PRESENTACIÓN

Es para nuestra empresa un gran orgullo presentar el libro Tierra del Fuego, Retratos y Paisajes , un ensayo fotográfico que retrata a descendientes de los pueblos ancestrales que habitan actualmente Tierra del Fuego a través del lente del destacado fotógrafo chileno, Max Donoso.

En el aniversario de los 500 años del descubrimiento del Estrecho de Magallanes, esta publicación destaca el valor de esta región y su gente, constituyendo un homenaje y reconocimiento a quienes habitaron por siglos este territorio.

Estamos contentos de apoyar este extenso relato que nos muestra, a través de retratos de pescadores, gauchos, estibadores, buscadores de oro, madereros, entre otros, cómo los chilenos hacen soberanía en el paisaje más austral de la tierra.

Felicitamos a Max Donoso y a todo el equipo a cargo del proyecto, por el esfuerzo para contribuir al conocimiento de nuestra propia identidad e historia.

Fernando Larraín C. Presidente LarrainVialDear all,

It is with great pleasure that we present Tierra del Fuego, Retratos y Paisajes, a compelling photographic essay portraying the descendants of our First Nations who continue to live in Tierra del Fuego, captured through the lens of reputed Chilean photographer, Max Donoso.

In the 500th anniversary of the discovery of the Strait of Magellan, this publication underlines the value of the region and its people and pays homage to the territory’s inhabitants through the centuries.

LarrainVial’s contribution to this book confirms our firm’s historical commitment to promoting and recognizing Chile’s cultural heritage.

It has been deeply rewarding for us to take part in the production of this detailed narrative, which portrays fishermen, gauchos, port workers, gold prospectors, lumbermen, among others, and experience from these images how Chileans live in sovereignty in the world’s southernmost landscapes.

We would like to congratulate Max Donoso and all the team involved in this project for their joint efforts in helping us expand our knowledge and appreciation of our own identity and history.

Fernando Larraín C. President LarrainVial

TIERRA DEL FUEGO REPRESENTADA LA HUMANIDAD «FUERA DE LOS LÍMITES DE ESTE MUNDO»

Margen, confín, paisaje extremo, sur del sur, territorio de frontera. Antípodas, aventura, aislamiento. Infinitud, territorio inexpugnable. Epopeya y fin de mundo, belleza del vacío, soledad absoluta… Estos son algunos de los adjetivos y conceptos que se repiten cuando cronistas y autores aluden a Tierra del Fuego, una isla también considerada como «territorio fuera del mundo», el que permaneció ajeno a la ecúmene y al mundo conocido por los europeos durante la mayor parte de la historia de la humanidad, situación que también fue estimulada por los sucesos épicos verificados en su entorno. Hoy, el mismo territorio resulta muy atractivo en un mundo en el que la capacidad de sorprender resulta cada vez más escasa.

Según relata Robert Fitz-Roy en el diario en que narra el viaje del Beagle, que el marino e hidrógrafo inglés comandó hasta su arribo a Tierra del Fuego en diciembre de 1832, ese territorio permanecía «aun inexplorado»; testimonio que es un elocuente reflejo de la situación y condiciones de Tierra del Fuego y del archipiélago del que forma parte que, entre 1520 y 1832, sólo fue recorrido por los selknam, yaganes y kawésqar, pueblos originarios que lo habitan desde hace miles de años.

Tal vez sólo los hermanos Gonzalo y Bartolomé Nodal tuvieron la oportunidad de conocer algo más que las costas de Tierra del Fuego cuando, en 1618 debieron guarecerse en la Bahía del Buen Suceso en su afán por alcanzar el Cabo de Hornos, territorio que en 1616 había descubierto la expedición de Jacob Le Maire y Willen Schouten. Pero lo cierto es que no se adentraron en la isla que los exploradores neerlandeses habían demostrado

que no era un continente o Terra Australis, como hasta entonces se imaginaba y representaba en los mapas, lo que deja de manifiesto una vez más el carácter inédito que alguna vez tuvo Tierra del Fuego.

Por la situación y condición geográfica de Tierra del Fuego y el conjunto del que forma parte, y por el misterio que durante tanto tiempo la cubrió, hablamos de un territorio que representa lo extremo, hecho también ratificado por un paisaje telúrico modelado por los movimientos de la corteza terrestre y por agentes como el viento, el hielo, el agua y el mar, que le dan su carácter e imponen una impronta implacable y sin contemplaciones. Este carácter también está marcado por las aventuras que la humanidad ha protagonizado en esta geografía rigurosa, azotada por condiciones ambientales que para muchos parecen insoportables, pero a las que los pueblos originarios de la región, como los selknam, supieron adaptarse, convivir y sobrevivir, situación que impactó a los exploradores y viajeros que desde el siglo XVI han surcado los mares del sur, y que ha contribuido también a alimentar la sensación de fragilidad y desamparo que tanto la lejanía como las duras condiciones naturales de la región impusieron por largo tiempo. Actualmente, estos escenarios representan un activo que atrae la atención hacia la zona, acrecentada por la impresión de vacío, soledad y melancolía de un paisaje en el que la humanidad está presente a través de objetos materiales, restos y construcciones, pero rara vez por su permanencia, dando forma así a un paisaje sublime por su belleza, pero también por su capacidad de evocar un potencial

drama en una tierra también descrita como inerme e indefensa ante la acción de personas que, sucesivamente y motivadas esencialmente por intereses económicos, la ha expoliado.

Así, Tierra del Fuego, como consecuencia de su geografía e historia, ofrece un amplio margen de posibilidades para ejemplificar el quehacer de la humanidad: desde la conquista, la búsqueda de la belleza y el espíritu de superación para enfrentar la naturaleza, hasta la violencia despiadada y la depredación propia de nuestra especie.

Hito geográfico mundial, por su condición de antípoda y extremo, confín del mundo, Tierra del Fuego, junto con la Patagonia y el estrecho de Magallanes, es un patrimonio histórico-geográfico de Chile dotado de una identidad particular, tanto por su realidad física como por las representaciones que de ella y sus habitantes se han hecho desde el siglo XVI en adelante.

NATURALEZA E HISTORIA

Asociada a la exploración y a la aventura más allá de los límites conocidos, a la naturaleza salvaje, pero también a lo histórico, lo dramático y lo épico, incluso a lo maravilloso, fantástico y nunca visto, el extremo sur de América desde comienzos del siglo XVI representa para el mundo occidental una frontera, el finis terrae del mundo, un lugar donde todo es inédito, una tierra incógnita. El imaginario de esta zona del planeta encuentra sus orígenes en Europa occidental, en la época de los descubrimientos, la que se inicia con la navegación trasatlántica, continúa con los viajes de circunnavegación y la exploración antártica y cada cierto tiempo se nutre de la tragedia, del dolor y el sacrificio, los que a su vez hacen posible los actos heroicos, de valor y de humanidad que quedan en la historia asociados a la región, así como en la época contemporánea lo están la violencia ejercida desde el siglo XIX en adelante en contra de los selknam, lo que significó prácticamente su exterminio, y más recientemente, las manifestaciones culturales de los pueblos fueguinos que el respeto irrestricto de la humanidad, la empatía con los perseguidos y, en definitiva, una cada vez mayor conciencia de la dignidad inherente a todo ser humano han contribuido a apreciar, recuperar y conservar como patrimonio cultural.

Algunos de los elementos de su geografía como el Paso Drake, el Cabo de Hornos, Tierra del Fuego, el océano Pacífico, el estrecho interoceánico, incluso la Antártica, remiten en la Patagonia a la aventura y a condiciones extremas para habitarla, las que se expresan a través del viento, la lluvia, el frío, la nieve, el mar y las olas, naturaleza que la mayor parte del tiempo se hace presente de manera implacable, tormentosa y, por eso mismo, sublime

tanto por la belleza conmovedora que ofrece como por su potencial trágico. Aun hoy algunos nombres como Magallanes, Drake, Cook y Darwin permiten asociaciones geográfico-históricas que hacen posible valorar la región, otorgarle sentido a lugares y sitios que evocan hitos de la humanidad; en esta zona la toponimia alude a sucesos y momentos que han sido representados como hazañas de todos los tiempos, fueran de un imperio, un Estado o un hombre. Palabras, y entre ellas los nombres otorgados a los pueblos originarios de la zona como los patagones, que excitan la imaginación, que evocan el drama o que aluden a un patrimonio cultural que se resiste a desaparecer a pesar de la violencia y del despojo de que ha sido objeto.

Así, desde su ingreso en la historia occidental, la Patagonia en el extremo sur de América ha sido considerada un espacio, una geografía concreta y real, aunque siempre por terminar de conocer, a partir de la cual se proyectan representaciones fantásticas, míticas, épicas, incluso dramáticas, y que tienen en la historia, en este lugar alejado de todo y de difícil acceso, uno de sus principales fundamentos, pues ha sido el escenario de numerosos hechos que han alcanzado repercusión mundial. Esto, unido a las representaciones e imágenes de los lugares en que han ocurrido, la dotan de una identidad histórico-geográfica imposible de obviar, enriquecida además por la promesa de lo fantástico, la posibilidad del encuentro con algo que nunca se deja capturar, lo que renueva las expectativas sobre la región cuyo paisaje es parte de la historia y no solo de la naturaleza.

