PRECARIOUS WATERS

Spatializing Agency among Dispossessed Fisher Women of Lake Chilika

(cover image) - fig. 001: Earth Observatory. NASA. MODIS Land Cover. [Chilika Lake and Nalabana Bird Santuary].

March 19, 2014.

PRECARIOUS WATERS

Spatializing Agency among Dispossessed Fisher Women of Lake Chilika

Amy Brar MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design Projective Cities 2021/23

To Nani and Mom

Amy Brar MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design Projective Cities 2021/23

To Nani and Mom

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My deepest thanks to the people of Chilika Lake, without whom this body of work would not exist. A special thank you to the girls and women who took part in interviews, conversations, focus groups and drawing exercises for their time and attention. Thank you to my friends, Ms. Jhilli Jalli and Mr. Jhullu Jalli, for the tea, food and warmth in Khatisahi village, where this research is predominantly rooted. A big hug to Ms. Kabita Sethi and her mother-in-law for sharing their difficult personal stories.

My sincere thanks to the Administration Services of the Government of Odisha. Particularly, Mr. Manoj Kumar Nayak, Block Development Officer (BDO) of Krushnaprasad, for the unwavering support, facilitation and encouragement. I extend my thanks to the Revenue and Forest Services for their expertise and guidance in navigating unfamiliar waters. I am grateful to my boat drivers, Mr. Naba Jena of Maensa and Mr. Sudham Babu of Berhampur, for transporting me safely every day. To my friend, Mr. Biranchi Narain Pattanayak, thank you for your support in translating from Odiya to Hindi, and for being an irreplaceable energy in the fieldwork.

Thank you to my professors, Platon, Hamed and Doreen, for believing in my research, expanding my knowledge, encouraging my remote fieldwork and guiding me through to the end. Thank you also to Cristina, Roozbeh and Daryan for the inputs that made this work possible. To my incredible cohort, thank you for the laughs, beers, coffees, late night conversations, emotional support, etc etc etc....

Big thanks to my best friend, Gaurav Sawhney, for the beautiful photographs during the site visit of March 2023. Finally, thank you to my wonderful family and all my friends for their love and unconditional support. Especially the two special women of my life, Nani and Mom.

7

ABSTRACT

1 Elizabeth Grosz, Space, Time, and Perversion: Essays on the Politics of Bodies (New York: Routledge, 1995), 94..

“Precarious Waters” examines and spatialises forms of water-living central to the lives of fisherwomen of Lake Chilika, to reposition water rituals as a vehicle for enhancing agency in the context of marginalised fishing communities. By subverting the homogeneous, universal, and regular readings of [wet-]space that reinforce inequity across space and time1, the dissertation proposes a fundamental shift in understanding notions of value and productivity, by learning through the embodied knowledge, rituals, and practices of Chilika’s traditional fisherwomen. Rather than simply viewing their conditions as lack of infrastructure, “Precarious Waters” argues that there are existing protocols, generating forms of living different from dominant developmental discourse, which can stitch the fractured socio-ecological spatiality proliferating around Chilika.

By revealing that wet spaces in these villages are collective and external to the domestic, the research demonstrates the formation of an invisible network of protocols at settlement scale. These invisible networks, choreographed by fisherwomen, are instrumental to the socio-spatial relationships of these marginalised fishing communities. Through a series of design interventions informed by empirical and anthropological research, the dissertation aims to enhance spatial agency by working with fisherwomen at the intra-village scale. Furthermore, by expanding into the territorial trialogue between fishers, non-fishers and administrators, the spatialised network functions as a threshold for negotiation and exchange between historically non-cooperating social groups. “Precarious Waters” confronts existential threats resulting from the socio-spatial hierarchy embedded in modern water infrastructure, by adopting a collaborative and heterogeneous modus operandi, and highlighting value through the subaltern female body.

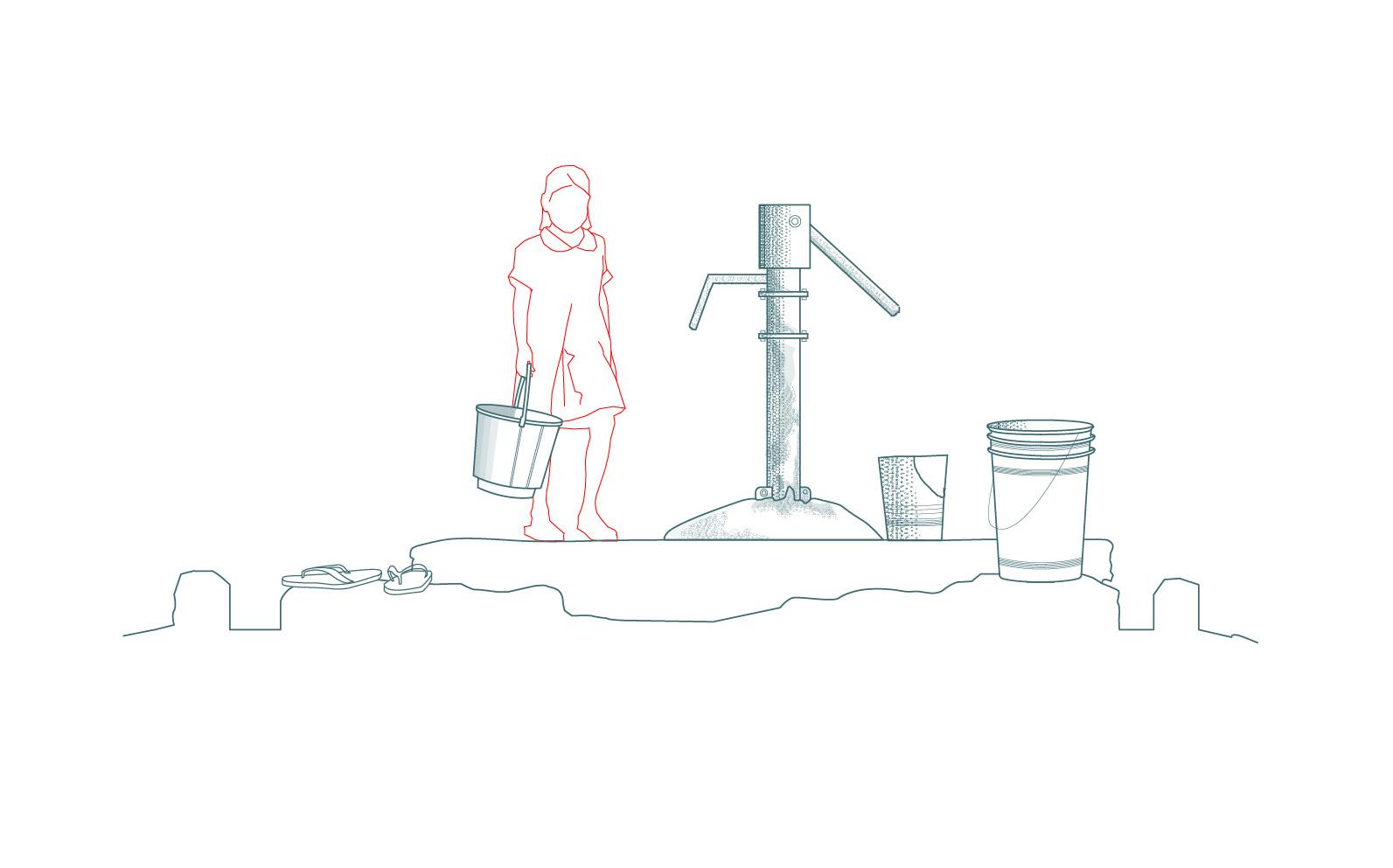

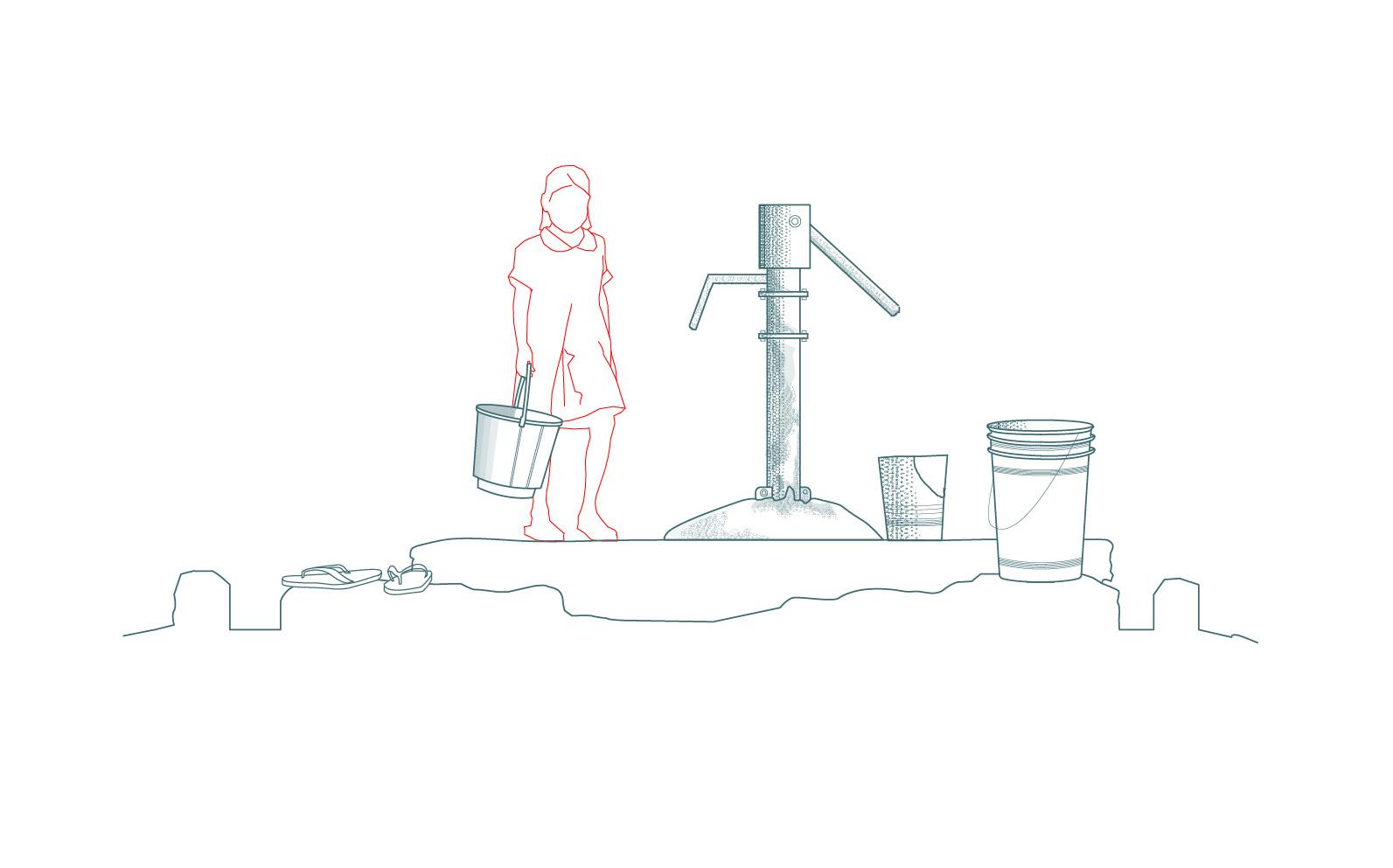

(page left) fig. 002: Lakeside handpump in Berhampur. October 2022. Source: Author.

9

Precarious

/Prɪˈkɛːrɪəs/

Adjective

Not securely held or in position; dangerously likely to fall or collapse

Dependent on chance; uncertain

PROLOGUE

2 Mouza is the official term for a type of administrative land unit composed of multiple villages. Local administration services continue to operate at the district, block, mouza and village level to monitor land and tax.

3 Gram Panchayat is the official term for a basic village-governing institute in Indian villages and is a democratic structure at the grass-roots level. A Gram Panchayat is a collection of Revenue Villages under 1 head village. For example, Khatisahi is a Revenue Village in the Nuapada Gram Panchayat, which contains other villages of Anlakuda, Barunakuda, Gurubai, Jahnikuda and Nuapada as well.

Precarity – used here to signify fragility, ephemerality, and uncertainty – is embodied firstly through the aqueous nature of Chilika’s geography. With dry-wet boundaries in constant flux, varying with weather conditions ranging from intense monsoons to dry winter spells, the relationship between bodies and their environment is as fluid as the geography itself. This dynamic socio-spatial relationship results in specific and localised forms of living, which are born out of an aqueous precarity. Precarity in the context of Chilika’s fishing villages arises not only from environmental, but also spatial, sociological, and economic constructs. And with regard to fisherwomen, an additional layer of precarity is generated through gender inequality, where the female is often considered to be inferior to the male members of the family – elder brother, father, father-in-law, or husband.

A second layer of precarity – territorial precarity - stems from the spatial organization of the fishing villages. On analyzing the territorial distribution of these villages, a scattered pattern of settling emerges. In the specific case of the coastal Krushnaprasad block of Chilika, of the 96 mauzas2 only 11 are considered by residents and officials as Matsyajibhi or “fishing communities”. Additionally, there is no official documentation of this classification between fishers and non-fishers; information regarding this classification is purely embodied knowledge that can be extracted through oral testimony. Having settled in a scattered constellation across the block, Matsyajibhi are physically separated from one another by other (non-fishing) communities as well as natural barriers like forests and open waters. The nonfishing communities are also involved in fishing for their livelihood, but do not derive their identity from the profession. Furthermore, the non-fishing communities often belong to higher ranks in the Hindu caste system and possess greater assets in the form of land. The status of the Matsyajibhi as a minority community not only within the region, but also within their gram panchayat3 boundaries, has led to this precarity.

11

: ON PRECARITY

A third type of precarity – occupational precarity – is intricately linked with territorial precarity, rooted as they both are in the social marginalization dictated by caste. Being considered socially inferior to non-fishing communities, the fisherfolk often succumb to financial and social pressure in decision-making. The relative inability to access financial, educational, and political resources allows the fishing communities to be dominated by their counterparts in critical decision-making regarding the operation of the village and gram panchayat. As a concrete example, most brackish waters leased from the government by fishing communities get de facto subleased to non-fishing communities at nominal rentals. As a result, fishing communities have reduced access to shallow water for shrimp culture, forcing them to venture into volatile waters, thus experiencing a dramatic reduction in daily catch. The wide awareness gap between the fisherman’s financial expectation and the actual export market value of cultured prawn is a major blind spot that non-fishers further exploit, resulting in occupational precarity. A residual effect of this occupational displacement is an erosion of the fisherfolk’s historical identity itself.

PROLOGUE

Lastly, the clear discrepancy between cadastral divisions and settlement patterns at village scale are indicative of how local forms of living are unable to conform with top-down planning policies, generating an uncertainty with regards to land rights and ownership. The cadastral map of Khatisahi village reveals a micro-parceling of land: the average residential plot of land is 0.02 hectares, and all land parcels have multiple named tenants. Additionally, the land in these coastal fishing villages is deemed to be of the least economic value since it is uncultivatable due to high salinity levels. This situation essentially prevents the fisherfolk from availing any substantial loans against their land deeds, resulting in economic precarity.

13

: ON PRECARITY

15 acknowledgments 7 abstract 9 prologue: on precarity 10 contents 15 list of figures 16 introduction 23 research context 33 2.1 site context 34 2.2 fisherwomen and dispossession 40 2.3 fishers vs. non-fishers 48 2.4 settlement type + morphology 58 2.5 from architectural to spatial 90 2.6 material precarity 102 macro-waters 109 (fisher) women & water(s) 117 micro-waters 139 liquid field of dreams 151 6.1 design brief 154 6.2.i types of water 158 6.2.ii cycles of water 160 6.2.iii construction and assembly 164 6.3 design typologies 168 6.3.i wash typology 170 6.3.ii toilet typology 180 6.3.iii fountain typology 194 6.4 conclusion 212 bibliography 219 appendix 231 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. CONTENTS

fig. 003: figure-ground of Noliapatana Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 001: Earth Observatory. NASA. MODIS Land Cover. [Chilika Lake and Nalabana Bird Santuary]. March 19, 2014.

fig. 002: Lakeside handpump in Berhampur. October 2022. Source: Author.

