic designer and visual artist. She works with such subjects as public space, the material world, and «temporary inconvenience». She is a graduate of the Canactions Studio 1 school of urban planning and a co-founder the «Series » project, dedicated to Ukrainian panel buildings.

Elena Orap is a Ukrainian architect, researcher, and artist. She is a co-founder of the «Series » project, dedicated to Ukrainian panel buildings, and works with the following topics: mass housing, self-identification, borders and temporary architecture.

Alexey Shmurak is a Ukrainian composer and sound artist. Born in Kyiv. He has worked as a performer and composer in classical and contemporary classical music, experimental music, and multimedia performances, and now works with themes such as genre boundaries, nostalgia, deconstruction, and attention gaps.

47

Третій діалог: Каріна Синиця

і

Настасія Лелюк

26 січня‐26 лютого 2023 року

Ця виставка є спробою проявити ті непрості для художниць теми, про які вони говорили в межах відеорозмови

із серії «Одне з одним» у Малій Галереї: усвідомлення масштабів війни, проживання болю і його надмір, втрата дому, зникнення

звичного світу. У межах виставки художниці розмірковують над тим, як трансформувалися відчуття приватного і публічного простору, якими образами та патернами вони насичені та в який спосіб ми створюємо безпечний простір для себе.

Настасія Лелюк — художниця родом із Луганська. У своїй практиці Настасія намагається грати з об’єктивною правдою та глобальними культурними наративами через повсякденні, впізнавані елементи. Вона часто створює ситуацію, в якій глядач стикається з межами власного сприйняття і змушений переглянути свою позицію.

Каріна Синиця — художниця родом із Сєверодонецька. Її практика базується на відображенні людських почуттів. У своїх роботах Каріна їх відтворює і вмонтовує в образи ландшафтів, сконструйовані з фрагментів власних спогадів.

50

51 ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

Third dialogue: Karina Synytsia and Nastasiia Leliuk

January 26‐February 26, 2023

This exhibition is an attempt to expand themes that are not easy for artists, which they talked about in a video conversation from the series «One With The Other» in the Mala Gallery: awareness of the scale of war, living in pain and its excess, loss of home, the disappearance of the usual world. Within the framework of the exhibition, the artists reflect on how feelings of private and public space are transformed, with what images and patterns they are saturated, and in what way we create a safe space for ourselves.

Nastasiia Leliuk is a Ukrainian artist from Luhansk. In her practice, she tries to play with objective truth and global cultural narratives through daily, recognisable elements. She often creates situations in which the viewer is confronted with the limits of their perception and has to reconsider their position.

Karina Synytsia is an artist from Sieverodonetsk. Her practice is based on reflecting human feelings. In her works, the artist reproduces these states, placing them in constructed images of landscapes consisting of fragments of her memories.

52

53 Spatial Dialogues

30

Проєкт Вікторії Розенцвейг та Асі Гармаш розмірковує над тим, чим є стан очікування в часи війни, про зміну сприйняття часу і те, як цей стан поєднує їхні творчі практики. Обидві художниці навчалися на кафедрі вільної графіки в Національній академії образотворчого мистецтва та архітектури, що багато в чому визначила їхню стилістику й використання технічних засобів. Однак, поза формальними дисциплінами на кшталт композиції, перспективи чи кольору, Вікторії та Асі завжди йшлося про роботу з міським середовищем і радянським спадком у ньому. Повномасштабне вторгнення Росії змінило їхнє бачення речей і розуміння своїх практик.

Ася Гармаш — художниця родом із Києва. У своїй практиці досліджує тему тілесності, взаємозв’язок між людьми через візуальне і вплив вигляду міських вулиць і будівель на суспільство. Працює у друкованій та цифровій графіці, однак її основний підхід до роботи — мішана техніка: поєднання акрилу, олійної пастелі та чорного олівця на папері.

Вікторія Розенцвейг — художниця родом із Нової Каховки. Працює з графікою і часом доповнює її новими медіа. Останнім часом активно експериментує

з формою художнього твору, поєднуючи візуальні експерименти з графічною традиційністю. Цікавиться урбаністикою та взаємодією людей із міськими просторами, а також присутністю радянської архітектури і сенсів минулого в сучасності. Брала участь у низці групових виставок і проєктів, зокрема у презентації Citizenship Ukraine на Documenta 15.

