Alternative Breathers

On the modes of existence of Comfort

Luyao Luo

Dissertation

MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities), 2020/2022

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

COVER SHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2021-2022

PROGRAMME: Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

NAME(S): Luyao Luo

SUBMISSION TITLE: Alternative Breathers: On the mode of the existence of comfort

COURSE TITLE: Dissertation

COURSE TUTOR: Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi

DECLARATION:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student(s):

Date: April, 2022

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my tutors Dr Platon Issaias and Dr Hamed Khosravi, who have guided and supported me continuously along this amazing journey. I am indebted to their wise knowledge and remarkable patience, which turned this research possible. My sincere thanks go to Dr Doreen Bernath, for her invaluable inspiration and support in each step of this thesis. I am also thankful to Roozbeh Elia-Azar, Cristina Gamboa, and Raul Avilla-Royo and for their kind help and input during my studies.

Colleagues and friends from Projective Cities and AA beyond generously gave their time and shared ideas. They have broadened this dissertation through diversified discussions, which without a doubt have enriched my thinking and made AA feel like a harbour.

Finally, a special note of gratitude to my family, who has been preciously supportive throughout my life with unimaginable love and trust.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Introduction Chapter One: HEALTHY COMFORT 1.1. The minimum comfort 1.2. The manufacture of Atmosphere 1.3. The introduction of Atmosphere 1.4. Design Proposal 1: Divider Bibliography Chapter Two: THERMAL COMFORT 2.1. Disciplinary Air 2.2. Commercialized Air 2.3. Energy Policies in the UK (1970s-2020) 2.4. Design Proposal 2: Connector Bibliography Chapter Three: FUNCTIONAL COMFORT 3.1. Space Standards/Comfort in the Metropolis 3.2. Temperature Standards 3.3. Conclusion 3.4. Design Proposal 3: Moderator Bibliography 0 2 C H 11 17 27 35 B C T 51 53 61 67 B C F 87 93 97 105 Bibliography

Abstract

The thesis ‘Alternative Breather’ focuses on the spatial connotation of comfort in relation to environmental control in the UK context and its social and economic origins and consequences.

It takes its cue from the changes in home heating systems and the spatial typological transformation of the British home in order to explore new modes of living in the UK today.

The research focuses on the construction of self by taking care of oneself in a way that challenges the shared perception of comfort. These notions of comfort are interfered with by a range of shared ideas, including material culture and health norms. The most significant case is the emergence of consumer culture in the UK since the late eighteenth century, where the idea of comfort underwent a major shift towards the naturalisation of selfconscious satisfaction with the relationship between one's body and its immediate physical environment. It was revealed as a means of control in the early years of capitalist society. The balance within the dialectical process can find its echo in the deteriorating energy problems in the UK, such as energy poverty. However, the aim of this research is not to solve the problem by increasing the viability or the effectiveness of specific energy practices that embrace sustainability either by technological means or architectural logic. Instead, it constitutes the basis for addressing comfort as a design problem by delineating the notions of comfort and the power of the opposite.

In order to do this, the genealogy of the research is derived from a series of historical case studies that embrace different states of self-care associated with heating systems: From the prevailing norms of health and the environmental control objectives that shaped them since that late-eighteenth century, to glass houses and climate therapy; from registered chimneys that hierarchised spaces and central heating, to valves, control panels, auxiliary heating and air conditioning that shapes the space.

Through historical and typological analysis, cultural and architectural characteristics of domestic heating systems are unfolded in order to be instrumentalised towards alternative domestic living models within three housing types. When the individuality of the body is incorporated into the sociality of environmental control, the body is encouraged to find its exit by multiple ways.

Introduction

Comfort is the characteristic of modern interior living. Its manifestation in the mass media, standardised building codes, legal frameworks and the objects it accommodates – soft furniture, supple clothing, convenient objects, clean air, variable temperatures – constantly constitute and enrich our imagination of the ideal life. The term is derived from the English comfort and this, in turn, from the French confort. Its true derivation is from late Latin, confortare, derived from com-fortis, to render strong and, by extension, to alleviate pain or fatigue. Its modern connotation – self-conscious satisfaction with the relationship between one's body and its immediate physical environment – reveals the great leap in productivity within the consumer revolution and scientific progress by emphasising the pleasures of private life. Before the Industrial Revolution, the need (or expectation) for comfort – in the sense of convenience, ease, and habitability – was a privilege of the few. If the progressive diffusion of comfort to the masses in Victorian England was not accidental, then there is no doubt that it played a fundamental role from the beginning in the tasks of controlling the social fabric of the nascent capitalist society and powering the modernisation process.

Domestic heating was one of the first stages on which the transformation of the concept of comfort took place. From its introduction as a fashion in England during the Renaissance to its gradual revelation of hygienic and medical value during the late-eighteenth century, and the technological upgrades that accompanied this process, the transformation in the role of the chimney fireplace not only reveals a continually changing dynamic in terms relating to supply and demand – comfort does not always come in the same way – but it also illustrates the core values of modernity, where the binomials of hygiene-morality, cleanliness, dignity and physical and mental health began to take an impressive form. A clean city is also a combination of clean houses, completing the transformation from an open living space of fluid, imprecise, fugitive confines typical of the environmental context of the traditional family to a closed space, articulated in a system of rigidly fixed functions within a nuclear family.

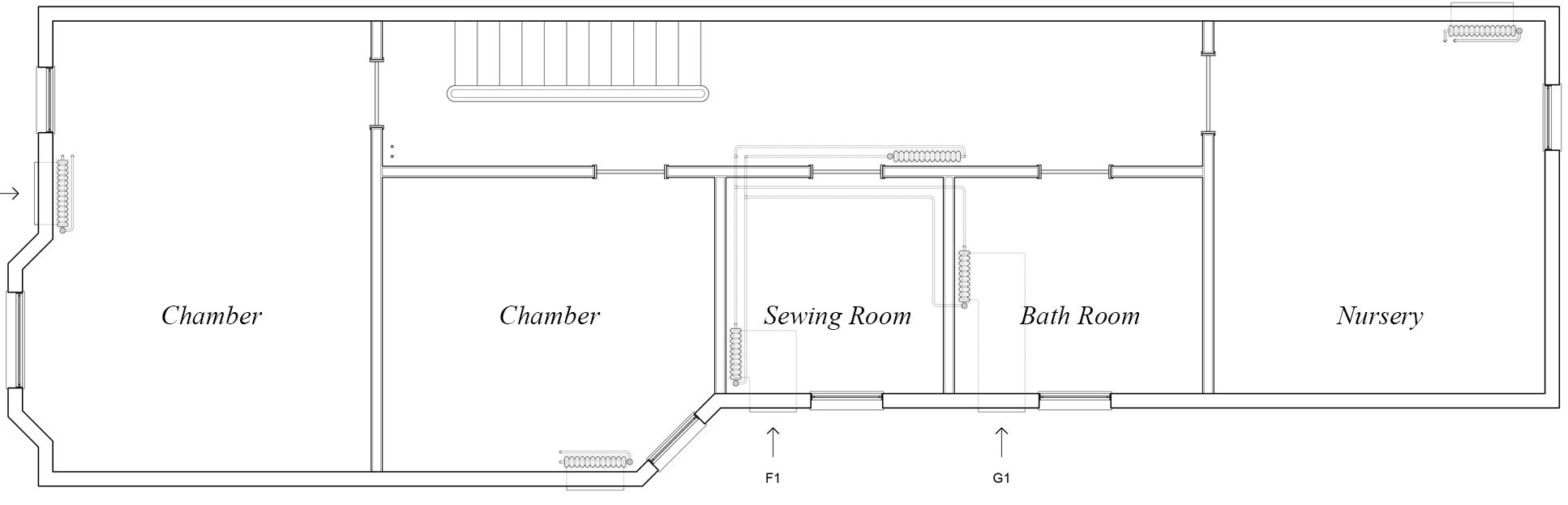

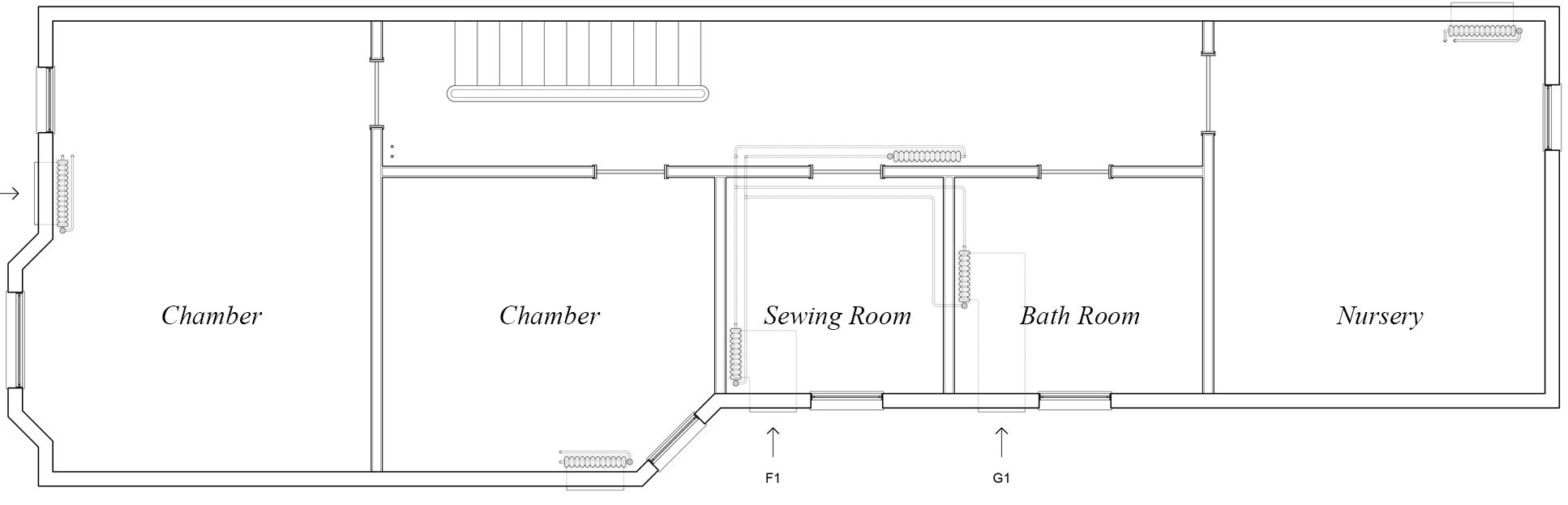

The question of whether bathrooms should be provided with space heating has been a focus of domestic comfort in relation to environmental control. Proponents of adding heating argue that it is easy to catch a cold in winter without access to a warmed environment after bathing; bedrooms tend to be cooler because of other warming options (clothes, quilts). Even if a strict functional division (dining room, living room, bedroom, kitchen, bath, etc.) constitutes an ordered life, living space is also a material regimen. It is an arrangement of movable and immovable objects (equipment and utensils for making and saving food, the care and assistance of children and hygiene and cleanliness; installations

2

for the control of temperature; gadgets for recreation and communication; furniture; household goods; etc) that establish the concept of comfort at the intersection of functionality, physical well-being and space, which is represented in the media as a warm and healthy home.

Interior decoration is the magical process that transforms a ‘house’ into a ‘home.’ It covers the rigid structure; the building materials and their materiality; the rough, stark joints and the clumsiness and imperiousness of industrial production. The spatial atmosphere of a home should exhibit a colourful richness, feature the warmth of a human touch and give a sense of artistic taste to make the living space feel softer, tender, warmer, more harmonious and closer to nature. The spatial home atmosphere with such features plays an important role in attenuating the hegemony and violence of power, massaging the inner logic of spatial politics and increasing the unity and harmony of the family, rendering the home a place of rest and relaxation. The room is an architecture of silence. Yet despite its monopoly over silence, it forbids silence from its inhabitants. It is a space of coerced chatter. The space of the interior speaks one phrase endlessly: ‘everything is ok.’ In this way, life voluntarily reproduces its most innocent, automatic gestures.

As stated in the building code, it takes 1 kWh to warm every 10 square meters within an average British house, but it is much higher than that in actual consumption. These energy products and the pipes, valves and metering technologies supporting them have contributed to a significant misunderstanding of the home as a space autonomous from society, thus maintaining an unequal spatial order in the city, creating a relationship of responsibility and the apportioning of benefits across the state, society, corporations and the customer.

Although temperature standards are still set according to functional plans, the wide range of standard temperatures makes it difficult to find one for each room: according to the latest housing standards introduced by the World Health Organization, the indoor temperature of a home should be kept between 18–21°C during winter, which is wide enough to include the standard temperatures ranging from living rooms to kitchens and from bathrooms to bedrooms.

At the same time, except for control valves and control panels, temperature adjustment-related technology continues to proliferate. Those who consume electrical energy are either wired to sockets, often fitted with wheels at the bottom, or are battery-driving and hung around the neck. When a well-tempered environment seems unable to encompass the ever-accelerating flexibility and complexity of life, one must ask: do we have a

3

chance to free comfort from a world of things and socio-technical systems that have a stabilising effect on routines and habits?

4

Healthy Comfort

Healthy Comfort

In his autobiography, Roland Barthes enumerates his habits and hobbies. They seem insignificant and bizarre, but he argues that these habits and hobbies, which originate in the body, are the mark of his own individuality, the difference between you and me. I am different from you because ‘my body is not the same as yours’1. This is a common and figurative statement of Nietzsche’s philosophy. The difference between people is no longer measured in terms of ‘thought’, ‘consciousness’ or ‘spirit’, or even in terms of ideas, upbringing or culture. That is to say, the fundamental difference between people is inscribed on the body, on the habits and on the objects around, and this is assigned great intrinsic value in the consciousness of him.

In The History of Sexuality, Foucault presents a particular view of the ‘Care of the Self’. In his view, ‘Medicine was expected to propose, in the form of regimen, a voluntary and rational structure of conduct.’ This sufficient medical knowledge allows that a healthy person should not be subjected to a physician, thus ensuring this self-reliance. Foucault reveals a ‘practice of health’2 in relation to an architectural space and environment by invoking the analysis submitted by Antyllus of the different medical ‘variables’ of a house: its architecture, its orientation and its interior design. A series of compartments within such a house would either be harmful or beneficial as regards possible illness. It involves the ventilation, orientation, materials and temperature of the building, which requires the occupant to evaluate the surrounding conditions related to the body.

Within this overall context marked by concern for the body, health, environment and circumstances, Henry Robert framed the question of housing, convincingly pointing out a set of practice of health and morality related to light, ventilation, materials, etc. associated with architectural space, this resourcefulness and the rational structure of behaviour is, precisely, regimen. According to Foucault, all themes of regimen had remained remarkably continuous since the classical period. This thesis of permaculture continued to exist after the classical period; ‘the general principles stayed the same; at most, they were developed … They suggested a tighter structuring of life, and they solicited a more constantly vigilant attention to the body.’3 In this vision relating to order and hygiene, according to the words of M. Roncayolo, comfort may be expressed as a restrictive design that does not allow for a diversity of individual behaviour.4 The light, the windows, the beds, the tables, the doors and the atmosphere that permeates them – the air currents, the humidity, and the temperature they carry, which defined working class.

In this sense, ensuring self-reliance through regimen would be

8 CHAPTER 1

unproductive because it has been incorporated into an array of social norms, or morality, manifested in the objects that surround people, the spaces they live in and architecture more generally. In this regard, Jacques Tati’s 1967 masterpiece Playtime5 provides us with two lenses that show both the tendency to challenge the shared notion of comfort and a particular way of identifying the ‘Self’.

In the first scene, M. Hulot enters the company waiting room, where everything in the empty space is arranged in a way that seems to make him feel uncomfortable. He looks around curiously, then either steps on the floor to feel its hardness or squeezes his hands on the unfamiliar material. He finally sits on a leather chair fixed to the floor and tries to change its position but fails to do so. The camera switches to the outside of an apartment and a hotel. Behind the giant glass of these comfortable architectural types is the desire to show who they are. The camera allows us to identify the subtle differences in the ‘show windows’ by switching frequently. The difference exists in the arrangement of the furniture, the wine bottles and the paints, which respond to functionality in general that make a room a living room, a comfortable room.

Functional objects are emancipated now from ritual –from ceremony – and from any ideologies that reflect a human structure in relation to family, class or gender, etc., and this reflects a greater openness in social relationships. As a result, the subtle differences in the ‘show windows’ epitomise the hesitancy of self-relationships within the consumer society that make everything ‘comfort’. In this sense, do the boundaries between interior and exterior, private and public, the self and the other, the individuality and sociality of the body still exist? And what specific problems does it create?

Connecting discussion above to a series of buildings from late-eighteenth-century England, which were labelled as having minimal comforts, allows us to reassess both the neoclassical style of buildings from the late eighteenth century and the plans and architectural elements found within them.

Neoclassicism has infected all areas of British cultural life, consumer cultural life and consumer culture since the early eighteenth century.6 Its art and design provided the aesthetic counterpart to the Enlightenment tenets of rational enquiry and progress, which saw practical

HEALTHY COMFORT 9

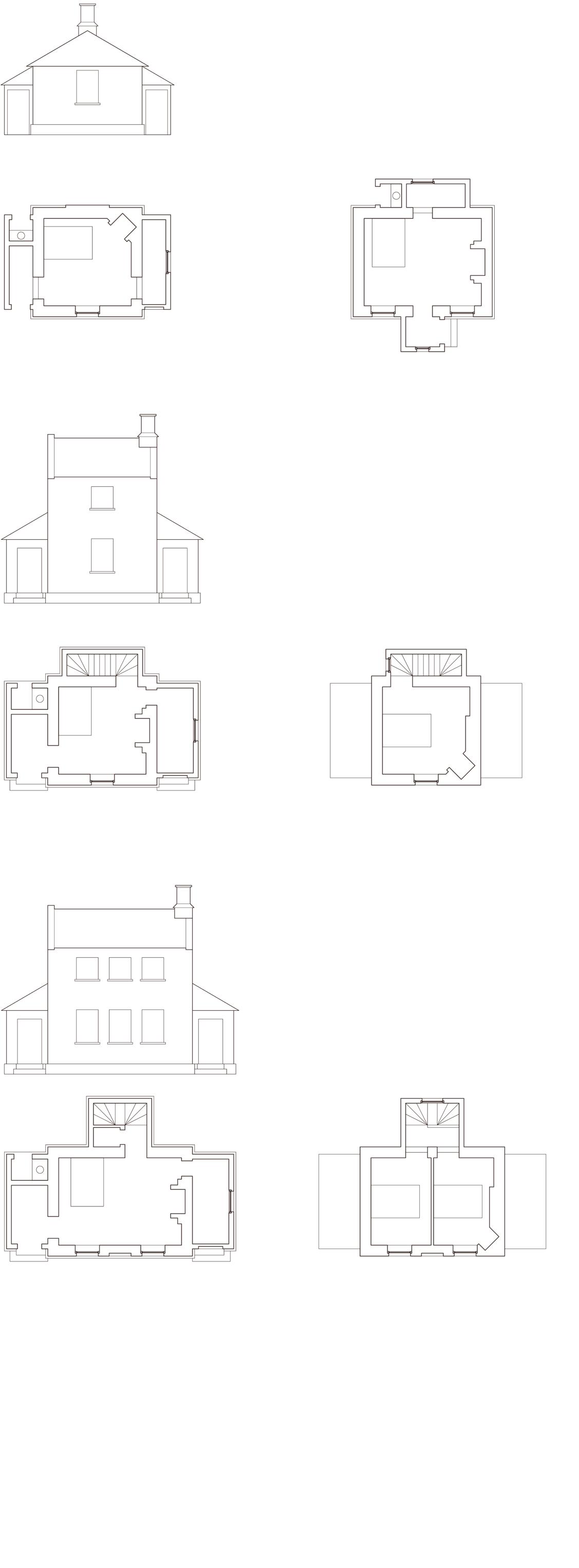

03 02 01 04

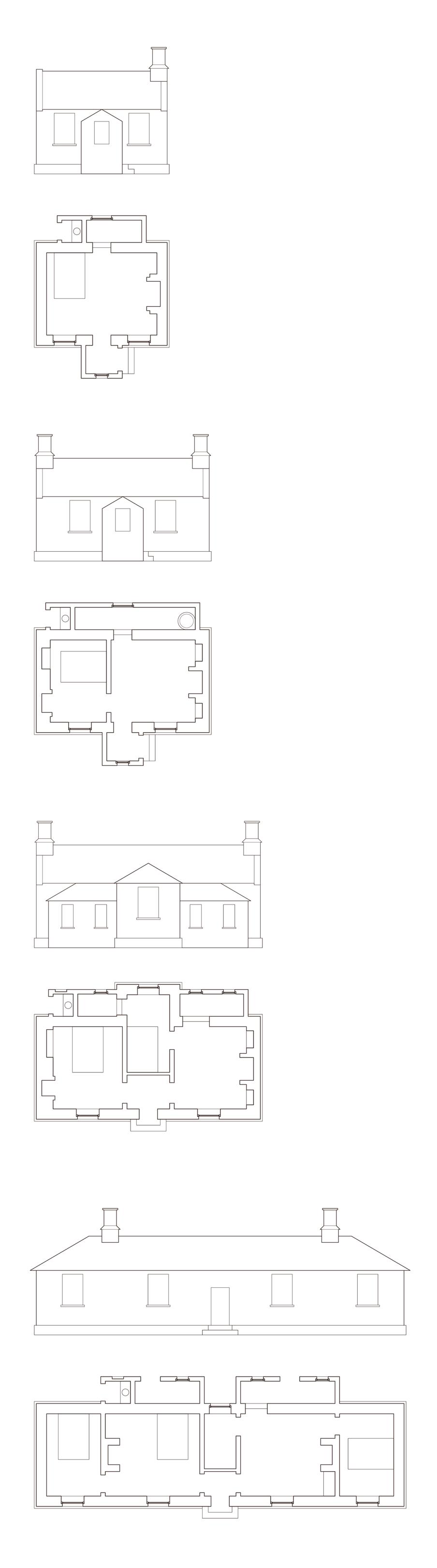

application in the ‘improvement’ of Britain’s agriculture, factories and civic infrastructure (roads, canals, harbours, etc.). For John Wood, the designer of ‘A Series of Plans for Cottages or Habitations of the Labourer’ and an archetypal figure of progressive European Enlightenment thinking and mid eighteenth-century neoclassical culture, writing shortly before his death in 1782, neoclassicism was unquestioningly equated with beauty; in his sixth principle he states: ‘I would by no means have these cottages fine, yet I recommend regularity, which is beauty, regularity will render them ornaments to the country’.7

10 CHAPTER 1

The Minimum Comfort

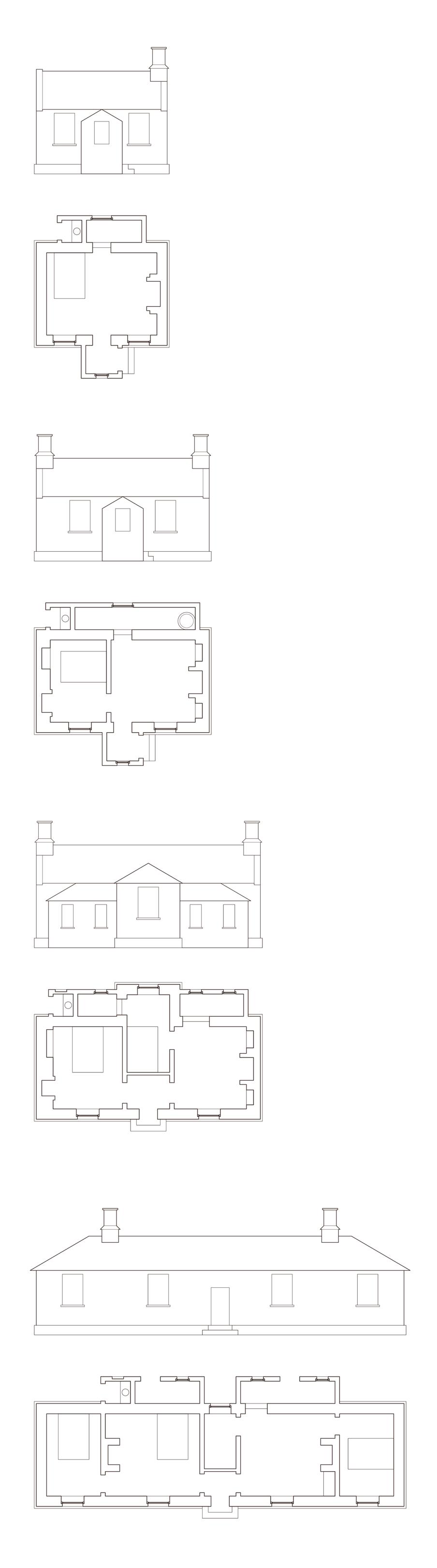

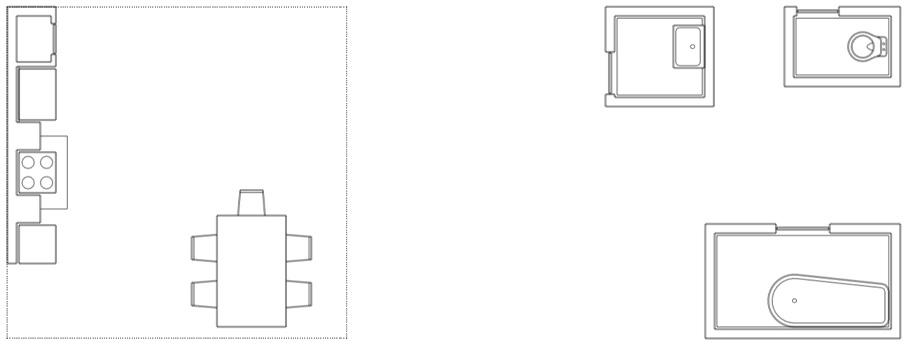

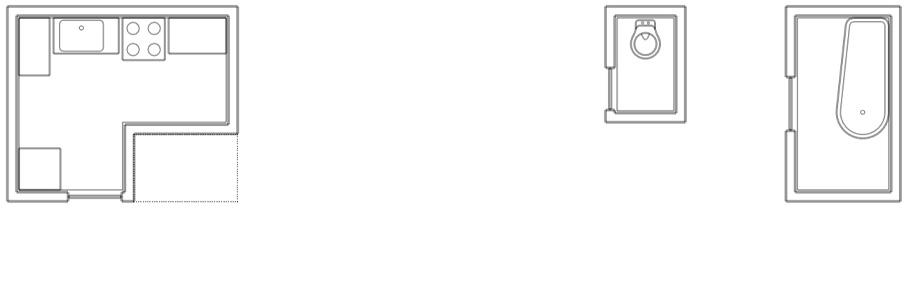

A series of cottages, John Wood, 1780s

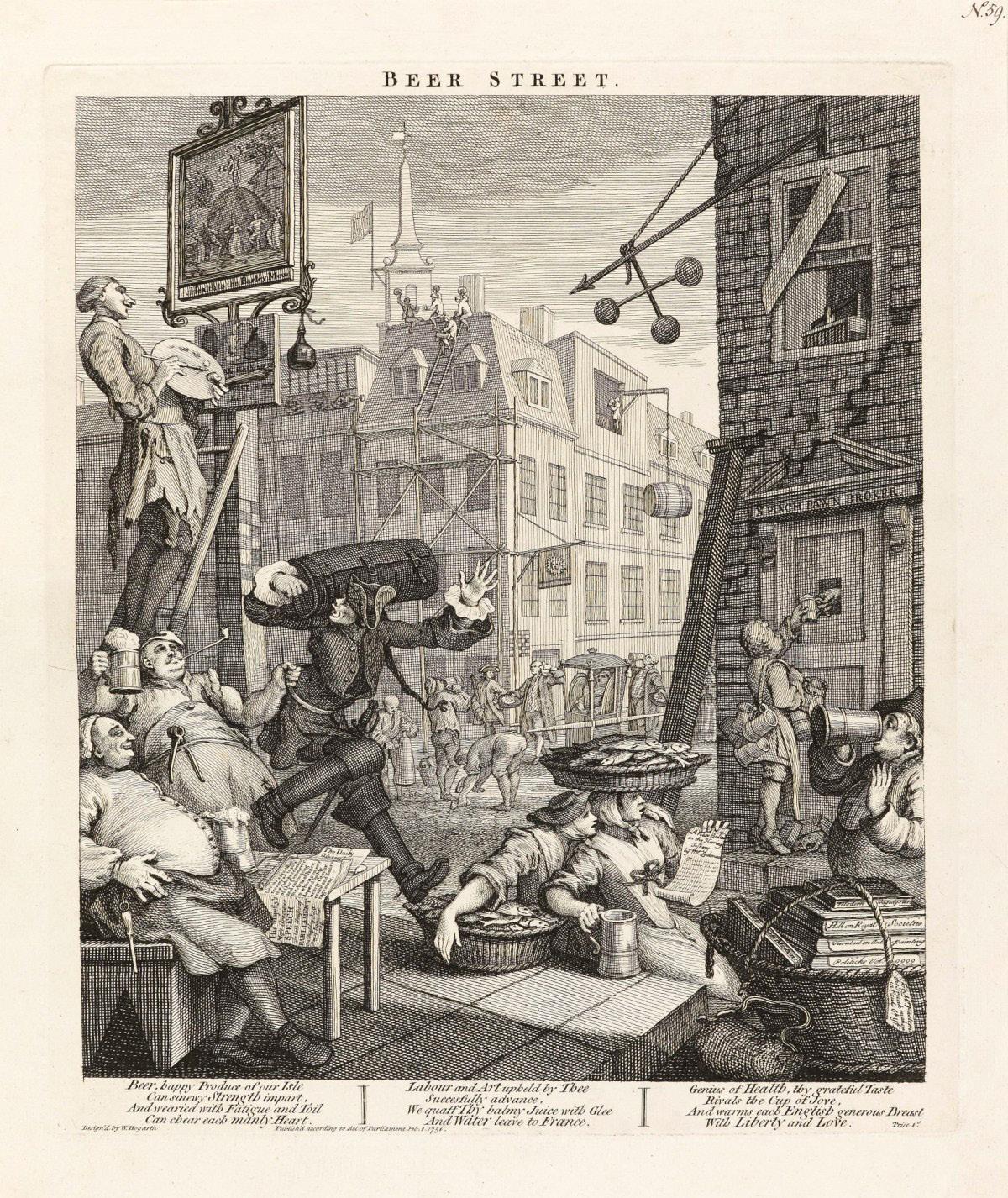

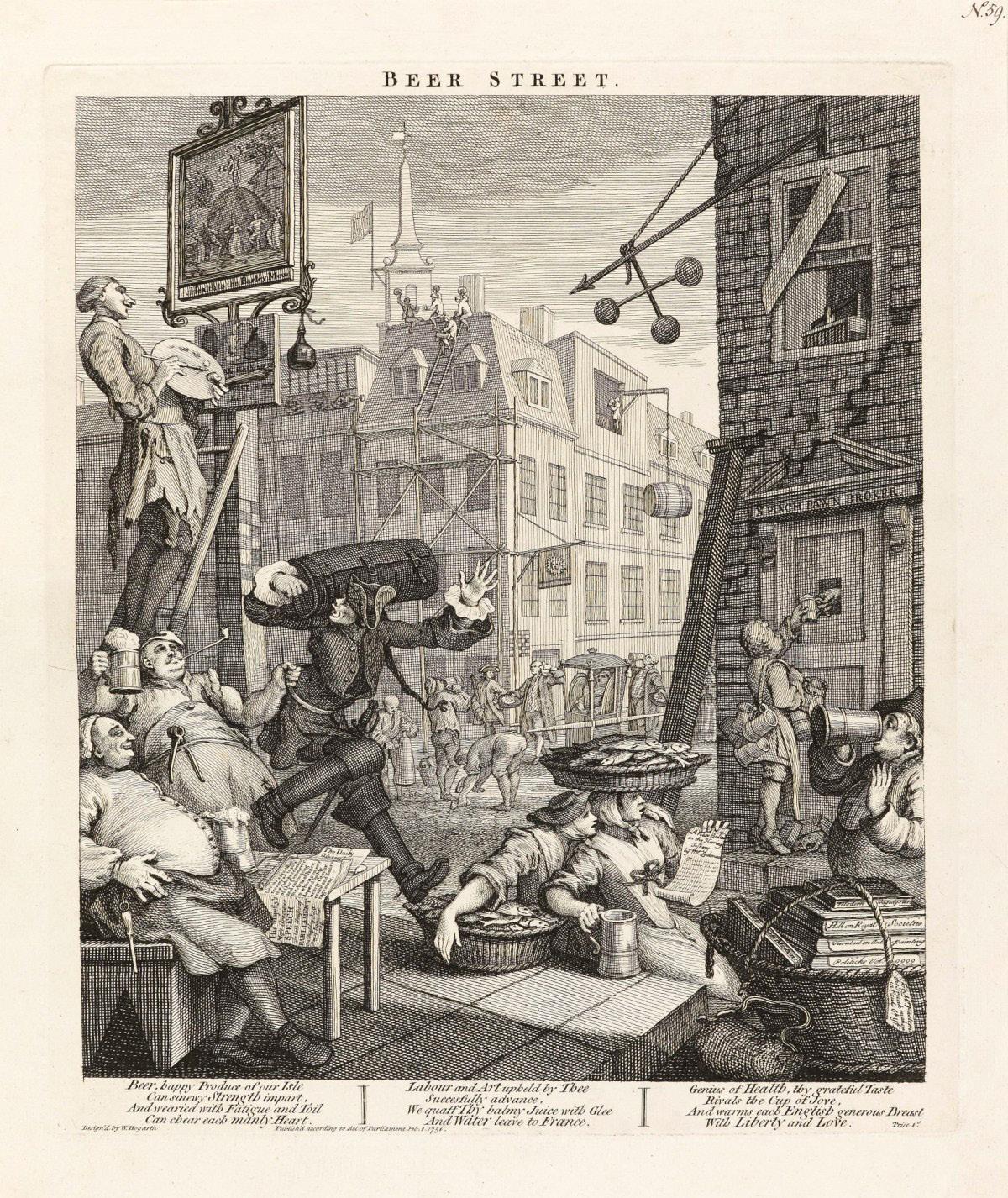

In the UK, since the late seventh century, the consumption revolution has bred a humanitarian reformation, which has urged people to use sympathy to appreciate the rights of others to physical comfort.8 By the last decades of the eighteenth century, the ideal of comfort had obtained sufficient ideological force for humanitarians to integrate it – as a moral act – into their appeals for social justice toward the poor, whose lack of comfort needed to be remedied.

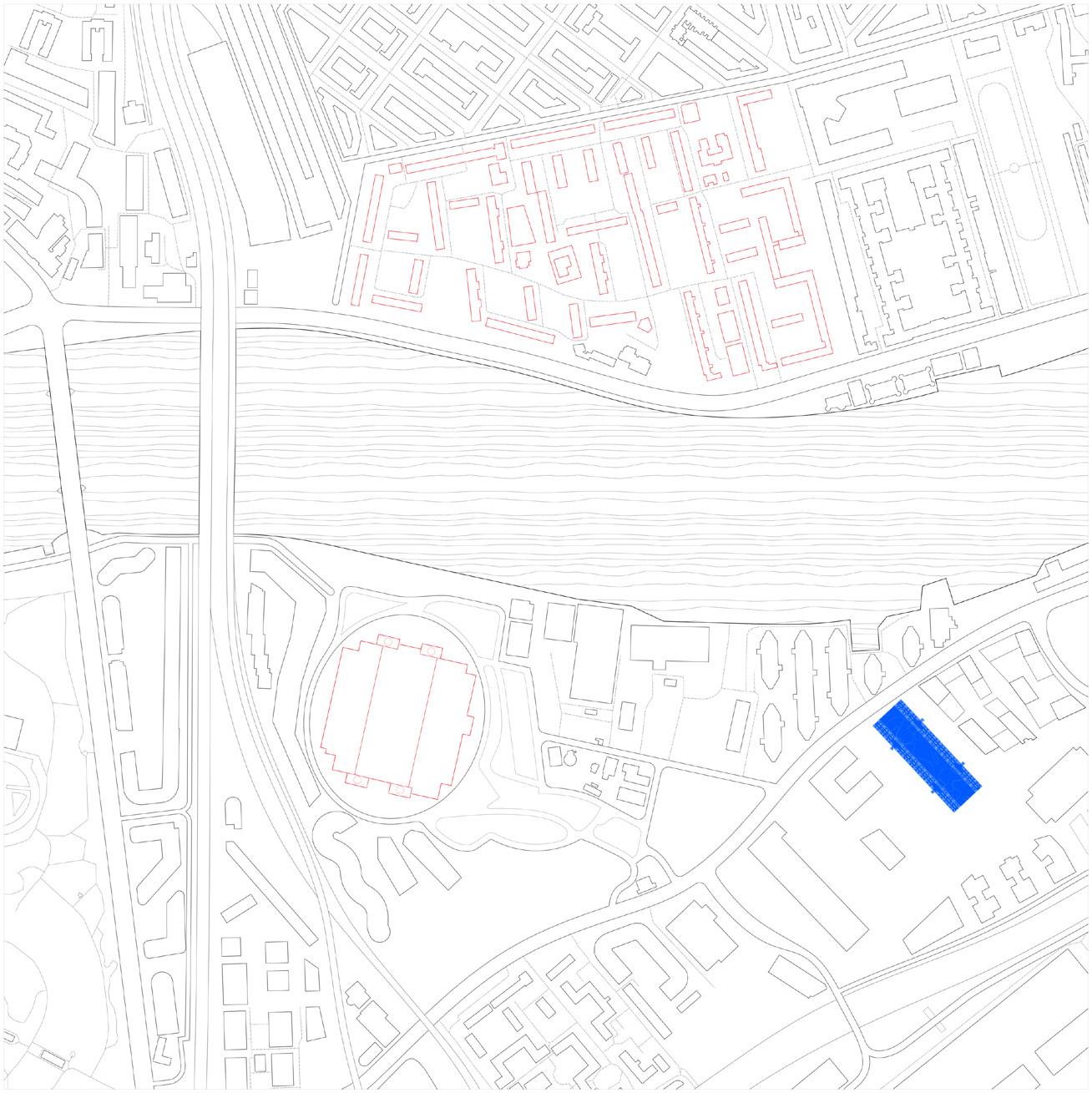

To apply the cultural dialogues of neoclassicism to the practicalities of economic agricultural reform (or ‘improvement’) and its social consequences——predicted increasing in displaced rural population, ‘A Series of Plans for Cottages or Habitations of the Labourer’ was proposed to codify a type of building as a standard component of agricultural improvement in Britain by the late eighteenth century. It identified ‘Seven principles upon which all cottages should be built’ - Dry, Healthy, Warm, Cheerful, Comfortable, Convenient and Economical - within Habitations of the Labourer first published in 1781.9

When virtue and vice were regarded as being as dependent upon physical conditions as health and disease, and when the fixed relation between comfort and morality was conceived, there existed a terrible positive connection between physical and spiritual degradation. It cannot be too often repeated that dwellings regulated the health and morals of the people.

To avoid any space of inconvenience, let all people – males and females, fathers and daughters, the healthy and the dying – living together thus preserve the ordinary decencies of life. The individual rooms were not multi-functional spaces, as that would be found in a vernacular dwelling of a similar size. Each room was assigned a specific function (principally sleeping or cooking), separating public and private spaces and removing less hygienic functions such as sheltering livestock and disposing of human waste.

Significantly for health, John Wood introduced large windows and chimney fireplaces in these cottages to eliminate the darkness and dirt that was often found in a traditional airtight cottage, but this came at the expense of the warmth and cheer produced by centrally heating.

HEALTHY COMFORT 11

Although the chimney fireplace was originally introduced in England as something fashionable during the Renaissance, the acknowledgement of its health value grew rapidly in parallel with the great leaps forward that were being made in the medical, physical and chemical knowledge presented in innumerable home economics manuals in the late nineteenth century, which recommended that every room should have an open fireplace to ensure the health and comfort of its occupants. Therefore, the introduction of the chimney fireplace came to be understood as a health protocol for moral construction; this is further emphasised by the architectural form.

The composition of each cottage – the arrangement and articulation of the plan and elevation (including windows, doors and the chimney) – was carefully controlled by a proportional system that was fixed according to established scales as a response to neoclassical principles. The bed, as the only guest object that could be arranged in the room, was positioned in the corner of the room, thus avoiding the footprint of the ventilation in the intersection between the chimney fireplace and the windows and doors.

Clothes and the human body combine to form a perfect assemblage.10 They exist for each other and are interdependent. They are so closely related that clothes, and underwear in particular, are regarded as part of the body or even imagined to be its skin, as if anything that has been worn by a person carries his or her personal smell. Clothes carry the smell of the body’s excretions (which is one of the reasons why they need cleaning), hence accentuating the connection between clothes and the human body. The uncleanness of clothes is equivalent to the uncleanness of the body wearing them.

Smith’s writings reveal a peculiar perception of a cultural understanding that primarily regards comfort as a matter of social habit and not physical satisfaction: ‘By necessaries I understand, not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life, but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without.’11 The

12 CHAPTER 01

HEALTHY COMFORT 13

FIG.05 Prosperity. On Beer Street, trades and consumption thrived together: meat, drink, fish, clothing,shoes, books, even art. William Hogarth, Beer Street and Gin Lane, 1751

05

FIG.06 The Happy Cottagers, 1793

14 CHAPTER 01 06

word ‘comfortably’ was used to explain how linen shirts could be considered a decency in contemporary Europe while being unnecessary among other civilised peoples such as the Romans.12

The development of linen clothing was deeply influenced by the social value of cleanliness and the need to give it a material expression in public. Clothing made of linen came to form a close connection with the image of personal health, since such clothing is able to avoid gathering dirt from sweat or pests.13 Back in the Middle Ages, shirts of fine material (often linen) constituted what was thought of as a protective second skin. For those convinced of the body’s porosity, and for those subscribing to a humourbased theory of disease, this kind of underwear had the dual function of both excluding unwanted influences from the outside and also mopping up the outpourings of the body and its parasitic residents, thus providing physical comfort. In mid-sixteenth century France, changing the shirt reputedly took the place of activating, refreshing and washing the body. In the seventeenth century, certain forms of clothing, including elaborate ruffs, lace collars and cuffs, maximised opportunities for an increasingly conspicuous exhibition of inner cleanliness. The lack of a linen shirt in eighteenth-century Europe marked ‘that disgraceful degree of poverty, which, it is presumed, nobody can well fall into without extreme bad conduct.’14

In contrast, since the second half of eighteenth century, objects that were of some health value but were physically uncomfortable were gradually abandoned. Before the second half of the eighteenth century, people did not often record complaints about the sheer discomfort of their stays, even though every woman had to wear them, for reasons of health and respectability as well as to achieve the ideal body shape; they were, however, condemned by medical experts on account of their potential risks to health. The use of stays among children was relaxed in the second half of the eighteenth century, but women did not cease to use them until the late 1780s when an avant-garde fashion temporarily dictated abandoning them in the name of neo-classical simplicity. Informal ‘undress’ became fashionable as ‘natural elegance, in which the body is left to that freedom so congenial to common sense.’15

HEALTHY COMFORT 15

FIG.07 PETER DE CUPERE, “SWEAT”, 2010

FIG.07 PETER DE CUPERE, “SWEAT”, 2010

The manufacture of Atmosphere

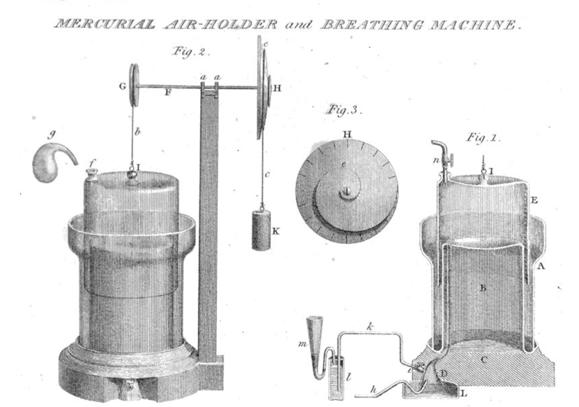

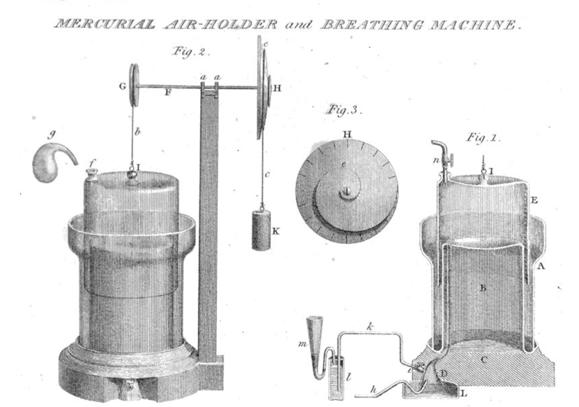

Climate therapy was an established medical practice during the early nineteenth century. Before medical authorities expressed considerable interest in the ability of artificial climates to replicate the supposed effects of health-inducing geographies located throughout southern Europe, self-care was conducted by travelling to foreign countries. To overcome the drawbacks of medical tourism, such as the overstimulation and exhaustion of a delicate patient’s nervous and physical systems, the Pneumatic Institute Beddoes was founded at Bristol in 1799. By the 1820s, the curative powers of the medical south were being tested by scientifically-minded builders who employed the latest glassmaking, heating and ventilating technologies to relocate healthy climates inside Madeira houses, winter gardens and other pseudo-medical institutions.16

Such institutions were stigmatised as pseudo-medical institutions because their medical value was widely questioned. An opposition to this category of therapy was voiced in a range of mass media as early as the early nineteenth century. For example, in 1843, the humour magazine Punch ridiculed one such establishment, calling it a ‘social hot-house’ for ‘sick servants . . . consumptive cooks, bilious butlers, paralytic pages, hysterical housemaids, and feverish footmen.’17 In 1848, Punch again mocked these efforts in a parody of what it called ‘the Cold-Earth Cure’. Together with a series of burlesque illustrations showing how patients, tended by ‘medical gardeners’, were submerged in soil, fertilised and watered before being transplanted to a conservatory for several hours, the magazine reported that ‘by these means you are restored to the flower of your youth, and live to a green old age.’ ‘Flesh may be grass’, the article continued, ‘but still we cannot imagine that a kitchen-garden was ever intended as the hospital to cure all the “ills that flesh is heir to”’.18

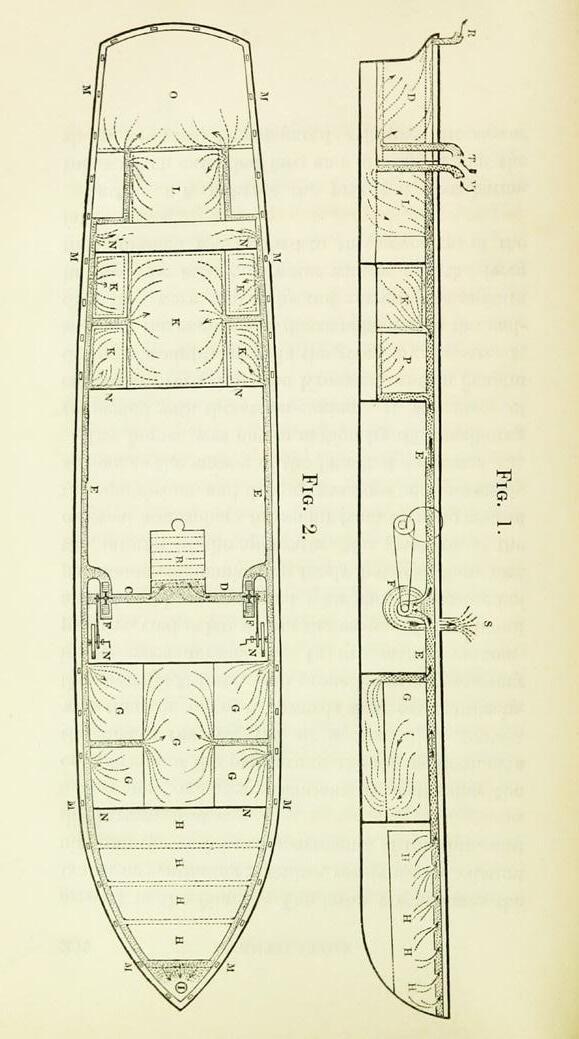

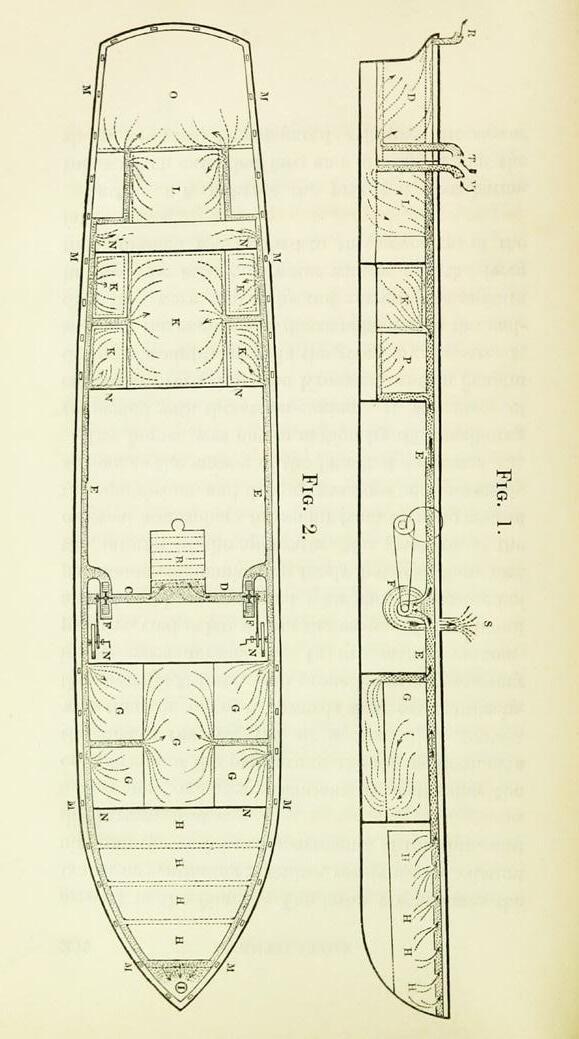

In the meantime, the British fear of the tropics was compounded by the ideas of racial theorists who argued that hot and humid climates had a degenerative effect on the moral and physical capacity of Europeans. Physicians also warned that warm and humid climates, which interfered with perspiration and blood flow, encouraged the accumulation of morbid poisons in the body. A key event in the growing scepticism of climate therapy occurred in 1841 when Niger Vessel attempted to produce a native British climate on a vessel to minimise the exposure of white sailors to the dangerous external tropical climate. Of the 145 white officers, seamen, marines and sappers aboard the expedition, 130 became ill, and of these, 40 died; in contrast, only 11 of the 158 black crew members aboard the expedition became ill.19

08 09 10 HEALTHY COMFORT 17

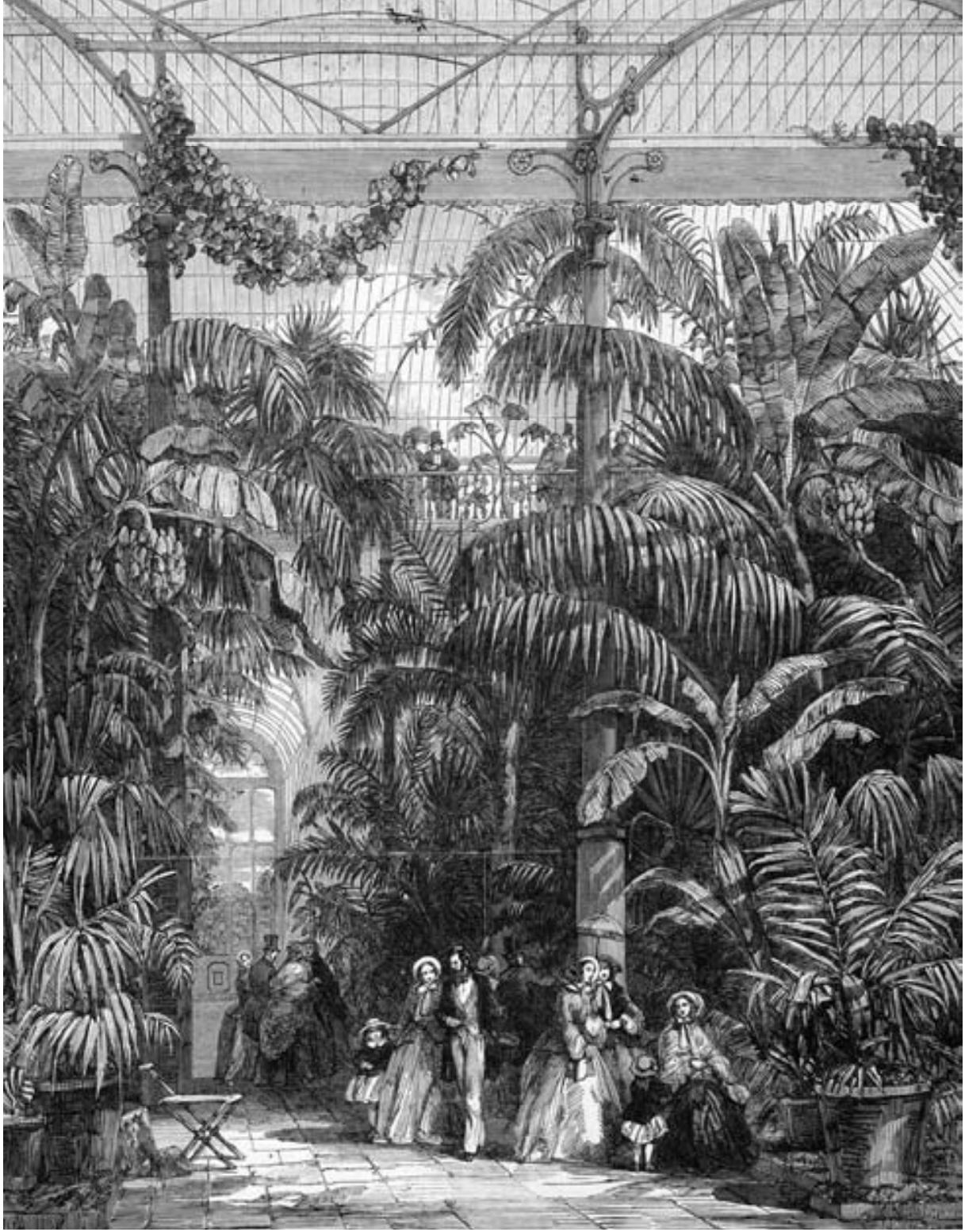

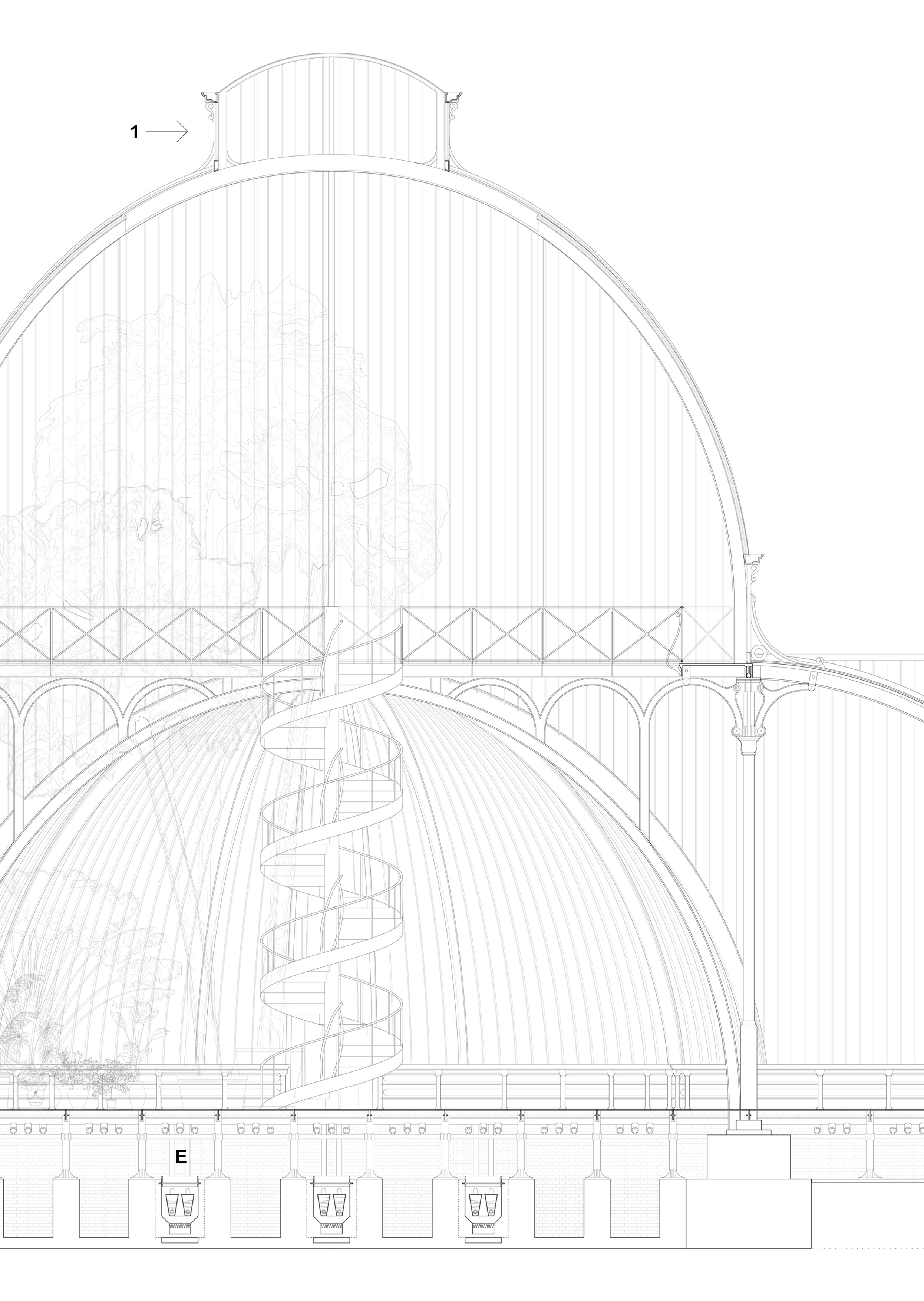

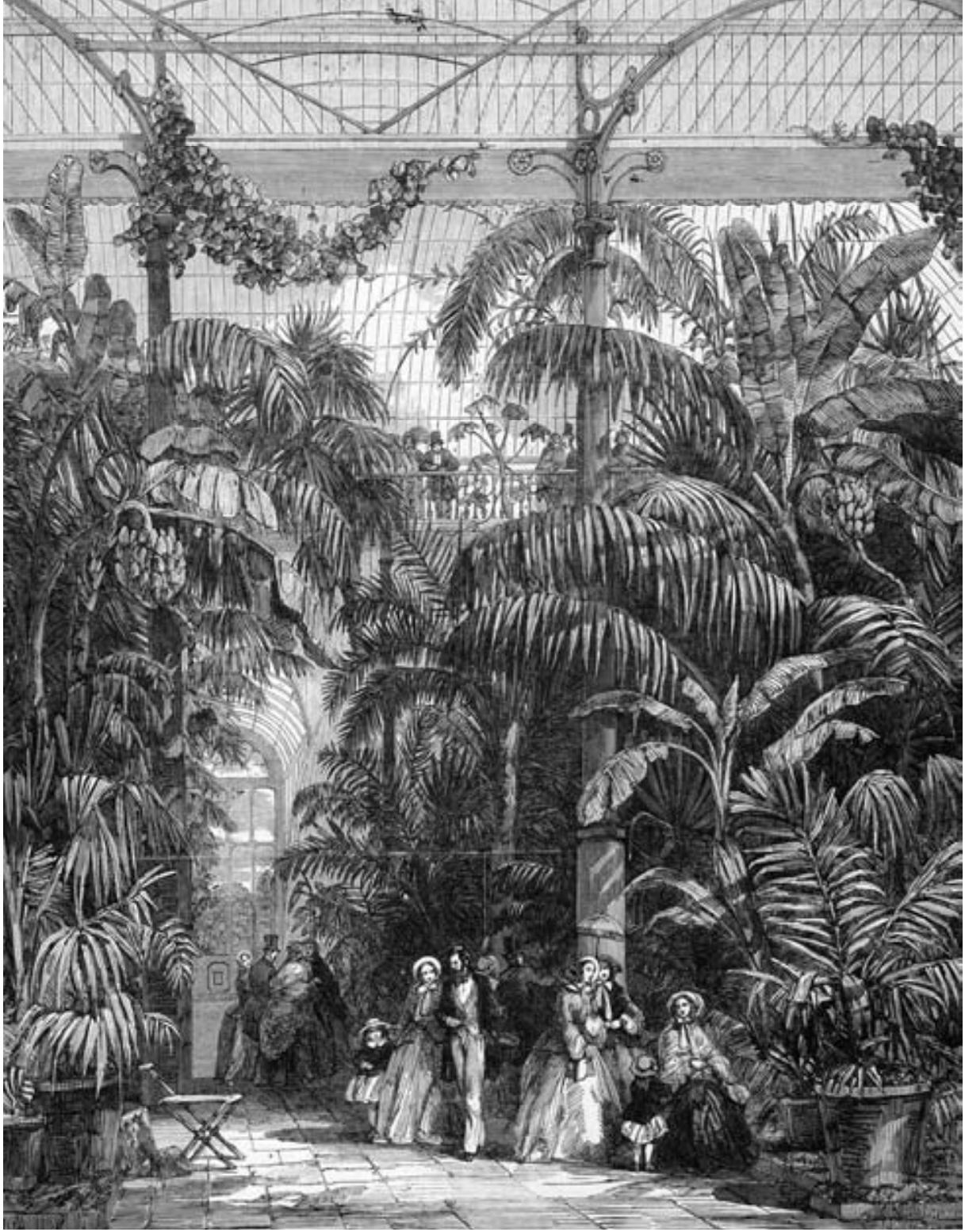

Ultimately, the ability of artificial climates to facilitate encounters between Victorians and the tropics acquired new authority through a series of large, public glasshouses that employed complex, mechanically-aided climate control systems. But within these buildings, the torrid zone was both literally and metaphorically present. Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of 1851, for example, contained exhibits of African goods and people, while fountains and vegetation placed along the building’s transept – nicknamed the Equator – evoked tropical geographies.