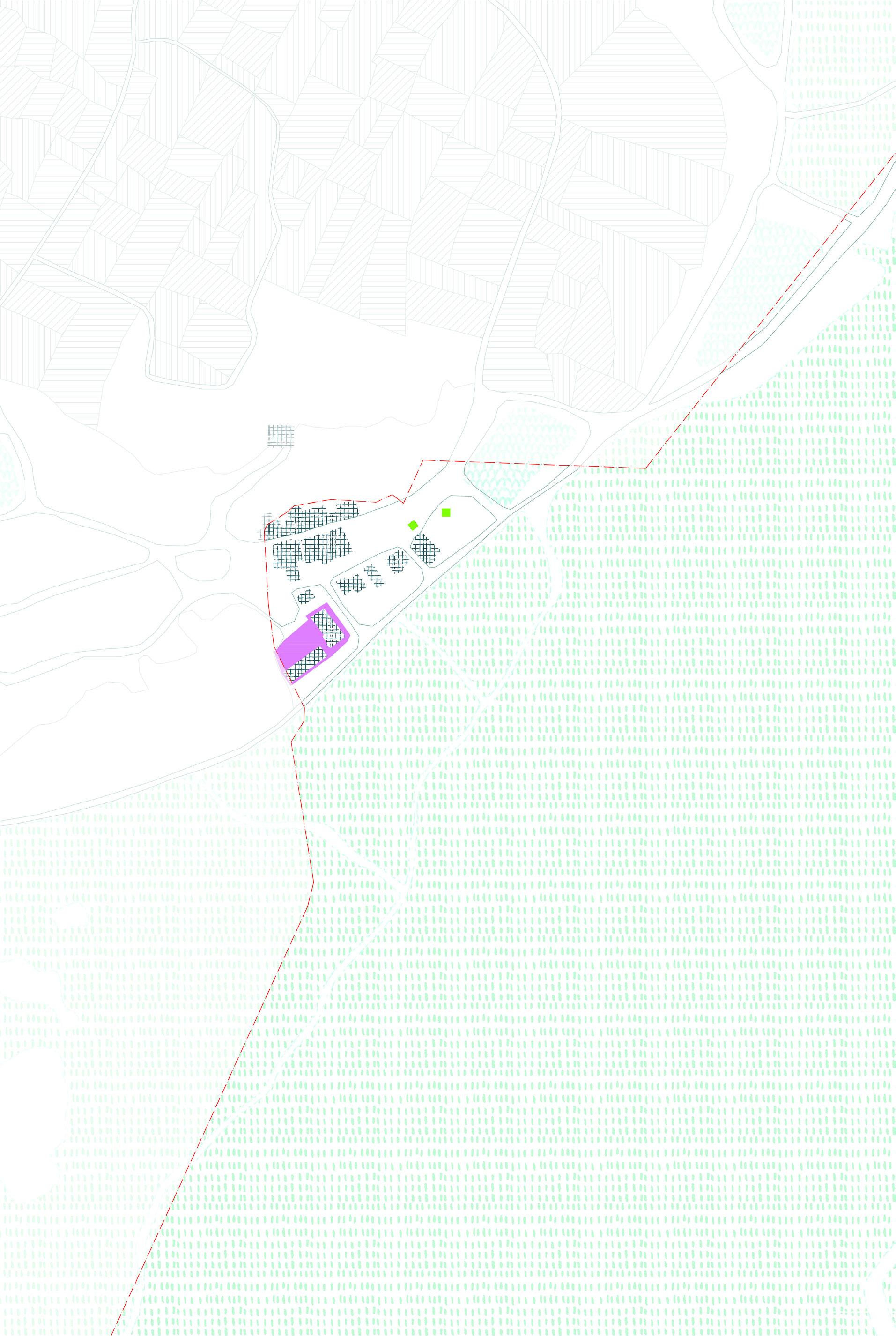

fig. 003: figure-ground of Noliapatana Village. Drawn by Author.

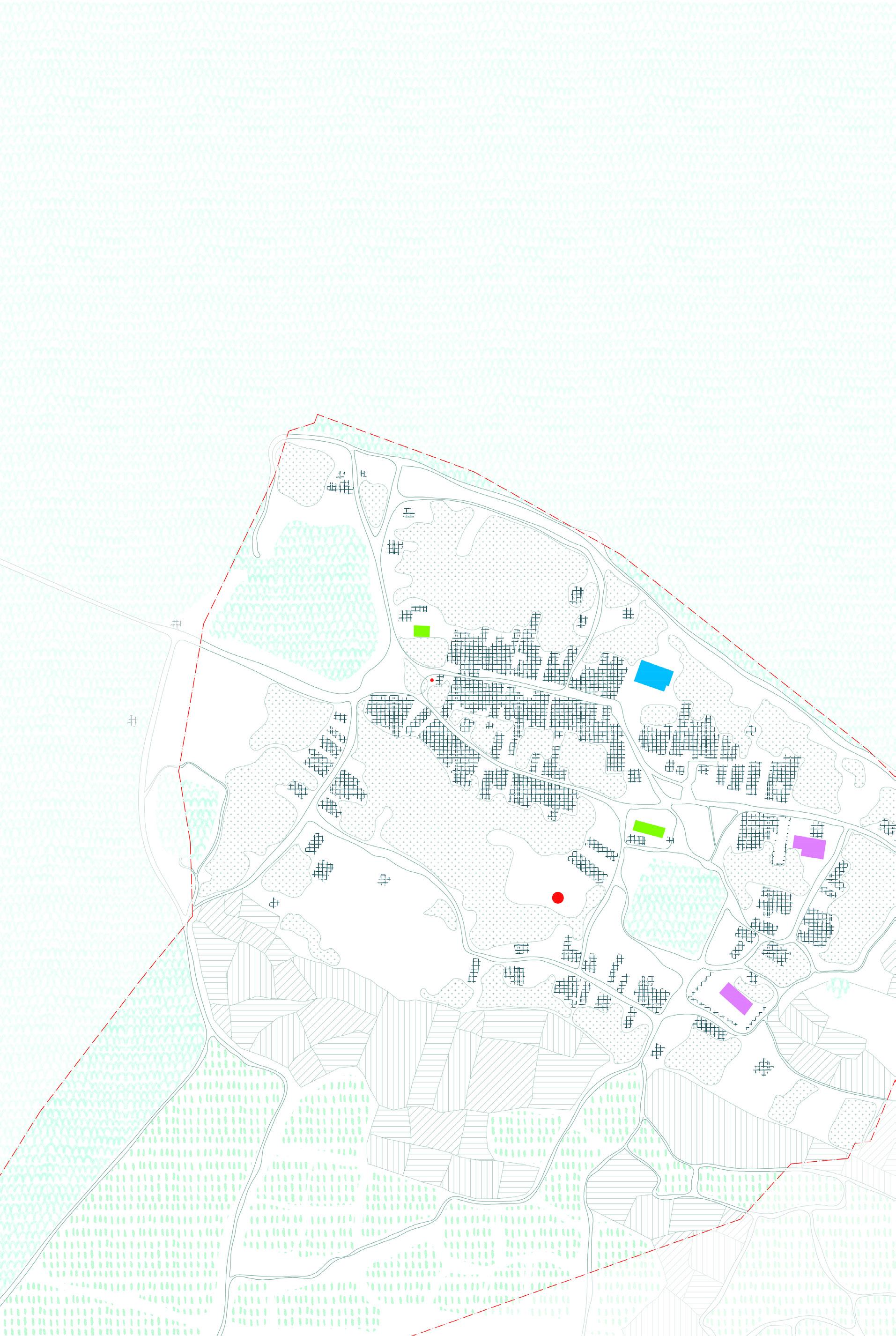

fig. 004: figure-ground of Kuanarpur Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 005: figure-ground of Rasakudi Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 006: location of Chilika Lake on the Political Map of India. Drawn by Author. fig. 007: illustration of seagrass. Drawn by Author.

fig. 008: location of 11 traditional fisher revenue villages. Krushnaprasad Block, Puri, Odisha. Drawn by Author. fig. 009: Khatisahi Revenue Village. Krushnaprasad Block, Puri, Odisha. Drawn by Author. diagram 2.1: structural system of governance in villages of Krushnaprasad Block, Puri District. fig. 010-019: stills from 'Woman Fills Her Bucket in Noliapatana". October 2022. Source: Author. fig. 020-029: stills from 'Woman Walking to take a bath". October 2022. Source: Author. diagram 2.2: roots of dispossession among Chilika's fisherwomen.

fig. 030-39: stills from 'A fisherwoman cooking on an outdoor stove'. Noliapatana. October 2022. fig. 040: fishermen of Khatisahi drag- net fishing. Khatisahi. March 2023.

fig. 041: illustration of a tiger shrimp. Drawn by Author.

fig. 042: cadastral map no.95, Berhampur Village, 1963. Source: Krushnaprasad Tehsil Office. fig. 043: Krushnaprasad Garh (Palace), Constructed by Raja Sri Bhagirath Mansingh. Established 1798. Krushnaprasad. September 28, 2022. Colour 35mm Film. Source: Author.

fig. 044: During an inspection of shrimp-nets at 6 am with a fisherman from Rasakudi Village. Rasakudi. September 28, 2022. Colour 35mm Film. Source: Author.

diagram 2.3: division of brackish water leases in Chilika Lake.

diagram 2.4: timeline of land rights and historical events from 19th century Odisha. diagram 2.5: definition of one-standard acre in Odisha.

fig. 045-54: figure-ground studies of 11 traditional fishing communities in Krushanprasad, Puri, Odisha.

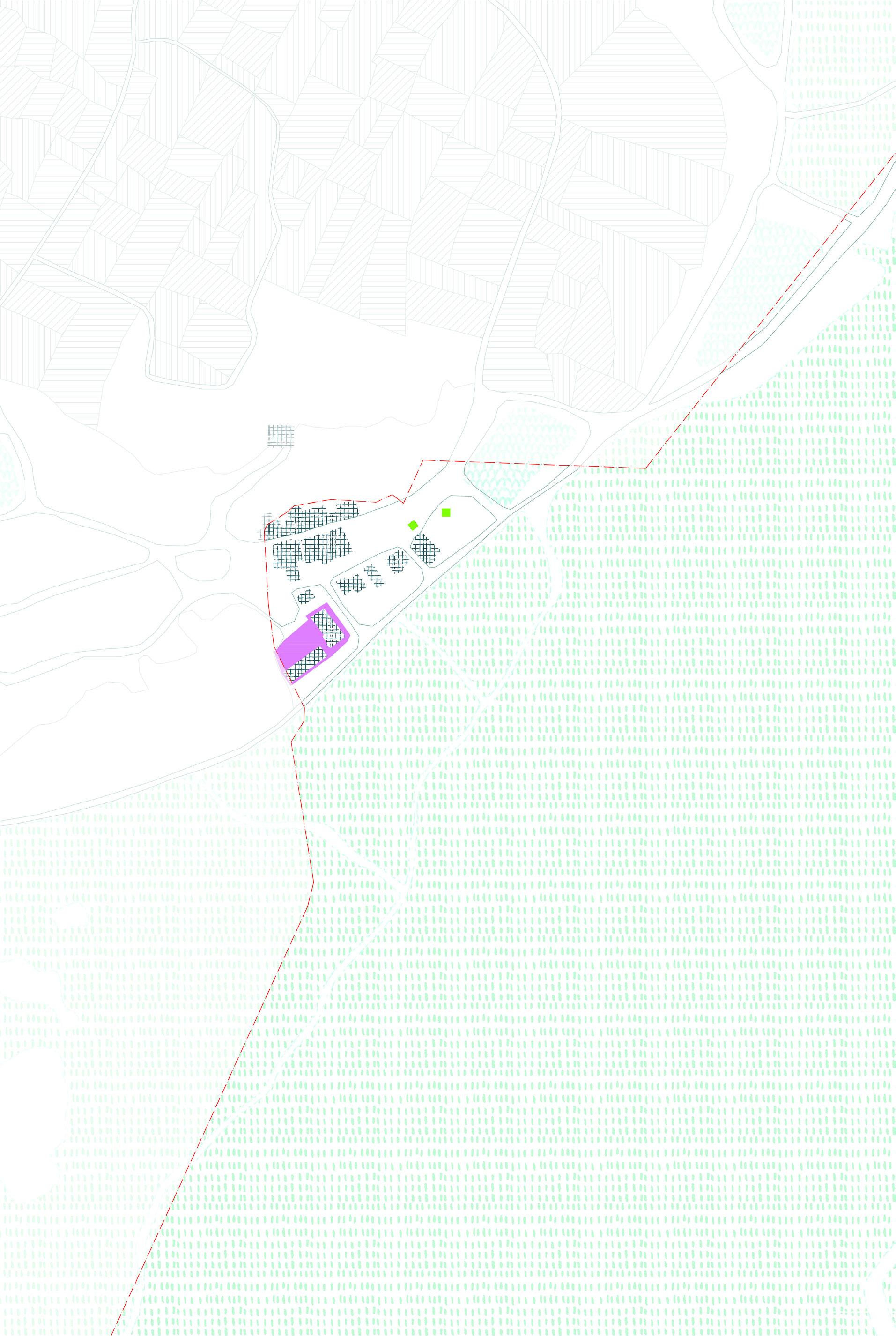

fig. 056 Location of Kuanarpur Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 057: Settlement plan of Kuanarpur village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 058 Location of Patanasi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 059: Settlement plan of Patanasi village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 060 Location of Noliapatana Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 061: Settlement plan of Noliapatana village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 062 Location of Rasakudi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 063: Settlement plan of Rasakudi village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 064: Location of Kandaragaon Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 065: Settlement plan of Kandaragaon village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 066: Location of Alandapatana Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 067: Settlement plan of Alandapatana village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 068: Location of Biripadar Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 069: Settlement plan of Biripadar village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 070: Location of Khirisahi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 071: Settlement plan of Khirisahi village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 072: Location of Khatisahi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 073: Settlement plan of Khatisahi village. Drawn by Author.

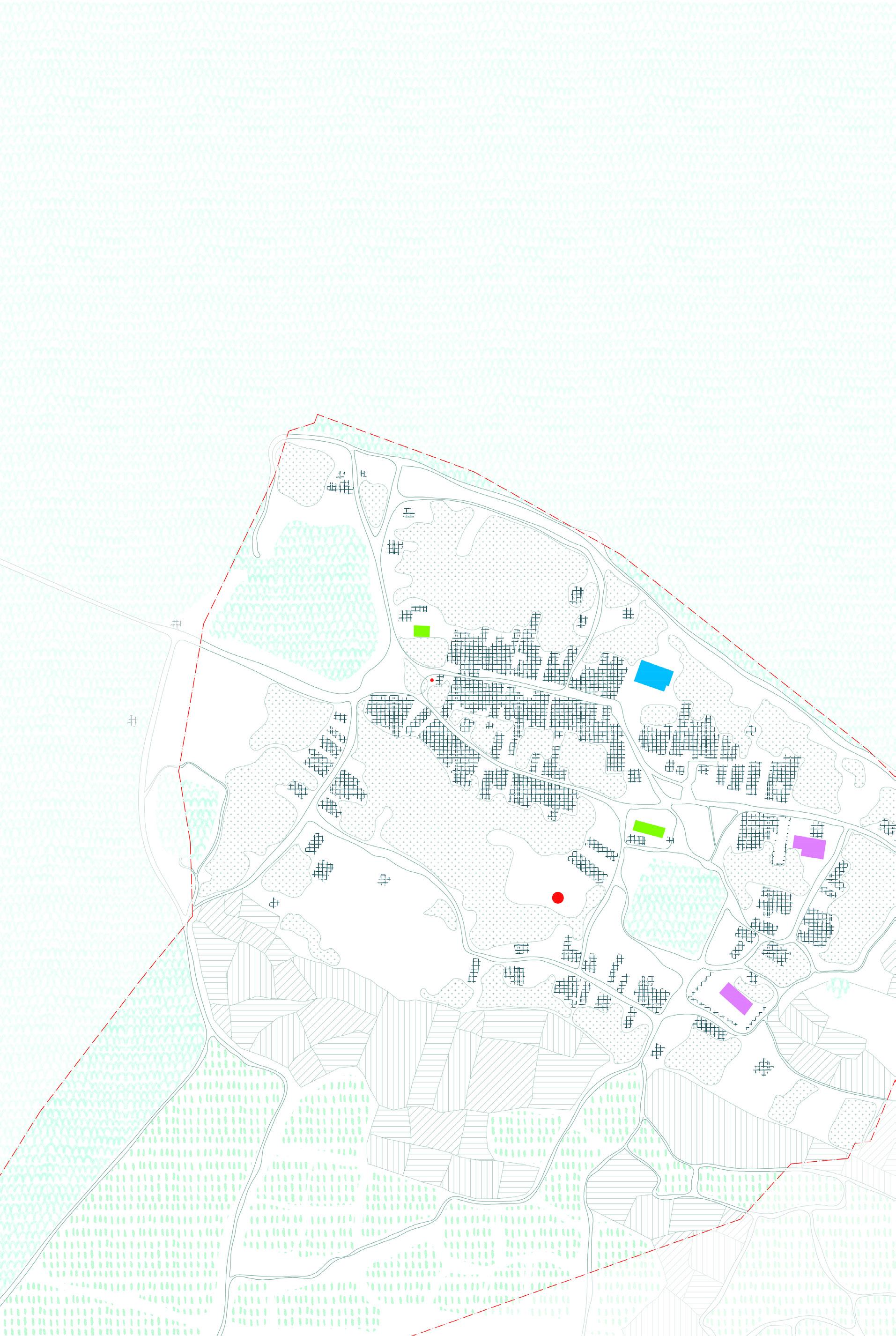

fig. 074: Location of Maensa Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 075: Settlement plan of Maensa village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 076: Location of Berhampur Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

fig. 077: Settlement plan of Berhampur village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 078: Settlement Section of Khatisahi Village. Pre- Monsoon Season.

