SPRING 2007 Volume 1

FREE!

Zenand and the theArt of...

win reef stuff @ www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com

Features

Spring 2007 | Volume 1

RHM Staff Executive Editor

10

Deadly Beauty: Zoanthids. Norman Tom is a respected enthusiast in the zoanthid hobby, where he is better known as “Mr. Ugly”. In this article, Norm introduces us to the deadly side of the beautiful creatures he loves.

12

Clownin’ Around: a Basic Guide to Clownfish Care Part 1. Robin Bittner is a well known, professional clownfish breeder in Northern California. Here Robin shares his extensive knowledge of clowns with his fellow hobbyists.

On The Cover

4

Jim Adelberg

Art Director

Tamara Sue

Zen and the Art

Advertising

Dave Tran

of... Jim Adelberg is an advanced hobbyist and industry professional from the San Francisco bay area. This series of articles will examine the fundamentals of successful reefkeeping.

Images Greg Rothschild

gregrothschild.com

Tell us what you think at comments@rhmag.com

Come visit us online at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com And see what we have to offer you!

5

• • • • •

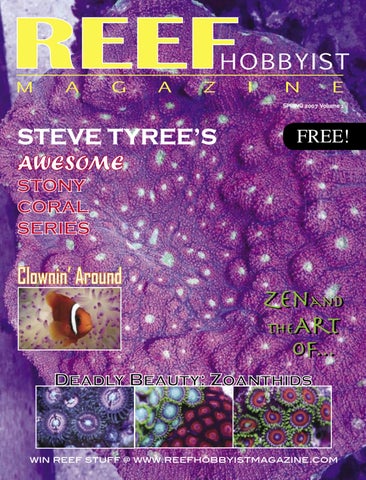

Steve Tyree’s

AWESOME STONY CORALS

Steve Tyree grows some of the rarest and most desirable corals in our hobby and has been an avid collector of rare corals for years. In this series of in-depth articles, Steve will highlight some of his personal favorites.

Join Us! RHM WANTS YOU!

We’re constantly looking for the best writers and photographers to contribute to our free magazine. We believe that free quality information is the key to helping our hobby advance. If you’d like to join us in our mission, please contact our editor Jim Adelberg via email: jim@rhmag.com.

Read Reef Hobbyist Magazine online. Ask our editor questions in the Q & A section. Watch and submit videos in our video library. Participate in our photo contests for cool reef prizes. Communicate with other reefers and manufacturers on our forums.

Interested in Advertising... ...with Reef Hobbyist Magazine? Email advertising@rhmag.com for information on the most cost-effective advertising package in the industry!

Refill

Can’t find free copies of Reef Hobbyist Magazine at your LFS? E-mail us at distribution@rhmag.com with your LFS’s name and phone number and we’ll make sure they have copies available for you in the future. Local Fish Stores! Did you run out of RHM? Email us and we’ll make sure you’re stocked up as soon as possible.

hether you’re a brand new marine hobbyist or a salty old reefer we all must confront the same basic issues in order to keep our tanks healthy. The first and most important concept is one of balance. Keeping any animal that comes from a really large body of water in a much smaller body of water is a delicate matter of balancing a number of different concerns and priorities. These issues are all relatively easy to understand and learning just a bit about them will help you keep your tank in top condition. I try to start by looking at the differences between a tank and the ocean from the animals’ perspective. The biggest difference is clearly water volume and the consistent, high water quality the oceans provide for most of the animals living there. Maintaining high water quality should be every hobbyist’s primary concern. After all, there are lives depending on it!