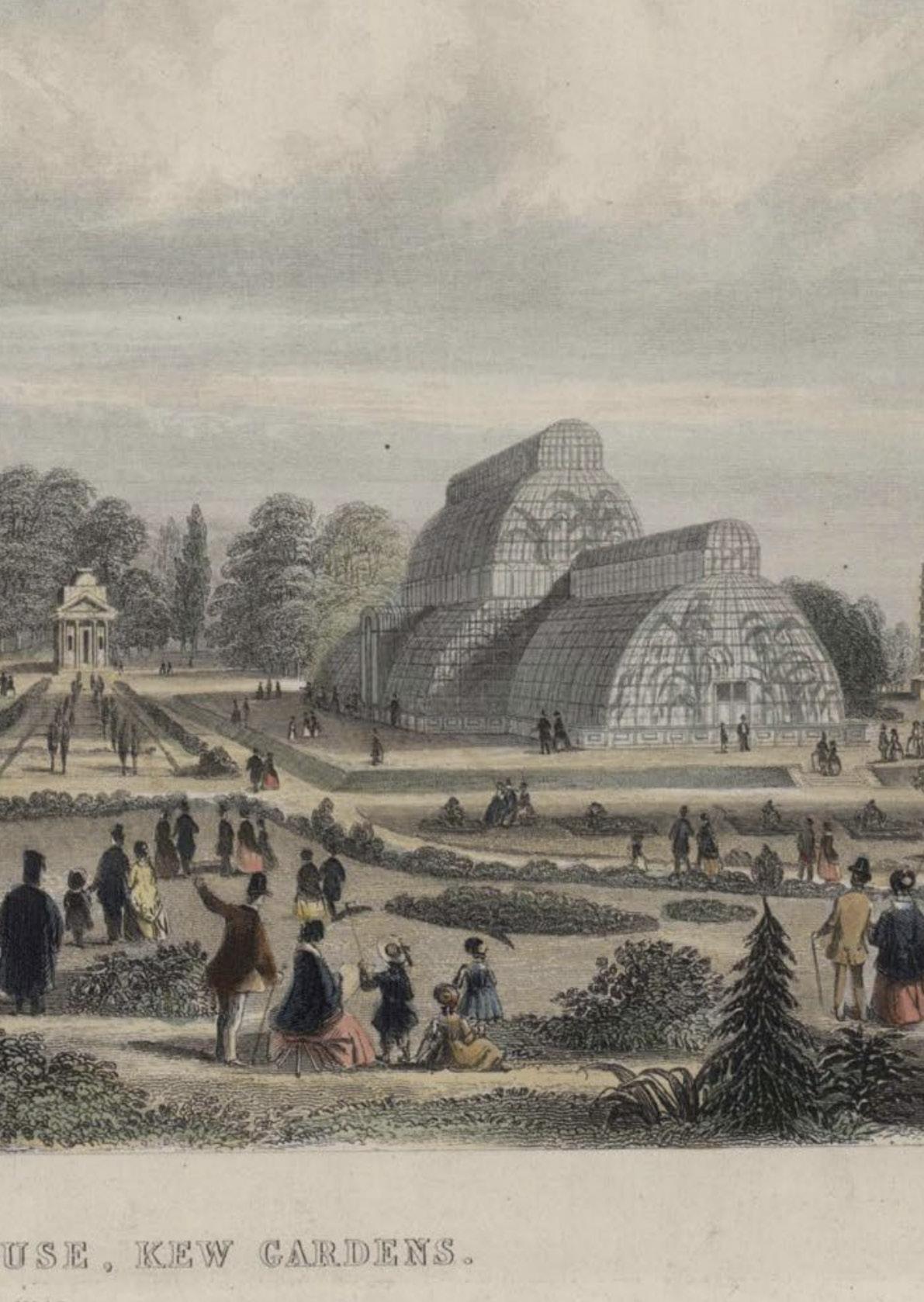

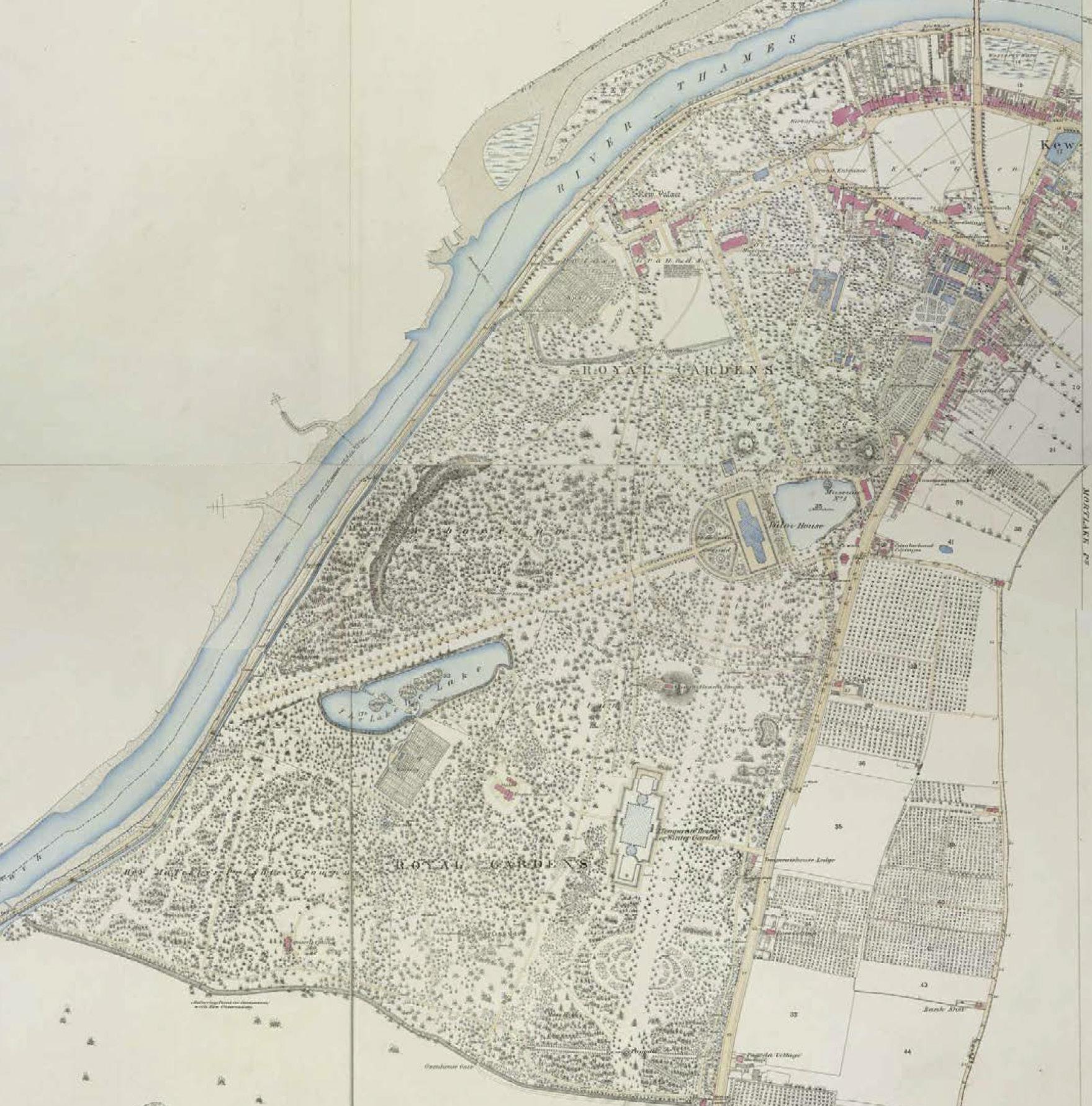

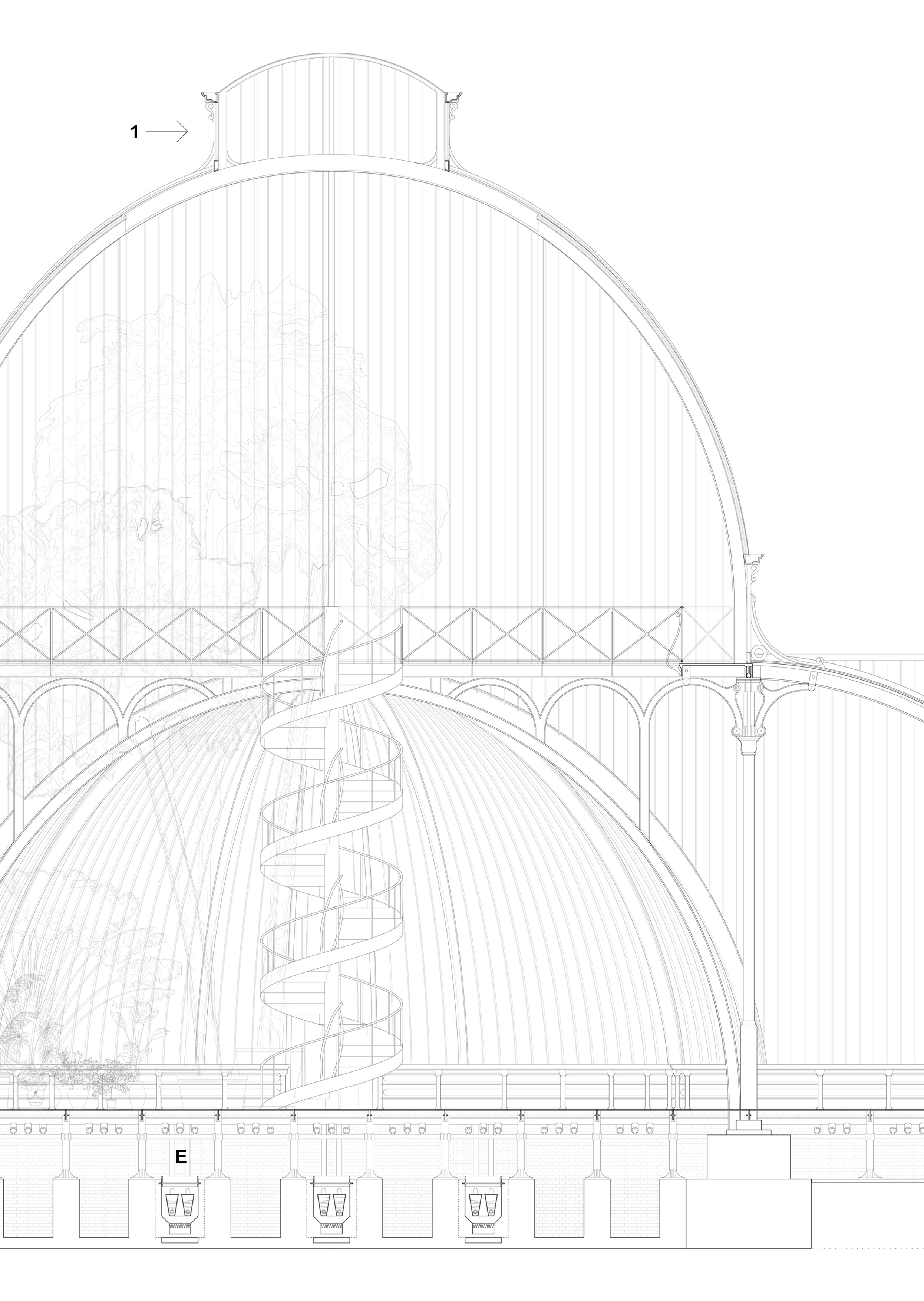

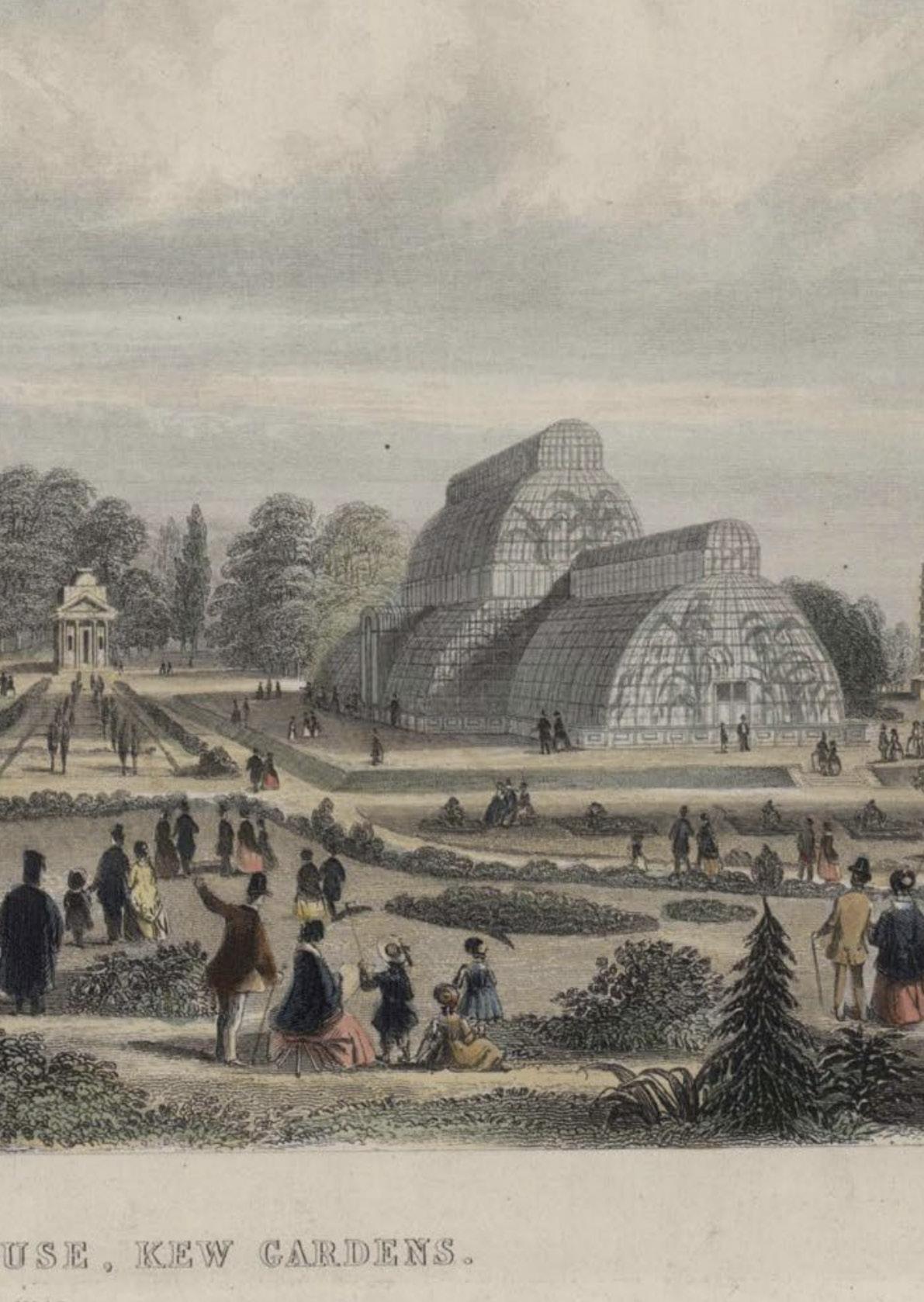

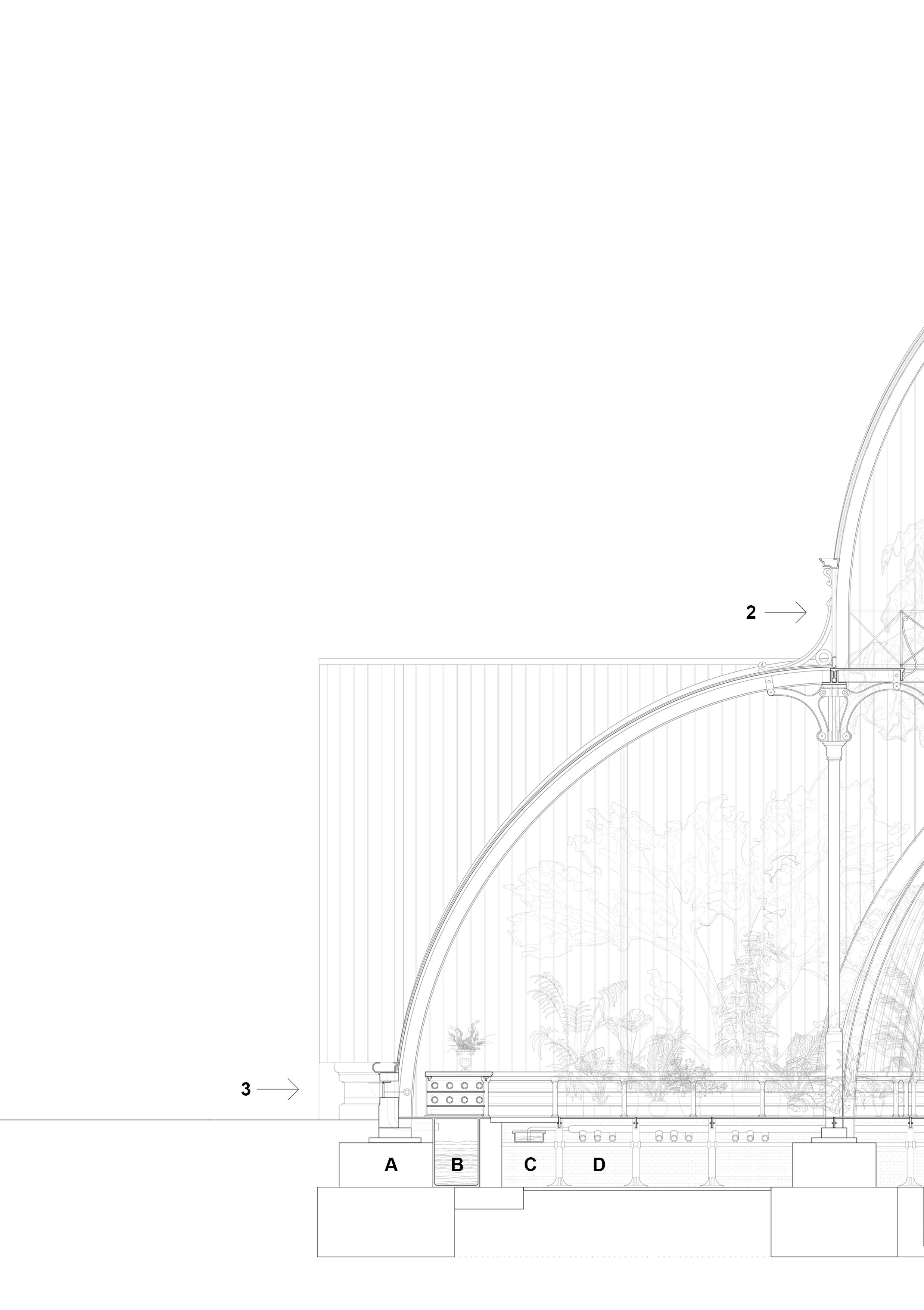

Palm House in Kew Garden, 1840s

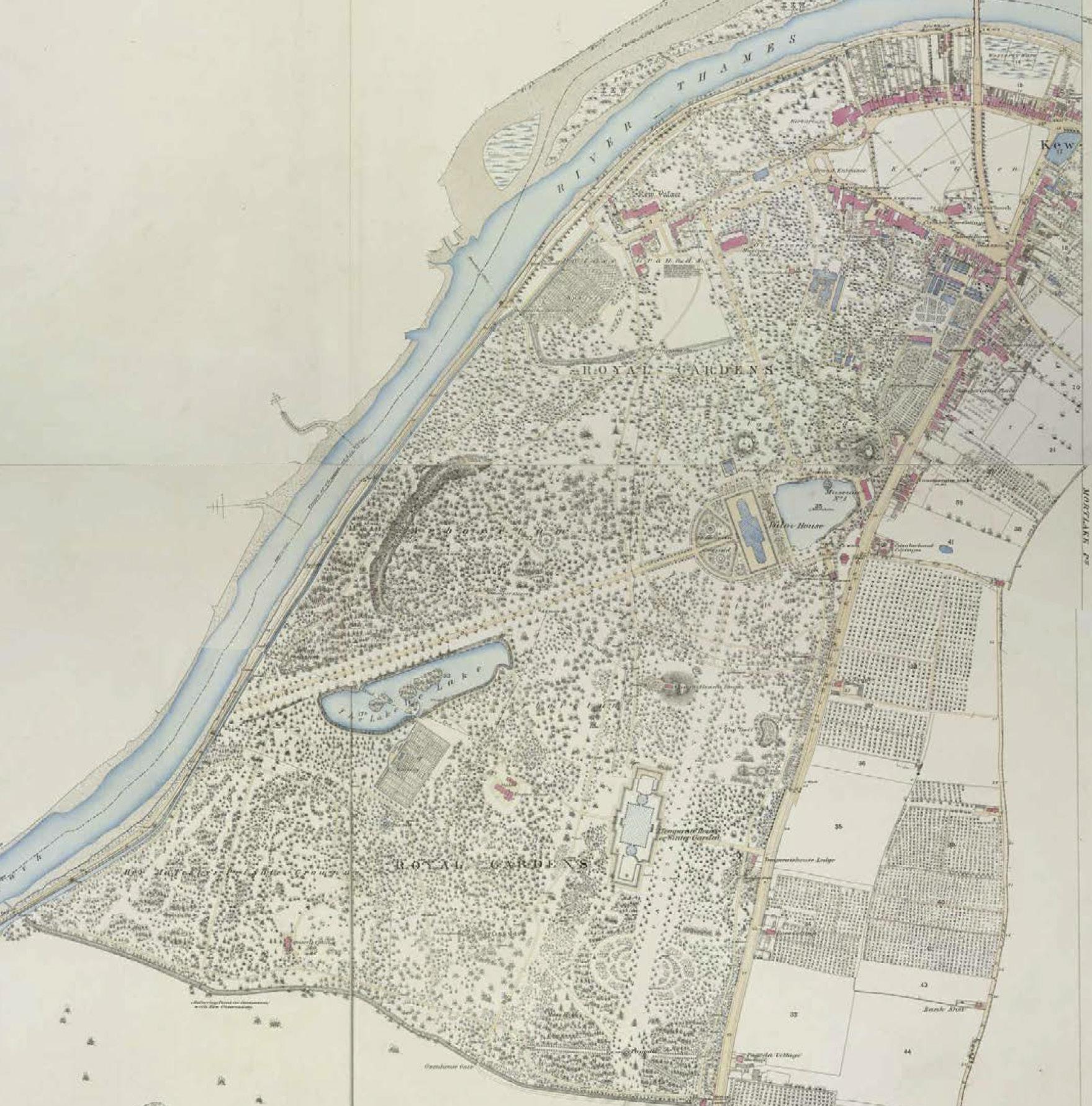

The popularity of public glasshouses was reflected in medical discourse. Conservatories and winter gardens attracted the interest of health seekers who sought out warm artificial climates in which to convalesce. The second case study shows a stage within the dialogue in relation to artificial climate and health discourse. In 1840, Kew Gardens ceased to be the private property of the monarch, being transferred from the control of the Office of the Lord Steward to that of the Commissioners of Woods and Forests. To relieve the desperate congestion in the existing houses, the desirability of a new greenhouse was raised once again, ten years after it had first been mentioned in 1832. The new greenhouse – namely Palm House – was completed in 1848 and opened to the public.

The greenhouse was one of the most widely acknowledged symbols of comfort in the nineteenth century thanks to the

18 CHAPTER 01

11 12

FIG.08,09 “The Cold-Earth Cure”, 1848

FIG.10 Breathing machine in Pneumatic Institute, 1790s

FIG.11, 12 Niger Vessel with climate control system, 1841

harsh urban environment of the time and the spread of a range of environmental knowledge. Along with the publication of a series of scientific readings, British city dwellers, especially in London, were generally plunged into anxiety because of a clearer understanding of the dangers of the environment in which they lived. Various theories prevailed throughout the time cast soil and water as sources of contagion or infection. They emphasize the necessity for people to identify these potential threats through touch, smell, and visible phenomena such as the growth of mould on walls, furnishings and clothing or by condensation on windows. At this point, these greenhouses have been welcomed for their value in revealing the power of science over nature and the potential for, and limits of, human control over the vagaries of geography and climate. This has encouraged new ways of thinking about one’s surroundings, particularly with regard to nature’s fundamental elements of earth, air and water, in order to combat the anxiety caused by disease and moral decay.20

Plam House's geographical layout and form echoes the above discourses, and rendering itself as the elucidator of comfort. The placement of the Palm House at Kew appears to be in response to the prominence of gardens as a public institution and the desire to present buildings and collections from a suitable vantage point. It appears to respond more to aesthetic than scientific purposes. Being glazed on all sides, such buildings lacked the masonry wall that would have formed a northern ‘back’ to the forcing-house, which serves to absorb the sun’s heat. Given the improvements in heating systems, the provision of this wall was 15

HEALTHY COMFORT 21 14

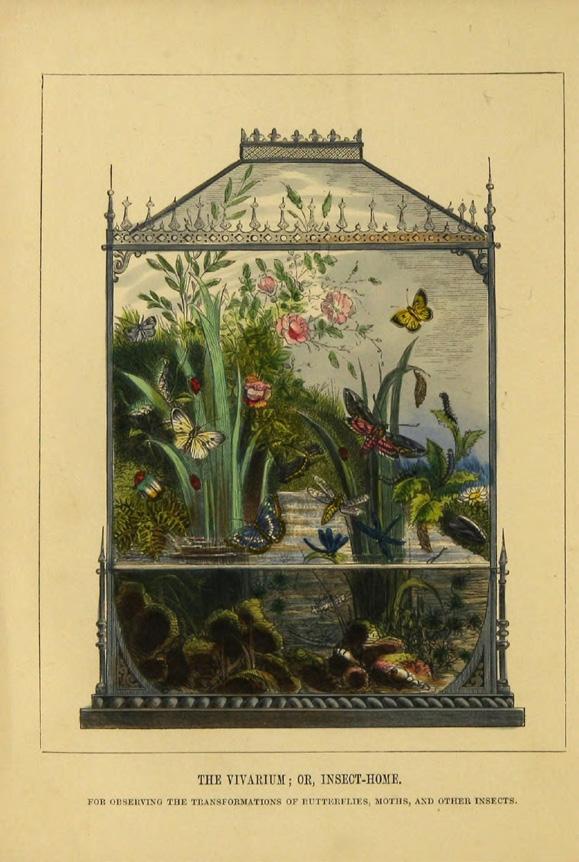

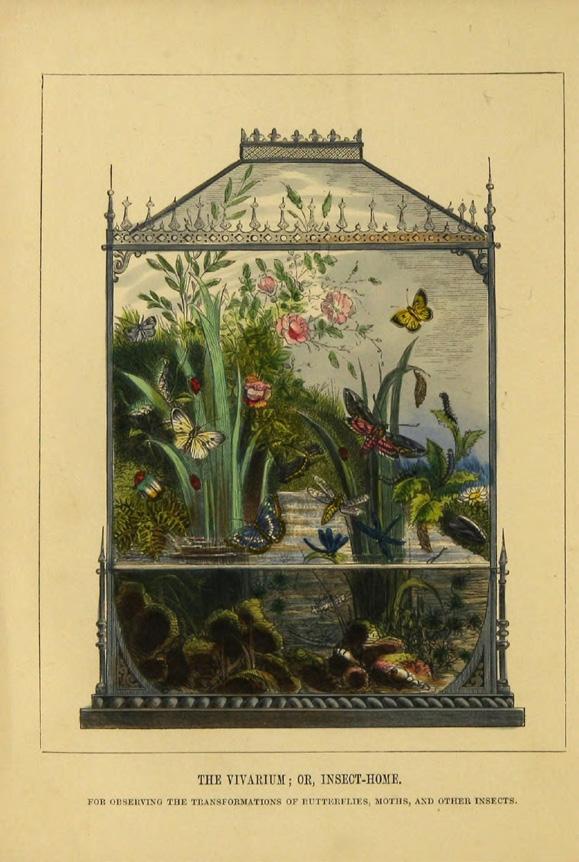

FIG.14 The Butterfly Vivarium, 1830s

FIG.15 Site plan of Palm House in Kew Garden

22 CHAPTER 01

HEALTHY COMFORT 23

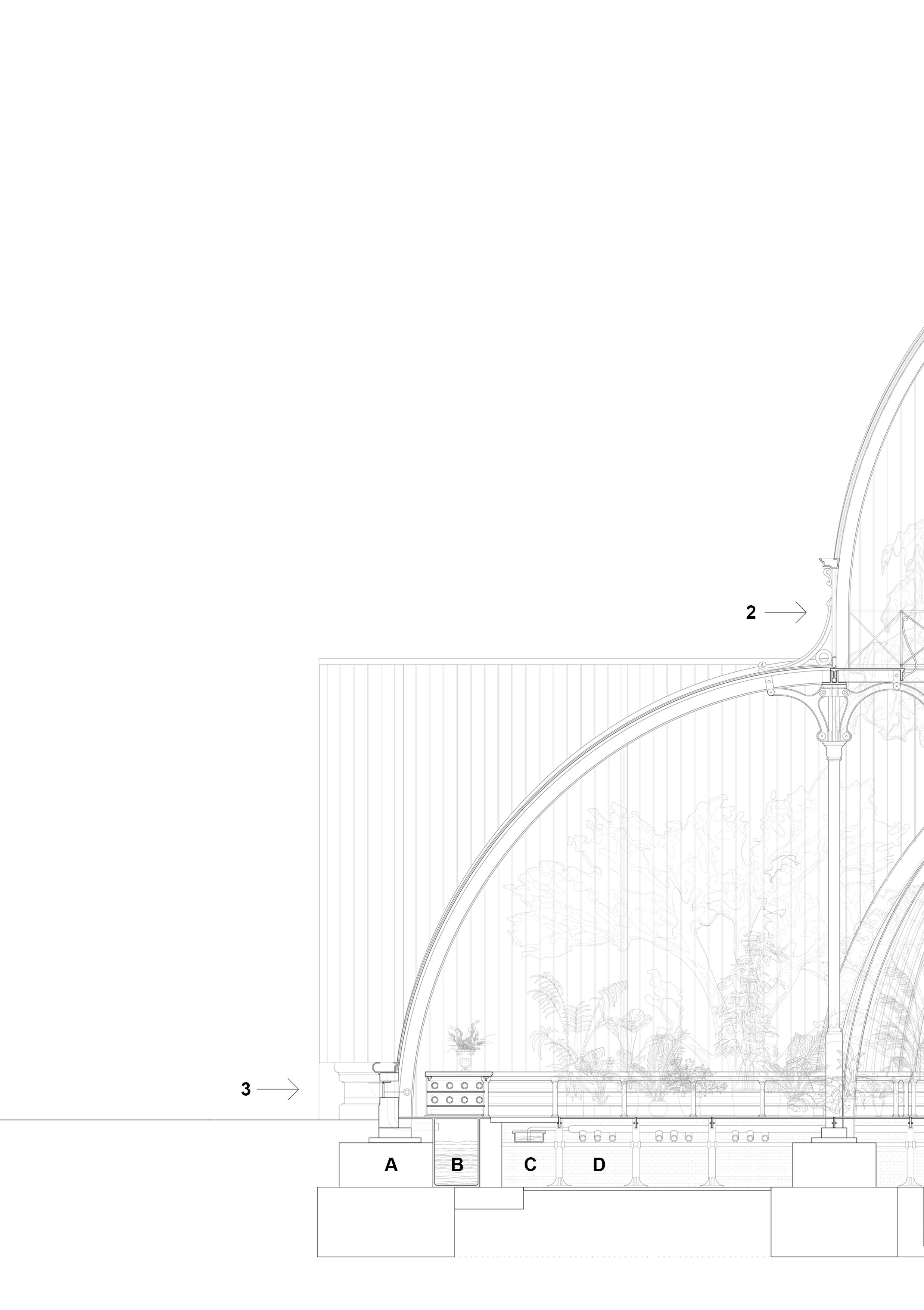

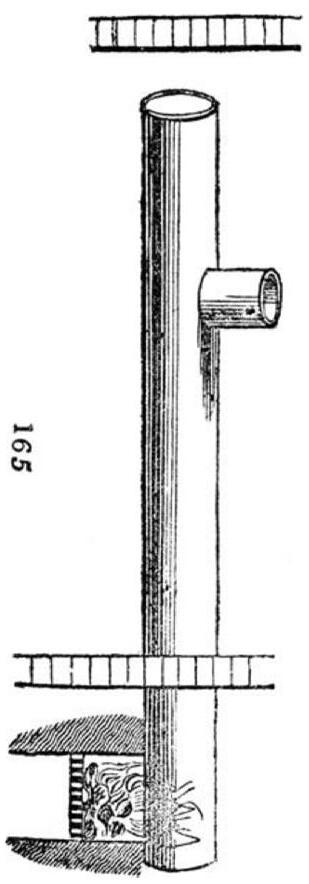

no longer necessary, thus affording greater flexibility in the positioning of glasshouses. However, doubting voices did not cease to share their opinions on these architectural form through statements such as ‘I do not think that it would be judicious to adopt in a building constructed of glass and iron where light is the great object, any decided style of architecture such as exists in buildings erected of Masonry’21 and ‘The Ecclesiastical or Gothic style therefore in which the Elevations are designed, appears to me to be objectionable, and the numerous ornamental details in fret work, crockets, perforated parapets, etc., to be out of place and tending uselessly to increase the amount of the estimate.’22 In addition, twelve boilers served certain hot water pipes to produce an ideal micro-climate control for plants in different parts of the building,

HEALTHY COMFORT 25

FIG.16 Decimus Burton and Richard Turner, Palm House at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 1840–48

26 CHAPTER 01 16

The Introduction of Atmosphere

In ‘Education of the Senses’, Peter Gay proposes a phenomenon of ‘the democratization of comfort’, arguing that when comfort is gradually manifested as a restrictive design, a subtle, progressive change in sensibility, modes of being and preferences takes shape.23 Gradually, these changes became widespread, through the self-presentation of the middle class, which eventually also became a role model for the lower income classes. Although modern urban life arises from the elimination of all fixed and rigid relationships and the notions and opinions that were venerated to fit with, followed by the emergence of the masses without specific class, it has undoubtedly contributed to a great deal of expression, manifested in climatotherapy and glasshouses. As moral norms are translated into objects, mass consumer goods, and architecture, the genealogy of environmental control further reveals the introduction of central heating, the emergence of communities for multi-classes, and how the acute impulse of taking care of the self finds its resonate in multifunctional space.

Horticultural developments since the nineteenth century have resonated with the sanitary reformers who warned about the dangers of vitiated atmospheres and cold climates while championing the curative powers of warm retreats. Horticultural glasshouses, and the artificial climates they contain, garnered considerable interest among English sanitary reformers. Like gardeners, medical professionals valued artificial climates for their ability to erase geographical differences, and they sought to transfer this knowledge into medical practice. In this, they were helped by engineers who sought to develop a practical and theoretical corpus for heating and ventilating buildings and who drew on popular analogies in medicine and horticulture to justify the need to construct healthy, artificial climates for human habitation. Even though the questions regarding artificial climate have not yet gone away, they cannot wait to be thrown into the unpredictable process of densification and urbanisation.

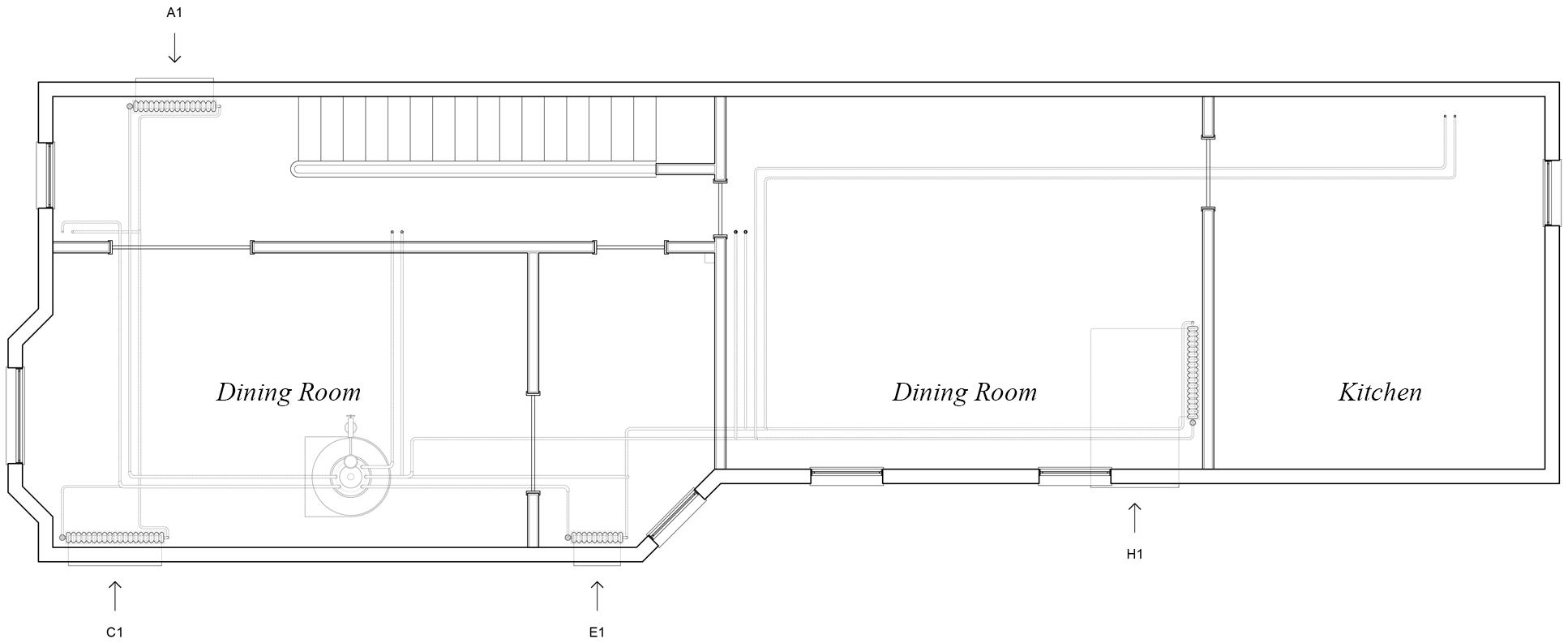

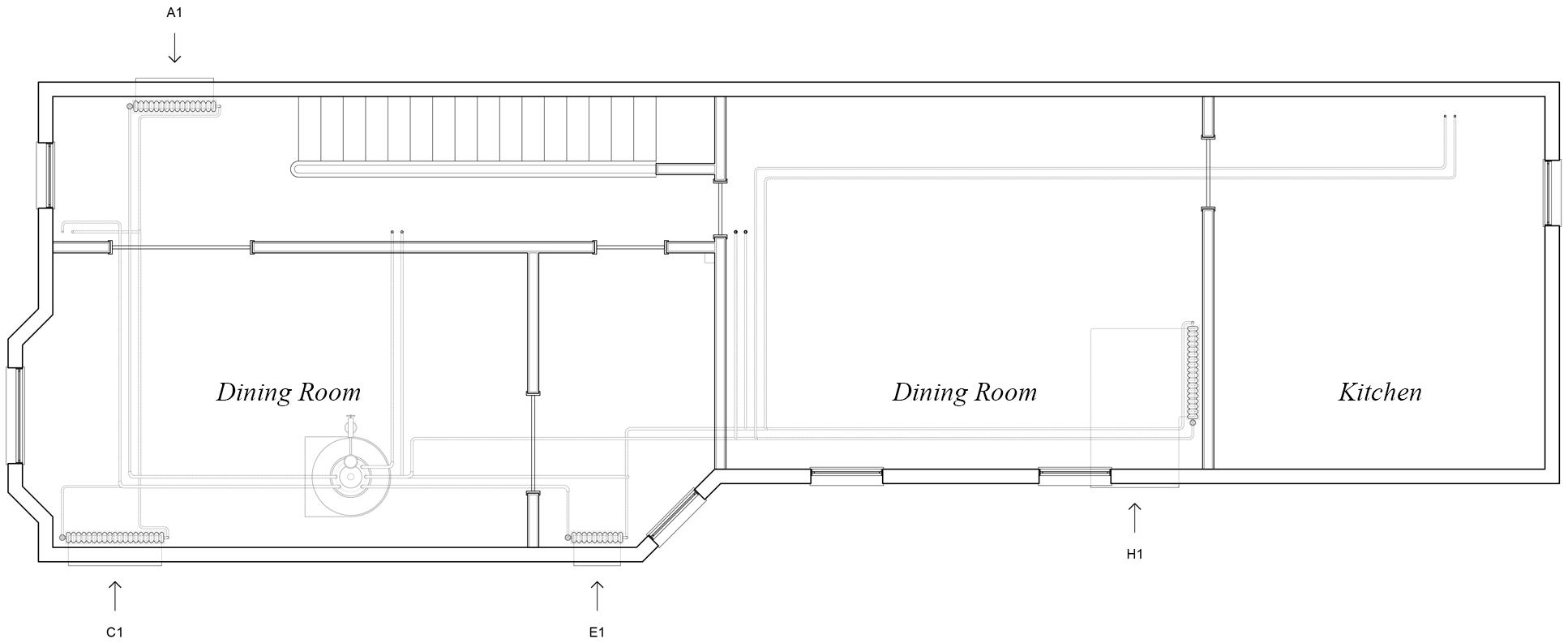

Eighty dwellings for the labouring classes, 1832

This co-operative house, which was planned to be located in an industrial area of London, suggests a new relationship between the individual, the body and the artificial climate as the desired object, in which functional flexibility is a central rule through which the community as a whole suggests a universal urbanism (comprising equal people, equal houses, equal housing requirements and equal values) that has been in place since the Enlightenment.

Since the designers Loudon and Junius Redivivus began to share their congenial views on economical housing, they have

17 18 HEALTHY COMFORT 27

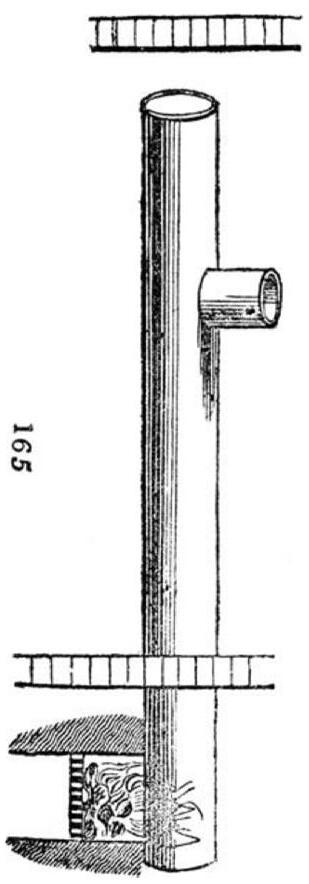

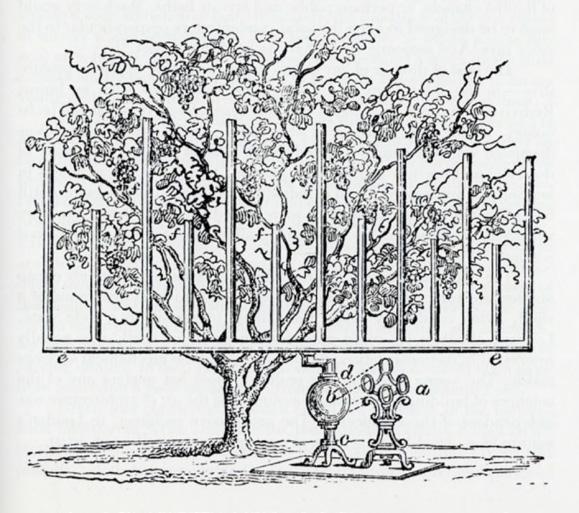

FIG.17 John Barrow, “Some Account of the Experiments Made by William Atkinson, Esq.F.H.S., Which Led to the Heating of Hot-Houses by Hot Water,” 1828

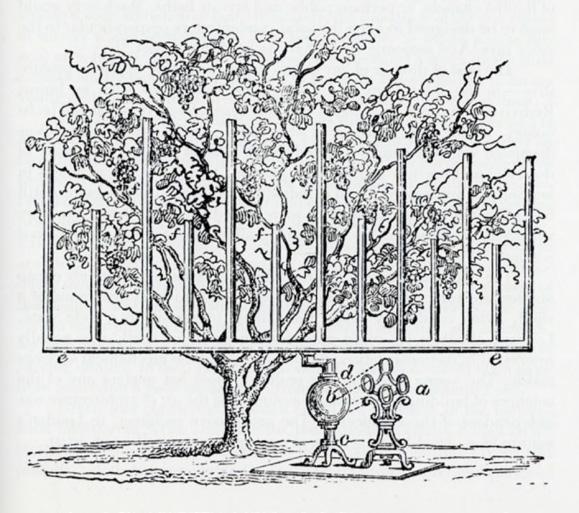

FIG.18 Apparatus for forcing fruit trees by concentrating solar energy on a hollow cast-iron ball, Robert Gauen, 1827

28 CHAPTER 01

emphasised the technical superiority and affordability of mechanical services, believing, for example, that ‘children, in warm climates, thrive best naked,’ while ‘in cold and variable climates they will not bear it. Make then an equable artificial climate, and the difficulty will be removed. Children may then be reared as easily as grapes and pineapples. . . . What an advantage would it be to the poor children, to need no more sleeping potions of gin and Dalby’s!’24

While not being represented in their sketchy plans, the flexibility was emphasised in order to accommodate individual tastes and needs. While all bedrooms would face the street and all sitting rooms would face the galleries and courtyard, some apartments might be joined together for larger families. One apartment might be shared by unmarried women, another by unmarried men, while furniture, built-in closets, a lending library, and space for lectures might also be provided.25

The building exhibits a highly homogeneous urbanism where, in addition to the living spaces, the centrally located public services in the centre (which includes libraries, storage, schools, etc.) are also heated equally by hot-water heating, supported by boilers placed in the centre. In addition to the cost factor, this arrangement was probably intended for specific formal goals. As recorded: ‘The implications were clear: while labor remained relatively cheap and architecture was still considered an exercise in the decoration of a shell, living conditions inside were likely to remain in a rude state.’ In this sense, the architecture once again became a mediator between the interior and the exterior.

HEALTHY COMFORT 29

30 CHAPTER 01

FIG.19 Tropical Islands

''DIVIDER"

Divider/Design Proposal 1

In X-Ray Architecture, Beatriz Colomina presents a particular view of the body. From her view, the X-ray is not simply an image of the body, but rather is an image of the body being imaged.26 X-ray, norms, standards and technologies allow the public to reconstruct a clean, robust, healthy – and therefore comfortable – body image, even if it is not actually there. Modern architecture is an attempt to discipline the body with a new regime of synchronised medical, technological and architectural protocols. At this point, as the model for modern architecture, hospitals and sanatoriums have undoubtedly been one of the most widely shared signs of comfort since they were invented. From colour to material, from smell to temperature, all the elements and objects in these buildings constitute our imagination of comfortable living. Furthermore, these architectures consider the modern subject to have many bodily and psychological diseases, reversing the usual perception of sickness as an exception.

