ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

COVER SHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2022-2023

PROGRAM: Projective Cities, Taugh MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

NAME: Alison Bartlett

SUBMISSION TITLE: RESONATE BEASTS

DEMYSTIFYING THE ROMANTICIZATION OF THE FRENCH-CANADIAN IDENTITY

COURSE TITLE: Dissertation

COURSE TUTOR: Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi

DECLARATION:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student:

Date: 24 April, 2023

impurity of Englishness. It is the point of contingency, where the proper and the aproper — the appropriated — are brought into tension and architectural markings become imbued with a symbolic order, enabling the construction of identity to embody a mythic form. An underlying issue to defining the French Canadian and Quebecois nation is the shifting conceptualization of the pure French identity with the plurality of the rapidly modernizing and globalising Canada. Questions of national identity, sovereignty and Quebec’s place in Canadian federalism remain an ongoing issue.

Through a multi-scalar survey, three case studies—the wayside cross, the seigneury grid and the French-Canadian farmhouse— challenge the esteemed creed mummified by French-Canadians: Pays-Paysages-Paysans (Countries-Landscapes-Peasants) in which the nationalist party uses as leverage in the construction of French-Canadian identity.

The intention of this thesis is to reveal how ones that threaten the nationalist movement’s propaganda and are therefore silenced in attempt to hermetically embalm a romanticized ideal. It understands that space is never neutral and thus it should not be the intent. Rather than relegating the past to the past, Resonate Beasts proposes gestures of re-articulation per case study: formal re-readings of architectural artefacts influenced by the critical art practices of Donald Judd, Francis Alys and Gordon Matta-Clark who in their own regards, address themes of monumentality, mythmaking, and materiality.

The three projective re-readings of the wayside cross, the seigneury grid and the French-Canadian farmhouse serve not to break the symbolic order perpetuated within the French creed, but to complicate it, to poke holes in it, to fragment and shatter it with the aim of a never-ending process of engaging new subjectivities, re-articulating concealed histories and demystifying the proper by tarnishing the pure.

To quote William Butler Yeats’ poem3, The Second Coming: Turning and turning in the widening gyre; The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.

3. The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats / Turning and turning in the widening gyre / The falcon cannot hear the falconer; / Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, / The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and /everywhere / The ceremony of innocence is drowned; / The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity. /Surely some revelation is at hand; / Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are / those words out / When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi / Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert / A shape with lion body and the head of a man, / A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, / Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it / Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. / The darkness drops again; but now I know /That twenty centuries of stony sleep / Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, / And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The following document Resonate Beasts should not be read in any conclusive or absolutist resolution. Rather, it is a compendium of rehearsals,1 of re-enactments, that occupy—in reciprocal negotiation—two states: that of the observer and that of the actor. The role of the observer encompasses the gathering of research materials: images, drawings, land surveys, biographies and other archival documents that begin to inform the narrative, or in this case, the narratives. On the other hand, the role of the actor proceeds to re-read these distilled narratives, offering new means of representation, of gestural re-articulations.2

This investigation is, at its most fundamental, an inquiry into subject-object relationships within the context of nationalist rhetoric and instrumentalization. It is interested in identifying the symbols and deconstructing the mechanisms employed by nationalist movements that propagate an idealized—a romanticized—image. Such agendas mobilize a regime of representation that ultimately permits a singular objective narrative to hold hostage over the subjects’ experiences.

Therefore, this thesis intends to deconstruct the process of romanticization in relationship to the construction of nationalist ideologies, which intrinsically inform cultural identity and by association, the status quo. This document will not provide an absolute resolution by designing a new symbol, building or urban plan, as this would inevitably result in falling victim to yet another colonial projection or re-placqeuification . Rather, it offers a space of mediation—of rehearsal—to poke holes in and fragment the symbolic whole in pursuit of the representing new subjectivities.

1. Jean-Louis Barrault “The Rehearsal the Performance.” Yale French Studies, no. 5, 1950, doi:https:// doi.org/10.2307/2928918, 3, Where Barrault notes the difference between a performance and a rehearsal as “During the rehearsals, all problems must be faced and solved. In the performance, each problem must have been solved. The performance is a happening. It is the intrinsically poetic moment; the moment when, with the spectators’ presence contributing the final drop, the chemical precipitate appears.” He notes that it is the period of facing unsolved problems in real-time, rather than those already solved where, “Now is the time for mapping things out, for discipline and construction.”

2. Miessen, Markus, and Zoë Ritts. Para-Platforms : On the Spatial Politics of Right-Wing Populism. Sternberg Press, 2018, Mahmoud Keshavarz. Sketch for a Theory of Design Politics, 13-15. Keshavarz suggests the definition of articulations as a link between two different elements, binding incongurencies, they are materially embedded in the processes of social and political formations that have become engrained in a certain preferred combination through history over time. Situating linkages is an important term, because it is introducing possibility between two, previously considered, heterogeneous element.

projects, with zero tolerance for adaptation to the present. They become inflated in states of heightened threat that ultimately result in a process of perpetual romanticization. These projects are reliant upon symbols within the physical environment, what Jacques Ranciere calls the Distribution of the Sensible,2 in which physical artefacts—aesthetic carriers—inform the perceiver with the logic of power structures; those that are represented and those that are Other than. Certain aesthetic carriers become instrumentalized within nationalist agendas; becoming symbols of rejection of adaptation and plurality; of Otherness. They become symbols of a romanticized past, indulgent for an ideal that can never be returned to, which inevitably always leads to failure.

French-Canadian Identity Crisis3

Resonate Beasts looks at this phenomenon with particular focus on the longstanding crisis in Quebec, Canada. It is an instance of struggle for cultural preservation—hardly a novel concept—since Quebec’s own internal colonizing efforts in the mid-nineteenth century to suppress England’s usurpation of power in 1759, claimed during a thirty-minute battle in Quebec City’s Plains of Abraham. Since 1534, the French established reign marked by Jacques Cartier with a nine-meter-tall wooden cross on the eastern coast of Canada, known today as Gaspé, of which held a plaque with three lilies and a declaration that read “Vive Le Roi De France.” In the two centuries of reign over the territory established as New France, the indoctrination of land, class and economy was imbued with French values. It is these values of sacramental pureness that came under threat when countered with the impurity of Englishness. This becomes the point of contingency where the proper and the aproper— the appropriated—are brought into tension and the creed Pays-Paysans-Paysages (Countries-Peasants-Landscapes) takes prominent form—in defying pride—of the true FrenchCanadian embodiment. The irony that must be mentioned, lies of course within the circumstances responsible for creating the idealized French-Canadian image: propagated within the artefacts of cooperating countries, the peasant lifestyle and the rural landscapes that all stand defiantly amongst the scars of a successful colonial project are, in effect, products of revocation. They represent the rescindment of the new English reign, facilitating a process of internal colonization that became so deeply ingrained into the culture that it remains, to the present

2. Jacques Rancière and Gabriel Rockhill. The Politics of Aesthetics

The Distribution of the Sensible. London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. Under this notion, it rejects a single authority that concerns itself with maintaining the status quo, suppressing other manners of acting, which he refers to as Othering. Those that are Other than, are not categorized within previously established and defined identities, places and spaces.

3. The term “French-Canadian Identity Crisis” is used throughout this document in context of the Canadian nationalist movement’s rhetoric, from their perspective of their own identity being threatened by the ascending authority of Others. It should by no means be understood as a binary issue between the French and the English. While historically, it was the English who first threatened the integrity and purity of the French culture, by today’s standards to assume a binary condition is a dangerous simplification. As many nationalities emigrated to Canada defining its multi-cultural demographic; and as the province of Quebec became home to those other than English or French speaking—known as an Allophone—”the English” becomes a representative term of “the Other;” in that their presence has the potential to tarnish the French-Canadian virtue. The state of crisis and Quebec’s relationship with it is rigorously analyzed in Ian Morrison’s Moments of Crisis: Religion and National Identity in Quebec.

4. Ian A. Morrison. Moments of Crisis, UBC Press, 1 Sept. 2019, 5-8.

5. Richard Foot. “Separatism in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia.” Accessed February 26, 2023, thecanadianencyclopedia.ca, 2019, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ article/separatism.

6. “The FLQ and the October Crisis,” The Canadian Encyclopedia.” 2022, Accessed February 26, 2023, www. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ timeline/the-flq-and-the-octobercrisis.

day, as the haunting ideal of what must be preserved and returned to; the beasts that continue to resonate.

