23 minute read

A delicate return

Contributing Editor, Nancy D. Yamaguchi, takes a look at the post-pandemic oil industry in the Middle East, and questions the extent of its recovery.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused untold suffering in 2020, until at last, in 2021 it seemed the worst was over. Economies around the globe began to reopen. Crude oil prices rose. In July 2021, the OPEC+ group announced that it would begin to phase out its production cut agreement. The group noted clear signs of improvement in demand and a reduction in crude oil stocks. The plan is to allow 400 000 bpd of additional supply each month, beginning in August. This halted the upward trend in oil prices, but it did not cause a massive reversal. It suggested that the market is ready to absorb additional supply, but not a massive volume and not all at once.

Yet the questions remain: is the global economy truly on its way to recovery? Is the COVID-19 pandemic truly under control? The desire to believe this during the fi rst half of 2021 caused a wave of exuberance, which opened the door for an increase in infections, particularly from the Delta variant. As this article is being completed in early September 2021, full economic recovery remains in jeopardy in key markets. COVID-19 has infected over 222 million people and caused over 4.6 million deaths. All Middle Eastern countries are affected by the virus – crude oil producers, refi ners, traders, and marketers. Cases have trended back up noticeably in Iraq and Iran, the two most populous countries in the region and two of the largest oil producers and consumers. At the time of writing, Iran had over 5.2 million confi rmed cases and over 112 000 deaths. Iraq had over 1.9 million cases and over 21 000 deaths.

The Middle Eastern countries fi nd themselves pondering the correct course in a world where the pandemic seemed to be coming under control, but the current resurgence shows that it has not yet

Table 1. COVID-19 in the Middle East

COVID-19 cases Deaths

Iran 3 603 527 87 837

Iraq 1 518 837 18 020 Israel 855 552 6454

Jordan 762 706 9922 UAE 665 533 1907

Lebanon 552 328 7888

Saudi Arabia 513 284 8115

Kuwait 388 881 2255

State of Palestine 315 876 3591

Oman 289 042 3498

Qatar 224 638 600 Bahrain 26 092 2381

Syria 25 849 1905 Yemen 6997 1371

Middle East 9 749 142 155 744

Source: Johns Hopkins, 21 July 2021 been defeated. Each country charts a delicate course, assessing the harm to their own populations and domestic economies, then rethinking developments in the global market and how they may change oil sector activity and investments. Now, achieving the delicate balance may grow more delicate.

Internationally, even before the pandemic, global oil supplies from non-OPEC sources were growing, including light tight oil (LTO) production from US shale plays, and increases in Russian output. Oil demand growth was slowing in many countries, and demand was even starting a downward slide in many of the European countries that had been key customers for crude and product. Delegates from 195 countries have just approved a report authored by the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which warned that the planet will warm by 1.5°C in the next two decades without drastic cuts to pollution. Some cuts in fossil energy use will be structural, and not related to the pandemic. Middle Eastern oil producers were already fi ghting to support prices without losing too much market share.

During the worst of the pandemic, there was little to be done. But this year, as the world appeared to be emerging from the pandemic, Middle Eastern and allied producer countries began to consider when and how to relax their voluntary production ceilings. Oil prices in the vicinity of US$50 – 60/bbl seemed at fi rst the essence of stability, then the fi rst half of 2021 brought price recovery to US$70 – 75/bbl, causing exuberance. This article focuses on Middle Eastern oil in the lingering COVID-19 pandemic, which continues to grip the world. All through the region, the questions remain: Is the pandemic truly coming to an end? Will the delta variant delay or derail recovery? When shall we make the plans and investments to expand crude and refi ned product availability?

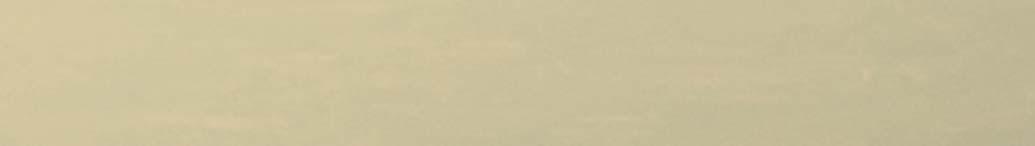

Figure 1. Middle Eastern oil producers recent rise in COVID-19 infections.

