1.1 Pre-cinemas

At the beginning of the 19th century, the theatre was crucial in representing urban life. It brought up the relation of distance and tentativeness between the stage performance and the action of the spectators and gave imagery of city entertainment. The places of theatre in the community allow recreational activity between the provider and the audience in a physical location. It expands and augments social networks and situates possible collective action through stage acting and shared circumstances. Early cinema was characterised by constant moving and communicating action. The coming and going activities allow the viewing space to conduct the public experience as an outside environment. In 1841, the West End appeared like a resembled haphazard fairground. Projective spaces such as the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, the Panorama in Leicester Square, and the Cosmorama in Regent’s Street draw crowds of the population to the streets.4

The invention of the panorama indicates an architectural approach to engaging with the city and reveals a unique relationship between the viewer and the image. The structure enables the simultaneous projection of two paintings and provides a circular platform for viewers to experience the oneto two-thousand-square-foot panoramic paintings from all sides while pacing and communicating with each other.5 Panorama created a way of touring an imaginative cityscape and brought the filmic connection between London and other places around the world. Inside the constructed space, the circular shape of the viewing area allows a mobile gaze, which recreates a motion of sightseeing and offers a visual voyage like the flanerie.6

4.Gras, Henk. “Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840—1880. By Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001.

5.Sharp, Dennis. The Picture Palace, And Other Buildings For The Movies. London: H. Evelyn. 1969.

6.Nord, Deborah Epstein. “The City as Theater: From Georgian to Early Victorian London.” Victorian Studies 31, no. 2 (1988): 159–88.

29

Fig4. Panorama, Leicester Square, inventor Robert Barker 1801

Fig4. Panorama, Leicester Square, inventor Robert Barker 1801

32

Fig6.Bullock’s Museum, (Egyptian Hall or London Museum), Piccadilly. Engraving by A. McClatchy, 1828

At the same time, Egyptian Hall also performed magic shows and other events for the audience’s participation. On top of the building, the exhibition space was transformed into an auditorium with a screen and a stage at the front. Although the space for viewing the magic show looked similar to the type of cinema theatre, it was still different from the cinema buildings as the space was highly interactive. When the show was running, the materials supporting the projection of a phantasmagorical image occupied the same dark atmosphere as the spectators.7 It created a temporal community and allowed people who participated in the show to form a collective memory and social experience. A decade later, early cinema moved from the interior of the building to the outside open space. The bioscope shown at the fairgrounds was popularly used to display moving images.8 The design of the space was simplified and used a lightweight structure for mobility. The showroom looked like a small lecture room with a screen in the centre and a few rows of seats. The appearance of the Bioscope Show only lasts a short time, but its architecture illustrates the usage of cinema as a means to interact with the city and spectators.

By examining the three early cinematic building styles, it can be seen that the viewing space was initially designed to accommodate a variety of social activities. The stage provided a central focus point for the audience to concentrate on and engage, allowing them to express themselves along the show and form a highly interactive indoor social environment.

7. Sœther, Susanne, and Synne Bull. Screen, Space Reconfigured. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

8.Livingstone, Sonia. “Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere.” 2005.

Fig7.Bullock’s Museum, (Egyptian Hall or London Museum), Piccadilly. Engraving by A. McClatchy, 1828

33

0 5 10 15 20 m

34

Fig8. Floor Plan of Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly. 1828

0 5 10 15 20

m 35

Fig9. Section of Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly. 1828

36

Fig10. Bioscope at Fairground, 1910

37

Fig11. Structure of Bioscope at Fairground, 1910

1.2 The rise of the cinema typology

In the 1970s, the Brunswick Centre proposed embedding the cinema inside the residential building complex. This indicates having a space for cinema viewing has become part of people’s living habits. Nowadays, many independent cinema companies have a network emerging from the cinema building and the film industry, theatres have developed into multipurpose spaces that not only represent the film but also provide the space and equipment for film seminars, conferences, and workshops.9 In comparison, most chain commercial cinema companies keep the tradition by having the auditorium inside the cinema theatres turned into a private space, where the audience is restricted to having social engagement with the others, and the rest of the space is simplified in function and programmed for specific purposes.

Since 1910, the typological transformation of cinemas reveals a clear pattern of how architecture creates social spaces for audiences through cinema. Changes in cinema regulations, architectural design, and technology all have an impact on this progression. Through a typological study of the development of cinema buildings, the changing engagement in the process of internal and external viewing was revealed.

During the first decade of the 20th century, regulated, purposely built theatre soon replaced the various unregulated dark spaces and unsafe conditions that were present in the past. The transformation of the new medium for representing cinema was affected by the audience's mixing of classes, races, and genders.10 The challenge of promoting regular attendance is resolved by the new purpose-built cinema theatre that has replaced the bioscope. It addresses the location’s safety and eliminates the restriction on the amount of time that can be rented in the auditorium. The innovations of the cinema building extend the existing auditorium and adapt to the requirements of cinematic technology, from traditional music halls to the ambitious super cinema.

9.Livingstone, Sonia.

10.Hiley, Nicholas. “At the Picture Palace”: The British Cinema Audience, 1895-1920” In Audiences edited by Ian Christie, 25-34. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

Fig12. Curzon Bloomsbury Cinema, The Brunswick Centre 2015

“Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere.” 2005.

38

39

Fig13. Plan of Regent Street Polytechnic 1910

40

Fig15. Section of Regent Street Polytechnic 1910

The development of cinematography responded to public demand and was always explored internationally. It can be traced back to the 16th century with the use of magic lanterns. The representation of the images through the early projection offered theatrical narration of scenes for plays.In London, Magic Lantern was projected at the lecture hall of the Regent Street Polytechnic (formerly the Regent Street Cinema) as an experiment for scientific research, and Lumiere Brother’s cinematographe was also presented at the place.11 After the realisation of public demand, the lecture hall was converted into an early cinema viewing area, and films are still scheduled to be shown there.

During the 18th century, Robertson presented a new form of public entertainment in Paris.The dark viewing box was converted into a projection mechanism, much like the magic lantern, to produce such ‘dispositif’12 effects that drew the audience into the scene.When the layout of Robertson's room was developed in the spatial innovations, large spaces in buildings had the possibilities to perform the projection of images, such as panoramas or dioramas, and that was the moment to consider the architecture with the cinema system. In this case, the indication of the early cinema building is the film spectators’ fascination with the cinema as a new visual experience; it afforded the opportunity for them to witness other places’ events.

At that time, the film content dominated the cinema's popularity, and it attracts people from all over the city came to watch it, which drove the cinema's operation and revenue. As the cinema evolved, the size of the auditorium and the number of seats continuously increased to accommodate the audience. In addition, the auditorium was equipped with a classic barrelvaulted structure13 to replace the columns or make room for additional stalls and balconies.During the 1930s, when the influence of the American super-cinema arrived,architects were

11. Grainge, Paul, Jancovich, Mark and Monteith, Sharon. Film Histories: An Introduction and Reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

12.Nord, Deborah Epstein. “The City as Theater: From Georgian to Early Victorian London.” Victorian Studies 31, no. 2 (1988): 159–88.

13.Spankie, Ro. The “Old Cinema” dissolving view, The Magic Screen, pp.15-61.

Fig14. A Phantasmagoria Lantern used by Etienne Gaspard Robertson

Note1: The magic lanterns are placed behind the screen and allow for a maximum of eight scenes on a long glass slide to produce a composite image.

41

42

Fig16. Trocadero Cinema, Elephant Castle,1933

to work on the details of the decoration to meet demand for a "greater illusion, elegance, and comfort"14 cinema space. Materials such as ceramic tiles, fewer windows, and large amounts of pseudo-period motifs were commonly used. George Cole's first colossal super-plex at the Elephant and Castle clearly shows how these criteria were translated into the design outcome of this new, modernised cinema building. Influenced by the modern architecture of the time, the renovation of the cinema removed the ornate decorations, shrunk the overall size, and allowed the interior circulation to be further simplified.

Due to technological advancements, cinemas no longer rely on the content of the films to attract customers but rather on the interior atmosphere and proximity to the city centre or community, including the Curzon Mayfair and Prince Charles Cinemas. Also, the social space for pre-watching and duringviewing is divided by a section of the lobby and screen areas. Temporal social interaction develops into a habit at the theatre, where patrons are invited to stay for "a pleasant and amusing hour"15. During this period, the emergence of cinemas in the city encouraged the production and consumption of films. Going to the theatre became a public social activity in which individuals of all social classes could partake. It served as a means of escape from the pressures of everyday life and personal entertainment.