Since the early nineteenth century, Québec has been in a state of crisis where the beginnings of French-Canadian nationalist groups, such as The Patriots, began to take form in political arenas, infusing questions of national identity, sovereignty and the place of Québec and French-Canadians within Canadian federalism and the remainder of North America. An underlying issue to defining the French-Canadian and Québécois nation is the shifting conceptualization of the pure, religious and traditional notions of French identity with the tarnished, secular and modernizing role in the globalization of Canada. The question at the root of these debates circles back to “the determination of the values of which the boundaries of pluralism, and therefore, belonging in Quebec are to be based. (…) It concerns the nature and limits of national identity and, therefore, of the nation itself.”4

In Québec’s vulnerable instability and melancholy for nationalism a sequence of contemporary revolts has plagued the nation since the 1950s when the separatist movement was re-established through subsidiary and fringe political groups.5 These groups continued to gain a proliferation of votes into the mid 1960s, with the most prominent being the FLQ, garnering notability in the October Crisis of 1970. It was the only instant during peacetime in Canadian history that the Armed Forces were deployed, imploring the War Measures Act to diffuse a tenuous year of terrorist attacks involving over 200 bombings, dozens of robberies, kidnappings and murders of the British trade commissioner and the cabinet minister.

This was the zenith of socio-political unrest that had been building since the early 1960s, a period referred to as “The Quiet Revolution,” which stood in vehement defense of conservative ideology, comprising of outdated traditional values that sought to preserve the purity of the French culture and language. Over the next few decades, various measures were passed in attempt to diffuse tensions and improve federal-provincial relations by establishing policies of official bilingualism at a federal level to dissuade nation-state rhetoric and encourage francophone participation into the remainder of Canada as a single united nation.6 However, tensions continued to be a strenuous presence and in 1991 the separatist movement established a political party

at federal level called Bloc Québécois. In the national electoral field, this meant Canada now had five parties of electoral influence. An underlying issue to defining the French Canadian and Quebecois nation is the shifting conceptualization within the relationship of religion and the secular to national identity. Until the mid-twentieth century, Catholicism had defined national identity and embedded the lived experience into relics that held onto the image of a cultural heritage. On November 7, 2013, the Charter Affirming the Values of State Secularism and Religious Neutrality and the Equality between Women and Men and Providing a Framework for Accommodation Requests...also known as the Charter of Values was introduced. This bill sought to accommodate pluralistic religious symbols and practices in the public sphere, a long-standing, tenuous debate since the early 1990s. It is this pluralistic state that opponents of the Charter of Values deem threatening to their national identity as FrenchCanadians. Today, this crisis can most overtly be seen through rigid preservation efforts in the passing of Bill 96 in May 2022, mandating a ‘French First’ language policy. This is enforced by the ‘Language Police,’ who ensure all social, governmental, and independent sectors abide ‘French first language laws’ and abstain from publicly displayed religious symbols and clothing. The ‘French First’ language policy penetrates the politics of the aesthetic field, not only through signage, but by literally making French heard on a daily basis.

While the October Crisis marks only the beginning of modern Quebec’s socio-political instability—as these issues persist today in varying deviations—it questions features of crisis that enable highly influential power structures to ascend on the premise of romanticization. Crisis can be understood as responding to a threat which inherently requires a concurrent acknowledgement of the established conditions with those it is rejecting. This means that the essential features that define the separatists’ movement are not always explicit but rather implicit in what is being revoked: globalization, secularization, plurality of which implies values of tradition, religion and hegemony.7 In the very declaration of crisis, this explicit-implicit relationship is triggered, destabilizing values in disproportionate potencies with associated physical artefacts.

The Process of Romanticization

It is in a moment of crisis where reconstitution is directly

7. Morrison. “Moments of Crisis,” 9-11

Fig. 003, Newspaper clipping discussing English and French Quebec and the insinuating language laws.

7. Morrison. “Moments of Crisis,” 9-11

Fig. 003, Newspaper clipping discussing English and French Quebec and the insinuating language laws.

Fig. 004, Newspaper article from the national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, articulating the residual effects of The October Crisis.

Fig. 004, Newspaper article from the national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, articulating the residual effects of The October Crisis.

Fig. 005, News bulletin for a national radio program discussing ongoing issues for English Quebec.

Fig. 005, News bulletin for a national radio program discussing ongoing issues for English Quebec.

8. Mark Cousins, The Ugly I, II, III. Arq Ediciones. 2020. Cousins builds on Lacan’s Object petit a and Freud’s psychoanalytic concept of the lost object, as one that is never recovered and rather in the process of searching a new object will surface, but it will never satisfy, thus inevitable failure, inciting a perpetual loop of desire of another chronological order.

9. Roland Barthes. “Mythologies.“ Points, 1957, 136

correlated to what is being undone. In this perpetual process of romanticization: of articulation, de-articulation and rearticulation, the nation is never reproduced in the identical form it seeks to return to. It craves the lost object,8 evoking a fantasized state in between the economy of desire (anchored in the past) and that which will satisfy (anchored in the present). This romanticized, idealized state survives off the mythic: becoming an enabler that short circuits the signifier and the signifier in favour of preserving the idealized—and consequently propagated status quo—image of nation, culture and identity. In its simplest form, myth is a means of communication, it is a mode of signification where the sign—a summation of the signifier and the signified—become disproportionate to that which it signifies.9 This new mythic entity suppresses and mutes the affiliation between the material object anchored in the present symbolic order and the extrapolated signification of the idealized past. This aversion to shifting meaning over time—the re-territorialization of the present—creates a gap that grows in every moment of crisis, in every revolt or political action; it enables a perpetual re-evaluation of terms that will never replicate the past but will always create something new. In attempt to close the gap, it becomes filled with romanticization, which produces an excess of meaning, of latent idealizations that will never attempt to close the gap of correspondence between the Symbolic and the Real, latent idealizations and present reality. Satisfaction will never be fulfilled.

This analysis therefore identifies three physical artefacts in the Quebecois landscape and urbanization of Montreal: the wayside cross, the seigneury grid and the French-Canadian farmhouse. Each are exemplary architectural artefacts enabling a two-fold investigation: first through addressing the process of romanticization—the larger theoretical framework—into themes of monumentality, mythmaking and material deadliness and second, by deconstructing the means by which the FrenchCanadian nationalist movement embed these artefacts into the production of a culture and identity. The wayside cross, seigneury grid and French-Canadian farmhouse, have become aesthetic carriers caught in the tropes of romanticization; instrumentalized in the separatist movement to preserve an idealized symbolic order of the past, the propagated true authentic identity of French-Canadians rooted in the creed Pays-Paysages-Paysans. This romanticization has prevented the nationalist movement from accepting the historical continuity and the adaptation of

meaning and in large part, the encompassment of secularization each artefact has come to adopt today. Therefore, it is not the intention to establish a new symbolic order, as it is cultural hegemony that has created this predicament and, as previously mentioned would fall victim to the colonial paradox of replacqueification. Rather, ResonateBeasts seeks to engage in what the nationalist party continues to avert: the re-territorialization of symbolic meaning through acts of re-articulations that challenge the romanticized mythic status quo of the pure French Canadian identity.

The thesis comprises three dossiers, each focused on the wayside cross, the seigneury grid and the French-Canadian farmhouse, which respectively address secondary themes of monumentality, mythmaking and material deadliness. Each dossier becomes a space of mediation that strings together moments of history into three acts of appropriation: the first act addresses the physical artefact in the initial appropriation of land by colonial France, the second act discloses their shift in spatialization and form as the English take reign and the province secularizes and globalizes, and the third act is the proposal; a projective re-reading of the artefact. Supported by a parallel narrative that looks to the critical art practices of Donald Judd, Francis Alys and Gordon Matta-Clark—who each question the role of representation and aesthetics—Resonate Beasts re-articulates the wayside cross, the seigneury grid and the farmhouse to engage with new pluralities that have historically been denied cultural adaptation under the premise of threatening the integrity of the romanticized FrenchCanadian identity; and hence continue to resonate.

COUNTRIES THAT CANNOT HOLD

THE WAYSIDE CROSS

(1534-PRESENT)

STATEMENT OF REIGN

THREE ACTS OF APPROPRIATION

ACT I

ACT II

ACT III

JACQUES CARTIER FOUNDS NEW LAND, MARKING FRANCE’S NEW TERRITORY AND REIGN WITH THE FIRST CROSS.

FARMERS ERECT THEIR OWN CROSSES DELINEATING ROADSIDE LANDMARKS, PROPERTY LINES & FUTURE PARISHES. NEW SYMBOLS ARE ADDED,SHIFTING THE OBJECT INTO SECULARIZED TERMS.

THE WAYSIDE CROSS IS RE-READ THROUGH ACTS OF DUPLICATION TO ENCOMPASS THE OBJECT’S FORMAL AND SYMOBLIC MUTATIONS.

1. Sensual cues as per Rancière, includes not only those within the visual field, but also smell, sound, taste.

2. In Rancière’s, “The Distribution of the Sensible,” defines the status quo as the sensual authority that informs the cultural logic.