COVID-19 and the Middle East

As of late July 2021, there were over 9.7 million confi rmed cases of COVID-19 in the Middle East, and 155 744 deaths attributed to the disease. Iran had the highest number of cases, over 4.1 million, and the highest number of deaths, over 94 000, as of early August. By September, these numbers had risen to 5.2 million and 112 000, respectively. Table 1 provides country-level details on Middle Eastern COVID-19 cases and fatalities.

Adding to concerns, there has been a recent uptick in infections. Figure 1 displays this trend for the fi ve major oil producers: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. In order to compare the countries side by side, the data provides smoothed trend lines showing new infections per million population, illustrating a clear upward movement.

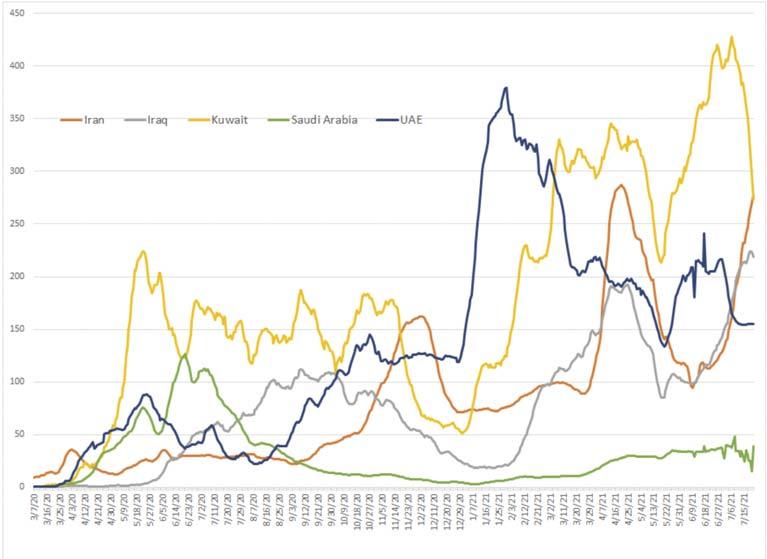

Figure 2. Brent crude spot prices.

The pandemic and oil price volatility

Figure 2 illustrates the COVID-19 pandemic’s profound impacts on Brent crude spot prices from the beginning of 2020 to early September 2021.

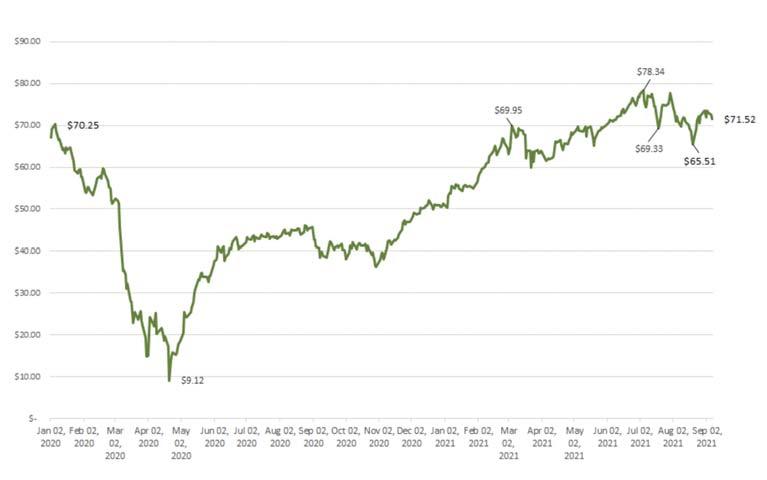

Figure 3. Middle East OPEC crude protection, January 2020 – June 2021, ‘000 bpd (source: OPEC).

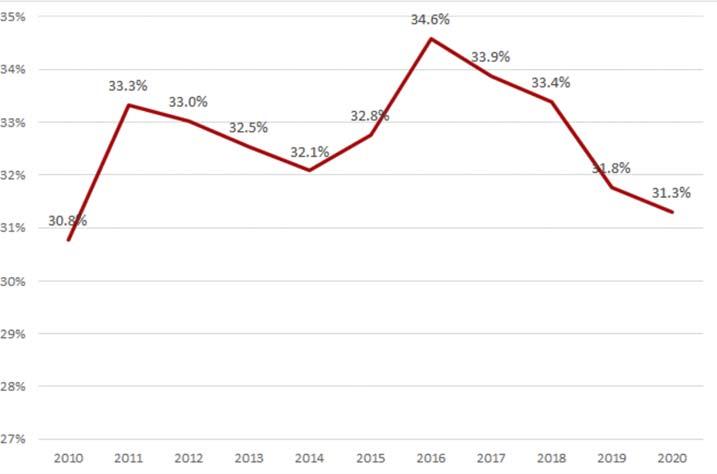

Figure 4. Middle East shrinking share of global oil production, % (source: BP).

