WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 17, N° 4, 2023

Indexed in SCOPUS

WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 17, N° 4, 2023

Indexed in SCOPUS

A peer-reviewed quarterly focusing on new achievements in the following fields:

• automation • systems and control • autonomous systems • multiagent systems • decision-making and decision support • • robotics • mechatronics • data sciences • new computing paradigms •

Editor-in-Chief

Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Advisory Board

Dimitar Filev (Research & Advenced Engineering, Ford Motor Company, USA)

Kaoru Hirota (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan)

Witold Pedrycz (ECERF, University of Alberta, Canada)

Co-Editors

Roman Szewczyk (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Oscar Castillo (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Marek Zaremba (University of Quebec, Canada)

Executive Editor

Katarzyna Rzeplinska-Rykała, e-mail: office@jamris.org (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Associate Editor

Piotr Skrzypczyński (Poznań University of Technology, Poland)

Statistical Editor

Małgorzata Kaliczyńska (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Typesetting

SCIENDO, www.sciendo.com

Webmaster

TOMP, www.tomp.pl

Editorial Office

ŁUKASIEWICZ Research Network

– Industrial Research Institute for Automation and Measurements PIAP

Al. Jerozolimskie 202, 02-486 Warsaw, Poland (www.jamris.org) tel. +48-22-8740109, e-mail: office@jamris.org

The reference version of the journal is e-version. Printed in 100 copies.

Articles are reviewed, excluding advertisements and descriptions of products.

Papers published currently are available for non-commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. Details are available at: https://www.jamris.org/index.php/JAMRIS/

LicenseToPublish

Editorial Board:

Chairman – Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Plamen Angelov (Lancaster University, UK)

Adam Borkowski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Wolfgang Borutzky (Fachhochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg, Germany)

Bice Cavallo (University of Naples Federico II, Italy)

Chin Chen Chang (Feng Chia University, Taiwan)

Jorge Manuel Miranda Dias (University of Coimbra, Portugal)

Andries Engelbrecht ( University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa)

Pablo Estévez (University of Chile)

Bogdan Gabrys (Bournemouth University, UK)

Fernando Gomide (University of Campinas, Brazil)

Aboul Ella Hassanien (Cairo University, Egypt)

Joachim Hertzberg (Osnabrück University, Germany)

Tadeusz Kaczorek (Białystok University of Technology, Poland)

Nikola Kasabov (Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand)

Marian P. Kaźmierkowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Laszlo T. Kóczy (Szechenyi Istvan University, Gyor and Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Hungary)

Józef Korbicz (University of Zielona Góra, Poland)

Eckart Kramer (Fachhochschule Eberswalde, Germany)

Rudolf Kruse (Otto-von-Guericke-Universität, Germany)

Ching-Teng Lin (National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan)

Piotr Kulczycki (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Andrew Kusiak (University of Iowa, USA)

Mark Last (Ben-Gurion University, Israel)

Anthony Maciejewski (Colorado State University, USA)

Copyright

Krzysztof Malinowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Andrzej Masłowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Patricia Melin (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Fazel Naghdy (University of Wollongong, Australia)

Zbigniew Nahorski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Nadia Nedjah (State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

Dmitry A. Novikov (Institute of Control Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia)

Duc Truong Pham (Birmingham University, UK)

Lech Polkowski (University of Warmia and Mazury, Poland)

Alain Pruski (University of Metz, France)

Rita Ribeiro (UNINOVA, Instituto de Desenvolvimento de Novas Tecnologias, Portugal)

Imre Rudas (Óbuda University, Hungary)

Leszek Rutkowski (Czestochowa University of Technology, Poland)

Alessandro Saffiotti (Örebro University, Sweden)

Klaus Schilling (Julius-Maximilians-University Wuerzburg, Germany)

Vassil Sgurev (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Intelligent Systems, Bulgaria)

Helena Szczerbicka (Leibniz Universität, Germany)

Ryszard Tadeusiewicz (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Stanisław Tarasiewicz (University of Laval, Canada)

Piotr Tatjewski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Rene Wamkeue (University of Quebec, Canada)

Janusz Zalewski (Florida Gulf Coast University, USA)

Teresa Zielińska (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Publisher: All rights reserved

VOLUME 17, N˚4, 2023

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4-2023

1

Matrix Transposition Algorithm Using Cache Oblivious

Samuel Guzmán López, Adolfo Javier San Gil Santana, Jorge Alberto Cuba Alonso del Rivero, Sonia Pérez Lovelle, Humberto Díaz Pando

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/25

8

On Various Types of Soft Ground – A Case Study on Various Types of Soft Ground – A Case Study

Maciej Trojnacki, Przemysław Dąbek

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/26

17

The Overview of Challenges in Detecting Patients’ Hazards During Robot‐Aided Remote Home Motor Rehabilitation

Julia Wilk, Piotr Falkowski, Tomasz Osiak

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/27

28

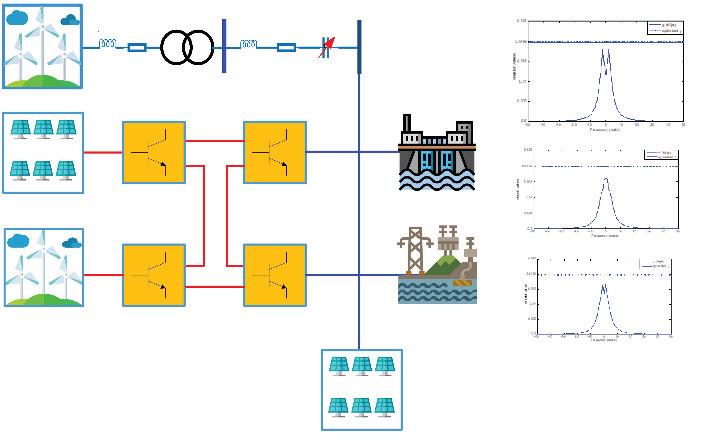

Binary Shuffled Frog Leaping Algorithm for Optimal Allocation of Power Quality Monitors in Unbalanced Distribution System

Ashkan Doust Mohammadi, Mohammad Mohammadi

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/28

40

Lyapunov‐L Lasalle Based Dynamic Stabilization for Fixed Wing Drones

Jean Sawma, Alain Ajami, Thibault Maillot, Joseph el Maalouf

Doi: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/29

49

New Robust Model for Stability and H∞ Analysis for Interconnected Embedded Systems

Amal Zouhri

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/30

56

Wimax Network Optimization Using Frame Period with Channel Allocation Techniques

Mubeen Ahmed Khan, Awanit Kumar, Kailash Chandra Bandhu

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/31

68

Extended State Observer Based Robust Feedback Linearization Control Applied to an Industrial CSTR

Ali Medjebouri

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/32

79

Implementing Visual Assistant Using YOLO and SSD for Visually‐Impaired Persons

Ratnesh Litoriya, Kailash Chandra Bandhu, Sanket Gupta, Ishika Rajawat, Hany Jagwa

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/33

Submitted:11th January2023;accepted:18th March2023

DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/25

Abstract:

TheParallelandDistributedComputinggroupbelonging totheIntegratedTechnologicalResearchComplex(CITI). hasbeenengagedinthecreationofgeneral‐purpose componentsthatsupporttheprocessingoflargevolumes ofinformationthatcharacterizetheproblemsinvolvedin parallelcomputing.

Usingtheobliviouscachemodel,whichworksinde‐pendentlyofthecomputerarchitecture,andthedivide andconquerprinciple,analgorithmformatrixtrans‐positionisimplementedtoreducetheexecutiontime ofthisalgebraicoperation.Thealgorithmensuresthat mostofthedatacontentisloadedtothecacheforfast processing,andmakesthemostofitsstayinthecache tominimizemissedreadsandachievegreaterspeed.

Theworkincludesconclusionsandstatisticaltests carriedoutfromexperimentsoncomputerswithdifferent architectures,reflectingthesuperiorityofthealgorithm thatusesobliviouscachefromanorderofmatrixdeter‐minedaccordingtothecharacteristicsofeachPC.

Keywords: Cacheoblivious,Matrixtransposition,Missed readings

TheIntegratedTechnologicalResearchComplex (CITI)wascreatedasacoordinationprojectbetween the TechnologicalUniversityofHavana(CUJAE)and theMinistryofInterior(MININT).Thisentityis designedtohostthemostadvancedtechnologies beingworkedwithworldwide[1].

CITI’smissionistodeveloptechnologiesto enhancethesecurityandinternalorderofthe country.Itsvisionistobeacreative,innovative andbenchmarkorganizationinhumancapital management.Inaddition,tobeareferencein theapplicabilityoftheresultsobtainedinthe developmentofsystems,technologiesandinnovative integratedapplications,withimpactonsecurityand internalorder,forwhichitwillbaseitsworkonthe integrationofhighlyquali iedprofessionalswith talentedstudents[1].

AtCITIthereareprojectsinwhichmatrixtranspo‐sitionisintensivelyused,sothistaskwasassignedto theParallelandDistributedComputinggroup,which isdedicatedtoreducetheexecutiontimeofvari‐ousalgorithmsbyemployingparallelismandrecur‐rencetechniques.Thistime,thetechniqueselectedby thegroupwasthecacheoblivious,arecurrenttech‐niqueaboutwhichthereissomeliteratureandimple‐mentationtestedanddocumentedbyotherauthors [2–4].Thismethodwasusedbytheauthorsina researchworkonmatrixmultiplicationobtaining goodresults[5].

Cache‐awarealgorithmstakeintoaccountthe hardwarearchitectureonwhichtheyarerunning, mainlythecachearchitecture,i.e.thenumberofcache levelsandthesizeofeachlevel.Theyarespeci ically developedtoperformaswellaspossibleintheenvi‐ronmentforwhichtheywerecreated.

Thisposesaproblemwhenchangingtheenviron‐ment,sinceifacache‐awarealgorithmisexecuted outsidethearchitectureforwhichitwasdesigned, itwillnotperformwell.Tocounteractthisproblem, cacheobliviousalgorithmswerecreated,ablework ef icientlyonanyarchitecture[6].

Cacheobliviousalgorithmshaveadesignthatwill alwaysbe“cache‐optimal”,regardlessofthecache hierarchy.In1996,theideaofrealizingalgorithms thatdonottakeintoaccountthearchitectureofthe computerwheretheyareexecutedwasconceivedby CharlesE.Leisersonandcalledcacheobliviousalgo‐rithms.Thistopicwas irstpublishedin1999byHar‐aldProkopinhismaster’sthesisattheMassachusetts InstituteofTechnology[4].Theuseofthecache obliviousmodelhasawidevarietyofapplications suchas:matrixmultiplication,matrixtransposition, Bioinformatics(RNAsecondarystructureprediction), ShortestPathAlgorithmwithorderO(n),dynamic programmingoftheGaussiansolution(Numerical Mathematics).

Theuseofthecacheobliviousmodelaimsto decreasemissedreadsorcachemissessincethese algorithmsusethedivide‐and‐conquerprincipleto dividetheproblemintosmallsubproblemsuntila cache‐ ittingsizeisreached,regardlessofthesizeof thecache.

Byreducingthenumberofmissedreadsorcache misses,executiontimesaresigni icantlyreduced, resultingingreateref iciency.

Oneofthefeaturesbywhichitoutperformsthe traditionalcacheisself‐tuning.Intypicalcachealgo‐rithms,thealgorithmsrequiretuningtovariouscache parametersthatarenotalwaysavailablefromthe manufacturerandareoftendif iculttoextractauto‐maticallywhichhinderscodeportabilitywhereasin cacheobliviousalgorithmsnosuchtuningisrequired, asinglealgorithmshouldworkwellonallmachines withoutanymodi ication[3,4,7–9].

Matrixtranspositionisafundamentaloperation oflinearalgebraandothercomputationalprimitives suchasthemultidimensionalFastFourierTransform; itisalsoappliedinnumericalanalysisineconomics, imageandgraphicsprocessing,aswellasbeingused incryptographicmethods[10].

Thisseeminglyinnocuouspermutationproblem lacksbothtemporalandspatiallocalityandisthere‐foredif iculttoimplementef icientlyformatriceswith alargevolumeofdata.Infact,thereisnotemporal localitytoexploit,sinceeachelementofthematrixis accessedatmostonce[10].

Asfarasspatiallocalityisconcerned,thematrix elementswaps(i,j)and(j,i)implicitinthetranspose semantics,whentranslatedintomemoryaddresses usingcanonicalrow‐majororcolumn‐majorordering, equalsthememorylocalitiesni+jandnj+i.Depending onthevaluesofiandj,thesemaybecloseorfar apartintermsofcachesetsormemorypages.Care‐fulschedulingoftheseswapoperationsisrequired togainanyadvantagefromthesemultiwordcache lines[10].

Explicittranspositionofanarrayintomemorycan oftenbeavoidedbyaccessingthesamedatainadif‐ferentorder.Forexample,softwarelibrariesforlinear algebra,suchasBLAS,generallyprovideoptionsto specifythatcertainmatricesshouldbeinterpretedin transposedordertoavoidtheneedfordatamove‐ment[10].

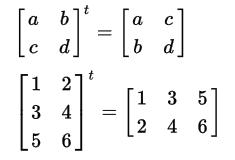

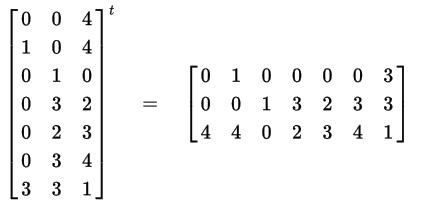

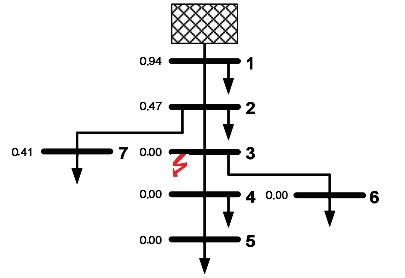

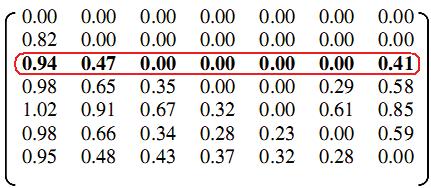

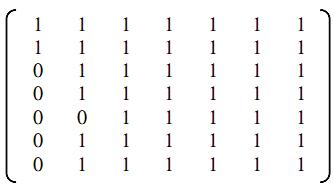

Describingthealgebraicoperationassuch,atrans‐posedmatrixistheresultofrearrangingtheorigi‐nalmatrixbyexchangingrowsforcolumnsinanew matrix(seeFigures1and2).

Inotherwords,thetransposedmatrixistheaction ofselectingrowsfromtheoriginalmatrixandrewrit‐ingthemascolumnsinthenewmatrix.

Examples:

Themanipulationofmatriceswithalargenum‐berofrowsandcolumnsinvolvesbigproblems,even whentheyarehandledwithacomputer.Therefore, itisofteninterestingtoknowhowtodecomposea problemusinglargematricesintosmallerproblems, i.e.,usingsmallermatrices[11].

Thepossibilityofdecomposingamatrixinto smallermatriceshasmanyapplicationsincommuni‐cations,electronics,solvingsystemsofequations,tak‐ingadvantageofthevectorstructureofsomecomput‐ers,andsoon.And,especially,itgivesthepossibility ofwritingamatrixinamorecompactway[11].

Theblocksareobtainedbydrawingimaginaryver‐ticalandhorizontallinesbetweentheelementsofthe matrix.Theirdimensiondependsonthesizeofthe cacheblocksandaimstostoreasmuchinformation aspossible.

Thefundamentalideaistoreducethetransposeof amatrixtothetransposeofsmallsubmatrices.Thisis achievedbydividingthematricesinahalfalongtheir largestdimensionuntilonlyonematrixtransposethat itsinthecacheneedstobecarriedout(intheory, onecouldfurtherdividethematricesdowntoabase caseofsize1×1,butinpracticealargerbasecaseis used,e.g.,16×16,inordertoamortizetheoverhead ofcallingrecursivesubroutines)[12].

Insection 2,allthetheoreticalfoundationsthat supporttheimplementationofamatrixtransposition algorithmusingthecacheobliviousmodelwerepre‐sented.Algorithm 1,adaptedfromtheonefoundin https://es.stackoverflow.com,wasused.

Thisalgorithmhasfourintegersandapointeras parameters,ofwhichthe irstandthirdarefunda‐mentaltodividetheoriginalmatrixintosmallsub‐matrices.Thesecondandfourthrefertothenumber ofrowsandcolumnsrespectively,whilethepointer referstotheresultmatrix.

Table1. Computercharacteristics

Characteristics

PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6 PC7

Processor Intel(R)Core (TM) i3‐5020UCPU @2.2GHz 2.2GHz

RAM 4,00GB

Single‐Channel DDR3 @798MHz

Intel(R) Celeron(R) CPUG3900@ 2.8GHz 2.8GHz

4.00GB

(2.95GB utilizable) DDR4‐2133

Intel(R) Celeron(R) CPUG1840@ 2.8GHz 2.8GHz

2,00GB

Single‐Channel DDR3 @665MHz

Intel(R)Core (TM) i3‐7130UCPU @2.7GHz 2.7GHz

8.00GB (7.95GB utilizable) DDR4‐2400

Intel(R)Core (TM)i3‐4130 CPU@ 3.4GHz

Intel(R)Core (TM) i7‐1165G7@ 2.8GHz 2.8GHz

8.00GBDDR3 16.2GB (15.8GB utilizable) DDR4‐3200

Intel(R) Pentium(R) CPUG4560@ 3.50GHz 3.50GHz

8.00GB (7.95GB utilizable) DDR4‐2400

Typeof system Windows64 bits Windows64 bits Windows64 bits Windows64 bits Linux64bits Windows64 bits Windows64 bits

Motherboard ASUSTek COMPUTER INC.X540LA

Gigabyte Technology Co.,Ltd. B85M‐DS3H

Gigabyte Technology Co.,Ltd. B85M‐DS3H

voidcachetranspose(int rb, int re, int cb, int ce, Matrix*T)

{int r=re-rb,c=ce-cb; if (r<= 16 &&c<= 16){ for (int i=rb;i<re;i++){ for (int j=cb;j<ce;j++){

T->data[j*rows+i]=data[i*columns+j];}}} else if (r>=c){

cachetranspose(rb,rb+(r/2),cb,ce,T); cachetranspose(rb+(r/2),re,cb,ce,T);} else {

cachetranspose(rb,re,cb,cb+(c/2),T); cachetranspose(rb,re,cb+(c/2),ce,T);}}

Algorithm1. Recursivematrixtranspositionalgorithm usingcacheoblivious

Forthedevelopmentoftheexperimentsitwas necessaryapreviousstudyofseveralalgorithms(tra‐ditional,blocksandblocks_for_squared_matrices)to establishacomparisonwiththoseusingthecache obliviousmodel(forsquareandnon‐squareorders). Theseexperimentsconsistofrunningeachalgorithm 5timesonorderswithdifferentcharacteristics(see Table1).Fromtheresultsobtained,astatisticalanaly‐sisisperformedtodeterminewhetherthealgorithms usingthecacheobliviousmodelaresuperior(interms ofexecutiontimeandmissedreads)tothosethatdo notusethismodel.