ACT I

THE WAYSIDE CROSS

(1534-PRESENT)

STATEMENT OF REIGN

3. Lucas Van Rompay, et al. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II.” UNC Press Books, 1 July 2015, p. Chapter 5: Quebec’s Wayside Crosses and the Creation of Contemporary Devotionalism, 180

The monument, monumental and monumentality are pertinent themes amongst the subject-objecthood relationship in the context of nationalism; where nation building is informed through, in part, by sensual1 cues, aesthetic carriers that enforce a singular political ideology and by default, mechanisms of representation advising the status quo.2 This is the construction of a singular reality, a universalism filtered through the preferences of a single agency enabling a “colonial projection” that continues to fuel contemporary battles over objects in the public arena today. The wayside cross, in even its most stable of circumstances, was always an object in flux,3 an object of monumental power and resonance that became deeply entangled in the tropes of romanticization.

JACQUES CARTIER FOUNDS NEW LAND, MARKING FRANCE’S NEW TERRITORY AND REIGN WITH THE FIRST CROSS.

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

Fig. 007, Jacques Cartier’s route in the Bay of Gaspé and marking of new territory with a wooden cross measuring 9 m tall. The crew had initially sought initially for shelter from a storm and with fortuity, discovered land, known today as eastern Canada. The 1534 exploration did not result in any further territorial discoveries on their return route back to Saint-Malo, France.

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Jacques Cartier’s return route to France. The 1534 exploration did not result in any further discoveries or territorial claims.

Fig. 007

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Fig. 008, Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspé, signaling allegiance between the two territories under the reigning power of the King of France, Francis I.

Fig. 009, An etching of an drawing, “drawn on the spot” by Cap. Hervey Myth of Miramichi, a french settlement in the Gulf of SaintLawrence.

Fig. 009, An etching of an drawing, “drawn on the spot” by Cap. Hervey Myth of Miramichi, a french settlement in the Gulf of SaintLawrence.

Ancestral Origins

Under the direction of the King of France, Francis I, a wooden cross was first mounted upon Jacques Cartier’s successful expedition in 1534 westward to the New World. Twenty days after leaving his home port of Saint-Malo in Brittany, France, the crew came across the rocky territory of what is known today as Gaspé, on the eastern coast of Canada. Formally, these two perpendicular wooden posts stood at nine meters tall and bore two plaques. The first was a shield of three fleurs-de-lys (white lily) a symbol of French royalty denoting perfection, light and life,4 while the second, “Vive le Roi de France” was a declaration to the longevity of the King of France. In honour of their new colony, the same wooden cross was mounted at Cartier’s departing port in Saint-Malo. Symbolically, the sum of these components was united in representing French reign over a new colony and territory, one that would endure for the next two centuries.

The French-Canadian national myth understands the Quebec Croix-de-Chemin, Path of Crosses, to be associated with their distant ancestral heritage that goes beyond Jacques Cartier and his first marking of land with a singular cross, extending into the region of Brittany, France, from where he hailed.5 However, the marking of land with crosses wasn’t only practiced in France, but throughout all of Catholic Europe. They were popularized in the thirteenth century, originally being made of stone, wood or iron and carved with ornamentation. In the fifteenth century, professional artisans were hired to depict symbols from the passion of Christ and Jesus’ crucified body was slowly incorporated onto the object. It was not until the French were defeated in 1759, in which England took reign that the French Quebec elites became sharply aware of their vulnerable position; to the potential reality of the French-Canadian identity becoming obsolete.6 The wayside cross was first documented in the 1896 issue of the Bulletin des Recherches Historiques, proposing these wooden crosses as the “perfect encapsulation of religious nationalist ethos.”7 The wayside cross became instrumental in propagating French identity, “rooted in a romantic vision of the peasant farmer—simple, unchanging and catholic”8 that provided symbolic reinforcement throughout the Quebec landscape of the French-Canadian people. In part, this spurred a construction boom of wayside crosses across Quebec throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

4. Serge Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” UBC Press, 2007. ProQuest Ebook Central, https:// ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aaschool/detail.action?cID=3412619, 90

010,

5. Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II,” 177-178.

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. Ibid

The cross in Gaspé is therefore, by no means, seen as a blight of colonial imposition but is celebrated as a symbol of historical significance and serves a fundamental role in Canada’s heritage.

In 1934, in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Jacques Cartier’s landing, the Historic Sites and Monuments of Canada commissioned by the Government of Canada, revealed a monolithic granite cross standing ten meters tall and weighing over forty-two tons. A team of artisans carved the cross from a single block of granite in a quarry across from Quebec City called Riviere-a-Pierre. The cross travelled by rail for over twelve hours before it reached its destination on Queen Street in downtown Gaspé, across from the Place Jacques-Cartier business center. The raising of the cross involved a ceremonious effort incorporating a team of horses and tractors to operate the pulley and cable system. It has subsequently been relocated twice but stands, since 2012, at its new commemorative site at the water’s edge near the Gaspé bridge with an honorary plaque, “Gaspé, Cradle of Canada” instilling the—otherwise irrelevant—town and cross together as a prominent place in Canadian history.

It is important to note the style and material that was chosen for the commemorative replicative cross at Gaspé, did not take influence from Quebec’s respective wayside crosses that had, by 1934, experienced a huge construction boom and scattered the rural landscape but rather, resembled those in Brittany, France. Meanwhile, the wooden cross at the port of Saint-Malo still stands today in its original form.

Fig. 011, Image of the pulley and chain system mounting the new monolithic granite cross marking the 400th anniversary of Cartier’s landing. Since the cross’ first location in downtown Gaspe across from the Jacques Cartier business center, it has since moved twice. Today it sits on the water’s edge, near the Gaspe bridge. Fig. 012, An old postcard featuring a photo of the 400th anniversary monolithic granite cross, overlooking its third and current position at the water’s edge near the Gaspé bridge.

Fig. 012, An old postcard featuring a photo of the 400th anniversary monolithic granite cross, overlooking its third and current position at the water’s edge near the Gaspé bridge.

1. A rural grouping of houses

2.

THE WAYSIDE CROSS

(1534-PRESENT)

STATEMENT OF REIGN

ACT II

FARMERS ERECT THEIR OWN CROSSES DELINEATING ROADSIDE LANDMARKS, PROPERTY LINES & FUTURE PARISHES. NEW SYMBOLS ARE ADDED, SHIFTING THE OBJECT INTO SECULARIZED TERMS.

While the cross in Gaspé stands in questionable pride of France’s colonial assertion, the object nevertheless proliferated as parishes and civilians saw its symbolic importance as motivation to raise their own. Between the 1870s and 1950s, there was a widespread resurgence of wayside cross construction throughout rural Quebec that was in response to three circumstances. The first two reasons for the raising of crosses during this period were direct influences from Europe that sought, firstly, to commemorate the founding of a new parish or school and, secondly, to protect against disease, death, forest fires, drought and agricultural pests. The third reason is unique to Quebec and a consequence of the widely dispersed agricultural settlements, which prevented families of a rang1 from visiting the parish church on a regular basis.2 Therefore, the crosses were raised at more convenient and accessible intervals that served as a

Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II,” 178 FLEUR-DE-LIS Fig. 014, Quebec’s national flower, the fleur-de-lysproxy for rangs to gather for prayers. The crosses were adorned with instruments of the Passion such as the ladder, the lance, the Sacred Heart, a rooster and an abstracted sun (sometimes depicted as a circle), taken from the crown of thorns. They were unique from those in Europe, through their white coating of paint and low position to the ground often in an encircled garden. The crucified body of Jesus was absent, which may be a consequence of Quebec’s lack of funding and artisanal sources compared to those in Europe rather than an intentional choice.3 Today, there are nearly three thousand crosses throughout rural Quebec, with twenty-six classified as historical monuments.

The wayside cross became a prolific symbol amongst the Laurentian territory as individual farmers and families mounted their own alongside the roads and in front of their houses. However, in the perpetual attempt to return to the idealized object anchored in the past—the object with lost significance and exists therefore as a resonance, a beast of the past—a new one will always be created.4 In this string of continuous replications, holding the symbolic order always in its romanticized state, mutations start to incur where new symbols are formed, old ones lost and inevitably create a new object, a kind of exalted Frankensteinian monument. Styles and symbols changed, where for instance the literal depiction of popular devotion to the Sacred Heart became abstracted into a stylized heart; the cross continued to move further away from Christian devotion and started to adopt agricultural piety. Ultimately, the crosses came to be associated with le seigneur (the Lord; owner of the land and management of the peasants) and were honoured as protection against climate devastations, poor health and unexpected death.5 Even as the semi-feudal system was abolished in 1854 (where in the British system Crown land could only be acquired through petition to the Governor),6 devotion to the seigneur was transferred onto the prosperity of the land. The month of May was traditionally known in religious contexts as the Month of Mary, where residents of rangs would gather to pray a novena, a nine-day devotion, or if a priest was available, to hold a mass. However, these prayers were largely focused on the prosperity of the land and plantings. It is during this period, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that the crosses started to shift from objects of colonial France indoctrinated through the Catholic institution to demonstrations of agricultural prosperity. A survey taken in 1970, reinforces this changing demographic that revealed over eighty percent of prayers were focused on

Fig. 015, The rooster on the wayside cross symbolizing Intruments of Passion.