Another balance that must be achieved is related to stocking levels and overall bioload in the tank. Almost all reef tank creatures, from the smallest bacteria on up, consume food and oxygen and produce waste products and CO2. Some of these waste products and gases can be consumed and bound up in the growth of plants and anaerobic bacteria (in the case of a deep sand bed) but much of it just builds up in the tank’s water and must be diluted through water changes. This is a good time to mention that most of the gas exchange in home reef tanks occurs at the surface area of the display tank and tanks with a higher surface area to volume ratio (squatter, wider tanks) will naturally have a higher dissolved oxygen level. It is the dissolved oxygen in your tank water that allows your animals to breathe and use nutrients to grow. Although it is very difficult to keep the D.O. (dissolved oxygen) levels at or above saturation, like in the ocean, low D.O is often what limits our animals’ growth in captivity. The easiest way to keep your tank’s D.O. at an acceptably high level is through the use of various water pumps and powerheads designed to move the water By Jim Adelberg in the tank so that low D.O. water is brought to the surface to be re-oxygenated. A strong and well-maintained protein skimmer will also be useful here because protein skimmers remove the dissolved organics from the water which otherwise would reduce the waters oxygen carrying ability. Naturally, water changes also help in this regard.

Zen and the Art of...

Foods, and feeding issues, are next on the priority list and luckily, the hobby has come a long way in this field. There is a large selection of commercially available foods, which are designed to specifically feed certain fish, corals etc... The problem with feeding is that, without the massive dilution effect of the ocean at work, the waste products can build up pretty quick! Without adequate water quality, marine animals don’t do well. Without adequate and appropriate feeding marine animals don’t do well. Achieving the right balance between feeding and water changes is critical. Good skimmers and filters can extend the periods between water changes, but in the end, more feeding means more water changing. Another way of “feeding” photosynthetic animals is by exposing them to the right intensity of the right spectrum of light. This allows the zooxanthellae living inside the animal to photosynthesize and produce simple sugars, which the animal can consume. There are currently only a few high intensity lighting options available in the hobby and all the highest output bulbs are either metal halide or high-pressure sodium bulbs. Light levels are measured in 2 ways for

photo by Jim Adelberg

Regular, partial water changes are the backbone of any successful tank but exactly how much and how often will vary greatly, tank to tank. Anywhere between 25% weekly and 25% monthly seems to be the norm. Heavy protein skimming and light feeding will allow your water quality to stay higher for a longer time between water changes, but at least some feeding is required for most of the animals we keep.

aquaria, Lumens and PAR (photosyntheticly active radiation) and PAR is the more important value since that’s the one the zooxanthellae respond to.

In future installments of this series, we’ll go into more detail regarding the specifics of each of these issues but for now there’s one other major challenge we all face and it bear mentioning here. Marine tank hobbyists are well served by a healthy dose of patience. Once someone has spent a bunch of time and/or money assembling a tank, there is a very natural expectation that it should look good right away. Unfortunately that simply cannot happen for a few reasons. First, due to the process of “cycling” which every tank must go through. The patience required during the initial cycling of a new tank, and the slow stocking of livestock can at times be frustrating, but is critical to the long-term success of your system. The second reason is that, much like planting a terrestrial garden, time is required to achieve the grown-in look that is so satisfying. In the next edition of this series, we’ll dissect and analyze the decision-making process that goes into a new tank set-up.

Want to win cool reef stuff? Visit us online at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com today!

4

photo by Greg Rothschild

<< Part 1

Awesome Stony Coral Series By Steve Tyree

Series Introduction and the Awesome Watermelon Corals

It may seem shocking to new captive reef aquarists, but there was a time in the recent past when Reef Building Stony Corals were actually considered to be ‘impossible to keep’. That was the original challenge that many of the pioneering stony coral aquarists had to overcome about 15 years ago. After we had actually acquired our first captive Acropora specimens, the ‘impossible to keep label’ was quickly discovered to be a misnomer. Although these stony corals were more difficult than soft corals and fish, there were some basic reef keeping techniques that allowed us to successfully maintain Reef Building Stony Corals. Proper calcium additions and proper carbonate buffer maintenance not only maintained their health, but quite a few of those first Acropora specimens actually grew at decent growth rates. While witnessing stony coral growth in our captive systems some 13 to 15 years ago, we were amazed to realize that actual reef structure was being created within captivity. That was the first real attraction or first real ‘buzz’ that Reef Building Stony Corals created within the captive reef market. The mainstream reef community acknowledged our success, but we were still unfortunately considered to be the odd or weird hobbyists who were strangely attracted to those boring Reef Building Stony Corals. Some of the common complaints I heard 12 years ago were, ‘They have no color’ and ‘They do not move’. Some of us ‘oddball’ hobbyists still found the corals interesting and while we were improving our understanding of the corals’ captive 5

