JOCKEY CLUB New Arts Power, launched in 2017, is an annual Arts Festival presented by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council with the funding support from The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. The Festival brings together established and emerging local artists to produce creative, approachable and engaging arts experiences for all.

Over the past three years, 38 arts groups have participated in the Festival. Together they produced 72 live performances and a remarkable number of major exhibitions. Uniting arts groups and various organisations from the social welfare, academic and commercial sectors, the Festival held over 450 community and school events, reaching some 380,000 participants.

JOCKEY CLUB New Arts Power 2020 / 2021 will be held from September 2020 to January 2021, featuring a total of 9 selected programmes that include dance, theatre, music, xiqu, multimedia and visual arts exhibition, as well as presenting more than 100 community and school activities.

Table of Content

About

Theatre

Pants

Production About Sweet Mandarin The Adaptation of Sweet Mandarin A Taste of Home A Short History of Overseas Chinese Chinatown An Introduction to Diaspora From Ethnic Chinese to British National From Lawyer to Chef Who am I? 2 2 4 6 8 10 11 12 14 16

About Pants Theatre Production About Sweet Mandarin

Founded in 1995, Pants Theatre Production defines itself as a “social witness on stage”. With Wu Hoi-fai as the artistic director, the Company believes that theatre is a way to relate to the society: to respond, reciprocate and reform. Pants Theatre Production has produced a number of inspiring and socially engaged theatre works, while taking three directions towards “theatre productions”, “applied theatre” and “research & preservation”. In recent years, the Company focuses more on documentary theatre. Recent critically acclaimed productions include What about Art in Hong Kong, A Hongkonger’s Political Journey: Long Hair, 1967 (premiere and rerun), On the Record, Estate Agents and translated documentary theatre such as Gross Indecency – The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, The Laramie Project and its sequel.

Pants Theatre Production is a recipient of the Three-Year Grant from the Hong Kong Arts Development Council.

Pants.Production pants.theatre.production

“You want to be a chef, instead of a lawyer?!” Helen’s father is stunned.

Catering is probably the most common business in the overseas Chinese community. The older Chinese generation labours day and night in order to free their younger generation of the chore of the kitchen. Helen, a British born Chinese, against all expectation leaves her lawyer job to set up her own restaurant. She discovers that her family cuisines are not only tasty but also full of dramatic stories, spanning almost a hundred years and crossing from Guangzhou via Hong Kong to England.

Helen Tse was awarded MBE for her contribution to the food and catering industry in UK in 2014. Her latest cookbook Dim Sum became a Times bestseller. In 2006, she put the remarkable journey of her family and her own into Sweet Mandarin, which was published in 33 countries to great acclaim. Pants Theatre Production’s Sweet Mandarin premiered in 2015, and was featured in Hong Kong Theatre Month in Shanghai 1862 Theatre.

2

Three Generations of Overseas Chinese

Grandma – Lily Kwok

In the 1920s, Lily migrated from Guangzhou and settled in Hong Kong with her father, who was soon murdered. Lily worked as a maid in the Woodman family, and followed Mrs. Woodman to England. Mrs. Woodman left some money to Lily after she died, and with that Lily started Lung Fung, the first Chinese restaurant in Middleton. Later when she became a gambling addict, her daughter Mabel and son-in-law Eric convinced her to sell Lung Fung to repay debts.

Mother – Mabel Kwok Mabel was raised by her grandma (Lily’s mother), and went to England with her brother in the 1950s to live with their mother. She found it hard to get used to her new life, and the only comfort was her mother’s chicken pot. She met Eric in Manchester and got married. They ran a takeaway chip shop to make a living, and raised four kids: Helen, Lisa, Janet and Jimmy.

Daughter – Helen Tse

Born and raised in Manchester, Helen graduated from Cambridge University majoring in Law, and worked as a lawyer in London. Before she started her six-month secondment to Hong Kong, she brought the whole family to visit Hong Kong and Guangzhou, and learnt much more about her Grandma’s past. She and her twin sister Lisa decided to start a restaurant so as to pass on Grandma’s culinary art, but faced opposition from their parents…

3

The Adaptation of Sweet Mandarin

Original Novel

Sweet Mandarin is adapted from the same-titled novel by British Chinese writer Helen Tse. The title of this novel is taken from the name of the restaurant that she started in Manchester in 2004, with her grandmother’s recipes. The biographical novel chronicles stories of three generations of her family, spanning almost a century.