56

Четвертий діалог: Вікторія Розенцвейг і Ася Гармаш

березня‐30 квітня 2023 року

57 ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

Fourth dialogue: Viktoriia Rosentsveih and Asya Harmash

30 March‐30 April 2023

Within the framework of this exhibition, artists Viktoriia Rosentsveih and Asya Harmash reflect on what the state of waiting is during wartime, on the changing perception of time and how this state connects their creative practices. Both artists studied in the Free Graphics Department at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture (NAOMA) in Kyiv, which largely determines their style and technical means. Beyond formal disciplines such as composition, perspective, colour, etc., in their work, Viktoriia and Asya always focus on working with what is around them – the urban environment and the Soviet heritage in it. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine changed both artists’ ways of seeing things and their attitudes to their practices.

Asya Harmash is an artist from Kyiv. In her practice, she explores the subject of corporeality, the relationships between people through the visual, and the influence of the appearance of city streets and buildings on society. She works in print and digital graphics, but her main approach to work is mixed media: a combination of acrylic, oil pastel, and black pencil on paper.

Viktoriia Rosentsveih is an artist from Nova Kakhovka. She works with graphics and sometimes complements it with new media. Recently, she has been actively experimenting with the form of artwork, combining her searches with traditional graphics. She is interested in urbanism and the interaction between people and city spaces, as well as the presence of Soviet architecture and the meanings of the past in the present. She has participated in a number of group exhibitions and projects, in particular in the presentation of «Citizenship Ukraine» at Documenta 15.

58

59 Spatial Dialogues

витіснення

5‐28 травня 2023 року

Учасники та учасниці виставки: Катерина Алійник, Нікіта Кадан, Віталій Кохан, Кристина Мельник, Найджел Ралф, Антон Саєнко, Ярослав Футимський.