On the one hand, the development of cinema buildings not only influences the development of filmmaking but also brings the cinema space into the city as a reconfigured urban leisure space and changes the use of the city. This public acceptance is significant in terms of social interaction.16 On the other hand, the transformation of the cinema theatre's typology causes the sociality of the viewing space to be limited. For example, viewers in the cinema auditorium are usually quiet throughout the film to prevent interrupting the film or disturbing others. This action creates a communal viewing experience but also isolates the audience. Simultaneously, the spectators’ desire to share tends to form a film network of small individuals who watched the same film.

14.Livingstone, Sonia. “Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere.” 2005.

15.Hiley, Nicholas. “At the Picture Palace”: The British Cinema Audience, 1895-1920” In Audiences edited by Ian Christie, 25-34. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

16.Cairns, Graham. The Architecture of the Screen. 1st ed. Intellect Books Ltd. 2013.

43

0 5 10 20 m 44

Fig17. Plans of Trocadero Cinema, Elephant Castle,1933

0 5 10 20 m 45

Fig18. Section of Trocadero Cinema, Elephant Castle,1933

0 5 10 20 m 0 5 10 20 m 46

Fig19. Plan and Section of Odeon Cinema, Elephant Castle,1964

47

Fig20. Front Entrance of Odeon Cinema, Elephant Castle,1964

1.3 Film immersion and the attraction of the cinema

The term ‘two bodies at the same time’17 first appeared in Barthes’s description of the mode of spectatorship in ‘Leaving the Cinema’ (taking the cinema with you—as a proposition); it excluded the technology of cinema and introduced a new aspect of the cinematic experience. This indicates that one body is attracted to the screen’s psychological situation while another is immersed in the cinematic situation on the screen. It forms a ‘space inbetween’18 condition towards understanding the viewing space when a film is playing. The cinema immerses the spectator in the film world by displacing the spectator from the auditorium.

The sense of cinematic immersion is created partly by cinema technology and architectural space. In Kittler’s terms, cinema began with the actions of cuts, stitches, and reels.19 The reference to Foucauldian ‘discourse’20 introduces the similarity of this movement of discontinuous temporality between other media and cinema. The method of montage and the change of time translate the content into the spectator’s desires, so the viewing experience is "enchanted and unthinkable"20. Edgar Morin’s formulation demonstrates the scientific theory of perception. As the screen played with the running of fragmented clips, the eye's system automatically inverted the moving image through the retina, and there was an afterimage left by the passing of each image projected. The process of forming this sense of realisation allows the stimulus of the image to be transformed into continuous stories, so that it is then detailed with one's own understanding of the film. It brings the technological manifestation to the psychological apparatus. The image of the cinema in the mind of the body is "shadowy, fleeting"21 .

The BFI Imax has a larger screen that can hold many audiences to see films under the huge impact of the giant projection. In addition, the distance between the eye and the image is much closer than when the film is shown in a standard projection room, and the detail of the moving images shown on the screen can be modified to add extra layers of content, allowing viewers to zoom in and see these details.

17. Barthes, Roland, ‘Leaving the Movie Theatre’, The Rustle of Language. University of California Press, 1989.

18. Schulte Strathaus,“Showing Different Films Differently”: Cinema as a Result of Cinematic Thinking’, The Moving,2004.

20.Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford University Press, 2006.

20.Foucault, Michel.The Archaeology ofKnowledge and The Discourse on Language. Traqs. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York.1972.

21.Freud, Sigmund, and Karl Abraham. Briefe 1907-1926. Ed. Hilde C.Abraham and Ernst L. Freud. Frankfurt a.M. 1980

48

In addition, the screen can be physical or a reciprocal that is created by the spectator.22 It forms the social-emotional interaction with otherness, which would appear to empathise with or identify with the characters in the recycling of the mental screen. The reflected screen between the brain and the cinematic representation of the immersive experience can be played and repeated in an extended loop. Therefore, the use of cinematographic technology is not an imitation of moving images or stories. Films contain the double effect of being connected with emotions, memories, and imaginations.

Thus, the viewing space begins in a very social state before eventually differentiating from the city and other public social areas. The prior social embeddedness of early cinema had become lost here. This is also where the typology stopped evolving and became more of a standard element in cities. According to the independent cinema office guidelines, film collectives, societies, and community cinemas can implement screening outside the theatre building. The ideal of perfecting the functionality of cinema in accordance with the fixed relation between static spectators and the spectacle is also the perpetuation of cinema as a space of consumption and the film as a commodity that feeds it.23 The essential social relationship built in public spaces is the possible connection between people and the city on numerous scales, creating a negotiating platform. Therefore, the demise of the cinema may indicate a departure from the current generation of cinema architecture, enabling people to perceive and express their appreciation for a wider variety of cinematic environments.

22. Rushton, Richard. The Reality of Film Theories of Filmic Reality. Manchester University Press, 2011.

23. Bayer, Mark. Theatre, Community, and Civic Engagement in Jacobean London, University of Iowa Press, 2011.

Fig23. Expanded Reality 2022

Fig24. Expanded Reality 2022

Fig23. Expanded Reality 2022

Fig24. Expanded Reality 2022

49

1.4 Design Proposal 1: Angel Odeon: New Panorama

Fig25. Axometric view of Design Proposal 1

50

“the early 1970s were not only the age of apparatus theory, which characterized the cinematic situation as a captivity, but also a time of utopian ideas about the cinema as a place of focused, concentrated perception.”24

In cinema theatres, the shared conscious experience of the audience is often predominantly explicit. Viewers have a shared memory with others without direct interaction or awareness of the appearance of others.25 In the cinematic world, a uniform view of the camera may give the impression of a reflection, like a mirror, but it can never reflect individual experience. The work "Cinema" (1981) by Dan Graham illustrates the decomposition of cinema architecture. It challenges the perspective of seeing cinema space by using the material of the double-layered glass to expose the auditorium under the light.26 This façade blurred the boundary between film and reality by creating overlapping effects on both sides of the live images. Film and glass were combined to create a highly engaging live film with the city and its people, leading to an active ‘urban landscape’ based on audience participation.

The design proposal aims to challenge the current theatre-based spatial programme and introduce an alternative structure for cinema audiences to experience screens and cityscapes. It aims to create a new way of presenting moving images to the public and liberating the auditorium from the theatre. It also brings new forms of viewing experiences where the film can be viewed and recreated.

24. Rushton, Richard. The Reality of Film Theories of Filmic Reality. Manchester University Press, 2011.

25.Pepperell, Robert, and Michael, Punt. Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind, and World. Brill, 2016.

26.Connolly, Maeve. The Place Of Artists’ Cinema. Bristol, UK: Intellect.2009.

Fig26.Angel Odeon on map

Fig27.Angel Odeon Site Photo

51

52

Fig28. Auditorium of Angel Odeon

The site is located at the existing Angel Odeon cinema. The main body of the auditorium has been demolished, leaving only the front tower. The design aims to construct a new panorama to represent the timing and movement of the cinematic space between the city and the architectural fabric. The original building is the foundation(26m2), and a spiral staircase leads the viewer directly to the top floor of the panorama(17m2). At the top, the glazed façade overlooks the internal curved screen(10m2) on which the films are displayed, creating this time-lapse of two worlds (reality and film). (reality and film). There are seven individual screens of different sizes(0.7m2 to 3m2) located around the front and rear of the tower for the community to arrange public activities, workshops, and seminars.

The colour in the film translates the abstraction of the emotional movement. Here, the blue represents the mental screen and the physical screens that bring the ideal moving image to the mind and body. The green is the teleport that brings the audience to the screen, and the red and purple are the reflecting and receiving backgrounds that provide the audience with an additional viewing environment. The pure colour makes the depth of the space disappear, making the space boundary difficult to recognise, just like in the film world, and making it hard to describe it as being in the city or in the mind.27 Overall, the design creates a new form of imaginative cinematic building, allowing the audience to engage in traditional screen viewing while adding additional spatial conditions to increase the realisation of the two—a doubling of the city and the cinema.

When the cinema blends into the urban environment, what kind of cinematic space can the city provide for alternative public hybridity? In the next chapter, this study examines other types of cinema spaces in public venues and identifies the significant elements of these cinematic environments.

53

27.Vacche, Angela Dalle. Cinema and Painting: How Art Is Used in Film. University of Texas Press, 1997.