PATAGONIA ÉPICA

Fue el 1 de noviembre de 1520, como escribe Antonio Pigafetta en su relación, que las naves de Fernando de Magallanes, en su derrota hacia el Polo Antártico, ingresaron en el estrecho que hoy lleva el nombre del portugués. Un nombre que contrasta de manera elocuente con la toponimia asignada a muchos sitios de la región, cuyas duras condiciones quedaron de este modo representadas para la eternidad y aún hoy estremecen: Puerto de Hambre, isla Desolación, golfo de Penas, seno Última Esperanza, bahía Salvación, cabo Deseado, puerto Misericordia, todos nombres que grafican las dificultades que las condiciones geográficas y climáticas impusieron a los europeos, así como la impresión y conmoción emocional que causaron en ellos, e incluso en nosotros hoy como efecto del peso de las historias asociadas a estos navegantes. Como una forma de alivianar las penalidades e infundirse ánimo, además del calendario cristiano que los condicionó, puede interpretarse también la toponimia religiosa con que bautizaron

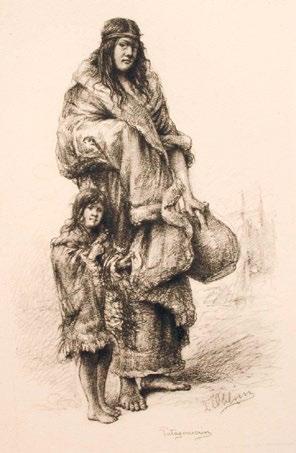

Mujer aónikenk con su hija, 1884. En Theodor Ohlsen, Durch Süd-Amerika, Hamburg, Louis Bock & Sohn, 1894. Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

PÁGINA ANTERIOR

Diego Gutiérrez, Americae sive quartae orbis partis nova et exactissima descriptio, [Amberes], 1562 Colección: Biblioteca Congreso USA

otros sitios, como San Julián, Santa Cruz y Todos los Santos. Incluso, las características extremas de la región, así como los riesgos para la navegación en el cruce del Cabo de Hornos y la derrota por los canales y la Mar del Sur que impidieron la colonización de un territorio considerado de escasos recursos, a modo de placebo dieron lugar a la mítica ciudad de los Césares como una forma de atraer colonos a la Patagonia.

Asimismo, de gran trascendencia ha sido un nombre que, a su vez, evoca una de las primeras leyendas que causaron gran impacto en el mundo europeo y que surgió con la llegada de las naves españolas: «Un día, de pronto, descubrimos un hombre de gigantesca estatura, el cual sobre la ribera del puerto (San Julián), bailaba, cantaba y vertía polvo sobre su cabeza. Era tan alto él que no le pasábamos de la cintura». Se había creado así el mito de la existencia de una tribu de gigantes.

Sin embargo, aunque el carácter de aventura, épica y drama sea tal vez el principal patrimonio legado por la empresa europea, no debemos olvidar otra de sus cualidades: ser la primera

que completó la circunnavegación del globo terráqueo, una hazaña que fue posible gracias al carácter de su líder. Alcanzar en 1520 las inmediaciones de lo que Pigafetta llama Polo Antártico, superar todos los desafíos impuestos por la naturaleza y dominar los excesos producidos por la ansiedad de encontrar un paso interoceánico luego de sucesivas frustraciones, reflejan la convicción de los europeos, quienes, a pesar de su gran degaste y ante el hallazgo de la entrada oriental del estrecho –para ellos un verdadero milagro– lo nombraron Cabo de las mil Vírgenes, reflejando una vez más la disposición anímica de los protagonistas de la aventura.

Además de transformarse en un antecedente fundamental de la llamada globalización, otro hito histórico-geográfico de un fenómeno plenamente vigente y estimulante, Magallanes organizó, encabezó y persistió en una comisión que debió enfrentar obstáculos que parecían insuperables, transformándose en un modelo universal; un ejemplo para mostrar virtudes superiores gracias a las cuales se conoció el mundo como totalidad y se

completó el planeta, haciendo posible entonces la creación del «fin del mundo», es decir, Tierra del Fuego.

Aunque Magallanes logró superar, como muchos otros después, los desafíos que la naturaleza del extremo sur de América impone, el relato de las duras condiciones geográficas de la región la transformaron en el escenario privilegiado de la aventura de la humanidad por dilatar el mundo conocido, un factor estructural y permanente en la historia. También lo fue la colaboración que los europeos recibieron de los pueblos originarios, pues el contacto entre grupos humanos, pueblos y culturas es otra de las constantes de la evolución histórica de la humanidad, incluso si se da de modo violento y dramático. Así, nombres como Patagonia y Tierra del Fuego, otorgados por los europeos a partir de expresiones culturales de sus pueblos originarios, tienen en los habitantes existentes en la región desde tiempos inmemoriales, en sus formas y costumbres, el origen de topónimos de significado e impacto mundial, también imperecederos, que alimentan la curiosidad permanentemente.

Typus Orbis Terrarum. En Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum orbis terrarum: opus nunc denuò ab ipso auctore, recognitum, multisquè locis castigatum..., Amberes, Apud Ant. Coppenium Diest, 1573.

Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

UN PAISAJE SOBERBIO Y SALVAJE

En las instrucciones que recibió Robert Fitz-Roy del almirantazgo inglés para su comisión de reconocimiento y exploración del extremo sur de América, al aludir a Tierra del Fuego e islas y canales circundantes se refieren a tareas que se verificarán en «la región más inhóspita» o en «lóbregas regiones», advirtiendo al hidrógrafo que en la parte oriental del estrecho había bastante más trabajo que hacer, pues la costa fueguina desde el Seno del Almirantazgo hasta el cabo Orange no había sido «tocada».

Rumbo a Tierra del Fuego, luego de visitar las islas que llama Falkland (hoy Malvinas), el capitán Fitz-Roy relata que en la travesía su nave enfrentó fuertes vientos del sur, furiosas y repetidas turbonadas y tiempo frío, a pesar de que ya estaban en verano. Acercándose a tierra por el cabo Domingo, fondeó frente a Santa Inés, maniobra que demoró pues una fuerte marejada que fluía hacia la costa no sólo la dificultó, sino que creó una situación peligrosa para la nave por el riesgo de encallar en la costa. Así,

Encuentro de tripulantes de la expedición de Thomas Cavendish con pueblos originarios de la región magallánica (1586). En Twee vermaarde scheeps-togten van Thomas Candisch, engels edelman, De eerste rond-om de geheelen Aard-kloot, Gedaan in the jaar 1586..., Leiden, Pieter Vander Aa, 1706.

Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

con esta breve descripción, reveló algunos de los elementos que hacían siempre riesgosa la navegación por la región, a los que agregó el mal tiempo, rompientes, fuerte marea creciente, viento y una alta marejada.

La descripción de las costas de Tierra del Fuego en el extremo sur de la isla grande, con riscos y montañas boscosas, altas y abruptas que ascienden desde el agua profunda, llevan a Fitz-Roy a hablar del «negro precipicio» que, creía, amenazaba su nave, la que también estaba sometida a los efectos de una mar gruesa y fuerte temporal. Su retrato del cielo al ponerse el sol, de aspecto rojizo con nubes que pasaban sobre la cima de las montañas en masas rasgadas y separadas, presagio de un temporal que el barómetro confirmaba, antecede a su confesión de que su tripulación se encontraba cansada e impaciente a causa del mal tiempo de la región, el que incluía sucesivas y gigantescas olas, ráfagas de viento, granizo y lluvia. Este escenario lleva a Fitz-Roy a aludir a los navegantes que lo antecedieron en las aguas que rodeaban el cabo de Hornos que, como George Anson en el siglo XVIII ,

debieron enfrentar durísimas condiciones de navegación en buques desvencijados, con ineficientes tripulaciones y en costas desconocidas que, efectivamente, él era el primero en explorar de manera cuidadosa y sistemática. El conocimiento acumulado de la zona lo llevó a afirmar que la Tierra del Fuego abarca todas las islas hacia el sur del estrecho de Magallanes, hasta tan lejos como las islas Diego Ramírez; un territorio compuesto por diversos paisajes según el lugar en que se encuentren, si en el interior de la isla grande, en el litoral o en medio de los canales. Así, Fitz-Roy describe un territorio abierto, bastante llano, con colinas ocasionales y las que llama cordilleras de cimas niveladas, que denomina estepas, con muy pocos árboles y agua escasa.

Por su parte, la porción nororiental de Tierra del Fuego ofrece boscosas montañas en las islas suroccidentales que se suceden hacia la región nororiental bajo la forma de colinas de moderada altura, parcialmente cubiertas de monte; a su vez, hacia el norte se presentan extensiones niveladas casi libres de bosque, pero cubiertas con hierbas aptas para el pastoreo de ganado.