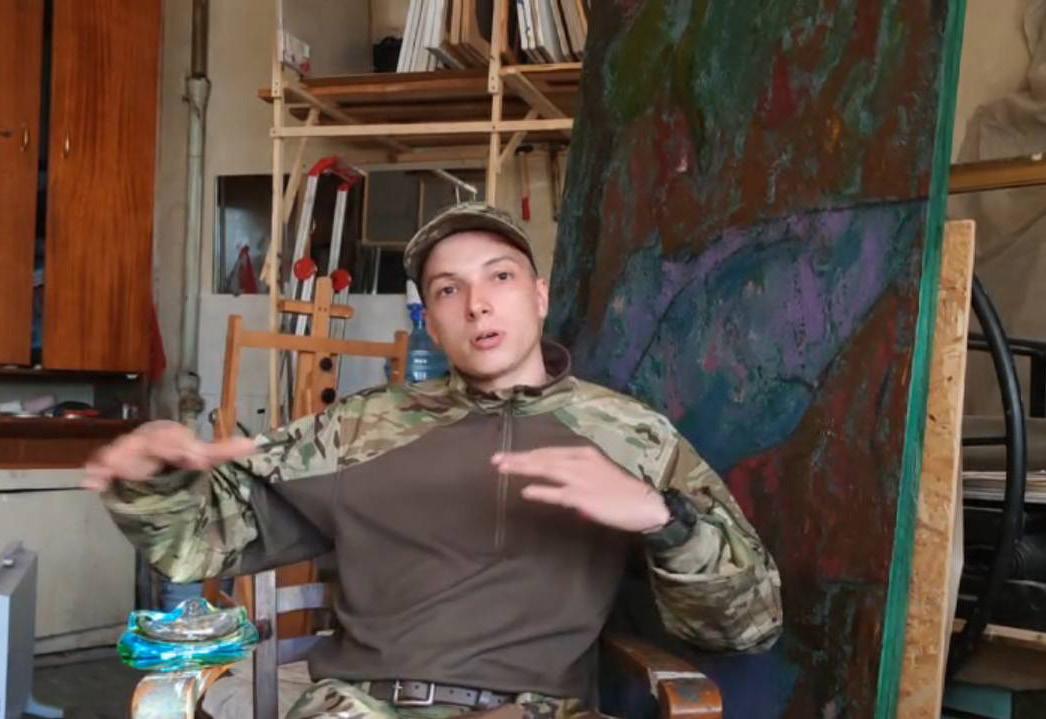

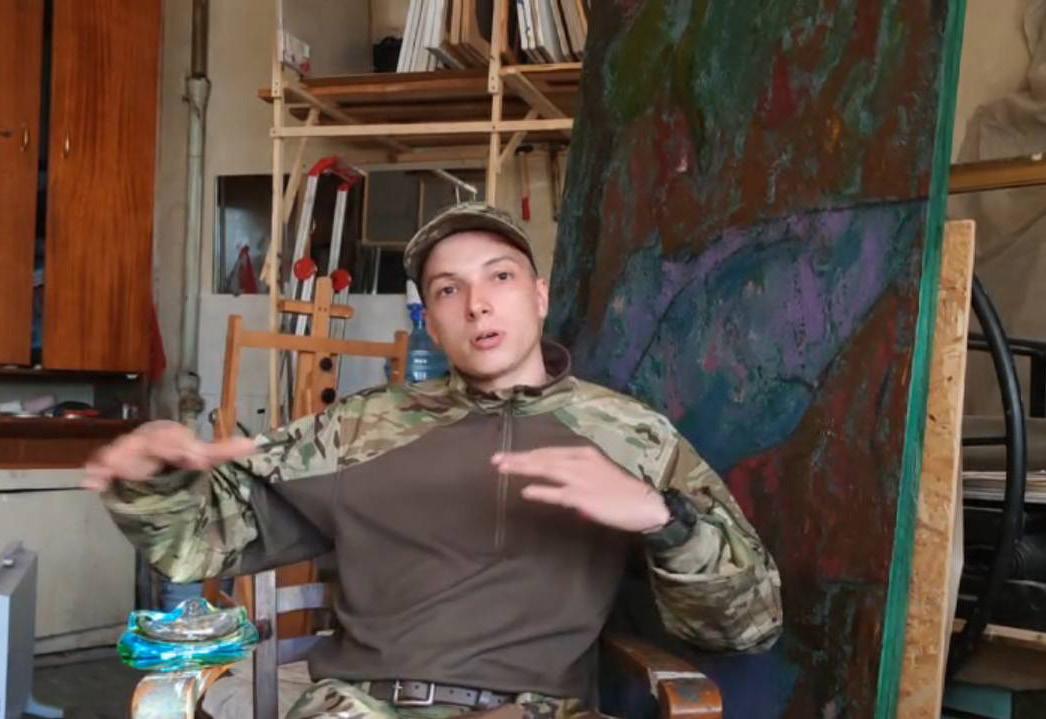

Для цієї виставки художники Ярослав Футимський і Антон Саєнко, яких запросили до діалогу, створюють простір для колективної розмови про землю, пейзаж, мову і проростання. Оскільки мистецтво є мовою, то зараз, проживаючи разом досвід війни і думаючи про роль мистецтва в часи катастрофи, ми всі так чи інакше говоримо про одне й те саме.

П’ятий діалог: географія

Катерина Алійник — художниця

родом з Луганська. Має ступінь

магістра живопису, здобутий

у Національній академії

образотворчого мистецтва

та архітектури. Навчалася

у KAMA (Kyiv Academy of Media Arts) і Метод Фонді.

Працює переважно з живописом

і текстом. Зараз досліджує

теми війни та окупації Донбасу через зображення природи та неантропоцентричну оптику. З 2016 року живе та працює у Києві.

Нікіта Кадан — художник родом із Києва. Був активним учасником групи Р.Е.П. (Революційний Експериментальний Простір) з 2004 року, співзасновником та учасником кураторської групи «Худрада» з 2008 року. Працює з інсталяцією, графікою, живописом, настінними малюнками. Часто долучається до міждисциплінарної співпраці з архітекторами, правозахисниками чи істориками.

Віталій Кохан — художник родом із Сум. Працює з живописом, скульптурою, графікою, інсталяціями, фотографіями, відео та лендартом. Учасник лендарт-симпозіуму «Могриця», міжнародного симпозіуму сучасного мистецтва BIRUCHIY, виставок у Муніципальній галереї (Харків, 2018) та Інституті проблем сучасного мистецтва (Київ, 2018), виставки номінантів Премії PinchukArtCentre (Київ, 2018), Другої Бієнале молодого мистецтва (Харків, 2019) та багатьох інших проєктів.

