NEIGHBOURSHEDS

In many cities today, the urban environment and watershed are two distinct territories, linked together by a series of pipe networks. This design thesis seeks to define a new form of watershed that would reconcile the urban grid with the actual natural watershed; and in so doing, set up a new contractual relationship between people and their watershed.

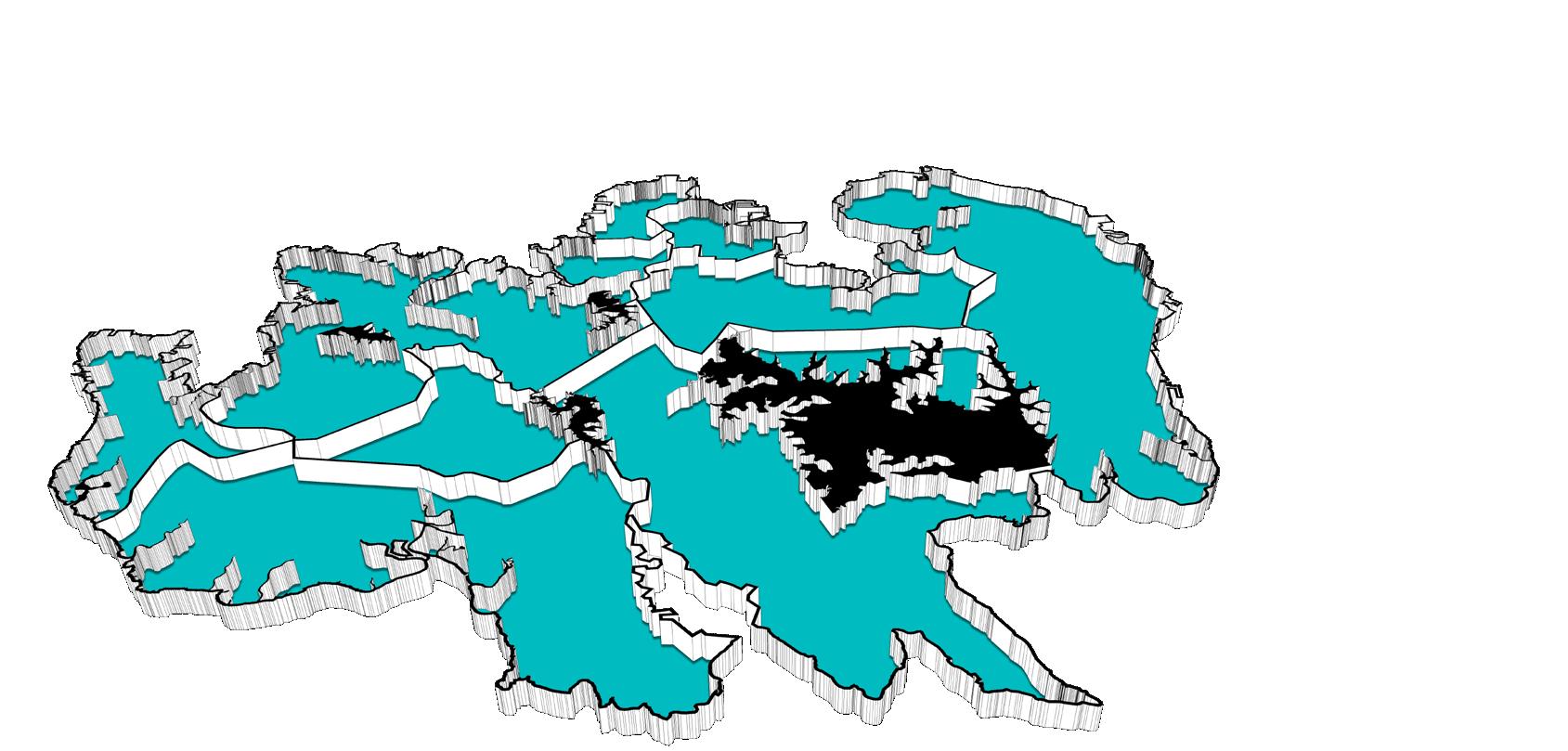

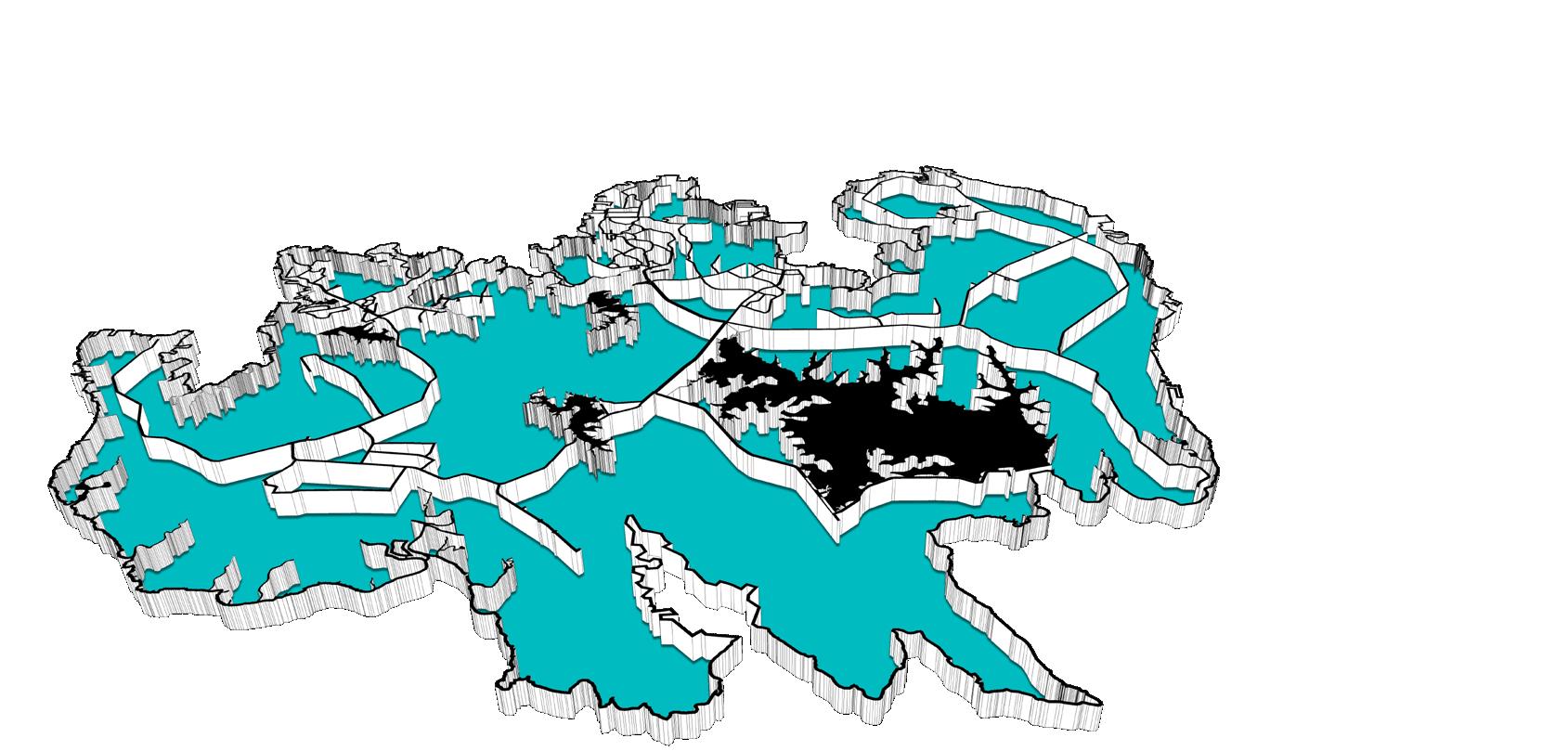

“Neighboursheds” is the term used to describe this reinterpretation of the watershed. It refers to a neighbourhoodbased watershed, where the boundaries of the watershed are defined by the limits of a neighbourhood community instead of topography. The “neighboursheds” scheme is a system of distributed water infrastructure located at the community level, intermediating between two extreme scales in Batam’s urban water system – the large, highlycentralized city reservoirs and the small, household level of domestic wells.

