Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to the many people who supported me in completing this dissertation on the story of the hidden village. I want to show my gratitude to my parents, Chen Hongzhi and Wang Xiufeng, for their immeasurable support and immense sacrifices in my life. I want to thank my family in the mountain village, my uncle Mr. Wang Shuqing; my aunt Lady Tian Fengying, and my grandmother Lady Xia Guilan, for the trip to the mountain village last summer, where they believed in and supported me, and generously shared their lives and memories.

I would particularly appreciate my Projective Cities crews, who supported me with the endless conversations about the thesis idea and stood by me through the countless difficult moments; because of you, this journey was so dreamy. I also want to thank my professors and friends in Beijing, whose support for nine years of ever-motivated exploration; this is an important reason for my enthusiasm for this work.

Most importantly, I would like to thank my tutors at Projective Cities. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Platon Issaias and Hamed Khosravi. Your constant support and criticism of my work and unreserved help over the past two years motivate me to keep pushing myself. I would also like to thank Roozbeh Elias-Azar, Cristina Gamboa and Daryan Knoblauch for all the discussions in the past, which have had a tremendous impact on my thinking about architecture. Special thanks also goes to Doreen Bernath for the countless conversations with me to run wild imagination over the past two years, about Hutong, Youth culture, Village and Spirits... it often inspires me suddenly see the light.

Finally, I want to pay homage to my beloved grandfather, who passed away in 2021; I regret that you cannot read this work, but your passing has made me realise the need to do this work, not only for the sake of nostalgia, but as a permanent reminder of the importance of the mountain village, not only for the family memories, but also for the collective meaning of the times. This dissertation is dedicated to you.

Contents Abstract Introduction Chapter 1 A Contemporary Statement of Rural Ideal 1.1 The Rural idealisation: from the Peach Blossom Spring to Rural tourism 1.2 The idealization internal: living with the environment 1.3 Mountain village in Beijing as the context Chapter 2 From cooperation to self-built 2.1 The basis of cooperation: a self-designed personal life 2.2 The case for cooperation: Returning to the countryside 2.3 The framework for cooperation: Hybrid network in co-environ life Chapter 3 Hamlet Assembly 3.1 Opening up the land: the hamlet's formation 3.2 From settlements to living networks 3.3 Micro typology: thresholds for gathering ● Co-environ network Scale 1: Restructuring family scale Chapter 4 Landscape Boundary 4.1 The evolution of the farmland allocation system 4.2 Environment boundaries are unbounded 4.3 Trail typology: Landscape from private to collective ● Co-environ network Scale 2: Rendering the memory of the landscape Chapter 5 Flowing Village: a new urban infrastructure model 5.1 Flowing: village daily life 5.2 From hamlet to infrastructure: regional connection of the environment ● Co-environ network Scale 3: The community as infrastructure Conclusion Image Sources Bibliography 1 2 8 9 14 18 24 25 28 36 46 47 60 62 70 90 91 94 102 116 120 121 126 128 152 156 160

Abstract

In China, the traditional village has long been closely associated with the environment, which gathered idyllic imagination from an external gaze, represented by portrayals of rural lives from Tao Yuanming's idyllic poems from the early fifth century, written as a result of his political deportation, to the rural communes of modern time during the Down to the Countryside Movement between the 1950s and 80s. This idyllic imagination continues to be strong in the current trend that calls for a return to the countryside, where ideas such as selfsufficiency, back to the mountain, and seclusion have taken on different forms of rural idealisation as the relationship between urban-rural shifted over time.

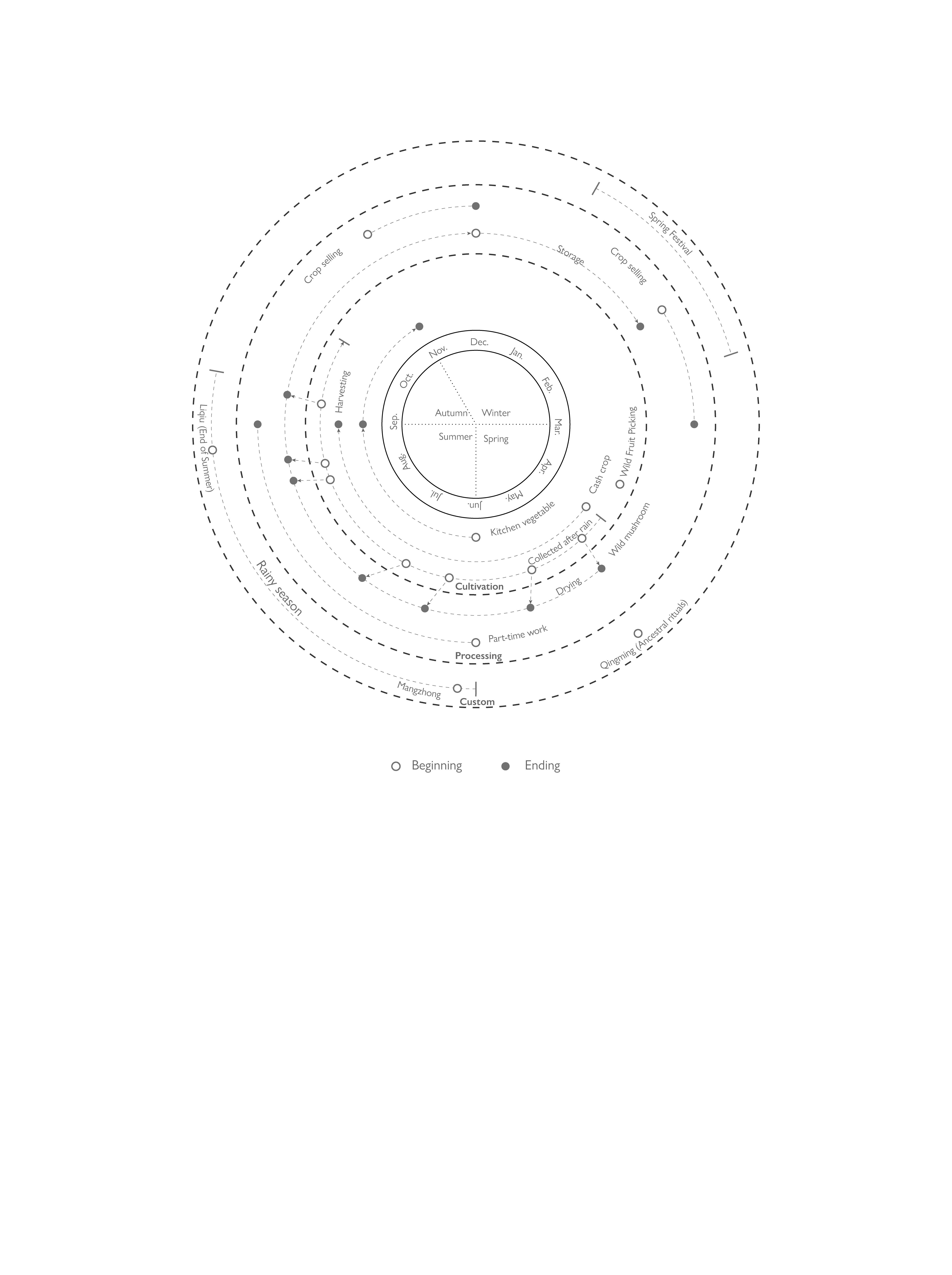

However, from the internal perspective of village life, the idealization are not a desire for landscape, but rather a focus on pragmatism of village and it environ. The fever of immersing in nature, opening up wasteland and creating quaint society reveal the potential of this traditional form of live to cooperate not only within one another, but also with the environment. The research is based on the mountain villages of Beijing as a case to retrace the co-environ village life. Historically, this reveals the spatially cooperative activities of different groups, such as families, kinship networks, and production collectives, as well as family gatherings, farming, and festival rituals. These daily rituals occur in spaces closely linked to the environment, such as hamlets, farmlands, and natural spots. They are not nature, but exist as border territories, thus defining a continuous and hybrid landscape.

The core of the argument is to rediscover and deconstruct the daily rituals of village cooperation; By articulating these co-environ devices, the project proposes to unravel the diagrammatic relations that describe the contact between collective organization and cooperative space.

The dissertation ultimately aims to conceive the current and future co-environ living approach, which implies how the village can be sustainable in the rural flight trend of the metropolitan context.

1

1 Fei Xiaotong's speech at the London School of Economics in 1947, which highlighted the differences between Western urbanisation and Chinese rural tradition.

2 The word “environ” comes from the Old French verb “environner”, meaning “to surround” or “encircle”.

3 Xiaotong, Fei. " 乡土中国 ." People's Publishing House (2008). 2-8.

Introduction

This dissertation aims to reveal two ways of life in rural China, symbolic from the external and pragmatic based on farming. Those image of rurality is not from the urban-rural dichotomy but from the long-standing farming tradition. From the ancient idyllic poetic by the literati, to the production movement during the periods of the Planning economy, to the current mass culture of rural tourism; the village has never been only about the production; instead, in China, the village and the city are always continuous: the village is a way of life. However, as Fei Xiaotong wrote in his critique of rural traditions in the 1930s: ''The sense of 'leisurely seeing the mountain' is idyllic, although it can entertain people's spirit, but there is no innocent paradise in the new situation. ''¹ Despite the gap between urban and rural areas, village life still persists. This is due to a range of factors, including massive and often unnoticed urban changes in the village, resulting from the pervasive sense of “backwardness” and poverty associated with rural areas. Nonetheless, the reason for the continued existence of village life remains a subject of inquiry.

Village, Farmers and Urbanisation

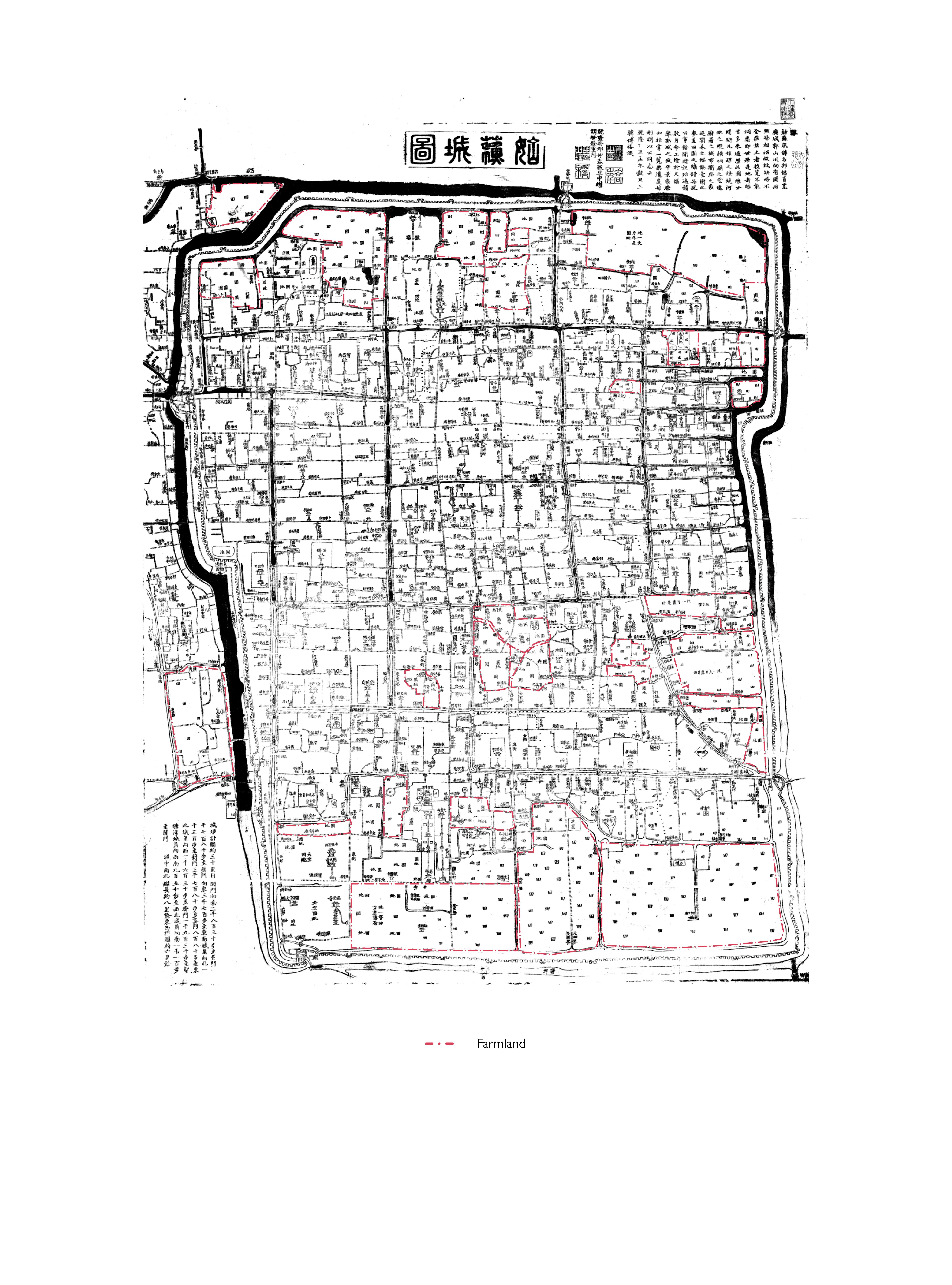

The Chinese rural way of life is deeply connected to the land and the environment, as evidenced by early poetry from the 5th century that emphasised the importance of leisure and farming in nature as an expression of life in an urban society with limited opportunities. However, this way of life is not just a fantasy, but a pragmatic selfdesigned lifestyle that emphasises learning and understanding the natural environment. In ancient times, the basic needs of farming led to the selection of settlements in nature, the opening up of farmland, and the identification of environ² for leisure activities, all guided by the principles of “Feng Shui”. Cooperation with the environment creates a natural landscape that bridges the private and public spheres. Due to the small-scale nature of personal (family) farming, settling in nature was not a means of transforming it, but rather a way of fitting in better with the specific environment elements. As Fei Xiaotong noted in his book, "People who depend on the land cannot leave it easily",³ indicating that achieving a self-sufficient life requires long-term learning and experience in opening up the land.

2

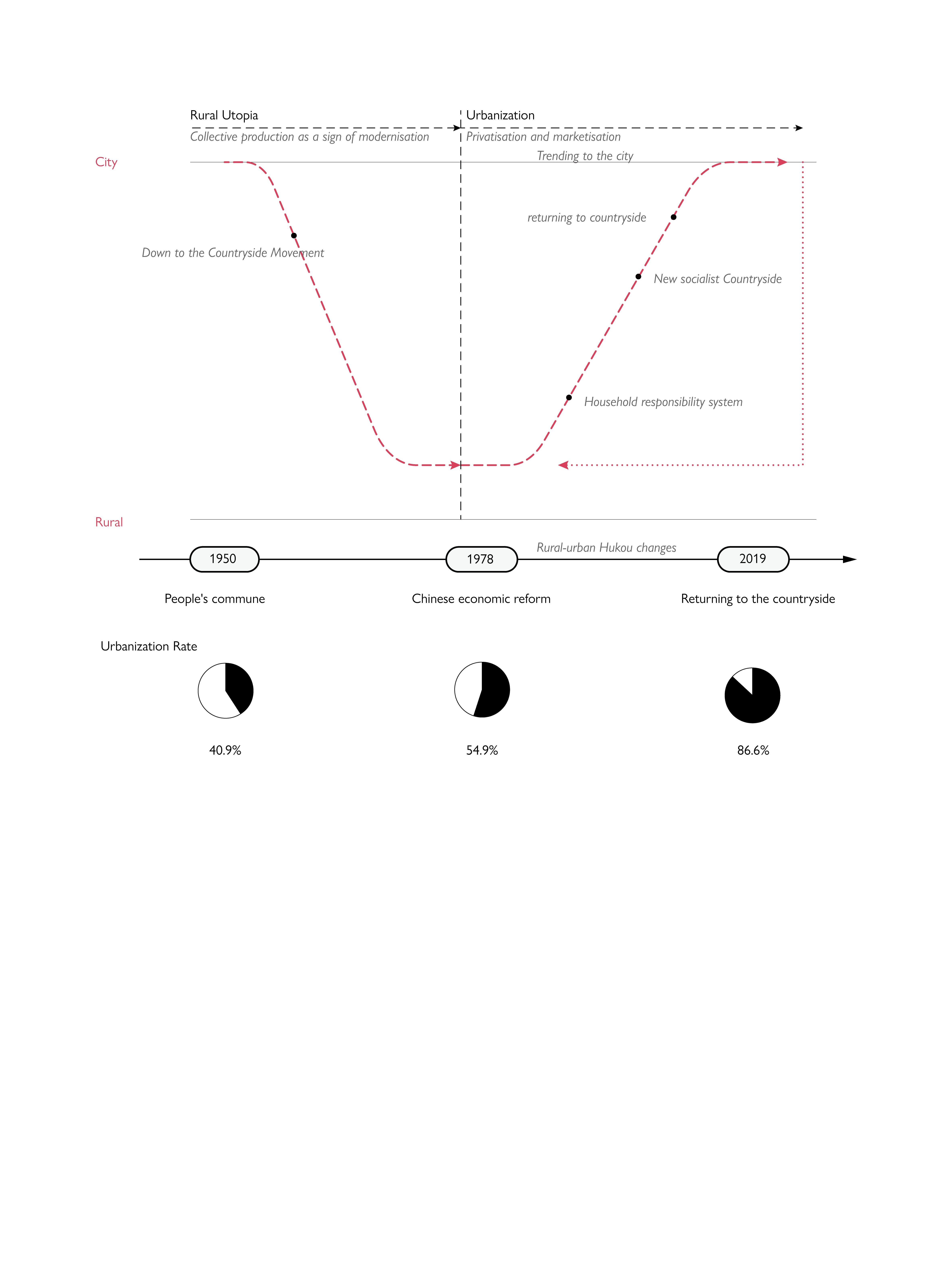

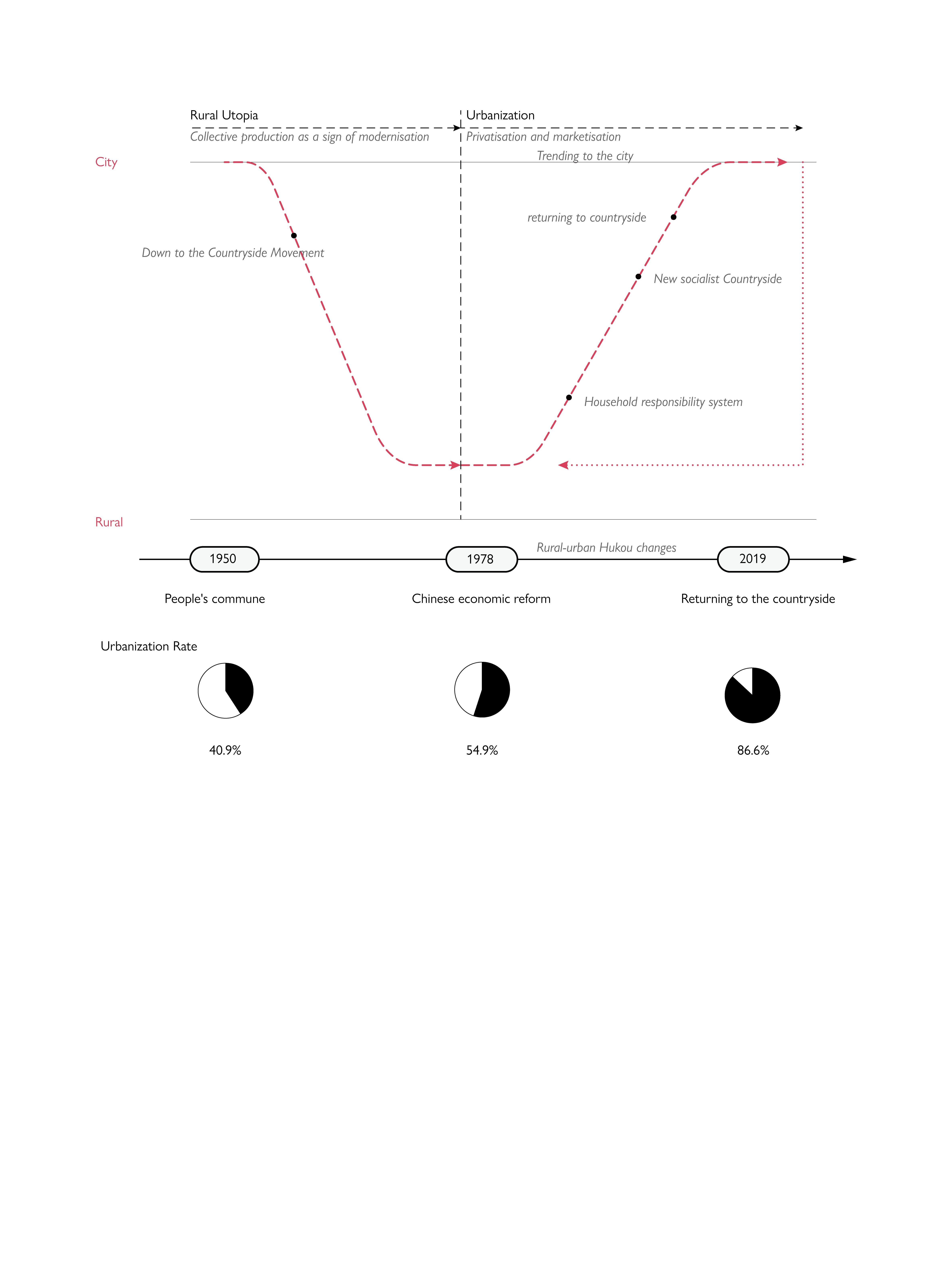

However, traditional farming life in China has been impacted by policy and urbanisation in recent history. The Chinese village is now recognised as a collective administrative formation that is distinct from the city. From the founding of People’s Republic of China onwards, the countryside has existed in different forms of collective administrative formations. In 1958, during the planned economy, the government proposed the formation of rural people's communes and production brigades comprising different villages. This transformed the peasants involved in labour into a collective labour structure from an administrative perspective. After 1978, the policy known as the Household responsibility system led to village back to administrative individuals again, with production brigades being replaced by village committee.⁴ Today, in the midst of rapid urbanisation, a significant amount of rural farmland has been industrialised and intensified. While an increasing number of farmers are moving to the cities, ruralurban migration remains a one-way flow from the rural to the urban areas. In short, the village collective is exclusively formed by those who remain in the village as farmers, as urban residents do not participate in farming activities. Although the government defines urbanrural integration as a new stage in China's modernisation and urban development in the 21st century, the decreasing proportion⁵ of the rural population each year undeniably reveals the reality that rural collectives are declining.

The process of urbanisation has led to the integration of urban and rural lifestyles, creating a trend of ‘returning to the countryside’. This has resulted in the emergence of rural flight and gentrification in the village.⁶ In 2008, the Chinese government introduced the concept called 'basic farmland'⁷ and set a red line of 1.8 billion mu of farmland, which meant that agricultural production was still considered extremely important in the urbanisation process. However, this has led to a long-standing misconception that the countryside still belongs entirely to the farmers. From an administrative point of view, it is true that the village host a large number of farmers, but spatially, rural settlements and environments are moving towards a functional separation: on the one hand, the productive elements of the countryside are being replaced by advanced mechanical production, with farmland thereby becoming part of urban industry; on the other hand, the rural landscape is being extracted, from an urban perspective, into a middle-class idyllic imaginary. This results in the rural settlement as a collage of unstable forms, which also participates in the

4 Tiejun, Wen. "Eight crises, Lessons from china, 1949-2009." People's Oriental Publishing (2013). 73-106.

5 According to national statistics, the rural population has decreased from 89.36% in 1949 to 36.11% in 2021, and the rural population has decreased by 164.36 million in 2021 compared to 2010.

6 The transformation of the village into a holiday villa for some of its original inhabitants has led to its removal from farming life and even to its use in some cases as a consumption destinations.

7 In 2006, the Outline of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development, adopted at the chinese government, formally proposed a red line of 1.8 billion Mu(1.8 billion mu is 1.2 million square kilometres) of land, which stressed that is a binding target with legal effect and a food safety red line that cannot be crossed.

3

8 Quoted from : Wu, Liang Yong. "Introduction to sciences of human settlements." China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China (2001), 233.

urbanisation process, becoming a complex type of settlement between urban communities and traditional villages. As a result, defining the current village in terms of both spatial form and social relations becomes complicated challenges.

Co-environ as the framework

Tracing the trajectory of history, the long-standing rural cooperation is based on a consensus of learning environments. The use of the living environ as a place of daily life, such process of self-construction makes the spatial landscape not a territorial form based on ownership, but with negotiated with the blurred boundaries. As C.A.Doxiadis points out that, human settlement is a synergistic phenomena.⁸

9 Derived from the concept of "postrural", source: Long H, Woods M. "Rural restructuring under globalization in eastern coastal China: What can be learned from Wales?" Journal of Rural and Community Development(2011), 6(1), 70-94.

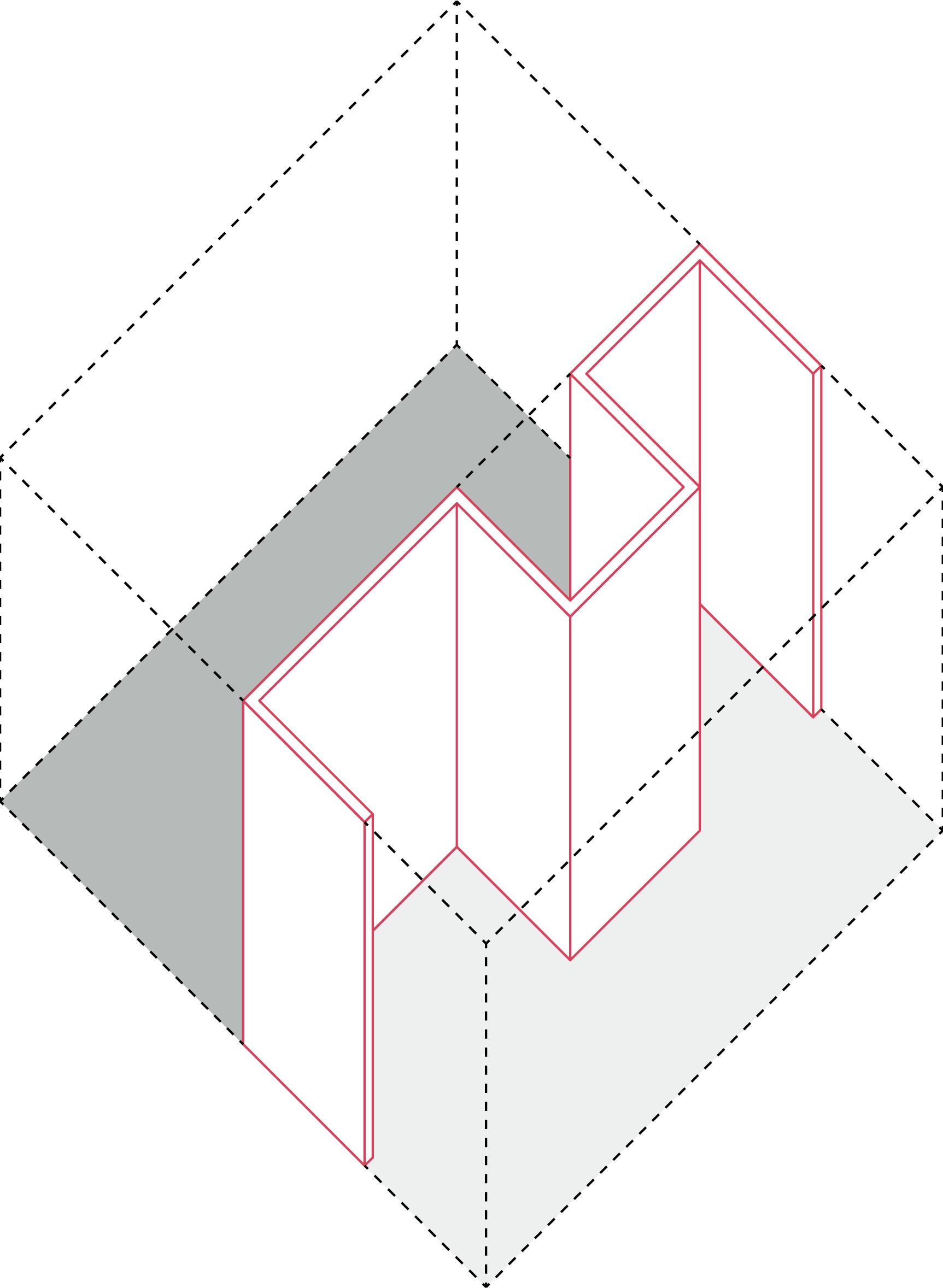

The idealistic kernel of the traditional village has the potential to be sustainable and transformative in the impact of urbanisation with the sense of being shared by the environment. The dissertation identifies this environment-led mode of settlement as co-environ, and seeks to deconstruct the farming-based idealisation of the village, using the co-environ as a framework for reconceptualising the connection between the village and its environ. co-environ produces a village that is different from the produced by collective, and emphasis on the fundamental position of the environment within the locality.⁹

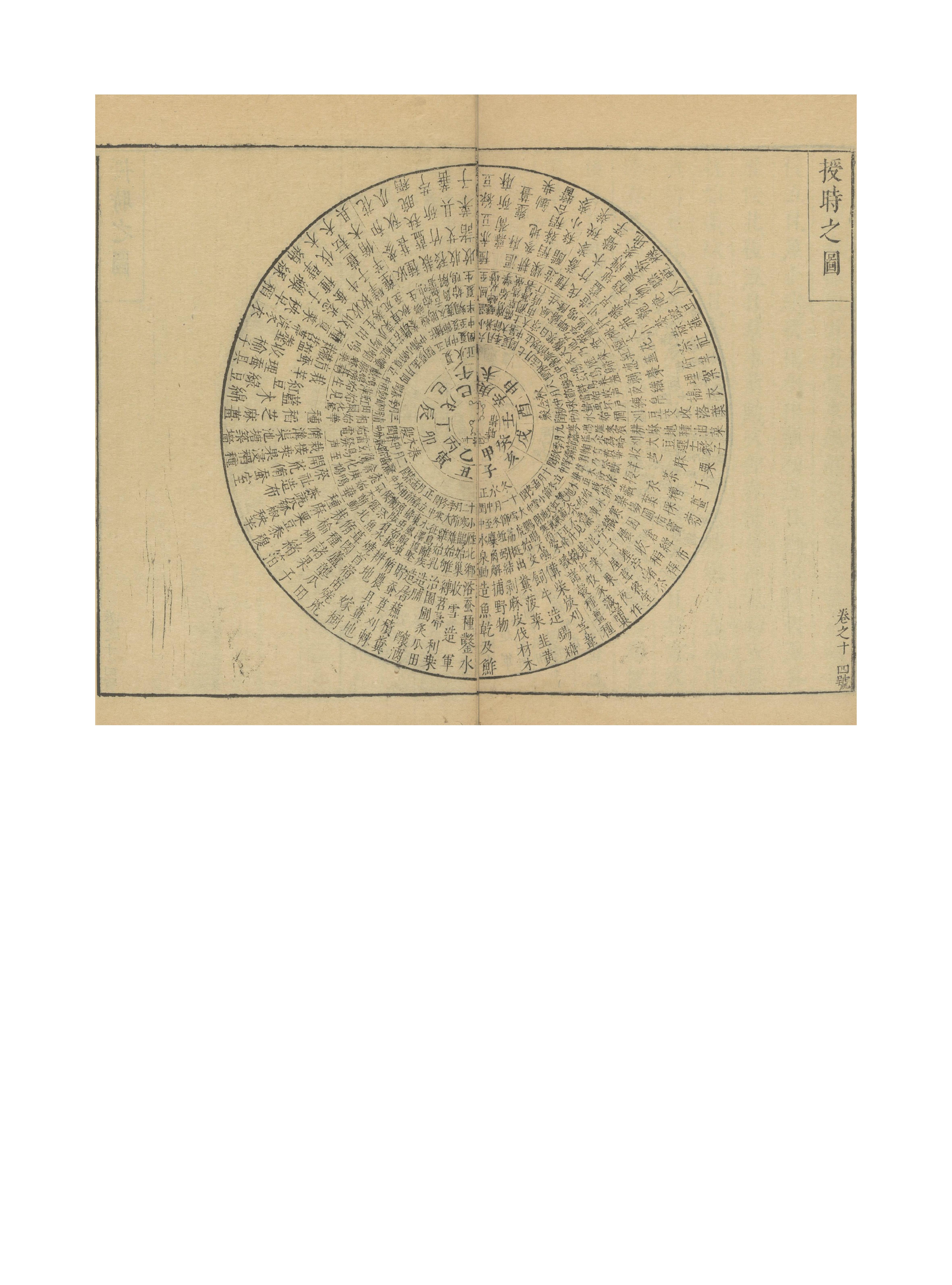

The co-environ is at the core of the idealisation of rural life, and its longevity is based on an internal deconstruction of externally imposed territorial boundaries. Spatially, the environment goes beyond the geographical vision of territory; it shapes the collective social network. This manifests itself in the rituals of villagers' daily life, the space in which specific rituals are produced through the understanding of the environment. Villagers become experts in the interpretation of territory, marking the environment itself through their own means, a pond, a piece of farmland, a tree becomes, through identification, elements of different scales, of different roles, defining not only private life but also the way in which they cooperate with the other in their daily lives.

The co-environ is also an essential social device for defining peasant identity, for establishing a sense of familiarity. The long-term village is not backward, the village is a dynamic and changing collective way of living. It is closely linked to the environment that makes up the village, and from the internal perspective of the villagers, the idea of

4

the collective is about how to reclaim a new field, how to use a stream for drinking, how to build a new courtyard from the stone around it. Such process make the territory defining replaced by cooperation, thus generating mutual learning, negotiation so as to optimise productive activities and adapt to each other's customs and practices.

The co-environ also challenges the stereotypical landscape aesthetics of the rurality, while reconstructing the complicated Geo-spatial sequences constituted by daily rituals. The personal understanding of the environment is expanded into a process of self-learning about the territory, which allows for the expansion of the village into an unbounded natural space beyond its administrative boundaries. Constructing boundaries thus becomes a primitive and stable method of forming cooperation, resulting in a narration of village life in a spatial sense.

Redefining co-environ life in urban context

At present, the cultural village is those villages that are still in related with its environ and, especially in urban contexts, is evolving into a place of consumption without farming. The dissertation aims to use this type of countryside as a contemporary design basis for co-environ to investigate the relationship between environment, community and personal life. Beijing's mountain villages become the case study for the research. These mountain villages, located within the administrative boundaries of the Beijing metropolitan area, are unaffected from the urban areas by certain distance restrictions and become a quiet territory. As a result, these villages often act as a utopia for Beijing's urban middle class, especially in the returning to the countryside trend, and gradually detach themselves from their environ to act as a purely rural cultural imaginary location.

Within the villages, however, the pragmatic urbanisation shift goes well beyond the typical idyllic imagination. External conditions are an important factor: include government subsidies for cultivation, the advantages of a rural 'Hukou' (household registration), and the vast differences that still exist between rural and urban life. From the external perspective, these villages do not appear to have been affected by the growth of the Beijing metropolitan area. However, the gradual abandonment of courtyard, the isolation of farmland, and the transformation of villages into tourist attractions reveal that these

5

10 Investment in the village relates to the way urban dwellers settle in rural areas and their access to rental, or home ownership, and also access to land resources. In fact, this has already been implemented in some provinces of China to activate the gradually shrinking rural land resources.

villages continue to experience a shrinkage. So these villages can serve as important typical cases at present for studying the environment connections between rural idealisation and internal life.

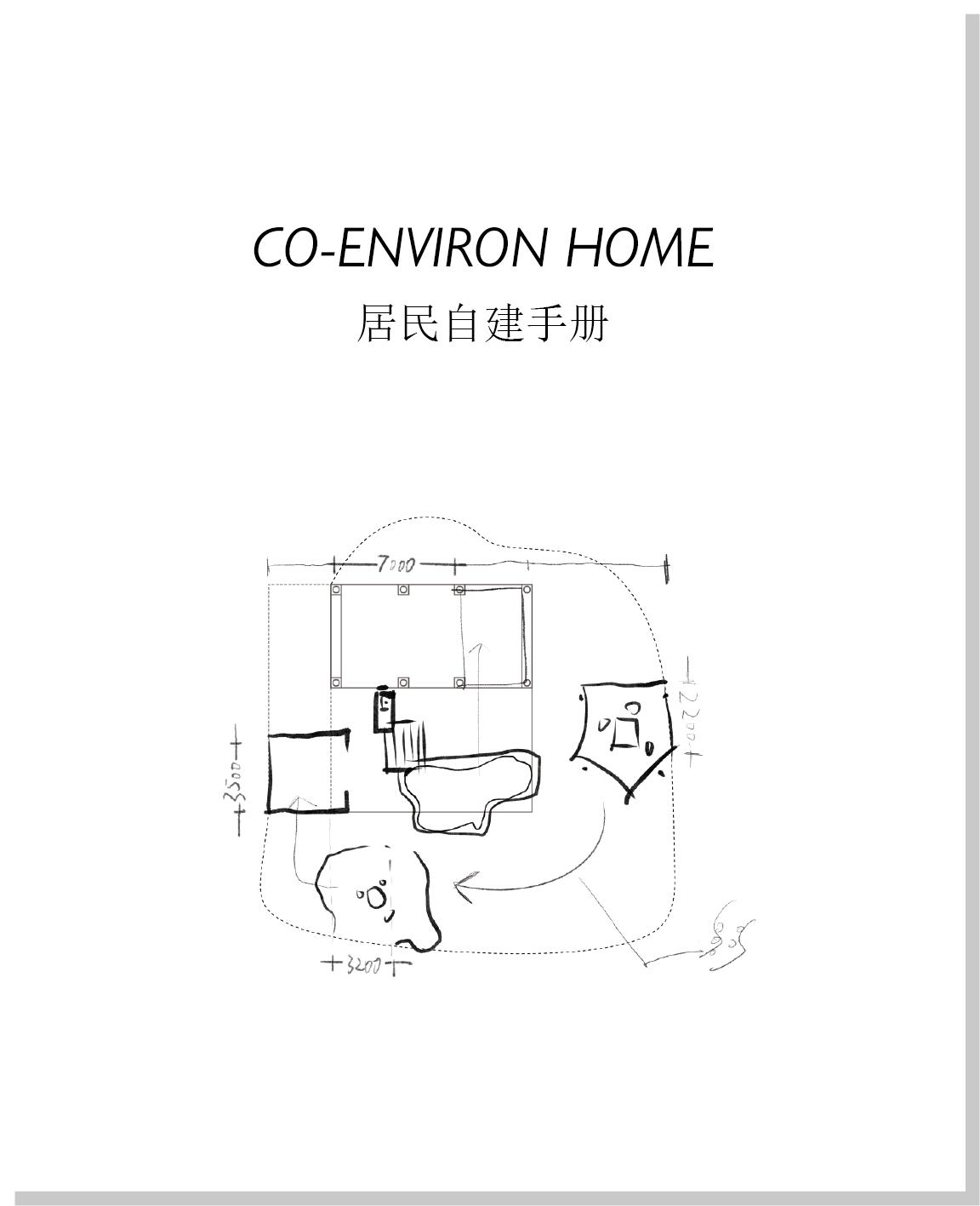

The dissertation recognises the radical impact of current urbanisation on these villages and their environ, such as the shift in courtyard forms and the demand for rural facilities; and argues that this radical shift somehow has the potential to reshape the co-environ method of living in integrating urban life with farming. The research attempts to capitalise on the current trend towards the shrinking of the village and to reframe its living network in relation to the environment as a concept of geo-spatial territory. Through the conception of a trust composed of villagers, a sustainable process of investment in environment by conceiving the flowing of people in the village.¹⁰ This involves the possibility of new urban living which, on the one hand, makes the village sustainable and allows for a bottom-up approach, providing local villagers with the support to continue living as well as farming, rather than being shaped exclusively by policy and economic support; more importantly, the co-environ approach allows for urban areas to develop in mountain regions in a new model of urbanisation. It is not a response to the follow the rural tourism; on the contrary, this new possibility supports the idea of farming as a threshold model of living in partnership with the environment, by focusing on small-scale cultivation to revalue this self-design of living and the autonomous role of small-scale modes of production in the metropolitan.

The dissertation investigates and emphasises the spatial relevance of the cooperation generated by people and the environment in the process of forming communities. Based on a retracing of the coenviron approach and the test of potential futures, which examines how the village can serve as a hybrid spatial network to organise the combination of new urban and rural communities. This transcends long-standing stereotypes of urban communities and challenges the previous position of China's rural areas in the definition of urbanisation, allowing them to live sustainably under a non-agricultural model. C o-environ does not seek a new idealisation, but rather offers a new model of transformation for the rural areas by emphasising this relevance to the environment, and the architecture makes the transformation an ongoing project, with villagers' self-build as the opportunity, the foundational of the environment to be emphasized, so viewing it as a new potential strategic plan for urbanism.

6

Aims

Due to the fragmented and specific features of the mountain village environment, the dissertation builds an Geo-spatial sequence based on the daily life of villagers through a series of fieldwork, comparison and analysis with historical archives. The following objectives are achieved:

• Identify and extract elements of the environment and recognise them as types of cooperation, demonstrating the potential for creating new communities in mountain villages.

• Develop a new organisational framework for Beijing's infrastructure that challenges traditional urban agglomeration structures and transforms mountain villages into sustainable communities.

Research Question

Disciplinary question

•How the Co-environ living within the mountain village is sustainable in the changing urban-rural context?

Typological question

•How do the types of frameworks offered by collective cooperation relate to the environment?

•How do these cooperation frameworks, which are closely related to the environment, define the different ownership territories?

Rural-Urban question

•How village communities can integrate farming work with idyllic living.

•How can the new rural community model challenge the hierarchical town centre system and establish a new type of community autonomy within the metropolitan area?

7

8

A Contemporary Statement of Rural Ideal

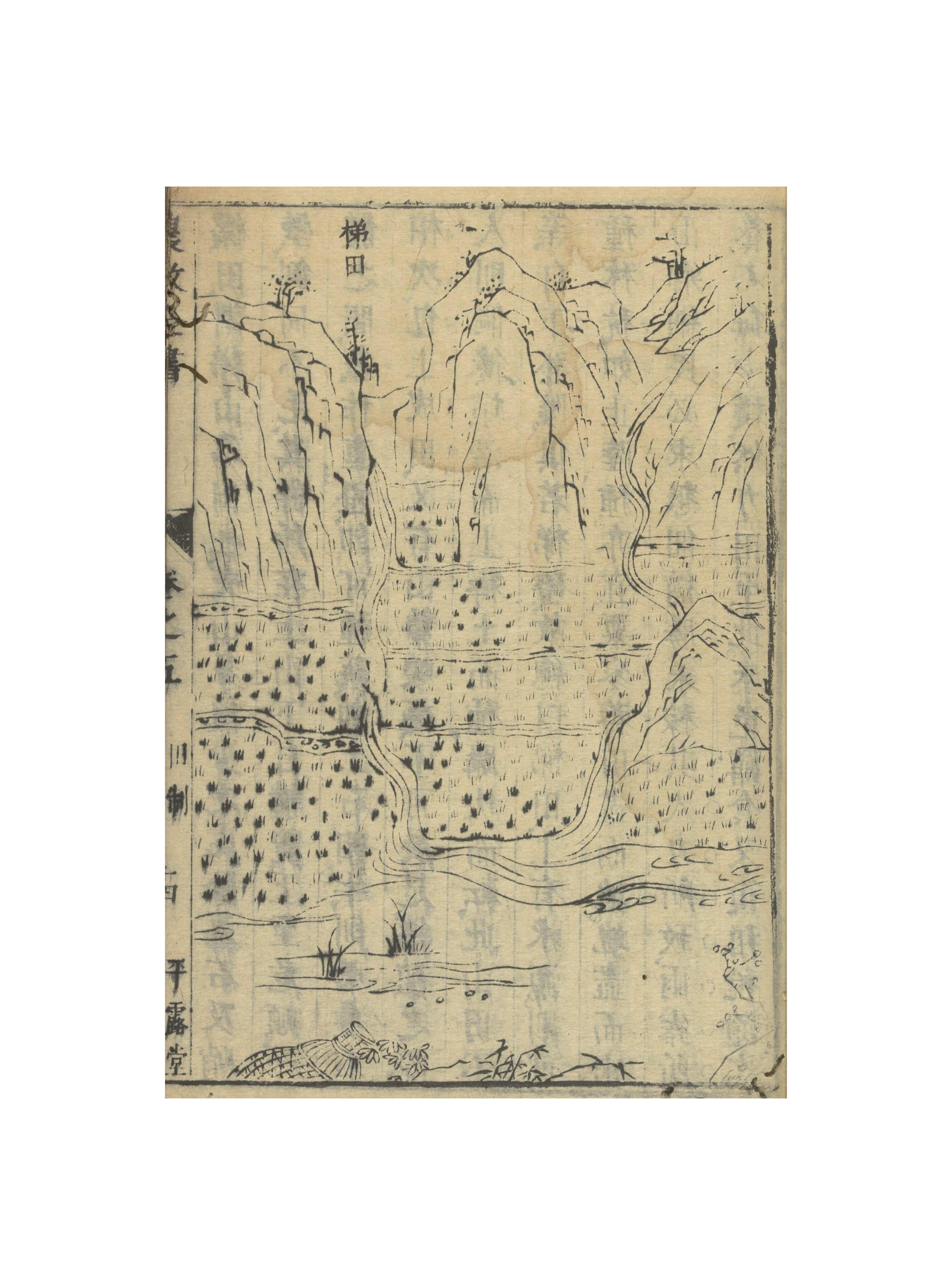

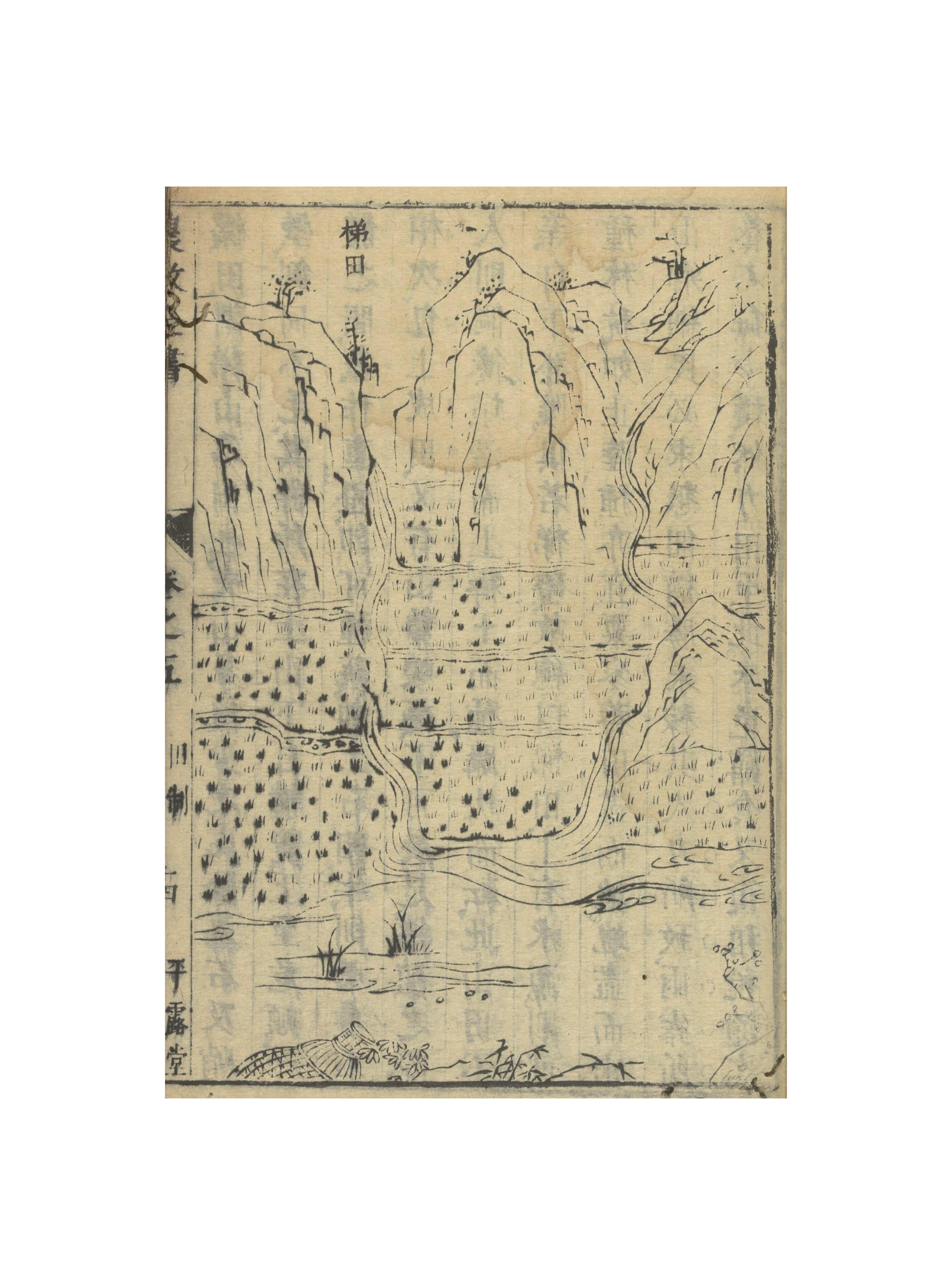

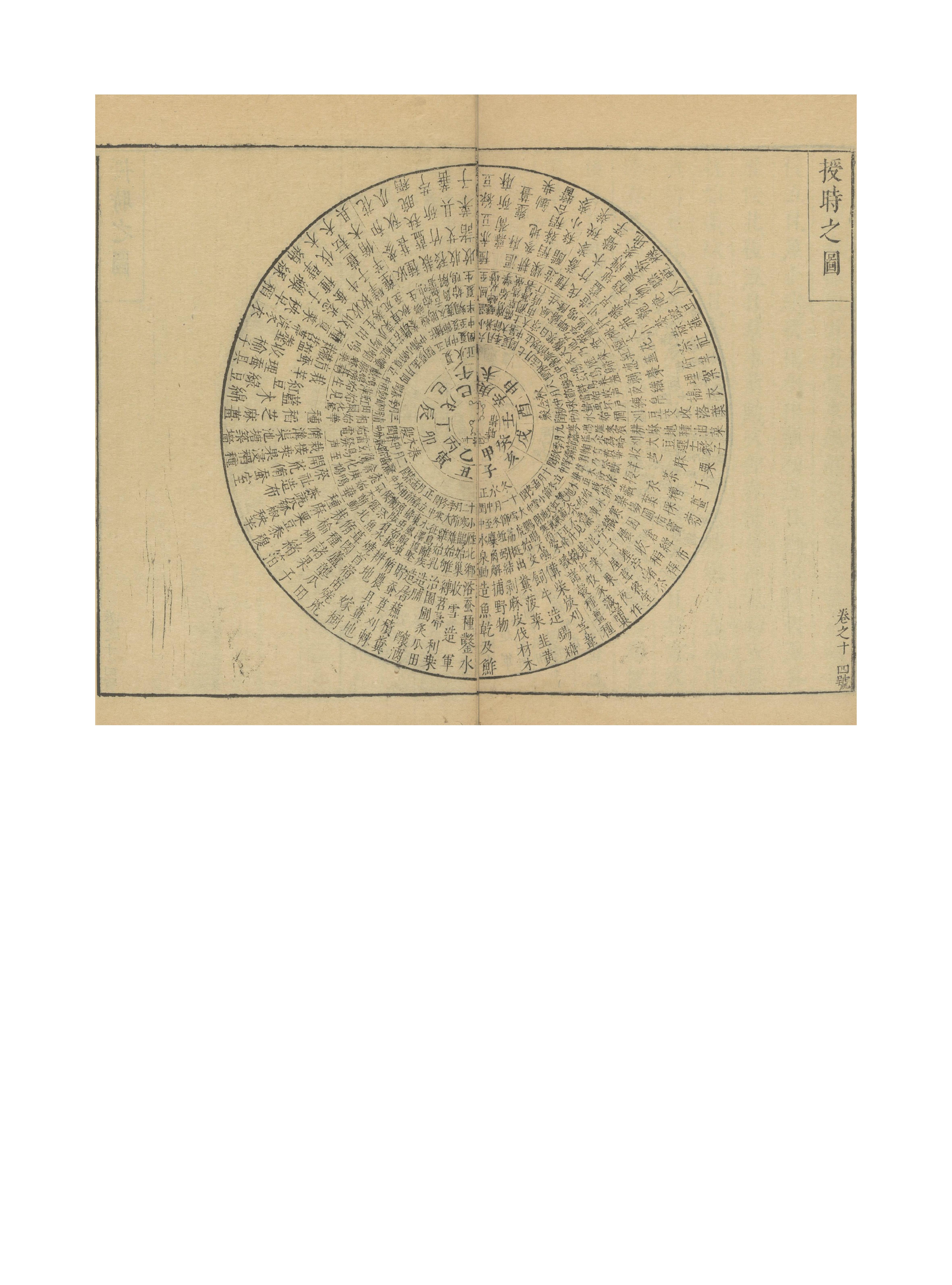

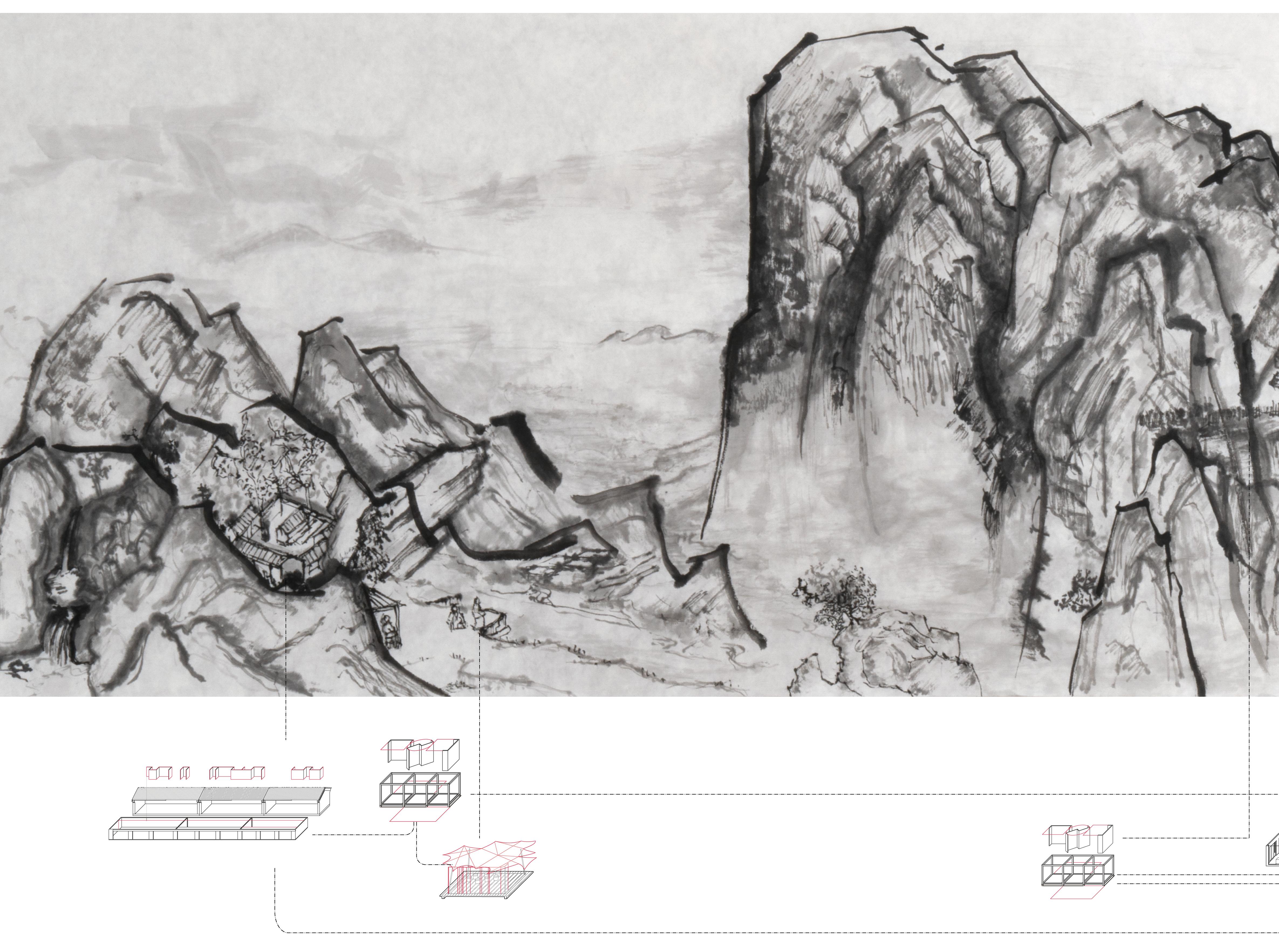

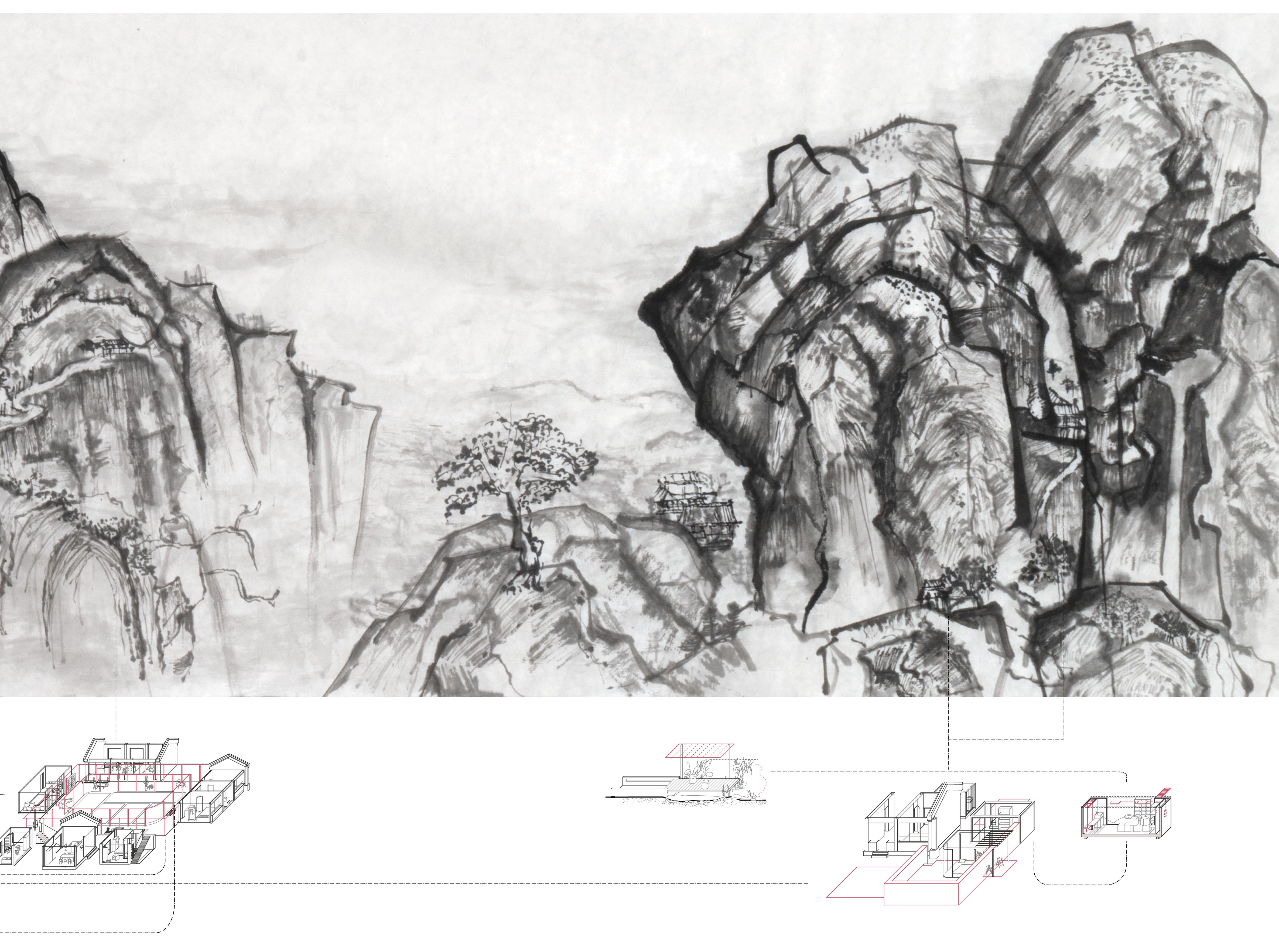

1.1 The rural idealisation: from The Peach Blossom Spring to Rural tourism

Chinese rurality exists not only as an agricultural entity but has gradually become a symbolic culture with clear boundaries in the context of long-standing public discourse within the urban-rural sphere. In ancient times such symbol often used to add to the narrative in landscape painting. Taking a case of an ancient landscape painting of a story called The Peach Blossom Spring,¹ in which he tells of a fisherman who accidentally enters a beautiful village with rich fields and landscapes and people who live a peaceful and simple life. An interesting point is that the poet Tao Yuanming emphasises an episode in the last line of this poem when he writes of a literati who heard of this place and went in search of it, but failed to find it until he died. This actually implies a contrast with the literati in ancient times, who usually turned to the ideal landscape because of their inability to change the social status , which creates a kind of idealisation of rurality from an external perspective.

This literati take on the rural ideal is known as 'Zhuo Zheng' in Chinese( 拙政 ), which means relying on the landscape for survival, self-serfitiont, and pursuing simple interactions.² So the core of this ancient idealisation of living in the environment can be found in all

1 This painting was made during the Song Dynasty(1533) and is taken from the Peach Blossom Garden(420). This was the custom of the ancient literati. Inspiring by poetry to create a landscape scroll rather than an croquis drawing.

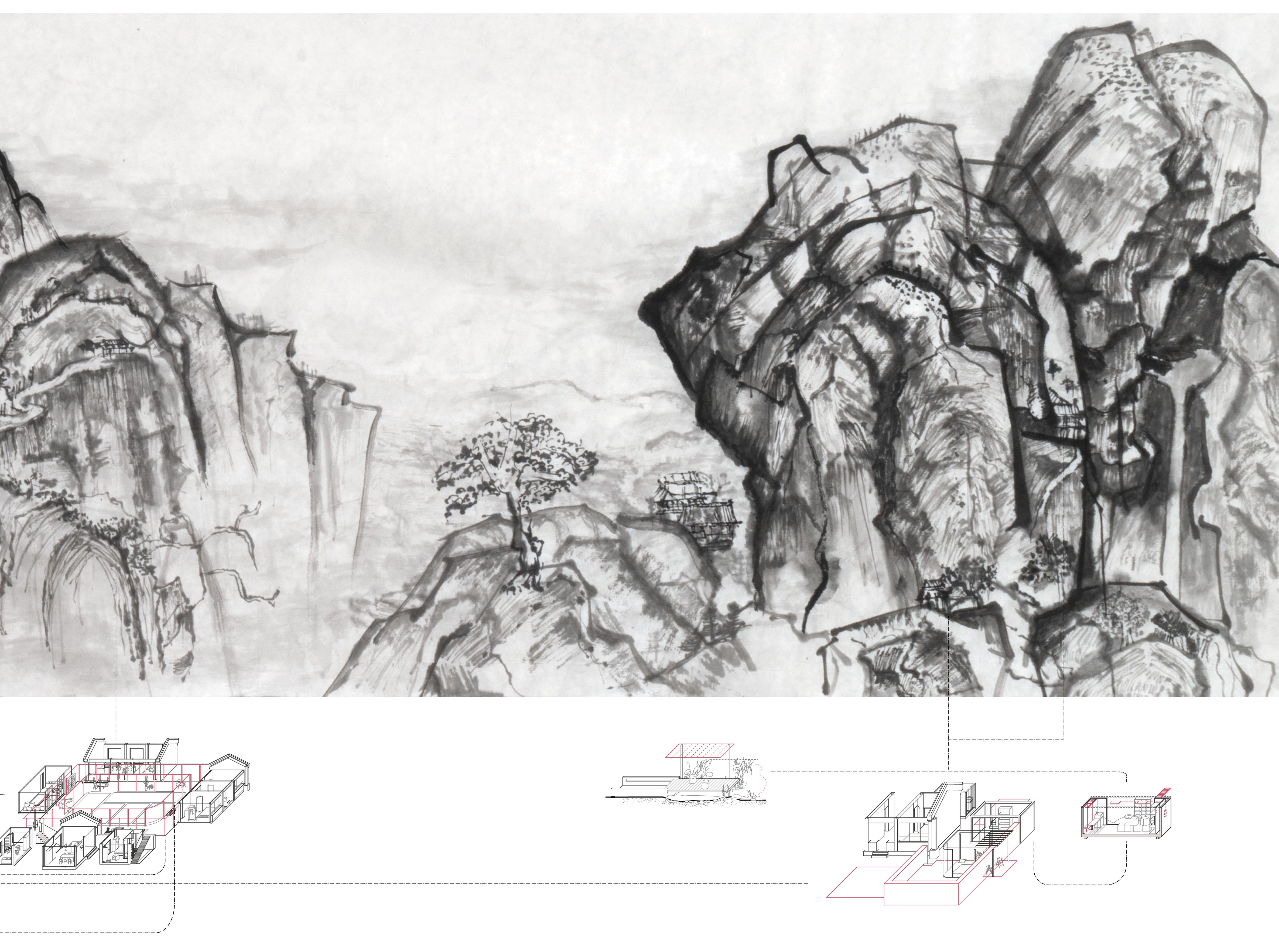

FIG 1. 1

2 Clunas, Craig. "Fruitful Sites." Gafden Culture in Ming Dynasty China. London (1996).

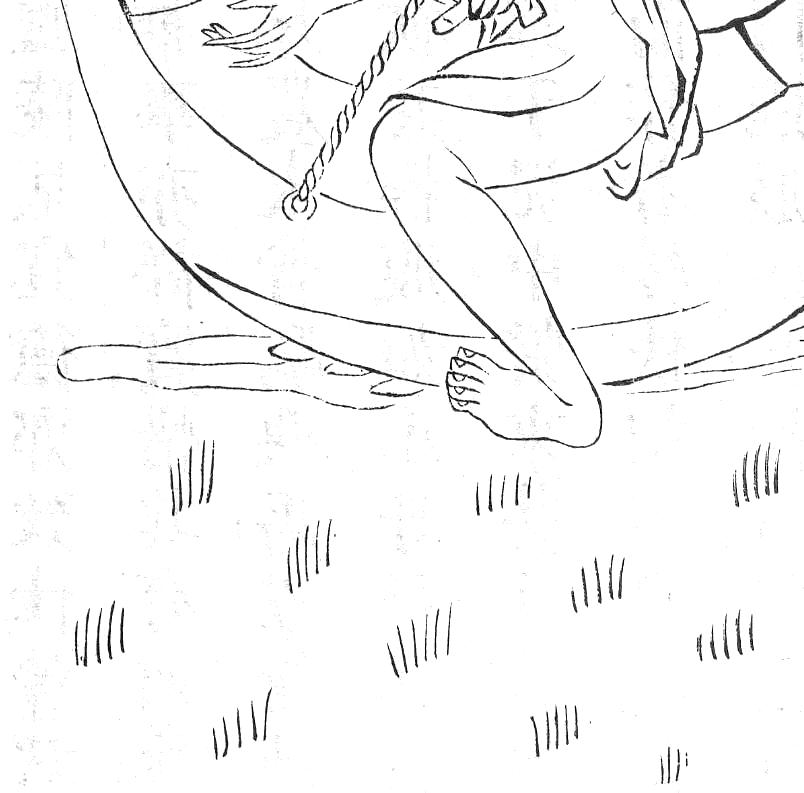

←FIG 1. 0 Rural symbolism

9

1

Chapter

The Chinese landscape painting is created and reads as a synchronised work.

It commonly stems from a poem or a story, so the tiny details of these rural life narratives are as important.

10

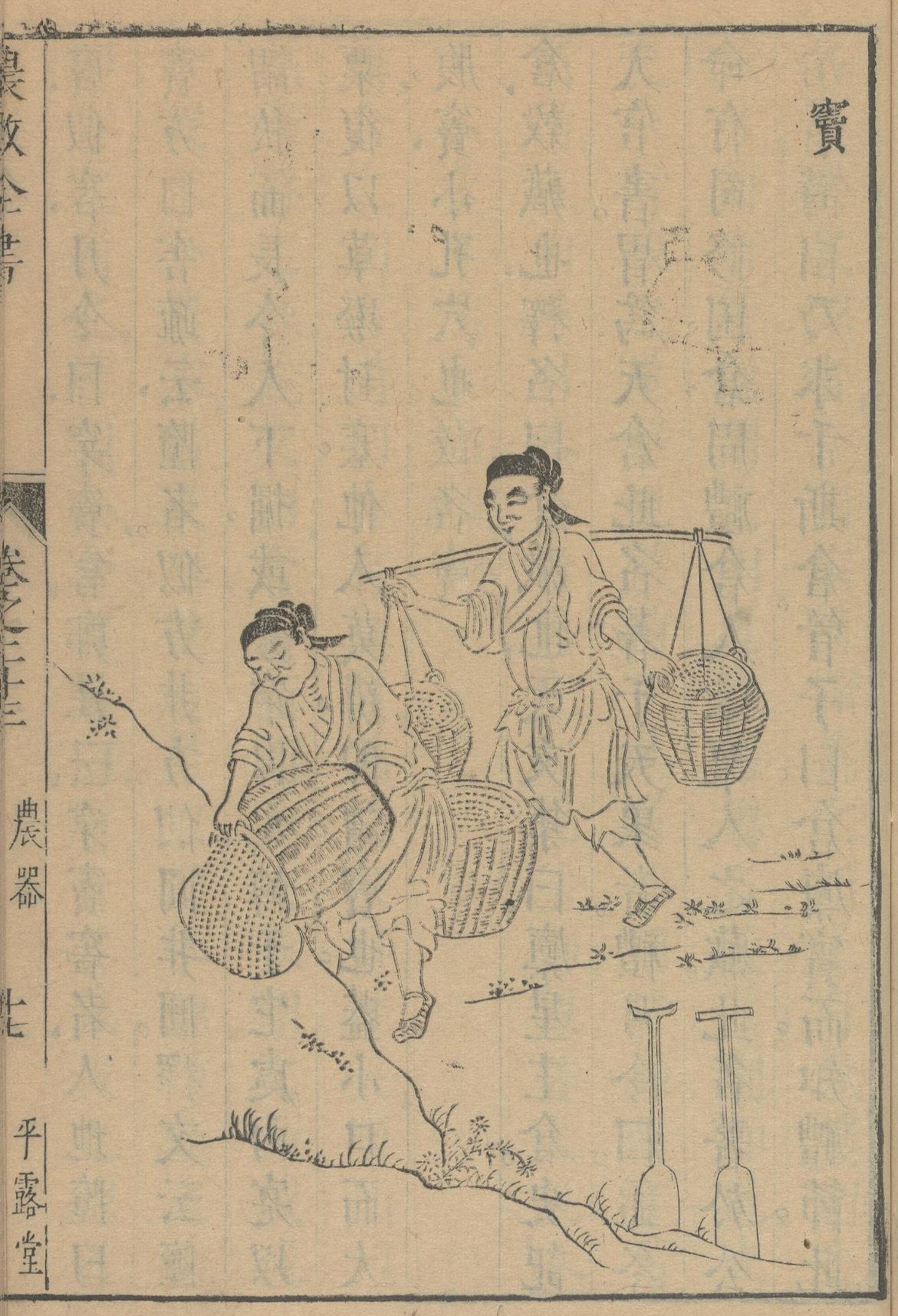

FIG 1. 1 THE IDEAL MODEL OF ANCIENT VILLAGE LIFE

11

3 Most of young people went to the countryside to participate in the production of the countryside. At that time, such tendency was considered to be the most fundamental work of nationmodernisation in the popular discourse of the society.

4 Yong Xu. "1980s' Novels And the Problem of the Youth." PhD diss., Peking University, 2012. 57.

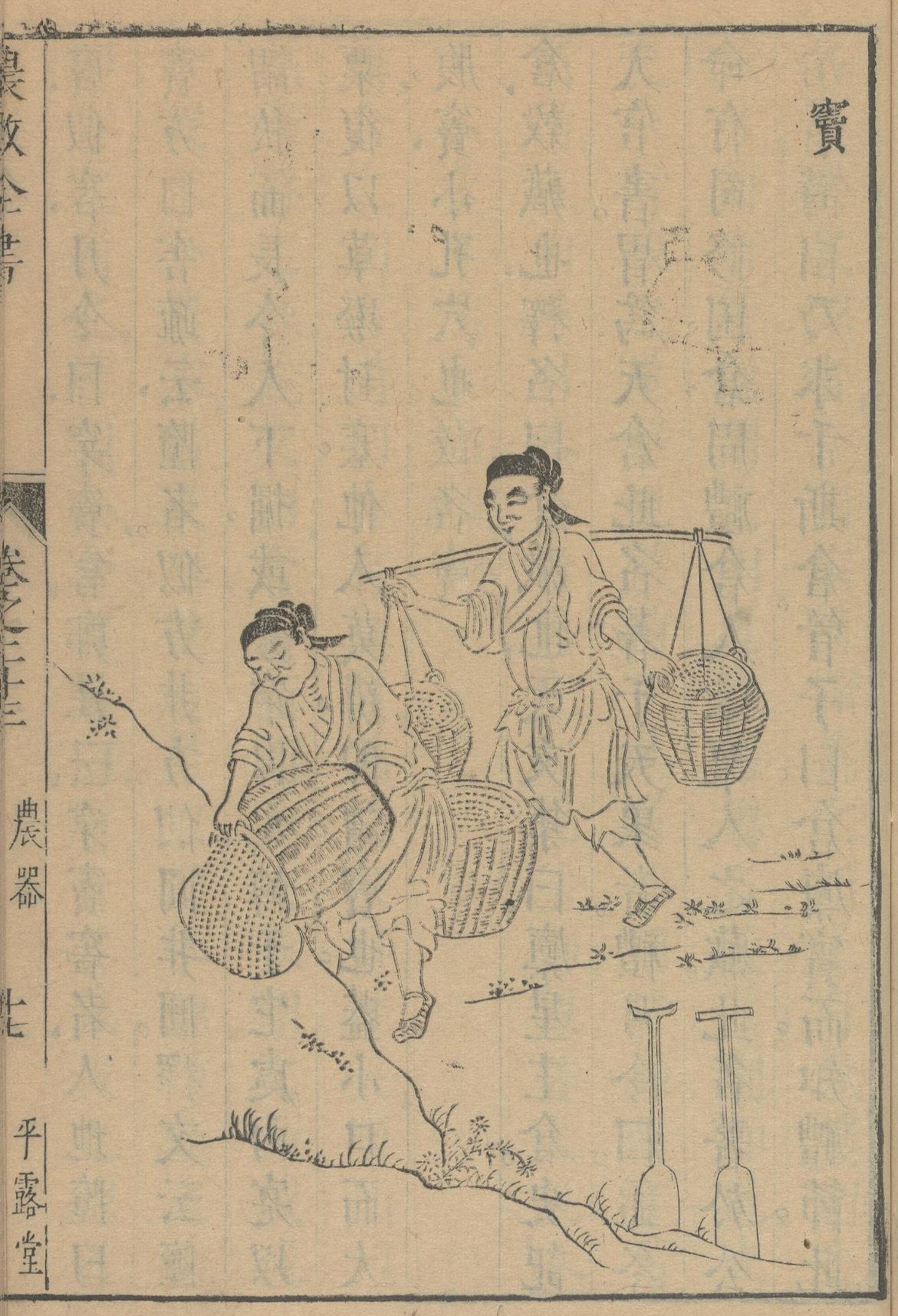

of these landscape paintings, which include not only the construction of a house, but also the expansion of it to include daily life within the natural environment through touring, viewing, and feeling. Therefore, the ancient landscape painting can often be considered a simple narrative approach to describing the idealisation of rurality. Such paintings, created from the perspective of a personal 'excursion', usually do not simply describe the landscape but often fictionalise it as a backdrop; while the village, with the particular environment, is depicted in more realistic strokes, even if it is tiny to hidden within the vast canvas. The idealisation is realised through the extraction of life that responds to a particular space, based on the environment. This symbolic depiction of detail deconstructs the idealisation to correspond to the long-last rurality based on the pragmatism of farming.