Кристина Мельник — українська

художниця родом з Мелітополя. У своїй образотворчій практиці працює з поняттями класичного

і сакрального, намагаючись

знайти підхід до проживання

сакрального досвіду. Серед її вибраних виставок — випускна виставка КАМА (Kyiv Academy of Media Arts) «Жити разом», (The Naked room, Київ, 2019), групова виставка «Перехресне море» (Voloshyn Gallery, Київ, 2019), персональна виставка у креативному просторі ОКНО (Київ, 2020).

Найджел Ралф — ірландський перформер, відеохудожник, куратор і дослідник.

Антон Саєнко — художник родом із Сум. Займається живописом, інсталяцією, фотографією, перформансом, лендартом. Саєнко шукає особливу візуальну мову, яка не була б залежною від словесної мови. Йому

цікаво працювати з тим, що не розповідає ніякої історії, нічого не означає, що неможливо описати словами. Постійний учасник лендартсимпозіуму «Могриця». Лауреат Спеціальної премії Shcherbenko Art Center (2015) і

спеціальної відзнаки від журі PinchukArtCentre Prize 2022. Живе і працює в Києві.

Ярослав Футимський — художник, перформер і будівельник

родом із селища Понінка

на Хмельниччині. Працює з поезією/текстами, аналоговою півкадровою фотографією, інсталяцією, мовленим перформансом. Пов’язаний

із панк/графіті/художніми/ активістськими спільнотами різних міст і країн.

63

Fifth dialogue: geography of displacement

5‐28 May 2023

Exhibition participants: Kateryna Aliinyk, Nikita Kadan, Vitalii Kokhan, Krystyna Melnyk, Nigel Rolfe, Anton Saienko, Yaroslav Futymskyi.

For this exhibition, artists Yaroslav Futymskyi and Anton Saienko, who were invited to the dialogue, create a space for a collective conversation about land, landscape, language, and germination. Since art is a language, living together through the war experience and thinking about the role of art in times of disaster, we are all talking about the same thing in one way or another.

Kateryna Aliinyk is an artist from Luhansk. Her primary mediums are painting and text. Now she investigates the topics of war and occupation of the Donbas region through images of nature and non-anthropocentric optics. Lives and works in Kyiv since 2016.

Nikita Kadan is an artist originally from Kyiv. He has been an active R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space) group member since 2004 and co-founder of the Hudrada curatorial group, participating in its activities since 2008. Nikita works with installation, graphics, painting, and wall drawings. He is often engages in interdisciplinary collaborations with architects, human rights activists, or historians.

Vitaliy Kokhan is an artist from Sumy. He works with painting, sculpture, graphics, installations, photographs, video and land art. He is a participant of the International Land Art Symposium ‘Borderline Space. Mohrytsia’, BIRUCHIY International Contemporary Art Symposium, exhibitions at the Municipal Gallery (Kharkiv, 2018) and the Institute of Contemporary Art Problems (Kyiv, 2018), PinchukArtCentre Prize nominees’ exhibition (Kyiv, 2018), the Second Biennale of Young Art (Kharkiv, 2019) and many other projects.

Krystyna Melnyk is a Ukrainian artist originally from Melitopol. In her artistic practice, she works with the concepts of the classical and the sacred, trying to find an approach to living a sacred experience. Her selected exhibitions include the group exhibition of KAMA (Kyiv Academy of Media Arts) «Living together», The Naked Room, Kyiv (2019); the group exhibition «Crossroads Sea», Voloshyn Gallery, Kyiv (2019); and a personal exhibition in the creative space OKNO, Kyiv (2020).

Nigel Rolfe is an Irish performance and video artist, curator, and researcher.

Anton Saienko is an artist from Sumy. He works with painting, installation, photography, performance, and land art. Saienko is looking for a special visual language that is not dependent on verbal language. He is interested in working with something that doesn’t tell a story, doesn’t mean anything; something that can’t be described in words. He is a permanent participant in the Mohrytsia Land Art Symposium, a winner of the Shcherbenko Art Centre Special Prize (2015), and a special award from the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2022 jury. He lives and works in Kyiv.

Yaroslav Futymskyi is an artist, performer, and builder originally from the village of Poninka in Khmelnytskyi region. He works with poetry/texts, analogue halfframe photography, installation, and speech performance. He is also associated with punk/graffiti/art/activist communities from different cities and countries.

