The Confluence of Space

Rethinking the coexistence condition of urban river and the city in the case of Kuala Lumpur

KS (Bryan) Chee

AA Mphil Projective Cities 2022/ 2024

Rethinking the coexistence condition of urban river and the city in the case of Kuala Lumpur

KS (Bryan) Chee

AA Mphil Projective Cities 2022/ 2024

Rethinking the coexistence condition of urban river and the city in the case of Kuala Lumpur

KS (Bryan) Chee

AA Mphil Projective Cities 2022/ 2024

When I first initiated the thesis to investigate Kuala Lumpur, where I came from. It was not a nostalgic decision but a cautious move in taking it up as a challenge to imagine what would the possibilities are in constructing a project through research, at the same time to find a potential proposal for the investigation. Moreover, some of the ideas of the subject of the research are a continuous reflection and questions that I have derived while pursuing the 18-months’ Mphil projective cities programme. Hence, this thesis adopts the methodology learned and applied into the context of the research. The proposal in the research is a mixture of pragmatic and speculative approach which intend to reimagine the city through a project. The process of the research is not a linear process but a constant reflection and discussions with various experts, individuals, cohorts, and professors in order to derive a potential solution. In fact, the research has stumbled across various challenges, such as the availability and accessibility of information and archival material, the understanding of the research subject in a technical aspect and conducting the research in a remote manner. However, all these challenges are part of the learning process which provides a different approach in understanding the research and finding different strategies in the material research such as site walking, interview, participation of the Klang River Festival, analysing the postcards images and adopting drawing as a method in order to construct an understanding and put forward an argument to the subject of the research.

My heartfelt gratitude goes to various individuals who are kind to assist me during the research either by meeting me in person or through online remotely. A special thank you to Ms. Jun Yi Mah, who connected me to various experts and the Klang River Festival. Mr. Dennis Ong and Assistant Professor Chee Keong Teoh, who kindly shared their research knowledge and information on the history of Kuala Lumpur. A special gratitude goes to the organiser of the Klang River Festival who curate and promote events to bring awareness to the river.

My deep respect to Mr. Michael Kennedy, the river activist who keeps contributing his tremendous effort in leading the community to clean up the river. I am very grateful to him for offering an expedition to explore the source of the Klang River. Similar gratitude goes to Mr. Jeffrey Lim, who provided his insight experience of

self-initiated rivers mapping project, and through his introduction, I managed to join Mr. Gregor, a passionate cyclist to explore the ongoing River of Life project through a cycling expedition. I would also like to thank Mr. Si Hou who shared his vision in organising a cooperative living through his initiative at the edge of the Klang River. A huge gratitude to their contribution to the environment of Kuala Lumpur and their willingness to meet, organise expedition, participate in the interview voluntarily, without them this thesis would not be complete.

In addition, the impetus behind this research is indebted to Mr. Huat Lim, who envisioned the Klang River as a city. His generosity in sharing the challenges and successes of the project is invaluable to the research. Moreover, the research owes a debt of gratitude to Ms. Sheau Lim, whose research on the Kuala Lumpur Linear city has inspired and offered me a clearer understanding of the unrealised yet scarce archival materials relating to the Kuala Lumpur Linear City Project. To my friend, Mr. Nazmy Anuar, thank you for your support and discussion on the project, which convinced me that this research should be grounded in our beloved country.

Thank you to the professors and teaching staffs of the programme, especially Sam Jacoby, who introduced and accepted me to the programme during my first application. Thank you to Platon and Hamed who later offered similar gestures and believing in the research thesis. I would also like to thank Doreen and Anna who are enormously patient in teaching and supportive when I have doubts on the research. Further thank you extends to Roozbeth, Daryan and Cristina in offering different perspectives to the research. My diverse cohorts, who come from different parts of the world, each with unique perspectives and life experiences- your motivation and support have been invaluable. Without our journey together through peaks and valleys, this study would merely be just words on paper. Your camaraderie has made this research meaningful.

Lastly, I would like to extend my gratitude to my family who constantly tolerate and support me throughout this period. I am deeply grateful to my father, Michael Tang who made this research journey possible. To Ching Yee and Zoe, who joined me on this roller coaster ride. I hope when we look back this would be a memorable journey for us.

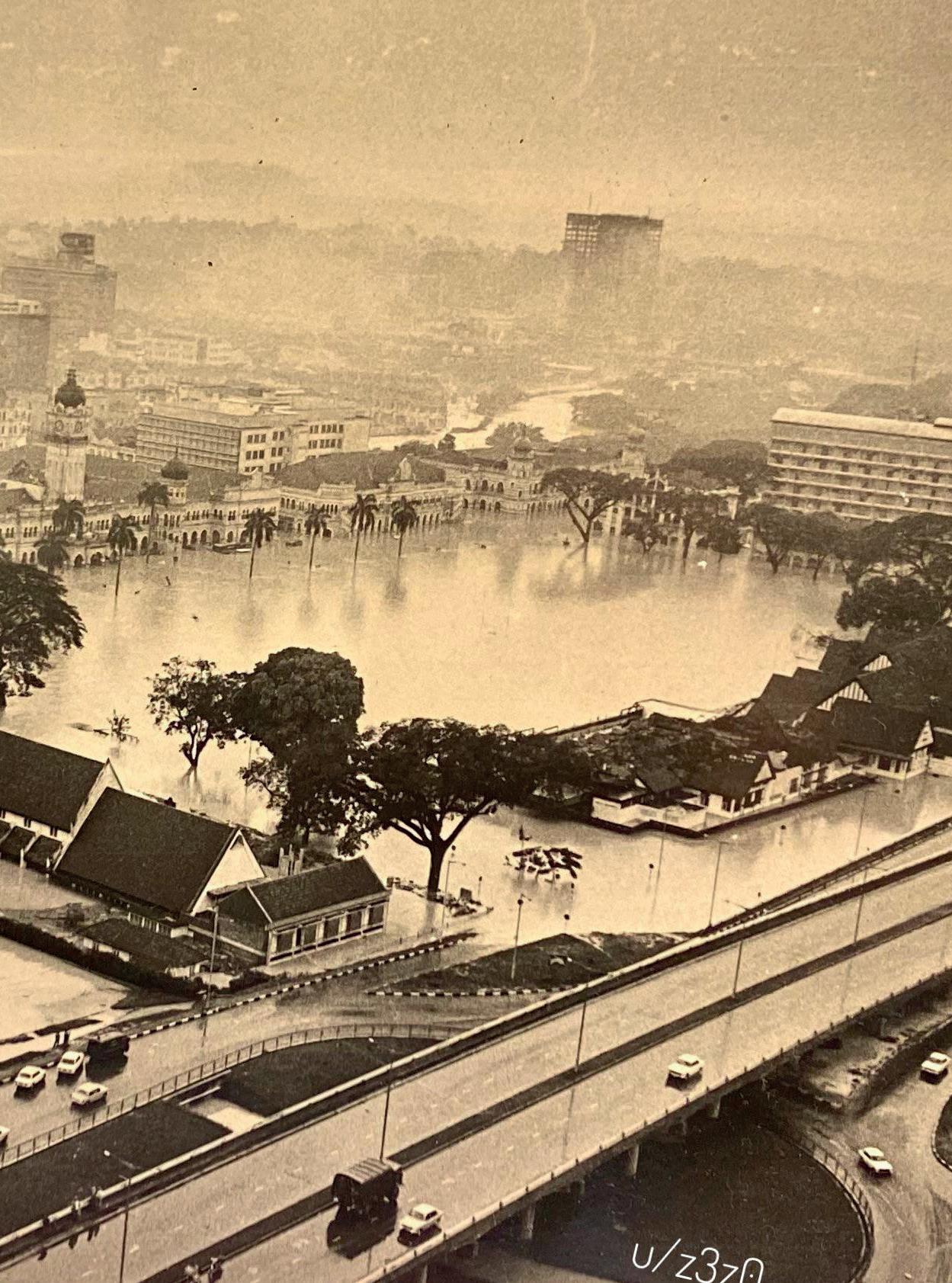

Similar to most urban river worldwide, the Klang River in Kuala Lumpur is bordered by the concrete river walls which disconnected it from the city. The river and its surrounding landscape are always loose, neglected and underutilised. This thesis examined the interrelationship between the Klang River’s role in the development and the identity of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Historically, rivers play a pivotal role in shaping urban settlements, serving as a lifeline for sustenance and vital waterways. Moreover, the river itself is a living organic entity meandering around us, providing a balance ecosystem to multi species and environment. However, industry revolution and technological advancement has confined the river’s nature flow and transformed its waterfront dramatically to satisfy the development of the human. The decline of the industrialisation has led to many waterfront spaces being neglected, therefore triggering the city to revitalise it to become an economic, leisure and tourism purposes.

Kuala Lumpur transformed from a tin mining settlement to a vibrant metropolis which has a close relationship with the confluence of the Klang and Gombak Rivers, signifying the historical significance and laid the foundation to the growth of the city. Despite this, the waterfront has often been overlooked and being regarded merely as an infrastructural for water supply, drainage or flood mitigation system, while the riparian edges are seen as ambiguous spaces.

“The Confluence of Space: Rethinking the coexistence condition of urban River and the city in the Case of Kuala Lumpur,” advocates the word “confluence” which has a broader definition. The term posits beyond a physical merging of rivers, it encapsulates both an arena where human activities take place and the biodiversity inherent in nature. Through site expedition, participation of Klang River Festival, interview, archival research and analytical drawings, the thesis further examines Kuala Lumpur’s neglected and ambiguous riparian edges and suggests potential interventions to reimagine these interstitial space. In addition to this, the thesis undertakes a comprehensive review of the city’s open ground and public spaces, with two-fold objectives: formulating an integrated system that combats urban flooding and also reviving nature-culture symbiosis.