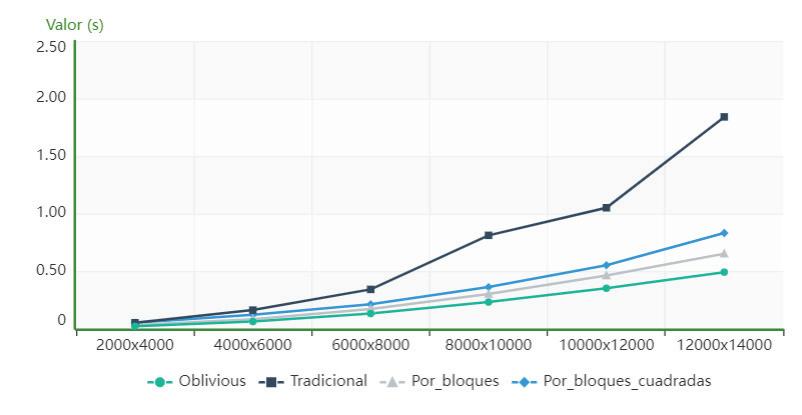

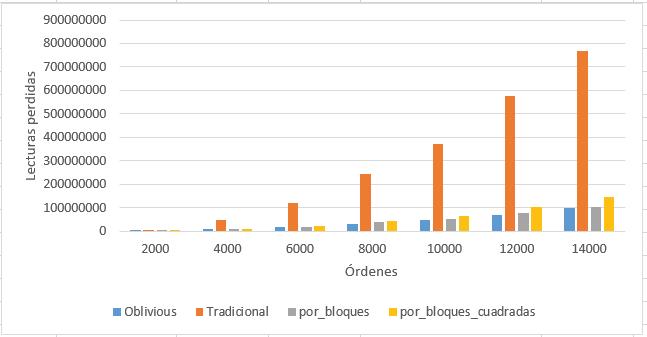

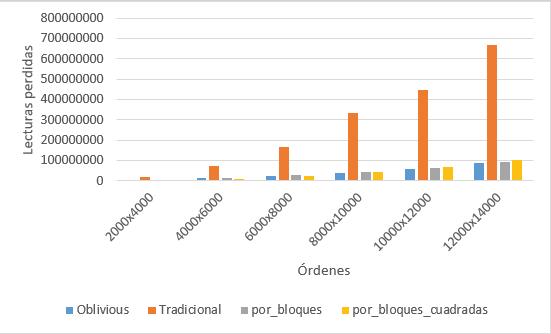

Inthissectionwepresentdiagramsshowingthe averageexecutiontimeandthemissedreadings(the latteronlyinPC5),foreachofthealgorithmsanalyzed.

Inthosecases,wherenon‐squaredmatriceswere tested,thesewere illedwithzerosinordertousethe blocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmforthecorre‐spondingcomparisons.

DellInc. 02DG7R (U3E1)

VersiónA00

Gigabyte B85M‐DS3H HPSpectre 14‐EA GigabyteGa‐H110m‐S2h

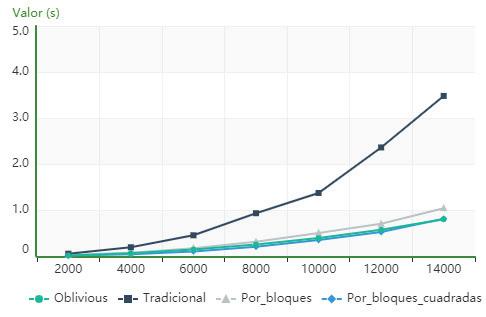

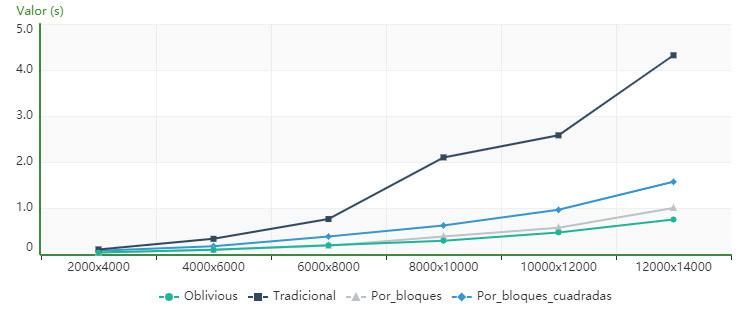

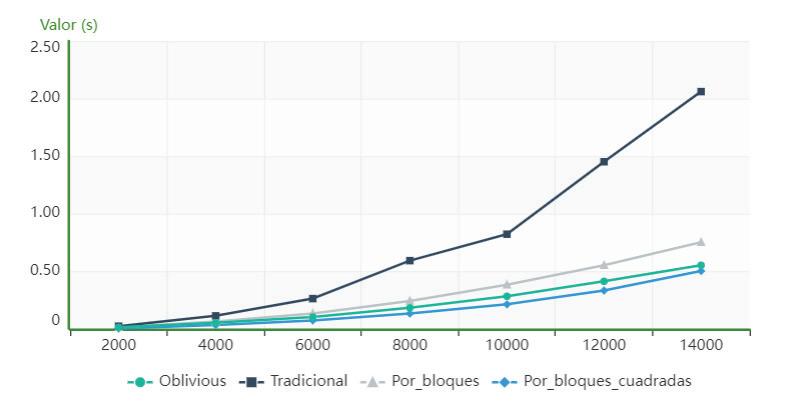

AscanbeseeninFigure3,forthecomputeriden‐ti iedasPC1,theblocks_for_squared_matricesalgo‐rithmisfasterthantherestofthoseanalyzedfor orderslowerthan14000,fromwhichthealgorithm usingcacheobliviousstartstobesuperior.

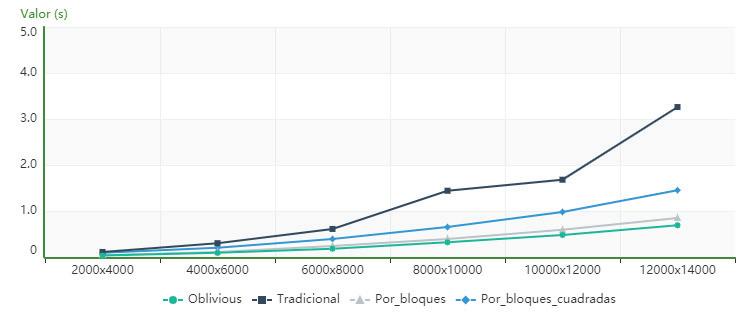

Figure4showsthatforthecomputeridenti iedas PC1,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

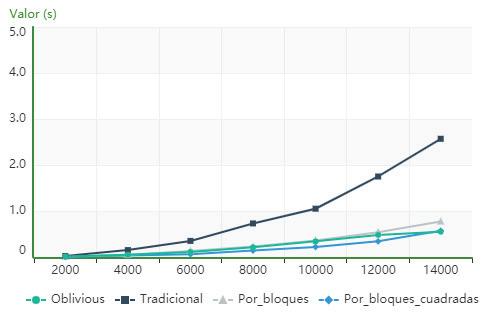

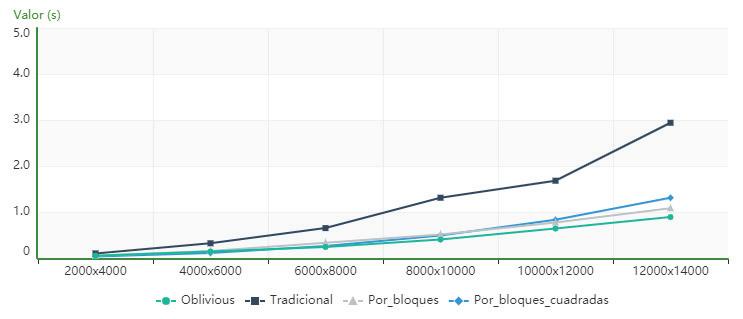

ItisevidentfromFigure5 that,forthecomputer describedasPC2,thealgorithmusingcacheoblivious issuperiorintermsofexecutiontimetothetradi‐tionalandblockalgorithmsforallorders,whilethe blocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmhasloweror similartimestotheoneusingcacheobliviousupto order10000,fromwhichthecacheobliviousalgo‐rithmpresentslowervalues.

Figure6showsthat,forthecomputeridenti iedas PC2,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

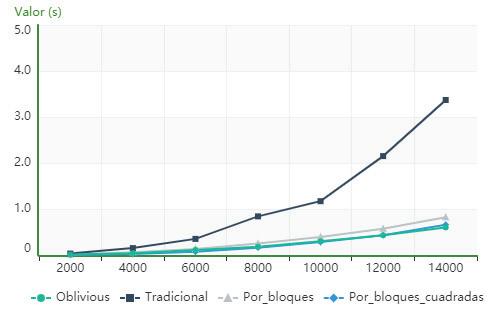

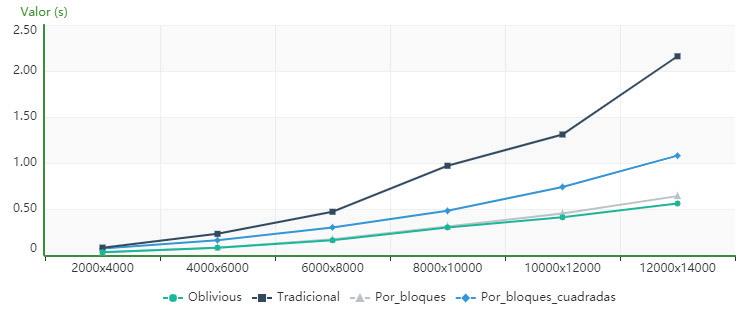

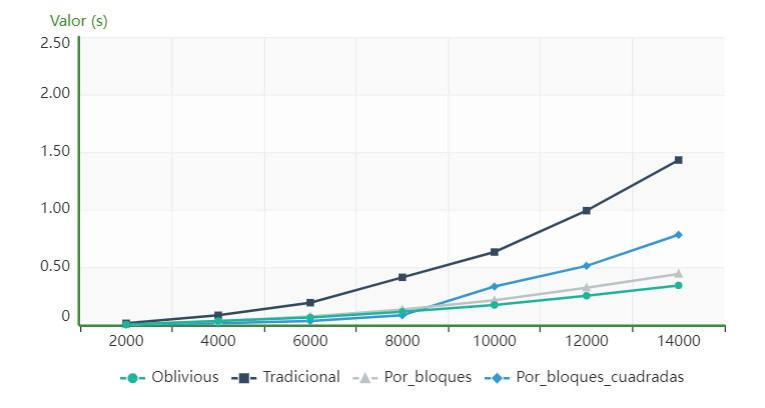

Figure 7 showsthat,forthecomputeridenti‐iedasPC3,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousis superiorintermsofexecutiontimetothetradi‐tionalandblockalgorithmsforallorders,whilethe blocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmhaslowerexe‐cutiontimesthantheoneusingcacheobliviousup toorder6000.Between8000and12000theresults aresimilarandfromthelatter,thecacheoblivious algorithmstartstohavelowervalues.

Figure8showsthat,forthecomputeridenti iedas PC3,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

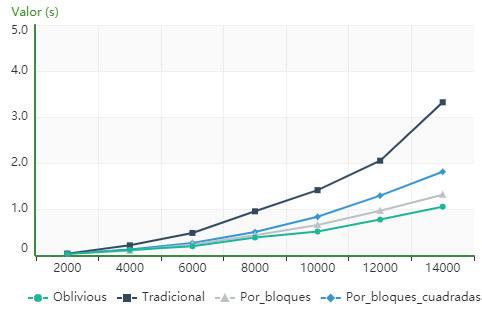

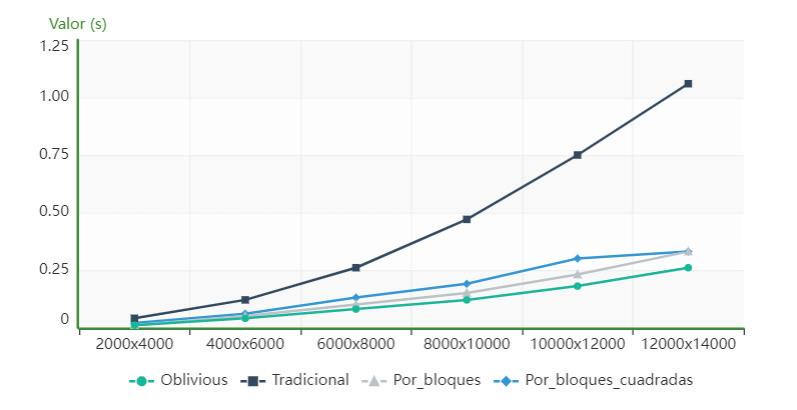

non‐squareorders

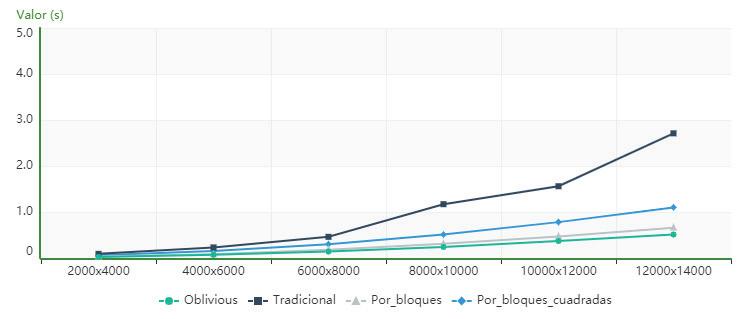

Figure 9 showsthat,forthecomputeridenti‐iedasPC4,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousis superiorintermsofexecutiontimetothetradi‐tionalandblockalgorithmsforallorders,whilethe blocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmhaslowerexe‐cutiontimesthantheoneusingcacheobliviousuntil order12000,whentheystarttohavesimilarvalues.

Figure10showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC4,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_square_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

Figure11showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC5,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

Figure12showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC5,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

ItisevidentinFigure 13 that,forthecomputer identi iedasPC6,thealgorithmusingcache

Figure17. Performanceofthealgorithmsintermsof missedreadingsonPC5forsquareorders

Figure18. Performanceofthealgorithmsintermsof missedreadingsonPC5fornon‐squareorders

obliviousissuperiorintermsofexecutiontime tothetraditionalalgorithms,byblocksand blocks_for_squared_matrices,startingfromthe order10000x10000.

Figure14showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC6,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block

andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

Figure15showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC7,theblocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmis superiortotheothersanalyzedanditcanbeobserved thatthealgorithmusingcacheobliviousobtainsa certainparityfromtheorder14000x14000.

Table2. ResultsobtainedinPC1forsquareorders

Algorithms traditional blocks blocks_for_squared_matrices

Table3. ResultsobtainedinPC1fornon‐squaredorders

Algorithms traditional blocks blocks_for_squared_matrices

Table4. ResultsobtainedinPC5formissedreadingsinsquareorders

Algorithms traditional blocks blocks_for_squared_matrices

Table5. ResultsobtainedinPC5formissingreadingsinnon‐squareorders

Algorithms traditional blocks blocks_for_squared_matrices

Figure16showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC7,thealgorithmusingcacheobliviousissuperior intermsofexecutiontimetothetraditional,block andblock_for_squared_matricesalgorithmsforallthe ordersanalyzed.

4.1.1.Missedreadings

ThePAPI(PerformanceApplicationProgramming Interface)library,developedattheUniversityofTen‐nessee,wasusedtoaccountformissedreads.Itsmain purposeistoprovideaccesstothePMCs(Perfor‐manceMonitoringCounter)ofadiversecollectionof modernprocessors[13].PAPIprovidesanabstraction layerthatallowsdeveloperstoaccessPMCs.Instead, thedeveloperusescallstothePAPIAPI(Application ProgramingInterface),makingthecodeportable,i.e. itcanbeusedonanyarchitecturesupportedbythe librarywithoutmodifyingaccesstoPMCs[14].

ThemissingreadingswerecountedonthePC5 computer,whichhasaLinuxoperatingsystem becausethelibraryused(PAPI)hasnotprovidednew updatessincetheXPversionofWindows.

Figure17showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC5,thealgorithmthatusescacheoblivioushasthe lowestnumberofmissedreadings.

Figure18showsthat,forthecomputeridenti ied asPC5,thealgorithmusingcacheoblivioushasfewer missedreadings.

TheWilcoxonnonparametrictestwasusedforsta‐tisticalanalysis.Itwasselectedsinceitwasproven thatthedatadonotfollowanormaldistributionand duetothesmallsamplesize.Itisexpectedthat,when thetestisrun,itwillreturnap<∝value,ifthisoccurs H0 isrejectedanditisconcludedthattheexecution timeofthecacheobliviousalgorithmislessthanthat ofthetraditionalalgorithm.

Severalsignedranktestswereappliedwhenthe sampleswerepaired,oneforeachofthelastthree ordersofthealgorithmsoneachcomputerdescribed.

ThefollowingaretheresultsobtainedonPC1in termsofexecutiontimeandonPC5intermsofmissed readings:

ItisevidentintheresultsofTable 2 thatthe blocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmisfasterthan therestoftheanalyzedalgorithmsfororderslower than14000,fromwhichthealgorithmusingcache obliviousstartstobesuperior.

TheresultsinTable 3 showthesuperiorityin termsofexecutiontimeofthealgorithmusingthe cacheobliviousmodelforalltheordersanalyzed.

Table 4 showsthesuperiorityintermsofmissed readingsofthealgorithmusingthecacheoblivious modelforallordersanalyzed.

Table 5 showsthesuperiorityintermsofmissed readingsofthealgorithmusingthecacheoblivious modelforallordersanalyzed.

Thetestwasperformedwiththestatisticalsoft‐wareR.Afterthetestitwasdemonstratedthatthe matrixtranspositionalgorithmusingthecacheobliv‐ious,dependingonthearchitectureofthecomputer whereitwasusedandfromacertainorder,willbe betterthantheotheralgorithmsanalyzed.

Underthecomputationalconditionsusedforthe experiments:

1) OnacomputerwithaWindowsoperatingsystem, inthematrixtranspositionoperation,forsquare ordermatricesitisnotfeasibletoemploythealgo‐rithmusingthecacheobliviousmodelforanorder lessthan14000x14000.

2) Regardlessofthecomputerarchitecture,itwas shownthatfromorder6000x8000fornon‐square ordermatrices,thematrixtranspositionalgorithm usingcacheobliviousisfasterthantherestofthe algorithmsstudied.

3) Theblocks_for_squared_matricesalgorithmhasa lowerperformancewhenusedfornon‐square matricessincethesemustbecompletedwithzeros untiltheirorderissquareandthereforethealgo‐rithmincreasesitsexecutiontime.

4) Forlargevolumesofinformation,theexecution timeisindirectcorrespondencetothemissed readings.

5) Algorithmsthatusethecacheobliviousmodelfor largevolumesofinformationhavefewermissed readingsthantherest.

SamuelGuzmánLópez∗ –TechnologicalUniversity ofHavanaJoséAntonioEcheverría,Cuba,e‐mail: samuguzmanlopez97@gmail.com.

AdolfoJavierSanGilSantana –TechnologicalUni‐versityofHavanaJoséAntonioEcheverría,Cuba, e‐mail:asang@ceis.cujae.edu.cu.