In this sense, the separation from the city, the sunbaths on balconies and the gymnastics and other activities in relation to touching nature are not a kind of self-care of aesthetics. On the contrary, they constitute a significant part of medical science

HEALTHY COMFORT 35

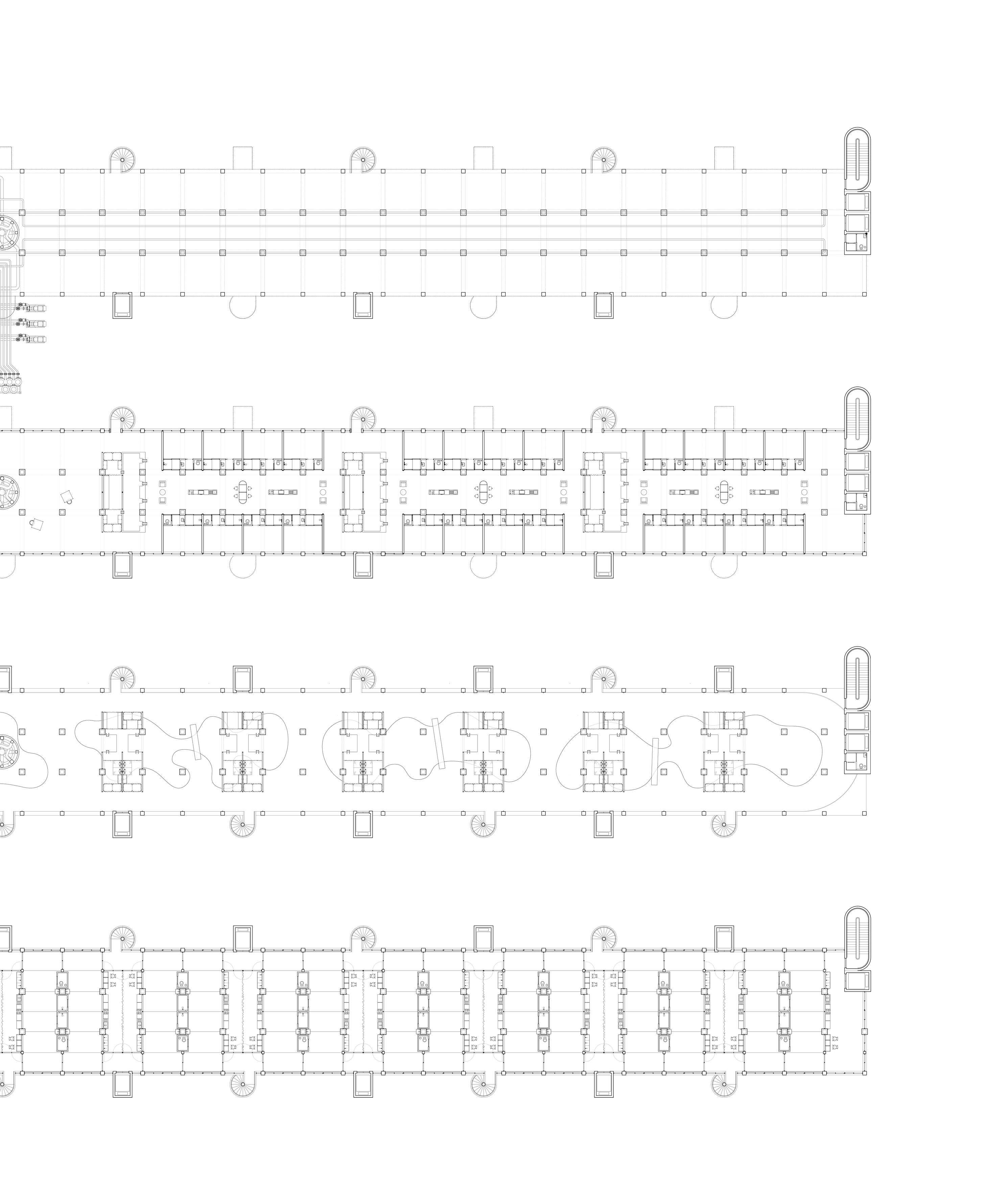

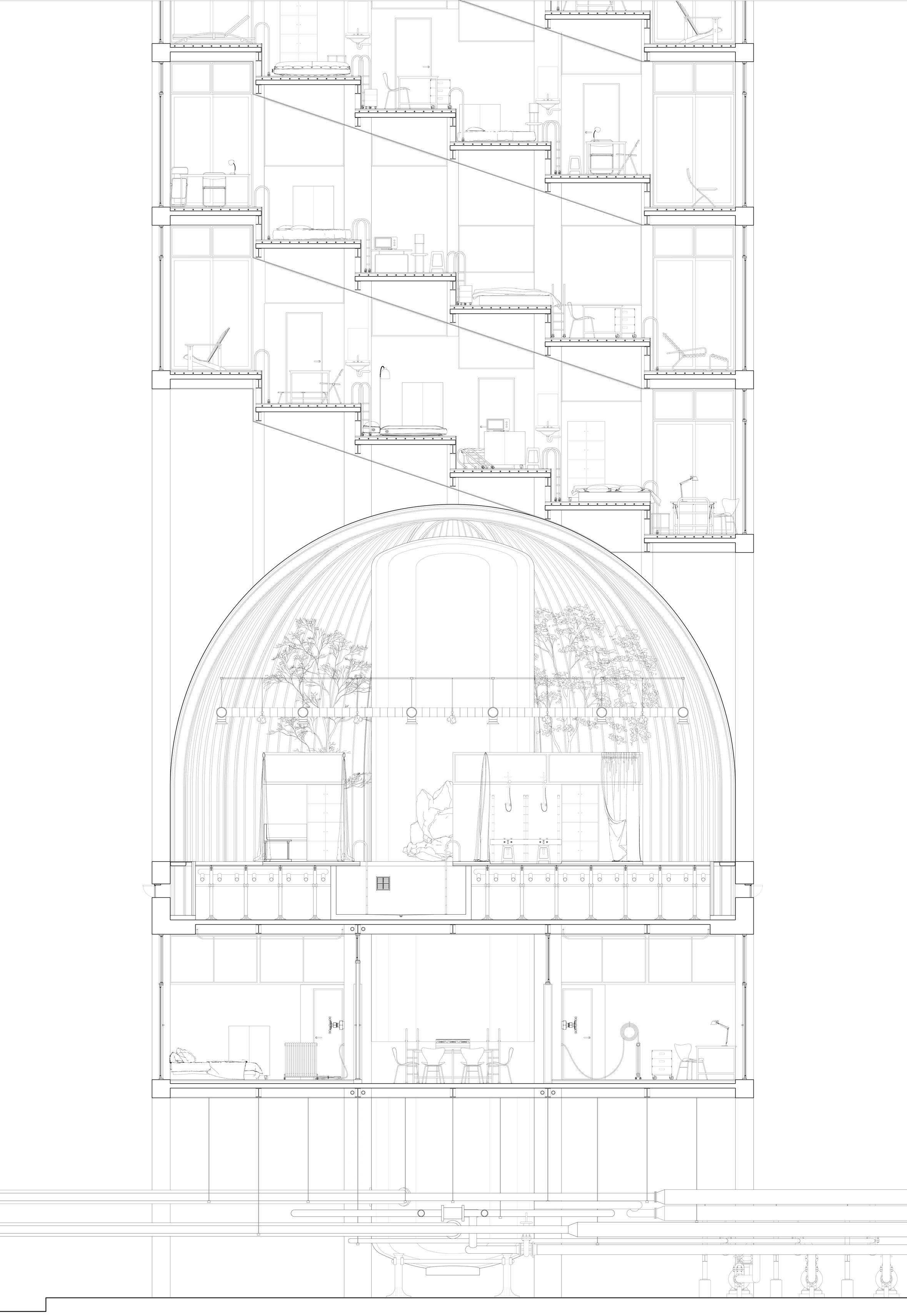

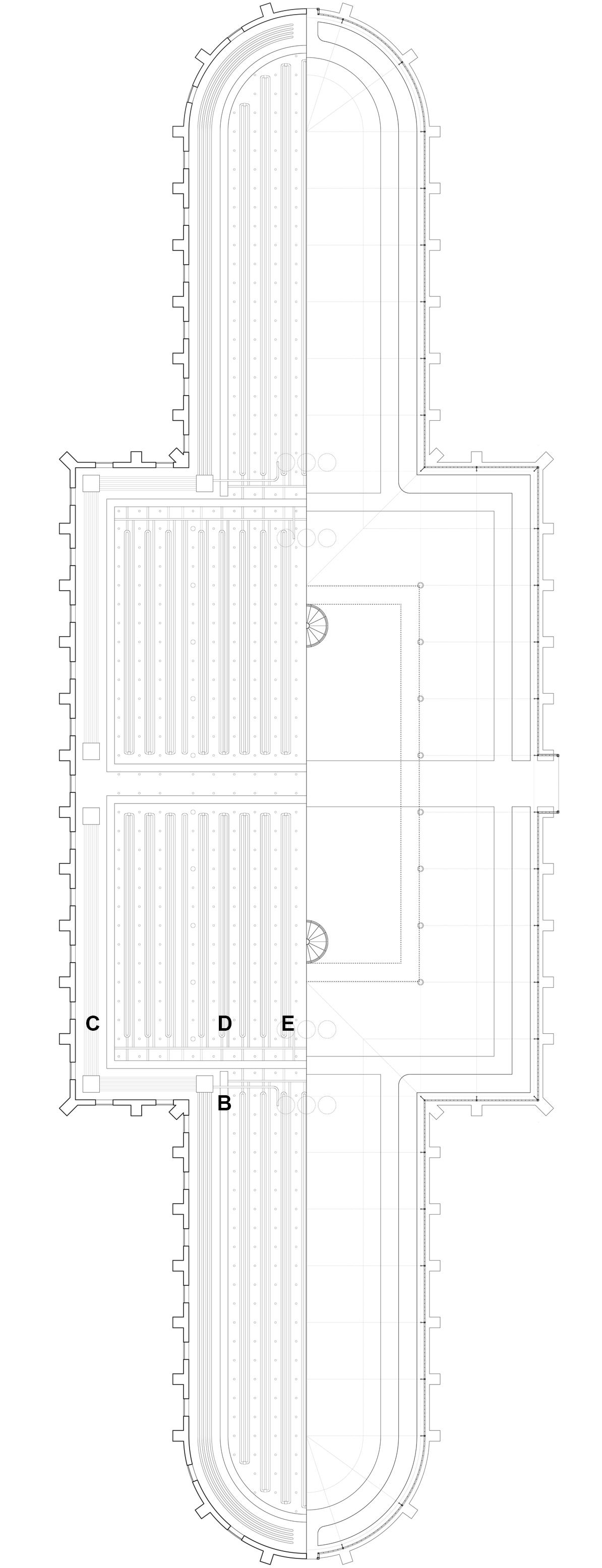

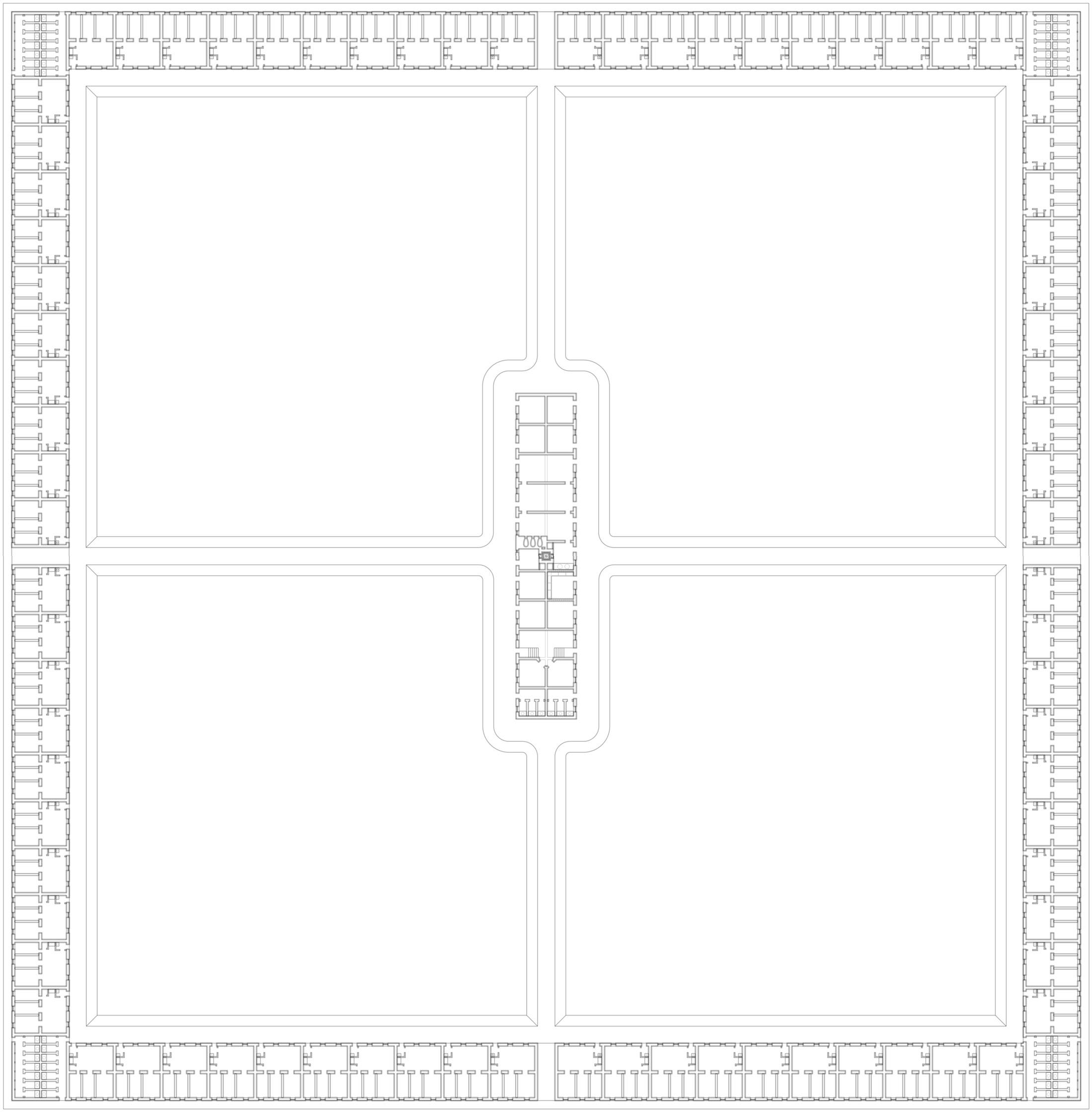

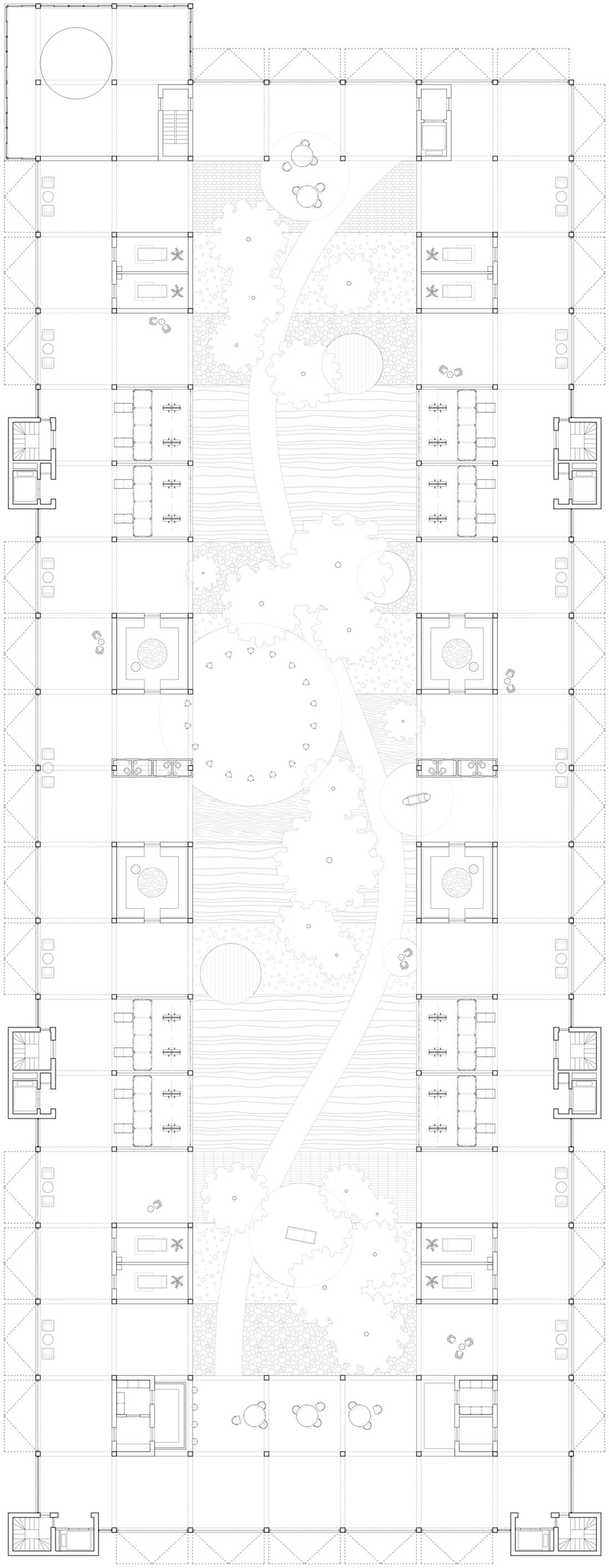

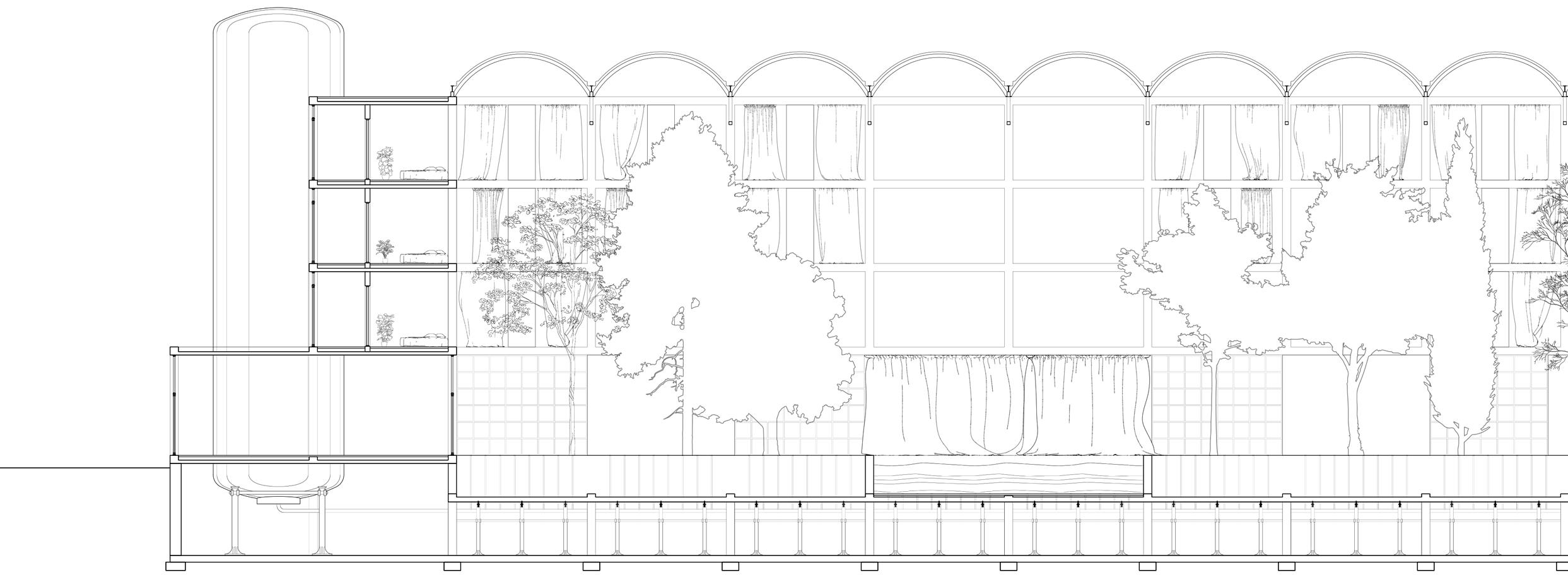

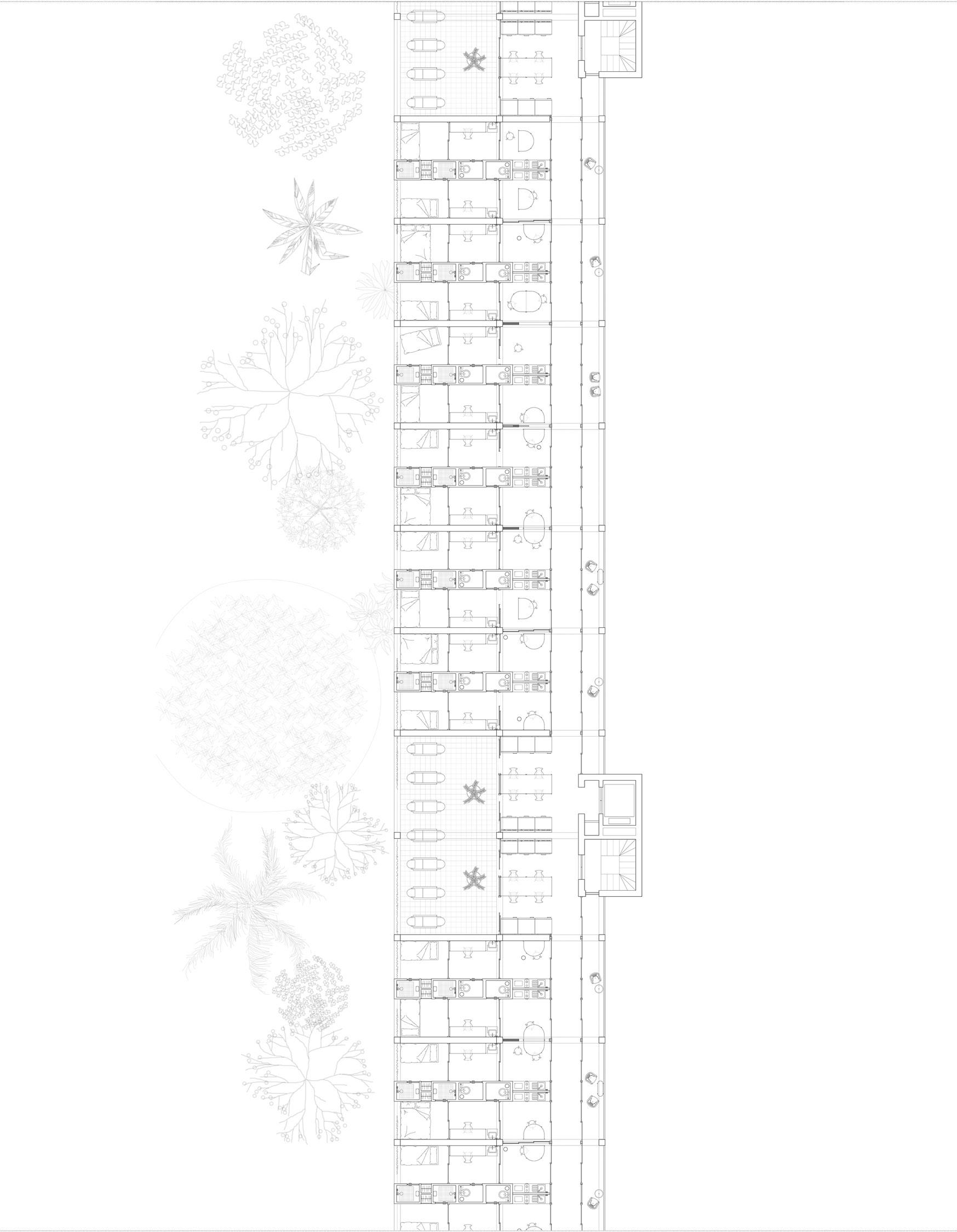

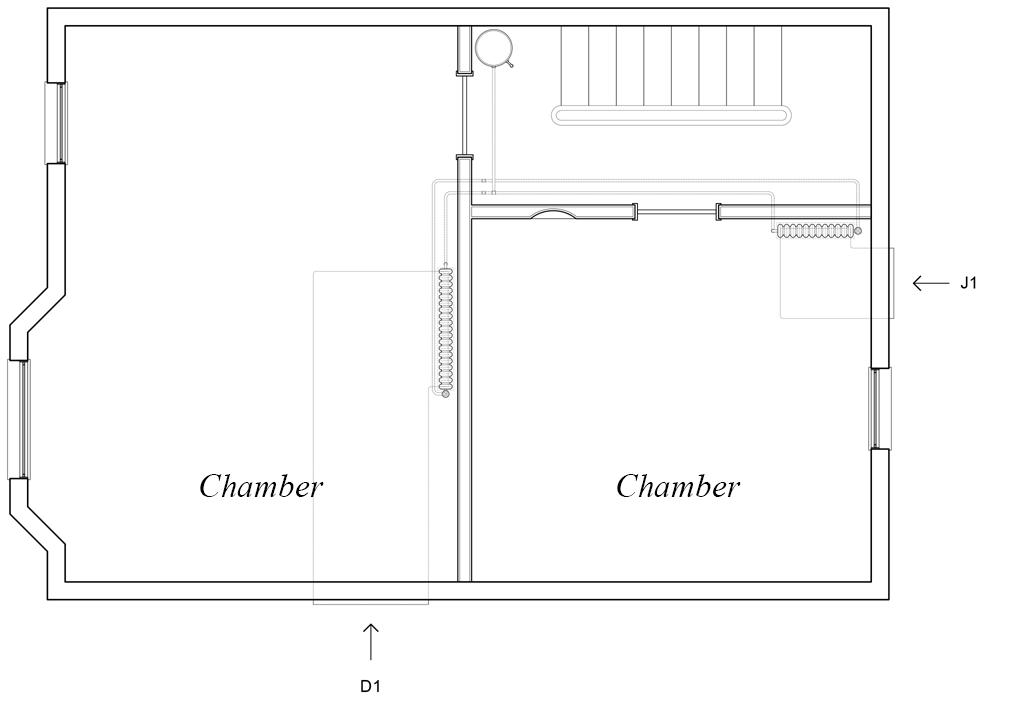

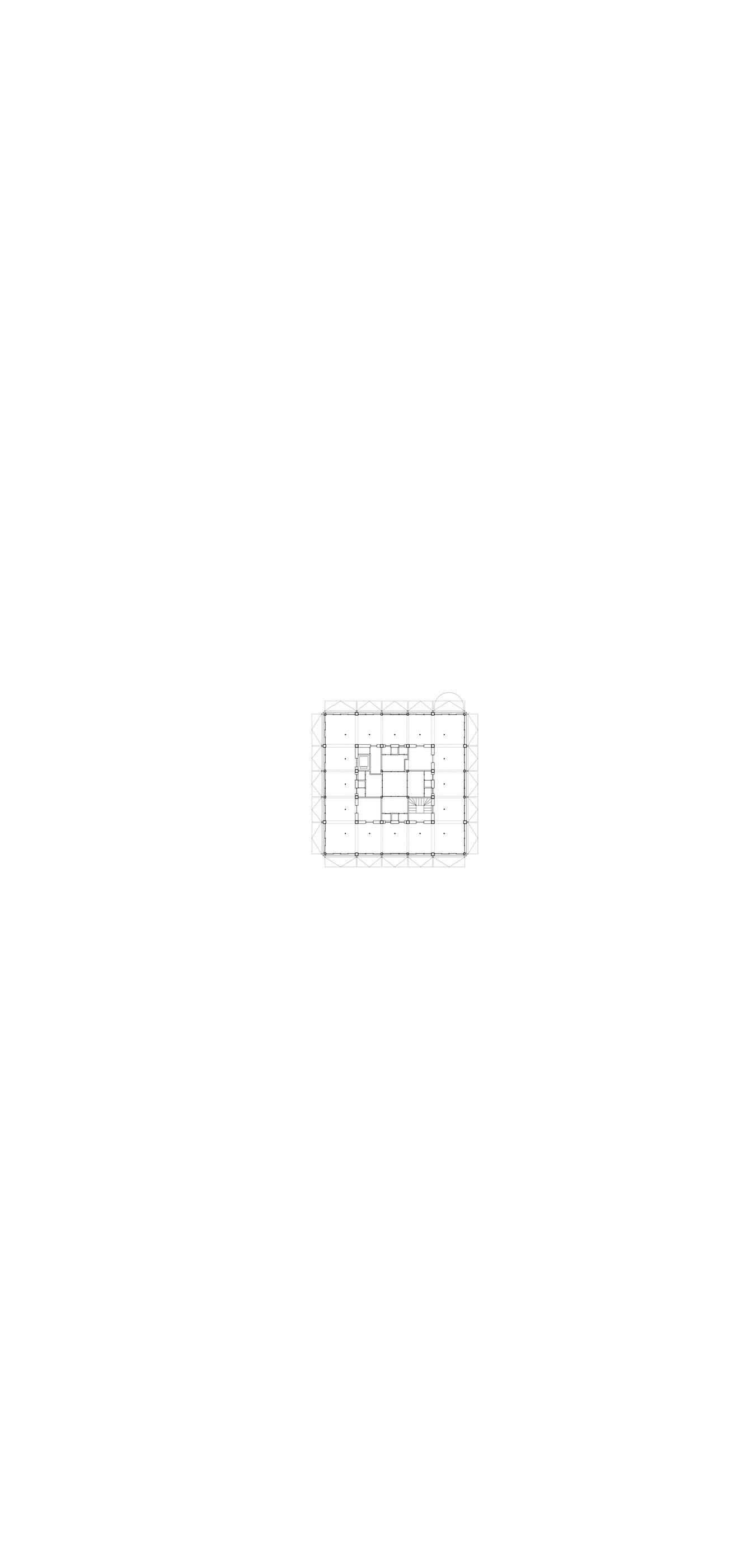

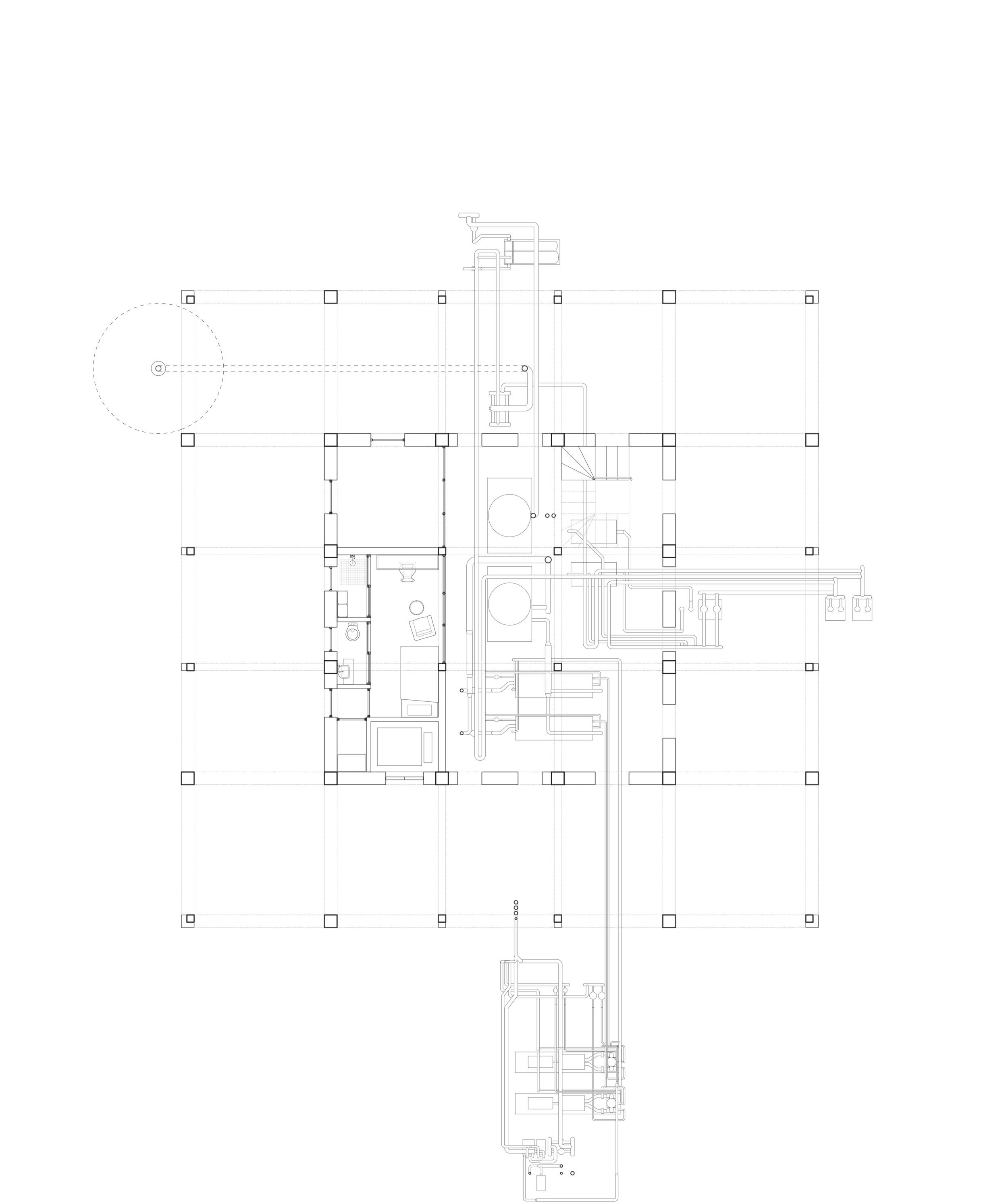

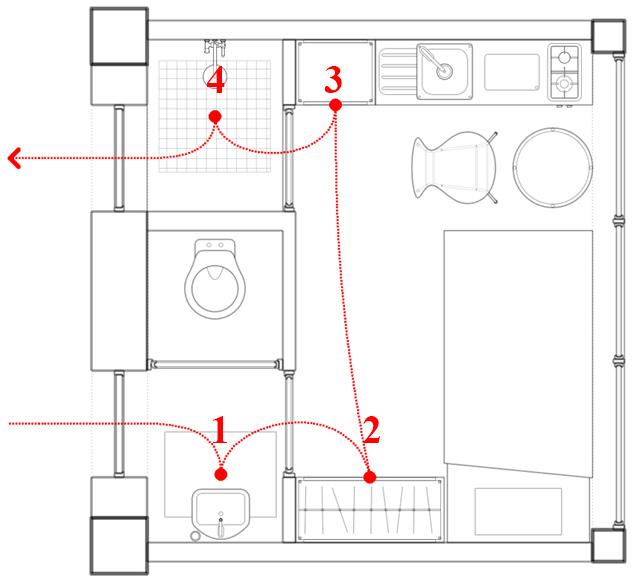

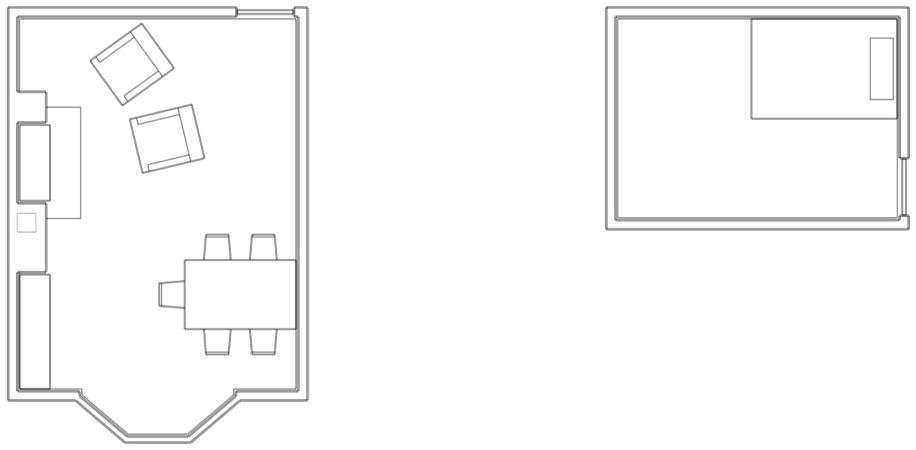

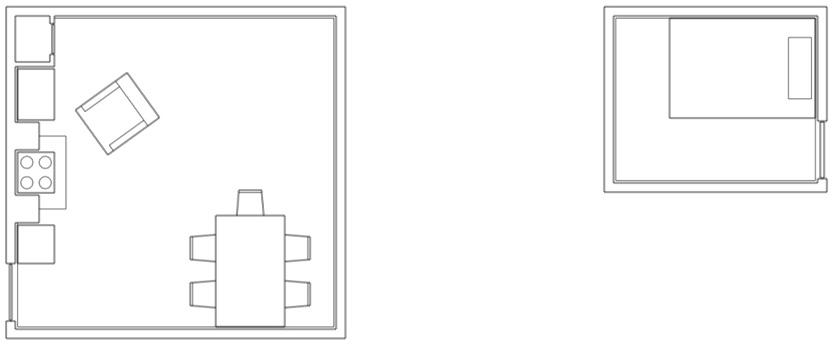

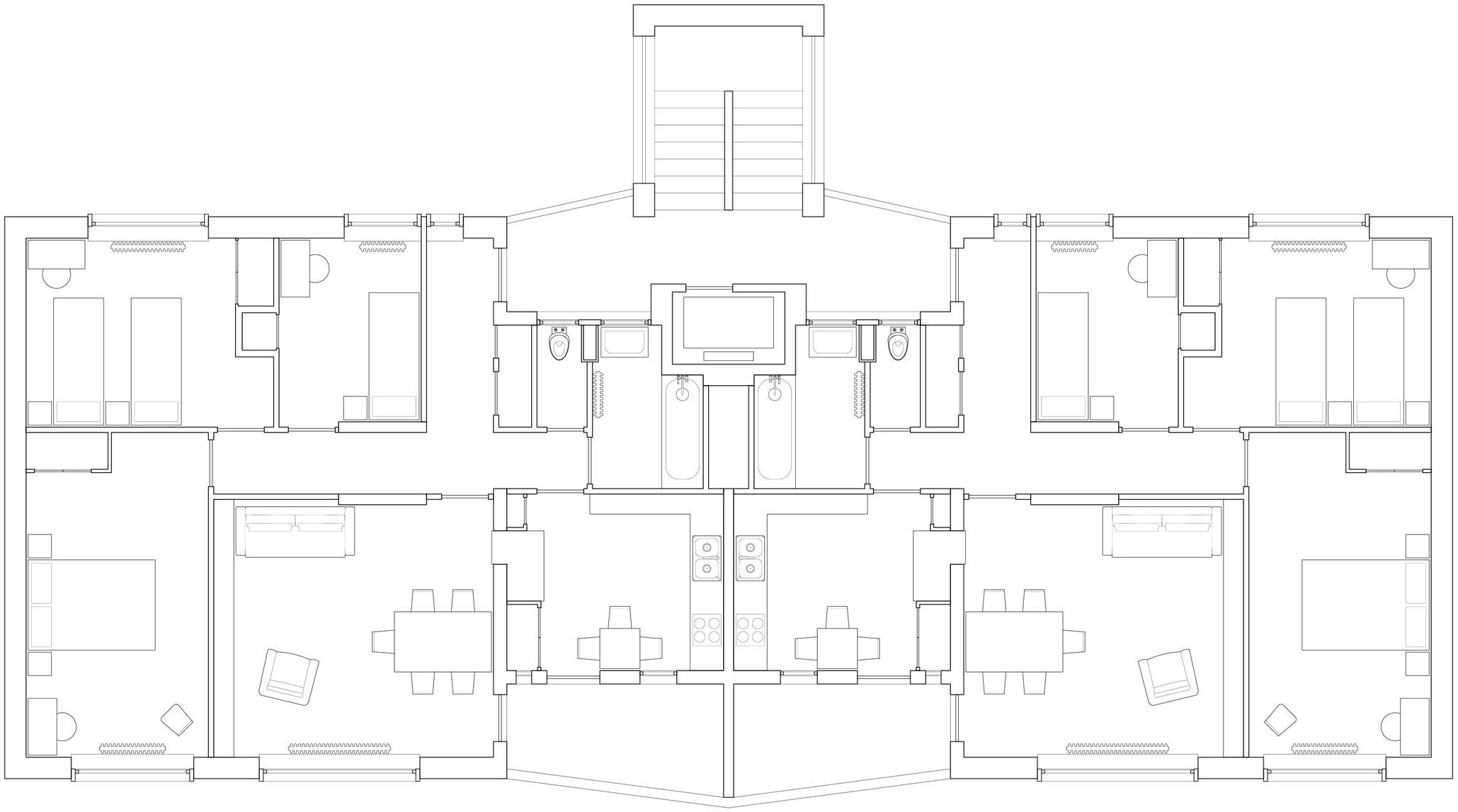

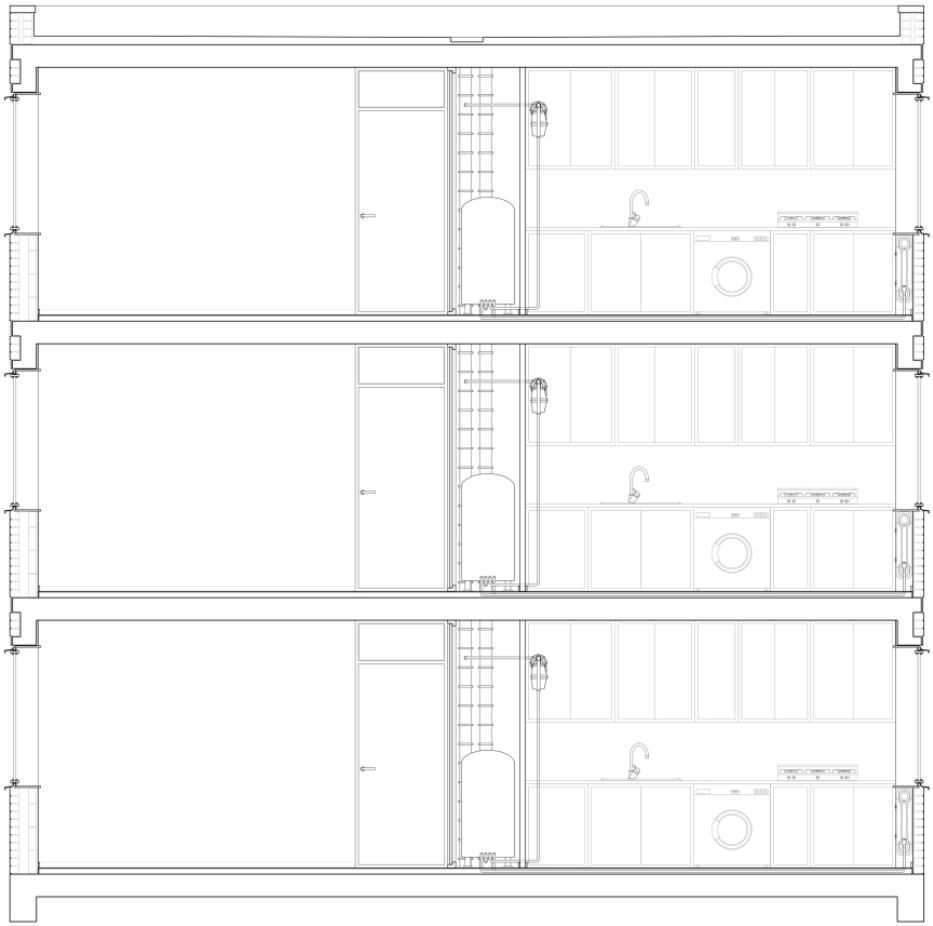

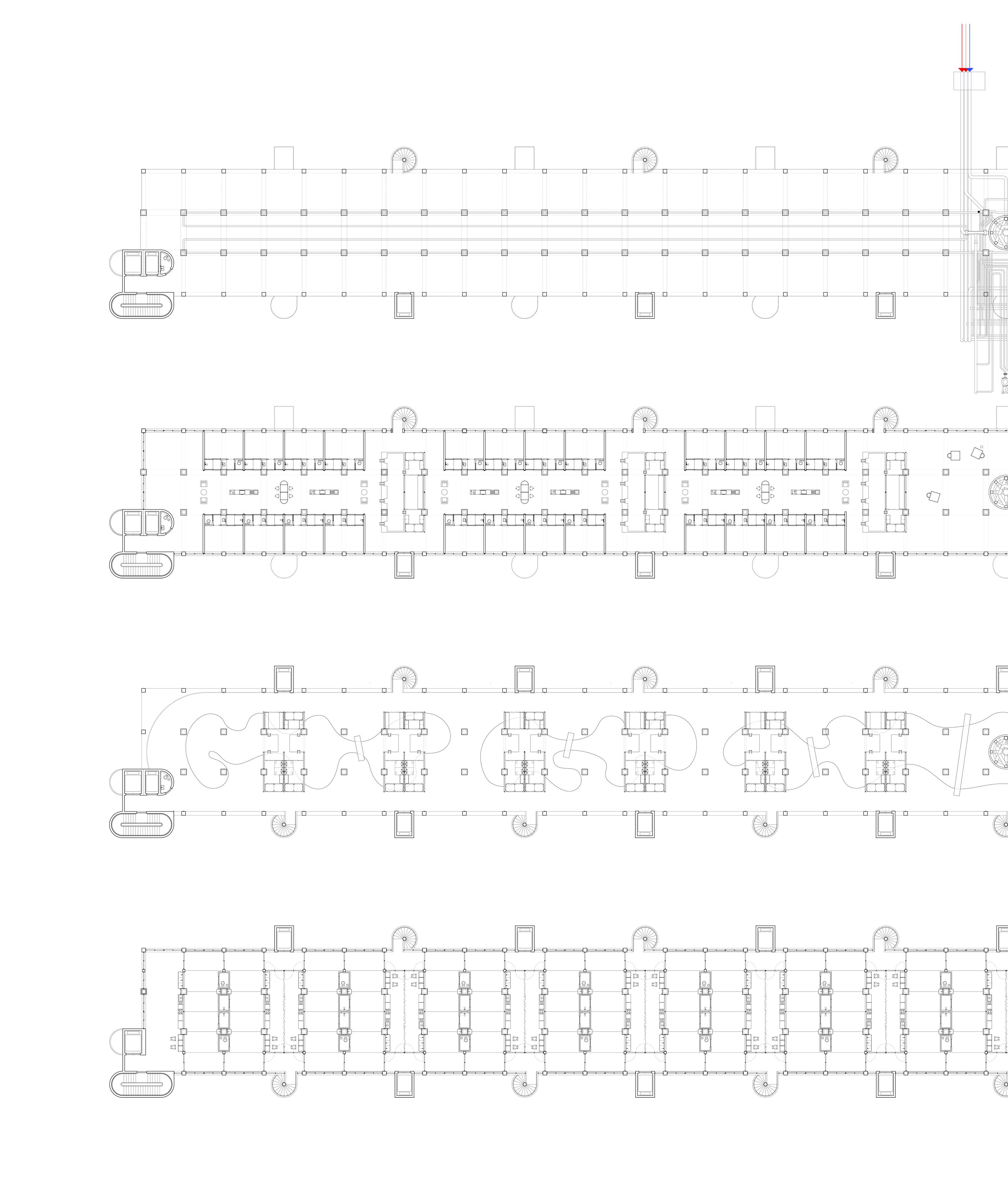

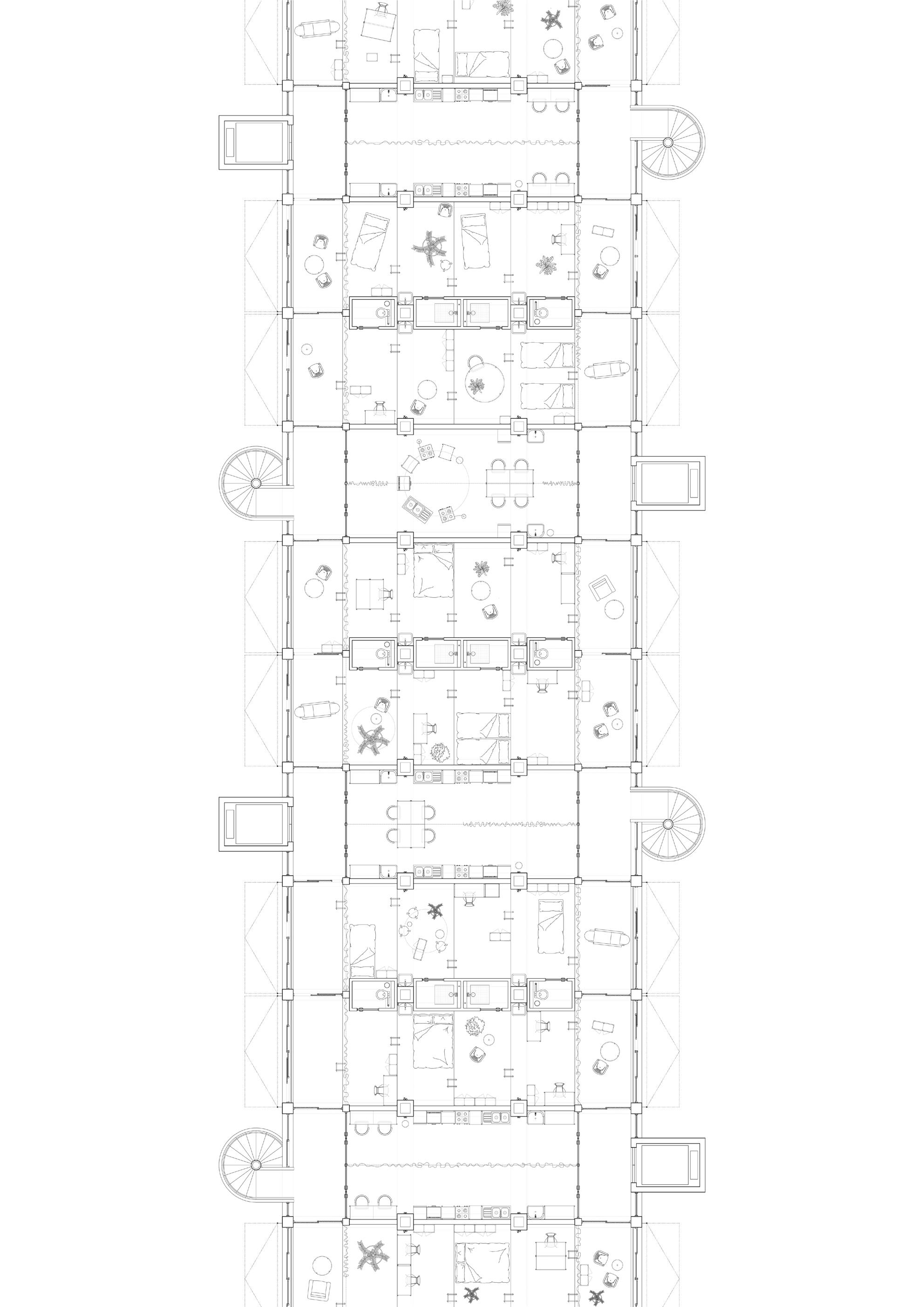

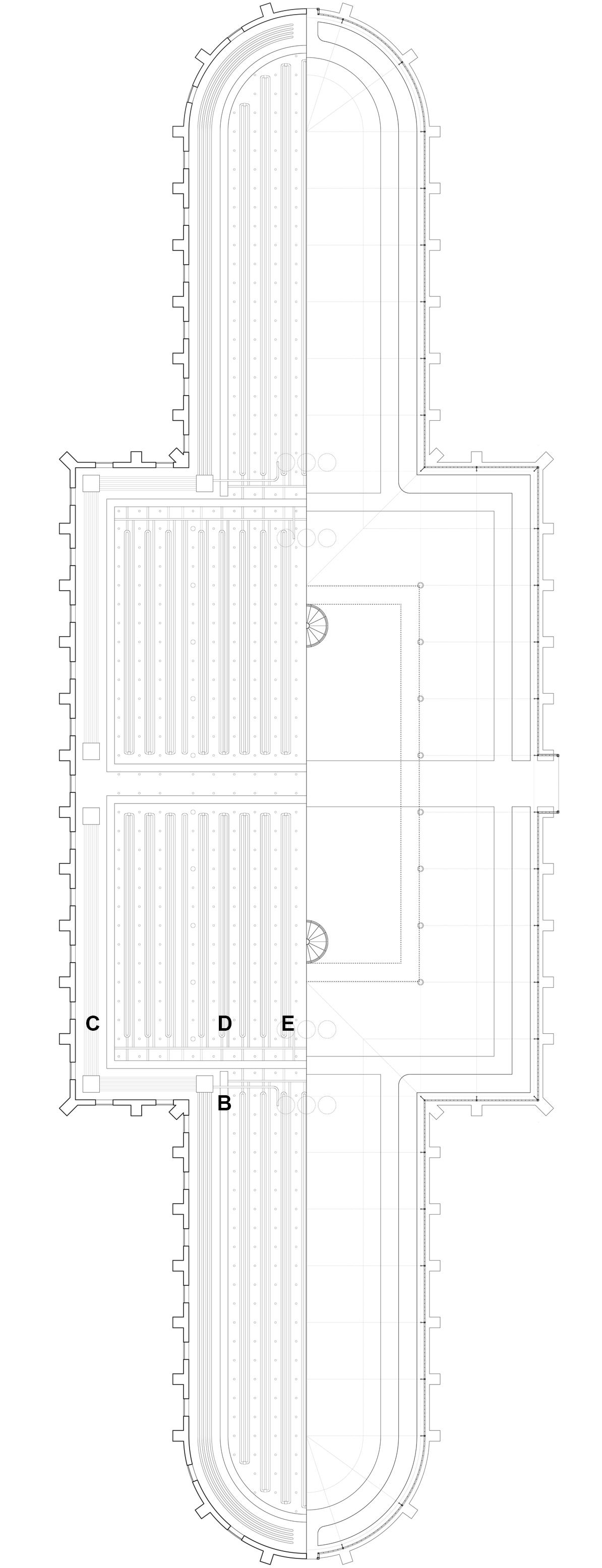

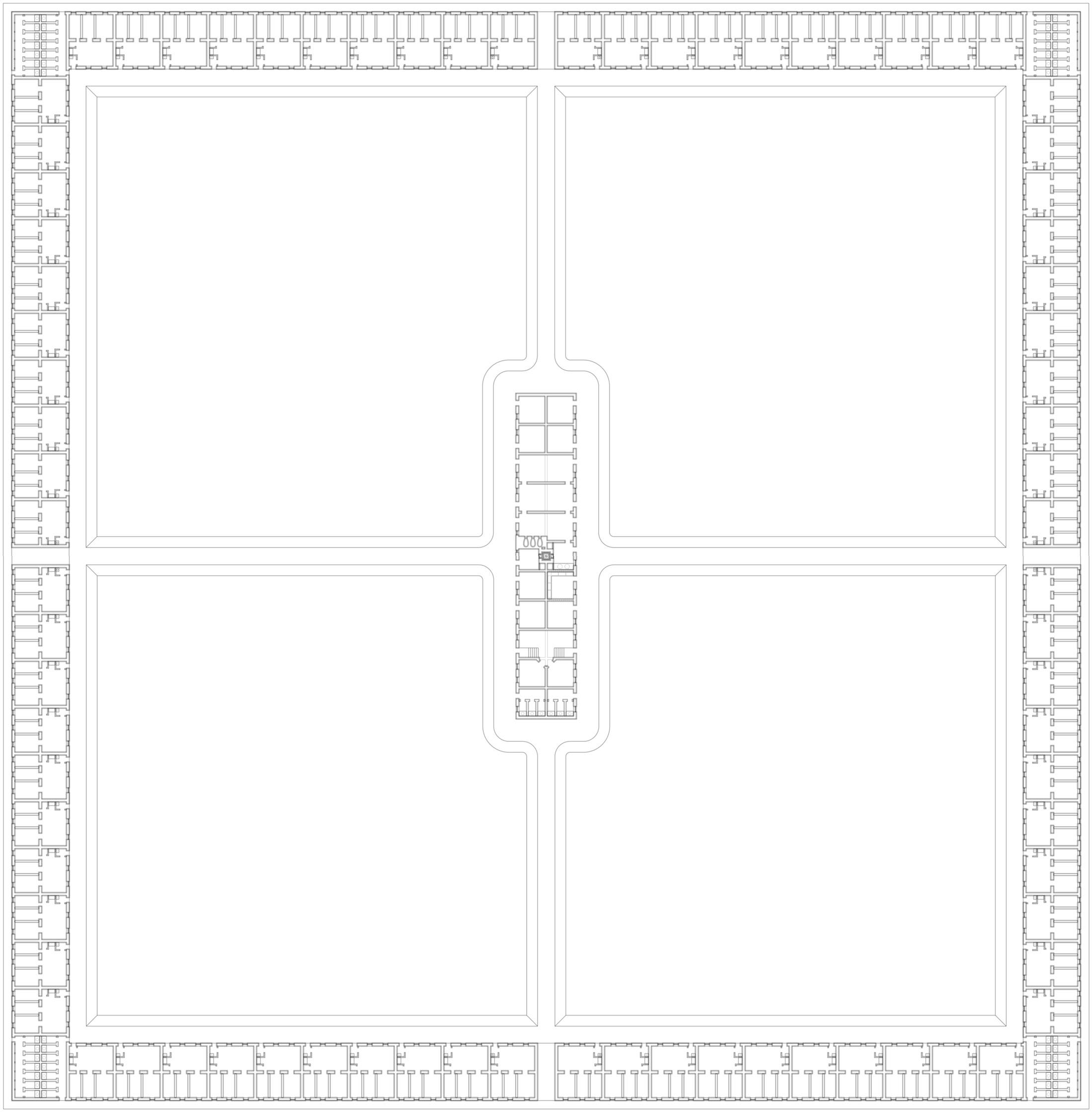

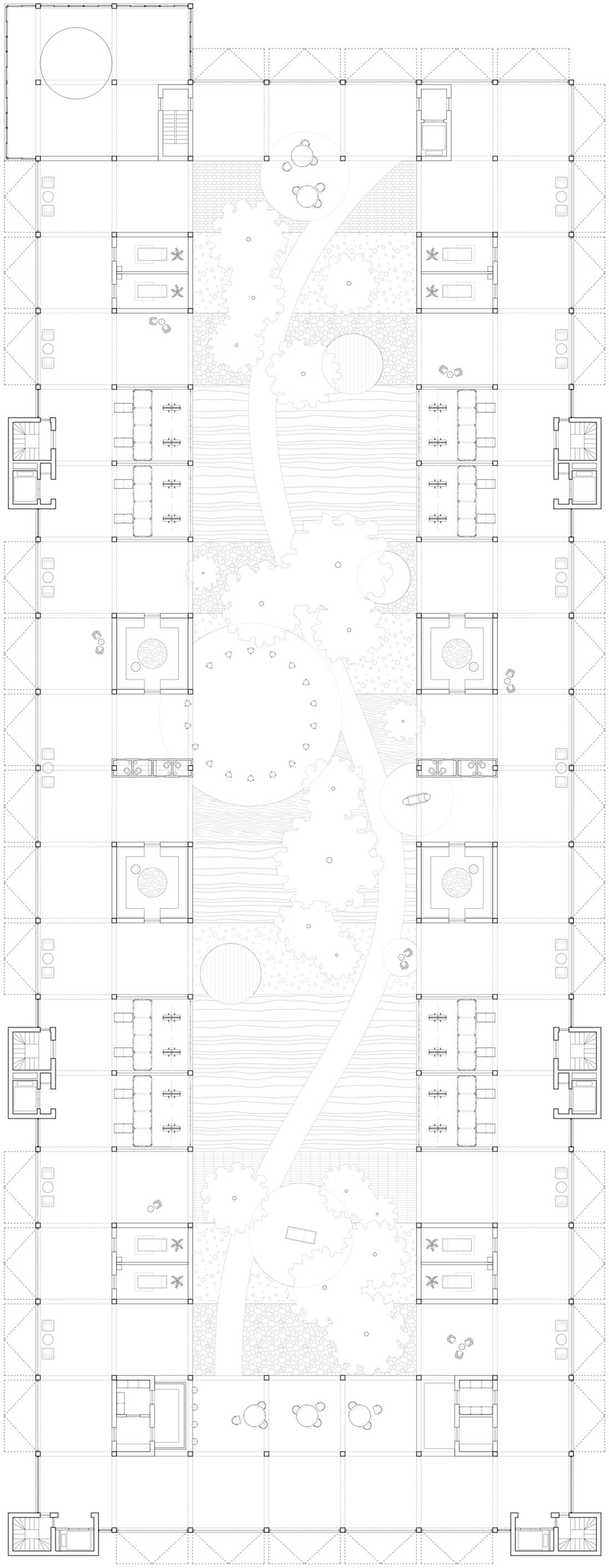

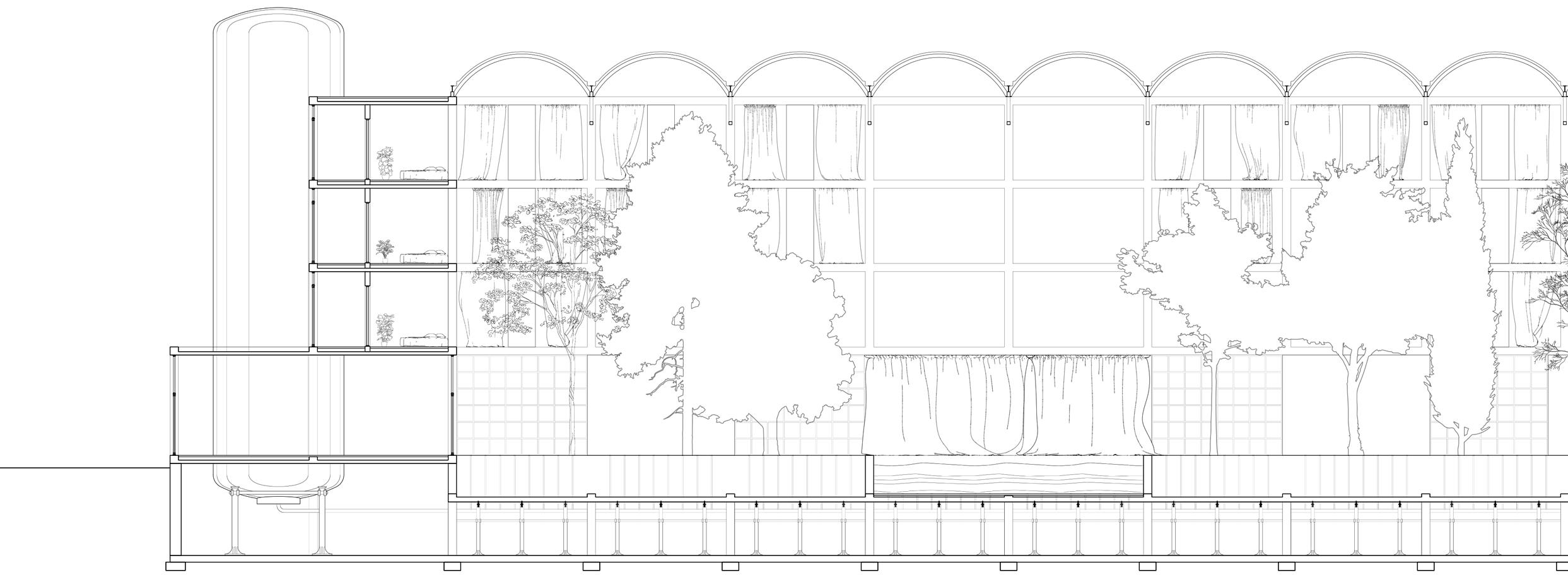

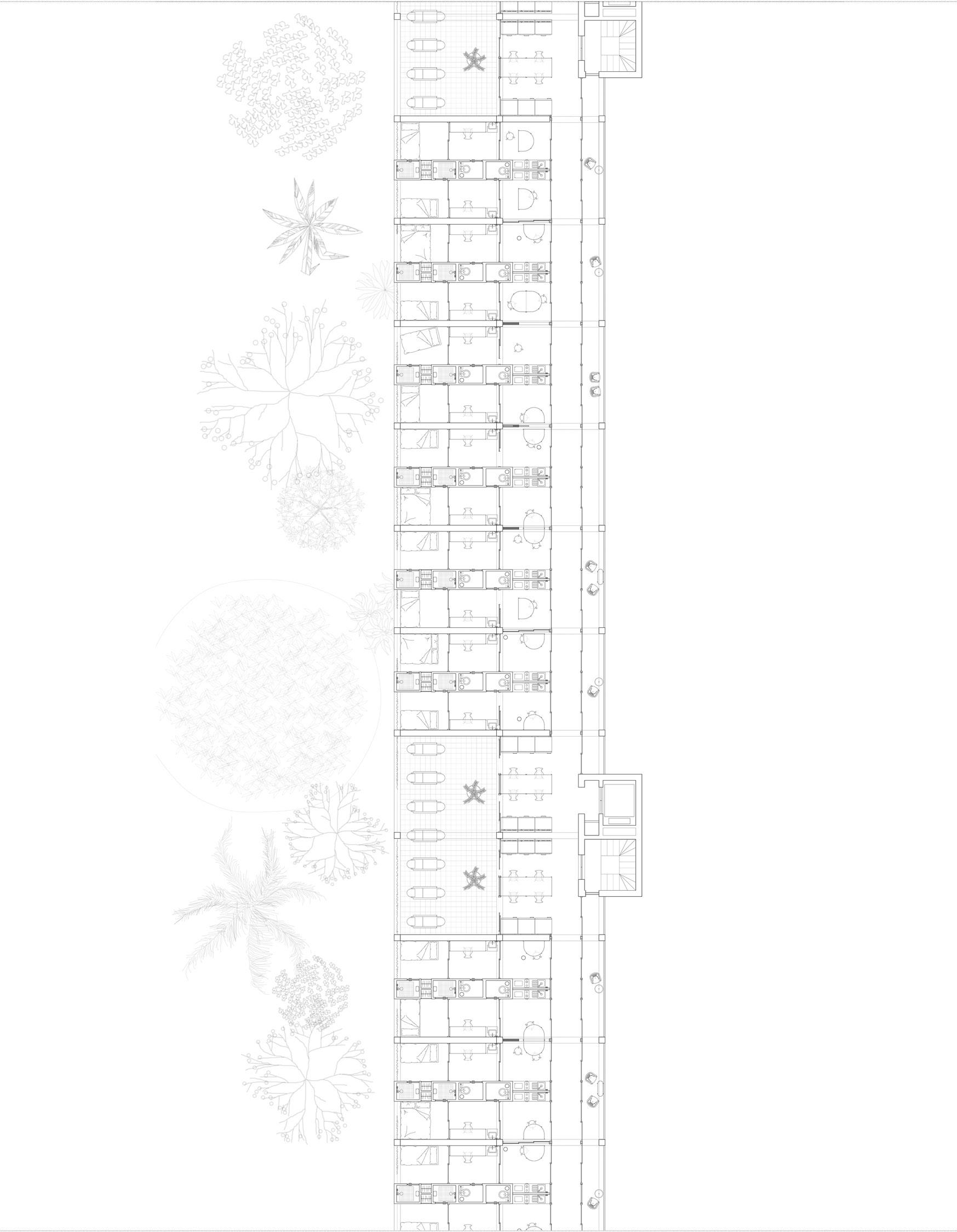

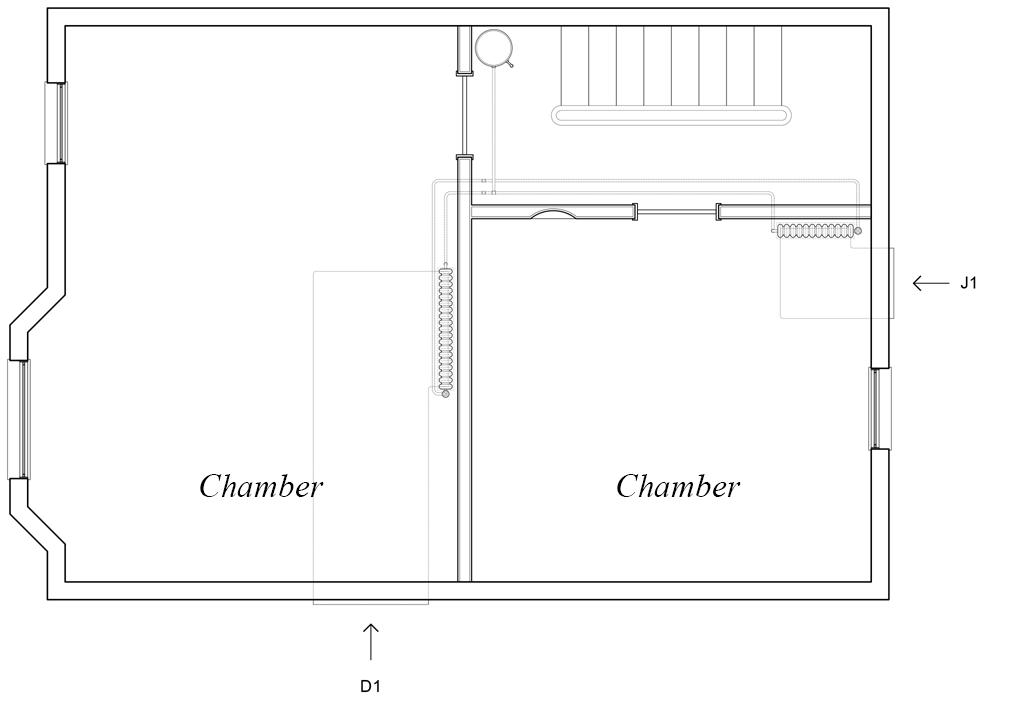

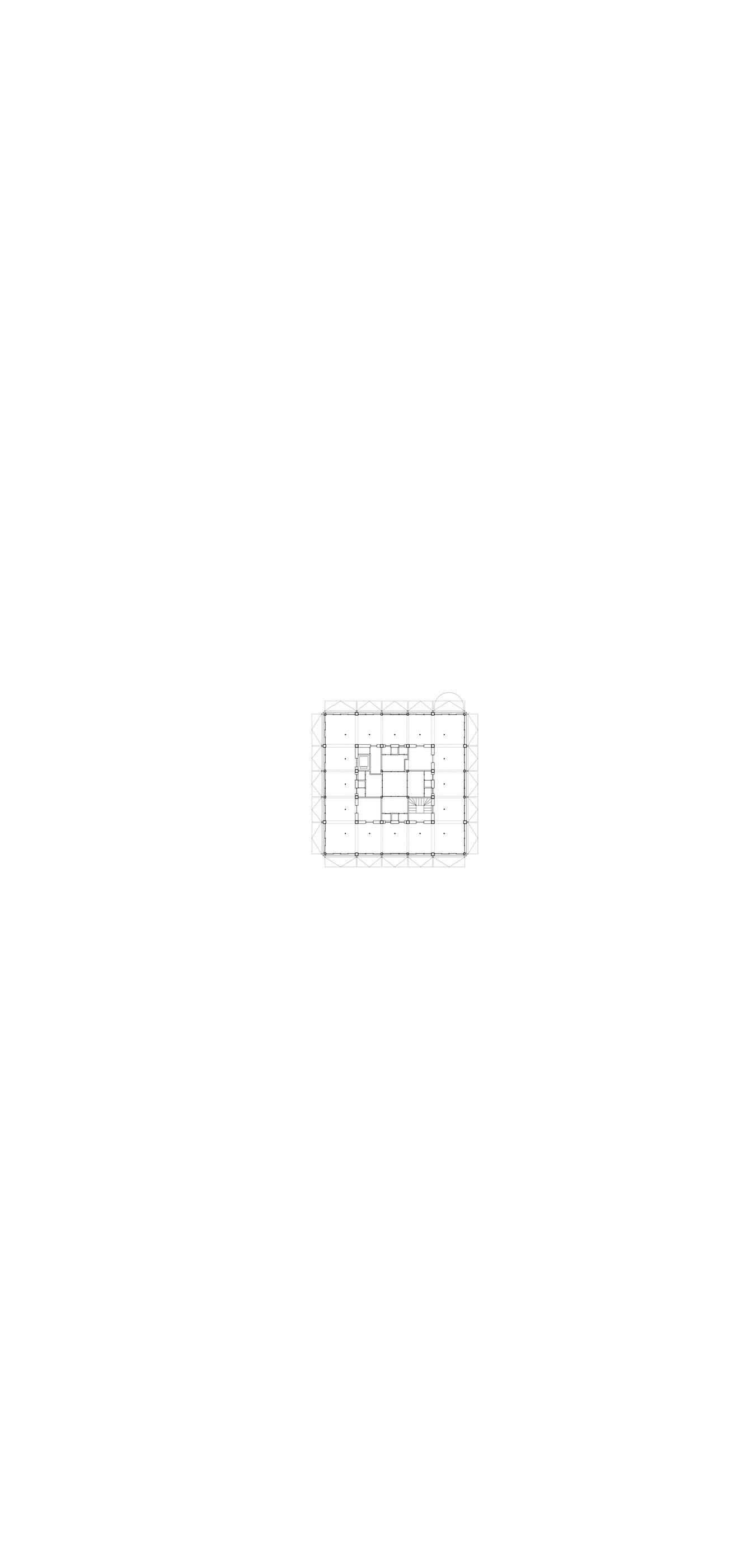

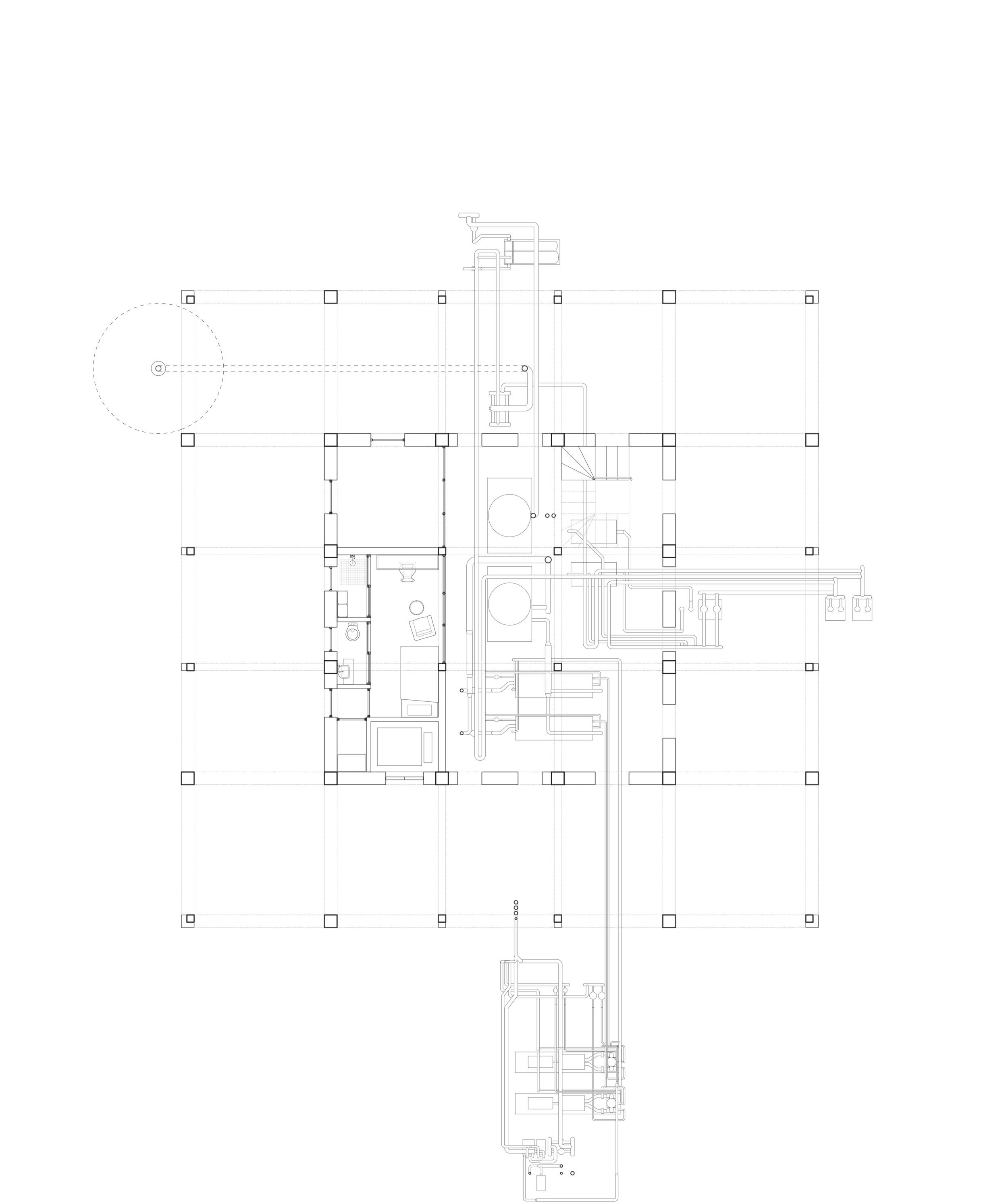

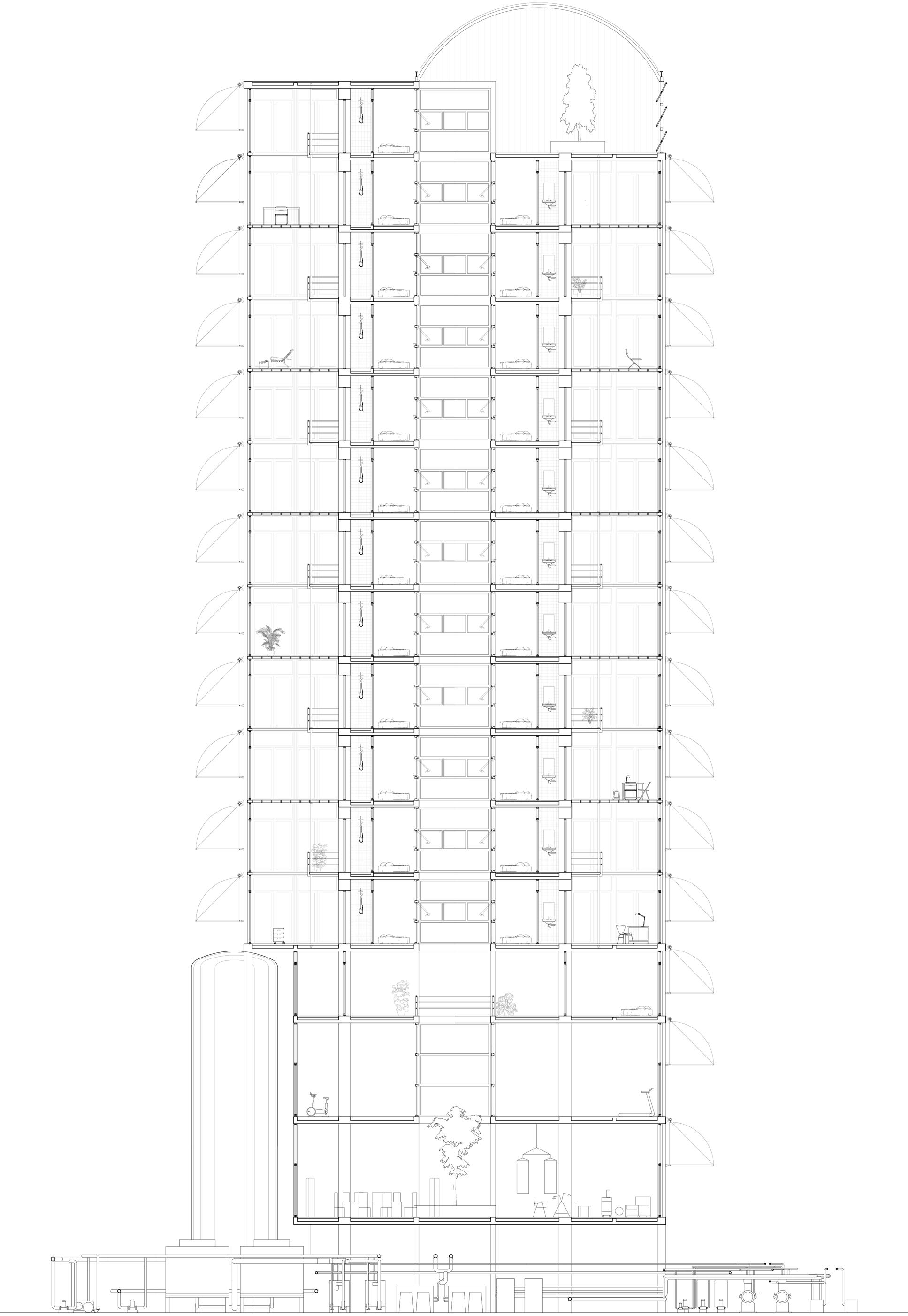

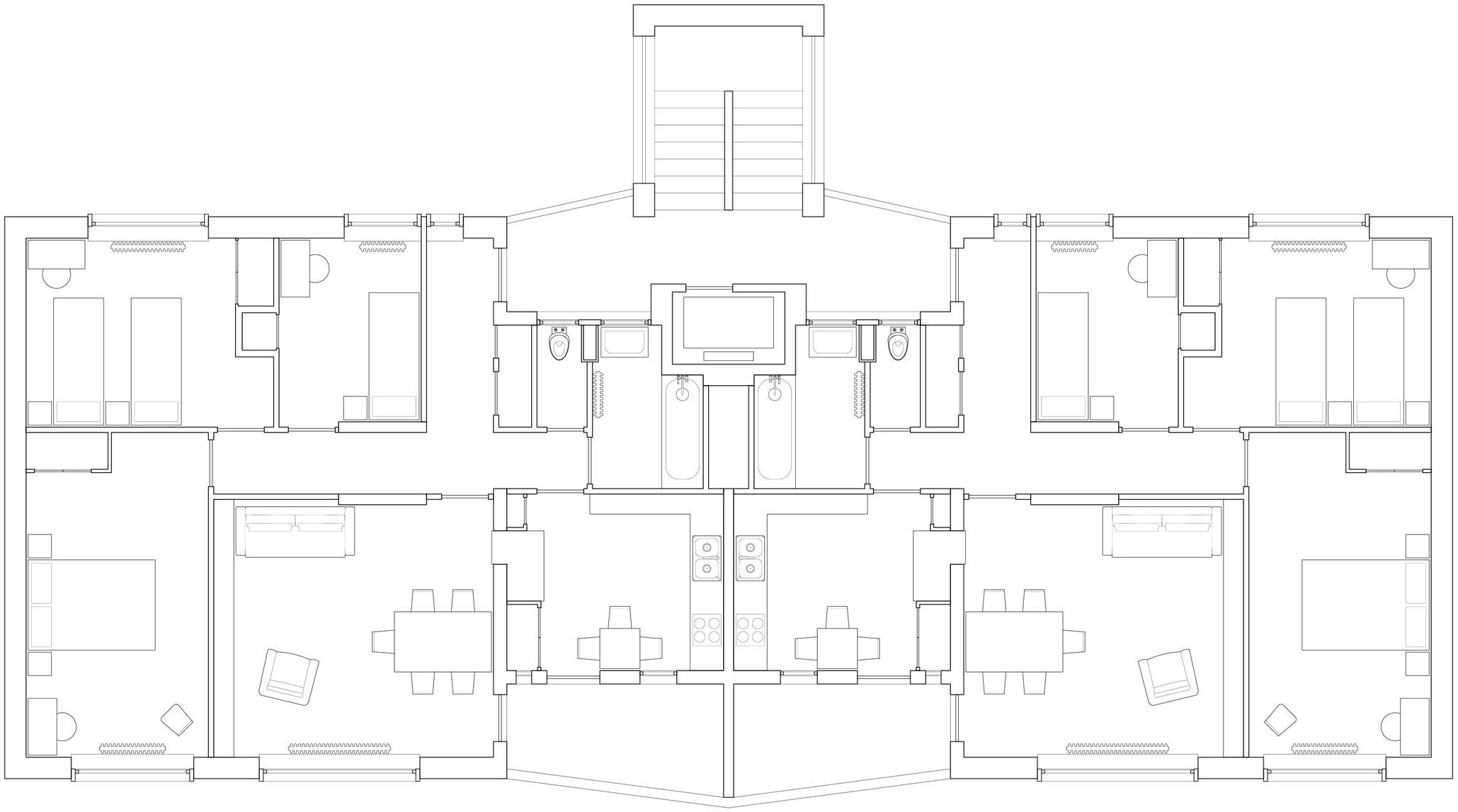

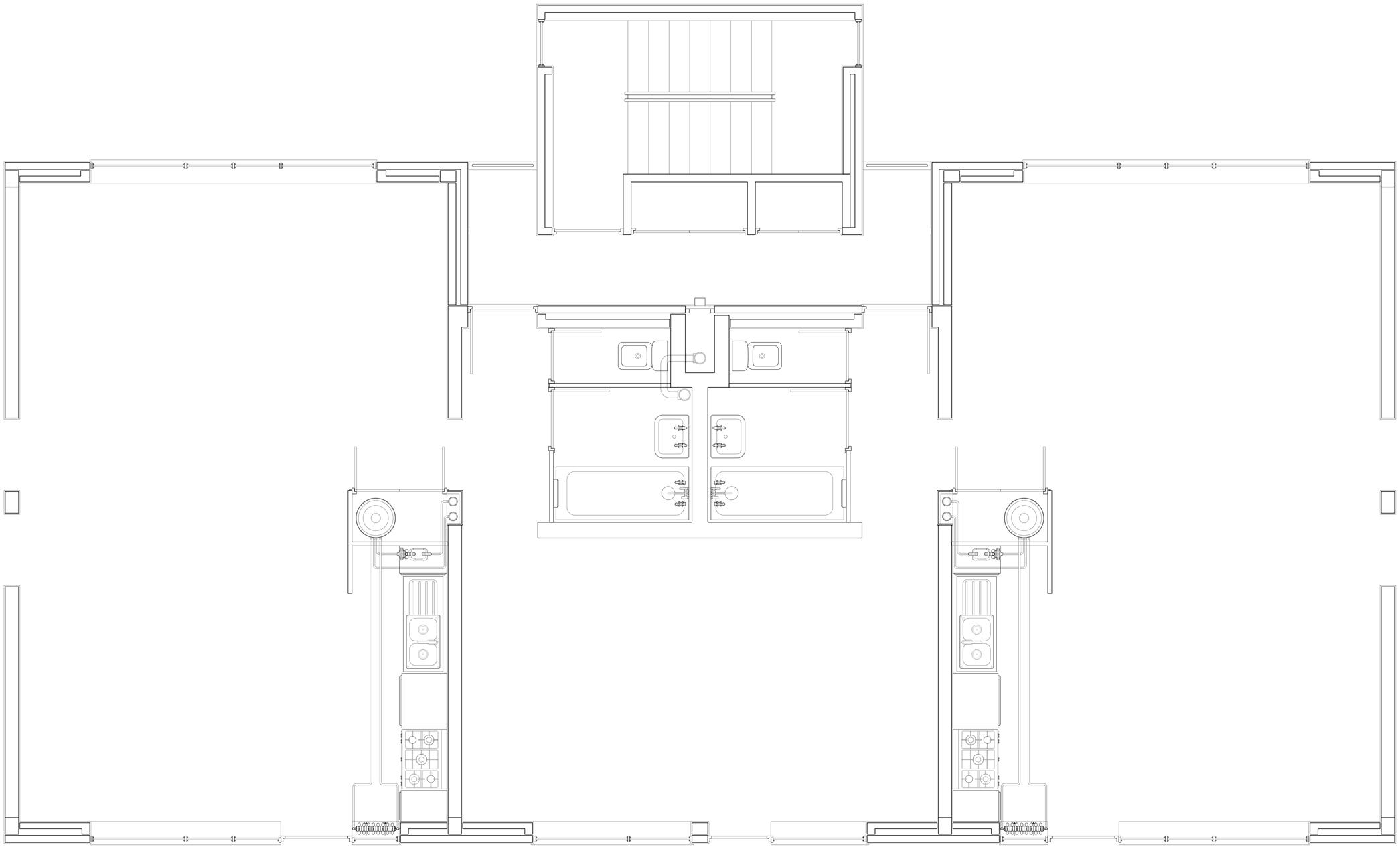

36 CHAPTER 01 Divider, Ground Floor plan

and technology and have become necessary in maintaining the physical and psychological health of the modern subject.

Therefore, ‘Divider’ is a sanatorium built in the city. It provides an artificial temperate climate, allowing workers who suffer psychological stress to take care of themselves by living within it, rather than rendering themselves as comfortable recipients who are immersed in nature.

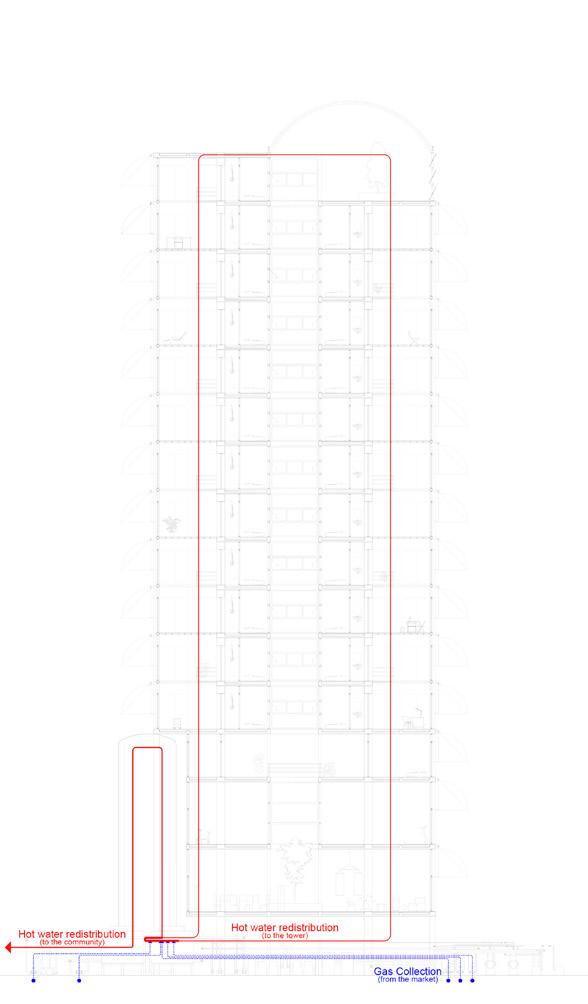