4. Mark Cousins, The Ugly I, II, III. Arq Ediciones. 2020. Cousins builds on Freud’s psychoanalytic concept of the lost object, is never recovered and rather in the process of searching a new object will surface, but it will never satisfy, thus inevitable failure, inciting a perpetual loop of desire of another chronological order.

Fig. 016, The ladder on the wayside cross symbolizing Intruments of Passion.

3. Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II.” 180 5. Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II,” 183 6. “Welcome to the Quebec Family History Society.” Accessed 7 Mar. 2023. www.qfhs.ca.

Fig. 018, An illustration of a painting by H. Bunnet of the Farm of Saint Gabriel. The wayside cross is depicted to be prominently visible to passers-by. The original painting is in the McCord Museum in Montreal.

Fig. 018

Fig. 018, An illustration of a painting by H. Bunnet of the Farm of Saint Gabriel. The wayside cross is depicted to be prominently visible to passers-by. The original painting is in the McCord Museum in Montreal.

Fig. 018

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

Fig. 019

Fig. 019, Map demonstrating the location of the wayside crosses known as the Croix de Chemin (the Path of Crosses) along the Saint-Lawrence river.

Jacques Cartier’s return route to France. The 1534 exploration did not result in any further discoveries or territorial claims.

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

the concerns of the land and the sustenance of the approaching harvest season.7 This entanglement between religion and a more secularized agricultural devotion heightened abruptly as the twentieth century approached the decade leading up to the October Crisis in 1970. The 1960s were known as the Quiet Revolution, in which the tensions surrounding secularization garnered inescapable attention as the province experienced rapid urbanization and secularization. This required disentangling the Catholic institution from its historical role integral to the operation of affairs amongst civil society in rural areas, entailing the transference of healthcare, education and local politics to be managed by state-led institutions.

HAMMER ROOSTER

Fig. 020, The hammer on the wayside cross symbolizing Intruments of Passion.

ENCLOSURE

PLINTH HAMMER ROOSTER FLEUR-DE-LIS SUN PLIERS ENCLOSURE

Fig. 021, The pincers on the wayside cross symbolizing Intruments of Passion. Drawn by author

FLEUR-DE-LIS SUN PLIERS LADDER

HAMMER ROOSTER

In this moment of post-October Crisis—in the deep affectual field of Quebec’s Catholic malaise—a process known as patrimonialisation incurred, where past religious objects evolve into the cultural heritage (through a kind of retrospective awareness); and symbols that once reinforced the Catholic institution’s propagations were no longer property of the Church. Instead, religious objects and rituals became integrated as immaterial heritage in the shift towards a collective secular identity. As infrastructure continued to modernize into the late twentieth century, many wayside crosses were knocked down in the widening and repaving of roads. Along with the forces of natural decay and a weakened devout population, these objects began to disappear.8 However, under the notions of patrimonialization, the wayside cross held greater importance to the Quebecois, not as a religious object, but as a secularized symbol deeply ingrained into their cultural heritage and identity. Under the nationalist agenda, the symbolic order becomes confused between its potentiality of engaging with new subjectivities anchored in present symbolic order to include secular or other religious demonstrations and being relegated to its singular past. Threatened by a de-territorialization of the present (a rupture in the Symbolic), the separatist hysteria propagates the latter— in fear of the French Catholic distinction becoming conflated with and diffused into a secular cultural heritage—rescinding any potential symbolic mutation. This continued aversion between the past symbolic order and that of the present, which is ever evolving in the attempt to return to the old object, bequeaths an inescapable gap of excess meaning that can only be filled through the process of romanticization. The process inherently perpetuates further romanticization in the attempt to preserve the ancestral French Catholic past: simple, traditional peasant

8. Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II,” 175, “They were numerous once, these croix du chemin/ It was a sign of faith, from the people who came from France / Today, we have forgotten these croix du chemin/ like a wounded being, they attract pity”

Fig. 022, The lance on the wayside cross symbolizing Intruments of Passion. Drawn by author

7. Van Rompay. “The Long Shadow of Vatican II,” 180farmers—the object of lost significance, the beast of the past that continues to resonate.

However, the wayside cross that seeks to exist in the modernising and secularizing Quebec is not completely neglected. In the late 1990s, in an issue of the local community paper, there was a call for caretakers to help restore the crosses. The caretakers see the crosses as objects for everyone, “every practice of faith, for peace and community” a kind of spirituality that is exempt from religious practice. In this entwinement of religion that is so fundamental to defining the French-Canadian identity, the caretakers have become the force that closes the gap and anchor it in the present in compatibility with Quebec’s evolving modernization into the twentieth century. The role of the wayside cross and its monumental power began to engage other subjectivities than Jacques Cartier’s projected colonial reign, transitioning in meaning for who and what it represented.

ENCLOSURE

(index_e html)

(index_e.html) (mbb0000e.html) (mbp0000e.html) (mbf0000e.html) (mbh0000e.html) (mby0000e

28. Fig. 026-039 are photographs from Edouard Zotique Massicotte’s documentation of wayside crosses across the Quebecois countryside

3e html) print();)

Wayside cross with fleur-de-lis endpoints, adorned with a sun and a heart at its axis, a rooster on top and other devices. Saultsaux-Récollets,

YOUR COUNTRY. YOUR HISTORY. YOUR MUSEUM.

https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/barbeau/mb0715be.html

Québec, [191-]. © CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, B557-6.27, CD2004-1257 © Canadian Museum Fig. 026, Papineauville, Quebec, 1992 Fig. 027, Saults-aux-Recollets, Quebec, 191- Fig. 026

028

Civilization.ca - Marius Barbeau(index_e html)

bp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

Fig. 029

Fig. 030

Fig. 028, Saint-Telesphore, Quebec, year N/A

Fig. 029, Saint-Joseph-du-Lac, Quebec, 191-

Fig. 030, Replica, Grand-Pre, Quebec, 2008

Wayside cross with clover endpoints and niche on axis Saint-Joseph-du-Lac, Québec, [191-]. © CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, B557-5.38, CD2004-1254 FRANÇAIS2/7/23, 10:36 AM

Fig. 031, Replica, Saint-Janvier-deWeedon, Quebec, date N/A

Fig. 031

Civilization.ca - Marius Barbeau(index_e html)

Civilization.ca - Marius Barbeau(index_e html) (mbb0000e html) (mbp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(index_e html) (mbb0000e html) (mbp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

Fig. 032, Quebec, 1925

Fig. 033, Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec, 1827

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

Fig. 032

Fig. 033

© Canadian Museum of History

Jubilee cross with fleur-de-lis endpoints, sun on axis and bearing the inscription, «Hommage au Christ Rédempteur», 1925. © CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, 66357, CD96-763-0030(mbp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

mbp0213e html)

window print();)

©

HISTORY.

2/7/23, 10:34 AM Civilization.ca - Marius Barbeau(index_e.html)

© Canadian Museum of History

BACK TO EXHIBITIONS

(index_e html) (mbb0000e html) (mbp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window.print();)

Wayside cross with fleur-de-lis endpoints, 1925.

© CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, 66350, CD96-763-0029

HISTORY.

© Canadian Museum of History

(index_e html)

(index_e.html)

(index_e html) (mbb0000e html) (mbp0000e html)

0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(mbp0213e html)

pt:window print();)

Wayside

2/7/23, 10:37 AM

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

(mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

Metal wayside cross with fleur-de-lis endpoints and rooster on top Bécancour, Québec, 1924.

© CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, 60023, CD96-707-0001

YOUR COUNTRY. YOUR HISTORY. YOUR MUSEUM.

Civilization.ca - Marius Barbeau(index_e html)

© CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, 62868, CD96-731

FRANÇAIS

BACK TO EXHIBITIONS

(index_e html) (mbb0000e html) (mbp0000e html) (mbf0000e html) (mbh0000e html) (mby0000e html)

(mbp0213e html)

(javascript:window print();)

© Canadian Museum of History

https://www.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/barbeau/mb0724be.html

.historymuseum.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/barbeau/mb0729be.html

YOUR COUNTRY. YOUR HISTORY. YOUR MUSEUM.

© CMC/MCC, Edouard Zotique Massicotte, 65797, CD2002-140-014

1/1

© Canadian Museum of History

1/1

cross in Saint-Eustache, just erected, Québec, 1923.

1. New as defined by Mark Cousins, building on Lacan’s Object petit a and Freud’s lost object Mark Cousins, is never recovered and rather in the process of searching for the old object, a new object one will inevitably surface, but it will never satisfy. This inevitable failure, incites a perpetual loop of desire of another chronological order.