La vertiente occidental de la Patagonia, de la que forma parte Tierra del Fuego es, según Fitz-Roy, la peor parte del territorio por tratarse de una cordillera de montañas medio hundida en el océano, estéril hacia el mar, impenetrablemente boscosa hacia el continente y con frecuentes lluvias que no secan nunca por evaporación antes de que caigan nuevos chaparrones.

Opinión calificada por provenir de quien primero exploró detenidamente el confín del extremo sur de América reconociendo y levantando sus costas para el imperio británico, la travesía y relación de Fitz-Roy no sólo quedó reflejada en su diario, sino también en mediciones, registros, tablas, observaciones, cartas y mapas que, como el de Tierra del Fuego, Cabo de Hornos e islas Diego Ramírez, reflejan la calidad de su trabajo, en el que también se ocupó de describir a la población que encontró a su paso, tribus que genéricamente llama fueguinos, las que deambulaban por las planicies azotadas por el viento y los canales que rodeaban las isla, según su relato.

Por su parte, Charles Darwin también refirió su paso por Tierra del Fuego alternando su descripción del paisaje con la de sus habitantes, los onas o selknam, expresando así el impacto que la naturaleza y las culturas originarias le causaron. Sobre el paisaje, inicia su relación aludiendo a un lugar en que el Beagle ancló, la bahía del Buen Suceso, que describió rodeada de montañas redondeadas y de poca elevación, de esquisto arcilloso y cubiertas hasta la orilla del mar de espeso bosque. Una visión que fue suficiente para asentar en su diario que una sola ojeada sobre el paisaje le había bastado para saber que iba a ver allí cosas enteramente distintas de las que había conocido hasta entonces.

Respecto de los habitantes, a los que llama indistintamente indígenas, salvajes o fueguinos, su primer encuentro con ellos lo llevó a señalar que fue el espectáculo más curioso e interesante que había presenciado en su vida, concluyendo que no se imaginaba cuán enorme era la diferencia que separaba al que llama hombre salvaje del hombre civilizado. Realidad, además de su origen, educación y condición sociocultural, que lo llevó a calificar a los fueguinos como raza innoble y asquerosos salvajes.

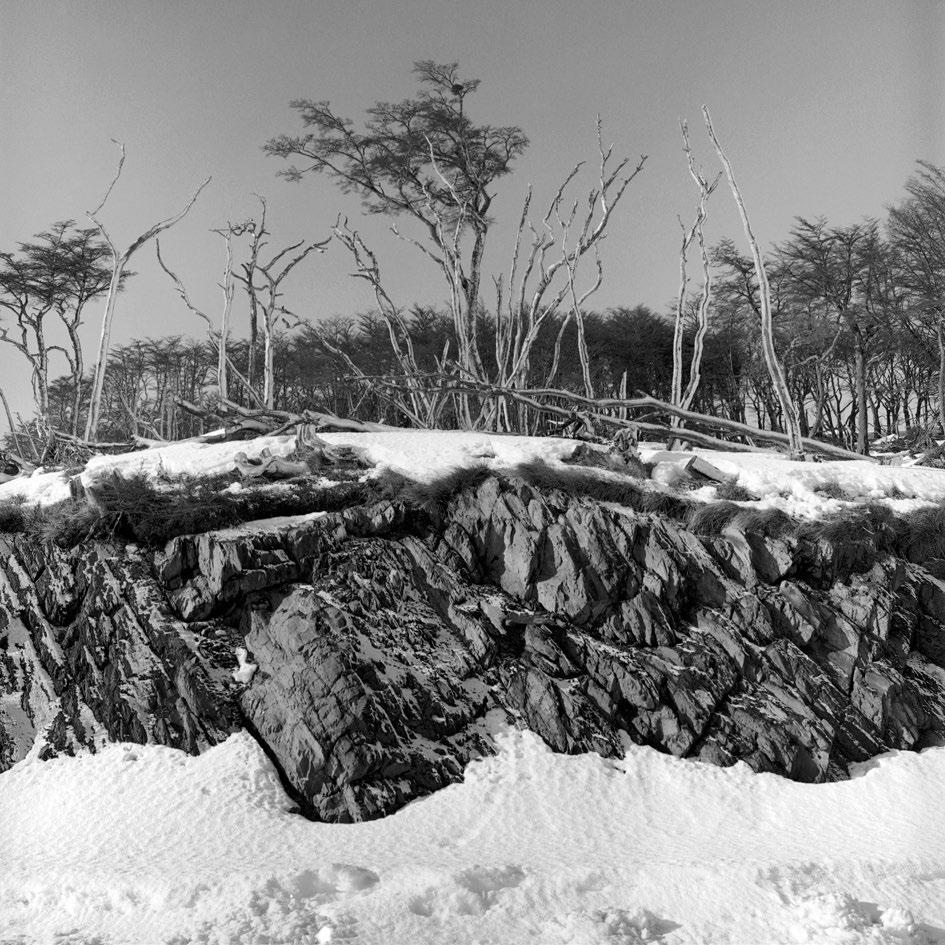

Habiendo incursionado hacia el interior de la isla, el naturalista y entonces entusiasta geólogo la describió como un país montañoso, en parte sumergido, ocupando por tanto el lugar de los valles profundos estrechos y extensas bahías. También aludió al inmenso bosque que se extendía desde las cimas de las montañas hasta la orilla del mar, cubriendo las vertientes con la excepción de la occidental. Al bosque le seguía una faja de humedales o turberas cubierta de plantas y sobre ellas, la línea de nieves perpetuas. Adentrándose en el bosque, y más tarde siguiendo la huella de un torrente y observando en las llanuras la espesa capa de turba

pantanosa que las reviste, Darwin también enumeró las cataratas y numerosos troncos de árboles caídos que le cerraban el paso por el lecho de la corriente, el que, sin embargo, describe que de pronto se ensanchó por el destrozo que en sus orillas producían las inundaciones. Avanzando por las rigurosas y descarnadas orillas del torrente, relata que luego vio recompensadas todas sus fatigas ante la magnificencia y belleza del panorama que contempló, en el que se fundían la profundidad sombría del barranco con los signos de violencia, pues por todas partes, a un lado y otro, se veían masas irregulares de rocas y árboles, algunos arrancados y otros todavía de pie, pero podridos hasta el corazón y a punto de caer. Esta confusa masa de árboles robustos y árboles muertos lleva a Darwin a hablar de «estas tristes soledades donde parece que, en lugar de la vida, la muerte reinaba como soberana». Aquí, describe, el viento se enseñoreaba, explicando que a determinada altura se presentaran árboles gruesos, achaparrados y torcidos en todas direcciones; un paisaje, concluyó, de aspecto triste y sombrío que ni siquiera los rayos del sol alegraban, compuesto por cadenas de colinas irregulares, masas de nieve aquí y allí, profundos valles verde-amarillentos y brazos de mar que cortan las tierras en todas direcciones, todo siempre cruzado por un viento fortísimo y horriblemente frío y una atmósfera corrientemente brumosa.

Sin embargo, este paisaje también tenía compensaciones, como la que encontró luego de recorrer un sendero abierto por los guanacos y alcanzar hasta una colina, la más elevada de esos contornos –aseguró– y que le permitió disfrutar del paisaje circundante, porque si al Norte se extendía un terreno pantanoso, al Sur se distinguía un cuadro que calificó de «soberbio y salvaje», muy digno de Tierra del Fuego.

En el extremo sur de América, en medio de las islas adyacentes a Tierra del Fuego, Darwin tuvo a la vista la cordillera de los Andes y, con ella, su primera impresión: «Esas masas inmensas de nieve, que no se funden jamás y parecen destinadas a durar tanto como el mundo, presentan un gran, ¿qué digo?, un sublime espectáculo. La silueta de la montaña se destaca clara y bien definida». Junto a la monumentalidad material de la cordillera, lo que más impresionó al viajero fueron «las particularidades geológicas» del territorio: «¡Quién podría dejar de admirarse pensando en la potencia que ha levantado estas montañas, y más todavía en los innumerables siglos que se han necesitado para romper, trasladar y aplanar partes tan considerables de estas colosales masas!». Una vista que lo llevó a exclamar: «¡Qué misteriosa grandeza en aquellas montañas que se elevan unas tras de otras!». Concluye su relación asegurando que, vistos desde aquel punto, los numerosos canales que se pierden en las tierras y entre las montañas,

revestían tintes tan tétricos que parecía «como si condujeran fuera de los límites de este mundo».

Esta representación tiene su correspondencia en las reflexiones que Darwin hizo a propósito de los que llama «salvajes», cuya visión lo llevó a preguntarse: «¿De dónde proceden? ¿Quién puede haber decidido, quién ha forzado a una tribu de hombres a abandonar las hermosas regiones del Norte, a seguir la cordillera, a inventar y construir canoas y, por último, ir a habitar uno de los países más inhóspitos del mundo?» Dudando de la pertinencia de sus interrogantes, dejando ver el impacto que los habitantes del extremo sur de América tendrían en sus planteamientos científicos, concluyó: «la naturaleza, haciendo omnipotente el hábito y hereditarios sus efectos, ha adaptado al fueguino al clima y a las producciones de su miserable país».

