RIVIERA

What happens when summer ends?

by Fiorenza Giometti Architectural Association School of Architecture 2021/2023RIVIERA

What happens when summer ends?

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requiriments of Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design - Projective Cities by Fiorenza Giometti

Architectural Association School of Architecture 2021/2023

Coversheet for submission 2022-2023

Programme: Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

Name(s):

Fiorenza Giometti

Submission title:

RIVIERA: What happens when summer ends?

Course title:

Dissertation

Course tutor(s):

Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi

Declaration:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student(s):

Date: 24th of April 2023

CONTENTS

Paraphernalia: the seasonal infrastructure of Riviera Design: Leisure is a Folly

Chapter 1

Performance: from indoctrination to recreation

1.1 Balneare: an introduction to the democratization of leisure

1.2 The role of architecture: the summer colonies for the working-class

1.3 Collettivo armonico: individual desire builds masses

Design: the Tower is a Frame

Interlude 1

Mega-genealogies: a local evolution of summer colonies

Design: the Dormitory is a Home

Chapter 2

Edge: from linearity to alienation

2.1 Seaside: the role of mobility

2.2 Morphology: the secondary town

2.3 Linearity: the sea as an alien border

Design: the Town is a System

Interlude 2

Ways of Living: field research

Design: the Colony is a Community

INTRODUCTION

Riviera Romagnola is a stretch of coast, overlooking the Upper Adriatic Sea. 91 kilometers long, starts from the mouth of the Reno River, extending until Pesaro and Urbino 2

Touristification is the process by which a place changes as it becomes an object of tourist consumption.

Antonio B. Ojeda, Maxime Kieffer, “Touristification. Empty concept or element of analysis in tourism geography?”, Geoforum

Volume 115, October 2020, p. 143

The thesis investigates seaside settlements of coastal Italy, particularly framing the design proposition in the context of Riviera Romagnola, 1 on the north side of the Adriatic Sea. Through the critical investigation of historical and present developments, the research unfolds how these secondary towns have historically become laboratories for social, architectural, and planning experimentations. Beyond the idyllic coastal landscape of Riviera, or the collective imaginary of it, the aim is to deconstruct a process of territorial definition and political representation. Ultimately, revisioning the narration of Italian coastal development through a series of explicit political projects positions the argument in a wider discourse about territorialization of the coast, touristification2 processes, and democratization of leisure.

The thesis proposes to deconstruct the concept of Riviera and its linear urban phenomenon. In this particular morphology, the abandoned megaforms of the summer colonies, mainly built during the Fascist regime, seem to be the only urban exception acting perpendicularly to the coast, connecting different parallel stripes of territory. Those buildings, once the architectonical pivotal moments of urban development, thanks to their neglected condition, their enclosed gardens, and their parks are the last empty opportunity for contrasting the density of the urban grain, and consequently the starting point for the design proposition.

Context:

Italian Riviera.

Macro-topics:

Performance: free time and body.

Edge: secondary town and Mindset.

Megastructure: territorial gestures

Design Questions:

Flexibility, Seasonality, Linearity

INTRODUCTION

OBJECTIVES AND QUESTIONS

Objectives:

Research:

- To analyse the process of invention of the Riviera concept, as a result of territorial and social circumstances.

- To investigate the formation of specific secondary towns along the Italian coasts by deconstructing their morphological, historical, and social ingredients.

- To trace parallelisms between different historical periods, influences, and politics involved.

Design:

- To rethink the Riviera through de-territorialization.

- To break the linearity as socially privileged and unequal spatial connotation.

- To work with summer colonies as a design tool.

The key questions guiding the research are:

- What is the role of architecture in the process of free time invention and instrumentalization?

- What are the historical agents responsible for coastal modifications that have led to mass tourism?

- What does edge mean in a linear morphology, and what kind of alienation paradigms does it produce?

- What kind of social structure is constructed following the subdivision of time (seasonality) and the spatial hierarchy in seaside settlements?

- What is the character of the coastal system, the forms and logic of space driven by the presence of the sea?

- What can be defined as seaside infrastructure?

The key questions guiding the design are:

- How can Riviera be rethought today behind the invention?

- How to reconsider the alienation of these towns as a necessary quality rather than a lack?

- How to invent a projective strategy for landscape and architecture working respecting a territory of anthropogenic exploitation?

- How can these urban settlements be transformed into mega-environments?

- How can summer colonies be organized to host seasonality and flexibility?

3

Thomas Rowlandson, “A woman swimming in the sea in Margate”, Kent, c.1800

4

Daniela Blei, “Inventing the Beach: The Unnatural History of a Natural Place”, The Smithsonian, 23 June 2016

5

The International Labor Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations, founded in 1919. It is responsible for promoting social justice and internationally recognized human rights

INTRODUCTION

STRUCTURE OF THE THESIS

The thesis structure is divided into three main chapters. Firstly, Chapter 1, named Performance, serves as an introduction to the democratization of leisure, and the role of architecture in the process of definition and instrumentalization of free time, focusing on Modern architecture and particularly on the summer colonies phenomenon in coastal Italy. Throughout Chapter 2, titled Edge, the analysis shifts towards the urban scale, unfolding the notion of secondary town, the Riviera mindset, and the consequent subjectification they produce. And lastly, Chapter 3, called Megastructure, discusses the historical, and present condition of the territory between the coastal and the maritime, finally introducing a projective challenge to this territorial dominance. Between the main chapters, three interludes are introduced, three booklets that work as autonomous insights, collecting the fieldwork investigations about seaside objects, architectural genealogies, and ways of living. Every chapter and interlude proposes a design intervention embedded in the context of Riviera.

The prelude proposes a study of margins, marks, and inhabitation of the beach. The fetishization of the Riviera paraphernalia, so to speak the seasonal infrastructure of the seaside imaginary, constitutes a process of enrichment towards the mindset itself. Holiday equipment composes a constellation of apparatuses, linearly connected along the coast, adopting the territorial scale. Therefore, the design response deals with seasonality in the attempt to break preconditions given by modes, customs, and rituals of the seaside.

Chapter 1 unfolds a methodology of comparison through the use of interdisciplinary sources and architectural examples, historical events with contemporary experiences. The intent is to present parallel narrations of the Riviera performance, arguing how present-day practices, rituals, and strategies are inherited constructs. In the Western culture, over the past three centuries, the coastal territories’ conception has shifted from risk to cure, and then from prevention to leisure, and in particular, Great Britain3 is the first to arise (quite often) scientifical awareness of the therapeutic advantages of visiting the sea. Despite the original elitist character, in about a century, the lower classes aimed for the seaside well-being too, with the formation of the first coastal settlements dedicated to workers, designedly following the newly constructed mobility lines.4 Moreover, in 1919, the ratification of the 48-hour working week, a proposition of the Organization Internationale du Travail, 5 subdivided the day into three “eights”: eight hours for sleeping, eight for working, and eight for resting. The right to

rest, and consequently to leisure, was declared as a state duty, opening up the appropriation of the seaside by the working class. Consequently, relatively new concepts such as summertime and holidays have imposed a perception of time that has ultimately contributed to the consolidation of the seaside mass tourism, if not even suggested its model. In the frame of the new seaside perception, the role of planning and architecture, following the political scenario they were operating in, has been alternatively the one to question or the one to guide a new idea of leisure. According to Susana Lobo, curator of the International Docomomo Journal about the architecture of the sun, 6 the 20th-century invention of free time has been instrumentalized by democratic as well as dictatorial powers in the history of Western countries for the construction of national identity. In this process, the 5th CIAM, held in Paris in 1937, titled Housing and Leisure,7 linked what was considered the most urgent problem at that time, dwelling, to the inseparable notion of leisure. Ultimately, placing the spatialization of leisure as a priority in the Modernist agenda was a political statement: it was the declaration that the main architectural platform of debate at the time, was in line with the policies for the right to remunerated leave. Thanks to paid holidays, the modern notion of leisure expanded from spare time to weekly and annual spheres, including not only rest and sports but culture and personal experience.