In this way, ‘Divider’ reframes this sanatorium as a form of energy infrastructure for collective use. Since the beginning of the energy efficiency framework implementation in the 1980s, companies; commercial organisations; public sector organisations, such as universities; transportation hubs, such as airports; and hospitals have been expected to operate more rationally in terms of energy use.27 They have improved their energy efficiency by, for example, changing the material makeup of their buildings, installing new windows and doors and using more efficient air conditioning and heating systems. As will be revealed in Chapter 2, the costs of these technological solutions are often passed on to society in the form of higher energy bills, affecting households in energy poverty.

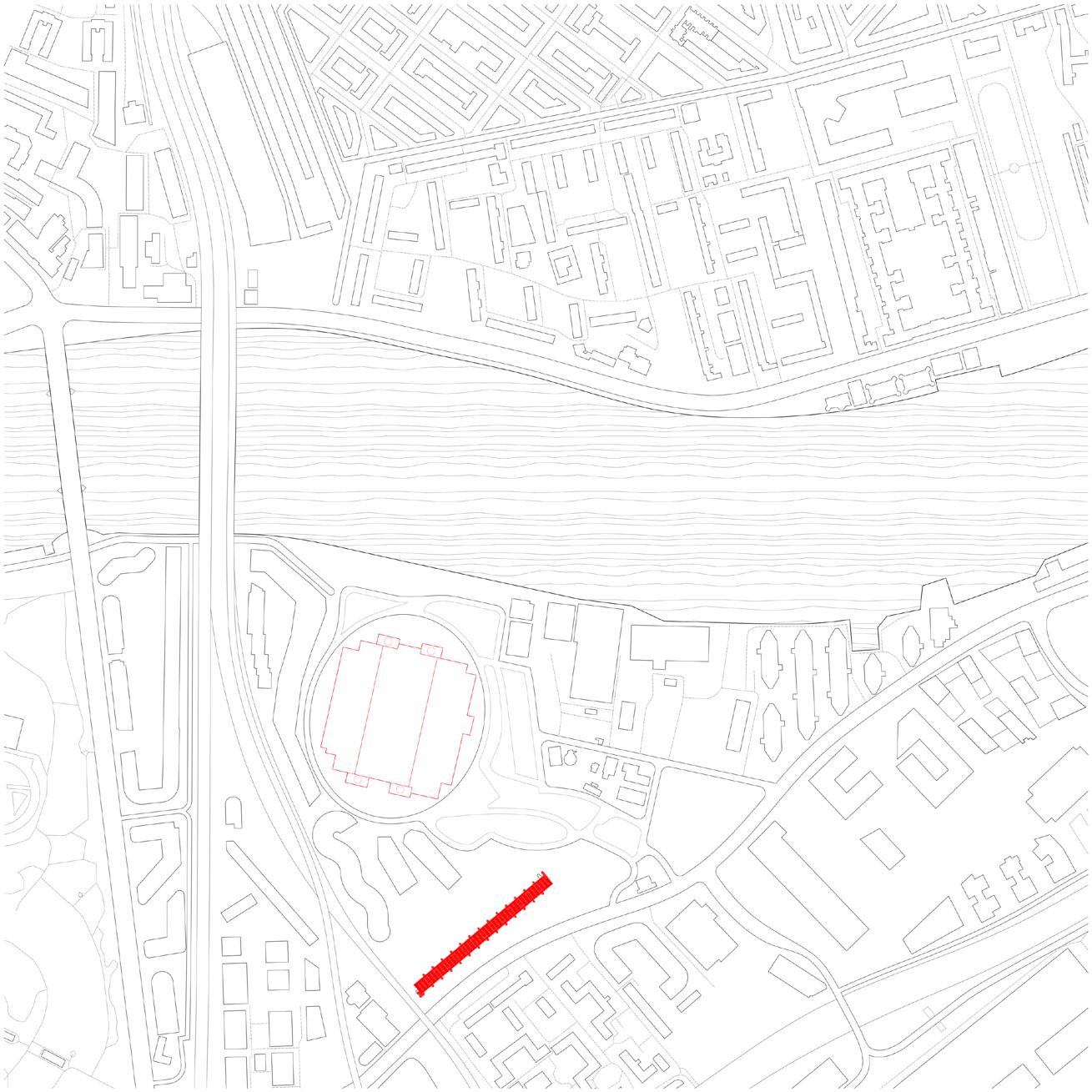

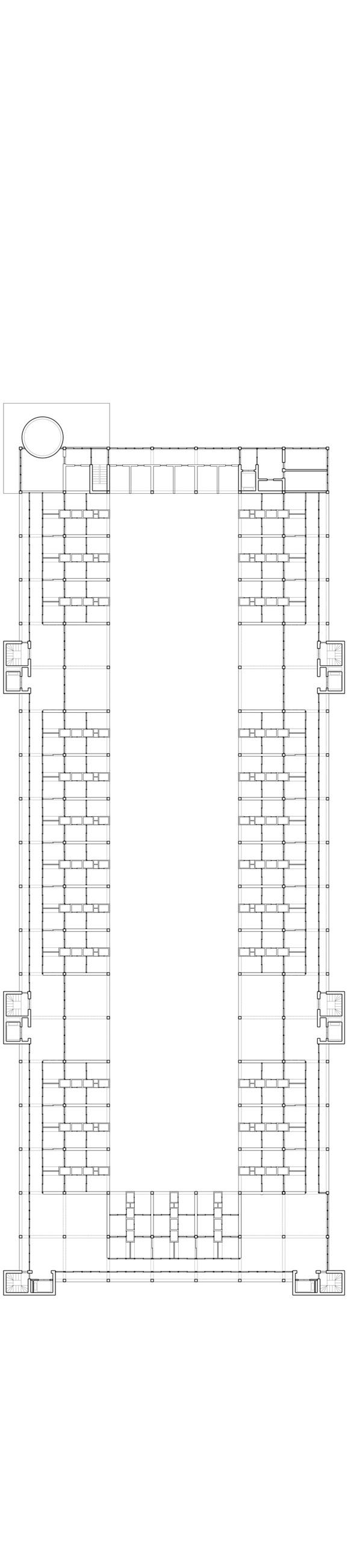

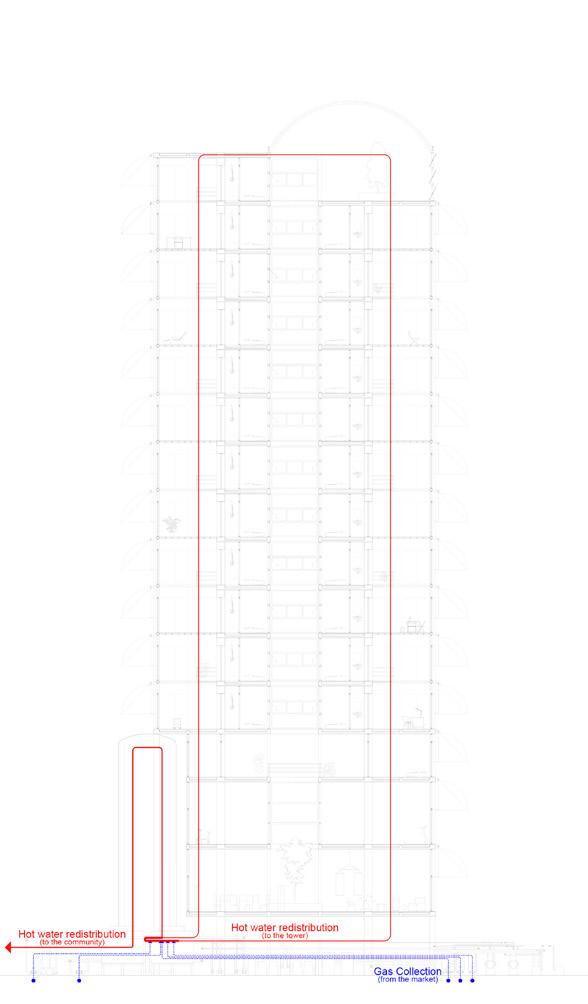

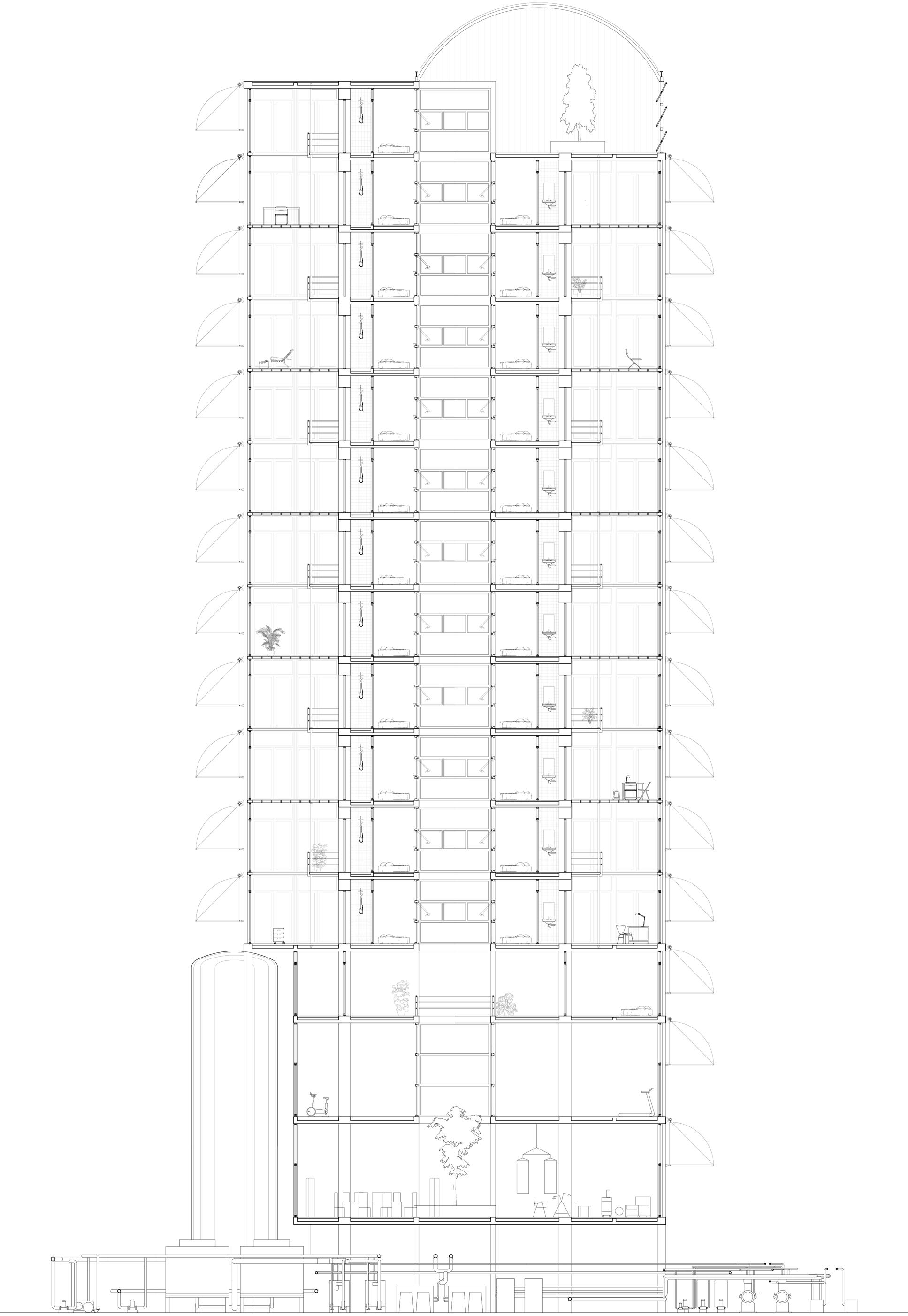

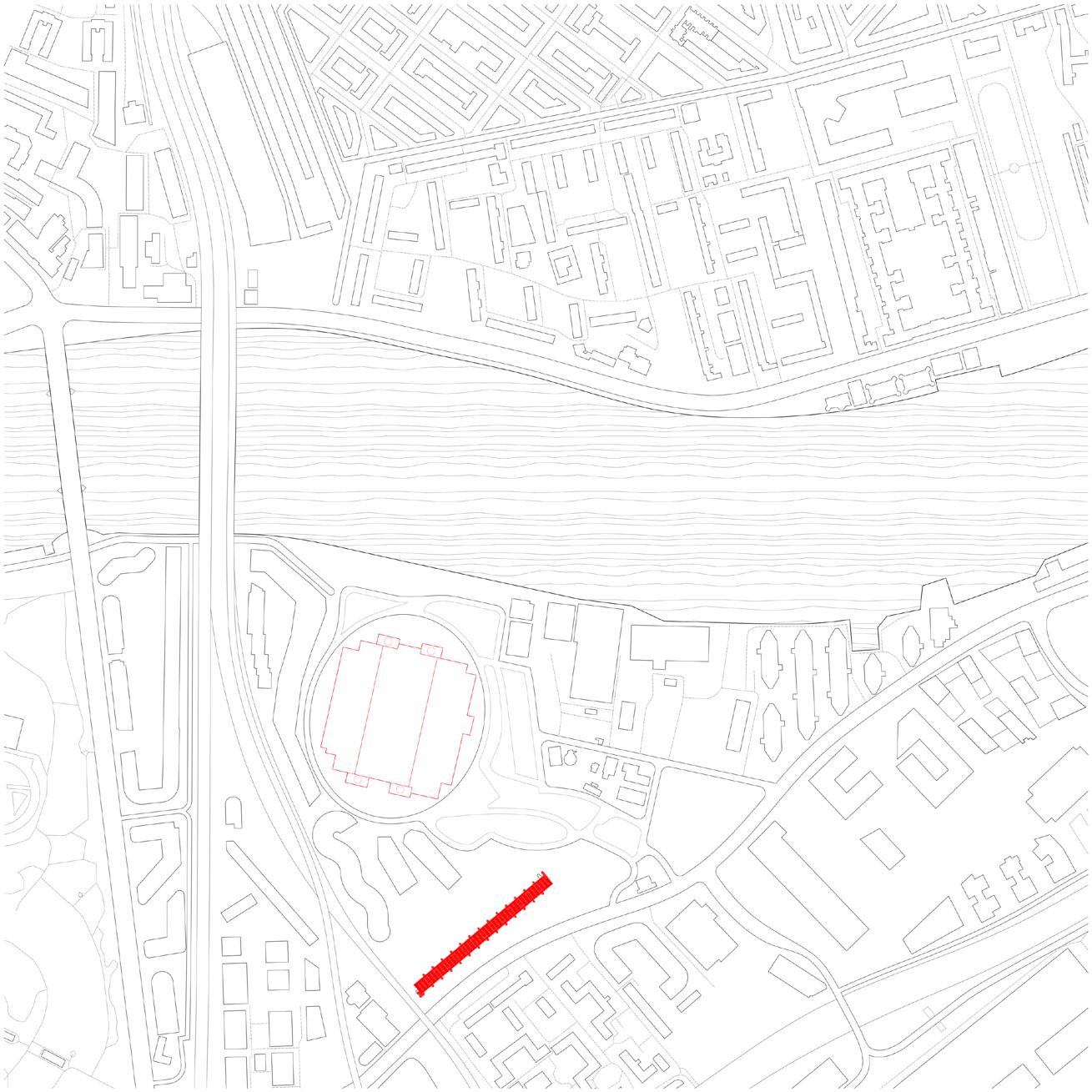

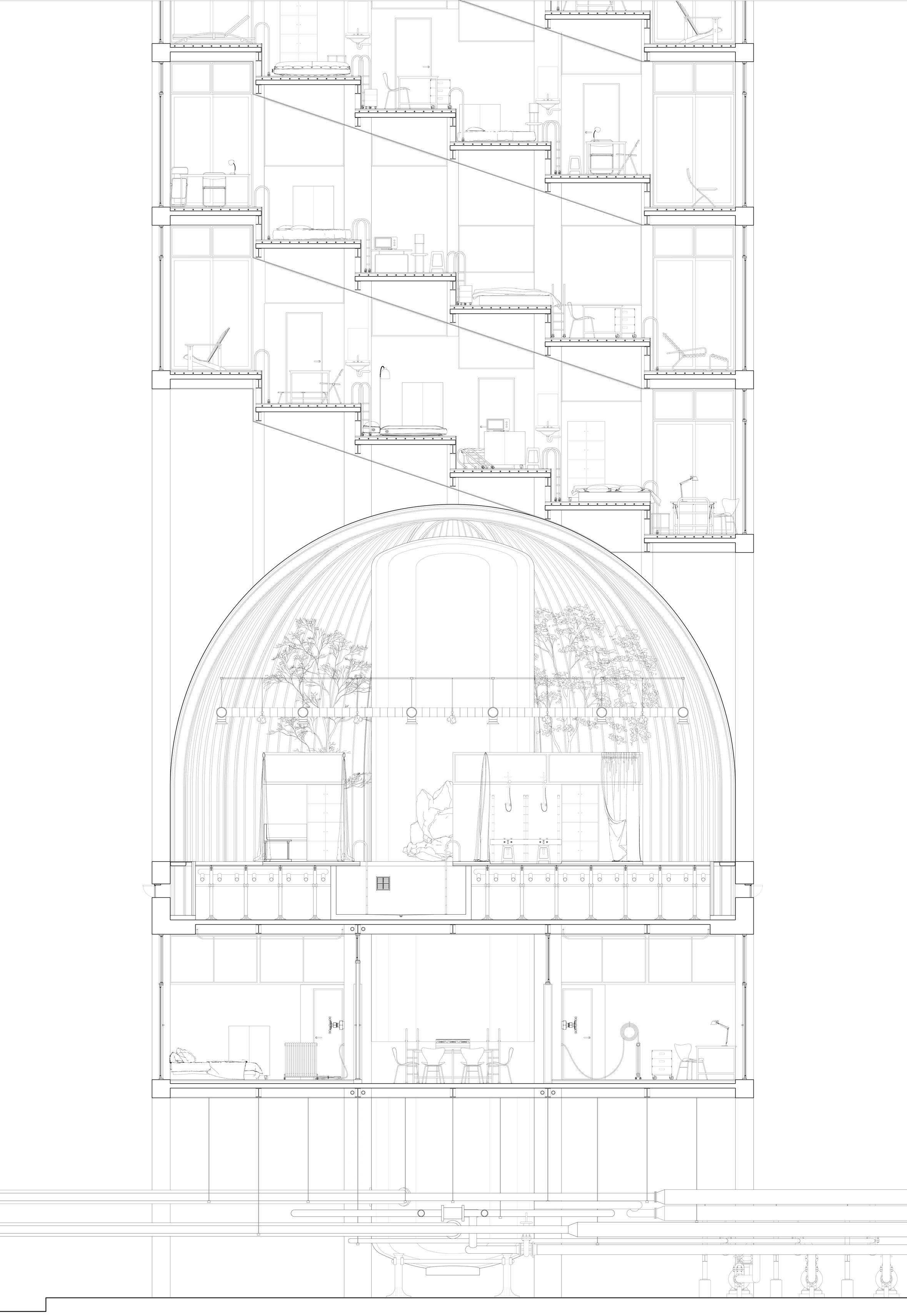

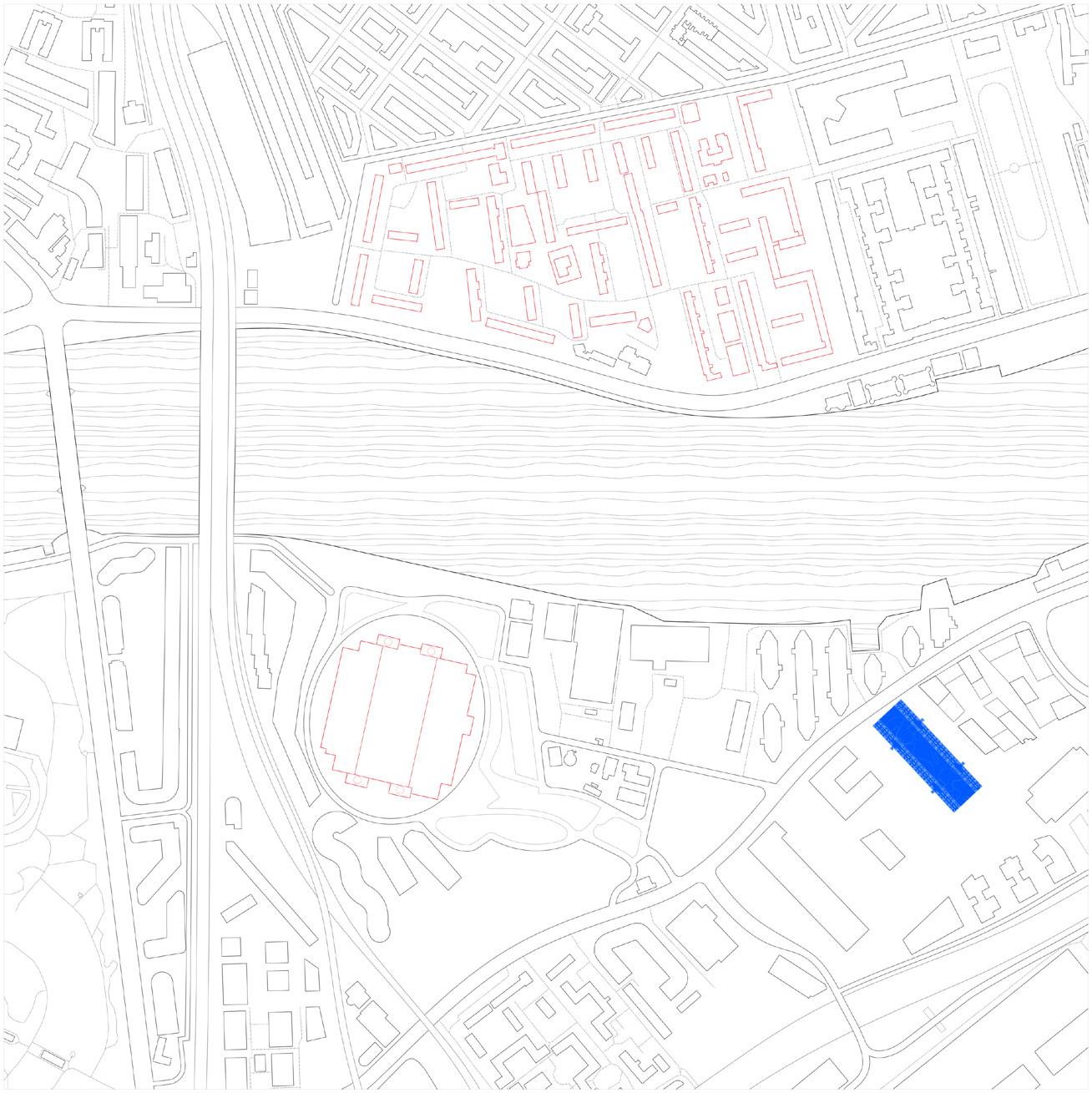

‘Divider’ is located in Battersea, London. With the goal of eliminating further exploitation, it is constructed to make full use of district heating coming out of Battersea Power Station. It participates in the governance structure in terms of energy consumption in the Churchill Gardens estate, which frames energy as a social good, by working on both governance and infrastructure. The hot water maintaining the artificial environment is supplied at a fixed time during the day, which allows for the modelling of expected system costs to charge tenants. Furthermore, the sociotechnical system is provided with flexibility based on the accumulator placed on the north side of the building. It can boost supplies either on particularly cold days or when the power station breaks down, thus avoiding any situations that would make occupants question their investment. The roof is made of curved polycarbonate panels that can be opened for ventilation in the summer and closed to store heat in the winter.

