6 minute read

Shop Class As Soulcraft

b. Shop Class As Soulcraft In his argument, Crawford criticizes the impact of the Taylorization of society and seeks to remind the world that the intangible universe in which we live today generates an erroneous estimation of what the world of crafts is like. However, its objective is not to bring out a kind of nostalgia for a simpler work. As mass production has become one of the pillars of our society, it results in a global standardization of work due to the need to produce quickly and extensively. This results in a lack of individuality and personal expression. A passage from his work sums up very clearly, in my opinion, the questions that guide his thinking.

« So what are the origins, and therefore the validity, presuppositions that lead us to consider our increasing remoteness as inevitable, or even desirable any manual activity ?33

Advertisement

Through multiple examples, he explains the origin of the rift between people and the objects that surround them. Industrialization and assembly line work, which no longer requires much personal investment on the part of employees, tend to reduce the level of technical knowledge and general expertise or to move them to highly qualified ad hoc operators. This intermediate position in the manufacturing process detaches the manufacturer from what he produces and can lead to a lack of satisfaction with the finished work and the pride that should be attached to it. All this is due to the Taylorist process that sequels production and separates planning and execution tasks, so much so that ultimately no one is able to execute a complete process.

The development of factories has also meant the bankruptcy of many small craftsmen, unable to compete. One of the first consequences of this, Crawford points out, is the disappearance of technology courses in schools. Under the pretext that they were expensive and dangerous, these tools have therefore gradually been replaced by computers. This transition has also been noticed in the educational programmes, where all university courses are now highlighted. There is therefore a feeling that success is to be found in studies, leading society towards a general denigration of manual labour. This world of the factory has therefore led to the standardization of functions; the freedoms of action have been limited, faced with the obligation to respect precise specifications defined by others. This creates a new distance between people and their work, a disempowerment that leads to dependence on the system.

« We are loathe to have simple individuals concentrating too much authority in their hands. With its deference to neutral procedures, liberalism is by definition a policy of irresponsibility. Initially, this tendency starts with the best of

intentions — to protect our freedoms from abuses of power — but it has turned into a monstrous phenomenon that eliminates individual initiative. »34

Crawford explains that the machining of objects and their standardized production in large quantities generate a merchandising process where the product is shaped for the consumer to satisfy his desires without him being able to invest anything other than money. This lack of personal investment in making objects has made their users forget how they are produced and they assume that it would be too complicated or time-consuming to learn to repair them themselves. The mystery hangs over the origin of all the objects we own, the identification with objects is done through a marketing process where we choose the characteristics of the objects we buy according to our needs. But choosing is not creating and it is essential to understand the limitations of such a system.

The author argues that the rationalization of the system is the source of a general disempowerment of the professions. His thinking is based on the fact that rationalization generates very precise rules and that they tend to cut off personal initiatives. This lack of flexibility at work further widens the gap between personal and professional life. The worker no longer feeling concerned by his work is relieved of responsibility, he works for the interest of someone other than himself. This de-skilling of craftsmen would therefore be due to the dissociation between the cognitive aspects of work and the manual aspects. Employers, in order to pay less for their labour, only hire unskilled workers, whom they train for a specific task. This marks the end of the skilled craftsman who can no longer compete financially. This segmentation of the process leads in this case to craftsmen with limited and highly targeted knowledge. This disempowerment is not reserved for the world of craftsmanship, it has affected the entire population and if we want to restore the concern for the object, it is necessary to have a good understanding of its place in the material environment on which it depends. Teaching object making would pave the way for awareness of some companies’ strategies: programmed obsolescence, the idea that a product can only be used if it is owned, the willingness to repair broken objects, or gendered design.

On the other hand, returning full control of the manufacture of the object to the user allows him to work in an environment where he imposes his own constraints. This opportunity to develop and manage a personal project can transform the consumer into a conscious consumer.

At the same time, this segmentation has also been introduced in the building industry. Only fifteen percent of the workers will still be on the site when it ends, as a result of a time crunch in terms of labour requirements. Despite everything, the construction world has not really followed the curve of industrialization, most construction site work is still done manually. The architect Pierre Bernard sums up the reason for this situation well:

« On peut repérer au moins trois facteurs, trois explications à cette résistance. La première : le rapport au sol qu’entretient tout bâtiment. (...) La deuxième explication : Il n’y a pas de distinction entre le lieu de production et le produit. (...)La troisième explication : Il n’y a pas d’objectivation du processus de production.1 »35

The building is therefore difficult to industrialize, because it has a relationship with its context specific to each situation. However, there is a gap between architect and worker, due to the fact that they almost never share their work. The worker does not take part in the design and the architect in the manufacture. This lack of exchange is therefore a source of inconsistency and sometimes even frustration.