JorgeAlbertoCubaAlonsodelRivero –Techno‐logicalUniversityofHavanaJoséAntonioEcheverría, Cuba,e‐mail:jcuba@ceis.cujae.edu.cu.

SoniaPérezLovelle –TechnologicalUniversity ofHavanaJoséAntonioEcheverría,Cuba,e‐mail: sperezl@ceis.cujae.edu.cu.

HumbertoDíazPando –TechnologicalUniversityof HavanaJoséAntonioEcheverría,Cuba,e‐mail:hdi‐azp@ceis.cujae.edu.cu.

∗Correspondingauthor

[1] www.portal.citi.cu.(accessed4/6/2019).

[2] C.Mayer.“Cacheobliviousmatrixoperations usingPeanocurves,”DepartmentofComputer ScienceTechnischeUniversityMunchen,Ger‐many,2006.

[3] M.Frigo,Leiserson,H.Prokop,andRamachan‐dran.“CacheObliviousAlgorithms”,MITLabo‐ratoryforComputerScience,Cambridge,USA, 1999.

[4] H.Prokop.“Cache‐ObliviousAlgorithms,” DepartmentofElectricalEngineeringand ComputerScience,MassachusettsInstituteof Technology.,Massachusetts1999.

[5] A.J.SanGilSantana,S.GuzmánLópez,andJ. A.CubaAlonsodelRivero.“Algoritmodemul‐tiplicacióndematricesutilizandocach incon‐scienteycurvadePeano,” XVIIIConvencióny FeriainternacionalInformática2020, 2020.

[6] T.M.Chilimbi.“CacheConsciousDataStructues DesingandImplementation,”UniversityOfWis‐consin1999.

[7] M.Frigo,C.E.Leiserson,H.Prokop,andS. Ramachandran.“Cache‐ObliviousAlgorithms,” ACMTransactionsonAlgorithms, 2012.

[8] Ritika.“Cache‐awareandcache‐obliviousalgo‐rithms,”MasterofEngineeringComputersci‐enceandengineering,ThaparUniversityPatiala 2011.

[9] S.NeerajandS.Sandeeep.“E?cientcacheobliv‐iousalgorithmsforrandomizeddivide‐and‐conqueronthemulticoremodel,”2018.

[10] S.ChatterjeeandS.Sen.“CacheEf icientMatrix Transposition,”DepartmentofComputerSci‐ense,UniversityofNorthCarolinaChapelHill,NC 27599‐3175,USA–IndianInstituteofTechnol‐ogyNewDelhi110016,India,2005.

[11] M.Palacios.“Matrices,”Departamentode MatemáticaAplicadaUniversidaddeZaragoza, 2018.

[12] D.Tsifakis,P.Alistair,Rendell,andP.E.Strazdins. “CacheObliviousMatrixTransposition:Simu‐lationandExperiment,”DepartmentofCom‐puterScience,AustralianNationalUniversity Canberra,Australian,2004.

[13] V.M.Weaveretal..“PAPI5:MeasuringPower, EnergyandtheCloud,” International-Symposium onPerformaceAnalysisofSystemsandSoftware, 2013.

[14] P.J.Mucci,S.Browne,C.Deane,andG.HO.“PAPI: APortableInterfacetoHadwarePerformance Counters,”UniversityofTennessee,Knoxville, Tennessee,1999.

Submitted:13th October2023;accepted:27th November2023

DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/26

Abstract:

Aproblemofinfluenceofthreetypesofsoftground onlongitudinalmotionofalightweightfour‐wheeled mobilerobotisconsidered.Kinematicstructure,main designfeaturesoftherobotanditsdynamicsmodel aredescribed.Anumericalmodelwaselaboratedto simulatethedynamicsoftherobot’smulti‐bodysystem andthewheel‐groundinteraction,takingintoaccount thesoildeformationandstressesoccurringonthecir‐cumferenceofthewheelintheareaofcontactwith thedeformableground.Numericalanalysisinvolvingfour velocitiesofrobotmotionandthreecasesofsoil(dry sand,sandyloam,clayeysoil)isperformed.Withinsim‐ulationresearch,themotionparametersoftherobot, groundreactionforcesandmomentsofforce,driving torques,wheelsinkageandslipparametersofwheels werecalculated.Aggregatedresearchresultsaswellas detailedresultsofselectedsimulationsareshownand discussed.Asaresultoftheresearch,itwasnoticed thatwheelslipratios,wheels’sinkageandwheeldriving torquesincreasewithdesiredvelocityofmotion.More‐over,itwasobservedthatwheels’sinkageanddriving torquesaresignificantlylargerfordrysandthanforthe otherinvestigatedgroundtypes.

Keywords: Lightweightwheeledmobilerobot,Longitudi‐nalmotion,Deformableground,Dynamicsmodel,Tire‐groundinteraction,Wheelslip,Wheelsinkage,Simula‐tionstudies

Lightweightwheeledmobilerobotsareversatile vehiclesthatworkinbothindoorandoutdoorenvi‐ronments.Thelargestgroupofsuchvehiclesare lightweightmobilerobots,anexampleofwhichare robotsforspecialapplications.Suchrobotsmoveon avarietyofsurfaces,bothpaved[1]andunpaved[2].

Atthestageofdesigningrobotstructuresand controlsystems,itisbene icialtoknowtherobot dynamicsmodel[3,4].Theformoftherobotdynamics modelisfundamentallyin luencedbyitskinematic structure[5],whichdependsontheareaofapplication oftherobot.Suchamodelcanbedevelopedusingclas‐sicalmethods,e.g.,usingtheNewton‐Eulerformalism orLagrangeformalism[6].

Alternativemethodsmayalsobeusedinwhichthe dynamicsmodelcanbebuiltusingsystemidenti ica‐tionthroughmeasurementsoftheinputandoutput signalsofthesystem[7].Thisprocesscanbecar‐riedoutbothof line[8]andonline,dependingonthe method.Italsomayormaynotrequiretheknowledge oftherobot’smodelstructure.Arti icialintelligence methodscanalsobeused[9],e.g.,basedonarti icial neuralnetworks[10],toapproximateunknownnon‐linearfunctionsinthedynamicsmodel.

Regardlessoftheadoptedmethodofcreating thedynamicsmodel,itisimportantthatittakes intoaccountthewheel‐groundinteraction.Forthis purpose,tiremodelsareintroducedinthedynam‐icsmodel.Tire‐groundinteractioninthecaseof lightweightmobilerobotsmovingatrelativelyhigh speedsshouldtakeintoaccountthepossibilityof wheelslippage.Ifrobotmotionoccursondeformable ground,theninadditiontowheelsliptheground deformationhastobeconsideredaswell.Modeling theinteractionofwheelswithunpavedgroundisthe subjectofterramechanics,thebasisofwhichwasfor‐mulatedinthework[11].

Theproblemofmotionondeformablegroundis ofcriticalimportanceinthecaseofoutdoorwheeled mobilerobotsusedforreconnaissanceincivilandmil‐itaryscenariosandisrelatedtotheproblemofrobot mobility.Inthiscase,thequestionsofhowtheground typeanddesiredrobotvelocityaffectwheelslips,soil deformation(orwheelsinkage)anddrivingtorques shouldbeanswered.Examplesofstudiesofmotion ofvehiclesondeformablegrounds,especiallytracked andwheeledones,are[11,12]and[13].Themajority ofworksisfocusedonmannedvehicles;however, onecanalso indworksconcerningwheeledmobile robots,forinstance[14],andinparticularplanetary rovers[15,16].Heavyoff‐roadvehiclestypicallyuse pneumaticwheels.Apartfromthetread,theirdriving propertiesaredeterminedbytirepressure,aswellas wheeldiameterandwidth.Theresearchresultsinthis areaaredescribed,amongothers,inworks[11,12]. Inturn,lightweightvehicles,suchasmobilerobots forspecialapplicationsoftenhavenon‐pneumatic wheels.Therefore,intheircase,themechanicalprop‐ertiesofthewheel illingsusedareimportant.

Theaimofthispaperistostudythein luence ofthreetypesofdeformablegroundonthemotion parametersofalightweightwheeledmobilerobot duringitslongitudinalmotion.Theanalysisiscar‐riedoutfortherobotmovingwithvariousdesired velocitiesonthreedifferenttypesofsoftground,i.e., drysand,sandyloamandclayeysoil.Inthepresent work,thenumericalanalysisonlyispresented,but asimilarstudywithexperimentalveri icationwas carriedoutfordrysandinpaper[17].Inthepresent article,theissueoftheinteractionofthewheelwith thesoftgroundisalsodescribedinmoredetail.Inpar‐ticular,thedistributiononthewheelcircumference ofsoildeformationsandstressesinthecontactarea ofthewheelwiththegroundisanalyzed,whichis verydif iculttoperformatthestageofexperimental research.

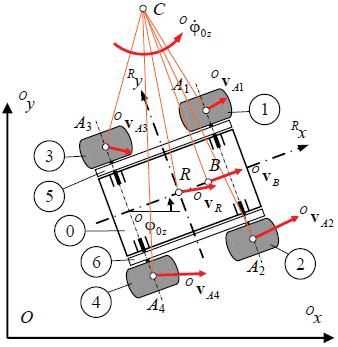

Withinthispaper,thePIAPGRANITEfour‐wheeledmobilerobotwithnon‐steeredwheelsis analyzed.Therobot’swheelsarenon‐pneumatic,i.e., theyare illedwithstiffeningfoam.Thisrobotisa platformdedicatedtoresearch(Fig. 1a).Therobot’s kinematicstructureisillustratedinFigure1b,where theparticularsubsystemsaredistinguished,i.e.:0–body,1–4–wheels,5–6–optionaltoothedbelts.

Therobotcanbecon iguredtoworkinseveral versions,i.e.:1.thefrontorreardrivecanbedecou‐pledandonlytheremainingwheelscanbedriven; 2.onlythefrontorrearwheelscanbedriven,but additionaltoothedbeltscanbeusedtotransferdrive totheremainingwheels;3.allwheelscanbedriven independently.Inthecaseanalyzedinthispaper,the toothedbeltswereremoved,andindependentdriveof allwheelswasused.

Inthecaseoftherobotmovingonsoftground, doublewheelswereusedbecausetheuseofstandard‐widthwheelsresultedintoomuchwheels’sinkageon sand,makingtherobotunabletomove.Thefollowing designationsofgeometricparametersoftherobot wereintroducedinFigure1b: L –wheelbase, W –track width(��1��3 =��2��4 =��,��1��2 =��3��4 =��),����,���� –respectivelyradius,andwidthofthe i‐thwheel,where ��=1,…,4

Thevelocityofthepoint R oftherobotwas assumedasthegivenparameteroftherobot’smotion, thatis �������� = ����������.Theleftsuperscript O means thatthedesiredvelocityisexpressedinthestation‐arycoordinatessystem.Iftherobotisinlongitudinal motion,thevelocitiesofthegeometriccentersofthe wheelsareequaltothevelocityofpoint R,i.e., �������� = ���������� = ��������

Withregardtodesiredangularvelocitiesofwheel spins������,iftherobotmoveswithoutslip,theycanbe determinedbysolvingtheinversekinematicsproblem forthemobileplatform,thatis,fromtherelationship:

���� = ��������/���� (1)

Figure1. PIAPGRANITErobotduringtestsinacontainer filledwithsand(a),kinematicstructureoftherobot(b)

However,wheelslippagemayoccurwhilethe robotismoving.Themeasuresofthatslippageare instantaneouslongitudinalslipratios ���� andmean longitudinalslipratio���� (longitudinalslipratioofthe wholerobot).

Thoseslipratiosaregivenwiththeformulas:

–wheelcircumferentialvelocity,

–distancetraversedbypoint R oftherobotinlon‐gitudinaldirection,�������� –desireddistancetraveledby point R whenrollingwithoutslip.

Forthepresentinvestigations,thefollowing assumptionsareadopted:

‐ wheelsaretreatedasrigidbodies, ‐ theso‐calledmulti‐passeffect(inwhichafollow‐ingwheelissubjecttosmallerrollingresistance, becauseitmovesinarutmadebyaleadingwheel) arenotconsidered,

‐ treadblocksoftiresareneglected.

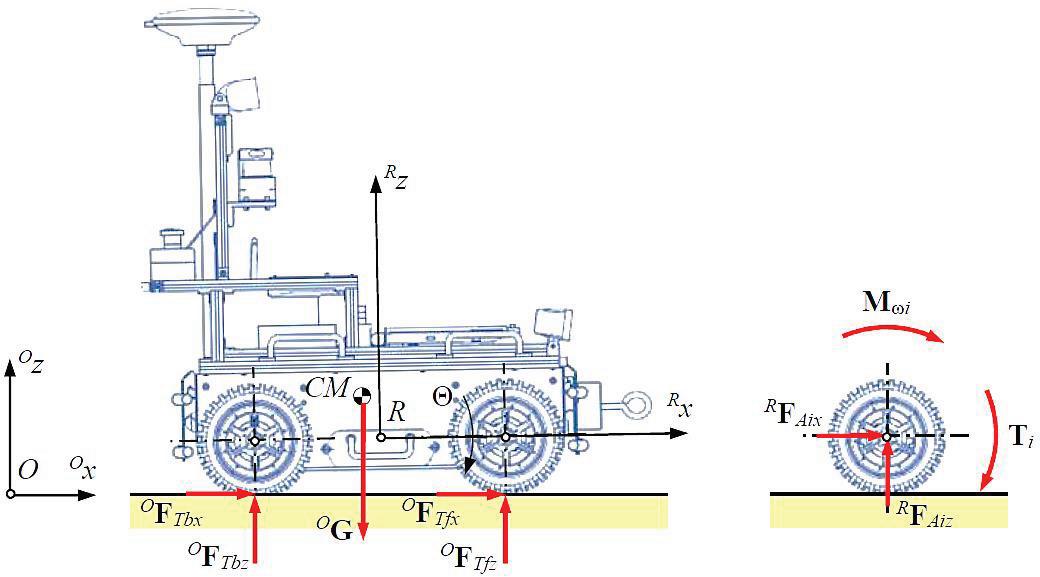

Amulti‐bodydynamicsmodelwasderivedforthe robot.Itwasassumedthatontherobotacttheground reactionforces,i.e., ��F���� =[����������, ����������, ����������]�� (��= 1,…,4)andgravityforce ��G =���� ��g (Fig.2a),where ���� isrobottotalmass, ��g =[������, ������, ������]�� the vectorofgravityacceleration,andtheleftsuperscript R meansthatmentionedvectorsareexpressedinthe movingcoordinatesystemattachedtotherobot.

Thefollowingindexesareintroducedforindivid‐ualpairsofwheels: f –frontwheels(��=1,2), b –rear wheels (��=3,4).Oneachwheel,apartfromforce ofgravityandforcesfollowingfromtheinteraction withtheground,actdrivingtorque ��T�� =[0,����,0]�� andmomentofmotionresistance��M���� =[0, M����,0]�� (Fig.2b).

Asaresultofthereductionofforces ��F���� tothe axesofrotationofwheels,theforces ��F���� = ��F���� = [����������, ����������, ����������]�� areobtained.

Themulti‐bodydynamicsmodelisbasedonthe followingequationsofdynamicsforthewholevehicle andforindividualwheels(associatedwiththeirspin):

Θ and ���� = ���� –angularaccelerationsofrotationof respectivelymobileplatformandwheelaboutmen‐tionedaxes, ���������� and ���������� –componentofthe linearaccelerationoftherobotmasscenter.

Thedevelopedmodelenablesthesolutionofthe forwarddynamicsproblemfortherobot.According tothismodel,inasingletimestepofsimulation,the followingquantitiesaredetermined:

1) Instantaneousslipratiosforwheels���� (��=1,…,4) andfortherobot���� fromequations(2)and(3).

2) Geometricquantitieslikemaximumwheelsinkage ��0�� andanglesofwheel‐terraincontact ��1�� and ��2�� =����2��1�� (Fig.3a).

3) Soilsheardeformation ����(��1��)accordingto[13] andwheelsinkage ����(��1��) intherangeofwheel‐terraincontactanglesfrom −��2�� to ��1�� basedon dependencies:

����(����)=����((��1�� −����)−(1−����)(sin��1�� sin����)), (8) ����(����)=max(��0�� −����(1−cos����),0). (9)

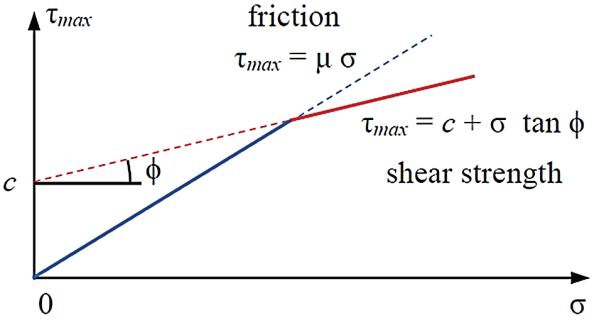

4) Pressure����(��1��)accordingtoBekker[11]:

����(����)=��(����(����))�� = ���� ���� +���� (����(����))�� , (10) where: ����(����)–cohesive(frictional)modulusof terraindeformation, n –terraindeformationexpo‐nent.

where: ������ =��/2−��������, ������ =−��/2−��������, �������� and �������� –robotmasscentercoordinates, �������� –robotmassmomentofinertiaabouttheaxisparallel to ���� andpassingthroughrobotmasscenter, �������� –wheelmassmomentofinertiaaboutitsspinaxis,E=

5) Normalstress����(��1��)≈����(��1��),maximumshear stress ����������(��1��),basedonmodi iedMohr‐Coulombfailurecriteria[18](Fig. 3b)including thecaseofmovingtiresurfacewithrespecttosoil: ����������(����)=min(��������(����),��+����(����)tan��), (11) thatistakingintoaccountsoilcohesion c,internal frictionangle��andcoef icientofstaticfriction���� forthewheel‐terrainpairaccordingto[19].

6) ShearstressesaccordingtoJanosi‐Hanamoto hypothesis[12]intherangeofwheel‐terrain contactanglesfrom−��2�� to��1��:

where K isthesheardeformationparameter.

7) Forcesandmomentsofforcelike:staticnormal load����,tractionforce����,motionresistanceforce ������ andmomentofmotionresistance������ basedon theknownstressdistributionoverwheelcircum‐ference,accordingtoformulasin[13],i.e.,basedon equations:

and inally,resultantforces:longitudinal ���������� = ���� +������ andnormal ���������� =���� +������,which includescomponentforceresultingfromthetire‐groundsystemdamping������ =������ 0��sgn(��0��).

8) Linearandangularaccelerations,i.e.: ����������, ����������, Θ and ���� (��=1,…,4),forthemulti‐body systemoftherobotbasedontheequationsof dynamics(4)–(7).

Itshouldbenoted,thatvelocities ������, ����������, ���� necessaryfordeterminationofslipratios ���� and ���� inthe irststageofthealgorithmdescribedabove, coordinatesofcentersofwheelsnecessaryforcalcu‐lationofwheels’sinkage��0�� andangles��1�� and��2�� in thesecondstageofthatalgorithmaretakenfromthe previoustimestepofcalculations.

NumericalstudieswereconductedintheMat‐lab/Simulinkenvironment.

