Housing Not Only For Living

Removation of Left-unfinished Commercial Housing in Southern China

by Fanyu Song

Projective Cities Programme 2021-2022

Architectural Association School of Architecture Graduate School

Housing Not Only For Living

Removation

in Southern China

Mphil in Architecture and Urban Design Projective Cities, 2021/22 Architectural Association School of Architecture Graduate School

Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design by Fanyu Song

of Left-unfinished Commercial Housing

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

GRADUATE SCHOOL PROGRAMMES

COVERSHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2021-2022

PROGRAMME: Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban design

STUDENT NAME: Fanyu Song

SUBMISSION TITLE: Housing Not Only For Living Removation of Left-unfinished Commercial Housing in Southern China

COURSE TITLE: Dissertation

COURSE TUTOR:

Platon Issaias

Hamed Khosravi

Doreen Bernath

Raul Pere Avilla

Cristina Gamboa

SUBMISSION DATE: 22/04/2022

DECLARATION:

"I certify that this piece of work is entirely my own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged."

Signature of Student(s):

Date: 22th of April 2022

Housing Not Only For Living

Removation of Left-unfinished Commercial Housing in Southern China

Mphil in Architecture and Urban Design Projective Cities, 2019/21 Architectural Association School of Architecture Graduate School

Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design by Fanyu Song

Acknowledgement

Throughout the writing of this dissertation I have received a great deal of support and assistance.

First and foremost, I would like to thank all those who helped me during my time at the Architectural Association (AA) for their help, encouragement and advice. In particular, I would like to thank my tutors Dr Platon Issaias and Dr Hamed Khosravi, who gave both helpful advice and heartful encouragement when I lost direction in my studies. Moreover, I wish to thank Raül Avilla-Royo and Cristina Gamboa for their help during my studies. My Special thanks also goes to Dr Doreen Bernath who always gives enlightening ideas and privides necessary meterials for my studies.

In addition, I want to thank all my colleagues and friends in Projective Cities and China during my three years of study at the AA. It is the conversations that helped me get rid of the difficulties and gain the courage to move forward.

Finally, I owe my parents, Hongjie Song and Ruxing Zhao, my heartfelt gratitude for their unconditional support and loving consideration over the years. My heartfelt thanks go to my loved ones.

Abstract

After the Open and Reform Policy was proposed in 1976, a commercialized housing system was raised in China in 1998, the year of Reform of Urban Hosing System was implemented. The reform policies encouraged the local government to maximize the commercial nature of housing to realize the growth of the urban land economy. The local government's response to this reached an unprecedented level with the prospects for rapid urbanization through rapid city construction. However, the refinement of the regulatory system of the commercial housing market was not developed correspondingly. So, the chaos of the marketing and construction of commercial housing have left and will keep leaving more and more unfinished buildings in the cities which are posing great pressure to the urban development and economy. The delay of the supervision created a vacuum of the guidelines and measurements after the planned housing was partly built and left uncompleted. What’s more, the problem is quite hard to be solved because of not only the huge lack of funds but also the indistinct ownership and property of the left-unfinished buildings. This uncertainty does not prevent desperate residents, who should have become flat owners, from living in such rough and simple concrete constructions without basic livelihoods and social welfares.

These City-building movements which are widely promulgated all over cities of different tiers in China have been going to create more contrived ruins. At the same time, myriad people will be involved as victims of these notorious failures caused by eager rapid urbanization without proper regulations and supervision. This research commences with this observation on the phenomenon and the collective living mode of the flat owners who are living in the left-unfinished commercial housings, with the analysis of the basic spatial

and structure types of commercial housing in southern China as a research basis. Furthermore, the research will be deepening on re-understanding left-unfinished commercial housing through three different dimensions:"Time", "Spatial Legality and Right", and "Collectiveness and Publicity". This reinterpretation, from the three perspectives mentioned, is not only focusing on observing and classifying the behaviors and activities of the occupants in this space, but also analyzing the existing renovation of these uncompleted buildings.

As for the further comment, the design experiments are trying to take it back to the fore that the presence of people and the initial function, living, of the unfinished housing, rather than its commercial characteristics. Consequently, the design and experiments no longer take a certain result of the renovation goal as a method to solve the problem of the left-unfinished buildings but explore the spatial variations formed under the combination of different variables in the three dimensions. Additionally, the design takes the variations of these spatial models as processes of dynamic space of open-ended evolution. The final design aims to experiment dynamical and open-ended results by combining policy support and various levels of spatial transformation strategies, in order to create a collection of spatial utilisation methods for the left-unfinished commercial housing.

Contents

Abstract Introduction Part I Historical Morden Housing in China before Open Policy Part II Present Commercial housing in Southern China Left Unfinished Commercial Housing in China Part III Research Frame Dimension 1 Time 2.1 Everydayness Challenges Permanent 2.2 In-progress Long-term Dwelling 2.3 Experiment #1 Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 3.1 Illegality VS. Spatial and Social Right 3.2 Policy Framework & Management 3.3 Experiment #2 Dimension 3 Collectiveness and Publicity 4.1 Declaration of Privacy 4.2 Self-organized collectiveness 4.3 Isolated Publicity 4.4 Experiment #3 Conclusion and future discuss Bibliography 00 01 01 01 11 11 14 32 34 34 46 58 63 63 76 80 82 82 88 89 92 123 125

INTRODUCTION

Part I Historical

Housing in the Primary Stage of Planned Economy System

Housing During the "Great Leap Forward" & the "People's Commune" Movement

Part II Present

Commercial housing in Southern China

Left Unfinished Commercial Housing in China

Part III Research Frame

Introduction

Part I

Historical

1.1 Morden Housing in China before Open Policy

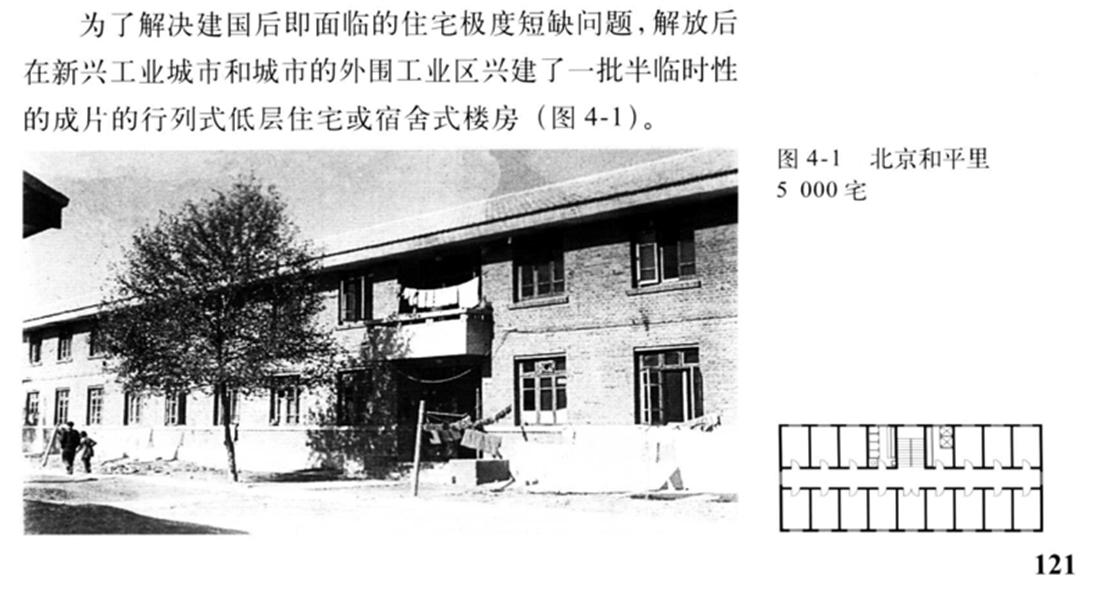

The period from 1949 to 1952 was a time of economic recovery following the establishment of the PRC. The government's main tasks on the economic front were to keep prices down, curb inflation, and ensure the supply of basic consumer goods 1 . The main economic strategy adopted in this process was the establishment of a Planned Economic System through the government of the PRC and centralised and unified management of the economy.

At the same time, with the start of China's first Five-Year Plan in 1953 with the assistance of the Soviet Union, such an almost wholesale imitation of the Soviet model further reinforced this system of Planned Economy with a high level of centralised power. Meanwhile as the Chinese government adopted an economic development strategy of prioritising heavy industry at that time, making the construction of houses, especially in the emerging cities and their surroundings, became a complementary service to industrial development. In this context of economic policy and social development, the construction, distribution and management of urban housing were also

Housing in the Primary Stage of the Planned Economy

From Domestic to Communal

1 Junhua Li, "Modern Urban Housing in CHina 1840-2000", Tsinghua University Press (2002), p.109

Source: Beijing Construction History Book Editorial Committee, "Urbanism in Beijing since the founding of the country"(1985)

Fig.1 Investment on Infrastructure , unproductive Construction and Housing in China (1950-1978)

:

Introduction 1

1950 100 200 300 100million Yuan Year 400 500 600 1952 1954 1956 1958 1960 1962 1964 1966 1968 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 Infrastructure investment Productive construction Unproductive construction Residential construction 1953 30.0 40.0 50.0 % 60.0 1954 1955 Year 1956 1957 Changes in the proportion of completed residential units to total completed buildings in Beijing during the "First Five-Year Plan" period 14.00 16.00 18.00 Changes in housing investment 1958-1965

Source: Redraw by the Author base on the souces from Beijing Construction History Book Editorial Committee, "Urbanism in Beijing since the founding of the country"(1985).

centralised, resulting in the Welfare Housing System that was in place until the Chinese economic reform.

With the end of the Transitional Period of Socialism from 1949 to 1952, China entered the period of socialism, and the accelerated implementation of common ownership led to the official presentation of the 'Opinions on the Current Basic Situation of Private Urban Property and the Conduct of Socialist Transformation' in 1956, which marked the beginning of the common ownership of private housing and the start of large-scale construction of housing around industrial areas during this period.

However, due to the limitations of productivity in the early years of the country, investment in construction was also aimed at 'production first, then living'. As a result, there was still a huge mismatch between the investment in housing construction and the population it needed to accommodate. This mismatch was reflected in the low living space per capita in residential buildings. In the new communal houses of the city, the living space per person is between 4 and 7 square metres, with the actual design of kitchens, toilets and other spaces being shared by several households. In this case, the housing shortage, as mentioned above, had prompted the owners of the housing units, i.e. the state institutions, to group the housing units they had built together for the common use of several households, significantly reducing the space available to the people who actually lived in them. This means that at this stage, the number of residents sharing one set of living services which with the kitchen and toilets was excessive, creating a great deal of space and activities in common in these necessary living spaces. In 1955 Beijing, for instance, the actual living space per capita for the entire population was only 2.69 square meters. This “rational design but not rational use” of urban housing reduced the living conditions of people, but at the same time, the sharing of infrastructure and

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 2

Fig.2 Ratio of Housing Construction (m2) to All New Construction(m2) in Beijing During the "First Five-year Plan"

1950 100 200 300 100million Yuan Year 400 500 600 1952 1954 1956 1958 1960 1962 1964 1966 1968 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 Infrastructure investment Productive construction Unproductive construction Residential construction 1953 30.0 40.0 50.0 % 60.0 1954 1955 Year 1956 1957 Changes in the proportion of completed residential units to total completed buildings in Beijing during the "First Five-Year Plan" period 1953 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00 14.00 16.00 18.00 100million Yuan Year Changes in housing investment 1958-1965

Fig.2

living services also led to the creation of a new type

SIjun

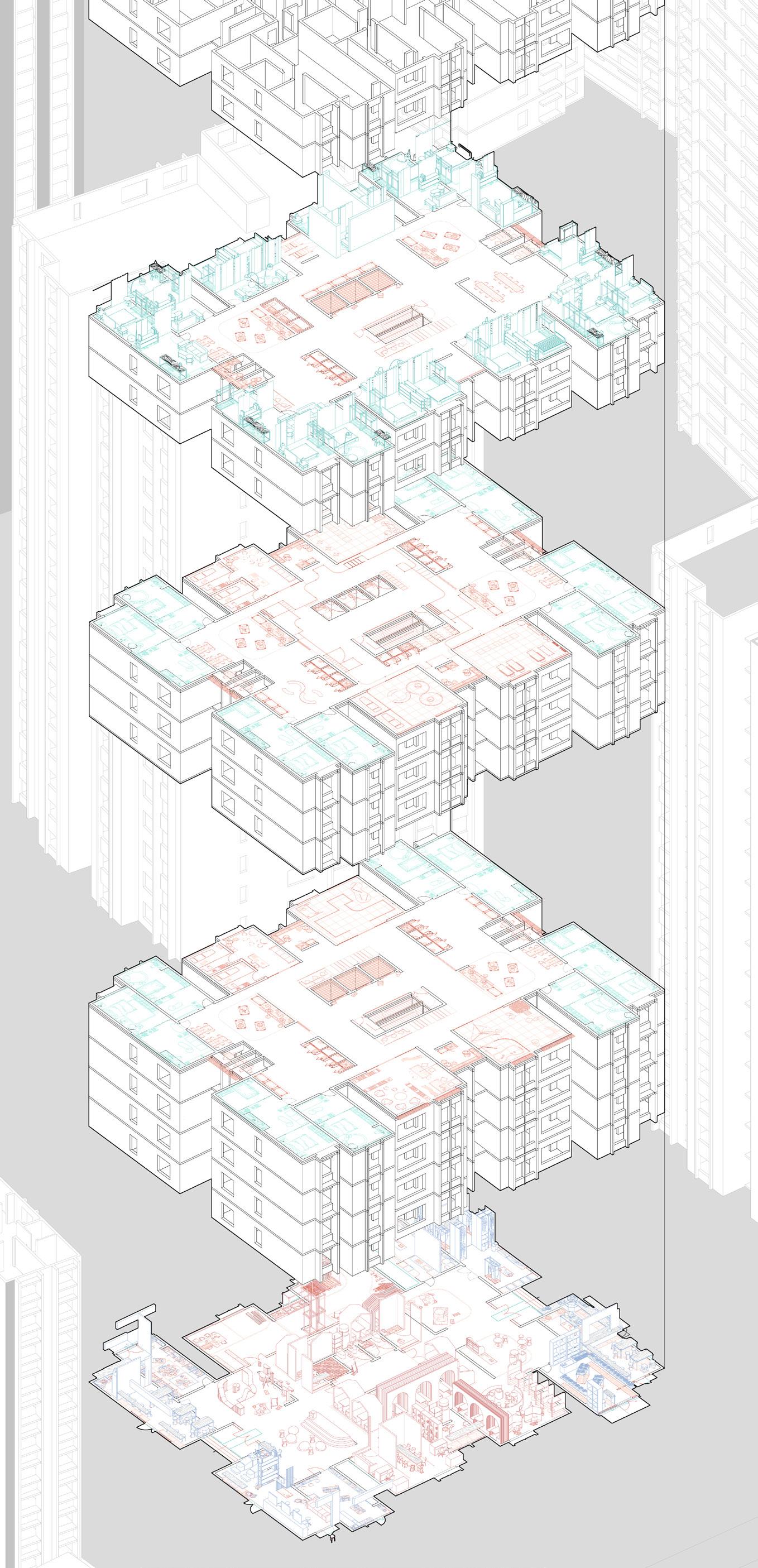

population that proliferated as a result of industrial development, the 5000 houses in Hepingli, Beijing, for example, had a common concentration of whole floors of apartments near the vertical circulation core, which together with the 15 apartments evenly distributed in size formed a standard single-storey flat living unit. In actual use, each household was allocated 1-3 of these rooms according to the number of family members, and the rest of the kitchen, toilet, bathroom and other facilities were mostly shared.

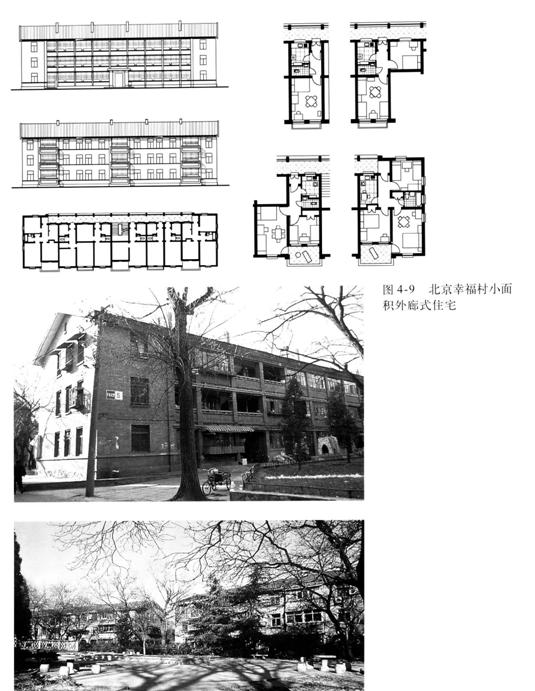

Source: Junhua Li, "Modern Urban Housing in China 1840-2000", Tsinghua University Press (2002)

Source: Drawing by the Author

Introduction

Fig.3

3

Fig.4

Fig.3 Photography of 5000 Houses in Hepingli, Beijing, China

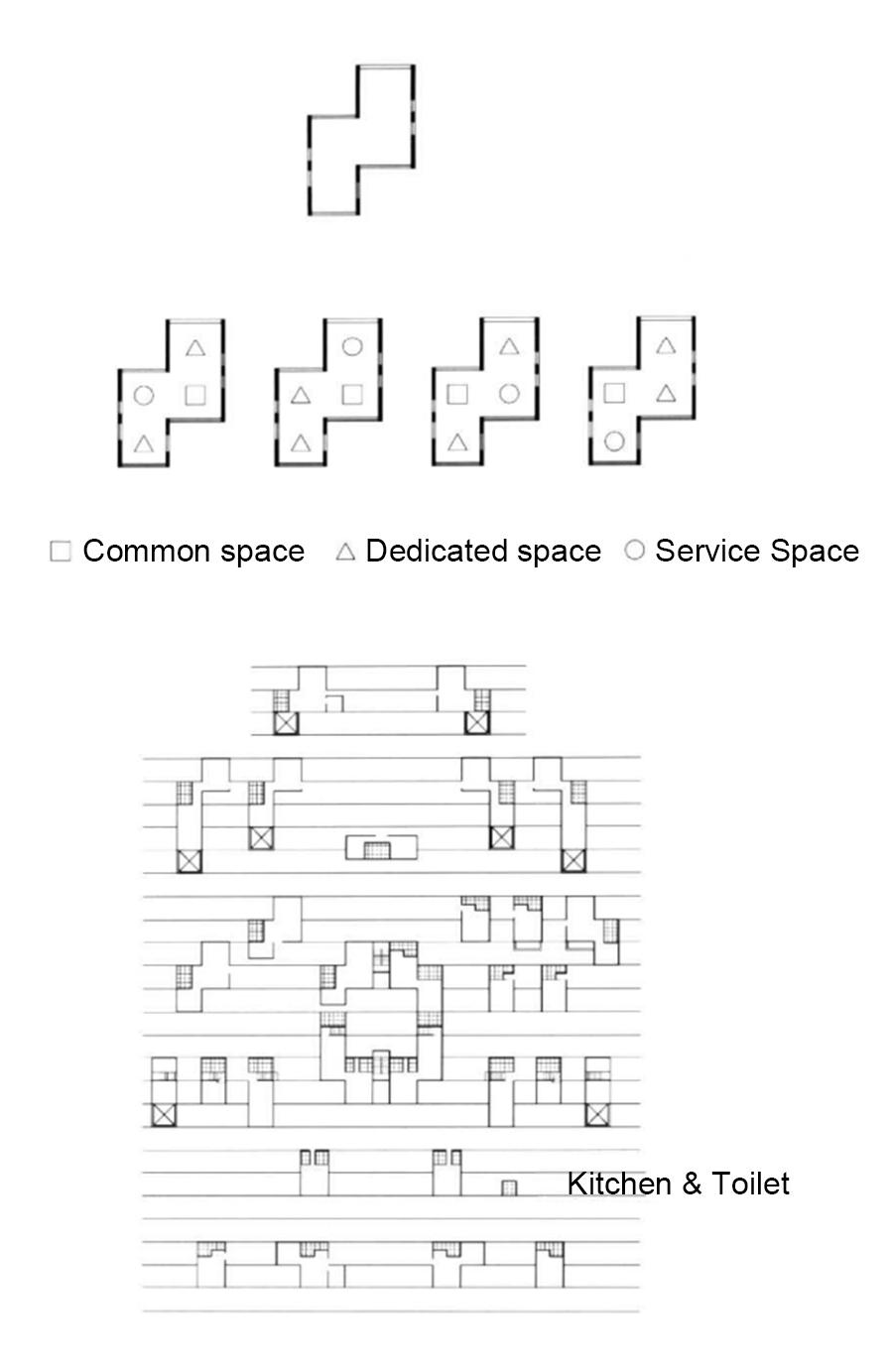

Fig.4 Programme Diagram of 5000 Houses in Hepingli

1

Wang, "A study on the regional development of urbanisation in China"(1996), Beijing, Higher Education Press

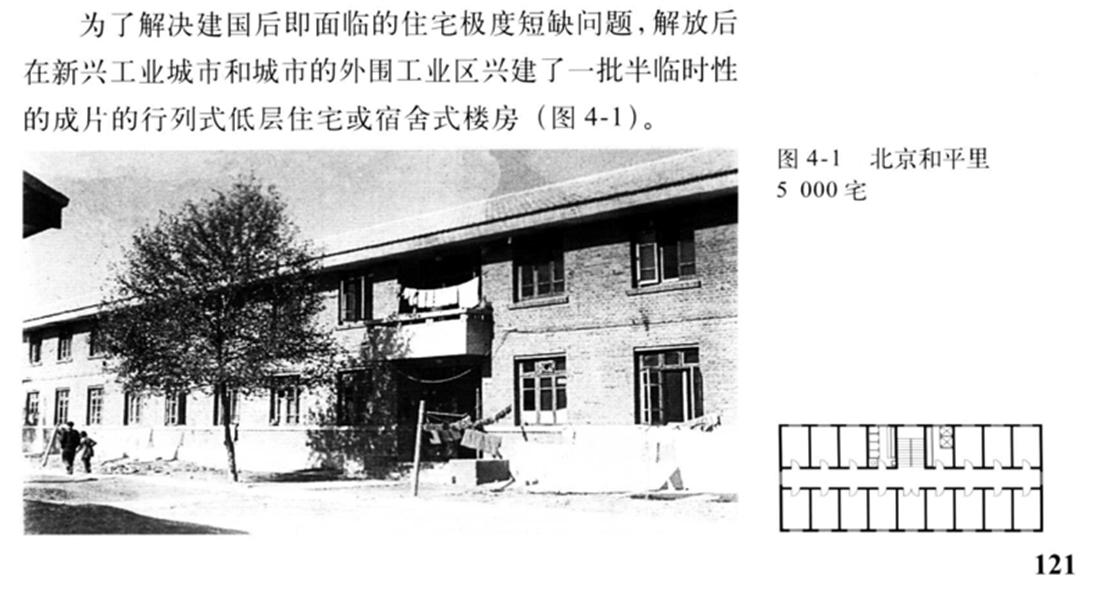

Later, as the Soviet system of quotations and indicators as well as the unit plan with inner corridor was introduced into China, the strategy of designing higher standard dwellings according to the longterm standard and splitting several families to share in the short term was formed. A large number of

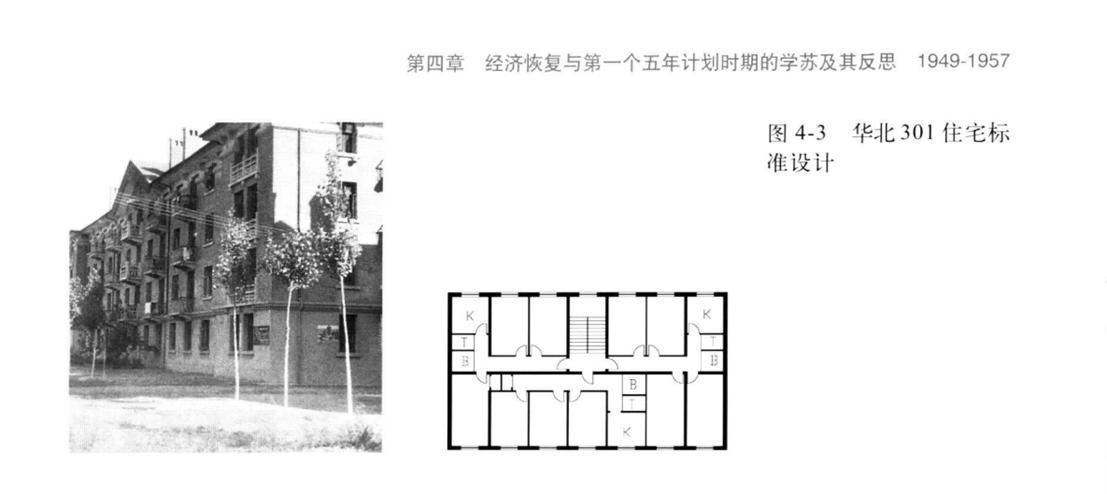

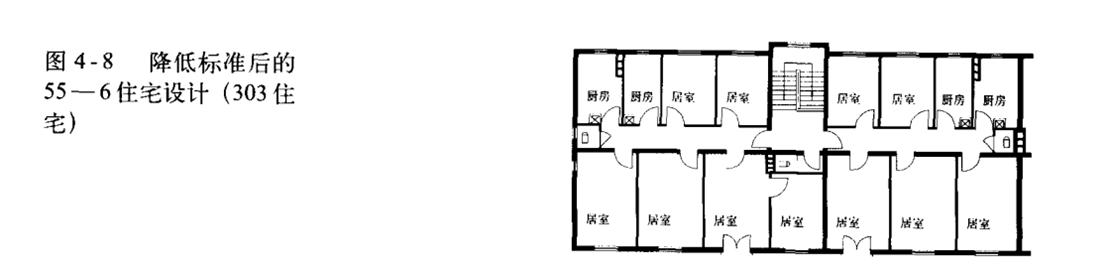

Fig.5 Typical Plan of #301 Residential Regulation in North China

Fig.6 Photography of #301 Residential Regulation in Northern China

Fig.5 Typical Plan of #301 Residential Regulation in North China

Fig.6 Photography of #301 Residential Regulation in Northern China

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 4

Source: Junhua Li, "Modern Urban Housing in CHina 1840-2000", Tsinghua University Press (2002)

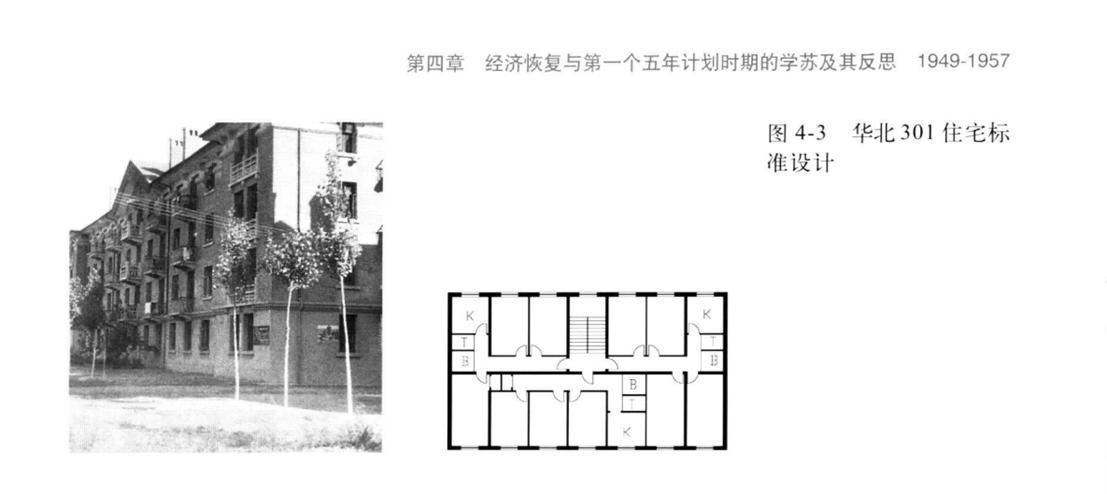

Similarly, the '303 Residential Regulation in Northern China' was created to maintain its spatial layout and reduce the standard of space for each person.

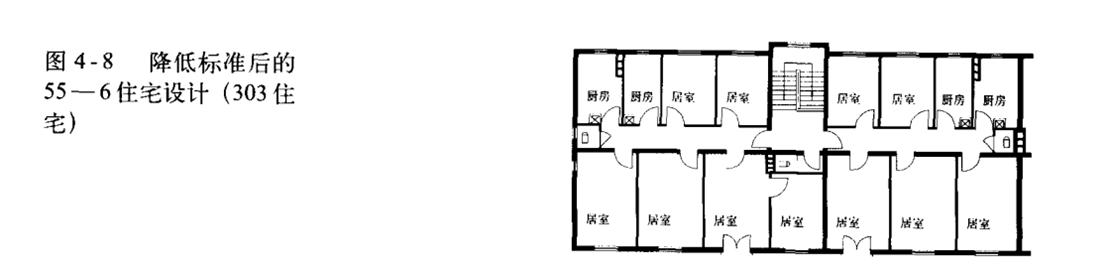

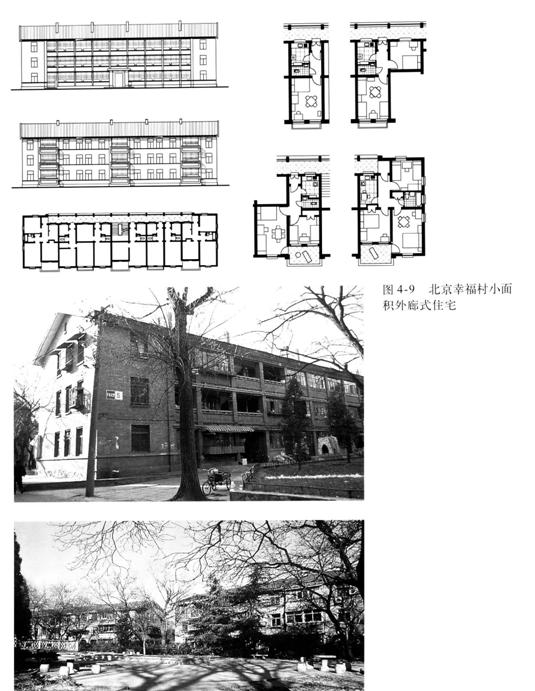

As a result of this difference in design and usage, many of the rooms that are reallocated for use are only allocated to completely bad orientations, with no direct daylight all year round. At the same time, the lack of a complete set of internal spaces running through the building means that natural ventilation is poor in order to ensure the privacy of the rooms. In response to these two problems, communal housing with external corridors has been proposed, which means that people have access to a more fully functional internal space (with kitchen and bathroom space), as well as a living unit with north-south ventilation and good light. However, the corridors that were created also connected all the north-facing windows and doors of the living units, meaning that the horizontal access corridors increased the level of light in the north-facing rooms while reducing their privacy. In contrast to the original inner corridor houses, however, the public corridor, although uneconomical in terms of increasing the area for public transportation, also became a popular space for mixed-use and neighbourhood interaction at the time.

In general, the early centralised housing in China was influenced by the housing forms of the Soviet period, which gave rise to a large number of equally distributed forms of housing with a common infrastructure. This form of housing accommodated and further guided people into communal living.

Fig.7

Fig.8

Fig.7

Fig.8

Introduction

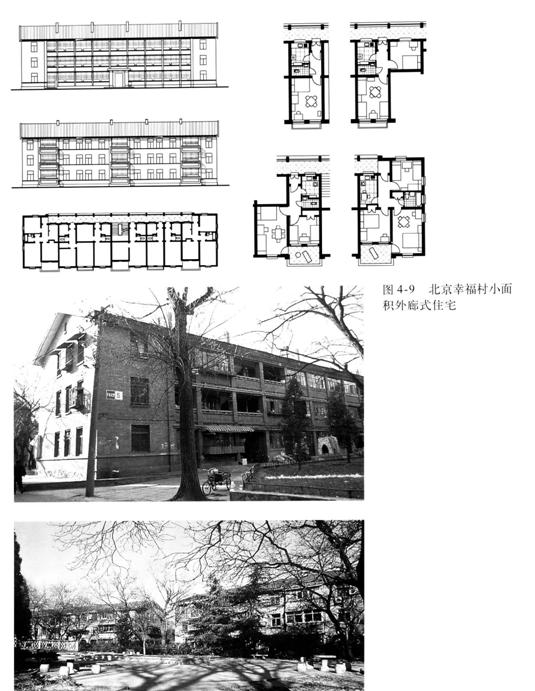

Fig.8 Photography of Housings in Xingfucun, Beijing

Housing During the "Great Leap Forward" & "People's Commune" Movement From communal to collective family

The "Great Leap Forward", which began in 1958, saw a decline in the level of investment and construction of housing as the country's authorities were blindly pursuing the doubling of industrial steel production, which was an economic development target, and the whole country threw itself into increasing industrial and agricultural production.

(Unit:100 million RMB)

Source: Beijing Construction History Book Editorial Committee, "Urbanism in Beijing since the founding of the country", 1985.

1 Oubu Jin, "Architectural design must reflect the new situation of large urban people's communes", China, Architectural Journal, (11)1958

2 Oubu Jin, "Architectural design must reflect the new situation of large urban people's communes", China, Architectural Journal, (11)1958

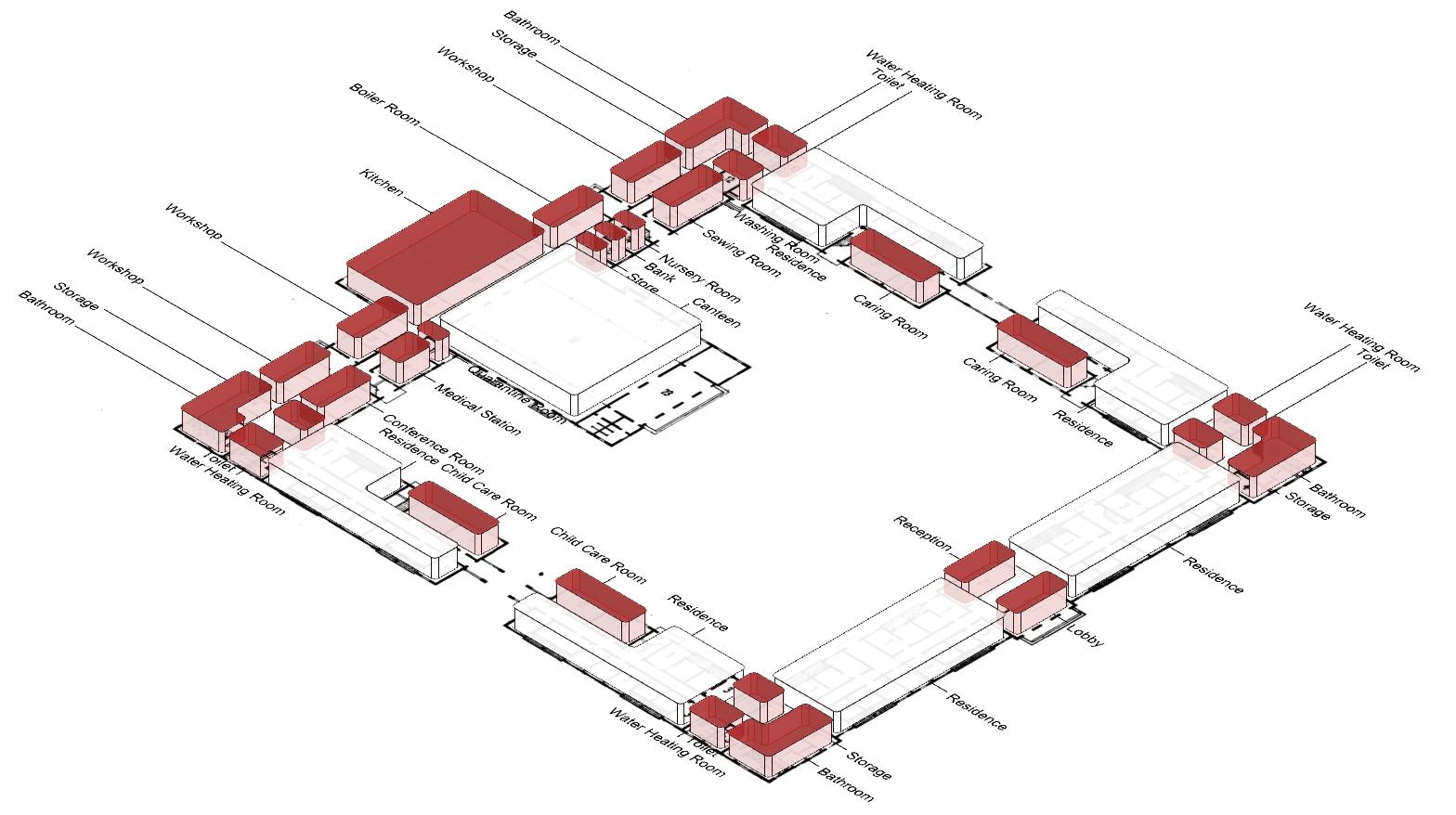

Even so, the urban people's communes formed during this period influenced the architecture of living and everyday life at the time, creating a new spatial vision based on the collective formation of people. The people's commune was a reform of the top-down management model, linking people's production and life as the ideal socialist mode of life provision. From a management point of view, the urban people's commune was a threelevel structure, with a basic unit of around 2,000 people, which replaced the old urban administrative grassroots organisation. The required number of people, 2,000, was determined by the number of people who could be fed using the same communal canteen and the space available at the time.1

In addition to combining residential areas with industrial life to form matchable function urban areas, shortening the distance between workers and factories, and setting up military training grounds in some settlements to prepare civilians for war, the collective life which was most emphasised in urban communes was also reflected in the design of buildings and sites. For example, meals were served in uniform canteens, no kitchens were set up in each family's house, the unpacking and sewing of each family were done by collective labour, women were assigned to work in the community, childcare and elderly care were organised by the community, etc.2

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 6

Fig.10

Fig.10 Investment in Housing (1958-1965)

1950 100 200 300 100million Yuan Year 400 500 1952 1954 1956 1958 1960 1962 1964 1966 1968 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 Infrastructure investment Productive construction Unproductive construction Residential construction 1953 30.0 40.0 50.0 % 60.0 1954 1955 Year 1956 1957 Changes in the proportion of completed residential units to total completed buildings in Beijing during the "First Five-Year Plan" period 1953 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 0.00 2.00 4.00 6.00 8.00 10.00 12.00 14.00 16.00 18.00 100million Yuan Year Changes in housing investment 1958-1965

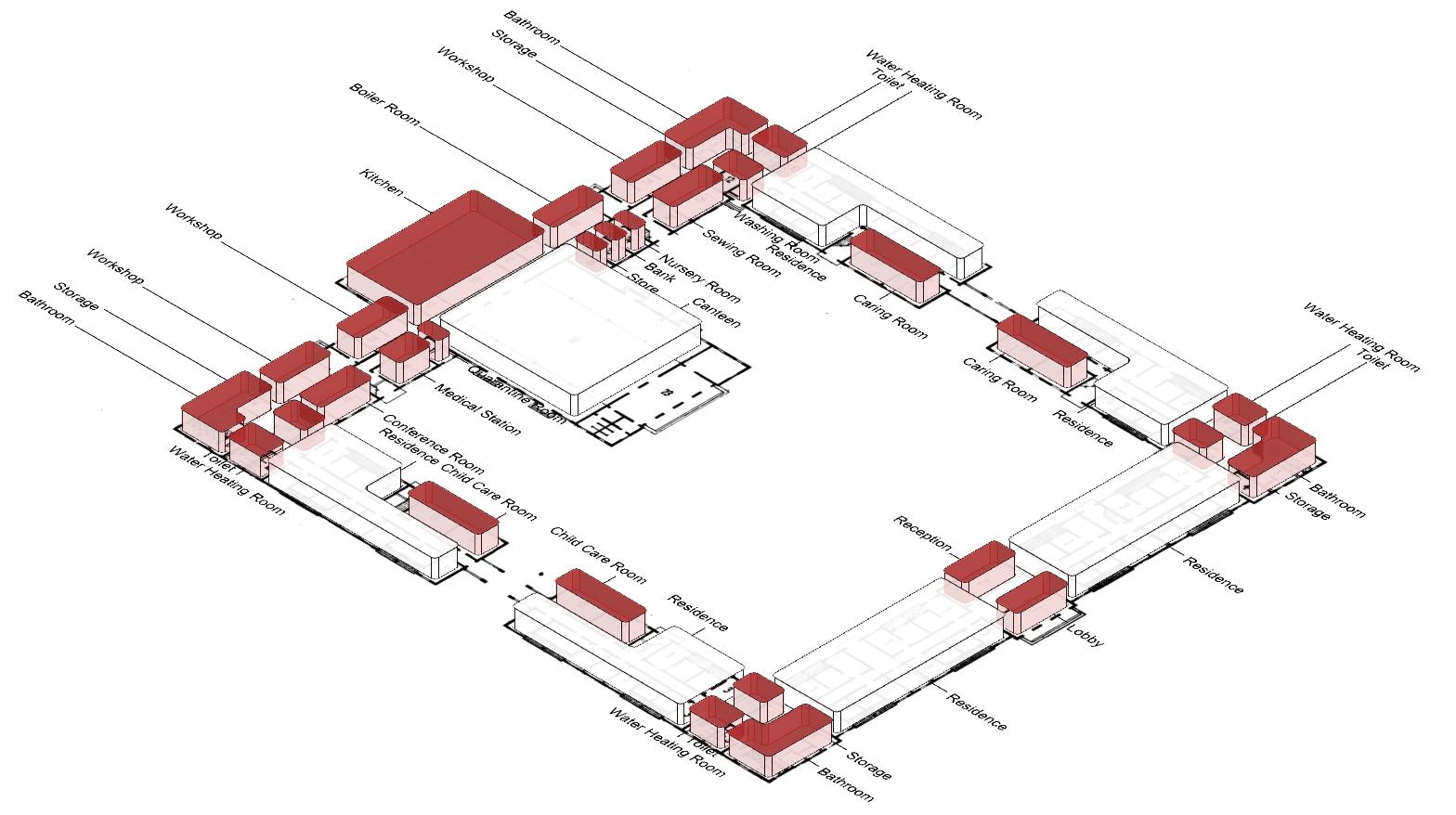

In the case of Tianjin Hongshunli, the designer expresses in his personal design description that the proposal for the Hongshunli house should not be used as a residential building as a reference, but rather as a place where the inhabitants can form a new way of life 1 . The collective system requires people to move from scattered family life to collective life, where they work, live, study and play together. In addition to placing some of the production workshops in the living space, the building also provides collective canteens, washrooms, medical stations, hot water rooms, showers, kiosks, banks, retirement spaces, kindergartens, laundry rooms and other living service spaces suitable for the collective. In terms of the arrangement of functions and the combination of spaces in this way, the floor plan of Hongshunli was an attempt to spatialise the system.