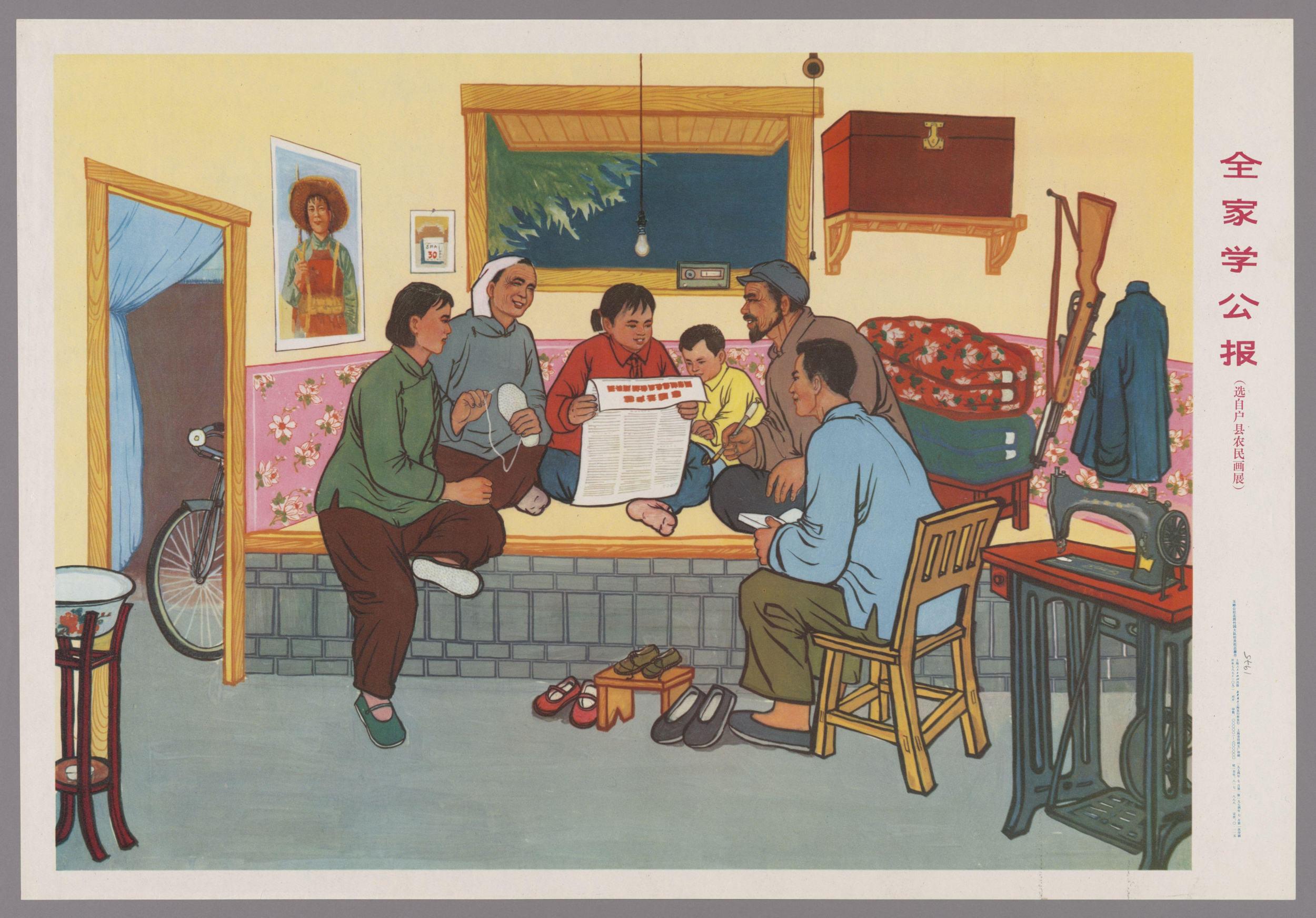

The ideal image of the natural environment has evolved over time and was initially viewed as a progressive solution to state modernisation during the 'Down to the Countryside' movement. In terms of idealistic descriptions, it did not lead a particularly tough life, as we later discovered, but it did attract a large number of young people to the countryside in its early days.³ A comparison between the prewar and post-war literary works still reveals this utopian imagining of the countryside. The isolation from the environment and the transformation of identity demonstrate the transformation of the rustic as a symbol into a tool against urbanisation.⁴

"Chadong is located at the border between two provinces, and for ten years the local military has been in charge of it, focusing on security and conservatism, and it has been handled properly, without any changes occurring."

——Congwen Shen. Border Town. 1934.

"Twenty years later, I realised that sorrow and anguish had been with me since the day I left Dihua. I did not get rid of the suffering that is always associated with life, while looking back on my days in the village, they became so clear and happy."

——Pingwa Jia. I am a peasant. Yilin Press. 1997.

This perception of the village as a symbol of moral quality has influence the Chinese, particularly the young literati and urban middle class, who see it as an artless way of life that respects the natural environment.

12

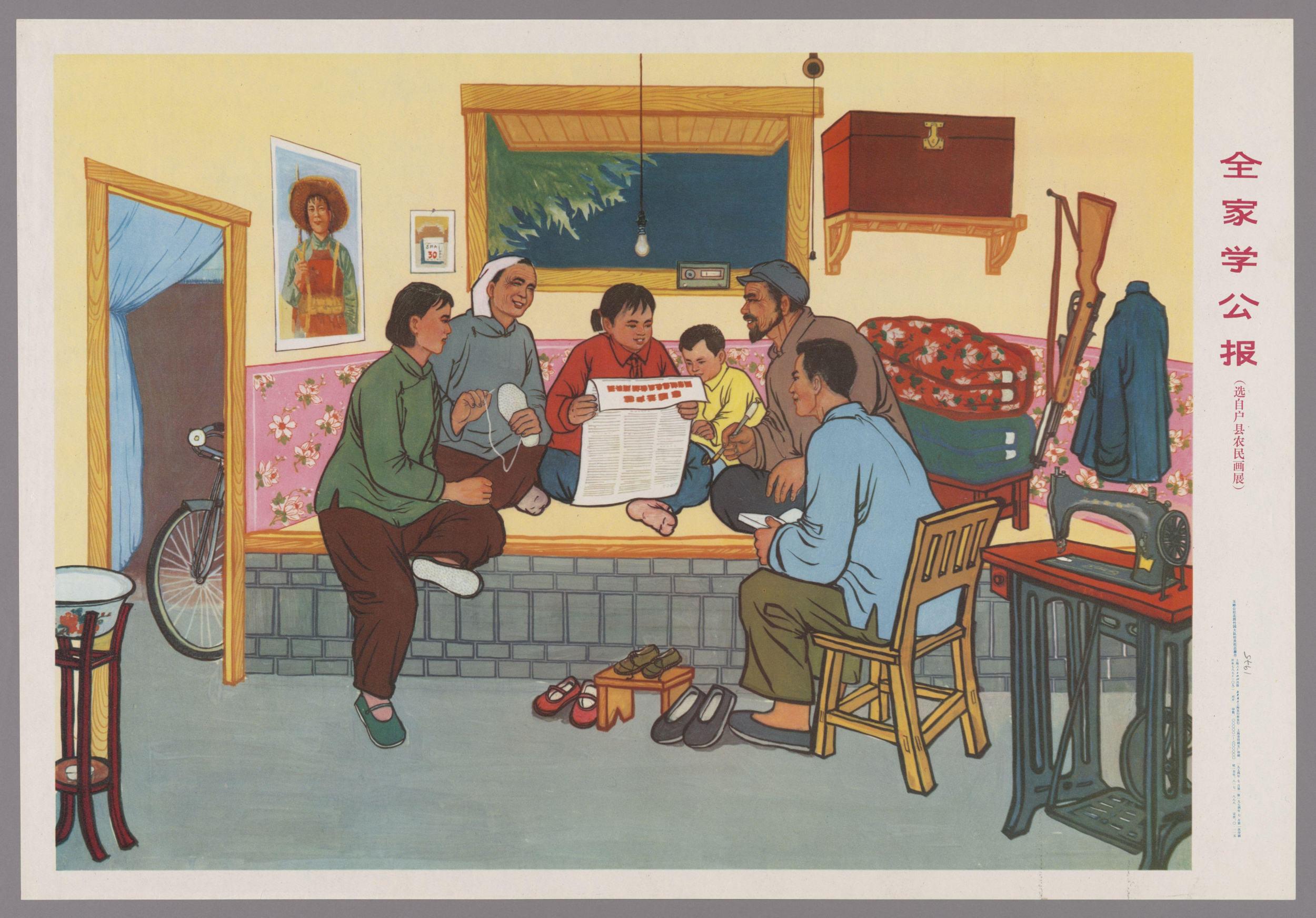

FIG 1. 2

FIG 1. 1

13

FIG 1. 2 PROPAGANDA POSTER 1950

The rurality - a symbol of socialist advancement

5 Since 2006, there was a policy named village mergers have been used as a common method of improving the living conditions of the villagers, with the consolidation of land and the gathering of settlement to reshape the territorial structure of the village area. However, statistics show that very few villages have been successfully merged.

6 Beijing WTown is a completely fake rural tourist area in the mountains of Beijing, which is modelled on the ancient water villages, which perfectly satisfies the idyllic appetite of city dwellers.

In the present, the symbolic metaphor has led to a dichotomy in the urban-rural context of villages, which the village flight and the mess culture of rural tourism coexist in the same space. On the one hand, government projects intended to improve rural life have transformed farming methods into an industrialised model, making small villages that still rely on traditional farming methods to become hard to sustain and forcing their inhabitants to migrate to cities.⁵ On the other hand, vanishing traditional villages and the symbolic culture of rural life have made them a rare "accessory" of large cities for urban residents. Even when village theme parks like Beijing Wtown⁶ appear out of nowhere, they are incredibly popular.

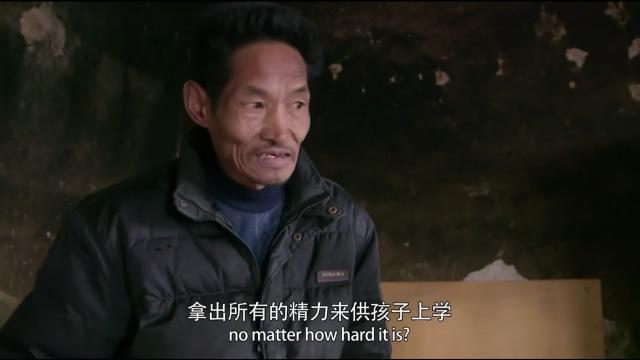

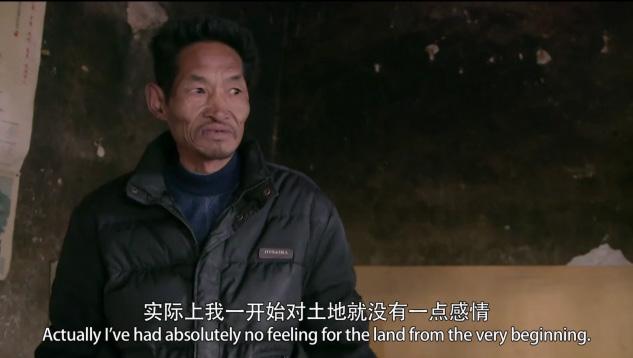

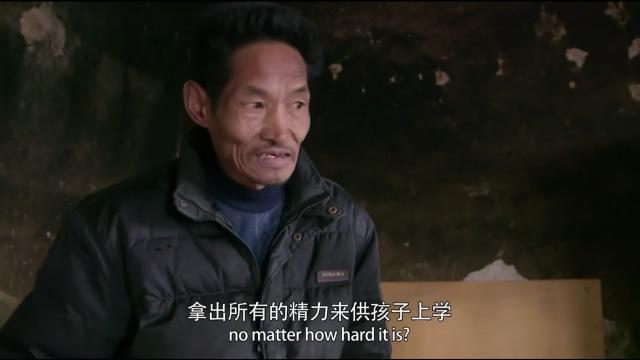

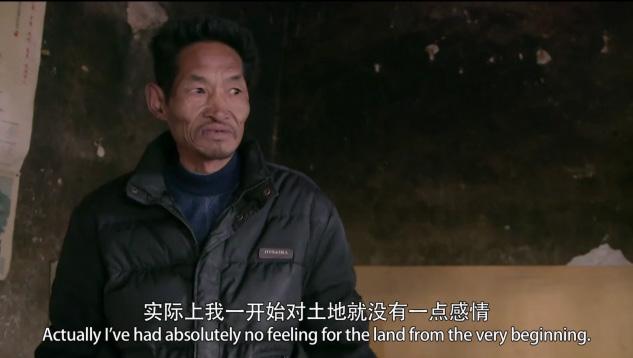

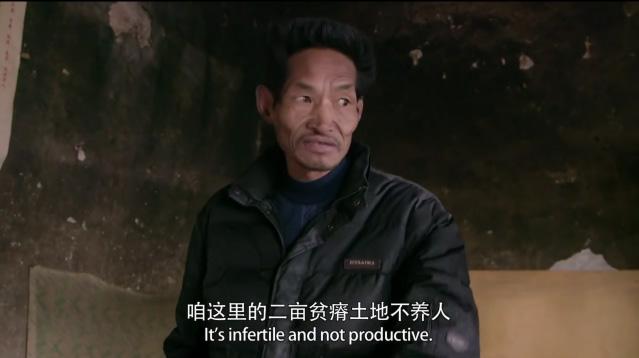

For cities, the heterogeneity of villages puts them in an awkward situation caught between policy and economic forces. In the film, "Village diary," the director clearly depicts the absolute boundary between the village and the city. In one scene, the leading character, who belongs to a generation living in the village, often tells his child that the village is not developing. However, when the trees in the village are cut down, he becomes angry, believing that it is destroying the land and home left by his ancestors.

7 Data stem from The report on urbanrural development of china’s capital (2007). Due to the Beijing government's control of rural land use, the transformation of small villages is slow after 2010.

Although this illustrates the current concerns of farmers about the rural flight, the reality is that these villages have not disappeared as the public imagines. For example, in Beijing, fewer than 400 households village still make up over 70% of the total village, which means that the long-standing small-scale farming lifestyle continues to exist.⁷ The boom in rural tourism proves that the idealisation of rural life still exists, and for urban residents' perspective, their idealism of rural life is derived from this long-standing practical thinking that is lacking in urban life. This is not entirely a nostalgic or curious thought, but rather an fever for the symbolic representation of pragmatism in real rural villages. This appeal to the symbolism of rural pragmatism poses a challenge in the face of negative rural migration trends.

1.2 The idealisation internal: living with the environment

To understand the conflict between the external symbolisation of rural areas and the internal negativity of migration, it is necessary to clarify that the symbolisation of rural areas does not reflect the isolated difference between rural and urban areas. On the contrary, rural areas have long been considered a fundamental pattern of urban composition

City Village Pragmatism Lifest yle Imagination 14

FIG 1. 3 NEGATIVE CYCLE

FIG 1. 4

15

FIG 1. 4

Clips of "Village Diary". by Bo Jiao, 2013. The film's conflict arises from its document of a farmer who enjoys literature and classical Chinese instruments. This character represents both the ideal of the village as seen from an external literary perspective, also the peasant who participates in the creation of this pragmatic idealisation.

8 Mote, Frederick W. "A millenium of Chinese urban history: Form, time, and space concepts in Soochow." Rice Institute Pamphlet-Rice University Studies 59, no. 4 (1973).49-53.

9 Chang Xu. Living near chang'an: Rural society in the metropolitan area in the Tang. Beijing: SDX & Harvard yenching academic library, 2021. 398-400.

Self-management

in China. In F.W. Mote's concept of the rural-urban continuum⁸ in his research on ancient Suzhou in China does not mean that the concept of continuity implies a distinction between the areas inside the city walls and the surrounding rural areas. Rather, it refers to a regional context. Another research on Tang Dynasty materials,⁹ it was found that in the Tang Dynasty capital city of "Chang'an" and its surrounding areas, villages and cities presented a heterogeneous combination in spatial structure. Rural areas are usually seen as more consensual and autonomous communities. This is because farming was regarded as a basic means of survival in ancient times, rather than a choice of profession. Apart from the royal, residents living in rural areas had more autonomy due to the limited control of the court over local territories. These rural areas were generally controlled by relationship networks formed by clans or gentry. The homogenisation of villager identity gave them more links in social relations. Therefore, rural areas exist primarily as a settlement pattern of identity recognition. Farming is part of the village management structure in daily life, rather than being managed by the state. It can be considered that rural areas, which have long been coupled with the environment, have become a type of settlement that represents both the quality of traditional rural life and the complex erosion and interaction with the current urban-rural environment.

The idea of coexisting with the environment stems from the long-

16:00

Weeping and worshiping

9:00

Temporar y church

Villager committ ee

16

Clan Local gentr y

FIG 1. 5

The logic of the ancient village management, a bottom-up approach

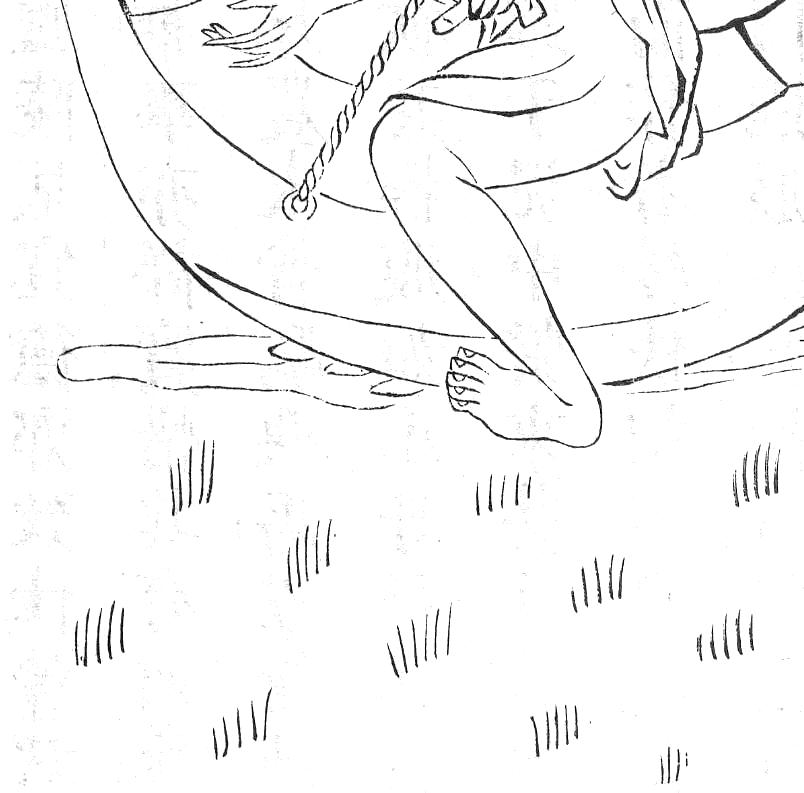

term development of this unique type of rural settlement, which is based on the common construction foundation of traditional farming development and is usually understood as a self-sufficient culture. Similarly, in ‘Village diary’, a clip of weeping at the grave fully shows the concept of living with environ. This records a plot in which a young person who went out to work unexpectedly died. After learning of this, the relatives in the village organised a funeral. Interestingly, the venues for these activities, such as the funeral hall, the dining place, and even the cemetery, are all constructed within the existing space, and some are even temporary.¹⁰ This strongly implies the villagers' familiarity with the environment. These rituals are not limited to production, but are different spatial paths that are combined with the objective environment in which the village is located. In fact, this has become a geographic concept, that is, how an individual's territory negotiates with others to form a collective cooperative area. Therefore, the concept of the village is blurred in this life representation. On the one hand, the recognition of the environment goes beyond farming itself, and on the other hand, the long-term cooperation with the environment has enabled villagers to form their own and collective identities towards different spaces.

This dissertation argues that this mode of environmental cooperation transcends the cultural value of idealisation and embraces new possibility of urban development. The research attempts to

10 According to traditional Chinese rules of superstition and Feng shui, these hilly, pine-covered areas are the best burial grounds. In the village, however, the cemetery's designation is based on a long-standing territorial identification. This wood is the location of the village's ancient cemetery in the documentary. Following the priest's (actually a village elder's) blessing of the deceased, the coffin of the young man is buried in a freshly dug grave.

←FIG 1. 6

A village ritual process. With different environment points throughout the village. FIG 1. 6

Cemetery Another day Burial 17

11 Massey, Doreen. For space. Sage, 2005. China Architecture & Building Press. 2014.7-15.

12 Massey, Doreen. For space. Sage, 2005. China Architecture & Building Press. 2014. 117-124.

13 Ibid, p117.

14 The counterurbanization of the countryside is common globally, but for diverse reasons, yet the common factor is that it goes a new model of collective beyond the urban life, different from cultivation, but rather the conception of the territory from private to collective autonomy through the environment. More references:

Williams, Raymond. The country and the city. Vol. 423. Oxford University Press, USA, 1975.

ETH Zurich Department of Architecture. "Architecture of Territory." Accessed July 15, 2022. https://topalovic.arch.ethz.ch/ Courses/Design-Studios.

15 Rem Koolhaas. Countryside: A Report. Cologne: Taschen. (2020), 3.

reinterpret the spatial sequences shaped by different daily rituals with the environment, which is based on Doreen Massey's theory in the geography of spatial narrative,¹¹ in order to further unravel the dichotomy of this rural idealisation in the urban-rural environment and the complex process of change for its own developmental continuity. By stringing together scenes from different historical periods, the approach to the spatial representation of the concept of geography in the research methodology produces multiple ritual sequences of life from the private to the communal. Doreen Massey cites Raymond Williams as follows: "a woman in her pinny bending over to clear the back drain with a stick. For the passenger on the train she will forever be doing this. She is held in that instant, almost inunobilised. Perhaps she's doing it ('I really must clear out that drain before I go away') just as she locks up the house to leave to visit her sister, half the world away, and whom she hasn't seen for years. From the train she is going nowhere; she is trapped in the timeless instant."¹² Therefore, space is not just a completed plan form, but also a theatre of memory of various moments in time, and thus a means of combining multiple trajectories. As she writes in the text "Space as a collage of the static,"¹³ geography's approach to spatial description is a situationist-inspired narrative.

1.3 Mountain village in Beijing as the context

The village fever from the cultural perspective projects the difference in urbanisation between the urban and rural. The focus is to make clear that by placing city and rural in the same discourse. The changes in the countryside are hidden from the perspective of urbanisation, with cultivation on the one hand as a central framework of life; but it is also no longer central to the shaping of the rural land. The countryside is experiencing a global reverse movement;¹⁴ unlike the idyllic imagining of the countryside in 18th century England, it is not a mere nostalgic trend from the city to the countryside, but a new mode of settlement. As Rem Koolhaas talks about the contemporary countryside: the countryside is a place "enable us to experience a realm that we ignored at our, and its, peril."¹⁵ This reminds us to understand the stability in the invisible changes of the village, which in China is not only seen by the government as a balance between rural-urban relations; rather, due to its internal pragmatism, the continuous urban-rural life is presented as a flowing in two distinctive territories. Consequently, it is necessary to explore the long-term ‘rural quality,’ offering its imagination for contemporary resettlement in the countryside.

18

1. 7

FIG

19

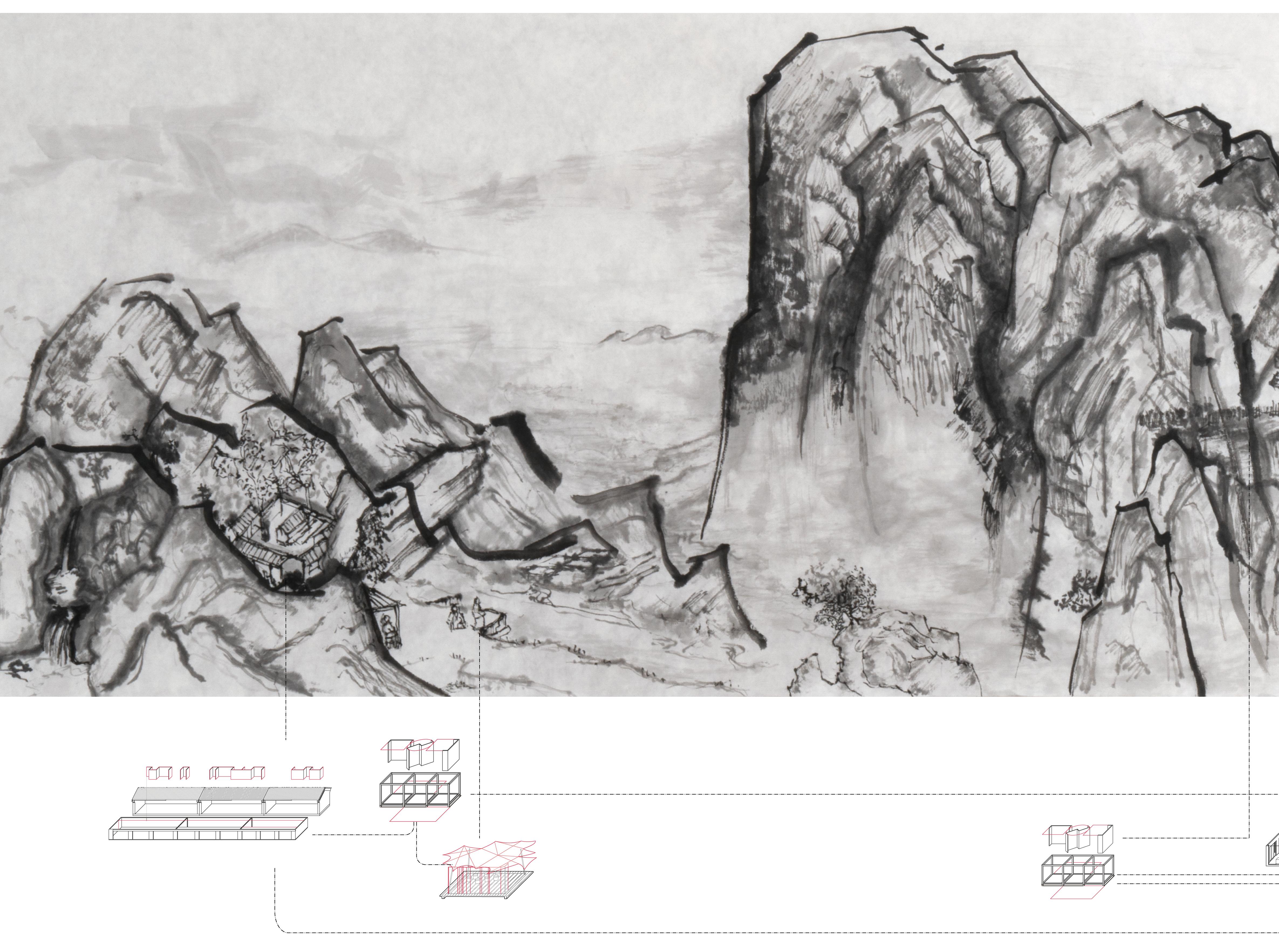

FIG 1. 7 RESEARCH PROTOTYPE: GEO-SPATIAL SEQUENCE Spatial expressions of villagers' daily ritual constructions

Data sources: Long, Y. (2016). Redefining Chinese city system with emerging new data. Applied Geography, 75, 36-48.

20

FIG 1. 8

Urban area in contrast to Mountain area

1 km 1 km 21

FIG 1. 9

Suburban villages in contrast to mountain villages

16 Due to the complexity of the geographical conditions in the mountain village area, and the land resources are not as a completely scale as flat village; the regulations governing the land are usually not particularly strict. For example, as in the case of suburban villages any structures are limited to the farmland, while in the mountain village this regulation is to some extent looser.

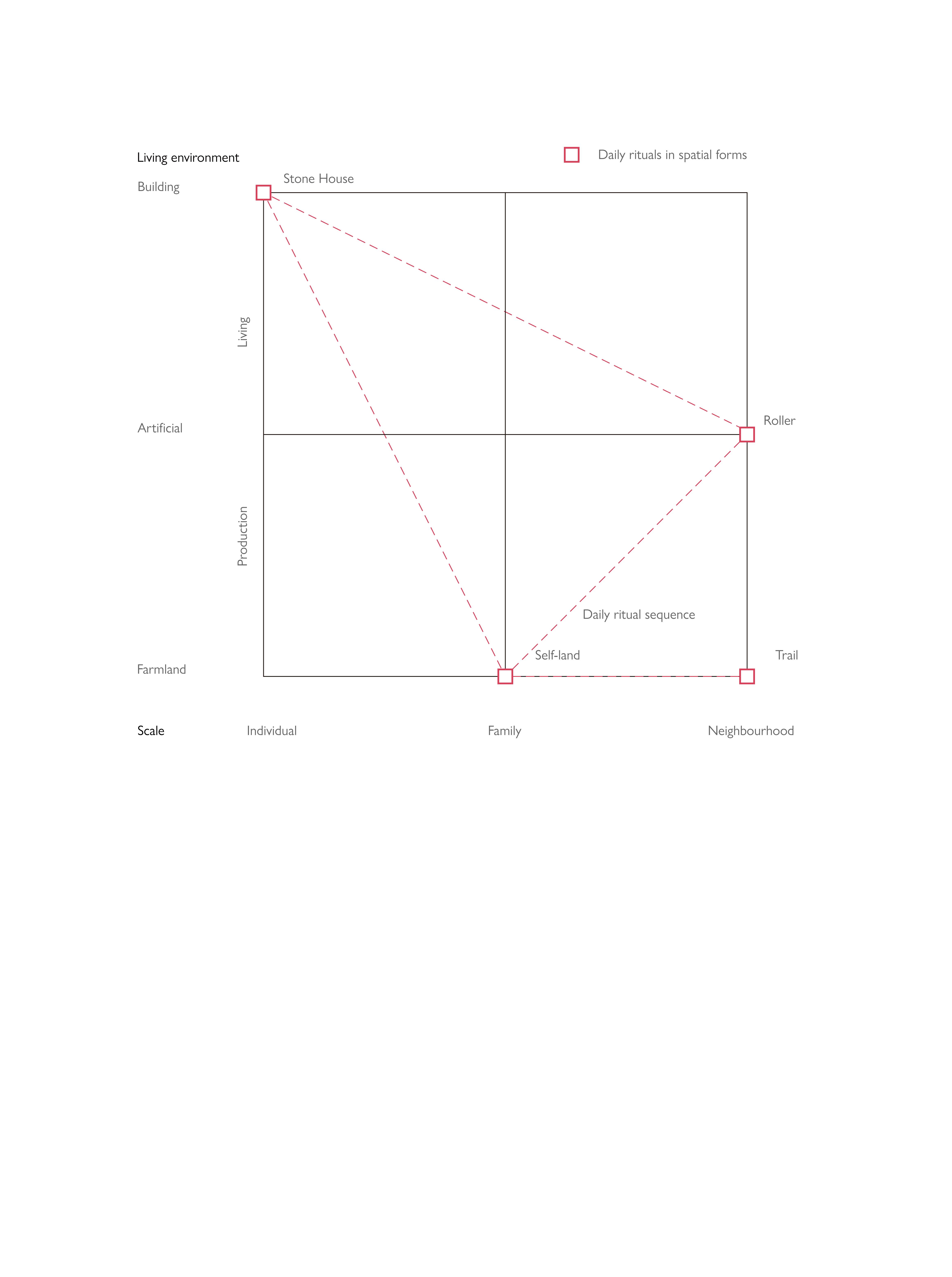

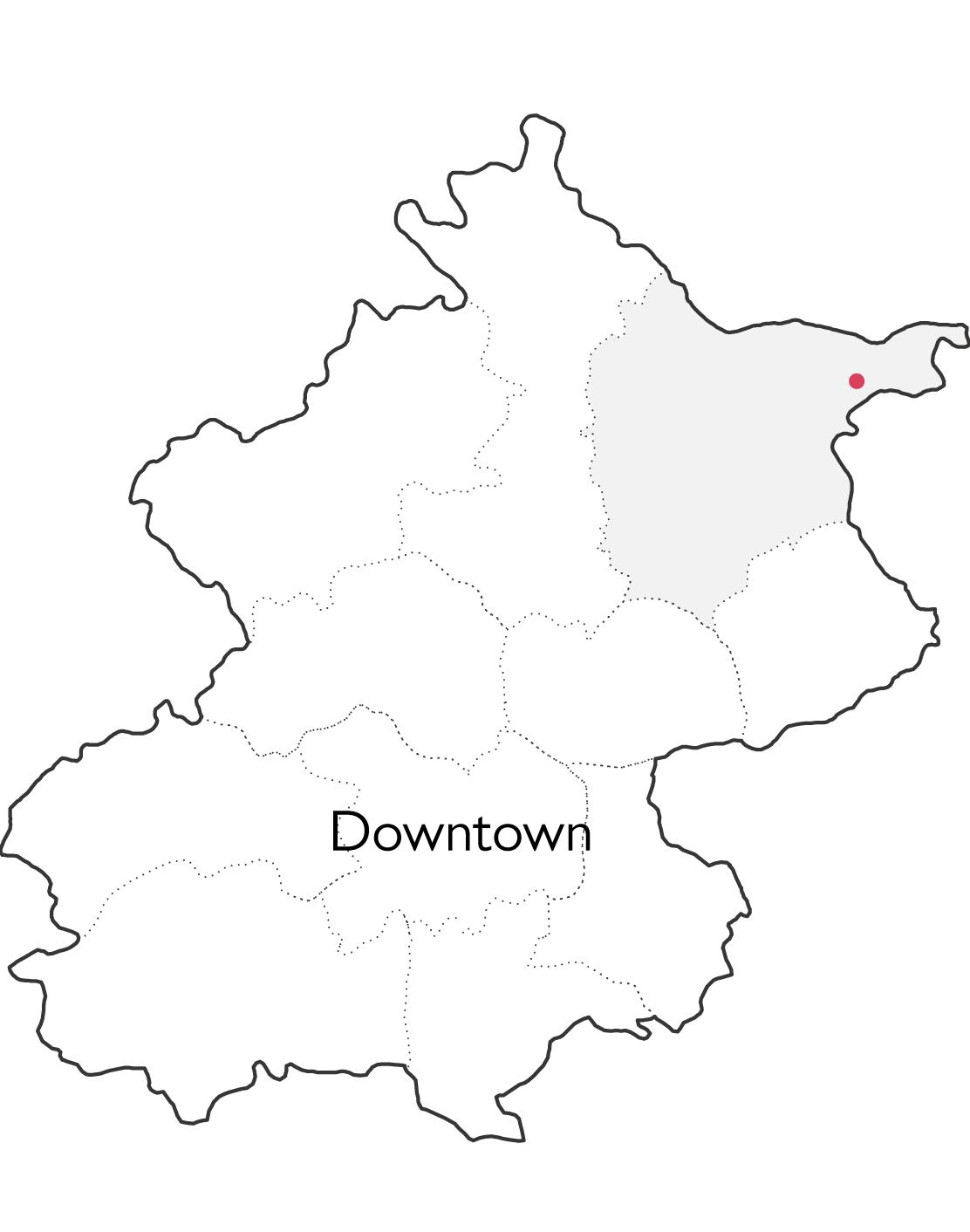

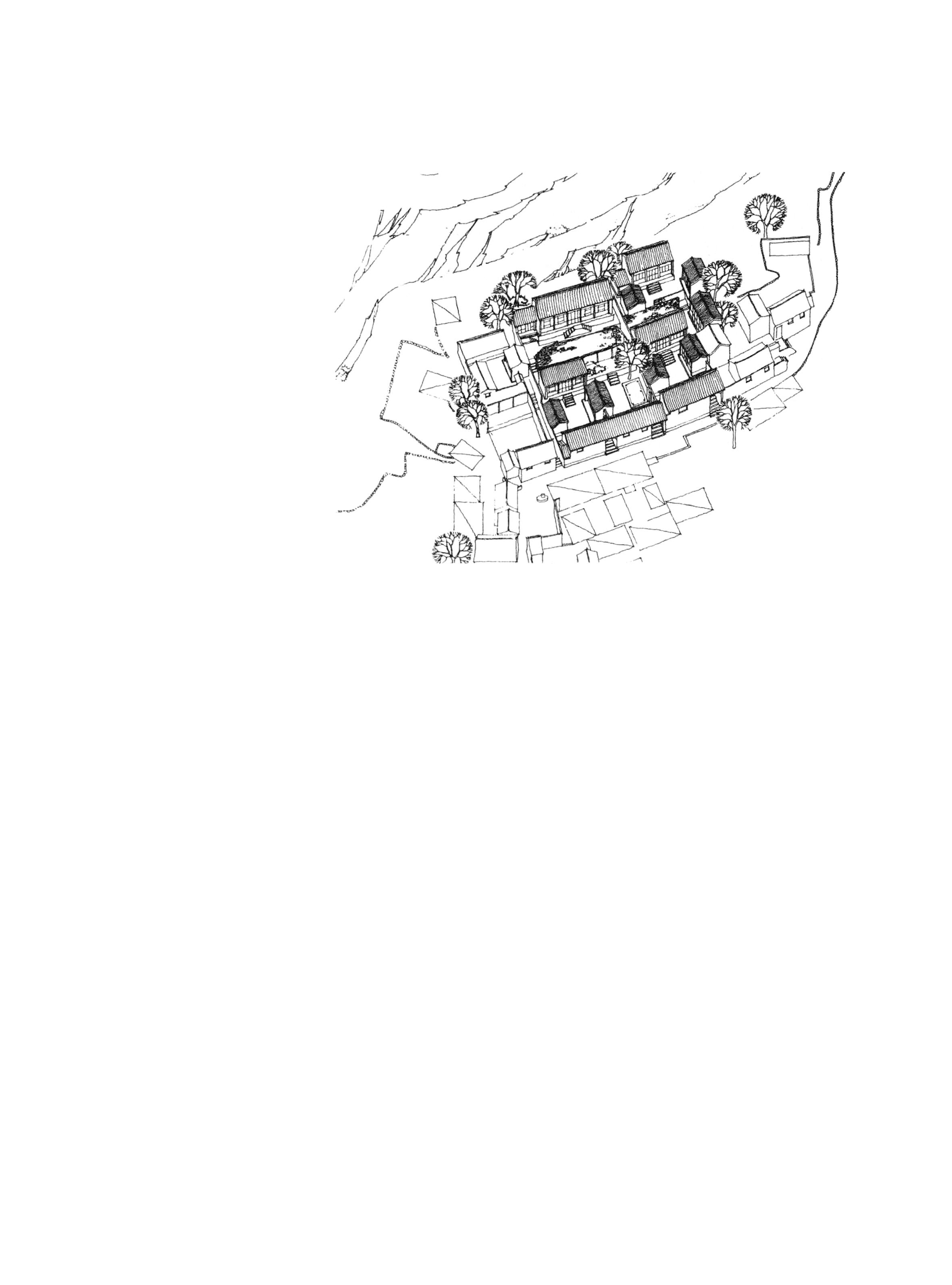

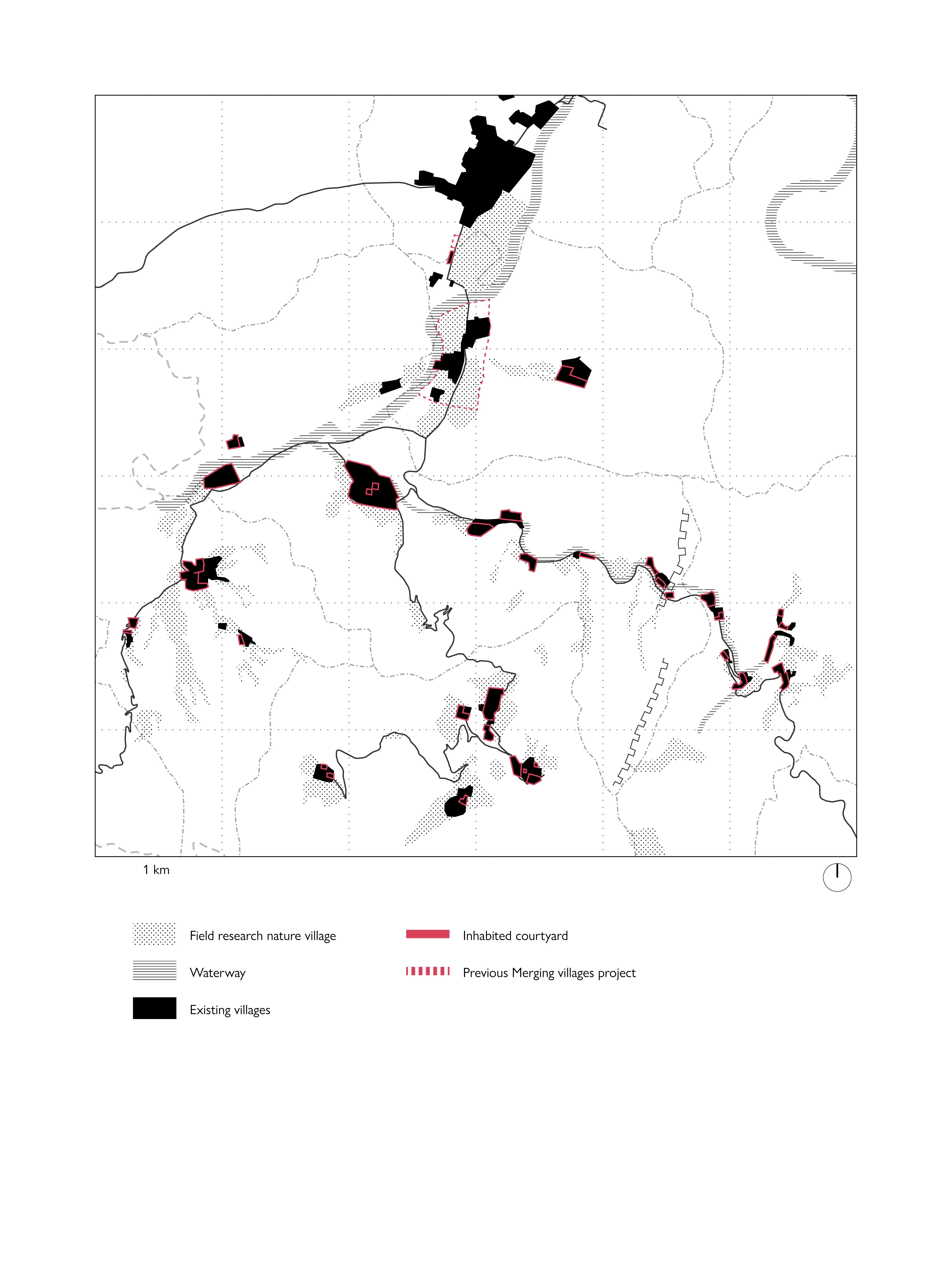

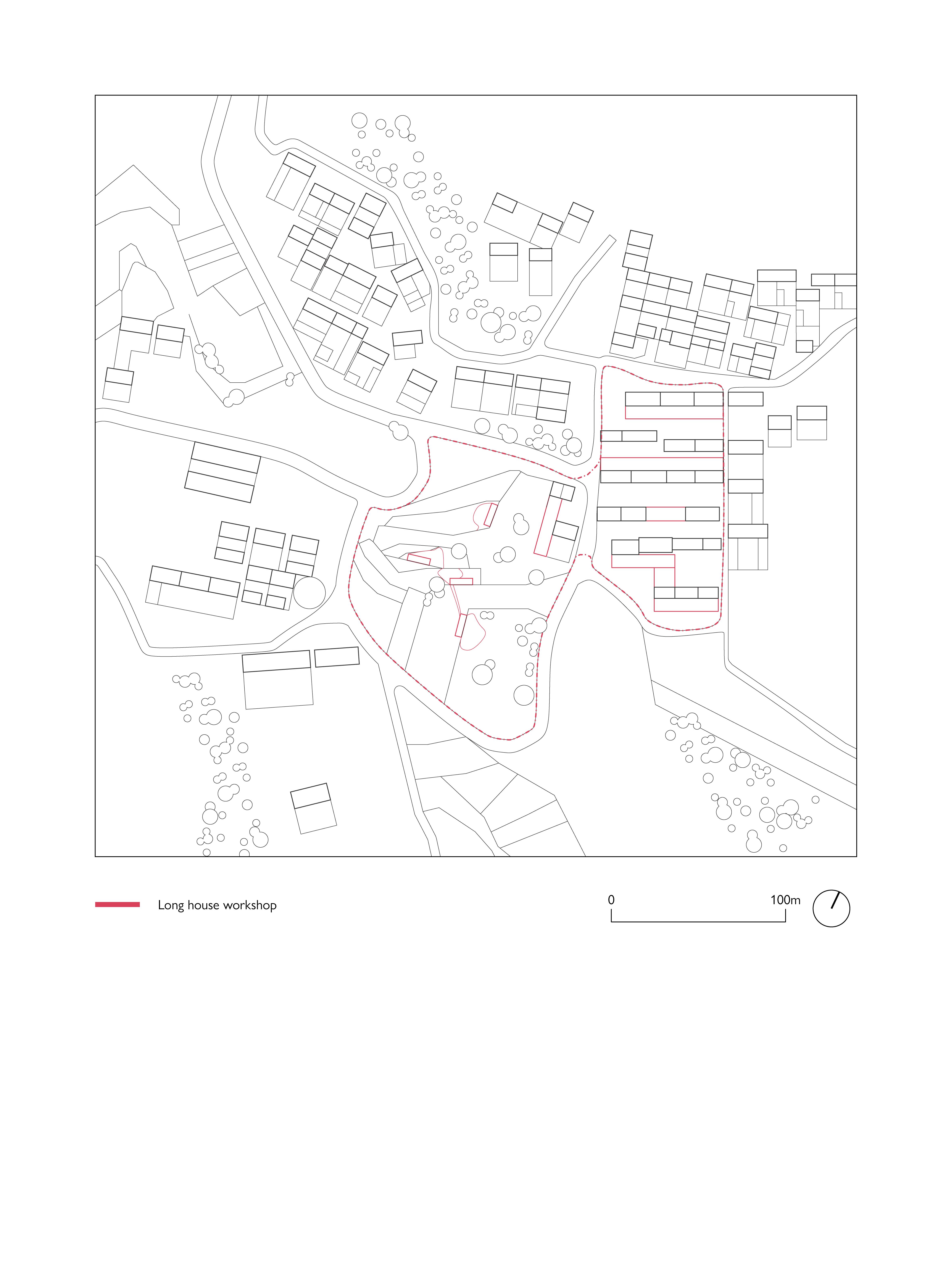

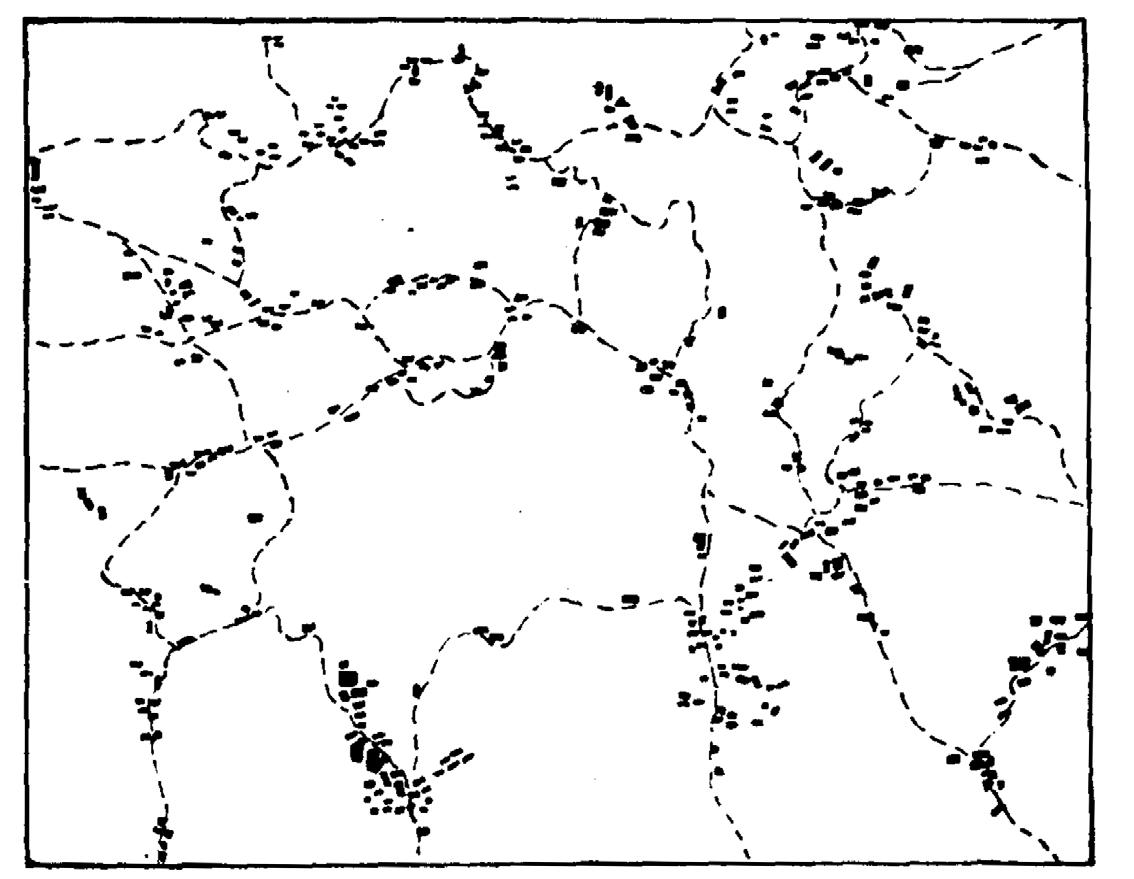

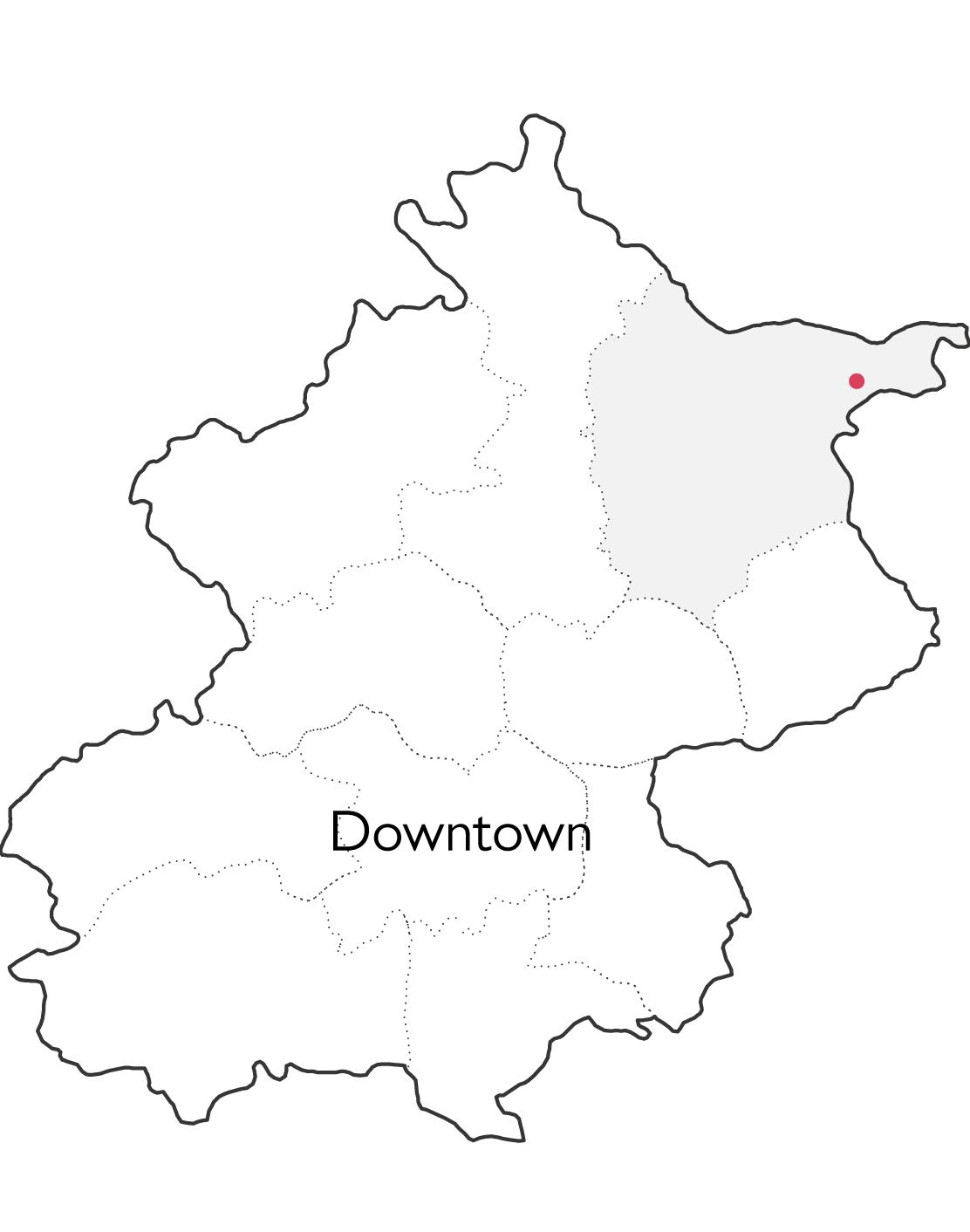

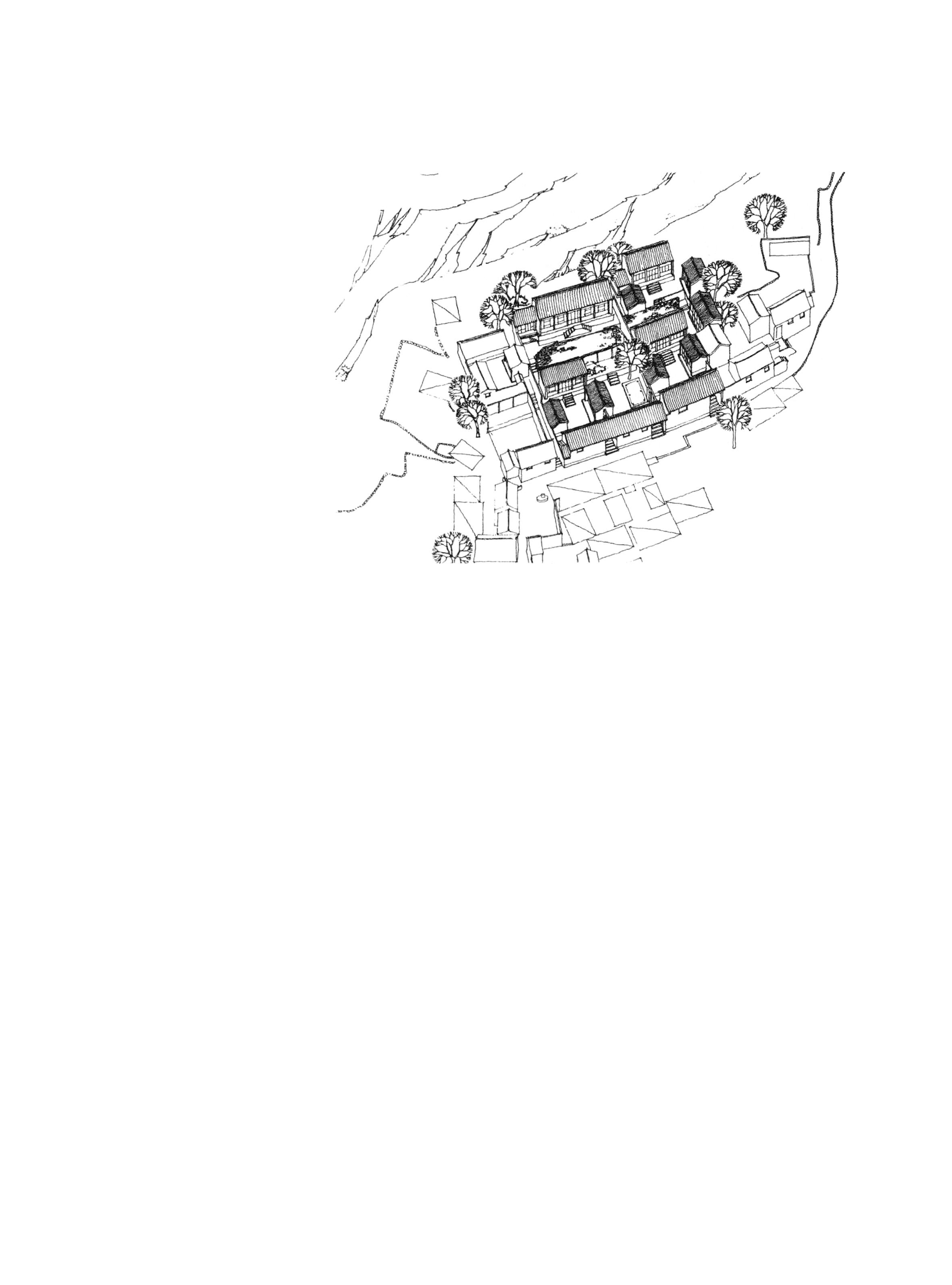

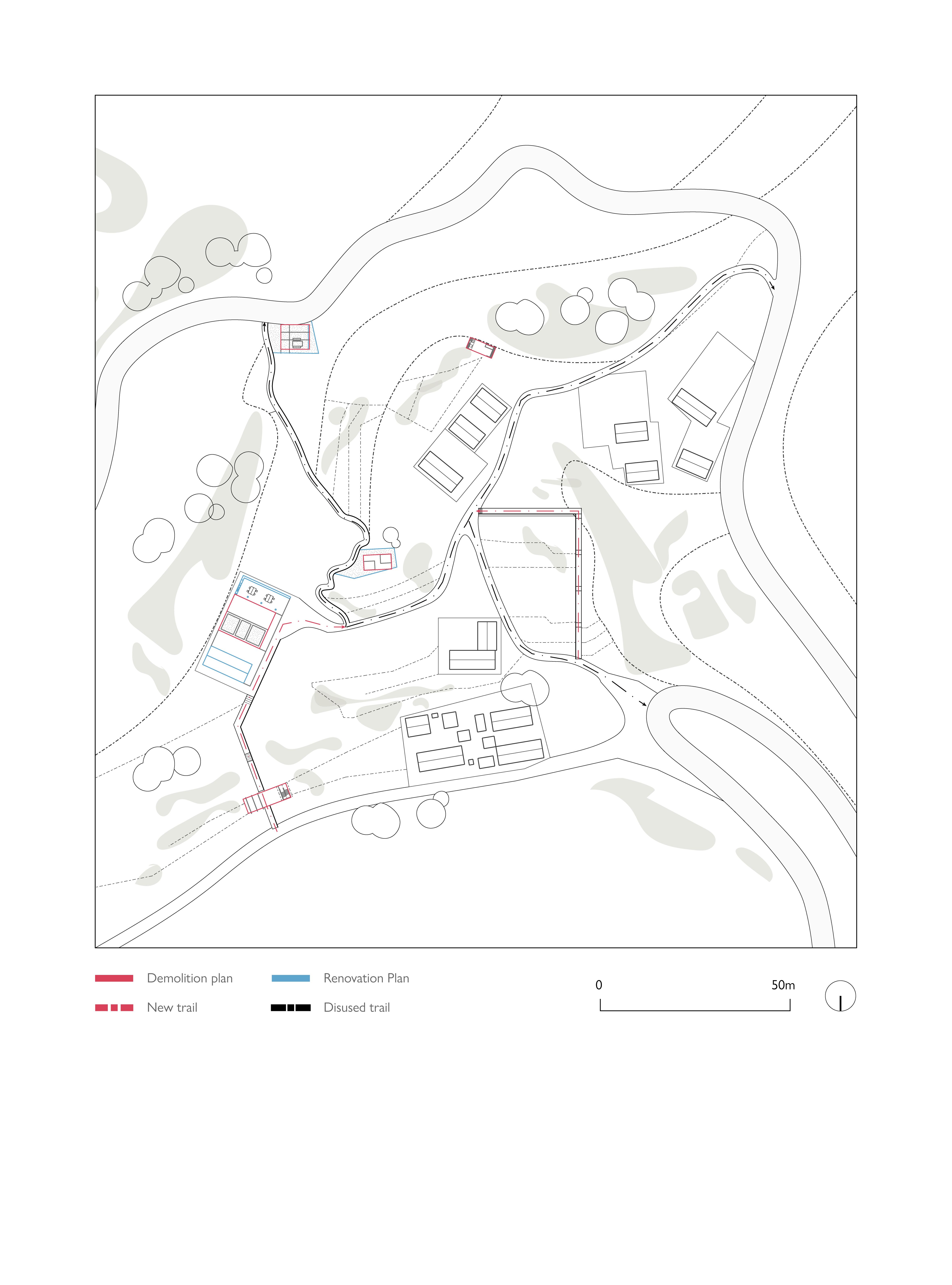

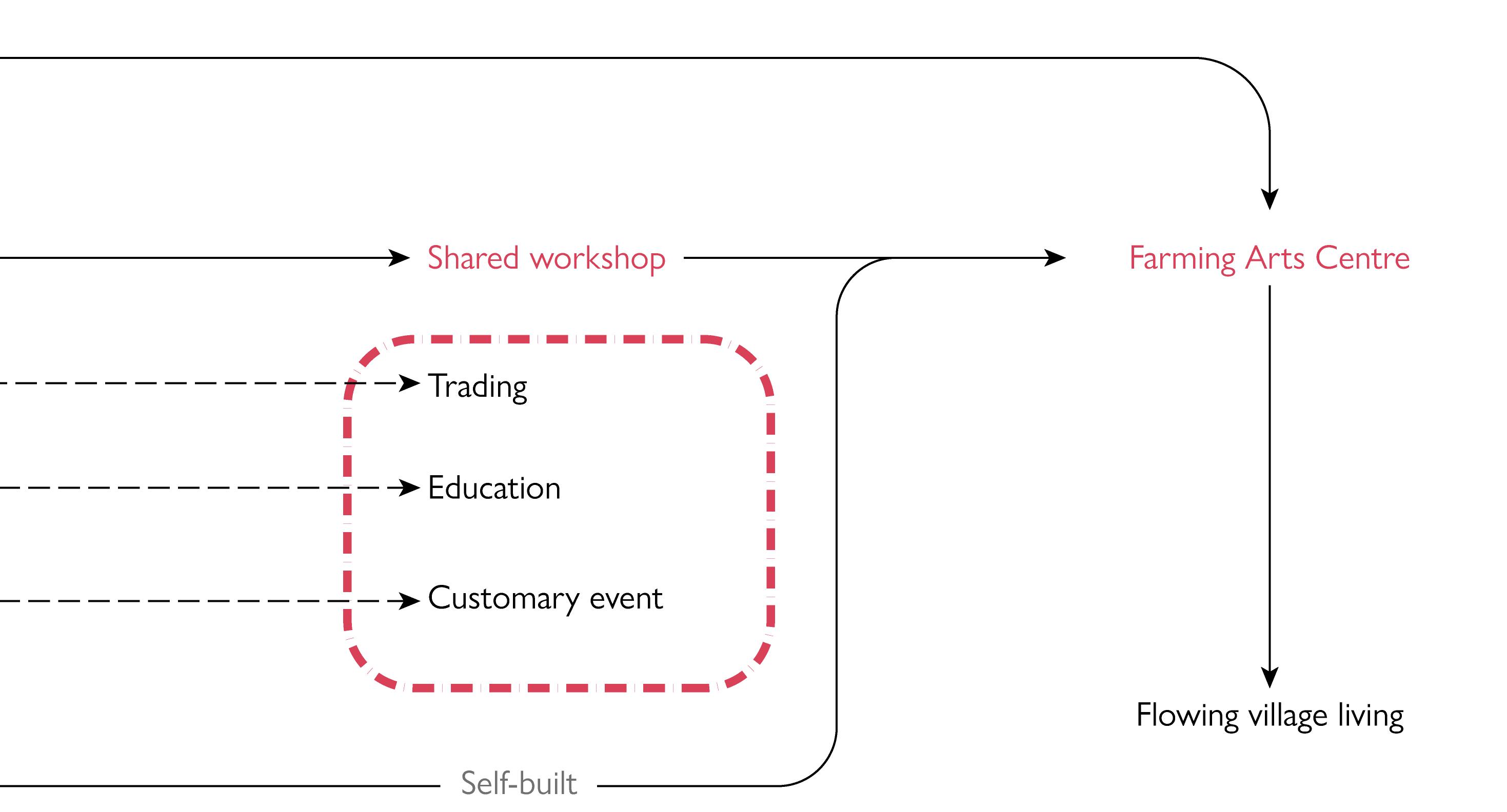

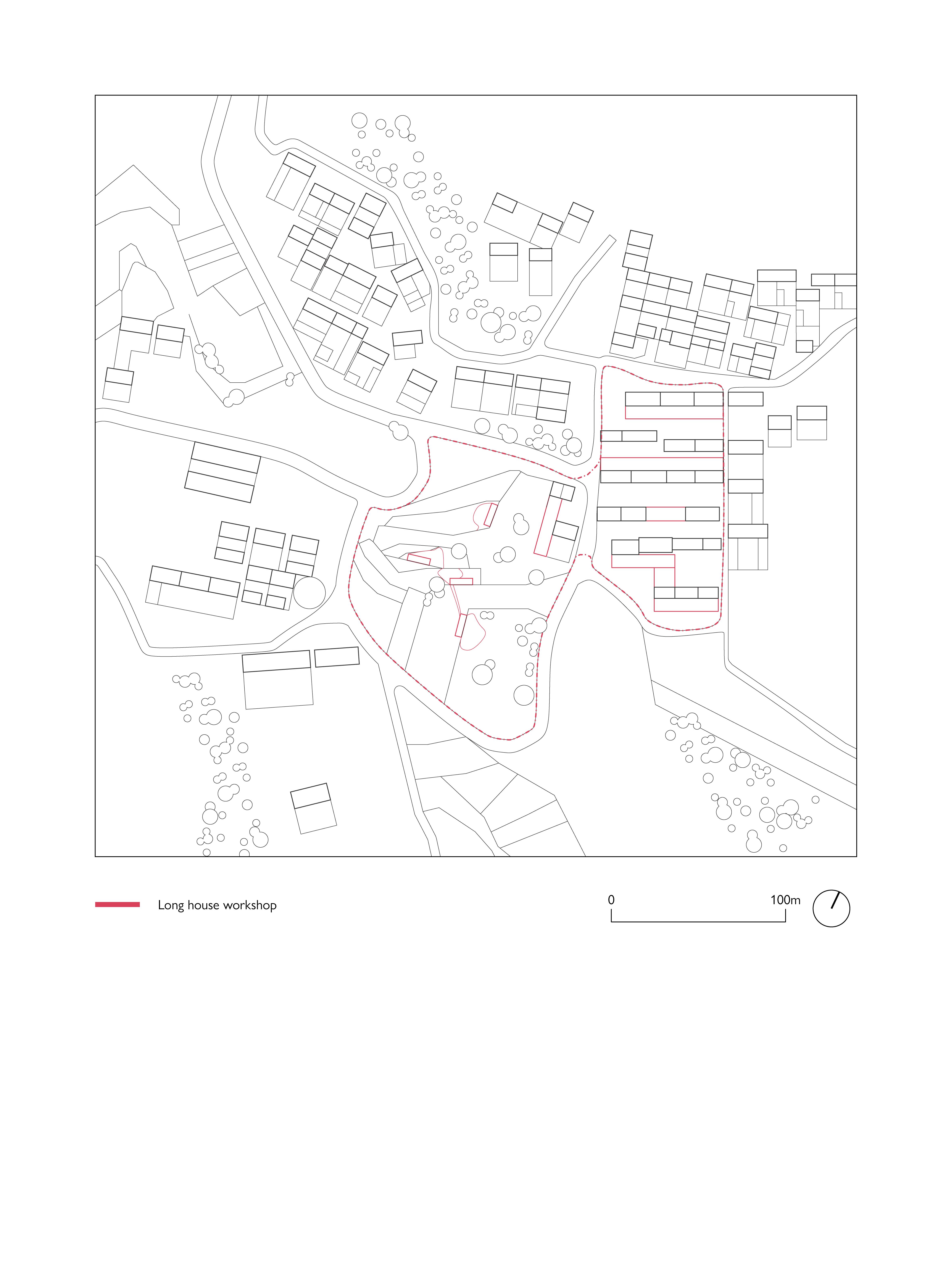

In order to investigate this unique type of village, which is generated by its environ and the long-lasting distinctive way of life, the dissertation focuses on the Beijing mountain villages as the case. Within the vast administrative boundaries that the government has drawn up, Beijing contains a large area of unurbanised, long-lasting villages. On the north-western side, the fragmented villages are entirely in mountain terrain. This geographical differentiation has resulted in two completely separate lifestyles in the Great Beijing. Due to the 'Hukou system', transportation distances, and the concentration of careers in the city, those villages have become islands. As mentioned previously, the dichotomy between urban and rural areas has gradually increased in this heterogeneity, although urbanisation has spread to formerly rural areas and mountain areas have maintained a long-standing pattern of living with its environ due to their complex geography. However, the new generation of villagers migrating to the city and the tendency of the urban middle class to be attracted to the rural landscape are transforming this living with environ kernel of subsistence.

By observing between mountain village area and suburban rural area in Beijing, there is a visible difference in boundaries. The remote and limited geographical conditions of the mountain villages provide them with farmland and also extensive geographical resources, although they are also subject to various countryside regulations and laws. The geographically limited makes villages have the conditions the dissertation needs to discuss: Autonomy¹⁶ in the environment. With the complex environmental conditions, these villages are shaped to exhibit complexity in their formation time, background, and spatial forms. Therefore, the fieldwork chose a specific village area in northern Beijing for research. There are several reasons for choosing this area:

1. The diversity of family structures in the village, from ancient kinship to recent new village structures;

2. It is far enough from the city area but still within the limits of Beijing, allowing for a discussion of the value of remoteness;

3. This area is close to tourist attractions such as the Great Wall, but still mainly follows a long-lasting village lifestyle, which helps to observe the two perspectives of idealisation from the villagers and outsiders.

Despite for these factors, the research chose these villages also had a particular convenience. The fieldwork in a short period required a rapid familiarity with the villager due to the long-term autonomy of the village and the closed communication environment of the familiar

22

FIG 1. 9

FIG 1. 8

society. However, it was not possible to directly to observe the daily life of the villagers in an unfamiliar village. By using the advantage of my grandmother's family living in the area and personal connections, it was able to establish a quick familiarity with the local villagers, which helped to look for some of the private facilities in the environment and even specific abandoned structures of the past. Moreover, the family connections to this village area allowed my family to continuous provide me with more personal information and archives. So it allowed the research to engage directly with the environment of the area itself on a changeable micro level.

In the following four chapters, the investigation begins with personal archives to make an individual's perspective idealisation, and the actual factors projected behind it in shaping environ space. The highlight is to construct a model of villagers' daily activities towards the living environ. Each chapter then organises around one of three different scales of environ type within the daily sequence: the Settlement, Natural resources path and the whole region; each scale traces the spatial transformations shaped by family, history and politics; as well as the impact of the different organisation and cooperation they project. The reshaped structures with environment were then used to test the new cooperative approach in the proposal, further discussing the value of this unique mode of living in an urban-rural context. In addressing the topic of rural idealisation in urban-rural contexts, the living sequences studied provides a sociological long-term understanding of the construction of a discussion of the current problem of rural flight and what it means to be sustainable. It aims to present its changing forms within a sequential network between mountain geography and specific environ space.

The typological features of mountain villages often make different villages to form a region, linked by the environment and thereby gaining access to a wider social network of familiarity.