ACT III

THE WAYSIDE CROSS

(1534-PRESENT)

2. Cousins. “The Ugly,” 29-34, Where Cousins refers to the negative topography of the rejected existences, in the continuous search for the object of desire.

THE WAYSIDE CROSS IS RE-READ THROUGH ACTS OF DUPLICATION TO ENCOMPASS THE OBJECT’S FORMAL AND SYMOBLIC MUTATIONS.

In each attempt to resurrect the old object, with the embedded desire of the idealized object anchored within Jacques Cartier’s monumental wooden cross, new1 iterations were formed. It began to adopt new subjectivities that welcomed secularization and religions beyond Catholicism. This meaning anchors itself in the present day however is denied by the French nationalist movement as it is perceived as a new, foreign object, seeking to undermine the preservation of the idealized French-Catholic ancestry and ultimately dilute French-Canadian identity. But in fact, the categorization of the new does not ever exist. The new can only be understood as an absence of the old, that which is no longer there brought only into presence when countered with an alternative. This informs a negative topography2 of haunting pasts that are denied existence in the present symbolic order, while concurrently informing its very production.

Fig. 040

Fig. 040

3. Tadeas Riha, Roland Reemaa, Linsi Laura. “Weak Monument: Architectures Beyond the Plinth.” Park Books, 2018. 14

4. Pewter is a malleable metal alloy of varying proportions of tin, copper, antimony and bismuth. Softer than aluminum, it’s melting point is 247290 degrees Celcius compared to that of aluminum’s at 660.3 degrees Celcius

5. See Fig. 054-071

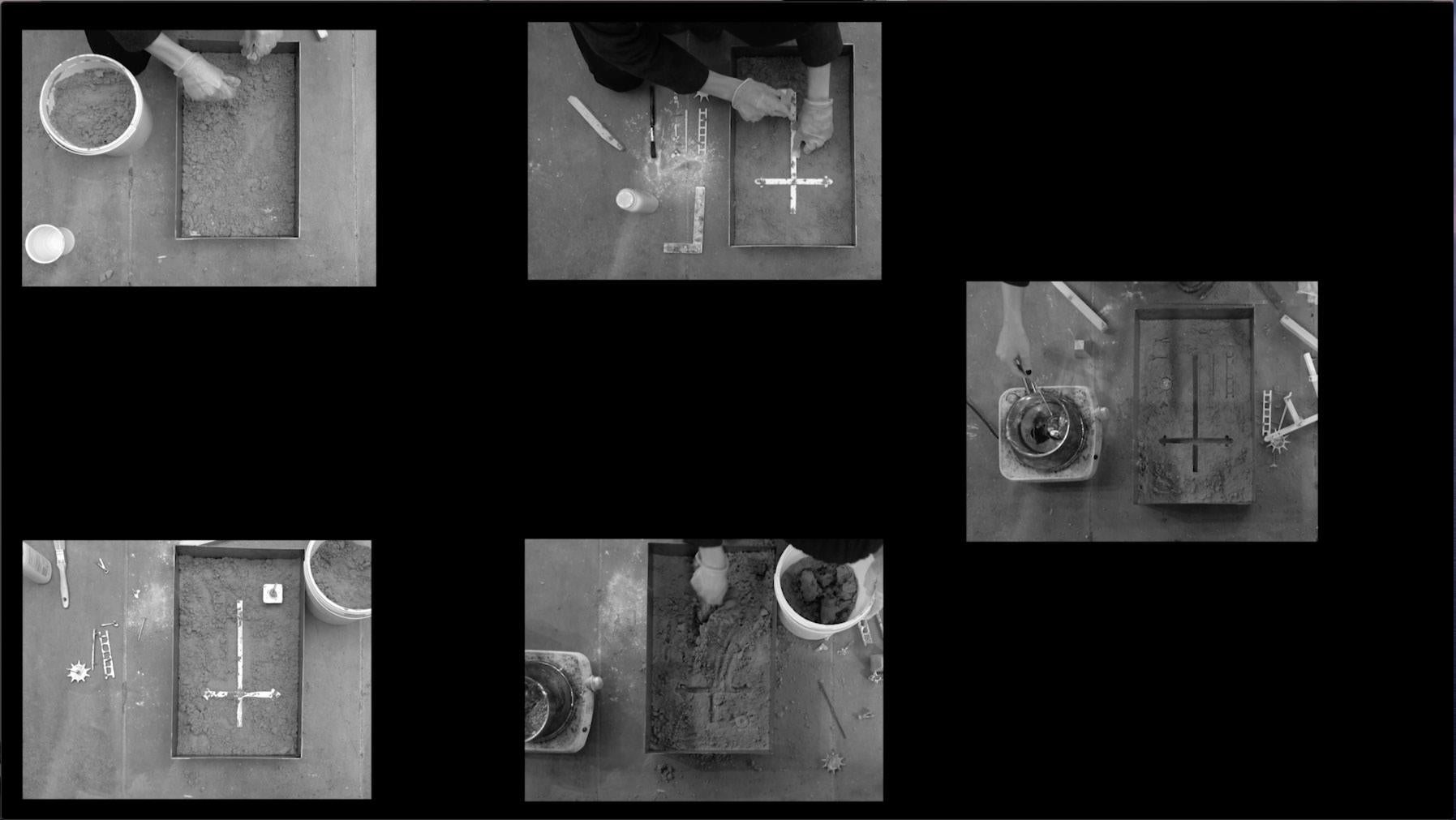

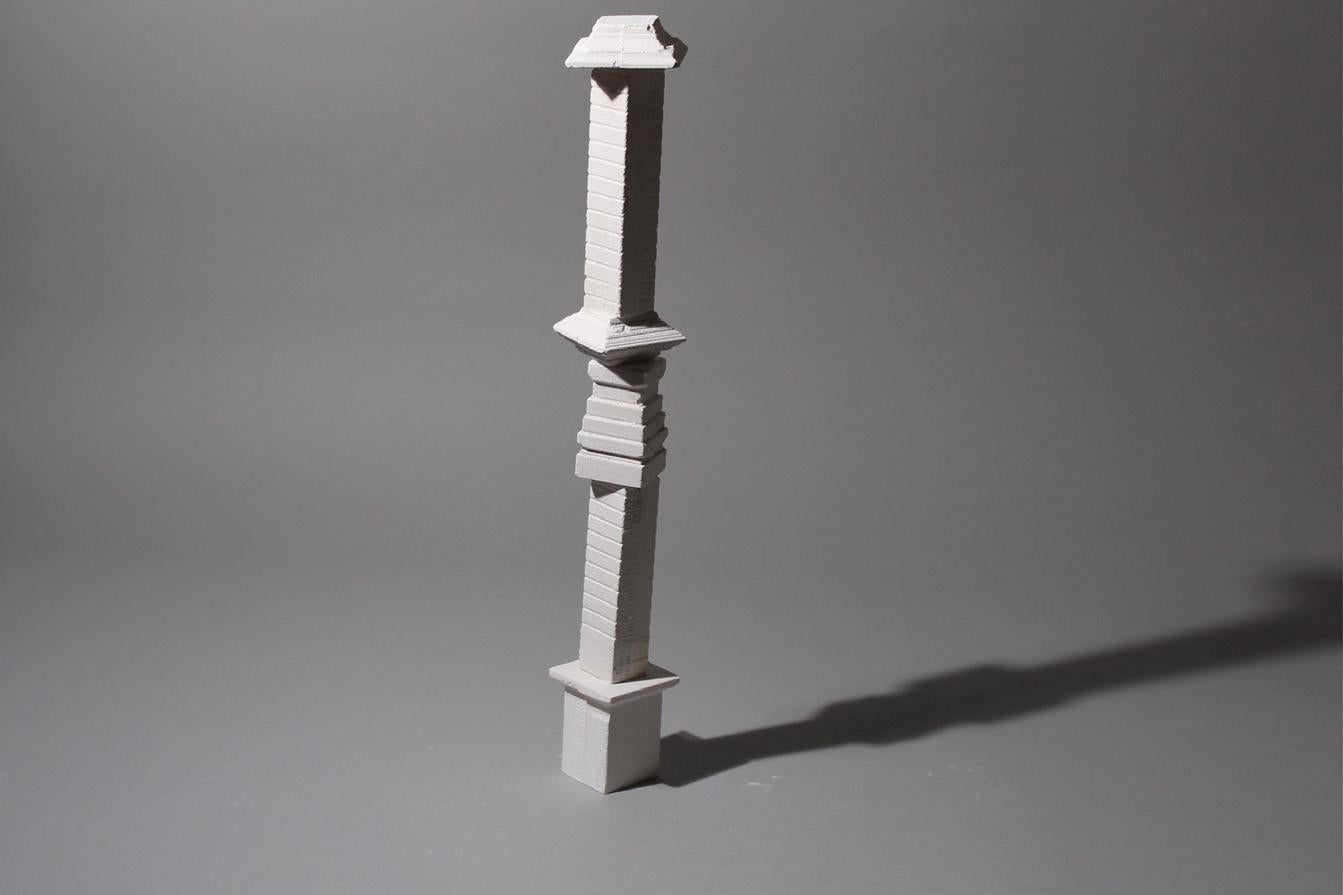

Therefore, Act III engages in a critical material re-reading of the wayside cross that enables the presence of old and new symbolic orders to be acknowledged through repetitions of renegotiation to address new subjectivities. It recognizes the old, not as an absence, but what informs the negative topography as a charged void “supported by the fragments of the original.”3 Through the act of sand-casting pewter,4 it seeks to materialize the inevitable failure with romanticization, in that the object of desire exists only in the regime of representation and in the repeated attempt to return to the old, something new will inescapably be made.