In January 2020, Brent spot prices were approximately US$70/bbl. As the virus spread and economic activity was curtailed, prices went into freefall, bottoming out at US$9.12/bbl on 21 April 2021.

The path back took over a year, with Brent spot prices not re-attaining the US$70/bbl level until June 2021. Prices strengthened to US$78.34/bbl on 5 July, the highest daily spot price in over three years. Prices have cycled up and down since then, however, as market caution returns alongside the rise of COVID-19 infections combined with the planned increase in OPEC+ crude supplies. Brent spot prices have been hovering around US$66 – 72/bbl.

OPEC continues to monitor and support prices via its ‘Declaration of Cooperation’, which is nicknamed ‘OPEC+’. The group has also been nicknamed ‘ROPEC’ to emphasise the importance of Russian participation, which is not always in accord with Middle Eastern goals. Saudi Arabia remains the leader of the OPEC members while Russia is the leader of the non-OPEC members. The members often reported heated debates at their OPEC+ meetings, yet the group has demonstrated resilience and an ability to reach consensus time and time again. During the fi rst half of 2021, prices rose strongly as markets reopened. The two top producers, Saudi Arabia and Russia, agreed in principle to increase supply. The UAE objected to the initial baselines from which production would be allowed to rise, since the Emirates have invested in production capacity and are able to go well above the initial baseline. A compromise was reached that allowed OPEC+ to reach consensus once again.

In mid-July 2021, the OPEC+ group announced that it would begin to increase output, adding 400 000 bpd of supply each month, beginning in August. Oil prices stuttered but did not collapse. The longer-term impact on prices will depend largely upon the health of demand as the months proceed and new supplies hit the market.

With COVID-19 cases disturbingly on the upswing, demand recovery may be threatened. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) noted that Brent spot prices averaged UA$73/bbl in June, but the agency forecast that global supply will grow faster than demand in the second half of 2021, resulting in modest decline in Brent spot prices to US$72/bbl on average. This forecast has not yet been revised to account for the current resurgence in COVID-19 cases, which has the potential to drag prices below US$70/bbl.

Pandemic impacts on Middle East oil production

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a huge drop in

Middle Eastern OPEC production. The OPEC+ production cut agreement kept output at a restrained level during the remainder of 2020 and into 2021. These cuts could not forestall a collapse in oil prices, but they helped stabilise prices over the ensuing year. Figure 3 shows the trend in

Middle Eastern OPEC crude production from

January 2020 through June 2021. Output hit a peak of 25.08 million bpd in April 2020, as producers bumped up production in anticipation of the cuts to come. Output then plunged to 17.62 million bpd in June 2020, a massive drop of 7.46 million bpd in a mere two months. Output crept back to the vicinity of 19.5 million bpd by the summer of 2020. OPEC reports that these key producers raised production by 0.97 million bpd in May and June 2021. Total OPEC production in June 2021 averaged 26.034 million bpd.

Middle East petroleum in the greater market

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a tribulation across many economic sectors around the world, and it has had a huge impact on the Middle East. Millions of residents have suffered through the disease, thousands have lost their lives, and the disease continues to spread. In the petroleum sector, the region’s key oil producers had been serving as global swing producers, working together to support prices by keeping millions of barrels off the export market. Many of these producers are concerned about losing market share, and as Figure 4 illustrates, this concern is valid. The Middle East has seen its share of global oil production shrink. According to British Petroleum (BP,) Middle Eastern petroleum accounted for 35% of the global total in 2016, and this share fell to 31% in 2020.