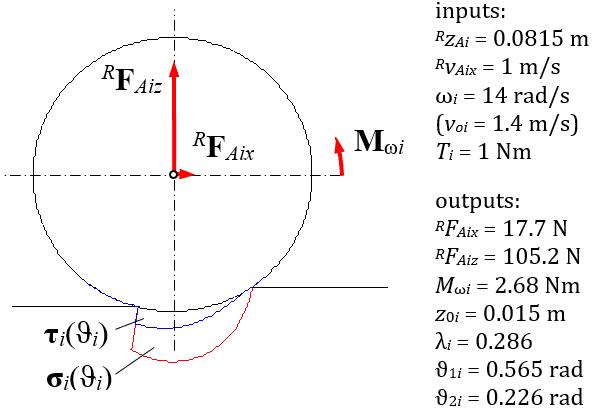

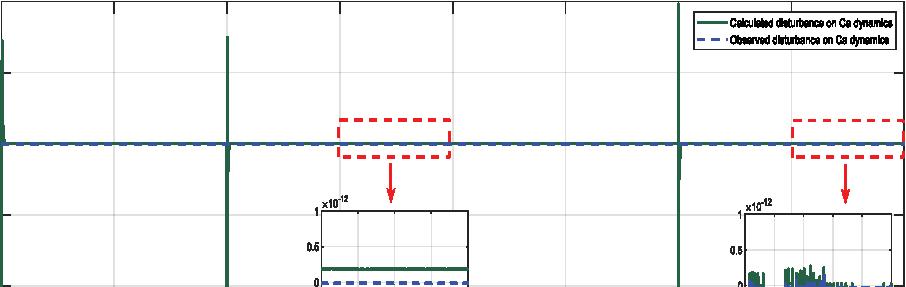

Aspartofthepreliminarysimulationtests,a numericalveri icationofthewheel‐groundinterac‐tionmodelwascarriedout.Inthesestudies,theprevi‐ouslymentionedparametersofthismodelweretaken intoaccount.

Inthecalculations,itwasassumedthatthechange oftheangle���� ∈⟨−��2��,��1��⟩willbeimplementedwith astep Δ��=��/180 rad.Moreover,itwasassumed that ��2�� =����2 ��1��,where ����2 =0.4.Calculations wereperformedforthefollowinginputdata: �������� = 0.0815 m, ���������� =1 m/s, ���� =14 rad/s, ���� = 1Nm.Theassumedangularvelocityofthewheelsis themaximumfortheGRANITErobotandcorresponds tothecircumferentialvelocityequalto������ =1.4m/s.

Figure4showsthestressdistributions����(����)and ����(����)onthewheelcircumference,theresultingforces ����������, ���������� andmomentofforce M���� aswellasthe inputandoutputdatafortheanalyzedtest.

Illustrationofthedistributionofstresses ����(����) and ����(����) onthewheelcircumferenceaswellas theresultingforces ��F������, ��F������ andmomentof force M����

������ =−����(����)2 ��1�� −��2�� ����(����)d����, (16)

Itshouldbenotedthattheobtainedvalueofthe groundnormalreactionforceisequalto ���������� = 105.2N.Inthecaseoftheanalyzedtire,suchaforce wouldcauseitsradialdeformationequalto Δ���� = 0.0026m,whichissmallincomparisonwiththemax‐imumgrounddeformation��0�� =0.015m.

Inturn,Figure5presentsdistributionsofdeforma‐tionsofthegroundandstressesonthewheelcircum‐ferenceasafunctionoftheangle���� fortheanalyzed case.

Accordingtothepreviouslygivenformulas,after integrationofstresses w��(����), r����(����), f��(����), f����(����) and����(����),theresultantforcesandmomentofforce, areobtained,i.e.: W��, R����, F��, F���� and M����.

Itcanbenoticedthatthevalueoftheforce F���� is signi icantlyin luencedbythestressdistributionin therearpartofthetireinrelationtothedirectionof movement.

Inparticular,stress r����(����)hasnegativevaluesin therange ���� ∈(0,��1��) whilstpositivevaluesinthe range ���� ∈(−��2��,0),whilestress f��(����) haspositive valuesintherange���� ∈(−��2��,��1��),withthelargestin therange���� ∈(−��2��,0).

Aspartofthemainsimulationstudiesforthe entirerobot,thelongitudinalmotionfordesiredmax‐imumvelocities ������ from0.2m/sto0.7m/swas analyzed.Desiredmaximumacceleration���������� dur‐ingspeedingupandbraking,aswellasdesiredtotal distance���� tobetraveledwerechosenindividuallyfor theparticularcaseofmotion.Desiredparametersof robotmotionaresummarizedinTable1

ThevaluesofthebasicparametersofthePIAP GRANITEmobilerobotusedinsimulationstudiesare showninTable 2.Soilparametersrequiredbythe adoptedmodelandbasedonwork[14]arepresented inTable3

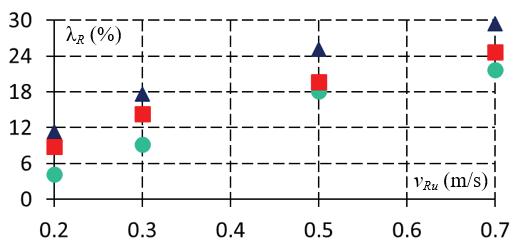

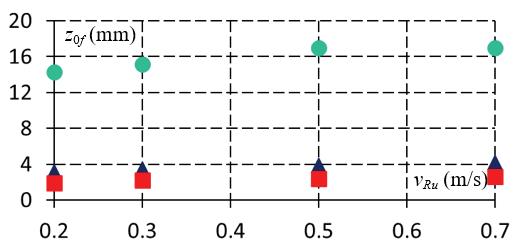

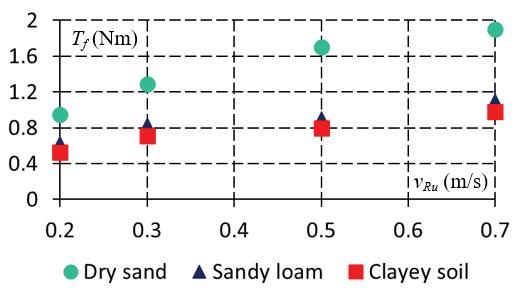

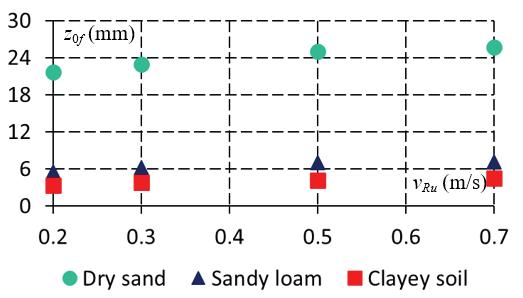

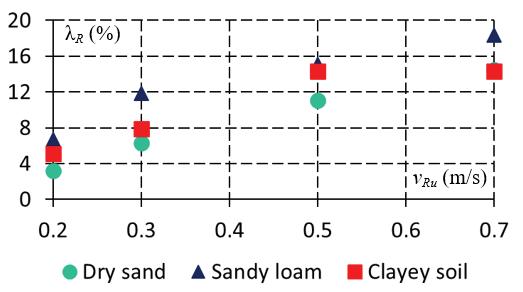

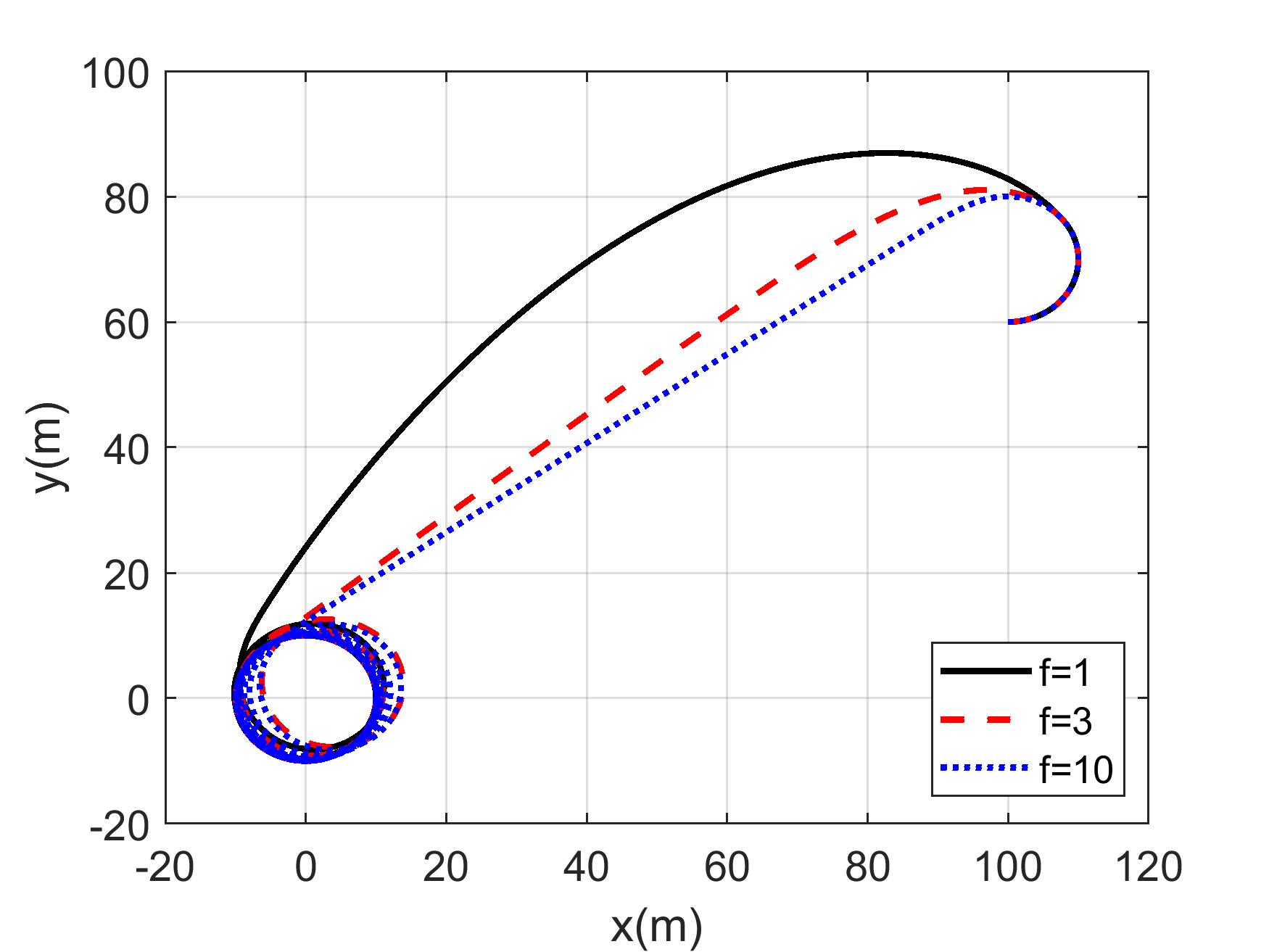

Theaggregatedresultsoftheresearchareshown inFigure 6.Itcanbenoticedthatthesmallestslip ratiosarefordrysandandthelargestforsandyloam andthattheslipratiosincreasewithdesiredvelocity. Thelargestwheelsinkageoccursfordrysand,andfor theotheranalyzedgrounds,itismuchsmaller.The wheelsinkageincreasesslightlywithrobotvelocity.

Inthecaseofdrysand,wheelsinkageismuch largerincomparisontoradialdeformationofthetire, whichwouldoccuronrigidground.Tireradialdefor‐mationwouldbe2–3mmbecausetheradialstiffness ofthetireis������ =40,000N/m[17].Fortheremaining typesofground,wheelsinkageisofcomparableorder tothisdeformation.Thedrivingtorquesincreasewith velocity,i.e.,torquesincreasenearlytwotimeswhen comparingresultsfor0.2m/sand0.7m/scasesof desiredrobotvelocity.

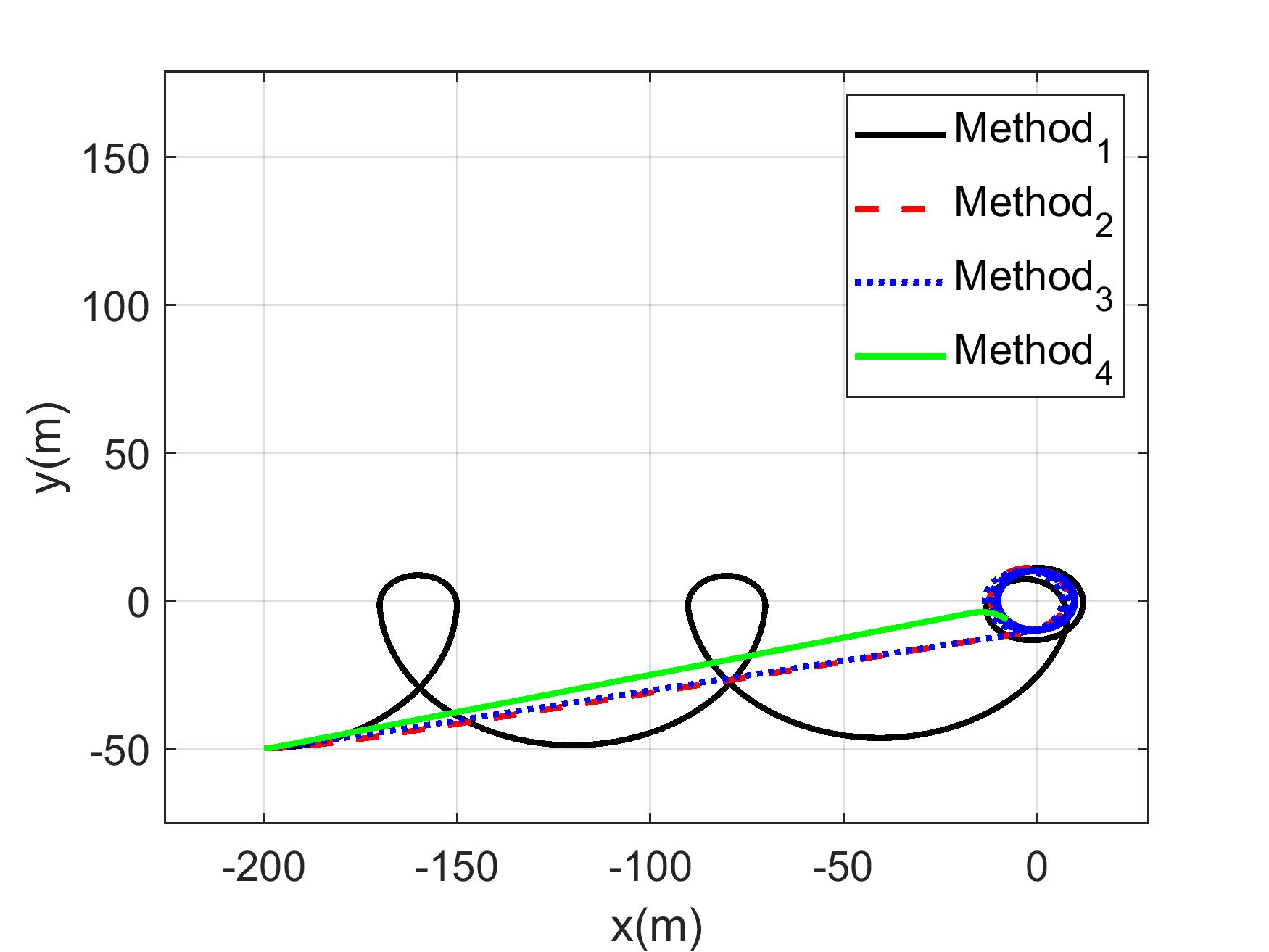

InFigures7–10,detailedresultsforrobotmotion withdesiredvelocity �������� = 0.5m/sondrysand, sandyloamandclayeysoilareillustrated.

Figure5. Distributionsonthewheelcircumferenceof soildeformations:tangential ����(����) (a)andnormal ����(����) (b),aswellasstressesresultingfromthem: tangential ����(����) (c),normal ����(����) (d)andresultants: w��(����), r����(����), f��(����), f����(����)= r����(����)+ f��(����) (e–h)

Table1. Desiredrobotmotionparametersforthe investigatedcases

Table2. BasicparametersofthePIAPGRANITEmobile robotusedinsimulationstudies

Dimensions ��=0.425m, ��=0.59m, ���� =0.0965m, ���� =2⋅0.064m

Massesofthebodies ��0 =36.54kg, ���� =1.64kg

Robotmasscentercoordinates �������� =−0.012m, �������� ≈0m, �������� =0.06m

Massmomentsofinertia ������ =0.016kgm2 , �������� =0.51kgm2

Tireparameters ������ =40000N/m, ������ =1000Ns/m

Table3. Soilparametersassumedfortheresearch[14]

Figure6. Influenceoftypeofsoilanddesiredmotion velocityon:longitudinalslipratiosfortherobot(a), wheelsinkage(b),drivingtorques(c)

InparticularinFigure7,timehistoriesofdesired andactualrobotvelocitiesaswellascircumferential velocityresultingfromwheelspinarepresented.It canbenoticedthatduringsteadymotion,valueof theactualrobotvelocity �������� isnoticeablysmaller withrespecttodesiredvelocity ��������.Thisisbecause therobotdoesnotachievethedesiredacceleration, especiallyintheinitialstageofmovement.

This,inturn,resultsfromthehighvaluesofthe longitudinalslipratiosofthewheels ���� occurring especiallyduringtheaccelerationoftherobot.The robot’sactuallongitudinalvelocity �������� isclosestto thedesiredvelocity �������� forthecaseoftherobot movingondrysand.Inallcases,itcanbeseenthat themaximumcircumferentialvelocityofwheels���� is reachedwithadelay,whichresultsfromtheinclu‐sionofthedynamicsofthedriveunitsinthemodel, describedinpaper[17].

InFigures 8–9 thetimehistoriesoflongitudinal slipratiosandsinkageforfrontandrearwheelsare shown,respectively.Thetimehistoriesoflongitudi‐nalslipratiosaresimilarforfrontandrearwheels. However,adifferencecanbenoticedinthecaseof wheels’sinkage,duetothefactthatthecenterof massislocatedintherearpartofthevehicle.For thisreason,highervaluesareobtainedfortherear wheels.Similartothevelocity,thetimehistoriesofthe longitudinalslipratiosaresimilartoeachotherforthe

analyzedgroundcases,butduringaccelerationthey areapparentlythesmallestforthemovementondry sand.However,therearelargedifferencesinthetime historiesofwheels’sinkagefortheanalyzedtypesof theground.De initelythehighestvaluesofwheels’ sinkageoccurfortherobot’smovementondrysand. Inturn,thesmallestvaluescanbeseeninthecaseof clayeysoil.

Finally,inFigure 10,thetimehistoriesofdriving torquesforfrontandrearwheelsareillustrated.Dur‐ingacceleration,thehighestvaluesofdrivingtorques areachievedwhentherobotmovesondrysand.Inthe caseofothergrounds,similarresultswereobtained, moreover,thedrivetorquesforthefrontandrear roadwheelsarelessdifferentiatedinrelationtothe movementondrysand.