The following steps explain the process of sand-casting.5 The sand is imprinted with the object of desired production, creating the mould to pour the pewter and cast the object. This process is conducted repetitively, using the newly casted object to create the subsequent mould, imprinting the old in the sand to inform the new. However, it is quickly realized that in the object’s attempt to replicate its predecessor, a mutation will always occur, breaking the romanticized hegemonic ideal and shifting the agency to the subject; ultimately engaging in new subjectivities that are inherently informed by its predecessor. The moulds, the imprints in the sand create a negative topography that become equally important to the positive object.

Fig. 042

Fig. 042

Fig. 043, Step 5. Acquire enclosure of minimum cast dimension

Fig. 044, Step 7. Pack sand into acquired enclosure spread sand across surface area & pack in thin layers until a firm base is formed

Fig. 045, Set of instructions, steps 1 through 10.

Fig. 043, Step 5. Acquire enclosure of minimum cast dimension

Fig. 044, Step 7. Pack sand into acquired enclosure spread sand across surface area & pack in thin layers until a firm base is formed

Fig. 045, Set of instructions, steps 1 through 10.

Fig. 046, Set of instructions, steps 12 through 15 and re-casting steps 7 through 10 x2

Fig. 046

Fig. 046

Fig. 048, Step 8 : Brush object with talk & firmly press into sand

Fig. 049, Step 10 Remove object from sand via pull mechanisms

Fig. 051, Step 13 Once pewter is melted, pour into sand mould to cast object

Fig. 050

Fig. 048, Step 8 : Brush object with talk & firmly press into sand

Fig. 049, Step 10 Remove object from sand via pull mechanisms

Fig. 051, Step 13 Once pewter is melted, pour into sand mould to cast object

Fig. 050

Fig. 053, Step 14 : Once cool enough to touch, remove. The mould is now reaady to re-cast.

Fig. 052

Fig. 053, Step 14 : Once cool enough to touch, remove. The mould is now reaady to re-cast.

Fig. 052

Fig. 054

Fig. 055

Fig. 056

Fig. 054, min. 0.01

Fig. 054-071 Documents 18 stills at 5 second intervals capturing the process of casting and re-casting to produce four pewter casted wayside crosses, each a mutation of each other.

Fig. 055, min. 0.05

Fig. 054

Fig. 055

Fig. 056

Fig. 054, min. 0.01

Fig. 054-071 Documents 18 stills at 5 second intervals capturing the process of casting and re-casting to produce four pewter casted wayside crosses, each a mutation of each other.

Fig. 055, min. 0.05

Fig. 057

Fig. 058

Fig. 059

Fig. 057, min. 0.15

Fig. 058, min. 0.20

Fig. 057

Fig. 058

Fig. 059

Fig. 057, min. 0.15

Fig. 058, min. 0.20

Fig. 0.60

Fig. 061

Fig. 062

Fig. 0.60, min. 0.30

Fig. 061, min. 0.35

Fig. 0.60

Fig. 061

Fig. 062

Fig. 0.60, min. 0.30

Fig. 061, min. 0.35

Fig. 063

Fig. 064

Fig. 065

Fig. 063, min. 0.45

Fig. 064, min. 0.50

Fig. 063

Fig. 064

Fig. 065

Fig. 063, min. 0.45

Fig. 064, min. 0.50

Fig. 0.66

Fig. 067

Fig. 068

Fig. 0.66, min. 1.00

Fig. 067, min. 1.05

Fig. 0.66

Fig. 067

Fig. 068

Fig. 0.66, min. 1.00

Fig. 067, min. 1.05

Fig. 069

Fig. 070

Fig. 071

Fig. 069, min. 1.15

Fig. 070, min. 1.20

Fig. 069

Fig. 070

Fig. 071

Fig. 069, min. 1.15

Fig. 070, min. 1.20

Fig. 76, First sandcasted pewter wayside cross and objects

Fig. 76, First sandcasted pewter wayside cross and objects

Fig. 077, Second sandcasted pewter wayside cross in casting sand

Fig. 078, Third sandcasted pewter sundial

Fig. 079, Fourth sandcasted pewter ladder

Fig. 077

Fig. 078

Fig. 077, Second sandcasted pewter wayside cross in casting sand

Fig. 078, Third sandcasted pewter sundial

Fig. 079, Fourth sandcasted pewter ladder

Fig. 077

Fig. 078

NOTES ON MONUMENTALITY THROUGH DONALD JUDD

The definition of the monument, monumental, monumentality1 has changed drastically from the eighteenth to twentieth century. Historically, monuments were created in honour of historical events, places or people. They were conceived of higher ideals including sovereign worship and a documentation of the nation’s achievements, subsequently informing places of commemorative rituals.2 This was the context in which Jacques Cartier planted a nine meter-tall wooden cross in honour of the King of France, Francis I, a monument to the French reign that became deeply embedded within French-Canadian symbolism, reverberating throughout the Laurentian territory in the form of an object that would come to be known as the wayside cross.

Over the course of the twentieth century however, the meaning of the monument became embedded with negative connotations, entangled in national rhetoric and political misuse, where

1. For the purpose of this discussion, these three terms are used intermittently as per description requires

2. Heike, Hanada. “Monumental_Public Buildings at the beginning of the 21st century.” Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther Konig. 2021. 91

3. Ibid.

4. J. L. Sert, F. LŽger, S. Giedion. “Nine Points on Monumentality 1943.” Academia.edu, 2019, www.academia. edu/19870956/Nine_Points_on_ Monumentality_1943

5. The affectual field is a concept developed on the premise of Rossi’s urban artefact instilled with collective memories activating the ‘city as a theatre.’ This allows for introspection and access to multiple subjectivities, rather than one agential preference

6. Hanada. Monumental, 23

7. Hanada. Monumental, 91

8. As per German architect and academic Heike Hanada

9. MOMA. “Donald Judd. Untitled, 1969.” MOMA. Accessed March 08, 2023. www.moma.org/audio/3946. Judd disagrees in the interview that his work should be considered within the minimal art movement.

10. Donald Judd. “Donald Judd Writings.” Judd Foundation, 1975. Specific Objects, 1965,134-145

Fig. 082, Judd’s Untitled 1969, Untitled 1991 & Untitled 1989, xerox copied, acetone trasferred collage

“monuments of the past emerged from a fusion of idea and form rather than from social and political conditions.”3 The topic of monumentality did not escape modernist architectural discourse and in the later part of the twentieth century included the likes of Giedion’s ‘Nine Points of Monumentality,’4 Rossi’s recurrent urban artefact, Rem’s bigness or Venturi/Scott-Brown’s semiotic readings, each respectively addressing methods of reading an architectural object’s formal and symbolic conditions. In other words, it became an object of instrumental power to nationalist projects that sought to hold hostage over the affectual field: the potentiality of introspection that allows access to a multiplicity of memories and histories.5 In an environment already fraught with contempt over monumentality’s entanglement with fascist ideology, it only became exacerbated by modernism’s failure, further cementing notions of “anti-democratic aggrandisement and political claim to power, so much that an open discourse cannot take place.”6 The meaning of the monument underwent a transformation “into quite an unspecific object and one instrumental in constructing the identity of the modern state.”7 This is the point where, art and architecture distinguish themselves uniquely in approaching and comprehending monumentality.8 The protagonist of this historical break is the minimal art movement, in which Donald Judd—disapprovingly9—finds himself a part—and a critique—of. At the core of Judd’s work, he is questioning the relationship objects have with space; how the viewer is positioned and therefore how they are perceiving the object. He provokes themes of absence through degrees of visibility, colours, material and form.

