WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 18, N° 4, 2024

Indexed in SCOPUS

WWW.JAMRIS.ORG pISSN 1897-8649 (PRINT)/eISSN 2080-2145 (ONLINE) VOLUME 18, N° 4, 2024

Indexed in SCOPUS

A peer-reviewed quarterly focusing on new achievements in the following fields: • automation • systems and control • autonomous systems • multiagent systems • decision-making and decision support • • robotics • mechatronics • data sciences • new computing paradigms •

Editor-in-Chief

Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Advisory Board

Dimitar Filev (Research & Advenced Engineering, Ford Motor Company, USA)

Kaoru Hirota (Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan)

Witold Pedrycz (ECERF, University of Alberta, Canada)

Co-Editors

Roman Szewczyk (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Oscar Castillo (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Marek Zaremba (University of Quebec, Canada)

Executive Editor

Katarzyna Rzeplinska-Rykała, e-mail: office@jamris.org (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Associate Editor

Piotr Skrzypczyński (Poznań University of Technology, Poland)

Statistical Editor

Małgorzata Kaliczyńska (Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Editorial Board:

Chairman – Janusz Kacprzyk (Polish Academy of Sciences, Łukasiewicz-PIAP, Poland)

Plamen Angelov (Lancaster University, UK)

Adam Borkowski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Wolfgang Borutzky (Fachhochschule Bonn-Rhein-Sieg, Germany)

Bice Cavallo (University of Naples Federico II, Italy)

Chin Chen Chang (Feng Chia University, Taiwan)

Jorge Manuel Miranda Dias (University of Coimbra, Portugal)

Andries Engelbrecht ( University of Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa)

Pablo Estévez (University of Chile)

Bogdan Gabrys (Bournemouth University, UK)

Fernando Gomide (University of Campinas, Brazil)

Aboul Ella Hassanien (Cairo University, Egypt)

Joachim Hertzberg (Osnabrück University, Germany)

Tadeusz Kaczorek (Białystok University of Technology, Poland)

Nikola Kasabov (Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand)

Marian P. Kaźmierkowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Laszlo T. Kóczy (Szechenyi Istvan University, Gyor and Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Hungary)

Józef Korbicz (University of Zielona Góra, Poland)

Eckart Kramer (Fachhochschule Eberswalde, Germany)

Rudolf Kruse (Otto-von-Guericke-Universität, Germany)

Ching-Teng Lin (National Chiao-Tung University, Taiwan)

Piotr Kulczycki (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Andrew Kusiak (University of Iowa, USA)

Mark Last (Ben-Gurion University, Israel)

Anthony Maciejewski (Colorado State University, USA)

Typesetting

SCIENDO, www.sciendo.com

Webmaster TOMP, www.tomp.pl

Editorial Office

ŁUKASIEWICZ Research Network

– Industrial Research Institute for Automation and Measurements PIAP

Al. Jerozolimskie 202, 02-486 Warsaw, Poland (www.jamris.org) tel. +48-22-8740109, e-mail: office@jamris.org

The reference version of the journal is e-version. Printed in 100 copies.

Articles are reviewed, excluding advertisements and descriptions of products.

Papers published currently are available for non-commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. Details are available at: https://www.jamris.org/index.php/JAMRIS/ LicenseToPublish

Open Access.

Krzysztof Malinowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Andrzej Masłowski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Patricia Melin (Tijuana Institute of Technology, Mexico)

Fazel Naghdy (University of Wollongong, Australia)

Zbigniew Nahorski (Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland)

Nadia Nedjah (State University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

Dmitry A. Novikov (Institute of Control Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia)

Duc Truong Pham (Birmingham University, UK)

Lech Polkowski (University of Warmia and Mazury, Poland)

Alain Pruski (University of Metz, France)

Rita Ribeiro (UNINOVA, Instituto de Desenvolvimento de Novas Tecnologias, Portugal)

Imre Rudas (Óbuda University, Hungary)

Leszek Rutkowski (Czestochowa University of Technology, Poland)

Alessandro Saffiotti (Örebro University, Sweden)

Klaus Schilling (Julius-Maximilians-University Wuerzburg, Germany)

Vassil Sgurev (Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Department of Intelligent Systems, Bulgaria)

Helena Szczerbicka (Leibniz Universität, Germany)

Ryszard Tadeusiewicz (AGH University of Science and Technology, Poland)

Stanisław Tarasiewicz (University of Laval, Canada)

Piotr Tatjewski (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Rene Wamkeue (University of Quebec, Canada)

Janusz Zalewski (Florida Gulf Coast University, USA)

Teresa Zielińska (Warsaw University of Technology, Poland)

Publisher:

1

VOLUME 18, N˚4, 2024

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4-2024

Influence of Migration on Efficacy and Efficiency of Parallel Evolutionary Computing

Sylwia Biełaszek, Leszek Rutkowski, Aleksander Byrski

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/27

13

Mutual Inductance Model of the Mechanical Stress Sensitivity of a Power Transformer’s Functional Parameters

Paweł Rękas, Roman Szewczyk, Tadeusz Szumiata, Michał Nowicki

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/28

22

Nonlinear Optimal and Multi‐Loop Flatness‐Based Control of Omnidirectional 3‐Wheel Mobile Robots

Gerasimos Rigatos, Masoud Abbaszadeh

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/29

47

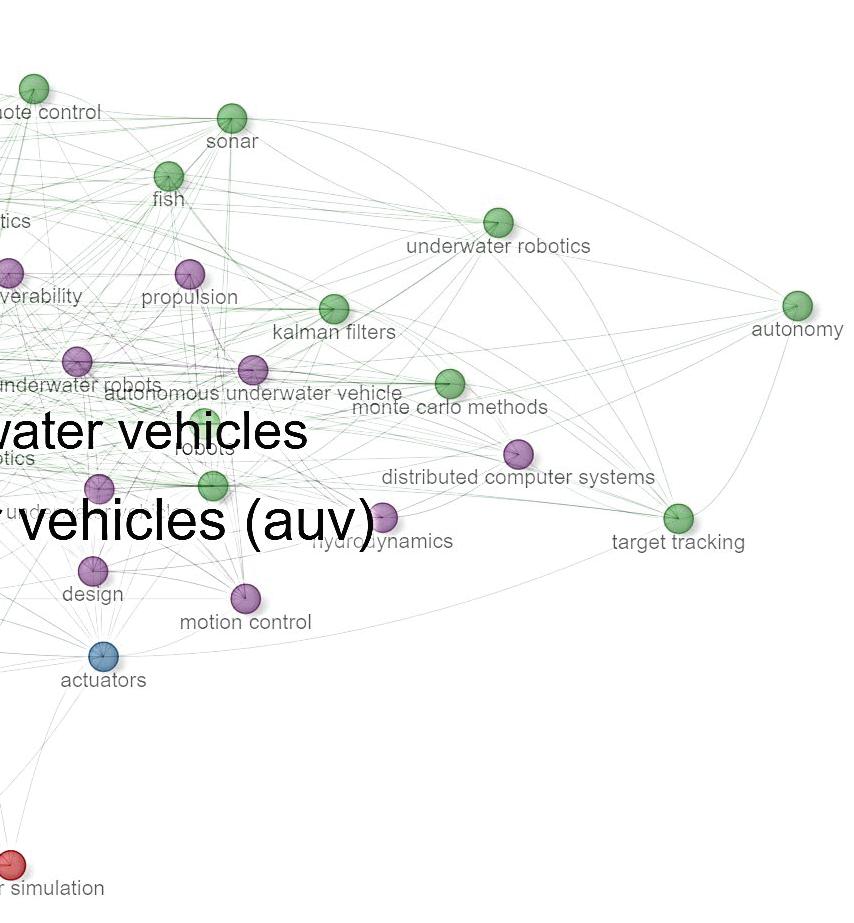

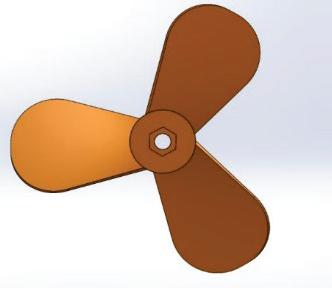

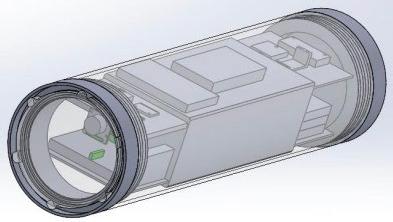

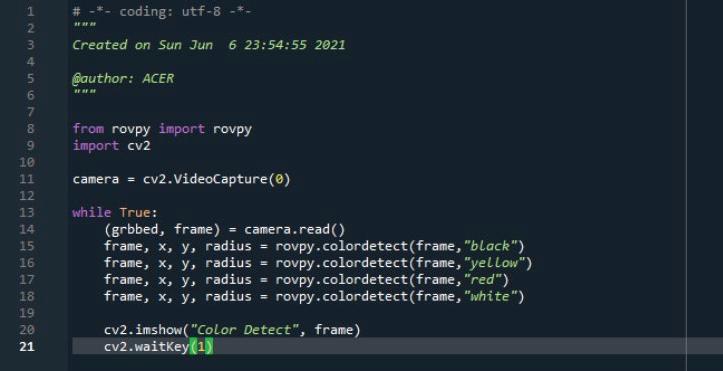

Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Design and Development: Methodology and Performance Evaluation

Ismail Bogrekci, Pinar Demircioglu, Goktug Ozer

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/30

62

Comparison of Open Source SDN Controllers and Cloud Platforms in Terms of Performance, Stability, and Infrastructure Flexibility

Andrzej Mycek

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/31

Implementation and Performance Evaluation of Intelligent Techniques for Controlling a Pressurized Water Reactor

Ahmed J. Abougarair, Abdulhamid A. Oun, Widd B. Guma, Shada E. Elwefati

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/32

Efficient Vehicle Detection and Classification Algorithm Using Faster R‐CNN Models

Imad EL Mallahi, Jamal RIFFI, Hamid Tairi, Mohamed Adnane Mahraz

DOI: 10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/33

Submitted:22nd September2023;accepted:10th April2024

SylwiaBiełaszek,LeszekRutkowski,AleksanderByrski DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/27

Abstract:

Metaheuristics,suchasevolutionaryalgorithms(EAs), havebeenproventobe(alsotheoretically,see,forexam‐ple,theworksofMichaelVose[1])universaloptimization methods.Previousworks(ZbigniewSkolickiandKenneth DeJong[2])investigatedimpactofmigrationintervalson islandmodelsofEAsintheirworks.Hereweexploredif‐ferentmigrationintervalsandamountsofmigratingindi‐viduals,complementingSkolickiandDeJong’sresearch. Inourexperiments,weusedifferentwaysofselecting migrantsandpavethewayforfurtherresearch,e.g., involvingdifferenttopologiesandneighborhoods.We presenttheideaofthealgorithm,showexperimental results.

Keywords: parallelevolutionarycomputing,metaheuris‐tics,migration

1.Introduction

SinceseminalworkofWolpertandMacReady[3] andformulationofNoFreeLunchtheoremweknow thateachmetaheuristicalgorithmsmustbeproperly parameterizedinordertomakeitfeasibleforapar‐ticularproblem.ResearcherssuchasSudholt,Cantu‐PazorSkolnickiandDeJongworkedontheparal‐lelmodelofanevolutionaryalgorithm(EA)[4][5] arguingthatdecompositionofpopulationincreases diversityandtheef icacyofthewholealgorithm.We havebeenexaminingthisproblemandthispaperis devotedactuallytoextendtheresultsdescribedby SkolnickiandDeJongdescribedin[2].

Whilestudyingthein luenceofvariousmigra‐tionssizes(migrationrate)andmigrationintervals onislandmodels,researchersnoticedthatthemigra‐tionintervalseemedtobeadominatingfactortothe bestsolutionfound,toofrequentlymigrationscause islandstodominateothersandloseglobaldiversity, toorarelymirationsperformdegradedperformance duetoslowconvergence,butevensmallmigrations alreadymakeasigni icantimpactontheresultofan islandmodel.

Therefore,wefocusedonfurtherparametrization oftheparallelEAstrivingtowardscheckingwhatkind ofcon igurationswillhelpusreachingbetteref icacy, usingthepopularmultimodalbenchmarksascase studies.

Thepaperisorganizedasfollows:Inthenextchap‐terweintroduceparallelmodelsofEAs.Inthethird chapterwedescribeconsideredalgorithm.Inchapter fourwepresenttheresultsanddiscussthem.Inthe ifthchapterwecometotheconclusion.

2.ParallelModelsofEvolutionaryAlgorithms

EAsarewellknownandwidelydecribedinthe literature[6–8]asprobabilisticoptimizationmethods inspiredbybiologicalanalogies(naturalevolution). TheessenceofEAsistocombinethephenomenonof random(undirected)genotypechangeswithstrictly directedenvironmentalpressureonthephenotype.It isapowerfulmethodforsolvingalargescaleofprob‐lemsthatcanbedescribedinanappropriateform. Itconsistsofchoosingtherighttypeofalgorithm, designingthemethodofcodingsolutions(creatinga solutionspaceoftheproblem)andconstructingthe objectivefunction.To indasolution,weneedtoknow almostnothingaboutthefunctionbeingoptimized (“blackbox”).Theremayevenbenoobjectivefunction atall:wecanuseevolutionaryalgorithmsevenwhen theonlythingwecansayaboutthepointsinthestate spaceiswhichofthetwopointsisbetter(tournament selection).