The research examines two revitalisation projects: the unrealised Kuala Lumpur Linear city and the successful River of Life project, both aimed at improving the city’s waterfront but yet leaving challenges that were unaddressed. Through engaging with the local communities, initiative and various stakeholders, this thesis gathers an insight into the collective effort which is essential for the success of revitalising the river. This process not only emphasised the sense of community pride but also highlighted the standards of sustainable living in such context. Through this comprehensive study, the thesis further examines three themes: Edges, Nodes and Spine, by providing a comprehensive understanding of the Klang River’s potential as a vibrant, inclusive and ecologically sustainable urban space within Kuala Lumpur.

The interrelationship of the river and the city has a long profound history. Historically, rivers function as a source of sustenance and are important waterways for human and early settlements. The development of waterfront gained its momentum during the industrial era, hence, many cities associated with the river and coastal has championed their economic gained and political power through its waterways. However, the industrialisation declined in the late 20th century, as a result this led to the waterfront area became a neglected urban phenomenon. Starting in the 20th century, many cities in the global north have recognised the potential value of the waterfront towards their economic development, recreation and tourism. As a result, the once neglected waterfront area has became an important urban renewal project to revitalise with the aim to attract tourists and as an investment to compete with other cities. Through industrialisation, technological advancement, urbanisation and the human’s desire to control nature it led to the straightening and alteration of once meandering rivers. These efforts were driven by the pursuit of advancement and to accommodate various forms of human development. As a result, these transformations have caused a significant impact to the rituals and environmental dynamics interconnect relationship between human, nature, urban environment and the aquatic ecosystem.

Kuala Lumpur, the capital city of Malaysia, emerged from its tin mining industry, transforming from a settlement to a metropolis due to its river. In fact the name “Kuala Lumpur” is associated with the confluence of the two major rivers, the Gombak River and Klang River, signifies the vital role of the waterways in the city’s development. The Klang River, meandering through the vibrant landscapes of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor in Malaysia connecting the inland capital to the straits, it offers an opportunity to initiate a transformative and strategic project on a territorial scale.

Although the river in the city historical significance is deeply ingrained in the collective memory of the people, value it as a lifeline and characterised as a “confluence’”, it is regrettably overlooked by some. For them, the river merely a functional entity, regarded it as a water supply, drainage or flood mitigation system, while the riparian reserve and riverbanks perceive as leftover, abandon, untidy, dirty or dangerous. Nevertheless Ignasi de Sola-Morales would contend that this vacant spaces and interstitial areas between the land and

1 “Terrain Vague”, is a term coined by Ignasi de Sola- Morales, to highlight abandoned, obsolete, and unproductive spaces and buildings—often indistinct and boundary-less within the city. For him, it is important to preserve their state of ruin and unproductivity rather than reintegrate these spaces into the productive mechanisms of the city. Furthermore, Solà-Morales argues that it is precisely in this undeveloped state that these urban spaces can truly offer freedom, providing an alternative to the profit-driven norms of late capitalism. In his opinion, these places embody an anonymous reality, standing apart from the commercial mainstream. - Manuela Mariani and Patrick Barron, Terrain Vague : Interstices at the Edge of the Pale (New York ; London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 24-30.

2 Tariqur Rahman Bhuiyan et al., “Facts and Trends of Urban Exposure to Flash Flood: A Case of Kuala Lumpur City,” Improving Flood Management, Prediction and Monitoring, November 8, 2018, 7990, https://doi.org/10.1108/s2040726220180000020016.

water, whether on the fringe or within the city, are integral part of our everyday living spaces, a “terrain vague” which consistently overlooked and neglected.1

In addition, Kuala Lumpur’s urban flood is becoming constant and alarming. According to the research by Tariqur Rahman Bhuiyan, the city centre is the most risk prone to flash flood with 39% of flash floods often happening at this place. The reason behind this is due to the anthropogenic causes that are linked to the urbanisation, especially the alteration of land use at the surface. As a result, the nature ground that was once porous has now turned into hard surfaces, as well as the reduction of vegetation and other factors, have affected the water run-off, distribution and infiltration system. Hence there is an urgent need to improve flood management and urban planning in the city.2

In a recent initiative aimed at revitalising the rivers, the Klang River has become a limelight, taken as a project to enhance the city’s identity and image. While the visionary Kuala Lumpur Linear city faced constraints and not fully realised due to the financial crisis in the late 90s, its intention does not only serve to propel the urbanised Kuala Lumpur, but also as an advanced city within its region. On the contrary, the River of Life project, launched in early 2020, focused on the remediation in cleaning up the polluted Klang River and beautification of the city waterfront. Both projects’ objectives carry the same goal to revitalise the waterfront of Kuala Lumpur. Despite the successful of River of Life project in revitalise the Kuala Lumpur riverfront, however, such ambiguous terrain persist. Therefore, it is important that we review, reimagine and repurpose such marginalised spaces to create a new urban experience encompass with social, cultural and ecological purpose.

The Confluence of Space: Rethinking the coexistence condition of urban river and the city in the case of Kuala Lumpur, arguing the definition of “confluence” extends beyond its physical attributing merging of two rivers. It encapsulates the notion of a communal space that accommodates various human activities and fosters nature biodiversity within the riverbanks and urban environment of Kuala Lumpur. It starts with investigating the range of ambiguous and neglected riparian river edges within the proximity of Kuala Lumpur city, from upstream to downstream, hard edges

to soft edges, urban to suburban condition. It then suggests potential applications to reimagine the interstitial spaces between the land and water. The research extends to review the associated open ground and public spaces within the city, to formulate an integral system to tackle the constant urban flood and reclaim the coexistence relationship of the nature and culture in Kuala Lumpur.

The research employs site expedition and participation in the annual Klang River Festival during September 2023. Extensive visits were conducted with the guidance of local experts or on my own along the 120 km length of Klang River, from the source of the river at the upstream at Klang Gates Dam to the mouth of the river at Ports Klang where the Klang River eventually join with the Straits of Malacca. Such expedition includes walking in the urban centre, periphery of the city and cycling along the River of Life project. Nevertheless, the site expedition has its limitation due to the river’s length and accessibility and areas which are undeveloped. Although the thesis focuses within the context of the city of Kuala Lumpur, the condition applies, however, such expedition is crucial in order to have a better understanding, observation and in person experience towards the conditions of the Klang River in relation to the urban development of Kuala Lumpur.

Afterwards, a series of sections was drawn, dissecting the Klang River into various sections traverse across the city, from the urbanised hard edges to the suburban soft edges within the proximity of Kuala Lumpur. Such redrawing exercises are crucial to the thesis to examine the river’s relationship with the urban built form and to use it as an analytical tool.

The Klang River Festival was an annual river awareness event initiated by the local community since 2022. By participating in the festival and some of its associated events (e.g. art installations, photo exhibitions, film screenings, workshops, dialogues, guided walks etc.) both indoors and outdoors, along with the experiences within, around and along the river, including the often-overlooked interstitial spaces between the land and water within the city, it provides information of the issues faced by the river, various public and private agencies in managing the rivers, creative occupation and interpretation of the rivers and its interstitial spaces within the city.

Furthermore, interview was conducted with the initial design team of the Kuala Lumpur Linear City. Although there is lack of archival material of the project, the interview forms the primary source in providing the background and challenges faced by the unrealised urban vision. Interview and visits were also made with two different collectives, Alliance River Three and the Kongsi Coop, who initiated their community programmes next to the Klang River. While the Alliance River Three focused on river conservation, protection and building a rehabilitation park, the Kongsi Coop, on the other hand, is a co-creative community that focused on sustainable living. Through the interviews and visits the thesis gained valuable insights, by understanding the existing community network, challenges and potential faced living or working adjacent to the river.

The research also focuses on the postcards and photos, which allow me to reevaluate and analyse the river usage, historical development of the Klang River and Kuala Lumpur in contrast to the current urban environment. Such pictorial material is essential as an inspiration as well as providing space for personal interpretation, to formulate the design brief and speculate the possibilities for the intervention later.