fig. 079: Settlement Section of Khatisahi Village. Post- Monsoon Season.

fig. 080: Key Map of Khatisahi Village.

fig. 081: Settlement Scale Plan. Khatisahi Village.

fig. 082: Existing Water Use overlayed on a Natural Features Map of Khatisahi Village.

fig. 083: Existing Water Use overlayed on the Settlement Map of Khatisahi Village.

fig. 084-89: walking along the dike. Six views from Khatisahi, Biripadar and Noliapatana Villages in the monsoon and winter.

fig. 090: Figure-ground diagram of Residence Type A: Individual Box.

fig. 091: Figure-ground diagram of Residence Type B: Composite Linear.

fig. 092: Floor Plan of Residence Type A: Individual Box.

fig. 093: Floor Plan of Residence Type B: Composite Linear

LIST OF FIGURES

17 2 8 14 23 33 34 35 36 38 39 40 43 45 46 49 49 51 52 52 53 53 54 56 57 58 61 61 63 63 65 65 67 67 69 69 71 71 73 73 75 75 77 77 79 79 81 81 82 82 84 85 85 87 88-89 93 93 94 95

fig. 094: Floor Plan of Outdoor Communal Kitchen.

fig. 095: Floor Plan of Street-Facing Domestic Platform.

fig. 096: Elevation of Communal Hand-Pump/Tubewell.

fig. 097: Lakeside Dike: a buffer to separate brackish waters from the village settlement.

fig. 98: Location of Spatial Registry through a Section of a typical Sahi (Street) in Khatisahi.

fig. 99: Annual roof-thatching. Noliapatana Village. October 2022. Source: Author.

fig. 100: Vacant Site: where a house once used to be. Khatisahi Village. October 2022. Source: Author.

fig. 101: figure-ground of Kandragaon Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 102: Cover of 'Water Everywhere, And Nowhere'. Source: John Stanmeyer.

fig. 103: Plan of The Karl Mueller Public Bath House, Munich, Germany (1897-1901). Source: Paul Gerhard, 1908.

fig. 104: Ground Floor Plan of Hicks St. Baths, New York. 1903. Re-drawn by Author.

fig. 105: Thermal Spray Bath in Mental Asylum. France, 1880. Source: Unknown.

fig. 106: figure-ground of Alandapatana Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 107: two fisherwomen return with drinking water at dusk. Khatisahi Village.

fig. 108: Kabita Sethi's mother-in-law walks home after collecting water from the communal tube well.

fig. 109-11: Scans of Hand Drawn Maps of the Village Settlements by married Fisherwomen in their 20s.

fig. 112-14: Drawing exercise 1. Scans of Hand Drawn Maps of Daily Rituals by children. March 2023.

fig. 115-17: Drawing exercise 2. Scans of Hand Drawn Maps of the Village Settlements by children. March 2023.

fig. 118: An afternoon of mapping exercises at school with two young girls.

fig. 119: Matrix of Water Rituals and their location at Village Scale.

fig. 120: Location of Water Rituals and their location at Village Scale, for women.

fig. 121: A fisherwoman carries a bag of rationed rice home.

fig. 122: With Kabita Sethi and her mother-in-law at their home.

fig. 123: A fisherwoman in her tailor room. Biripadar Village.

fig. 124: An old widowed fisherwoman cleans dried fish on the site of her partially collapsed home.

fig. 125: figure-ground of Biripadar Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 126: A dug-well along the banks of Chilika Lake. Khatisahi Village.

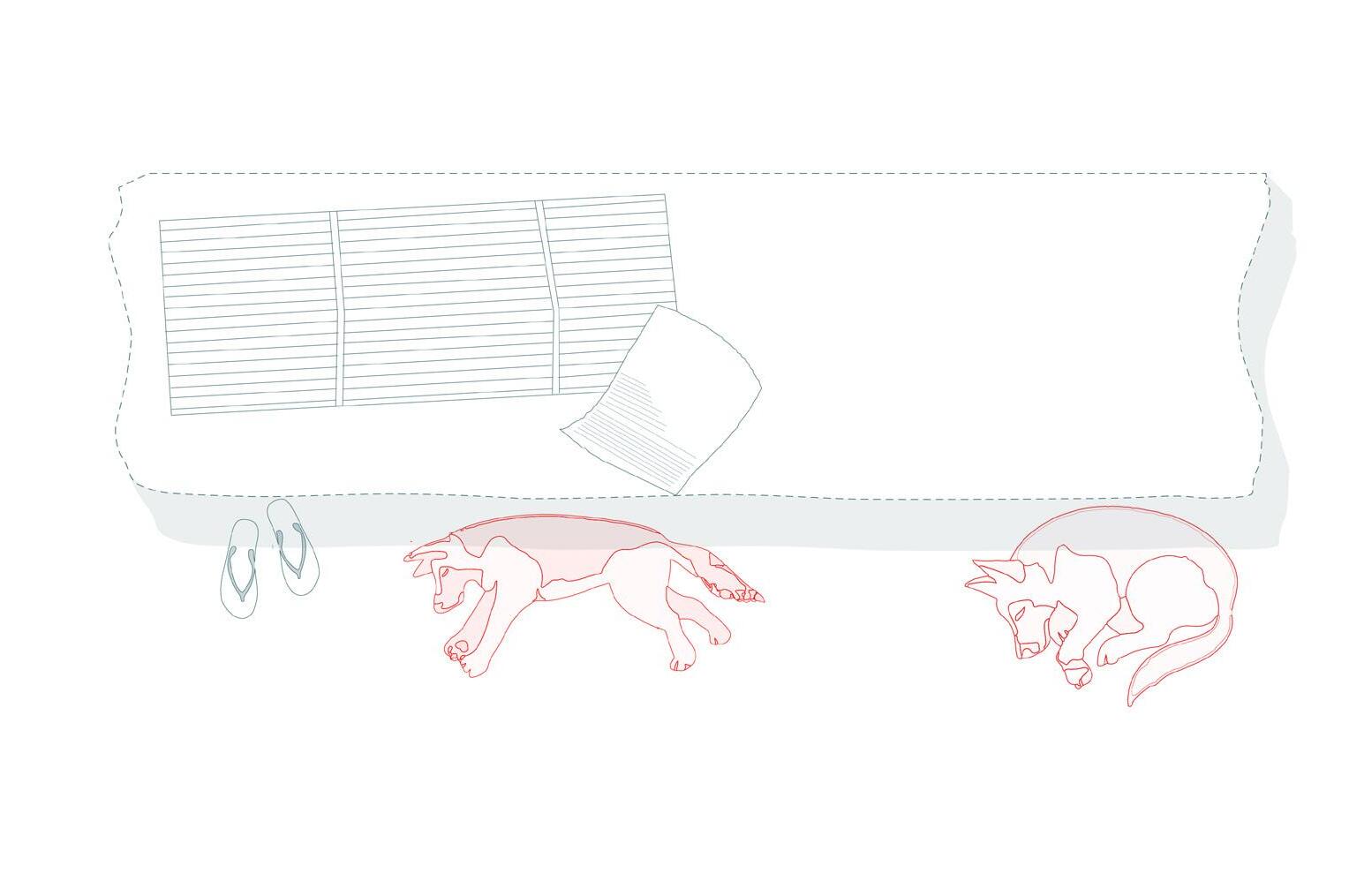

fig. 127: Bathing area for women in Jhilli Jalli's family backyard. Khatisahi Village. March 2023.

fig. 128: A woman drawing water from a well. Bani Lal. Patna, India. 1880. Source: V&A.

fig. 129: Three women of varying ages carry water to their home. 144 (page left) - fig. 130: figure-ground of Khirisahi Village. Drawn by Author. (page left) - fig. 131 Kabita's hatchery. Khatisahi Village. March 2023.

fig. 132: thresholds in water. Noliapatana Village. October 2022 152

fig. 133: Proposed Water Use overlayed on a Natural Features Map of Khatisahi Village.

fig. 134: Proposed Water Use overlayed on the Settlement Map of Khatisahi Village.