Theschemeoftheclassicalevolutionaryalgorithm includesthecreationofaninitialpopulationconsist‐ingofrandomindividuals,theuseofgeneticopera‐tors(i.e.certaintransformationsofthegeneticcode ofindividuals),calculatingthevalueoftheobjec‐tivefunctionofindividuals,selection.Theoperations describedabovetakesplaceinacyclethatendswhen thespeci iedterminationconditionismet.The inal populationineachcyclebecomesthecurrentfornext oneandevolutioncontinues.Thealgorithmstopsat theuser’srequest,afteracertaintime,certainnum‐berofsolutionevaluationsorwhenacertainsolution qualitythresholdisreached.Thealgorithmisnon‐deterministic(randomactionofmutation,crossing andselection),wehavenoguaranteethatthesolution foundisoptimal,buttheygiveahighprobabilitythat theresultwillbeclosetotheoptimaloneandwewill getitinatimethatsatis iesus.Thegeneticoperators: mutation,crossoverandselectioncanbeusedindif‐ferentvariants.

ThebasicandthenecessaryelementsofanEAare:

‐ Individual–anexemplarysolutionoftheproblem–placedinacertainenvironmenttowhichhemaybe betterorworseadapted.The“goal”ofevolutionisto createanindividualthatisaswelladaptedtoagiven environmentaspossible.

‐ Phenotype–characteristicsofagivenindividual.In thecaseofEAs,thesearetheparameters(features)of thesolutionthataresubjecttoevaluation.

‐ Genotype–acompleteandunambiguousdescription ofanindividualcontainedinitsgenes.

‐ Chromosome–theplacewherethegenotypeofan individualisstored.

‐ Population–agroupofindividualslivinginacommonenvironmentandcompetingforitsresources.

‐ Solutioncoding–awayofstoringanyacceptable solutiontoaproblemintheformofanindividual’s genotype(e.g.astringofbits).

‐ Functionofadaptation( itness)–afunctionthat allowstodetermineitsqualityforagivenindividual (fromthepointofviewoftheproblembeingsolved). Itsvaluesarerealnon-negativeandahighervalueof thefunctionalwaysmeansthatagivenindividualis better.Inthecaseofnaturalevolution,theequivalent ofsuchafunctionisthegeneralassessmentofan individual’sadaptationtoagivenenvironment.In practice,thisfunctionisusuallyaslightmodi ication oftheobjectivefunctionoftheproblembeingsolved.

‐ Geneticoperators:mutation,crossoverandselection canbeusedindifferentvariants

2.1.MainkindsofPEA’s

Asigni icantimprovementintheoperationofthe EAisobtainedbyusingaparallelEAmodel(PEA).The basicideaistodivideataskintosubtasks,andtosolve themsimultaneouslyusingmultipleprocessors.

Realizationtakesplaceasworkonsinglepopu‐lationoronseveralrelativelyisolatedpopulations, usingmassivelyparallelcomputerarchitecturesor multicomputerswithfewerandmorepowerfulpro‐cessingelements.

TherearethreemaintypesofparallelEAs;there areglobalsingle‐populationmaster‐slaveEAs,single‐population ine‐grainedEAs,andmultiple‐population coarse‐grainedEAs.

The irsttypeofparallelmodelsisthemaster slave[9].It’saneasytoimplementandveryef i‐cientmethodofparallelisationwhereweuseasin‐glepanmiticpopulation,justlikeinasimpleEA,but evaluationoftheindividualsandgeneticoperatorsis parallel.Thismodeldoesnotassumeanythingabout theunderlyingcomputerarchitecture.Eachindividual maycompeteandmatewithanyother(thusselec‐tionandmatingareglobal).Selectionandcrossover considertheentirepopulation.Inthismodelmaster storesthepopulation,andslavesevaluatethe itness ofanindividualwhichisindependentfromtherest ofthepopulation,andassigningafractionofthepop‐ulationtoeachoftheprocessorsavailable.Commu‐nicationbetweenmasterandslaveoccursonlywhen

eachslavereceivesitssubsetofindividualstoevaluate andwhentheslavesreturnthe itnessvalues.The algorithmisusuallysynchronous.

Thesecondtype, ine‐grainedparallelEAs[10] consistofonespatially‐structuredpopulationthat limitstheinteractionsbetweenindividuals.Selection andmatingarerestrictedtoasmallneighborhood,but neighborhoodsoverlappermittingsomeinteraction amongalltheindividuals.Theidealcaseistohaveonly oneindividualforeveryprocessingelementavailable. Themostpopularstructuresusedforthismodelare ring,torus,cubeorhypercube.Thismodelissuitedfor massivelyparallelcomputers.

Third,themostpopularmethodofparallelimple‐mentationofEAsismultiple‐populationEAs[4].It consistinfewrelativelylargesubpopulationswhich exchangeindividualsoccasionallyinprocessnamed migration,controlledbyseveralparameters.

Theyareknownas“distributed”EAs,because theyareusuallyimplementedondistributed‐memory MIMDcomputers(possiblyalsousingVLSIcircuitsyn‐thesis,GPGPUorHPC)orthe“islandmodel”because relativelyisolateddemeswecancall“islands”.They arealsocalledcoarse‐grainedEAs,sincethecompu‐tationtocommunicationratioisusuallyhigh.

Themainideaisthatcopyofthebestindividual foundineachdemeissenttoalloroneofitsneighbors aftereverygeneration.

Itispossibletousedifferentapproachestosolve thisproblem[11],suchasworkwithisolateddemes andwitha“delayed”migrationschemeinwhichcom‐municationsbeganonlyafterthedemeswerenear convergence(veryhighmigrationrate).Inthiscase thesolutionfoundbyisolateddemeswasmuchlower thanthatreachedwithasinglelargepopulation,how‐ever,thisdelayedschemefoundsolutionsofthesame qualityasthepanmicticpopulationandasmultiple demeswithfrequentmigrations.Wecanalsomigrate solutionsbetweendemesafterthedemesconverged completely[12,13].

Sometimesmigrationhappensatregularinter‐vals,andsometimes[13]migrationoccursafterthe demesconvergedcompletely(theauthorusedthe term“degenerate”)withthepurposeofrestoring diversityintothedemestopreventprematureconver‐gencetoalow‐qualitysolution.

Inpracticewetakeafewconventional(serial)EAs, runeachofthemonanodeofaparallelcomputer,and atsomepredeterminedtimes,ornumberofcarried evaluationsinanEA,exchangeafewindividuals.

Mostofthetime,populationsareinequilibrium (i.e.,therearenosigni icantchangesinitsgenetic composition),butthatchangesontheenvironment canstartarapidevolutionarychange.Therefore,the arrivalofindividualsfromotherpopulationscan punctuatetheequilibriumandtriggerevolutionary changes.

2.2.PEA’sMainParameters

Mainparametersofmigrationarethetopology thatde inestheconnectionsbetweenthesubpopula‐tions,migrationratethatcontrolshowmanyindivid‐ualsmigrate,andmigrationintervalthataffectsthe frequencyofmigrations,thenumberofislands,and thepopulationssizes.

Researchers[11, 14]aretryingto indrelation‐shipsbetweenimportantPEAparameters.Itisdif i‐cultanddiffersfordifferentmethodsofemigration andimmigrationandtheproblembeingsolved.

Findingthesedependencieswouldbealsohelpful inestimatingtheoptimalnumberofprocessorsfor solvingproblemsintheparallelmodel.

Soitisworthtotestitformanzdifferentsettings.

Alsodifferentwaysofcreating itnessandmuta‐tionandcrossoverfunctions,usingasinglepopulation ormultiplesubpopulations(dems),differentwaysof exchangingmigrantsandhowselectionisapplied (globallyorlocally)wereinvestigated[15].

2.3.Topologies

Manyresearchershavestruggledwiththetopicof islandmodelcommunicationtopology.Itisamajor factorinthecostofmigration.Denselyconnected topologymaypromoteabettermixingofindividuals, butitalsoentailshighercommunicationcosts.The generaltrendistousestatictopologiesthatarespec‐i iedatthebeginning,butsomeanalyse[4]ofthe designandexpectedoptimizationtimesdepending onthetopologyleadtochangesduringtheexecution ofthealgorithmaccordingtothesettings.Wecall itdynamictopologyschemes.Itspeedsuptheopti‐mization.Migrantsaresenttodemesthatmeetsome criteria.

[16]alsostudiedthesizeoftheconnectiontopol‐ogyimpactandtheappropriatetopologychoicesfor differentapplications.Migrationtopologyrankings (moreprecisely,preorders)werebuiltforadifferent numberofislands,differentoptimizationproblems anddifferentbasicalgorithms.

Therearesomeunresolvedquestionsinthis model,suchas:

‐ whatisthelevelofcommunicationnecessarytomake aparallelEAbehavelikeapanmicticEA?

‐ whatisthecostofthiscommunication?

‐ isthecommunicationcostsmallenoughtomakethis aviablealternativeforthedesignofparallelEAs?

2.4.EA’sSequentialContraParallelVersions

SequentialEAsareveryeffectiveinmanyapplica‐tions.However,thereare[15]problemsintheiruse thatcanbesolvedwithPEA.

ItalsohappensthatsequentialEAscangettrapped inasub‐optimalregionofthesearchspace.

PEAscansearchdifferentsubspacesofthesearch spaceinparallel,thusreducingthelikelihoodofbeing trappedbylow‐qualitysubspaces.

Migrationofindividualsbetweenpopulationsmay increasetheselectionpressure[5].Thishasthedesir‐ableconsequenceofspeedingupconvergence,butit mayresultinanexcessivelyrapidlossofvariationthat maycausethesearchtofail.

Forexample,sometimesproblemsrequirethe useofverylargepopulations[17],andthememory neededtostoreeachindividualcanbesigni icant.In somecases,thispreventsanapplicationfromrunning ef icientlyonasinglemachine,sosomeparallelform ofEAisnecessary.Afterdividingitinsub‐population, asdifferentislandsretainadegreeofindependence andthusexploredifferentregionsofthesearchspace, theprobabilityofanimprovedscoreincreases.When theperformanceofasplitevolutionaryalgorithmis similartothatofalargepopulation,theuseofmigra‐tionmakestheperformanceequaltoorexceedthatof alargepopulation.

2.5.DynamicsofPEA’s

SkolickianddeJong[18]describedthemechanism ofimprovingtheresultsofpeaoperation,usingthe two‐leveldynamicsoftheislandmodel,dividingit intolevels:localoneachislandandinter‐islandinter‐actions.Thesetwoevolutionaryprocessesinteract andmaycontributetotheoveralloutcometovarying degrees.Butitisimportanttochoosethenumberof islands(global)andpopulationsize(locallevel)on theseislandsaccordingly.Andtochooseamigrant attherightmoment,sothatheisgoodenoughand admittedattherighttimesothathedoesnotdisrupt theprocessestakingplacethere.

In[2],researchershaveexperimentallystudied thein luenceofvariousmigrationssizes(migration rate)andintervalsonislandmodelsusingasetof specialfunctions.Theynoticethatthemigrationinter‐valseemstobeadominatingfactor,withmigration sizegenerallyplayingaminorrolewithregardto thebestsolutionfound.Toofrequentlymigrations causeislandstodominateothersandloseglobaldiver‐sity,evensmallmigrationsalreadymakeasigni icant impactonthebehaviorofanislandmodelbutrare migrationscauseadegradedperformanceduetothe slowconvergence.

Whileexaminingthebehavioroftheislandmodel, weidenti iedtheneedtostudytheimpactofmigrant selectionstrategiesonthequalityofthesolution.In ourapproach,wecopyselectedmigrants(notrelo‐cate,likemostofresearchersbefore)andjointhe populationonthetargetislandwheretheytakepart ingeneticoperations.Attheend,theyaresubjected toselectiontogetherwiththerestofthepopulation, i.e.,weallowthemtotakepartingeneticoperations togetherwiththeresidentsoftheisland.

Usingdifferentmigrantselectionstrategies,we foundthattheyhadanoticeableimpactontheresults obtained.Weusedtwostrategiestoselectthebestand mostdistantmigrants.Thecontrolstrategyofrandom selectiondidnotgivesuchsigni icantimprovement. Therehasbeenabigprogresswithmanysettings(dif‐ferentmigrationintervalsandnumberofmigrants) regardingthemigrationintervalandthesizeofthe migrantgroup.

Figure1. Threewaysofselectingmigrantsstudied.The colorsusedarereferencedtobarresultscharts

Intheislandmodel,weusethreemigrantselec‐tionstrategies:“best”and“maxdistance”(“mDist”) withoutrepeats,and“random”.Thosestrategieswill bediscussedindetaillater.