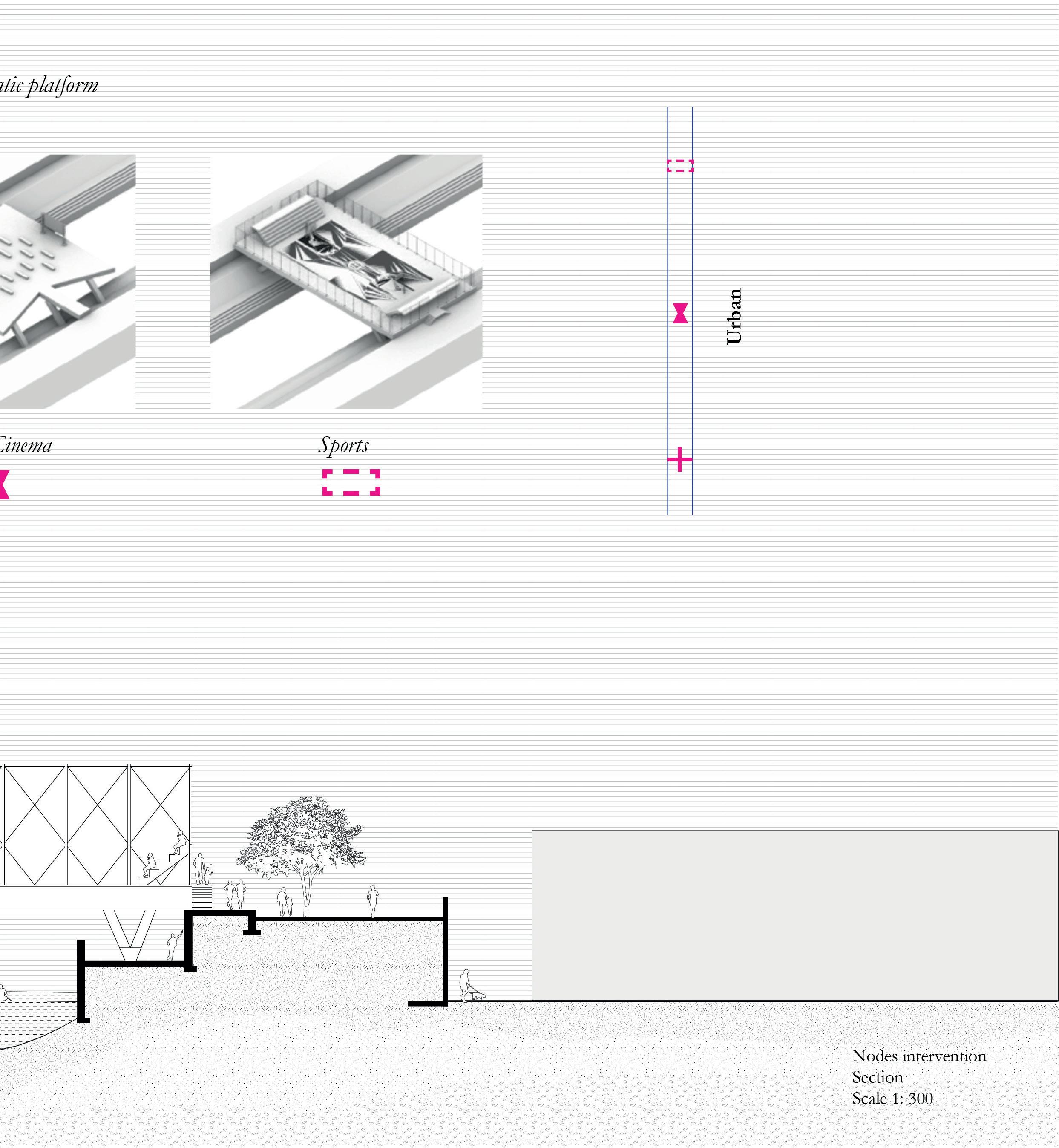

The research is in 3 parts which delve into 3 themes: Edges, Nodes and Spine. Each of the part signifies ways of treating the river and the city. The thesis is divided into 3 chapters. The summary of the chapters is shown below:

Introduction outlines the research on the background and the issues, it provides the scope of the research, thesis structure and the overall organisation of the chapters. It also states the aim, research questions and objectives of the research.

Chapter One, Edges: From Lifeline to a Line, provides an introduction background of the interrelationship of Klang River and the urban development. Through examining the history, river usage, urban development, it serves as a reference and the starting point for the research, by focusing on the river evolution, river edges and it’s adjacent urban phenomenon, to provide my observation and view through the site expedition.

Chapter Two, Nodes: Living by the Water, examines the human relationship with the river and the waterfront development in the context of Kuala Lumpur. This chapter will investigate into two major projects. It reviews the Kuala Lumpur Linear City from the 1990s that was never built and also examines the new the River of Life project from 2010s. Both projects shared the vision to revitalise the waterfront area of Kuala Lumpur.

Chapter Three, Spine: Beyond a Line, explores the contemporary urban flood issue in the city through a territorial scale. It is understandable that technology advancement in managing floods works well to keep them under control, however, this chapter argues that the fundamental issue of the flood is caused by the urbanised city with lack of porosity to absorb and drain away the water. Today, urban floods are common and widespread danger all over the world. The chapter stresses on the importance of integration of the natural landscape such as wetland and urban forest within planning, by considering it as a potential system to mitigate and normalise the disaster that happens every year.

Design Intervention, is a chapter for proposal and strategy framework. There will be three parts of design reflects on the notion of Edges, Nodes and Spine.

Conclusion: This is the concluding chapter which synthesises the insights from the preceding chapters to reimagine the Klang River and Kuala Lumpur. It aims to provide new ways of envision a potential collective ecological space for the city.

The aim of this thesis is to redefine and enhance the symbiotic relationship between the Klang River and the urban environment of Kuala Lumpur. To do that, the thesis seeks to reframe the river as an inviting communal space for collective activities and biodiversity. In addition, to posits the nature-culture as a solution to develop the city. Through the development of sustainable strategies, this research seeks to reimagine Kuala Lumpur as an inclusive habitat fosters for human wellbeing and ecological balance. The objectives of the thesis include:

- To investigate the historical evolution of the Klang River in relation to the development of Kuala Lumpur.

- To analyse the Klang River edges condition by assessing the river’s usage and spatial configuration through site expedition, festival observation, engaging with the community, analytical drawing and project review.

- To formulate a sustainable design strategy and propose interventions to enhance the waterfront, community and boost its biodiversity while tackling the urban flood challenge.

Typological question:

How can redesign the riverbanks such as the river wall dissolve the distinction between the land and water, as well as human and natural environment?

Urban question :

What form of waterfront development approach is vital to Kuala Lumpur’s need, other than centralisation, commodification and tourism?

Territorial question :

How can rethinking of integral natural ecosystem a strategy to contribute to a more sustainable, resilient and liveable city?

Scale 1: 150 000

ISource:

Scale 1: 150

Source: Redrawn by Author.

3 Dilip Da Cunha, The Invention of Rivers : Alexander’s Eye and Ganga’s Descent (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University Of Pennsylvania Press, 2019)

The relationship of human and water is inseparable, starting from the average ideal body with an amount of 60 % filled with liquid, nevertheless, 71% of the earth is covered by water. From consuming the water as food source to treating it as production resources, water has also long associated with human as religious ritual and spiritual in various civilisation and culture. It is not surprising that many early civilisation arise from the river valley such as Indus River, Yellow River, Nile River, Tigris and Euphrates Rivers where access to the water are vital for defence, agrarian, transportation system, trading network and food system. At this time the relationship of land and water is not clearly defined in a single line that appear in the colonial cartography map.3 Wetlands are usually visible between the land and water - from the eyes of the indigenous - as the mediator to mitigate the flood and accommodate various living species. The indigenous never treat the flood as an issue since they live in a nomadic lifestyle, hunt, and irrigate during the dry season while migrate to the higher land when monsoon is approaching. The human’s needs and how rivers surrounded around their living environment, force them to find ways to adapt, accommodate and even control it to their benefit. However, rivers are not only a channel to satisfy the human needs, but it also forms a larger complex system as the nature and breeding ground for multi-species to thrive. Hence, rivers are always treated as sacred ground, and it is essential to keep it healthy as it forms an essential part of the ecosystem.

The river, that was long associated with the history development of the Malay Kingdom has evolved over time. From the early periods, the river served as a pivotal hub for the local communities, who reside closely and relied on the water for essential daily activities such as washing, cooking, bathing, fishing, farming and etc. The architecture at this period was characterised by its primitive, lowtech nature, constructed through inherited ancestral knowledge and local accessible building material from the nature. These structures usually adapt to the precarious conditions, weather changes and climatic constraint are never an issue as the local riverine community integrated their life in accordance with the cycle of the season and weather. As a result, most of the built structure along the river are usually elevated on wooden stilts or piles which keep them away from the flood and wild animals. The roofs are pitched and cantilevered typically in thatch made from dried leaves of the Nipah palm and other palm leaves. The roofing covering the building mass

effective in keeping the dwelling away from the heat and protect it from heavy tropical rain.

Apart from that, the nomadic lifestyles were common in the early communal life, with some communities residing on floating river boats. This mode of living enabled the communities to be mobile, travelling across waterways and changing their habitats in accordance with the seasonal changes, resources availability and socio-economic opportunities. By living on the water, these floating communities adapt their lifestyle with the riverine environment and took advantage of the rivers for fishing, trade and transportation. The boat is not just a home but also serves as livelihood, it reflects the floating community’s deep knowledge of accommodating with the aquatic environment. In comparing the materials and spatial organisation of these houseboats, known locally as “perahu kajang” with traditional Malay houses, one can find the similarities. The roofing of the houseboat, constructed with woven palm leaves and pile, tapers at both ends cover the space underneath. This design reflects the pragmatic and aesthetic sensibilities seen in the traditional Malay house. The interior of the houseboat, the central space is the family living space, which enables the members to relax and sleep at night. At the rear side of the boat is the kitchen and bathroom which serve the practicality and efficiency of the household. The walls are covered with panel boards with punctuated holes which function as windows. This feature reminiscent to traditional Malay houses, which not only offers a view, but also facilitates cross ventilation, ensuring a comfortable living environment within the enclosed space of the boat house. The similarities between the Malay houses and the houseboats most likely inherited the same heritage of craftsmanship. It is possible that the artisan who constructed the houseboats are involved or shared the architectural principles influence of both type of dwellings in the Malay culture. This shared knowledge reflects the practicality, adaptivity and deep understanding of the material, which also shows the strong connection of the community with their environment either on land or water.4

“The native are true Malay, never building a house on dry land if they can find water to set it in, never going anywhere on foot if they can reach the place in a boat.” 5

4 & 5 Mohamad Hanif Abdul Wahab and Azizi Bahauddin, “The Similarity of Malay Architecture Terminology: Perahu and House,” Social and Management Research Journal 14, no. 1 (June 30, 2017): 33, https://doi. org/10.24191/smrj.v14i1.5278.

Fig 13: Candi at Bujng Valley. Source: Wikipedia

6 Iklil Zakaria, Saidin Mokhtar, and Jeffrey Abdullah, “Ancient Jetty at Sungai Batu Complex, Bujang Valley, Kedah,” 2011, https:// www.researchgate.net/publication/288890501_ANCIENT_JETTY_ AT_SUNGAI_BATU_COMPLEX_ BUJANG_VALLEY_KEDAH/ references.