Stage Adaptation

Director Wu Hoi-fai first had the idea of adapting Sweet Mandarin into a play in 2007, when he was studying for his Master’s degree in the UK. As an assignment for his study, he picked the murder of a Chinese takeaway shop owner for documentary theatre. When doing his research, he realised there were not many publications on British Chinese, and Sweet Mandarin was one of the few.

“I was deeply moved when reading these books, particularly after knowing the background. When you were among the ethnic minority, you felt compelled to be aware of your national identity.” Gender identity also plays an important part in the novel. The whole book is narrated from a female point of view. He therefore invited Cheang Tik-ki, a female playwright, to pen the script. “I believe that a woman knows other women better,” says Wu.

4

About the Director: Wu Hoi-fai

After graduating from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, Wu Hoi-fai received his master’s degree from the Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London in 2008. He was awarded a fellowship by Asian Cultural Council to research in the States in the same year. Currently Artistic Director of Pants Theatre Production, his latest interest is in documentary theatre.

About the Playwright: Cheang Tik-ki

Cheang Tik-ki has obtained the BSc in Occupational Therapy (first-class Honors) from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the BA in Music from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She was also awarded the Licentiate of the Royal Schools of Music (Distinction) and the MFA in Drama (Playwriting) of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (Distinction). Her premier play, Angel’s Gift , won the distinguished award in the 3 rd Youth Playwright Scheme of Cinematic Theatre and was nominated the Best play in the 6 th Hong Kong Theatre Libre.

Reading

Other Stage Adaptations

In-sook Chappell, a British Korean, has also adapted Sweet Mandarin into a stage play, titled Mountains: The Dreams of Lily Kwok, directed by Jennifer Tang, a British Chinese, and jointly produced by Yellow Earth Theatre, Black Theatre Live and Royal Exchange Theatre. Take a look at the trailer of their version, and compare with Sweet Mandarin by Pants Theatre Production.

Sweet Mandarin Cookbook (Helen & Lisa Tse, 2014) Dim Sum (Helen & Lisa Tse, 2015)

Soon after Sweet Mandarin made its name in the British catering industry, Helen and her twin sister Lisa published two cookbooks that promote their grandmother’s as well as their self-invented recipes. In Sweet Mandarin Cookbook, they even tell the story of each dish, sharing with readers its meaning in either Chinese culinary tradition or their family memory.

5

Extended

Trailer

A Taste of Home

Sweet Mandarin mentioned “comfort food” – Helen’s fried eggs with shrimps and tomatoes, Lisa’s stir-fried noodles with beef, and, of course, Mabel’s chicken pot. The term first appeared in 1966, in a news story about obesity in Palm Beach Post which reported that “when under severe emotional stress” one would turn to “comfort food – food associated with the security of childhood”. That is perhaps why “comfort food” are often dishes we had at home when we were kids.

Fried eggs with shrimps and tomatoes

Stir fried noodles with beef

1. What is your favourite dish at home?

2. When you are abroad, do you miss this dish? What memory does it evoke?

3. Do you know how to make this dish? If so, does it taste the same as when you were a child? If not, have you thought of learning? Why?

6

Questions

Food is intricately related to memory. Ordinary meals and sumptuous feast alike combine visual, olfactory and gustatory experiences. We can record how a dish looks like with the camera, but its taste and smell can only be remembered by our brains.

Any attempt to recall the tastes and smells of food evokes memories of the time when we consumed them, and of the bonding with people with whom we enjoyed the food. This perhaps explains why family memories are often built over the dining table.

If “comfort food” can link an individual to the family, then dietary habits may connect one to his cultural identity. Every culture has its unique practices in food consumption. For example, people in southern China must include rice in their meals, but those in the north have noodles and dumplings as their staples. The choice of ingredients, ways of cooking, preferences over taste, etc. are all embedded in one’s own culture.

Deconstructing Taste: A Literary and Cultural Study on Hong Kong’s Food Culture (Siu Yan-ho, 2019)

A chef-turned-lecturer writes about food in literary and cinematic works and explores the meaning behind different dishes and drinks.

Taste / Sound (Chan Wai, 2000)

The novel Taste has its chapters named after different kinds of food, denoting the experiences of the protagonist at different times.

7

Extended Reading

A Short History of Overseas Chinese

Sweet Mandarin is a story of three generations of overseas Chinese. Chinese emigrated overseas for different reasons throughout the centuries, with a few tides of migrations in history.