23

FIG 1. 10 SCATTERED VILLAGES

24

Chapter 2

From cooperation to self-built

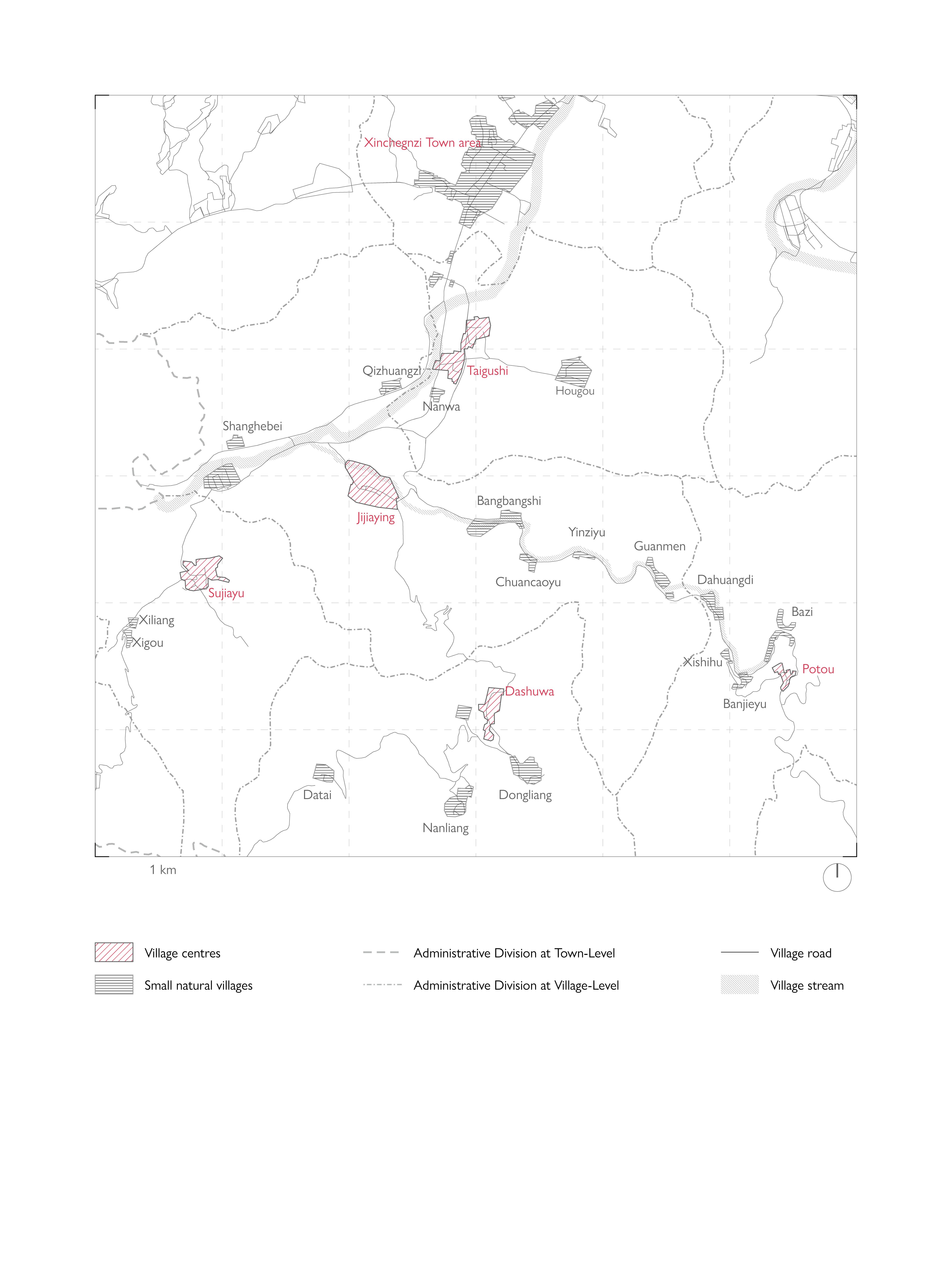

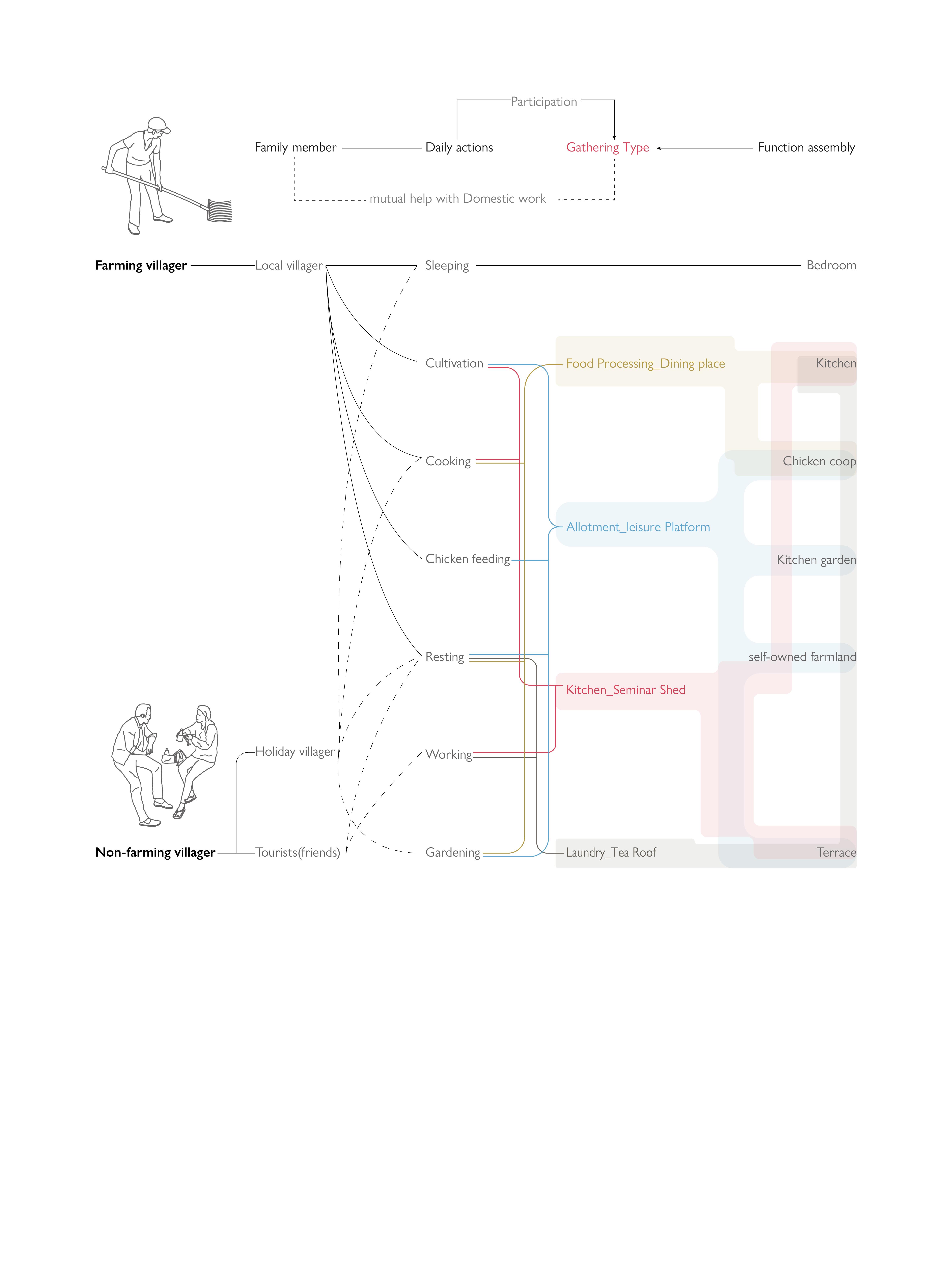

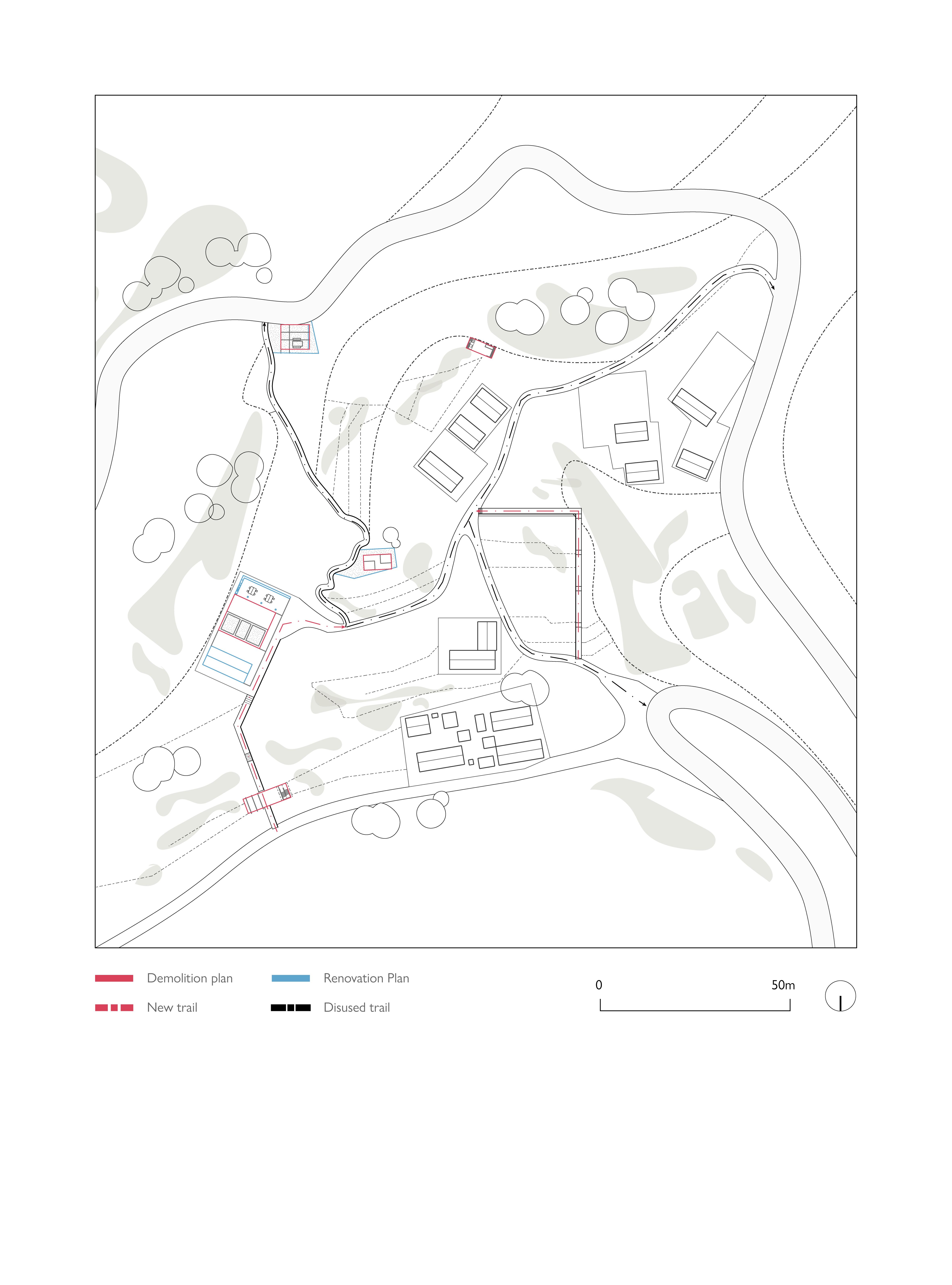

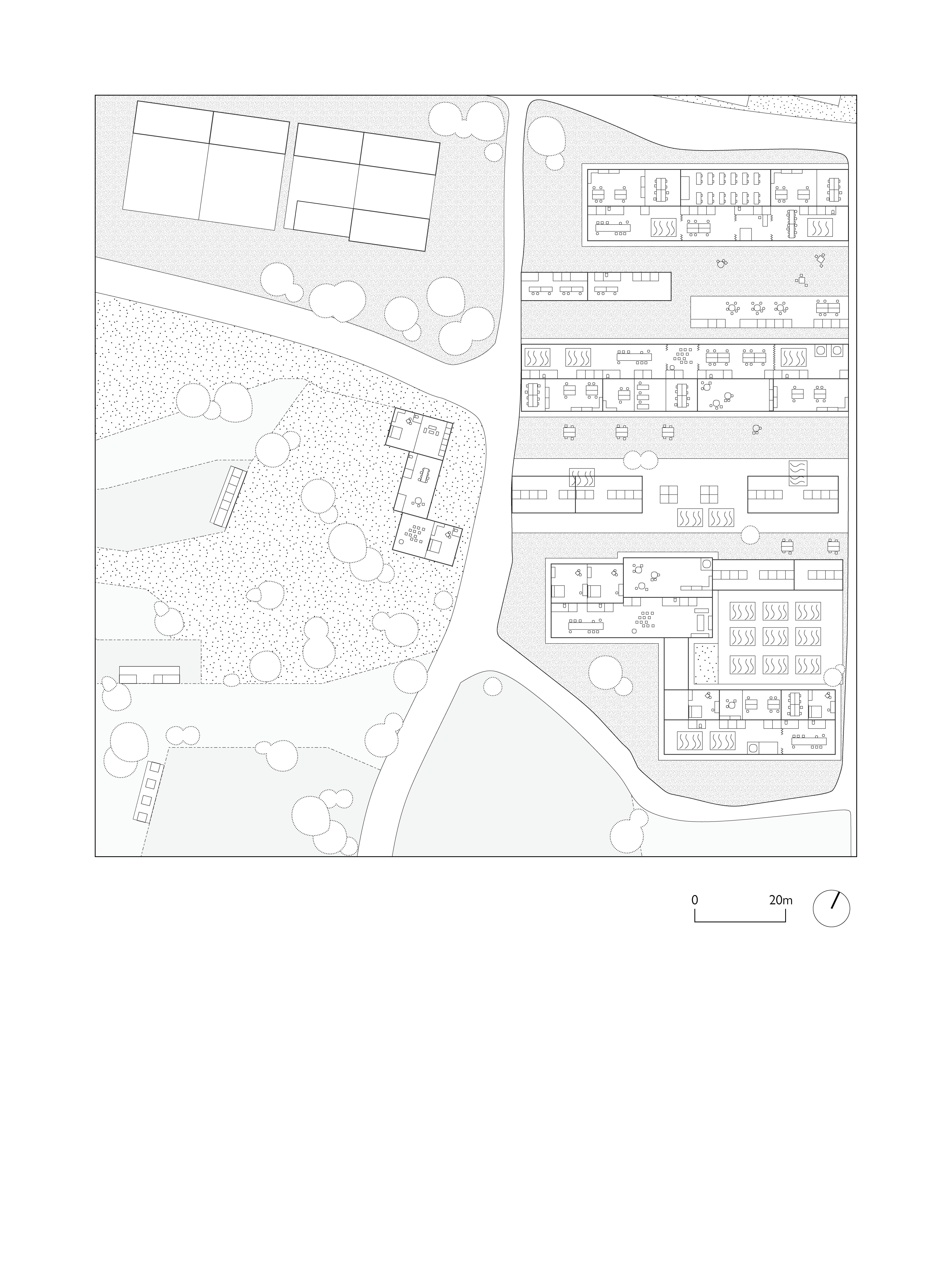

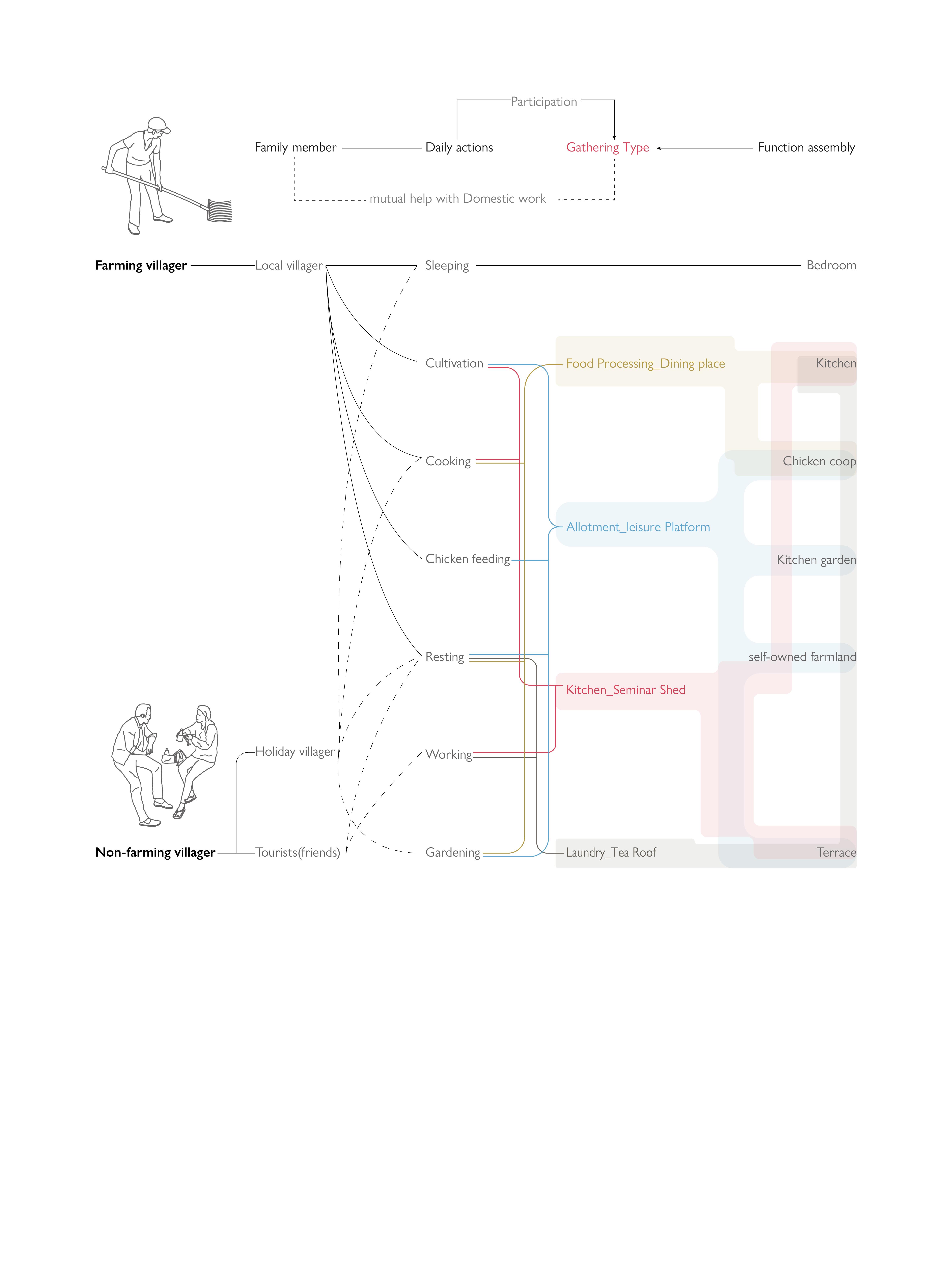

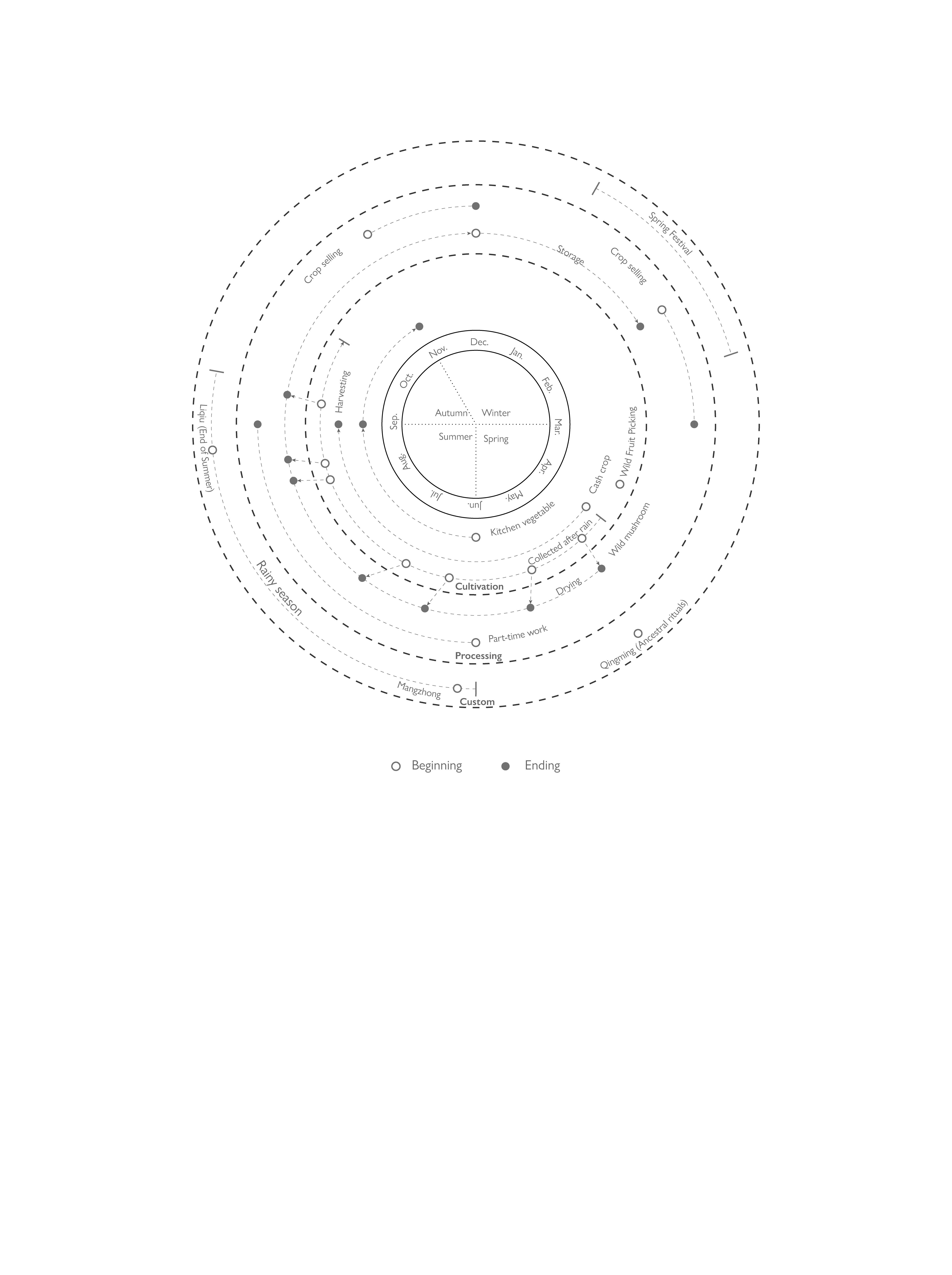

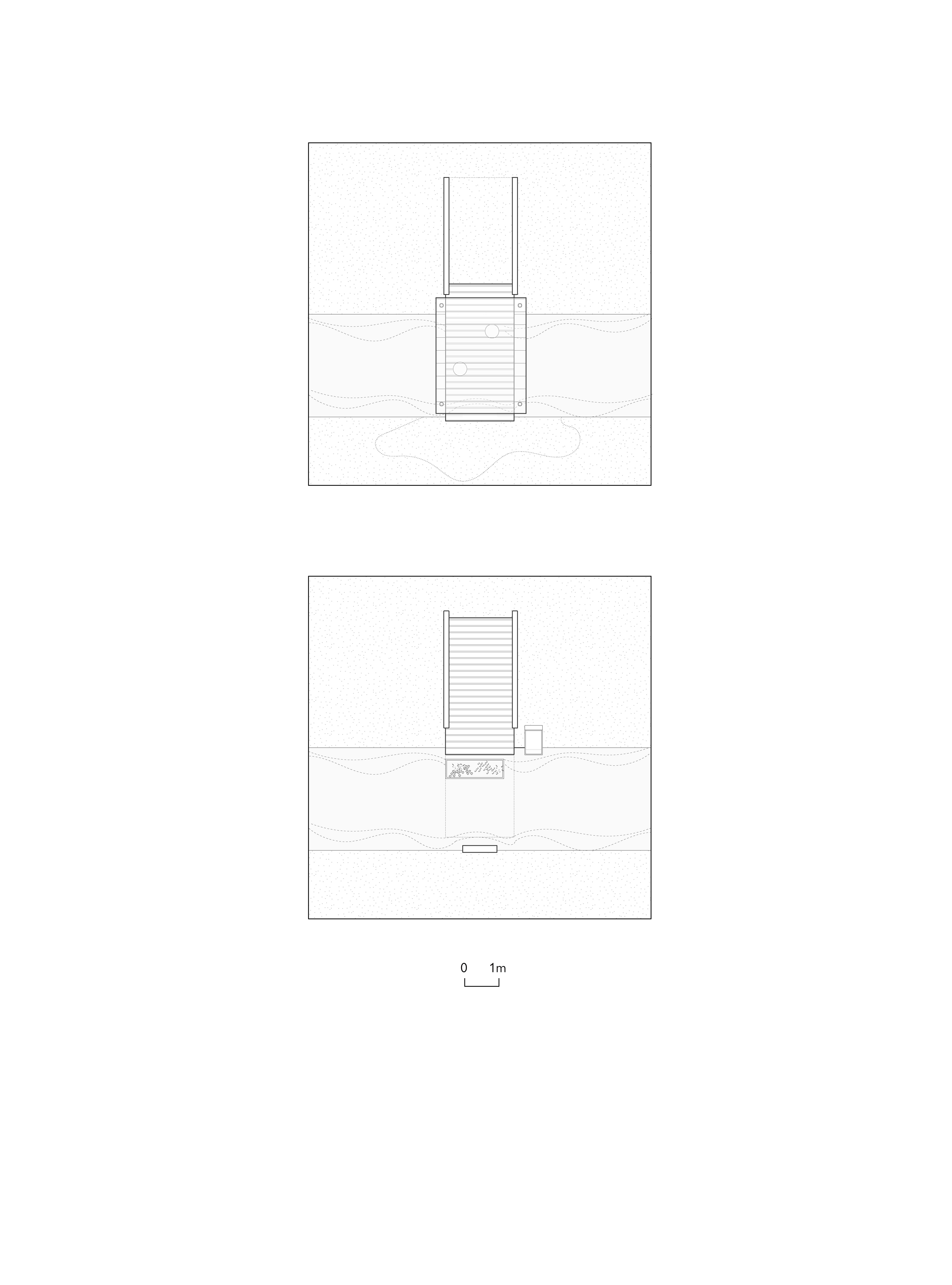

The chapter brings a core argument that the rituals of villagers' cooperation with the environment are spatially projected as selfbuilt activities. The autonomy of villagers is designed at three different spatial scales based on daily life sequences: settlements, natural resource sites, and natural regions. As previously stated, the research will take a field trip to the village area known as 'Xinchengzi' in Beijing.¹ An archival study of my grandmother's home will be used for a qualitative investigation in this chapter; By exploring the phenomenon of “Returning to the Countryside” as a current trend in urban-rural relations, the chapter argues that a hybrid network of cooperative living emerges within the environment, responding to the rural-urban continuum.

2.1 The basis of cooperation: a self-designed personal life

The village where the fieldwork was conducted is in the administrative area known as 'Xinchengzi' town. It is situated in the mountains in the northeast of Beijing, approximately an hour's drive from downtown Beijing. The villages in this area were not formed at a specific time but were shaped by different histories. It dates back as far as the Ming Dynasty(17th century), when military camps² were set up to defend the Great Wall, and then developed into large clan-based villages; besides this, most of the small villages were established in the early

1 Xinchengzi is a town and the field trip selected the southern area consisting of fragmented small villages.

FIG 2. 2

FIG 2. 1

Anthropology fieldwork site.

FIG 2. 3

2 Ying" ( 营 ) and "Tun" ( 屯 ) are both Chinese words that can mean "camp" or "garrison", suggesting that the village may have been founded as a military camp.

←FIG 2. 0

PERSONAL ARCHIVE

Grandmother and aunt were making dumplings. (1994)

25

3 A migration movement, due to war and famine, refugees from the Shandong province move to North China. For more details: Junke Yin. " 北京郊区村落发展史 ." Peking university press (2001): 288-291.

4 Production groups are established within the production team organisation, generally with the original 1-2 small villages as a group.

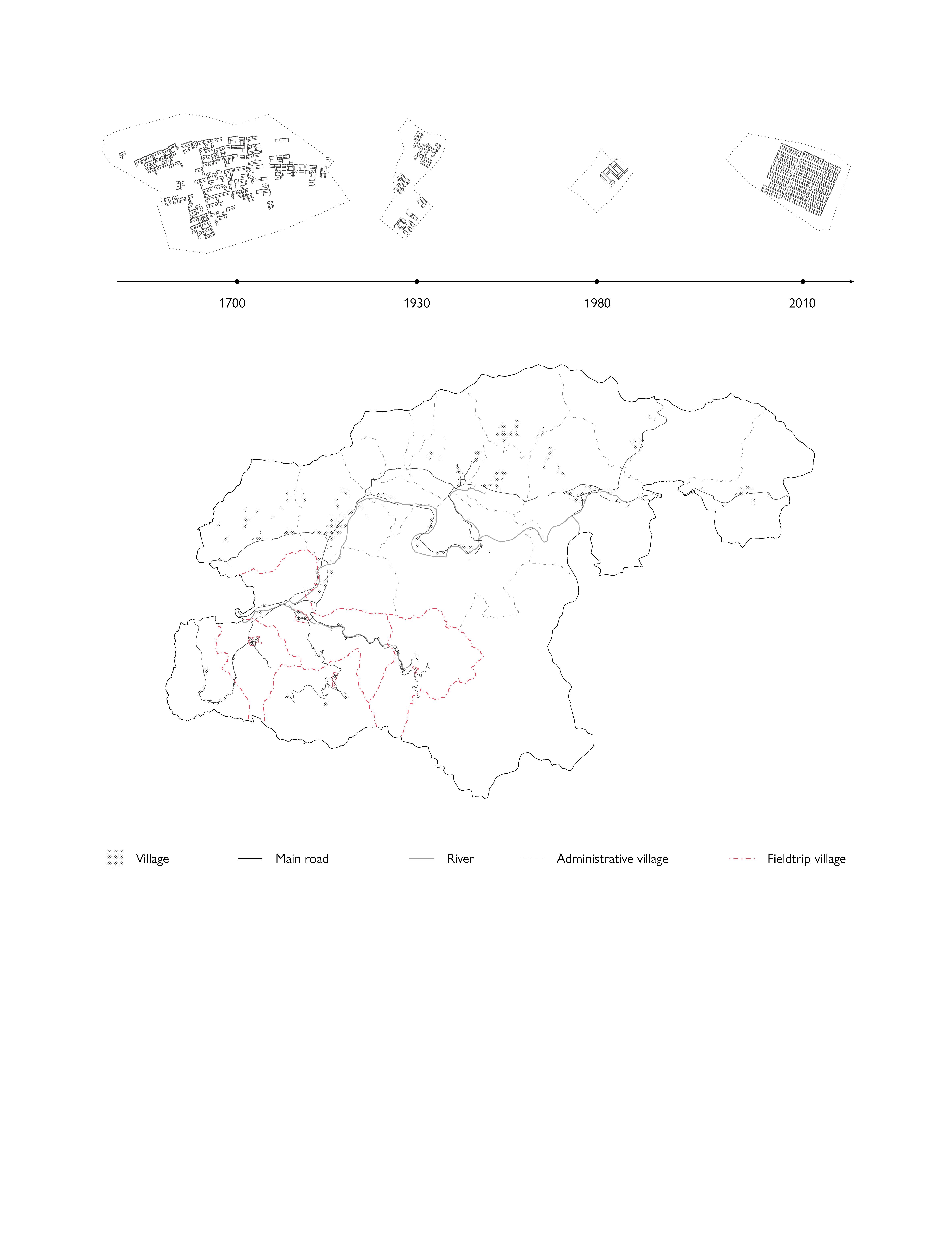

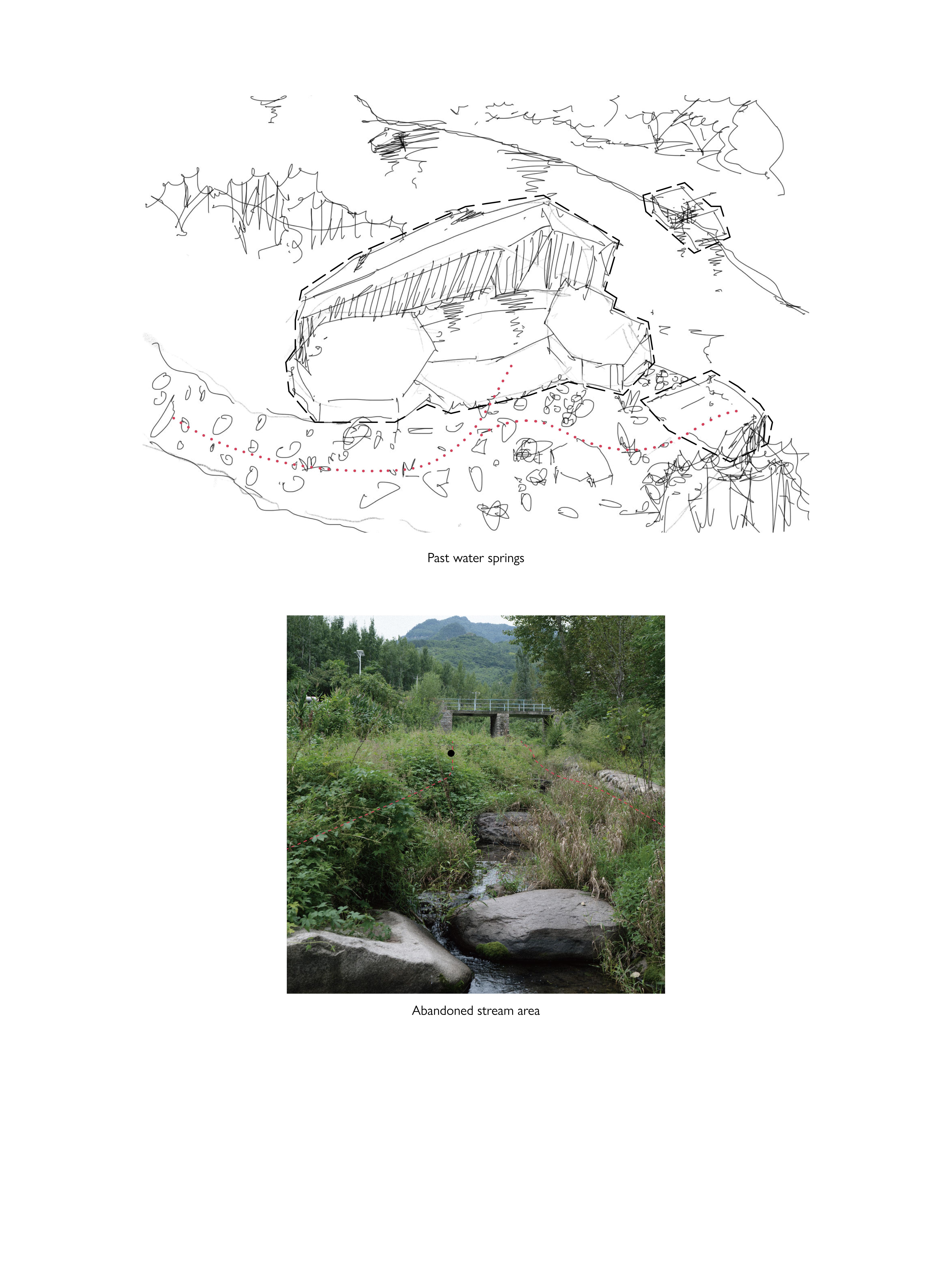

20th century during The Great Migration from North China to Manchuria movements,³ scattered across the mountains on cultivated terraces. In geo-spatial, most of the villages are arrayed along the streams between the valleys; however, due to the need for farming, these strung villages are closely integrated with the environment, yet separated from each other. It implies that personal life was based on the family or settlement as a joint development. Following the streams, different families or groups of refugees gradually expanded outwards the Great wall, which defined specific environment units and formed village clusters based on different families. During this period, traditional small-scale farming practices were based on land resources and self-sufficiency.

5 A form of shop from the people's commune period.

During the period of 1950-1970, the natural territory of the villages was reorganised by the implementation of production teams, This system shifted the villagers’ connections from being based on kinship to social relations framed by production. During this period, the government combined different villages into larger administrative units, and production organisations known as different production groups⁴ to carry out specific agricultural production tasks. Within the framework of collective production, village activities widened and their boundaries of activity were no longer based on the family environ; new sequences of village activity were formed in the new communal courtyards organised by the production teams. In the recollections of my mother, Lady Wang, about her childhood, she spoke of a range of activities between the primary school, the supply and marketing cooperatives⁵ and the home. It suggests that not only did the farmland around the family serve as a playground for the kids, but it was also extended to a broader area within the production team.

The process of consolidating village boundaries has had an impact on traditional family divisions, particularly during the period from the 1960s to 1980s when it was more common for families to have more than one child. With adult children seeking to establish their own households, the division of families no longer depended entirely on the allocation of natural resources but could be negotiated with villagers in other locations within the production team to create new courtyards. This has resulted in the emergence of separate courtyards belonging to two or three families scattered throughout the village. The homestead choice is not completely random, but rather a choice to be incorporated into an existing village settlement. At this stage, the negotiations

26

FIG 2. 4

FIG 2. 5

FIG

2

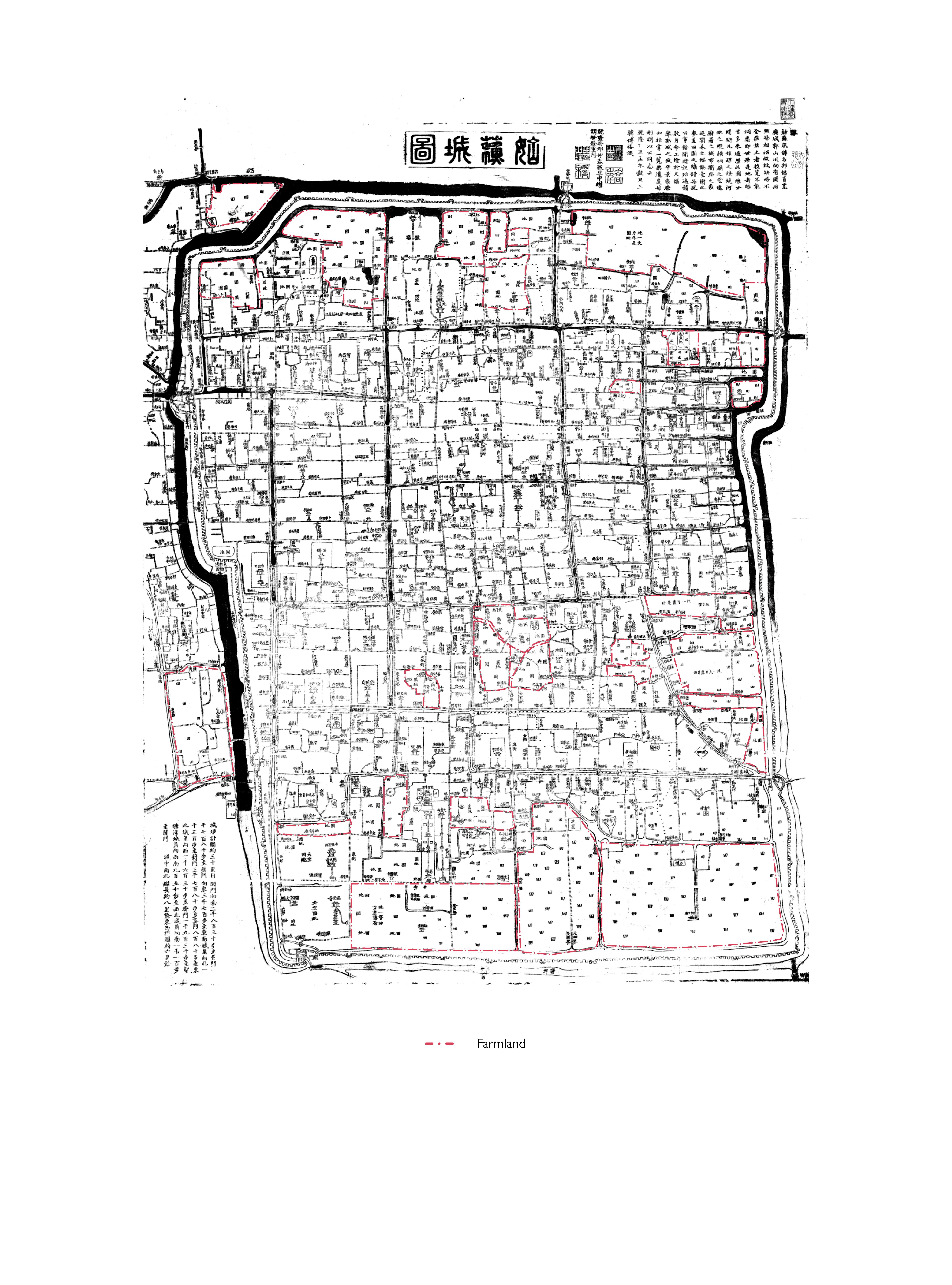

The City Map of Soochow (1745). The red line shows that the city, rural and farmland were integrated; illustrating the small farm as a mode of life instead of a production activity.

27

2.

ANCIENT URBAN-RURAL CONTINUUM

6 The policy known as the Household responsibility system allowed villagers to re-let land and make their own decisions about cultivation.

that took place in a particular village setting were based more on the production team allocation system, which allowed those newcomers to maintain a strong connection with the family not only because of the allocation of natural resources; but also gradually integrate themselves into the villagers' activities in the new settlement.

When the production team system ended in the 1980s, villagers could choose their land again and cultivate it independently.⁶ However, the long period of integration has resulted in multiple village groups living as a multi-layered unity. In terms of kinship, the different family members have fragmented into different village settlements, but they still maintain close connections; from the planting resources, private farmland is no longer confined to the settlement environs but is spread over a wider village area. This allows the traditional self-sufficient small-scale farming mode to no longer be defined by family environ resources but to form a long-term sequence of personal daily life. This stems from a long-term identification of the environment that transcends the limits of the private area and still creates a proximal connection, beginning with the activity of cultivation, defining personal life forms multiple layers of specific self-built approaches.

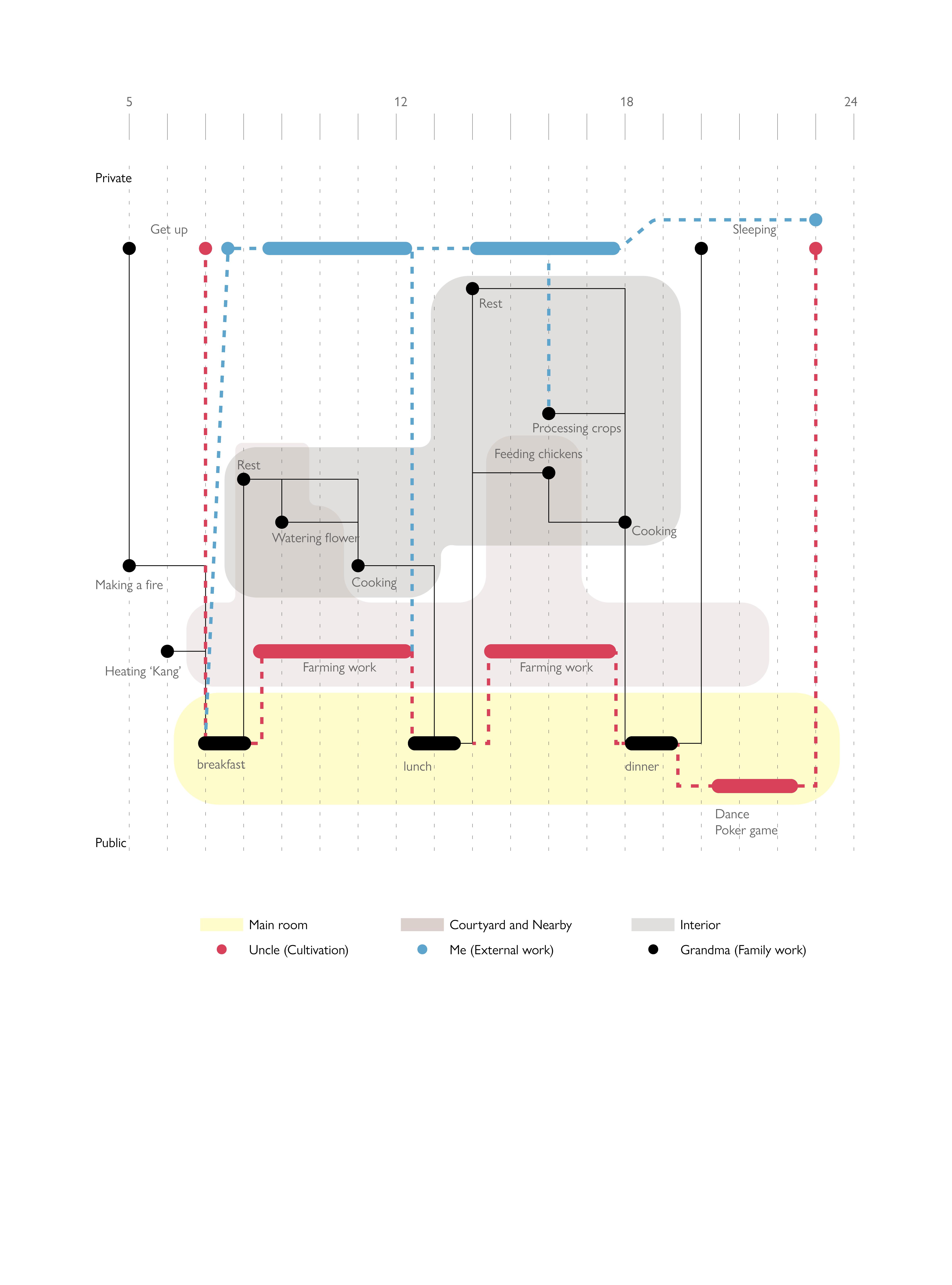

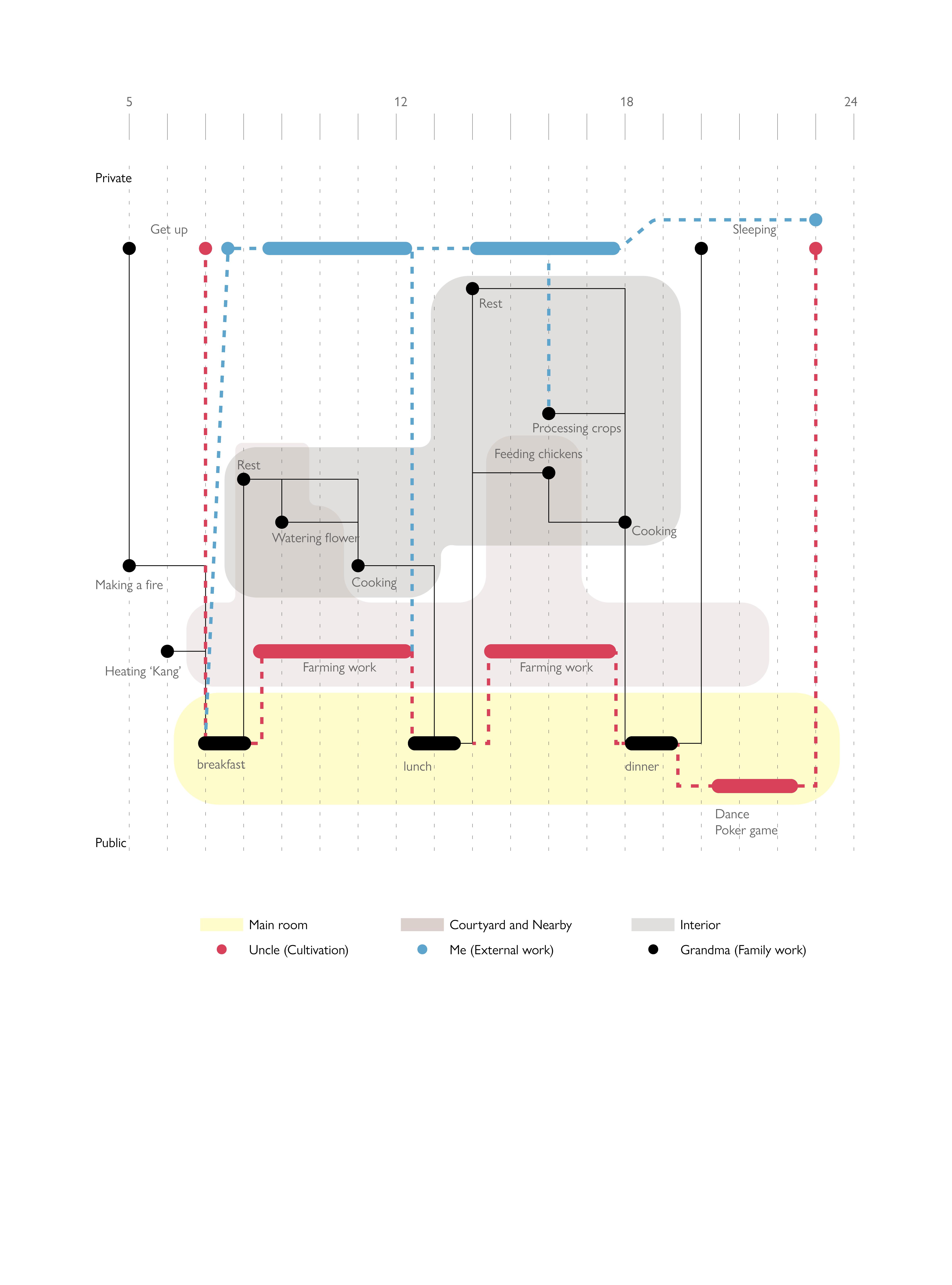

A notable case is the self-built objects in the yard of Grandmother's house (Lady Xia). When she tried to describe the purpose of these mess objects, she went into great detail: 'The stacked firewood is to be used as a base for piles of corn in winter, and the bucket is for pickles; this cupboard is a nostalgic object of the past...' Although objectively, these objects are cluttered and unidentifiable, for long-time personal use, this forms an imaginary of the self's living space. Shaped by the environment over time, this design of self-living is not restricted to the home, but becomes a personal life route within the village area. The renovation of courtyards to the informal structures that mark natural spots or farmland; the cooperation with the environment allows for the entanglement of self-built activities with the landscape. These self-built activities create heterogeneity between different geo-spatial area, while at the same time depending on common environmental contexts.

2.2 The case for cooperation: Returning to the countryside

The contemporary mountain village space is shaped by intergenerational differences in the 30 years since the end of the production team system. China's implementation of a market

28

FIG 2. 6

29

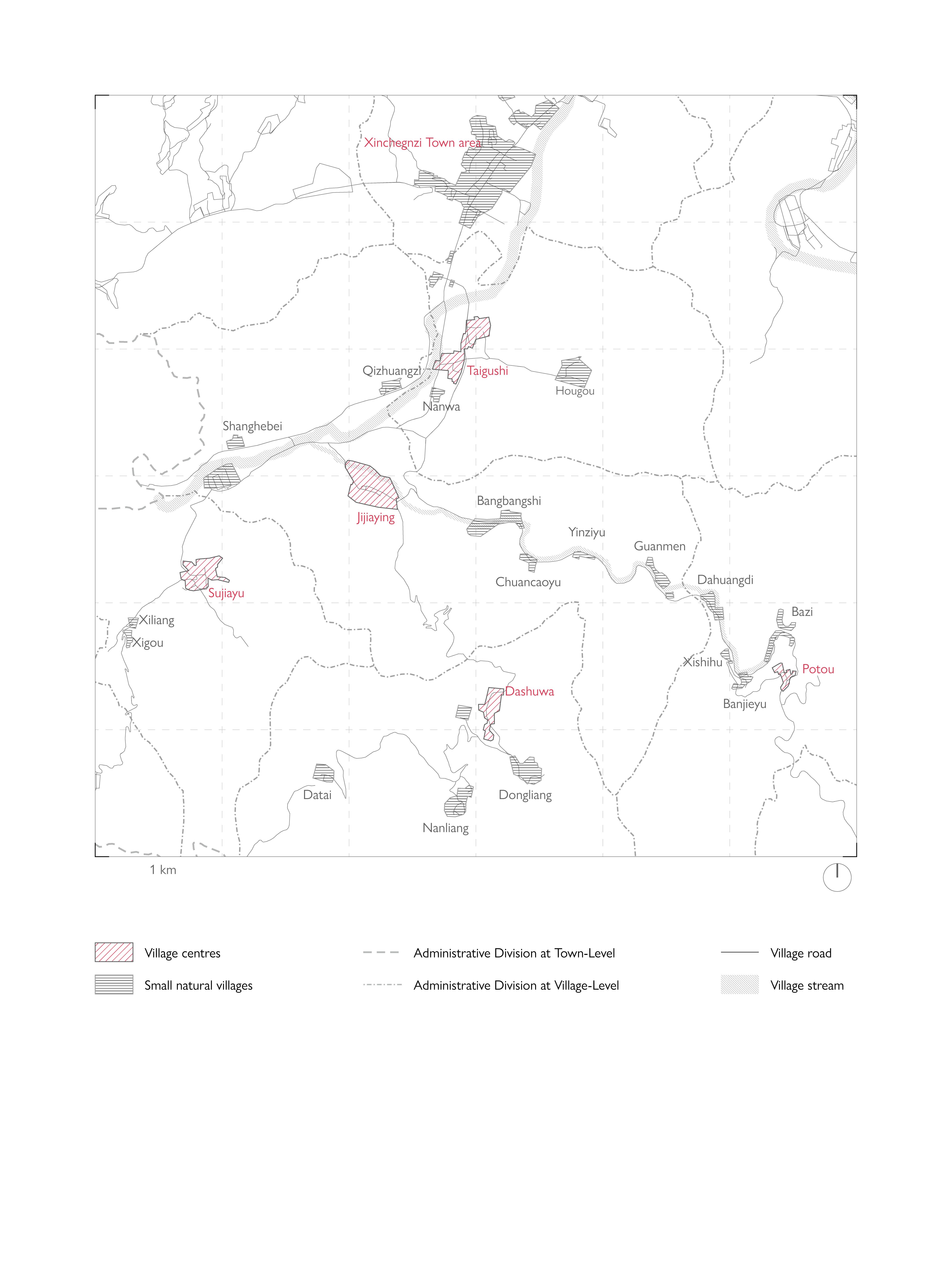

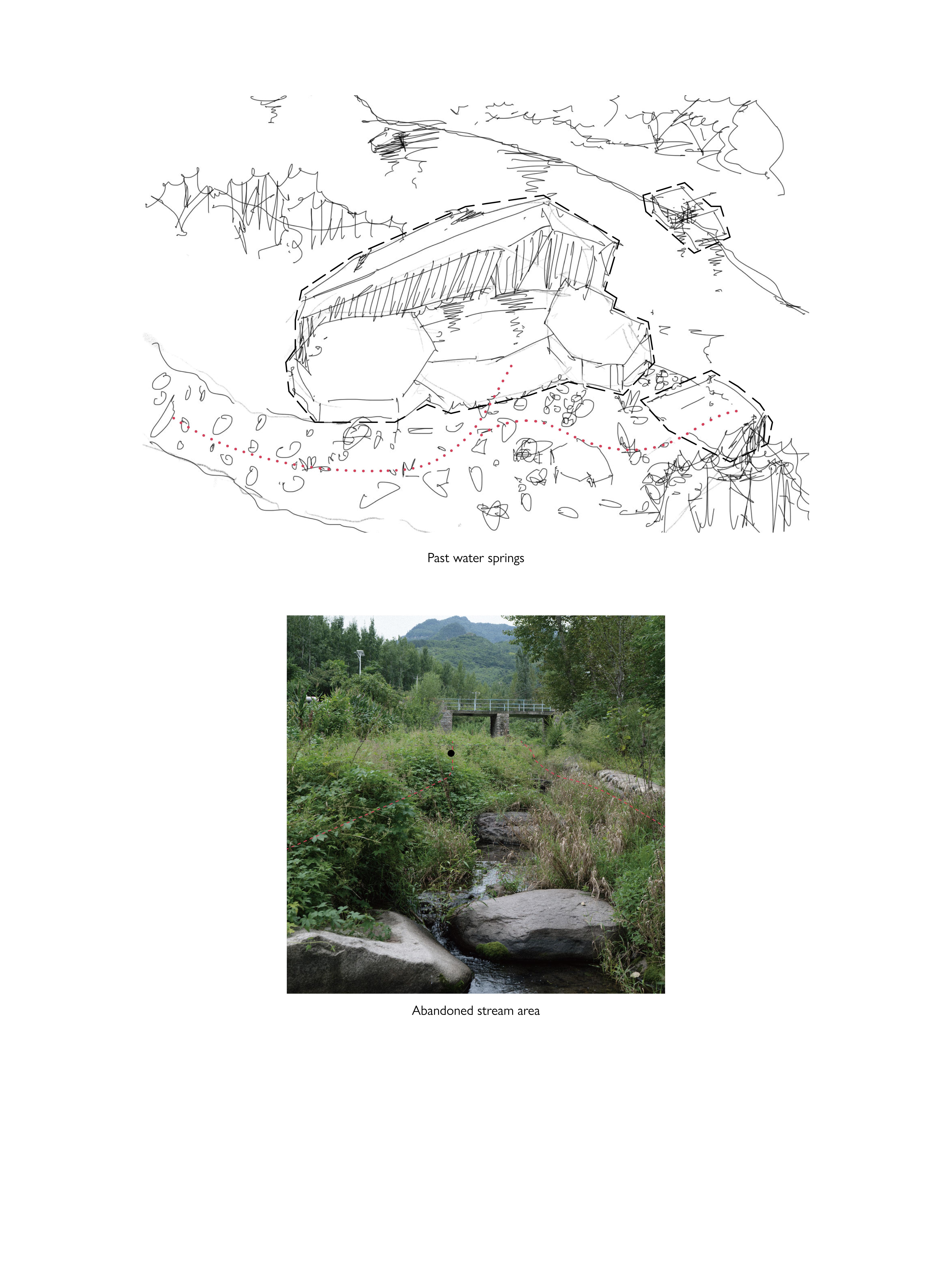

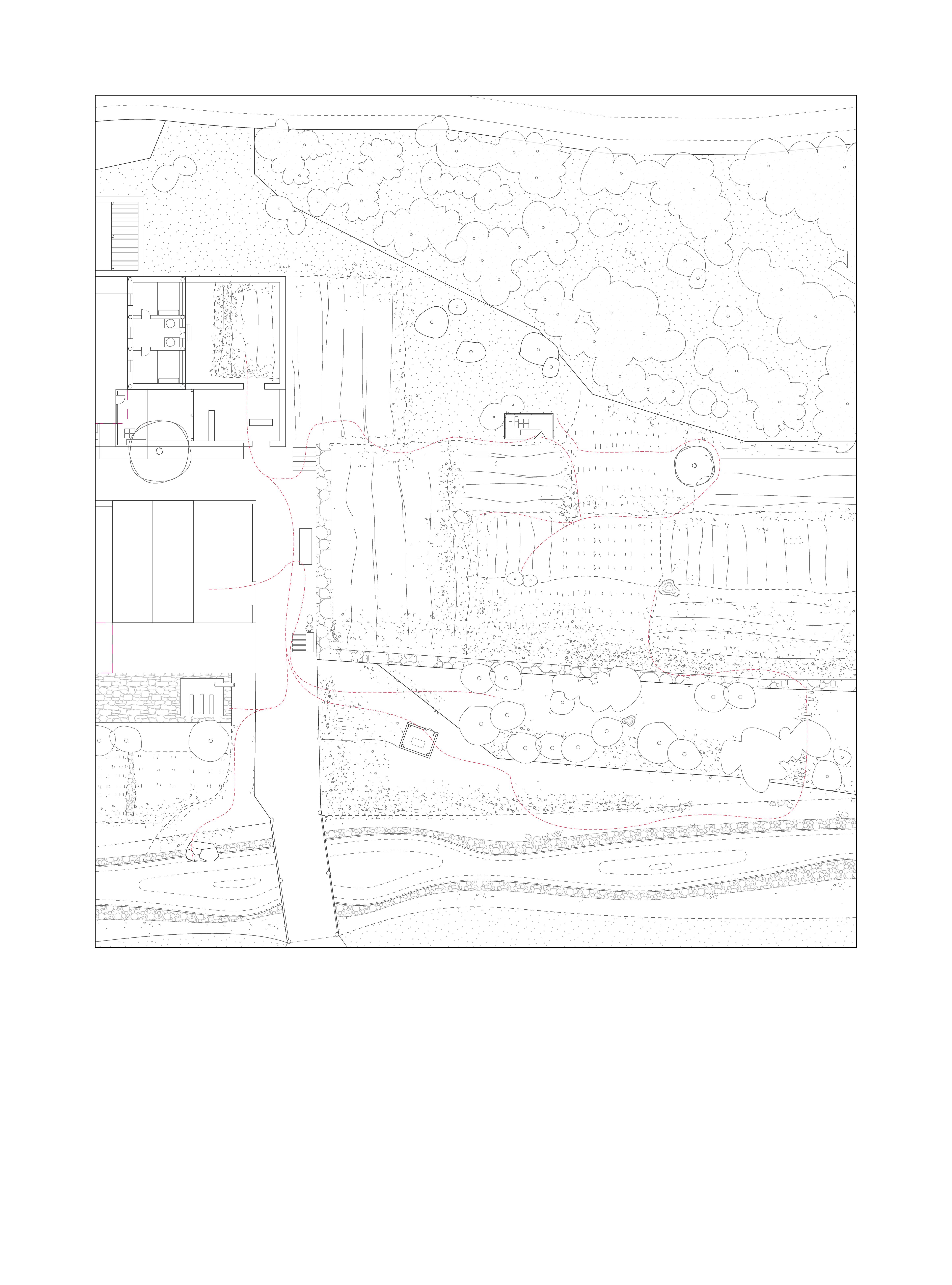

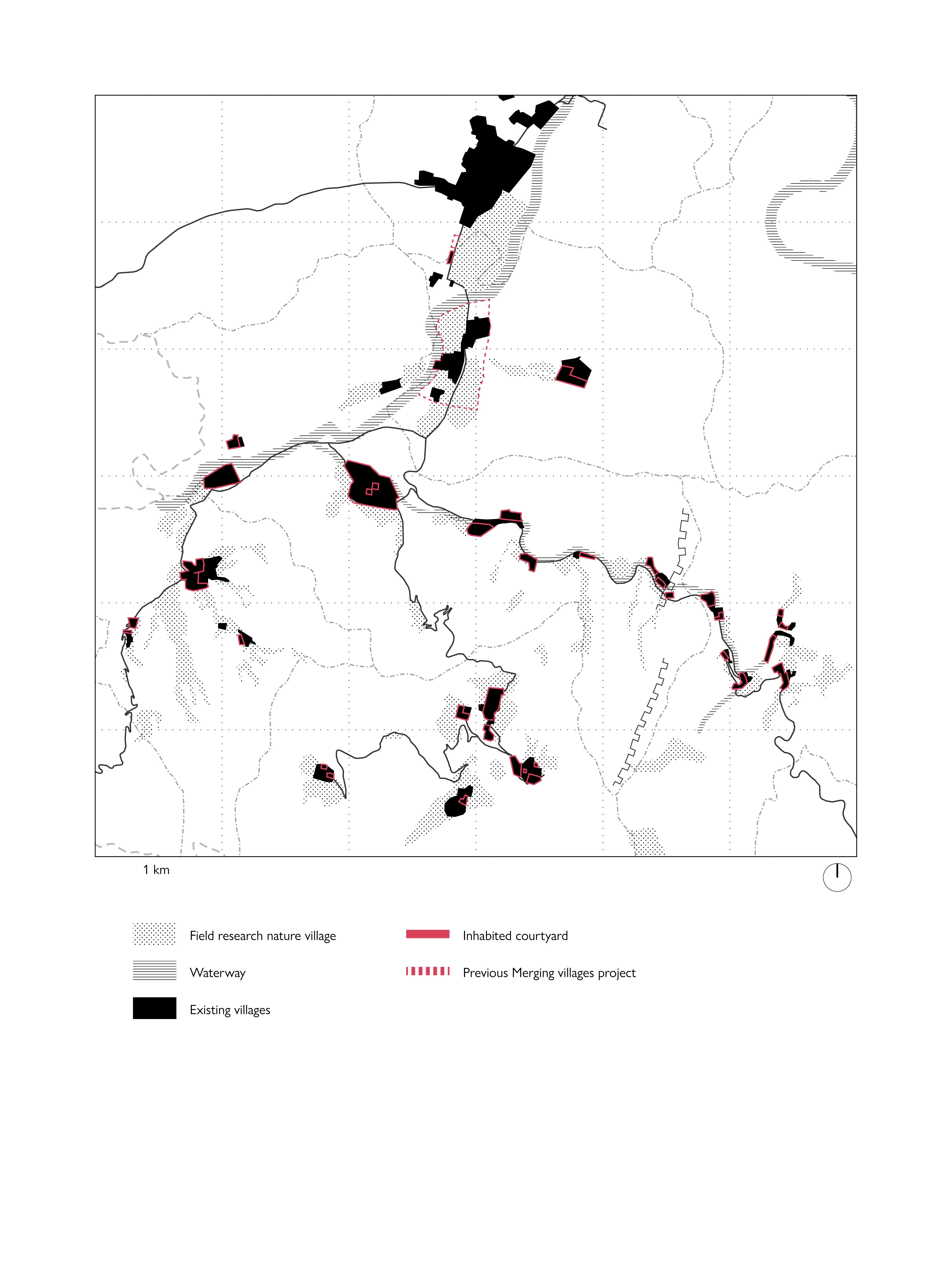

FIG 2. 3 CASE STUDY SITE

This rural area in the northern mountains of Beijing is called Xinchengzi town, and fieldwork was done in its southern part. Containing a series of small, fragmented villages.

The area investigated covers four administrative villages with a large number of small villages. This is a legacy of the village structure from the production team period.

30

FIG 2. 4 FIELDWORK AREA

31

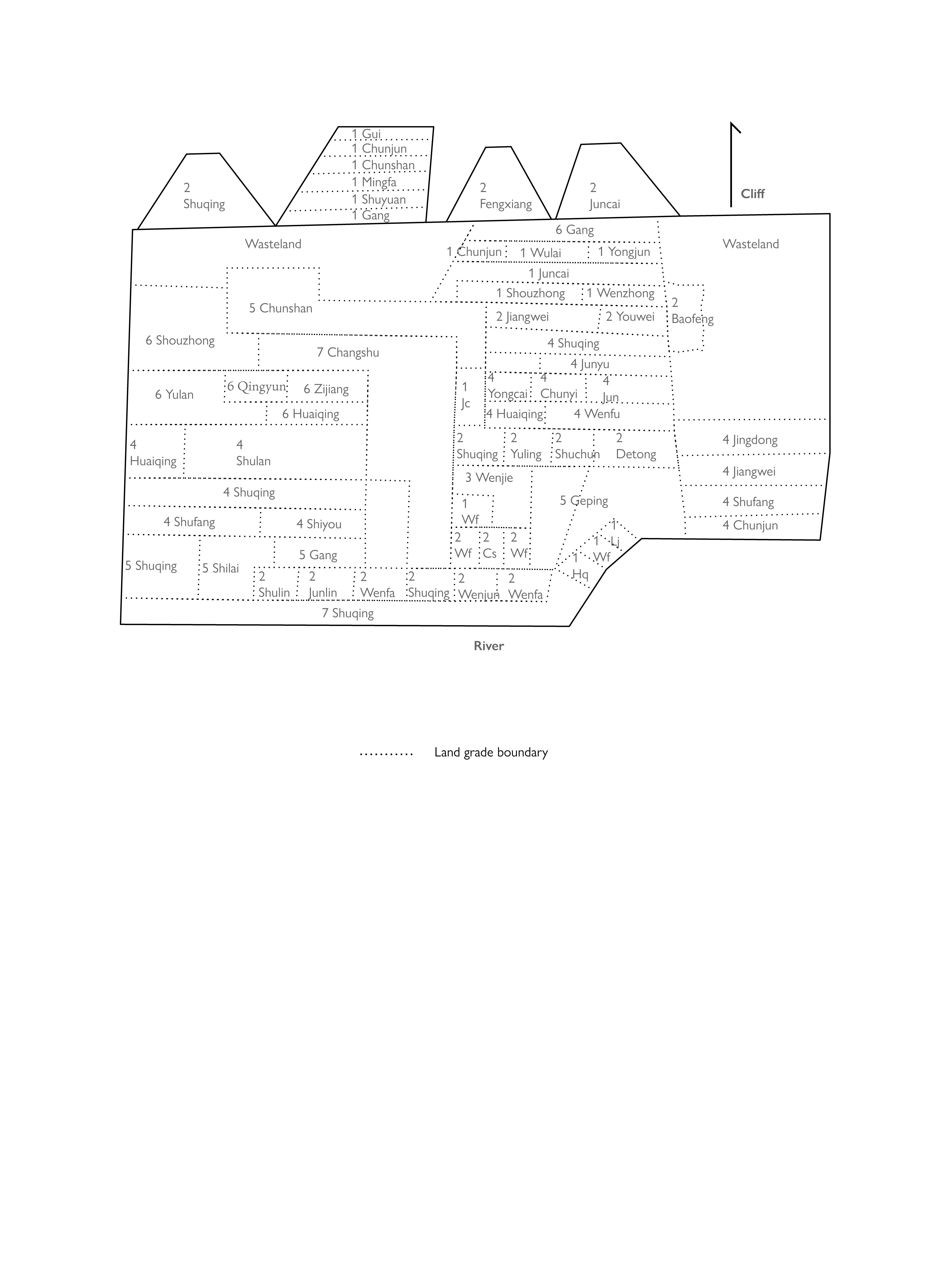

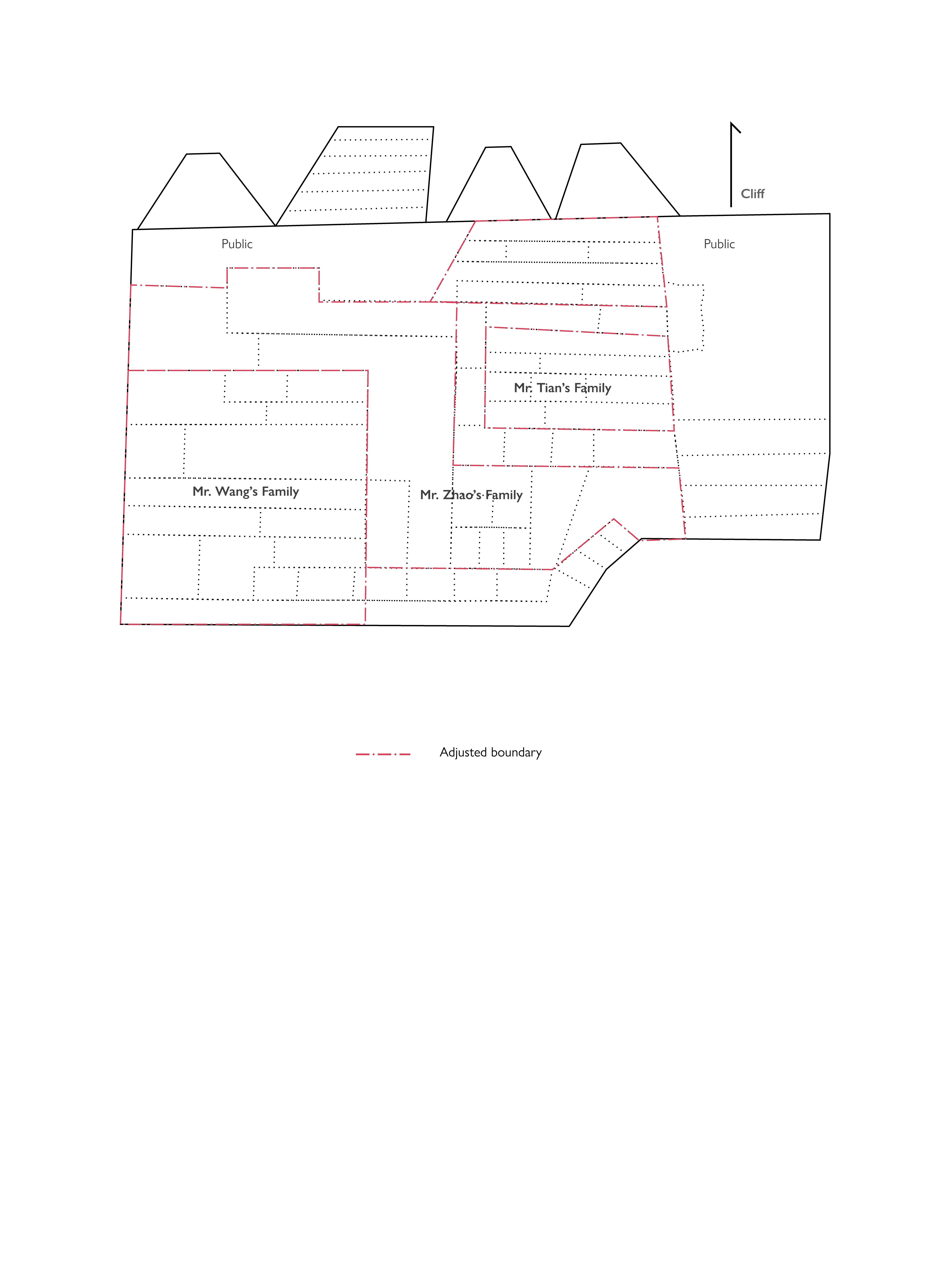

FIG 2. 5 CASE OF POTOU VILLAGE PRODUCTION TEAM ARCHIVE

A reshow of the village collective facilities during the production team period through interviews with villagers.

32

Firewood pile (Frameworks for winter food storage) Cleaning Kits and Pickle jar

FIG 2. 6

CASE OF MY GRANDMOTHER'S YARD

Tiny storage area Old closet in 1980 33

7 Data sources: China, Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics, Beijing statistical yearbook(Beijing: China statistics press, 2020).

8 Kai Wang. Ming Chen. "The Transition of Urban Planning Philosophies under the Background of Rapid Urbanisation in the Recent 30 years," Urban planning forum 179 (2009): 9.

9 If a farmer still holds a rural Hu Kou, he is considered a rural worker, and although he can continue to hold the land use rights in the village, he cannot enjoy the social welfare benefits of a citizen.

economy from the 1980s onwards led to rapid urbanisation in Beijing, increasing from 54.93% in 1978 to 86.60% in 2019.⁷ The consequent urbanisation fever among the new generation living in villages is argued to be the result of the reform of the rural allocation system, which released a large amount of surplus labour following the reform of the Household Responsibility System, subsequently promoting the rural economy.⁸ Meanwhile, the government liberalised the Hu Kou system, which made it possible for peasants to move to the cities. As a result, new urban dwellers emerged during this period, moving from the villages to the city, changing to urban Hu Kou and gradually integrating into urban life. The change in Hu Kou status meant that they lost their rights to homesteads, houses, and farmland in the villages.⁹ The critical reasons for this trend are mainly two-fold: firstly, the higher quality of urban life and the increased demand for employment led the new generation of farmers to migrate; secondly, it was still common for rural families to have more than three children during this period, and the demand for land was already full, with the idea of 'inheritance', so that usually only one child would typically remain in the village.

However, the younger generation who migrated to the cities in the 1980s did not completely sever their ties with the villages. Even after spending many years in the city, they began to revert to a trend called known as “returning to the countryside”. For them, this resulted in a complex hybrid of cultural experiences. Their collective memories of rural life in their childhood and the impact of urban living and production in adulthood have transformed returning to the countryside into a nostalgic cultural activity that extends beyond merely maintaining family ties.

On the contrary, for the new generation in the villages, this desire for urban life is gradually deepening; although the villages are becoming closer to the downtown city in terms of living conditions, the villages have always been associated with isolation, both in terms of popular culture and in terms of individual career development. This has resulted in a returning to the countryside within the Beijing urban context not as a form of counter-urbanisation, but rather as a homogenisation of the village with the urban. Considering the fragmented rural land use, unlike urbanisation in the city, urbanisation is not visible in these fragmented mountain villages. Also, the restrictions on homesteads and land gradually limit individual life to the boundaries set. The traditional awareness of personal life development is only about a way

34

FIG 2. 7 VILLAGE VILLA Private villas developed by holiday villagers, some of which have gradually become B&B commodities because of their wonderful natural landscape.

FIG 2. 8

FIG 2. 9

35

FIG 2. 8 URBAN-RURAL MIGRATION TENDENCY

10 The government has enacted several policies over the last 30 years to maintain the sustainability of the mountain villages, including the Socialist New Countryside Project, the Village Water and Power Upgrading Programme, the Household responsibility system, and Cultivation subsidies.

of living for the returning villagers, rather than cooperating with the environment. The traditional urbanisation of private property results in the villagers' rural life becoming fragmented and isolated from the environment. The dissertation takes the case of my grandmother (Lady Xia) and my sister (Lady Wang) as cases, illustrating the connections and differences between this urbanisation from personal life, the village and the environment.

Therefore, the return to the countryside is not only a trend belonging to that generation of new citizens who moved to the city, but in current times it has gradually developed into a popular culture. The mountain villages are still seen as the opposite of the city and have become a nostalgic commodity. As mentioned above, On the one hand, mountain villages are thought to be in need of tourism resources; however, from the perspective of the young villagers, they are still attempting to escape the village's 'closed' identity. The paradox is that, from the inside, the rural flight has led to an unsustainable pattern of life linked to the environment; while from the outside, the desire for nostalgia has led the village to become a highly artificial, private archipelago of the landscape.

2.3 The framework for cooperation: Hybrid network in co-environ life

The trend of returning to the countryside not only explains the reasons behind rural flight and isolation, but also highlights the rural-urban continuum in long-term evolution. The long-term awareness of the small personal farm model, which has gone beyond the ancient need for self-sufficient survival, has become a cultural symbol of a longterm development that includes nostalgia and the development of selfidentities. One valid evidence of this is that gardens in Xiao Qu are often used as shared allotments for different residents, and some fixed locations become marketplaces with specific times. Such patterns of integration in the early years of the mass movement of rural residents into the city created a close association based on the new community and the original village. The self-designed life, while leading the current rural urbanisation towards a disconnection from the environment. However, as revealed in the village's policy protection,¹⁰ in the farmers' long-term localisation, and most crucially in the long-term cultural symbols projected by these villages, the self-designed life still has significant possibilities, not only for small-scale farming life, but also for the self-designed urbanisation.

36

FIG 2. 10-13

FIG 2. 16

This photograph was taken in the 1990s and shows my uncle and father. The new fashionable clothing shows a generation of young people of the time who were gradually changing their thinking about traditional peasant life.

This photograph, taken in the early 21 st century, shows my brother as a child. It is incredible that the village is still in a state of extremely slow development as it was almost 20 years ago. The road to his left can be seen as still a dilapidated dirt road. The dichotomy between the countryside and the city has made this generation of young people want to leave the area even earlier.

A persistent issue spanning three eras - the village is no longer an attractive place to live, but rather a place that locks them.