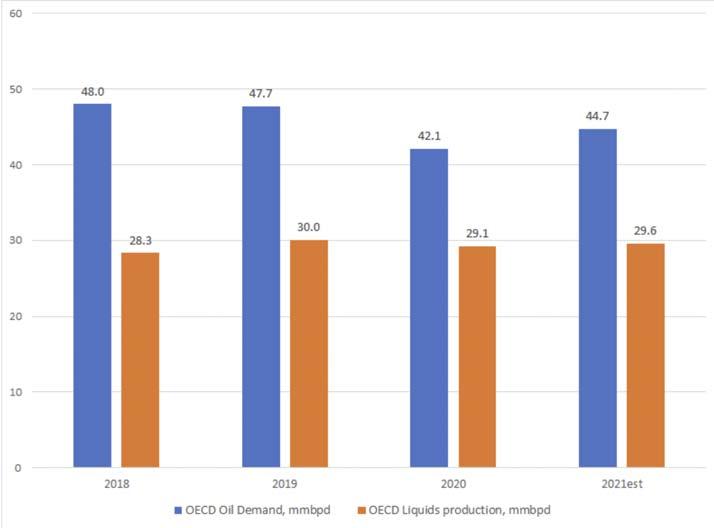

Figure 5. OECD liquids supply and demand, million bpd.

Middle East recent market developments

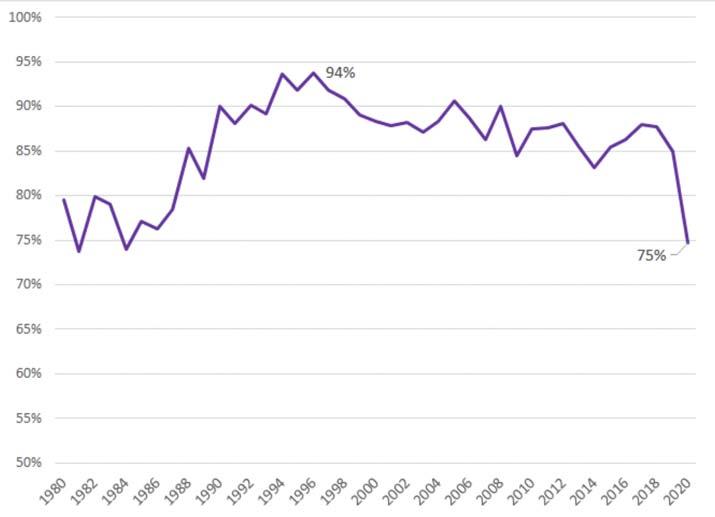

Figure 6. Middle East refinery utilisation is falling, % (source: BP).

While it is true that producers outside the Middle East have also suffered from the pandemic, the Middle East has borne a relatively larger share. Figure 5 shows the liquids supply and demand balance for the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In 2018, OECD liquids supply was 28.3 million bpd, juxtaposed against demand of 47.99 million bpd, giving a supply defi cit of approximately 19.69 million bpd – a rough estimate of the call on imports. In 2019, OECD liquids production rose to 30.01 million bpd, while demand declined to 47.69 million bpd, cutting net import requirements by 2 million bpd. In 2020, the pandemic caused OECD demand to constrict to 42.06 million bpd, a drop of 5.63 million bpd. Production, however, declined by only 0.86 million bpd, to an average of 29.15 million bpd. This cut OECD import requirements by another 4.77 million bpd.

Therefore, between 2018 and 2020, OECD demand dropped by 5.93 million bpd, but its production rose 0.86 million bpd. The net import requirement fell from 19.69 million bpd in 2018 to 12.92 million bpd in 2020. Without the restraint shown by Middle Eastern oil producers, the oil price collapse would have been far worse. OPEC anticipates that OECD demand will recover by 2.65 million bpd in 2021, and production will rise by 0.41 million bpd. The net import requirement will creep back up to 15.16 million bpd, still 4.53 million bpd below its 2018 level.

The Middle East is also facing a drop in refi nery utilisation rates, as shown in Figure 6. In the early 1990s, refi nery utilisation rates were often 90% and higher. Utilisation rates trended gently down until the pandemic caused a sharp drop to 75% in 2020, according to data published by BP. Without a signifi cant recovery in global demand, coupled perhaps with refi nery closures abroad, low refi nery utilisation will stifl e enthusiasm for refi nery investment plans.

