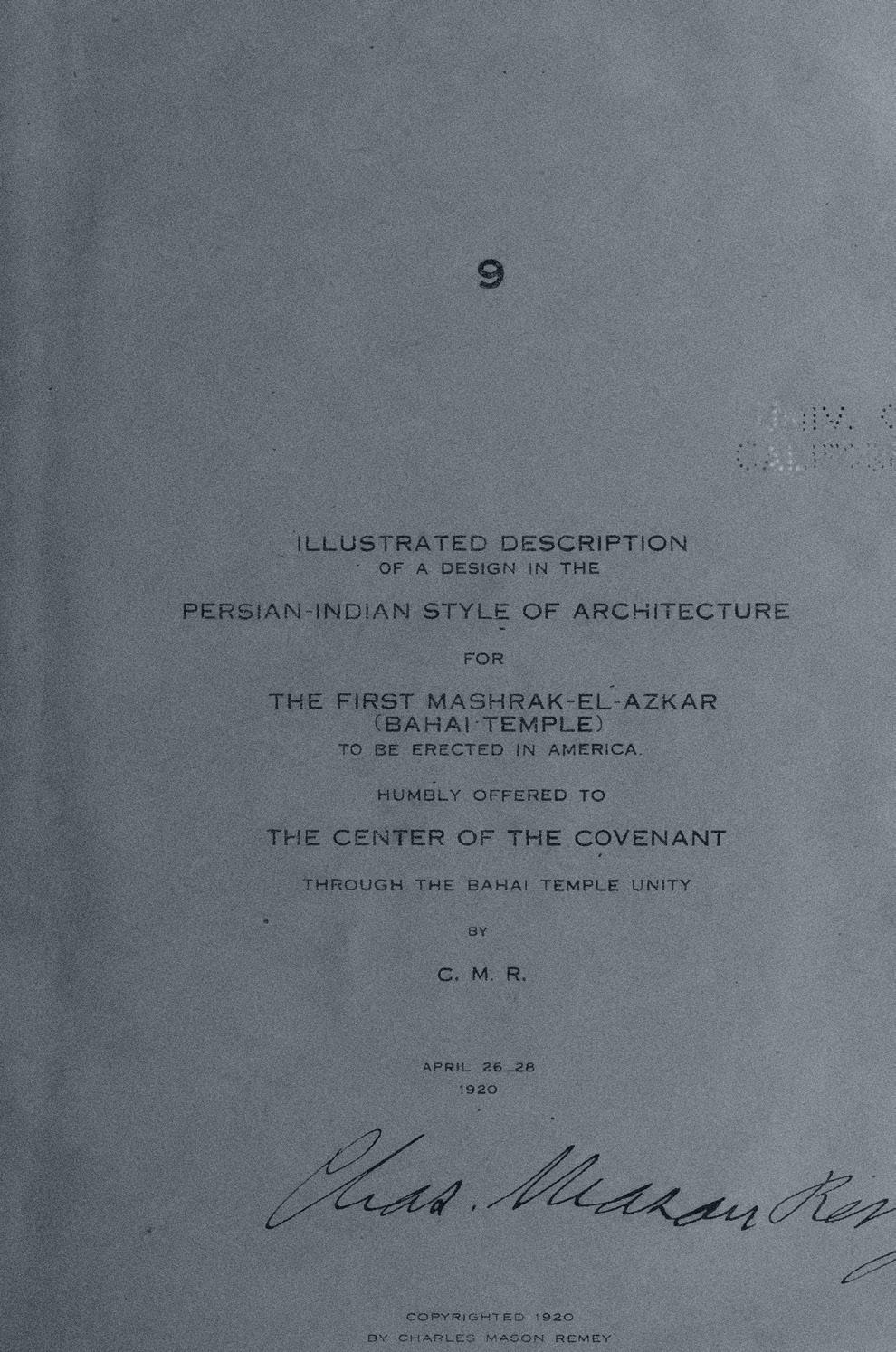

RESEARCH INVESTIGATIONS

-Through a critical analysis of historical, existing and contemporary precedents, the proposed research posits an examination into the complex and interrelated relationship between the concept of sanctity and its formation and use in architectural space. Moreover, From the Sacred to the Profane explores the role of design as a means to enhance and ground the communal understanding of key concepts related to the specificities of architectural space- regardless of their meta-realistic nature in the Baháʼí religion.

12

13

INTRODUCTION

The intricate relationship between human beings and the spaces they inhabit has been a subject of perpetual fascination and inquiry for scholars and practitioners alike. The concept of space transcends the mere physicality of its confinesextending into realms of subjective human experiences, emotions and perceptions.

One such realm that has garnered significant attention is the notion of sacredness, which plays a pivotal role in the formation and employment of space within various religious and spiritual contexts- particularly the Baha’i faith. Drawing from the rich body of literature on spatial theory and sacred spaces, this research employs a multidisciplinary approach to examine the Baha’i faith’s unique understanding of holiness and its influence on the formation and use of spaces. In doing so, the study embarks on a comprehensive exploration of individual and collective spatial experiences, encompassing a wide range of experiential qualities such as privacy, kinship, self-awareness, sensorial experiences, proxemics and intimacy.

As Lefebvre posits, “space is a social product.”1 Therefore, the investigation of sacred spaces within the Baha’i faith offers valuable insights into the diverse ways in which human beings engage with and perceive their environments. Through a meticulous examination of scriptural texts, interviews and case studies, this research dissects the underlying spatial principles that govern the design and use of spaces within the Baha’i faith, and subsequently, how these principles can be translated into architectural projects that embody the experiential qualities and essence of sacredness. For this reason, the thesis is structured into four distinct chapters, each addressing a specific aspect of the relationship between sacredness and spatial character within the Baha’i faith.

