3 minute read

The Language of Love

MAGAZINE What’s in a name?

Lowri Llewelyn discusses Welsh place names, and how they are just as vital to our national identity as the places themselves...

Ynys Llanddwyn

I was browsing social media this week when I came across a photo of Ynys Llanddwyn, so named because of its association with Dwynwen, Welsh patron saint of lovers. The photo had been tagged “Lover’s Island”. When prompted, the poster asserted that their version was “more poetic” than the actual Welsh name.

Porth Trecastell

As a first language Welsh speaker, I’d like to explain why

this Anglicisation of ancient names hurts my heart.

Between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, Welsh school children caught speaking their mother tongue were physically punished, having already endured the humiliation of wearing a heavy wooden plaque reading “Welsh Not” around their necks.

In 1870, the Education Act stated that children must be taught in English only. In 1847, a school report known today as the “Treachery of the Blue Books” blamed the Welsh language for stupidity, insolence and even sexual promiscuity. In 1536, English was made the only legal language of Wales.

We have been forced to defend our language for many centuries. Though at first glance it may

seem like we have finally gained respect, as a

Welsh speaker, I feel quite differently. Yes, we have bilingual road signs, but that’s because Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (The Welsh Language Society) took it upon themselves to deface and remove English-only signs.

Llyn Bochlwyd

Yes, we have Welsh-language television channel S4C, but that’s because activist Gwynfor Evans threatened to starve himself to death.

Ynys Llanddwyn isn’t an anomaly. Porth Trecastell on Anglesey is now largely known as Cable Bay, yet in a YouTube video titled “Disappearing Welsh Names”, comedian Tudur Owen explains that “Porth” translates as “access point” or “gateway” for travel, trade and fishing, while “Trecastell”

suggests an ancient fort or castle that would have defended this stretch of coastline.’

These aren’t just names, but stories.

Another notable example is that of Llyn Bochlwyd in Eryri (Snowdonia), now known in some guidebooks as Lake Australia. While “Llyn” means “Lake”, “Bochlwyd” actually means “Greycheek”, referencing an old grey stag which plunged headfirst into the lake to evade hunters, cheek

bobbing above the surface as it swam to safety. Lake Australia represents nothing but the water’s outline.

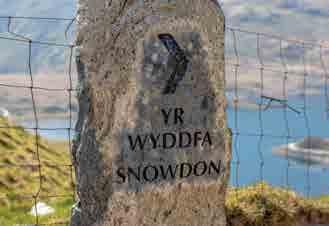

You might have heard recently of calls to officially refer to

Snowdon by its native name Yr Wyddfa. While Snowdon refers to the mountain’s snowy peak, Yr Wyddfa marks the gravesite of the giant Rhita Gawr, slain by King Arthur.

This disregard of our language is all around us. A Sky News presenter asked on UNESCO’s Mother Language Day whether Welsh is the most “pointless” language, and a Telegraph travel journalist stated that we don’t deserve to reclaim the name of our tallest peak because we had the audacity to build a café on top of it. Welsh, for the most part, is the way I interact with the world. I speak Welsh with my family, friends and colleagues. I greet my bus conductor in Welsh, I sing my national anthem in Welsh – I even think in Welsh.

So yes, at first glance Lover’s Island may seem like nothing

more than a twee nickname, but when a culture is erased we’re essentially picking and choosing which part of its history is convenient to us. Remember that a language’s value is not based on the number of people who use it.

I can’t rewrite history but what I can do is humbly ask that, going forward, the native language of my country is treated with respect. Make an effort to use native names – we promise not to laugh if you get them wrong! Make an effort to greet us and thank us in Welsh; yes, we all understand English, but the 279,300 Welsh speakers here in North Wales will genuinely appreciate the gesture.

Diolch o galon. n

Lowri Llewelyn is a North Wales based journalist who is endlessly curious [read: nosy] and loves everything to do with this beautiful region that she is lucky enough to call home.