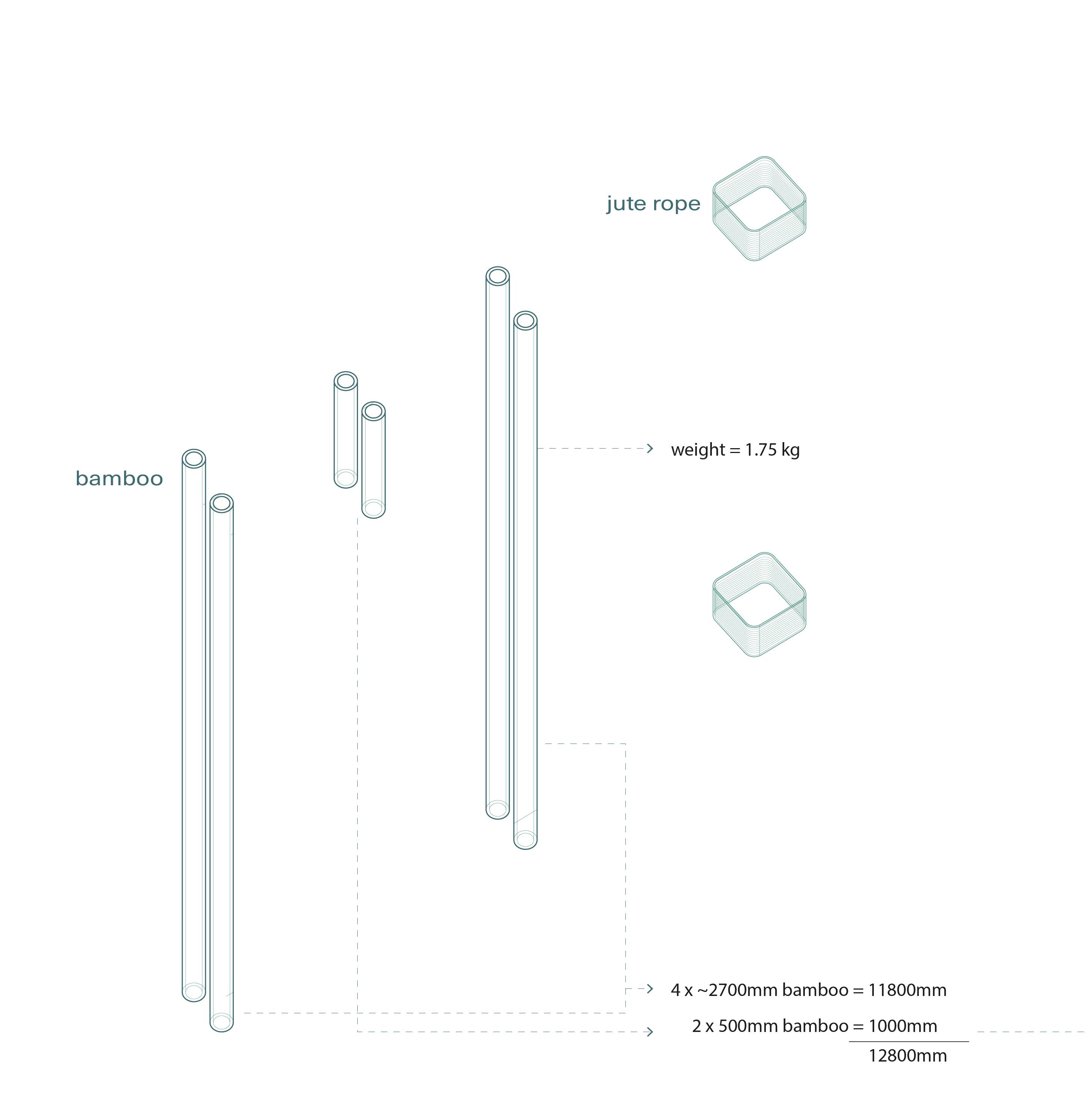

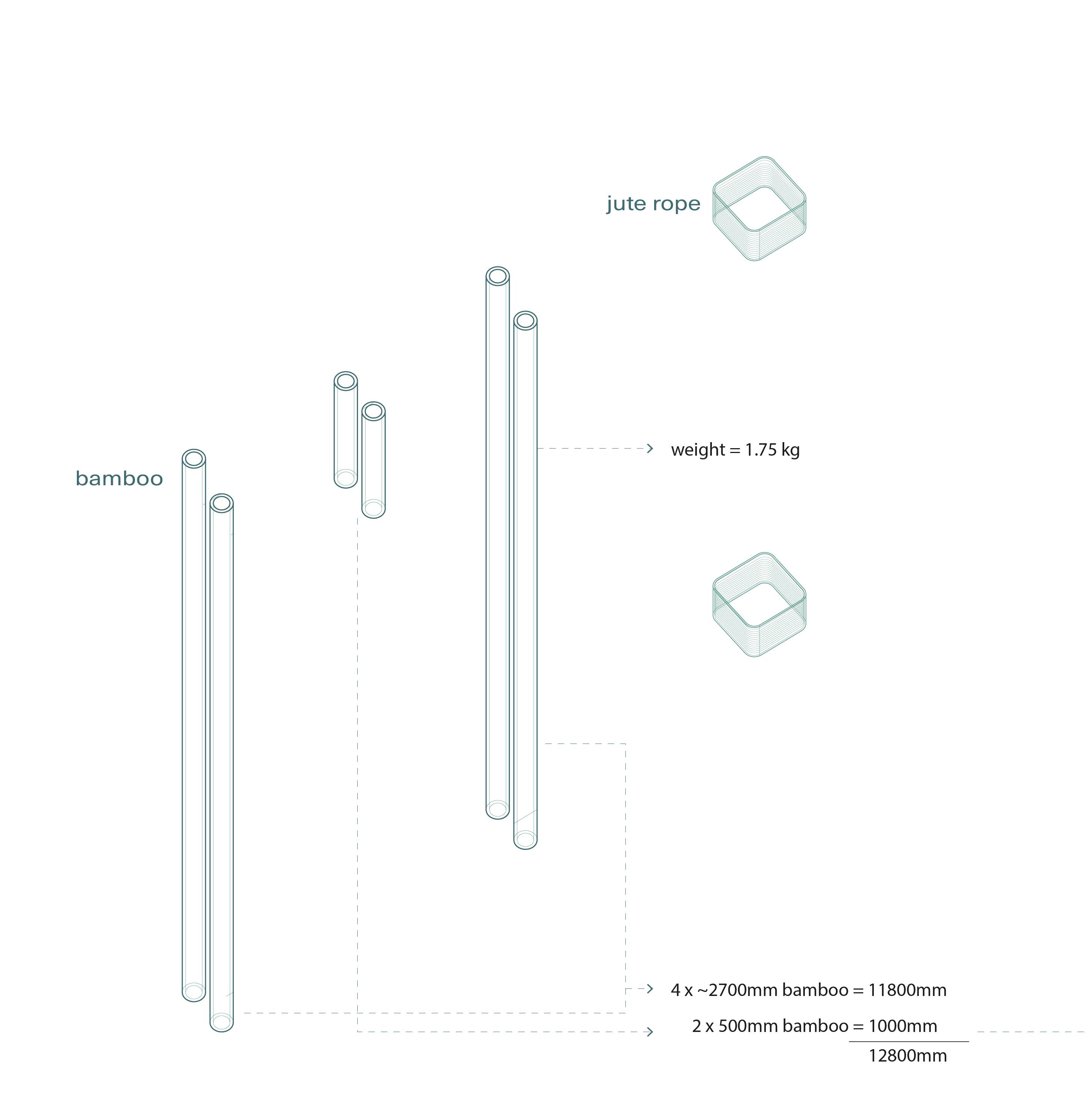

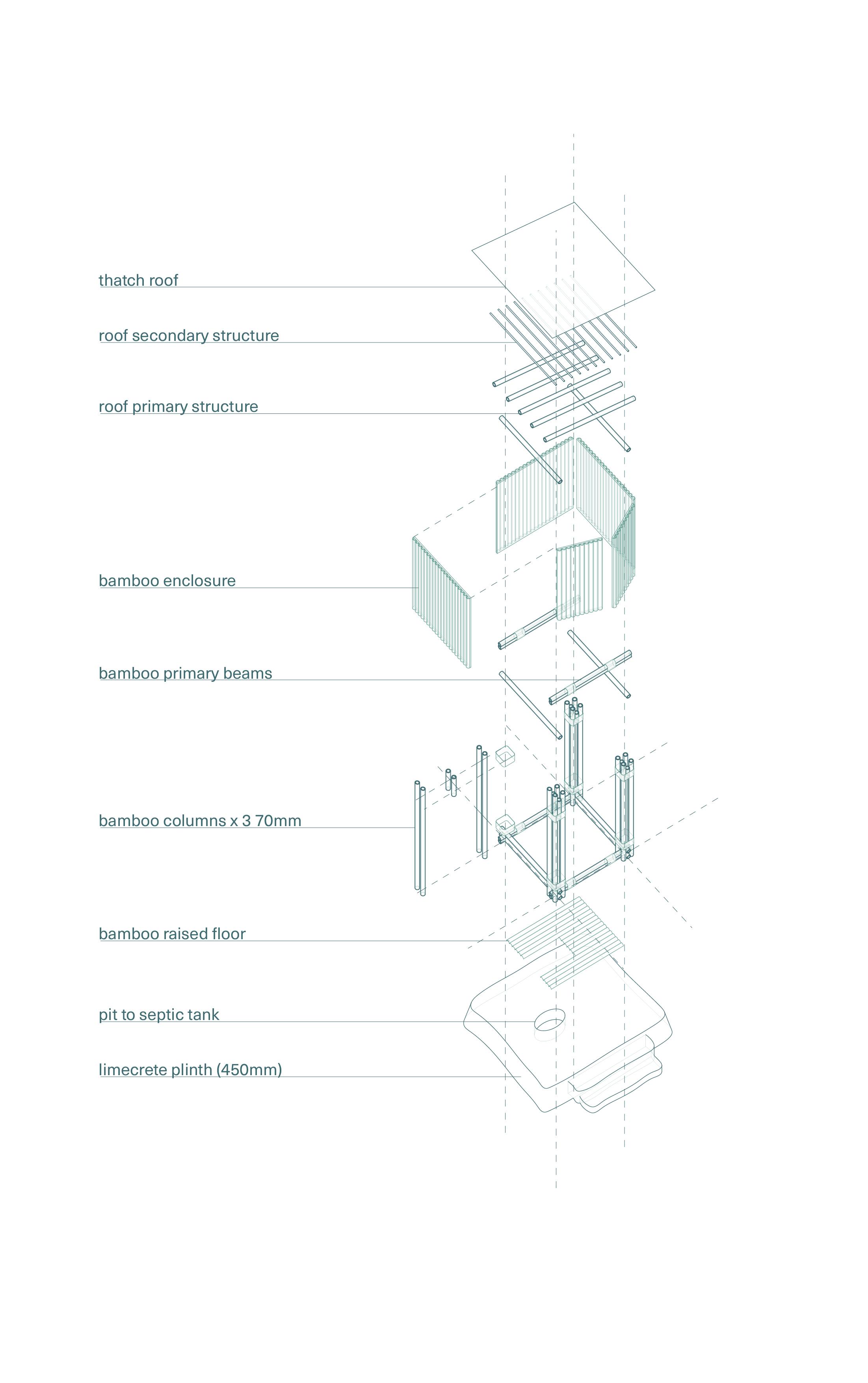

fig. 135: joint assembly test. 1:10 model.

fig. 136: Elemental Bamboo Construction Unit for Design Propositions.

fig. 137: Size of Elemental Bamboo Unit in reference to fisherwomen.

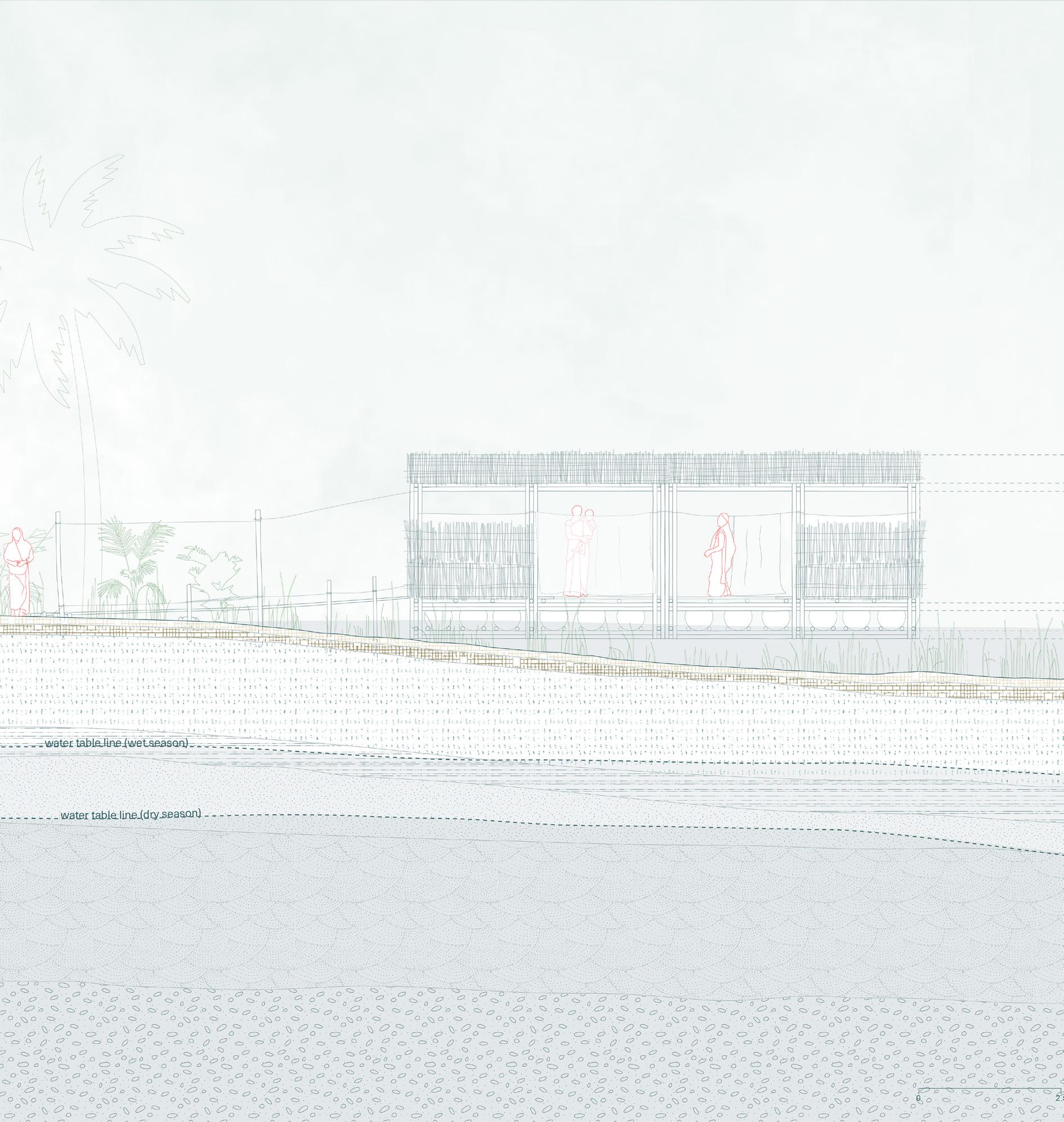

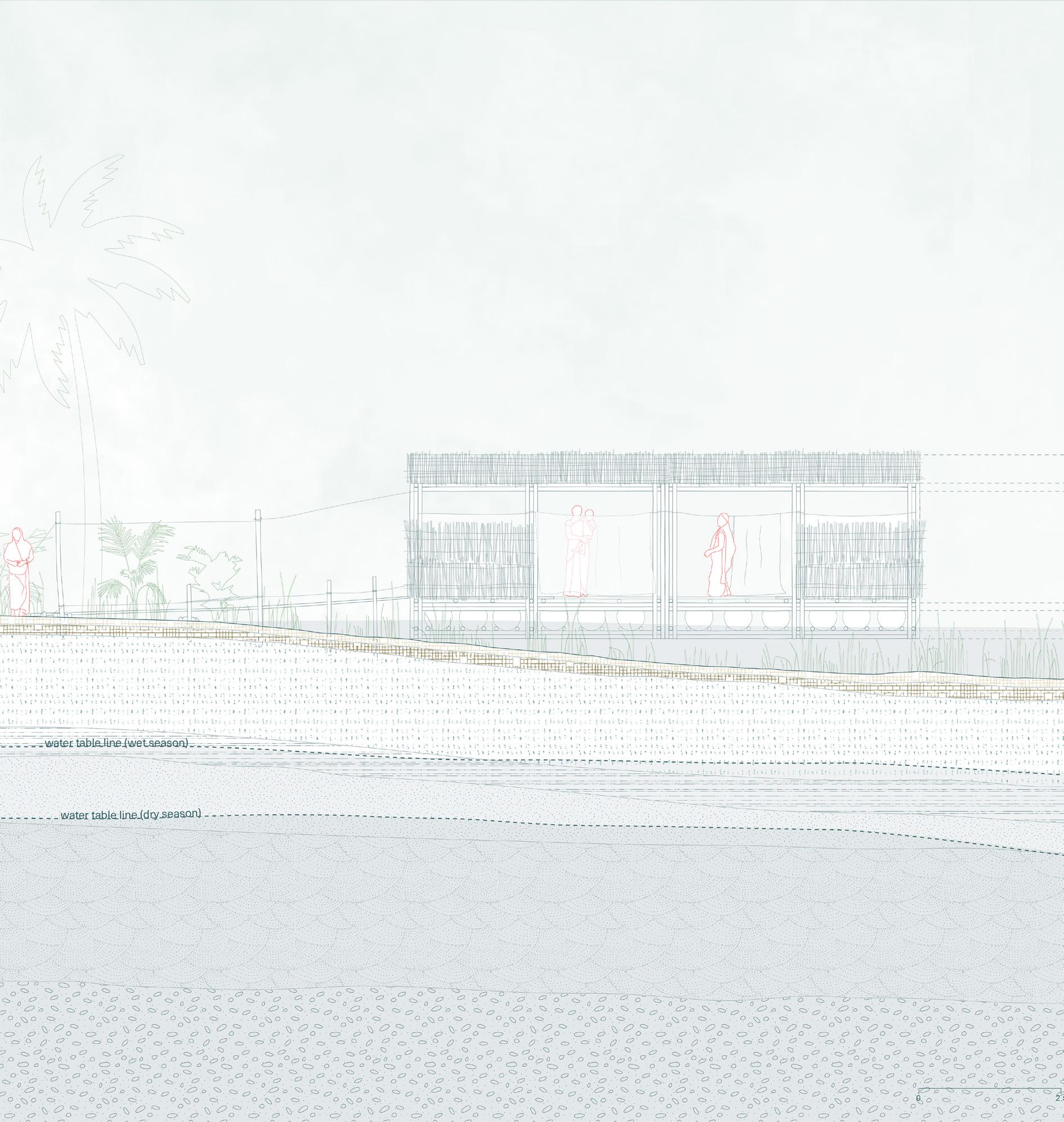

fig. 138: section of wash pavilion floating on a pokhari (pond).

fig. 139: section of dike-side toilets.

fig. 140: section of communal sheltered fountain.

fig. 141: wash pavilion floating on a pokhari. Drawn by Author.