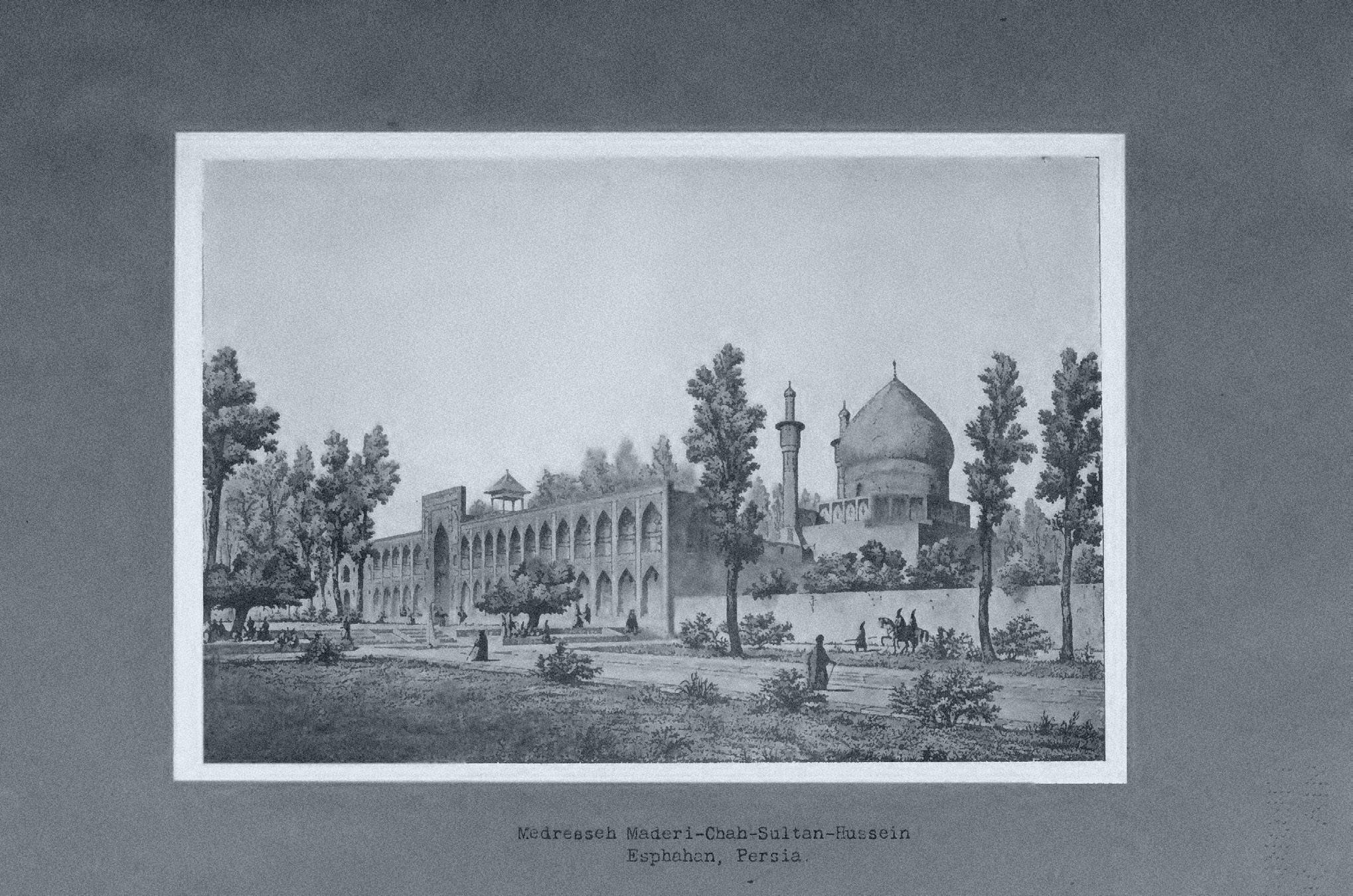

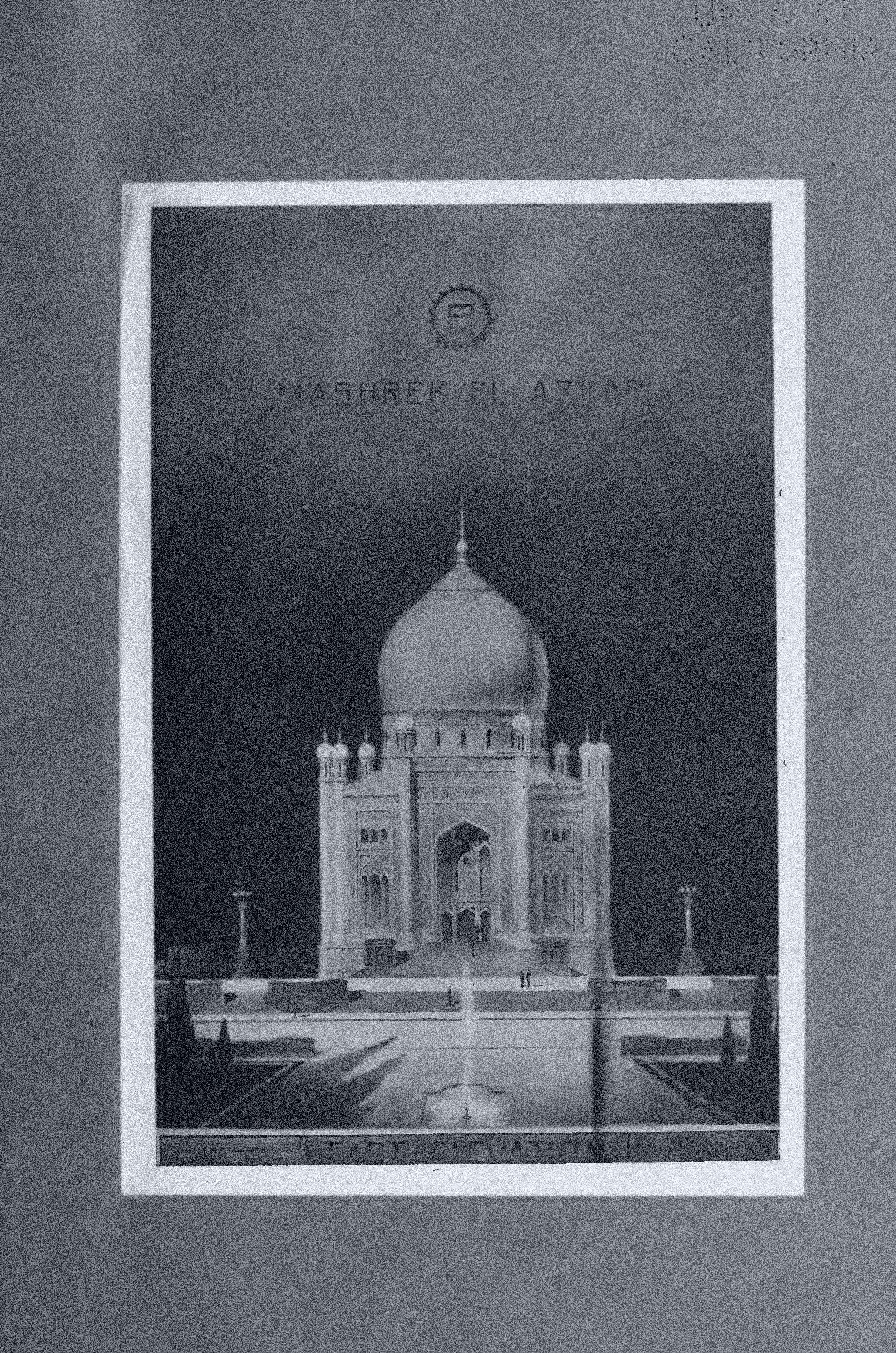

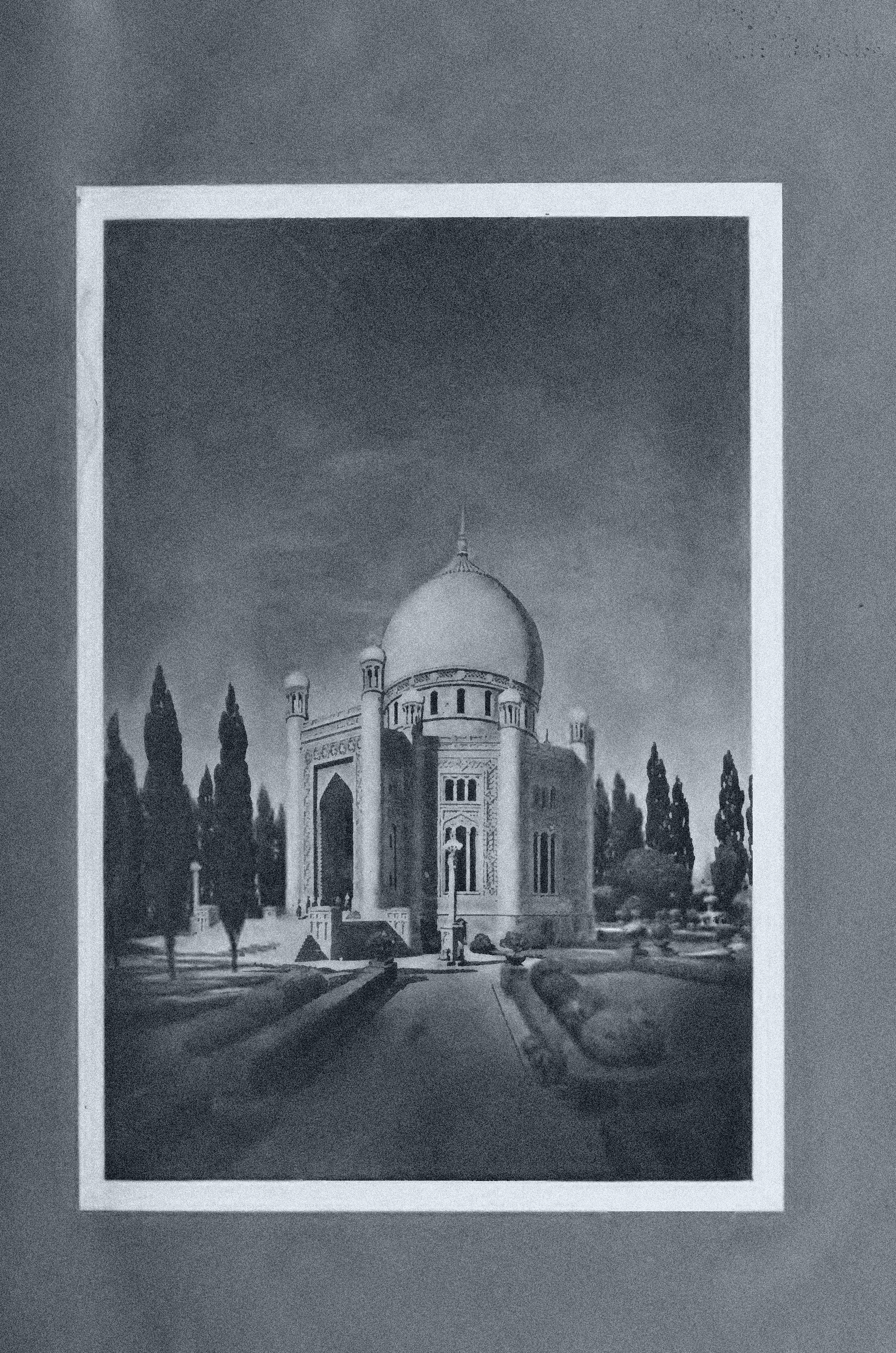

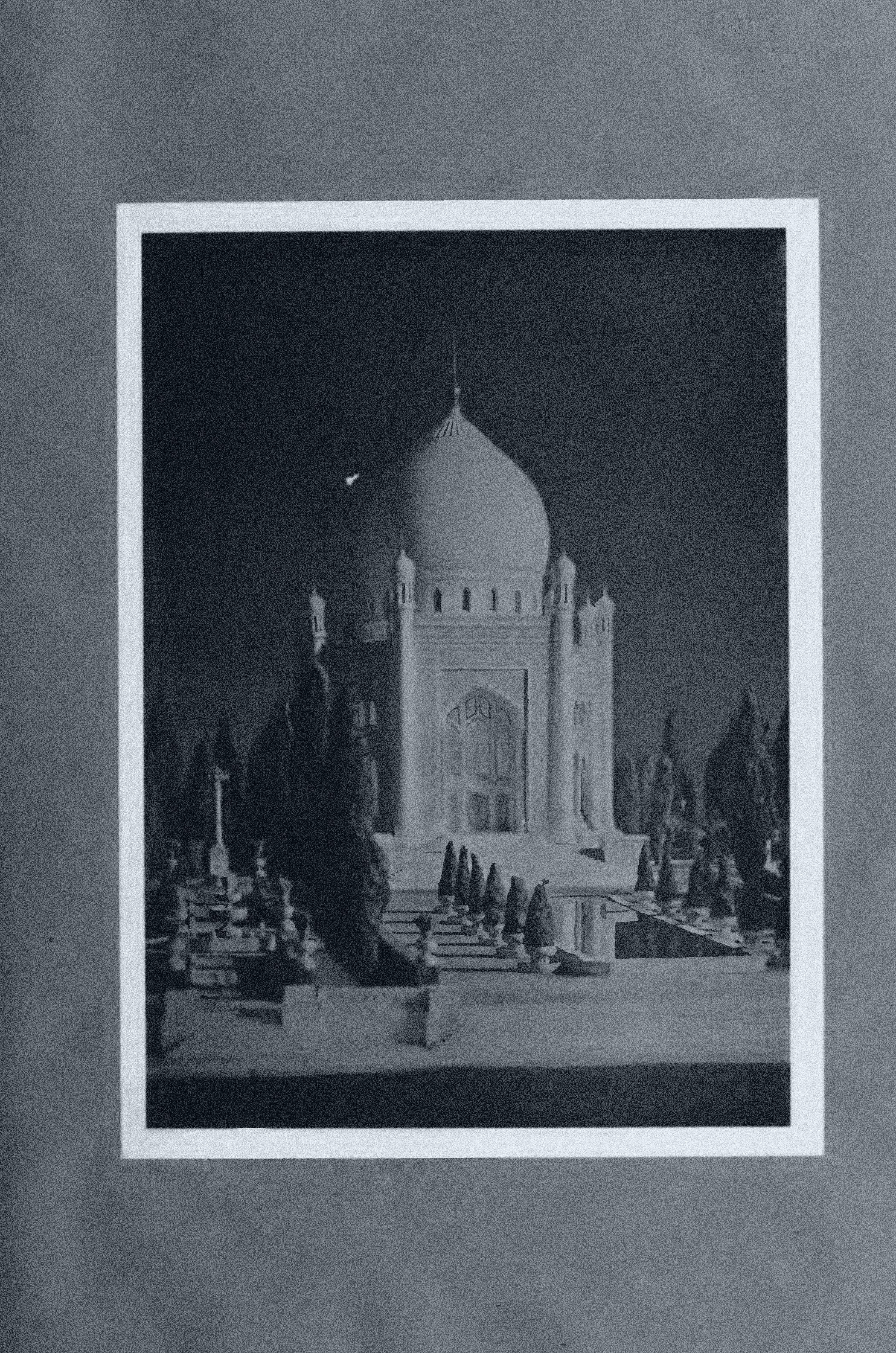

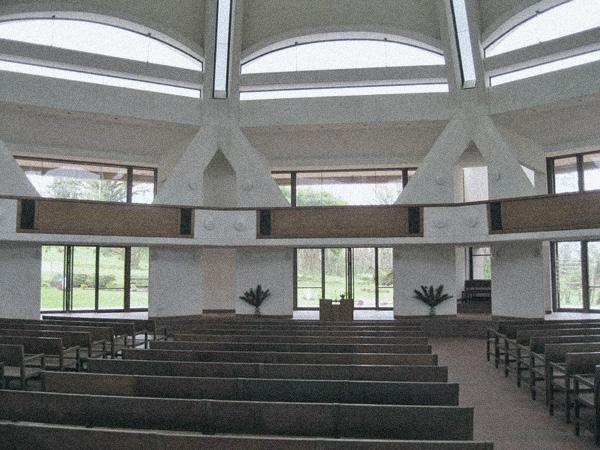

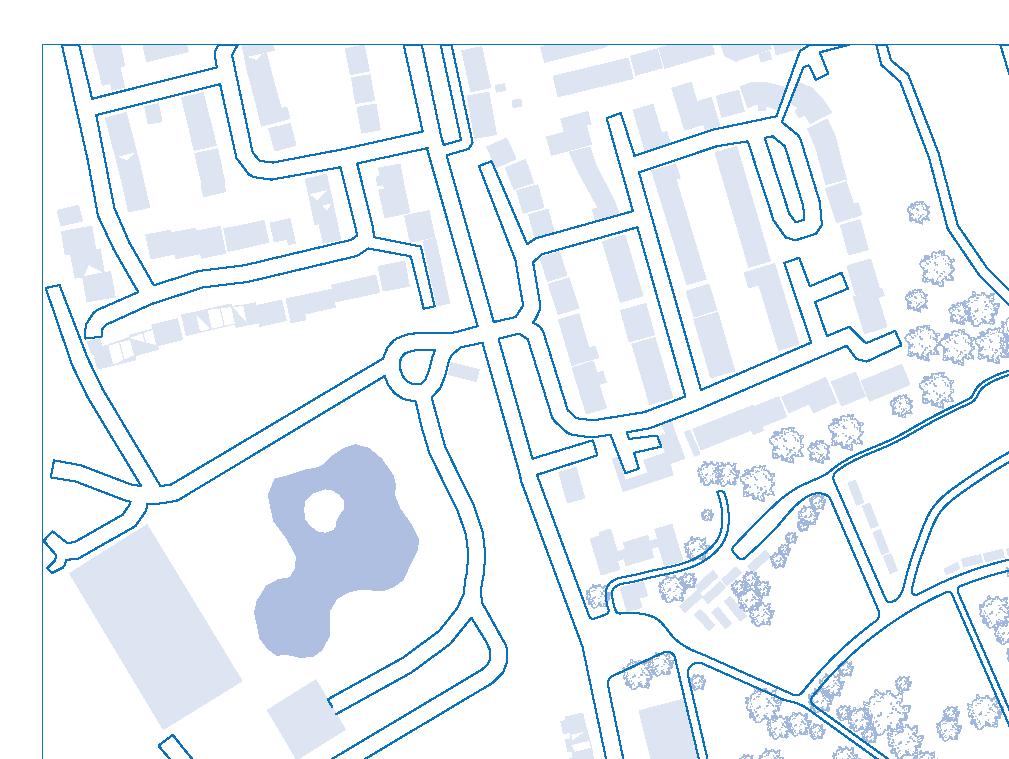

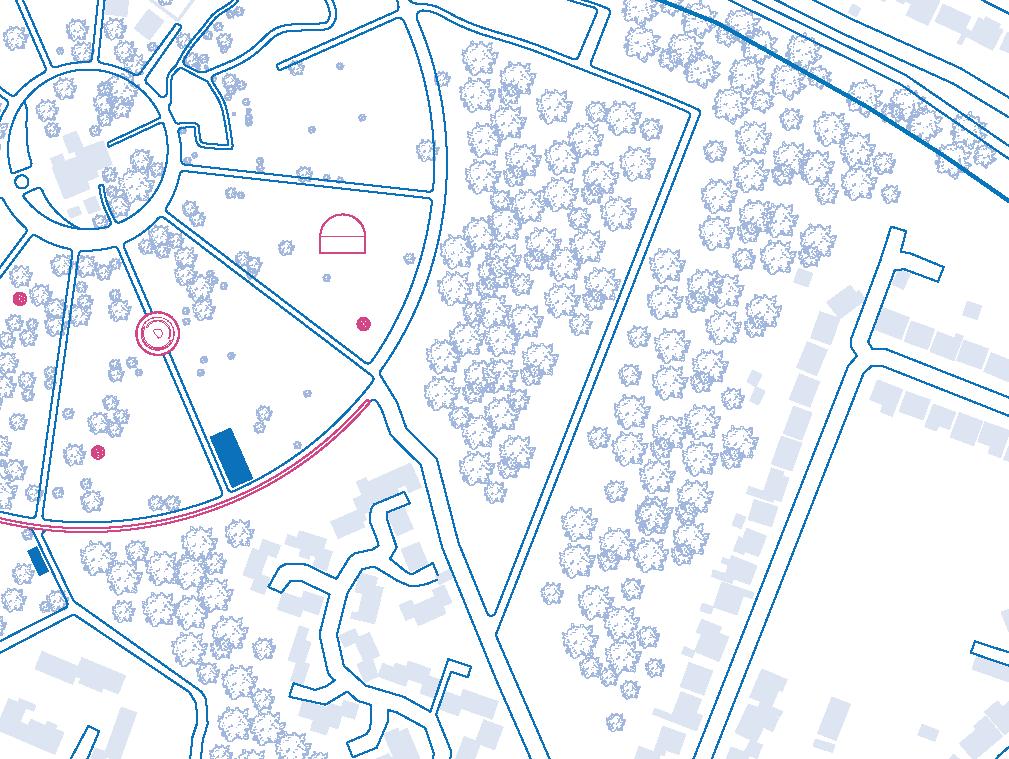

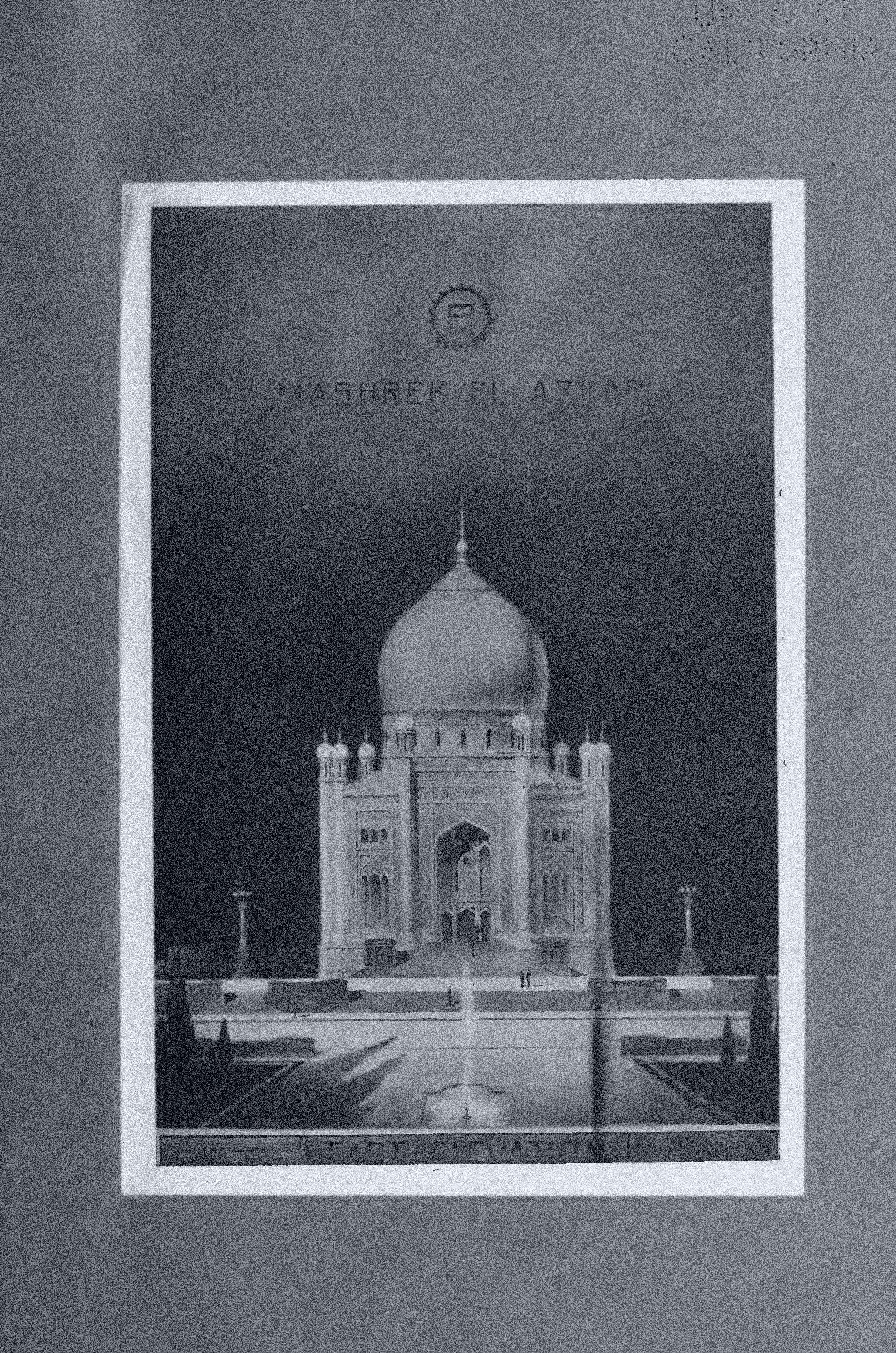

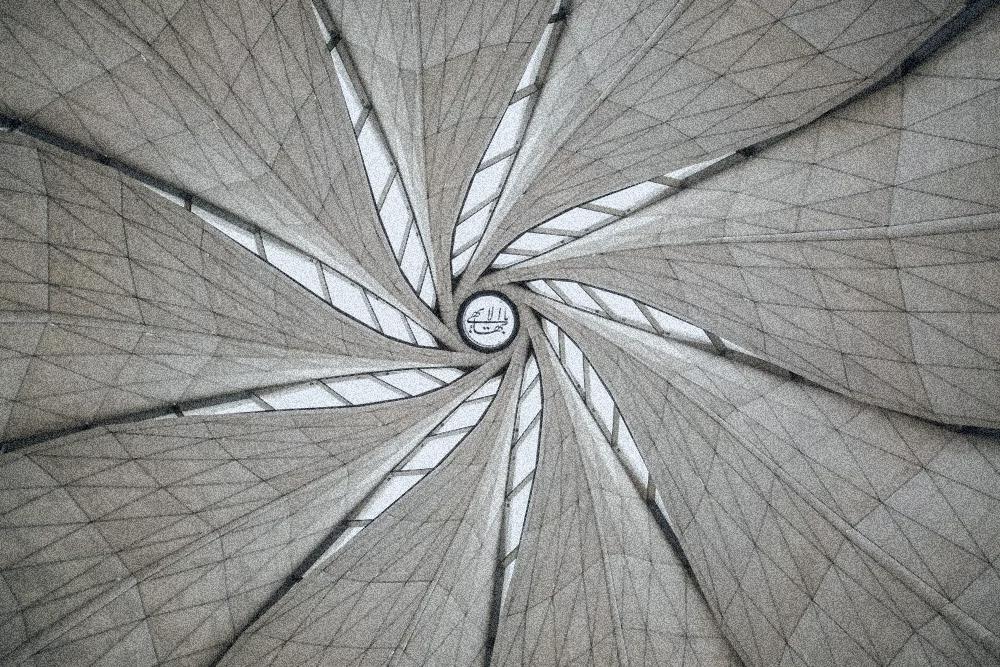

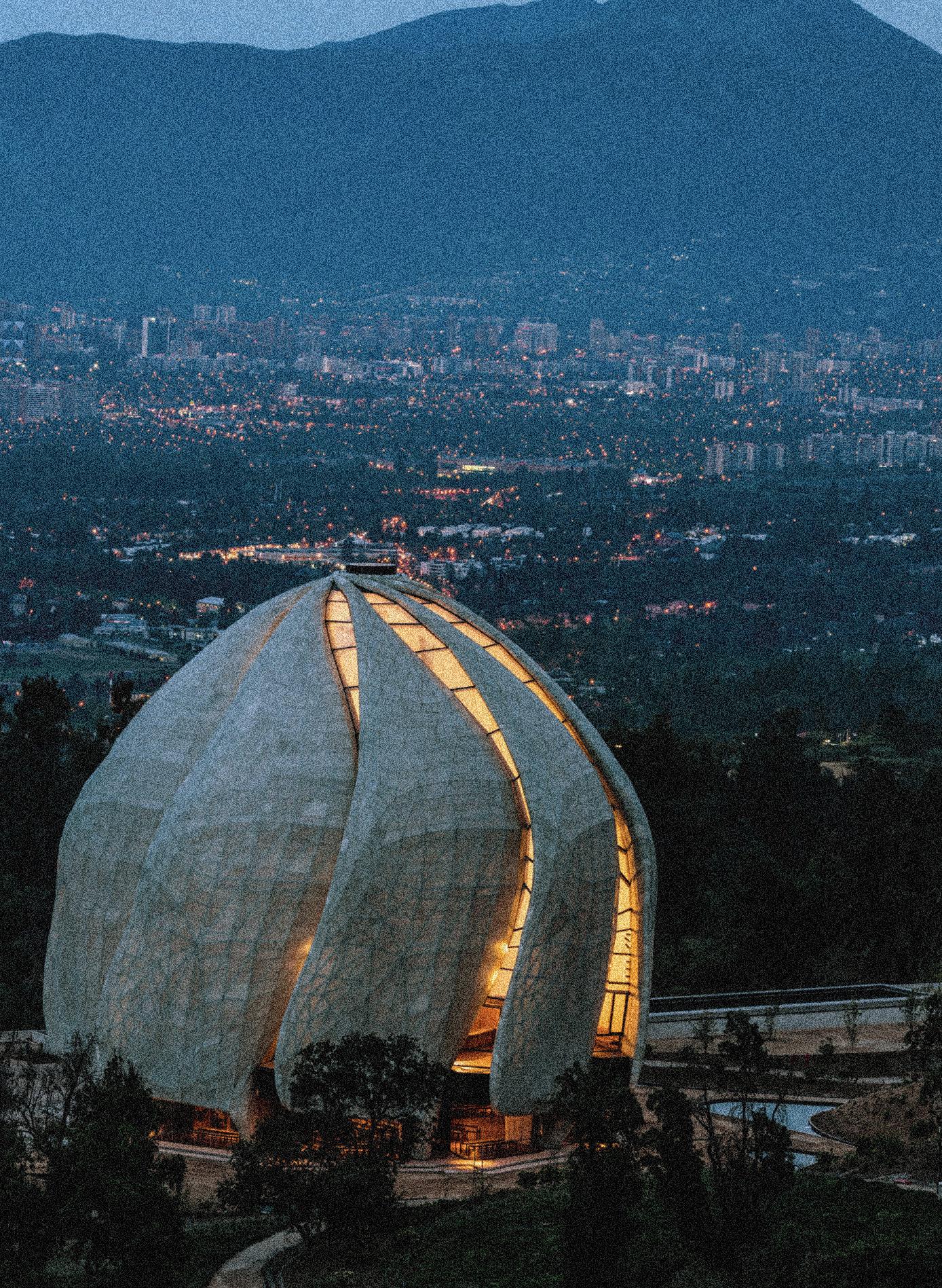

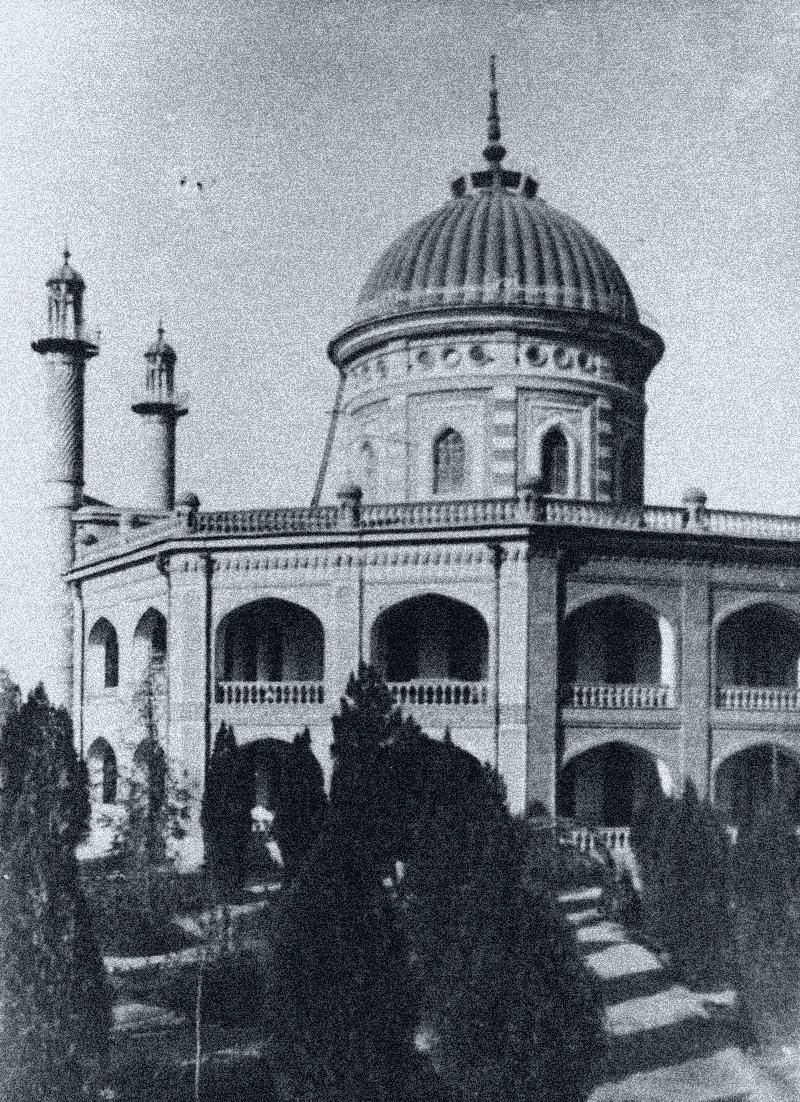

The first chapter delves into the individual’s connection to sacred space, examining the role of scripture, rituals and personal spiritual practices in shaping the perception and use of these spaces. The second chapter turns its focus to the domestic realm, investigating the impact of collective religious activities, such as the Nineteen Day Feast, on the design and occupation of Baha’i domesticity. By studying the spatial configurations and dynamics of these domestic spaces, this chapter unveils the subtle interplay between sacredness, privacy and kinship within the context of the Baha’i faith. The third chapter of this thesis explores the architectural language of Baha’i temples, or Mashrek al-Azkar, and their role in facilitating collective spiritual experiences. Through analytical investigations of Baha’i temples, this section elucidates how these temples, adhering to typological structure, convey the religion’s goals to its users via architecture. The fourth and final chapter expands the scope of the study to consider the broader urban context, examining the relationship between the Baha’i faith and the city, as well as the social service structures that emerge through the integration of sacred spaces within urban environments. The methodology of discourse consists of two parts presented in the first and second chapters. Firstly, in examining the Bahá’í sacred text and related sources and secondly, by conducting interviews with Baha’is and analyzing their relationship to their individual and collective home environments. To ensure the safety of the Baha’is who reside in Iran and face pressure from the government, their identities and exact locations are kept anonymous in this dissertation. Instead, a three-part code has been devised as a reference- indicating their gender, age, and house number. Various comparisons of characteristics of the people and houses under investigation can be found in Figure I and Figure II. Furthermore, the basis for the designs outlined in these two chapters has been extrapolated and drawn primarily from the houses under investigation.

1.Henri

14

Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 26.

15 Fig I

16

II

Fig

CHAPTER 01-

The notion of space in the Baháʼí faith: translating religious principles into spatial configurations

17

01-1. ACTS OF THE BODY

The intricate connection between the human form and religious practices is multifaceted and complex. As both a biological and cultural creation, the body exists as a physical and emblematic entity, continuously situated within a particular social and environmental framework. This conscious body is actively molded through each social interaction and its history, functioning as both a dynamic participant and a subject of power dynamics.

The living body serves as our primary means of understanding society, with each individual’s physical body (and thereby all lived, and dynamically specific) experiences differing from the objectively observed form. The body is an essential component of one’s identity and is closely associated with the self. Our interaction and perception of the world are rooted in physical embodiment. This specific embodiment is deeply social, influenced by acquired roles and expectations, shaped by the immediate social setting and historical precedents, and conveyed through language and cultural symbols.

The relationship between the body and religious practice has been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. As Bialecki and Sosis note, “the sacred is not simply a realm of supernatural or divine powers, but is also constituted by the active engagement of human bodies in the world.“1 In other words, the way in which individuals use their bodies in religious practice is an important part of how they understand and experience the sacred. This understanding of the relationship between the body and religious practice has important implications for the design of religious spaces. As Lang notes, religious architecture is often designed with specific bodily movements and actions in mind, intended to help worshippers connect with the divine and reinforce the tenets of their faith.2

For example, the design of Islamic mosques is often influenced by the practice of prayer, with the layout and orientation of the mosque designed to facilitate the performance of prayer. The use of water features and geometric patterns in mosque design is also reflective of Islamic beliefs and aesthetics. Similarly, the design of Christian cathedrals and churches has historically been influenced by the practice of the Eucharist, with the altar and tabernacle serving as central features of the space. The use of stained glass windows and iconography also serve to connect the physical space to religious beliefs and allegories. It is important to note, however, that the relationship between the body and religious practice is not just limited to transcendental beliefs or experiences.

The manner in which individuals use their bodies in religious practice is a crucial aspect of how they understand and experience the sacred, but it is often intimately tied to cultural, social and political contexts. Therefore, it is important to approach this topic with a nuanced and intersectional perspective. By investigating the act of the body in religious rituals in relation to the architecture of space, one can gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which religious practices shape (and are shaped by) the physical environments in which they occur. By examining the bodily movements and actions that occur in religious spaces, there is an insight into the individual connection with the divine which shapes their profoundly personal understanding of the sacred, while also recognising the complex cultural, social, and political contexts that influence these practices.

1.Bialecki, Jon, and Richard Sosis. “Introduction: Understanding Religion and the Body.” In The Anthropology of Religious Experience, 1-23. AltaMira Press, 2007.

2.Lang, J. T. (1987). Creating Architectural Theory: The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental Design. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

18

19

Fig 1. Skeletal Anatomy in Prayer

Cheselden, William. Osteographia, or The Anatomy of the Bones. 1733. Illustration Plate. National Library of Medicine, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/2651377R

In Baha’i theology, the human body is viewed as a temple that houses the spirit, which is seen as a reflection of the divine reality. According to Baha’u’llah, the founder of the Baha’i faith, “the body is a divine trust committed to our care and attention, and consequently, we must guard it from the intrusion of any harmful element.”3

Moreover, Baha’i teachings emphasize the importance of the harmonious development of the physical, intellectual and spiritual aspects of human nature. The physical body is seen as a vehicle for spiritual advancement, and its health and well-being are considered essential for the fulfillment of one’s spiritual potential.Furthermore, Baha’i teachings reject any form of asceticism or denial of the physical body as a means of spiritual purification or enlightenment. Rather, the physical body is viewed as a necessary and integral part of the human experience, which must be cared for and nurtured in order to facilitate spiritual growth.

The Bahá’í Obligatory Prayer is an essential aspect of the Bahá’í faith, and it is considered a fundamental duty for all believers. The Obligatory Prayer is comprised of three different prayers, each with its unique purpose and time of day. The first and most time-encompassing prayer is to be said once in 24 hours and involves an intricate set of ritual movements and recitations of the Greatest Name (Alláh-u-Abhá). The second prayer is to be recited three times a day and includes verses to accompany one’s ablutions and prescribed movements to accompany various sections of the prayer. The third and final prayer is to be said once a day between noon and two hours after sunset, and it is the only one without ritual movements and recitations of the Greatest Name. In addition to the physical actions and prayers themselves, the direction in which the prayer is performed is also significant in the Bahá’í Faith. The individual performing the prayer is required to face toward the Qiblih, which is the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh located in Bahjí, Israel. This directionality helps to create a sense of unity and connectedness among Bahá’ís around the world, as they are all facing toward the same sacred spot during their daily prayers.

In terms of the required space for performing the personal obligatory prayer, the Bahá’í teachings emphasise the importance of cleanliness and purity. The place where the prayer is performed should be swept and free from all that is unclean, and the person performing the prayer should wear clean clothes. Bahá’u’lláh wrote “every clean and polished surface is conducive to prayer,”4 emphasizing the importance of a clean and tidy space for prayer.

The domestic space also plays a crucial role in the performance of the personal obligatory prayer. Bahá’ís are encouraged to set aside a specific area of their home for prayer and meditation, which can be a room or even just a corner. This designated space helps to create a sense of sacredness and mindfulness and allows the person performing the prayer to focus more fully on their spiritual practice.

3.Baha’u’llah. Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1990, p. 259.

4.Bahá’u’lláh. (1992). Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust.

20

21

Fig 2. Bahai Obligatory Prayer Rituals, drawn by the author

It is striking how private and personal the most fundamental spiritual exercises of prayer and meditation are in the Faith. Bahá’ís do, of course, have meetings for devotions, as in the Mashriqu’l-Adhkar or at Nineteen Day Feasts, but the daily obligatory prayers are ordained to be said in the privacy of one’s chamber, and meditation on the Teachings is, likewise, a private individual activity, not a form of group therapy.

Universal House of Justice, Meditation, Prayer, and Spiritualization, 1 Sept. 1983

The Bahá’í faith insists on the importance of individuality in its obligatory prayer. The daily prayers are meant to be said in the privacy of one’s chamber, allowing believers to engage in a personal relationship with their faith. This emphasis on privacy and individuality encourages self-reflection and introspection, allowing individuals to connect with their inner selves and gain a deeper understanding of their spiritual needs.

Q: What do you consider to be the proper condition for your body when you pray?