Jumping into the Italian contest, the summer colonies’ experience of the Inter-war represented the moment in which architecture and working-class division of time met. The space of leisure, in the frame of fascist Italy, supported the construction of the regime, while the institutionalization of the organisms in charge of the youth’s free time, constituted an operative step in the process of mass subjectification. In this operation, Modern architecture undertook the role of stage indoctrination as a form of recreation. Before the Fascist dictatorship, the social assistance model of the summer colony (the first form of sea-side hospitality dedicated to the working class), was generally expressed through a specific typology.8 With the purpose of sun therapy, children were accommodated in linear buildings with perpendicular arms, tracing the pre-existent diagram of hospitals and asylums. But during the totalitarian state, for better pursuing the scope of propaganda and control over subjects, the architecture needed a different frame. Therefore, is visible a link between a typological understanding of summer colonies, to a programmatic standardization, that worked more with time schedules, functions, and fluxes. Specifically, the vertical volume at the centre of the summer colonies, usually the vertical distribution, but also the water collector, or the clock tower, was used as a stage for the children’s morning march, spatially tracing a routine of indoctrination. Moreover, through a militaristic choreography starting from the garden and culminating at the top of the tower, the vertical object consequently performed and commanded a loss of body’s identity, but also a territorial dominance. The design concluding Chapter 1 specifically focuses on summer colonies’ towers aiming to subvert their perception. By simply considering them as concrete frames, the project attaches to the structure the role of energy production support, to self-sustain future public interventions dedicated to the reuse of abandoned

6

7

8

9

10

buildings. Rather than a territorial gesture, the tower, freely accessible to everyone, becomes a visual support to the landscape, framing it.

To systematize a design strategy for the other parts of the summer colonies, that present a high level of architectural variations, is fundamental to theorising an evolution from typology to programme. The interlude Megagenealogies, with the application of local genealogies, identifies proximity, construction companies, and personal relations between architects, as key elements for the understanding of these proto-megastructures. From the study emerged that the only spatially constant element of summer colonies is the dormitory, designed following the logic of the comrade. With the repetition of the same dimensions, it is ultimately reduced to the smallest unit of the bed, therefore the unit of the body. However, in the realm of the summer colonies, through a learned succession of rituals and gestures, the body switched from unit as an individual to unit as a collective. This passage is responsible for the phenomenality of conflict, between singularity and mass, normed body and projected space. In this logic construction, space, equipment, and programs, are not just formulated for the body, yet they become an extension of the body. A process that in the context of the seaside, will slowly sediment the way architecture and landscape are structured, turning the coastline into a line of subjectification, reaching the level of agency capable of territorial modifications. The following design exercise presents a general strategy of intervention in abandoned summer colonies, to propose forms of collective living, working, and services that could adapt and be appropriated by the fluid condition of seaside towns. Starting from the summer colony repeated elements of the dormitory, and from the approximation of its average dimensions, results in an invented “typical” dormitory plan, a linear diagram working with one, two, or three bays. From the typical plan, have been designed different options, flexible to different conditions, but also kinds of ownerships. These invented plans represent a set of general guidelines for the intervention in abandoned summer colonies.

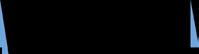

Chapter 2 explores the urban scale, identifying a clash between collettivo armonico (the concept of the harmonic collective as a way of living where everything is shared), and the individual desire for leisure of the middle and working class, a key turning point for the urban development of Riviera. In 1940 Casabella Editoriale9 launched a first and unique attempt to catalogue the summer colonies-built examples. In the same years, Domus Magazine, 10 presented propositions for the seaside house, initially on the Libyan colonized coasts with Enrico Rava projects, and later in the Italian ones with Gio Ponti, Lina Bo Bardi, and Giuseppe Pagano. As a result of this particular imagining of seaside inhabitation as something singular, Riviera morphology has developed what has become the dominant urban texture. Specifically, a morphology that can be mapped along the Mediterranean coasts, in the space of in-betweenness, from one primary city to the next. It was not until 1964, that we were able to identify Riviera as the theoretical concept of Secondary-Town, defined as such by Ernesto Nathan Rogers on the pages of Casabella Continuità in a two volumes investigation about coastal

settlements and architectures of Italy.11 These pages proposed urban plans for the development of seaside settlements, both catalysing and interdependent. The secondary town is characterized by a linear morphology developed through stripes of dense orthogonal grids, constrained by the coast and transportation infrastructure. However, with the collection of case studies, the thesis argues that since these urban plans were projective rather than analytical, there is evidence of a planned, rather than spontaneous urban condition. The touristic development zones of these towns occupied, and still do, predominantly the areas adjacent to the sea, while the council housing propositions12 were always placed on the outskirts of the settlement. Even though the secondary town exhibits a linear morphology, it reproduces and even reinforces, the social hierarchy of the concentric city. This chapter concludes with a design proposition that operates at the urban scale, connecting the secondary towns through a diffuse system operating in opposition to linear urban development.

However, the notion of seasonality, and the space of non- proximity, reflect a reductive interpretation of the Riviera condition, inherited from a speculative understanding of the seaside as a mono-functional tourist machine. Through a series of site visits and interviews, Interlude 2 seeks to deconstruct the complex stratigraphy of the actual “ways of living” of secondary towns as well as to document the role of the sea in the terraferma spatial routine. The main focus is the exploration of transitional relations and liminal zones of fluidity. The feeling of alienation caused by living the edge, is the common denominator. “Solastalgia”, is a neologism coined by the philosopher Glenn Albrecht in 2003,13 which in tourism science, is defined as the collective melancholia that a community feels when its space is touristified. It is a feeling of homesickness while being at home. In the design response, general guidelines previously developed with the first interlude Mega-genealogies are adapted to selected case studies of summer colonies.

Lastly, Chapter 3 moves the analysis to the territorial scale. In the 19th Century, Italy was determined to become an industrial power in the European contest, leading to the development of infrastructural lines along the coasts. Consequently, territories affected by malaria needed to be sanitised, starting actions of land reclamation sold as propaganda. A process that can be defined as internal colonialism, involving migratory and exploitative processes. Paradoxically, in just a century, the same areas, once perceived as polluted and dangerous, became curative, and consequently leisurely, linking back to the etymology of riviera: from Latin ripa, a stretch of coastal land, considered “safe”.

Moreover, if summer colonies can be defined as proto-megastructure, so can their territorial gesture. Based on the planimetries of the current condition, one can observe a continuity between the coastal system, the agricultural fields at the edge of the secondary town, and the parks of the abandoned summer colonies. Therefore, the last design focused on the “other megastructure”. A system that integrates all the other previous design tests, to connect different areas of the

11

Casabella Continuità, Rivista Internazionale, 1964, n. 283 / 284

12

The P.E.E.P. (acronym for popular economic building plan), in Italy, is an urban planning instrument. Introduced into law April 18, 1962, imposing to every municipality a development in terms of council housing

Riccione Diptych, Massimo Vitali, 1997

Postcard

13

Glenn Albrecht, “Solastalgia: a new concept in human health and identity”, Philosophy Activism Nature, n. 3 , 2005, p. 41-55

secondary town, challenging and breaking its subordinate order. In addition to reconnecting through the dunes, the project proposes different ways of shared living for Riviera settlements, in order to embed rather than suffer seasonality. Rethinking the coastal system by thresholds of encounter, rather than touristic speculation or given rituals, is a strategic tool for preservation but together re-visualization.

The design goal is to reconceptualise summer colonies through housing, collective services, and communal workshops. Both the summer colony and the dune system are devices acting explicitly against the mainstream perception of secondary towns.

In conclusion, having a broader de-territorial potential, both research and project attempt to set both outwards and inwards, from the sea, towards the land. The atmosphere of alienation and decadence, that is the present condition of Riviera, is the result of a forced economic and urban model repetition. A system closed in invisible limits, that refuses to self-recognize or accept new subjectivities and communities. By deconstructing and then revealing, the thesis proposes a new idea of Riviera, based on actual qualities rather than inventions. Presented is a real and intimate portrait of a contradictory territory, in which the beach is public, the use is private, and the border is closed, but the coast is elastic.

PARAPHERNALIA:

the seasonal infrastructure of Riviera

The object of investigation of the following study is the seasonal infrastructure of Riviera: the constellation of objects in support of the seaside touristic function. Through the analysis of beach paraphernalia, the intent is to disclose the spatial understanding and the implicit customs of the touristic coast.