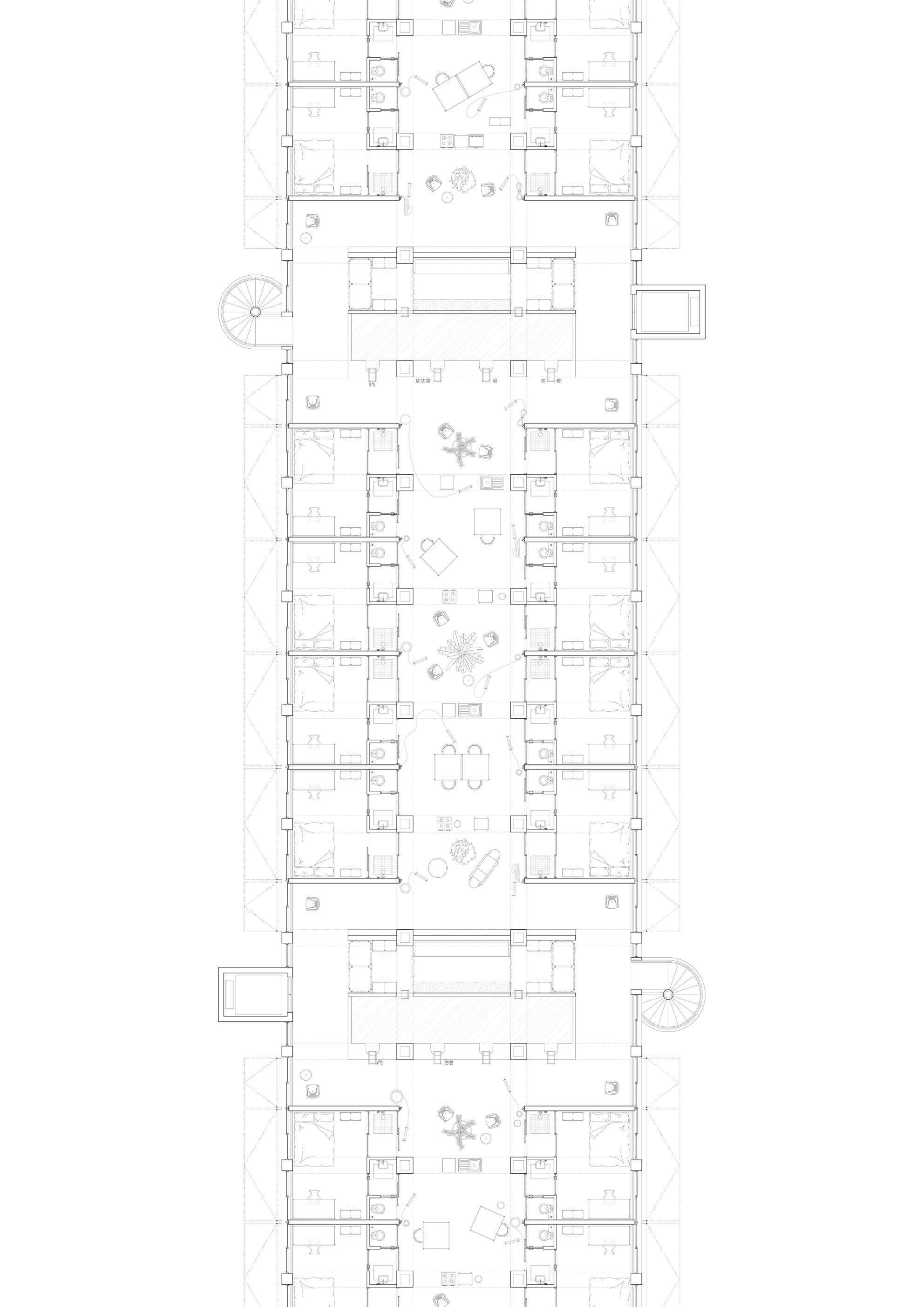

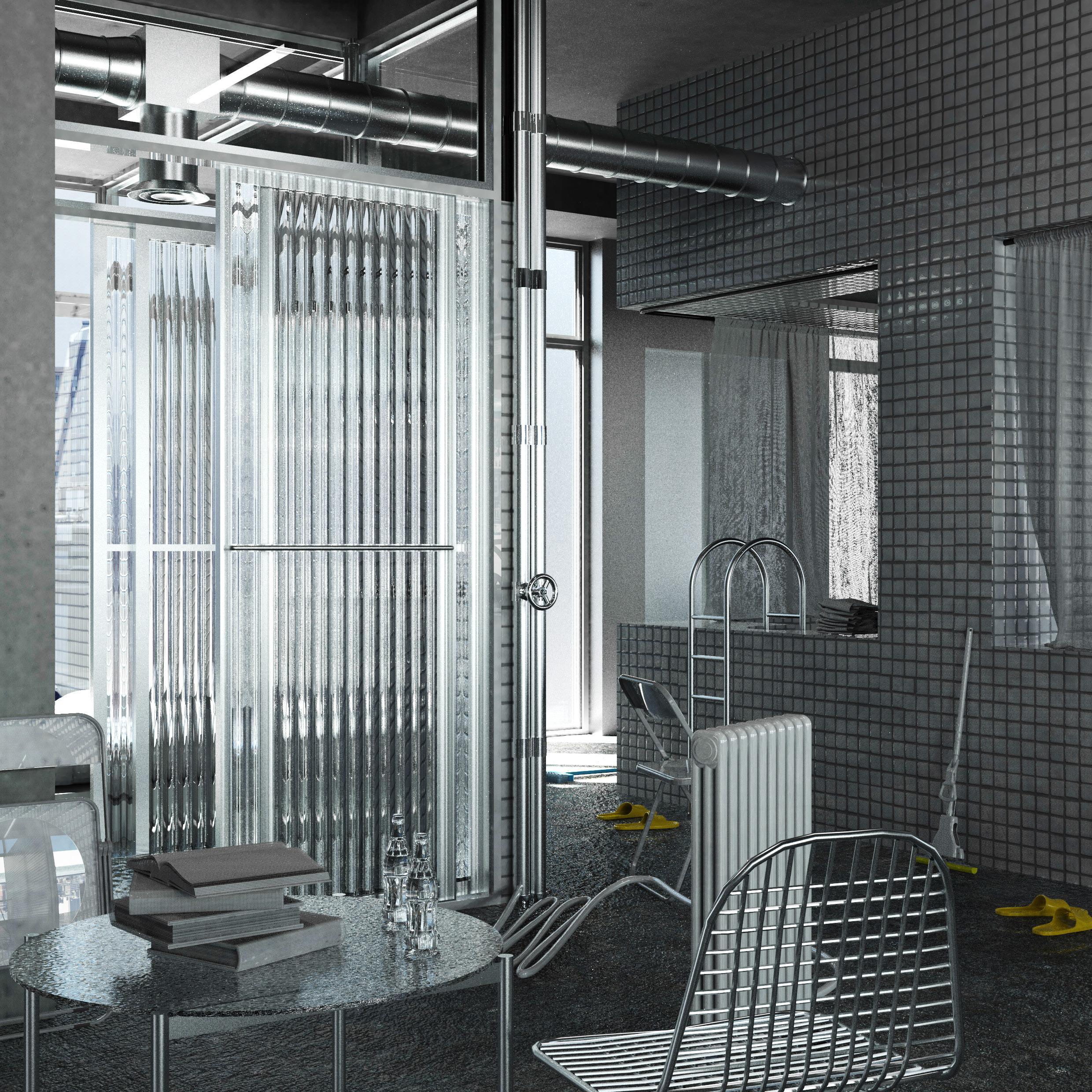

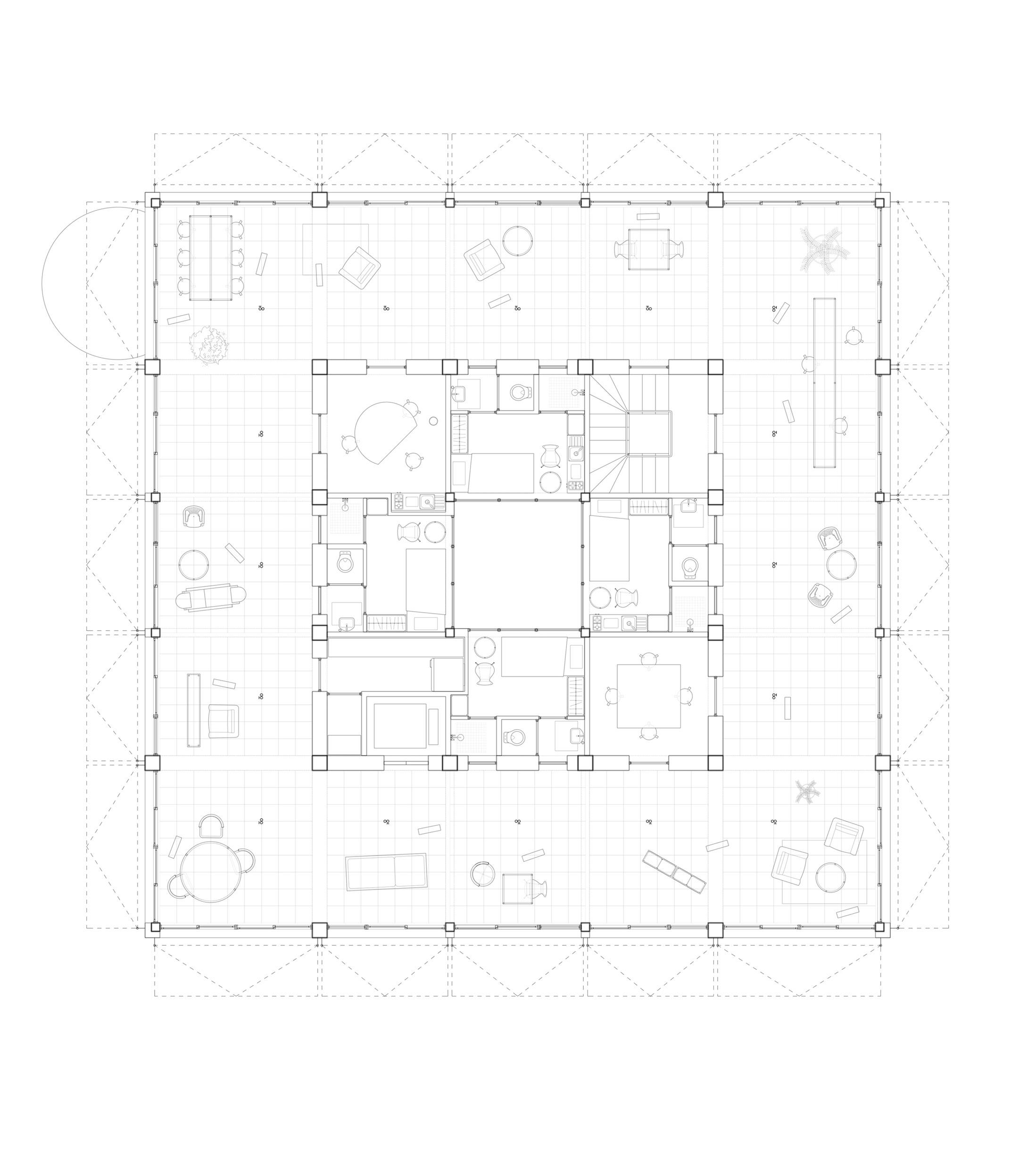

The building is constructed following a 5 × 5-metre column grid. In addition to the botanical garden immersed in the artificial climate at the centre, the ground floor accommodates functions that provide a distinctive atmosphere and challenge the shared perception of skin, including a sauna, spa, bath, and hydrotherapy.

To exhibit the differences in the relationship between the body and temperature, each function in the living unit is arranged separately in a 4-square-metre space, thus excluding other uses. From the inner to the outer side, each living cell hosts a bedroom, production space and kitchen. The bathrooms and restrooms are arranged in between adjacent units. Self-temperature adjustment is achieved by drawing curtains and pulling doors shut. Adjacent kitchens can be connected by opening a sliding door. Pieces of

HEALTHY COMFORT 37

38 CHAPTER 01 Divider, Typical Floor plan

communal infrastructure, including a gym, canteen and artificial sunbath, are placed within the threshold of the vertical circulation.

To distinguish from the prevailing type of sanatorium, which often puts effort into maximising the use of the natural environment, the present one ignores any specificity of site, including the natural conditions, thus emphasising the artificial environment inside. In this sense, before the public enters the building, which is presented in its pure geometric form, the people inhabiting it will already have expressed themselves through the architectural form.

HEALTHY COMFORT 39

40 CHAPTER 01

HEALTHY COMFORT 41

42 CHAPTER 01 Divider, Typical Floor plan in detail

HEALTHY COMFORT 43

44 CHAPTER 01 Divider, Courtyard, Artificial Environment

HEALTHY COMFORT 45

46 CHAPTER 01 Divider, Living Unit

01. Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. Roland Barthes. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. Print.

02. Foucault, Michel, and Robert Hurley. The History of Sexuality: Volume 3. , 2020. Print.

03. Ibid

04. Roncayolo, Marcel. Le Geographe Dans Sa Ville. , 2016. Print.

05. Maurice, Bernard, Jacques Tati, Barbara Dennek, Rita Maiden, France Rumilly, France Delahalle, Valrie Camille, Erika Dentzler, and Alice Field. Playtime. , 2014.

06. Maudlin, Daniel. “Habitations of the Labourer: Improvement, Reform and the Neoclassical Cottage in Eighteenth-Century Britain.” Journal of Design History, vol. 23, no. 1, 2010, pp. 7–20.

07. Wood, John. A Series of Plans for Cottages or Habitations of the Labourer. Farnborough: Gregg, 1972. Print.

08. John Loudon. “An encyclopædia of cottage, farm, and villa architecture and furniture”, 1846

09. Ibid

10. Wang,Minan, . Shen Ti,kong Jian Yu Hou Xian Dai Xing =: Body, Space and Postmodernity. Nanjing: Jiang su ren min chu ban she, 2015. Print.

11. Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations: Books 1-3. Lexington, Ky.: Seven Treasures Publications, 2009. Print.

12. Crowley, John E. The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities Et Design in Early Modern Britain Et Early America. , 2010. Print.

13. Shove, Elizabeth. Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. Oxford: Berg, 2004. Internet resource.

14. Ibid

15. Crowley, John E

16. Dustin Valen, « Imperial Atmospheres: Race and Climate Control on the Niger », ABE Journal [En ligne], 17 | 2020, mis en ligne le 20 janvier 2022.

17. Dustin Valen. “On the Horticultural Origins of Victorian Glasshouse Culture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 75, no. 4, 2016, pp. 403–23.

18. Ibid

19. Dustin Valen

20. Taylor, William M. The Vital Landscape: Nature and the Built Environment in Nineteenth-Century Britain. , 2022. Print.

21. Diestelkamp, Edward. (2012). The design and building of the Palm House, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. The Journal of Garden History. 2. 233-272.

22. Ibid

23. Gay, Peter. Education of the Senses. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999. Print.

24. Simo, Melanie L. Loudon and the Landscape. Ann Arbor, Mich: University Microfilms, 1980. Print.

25. John Loudon. “An encyclopædia of cottage, farm, and villa architecture and furniture”, 1846

26. Colomina, Beatriz. X-ray Architecture. , 2019. Print.

Bibliography:

HEALTHY COMFORT 47

Thermal Comfort

00 CHAPTER 01

Thermal Comfort

Identity is captured by taking care of the self and aiming to make one's lifestyle a work of art.

Within Soviet modernism, the commune was supposed to act as a matrix for the ‘New Soviet man’, who would be fit for the collective. Within Western modernism, the apartment released the individual, who devotes him or herself to the cultivation of self-relationships. As observed by Gabriel Tarde in the 1880s, ‘In reality, the civilised man of today is inclined to do without the assistance of his fellow’.1

Good air – air with the appropriate humidity, temperature and flow rate – was considered an important part of a comfortable interior atmosphere in the nineteenth century. Historically, the tamers of good air were fathers, doctors and the creators of building codes, who worked to emphasise the home as a pleasant place to live through various technical and technological means. Women were the users and maintainers of good air, an idea which is still heavily present in the mass media through air conditioning advertising and shopping campaigns.

Before the 1860s, the choice of domestic furnishing seems to have been primarily a male activity, as is suggested by the opening of a novel published in 1854, The Mother’s Mistake: ‘A recently married couple go round the house which the husband has furnished, and he asks his wife, “Is this not sufficient?” to which she replies, “You have done all, and more than all, I could have imagined, to make me happy”’.2

Moreover, an article in The Family Friend in 1867 emphasised the moral value of beauty not only in the home but in wives as well: ‘One of the grandest points to be attended to, in making a home happy, is to make it attractive. The husband should do his best to render it comfortable and attractive to the wife, as she should to the husband and children . . .’3

Up to the present day, it is imaginable that the temperature standard in space, especially in production spaces (offices, factories, etc.), has remained dominated by males and that women’s discomfort with cold air has forced them to wear thicker clothing in the office. The dominance of men and physicians in shaping the atmosphere of domestic comfort has significantly impacted architecture. One of the houses, which has windows that cannot be opened, reveals how the body is completely anchored in the relationship between space, ventilation and heating technologies that unfolds around health norms and moral codes, as well as that this relationship finds echoes within an architectural discourse that disciplines the body.

50 CHAPTER 02

Disciplinary Air

Deeply influenced by medical discourses, the British rejected ventilation achieved by leaving windows open for long periods of time. Warm stuff – a warm room, warm quilt or warm food – was once considered a measure for treating plagues, such as smallpox. While fresh air was understood to be harmful, cold air was thought to be even more deadly.4 This medical reading of the air had huge repercussions on architecture, especially during a period when the safeguarding of health was so important for expansion, densification and social reform. Accordingly, the voice of medical men was highly important. They commonly condemned the inhibitions of convention and often held a rationalist belief in direct physical action. They not only exerted political leverage at the local and national level; some also built exemplary architectural structures.

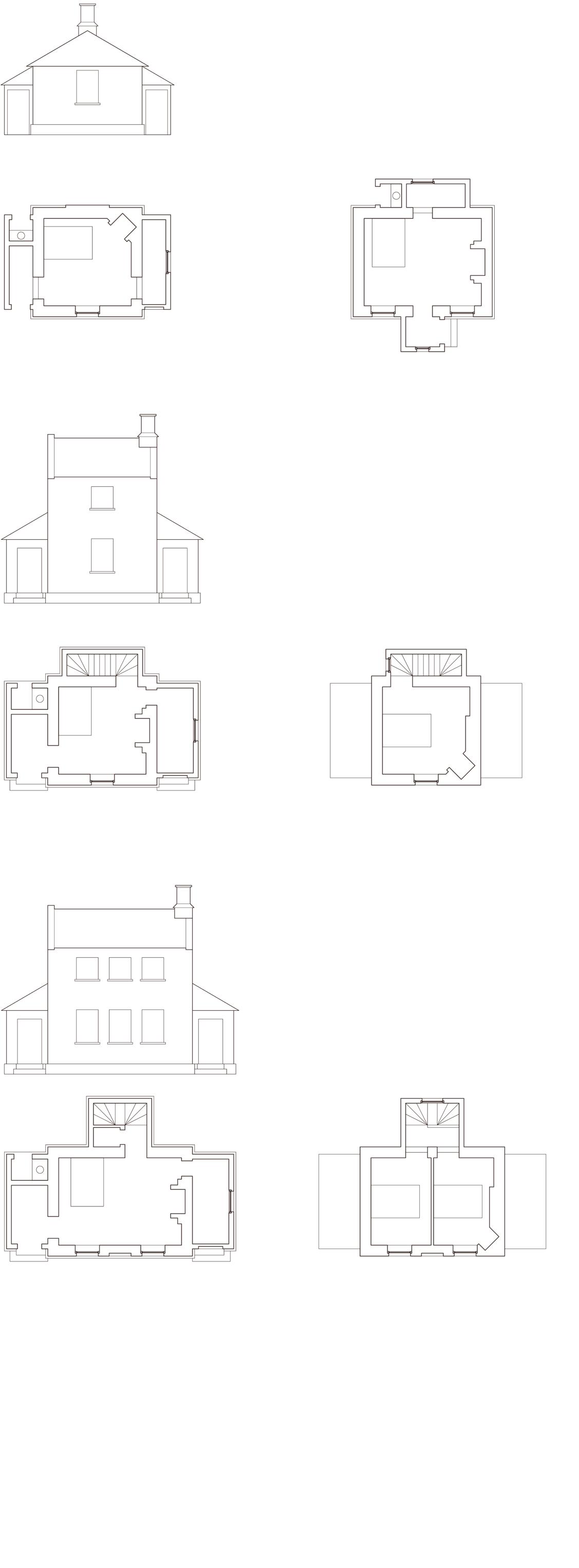

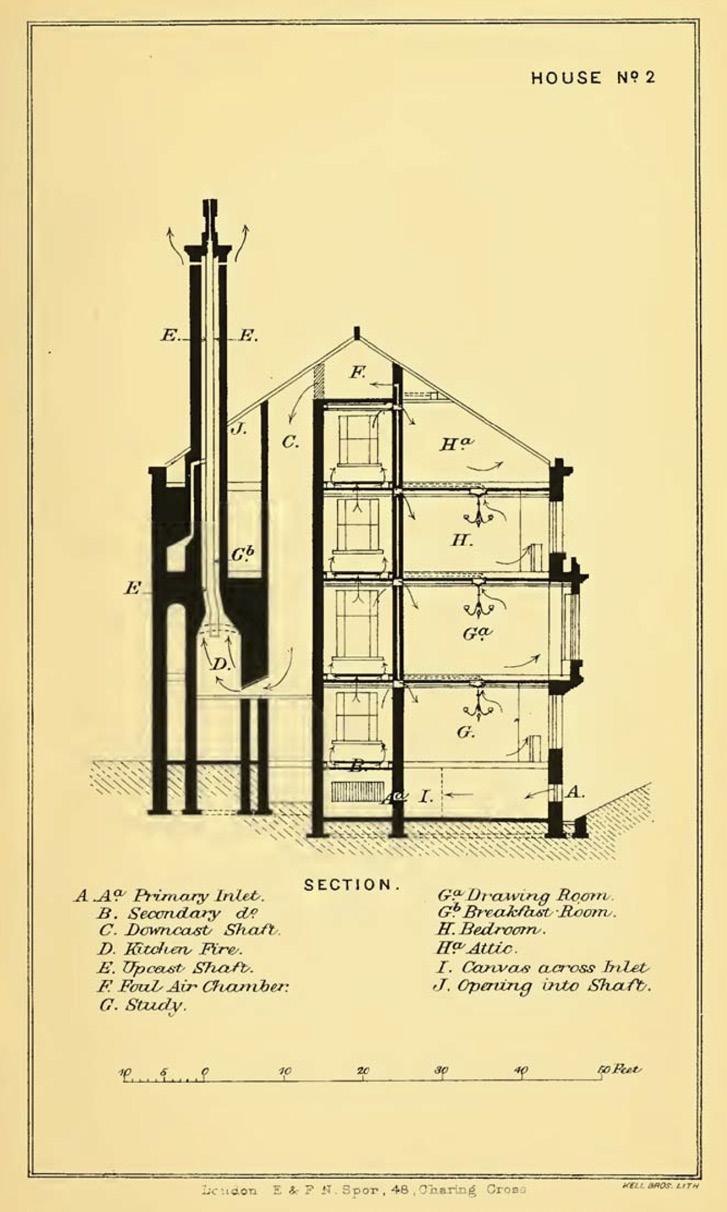

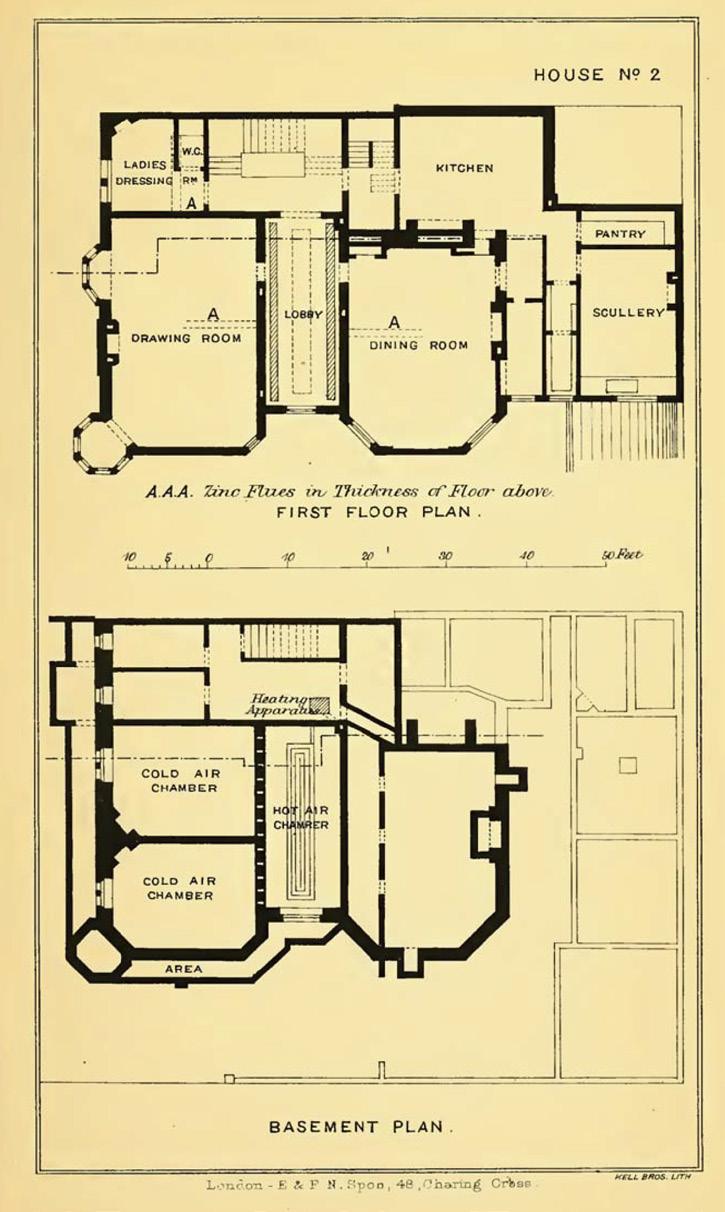

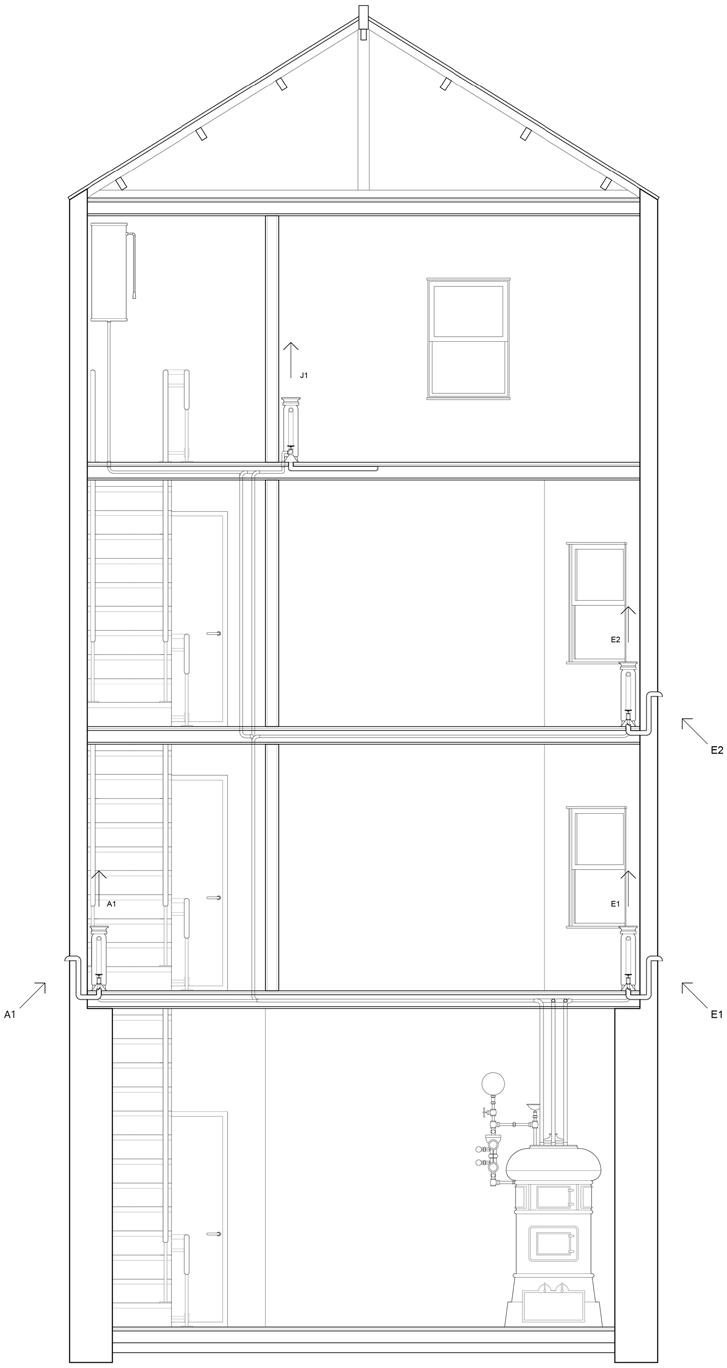

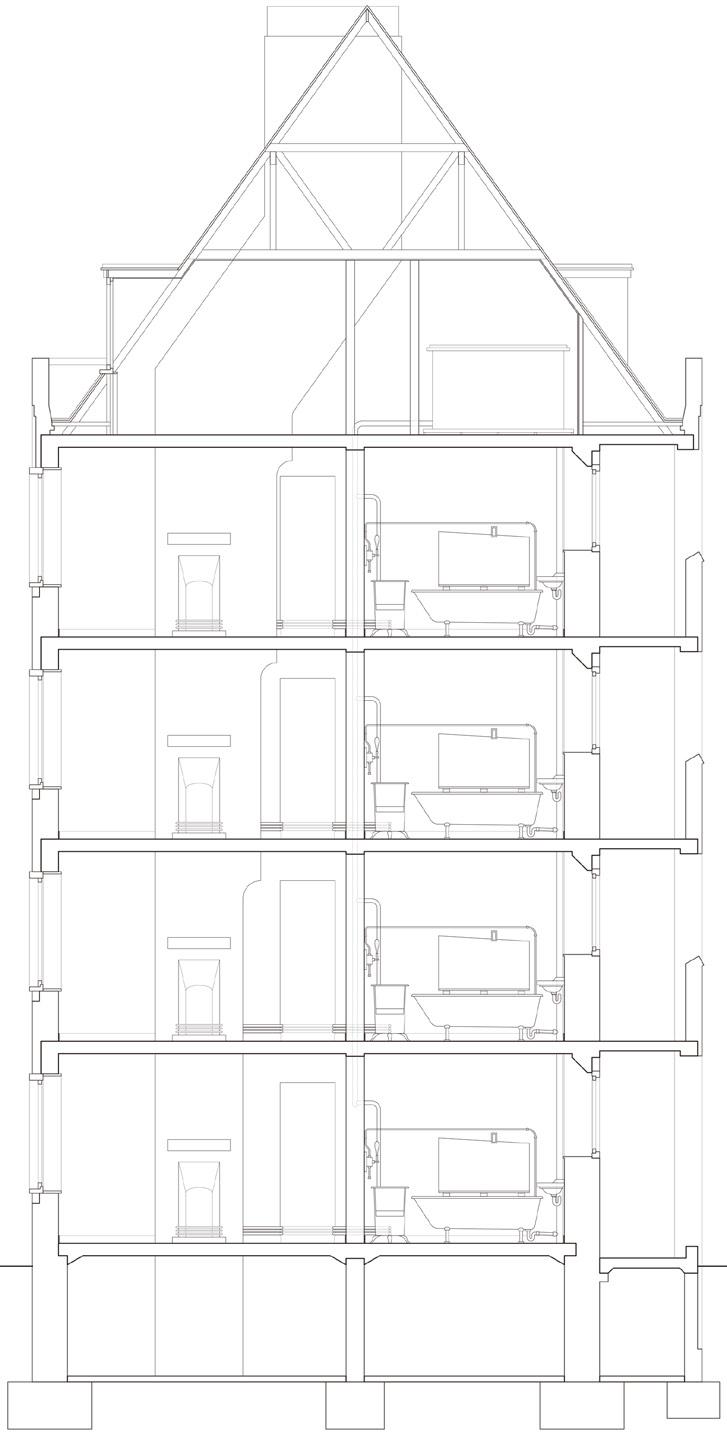

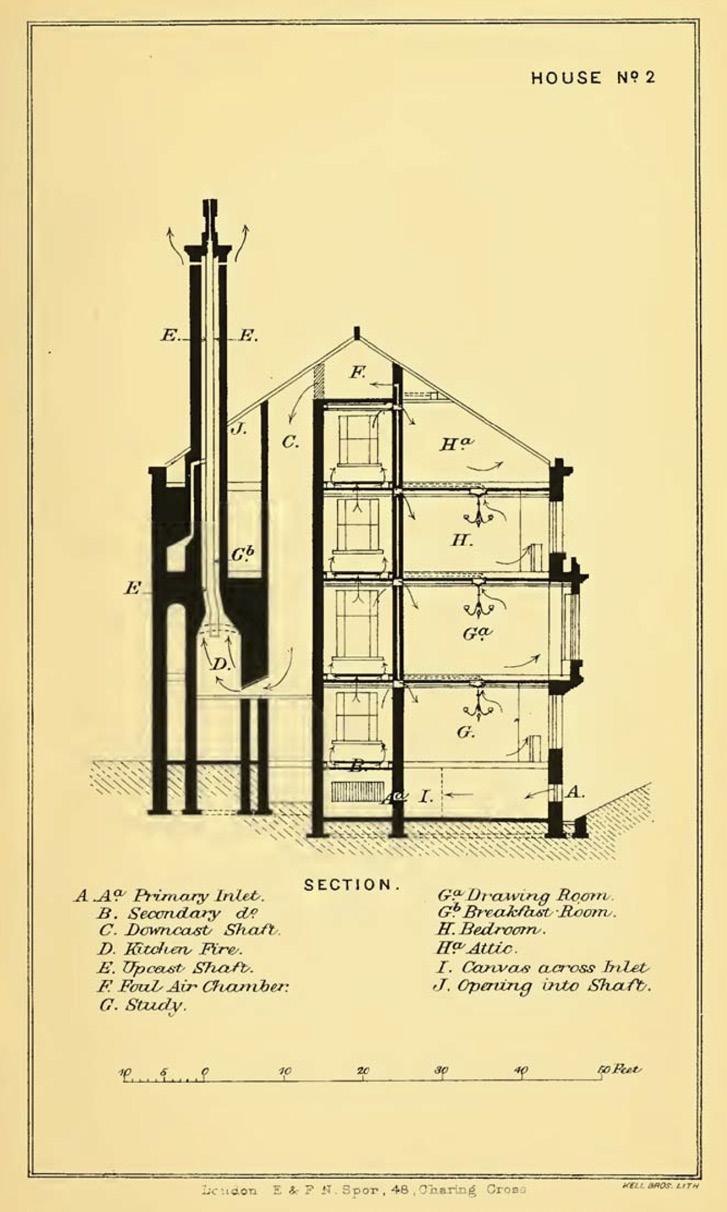

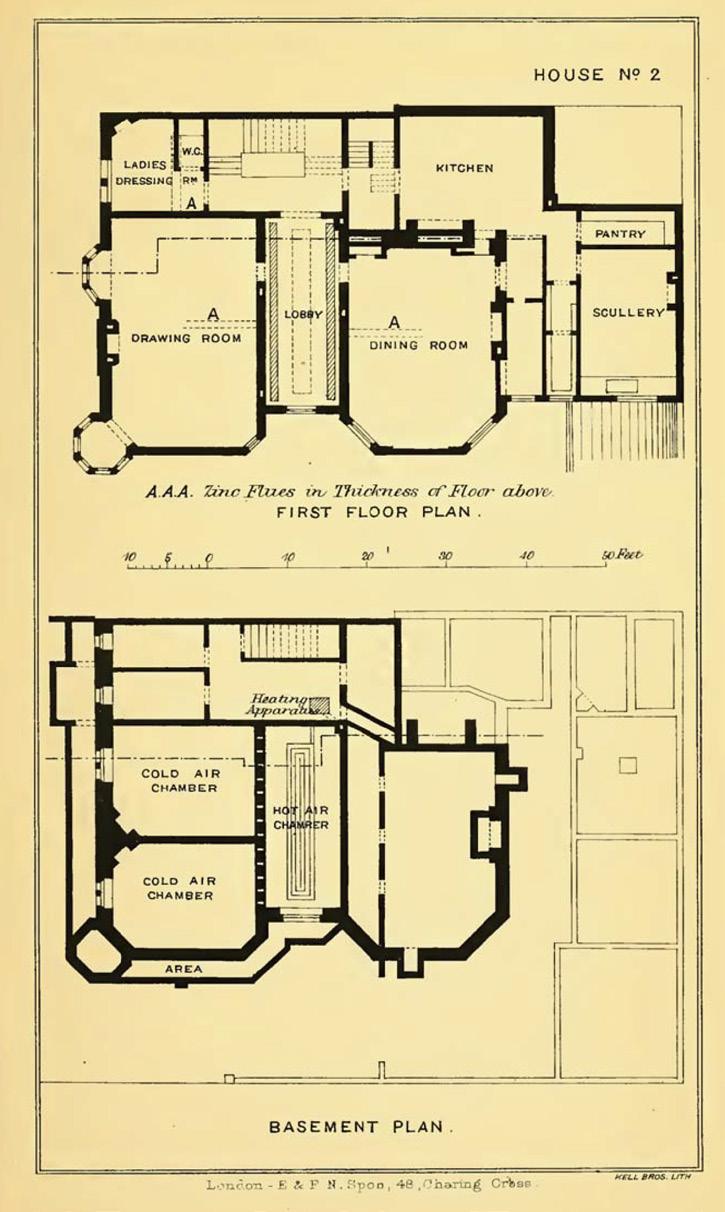

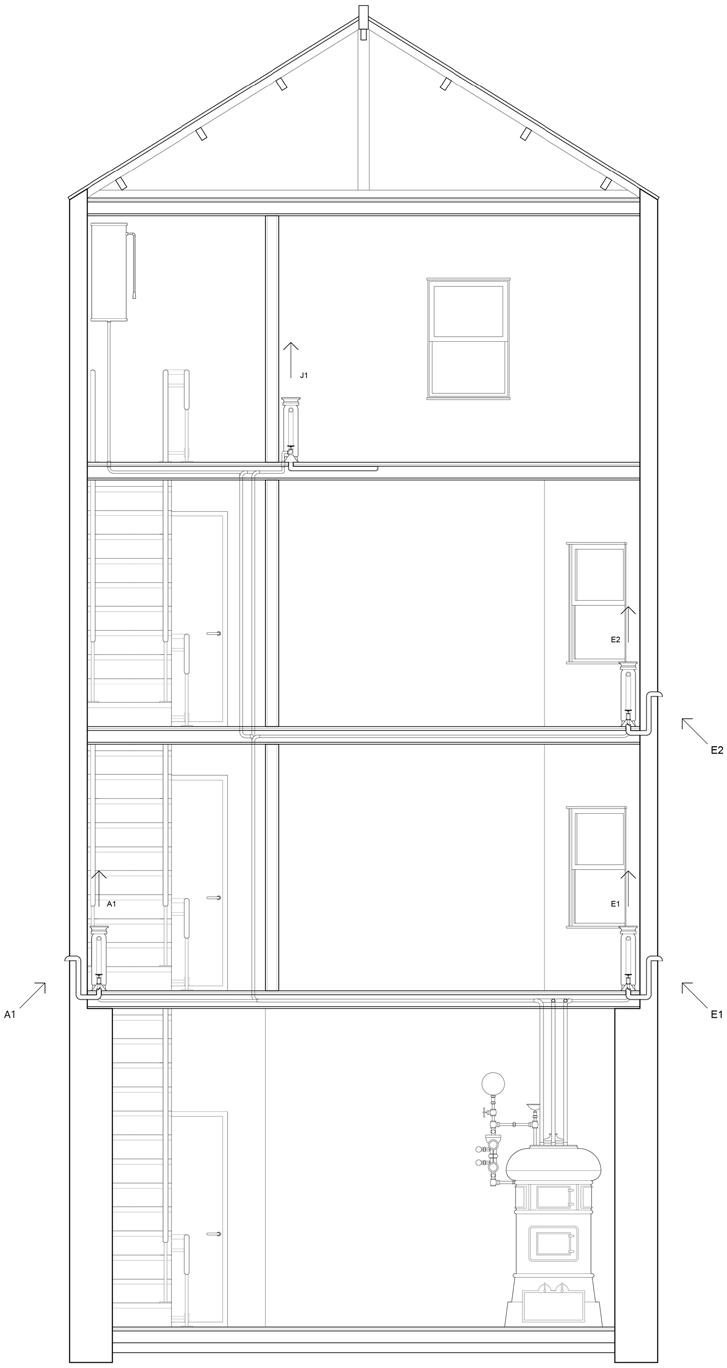

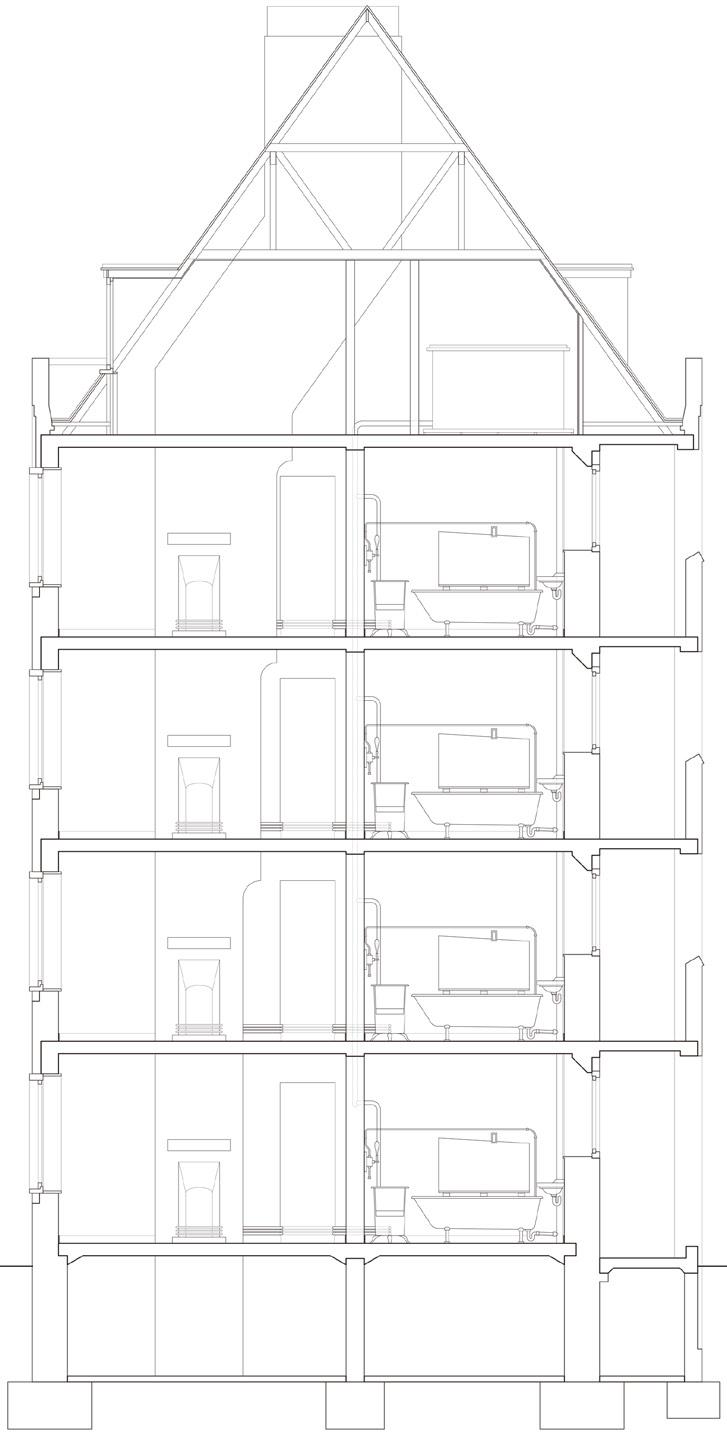

A house built in the 1860s and documented in the collaborative textbook Health and Comfort in House Architecture by the physicians Dr Drysdale and Dr Hayward shows the relationship between the standardised body, space, function and the heating system.5

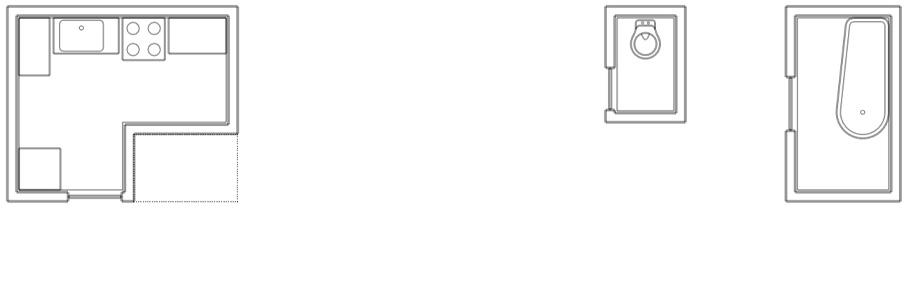

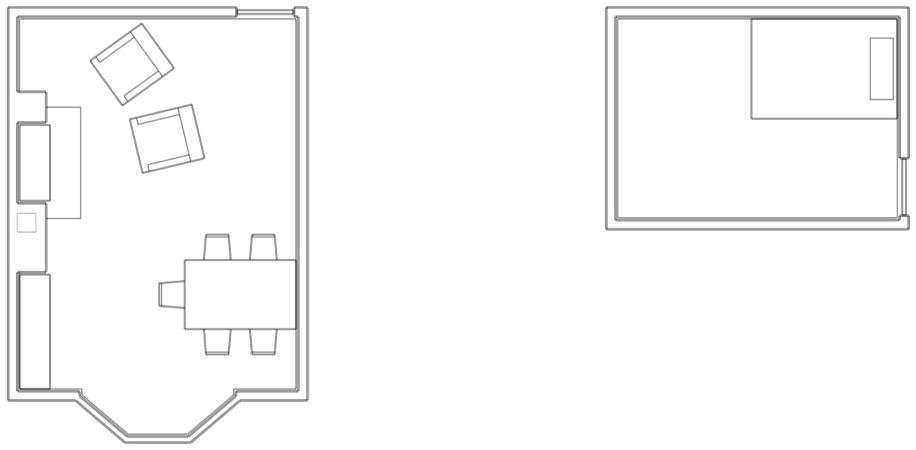

The Octagon by Drysdale, J. J. & Hayward, John Williams,1872

To protect the house from cold wind, the windows were made of thick plate-glass with no shutters, while the casements opened outwards and are made to shut tightly. Apart from the kitchen, bathroom and other shared areas, individual rooms were equally served by the warm airflow from the heating chamber in the basement, which could work well under superintendence from the original proprietor of the house or the best-trained servants. In a room, ‘the ventilation would be restricted to a shallow zone below the ceiling, the air entering through the perforated cornice and leaving through the ornamental rose over the gas lamps’. Heating was mainly provided by a chimney fireplace in every room instead of by warm air, which meanwhile served as the driver for ventilation by burning air. Again, the fireplaces, according to the recommendation of the Blue Book, were in the corners of the rooms, thus

THERMAL COMFORT 51 01

radiating the heat equally.

The house was more like a hospital or even a prison than a home. Although Drysdale argues that the necessity of thermal comfort is fulfilled by adjusting the temperature and ventilation intensity within the heating chamber, this only works for a portion of the people in the house; the ventilation valves in each room can only be used to adjust the amount of ventilation and cannot change the temperature of the constant supply. Moreover, the process of disciplining the body with health norms is recorded in his writing: ‘If all the arrangements of a house are fixed and permanent, discomfort and unhealthiness must inevitably result; for the number of occupants will vary, and the seasons will change, and we must either submit to the misery of these discomforts or to the trouble of obviating them’.6

Therefore, developing a person’s physical condition by limiting his or her activities to health guidelines related to temperature and ventilation (a social agenda) means that the person needs to adapt to the environment he or she lives in rather than using it at will according to his or her needs.

From the standardised size of fireplace openings in registered chimneys to the central heating systems in schools, prisons, hospitals and other institutions, the disciplining of the body with air was one of the focuses of environmental medicine in the 19th century. This highly regimented structure for the body undoubtedly contributed to a plethora of repressed desires and their expression in the urban realm.