W28H5: The most important thing for me is silence and privacy. I feel that I can fully concentrate on my prayers when I’m alone and there are no distractions around me. Unfortunately, my partner and I live in a small studio flat, and we don’t have a separate private space. When my partner is present, I don’t feel comfortable praying in front of him. Early mornings or late nights are better for me to pray because I feel more calm and focused. Also, during those hours, the city around us is relatively quiet with less noise from cars and fewer people on the streets. However, I’m usually not alone at home during those hours, which can be bothersome.

W58H1: Usually, it’s important to me that I wear proper and clean clothes and face the right direction (qibla). I try to maintain a neat appearance as a sign of respect for prayer. In terms of the environment, I can usually concentrate even if there is some noise around me. However, I prefer to pray in a quiet environment without any distractions. It bothers me when someone walks in front of me or does something while I’m praying because it breaks my concentration. Most of the time, I can create these conditions for myself at home. I try my best to find a quiet corner or space where I can focus and pray without any interruptions.

22

23

Fig 3. Living Room,House #1, drawn by the author

24

Fig 4. Religious Artefact, House #1 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

25

Fig 5. Religious Artefact, House #7 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

01-2. HOMOGENEITY AND HETEROGENEITY

For religious man, space is not homogeneous; he experiences interruptions, breaks in it; some parts of space are qualitatively different from others. “Draw not nigh hither,” says the Lord to Moses; “put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” (Exodus, 3, 5) 5

Human beings possess an inherent longing to connect with a higher power, and for many, this connection is established through prayer. According to a study by G. Spilka and others, individuals across various cultures and religions throughout history have employed both objects and space to gratify this desire, thereby creating sacred spaces and rituals that facilitate communication with the divine.6 The use of objects and space to support prayer is a crucial component of human spirituality.

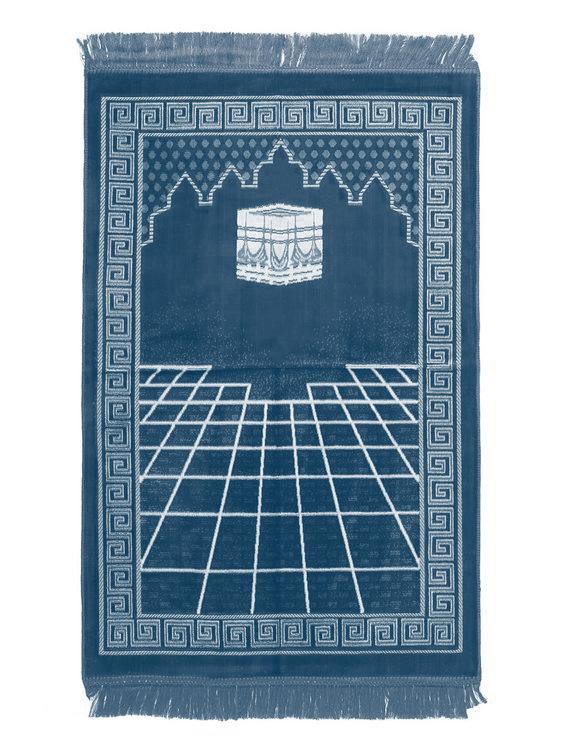

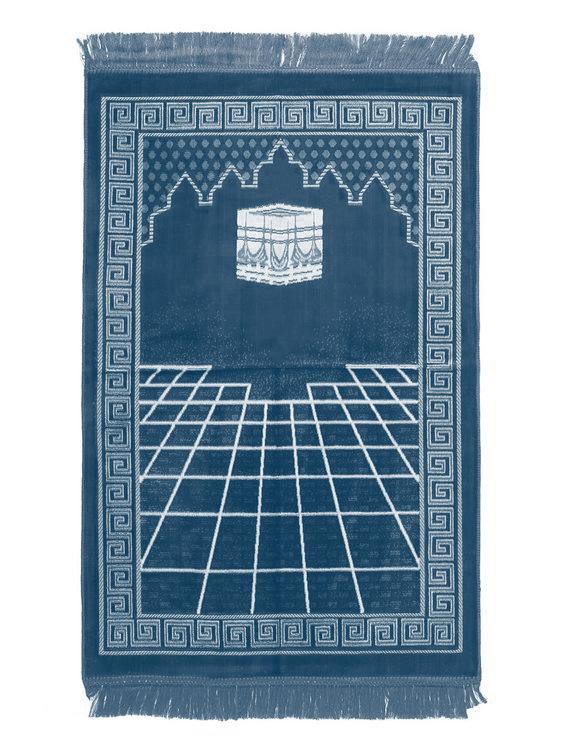

Objects play a crucial role in enabling prayer. Using Christianity as an example, rosaries, prayer beads and crucifixes are often employed during prayer to form a physical link with God. Cross-culturally, and as noted by M. A. Seddigh, the use of prayer beads in Islamic culture has been found to facilitate the recitation of prayers and create a sense of unity among Muslims.7 In Islam, prayer rugs or mats are utilised during daily prayers to develop an environment that promotes worship. These objects serve as a physical reminder of the divine and can assist individuals in concentrating their attention and directing intention during prayer.

The use of rugs provides a common illustration of the use of objects and space to differentiate between the sacred and the profane. Within Islam, these rugs frequently feature intricate designs and symbols that serve as a physical reminder of the divine. Moreover, they also demarcate the location where prayer is taking place, creating a specified area that is distinct from the remainder of the world. Through the use of a rug, Muslims can establish a space that is sacred and separate from their everyday lives, enabling them to concentrate on cultivating their relationship with the divine.

According to the case studies in the research, in Baha’i domestic settings, specific images and symbols are utilised to adorn particular areas or sections of the house, with the aim of creating a sense of spirituality and a conducive atmosphere for prayer. Usually, one of these objects is an image of the countenance of one of the most prominent figures in the Baha’i religion. These decorations serve as ever-present reminders of the importance of prayer and the spiritual teachings of their faith, helping to create an atmosphere that fosters spiritual growth and development.

5.Eliade, Mircea. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World.

6.Spilka, Bernard, Ralph W. Hood Jr., Bruce Hunsberger, and Richard Gorsuch. 2003. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach, 4th ed. Guilford Press.

7.Seddigh, Maryam A. 2005. “Prayer Beads in Islamic Culture.” Muslim World 95(1): 43-54.

26

27

Fig 6. The Rituals of Prayer

Paley, Matthieu. A man performs evening prayers in the city center of Jacobabad on June 27. 2019. Photograph. TIME, https://time.com/longform/jacobabad-extreme-heat/

The use of specific images and symbols in prayer reflects the significance of representation in human spirituality. They serve as a symbolic depiction of the divine, providing a tangible and meaningful way of accessing the spiritual realm. This underscores the importance of visual representation in religious practice, as well as the ways in which iconography can shape our understanding of the divine.

Moreover, by carefully selecting objects to express identity, both the object and space used in prayer are inherently imbued with deep cultural and historical significance, serving as a tangible representation of a community’s beliefs and values. The aforementioned Islamic prayer rugs can be traced back to the early days of the faith, when Muslims would pray on whatever surface was available to them; overtime, the significance of the rug transformed from integratation as common practice, to a manifiestation of designs and symbols reflecting the cultural and historical context of the community. Similarly, the use of prayer beads in various religious traditions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, becomes a further expression of cultural and religious identity, while simultaneously serving a practical purpose in facilitating prayer and meditation. The object now becomes imbued with spiritual gravity.

From a philosophical perspective, the use of objects and space in prayer highlights the fundamental human desire for connection to the divine. This desire reflects an essential and primal aspect of human nature, as we are beings who seek meaning and purpose beyond our individual selves. As noted by the philosopher Martin Heidegger, human existence is characterized by an inherent “yearning for Being,” a desire to transcend the limitations of our finite selves and connect with something greater than ourselves. This yearning is expressed in the use of objects and space in prayer, which enables us to create a tangible link between ourselves and the divine.8

Q: Can you tell me about your approach to prayer and the tools or objects that you use during your prayers?

M69H2: Sure, I don’t use special tools like Janmaz(prayer rug) or Mohr, because they are not recommended in Bahá’í faith. I mostly try to keep the place of the house where I usually pray clean, also cleaning my body and clothes is very important to me and I like to do this in front of the holy picture of Hazrat Abd al-Baha. From my understanding, the Bahai teachings emphasize the spiritual aspects of prayer rather than the physical acts or objects used during prayer. So, while some Bahai individuals may use special tools or objects during prayer, it’s not a requirement or recommendation in the faith. I remember that my mother used Janmaz all the time, which I think is more related to Islamic tradition than Bahai, of course, my mother was Bahai, but I think it was a cultural influence that was passed on to her through the generations before her. So, I think there can be cultural influences on the objects or tools used during prayer for some Bahai individuals.

8.Heidegger, Martin. “What Is Metaphysics?,” in Basic Writings, edited by David Farrell Krell, 93-110. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

28

29

Fig 7. Contemporary Turkish Prayer Rug

ALHANNA. Contemporary Turkish Prayer Rug with Kaaba Motif. 2022. Photograph. ALHANNA Islamic Clothing & Accessories, https://www.alhannah.com/product/turkish-prayer-rugwithkaaba-motif-red-ii1474/

Q: Can you tell me why you have religious images in your home?

W26H7: Yes, of course. The existence of these religious images is important to me because the feeling I get from them is as if the person who is sacred to me is present there. This image is a kind of window for me to connect with the concept that I initially received from that person. Therefore, in placing his picture on the wall, I tried to respect a kind of hierarchy compared to other pictures. I placed his picture above the rest of the objects and tried to choose the best and most suitable place for it

I placed this image in the most desirable place in the house, i.e. the living room, where when the people I love come to my house, I welcome them there. This image is alive for me like a human being, it is respectable for me and I try to behave in front of it in a way that suits the conditions of being in front of a respectable and important person for me. This is quite evident in the way I dress and the way I sit when I pray in front of this picture.

30

Fig 8. Living Room, House #6 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

31

Fig 9. Religious Artefact, House #6, drawn by the author.

32

Fig 10. Living Room, House #6, drawn by the author.

33

Fig 11. Religious Artefact, House #6 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

34

Fig 12. Religious Artefact, House #8 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

35

Fig 13. Living Room, Bahá’í Family House 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

As a child, I always felt a sense of fear and respect when I saw this religious image. It reminded me of my grandfather, who was kind but of serious expression. The picture was placed in the best spot in the living room, and my parents had taught me to sit in front of it with complete politeness. I made sure to wear appropriate clothing when I sat in front of it. As a child, I believed that the image was alive, and I would sometimes talk to it. Other times, if I was up to some childish mischief, I would try to hide from it. The presence of this image established a code of conduct in our living room that we all followed.

36

Fig 14. Living Room,House #2, drawn by the author

Fig 15. Living Room, House #2 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

37

Fig 16. Ritual Protocols, House #2

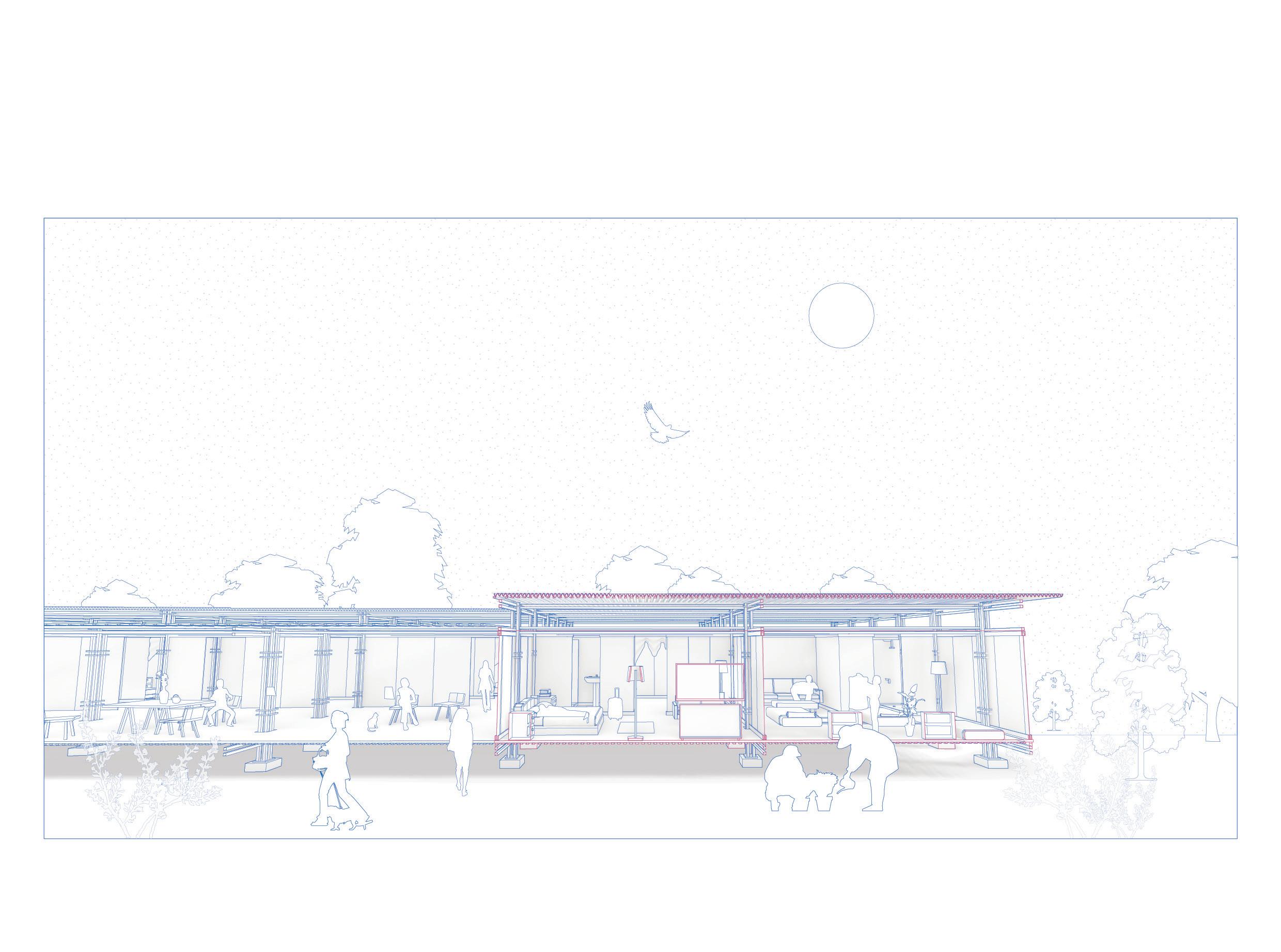

DESIGN 1-1

This design project is a purposeful exploration into the complex interplay between space and spirituality. The young couple in question faces a conundrum that is all too common in modern urban living- the tension between the need for minimal living space and the desire for a home that accommodates their unique interests and beliefs. In this case, their passion for books and their religious needs have led them to seek a solution that combines both into a single functional object.

At the core of this project lies a deeper philosophical inquiry into the meaning and purpose of space. By creating an object that can house their books and facilitate their religious practices, the design redefines the traditional boundaries between sacred and mundane space. The very concept of programmable space becomes fluid and malleable, as the object allows for the seamless integration of different elements and functions within a limited physical area.

In addition to its practical function, this design holds its aesthetic and symbolic significance. The object not only provides a private platform for prayer but also allows users to display religious decorations and perform rituals, creating a unique and personal environment that reflects their metaphysical identity. By doing so, it challenges the notion of space as a neutral, objective entity and highlights the subjective, experiential dimension of space as a deeply personal and meaningful construct.

Overall, this project represents a bold and innovative approach to the challenges of modern urban living for people of faith; offering a creative solution that simultaneously addresses the practical, aesthetic and spiritual needs of its users. By blurring the boundaries between sacred and mundane space, it invites the questioning of preconceptions and assumptions surrounding the nature of space and its role in shaping the daily lives of its inhabitants.

38

39

Fig 17. DESIGN 1-1

THE MULTI-PURPOSEFUL OBJECT

40

Fig 18. DESIGN 1-1 Transformation Process

41

Fig 19. DESIGN 1-1

Placed in House #3

01-3. SACRED DOMESTICITY AND MUNDANE EXISTENCE

In the eyes of most, the house is a secular apparatus that has emerged based on the human need to have shelter. This structure has found the ability to meet the updated human needs throughout history. The Bahá’í writings describe the home as a place of unity, where family members can develop their spiritual and corporeal capacities, and where hospitality and kindness are extended to guests.

The importance of the home as a site of spiritual development is reflected in the practices and rituals across many religious traditions. In Hinduism, for example, the home is seen as a sacred space that should be kept clean and pure in order to facilitate spiritual growth. Similarly, in Judaism, the home is central to the celebration of many holidays and the performance of various rituals, underscoring the importance of the domestic sphere in religious life. This highlights the ways in which the home can serve as a site of spiritual development and a space for cultivating virtues and moral character.

The Bahá’í teachings emphasise the importance of creating a harmonious and loving environment within the home and recognise it as a place where individuals can cultivate their virtues and moral character.9

The particular methodology which becomes extrapolated from the text requires that the results obtained from the interviews and investigations of Bahá’í houses be examined in parallel with information found in scripture and other related sources. The insight deducted from the comparison between scriptural text, typological analysis and interviews must be examined wholistically.

M34H1: When I lived at home with my parents and brother, prayer was a daily occurrence in our household. Usually at a certain time of the day, either my mother or father would pray in the living room. During those hours, I tried to be as quiet as possible so as not to disturb their concentration and peace. If I was at home, I would stay in my room or move as quietly as possible in other parts of the house. However, the issue was that if I needed to use the kitchen, which was open to the living room, I would inevitably disrupt their concentration and peace. As a result, we were limited in terms of using the space in our house.

At times, yes. When I wanted to pray, I preferred to do so in the privacy of my own room. It was a safe and comfortable space where I could focus without any distractions. Interestingly, after I moved out of my parents’ house, they actually converted my old room into a designated prayer room.

9.Bahá’u’lláh. (1990). Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust.

42

43

Fig 20. House #1, drawn by the author

W58H1: The problem with the prayer room was that it only provided enough space for one person to use at a time. My wife and I both found the idea of having a prayer room at home very appealing, but unfortunately, we couldn’t use it simultaneously. Despite this limitation, we still appreciated the benefits of having a private space for prayer in our home.

44

Fig 21. Prayer Room, House #1 2022, personal photograph, in Author’s Collection.

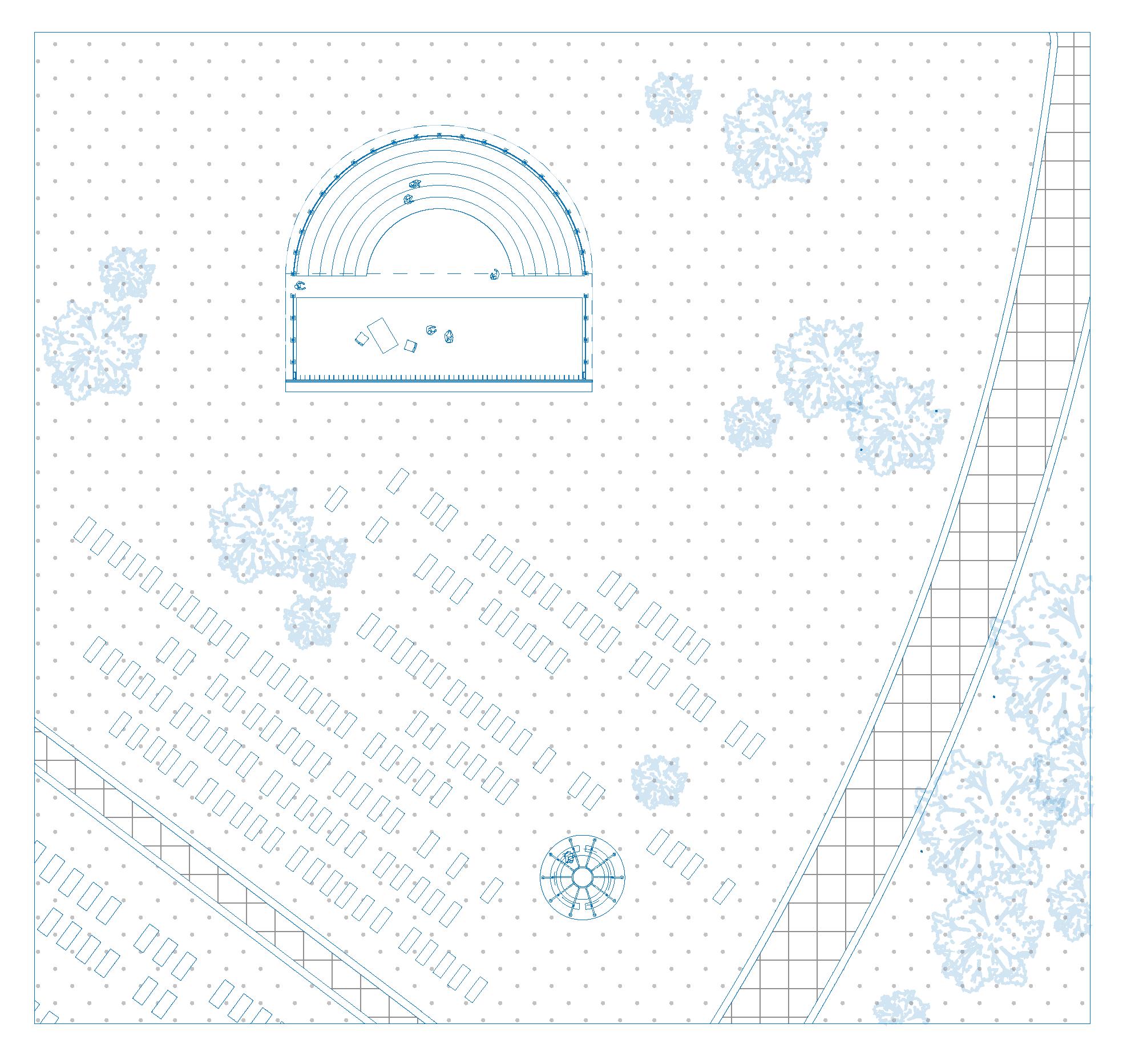

DESIGN 1-2

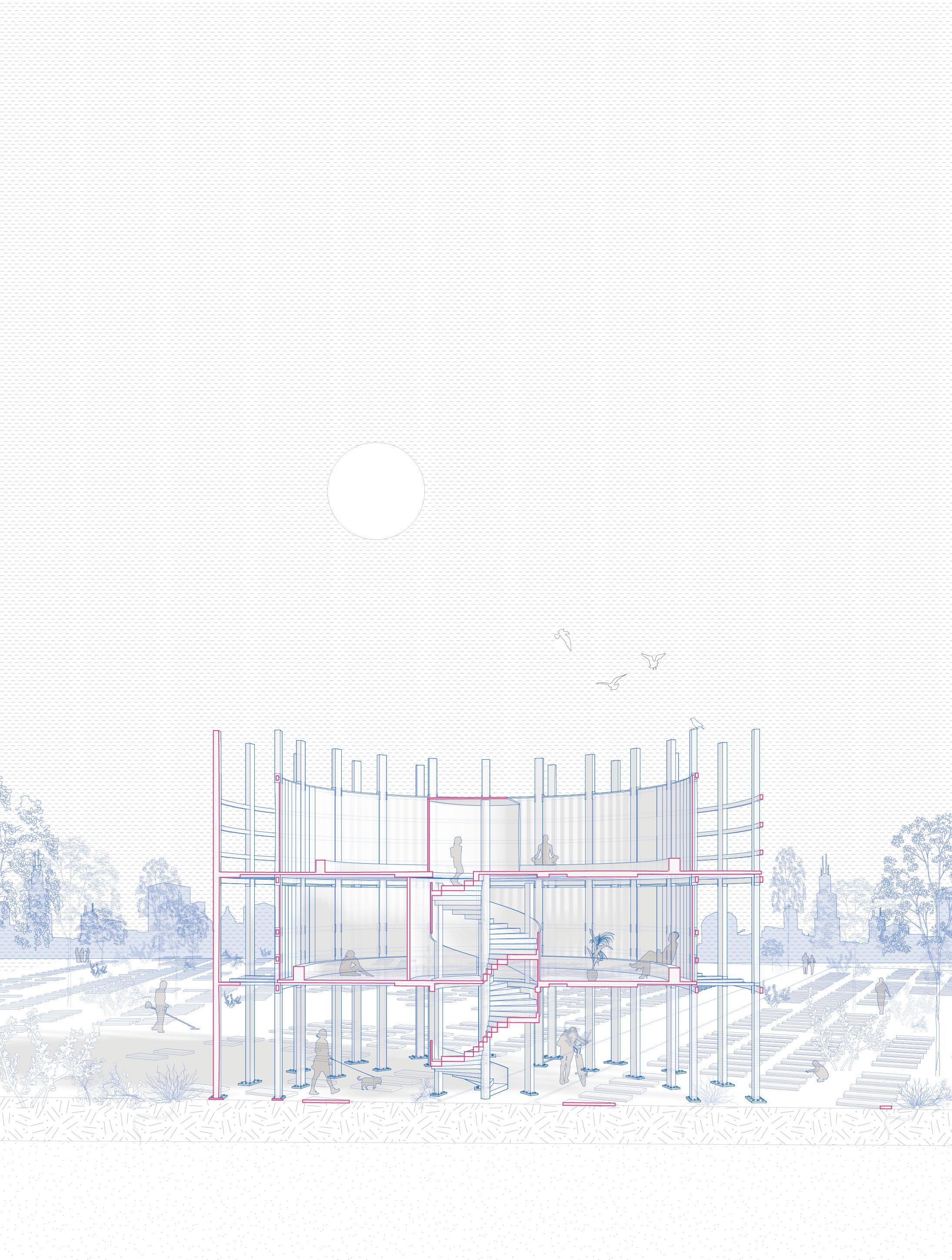

This design exploration focuses in on the interplay between spirituality and its physical environment. At its core, its purpose is to create a space that allows two individuals to practice their faith in a small room that has been reserved for prayer. However, the design needs to provide criticality beyond simply creating a functional space, instead delving into the deeper implications design choices.