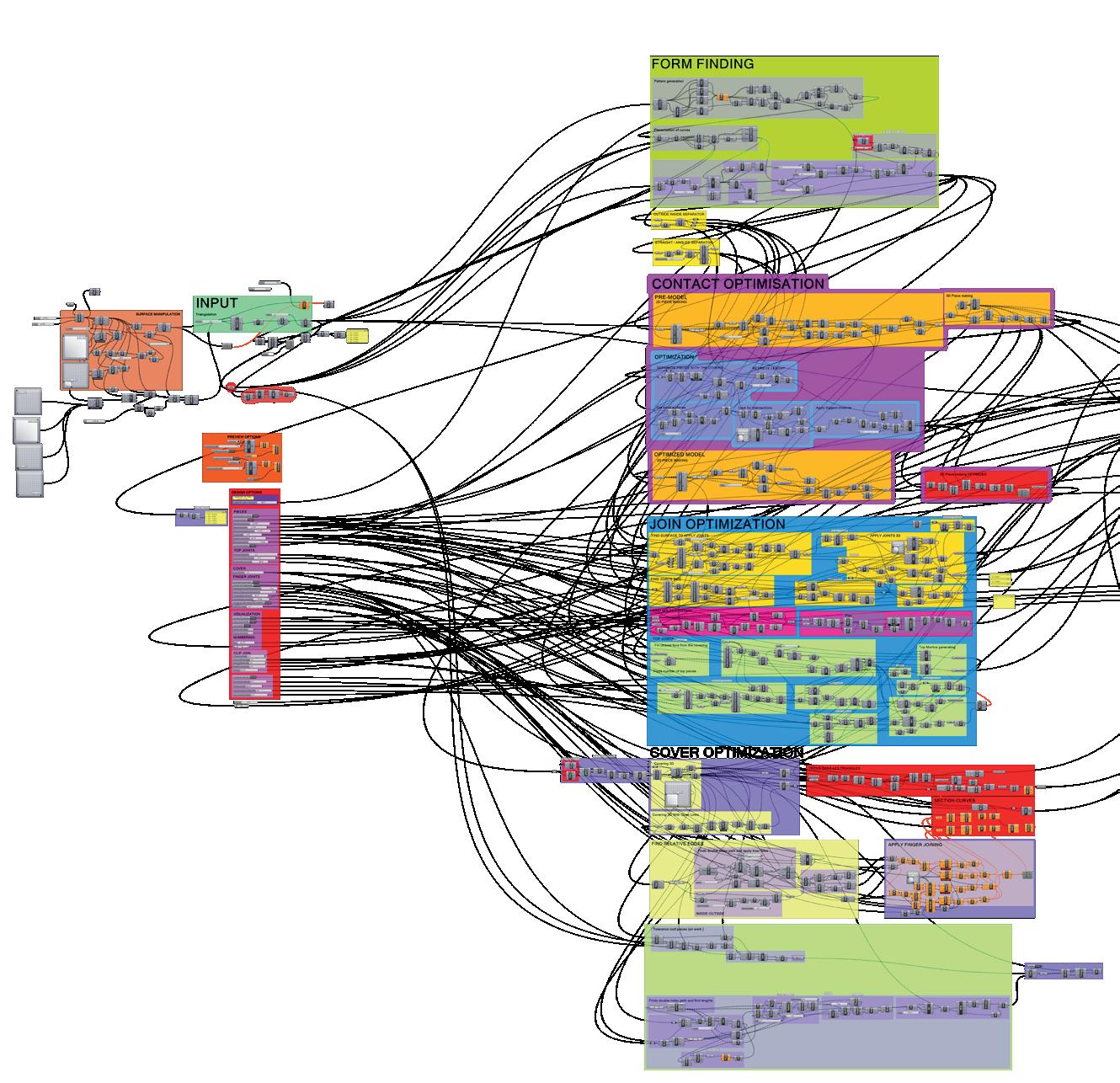

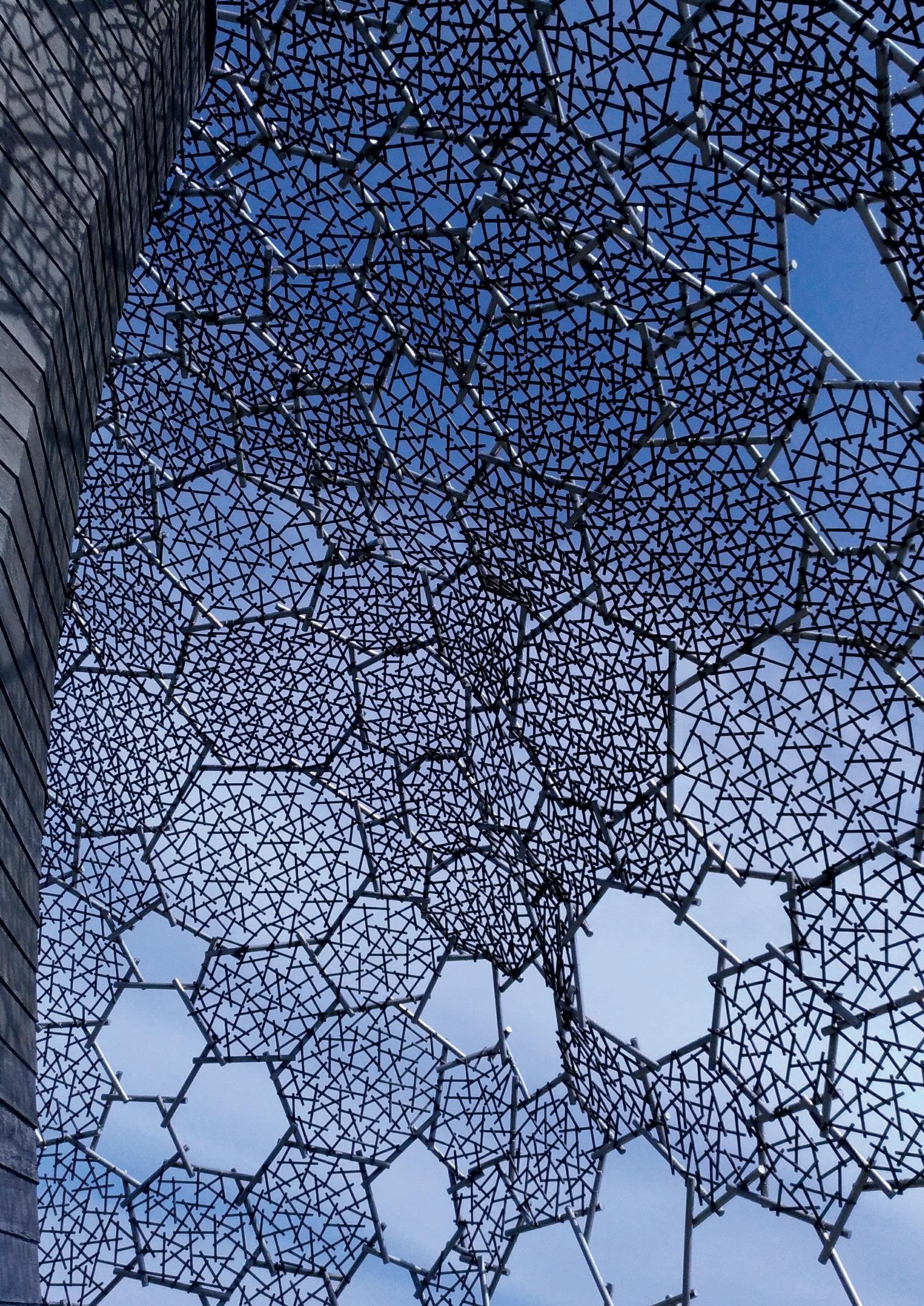

The Wikihouse project would then provide answers on several of the above-mentioned plans. The project would return control of habitat production to the inhabitants, who are therefore able to maintain it and, above all, will be willing to do so, because it represents an enormous personal investment. It also supports the consolidation of the production, manufacturing and construction process under a single step. The process is anti-taylorist in its essence and offers an opening to all those who are eager to get out of our business model. In addition, I find it particularly interesting that a digital production can embody the return on a tangible personal investment.

1 « At leAst three fACtors CAn be identified, three eXplAnAtions for this resistAnCe. the first is the relAtionship to the ground thAt every building hAs to the ground. (...) the seCond eXplAnAtion: there is no distinCtion between the plACe of produCtion And the produCt. (...) the third eXplAnAtion: there is no objeCtifiCAtion of the produCtion proCess.»