54

Fig29. Change of active interaction in the movement of function space merges with cinematic installations

55

Fig30-32. Render images showing screen position in relation to new functional spaces

56

Fig33. Design Renders of the double layered panorama and backyard cinema screen

57

Fig34. Design Renders of the double layered panorama and backyard cinema screen

5 10 15 20m 58

Fig35. Design Section1:200

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland, ‘Leaving the Movie Theatre’, The Rustle of Language. University of California Press, 1989.

Cairns, Graham. The Architecture of the Screen. 1st ed. Intellect Books Ltd. 2013.

Clarke, David. The Cinematic City. Routledge, 2009.

Connolly, Maeve. The Place Of Artists’ Cinema. Bristol, UK: Intellect.2009.

Foucault, Michel.The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Traqs. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York.1972

Freud, Sigmund, and Karl Abraham. Briefe 19071926. Ed. Hilde C.Abraham and Ernst L. Freud. Frankfurt a.M.1980.

Gras, Henk. “Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840—1880. By Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2001.

Hanich, Julian. The Audience Effect: On the Collective Cinema Experience. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

Hiley, Nicholas. “At the Picture Palace”: The British Cinema Audience, 1895-1920” In Audiences edited by Ian Christie, 25-34. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

Kittler, Friedrich Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford University Press, 2006.

Lant, Antonia. ‘Haptical cinema’, p45–73. 1995.

Livingstone, Sonia. “Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere.” 2005.

Nord, Deborah Epstein. “The City as Theater: From Georgian to Early Victorian London.” Victorian Studies 31, no. 2 (1988): 159–88.

Pepperell, Robert, and Michael, Punt. Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind, and World. Brill, 2016.

Rushton, Richard. The Reality of Film Theories of Filmic Reality. Manchester University Press, 2011.

Sharp, Dennis. The Picture Palace, And Other Buildings For The Movies. London: H. Evelyn. 1969.

Sœther, Susanne, and Synne Bull. Screen, Space Reconfigured. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Spankie, Ro. The “Old Cinema” dissolving view, The Magic Screen, pp.15-61.

Schulte Strathaus,“Showing Different Films Differently”: Cinema as a Result of Cinematic Thinking’, The Moving,2004.

Vacche, Angela Dalle. Cinema and Painting: How Art Is Used in Film. University of Texas Press, 1997.

59

Cinema and Cinematic Architecture

2

Nine Screens 2013 61

Fig1. Isaac Julien

When discussing cinema architecture and the moving image, the Italian author Gabriele Pedulla once stated that if the cinema building were to cease to exist, its structural form, symbols, and behavioural codes would vanish. After the demise of the theatre, cinema has changed its style, and without the large screen, the cinema and its audiences will be different in the future. In considering the dispersion of cinema into various new media systems, her contribution to concerns about it and the screen linked the history of the moving image research paradigm to the function of architecture.1

There has been a new emphasis on the moving image in museums and galleries since 1990. The growing prominence of artists’ cinema during this time can be partly explained by artists and art institutions’ expanded access to production, post-production and projection technology.2 In Nicolas Bourriaud’s words, contemporary work and its exhibition spaces are presented as periods of living, and art projects, especially in the avant-garde, are a vital part of participation in life. Among the various film publications, programmes and exhibitions, the term ‘artists’ cinema’ refers to the dynamic link between art practice and filmmaking, both now is becoming concurrent with life, or being a ‘live medium’, rather than the durational separation between making and viewing. Thus, this is creating a different demand on what is cinema architecture is as it responds to such an imperative. Works such as experimental films, video installations and performances were once claimed to be as an extension of art practice. They not only sought to produce aesthetic-level work but also attempted to challenge the public nature of space and public engagement.3 It is public not so much in the sense that it is simply being shared by many when being viewed but because it is ‘live’ and has an immediate relationship between all those who are simultaneously making and viewing films.

1.Pedullà, Gabriele: In Broad Daylight. Movies and Spectators After the Cinema. London: Verso, 2012.

2.Connolly, Maeve. The Place Of Artists’ Cinema. Bristol, UK: Intellect.2009.

3.Bourriaud, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics [1998], Trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2002.

62

This also leads to the case that even the most internal or private of spaces, when taking on the transformation of cinema architecture, are immediate, connected, and contingent on some kind of public domain.

In addition, cinema as an art form has altered its representation by refracturing images and time to accommodate the function and circulation of galleries' spatial programming. The projection of the "cinema situation" with modern multi-screen projections can psychologically absorb and undermine the bodily awareness and existence of other individuals by offering visually appealing images with strong imaginary identification. Following Giuliana Bruno's argument, cinema is another architectural art form in which the artwork dissolves into the cinema space, and installation spaces can be transformed into cinematic spaces via screen projection.4 Through the use of projections or monitor displays, museum and gallery exhibition spaces may serve as "decomposition" spaces for filmmakers. In addition, the creation of intimacy within the realm of art is an architectural and hybrid activity in terms of archiving, collecting, and exhibiting. By entering and exiting an installation, the memory of experience in multiple forms of emotion, cultural habitation, and liminality in the process of inhabiting a cinema can be recalled.

This chapter aims to understand the relationship between cinema (as a means of representing the specific characteristics of multi-open spaces) and public participation (viewers) in the field of moving images. Through a series of data and spatial analyses, it will also seek to identify potential patterns of spatial transformation between screen space in theatres and galleries.

63

4.Bruno, Giuliana. Public Intimacy in The Visual Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2007.

2.1 Art cinema and cinematic architecture

As described in the first section, theatre type articulates cinema architecture, which refers to the architectural space in which a film is viewed using fixed cinematographic equipment, while the cinematic architecture (represented in architectonics as a spatial effect or designed film scenes) refers to the architectural space in which the building itself has cinematic elements or is filmed in the cinema. By understanding the similarities and differences between the two, this section investigates the cinema viewing space in other public venue as moving images and video installations, and seeks to identify potential cinematic space types that can bring new spatial conditions to the viewing space.

Avoiding the conventional commercial cinema, the chapter particularly looks at art cinema and its exhibited spaces to discuss this type of cinema viewing space and its relationship with the social community. Art cinema creates this space inbetween by amplifying the abstraction of the complexation of psychological characteristics and diverting the connection with a real location or real problems.5 This space, which is distinct from a cinema auditorium, may contain single or multiple screens, and the manner in which they are viewed in the space varies based on the particular means of projection of art cinema, as well as the strategy adopted by the public space in integrating the type of projection.

As David Bordwell explained, the type of cinema in the art form splits from the narrative lead structure, breaking the strings between "the coherence of the fiction and the perceptions". It modifies itself as a new cinema category and challenges the traditional mainstream form of the construction of the cinema through the process of decomposition. The significance of the art cinema is that it has a strong social representation as do other artworks, and it challenges the way film is presented. Comparing it with the movies produced by the Hollywood studio system, art cinema usually creates an open discussion for the spectators and brings new questions to the depiction of the represented subjects, whether they are realistic or culturally based.

5.Froehlich, Dietmar. The Chameleon Effect: Architecture's Role in Film. Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, 2018.

6.Caglayan, Orhan, Screening Boredom: The History and Aesthetics of Slow Cinema. University of Kent, 2014.

64

In the case of the avant-garde film exhibition "Film as Film" at the Hayward Gallery in 1979, a series of projections and installations were shown in a large number of screenings. Artist filmmaker Chris Welsby experimented with the camera, not using it as a replacement for the human eye, and explored the natural landscape through different perceptions.7 In his work 'Seven Days' (1974), he used a fixed camera to capture the changes in the sky in the Welsh mountains. The film challenges the awareness of time and the environment by producing a series of moving images showing the way life changes in nature. Different from a documentary, it records the elements of nature as an abstraction of time rather than directly describing the existing materials. By watching the sequence of the changes in the landscape, his video installation encourages viewers to engage in contemplation.

Various screens imply a range of different viewing modes and they often comes in adjustable sizes, scales, and image resolutions. Liz Rhodes tested the screen position in her work "Light Music" (1975) by changing the projections and the screens side-by-side and creating a barrage of flashing matrices of structured film strips. The work aimed to bring the notion of the cinema's limits to the spectatorship and to challenge the boundary between the wall and the cinema.

Fig2. Chris Welsby Seven Days 1974

65

7..Rees, A. L, and Payne Simon. 2020. Fields Of View Film, Art and Spectatorship. The British Film Institute, 2020.