7 J M Gullick, Old Kuala Lumpur (Oxford University Press, USA, 1994), 1-9.

Apart from the individual dwellings, the river banks were strategic location for the community to set up their base. The recent notable archaeological remnants found at the Bujang Valley show the early Malay civilisation adept and utilisation of natural waterways as lifeline and international commerce.6 The Bujang valley is not only a thriving trading centre but is also a cultural and religious hub from the 5th to the 14h centuries. The rivers surrounding the Bujang Valley serve for the movement of goods, sharing knowledge and cultural practices, connecting the ancient Malay Kingdom with other trading networks across Asia and other regions. In the case of Kuala Lumpur, a variety of building types was depicted in Frank Swetenham’s sketches, such as Malay cemeteries, market, mosque and gambling facilities were evidently present and accessible from the river.7 This accessibility and the riverbanks were crucial, as the inlands were largely undeveloped and covered in lush tropical forest in this period. Therefore, the river emerged as a vital route, becoming a central hub for socioeconomic, cultural and ritual activities. Over time, as these hubs expanded and connected with other communities and regions, they transformed into trading centres.The relationship of local communities with the river systems exemplifies the river as a lifeline in the early civilisation in the Malay Kingdom.

Fig 14 [Right]: Perahu Kajang Plan and Elevation.

Source Redrawn: by Author

8 The term “kongsi” is from the Hokkien dialect, widely used across Southeast Asia which refers to a firm, partnership, or society. Historically, it refers to collective Chinese enterprises crucial for the development of industry, commerce, and navigation in the region. Originally family-based with shared capital under a patriarch, kongsi have evolved over time into broader business entities.- Wang Tai Peng, “The Word “Kongsi”: A Note,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 52, no. 1 (235) (1979): 102-5, https://www.jstor. org/stable/pdf/41492844.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A178b9e9ecf277ac416e5c1e1925d4e16&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1.

The history of Kuala Lumpur is deeply intertwined with its rivers. The name Kuala Lumpur is derived from kuala (river confluence) and lumpur (mud), named after the muddy confluence of the Klang and Gombak Rivers, where the city was established as an informal settlement. Over time, Kuala Lumpur transformed from a simple settlement at a muddy river junction to a small town, and then became the capital of the nation. The tremendous development was facilitated by the discovery of tin in 1857 in an area now called Ampang. The Klang River, however, was especially important since it served as an artery that supports the growth and development of Kuala Lumpur. It connects the Klang River which not only serves as a major transportation route for the tin and other goods, but also became a central area which offers the opportunity for social, economic and cultural life. As the city grew, the Klang River contributes to several key moments in the city’s history.

Initially, at the east of the river confluence populated with wooden huts set up by the Chinese settlers who were sent by the Malay chiefs to prospect the tin. During this time, the river confluence was a vital dwelling zone with essential facilities constructed next to the waterways. This strategic location became a key landing point for boats, as the upper river got narrower and shallower. Miners were compelled to disembark here and make their way trekking to the inland of tin mines located in Ampang. Over time, the area around the river confluence evolved into a significant landmark, serving as an important landing point and a commercial hub. As settlement expands, the area slowly emerged with trading posts and stores, catering to the daily necessities of the community and facilitating the export of tin, coffee and gambier, with the Klang River acting as the primary mode of transportation. At the same time, the central market adjacent to the river became the centre of activity, showcasing the vibrant daily life and the operation of the tin mining boomtown. With the discovery of more new mines, the town was slowly populated with the influx of prospectors leading to the establishment of more temporary shelters, or ‘kongsi’ 8 was set up to accommodate the labourers. Gradually, the shelters interconnected by tracks, formulate the primary road patterns that would shape the urban layout of Kuala Lumpur. This network path served its purpose not only for movement within the town but also marked the beginning transition of Kuala Lumpur from a temporary mining can to an organised urban settlement.

To the north of the landing point, the Sumatra Malay community established their trading post along the Klang River. Within the close proximity of the river, they operate both the mining and farming activities. Due to the Malays who were predominantly engaged in riverine farming and fishing, and who traditionally abhorred a wage-based economy, consequently, tin mining among the Malay community was probably carried out by individuals bound by debt or by slaves under the local Malay chief. Alternatively, mining might have served as a supplementary activity, conducted during the interim periods between the agricultural cycles.9

In the latter half of the 19th century, rising tin prices led to more encroachment into the jungle for tin exploration and mining, as well as accommodating the expansion of Kuala Lumpur and its population growth. The land use within and around the area was featured with a mix of diverse and multifunctional land with agricultural activities alongside with mining and trading in the early development of Kuala Lumpur. Vegetation cultivation and rice farming along and around were essential, forming an integral part of the local economy, in order to sustain the needs of the population. This era showcasing Kuala Lumpur’s landscape was characterised with a mix pattern of farming, mining and trading activities, reflecting the city’s self-sufficiency and dynamic integration of various economic activities. Despite of this, the city reliance on the river for farming, mining and transportation was fundamental, not only for the economic gain but also the population’s daily sustenance and livelihood, reinforcing the river’s role as a lifeline for Kuala Lumpur’s diverse and thriving community.

In the 1880s, Blommfield Douglas, the British Resident, convinced the Sultan of Selangor to implement a comprehensive urban development plan, which notably included the relocation of the government from Klang to Kuala Lumpur. This pivotal move signified Kuala Lumpur’s transformation into the capital of Selangor, hence necessitating a new spatial planning to reflect its elevated status. Douglas meticulously selected a site for the British administrative centre to the west bank of the Klang River, strategically positioned away from the unsanitary conditions of Malay and Chinese settlements. The selection of the location was intentional, aiming to reduce the risk of flooding and provide a defensible position in case of any potential uprising from the mining community, there-

9 Jackson, N. R. “Changing Patterns of Employment in Malayan Tin Mining.” Journal of Southeast Asian History 4, no. 2 (September 1963): 141–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s0217781100002830.

Fig. 16 [Left]: Early postcard captures the essence of vernacular architecture harmonizing with the natural landscape through the artful integration of an embankment.

10 Tai Chee Wong, “From Spontaneous Settlement to Rational Land Use Planning: The Case of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia,”Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 6, no. 2 (August 1991): 240-62, https://doi.org/10.1355/sj62c.

by utilising the river as a natural defence mechanism. Subsequently, an area of marshy and uneven ground adjacent to the Klang River was cleared, levelled and drained to be used as the police training ground. This patch of land, initially referred to as the Parade Ground, was later known as the Padang. The colonial blueprint for Kuala Lumpur was basic. The land closest to the river confluence and landing spots were designated as the centre for governmental and commercial activities, housing the city’s landmark buildings.10

11 Amarjit Kaur, “Road or Rail?-Competition in Colonial Malaya 1909-1940,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 53, no. 2 (238) (1980): 45-66, https://www. jstor.org/stable/41493593.

During the late 19th century, British governance implemented a major infrastructural plan, in order to rule their colonial subject. Historically, tin ore was exported to coastal port through river transportation or carts on tracks that connect mines to riverine villages. The inadequate connection of the tin mines directly with the port hindered Kuala Lumpur’s economic progress. This led to Swettenham, the colonial administrator, with a keen interest in economic development to initiate the construction of a railway line between Klang and Kuala Lumpur. This rail network was vital for transporting tin from the mines to the nearest port for export, marking a significant period of economic transformation for the city. The need for the rail transport system was primarily due to the logistical challenges and risks associated to the river transportation from Kuala Lumpur to port Klang. Traditionally, the travel journey could take up three days by boat and often hampered by unpredictable weather. Consequently, the British governance decided to invest in the railway system as a more reliable and efficient means of transportation to support the exportation of the tin industry and other raw material produce. By 1886, Kuala Lumpur operates its own rail line to connect to the nearest port in Klang.

The strategic focus on rail infrastructure led to a developmental shift away from the river as the primary mode of transportation. As railway stations became the focal points of economic and urban development, towns and industries gravitated towards these new hubs. This shift had a profound effect on the urban landscape, with new commercial centers, residential areas and industrial zones emerging along the rail lines, reducing the historical reliance on river transportation. The rail network’s influence extended beyond economic restructuring to shape the spatial organisation and growth patterns of Kuala Lumpur and the surrounding areas. The transition from river-based to rail-based logistics and transportation marked a significant evolution in the region’s infrastructure and urban form, reflecting a broader trend of modernisation and development during the colonial period. This transformation, rooted in the principles of the Marshallian theory of agglomeration, illustrates the complex interplay between infrastructure, economic strategies and urban development in shaping the historical trajectory of Kuala Lumpur.11

Source: Author.

19: The evolution of river in relatiohsip to Kuala Lumpur.

Source: Redrawn by Author.

As the reliance on river transportation wand with the advent of railways and roads the riparian landscape fell into neglect. In these transformative times, not only did we witness a reconfiguration of the natural landscape, but also an evolution in the city’s relationship with the river. The once wandering river has been redirected into controlled linearity. Initially, the Klang River acted as fertile grounds for diverse ecosystems; they were embraced by the city architecture with terraces and platforms that integrated with flowing waters. For instance, the Masjid Mosque was built contextually with a series of steps guiding the Muslims who approach the mosque through boat. The steps function as a transition area enable for social interaction, as well as bridging the gap between the land and water. With urban expansion, the Klang River was reengineered into constraints channels infrastructure with the aim at managing water flow and preventing floods.This shift created a stark division. From the robust colonial constructed embankment to the grey structure now, it demarcated the boundary between land and water, eventually distancing human from nature. As a result, this barrier not only alters the riparian landscape but also the connection to the natural world.

Inhabitable Edges

Map showing Kuala Lumpur’s layout alongside the proposed sectional cuts that traverses the Klang River.

Malaysia is located in the global southeast where it is neighbour with Brunei, Singapore, Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines. Similar to most of the global and regional situation, most town and city of Malaysia emerged from the riverbanks. The river is the lifeline that sustains the local’s daily living and a place to trade in the past. However, the role of the rivers has declined since the industrialisation as the expansion of the city moved towards the inner land when the jungles and hills turned into land for planting and development. Moreover, the introduction of modern sanitary infrastructure to provide fresh and safe water for cleaning, washing and cooking kept people away from relying on the river as the only water source. Hence, the city and its people’s response to the waterfront are detached, sometimes turning away or totally ignoring it. Nevertheless, this should not be an excuse for the city for not integrating its waterfront in order to create a liveable living atmosphere for its citizen.