Source: Drawing by the Author

1 Tianfeng Xu, "Tianjin Hongshunli Socialist Family Architectural Design Introduction",China, Architectural Journal, (10),1958, p.34-35

Introduction 7

Fig.11

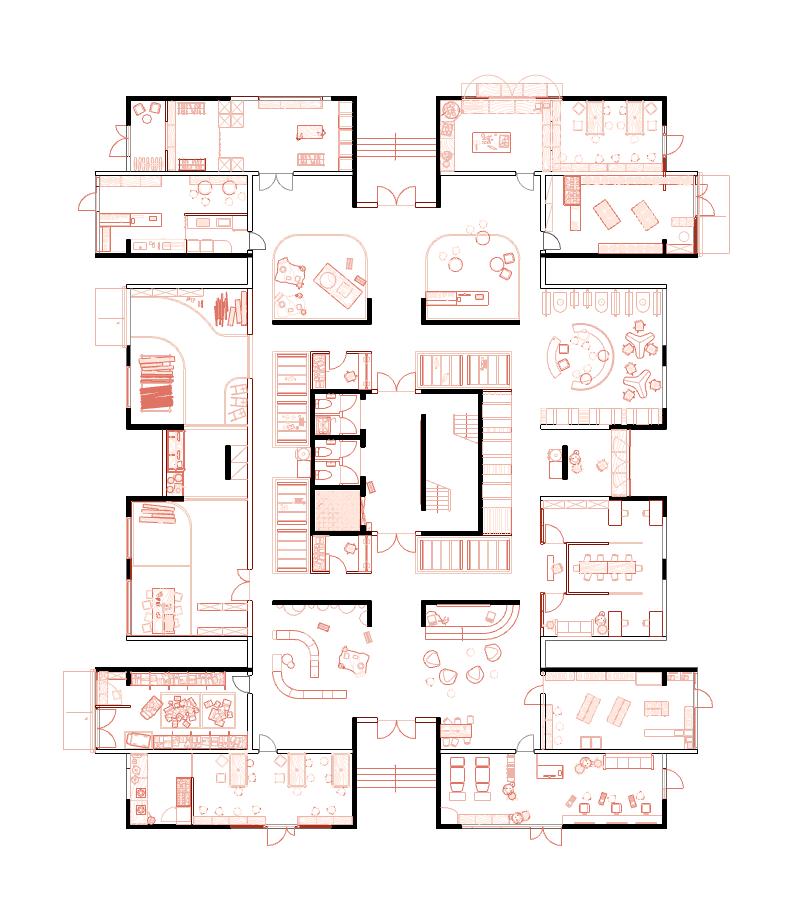

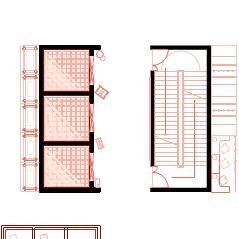

Fig.11 Programme Diagram of Hongshunli Communal Housing, Tianjin, China

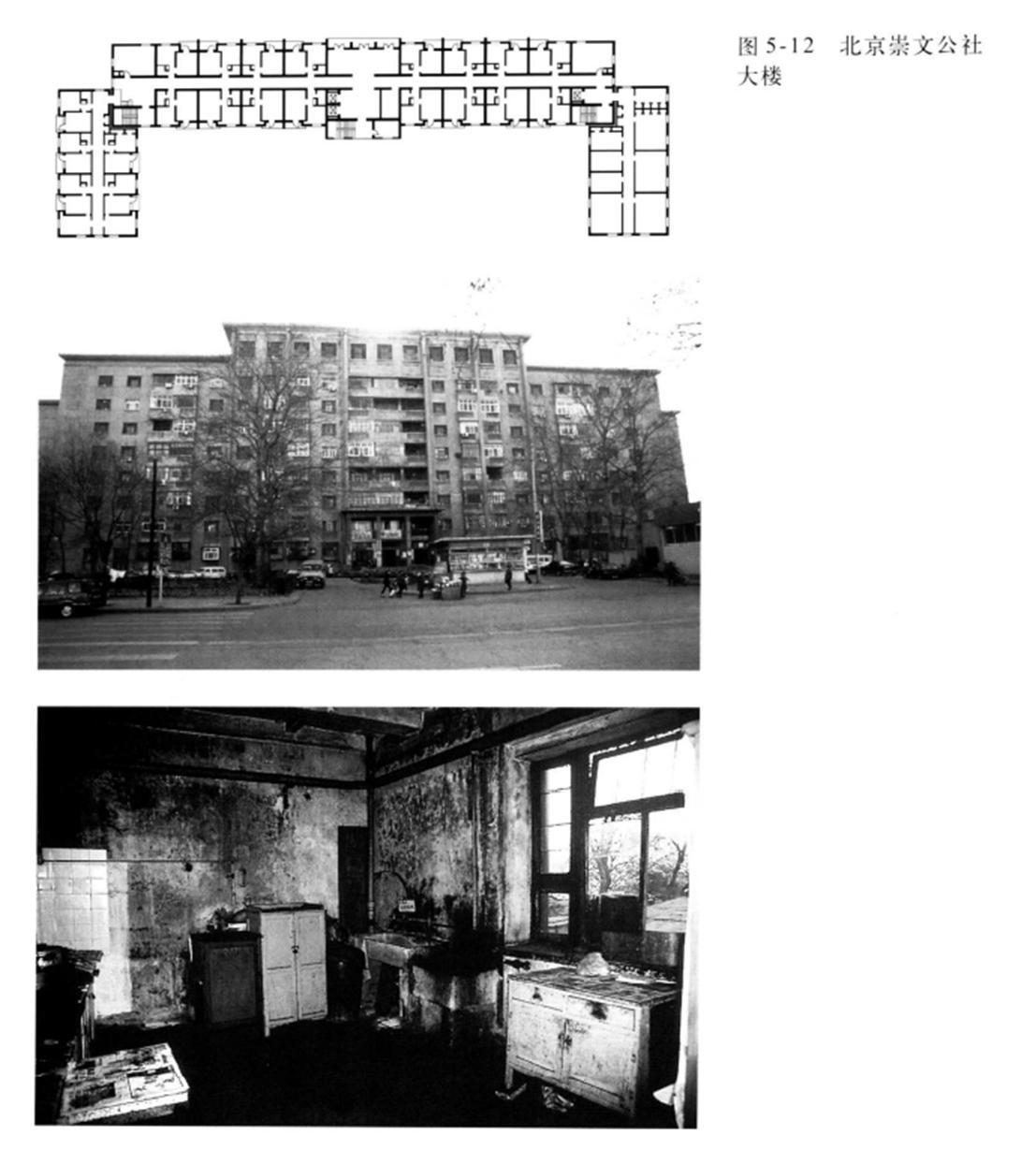

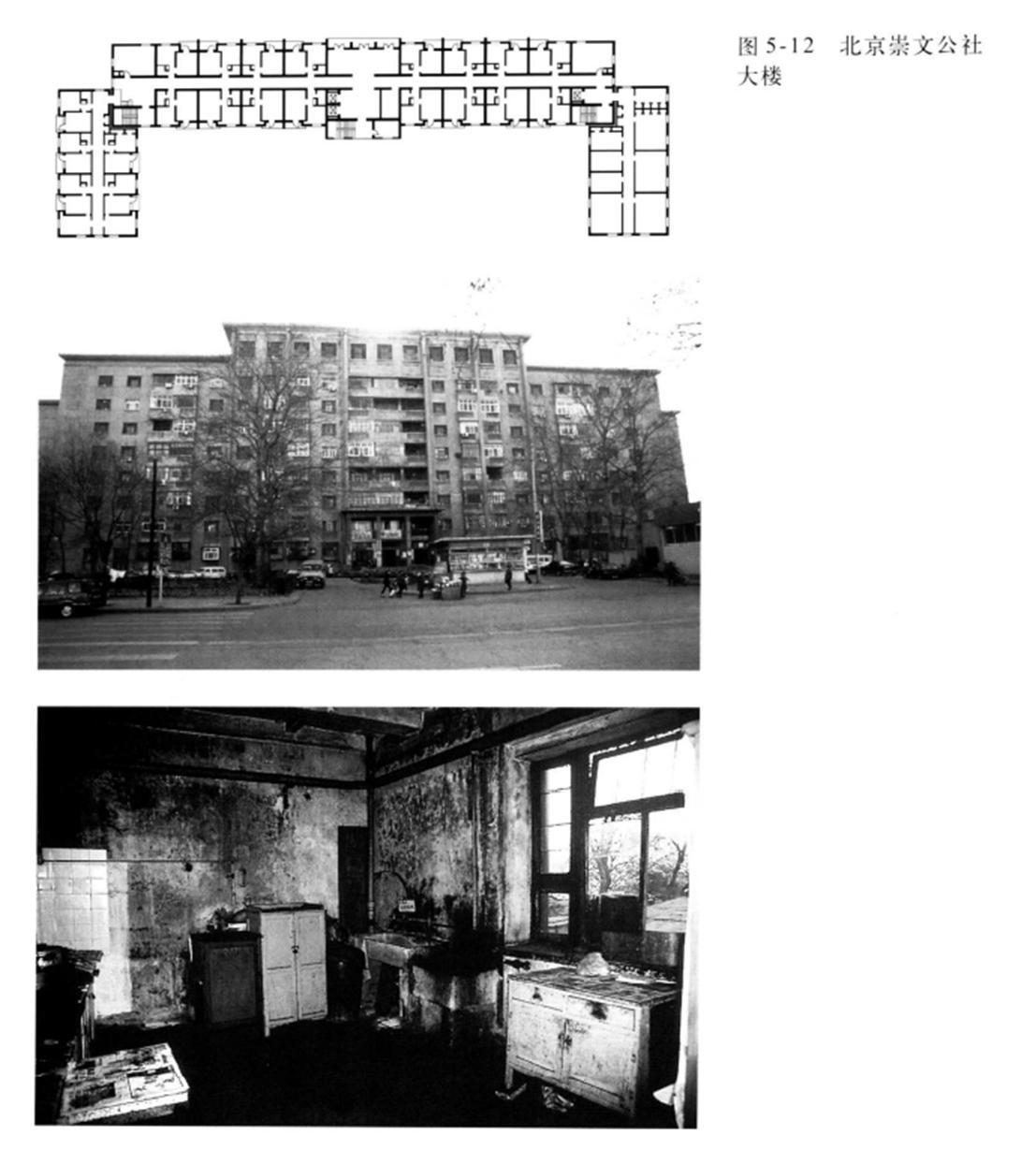

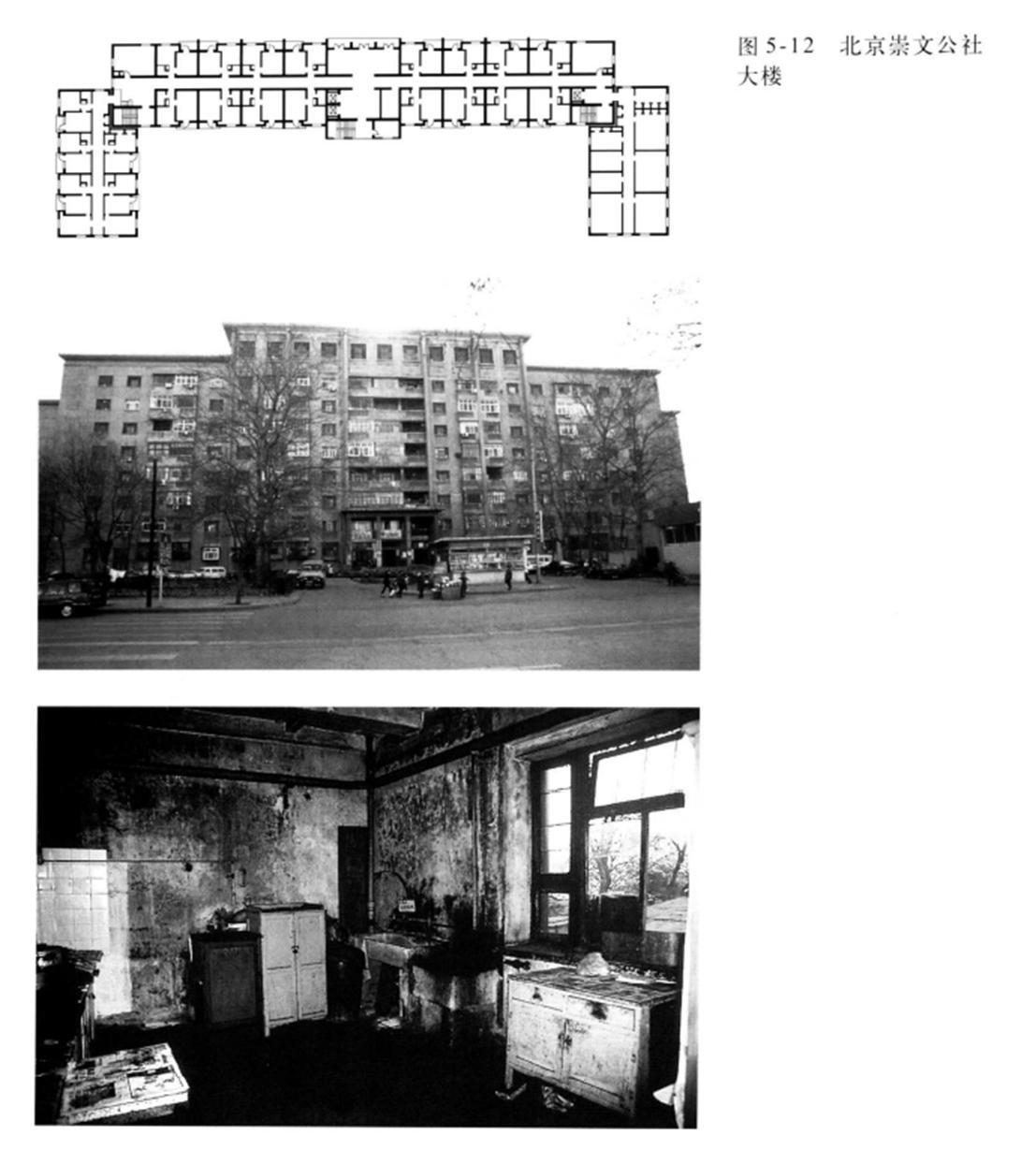

It not only included variations in the design of the functional compounding of living spaces but also proposed a model of economic operation in which residents would raise their own provident funds to pay the workers who provided living services and participated in collective labour. Because of this intensive model of living, it was predicted at the time that it would save nearly half of the living resources such as coal consumption, food and water on a collective basis. Similarly, other city communal housing in Beijing like Chongwen Housing were designed with the same spatial structure.

It is noteworthy that in these two spatial plans there are some ideas that were ahead of their time, such as the rejection of strict urban division, the emancipation of women and the socialisation of domestic work. Such spatial imaginings lacked practical experience and rationality in terms of material operations at the time, and some scholars have argued that they cannot be regarded as advanced and rational. However, it still offered the imagination of a place for collective living, where mutual activities and solidarity had the potential to construct a higher level of collective living than that of individual subsistence when productivity was lacking and material goods were scarce.

Fig.12 Ground Floor of Chongwen Communal Housing, Beijing, China

Fig.13 Photography of Chongwen Communal Housing's Facade, Beijing, China

Fig.14 Photography of Chongwen Communal Housing's Interior Space, Beijing, China

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 8

Source: Junhua Li, "Modern Urban Housing in CHina 1840-2000", Tsinghua University Press (2002)

It was not until 1961, when China entered a period of economic adjustment after the Great Leap Forward, that academic research and free discussion on housing was organised at the annual meeting of the Chinese Institute of Architecture in December 1963, and it was only from this time onwards that the issues of architectural space and use in relation to housing began to be gradually objectified.

During this period, housing types arose that solved the problem of practical use within the space of the living unit. Firstly, there were spatial measures that addressed the actual physical comfort of the interior, such as the house with patios that solved the problem of ventilation of the kitchen and bathroom spaces in the south (take the example of the Fanguanong in Shanghai).

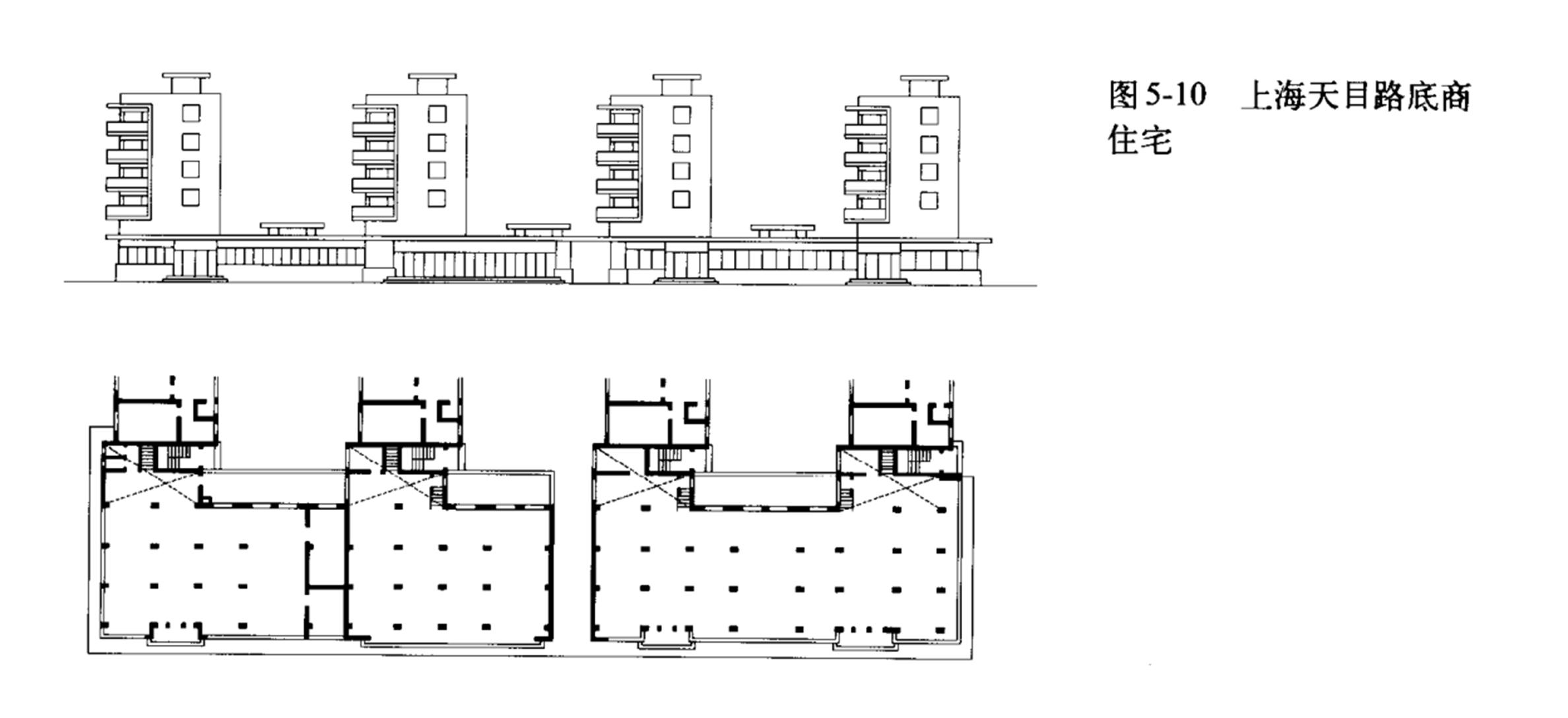

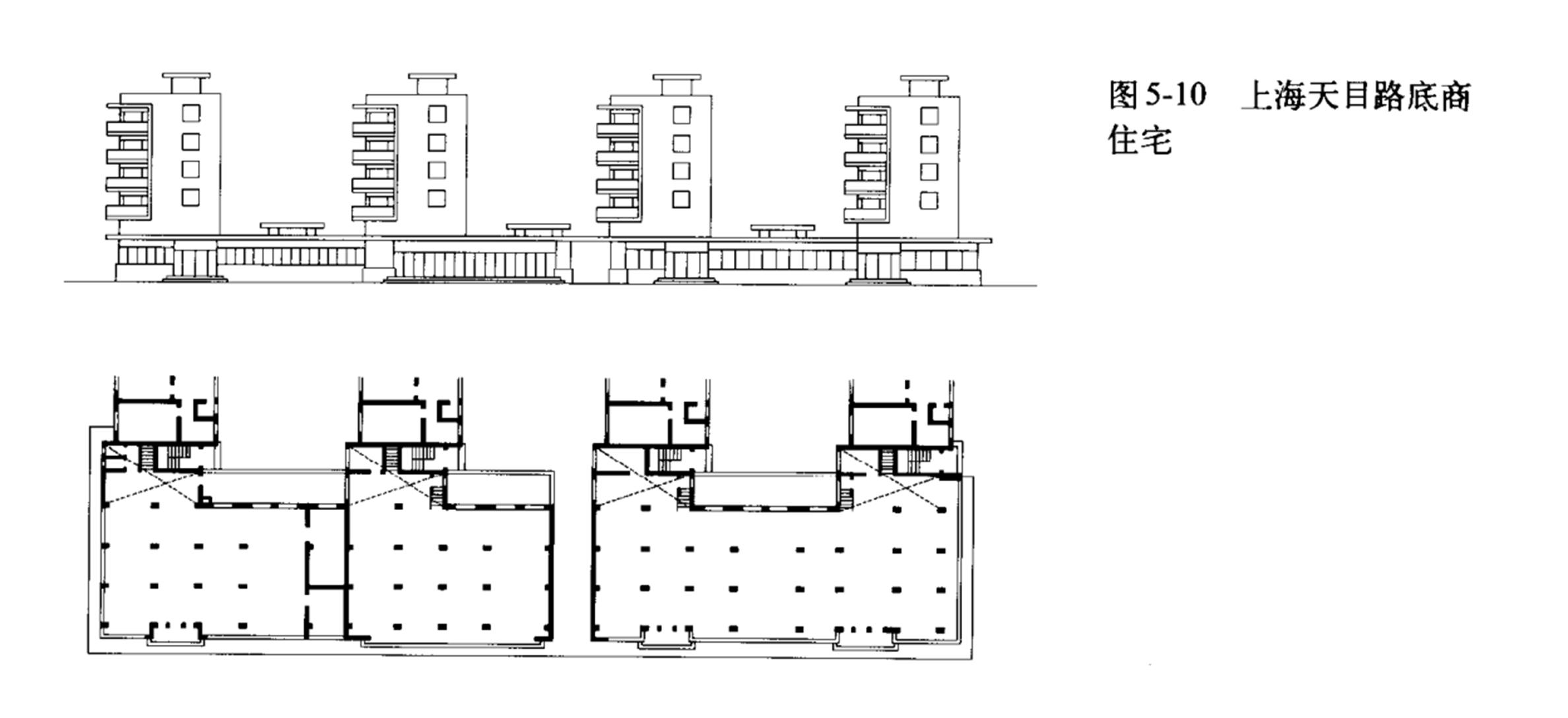

Secondly, the design of residential buildings in this period also gradually began to pay attention to the allocation of space for other service functions other than living, with commercial or service spaces on the ground floor and residential units on the upper floors emerging one after another.

Source: Drawing by the Author

Source: Drawing by the Author

Fig.16

Fig.16 Typical Floor of Fanguanong Housing, Shanghai, China

Fig.15 Photography of Fanguanong Housing, Shanghai, China

Fig.17 Diagram of the Commercial Space of the Tianmulu Housing, Shanghai, China

Introduction 9

Fig.17

Housing during the Cultural Revolution

Stagnation of Expansion & Increase in Urban Density

Source: Drawing by the Author

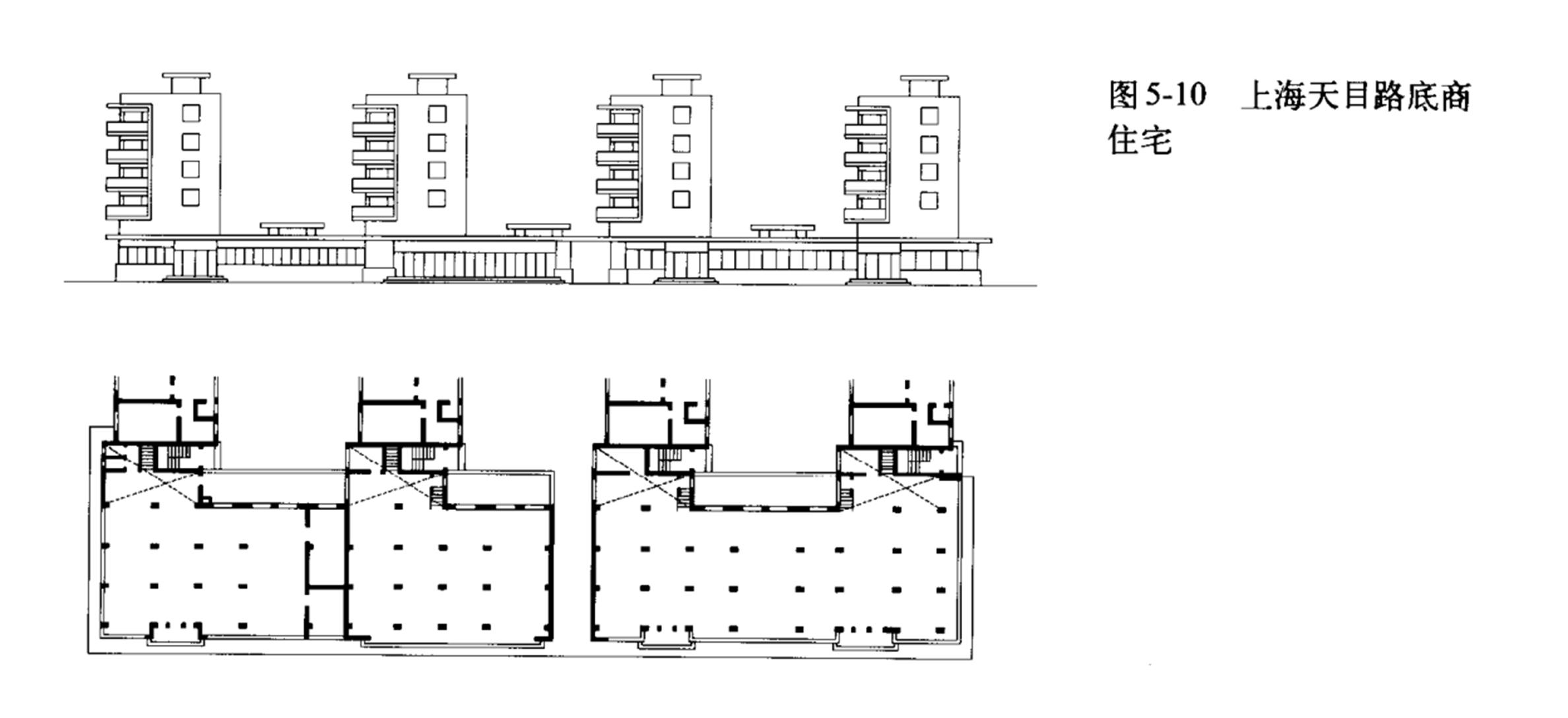

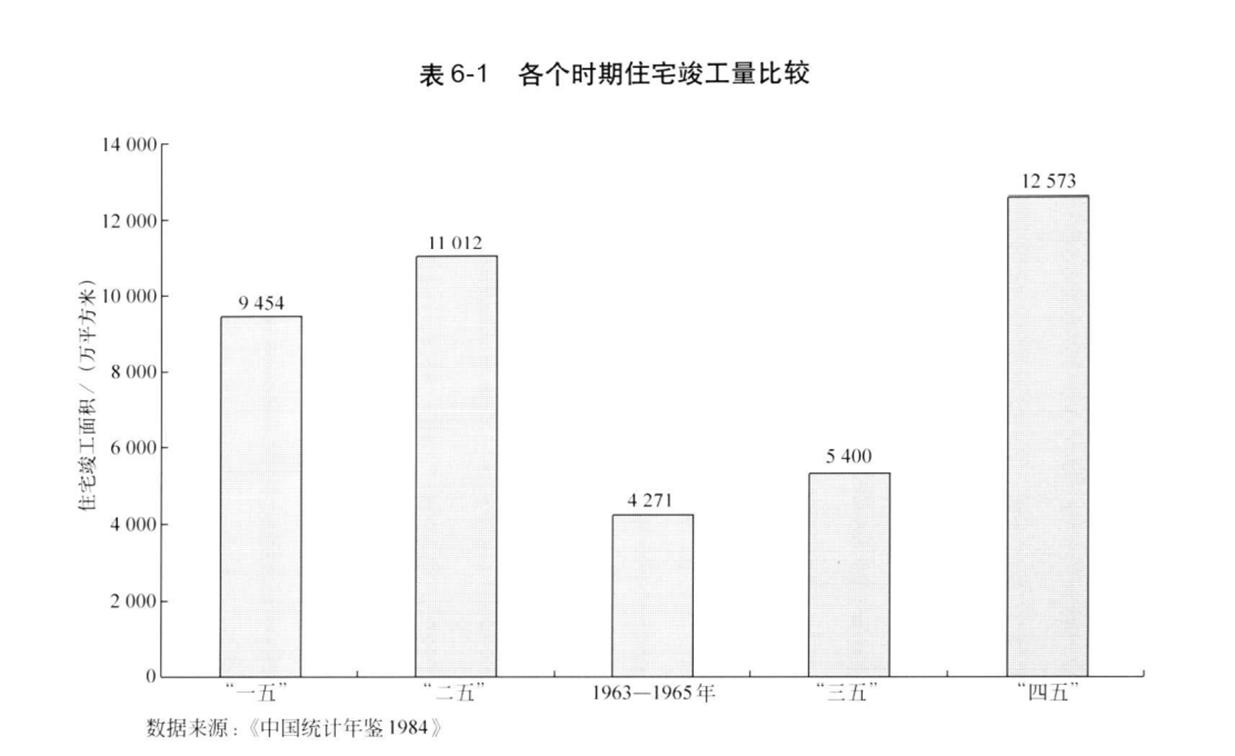

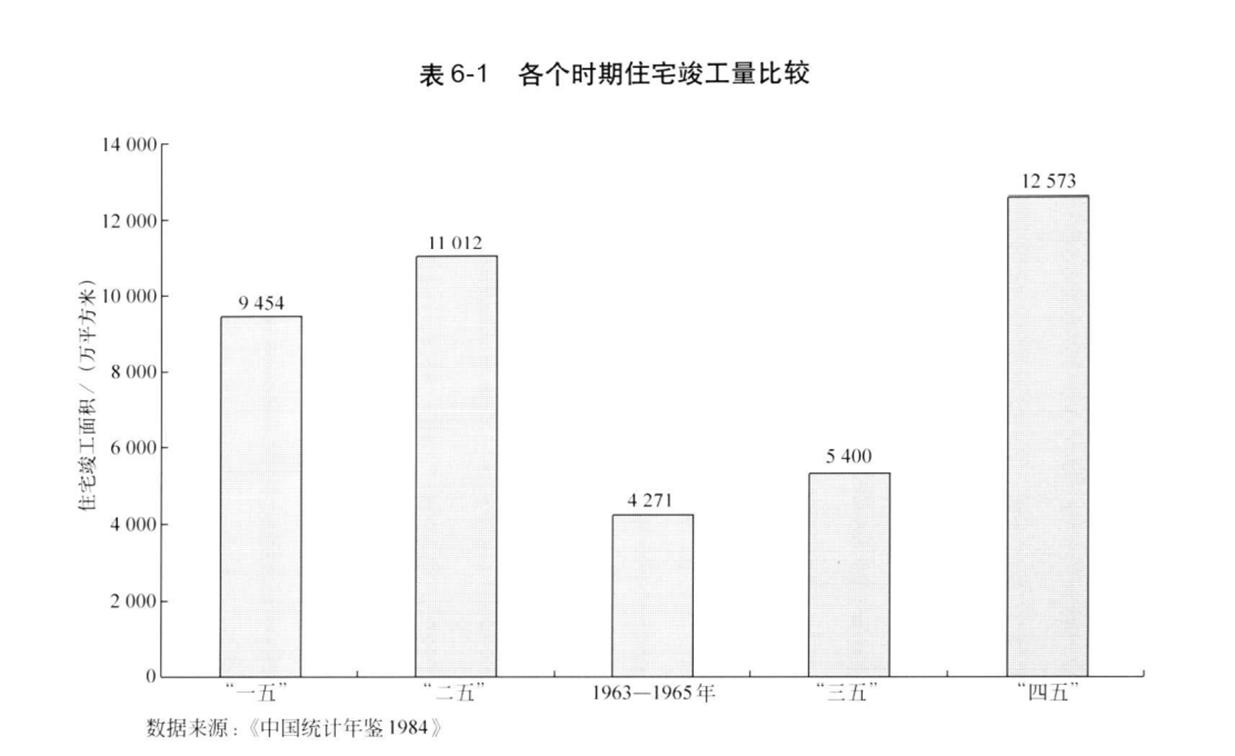

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, the normal order of social productivity and life was disrupted, resulting in the stagnation of residential construction in the cities. The per capita living area had not increased, and the total area of housing built during the Third Five-Year Plan period (19661970) was less than half of that built during the Second Five-Year Plan period (1958-1962).

The housing built during this period was partly an adjustment and enrichment of the original housing; partly an appropriate arrangement in conjunction with the demolition of key projects and the renovation of old houses. In terms of public facilities in the city, very little construction of municipalities, public utilities and public services were launched.

Because of this, the contradiction between urban population and land became increasingly prominent. in the early 1970s, the central leadership put forward the strategy of protecting farmland and developing cities vertically. In densely populated cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, the construction of highrise buildings with higher residential density began. The prerequisite for this type of construction was the development of the housing industry, which was required for the framing and prefabricated light formwork construction methods.