Furthermore, it was also spatially presented to create a special condition of viewing. It provides a spatial understanding of cinema by presenting a change of screen and simulating emotional effects. In addition, when Anne Friedberg defined the virtual window as the dispositive screen, the definition of the screen was expanded to become as a new type that capable of affecting the cognition of the space.8 Further, the digital generation screen technology helps the viewers construct an image of themselves through the new media contexts. The innovations of the screen and interface provides a new way of affecting the viewer’s sensibility. The lighting effects can be changed and overlaid with the projected image, mapping out the surface with certain cinematic features. Instead of the physical term "film audience”, the viewers watching the screen installations and moving-images are named the "semi-audience"9 which suggests a casually formed potential community of the new viewers.

As such, the representation of art cinema gives the viewers new experiences spatially and visually. It frees the restrictions of theatre buildings and any screen limitations, and allows the content of the moving-images to be socially active and the viewers to explore and re-consider about their environment, the social crisis, and life. In addition, it opens up opportunities for multiple public spaces to be converted into new cinema viewing spaces within the field of mass media and public cultural activities.

8. Chateau, Dominique, and José Moure, eds. Screens. Amsterdam University Press, 2016.

9. Casetti, Francesco: The Lumière Galaxy. Seven Keywords for the Cinema to Come. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

66

Fig3. Chris Welsby Shore Line II 1979

Fig3. Chris Welsby Shore Line II 1979

67

Fig4. Lis Rhodes Light Music 1975

68

Fig5. Jane and Louise Wilson Stasi City 1997

2.2 Screen installations and viewing experience

In the previous chapter, one of the functional structures of the screen was to reveal the architecture of the psyche and make it coherent with emotions or meaningfulness. The design of the screen in terms of position, size, and number can provide multiple perspectives and stimulations, thus causing different interactive responses in the viewers as they explore the space. At this point, "cinematic consciousness"10 embodies the space and shares the common experience in the installations through its spatiality during conscious and unconscious interactions with the spectators. The cinematic unconscious is a state of shared experience that the film induces, allowing the viewer to navigate and change position, thereby altering their gaze on the film. In the cases above, the video installation uses the screen or multiple screens as the medium to set up this double-vision architectural space allowing the viewers to have their moment of immersion in it, to think about it, and to empathise with it. The term "cinematic" in this context refers to the functional element of representation that brings together the history of moving image conventions, techniques, and genres.

Screens installations are often presented as large-scale multipleprojection images which challenge the physical distance between the screen and projectors and the notion of the surrounding spaces. The arrangement of screens, seating positions, and projected images ensures a collaborative association between the plot and setting. The mounted screen facade changes the architectural media form in the city. The moving images are flowing across the building’s surface and turn the skin of the building into an element of a moving structure In Jane and Louise Wilson's work, the strategy of using video projection to create a performative, explicit, and implicit space has become a significant genre of moving image representation, another kind of multimedia theatre.11 The space is reflective of their shadows, thus becoming active through the narrative and rhythmic nature of the spatial performance. "Stasi City" (1997) and "Gamma" (1999) use two pairs of folded screens projected on the wall diagonally position opposite each other.The architectural layout of this

10. Pepperell, Robert, and Michael Punt. Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind and World. Brill,2006.

11.Cairns, Graham. The Architecture of the Screen. 1st ed. Intellect Books Ltd.2013.

69

70

Fig6. Jane and Louise Wilson Gamma 1999

installation reveals a double vision of the film and creates a mirror effect of the inner mind. In this way, the screen is designed to have a plane of vision, and the intricate layers of visual intersection may be enhanced. Besides, the setting of the installation of moving images advances the notion of space as a compound of volume with the shown film, and the two screens can be surrounded by the physical environment (interior or exterior) and also separated as independent entities.

In terms of the behaviour during the viewing experience, the ability of the viewers to share emotions through the process of collective viewing cannot be controlled, with the emotional reactions immediately being reflected in their expressions. In the cinema theatre, although the majority of the audience will concentrate on the screen, some of the audience's attention may be diverted by others during the viewing and their focus may shift from the screen to other members of the audience.12 This is usually due to expressive emotional responses. Such interactions often occur when film-related communication prompts viewers to respond to each other. This social phenomenon is also evident in the time spent viewing moving image installations in other viewing venues.

Viewers in the gallery space, for instance, also accept the idea of watching the same films with strangers and may engage in brief conversations or share thoughts about the content. In this case, the subject of the film triggers the interaction during times of expressive, distracted viewing. As the gallery setting is more conducive than a fixed theatrical setting to wandering, individual, or distracted viewing patterns, it creates a new type of cinematic space that allows the spectators' engagement to be diverse. The motion in the viewing process is related to the time of the experience's completion and the moment viewers enter or exit the space with films. The characteristic of gallery viewing requires a primarily "cognitive"13 rather than experiential approach because the time spent viewing different exhibitions and art pieces is fragmented and disengaged. In most situations, video installations tend to play in loop mode. Any moment when entering the space can be the beginning of the film, and the narrative may be re-read according to when the viewers begin to interact with the screen.

12.Hanich, Julian. The Audience Effect: On the Collective Cinema Experience. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

13.de Luca, Tiago. "Slow Time, Visible Cinema: Duration, Experience, and Spectatorship." Cinema Journal 56, no. 1, 2016.

71

72

Fig7. Cao Fei Blueprints 2020

2.3 Public screen installations and social

The movement of the cinematic development entered a new level of cinematic representation in the era of artistry in institutional moving images. This critical perception of the “social turn”14 in contemporary art seems to be more significant than regarding purely artistic experiences. It has become the new contradictory direction for the artist's films. In the 1970s, experimental practices aimed to reveal the contamination of bourgeois ideology by dismantling the structure of the original forms of cinema.15 Similar to other artistic experiments, these practices devise social situations by vitalizing life using details and dematerializing matters using politics or consumption. Art cinema extends the condition of viewing space and opening up its internal space to the public, so that the auditoria in theatre buildings are transferred into a public and unsure spaces, i.e, a place where inverse public exists, and where the social interaction between the public audience and cinema changes from a fixed relationship. The viewing space and cinema are socialised by the spectator, so that the spectators are no longer the viewer but also participators.

In terms of media communication, mass spectatorship is situated between the image and the space in the city, re-centring itself to the discourses of bodies, space, and memory.16 Although, Crary was concerned about the change in the urban environment regarding the insertion of screens. He argued that their prevalence and the moving images they present in public spaces may be perceived to be a distraction. Because of the attraction that the screens can create, they could deform the legibility of the urban environment, reduce sociality, and de-historicize a city.16 Public screen installation can represent publicness in a city because, as Kester noted, the public sphere could be revealed and questioned rather than suppressed. As the surfaces of buildings are having more screen elements, projection, or LEDs installed on them, they become like screens. And residents are more commonly finding themselves surrounded by these giant public and interactive, participatory digital artworks and experiences.

14..Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells : Participatory Art And The Politics Of Spectatorship. 2012.

15.Murphy, Jill and Rascaroli, Laura. Theorizing Film Through Contemporary Art: Expanding Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

16.McQuire, Scott. Geomedia: Networked cities and the future of public space. Cambridge: Polity. 2016.

73

“A Free and Anonymous Monument” (2003) is another famous piece by Wilson, which is presented in digital media and set up in immersive spatial configurations of 13 projection screens. The significance of the work is instructive of how art in public space can reveals the relationship between spectators, architecture, and moving-images, and the architecture turns into an interface and interactive field. This volumetric architecture includes a kinaesthetic environment and provides a dramatic effect to the audience when they walk around. Such engagement with the screens and the architecture is essential to consider the changing qualities and characteristics of public space and shaping public culture more directly.17 Also, this new strategy provides a framework which supports creativity and criticality in the community and delivers a non-place18 identity to the experience in the city.

Overall, the space in which the spectators engage with the cinema in the theatre and other venues experiences the same reactions of understanding to the content of the narrative and psychological reflections. The difference is that the occupation of the theatre buildings oriented around the city is symbolic of the community as a place for recreational activities. It offers a tangible public sphere in which various aspirations and goals can be understood. In addition, the theatre buildings and other viewing spaces are showing the ability to gather and form cinema communities through the expansion of their network. Various viewing conditions in those cinema spaces enable the viewers to see films in a different order and to influence it through their presence. In the next part of the chapter, a series of typological analyses of the elements of cinematic architecture will be introduced and explored for further experiments and design iterations.

Note1: The work turned the building façade into the screen surface upon which moving images may be projected, with the inside space becoming a public cinematic social space.