65

Шостий діалог: (про)мови

22‐25 червня 2023 року

(про)мови — спільний проєкт

української зін-спільноти та художниці Марії Матяшової, в якому проявляється

варіативність мови. У просторі

виставки мова як така постає водночас самоцінною, сповненою краси та дуже вразливою, такою, що постійно повертає

до питання: «Чому тепер

такі красиві слова мають таке жахливе значення?». З іншого боку, вона також є інструментом для вираження себе і своїх почуттів, важливим способом творення.

Українська зін-спільнота — проєкт, що створює, зберігає

та поширює зіни. Це спільнота, де можна дізнатись про нові та старі видання, познайомитись з їхніми авторами й авторками, показати свої роботи. З метою їх популяризації спільнота

проводить події і читання

зінів у різних містах. Також спільнота формує цифровий архів і фізичну бібліотеку з метою збереження та популяризації зінів.

Марія Матяшова — українська мисткиня. Працює на перетині різних медіа, серед яких відео, фотографія, текст, перформанс, інсталяція та публічні інтервенції.

Досліджує особисту пам’ять, стосунки між людьми та соціальні норми, мову, а також вплив цифрових технологій на людську поведінку й суспільні процеси. Наразі працює із темою вторгнення росії в Україну. Брала участь у групових виставках в Україні, Німеччині, Швейцарії та Польщі. Живе і працює у Києві.

69

ПРОСТОРОВІ ДІАЛОГИ

Sixth dialogue: (pro)movy

22‐25 June 2023

70

The (pro)movy exhibition is a project by the Ukrainian zine community and artist Maria Matiashova displaying the variability of language. In the exhibition space, language appears to be valuable, full of beauty, and extremely vulnerable at the same time. The reality constantly refers to the question: «Why do such beautiful words have such a terrible meaning now?» On the other hand, language is a crucial tool for expressing oneself and one’s feelings, and an important creative method.

The Ukrainian zine community is a project that creates, preserves, and distributes zines. It is a community where you can learn more about new and old zines, meet their authors, and show your work. To promote them, the community organises events and zine readings in various cities. The community is also shaping a digital archive and a physical library to preserve and popularise them.

Maria Matiashova is a Ukrainian artist. She works at the intersection of different media, including video, photography, text, performance, installation and public interventions. She explores personal memory, human relationships and social norms, language, and the impact of digital technologies on human behaviour and social processes, currently working on the subject of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. She has participated in group exhibitions in Ukraine, Germany, Switzerland, and Poland. She lives and works in Kyiv.

71

Spatial Dialogues

ПРАЦІВНИКИ МИСТЕЦТВА

НА ВІЙНІ: ЯК УКРАЇНСЬКІ АРТ СПІЛЬНОТИ

ОБ’ЄДНУЮТЬСЯ, ЩОБ ЗАХИСТИТИ КУЛЬТУРНУ СПАДЩИНУ

Уперше опубліковано на artreview.com 17 березня 2022 року. Повторно опубліковано з дозволу та зі скороченнями

Злочинне повномасштабне вторгнення Росії в Україну, яке триває вже четвертий тиждень, спричиняє безпрецедентні руйнування. Російські ракети не оминають ані житлових будинків, ані шкіл чи дитячих лікарень, ані пам’яток та музеїв. У цій загрозливій ситуації українські робітники мистецтва об’єднують свої зусилля, щоб захистити культурну спадщину країни. Вони вихоплюють твори мистецтва з полум’я, долають тисячі кілометрів із деталями інсталяцій у багажнику, та перевинаходять галерейні простори як укриття.

Рушієм цих дій є стосиле почуття обов’язку: врятувати не лише українські твори мистецтва, а й світову спадщину, що перебуває в країні. Так, наприклад, винятково різноманітна колекція Харківського художнього музею зазнає ризику зберігання через пошкодження будівлі музею російськими ракетами. Команда музею докладає значних зусиль задля захисту творів ранніх нідерландських, індійських, китайських, французьких, італійських та російських митців, щоденно забезпечуючи їм належні умови

74

ПОЛІНА БАЙЦИМ

посеред моторошних вулиць, вкритих небіжчиками, та масованих обстрілів. З цього приводу Кирило Ліпатов, завідувач наукового відділу Одеського національного художнього музею, влучно зазначив: важко осягнути той факт, що українські музеї зараз рятують російські шедеври від російської агресії. Спустошення культури супроводжує нищення життів. У Чернігові — місті на межі гуманітарної катастрофи без тепла, електрики та безпечних шляхів евакуації для його мешканців — російські ракети зруйнували Музей українських старожитностей Василя Тарновського, архітектурну пам’ятку кінця ХІХ століття; розташування його колекції наразі невідоме. В оточеному Маріуполі — місті, де на руїнах свого будинку від зневоднення померла шестирічна дівчинка — російські військові обстріляли мечеть султана Сулеймана Пишного та його дружини Роксолани, в якій укривалися понад 80 людей (з них 34 дитини).