Aunque imbuido de una mirada imperial decimonónica, ya al final de su viaje, Darwin muestra conciencia de que «el hombre blanco desempeña un papel destructor» pues, «donde quiera que el europeo endereza sus pasos parece que persigue la muerte a los indígenas». A propósito de lo que conoció de América, Polinesia, Sudáfrica y Australia, aseguró: «En todas partes observamos el mismo resultado». Realidad social que inmediatamente lo llevó a concluir, anticipando el mecanismo de la selección natural: «Las variedades humanas parece que reaccionan sobre otras de la misma manera que las diferentes especies animales, destruyendo siempre el más fuerte al más débil». La Patagonia queda de este modo –ahora como escenario– estrechamente ligada a una de las principales teorías científicas existentes, transformándose las evidencias que contiene en un foco de atención permanente.

«EL EXTERMINIO VENDRÁ»

Aproximadamente hasta los comienzos de la década de 1880 pudo desenvolverse la existencia corriente y pacífica de los pueblos originarios de Tierra del Fuego, pues su hábitat aun no era objeto de interés de aventureros o colonizadores, entre otras razones porque no se conocían las posibilidades que ofrecía esa tierra de extremos.

Los buscadores de oro llegados desde 1881 en adelante, y las compañías ganaderas, que lo hicieron a partir de 1883, «iniciaron el poblamiento blanco» de Tierra del Fuego, como afirma Mateo Martinic, y fueron los mineros los primeros en ejercer la violencia contra los selknam, depredándolos en su afán de capturar mujeres y niños.

A continuación, las prácticas de explotación ganadera realizadas por la Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego, en su

afán por imponer sus términos y enfrentando la resistencia de la población, derivaron en una persecución de los selknam, haush, yaganes y kawésqar, materializada en asesinatos y en captura para ser deportados a las misiones salesianas instaladas en la isla Dawson, donde serían «civilizados», es decir, adoctrinados en el culto católico y domesticados para el trabajo asalariado. En dichas reducciones, las condiciones de hacinamiento y malnutrición causaron enfermedades que los diezmaron y contribuyeron a su extinción.

La historiografía tiene suficientemente acreditada la violencia desatada sobre los fueguinos. En las palabras de un sobreviviente Selknam reproducidas por Anne Chapman en su libro Fin de un mundo. Los Selknam en Tierra del Fuego (2002) se consigna una elocuente expresión de sus motivos: «¡Para poner ovejas, mataban los indios! Se hicieron una limpieza y más por la pampa mataron más, para limpiar que no haiga ningún indio, entonces metieron ovejas ellos. Entonces estaban tranquilos con sus ovejas, para que puedan poblar, producir con las ovejas esas, para su ganancia, para su producto, con eso tenían sus ganancias. Por eso mataban los indios». Asimismo, Alberto Harambour, en el estudio que abre su libro Un viaje a las colonias. Memorias y diario de un ovejero escocés en Malvinas, Patagonia y Tierra del Fuego (1878-1898) (2016), cita a Joaquín Bascopé para asegurar que las autoridades también fueron «agentes de violencia, que apenas si podían distinguirse de los cazadores privados».

El pronóstico de John Spears en su libro sobre la vida en Tierra del Fuego y la Patagonia, publicado en 1895, ya estaba prácticamente cumplido a comienzos del siglo XX : «el ovejero terminará por arrinconar [a los onas] extendiendo sus cercas de alambre, y luego el exterminio vendrá». Esto explica que Mateo Martinic concluya que «la ocupación colonizadora de Tierra del Fuego, admirada como exitosa, había tenido un costo humano horroroso, con la extinción virtual de los nobles y milenarios selknam».

LOS CUERPOS PINTADOS

«Cazador de sombras» fue el nombre que Martín Gusinde asegura que los selknam le otorgaron. En los cuatro viajes que el sacerdote y antropólogo realizó entre 1918 y 1924, investigó y fotografió los que consideró «últimos restos de los tan poco apreciados fueguinos», cuando estos se encontraban muy mermados, «arrastrando una penosa existencia» como consecuencia de la depredación que habían sufrido. De acuerdo con las exigencias de la etnología moderna, Gusinde no se contentó con la descripción de los aspectos externos de los selknam, sino que intentó ir más allá y abarcar su «propiedad cultural en su armoniosa totalidad»,

Fondo del río Gennes, 1838. En Jules

Sebastian Cesar Dumont d’Urville, Voyage au Pole Sud et dans l’Océanie sur les corvettes…, Paris, Gide et Cie., 1842-1847.

Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

buscando también descubrir los que llamó principios fundamentales e impulsos de su vida espiritual.

Su primera reacción al conocerlos fue de preocupación al «ver sus cuerpos repulsivos y sus salvajes ademanes», como escribió en su libro Hombres primitivos en la Tierra del Fuego (1951), sin embargo, luego de convivir y conocerlos, los reconoció como «hombres cabales, con todas las pasiones y debilidades inherentes a la condición humana, sin distinción alguna», como registró en su obra Los indios de Tierra del Fuego. Los Selk’nam (1982). Sin duda una forma de abordar el tema, hoy superada por las nuevas perspectivas que no parten de la premisa de estudiar un pueblo extinto, sino que vivo y presente en el archipiélago, pero que en el caso de Gusinde, y en la época en que escribió, contribuyó a humanizarlos y a valorar su cultura y patrimonio.

Martin Gusinde documentó la sobrevivencia de los pueblos originarios de la Tierra del Fuego, también su sensibilidad espiritual, la que se expresa en las elocuentes fotografías que realizó de sus «cuerpos pintados» y enmascarados para los rituales Hain y Chiejaus. Se trata de un acervo de alrededor de mil placas que, en la afortunada interpretación de Xavier Barral en la presentación del libro sobre Martin Gusinde y los selknam, yámanas y kawéskar (2015), «celebran el espíritu de los habitantes del fin del mundo», y que, en las más concretas palabras de Marisol Palma, ofrecen una «mirada fotográfica que se esfuerza más por reconstruir las tradiciones culturales y materiales destruidas por el genocidio».

TIERRA DEL FUEGO, PAISAJE CULTURAL EXTREMO

Opacada por el estrecho de Magallanes, un paso interoceánico pleno de significados geográficos e históricos, Tierra del Fuego no ha sido objeto de estudios particulares que la proyecten como entidad. Una situación que ya comenzó a superarse y que tiene en el libro Tierra del Fuego. Historia, arquitectura y territorio (ARQ Ediciones, 2013) de Eugenio Garcés y sus colaboradores, un antecedente fundamental. Esta obra tiene el gran mérito de ocuparse exclusivamente de la isla, abordando diversos aspectos fundamentales que conforman su patrimonio geográfico, histórico y cultural. Este ejercicio básico transformó a Tierra del Fuego en parte de la ecúmene, del mundo conocido, señalando sus características, las mismas que la rotulan como un lugar único y épico, ya sea que se le aborde desde la geografía que permanece, o de la historia que alguna vez sucedió y que seguirá ocurriendo.

A través de su paisaje melancólico, en el que la falta de puntos de referencia agudiza la sensación de soledad y vastedad que marca este territorio, Tierra del Fuego se muestra a través de las

huellas que su evolución ambiental ha dejado, pero también gracias a las manifestaciones de la actividad humana y los sucesivos estratos de ocupación que la han modelado hasta la actualidad, los que también reflejan las formas en que sus habitantes han ocupado y convivido con la naturaleza en esta zona. Todas estas expresiones tienen en las imágenes, particularmente en las fotografías, un elocuente registro de la vastedad y aislamiento de un espacio potencialmente trágico que las imágenes de artefactos mecánicos y artificios tecnológicos propios de las estancias ovejeras contribuyen a acentuar.

El estudio histórico centrado en Tierra del Fuego demuestra la incapacidad para generar «tejido social» dadas las formas de ocupación que se han sucedido desde el siglo XIX en adelante en ese territorio. La evidencia muestra que ni la minería del oro, ni la actividad ganadera ni la petrolera lograron afincar población en la región, de modo tal que no es sorprendente que en la actualidad esta solo sea de algunos miles de habitantes y que los centros poblados sean fruto de iniciativas públicas y deban estar permanentemente subsidiados.

En un clima hostil como el de Tierra del Fuego se entiende el papel que la fuente de calor, el fuego, la calefacción tiene en la vida de sus pobladores, señalando la permanente necesidad de protegerse del frío, la lluvia, el viento y la nieve. Las condiciones ambientales también explican los estilos arquitectónicos que se han sucedido desde fines del siglo XIX , y con ellas las formas de sociabilidad propias de las estancias ganaderas.

Menos edificante resulta constatar que Tierra del Fuego, a propósito del actuar contra sus pueblos originarios, también puede ser caracterizada como una tierra indefensa frente al quehacer de la humanidad que sucesivamente, y motivada esencialmente por intereses económicos, la ha violentado y aniquilado. La imprescindible puesta en valor de un patrimonio prácticamente desconocido así como el relevamiento de la riqueza cultural y natural de Tierra del Fuego, permitirá no sólo conocer las características geográficas de la región, las representaciones que de ella se han hecho en la cultura occidental, las formas y condiciones de la ocupación en la zona, sino que, sobre todo, será una evidencia más del quehacer de la humanidad, que en Tierra del Fuego se ofrece en todo su amplio margen de posibilidades. Desde las sorprendentes formas de adaptación de los fueguinos a la naturaleza, plena de manifestaciones culturales inéditas, pasando por la urgencia de explorar, descubrir y hacer ciencia, o la búsqueda de la belleza y el espíritu de superación y constancia para permanecer, hasta la violencia despiadada y la depredación propia de nuestra especie.