17.McQuire, Scott. Geomedia: Networked cities and the future of public space. Cambridge: Polity. 2016

18.Auge,Marc. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity . London,Verso Books. 2009

74

75

Fig8. Jane and Louise Wilson A Free and Anonymous Monument, 2003

76

Fig9. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer Body Movies, 2001

Bibliography

Auge,Marc. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. London, Verso Books. 2009

Bishop, Claire, Artificial Hells : Participatory Art And The Politics Of Spectatorship. 2012.

Bourriaud, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics [1998], Trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2002.

Bruno, Giuliana. Public Intimacy in The Visual Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2007.

Caglayan, Orhan, Screening Boredom: The History and Aesthetics of Slow Cinema. University of Kent, 2014.

Cairns, Graham. The Architecture of the Screen. 1st ed. Intellect Books Ltd. 2013.

Casetti, Francesco: The Lumière Galaxy. Seven Keywords for the Cinema to Come. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015.

Chateau, Dominique, and José Moure, eds. Screens. Amsterdam University Press, 2016.

Connolly, Maeve. The Place Of Artists’ Cinema. Bristol, UK: Intellect.2009.

De Luca, Tiago. "Slow Time, Visible Cinema: Duration, Experience, and Spectatorship." Cinema Journal 56, no. 1, 2016.

Froehlich, Dietmar. The Chameleon Effect: Architecture's Role in Film. Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, 2018.

Hanich, Julian. The Audience Effect: On the Collective Cinema Experience. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

McQuire, Scott. Geomedia: Networked cities and the future of public space. Cambridge: Polity. 2016

Murphy, Jill and Rascaroli, Laura. Theorizing Film Through Contemporary Art: Expanding Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Pedullà, Gabriele: In Broad Daylight. Movies and Spectators After the Cinema. London: Verso, 2012.

Pepperell, Robert, and Michael Punt. Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind and World. Brill,2006.

Rees, A. L, and Payne Simon. 2020. Fields Of View Film, Art and Spectatorship. The British Film Institute, 2020.

77

Elements of Cinematic Architecture

3

79

Fig1. Lars von Trier Dogville, 2003

Since Lefebvre defined spatial space as “the environment of the group and of the individual within the group”1, that the space becomes a fabric of everyday networks. Instead of looking into the architectonic of the space, Professor François Penz brought up a “life turn” of architecture and cinema together to investigate the new awareness of the everyday in the city. Following from the identification of fundamental elements of architecture by Koolhaas, the study of cinematic design by Penz reveals the architectural form of the cinema, looking in particular at the use of architectural elements concerning the expression of everyday life. The main hypothesis of Penz’s verision is the capacity of the extension of knowledge on everyday environment that is carried by the cinema architectonic. “…as most films are the architectonic in the sense that they invariably include doors, windows…”.2 The term of cinema architectonic in here refers to both the pertain of buildings elements and its cinematic functions.

For example, the element of door tends to mean an entrance, a sign of leading directions, or an exit; meanwhile, the cinematographic door changes its nature to a passage of conveyance for mental states. Moles and Rohmer added to the definition of this cinematic character by construing the door as having built-in movement because the special topology configuration is affected by the accessibility of the element. A [door] “is the way into the main space where often the action will take place”3. Bachelard also noted that the given structure of space in intimate scenes is an ambiguous space between the inside and outside, through which the mind navigates freely.4

1. Lefebvre, Henri. Critique of everyday life. The three-volume text. London: Verso. 2014

2. Penz, François. Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. Routledge, an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

3. Moles, Abraham. and Rohmer, Eric. Psychosociologie de I’Espace . Victor Schwach. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan. 1998.

4. Bachelard, Gaston. The poetics of space. Boston: Toronto: Beacon Press, 1964.

Fig2. Rem Koolhaas Elements’ at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2014

80

In this case, the cinematographic door refers to the Deleuzian notion of the movement-image and operates as the mediator of the public and intimacy.5 In short, the door could represent a rejection, an expectation or hope.

Therefore, through the study of cinematic architectural elements, the experiments would find the possible spatial correlations between the screen, the cinematic placement of architectural elements, and any causes for the transformation of the spectator's experience of viewing. By analyzing both experiments, the following typological questions will also be considered:

What are the features of the new cinematic space?

What kind of engagement can the new cinematic space facilitate regarding the spectator?

How can the element of cinematic architecture be instrumental in creating new types of cinematic spaces to adapt to different urban conditions?

The design proposal of this chapter challenges notions of cinematic architecture by experimenting with cinematic architectural elements and creating a new spatial programme for potential viewers to [re]engage with cinema buildings through cinematic spatial structures.

5.

81

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: the time image. London: Athlone.1989.

82

Fig2. illustration of the circulation of Serpentine South Gallery

83

Fig3. illustration of the circulation of Serpentine North Gallery

84

Fig4. position map of the moving image installation

85

Fig5. position map of the moving image installation

86

Fig6. cinematic space emerges with the space in Serpentine South Gallery

87

Fig7. cinematic space emerges with the space in Serpentine North Gallery

88

Fig8. explored cinematic spatial elements in Serpentine South Gallery

89

90

Fig9. explored cinematic spatial elements in Serpentine North Gallery

91

3.1 Experiment of Cinematic Space type

Experiment1: elements of cinematic viewing spaces in a gallery

The experiment was to analyse both the architectural elements and the screen regarding the creation of cinematic spaces and the viewing conditions that the settings of these elements can provide using spatial extraction. The experiment was set in the Serpentine Galleries (North and South) and included video installations, multiple screen structures, and scenic settings. As mentioned in the first part of this chapter, the architectural features of the moving image had been considered concerning the space in the gallery being sensible to the intersection of the physical and cinematic spaces, and they were intended to enhance the viewer’s immersive experience in the process of engagement. Each selected space in the exhibition gallery contained the projector, the receiver of the projection (the screen), and any supporting structures, all of which produced the cinematic character in different arrangements, orientations, and shaped conditions. Through re-modelling and setting each presentation, and by comparing the spatial conditions when the film was playing or was turned off, this experiment directed the typological transformation of the cinematic space towards the discussion of social engagement.

92

93

Fig10. extracted cases with cinematic spatial elements

The cinematic viewing wall:

The assembled viewing wall was a flexible structure. It combined the supporting framework and the base of the monitor. According to Giuliana Bruno’s description of the relationship between the screen and the wall in terms of architecture, the wall becomes a light space or literal screen, and the output of the created media includes representations of cultural history and social engagement.6 There were two conditions set in the space of the galleries (understood as cinema architecture): the performance of cinema was either active or inactive. The two conditions were integrated during the times of public opening and closing, providing different cinematic social spaces for the viewers to navigate.

What happens when a wall has an inactive cinema performance:

Without the representation of cinematic illumination, the wall functions as a flat canvas. It amplifies the original function of an architectural element by helping to direct, separate, and enclose spaces and it intensifies the journey of exploration inside the exhibition area.7 Moreover, the viewing wall also reflects the psychological aspects of the potential audience, especially those with high expectations. The audience will continue to view the wall from a distance even if the screen remains closed, and this observation of the changing behaviour suggests a different approach from the reaction to a wall when it is not equipped with a screen.

What happens when a wall has an active cinema performance:

The moment a viewing wall becomes cinema architectonic is the moment when the screen is turned on. When entering the cinematic space, the expectations of the viewing experience would vary according to the level of immersion. The response of the audience is contingent on the orientation and layout of the viewing walls. Various wall configurations distinguish the type of cinematic viewing space based on the influence of the cinematic performance and the viewing mode of the audience within the space.

6. Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. University of Chicago Press. 2016.

7. Penz, François. Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. Routledge, an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

94

Walls may fulfil different roles:

There are those with a broad, flat surface for displaying projections in a continuous, linear position that draw spectators to the centre;

Parallel walls establish a gap in the narrative and lend a montage-like quality to the cinematic effects;

Opposing walls reflect a two-directional narrative, confining the audience to the space between the two cinematic events;

Walls that intersect with each other can be folded or placed to create a range of diverse viewing conditions for viewers to follow the narrative by switching sides.

95

Fig11. Typology diagram of cinematic viewing wall

The cinematic viewing corridor:

Apart from its appearance in Koohass's architectural elements, the corridor, which is not often discussed as an individual element in architecture, has a long history of participation in films. According to the architectural interpretation of the corridor, it is a space between the semi-private and the semipublic, the nature of which offers an inevitable chance of meeting someone or leading to certain places.8 The cinematic viewing corridor, on the other hand, has a new type of spatial element through the combination of screens and projection devices. It is not the linear continuum of segregation but it provides different viewing modes for the audience in association with the various forms of interaction between viewers, walls, and screens, creating a new rhythm of viewing during the journey of exploration.