The waterfront in Kuala Lumpur is no different, the river and its edges have been engineered. The residue space at the banks is either canalised, straighten, embanked or described as a terrain vague between the land and water.

Section K 01 - K 05

Moving from section K01 to K05 situated at Old Klang road, historically suburban areas now urbanising rapidly, showcase diverse developments. Older, low-rise structures prioritise a tangible connection to the river, while new, high-density blocks often treat the river as a backdrop, distancing the city from its waterfront. Strict regulations preserve river edges, but a lack of facilities hinders their utilisation.

Section K 06

Deriving its name from the central position, “Mid Valley” is located in the Klang Valley, it epitomises a vast urban development that integrates retail spaces, offices, hotels, educational institutions and recreational amenities. The development aims to offer more than just a typical mall experience but aspiring instead to become a Megamall- a city within a city, that infuse various elements in one cohesive place. Originally, the area is populated by low-cost flats and Malay villages with the Klang River meandered naturally in the area. However, the existing community had to be relocated, while the natural river underwent alteration for development to transform it into an urban hub. The transformation indeed introduced multi-lane ring roads around the development, effectively separating the waterfront and severely limiting public access to the river. This showcased a missed opportunity for contextual integration with the Klang River as an infrastructure to seamlessly connect the development and the natural river.12

12 Rachael Lee, “Constant Improvements, No Complacency the Key to Success,” The Edge Malaysia, November 7, 2017

The research notably observes: the rail network such as the monorail and land transit train positioned alongside the river has created a significant influence. Commonly, cities choose an above-ground transit system and stations in order to mitigate traffic congestion. This kind of strategy is particularly pragmatic during urban expansion phases especially confronted with land acquisition challenges and limited open space. Therefore, the government often earmarks state-owned river reserve lands as ideal cost-effective solutions for executing infrastructure projects. The consequences of this infrastructure planning manifest themselves with the creation of interstitial spaces form beneath the rail structures. However, in cases where land availability tightens its grip such as when space is limited, the rail system tends to encroach upon river reserve edges. As a result, the potential of the river edges disappears, and on top of that, the ecological importance is significantly affected as well. Consequently, the city is battling towards spatial delineation and functionality over symbiosis with nature. In addition, the rail system enforces a robust physical boundary that impedes seamless integration of the river into urban context already established.

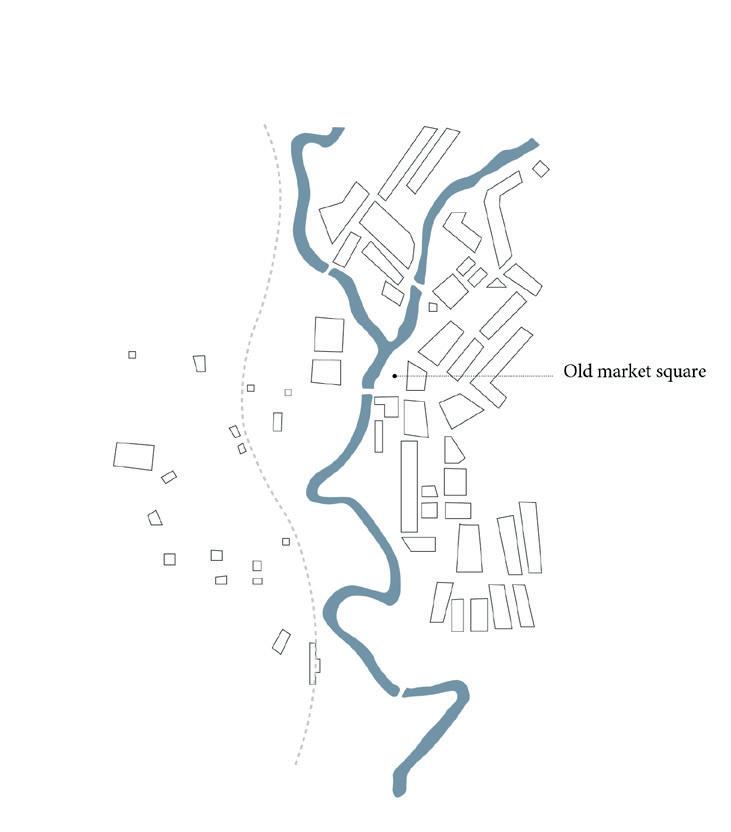

The iconic Jamek Mosque, a testament to the Moorish influence in its architecture, stands at the confluence of the Klang and Gombak Rivers before they merge as the main Klang River. From here we can locate the British colonial administrative centre which resides on the west of the river; on its east bank is where the Chinese settlement and old market square used to be located. Historically, boats would halt at this vital confluence, due to both rivers at the further up stream getting narrower and shallower. The miners will then set foot towards the Ampang tin mines. At present, the area has transformed into a blend of heritage and commercial zones, with the confluence as an integral part of Kuala Lumpur’s River of Life Project. This area is filled with thematic ambiance through

periodic water mist release and vibrant night displays it has become a popular tourist destination.

Although there are significant improvements of the area, however, both banks’ waterfronts suffer from the constraints imposed by the concrete river walls. The waterfront does not only limit public access but also directly hampers the engagement with the river. The buildings along these edges predominantly face to the main road, which potentially missed the opportunity for a more integrated waterfront with the existing urban fabrics.

Section K13

Lorong Bunus 1, situated in the north of the downtown confluence in Kuala Lumpur, features a characterisation of mid-rise shop buildings, shop lots and residential housing. Similarly, the river at this area has been straightened and embanked the riverbanks with concrete water walls, hence, public access to this area’s river remains inaccessible. Despite this limitation, the existing developments subtly integrated the river view. The presence of the waterfront notably enhances the overall ambience of the area. Even though direct public interaction with the waterway is still restricted, but the effective surroundings demonstrate a deliberate integration of the river into urban landscape.

Section K 14

Kampung Bharu, situated at the fringe of the Kuala Lumpur central business district, remains as one of the oldest Malay villages in the city. The village is under a Malay reserve land with a strong presence of the vernacular Malay houses and existing community. At close proximity, the Jalan Ampang cemetery which was established since 1819, is a significant Muslim cemetery next to the financial district of the city. The contactual relationship of the river

13 Ampang–Kuala Lumpur Elevated Highway (AKLEH), is the first elevated highway in Malaysia. The 7.9 km elevated highway connects Ampang and Kuala Lumpur. This highway was built to reduce traffic jams at Jalan Ampang and make access to the city more convenient.

and its water front in this area is insignificant due to the blockage by Ampang- Kuala Lumpur Elevated Highway (AKLEH).13

14 Mohamed Ikhwan Nasir Mohamed Anuar and Raziah Ahmad, “Exploring Possible Usage for Elevated Highway Inytersitial Spaces: A Case Study of DUKE and AKLEH, Kuala Lumpur,” Planning Malaysia Journal 16, no. 7 (November 4, 2018), https://doi. org/10.21837/pmjournal.v16.i7.512.

As we stretch alongside the AKLEH elevated Highway, the impact of infrastructure planning on the river edges will be notably significant. The nation’s first intra-urban elevated highway is also a towering structure encroaching into the river space with its presence. The elevated highway not only casts an imposing shadow over its riverscape below, but it also creates a pronounced barrier that limits the engagement with it. Moreover, the multi-lane highway acts as a boundary which distinctly limits the neighbourhood interaction with the water. In this particular context, the river has meticulously undergone engineering transformation. Consequently, its structure mimics that of a canal due to the surrounding infrastructure influence.14

Section K01

K0

Scale 1:750

Scale 1:750

Section K02

Scale 1:750

Section K03

Scale 1:750

Section K04

Scale 1:750

Section K05

Scale 1:750

Section K06

Section K06

Scale 1:750

Section K08

Scale 1:750

station. Source: Google Map,

Section K10

Scale 1:750

Section K11

Scale 1:750

Section K12

Scale 1:750

Section K13

Scale 1:750

Section K14

Scale 1:750

Driveway segregating the neighbour hood with the River.

Source: Paul Gadd, Archdaily, Nov 23, 2021.

Section K15

Scale 1:750

Source: Google Map, 2023.

Fig 20 [Top Left] The Kuala Lumpur embankment, 1926.

Source: Vijaya Kumar Ganapathy

Fig. 21 [Bottom Left]: Klang River, 2017.

Source: New Straits Times

In summary, the water front at the city centre encompasses with the heritage and commercial zone, which focuses on the commercial, recreation, heritage and tourism industries. Although the River of Life project has managed to revitalise the waterfront as part of the centre (Sections K10 to K12) which attracts tourists and local visitors, however, the waterfront at this area has limited public access and usually both banks are embanked with concrete water wall. Therefore, the public engagement with the river at the waterfront is restricted to gazing the river from a distance.Furthermore, the infrastructure obstruction such as rail transit elevated highway and road systems (Sections K06, K14 & K15) seems like a massive barrier to the Kuala Lumpur waterfront. There is a need for a more thoughtful approach to the infrastructure development is underscored by this impact with urging solution towards ensuring a harmonious relationship between the infrastructure planning and the river.Moving away from the central city, the suburb area at the up and down stream, usually has a mix of nature (Sections K02 to K05) and manmade edges (K01). The man-made edge (Section K01) is due to the alteration of river for development and mitigate flood. The soft edge is the space which is usually left empty, under developed and lack of maintenance. At the same time, it provides an opportunity to rethink and make this space a better integrated waterfront with the city.

Where historical sections intersect with business areas, the city center pulsates with life; it serves as a bustling hub for trade and preservation of cultural traditions. Furthermore, this locale entices tourists with its manifold attractive qualities. The successful refreshment of an area between Sections K10 and K12 at the central waterfront significantly enhances its attractiveness. The River of Life project accomplished this feat by drawing in numerous tourists and locals to visit. However, one drawback which remains is the solid water barriers that restrict public entry, limiting interaction and allowing only far-off viewing from both sides.