Analysing for questioning the inherited rituals of the beach, the category of the “tourist” itself is dismantled, with the identification of different grades of temporality and permanency. Furthermore, with the study of margins, marks, paths, grids, and inhabitation, the thesis aims to underline the territorial character of the Riviera paraphernalia. The holiday equipment composes a net linearly connected along the coast, overtaking the territorial scale.

In-habitable Signages

SECTION: OBJECT: ACTION: Cleaning Drinking Playing Sitting Gambling Watching Eating Storaging Sunumbrella Billboard Shadowing Marking

Tables Sunbed Kiosk Cabanas Sunumbrella

Beach Paraphernalia Showers Playground Lifeguard tower

Margins

Advertising Delimiting Pine grove Buoy Line Wooden Pier Cement tile Breakwaters Artificial dune Protecting Shadowing Guiding Saving

Tables and chairs

Playing / Arguing / Eating / Drinking

Beachmat

Sunbathing / Relaxing / Exposing

Kiosk Cooking / Storaging / Exposing

For each beach its own imaginary

for each beach its own beach umbrella site: Ravenna

Re di

Incredibly functional, and minimal in its precise adherence to the dimensions of the standard body, the Riviera paraphernalia perpetuates a hegemonic perception of beach and leisure time. The design proposition for “Riviera Paraphernalia” deals with the seasonality of the beach, with the attempt of breaking pre-conditions given by modes, customs, and rituals. As the first approach pier structures hosting Riviera activities. Second, a continuous but porous wall, containing the dunes with their natural growth, and third a system of punctual objects. Reflecting on the spatial role of the seaside infrastructure, the aim of the design exercise is to challenge the current understanding of the coastal space. In fact, with the design of these beach objects, which are anything but follies, the project intends to group the beach activities for a proposition of collective use.

Against touristic speculation, the project is a counter-proposal to the anthropic development of the beach, catalysing specific built elements only in some specific points, and leaving the rest of the coast free for the natural growth of the dunes. Moreover, these built elements imbed both, the ways of living the beach, and the secondary town. Thought by functional

need, they’re meant to combine different uses and cross subjectivities, with the ultimate purpose of collective gathering.

Object of intervention: Beach Paraphernalia

Aim:

To challenge the social and spatial understanding of the beach

Architectural aspirations: Popular as functional

Actions:

- First public investment for the construction of the “follies”

- The establishment of a yearly run competition for the assignment of the follies management to cooperatives, where the result is obtained through a democratic vote from the inhabitants of the seaside settlement

- The construction of reversible wooden paths connecting the follies

Timeline:

- The management of the “follies” is a contract between the public and cooperatives, to be renewed every summer, against the seaside speculation and private nepotism

- Different subjects gather together in the follies, creating a new collective reality of the beach

- The dunes can grow naturally

- The reversible system of wooden paths changes every season according to the mutation of the dune system

First strategy: Perpendicular Pier Second strategy:

Wall

Third and Final strategy: Punctual intervention. Combined objects for seaside actvities

Next page:

a Lifeguard Tower + Belvedere + Toilette

b Shower + Drinking water

c Petanque + Belvedere + Energy production

d Playground + Storage + Shadowing

e Kitchen and Barbecues + Tables + Shadowing

CHAPTER 1

PERFORMANCE: from Indoctrination to Recreation

Chapter 1 analyses the seaside performance tracing parallelism between historical, modern, and contemporary examples. Subchapter 1.1 analyses the concept of balneare. The discrepancy between the Riviera jargon and its literal translation to other languages is indicative of a specific understanding of macro concepts such as sea, shore, and tourism, in the gaze of place, time, and politics. Subchapter 1.2 follows a general introduction to the perception of the seashore as leisure and the democratization of free time, particularly focusing on the role of Modern architecture in this process. Moving to the Italian context is introduced the summer colony experience of the inter-war. Lastly, Subchapter 1.3 confronts collective in opposition to individual perceptions of the seaside, and their influences on the spatial development and mindset construction of Riviera.

Previous page: Summer colonies genealogy, eight case studies

BALNEARE:

an introduction to the democratization of leisure

1 From Collins Dictionary

2 Michael Lambton Este, “Remarks on baths, water, swimming, shampooing, heat, hot, cold and vapor baths”, 1812, welcome collection

3 Eric Chaline, “How Europe Learnt to Swim”, History today, 16 Jul 2018

4

Iribas José Miguel, “El turismo no es una industria del espacio, sino del tiempo”, La Opinión A Coruña, 14 May 2010

5

“Governo De Gasperi V”, the fifth Italian government headed by the politician Alcide De Gasperi, remained in office from 1948 to 1950 for a total of 613 days

/bal·ne·à·re/

The Italian term “balneare” could be directly translated into English to the adjectives bathing or seaside.1 But what is notable in the gaze of the thesis is the actual use of the word, the descriptive construction it gives when coupled together with a noun.

Even if the leisure conception of seaside baths2 in the frame of modern tourism is an English invention3 Stabilimento balneare would be unsatisfactorily translated to bathhouse or cabanas. In Italian the term indicates a bigger system of summer services, rather than the physical architecture defined by constructed borders. It also comprehends the space of the beach dedicated to rentable equipment for leisure, and where the touristic performance takes place. But it doesn’t have a clear definition in terms of margins, often blurred and subjected to seasonality. Moreover, “tourist” in Riviera is translated with bagnante, the same root as balneare. What’s clear then is who is welcomed to stabilimento balneare during summer, and consequently, who will re-appropriate this space during winter.

Firstly, Località balneare means seaside town, but instead of the seaside, which indicates the location in relation to the natural feature, balneare is attaching to the settlement a touristic agency, even if this function is operative for barely half of the year. Secondly, Stagione balneare means summer season, it doesn’t indicate the period of bathing, but the period of tourist activity. Both are coherent expressions according to the argument of the urban sociologist Josè Miguel Iribas, stating that time, rather than space, is the core of the tourist experience.4 Lastly, governo balneare. It indicates a short-term and transitional (seasonal) mandate, to give a sort of summer break to political tensions within a parliamentary majority. A term that became popular in Italy in 1951, contemporary with the mass tourism boom.5 While Bathhouse could be an acceptable translation, bath-town would have no meaning, as well as bath-season or bath-government. Therefore, identifying place, time, and politics on the basis of the “bathing” function, which specifically conveys a constructed imaginary, it’s symptomatic of a specific instrumental understanding of the coast, where the exploitative character represents the intrinsic identity. Chapter 1 aims to analyze the construction process of the Riviera performance, a mindset that can’t be solely explained as a consequence of the modern perception of leisure, universally declared as an CHAPTER

essential human right by the United Nations in 1948 with the claim of periodic paid holidays for every person.6

In Western culture, over the past three centuries, the coastal territories’ conception has shifted from risk to cure, and then from prevention to leisure. In fact, until the XVII Century, the ocean has been related to the Christian narration of the Great Flood, leading to a popular imaginary of the beach as wild and dangerous.7 If it wasn’t for natural hazards, the exposure to pirates was anyway enough for perpetrating a convincing anti-waterfront narration. But the first turning point has been represented by Dutch Realism, in particular the school of seascape painters led by Jan van Goyen.8 Gaining international success, the Dutch Baroque started a process of profane pilgrimage that we could compare to contemporary environmental tourism.9 However, is the Great Britain, in the mid-XVIII Century, to arise (quite often) scientifical awareness on the therapeutic advantages of visiting the sea. Doctors started to prescribe to upper-class sea baths as a cure for a wide spectrum of diseases, from melancholy to tuberculosis, gradually testing the benefits of the sun, salt water, and sea air. Becoming a trend soon, remedy turned into prevention, a luxury denoting a certain social status. The seaside become then a net of social interactions and activities that, although still related to health, was mainly focused on leisure.10 Despite the original elitist character, in about a century the seaside phenomenon interested the lower classes too, reaching the level of agency capable of territorial modifications.