The fundamental inquiry of this project is the concept of privacy- an essential element of religious practice. The design theme recognised that two individuals practicing their faith in a small room could be a challenge, particularly if they required privacy to do so. To address this challenge, the development of a design that utilised fabric separators to create a private space within the larger room was employed. The circular shape of the separators allows for flexible degrees of aperture and closure, depending on the individuals’ preferences, and allows for a more intimate and focused religious practice.

This focus on privacy highlights a broader inquiry into the meaning and purpose of sacred space. The very act of designating a specific area for prayer suggests a belief in the power of physical space to influence spiritual experience. For this reason, the approach recognises that the physical environment can shape religious practice in subtle yet powerful ways, and the creation of a private space within a larger room is acknowledgement of this fact.

Overall, this project represents a thoughtful and nuanced approach to the challenges of religious practice in a small space. By exploring the relationship between physical environment and spirituality, the created space is both functional and philosophical, while also being aesthetically pleasing. It is a testament to the power of design as having the ability to shape experiences of the world surrounding its inhabitant and the potential for even the smallest design choices to leave a lingering, profound impact.

45

46

Fig 22. DESIGN 1-2 Personal Space Partitioner

47

Fig 23. DESIGN 1-2

Designed for personal prayer room, House#1

1.While my parents were praying in the living room, it became completely useless for watching TV since the sound of the TV disturbed the concentration of the person praying.

2.On occassion, my parents would use my room for prayer due to the noisy atmosphere in the house, and it was at times inconvenient for me not to be able to use my own room.

3.The furniture arrangement in my parents’ room made it impractical for performing religious rituals, so the room was usually not used for prayer.

48

Fig 24. House #2 Rituals and Protocols

DESIGN 1-3

In this world of hustle and bustle, we seek to create a space, a castle. a threshold that sets us apart, from the chaos that engulfs our heart.

An apparatus, we seek to design, that accompanies us, a faithful sign. a tool that becomes an extension of self, to create a boundary, an invisible shelf.

A portable structure, that moves with us, a shield that protects, an aid in the fuss. it defines our boundaries, our personal space, and keeps us secure in a crowded place.

It may be simple, or complex in its make, an architectural feat, a piece to partake. it may be a cloak, a hat, or a bag, a device that saves us from an unwanted tag.

It could be a force field, a barrier of light, a device that brings us calm, that gives us might. a tool that creates a bubble of privacy, in a world where we’re exposed to scrutiny.

So let us build this apparatus, this shield, a creation that brings us a sense of yield. a tool that accompanies us, on this earthly ride, a device that helps us, to create our own divide.

Design 1-3 is a striking example of the power of design to facilitate spiritual practice in a world where space is often at a premium. At its core, this design project creates a platform for prayer that can be used in a variety of environments, both indoors and outdoors. However, the design goes beyond the functional requirements of the project, delving into deeper philosophical and theoretical considerations.

49

Untitled poem written anonymously by friend of the author pertaining to the topic of this section. Reproduced by permission.

At the focus of this project is the concept of directionality- a fundamental aspect of many religious traditions. The design concept recognised the importance of having a platform that could accurately show the proper direction of prayer and incorporated a compass-like feature to fulfill this need. This attention to detail speaks to the designs’ deep understanding of the nuances of spiritual practice and commitment in creating a platform that can truly facilitate the user’s experience.

In addition to its functional features, this design is also notable for its flexibility. The platform can be used in a variety of environments and the degree of privacy can be adjusted to meet the user’s needs. This adaptability recognises the significance of creating a space that is simultaneously practical and personalised.

However, beyond these practical applications, this design project raises important theoretical and philosophical questions. At its core, it highlights the complex interplay between physical environment and spiritual experience. The creation of a platform that can accurately show the proper direction of prayer is a recognition of the profound ways in which the physical world can shape spiritual practice. Similarly, the ability to adjust the degree of privacy highlights the importance of creating a space that is tailored to the individual’s needs and preferences.

50

Fig 25. DESIGN 1-3

51

Fig 26. DESIGN 1-3

The rituals of religion and the mundane activities of everyday life may seem worlds apart, but upon closer examination, it becomes clear that they share more similarities than differences. Both involve a set of prescribed actions, repeated over time, with the intention of creating meaning and significance.

In essence, both religious rituals and domestic activities are found in the concept of the threshold. Thresholds are the points of transition between various spaces or states of being- whether physical or emotional.

They mark the boundary between the sacred and the profane, the mundane and the transcendent.

In religious rituals, thresholds take on a particular significance, as they identify the transition from the everyday world to the realm of the divine. This can be seen in the use of physical spaces, such as churches, temples, or mosques, which are designed to create a sense of separation from the exterior, secular world. Within these spaces, ritual actions, such as prayer, chanting, or meditation, serve to create a connection with the divine and to mark the boundary between the sacred and the profane.

Similarly, in domestic activities, thresholds serve a similar purpose, marking the transition from one programmatic state of being to another. This can be seen in the use of spaces within the home, such as the kitchen or bedroom, which are designed to create a sense of separation from the rest of the house.

Moreover, the repetitive actions within both religious rituals and domestic activities serve to create a sense of continuity and meaning. Whether it is the daily recitation of prayers or the daily routine of cooking a meal, these actions provide a sense of structure and purpose in daily life. They create a rhythm and flow that can be comforting and reassuring, providing a sense of stability and grounding amidst the chaos of the every day.

Furthermore, both religious rituals and domestic activities involve a degree of intentionality and mindfulness. In the former, the focus on intention and attention to the present moment is central to creating a connection with the divine. Similarly, in the latter, the focus on intention and attention to detail is central to creating a sense of purpose and meaningfulness in everyday tasks. There is a shared degree of mindfulness, whether it is the mindfulness of prayer or the mindfulness of washing dishes.

In this way, the similarities between religious rituals and domestic activities highlight the interconnectedness of all aspects of our lives. They demonstrate that the mundane and the sacred are not as separate as one’s preconceptions, but rather part of a larger whole. In recognizing the shared elements of these seemingly different practices, there is an inherently deeper appreciation for the richness and complexity of the human experience.

52

1.Baha’u’llah. Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1990.

2.Bahá’u’lláh. Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1992.

3.Bahá’u’lláh. Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1990.

4.Bialecki, Jon, and Richard Sosis. “Introduction: Understanding Religion and the Body.” In The Anthropology of Religious Experience, 1-23. AltaMira Press, 2007.

5.Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World, 1959.

6.Heidegger, Martin. “What Is Metaphysics?” In Basic Writings, edited by David Farrell Krell, 93-110. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2008.

7.Lang, J. T. Creating Architectural Theory: The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental Design. Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1987.

8.Seddigh, Maryam A. “Prayer Beads in Islamic Culture.” Muslim World 95, no. 1 (2005): 43-54.

9.Spilka, Bernard, Ralph W. Hood Jr., Bruce Hunsberger, and Richard Gorsuch. The Psychology of Religion: An Empirical Approach. 4th ed. Guilford Press, 2003.

53

CHAPTER 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY

54

CHAPTER 02Baháʼí Domesticity

55

02-1. THE NINETEEN DAY FEAST

“Verily, it is enjoined upon you to offer a feast, once in every month, though only water be served; for God hath purposed to bind hearts together, albeit through both earthly and heavenly means”

(Baha’u’lla h, The Kita b-i-Aqdas,)

The Nineteen Day Feast, a sacrosanct observance in the Bahá’í Faith, occurs at nineteen-day intervals and serves as a time for spiritual introspection and community assemblage. The feast is conducted in local Bahá’í communities and comprises elements of worship, conviviality and administrative decision-making. The term “Ziafat” which originates from the Arabic lexeme connoting hospitality, is frequently utilized to characterize this sacred observance.

According to Bahá’í scripture, the feast was instituted by the Báb, or the herald of Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith. The Báb consecrated the nineteen-day interval as a period of contemplation on the divine and spiritual aspects of existence, and the feast continues to serve this purpose for Bahá’ís today. In the Kitáb-i- Aqdas, the central book of Bahá’í law, Bahá’u’lláh writes: “It hath been ordained that the believers should hold a gathering every nineteen days, in such a manner as is deemed best, in order that they may remember God and put their trust in Him.” 1 The Bahá’í Prayers, a collection of Bahá’í prayers, contains a prayer specifically designated for the Nineteen Day Feast: “O Thou kind Lord! This gathering is turning to Thee. These hearts are radiant with Thy love. These minds and spirits are exhilarated by the message of Thy glad-tidings.” 2

The format of the Nineteen Day Feast varies to some extent from community to community, but typically includes three elements: a devotional portion in which prayers and readings from Bahá’í scripture are shared, a social portion where members of the community come together to share food and conversation, and an administrative portion where the business of the local Bahá’í community is discussed and decisions are made. The devotional portion of the feast often features prayers, passages from the Bahá’í holy writings and music. The social portion provides an opportunity for community members to catch up with one another and strengthen their bonds, while the administrative portion allows for the efficient and democratic running of the local Bahá’í community.

1. Bahá’u’lláh, Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1992), 72.

2. Bahá’u’lláh, Bahá’í Prayers: A Selection of Prayers Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh, the Báb, and `Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2002), 144.

56

57

Fig 27. A traditional Baha’i gathering Sabouri, Bayan. A spirited Baha’i Feast in a Chicago neighborhood. 2014. Photograph. Nineteen Months, https://www.nineteenmonths.com/5-things-anyone-can-do-to-revive-community-spirits-at-feast/

The practice of hospitality and serving is a critical aspect of the Nineteen Day Feast. The feast typically takes place in the private homes of Bahá’ís and affords community members the opportunity to come together for worship, conviviality and administrative decision-making. The employment of dwelling as architectural elements in the feast accentuates the central role that hospitality and serving play in the progression and sustenance of the community.

Hospitality is a paramount principle in the Bahá’í Faith, and the Nineteen Day Feast affords community members the chance to embody this principle. During the social component of the feast, attendees are exhorted to partake in sustenance and conversation and to demonstrate warmth and generosity towards one another. This serves to bolster the bonds of community and to engender a sense of belonging among attendees. 3

The utilisation of the dwelling as architectural elements in the Nineteen Day Feast also highlights the significance of service in the evolution and preservation of community. During the feast, attendees are encouraged to alternate as hosts, and to prepare and serve food for their fellow community members. This serves to foster a sense of shared responsibility and to reinforce the principle of service within the community. 4

This utilisation reflects a broader philosophical tradition in which the home is perceived as a microcosm of the larger society. In this tradition, the home serves as a space for the cultivation of moral and spiritual values that can then be extrapolated to the wider community. 5 This is particularly poignant in the Bahá’í Faith, where the home is regarded as a central place for the development of spiritual and moral qualities. 6

In conclusion, the importance of hospitality and service and the integration of dwelling as architectural elements in the Nineteen Day Feast are vital aspects of this sacred observance in the Bahá’í Faith. They serve to bolster the bonds of community and to accentuate the central role that hospitality, service and the home play in the progression and preservation of community.

- POWER RELATIONS

The utilization of architecture in shaping power relations and administrative aspects of religious institutions has been a prevalent theme throughout human history, particularly within the Islamic faith. The philosophical ideas underlying this utilization can be traced back to ancient times, where the design and construction of religious buildings served as a means of reinforcing the authority of religious leaders and the legitimacy of religious institutions.

3. Bahá’í International Community, “Hospitality,” n.d., accessed March 11, 2023, https://www.bahai.org/actions/hospitality/.

4. Bahá’í International Community, “Service,” n.d., accessed March 11, 2023, https://www.bahai.org/actions/service/.

5. Bahá’í International Community, “The Home as a Microcosm of Society,” n.d., accessed March 11, 2023, https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/19931230_001/.

6. Bahá’í International Community, “The Home as a Place of Worship,” n.d., accessed March 11, 2023, https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/19931230_001/.

58

This can be seen as an example of the use of symbolic capital, where the architectural design of religious buildings is used to convey the prestige and power of the religious institution, thereby reinforcing its authority and legitimacy. 7

In addition to serving as symbols of religious authority, religious buildings also reflect the broader cultural, social and philosophical ideals of the religious community. The use of symbolism, such as the use of religious symbols, images and iconography, serves to reinforce cultural values and beliefs, and to express the religious ideals of the community. 8 Furthermore, the design of religious buildings often reflects the relationship between the divine and the physical realm, and can serve to reinforce the importance of this relationship in the religious community. 9

W28H5: By displaying this sacred image in my living room, I am constantly reminded of the strong connection I have to a larger community that shares my beliefs and values. This image not only serves as a symbol representing the community I am a part of, but also as a visual anchor that keeps me grounded in the traditions and cultural practices that have shaped my identity. As a result, I feel a deep sense of belonging and unity with my fellow community members, which in turn fosters a sense of comfort and reassurance in my daily life.

7.Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J. G. Richardson (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986), 241-258.

8.John Bowker, The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

9.Richard Ettinghausen, “The Mosque: Its Early Development in Syria and Iraq,” in The Arab Heritage (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967), 75-89.

59

Fig 28. Living Room, Bahá’í Family House, drawn by the author

The design and construction of religious buildings have been used to create spaces that are considered sacred, and which serve as a means of communicating with the divine. This has been particularly evident in the Islamic faith, where the design and construction of mosques has been used to create sacred spaces that serve as a means of communing with Allah.10 In many cases, the mosque serves as the hub of community life, providing a space for social interaction, economic exchange and political discourse. For example, the mosque has often been used as a centre of dispute resolution, where members of the community come together to resolve conflicts and make decisions on important matters. In this way, the mosque serves as a symbol of community unity and, similarly, as a centre of administrative power.

Moreover, the mosque has also been used to reinforce the authority of religious leaders, who serve as the gatekeepers of religious knowledge and as the intermediaries between the community and the divine. The design and construction of mosques, with their intricate geometric patterns, calligraphy and other forms of decoration, serve to reinforce the authority of religious leaders and to create a sense of awe and reverence for the mosque as a sacred space.11

For example, the use of pulpits in mosques is a significant aspect of the representation of power and authority of religious leaders. Pulpits, also known as “minbars,” are raised platforms from which the imam delivers sermons and leads congregational prayers.12 In addition to their symbolic significance, pulpits have also been used to convey messages to the community and to address social and political issues. The imam, as the gatekeeper of religious knowledge and the intermediary between the community and the divine, has used the pulpit to communicate messages that are intended to shape the community’s beliefs and behaviour.

In the Bahá’í faith, the shift in the locus of religious activity from the temple to the house has had a transformative effect on the importance of space and household items. The concept of the house has undergone a metamorphosis and has become the foundational element that shapes the administrative structure of the religion. It has evolved from being merely a private space to a sacred site that holds sway over the entire architecture of the Bahá’í faith.

10.Isma’il R. Al-Faruqi, “The Concept of Sacred Space in Islam,” in The Sacred in the Modern World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 170-189.

11.Anthony Giddens, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

12.Robert Hillenbrand, Islamic Architecture: Form, Function, and Meaning (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1994), 56-57.

60

https://www.wikiart.org/en/kamal-ud-din-behzad/behzad-beggar-at-a-mosque-1488

61

Fig 29. BEHZAD BEGGAR AT A MOSQUE

Behzad, Kamal ud-Din. Behzad Begger at a Mosque. 1488. Painting. WikiArt Visual Art Encyclopedia,

W1H7: Although I was born in England and live in an English-speaking community, I identify myself as part of the larger Baha’i community. Within this community, I experience a strong sense of comfort and kinship with my fellow members. For instance, during our nineteen-day feasts, I feel completely at ease with the Baha’i community members coming and going in my kitchen, a space I consider personal and generally do not allow strangers to enter. However, the members of the Baha’i community feel like an extension of my own family, and I share a deep sense of trust and connection with them.

Q: Can you describe how your approach to hosting guests in your home differs during the Nineteen Day Feast compared to other occasions?

W1H7: On regular occasions when we have guests over, I prefer to maintain my privacy by keeping the kitchen door closed. I prepare the food in the kitchen and serve it to our guests in the living room. However, during the Nineteen Day Feast, the atmosphere is more relaxed and inclusive. We sometimes even utilise the dining table in the kitchen for this purpose, embracing the shared experience and closeness within our community.

62

63

KITCHEN LIVING ROOM

Fig 30. Plan, Ground Floor, House #7, drawn by the author

- ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE

The administrative structure in the Bahá’í Faith is a complex system that has been designed to ensure the smooth functioning of the community and to facilitate the realization of the spiritual principles and goals of the faith. This structure is characterized by a decentralised nature, emphasising the group dynamics of consultation, and thus, commitment to unity and harmony.

At the heart of this administrative structure is the Universal House of Justice, which is the supreme governing body of the Bahá’í Faith. Established by Bahá’u’lláh in His writings, this institution is responsible for guiding and directing the affairs of the worldwide Bahá’í community and for enacting legislation on matters that are not explicitly addressed in the Bahá’í scriptures.

“It hath been decreed by Us that the Word of God and all the potentialities thereof shall be manifested unto men in strict conformity with such conditions as have been foreordained by Him Who is the All-Knowing, the All-Wise. We have, moreover, ordained that all matters be referred to the House of Justice in a manner conformable to the exegetic verses of the Book and to the established practices of the people of God.” 13

The Universal House of Justice is supported by a number of other institutions, each with its own specific responsibilities and functions. These institutions include the National Spiritual Assemblies, which are responsible for overseeing the affairs of the Bahá’í communities in their respective countries, as well as the Local Spiritual Assemblies, which are responsible for the administration of local Bahá’í communities. 14

The process of electing the Universal House of Justice begins at the local level, with the election of the Local Spiritual Assembly. The members of the Local Spiritual Assembly are elected annually by the members of the local Bahá’í community through a process of prayerful deliberation and consultation. Once the Local Spiritual Assembly is elected, it is responsible for electing the delegates who will represent the local community at the national level. These delegates are chosen based on their spiritual qualities and their ability to serve the community. They are responsible for electing the members of the National Spiritual Assembly.

The National Spiritual Assembly is the governing body of the Bahá’í community in a particular country or region, and it is responsible for overseeing the affairs of the Bahá’í community at the national level. The members of the assembly are elected annually by delegates representing the local, regional communities. They are further responsible for the election of members in the Universal House of Justice internationally- gathered at the Bahá’í World Centre in Haifa, Israel, for a period of several days. The election takes place every five years, during a special convention known as the International Bahá’í Convention. 15

13. Baha’u’llah, “Tablet of Carmel, paragraph 15,” in The Kitab-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book, trans. Shoghi Effendi (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1993), 35.

14. Universal House of Justice, The Institution of the Counsellors, 2010, accessed [Access Date], https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/ the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/20101112_001/20101112_001.pdf.