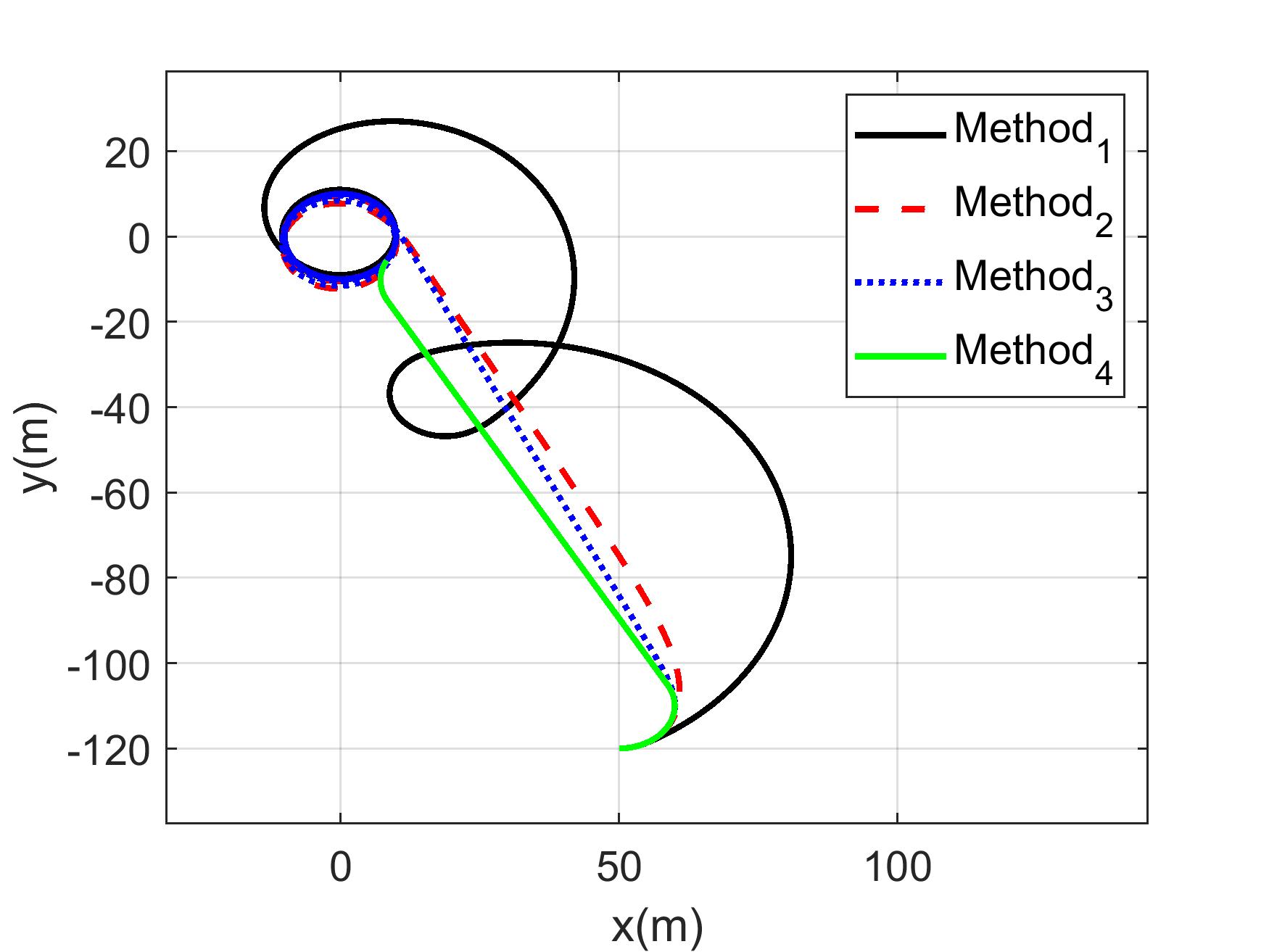

Simulationstudieswerealsocarriedouttoanalyze theimpactofwheelgeometricparametersonlongitu‐dinalslipratios,wheelsinkageanddrivingtorques.

Inthisresearch,inrelationtostandardcon igura‐tionoftherobot,thefollowingwheelsolutionswere analyzed:

1) wheelswithwidthreducedby50%,

2) wheelswithadiameterincreasedby50%.

Theresultsofsimulationresearchindicatethat fortheanalyzedrobotmotionvelocities,changing thegeometricparametersofthewheelshasasmall impactonthedrivingtorques.

Figure7. Timehistoriesofdesiredvelocity ��v���� and actualvelocity ��v���� oftherobotaswellas circumferentialvelocityofwheels ���� obtainedin simulationoftherobot’smovementwiththemaximum velocity ������ =0.5 m/son:drysand(a),sandyloam(b) andclayeysoil(c)

Figure9. Timehistoriesofsinkageforfrontandrear wheelsobtainedinsimulationoftherobot’smovement withthemaximumvelocity ������ =0.5 m/son:drysand (a),sandyloam(b)andclayeysoil(c)

Figure8. Timehistoriesoflongitudinalslipratiosfor frontandrearwheelsobtainedinsimulationofthe robot’smovementwiththemaximumvelocity ������ =0.5 m/son:drysand(a),sandyloam(b)and clayeysoil(c)

Figure10. Timehistoriesofdrivingtorquesforfrontand rearwheelsobtainedinsimulationoftherobot’s movementwiththemaximumvelocity ������ =0.5 m/s on:drysand(a),sandyloam(b)andclayeysoil(c)

Whenwheelswithasmallerwidthwereused, slightchangesinlongitudinalslipratiosandasignif‐icantincreaseinwheelsinkagewereobserved.The changeinwheelsinkagecanbeseenfromthecom‐parisonoftheresultsshowninFigure6bforwheels withalargerwidthandinFigure11forwheelswith asmallerwidth.Thisobservationisconsistentwith theeffectsofpreliminaryexperimentaltestsforthe PIAPGRANITErobotandwasthereasonfortheuse ofwheelswithlargerwidth.

Theresultsofsimulationstudiesalsoindicatethat theuseofwheelswithadiameter50%largerleads toareductioninwheelsinkage,butthischangeis notsigni icant.However,theuseoflargerdiameter wheelsleadstoasigni icantreductioninlongitudinal slipratios,especiallyathighervelocities.Thiscanbe seenbycomparingtheresultsshowninFigure6afor wheelswithasmallerdiameterwiththeresultsin Figure12forwheelswitha50%largerdiameter.

Withinthispaperthesimulationstudiesofin lu‐enceoftypeofdeformablegroundonlongitudinal motionoflightweightwheeledrobotwascarriedout.

Investigatedcasesincludedfourdesiredvelocities ofmotion,i.e.:0.2m/s,0.3m/s,0.5m/sand0.7m/s andthreetypesofground:drysand,sandyloamand clayeysoil.

Forallthosecases,aggregatedresultsofwheelslip ratio,wheelsinkageandwheeldrivingtorquewere

presented.Detailedresultsforthecaseof0.5m/s velocityonallanalyzedtypesofsoilwerealsoshown. Thefollowingmainconclusionscanbedrawnfrom theconductednumericalresearch.

Ifalightweightwheeledmobilerobotmovesona deformableground,then:

‐ longitudinalslipratiosigni icantlyincreaseswith desiredvelocity;

‐ wheelsinkageincreaseswithdesiredvelocity–in caseofmotionondrysand,wheelsinkageismuch largerthanradialdeformationoftirewhichwould occurforcomparablewheelloadonrigidground;

‐ wheeldrivingtorquesincreasewithvelocityand reachthelargestvaluesforrobotmotionondry sand;

‐ changingthewheelwidthsigni icantlyaffectswheel sinkage,i.e.,itishigherfornarrowerwheels;

‐ changingthewheeldiametercauses,inturn,a changeinthelongitudinalslipratios,i.e.,they decreaseasthewheeldiameterincreases.

Thescopeoffurtherresearchmayinclude:

‐ modelingthedynamicsofbothlightweightand heavyvehiclesusingwheelswith illingsofvarious mechanicalproperties;

‐ simulationstudiestakingintoaccounttiredeforma‐tion,treadblocksandmulti‐passeffectintiremodel;

‐ experimentalstudiesoftherobotmotiononsandy loamandclayeysoil;

‐ simulationandexperimentalstudiesofrobotturn‐ingandrotationinplaceforvarioustypesofthe ground.

MaciejTrojnacki∗ –WarsawUniversityofTechnol‐ogy,FacultyofMechatronics,InstituteofMicrome‐chanicsandPhotonics,Boboli8,02‐525Warsaw, Poland,e‐mail:maciej.trojnacki@pw.edu.pl.

PrzemysławDąbek –ŁUKASIEWICZResearch Network—IndustrialResearchInstitutefor AutomationandMeasurementsPIAP,Al. Jerozolimskie202,02‐486Warsaw,Poland,e‐mail: przemyslaw.dabek@piap.lukasiewicz.gov.pl.

∗Correspondingauthor

[1] K.Zhou,S.Lei,andX.Du.“Modellingand dynamicanalysisofslippagelevelforlarge‐scaleskid‐steeredunmannedgroundvehicle,” SciRep,vol.12,no.1,Art.no.1,Sep.2022,doi: 10.1038/s41598‐022‐20262‐z.

[2] J.Guo,H.Gao,L.Ding,T.Guo,andZ.Deng.“Linear normalstressunderawheelinskidforwheeled mobilerobotsrunningonsandyterrain,” Journal ofTerramechanics,vol.70,pp.49–57,Apr.2017, doi:10.1016/j.jterra.2017.01.004.

[3] M.Ciszewski,M.Giergiel,T.Buratowski,andP. Małka, ModelingandControlofaTrackedMobile

RobotforPipelineInspection.SpringerNature, 2020.

[4] L.Liangetal.“Model‐BasedCoordinatedTrajec‐toryTrackingControlofSkid‐SteerMobileRobot withTiming‐BeltServoSystem,” Electronics,vol. 12,no.3,Art.no.3,Jan.2023,doi:10.3390/elec‐tronics12030699.

[5] A.J.Moshayedi,A.S.Roy,S.K.Sambo,Y.Zhong, andL.Liao.“ReviewOn:TheServiceRobotMath‐ematicalModel,” EAIEndorsedTransactionson AIandRobotics,vol.1,pp.e8–e8,Feb.2022,doi: 10.4108/airo.v1i.20.

[6] K.Peng,X.Ruan,andG.Zuo.“Dynamicmodel andbalancingcontrolfortwo‐wheeledself‐balancingmobilerobotontheslopes,”in Proceedingsofthe10thWorldCongressonIntelligent ControlandAutomation,Jul.2012,pp.3681–3685.doi:10.1109/WCICA.2012.6359086.

[7] P.Lichota.“WaveletTransform‐BasedAircraft SystemIdenti ication,” JournalofGuidance,Control,andDynamics,vol.46,no.2,pp.350–361, Feb.2023,doi:10.2514/1.G006654.

[8] S.SutuloandC.GuedesSoares.“Analgorithmfor of lineidenti icationofshipmanoeuvringmath‐ematicalmodelsfromfree‐runningtests,” Ocean Engineering,vol.79,pp.10–25,Mar.2014,doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2014.01.007.

[9] J.Giergiel,K.Kurc,andD.Szybicki.“Identi ica‐tionoftheMathematicalModelofanUnderwa‐terRobotUsingArti icialInteligence,” MechanicsandMechanicalEngineering,2014,Accessed: Jan.16,2024.[Online].Available:https://www. semanticscholar.org/paper/Identification‐of‐the‐Mathematical‐Model‐of‐an‐Giergiel‐Kurc/5 b4cfa76e8916013fa613c40ff06d3a966542853

[10] A.PerrusquíaandW.Yu.“Identi icationandopti‐malcontrolofnonlinearsystemsusingrecurrent neuralnetworksandreinforcementlearning:An overview,” Neurocomputing,vol.438,pp.145–154,May2021,doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021. 01.096.

[11] M.G.Bekker, Off-the-roadLocomotion:Research andDevelopmentinTerramechanics.University ofMichiganPress,1960.

[12] J.Y.Wong, TheoryofGroundVehicles,3rdEdition, 3rdedition.NewYork:Wiley‐Interscience,2001.

[13] Sh.Taheri,C.Sandu,S.Taheri,E.Pinto,andD. Gorsich.“AtechnicalsurveyonTerramechan‐icsmodelsfortire–terraininteractionusedin modelingandsimulationofwheeledvehicles,” JournalofTerramechanics,vol.57,pp.1–22,Feb. 2015,doi:10.1016/j.jterra.2014.08.003.

[14] K.IagnemmaandS.Dubowsky, MobileRobots inRoughTerrain:Estimation,MotionPlanning, andControlwithApplicationtoPlanetaryRovers. Springer,2004.

[15] L.Ding,H.Gao,Z.Deng,K.Yoshida,andK. Nagatani.“Slipratioforluggedwheelof planetaryroverindeformablesoil:de inition andestimation,”in 2009IEEE/RSJInternational ConferenceonIntelligentRobotsandSystems,Oct. 2009,pp.3343–3348.doi:10.1109/IROS.2009. 5354565.

[16] Z.Wangetal.“Wheels’performanceofMars explorationrovers:Experimentalstudyfromthe perspectiveofterramechanicsandstructural mechanics,” JournalofTerramechanics,vol.92, pp.23–42,Dec.2020,doi:10.1016/j.jterra.202 0.09.003.

[17] M.TrojnackiandP.Da̧bek.“Studiesofdynamics ofalightweightwheeledmobilerobotduring longitudinalmotiononsoftground,” Mechanics ResearchCommunications,vol.82,pp.36–42,Jun. 2017,doi:10.1016/j.mechrescom.2016.11.001.

[18] G.N.B.Hathorn,K.Blackburn,andJ.L.Brighton. “AnInvestigationintoWheelSinkageonSoft Sand,” TireScienceandTechnology,vol.42,no.2, pp.85–100,Apr.2014,doi:10.2346/tire.14.42 0201.

[19] “Tirefrictionandrollingcoef icients,”HPWiz‐ard.Accessed:Jul.25,2023.[Online].Available: https://hpwizard.com/tire‐friction‐coefficient. html

Submitted:13th September2022;accepted:6th March2023

DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2023/27

Abstract:

Minimally‐supervisedhomerehabilitationhasbecome anarisingtechnologicaltrendduetotheshortages inmedicalstaff.Implementingsuchrequiresproviding advancedtoolsforautomaticreal‐timesafetymoni‐toring.Thepaperpresentsanapproachtodesigning thementionedsafetysystembasedonmeasurements andmodellingtheinterfacebetweenapatient’smuscu‐loskeletalsystemandarehabilitationdevice.Thecon‐tentcoversthesegmentationofpatientsregardingtheir healthconditionsandassignsthemsuitablemeasure‐menttechniques.Thedefinedgroupsaredescribedby thehazardswithwhichtheyaremostendangeredand theircauses.Eachcaseiscorrelatedwiththeappropriate datatypethatmaybeusedtodetectpotentialrisk. Moreover,aconceptofusingpresentedknowledgefor trackingthesafetyofbonesandsofttissuesaccordingto thebiomechanicalstandardsisincluded.Thepaperforms asetofguidelinesfordesigningsafetysystemsbasedon measurementsforrobot‐aidedhomekinesiotherapy.It canbeusedtoselectanappropriateapproachregarding aspecificcase;whichwilldecreasecostsandincreasethe accuracyofthedesignedtools.

Keywords: Biosignals,Biomechanics,Homerehabilita‐tion,Kinesiotherapy,Minimally‐supervisedtreatment, Rehabilitationrobotics

1.Introduction

Kinesiotherapyistreatmentwithmotiondesigned torestoremaximumfunctionalityofpatients.Itspur‐poseistorecoverfromdiseasesofthemusculoskele‐talsystem.Duringkinesiotherapyofextremities,a physiotherapistinteractsphysicallywiththepatient’s limbsinaspeci icwaytoregaintheirmobility[61].

Bringingbackmaximumfunctionalityisessen‐tialforbasicdailyactivities(ADL).Themotortreat‐mentoftenrequiresalotofprofessionalphysical engagement,whichmaybeovertakenbyrehabili‐tationrobots.Moreover,workingwithpeoplewho donothavetheabilitytositorstandthemselves oftenrequiresuprightstandingwiththehelpofup tothreephysiotherapists[21].Inaddition,theageing societyrequiresmoreintensiveandfrequenttreat‐mentwhilethenumberofmedicalpersonnelongo‐inglydecreases.Hence,themostsigni icantproblemis

aninsuf icientnumberofphysiotherapistsandcare‐giversinnursinghomes[50].Itispossibletoreduce theparticipationofprofessionalsinthetherapyeven whilebeingdependentonfamilymembers.However, thisrequiresthedevicestosupportperformedexer‐cisesinapreciseandcontrolledway[53].Research indicatesadvantagesofprovidingstrokepatientsand peoplewithparesis,whorequirepermanentrehabili‐tation,withtransportable,lightweight,andwearable devices.Suchmaybeinvolvedinthepost‐discharge homerehabilitation[60].

DuetotheCOVID‐19pandemic,patientsneeding constanttherapywereseverelydisadvantaged.This wascausedbypandemicrestrictionsinhumanmeet‐ings[25],overcrowdingofhospitals,andtheshortage ofhealthcaremembers.Toavoidsuchsituations,it iscrucialtodevelopwell‐validatedtoolsforremote homerehabilitation[26].

Consideringthementionedconditions,adapting rehabilitationdevicestohomeself‐useisanarising needandchallengeformedicalrobotics.Asthether‐apistmaybenotprovidedwithhapticfeedbackdur‐ingremotehomerehabilitation,developingarobust safetysystemiscritical[80].Suchshouldanalyse dynamicsoftherehabilitatedbodysegmentandaddi‐tionalmeasurementstoassessthesafeoperationof auserwithoutinvolvingaphysiotherapist[23].The followingpaperpresentsanapproachtomodelling patients’physicalloadstodetectpotentialpainor discomfortautomatically.Thisispossibleforpartic‐ularcasesbymeasuringandinterpretingbiosignals ordynamicparameters.Thepaperclassi iespatients accordingtotheirdisorderslevel.Basedontheselev‐els,potentialhazardsduringkinesiotherapyarelisted andmatchedwiththecorrespondingmeasurements. Thesemaybeusedtobuildamodelenablingcontinu‐oushuman‐lesssafetymonitoring.

Basedonaliteratureoverview,thepaperconsists ofasystematicanalysisofthepotentialautomatic detectionofhazardoussituationsduringremotehome treatment.Thisincludesdiseasecasesegmentation, possiblecausesofinjuries,andmeasurementmeth‐ods.Withthese,amultibodymodelmaybecreated andusedtoassessthesafetyofthetreatment.

TheScopus,ResearchGate,GoogleScholar,and PubMeddatabaseswereanalysedtocreatethis paper.Thefollowingkeywordswereused:home telerehabilitation,kinesitherapy,stroke,paresis, spasticity,extremityexoskeleton,paindetection, measurablebiologicalsignals,ROMmeasurement, OpenSim.92articleswerereviewedwiththe limitationofbeingpublishedin2016orlater,of which37wereconsiderednottocontributemuch tothispaper.Papersdescribingtheexactconcept ofspeci icrehabilitationdeviceswererejected. However,itisworthnoticingthatmostofthem assumetheconstantpresenceofaphysiotherapist nexttothepatientorpriorlimitingjointsrangeof motion(ROM),whichaffectsthedevice’sworking area.Papersmainlydealingwiththepharmacological treatmentofstrokes,spasticity,orparesiswerealso rejected,asthisisnotrelevantfortheuptakentopic.