Fig.18 Diagram of the Commercial Space of the Tianmulu Housing, Shanghai, China

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 10

Fig.18

Part II

Present

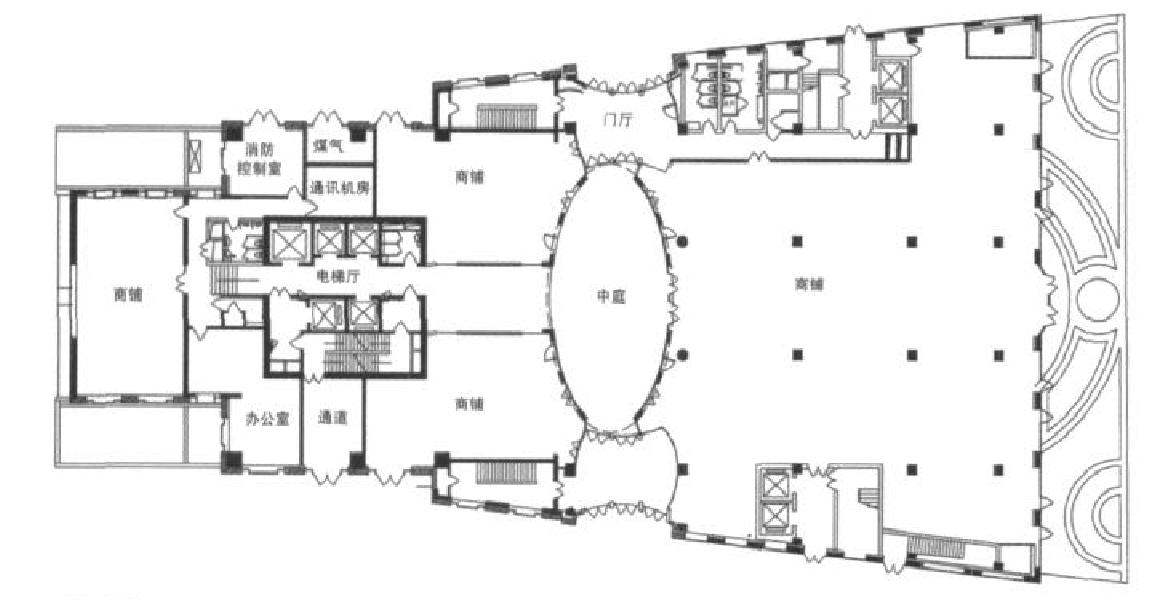

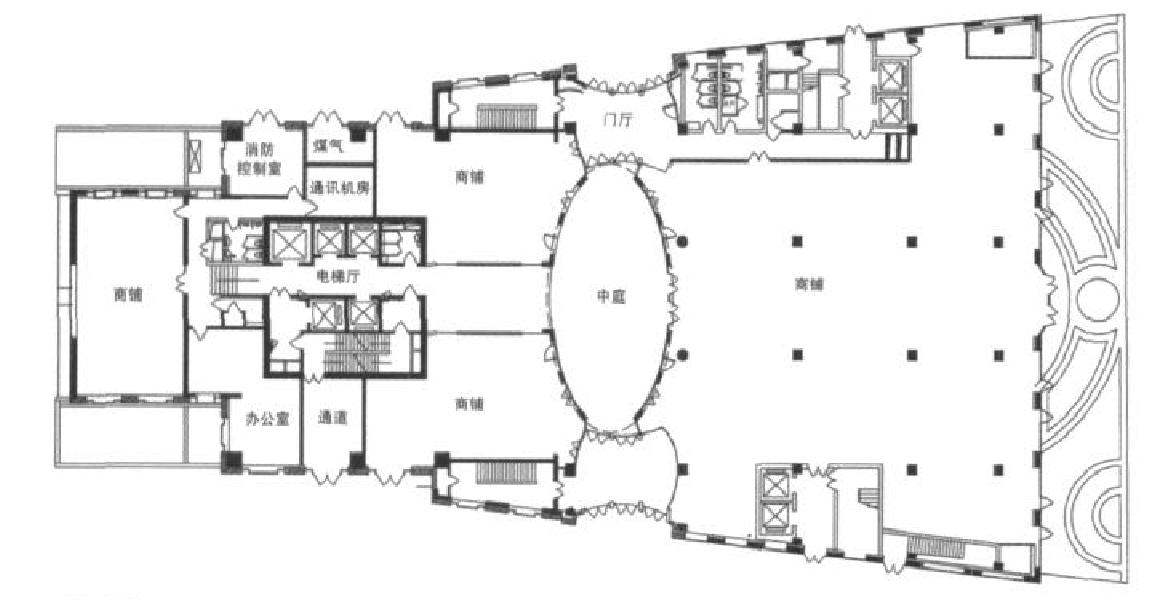

1.2 Commercial housing in Southern China

From 1979 onwards, China entered a phase of sustained and rapid development with Reform and Opening-up as the leading approach. In the 22 years between 1978 and 2000, there was a gradual shift from a planned economy to a market economy and a change in ownership from a single Common Ownership System to the co-existence of multiple economic systems with the Common Ownership System as the mainstay. After the Reform and Opening-up, the reform of urban housing policy completed the transformation from a Welfare Housing System to a Socialised Housing Security System.

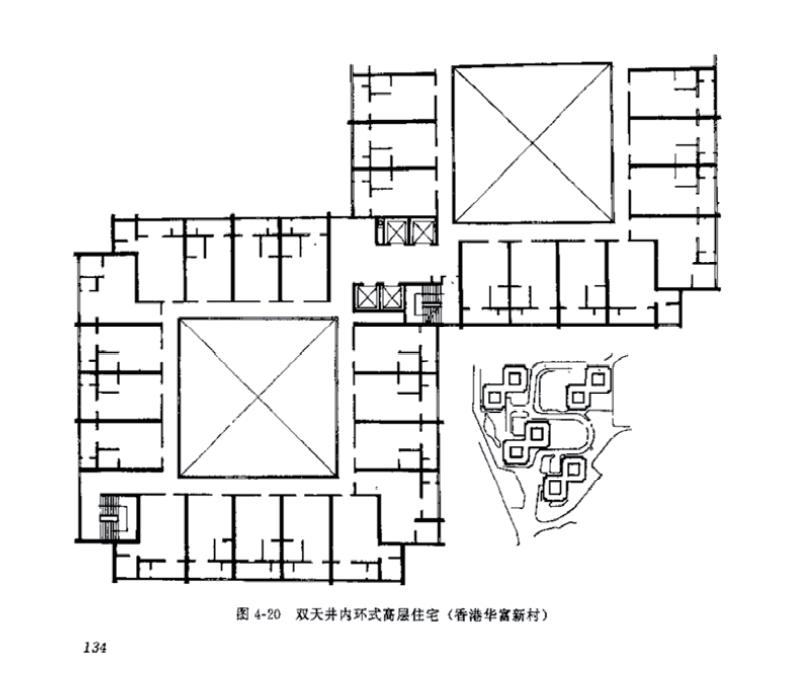

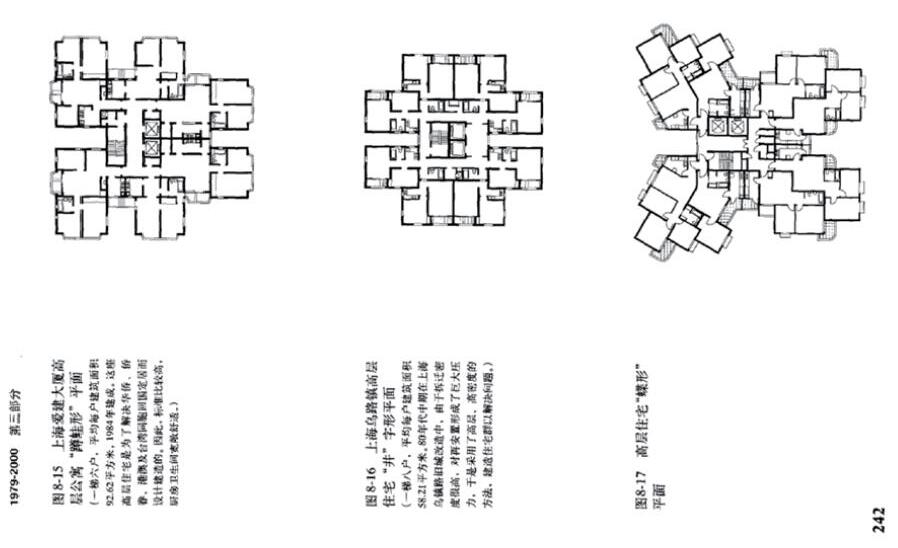

The commercialisation of housing and the implementation of policies for the paid use of urban land had led to a major increase in urbanisation. This has meant that the expansion of the urban population has stretched the urban land for construction which made the situation even worse. As this conflict became more serious, experts and scholars argued about the benefits and drawbacks of building high-rise housing. Scholars, represented by Zhang Kaiji, argued that its low floor-use ratio, high unit cost, high management costs and overall construction were uneconomical, and advocated the construction of multi-storey, high-density housing in cities to alleviate the urban housing shortage1. On the other hand, the productivity level at that time could not well support the construction of a large number of high-rise buildings, which included not only the mature industries of material production, pre-fabrication and processing as well as on-site construction, but also the equipment that high-rise buildings must have, such as electrical equipment2 This can be seen in the opposing views of scholars such as Cheng Nai-kyu in 1981, who argued that the economics of high-rise housing should be measured in terms of the overall economic benefits of urban construction, and that the demand for high-

Introduction 11

1 Zhang Kaiji, "Improved housing design to save land",China, Architectural Journal, (1),1958

2 Zhang Kaiji,, "The multi-storey versus high-rise debate: the debate on building highdensity housing",China, Architectural Journal, (11),1990

rise housing would also demand the development of the productivity of the related equipment industries, which could certainly be addressed. In the practice of construction, high-rise housing has developed rapidly because of its advantages in terms of land saving. Until the mid-1980s, the proportion of highrise housing in residential construction in Beijing increased from an initial 10% to over 45%. This is a substantial increase from the total of 416 high-rise buildings built nationwide before 1981.

It was not until 1986 that China's residential construction began an era of concern for the improvement of the quality of living within households. 1985-1986, before the Second Land Reform, a nationwide housing census was carried out, and there were still a large number of shareduse conditions among the 39.77 million urban households that were surveyed. In this period, there were a total of 9.662 million complete sets of housing in urban housing, only 24.29% of the total. For instance, 62.56% of all houses had kitchens for exclusive use, 6.48% shared kitchens and the rest built their own or used temporary kitchens added in building corridors. This has led to progressively clearer standards for the requirements of the housing sector in the new era, in terms of the functionality and comfort of living inside the dwelling, and the construction of infrastructure in it, as well as the site formation and utilisation.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 12

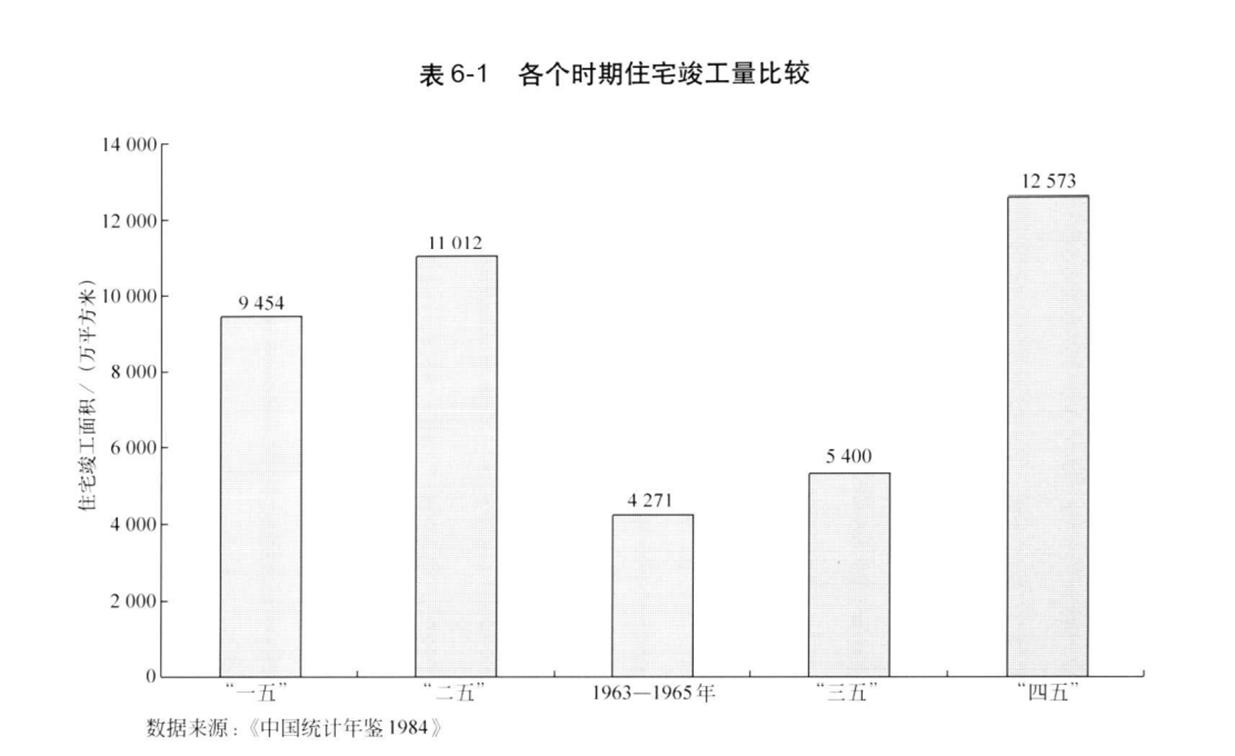

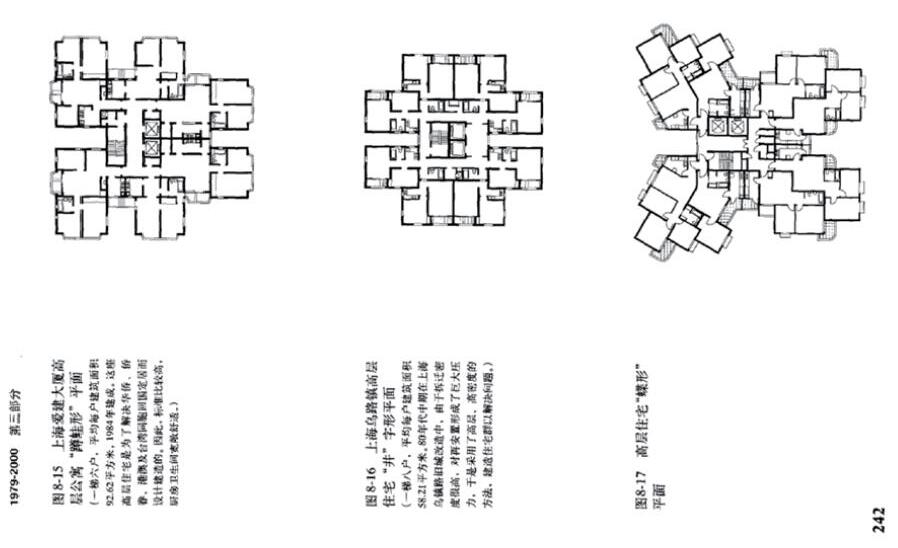

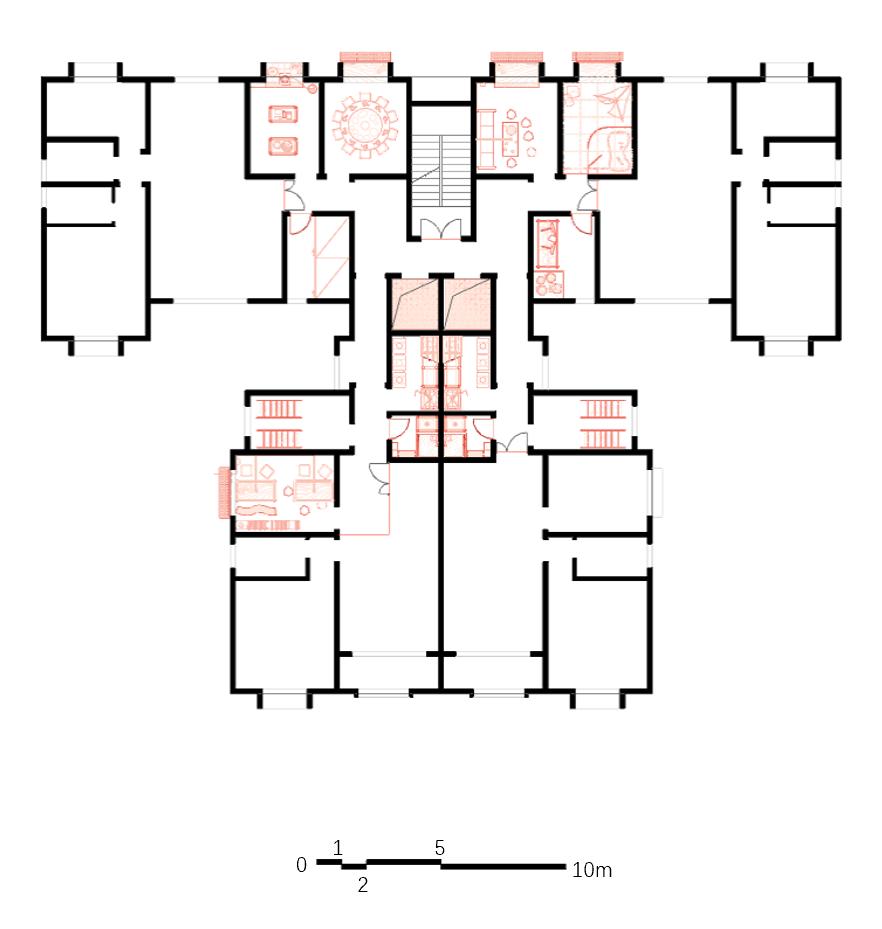

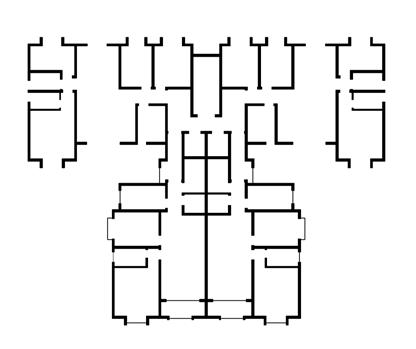

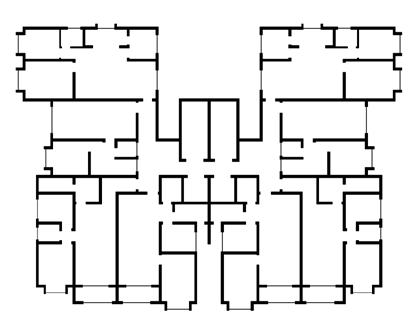

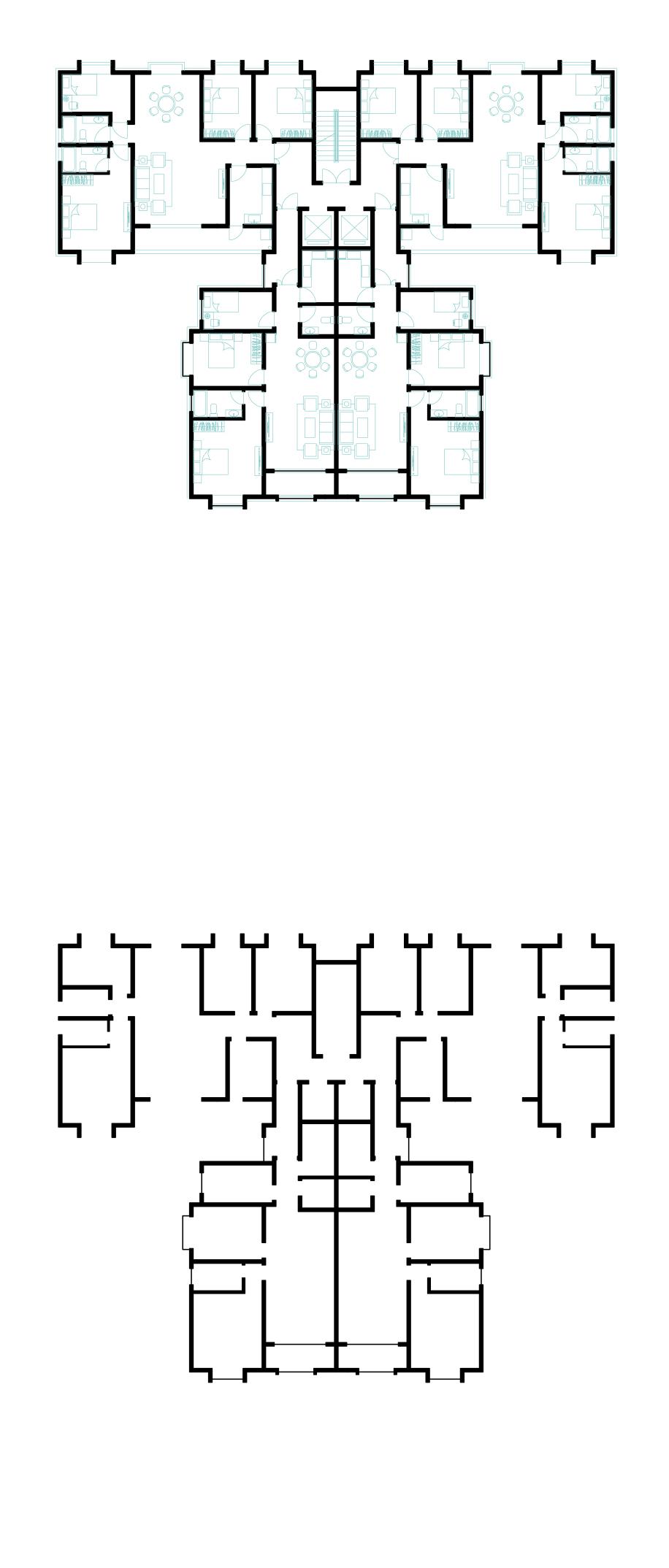

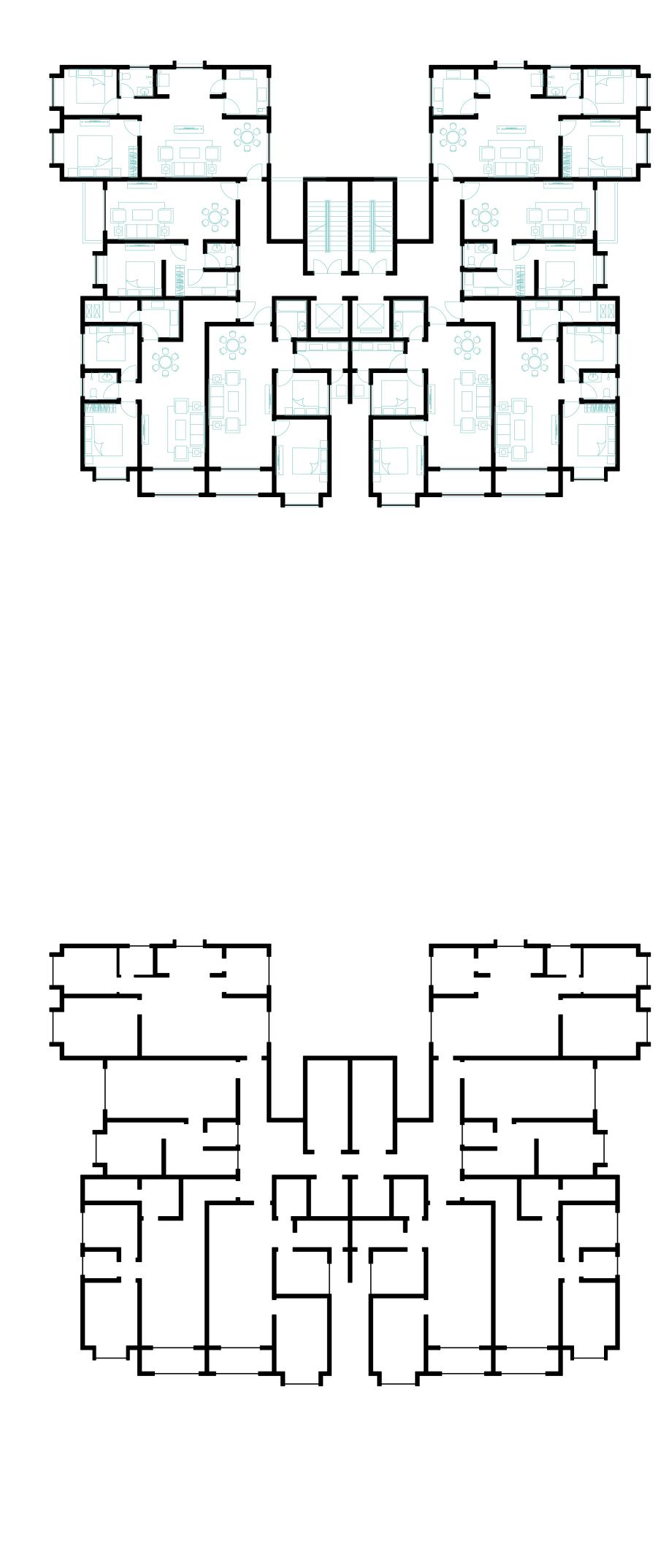

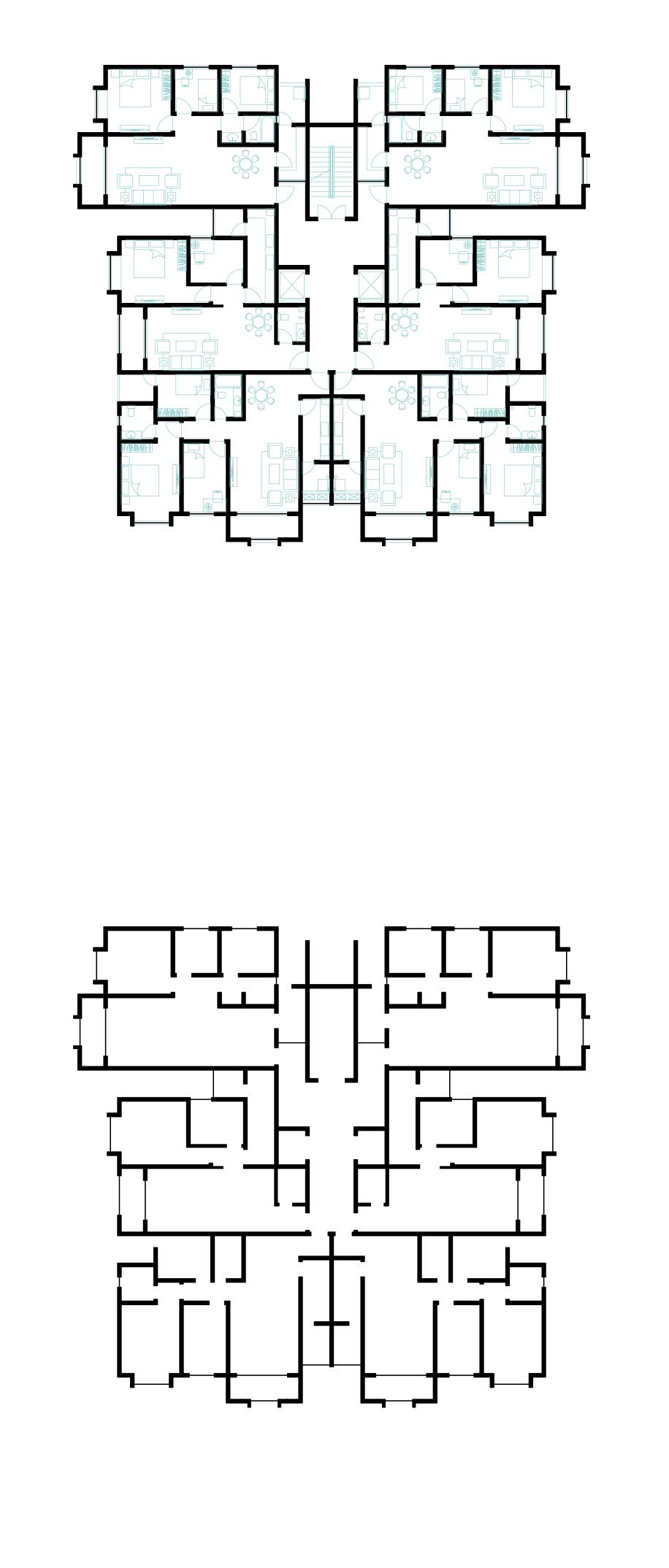

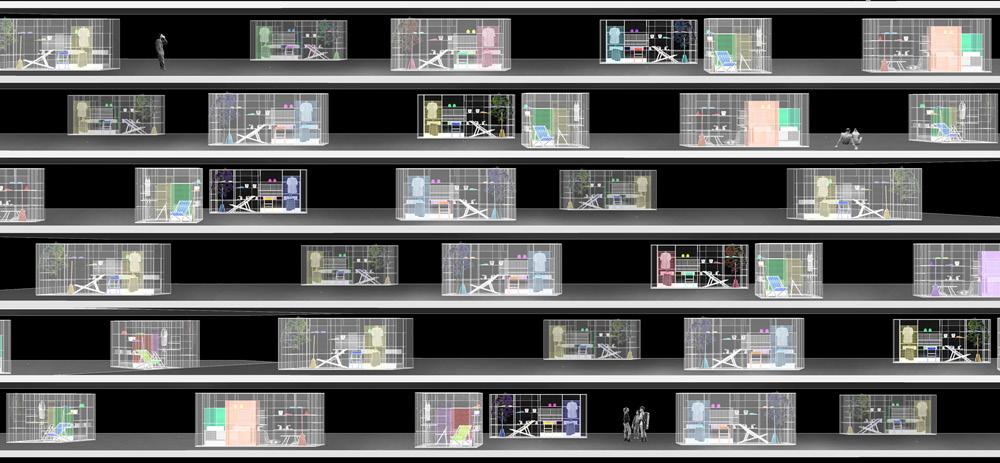

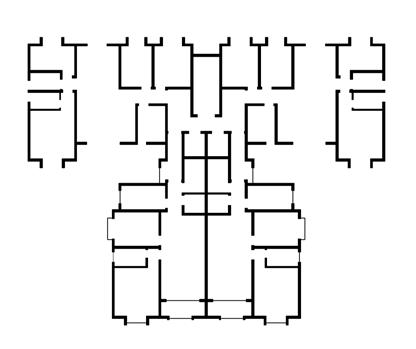

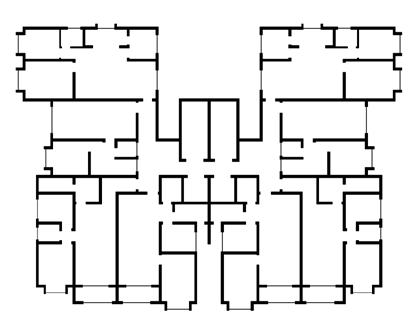

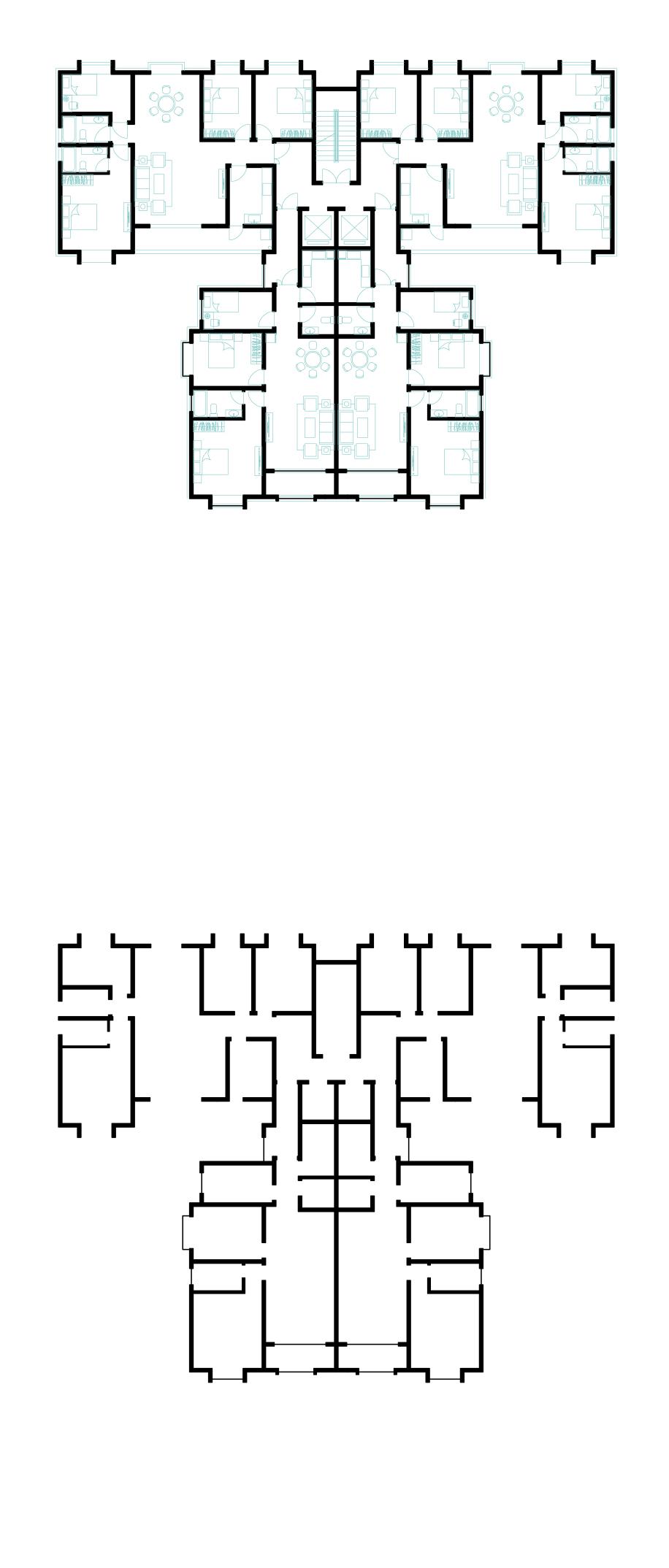

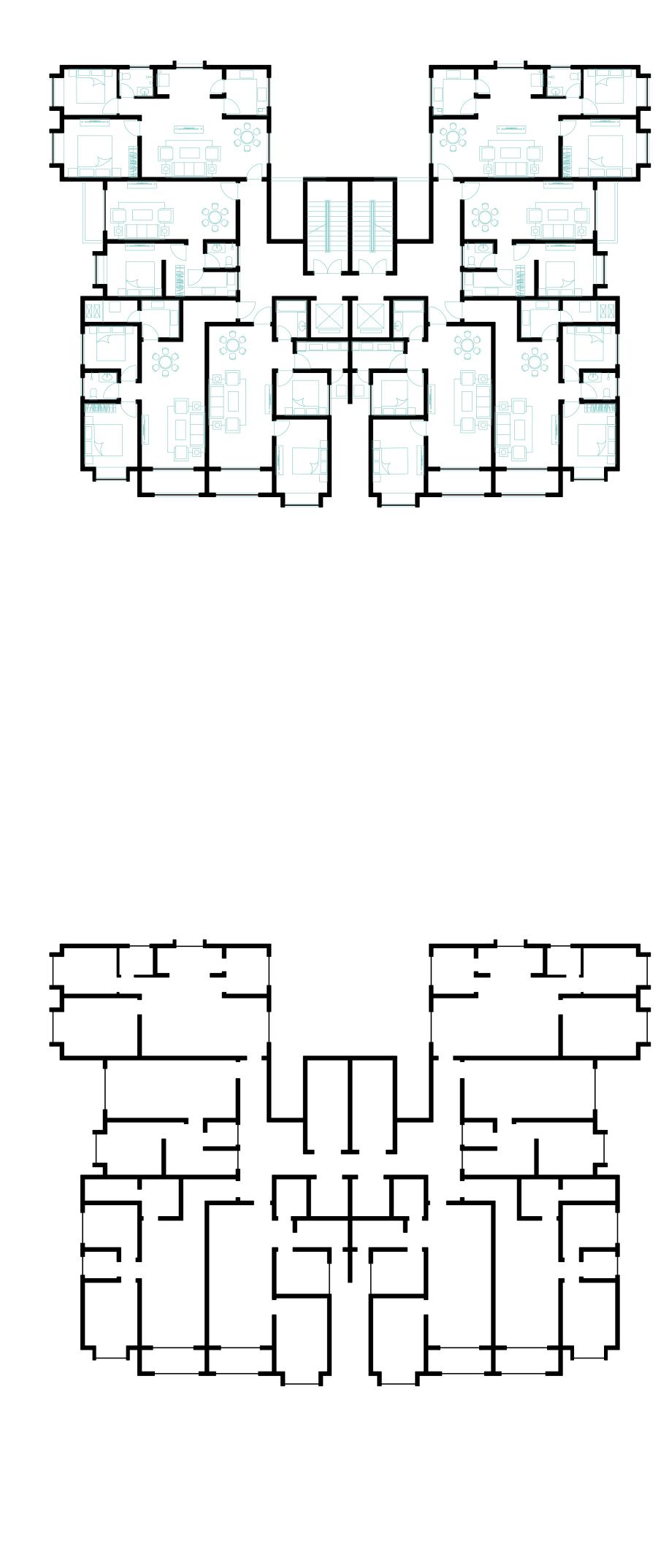

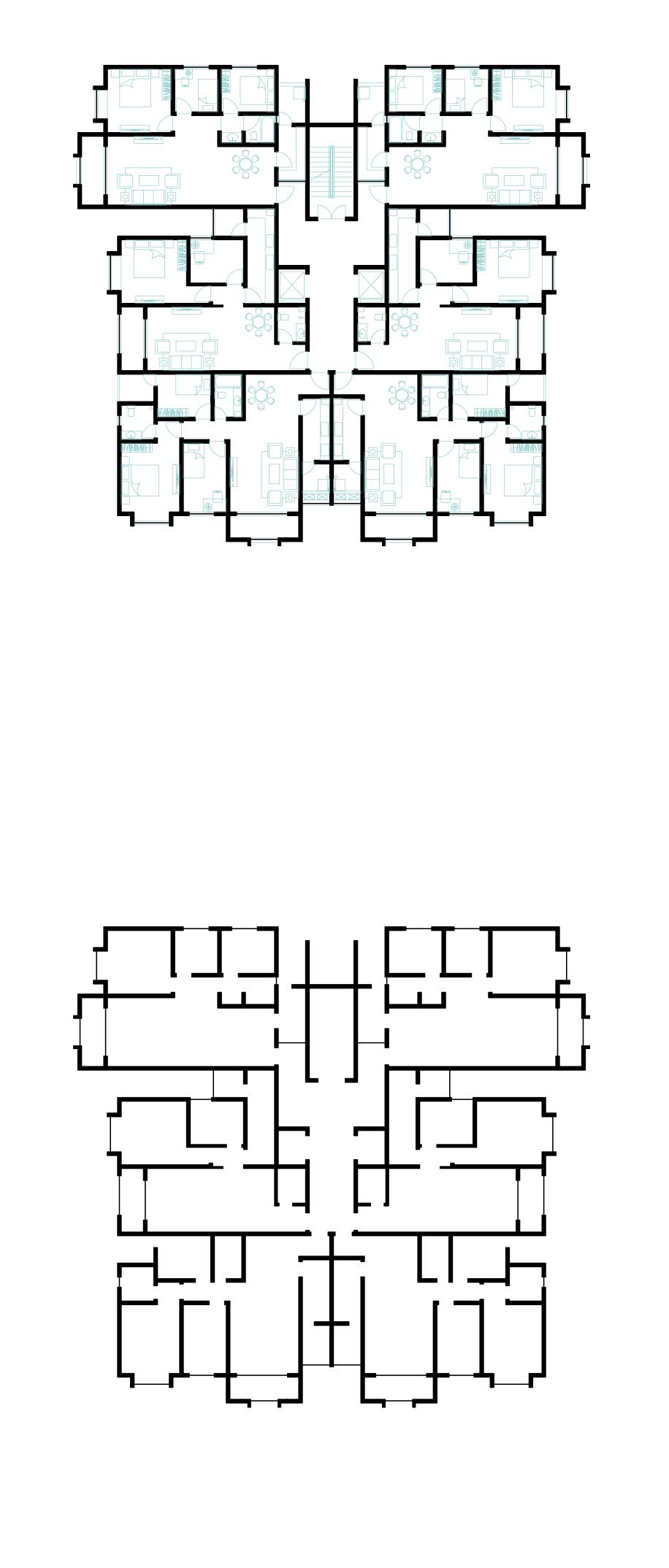

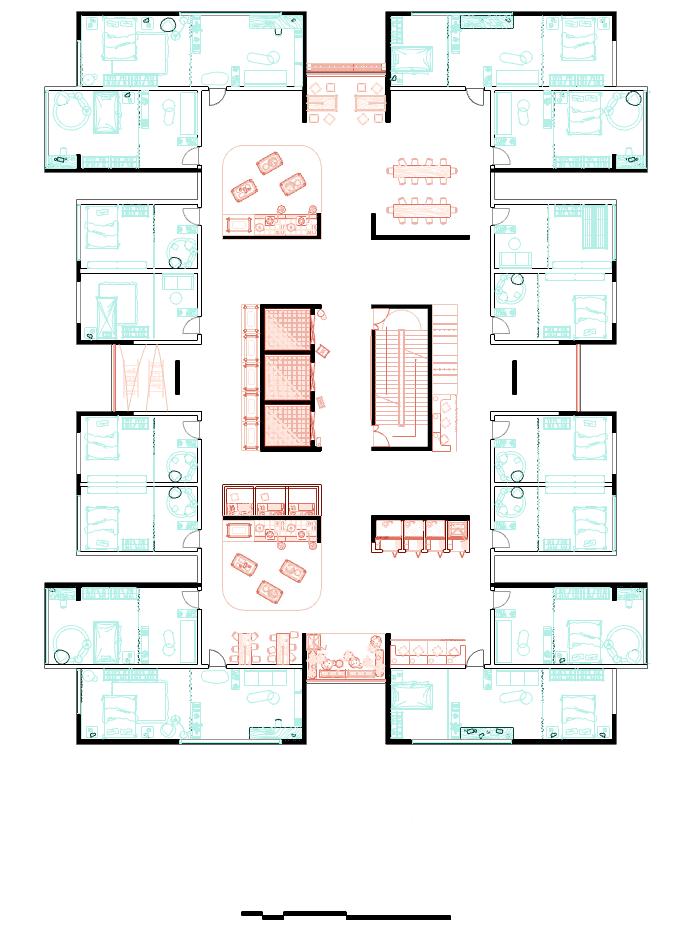

On this basis, as the construction of high-rise housing continued, the flexibility of the plan gradually emerged, resulting in a variety of different forms of standard floor plans in the form of units combination, promenades and towers1

It is worth mentioning that after decades of development, residential construction in China has moved from singularity to diversity, from the goal of relief to the pursuit of comfort, with the compounding of functions and an increase in the area within individual residential units, and the setting up of shared other functional spaces in common areas resulting in a waste of space. But in contrast to this, on the other hand, due to the commercial nature of commercial housing, in order to maximise and rationalise the privatisation and sale of space within residential buildings. The vast majority of consumer-oriented commercial housing tends to centralise public transport space (both vertical and horizontal) in order to save construction costs and increase the size of the living units2. While this improves the quality of living, it also results in the loss of communal space and shared functions within the standard floor (i.e. the residential floor) plan of current commercial housing.