Moreover, the infrastructure imposing presence - rail transit, elevated highways and road systems in Sections K06, K14 & K15 - forms formidable barriers along Kuala Lumpur waterfront. This underscores an urgent need for a more thoughtful approach to develop infrastructures, one that not only caters for practical requirements but also guarantees harmonious cohabitation with the natural river

Source:

environment.Beyond the busy city center, if we shift to the suburban areas along the upstream and downstream (Sections K02 through K05), we will encounter a mix of natural with manmade river edges (Section K01). Section K01 showcases the alterations with the construction of a concrete river wall in a terrace form is evidence that the rivers have been shaped for development and the measure of flood mitigation. Despite this, there is no public access, the river wall at this particular section is in a terrace formation which enables the room for nature to grow yet creates a harmonious water edge.

On the contrary, the soft edges at the river which are often underdeveloped or overlooked, serve as the river reserve to mitigate flood. Despite their maintenance deficiencies, we can certainly convert these areas into integrated waterfront spaces that harmoniously fuse with the cityscape. This transformation presents a unique opportunity to reimagine how these spaces may enhance both aesthetics and functionality of our city’s waterfront.

Source:

24: Early riverine activities from fishing, hunting, frming, transporting via boat. Source: Online media

Source: https://cilisos.my

Fig 26: Various riverine ritual perform by diffrent ethnic group.

Source: Online Media.

The Chapter “Living by the Water” explores the relationship between the river and the human settlement pattern, as well as the waterfront development in Kuala Lumpur. It is undeniable that the element of water is a vital natural element in both the existence of human being and urban development, it is more than just a beautification and essential necessities. Water fosters a sense of tranquility enabling human to connect with the nature around us, as well as facilitating healing and rejuvenation of our life. Historically, the Klang River which functions as the vital conduit for the community and commerce specifically exemplifies this idea. The river invites human being to interact with its water bodies freely and encourages a strong bond with the nature. This relationship with the river is unique and different from each individual to another, signifying that the proximity with the river will shape a different urban experience and perception towards the natural world.

The early archival postcard offers us a glimpse of the intimate relationship between human being and nature, particularly to the water. It can be seen that these visual records highlighted the riparian community’s daily life around the river, it highlighted the life surrounding the natural water bodies are essential to them. During this period, the riparian landscape was wild and idyllic, it offers a breeding ground for the human being and multi species. Moreover, the riparian community was living and working within a close proximity of the rivers. They embraced the concept of coexistence with the nature and appreciate the importance of utilising the available natural resources for sustenance and livelihood. They are natural with their skills in fishing, framing and building their living alongside the waterways. The film “Chinta” in 1948 uncovered the exact scenario by capturing the riparian villagers’ moments of the character dips in the pristine-looking waters as leisure, rowing sampans as a mode of transportation with the natural landscape as backdrop as well as frolicking among the riparian landscape.

In addition, rituals have been eminent in the human life. They give a signal to the world by explaining and describing who we are, and by that, we can recognise the role which we play in representing the world. The oldest cultures engaged in ritualistic behaviour to unite with their beliefs and be united with each other. These are still present in the modern world.15 It is at this point that, the intrinsic value of rivers and water have profoundly interconnected the rela-

Fig 29: Movie scene from “Chinta”, 1948. Source: Singapore film locations archive.

15 Richard, Smriti. “Rituals, the Sacred Predecessor to Routines.” On the Seesaw, January 31, 2024. https:// medium.com/on-the-seesaw/rituals-the-sacred-predecessor-to-routines-bb5917468f5c.

16 Water.gov.my. “View of Malaysian River Project Management with Maslahah from the Technical Department Perspective | Journal of Water Resources Management,” 2024. https:// journal.water.gov.my/index.php/jowrm/article/view/1/1.

17 Australia. Department of Education. 216 cdaae7b0-2372-56d1-95bf112e624d78f3 (1964-08-01). MANDI SAFAR IN MALAYSIA (1 August 1964). In Hemisphere. 8 (8), 28.

tionship with Malaysia’s diverse yet multi-racial communities’ belief and ritual. For instance, the preciousness of the river and water are frequently mentioned in many verses in the Quran and Hadith. Thus, this is reflected in the Muslim’s life where the process of ablution is an obligation process prior to praying.16 As well as communal bath ceremony (Mandi Safar) for cleansing17, pre-wedding river water is used in engagement ceremony, symbolising purity and the flow of life are some of the other notable river ritual performed by the Malay. Similarly, the Chinese community in Malaysia celebrates the Dragon Boat Festival (which is a boat racing competition to commemorate the death of ancient poet Qu Yuan), Nine Emperor Gods Festival (a welcoming and departure ceremony for the God) and Cap Goh Mei (where people pray to find love and fortune), to each of these festivals and its ritual have strong ties to the rivers. For the Hindus, rivers hold a sacred place. During Thaipusam festival, the Indian community and its devotees will perform cleansing rituals in the rivers before proceeding to temples to fulfil their vows. The water from the river is considered as purifying and is used to prepare oneself for the spiritual journey ahead.

18 Dimitris , Xygalatas. “How Rituals Created Human Society.” Big Think, September 22, 2022. https:// bigthink.com/the-past/how-rituals-created-society/.

According to the French sociologist, Émile Durkheim, religion and its rituals are socially functional issues, rather than matters of faith or spirituality. In other words,, religion involves a basic social phenomenon that binds people together into a commonality, a sense of belonging, which only reasserts its very own social bond, weaving a community. In this case, rituals are not only traditions or ceremonies but also the heartbeats of this process. They serve as essential devices in developing and maintaining a shared system of beliefs and values. This is essential to the health and order of the society.18

30 Klang

is flowing in the middle of the photo with the old bridge built across it while almost a part of the river under cosntruction.

Source: Online Media

19 Umut Pekin, “Urban Waterfront Regenerations,” Advances in Landscape Architecture, July 1, 2013, https://doi.org/10.5772/55759.

20 Lanegran, David A. (2002)

“Reflections on Malaysian Urban Landscapes: Unplanned, Planned, and Preserved,”Macalester International: Vol. 12, Article 18.

21 S. Shamsuddin, N. S. Abdul Latip, and A. B. Sulaiman, “Waterfront Regeneration as a Sustainable Approach to City Development in Malaysia,†The Sustainable City V, August 29, 2008, https://doi.org/10.2495/ sc080051.

Traditionally, cities evolved near the river where agriculture and trade are surrounded in this area, making it an important economic, social and cultural hub. However, there is a shift from this river focused urban development to coastal areas. This change enables the cities to connect broadly with the sea and ocean, hence, it offers opportunities for international trade, recreation and urban growth. 19 Likewise, waterfront developments emerged since the early modern period due to the quest of globalisation and growth of global interconnectedness.

The establishment of Straits Settlements in 1826 exemplifies the British Empire’s strategic expansion in the Southeast Asia. This establishment included port cities such as Penang, Singapore and Malacca, significantly strengthen the British colonial power within the region. Such ports not only served as important maritime trading node but also facilitated the British Empire’s broader geopolitical and economic objectives in the Southeast Asia. In 1857, the discovery of rich tin deposits in Ampang, Kuala Lumpur quickly drew the British Colonial’s attention to spur further expansion into the inland of Malay Peninsula.20 Despite this inland exploration, Kuala Lumpur faced its challenge to become a port city due to its geographic location which is situated away from the coast. Moreover, the Klang River within the city is inaccessible for large ships. For this reason, Port Swettenham (now known as Port Klang) which is located at the mouth of the river and faced the Straits of Malacca, emerged as a strategic and major port location.21

During the British administration, the Klang River was under significant alteration and engineering works. Firstly, they introduced the railway system to connect Kuala Lumpur with the port and other mining towns. These infrastructure improvement works dramatically decreased the city’s reliance on the river. Having said that, the railway tracks which aligned parallel with the river, disrupted the connectivity between the city and the river, forming a substantial barrier. Secondly, Kuala Lumpur constantly faced flood threat due to its geographic position at a valley. As a result, the British administrator had no other choice but to undertake embankment projects to mitigate the flooding. These projects include straightening the river to direct the river flow and reclaiming land for development. Consequently, the river was transformed into a linear channel, wetlands were filled and flatten for land use, and river access

was blocked, leading the detachment of human interaction with the waterway.

The British administrator also relied on sanitation as a mode of governance in Malaya. As argued by Lynn Hollen Lees, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, this strategy is similar to the practice in nineteenth-century Britain, where a series of modernised infrastructure work has been implemented to improve the public health as well as to control its urbanised population at that time. For example, Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s modern sewerage system managed to wipe out the cholera outbreak in London. This effective governance strategy not only demonstrated the administrative efficiency but also significantly mitigated disease. Likewise, similar strategy was introduced to improve public health and economic development in Malaya. For example, installation of water piping system, standalone pipes and dams, which gradually provided a stable and cleaner water supply for hygiene and sanitation. Moreover, the British built extensive sewer system in urban area with high population density, such as Kuala Lumpur and George Town, to prevent the outbreak of cholera and malaria diseases. To put it in another way, the British’s investment in infrastructure works in Malaya not only improved the public health and flood mitigation, but it is also a strategy to rule and protect its economic profits. For instance, by straightening the river into a navigable canal and embankment of the riverside were primarily aimed at enhancing the efficiency of resource extraction and urban management.22

It is not difficult to see the impact of the colonial and human interventions towards habitation patterns in natural environment along the river. By that I mean, the initial natural, soft, muddy riverbank has transformed into rigid yet ordered structures, significantly disrupted the local community’s traditional ways of interacting with the river. For this reason, the river-based activities such as fishing, bathing and ceremonial rituals, once integral to the daily life either diminished or changed its mode of practice on land. In the post-colonial era, Kuala Lumpur underwent even more development and with much severe flooding. The city began to construct additional river walls to manage the river flow as well as flood control. These functional, linear, grey structures effectively cut off the river from the community and the city. Consequently, the river is perceived as a functional drain rather than a naturally meandering feature. The

22 Lynnnn Hollen Lees, “Discipline and Delegation: Colonial Governance in Malayan Towns, 1880-1930,” Urban History 38, no. 1 (April 5, 2011): 48-64, https://doi.org/10.1017/ s0963926811000034.