The ratification of the 48-hour working week represented for the Industrialized countries the official turning point in the democratization of leisure, and consequently the beginning of the appropriation of the seaside by the working class. The Organization Internationale du Travail was proposing a subdivision of the day into three “eights”: eight hours for sleeping, eight for working, and eight for resting. The right to rest, and consequently to leisure, was declared as a state duty. Ahead in time, the English Blackpool, founded in 1840, is the first coastal settlement dedicated to workers,11 providing a precedent for the next international developments, a seaside-town model exported from England to Normandy, Northern Germany, Scandinavia, and the US.

On the one hand, the invention of free time has been a crucial achievement in the history of the working class, but on the other, it has been instrumentalized, especially by the European dictatorships of the XX century, for the propagandistic construction of national identities. In particular, the thesis aims to unfold the historical processes that through subjectification, territorialization, and colonization have led to the exploitative phenomenon of mass tourism.12 The methodology adopted in the Subchapter 1.2 is to compare, with the use of interdisciplinary sources and architectural examples, historical events, and modern, and contemporary experiences. The intent is to present parallel narrations of the Riviera performance, arguing how present-day practices, rituals, and strategies are inherited constructs.

6

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the 1948 is a historic document which outlined the rights and freedoms everyone is entitled to. It was the first international agreement on the basic principles of human rights, stipulated by the United Nations

7

Daniela Blei, “Inventing the Beach: The Unnatural History of a Natural Place”, The Smithsonian, 23 June 2016

8

Jan van Goyen, “View of Dordrecht from the Dordtse Kil”, 1644, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund

9 Reference to the pheonomenon theorized by Valene L. Smith in “Hosts and guests: The anthropology of tourism”, 1989

10

“A group of people enjoy the water from their wagon in an unidentified location circa 1910”, Ullstein Bild Dtl, Getty Images. The bathing machine have been invented by Benjamin Beale, in Margate, Kent in 1750

11

John Urry, “The tourist Gaze”, 1990

12

According to Valene L. Smith, the mass-tourism model has been invented by Thomas Cook, a Baptist minister and social reformer that, taking advantage of the new railway system, combined his visions of democratic travel with the chance to profit financially.

13

Susana Lobo is an architect and researcher in Portuguese architecture, urbanism, and design of the XX century, with expertise on tourism and leisure infrastructure

14 Docomomo Journal, “Architecture of the Sun”, n 60, 2019

15 International Congress for Modern Architecture, “Logis et loisirs”: 5e Congres CIAM, Paris, Editions de l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 1937, n. 6

16 José Luis Sert, “Can our cities survive? an ABC of urban problems, their analysis, their solutions”, 1942

18

Enrico Bellasi, “Branda biposto pieghevole con capotte”, exposed at the XIII Triennale di Milano, 1964

CHAPTER 1.2

THE ROLE OF ARCHITECTURE:

the summer colonies for the working-class

The 20th-century invention of free time has been instrumentalized by democratic as well as dictatorial powers in the history of Western countries. Relatively new concepts such as summertime and holidays have imposed a perception of time on the working class that ultimately has contributed to the consolidation of the seaside mass tourism, if not even suggested its model. Therefore, the role of space has been alternatively to question or to guide these new perceptions of time in the frame of the political scenario they were operating. The architecture of recreation has been then a political tool throughout the history of the past century. According to Susana Lobo,13 curator of the sixtieth Docomomo International issue on the “Architecture of the sun”, 14 there are two main episodes in the history of Modern architecture, that internationally recognized the necessity to discuss free time: the 5th CIAM, in 1937, and the XIII Triennale di Milano, in 1964. Furthermore, these two episodes, not only represented pivotal moments by acknowledging the importance of free time in the realm of architecture, but they both represent a contingent and collective understanding of “modern” leisure.

The 5th Internation Congress of Modern Architecture, held in Paris in 1937, on the theme of Logis et Loisirs (Housing and Leisure),15 linked what was considered the most urgent problem of the time, dwelling, to the inseparable notion of leisure. It was already been defined as one of the four fundamental urban functions in the previous congresses, but until the 5th CIAM, it was perceived just as an activity for occupying the daily after-work in the green spaces of the city. However, in 1937, Modern architecture officially recognized leisure as essential good that should have been guaranteed as much as public services and housing. Placing the spatialization of leisure as a priority in the Modernist agenda16 was a political statement: it was the declaration that the Congress, the main architectural platform of debate at the time, was in line with the policies for the right to remunerated leave. In summary, thanks to paid holidays, the modern notion of leisure expanded from spare time to weekly and annual spheres, including not only rest and sports but culture and personal experience. As consequence, the general notion of leisure drastically changed, enlarging into the democratization of the tourist experience. In this process, the representative voices of architecture were pointing out the need to translate this process into designed, and planned space.

15

Cover of International Congress for Modern Architecture, “Logis et loisirs”: 5e Congres CIAM, Paris, Editions de l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, 1937, n. 6

17

Massimo Vignelli, poster for the XIII Triennale di Milano, 1964, Triennale Photo Archive

19

“Corridor of Captions, Introduction section with an international character”, curated by Vittorio Gregotti and Umberto Eco, XIII Triennale di Milano, 1964, Triennale Photo Archive

“One of the dangers of industrial civilization is that free time is organized by the same power centers that control working time, in which case free time is consumed according to the same rhythm as working time. Having fun means being integrated”

20

Bruno Zevi, “XIII Triennale di Milano. Tempo sprecato sul tempo libero”, l’Espresso, 16 August 1964

Nearly thirty years later, with the XIII Triennale di Milano, for the first time17 an international exhibition reflected on the topic of free time, the role of mass consumption, and its relationship with working time. The exhibition, titled “Tempo Libero”, was meant to challenge the actual social value of leisure representing its qualitative18 and quantitative aspects through pop culture. While in 1937 the fifth CIAM introduced a new conception of free time, demanding its investigation, in 1964 the Triennale was portraying it as a reality already consolidated. If the exhibition was celebrating rather than questioning the notion of leisure, has been (and still is) under debate. Although the most famous Italian architects of the sixties have been involved in the organization, it has been one of the most contested episodes in the history of the Triennale. What is notable in the XIII International exhibition, is exactly the fact that it was not notable. Or else, the deliberate choice of bringing the popular and the ordinary into a high-profile institution. The Triennale of 1964, staging leisure in its mass scale and pop quality has been one of the most successful portraits of politics, society, and design of its time.19 Indeed, while being branded as an “ideological vacuum” by Bruno Zevi in 1964,20 it has been restaged for the exhibition “A Tradition of the New”, a display collection of past sources from the Triennale archive, curated by the director Marco Sammicheli, in July 2022.

21

F. Gibon, “Colonies de Vacances. Compte rendu du Congrés National de Paris 1910, Paris

22

23

In the next pages: Plan of Prora, Clemens Klotz, Prorer Wiek, Rügen, 1936

Jumping into the Italian Modernist contest, the summer colonies’ experience of the Inter-war represents the moment in which architecture and working-class partition of time met. The construction of national identity was a shared process of instrumentalization of charitable institutions between the main European powers of the time.21 And the space of leisure, in particular in the frame of fascist Italy, has been used as support for the construction of the regime. The institutionalization of the managerial organisms in charge of the youth’s free time has been an operative step in the process of mass subjectification. In this operation, Modern architecture had the role to stage indoctrination as a form of recreation, becoming an active tool in fascist propaganda.

Healthcare and education are the two key concepts based on the history of the evolution of summer colonies. The dedicated literature considers the Sea Bathing Infirmary in Margate, the first officialised institution as such.22 In fact, the building represented a first model of seaside hospitality dedicated to working-class children with the purpose of sun-therapy and social assistance through philanthropic contributions. Founded in 1796, the hospice was established when the settlement of Margate was already famous for its recreational agency. Caritative management and architectural typology were later exported in the coasts of France as hospices maritimes, Germany as Seehospize,23 and Italy as ospizi marittimi, for contrasting the sanitary emergency of tuberculosis, and representing the first approach of the working-class to seaside leisure. In Italy the first to be built was the “Ospizio Marino di Viareggio”, opened in 1842 in Tuscany, and followed during the next two decades by many examples on the Adriatic, Sicilian, and Sardinian coasts. However, when in 1918 Gallo Calabrini,24 an officer of the Ministry of Education in charge of the maritime hospice census,

approached the technical relation for the ministerial survey, was forced to use a wide range of different terms to describe the Italian reality of about one hundred built examples.25 In a few decades the model of the hospice had already expanded into a complex and various constellation of practices, managements, typologies, and scales. Nonetheless, during the first decades of the XX century, for the cases meant to host big numbers of children, one main typology has been repeated. The so-called pettine distribution was a re-interpretation of the plans adopted for asylums and hospitals during the XIX century.26 It is a simple plan, with a linear distribution expressed by wide corridors, leading to perpendicular arms dedicated to dormitories. The diagram can be expressed by a cob (pettine).27 Volumetrically, the central part hosting entrance and staircases is more monumental than the rest of the symmetrical system, but overall, there are no variations, as it’s meant to be a functional28 and economic construction.