1 Zhu Changlian, Residential building Design Principles, 2nd Edition, Chongqing University Press, P. 137

2 Renjun Hu, "Residential building Design and Principles", China Architecture & Building Press, (2007) p. 237

13

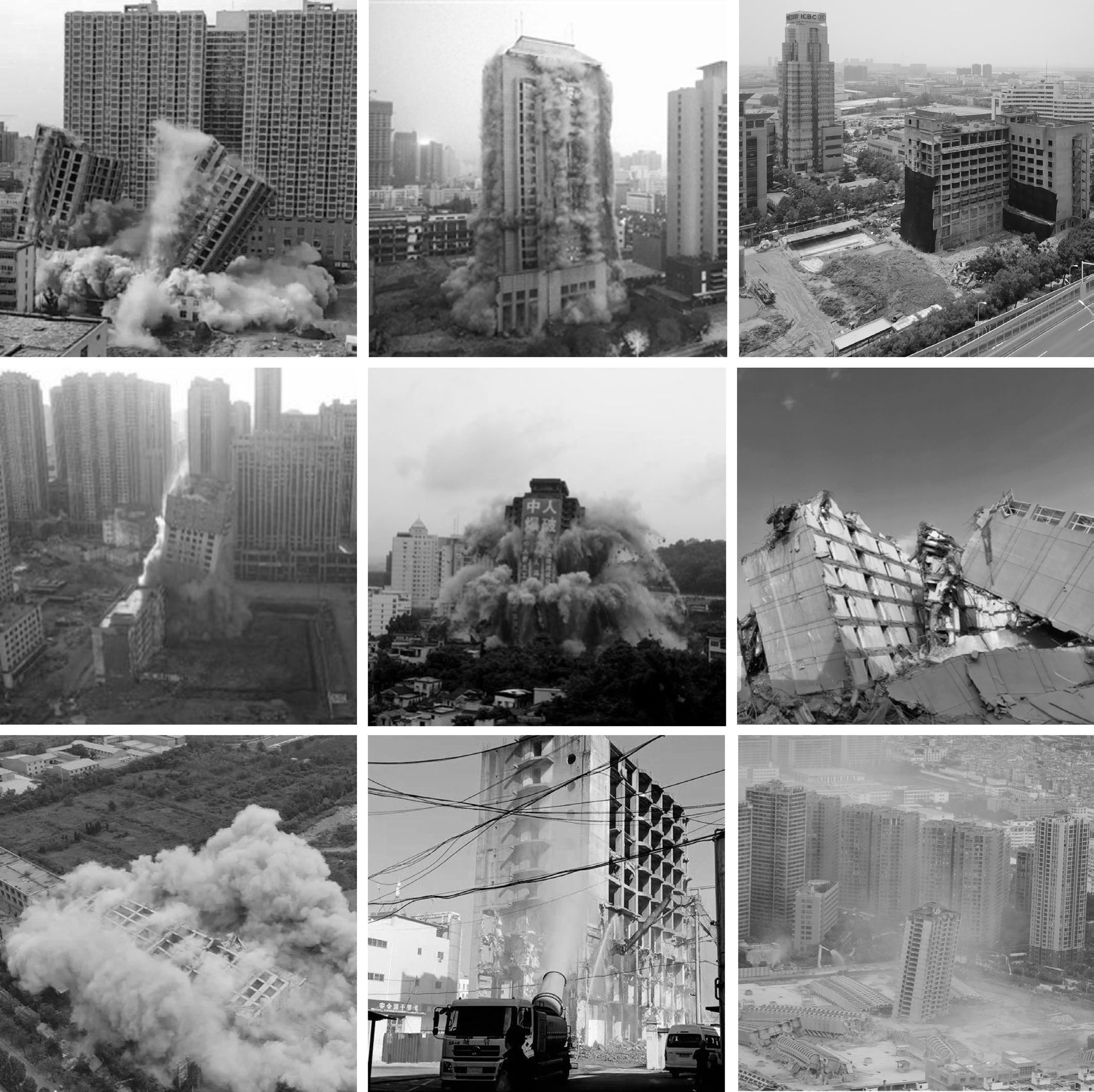

1.3 Left Unfinished Commercial Housing

The term "Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing" refers to real estate projects that have undergone land use and planning procedures, but have been halted for more than a year after a lack of investment and construction due to a break in construction funds, judicial disputes involving the project, or irregularities in construction by the developer, and also includes real estate projects that have been completed but the project quality is not up to standard and cannot pass the completion inspection, or the supporting facilities such as water, electricity and transportation are incomplete1

Source: Compiled by the author base on sources from Baidu Map

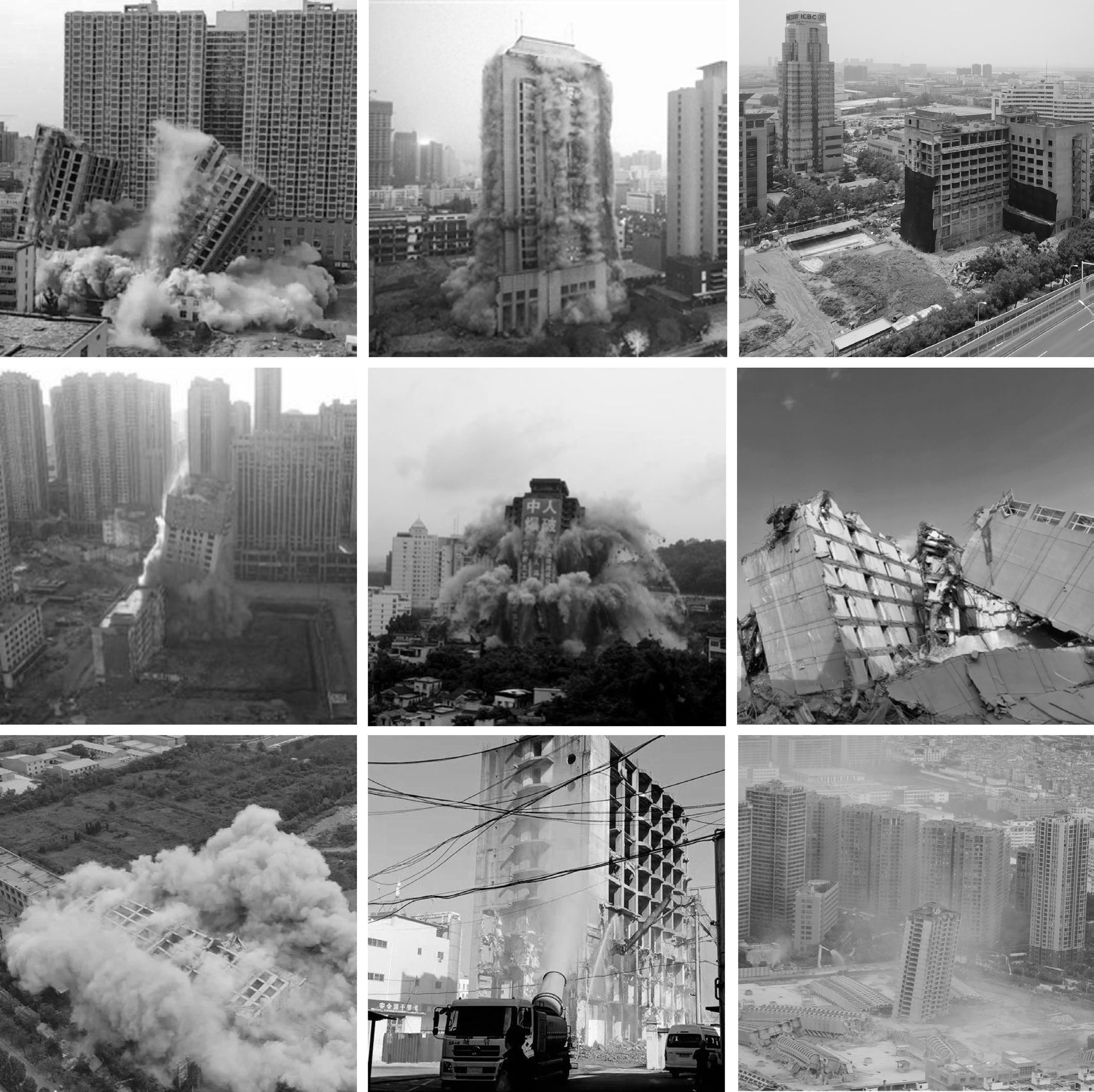

Fig.20 Photographs of the demolishment of left-unfinished commercial housing , China.

Fig.20 Photographs of the demolishment of left-unfinished commercial housing , China.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 14

Fig.20

1 Junman Li, "The research for the Renovation design of Unfinished Building based on the perspective of Urban Design", JiLin Jianzhu University, (2016) p. 12

The whole process of developing residential buildings involves regulation and supervision by government departments, asset institutions such as banks, development and construction companies, etc. The whole development process is procedurally complicated and time-consuming. All of these uncertainties could lead to Left-Unfinished Commercial Houses.

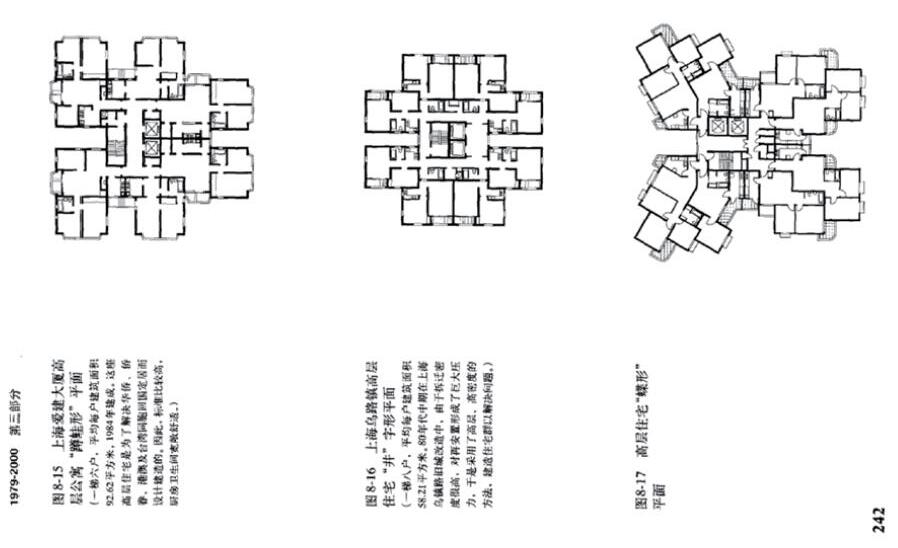

Additionally , main reason for this was policy and management. Cities in China faced a housing shortage in the new wave of urbanisation after the Reform and Opening-up.To stimulate the vitality of urban land development and construction, “Measures for the Administration of Pre-sale of Urban Commercial Housing” were proposed in 1995, only one year after the openness of the free market of commercial housing in China. The Measures relaxed the requirements of the saleflow of the commercial housing, which allows the developers to sell the houses to purchasers even before the buildings were partly built2.

Such a pre-sale system and sales process, while emphasizing the commodity nature of commercial housing, neglects the establishment of regulatory mechanisms on the long cycle of development and construction. In other words, problems with funding, qualifications, regulation and approval at any one of these points in the long development cycle can lead to problems with rotten developments.

From the perspective of government departments, the development of real estate means a large amount of remunerative land use, expanding employment and increasing local fiscal tax revenue. The government sector's over-reliance on real estate to drive economic development had led to the blind introduction of foreign investment, backroom deals and lax supervision in the approval of land sales and development. The poor continuity of urban planning and construction and frequent changes in planning sometimes result in projects not being completed when the planning has already been modified and the projects rotting due to changes in urban functions. On the other hand, the

Reasons for the arising and longterm persistence of the problem

2 Ran Tan,"Causes of rotten buildings and preventive measures", EconomyManagement- Overview, China, (1)2018

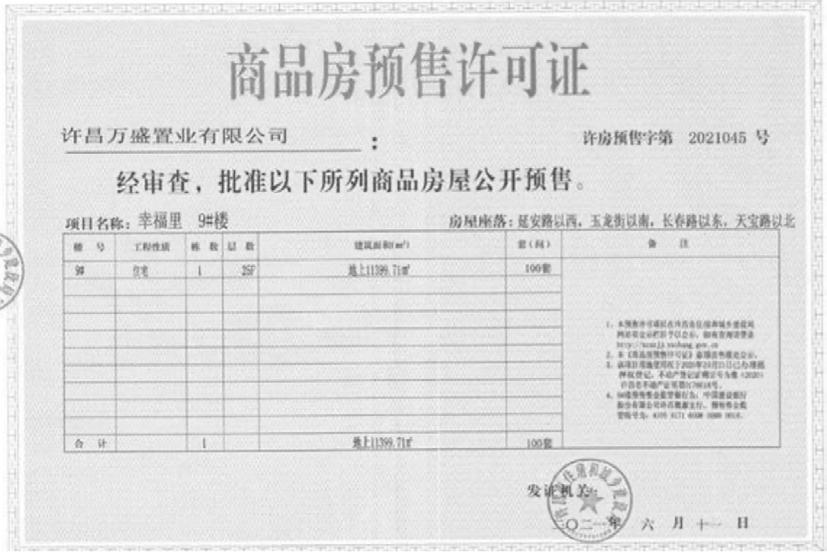

Fig.21 Scanning of Pre-sale Permit for Commercial Housing (Sample), China, 2006

Source: Ministry of Housing an UrbanRural Development of the People's Republic of China,"Notice on further rectifying and regulating the order of real estate transactions" (2006)

Introduction 15

Fig.21

irregularities in the management mechanism of the real estate market, the lagging and immaturity of urban planning, and the low threshold of access to urban land development had led to chaotic market order as well as insufficient convergence of relevant policies and regulations, resulting in blind speculative construction by developers. In Kunming city, for example, in 2008, the Kunming government issued a policy document planning to complete the transformation of all 336 urban villages in Kunming within the next five years. This planning decision, which was much more policy-oriented than practical, was called a city-making campaign by the municipal government, and under the influence of this decision, a large number of local small and medium-sized development enterprises invested in real estate development, which, coupled with the lax financial supervision and the impact of the global economic crisis, resulted in a large number of properties are left-unfinished, leaving the number of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing in Kunming to 112 in the 2022 statistics, affecting at least 100,000 home buyers who were caught in a situation where the construction of their purchased houses was halted and they were not able to move in as scheduled.

In terms of market regulation and economic policy, the establishment of the socialist market economy theory in the early 1990s led to unprecedented growth in the real estate industry, but institutional inadequacies caused the phenomenon of a bubble economy, which was only stabilised again through governance and consolidation. For example, after the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the collapse of the market economy bubble, a large number of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing appeared in several cities in China. This included the Shanghai World Financial Centre, a 101-storey, 492-metrehigh building with a total investment of over US$1 billion, which was also affected by the financial crisis and construction was halted until 2005 when work resumed and was completed in 2008.

From the perspective of capital investment and regulation in the development and construction

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 16

of commercial housing, the problem of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing can be seen. After the Asian financial crisis, the state put forward the economic strategy of "Making the housing industry a new hotspot of consumption and economic growth", hoping to boost economic growth through residential consumption, and intensified its housing policy reform. They even set a deadline for the elimination of welfare housing by the year 2000. As a result, China saw the second boom in commercial residential construction in its market economy. Real estate financing in China, under the influence of the pre-sale system, mainly came from three components: bank loans, corporate self-financing and house pre-sales. Most of which were in turn personal housing loans granted by banks to buyers, so more than half of the funds for real estate development originated from bank loans. The single source of financing, resulting in national macrocontrol or credit contraction due to the financial crisis, can cause operational risks to real estate development enterprises.

Violations in the process of development, construction and sales from a company may also lead to Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing. From the perspective of the development company's own management problems: the developer's inaccurate market targeting of investors, or the long term development of real estate and significant market changes during the development process, leading to deviations in project positioning, which could dim sales prospects for the product, and investors might change their direction of investment and abandoning investment in the construction of the project, these all can lead to project failure. Developers engaged in fake mortgages and misappropriation of construction funds, resulting in a broken chain of construction funds at a later stage, which can also lead to the project being halted. There were also some property developments that were left-unfinished because the real estate developers ignore the approval requirements for illegal construction, which caused the project to be ordered to stop as it did not comply with the urban planning and related construction requirements. In

Introduction 17

addition, from the point of view of the responsibilities of the construction unit, the quality of the project was not up to standard causing land, planning, construction and other related procedures to fail to pass the approval; the developer sold single houses for multiple times, repeated mortgages, etc. so that the property's rights were in constant dispute, or the project was involved in other judicial disputes resulting in the project being forced to stop work. For example, the Bank of China Building in Wenzhou city, which was under construction for about eight years, was eventually forced to be demolished due to serious quality problems that made it unable to pass the engineering inspections.

In general, there were complicated causes of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing, such as unclear division of authority and responsibility, the huge funding gap caused by problems such as a broken funding chain, all made solving the problem of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing a complex issue and eventually left in an unfinished state in the urban space for a long time to become a new urban problem. When the construction of Left-Unfinished Commercial Houses stops, the structural elements are left exposed in the city, which is extremely incongruous with the surrounding environment and becomes a weak point in the urban landscape which would damage the image of the city. There is a theory in criminal psychology named "Broken windows theory" which states that when the image and quality of the external environment are very poor, the positive factors for improving the quality of the surrounding external environment are lost and crime rates will increase. The presence of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing is often the first 'broken window', becoming a negative urban space where residents lose their sense of identity with their surroundings.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 18

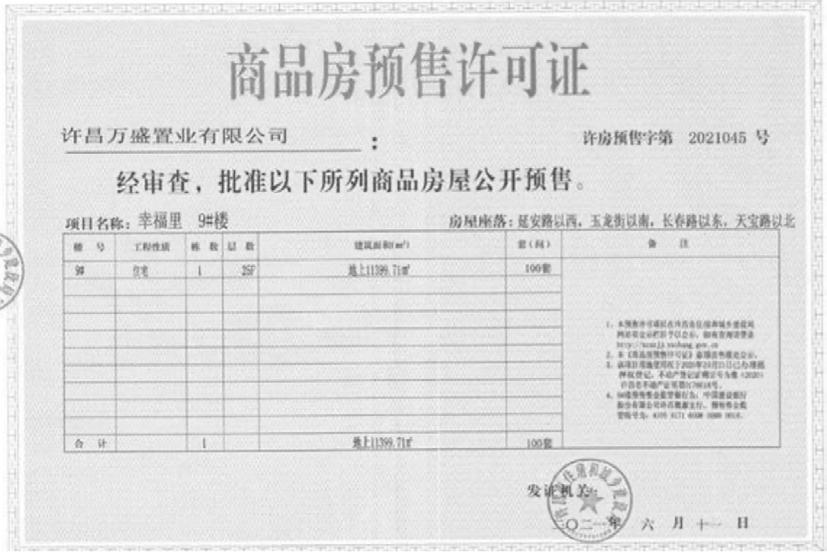

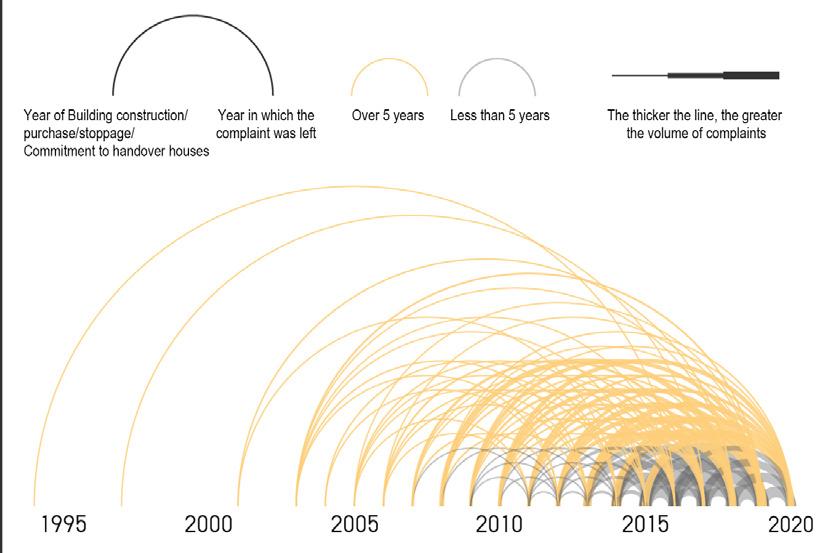

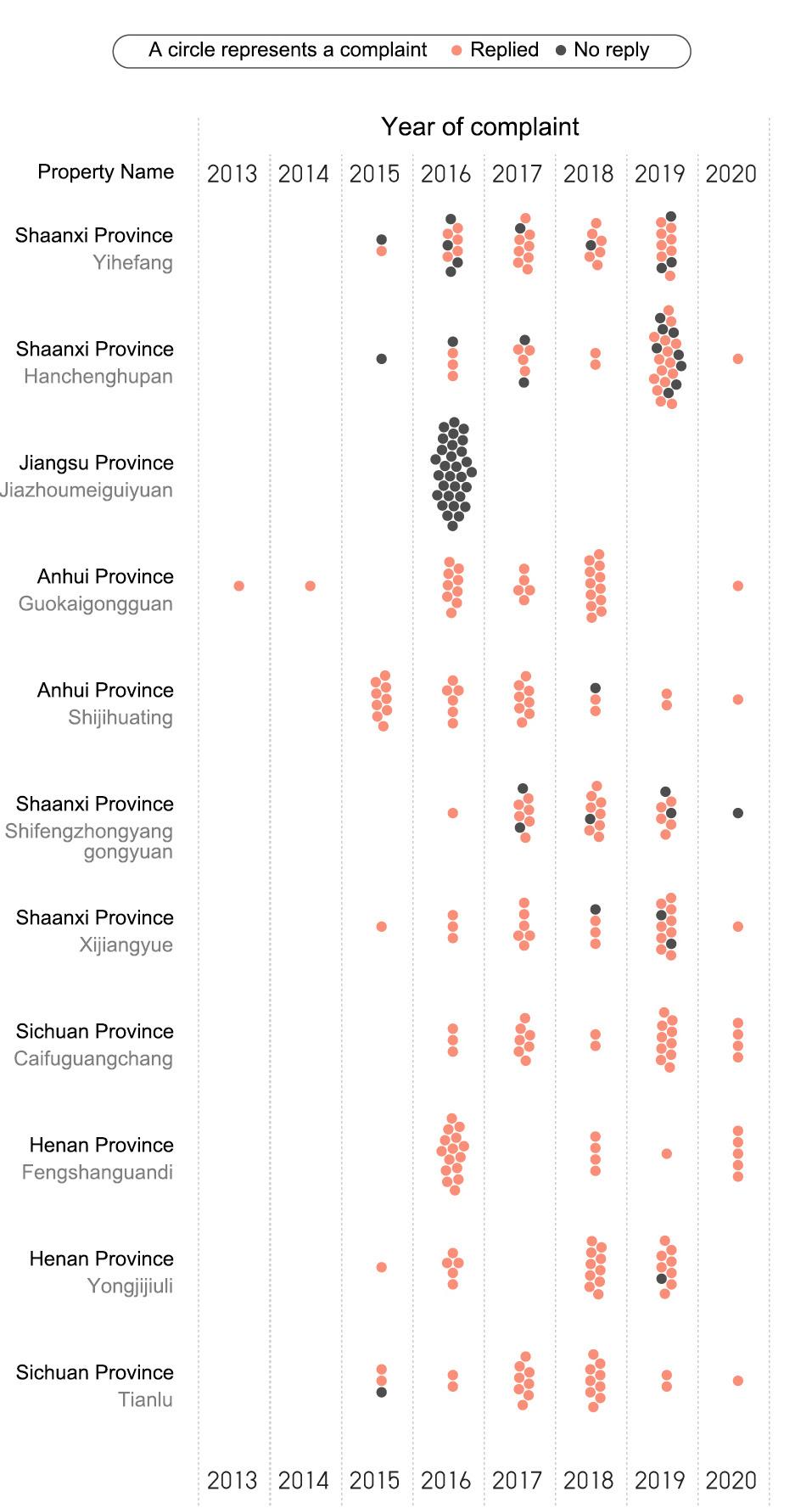

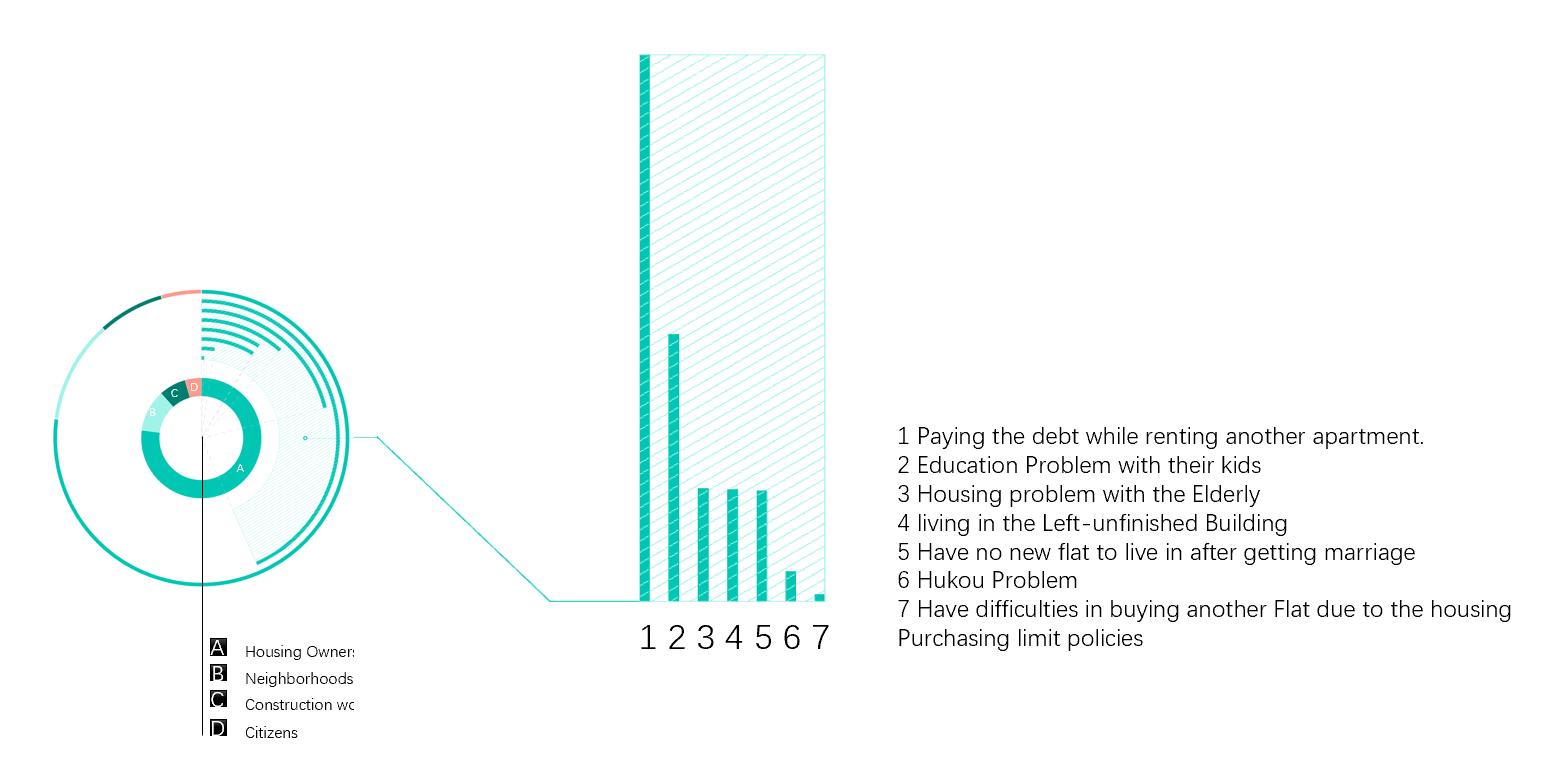

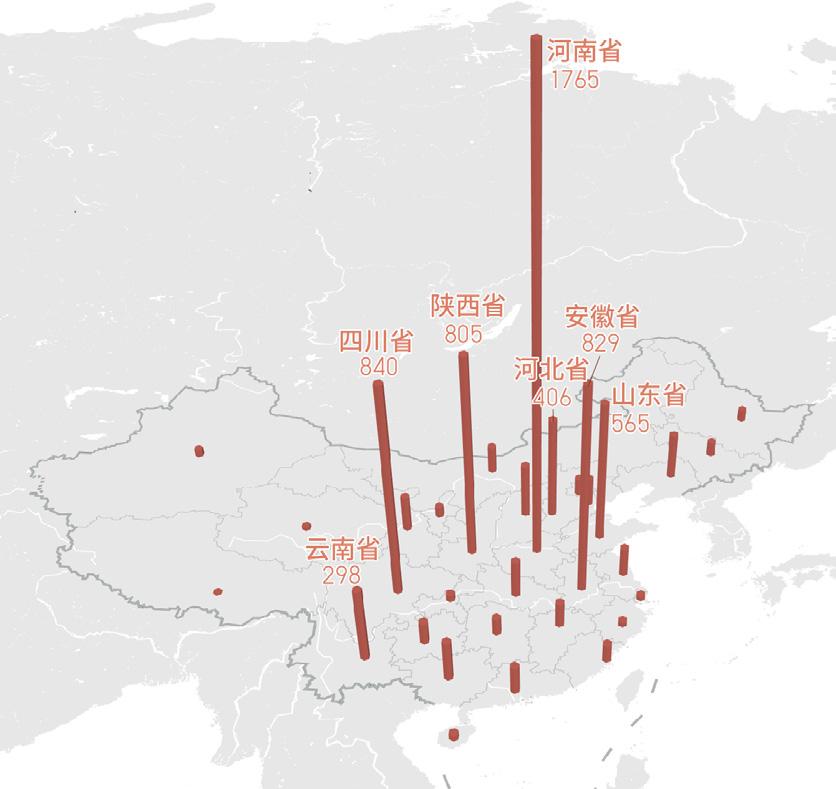

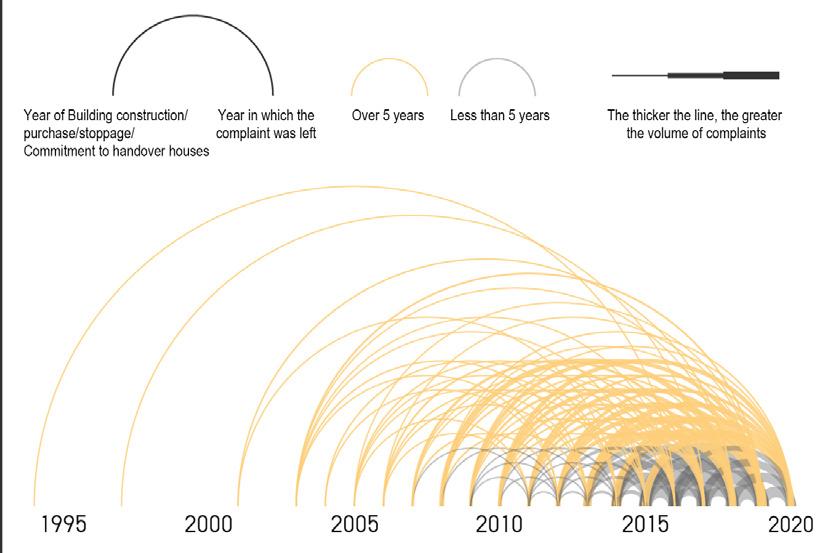

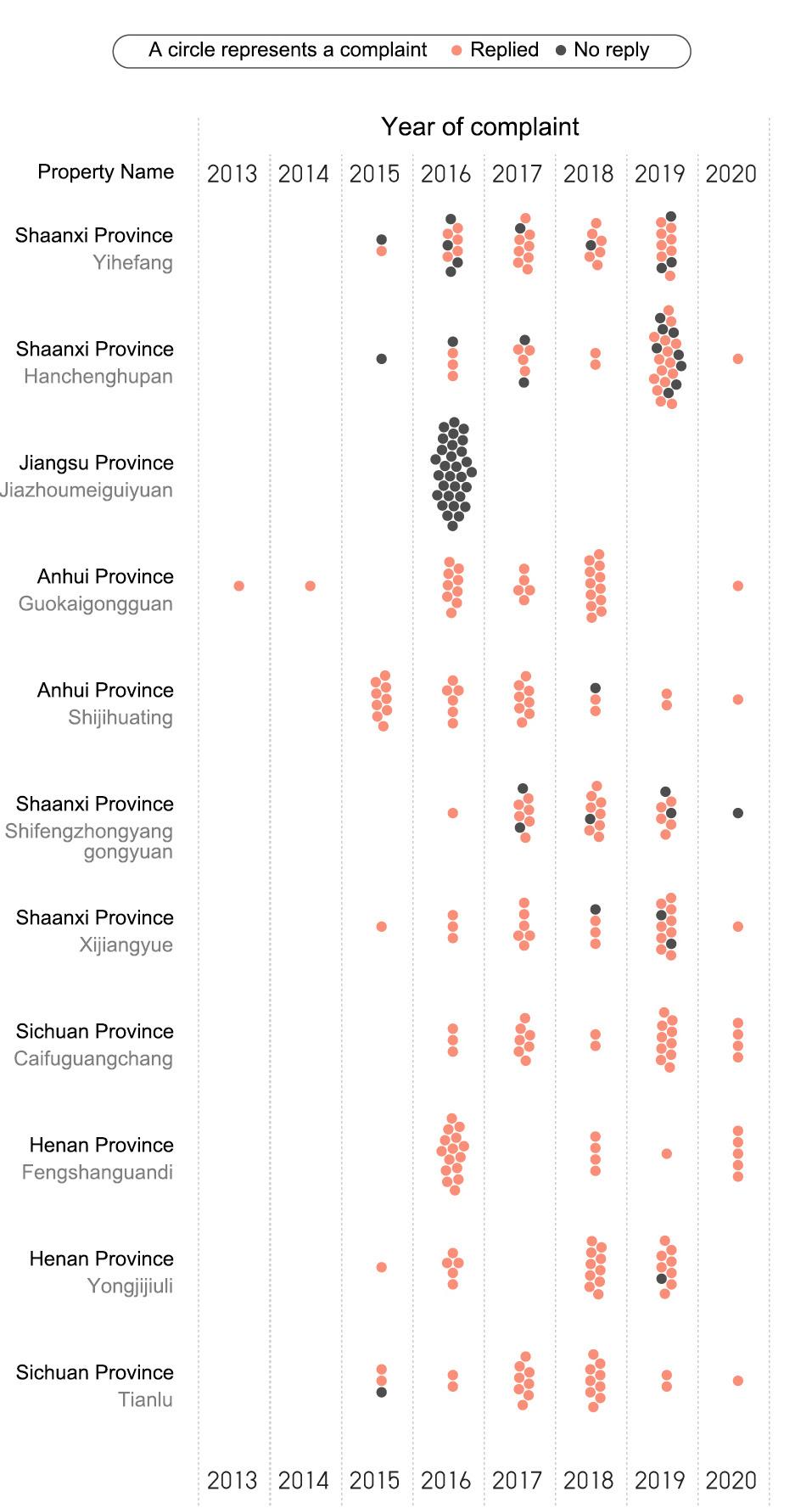

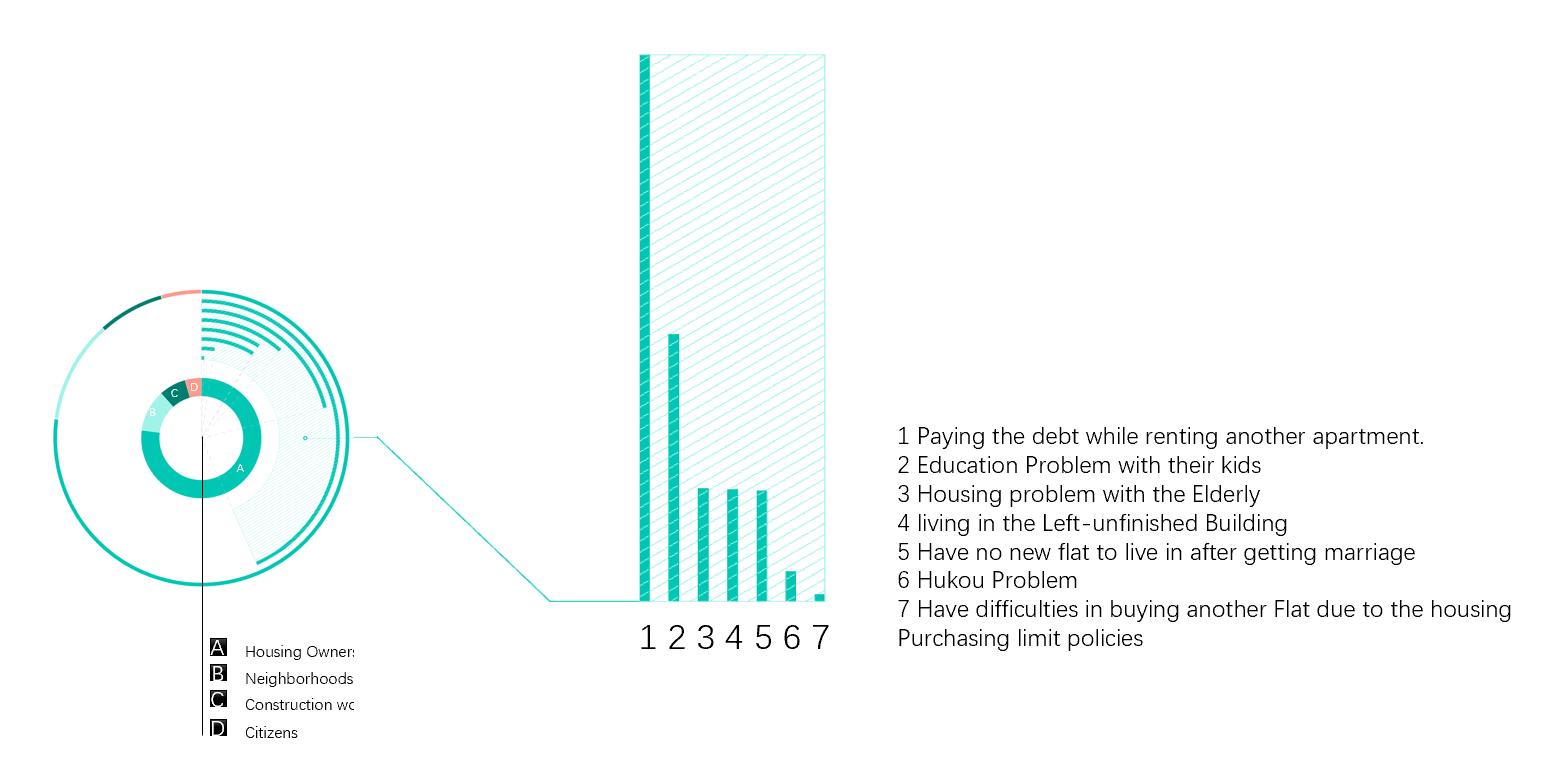

Because of the complexity of the problem of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing and its relevance to the work of the government, the level of information disclosure is not as high as expected. However, when we look indirectly at other bottom-up information feedback, on the "Leadership Message Board", the only nationwide message board for leaders in China created by the People's Daily website, there were more than 8,000 messages related to "Left-Unfinished" from 20102020. There were 7,478 complaints directly related to the housing projects, involving more than 3,188 properties.