Each neighbourshed has its own grammar of collecting and managing water. The strategies employed in each one are site-specific calibrations to the different financial, topographical and pollution realities of different neighboursheds.

In Batam where the government cannot always be relied upon for the supply of water, “neighboursheds” presents an alternative to the state’s singular system of water provision. Here, infrastructure is reconceptualised as a means to organize landscape so as to create community identity and a personal sense of orientation. It is also incorporated as an essential visual component in the urban environment so that the position of water in people’s consciousness is elevated and a stronger connection with water is drawn. When people learn to take up responsibility over the well-being of their watershed, water sources can be safeguarded through community-level action.

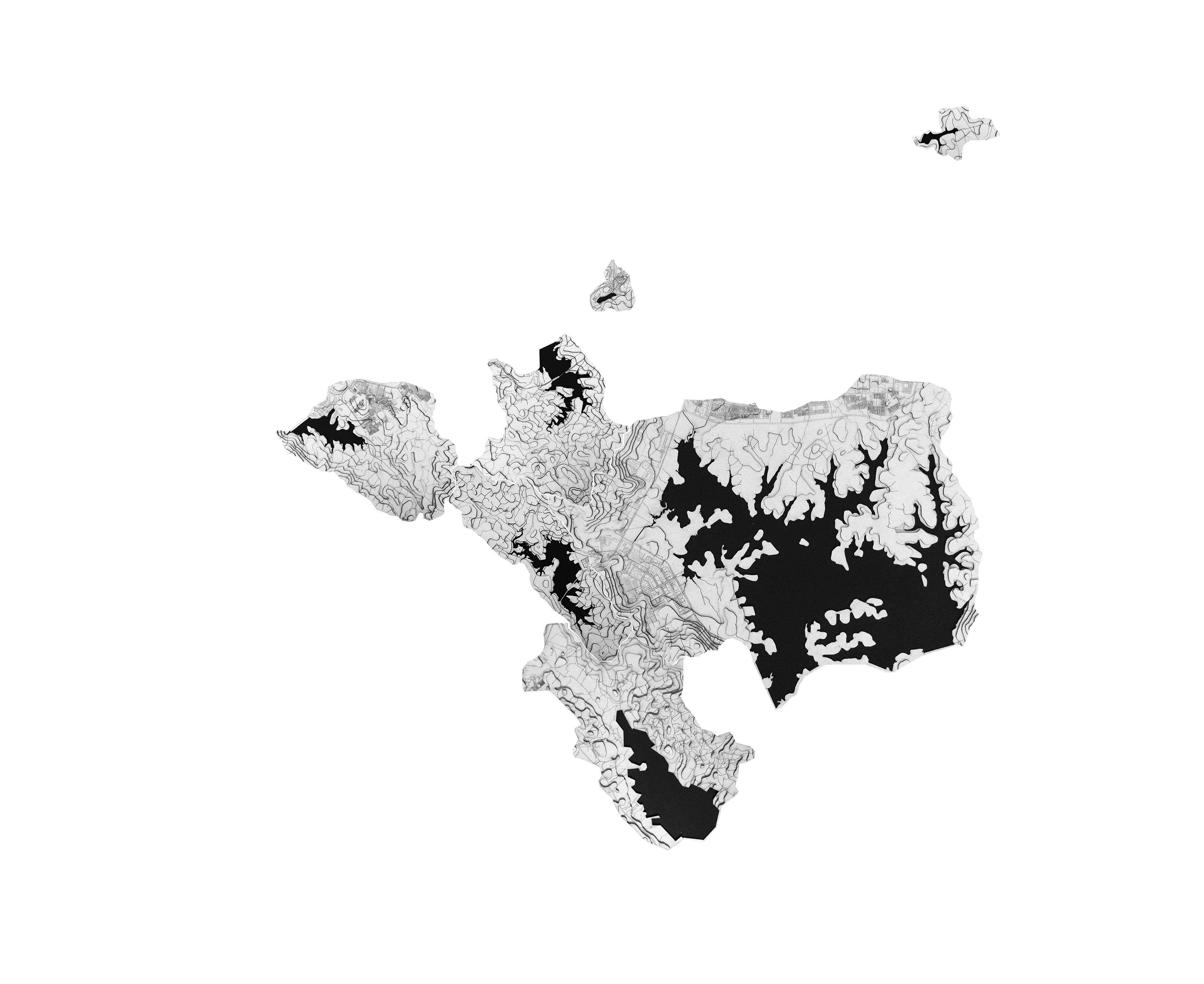

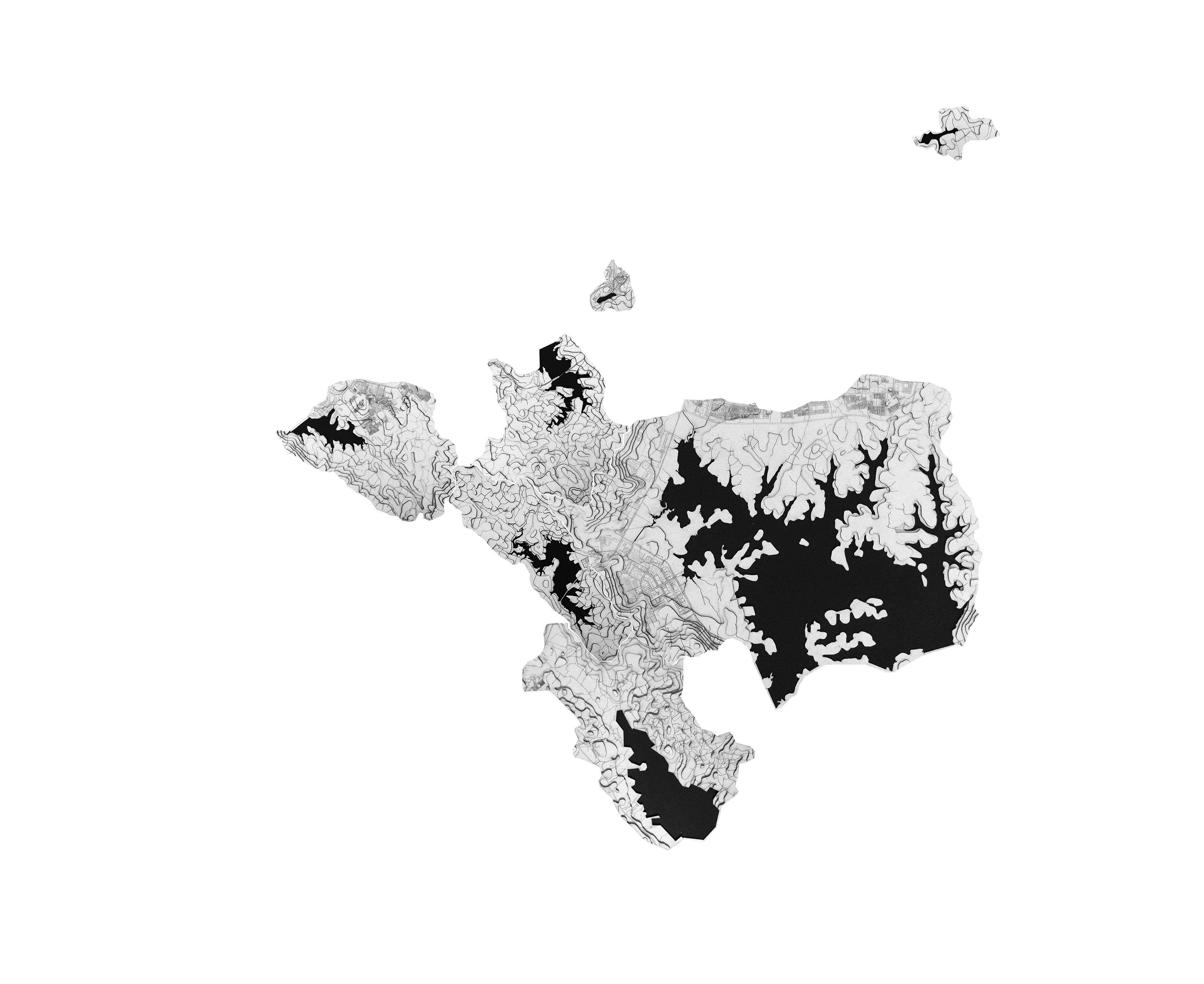

The city of Batam is facing a water crisis: it is expected to run out of clean water by 2015 based on business and population expansion estimates. Batam – like 99.83% of Indonesia’s islands – has no groundwater basin and its impermeable soil structure mean only a small portion of rainfall infiltrates the ground. Moreover, small islands like Batam are characterized by narrow coastal areas and hills with steep topography, causing much surface runoff to be wasted into the sea. Hence, almost 100% of Batam’s raw water supply comes from rain-fed reservoirs.

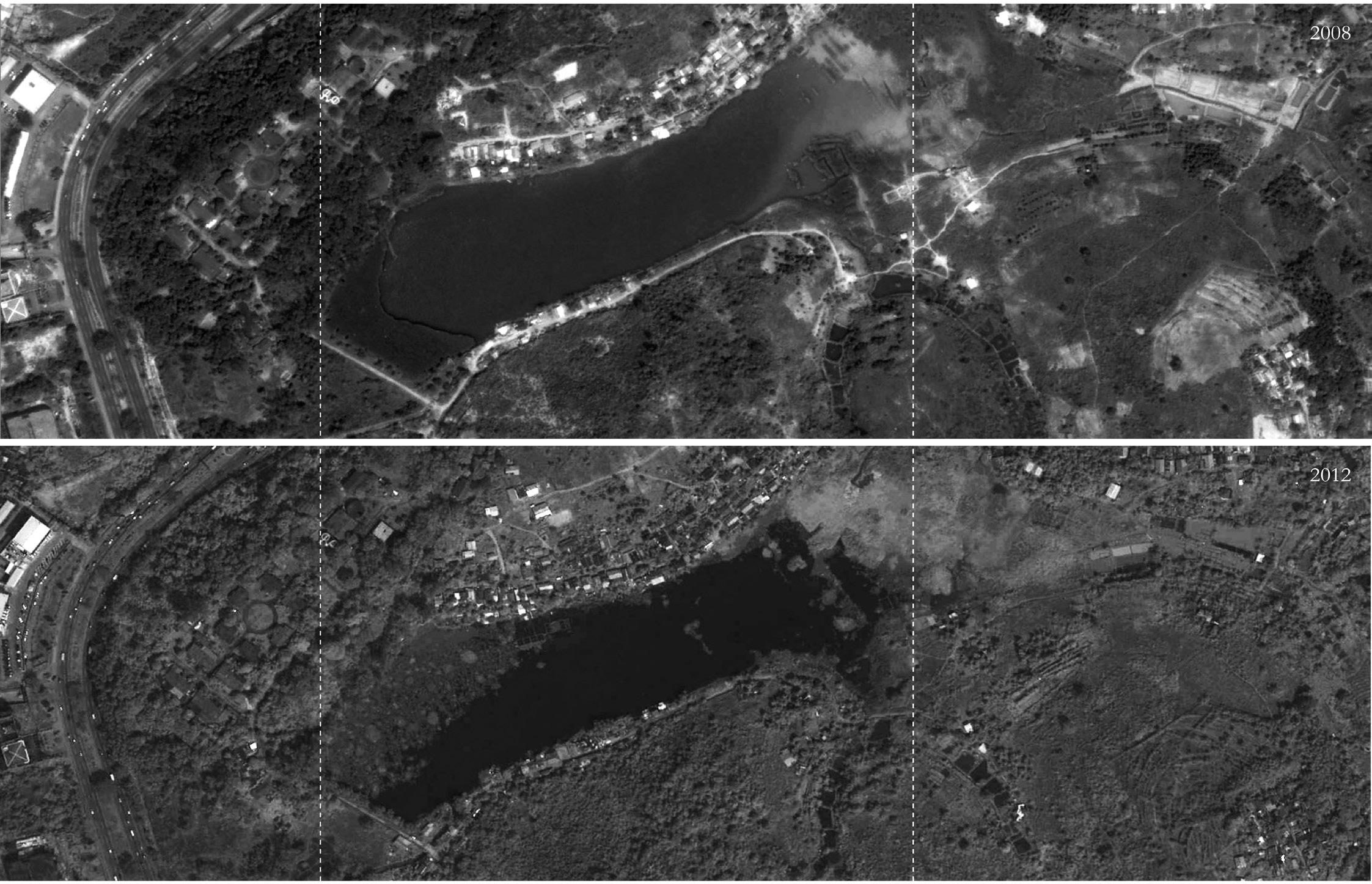

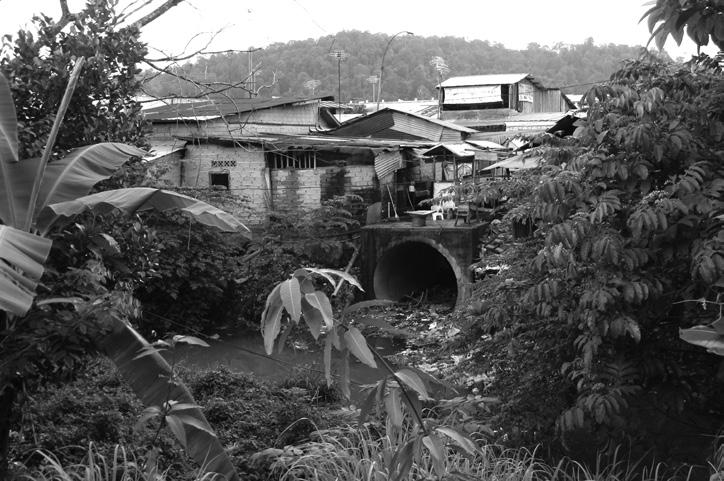

However, rapid economic development on the island since the 1980s has taken a toll on the environment and the quality of raw water. As part of the Singapore-JohorRiau (SIJORI) Growth Triangle scheme, Batam was designated as Singapore’s provincial hinterland - it provided land and cheap labour for Singapore’s electronics manufacturing industry. Without proper law enforcement, protected areas within the watersheds of Batam’s reservoirs

have become increasingly encroached upon by housing and industry. Not only has this led to a removal of forest cover, but the lack of proper waste management infrastructure also means household and industrial waste is discharged directly into water bodies. In addition, squatters – made up of low-income migrant workers – have also colonized the protected forests of reservoirs because the lack of affordable housing has squeezed them out of the formal housing sector. These intrusions reduce the amount of catchment area for rainfall and weaken the watershed’s ability to naturally cleanse itself. Consequently, the system is overloaded by pollution, causing some reservoirs in Batam to be highly contaminated. This eventually led to a fall in supply of drinking water and the proliferation of waterborne diseases amongst informal dwellers. To complicate matters, the problem of water pollution takes place against a backdrop of murky politics, backdoor deals and territorial disputes. Addressing the issue at hand calls for one to navigate difficult waters.

Development of Sei Baloi area into business district begins; businessmen apply and pay for land even though Sei Baloi is a protected area

CLOSED

’77 ’78 ’79 ’80 81 ’82 ’83 ’84 ’85 ’86 ’87 ’88 ’89 ’90 ’91 ’92 ’93 ’94 ’95 ’96 ’97 ’98 ’99 ’00 ’01 ’02 ’03 ’04 ’05

BATAM IN CRISIS

- A Batam worker describing life in Batam

dam forest is closed conversion of into a commercial zone

Water Kiosk Program is implemented in Ruli Baloi, reducing amount of water leaks

Batam is predicted to run out of water 2007

The Jakarta Post, 18 March 2011

Duriangkang IPA is upgraded to double its operational capacity and construction of Tembesi IPA begins

Tembesi IPA is completed but its water is far too polluted for the reservoir to be operational 2007

$ ’05 ’12 ’13 ’06 ’07 ’08 ’09 ’10 ’11 ’16 ’17 ’14 ’15

constantly sought for new water sources by commissioning new reservoirs and water treatment plants. In 2012, the miminum wage in Batam was increased, causing several investors to relocate their factories. Many workers were laid off. Hence, in 2013, Batam’s population dipped for the first time. While that has slightly eased the population pressure on water, the city still faces an uphill task of dealing with water scarcity.

Tempo Interactive, 5 January 2011

The Star, 5 June 1999

The Straits Times, 16 September 1997

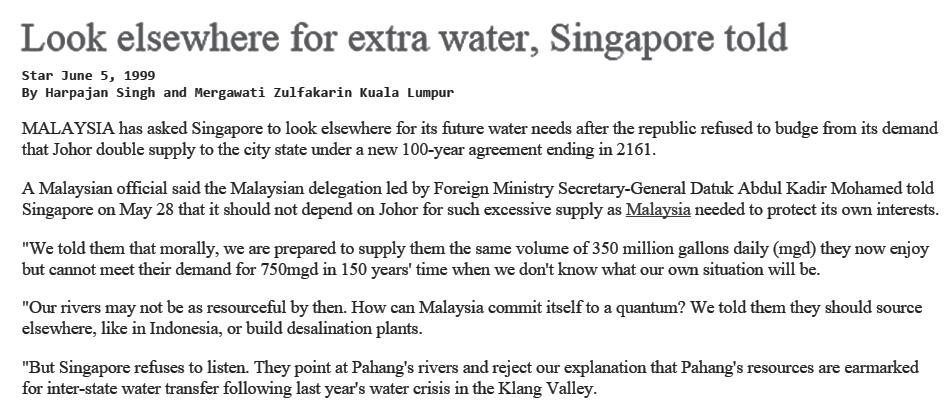

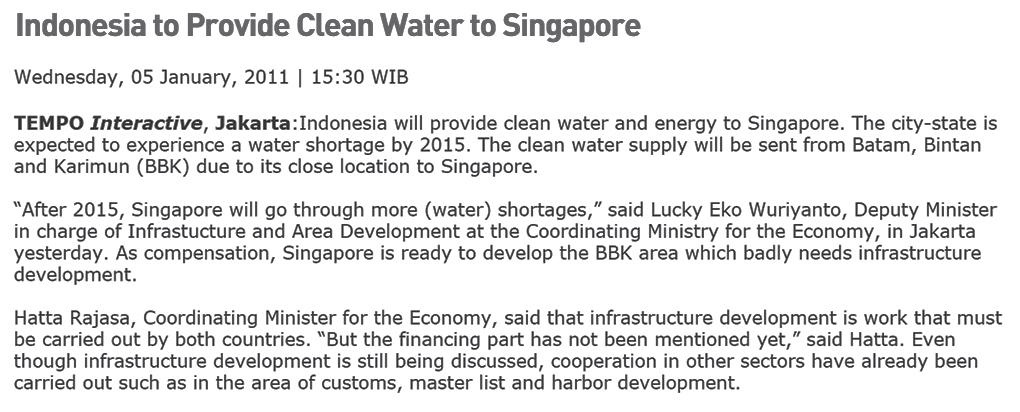

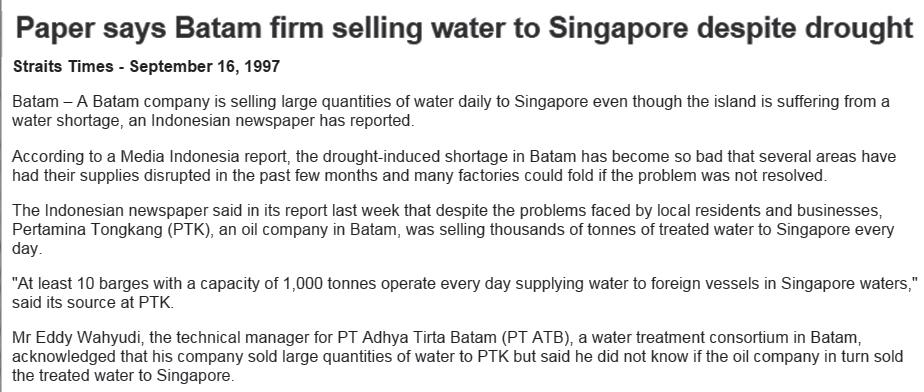

Yet, even as Batam is facing its own water crisis, it was reported in the very same year that plans were underway for Batam to supply water to Singapore, who was also scouting for new sources of water.

Batam has had a history of selling water to Singapore, even when its own water supply was running low. Water sold to Singapore could fetch seven times the local price.

Total Land Area: 415 km2

Total Catchment Area: 129km2

Batam receives an annual rainfall of 2330.7 mm (2013), which is comparable with Singapore’s 2340 mm. Most of the rainfall is collected in reservoirs through surface runoff or channelled through ditches and streams. Many parts of Batam are not reliable as sources of water availability because rainfall received in that area is channelled straight into the ocean. The condition of topography is, undoubtedly, an important factor in ascertaining the suitability of an area as water catchment.

The management and provision of Batam’s water supply is handled by a private water company, Adhya Tirta Batam (ATB). It was given a 25-year concession by the government in 1995 to operate, manage and develop water facilities in Batam.

ATB is jointly owned by Dutch water firm Cascal and Bangun Cipta Kontraktor (BCK). 98% of Cascal’s equity is owned by Sembcorp Utilities, which Temasek Holdings - an investment company wholly owned by the Singapore government - has a majority stake in. Meanwhile, BCK is part of the larger group of Bangun Tjipta Sarana companies owned by Siswono Yudo Husodo, an ex-cabinet minister and a 2004 presidential candidate for Indonesia.

Local regulations set out by the Batam Industrial Development Authority (BIDA) prohibit ATB from extending water pipes to informal settlements since residents there do not have land rights. ATB can only extend its pipes to a point (in the form of a water kiosk) where residents purchase water from an operator. Those living in informal settlements without water kiosks would have to obtain water through alternative means.

ATB is only responsible for distribution mains up to the water meter; thereafter, it is the customer’s responsibility to maintain and repair the pipes leading to his home. To receive connection to ATB’s water meters, the customer has to make an application to ATB and pay an installation fee. Only those with land rights are eligible. However, ATB has been restricting connections to new customers since 2008 due to the water shortage. The firm explained that new connections will only lower the quality of service for existing customers as demand exceeds ATB’s production capacity. Indeed, some ATB customers are already facing water supply disruptions on a daily basis.

Those unable to access municipal water pipelines may resort to stealing water, causing leakages that lead to the rise of non-revenue water (NRW), which ATB believes is exacerbating the water shortage crisis.

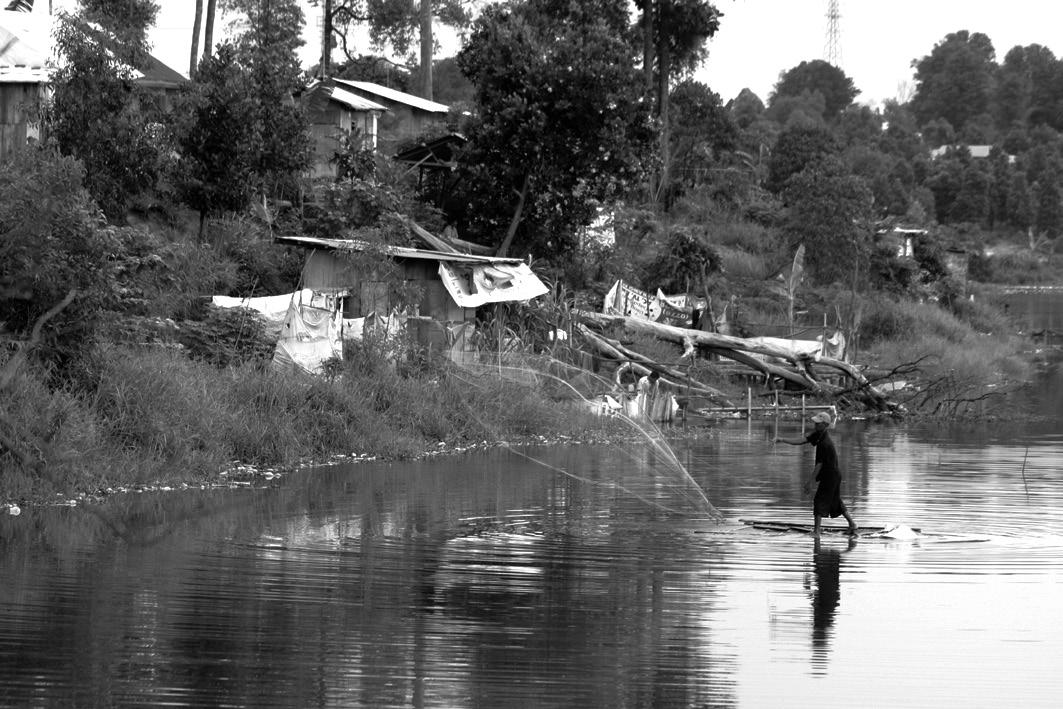

Informal dwellers, or non-ATB customers, have informal means of obtaining water. These include purchasing water drums from water kiosks or water trucks, buying bottled water or water tanks from private vendors, or stealing water from municipal pipelines. Finding water itself is not an issue, but getting clean water is where the difficulty lies – there isn’t enough of it. Moreover, bottled water is expensive.

While ATB customers spend only 3% of their income a month on water expenses, non-ATB customers - most of whom work in the informal sector - can spend as much as 28% of their income. The onslaught of a water crisis only means more trouble for non-ATB customers who are already struggling to afford clean water.

Solid waste generation - comparing amount transported (to final disposal site) vs. amount untransported

source: Dinas Kebersihan dan Pertamanan (DKP) Batam

COLLECTION

waste is brought to a temporar y disposal site by the resident or a conveyor company who collects g arbage door-to-door with a g arbage car t.

STORAGE

waste is left at the temporar y disposal site (TDS) until it is transpor ted away

TRANSPORTATION

garbage trucks transport waste

from TDS to a landfill. This is

managed by a private contractor

PT Royal Gensa Asih, under a contract with the City of Batam.

LANDFILL

waste is brought to the Telaga Pung gur Final Disposal Site (FDS), which is operated by DKP. Contractors need to receive a per mit from DKP to dispose waste at the FDS

To compound problems arising from the shortage of clean water, Batam also suffers from poor solid waste management infrastructure.

Waste is usually brought to a temporary disposal site (TDS) before it is transported to the Telaga Punggur Final Disposal Site (FDS) by a conveyor company. However, only 38% of the total amount of waste generated reached the landfill site in 2012. The remaining 62% either did not reach the TDS in the first place, or were left sitting at the TDS waiting to be transported. There are simply not enough TDS sites in Batam and many residents do not know where these sites are located too.

As a result, waste that is left by the roadside or by drains and canals are washed into streams and other water channels during heavy rains, clogging up these waterways and increasing their potential as a carrier of diseases.

Although 70% of the toilets in Batam are equipped with septic tanks, most do not comply with basic sanitation requirements. Due to the impermeable nature of Batam’s soil conditions, as well as cost considerations, the septic tanks are not equipped with a diffusion system where excess liquid can be drained into a leach field. Consequently, water leaving the septic tank into the drainage system still contains a high bacterial content.

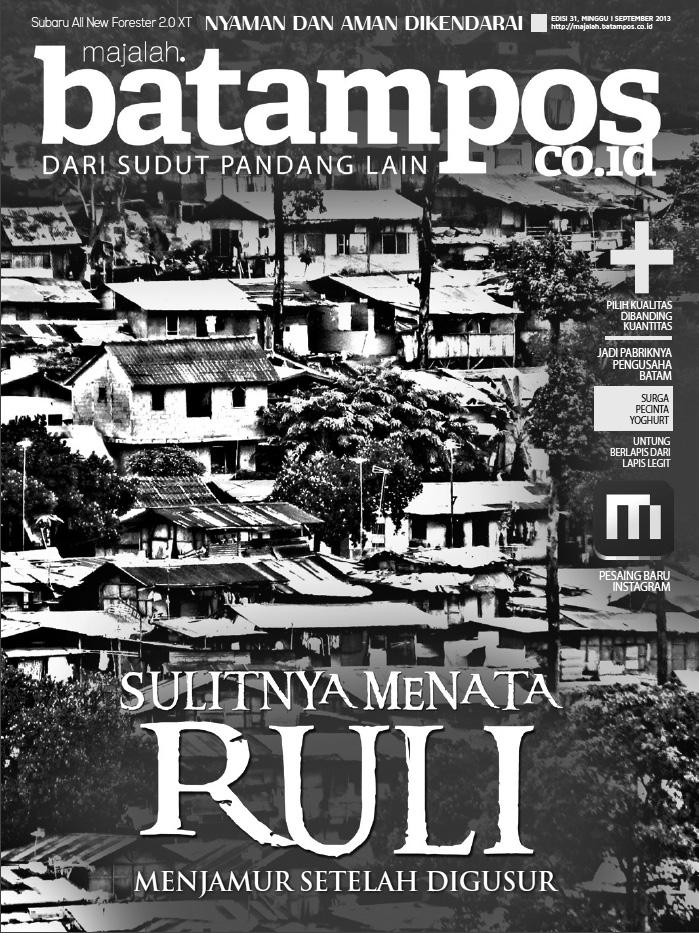

Affordable housing in Batam comes in the form of fourto five-storey rental flats called Rumah Susun (rusunawa). Yet, while demand for rusunawa is high, the number of blocks that have been built so far is less than 5% of what Batam authorities had set out to construct. The lack of housing infrastructure catered for the lower income sector force thousands of migrant workers to set up home on squatted land, forming informal settlements - otherwise known as Rumah Liar (ruli) to locals. Most rulis develop on protected forestry areas which are within close proximity to factories and industrial parks, where residents work.

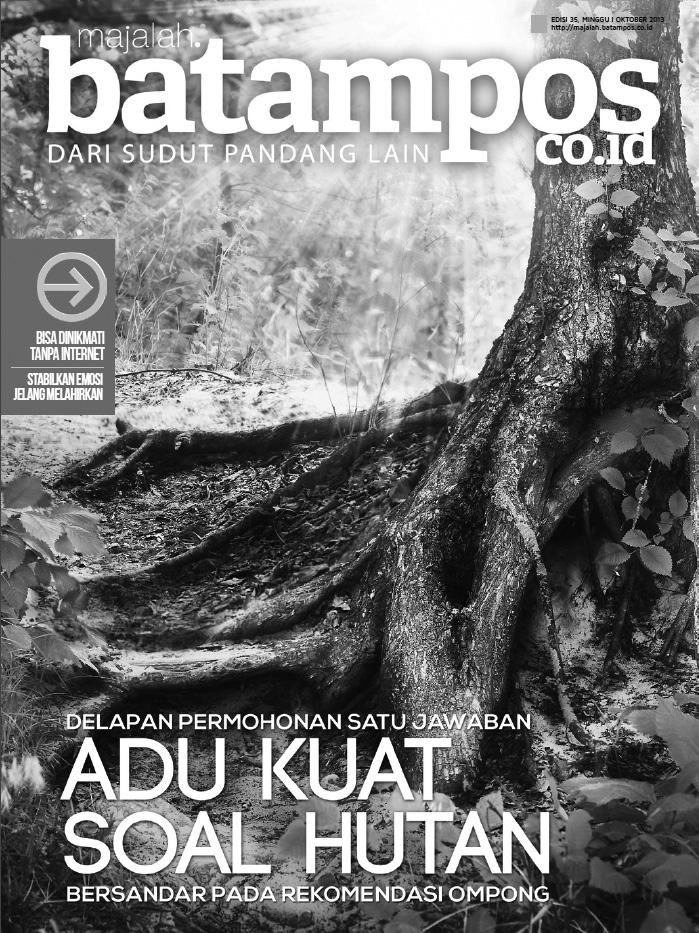

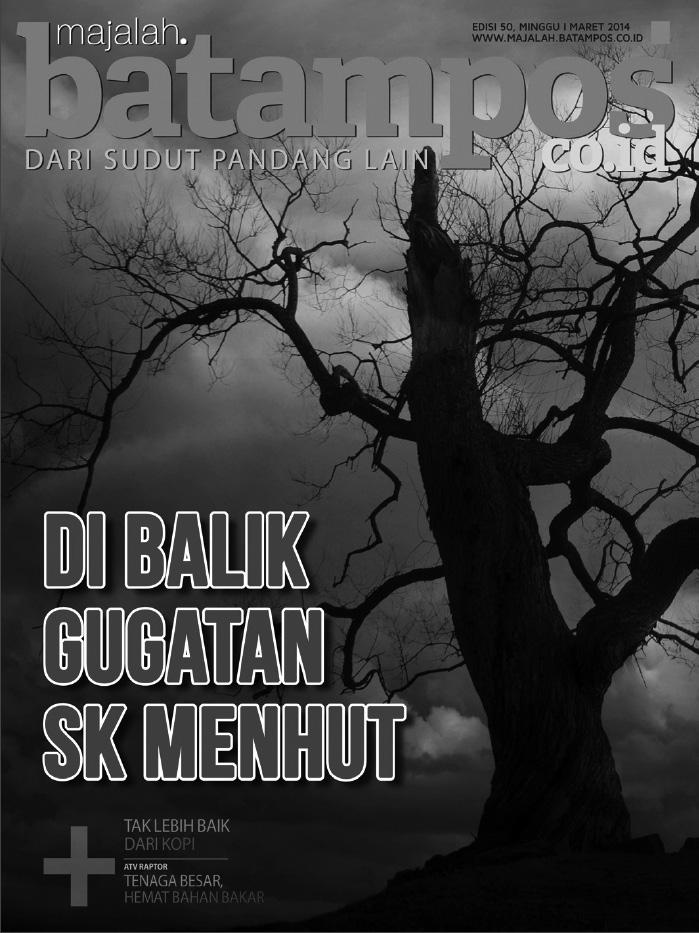

In an effort to recover the staggering loss of Indonesian forests to urbanization, the Ministry of Forestry (Indonesia) made a radical proposal in 2013 to convert developed areas back into forested areas. This would call for largescale reforestation all across Batam. The proposal met with strong opposition from BIDA and the matter was brought to court. In the end, BIDA won the case and the reforestation proposal was overturned.

Most of Batam’s water needs arise from the domestic sector, which accounts for 72% of the island’s annual water consumption. Water is supplied from Batam’s six operating reservoirs, namely; Sei Ladi, Sei Nongsa, Mukakuning, Duriangkang, Sei Harapan and Sei Baloi. The seventh, Sei Tembesi, is an upcoming reservoir that has not begun operation. Of the six reservoirs, Duriangkang is the largest of all and it alone is responsible for supplying water to 70% of Batam’s population. On the other end of the spectrum, Sei Baloi is the smallest reservoir at merely 0.004% the size of Duriangkang. In spite of its size, Sei Baloi is the most polluted reservoir, with its opacity level (measured in True Colour Units) far exceeding any other reservoir.

53,594,496 m3

m3

Duriangkang

Opacity (in True Colour Units)

Standard: 15

E-Coli (in MPN/100ml)

Standard: 100

Ammonia (in mg/l)

Standard: 0.5

Based on “Tesis” by Muhammad Dicky

Batam’s Reservoirs (in increasing order of water pollution)

0 0.2km 1km

Water samples taken from Batam’s seven reservoirs show that the level of water contamination positively correlates with the extent of human activity intruding on the watershed, and negatively correlates with the amount of forest cover left within the watershed. E-Coli is a form of bacteria that could cause bloody diarrhea and urinary tract infections if left untreated. Ammonia content in water is indicative of pollution from domestic waste.

The watersheds of Sei Ladi, Sei Nongsa and Mukakuning – the top three cleanest reservoirs in Batam – have more than 90% of their forest cover left intact.

At fourth place, Duriangkang receives a considerable amount of pollution from Batamindo Industrial Park, the largest in Batam housing more than 70 MNC manufacturers along the western edge of the reservoir.

Still, Duriangkang is not as polluted as Sei Harapan, which

is abutted by middle-class housing estates without proper sanitation systems.

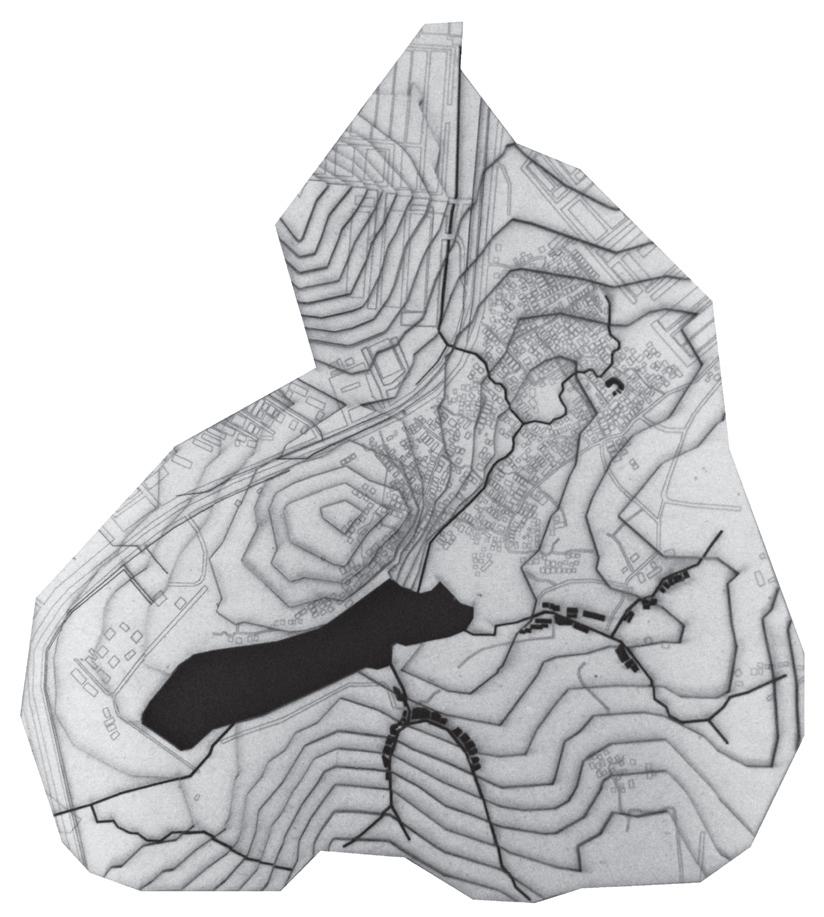

Sei Baloi is the dirtiest; it is almost 4 times more polluted than Sei Harapan. Hemmed in by Ruli Baloi - an informal settlement - and Indah Industrial Park, untreated wastewater produced from these two sources severely contaminates its raw water supply. Moreover, the intrusion of human activity on its watershed has left Sei Baloi with merely 3% of its forest cover.

middle- to upper-class housing

ruli kampung aceh

batamindo industrial park workers’ dormitories

ruli kampung selayang

So serious is the extent of pollution in Sei Baloi that its water treatment plant had to be shut down in 2012 as the cost of treating its water had exceeded the amount that could be earned from its sale. Two years earlier, the forest surrounding Sei Baloi lost its status as “protected forest” and was reclassified as “production forest”. To “compensate” the loss of Sei Baloi as a water source and its forests, Batam authorities proposed for a new dam at Tembesi with a watershed eight times the size of Sei Baloi. However, although construction work has been completed at

Sei Tembesi, the dam is not in operation due to high turbidity of the water.

Many also question the appropriateness of replacing Baloi with Tembesi. After all, much of Tembesi’s forests have already been cleared to make way for agricultural activities. The forest is not “pristine enough” to receive a protected status. Farmers are also concerned about Tembesi’s new protected status presenting a threat to their livelihoods.

Bengkong

- housing district

- highest population density

Nagoya

- commercial district

- highest land prices

Batam Kota

- housing district

- administrative centre

“What happened to Baloi could happen to the other reservoirs.”

for. Disgruntled, they now demand compensation from BIDA.

The dam at Sei Baloi was the first to be built in 1977 and it was the main source of water supply for the city back then. However, the reservoir is no longer a source of raw water for the city since 2012 due to high levels of pollution.

Yet, even as the water at Sei Baloi is deemed “useless” in the eyes of the city, the land that it sits within is referred to by businessmen as the golden triangle – not least because of its strategic location and for its shape. BIDA has long wanted to convert the land into a business park. In fact, it had secretly sold plots of land to businessmen, even when Baloi forests were still protected. Some businessmen admit depositing money into a bank account owned by BIDA. However, since this deal was not legally recognized, the investors received no land titles. Hence, they are unable to contest for the “land” they have paid

The notion of the golden triangle takes on a different meaning from the perspective of Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry, which sees the triangular plot of land as the last piece of nature that has not been taken over by urban development within that region of Batam. To them, Sei Baloi is important as it serves as a flood barrier during heavy rains; it cannot be developed.

For residents of the informal settlement, Sei Baloi is a golden triangle where they can cultivate freshwater fish and obtain water easily.

Indeed, Sei Baloi should not be written off for its small size. Although it only serves a fraction of the population that Duriangkang serves, its close proximity to the highly populated areas of Nagoya, Bengkong and Batam Centre – where the city centre is – makes it a valuable source of water. This is especially so given that Baloi’s surrounding areas of Bengkong and Batam Centre have been experiencing high frequencies of water supply disruptions ever since Sei Baloi’s water treatment plant was shut down.

CAUSE EFFECT WHICH SIDE OF THE EQUATION?

moretreatmentwater facilities

SOLUTIONS STAGES micro macro

CRISIS RELIEF

The case of Sei Baloi is not unique, it is a problem faced in many developing countries - one defined by the conflicts between economic development, environmental protection and social equity. How can an architect intervene?

Although the land at Sei Baloi has been slated for development into a business park by BIDA, there is – in actual fact – an oversupply of business park areas in Batam. 70% of Batam’s 23 business parks are not in full operation, and the shortage in demand is compounded by the reality that many investors have been relocating their factories to other Southeast Asian nations ever since the minimum

high costs of treating polluted water passed on to consumers by private water monopoly water pipes do not reach informal settlements so informal dwellers have little access to clean water

increase water tarriffs

explore alternative water sources suitableexploreareas for catchmentwaterand storage

improve informal system of obtaining water design water filtration device for people to treat their own water design rain harvesting system for households

micro macro anthropocentric business-centric ISSUES SOLUTIONS STAGES legendground

wage increased in 2012. In short, there is no urgent need for Sei Baloi to be developed; and that partly explains why authorities have been dragging their feet on the removal of Baloi’s squatters. Clearing the informal settlement may be the most direct solution to the problem of Sei Baloi’s polluted watershed. But there is nowhere else these lowincome migrant workers can relocate other than to colonize the protected forests of another watershed. Hence, depopulating the watershed only shifts the problem.

A NEW “WATERSHED”?

Perhaps a more helpful approach to the problem is to look at the notion of “watershed” from a different perspective.

CENTRALIZED

large treatment plants

large treatment plants

small treatment plants

small treatment plants

distributed

large clusters

large clusters

small clusters

individual systems

small clusters individual systems

DECENTRALIZED

Decentralizing Batam’s water supply

A watershed is conventionally known as an area of land that captures and drains water to a common point of discharge. It is a system where topography governs the flow of water through the landscape. Against an increasingly urbanized world, however, it is evident that this traditional notion of the watershed has not been displaced fast enough or far enough to accommodate human activity. In many cities today, the urban environment and watershed are two distinct territories, linked together by a series of pipe networks. The urban grid and site design bears no semblance to the actual natural watershed.

In Batam, the pristine watershed has been contaminated by rapid urbanism. Protected areas within immediate proximity to Batam’s drinking reservoirs have been encroached upon by housing and industry, clearing large tracts of forested land that had served as water catchment area, while discharging enormous quantities of untreated wastewater into the environment. The watershed’s capacity to retain stormwater is reduced and its ability to cleanse

itself naturally weakened. Consequently, the city is plagued with severe rainfall-induced flooding and rising water scarcity due to poor raw water quality. At the same time, its urban water infrastructure is succumbing to the pressures of increasing water demands, with sectors of the population experiencing water supply disruptions daily.

My thesis seeks to define a new form of watershed, using the concept of “neighboursheds” – a term I use to describe a neighbourhood-based watershed. Each neighbourshed is defined by the perimeters of a neighbourhood community and has its own grammar of collecting and managing water. Strategies employed are site-specific calibrations to the different financial, topographical and pollution realities in each neighbourshed. The “neighboursheds” scheme is a system of distributed water infrastructure located at the community level. It intermediates between two extreme scales in Batam’s urban water system – the large, highly-centralized city reservoirs and the small, household level of domestic wells.

The chosen site for the project is the region of Sei Panas, nestled in the middle of Batam’s three most highly populated districts and home to the smallest but most highly-polluted reservoir, Sei Baloi. In 2012, Sei Baloi was shut down after authorities deemed it to be beyond remedy. Since then, Sei Panas has been experiencing one of the highest rates of flash floods and water supply disruptions.

The site is divided by land use into four neighboursheds, each at a different standing in the socioeconomic strata.

The blue lines represent the project’s intervention, or ‘acupuncture’ points in the neighbourshed. The higher the socioeconomic standing of the neighbourshed the fewer acupuncture points per area is required.

At the lowest rung of the ladder is the informal housing settlement, which is further broken up into subneighboursheds each comprising 15-30 households along pre-established pathways.

A repetitive deployable system with minimal aesthetics is implemented here. Rainwater collected from the rooftops of homes is channelled outwards by gutters into a network of water channels which then feeds into a rainwater tank planted in the heart of every cluster. A perimeter of empty space surrounds the water body to objectify it and avail it as a community gathering space. It takes the recognizable form of a circle to serve as an orienting device. The entrance into each cluster is also marked by a grove of banana trees where greywater collected from households is discharged. This supports the growth of the banana trees, which thrive on nutrients from decaying organic matter.

Here, infrastructure is reconceptualized as a means to organize landscape so as to create community identity and a personal sense of orientation.

On the next rung of the ladder is a resettlement site where previous squatters have been newly relocated to.

Neighboursheds of 30-40 households develop in a linear fashion along a drainage channel that runs down the hillside and terminates in a bio-sand water filtration tank - a water kiosk where clean water can be drawn from. An enclosure marks the location of the kiosk and residents descend to the foot of the water tank through a spiral ramp.

Rainwater is directed by gutters into culverts that extend into the drainage channel as baffles to retard the flow of water down the steep gradient. The gutter downspout is displaced from the centre of the roofline as a counterpoint to the symmetry of the building’s elevation.

By rendering visible the flow of water from point of collection to point of discharge, the position of water in people’s consciousness is elevated and a stronger connection with water is drawn.

The third neighbourshed comprising formal housing sits on one of the higher rungs in the socio-economic stratum. It has the highest degree of formality and level of order amongst the residential neighboursheds, thus requiring fewer acupuncture points per area.

Here, each sub-neighbourshed consists as many as 80-120 households. The flat roof is profiled to lead water into gutters that wedge in between alleys, draining into a community cistern located at the end of every block. The overflow of water from these cisterns is then channelled via overhead gutters to irrigate and support reforestation at vacant sites across the neighbourshed.

At each reforested site, rainwater is discharged into a circular receptacle before it flows into a linear trough that directs one along a path towards an irrigation tank. The path cuts into the circular pool and a concrete stairway allows one to descend to the level of the water surface.

Finally, sitting on the upper end of the strata is the industrial neighbourshed which consists of factories and warehouses owned by MNCs. Strategies proposed for this neighboursheds requires the greatest capital deployment.

Highway setbacks are converted into a series of reed beds to store and treat rainwater collected from the roofs of warehouses, thereby forming an interconnected sequence of gardens, framed by stormwater aqueducts along the highway. As the water travels from both ends of the highway down to the midpoint, it undergoes a natural process of filtration and is at its purest at the lowest point of the topography. Here, a water treatment plant purifies and treats water that can then be distributed and sold to the residential neighboursheds through an aqueduct bridge spanning across the highway. Water collected in residential neighbourhsheds is non-potable; it is only here in the industrial neighbourshed where water can be made potable through purification.

Ancillary structures that are added to the roofs increase rainfall catchment area and gives rhythm to the roof profiles.

Ladders diagram - water network flow logic

It takes a village to protect a watershed. Neighboursheds are an alternative to the state’s singular system of water provision where people have been absolved from the responsibilities over the well-being of their watershed.

By incorporating water infrastructure as an essential visual component in the urban environment, the “neighboursheds” framework sets up a new contractual relationship between people and their watershed, thus enabling the safeguarding of water sources through community-level action.

Failed Attempt 1: Remediating Sei Baloi with Constructed Wetlands and Urine Diversion Toilets

STRATEGY: CONSTRUCTED WETLANDS + URINE DIVERSION TOILETS

SUBSURFACE FLOW CONSTRUCTED WETLAND (SSFCW)

STRATEGY: CONSTRUCTED WETLANDS + URINE DIVERSION TOILETS

VERTICAL FLOW SSFCW HORIZONTAL FLOW SSFCW

URINE DIVERSION TOILET (UDDT)

HORIZONTAL FLOW SSFCW

URINE DIVERSION TOILET (UDDT)

RELOCATION OF HOMES SUBDIVISION OF NEIGHBOURHOODS

BUFFER AROUND RELOCATION OF HOMES SUBDIVISION OF NEIGHBOURHOODS

BUFFER AROUND EXISTING

SOURCES

p10-11: http://gis.bpbatam.go.id:8080

p12-13: http://www.globalwaterintel.com http://www.temasek.com.sg, http://sembcorp.com http://www.ptbck.com

p14-15: http://www.atbbatam.com Batam Dalam Anka 2014 batampos edisi 52: Membuka Kontrak ATB

p18-19: Dinas Kebersihan dan Pertamanan (DKP) Batam

p44-45: International Refereed Journal of Engineering & Science

by the grace of God this thesis is complete.