Inourapproachmigrationsconsistofcopying(not moving)selectedindividualsfromthesourceislandon destinationisland.Fourmigrationintervalswereused every5th,15th,25thand35thevaluation,andthere werefourmigrantgroupsizesettings:1,4,9and12 individuals.

Migrantadmissionstrategywastojointhemtothe populationondestinationisland,thenusingcrossover andmutationoperators,thenselection.

Threemigrantselectionstrategieswithoutrepeti‐tions(showninFig.1)wereused:

‐ “best”–nindividualswereselectedinorderof itness values,startingfromthebestone

‐ “random”–nrandomindividualswererandomly selected

‐ “mDist”–Euclideandistancesofallindividualswere testedinpairsandthenthefarthestoneswere selectedinpairs(ifpossible)untilthenumberof migrantssetintheparameterswasexhausted Eachofthealgorithmsettingsweretested10times andtheresultswereaveraged.

AllcomputationswereperformedonaPCwork‐stationwithWindows10IntelCorei5‐2520M2.50 GHz,8GBRAMmemoryandusingIntelHDGraphics 3000graphiccard.

ThealgorithmwascreatedusingthejMetalPy framework,andthemovementofmigrantsbetween theislandswascreatedusingrabbitMQ,Dockerand Pika.WeinvestigateRastriginandSphere(DeJong) problemsindimension200.Thetopologyconsistsof 5islandsconnectedinaringwithtwo‐waytraf ic.The populationsizeoneachislandis16andtheoffsetis4. Westudytheresultsofthealgorithmforoneislandby reference.Thenthepopulationhasacardinalityof80 andanoffsetof20.

Whencomparingevolutionaryalgorithmsrunning ondifferenthardware,itisimportanttohaveanequal numberofevaluationsperformedinthealgorithms. Thisisbecauseenvironmentparametersaredifferent, e.g.,thesizeoftheoperatingmemory,whichaffects thespeedofthecomputer.

Similarly,thisistruewhencomparinganalgorithm runningononeislandtoonerunningon iveislands. Butit’snotonlythenumberofevaluationsthatmat‐ters.Itisalsoimportantthatthenumberofcyclesof thealgorithmisequalononeislandandeachofthe iveislands.Weachievedthisbyequalizingthepopu‐lationandoffsetononeislandandthetotalnumber onmanyislands,aswedescribedabove.

Theendcriterionwasthemaximumnumberof evaluations.Forthe iveislandsmodel:15,000for theSphereand20,000fortheRastrigin,andforone island,75,000fortheSphereproblemand100,000for theRastriginproblem.Thismeansthatnotonlythe stopcondition,butalsothesizeofthepopulationare thesameinthecomparedstudies.

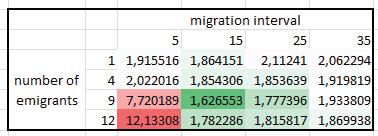

InFigures 2 and 3 (fortheRastriginandSphere problemswithdifferentmigrationstrategies,respec‐tively),thecolorscale(fromtheworstresult–dark redtothebestresult–darkgreen)showstheaverage resultsofvarioussettings:themigrationintervaland thesizeofthemigrantgroup.Wecanseethatthered colorvaluesaregroupedinthesameareaandthe greencolorvaluesinapproximateareas.

Thesamething,butintheformofa3Dspatial graph,canbeseenincharts4and5(fortheRastrigin andSphereproblemswiththeexaminedsettingsof themigrationintervalandthenumberofmigrants, respectively).Thebestresultsarethosewiththelow‐estpositioninthedrawings,andtheworstarethose placedhighest.Theworstresultsareinthesameplace inallthedrawings,andthebestonesoccupysimilar areas.Wecanseeasimilarinclinationandshapeof theplanescreatedforthesesamples–whichindicates thatthesizeofthemigrantgroupsandtheinter‐valsworksimilarlyforthesedifferentproblemsand strategies.

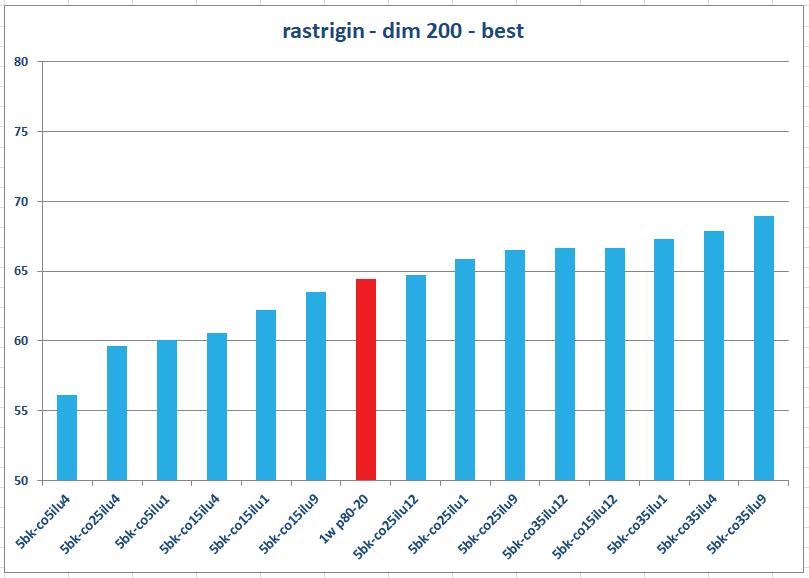

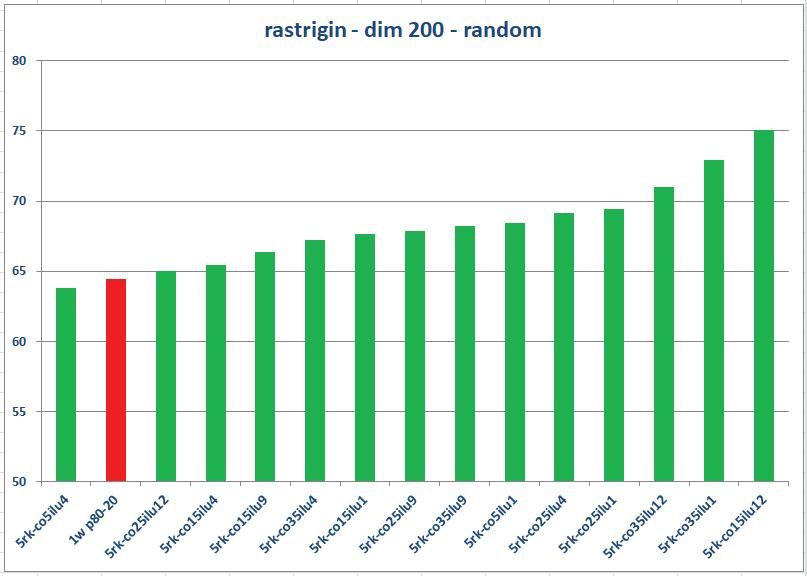

InFigures 6 and 7 (fortheRastriginandSphere problems,respectively),thebargraphsshowthecom‐parisonofaverage inalresultsofthe ive‐islandand one‐islandsettings.Herewecanclearlyobservehow manyattemptsofthetestson iveislands(interval, sizeofthegroupofmigrants)ledtosuccesswith agivenmigrantselectionstrategy,i.e.improvedthe resultofthesingle‐islandmodel(itsgraphistothe leftofthebarofoneisland).Forexample,thestrategy “best”and“mDist”inmanysettings(interval,sizeof thegroupofmigrants)ledtoanimprovementinthe resultinrelationtothesingle‐islandmodel.Andinthe “random”strategy–comparative,becausethemigrat‐ingindividualsweresimplydrawnrandomly,itdidnot improvetheresultofoneislandatall(forSphere)or almostatall(forRastrigin).

(a)Rastriginwith“best”migrationstrategy(left)andwith“mDist”(right)

(b)Rastriginwith“random”migrationstrategy

Figure2. AverageresultsachievedforRastriginproblemwithdifferentmigrationstrategies.Resultstabulatedby migrationintervalsandnumbersofmigrants.Colorscaleandintensity–worstresult–darkred,bestresult–darkgreen

(a)Spherewith“best”migrationstrategy(left)andwith“mDist”(right)

(b)Spherewith“random”migrationstrategy

Figure3. AverageresultsachievedforSphereproblemwithdifferentmigrationstrategies.Resultstabulatedbydifferent migrationintervalsandnumbersofmigrants.Colorscaleandintensity–worstresult–darkred,bestresult–darkgreen

TableinFigure 8 describes(foreachproblem, eachwayofselectingmigrants,differentmigration intervalsandnumbersofmigrants)ranking(inplus orminus)oftheresultsobtainedinrelationtothe correspondingresultobtainedononeisland.

Thefollowingsymbolshavebeenusedinthetable Figure8:

‐ 0–referencepoint–resultforamodelwith1island

‐ positivenumbers–positionof iveislandmodelwith speci icparametersinrankingofresultsbetterthan appropriate“reference”ononeisland

‐ negativenumbers–positionof iveislandmodelwith speci icparametersintherankingofresultsworse thantheresultofappropriate“reference”onone island

The irstthreecolumnsintheTable 8 describe algorithmstartparameters:thenumberofislands, themigrationintervalandthenumberofmigrating individuals.

Figures 12 and 13 showtherunsofthe10‐trial averageforeachsetting(interval,migrantgroupsize) inthewinningstrategiesforagivenproblem.

ForeasierunderstandingofFigure8,pleasecom‐pareFigure13showingalllineresultsofSphere200in “best”version,it’svaluesshowninFigure3aandthe forthcolumnoftheResultstableTable8,i.e.,Sphere 200/“best”column.Findtheresultobtainedonone islandinthegraphandnoticethatsubsequentresults havethesamenumberinthetableasthedistanceof theirgraphfromthegraphobtainedononeisland.

Similarly,whenconsideringRastriginproblem, Figure12,Figure2aandTable8(theseventhcolumn, ie.Rastr200/“best”column)shouldbeconsidered.

Thebest,takingintoaccountmigrantsselection strategies,were:“best”,then“mDist”and inally“ran‐dom”.

(a)“best”(left)and“mDist”(right)migrantselectingstrategy

(b)“random”migrantselectingstrategy

Figure4. ComparativeresultsofRastriginproblem,withtheexaminedsettingsofthemigrationintervalandthenumber ofmigrants

(a)“best”(left)and“mDist”(right)migrantselectingstrategy

(b)“random”migrantselectingstrategy

Figure5. ComparativeresultsofSphereproblem,withtheexaminedsettingsofthemigrationintervalandthenumberof migrants

(a)“best”(left)and“mDist”(right)migrantselectionstrategy

(b)“random”migrantselectionstrategy

Figure6. GraphsofresultsofRastriginproblem,obtainedwithdifferentsettingsofthemigrationintervalandthenumber ofmigrantsonthefiveislands.Forcomparison–redbar–theresultachievedononeislandwithcomparablesettings

(a)“best”(left)and“mDist”(right)migrantselectionstrategy

(b)“random”migrantselectionstrategy

Figure7. Graphsofresultsofsphereproblem,obtainedwithdifferentsettingsofthemigrationintervalandthenumber ofmigrantsonthefiveislands.Forcomparison–redbar–theresultachievedononeislandwithcomparablesettings

Figure8. Ranking,foreachoftheexaminedmigrationintervalsandthenumberofmigrants,(inplusorminus)theresults obtainedinthePEAwithfiveislandsinrelationtotheEAresultobtainedononeislandforthesameproblemandthe methodofselectingmigrants

Figure9. Comparingthebestandworstresultsinfiveislandmodeltooneislandmodelfordifferentmigrantsselection strategies.Rastriginproblem)

InSphere200/random,nosettingsconnectedwith iveislandsgaveresultsbetterthantheoneisland score,andinRastr200/randomonlyonesetting (co5ile4)gavebetterresultswhencomparinganalo‐gously.

Intheotherversionsofthemigrationstrategy (“mdist”and“best”),forbothproblems,thereare alwayssome iveislandresultsthatperformbetter thanoneisland.

Thismeansthatourselectiveselectionofmigrants onsourceislandisworking.Weachievethebest resultswhenweselectthebestormorediverseindi‐viduals(themostdistantinourcase),theresultsare thensigni icantlybetterthanwhenweselectmigrants randomly.

ThebestresultsintheSphereproblemwere achievedwiththe“best”strategy(settings–interval5, groupof4migrants),worsewiththe“mDist”strategy (interval15,groupof9migrants),andallsettingsof “random”strategyachievedworseresultsthanresults ofoneisland.

Figure10. Comparingthebestandworstresultsinfiveislandmodeltooneislandmodelfordifferentmigrantsselection strategies.Sphereproblem

Figure11. Comparingtheimprovedresults(persixsettings=2problems*3strategies)ofPEAwithfiveislandsin relationtotheresultofEAononeisland,obtainedfortheexaminedmigrationintervalsandnumbersofmigrants

ThebestresultsoftheRastriginproblemwere achievedwith“best”strategy(settings–interval5, groupof4migrants),followedby“mDist”(settings–interval15,groupof4migrants)andonlyone“ran‐dom”strategysetting(settings–interval5,groupof4 migrants)wasbetterfor iveislandsthantheresults ofoneisland.