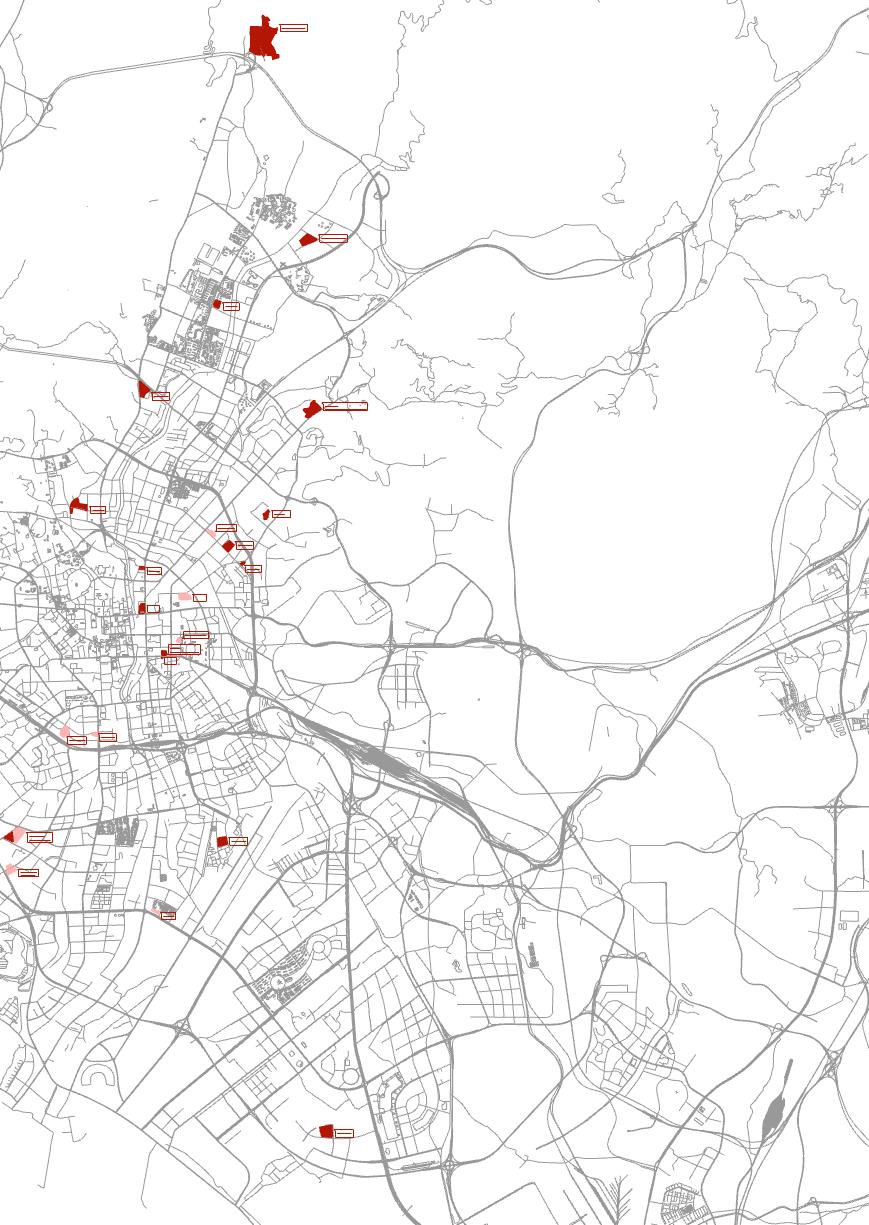

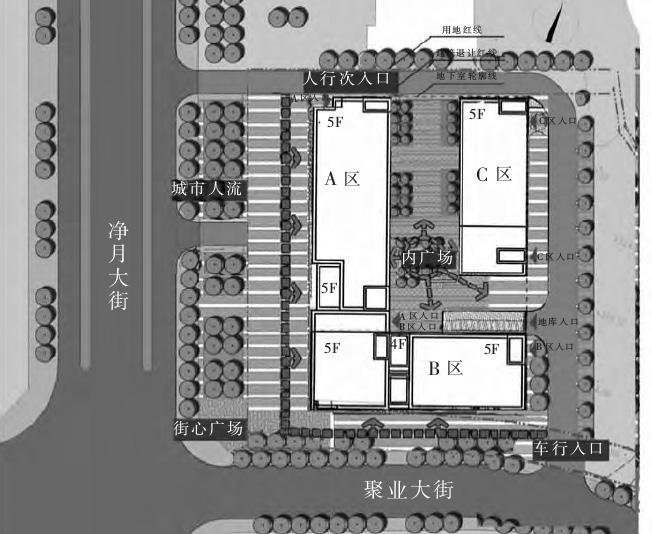

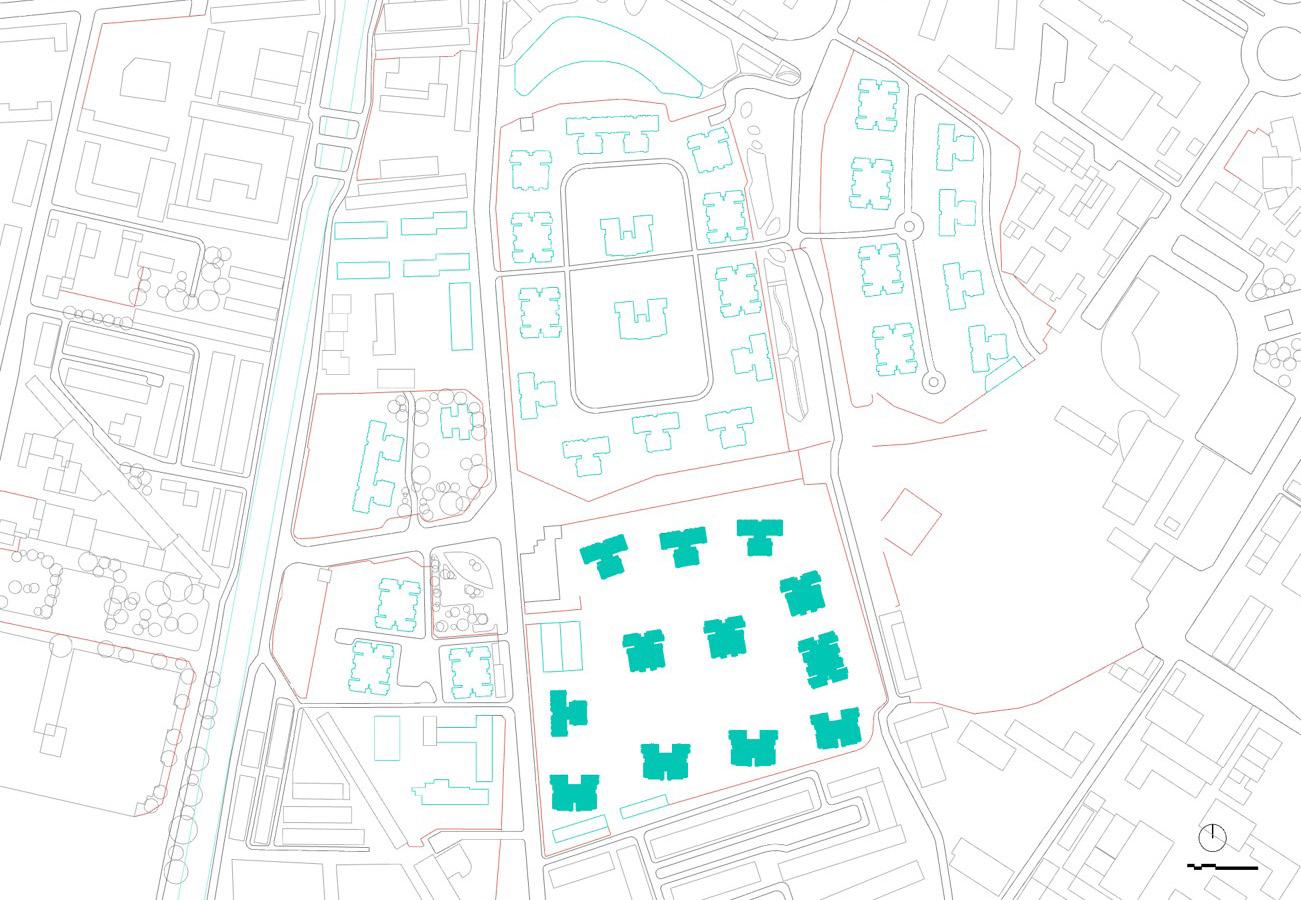

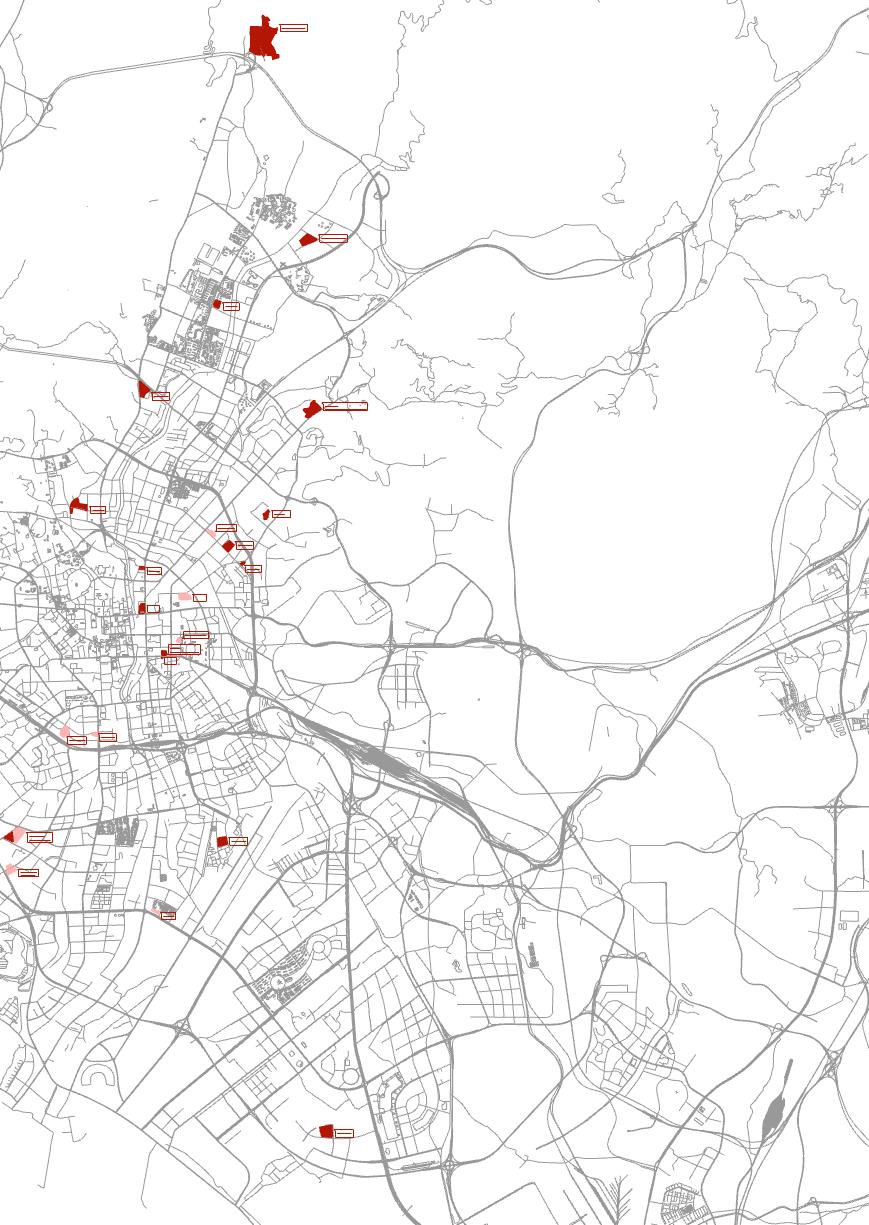

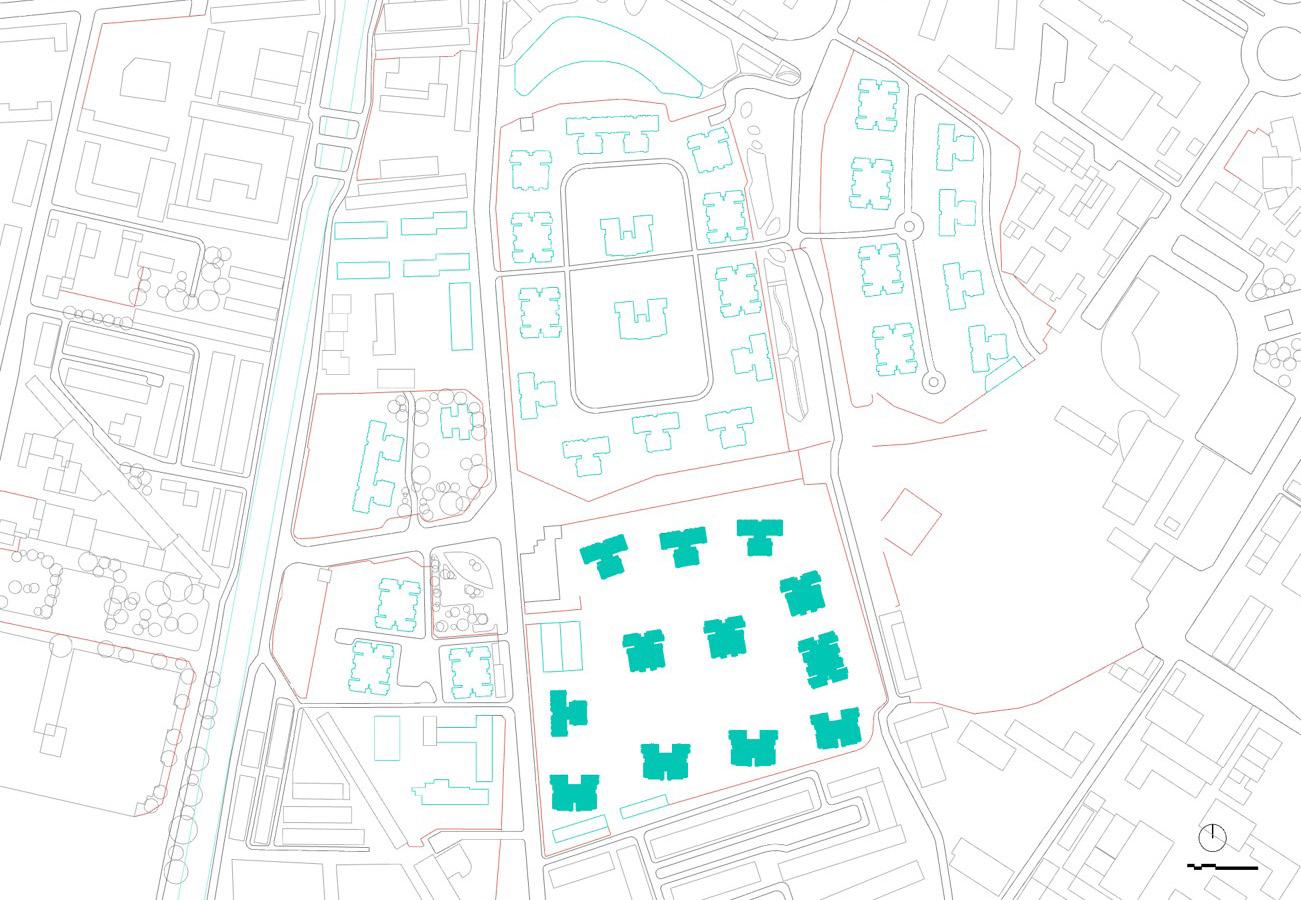

In terms of the number and distribution of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing, at least 429 of the messages mentioned that they or others were living in Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing. And the 3,188 sites of Left-Unfinished projects that were fed back were spread across 34 provinces across the country. And narrowing this analysis down to the Yunan province which is the province of Kunming city, where the cases this study focuses on are located. The statistics from the government's preliminary survey in 2019 alone, in which it is focusing on rectifying Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, yield 112 Left-Unfinished property projects in the city of Kunming alone that are in urgent need of rectification. By looking at the distribution of these 40 Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing which were used for residential and mixed commercial purposes in the city. Their distribution in the city centre, suburbs, and even satellite urban areas has affected the entire urban environment of Kunming on a large scale.

In terms of the years, their works were stopped and the resolution of the situation. In these complaints, the average number of years after a property continues to be left unfinished is 2.1 years, and a large number of properties are still left unfinished after a delay of more than 5 years, while the longest span of years is as long as 22 years.

In the process, a large number of complaints went unanswered, while a large number received

Needs to focus on the issue of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing

Stagnation of Expansion & Increase in Urban Density

Source: People's Daily News, 2006

Introduction 19

Fig.22 Statistics on the Number of Complaints about Left-unfinished Housing Cases by Province, China, 2019

Fig.22

Fig.23

Fig.24

Fig.25

only suggested responses, and the vast majority of problems with left unfinished developments remained unresolved until seven years after their complaint. This phenomenon is also present in the case of Kunming city. As the chart shows, the vast majority of projects have been left unfinished for more than five years, and more than half of them have been left unfinished for between five and ten years, with the longest-running project having been left unfinished for more than ten years.

Thus, the urban problems caused by the large stock of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing in China, the wide range of its impacts and the long duration of abandonment, have been and will continue to be a problem that has a need for research in the topic of urban studies.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 20

Fig.23 Years of Being Abandoned of the Cases

Fig.24 Complaint Resolution Statistics of the Left-unfinished Housings

Source: Redraw by the author based on souces People's Daily News, 2006

Source: Redraw by the author based on souces People's Daily News, 2006

Source: Compiled by the author base on sources from Baidu Map

Fig.25 Satellite Map of Left-unfinished Housing Sites in Kunming,Yunnan Province, China

Introduction 21

Source: Drawing

Fig.26 Left-unfinished Housing Sites

Fig.26 Left-unfinished Housing Sites

Kunming,Yunnan Province, China

author

Drawing by the

in

Public Perception and Art Practice

Fig.28

Fig.29

It is clear from the public discourse that this issue has had a large number of victims and has caused an impact on the surrounding urban environment. In the above statistics, the people who complaints that wanted to solve the problem of the LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing were not limited to the purchasers of the Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, but also include the neighbouring residents, migrant workers, and other citizens who are concerned about its impact on the image of the city.

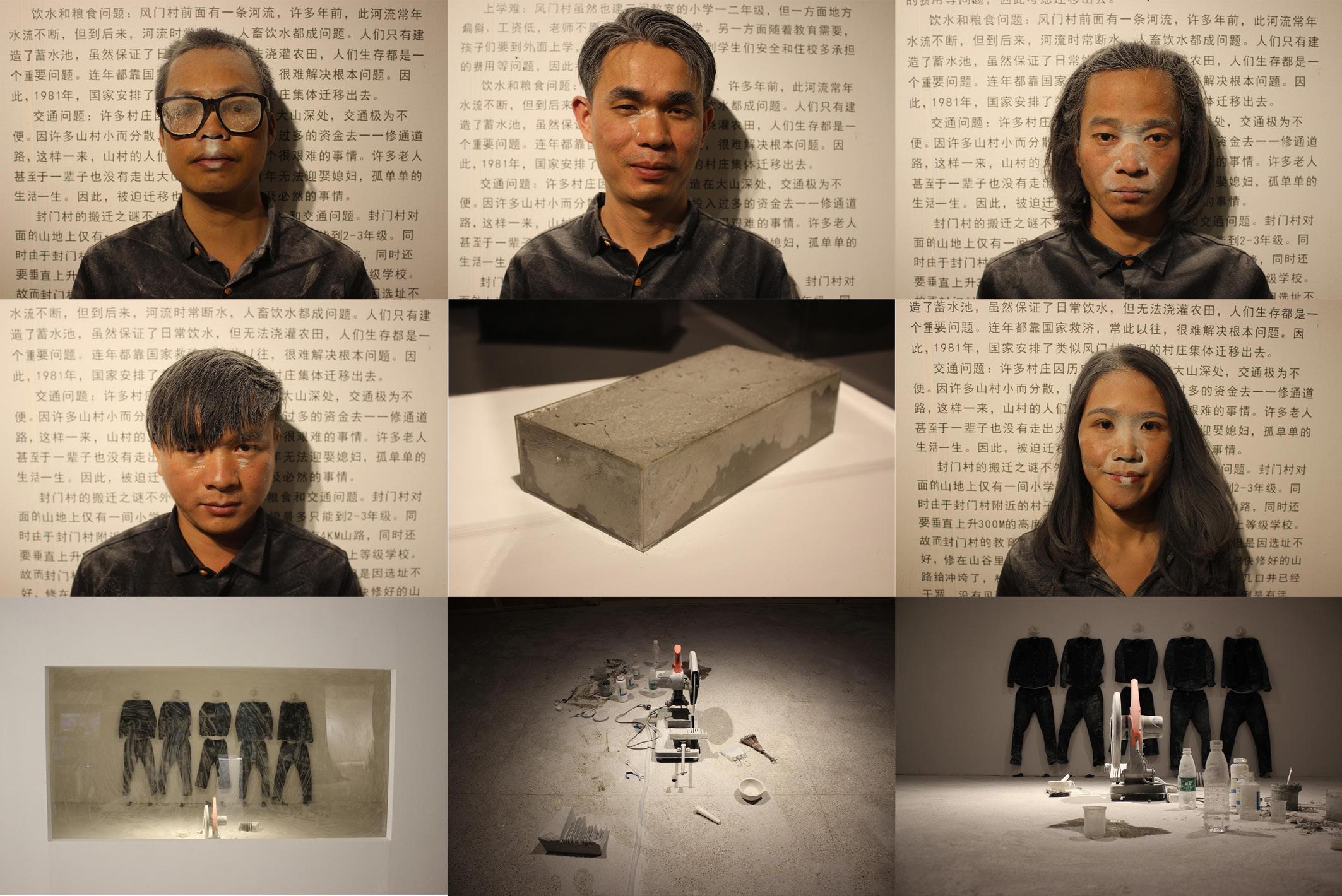

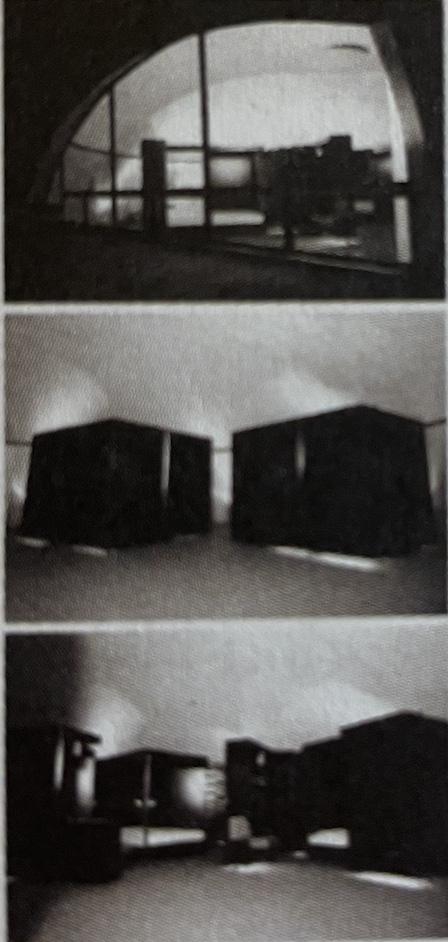

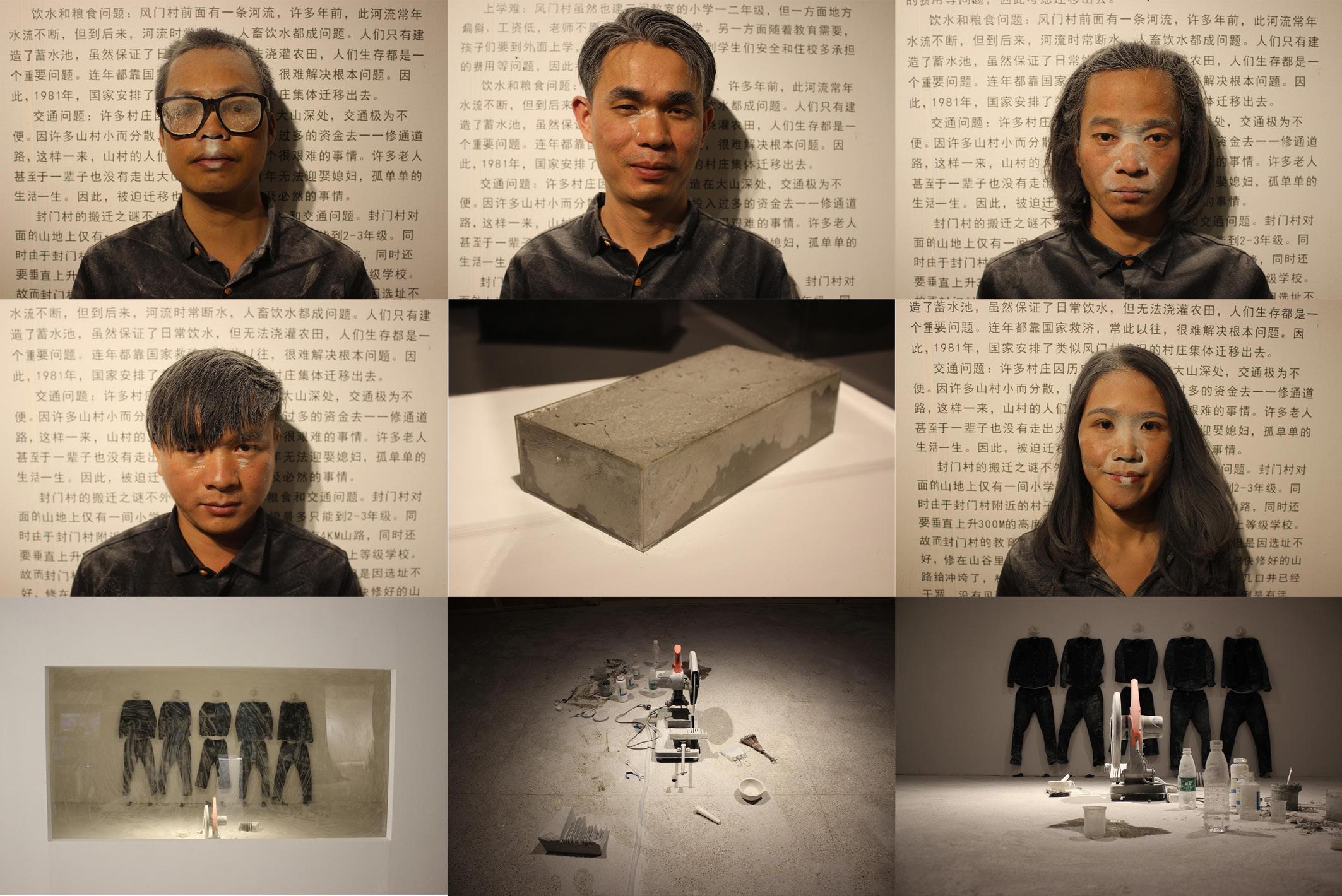

Artists groups like Erdaliu in Guangzhou China began to focus on the problem and started their work of sleeping in unfinished projects around China and took photos of their activities since 2009 till now.

Source: Drawing by the Author based on China Statistical Yearbook, 1984.

This concern for the Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing is also reflected in some of their other experimental artworks, which reconstitute some of the building materials collected from the LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing, including concrete and rebar. The concrete is broken up and reconstructed into new smooth bricks, and the rebar is rewelded into tree-like sculptures. More importantly, they began to focus on the living objects that appeared in these kinds of buildings to signify that someone was living in them. In Gift from a Ghost Town, they have attempted to solidify the living objects collected from the project by spraying them with materials that are often considered to be solid and everlasting. They may have been left behind by construction workers, or other people who used the frames to temporarily inhabit them. This series of sculptures made up of everyday objects reveals in detail the conflict between the ordinariness of life and the timelessness of architectural space.

Fig.27 Residential completions(Unit: 10000m2) by period

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 24

Fig.30-32

Fig.28-29 Experimental Art Record: Sleeping in Ghost Cities

Fig.28-29 Experimental Art Record: Sleeping in Ghost Cities

Introduction 25

Source: Erdaliu Artist Group, (2009-Unknown)

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 26

Fig.30-31 Experimental Art Record: A Piece of Brick from a Ghost City

Source: Erdaliu Artist Group, (2019)

Introduction 27

Fig.32 Experimental Art Record: Gifts from Ghost Cities

Source: Erdaliu Artist Group, (2019)

Source: Biyu Zou, Three Shadows Gallery Archive, https://www.threeshadows.cn

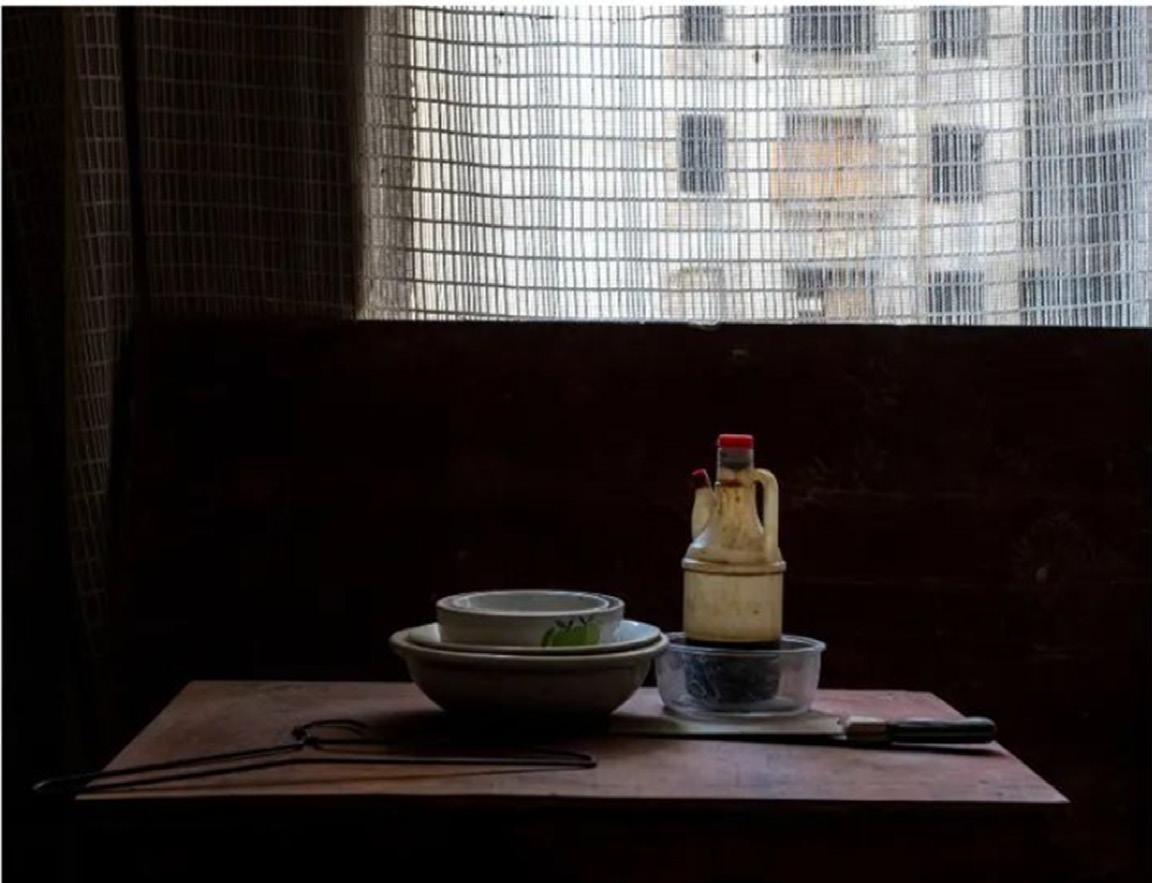

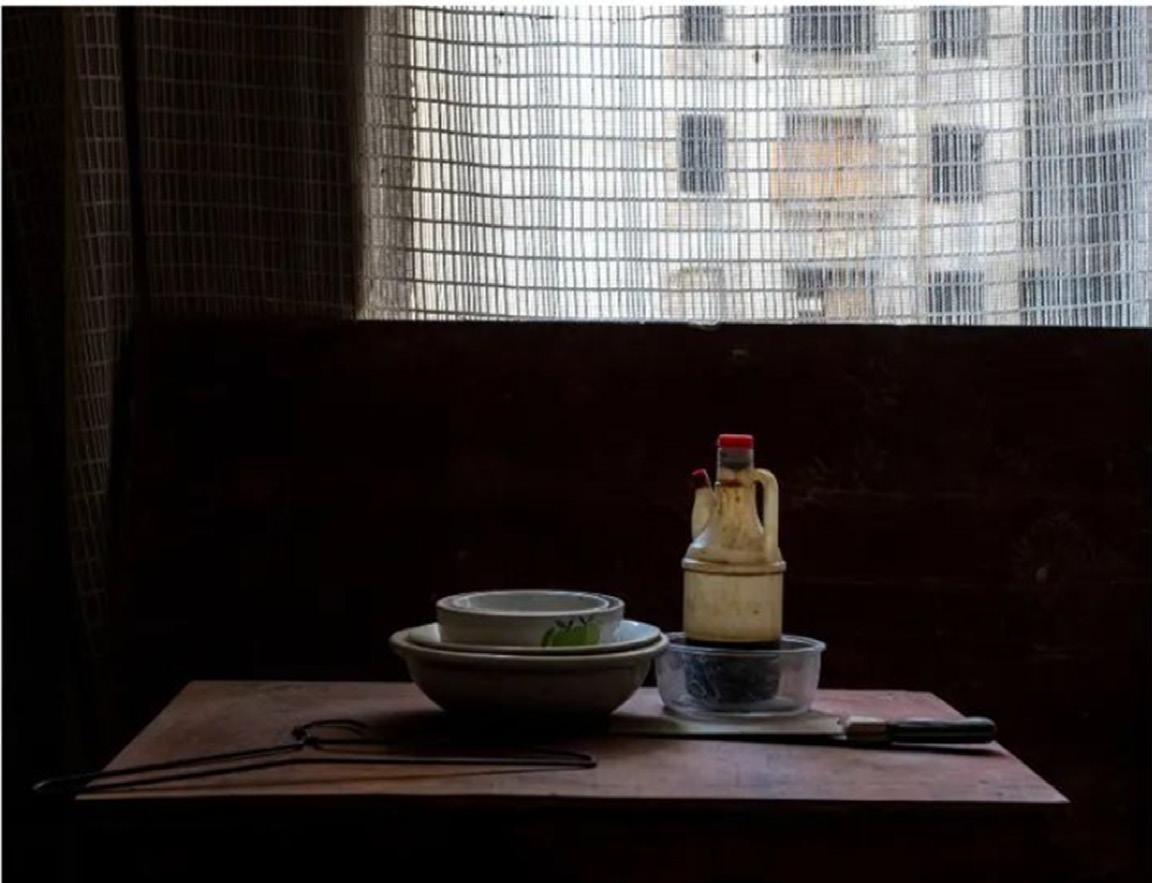

Chinese documentary photographer Zou Biyu captured scenes of the lives of more than 40 householders living inside the Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing community named Different Happiness in Kunming city, Yunnan Province. The photographer arranged the photographs of these living scenes into a series of photographic works and exhibited them in a constructed indoor scene in an art gallery. The photographs not only documented the necessities and furnishings of their lives but also record the vibrant life activities such as the flowers and potted plants they use to decorate their lives. The furniture on display in this exhibition is handmade from wooden panels collected from those Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing.

The attention paid to Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing and the lives within them in these artists' works also illustrates another aspect of the fact: As an inevitable by-product of China's rapid urbanisation, the huge problems caused by unfinished buildings have attracted widespread social attention.

Fig.33-34 Exhibition: A Life that Came to a Screeching Halt

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 28

Fig.33 Fig.34

The existing research on the renovation of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing with systematic studies focuses on structural inspection, renovation and structural science research.

From the perspective of architectural design, the existing academic studies are mostly based on the design practices of individual cases such as facade improvement and commercialisation of internal functions.

In general, there are three approaches to the renovation of a left-unfinished building, depending on the existing site and context constraints.

Firstly, for the cases that have reached a high level of completion, which cause the nature of the originally planned site cannot be changed, the design of the renovation would be restricted. In this type of renovation, the original design should generally be kept therefore just makes the new design to meet the requirements of the regulations.