37

FIG 2. 9 PHOTOGRAPHS OF TWO GENERATIONS

The yard as a farming facility (NO.1 around)

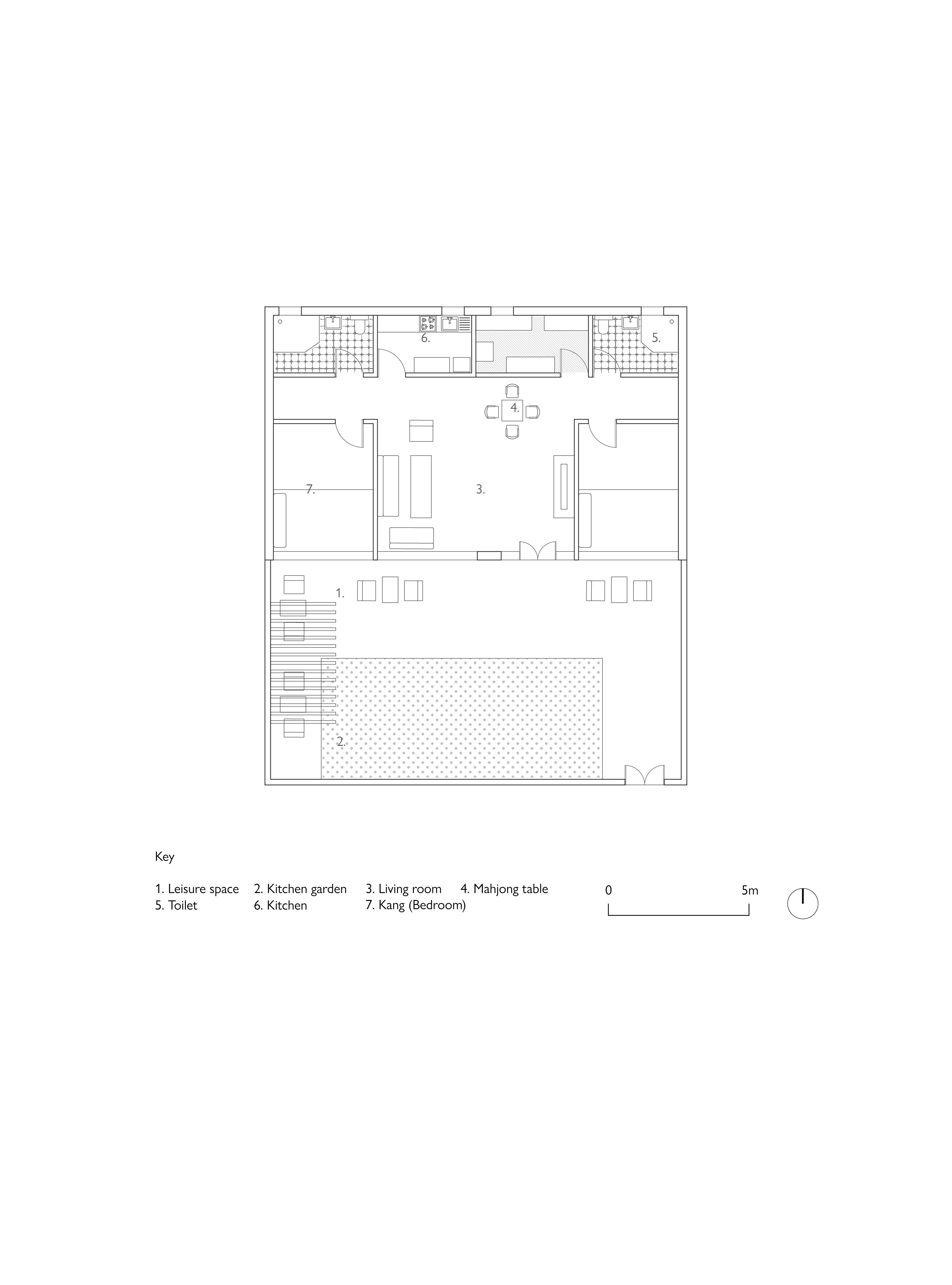

The yard is transformed from the traditional paradigm into an farming facility, starting with a kitchen garden in the traditional farming courtyard for planting peppers or cabbage for daily meals; it is also transformed into a place for drying grain or for storing harvested corn, depending on the weather and the season.

Connected to the outside farmland (NO.6 around)

The courtyard was gradually connected to the exterior as it was being extended. This kitchen garden was built on a natural terrace which used to be used for growing corn, as was the exterior; it was also used for a simple toilet. Now it is the outside part of the kitchen, as it is just opposite the kitchen, with the sink set beside it, and the planting is more oriented towards growing vegetables that are ready to be cooked immediately.

38

2. 10

FIG

ORIGINAL

FARMING VILLAGER‘S YARD

39

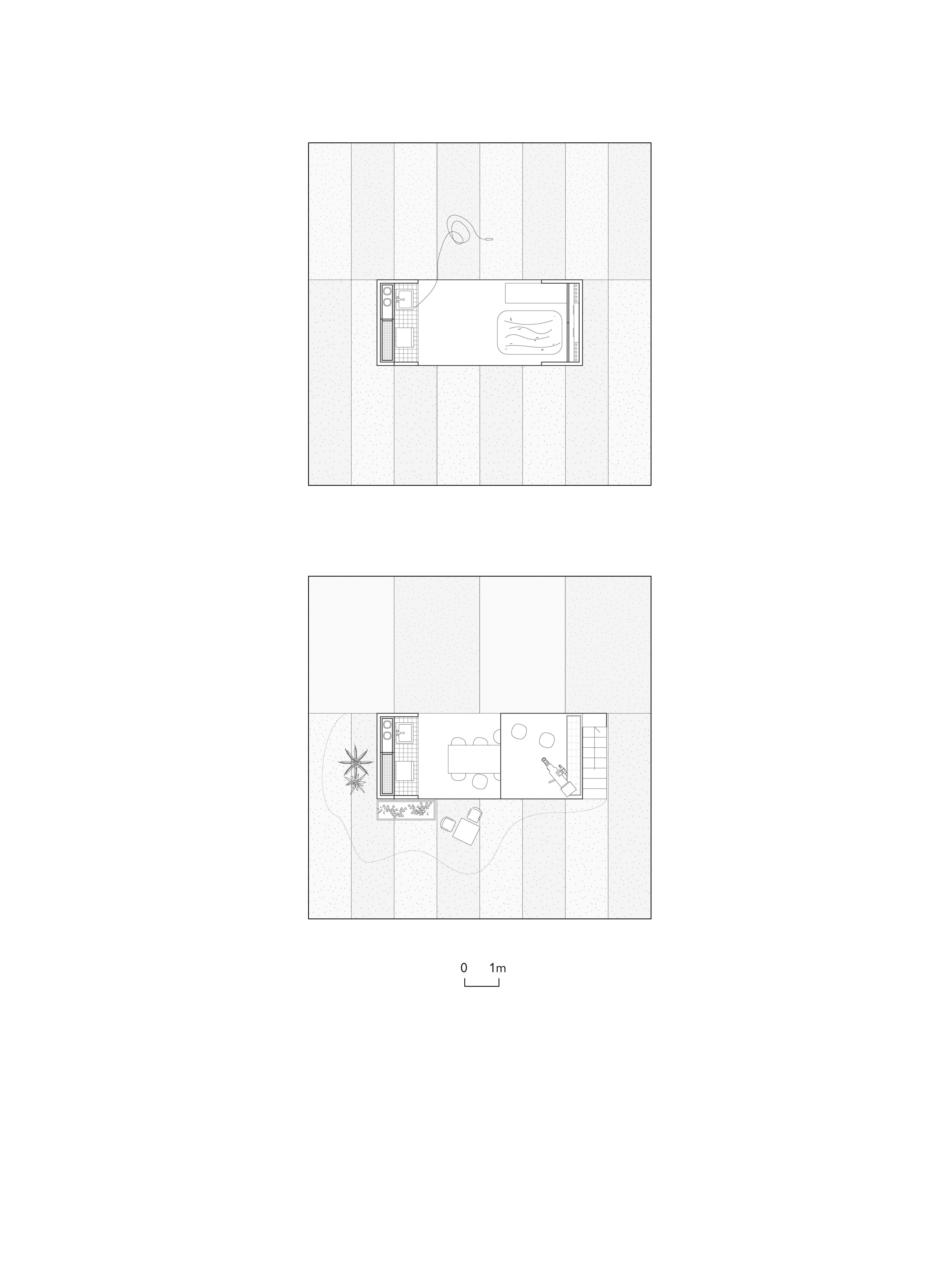

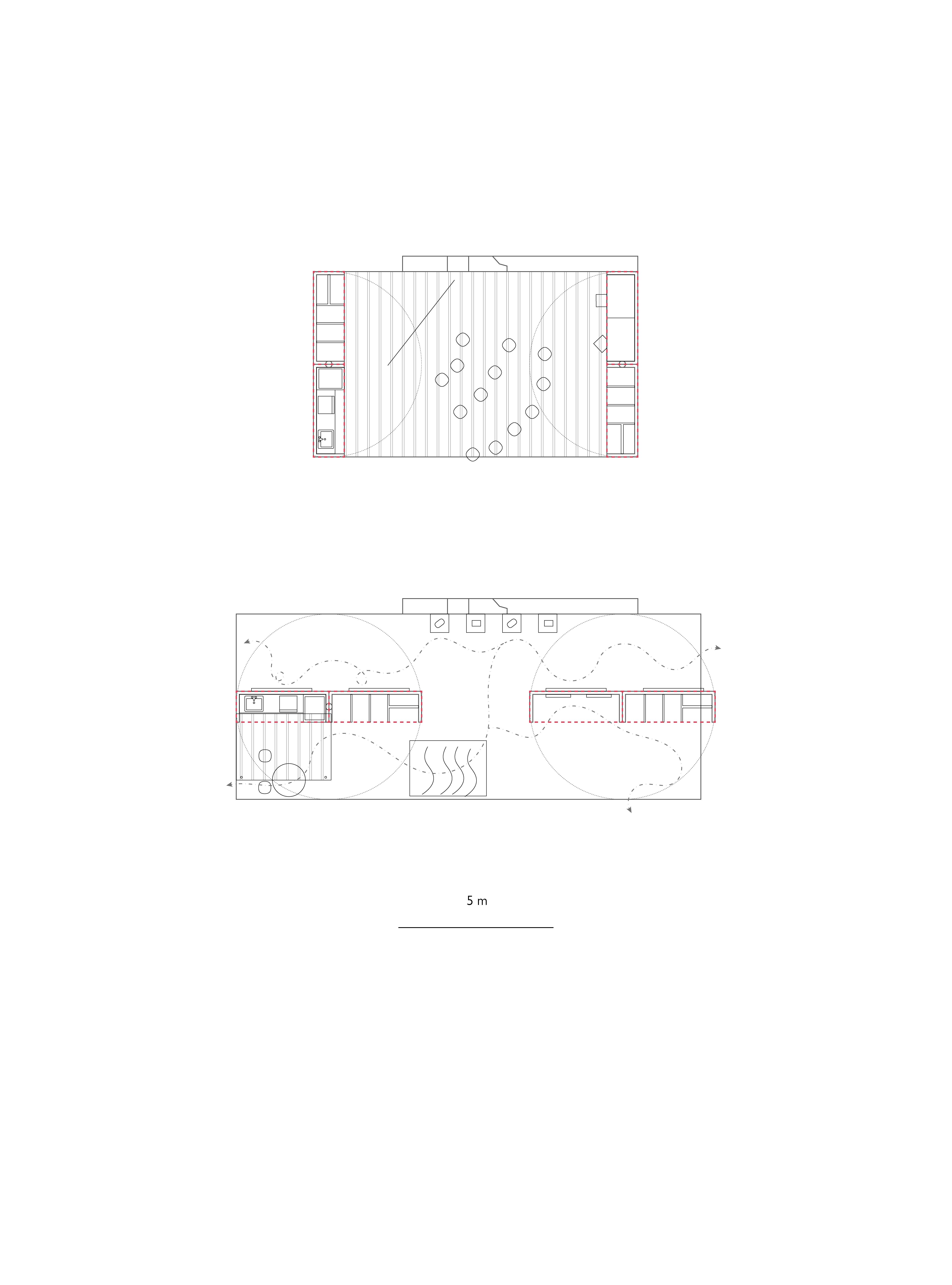

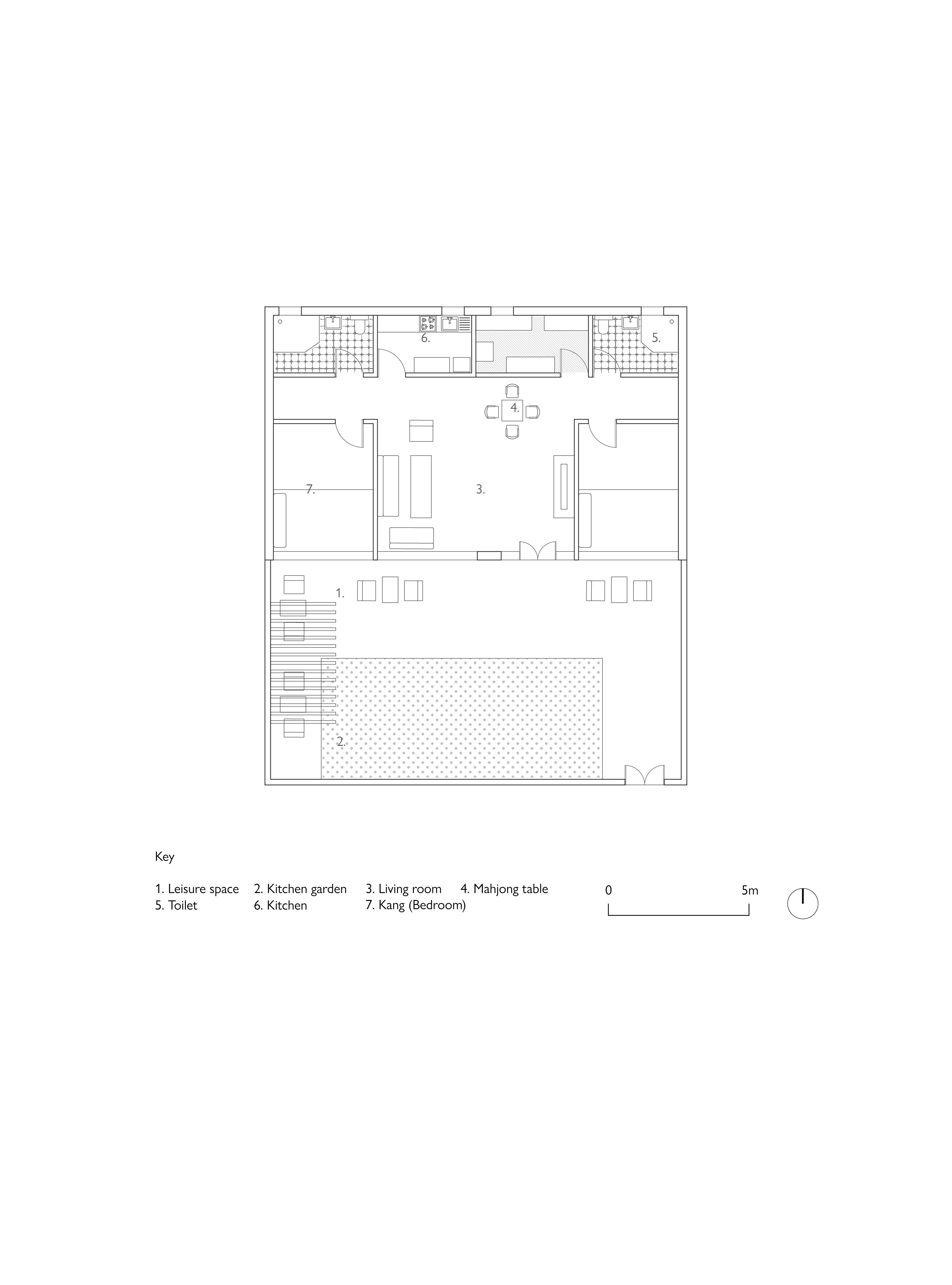

FIG 2. 11 PLAN OF THE FARMING VILLAGER‘S YARD

The yard for leisure

My sister's new courtyard built in 2018, is mainly used as a place for her to stay when she returns for the holidays, and her yard is placed with plenty of outdoor furniture that can enjoy the sun, like a shed and a picnic table. During the week, my aunt helps out with the yard and grow some vegetables as well. The yard is not divided into different areas by different self-built devices, like the farming courtyards in the past.

The living room

The interior design of the room makes reference to the layout of modern city life, as seen in this living room's tiles and sofas, which are typically unsuitable for a farming style of living. However, in the new courtyard construction options that are popular among villagers, this urban-inspired design is gaining popularity.

40 FIG

2.

12 HOLIDAY VILLAGER‘S YARD AND HOUSE

41

FIG 2. 13 PLAN OF THE HOLIDAY VILLAGER‘S COURTYARD

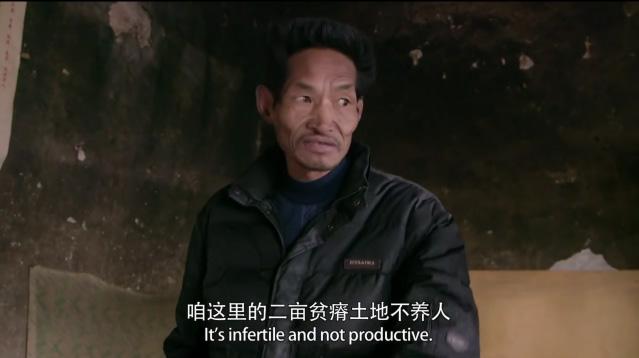

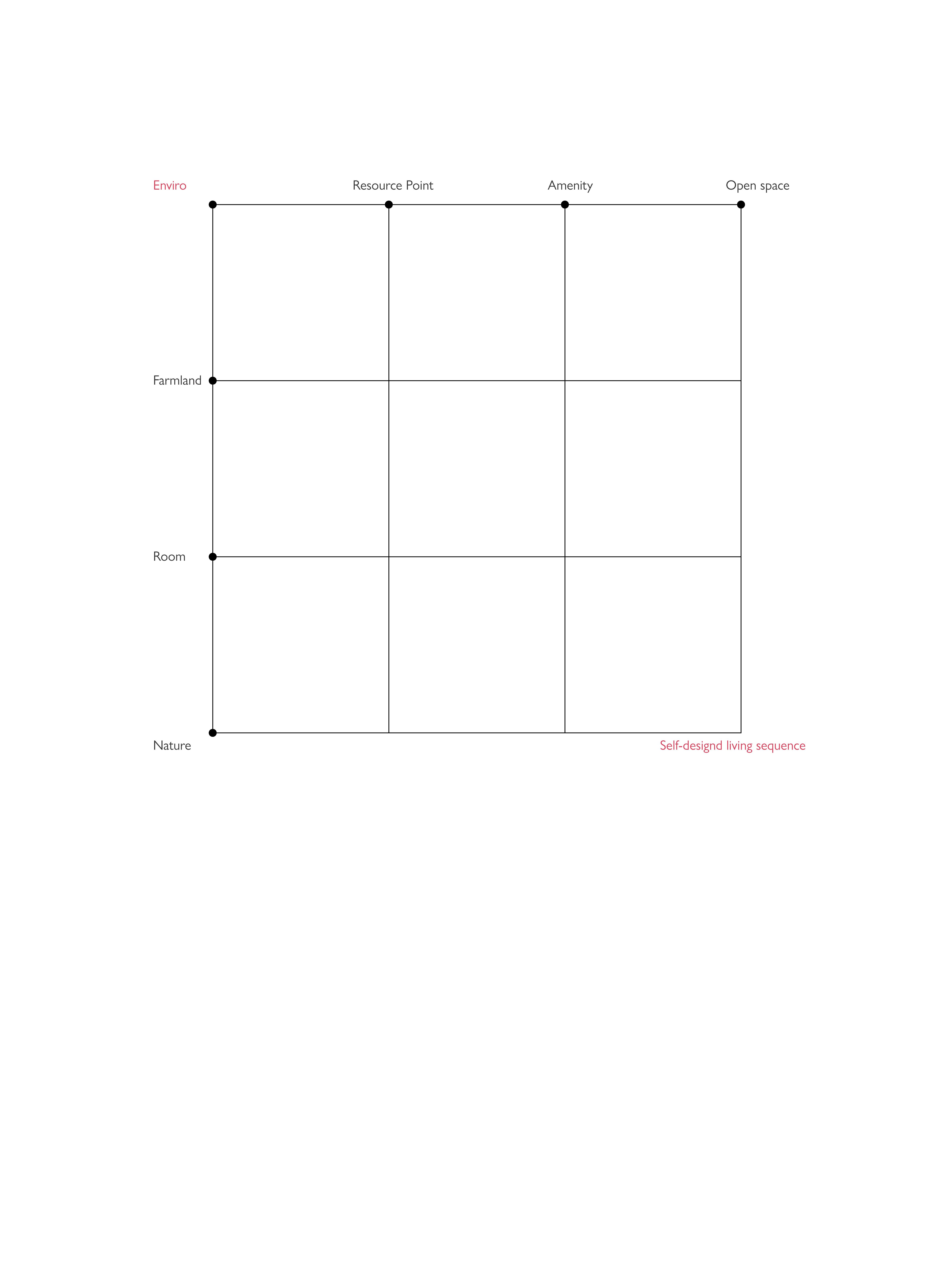

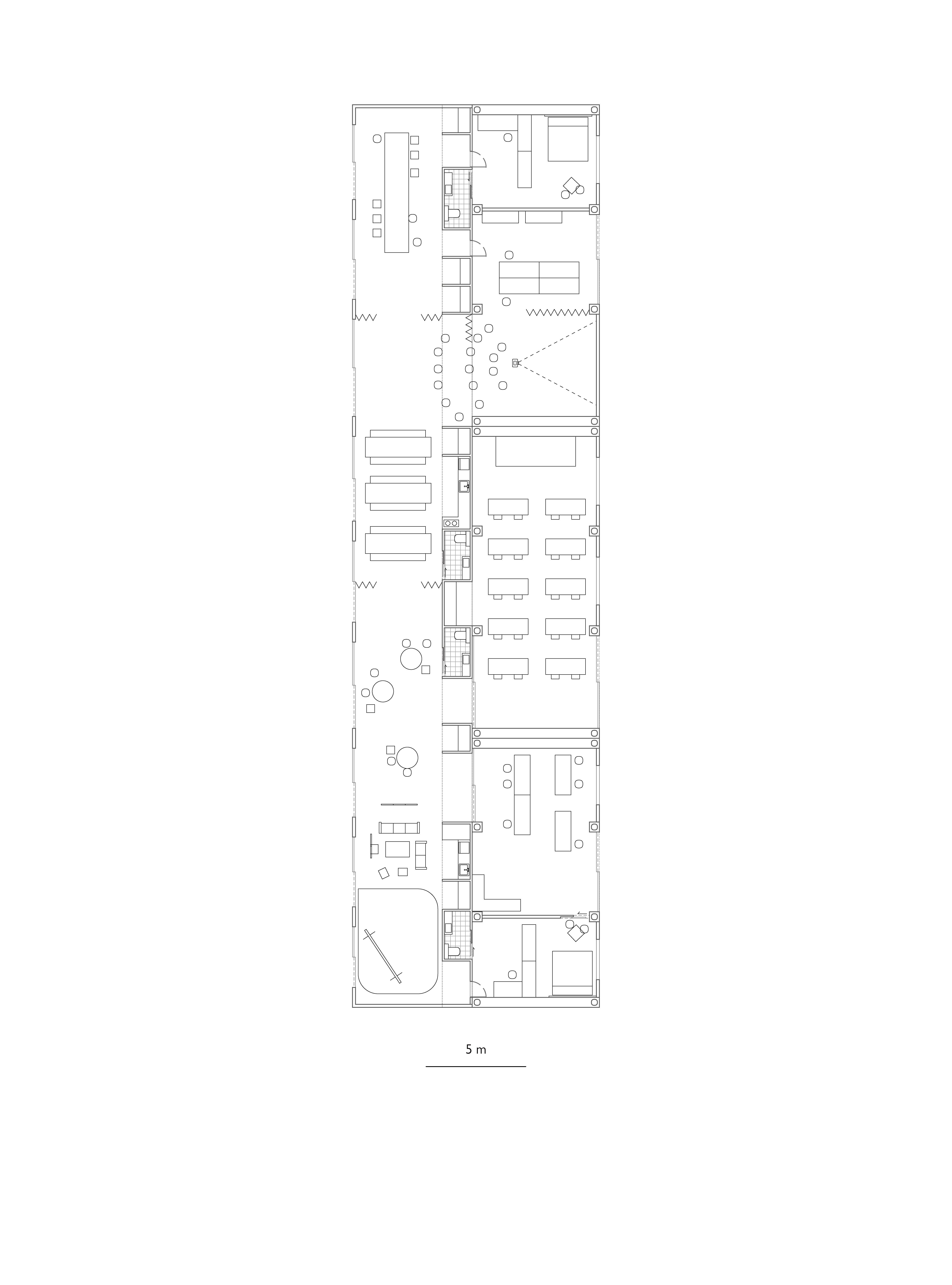

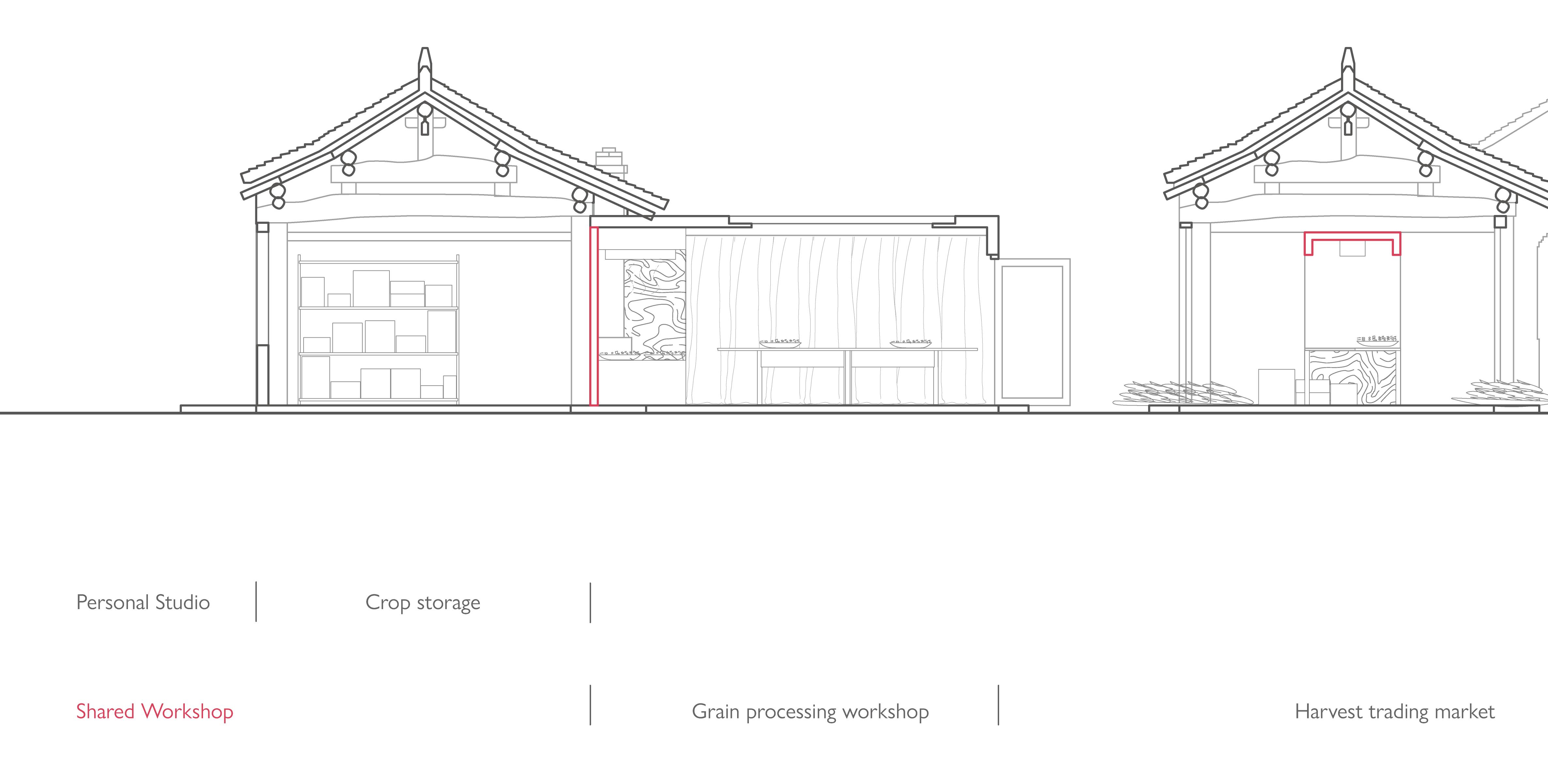

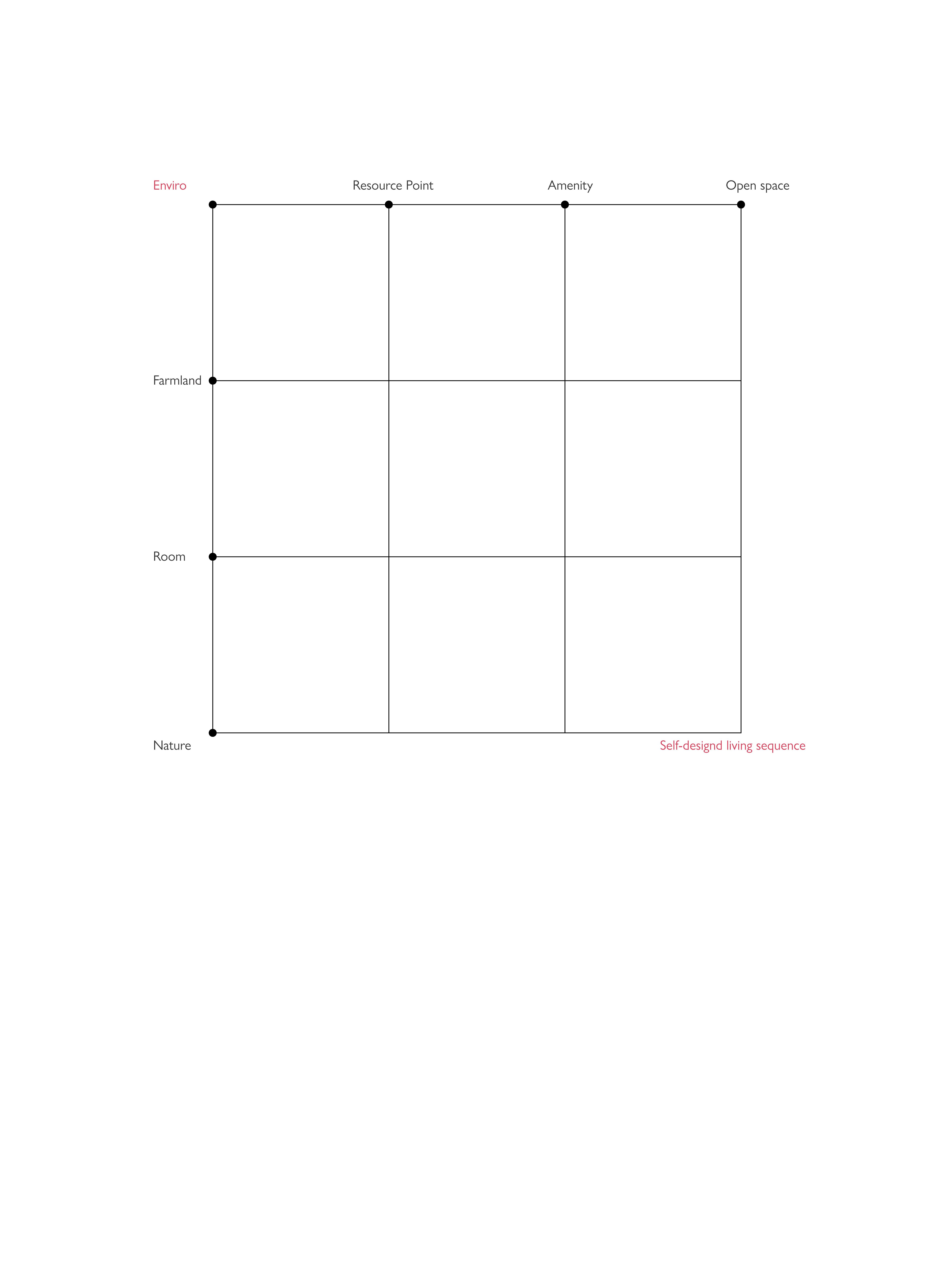

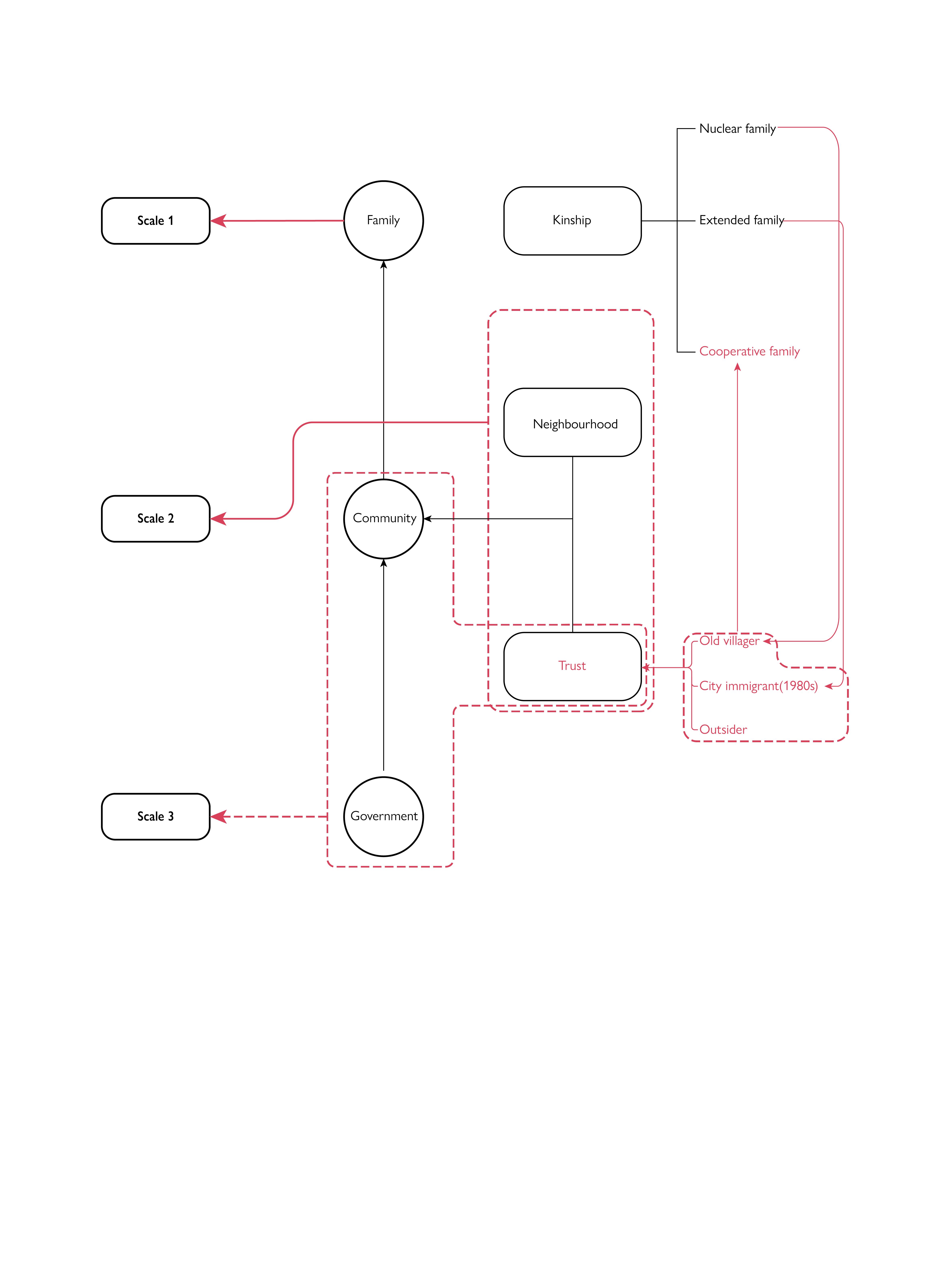

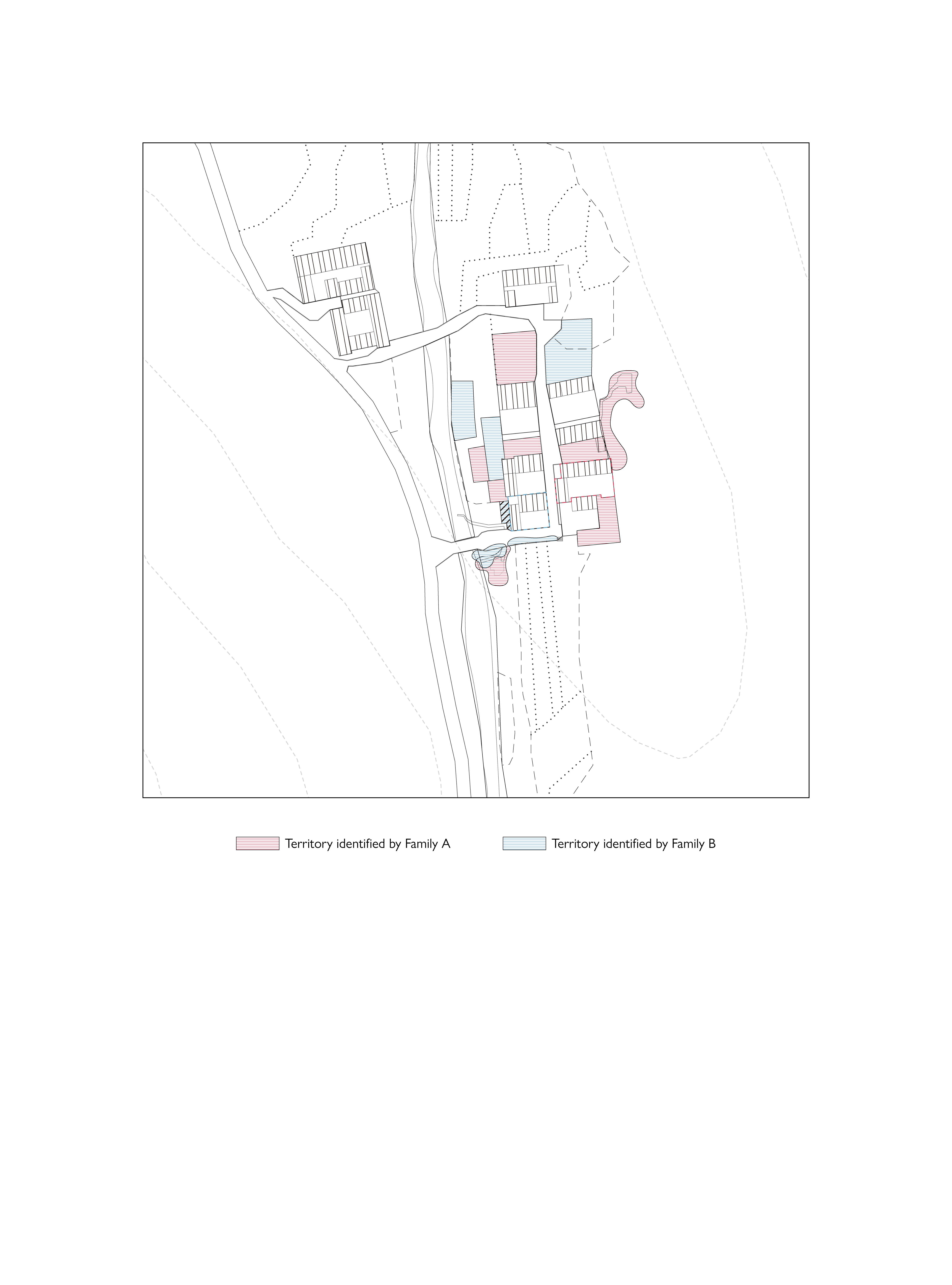

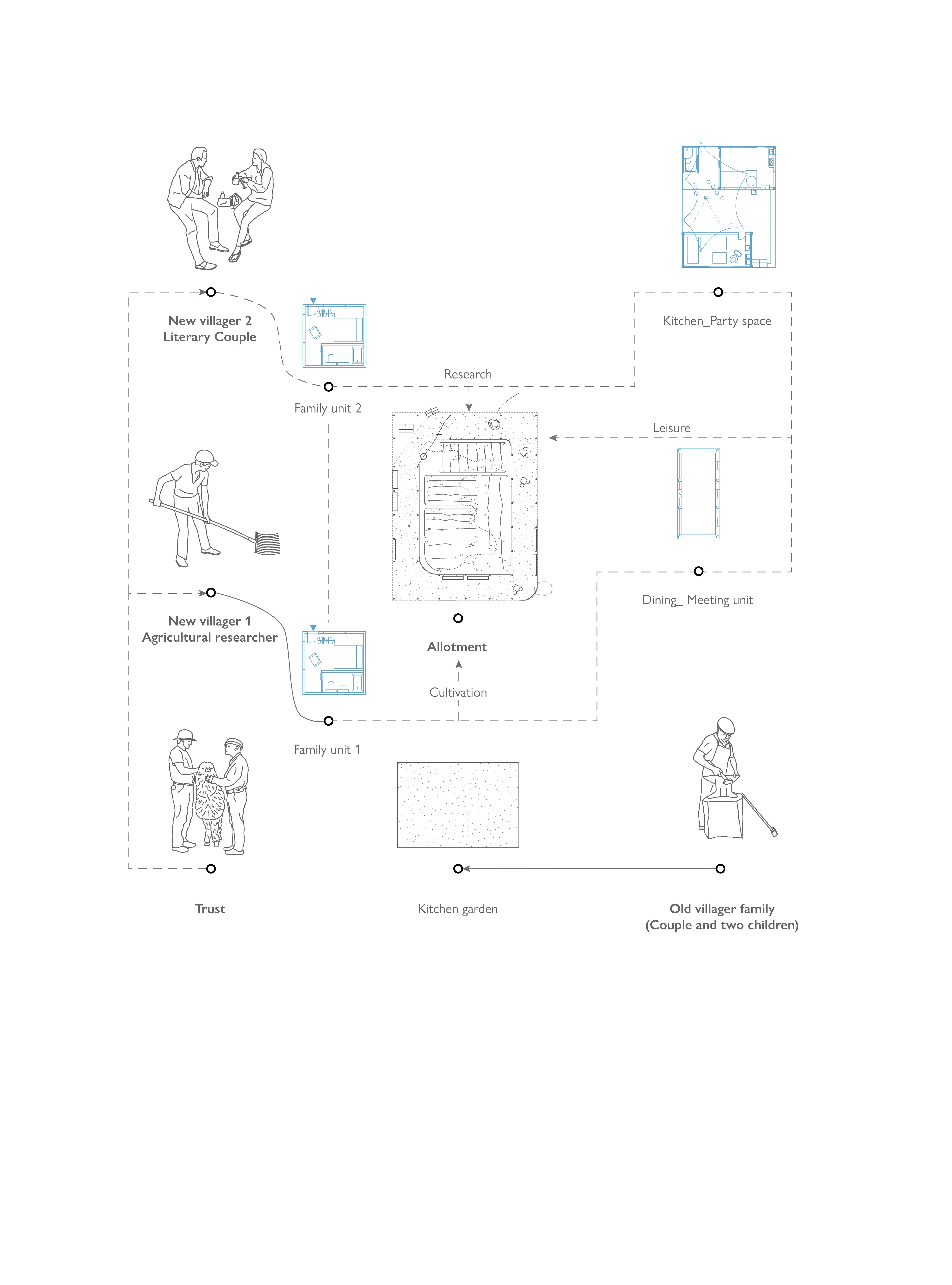

Therefore, the dissertation's central argument is that the mountain village is a hybrid network, with the environment as the medium, the village is highly connected to natural entities from personal to multiscale group cooperation, connected through 'daily rituals', resulting in a series of flowing. Starting from traditional farming, this environmentmediated generation of a cooperative life (co-environ) allows the autonomy of the villagers to form a multi-layered connection based on different personal sites. Due to the long-term entanglement and overlay of these environmental elements, the self-designed life is created from negotiation with various groups, mutual learning, and forming communities. This village quality offers a possibility for a future new urbanisation of self-design that redefines the legalised landscape framework. For local villagers, the long-standing identification of farmland, streams and self-built structures, has often led to the breaking of policy boundaries of land and creating a number of shared ambiguous areas. This sharing, is also used in the new integration of the villagers, which differs from the privatisation of land and resources, but goes beyond property ownership to redefine the boundaries to generate cooperation, so as to create a hybrid of traditional modes of connection.

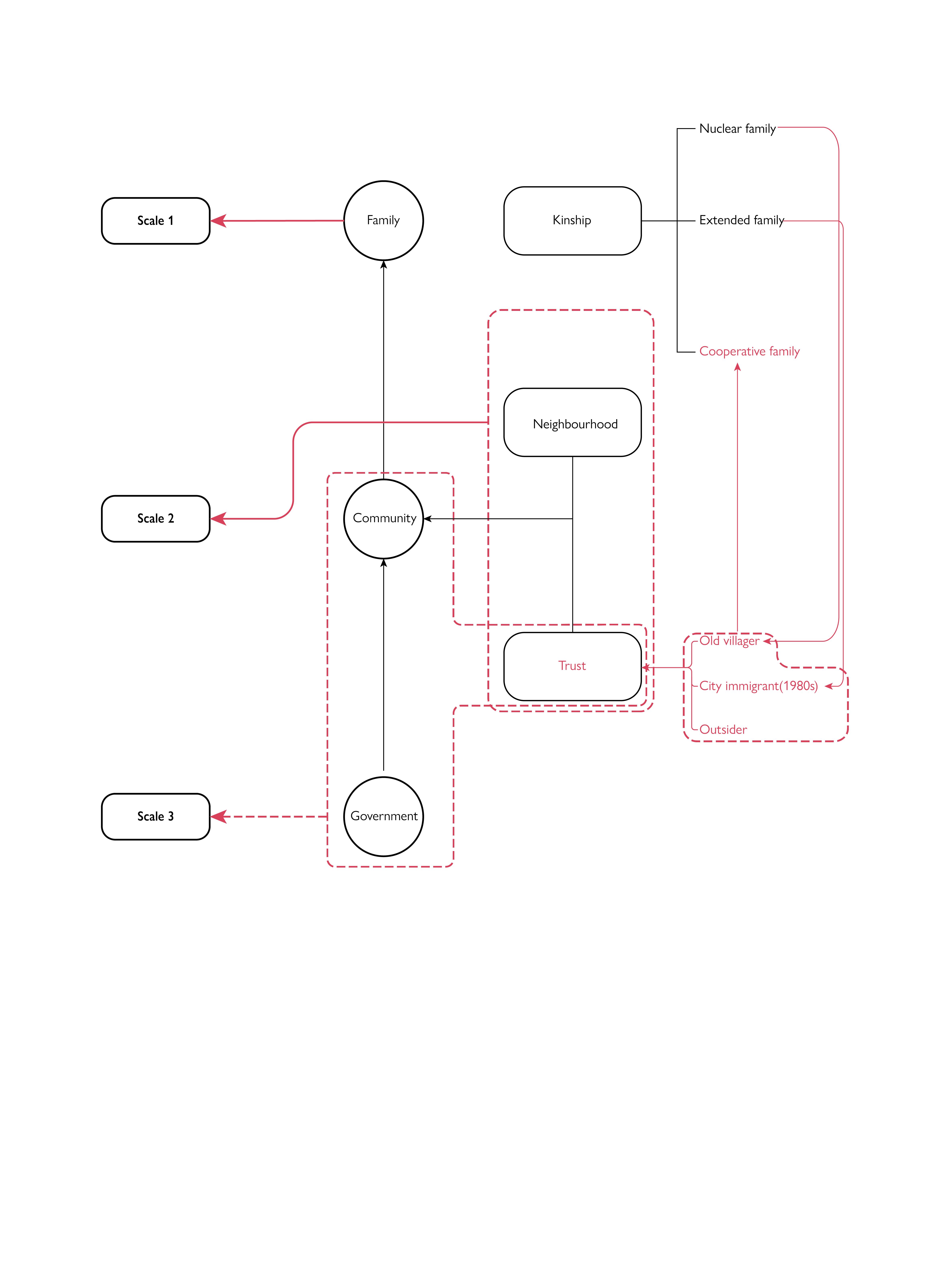

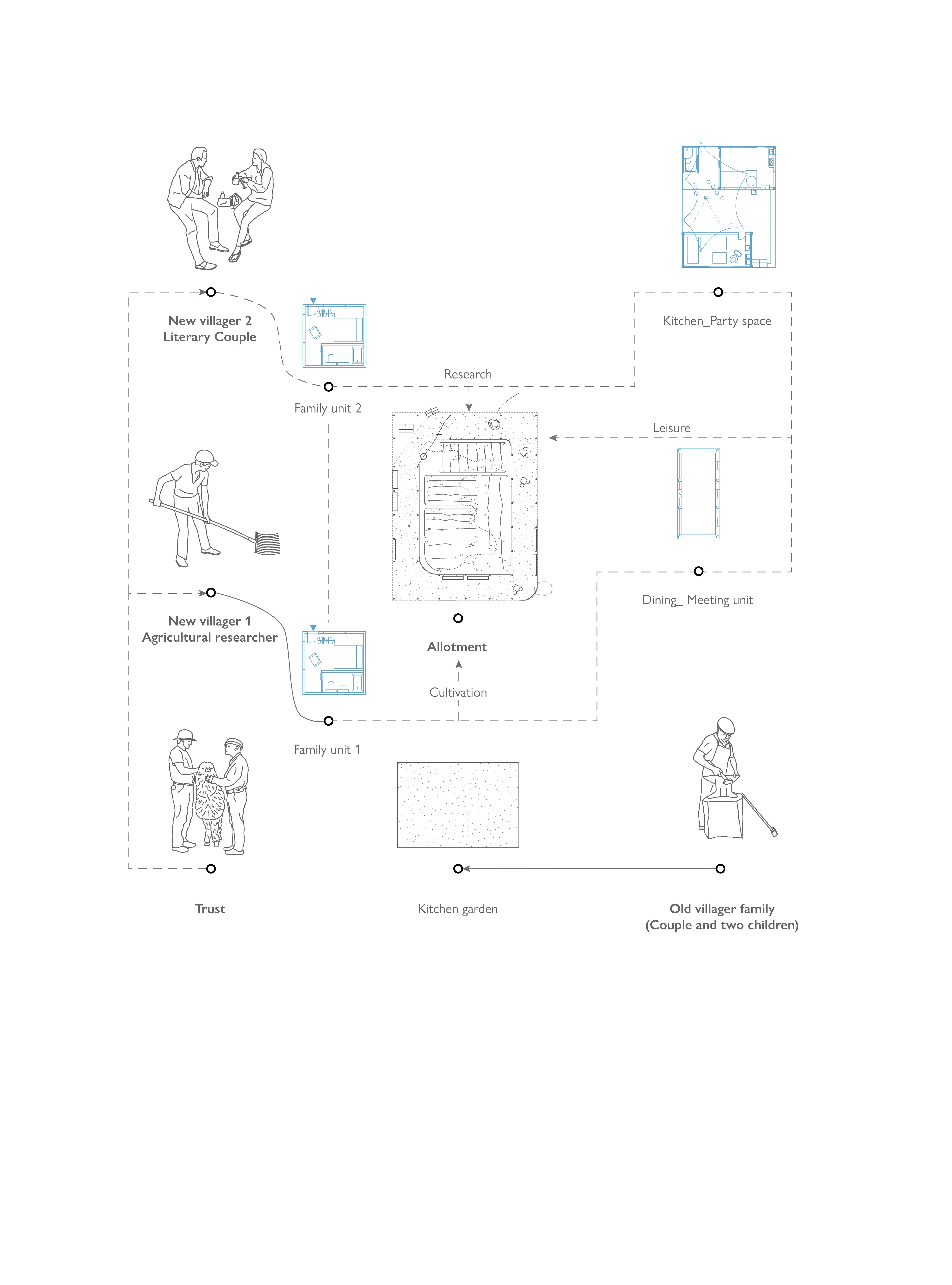

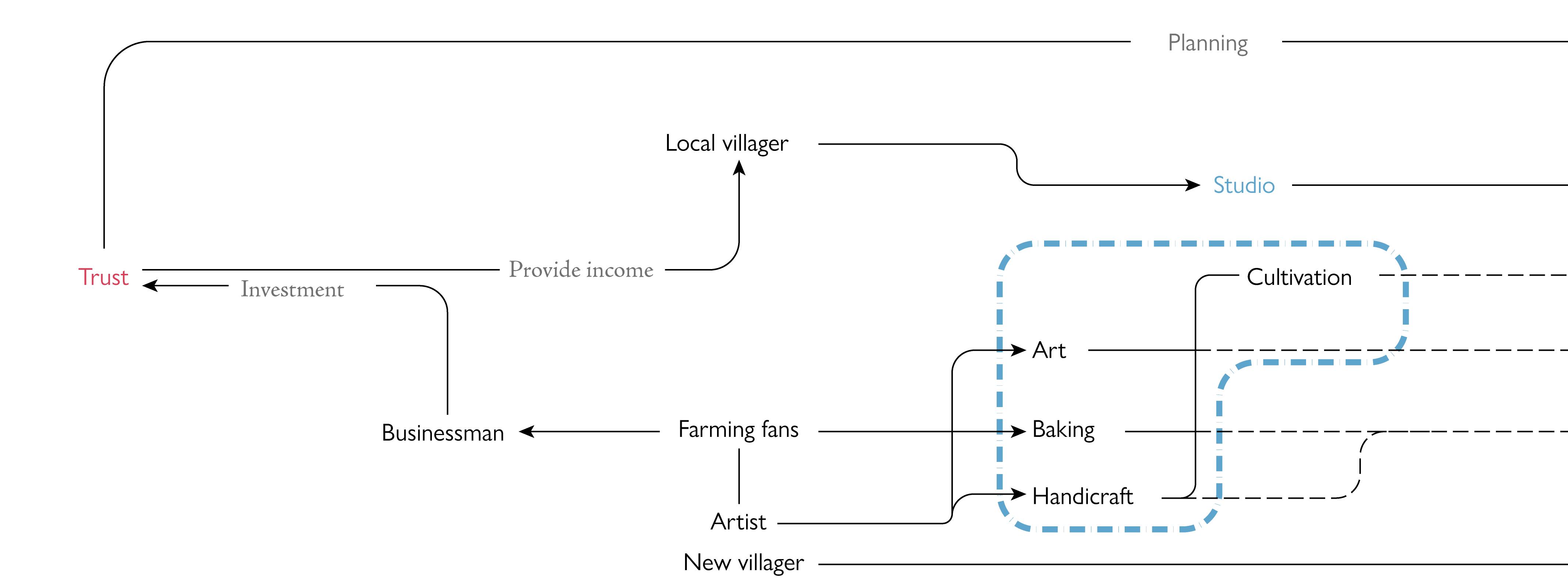

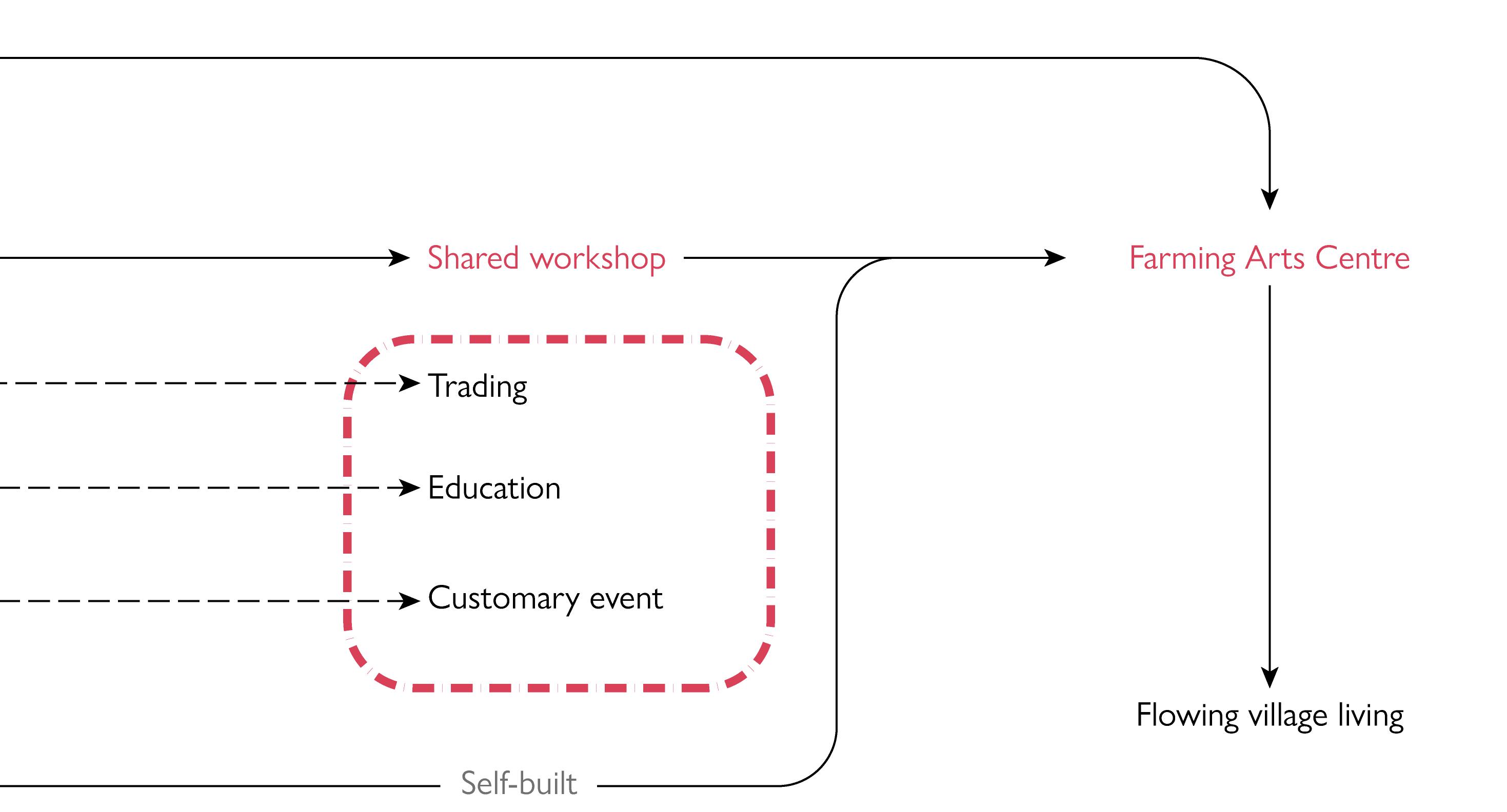

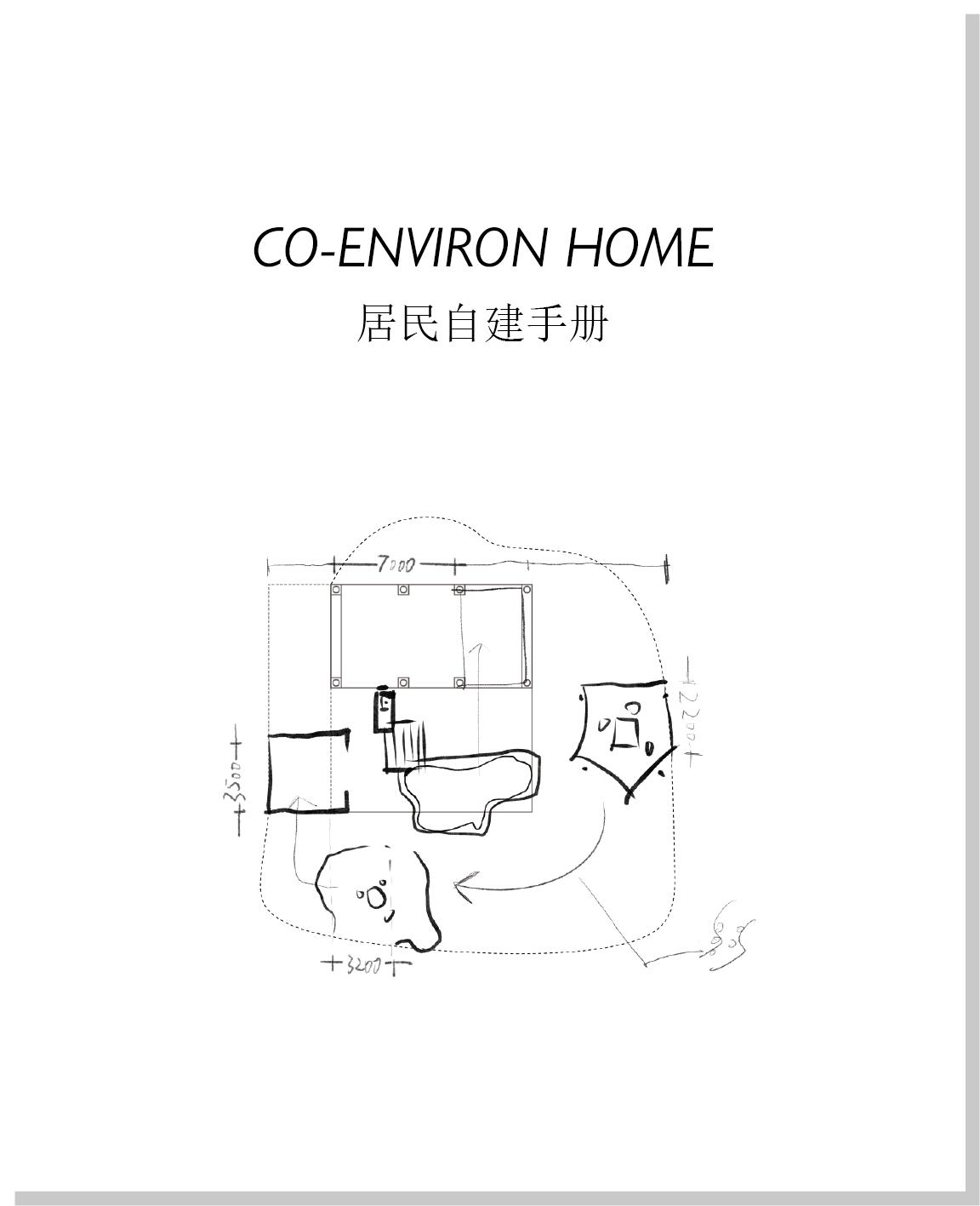

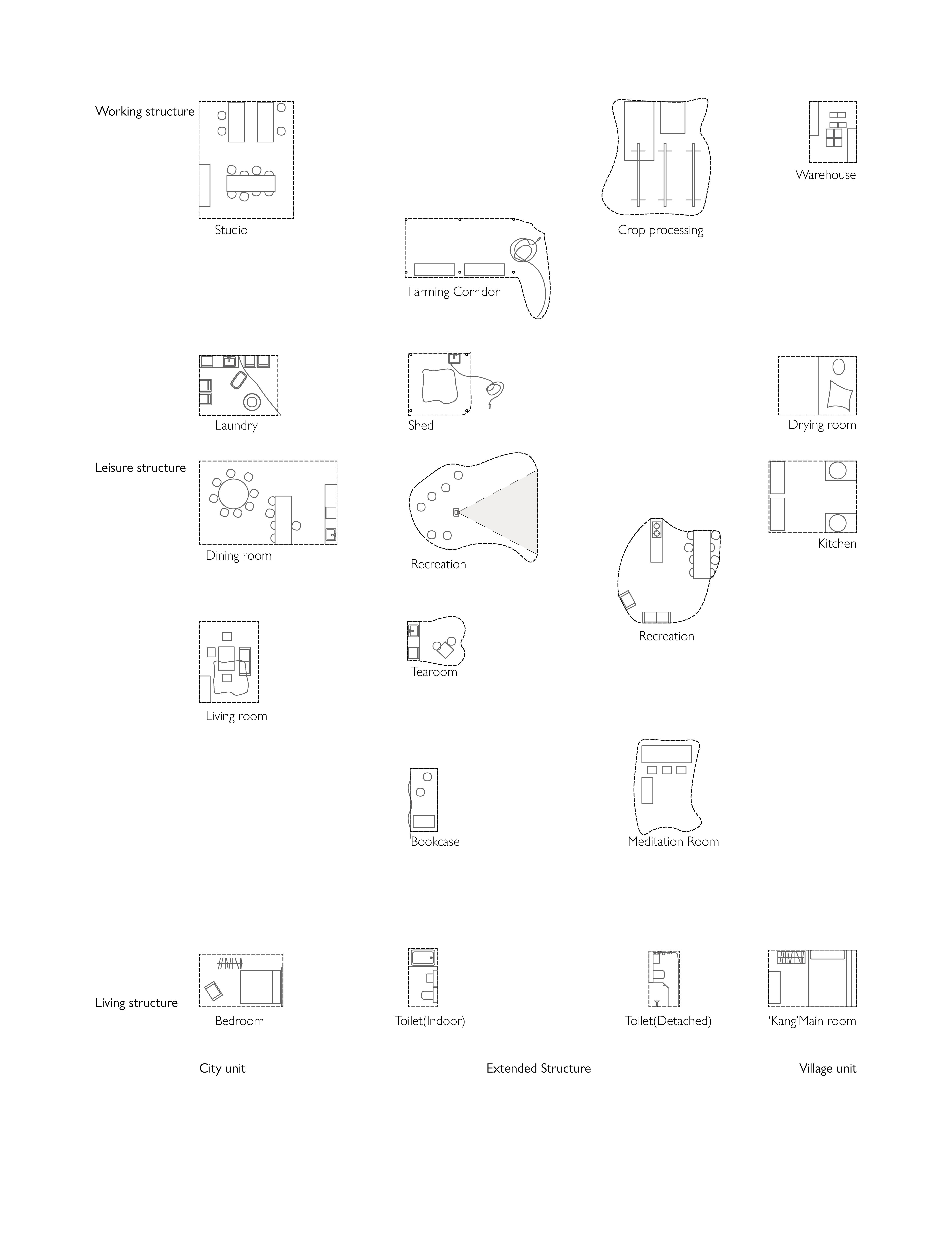

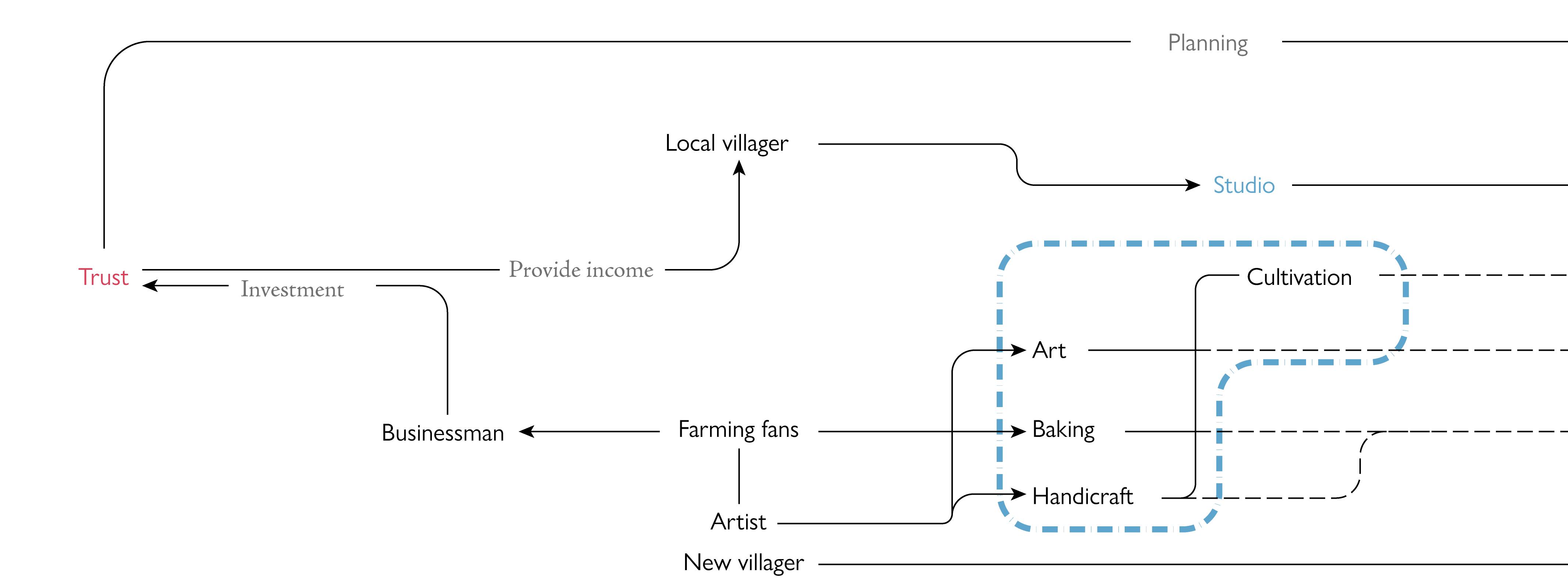

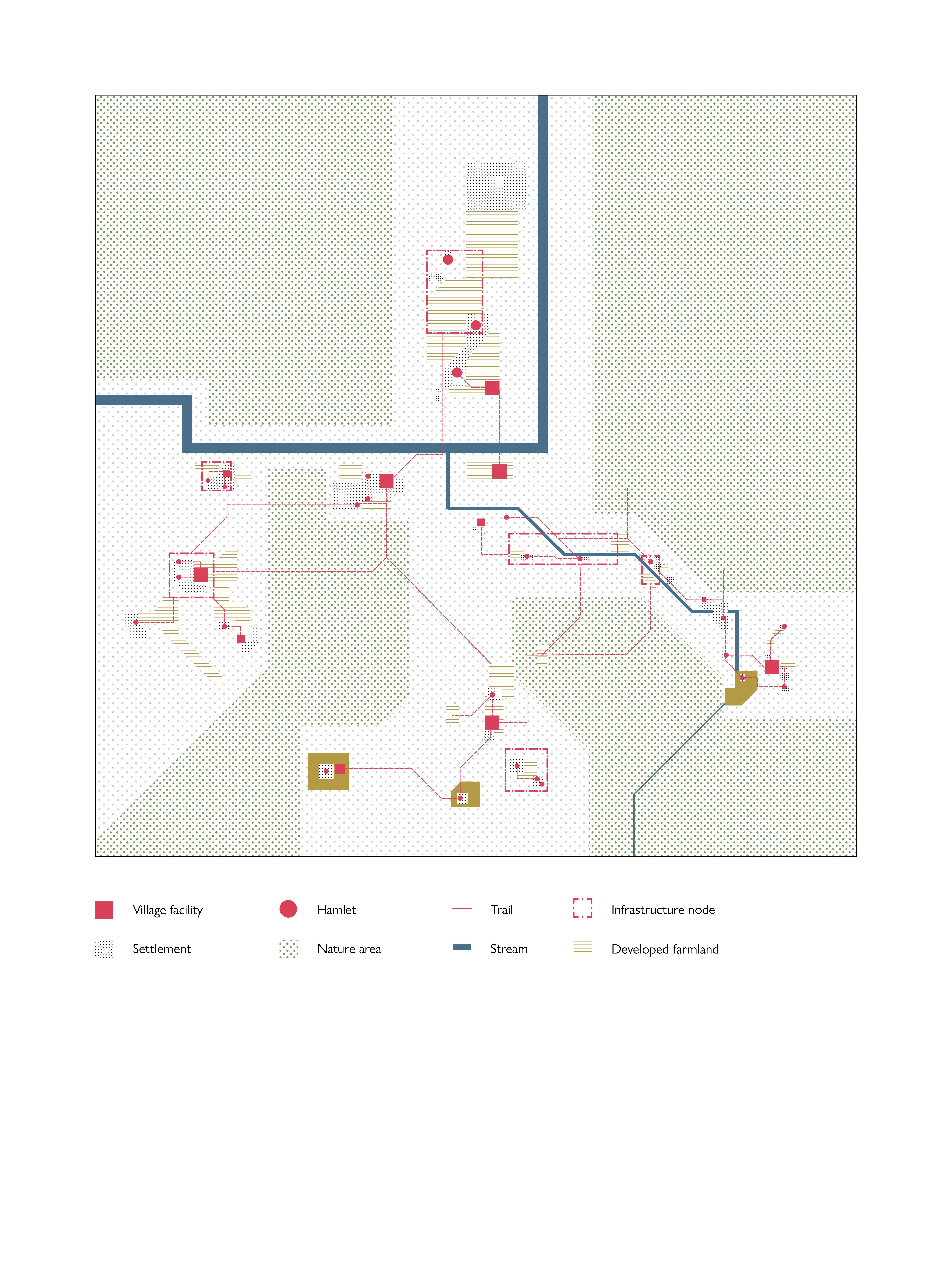

As a result, this new self-designed living becomes a contemporary design of the metropolis, not to restore the self-sufficiency of the rural life, but to offer a new possibility for the rural to become an alternative development to the urban community. To further discuss the cooperation mechanisms in this co-environ living mode, the dissertation divides it into three scales: the family, the neighbourhood and the region. A trust, formed by villagers, is conceptualised to explore new approaches to current ways of identifying the environment, as well as testing cooperative agreements based on an environmental selfdesign between different types of residents, such as people from the city, holiday villagers and local villagers, resulting in contemporary community networks that transcend farming. The project may not ultimately be able to shift the trend towards rural shrinkage, but it aims to re-imagine how the awareness of connection to the environment as a long-lasting 'rural quality' shapes our rural-urban continuum.

42

FIG

2. 14

FIG 2. 15

FIG 2. 16

Dissertation framework: reconnecting environments - settlement, territory, regional multi-level cooperation

43

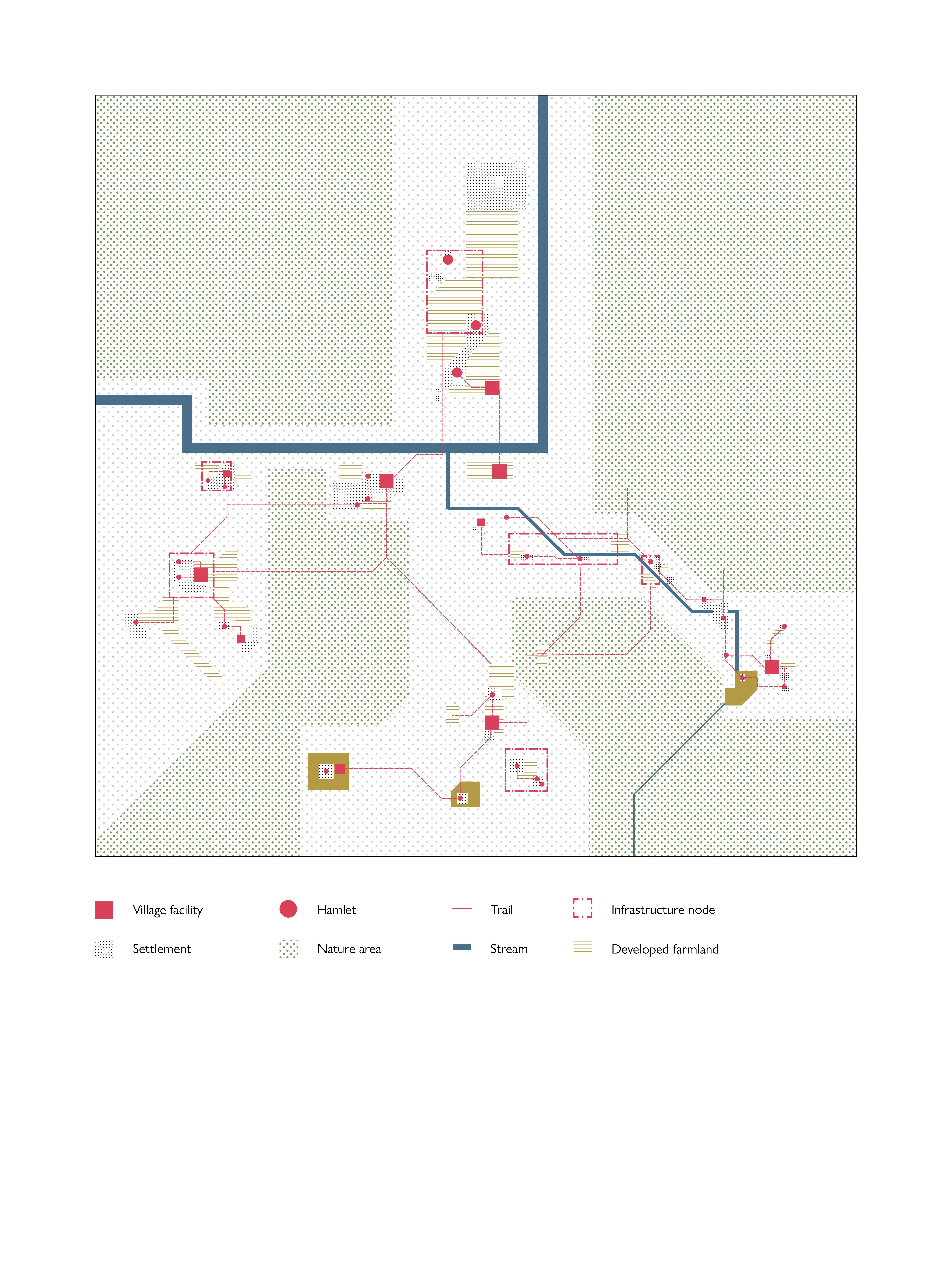

FIG 2. 14 HYBRID NETWORK

The dissertation proposes a new autonomous framework for villagers, where self-build and investment activities are guided by the trust of villagers, rather than by policy.