The hospice typology was converted into youth colonies according to an initial strategy of reuse and adaptation of the existent during the first decades of the XX century. The difference between hospice and colony was in the main agency: while the hospice just provided healthcare, the colony was meant to couple it with education.29 However, when the fascist regime gained great popular consent, even if the summer colony model was an already existing phenomenon, prevention subordinated to education (or indoctrination). The healthiness propaganda was an instrument of control over individuals through a keen and hierarchical nationalism. The first one to coin the term ferienkolonien was the Swiss pastor Walter Hermann Bion in 1876. Quoting from his Les colonies de vacances. Mémorie historique et statistique of 1887, summer colonies aimed to literally “colonize the children”, by taking them away from the city during summer as a preventive practice against diseases. Even more in the realm of the Italian dictatorship, the use of the word “colony”, clearly didn’t just refer to the idea of children’s community, but mostly suggested an appropriation of children’s bodies and minds, for “the protection and propagation of the lineage”.30 “Physical and moral reconstruction of the race” became one of the strong priorities of Fascism. With these new aims, youth programmes needed a different configuration, dividing the architectural debate into conservative and Modernist approaches towards the topic of the fascist colony. Therefore, after the reuse, a second stage of the process of summer colonies spatialization will see the contrast between, on the one hand, the literal reproduction of the old typology, as in the case of Colonia Bolognese in Rimini, constructed tracing the plan of the twenty years older Colonia Murri (analysed as a case study at page 86). And on the other, the Modern interpretation of the summer colony theme, that detaches from the general evolution of the hospital typology.31

According to the historian of education Tracy Koon,32 there are two intrinsically different pedagogical approaches in autarchic and totalitarian regimes. In traditional autarchic political systems, subversive ideas are censured from media and education. The intent is to contrast the diffusion of potential insurgency. But in a totalitarian system, the exertion comprehends every kind of idea, also

33

Marco Muzzolani, “Holiday colonies for Italian youth during Fascism”, in Docomomo Journal, n. 60, February 2019

the ones that potentially would be in line with the view of the regime. The aim is to provide the only educational source, not only to stay in power but to proselytize a new “faith”. The first summer colonies were based on philanthropic initiatives of educational and social missions, mainly administrated by Catholic organizations. Initially, the fascist party juxtaposed the pre-existing model, for gradually appropriating the majority of the youth programmes and declaring illegal the alternatives. Aiming to the educational monopoly, it later became competitive even against public schooling, which didn’t focus enough on the “construction of the body”, and parents, separating the children from their families for all summer.33

36

Diller+Scofidio, “Back to the front: Tourism of War”, Princeton, 1996

About the context, compared with other national Modernist examples, summer colonies innovatively worked with the surrounding landscape. Especially during the post-war, these buildings were enlarging into bigger complexes, actually becoming pivots of the unstoppable tertiary development. Their attractive character and their seasonal activation, were catalysers of a new vision for the overall Italian coasts, being the first infrastructural elements opening the land to touristic exploitation processes after decades of land reclamations, and agricultural conversions. Not only summer colonies were the first institution to connect leisure and masses in a territory that wasn’t meant to be touristic before, but they also convey a perception of the body as a constructed and collective object, that will resonate with the Riviera establishment. The process of indoctrination could be ultimately translated into the complete loss of body identity, but also in its construction as a product of a specific system of functions. The march, the morning exercise, the medical controls. Actions operating as subjectification, to create the perfect fascist, the perfect man, the perfect soldier, the perfect woman, and the perfect wife. Not only the physical exercise, but the choreography of the march, in the frame given by the summer colony, represents a learned succession of gestures, in which the body switch from being a unit, to be a collective. At the same time, the body of tourism34 is normed by gestures, customs, and rituals as much as the body of indoctrination.35 Never fully private, never fully public. Borderline between ostentation and shame. Is the body that defines the way of time, calendars and seasons are used. But is the performance that causes itself a phenomenality of conflict,36 between singularity and mass, between normed body and projected space. And the performance, in the context of the seaside, will slowly sediment the way architecture and landscape are structured, turning the coastline, as stated by Fredéric Migayrou in the essay The extended Body, published in Tourism of War by Diller+Scofidio, into a geometric entity. In this logic construction, space, equipment, and programs, are not just formulated for the body, yet they become an extension of the body, literally “lines of subjectification”.

37

“Sintesi del regime”, speech given by Mussolini in Rome on 14 March 1934. The words of Mussolini formed the epigraph of the catalogue of the summer colonies exhibition

To control youth subjectification, the fascist party founded several organizations in charge of educating the “complete fascist”, namely those born and raised during the dictatorship.37 Firstly, the ONB Opera Nazionale Balilla, in 1926, for giving the general pedagogical guidelines, and then the OMNI, Opera Nazionale

Children in a summer colony, 1920 circa, ISREC Archive

38

Giulio Roisecco, “Schema del movimento giornaliero e dei percorsi di una colonia marina”, 1933 / Armando Melis, “Schema funzionale di una colonia marina”, 1939

46

39

De Martino, Stefano, and Alex Wall, “Cities of Childhood, Italian colonie of the 1930s”, London: Architectural Association, 1988

40

“Mostra delle colonie estive”, Archivio LUCE, Rome, 1937

41

Mario Labò, Attilio Podestà, “Colonie Marine I”, Costruzioni Casabella, November 1941

42

PNF, “Pubblicazione rivolta alle vigilatrici”, Source: BSCO, 1938

Maternità ed Infanzia, for the classification of the children’s state of health. In 1931 was then created the EOA Ente Opere Assiztenziali, in charge of a general reorganization of population assistance. And last, in 1937, the GIL Gioventù Italiana del Littorio. These organizations were all operating on behalf of the regime, but while the collaboration towards common pedagogical guidelines was strong, with clear directions regarding medical controls, division of time, and educational activities, a standardized architectural model was missing. The only instructions given for the summer colonies were programmatic schemes, depicting functions and fluxes.38 For this reason, in the frame of Modernist architecture, a typological translation of the summer colony programme is not possible. As a result, a great variety of architectural examples are present along the Italian coasts. And depicting a State in favour of workers and masses, the summer colonies were advertised as one of the biggest fascist achievements. Conversely, the fact that they were diverse gestures, wouldn’t have harmed the propagandistic spectacularism. Furthermore, summer colonies have been used by the Modern movement as an occasion of wild experimentation.39 In these examples the fascist monumentality is melted with rhetorical formalisms, playful shapes, and contexts. They’re surreal, non-referential buildings, meant to suppress individual freedoms.