The recent swings in global oil prices and demand have had varied impacts within the Middle East. There is a divide between the net oil importers and net oil exporters, in terms of both crude oil and refi ned products. Looking fi rst at the product importers, Israel has two refi neries, but the larger one, Oil Refi neries Ltd (ORL) at Haifa is under threat of closure by the government, which has proposed shutting down the heaviest polluting factories. ORL has proposed investments to become a cleaner energy company, but such a project could be years in coming, and the country would rely more on imported fuels. Jordan,

Lebanon, Syria and Yemen rely heavily on product imports, though all four either have or have had refi neries, and all appear to have plans to restore and/or expand their refi nery presence. Yemen has continually proposed refi nery construction plans, but nothing can be considered fi rm. The country has been embroiled in civil war since 2014. Jordan’s 90 000 bpd Zarqa refi nery has run at low utilisation rates, but an expansion and upgrade project is planned. Syria has a nameplate capacity of 240 000 bpd, but refi nery output has been less than half of this. Both of Syria’s refi neries are slated for upgrades, and the Banias refi nery is reportedly back in operation. These countries have modest-sized oil markets, with demand typically in the 100 000 – 200 000 bpd range. Their fuel needs are met with relative ease by regional refi ners.

The larger exporters have sophisticated refi neries capable of producing EURO specifi cation fuels, and they made investments based on the presence of these external markets. After a wave of optimism in mid-2021, export refi ners face an uneasy prospect of another COVID surge derailing demand recovery.

Most of the Middle Eastern countries have refi ning industries and goals to capture the value-added of processing and exporting petroleum and natural gas resources. For some, the presence of large domestic markets supported initial stages of refi nery construction. As fuel quality standards tightened abroad and at home, billions of dollars were spent to upgrade and modernise refi neries. At the present time, however, many export-led ambitions have been put on hold. As noted, refi nery utilisation rates have fallen, and there is no guarantee of demand growth in the customary export markets. How are these refi ning centres faring, and do they

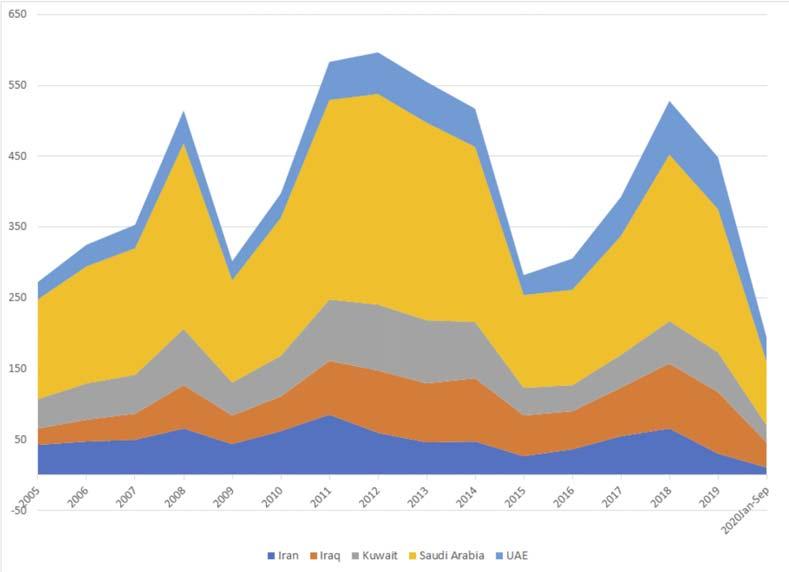

Figure 7. Drop in oil export revenues, Middle East OPEC, billion US$ (source: US Energy Information Administration).

have plans to expand capacity? Plans remain on the books, but ability to pay is a signifi cant barrier.

Figure 7 shows oil export revenues in the Middle Eastern OPEC countries Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA.) In 2018, these fi ve countries earned US$528 billion in oil export revenues. This declined to US$448 billion in 2019, then plunged to US$194 billion in the January – September period of 2020 – a drop of 63%. Iran suffered the largest drop; crude oil export revenues of US$66 billion in 2018 collapsed to US$11 billion in the January – September period of 2020. This was a drop of 83%.

The following sections provide a brief look at developments in the key refi ning countries.

Bahrain

Bahrain has had a refi nery expansion and modernisation project underway at its 262 000 bpd Sitra refi nery for several years. The project is largely complete, but full commissioning may be pushed back to 2022. The project is adding approximately 100 000 bpd of crude capacity, plus hydrocracking, coking, and diesel hydrotreating. The domestic market is small, approximately 31 000 bpd in size, so the additional product would be destined for export markets. Because the existing output from the Sitra is already more than ample, there is no rush to expand.