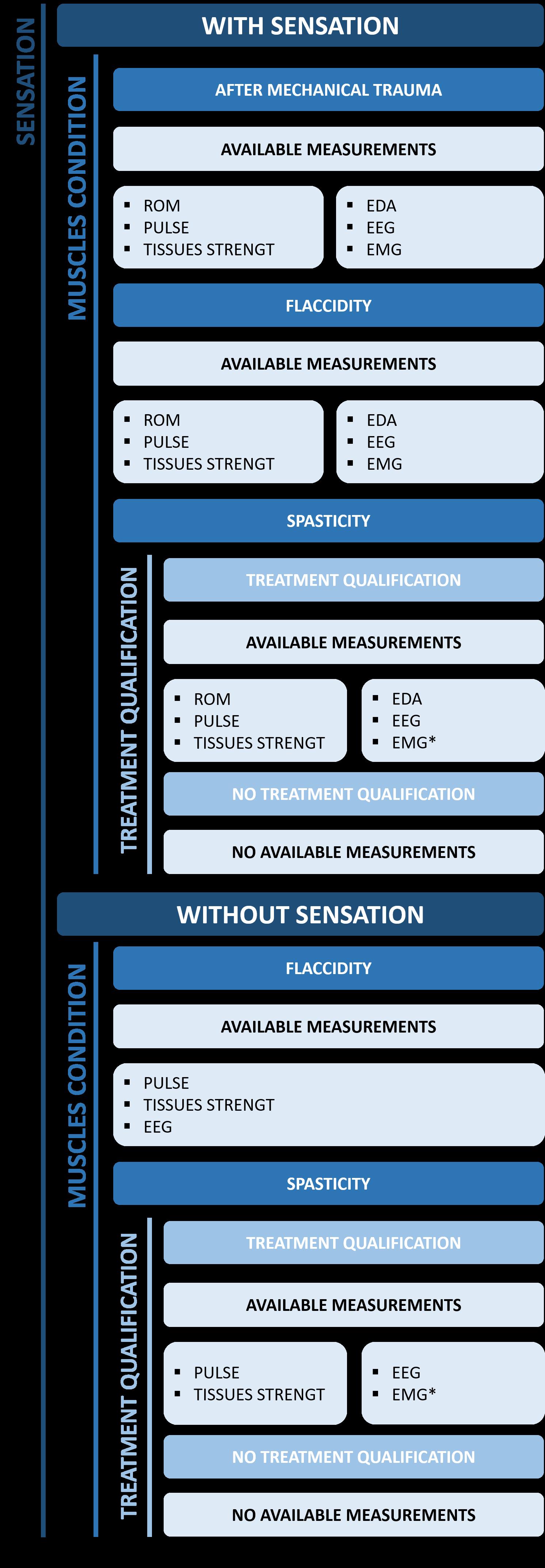

3.1.SegmentationofCases

Thepatientsweresegmentedinto ivegroupsto assignthemcorrespondingpotentialrisks.Thanksto this,thenumberofmeasurementtechniquesneeded forsafetymonitoringislimitedforeverycase.The de inedgroupsare:

1) Patientswithsensationaftermechanicaltrauma (e.g.,fractures)orlightmusculoskeletaldisor‐ders(e.g.,jointcalci ication)andpost‐surgical patients–withapossiblecompletereturntopre‐injuryperformance

2) Patientswith laccidmuscles,deprivedofsensa‐tion

3) Patientswith laccidmuscles,withsensation

4) Spasticpatients,deprivedofsensation

5) Spasticpatients,withsensation

Thepatientswithmuscle laccidityareunderstood astheoneswithmissingconnectionsbetweenthe brainandspinalcordcircuitsessentialforvolun‐tarymovement[22].Spasticityisamotordisorder characterizedbyavelocity‐dependentexaggerationof stretchre lexesresultingfromabnormalintraspinal processingofprimaryafferentinput.Suchmalfunc‐tioningimpliesincreasedmuscletone,enhancedten‐donre lexes,andextendedre lexzones[14]andis usuallytheresultofstroke[8].Tocorrectlyreferto individualcasesinthepaper,theyareassignedwith thenumbersoftheabove‐proposedsegments.

Thedivisionaboveincludescasesofpatientseli‐gibleforrobotichomerehabilitationandreferstothe partofthebodyrehabilitated(e.g.,whileperforming kinesiotherapyofthelowerlimbofapatientwiththe laccidlowerhalfofthebodyandsensation,theyare treatedasthegroup3–eventhoughtheirupperhalf ofthebodymaybenotaffectedbyanydisorder).For everygroup,thesignalswhichcanbemeasuredfor paindetectionpurposeswereselected.Theproposed approachtodetectriskpriortopatients’injuriesby theroboticrehabilitationsystemsispresentedbelow.

Selectionoftheappropriateapproachto measurementspriortoandduringkinesitherapeutic robot‐aidedsessionsiscriticaltoautomatingthe process.Themethodsmaybecombinedandused alongwitheachothertoimprovethereliabilityof thesafetysystemofthedevice.Currently,themost commonsensorsforrehabilitationdevicesareIMU, encoders,pressuregauges,andEMGsensors.The irst twoareusedtoobtaininformationonthedevice’s kinematicscon iguration,whiletheothersarefor biofeedback[19, 72].Thissubsectionpresentsan overviewoftheconsideredtechniquesandcorrelates themwiththesegmentspresentedbefore.

Measurementofthepatient’srangeofmotion

Measurementofthepatient’srangeofmotion(ROM) isconnectedwithactivelyexercisedjoints.The resultedvaluesdescribetheoperationalspaceofthe individualbodysegment,wheretheexercisemay beperformedwithoutpainoranyriskoftrauma. Suchmeasurementmayberealisedmanuallywith goniometersorwitharehabilitationdeviceitself, e.g.,bytheSFTRmethod[31].Beforestartingthe actualtreatmentsession,thedeviceshouldlauncha measuringmoduletodeterminethepatient’sROM andadjusttheexercisespace.

Thereisnocertaintythatstayingwithin singlejointlimitswillensurethepatient’ssafety duringcomplexmovements.Inotherwords, thedecompositionofacomplexmotionintothe appropriatecomponentsinthefundamentalplanes: sagittal,frontalandtransverse,doesnothave tocorrespondtothesumofthesemovements intermsofthemuscleloads.Moreover,sucha measurementshouldtakeplaceseveraltimesthe duringrehabilitationprocesstoconsiderpotential ROMincreaserelatedtotheconvalescenceprocess[2]. However,thistime‐consumingprocessdoesnotfully safeguardfurtherautomatickinesiotherapy.Ifsucha calibrationistobeperformedwithoutanadditional operatorofthesystem,eitherintelligentalgorithms havetosensemotionlimitsorthedevicemust receiveequivalentinformationfromapatient.The irstapproachisdif iculttoimplementforpatients withsevereneuraldiseases.Ontheotherhand, con irmingtheendofpossiblemotionrequiresthe user’scapabilityofphysicalinteractionwiththe human‐machineinterface(HMI)orimplementation ofvocalcommands.Thisimpliestheneedforan excellentcommandandsoundrecognitionsystem, potentiallywithanadvancedneuralnetwork[37]. Theserequirementsalsoaffectthenumberofpatients whomayusethedevice.

TomeasurepulseorECG,thedevicehastobe equippedwiththededicatedsensors.Asthesevere stressrelatedtopainsensationscausesthechange inreadings[71],thistechniquecanbeusedto detectemergencystatesoftherehabilitation

system.However,thevaluesofrestingheartrate andthemeasurementsduringexercisingvaryfor individuals[78].Additionally,theabnormalitiesmay beregisteredtoolatefortherobottoreactbefore harmingthepatient.Moreover,theexpectedaccuracy ofaround60–80%andnodistinctionbetweenpain levelsmaynotbeenoughreal‐timepainrecognition forrobot‐aidedkinesiotherapy[56].

Thesafetyalgorithmscanbebasedonthemultibody modelofthecooperatingdeviceandmusculoskeletal system.However,thisapproachrequirescomparing computedresultsofloadswithinindividualtissues withtheirstrengthparametersdifferentforeveryper‐son.

Themostvulnerabletoinjuriesaretendonsand ligaments[42].Forthisreason,machinesshouldnot exceedthestrengthlimitsofthesetissues.Itispartic‐ularlychallengingtoobtaindataontheirparameters, suchasYoung’smodulus.Thecorrespondingexper‐imentaltrialsareusuallycarriedoutonanimals[7] ortissuesfromthedeceased[34],whichdonotfully correspondtothetissuesofalivehumans.Moreover, tissuepropertieschangewithage,gender,andexperi‐encedillnesses[59].

Topreventhazardoussituations,estimatingthe tensilestrengthismostcriticalforindividualsoft tissues,astheyaremostvulnerabletodamagein thisdirection[3].Beforethetreatment,theirvalues maybeobtainedwithaspeci icdevicesuchas MyotonPRO[5].Themeasurementmethodconsists ofregisteringthedampednaturalvibrationsofsoft biologicaltissueintheformofanaccelerationsignal andthencalculatingthedesiredparameters.Such technologyenablesmeasuringthetone,stiffness, lexibility,relaxation,andcreepoftissues[5].The proposedsolutioncouldalsobetransferredto therehabilitationrobotbyequippingitwitha dedicatedsensorysystem.Nevertheless,thereare alsolimitationstothismeasurementtechnique,e.g., theresultsarelessaccurateforobesepatientsaswell asthedeeplylocatedandtoothintissuesaredif icult toworkwith[1].

EDAmeasurement

EDAiselectrodermalactivity,demonstratedtobe effectiveinarousalestimation[73].Asapatient’s sweatingchangesattimesofseverestress[32], analysingcorrelatedEDAsignalscancontributeto detectingincreasingpain.Thistechnologyisbeing continuouslydeveloped,anditdoesnothavemany validatedapplicationsyet[4].Thereareserious doubtswhetheremotionssuchasjoyorstresscaused byprovidingtreatmentbyarobot,notahuman,will notcauseexcessivesweating[64].Suchaneffectcan leadtoconfusionofhazardsituationswitharegular operationofthedevicebytheautomaticsafety monitoringsystem.Forthisreason,implementing EDAwithinareal‐timesystemfordetectingrisksin homerobot‐aidedtreatmentisnotsuggested.

EEGmeasurement

EEG,electroencephalography,isanon‐invasive methodofanalysingbrainelectricalactivitybased ontherecordingsfromthescalp.Asapatient’s intentionsaredetectablewiththismeasurement[46], arehabilitationrobotcanuseEEGsignalsfor predictivecontroltointeractwithauserandnot exceedtheirrangeofmotion[80].However,not everyintentionofmotionresultsinthemovement–itsimagemaybeenoughforthecorresponding areaofthebraintobecomeactive[49].Onthe otherhand,researchersprovedthatphysicalpain, particularlyacute[70],canbedetectedbasedon EEGwithanaccuracyofalmost95%andusedfor real‐timere lexinprostheses[75].Thisimplies theapplicabilityofthetechniqueforrobot‐aided rehabilitation.Nevertheless,usingadvancedEEG systemsisrelativelyexpensiveandrequiresprecise placementoftheelectrodesonapatient’sscalpto providerepetitiveresults[12].Thesemightbethe mainbarrierstousingsuchforhometherapy.

EMG,electromyography,maybeeitheraninvasive ornon‐invasiveinvestigationoftheelectrical activityofmuscleunitsorwholegroups.Registered signalsprovideinformationregardingthetemporal behaviourandmorphologicallayoutofactivemotor unitsduringmusclecontraction[68].Thismaybe usedtoestimateinternalstressinthesetissues andcomparethemwiththeirbiomechanicallimits. Thesafetysystemmustreacttosuddenpeaksin theregisteredsignals.Thesemayeitherberelated tothenociceptive lexionre lexcausedbypain stimuliorthespasticre lexcausedbyasudden noise,unexpectedtouch,orstress[13].Thetwo mentionedhavetobedistincted.Hence,theEMG maybeuselessfordetectinghazardoussituations forspasticpatientsinspasticity‐relatedsituations. Theresearchersalsopresentthemethodofdetecting painbasedonEMG‐registeredfacialexpressions. However,thisrequiresnon‐affectedfacialmuscles andgeneratessimilarproblemsasforEEG,including preciseplacementoftheelectrodes[39].The valuesregisteredwithEMGcanbeusedtoestimate temporarymuscletension[58].However,thesurface EMG,theonlyapplicablewithinrobot‐assistedhome kinesiotherapy,isvulnerabletonoisesfromelectrical devices,othermusclegroups,andfatlayers[77].

Inordertoproposethesolutiontailoredtothecapa‐bilitiesofaspeci icgroupofpatients,adecisiontree formeasurementselectionispresentedinFigure 1. The irststepistoassesswhetherapatienthasphysi‐calsensations.Itisassumedthatpost‐traumapatients meetthisrequirement–ifnot,theyareassignedto groups2or4.

Moreover,patientswithspasticityhavetobemed‐icallyquali iedforrobot‐aidedexercising.Thisdeci‐siondependsontheseverityoftheproblemaccording tooneofthescalessuchasAshworthscore,modi ied Ashworthscore,Tardieuscale,ormodi iedTardieu scale[74].Theoneswiththedegreeofspasticity exceedingacertainthresholdcannotworkoutby themselvesduetotheirspastic,uncontrolled,intense musclecontractions[14].Suchapre‐treatmentmed‐icalassessmentshouldbebasedonseveraldoctors’ independent,expertopinions[35].

Ontheotherhand,patientsdeprivedofsensation oftensufferfromexcessivesweating[33].Theyare unabletoidentifytheirownpainailments[33],and thus,theiravailablerangeofjointmobility.

AsmaybeobservedinFigure 1,patientsfrom groupnumber1aresuitableforallthemeasurement methods.Themostchallengingtaskistomeasure biologicalsignalsforgroup2becauseitisnotpossible togatherdatarelatedtotheirmuscletensionortheir senseofmotionlimits.

Moreover,thereisadifferenceintheapplicability ofEMGmeasurementsbetweennon‐spasticandspas‐ticpatients.Forthe irstgroup,thesensedelectrical signalsmaybecorrelatedwiththemuscularforces andthenanalysedregardingbiomechanicallimitsfor safeguardingpurposes.Whenitcomestothesecond group,theiruncontrolled,rapid,andseveremuscle contractionsmayturnEMGsignalsunabletobeused asdescribedabove.However,signi icantchangesin themeasuredsignalscanbeassignedtotheemer‐gencystopoftherehabilitationdevice(markedin Figure 1 asEMG*).Thismaycounteractthehazard ofmusclerippingduringtheinvoluntary,disease‐relatedcontraction.Furthermore,forpatientswithout sensation,theROMrangecannotbemeasuredasthey cannotfeeltheirphysicallimits.

Besidesthementionedabove,itisnecessarytobe awarethatforindividualcasesfallingintooneofthe proposedsegments,assignedmeasurementsmaynot giveexpectedresults.Therefore,thepatientshouldbe treatedas ittinganothergroup,eventhoughtheydo notmeetitscriteria.

Apartfromavoidingauser’sdiscomfort,theauto‐maticsafetysystemforrehabilitationrobotsshould preventsituationscausingphysicaldamagetotissues. Thismayberealisedbymodellingthecausesofpar‐ticularhazardsandcomparingtheirreal‐timevalues withestimatedthresholds.Table1containssegmen‐tationofthese.Iftheriskofaparticularcauseoccuring istypicallyneglectableduringrobot‐aidedtreatment, the“high‐riskgroups”cellislabelledas“lowrisk”.

Thebone‐relatedtraumasaretypicallyhazardous forthepatientsrehabilitatedaftersimilartraumas. Regardingsegment1ofpatients,itissimilarforthe injuriesofmuscles,ligaments,andtendons.Therefore, high‐riskgroup1*referstothepersonaftersimilar fracturesordamagetothesofttissues.Onthecon‐trary,B4traumamayonlyappearduringlong‐time forceappliedtotheextremity’ssegment,whichis noticeableasapainstimulusbypatientswithunaf‐fectedsensation.Thedevicemaybestoppedimme‐diatelyinsuchasituationandnotcauseanyharm. Onlygroups2and4arenotabletonoticesucha casethemselves.Therefore,anadditionalsafetysys‐temmonitoringcontinuousloadshastobeprovided.

Trauma Symbol Cause High-riskgroups Measurementtechnique(otherthan trackingdevice’sdynamicparameters)

Transversebonefracture

Impactedbonefracture

Thedevicehastoreacttotheriskofbonefractures beforeanactualdangeroussituationappears.There‐fore,nopain‐basedmeasurementswillbehelpful. Instead,theoverallsystemshouldbemonitoredbased onitsmultibodymodelsuppliedwiththemeasured dynamicparameters.Moreover,greenstickfractures andsimilar,morecomplexvariants(B4,B7,B8)may appearwhileexceedingnaturalROM.Therefore,this shouldalsobeimplementedforsafeguardingsuch cases.

Asthestrainsandcontusionsarelessseverethan othertypesoftraumarelatedtosofttissues,theymay bedetectedwithpain‐basedmethods.Moreover,they typicallyappearprecededbynoticeablephysicaldis‐comfort.Therefore,thedevicemaybestoppedbefore harmingtheuser.Formuscletearsandligamentor tendonruptures,thesystemhastoreactpriortothe contusion.Hence,apredictionbasedonthemulti‐bodymodelandmeasureddynamicparametersofthe deviceissuggested.

Moreover,asthemajorityofmuscles’andliga‐ments’traumas(notM3)arerelatedtotheforcegen‐eratedinthecorrespondingmuscles,theyarerelevant onlyfornon‐ laccidpatients.Furthermore,theirrisk maybetrackedwithEMG.Forthepatientswithno sensation,anadditionalsystembasedonthemulti‐bodymodelandthedevice’sdynamicsparametershas tobeprovided.

Thedamagetosofttissuesmayalsobecausedby exceedingtheindividual’sanatomicallimits.There‐fore,constantmonitoringofthedevice’scon iguration relatedtothemeasuredROMshouldberealised.

Apersonassignedtooneofthesegmentspre‐sentedbeforehandshouldbeassignedtothepoten‐tialrisksbasedonthe“high‐risk”columninTable 1 Subsequently,asensorysystemandamathematical modelshouldbebuilttodetectandreacttohazardous situations.Thankstosuchanapproach,arehabilita‐tiondevicemayimplementitsemergencyroutines whenriskappearstopreventharmtoauser.Asmay beobserved,detectingeverypossibletraumarequires trackingthedevice’sdynamicsparametersandbuild‐ingatleastasimplemultibodymodelofaphysical interfacebetweenamachineandahuman.

Themeasurementsproposedintheprevious section,alongwiththedynamicsparametersofthe device(drives’torquesandencoders’positions),can beusedtobuildamultibodymodelofthesystem. Suchcanbeusedtoestimateinternalforces,torques andstressesoccurringinthebodysegmentsduring atreatmentsession.Thesevaluesshouldremain belowtheacceptablethresholds,whichmayvary forindividualcases.Assumingcorrectestimations regardinganatomy,comorbidities,andapatient’s medicalhistoryregardingavailablebibliography sourcesenablesthebuildingareliablesafetysystem. Thefollowingsectionpresentstheindividualtissue strengthparametersforvariouscases.