In 1933 the Triennale dedicated an exhibition to the summer colonies, which was proposed bigger three years later in Rome with the “National Exhibition of Summer Colonies and Child Assistance”.40 The exhibition itself was a grandiose reproduction of “The City of Childhood”, a sort of cluster of summer colonies. However, even if displayed for the occasion, summer colonies were still not regulated by a projective standard. The regime was using a strategy of non-definition41 in terms of architecture, patronizing the same imposed rituals rather than a coordinated type of space. Special posters and postcards were designed with images of the most monumental summer colonies, advertising the victories of social assistance. The educative performance itself was the real protagonist of the exhibition. Indeed, groups of kids and educators were acting the typical colonial day for the audience of the exhibition, with uniforms, medical controls, and flag-raising.42 The conception of education as performance is something that could be found in every fascist program dedicated to youth. The majority of the historical photographs of the colonies would reveal a specific iconography, portraying a comrade of children performing the fascist salute in front of a fascist hierarch. The idea of performing the march itself, from the garden of the colony to the top of the tower,43 denotes the intention to stage the “miraculous” results of fascist education. Even more, if the exhibition reproducing the colony, and the colony itself, are perceived as scenography, the extended body of the beach is potentially a scene too. Even more, the architectural frame wouldn’t comprehend the full potential of the social arena if the audience targeted extends from the working-class parents to the upper classes and the hierarchs. But the seaside, which gradually becomes leisure, does. We can see then beach billboards, with fascist propaganda, marking the becoming-geometric space of the beach.44 Furthermore, the fascist signages represent the first

46

Mario Labò, Attilio Podestà, “Colonie Marine I”, Costruzioni Casabella, November 1941, and Mario Labò, Attilio Podestà, Colonie Montane e Elioterapiche II, Costruzioni Casabella, December 1941

47

“Cartolina Ex colonia le navi di cattolica - Dettagli della Colonia Figli Italiani all’ Estero”, Archivio Municipale di Cervia - Milano Marittima, 1945

48

Marcello Flores, “Perchè il fascismo è nato in Italia”, 2022

49

Elena Mucelli, “Colonie di vacanza italiane degli anni ‘30. Architetture per l’educazione del corpo e dello spirito”, Milano, 2009

establishment of a speculative perception of the coast: a commercial product, a place for and to advertise, perfectly in line with the Riviera imaginary of the seventies.45

Going back to the architecture of the summer colonies, the first attempt to catalogue and classify different examples is an investigation of two volumes on the pages of Costruzioni Casabella, conducted by Mario Labò and Attilio Podestà in 1941.46 With the publication, the architectural discourse was finally dealing with the summer colony problem, trying to divide the most iconic built examples into different typological categories. As a line of analysis, it proved to be a little simplistic, and for this reason in the same year, the fascist party drew up a set of specific dimensions in relation to the needed function,47 as well as limitations in the number of volumes to be constructed. There was a preference for having huge megastructures capable to host large numbers of children of different ages, rather than smaller pavilions more diffused in the territory. The reason was partially for a better logistic of transportation, linking the holiday settlement, and the children’s provenience through the main mobility lines, but mainly for the idea that the colony should have trained children to perceive everyday sociality as a “harmonic collective”.48 Individualities were annulled, in favour of a militaristic perception of the group as a comrade.49

50

51

52

COLLETTIVO ARMONICO: individual desire builds masses

Enrico Rava’s colonial architecture, on the pages of Domus during the thirties was advertising the construction of the Libyan touristic experience.51 In this process of the urban and architectural transformation of the colonial settlements overseas, there were two principal approaches. Firstly, the colonial village, thought for the working-class colonizers, often dispossessed and forced to move. Secondly, the villas for the affluent dignitaries. In contemporaneous with the attempt to standardize summer colonies by Labò in 1939, on the pages of Domus Editoriale, Rava-looking-alike villas, were starting to be advertised on the shores of the Italian Riviera. Proposing detached-house solutions working with minimum space, the Modernist approach was different from the Neoclassical examples of the most famous seaside locations in Europe. The Rational ideas were circulating, but also the target or the seaside subject was changing, adding layers of complexity to the Riviera social net. The idea of free time started then to be perceived as an individual experience, rather than a collective one. In particular in 1940,52 Gio Ponti proposed the seaside house as a form of escapism, particularly indicating as diagrammatical drawings, the roles of the inhabitant in relation to the use of space, household tasks, and also free time experience.53 In the same issue we can see a project of Lina Bo Bardi and Giuseppe Pagano, CHAPTER

The harmonic collective is a concept of total sharing of space, capable of transforming a group of individuals from independent subjects to a compact community. Every space of the summer colony, from the refectory to services, and bedrooms, was oversized and communal. The concept of privacy or autonomy was not conceived, both in the spatial and temporal spheres. The strict schedule of the day included activities throughout all children’s stay, even considering playtime as a control tool. The colony was then, in the most Foucauldian way,50 a dispositive of control working through free-time management. Moreover, from the perspective of the working class the colonies have contributed to the conception of the coast as leisure, but they also suggested a seasonal migratory phenomenon of large numbers. However, even though invested in the lower-middle classes, the subsequent mass-tourism development has been at the antipodes of the concept of the colony, becoming even antagonistic to this model in the Post-War. The intrinsic palatability of mass tourism hasn’t been to generally make seaside leisure accessible, but to make it (apparently) customizable. The concept of individual desire is the key to understanding the seaside touristification process.

54 Domus 1940, n 152 p. 70

55

L’Architecture d’Aujourdhui, “Italie constructions diverses”, n. 48, 1953

56

Gaetano Minnucci, “Progetto per il Mercato del pesce Sala delle aste studio prospettico”, 1946, Archivio di Stato di Ancona Fondo Eusebio Angelo Petetti

57

“L’architettura delle colonie marine italiane”, Editoriale Domus n. 659, March 1985

again on the topic of the seaside villa, and an article about hotel bedrooms in Riviera exposed at the Triennale.54 Moreover, on this number of the magazine is expressed concern for the problema alberghiero, the hotel problem, described as a delicate matter of representation. Leisure acts then as a tool for identity construction, and in doing so, it generates a constructed reality, referring to the realm of the imaginary.

In number 48 of “L’Architecture d’Aujourdhui” of 1953 dedicated to Italian architecture,55 written by Vittorio Viganò, an entire section is spent on holiday architecture. What is curious is that in this category is appearing the project for a Fish Market in Ancona, by the architect G. Minucci56 who has been a collaborator of masters such as Marcello Piacentini and Adalberto Libera. Not only commercial and productive functions are identified as touristic, but the project itself conceives the market as a theatrical scenography, designing stage and stands, to display the performance. Furthermore, in this chapter, we can also find the only Past-War reference to a summer colony of the fascist period, written by an Italian scholar. The fact that it was a foreign magazine and that the summer colony was defined as colonia di vacanza, (more French and appealing, less dictatorial, stressing the ludic character) is certainly a detail to take into consideration. In fact, after the fall of the totalitarian regime, fascist summer colonies have been excluded from mainstream discourses in the frame of the Italian debate, re-appearing again 30 years later as abandoned derelict, on the pages of Domus Editoriale in 1985.57

58

Emilio Ambasz, “Italy: the new domestic landscape achievements and problems of Italian design”, 1972

Moreover, following the popular understanding of the seaside, starting from the fifties, concepts such as free time and individual desires are explored by architects, and even fetishized. For example, Cabanon de Vacances of Le Corbusier, in 1951, a minimum unit of just 14 squared meters, was pointed out as a political statement. But because of the lifestyle proposition attached to it, a sort of holiday mindset, the Cabanon has lost the political charge of the Calvinian shelter. In the Italian discourse, are the Radicals to bring at the MOMA, with the cupboards of Ettore Sottsass,58 the seaside equipment59 as an element of Italian design, or with Cabine dell’elba Aldo Rossi recognized in the Riviera rhetoric a possibility of systematization, re-proposing the object as a student dorm 1976.60