44

FIG 2. 15 VILLAGE TRUST

Dissertation proposition: Imagine a new type of urban community life, a collective living mediated by the environment, to reconnect these village archipelagos.

45

FIG 2. 16 CO-ENVIRON UNIT AS A NETWORK

46

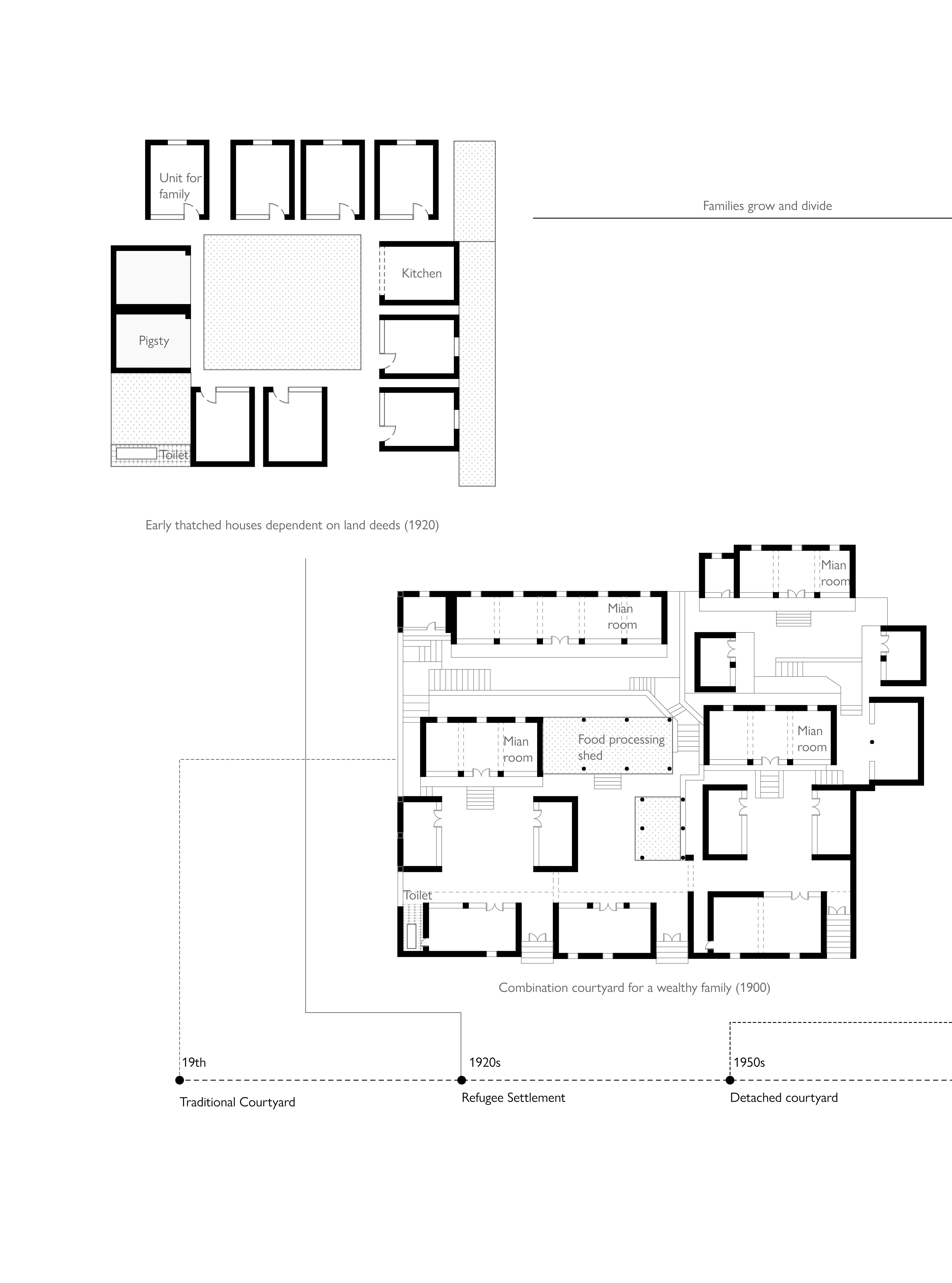

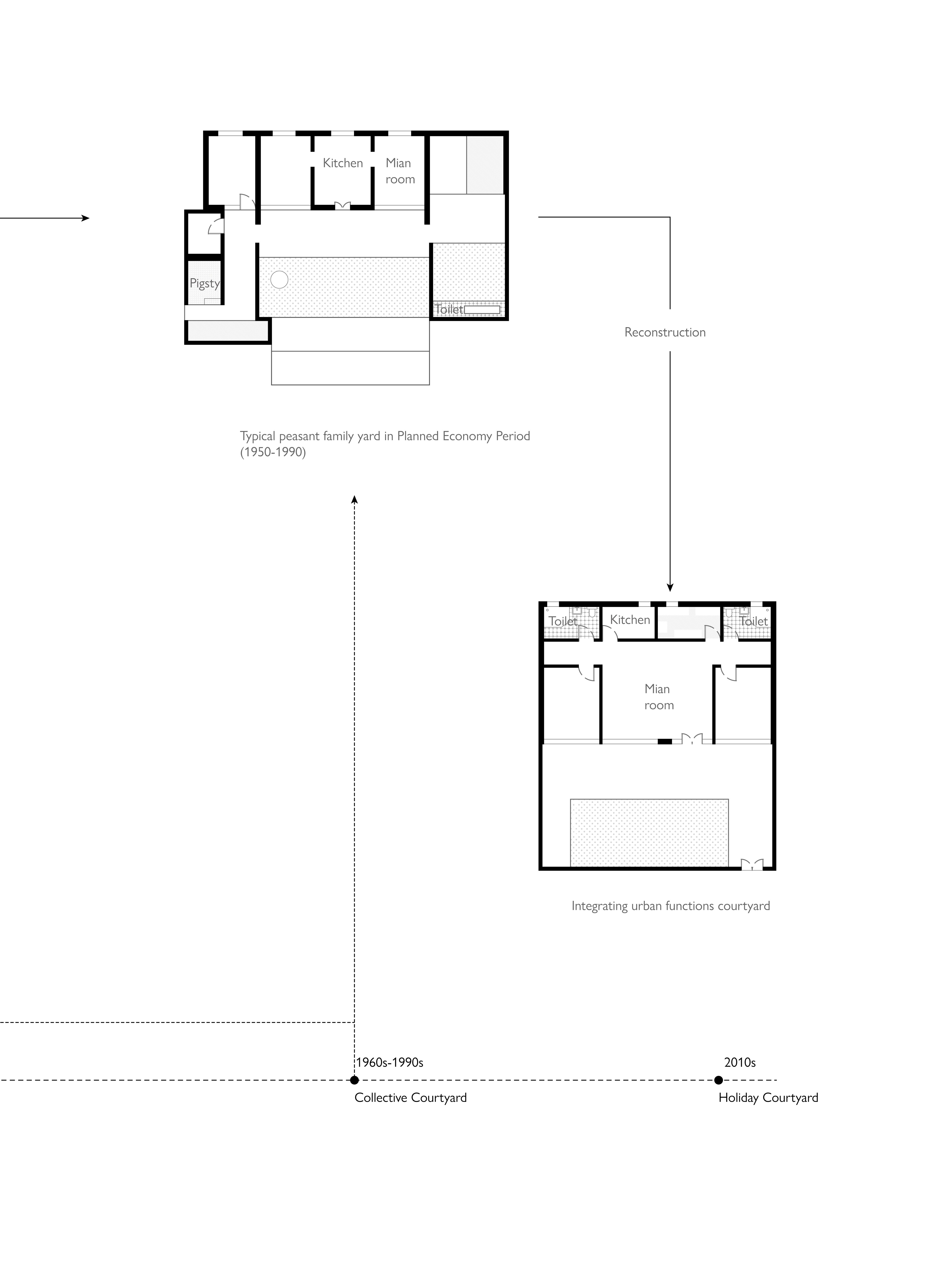

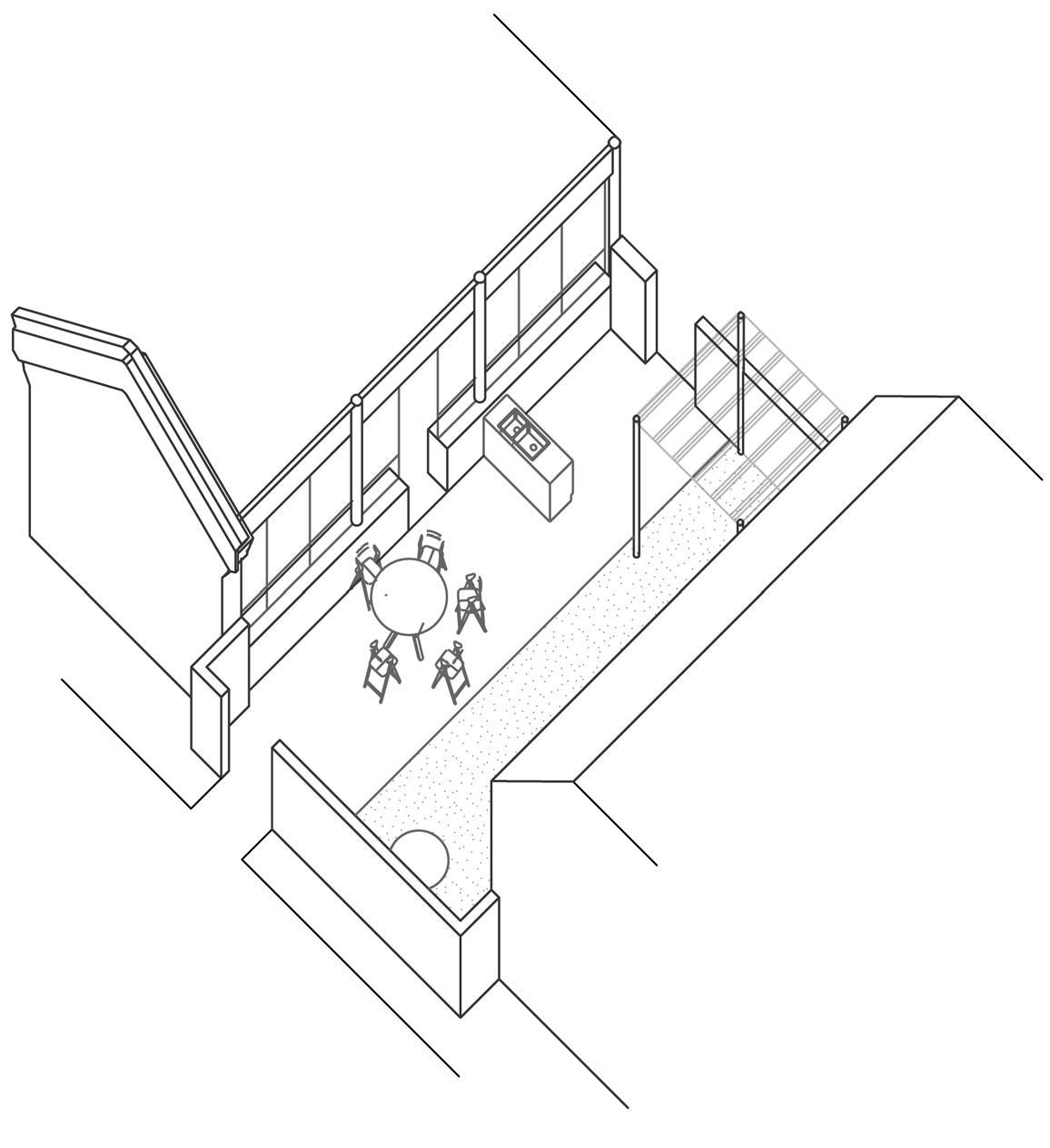

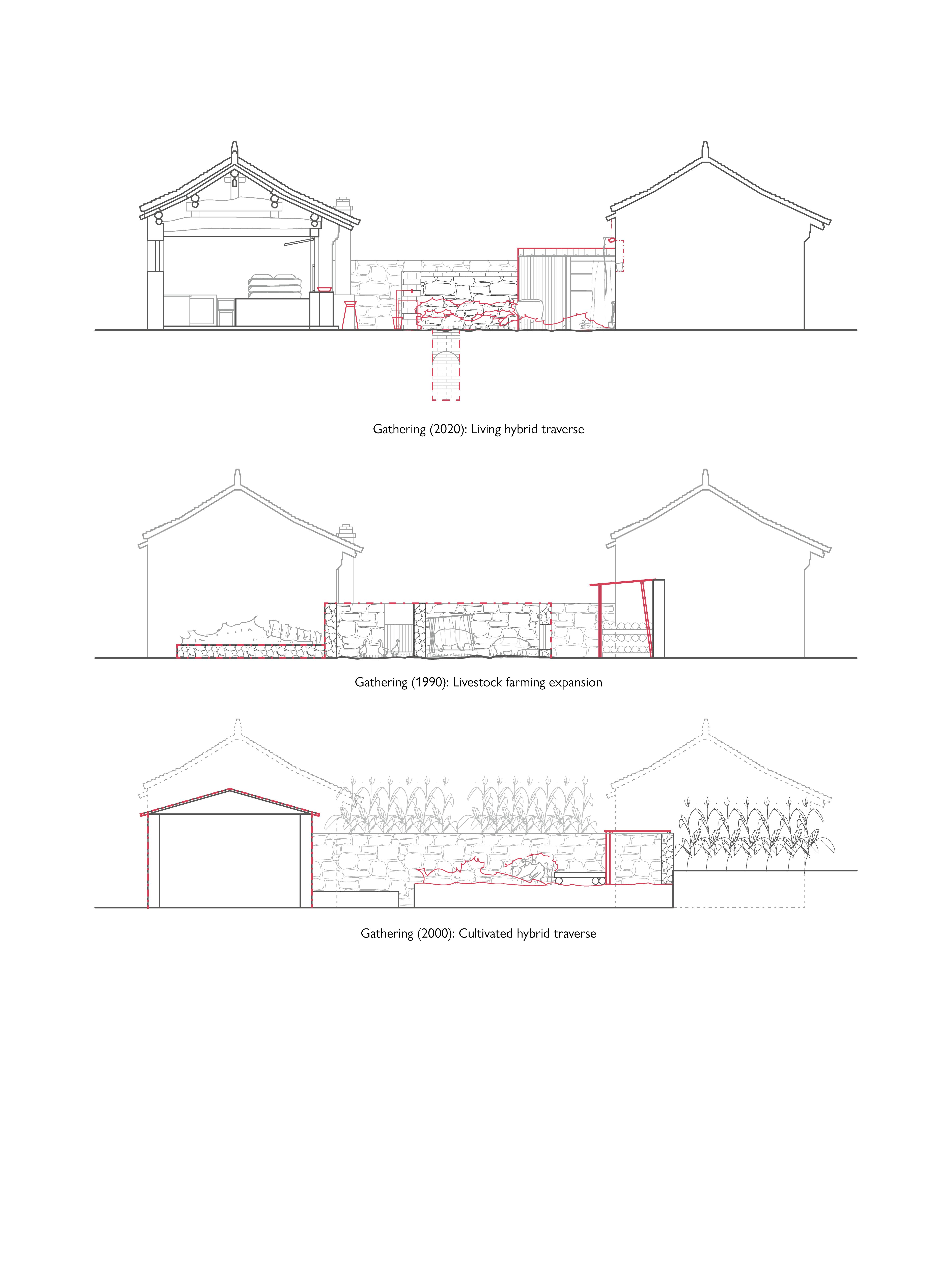

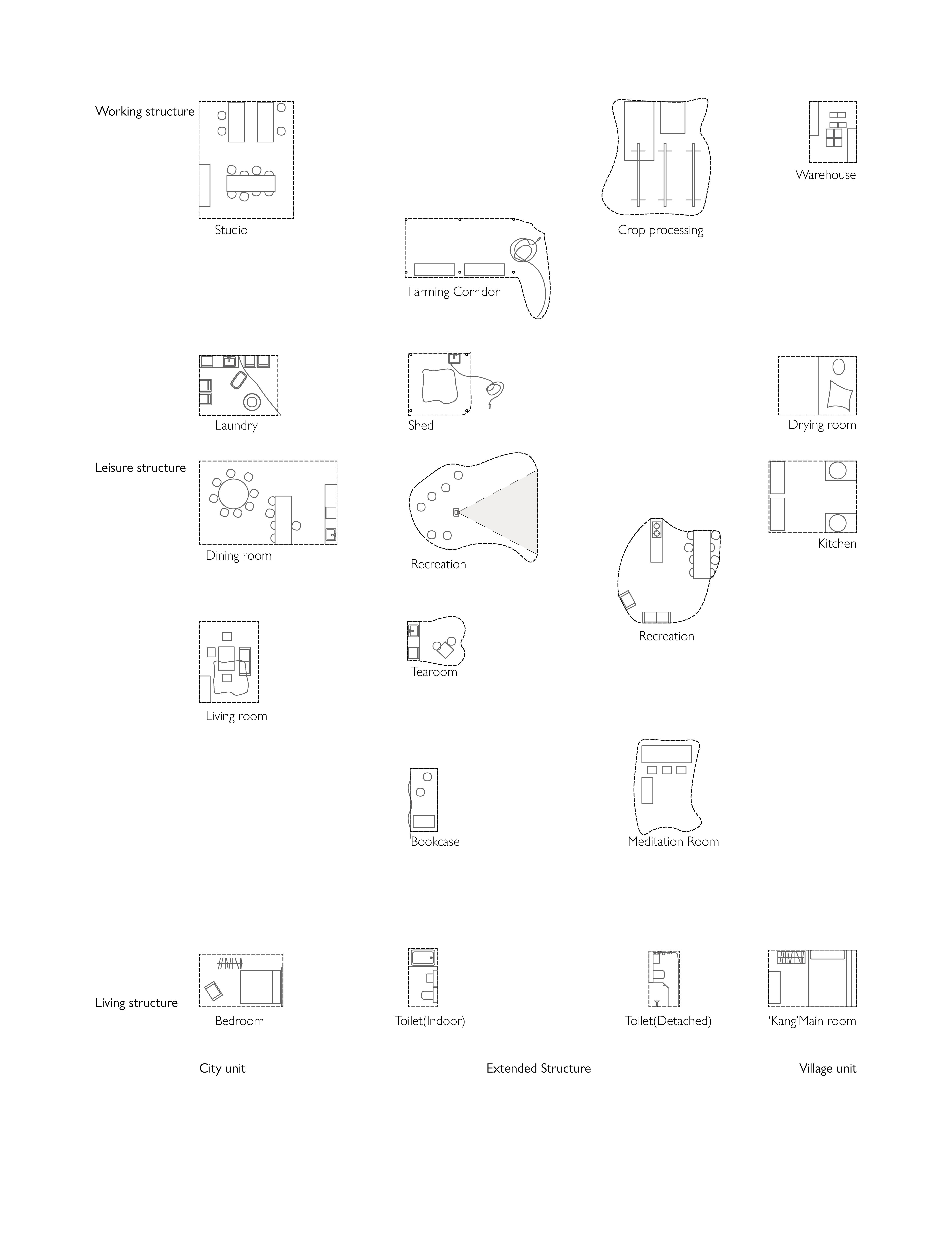

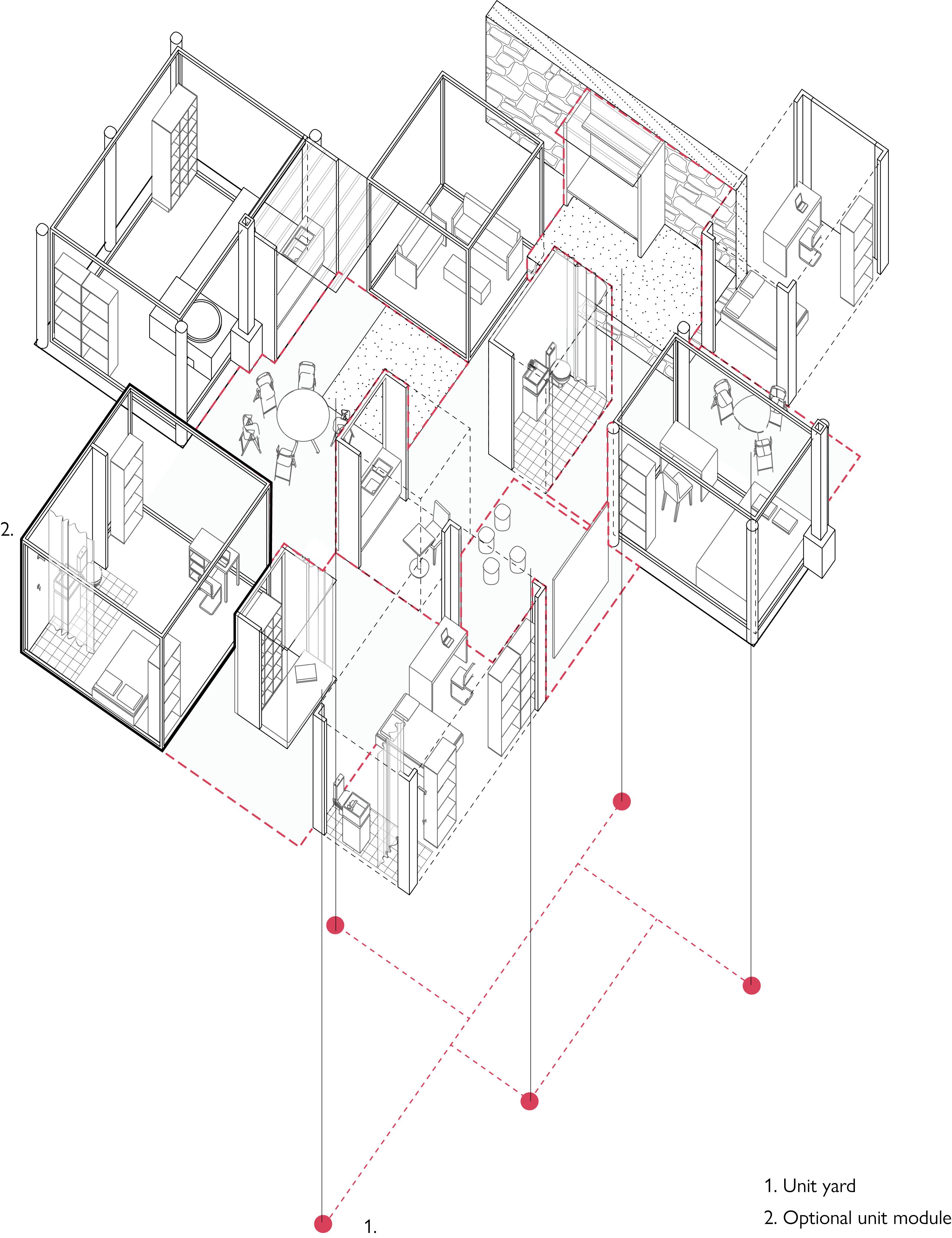

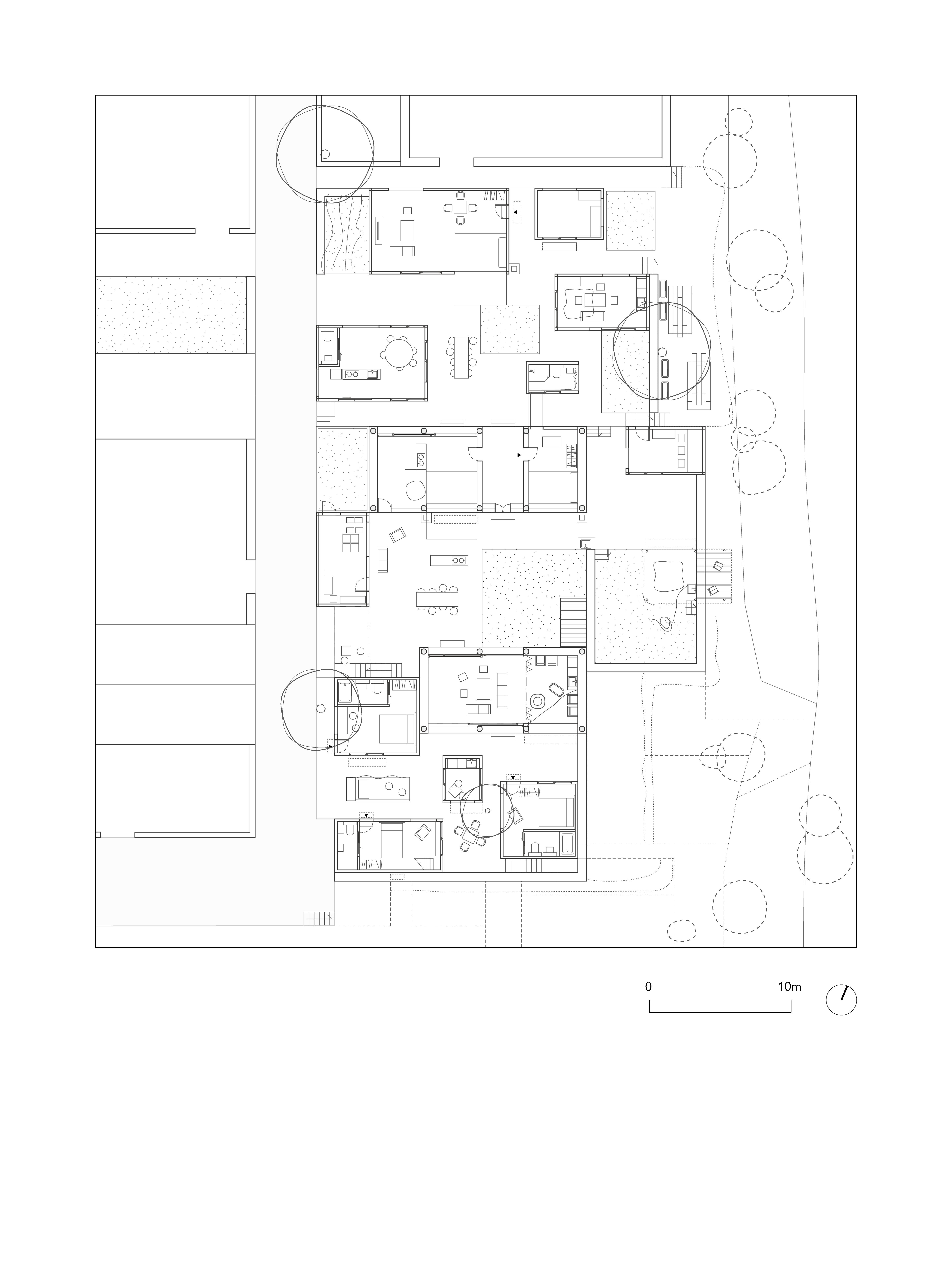

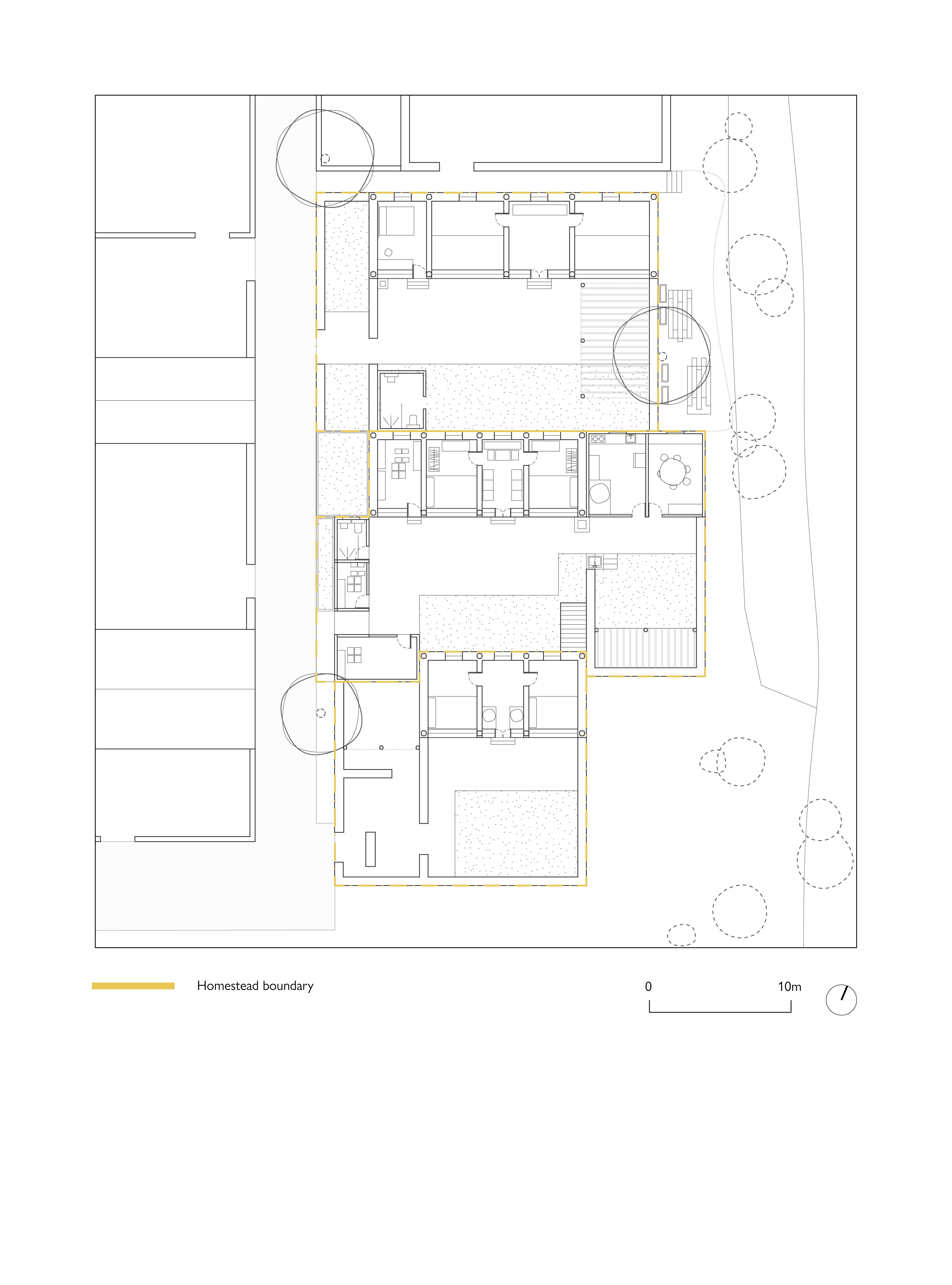

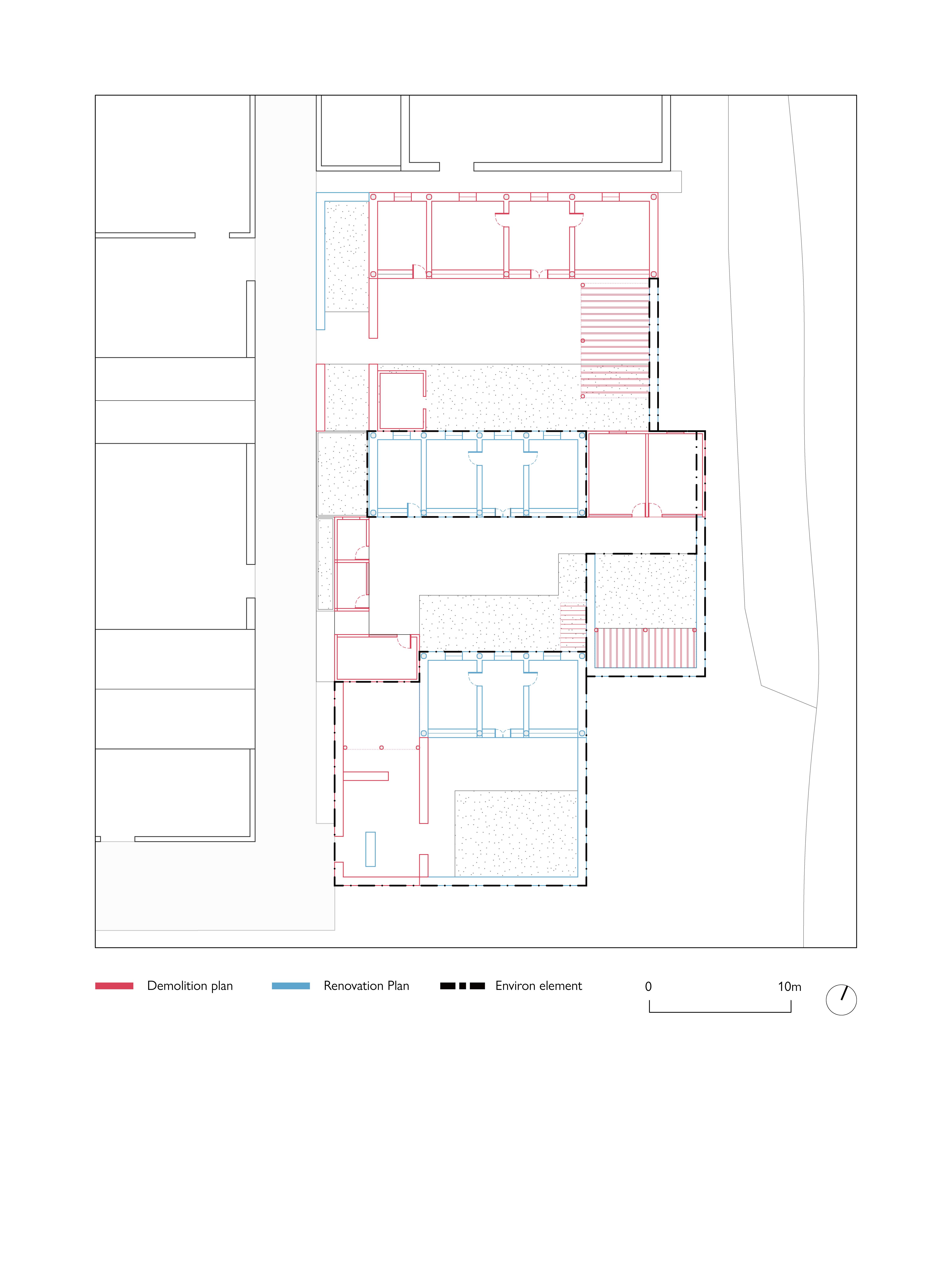

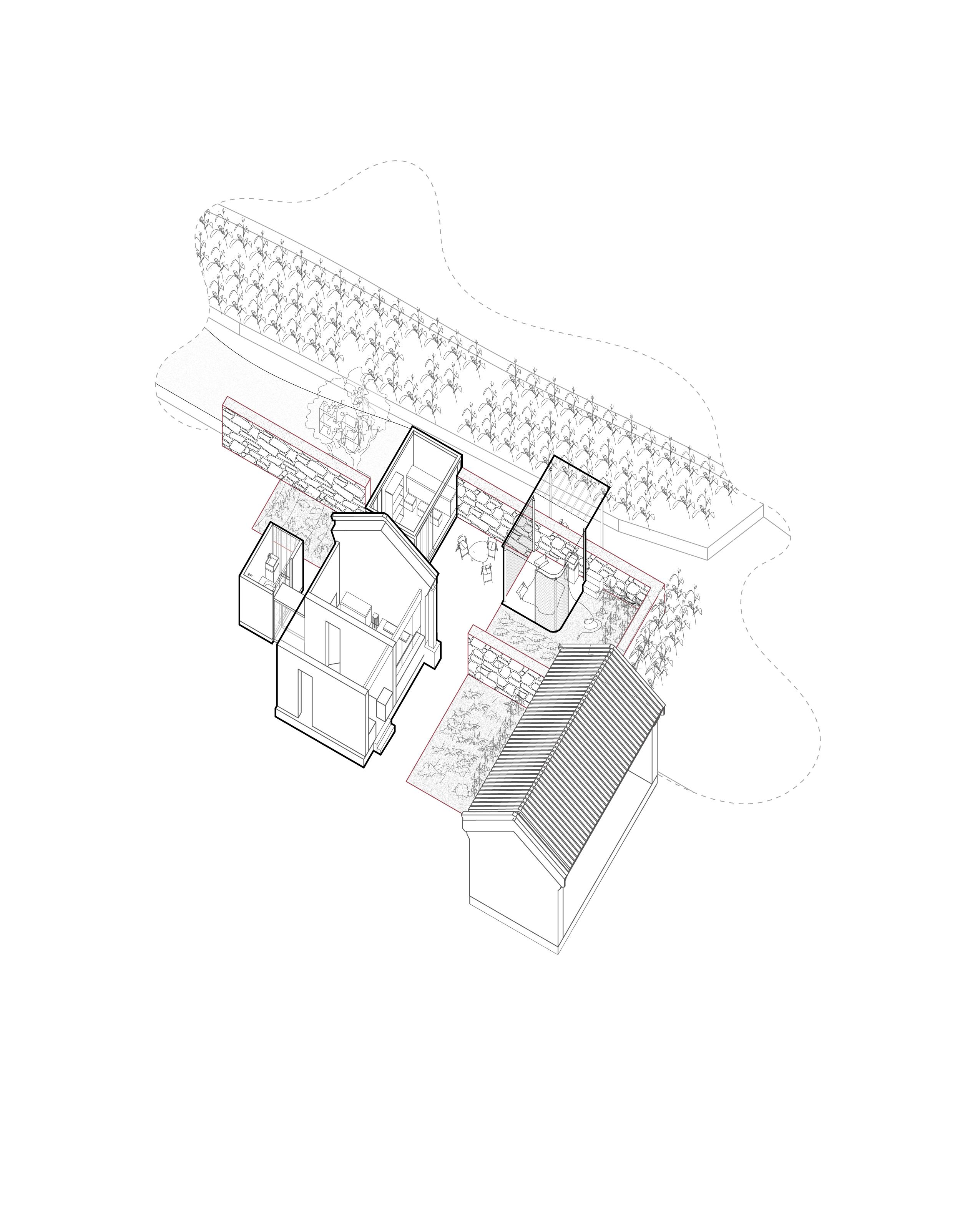

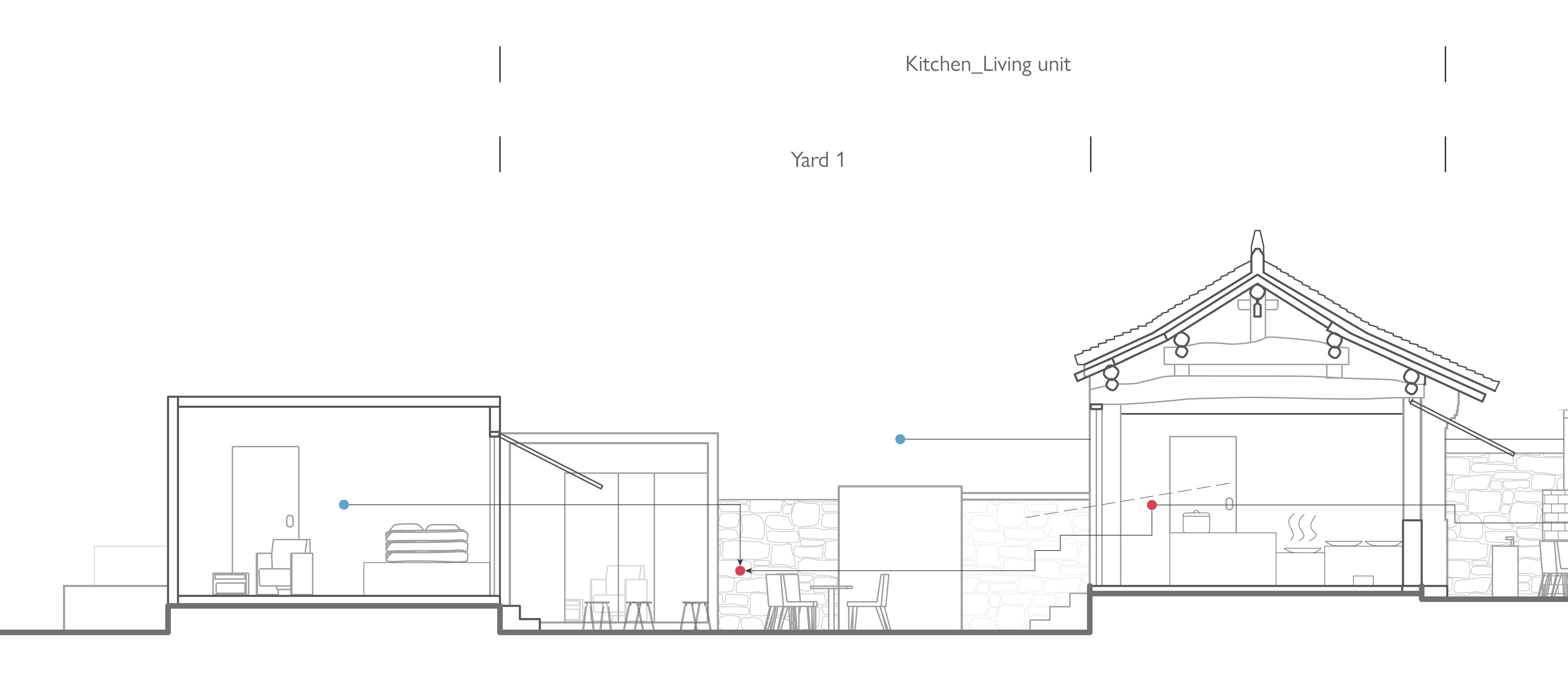

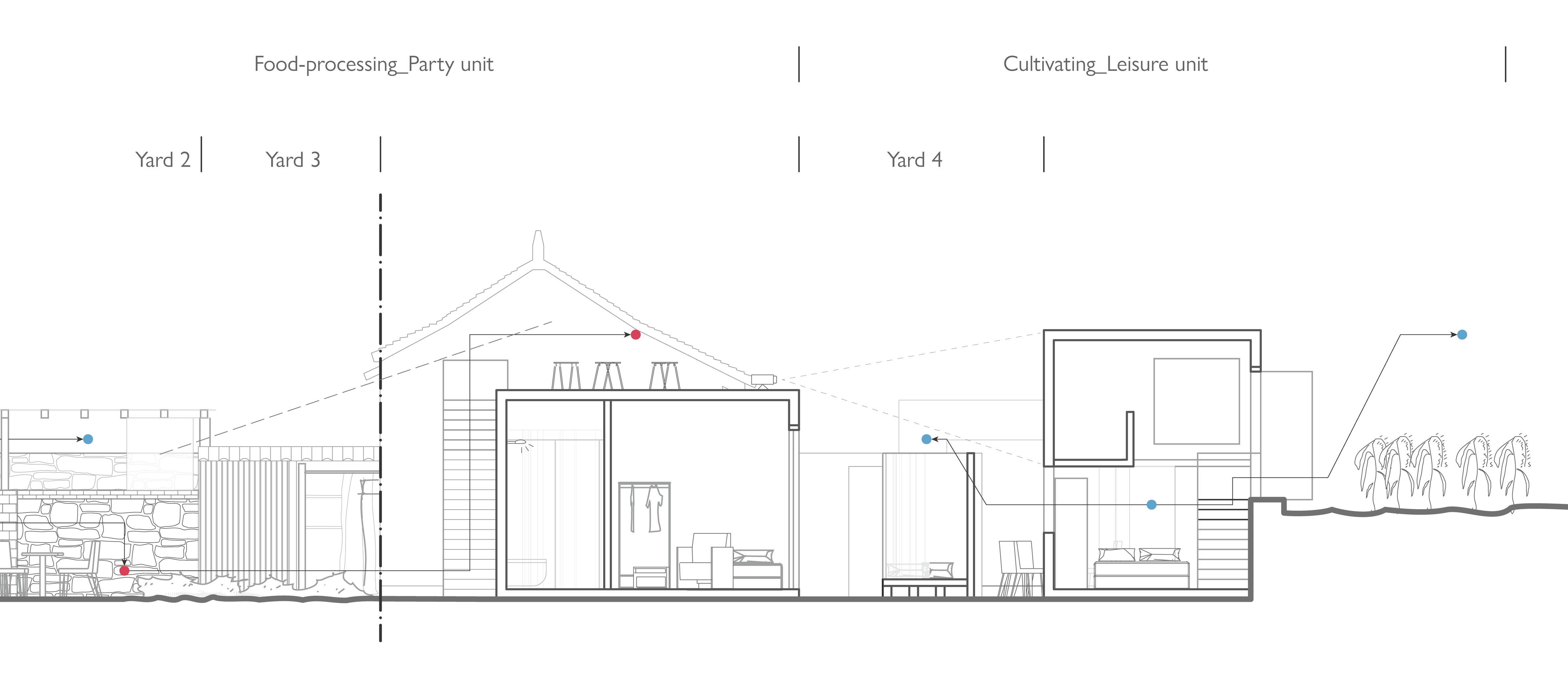

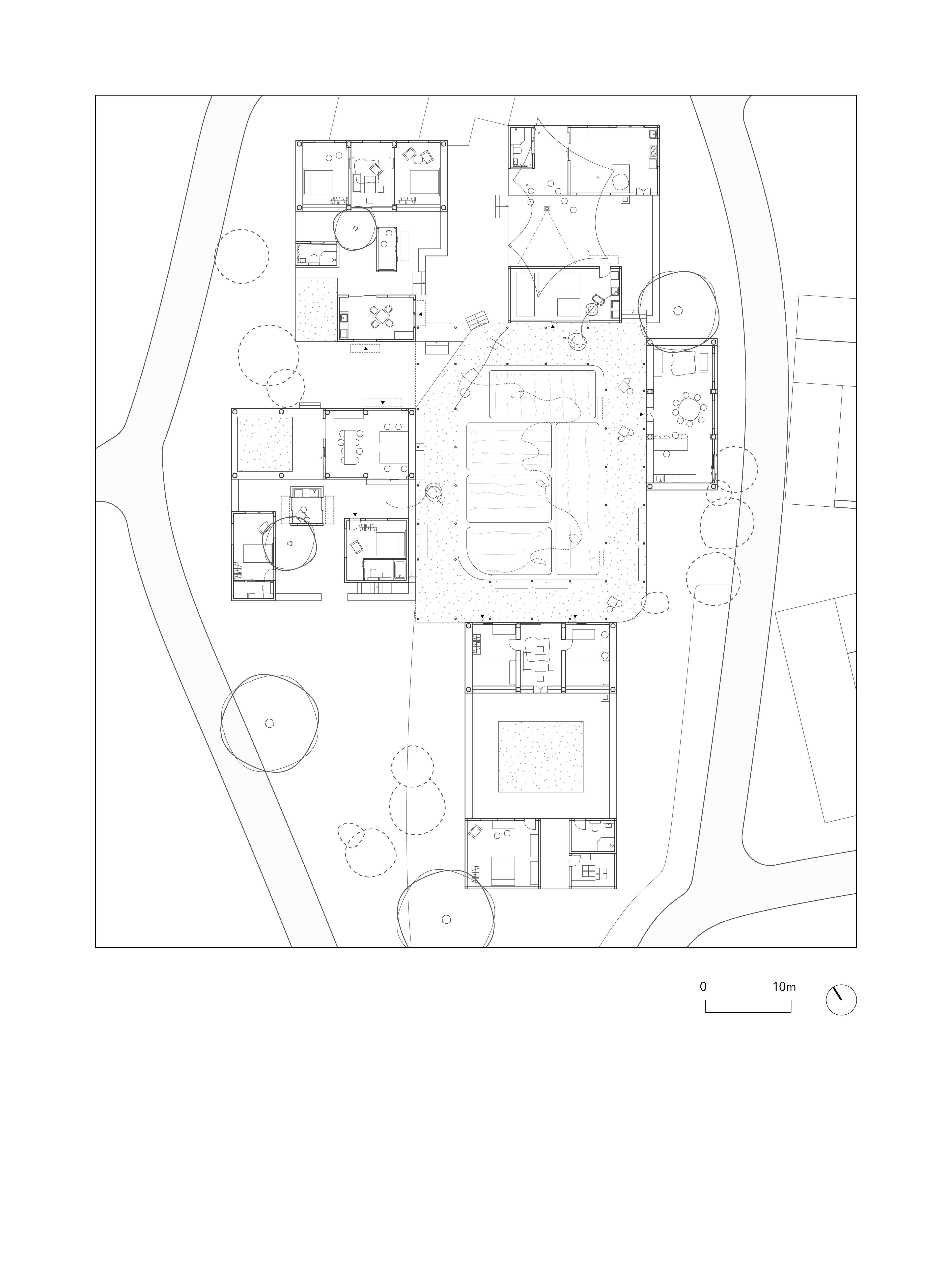

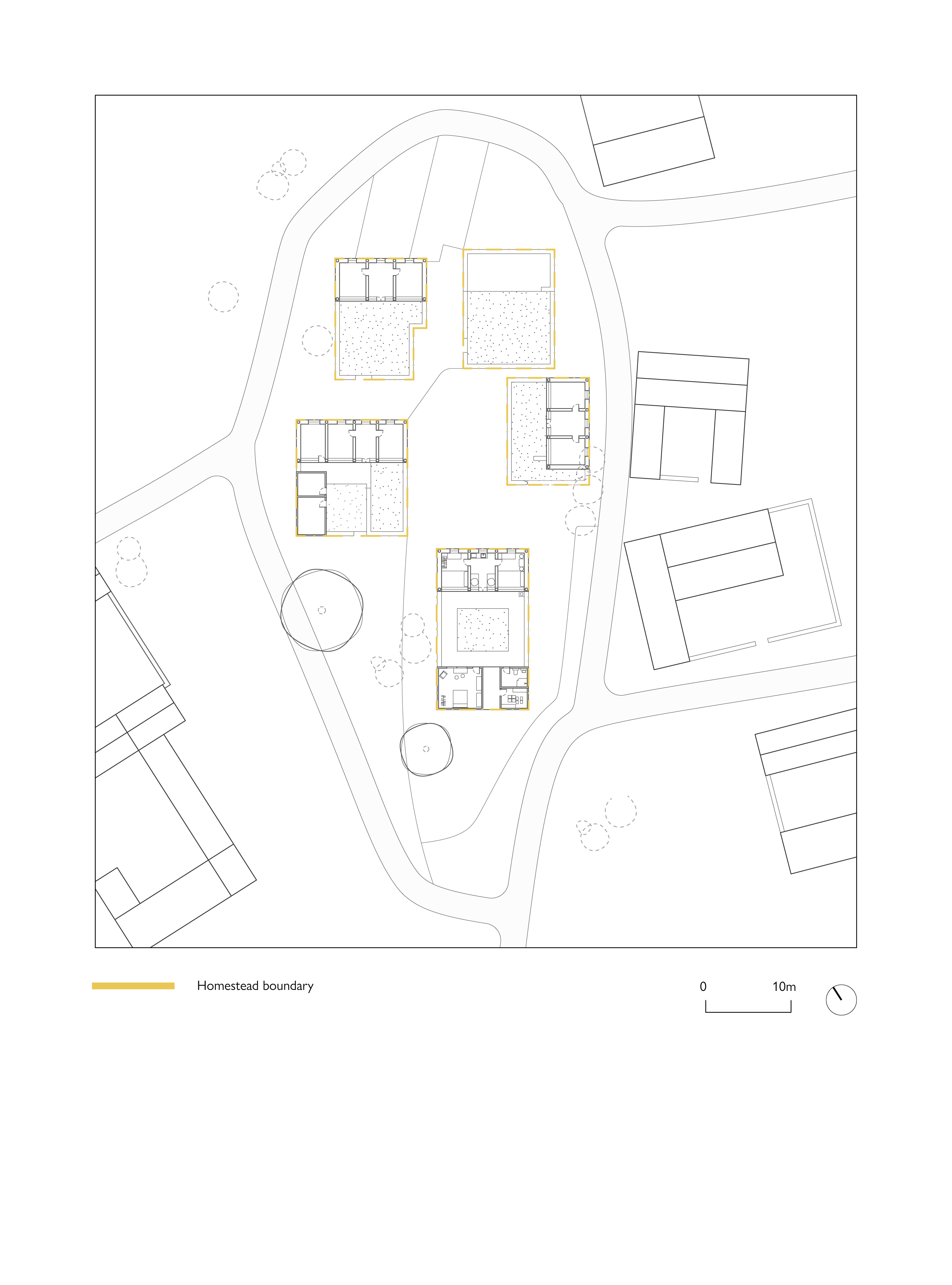

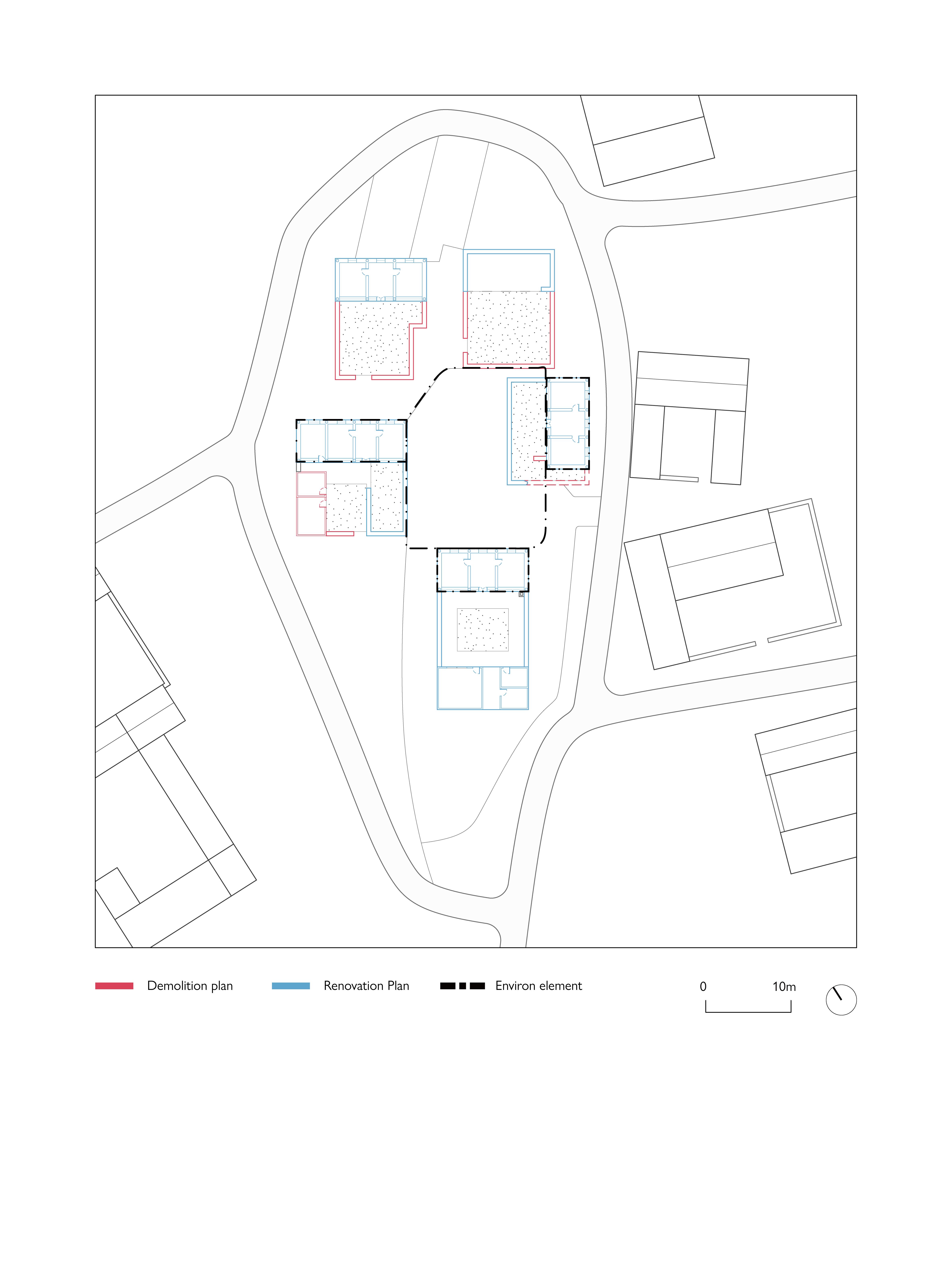

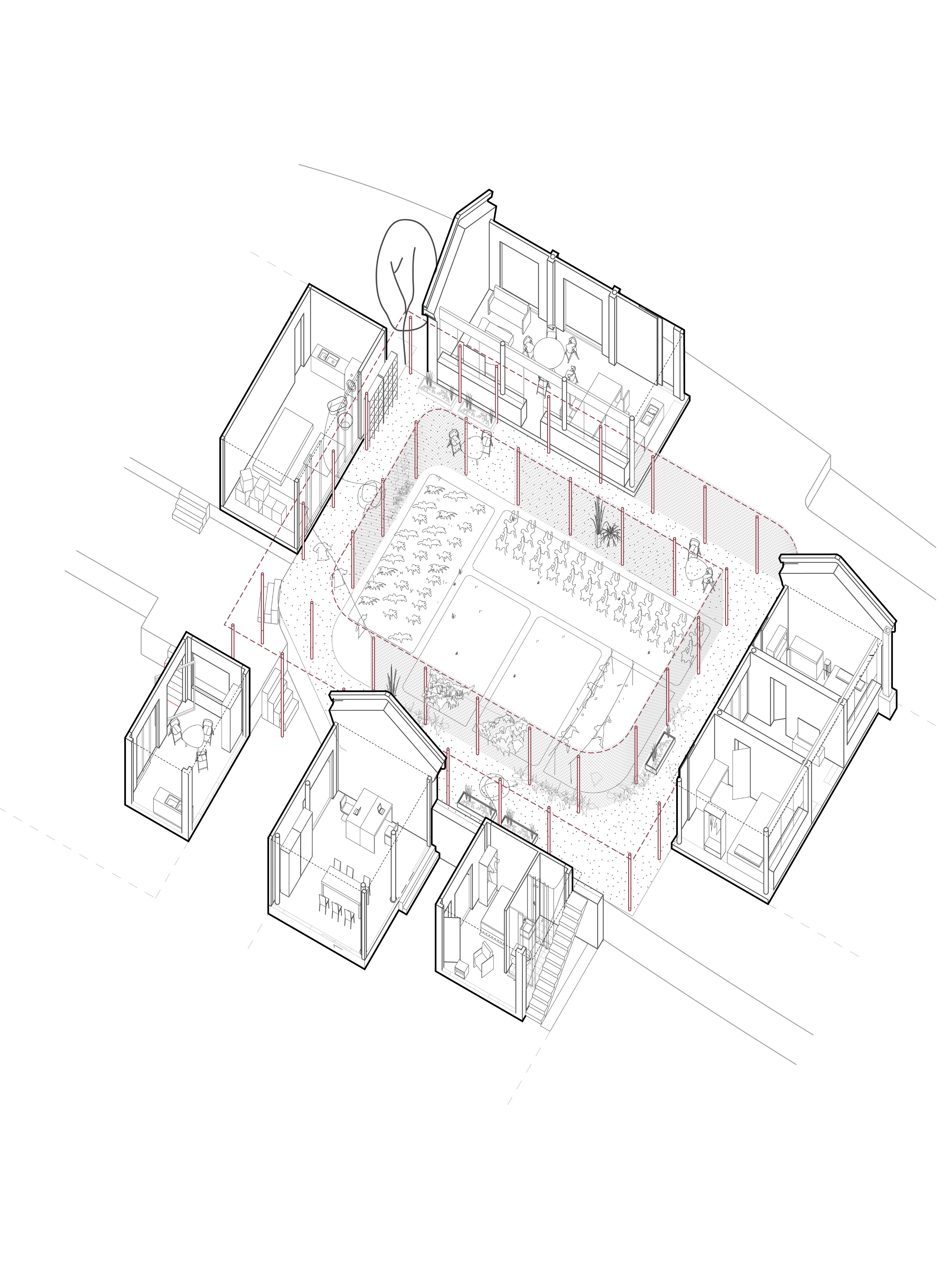

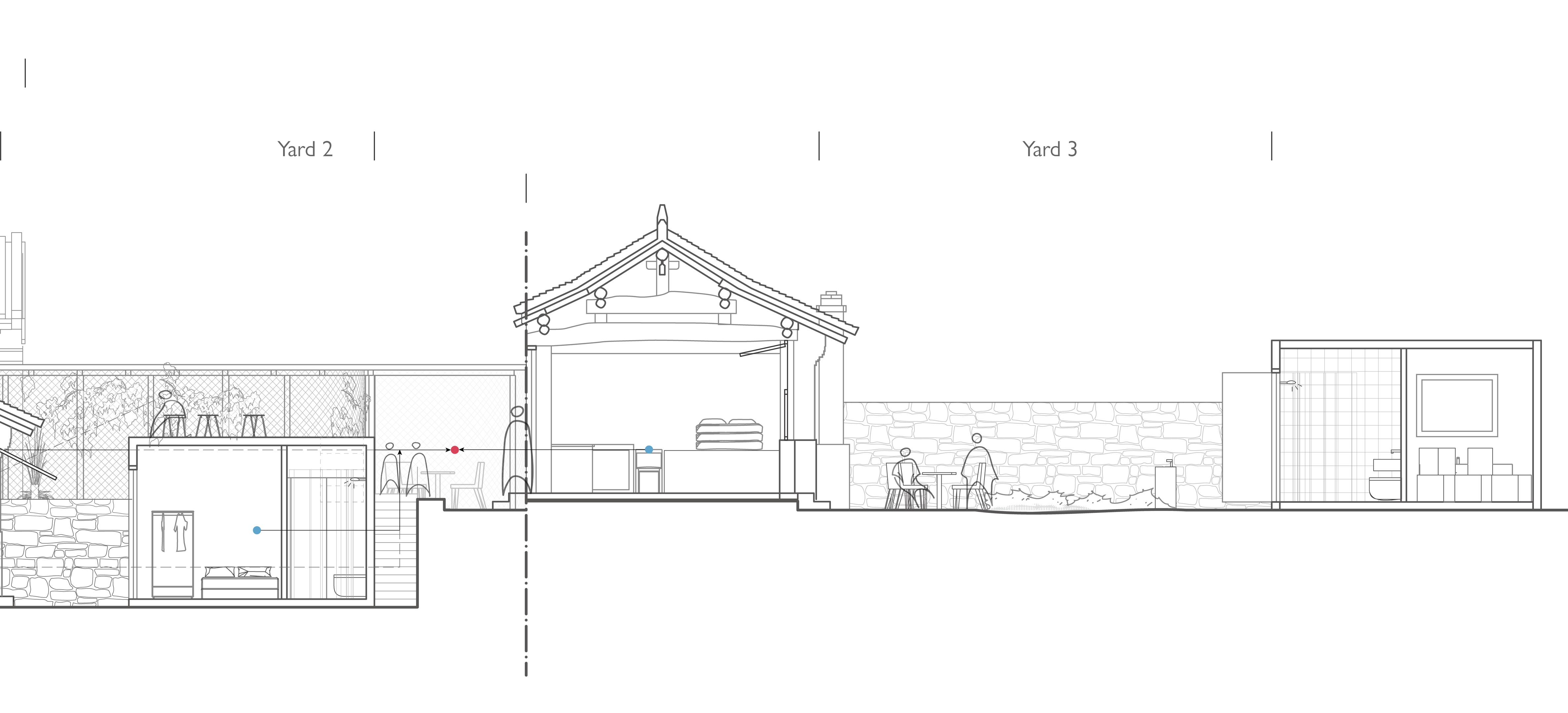

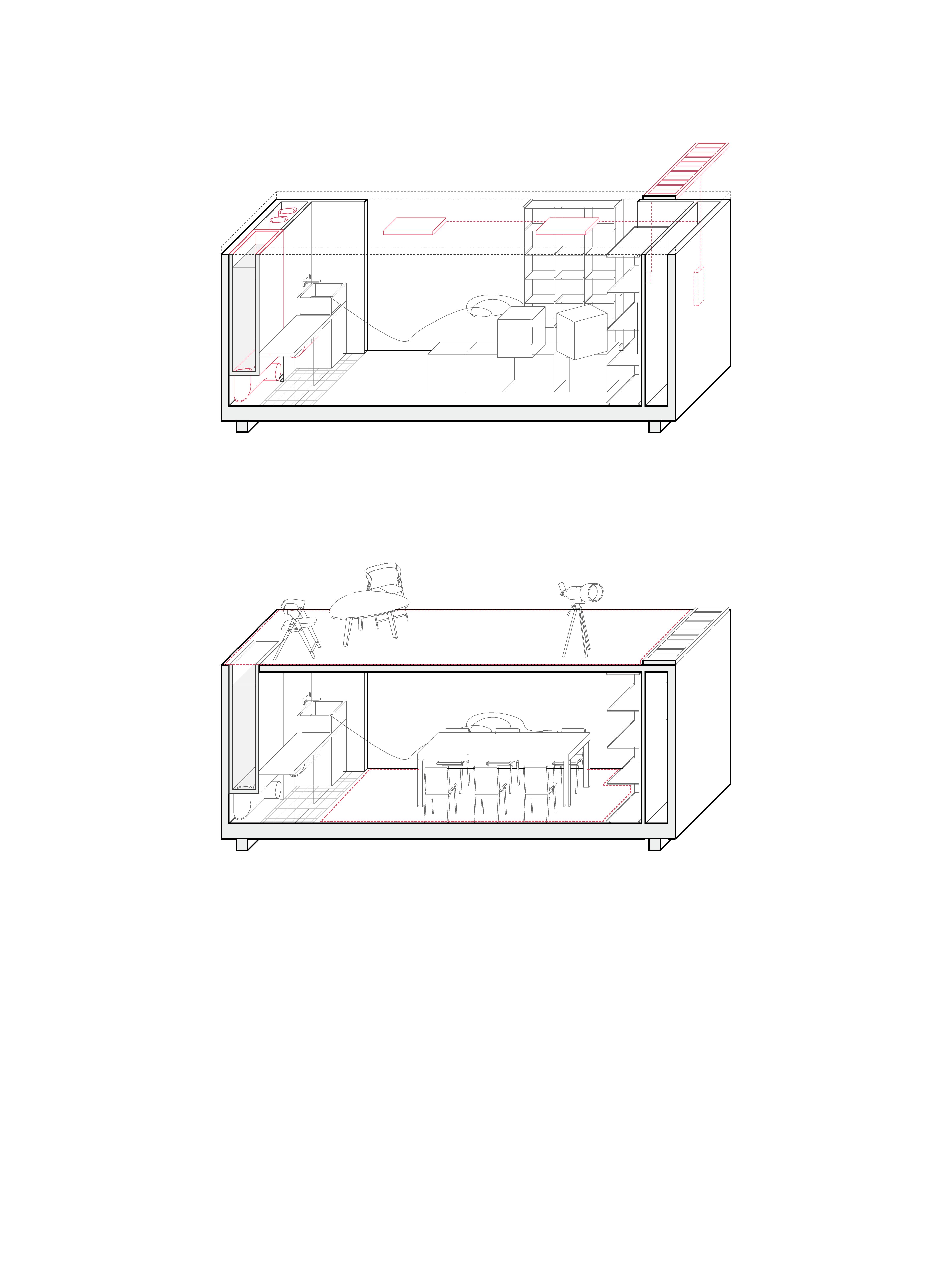

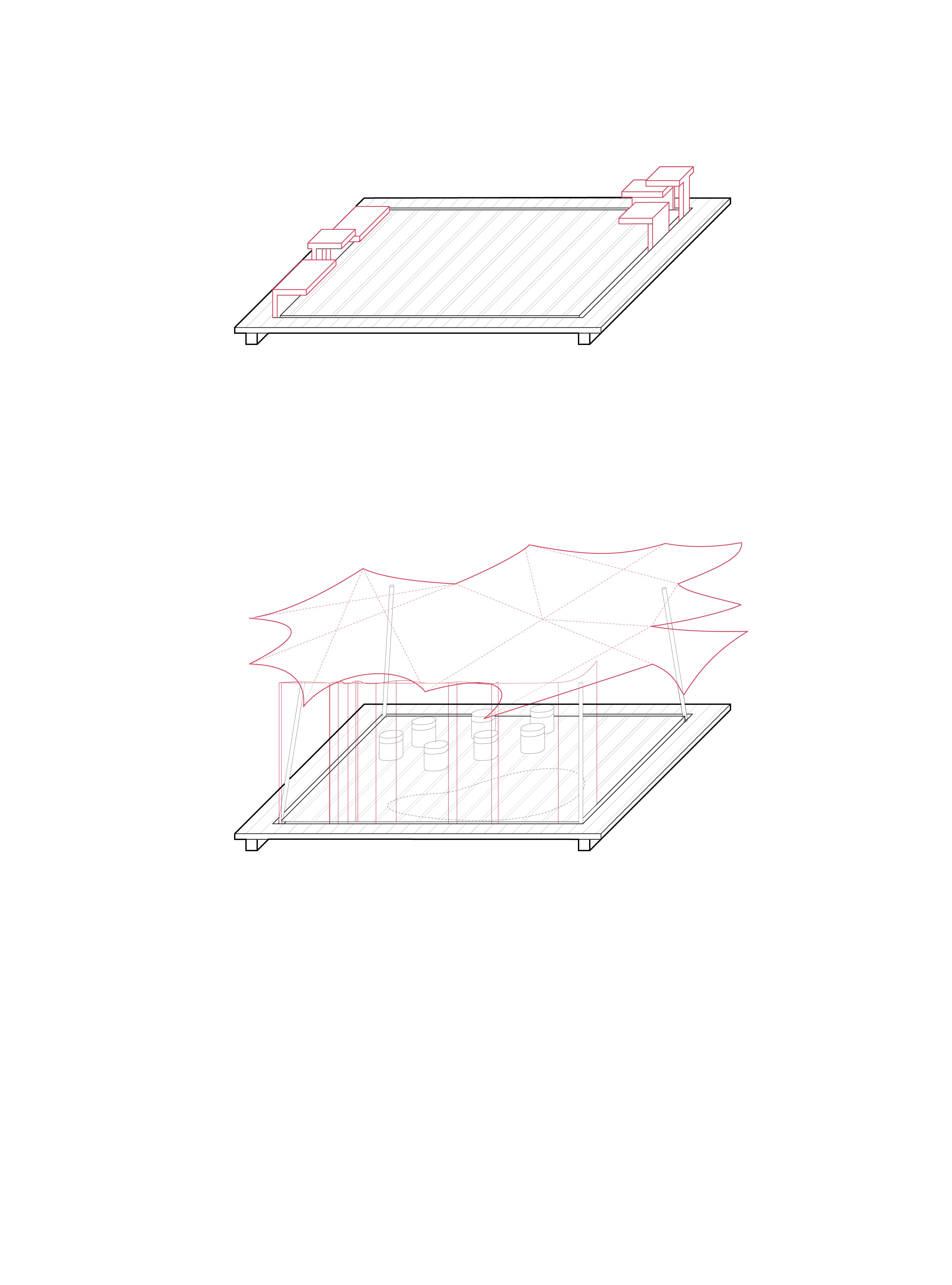

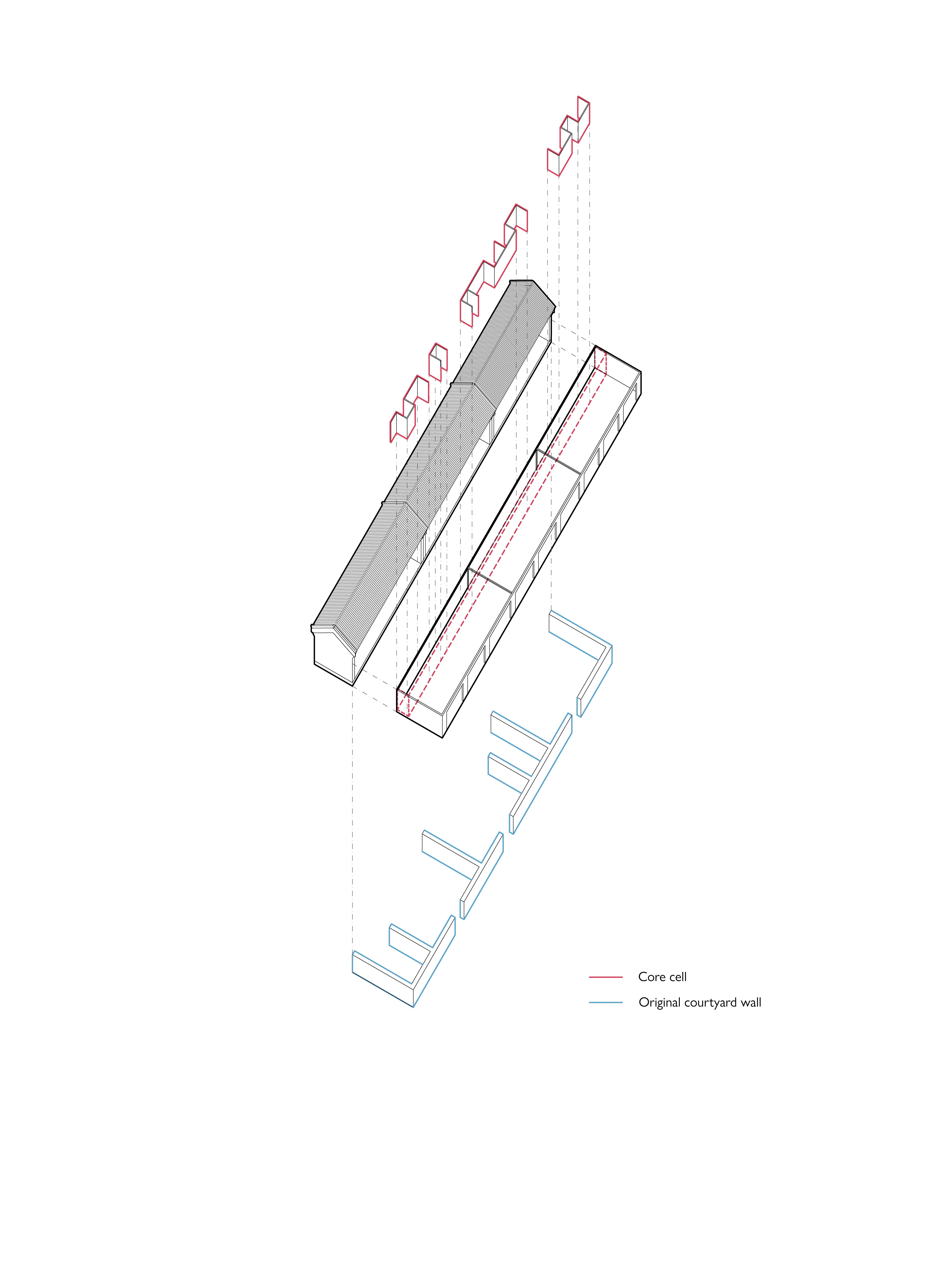

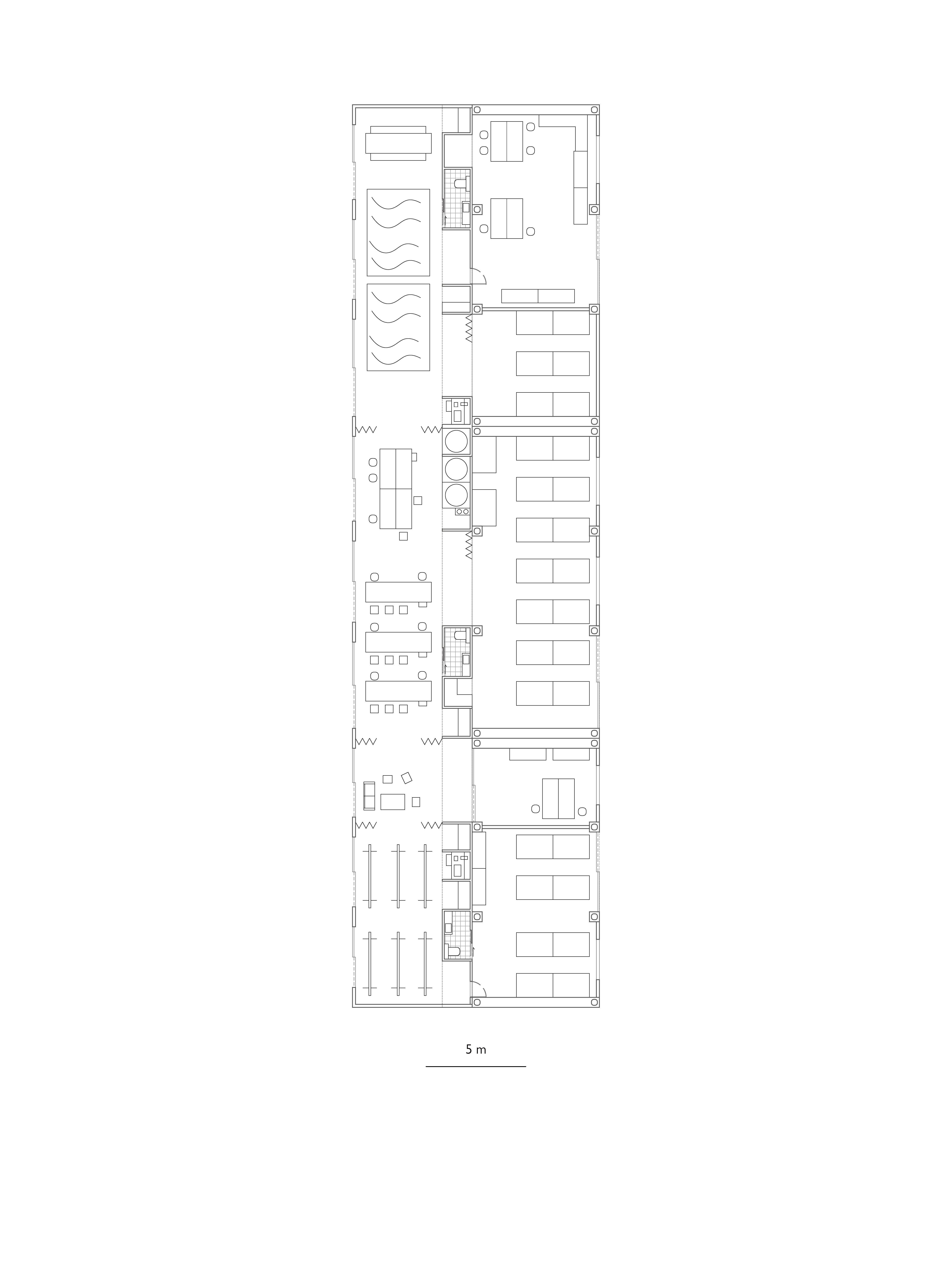

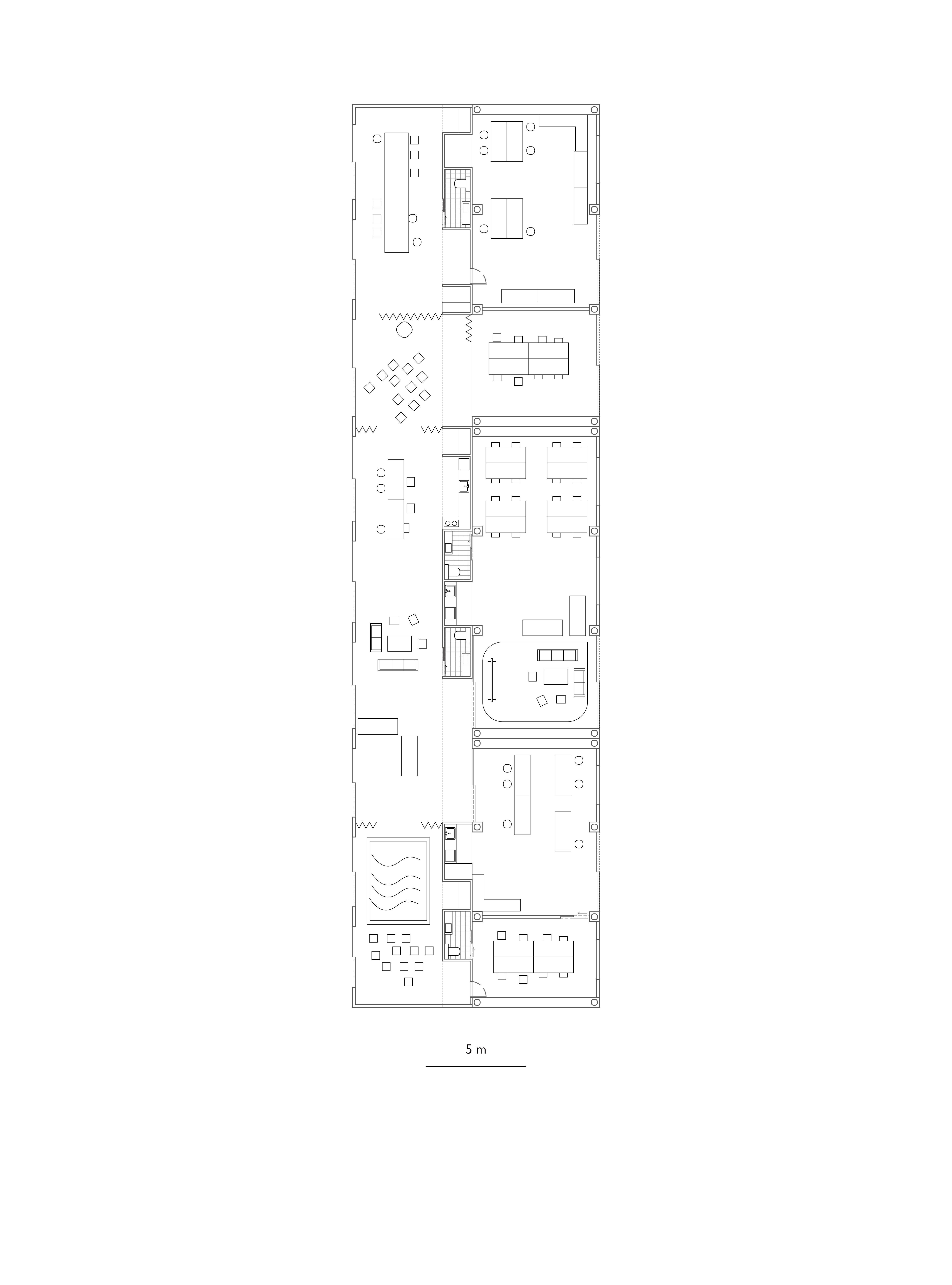

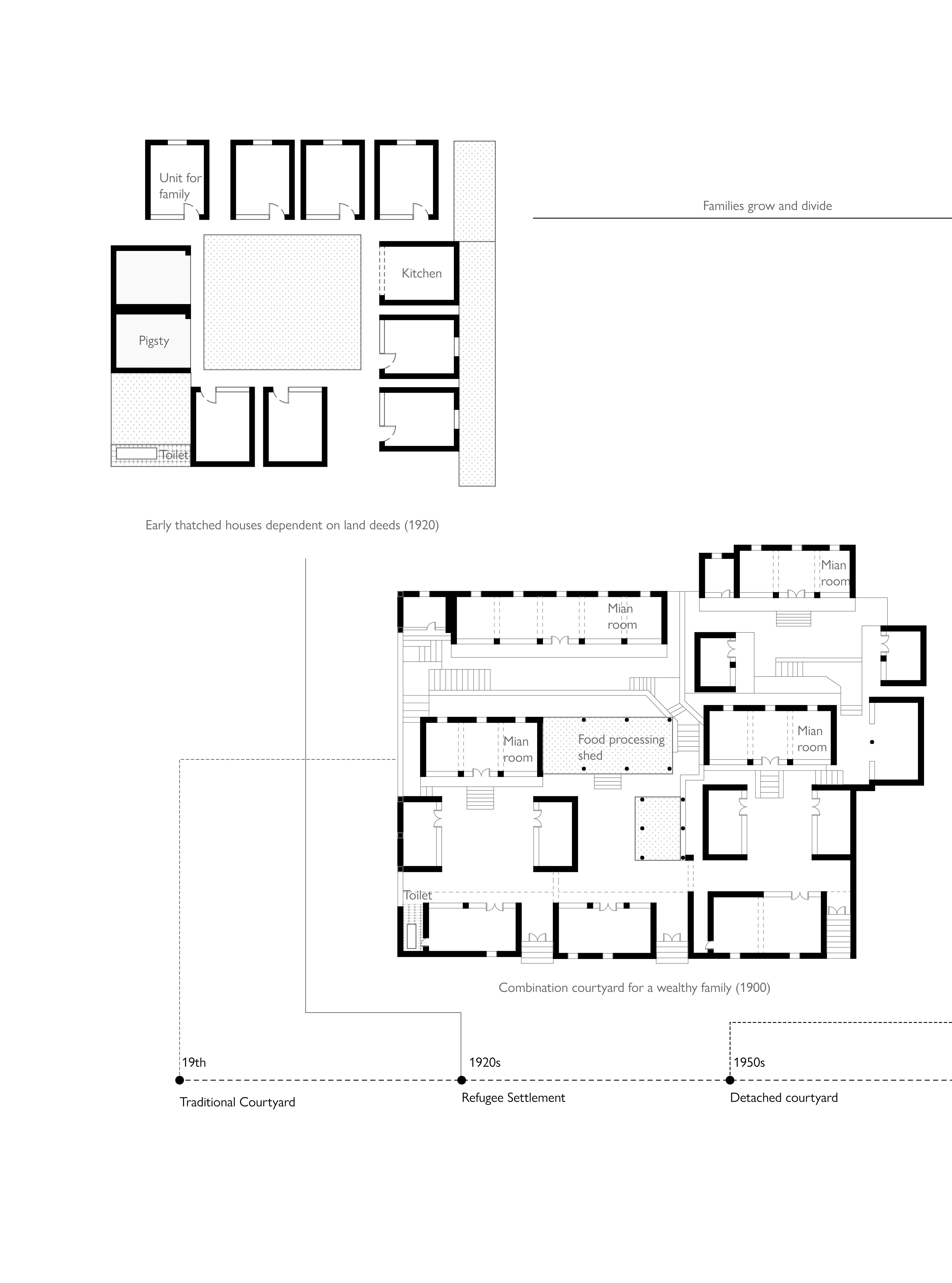

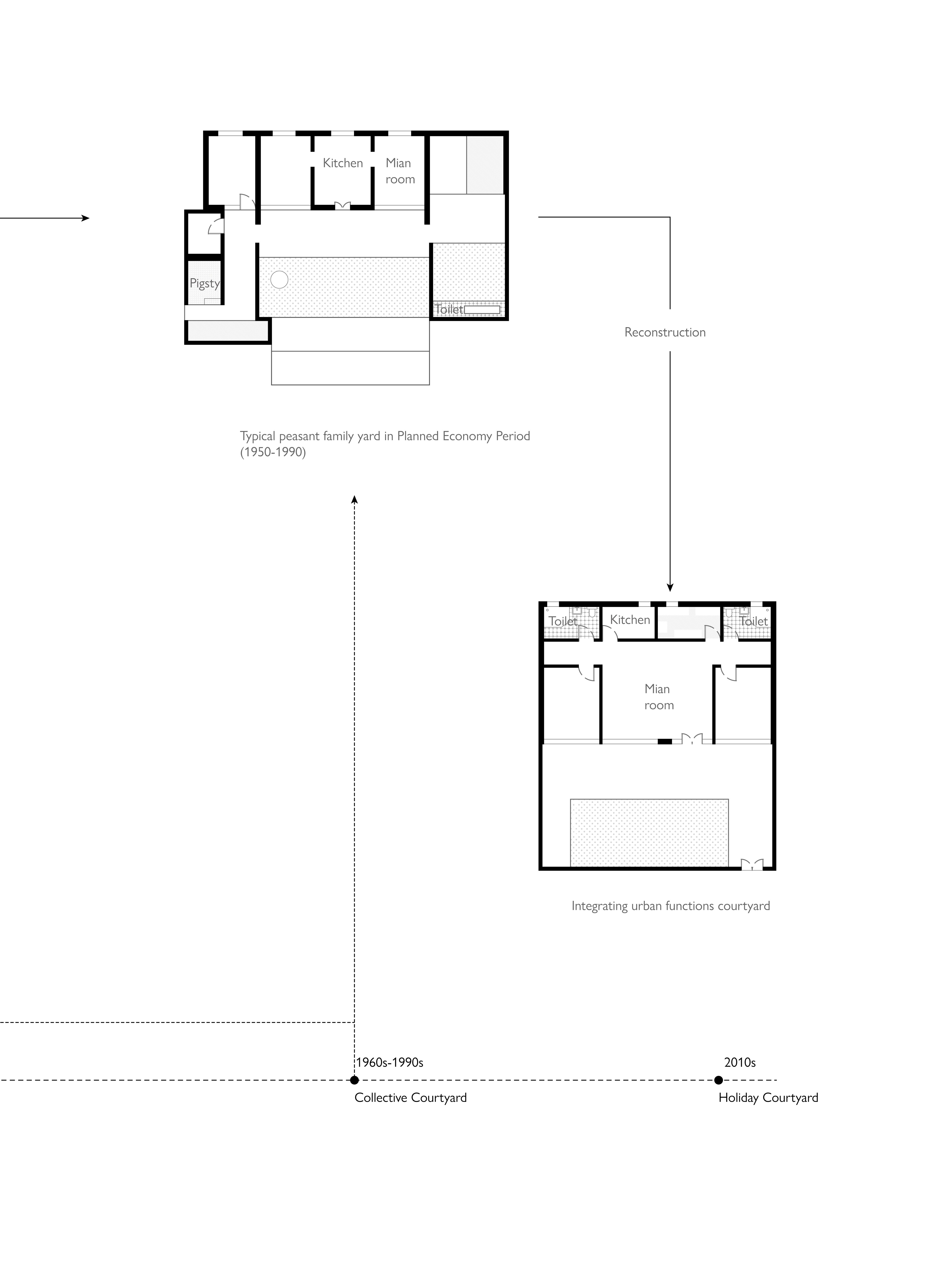

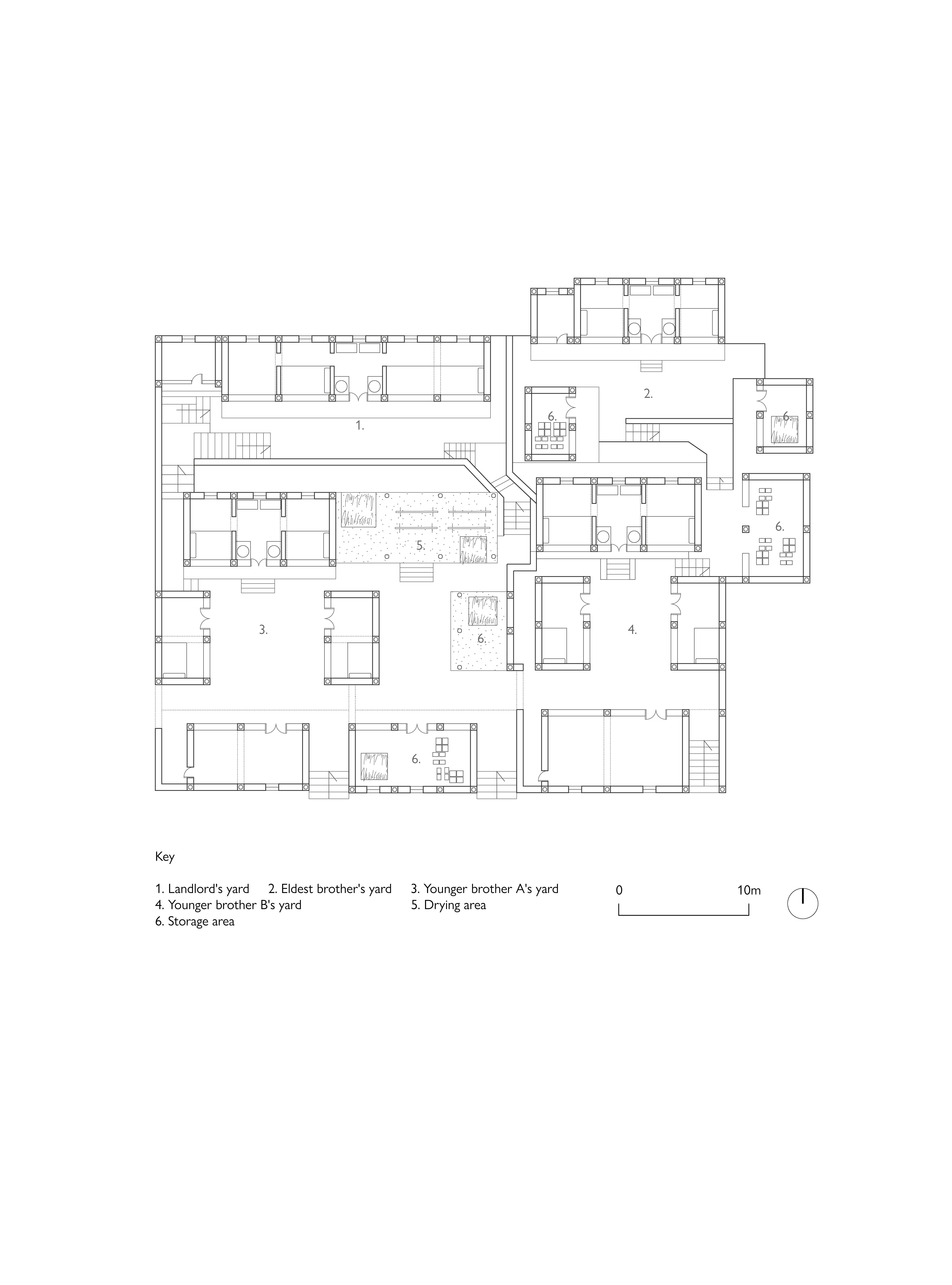

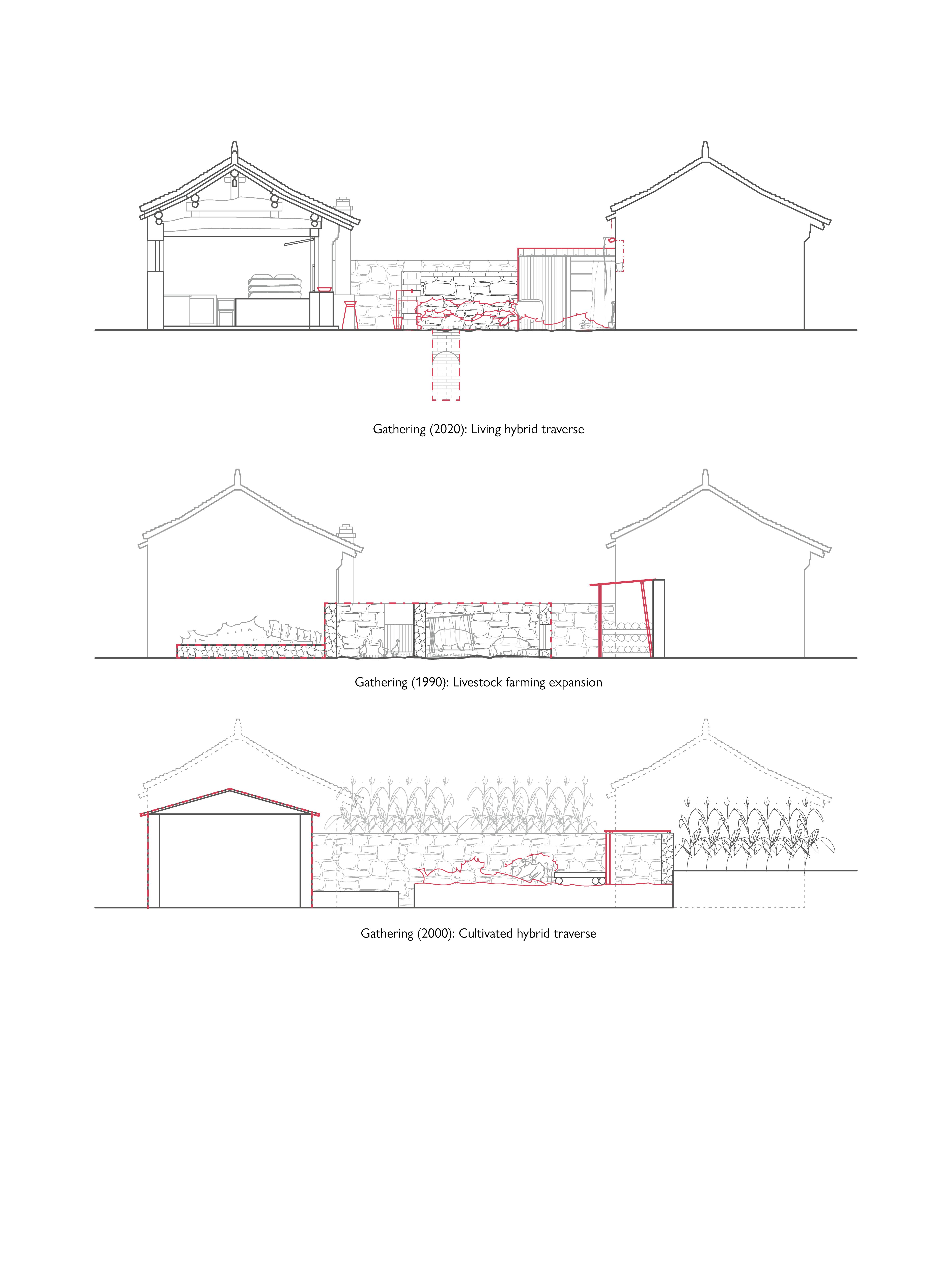

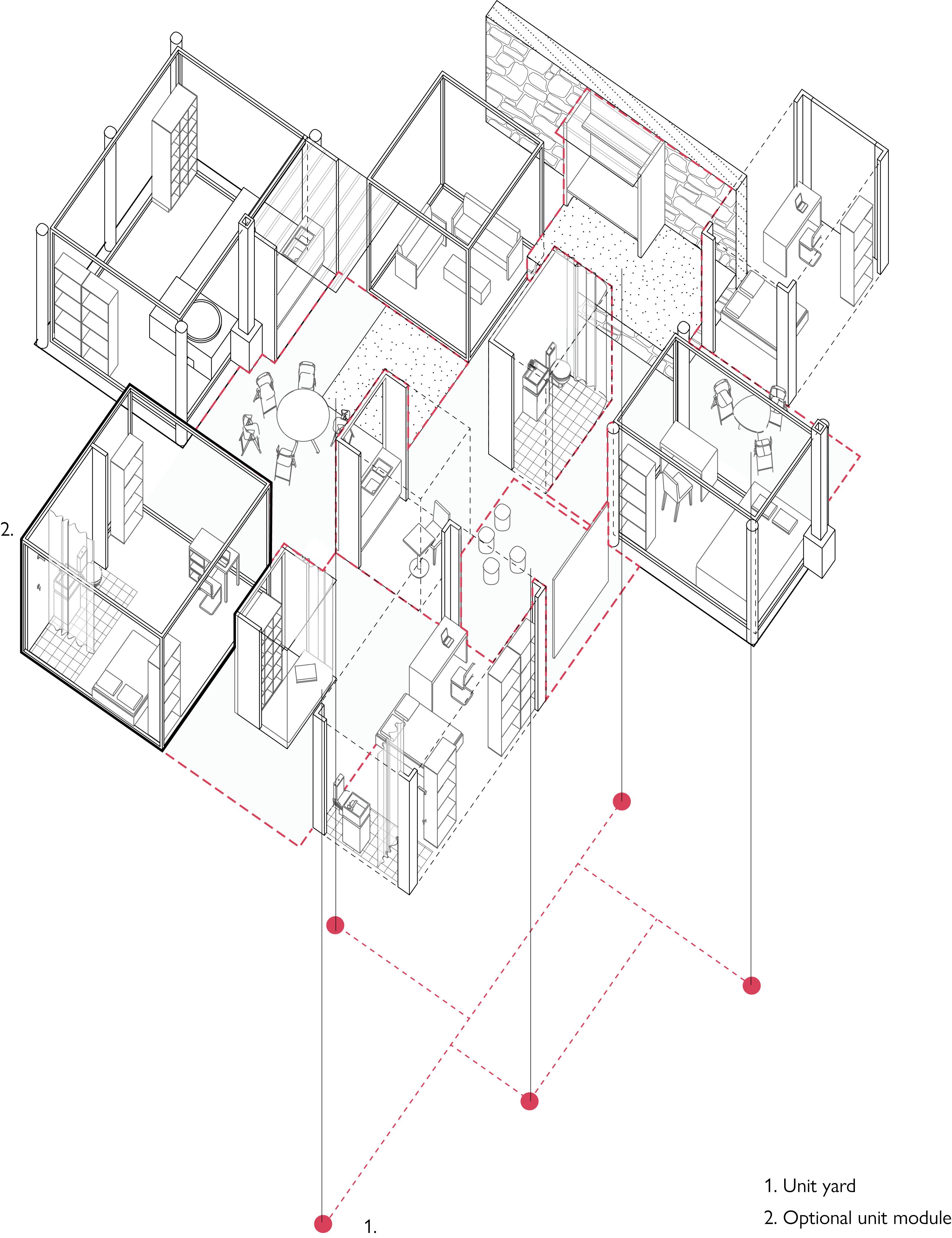

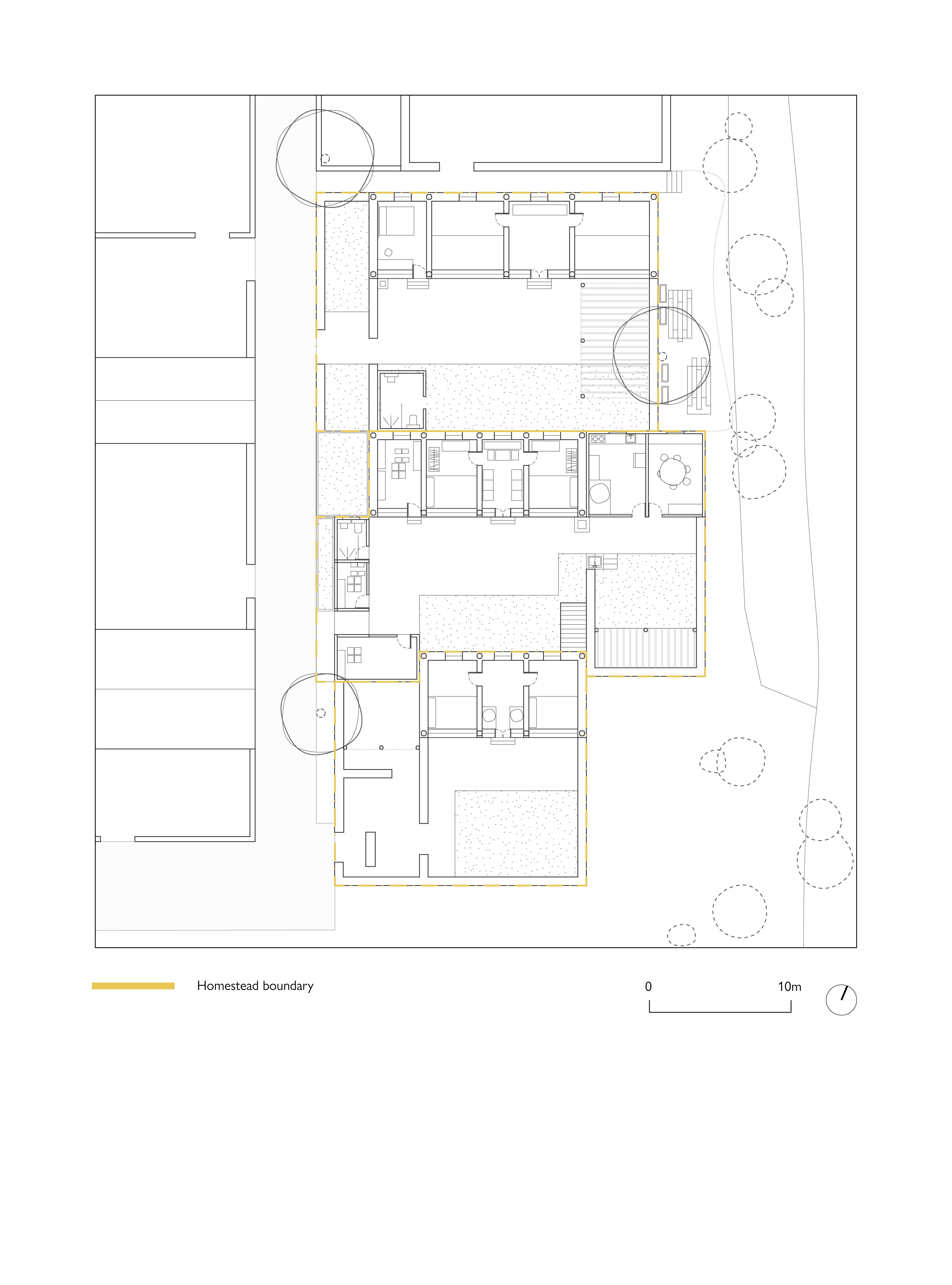

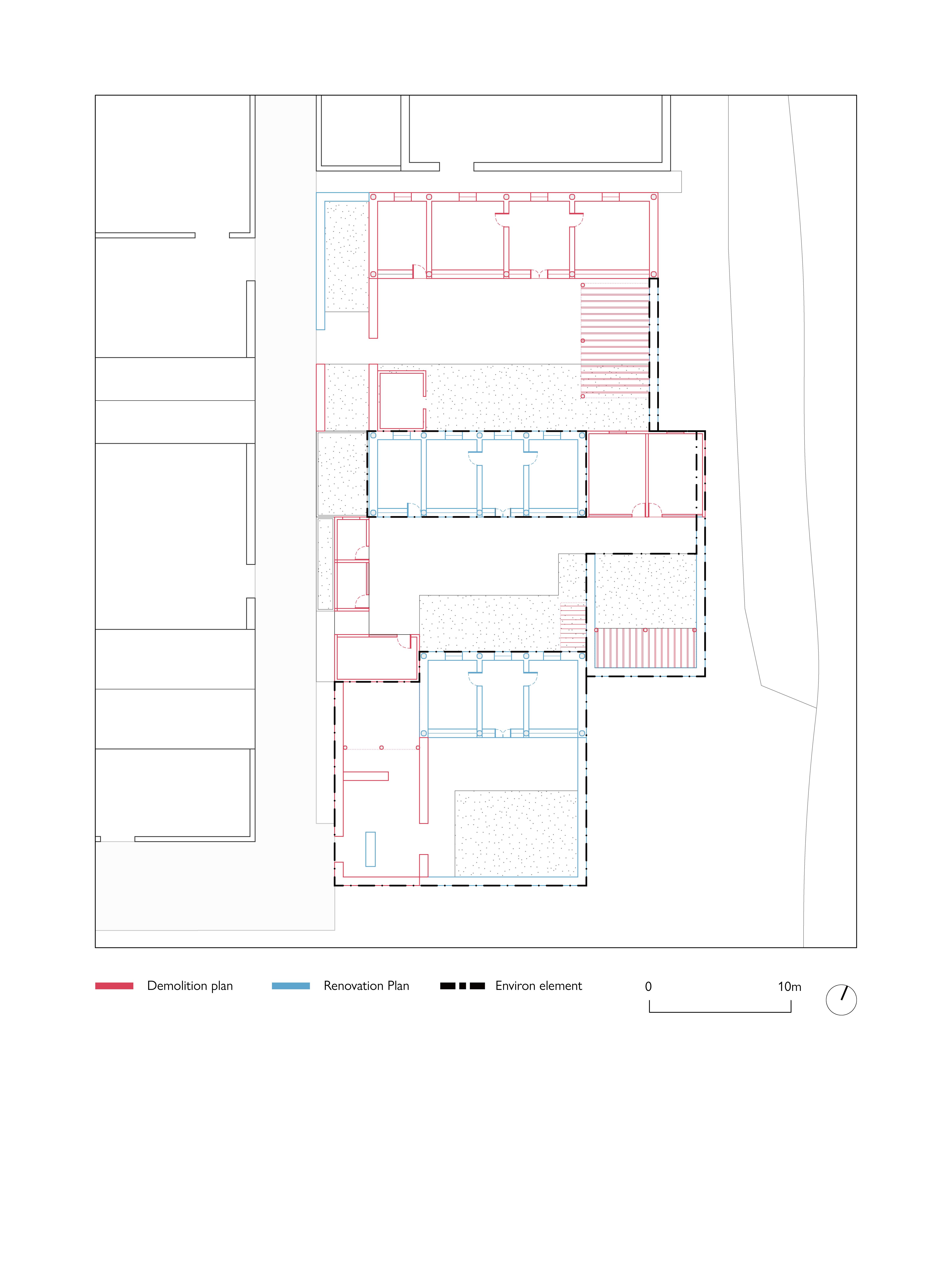

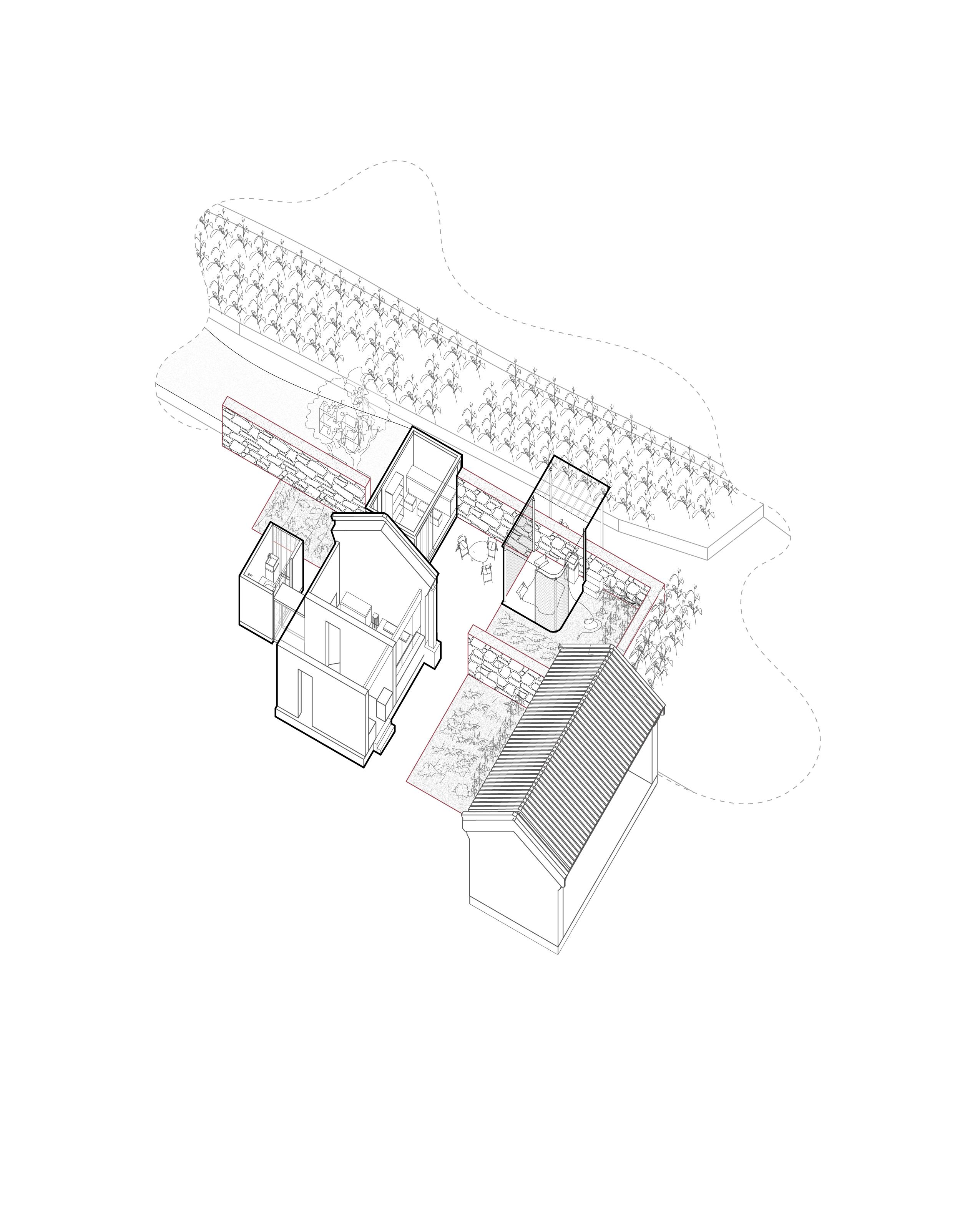

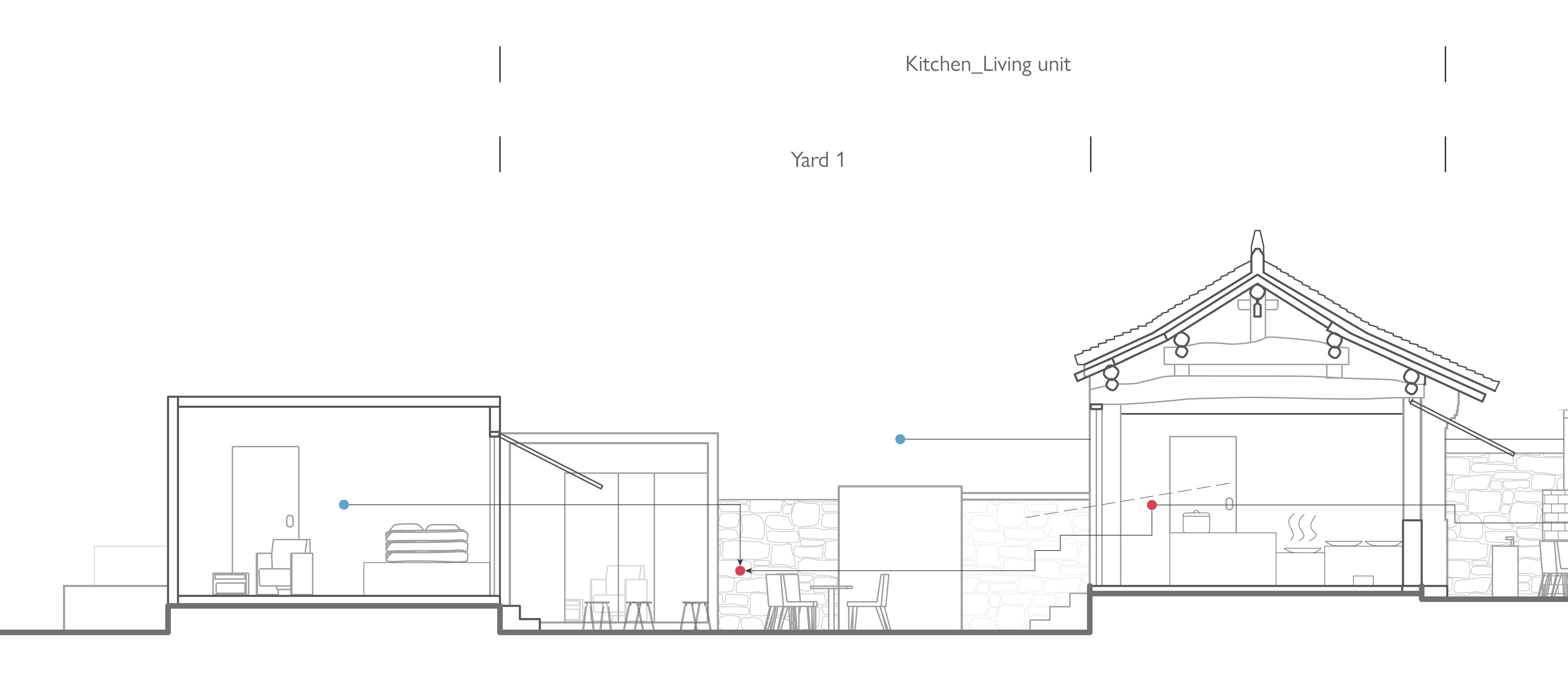

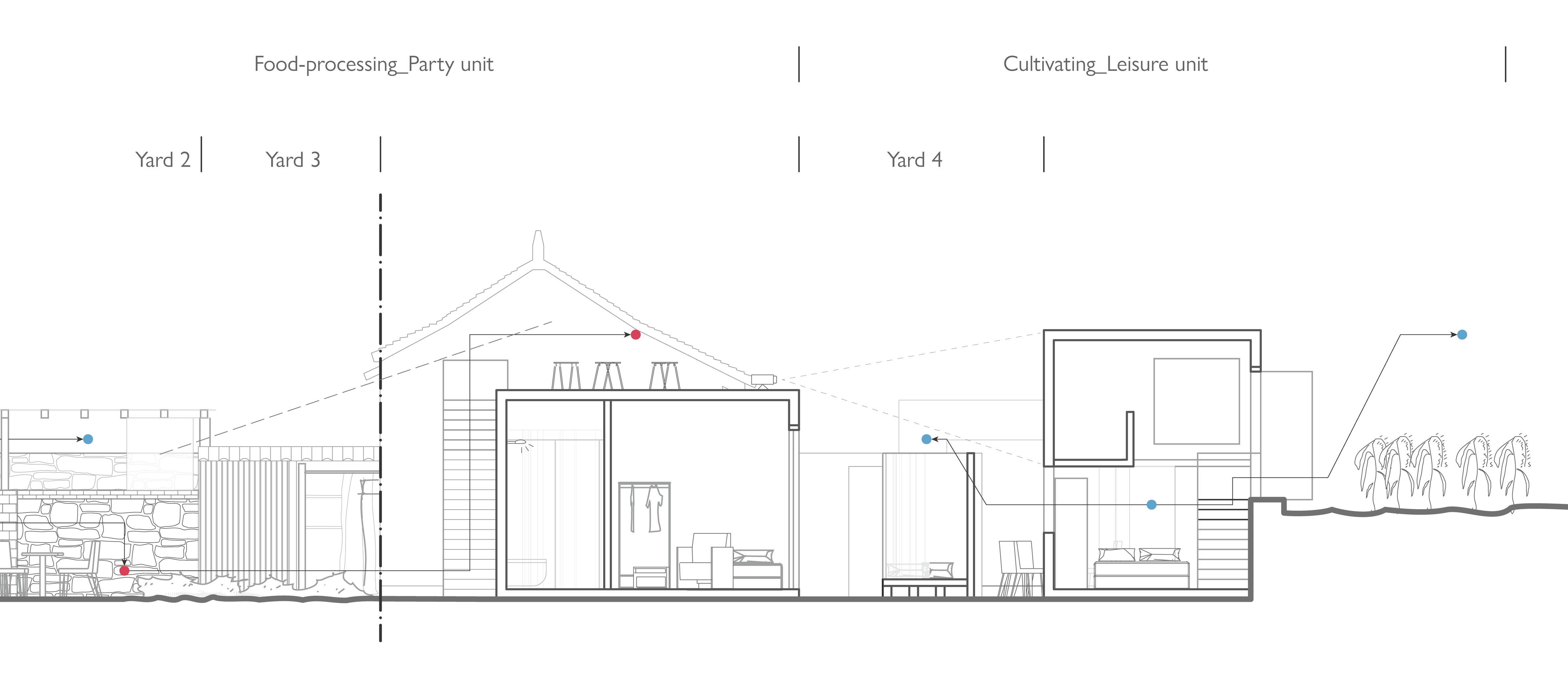

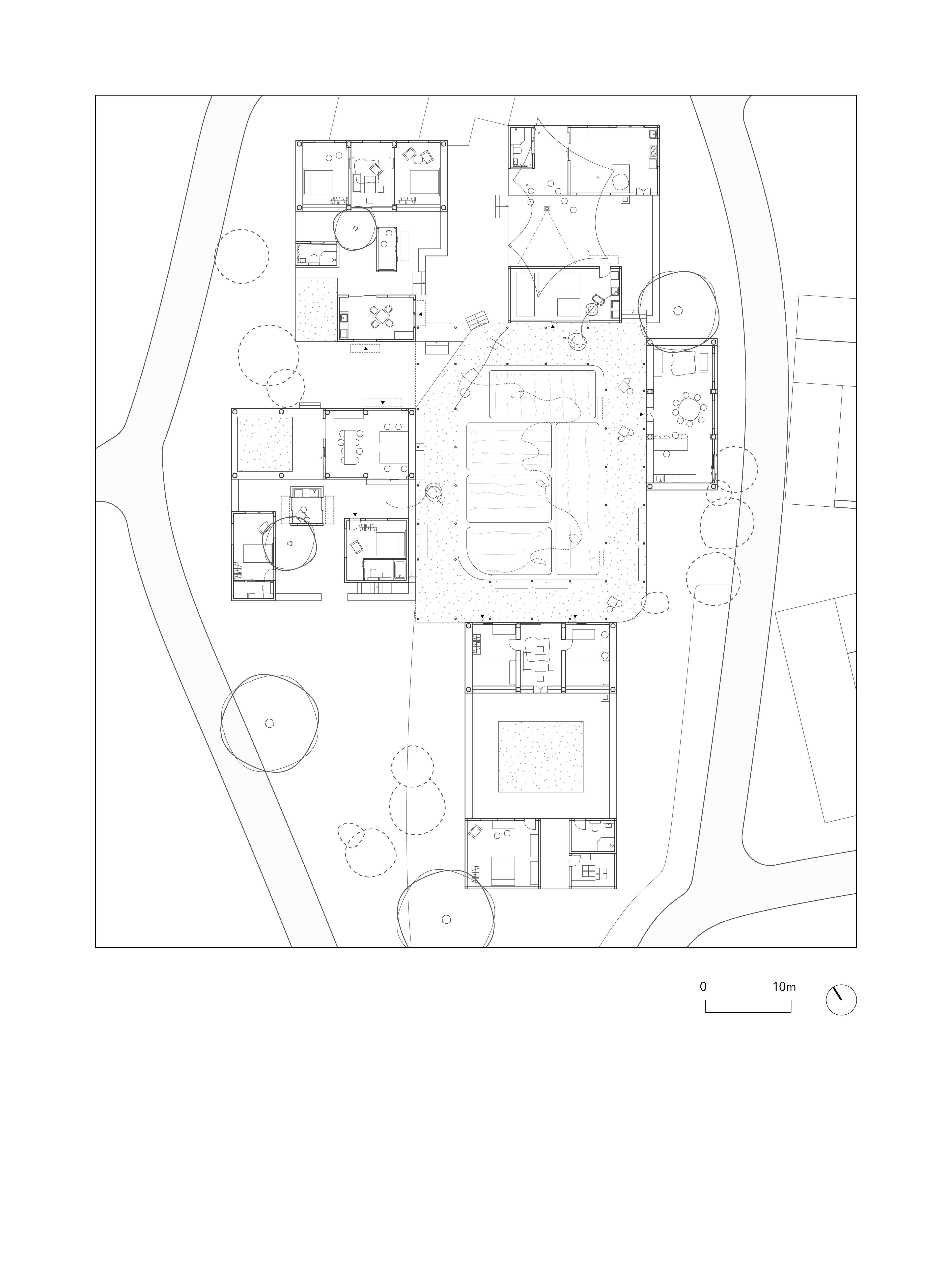

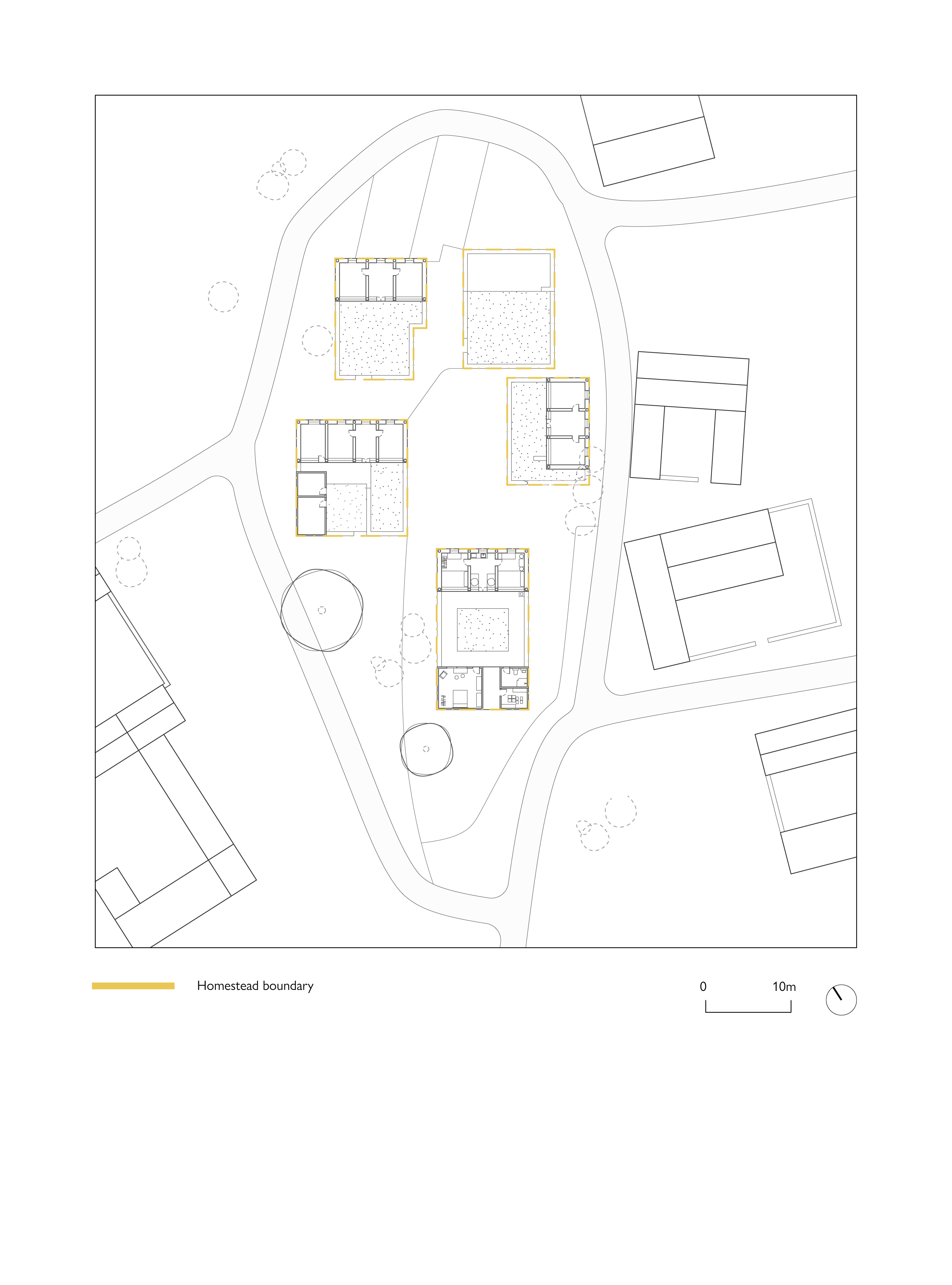

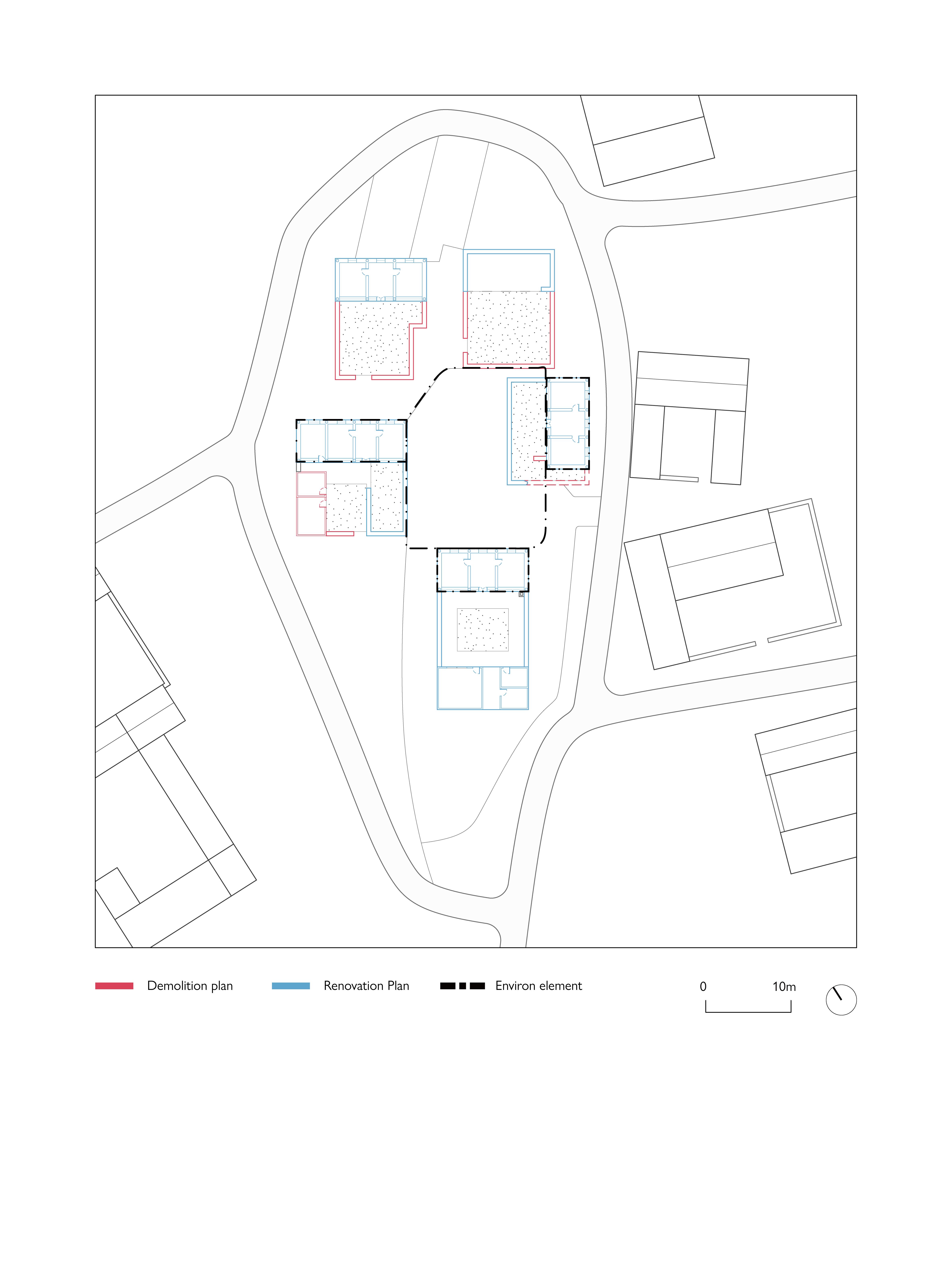

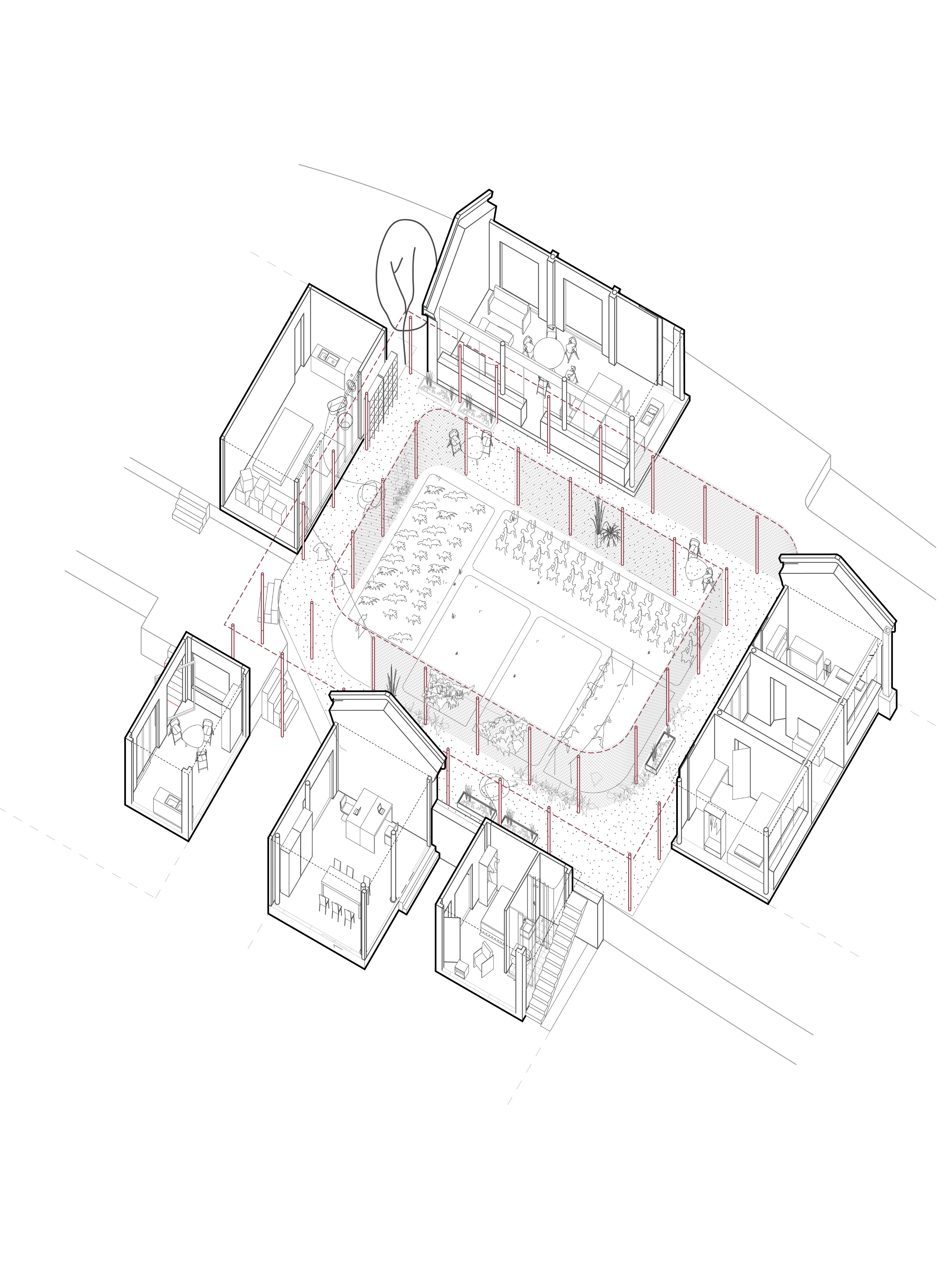

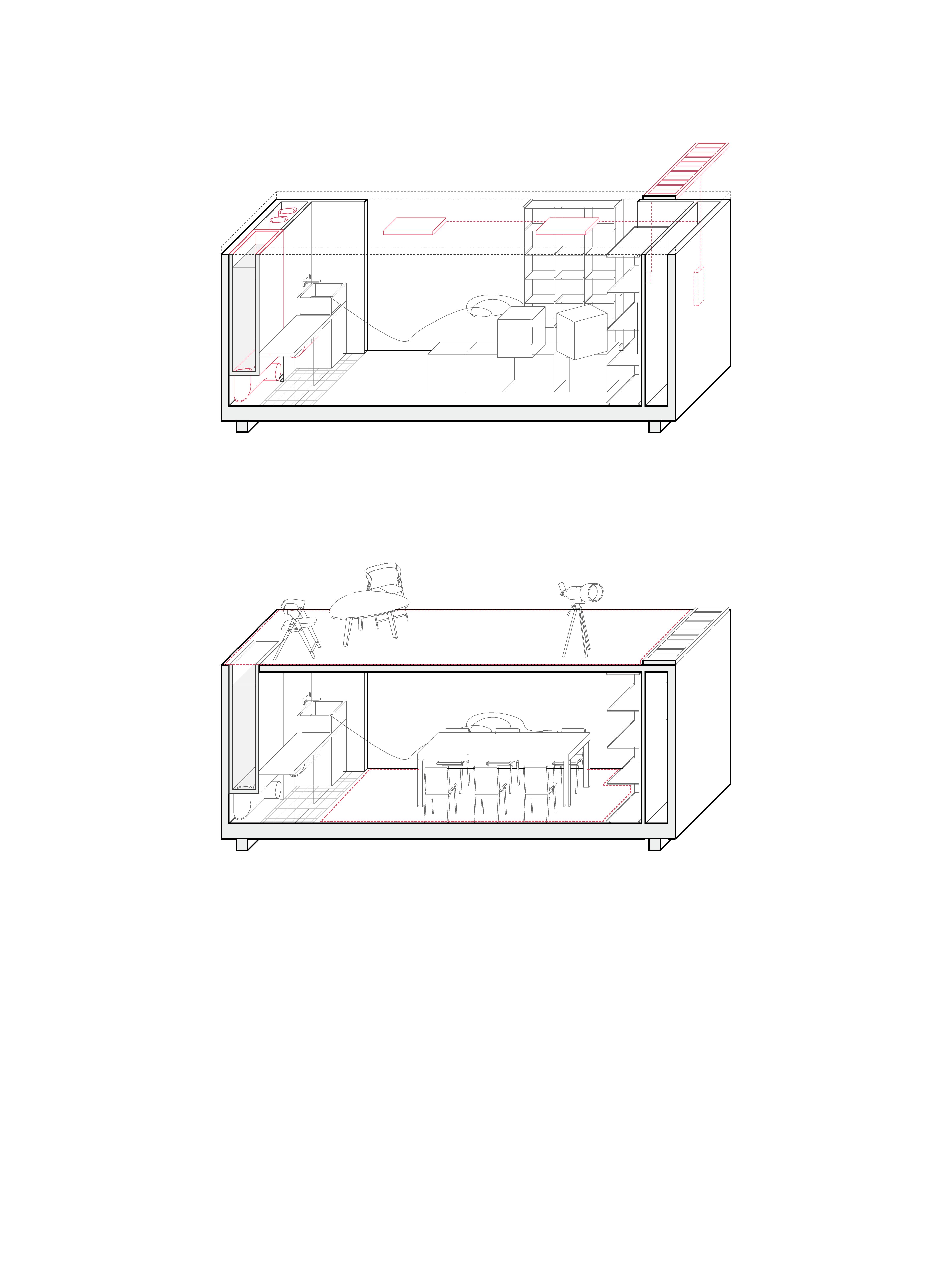

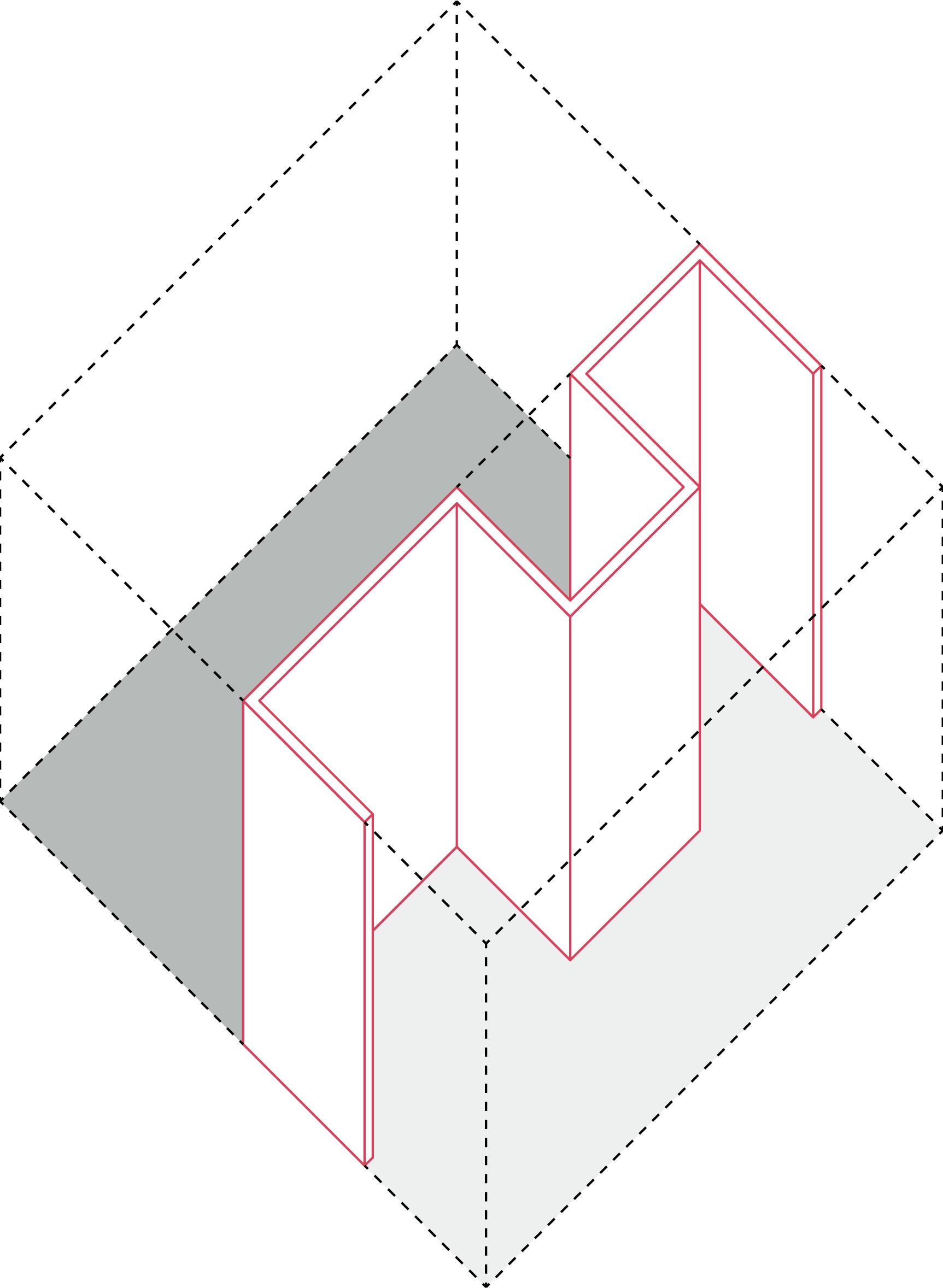

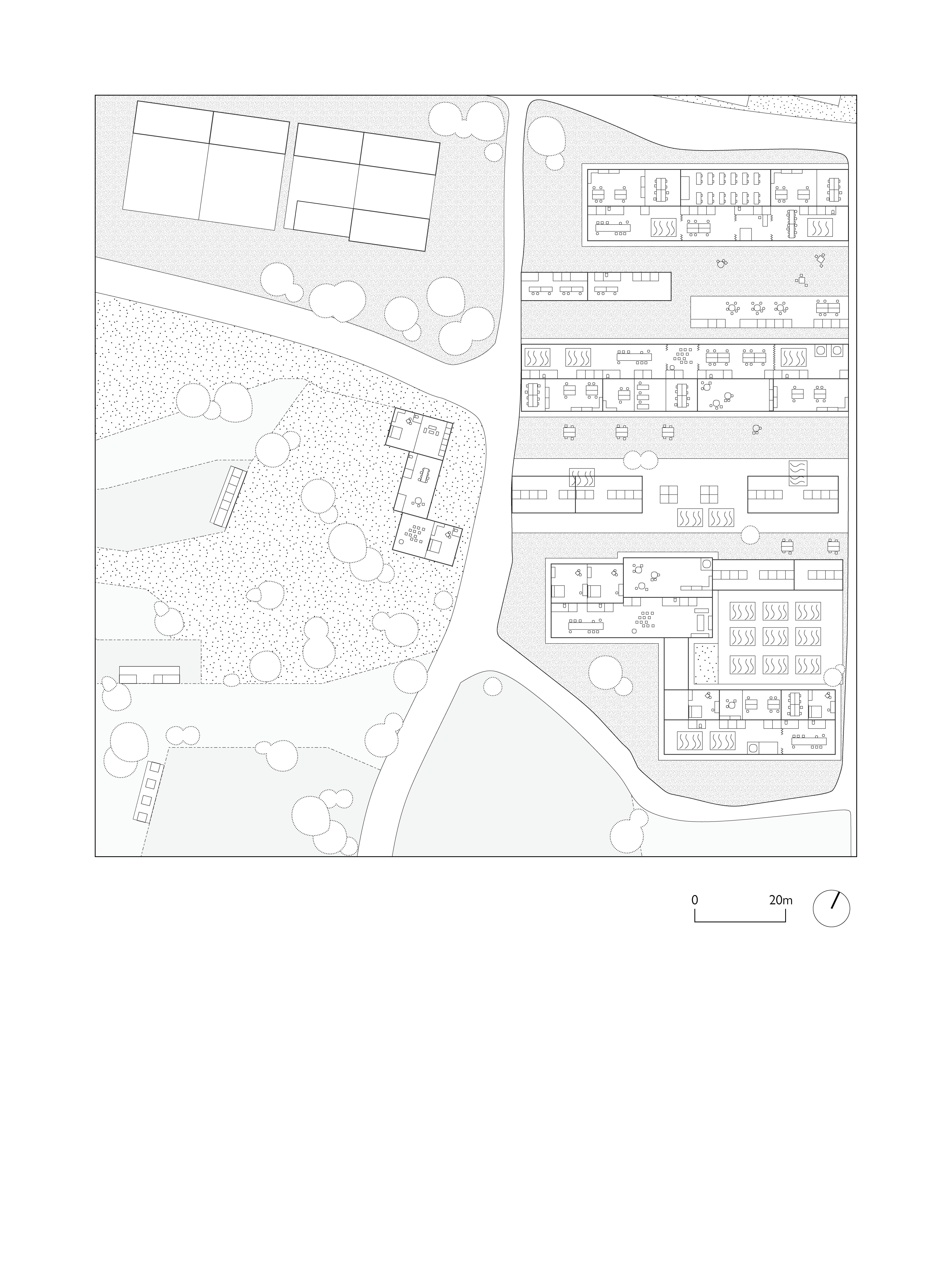

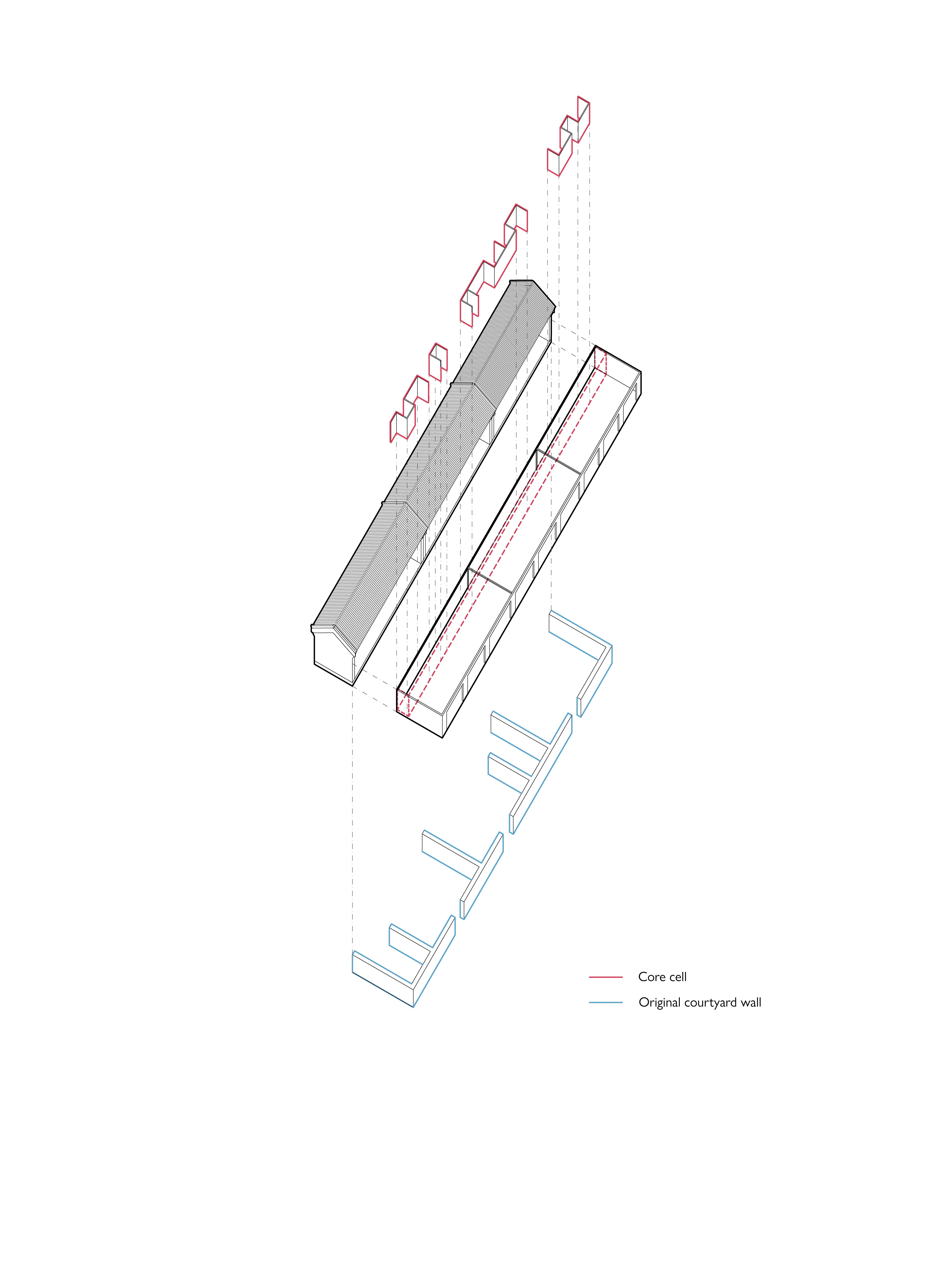

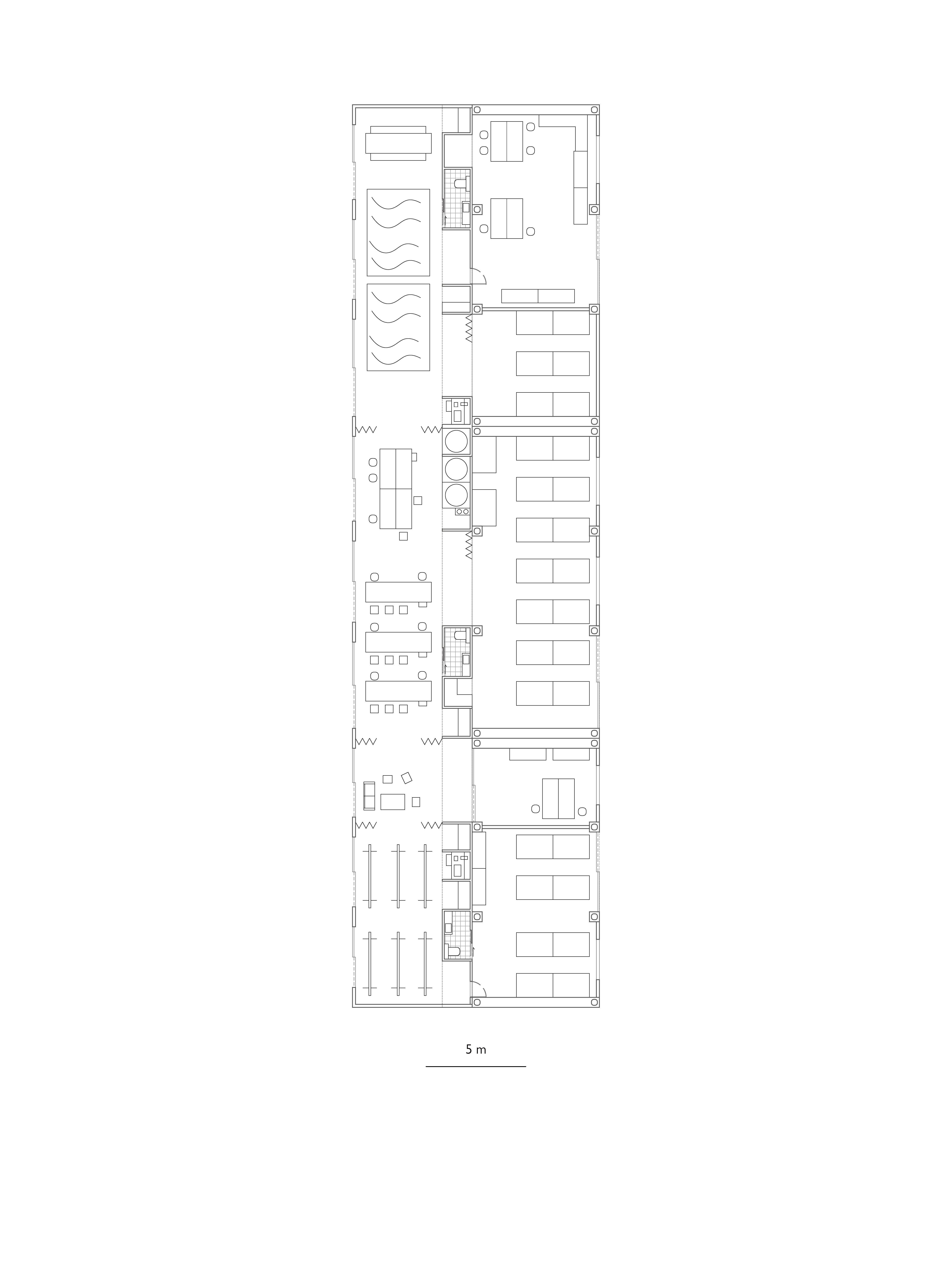

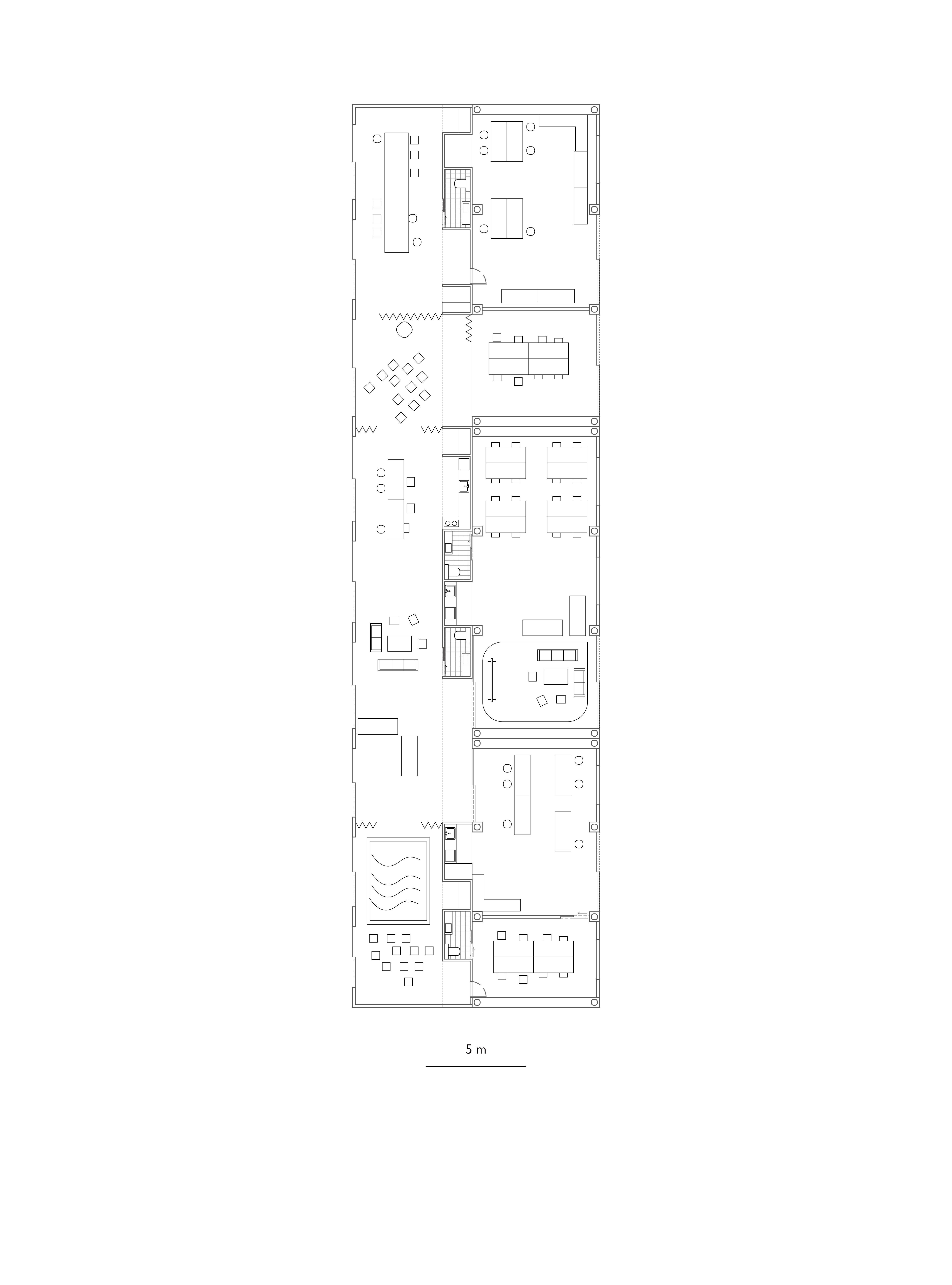

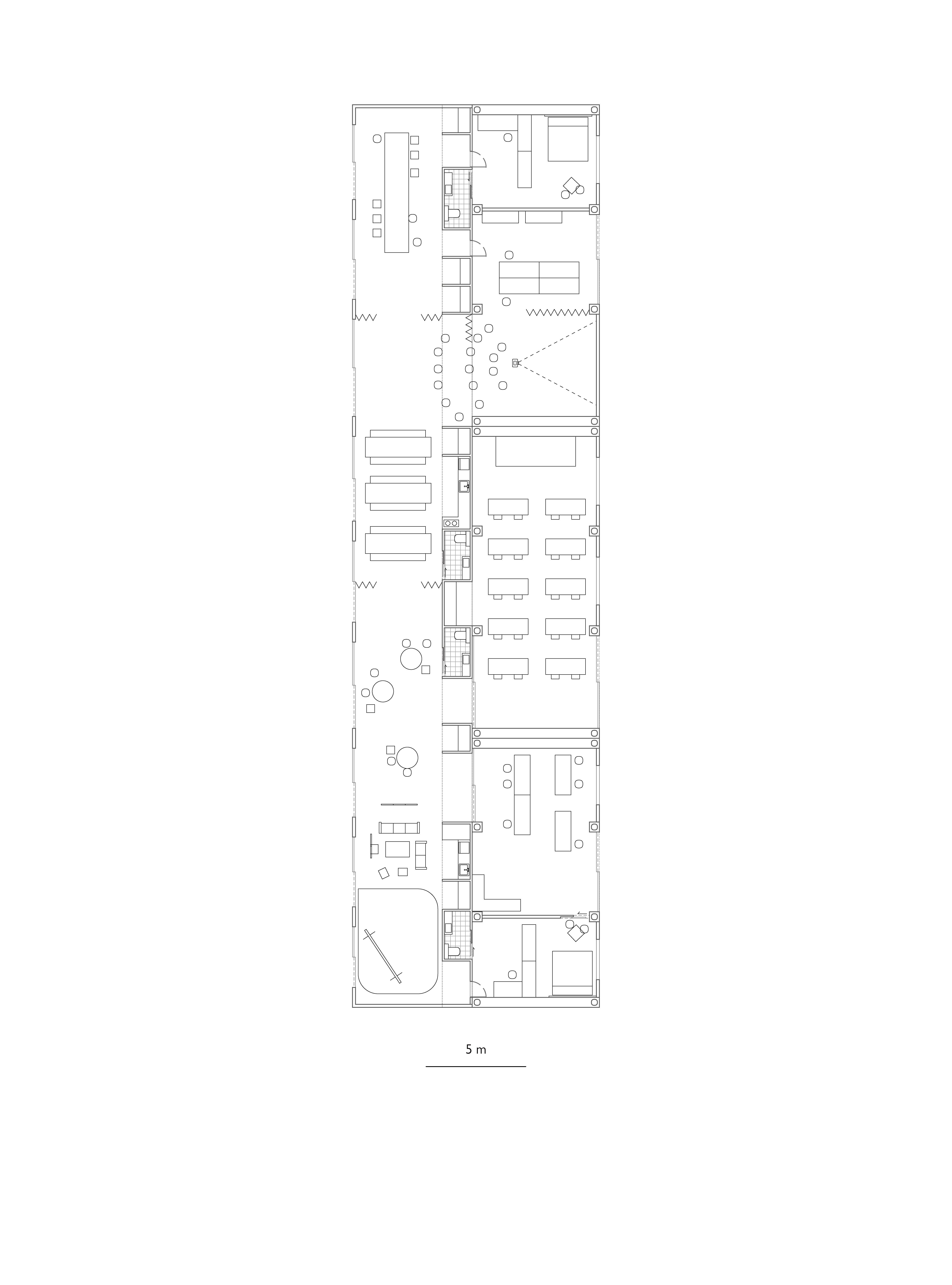

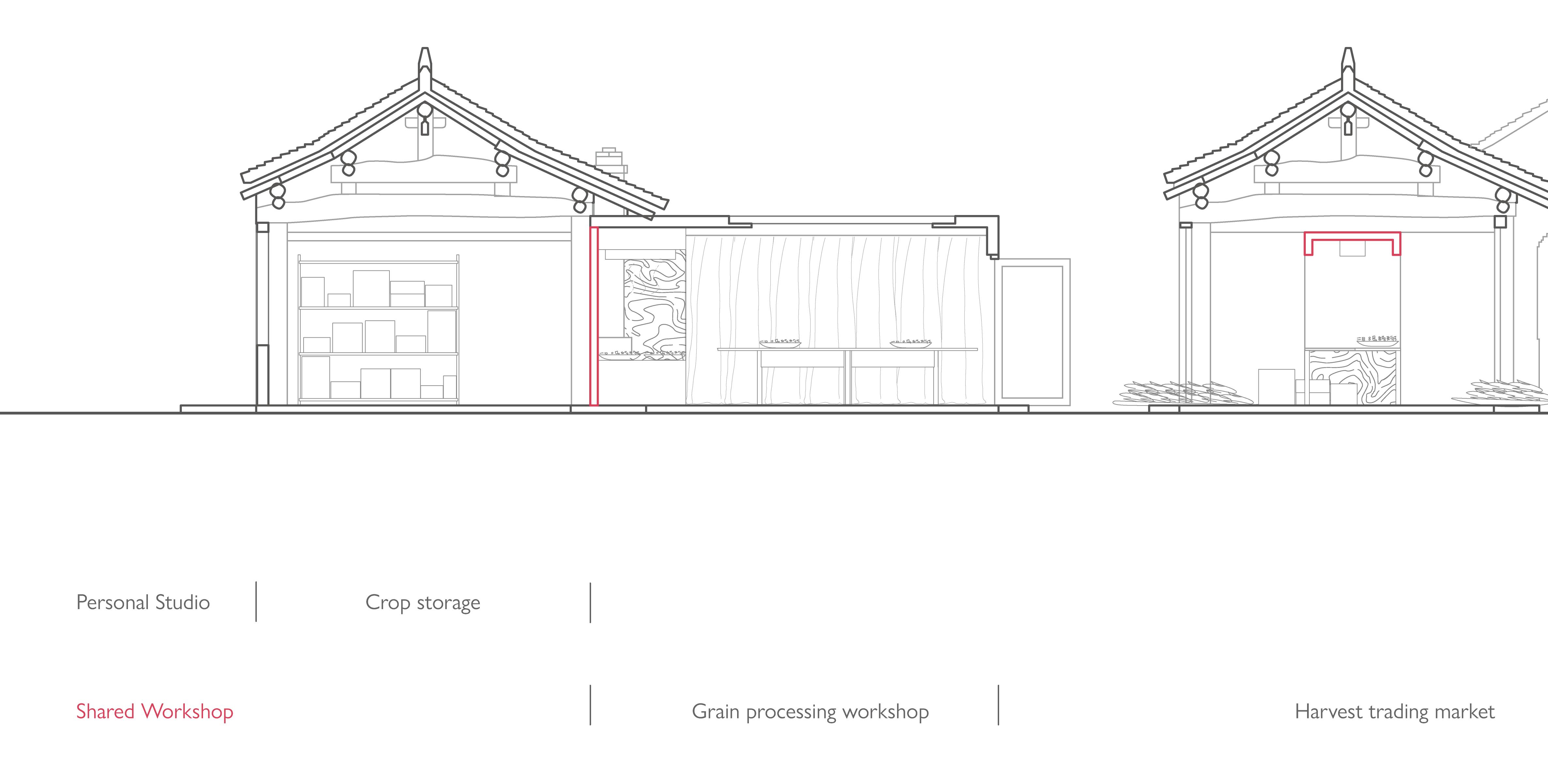

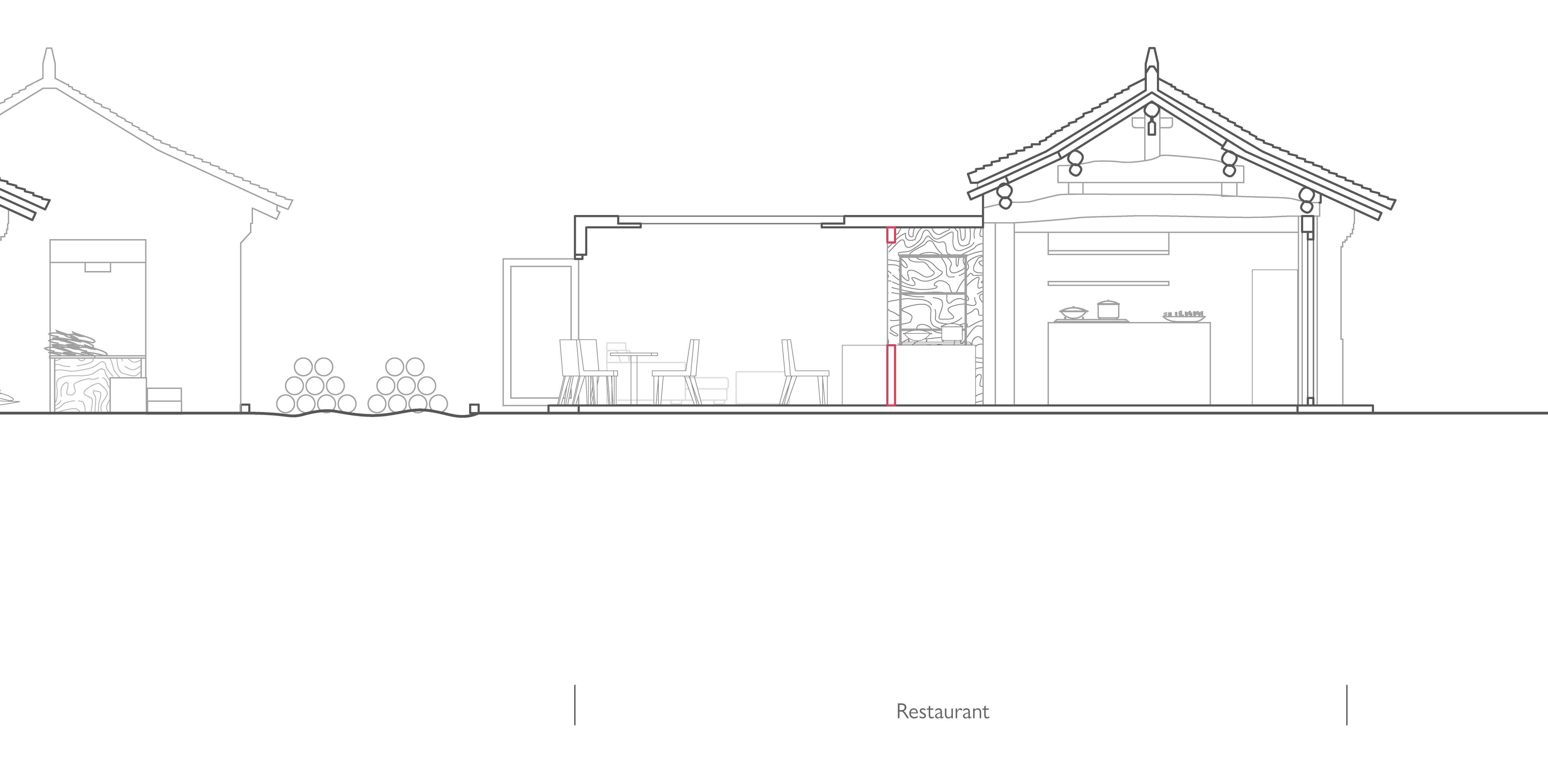

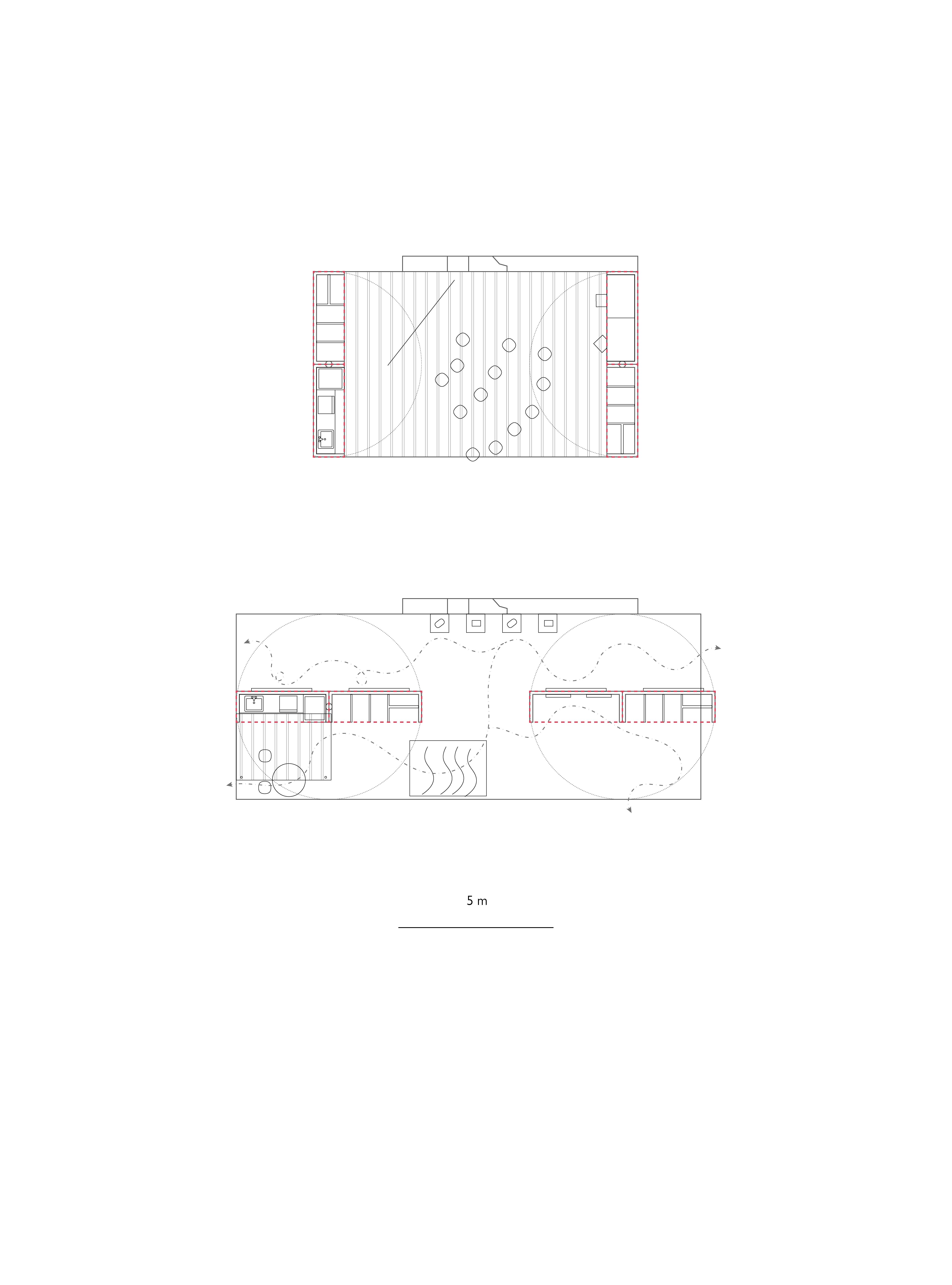

The chapter focuses on the courtyard and the settlement, the basic spatial unit in the co-environ model, which relates to cooperation on a family scale. In particular, the courtyard has evolved over time in several major spatial forms transformed, by the political and personal life design shaping over time. With the courtyard as the environment, long-term occupation manifests a complex transformation of assembly, hybrids and connections, so the long-standing spatial form is no longer stable.¹ Above all, the evolving activities of the family, based on selfbuild, linked the environment elements and provided the possibility of future family evolution.

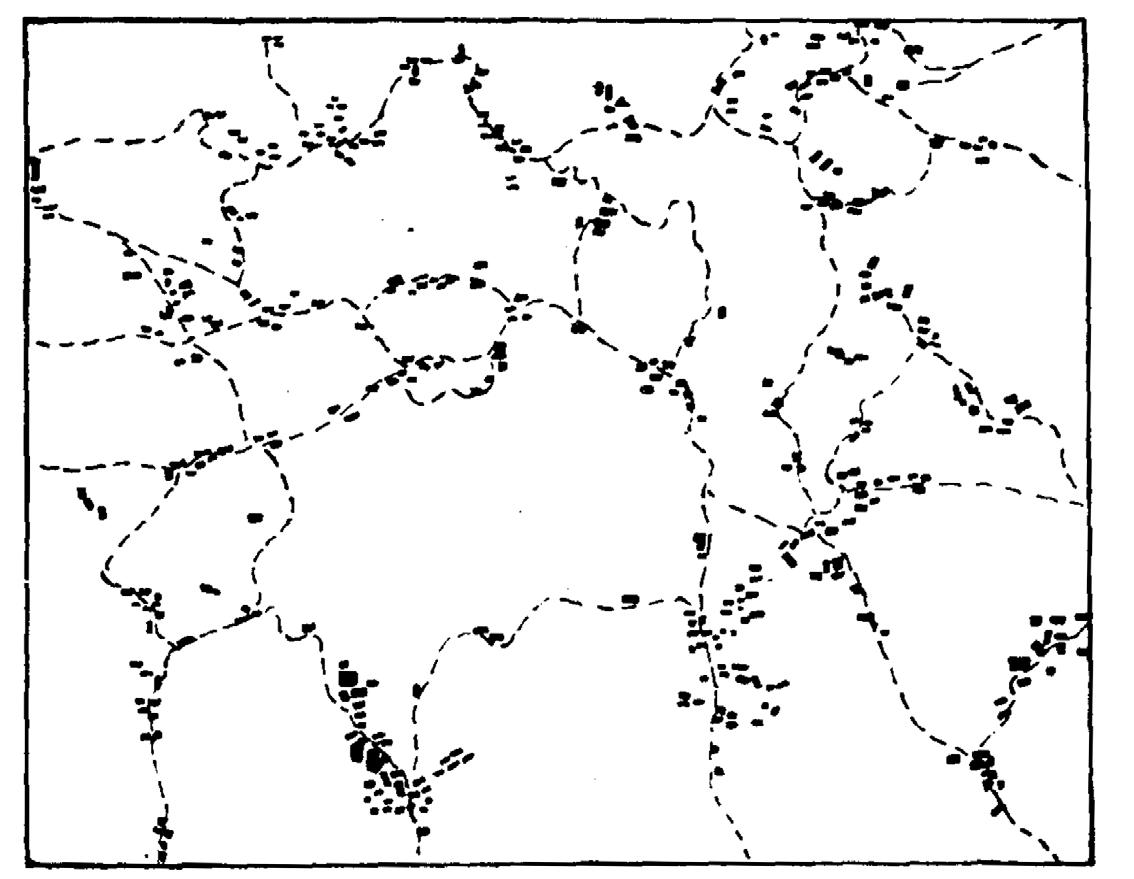

3.1 Opening up the land: the hamlet's formation

The spatial form of the courtyard in the mountain villages follows the locality. It is shaped by the combination of production, specific environments, and family cooperation. Firstly, the typical courtyard of rural settlements still follows the traditional courtyard paradigm, which has long been considered a 'Feng Shui' requirement for building houses. At the early stages of building, villagers would use a basic unit called a 'Jian'² to define the size of the house. The orientation towards the south-facing light plays a crucial role in ascertaining the quality of living in the rural courtyard. Liang Sicheng describes the plan form of the 'Si He Yuan' as a collection of units,³ revealing that the function of