Iran

Weighed down by years of sanctions, Iranian crude oil exports have plunged, revenue has fallen, and outside investment has faded. Despite limited revenue, the country forged ahead with internal projects. The key refi nery project was the Persian Gulf Star refi nery, a three-phase gas condensate refi nery at Bandar Abbas. Production commenced in 2018, and in 2019, Iran at last became a net exporter of gasoline. Prior to this, Iran had been heavily dependent on gasoline imports. Product exports reportedly rose to 680 000 bpd in 2020. Iran has the largest market in the Middle East. BP reports that Iranian oil demand rose from 1 717 000 bpd in 2018 to 1 841 000 bpd in 2019, before retreating to 1 715 000 bpd in 2020. Upgrade programmes are planned at essentially all key refi neries, but timing will be determined by availability of funds, materials, and contractors. The country is working to improve gasoline and diesel quality. Large grassroots projects are unlikely while sanctions remain, so the focus is on upgrading and expanding existing refi neries, including the recently completed Persian Gulf Star plant. Lack of investment is expected to cut Iran’s crude production capability severely, so that even if sanctions are lifted, crude output may never regain historic levels. Iran placed its production capacity at 4.7 million bpd, but actual production in 2020 was less than 2 million bpd. As noted, the EIA reported that Iran’s crude oil export revenues collapsed from US$66 billion in 2018 to US$11 billion in the January – September period of 2020. A rebound in crude export revenues will be critical for many government initiatives. It is also seen as essential to tackle years of mismanagement of the agricultural sector and water supply. Energy and food have been heavily subsidised, and Iran has been declared ‘water bankrupt’ with respect to renewable water supply.

Iraq

Iraqi crude production has declined signifi cantly since COVID-19 hit. In 2019, production averaged 4.678 million bpd. This fell by 0.627 million bpd in 2020 to an average of 4.051 million bpd. OPEC data for the fi rst half of 2021 place Iraqi output at 3.915 million bpd, a drop of an additional 0.136 million bpd.

Iraq’s refi ning industry is organised mainly around three regional nodes: the North Refi ning Co.’s Baiji refi nery, the Midland Refi ning Co.’s Daura refi nery, and the South Refi ning Co.’s Basra refi nery. Smaller refi neries, some modular, have been installed to help meet local fuel needs. Total crude capacity is approximately 1.1 million bpd. Sophistication is low, however, and gasoline output lags demand while fuel oil is in surplus. BP reports that Iraqi oil demand was 919 000 bpd in 2020. The Basra and Baiji refi neries are slated for upgrades, but these are not expected to be completed for several years. Work on the expansion at Basra was halted during the pandemic.

A government-funded grassroots refi nery of 150 000 bpd capacity is underway at Karbala. In recent years, there have been multiple proposals for new refi nery projects, but the weak market quelled investor interest, and some projects were dropped. Recently, the government announced that it had awarded the contract for the long-planned Al-Fao (also spelled Al-Faw) refi nery to the China National Chemical Engineering Co. (CNCEC.) The government announced that the refi nery will have a capacity of 300 000 bpd and will include a petrochemical plant. The Chinese government reportedly will provide funding. No schedule has been announced.

Kuwait

According to OPEC, Kuwait cut its crude production from 2.689 million bpd in 2019 to 2.431 million bpd in 2020, and to

2.341 million bpd during the fi rst half of 2021. This is a reduction totalling 348 000 bpd.

Kuwait operates two large refi neries, Mina Abdullah and Mina Al-Ahmadi, which have a combined capacity of 736 000 bpd. An older refi nery, Shuiba, was decommissioned. Commissioning of the giant 615 000-bpd Al Zoor refi nery project has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This refi nery will be the largest in the Middle East when complete. It was scheduled for 2020 startup, but contractors tried to invoke force majeure because of COVID-19 restrictions. A launch in 2021 remains possible, but only if the pandemic is under control and people and materials begin to travel more freely.

Kuwaiti oil demand fell 468 000 bpd in 2018 to 446 000 bpd in 2019 and to 411 000 bpd in 2020, according to BP.

Oman

According to BP, Oman’s oil demand fell from 240 000 bpd in 2019 to 209 000 bpd in 2020. The country has two refi neries, Mina Al-Fahal and Sohar, with a combined capacity of approximately 222 000 bpd. The Omani government is working with Kuwait Petroleum Intl to build a joint venture refi nery known by the abbreviation ‘OQ8’ at Duqm. This will be a 230 000 bpd deep conversion refi nery with hydrocracker plus coker. The project is reportedly over 80% complete, though market conditions provide no urgency for full commissioning.