15. Moojan Momen, An Introduction to the Bahá’í Faith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

64

65

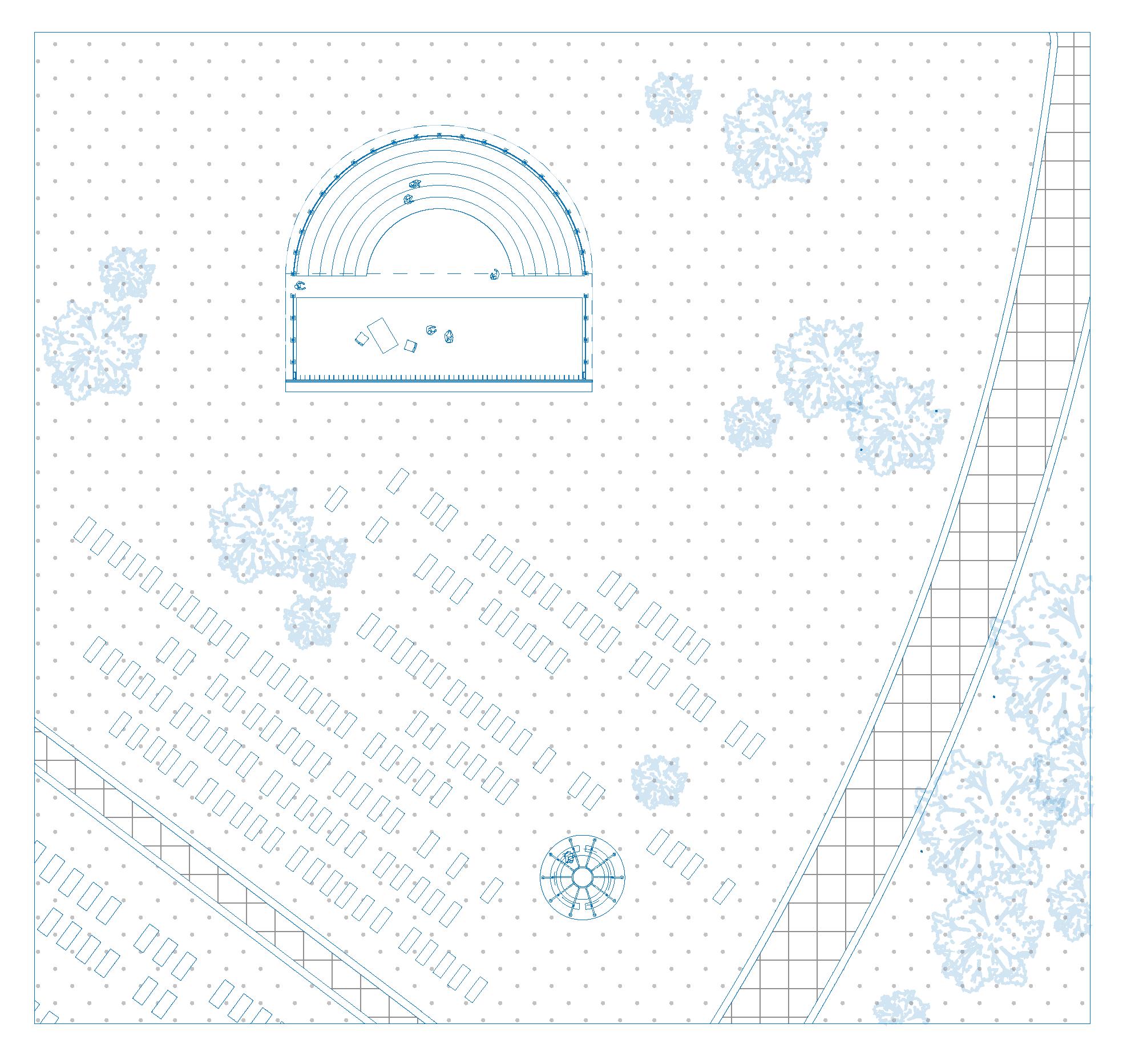

Fig 31. ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE OF THE FAITH, drawn by the author

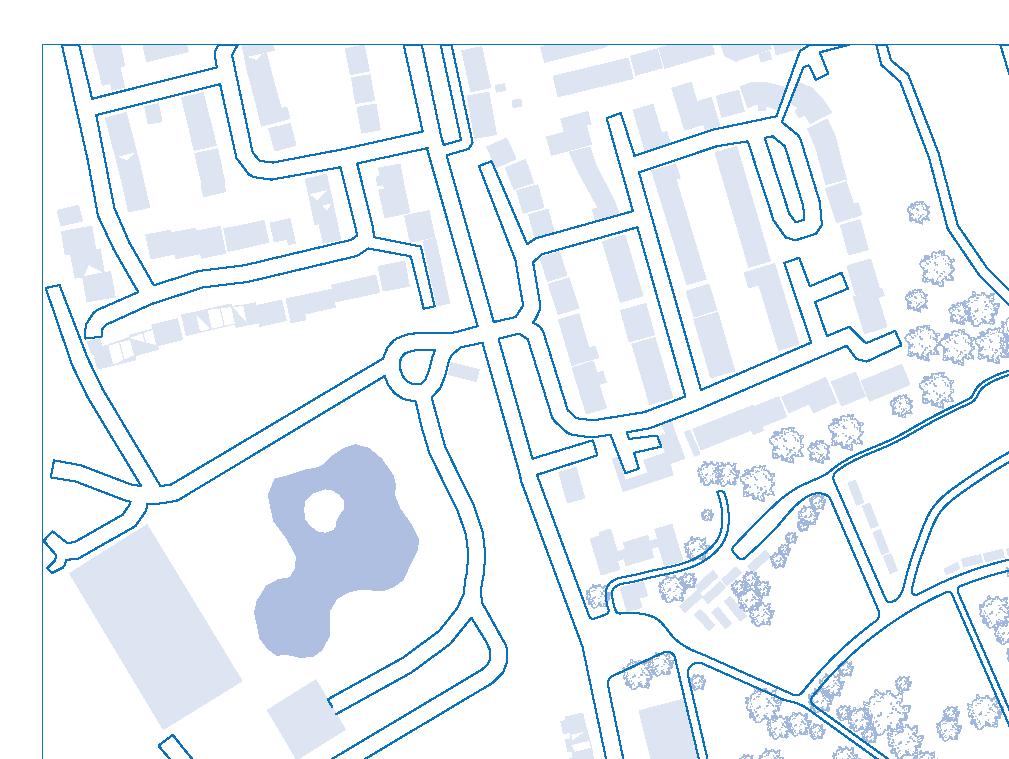

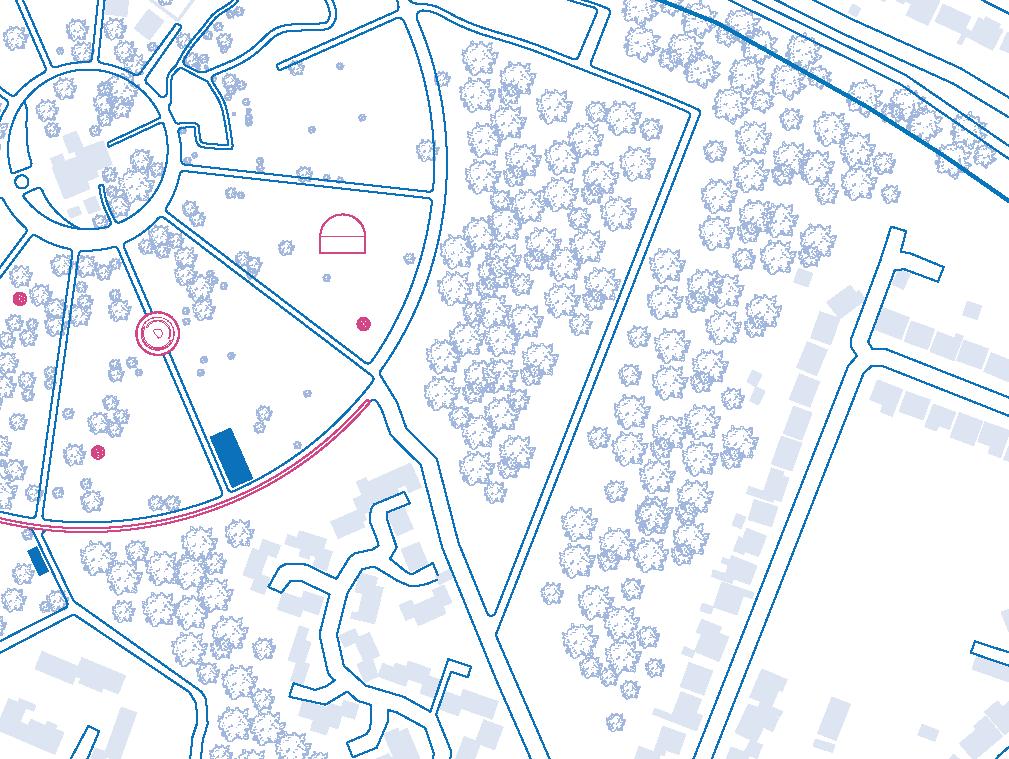

BAHAI HOUSE IN ONE TEHRAN CITY QUARTER

The administrative structure of the Bahá’í Faith places a strong emphasis on the role of the house and the Nineteen Day Feast. The house has become a central space for the Bahá’í community, serving as a site for spiritual gatherings, consultation and decision-making. The Nineteen Day Feast, held every Bahá’í month, is a community gathering that takes place in the house, where members come together for prayer, consultation and fellowship.

The Local Spiritual Assembly is responsible for organising the Nineteen Day Feast and its members are tasked with determining the location and timing of the gathering. In some cases, the Local Spiritual Assembly may designate a specific location, such as a Bahá’í center or a community hall, for the Nineteen Day Feast. In other cases, they may encourage Bahá’ís to host the gathering in their homes, rotating the location each month to allow for a variety of experiences and to encourage participation and involvement in the community.

“The Nineteen Day Feast is a time when matters are openly discussed and the rank and file have the opportunity to make suggestions and offer criticisms. It is also a time when the Local Spiritual Assembly presents its report, and when the believers can acquaint themselves with the activities and achievements of the community.” 16

“…Thus hath it been decreed by God, that every man may, in this dispensation, take hold of the Book of God, and read therein what hath been revealed in such clear and perspicuous language, that none can fail to understand.” 17

In conclusion, the democratization of the Baha’i Faith is a fundamental aspect of the religion. The absence of a single priestly class or hierarchy of individual spiritual leader is a testament to the Baha’i commitment to individual agency and responsibility. The Baha’i Faith offers a path to spiritual enlightenment that emphasises the importance of personal engagement with the teachings of Baha’u’llah, rather than reliance on the authority of religious leaders. The Baha’i Faith places a great emphasis on the role of the individual in shaping their own spiritual destiny. This emphasis on individual responsibility is reflected in the democratic structure of the Baha’i community, where every member is encouraged to participate in the decision-making process and to contribute to the betterment of the community. This focus highlights the importance of domesticity and family life as a foundation for spiritual and social development. The democratisation of the faith begins within the realm of the family, where each individual is encouraged to take an active role in the collective activities of the community, and extends out to foster collective care-taking practices.

Q: It seems you have a strong desire to host the Nineteen Day Feast in Tehran, but you’ve mentioned facing some challenges. Can you share more about your experience and the reasons behind not being able to host the feast?

W1H6:I am truly passionate about participating in the nineteen-day feast in our area in Tehran and have always wanted to host it myself. However, due to the limited space in my home, I’ve been unable to do so. There are about 15 people in our feast group, and although it’s possible they could fit into my house, I don’t have the proper facilities to accommodate them comfortably. The members of our feast group are like family to me, and I am at ease with them visiting my home. However, I believe in hosting them in a suitable manner that ensures their comfort and enjoyment. As a result, I have yet to host the nineteen-day feast at my residence.

16. Shoghi Effendi, letter on behalf of the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, to an individual believer, March 28, 1939.

17. Bahá’u’lláh, The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book, paragraph 29 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1993).

66

67

Fig 32. House #5 draw by Author

02-2. BUILDING, DWELLING, THINKING

“Building Dwelling Thinking,” a seminal essay by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, published in 1951, delves into the intricate relationship between human beings and the built environment. Heidegger argues that the act of building is not just a physical act but is an expression of our being in the world, a mode of existence, which shapes our very identities.

Heidegger uses the concept of dwelling to express the significance of the relationship between human beings and the built environment. He emphasizes the crucial role that building plays in creating a sense of belonging and identity in the world.18 He argues that dwelling, which he defines as ‘remaining in the domain of one’s own,’ is a condition of human existence and that the act of building is a way of creating a sense of place where people can exist comfortably.19

Furthermore, Heidegger contends that building is not just a means of creating a physical environment, but it is also a way of thinking about the world. By building, we reveal our relationship with the world and we come to understand it in a way that is deeply rooted in our experience. Heidegger’s argument posits that building is a way of thinking about the world that is closely tied to human existence.20 As mentioned in previous texts, the Baha’i perception of the house has undergone a transformation, from a common physical structure to encompassing the concepts of the house as a temple or as an administrative institute.

Q: You’ve mentioned your desire to host a Nineteen Day Feast in your home. Can you elaborate on the specific limitations you face in terms of space and what you believe would make hosting possible?

W1H6: I’ve always imagined that if I had enough room for a large table, I could potentially host a Nineteen Day Feast. With a big table, we would have the space to gather around for the different segments of the feast and comfortably accommodate our guests. Unfortunately, the dimensions of my current home do not allow for such a possibility, which has been a significant constraint in realizing my desire to host a Nineteen Day Feast.

18. Heidegger, Martin. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” In A Companion to Heidegger, edited by John Haugeland, 95-97. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1993.

19. Heidegger, Martin. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” In Basic Writings, edited by David Farrell Krell, 345-366. New York: Harper Collins, 1971.

20. Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology, and Other Essays. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

68

DESIGN 2-1

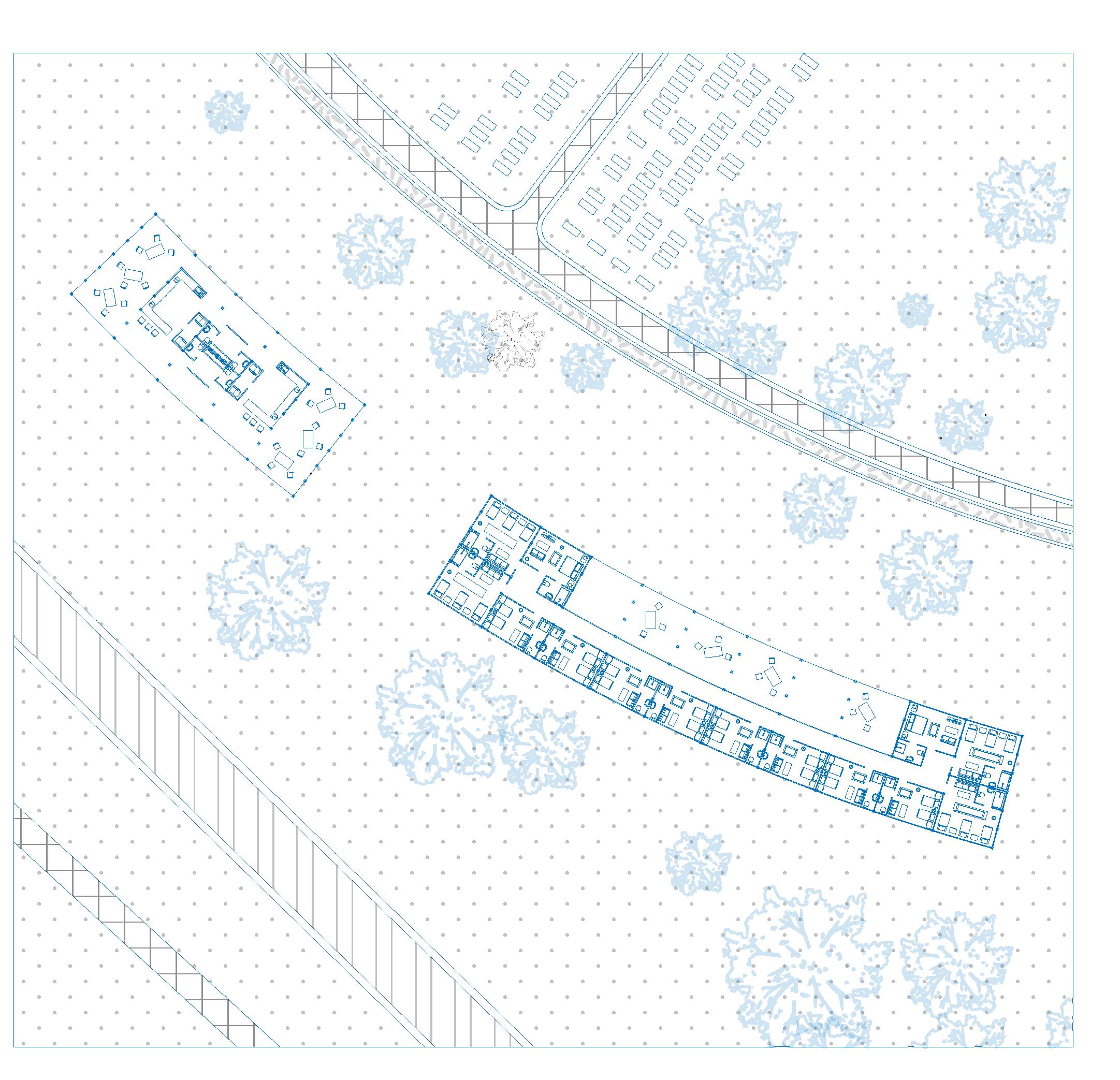

The design challenge at hand involves creating a multifunctional shelf that can effortlessly transform into a table when needed, seamlessly connecting the kitchen and living spaces of the home.

This solution should empower the homeowner to accommodate a larger number of guests comfortably, thus fostering a sense of belonging and togetherness during gatherings. Furthermore, the design should include versatile furniture that can serve dual purposes- such as pieces that function both as seating and table chairs, enhancing the adaptability and efficiency of the space. By incorporating elements of modularity and versatility, the object comes to embody the notion of interconnectedness; transcending the boundaries of conventional domestic spaces and promoting a harmonious relationship between form, function and human experience.

The ultimate goal is to create a thoughtfully designed environment that caters to the social and emotional needs of the homeowner and their guests, providing an adaptable space that fosters genuine connections and encourages communal experiences, while also addressing practical constraints.

69

Fig 33. DESIGN 2-1

The multi-functional shelf

Fig 34. DESIGN 2-1

Stages of transformation between shelf to table

70

71

Fig 35. DESIGN 2-1

Designed for personal prayer room, House#5

During the Nineteen Day Feast, my parents were quite resourceful in adjusting the arrangement of our household items to better facilitate the event. They moved our dining room table from the living room to the smaller living area, allowing it to hold food for guests more effectively and to be in closer proximity to the kitchen for easier food preparation and service.

To make up for the vacated space in the living room, extra chairs were brought in to accommodate the large number of guests in our modest home. Remarkably, all the private spaces of the house were transformed into public spaces during the feast. My parents’ bedroom became a designated area for guests to place their coats and belongings, while the kitchen turned into a communal space for those who wanted to lend a helping hand in preparing the food.

This adaptability showcased my parents’ commitment to hospitality and the sense of community, embracing the spirit of the nineteen-day feast by fostering an environment of togetherness through ingenuity, despite the limitations of our living space.

72

Fig 36. Living Room,House #2, drawn by the author

73

Fig 37. Nineteen Day Feast Protocols in House #2

02-3. SACRED KITCHEN

The practice of serving food during the Nineteen Day Feast holds a significant role in the Baha’i community, reflecting the importance of service in promoting social progress. Baha’u’llah emphasizes the significance of providing food to others, stating that, “the essence of hospitality is to feed one’s guests.”21 This act of serving food during the Nineteen Day Feast also reflects the Baha’i belief in the importance of collective action in building a community.

W1H8: I believe that the beauty of spirituality lies in its ability to transcend the boundaries between the mundane and the sacred. In our Baha’i household, our dining table serves as a perfect example of this transformation. During ordinary days, the table is a place for family meals, homework sessions and casual conversations. It is an essential yet unassuming part of our daily lives.

However, during the Nineteen Day Feast, the dining table takes on a new, sacred role. It becomes a place where we serve food to our fellow Baha’i community members, nurturing both our physical and spiritual connections. This transformation of the table from an ordinary object to a sacred space highlights the power of spirituality to elevate and sanctify our daily lives.

The importance of our dining table in these spiritual gatherings reminds us that even the most mundane objects can serve a higher purpose, allowing us to create meaningful experiences and foster unity within our community. It demonstrates that spirituality is not limited to specific places or objects but can be found and cultivated in every aspect of our lives, even through something as simple as a dining table.

74

21.Bahá’u’lláh, Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, paragraph 31 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988).

75

Fig 38. Dining area, House #8, draw by the author

The transformation of the kitchen from a private space for dwellers to a place of service, gathering and communication during the Nineteen Day Feast is a reflection of the unique and dynamic nature of Baha’i domestic life. The kitchen, which was once viewed primarily as a functional space for preparing and consuming food, has been transformed into a site of spiritual and social significance.

The transformation of the kitchen is emblematic of the larger transformation occurring in Baha’i domestic life, wherein the private realm of the home is opened up to the public sphere of the community. The kitchen is no longer a place solely for the consumption of food by the dwellers, but rather a space that can accommodate the needs of the community at large. It has become a site of hospitality, generosity and service, embodying the values of the Baha’i Faith.

In Baha’i belief, the kitchen represents a space where individuals can come together to engage in collective action, socialize and celebrate the progress of the community. The act of cooking and serving food during the Nineteen Day Feast is considered a form of worship and is seen as an essential aspect of building a vibrant and harmonious community.

In the realm of Baha’i domesticity, the kitchen serves as a site of communion and social engagement where individuals can gather in unity and solidarity, transcending the private realm of the individual and embracing the collective space of the community. It undergoes a transformative shift, entering the hallowed domain of the sacred through its involvement in religious collective activity. As the kitchen transitions from its profane visage to one befitting the sacred realm, its purpose takes on new significance and the object previously under scrutiny no longer befits its greater repurposing.

The concept of the sacred kitchen has been explored in depth by a number of scholars, including Cynthia Eller in her book “The Sacred Kitchen: Higher Consciousness Cooking for Health and Wholeness.” Eller argues that the kitchen is a site of transformation, where raw ingredients are transformed into nourishing meals that sustain and energize the body and the spirit. By approaching cooking as a sacred act, she argues, we can create a deeper connection to the food we eat and to the earth that provides it.22

Other scholars, Mary Douglas in her book “Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo,” have explored the relationship between food, domesticity, and the sacred in traditional societies. Douglas argues that food is not only a physical substance, but also a symbolic and social one, reflecting the complex relationships between individuals, groups and the natural world.23

The role of the kitchen in Bahai domestic life reflects a transformational shift from its mundane function to one that is regarded as sacred, amplifying its purpose and importance. This concept reflects the evolving relationship between modern domesticity and the sacred, and the increasing attention given to both alternative lifestyles and the environmental impact of industrial food production. By regarding cooking as a sacred act, it is possible to foster a deeper connection to the food that is consumed and the earth that provides for all; reinvigorating the communal and sacred dimensions of what was just the kitchen. The sacred kitchen is not only a space of nourishment, but also a space of spirituality, creativity and social engagement- transforming the potentialities of the domestic realm.

22. Eller, Cynthia. The Sacred Kitchen: Higher Consciousness Cooking for Health and Wholeness. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company, 2005.

23. Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, 2002.