1 The courtyard layout, with the 'Si He Yuan' at its paradigm, has long been regarded as a fundamental element of the family. It is reflected in the 'Feng Shui' of the relationship between the major and the minor of the house. For more details: Sicheng Liang. " 中国建筑的特徵 ." Architectural Journal (1954): 36-39.

2 In the ‘Qing Structural Regulations’, Liang Sicheng defines 'Jian' as the area enclosed between the four columns

3 Sicheng Liang. " 中国建筑的特徵 ." Architectural Journal (1954): 36.

FIG 3. 6

←FIG 3. 0

Xiaosai Hao. Research in Feature of Courtyard Space in Northen Mountains -through the Ancient Village of Chuandixia in Beijing. (2002)

47

3

Chapter

Hamlet Assembly

48

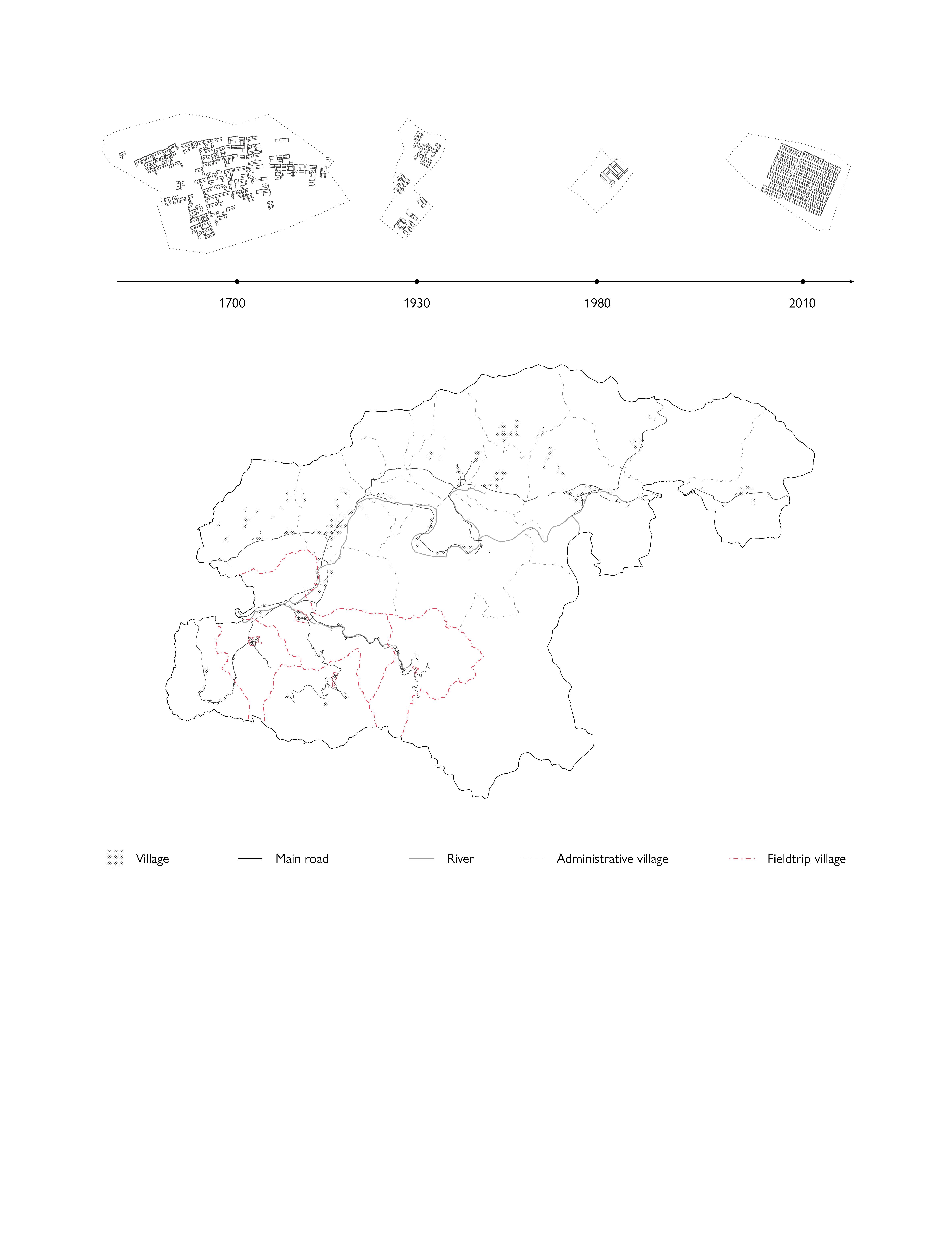

FIG 3. 1 TYPOLOGY OF THE EVOLUTION OF COURTYARD From ancient huts to modern courtyard

49

these houses was defined by the combination of 'Jian' rather than by a particular scale.

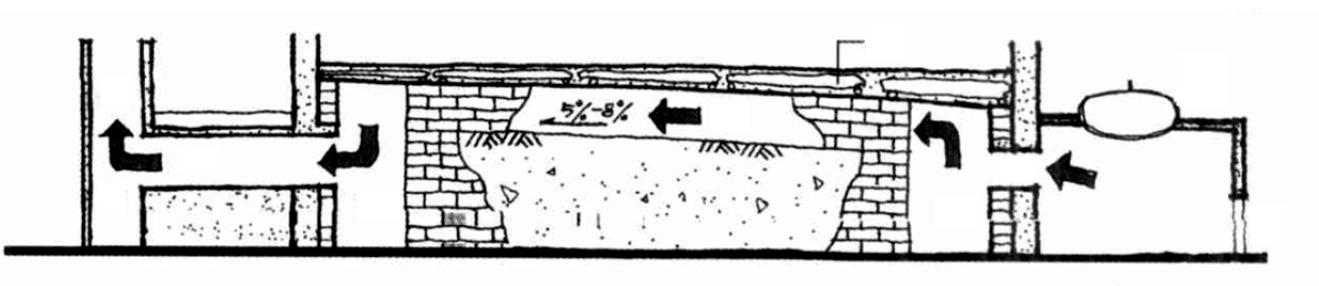

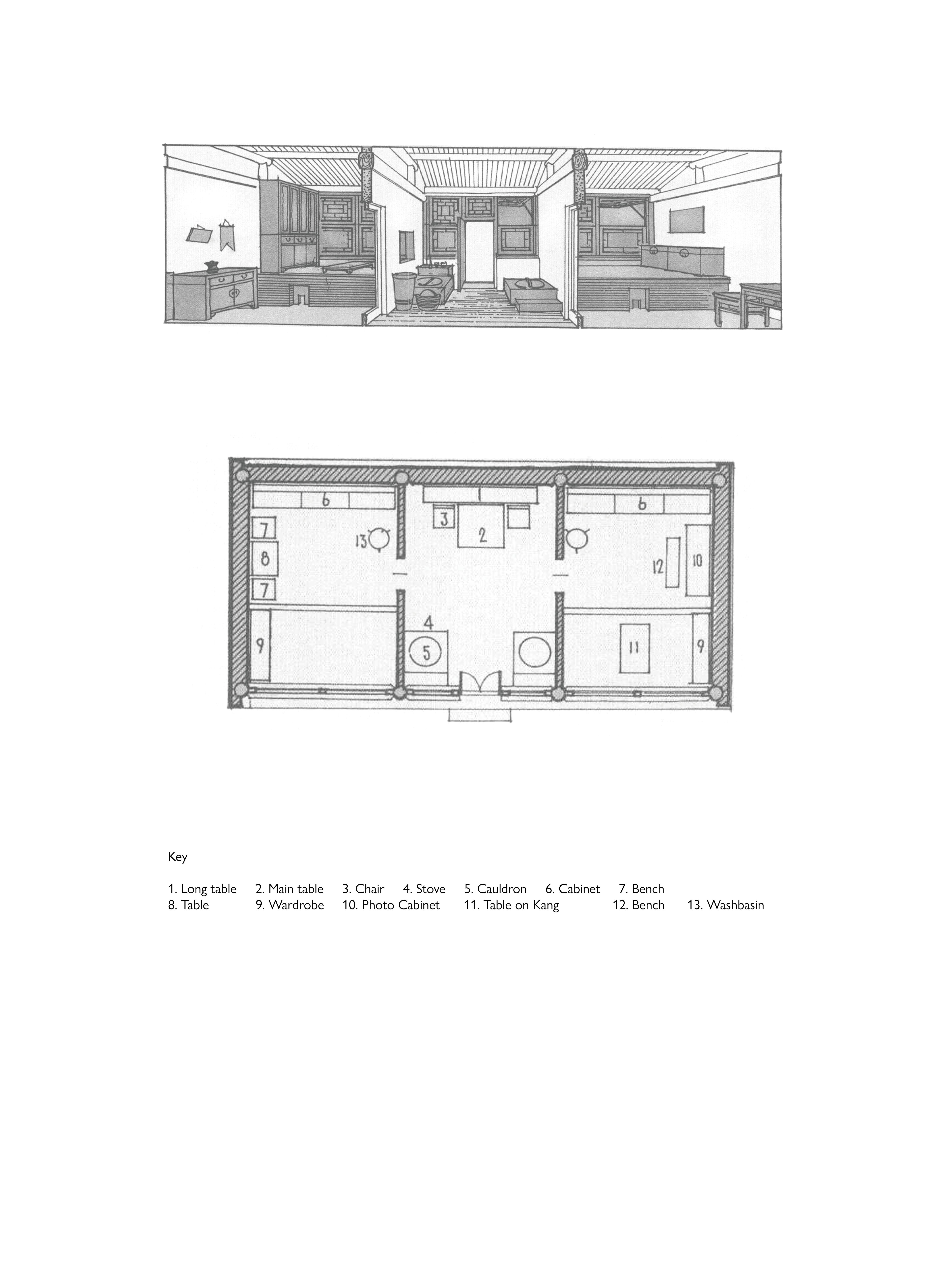

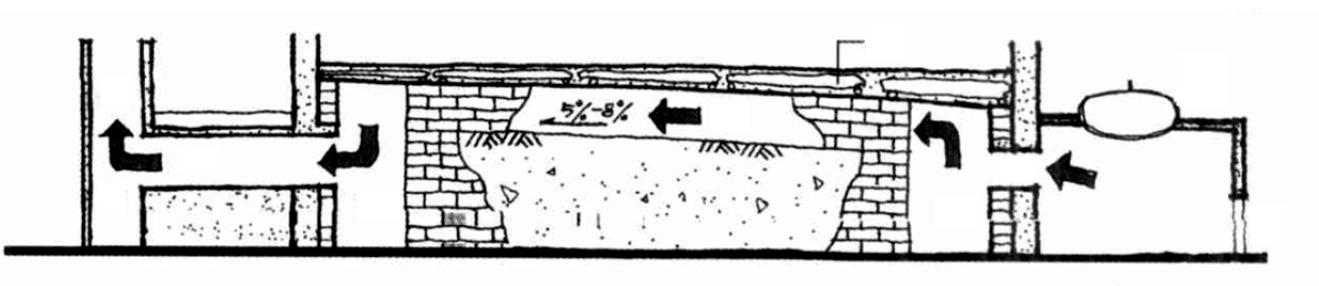

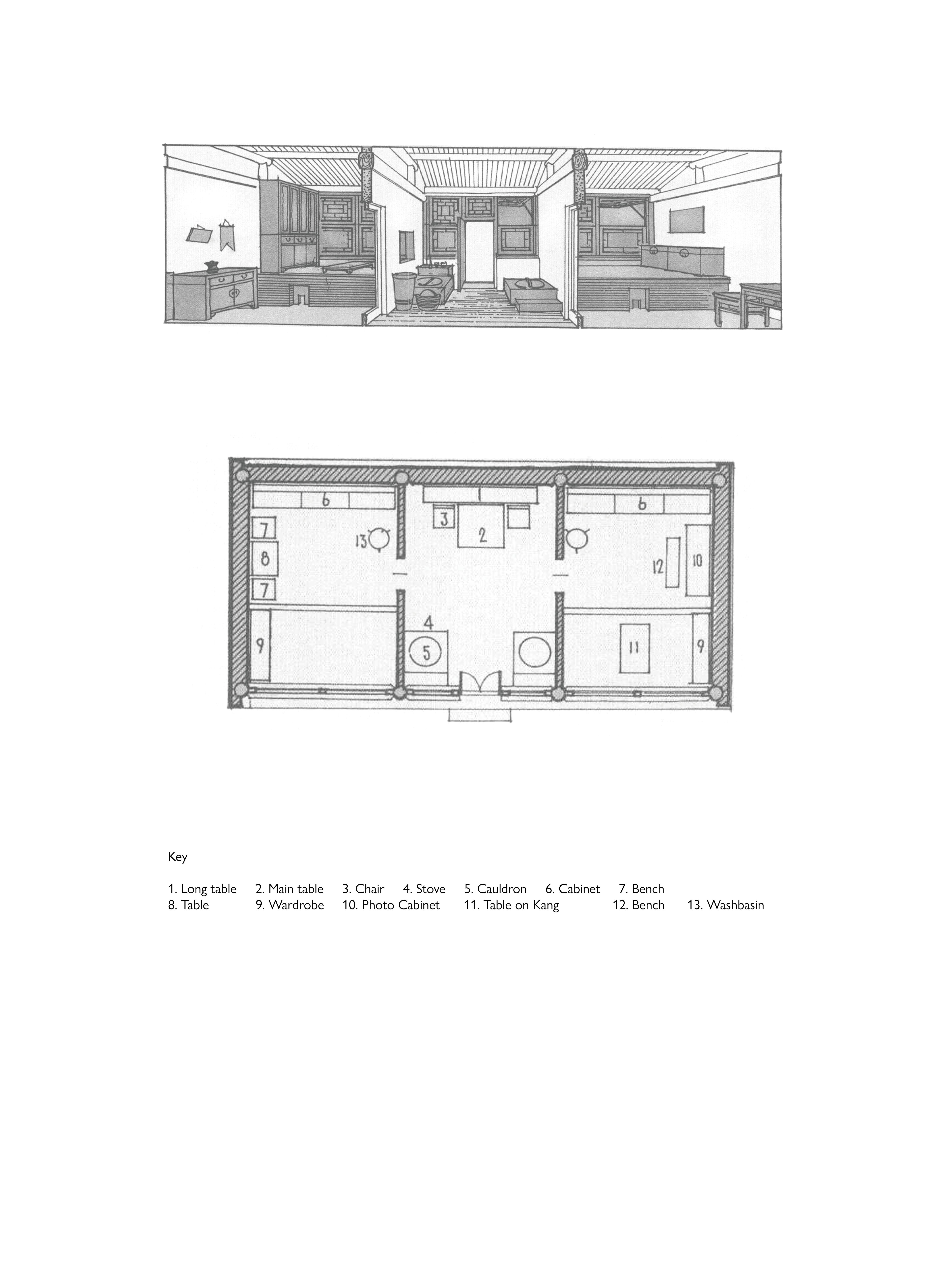

However, in the mountain village settlement, the courtyard structure, which takes the architecture paradigm as its point of departure, usually requires evolving how the different farming and daily activities are applied. A typical example in the house is the living room, known as the room have 'Kang'. Usually, these rooms are placed symmetrically in a 'Jian' on either side of a standard south-facing house. The Kang is a bed-like 'platform' with a heating channel for burning, which is connected to the kitchen stove. With the need for heating resources, the Kang is not only used as a gathering place for family rest, it is also used in a diversity of temporary scenarios, such as dining, heating and drying processed mushrooms and other crops, which transcends the stereotypical 'Jian' and emphasises the hybrid of the space.

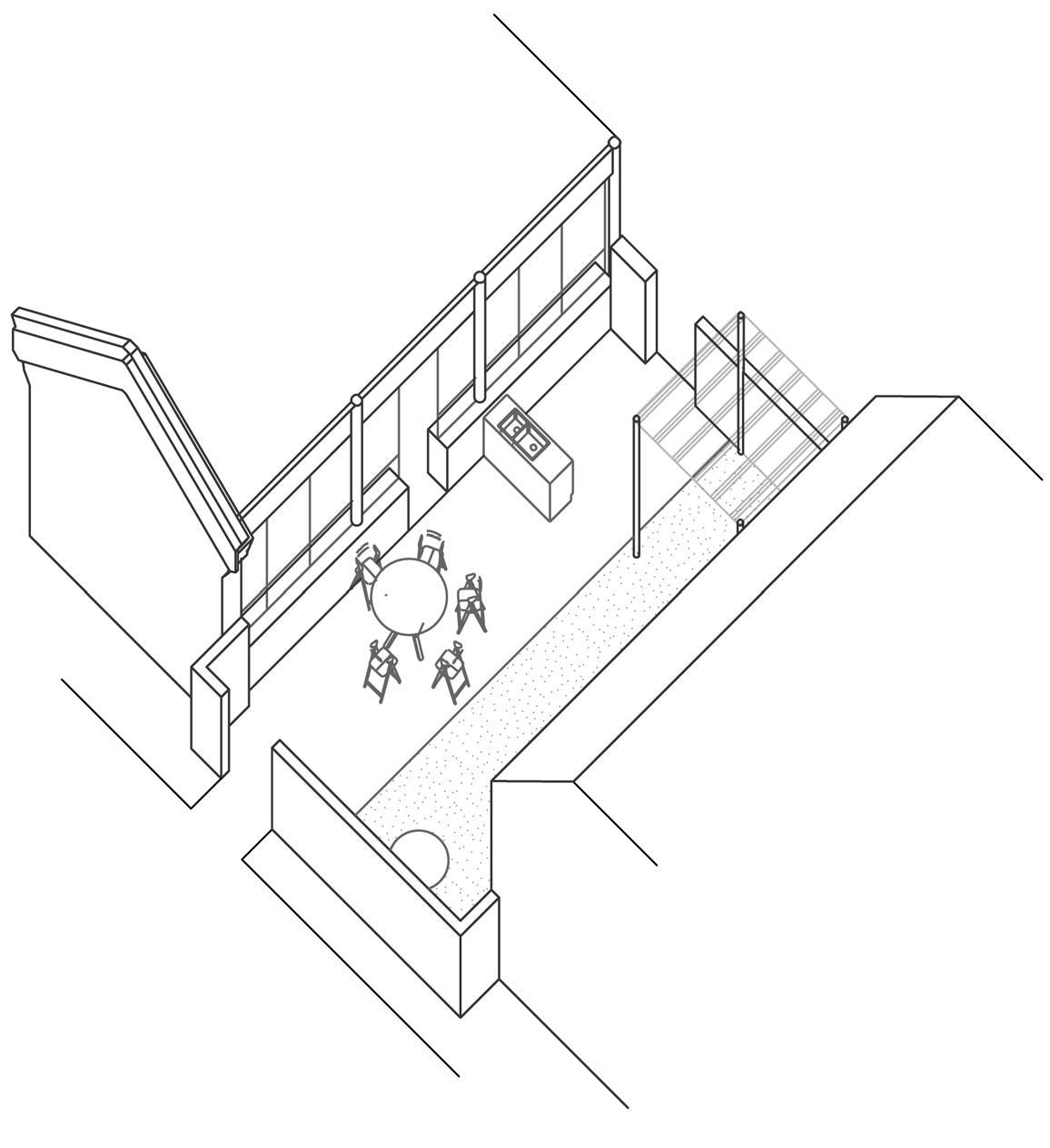

Extended to the whole courtyard, the same hybrid happend between the house and the open space. An example is the extension of kitchen and kitchen gardens. Often, the villagers used to place the tap or devices for handling vegetables next to the kitchen garden rather than indoors. This allows the wall to no longer fully define the interior, but to become an annexe to the kitchen in the courtyard. Often, these earthen walls are thick that make the window ledge a platform for different processes of living and storing household items, and even, with horizontal window openings, spaces such as the kitchen spread out fully into the open space, so that the interior and exterior become a whole with a traversing quality.

4 According to the records, a huge number of Beijing's mountain villages were the refugee to the Shuntian (Beijing) around the mid to late 19th century during the Qing dynasty, and due to activities such as the royal enclosure of the land, they could only establish small settlements in the mountains, which in turn allowed this traditional pattern of family cultivation to continue for a long time.

Meanwhile, comparing the similarity and differences in the courtyard between the different periods: in the transformation of the thatched hut into the typical farming courtyard, the product needs of the courtyard reveals the link between farming life and natural resources. Even though family and policy strongly influenced the shaping of the land in the transformation of house forms, it needs to be argued that most of these long-standing villages were not actually 'traditional'. Those ancient villages that have existed for more than 200 years are few in the mountain village area, so these small and fragmented villages are often less influenced by the extended family, such as kinship, and more directly shaped by the environment.⁴ Therefore, this courtyard formation can be considered a continuous opening up of the environment within the background of families and policy.