Retrato de grupo de mujeres indígenas del pueblo kawésqar, sentadas en el suelo, cubiertas con un manto de piel de la cintura para abajo y el torso descubierto. Fotografía tomada en el Campamento Río del Fuego, en el extremo austral de América del Sur Colección: Fotografía Patrimonial – Museo Histórico Nacional

PATRIMONIO DE LA HUMANIDAD

En lo más hondo de la tierra, en lo más lejano, en lo más frío, es decir en Chile, desde tiempos inmemoriales Tierra del Fuego y la Patagonia han estado asociadas a una existencia aislada entre los imponentes fenómenos naturales que la contienen: a una subsistencia marcada por el rigor y la austeridad; a un acontecer histórico desde siempre asociado a la epopeya, a las grandes acciones, a protagonistas que inevitablemente resultan ser personajes heroicos, siempre pioneros; a gestas gloriosas o trágicas dignas de recuerdo; a existencias como las de los colonos, tan anónimas como persistentes; a hechos legendarios o ficticios, o incluso cotidianos, que hoy atraen la atención, también por el escenario en que ocurrieron. A sucesos que alguna vez fueron historia y que en la actualidad han sido sobrevenidos por el acaecer de vidas sencillas, ásperas y sacrificadas, que se han transformado en patrimonio de la Patagonia.

Desde el explorador Magallanes en adelante, el drama y la lucha propios del acceso y sobrevivencia en un medio extremo, el sacrificio, el dolor, los hechos atrevidos, audaces y temerarios

protagonizados por sujetos valientes e intrépidos, por héroes y heroínas insuperables desafiados por condiciones imposibles, han contribuido a dotar de contenido a la historia, a la identidad y al patrimonio de los habitantes de la Patagonia, vinculando esta región geográfico-histórica con los sucesos y procesos de que ha sido escenario, objeto o sujeto, como su gran activo frente al resto del mundo. Hoy, además, acentuado por la valoración de las culturas originarias que la habitaron.

En un mundo cada vez más globalizado, con evidente conciencia ecológica, con un creciente interés por la naturaleza y ansioso por alcanzar lo salvaje, rústico, virgen, primitivo e impoluto, Tierra del Fuego se presenta como un sitio privilegiado. Un placebo para sujetos ansiosos de vivir y experimentar lo natural, estimulados por la expectativa de encontrarse en un lugar asociado a lo épico, lo dramático, lo histórico en medio de un entorno «salvaje» que permite sustraerse del ambiente citadino, artificial, monótono y previsible como para muchos aparece cotidianamente la sociedad moderna.

La valoración y comprensión de las culturas ancestrales, de las identidades particulares, de la humanidad que se expresa, por

Entrada a los bosques del río Sedger, 1838. Jules Sebastian Cesar Dumont d’Urville, Voyage au Pole Sud et dans l’Océanie sur les corvettes, Paris, Gide et Cie., 1842-1847.

Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

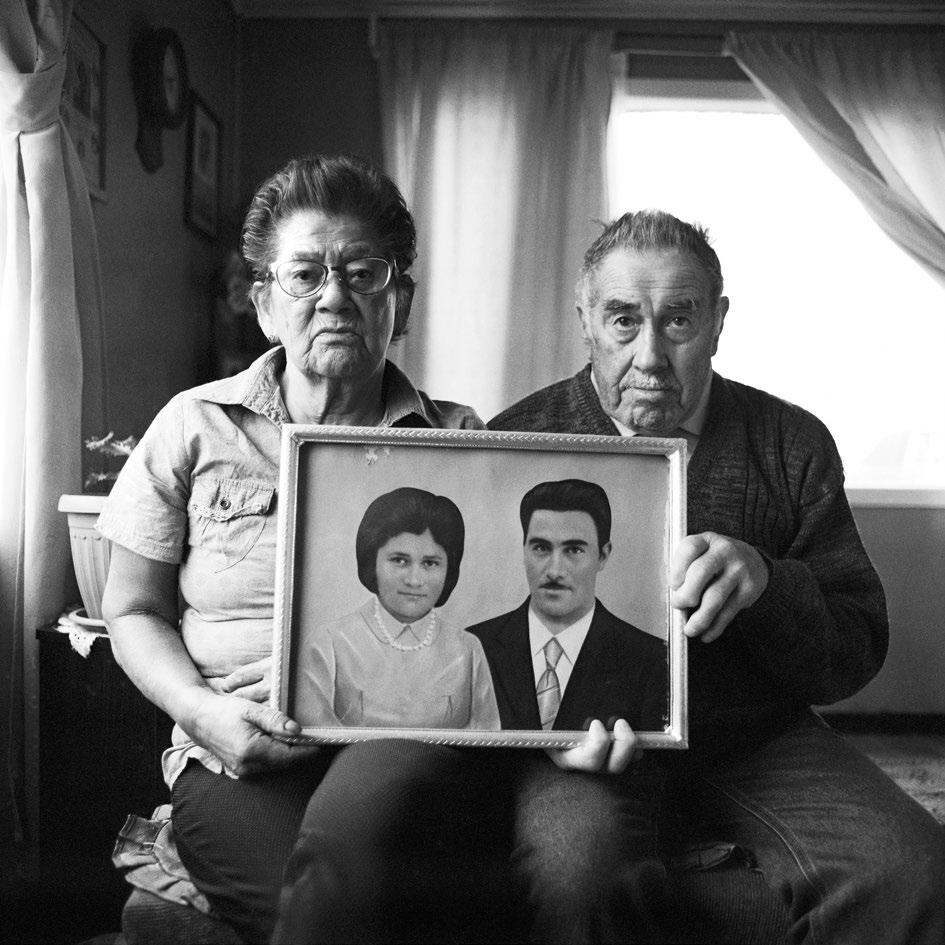

ejemplo, en pueblos como los selknam, yáganes, haush o kawésqar, en su momento todos nombrados fueguinos, es otro activo de Tierra del Fuego. Hombres y mujeres que, como lo demuestra su existencia milenaria, no sólo se adaptaron y sobrevivieron a las duras condiciones del medio ambiente, sino que además desarrollaron formas, prácticas, usos, creencias, ritos y otras tantas manifestaciones de su cultura que hoy se aprecian por ser expresiones ancestrales de la humanidad de la cual formamos parte. Historia que se relaciona también con los actuales habitantes de la Patagonia y, sobre todo del archipiélago de Tierra del Fuego, cuya determinación y voluntad de permanecer, vivir, desenvolverse y prolongarse a través de sus descendientes, al igual que

los que los precedieron a lo largo de la historia, se expresa en sus rostros, miradas, gestos, palabras, proyectos, prácticas, ideas y creencias; pero también en los objetos de la cultura material que cotidianamente utilizan, en los vestigios, entre ellas fotografías del pasado familiar que atesoran y exhiben; pero sobre todo, en los inmuebles que les sirven de refugio, espacios de calor y confort, de sociabilidad, ámbito de sentimientos y pasiones, lugar de encuentro, en definitiva, un hogar en medio de una naturaleza cuya dureza y aislamiento hacen todavía más valorable su residencia, por las razones que sean, en este lugar alguna vez considerado «fuera de los límites del mundo», pero donde lo humano se desenvuelve y manifiesta en plenitud.

Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Tabula

Magellanica qua Tierrae del fuego, cum celeberrimis fretis a F. Magellano et I. Le Maire…, [Amsterdam, 1640].

Colección: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

100

Rubén Barrientos, Estancia Armonía

100

Rubén Barrientos, Estancia Armonía

111

Sergio Ruiz, Cementerio Porvenir

111

Sergio Ruiz, Cementerio Porvenir

Fringe, end, far landscape, south of the south, frontier territory. Antipodes, adventure, isolation. Infinity, impregnable territory. Saga and end of the world, the beauty of emptiness, absolute solitude… These are some of the adjectives and concepts that are repeatedly mentioned when chroniclers and authors refer to Tierra del Fuego, an island that is also considered “a territory outside of this world” that has remained detached from the ecumene and from the world as known by Europeans during the largest part of the history of humanity; this situation was reinforced by the epic events that took place in its surroundings. In today’s world, where the ability to surprise is increasingly rare, this territory has become very appealing.

According to the accounts Robert Fitz-Roy wrote in his diary about the journey on the Beagle – which the British seafarer and hydrographer commanded until his arrival in Tierra del Fuego in December 1832 – this territory still remained “unexplored”; this testimony is an eloquent reflection of the situation and conditions of Tierra del Fuego and the archipelago it is part of, which, between 1520 and 1832, had only been traversed by the selknam, yaganes and kawéqar, native peoples that had lived there for thousands of years.