76

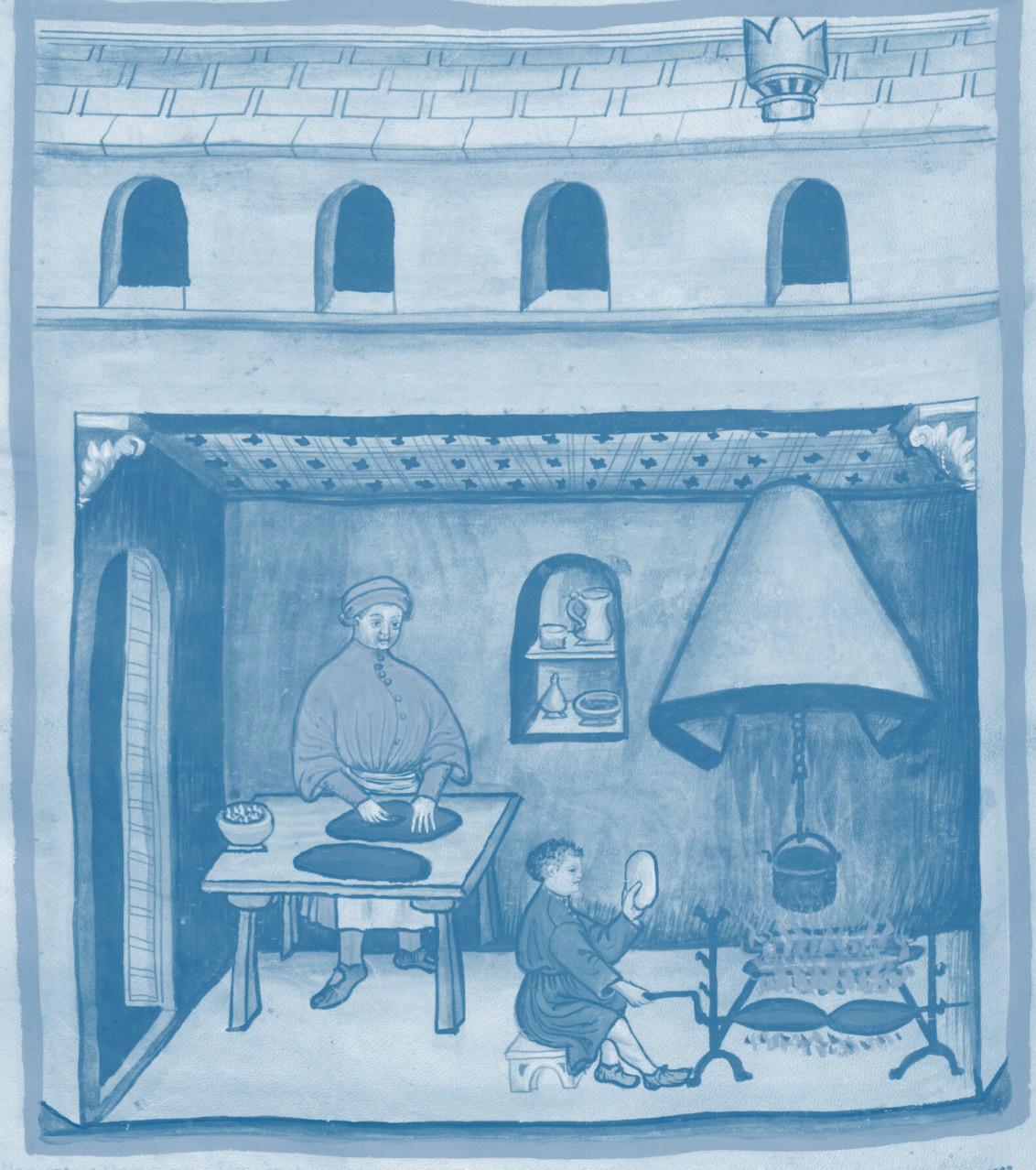

Code Ser. n. 2644, fol. 80v: Tacuinum sanitatis: Splenes. 1380. Illustration. The Austrian National Library Diigital Archive, http://data.onb. ac.at/rec/baa5003784