Generally,inmaterialengineering,theleadingtest carriedouttoidentifythestrengthpropertiesofa materialistheuniaxialstatictensiletest.Themajor challengeistoselectthetestingsampleshape.This isduetothefactthatsofttissuesarepreparedpost‐mortem(tissuesofbloodvesselsandskintissues, amongothers)and,hence,theyarepre‐tensioned. Therefore,theirsusceptibilitytodeformationmakes itchallengingtopreparetheappropriate ittingof asample.Forthisreason,softtissuesareusually examinedintheformofabar[47].

Thereisastrongcorrelationbetweenanindividual’s gender,age,orbonetypeandthetissue’sstrength.For example,loadingawoman’sradiusorhumeruswitha torqueofapproximately61Nmwillcauseafracture witha50%probability[63].Thedifferencesinthe criticalvaluesmaybeassigni icantas100Nmforthe criticalbendingmomentofthehumerus,depending onthegender.Analysingshearforceinthisbone, itscriticalvalueis1.7kNforwomenand2.5kNfor men[63].

Itismuchmoredif iculttodamagethelowerlimb. Theprobabilityofaninjuryincreasesoutstandingly whentheforceof5kNisexceeded[63].Withinthe lowerlimbs,the ibulaisthemostvulnerablebone. Itstensilestrengthisuptotentimeslessthanthe femur’s[63].Formanyapplications,thecriticalbone resultantstresscanbetakenas150MPa[20]and shouldbescaledaccordingtotheindividualcase. Moreover,extraordinaryattentionshouldbegivento theweakestboneoftheexercisedbodypart.

Muscles

Thereisacorrelationbetweenthedirectionofmuscle tensionanditsforce.Moreover,harmtothesetissues istypicallycausedbythetendons’force,orexcessive strain[11].Forthisreason,musclesareoften analysedwithtendonsasuniformbodiesofaverage strengthproperties[41].Correlatedstress‐strain curvespresentthatastrainover0.4leadstoarapid increaseinstressashighas200kPa[63].Moreover, themaximumforceappliedtothemusclemaybe calculatedasthemultiplicationofPCSA,andestimated tetanictension,e.g.,22.5N/cm2 formammalian muscles[51].Thisrequiresmeasurementofthe initialmusclelengthsandmonitoringkinematics oftheextremityduringexercises.Hometreatment shouldberealisedwithalowereffortforthepatient’s safety.Aspresentedintheliterature,monitoring offorceoccurringinthissofttissuecanberealised bybuildingacomputationalmultibodymodelor analysingtheirmeasuredexcitation[15].Hence, apotentiallydangeroussituationresultingfrom exceptionalmuscletensioncouldbedetectedas therapidincreaseoftheEMGsignal,whichleadsto reachingbiomechanicalthresholds.

Thestrengthandstiffnessofligamentsandtendons dependonapatient’sageandlevelofphysicalactivity. Themaximumforcethatcanloadthesetissuesfora young,athleticpersonisestimatedas6.1kN,while foranolderpersonwithastaticlifestyle–only4.6 kN[16].About10%–15%extensionofthetendon causesstressbeyondtheelasticlimit[63].Thiscre‐atesstressofapproximately50kPaandresultsin adeformationof4mmonaverage[52].Theforce generatedinthetissueisthencloseto200N[20]. Forelderlypeople,Young’smodulusofligamentsand tendonsincreases.Theyaremoredif iculttostretch andbecomeless lexible.Nevertheless,theelastic‐ityofthesetissuesguaranteestheirproperfunction‐ing[20].

Moreover,theworkstateofthetissueisalsoacriti‐calfactorforestimatingsafetythresholds.Contracting tissuesgeneratemorestressandaremoreexposedto thedamagethantheextensingones[20].Ingeneral, Young’smodulusofthetendonmaybeestimatedas 0.9–1.4GPa[20].

Asmentionedbefore,thepropertiesoftissuesdif‐feramongindividuals.Thesolutiontopredictthe effectsofagivenexerciseforaspeci icpersonisto

createadigitaltwinofthepatientandarehabili‐tationdevice[27,80].Itispossibletobuildsucha mathematicalmodelinopensoftware,e.g.,OpenSim. Thegeometricalparametersofthefreemodelsmay bemodi ied,aswellasthestrengthparametersofthe tissues[65].

Modellingthephysicalinterfacebetweenareha‐bilitationdeviceandauserenablesthepredictionof thesystemdynamicsinreal‐time.Hence,hazardous situationsmaybemitigatedbeforetheyoccur[25]. Moreover,thismaycontributetooptimisingtherapy effects.

Internalforcesinthetissuesmaybeanalysed regardingtheexternalloadsapplied[62],alsoinan externalenvironmentastheexportedtimeseries[44]. Thankstothis,itispossibletosimulatetheresultsof themostdangerousmovementsforpatientswithpar‐ticulardiseasesandacertainage.Basedonthesesim‐ulations,thepatientmaybequali iedonlyforlimited accesstothedevice’sfunctionality.Thus,thehome treatmentremainssafe.Moreover,theregisteredEMG signalscanbeincludedinthemodelasadditional validationofthesimulations[55].However,inEMG‐basedcontrol,themajorchallengeissigni icantsignal noise[66].Duetotheneedto ilterthisout,almost real‐timeprocessingishindered.Inaddition,themea‐suredparametersvarybetweenindividuals.More‐over,thistypeofcontrolcanonlybeusedbypeople capableofgeneratinganelectricalactivityexceeding acertainthreshold[48].Therefore,theEMGmeasure‐mentsshouldnotbeconsideredastand‐alonetoolfor automaticpainmonitoring.

Withinthepresentedmethodology,buildingan accuratemodelofthepatientandthedeviceiscritical forprovidingthesafeoperationoftherehabilitation robot.Themodel’sgeometryshouldre lectareal‐life patient’sanatomy,whilethesimulatedtissueshaveto beprovidedwithadequatematerialparameters.The researchersprovethattheready‐madeopenhuman bodymodelsmaybeeffectivelyenhancedbyadding rigidmultibodymodelsoftherehabilitationdevices andusedasproposedinthepapers[40,62,65].

Mostoftheexistingrobot‐aidedrehabilitationsys‐temsneedthephysicalpresenceofaphysiothera‐pist[79].Forthisreason, indingavalidatedcontext forthepresentedproblemisdif icult.Moreover,the methodsofreal‐timesafetymonitoringbasedonmea‐surementsarenotthesameforallpatients.

Duringthetreatment,physiotherapistsmanu‐allyrecognisesoft(muscular)andhard(bone)resis‐tance[9].Theyknowhowmuchtoexceedthesoft resistancetoimproveapatient’sconditionwhile notexposingthemtoinjury.Thishapticfeedback withaprofessional’sexperienceneedstobetrans‐ferredintomachinealgorithms.Existingpainscales suchastheVisualAnalogueScale(VAS),theVerbal RatingScale(VRS),andtheNumericalRatingScale (NRS)[38]aresubjective.Moreover,theyaremainly basedonapatient’spreviousexperiencecomparedto thepresent[43].

Onthecontrary,theproposedsegmentation allowsfocusingonindividualdiseaseentitiesand developingdetectionmodelssuitableforspeci ic cases.Inthebeginning,therobot’saimshouldbe de ined.Thiscaneithersupportpeopleafterlighter injuries[17]orserveforagradualrecoveryofmotor activitiesforpeoplewithsevereimpairment[6].

Forthesecondcase,thedevicemaynotevencor‐rectinaccuratemovementsinitiallytoregainbasic mobilitywithoutthepain.Suchshouldbeincludedin therulesforhazardsdetectionalgorithms.

Arti icialintelligencecanbeusedforthesepur‐poses,asitincreasestheaccuracyoftherapists’and doctors’decisions.Moreover,theneuralnetworkscan contributetooptimalsearchamongthepossibleail‐mentscausesandtreatmentoptions.Inaddition,this approachiseasilyscalable.Therefore,itcanbeusedto thoroughlyanalyselargedatasetsonthecourseofthe diseaseandthepatient’streatment[19].

Furthermore,rehabilitationdevicescanbebet‐tersuitedtospasticpatientsbyprovidingthemwith awarming‐upmoduleinvolvingsimple,low‐speed motions.Thiswillnotonlymentallyfamiliarisea patientwiththerobotbutalsorestrainmusclecon‐tractionswithinthemainsession[14].

Thecurrentchallengesinthesafetymonitoringof robot‐aidedkinesiotherapydependonbothsoftware andhardware.Theformerincludesthespeedofreal‐timedataandtheautomaticselectionofaccurately restrainedROM.Thesystemsenablingthesehavenot beenimplementedinanydeviceyet.Thelattercon‐sistsofthemechanicaldesignrequirementstosuit peopleofdifferentanatomyandphysicallylimitthe excludedROM[24,36].

Therefore,whiledesigningthesystemforreal‐timehazardsmonitoringduringthehomerobot‐aided therapy,thefollowingshouldbevalidatedexperimen‐tally:

‐ howcanamuscletensionincreasedtothepainlimit affectthemeasuredsignals;

‐ isthechangeinthesignalrelatedtothehazard confusablewithothersafesituations;

‐ howbigisthesignal‐registrationanddevice‐processingdelay;