52 CHAPTER 02 02

FIG.01 Section of “the Octagon”

FIG.02 Basement plan and Ground floor plan of “the Octagon”

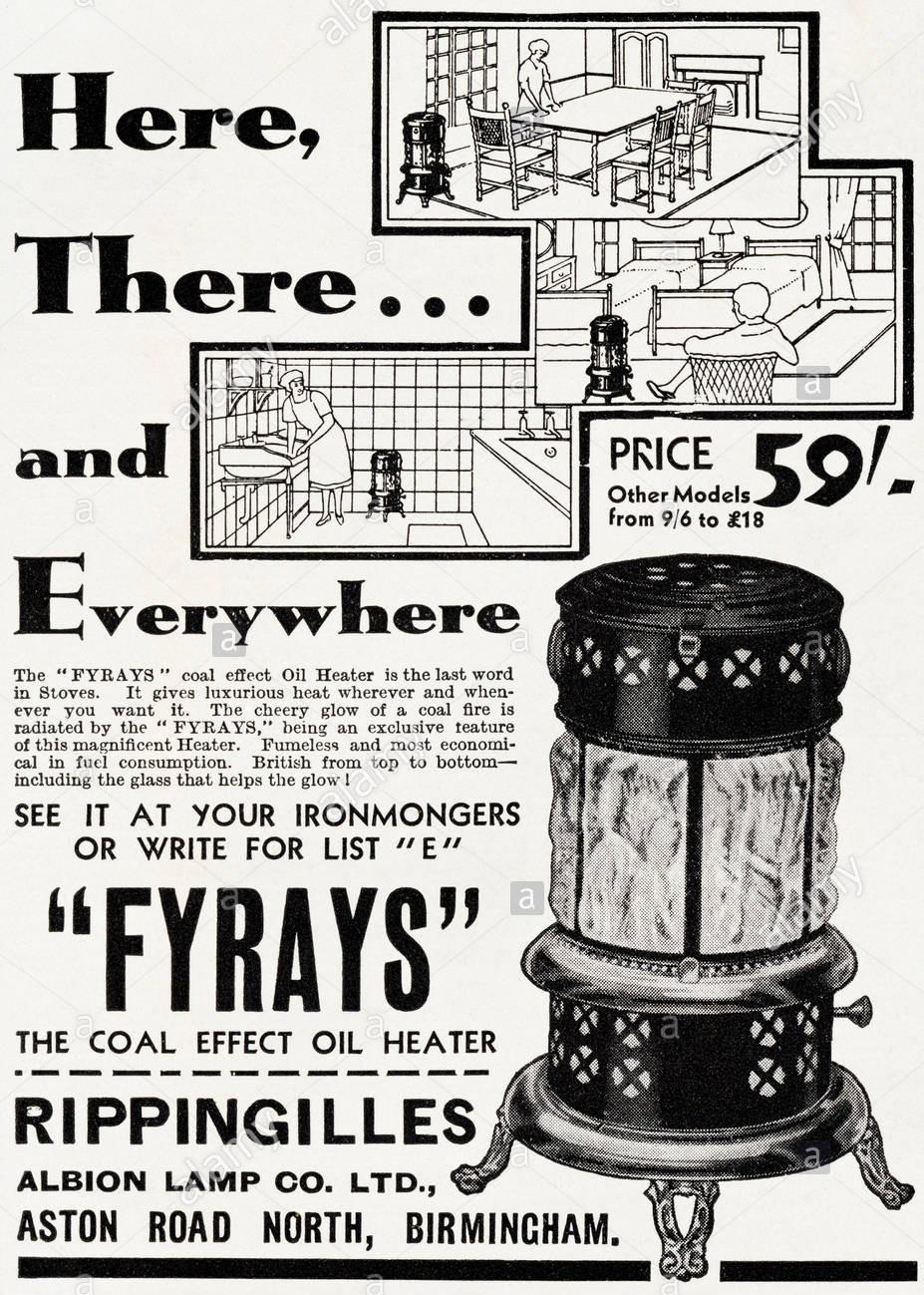

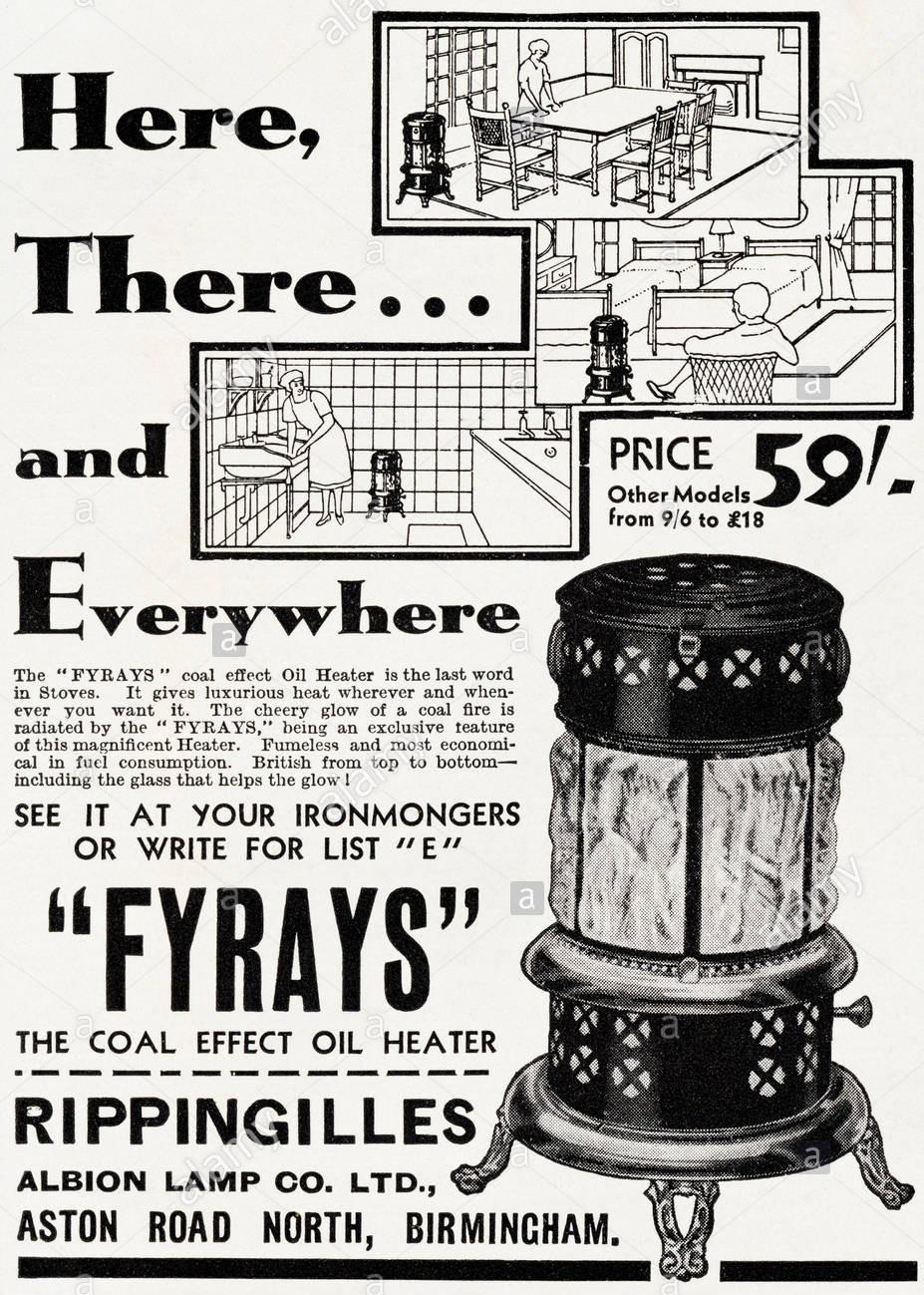

Commercialized Air

In his art work “Le Grand Verre,” Marcel Duchamp unfolded a peculiar perception of sex through an enigmatic fantasy drama of competing passion: All the bachelors hope and strive to bed the bride, but fear of vague consequences holds them back in a state of frustration, which introduces the important psychosexual function of the chocolate grinder, that nearly dominates the Bachelor Apparatus zone. Those mechanical sex machine enable us to move beyond the male gaze towards complex and ambiguous hermaphrodite-like conceptions of bi- and pansexual cyborg bodies and a-sexual artificial life.

“After all, if women were at home doing housework, they might as well attend to the heating as well”.7

“She was ashamed of her cold-hearted home”8

Traditionally, in the UK, the women of the household, who bore the main responsibility for the collection of materials for firing most of the time, maintaining the fire, kept the hearth spotlessly clean and lavished great care on its appearance. The hearth was a potent symbol of the family, of hospitality, and of life itself. In the majority of households where only one fire burned at a time, in the main living room, the hearth was treated like an altar. Such was the power of fire addiction that even Mary Wollstonecraft, one of Britain’s most remarkable feminists, was a victim.9

Writing there of what he called “The Prometheus Complex,”10 Bachelard recalled himself as an invalid, and his father as the primordial focarius, the first stoker, the mythic fire-man. For Bachelard, the Prometheus Complex was, as he put it, “the Oedipus Complex of the life of the intellect,” under which rubric he proposed to gather all those “tendencies which impel us to know as much as our fathers, more than our fathers.” Here the basic drama of civilization becomes a kind of competitive “quest for fire” in which knowledge is hearth-craft, and hearth-craft is, as it happens, patriarchy.

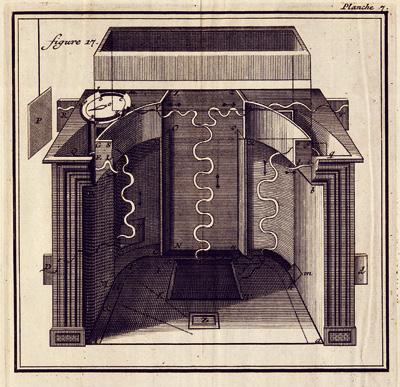

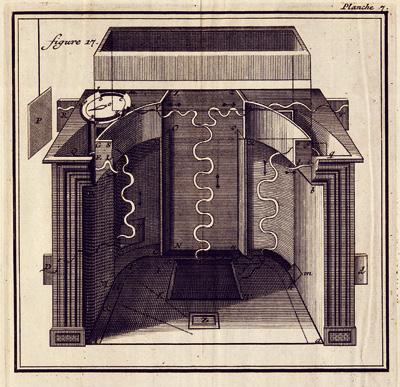

It was not until the invention of the Gauger furnace that women were emancipated from the heavy work of using bellow to control the fire.

THERMAL COMFORT 53

FIG.03 Le Grand Verre, Marcel Duchamp, 1915-1923

54 CHAPTER 02 03

Gauger was a “practical Cartesians”, inspired by the ésprit géometrique, he reversed the widespread belief that “warm air is unhealthy” by looking at heat and cold as particles of different shapes and speeds interact with the body. Therefore, Gauger touted his improved fire-mechanisms as something more than the rational taming of the ancient violence of flame, though they were certainly that. However, they were also therapeutic devices, ideally crafted to improve health, sanitation, and domestic welfare.11 Rooms were served could be continuously heated by a gentle, adjustable stream of fresh, warm air. To conquer the indoor climate completely, the ratio of hot to cold air can be adjusted by rotating the control valve located in the upper left corner of the furnace, thus changing the temperature.

The benefits would fall above all, of course, to women, whose delicate skin, sensitive eyes, and vulnerable complexions would be guarded from the insults of smoke and flame, draft and chill. Once understood as the essential tenders of the hearth, women were, by 1714, well on their way to being reimagined as hothouse flowers. And the mechanical hearth, which accommodates all those tendencies that impel men to replace their women with machines becomes the prehistory of what Duchamp would eventually call the machine célibataire.

The significant role of the pursuit of comfort in stimulating mass consumption is undeniable. It was considered the most dynamic centre of consumer society, where sex became the driver for promoting a new way of life within fierce competition among energy producers and the urgency of the urban environment. The pursuit of comfort played an important role first and foremost among the upper classes. For example, the brochures of ROBERT BOYLE & SON LTD – the most famous British manufacturer and installer of ventilation and heating facilities during the last few decades of the 19th century – included a large number of successful examples of ventilation and heating retrofitting projects for the upper classes in addition to public buildings projects they had joined.

However, the relationship between the technical object itself and the function it served is questionable. The intense debate between open-fire fireplaces and high-efficiency metal stoves without fire was not alleviated from the time of the latter’s invention up until the Great Smog of London in the 1950s. The reason for this was that people could not easily abandon the fireplace as a symbol of comfort, either psychologically or physically. Moreover, the houses appearing in brochures did not have a space occupied by multiple forms or accommodating a variety of activities that required specific temperature conditions.

THERMAL COMFORT 55 03

FIG.03 Gauger Fireplace, 18th Century

FIG.04 thm7, Loris Checchini, 2002

56 CHAPTER 02 04

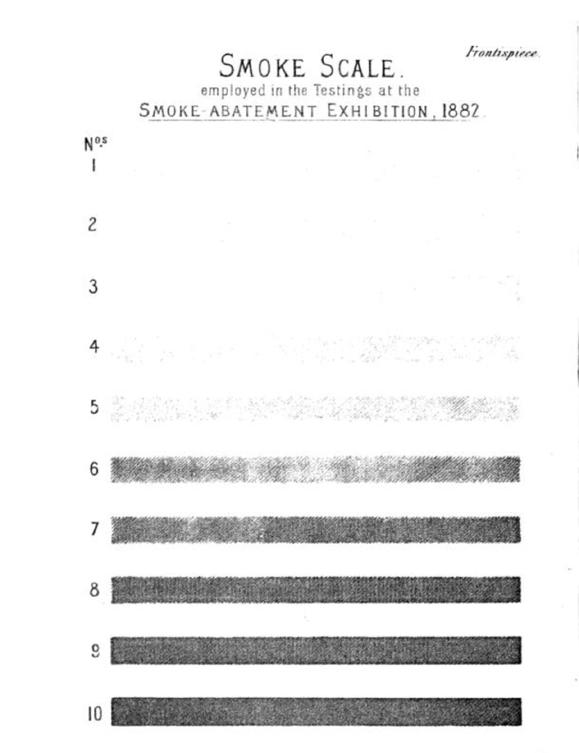

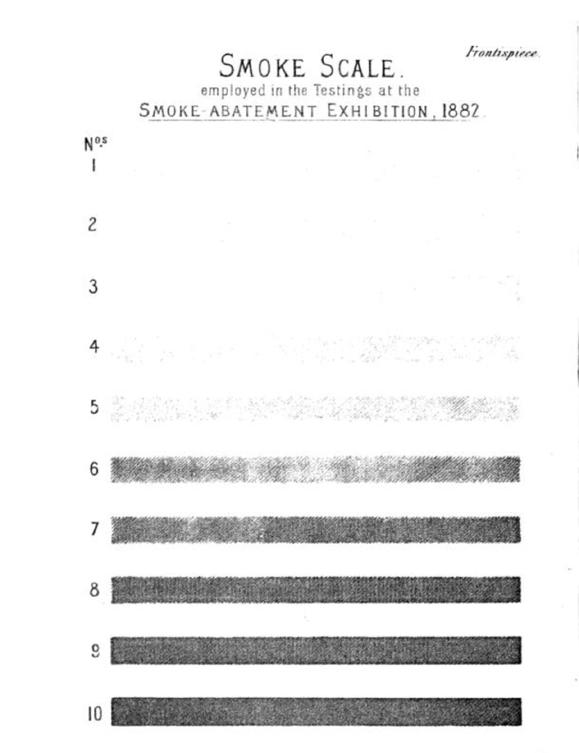

Concerns about Britain's depressed economy in the 1880s overlapped with fears of political and social disturbances, and smoke-filled air provided an apt symbol for people's inability to see what lay ahead. Intending to prevent excessive production of smoke in household grates and in the furnaces and boilers of manufactories, and thus to remove from the fogs of great cities, and especially of London, one of their most offensive constituents, and that which is most potent in darkening the cities over which they spread themselves, an Smoke-Abatement Exhibition, which would be of national value, was opened at South Kensington. It will tend directly to a better utilisation of coal and coal products, by determining practically and scientifically the means which are actually available for heating houses as at present (and as may be) constructed without producing smoke, as the Committee will be enabled to examine the subject generally and to report for public information upon the relative adaptability of the various coals and appliances to the requirements of every class of the community.

Ernest Hart, the editor of the British Medical Journal and the chair of the National Health Society, urged his organization to take action. The society, a quintessentially Victorian assemblage of upper-class men and women that focused on instilling "sanitary knowledge"12 in the working class, responded quickly to Hart's suggestion.

The Exhibition is described as “international”;13 that title is, however, often given on rather a slender basis; and from what we can at present see, the main exhibits are British, although a few interesting objects are sent from Germany, Canada, and France. Deeply influenced by medical and health traditions in the UK, the majority of smoke-proof appliances which has been in large use in the other parts of Europe since eighteenth century were not accepted until the early twentieth century.

Instead of accepting manufacturers' claims about the smoke-preventing properties of their stoves, grates, and boilers, the exhibition subjected them to impartial and scientific trial. In addition, visitors had the opportunity of inspecting and associating with these a large variety of apparatus for regulating and registering their action. Again, the economy of the use of various kinds of fuel received illustration, as also the advantage of greatly diminishing the imperfection of combustion of illuminating materials. Thirteen thousand people visited the exhibition in its first

THERMAL COMFORT 57

05

week, by the time it closed, 116,000 people had seen it.

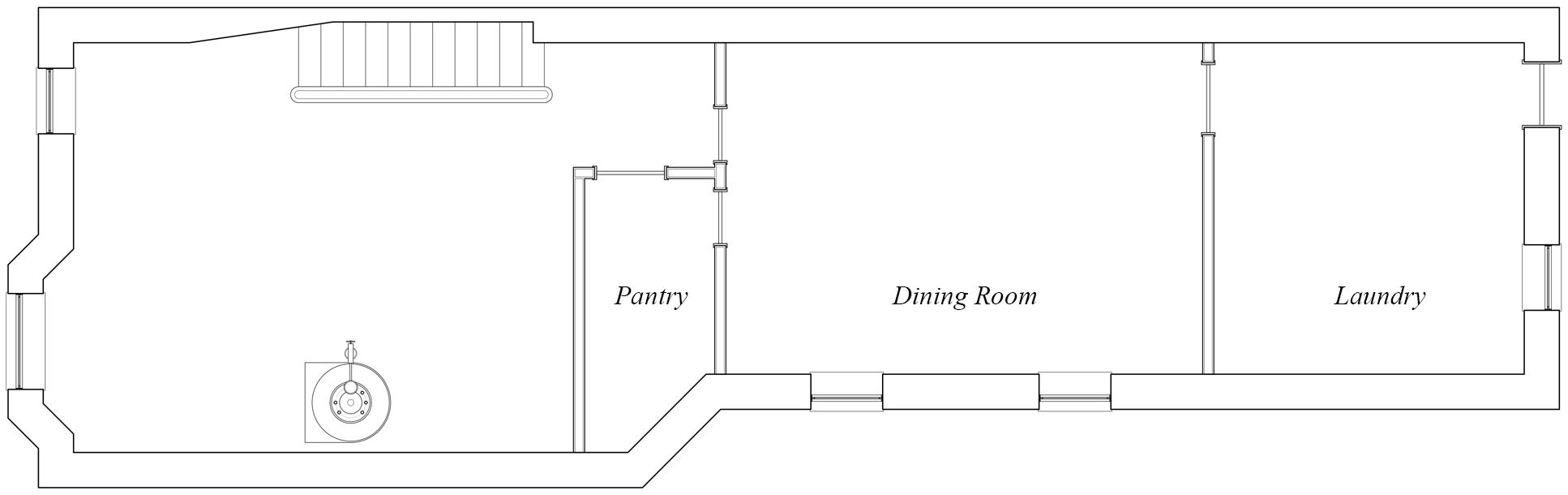

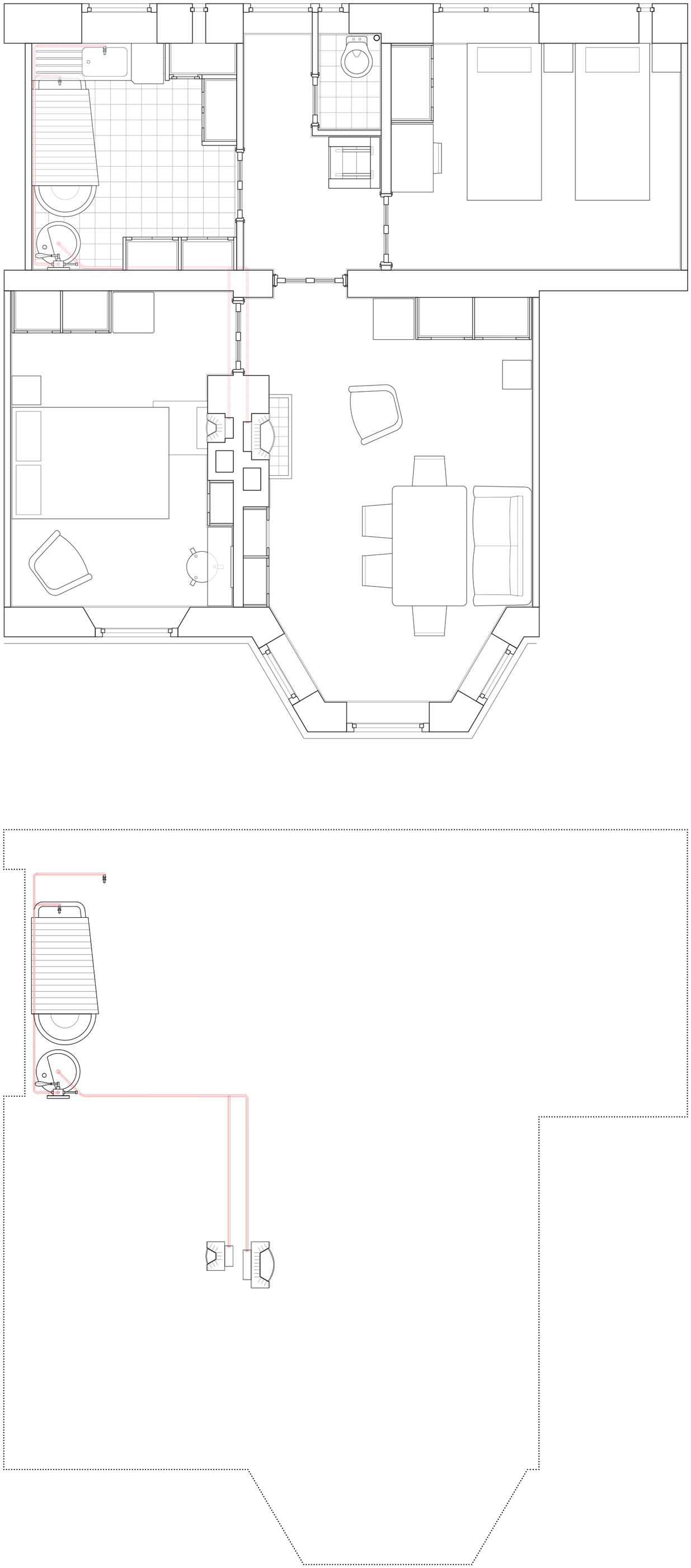

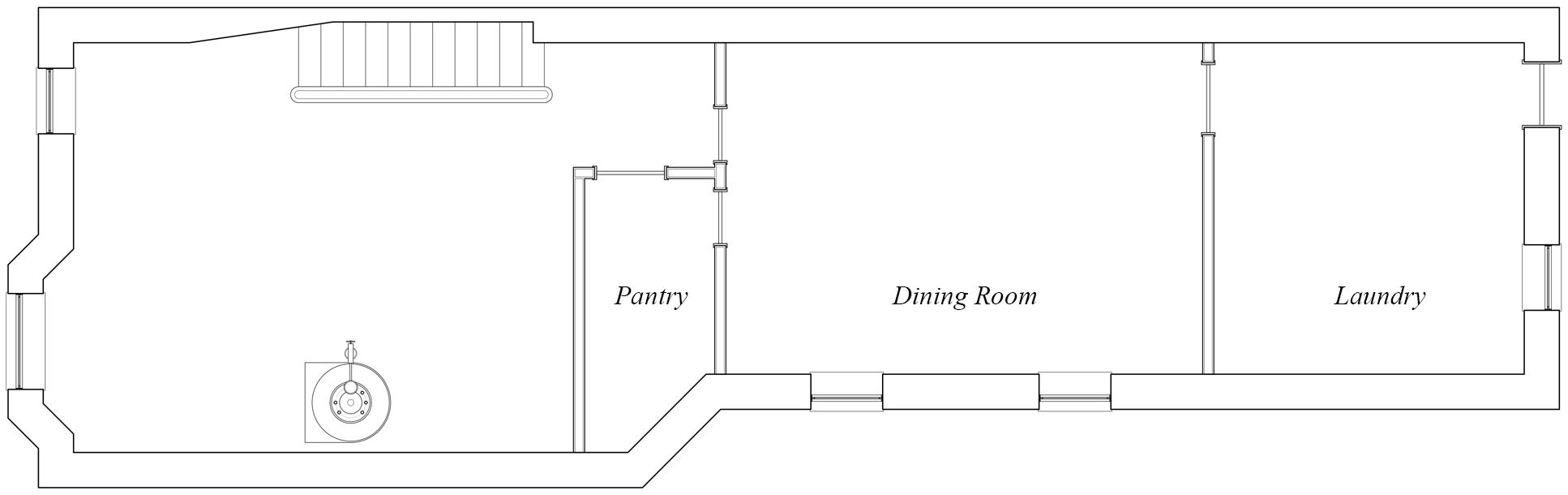

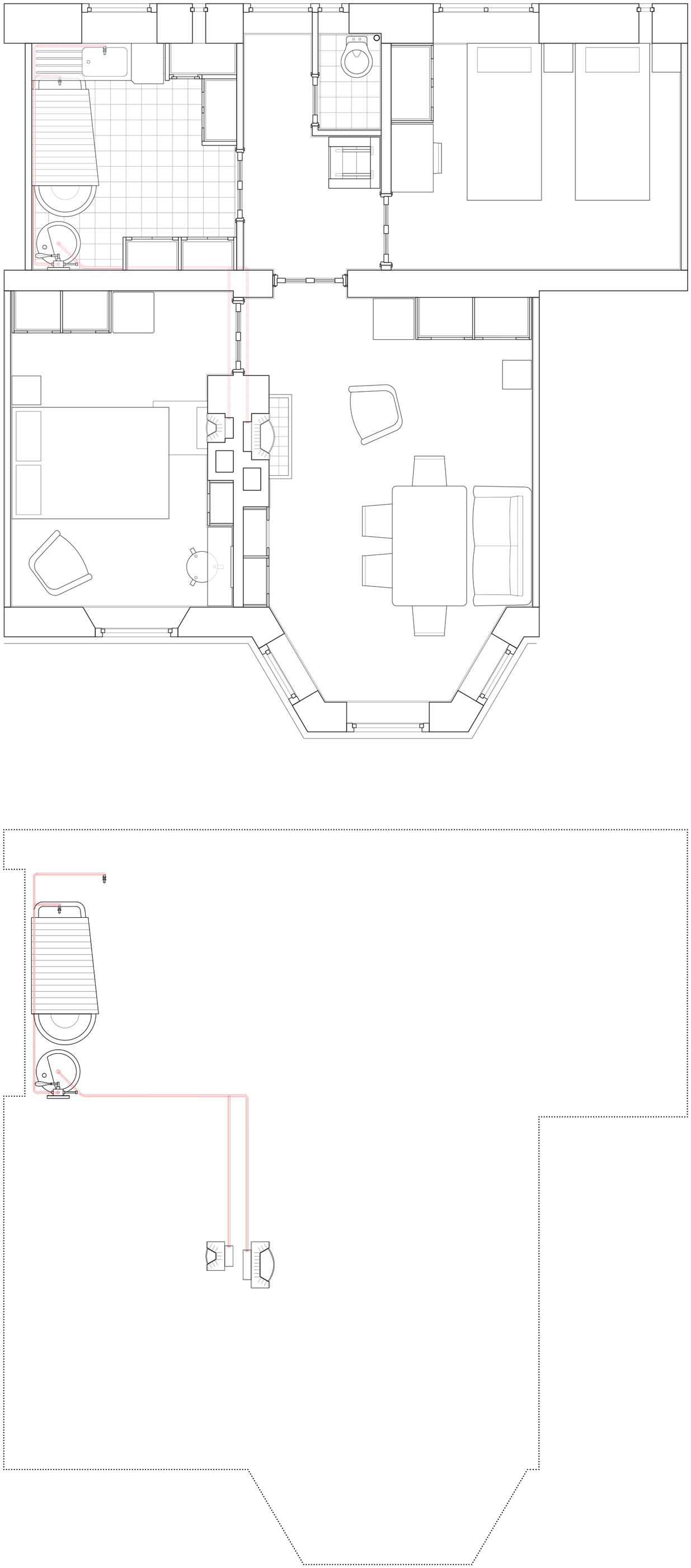

Carrick’s House, 1893

Notably, the manufacturers appearing in this exhibition not only emphasized and demonstrated the energy efficiency of these technologies in a variety of ways (experiment reports, try it yourself, etc.), but also used their temperature adjustability that benefits various activities as a selling point, thereby linking morality, a life in order, and self-care. Three objects in relation to interior environmental control within the following case study built in 1889 the interwoven complexity of the layout, which helps

58 CHAPTER 02

06

FIG.06 From top to bottum shows Under ground floor to attic floor plan

for understanding the implication of the objects in the past and present.

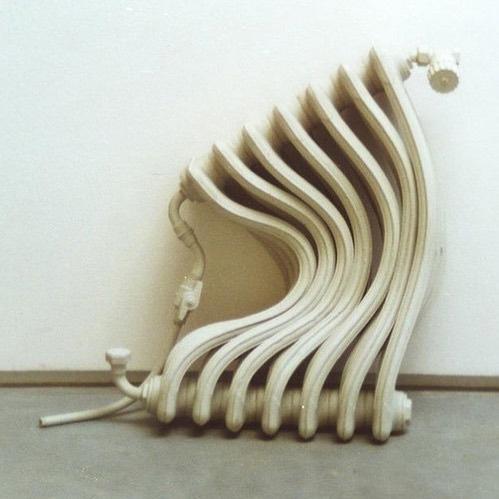

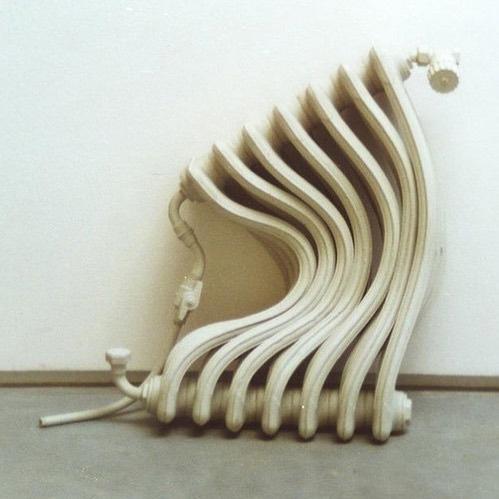

The first object that must be carefully examined is the valve in the house, or more precisely, the thermostat. Its importance had been repeatedly stressed in the Smoke-Abatement Exhibition. While it can be found in every individual room that has not been assigned with a specific function, its absence in family-shared functional rooms (kitchen, dining room, bathroom, hallway) is equally important. It seems to echo the subtle relationship between the way the room is occupied and the corresponding temperature. Moreover, temperature preferences became a matter of individual physiological differences between women and men, adults and children, young and old. Such differences persist to this day.

The second object that needs to be checked in depth is the ventilation valve. In order to emphasize the commodity properties of the heating system that can adapt to any structure, the heating was not arranged under the windows as it is now, but constituted a separate sanitary system with its own vents to ensure the comfort of the house occupants. Thermal comfort that serves multifunctionality of the room and comfort as health with a physical sensitivity in the beginning started have shown a tendency to merge into one.

The third object that needs to be scrutinized is the radiator, which can be seen in its length strictly according to the area of the room, presumably with the aim of generating the same temperature in each room in response to health norms and the protocols it should follow as a mass-produced commodity. While the production of a thermal environment according to the function of the room and the specific activities it houses is assigned to the control valve. Until now, we can still see heaters in stores that can be separated.

THERMAL COMFORT 59

FIG.07 Guillaume Bijl, Heating stand, 1990

60 CHAPTER 02 07

2.3. Energy Policies in the UK

During that period, the increasing integration of energy into the economic, social and domestic life of expanding urban areas coupled with its relationship to the natural environment not only changed the spatial order of cities but also gave birth to a set of economic and scientific practices related to energy use that had echoes in unequal energy distribution.

The infrastructure of energy sustains the artificial environment within active architecture. Each building is connected to an infrastructure system powered by coal, gas, nuclear, biomass, and hydroelectric power plants. Houses, flats, and workplaces, free of smoke and odors, are uniform thermostatic areas with a variety of plugs for lighting, radiators, boilers, fridges, TVs, computers, and so on. Buildings are increasingly serving as switchboards, sockets, and chargers, rather than internal combustion engines. Basically, neotechnic architecture is about the design of output terminals and charging points.14

In the UK, before plugboards were invented, the design of ports and charging points, from their number to their location, was highly dependent on the function of the space and the array of objects that enabled that function.15 The same was true for gas

THERMAL COMFORT 61 08

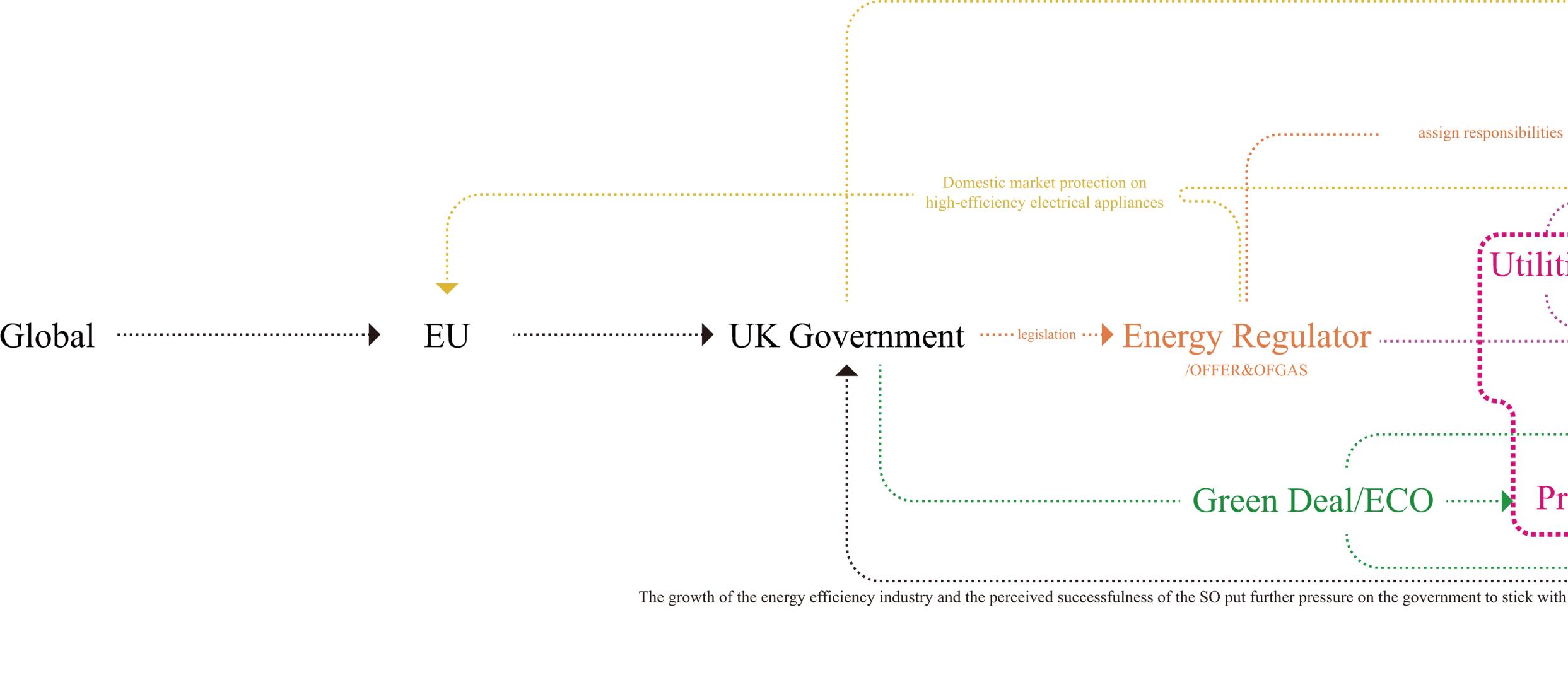

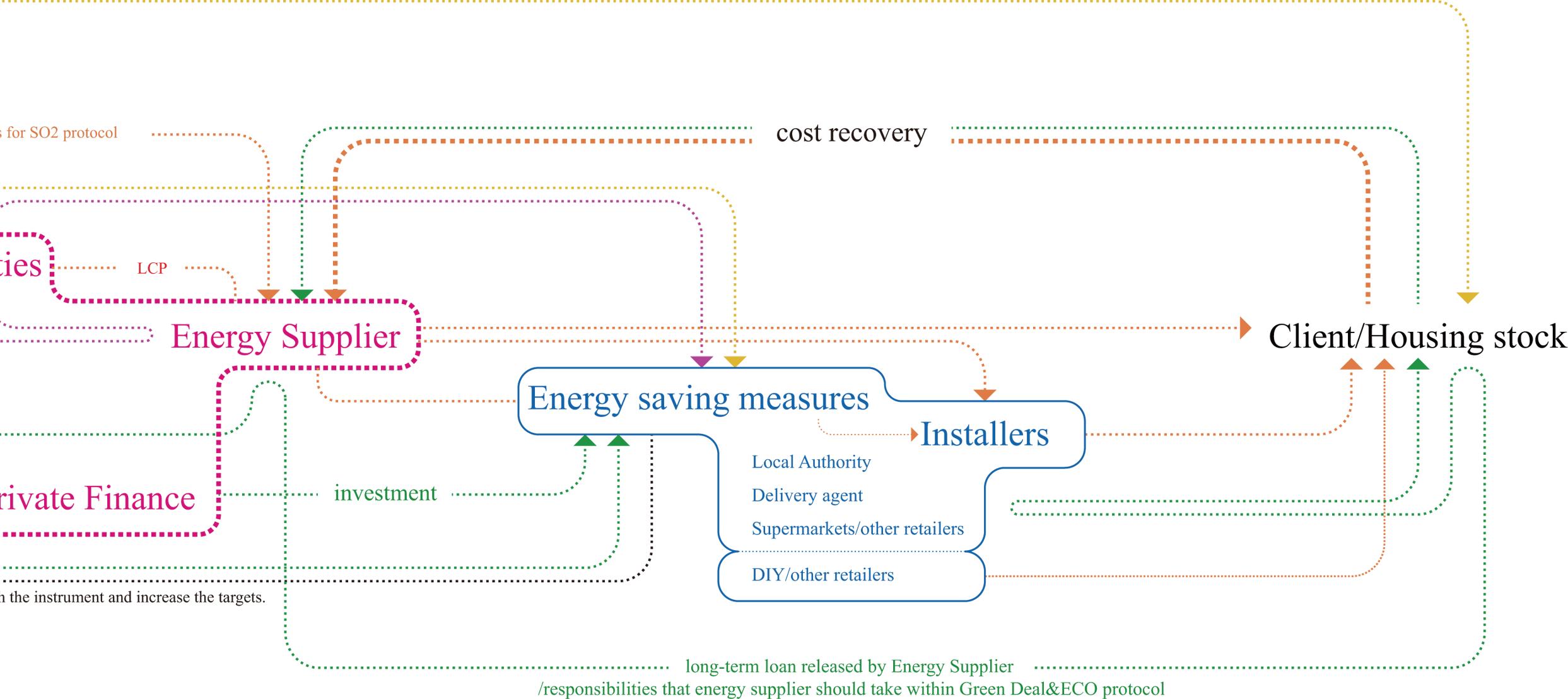

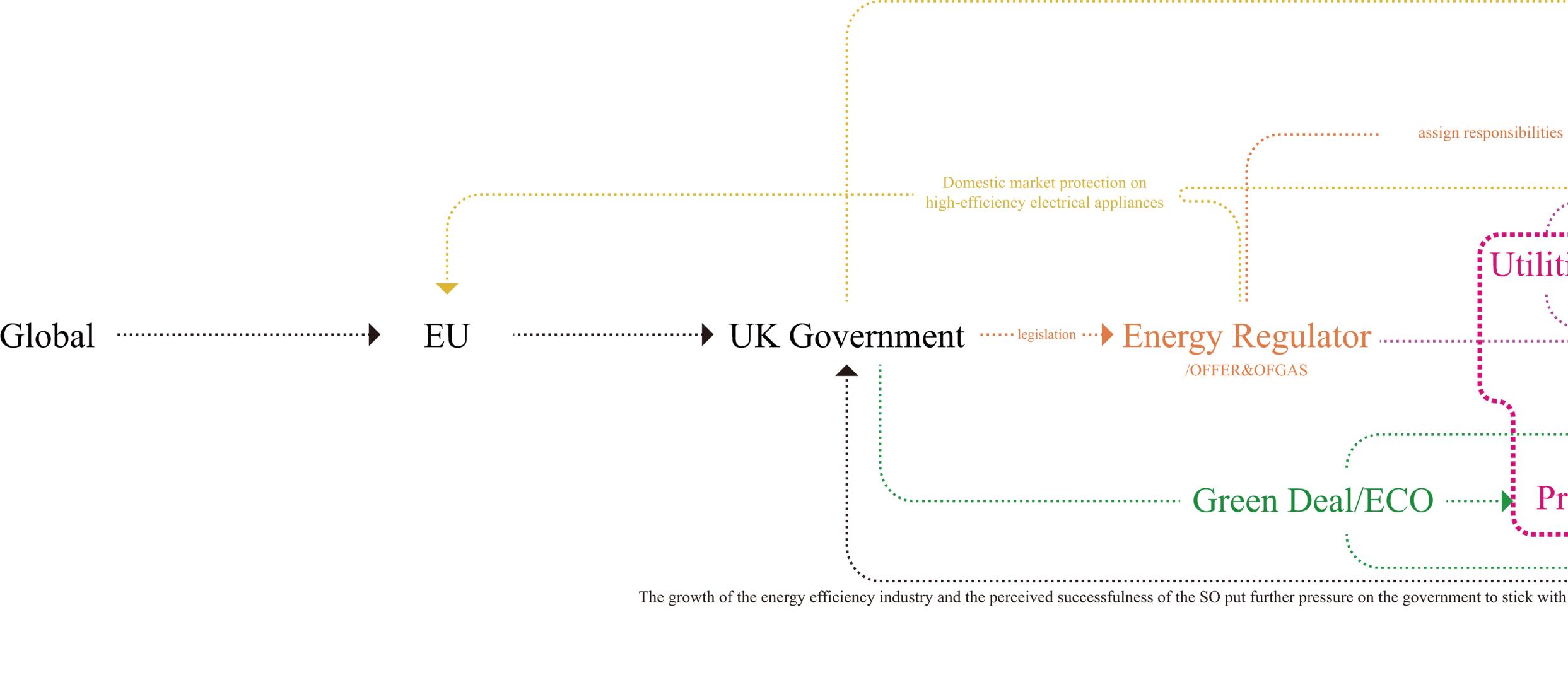

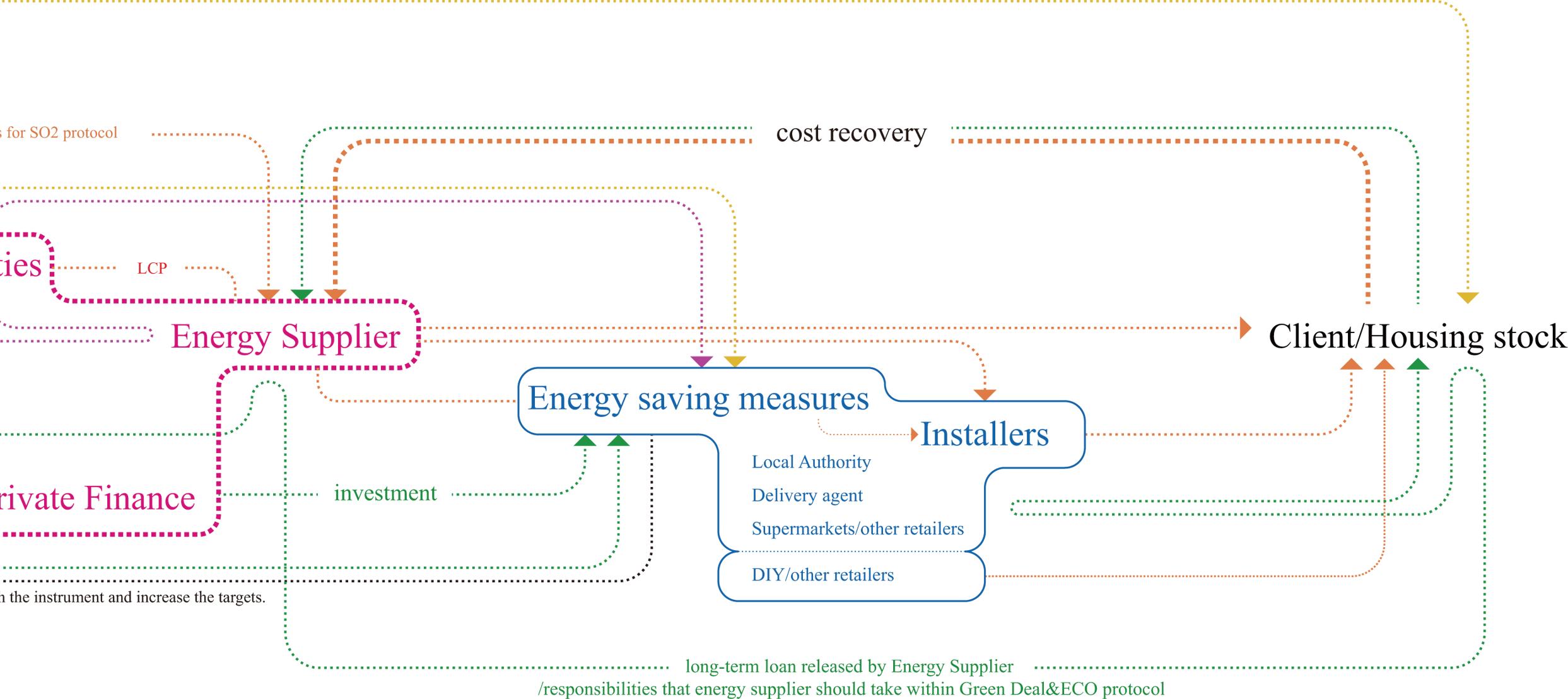

FIG.08 a relationship of responsibility and the apportioning of benefits across the state, society, corporations and the customer from 1970s to 2020s

connections. Today, while a room is allowed to be occupied in multiple ways, the environmental control of objects that support a variety of activities is considered equally important.

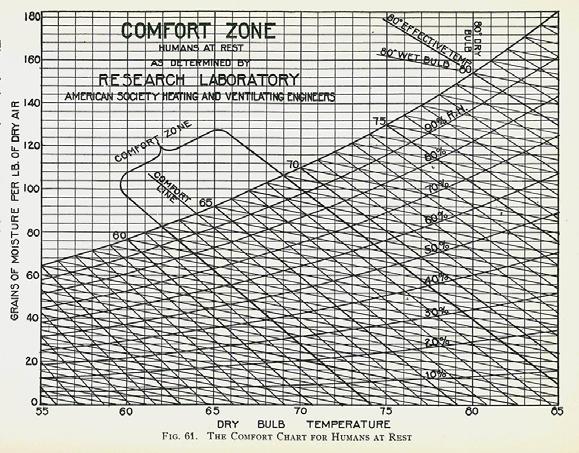

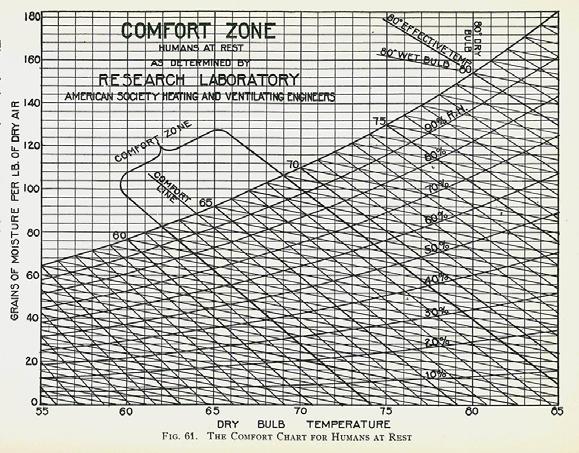

Quantifications and specifications related to temperature and humidity have been given to scientific experiments and commercial organisations. Up until now, international codes, such as those developed by the American Society of Heating Refrigeration and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), have proved to be immensely influential, acting as a common point of reference and as a coordinating mechanism powerful enough to align engineering and manufacturing practices around the world.16

‘The drive for quantitative accuracy was fuelled not only by the desire to supply engineers with the surety of quantitative values in the rugged debate before the public in general and regulatory agencies in particular but also by the need for accurate information on which to build effective designs’.17 Therefore, the process of developing temperature standards is the process of collecting data on bodies, which involves the skin’s perception of its surroundings during activity in various contexts, with the aim of maintaining proper movement of the body. These standards have been repeatedly spelled out in building standards and the mass media, and through thermostatic radiator valves (TRVs) on radiators and sleeping modes on air conditioning control panels and their manuals. Finally, the masses accepted adjusting temperature to support their indoor activities as a form of selfcare. As such, individuals became ‘consumers of comfort’.18 Any restrictions on energy use, from space to quantity used, are

62 CHAPTER 02

undoubtedly inefficient in a free market.

The idea that the government should play a strategic role in managing energy demand in the UK began with the first oil crisis in 1973. Through strong intervention, a series of mandatory energy conservation measures, including a limiting of the maximum allowed temperature, were widely implemented.

This strong intervention continued until the Thatcher government took office. In May 1979, the Conservatives, under Margaret Thatcher, won the general election based on a commitment to reducing state interference in markets. Energy secretaries David Howell and Nigel Lawson, both free-market enthusiasts, advocated for the role of energy prices, which were rising following the second oil shock, in reducing energy demand. The argument stated that industry and householders, as rational economic actors, would install energy conservation measures without subsidies because they were cost-effective. Unfortunately, the same argument was applied in reverse when prices fell in the early 1980s: If energy conservation was no longer cost-effective, there was no point in the government second-guessing the market.

Based on a belief in ‘warmer homes, lower bills, greater productivity’, two independent energy regulators, the Office of Electricity Regulation (OFFER) and the Office of Gas Supply (OFGAS), were established, to lead a paradigm shift from ‘energy conservation’ to ‘energy efficiency’ in the early 1970s. This also created a particular relationship between the consumer, state and energy supplier within the neoliberal market, which emphasised economic and social benefits.

After a landmark speech to the Royal Society by Thatcher in 1988, domestic energy efficiency and the associated carbon emissions were beginning to attract consideration. Within this new political area, the principle of statutory obligation among energy suppliers was extended to incorporate a broader moral obligation regarding ecological futures. Energy suppliers' clients were encouraged to reduce consumption of their products and provided with long-term loans to purchase energy-efficient facilities. Additionally, the loans were returned in the form of increasing energy bills to satisfy the interests on the energy consumption side. The energy efficiency industry was made stronger through this progress, and it now continuously places pressure on the government to increase carbon emission targets that further the bill on the basis of higher international energy costs and in the name of climate change.

As a result, utilities are benefiting their own profits. Those who

are better off are also benefitting as they are better equipped to take advantage of technological solutions and government incentives. This is occurring at the expense of households in energy poverty, who are most often required to make behavioural adaptations.

Based on the above analysis of the Smoke-Abatement Exhibition and UK energy policy, it can be concluded that a uniform set of perceptions and social behaviours has rationalised the array of highly individualised energy consumption practices by blurring the boundary between the ways of taking care of the self and health norms. Additionally, these practices have been further incorporated into the free market.

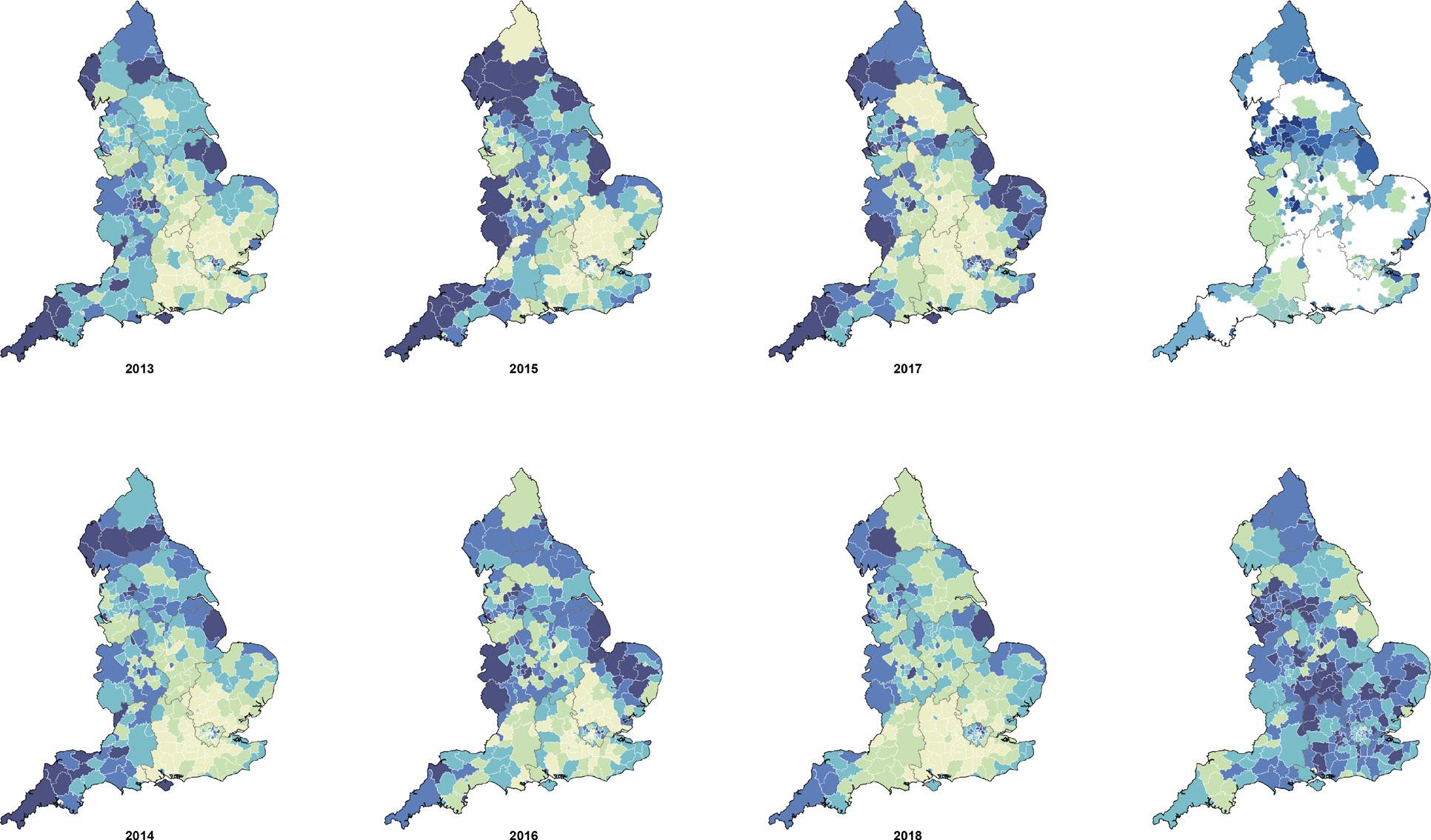

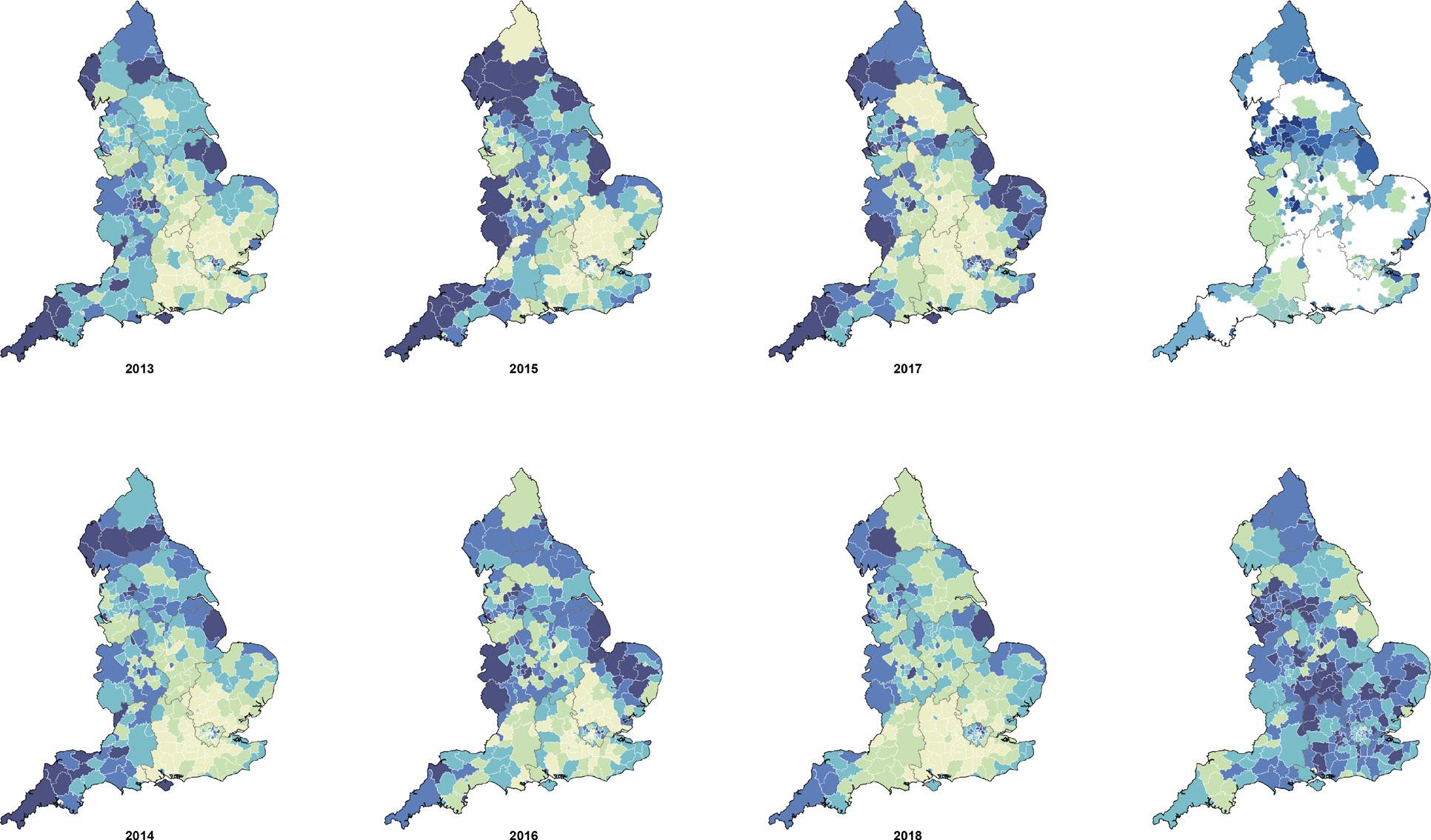

Proportion of fuel poor households (%) Most Deprived Least Deprived High Efficiency Low Efficiency

FIG.09 ONS estimates of energy poverty in England from 2013 to 2018

FIG.11Deprived Condition

09 10 11

FIG.10 Energy efficiency of dwellings, 2019

FIG.12 The Great Indoor, Martain Parr, 1996

THERMAL COMFORT 65

66 CHAPTER 02 ''CONNECTOR"

Connector/Design Proposal 2

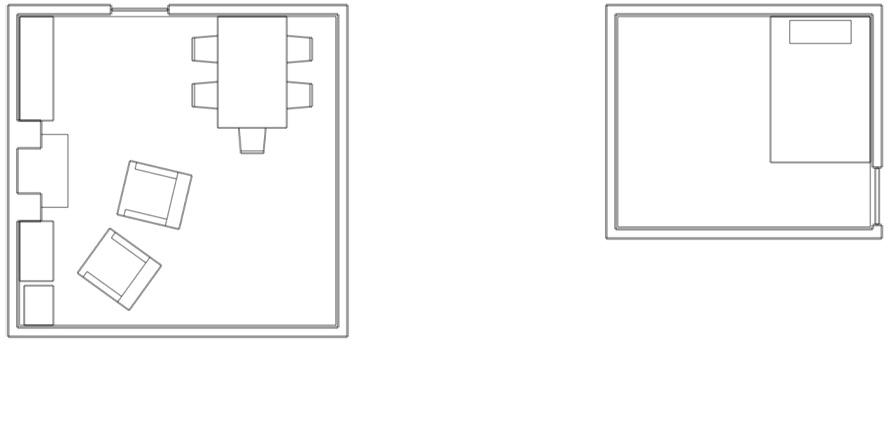

As the case studies reveal, whatever form they take, these buildings aim to emphasise the body as a situationalized recipient of heat to maintain normal bodily functions, whether through homeowners and servants as their substitutes disciplining themselves by supplying equal volumes of warm air into rooms or through the provision of clean personally controllable warm supplementary air in multi-functional spaces. From sleep to exercise and solitude to gathering, the room not only began to host multiple activities but also to instil forms of self-care, as the two case studies emphasise in a progressive manner. An analysis of energy policy in the UK over the past half century reveals how, by understanding care for oneself as a rational health practice, the results – personalised energy practices and the ability and power of energy consumers to maintain such practices – were codified in a framework of energy-related responsibilities compiled between the state, businesses and utilities.