50

FIG 3. 2

The "Kang" scenarios, a multifunctional space

FIG 3. 3 HOW 'KANG' WORKS

FIG 3. 4 OPEN SPACE AS A 'JIAN'

The wall as a threshold and device, linking the indoor and outdoor space

FIG 3. 1

51

FIG 3. 5 TYPICAL FARMING COURTYARD

This farming courtyard illustrated pragmatism, the farmland in front of the houses was known as the self-owned farmland.

5 As mentioned above, Open up land is a reshaping activity to adjust the Geo-special territory through policies and family-based collective structures, and cooperation arises from this long-term process; identifying the environment and territory with multiple uses.

6 Ronald G. Knapp mentioned such a small village cluster as a hamlet, emphasising that several different settlements forming a cluster included farmland and shared farming facilities. Knapp, Ronald G., ed. Chinese landscapes: the village as place. University of Hawaii Press, 1992. 262-265.

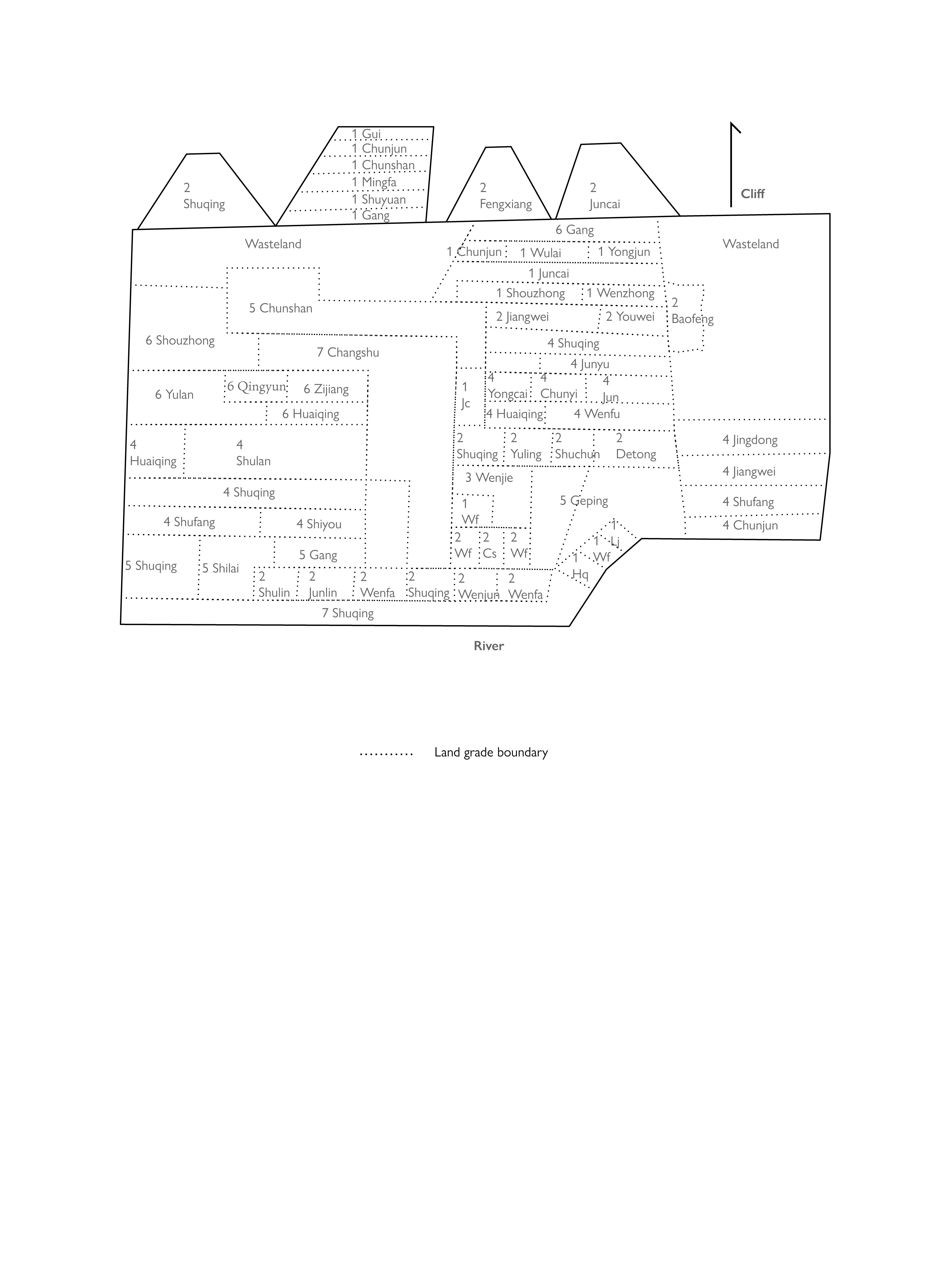

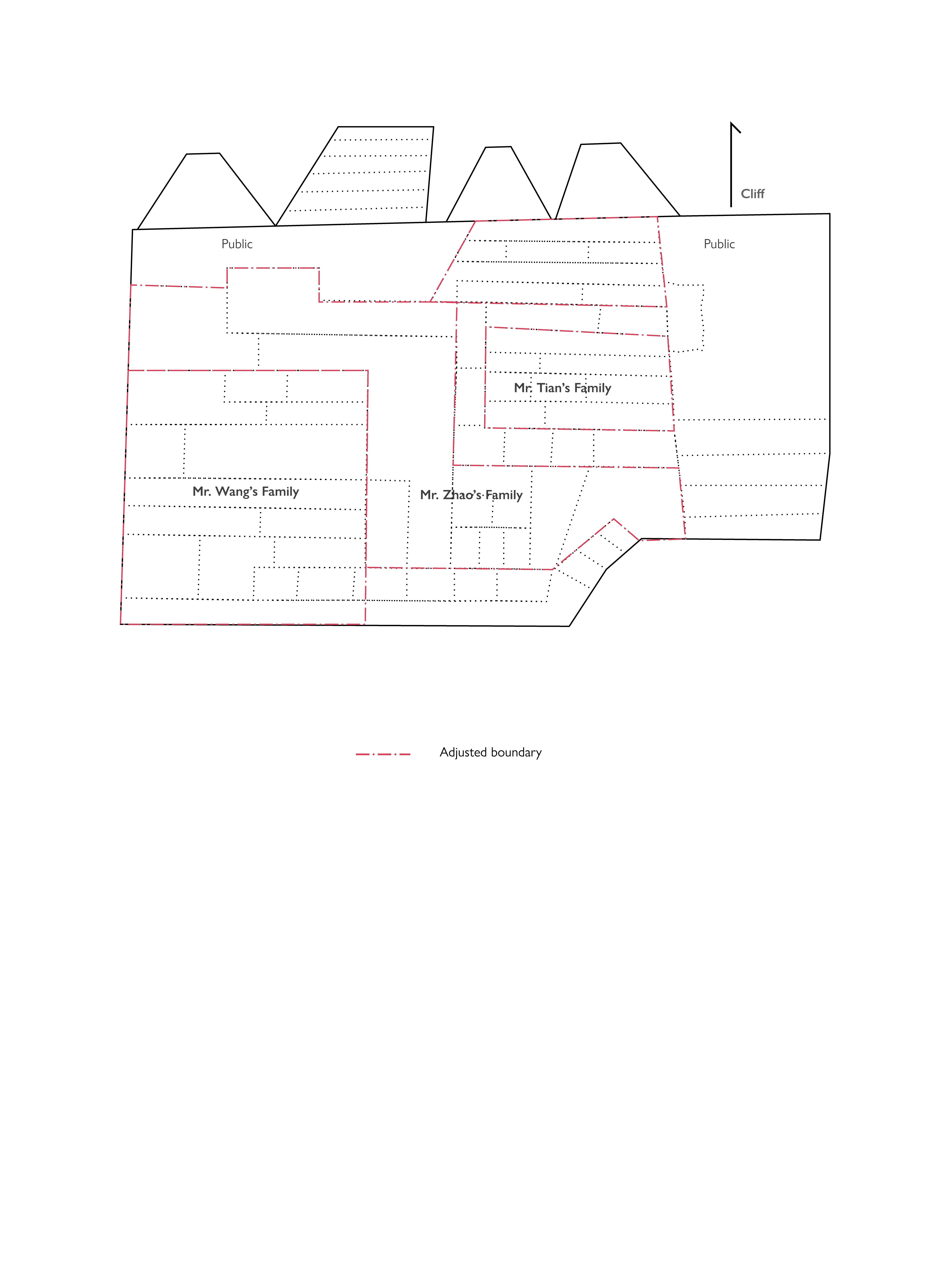

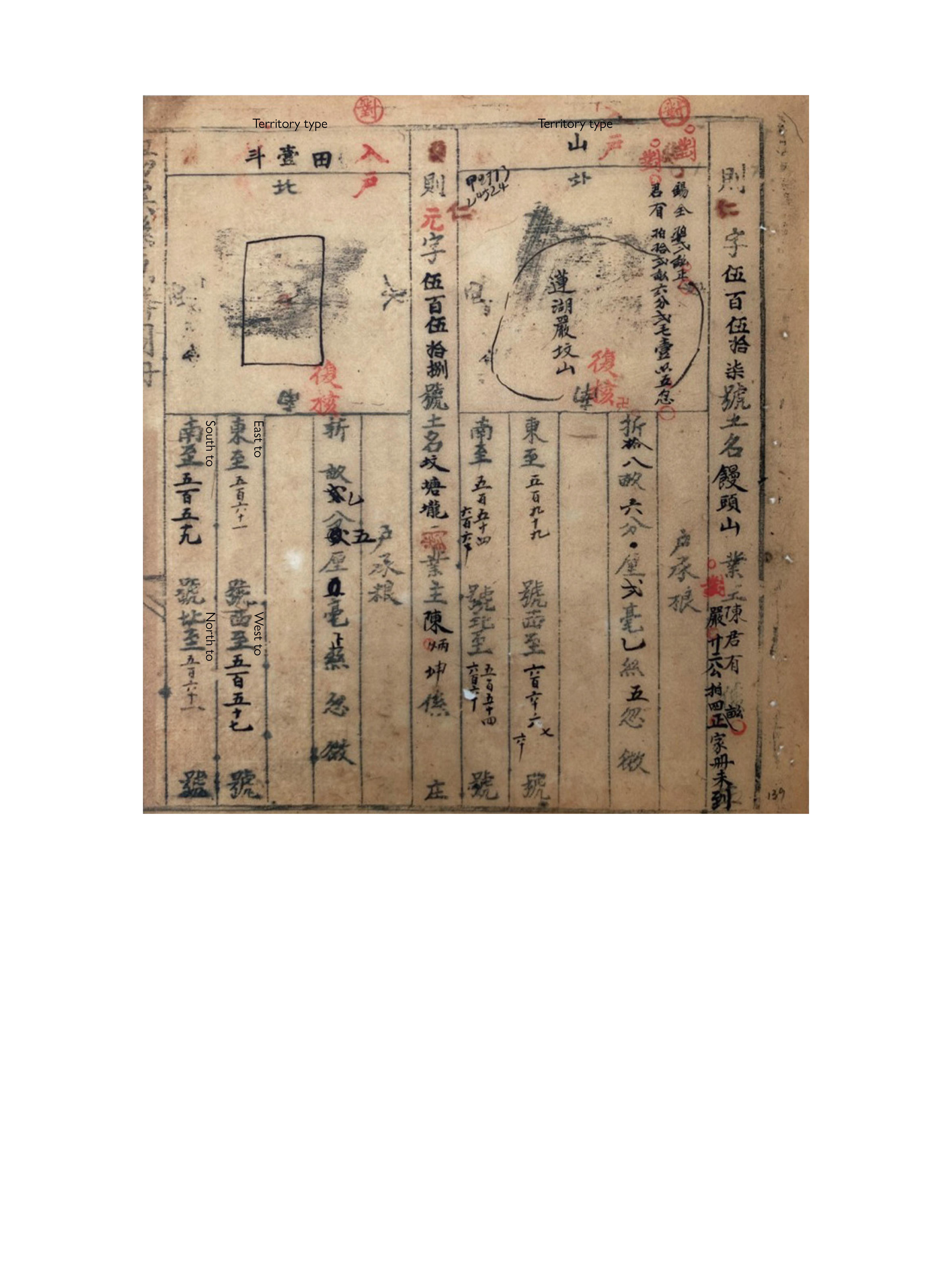

The evolution in the courtyard is also directly linked to the changing rules of homestead policy. From land deeds to a model of collective ownership of land controlled by the state, villagers' autonomy over their territory is expressed in self-designed space structures. This is not a one-off work but a long-lasting process of opening up the environment.⁵ The courtyard therefore as a projection of the family does not only exist as a sequence of personal living; on the contrary, it constitutes a network of relations linking the different courtyards. Such a network reveals the pattern of settlements in the mountain villages, with shared environment elements forming cooperation of negotiation in the neighbourhood. It is a gradual process in which family living breaks out of the courtyard itself, transcending the limitations of the architecture paradigm and the homestead policy, forming a sequence of life more related to the living environ. This argument matches Ronald G. Knapp's study of villages in middle China, which refers to a model of small villages with four to six households living together in farming. The dissertation will follow the Hamlet⁶ concept to define these groups of courtyards linked through the environment.

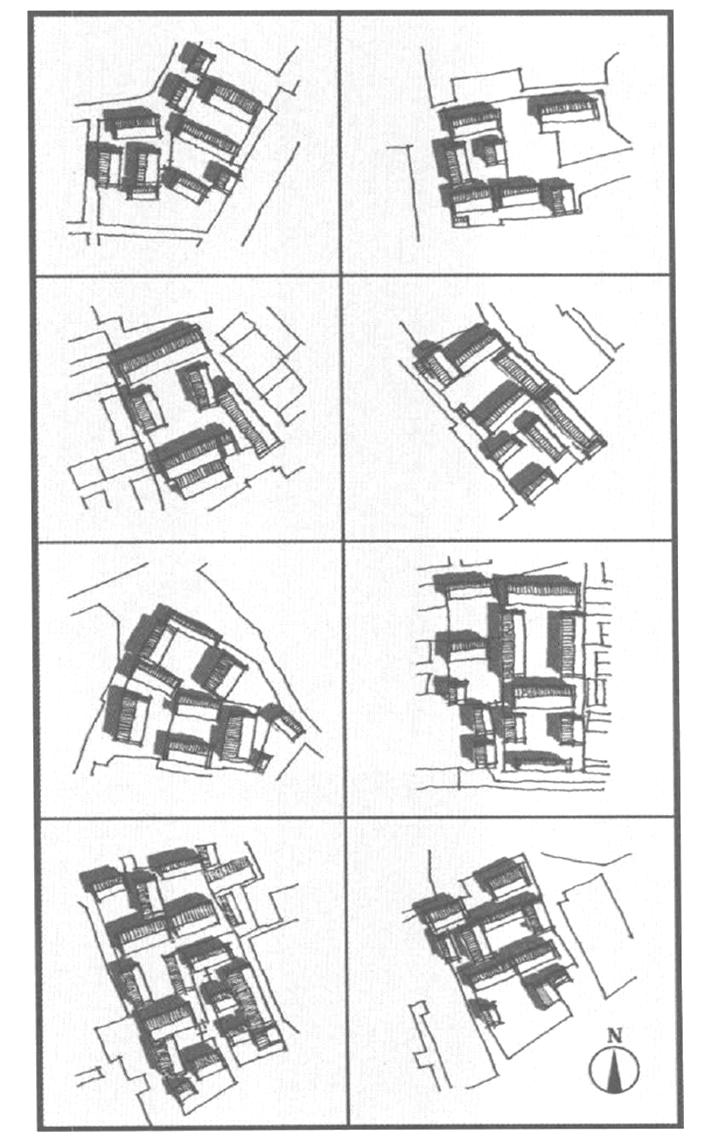

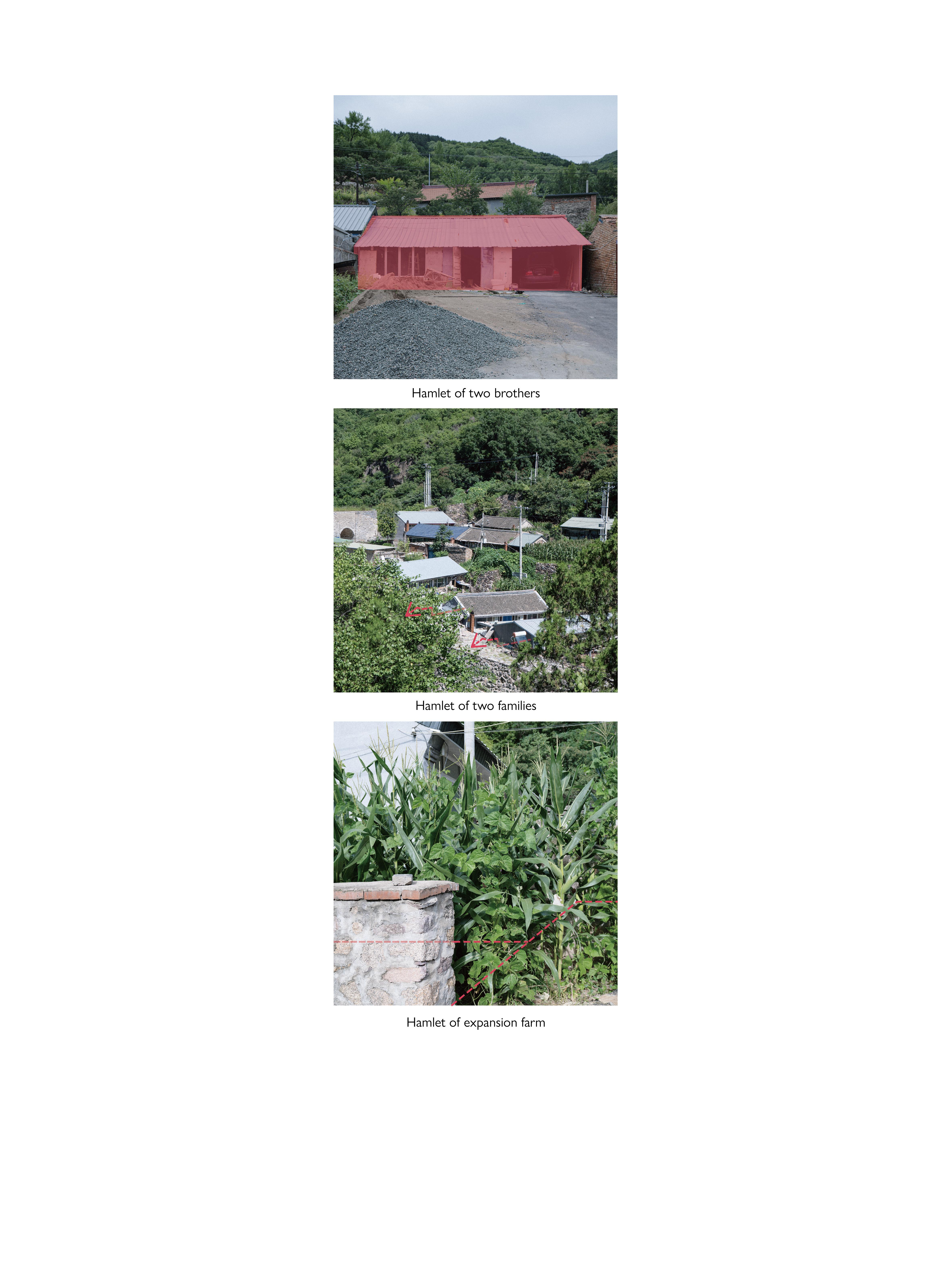

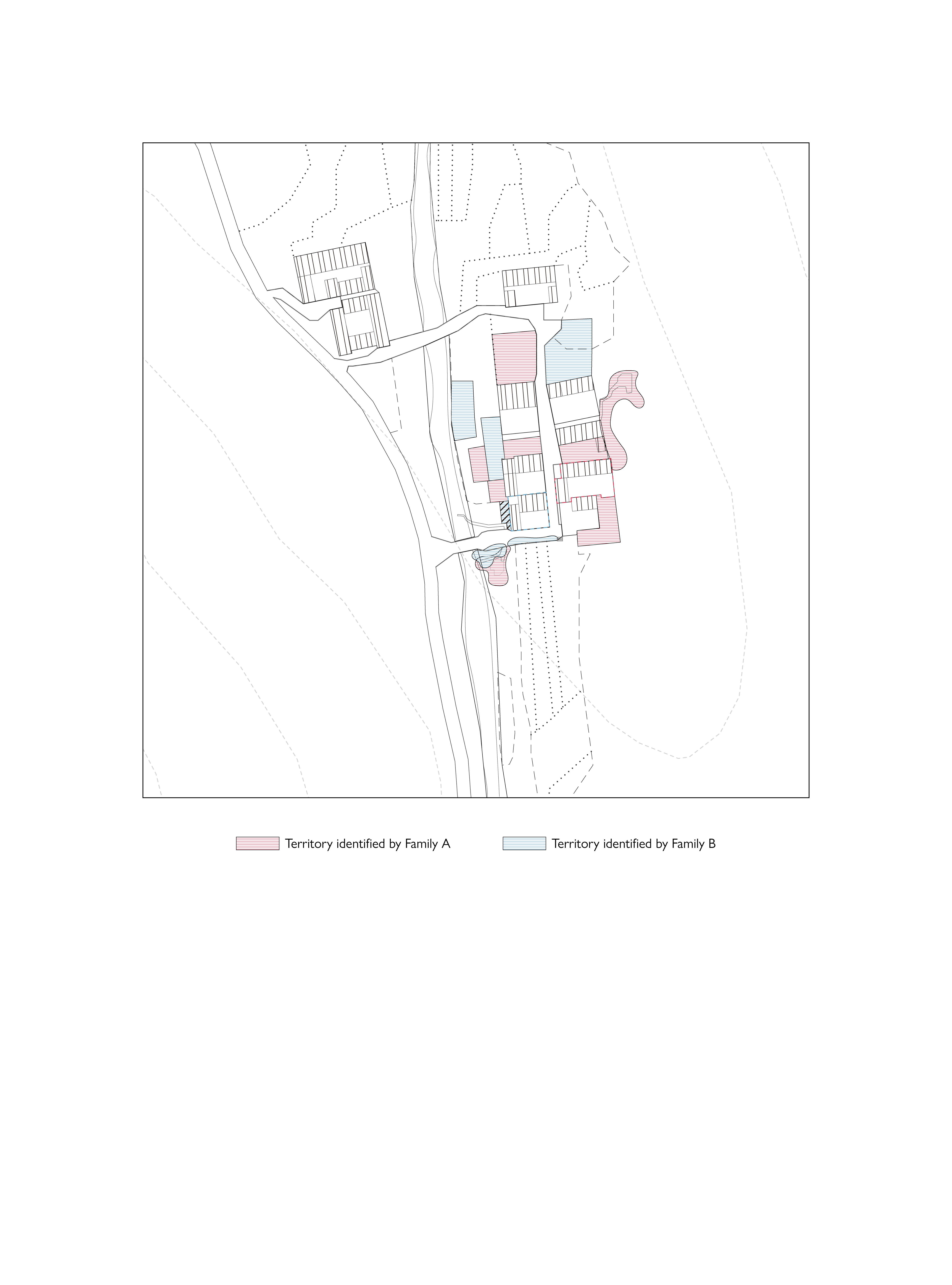

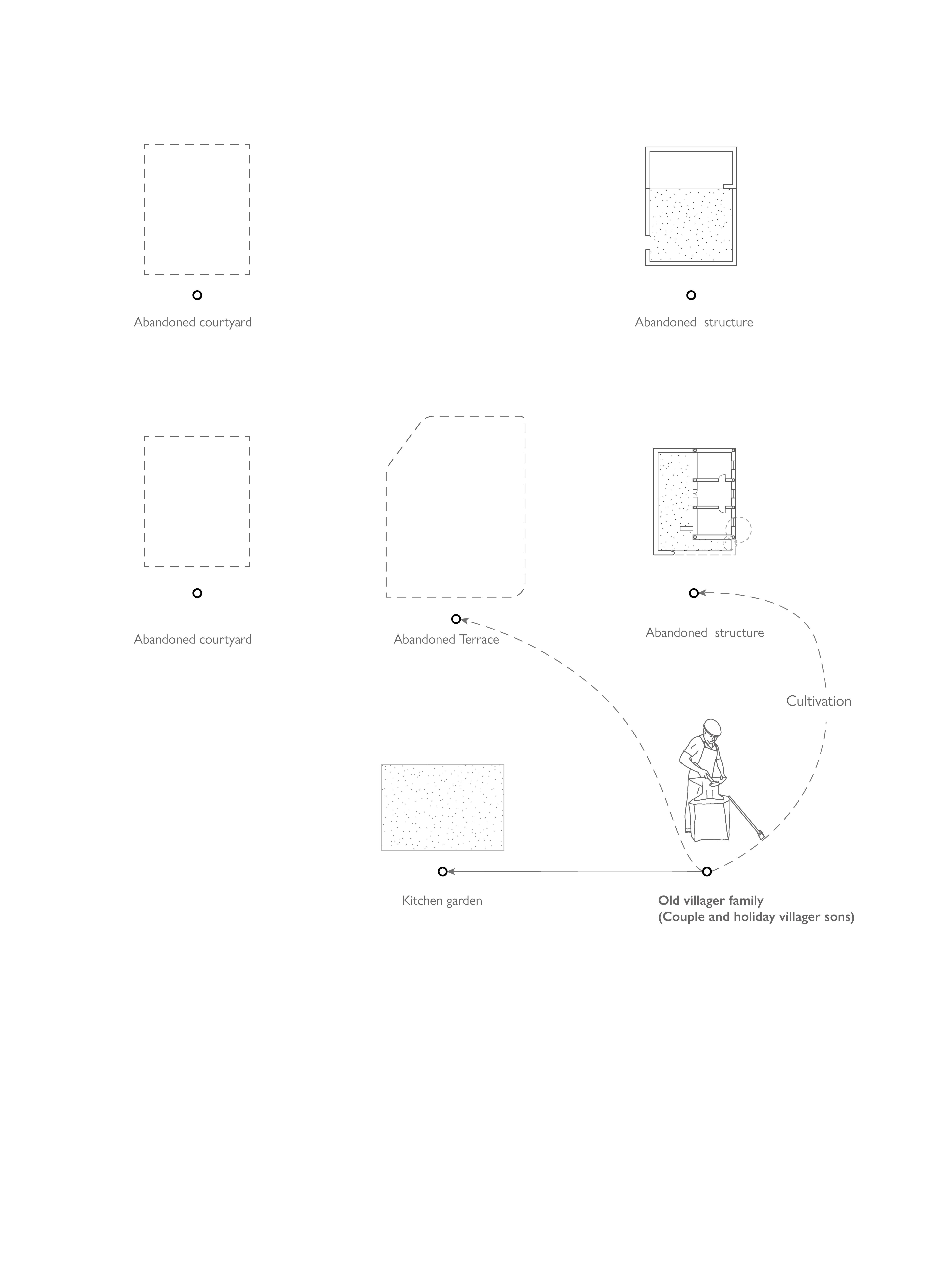

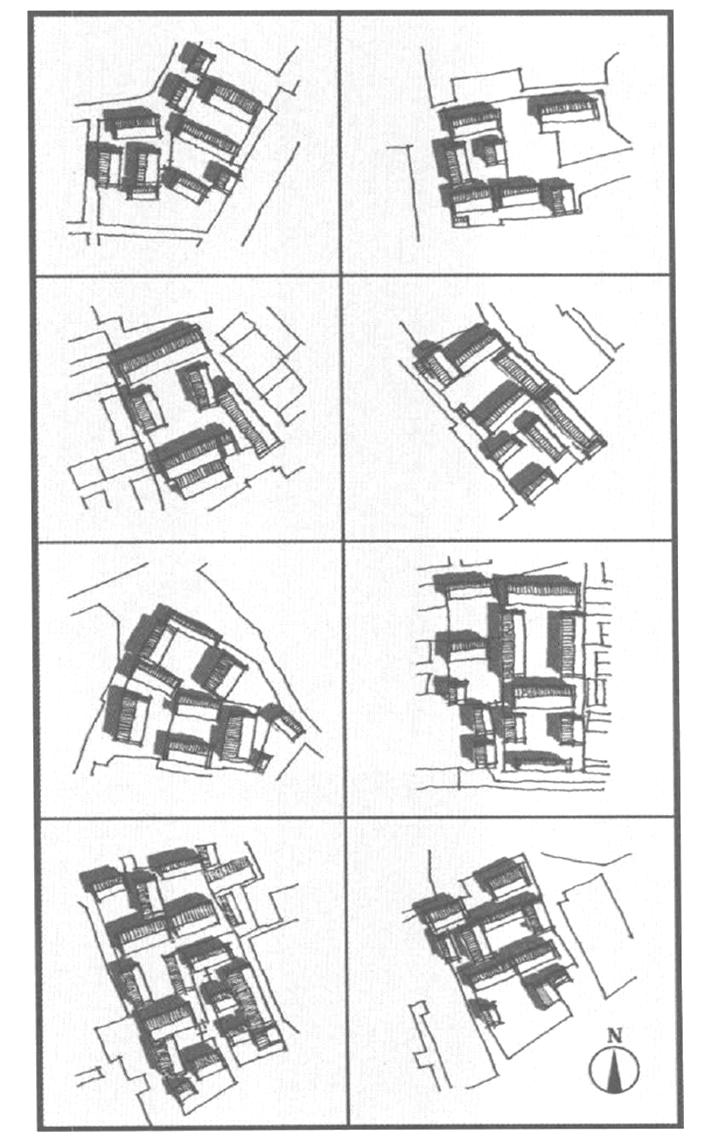

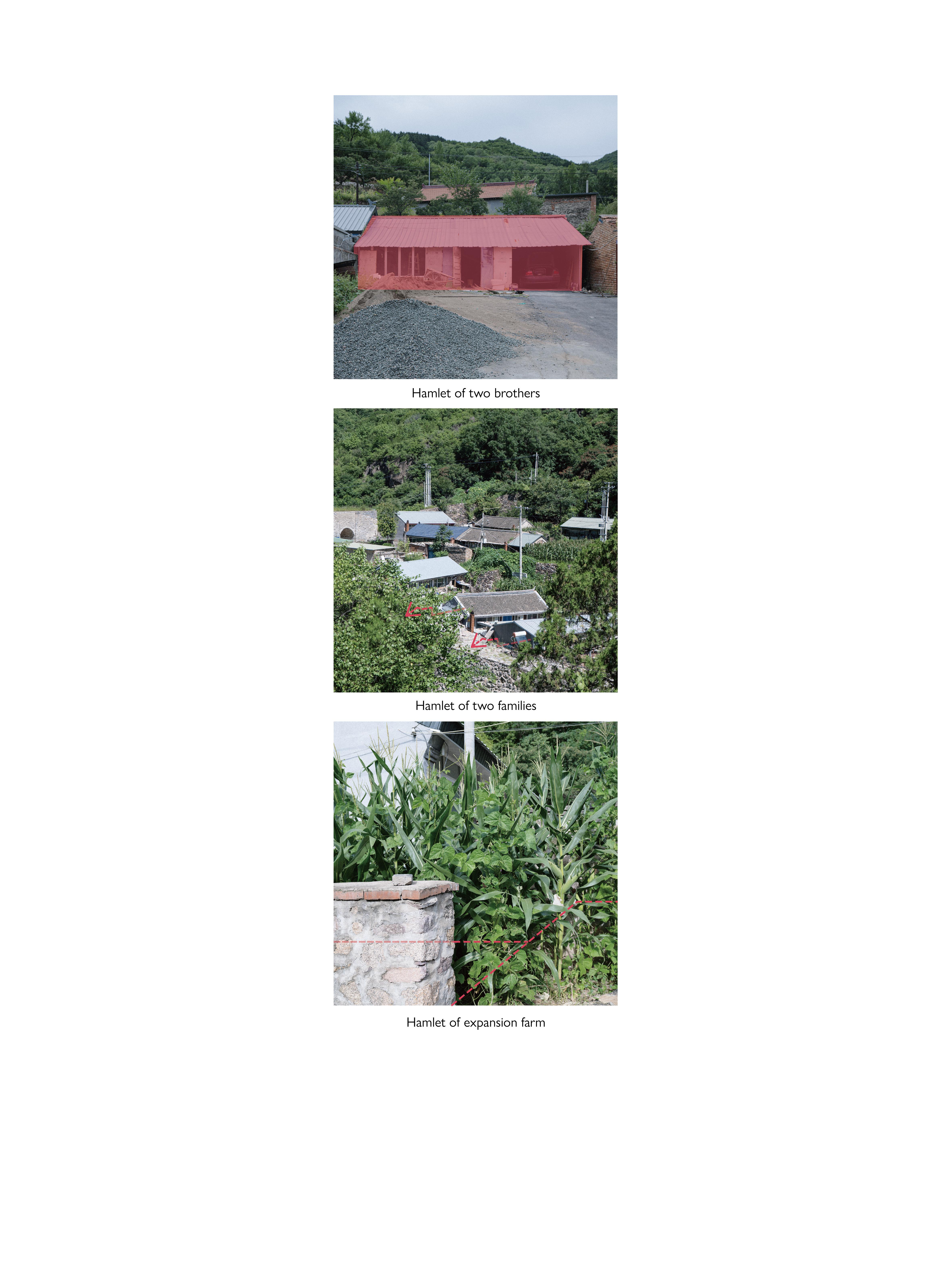

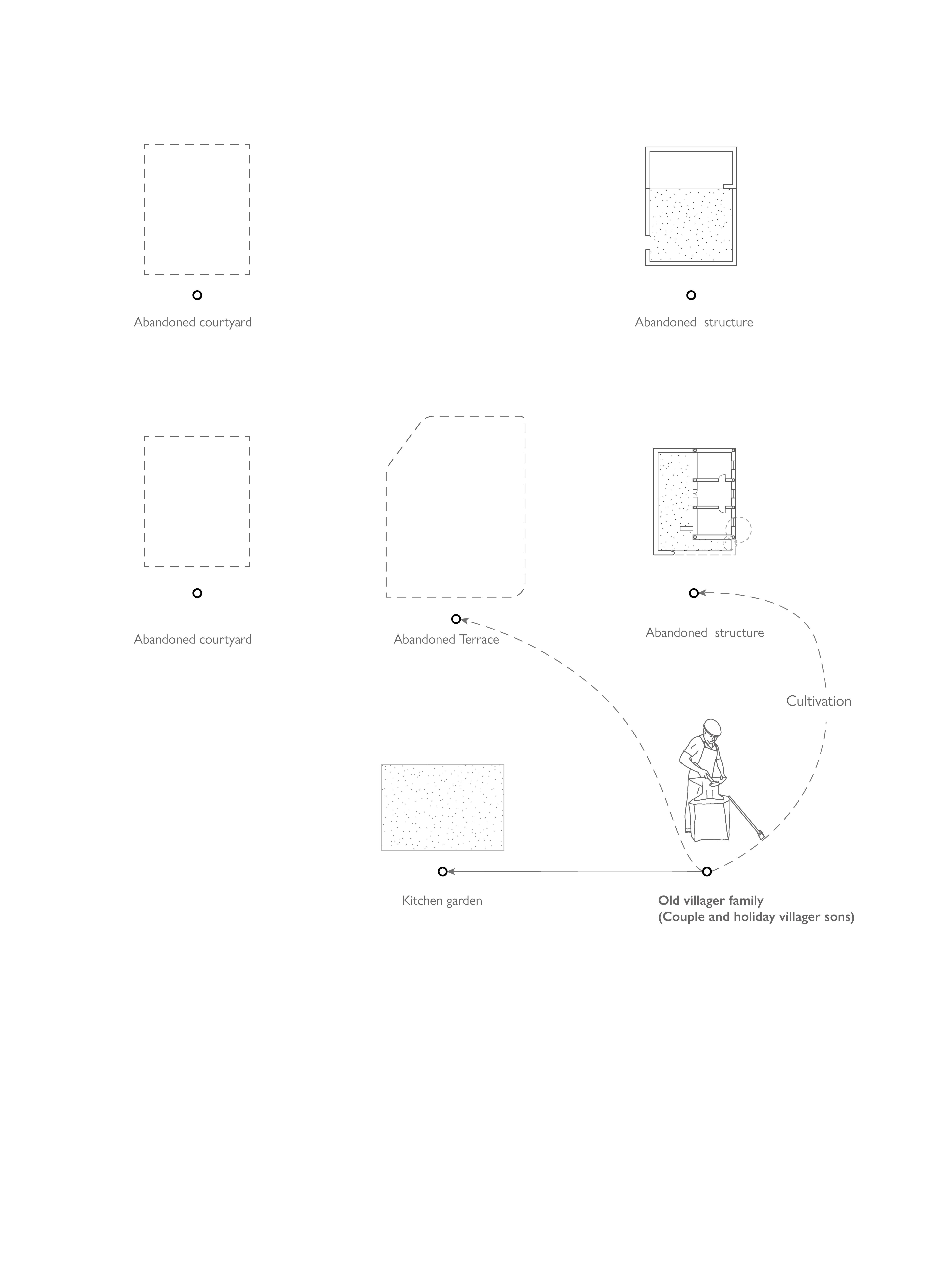

In the chosen villages area, three cases were used as prototypes for the hamlet in terms of what forms the basis for family cooperation: The family connections (prototype 1); The environment sharing (prototype 2); and The union management (prototype 3). These prototypes were chosen due to the fact that they are based on the expansion of new connections between the courtyard and the environ, which in turn transform the courtyard's original structure and constitute gathering outside the courtyard. In addition, this leads to an innovative conception of the family that departs from the traditional kinshipbased gathering model and shifts the focus to the environment's impact on gathering life.