Note1: In the film "Playtime" (1967), the waiting scene in which Hulot meets Giffard by repeatedly crossing a ridiculously long and echoing corridor signifies the cinematic sense of this type of architectural element, which holds back rather than accelerates movement.

In films such as Tarantino’s "Pulp Fiction" (1994) and Godard's "Alphaville" (1966), corridors are often used in violent scenes to heighten the sense of infinity and reintroduce the concept of non-place9 .

A corridor may be a cinematic screening space: the screens and installations are placed side-by-side and the images are guided by a linear circulation across the fixed structures.

A corridor may separate two screen spaces in that two screens can be placed in different corners of the space and a wall set in between them to allow for a varied itinerary.

A corridor may lead to a central screen with a single means of entry and with the exit leading to the main area for the performing cinema.

8. Penz, François. Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. Routledge, an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

9.Augé, Marc. Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity London: Verso. 2009.

Fig12. Corridor Scene in Playtime 1967

96

97

Fig13. Typology diagram of cinematic viewing corridor

98

Fig14. Floor plan of 180 Strand Exhibition Universal Everything 2022

99

Fig15. Floor plan of 180 Strand Exhibition Future Shock 2022

100

Fig16. extracted typology cinematic interface in exhibition Universal Everything 2022

101

Fig17. extracted typology cinematic interface in exhibition Future Shock 2022

The cinematic viewing screen:

In the case of two immersive exhibitions at the 180 The Strand building, the underground space is converted into a field of screens. Giuliana Bruno defines the screen as "an environment of 'projection’"10 that serves as an architectural gateway. For her, the screen is not only a visual fabric but also a piece of material culture, an inhabitable element of the domestic interior, which acts in the negotiation of the interior and exterior and transformed space materiality. The space created by the projective environment separates and mixes the two sides of the world, traversing the dialogue between the visual and spatial forms of cinema. It can be seen as Dagognet’s notion of "the interface", which maintains the state of "being on the boundary". The interface is "a fertile nexus" in which the image contains information and allows access in both directions of the space.11 The viewing screen integrates the implications of "interface" and "field of screen"12, and transfers them into a new spatial concept, the cinematic interface. It comprises the edges of the two environments together with the spatiality of the screen field, which includes the cinematic consciousness and functional elements of representational techniques.

Multiple screens on the wall may show either the same or different scenes from a film through projection that can be positioned on any axis. This creates multiple timelines to enhance the customised viewing experience.

Regarding a screen filling a single wall, a large LED screen may stand as a singular tectonic element. It can be used as a freestanding element or blend in with the other viewing walls to deliver a new combination of the exhibited narrative.

Interactive screens have interactive sensory devices implanted in them that require the stimulation of moving bodies to activate the narrative of the film.

Virtual reality and mixed reality can be offered through headsets or garments with a built-in programme to immerse viewers in the world of cinema by moving their bodies or touching monitors.

10. Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. University of Chicago Press. 2016.

11. Dagognet, François . Faces, Surfaces, Interfaces. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1982.

12. Galloway, Alexander. The Interface Effect. Polity, 2012.

Fig19. Exhibition Future Shock 180 Strand 2022

Fig18. Exhibition Future Shock 180 Strand 2022

Fig19. Exhibition Future Shock 180 Strand 2022

Fig18. Exhibition Future Shock 180 Strand 2022

102

Fig20. Exhibition Universal Everything 180 Strand 2022

103

Fig21. Typology diagram of cinematic Interface

104

Fig22. Analysis diagram shows the transformation between cinematic spatial elements to new cinematic space and sptaial conditions

105

106

Fig23. Categorized element type to adapt the space condition

107

The new, transformed typology of cinematic spaces

Through a combination of both the element of cinematic architectonics and of a cinematic interface, a new series of transformed cinematic space types can be generated.

Common space is a central space for the gathering of viewers and the hosting of activities; In most cases, this space will be located at the beginning or middle and it will contain at least one large screen to centralize the area of attention.

Personalised space is used for organized temporary activities serving indoor liberal exploration. A large, open space may be rearranged into clusters, each cluster comprising settings which can be customised.

Directed space is used to accommodate temporary functions or provide support for the viewers to engage in activities. Clear directions will be presented for guiding purposes, while the narrative of the film can still be visible.

Divided space involves the creation of sectors for different purposes and experiences. Open spaces will be divided into small sections to make enclosures or semi-enclosures.

Bridged space connects multiple spaces to create a multifunctional venue for large activities.

Personalised

Directed Space 108

Fig24. New transformed cinematic spaces

Common Space

Space

In summary, through the typological spatial analysis of the cinematic architectonic elements, Experiment 1 has identified the cinematic spatial quality and viewing conditions of the key features of the new types of the cinematic viewing space. The investigation of the three elements—the viewing wall, the viewing corridor, and the viewing screen—enables the extraction of both architectural and cinematic features that can be utilised to transform these elements into new cinematic spaces. The new types of cinematic spaces are fully flexible and can be easily adopted. They create a series of new "lived spaces" where the scenario of the cinema and the structure of the presentation of cinematic features correlate. The space shares the narrative of the cinema by having different modes of elemental arrangements that reflect multiple layers of content. The transformation of the cinema space is deconstructed into these elements and then reconstructed with cinema and cinematic consciousness. This allows each type of space to engender a distinct relationship between the viewer and the assemblage of elements and provides an alternative level of interaction for social engagement by using different means of cinematic interface.

Regarding the further investigation in the new typological study, the second half of the experiment focuses on spatial conditions and directly tests the spatial adaptability and design constructs to find viable propositions for multiple circumstances.

Space Devided Space Bridge Space 109

110

Fig25. Spatial configurations of new cinematic spaces

111

112

113

Fig26. Screen configurations of new cinematic spaces

Experiment 2: cinematic spatial configurations in various viewing conditions

The typological transformation of the cinematic space in Experiment 2 was further investigated by testing the arrangement options of the cinematic spaces in Experiment 1 and their corresponding engagement conditions. The experiment reintroduced the transformed spaces into the gallery space to determine how the various spatial conditions corresponded to the cinematic engagement activities. The investigation reassembled the ground-floor exhibition area at the Whitechapel Gallery and used the open space to evaluate cinematic space types and viewing conditions. In addition, the layout of the testing clusters accommodated the prospects of a change in viewing experience, which highlighted the significance of making important adjustments to the spatial configurations under the condition of cinema displaying.

Focus Distract 114

Considering Finnish film director Pia Tikka's meaning of the cinema as an "externalisation of consciousness," the use of her position concerning the cinema and internal consciousness was considered in the experiment. Cinematic elements thus became the "constitutive mechanisms of cinematic experience"13 .

The designed modification of the clusters would provide a certain framework for the potential cinematic viewing space to function in the city. It took into account the mechanical movement of the materiality of those elements in formal and spatial transformation and classified it as the motions of rotation, folding, and translation to determine the flexibility of the element in different degrees. At the same time, the viewer’s body movement in each configuration was considered, along with the spatial conditions.

13. Pepperell, Robert, and Michael Punt.

Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind and World. Brill,2006.

Note2: Following Eisenstein’s idea of embodiment, the characteristic feature of the cinema is always attached to timing and synchronicity.

Note3: The mind as the lens to observe the functional structures in the procedures of its productivity

Fig27. spatial arrangement of new cinematic spaces based on different cinematic spatial conditions

Fig27. spatial arrangement of new cinematic spaces based on different cinematic spatial conditions

Cross Trace Linked

115

The finalized formation of those conditional spaces is:

Focus: This represents a meeting place where people gather around the large screen. Walls and screens are modified to create an enclosed space suitable for long-term activities. The position of the viewing spots and the projection are fixed, allowing the viewers to locate themselves within the field of cinematic spaces.

Distract: The implementation of a multi-gazing system within a space. Walls, screens, and projectors are situated in parallel and offer continuous strips of gaps. The function of the wall that joins the edge of the screen is to allow people to move non-stop through the gap. It provides the opportunity for viewers to selfdetermine which perspective they wish to see.

Cross: This involves changing the depth of interspersed space with overlaying screens. The combination of screens and walls does not direct the flow of the viewer but, rather, allows the viewer to position themselves between the various depths of the screens. Several methods of projection are applied with changeable wall positions for the creation of multiple intersections between the cinema and the viewers.