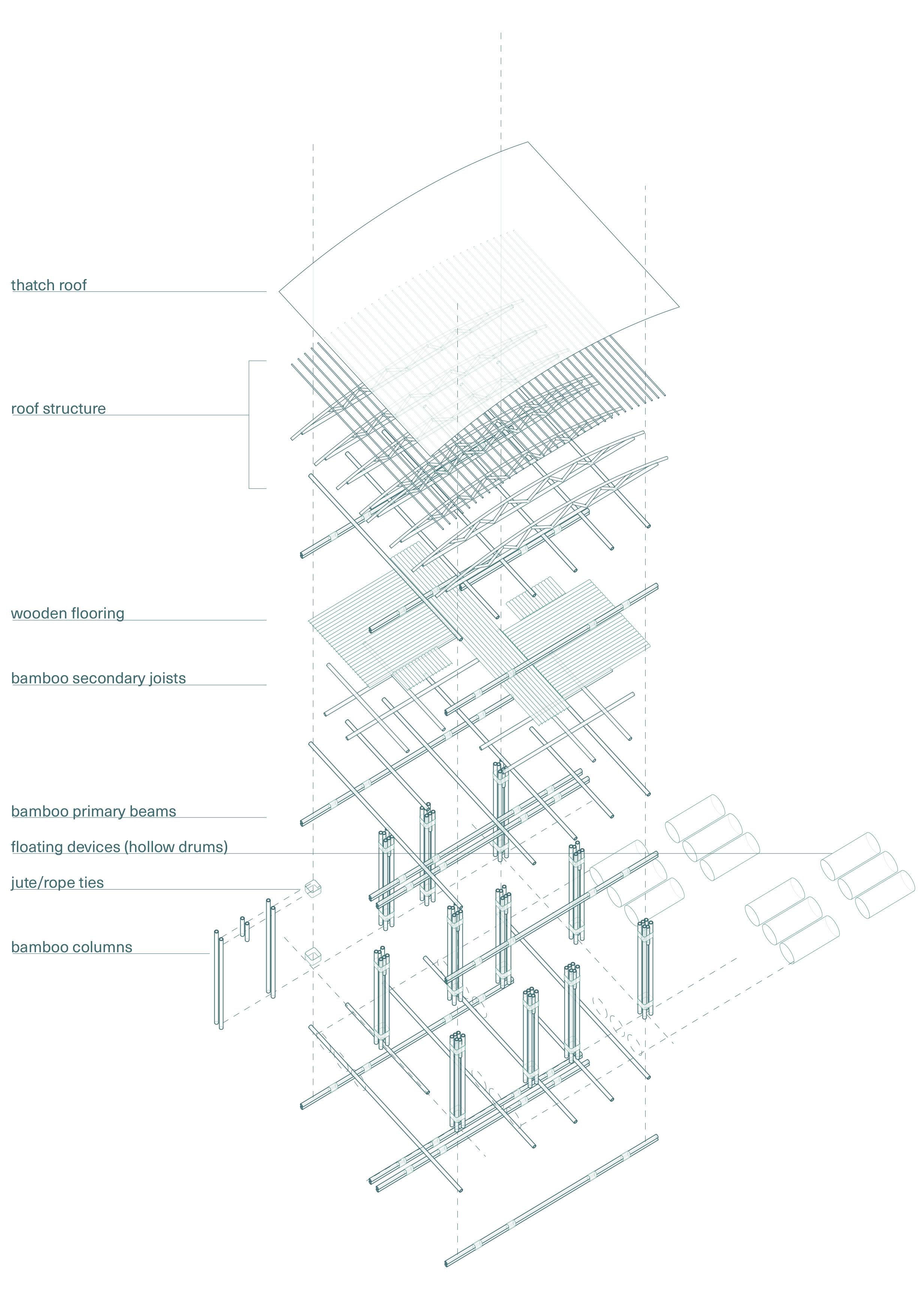

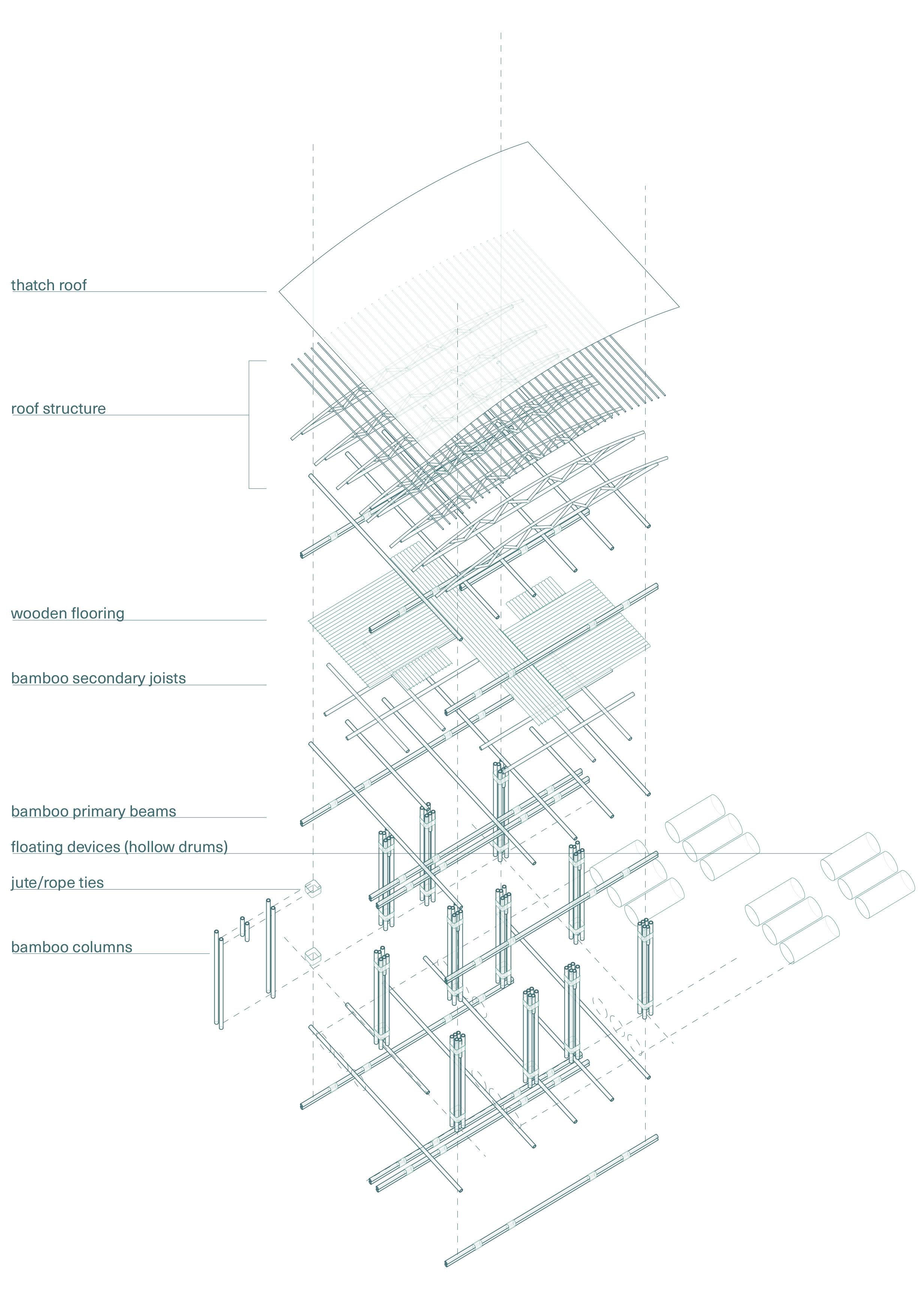

fig. 142: exploded axonometric of wash pavilion structural assembly.

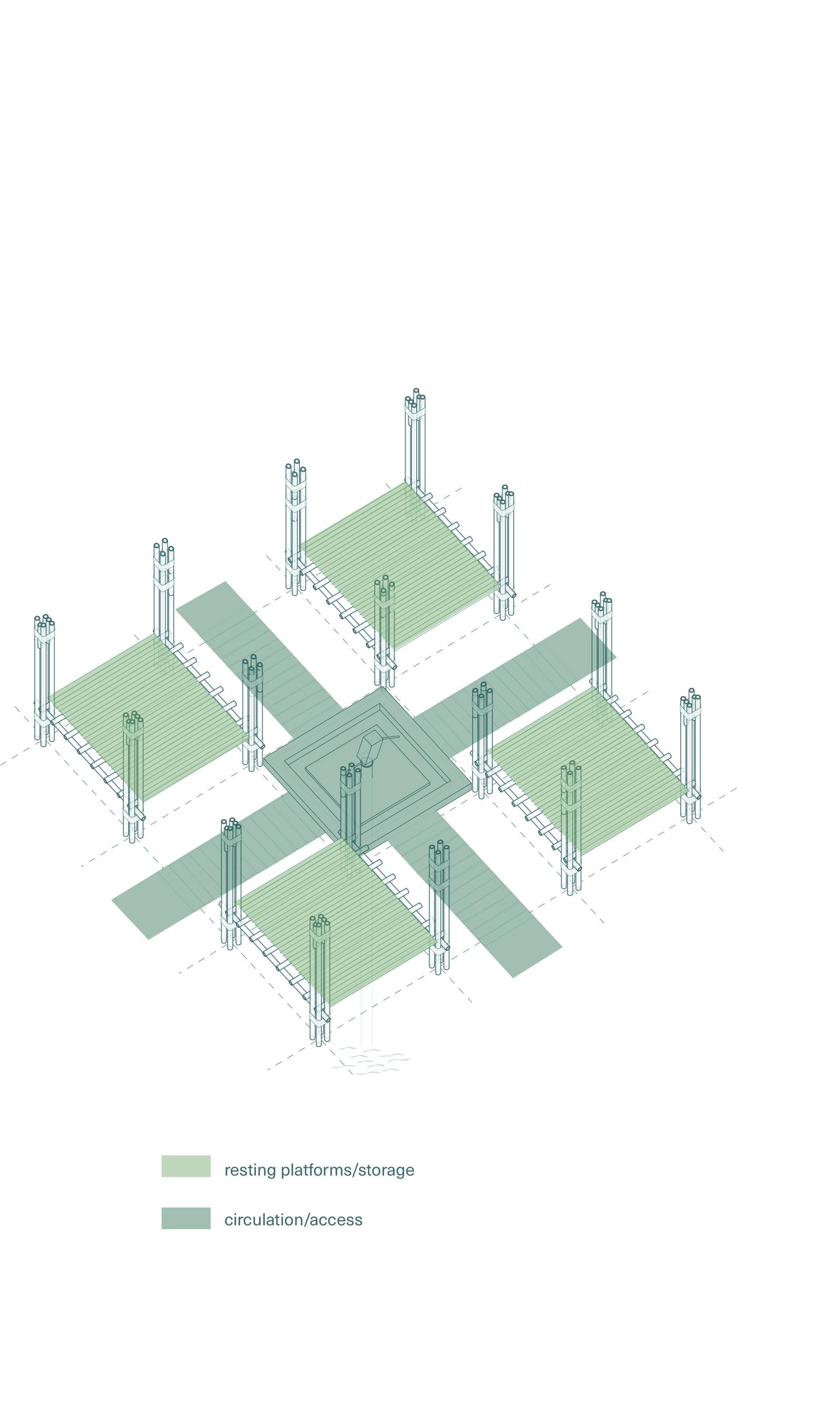

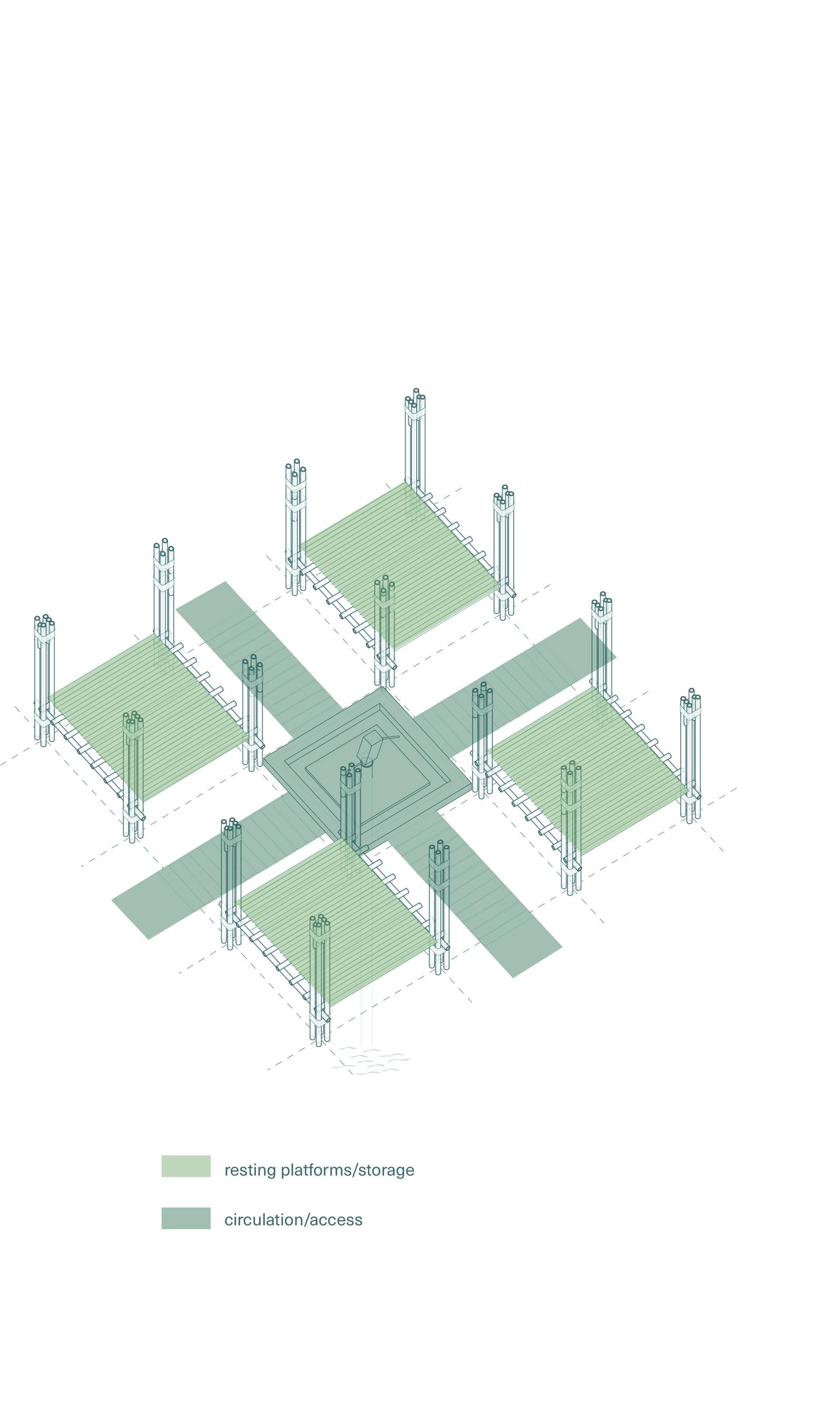

fig. 143: spatial diagram of basic unit of the wash pavilion.

fig. 144: floor plan of basic unit of the wash pavilion.

fig. 145: section through a basic unit of the wash pavilion.

fig. 146: external elevation of the basic unit of the wash pavilion.

fig. 147: 6 wash pavilion units assembled over a water body.

fig. 148: a view through the circulation corridor of the floating wash pavilion.

fig. 149: a dike side toilet. Drawn by Author.

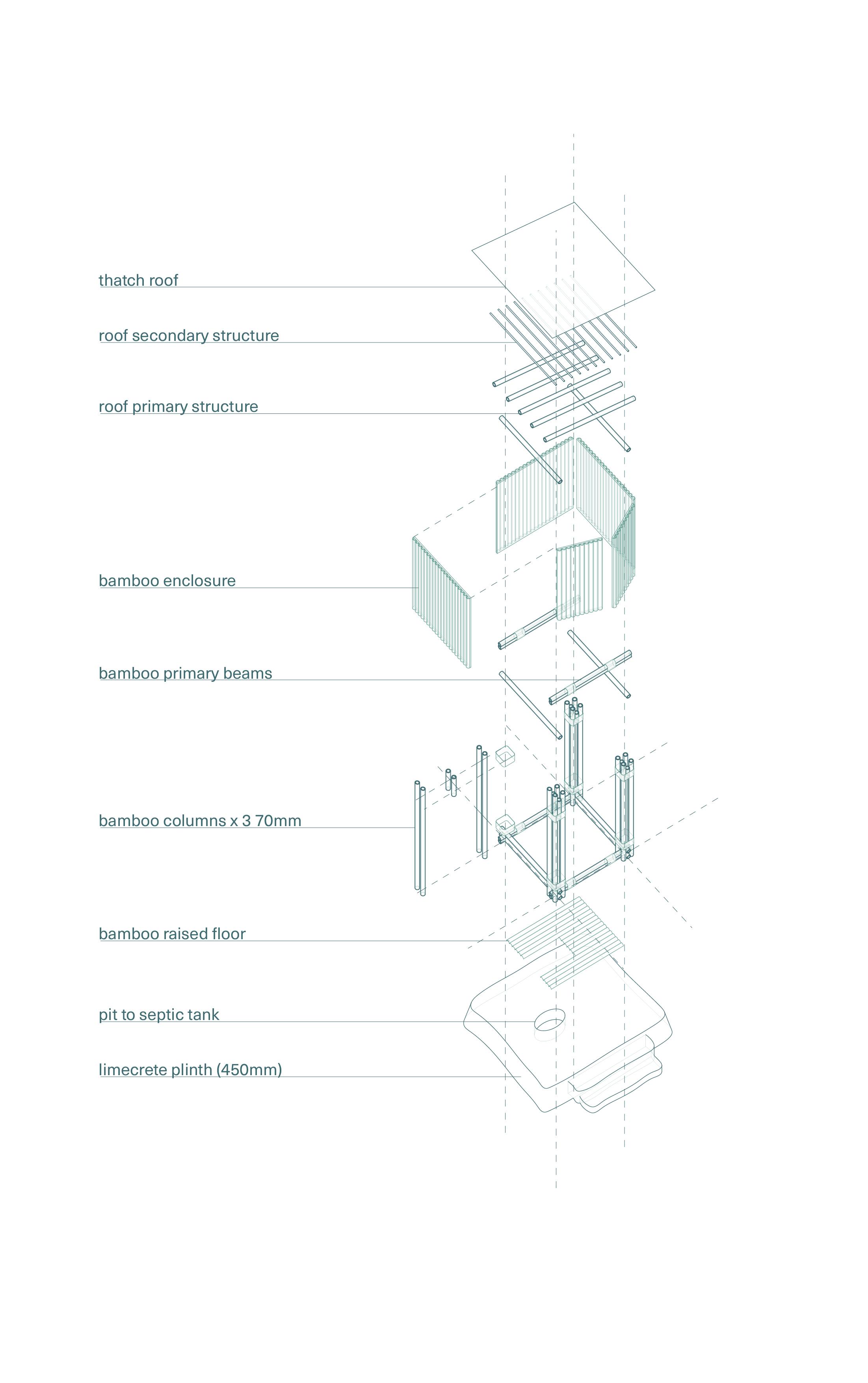

fig. 150: exploded axonometric of toilet module structural assembly.

fig. 151: spatial diagram of basic units of toilet modules.

fig. 152: plan of the toilet module. stage 1.

fig. 153: section of the toilet module. stage 1.

fig. 154: elevation of the toilet module, from the village. stage 1.

fig. 155: plan of the toilet module. stage 2.

fig. 156: section of the toilet module. stage 2.

fig. 157: elevation of the toilet module, from the village. stage 2. 186fig. 158: plan of the toilet module. stage 3.

fig. 159: section of the toilet module. stage 3.

fig. 160: elevation of the toilet module, from the village. stage 3.

LIST OF FIGURES

19 96 97 97 99 101 102 105 109 110 111 112 112 117 119 120 123 123 125 127 128 129 130 133 134 137 139 140 143 144 146 151 153 154 162 163 165 166 168 169 169 169 172 172 172 174 175 175 176 178 182 182 182 184 184 184 186 186 188 188 188

fig. 161: day-time view of the dike-side toilets in the monsoon from lake chilika.

fig. 162: night-time view of the dike-side toilets in the monsoon from lake chilika.

fig. 163: section through the sheltered communal fountain.

fig. 164: exploded axonometric of sheltered fountain structural assembly.

fig. 165: spatial diagram of the sheltered fountain.

fig. 166: typical plan of the sheltered pavilion.

fig. 167: typical section of the sheltered pavilion.

fig. 168: Kabita's mother-in-law walks towards the sheltered fountain on a rainy evening.

fig. 169: liquid field of dreams: plan of a village fragment and a constellation of three water equipments (present scenario).

fig. 170: liquid field of dreams: plan of a village fragment and a constellation of three water equipments (a week later).

fig. 171: liquid field of dreams: plan of a village fragment and a constellation of three water equipments (8 months later).

fig. 172: liquid field of dreams: plan of a village fragment and a constellation of three water equipments (a few years later).

fig. 173: (page right) illiustration of Chilika from Balia Anla. Drawn by Author.

fig. 174: Jhilli Jalli's Mother.

fig. 175: a cloth drying in Jhilli's front yard. Khatisahi Village. March 2023.

fig. 176: figure-ground of Khatisahi Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 177: figure-ground of Maensa Village. Drawn by Author.

LIST OF FIGURES

21 190 192 197 197 197 198 199 201 202-209 203 205 207 213 215 216 218 230

23 INTRODUCTION

01

(page left) - fig. 004: figure-ground of Kuanarpur Village. Drawn by Author.