Qatar

Qatar’s oil demand fell from 375 000 bpd in 2019 to 296 000 bpd in 2020, according to BP. The country has two refi neries, Messaieed and Ras Laffan, with a combined capacity of 429 000 bpd. The Messaieed refi nery, also known as MIC because of its location at Messaieed Industrial City, is undergoing an expansion and modernisation programme. The refi nery completed its ultra-low sulfur diesel project in 2020. The refi nery fully supplies the domestic market with a 10 ppm sulfur ULSD standard consistent with EURO 5 quality.

Saudi Arabia

According to BP, Saudi Arabian oil demand has fallen for fi ve consecutive years, declining from 3 879 000 bpd in 2015 to 3 544 000 bpd in 2020, a drop of 335 000 bpd. The country remains the region’s largest crude oil producer, refi ner, and consumer, and it is the de facto head of the OPEC+ group. Saudi Arabian crude production rose from 9 198 000 bpd in 2008 to 10 317 000 bpd in 2018, a growth rate of 1.2% per year. The country has immense production capability, and it uses this capability to moderate global prices. Saudi Arabia went well below its quota under the production cut agreement, which was set at 10.508 million bpd, to ensure compliance. According to OPEC, Saudi Arabian crude output averaged 9.765 million bpd in 2019, 9.194 million bpd in 2020, and 8.471 million bpd during the fi rst half of 2021. This was a drop of 1.294 million bpd.

Saudi Arabia has a nameplate crude refi ning capacity of approximately 2.9 million bpd, centred around eight key refi neries. These include the highly sophisticated, modern joint venture refi neries known as SAMREF, YASREF, and SATORP. The 400 000 bpd Jizan refi nery is largely complete, with some units operating, but full commissioning is not expected until 2022. Market conditions have not recovered, and the facility has also been attacked by Yemeni missiles. Yet another complication stems from the fact that the refi nery receives crude feedstock via tanker, raising the possibility of seaborne attacks. Saudi Arabia has been working for a solution that will extricate it from the Yemeni civil war.

Saudi Arabia was the fi rst Middle Eastern country to invest heavily in export refi ning, and it is also a pioneer in integrating refi ning with petrochemicals. For example, Saudi Aramco and Total are building a joint venture petrochemical plant next to the SATORP refi nery.

UAE

Oil demand in the UAE has continued to grow despite the COVID-19 pandemic. According to BP, the UAE consumed 1.229 million bpd of oil in 2018, 1.307 million bpd in 2019, and 1.331 million bpd in 2020. The UAE expanded its crude production capacity, though it cut production in line with the OPEC+ agreement and market demand. OPEC reports that UAE crude output fell from 3.08 million bpd in 2019 to 2.793 million bpd in 2020 and 2.627 million bpd during the fi rst half of 2020. The UAE argued, with some success, that its OPEC+ production baseline should be increased, and its future allotment will grow from the new baseline. A compromise was reached that allowed the OPEC+ group to move ahead with its 2021 plan. The UAE then announced that it would increase export capability of its Murban crude.

The UAE has expanded its refi nery capacity, which now stands at approximately 1.14 million bpd. There are four main refi nery complexes, the largest of which is Abu Dhabi National Oil Co.’s (ADNOC) Ruwais refi nery. ADNOC reports that there has been signifi cant progress made on its crude fl exibility project, which will enable the plant to process up to 420 000 bpd of heavy sour crudes. Dubai’s ENOC refi nery is planning to add a 70 000 bpd condensate refi nery.

Conclusion: delicacy returns to a delicate balancing

The Middle East has grown accustomed to taking a balancing position in the global oil market, though this has cost market share. The oil producers in the region serve as the anchor in the OPEC+ agreement, which has been far more successful than originally expected over the past years of structural oversupply, and currently during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the fi rst half of 2021, it seemed that the coronavirus was fi nally coming under control. Oil demand and prices were heading up. Unfortunately, the highly contagious delta variant is contributing to another surge in infections, potentially jeopardising the economic recovery.

The Middle Eastern countries are proceeding with a gradual increase in crude production, and they are resuming some of their work on downstream upgrading and expansions. All have been battered by the pandemic, however. All have lost oil export revenue. This will limit how many projects can move forward. Even in cases where governments and investors are able to proceed, some are pondering when (and whether) they should. Thus, the summer of 2021 has failed to bring a full recovery, and there is no guaranteed end to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Middle Eastern oil producers and refi ners fi nd a new delicacy returning to their constant battle to fi nd a delicate balance in today’s global oil market.