These themes are expanded upon in his seminal 1964 essay, Specific Objects in which he critically analyses the future practice of art, questioning the very format and medium of his work and those of his peers. Through a deductive process, he describes the notion of a 3-Dimensional object: a singular thing, a whole entity (not a series of composites) that exists vulnerably in real space. It is not to be confined by a format, for instance the boundary of the canvas’ edge. It holds a relationship with its environment, whether that’s a wall, floor, ceiling…or nothing at all. As per Judd’s definition, the Specific Object is dependent upon the third dimension, the existence in real space, in order to remove the problem–the illusionary format—of the twodimensional canvas, of which his peers still use.10 Judd offers the subject a provisional agency to move around the object at their own will, enabling a sense of autonomy or as Michael Fried would

suggest, provides a sense of conviction: the ultimate success of art, holding the subject-object relationship in suspension and ultimately “accomplishes the dissolution of objecthood”11

Here Judd begins to flirt with themes of monumentality, not only in formality but in intentionality, when he refers to Marcel Duchamp’s drying rack as the purest example of a threedimensional object. The object becomes imbued with rhetoric, one that enables the subject’s potentiation of introspection (and thus the collapse of subject-object distinction). Through his use of voids, the specific object renegotiates objectivity’s hold on the subjective experience and offers potential for retaliation against conservative projections. While Judd’s essay is ultimately a critique of format and medium within the artistic practice in the late 1960s, it proves of worthy extrapolation in the attempt to address objects, such as the wayside cross, and the embedded monumental power activated by nationalist platforms to deny subjective experiences. If a “monument is a communication of societal values the society that has built them,”12 it must question how new mediums and formats of representation can deflate the symbolic propagations of the singular party to–as Judd’s specific object argues—return agency to the subject.

12. Hanada. “Monumental,” Essay by Adam Caruso. 100

Fig. 074 Marcel Duchamp’s bottle drying rack, 1914. Judd referes to this ready-made object as the ideal specific object

11. Michael W. Clune. “This Cannot Be Real: ‘Art and Objecthood’ at 50.” Nonsite.org, 17 July 2017, Accessed March 06, 2023. www.nonsite.org/ this-cannot-be-real/.

12. Hanada. “Monumental,” Essay by Adam Caruso. 100

Fig. 074 Marcel Duchamp’s bottle drying rack, 1914. Judd referes to this ready-made object as the ideal specific object

11. Michael W. Clune. “This Cannot Be Real: ‘Art and Objecthood’ at 50.” Nonsite.org, 17 July 2017, Accessed March 06, 2023. www.nonsite.org/ this-cannot-be-real/.

LANDS THAT CANNOT HOLD

THE SEIGNEURY

(1634-1854)

STATEMENT OF ECONOMY

FRENCH COLONIST COMPANIES BEGIN TO ARRANGE LAND INTO A CONTROLLED SEIGNEURIAL GRID SYSTEM ALONG THE SAINT-LAWRENCE RIVER

THE URBANIZATION OF MONTREAL DIVIDES THE LONG NARROW GRID SYSTEM INTO SQUARES AND PLAZAS THAT OFFICE TOWER BUILDINGS CONNECT TO VIA UNDERGROUND COMMERCE CHANNELS

THE LAND IS RE-READ BY SPATIALIZING FEUDAL TO CAPITALIST SYSTEMS OF LAND VALUATION THROUGH A COMPARISON OF HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL AXES AS QUEBEC BEGINS TO URBANIZE, GLOBALIZE, MODERNIZE

ACT I

THE SEIGNEURY

The Saint-Lawrence River enabled the success of the colonial companies’ “conquering” the land. Beyond serving as the initial trade route, it was the transportation corridor enabling settlement further inland (to what would later be developed into the Island of Montreal), while establishing key economic hubs. It was the driving force behind the orchestration of land that enabled the French to instill their European values into the harsh landscape of the Saint-Lawrence valley at the base of the Canadian Shield; a territory of granite rock sub-terrain, boreal forests covering the topographical plains. At first glance, it offered a barren landscape with a harsh climate and questionably arable land. The French however prevailed in their “conquering” of territory and began a series of irrevocable restructurings—appropriations— embedding European values into the creation of a mechanized landscape; one that proved to be a productive agricultural force

STATEMENT OF ECONOMYthat came to define the economy and society that still holds relevance today in its mythic entity.

Restructuring the Land

The seigneurial system was not officially introduced until 1628, almost a century after Cartier’s founding of New France, when the initial fur trade networks started to disintegrate for a system of a greater assertive colonial powers. In the early seventeenth century, France was concerned with domestic affairs (the Thirty Year’s War that held King Louis XIII’s attention) allowing small private companies to conduct their own lucrative fishing and fur trade businesses.1 Cardinal Richelieu, who held national reverence as a Catholic bishop and France’s secretary of state, installed two systems that would instill fundamental profits and control over New France, while concurrently asserting European values into the landscape. First, he merged one hundred merchants from hundreds of small private companies into a single entity, known as the Company of One Hundred Associates, which quickly established prominence: holding rights to land not only in New France, but longitudinally across the Americas from Florida to the Arctic. Over thirty years of operation, it came to distribute approximately seventy-four seigneuries, thus curtailing into Richelieu’s second installment. The seigneury2 was a semi-feudal system that operated under a multi-tiered power structure with the King of France, King Louis XIII, holding ultimate title-ship and the seigneurs (the lords) as local correspondents.3 This twofold presence proved to be the remedy King Louis XIII needed to first, pacify and populate the seigneurial fields and second, build a strong economic and social framework for rural colonization.4

Seigneurs were assigned long strips of land that measured on average three arpents.5 While the widths and lengths varied, all were defined by their fronteau—the front edge of the plot outlined by a road or waterway. The seigneur-habitant (lordpeasant) relationship not only informed one’s class and economy but the spatial settlement amongst the land. The first step in colonizing—”in making the land”6—into a European agriculture was to deforest the landscape.7 Trees were imbued with economic and symbolic meaning and became a defining element in the making of the land. From a utilitarian perspective, seigneurs felled timber for building mills and roads, in addition to the habitants’ needs to build homes, fences and provide heating. Many tense conflicts—sometimes resulting in the rearrangement of

1. “Company of One Hundred Associates.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed February 08, 2023. www. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/compagnie-des-cent-associes.

2. The seigneury was a standard land management practice under French regime over its new colonies, informing the settlements in Louisiana and New Oreleans to develop into the typological ‘Shot Gun’ houses

3. As the fishing and fur trade failed to sustain, so did the monopoly of the One Hundred Associates, and direct management of the land transitioned under control of French Crown.

4. Colin MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses of Landscape and Community in Early Quebec.” Internet Archive, Montreal [Que.] McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000, archive.org/details/metamorphosesofl0000coat/page/12/mode/2up, 49-53

5. Arpents were the French area metric, where 1 arpent is equivalent to roughly 3,418 square meters. When the English began surveying land in the 18th century, leagues became the new metric, where 1 league is equivalent to roughly 4,000 meters.

6. Serge Courville, Quebec : A Historical Geography, UBC Press, 2007. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest. com/lib/aaschool/detail.action?docID=3412619,174. From the beginning of French reign, colonization was understood by all as an opportuntiy to “make land” that wasn’t previously profitable.

7. MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 36

Fig. 084, Ship breaking through the frozen Saint-Lawrence River

Fig. 084, Ship breaking through the frozen Saint-Lawrence River

Fig. 085, The Saint-Lawrence valley sits at the bottom of the Canadian Shield, made of monolithic granite rock

Fig. 085, The Saint-Lawrence valley sits at the bottom of the Canadian Shield, made of monolithic granite rock

Fig. 086

Fig. 086, Archive image of cadastrals showing the value and ownership of land

Fig. 086

Fig. 086, Archive image of cadastrals showing the value and ownership of land

seigneurial boundaries—would arise in establishing the maximum travel distances to forested land. The distinction between these two land conditions was not only aesthetic, but also determined the value of taxable land. Cultivated land was the productive economic force with a tax valuation of fifty shillings per acre, while forested lands were only taxed at one shilling per acre. This valuation therefore provided a limit to the maximal extents one would be interested in deforesting.8

By the mid-seventeenth century, the gulf of the Saint-Lawrence was populated by a few thousand settlers, known amicably as “les habitants”9 whose homes were built no more than one and a half arpents in distance from each other. The land was further spatialized through the architectures of the habitant and manor estates, which created visible hierarchies: that of production and that of enforcement. The habitants lived close to the water’s edge—the fronteau—in proximity to the banal mill for productive efficiency, while the seigneur’s house was further inland. Land at the edge of the water quickly became the most valuable and foundational to social and economic organization. Consequently gristmills,10 built and maintained by the seigneur, became defining landmarks and productive elements of the seigneuries, dotting the edge of the Saint-Lawrence, secondary rivers or tributaries that extended much further into the landscape. By working the land, the peasants earned their keep, paying rent through agricultural produce.11 This semi-feudal system is how the French asserted their presence, in an urgent manner, defining the characteristics of the land that were reminiscent of old France and “reflected colonial officialdom.”12

The Idealized Landscape

While these economic and productive forces defined the SaintLawrence territory, they also indoctrinated the pacificated habitants with European ideologies of landscape that became deeply intertwined in French-Canadians’ own criteria of idealness, contending with any newcomer’s perspective. Documented in the late eighteenth century, British travelers along the SaintLawrence River commented “disparagingly on the lack of trees near the habitants’ homes. (…) the trees are all cut away around Canadian settlements and the unvarying habitations stand in endless rows, at equal distances (…) without a tree or even a fence of any kind to shelter them.”13 The effects of the French agricultural colonization not only fundamentally restructured the economy and labour field but instilled European values that came

8. MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 36

9. “Les habitants” refers to the farmers or peasants. However, it was a title they were honoured to have and deeply defined their identity. They are also referred to as the habitants in english.