Along with their increasing incorporation into individualised energy practices and health discourses, the multiple functions that control valves and panels gradually began to perform challenged their ontological proposition as a means of taking care of the self. They not only created a new image of the home as a bounded site of energy consumption and financial responsibility together with meters, energy bills and pipe arrangements but also acted as monuments to personal health. In this sense, the control valve's multiple meanings make unquestionably considering it as self-care unproductive.

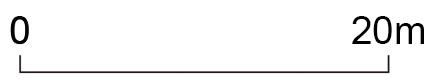

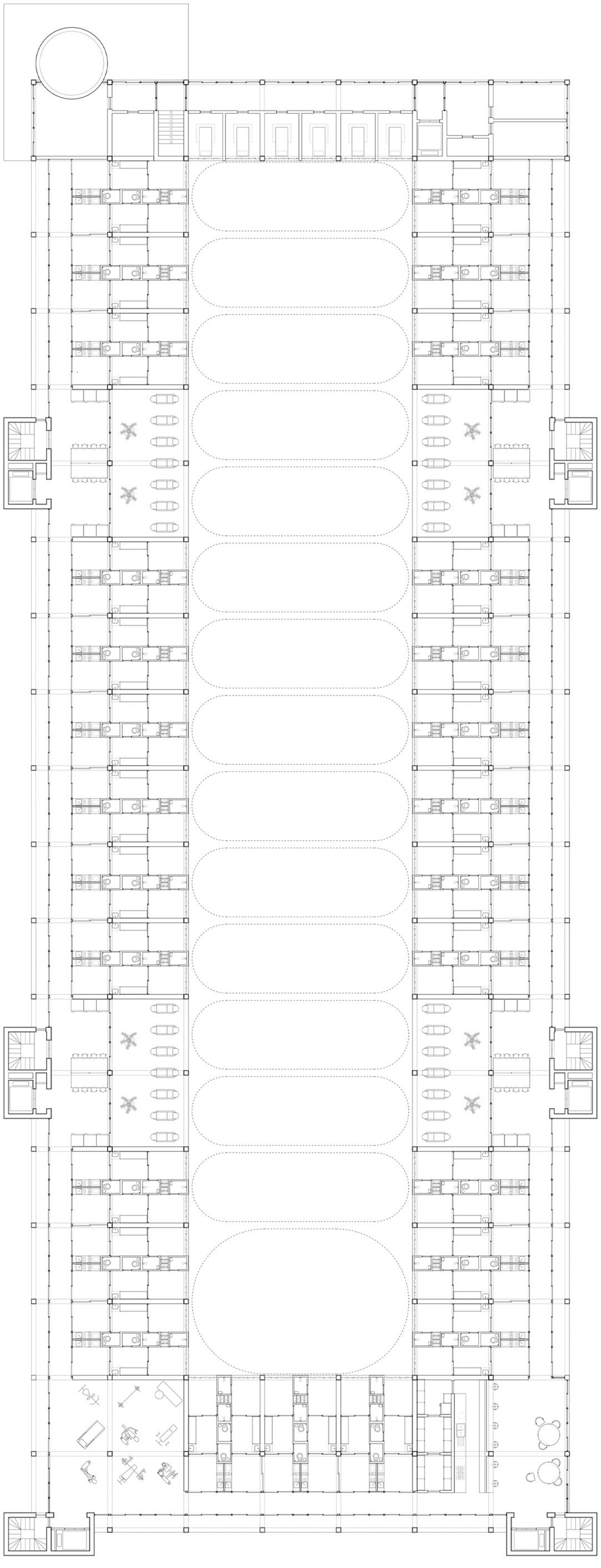

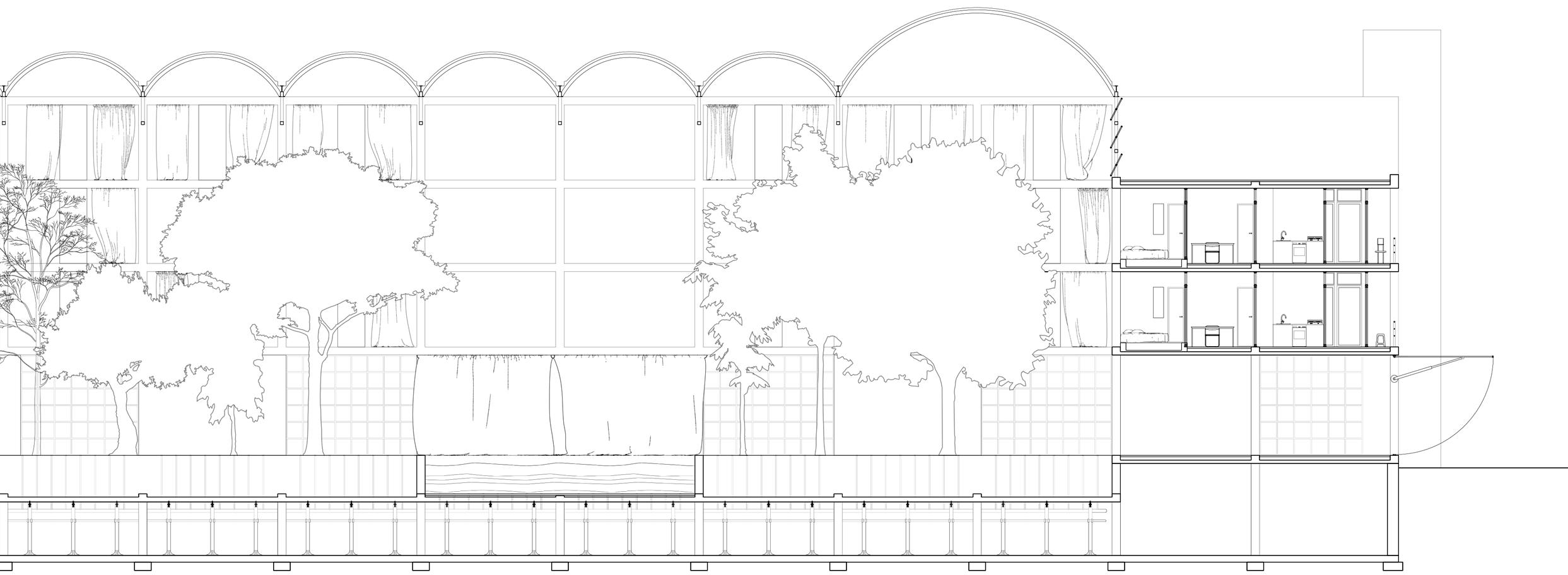

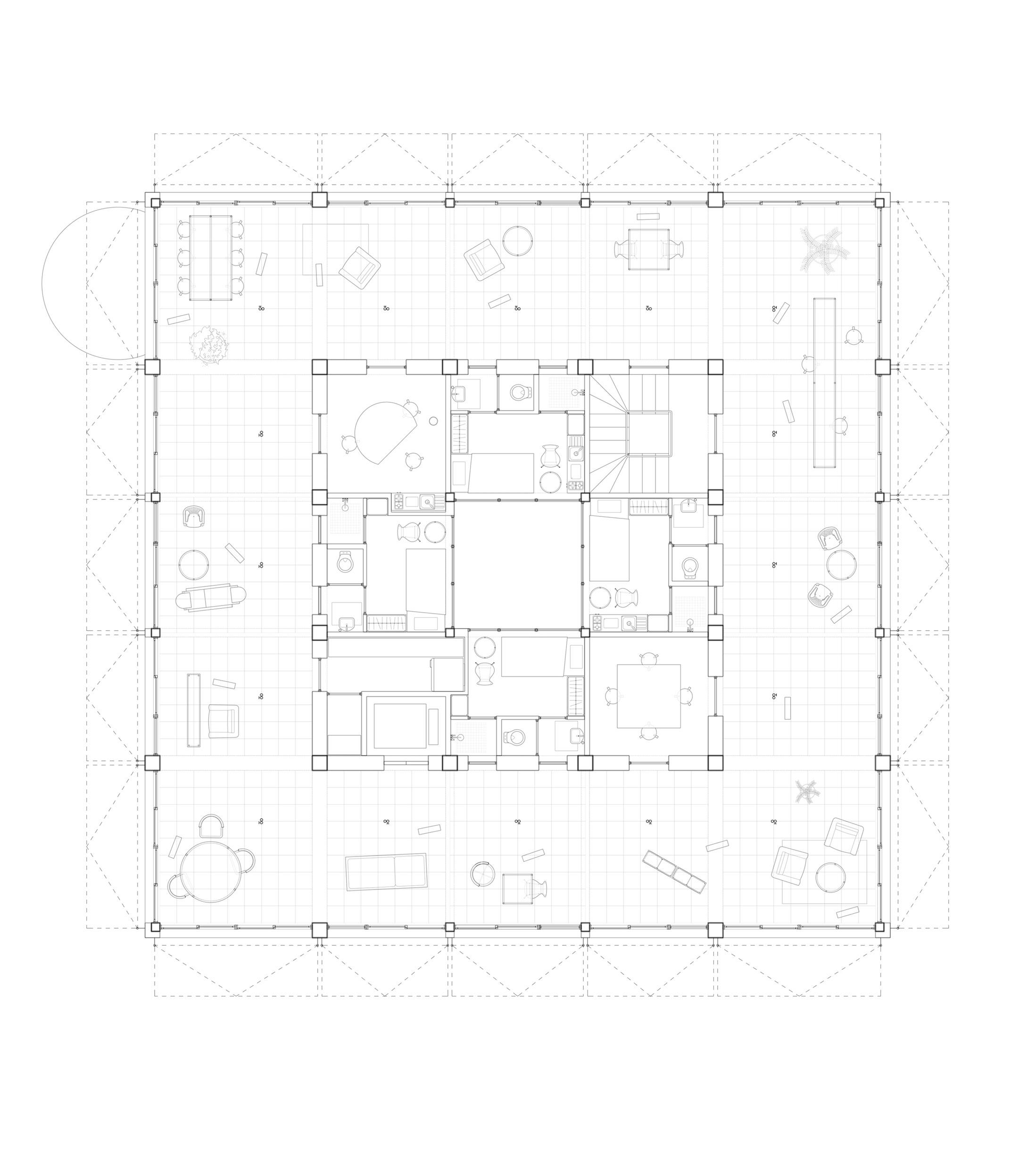

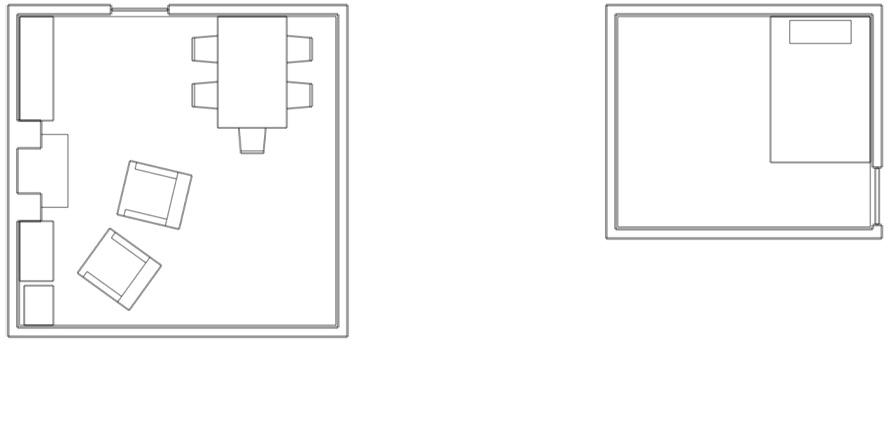

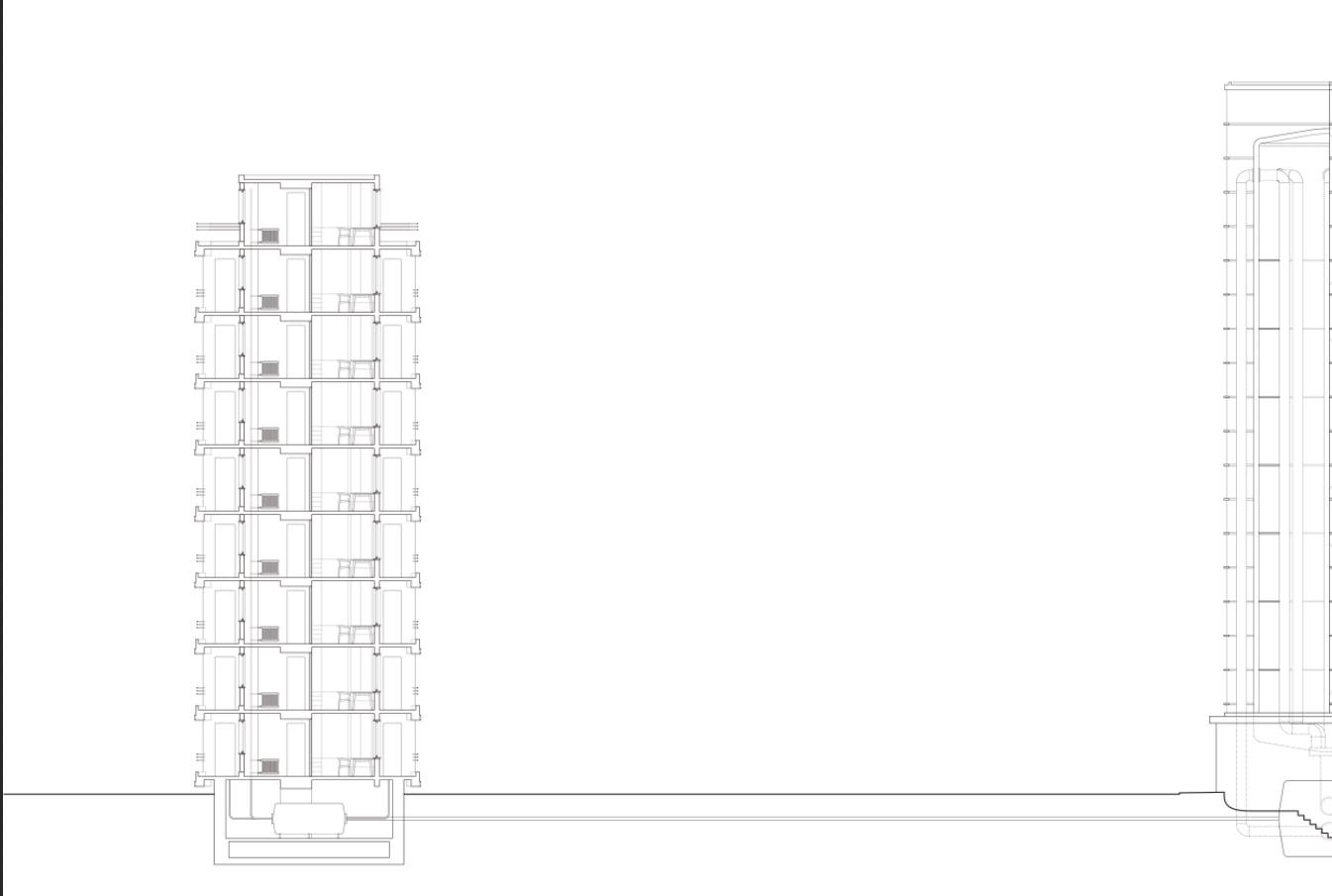

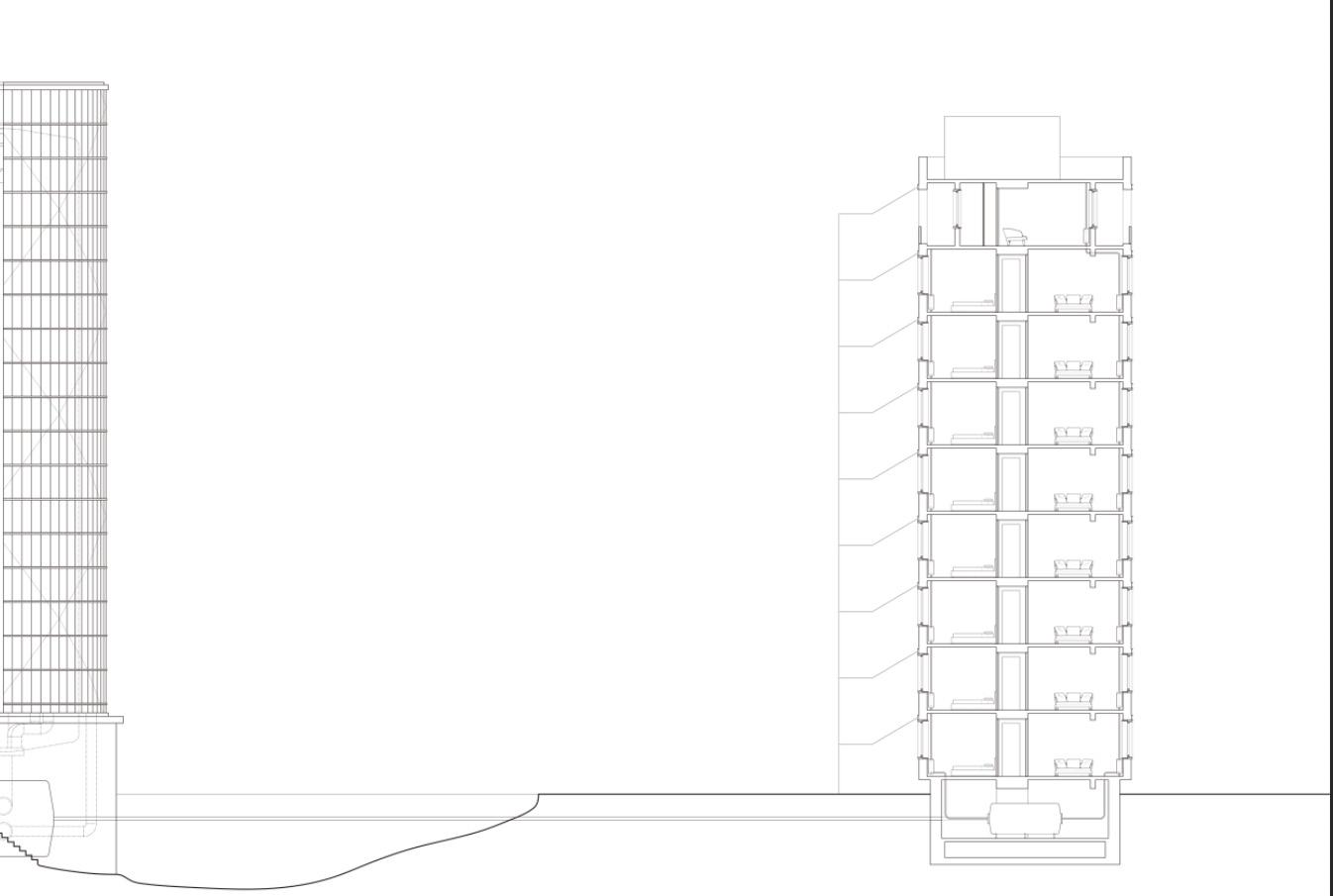

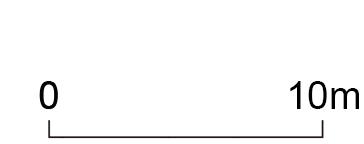

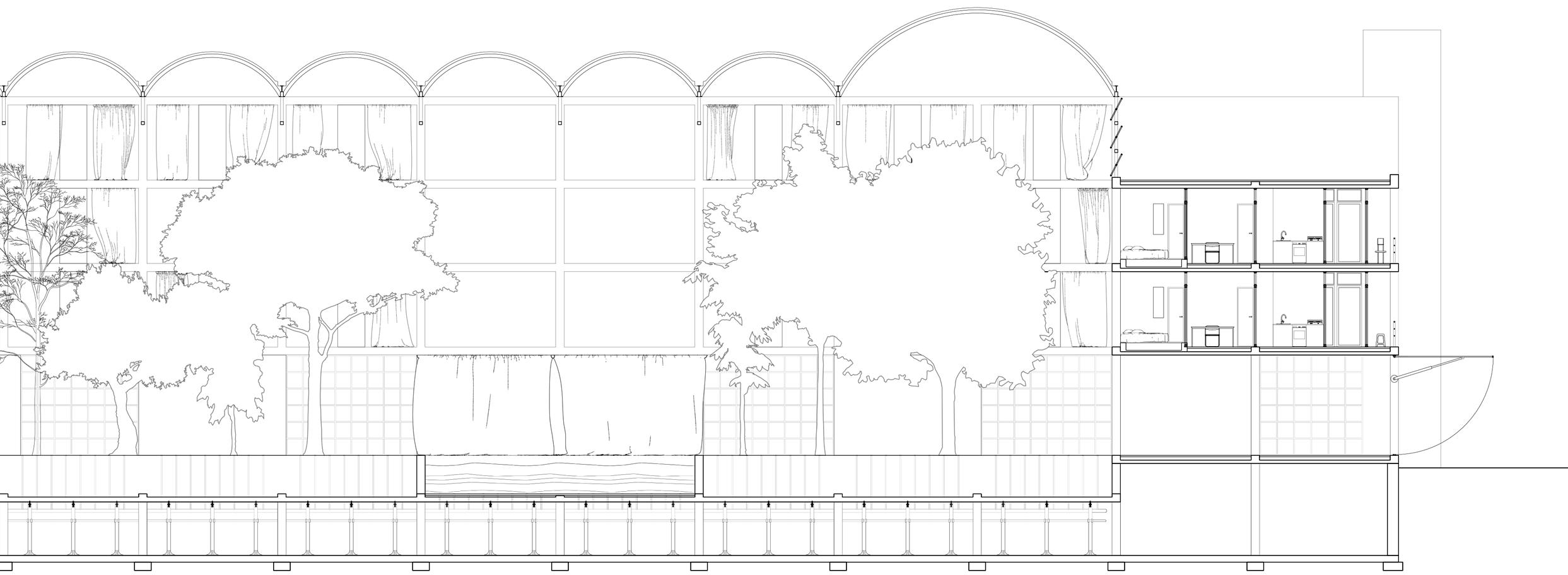

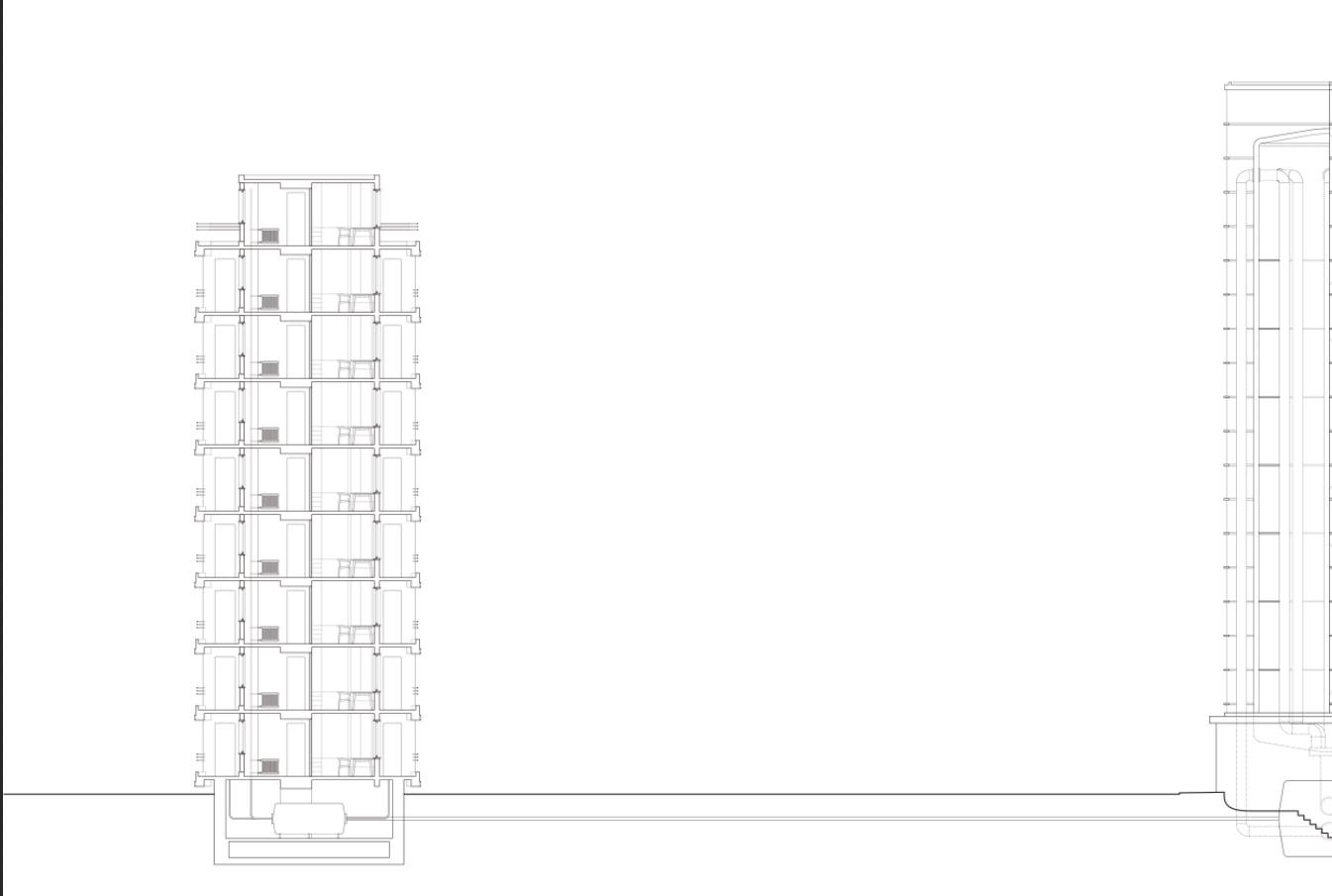

The goal of the ‘Connector’ is to propose a new mode of energy practice by emphasising the relationship between the body and the heating infrastructure. In houses built after the 1970s in the UK, gas meters were often arranged in the cabinets. In older terrace houses, each household had a separate gas meter deposited in the threshold of the ground floor. In northern China, the large chimneys of the heating stations scattered throughout the city are monuments of district heating, and the annual heating bills are calculated according to the area of the household. Meanwhile, in a country where illegal renovations are rampant, the sound of electric drills is always heard during break times. Pounding hard on vertical heating pipes has become the best means of resistance. Although the use of each room for multiple purposes is not new,

THERMAL COMFORT 67

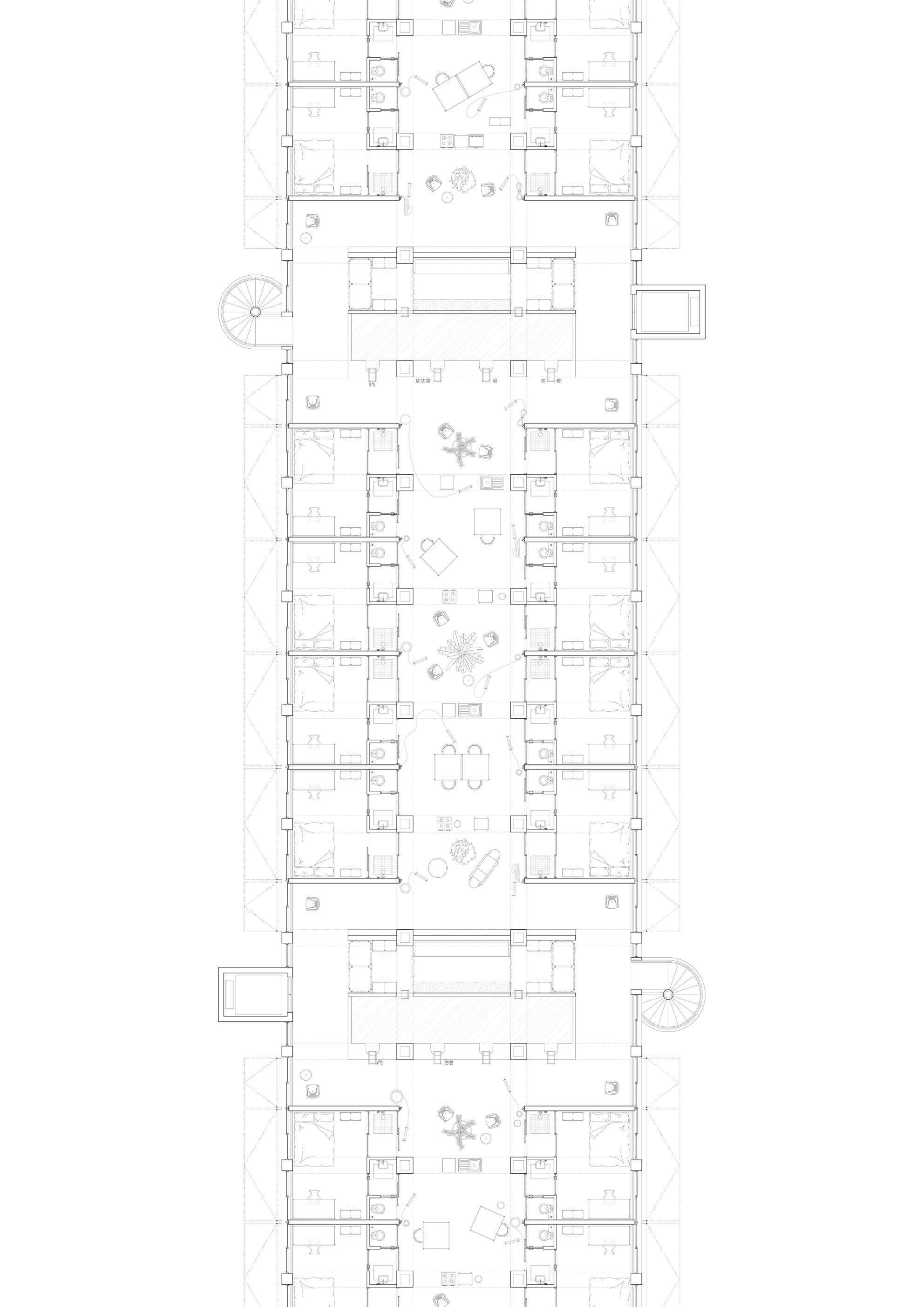

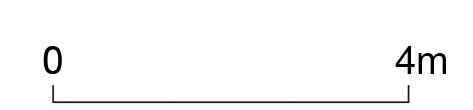

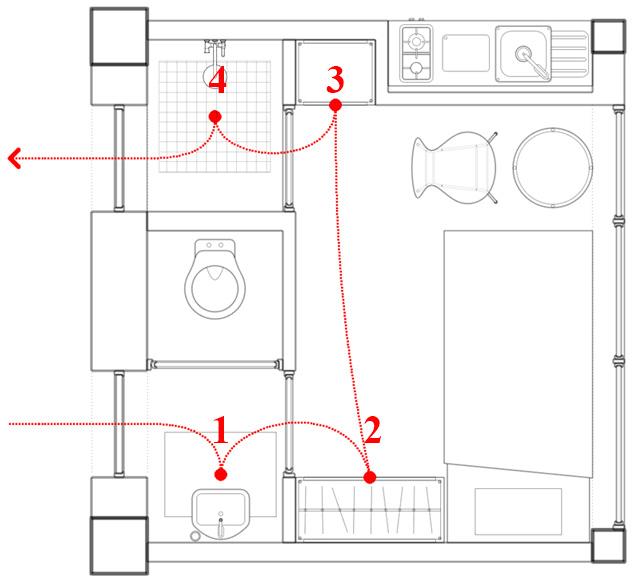

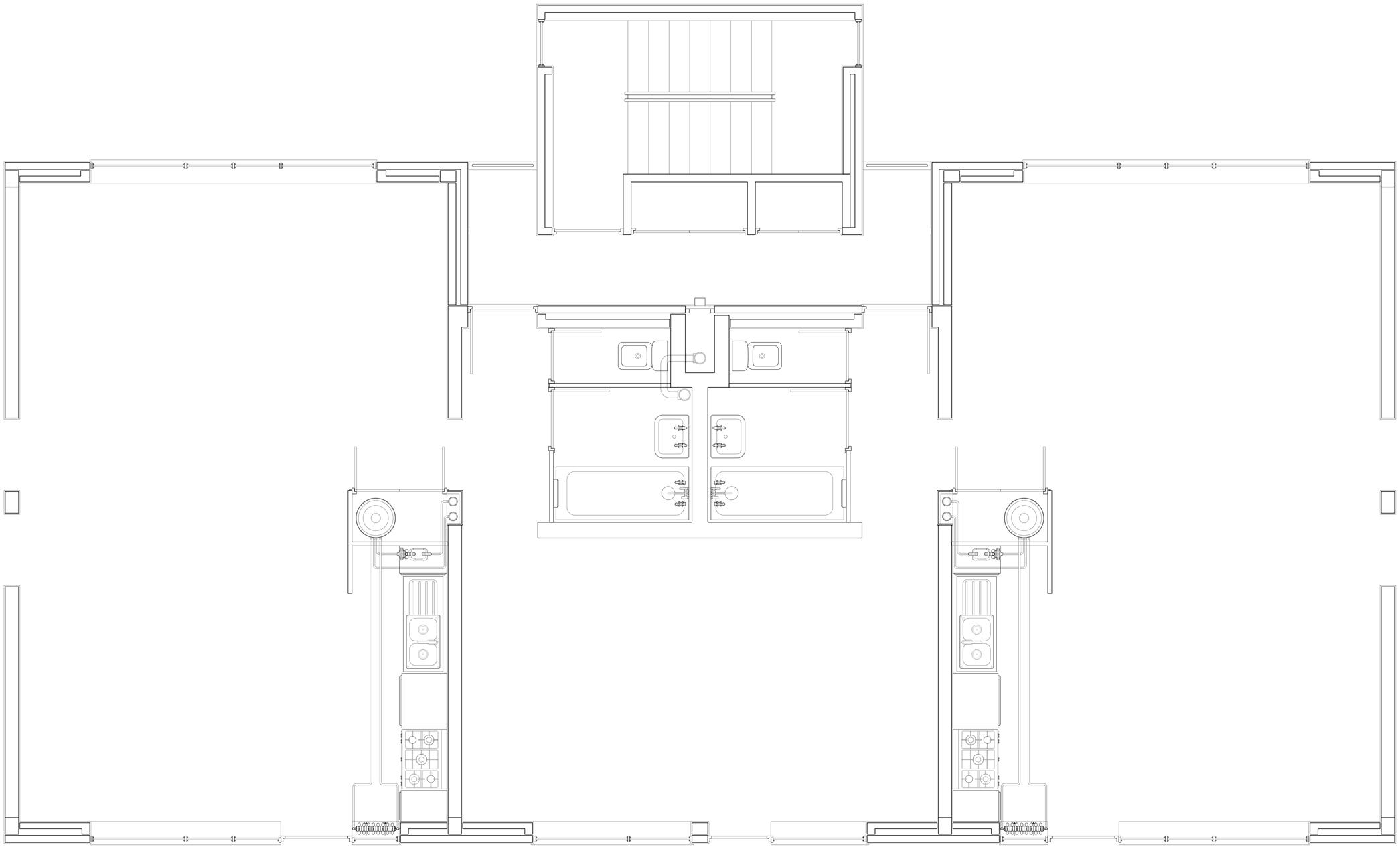

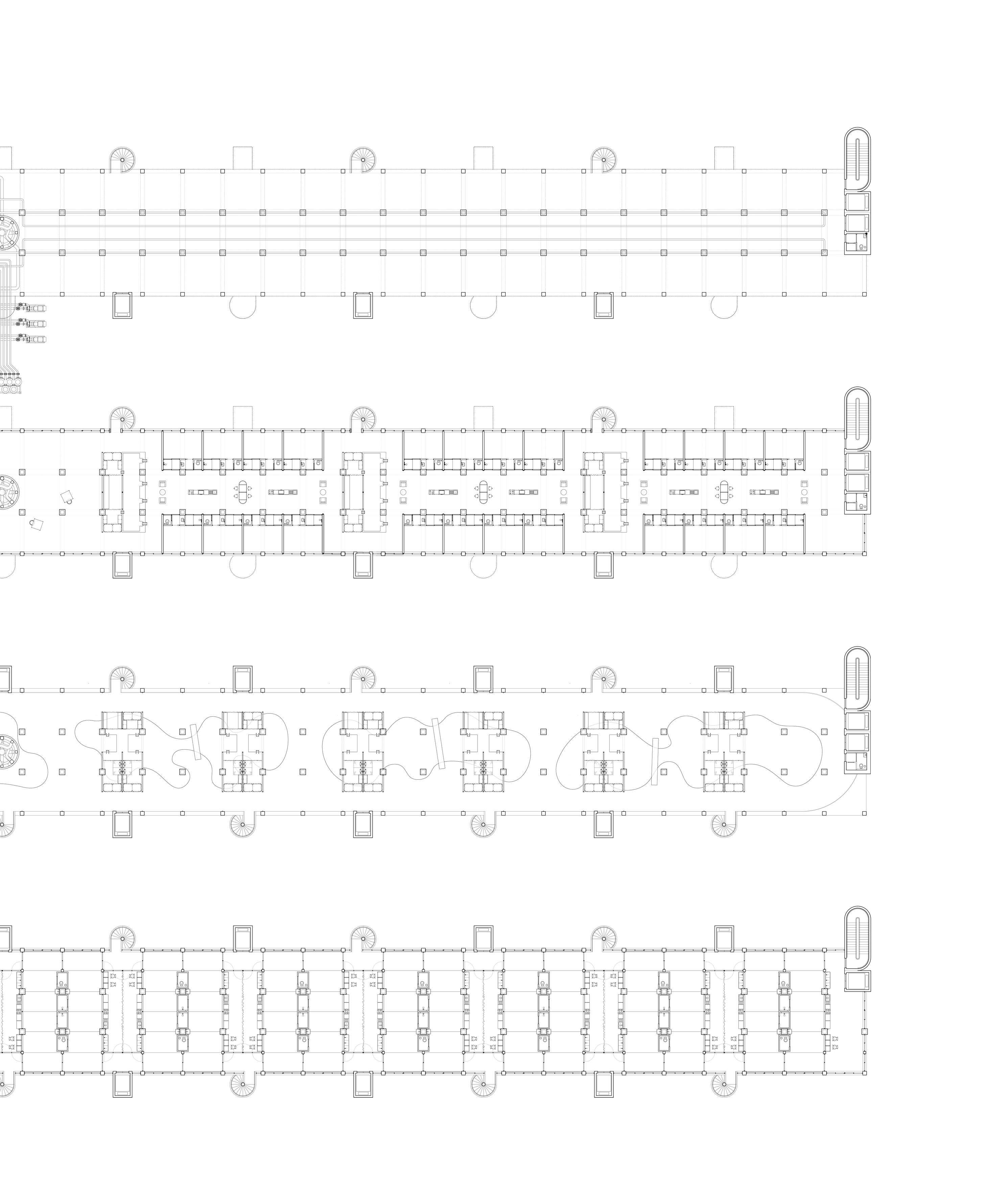

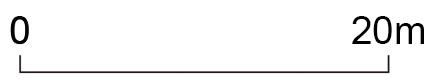

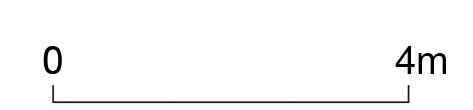

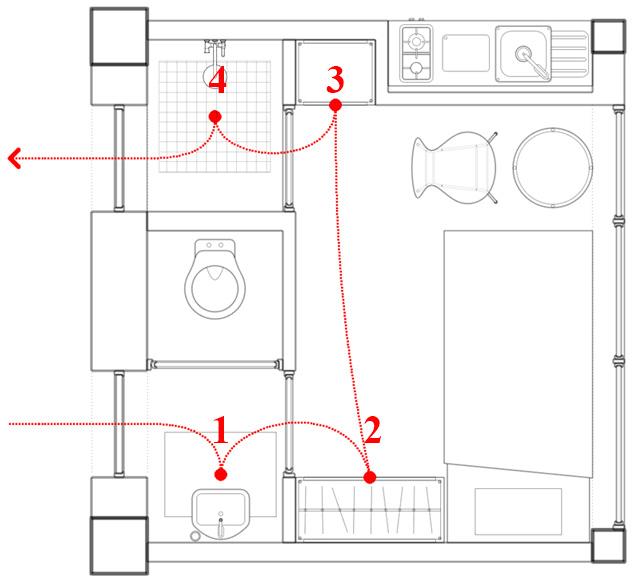

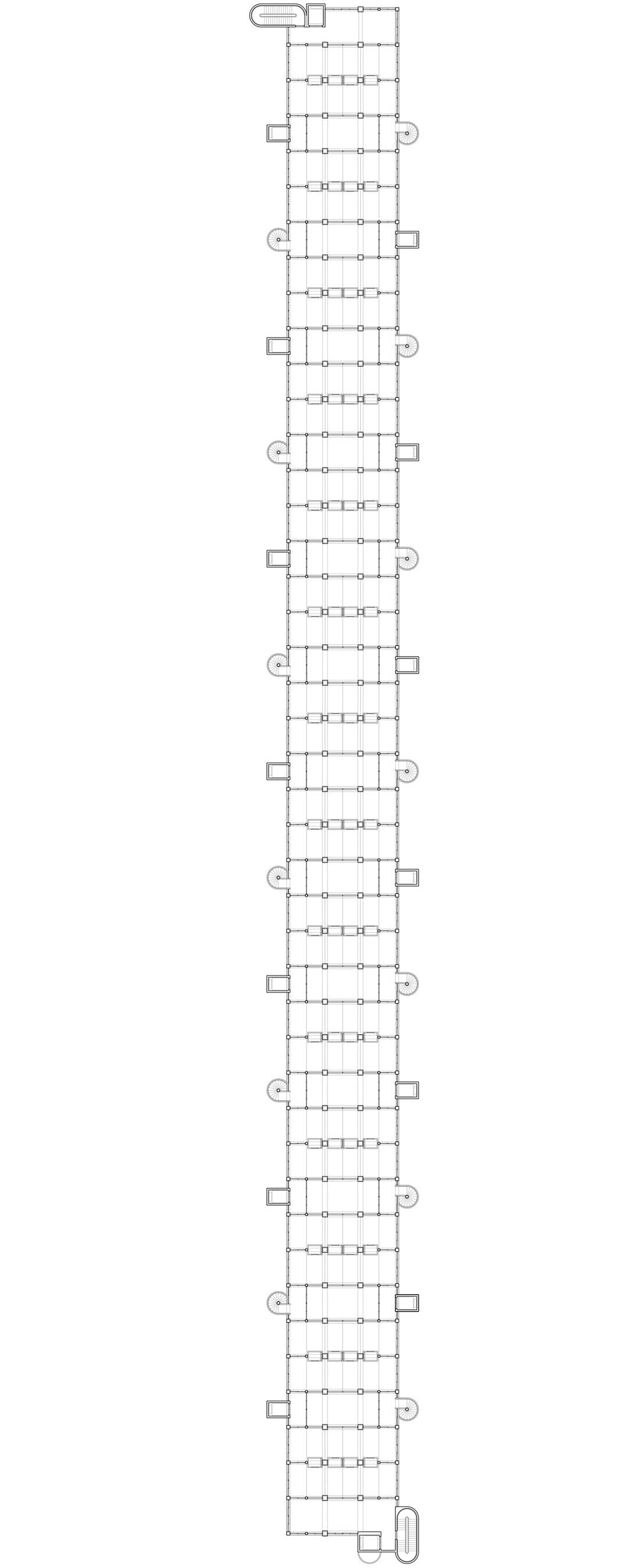

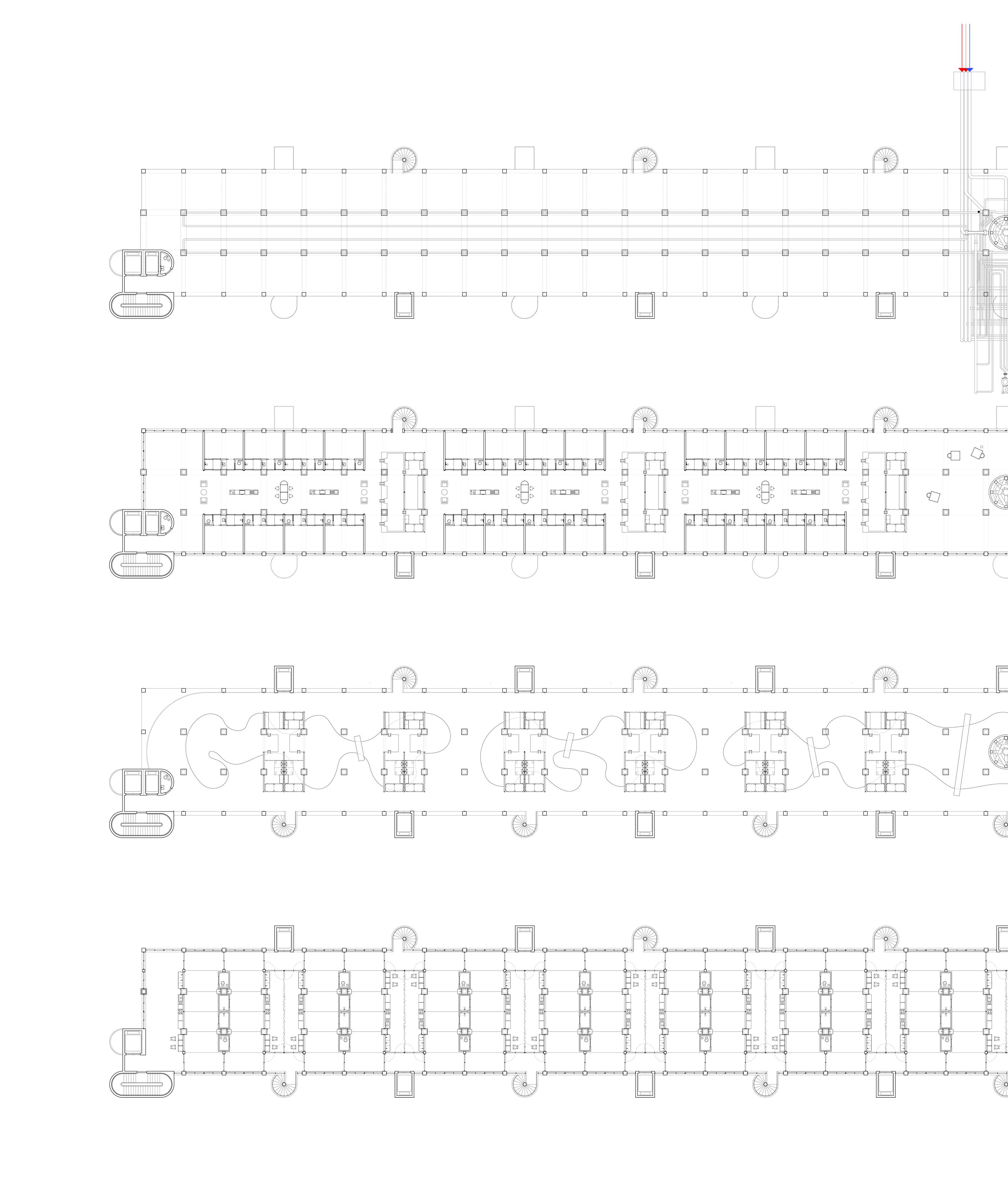

68 CHAPTER 02 Connector, Ground floor plan, Infrastructure

the ways in which the body, temperature and the activity that the room accommodates interact with each other when every room is equally heated will undoubtedly allow one to better know oneself. For example, in winter, it would be very challenging to exercise in a room at 26°C if the windows were not open. It has also been documented that some people put a basin of water on the floor at night before going to bed to avoid sweltering heat in their room.

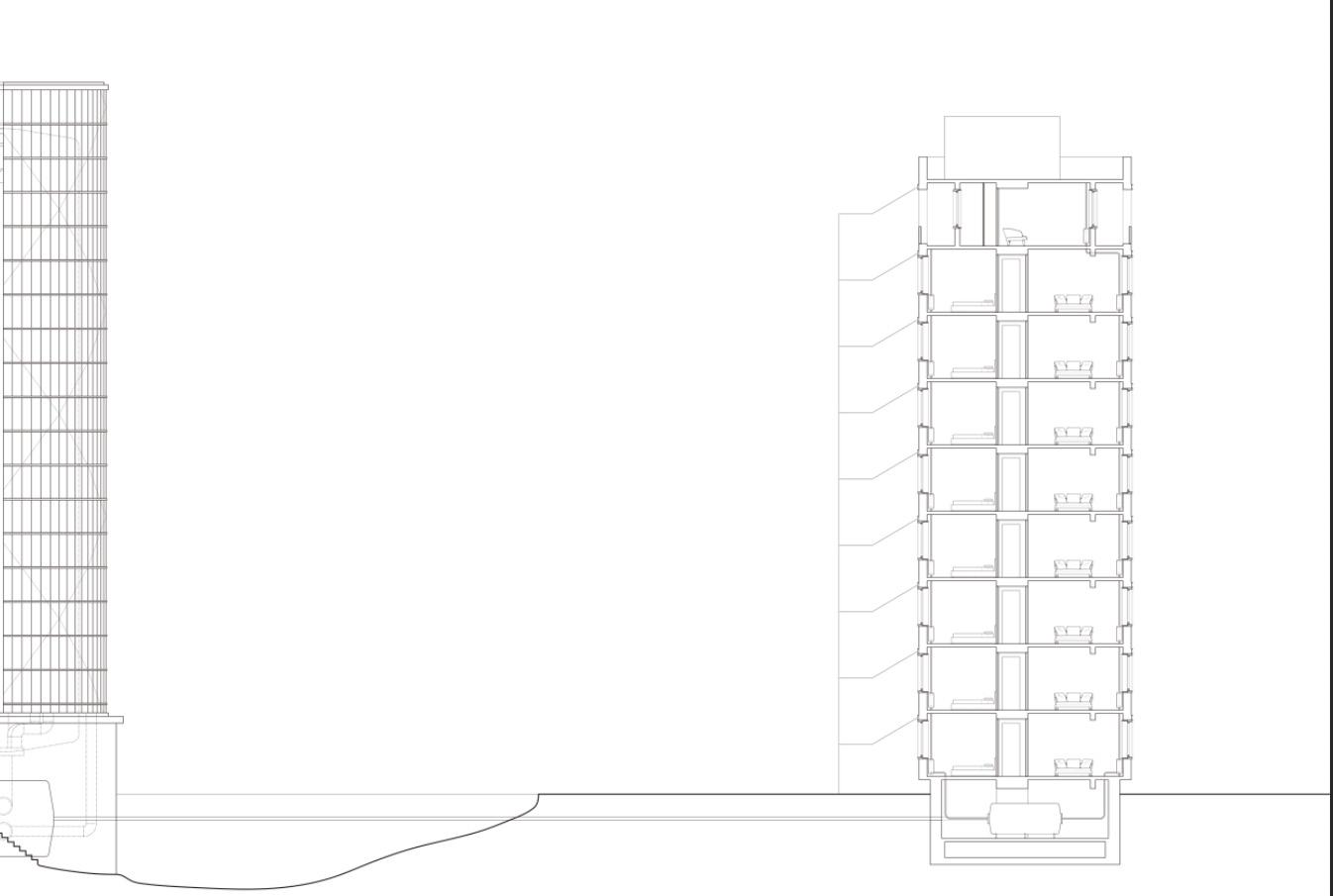

Similar to ‘Divider’ in Chapter 1, ‘Connector’ advocates collective energy use and treats energy as a social good. This tower-type apartment prototype, located in Brixton, London, aims to transform customers into co-managers of resources by rearranging energy commodity transmission/distribution and the infrastructure that supports them (pipes, meters, etc.) in order to seek a more equal distribution of energy for more than 100 households suffering from energy poverty in the region. In this way, local authorities and community groups can move into the utility sector alongside the incumbent industries and explore new models and partnerships for creating and distributing resources locally. Except for the exotic options in greenhouses and zoos, climate is today well on its way to becoming globally standardised. The airport in Singapore shares the same 22°C and 50% humidity as the airport in Moscow; working in an office in Montreal is no different in terms of atmosphere from working in an office in Dubai. This ideal has been widely questioned, as there is growing acknowledgement of the fact that ‘populations living in different climates have different susceptibilities, due to socio-economic reasons, and different customary behavioural adaptations’.19

However, Eva Horn proposes another view on the relationship between adaptation, in other words, self-adjustment, and local climate: ‘While Singaporeans (whether immigrants from Britain or Beijing, or born in the area) know just how to deal physically with the combination of heat and humidity, I did not miss a chance to do everything wrong’.20 She continues to develop this topic by bringing her own experience into the conversation, describing how she instinctively adapted to the relaxed, shadow-seeking pace of the locals in Singapore. In offices, men cannot understand why women wear air-conditioning blankets in such a ‘comfortable’ environment. In shopping centres in the summer, older people often wear thick clothes, while young people always wear short sleeves to enjoy the thermal pleasure of air conditioning. At this point, the potential of using homogeneous climates to identify the self from the others and the economic value this has historically been associated with requires attention.