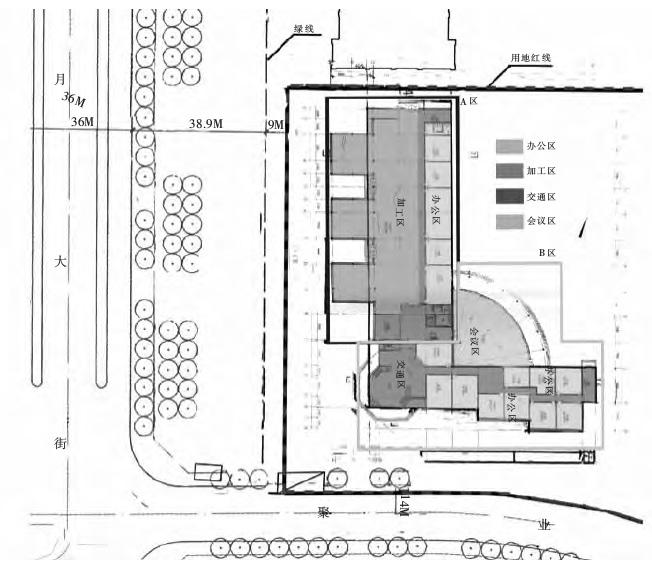

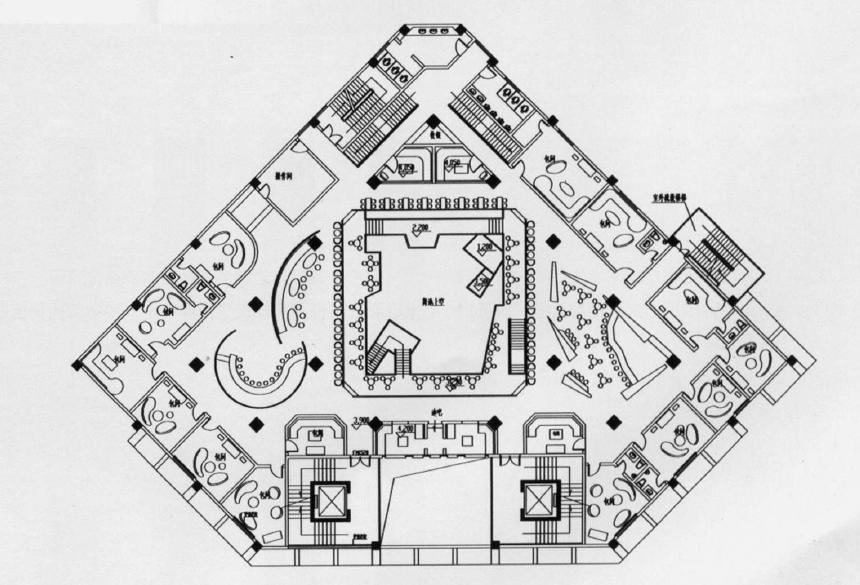

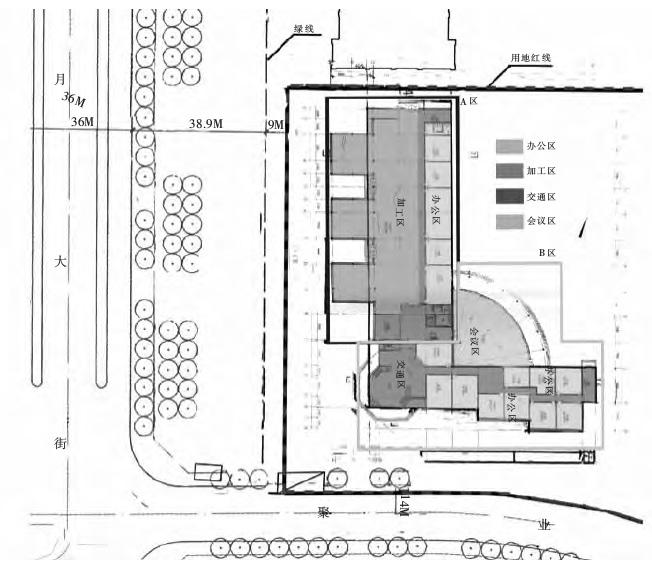

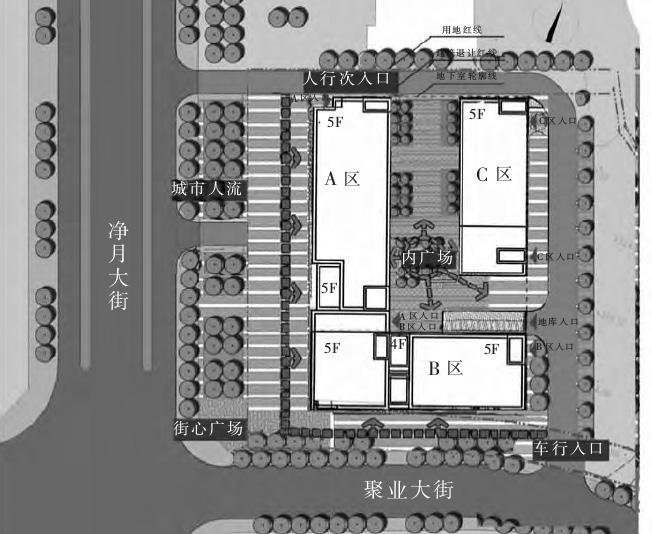

Secondly, another type of renovation is to add extensions to the original constructions. The limitations often come from the site and structure's ability to be sued. Take Jingyue #5 District Renovation project in Changchun, Jilin Provience as Example. In view of the economical design of the renovation, Zone A of the building was retained, Zone B was demolished and rebuilt, and Zone C was extended on the site1

Present Research & Design Practice

Renovation of Left-unfinished Commercial Housing

1 Xuebin Yin, "Study on the Rebuilding Method of Half-baked Building-Analyzes the Design on Rebuilding of Jingyue No.5", Journal of Jilin Jianzhu University (2016), Vol.33.

Source: Xuebin Yin, "Study on the Rebuilding Method of Half-baked Building Analyzes the Design on Rebuilding of Jingyue No.5", Journal of Jilin Jianzhu University (2016), Vol.33.

Fig.35 Site Plan: Status Mapping

Fig.36 Site Plan: Renovated

Introduction 29

Fig.36 Fig.35

1 Wei Cen, "Red Age, Liu Jiakun's Writing for Urban", Time + Architecture, (5/2002), p.4851

2 Huanyu Hou, "The Solution to Reconstruction and Revival of Building: A Creative Practice on Beijing Guoyuefu", WA, (03)2014,p.129-130

3 Hongli Li, "Renovation of Huizhi Mansion in Shanghai", China, Research in Design, (2007)

Thirdly, Retaining the original structure and adding facades or changing the internal functions are also effective measures to transform rotten buildings, especially in urban areas where site constraints are more restrictive. Take the example of architect Liu Jiakun's transformation of a rotting residential building in Chengdu into a bar. While retaining the internal structure, the designer has made flexible adjustments to the internal functions. The new design also incorporates another layer of steel envelope on top of the original dilapidated façade, which serves to decorate and reinforce and protect the original exterior envelope at the same time1

Similar cases, such as the Guoyuefu Project in Beijing 2 and the Huizhi Mansion in Shanghai 3 demonstrate how this method can be used to redevelop left-unfinished properties.

Source: Wei Cen, "Red Age, Liu Jiakun's Writing for Urban", Time + Architecture, (5)2002, P.4852

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 30

Fig.37 2nd Floor Plan of the Red Memory Bar Design by Jiakun Liu

Fig.38 Facade of the Red Memory Bar Design by Jiakun Liu

Fig.37-38

Fig.39-42

Source:

Source:

In first-tier cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, where the increase in urban land prices can offset the cost of redeveloping a rotten site, many unfinished buildings can be converted into commercial structures such as shopping malls, hotels, and so on, with no more than ten years remaining. However, the majority of less developed cities are unable to achieve such economic growth, and as a result, poorly constructed commercial properties sit vacant until they are demolished.

Introduction 31

Fig.39 BeforeI(Up) and after(Down) Guoyuefu Renovation Project

Fig.41 Renovation of Huizhi Mansion in Shanghai

Fig.40 Section Guoyuefu Renovation Project

Fig.42 Section Guoyuefu Renovation Project

Huanyu Hou, "The Solution to Reconstruction and Revival of Building: A Creative Practice on Beijing Guoyuefu", WA, (03/2014).

Hongli Li, "Renovation of Huizhi Mansion in Shanghai", China, Research in Design, (2007)

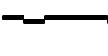

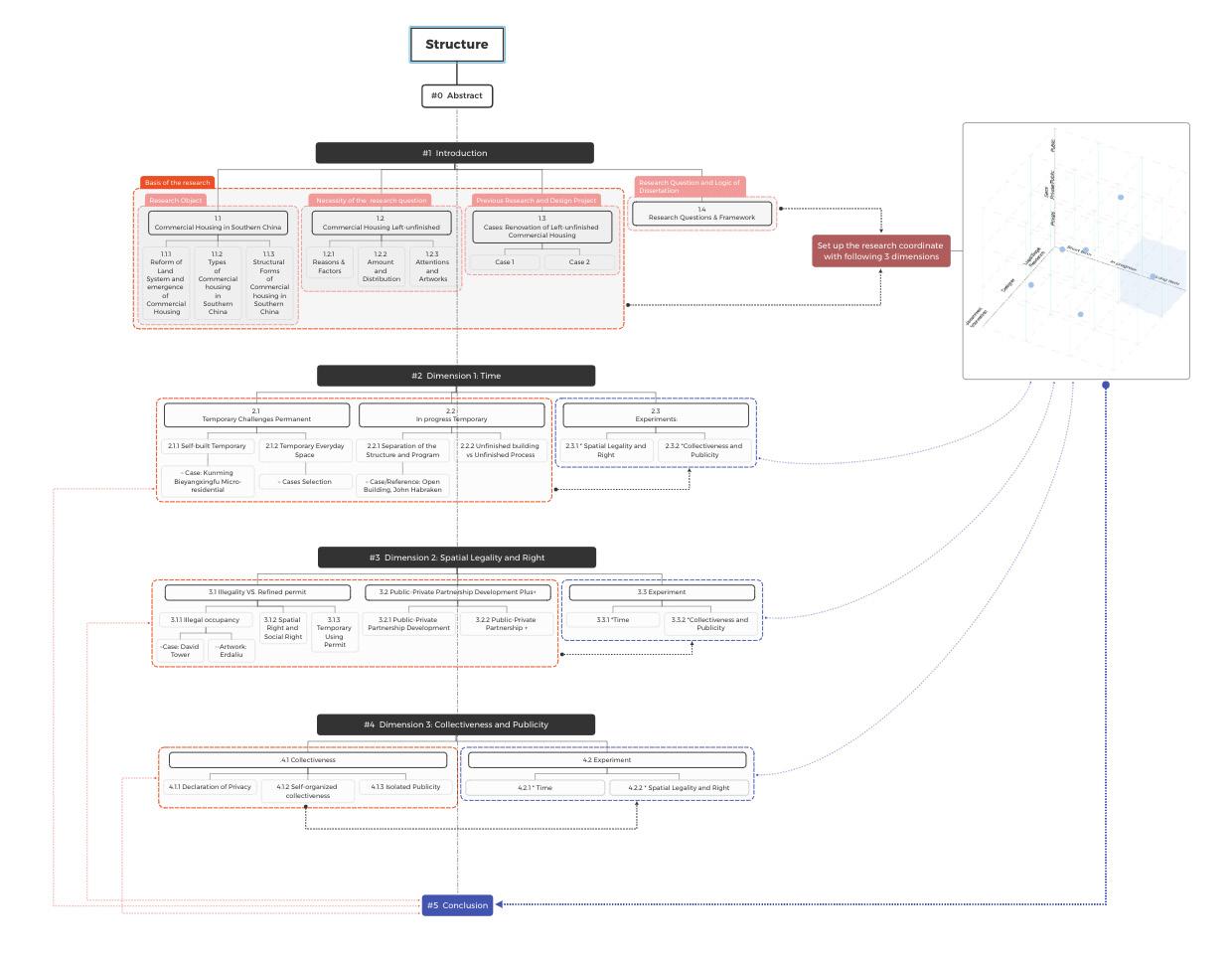

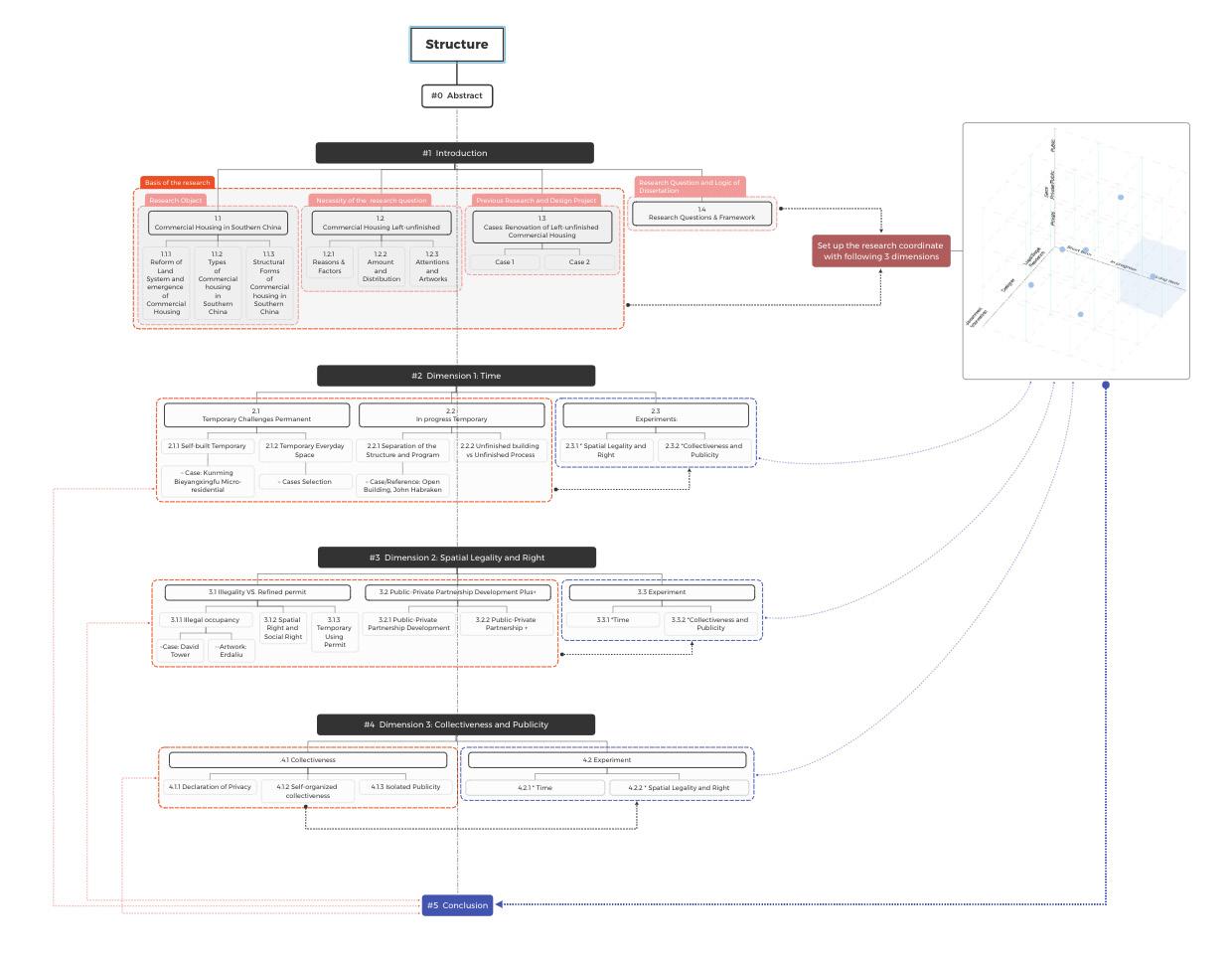

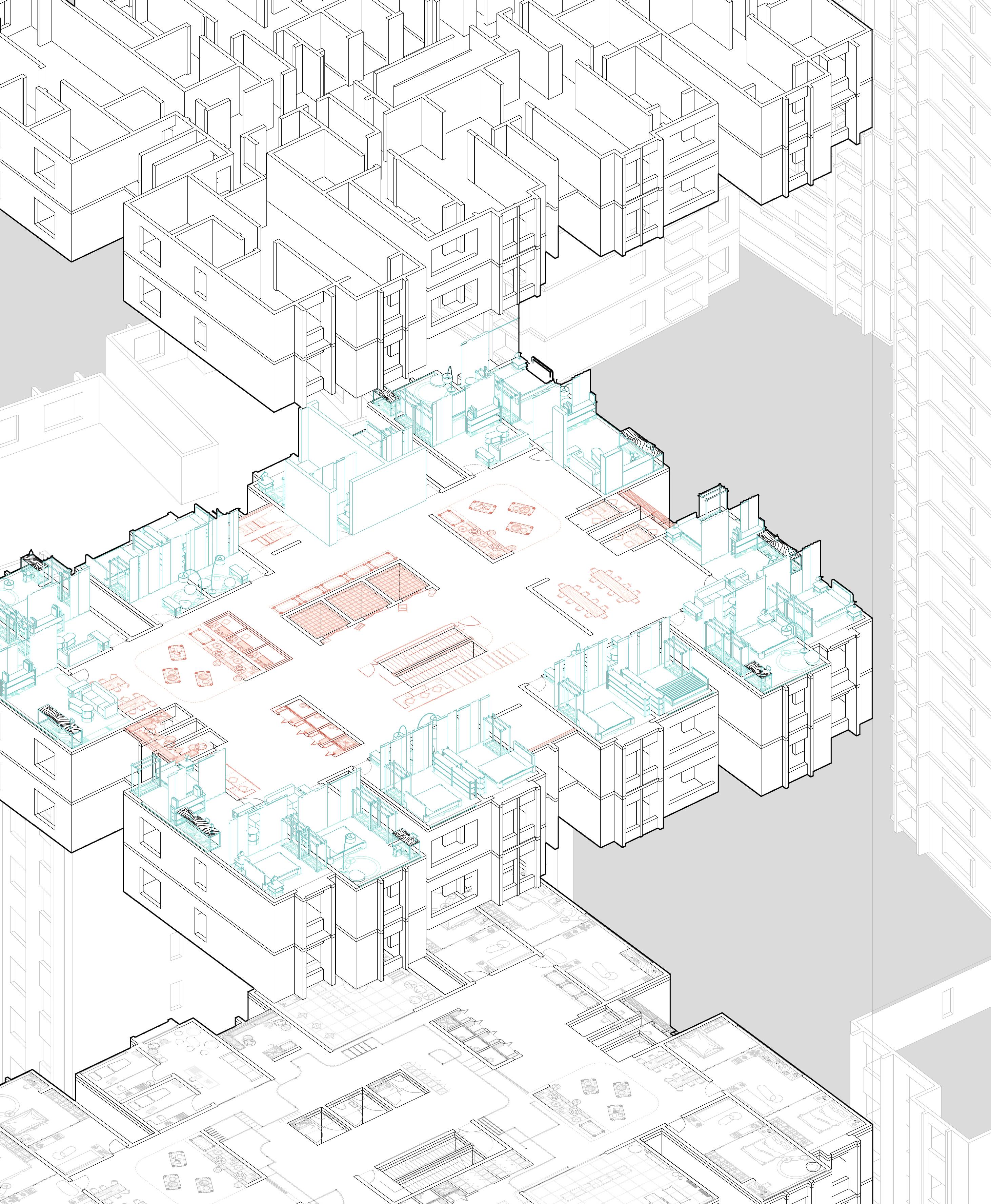

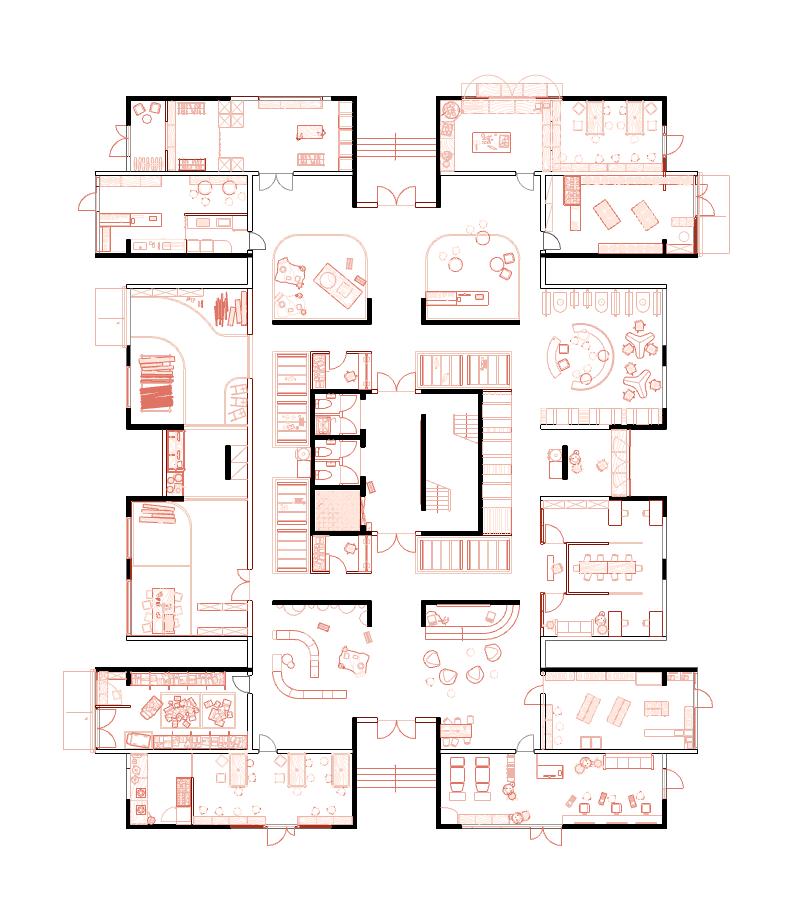

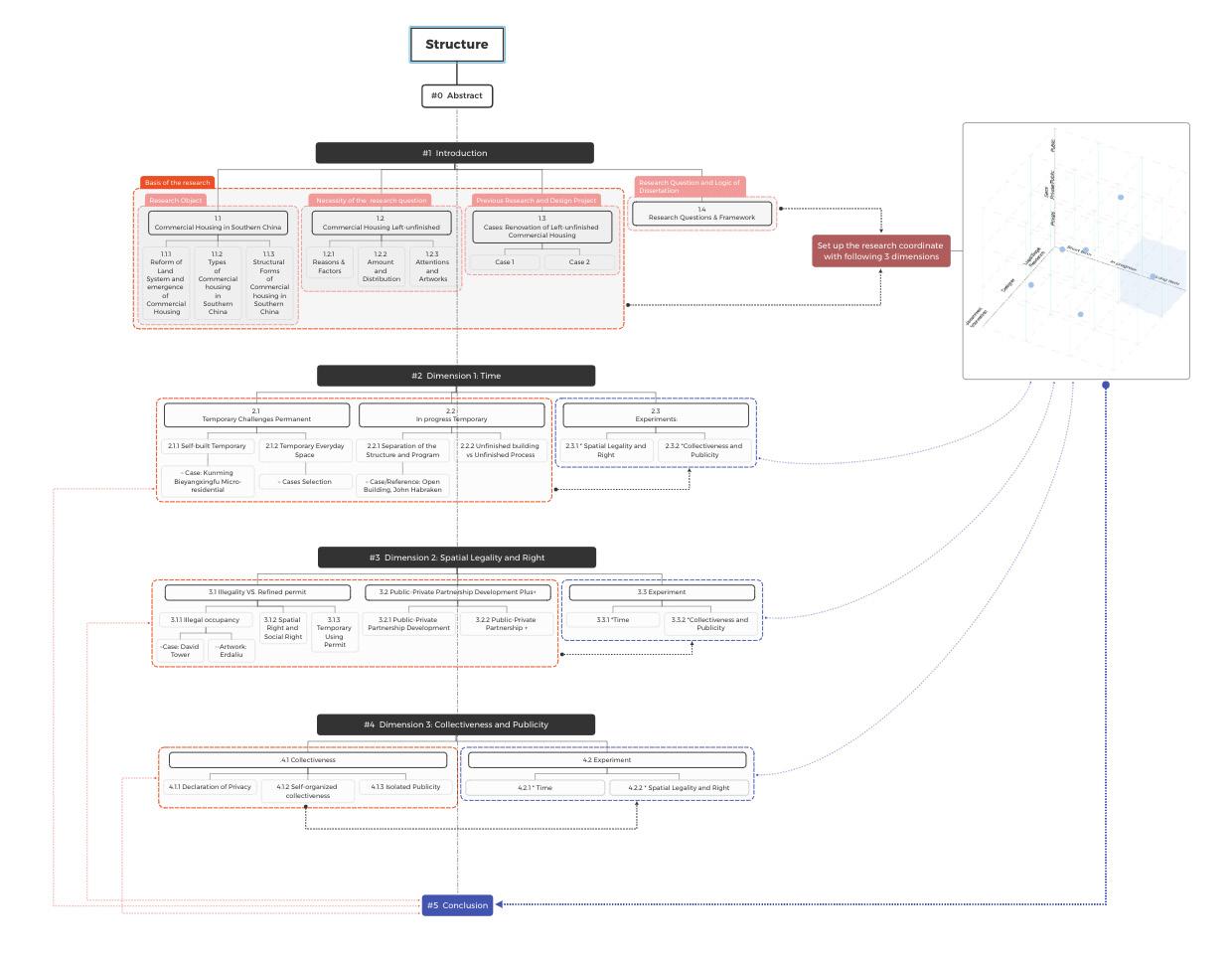

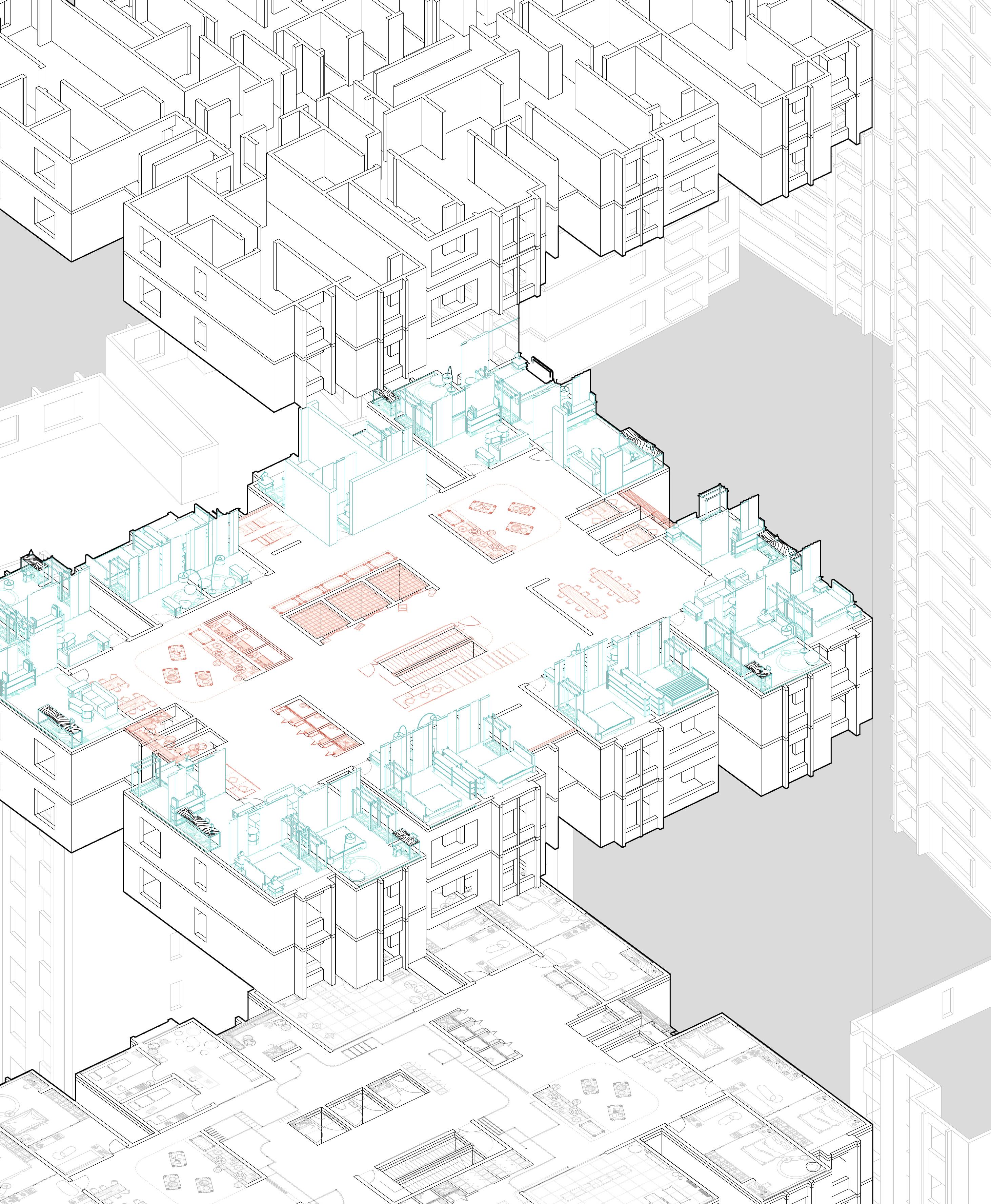

The study begins with an introduction to the typology and history of social and commercial housing in China, as well as the causes of left-unfinised buildings.

The Introduction chapter presents a concise analysis of the subject and established research and practise in order to establish the study's basic context.

Following that, three distinct dimensions are established, and each of these three chapters summarises a case study of incompleted buildings and research on the site for design.

The research findings are then related to the design variables in each chapter's experimental section, which discusses the approach to open-ended renovations of leftunfinished commercial housing.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 32

Introduction 33

Fig.43 Research Frame

Source: Drawing by the Author

DIMENSION 1

Time

Everydayness Challenges Permanent

Inprogress Temporary

Experiments #1

Dimension 1: Time

2.1

Everydayness Challenges Permanent

Compared with the everydayness that a person lives in a residential building, the time of rights for which a left-unfinished housing is originally refined, the lifetime of the building that designed, or the time of vacancy after failure development in a concrete frame pending redevelopment, are all long periods of time. This can be seen as a concrete response to the permanence of the building. While the transformation and redefinition of the home by the people who actually inhabit it in their private space is an additional layer attached to what can be seen as a long-lasting architectural structure.

The architecture does not have movement, which means that the beams and columns of a building are fixed, as are the walls that divide the rooms 1 But when we turn to the question of how a new daily life can be constructed in such an unfinished space in a structurally finished residential building, we can realise that this unfinished architectural space still has potential. The potential allows for the construction of new infrastructural systems and movable architectural adaptations necessary for living in them, according to one's own lifestyle and different living needs. This transformation can

1 Kim Seonwook/ Pyo Miyoung, "Construction and Design Manual: Mobile Architecture", DOM Publishers"(2012), p. 12-25

Dimension 1 Time 34

be oriented not necessarily towards transforming the building into a complete residential space, but rather towards a transformation that is less about the original environment and more about the use of movable and more architecturally designed furniture.

In fact, in some of China's left-unfinished project sites, the owners who have been forced to move into the buildings have begun to build their lives in them at a much lower cost. In their spontaneous renovation of unfinished building spaces, the most basic needs of everyday Tlife can be reflected in their measures to improve the space, which can be seen as a challenge of everydayness to permanence. Through such practices, the residential function of the building far exceeds its other values such as commodity value.

Self-built Temporary Living Space

Fig.44 Fig.45

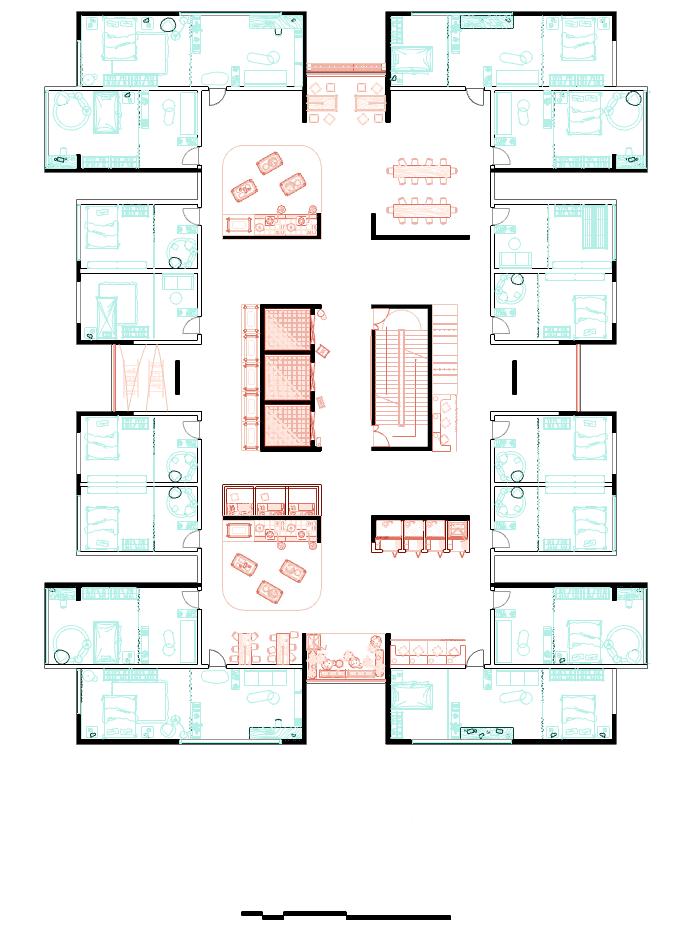

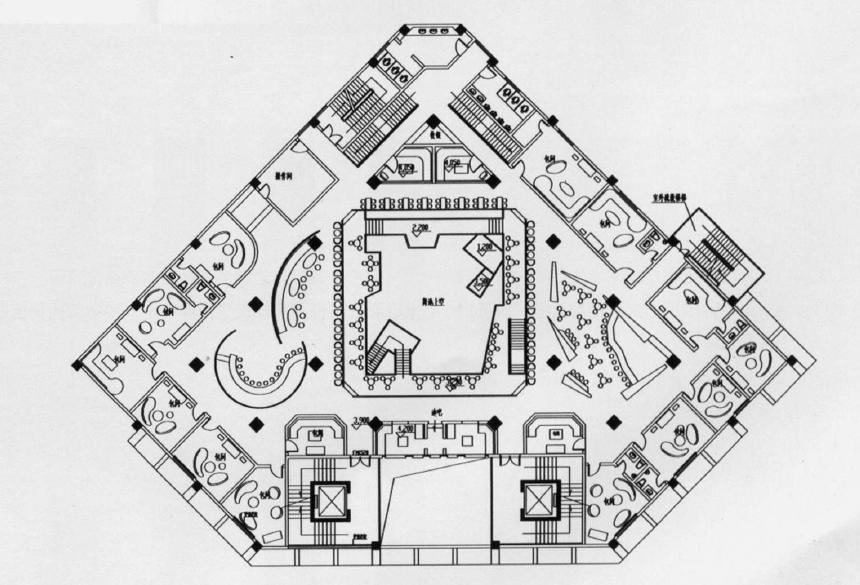

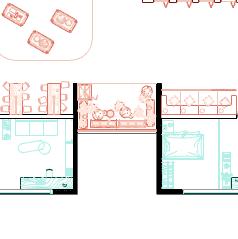

In the case of Kunming's Other Happiness District, all 12 commercial residential buildings on Lot 4, which were supposed to be completed and delivered to owners in 2015 according to the purchase contract, have been in a state of disrepair for over six years and have not yet been effectively resolved. Some of the owners who purchased their flats with bank loans have been forced to move into the site of the project (halted in 2014), as they find it difficult to afford both the loan repayments and the purchase or rental of other housing. By 2020, more than 40 owners will have moved into the homes they bought and started living in a low standard of life.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 35

Complete buildings

Left-unfinished buildings

Dimension 1 Time 36

Fig.44 Site Plan of Bieyangxingfu District

Fig.45 Photo: Site of Bieyangxingfu District

Source: Drawing by the author

This is by no means a good solution to the problem of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, but it certainly reminds us that people whose lives are affected by its purchases do face enormous challenges. And there is a need for better ways to help them build relatively stable new lives. And the spontaneous renovation and decoration of the residential spaces of those who have moved into Left-Unfinished Commercial Houses can give us some insights into the basic methods of building a place that can accommodate everyday life by using some temporary materials.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 37

Fig.46 Daily Life of Bieyangxingfu's Residence https://m1.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_ forward_9029333

Fig.47

Fig.48

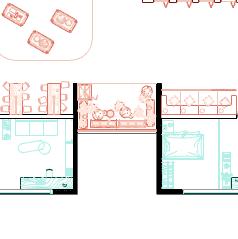

The analysis of the daily living space of the residents of the Bieyangxingfu Residential District goes from the scale of the entire site zoom in to their daily living rooms and the unfinished commercial flats that they have re-designated as their private domain.

In terms of the materials and reuse of the renovated spaces, the inhabitants of the Other Happiness community have adopted materials for the renovation that are not limited to what the architects recognise as solid and permanent materials such as stone, wood and metal. Due to the inhabitants' need for low cost and restorability, a large number of removable materials have been introduced into the space. Firstly, flexible materials such as plastic and curtains are hung in the windows in order to provide privacy and shade from the sun. At the same time, in order to ensure the safe use of the floor-to-ceiling windows that open out onto the building, a large amount of wire mesh fencing from the abandoned building during construction was collected and used as window bars to prevent falls and ensure personal safety.

Self-built Temporary Living Space

Dimension 1 Time 38

Fig.47 Interior View of Residents' Living Units

Source: Compiled by the author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 39

Fig.48 Photos of nterior View

Source: BIyu

Dimension 1 Time 40

BIyu Zou,2019

View of Residents' Living Units

Source:

Source:

By reusing the original building materials which were left on the construction site, or by purchasing second-hand, simple furniture, the residents are able to create a simplified living space that meets their daily needs.

This practice of self-organised renovation is partly a reflection of the fact that it is possible to create a living space within a solid, permanent structure that is more adaptable to everyday use, flexible, variable or even temporary for short or transitional periods.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 41

Fig.50 Photos of Interior View of Chenyanchun's Room

Fig.49 Photos of Interior View of Chenyanchun's Room

Biyu Zou,2019

Biyu Zou,2019

Fig.52

Dimension 1 Time 42

Fig.51 Residents Reuse 2nd-hand Furnitures

Fig.52 Residents Are Making Furnitures with Abandoned Meterial

Source: BIyu Zou,2019

Inequal Right to the Space & Social Walfare

Source:

Masayuki

The unplanned renovation within the permanent immovable structures by adding movable architectural furnitures has been adopted by the inhabitants who live in the Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, but in fact there are many architects involved in similar practical solutions for non-permanent living spacesthat take the changing characteristics of residential buildings and residential building design practice into account .

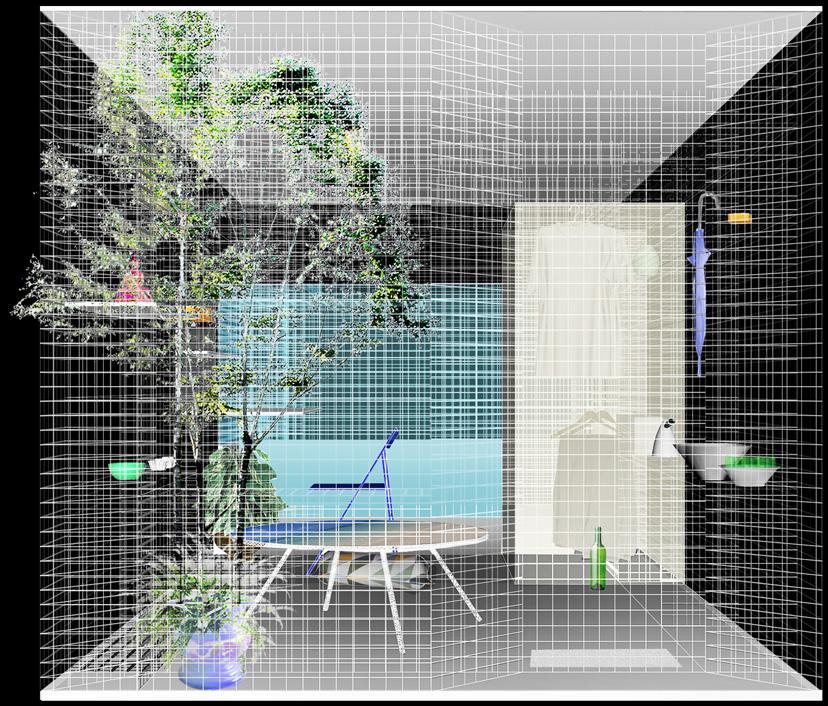

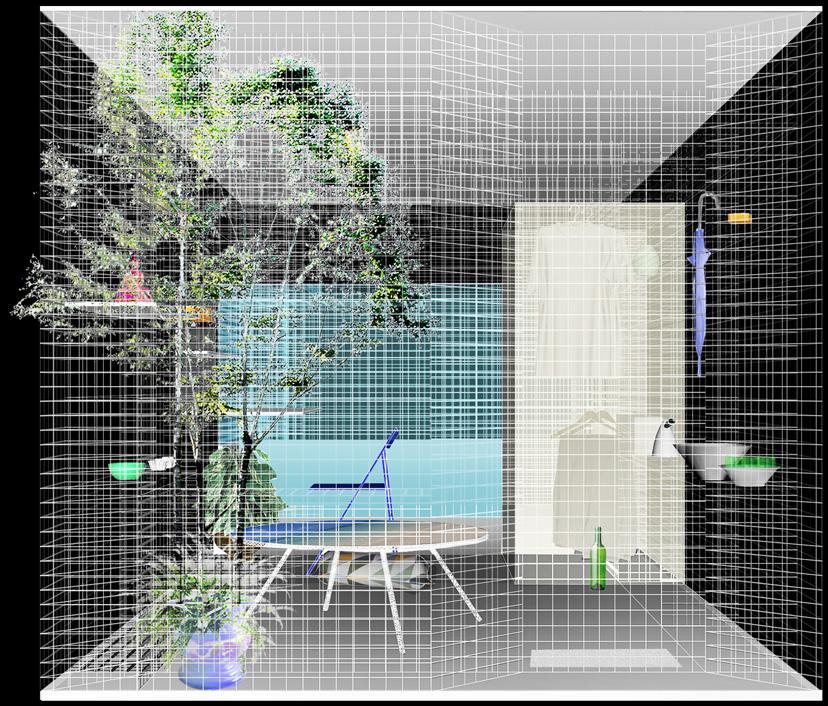

Take "Houses without Architecture" Project(1971)

Designed by Masayuki Kurokawa in Tokyo, Japan as example. Building wherein concrete dome skeleton and waterworks are only fixed and all the mremainning space is composed of huge movable furniture, so various arrangements are possible by their revolving. The architectural furniture is flexibly scattered in the building space with a more unified formal language, forming a livable space that can be changed at any time.