77

Fig 39. SACRED KITCHEN

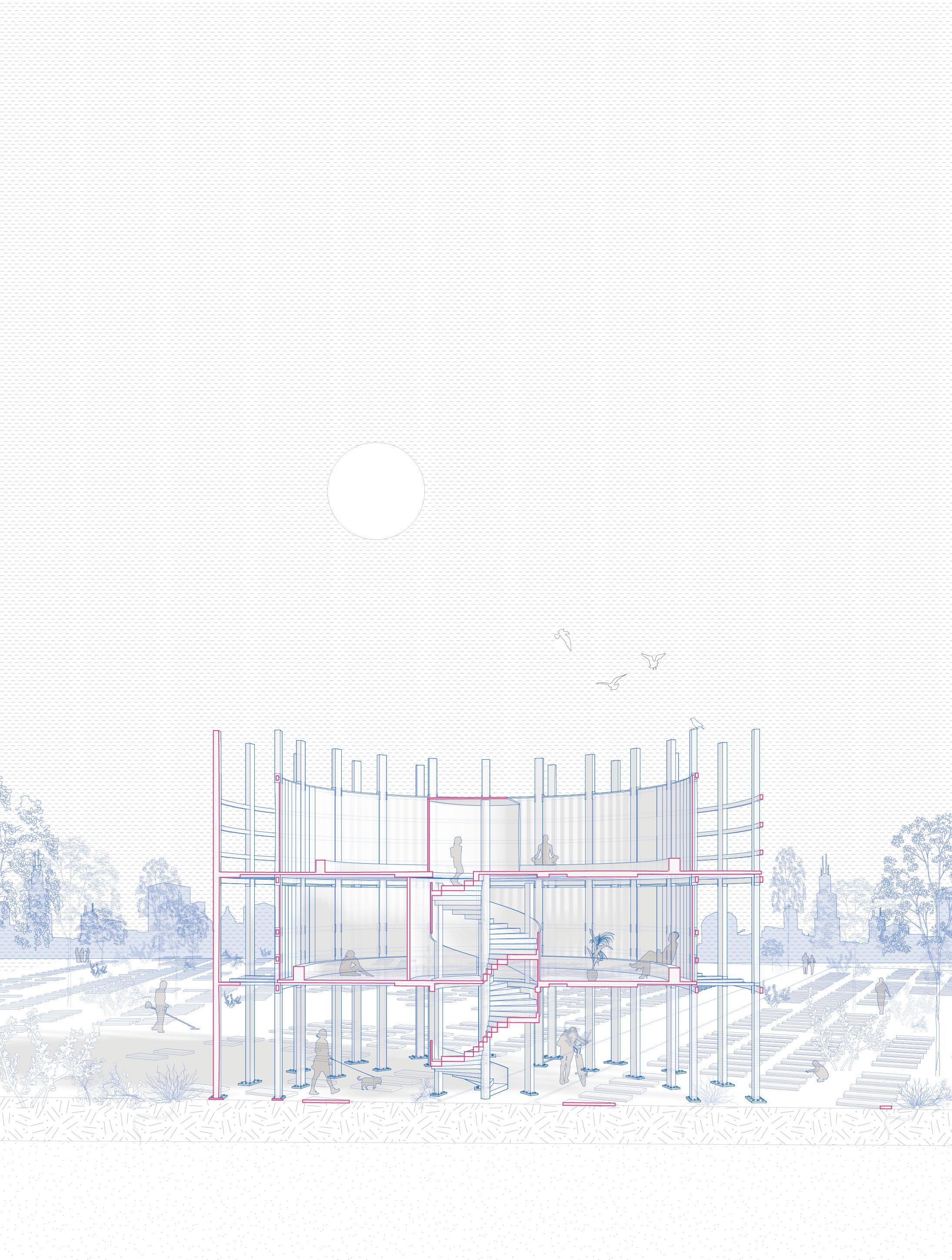

DESIGN 2-2

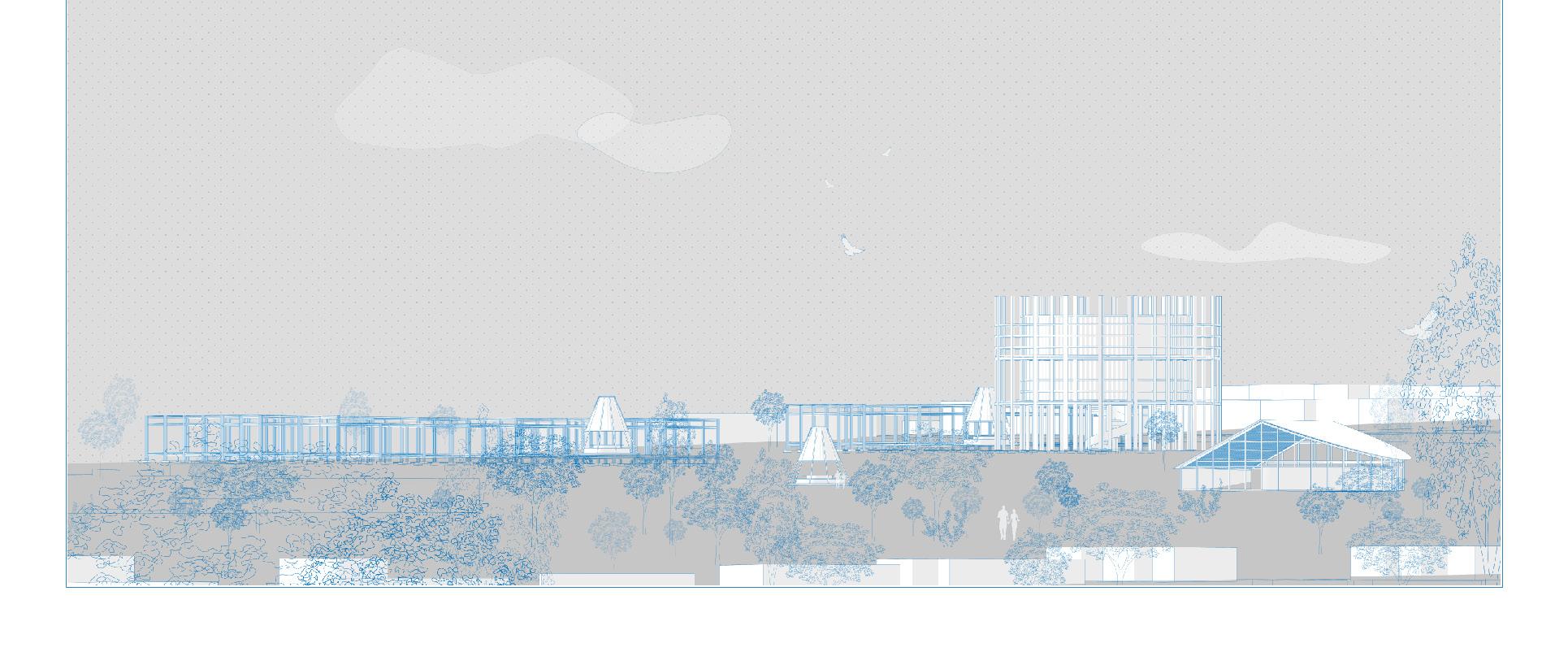

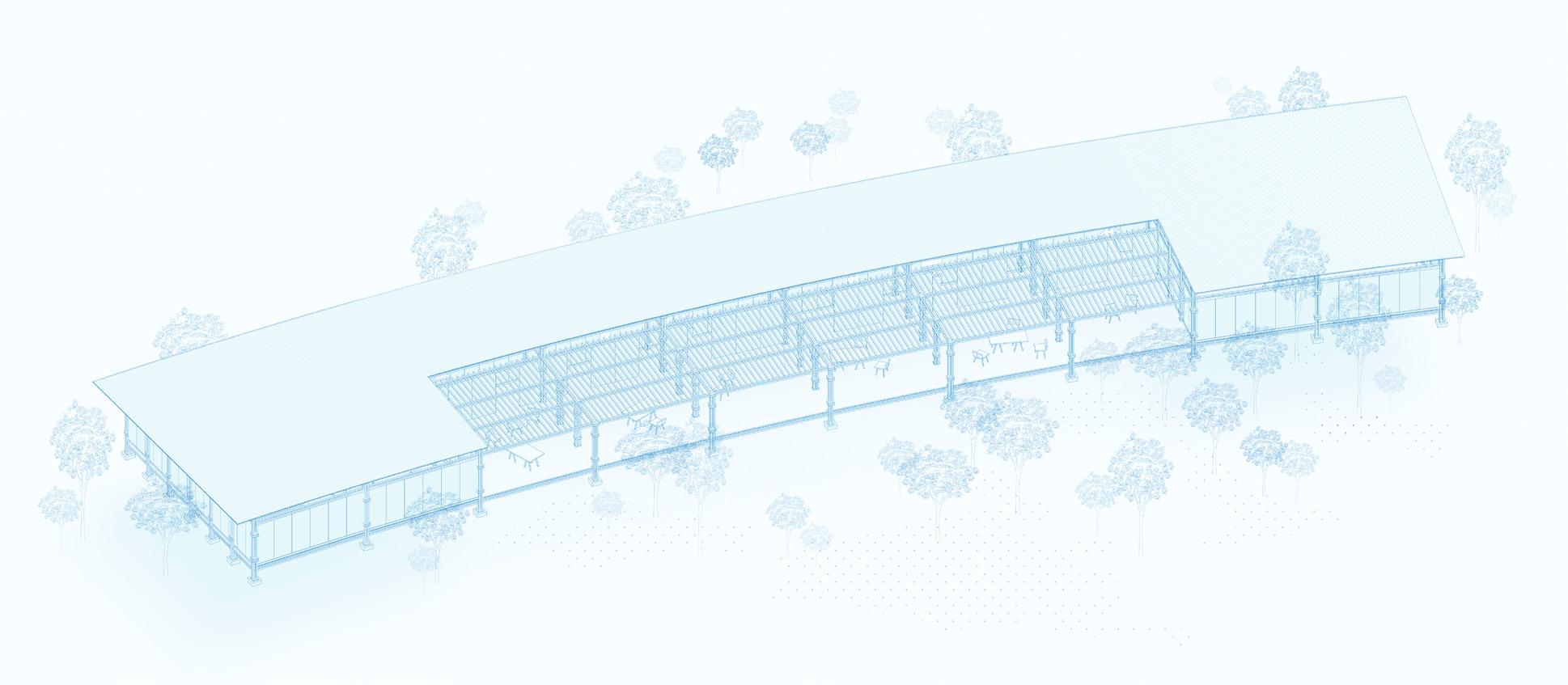

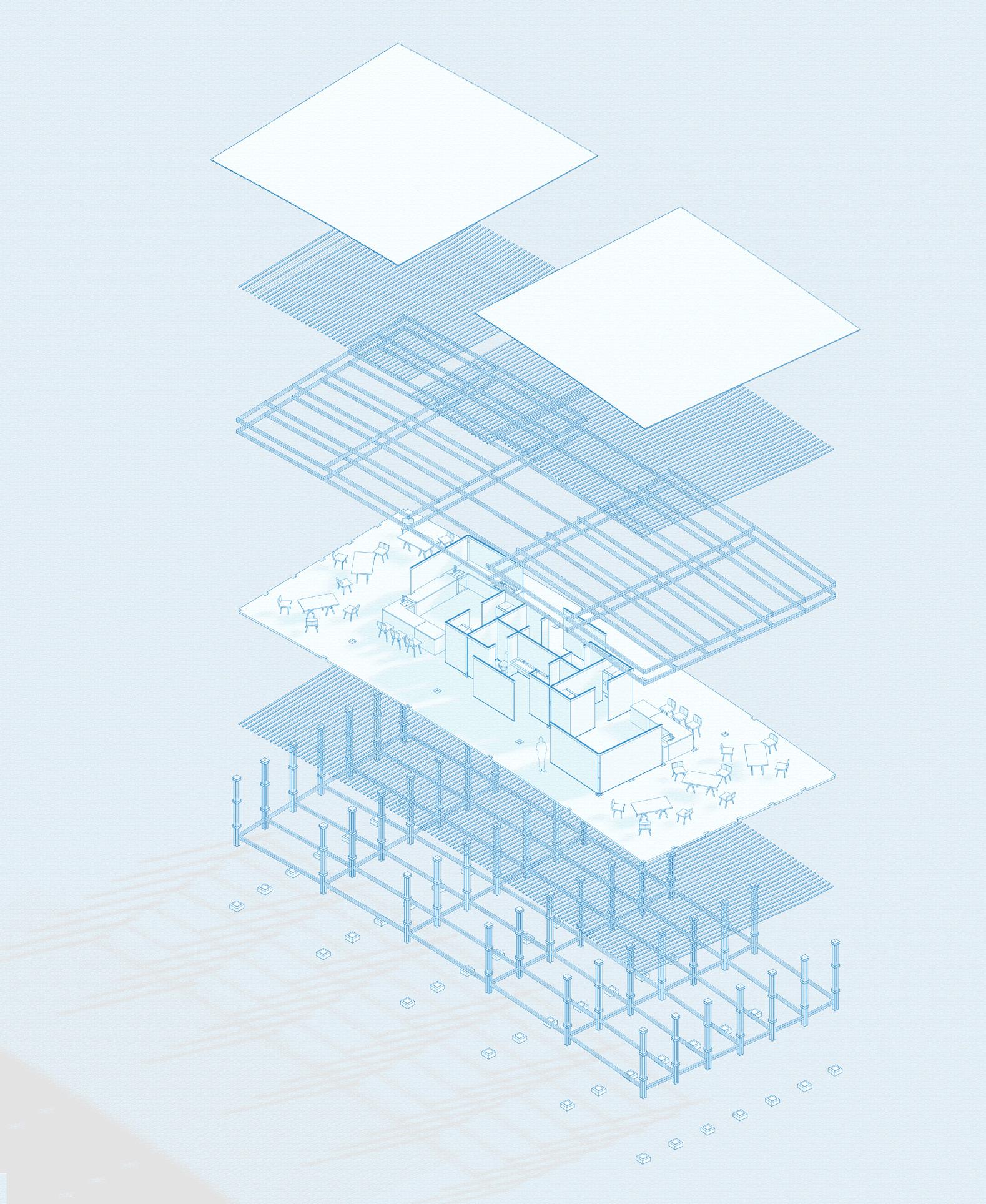

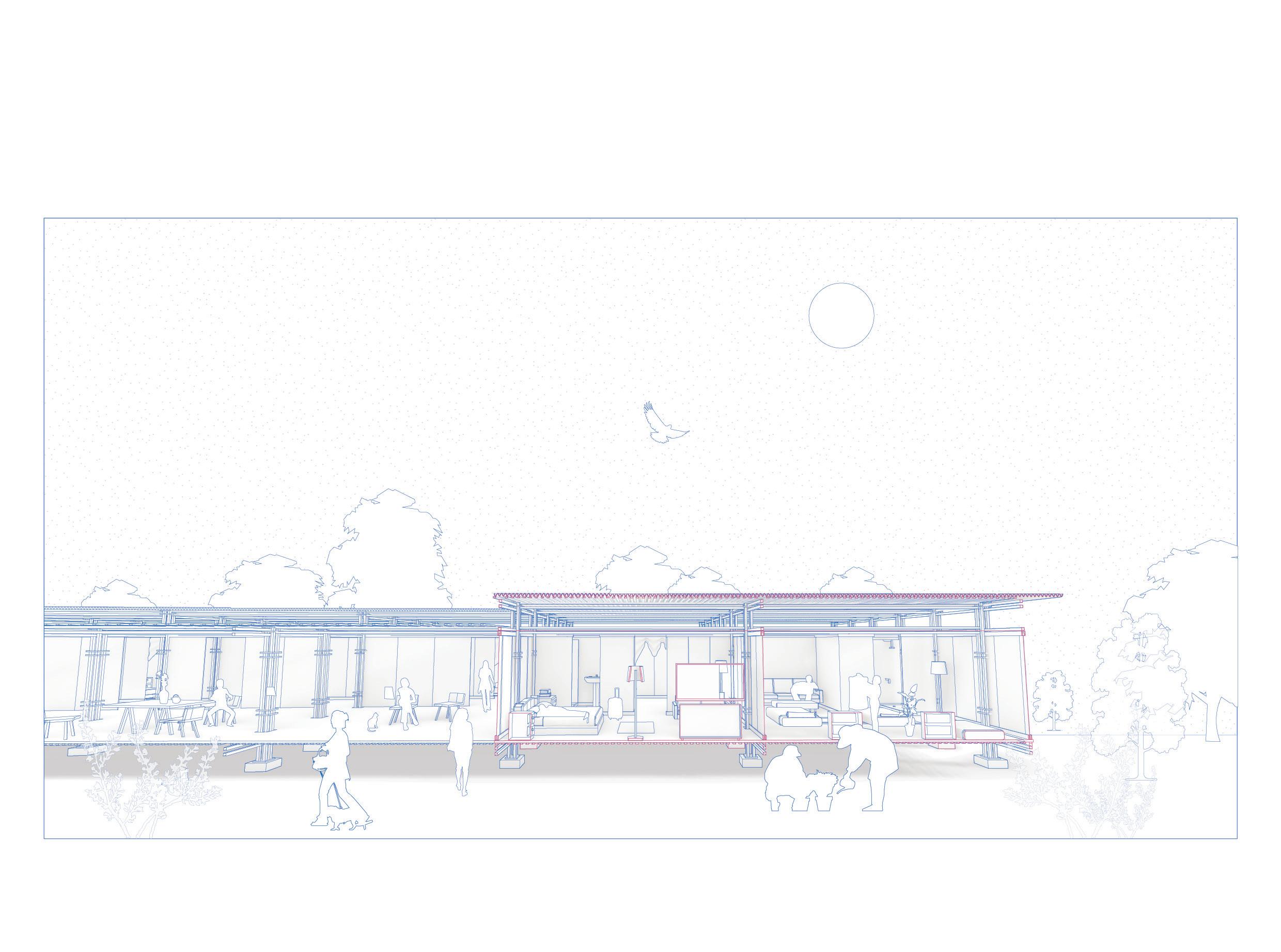

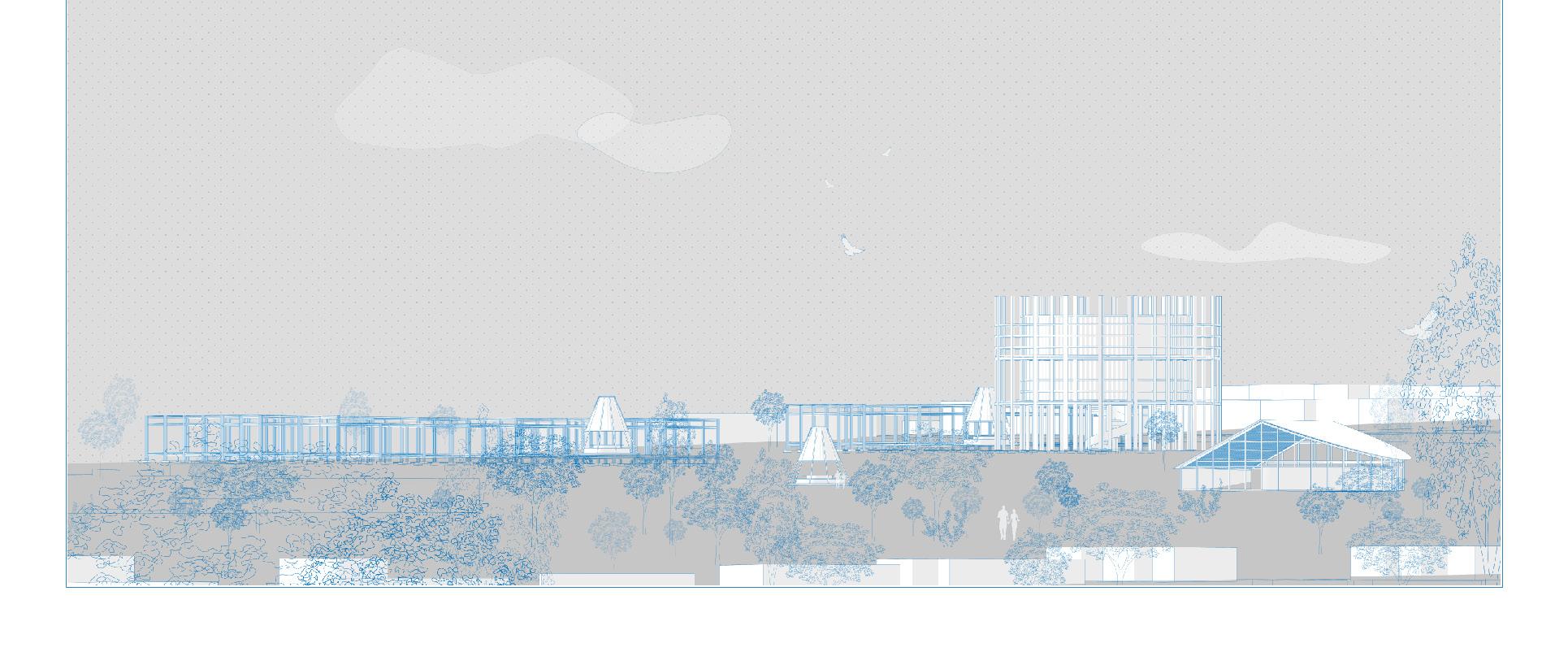

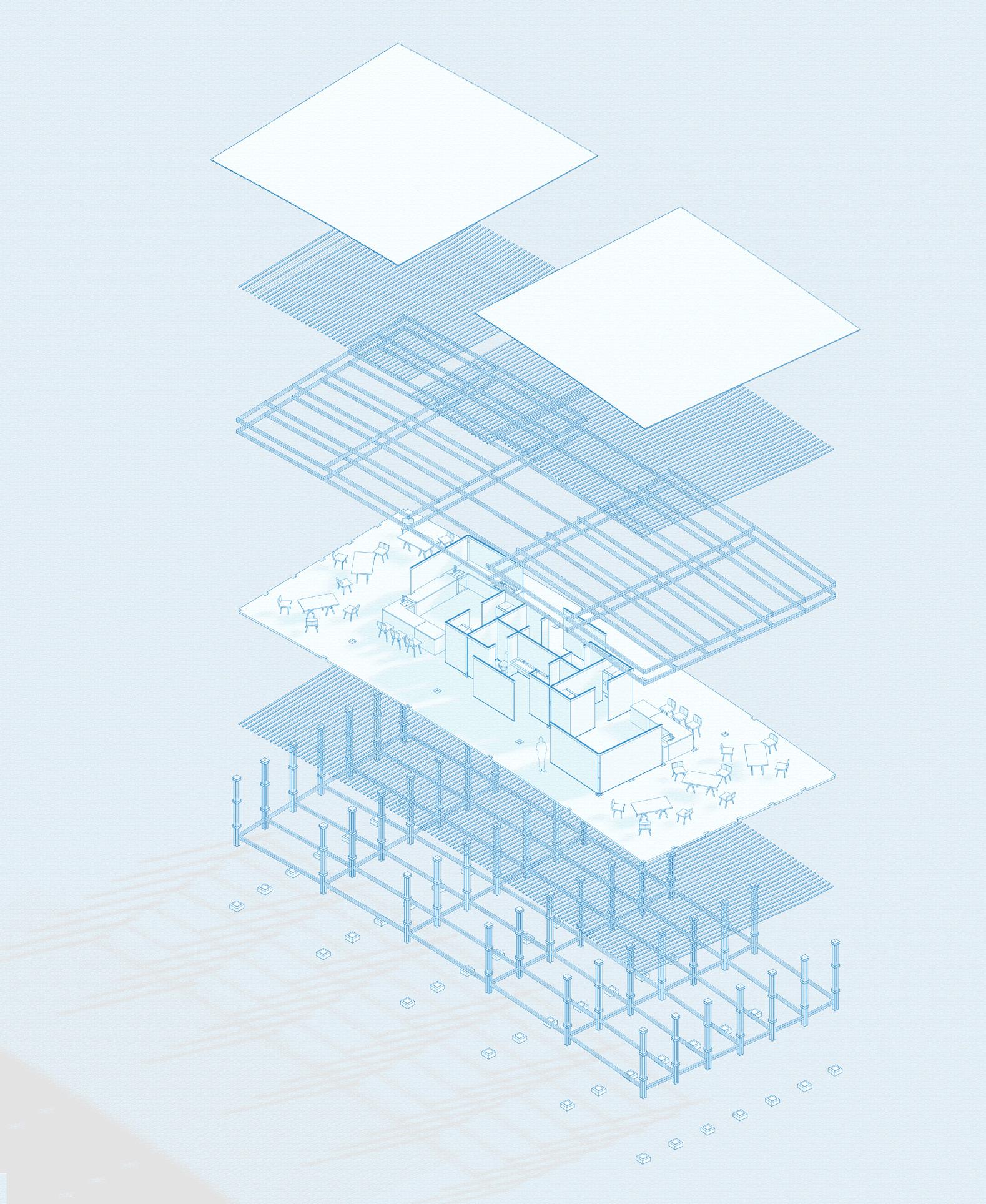

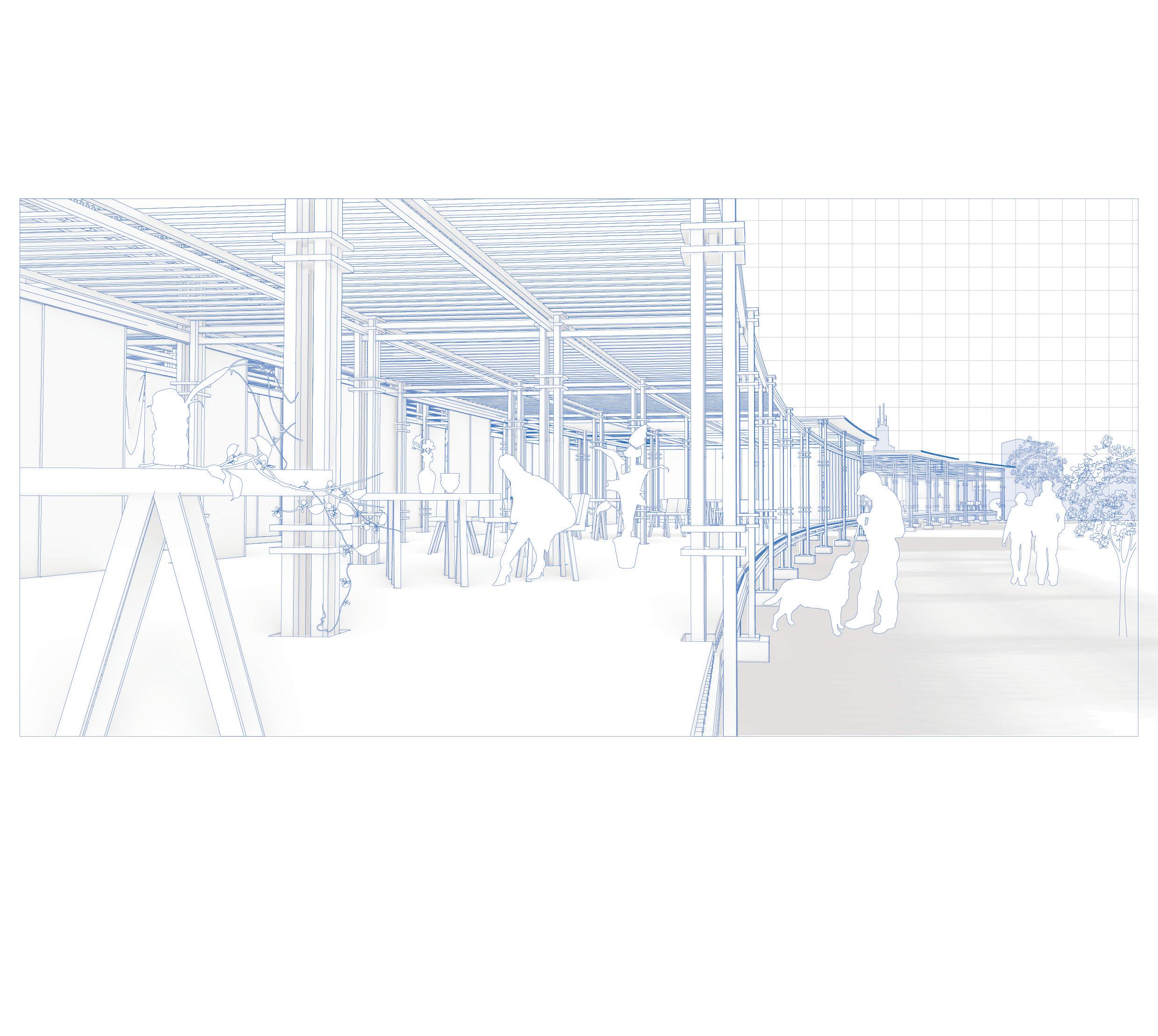

This design concept seeks to explore the notions of interconnectedness and collective effort within a community by envisioning a cooperative architectural structure that enables communal gatherings, shared cooking experiences and mutual hospitality. The structure exemplifies the strength derived from unity and thus, the inherent relationship between individuals and their environment; emphasising that ideas brough forth from collaborative efforts achieve greater outcomes.

The proposed structure is comprised of modular tables, cooking stalls and a central chimney, creating a flexible and adaptable space that encourages communal interaction through cooperation. The architectural design is deeply rooted in the philosophy of shared experiences, as it brings people together to participate in collective cooking and reception, fostering a sense of belonging and unity within the community.

One of the key features of this structure is the fabric dome that is suspended above the space, supported by the energy generated from the cooking activities. The central chimney serves as an energy storage system in harnessing the heat produced during cooking to maintain the dome’s structural integrity. This design element is emblematic of the interdependence between the community members and the structure itself.

As people participate in the communal activities within the structure, the dome is raised, signifying the collective effort and synergy derived from this communal collaboration. Conversely, a lack of participation disrupts the structure over time, emphasizing the idea that individual contributions are crucial to maintaining the stability and vitality of the community as a whole.

In essence, this architectural concept closely intertwines philosophy and design, creating a space that embodies the principles of unity, cooperation and the transformative power of shared experiences. It serves as a reminder of the profound impact that human connections and collaboration can have on both the physical and emotional landscapes of life.

78

79

Fig 40. DESIGN 2-2

80

Fig 41. DESIGN 2-2 Communal cooking device in operation

81

Fig 42. DESIGN 2-2 Communal cooking device not working

House number 4, being smaller than House number 2, which is my parents’ house, faces challenges in hosting a Nineteen Day Feast due to its limited space. To overcome this issue, these two households have come up with an innovative solution where they share their spaces during the feast.

In this arrangement, the living space of House number 4 is transformed into the reception area for House number 2. This allows House number 2 to better organise and utilizs its spaces to accommodate the event. To facilitate smooth communication and access between the two houses, the common staircase of the apartment building is used.

This collaborative approach between the two households showcases the importance of adaptability, resourcefulness and a strong communal awareness in order to overcome spatial limitations while simultaneously creating a welcoming environment for the Nineteen Day Feast.

Although the collaborative approach between House number 4 and House number 2 has been successful in terms of both addressing the limitations of space and creating a welcoming environment for the Nineteen Day Feast, there are some potential concerns that should be considered.

Firstly, the shared arrangement may raise privacy issues for both households, as personal spaces are being transformed into public areas during the event. This could lead to potential discomfort or inconvenience for residents in both houses, who may need to adjust their daily routines and personal boundaries to accommodate the feast.

Secondly, relying on the common staircase of the apartment building for communication and access between the two houses may present challenges related to accessibility and safety. In the case of an emergency or unforeseen circumstances, the narrowness of the staircase could hinder swift evacuation and potentially pose a risk for attendees.

Lastly, while this shared arrangement is a creative, temporary solution, it may not be sustainable long term, particularly if the number of attendees grows or the needs of the community evolve. This setup might work well for now, but it would be beneficial for the community to explore alternative solutions such as a larger shared space or a modular design that could adapt to the varying needs of the community during different events.

In conclusion, while the collaboration between House number 4 and House number 2 demonstrates resourcefulness and adaptability, it is essential to address the potential challenges and explore more sustainable solutions for the future to ensure the continued success and comfort of the Nineteen Day Feast gatherings.

82

83

Fig 43. Apartment A, drawn by author

DESIGN 2-3

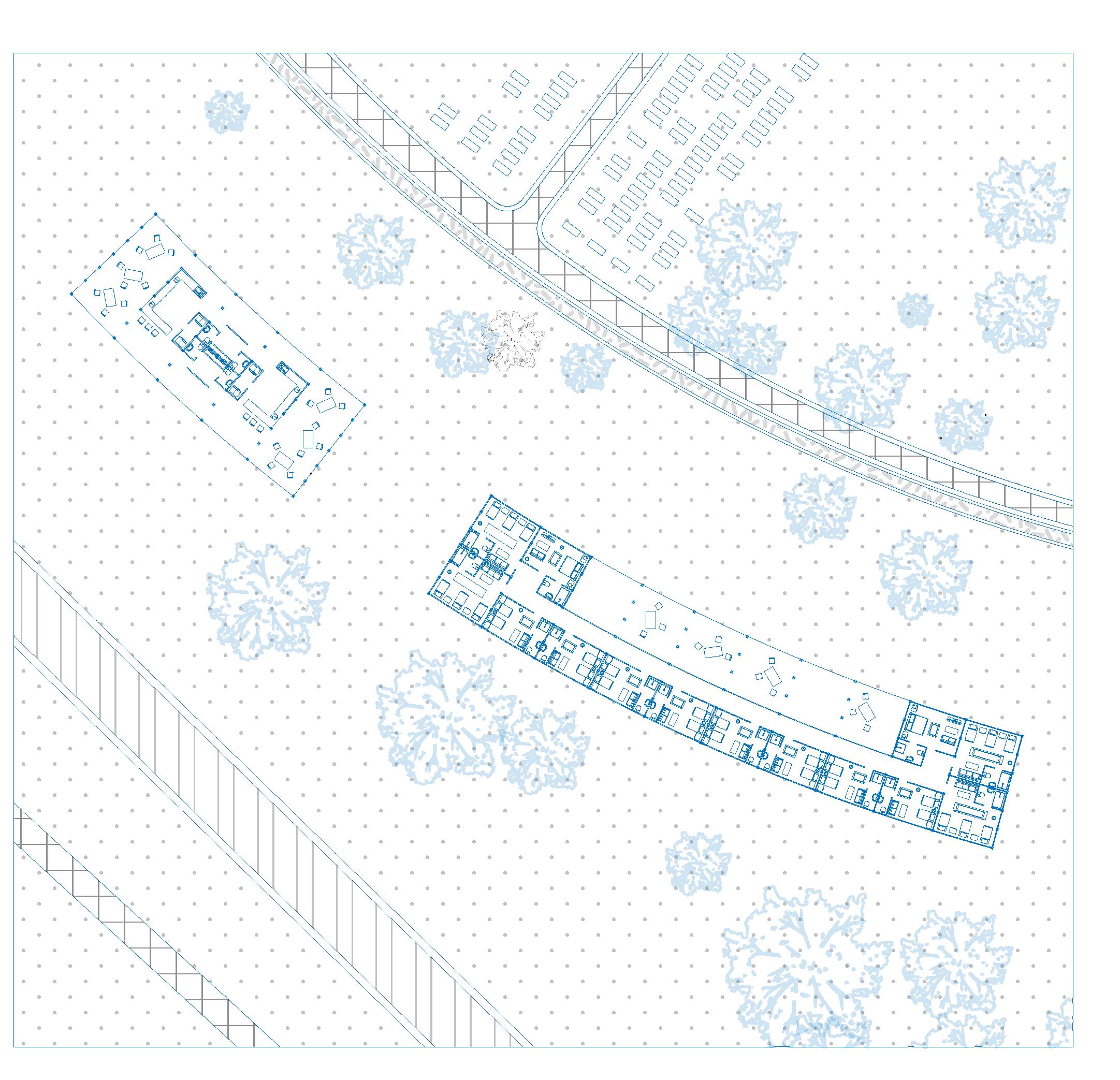

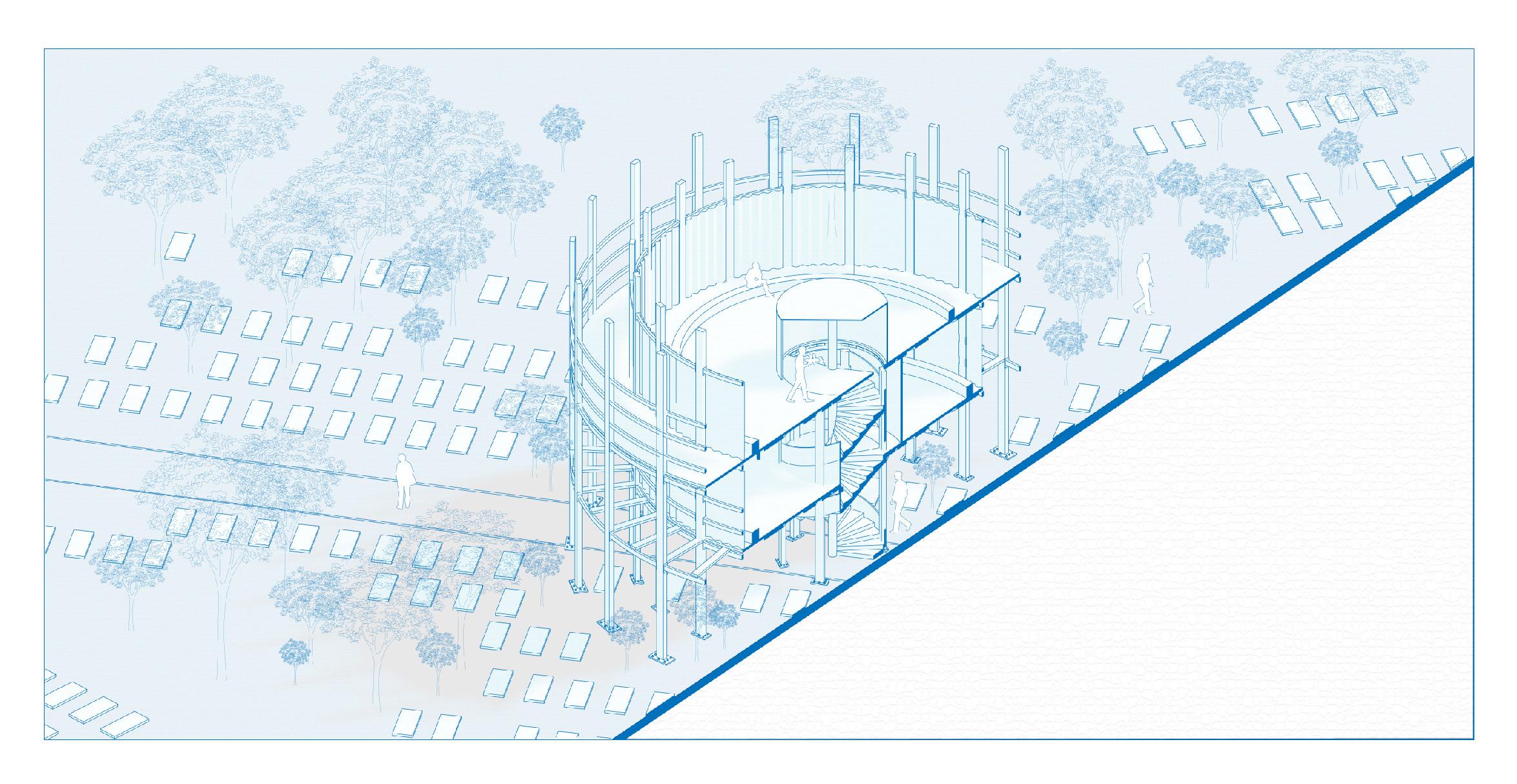

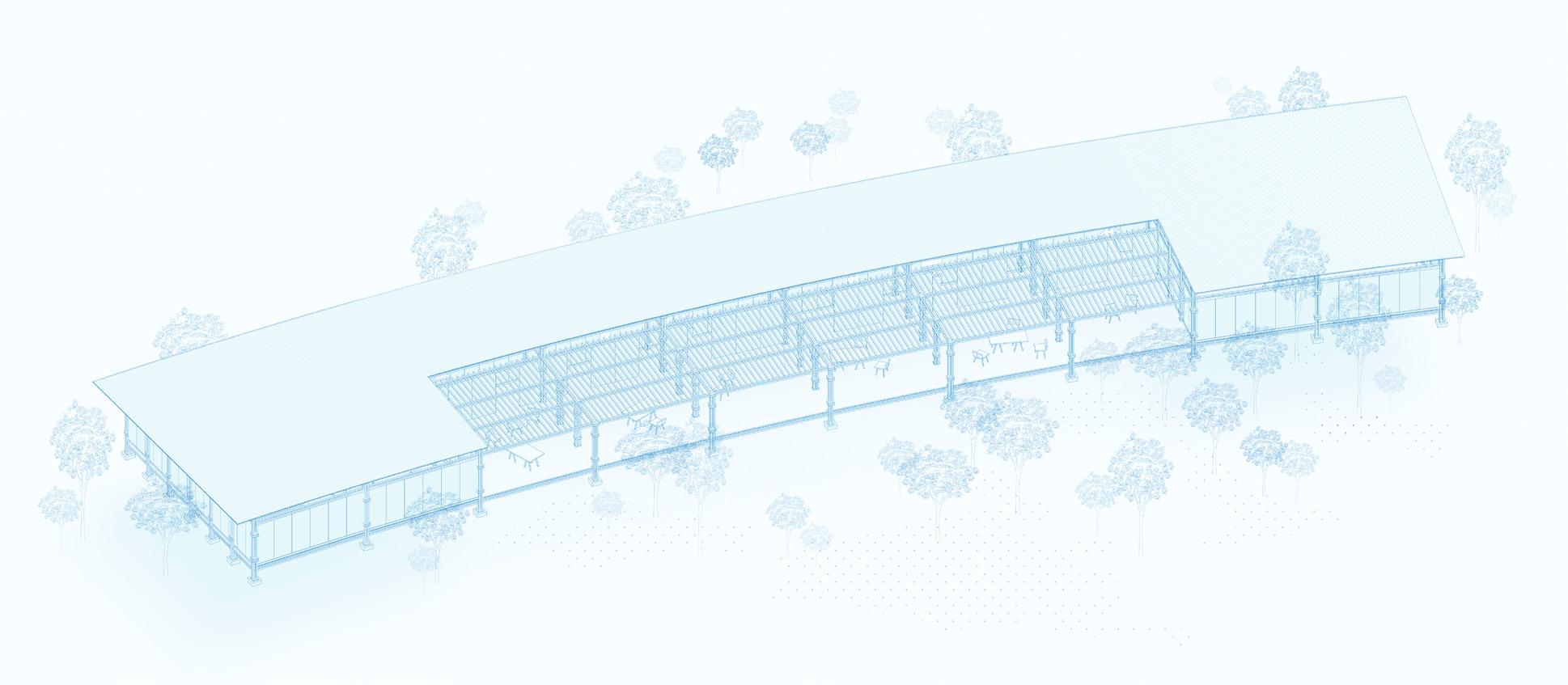

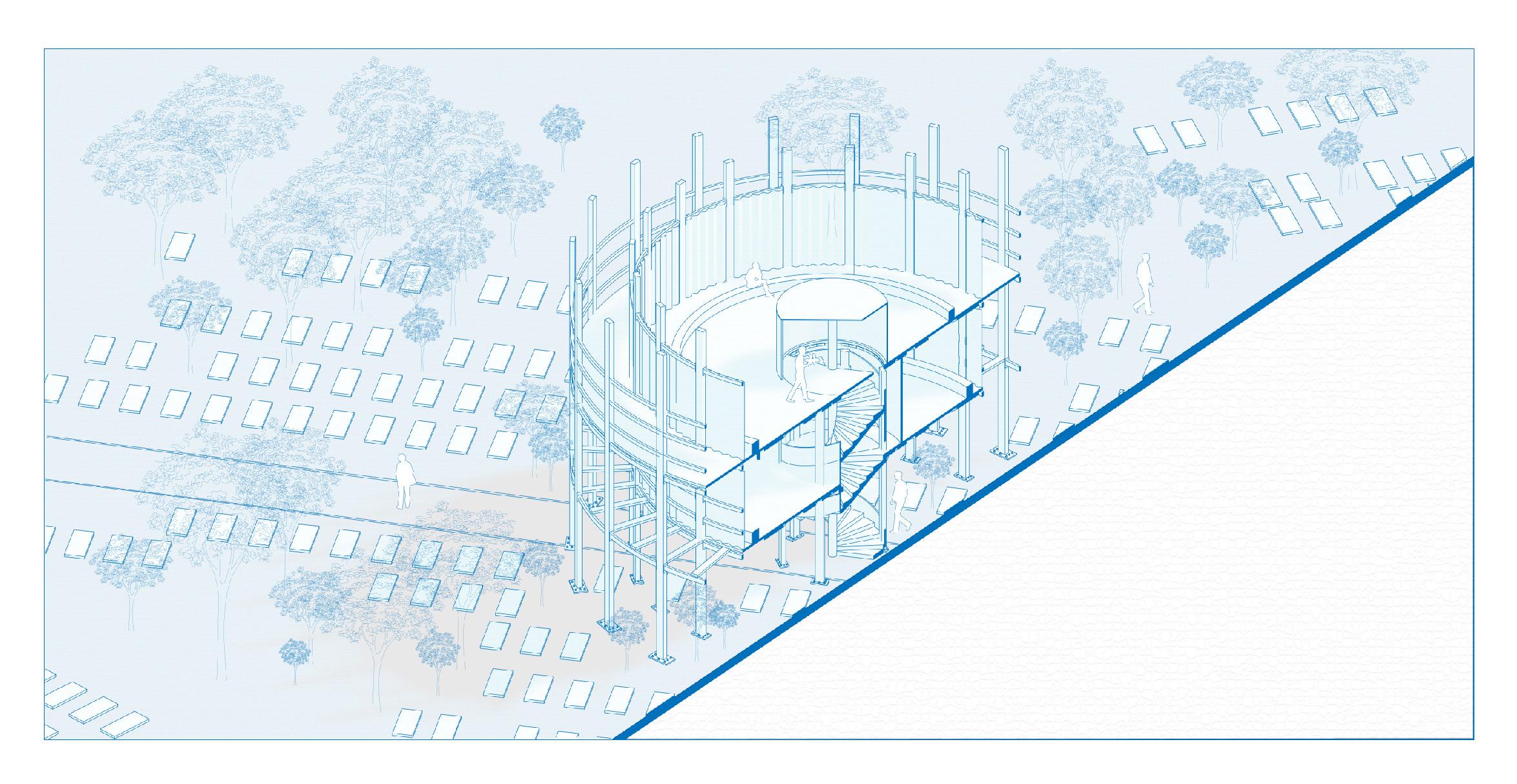

The communal approach between House number 4 and House number 2 during the Nineteen Day Feast, as well as the shared challenges and experiences, has inspired a new design impetus: a collective cooking project through the integration of the rooftop space in the apartment building. This concept addresses the limitations of individual living spaces, while fostering a sense of cooperation and kinship among the residents.