Perhaps only the brothers Gonzalo and Bartolomé Nodal had the chance to explore a little more than the coasts of Tierra del Fuego when they had to shelter in 1618 in Buen Suceso bay during their attempt to reach Cape Horn. The territory had previously been discovered by the expedition of Jacob Le Maire and Willen Schouten in 1616. But the truth is that they didn’t go deep into the island that the Dutch explorers had proven was not actually a continent or Terra Australis –how it was previously envisioned and depicted on maps – which shows once more how unusual Tierra del Fuego seemed to them.

Because of the location and geographical condition of Tierra del Fuego and its territory, and because of the mystery that surrounded it for so long, this is a territory that represents the extreme, and this idea is confirmed by the telluric landscape that was formed by the movements of the earth’s crust and agents like the wind, ice, water and sea, which define its character and make it relentless and ruthless. This character is also defined by humanity’s adventures in this severe geography. Its environmental conditions seem unbearable to many,

but the native peoples of the region, like the selknam, learned to adapt to them, coping and surviving, something which impressed the explorers and travelers that sailed the southern seas from the 16th century onwards, and which also contributed to increase the sense of frailty and forlornness imposed for so long by the remoteness and the harsh natural conditions of the region. Today, these conditions are an asset that draws attention to the area, intensified by the impression of emptiness, isolation and melancholia of a landscape where humanity is present through material objects, remains and buildings, but rarely by its permanence, thus molding a landscape that is sublime for its beauty, but also for its capacity to evoke a potential drama in a land that also seems unarmed and defenseless to the acts of individuals who, successively and motivated by economic interests, have plundered it.

So, as a consequence of its geography and history, Tierra del Fuego offers a wide range of possibilities to illustrate humanity’s endeavors: from the conquest, the search for beauty and the spirit of overcoming to confront nature, to ruthless violence and plundering that is characteristic of our species.

A global geographical landmark, for its condition of antipode and extreme, end of the world, together with Patagonia and the Strait of Magellan, Tierra del Fuego is a historical-geographical heritage of Chile that has a particular identity, because of its physical characteristics and the representations that have been made of the area and its inhabitants from the 16th century onwards.

NATURE AND HISTORY

Associated with exploration and adventure beyond every known boundary, with wild nature and also history, drama and the majestic, and even with the wonderful, fantastic and unknown, from the beginning of the 16th century the far southern end of America represents a frontier in the eyes of the west, the finis terrae of the world, a place where everything is unparalleled, a mysterious earth. The imaginary about this area of the planet has its origins in West Europe, during the time of the discoveries, which begins with transatlantic navigations, continues with the travels of circumnavigation and antarctic exploration and now and then draws upon tragedy, pain and sacrifice, which in turn give rise to

acts of heroism, courage and humanity that make their way into the history of the region; then, contemporary times are associated with the violence perpetrated from the 19th century onwards against the selknam and which practically led to their extermination. More recently, humanity’s new unrestricted respect, its empathy with the persecuted and in summation, a growing moral conscience of the inherent dignity of all human beings have contributed to the appreciation, recovery and conservation of the cultural expressions of the fueguino peoples as a cultural patrimony.

Some of the elements of Patagonia’s geography like the Drake Passage, Cape Horn, Tierra del Fuego, the Pacific Ocean, the strait between oceans, even Antarctica invoke the idea of adventure and extreme living conditions which are manifested in the wind, rain, cold, snow, the sea and waves: nature making itself known relentlessly, tempestuously, and therefore sublimely because of its stunning beauty and tragic potential. Even today some names like Magellan, Cook and Darwin evoke geographic-historical associations that make it possible to appreciate the region, give meaning to places and locations that remind us of humanity’s events; in this area the toponymy recalls events and moments that are seen as historical feats of all times, either of an empire, a State or a man. Words, and among them the names given to the native peoples of the area like the patagones, that arouse the imagination, evoke drama or refer to a cultural heritage that refuses to disappear despite the violence and plundering they have suffered.

Thus, since it became part of western history, Patagonia in the far south of America has been regarded as a space, a concrete and real geography, although persistently not completely known, from where fantastic, mythical, glorious, even dramatic representations are projected, and which have one of its main foundations in history, in this place far away from everything and difficult to access, as it has been the setting of many events of global repercussion. This, linked to the representations and images of the places where they have taken place, give it a historical-geographical identity that is impossible to ignore, and is also reinforced by the promise of the fantastical, the possibility of encountering something that never lets itself be captured, which refreshens the expectations of this region that has a landscape which is part of history and not only of nature.

TIERRA DEL FUEGO DEPICTED HUMANITY “BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF THIS WORLD”RAFAEL SAGREDO BAEZA Historian. Academic of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

EPIC PATAGONIA

As Antonio Pigafetta writes in his account, it was on November the 1st of 1520 that the ships of Ferdinand Magellan, after their failure to reach the Antarctic pole, sailed into the strait that now carries the name of the Portuguese. This name is in sobering contrast with the toponymy assigned to many places of the region, which are depicted into eternity by their harsh conditions and make us shudder even to this day: Port Famine, Desolation Island, Gulf of Distress, Last Hope Sound, Salvation Bay, Desired Cape, Port of Mercy, all names that evoke the difficulties that the geographical and climatic conditions forced on the Europeans, as well as the impression and emotional turmoil they caused them, and even us today as a result of the weight of the stories associated with these travelers.

The religious toponymy they used to name other locations, like Saint Julian, Holy Cross and All Saints, can also be interpreted – besides the Christian calendar that influenced them – as a way to alleviate the hardships and take heart. Moreover, the extreme qualities of the region, and the risks for navigation during the crossing of Cape Horn and the failure to navigate through the channels and the Southern Sea that thwarted the colonization of a territory that was considered to have limited resources, gave rise to the mythic city of Ceasars as a placebo and a way to attract colonists to Patagonia.

Likewise, there was a name of great transcendence that evokes one of the first legends that caused a strong impact in the European world and was born with the arrival of the Spanish ships: “One day, suddenly, we discovered a man of gigantic size, who, on the shore of the port (Saint Julian), was dancing, singing and throwing dust over his head. He was so tall, we didn’t reach further than his waist”. Thus the myth of the existence of a tribe of giants was created.

However, although the character of adventure, epic and drama is perhaps the main legacy of the European endeavor, we must not forget another of its virtues: it was the first complete circumnavigation of the globe, an achievement that was made possible thanks to the character of its leader. Reaching the proximity of what Pigafetta called the Arctic Pole in 1520, overcoming all the challenges imposed by nature and being able to dominate acts of intemperance caused by the anxiety to find an interoceanic pass after successive frustrations, show the conviction of the Europeans, who, despite their exhaustion and before discovering the oriental entrance to the strait – in their eyes a true miracle – called it the Cape of the thousand Virgins, once again reflecting the state of mind of the main actors of this adventure.

In addition to becoming a fundamental precursor of so-called globalization, another historical-geographical milestone of a stimulating phenomenon that is fully in force, Magellan organized, led and persisted in a commission that had to face seemingly insurmountable obstacles, and so he became a universal role model;

an example of superior virtues who made it possible for the world to be known in its totality and to complete the planet, thus leading to the creation of the “end of the world”, that is to say, Tierra del Fuego. Although Magellan managed to overcome, like many others later on, the challenges that the extreme south of America offers, the recount of the harsh geographical conditions of the region turned it into the preferred setting of humanity for embarking on the adventure of expanding the known world, a structural and permanent element of history. The same can be said of the collaboration the Europeans received from the native peoples, as the contact between human groups, peoples and cultures is one of the constants in the historical evolution of humanity, even if it happens in a violent and dramatic manner. So, names like Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego, given by Europeans based on the cultural expressions of their native peoples, have their origin in the people who inhabited the region since time immemorial, in their forms and customs, and have a worldwide meaning and impact that are also imperishable and that nurture a permanent curiosity.

A PROUD AND WILD LANDSCAPE

In the instructions received by Robert Fitz-Roy from the English admiralty for his commission of reconnaissance and exploration of America’s extreme south, when referring to Tierra del Fuego and its surrounding islands and channels, it alludes to tasks that will be verified in “the most inhospitable region” or in “destituted regions”, warning the hydrographer that in the oriental part of the strait there was much more work to be done, as the coast of Tierra del Fuego from Almirantazgo Sound to Cape Orange had not been “touched”.

On his way to Tierra del Fuego, after visiting the islands he calls Falkland (today Malvinas), captain FitzRoy recounts that during the crossing his ship faced strong winds from the south, furious and repeated squalls and cold weather, even though it was already summer. Approaching land through cape Domingo, it anchored in front of Santa Inés Island, a maneuver that took a long time; it was hindered not only by a strong current that flowed towards the coast, but it also caused a dangerous situation for the ship because of the risk of running aground on the coast. Thus, with this brief description, he revealed some of the elements that always made navigation risky through the region, which were compounded by bad weather, breakers, strong rising tide, wind and a high swell.