Вчора бомбардування цього ж населеного пункту

вщент зруйнувало будівлю Донецького академічного

обласного драматичного театру, де переховувалися

більше тисячі жінок і дітей (росіян не спинив

75

навіть напис «дети», виразно видимий з повітря).

Гуркіт, оглушливий та майже безперервний, лунає над Харковом — містом, всіяним ракетами, — як передвісник затяжного жаху, нових знищень та масових убивств. Тому його жителі не розголошують розташування укриттів, прагнучи втаємничити своє існування від окупантів.

Втрати значних творів мистецтва є незмінними подорожніми божевільних амбіцій Росії у відновленні кордонів імперії та встановленні «русского мира» будь-якою ціною. У висвітленні їх західними медіа часто оприявнюється бентежне невігластво в питаннях української історії та культури. Так реакція на перший зафіксований випадок знищення культурної спадщини — пожежу, що зруйнувала Іванківський історико-краєзнавчий музей, — відтворює звичні формули поверховості. Увага до робіт Марії Примаченко, врятованих від пожежі співробітниками музею, здається зумовленою захопленням її картинами канонізованими митцями на кшталт Пабло Пікассо. Вочевидь, останні спроби деконструкції культурних та географічних ієрархій в історії мистецтва нехтують контекстами України. Її

систематичне виключення з дискусії

розвитку східно-центральноєвропейських мистецьких сцен виправдовують бюджетними обмеженнями та (сміховинно!) відсутністю фахівців; подекуди навіть близькістю Росії та України (дискурс, який трансформується в універсалізацію російського досвіду в історичних, особливо довколарадянських дослідженнях).

Насправді ж творчий шлях Примаченко є зразком приборкання українського мистецтва за радянських часів: його зручно було вписувати в неповноцінні категорії «народне» та «національне», щоб потім подавати як «милі каракулі» «братського народу». Примаченко провела своє життя в українському селі Болотня, сумлінно навчаючи майбутні покоління українських художників, зокрема сина Федора та онука Івана. Вона прагнула створити альтернативу державній мистецькій освіті, яка проголошувала російське мистецтво «колискою творчої геніальності», — і надихала художників, які наважилися кинути виклик цій безглуздій генеалогії.

76

Чуйна до власної історії, мистецька спільнота України об’єднується, щоб врятувати культурну спадщину посеред бійні війни. Ольга Гончар, директорка Меморіального музею тоталітарних режимів «Територія терору» (Львів), ініціювала створення Музейного кризового центру. Цей проєкт встановлює зв’язки між працівниками українських

музеїв та міжнародними фондами, забезпечуючи різноманітну підтримку культурним установам по всій країні. Такий підхід пріоритезує безпеку музейних співробітників.

«Поки музеї на заході України перебувають у більш вдалому становищі, ми надаємо їм тару та вогнегасники, адже музеї в зонах жахливих бойових дій мають найпростіші потреби: їхнім командам бракує грошей на їжу та ліки. На цьому етапі вкрай важливо підтримати тих людей, які згодом збережуть спадщину. Якщо ми не забезпечимо їхні базові потреби, не лишиться живих істот, які могли б отримати вогнегасники та тару».