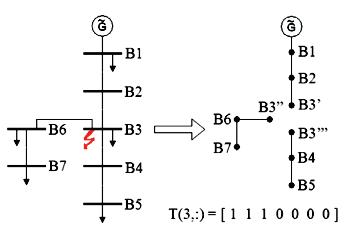

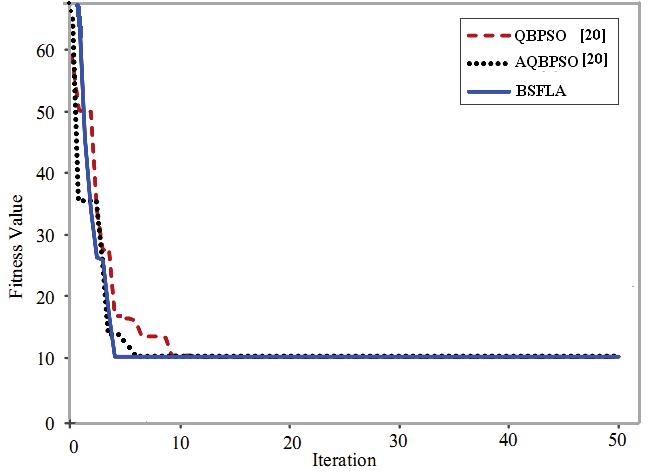

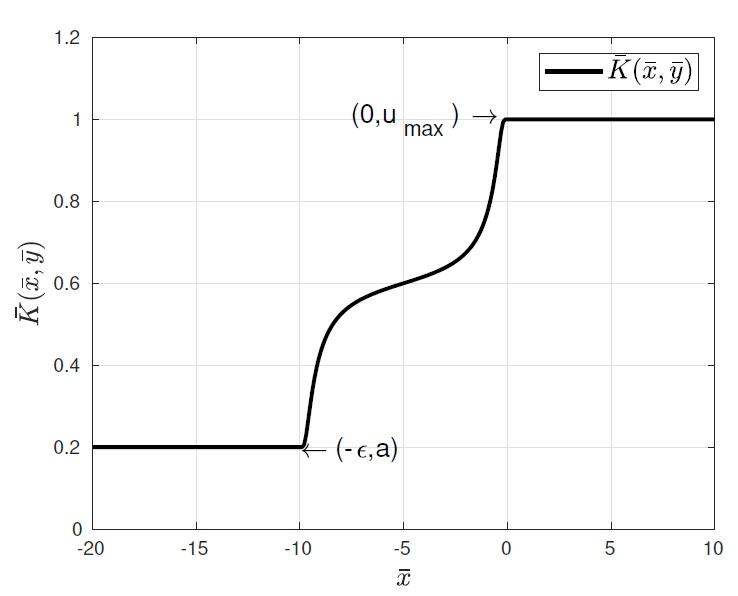

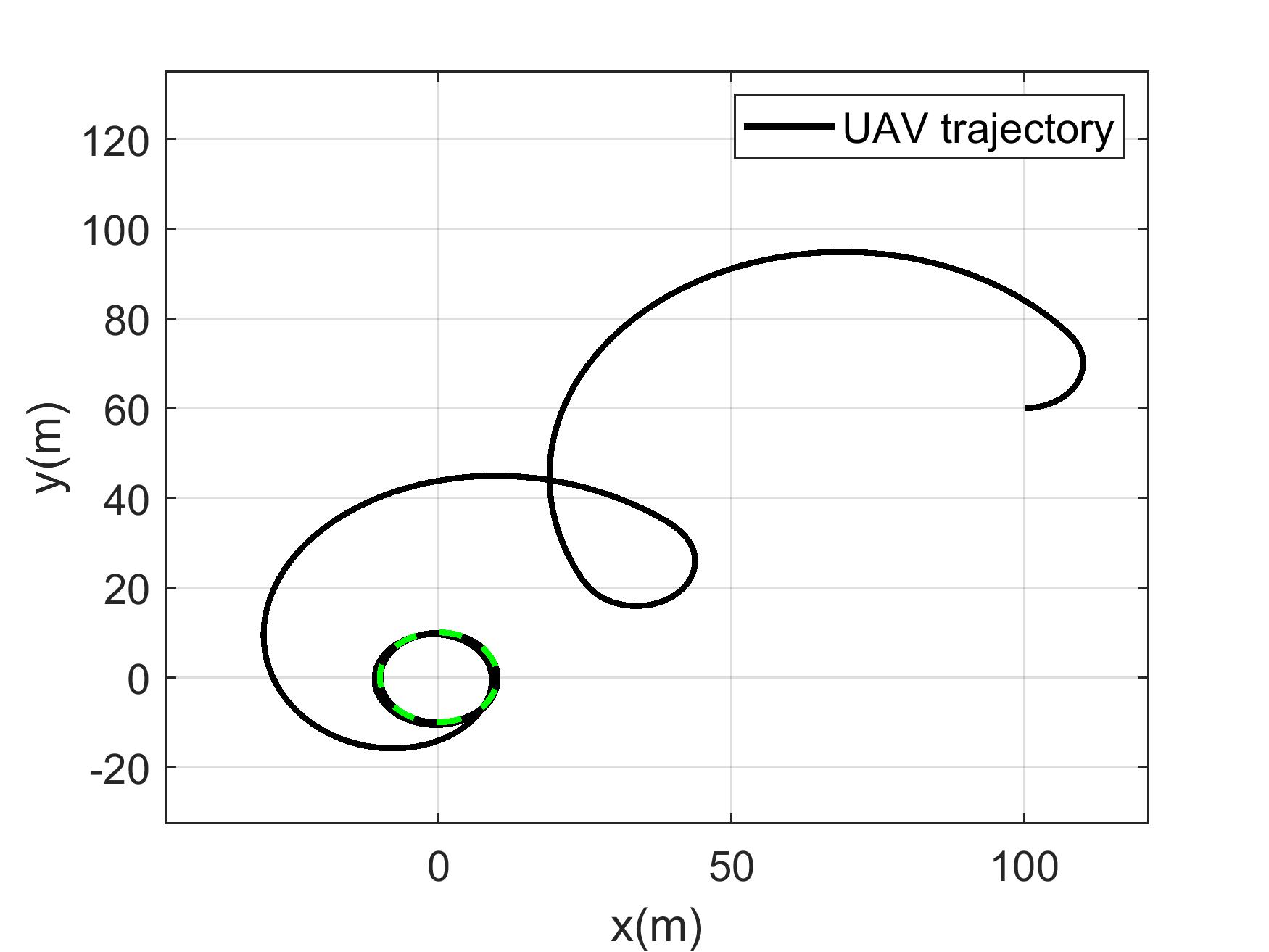

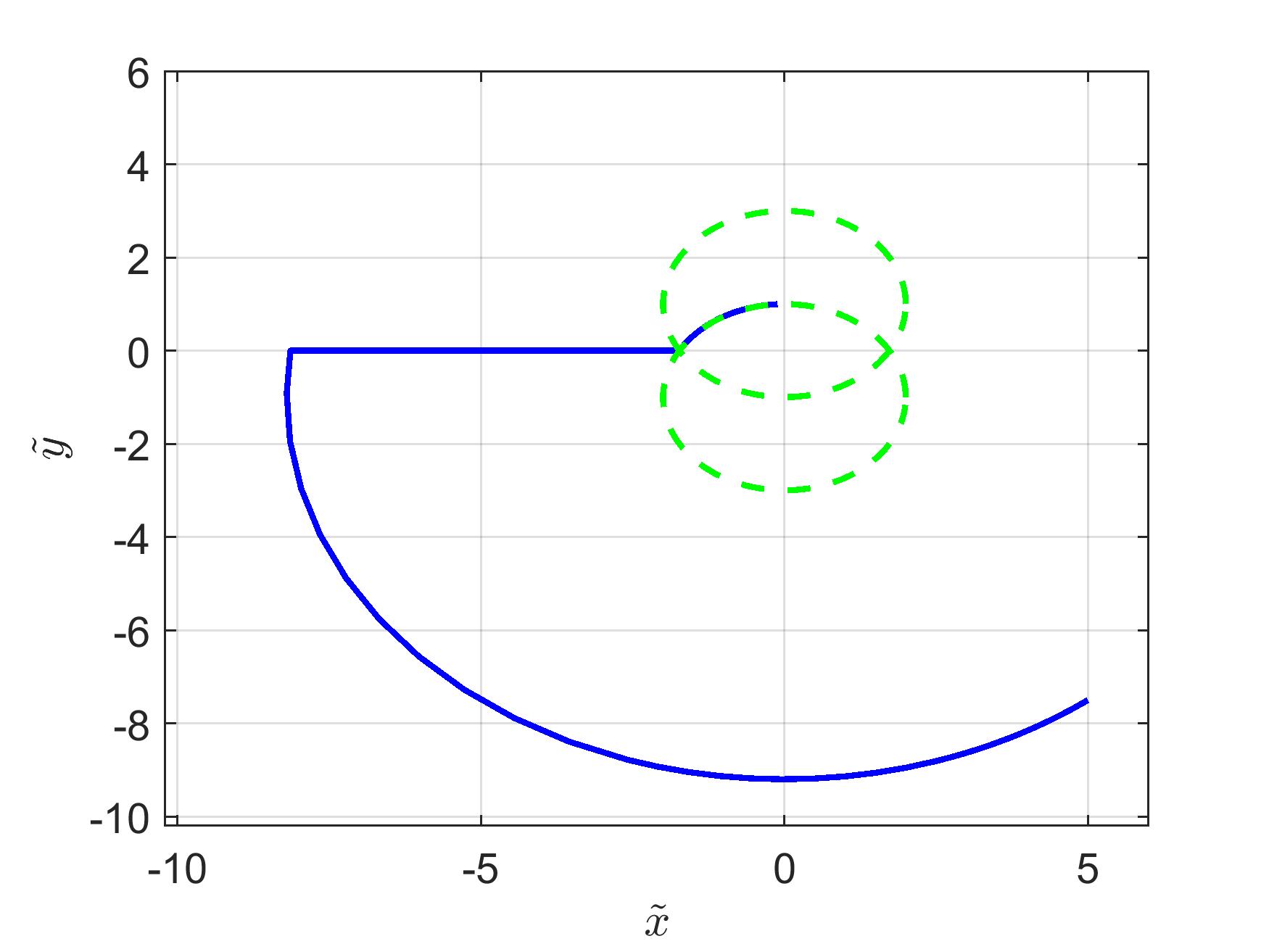

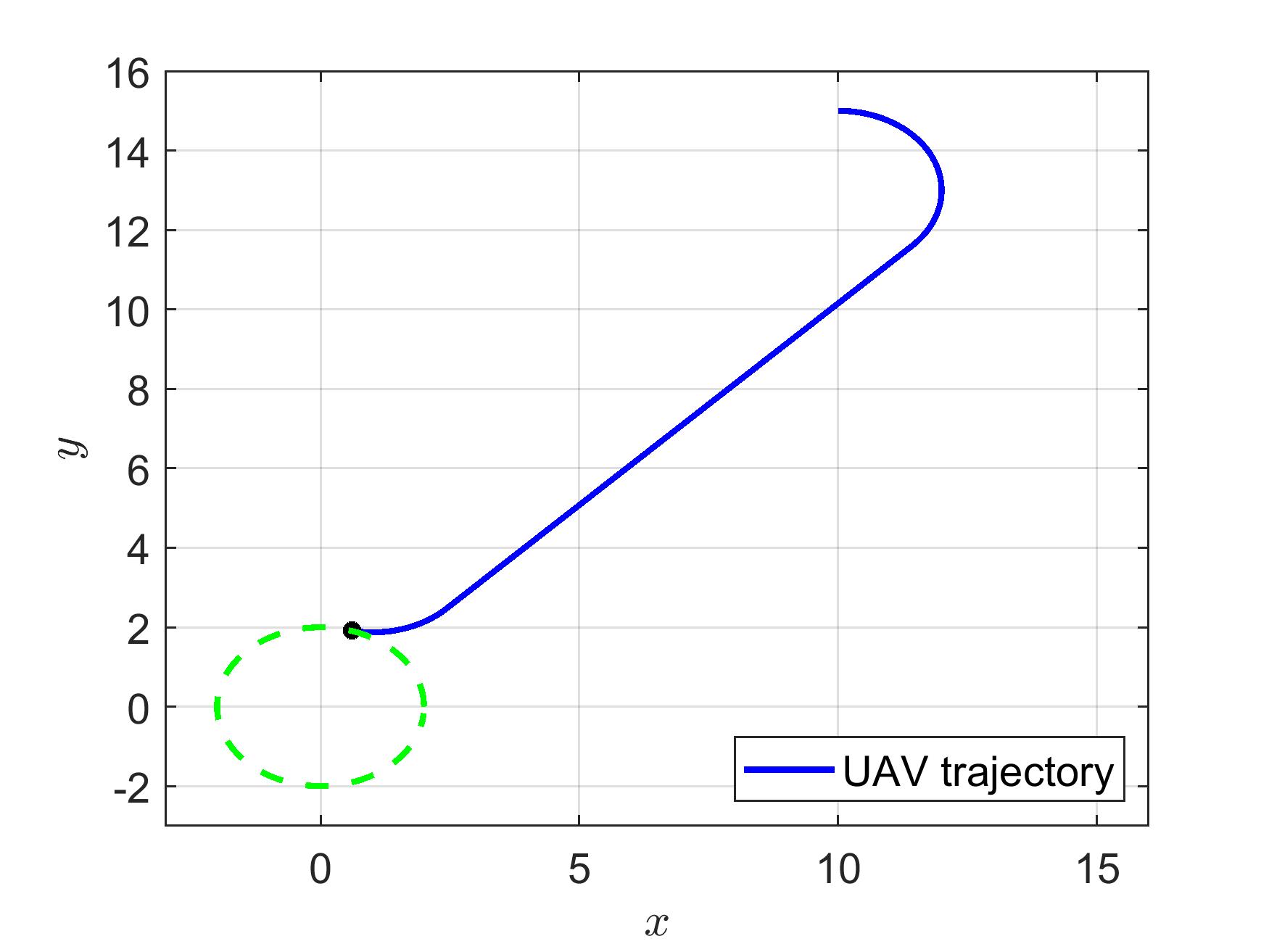

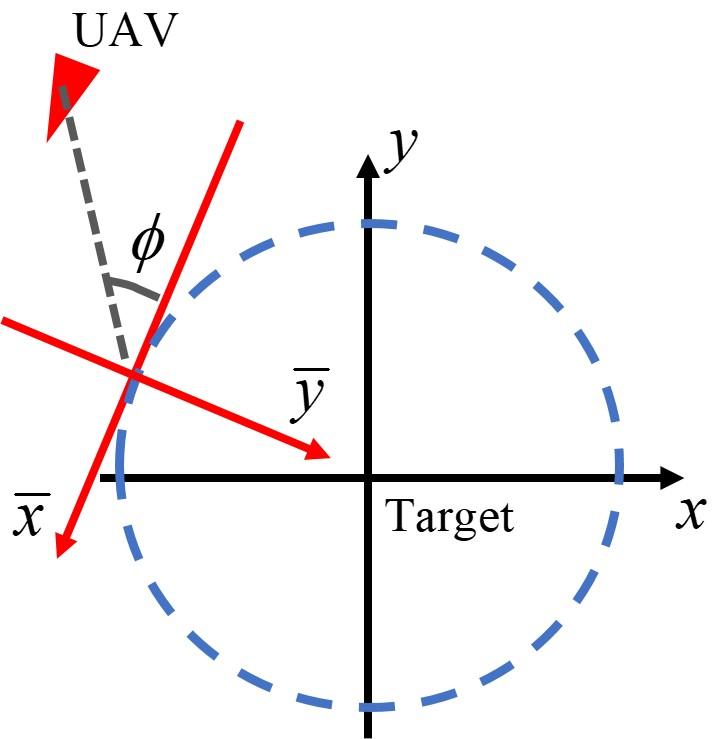

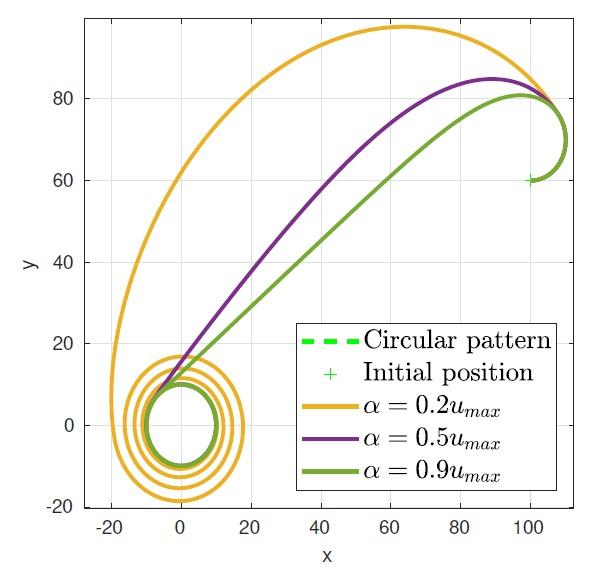

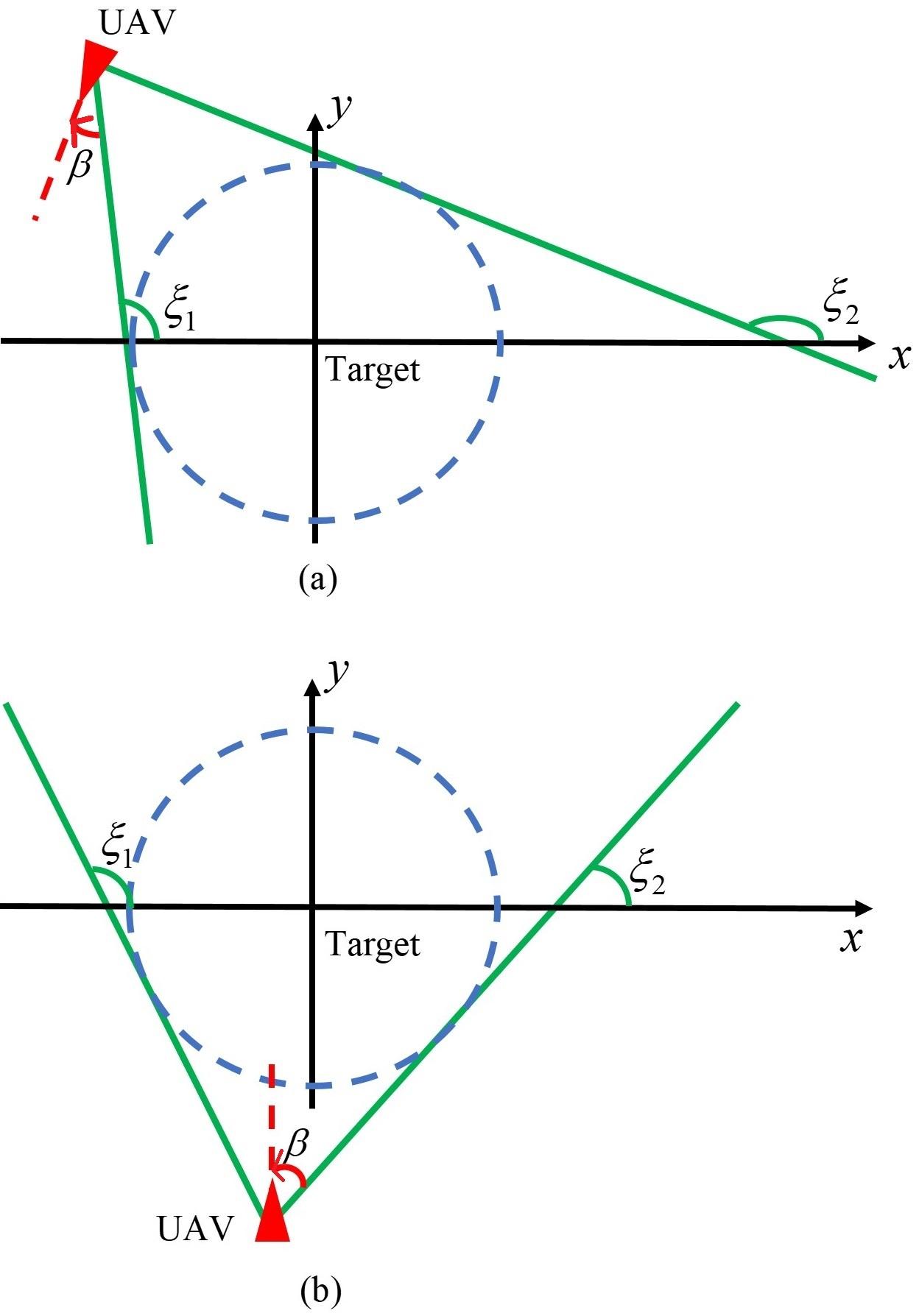

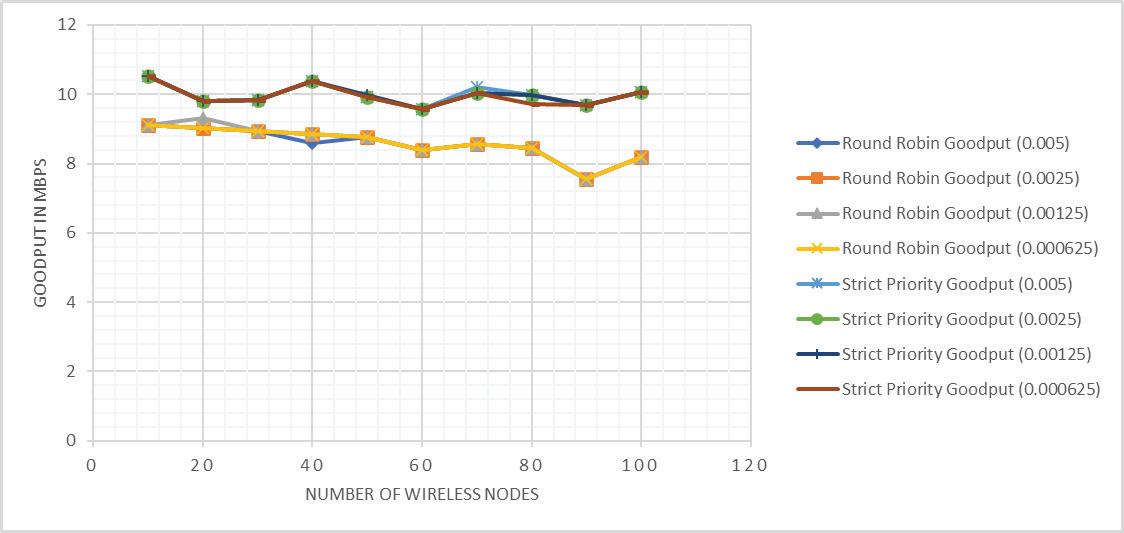

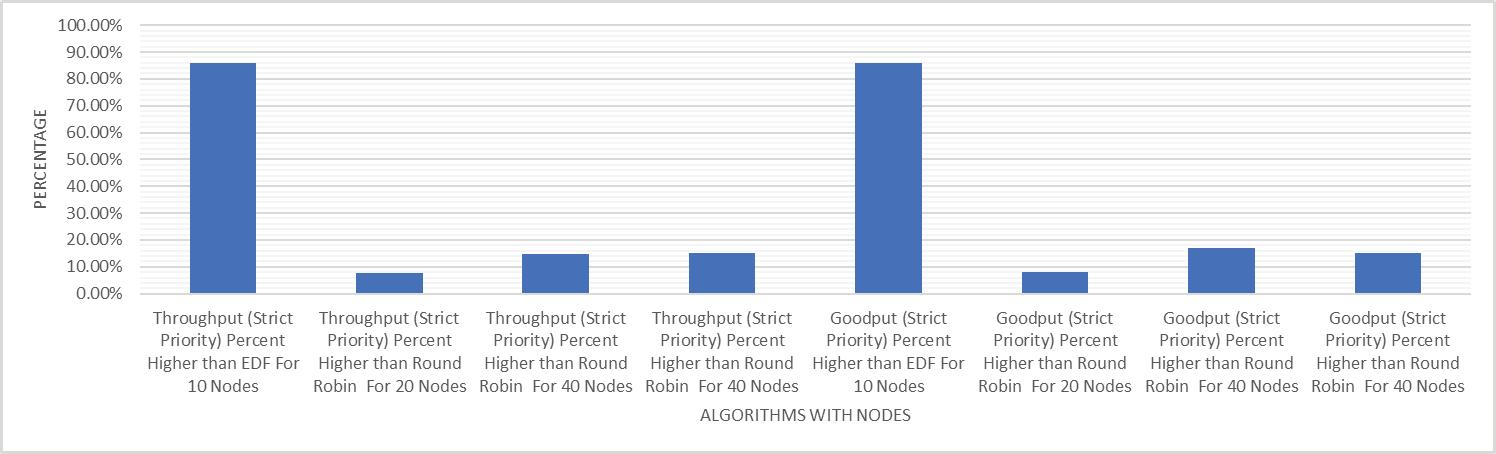

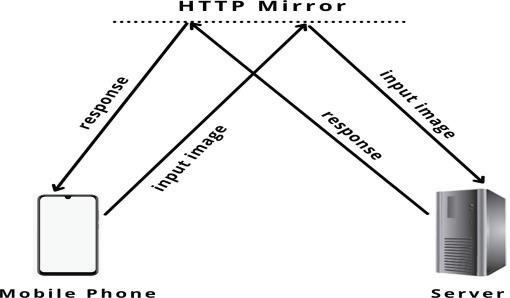

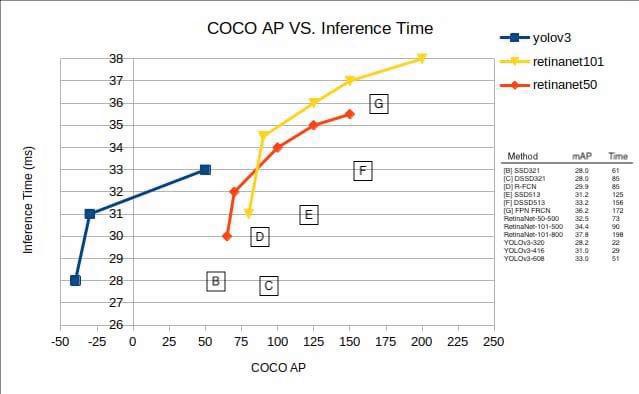

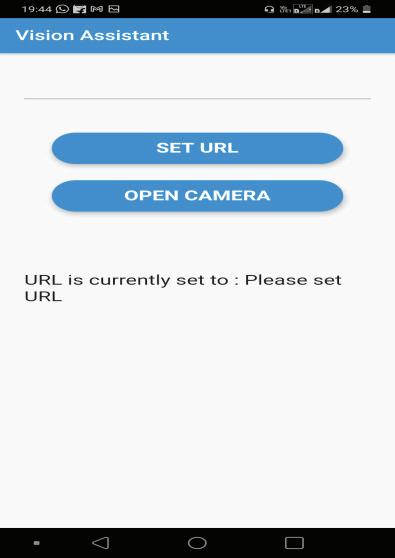

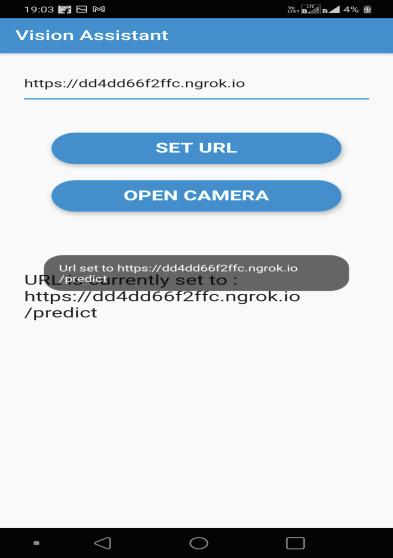

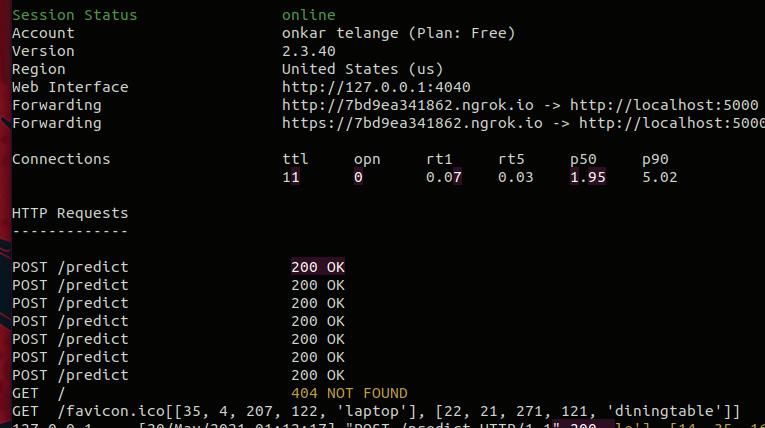

‐ whatarethetypicalvaluesofthemeasuredsignal fortheindividual.