A design concept for a temporary living space that is closer to the space of a bad building was designed and produced by a Bangkok studio All(zone). The designer has conceived a small temporary home intended to be set up inside unfinished high-rise buildings in tropical cities. Encompassing 11.5 square metres, the boxy micro dwelling sits on

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 43

Fig.53 Houses without architecturearchitectural furniture (Project)

kurokawa, 1971,Japan

Fig.53

Fig.54

Fig.55

https://www.dezeen.com/2015/10/07/micro-dwellingallzone-abandoned-towers-parasites-chicago-architecturebiennial-2015/

a floor made of plastic-laminated plywood. The home's frame consists of a polyeth ylene-coated metal grid, which also serves as shelving inside the structure.

“Recent housing projects are so closely tied up with global real estate investment that it's almost impossible for a young middleclass or a new generation of urban poor to live in the city on what they earn…The halftemporary condition of Light House would be perfect to get settled in such condition of the unused buildings…”

Designed on a $1,200 (£790) budget, the dwelling was conceived in response to rising living costs in tropical cities such as Bangkok

Dimension 1 Time 44

Fig.54 Perspective View of Source:

Source: https://www.dezeen.com/2015/10/07/micro-dwelling-allzone-abandoned-towers-parasites-chicago-architecturebiennial-2015/

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 45

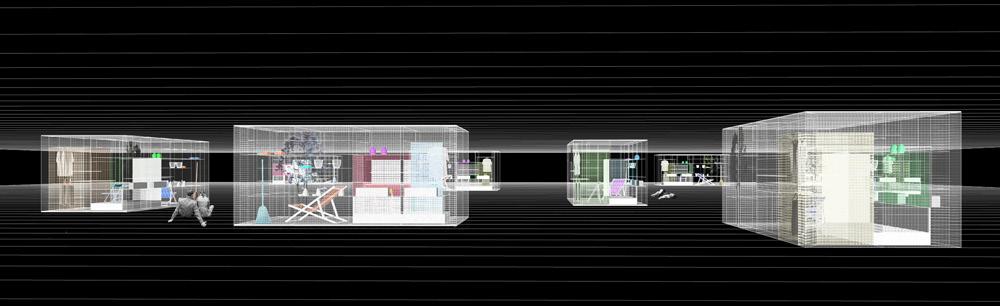

Fig.56 Diagram: Living Units of Micro-Dwelling

Fig.58 Temporary Living Space Consisting of Self-built Living units (Vertical)

Fig.57 Temporary Living Space Consisting of Self-built Living units (Horizontall)

These case studies offer a range of spatial possibilities in terms of spatial scale of living, design strategies for temporary living spaces, and choice of materials that can be implemented to a certain extent to accommodate some of the people who are badly affected by the problem of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing without modifying or demolishing the original building structure, but only by placing the living spaces in them such as furnishings.

2.2

In-progress Long-term Dwelling

These case studies offer a range of spatial possibilities in terms of spatial scale of living, design strategies for temporary living spaces, and choice of materials that can be implemented to a certain extent to accommodate some of the people who are badly affected by the problem of LeftUnfinished Commercial Housing without modifying or demolishing the original building structure, but only by placing the living spaces in them such as furnishings.

Like John Habraken Referred in his book "Supports: an alternative to mass housing"

"A Dwelling is only a dwelling, not when it has a certain form, not when it fulfils certain conditions which have been written down after long study, not when certain dimensions and provisions have been made to comply with municipal by-laws, but only and exclusively when people come too live in it. "

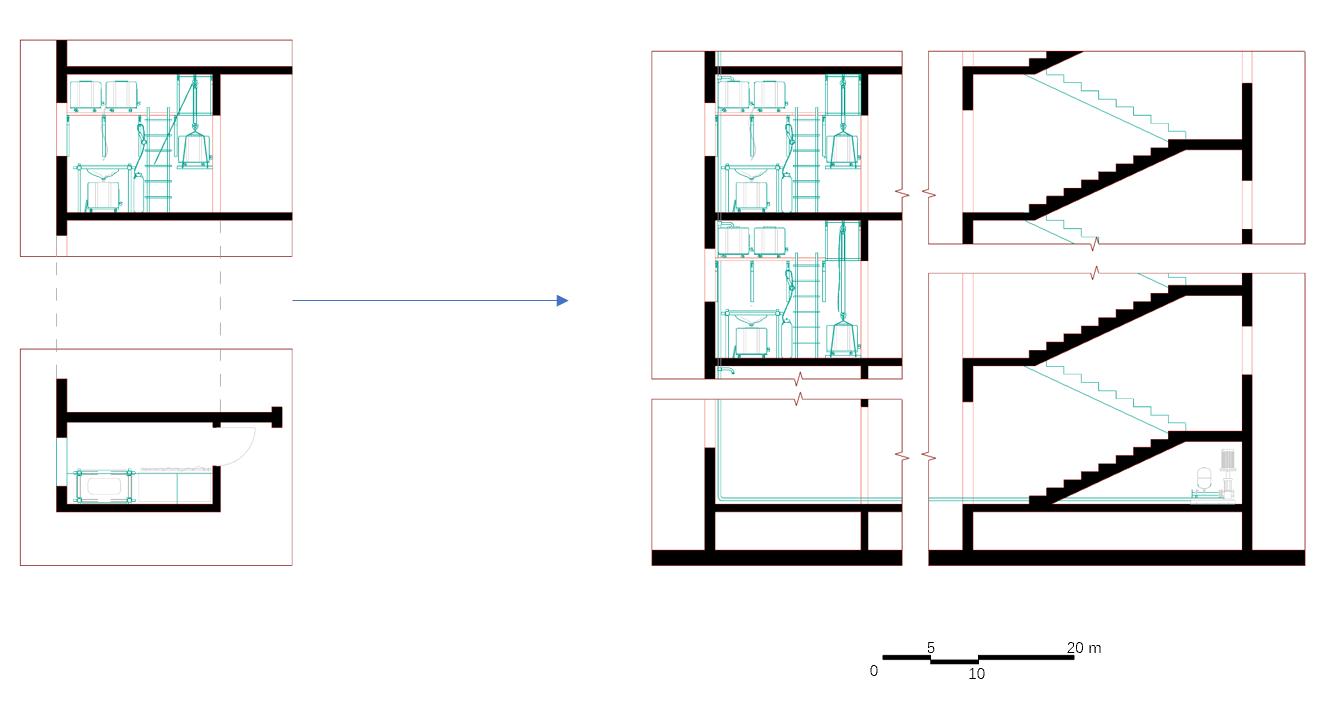

In the history of research on residential buildings in China, influenced by the Western architectural concept, the research and practice of supporting structure housing began in 1984 at the Nanjing

Dimension 1 Time 46

Engineering Institute (now Southeast University) in Wuxi city.

In the same way as John Habraken's vision of residential buildings, the supporting structure consists of the essential facilities such as loadbearing walls, floor and roofs that the building uses to support its own structure, as well as the infrastructure equipment required for residential construction.

The infill consists of the internal lightweight walls, modular furniture, etc., which were designed and built separately. This was in conjunction with China's housing reform policy of "shared responsibility by

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 47

Fig.59 Wuxi Support Housing

Source: Junhua Li, "Modern Urban Housing in CHina 1840-2000", Tsinghua University Press (2002)

Source:Redraw

Dimension 1 Time 48

Fig.60 Design Stategy for Plan of Wuxi Support Housing

by the Author

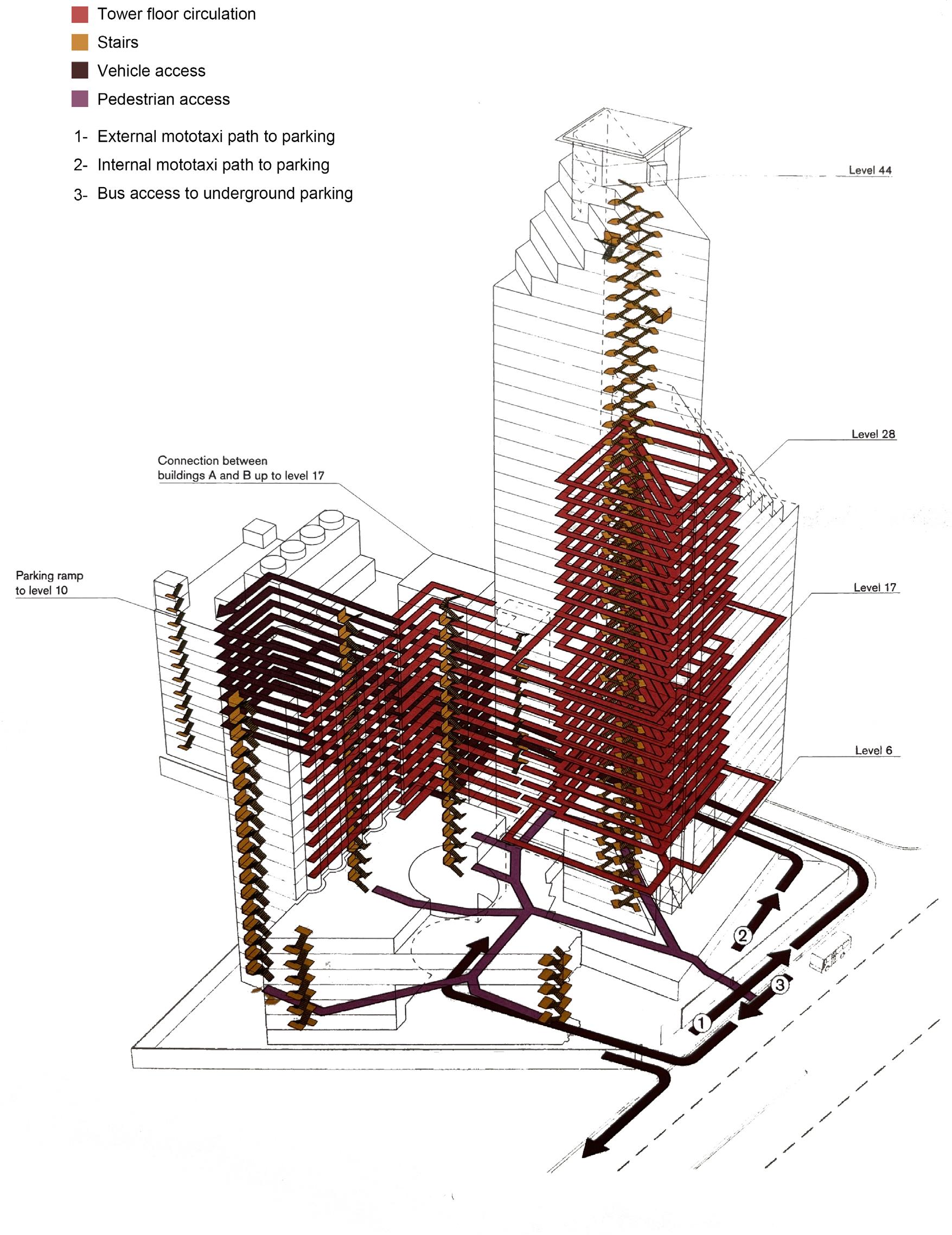

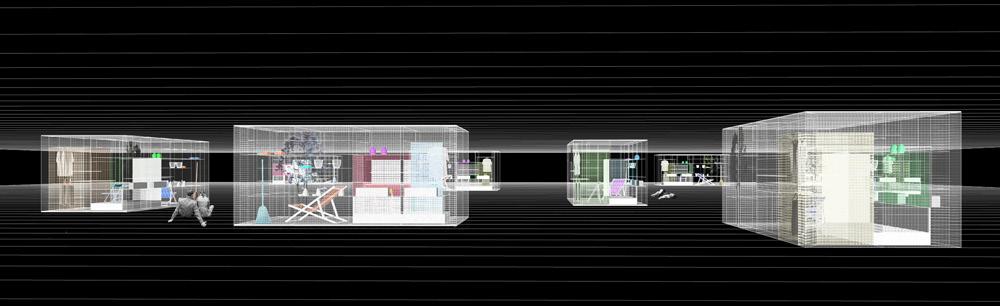

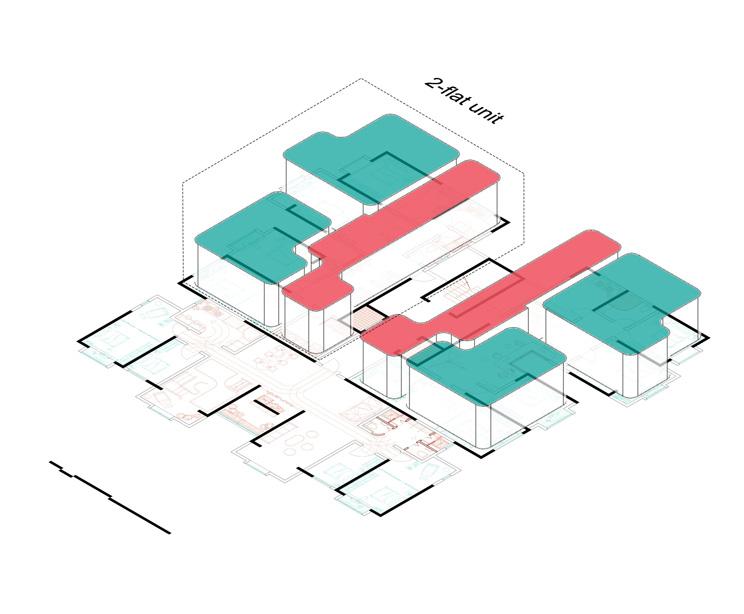

In the case which use similar design notion, "The Next 21" in Japan, the designer also set up a twostep design and construction strategy for housing. The fixed concrete skeleton of the building and structure with infrastructure that was set up and build first. Which allows the people who wants to live in the building to create their own flats that can fully meet their needs.

At the beginning of the architectural design (19891992), the spatial structure of the building's interior, consisting of the structure, equipments and reserved circulation space was established. Over the next two years, while the supporting structure was being built on the on hand, the householders who were to occupy there participated the design on the other hand, and the design was adapted to the occupants of each residential housing unit. The construction of the interior spaces was completed at the same time and was officially completed in late 1993.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 49

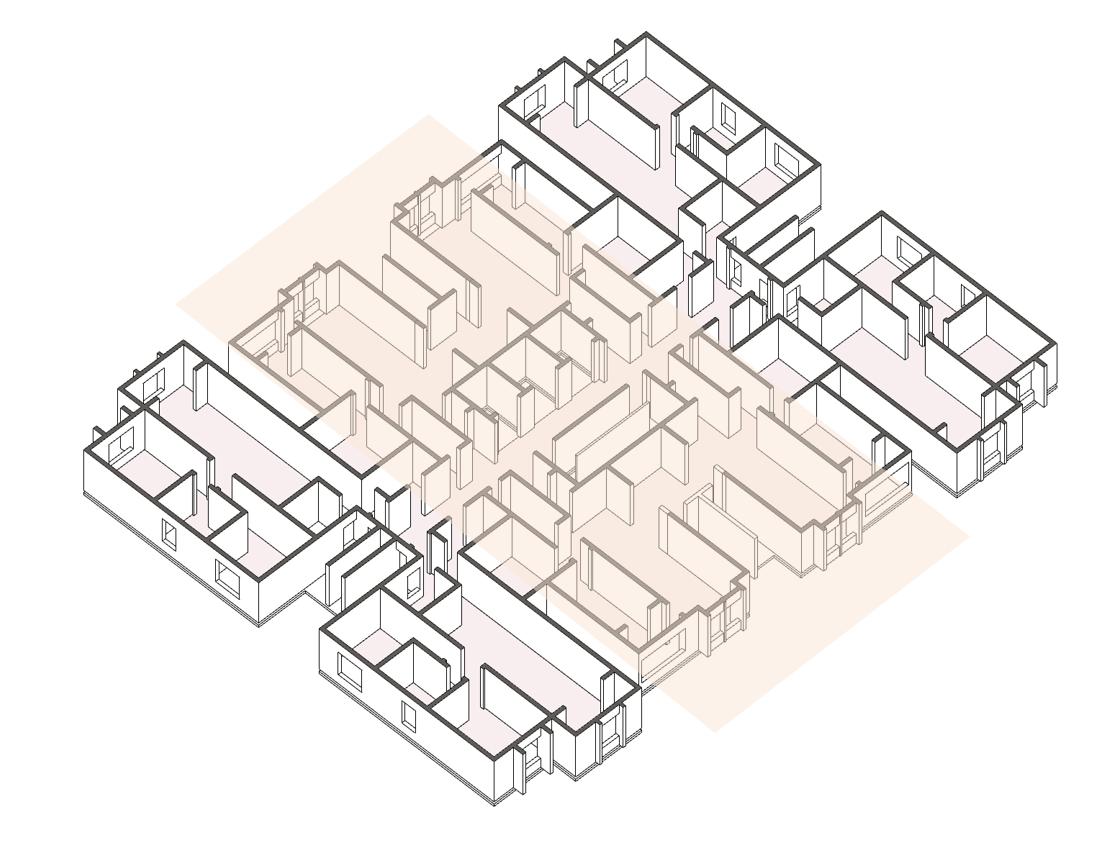

Comparing the forms of existence of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, most of those projects in Kunming city, for example, were more than halfway through the construction process, meaning that the main part of the building structure had already been completed. There are even some residential areas where the construction of the site and the outer shell of the building, etc., has been completed.

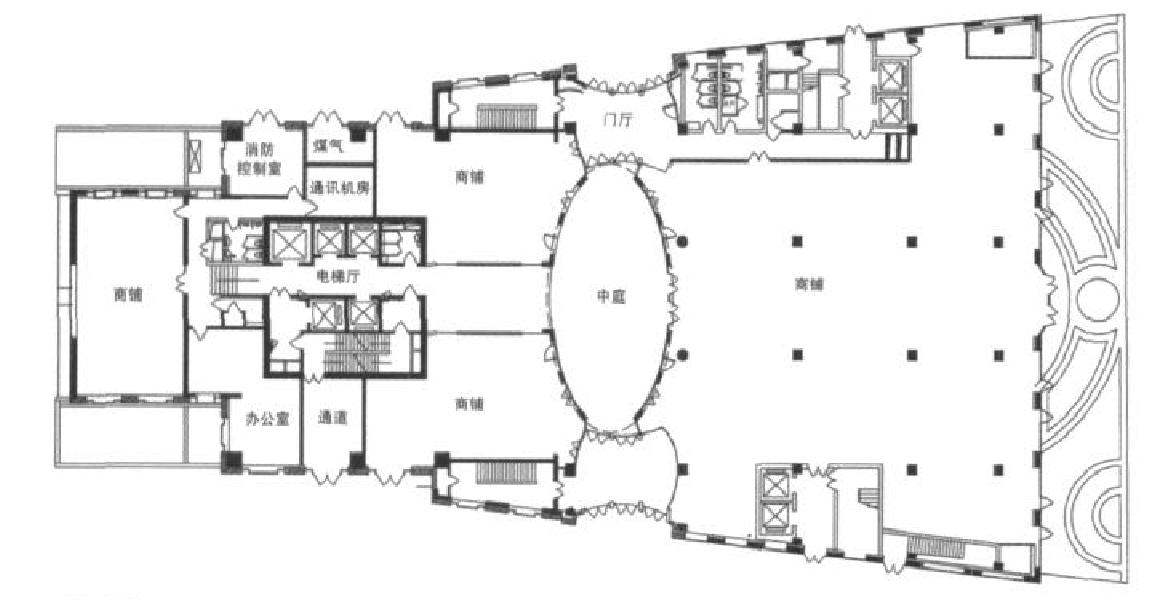

In the case of the Aozhou Shanzhuang Residencial, a Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing project in the suburbs of Guangzhou city. The project is located in Jinkeng Village, Xinlong Town, Huangpu District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, and was originally designed to cover an area of over 4 million square meters and was developed by the Guangzhou Aomei Real Estate Development Company. Construction of the actual project began in 1997 but was halted in 2001 due to a breakdown in AOMEI's funding chain. In order to

Dimension 1 Time 50

Unfinished building vs Unfinished Process

Fig.61 Abandoned Aozhoushanzhuang Distrrict

raise funds to complete the construction of the project, Aomei mortgaged or sold some of the land and housing assets of the Aozhou Shanzhuang, causing the original land of the Aozhou Shanzhuang to be divided and giving rise to a dispute over its ownership. With such unclear rights and responsibilities, it was difficult to make decisions about the future of that project (including renewal, conversion, or redevelopment). As a result, the project remained left unfinished since 2001.

In fact, most of the construction within the project had been completed, especially with a high level of completion of the residential buildings, although with the exception of the water, electricity and gas infrastructure, which could not be connected to the city's infrastructure network due to the lack of approval. The infrastructure of the buildings and the façade (including façade elements such as windows and doors) had all been completed.

As Yona Friedman said,

“The problem is not architecture. The problem is the reorganization of things which already exist1”

The classic history of architecture usually starts with the idea of the primitive hut as the first building and goes on to describe the development of the discipline as a n increasingly complex evolution of built structures. This is what is happening in China with regard to the problem of Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing, the neglect of the useable value of existing structures. This results in the majority of buildings being left for years until they have to be demolished.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 51

1 Alfredo Brillembourg, "Torrer David: Informal Vertical Communities", Lars Muller Publishers (2013).

Dimension 1 Time 52

Fig.62 Photographs of the demolishment of left-unfinished commercial housing , China. Source: Compiled by the Author

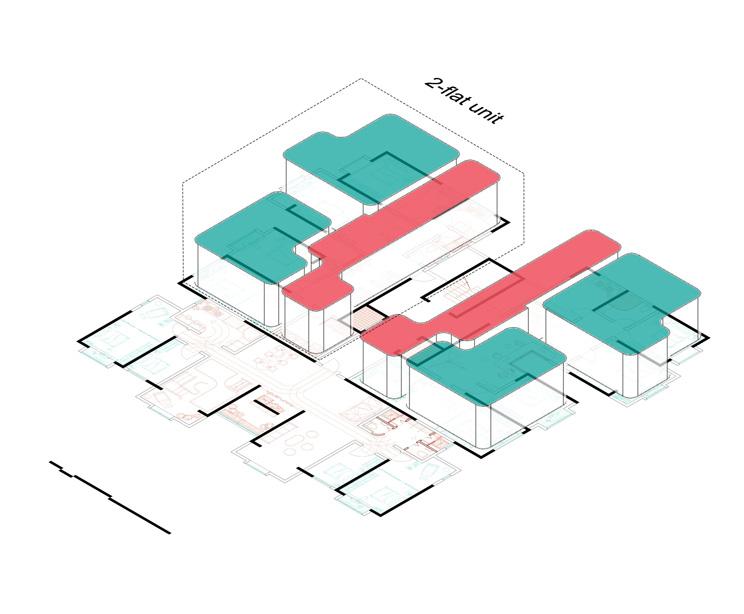

However, when comparing the reliable structures of that unfinished architecture with the supporting structure of the 2-step housing design mentioned above, all that is missing is the infrastructure facilities to accompany the housing construction. And there is a great similarity in their basic architectural support structures. In addition to defining Left-Unfinished Commercial Housing as a problem of urban development, we can also think of it as the first stage in the design of a residential building.

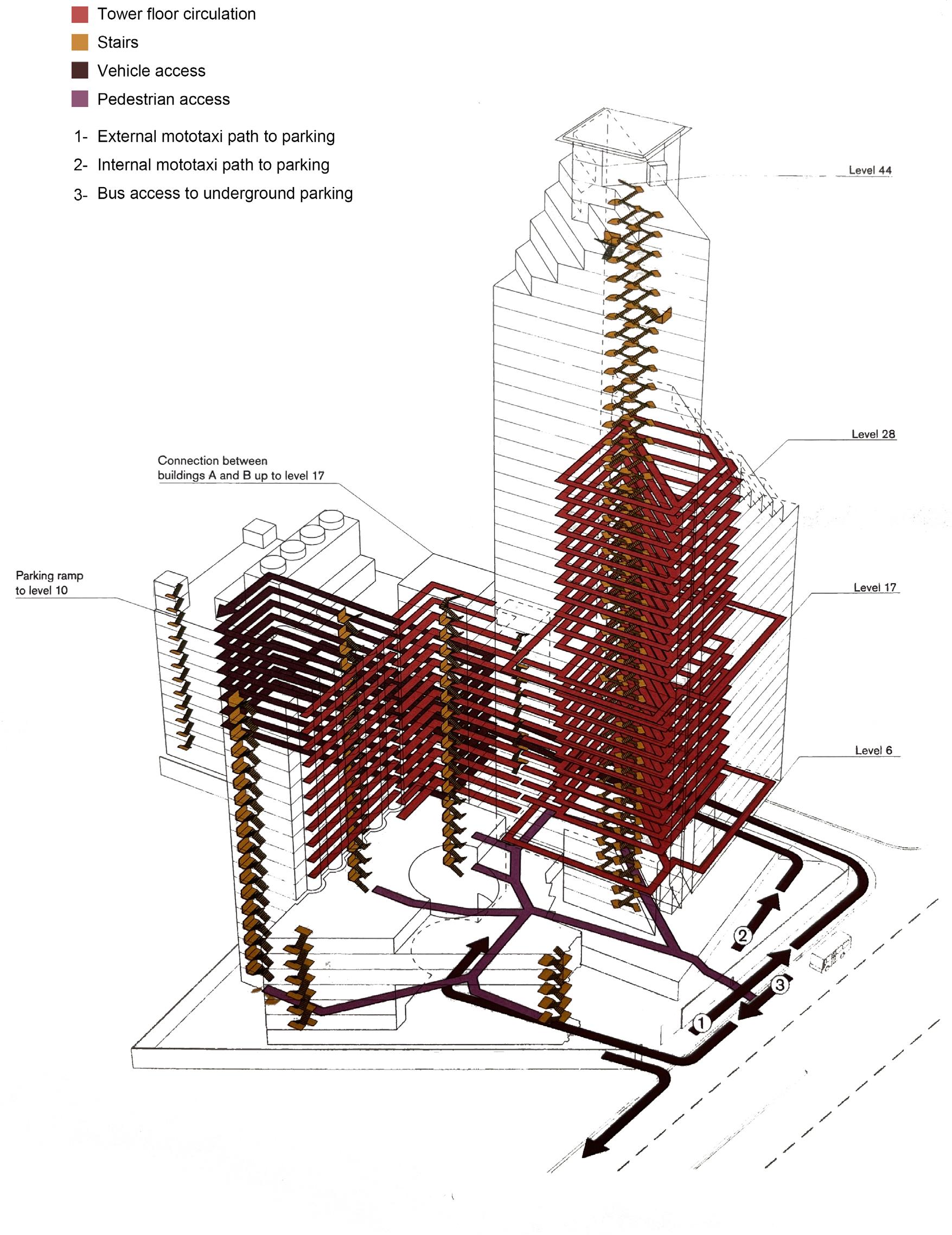

In the case of David Tower, the famous LeftUnfinished building that was appropriated for residential use, it was hoped that the building would become an iconic building for Venezuela's rapid economic development. However, with the outbreak of the Venezuelan banking crisis in 1994, the construction of the Carfax Financial Centre was suspended. In the 2000s, there was a shortage of housing in Caracas, and in 2007, after the building was occupied by some poor people, more and more of them moved into the building. At this time, the building still had no water or electricity supply and no lift. However, as the number of residents increased, the building became more and more equipped with the cooperation of the residents themselves1.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 53

Dimension 1 Time 54

Fig.63 Diagram of the Water Distribution System in Torre David

Source: Alfredo Brillembourg, "Torrer David: Informal Vertical Communities", Lars Muller Publishers (2013).

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 55

Source: Alfredo Brillembourg, "Torrer David: Informal Vertical Communities", Lars Muller Publishers (2013).

Fig.64 Diagram of the Electricity System in Torre David

Dimension 1 Time 56

Source: Alfredo Brillembourg, "Torrer David: Informal Vertical Communities", Lars Muller Publishers (2013).

Fig.65 Diagram of the Circulation in Torre David

In the case of David Tower, we can consider that it is the "invaders" who have completed the second definition of the remaining building structure, it is the daily life of the invading inhabitants who have transformed the building from an unfinished structure into a temporary living space that has not yet completed the process of construction, which as mentioned above is an unfinished process.

The case of Torre David is not a perfect solution to solve the problem of left-unfinished building, both from the aspect of legality and spatial problems, although in the course of the experiment, the community of residents has become incerasingly stable. The reason is that the legality of living in the David tower remained unsolved until 2015, when the intruders were relocated by the government to other social housing. Futhermore, the spatial problems of the building itself still exist.

However, what is significant is that these selfgenerated activities conflicted with the building's original structure and intended function. Thus, the potential can be revealed by analysing instances of such spontaneous formation of solidarity in order to exploit the existing space of unfinished processing. In comparison to the path-based development model, the unfinished commercial housing stock has the potential for re-designing once the infrastructure system is added.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 57

Dimension 1 Time 58 2.3

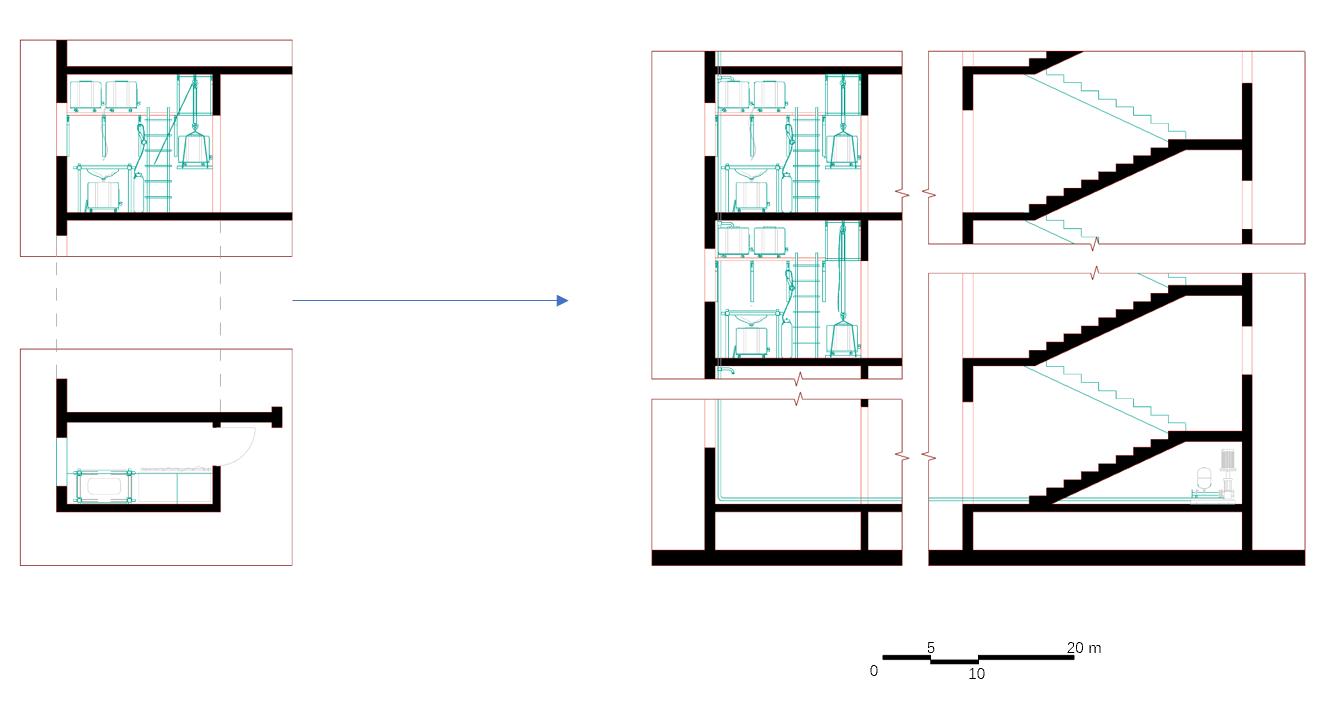

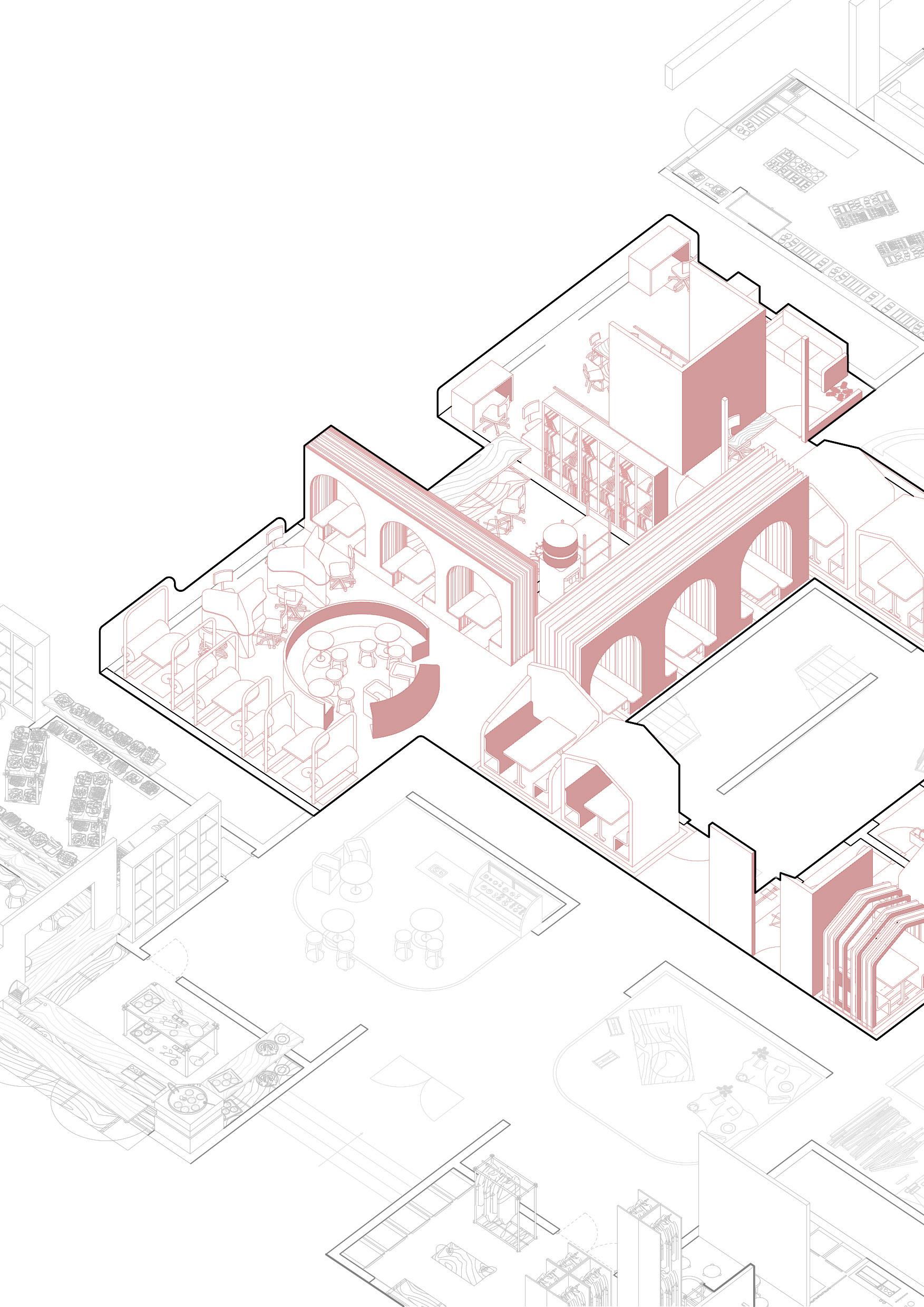

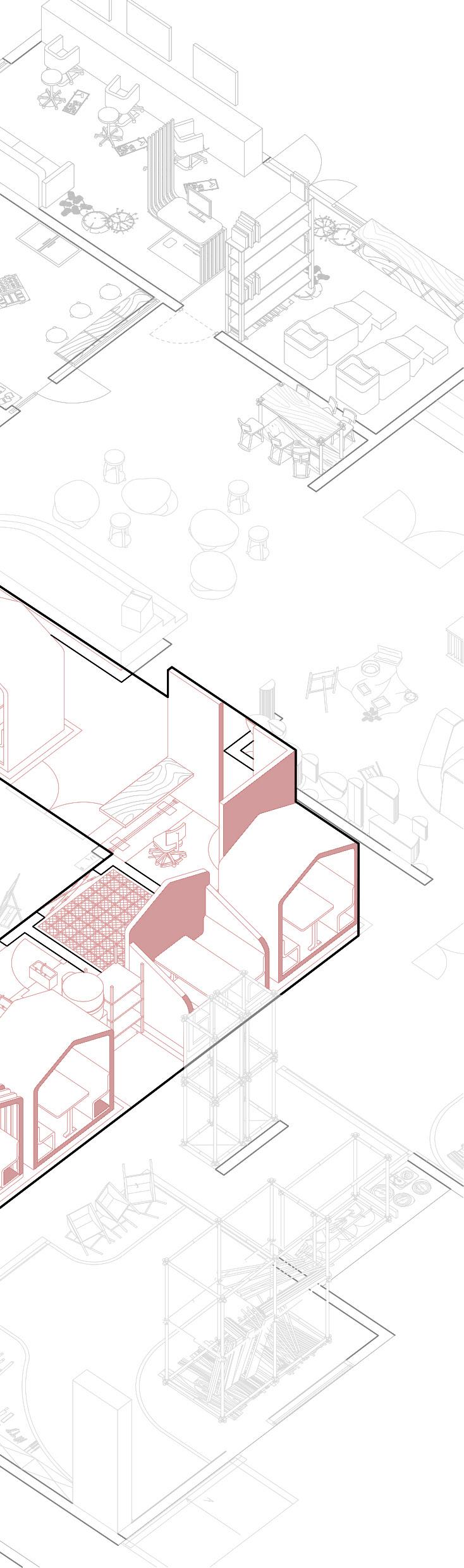

Experiment #1

Fig.66 Design of a Short-term Water Equipments

Source: Drawing by the Author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 59