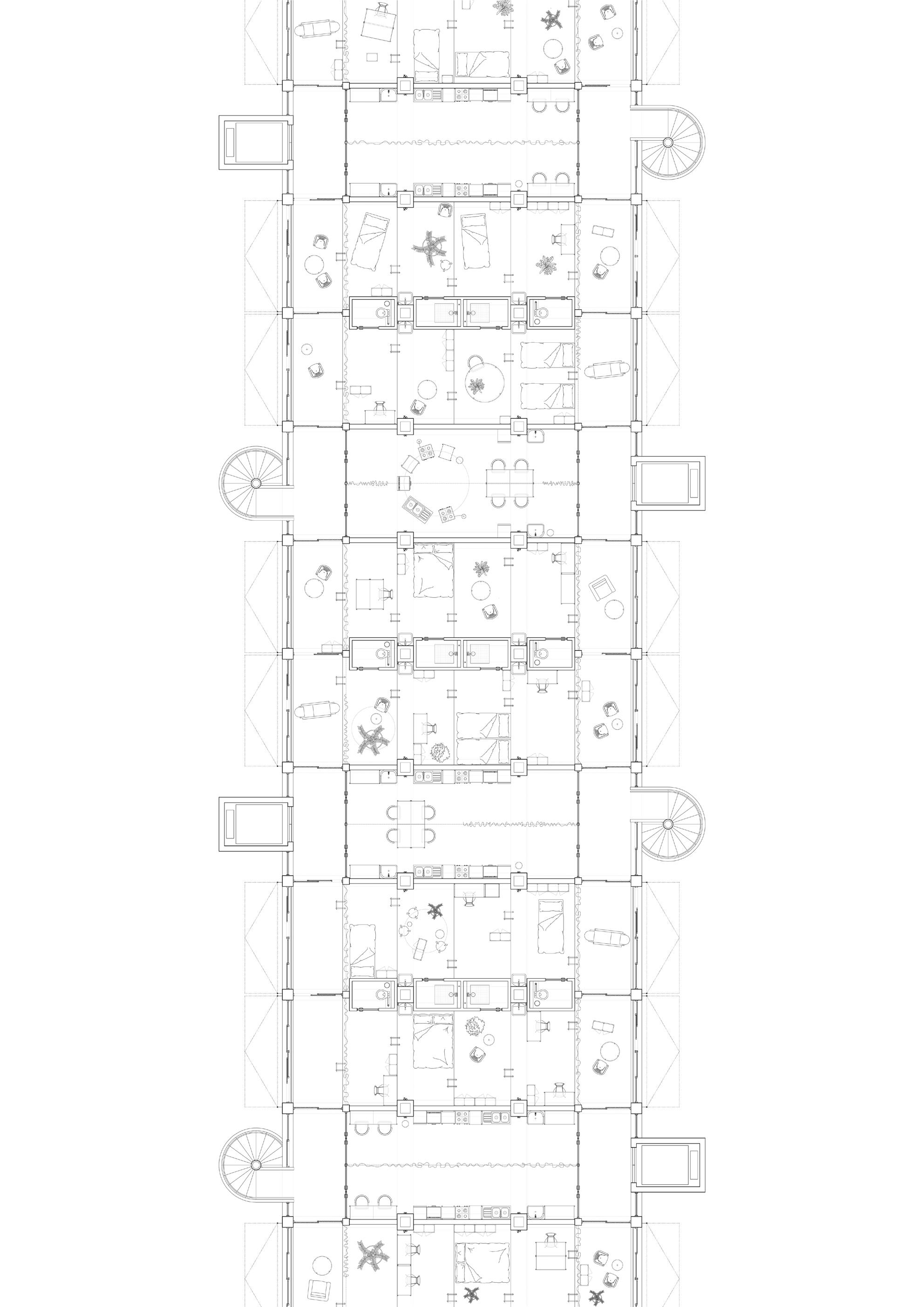

Therefore, the open plan of this building, supported by a constant and homogenous heat supply, is conceived as a stage

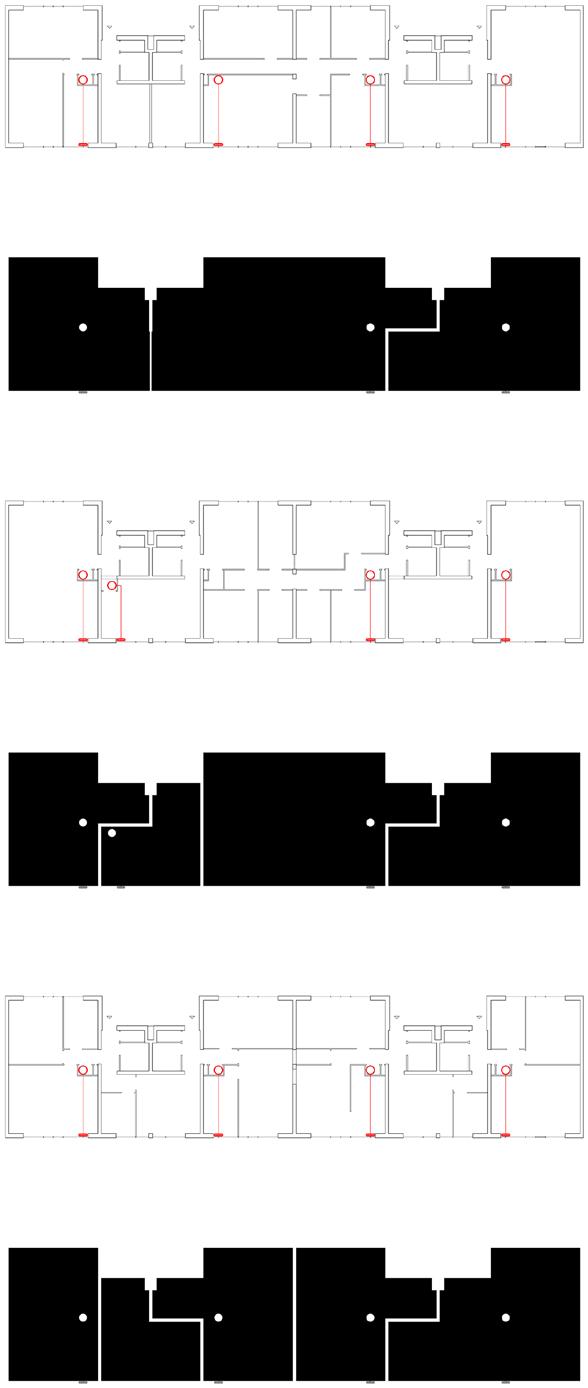

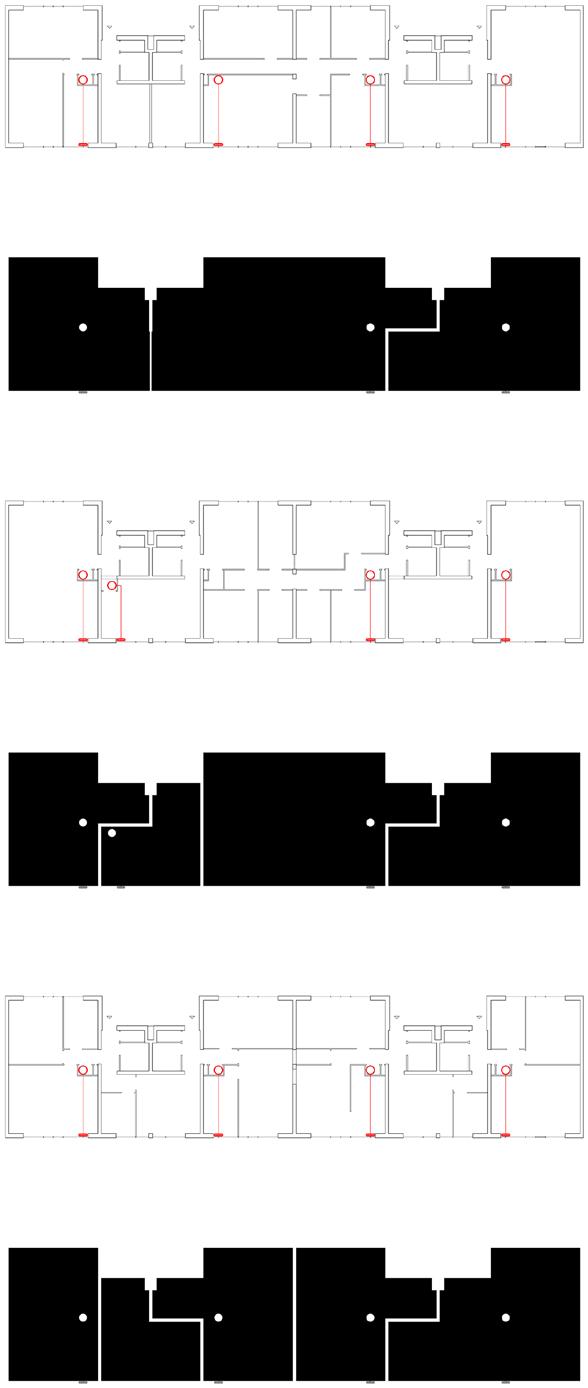

THERMAL COMFORT 69 13 14 15 16

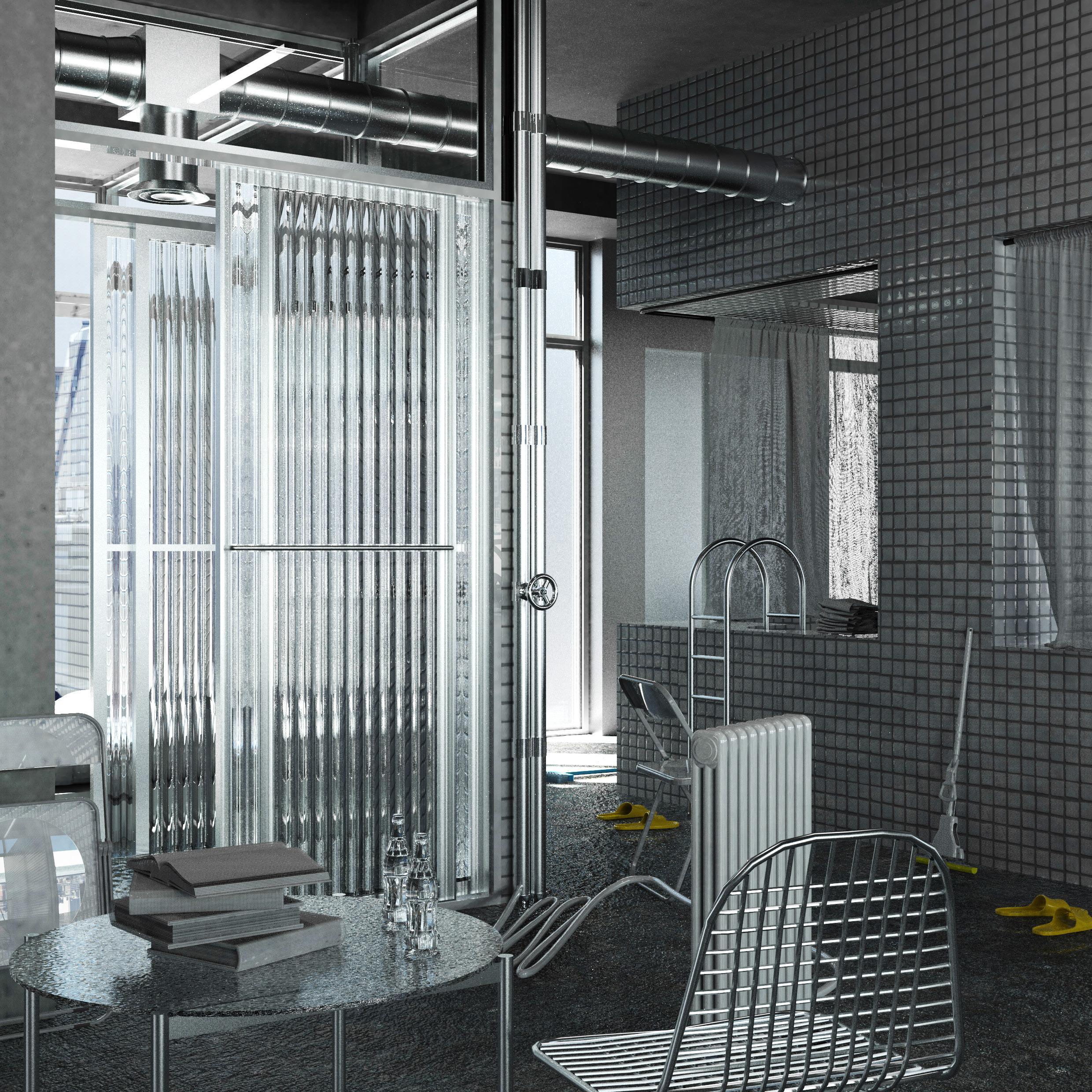

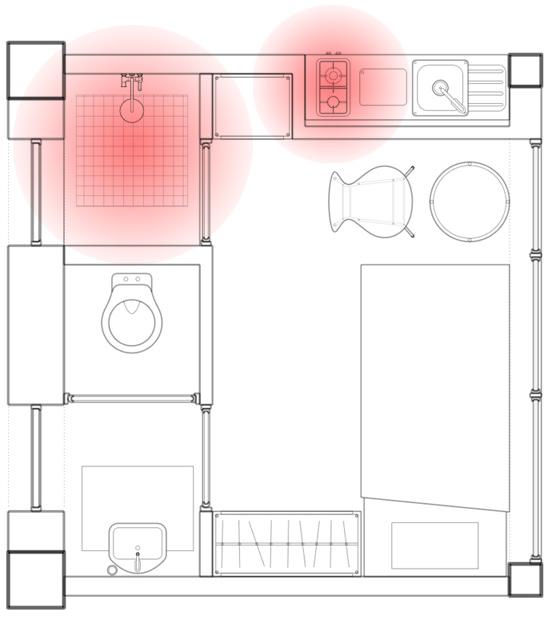

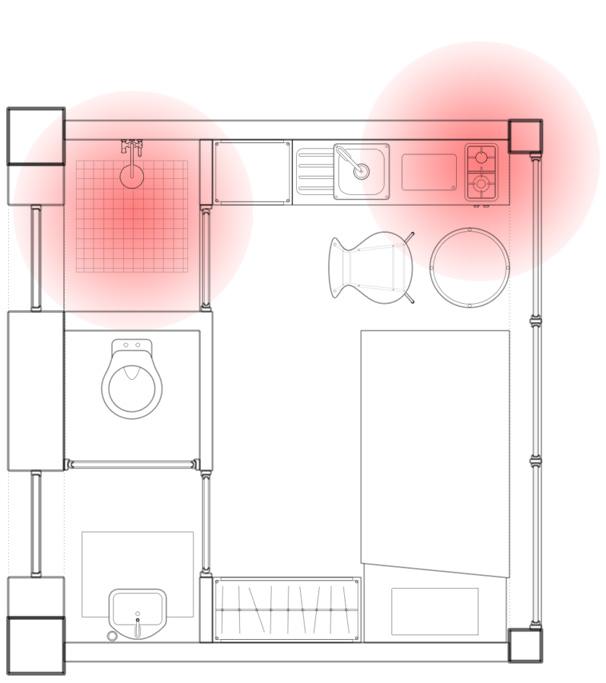

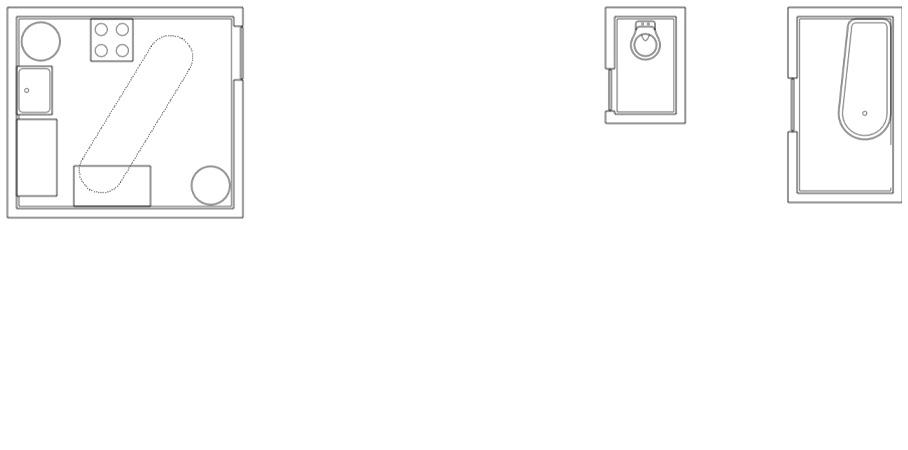

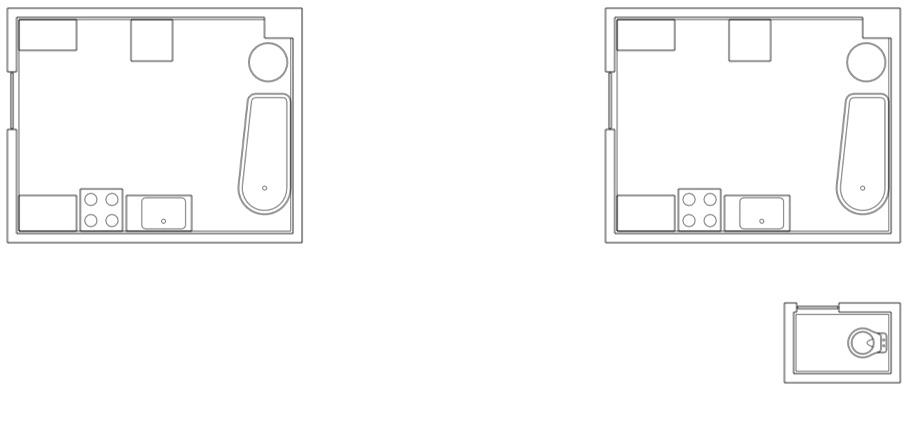

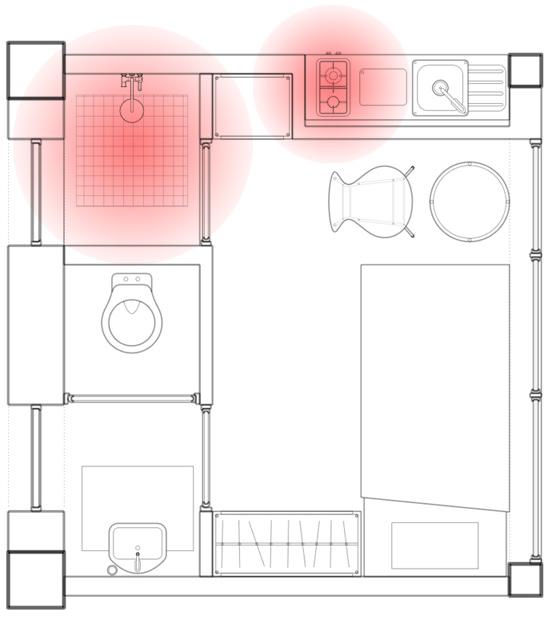

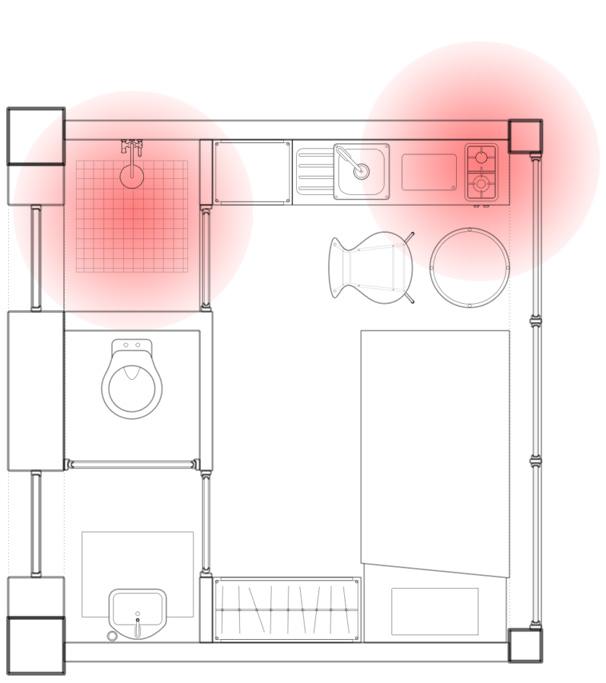

FIG.13-16 shows a. Moving body and Energy practise: 1. washing, 2. take the cloth, 3. storage, 4. showering. Finish with going back warm communal space; b. Occupation of Objects and Hot spot: bed, table, kitchen, and shower

70 CHAPTER 02 Connector, Typical floor plan, Living cell and Commual space

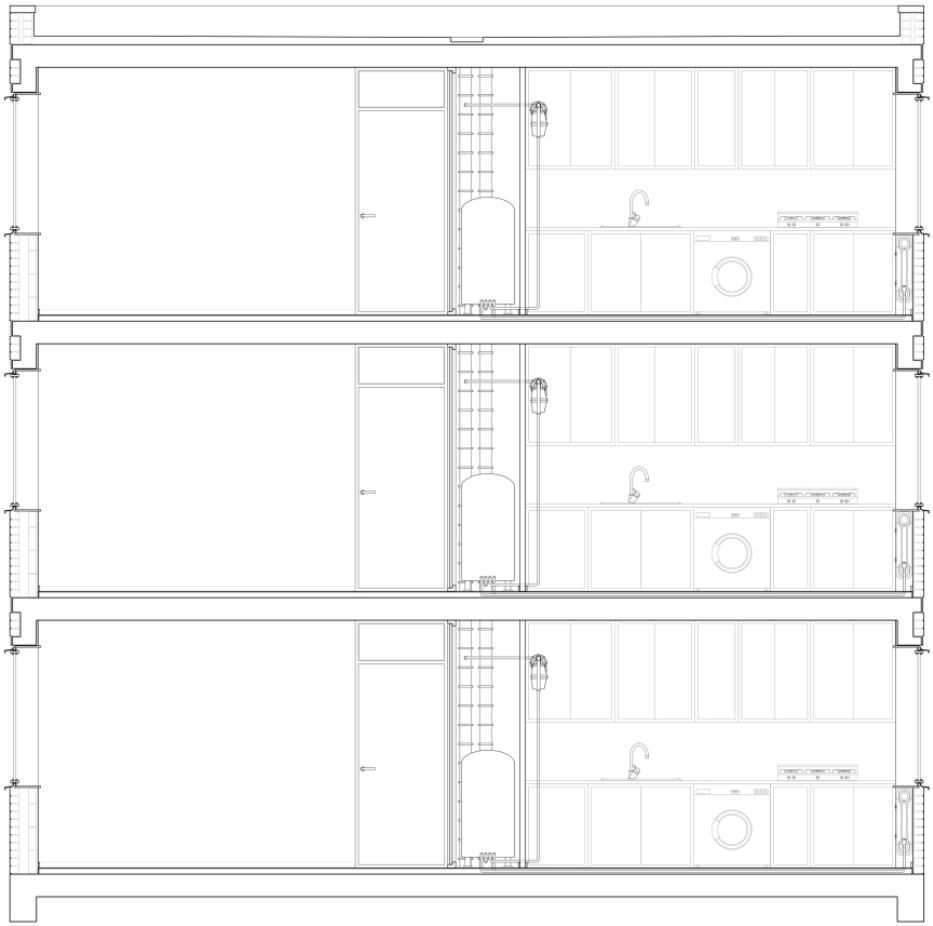

on which all kinds of adaptation are performed. The sandwich layout is organised according to the principle of lowering energy consumption to save energy for vulnerable households. The inner side houses the smallest beehive of 6 square metres, which accumulates heat during the day. It does not have a mechanical heating system. The movement of the body is assigned to spaces, and objects are arranged following the principles of lowering energy use and conforming to health norms. In the UK, whether a bathroom should be heated has been a point of debate in terms of environmental control, since there is strong belief that exposure to cold air after taking a shower will cause one to catch a cold. One can thus enter the communal space of warmth after a shower.

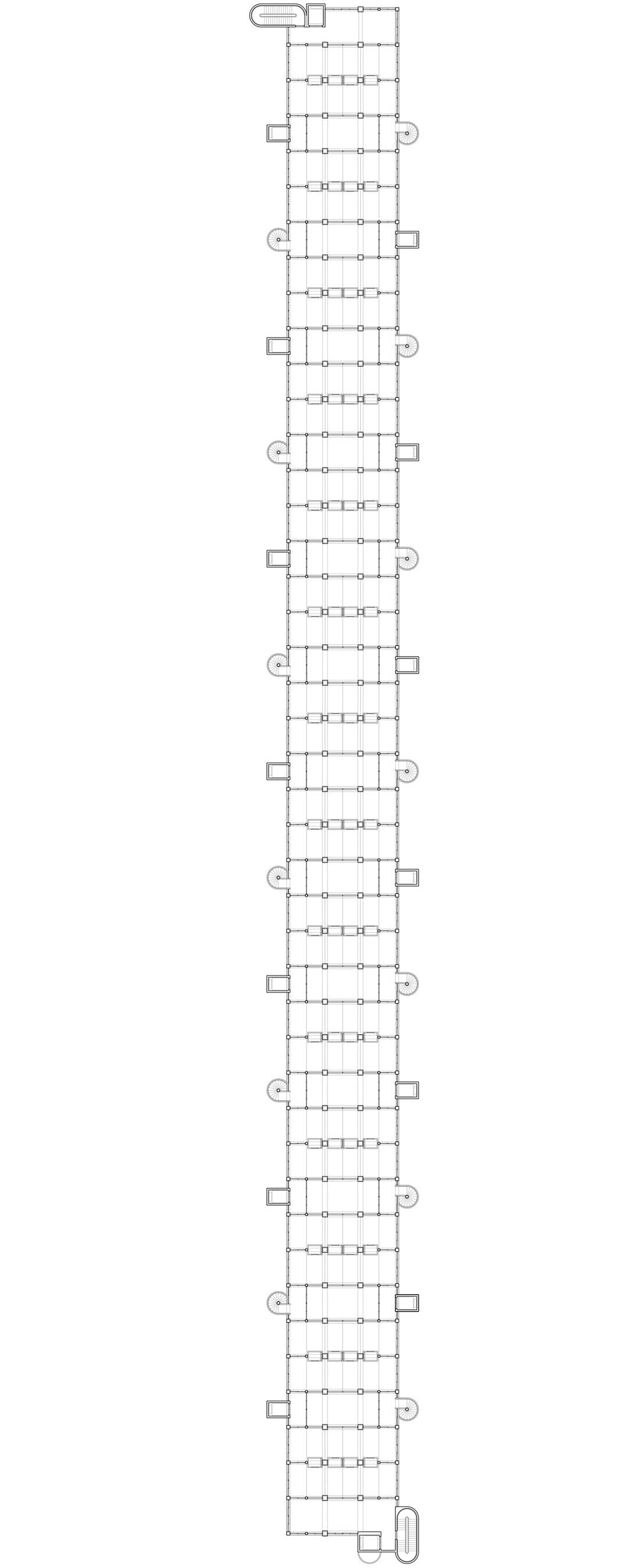

The communal space on the outer side can be occupied in a variety of ways, and one's individuality will unfold through the arrangement of furniture, the opening and closing of windows, the distance between the body and the moveable radiator and the thickness of clothing rather than by rotating a control valve. Hot water pipes are not only manifested as spatial elements but also structure the building. The communal supply of energy can be further identified through the glass blocks acting as floor slabs. In almost the same way, the atmosphere and its producer as social goods elucidate themselves through their relationship with the surrounding infrastructure before it touches our skin.

17 THERMAL COMFORT 71

FIG.17 Collector, Redistributor/Energy Infrastructure

Connector, section 72 CHAPTER 02

THERMAL COMFORT 73

74 CHAPTER 02 Connector, Communal energy supplement&consumption

THERMAL COMFORT 75

76 CHAPTER 02 Connector, Interior

Bibliography:

01. Sloterdijk, Peter. Spheres. , 2011. Print.

02. Forty, Adrian. Objects of Desire: Design and Society Since 1750. , 2005. Print.

03. Ibid

04. Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette,“Fashions in Physic”, No. 508, October 6,1825, p4

05-06. Drysdale, J. J. (John James); Hayward, John Williams, Health and comfort in house building, 1872

06. Hodson, Mike, and Simon Marvin. Retrofitting Cities: Priorities, Governance and Experimentation. , 2016. Print.

07-08. Rees, Emily, Television, gas and electricity: Consuming comfort and leisure in the British home, 1946–65, The Journal of Popular Television, Volume 7, Number 2, 1 June 2019, pp. 127-143(17)

09. Davidson, Caroline. A Woman's Work Is Never Done: A History of Housework in British Isles : 16501950. London: Chatto & Windus, 1983. Print.

10. Bachelard, Gaston. Fragments of a Poetics of Fire. Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture, 1990. Print.

11. Gauger, Nicolas. La Mecanique Du Feu Ou L'art D'en Augmenter Les Effets Et D'en Diminuer La Depense: Contenant Le Traite Des Nouvelles Cheminees Qui Echauffent Plus Que Les Cheminees Ordinaires Et Qui Ne Sont Point Sujettes A Fumer. Paris: L. Laget, 1980. Print.

12. Benjamin, Charles H. Smoke Abatement. Lafayette? Ind., 1915.

Internet resource.

13. Ibid

14. Koolhaas, Rem, and James Westcott. Elements. , 2014. Print.

15. Rees, Emily See also Pursell, Carroll. “Domesticating Modernity: The Electrical Association for Women, 1924-86.” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 32, no. 1, 1999, pp. 47–67.

16. Shove, Elizabeth. Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. Oxford: Berg, 2004. Internet resource.

17. Ibid

18. Ibid

19. Graham, James. Climates. Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary. Ennetbaden: Lars Muller Publishers, 2016. Print.

20. Ibid

THERMAL COMFORT 77

Functional Comfort

Functional Comfort

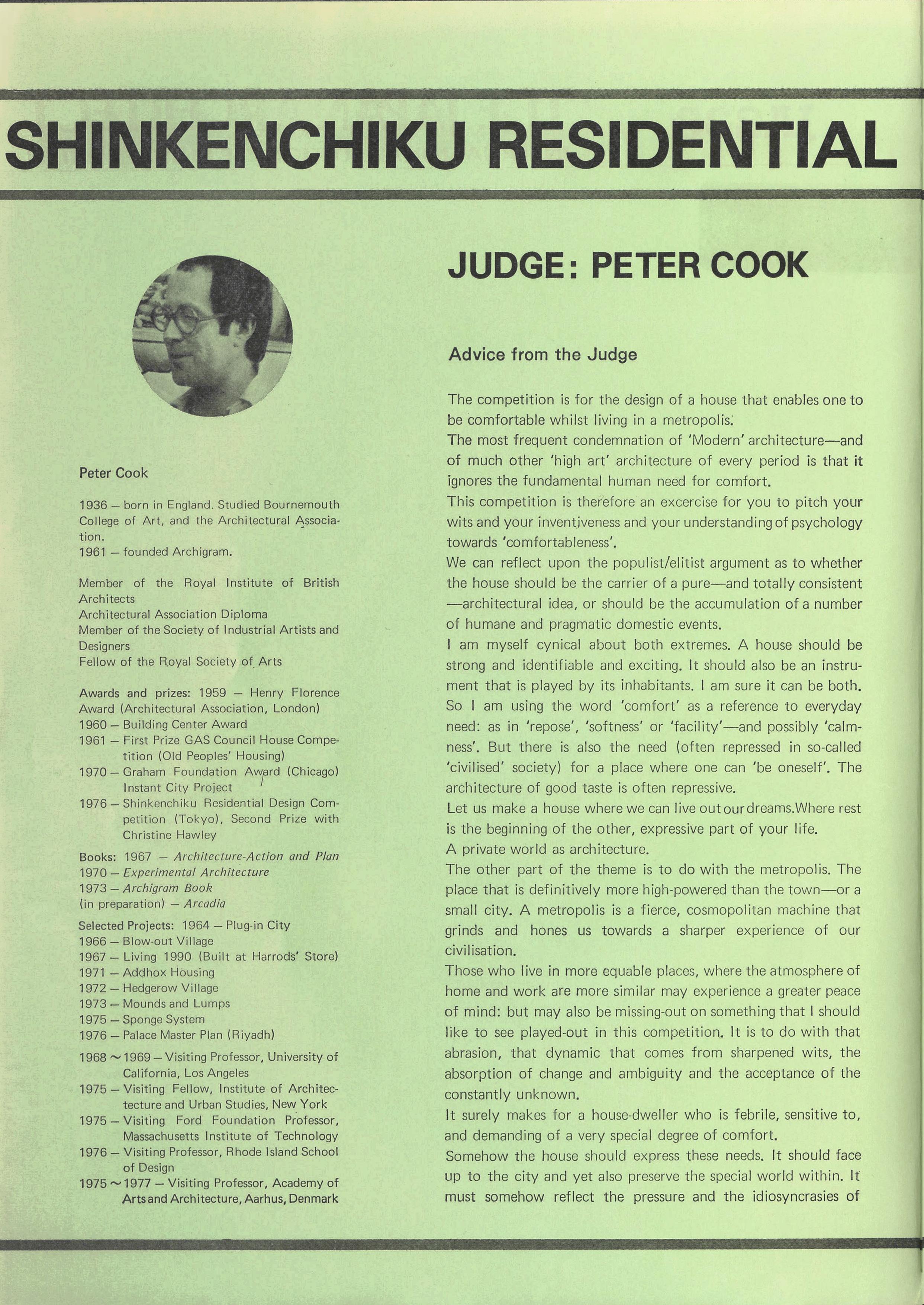

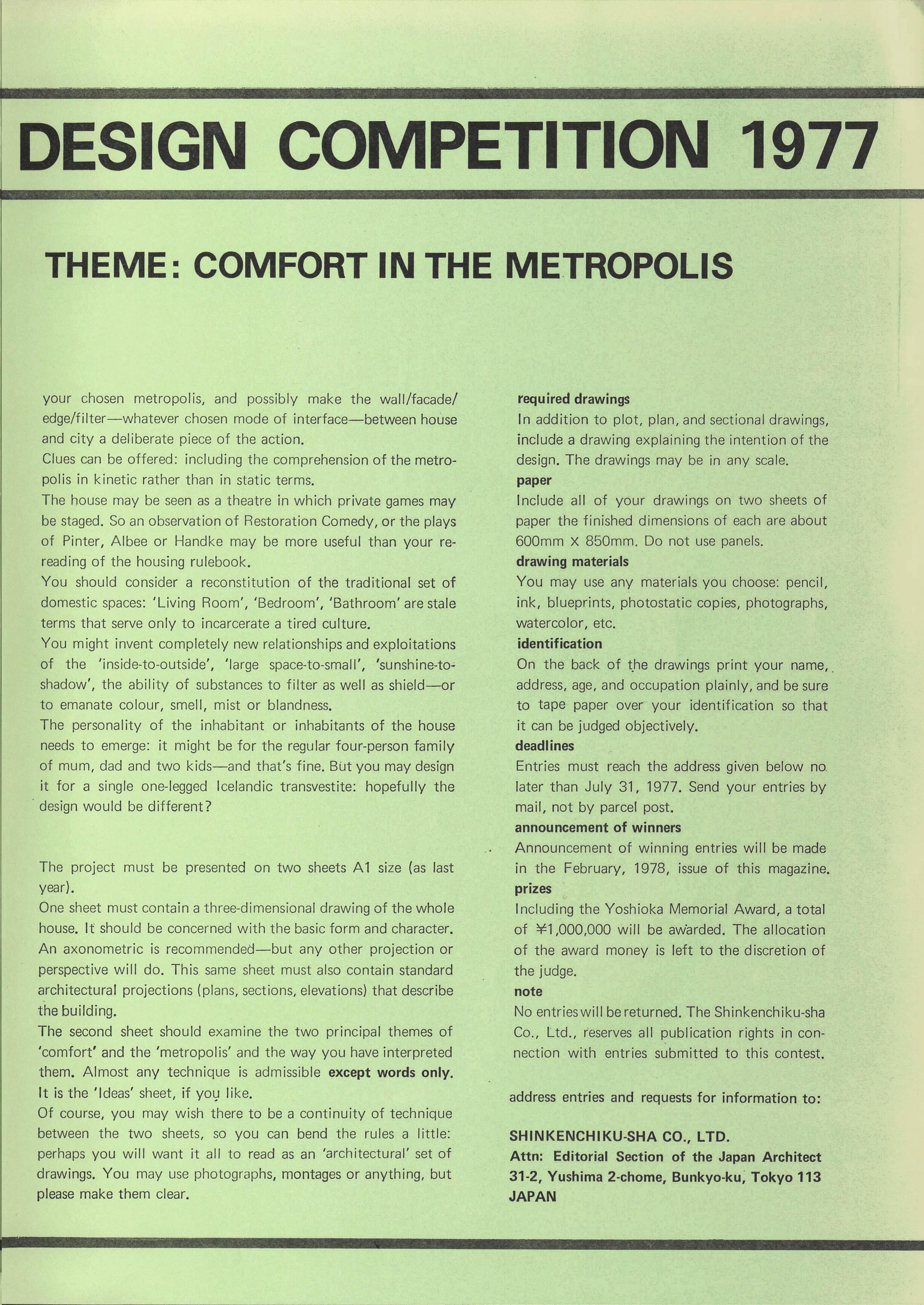

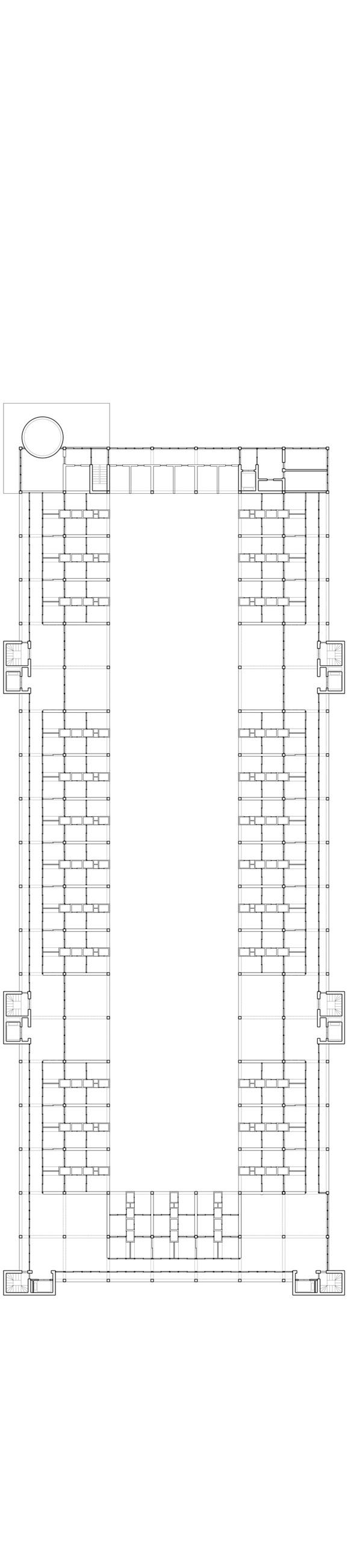

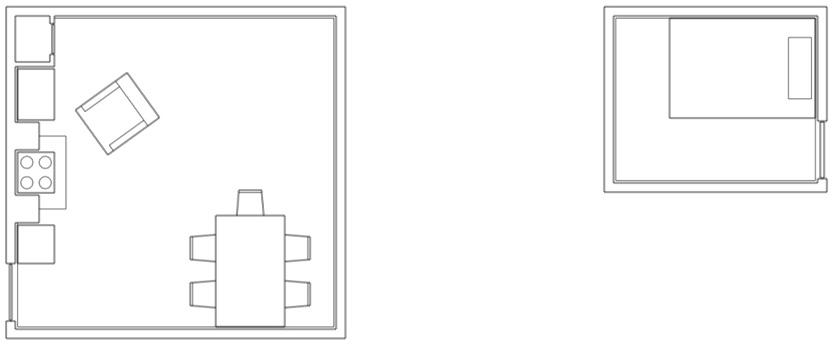

In 1977, the Japanese publisher Shinkenchiku invited Peter Cook to be the sole judge of an international housing design competition. In his competition brief, acknowledging that modern architecture had long ignored the fundamental human need for comfort, Cook invited contestants to develop ‘a house that enables one to be comfortable while living in a metropolis’. For Cook, the dynamics of a contemporary city are a ‘fierce cosmopolitan machine that grinds and hones us towards a sharper experience of our civilisation’.1 Cook clarified his concept of ‘comfort’ as an architecture that can provide physical ease and relaxation – ‘so I am using the word “comfort” as a reference to everyday need, as in “repose”, “softness” or “facility”, as possibly “calmness” … but there is also the need for a place where one can be “oneself”’. Therefore, taking a ‘rest’ is the start of another expressive part of our lives.

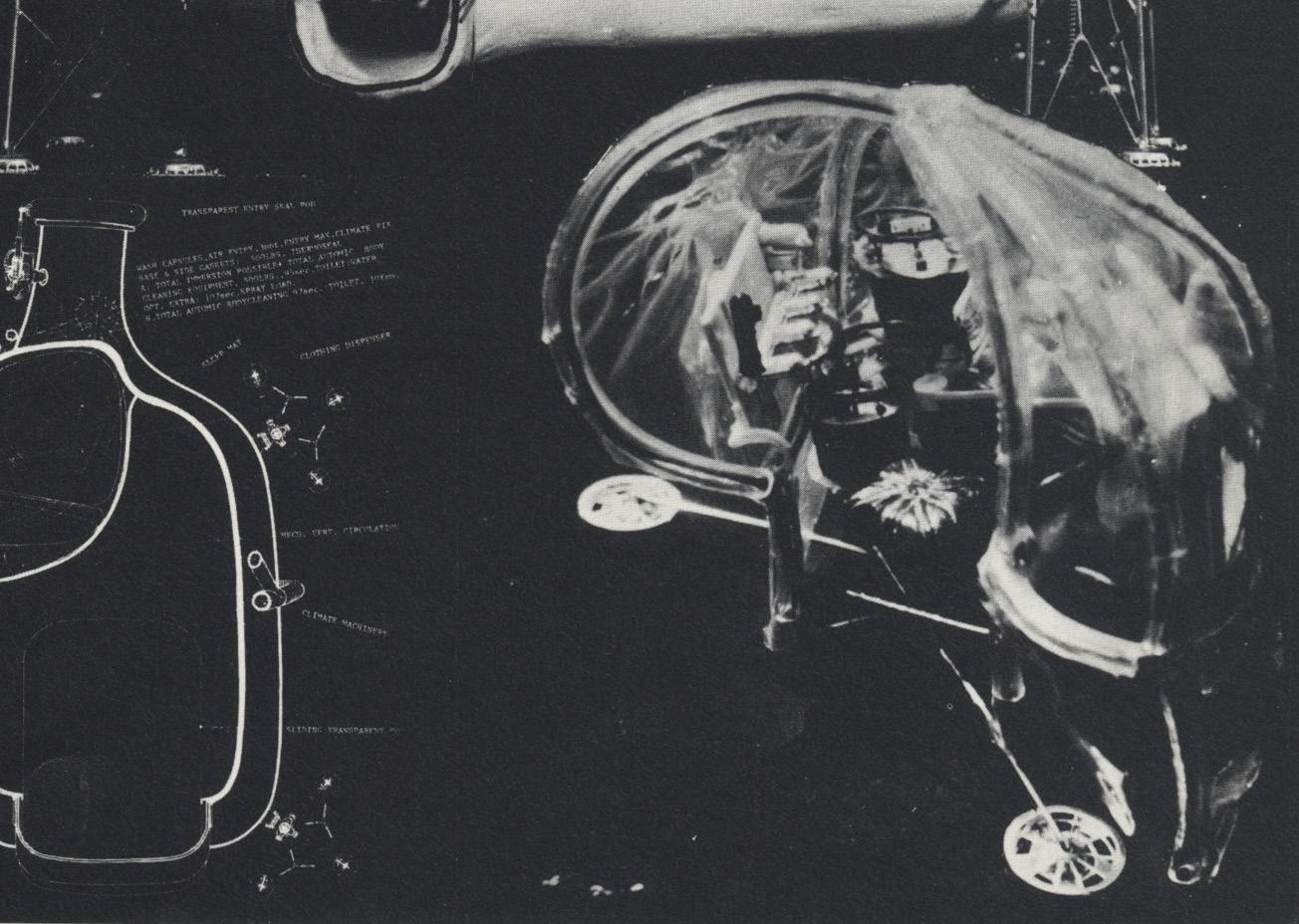

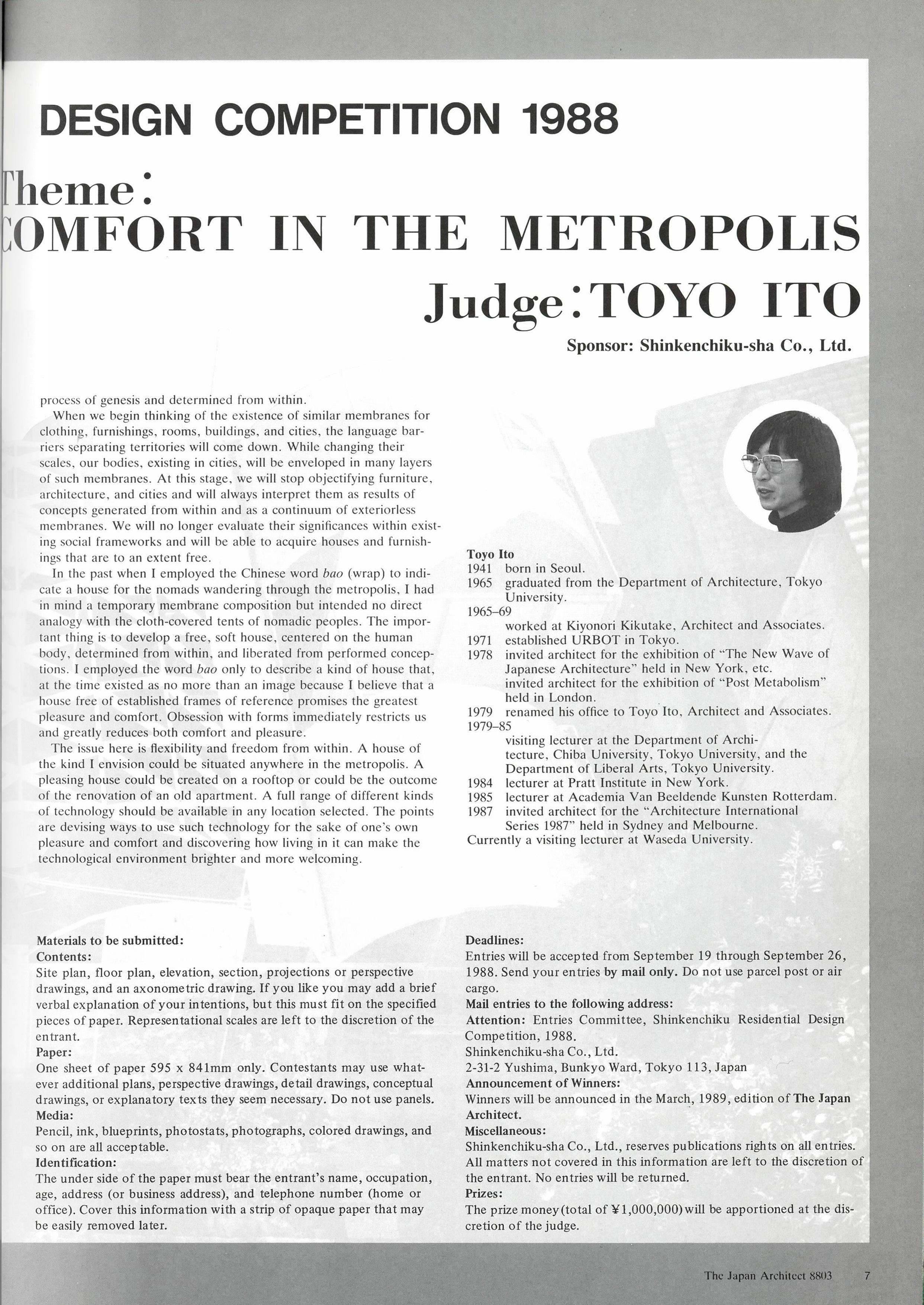

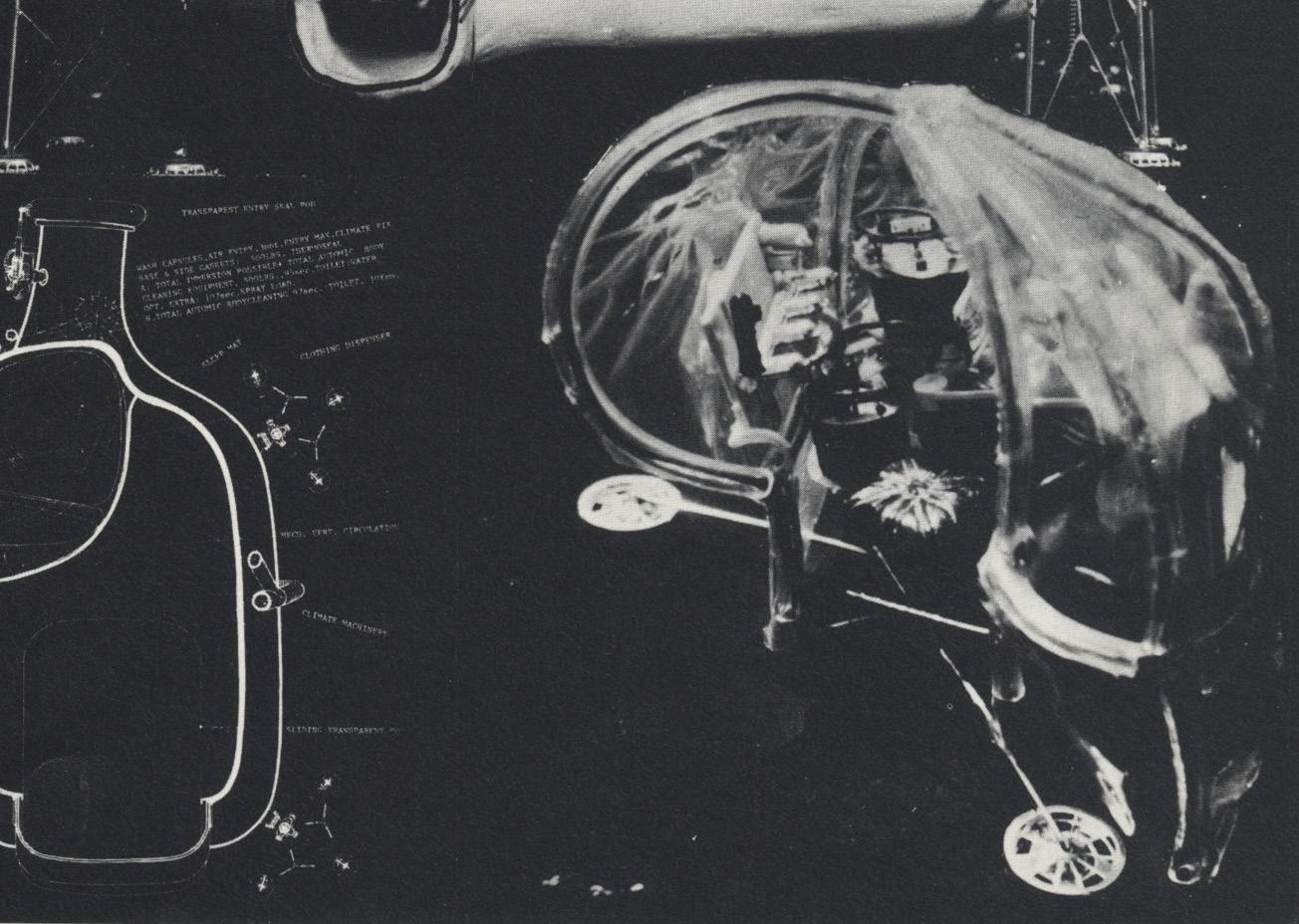

In 1988, despite using the same theme, Toyo Ito embraced an opposite interpretation of comfort when he served as the only judge in the same competition. His fascination with the dynamic yet incoherent urban environment of Tokyo was influenced by the rapid development of electronic technology and media in Japan during the 1980s’ economic bubble. Referring to his Pao design for a Tokyo Urban Nomad, Ito suggested in the competition brief that such a new housing concept could be a space only enclosed by thin and formless membranes. The key to success in this competition was the use of technology in such a way that it directly contributed to one’s pleasure and comfort while simultaneously creating a house that, from within, made the technological environment outside look brighter and more welcoming.2