Наразі ініціатива покладається на фінансову підтримку від Європейської комісії (в рамках проєкту «Сила тут», реалізованого ГО «Інша освіта»), Пінчук Арт Центру, MitOst e.V. та приватних донорів. За перші 15 днів роботи Музейний кризовий центр надав допомогу 36 закладам культури, зокрема 13 музеям Луганської області та 10 організаціям Донецької області. Крім того, Гончар висвітлює неоціненну роботу своїх колег у Києві: Дослідницький центр візуальної культури та Український фонд екстреної мистецької допомоги, створений ГО « Музей сучасного мистецтва» у партнерстві з медіаресурсом «Заборона» , Національний художньо-культурний комплекс « Мистецький арсенал» та галерея сучасного мистецтва «The Naked Room ». Марія Ланько, співзасновниця галереї та співкураторка Українського павільйону

на 59-й Венеційській бієнале, нещодавно розповіла мені:

«24 лютого, після перших вибухів, я поклала лійку [важлива частина інсталяції для виставки в Венеції] у багажник, сіла за кермо свого автомобіля з валізою, підготованою для дводенного візиту на виставку в Дніпро з деяким одягом, і відправилася

77

в дорогу на понад п’ять днів, щоб вивезти твір мистецтва за кордон. Зараз наша команда невпинно

працює над тим, щоб зберегти колекцію галереї в

Києві, до якої входять ключові роботи Олега Голосія (1965–1993), які ми повинні захистити».

Волонтерські зусилля працівників мистецтва

виходять за межі професійних спільнот. Команда «Території терору» подарувала обладнання та меблі для укриттів. Львівський муніципальний мистецький центр перетворив свої галерейні простори на громадський центр для біженців зі сходу та центру України. Художній центр імені Єрмілова у Харкові (вражаюче названий на честь українського авангардного художника, викинутого з художньо-історичних наративів за часів радянської епохи і таємно вивченого пізніше українськими мистецтвознавцями) служить бомбосховищем для Харківського національного університету. Там багато художників, зокрема автор вищезгаданого Венеційського проєкту Павло Маков, проводили дні і ночі, поки російські ракети накривали місто. Проєктний простір

«Асортиментна кімната» в ІваноФранківську, в якому досі проводяться майстеркласи, підтримує евакуацію мистецьких архівів. Попри ці зусилля, приватні колекції, особливо ті, які перебувають під опікою сімей художників, у найбільш ризикованих умовах.

Поки російська армія продовжує свої жахливі обстріли, навмисно націлюючись на житлові будинки та цивільну інфраструктуру, художня спадщина світового історичного значення залишається під серйозною загрозою. В Україні кожен день цієї війни розкриває життєво важливі взаємозв’язки тілесності та творчості. Заради мистецтва та життя, безсумнівно, українські працівники і працівниці мистецтва чинитимуть опір.

Постскриптум (або думки, що виникають під час перекладу цього тексту, півтора року після його написання)

З цілковитою щирістю і відкритістю до осуду я можу сказати про себе, що зазвичай гидую журналістськими текстами, бо в моїй голові я всі їх читаю так, наче

78

ось-ось перечеплюся (і так і не навчилася знаходити спільну мову з редактор(к)ами щодо спрощення моїх речень відповідно до їхньої авдиторії, яку я теж завжди уявляю собі по-своєму; впертість — не чеснота для кар’єрного зростання). У цій площині цей текст для мене не є винятком. Він виник як текст на замовлення, як результат звернення через «ти ж українка, напиши, що там в Україні», як спроба втілення власних відчуття жаху від побаченого, роздратування від прочитаного в західних медіа та гордості за дії колежанок та колег. І лише в цьому, останньому сенсі він зберіг для мене значення — як напівавтобіографічний документ перших двох тижнів війни. Композиційно він побудований навколо «нерозривності тілесності та творчості, мистецтва та життя»: описи постраждалих чи знищених культурних пам’яток зливаються з кровопролиттям. У ньому я також фіксую живі теми, які наразі посідають значне місце в моїх розмислах: професійна солідарність та перевизначення мистецьких просторів для потреб біженців, таке собі справжнє вивільнення мистецтва з-під натиску консервативного світу його виробництва та споживання.

Але, поза моїми власними опініями, цей текст існує як чергова реакція на знищення культури та реакція на реакції. В тому історичному контексті, в якому він створювався, вона здається мені виправданою потребою інформування та блискавичного створення англомовного знання про Україну. Десь через пів року після його публікації я зустріла людину, яка доволі довго мене переконувала, що, наприклад, в межах лондонської мистецької сцени (видання британське) цей матеріал був широко розповсюджений і мав значення, і врешті-решт таки переконала. Це я до чого: письмо завжди здається одномісним укриттям, облаштованим лише для себе, і, найімовірніше, ним і є; в надзвичайно рідкісних випадках воно досягає своїх читачок та читачів. Але чиї погляди не були хоч раз, хоч трошечки, вражені після одного, того самого, прочитаного?