Fig.67 Design of Self-built

Source: Drawing

Common Program +

Dimension 1 Time 60 Self-built Common Spaces

Drawing by the Author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 61

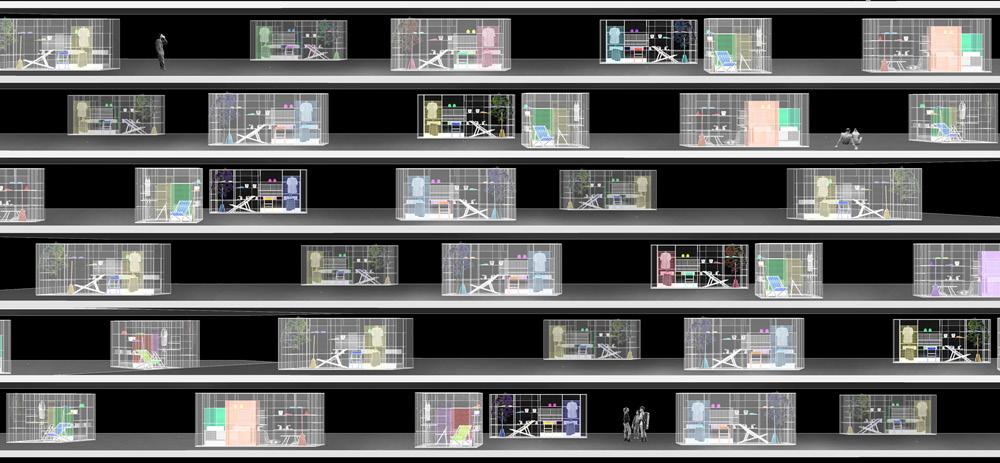

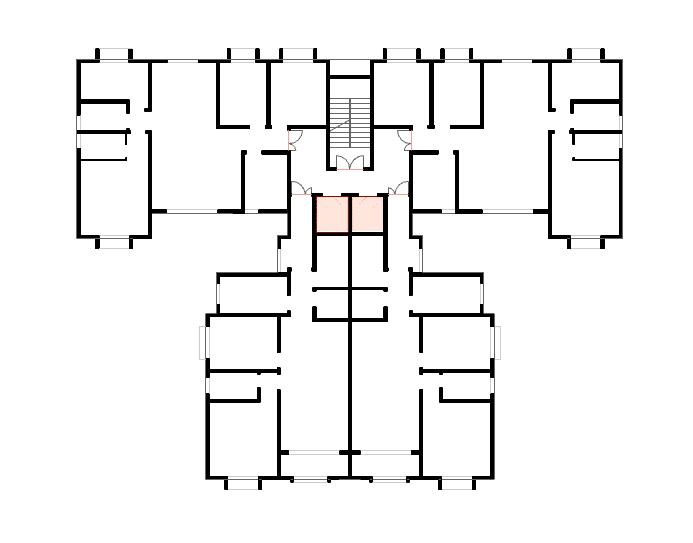

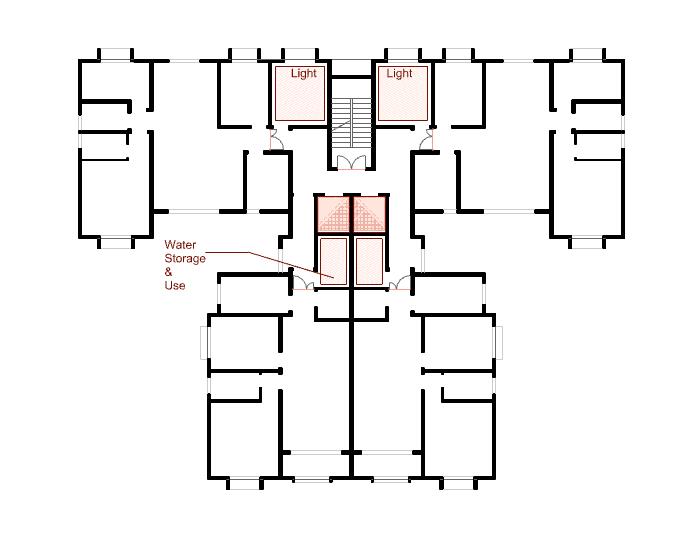

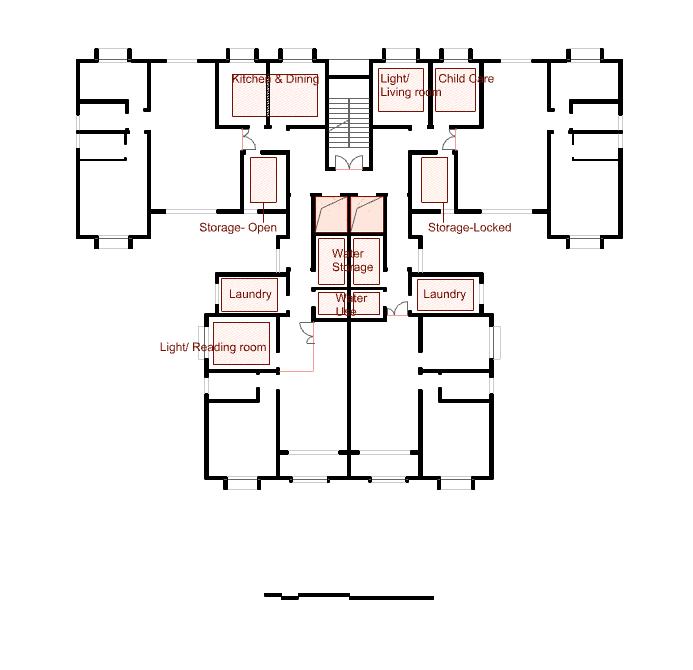

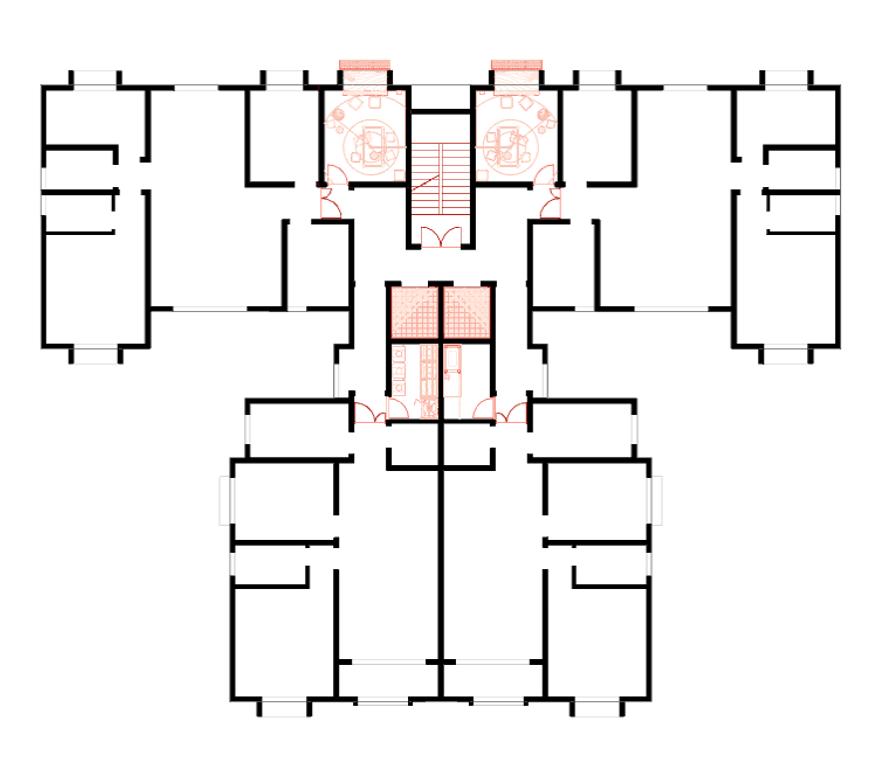

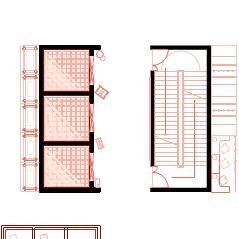

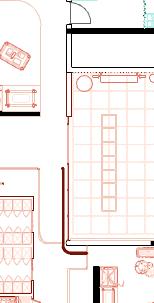

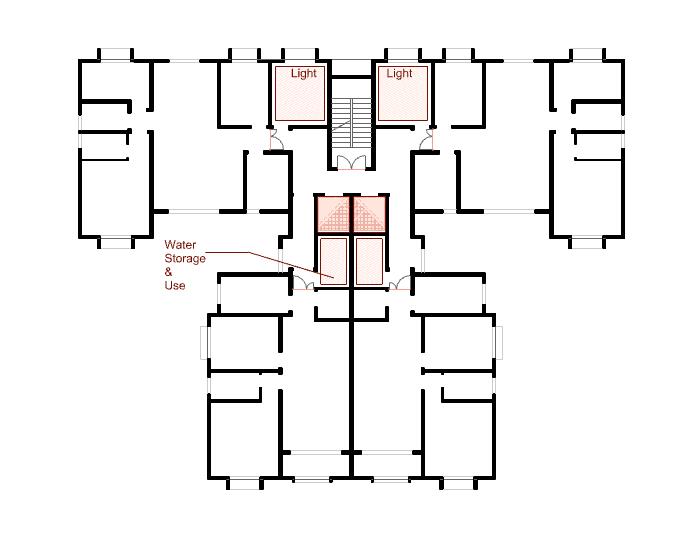

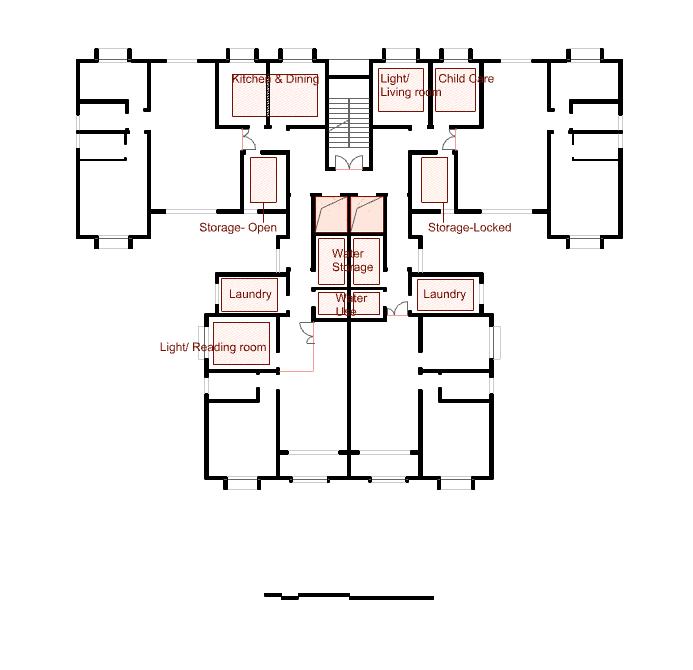

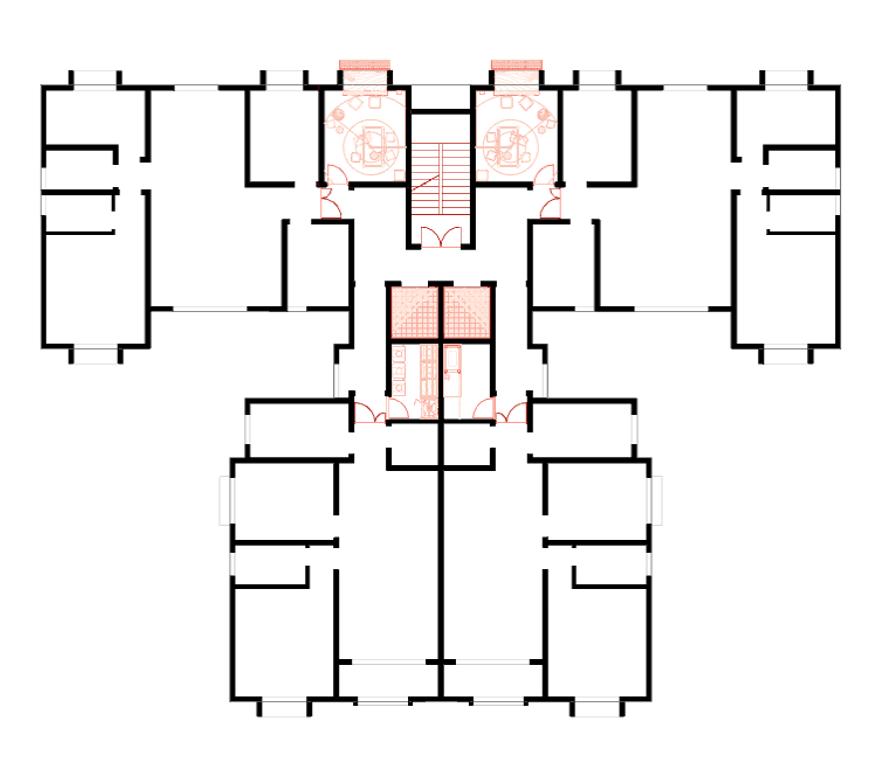

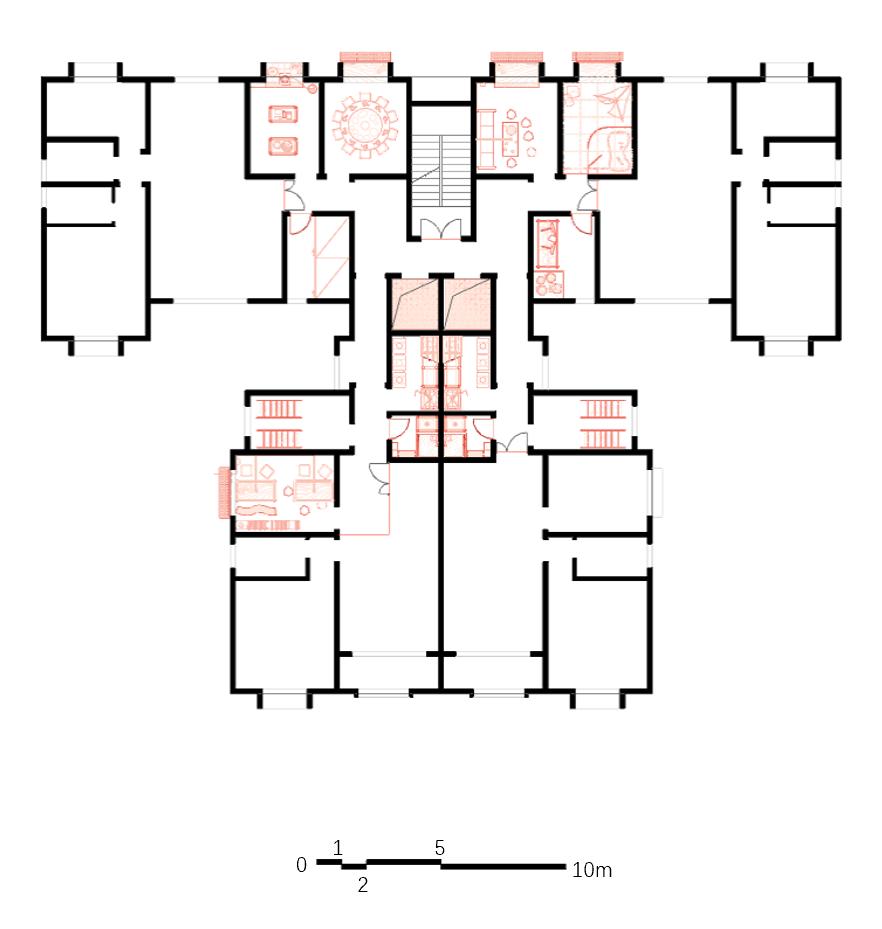

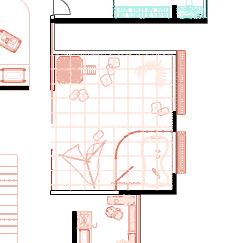

Fig.68 Diagram of Distribution of the Common Space in Typical Floor (Designed)

Source: Drawing by the Author

Dimension 1 Time 62

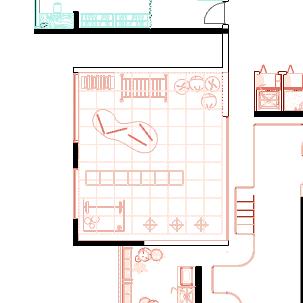

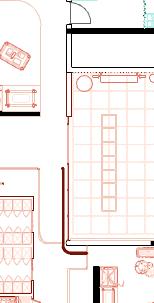

Fig.69 Plan of the Designed Self-built Common Space (Typical Floor)

Source: Drawing by the Author

DIMENSION 2

Spatial Legality and Right

Illegality VS. Spatial and Social Right

Policy Framework & Management

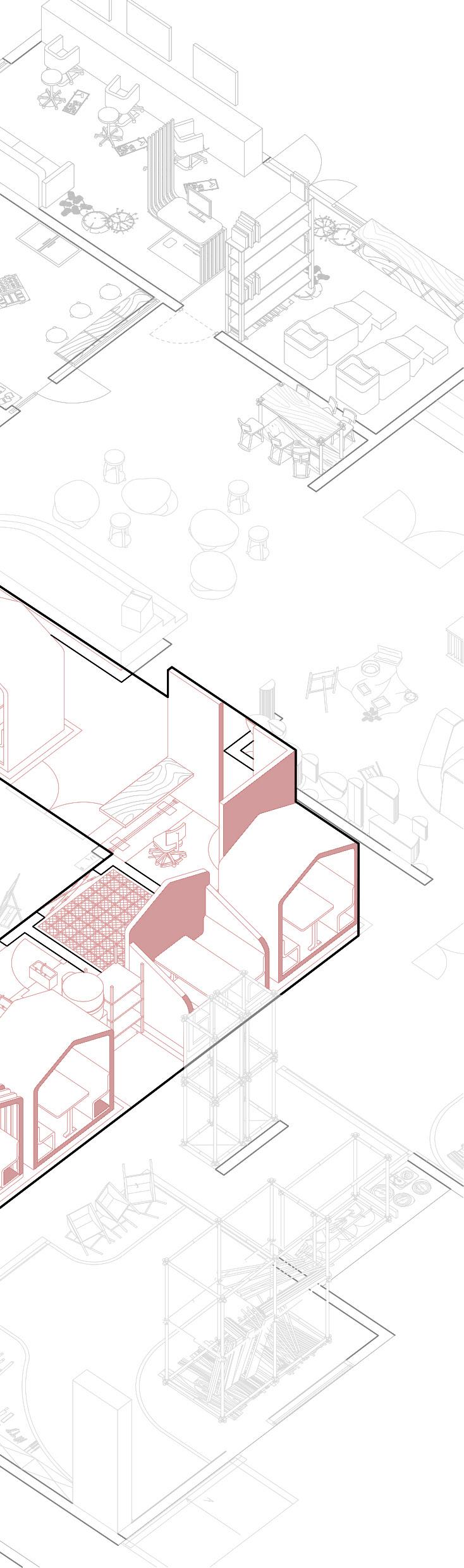

Experiment #2

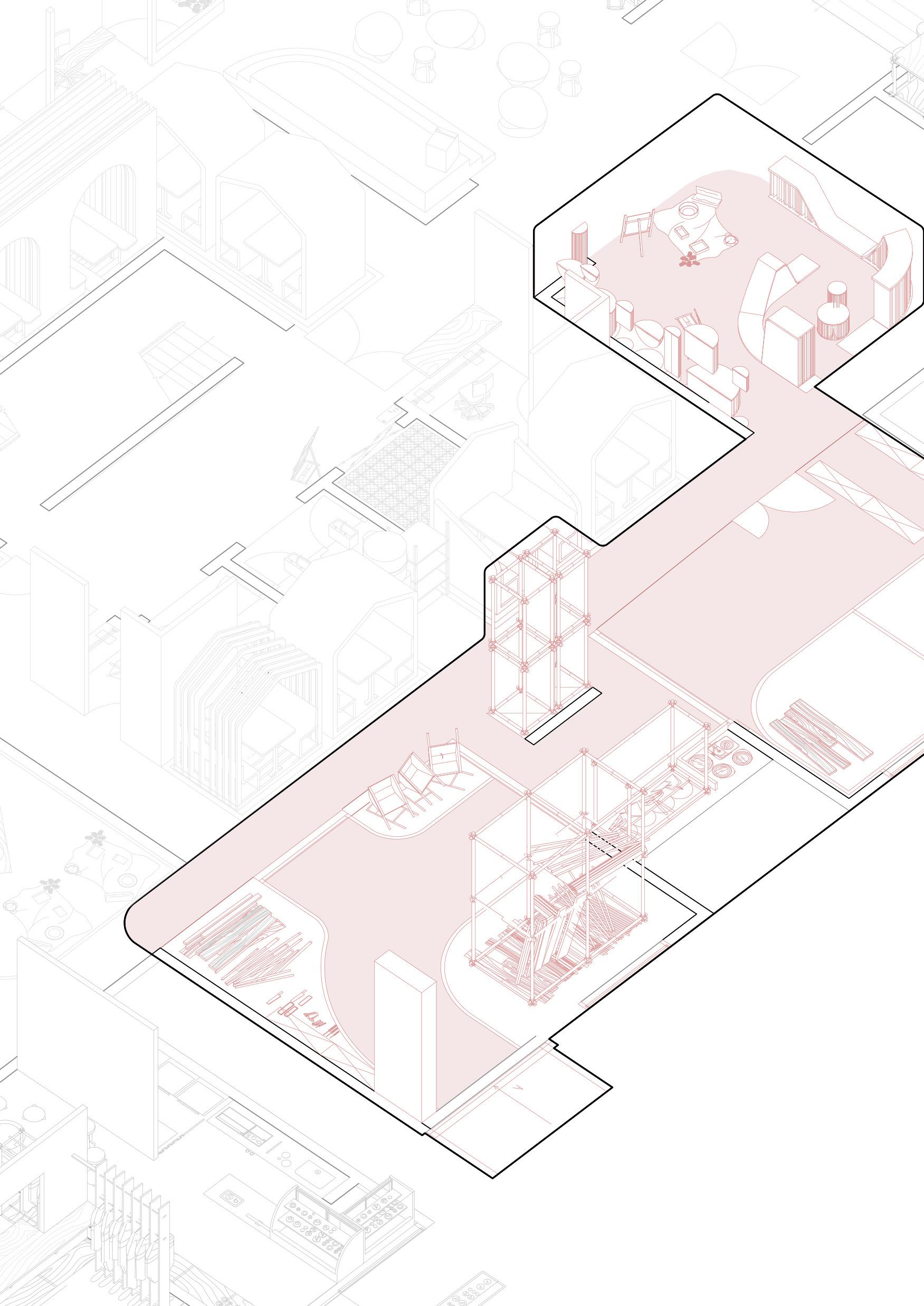

Dimension 2:

Spatial Legality and Right

3.1

Illegality Spatial and Social Right

With the accumulation of experience in China's urban construction management and the improvement of urbanisation levels, the government has put forward a call to strengthen the rectification of rotten buildings. At the same time, also due to the standardisation of the urban land supply market, land approvals have become increasingly stringent, and some developers with insufficient capital have turned to the acquisition of left-unfinished sites in order to circumvent the cumbersome land approval process required for the development of undeveloped land.

As mentioned above some of the left-unfinished housings are of high engineering quality and can be brought to market with only a small amount of renovation investment and a short construction cycle, resulting in a high return benefit, allowing some of the left-unfinished buildings to be renovated. However, there are still most of the projects in the city that have not been solved so far. The complex issues involved in left-unfinished buildings and the factors that limit the renovation of rotten buildings mainly lie in the unclear definition of authority and responsibility.

Illegal Saptial Occupancy

Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 63

Construction is a comprehensive process that involves complex debt and credit relationships. From the developer's financing stage, it involves debts and claims between the developer and the government, financial institutions and investment partners. During the project development process, it involves direct or indirect debt relationships between the developer and the designers, engineering contractors, material and equipment suppliers. During the pre-sale phase of the project, the developer is involved in the debt relationship with the owner. The suspension of the project involves the collection of funds and compensation for late delivery. The determination of the volume of work, compensation for delays, the original developer's mortgage and the interest on the liabilities arising from the mortgage, etc. can all give rise to debt and claim disputes. There are even complex direct or indirect disputes over ownership and debts arising from the unregulated and illegal operation of developers who sell twice in on house, repeat mortgages or set up multiple projects to rise fund illegally.

Under the conditions of such policy implementation, it is difficult to move forward to the next step of planning for renovation or redevelopment once the residences of the left-unfinished housing are in dispute over their ownership. Buildings that have not been constructed are not accepted and approved by the relevant authorities of the housing and construction departments in China. As a consequence, purchasers of a building in bad condition cannot obtain a certificate of ownership of commercial housing and a land use right certificate in China. Therefore, the existence and use of a building is illegal under the current legal framework.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 64

In the case of Torre David, the invaders are simply vulnerable people such as the homeless in the city, who have no relationship to the abandoned urban space. The mass invasion and habitation in the Torre David is more of a coincidences, as Andres Lepik states,

"…The current residents of Torre David Seized the opportunity of appropriating an existing structure, originally intended for a different purpose…"

Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 65

Fig.70 Self Renovated Facade of the Torre David Project

Source: Alfredo Brillembourg, "Torrer David: Informal Vertical Communities", Lars Muller Publishers (2013).

Unlike the intruders living in David's tower, in the case of the Bieyangxingfu neighbourhood discussed in this research, the occupants have paid for their housing in advance. In other words, they had paid for the housing and were supposed to be granted the right to live in and use the private housing with full ownership for the duration of the contract. However, it is still illegal for them to be compelled to live in the housing they have purchased because of the effects of its deterioration.

Jorge Morales, head electrician and resident of Torre David, also said that he was not convinced that this intrusion and the connection of Torre David's electrical system to the city's energy supply and the establishment of the initial building electrical installations was illegal.

"We knew that what we were doing was illegal, but it was beneficial to the new residentswe did it so that they would have a normal lifestyle."

Similarly, the residents of Bieyangxingfu Residential mentioned several times in interviews that they were fully aware that they did not have property ownership certificates for their flats, so they should not be here and do not like to be here. However, they have no other options.

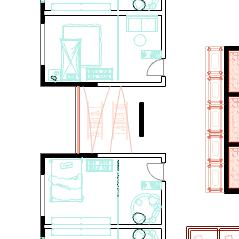

In terms of specific spatial measures, due to the chaotic division of property rights, it is even more unlikely that these non-ownership occupants will have the right to make renovations to the original building. This means that once the plot is re-sold by auction for redevelopment, all the structures on the original plot should be preserved in their original form by the secondary developer. Therefore, any modification of the building components of the completed part of the left-unfinished will be illegal.

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 65

Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 67

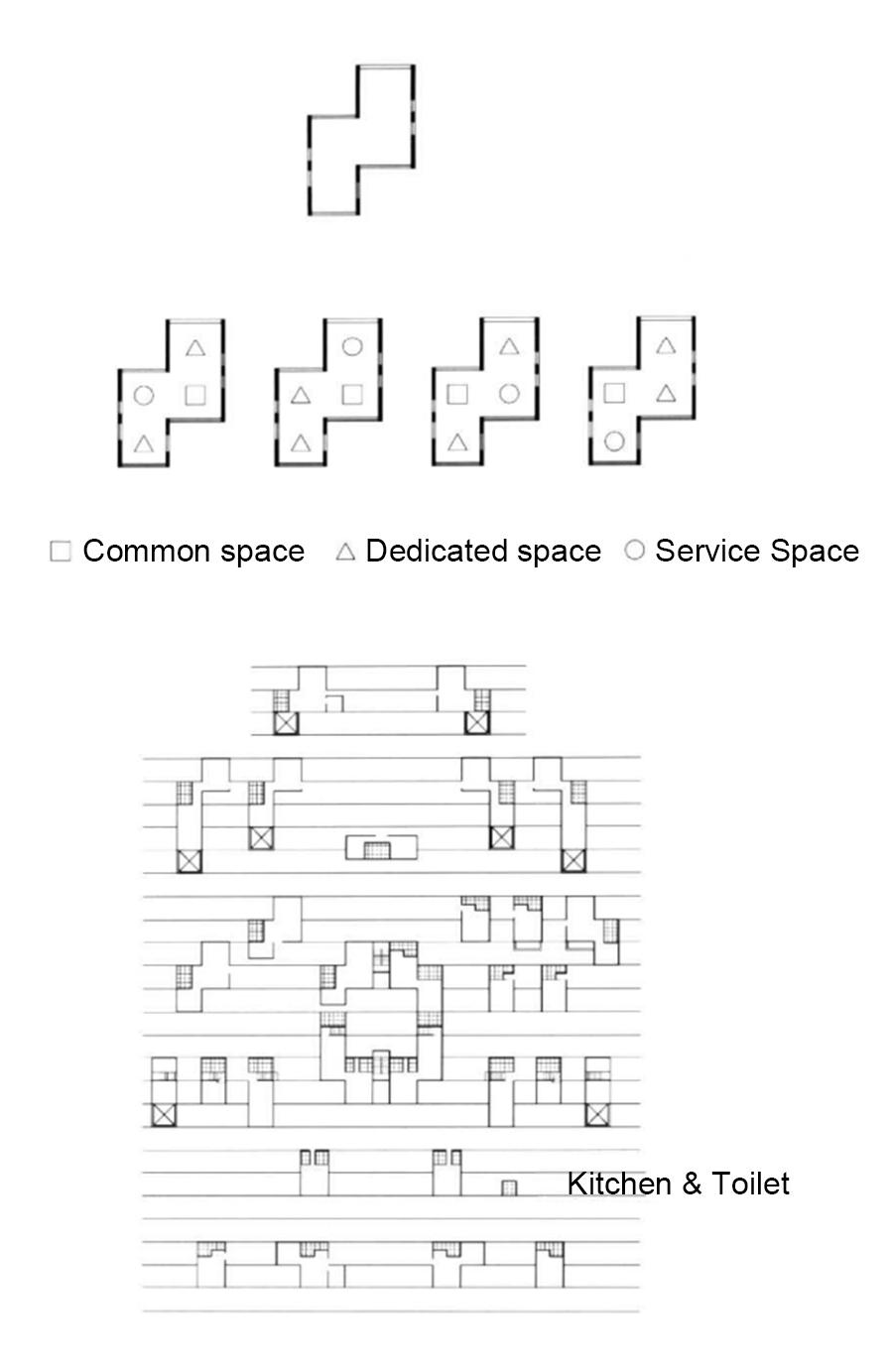

A Type B Type C Type D

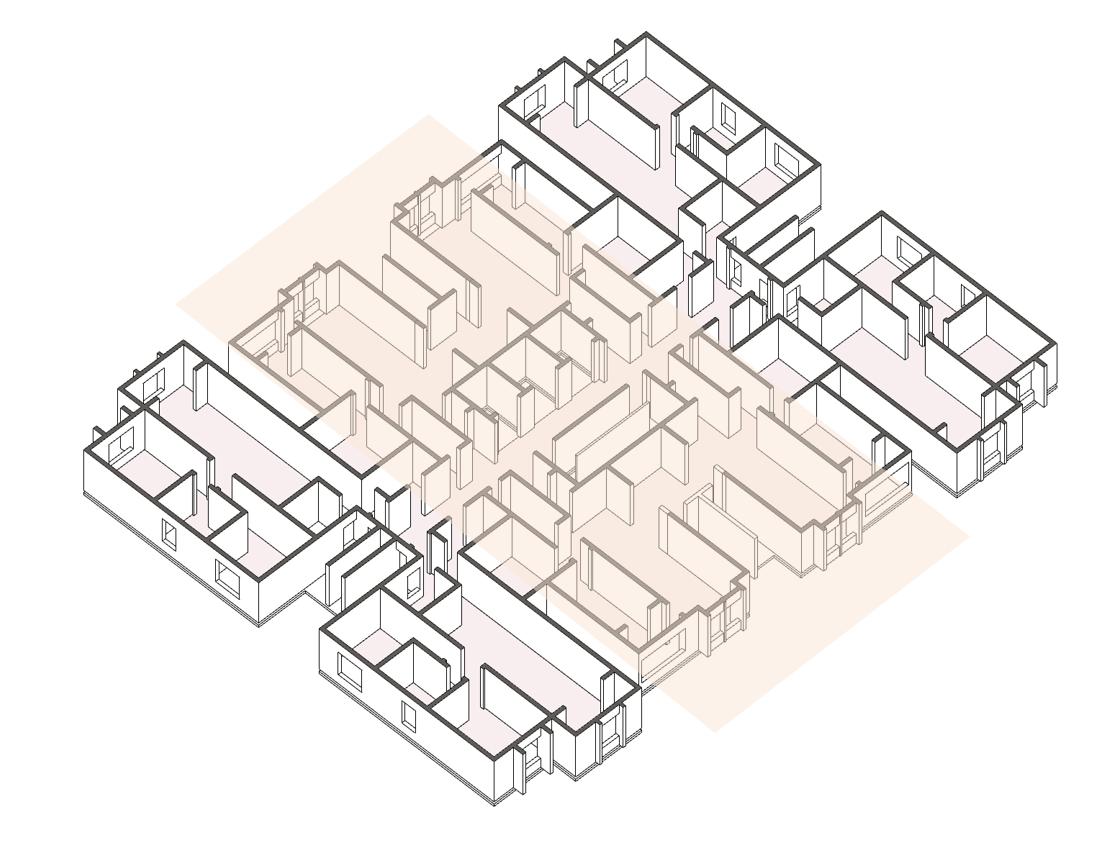

Fig.71 Distribution of Different Type of Housing in Bieyangxingfu Site

Type

Source: Drawing by the Author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 68

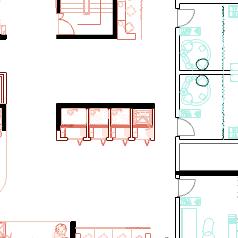

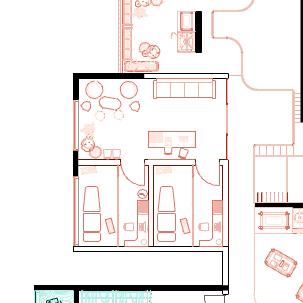

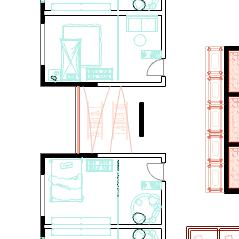

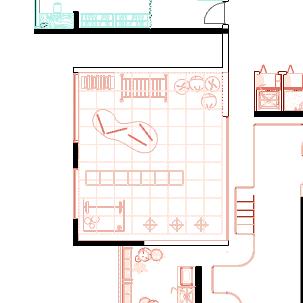

Fig.72 Designed Plan (Up) & Plan of Current Status (Type A)

Source: Drawing by the Author

69

Fig.73 Designed Plan (Up) & Plan of Current Status (Type B)

Source: Drawing by the Author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 70

Fig.74 Designed Plan (Up) & Plan of Current Status (Type A)

Source: Drawing by the Author

Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 71

Fig.75 Designed Plan (Up) & Plan of Current Status (Type B)

Source: Drawing by the Author

HOUSING NOT ONLY FOR LIVING 72

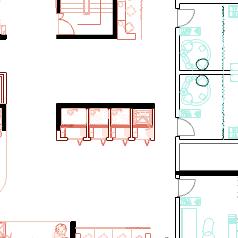

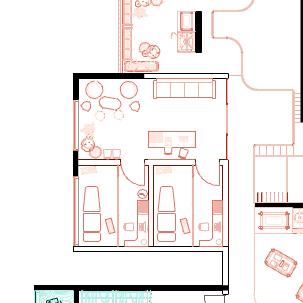

Fig.76 Different Types of Designed Living Units in Beiyangxingfu

Source: Drawing by the Author

Dimension 2 Spatial Legality and Right 73

Fig.77 Current Status of Living Units in Beiyangxingfu

Source: Drawing by the Author

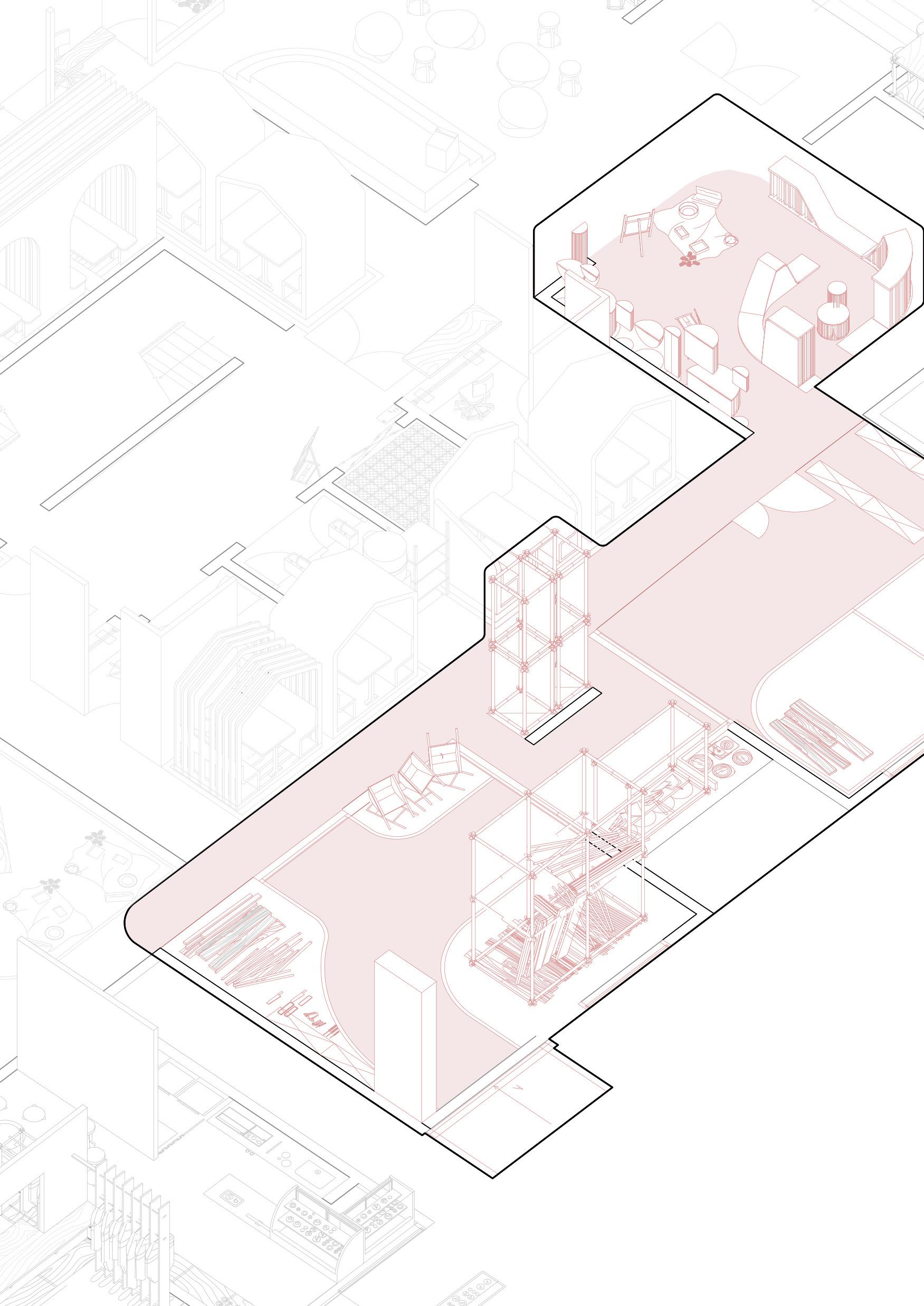

Inequal Right to the Space & Social Walfare

As mentioned above, this omission of policy and guidance further leads to a kind of inequality in the use of space for commercial housing. In the case of China's basic real estate sector, the paid use of land is a prerequisite for the commercialisation of land and buildings by the state, and it also means that government agencies hold the full authority to use land, allocate it, and administer its use in a granular manner. However, it is clear that these state institutions do not assume the risks and responsibilities that come with this power when land development runs into problems. This results in the actual users of the space being in a position of right vulnerability when it comes to changing the form and space of the building, especially as there is no effective way to change the existing power structure when problems occur and thus change the status quo from the bottom up.