61

Case study: Colonia

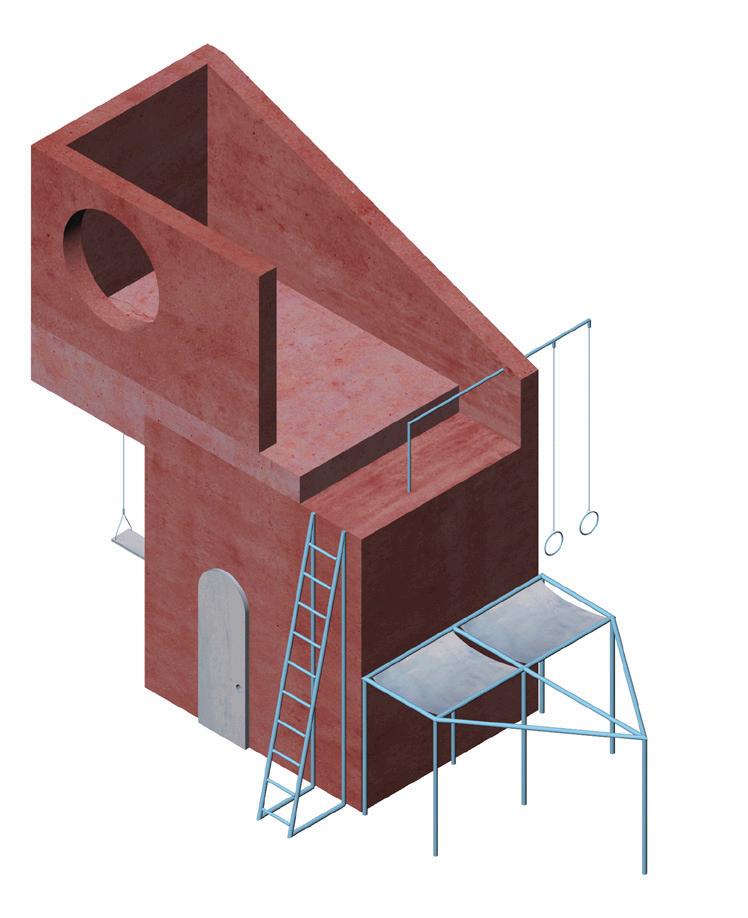

DESIGN

THE TOWER IS A FRAME

While summer colonies can’t be standardized into a unique typology, because they adhere to a functional understanding of space characteristic of the first decades of Modernism, they can be grouped by similarities about single volumes. Practically, while the distribution of each colony is different, the architectural elements of its composition are constant. Therefore, the overall design strategy consists of a plurality of punctual interventions on single parts of the colony, rather than a unique renovation for the entire building. It is identifiable a genealogy of dormitories, rectories, insulation pavilions, etc. In particular, the following design exercise focuses on the vertical volume at the centre of the summer colonies, usually the vertical distribution, but also the water collector, or clock tower, that has been used as a stage for the children’s morning march, spatially tracing a routine of indoctrination. The design tests are applied to Colonia Varese, in Lido di Savio.61

Moreover, through a militaristic choreography starting from the garden and culminating at the top of the tower, the vertical object consequently performed and commanded a loss of body’s identity, but also a territorial dominance. The first design, concluding Chapter 1, focuses on the towers of summer colonies aiming to subvert the perception. Simply considering them as concrete frames, the project attaches to the structure the role of energy production support, to self-sustain future public interventions dedicated to the reuse of abandoned summer colonies. Rather than a territorial gesture, the tower, freely accessible to everyone, become then a visual support to the landscape, framing it.

Object of intervention:

Vertical Connection of summer colonies

Aim: To open access to the public

Architectural aspirations: from Performance to Perception, from Landmark to Frame.

Actions:

. Public and municipal investment for the structural restoration,

. Installation of reversible apparatuses for the production of energy,

. Construction of public paths connecting the beach and structure.

Timeline:

. The initial investment for securing the structure is recovered by selling the produced energy,

. Further gains are then reinvested for building interventions,

. Colonia is accessible to everyone,

. The building interest is collective

The object of intervention: the vertical distribution

Next page: Colonia Varese timeline, changes of use, modifications

Project:

Arch. Mario Loreti

Construction: CMC Cooperative

First year as Summer Colony for Fascist Youth Education

Change of use: Concentration Camp

Change of use: Military Hospital and Mortuary

Change of use: Aircraft Depot

Change of use: Prison for German hostages

Bombing and destruction of the ramp structure

Reconstruction of the ramp structure

Listed Building by Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Ambientali

Dlgs.n°42/2004

National law for the regulation of listed buildings to sale to privates

Failed Attempt to sale

Colonia Varese

Collapse of the Structure

PUG (General Urban Plan)

Test 1 Facade study, Energy production Balustrade as solar panels

62

63

MEGA-GENEALOGIES: a local evolution of summer colonies

The Modernist colonies cannot be catalogued according to typological parameters, however, thanks to the exploration and site visits along the coasts of Emilia Romagna, Liguria, Tuscany and Lazio, the thesis proposes a reinterpretation of the distribution diagram in an evolutionary key. Visiting these case studies in person, following the railway infrastructure62 connesting the shores,63 makes clear how at the local level they are subject to common influences. To systematize a design strategy for the summer colonies, which present a high level of architectural variations, with the interlude Megagenealogies, the thesis theorizes the evolution from typology to diagram, with the application of a local lens.

The interlude focuses on the strip of coast from Ravenna to Rimini, analysing coupled case studies according to hypotheses of spatial development. Starting from Colonia Murri, which traces the traditional typology of the hospital, the research moves to the Modern variation of Colonia Bolognese (pages 86-87). With Colonia Croce Rossa (page 88) in Ravenna, the same linear distribution with perpendicular arms as dormitories encounter the shape-like volume of the boat, later adopted for Colonia Novarese (page 89) in Rimini, but with

a different configuration, subtracting the arms. Then with Colonia Mantovana (page 90) in Rimini is proposed a C shape, which is doubled and repeated in the subsequent Colonia Varese (page 91) in Ravenna. And lastly, Colonia Vittorio Emanuela III (page 92) in Ostia, although located in a different region, designed by Marcello Piacentini, one of the main architects of the Fascist regime, presents the hybridization of the linear typology with arms (the hospital), with the courtyard one. The same scheme is identifiable with Colonia Montecatini (page 93) in Ravenna. Consequently, proximity, construction companies, and personal relations between architects, are key elements for the understanding of architectural variations. From the study, it emerged that the only spatially constant element of summer colonies is the dormitory, designed following the logic of the comrade. Repeated with same dimensions, it is ultimately retraceable to the smallest unit of the bed, and therefore the unit of the body.

Colonie

Public Ownership

Good state of the property

Re-use Project

Lack of Public Funds

Delerict state of the property

Structural Project

Lack of Public Funds

Attempt to Sell Buyer

Private Investor

Project for: Hotels Luxury Flat Resorts

Attempt to Sell

Cooperative

Project for: Family flat Hostels No Buyer

Stalemate Period

Private Ownership

Good state of the property

Delerict state of the property

Public Land is back to the market

Collapse of the Structure

Declaration of “Inagibilità”

The Plot can be sold

A new Constrution can be built

The process of ownership and refurbishment through the frame of Italian regulations

Colonia Murri Bellariva, Rimini, Arch. Giulio Marcovigi, 1911

Colonia Croce Rossa, Marina di Ravenna, Ravenna, Arch. Giovanni Montanari, 1934

Colonia Bolognese Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Ildebrando Tabarroni, 1931

Colonia Novarese Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Giuseppe Peverelli, 1934

Colonia Murri, Bellaria, Rimini, Arch. Giulio Marcovigi, 1911

Colonia Murri Bellariva, Rimini, Arch. Giulio Marcovigi, 1911

Colonia Bolognese, Miramare, Rimini, Arch. Ildebrando Tabarroni, 1931

Colonia Bolognese Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Ildebrando Tabarroni, 1931

Colonia Croce Rossa, Marina di Ravenna, Ravenna, Arch. Giovanni Montanari, 1934

Colonia Croce Rossa, Marina di Ravenna, Ravenna, Arch. Giovanni Montanari, 1934

Colonia Novarese, Miramare, Rimini, Arch. Giuseppe Pevelli, 1934

Colonia Novarese Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Giuseppe Peverelli, 1934

Colonia Milano

Colonia Mantovana, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Guido Norsa 1933

Colonia Varese Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Mario Loreti, 1937

Colonia“Vittorio Arch.

Colonia Mantovana, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Guido Norsa, 1933

Colonia Mantovana, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Guido Norsa 1933

Colonia“Vittorio Emanuele III” Lido di Ostia, Roma, Arch. Marcello Piacentini, 1920

Colonia “Vittorio Emanuele III”, Lido di Ostia, Roma, Arch. Marcello Piacentini, 1920

Colonia“Vittorio Emanuele III” Lido di Ostia, Roma, Arch. Marcello Piacentini, 1920

Colonia Varese Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Mario Loreti, 1937

Colonia Varese, Lido di Savio, Ravenna, Arch. Guido Loreti, 1937

Colonia Montecatini, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939

Colonia Montecatini, Lido di Savio, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939

Colonia Montecatini, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939

Colonia“Vittorio Arch.