The proposed rooftop structure would serve as a versatile space for hosting guests and accommodating the needs of the entire apartment community. Both House number 4 and House number 2 could transfer part of their hosting requirements to this shared space, while other residents could also benefit from this communal facility. The design aims to promote the principles of service, collectivisation and social interaction, fostering an environment that nurtures connections and strengthens the bonds between neighbors.

By transforming the previously underutilised rooftop into a vibrant and functional space, the collective cooking project embodies the larger, intellectual implications of repurposing and reimagining urban landscapes to foster social cohesion and communal experiences. This design not only addresses the practical needs of the community but also taps into deeper philosophical themes of shared responsibility, adaptability and the creation of meaningful connections through these shared spaces and activities.

In essence, the rooftop structure becomes a metaphorical symbol of unity and cooperation, demonstrating that through innovative design and a shared vision, communities can overcome spatial constraints and cultivate a sense of belonging that transcends the boundaries of individual living spaces. By encouraging residents to come together and engage in collective experiences, this design proposal redefines the notion of urban living and promotes a more interconnected and compassionate society.

84

85

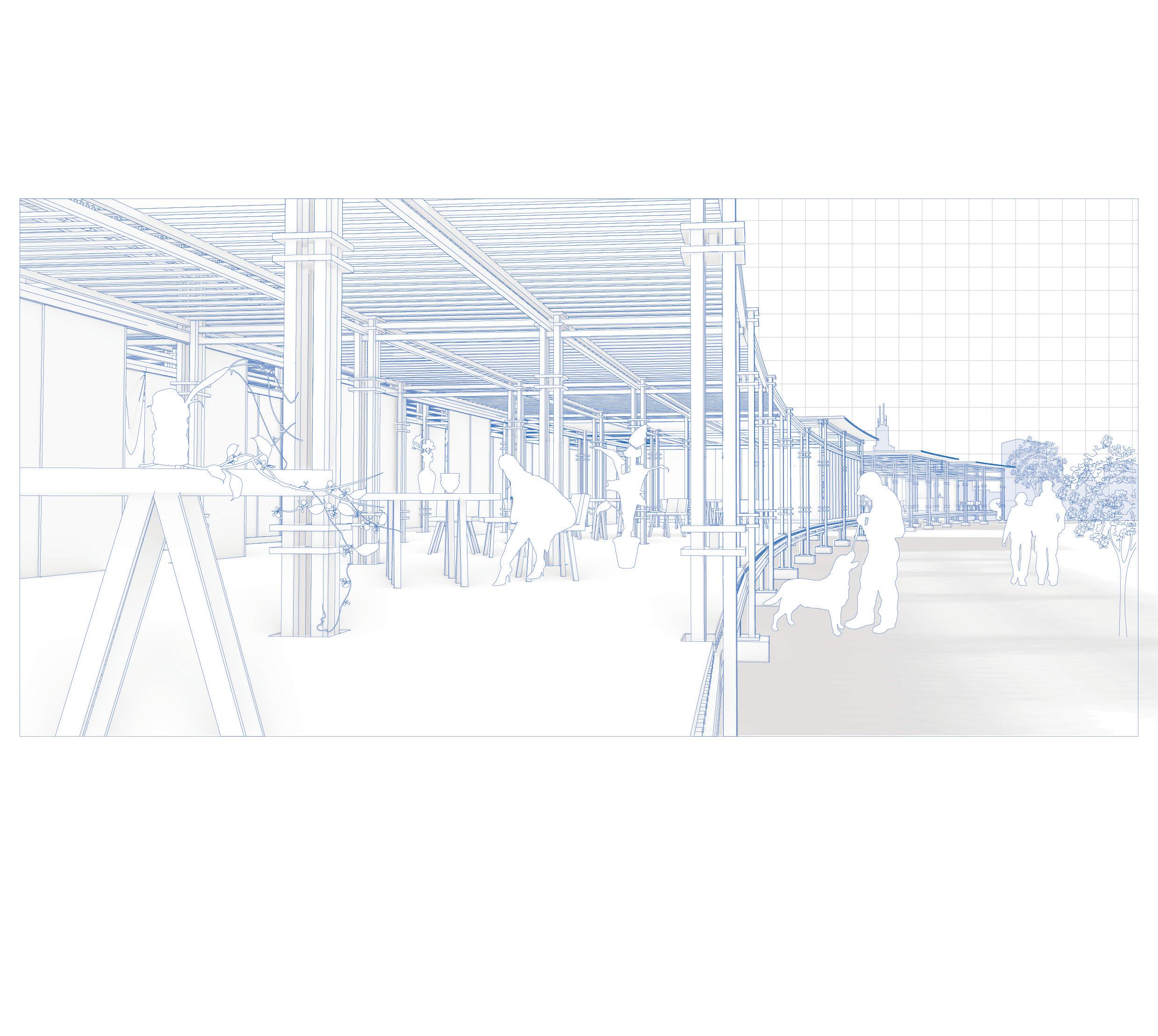

Fig 44. DESIGN 2-3

86

Fig 45. DESIGN 2-3

87

Fig 46. DESIGN 2-3

CHAPTER 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY

1.Al-Faruqi, Isma’il R. “The Concept of Sacred Space in Islam.” In The Sacred in the Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982. 170-189.

2.Bahá’í International Community. “Hospitality.” n.d. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.bahai.org/actions/hospitality/.

3.Bahá’í International Community. “Service.” n.d. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.bahai.org/actions/service/.

4.Bahá’í International Community. “The Home as a Microcosm of Society.” n.d. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/19931230_001/.

5.Bahá’í International Community. “The Home as a Place of Worship.” n.d. Accessed March 11, 2023. https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-universal-house-of-justice/messages/19931230_001/.

6.Bahá’u’lláh. Bahá’í Prayers: A Selection of Prayers Revealed by Bahá’u’lláh, the Báb, and `Abdu’l-Bahá. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2002.

7.Bahá’u’lláh. Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1992.

8.Bahá’u’lláh. “Tablet of Carmel, paragraph 15.” In The Kitab-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book, translated by Shoghi Effendi. Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1993. 35.

9.Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press, 1986. 241-258.

10.Bowker, John. The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

11.Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, 2002.

12.Eller, Cynthia. The Sacred Kitchen: Higher Consciousness Cooking for Health and Wholeness. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company, 2005.

13.Ettinghausen, Richard. “The Mosque: Its Early Development in Syria and Iraq.” In The Arab Heritage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967. 75-89.

14.Giddens, Anthony. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

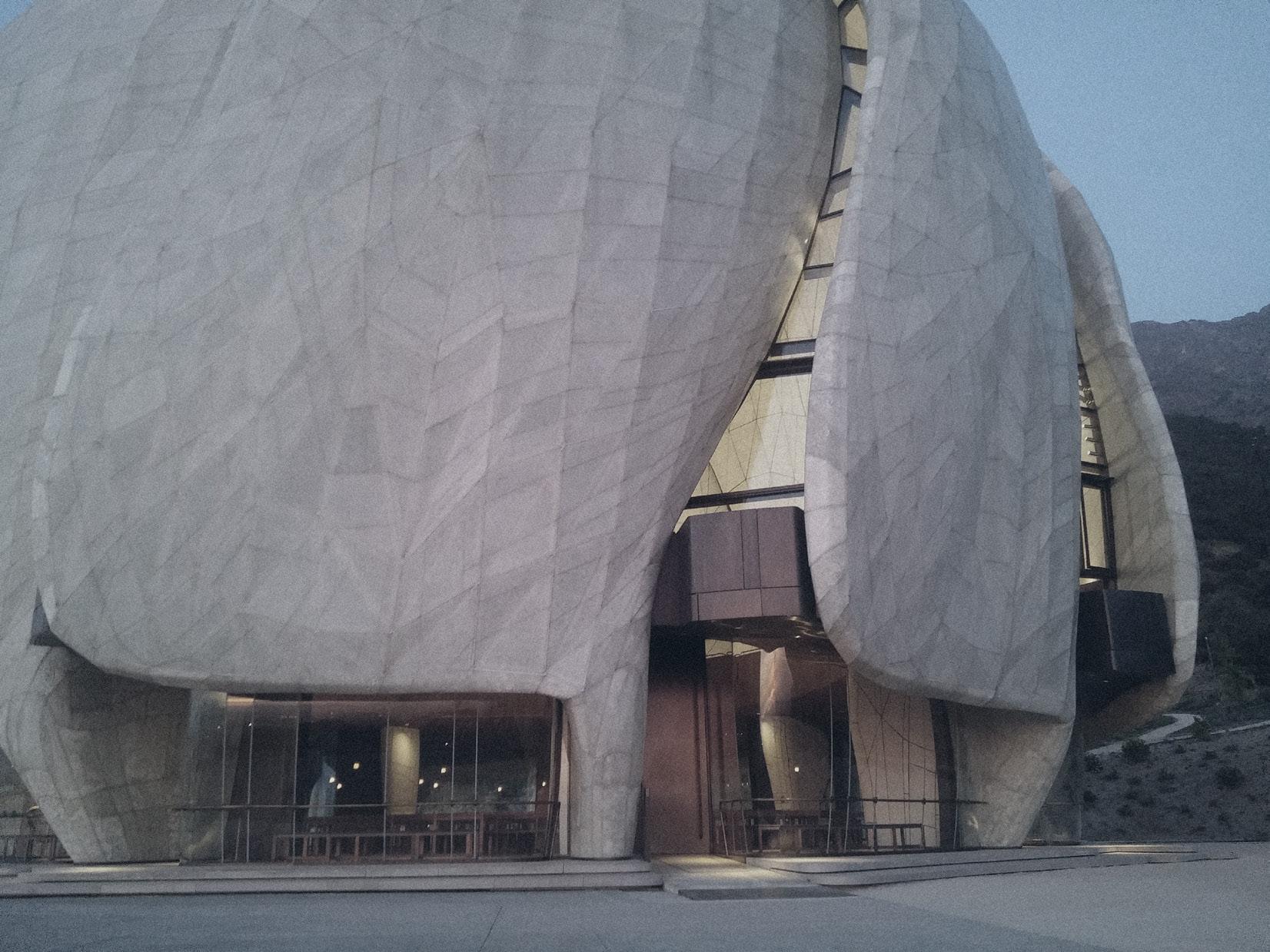

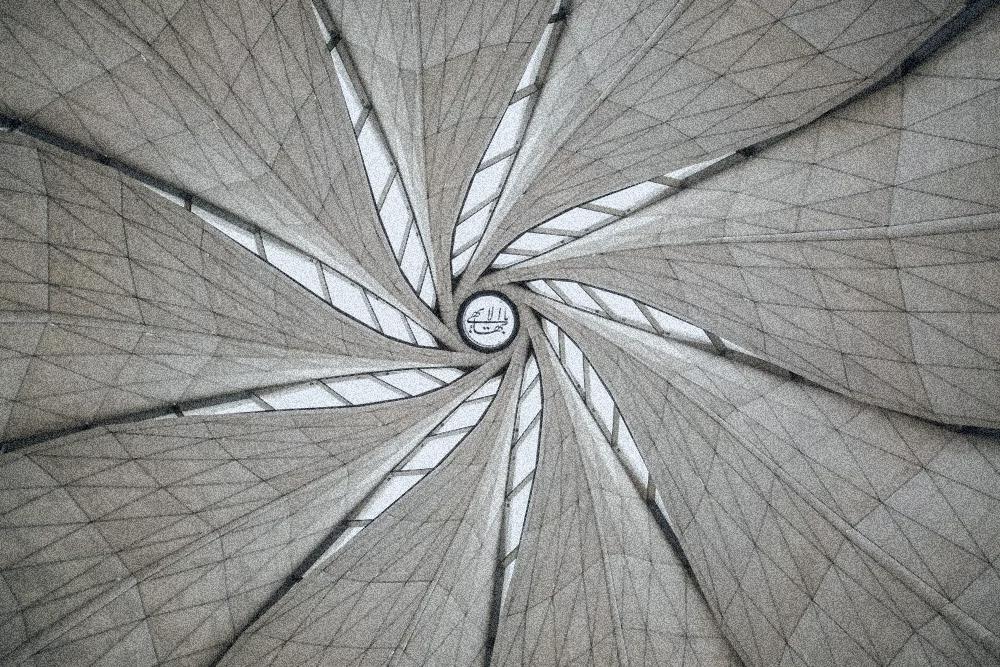

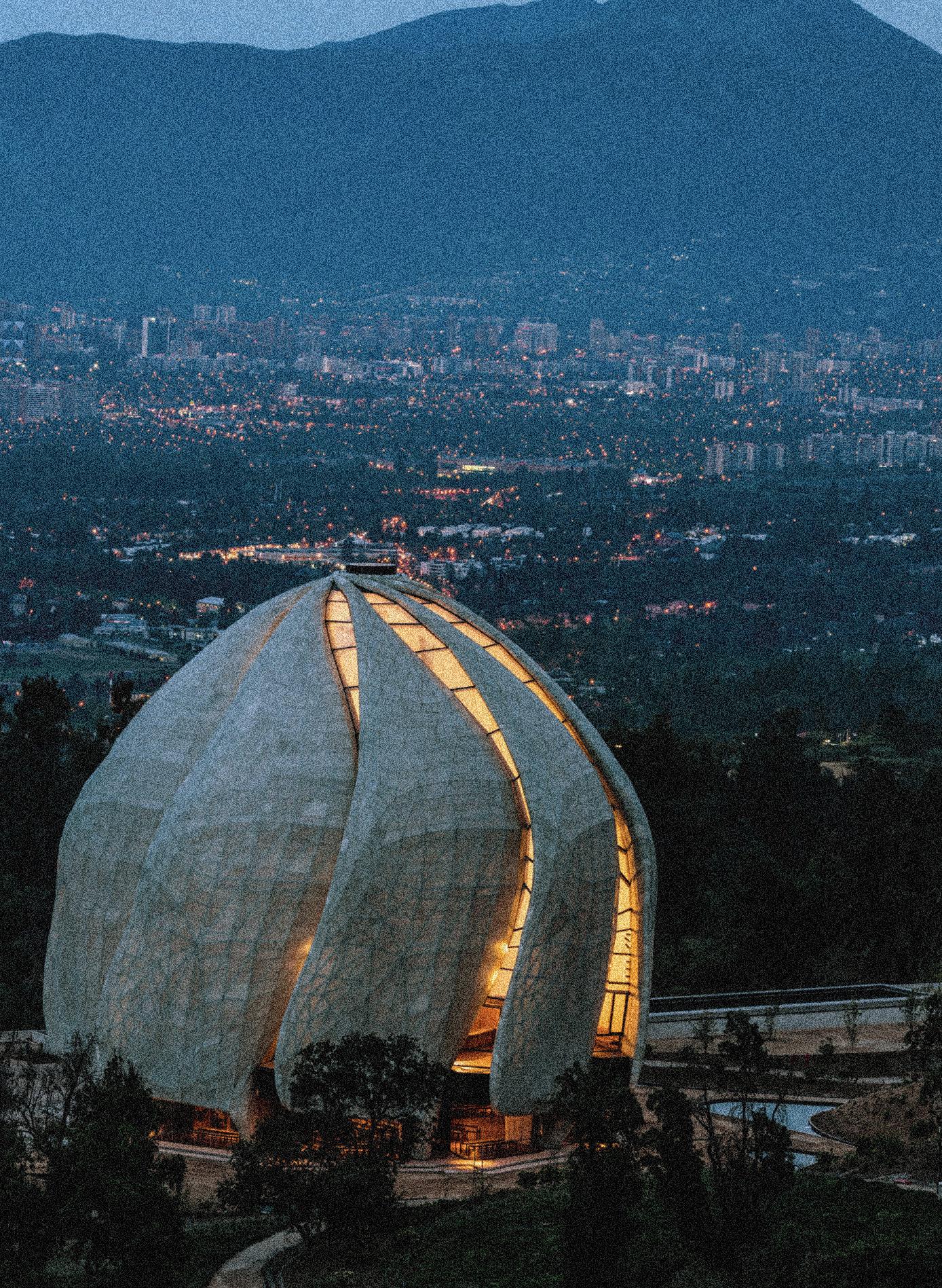

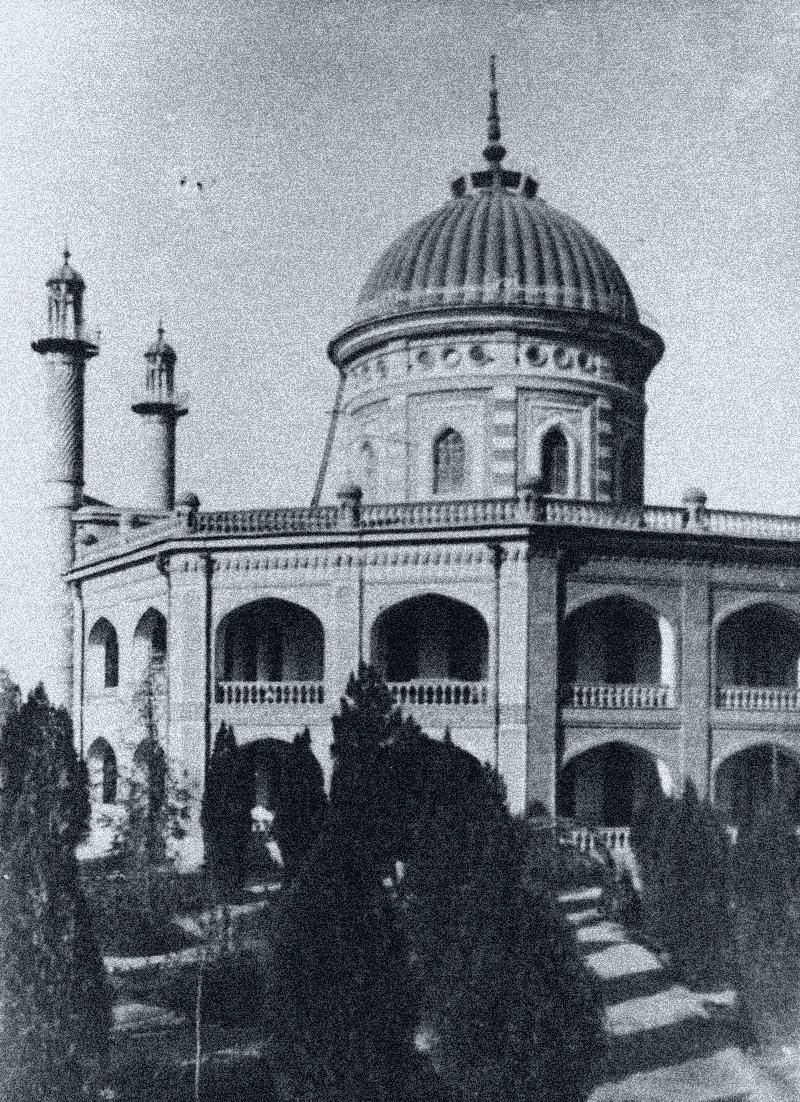

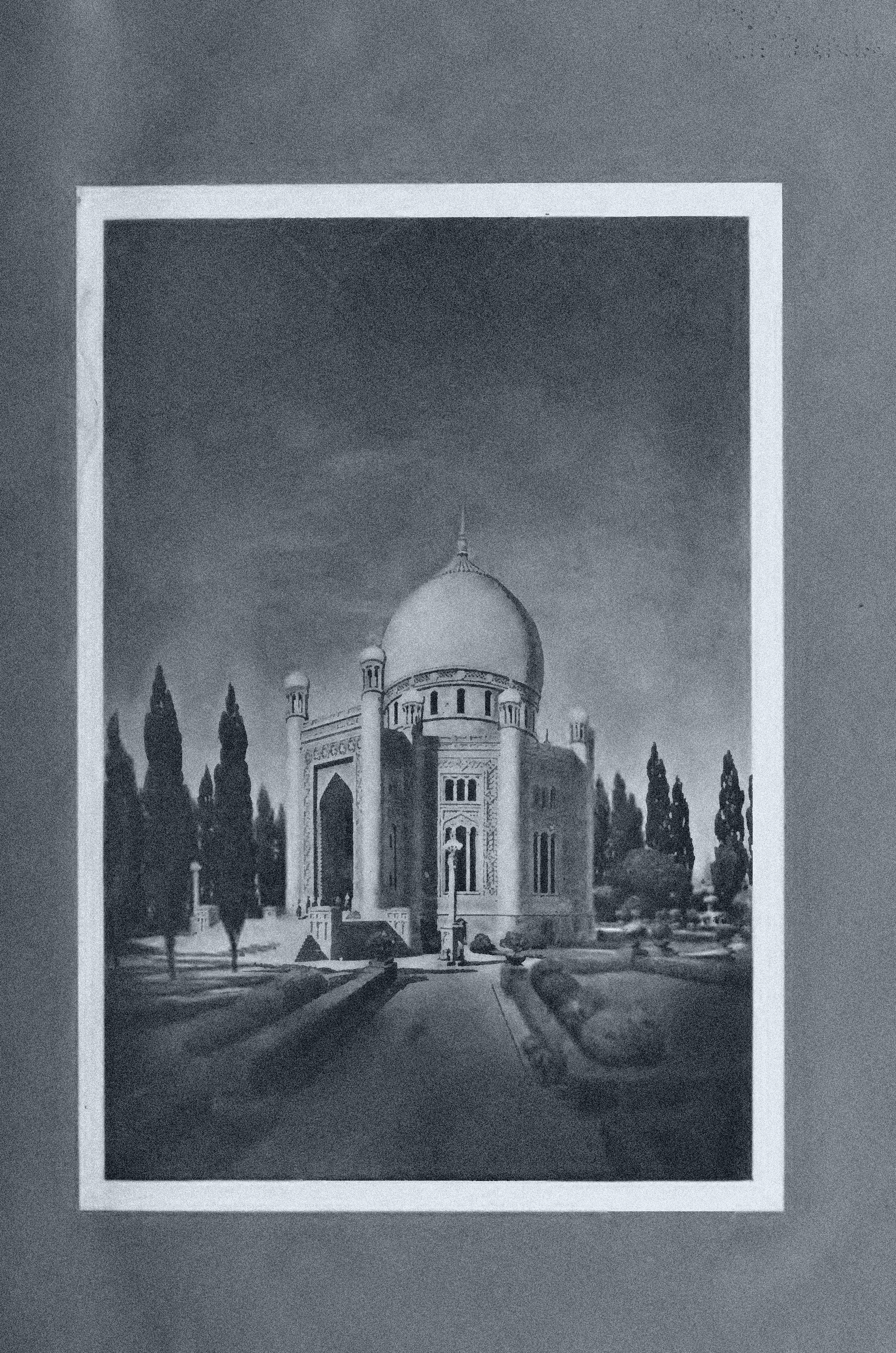

88