Inthe“random”strategy,individualsofdiffer‐entqualitywererandomlyselected.Therefore,their resultsareworsethaninstrategieswherecarefully selectedindividuals–thebestorthemostdiverse–migratequalitativelyorimprovethediversityonthe destinationisland.

Foreveryissueandmigrationstrategy,thesettings withinterval5andsizeofmigrationgroup9or12–alwaysperformedsigni icantlyworsethanallothers. Ithappensbecauseinsuchcasesmigrantsarrivingin largenumbersonthedestinationislandhinderthe evolutiononthisisland,almostreplacingitsexisting populationThesearecasesofshortmigrationinter‐valswithabignumberofmigrants(closetothesizeof thepopulation)atthesametime.

TheadditionalinformationinFigure 9 (forRast‐rigin)andFigure10(forSphere)showthenumerical valuesachievedon iveislands(bestandworstresult) andononeislandandshowthenumericaldifferences betweentheseresults.

Let’slookatthisdifferences.Aswecanseethe greatestvaluedifferencesbetweenresultsachieved on iveislandsandbiggestimprovementon ive islandsoverthescoresofasingleislandwereachieved for“best”migrantselectionstrategyinbothproblems. InRastrigin(Fig. 9)“best”surpassedtheoneisland scoreby8,13,“mDist”by5,72,anda“random”by0,66. InSphere(Fig.10)“best”surpassedoneislandscore by0,43,“mDist”by0,14,and“random”by0,05.

Figure11summarizespositivevaluesinFigure8 byrows.Ineach ieldattheintersectionoftheappro‐priatemigrationintervalandthesizeofthemigrant group,thenumberofresultsfrom iveislandsthat achievedsuccessappears,i.e.,theywerebetterthan theresultononeisland(outofsixpossible–two problems*threestrategies).

Figure12. Averagedrunsofparallelcalculationsonfiveislandsandreferencecalculationsobtainedononeislandfora winningmigrantselectionstrategy(“best”)fortheRastriginproblemwithdimension200

Figure13. Averagedrunsofparallelcalculationsonfiveislandsandreferencecalculationsobtainedononeislandfora winningmigrantselectionstrategy(“best”)fortheSphereproblemwithdimension200

Aswecanseethebestresultsweachievedforlow numberofmigrants(one,fourornine)andmorefre‐quentmigrations(afterevery5thorevery15theval‐uation).Thisisbecausetheseareshortintervalsand smallgroupsofmigrants–thatiswhytheyhavethe opportunitytoimprovethequalityofthepopulation onthetarget,andnotdisruptthecourseofprocesses onit.

Ifwefocusontheworstsettingsoftheinterval andthenumberofmigrantgroups,wecanseethat, asmentionedabove–largemigrationsdestroythe populationofthedestinationislandbyreplacingit, bothwhentheyarefrequent(parameters–interval5, migrantgroupsize:9,12),whentheyareverydisturb‐ing,andrare(parameters–interval35,migrantgroup size:9,12).

Anothergroupoftheworstattemptswereinwhich migrationswerefewandrare(parameters–interval–25,35,migrantgroupsize:1).

InspiredbytheworksofDeJongandSkolicki,we performedanexperimentforRastriginandSphere problems.Weusedfourmigrationintervalsandfour sizesofmigrantgroups,expandingtheexperiment withastudyfordifferentmigrationstrategies.

Weobservedthatthestrategiesweusedforselect‐ingmigrantsinmanycasesledtoimprovedresults comparedtoourreference,i.e.,theEAmodelworking asoneisland.

Inthe“best”strategy,wesentgroupofbestindi‐vidualsfromthesourceisland.Sotherewasapossibil‐itythatonthedestinationislandtheywouldbegood materialforthefurtheroperationoftheevolutionary algorithm.

Usingthe“mDist”strategy,wesentagroupof individualsthatwereasdistantaspossiblefromeach otherintermsofgenotype.Thus,theyhadachanceto increasediversityonthedestinationisland,orevento restorediversityifthepopulationonthedestination islandwastooconvergent.

Weintendtocontinueourresearchonthisimpor‐tanttopicinthefuture.Wewillconductourresearch usingHPConalargescale.Inaddition,weintendto studythebehaviorofaparallelizedEAinanenviron‐mentwithdelays,assumingthepossibilityofdesyn‐chronizationandtakingcareofscalability.Thiswill makeitpossibletocomparetheoperationofthealgo‐rithmincontrasttocoherentlyandsynchronously operatingmaster‐slavemodelsandtheclassicisland model.

AUTHORS

SylwiaBiełaszek –AGHUniversityofScienceand Technology,Al.Mickiewicza30,Krakow30‐059, Poland,e‐mail:bielsyl@agh.edu.pl.

LeszekRutkowski –AGHUniversityofScience andTechnology,Al.Mickiewicza30,Krakow30‐059, Poland;InstituteofSystemsSciencesPolishAcademy

ofSciences,ul.Newelska6,Warsaw01‐447,Poland, e‐mail:rutkowski@agh.edu.pl.

AleksanderByrski∗ –AGHUniversityofScience andTechnology,Al.Mickiewicza30,Krakow30‐059, Poland,e‐mail:olekb@agh.edu.pl.

∗Correspondingauthor

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ThisworkwassupportedbyNCNUMO‐2019/35/O/ST6/00571andthefundsassigned bythePolishMinistryofEducationandScienceto AGHUniversityofScienceandTechnology.

[1] L.D.Davis,K.DeJong,M.D.Vose,L.D.Whit‐ley,W.Miller,Eds.,EvolutionaryAlgorithms,Vol. 111ofTheIMAVolumesinMathematicsand itsApplications,NewYork,NY,Springer,1999, [Online].Available:doi:10.1007/978‐1‐4612‐1542‐4.

[2] Z.Skolicki,K.DeJong,Thein luenceofmigra‐tionintervalsonislandmodels,2005,pp.1295–1302,doi:10.1145/1068009.1068219.

[3] D.Wolpert,W.Macready,“NoFreeLunchThe‐oremsforOptimization”,IEEETransactionson EvolutionaryComputation,vol.1,no.1,pp.67–82,1997.

[4] D.Sudholt,ParallelEvolutionaryAlgorithms, Berlin,Heidelberg,SpringerHandbooks, Springer,2015,doi:10.1007/978‐3‐662‐43505‐2‐46.

[5] E.Cantu‐Paz,“OntheEffectsofMigrationon theFitnessDistributionofParallelEvolutionary Algorithms”,no.UCRL‐JC‐138729,2000,URLht tps://www.osti.gov/biblio/791479.

[6] D.E.Goldberg,GeneticAlgorithmsinSearch, Optimization,andMachineLearning,Addison‐Wesley,1989,google‐Books‐ID:2IIJAAAACAAJ.

[7] R.Chiong,T.Weise,Z.Michalewicz,Variantsof EvolutionaryAlgorithmsforReal‐WorldApplica‐tions,2012,doi:10.1007/978‐3‐642‐23424‐8.

[8] Z.Michalewicz,GeneticAlgorithms+DataStruc‐tures=EvolutionPrograms,SpringerScience &BusinessMedia,1996,google‐Books‐ID:vlh‐LAobsK68C.

[9] E.Cantú‐Paz,Master‐SlaveParallelGeneticAlgo‐rithms,GeneticAlgorithmsandEvolutionary Computation,Boston,MA,Springer,2001,doi: 10.1007/978‐1‐4615‐4369‐5‐3.

[10] E.Cantú‐Paz,Fine‐GrainedandHierarchicalPar‐allelGeneticAlgorithms,GeneticAlgorithms andEvolutionaryComputation,Boston,MA, Springer,2001,doi:10.1007/978‐1‐4615‐43 69‐5‐8.

[11] E.Cantú‐Paz,D.E.Goldberg,“Ef icientparallel geneticalgorithms:theoryandpractice”,Com‐puterMethodsinAppliedMechanicsandEngi‐neering,vol.186,no.2–4,pp.221–238,2000, doi:10.1016/S0045‐7825(99)00385‐0.

[12] Y.Sato,Y.Takai,M.Munetomo,“Anef icient migrationschemeforsubpopulation‐based asynchronouslyparallelgeneticalgorithms.”, Material:Proceedingsofthe ifthinternational conferenceongeneticalgorithms,S.F.Ed., SanMateo,CA:MorganKaufmann,1993, pp.649.

[13] H.Braun,“Onsolvingtravellingsalesmanprob‐lemsbygeneticalgorithms”,ParallelProblem SolvingfromNature,LectureNotesinComputer Science,H.P.SchwefelandR.Manner,Eds.Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer,1991,pp.129–133,doi:10 .1007/BFb0029743.

[14] E.Cantú‐Paz,D.E.Goldberg,OntheScalability ofParallelGeneticAlgorithms,vol.7,1999,pp. 429–449,doi:10.1162/evco.1999.7.4.429.

[15] M.Nowostawski,R.Poli,“Parallelgeneticalgo‐rithmtaxonomy”,1999ThirdInternationalCon‐ferenceonKnowledge‐BasedIntelligentInfor‐mationEngineeringSystems.Proceedings(Cat. No.99TH8410),1999,pp.88‐92,doi:10.1109/ KES.1999.820127.

[16] M.Ruciński,D.Izzo,F.Biscani,“Ontheimpact ofthemigrationtopologyontheislandmodel”, ParallelComputing,Issues,vol.36,no.10–11,pp. 555–571,1993,doi:10.1016/j.parco.2010.04. 002.

[17] D.Whitley,S.Rana,R.Heckendorn,“TheIsland ModelGeneticAlgorithm:OnSeparability,Pop‐ulationSizeandConvergence”,JournalofCom‐putingandInformationTechnology,vol.7,Dec. 1998.

[18] Z.Skolicki,K.DeJong,“Theimportanceofatwo‐levelperspectiveforislandmodeldesign”,Con‐ference:EvolutionaryComputation,2007.CEC 2007.IEEECongresson,IEEEXplore,2007,doi: 10.1109/CEC.2007.4425078.

Submitted:21st May2024;accepted:26th September2024

PawełRękas,RomanSzewczyk,TadeuszSzumiata,MichałNowicki

DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/28

Abstract:

Themutualinductancemodelenablestestingofthe behaviorofpowertransformersunderdifferentopera‐tionconditions,especiallyundertheenvironmentalinflu‐encesonthetransformer’score.Thispaperpresentsthe resultsofaninvestigationofthestressdependenceofthe magneticrelativepermeabilityofapowertransformer. Itwasobservedthatundertensilemechanicalstresses upto98MPaappliedtothecore,thetransformerinput currentamplitudeincreasesbyalmost67%,whereas thetransformer’sreactivepowerincreasesby53%.In industrialsystems,suchchangescanpotentiallyleadto unwantedpowersystemshutdownsduetooverloading. Thiseffectshouldbeconsideredduringthedevelopment ofcriticalpowersystems.

Keywords: mutualinductancemodel,magnetoelastic effect,electricsteel

1.Introduction

Specializedpowersuppliesoftenoperatewithin theirdesignconstraints,whereevenminorchanges cansigni icantlyaffectperformanceandsafety[1], includingtheriskofoverheating[2,3].Understanding theselimitationsiscrucialforensuringreliabilityand performanceindemandingapplications,suchasthe military[4],aerospace[5],andautomotivesectors[6].

Themechanicalstressdependenceofthemag‐neticfunctionalcharacteristicsofelectricsteelsheets hasbeenwidelytested,bothfornon‐oriented[7,8] andgrain‐orientedelectricsteels[9,10].Thispaper presentsatechnical‐orientedapproachandexamines theimpactofchangesinthemagneticpermeability oftransformercoressubjectedtomechanicalstress ontheirfunctionalperformance.Thestudyutilizeda speciallydesignedexperimentalsetup[11]toinvesti‐gatehowmechanicalstressaffectsthemagneticper‐meabilityofatransformercore.Thehypothesisposits thatvariationsinthecore’smagneticpermeability resultinaproportionaldecreaseininductance,acrit‐icalparameterfortransformerfunctionality.

The indingsofthisresearchareparticularlyrel‐evantfordesignersofthetransformersusedinhigh‐overloadapplicationswheremechanicalandthermal stressesaresubstantial.Designersmustthoroughly assesstheimpactofmechanicalstressontransformer performancetopreventpotentialfailures.

Additionally,attentionmustbepaidtoheatdis‐sipationduringinstallationtomitigatetheeffectsof stress‐inducedchanges.Thisconsiderationiscritical inspecializedinstallations,suchasaerospaceandmil‐itaryapplications,whereoverloadscanreachextreme levels.