Якщо вже так сталося, що ви пишете, не переставайте чинити опір.

79

ART WORKERS AT WAR: HOW THE UKRAINIAN ART WORLD HAS RALLIED TO PROTECT CULTURAL HERITAGE

Originally published on artreview.com on March 17th, 2022. Abridged and republished with permission

Russia’s criminal invasion of Ukraine – now entering its fourth week – has brought unparalleled destruction. Alongside residential buildings, schools, children’s hospitals, and maternity wards, the Russian missiles have not spared Ukraine’s landmarks and museums. In a perilous situation, Ukraine’s art workers have united in their efforts to protect the country’s cultural heritage. They’ve snatched artworks from fires, driven for days with installation pieces in the trunk, and reinvented galleries as sanctuaries.

In doing so, these people have drawn upon an acute sense of duty to save not merely Ukrainian artworks, but a broader, more expansive heritage situated in the country. In the aftermath of intense Russian airstrikes, the Kharkiv Fine Arts Museum suffered substantial damage, exposing its exceptionally diverse collection to the elements. The museum’s staff strove to secure artworks by Early Dutch, Indian, Chinese, French, Italian, and Russian artists amidst indiscriminate shelling and the unnerving sight of corpses on the streets. As Kirill Lipatov, the director of science at

80

POLINA BAITSYM

the Odesa Fine Arts Museum, recently said, it is scarcely possible to grasp the fact that Ukrainian museums are now saving Russian masterpieces from Russian aggression.

The destruction of lives goes hand in hand with cultural devastation. In Chernihiv, a city on the verge of humanitarian catastrophe with no heat, electricity, or safe escape routes for its residents, Russian missiles destroyed the Vasyl Tarnovskyi Museum, a fin-de-siècle architectural monument; the whereabouts of its collection are as yet unknown. In besieged Mariupol – a city in which a six-yearold girl died from dehydration in the ruins of her house – Russian soldiers shelled the mosque of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Roxolana, while more than 80 people (including 34 children) sought refuge inside. Yesterday, bombing obliterated the city’s Donetsk Regional Drama Theatre, in which more than a thousand women and children were sheltering (and despite the word «children» written in Russian outside the building, and visible from the sky). As the thunderous noises over Kharkiv – a city already encrusted

81

with rockets – portend continuous wreckage, terror, and mass murder, locals now desperately seek to keep the location of shelters a secret from the invaders.

Critical losses of indispensable art accompany Russia’s delirious ambition to recreate its former imperial borders and impose «the Russian world» at any price. Western accounts frequently display an alarming lack of understanding of Ukrainian history and culture. The first reported destruction of cultural heritage – the fire that razed Ivankiv’s Museum of Local History to the ground – ignited a rehearsal of familiar ignorance. The attention on the artworks of Maria Prymachenko, stored at the museum and rescued from the fire by the staff, inevitably recited praise for her work expressed by canonised male figures – namely Pablo Picasso. Evidently, recent endeavours to deconstruct cultural and geographical hierarchies fail to encompass Ukraine. Discussions of East-Central European art scenes often reprise the problems of budget constraints and – derisively – a lack of specialists, as well as the adversarial closeness between Russia and Ukraine (a discourse which translates into a universalising of Russian experience in historical, especially Soviet-related, studies).

In fact, Prymachenko’s creative trajectory exemplifies how Ukrainian art was tamed during Soviet times: conveniently wrapped around subsidiary categories of «folk» and «national», to be displayed as the «adorable scribbles» of the «brother nation». But Prymachenko spent her life in the Ukrainian village of Bolotnia, diligently teaching future generations of Ukrainian artists, including her son Fedir and her grandson Ivan. She sought to provide an alternative to the state education which proclaimed Russian art as the cradle of creative brilliance – an inspiration to art workers who dared to challenge this facile genealogy.

Sensitive to this history, the country’s art scene has come together to protect cultural heritage, put on the line as the carnage continues. Olha Honchar, the director of the «Territory of Terror»

82

Memorial Museum of Totalitarian Regimes in Lviv, initiated the Museum Crisis Center. The venture links museum personnel with international funds and provides various kinds of support to cultural institutions all over the country. Her approach prioritises the safety of the staff members. Honchar told me: