AR2102, AY 2010/2011

SINGLES & MULTIPLES

ANIRUDH CHANDAR

CHONG KAIYI

CONG WEN JIN

CHAU SHIYI FIONA

LIM YAN LING SHERILYN

PEH SZE KIAT IVEN

RI BERD

STEPHANIE WONG QING

LING

WYNN LEI PHYU

ZHANG XIAO

CHEN HUIHUA

CHEN SHUNANN

LIAM YUEXIN, JOLENE

LOW ZHU PING

NG ZUEMIN, SHERMIN

SEOW CONG MING, SHAWN

TAN KIM LENG, NICHOLAS

QUEK SEE HONG

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE

SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND ENVIRONMENT

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE

Singles & Multiples Studies

in Operations

Singles and Multiples is a graphical collection of research into the core of architecture and urban form performed at the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment at the National University of Singapore. Represented in orthographic drawings, axonometric projections, and black and white photographs, the elemental methods of architectural operations are explored and documented as a means to illustrate logic and formal understanding. Operations to the singular body are equated with the architectural object while deployment and modification of the multiple are understood as imminently urban; i.e. the collection and aggregation of objects. Purposely disconnected from the pragmatic, the work does not display research in finality but rather represents ideation, captures process, enables didactic conversations, and projects ideas of object-ness and aggregation as a means to think through basic architectural acts. Traced through the discourses of Fumihiko Maki’s Investigations of Collective Form, Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky’s Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal, and Paul Rudolph’s projects in the tropical local of Southeast Asia, Singles and Multiples returns the architectural and urban conversation to its operative foundations.

With 185 images and 119 drawings.

ISBN 978-981-07-6019-9

ISBN

7601997898109

Department of Architecture

School of Design and Environment

Singles & Multiples

Erik G. L’HeureuxSingles & Multiples

Erik G. L’HeureuxPublished by:

Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture

Department of Architecture, School of Design and Enviroment, National University of Singapore

4 Architecture Drive, Singapore 117566

Tel: +65 65163477

Email: akierik@nus.edu.sg

© Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture

National University of Singapore

© Individual Contributors

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher and author.

The publisher does not warrant or assume any legal responsibility for the publication’s contents. All opinions expressed in the book are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National University of Singapore.

© Assistant Professor Erik G. L’Heureux AIA, LEEDSINGLES AND MULTIPLES

Single

From Middle English, via old French: From Latin singulus,relatedtosimplus;simple Adjective:onlyone;notoneofseveral,consistingof onepart

Verb:tochoosesomeoneorsomethingfromagroup forspecialtreatment,toreducetoasingleline

Multiple

From seventeenth-century French: From Latin, multiplus,analterationofmultiplex

Adjective: having or involving several parts, elements,ormembers

Noun:anumberthatmaybedividedbyanothera certainnumberoftimeswithoutaremainder

Why Care About Form?

Form as a field of study appears old fashioned. It refers to an age in which geometry was celebrated by Sebastiano Serlio in his first book of architecture, Architettura, in which he states “how needful and necessary the most secret Art of Geometrie is”. This was in 1537. Philibert Delorme held geometry as a virtue in architectural thinking throughout his Nouvelles Inventions Pour Bien Bastir et à Petits Frais and Le Premier Tome de L’Architecture published in 1561 and 1567 respectively.

Form, however, is not geometry, nor is shape the same as form. They can be defined as distinct categories. They share interrelated attributes, though each has a different profile. Geometry is the mathematical study of lines, planes, surfaces and solids. Shape is the appearances of such geometries specific to external descriptions. Form comes from the Latin “forma”, meaning a mold. It is also the outward appearance of geometries as in shape. But in architectural discourse, form is also an internal organization typically understood

within a logical (or linguistic) framework. When we say that a building has a nice shape, we are referring to its exterior composition. When we say that architecture is a product of form, what we really mean is that the architecture is thoughtfully considered inside and out in terms of both its shape and its geometry. This “thoughtfulness” is aesthetics, as Serlio indicates by calling geometry an “Art”. Geometry alone is mathematics. But geometry that becomes observable as visible and spatial phenomena rendered through a thoughtful ambition becomes art, the aesthetics of geometry. It then follows that architecture is the transformation and intensification of geometry, shape and form into a system that holds our attention, a special kind of shape and geometry that is in contrast to ordinary geometry found around us. Of course any building is geometric and has a shape, but this alone does not make architecture. This book is about this intensification and the systems that hold our architectural attention on geometry that becomes form.

Considering the current milieu of crisis that confrontsurbanenvironmentsand,toasmaller degree, architecture today; from political turmoil to environmental deterioration; from climate change to economic disparity and poverty; the study of form—the study of formal intensification—appears isolated at best, or entirely self-indulgent at worst.

Though we can find a more contemprary axis of architects speaking on form. Colin Rowe spoke of form in great detail during his career as an educator and theorist. Peter Eisenman, mentored by Rowe, begins his career on form with his 1963 PhD dissertation, The Formal Basis of Modern Architecture.1 Likewise, Greg Lynn, a student of Eisenman and later an educator, continues writing about form through digital tools and the diagram. In Southeast Asia, and in Singapore in particular, from where this book springs, this important work is hardly understood, nor is the impact great.

Form takes on secondary and tertiary roles in a Singapore atmosphere of practicality

in which architecture’s role is relegated to positivistic social or technological ambitions. If the assumed larger and “more important” social and technological forces drive architecture, then architecture’s role is one of service. Indeed, in Singapore, architectural attention is firmly oriented toward the solving of problems. The assumption follows suit that “to make a better society one makes better architecture”. This is not a new relationship to architecture; rather, it emerges out of thinking put forth by CIAM decades earlier, when modern architecture was a vehicle for the benefit of larger social and developmentalist ambitions, and serving those ambitions was its aim. And indeed, Singapore’s urban environment is planned almost entirely under CIAM principles to create “solutions” for the nation’s housing and development agendas. The convenient adages “form follows function” and “form follows finance”, subjugating form to second place, emerge in the context of such thinking. These are misguided. Form has never entirely followed function, nor has it been a direct product of structure, culture or society. Form can never be viewed as a legitimate mode of architectural research if architecture’s role as service is already predetermined. Likewise, architecture cannot have any ability to shift society if its ambitions are only to serve.

In this context, Le Corbusier, a founding member of CIAM, spoke of form in service to society, yet produced his formal invention in architecture not from these social agendas but from a formal and painterly tradition emerging out of Purism. His compositional logic of shape, geometry and form guided the architecture not only of his villas but also of his urban planning propositions.

Form, I firmly believe, operates between its ownautonomouslogicandthecurrentlogicsof society, culture and the performance criteria required of it. At specific moments, form is a uniquedisciplinewithinarchitecture.Atother moments, form is influenced by symbolism, program, finance, technology, atmosphere and climate. A symbiosis between those two spheres—form’s own autonomous logic and

the environment in which it functions—is what makes form so compelling, fascinating and wrought with continual debate.

Singles and Multiples

Consider single and multiple elements in architecture. Those two categories are basic, even reductive. They are both clearly autonomous from politics, technology and society. What are the differences between single objects and multiple objects beyond a numerical counting? In what context can we speak of those differences?

When considering a singular element in a pictorial two-dimensional configuration, a conversation can be had about its own proportion: its width to length, its total area, and its organization. Is it composed of poche (the blacked-in portions of plans) or constructed of an enclosing line?

What is the thickness of that enclosing line in relationship to the interior body? In this example, the elemental form is Euclidean, assumed to be two-dimensional and perpendicular to the line of sight. Its poche might be solid, lined or stippled; it could operate as a pocket and contain internal organs, as Bernhard Hoesli described.2 The conversation is primarily interior to the rectangle itself; that it is understood as an autonomous object with its own internal organization independent of its surrounding.

Placing a singular rectangle on a table shifts the conversation to the relationship of the rectangle to the table’s size, the table’s perimeter, and the orientation between the rectangle and its frame. The juxtaposition changes the conversation about the rectangle itself as an autonomous construct to one of relationships, of context. As Fumihiko Maki writes in Investigations of Collective Form (1964), two elements form a compositional arrangement.3 Is that relationship between the two elements axial or asymmetrical? Do the two elements create a third space?

Multiple elements—more than two— establish primary relationships between

each of the constituent pieces. Questions of proximity, distance, orientation, location and position arise between each of the pieces. Parallel to the single rectangle positioned on another rectangle (represented by a table in Figure 2), a discussion of multiple elements is primarily one of externality and relationship. The space among and between each of the elements is primary. The proportions of the singular element are secondary.

Maki makes the urban argument that the organization of multiple elements may be categorized as compositional, megastructural, or group-form. Compositional form describes a discernible order among the elements separated in space. The megastructure category is produced by the aggregation of smaller elements into a larger structural framework. Group-form, or the collective, implies that the elements are similar in proportion and size and yet have an organization that is not entirely fixed or predetermined.

In Figure 3, a compositional organization illustrates rectangles organized about a Euclidean grid with clear spacing between each of the edges. Elements are positioned in parallel or perpendicular relationships. A negative space is produced between the four solid elements as cohesive glue. The elements themselves are all rectilinear and in orthogonal proximity to one another. The proportion of the elements, the resulting negative space, areas of solidity, and clear structure of organization are visible. The single element is articulated and remains

autonomous, though in precise position to its neighbors.

The linking of a series of smaller elements to a larger whole, as illustrated in Figure 4 through the spine- or mega-structure, utilizes proximity, overlap and adjacency to construct a larger entity. The single is repressed into a mega-framework where the coherence of the whole outweighs the articulation of the singular. The coherence of the larger agglomeration supersedes that of the individual elements of its fabrication.

Group form in Figure 5 is organized along a latitudinal structure; however, the position of each of the elements has no immediately discernible organization. A semi-spine separates two elements on the left from three on the right, though the spine is neither precisely positioned nor clearly visible. Likewise, a general massing of the elements keeps them in relative proximity, though the specifics of their internal aggregation are not evident. The multiple elements—the collective group-form—assert aggregation over order, informal over formal, and the pile over the structural. In that example, sequential order is favored over compositional order and the elements dissolve into the entire whole.

The compositional and mega-structural forms are closed-form organizations. Modifications to those organizations must explicitly follow the rules of composition or mega-structure; without considering those rules, the organization becomes highly incoherent and illogical.

By contrast, group-form organizations are [Figure

open-form organizations where additions and subtractions are tolerated in the overall structure. The openness of that formal system enables change and adaptability as long as the modifications are of similar size and scale.

Compositional form is based on positional logic while mega-structure is founded on hierarchal logic. Group-form organization, however, is an adaptable logic, more closely related to the urban field rather than the singular object itself.

A fourth organizational structure, one based on transparency as presented by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky in Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal (1963), constructs an argument for multiple interpretations of form at the same time.4

Multiplicity in architecture is accomplished by overlapping forms to create new and indeterminate organizations. An example of multiplicity, as shown in Figure 6, illustrates an orthogonal organization of elements, latitudinally displaced, yet overlapping.

In this figure, the elemental rectangle is multiplied, overlapped and transposed. Time is introduced if we imagine moving through the layers physically, or through the process of creating one layer placed over another. The overlapping of each element creates secondary and tertiary elements (smaller and larger rectangles and squares) that demand alternative readings of the organization. Those overlaps undermine the purity of the primary elements. Alignments and equivalent areas produce sub-structures, super-structures or mega-elements that emerge out of the overlapped elements. Indeed, more than one organizational logic may be read.

In this case, the graphical arrangement of rectangles on a two-dimensional surface

is projected into three dimensions, the implication being a collection of spatial layers in time that may be viewed by a moving eye, oscillating between two- and fourdimensions. The eye moves through the various layers as a camera lens might, focusing either on one layer or on the entire image at once.

Yet Rowe and Slutzky’s work is primarily about expanding the possibilities of the single architectural object through the complexities of internal organization. In effect, Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal extends the resonance of compositional and mega-structure form into the architectural object itself.

Digital Modifications

Maki’s group-form, rather than Rowe’s Phenomenal (or his later work on Collage City), has been extended most dramatically in recent architectural research.5 Digital tools including software that enhances simulation, modeling and fabrication, along

with scripting and algorithms, have enabled more complex geometries and organization. Gradients, permutations, folds, surface mutations, stretching, torques, liquefy, drapes, swarms, emergent, distributive, interpolation and approximations are part of the architect’s vocabulary, another tool that enhances architects’ understanding.

Much contemporary digital research and exploration is now predicated on creating basic and elemental rules within scripts, which affects all subsequent geometry. Parallel to Maki’s predilection for group-form, there is presently a preference for the aggregate and cellular found among many architects. Aranda/Lasch, MOS and Sou Fujimoto come to mind, though today the cellular is manifest through digital tools.

Compositional: Closed-Form, Object-Oriented,Single

Mega-Structure:ClosedForm,Urban Oriented,Singlewith multipleinteriors

Group: Open-Form,Urban Oriented,Multiple, Aggregate

Phenomenal: Closed-Form,Object Oriented,Multiples withinspaceoftheSingle

Parametric: ClosedForm,Urban Oriented,Multiples

The aggregate vacillates between its own internal singular logic, and the logic of the larger combined collection. In essence, it is a merging of the phenomenal transparency identified by Rowe—the complexity within the single architectural object—and Maki’s

group form with its complexity produced by aggregation. The merging of these categories produces a double legibility allowing geometry to operate on different scales and enabling different readings simultaneously. Geometry then oscillates between complexity and coherence. I have extended Maki’s categories by adding Phenomenal (even though it was published a year earlier) and by adding another category of the Parametric.

That double coding of the parametric creates the ‘double entendre’. In this case, the double entendre is not a product of creating specific postmodern allusions as found through proponents of Post Modernism (Venturi, Johnson, and Graves come to mind), but rather emerges out of the specific rules and configurations of geometry itself.

If the “single” relates to logics of interiority, exhibiting a disconnection from its context, then “multiple” relates to ideas of association based on exteriorities and represents collective ideas of combination in the context of urban forms. In short, singles are architectural objects, multiples are urban organizations. Today, in digital parametric circles, we find ambitions of combining the two.

Single and Multiple Lineages

The ambitions of the single and the multiple as found in this book have robust lineages. Design on the single—the architectural object—is found within the work of Giuseppe Terragni and the early studies of Peter Eisenman.

For Eisenman (and Rowe), the frontality, elevation and exterior surface of the singular form are primary: Le Corbusier, Terragni and Palladio all feature heavily as undercurrents, where the preference for the architectural object as a singular body is paramount. The multiple (urban) plays a secondary role to the singular as complexities are developed within and about the interiority—and autonomous nature—of architecture. For Eisenman, operations to and about the single architectural body drive his formal agenda.

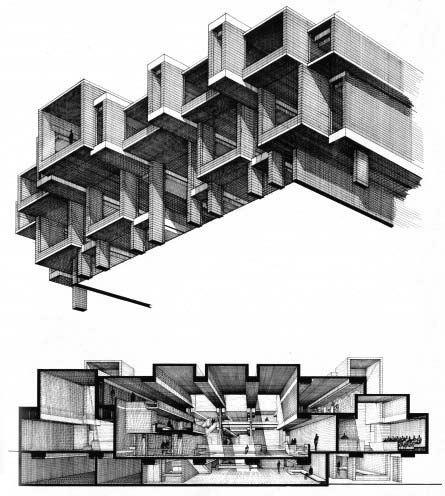

Research on the multiple is found in the

projects of Paul Rudolph (1918-1997), in which overhang, cellar multiplicity, stacking and aggregation are all evident. For Rudolph, geometric clarity merges with a preference for spatial complexity, combinatory planometric ingenuity, and legible formal logics. Rudolph produced a body of work more multiple than singular and more urban than object.

Traces of operative techniques found in Eisenman’s work are clearly evident in Rudolph’s work as well; multiplication, shearing, shifting and displacement are all highly visible. Yet Rudolph’s process is of aggregation related to heat, breeze and solar shading rather than the syntactical notations and internal referential displays of virtuosity in architecture evident in Eisenman’s work.

Rudolph’s early houses in Florida and his later work in Asia most clearly deploy combinations of multiple elements. The techniques of stacking techniques, both vertically and horizontally, and aggregation strategies created variegated arrangements of shade, terrace, volume and overhang.

Rudolph’s large-scale mid-career work in the United States embodies many of those formal ideas, though many seem inappropriate to the temperate northeastern states where much of his work was built. His preference for exterior spaces as a product of geometric operation has little relevance in the blustery winds of a New England winter, as we find in his University of Massachusetts Dartmouth campus. In Singapore, however, where Rudolph’s career later thrived, his work seemed to take on an ever-pressing relevance, where large overhangs, generous verandahs and covered exterior patios all make sense in areas of tropical heat and humidity. It is there that the geometrical manipulation of planar and volumetric elements produced unexpected and delightful configurations. Not for geometry’s sake alone, the spaces are relevant to the particularities of tropical living—both as naturally ventilated spaces and as enclosed areas that feature air-conditioning.

For Rudolph, having been educated in Alabama, and later, having worked in Florida,

designing spaces in tropical climates was part of his architectural upbringing. As a mature architect, The Colonnade along Singapore’s Grange Road, as well as his Wisma Dharmala Sakti office tower in Jakarta, Indonesia employ multiples to produce compelling exterior spaces shaded from the tropical sun, an extension of his work in the American South.

Rudolph employed geometry for compelling and contextual ends, creating verandah spaces, outdoor living spaces and breezeways rather than for operative meaning alone, as we find in Eisenman’s work. Rudolph extended the multiple and the urban into vertical configurations, as evident most spectacularly in the Colonnade Condominium, merging architectural singular complexities with the demands of urban densities unique to tropical Asia.

What is interesting about Rudolph is the combination of singular elements deployed in multiple configurations, creating intensely tropical and urban architecture.

The formal traditions are steeped in a long history. Rowe and Slutzky wrote Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal in the Yale Architecture Journal Perspecta 8 in 1963 some 50 years ago.2 Maki’s Investigations on Collective Form was published in 1965. Eisenman’s prolific career began in 1962. Paul Rudolph’s prolific career fell out of favor in America, after the 1972 publication of Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour’s now infamous Learning from Las Vegas though he reestablished his career in Asia working on large-scale projects through Southeast Asia until his death in 1999. Remment Koolhaas claimed to have a preference for the formal in his conversations with Maki: “I empathize with your side (implying group form), though I can’t quite participate in it.”6 For Koolhaas, the single—the architectural object— prevails.7

The work presented in this book is rooted in those traditions. The intent is to extend Maki and Rowe’s research on form, merging singular complexity with aggregate form; to

reinvigorate the conversation on form, the architectural body, and the urban collective in the contemporary tropics. The examples that we find in Rudolph seem to merge these categories more successfully, combining the formal and the tropical, the singular and the multiple into immensely urban and powerful forms. And yet we have too few examples of Rudolph’s work in tropical Asia to prove that such a mode of working is indeed successful.

The drawings and models in the following pages show two distinct modes of operations. The first chapter provides illustrations of architectural concentration on the single formal body, the second chapter on its multiplicity as an urban condition. The Parametric is held at bay if only to foreground and more thoroughly mine these earlier examples of compelling formal research.

To impact the urban and tropical world around us, starting at elemental ideas of the single and multiple—starting at form itself— remains an important act of architecture. The work in these pages is not fully architectural in its complexity—they are proto architectures composed of formal research in single and multiple operations. Yet in totality, the work suggests a potential for extension into the architectural sphere, a beginning, a suggestive possibility, a trigger for a more thoughtful conversation and extension of architecture’s core—its form.

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP BD+C Assistant Professor Department of Architecture School of Design and Environment, NUS

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP BD+C Assistant Professor Department of Architecture School of Design and Environment, NUS

Endnotes:

1. Eisenman was mentored by Colin Rowe during his time at England’s University of Cambridge.

2. Hoesli, B. (1997). A Note on Poche. In C. Rowe, R. Slutzky & B. Hoesli,Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal (p.118). Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Verlag.

3. See Maki, F. (1964). Investigations in Collective Form. St. Louis: School of Architecture,Washington University.

4. Rowe, C. and Slutzky, R. (1963).Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal.The MIT Press on behalf of Perspecta, 8, 45-54.

5. See Rowe, C. and Koetter, F. (1984). Collage City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

6. Koolhaas, R., Obrist, H.-U., Ota, K., & Westcott, J. (2011). Project Japan: Metabolism Talks. Köln:Taschen.

7. Koolhaas’s greatest architectural trick as a champion of the urban is the introduction of the urban (multiple) into the architectural singular body. In another word, for Koolhaas, urban experience becomes a device with which to intensify the architectural body. Rarely do his architectural bodies intensify the urban conditions in which they sit.

Images courtesy of: http://www.archigraphie.eu/wp-content/ uploads/2010/02/Terragni_Casa_fascio.jpg, accessed December 20, 2012.

http://archinect.com/features/article/2875457/5projects-interview-5-alexander-maymind, accessed March 20, 2013

http://ad009cdnb.archdaily.net/wp-content/ uploads/2010/11/1288678052-milamresidence1.png, accessed December 10, 2012.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_TSJ1g2k6Y4c/ Smegl70xiaI/AAAAAAAABAk/Z4MRy3nzvHk/s320/ wisma01.jpg, accessed December 12, 2012.

http://ad009cdnb.archdaily.net/wp-content/ uploads/2010/11/1288892010-oc1-125x125.jpg, accessed December 10, 2012.

http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NY-BQ036_ SPACES_G_20120502171528.jpg, accessed November 10, 2012.

http://structurehub.com/blog/wp-content/ uploads/2010/02/massachusetts-umass-dartmouthuniversity-library-brutalism-paul-rudolph-from-kelviinon-flickr2.gif, accessed December 10, 2012.

http://ad009cdnb.archdaily.net/wp-content/ uploads/2010/11/1290197902-5-125x125.jpg, accessed December 11, 2012.

http://farm3.staticflickr.com/2774/4437194998_ f057591b49_z.jpg, accessed December 12, 2012.

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003689352/ accessed February 13, 2012.

EXPERIENCING THE ITERATIVE

The iterative methodology is based on a process of incremental transformation, and unlike design that deals with a single overwhelming idea that manifests itself through hurried selffulfillment, the design process begins with a “characteristic” or set of rules that the designer cannot predict. The design, by virtue of itself—its materiality, its legibility and its syntax as an object (or collection of objects)—serves as the driver of the scheme.

Each step forward is enabled by the reading of the physical (objective) manifestation of the previous step.As opposed to an idea, the whole scheme’s direction is controlled by an oeuvre that emerges along with the clarity of the decision-making process. The primary method of critique and development is rationalization in the form of morphological discovery—discovery more than innovation, by virtue of the reading of the generated form taking precedence over the assumed intent.The keynote of this methodology is syntactical development as opposed to synthetic architecture (post-modern imagery recreation).1

Take the case of arguably the most notable of iterative purists—Peter Eisenman. For Eisenman, a self-generative architecture, or architecture that is independent of an author or architect, was a great impetus in his work. His agenda was always to construct a contextual disconnect within the architecture.

Context is not ignored; rather, it allows the morphology to be independent of the architectural “trend” of its time, thereby allowing for critical dialogue to be free of the same. His writings on architectural anteriority and interiority elucidate his stance on context and historical drivers in his work.2 Eisenman looked to collapse all dialogue regarding his work into itself and its context, as opposed to postmodernist dialogue involving references to elements from other syntaxes and contexts.

The two projects dealt differently with transformations imposed on one object (single) and transformations enabled by the combination of

several single units (multiple). Both worked under a strict morphological discipline but the operations involved varied greatly.

In a more generic way, these projects have taken on Eisenman’s oeuvre in wanting to attain a critical autonomy or displacement from historical anteriority.3 Through the privilege of restriction enforced by singular material use and black and white panels devoid of text, communication of ideas is allowed solely using the tools of the discipline (orthographic drawing) and representative models, weeding out deception and allowing for legibility of intent.

These ideas of interiority and anteriority relate to Eisenman’s views but express themselves through the two projects in particular ways. Focusing initially on the single or the manipulation of one object through certain operations, its interiority is far more acutely dealt with in terms of its space, form and internal dialogue. With the multiple, the object is not as diligently sculpted as the logic behind the accumulation or aggregate that is created using the simpler units.The aggregate or grouping is based on external stimuli with relevance to its enveloping context or site.

Morphologically, the two projects start without pretext, contextual reference or case study. The site itself plays a role only after a large part of the morphology is completed, by which stage the architectonic ideas need to be reduced into actual inhabitable architecture. This stage is representative of the reduction of the purely ideational to a level of compatibility with the normative.

The iterative as a methodology provides an escape from non-linear/indecisive development and, once adopted and experienced for the duration of a scheme, enables the growth of the designer’s individual approach to the discipline of architecture by virtue of the purity of its critical discourse. In enabling the creation of an apparatus and the functioning within its restrictions, critical subjectivity is almost removed from the dialogue.

In actual discipline, the purity of the methodology is arguably less valued by architects than the form or ideas it helps generate. The human element in architecture is what eventually engages the user and enables/disrupts the functioning of said user. As an educative tool, however, the iterative process is a potent methodology.

“A building is a building. It cannot be read like a book; it doesn’t have any credits, subtitles or labels like pictures in a gallery.” – Jacques Herzog

1. Gandelsonas ,M. (1972, March). On Reading Architecture. Progressive Architecture, 53, 66-88.

2. Eisenman, P. (1999). Diagram Diaries. New York, NY: Universe Pub.

3. Eisenman, P. (2004). Eisenman Inside Out: Selected Writings, 1963–1988. New Haven:Yale University Press.

Anirudh Chandar

Level 4

Department of Architecture

School of Design and Environment, NUS

Design is a thoroughly confusing thing. It involves many aspects thrown together, but not necessarily in a comprehensible order.The designs illustrated in this book follow a skeletal process.

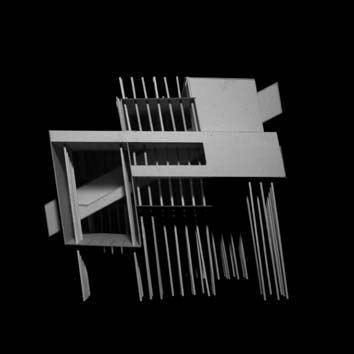

First, we start out with a vector.The designer develops his concept systematically and analytically, putting aside the multitude of considerations that would plague the architect in a real context. It is “ceteris paribus”, the term favored by economists to describe a predication with all other things being held constant. In the Single, it is a discourse on how structure guides the principles of design.We approach a design brief with a singular purpose, allowing us to concentrate on the different forms and concepts of structure.This is explored through the creation of a variation on a grid of columns, arranged in the manner providing the most compressive strength.

Then the design starts to take on many possibilities, and this is where control and rationalization come in. Structure is now seen in relation to spatial considerations. The focus is on creating a spatial field in terms of how space and structure interact.While structure is seen as the physical load-bearing system and space is seen as ascribing to programmatic needs, the process of design witnesses an exchange of compromise between the two and a convergence of their aims. Through resolving structural weaknesses and redundancies, certain structural forms give way to spatial considerations.There is a transformation of the scheme to the requirements of enclosure and program. In designing for a fishing platform set out in the sea, the grid of columns becomes the piles that form the structural core of the platform.

This introduces the limitation of the length of the piles and the need to keep the platform substantially above water. Structural joints now need to be considered in the design process. The question then becomes the extent to which programmatic considerations interfere with initial structural considerations, and which one takes priority in the design.

Similarly in the Multiple, the starting point is the most important part of the design methodology. At the beginning, we are not distracted by a multitude of considerations involving light, program and material, but thinking in abstraction; where the abstract first form of a module seeks to unearth the fundamental driving force that would see the scheme through to the final critique. Again, we are required to rationalize and control through a set of additions and subtractions to the modular form; however, instead of looking at structure, we deal with the repetition of a singular form and the design considerations it poses.

Design is a process of taking formative ideas and transforming them into architectural form, but the process itself is not that simply said. It is a dialectic between a person’s ‘soul’ and their intellectual rationalization, where many considerations compete for the architect’s attention. However, in the education of an architect, we are able to have an in-depth study and discourse on the intellectual rationalization of formal design that would not be possible in a real context, and this book displays the fruits of this investigation.

Sherylin Lim Level 4 Department of Architecture School of Design and Environment, NUSSingles

Multiples

Notes on a Methodological Education about Formal and Geometric Logics

The emphasis on elemental form based on singles and multiples represented in this book came about through dissatisfaction. In 2008, in a moment of frustration with the pedagogical directions of design studios with which I had been involved, I recalibrated my methods of teaching design. My frustration only peaked as I perceived my students’ inability to tackle design issues and problems seriously. They often resorted to solving design problems by providing a sampling of current formal experiments in the architectural community at large, however fanciful. In examples that bordered on almost blatant plagiarism, I was continually confronted by project after project where the copying of pre-existing aesthetics and formal orders were the modus operandi. And more often than not, students

had little clear understanding of why particular geometry was developed for a referenced scheme, never mind why cutting and pasting was an invalid technique for the production of architecture.

What resulted was a calibrated and yet thorough reconsideration of the early education of an architect, where the studio engaged discussions of the very ideas of methodology for design, and where the autonomous ideas of geometry, formal order and logic became instrumental.

Ideas produced by students that were originally free-formed became restricted, what was conceptual became operational, and what was a belief that original aesthetics would later emerge from student work became directed. At the threat of being labeled prescriptive or—worse—dogmatic, the pendulum within the studio swung from extreme individual expression to a rigid pedagogy of instilling specific operations on discrete formal problems. Restriction, rules and logic came first and innovation followed.

Students balked, as they often do, for the design studio is viewed as the place where they establish their individual artistic identities. The design studio represented, or so students came to believe, the space for extreme expression, asserting their will onto architectural

problems as they saw fit. The design studio symbolized a place for individual autonomy and pure creation where difference was celebrated, where artistic virtuosity privileged the innately talented, and where a culture of mimicry sufficed for the remainder. And yet, those very students had completed a mere 18 months of education, had understood little of the descriptive, historical or operational devices that shape our built environment. For most students, their own awareness of the world around them had only just begun. Geometry, formal order, informal organization and compositional understanding had little importance in a culture where sampling precedents and half-hearted attempts at tracing over the “masters” ruled.

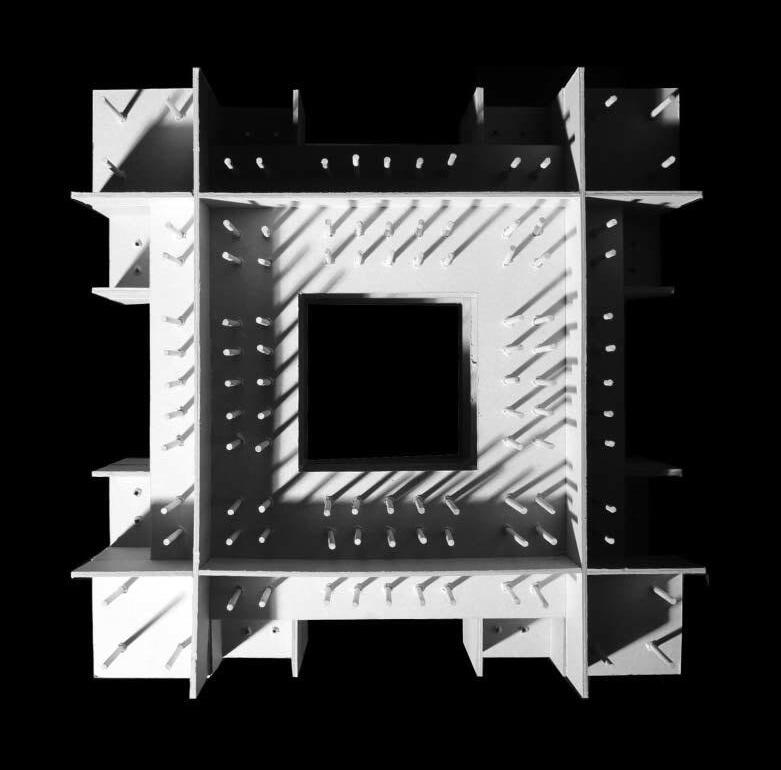

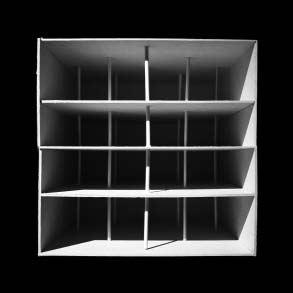

Through a series of discrete steps titled “probes”, I presented elemental formal challenges to the students. One challenge was based on the creation of internal logics within a singular volume. Constructed of planar and linear elements, the students were expected to produce a logical organization of line, plane, mesh and volume within the perimeters of a simple cube form. The formal research is primarily architectural: the logical application of form within and about the singular architectural body.

The first challenge began with a single cuboid 150mm by 150mm by 300mm, fabricated in greyboard and designed as inflexible in any visible manner. Through a series of probes, operations are made to the cuboid, adding and subtracting, altering and modifying. A second step impaled the volume onto a field of 20mm on center dowels, encapsulating a volume of 300mm by 300mm by 300mm. New logics emerged out of the interpenetration, yet the primary focus was the legibility

of the operations being performed interior to the single volume. Perforations, screenings and displacements, along with subtractions, erosions and bifurcations were implemented as a means to produce coherence. The first challenge, being singular, was primarily architectural; the second, one of multiples, was principally urban.

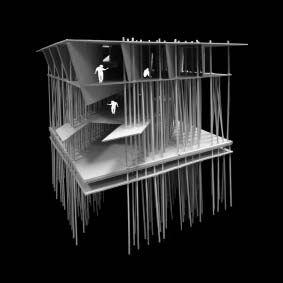

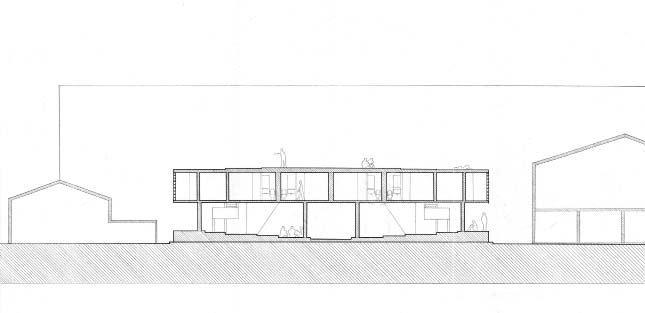

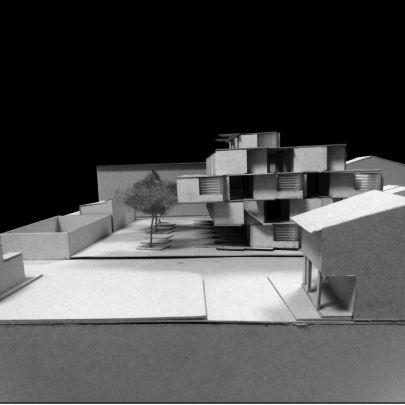

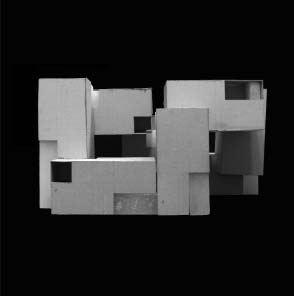

The second vector deployed multiple cellular elements to create variegated envelopes, organizations of overhangs and recesses, and varieties of spatial configurations relevant to the tropics. That formal research is primarily urban, where cellular construction is positioned in space to produce urban constructs of figure and void, square and block, fabric and urban landscape.

This study of the multiple began with a similar-sized volume. Through a series of probes, the greyboard volume of 150mm by 150mm by 300mm was modified with the introduction of a wax or plaster mass constituting 25 percent of the entire volume. The total volume was then duplicated, quadrupled, and intersected with itself.

The strategies for arrangements and position of the multiple units created organizational logics. The combination of individual cellular elements created larger meta-organizations. Each student examined the external logics created by their cellular deployments oscillating between the informal pile and formal meta-cuboid. Position, distance, proximity, intersection, superimposition and collision set the terminology for understanding how geometry created rules of organization for a proto-urban configuration.

The aggregation was then inserted into an

existing urban context. Scaled changes to the geometry accommodated forms of inhabitation, while the designs are reconfigured to imagine structure, ventilation, atmosphere and materiality. Aggregations transformed into space, geometry became functional, and modes of re-organizing exteriors impacted interiors.

What emerged from those operative methodologies were formal configurations that represent aspects of pre-design, calibrated to specifics of architecture, in this case, in a tropical atmosphere. That is form created for the realities of natural ventilation as well as the contemporary demands of air conditioning. In another words, the designs are situated between the permeable and the sealed. The configurations that result are a product of merging both an intuitive sense of geometry and logical demands. Utilizing drawings and models, representations described how the respective geometries are created and how they are read.

The results of the probes, though not fully architectural or urban in their complexity, nevertheless impart a foundation for students to develop original, thoughtful and rigorous solutions in formal understanding. These proto

architectural and proto urban lessons remain as fundamental and important basics informing the students’ repertoire of geometric and formal operations. As the students add more complexity and care to their capabilities over time, it is the foundation of probing deeply, thinking carefully, and producing original thought that I trust stays with them. For me, this is a powerful and robust antidote to a culture of sampling existing architecture and relegating architecture to mere problem-solving. The work represented in these pages offers proof of this methodology, proof that rigorous thinking and experimentation in form remains a valuable body of knowledge for the very formation of architectural ideas.

Erik G. L’Heureux, AIA LEED AP BD+C Assistant Professor Department of Architecture School of Design and Environment, NUSContributors

Erik G. L’Heureux AIA, LEED AP BD+C Assistant ProfessorDepartment of Architecture

National University of Singapore

Born in USA in 1973

Lives and work in Singapore

Erik G. L’Heureux AIA, LEED AP BD+C is an architect and educator. He is an Assistant Professor at the National University of Singapore where he researches utopian visions of the city, hydrology and density. A former boat builder, he practiced architecture in New York City while teaching at the Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union. Erik received a Master of Architecture from Princeton University, where he received the Susan K. Underwood Design Award. He studied as a Fitzgibbon Scholar at Washington University in St Louis, where he received his Bachelor of Arts in Architecture and was recently honored with a Distinguished Alumni Award.

Erik is a registered architect in the USA, American Institute of Architect Member, NCARB certified, and a LEED accredited professional. He has won several international awards including a 2012 AIA NewYork Design Award, a 2011 President Design Award from Singapore, and twoAIA NewYork State Design Awards, among many others. His work has been published in internally and he lectures widely.

Anirudh ChandarB.A.Arch Candidate

Department of Architecture

National University of Singapore

Driven towards the understanding, appreciation and pursuit of an expanding sphere of interests, Anirudh’s focus in architecture is an attempt to pry open the current affectations of architecture and to develop a critical methodology for himself. This idealistic goal is reflective of a struggle between a humanist practice and a selfindulgent discourse within his architecture. Punitive in his approach to most subjects, his curiosity acts as a significant motivator. With an almost pedantic taste in music and films, his pursuit of architecture arose from an internal obsession with geometry and puzzles.

Sherylin Lim

B.A.Arch Candidate

Department of Architecture

National University of Singapore

A great lover of film, literature and music, Sherilyn constantly draws inspiration from different places in designing. Architecture is, according to Sherylin, very much about the tangible experience as it is visually appraised. Whether through architectural design, writing or photography, she is most excited when creating something that conveys new ideas and different ways of viewing the world, and making it her own.

Selected StudentWork Exhibited

Year 2, Design Level 4

2011

Anirudh Chandar

Chong KaiYi CongWen Jin

Chau ShiYi Fiona

LimYan Ling Sherilyn

Peh Sze Kiat Iven

Ri Berd

StephanieWong Qing Ling

Wynn Lei Phyu

Zhang Xiao

2009

Chen Huihua

Chen Shunann

LiamYuexin, Jolene

Low Zhu Ping

Ng Zuemin, Shermin

Seow Cong Ming, Shawn

Tan Kim Leng, Nicholas

Quek See Hong

Credits and Acknowledgements

Appreciation is extended to the Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment at the National University of Singapore. Thanks goes to Head of the Department,WongYunn Chii, and the teaching staff of the Year 2 Design curriculum, all of whom encourage serious and thoughtful debate on architecture, design and pedagogy.

Concept & Design: Erik G. L’Heureux

Design Editing:Anirudh Chandar

Type Set: Perpetua

Perpetua is a serif typeface designed by the English sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill (1882-140). Designed between 1925 and 1929 at the request of Stanley Morison, advisor to Monotype, Perpetua Roman was issued as Monotype Series 239.

Paper: 120gsm Diva Prima Smooth Cream

Thread-sewn perfect binding

Printed by: E-Press Printing ServicesBlk 3023 Ubi Road 3, #02-15 UbiPlex 1, Singapore 408663

Every effort has been made by the author, contributors, and editorial staff to contact holders of copyright to obtain permission to reproduce copyright material. However, if any permissions have been inadvertently overlooked, we will be pleased to make the necessary and reasonable arrangements on the next printing.

Other books by the Author:

Additions + Subtractions: Studies in Form

Publisher: Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture (CASA), National University of Singapore

ISBN: 978-981-08-3748-8

SingaporeTranscripts

Publisher: Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture (CASA), National University of Singapore

ISBN: 978-981-08-6672-3

Probing Hydrological Urbanism: Cambodia/Singapore

Publisher: Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture (CASA), National University of Singapore

ISBN: 978-981-08-6722-5