Thearticlefocusesonstudyingtheimpactof mechanicalstressonthefunctionalparametersof apowertransformer.Intheinitialstage,exper‐imentswereconductedusingthreemeasurement yokesbasedontheEpsteinframe,withframesmadeof sheetmetalcutatdifferentanglesrelativetothestrip axisandtherollingdirection.Thisresearchaimedto verifytheaccuracyofthetransformermodelselec‐tionimplementedinMatlabSimulink.Inthesubse‐quentpartofthearticle,theeffectofmechanicalstress onthemagneticpermeabilityofM120‐27ssteelwas analyzed.Theresultswereusedtoassesschangesin thepermeabilityofthecoreofthesimulatedtrans‐formerundermechanicalstress.Theparametersofa samplesingle‐phasetransformerwereadoptedasthe initialvalues,re lectingtheunstressedcondition.The transformermodelfromtheMatlabSimulinkpackage, whichwasselectedasthebasisforthesimulation, mettheassumptionsveri iedbyEpsteinyoke‐based measurementsregardingtheconstancyofvoltagein thesecondarywindingandtheincreaseincurrentin theprimarywindingwithchanginginductancesofthe primaryandsecondarywindings.Inthe inalphase ofthestudy,theimpactofmechanicalstressonthe parametersofthesimulatedpowertransformerwas determined.

2.InitialTestingoftheModelUsingData ObtainedFromYokesBasedontheRescaled EpsteinFramewithNon‐stressedMaterials Tovalidatetheassumptionsregardingthetrans‐former’sresponsetochangesinthemagneticparam‐etersofthetransformercore,testswereconducted usingmeasurementyokesbasedontherescaled Epsteinframe[12, 13].Threemeasurementyokes wereemployed,utilizingstripsoftransformersheet metalcutat0∘,55∘,and90∘ anglesrelativetotheaxis ofthesheetstrip(magnetizationdirection)andthe rollingdirection.Themeasurementsystemwascon‐iguredaccordingtotheschematicshowninFigure1.

Table1. ResultsofthemeasurementyokesbasedontheEpsteinframe

Figure1. Wiringdiagramofthemeasuringyokebased ontheEpsteinframe

Initialinductancemeasurementsweretakenfor boththeprimaryLPri andsecondaryLSec windings ofthetransformer.Theinductancesweremeasured usingaHandheldLCRMeterTH2822A,manufactured byTonghui.Theresultsofthetransformerresponse andinitialinductancemeasurementsarepresentedin Table1

Theexperimentalsetupbeganwithafunctiongen‐eratorproducingasinusoidalwaveformat50Hzwith apeak‐to‐peakvoltage(Vpp)of20VAC.Thissignalwas ampli iedusingaKepcoBOP100‐2Mampli ier.The ampli iedsignalpassedthroughanammeter(Appa 207)anda0.1 Ω shuntresistorbeforereachingthe magnetizingwindingsofthemeasurementyoke.A voltmeter(Appa207)wasconnectedinparallelwith themagnetizingwindingtomeasurethevoltage.An oscilloscopemonitoredthevoltageacrosstheshunt resistorandthemagnetizingwinding.

Themeasurementwindingoftheyokewastested undertwoconditions:noloadcondition,wherethe windingwasnotconnectedtoanyexternalload, andloadedcondition,whereanoutputpowermeter (PWT‐5A)wasconnectedwithaloadsetat15 Ω. The15 Ω loadwasselected,underwhichthemost signi icantpoweroutputwasobservedfromthemea‐surementwinding.Themeasurementwindingwas connectedtothisloadthroughanammeter(Appa 207)anda0.1Ωshuntresistor.Avoltmeter(Tonghui TH1951)measuredthevoltageacrossthemeasure‐mentwinding,whiletheoscilloscopecapturedboth thevoltageacrosstheshuntresistorandthemeasure‐mentwindingvoltage.

Figure2. Wiringdiagramofthemeasurementsetup

Datacollectedincludedpowermeterreadings fromthemeasurementwinding,voltageacrossthe magnetizingwinding,currentthroughthemagnetiz‐ingwinding,andvoltageacrossthemeasurement winding.ThesevaluesaresummarizedinTable 1, demonstratingtheimpactofcoremagneticperme‐abilityonthetransformer’selectricalparameters.

Theresultsunequivocallyindicatethatasthemag‐neticpermeabilityofthecorematerialdecreases, thevoltageandpoweronthesecondarywindingof thetransformerremainlargelyunchangedwithinthe testedrange.However,asigni icantincreaseinthe currentontheprimarywindingisobserved.

3.TheMethodofMeasuringStressDepen‐denceof2DMagnetizationCharacteristics inElectricalSteelSheets

Aspecializedmeasurementsetupbasedonamag‐neticyokewasdevelopedtoinvestigatetheeffectof themechanicalstressdependenceonthemagnetic propertiesofelectricalsteels[11].Themechanical partofthesetupwaspreparedwithafocusonthe stressapplicationdevice[14],andaspeciallydesigned specimenshapewascreatedtoensureoptimalstress distribution[15].Anautomaticsystemforpositioning theyokethroughoutthetestingcyclewasalsodevel‐oped.Thetestingprocesscontrolsystem,signalanaly‐sis,anddataprocessingsystemwereestablished.This setupisdescribedindetailin[11].Thewiringdiagram isshowninFigure2

Schematicblockdiagramofthemeasurement setup

Theinformation lowdiagramispresentedinFig‐ure3.Thesetupiscontrolledbyacomputerequipped withLabViewsoftwareandaDAQDeviceNIUSB‐6341 dataacquisitioncard.Themagnetic luxintheyoke ismeasuredusingaLakeShoremodel480 luxmeter. Theactuatorsaremanagedbyanembeddedsystem basedonamicrocontrollerthatcontrolstherotation andlinearmotionoftheyokesystemhead.

3.1.TheExperimentalSetup

Thedevelopedsetupoperatesautomaticallyand performsacomplexseriesofmeasurements.Byusing specimenscutatvariousanglesbetweenthedirection oftheappliedstress(specimenaxis)andtherolling directionofthesheet,itispossibletostudychangesin magneticpermeabilityasafunctionofvaryingstress, theanglebetweenthestressdirectionandrolling direction,andtheanglebetweenthespecimenaxis andthemagnetizationdirection.Combinedwithan automaticallyrotatingyoke[11],thisfacilitatesawide rangeofpossibleresearch.

Themeasurementprocess,withtheexperimen‐talsetuppresentedinFigure 4,beginsbymount‐ingthespecimeninamechanicalmoduletoapply stresses(7).Themechanicalmoduleispositioned onamechanicalpress,whichappliestheappropri‐atestressestotheclampedsample.Theyokesystem head(5)withtheattachedmeasuringyokeispressed againstthesampleduringthemeasurement.Theforce appliedremainsconstantthroughoutasinglecycle duetotheuseofalinearoverloadclutchandthelock‐ingofthelinearactuatorinthemeasuringposition. Uponcompletingthemeasuringcycle,theyokesystem headretractsandperformsacontrolledrotarymotion tothenextmeasuringpositionusingtherotatorstep‐permotor(3).Theentireassembly,coupledtothe linearactuator,movesalongthelinearguide(4).

Figure4. Photographyofthemeasurementsetup:(a) testedsheetsample,(b)generalviewofthe measurementsystem,and(c)measuringheadduring themeasurementprocess:1–linearactuator,2–cushioningmechanism,3–rotatorwithsteppermotor, 4–linearrollingguide,5–measuringhead,6–tested sheetsample,7–mechanicalmoduleformountingand applyingstressestothetestedsample

M120‐27selectricalsteel[16]sheetsampleswith aspeciallydesignedshapewereusedforthemeasure‐ments.Thespecimencomprisesthreesections:the irstandthirdsectionswereusedsolelyformount‐ingthespecimensinthemechanicalmoduleanddid notparticipateinthestudyofmagneticproperties, whilethesecondsectionwassubjectedtostress,and itsmagneticpropertieswerestudied.Duringthetest, themeasuringyokeispressedagainstthemeasuring section.

Figure5. Themeasuringhead(5),madeof non‐magneticmaterials,featuresa2DCardan gyroscopicmechanismandameasuringyoke(8)

Thespecimen’sshapeisoptimizedusingthe inite elementmethodtoensureauniformstressdistri‐bution[11].Thespecimensareclampedinanon‐magneticmechanism.Onlytensilestressesareapplied duetothelowforcerequiredtobucklethespecimens.

3.2.AutomaticallyAdjustingtheYokeSystem Magneticyokesprovidethebestresultswhen measuringthedirectionalpropertiesoftransformer sheets.However,whenstudyingtheangularproper‐tiesofthesheetsoverafull360‐degreerangewith high‐resolutionyokepositioning,themanualopera‐tionbecomesinef icientduetothelengthymeasure‐menttimesinvolved.Thesolutiontothisproblem isimplementinganautomaticmeasurementsystem basedonamechatronicsetupthatpositionstheyoke accurately.

Automatedmeasurementsrequireensuringthat theyokeispressedagainstthesampleinthemost effectiveand,crucially,repeatablemanner.Thiscon‐sistencywasachievedbysuspendingtheyokeona Cardanjoint.Thedevelopedsystemallowstheyoketo maneuverwithfourdegreesoffreedom.Theposition‐ingoftheyokeitselfusestwodegreesoffreedom:XY andXZrotationoftheyokeinthehead.Additionally, theYZrotationoftheentireheadandlinearmovement alongtheX‐axisenablecomplete360‐degreetesting. AphotographoftheyokeholderwithCardansuspen‐sionandaxisdescriptionisshowninFigure5

3.3.UncertaintyAnalysisandErrorMitigationinthe MeasurementConfiguration

Thepresentedteststandwasdesignedtomeasure relativemagneticpermeability,withparticularatten‐tiontothedependenceofthispermeabilityonthe anglesbetweenthedirectionofexternalmechanical stresses,therollingdirectionofthetransformersheet, andthedirectionofmagnetization.Adetaileddescrip‐tionoftheuncertaintydeterminationmethodcanbe foundin[11].

Figure6. Theinfluenceofmechanicaltensilestresses �� ontheshapeofthemagnetichysteresisloopB(H)of M120‐27sgrain‐orientedelectricalsteel

Themainfactorin luencingchangesinrelative permeability(����)wasthevaryingintensityofthe magnetizing ield.Therefore,theA‐typeuncertainty, denotedas ��(����),wasestimatedbasedonthecal‐culatedvaluesof ���� witha95%con idencelevel, dependingontheappliedmagnetizing ieldstrength H.Itisworthnotingthatbeyondtheinitiallevelof H,wheresigni icantinteractionbetweenremanent magnetizationanddemagnetizing ieldsoccurs,theA‐typeuncertaintyoftheproposedmeasurementsys‐temdoesnotexceed0.5%.

Withthemaximumresolutionofpositioningthe measurementyokerelativetothesampleundertest— 200positionsovertheentire360‐degreerange—and consideringtheresponsetodifferentmagnetization ields,measurementscantakemanyhours.Under suchconditions,thedriftoftheLakeShore luxmeter model480canbeobserved.Thedriftaffectingthe measuredvalueswasaddressedbyautomaticcali‐brationofthe luxmeter,performedaftereachyoke rotation.

Mechanicalstressesareappliedusingahydraulic actuatorequippedwithapressurecontrolsystem, ensuringthestabilityoftheappliedmechanical stressesthroughoutthetest.

TheeffectofmechanicalstressesonM120‐27s grain‐orientedelectricalsteelwasmeasured,withten‐silestressesappliedintherollingdirection.Thespec‐imenwassubjectedto ivelevelsofstress:s1 =0 MPa,s2 =19.6 MPa,s3 =45.8 MPa,s4 =71.9 MPa,s5 =98.1MPa.Thesteelsheetwasmagnetized witha ieldstrengthof750A/minalignmentwiththe rollingdirection.Themeasuredhysteresisloopsare presentedinFigure6

Therelativemagneticpermeabilityofthesample duringeachstresswasdeterminedusingthefollowing relationship:

Figure7. TheMatlabSimulinkmodeloftheelectricaltransformersystemincludesamutualinductor.Theload,whichis switchedonhalfwaythroughthesimulation,ishighlightedwitharedbox

Itwasobservedthatasthestressappliedtothe sampleincreases,therelativemagneticpermeability decreases.Sincetheinductanceoftransformerwind‐ingsispartiallydependentonthemagneticperme‐abilityofthetransformercore,itisassumedthata decreaseinthemagneticpermeabilityofthestressed transformercorewillresultinaproportionaldecrease intheinductanceofboththeprimaryandsecondary windings.

5.ModelingtheImpactofMechanicalStress ontheFunctionalParametersofPower Transformers

Toinvestigatetheimpactofmechanicalstresson thefunctionalparametersofpowertransformers,the MutualInductormodelfromtheSimscapelibrarywas used.Themodelisgovernedbythefollowingequa‐tions[17]:

ThevoltageV1 ontheprimarywindingwasset to230VACRMSat50Hz.Initially,thevoltageV2 on thesecondarywindingwasano‐loadvoltagefromthe starttothemidpoint(t = 0.25s)ofthesimulation. Fromthemidpointtotheendofthesimulation,the secondarywindingwasautomaticallyloadedwitha resistorofR=8?.Forthepurposesofthesimula‐tion,thecoef icientofcoupling,whichdeterminesthe mutualinductanceM,wasassumedtobek = 0.9. Simulationswereconductedinthetimedomaint,with atotalsimulationtimeof0.5seconds.The igures illustratetheperiodfromt1 =0.2stot2 =0.3s.