The dissertation is organised in three segments – Front matter, Body and Back Matter.

The Front Matter contains acknowledgments, abstract and a prologue on precarity to frame the dissertation.

The Body contains Six Chapters.

The Back Matter of the book has an extensive bibliography and an appendix, which contains drawings, photographs, and other materials essential to the research.

Chapter One, Introduction, presents the research problem, the theoretical framework and scope of the dissertation, and states the research questions, aims and objectives.

Chapter Two, Research Context, is subdivided into 6 sections that provide an in-depth understanding of the research conditions, the case of dispossessed fisherwomen, social conflict between fishers and non-fisher stakeholders, analysis of 11 fishing villages, framing of a spatial argument and notes on material precarity.

Chapter Three, Macro Waters, is a mini-essay on the conception of Modern Water, Global paradigms of Western Capitalist driven infrastructure inextricable from development in water-use spaces, and a colonial appropriation of them. This chapter is to be read as an interlude that provides a background and theoretical frame to be challenged by the dissertation.

1.1 DISSERTATION STRUCTURE

Chapter Four, (Fisher) Women & Water(s), provides a contextual lens of the subaltern feminine body that can challenge the establishment of Macro Waters. This chapter provides a bridge between two theoretical interludes that lie on opposite ends of the spectrum, by positioning the knowledge and bodies of fisherwomen as the vehicle to do so. A series of interviews, photographs, original participatory sketches, and analytical drawings compose this chapter, and becomes a key method in the research process.

Chapter Five, Micro Waters, is the second mini essay and interlude, which addresses notions of extreme sharing and communing that resist an individualization of wateruse. Responding to the established conditions discussed in Macro Waters, this essay argues that possession is an invention, which can be demystified by the situated knowledge of fisherwomen. This essay adopts a projective position, towards a de-possession that reconsiders the meaning of dispossession.

Chapter Six, Liquid Field of Dreams, distills the research and theoretical positions into a series of projective spatial projects. The chapter is further subdivided into a design brief, construction, and assembly studies, followed by three design typologies, their network, and a conclusion. This chapter presents an aspirational glimpse into re-thinking cooperation and agency for fisherwomen, through the building and management of water devices in their villages.

25

In the words of Matthew Gandy, a geographer and urbanist, “water lies at the intersection of landscape and infrastructure, crossing between visible and invisible domains of urban space”4. Although waters flow and form aqueous links between terminals, the increasing opacity of their containers obscures that relationship, polarizing them into scenic and commodified waters, as landscape and infrastructure. The Global North and urban zones in the Global South have been popularly identified and examined for such latent flows, with the aim of questioning spatial production through the tension of water as nature and technology5. While the urban canvas exemplifies the contradiction of landscape and infrastructure for scholars such as Gandy, this dissertation argues that this contradiction is significantly heightened in rural contexts and for women – the geographically and sociopolitically other. Current ‘developmental’ projects directly administer infrastructure (processed through decades of urban histories) to rural contexts, producing uncanny and alien environments that are in stark contrast to the natural landscape and sensibilities of the rural subjects, particularly women.

Unlike the subterranean nature of water infrastructure in the Global North, the Global South has a much more tactile conception and spatial relation to how it sources water. Whereas in the West – and in urbanised zones the world over –water flows through pipes and valves, in remote and rural areas of the Global South there is continued dependence on bodies, buckets and basins. Female bodies, specifically, are at the heart of this reality. And so, questioning water rituals and their associated spaces in these contexts is inherently a feminist issue, which requires a re-formatting of Gandy’s binary of infrastructure and landscape, to a triad between infrastructure, landscape, and female bodies.

4 Matthew Gandy, The Fabric of Space: Water, Modernity, and the Urban Imagination, First MIT Press paperback edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts London: MIT Press, 2017), 1.

5 Gandy, The Fabric of Space; Nikhil Anand, Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

infrastructure landscape female bodies

1.2 INTRODUCTION

To examine this relationship, the dissertation situates itself within the wider socio-ecological discourse around small-scale fisheries in South Asia: communities that are marginalised. These settlements, identified in the coastal regions of eastern India, were selected for this study for three reasons:

Rupture in Social Systems

Inherent Socio-Political Marginalization

Multiplicitous Relationship to Water

Drawing on literature by environmentalists, sociologists, activists, and anthropologists, the dissertation develops a spatial case on small-scale fisheries around Lake Chilika, a coastal lagoon situated along the Bay of Bengal in Odisha, India. Since the 1990s, these fisheries have faced rapidly devolving socio-ecological conditions, resulting in an intense social, economic, and spatial dispossession. Within this marginalization of an entire community, the dissertation argues, the most dispossessed is the fisherwoman, who has historically been viewed as a support, or the other. The dissertation seeks to examine their rituals, protocols, and spatial consciousness, specifically in relation to water, in order to situate them as protagonists in rebuilding agency for themselves and, by extension, for the wider fishing community.

27

To research such remote settlements, specifically through an anthropological lens of the feminine, field work was conducted in the months of October 2022 and March 2023. Extensive visits were made to the village of Khatisahi, with supporting information collected from the villages of Biripadar, Noliapatana, Berhampur, Balia Anla, Rasakudi, Malud and Khirisahi. Although there is a plethora of literature for the context in the realm of environmental studies, geography, and sociology, which have proven to be crucial secondary sources, there was a gap in the spatial registration of these communities. Photographs, videos, interviews, and observations were gathered during the fieldwork to address this, providing a new scope for studying marginalised fisheries of Lake Chilika – a spatial one.

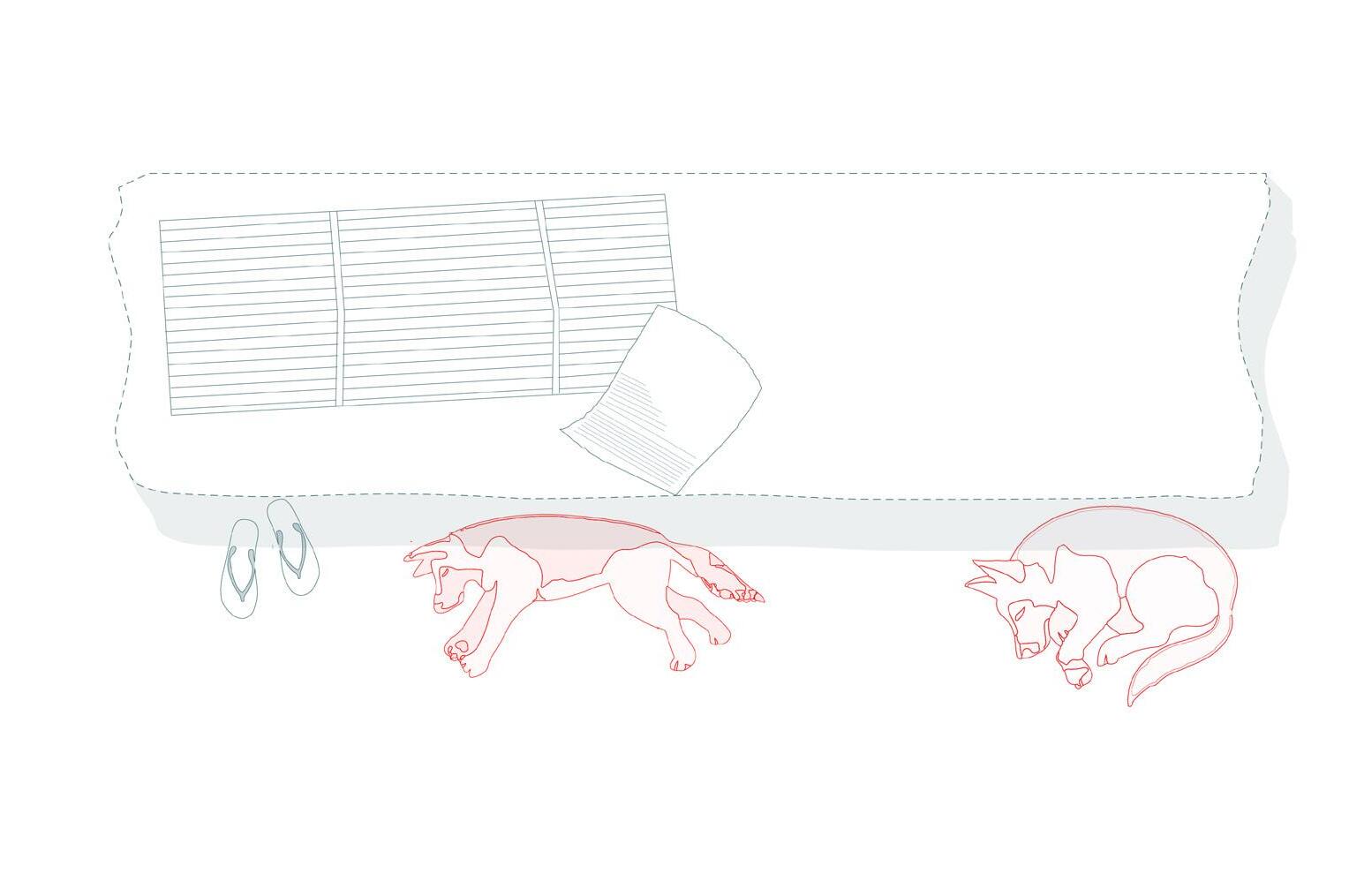

In a context where the relationships between vulnerable and protected, natural and man-made, and wet and dry challenge their supposed binary nature, existing as they do on a spectrum between two extremes, the dissertation seeks to re-evaluate the relevance of development projects that are rooted in histories of infrastructure and modern water. Such large-scale projects are predicated on systems of reliability and consistent operation and management; conditions that are alien to and visibly non-existent in such remote and marginalised areas. Focussing on fisherwomen and their water rituals, the dissertation seeks to construct specific spatiality determined by corporeal functions of washing, defecating, and drinking. For instance, the idea that kitchens are spaces for cooking and cleaning utensils is challenged in these settlements: kitchens are located in proximity to the house, used almost exclusively for cooking, and are kept dry; washing utensils is a separate activity which is located further away from the domestic space, and closer to water sources.

The research reveals that water rituals are not centralised activities limited to the interiors of the domestic but are instead a scattered series of points and vectors in the village landscape. Constructing an invisible constellation of rituals based on situated knowledge, these forms of living inherent to fisherwomen extend the limits of domesticity into a wider network of commons and extreme sharing. Responding through an intervention of architecture-scale devices, the project seeks to spatialise the acts of water living and their associated network. Instead of determining development against a universal truth, Precarious Waters leverages seemingly precarious conditions into advantages for building agency in the community. Utilising locally sourced materials, such as palm-leaf, bamboo, jute, nets and ropes, the project is predicated on self-building and re-building. These processes allow fisherwomen to have control over their structures in the face of such inevitable events as cyclones and water fluctuation and enable them to preserve a traditionally sustainable form of knowledge and to operate relatively independently of top-down facilitation by the state or nongovernmental agencies.

29

Outdoor Water Structures, Gender and Privacy

Re-structuring of daily life due to out migration in fishermen

Role of Architectural Design for socially, economically and geographically marginalized fisher women

Female Body Politics

Commoning and the Invention of Possession

Spatial Response to Local Network of Water(s)

Decentralized and Collectively produced of water structures

Collective MGMT of Water Infrastructures

New Type of Space: InterStructure Zone

Wash Fresh/Lake Water Fresh/Lake Water Fresh Water Grey Water Black Water Private Semi-Private Fresh Water Public Defecate Drink

Gradient of wetness: challenge binary of wet/ dry, natural/man-made, vulnerable/protected

DISCIPLINARY

ARCHITECTURAL

URBAN

Disciplinary Question(s)

What is the role of architecture and urban design in spatializing agency among dispossessed women in marginalised communities?

How can re-thinking spaces of water rituals of marginalised groups become the vehicle for challenging top-down planning structures?

Typological Question

How can type be extracted and constructed through an evolution of situated rituals and bodily movements, rather than through built examples?

Settlement Question

To what extent can decentralised spatial nodes of water structures become a collective form of water security at the village scale, whilst providing new spaces of communication and care?

Research Aims

To explore the relationship between subaltern female bodies and the production of localised water equipment in the context of remote fishing villages

To develop a design methodology that embraces precarity in the context, by learning from the situated knowledge of the fisherwomen.

31

1.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

33 RESEARCH CONTEXT

02

(page left) - fig. 005: figure-ground of Rasakudi Village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 006: location of Chilika Lake on the Political Map of India.

Drawn by Author.

fig. 006: location of Chilika Lake on the Political Map of India.

Drawn by Author.

6 Traditional fishing communities have mainly derived their livelihoods from fishing activities. Their occupation has given them their historical class position within the Hindu caste system. Regardless of contemporary occupational displacement, their caste remains essential in how they socially identify.

7 S. Mishra and Joygopal Jena, ‘Migration of Tidal Inlets of Chilika Lagoon, Odisha, India -A Critical Study’, 2014, https://www.semanticscholar.org/ paper/Migration-of-Tidal-Inlets-of-Chilika-Lagoon%2C-India-Mishra-Jena/ d15c42a2e1d9541a3958ba4ac730ea5eb669d5f0.

8 ‘Chilika Lake - UNESCO World Heritage Centre’, accessed 14 March 2023, https://whc.unesco.org/en/ tentativelists/5896/.

The dissertation focusses on traditional fishing communities6 of Chilika Lake, located on the eastern coast of India in the state of Odisha. Chilika Lake is Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon and an ecological hotspot, being arguably the largest Indian site for wintering migratory birds, not to mention a haven for large populations of crustaceans, fish, Irrawaddy dolphins, as well as being one of the pre-eminent nesting sites for Olive-Ridley turtles7. Chilika Lake was listed as a Ramsar wetland of international importance in 1981 and included in the Montreux Record (Threatened List) in 1993 following fundamental changes to its ecosystem8. Chilika Lake, also referred to as Chilika Lagoon, is an extremely shallow body of water and its annual tidal flux ranges from 0.2m to 2.4m. Considering that the deepest parts of the lagoon are around 5m, a 2.2m change in water level has a dramatic effect on the ecology and landscape of the lake.

35

2.1 SITE CONTEXT

fig. 007: illustration of seagrass. Drawn by Author.

fig. 008: location of 11 traditional fisher revenue villages. Krushnaprasad Block, Puri, Odisha. Drawn by Author.

fisher revenue village non-fisher revenue village Block Administration Boundary

9 ‘Environments || Chilika Development Authority’, accessed 14 March 2023, https://www.chilika.com/ environments.php.

10 See Appendix A and C; Prateep Nayak, ‘The Chilika Lagoon Social-Ecological System: An Historical Analysis’, Ecology and Society 19, no. 1 (17 January 2014), https://doi. org/10.5751/ES-05978-190101.

State: Odisha

District: Puri

Block: Krushnaprasad

GP: Ramalenka

1. Kuanarpur

2. Patanasi

GP: Siandi

3. Noliapatana

GP: Bada Anla

4. Rasakudi

7.

According to the Chilika Development Authority (CDA), the three distinct communities contributing to and depending on the lake’s resources are the fishermen (traditional and non-traditional), the farmers living around the lake, and those dependent on forest resources for fuel/timber requirements9

While Chilika supports the livelihood of around 400,000 traditional fishers and their families, living across 150 fishing villages10, this dissertation focusses on 11 fisher mouzas (revenue villages) located in the inter-tidal coastal mudflats, which fall under the Krushnaprasad Block in the District of Puri, in Odisha state. These villages are susceptible to greater precarity due to their extreme geographical isolation in a watershed along the Bay of Bengal. The 11 fishing villages are defined by their mouza boundaries set by the Block Tehsildar (land-based tax collector). These are Kuanarpur, Patanasi, Noliapatana, Rasakudi, Kandaragaon, Alandapatana, Biripadar, Khirisahi, Khatisahi, Maensa and Berhampur. The 11 fisher mouzas are surrounded by 85 nonfisher mouzas

Of these 11, the 5 villages of Noliapatana, Biripadar, Khirisahi, Khatisahi and Berhampur were the site for the field work of this research. Extensive research was carried out in Khatisahi, due to the co-operative nature of participants, proximity to the boat docking station and the availability of secondary information sources. Fieldwork was undertaken in September-October 2022 and February-March 2023, to study the context in its varying ecological conditions between the monsoon and dry seasons.

37

Alandapatana

Gomundia

5. Kandaragaon GP: Alanda 6.

GP:

Biripadar

Nuapada

Khatisahi

Berhampur

Khirisahi 10. Maensa 11. Berhampur

GP:

8.

GP:

9.

fig. 009: Khatisahi Revenue Village. Krushnaprasad Block, Puri, Odisha.