Fig 31 [Right]: KL River City (KLRC) project banking on River of Life project.

Source: New Straits Times

shift in how the river is appreciated and perceived has not only contributed to the river’s pollution but also diminished its ecological and cultural value.

Inspired by successful waterfront revitalisation projects around the world, including those in Singapore and Korea, Kuala Lumpur has invested substantial efforts in enhancing its waterfront in recent decades. This research examines two waterfront revitalisation initiatives, the Kuala Lumpur Liner City project (1996-1997) and the River of Life project (2012). These projects are a response to the persistent pollution problems of the Klang River, which was famously known as “teh tarik” or milk tea colour by the locals due to years of improper waste disposal. Apart from the environmental concern, both initiatives view the river’s potential as a branding tool to promote the city’s image by transforming the Klang River into a lively, sustainable urban asset.

Lineal ,1895

Linear City on the Volga River, 1929 N.A. Milutin

Linear Cities precedent studies.

Source: Redrawn by Author based on Ryan Oeckinghaus’ Avoiding the Real World.

The recent announcement of The Line in Neom in Saudi Arabia, an infrastructural project has spurred the world discussion and is considered as one of the most ambitious urban design projects that integrates with mixed use development, leisure and commercial all under one roof. The idea of planning the city in a line is revolutionised to other pioneer of the urban planning in a city, which in a radial and grid form, provides a fascinating way to link the city with other places in a straight line. However, such idea is not totally new and unprecedented. Historically Arturo Soria y Mata’s Linear city was considered as the forefront of this innovation. In the 19th century, he envisioned a city that is able to stretch along a linear infrastructure to overcome the overpopulation situation, reduce traffic congestion, improve transportation and enhance its living conditions. This concept, along with Edgar Chambless’s Roadtown, aimed to provide a stark contrast to the surrounding open fields, adopting a modest architectural style rooted in local housing traditions. Both Mata and Chambless’s designs spurred further modernist urban planning ideas, emphasising a central transportation axis to foster urban conditions. Moreover, the idea was further developed and expanded by other architects such as Nikolay Milyutin’s Linear city on Voga River, Ivan Leonidov’s Magnitogorsk, Le Corbusier’s Algiers plan and Hilberseimer’s redesign for Rock ford Illinois. Although there is distinction in terms of the planning of each work, however the fundamental similarity of each is surrounded with the idea of facilitating the main transit system conduit to connect with urban centres, housing and mixed used programme.

23 Holleis, Jennifer , and Kersten Knipp. “Saudi Arabia’s Neom: A Prestigious Project with a Dark Side – DW – 05/18/2023.” dw.com, May 18, 2023. https://www.dw.com/en/saudi-arabias-neom-a-prestigious-project-with-adark-side/a-65664704.

24 Abel, Boaz. “Environmental Impact of Saudi Arabia’s NEOM Line Project.” Medium, January 23, 2023. https://boazabel.medium.com/environmental-impact-of-saudi-arabias-neom-line-project-55bee4e072f4.

Despite the concept of linear cities is fascinating to architects and urban planners, however, it is met with mixed reactions. For instance, The Line in Neom in Saudi Arabia, Tabuk Province has sparked a controversial debate and protest, primarily due to the issue of its humanitarian abuse, displacement of the local tribes23 and potential impact on the local wildlife and ecosystems.24 The fascination of living in a linear city is well portrayed in the writing, “A year in the Linear City” by Paul Di Fillipo. The speculative fiction novel which explored the life in an infinite long city, a marvel of urban planning, that segmented distinct zones to accommodate various needs and aspects of human life. The river is a central axis, around which the city’s social and cultural dynamic revolve. It does

Source: Online Media

not only depict the potential and diversity of the place, but also offers a constant new discovery. As much as the extraordinary setting and opportunities for encounter with diverse communities and culture, however it does not shy away from highlighting the challenges faced in such linear urban plan. The novel also portrays the urban detachment, monotony and complex feeling of living in such linear system with no beginning or ending. In other words, it critically examines the potential for such a system to perpetuate social divisions and environmental neglect. In addition, The film ‘Snow Piercer” which provides a dramatic, thought-provoking exploration of how linear city principles might apply in a dystopian future, highlights the challenges in creating equitable, sustainable urban spaces within the constraints of linear design.25

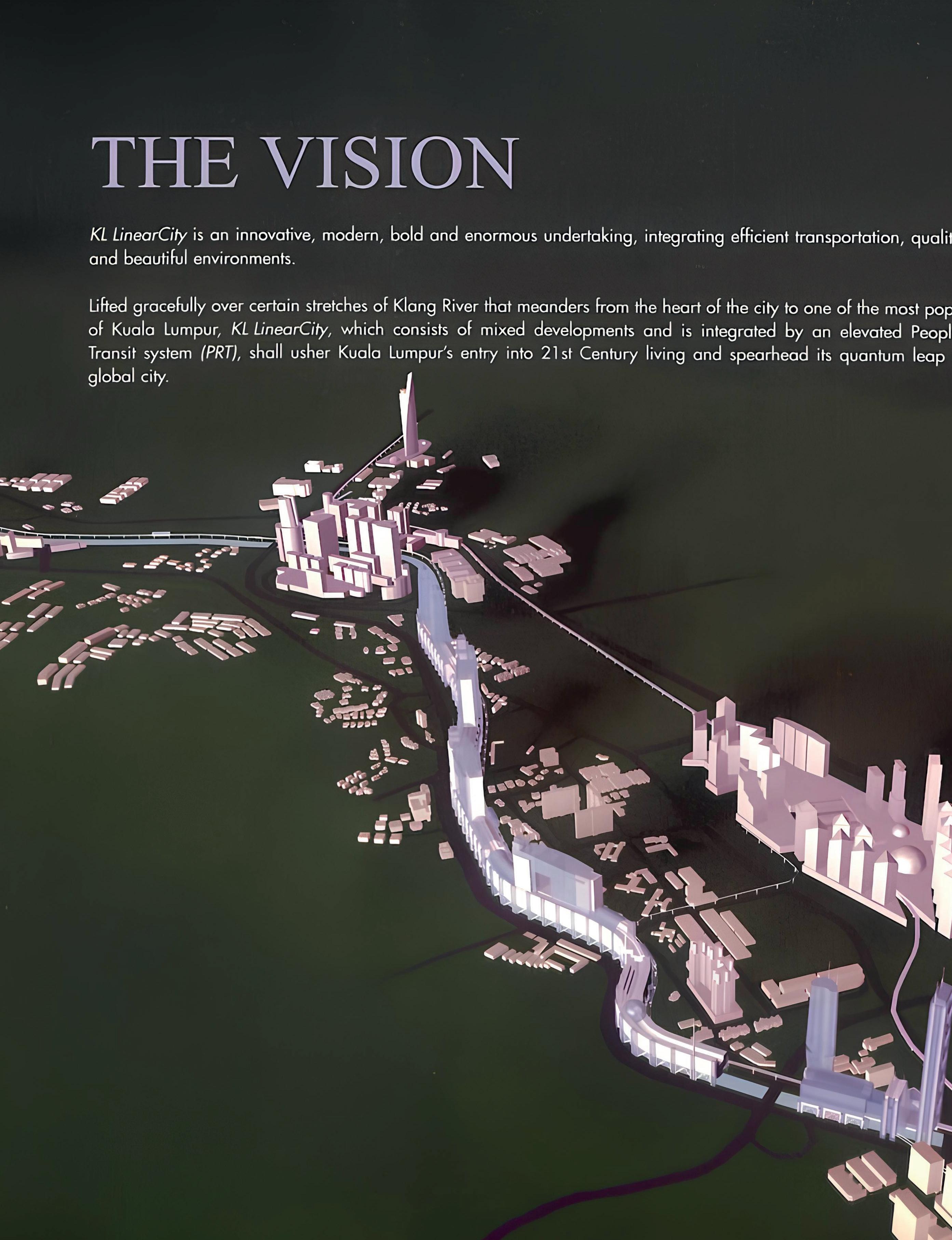

Kuala Lumpur has its own urban vision of linear city. Drawing inspiration from the concept of progression, technological advancement and economic growth, the Kuala Lumpur Linear City was an urban vision project that was driven by the momentum of Vision 2020.* As highlighted by David Chew, the notion of the development was driven beyond the stability of the economic growth but encompassed various factors to address the urgent challenges in the growing city of Kuala Lumpur. Furthermore, Chew emphasised that the Kuala Lumpur Linear City tackles some of the pressing issues, such as constraint posed by limited land availability, the rapid demand of commercial space, the need for housing solution, the increase of traffic congestion and social problems in the ever expanding Kuala Lumpur at that time. Therefore the city was in need of a innovative urban planning solution not only to accommodate the growing population, but also to improve the standard living of the city. In addition to the Malaysia long standing reputation for its progressive business and trading environment, the Kuala Lumpur Linear City’s aim is to establish itself as a powerful urban development that would elevate the status of the country globally.26

In light of the Vision 2020, Kuala Lumpur Linear City project is part of urban development with an ambition to project Kuala Lumpur into the world-city status while meeting the demands at the local and global scales. This urban project includes a 12km stretch