V1 representstheinducedvoltageacrosstheprimary winding,whileV2 istheinducedvoltageacrossthe secondarywinding.I1 isthecurrententeringthepos‐itiveterminaloftheprimarywinding,andI2 isthe currentleavingthepositiveterminalofthesecondary winding.L1 andL2 aretheself‐inductancesofthe windings,Misthemutualinductance,kisthecoupling coef icient,andtistime.

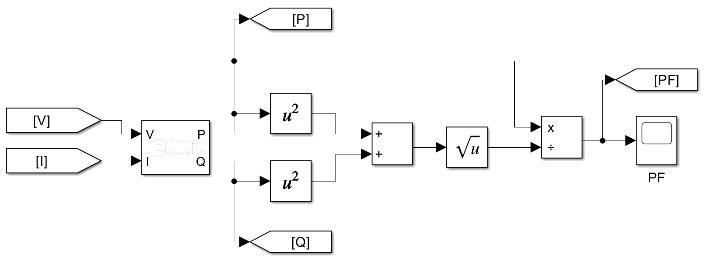

Othertransformermodelsavailablein Simscape[18]werealsoevaluated,butnoneyielded satisfactoryresultsconsistentwiththevalidateddata. The inalcon igurationofthemodelusedforthe simulationsisdepictedinFigure7.

Theinitialparametersforthemodelwerederived fromarealtransformer,modelTE‐4812167,manu‐facturedbyHuaJiaElectricApplianceCo.,Ltd.The transformeroperateswithaprimarywindingvolt‐ageof230–240Vat50Hz,asecondarywinding voltageof12V,andamaximumcurrentof1.67A. Thepowerratingofthetransformeris20VA.The inductancesweremeasuredusingaHandheldLCR Meter,modelTH2822A,manufacturedbyTonghui. TheinductanceLPri oftheprimarywindingwasmea‐suredtobe11.836H,andtheinductanceLSec ofthe secondarywindingwas35.323mH.Basedonthese valuesandthereductioninmagneticpermeabilityof thetransformersheetundermechanicalstress,the decreaseininductanceofboththeprimaryandsec‐ondarywindingsofthesimulatedtransformerwas calculated.Itwasassumedthatthereisalinearrela‐tionshipbetweenstressandmagneticpermeabilityin theinitialrangesofmechanicalstress.However,for higherstressvalues,thisrelationshipbecomesnonlin‐ear.Thevaluesusedinthesimulationarepresentedin Table2.

Inordertothoroughlyanalyzeandinvestigatethe impactofmechanicalstressonthefunctionalparam‐etersofpowertransformers,theactivepowerPand reactivepowerQwerecalculated.Thesevalueswere obtainedusingadedicatedSimulinkblock.

Table2. InductancesLPri andLSec oftransformer windingsasafunctionofsimulatedtensilestresses appliedtothetransformercore

Figure8. Themodelofanelectricaltransformersystem inMatlabSimulink—thesectionofthemodel responsibleforcalculatingactivepowerP,reactive powerQ,andpowerfactorPF

Table3. Measuredcurrentamplitude(I)intheprimary winding

ThepowerfactorPFwascalculatedastheratioof realpowertoapparentpowerinagivenmoment,as showninEquation(5).

ThecomplexpowerSwasdeterminedasthevec‐torsumofactiveandreactivepower,expressedas:

Thesectionofthemodelresponsibleforcalculat‐ingpowerisdepictedinFigure8

6.ResultsofSimulationStudiesonMechanical StressEffectsinPowerTransformers

Simulationswereperformedfor5different stresses.Theresultsofthesimulationsareshownin Figures9,10,and11andsummarizedinTables3–7

Table 3 showsthecurrentamplitudeinthepri‐marywindingofthetransformerfordifferentlevelsof stress��expressedinMPa,measuredattwomoments intime,t1 andt2.Increasingthestresscausesan increaseintheamplitudeofthecurrentinthepri‐marywinding.Themostsigni icantincreaseincur‐rentamplitudeisobservedwhenthetensionrises from0to19.6MPa.

Figure9. Resultsofthesimulations—oscillogramsof currentandvoltageonthewindingsofthesimulated transformer:(a)measuredcurrentintheprimary windingasafunctionoftime,(b)measuredcurrentin thesecondarywindingasafunctionoftime,and(c) measuredvoltageinthesecondarywindingasa functionoftime

Table4. Measuredactivepower(P)intheprimary winding

Table4presentstheamplitudeandaveragevalue ofactivepowerintheprimarywindingofthetrans‐formeratdifferentstresslevels,measuredattwo momentsintime.Theamplitudeandtheaveragevalue ofactivepowerincreasewithincreasingstress.

Table5showstheamplitudeandaveragevalueof activepowerinthesecondarywindingofthetrans‐formerfordifferentstresslevels.

Figure10. Resultsofthesimulations—oscillogramsof poweronthewindingsofthetestedtransformer:(a) activepowerPintheprimarywinding,(b)activepower Pinthesecondarywinding,and(c)reactivepowerQin theprimarywinding

Figure11. Resultsofthesimulations—powerfactorPF oscillogramintheprimarywinding

Theamplitudeofactivepowerinthesecondary windingisrelativelystable,suggestingthatchanges instresshavelesseffectonthiswinding.Theaverage activepowervaluesarealmostconstantregardlessof thestresslevel,whichmayindicatethetransformer’s ef iciencyinmaintainingpowerinthesecondarycir‐cuit.

Table5. Measuredactivepower(P)inthesecondary winding

Table6. Measuredreactivepower(Q)intheprimary winding

Table7. Measuredpowerfactor(PF)intheprimary winding

Table 6 illustratestheaveragevaluesofreactive powerintheprimarywindingofthetransformerat differentstresslevels.Reactivepowerincreasesas stressincreases,suggestingmoresigni icantinef i‐ciencyathigherstresslevels.Reactivepowervalues arehighestforthemostcriticalstresses,whichmay requirecompensationtoimprovetransformeref i‐ciencyoroverloadreactivepowercompensationsys‐temsforsystemsthatdonotanticipatereactivepower increasingwithcorestress.

Table7presentstheamplitudeandaveragevalue ofthepowerfactorintheprimarywindingfordiffer‐entstresslevels.Thepowerfactortendstodecrease withincreasingstress,indicatingadecreaseinpower ef iciency.Theneedtoimprovethepowerfactormay requireadditionalmeasures,suchastheuseofreac‐tivepowercompensation.

Applyingmechanicalstresstothetransformer coresigni icantlychangesitselectricalparameters. Itisworthnotingthatwithinthetestedranges, theoutputparameters,suchascurrentandvolt‐age,remainlargelyunchanged.However,signi icant changesoccurintheprimarywinding,wherethe currentamplitudeincreasesbyalmost67%under extremestressconditions.Thesearecriticalchanges, astheyhaveaprofoundeffectonthekeyoperational parametersofthetransformer.

Thisphenomenoncanbeextremelydangerous becausethesechangesarenotdetectableontheload sideofthetransformer.Thechangesinoperating parametersalsoaffectthepowersystem,asthetrans‐former’sreactivepowerisseentoincreasebyalmost 53%whenoperatingunderload,potentiallylead‐ingtounwantedpowersystemshutdownsdueto overloading.

Itshouldbehighlightedthataquantitative descriptionofthein luenceofmechanicalstresseson thefunctionalpropertiesofthepowertransformer playsavitalroleinboththeef icientdevelopment ofthepowertransformersystemaswellasduring itssafeexploitation.Onthebasisoftheproposed quantitativemodelandtheproposedmethod ofexperimentalmeasurementsofthestress‐dependenceof2Drelativemagneticpermeability,it ispossibletopredicttheoperatingconditionsand properlyselectthemagneticmaterialforthecoreof thepowertransformer.

Thesimulationresultswerecomparedwithmea‐surementsofthematerial’spropertiesanditseffecton thetransformer.However,fullvalidationoftheimpact ofstressonthetransformerrequiresthepreparation ofateststandundernaturalconditionsthataccurately re lectthedevice’sactualoperatingconditions.

AUTHORS

PawełRękas –FacultyofMechatronics,Warsaw UniversityofTechnology,Poland,e‐mail: pawel.rekas.dokt@pw.edu.pl.

RomanSzewczyk∗ –ŁukasiewiczResearch Network–IndustrialResearchInstitutefor AutomationandMeasurementsPIAP,Poland,e‐mail: roman.szewczyk@pw.edu.pl.

TadeuszSzumiata –FacultyofMechanicalEngineer‐ing,DepartmentofPhysics,KazimierzPulaskiRadom University,Poland,e‐mail:t.szumiata@uthrad.pl.

MichałNowicki –DepartmentofMechatronics, RoboticsandDigitalManufacturing,Facultyof Mechanics,VilniusGediminasTechnicalUniversity, Lithuania,e‐mail:michal.nowicki@pw.edu.pl.

∗Correspondingauthor

References

[1] L.Cesky,F.Janicek,andJ.Kubicaetal.,“Over‐heatingofPrimaryandSecondaryCoilsofVolt‐ageInstrumentTransformers,” 201718thInternationalScienti icConferenceonElectricPower Engineering(EPE),May2017.doi:10.1109/ep e.2017.7967359.

[2] K.Liu,“IntelligentIdenti icationMethodof TransformerOverheatFaultinDistributionSub‐stationBasedonDeepLearningAlgorithmand InfraredTemperatureMeasurementTechnol‐ogy,” 20233rdInternationalConferenceonElectricalEngineeringandControlScience(IC2ECS), Dec.2023.doi:10.1109/ic2ecs60824.2023.104 93404.

[3] K.S.Kassi,I.Fofana,andF.Meghne ietal., “ImpactofLocalOverheatingonConventional andHybridInsulationsforPowerTransformers,” IEEETransactionsonDielectricsandElectrical Insulation,vol.22,no.5,pp.2543–2553,Oct. 2015.doi:10.1109/tdei.2015.005065.

[4] C.Qingsongetal.,“AnalysisofTransformer AbnormalHeatingBasedonInfraredThermal ImagingTechnology,” 20182ndIEEEConference onEnergyInternetandEnergySystemIntegration(EI2),Oct.2018.doi:10.1109/ei2.2018.8 582496.

[5] K.FurmanczykandM.Stefanich,“Overview ofMultiphasePowerConvertersforAerospace Applications,” SAETechnicalPaperSeries,Nov. 2008.doi:10.4271/2008‐01‐2878.

[6] M.Yamamoto,T.Kakisaka,andJ.Imaoka,“Tech‐nicalTrendofPowerElectronicsSystemsfor AutomotiveApplications,” JapaneseJournalof AppliedPhysics,vol.59,no.SG,Apr.2020.doi: 10.35848/1347‐4065/ab75b9.

[7] N.Leuning,S.Steentjes,andK.Hameyer,“Effect ofMagneticAnisotropyonVillariEffectin Non‐orientedFESIElectricalSteel,” International JournalofAppliedElectromagneticsandMechanics,vol.55,pp.23–31,Oct.2017.doi:10.3233/ja e‐172254.

[8] M.Yamagashira,S.Ueno,andD.Wakabayashi etal.,“VectorMagneticPropertiesandTwo‐DimensionalMagnetostrictionofVariousSoft MagneticMaterials,” InternationalJournalof AppliedElectromagneticsandMechanics,vol.44, nos.3–4,pp.387–400,Mar.2014.doi:10.3233/ jae‐141801.

[9] E.Beyer,L.Lahn,andC.Schepersetal.,“The In luenceofCompressiveStressAppliedbyHard CoatingsonthePowerLossofGrainOriented ElectricalSteelSheet,” JournalofMagnetismand MagneticMaterials,vol.323,no.15,pp.1985–1991,Aug.2011.doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2011. 02.044.

[10] K.Fonteyn,A.Belahcen,andA.Arkkio,“Prop‐ertiesofElectricalSteelSheetsunderStrong MechanicalStress,” PollackPeriodica,vol.1,no. 1,pp.93–104,Apr.2006.doi:10.1556/pollack. 1.2006.1.7.

[11] P.Rȩkasetal.,“AMeasuringSetupforTest‐ingtheMechanicalStressDependenceofMag‐neticPropertiesofElectricalSteels,” Journalof MagnetismandMagneticMaterials,vol.577,p. 170791,Jul.2023.doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2023. 170791.

[12] P.Marketos,S.Zurek,andA.J.Moses,“AMethod forDe iningtheMeanPathLengthoftheEpstein Frame,”IEEETransactionsonMagnetics,vol.43, no.6,pp.2755–2757,Jun.2007.doi:10.1109/ tmag.2007.894124.