Drawn by Author.

fig. 009: Khatisahi Revenue Village. Krushnaprasad Block, Puri, Odisha.

Drawn by Author.

11 See Appendix B for the list of 96 Mouzas in Krushnaprasad in the Tehsil Office. Villages marked with a small ‘f’ are the fishing communities.

diagram 2.1: structural system of governance in villages of Krushnaprasad Block, Puri District.

The mouzas at times contain smaller village clusters, and when most of those clusters identify as traditional fishing communities, then the entire mouza is classified as such. Similarly, there are other neighbouring mouzas that contain micro fisher settlements; however, those are predominantly comprised of non-fishing communities. An example of this is the fishing hamlet of Balia Anla, that falls under the Nuagaon mouza of Titipa Gram Panchayat. While Balia Anla is a Nolia fishers hamlet, the mouza it falls under is predominantly populated by non-fishers. Of the 96 mouzas in the mudflats of Krushnaprasad Block, there are, therefore, only the abovementioned 11 that can be classified as fishing communities.

This distinction is complex to understand and is made further opaque as there are no official records of such social differences. Ultimately, an oral account of the distinction between the 11 fishing and 85 non-fishing mouzas was provided by an old office worker of the Krushnaprasad Tehsildar Office11. While these social distinctions may seem irrelevant since both the fishers and non-fishers engage in fishing activities along the coastal mudflats – the research will reveal socio-political discrepancies between the two that have led to a marginalization of the minority group – the fishers – particularly its women.

Krushnaprasad Block

gram panchayat(GP)

revenue village (mouza)

ham

let/settlement

39

2.2 FISHERWOMEN AND DISPOSSESSION

In this context, the dissertation demonstrates that fisherwomen are the most socio-ecologically vulnerable. While the dispossession of fisherwomen varies at intervillage and intra-village scales, there is a consensus on their precarity regarding food, shelter, and income. Synthesizing interviews, observations and secondary sources, the reasons for their dispossession can be broadly attributed to a loss of traditional skill and unemployment.

The first, loss of traditional skills, has been a slow development over generations of increasing dependency on men’s employment status and ‘modern’ forms of living. These two tendencies have led to a decline in the women’s ability to engage in activities related to fishing such as cleaning, drying, and salting. Further, it has negatively affected their abilities in roof thatching and building with mud/clay.

The second, unemployment, is closely related to loweducation levels, lack of work opportunities close to the villages, caste-based limitations in work selection, and decline in requirements of fish drying, salting, and selling. Since fisherwomen have traditionally supported the fishermen by processing their catch, a decline in the fishermen’s trade is key in understanding the dispossession faced by fisherwomen today.

The re-structuring of fisheries, especially since trade liberalization in the 1990s, has forced a larger percentage of fishermen to out-migrate to urban areas for work opportunities, leaving more women in the village for varying periods of time12. This has generated a shift in social relations within the villages, where the female members have become de-facto heads of their households13. Although most men send money back to their families in the villages and visit periodically, there is a fundamental repositioning of familial values; in some instances, the physical separation has led to men abandoning their village families altogether. Eventually these reasons have combined to generate socio-economic precarity among fisherwomen, centred on shelter, food, and

12 Prateep Kumar Nayak, ‘Fisher Communities in Transition: Understanding Change from a Livelihood Perspective in Chilika Lagoon, India’, Maritime Studies 16, no. 1 (15 November 2017): 21, https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40152-017-0067-3. Nayak elaborates on the general trend of out-migration in fishing communities. He cites the case of Berhampur, where 53% of households have pursued out-migration as a livelihood strategy since 2001.

13 Marina Laudazi, Gender, and Sustainable Development in Drylands: An Analysis of Field Experiences (Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 20). Laudazi’s study extends to Burkina Faso, Niger, Senegal; China, India; Morocco; South Africa; Sudan and indicates that an increase in women’s management, organization skills and decision-making responsibilities increased as a direct result of providing an income to their families. Interviews and observations from the field visit supported the conclusions from Laudazi’s report in the context of fishing communities as well. Women in the fishing communities of Lake Chilika are starting to occupy a greater role in the management of their families and daily household activities. In these cases, the extenuating circumstances position women as heads of their households.

fig. 010-019: stills from 'Woman Fills Her Bucket in Noliapatana". October 2022.

Source: Author.

41

fig.

social responsibility.

In response to, but not limited to, such cases of marginalization of women across the state, the Odisha State Government has promoted a micro-finance system called WSHG (Women’s Self-Help Group). The purpose of these grass-roots organizations is to provide women with employment opportunities and equip them with useful skills, so that they can contribute to the productive workforce. The state government provides these groups with subsidies to kickstart their endeavour and continues to aid them through interest-free loans. These groups usually self-organise into groups of 8 to 20 members, raise loans from the local government and invest the funds in income generating activities, like spice-mixing, wheat grinding, fish drying, etc.

However, interviews conducted in Noliapatana, Biripadar, Khirisahi, Khatisahi and Berhampur revealed that although women raised loans for activities such as grain-processing machines, pond polyculture and fish drying, these funds were actually utilised by the fishermen to buy boats, nets, equipment, etc. This subordination of women’s resources to the perceived occupational superiority of men has resulted in a loss of structured ‘productive’ work among women, and a linear decline in knowledge of local craft. In other instances when the women applied their funds for an WSHG activity, for example spice mixing, it soon became apparent that these activities were redundant and did not lead to any actual profits. In summary, although WSHGs work conceptually through the micro-financing models, they do not function sustainably within the fishing communities of this study.

43

020-029: stills from 'Woman Walking to take a bath". October 2022. Source: Author.

supply of rice/ grain from govt.

WSHG

machines for grain processing

subsidies for pond-polyculture

subsidies for fish drying/sorting

food precarity

inability to fish + related activities

dependence on external support

loss of local skills

DISPOSSESSION AMONG FISHERWOMEN

inability to build with mud/clay

low education

lack of opportunity

unemployement

inability to thatch social limitations

shelter precarity

out-migration among men

reduction in fish drying, salting, etc

economic precarity

decline in fish catch

reduction in fish in Chilika

increase in aquaculture farms

45

diagram 2.2: roots of dispossession among Chilika's fisherwomen.

To be able to find work outside of their villages on their own accord is an even greater challenge for fisherwomen. At times, there are specific social factors that prevent fisherwomen from being involved in income-generating activities. In the village of Khatisahi, where the fisherwomen belong to the Khatia caste, social structures prevent them from leaving the village for income generation; they have traditionally been relegated to the limits of their homes and village communal areas14. In other instances, caste positions exile women to activities like becoming daily wage labourers, as is the case with women belonging to the Khandra caste of Birirpadar15

Considering the expanding social role of fisherwomen, their growing presence (unlike the out-migrating men) in the functioning of village life and their proactive efforts in selforganizing through SHGs, they remain underrepresented in public spaces and decision-making, which prevents them from further developing their agency16.

In response, the dissertation positions spatial interventions as a method for the fisherwomen to re-possess agency in conditions of extreme marginalization. Supported by interviews and observations from the fishing communities, the thesis argues that fisherwomen are bodies that choreograph the socio-spatial fabric of their villages and are therefore, cornerstones to the future development and survival of the fishing communities.

14 Fatima Noor Khan, ‘Women and Environmental Change: A Case Study of Small-Scale Fisheries in Chilika Lagoon’ (Master Thesis, University of Waterloo, 2017), 21, https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/ handle/10012/11265.”plainCitation”:”Fatima Noor Khan, ‘Women and Environmental Change: A Case Study of Small-Scale Fisheries in Chilika Lagoon’ (Master Thesis, University of Waterloo, 2017

15 Khan, 22.many lagoons around the world have experienced environmental degradation resulting from impacts of various drivers of change (e.g., natural disasters and aquaculture Interviews with several women in Biripadar during the field visit in 2022 confirmed Khan’s findings that they engaged in daily wage labour activity as their only source of income to support their families. Middle men, also known as the contractors, arrive in Biripadar and solicit them for nominal wages and transport them to nearby non-fisher villages. These work opportunities are sporadic, unreliable, and exploitative.

16 Vineetha Venugopal et al., ‘Commoning Coastal Odisha’ (Bengaluru: Dakshin Foundation, 2021), 25.

fig. 030-39: stills from 'A fisherwoman cooking on an outdoor stove'. Noliapatana. October 2022. Source: Author.

47

17 Venugopal et al., 3.

18 Salinization of land has led to a decline in soil quality in these coastal island areas, leading non-fishers to adapt to marine activities like fishing, prawn culture, etc, for subsistence.

19 Venugopal et al., ‘Commoning Coastal Odisha’, 5. The Government of Odisha began leasing brackish waters to non-fishers in the 1980s, following the increasing global demand for shrimp.

To contextualise the position of the fisherwomen, it is of paramount importance to address the social conflict between the communities of fishers and non-fishers that has increased since the 1970-80s. While Chilika Lake supports the livelihood of around 400,000 traditional fishers, it has also indirectly supported around 800,000 non-fishers, who belong to higher castes and have historically engaged in farming, forestry, and other occupations17. Over time, the non-fishers have increasingly engaged in aquaculture and capture fishing due to a degradation of land-related resources in the coastal mudflats as well as for financial reasons, leading to conflicts of interest with traditional fishers18. And so, today, both communities operate within the same occupational ecosystem of fishing to some degree and rely on Chilika’s limited resources for survival.

Although scholars popularly identify the 1990s as the beginning of conflict between the two groups, attributing it to the policies of trade liberalization and aquaculture in1991, it can be argued that these relations began to disintegrate a couple of decades before that. Social conflicts between the fishers and non-fishers escalated in the 1970s and 80s, when the non-fishers began encroaching upon waters managed by the fishers19 .

fig. 040: fishermen of Khatisahi drag- net fishing. Khatisahi. March 2023.

Source: Author.

fig. 041: illustration of a tiger shrimp. Drawn by Author.

49

2.3 FISHERS V. NON-FISHERS

This type of forced alienation was defined by Maarten Bavinck as “the contested appropriation of coastal space and resources by outside interests”20, which disrupt the operations of self-governed Common Pool Resources (CPR), which form what American Political Scientist, Elinor Ostrom, popularly discusses as the ‘Commons’21. Popular Oriya cinema, such as Chilika Teerey (1977), are indicative of the commonplace awareness and representation of the conflict. Even before the crisis of the 1990s, concerns on managing CPRs began emerging because of overfishing, specifically with non-fishers using unsustainable practices such as motorised boats and nylon nets.

While traditional fishers, due to the caste system, have historically associated their entire identity with their vocation, the non-fishers engage in fishing for economic reasons. This became problematic for the fishers because the nonfishers occupy a higher position in the Hindu caste-based hierarchical system, leading to the de facto supremacy of the non-fishers and subsequent ability to displace the fishers.

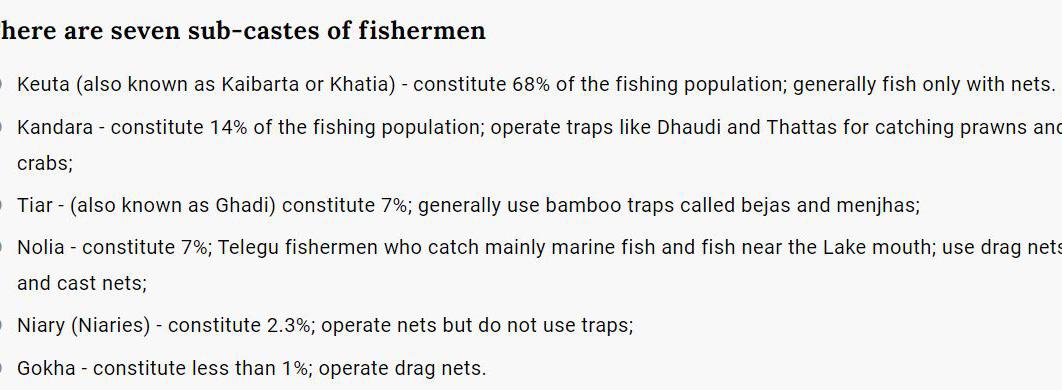

In the context of Krushnaprasad, fisher communities occupy the lowest class positions, live separately from other caste Hindus, and face a general isolation in the societal structure. The caste system is deeply ingrained in the social customs of the place. For example, the village of Khatisahi literally translates to ‘Street of Khatia’, where Khatia is the caste name of the people. The caste further determines the group’s specialised activities. In the case of the Khatia community, they traditionally specialise in using nets for fishing. Similar specialization is seen in other fishing communities: the Khandra of Biripadar use traditional traps called dhaudi or thattas to catch crustaceans, the Nolias of Noliapatana specialise in drag and cast nets for marine fishing, and so on.22 While traditional fishers use such artisanal techniques for fishing, the non-fishers oftentimes use environmentally exploitative methods such as zero-nets to make gheri bandhs (large enclosures of fine-mesh nets that catch juvenile fish

20 Maarten Bavinck et al., ‘The Impact of Coastal Grabbing on Community Conservation – a Global Reconnaissance’, Maritime Studies 16, no. 1 (December 2017): 30, https://doi. org/10.1186/s40152-017-0062-8.

21 Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Canto Classics (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

22 ‘Environments || Chilika Development Authority’.

23 . See Government of Odisha, “Orissa Prevention of Land Encroachment Act”, (1972).

fig. 042: cadastral map no.95, Berhampur Village, 1963.

Source: Krushnaprasad Tehsil Office.

that block ecological flows) and dike-constructed ponds for intensive aquaculture. Because of such unsustainable practices over the years, the natural catch of the lake has dramatically declined, forcing fishers to abandon their trade and out-migrate.

Additionally, fisher communities possess minimal lands compared with non-fishers, a fact easily ascertained from the cadastral maps of the villages obtained from the Tehsil Office and Odisha Remote Space Applications Centre (ORSAC). Being located close to the lake embankments, these lands are further compromised by their intense saline quality and are categorised as Class IV, i.e. ‘Other Non-Cultivatable Land’. According to the definition of One Standard Acre Land in Odisha, one would need to possess 5.5 acres of Class IV land to qualify as One Standard Acre23. The maps indicate that fisher families usually have legal rights to no more than 1 or 2 acres of Class IV land, making it difficult for them to raise loans for equipment, leasing of aquaculture ponds, investments, etc.

51

The earliest recorded evidence of a formal organization of Fishers’ rights to Lake Chilika can be traced as far back as the early 1500s24. Until the early 20th century, the Lake’s areas were controlled by Kingdoms that ruled these parts of Odisha and were solely reserved for the use of caste-based fisherfolk. In a system called bheti or salaami, fishers were expected to pay taxes to the zamindars, i.e., local landlords, who reported to the King. It is crucial to note that from 1803-1930, the Lake was managed by the King of Parikuda, who ruled out of his palace in the coastal mudflats of Krushnaprasad25, where this research is located. Even under the years of British Governance (1930-47), the traditional fishers’ rights were protected through the creation of Primary Fishers Co-Operative Societies (PFCS) and the construction of a Co-Operative distribution centre in Balugaon. Being the only ones entitled to Chilika’s resources for generations has formed a deep connection between traditional fishers, the lake waters, and their caste-based identity, called Matsyajibhi.

24 Nayak, ‘The Chilika Lagoon Social-Ecological System’.

25 Nayak, 4.

fig. 043: Krushnaprasad Garh (Palace), Constructed by Raja Sri Bhagirath Mansingh. Established 1798. Krushnaprasad. September 28, 2022. Colour 35mm Film. Source: Author.

26 After Indian independence in 1947, an open auction for Chilika’s waters began under the control of the Administrative Services between the years of 1953-59.

27 See fig.X for a detailed account of a timeline of traditional fishers’ land rights.

28 Matilde Adduci, ‘Neoliberal Wave Rocks Chilika Lake, India: Conflict over Intensive Aquaculture from a Class Perspective’, Journal of Agrarian Change 9 (17 September 2009): 484–511, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14710366.2009.00229.x.

A disruption of their rights, which begins to unfold in the middle of 20th century, has naturally generated a sense of alienation and marginalization for a community positioned in the lower ranks of the Hindu caste system26. Specifically, the period after 1960 marked a decline in traditional fishers’ autonomy in managing the lake’s resources, when the State Government dramatically increased lease costs, replaced co-operative societies with Governmental agencies and most importantly, allowed non-fishers into Chilika27. In 1964, the Chilika Matsyajibhi Mahasanga (CMM) was established, and represented the unionization of fishermen against informal credit networks, wherein they were economically exploited by socially mobile classes of non-fishers28. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, the CMM continued to advocate for better conditions for the fishing communities, especially by protesting against wholesale distributors of their produce.

fig. 044: During an inspection of shrimpnets at 6 am with a fisherman from Rasakudi Village. Rasakudi. September 28, 2022. Colour 35mm Film. Source: Author.