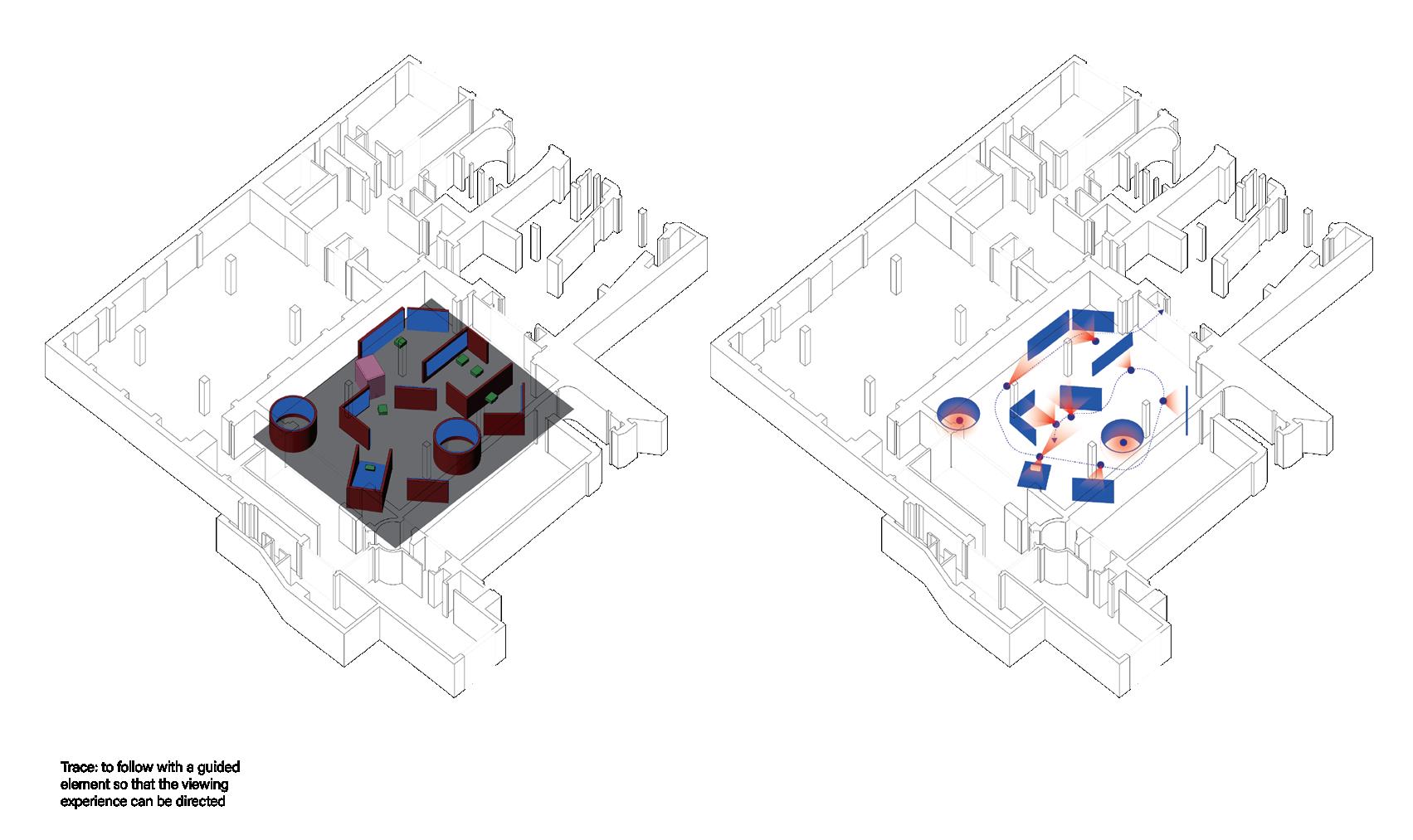

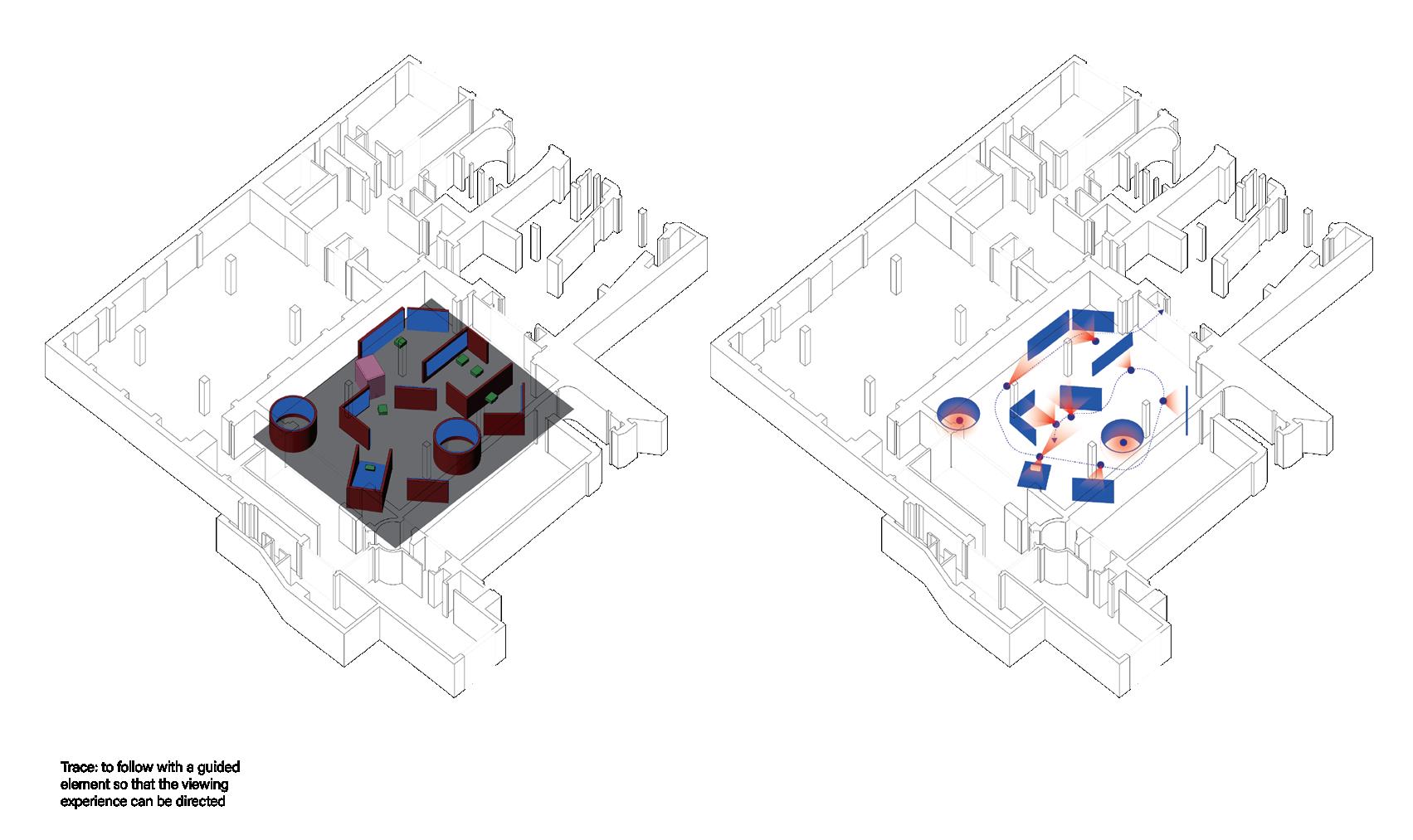

Trace: This represents a dominant space. It diminishes the liberalisation of exploring space by directing the viewers along paths. During this process of reading the cinematic narrative, the viewers can obtain a coherent memory with others.

Linked: A space of correlations is presented. The positions of the juxtaposed walls are constant, and the interpretation of the narrative can be organised through the internal structure of the mind.

116

117

Fig28. cinematic element assemblage in relation to viewing conditions

118

Fig29-30. cinematic element assemblage in relation to viewing conditions

119

120

Fig31-32. cinematic element assemblage in relation to viewing conditions

121

Hence, the experiment revealed the different combinations of cinematic space that produce a sequence when considering the viewing experience in cinematic interaction within these spatial conditions. The manifestation of architecture relied on the composition of formations, the repetition of columns, and the different openings.14 For the experiment, regarding the production of filmmaking, films were made shot-by-shot and edited into a non-chronological order. Based on Tschumi’s assertion, the architectural sequence, which relates to "space, events, and movement,"15 indicates the ability of communication to occur between space and narrative in the creation of the dynamic shift through active engagement.