The reason for introducing the hamlet as a new family framework for studying the villages is that, it not only understands the family territory in terms of the traditional courtyard paradigm projecting to the family members but also considers the long-term complexity of village space. As Liang Sicheng notes, 'the Si He Yuan is a collection of units', rather than a fixed paradigm only with 'Jian'. In response, the study will analyse two early examples of hamlet in detail, further arguing for the similarities and differences in the negotiated to form the hamlet with the shaping between environment and paradigm.

52

53

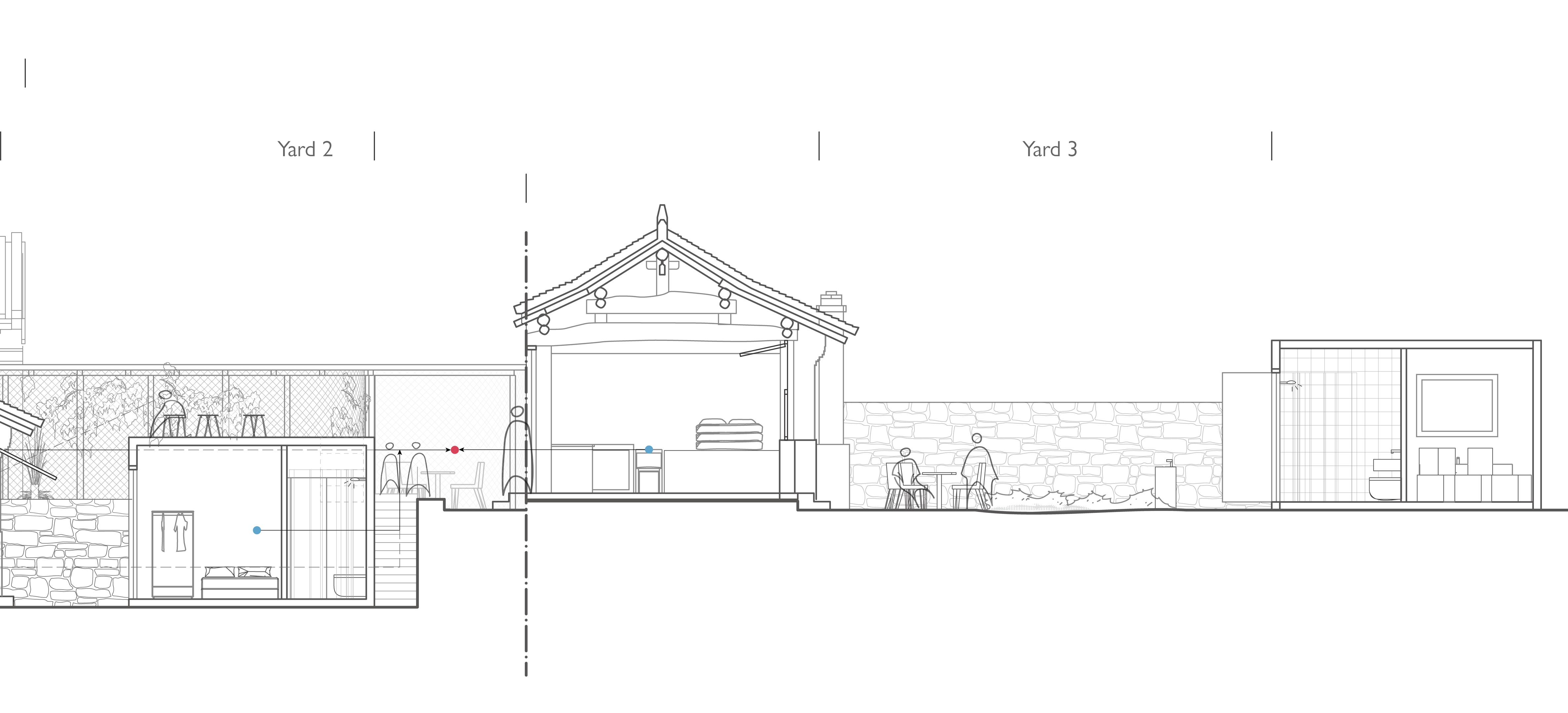

FIG 3. 6

A village house with a paradigm of 'Jian'. In the plan, the main house on the east side(right, matching left side room in the section.) , occupied by the parents of the family, with the kitchen in the middle heating the 'Kang' on either side.

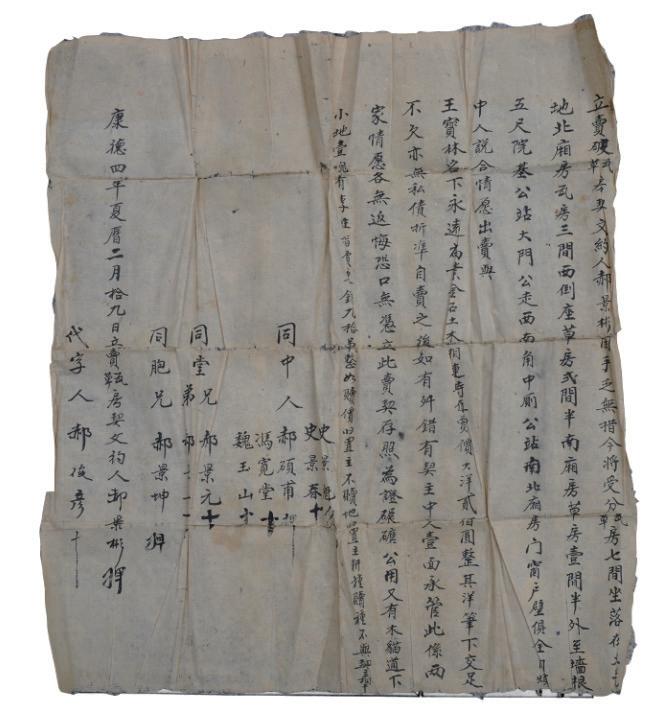

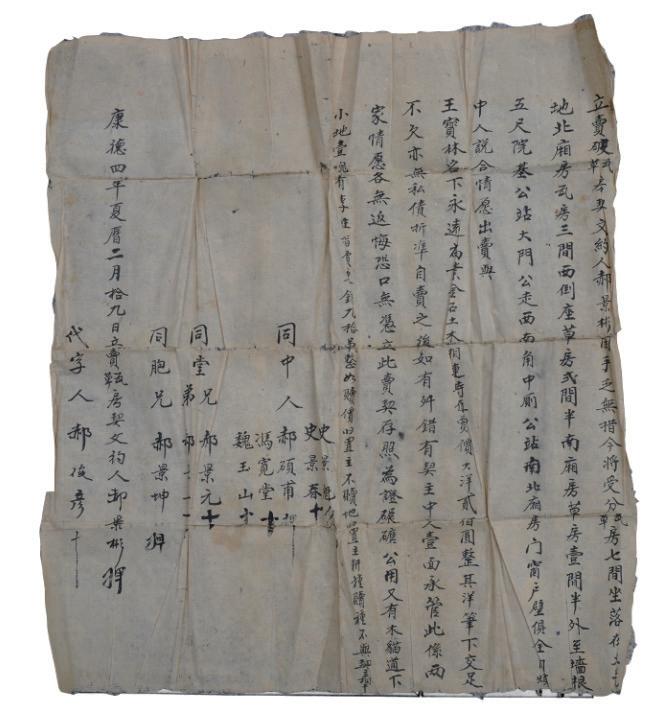

7 One of the original local village was formed during the Ming Dynasty(16th century) to garrison the Great Wall, so it follows the clan concept and is formed by three different clans.

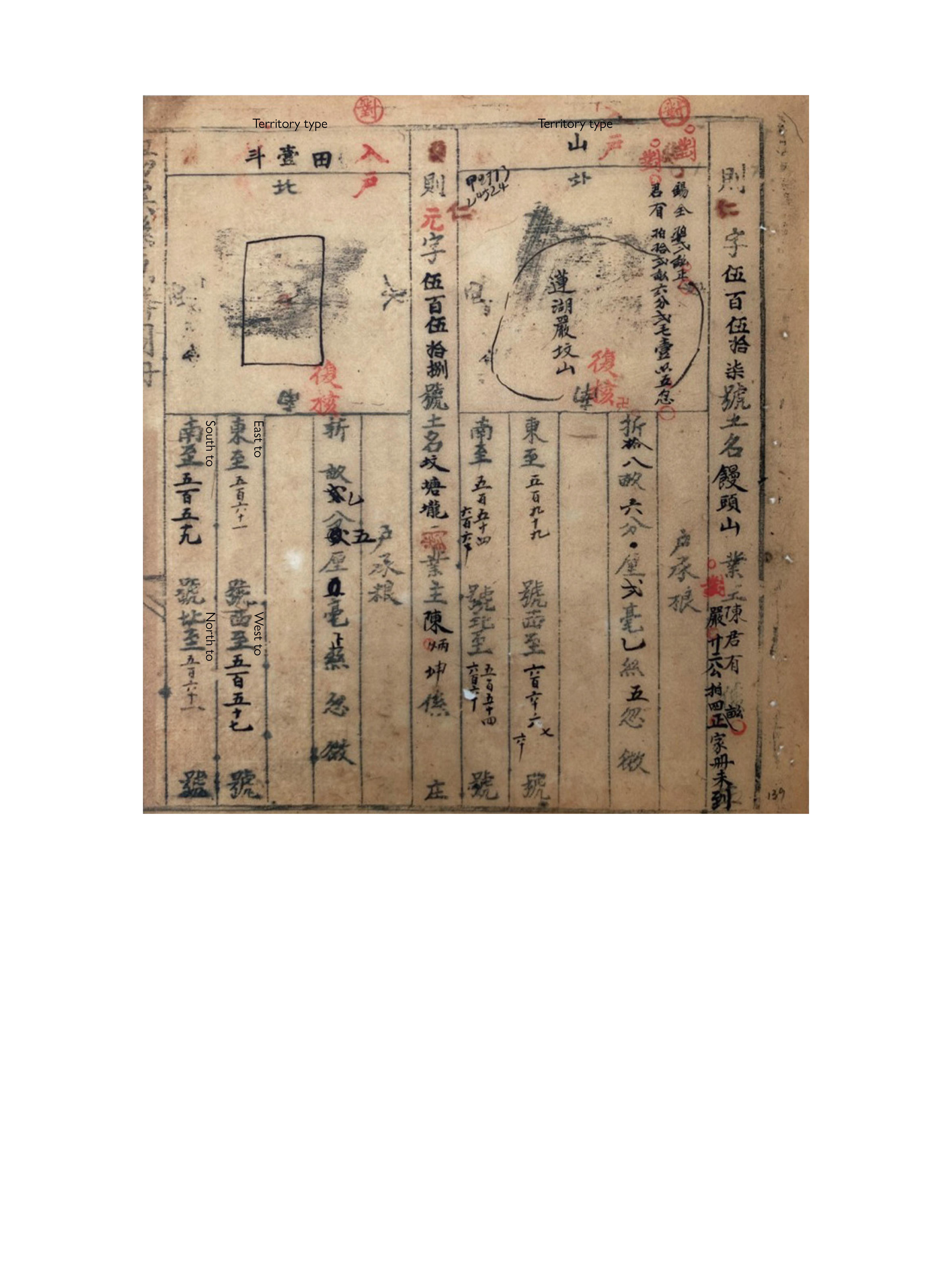

The ancestors first bought a plot of land with seven 'Jian'(units), which is mentioned in the archive deed as there are three units on the north side and three and a half units on the south side, to the terrace at five feet (152.4 cm). These data serve as the basic for defining the boundaries and area of the homestead.

Hamlet formed by environment negotiation

The plan was redrawn from the early deeds of the Grandmother's house and described details from interviews. It reflects how refugees arriving in the 1930s opened up the settlement. Because of the linear resource spread in the mountain villages, it was difficult for the refugees to join the villages that existed, so they had to find another flat place to build a settlement.⁷ The lack of materials and the urgency of survival made the pragmatism of using environment resources was a prime concern for self-build. In the plan of the settlement, villagers' thatched huts can be seen surrounding the farmland, with two shared livestock sheds on the west side, forming a collective land in the middle, which is not used for cultivation, but more like a place for processing and placing produce and tools. The awareness of the sharing of environmental resources made it an early type of hamlet, and even though it was later transformed into separate courtyards, the fact that these courtyards were coupled to each other but did not belong to the same family, which reveals their close connection with the environ farmland and the river.

54

FIG 3. 7 DEEDS ARCHIVE The earliest building process of the courtyard by the ancestors of the Grandmother's family.

55

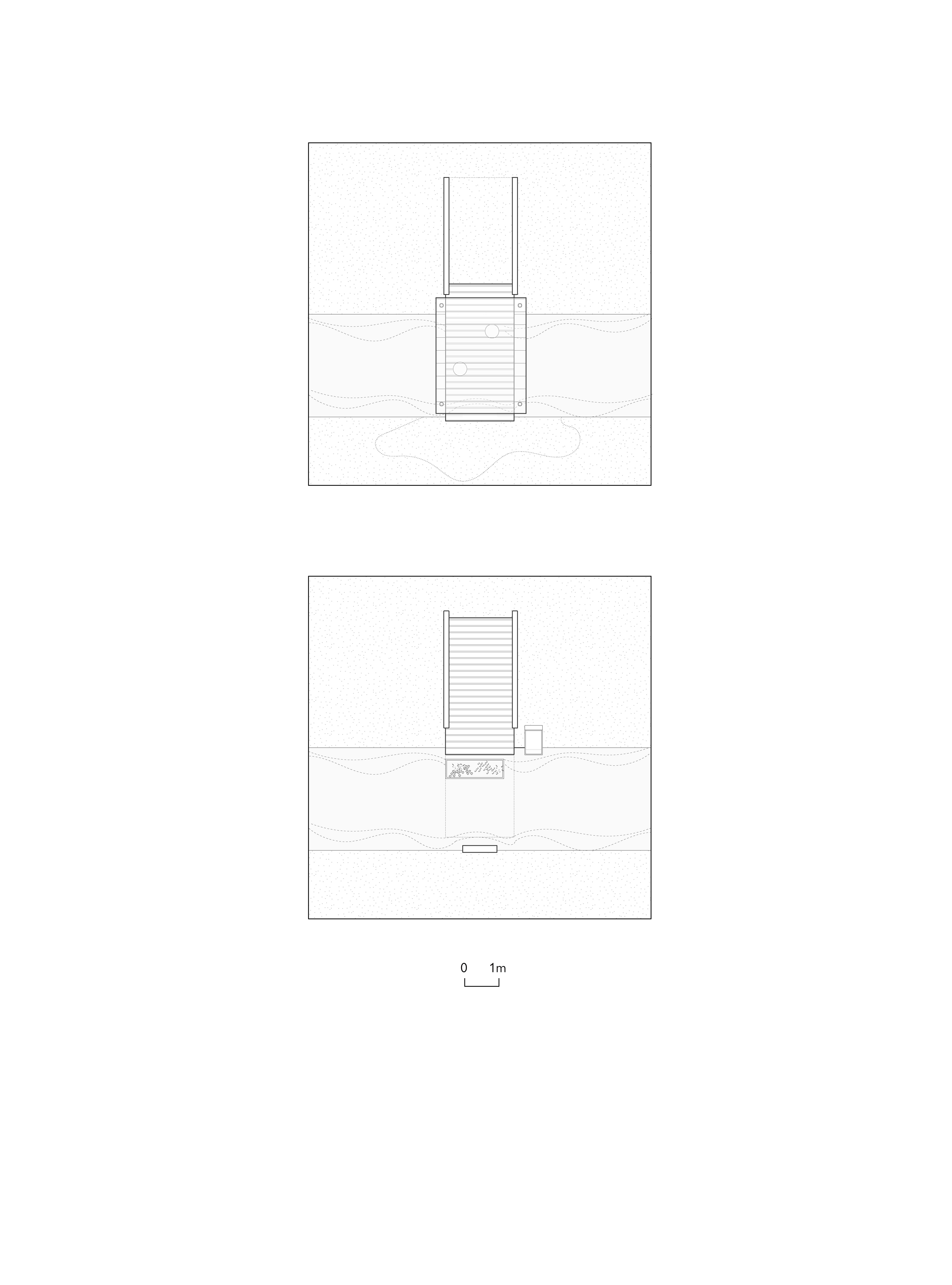

FIG 3. 8 HAMLET CASE STUDY 1: THATCHED HUT CLUSTER

Hamlet formed by family division

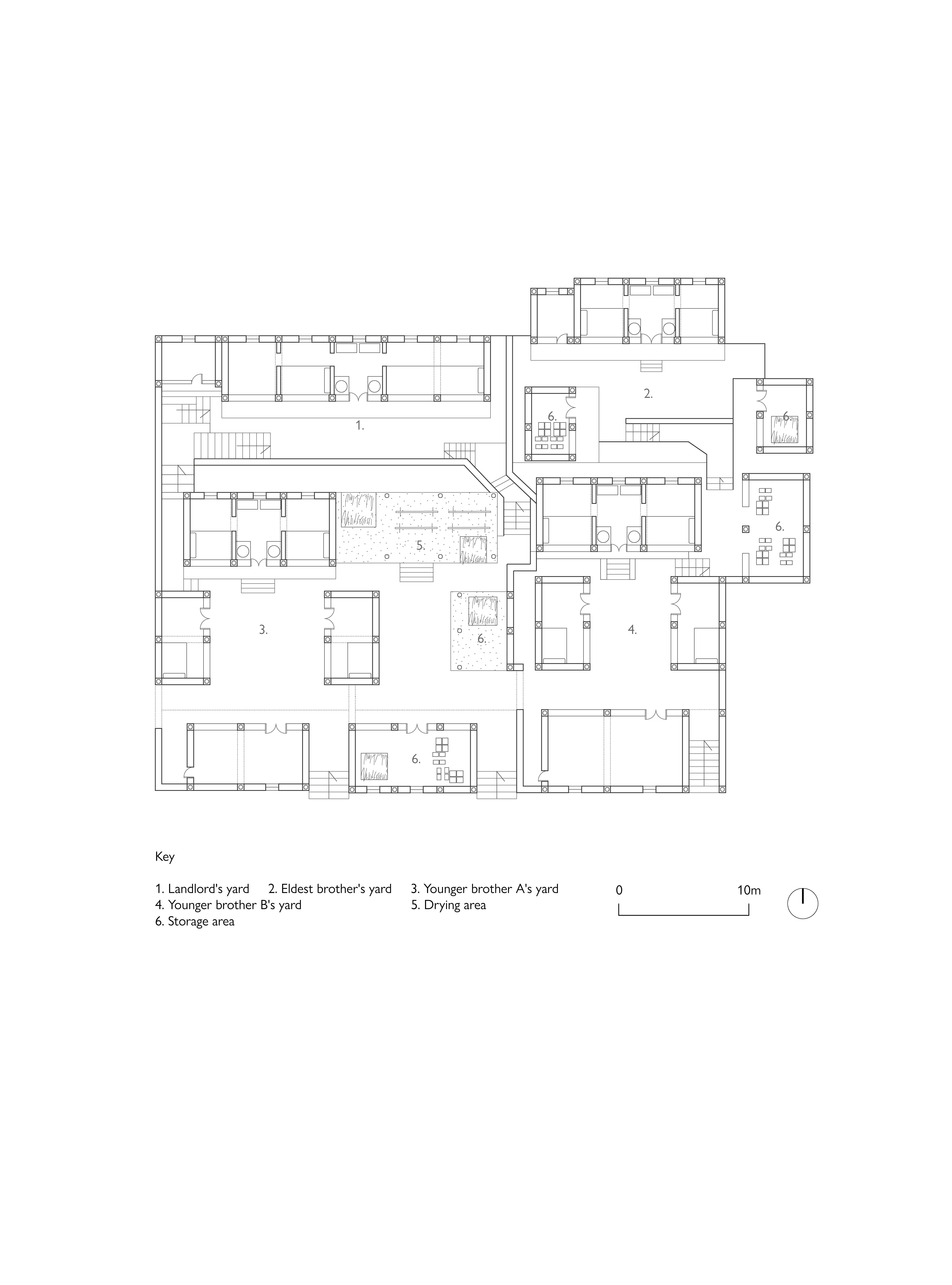

The hamlet at 'Cuan Di Xia' reveals how different family members responded to the environment's needs as the family divided. The hamlet is divided into smaller yards based on the topography; the highest five-room yard on the north side is the dwelling of the landlord of the family, the eldest brother lived in the northeast yard, and the other two brothers' families were located in the lower yards on the south side. In the middle of the unit cluster are a shared storage area and a space for drying and processing the crops, which is connected to the family courtyards by alleys and side gates. This internal division in families is common in long-developed villages, and hamlets like this are defined by the multiple combinations of the traditional paradigm. The hamlet's central crop area, and the multiple connections of the corridors, reveal the different types of family gatherings, therefore allowing for a change between private and public thresholds.

56

FIG 3. 9 CLAN HAMLET OF GUANGLIANG FAMILY

FIG 3. 10 Different courtyard clusters at 'Cuan Di Xia' village

57

FIG 3. 11 HAMLET CASE STUDY 2: CLAN COURTYARD CLUSTER

58

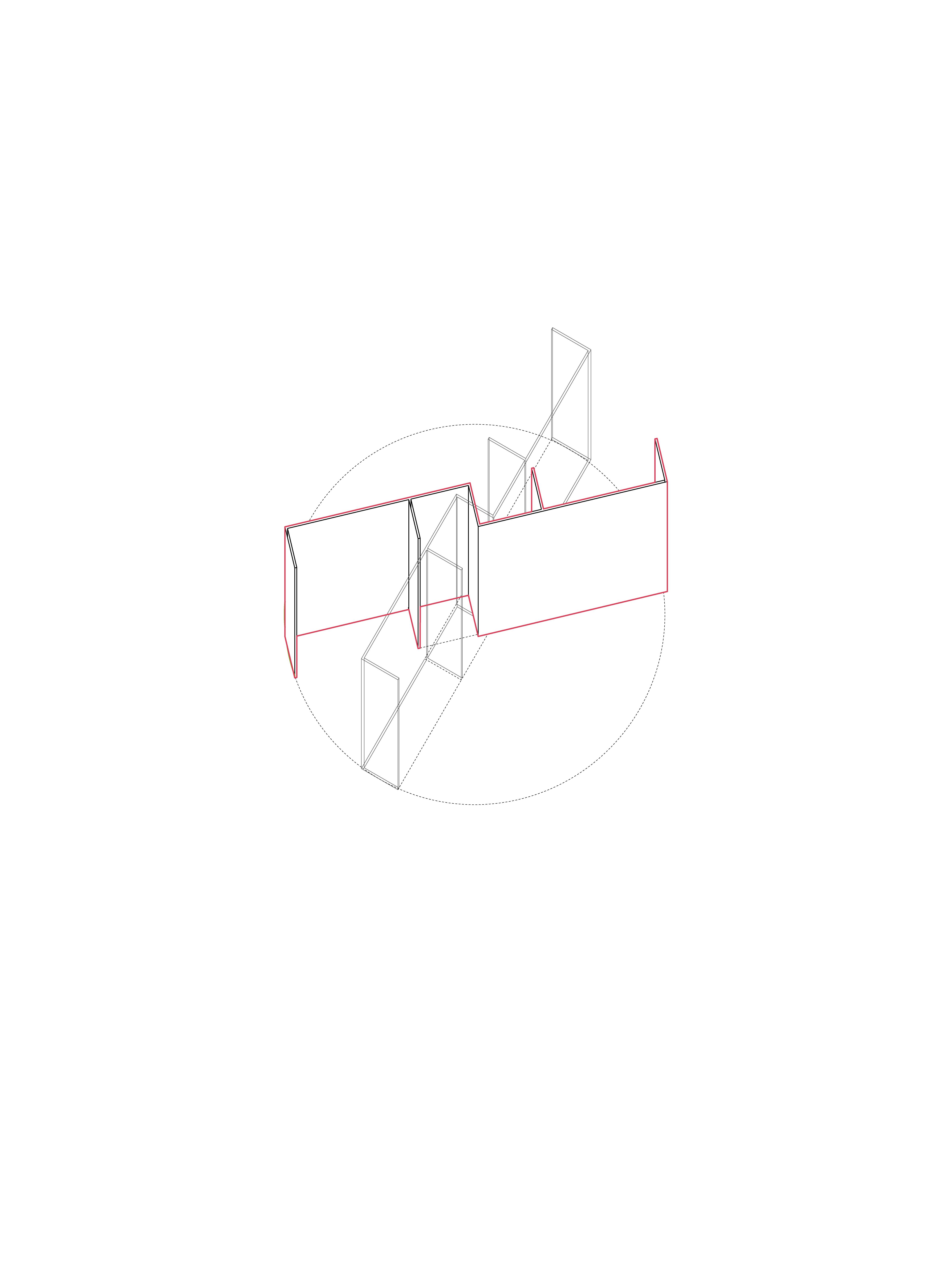

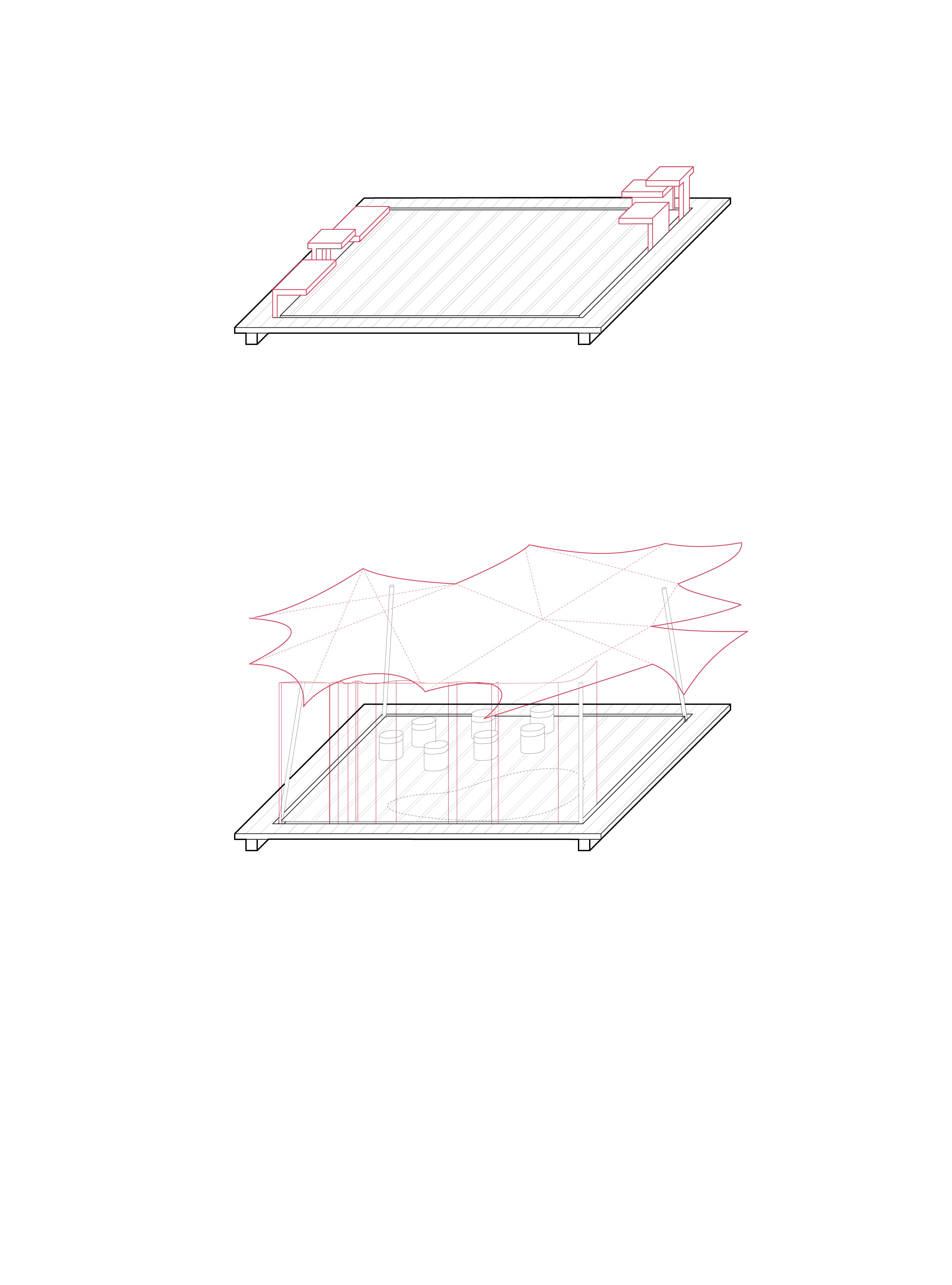

FIG 3. 12 PROTOTYPE OF HAMLET

59

FIG 3. 13 THREE MODES OF FAMILY GATHERING

8 Fei, Hsiao-t'ung, Xiaotong Fei, Gary G. Hamilton, and Wang Zheng. From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society. Univ of California Press, 1992. 31.

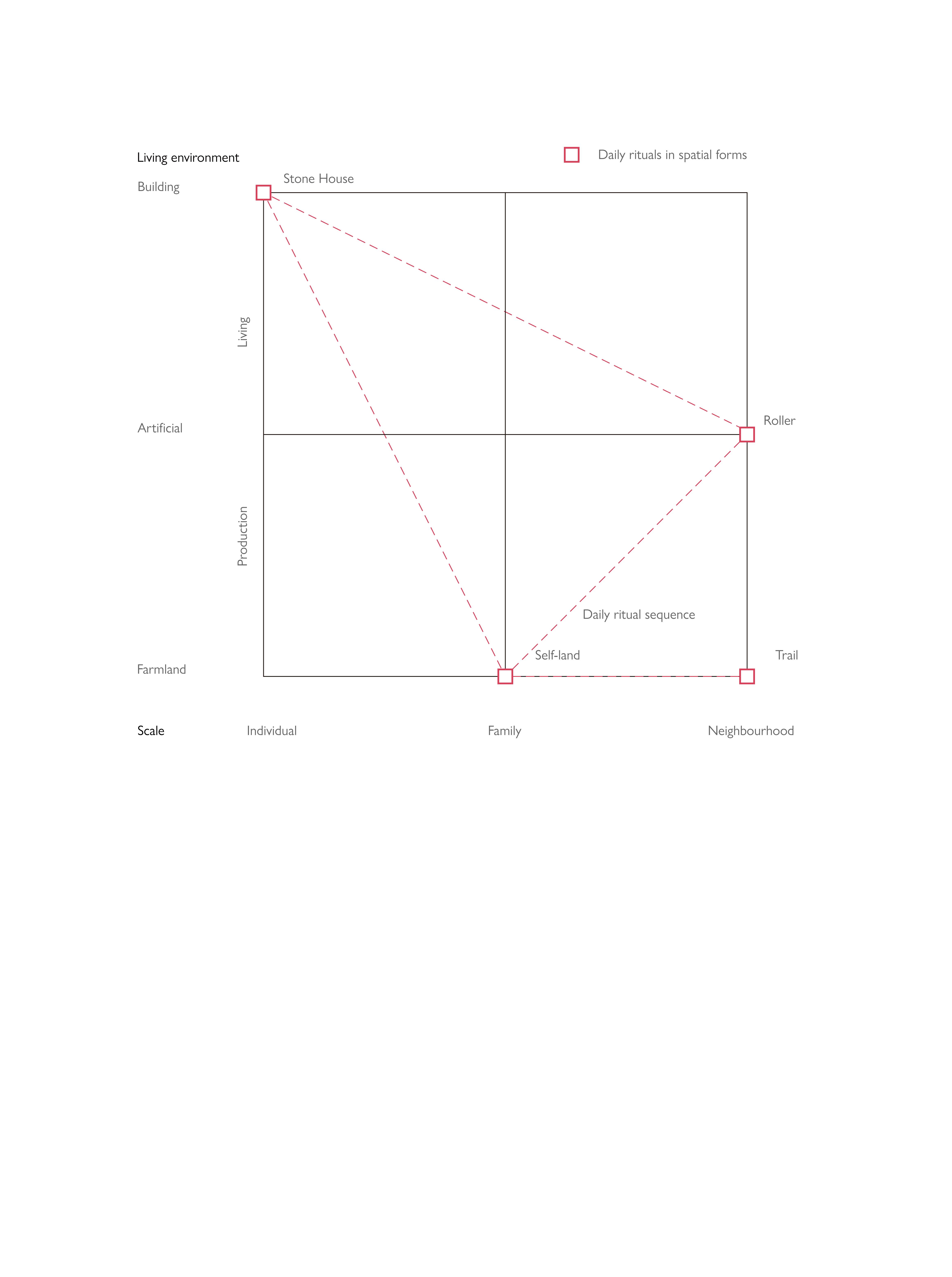

3.2 From settlements to living networks

The introduction of the hamlet concept raises questions about how to define the boundaries of a settlement and the shaping of the courtyard. The dissertation seeks to answer this question by defining groups of unit clusters by self-living design. As mentioned above, the hybrid network of the family is defined by the gathering of personal life, as addressed by Fei Xiaotong:"In this flexible network, there is always a 'self' at the centre. But it is not individualism, but egotism."⁸ The environ, which is bound up with the settlement, makes the personal life hybrid into these undefined units. In the interview with local villagers, they recalled their past life in which they seemed to be always busy, as the family was forever working in every place, such as making dumplings on the bed, picking vegetables in the yard, and collecting firewood along the wall. The family became a system that formed individual sequences into networks with a division of domestic works.

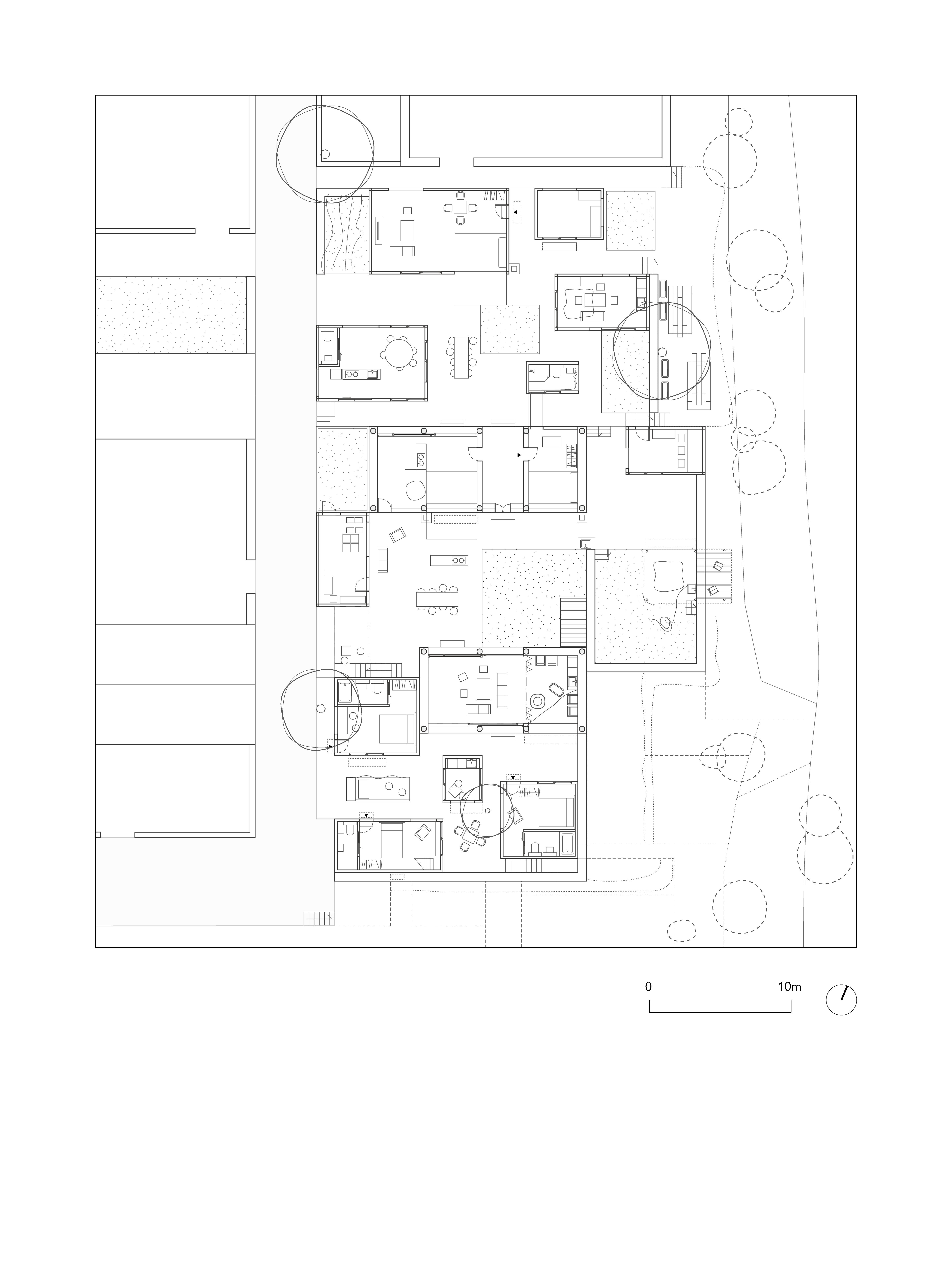

This hybrid space consciousness is strongly linked to farming, and unlike the 'Si He Yuan' paradigm, the village courtyard not only focuses on the coherence of living and farming but also reveals the interaction and gathering process by different habits of the family members. Redrawing the yard of Grandmother's house evolution at different times, the idea of extracting domestic devices within the environ is revealed. Family members participate in domestic work, not just cultivating but feeding livestock, processing crops and cooking. Personal life is blurred to meet the family's common needs, and more turned for gathering. The long-term hybrid setting of the courtyard allows for gathering to occur not in a specific space but through some particular ritual. Personal lives are projected onto these hybrid devices, and the blurring of boundaries extends beyond the courtyard to further interventions on natural farmland, creating an area between private and public land.

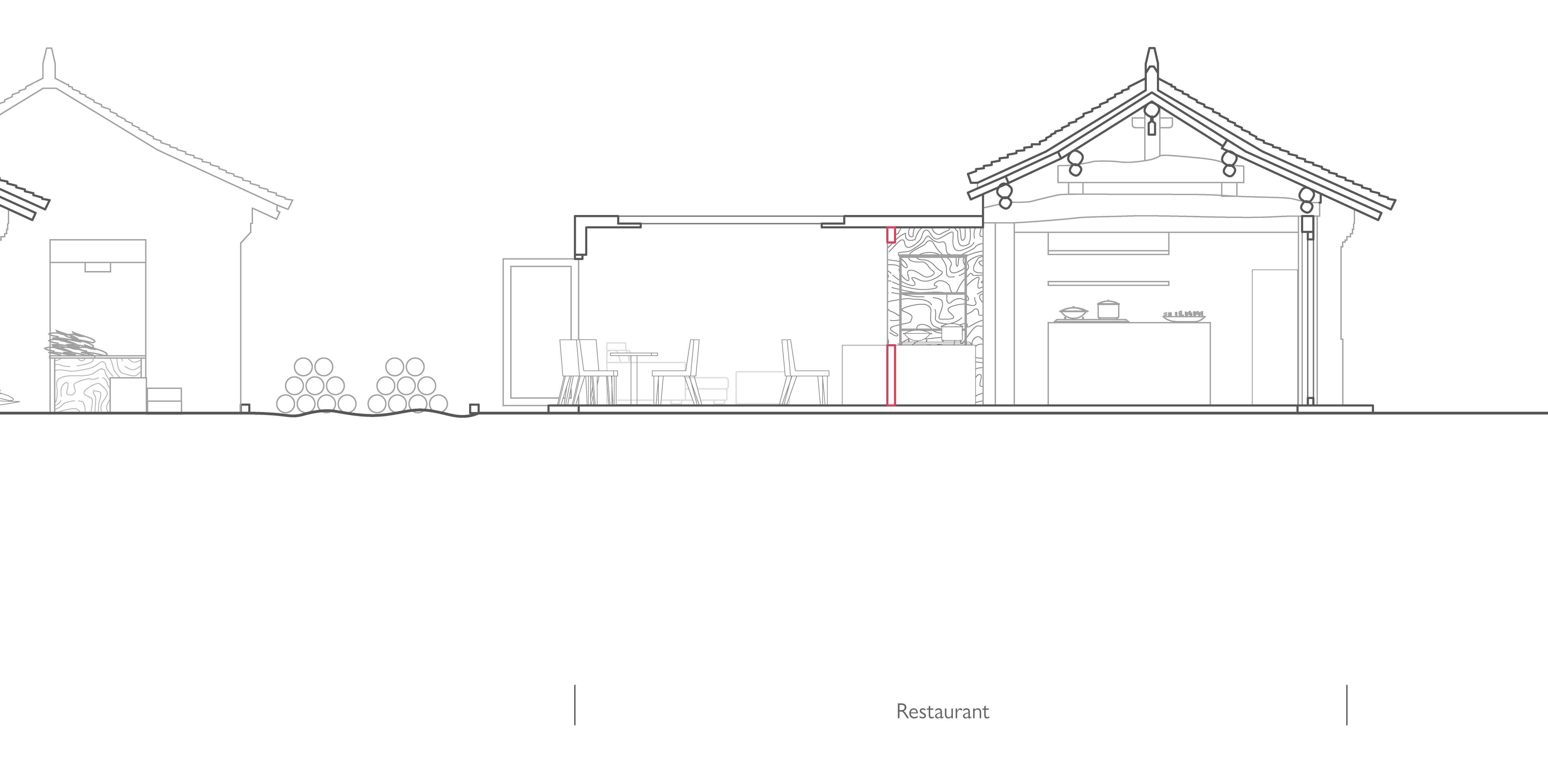

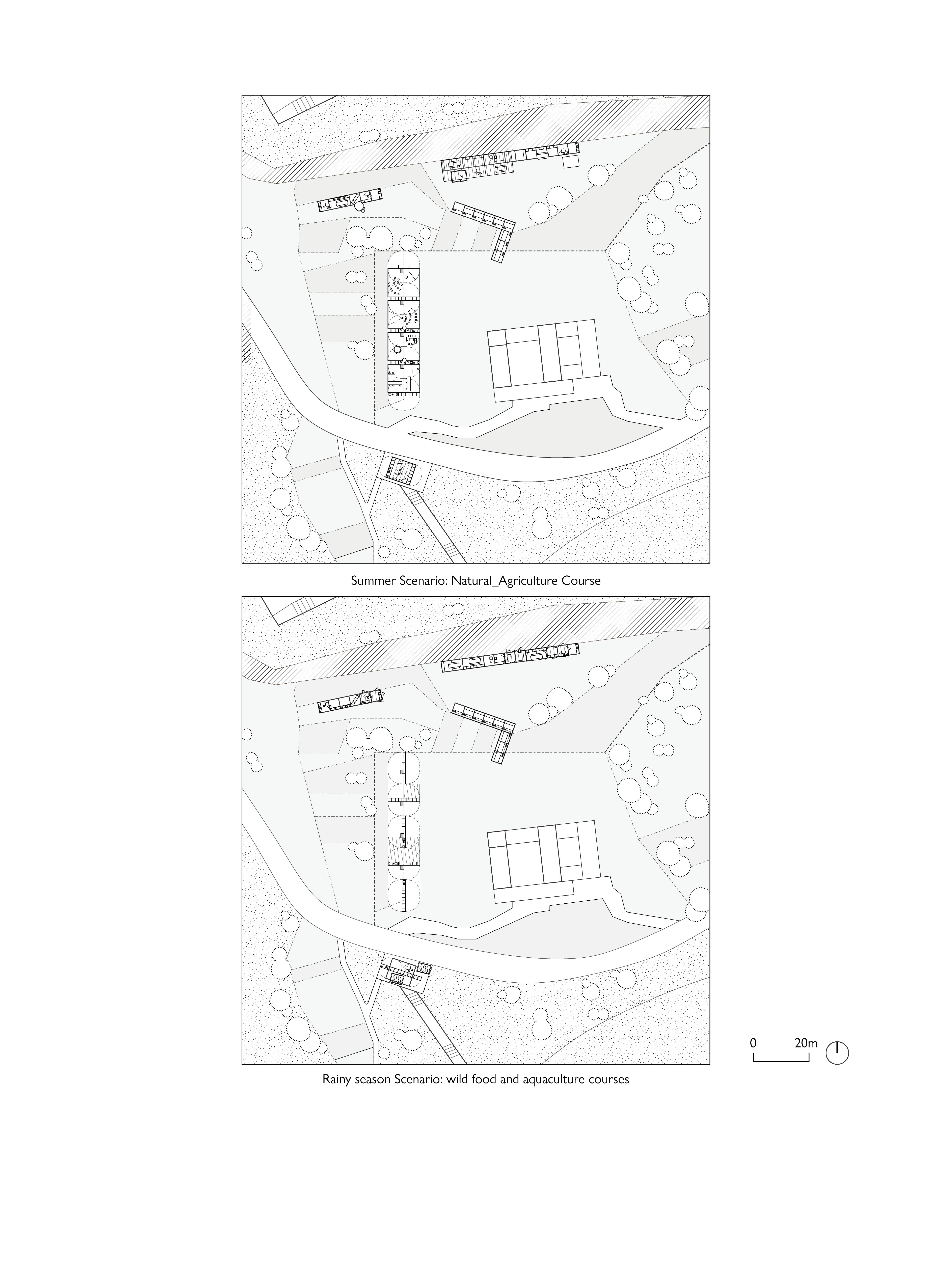

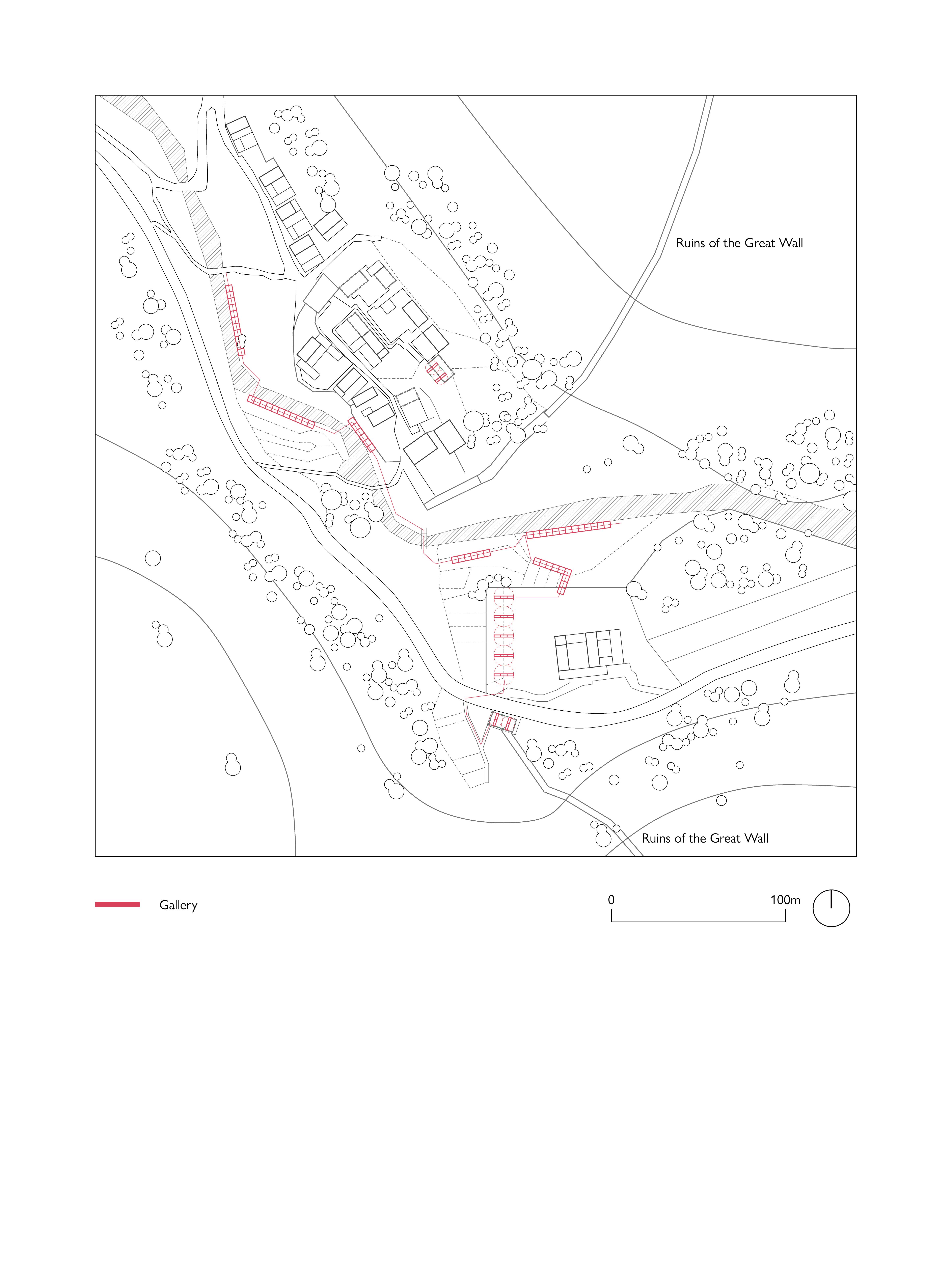

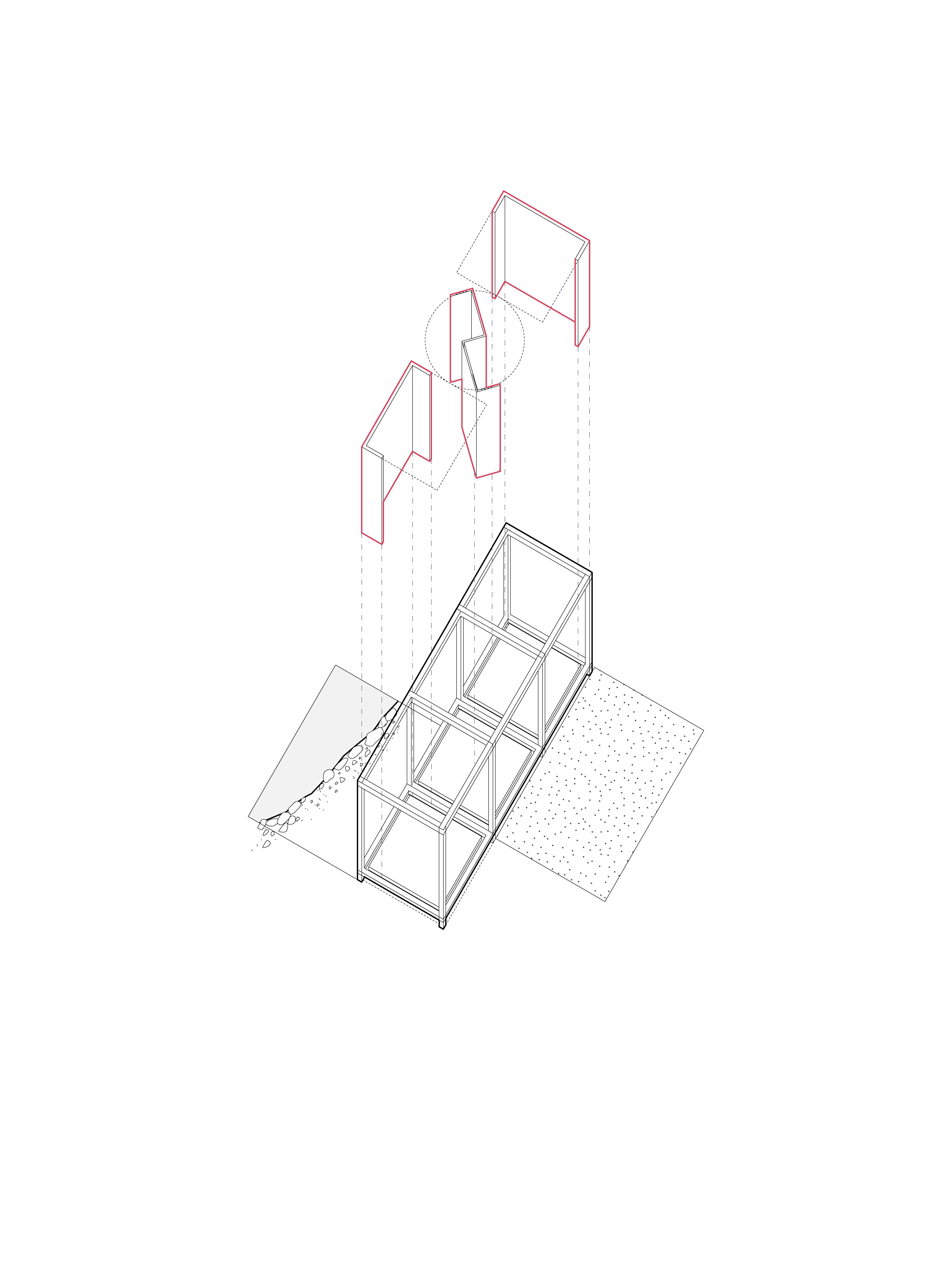

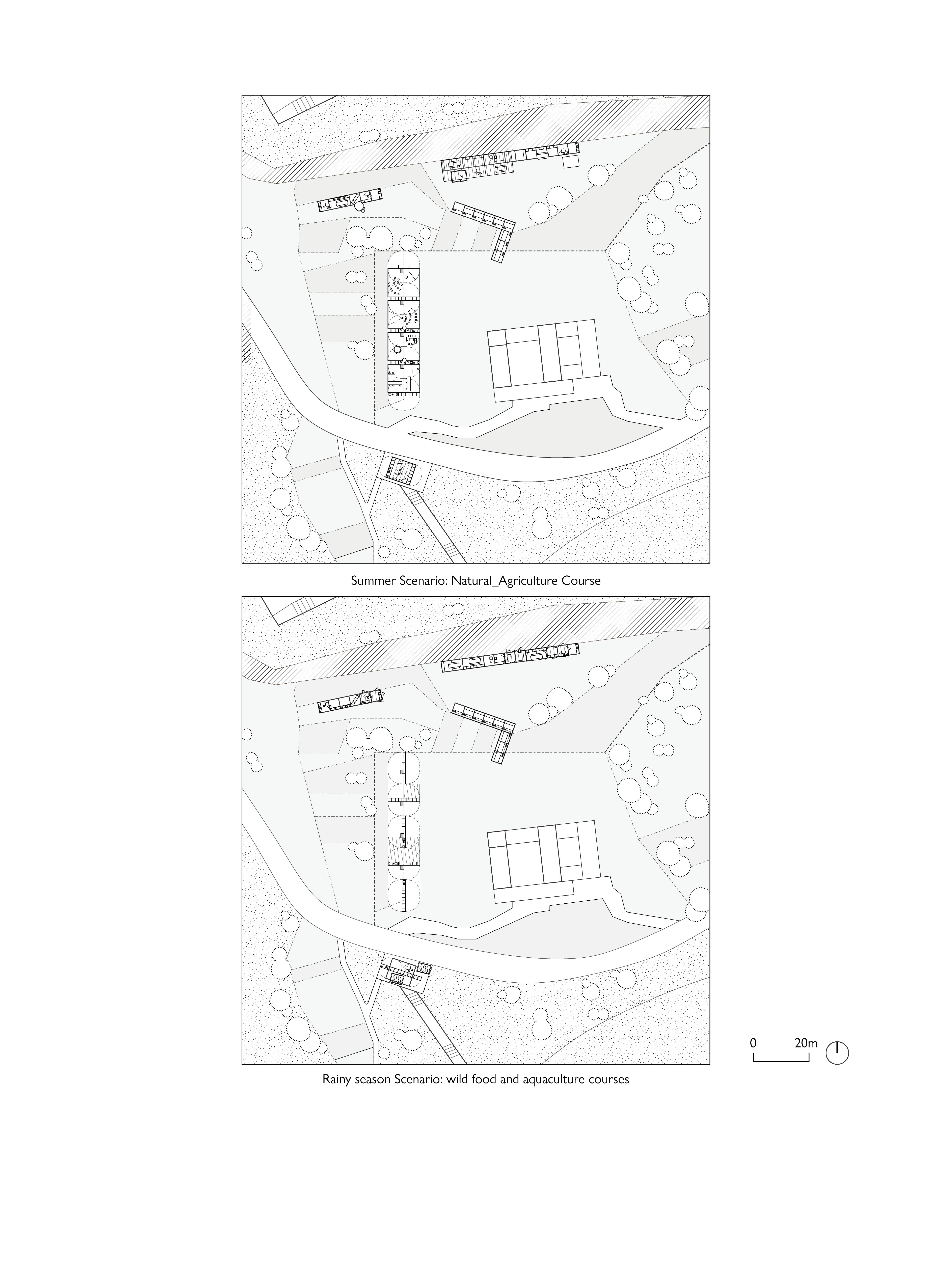

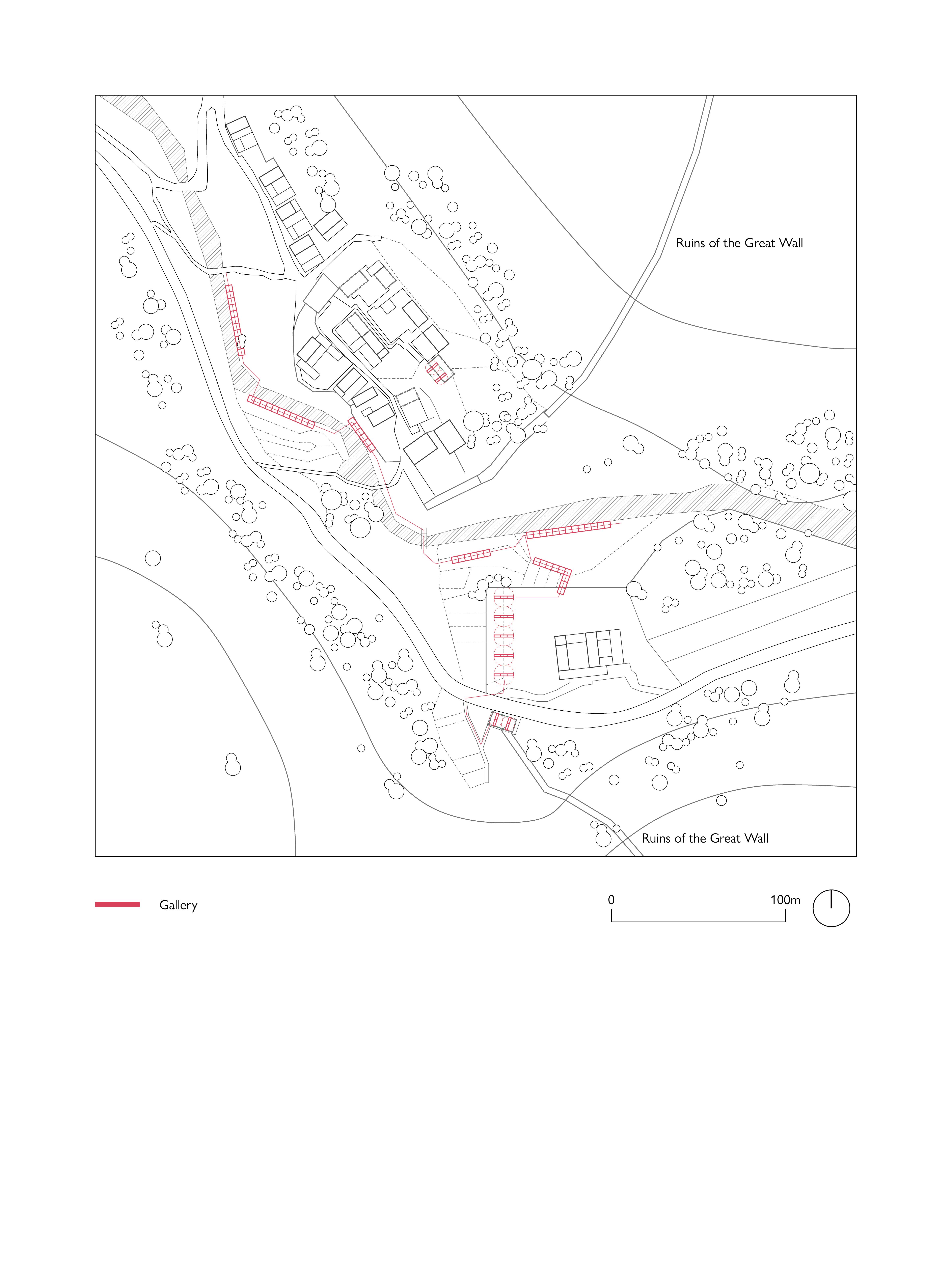

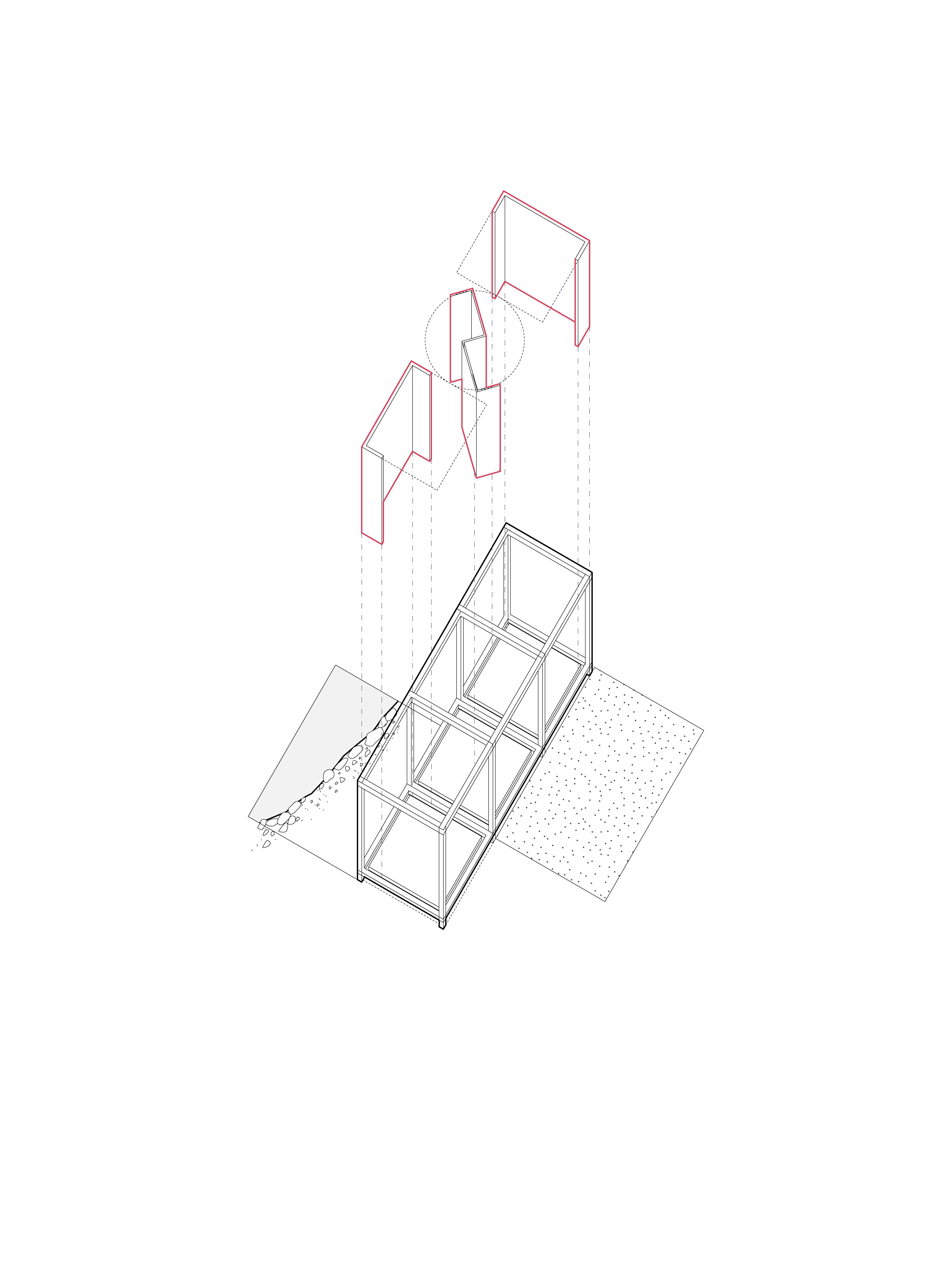

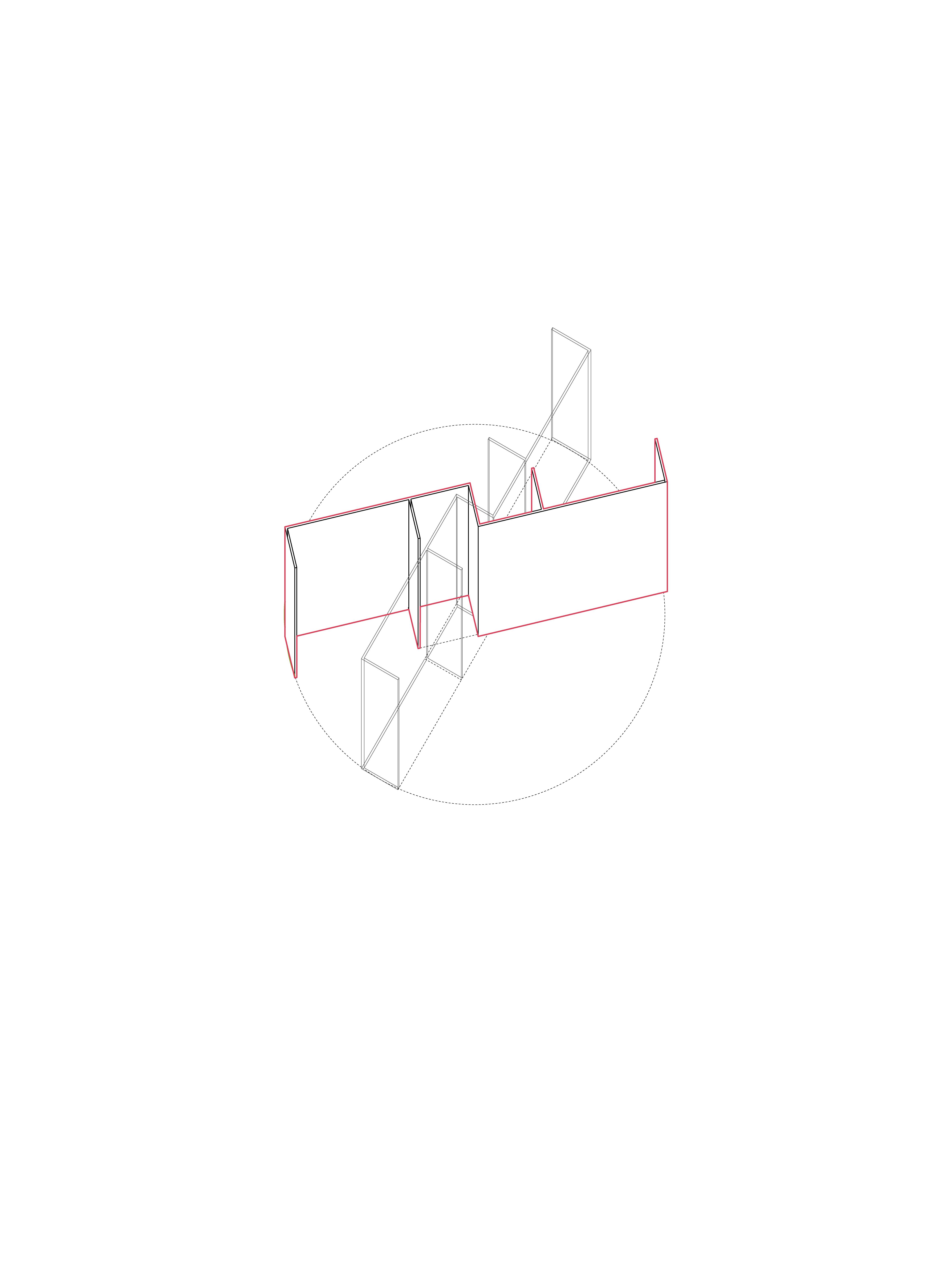

9 Growth of fragmented settlement usually occurred between the 1960s and 1990s, during the period when the government allowed villagers to own their homesteads (free of charge) when they became adults. After the planned economy period, following the migration to the city trend and the occupation of collective courtyards, this model of courtyard addition was gradually transformed into the development and purchase of existing courtyards.