The description of the coasts of Tierra del Fuego at the south end of the large island, with high and abrupt cliffs and wooded mountains that rise from the deep waters, inspire Fitz-Roy to talk about the “black abyss” that, he believed, threatened his ship, which was also subjected to the effects of a heavy sea and strong storm. His portrait of the sky at sundown, of russet hues and with clouds passing over the tips of the mountains

in frayed and separate masses and foreboding a gale confirmed by the barometer, precedes his confession that his crew was tired and impatient because of the bad weather in the region, with successive and gigantic waves, gusts of wind, hail and rain. This scenario led Fitz-Roy to refer to the sailors that preceded him in the waters around Cape Horn who, like George Anson in the 18th century, had to face extremely harsh conditions of navigation in dilapidated vessels, with inefficient crews and on unknown coasts that, in fact, he was the first to carefully and systematically explore. The knowledge acquired of the area made him state that Tierra del Fuego encompasses all the islands to the south of the Strait of Magellan, as far as the Diego Ramírez islands; a territory composed by landscapes that differed according to their location, be it inland the large island, at the coast or in the middle of the channels. So, Fitz-Roy describes an open territory, with a pretty flat terrain, with occasional hills which he calls mountain ranges with leveled peaks which he calls steppes, with very few trees and scarce water.

On the other hand, the northeastern part of Tierra del Fuego has wooded mountains in the southwestern island that succeed each other towards the northeastern region in the form of hills of moderate height, partially covered by scrubland; in turn, towards the north there are large leveled areas that are almost free of woods, but covered with herbage apt for the grazing of cattle. The western slope of Patagonia, of which Tierra del Fuego is part, is according to Fitz-Roy the worst part of the territory as it is a mountain range that is half sunk in the ocean, barren towards the sea, impenetrably wooded towards the continent, with frequent rains that never dry of evaporation before the next downpour.

As the first person who explored the south end of America in detail, mapping its coasts for the British empire, Fitz-Roy’s is a qualified opinion. His crossing and report is not only reflected in his diary, but also in measurements, records, charts, observations, letters and maps that, like those of Tierra del Fuego, Cape Horn and the Diego Ramírez islands, show the quality of this work, in which he also took care of delineating the population he found on his way, tribes that he generically called fueguinos, who roamed the windswept plains and the channels around the island, according to his recount.

For his part, Charles Darwin also referred to his journey through Tierra del Fuego alternating his descriptions of the landscape with its inhabitants, the onas or selknam, thus expressing the impact that nature and the native peoples caused him. As for the landscape, he begins his recount referring to the place where the Beagle anchored, the Bay of Good Success, which he described as encircled by rounded not very high mountains, of clayey schist and covered with thick forest up to the seaside. This vision was enough for him to write down in his diary that he needed only

one look at the landscape to know that there he would see completely different things than the ones he had known until then.

As for the inhabitants, whom he indistinctly calls natives, savages or fueguinos, his first encounter with them made him point out that it was the strangest, most interesting spectacle he had seen in his life, and concluded that he hadn’t imagined the extent of the difference that separated what he called the wild man from civilized man. A reality, besides of his origin, education and socio-cultural condition, that led him to characterize the fueguinos as a noble race and abominable savages.

Once he had ventured into the interior of the island, the naturalist and then enthusiastic geologist described it as a mountainous land, partly submerged, stretching over narrow deep valleys and extensive bays. He also mentioned the enormous forest that spread from the tops of the mountains to the seaside, covering the hillsides, except the one to the west. The forest was followed by a strip of wetlands or peat bogs covered by plants and above them, the line of perpetual snow.

Heading into the forest, and later on following the track of a stream, observing on the plains the thick marshy layer that covers them, Darwin also enumerated the waterfalls and many fallen tree trunks that blocked his path through the riverbed, which, however, would suddenly open up by floods that caused destruction on the riversides. Going forward through the severe and ruthless riverside, he writes that he soon saw all his weariness justified with the magnificence and beauty of the view he saw, where the bleak depth of the ravine merged with signs of violence, since, everywhere, in one and another direction, he saw irregular masses of rocks and trees, some pulled out and others still standing, but rotten to the core and about to fall. This confusing mass of robust trees and dead trees led Darwin to talk of “these sad solitudes where it seems like, instead of life, death reigned as sovereign”. Here, the describes, the wind rules, explaining that on certain heights there were thick, stocky trees, that twist in all directions; a landscape, he concluded, of sad and somber appearance that not even the rays of the sun could brighten, composed by chains of irregular hills, masses of snow here and there, deep green-yellow valleys and sea arms that cut the lands in all directions, all the time crossed by a very strong, horribly cold wind and a constantly misty atmosphere.

However, this landscape also had compensations, like the ones he found after traversing a track opened by guanacos and reaching a hill, the highest of the area – he assured – which allowed him to enjoy the surrounding landscape, because if to the north there was a marshy ground, to the south he saw an image he characterized as “proud and wild”, worthy of Tierra del Fuego.

At the south end of America, between the islands contiguous to Tierra del Fuego, Darwin could see the Andes mountain range and his first impression was “These immense masses of snow that never melt and

seem destined to last as long as the world itself presents a great – what am I saying?– a sublime spectacle. The mountain’s outline stands out clearly and well defined”. Together with the material monumentality of the mountain range, the thing that impressed the traveler the most were “the geological particularities” of the territory: “Who would not feel awe to think of the power that raised these mountains, and even more so of the countless centuries that had to pass to crush, move and flatten such considerable parts of these colossal masses!”. A view that made him exclaim: “What mysterious greatness in those mountains that rise one after the other!”. He concludes his account assuring that, seen from that point, the many channels that are lost in the lands and between the mountains are covered with such grim hues that it seems “like they lead outside of the limits of this world”.

This representation correlates with Darwin’s reflections regarding those he calls “savages”, the sight of which made him ask himself: “Where do they come from? Who could have decided, who forced a tribe of men to abandon the beautiful regions of the north, to follow the mountain range, to invent and build canoes and finally go inhabit one of the most inhospitable lands of the world?” In doubt of the pertinence of his questions, seeing the impact the inhabitants of the southern end of America would have on his scientific approach, he concluded: “nature, making habit omnipotent and its effect hereditary, has adapted the fueguinos to the climate and the productions of their miserable land”.

Though imbued with a 19th century imperial view, at the end of his voyage, Darwin expresses the realization that “white man performs a destructive role” considering that “wherever European man sets foot it seems death pursues the indigenous peoples”. Regarding his knowledge of America, Polinesia, South Africa and Australia, he assures: “We see the same result everywhere”. A social reality that immediately led him to conclude, anticipating the mechanism of natural selection: “Human varieties seem to react to one another in the same way as the different animal species, where the strongest always destroys the weakest”. In this way, Patagonia remains – now as a setting – closely linked to one of the main scientific theories in existence, making the evidence it contains into a permanent focal point.

“EXTERMINATION WILL COME”

Until the beginning of the 1880s approximately there was a peaceful everyday existence among the native peoples of Tierra del Fuego, as their habitat wasn’t yet of interest for adventurers or colonists, among other reasons because there wasn’t any knowledge of the possibilities offered by this land of extremes. The gold seekers who arrived from 1881 onwards, and the livestock companies that arrived since 1883, “initiated the white settlement” of Tierra del Fuego, as stated by Mateo Martinic, and the miners were the first to exert

violence against the selknam, depredating them in their quest to capture women and children.

Thereupon, the practice of livestock exploitation by the Exploitative Society of Tierra del Fuego, in its pursuit to impose its terms and facing the population’s resistance, led to a persecution of the selknam, haush, yaganes and kawésqar, with massacre and captures to be deported to the Salesian missions on Dawson island, where they would be “civilized”, that is to say, indoctrinated in the Catholic cult and domesticated to perform wage labor. In those camps, overcrowding and malnutrition caused diseases that decimated them and contributed to their extinction.

Historiography has sufficient recounts of the violence unleashed upon the fueguinos. In the words of a Selknam survivor reproduced by Anne Chapman in her book End of a world: The Selknam of Tierra del Fuego (2002) there is an eloquent expression of their motives: “To put sheep here, they killed the indians! They did a cleansing and more, for the pampas they killed more, to cleanse so there aren’t any indians, so then they put sheep there. So then they were happy with their sheep, so they could populate, produce with those sheep,for their gain, for their product, with those they had their gains. That is why they killed the Indians”. Likewise, Alberto Harambour, in the study that prefaces his book Un viaje a las colonias. Memorias y diario de un ovejero escocés en Malvinas, Patagonia y Tierra del Fuego (A journey to the colonies. Memoirs and diary of a Scottish shepherd in the Falklands, Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego) (1878-1898) (2016), cites Joaquín Bascopé to state that the authorities were also “agents of violence, that scarcely differed from private hunters”.

The prediction by John Spears in his book about life on Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia, published in 1895, had practically been fulfilled at the beginning of the 20th century: “the sheepherder will end up cornering [the onas] extending his wire fences, and then extermination will come”. This explains that Mateo Martinic concludes that “the colonizing occupation of Tierra del Fuego, admired as successful, had a horrific human cost, with the almost complete extinction of the noble and millenary selknam”.