[13] D.‐X.ChenandY.‐H.Zhu,“EffectiveMagneticPath LengthinEpsteinFrameTestofElectricalSteels,”

ReviewofScienti icInstruments,vol.93,no.5, May2022.doi:10.1063/5.0084859.

[14] P.Rękas,T.Szumiata,andR.Szewczyketal., “In luenceofMechanicalStressesNoncoaxial withtheMagnetizingFieldontheRelative MagneticPermeabilityofElectricalSteel,” IEEE TransactionsonMagnetics,vol.60,no.8,pp.1–9, Aug.2024.doi:10.1109/tmag.2024.3418668.

[15] T.Szumiata,P.Rekas,andM.Gzik‐Szumiataet al.,“TheTwo‐DomainModelUtilizingtheEffec‐tivePinningEnergyforModelingtheStrain‐DependentMagneticPermeabilityinAnisotropic Grain‐OrientedElectricalSteels,” Materials,vol. 17,no.2,p.369,Jan.2024.doi:10.3390/ma17 020369.

[16] EN10107:2022Grain‐OrientedElectricalSteel SheetandStripDeliveredintheFullyProcessed State.doi:10.3403/30092684.

[17] “MutualInductor,” MutualInductorinElectrical Systems–MATLAB, https://www.mathworks. com/help/simscape/ref/mutualinductor.html (accessedAug.11,2024).

[18] “SimscapeElectrical,” SimscapeElectricalDocumentation,https://www.mathworks.com/help /sps/index.html(accessedAug.11,2024).

NONLINEAROPTIMALANDMULTI‐LOOPFLATNESS‐BASEDCONTROLOF

NONLINEAROPTIMALANDMULTI‐LOOPFLATNESS‐BASEDCONTROLOF

Submitted:25th October2023;accepted:24th April2024

GerasimosRigatos,MasoudAbbaszadeh DOI:10.14313/JAMRIS/4‐2024/29

Abstract:

Inthisarticle,thecontrolproblemforomnidirectional3‐wheelautonomousmobilerobotsissolvedwiththeuse of(i)anonlinearoptimalcontrolmethod(ii)aflatness‐basedcontrolapproachwhichisimplementedinsucces‐siveloops.Toapplymethod(i)thatisnonlinearopti‐malcontrol,thedynamicmodeloftheomnidirectional 3‐wheelautonomousmobilerobotsundergoesapprox‐imatelinearizationateachsamplinginstantwiththe useoffirst‐orderTaylorseriesexpansionandthrough thecomputationoftheassociatedJacobianmatrix.The linearizationpointisdefinedbythepresentvalueofthe system’sstatevectorandbythelastsampledvalueof thecontrolinputsvector.Tocomputethefeedbackgains oftheoptimalcontrolleranalgebraicRiccatiequation isrepetitivelysolvedateachtime‐stepofthecontrol algorithm.Theglobalstabilitypropertiesofthenon‐linearoptimalcontrolmethodareproventhroughLya‐punovanalysis.Toimplementcontrolmethod(ii),that isflatness‐basedcontrolinsuccessiveloops,thestate‐spacemodeloftheomnidirectional3‐wheelautonomous mobilerobotisseparatedintochainedsubsystems,which areconnectedincascadingloops.Eachoneofthese subsystemscanbeviewedindependentlyasadifferen‐tiallyflatsystemandcontrolaboutitcanbeperformed withinversionofitsdynamicsasinthecaseofinput‐outputlinearizedflatsystems.Thestatevariablesof thepreceding(i‐th)subsystembecomevirtualcontrol inputsforthesubsequent(i+1‐th)subsystem.Inturn, exogenouscontrolinputsareappliedtothelastsubsys‐tem.Thewholecontrolmethodisimplementedinsuc‐cessiveloopsanditsglobalstabilitypropertiesarealso proventhroughLyapunovstabilityanalysis.Theproposed methodachievestrajectorytrackingandautonomous navigationfortheomnidirectional3‐wheelautonomous mobilerobotswithouttheneedofdiffeomorphismsand complicatedstate‐spacemodeltransformations.

Keywords: omnidirectional3‐wheelautonomousmobile robots,autonomousnavigation,differentialflatness properties,nonlinearoptimalcontrol,flatness‐based controlinsuccessiveloops,globalstability

The3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobotisaspe‐cialtypeofroboticvehiclethatiscapableofperform‐ingmotioninalldirectionsofthehorizontalplane withoutnonholonomicconstraints[1‐4].

Ithasthreedegreesoffreedomassociatedwiththe cartesiancoordinatesofitscenterofgravityinthehor‐izontalplaneandwithitsorientation(heading)angle withrespecttothehorizontalaxisofaninertialcoor‐dinatesframe[5–7].Itsactuationcomesfromthree DCmotorswhichmakethewheelsofthemobilerobot turnatthespeci iedspeed[8–10].Suchmobilerobots canbedirectedpreciselyalongcomplicatedpathsand haveimprovedmaneuverability[11–14].Toachieve controlofsuchrobotsandtheirautonomousnaviga‐tionalongspeci ictrajectories,suitablevaluesforthe turnspeedofthewheelshavetobereachedwhich inturnareassociatedwithspeci icvoltageinputsof itsmotors[15–17].Omnidirectional3‐wheelmobile robotsaremetinseveralapplicationsassociatedwith patrollingandsecuritytasks,cleaninganddisinfecting tasks,withthetransferofproductsinwarehousesand withautomateddeliverytasks,aswellaswithseveral agriculturaltasksforinstancespraying,weedingor harvesting[18–20].Omnidirectional2‐wheelmobile robotshavenonlinearandmulti‐variabledynamics andso‐farseveralnonlinearcontrolmethodshave beenproposedaboutthem[21–25].Incertaincases autonomousnavigationof3‐wheelomnidirectional mobilerobotshasbeenbasedonstateestimation‐basedcontrolorvisualservoing[26–29].Thepresent articledevelopsandteststwonewcontrolmethods forthedynamicmodelof3‐wheelomnidirectional mobilerobots.Thesemethodsare(i)anovelnonlinear optimalcontrolapproach,(ii)a latness‐basedcontrol approachwhichisimplementedinsuccessiveloops. Bothcontrolschemesavoidchangesofstatevariables inthedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheelmobilerobotas wellascomplicatedtransformationsofthestatespace modelofthissystem.

Inthe irstcontrolmethodwhichisproposedby thepresentarticle,thatisnonlinearoptimalcontrol, thedynamicmodeloftheomnidirectional3‐wheel mobilerobotundergoesapproximatelinearization through irst‐orderTaylorseriesexpansion[30–31]. Thelinearizationprocesstakesplaceateachsampling instanceandcomputestherobot’sJacobianmatrices aroundatemporaryoperatingpointwhichisde ined bythepresentvalueofitsstatevectorandbythelast sampledvalueofthecontrolinputsvector[32–34].

Themodellingerrorwhichisduetotruncationof higher‐ordertermsintheTaylorseriesexpansionis consideredtobeaperturbationwhichisasymptot‐icallycompensatedbytherobustnessofthecontrol algorithm.Fortheapproximatelylinearizedmodelof theomnidirectionalrobotanH‐in initycontrolleris de ined.Thiscontrollerrepresentsamin‐maxdiffer‐entialgametakingplacebetween(i)therobot’scon‐trolinputswhichtrytominimizeacostfunctionthat containsaquadratictermofthestatevector’strack‐ingerrorand(ii)themodeluncertaintyandexoge‐nousperturbationtermswhichtrytomaximizethis costfunction.Tocomputethecontroller’sfeedback gainsanalgebraicRiccatiequationhastoberepeti‐tivelysolvedateachtime‐stepofthecontrolalgorithm [35–36].Theglobalstabilitypropertiesofthiscon‐trolschemeareproventhroughLyapunovanalysis. Ata irststagetheH‐in initytrackingperformance criterionisshowntoholdwhichsigni iesrobustness tomodeluncertaintyandperturbations.Moreover, undermoderateconditions,globalasymptoticstabil‐ityisproven[37–38].Thenonlinearoptimalcontrol methodachievesfastandaccuratetrackingofrefer‐encesetpointsbythestatevariablesofthemobile robotundermoderatevariationsofitscontrolinputs. Besides,itachievesminimizationofenergydispersion bytheactuatorsoftheomnidirectionalautonomous vehicleandtheimprovementofthisrobot’sautonomy andoperationalcapacity.

Inthesecondcontrolmethodwhichisproposed bythepresentarticle,thatis latness‐basedcontrolin successiveloops,itisshownthatthedynamicmodel ofthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobotcanbe decomposedintosubsystemswhichareconnectedin chainedform[36].Inthischainedstate‐spacedescrip‐tionthestatevariablesofthesubsequent(i+1‐th)sub‐systembecomevirtualcontrolinputsinthepreced‐ing(i‐th)subsystem.Additionally,thevirtualcontrol inputsofthepreceding(i‐th)subsystembecomeset‐pointsforthesubsequent(i+1‐th)subsystem[39–40]. Itisalsoproventhateachoneofthesesubsystems, ifviewedindependently,isdifferentially lat.Thusit canbeconcludedthattheindividualsubsystemsare input‐outputlinearizableandastabilizing latness‐basedcontrollercanbedesignedforeachoneofthem throughinversionoftheirdynamics,asitiscommonly doneforinput‐outputlinearizedsystems.Thereal controlinputswhichareappliedtothemobilerobot arecomputedfromthelastsubsystem.Startingfrom it,thechainedstate‐spacedescriptionofthemobile robotistracedbackwards,thatisfromthelastto the irstsubsystem,withineachsamplingperiod.The globalstabilitypropertiesofthiscontrolmethodare proventhroughLyapunovanalysis.The latness‐based controlmethodissuboptimalinthesensethatitdoes nottargetexplicitlyattheminimizationofthevari‐ationsofthecontrolinputsoftherobot,howeverit alsoachievesprecisetrackingofreferencetrajecto‐riesinthe2Dplanebythe3‐wheelomnidirectional autonomousvehicle.

Thestructureofthepaperisasfollows:(i) inSection 2 thedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheel omnidirectionalmobilerobotisanalyzedandthe associatedstate‐spacemodelisformulated.In Section 3 anonlinearoptimalcontrollerisdesigned forthedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheelomnidirectional mobilerobotbasedonthecomputationofthesystem’s Jacobianmatrices.InSection4amulti‐loop latness‐basedcontrollerisdesignedforthedynamicmodel oftheautonomousroboticvehicleafterdecomposing itsstate‐spacemodelintosubsystenswhichare connectedinchainedformandwhichindependently satisfydifferential latnessproperties.InSection 5 simulationtestsareperformedtofurthercon irmthe ineperformanceofthetwoaforementionedcontrol methods.Finally,inSection6concludingremarksare stated.

2.DynamicModelofthe3‐wheelOmnidirec‐tionalMobileRobot

2.1.State‐spaceDescriptionofthe3‐wheelOmnidirec‐tionalRobot

Thediagramofthe3‐wheelomnidirectional mobilerobotisgiveninFigure1.Thediagramdepicts theposition(��,��)ofthecenterofgravityofthemobile robotinthehorizontalplaneandtherobot’sheading angle ��.Besides,thetwocoordinateframeswhich areusedinthede initionoftherobot’skinematic anddynamicmodelaregiven,namelythebody‐ ixed referenceframe ������������ andtheinertialreference frame ������������.Theparametersofthedynamic modeloftherobotareoutlinedinTable1[1],[3]:

Thedynamicmodelofthemobilerobotisgivenby [1],[3]:

(1)

Thedisturbancesvector ��=[����,����,����]�� com‐prisesfrictionforcesthustakingtheform ��= [��1̇��,�� 2̇��,�� 3��]��.Thecontrolinputsvectoris ��= [��1,��2,��3]��.Theinertiamatrix��isgivenby

TheCoriolismatrix��isgivenby

Thecontrolinputsgainmatrix��isgivenby

Figure1. Diagramofthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobotandtheassociatedinertialandbody‐fixedreference frames

Table1. Dynamicmodelof3‐wheelomnidirectionalrobot

Parameter

De inition ��=[��,��,��]�� robot’spositionandorientationininertialframe ̇��=[̇��,̇��, ��]�� robot’slinearandangularvelocityininertialframe ̈��=[̈��,̈��, ��]�� robot’slinearandangularaccelerationininertialframe �� gearsreductionratiobetweenthemotorsandthewheels �� radiusofthewheelsoftheomnidirectionalrobot �� massoftheomnidirectionalrobot ��

momentofinertiaofwheel,gearandmotor

motors’torqueandbackEMFconstants

momentofinertiaforrobot’srotationaroundtheverticalaxis ���� radiusoftherobot’scylindricalsection ���� viscousfrictioncoef icientofwheel,gearandrotorshaft ��

wherecoef icients��0,��1,��2 arede inedas

Theinverseoftheinertiamatrix��isgivenby

resistanceofthemotors’armature

ThenfromEq.(1)onehasthefollowingstate‐spacedescription:

Afterintermediateoperations,thestate‐space descriptionofthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalrobot

Thestatevectorofthe3‐wheelomnidirectional robotisde inednextas

��3 (11)

andusingthisnotation,thedynamicmodelofthe mobilerobotiswrittenas

Thedynamicmodeloftheomnidirectional3‐wheelmobilerobotcanbealsowritteninthenonlin‐earaf ine‐in‐the‐inputstate‐spaceform ̇��=��(��)+�� 1(��)��1 +��2(��)��2 +��3(��)��3 (12) where��∈��6×1 ,��(��)∈��6×1 ,����(��)∈��6×1 and����∈�� for ��=1,2,3.Aboutvectors��(��)and����(��)��=1,2,3one hasthat

2.2.DifferentialFlatnessofthe3‐wheelOmnidirec‐tionalMobileRobot

Thedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheelomnidirec‐tionalmobilerobotthatwasgiveninEq.(11)isdiffer‐entially lat,with latoutputsvector��=[��1,��2,��3]�� or��=[��,��,��]��.Indeedfromthe irstthreerowsof thestate‐spacedescriptionofEq.(11)oneobtainsthat

(15)

whichsigni iesthatstatevariables��4,��5,��6 arediffer‐entialfunctionsofthe latoutputsvector��.Moreover, fromthelastthreerowsofthestate‐spacemodelof thesystemonehasthat

Themodellingerrorwhichisduetothetruncation ofhigher‐ordertermsfromtheTaylorseriesisconsid‐eredtobeaperturbationwhichisasymptoticallycom‐pensatedbytherobustnessofthecontrolalgorithm. Theinitialnonlinearstate‐spacemodelofthesystem ofEq.(14)intheforṁ��=��(��)+��(��)�� ,isturnedinto theequivalentlinearizedstate‐spaceform

�� (17) where�� isthecumulativedisturbancesvectorwhich maycomprise(i)modellingerrorduetothetrunca‐tionofhigher‐ordertermsfromtheTaylorseries,(ii) exogenousperturbations,(iii)sensormeasurement noiseofanydistribution.TheJacobianmatricesofthe systemaregivenby:

Thelinearizationapproachwhichhasbeenfol‐lowedforimplementingthenonlinearoptimalcontrol schemeresultsintoaquiteaccuratemodelofthesys‐tem’sdynamics.Considerforinstancethefollowing af ine‐in‐the‐inputstate‐spacemodel

wherealltermsthatappearintherightpartofEq. (16)aredifferentialfunctionsofthe latoutputsvec‐tor,consequentlythecontrolinputs ��1, ��2, ��3 are alsodifferentialfunctionsofthe latoutputsvector�� Therefore,theentiredynamicmodelofthe3‐wheel omnidirectionalmobilerobotisadifferentially lat system.

Thedifferential latnesspropertyisanimplicit proofofthesystem’scontrollability,aswellasofits input‐outputlinearizability.Italsoallowsforsolving thesetpointsde initionproblem.

3.1.ApproximateLinearizationoftheDynamicsofthe 3‐wheelOmnidirectionalRobot

Thedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheelomnidirec‐tionalmobilerobotundergoesapproximatelineariza‐tionaroundthetemporaryoperatingpoint (��∗,��∗) whichisde inedateachsamplinginstantbythe presentvalueofthesystem’sstatevector ��∗ andby thelastsampledvalueofthecontrolinputsvector ��∗.Thelinearizationprocessisbasedon irst‐order Taylorseriesexpansionandonthecomputationofthe associatedJacobianmatrices.

(20) where ��1 isthemodellingerrorduetotruncationof higherordertermsintheTaylorseriesexpansionof ��(��) and ��(��).Next,byde ining ��=[∇����(��)∣��

Moreoverbydenoting ��=−����

)��

+��1 aboutthecumulativemodellingerror termintheTaylorseriesexpansionprocedureonehas ̇��=����+����+ �� (22) whichistheapproximatelylinearizedmodelofthe dynamicsofthesystemofEq.(14).Theterm��(��∗)+ ��(��∗)��∗ isthederivativeofthestatevectorat(��∗,��∗) whichisalmostannihilatedby−����∗ . TheJacobianmatricesofthelinearizedmobile robotarecomputedasfollows:

ComputationoftheJacobianmatrix

ComputationoftheJacobianmatrix

Ateverytimeinstantthecontrolinput ��∗ is assumedtodifferfromthecontrolinput��appearing inEq.(27)byanamountequalto Δ��,thatis ��∗ = ��+Δ�� �� =������ +����∗ +��2 (28)

Thedynamicsofthecontrolledsystemdescribed inEq.(27)canbealsowrittenas ̇��=����+����+���� ∗ −����∗ +��1 (29)

andbydenoting ��3 =−����∗ +��1 asanaggregate disturbancetermoneobtains

∗ +��3 (30)

BysubtractingEq.(28)fromEq.(30)onehas

(31)

Bydenotingthetrackingerroras��=��−���� and theaggregatedisturbancetermas����=��3 −��2,the trackingerrordynamicsbecomes

(32)

ComputationoftheJacobianmatrix

where��isthedisturbanceinputgainmatrix.Forthe approximatelylinearizedmodelofthesystemastabi‐lizingfeedbackcontrollerisdeveloped.Thecontroller hastheform

(33)

with ��= 1 �� ������ where �� isapositivede initesym‐metricmatrixwhichisobtainedfromthesolutionof theRiccatiequation[30]

(25)

ComputationoftheJacobianmatrix

00 000000

(26)

3.2.StabilizingFeedbackControl

Afterlinearizationarounditscurrentoperating point(��∗,��∗),thedynamicmodelofthe3‐wheelomni‐directionalmobilerobotiswrittenas[30]

1 (27)

Parameter ��1 standsforthelinearizationerror inthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobot’smodel appearingpreviouslyinEq.(27).Thereferenceset‐pointsforthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobot’s statevectoraredenotedby���� =[���� 1,⋯,���� 6].Tracking ofthistrajectoryisachievedafterapplyingthecontrol input��∗

Thepreviouslyanalyzedconceptaboutthenonlin‐earoptimalcontrolloopforthethree‐wheelomnidi‐rectionalmobilerobotisgiveninFigure2 where��isapositivesemi‐de initesymmetricmatrix. WhereastheLinearQuadraticRegulator(LQR)isthe solutionofthequadraticoptimalcontrolproblem usingBellman’soptimalityprinciple,H‐in initycon‐trolisthesolutionoftheoptimalcontrolproblem undermodeluncertaintyandexternalperturbations. Thecostfunctionthatissubjecttominimizationinthe caseofLQRcomprisesaquadratictermofthestate vector’strackingerror,aswellasaquadraticterm ofthevariationsofthecontrolinputs.Inthecaseof H‐in initycontrolthecostfunctionisextendedwith theinclusionofaquadratictermofthecumulative disturbanceandmodeluncertaintyinputsthataffect themodelofthecontrolledsystem.

Inthecaseofthe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobile robot,thevehicle’sdynamicmodelisnonlinearand isalsoaffectedbyuncertaintyandexternalperturba‐tions.Byapplyingapproximatelinearizationtothe3‐wheelomnidirectionalmobilerobot’sdynamicsone obtainsalinearstate‐spacedescriptionwhichissub‐jecttomodellingimprecisionandexogenousdistur‐bances.Therefore,onecanarriveatasolutionofthe relatedoptimalcontrolproblemonlybyapplyingthe H‐in initycontrolapproach.

Figure2. Diagramofthenonlinearoptimalcontrolschemefortheomnidirectionalthree‐wheelmobilerobot[Source: Authors’ownwork]

ItisalsonotedthatthesolutionoftheH‐in inity feedbackcontrolproblemforthe3‐wheelomnidi‐rectionalmobilerobotandthecomputationofthe worstcasedisturbancethatthiscontrollercansustain, comesfromsuperpositionofBellman’soptimality principlewhenconsideringthattherobotisaffected bytwoseparateinputs(i)thecontrolinput��(ii)the cumulativedisturbanceinput ��(��).Solvingtheopti‐malcontrolproblemfor �� thatisfortheminimum variation(optimal)controlinputthatachieveselimi‐nationofthestatevector’strackingerrorgives ��= 1 �� ��������.Equivalently,solvingtheoptimalcontrol problemfor ��,thatisfortheworstcasedisturbance thatthecontrolloopcansustaingives��= 1 ��2��������.

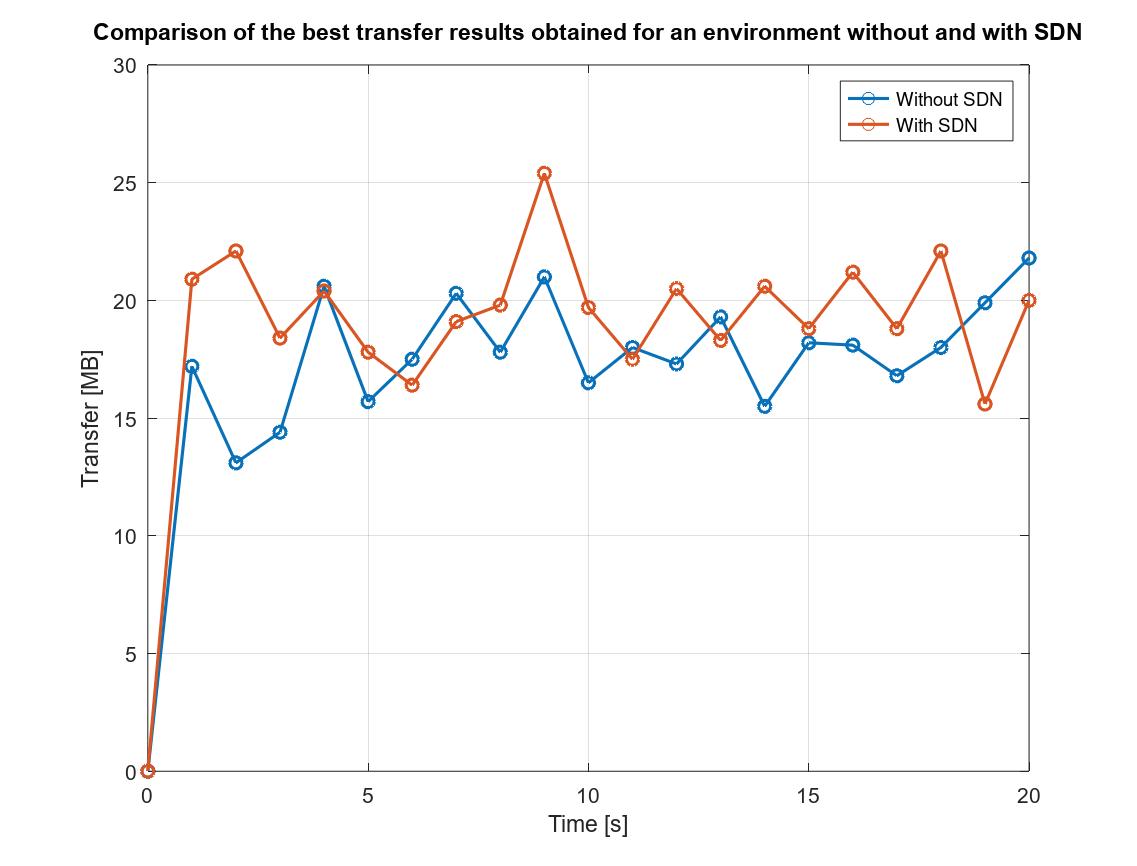

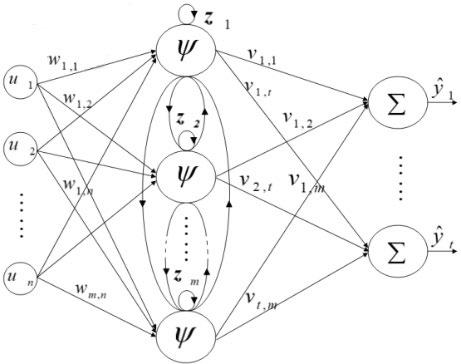

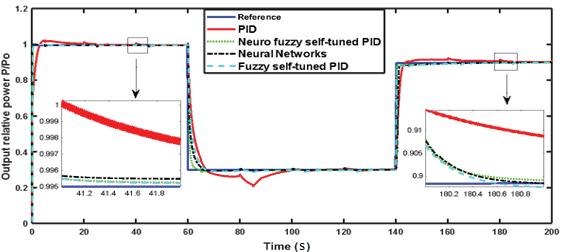

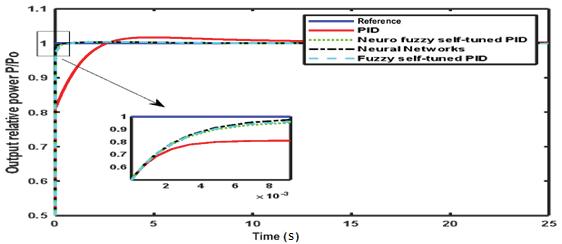

3.3.LyapunovStabilityAnalysis