Coolie Labour in America

In the mid-19th century, many Chinese living in coastal areas of Guangdong went to make a living overseas owing to famines and wars in their homeland. At the same time, there was a huge demand for labour for agriculture and silver mines in South America, for the “gold rush” in West Coast of North America, and for the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. Agents in China’s coastal cities recruited poor people to work overseas, but the terms were very harsh. Some agents even abducted the poor people to become coolies.

Do You Know?

Hong Kong was once a transit point for these labourers. The Jao Tsung-I Academy in Mei Foo is the only building remaining in Hong Kong that was once used as a dwelling for the Chinese labourers who waited in Hong Kong before embarking on their overseas journeys.

Caterers in Britain

There were far less Chinese in Britain as compared to the States before World War II. In the post-war Hong Kong, farmers in the New Territories could hardly make a living because of the changing economy. Many of them thus moved to Britain and the Netherlands to run or work in restaurants. Grandma in Sweet Mandarin were one of those in this emigration tide.

8

Jao Tsung I Academy (Photo by Mk2010)

“Astronauts” from Hong Kong

The Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed in 1984, determining Hong Kong’s future of returning to China in 1997. In the 1980s and 1990s, many Hong Kong people, in face of the uncertainties of the handover, emigrated to Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia. Most of them belonged to the middle class, and they found it hard to give up their careers in the then economically prosperous Hong Kong. So after naturalisation, the husbands return to Hong Kong to make money, and only visited their wives and children during holidays. These people were nicknamed “astronauts”.

Emigrants from Mainland China

The People’s Republic of China, after its establishment in 1949, imposed strict control over emigration until the economic reforms in the late 1970s. Therefore, in the 1980s and 1990s, there was an emigration tide from Mainland China to the Western world, mostly through studying abroad or as skilled migrants.

9

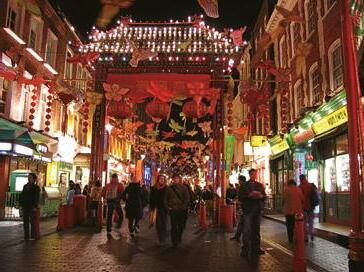

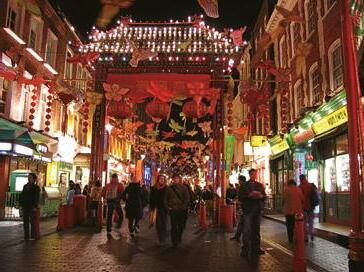

Early Chinese migrants often stayed in proximity to take care of each other when they arrived at an alien country. Communities gradually developed in cities where there were sizable Chinese populations, and these communities were known as “Chinatown”.

Chinese Restaurants

Limited by language ability and education level, most early Chinese immigrants could only work as low-skilled workers. Chinese restaurants were usually more economical and had longer opening hours than local ones, and could thus survived keen competitions. There were demands from overseas Chinese for their “comfort food” too!

To suit the tastes of their Western customers, restaurants in Chinatown often feature dishes with stronger tastes and thicker sauces, such as “Sweet and Sour Pork” and “Kung Pao Chicken”, which have all become signature Chinese specialties in Westerners’ eyes. This is perhaps also the reason behind the success of the sauces produced by Helen’s Sweet Mandarin!

The following two items are iconic of overseas Chinese restaurants, but have never existed in Asia. Perhaps Lily Kwok’s restaurant once offered them too!

This uniquely shaped food container for takeaways from Chinatown restaurants can indeed be unfolded to become a make shift plate!

Chinese restaurants in North America offer this as a dessert after the meal There is a small piece of paper inside the cookie, with a proverb or a prophecy printed on it

10

Oyster Pails

Fortune Cookies

Chinatown

An Introduction to Diaspora

The term “Diaspora” originally refers to the scattering of Jews in different parts of the world. In ancient times, the Jews lived near Dead Sea, and once established the Kingdom of Israel that was conquered in the 7th Century B.C. Since then the Jews were dispersed throughout the world. The country of Israel was established in 1948, by then the Jews had been in diaspora for over two thousand years.

The term entered English referring to large scale migratory experiences and dispersal of a people. The tides of emigration discussed in the previous pages can be regarded as “Chinese diaspora”.

Diasporic people, living in a foreign land, often attribute great importance to their own traditions, customs and religion, so as to pass on their culture. At the same time, they are facing problems and challenges much different from their fellow people in homeland. Diasporic people’s experiences are thus particularly touching, like those of our protagonists in Sweet Mandarin, when they have to negotiate between such sameness and differences.