PAINTED BODIES

“Hunter of shadows” was the name Martin Gusinde assures the selknam gave him. During the four travels the priest and anthropologist made between 1918 and 1924, he investigated and photographed the ones he considered “the last remains of the so little appreciated fueguinos”, when they were very diminished, “leading a painful existence” as a consequence of the depredation they had suffered. According to the requirements of modern ethnology, Gusinde wasn’t satisfied with a description of the external aspects of the selknam, but tried to go further and encompass their “cultural property in its harmonious totality”, also seeking to

discover what he called fundamental principles and impulses of their spiritual life.

His first reaction when encountering them was his concern when “seeing their repulsive bodies and their wild gestures”, as he described in his book Hombres primitivos en la Tierra del Fuego (The primitive men of Tierra del Fuego) (1951), however, after living with them and getting to know them, he acknowledged them as “complete men, with all the passions and weaknesses inherent to the human condition, with no distinction whatsoever”, as he wrote in his work Los indios de Tierra del Fuego. Los Selk’nam (The indians of Tierra del Fuego. The Selk’nam) (1982). Undoubtedly in the time Gusinde wrote these words his way of addressing the subject contributed to humanize them and to value their culture and heritage – in line with current perspectives that are no longer based on the premise of studying an extinct peoples but one that is alive and present on the archipelago.

Martin Gusinde documented the survival of the native peoples of Tierra del Fuego, as well as their spiritual sensibility, which is expressed in the eloquent photos he took of their painted and masked bodies for the rituals of Hain and Chiejaus. It is an archive of around a thousand images that, in the accurate interpretation of Xavier Barral during the presentation of the book about Martin Gusinde y los selknam, yámanas y kawéskar (Martin Gusinde and the selknam, yamanas and kaweskar) (2015), “celebrate the spirit of the inhabitants of the end of the world”, and that, in the more concrete words of Marisol Palma, offer a “photographic view that strives to reconstruct the cultural and material traditions destroyed by the genocide”.

TIERRA DEL FUEGO, EXTREME CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

Overshadowed by the Strait of Magellan, an inter-oceanic passage filled with geographical and historical meaning, Tierra del Fuego hasn’t been the object of particular studies that project it as an entity. This situation is beginning to change and has a fundamental antecedent in the book Tierra del Fuego. Historia, arquitectura y territorio (Tierra del Fuego. History, architecture and territory) (ARQ Ediciones, 2013) by Eugenio Garcés and collaborators. This work has the great merit of exclusively addressing the island, discussing diverse fundamental aspects that conform its geographical, historical and cultural heritage. This exercise transformed Tierra del Fuego in part of the ecumene, the known world, pointing out its characteristics, the same that label it as a unique and gallant place, either when addressed from the geography that remains, or the history that once took place and that will go on happening.

Through its melancholic landscape, where the lack of points of reference heighten the feeling of loneliness and vastness that characterize this territory, Tierra del Fuego is shown through the traces left by its environmental evolution, but also thanks to the manifestations

of human activity and the successive layers of occupation that have shaped it until today, which also reflect the ways in which its inhabitants have occupied and lived together with nature in this area. In the images, particularly the photographs, all these expressions are an eloquent register of the vastness and isolation of a potentially tragic space that is accentuated by the images of mechanical artifacts and technological devices of the sheep farms.

The historical study centered on Tierra del Fuego shows the incapacity to generate “social fabric” due to the ways of occupation that have successively been carried out from the 19th century onwards in that territory. Evidence shows that neither gold mining nor livestock farming or oil activity managed to establish a population in the region, so it is no surprise that today it only has a couple of thousand inhabitants and that the population centers are the result of public initiatives and must be permanently subsidized.

In a hostile climate like the one of Tierra del Fuego it is easy to understand the role the source of warmth, fire, heating has in the life of its inhabitants, considering the permanent need to protect themselves from the cold, rain, wind and snow. The environmental conditions also explain the succession of architectural styles since the end of the 19th century, and with them the ways of sociability that are characteristic of sheep farms.

It is less uplifting to note that Tierra del Fuego, because of the violence against its native peoples, can also be seen as vulnerable against the endeavors of humanity that has successively and essentially motivated by economic interests, violated and annihilated it.

It is necessary to place value on this heritage that is still virtually unknown, as well as to gather the cultural and natural riches of Tierra del Fuego, so as to know the geographical characteristics of the region, its representations in western culture, the forms and conditions of occupation in the area; above all this, it will be evidence of human endeavor, which can be seen on Tierra del Fuego in its broad range of possibilities. From the surprising ways the fueguinos managed to adapt to nature, full of unparalleled cultural manifestations, through the drive to explore, discover and do science, or the search for beauty and the will to succeed and the constancy to remain, up to the ruthless violence and depredation characteristic of our species.

HERITAGE OF HUMANITY

Buried deep in the landscape, at the farthest reach, in the coldest place, that is to say in Chile, since time immemorial Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia have been associated to an isolated existence among the imposing natural phenomena that contain it: to a subsistence marked by rigor and austerity; to a historical process that has always been associated to saga, to great actions, to protagonists that inevitably become heroic characters, always pioneers; to glorious or tragic feats that are

worthy of being remembered; to lives like those from the colonists, anonymous and perseverant; to legendary and imagined events, or even from daily life, that attract attention today, also because of the setting where they took place. To events that were once history and that today have been superseded by the occurrences of simple, rough and selfless lives, that have become the patrimony of Patagonia.

From the explorer Magallan onwards, the drama and struggle inherent to access and survival in a strange environment, the sacrifice, pain, the bold, brave and reckless acts performed by courageous and fearless individuals, by outstanding male and female heroes challenged by impossible conditions, have contributed to provide content to the history, identity and patrimony of the inhabitants of Patagonia, linking this geographical-historical region with the events and processes it has staged, as object or subject, as its great asset in front of the rest of the world. Besides, today this is accentuated by the appraisal of the original cultures that inhabited it.

In a world that is more and more globalized, with a clear ecological conscience, with a growing interest in nature and keenness to reach the wilderness, rustic, virginal, primitive and unpolluted, Tierra del Fuego appears as a privileged place. A placebo for individuals eager to live and experience the natural world, motivated by the expectation to find themselves in a place associated to the epic, dramatic, historical in the middle of a “wild” surrounding that makes it possible to evade an urban, artificial, monotonous and predictable environment, which is how modern society appears to many on a daily basis.

The valuing and understanding of ancestral cultures, of the special identities, of humanity that expresses itself, for example, in peoples like the selknam, yáganes, haush and kawésqar, at one moment all denominated fueguinos, is another asset of Tierra del Fuego. Men and women who, as shown by their millenary existence, not only adapted to and survived the harsh conditions of the environment, but also developed forms, practices, uses, beliefs, rites and so many other manifestations of their culture that are now valued as ancestral expressions of the humanity we are a part of. This history is also connected with the current inhabitants of Patagonia and especially of the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego, whose determination and will to remain, live, function and go on through their descendants, just like those who preceded them throughout history, is expressed in their faces, looks, gestures, words, projects, customs, ideas and beliefs; but also in the objects of material culture they use daily, in the remnants, among them photographs of the family past they treasure and display; but above all in the buildings that give them shelter, places of warmth and comfort, of sociability, a realm of feelings and passions, a place for meeting, in sum a home in the middle of a nature whose harshness and isolation make their residence even more valuable, for whatever reason, in this place that was once considered to be “beyond the boundaries of the world” but where humanity unfolds and manifests in fullness.

TIERRA DEL FUEGO RETRATOS Y PAISAJES

Inscripción Registro de Propiedad Intelectual N° 2022-A-9405 Derechos reservados. Prohibida su reproducción.

Tierra del Fuego, Retratos y Paisajes © LarrainVial

Fotografía: Max Donoso Saint

Texto: Rafael Sagredo Baeza

I sbn 978-956-414-084-1

dirección general y fotografía

Max Donoso Saint

a sistente de f otografía

Rodrigo López Porcile

t exto

Rafael Sagredo Baeza

d iseño e ditorial

Estudio Vicencio

s elección mapas y grabados

Jaime Rosenblitt Berdichesky

e dición de texto

Marcela Bañados Norero

digitalización negativos

Marcelo Ayala Urzúa

p ostproducción digital de imágenes

Eliana Arévalo Berríos

traducción ensayo

Cristina Labarca Cortés

i mpresión

Fyrma

Primera edición 2000 ejemplares.

Noviembre 2022. Santiago de Chile.

«Autorizada su circulación en cuanto a los mapas y citas que contiene esta obra, referentes o relacionadas con los límites internacionales y fronteras del territorio nacional por Resolución N°113 del 8 de noviembre de 2022 de la Dirección Nacional de Fronteras y Límites del Estado.

La edición y la circulación de mapas, cartas geográficas u otros impresos y documentos que se refieran o relacionen con los límites y fronteras de Chile, no comprometen, en modo alguno, al Estado de Chile, de acuerdo con el Art. 2°, letra g) del DFL N°83 de 1979 del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores».

AGRADECIMIENTOS

Fernando Callahan

Gloria Mansilla

Víctor Paredes

Juan Carlos Calisto

Ninoska Vera

Tiaren Garcés

Paula Zegers

Guy Wenborne

Martín Larraín

Andrea Velasquez

Paula Domínguez