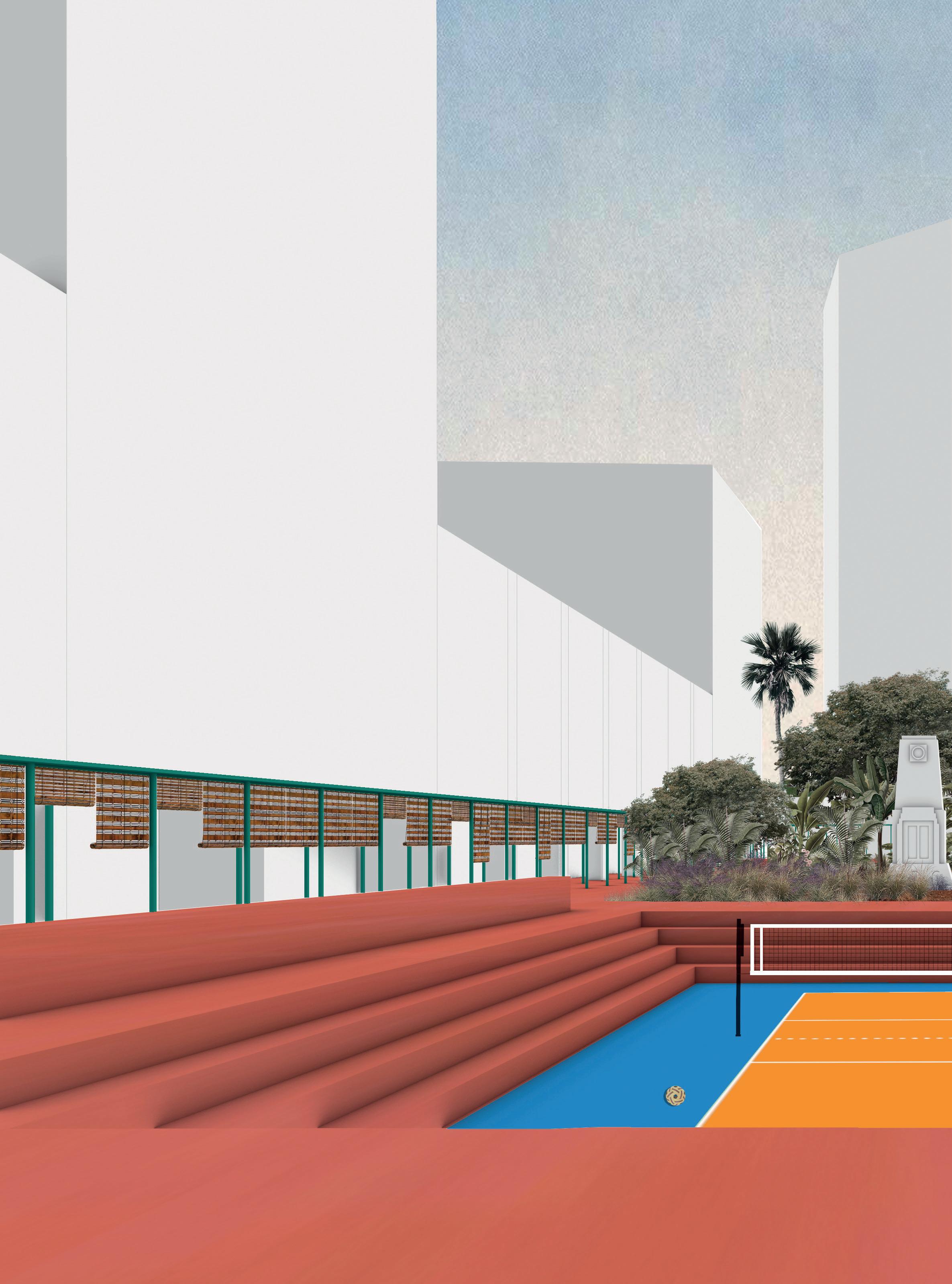

of the Klang River, taking over the air rights above the river. The major scope of the project includes (1) intra-city 16 km long monorail (People Mover Rapid Transit, PRT) elevated system within the city, (2) river cleaning and flood mitigation program, (3) resettlement of over 1,300 riverine families27, (4) landscaping of a 12 km long linear park, and a 2 km long urban commercial and tourism hub called Giga World.

The Kuala Lumpur Linear City’s aim is to integrate the urban fabric of Kuala Lumpur with the added bonus that the river holds historical significance for the development of the city. These facilities comprised of offices, hotels, retail areas, restaurants, apartments and even points of fun, which are all to be found under one integrated transport system. One of the developments, Gigaworld is a futuristic urban space suspended over the river featuring mixeduse spaces across twelve levels, designed to boost the commercial, leisure, and tourist attractions. The linear city is considered to demonstrate Malaysian’s ambition in securing a competitive edge in the world economy through investments in infrastructure. This is aimed at making the country a hub for Information Technology in Southeast Asia.

Positioned within the broader ambition of a strategic Malaysia plan, the Kuala Lumpur Linear City project attains a niche in meeting the challenges that came along with the opportunities provided by globalisation and urbanisation. This reflects strategic approaches towards urban planning and development within the context of global competition, symbolising major investment in the process of urban renewal, development of infrastructure and economic diversification. This would raise questions about the impact on the urban fabric of Kuala Lumpur. It also raises question of how a balance will be struck in ways that integrate globally with local identity and provide real benefits for the city’s inhabitants over and above the immediate attraction of the development itself.

Despite the visionary and ambitious plan, the Kuala Lumpur Linear City was put on halt as a result of the Asia financial crisis in 1997.

* “Vision 2020” was a development initiative launched by Malaysia in 1991 under the leadership of thenPrime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad. The main goal of Vision 2020 was to transform Malaysia into a fully developed country by the year 2020. The plan outlined nine strategic challenges that Malaysia needed to overcome to achieve this status, encompassing aspects such as economic prosperity, social well-being, world-class education, political stability, a robust public infrastructure, and a rich national identity.

Image Source: Malaysia Design Archive

25 Ryan Oeckinghaus, “Avoid the Real World” (2018), https://issuu.com/ ryanoeckinghaus/docs/18f-arc505-01-thesis_prep_document.

26 David, Chew. “Vision of a 21st-Century Public Place: GigaWorld, KL LinearCity, Kuala Lumpur.” In Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities. Springer Link, 2001.

27 Edition.cnn.com. “ASIANOW - Asiaweek.” Accessed April 15, 2024. http://edition.cnn.com/ASIANOW/ asiaweek/96/0705/nat2.html.

Scale 1: 500

Source: Redrawn by Author.

The launch of the River of Life project by the prime minister Datuk Seri Najib which signifies a vital achievement for his political party.

Kuala Lumpur has a waterfront. The reclamation of waterfront became a vital economic opportunity and urban transformation for the post-industrial city. Inspired by a global waterfront revitalisation effort such as Melbourne, Singapore and Seoul, the then Prime Minister, Najib Razak launched the River of Life project under his National Economic Transformation Programme in 2012. The river project spans across 10.7 km of the river within the proximity of Kuala Lumpur with the aim to maximise the social and economic of the Klang and Gombak waterfront. The RM 4.4 billion revitalisation project covers a total area of 781 hectares and 63 hectares of water bodies. The River of Life project’s ultimate goal is to bring the community ‘back’, connect with the river through transformation of the derelict waterfront to a vibrant zone that eventually attracts tourists as well as being a commercial investment. The River of Life project is a waterfront enhancement project that includes river cleaning, river masterplan and river development.

“I believe there will be a drastic change to Kuala Lumpur’s image”…”This is what Kuala Lumpur folks have been waiting for.

28 Schneider, Keith. “A River Restored Breathes New Life into Kuala Lumpur.” Mongabay Environmental News, August 8, 2018. https://news. mongabay.com/2018/08/a-river-restored-breathes-new-life-into-kualalumpur/.

29 Admin. “Press Statement: River of Life – a Vanity Project That Fails to Measure Up.” C4 Center, August 16, 2019. https://c4center.org/pressstatement-river-life-vanity-project-failsmeasure/.

30 Babulal, Veena. “River of Life Project Has Fallen Short of Objectives | New Straits Times.” NST Online, October 7, 2019. https://www.nst.com. my/news/nation/2019/10/527674/ river-life-project-has-fallen-short-objectives. .

The Klang River has all the elements to become an attractive waterfront bustling with daily activities. I visited the Cheonggyechoen River project in Seoul. The project is the best example of the transformation of a polluted and dirty river into a model river complete with beautiful walkways, bridges and fountains.” - Najib Razak28

Despite the effort and the intention, however the project was under criticism due to its controversial cost expenditure which did not justify the quality of the work delivered. Some of the concerns include cost overrun, delays and inefficiencies that suggested financial mismanagement and bureaucratic ineptitude. There were also allegations of corruption regarding the award of the contracts and management of funds which have further tarnished its reputation. Apart from that, the project also caused public concerns regarding its authenticity and cultural value to the city.29

“If by the time you want to implement something, the damage is done, you can’t restore the authenticity and time (age) to a place” - Dr. Shuhana Shamsuddin 30

“KL has great potential to integrate the river corridors with its fragmented developments, but what it did was change it into something new instead of conserving the landscape.” - Dr. Shuhana

31

According to Dr. Shuhana Shamsuddin, the lead consultant for City Hall’s heritage trail master plan, it raised concerns of the lack of sensitivity in the design elements and materials chosen for the project. In her view, the design elements such as the Spain’s Alhambra inspired long pool and sunken garden, the use of Turkish tiles and marble do not accurately reflect the city’s identity, nor are they suitable for the tropical heat. Besides that, Dr. Shamsuddin also believes that the project fails to recognise the city’s potential in preserving its unique landscape. Rather than pursuing a new development, she advocated for a conservation-focused approach that would maintain the existing environment and better integrate the waterway with the adjacent urban fabric.

“Does the landscape architect know that Malaysia is a tropical country? Now everything has to be maintained by DBKL at a high cost,” Rohayah said.32

Similarly, Dr. Rohayah Che Amat, an urban landscape specialist, suggested that the project has not succeed in conserving the historical heritage of the waterfront. This is because of the implementation of the project, which fails to preserve the existing raintrees and integrate the colonial building adjacent to the river effectively. Furthermore, Dr. Che Amat also questioned the City Hall’s duty to oversight and its responsibility as the planner and regulator of the project. They should supervise and ensure that these critical heritage elements are adequately protected and incorporated into the development. In her view, planning and sensitivity to the historical context are needed to maintain the integrity and continuity of the area’s cultural landscape.