Colonia Bolognese Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Ildebrando Tabarroni, 1931

Colonia Montecatini, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939

Colonia Montecatini, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939 SW

Colonia Montecatini, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1939 SW

N 0 10 50 mobility

N 0 10 50 mobility

On the top:

Colonia Murri, 1911, Bellaria; Rimini, Arch. Giulio Marcovigi 2.000 children

On the bottom:

Colonia Varese, 1937, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch, Mario Loreti, 800 children

On the top:

Colonia Mantovana, 1933, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Guido Norsa, 500 children

On the bottom:

Colonia Bolognese, 1931, Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Ildebrando Tabarroni, 1.000 children

On the top:

Colonia Novarese, 1934, Miramare, Rimini, Engr. Giuseppe Peverelli, 900 children

On the bottom:

Colonia Croce Rossa, 1934, Marina di Ravenna, Arch. Giovanni Montanari, 650 children

On the top: Colonia Montecatini, 1939, Milano Marittima, Ravenna, Arch. Eugenio Faludi, 1.500 children

On the bottom: Colonia Vittorio Emanuele III, 1920, Lido di Ostia, Roma, Arch. Marcello Piacentini, 800 children

BAY 1

BAY 2

BAY 3

DESIGN

THE DORMITORY IS A HOME

In the following design, the exercise is presented a general strategy of intervention in abandoned summer colonies, to propose forms of collective living, working, and services that could adapt and be appropriated by the fluid condition of seaside towns. Starting from the summer colony repeated elements of the dormitory, and from the approximation of its average dimensions, results in an invented “typical” dormitory plan, a linear diagram working with one, two, or three bays.

From the typical plan, have been designed different options flexible to different conditions, and ownerships. These invented plans represent a set of general guidelines for the intervention of abandoned summer colonies.

Object of intervention:

Standardization for summer colonies reuse strategy

Aim:

To challenge inherited ways of living and production of Riviera

Architectural aspirations:

To investigate the distributional potential of a linear system

Programme:

Mixed used +Residential +Community centre +Public Orts

Actions:

- To define a set of diagrams for possible distributions

- To design a manual of different scenarios of occupation

- To design a set of flexible systems

- To design a system capable of adapting to different ownership

Timeline:

- To Fragment the summer colony property

- To establish a cooperative structure for decision making

- To select the better option of adaptation from the designed guidelines

the 7 plans, explored in the next pages

Distributional schemes per bay BAY

Design guidelines

Max. occupation

Structural grid (existent)

Project Furnitures Flexibility

Structural grid (existent) Project Furnitures Flexibility

Max. occupation

Structural grid (existent)

Project Furnitures Flexibility

Structural grid (existent) Project Furnitures Flexibility

Max. occupation Structural grid (existent) Project Furnitures Flexibility

Structural grid (existent) Project Furnitures Flexibility

3 Bay option - Guidelines test

Floor Plan / Flat Combinations /Type of units / Flexibility

CHAPTER 2

EDGE: from linearity to alienation

Chapter 2, the Edge, focuses on Riviera Urbanization, identifying in the lotting process of the 20th Century the origin of the urban grain typical of Italian seaside towns. Moreover, at the scale of the settlement, the thesis considers this specific urban tissue a marginalizing device, intentionally perpetrating social division. The analysis will focus on the linear urban system of Riviera, transversally sectioning or delayering, its urban grain, and ways of living. The aim is to document and projectively challenge the division by bands typical of this kind of secondary town. A symptomatic subdivision inherited with the ascendency of building pivots such as maritime hospices and hotels for the upper classes, while Children’s summer colonies for the lowers.

In Subchapter 2.1, the research explains the role of the infrastructure of mobility as a driving force for the development of coastal settlements and the growth of the mass tourism phenomenon. Then with Subchapter 2.2, the focus shifts to the notion of the secondary town as the urban translation of the Riviera imaginary. Lastly, in Subchapter 2.3 “the sea as an alien border”, are discussed the qualitative aspects of secondary towns through the analysis of subjects and performances, the rituality related to the mindset of Riviera, and its ways of living. In particular, the research aims to deconstruct the concept of edge as living on the border of alienation.

Secondary town plan, Rimini municipalities: A case study

1

Ellen Furlough, “Making Mass Vacations: tourism and consumer culture in France, 1930s to 1970s”, in “Comparative studies in society and history,” n. 40, 2, 1998

2

Rudy Koshar, “German travel cultures”, Berg, Oxford-New York, 2000

3

John Walton, Jason Wood, “World Heritage seaside”, in British Archeology, n. 90, 2006

4

Municipal chalet on the beach of Giuliana, Bengasi, 1930, source: Italian touring Club

SEASIDE:

the role of mobility

The touristic landscape of the seaside has become progressively more diffused during the 20th century, increasing the anthropic character of the coasts. But because seaside leisure is a recent invention, tourism research has been a novelty of the last three decades, especially when related to the seaside. The consultation of scientifical journals has been fundamental for the construction of the thesis argumentation, in particular, the Annals of Tourism Research (from 1973), the Tourism Management (from 1980), the Tourism Economics (from 1985), and the Journal of tourism history (from 2009). While scholarships identify the mass-tourism development followed after the adoption of the American model of production and consumption, the agent of seaside modifications,1 Riviera: what happens when summer ends? considers the process of nation-building2 as the historical turning point of seaside urbanism. The shift from the elitist Grand Hotel of the beginning of the past century to the small guesthouse or hotel chain for the middle class3 doesn’t own the primary modification agency of the seaside urban tissue of Riviera.

5

Brian McLaren, “Architecture and tourism in Italian colonial Libya : an ambivalent modernism”, SeattleLondon: University of Washington Press, 2006

6

Ortensi, Dagoberto, Edilizia Rurale. Urbanistica di centri comunali e di borgate rurali con 1010 illustrazioni. Roma: Casa editrice Mediterranea, 1941

In 1934, in the frame of oversea Colonialism, the fascist government was incorporating its Tripolitania and Cirenaica conquests, into a unified Libyan colony. Doing so, it started an implementation process responsible for the imposition of a development strategy of infrastructural interventions and new agricultural settlement constructions. Libya wasn’t the only foreign appropriation of the fascist regime. However, conversely to traditional exploitation practices, after the first agricultural period, the colony faced a shift of purpose: from primary to tertiary production.4 Indeed, Libya became a touristic settlement meant to advertise the power of the fascist regime and the modern civilization’s achievements over the rebellion. Libya was consequentially depicted as an exotic and erotic land by the mass media of the time, attracting curious observers and academic anthropologists.5

The same passage from agriculture to the touristic agency has been applied to littoral Italy. After the first period of Land Reclamations campaigns, involving hydrogeological modifications of the coastal areas,6 in a few decades the seashore turned into tourism. The idea of safeness represented by the territories previously affected by malaria and later transformed into liveable and even idyllic areas is a key point for the construction of the Riviera mindset. Not only mobility has been the first agent of territorial modifications and drastic change

7

Rimini, 1980, in Luigi Coccia, Marco d’Annuntiis, “Oltre la spiaggia, nuovi spazi per il turismo adriatico, 2012

8

Mario Bellini, Kar-a-sutra, in the Moma publication “Italy: the new domestic landscape achievements and problems of Italian design”

Edited by Emilio Ambasz, 1972

9

Renzo Zavanella, “L’automotrice rimorchiante OM Belvedere”, in L’Architecture d’Aujourdhui n 27, 1949, p. 78

10

Angiolo Mazzoni, “Angiolo Mazzoni : 1894-1979 : architetto nell’Italia tra le due guerre : Galleria comunale d’arte moderna”, Bologna: Grafis, 1984

12

Gae Aulenti, Rimorchiatore lamp, in the Moma publication “Italy: the new domestic landscape achievements and problems of Italian design”

Edited by Emilio Ambasz, 1972

in the perception of the beach, 7 but it has also inspired the Radical narration of Riviera in the realm of pop culture.8 In fact, topics like logistics and mobility are the main concepts for the seaside as leisure construction.9