In both experiments, the typology of cinematic space articulated the flexibility of the cinematic spatial quality between the crossprogramming of cinema and events. The creation of this new type of space brings the notion of engagement into cinema spaces through various forms of representation. It connects the physical, virtual, and psychic platforms through the cinematic interface, which enlarges the accessibility of the three gateways within a building. Therefore, the created space has inherited the liberal features from the pre-cinema state (the hybridity of engaging within the panorama) and takes the cinema architecture to the contemporary condition of reinterpretation. In the second design iteration, existing cinema buildings would be tested once again to integrate the new pattern of the cinematic space and form a new internal living space in London.

14. Koeck, Richard. Cine-Scapes Cinematic Spaces in Architecture and Cities. Routledge, 2013.

15. Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1996.

Note 4: "events" can lead to a cinematic chain of cause and effect that is manifested on the screen as well as in meaningful architectural space.

122

3.2 Design Proposal 2: New Gallery Kinema:new event space

Fig33. Axometric view of Design Proposal 2

Fig33. Axometric view of Design Proposal 2

123

The design proposal illustrates the alternative adaptation of the transformed cinema space in the previous chapter to contemporary cinema architecture through the typological arrangements of cinematic architectural elements and specific spatial configurations in terms of social engagement. As Giuliana Bruno noted in "Public Intimacy", the cinema is an intimate terrain born of public emergence and linked to the notion of architecture.16 The architectonics of display and spatial promenades within the cinema buildings illustrate the mobility of public space implanted with the imaginary experience of spectatorial life.

This design aims to provide alternative options to the internal space of the existing cinema building through the performance of multiple cinematic situations and the insertion of different engagements for potential users, treating the space as a transformed living space in which the aspects of cinematic interaction are represented.

The site is located in the existing New Gallery Kinema on Regent Street, which has been converted into a fashion store. The design proposal focuses on the existing auditorium (600m2) and transforms the space into sectors composing of a combination of screen installations and movable walls. To achieve a harmonious relationship between the activities in the contemporary stores and the engagement with cinematic space in daily uses, the design presents multiple spatial conditions that diversify the movement of people by directing and distracting the gaze. Such movement is based on Tschumi’s notion of "events" (repeatedly taking place), in which the cinematic quality of the architecture is articulated through the designed spatial sequence of framings and openings.17

16. Bruno, Giuliana. Public Intimacy in The Visual Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2007.

17. Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1996.

124

Fig34. Site of original New Gallery Kinema

5 10 15 20m 125

Fig35. Floorplans of new cinematic space

The different levels of spatial conditions also allow the space to host events using different arrangements of the sectors and for different durations. The lower level of the building comprises sectors where a combination of screens(24m2), viewing walls(4x20m2), and seasonal products can be viewed. It reflects the most changeable conditions of daily activities by assembling the cinema fragments and merchandise products into various typologies of cinematic spaces. Through the act of walking, cinematic perceptions of space can be inherently linked to the presence of the human body. Such movements of travel create a particular form of mobile spectatorship where moving images and space intersect. In contrast, the duration of the time on the upper floor is much more temporal. The 30m existing corridor on the upper floor is used for runway shows with sidewall screen installations(24m2). In the centre, a (11m height) circular holographic device is installed facing an inserted auditorium space that can be accessed via a spiral staircase. It opens up the spatial quality of being a viewer to the audience in the form of movement.

In summary, the second design proposal offers a new way of transforming the space of the cinema with a supporting programme to meet the needs of daily functions. It challenges the auditorium not as a private, introverted space but as an internal social space where all kinds of events can take place. In addition, the architectural composition of the multi-layered designed spaces reveals the relationship between cinema and body movement through different passages of time using moving images and the physical world. By reconstructing cinematic tectonics, the potential spatial adaptation of cinemas can be seen.

Fig37. renovated lobby in Burberry store

Fig37. renovated lobby in Burberry store

126

Fig36. auditorium in New Gallery Kinema

127

Fig40. Render Images of screen projection showing double effects of body movement in new cinematic space

128

Fig40. Render Images of living with cinema in new cinematic space

129

Fig40. Render Images of active cinematic interaction in new cinematic space

130

Fig41. Render Images of screen position and designed cinematic space

Bibliography

Augé, Marc. Non-places: introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity. London: Verso. 2009.

Bachelard, Gaston. The poetics of space. Boston: Toronto: Beacon Press, 1964.

Bruno, Giuliana. Public Intimacy in The Visual Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2007.

Bruno, Giuliana. Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media. University of Chicago Press. 2016.

Dagognet, François . Faces, Surfaces, Interfaces. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1982.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: the time image. London: Athlone.1989.

Galloway, Alexander. The Interface Effect. Polity, 2012.

Koeck, Richard. Cine-Scapes Cinematic Spaces in Architecture and Cities. Routledge, 2013.

Lefebvre, Henri. Critique of everyday life. The threevolume text. London: Verso. 2014

Moles, Abraham. and Rohmer, Eric.Psychosociologie de I’Espace. Victor Schwach. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan. 1998.

Penz, François. Cinematic Aided Design: An Everyday Life Approach to Architecture. Routledge, an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

Pepperell, Robert, and Michael Punt. Screen Consciousness: Cinema, Mind and World. Brill,2006.

Tschumi, Bernard. Architecture and Disjunction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 1996.

131

4

New Cinematic Space in the City

133

Fig1. Cao Fei La Town Theater, 2014

Early understanding of the connection between cinema and the city led Baudrillard to claim that the cinema is "an exceptional version of itself"1, always seeping out of its surroundings and disseminating throughout other parts of the city. The observation of Shaviro’s notion in the cinema as a novel approach to encountering reality gives a new perception of understanding reality and sensational reality in the mode of living in the city.2 In this chapter, the recognition of the cinema and cinematic space is further explored by looking into the relationship both spatially and filmically between the cinema and the city, whereby the city translates itself into a variety of moving images.

In 1938, Sergei Eisenstein identified the sequence of montage in architecture as the mode of walking between buildings in the city recorded in a shot-by-shot composition of images.3

Giuliano Bruno also claimed that the emotional itinerary of walking around Gerhard Richter’s Atlas transfers the space created through the unfolding of the individual’s filmic map. The correlation between the means of filmmaking and navigation in the physical exhibition space suggests a new observation of urban form, as in the movement of the living with cinematic narrative, identified as a voyage.4 The notion of the voyage reveals the possibility of inhabiting narrative space by entering the intimate sense of spaces and turning architecture into shared intersubjective spaces. This creation of a mental journey involves physical spaces and the viewer's perception of the world, as in the filmic city. It differentiates the representation of everyday activities in cinematic space and brings a new understanding of life in the city by making the physical form of the city cinematic.

1. Baudrillard, Jean. America , London, Verso. 1988.

2. Shaviro, Steven. The Cinematic Body , Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press. 1993.

3. Eisenstein, Sergei. Film Form: Essays in Film Theory , London, Dobson. 1963.

4. Bruno, Giuliana. Atlas of Emotion: Journey in Art, Architecture and Film, Verso. 2018.

134

Fig2. Gerhard Richer Atlas 1999

From strolling through gallery spaces to traversing a city's various community spaces, the perspective of the cinema provides a unique means of documenting the city’s history and capturing shared memories. The cinematic shifting of urban and spatial elements makes the residents participants in the urban cinema in some way. The behavioural trajectory of life or an event is determined by the spatial and temporal migrations of city dwellers from one place to another. At the same time, the city has a distinct urban rhythm brought about by the narrative shifts of the cinematic urban life, a rhythm of recorded memories, and a different method of piecing together the fragments of the events in question. Thus, understanding the role of the elements of urban cinematography and cinematic space in the city allows for a deeper understanding of the psychological and spatial connection between the inhabitants and the city.

This chapter aims to explore the cinematic voyage by experimenting with the adaptability of new cinematic architecture in a larger context of urban spaces and discussing the forms of intermediate-scale cinematic engagement. The design proposal here challenges the notions of cinematic form in the city through a re-composition of spatial elements with the consideration of time, narrative, and movement. Related design questions are:

How can the new transformed cinematic space on the scale of the city portray this notion of voyage and comprehension of urban living scenarios?

How does the designed cinematic urban space provide new forms of public social engagement in which audiences may participate?

135

4.1 City Voyage