Chinese Diaspora and Hong Kong

In the late 1940s to the early 1950s, there was a huge influx of immigrants from Mainland, owing to the turbulences in China, bringing with them both labour and capital. This was the beginning of Hong Kong’s industrial take-off. These people, though not emigrating overseas, migrated to live under a different political and economic system, and maybe termed as “diaspora within China”.

As mentioned previously, many Hong Kongers worried about the uncertainties of handover and emigrated to the West. The early generations who moved to the West to make a living thought they would return home one day, but their next generation who moved away from Hong Kong saw their emigration as permanent – even the “astronauts” meant to retire overseas after making money in Hong Kong. A sojourner mentality has always followed Chinese diaspora.

11

From Ethnic Chinese to British National

“Where are you from?” This is often an ice-breaking question when we first acquaint someone. But for diasporic people, this can be a very difficult question. Imagine you were Lily Kwok in Sweet Mandarin, how would you answer?

I am from Manchester. I lived in Manchester for a few decades.

I am from Hong Kong. I grew up in Hong Kong, and my father told me to treat Hong Kong as home.

I am from China. My ancestors are Chinese and I grew up in Chinese culture.

I am from Britain. I hold British passport.

I am from Guangzhou. My father lived in Guang zhou for a long time, and I was born there.

In fact, at different times, asked by different people, Lily Kwok might have provided a different answer. A question about identity encompasses identification with a culture, with the place of birth and place of residence, with a nationality, etc. Identity issue is particularly complicated for diasporic people, for they grow up and live in different places, immerse themselves in distinct cultures, and have often changed their nationality.

12

Imagine you were Helen in Sweet Mandarin. If you were asked the question “where are you from,” how would you answer? What are your considerations?

Extended Reading

Imagined Communities

(Benedict Anderson, 1983)

(Benedict Anderson, 1983)

The above questions about Lily Kwok and Helen Tse are indeed about national identity. Political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson sees national identity as identification with an “imagined community”. If you belong to a community, even if you do not know every single person therein, you still regard your fate as shared with that of the community. Such identification, in other words, the national identity, is not innate, but changes with personal experience (such as Lily’s migratory experience) and knowledge (such as Helen’s knowledge about her grandma’s past).

13

? ? Question

From Lawyer to Chef

Career Decisions

12

In the play, Helen’s father strongly opposed her decision of giving up her legal career to become a restauranteur. Why are some occupations more desirable than others? vs 1. What are the criteria of an ideal job? Please select your answers and prioritise them. 2. In reality, do you consider the same criteria when you take a job? If not, why? 3 Did you ever consult your family about your career decision? Do they hold the same views as yours? High income Stability Short working hours Interesting job nature Job satisfaction Nice colleagues Contribution to society Vision fulfilment Others (please fill in): Questions

Career forms an important part of one’s identity, therefore “what do you do” is also a very common ice-breaking question. Making career decisions requires a balance between ideal and reality. But after all, people always hope to find a job that they can be proud of, don’t they?

Jobs for Men and Jobs for Women

Helen chooses to become a chef. Most chefs are male in famous restaurants in Hong Kong, while the ones who cook at home are usually female – mothers and female domestic helpers. So both men and women can be good at cooking, just like Helen’s grandma, mother and father are all great chefs.

But there are still many gender stereotypes as far as careers are concerned. For example, it is commonly believed that men are good at logical and rational thinking, so they are suitable for jobs in information technology and engineering. Women are thought to be detailed-minded and patient, thus would excel as secretaries and nurses. But all these are stereotypes and are not necessarily true.

In our upbringing, we internalise these stereotypes from information we receive from our parents, relatives and friends, as well as from the media and even textbooks. A person’s gender identity often affects how others see him/her, and may even influence his/her own life decisions without knowing.

15

Who am I?

There are so many dimensions to consider when we try to answer this question. National identity, occupational identity and gender identity that we have explored in this booklet are just a few facets.

In Sweet Mandarin , we have already seen Helen’s many identities: British Chinese, ex-lawyer, chef, restaurateur, woman, granddaughter, daughter, twin sister of Lisa, sister of Janet and Jimmy, resident of Manchester and London, alumna of Cambridge… Of course she has many more identities beyond those we know from Sweet Mandarin

In the play, she saw some identities as more important than others. In fact, the importance of any facet of one’s identity changes with time, occasion and the audience.

So, who are you now?

16

Publisher Hong Kong Arts Development Council Editor Cultural Connections Design Fundamental Stage Photography C. Production House Date September, 2020 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior permission of the copyright owner Participating Arts Group

18

(Benedict Anderson, 1983)

(Benedict Anderson, 1983)