53

Governmental policies continue to remain complicit in the polarization between these two social groups. FISHFED29, the governmental agency that replaced PFCS, allocates 50% brackish water leases in Chilika to the fishing communities to protect their right to the Lake and manage a stable income source. However, in practice, the water areas leased to fishing communities are forcefully taken over by nonfishers for nominal prices. And since the non-fishers are politically influential, they strongarm the fishermen into complying in exchange for receiving nominal payments from the profits they incur. As documented by scholars such as Nayak, Adducci, Samal and Meher, and through interviews conducted for this dissertation, fishers have continually explained that even a miniscule legitimization of non-fishers’ rights to Chilika spirals into a web of illegal practices.

In reference to this reality, the 2015 document released by the Fisheries & ARD Department Government of Odisha contains a fundamental error30. The document proposes the division of brackish waters among large scale business and small-scale fishers, co-operatives, SHGs and those below the poverty line. As aforementioned, in the context of Chilika, all these marginalised groups are often represented by the fishing communities, and so the document effectively divides the lease between fishers and others. Such policy frameworks promote separationist practices, rather than those based on cooperation and mutual benefit, which in the case of Common Pool Resources (CPRs) is paramount.

29 Odisha Fisheries Cooperative Corporation Ltd “(FISHFED) is an apex body of all Primary Fishermen Cooperative Societies in the State, which looks for the socio-economic interest, as well as welfare of the poor fishermen of the state.” Source: https://odishafisheries.nic.in:8443/?p=childmenupagecontent&pg=5

30 See Appendix D and diagram 2.3.i

diagram 2.3: division of brackish water leases in Chilika Lake.

Lease of Brackish Water

Areas in the Odisha

district level committees assess land suitable for brackish water pisciculture. suitable lands will be evenly divided between category 01 and category 02.

1. beneficiaries of antipoverty programs

2. persons below poverty line

3. fishermen by profession or caste

4. landless persons w/ >40,000 annual income

5. marginal farmers

1. educated unemployed persons

2. Self Help Groups

3. Primary Fisherman Cooperative Societies (PFCS)

4. Women Cooperatives

1. partnership firms

2. technical entrepreneurs

3. state owned corporations

4. companies/exporters registered in orissaW

segregation between social groups begins at the very inception of the process of aquaculture, when the state itself bifurcates land and water based on type and scale of the intended practice – a process by which existent divisons are intensified via polarity and conflict.

sub-group A sub-group B Category 01 Category 02 50% 50% 55

diagram 2.4: timeline of land rights and historical events from 19th century Odisha.

Land Rights and Ownership in Odisha Orissa Land Reform Act 1947 Indian Independence 1959 1936 Odisha State Established 1960 1978 Bengal Tenancy Act 1. 1. one standard acre of land in Odisha is defined 2. 2. Assessment Taxes applied: cannot be challenged in a civil court 1. PCFS replaced by FISHFED (state agency replaces co-op society) 2. 3 year leases replaced by annual leases (increased uncertainty) Increase in Lease Fees by 1978, the State increased the lake lease rents by 120% 2001 Odisha Fishing Chilika Bill 30% brackish water lease reserved for non-fisher castes 1988 FISHFED established 1. aquaculture leases allowed, encouraged non-fishers to engage 2. lease rent increased further 27% (impossible for fishers to pay) 3. neo-liberalization of Chilika and its resources 4. 1996 - Supreme Court rules abolishing aquaculture 1991 Aquaculture Legalized 2011 WSC Program 1. Women’s Support Center pilot project begins in Ganjam district 2. 23 centers established in Ganjam 3. 7,000 single women access to land rights (as of 2016) 1885 Fisher’s Land Rights Begin 1500s Bheti/Salami System 1790 Odisha Estate Abolition Act 1952 Orissa Survey & Settlement Act 1958 Co-Operative Society Set-Up 1926 pre-independence 1. lagoon access controlled by the king and zamindar (landlord) 2. lease of sairat (fishing ground) by paying tributes 3. practice continued till 1930, when the British Raj took over Chilika British rule over Orissa 1803 1. land under the Odisha State is transferred to the British Company 2. Chilika Lagoon access remains under the Parikuda King 3. Parikuda King fort and palace established in Krushnaprasad Islands British Survey Chilika Fishers 1880 1. all fishing rights of Chilika belong to traditional caste fishers 2. zamindars only leased Chilika waters to caste based fishers 3. fisher grounds divided based on location, species and tax brackets 4. surveyed by J.H. Taylor 1. bill passed by the Governor of the Bengal Provinces 2. appeasement of peasant uprisings against zamindars 1. 25 Primary Fishermen’s Co-Operative Societies (PFCS) established 2. co-op store for selling fish set-up in Balugaon (Khurda) by the British 1. Zamindari system abolished 2. All land and water rights transferred to the Administrative Department 1. comprehensive rules and regulations on land administration 2. complete centralisation of power to the State Administration Services Chilika Auctioned 1953-59: transition of Chilika into commodified State property. Disintegration of caste-based fishers’ rights. post 1960: policies begin to threaten fisher co-ops and their commons the 90s were a turbulent period of legal battles, wherein the fishers fought aquaculture until the highest judicial authority. Althouogh aquaculture was finally banned by the State in 2001, it continues illegally to this day and is common knowledge. the legalization of non-fisher involvement in shrimp culture has allowed for a greater illegal encroachment in areas of traditional fishers Land Rights and Ownership in Odisha Orissa Land Reform Act 1947 Indian Independence 1959 1936 Odisha State Established 1960 1978 Bengal Tenancy Act 1. 1. one standard acre of land in Odisha is defined 2. 2. Assessment Taxes applied: cannot be challenged in a civil court 1. PCFS replaced by FISHFED (state agency replaces co-op society) 2. 3 year leases replaced by annual leases (increased uncertainty) Increase in Lease Fees by 1978, the State increased the lake lease rents by 120% 2001 Odisha Fishing Chilika Bill 30% brackish water lease reserved for non-fisher castes 1988 FISHFED established 1. aquaculture leases allowed, encouraged non-fishers to engage 2. lease rent increased further 27% (impossible for fishers to pay) 3. neo-liberalization of Chilika and its resources 4. 1996 - Supreme Court rules abolishing aquaculture 1991 Aquaculture Legalized 2011 WSC Program 1. Women’s Support Center pilot project begins in Ganjam district 2. 23 centers established in Ganjam 3. 7,000 single women access to land rights (as of 2016) 1885 Fisher’s Land

Begin 1500s

System 1790 Odisha Estate Abolition Act 1952 Orissa Survey & Settlement Act 1958 Co-Operative Society Set-Up 1926 pre-independence 1. lagoon access controlled by the king and zamindar (landlord) 2. lease of sairat (fishing ground) by paying tributes 3. practice continued till 1930, when the British Raj took over Chilika British rule over Orissa 1803 1. land under the Odisha State is transferred to the British Company 2. Chilika Lagoon access remains under the Parikuda King 3. Parikuda King fort and palace established in Krushnaprasad Islands British Survey Chilika Fishers 1880 1. all fishing rights of Chilika belong to traditional caste fishers 2. zamindars only leased Chilika waters to caste based fishers 3. fisher grounds divided based on location, species and tax brackets 4. surveyed by J.H. Taylor 1. bill passed by the Governor of the Bengal Provinces 2. appeasement of peasant uprisings against zamindars 1. 25 Primary Fishermen’s Co-Operative Societies (PFCS) established 2. co-op store for selling fish set-up in Balugaon (Khurda) by the British 1. Zamindari system abolished 2. All land and water rights transferred to the Administrative Department 1. comprehensive rules and regulations on land administration 2. complete centralisation of power to the State Administration Services Chilika Auctioned 1953-59: transition of Chilika into commodified State property. Disintegration of caste-based fishers’ rights. post 1960: policies begin to threaten fisher co-ops and their commons the 90s were a turbulent period of legal battles, wherein the fishers fought aquaculture until the highest judicial authority. Althouogh aquaculture was finally banned by the State in 2001, it continues illegally to this day and is common knowledge. the legalization of non-fisher involvement in shrimp culture has allowed for a greater illegal encroachment in areas of traditional fishers

Rights

Bheti/Salami

diagram 2.5: definition of one-standard acre in Odisha.

Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV 1 acre Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Independence State Established Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV 1 acre Chilika Auctioned Chilika into property. caste-based fishers’ rights. begin to threaten their commons turbulent period of legal battles, fought aquaculture until the authority. Althouogh aquaculture by the State in 2001, it continues and is common knowledge. non-fisher involvement in allowed for a greater illegal encroachment fishers Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV 1 acre the aquaculture continues knowledge. illegal encroachment Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Indian Independence Odisha State Established Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV 1 acre Chilika Auctioned 1953-59: transition of Chilika into commodified State property. Disintegration of caste-based fishers’ rights. post 1960: policies begin to threaten fisher co-ops and their commons the 90s were a turbulent period of legal battles, wherein the fishers fought aquaculture until the highest judicial authority. Althouogh aquaculture was finally banned by the State in 2001, it continues illegally to this day and is common knowledge. the legalization of non-fisher involvement in shrimp culture has allowed for a greater illegal encroachment in areas of traditional fishers Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Indian Independence Odisha State Established Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV civil court society) uncertainty) 120% engage to pay) Ganjam district 1 acre (landlord) over Chilika British Company King Krushnaprasad Islands fishers fishers tax brackets established by the British Administrative Department administration Administration Services Chilika Auctioned 1953-59: transition of Chilika into commodified State property. Disintegration of caste-based fishers’ rights. post 1960: policies begin to threaten fisher co-ops and their commons the 90s were a turbulent period of legal battles, wherein the fishers fought aquaculture until the highest judicial authority. Althouogh aquaculture was finally banned by the State in 2001, it continues illegally to this day and is common knowledge. the legalization of non-fisher involvement in shrimp culture has allowed for a greater illegal encroachment in areas of traditional fishers Definition of One Acre Land in Odisha Indian Independence Odisha State Established Class I: Irrigated Land; 2+ crops grown within a year Class II: Irrigated Land; <1 crop grown within a year Class III: Paddy Cultivation Land Class IV: Other Non-Cultivation Land Class I Land Type No. of Standard Acres Class II Class III Class IV 1 acre Chilika Company Islands brackets established British Department Services Chilika Auctioned 1953-59: transition of Chilika into commodified State property. Disintegration of caste-based fishers’ rights. post 1960: policies begin to threaten fisher co-ops and their commons the 90s were a turbulent period of legal battles, wherein the fishers fought aquaculture until the highest judicial authority. Althouogh aquaculture was finally banned by the State in 2001, it continues illegally to this day and is common knowledge. the legalization of non-fisher involvement in shrimp culture has allowed for a greater illegal encroachment in areas of traditional fishers 57

045-54:

01. KUANARPUR

04. RASAKUDI

02. PATANASI

05. KANDARA GAON

01. KUANARPUR

04. RASAKUDI

02. PATANASI

05. KANDARA GAON

2.4 SETTLEMENT TYPE + MORPHOLOGY

03. NOLIAPATANA

fig.

figure-ground studies of 11 traditional fishing communities in Krushanprasad, Puri, Odisha.

59

06. ALANDAPATANA

09. KHATISAHI

07. BIRIPADAR

10. MAENSA

11. BERHAMPUR

08. KHIRISAHI

0 50

brahmandeo village

chilika

table 2. 4.i.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

61

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 22 2. population 1318 643 675 265 4. households 266 5. schedule caste 1305 638 667 3. workers 269 254 15 4 2 2 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well 2.4.i. KUANARPUR

Map Legend

fig. 057: Settlement plan of Kuanarpur village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 056 Location of Kuanarpur Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

0 50

chilika

2.4.ii. PATANASI

4.ii.:

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

63

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 4 2. population 302 160 142 4 4. households 58 5. schedule caste 302 160 142 3. workers 86 63 23 82 62 23 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well

Map Legend

fig. 059: Settlement plan of Patanasi village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 058 Location of Patanasi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

table 2.

village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

0 50

siandi village

chilika

fig. 060 Location of Noliapatana Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

2.4.iii. NOLIAPATANA

Noliapatana presents an exceptional case, where the size of the community is very small, with a disproportionately large area of brackish water31. Through interviews with residents, it was determined that all the brackish water within the village has been sub-leased to a local businessman. A fisherman from Noliapatana explained that working with this man was quite suitable to his current position of out-migrating as, “At least this way we have a reliable income source.” In other instances, fishermen appeared afraid or reluctant to speak out against the current conflict, and on the flip side there were those who were enraged by this marginalization.

cyclone shelter public tube well

table 2. 4.iii.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

31 The population of Noliapatana (without considering data on out-migration) is 145. The area of the village is 457 acres, of which 0.37% is dry land and 99.63% is brackish waters and other forest and beach areas.

fig. 061: Settlement plan of Noliapatana village. Drawn by Author.

65

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 457 2. population 145 73 72 5 4. households 27 5. schedule caste 6. schedule tribe--3. workers 52 44 8 47 42 5 a. main b. marginal

Map Legend

0 50

jagrikuda village

badadanda village

chilika

table 2. 4.iv.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

67

village

open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 187 2. population 522 357 165 81 4. households 83 5. schedule caste 5. schedule tribe 356 164 192 163 164 1 3. workers 136 88 48 55 19 36 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well 2.4.iv. RASAKUDI

Map Legend

buildings

fig. 063: Settlement plan of Rasakudi village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 062 Location of Rasakudi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

khatiakudi village

khatiakudi village

0 50

chilika

table 2. 4.v.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

065: Settlement plan of Kandaragaon

69

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 162 2. population 392 200 192 97 4. households 96 5. schedule caste 392 200 192 3. workers 126 110 16 29 19 10 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well 2.4.v. KANDARAGAON

Map Legend

fig.

village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 064: Location of Kandaragaon Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

alanda village

alanda village

0 50

chilika

table 2. 4.vi.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

71

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 714 2. population 395 195 200 83 4. households 86 5. schedule caste 391 192 199 3. workers 106 91 15 23 15 8 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well 2.4.vi. ALANDAPATANA

Map Legend

fig. 067: Settlement plan of Alandapatana village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 066: Location of Alandapatana Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

kamalsingh village

kamalsingh village

0 50

chilika

2.4.vii. BIRIPADAR

The settlement plan of Biripadar is a prime example of economic precarity resulting from irregularities between the physical settlement and its cadastral boundaries. As seen in this case, most village homes fall outside of the village cadastral limits and there is little land under the legal possession of this community. The leasable waters under their legal rights are all subleased to non-fisher communities.

table 2. 4.vii.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

73

Legend village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 23 2. population 533 246 287 73 4. households 137 5. schedule caste 533 246 287 3. workers 288 132 156 215 82 133 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well

Map

fig. 069: Settlement plan of Biripadar village. Drawn by Author.

fig. 068: Location of Biripadar Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

chilika chilika 0 50

fig. 070: Location of Khirisahi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

Map Legend village buildings

cyclone shelter public tube well

table 2. 4.viii.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

*. Sneha Krishnan, Building Community Resilience to disasters in WaSH (water, sanitation and hygiene) during recovery, (UCL, 2016). 166.

2.4.viii. KHIRISAHI

Khirisahi is a medium sized revenue village, under the Berhampur Gram Panchayat (GP). It has been classified as an island settlement typology and has 26 hand pumps and 1 pond*. According to ORSAC, there are no tube wells or freshwater sources in this village.

fig. 071: Settlement plan of Khirisahi village. Drawn by Author.

75

open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 12 2. population 877 430 447 188 4. households 183 5. schedule caste 81 44 37 3. workers 366 215 151 178 32 146 a. main b. marginal

gurubai village

gurubai village

0 50

chilika

table 2. 4.ix.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

073: Settlement plan of Khatisahi village. Drawn by Author.

Khatisahi is a medium sized revenue village, under the Nuapada Gram Panchayat (GP). Nuapada GP also includes the villages of Anlakuda, Barunakuda, Gurubai, Janhikuda and Nuapada — all non-fishing communities. Khatisahi is, therefore, a minority in its GP.

77

village buildings open water dike protected forest open land religious educational total male female 1. area (ha) 101 2. population 875 421 454 35 4. households 203 5. schedule caste 870 417 453 3. workers 249 420 258 214 198 16 a. main b. marginal cyclone shelter public tube well 2.4.ix. KHATISAHI

Map Legend

fig.

fig. 072: Location of Khatisahi Revenue Village in Krushnaprasad Block.

water tank

chilika

water tank

chilika

0 50

berhampur village

Map Legend

table 2. 4.x.: village statistics. source: State Census 2011.

*PWS: Piped Water Supply scheme. Department of Rural Development, Govt. of Odisha.

075:

79