10. The grist mills, used by the habitants to refine harvests, was colloquially referred to as the banal mill for its transactional exchange, sustaining the habitants’ livelihood.

Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 55

11. Colin MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 13

12. Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 91-92

13. Colin MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 37

Fig. 088, Landscape view of the seigneury plots in the SaintLawrence Valley

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

25 50 100 0 km

090

25 50 100 0 km

Jacques Cartier’s return route to France. The 1534 exploration did not result in any further discoveries or territorial claims.

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Upon Jacques Cartier’s return to Saint-Malo, they erected a replica of the cross at Gaspe signalling allegiance between the two territories under reigning power of the King of France

Fig.to define the mechanisms of class and identity that still informs ideals of the Quebecois picturesque landscape today, where “the practical labour of generations of habitants irrevocably altered the bases of society.”14 While, the life of the habitant involved laborious farming in objectively challenging geographic and climatic conditions, their status was not pejorative, rather their work and lifestyle was a source of fundamental pride. A strong sense of identity became associated with the life and lands of the habitant, instilling values of rural ideology: “love of work, simple pleasures and a quiet life echoing the rhythms of nature.”15

As the nineteenth century landscape began to show signs of industrialization under the new English reign, the picturesque rural landscape started to take mythic form as the prophesied utopia, beginning to embody the role of the protagonist in novels and paintings. Two novels in particular stand out as defining the cultural perspective at the time, Roman Paysan (Novel of the Land) and Charles Gurin. They are both built around prevalent themes of the time such as, “property lost to the English, the ruin of the family forced into urban exile and the privatization and chance restoration of property.”16 They demonized the English, who become vehemently associated with progress and modernization, tarnishing their picturesque landscape and way of life. This only provoked increased tension and divisiveness between the two cultures where, “if the French-Canadian ‘race’ wanted to survive and avoid being stripped of its arpents, it must stay on them, cleave to agriculture and Catholicism with patience and resignation.”17 This was further illustrated in the paintings of the Francophones. While landscape was a popular setting to paint among Francophones and Anglophones, they were depicted in vastly different ways. Francophones focused on rural settings, painting nature and open fields, home to “the famous colonization lands where the ecumene was created”18 and was portrayed as the achievement of ultimate beauty and balance. Conversely, the Anglophones painted the same rural landscape, yet rendered different qualities; one of industrialization, manufacturing and transportation that communicated a real sense of labour rather than leisure. It calls back into question the terms of which colonization is defined for the French, not as a negative imposition but as a positive potentiation associated with the agricultural development and the agrarian lifestyle, in that “colonization means the dedication to agriculture of a previous unoccupied ideal and generally wooded piece of land. Colonization creates new land.”19

14. Colin MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 12

15. Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 91-92

16. Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 163-164

17. Ibid.

18. Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 165

19. Courville. “Quebec : A Historical Geography,” 174

Fig. 091 Scale 1: 50. Map Chambly seigneurial plot with secondary fiefdoms. Settlements were kept close to the water for productive and thus economic value. Concession lines divided the land horinzontally away from the waterfront, losing value respectively.

Arts and literature became the mediums that enabled myth to sustain a stable breeding ground. As the utopian landscape of the habitants became tarnished through industrialization and urbanization, which was restructuring the Saint-Lawrence valley throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the French only became further entrenched in the past. Myth enables signification to become disproportionate to that which it signifies; it is a means of communication that silences the affiliation between the material object anchored in the present symbolic order and the extrapolated signification of the idealized past, of the picturesque agrarian landscape. Crystalized within cultural expressions such as novels and paintings, it is on the premise of myth that blinded the French from two factors that thrust the province of Quebec into economic downfall: first in their denial of the shifting labour force to meet new global market demands and second, of their own capitalist values embedded in their agrarian lifestyle. This ignorance and adoption of the shifting environment, welcome a period of intense retaliation and despair.

Fig. 093, “A Canadian Pastoral,” 1900 by Canadian painter Horatio Walker, depicting agrarian labour amongst the landscape.

Fig. 093, “A Canadian Pastoral,” 1900 by Canadian painter Horatio Walker, depicting agrarian labour amongst the landscape.

Fig. 094-099 Scale 1:200 A study of urbanization between the old city of Montreal compared to the still rural fields across the Saint-Lawrence River five decades

Fig. 094, Urbanization development 1655

Fig. 095, Urbanization development 1665

Fig. 096, Urbanization development 1675

Fig. 095

Fig. 094, Urbanization development 1655

Fig. 095, Urbanization development 1665

Fig. 096, Urbanization development 1675

Fig. 095

Fig. 097, Urbanization development 1685

Fig. 098, Urbanization development 1695

Fig. 099, Urbanization development 1705

Fig. 100, Seigneury settlement plan at the River of Jesus

Fig. 101, Seigneury settlement and mill plan at Mouline du Cap de Mardelaine

Fig. 100

Fig. 100, Seigneury settlement plan at the River of Jesus

Fig. 101, Seigneury settlement and mill plan at Mouline du Cap de Mardelaine

Fig. 100

Fig. 102, Seigneury settlement organization along the Saint-Lawrence River. Clearly showing concessions within fiefdoms and the plot’s frontage along a waterway

Fig. 102, Seigneury settlement organization along the Saint-Lawrence River. Clearly showing concessions within fiefdoms and the plot’s frontage along a waterway

Fig. 103, Seigneury settlements at St. Vincent du Paul

Fig. 103, Seigneury settlements at St. Vincent du Paul

Fig. 104 Seigneury settlements at St. Vincent du Paul

Fig. 104 Seigneury settlements at St. Vincent du Paul

Fig. 105, Seigneury settlements at Trois Rivieres

Fig. 106, Seigneury settlements at Hochelaga

Fig. 105

Fig. 105, Seigneury settlements at Trois Rivieres

Fig. 106, Seigneury settlements at Hochelaga

Fig. 105

Fig. 107

Fig. 108

Fig. 108, the Ramsay seigneuries

Fig. 107

Fig. 108

Fig. 108, the Ramsay seigneuries

THE SEIGNEURY

STATEMENT OF ECONOMY (1634-1854)

1. Courville. “Quebec A Historical Geography,” Time for change! was a reaction to the political tension and was focused on the urban population’s eagerness to “break with the past and embrace modernity,” 253

ACT II

THE URBANIZATION OF MONTREAL DIVIDES THE LONG NARROW GRID SYSTEM INTO SQUARES AND PLAZAS THAT OFFICE TOWER BUILDINGS CONNECT TO VIA UNDERGROUND COMMERCE CHANNELS

62. Colin MacMillan Coates. “The Metamorphoses,” 164

“Le temps que ca change!”1 is an appropriate exclamation of the rapid period of change Quebec experienced in mid-twentieth century, shifting an agricultural land to an industrial one. After the conquest of the British claimed power in the battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, the idealized landscape underwent a series of changes that shifted the means of production and the value of land. The English not only lacked the skills to maintain the farmland, but also the interest. The rural ideologies that thrived under a semi-feudal system began to weaken in the authoritative presence of the new industrial, capitalist urbanization. The status of the agrarian lifestyle was in a vulnerable state and tensions between the two modes of existence only spurred the “intertwinement of French-Canadian nationalistic sentiment and agrarian economic potential.”2 The abolishment of the seigneury system into crown land was not completed in one instance, but

through a series of episodic movements, it was finally eradicated into a structural resolution in 1935. As changes to the landscape became further institutionalized, tensions only grew between the French and the newcomers, which was premised on an innate sense of ignorance to a changing world.

Internal Colonization Efforts

The period post WWI marks the first wave of industrialization, in which the province witnessed rapid industrial growth with “manufacturing driving the economy at the expense of the countryside.”3 A rural exodus began as urban city centers started to develop into two primary cities, Montreal and Quebec City. In fear of losing not only their labour forces but preservation of their cultural identity, Quebec’s colonization department attempted to re-occupy these vacating farmlands through three assistant programs between 1932-1938. These programs clearly evidence and reinforce the degree of threat the francophones felt under the new English authority. While the hypocrisy may seem evident by today’s terms, in that French-Canadian identity is a by-product of colonization, the cultural power of myth allows for an impaired awareness. The French did not understand the process of colonization to be exploitive but rather a positive force—“the making of land”—that encouraged productive landscapes aligned with agrarian values.