requirements, a strange transformation began to occur with these ‘boring oddballs’ of the captive reef world. Many of the Reef Building Stony Corals began to extend their polyps during the day. This was an adaptation within captivity caused by the lack of natural coral polyp predators within our reef systems. On natural reefs these corals typically do not extend their polyps during the day. So now these ‘nonmoving’ boring Reef Building Stony Corals began to show movement as many species extended their soft polyps during the daylight photoperiod. There was however still one more challenge to overcome before the mainstream reef community completely accepted Reef Building Stony Corals. These corals were still considered to be the drab colored ‘ugly ducklings’ of the captive reef world. Compared to the bright green Sinularia, the blue and red Mushroom corals, the colorful polyp soft corals and even the bright green hammer corals, Reef Building Stony Corals were primarily colored drab brown with only the possibility of developing some green pigments. The main problem back then was in maintaining the corals’ natural pigmentation. Many of these corals were arriving here in the United States with brilliant pigmentation, but these original pigments were quickly fading in captivity. Then about 10 to 12 years ago, some new spectrum lights with higher wattages were introduced to the captive reef market. The original metal halides had emitted a color or spectrum of light that roughly approximated light at the surface of natural reef waters. These new lights were emitting colors or spectrums of light that better matched the type of light that corals were experiencing at depths between 15 and 50 feet. Those of us who quickly switched to the higher wattage and better spectrum lights, began

Looking for a reef club in your area? Search online at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com today!

to see some incredible pigmentation develop within our Reef Building Stony Corals. With this new lighting, freshly imported corals were maintaining their original pigmentation for far longer. Additionally, some of our older captive corals were developing more dramatic colorations. The final and last challenge had been successfully overcome. The ‘impossible to keep’ ‘ugly duckling’ corals were now some of the most colorful and interesting corals growing in captive reefs.

grow and maintain the SPS corals are also applicable to the LPS corals. Many of the pigments developed within the SPS corals can also develop on the LPS corals. There are some differences however between these two polyp-size based groups of stony corals. Large polyp stonies generally require lower light intensities. They can also readily be fed larger food particles within our captive reef systems. Many of the LPS corals also appear to be easier to maintain in captivity.

Some of these Reef Building Stony Corals are now called ‘SPS’ by the mainstream reef hobby. The term SPS stands for Small Polyped Stony and it is typically used to describe the Acropora, Montipora and Pocillopora corals. This term is based on the relatively small sized polyps that those corals possess. Besides the SPS corals there are also Reef Building Stony Corals that possess larger sized polyps. The mainstream hobby has coined the term ‘LPS’ to describe the Echinophyllia, Acanthastrea and Favia corals. The term LPS stands for Large Polyped Stony and its use is based on the relatively larger sized polyps these corals possess. I will be using the term Reef Building Stony Corals to describe both the SPS and the LPS corals that are primary reef constructors on natural tropical reefs. In our captive systems it has become very apparent that techniques developed to

Now that we have become successful with many of the easier to keep SPS and LPS species, experienced aquarists are experimenting with species and morphs that are more difficult to keep. Some of these more demanding SPS species require intense lighting and intense currents, while less demanding species generally require low lighting and weak currents. Learning the varied requirements of specific species has been challenging. Experienced Reef Building Stony Coral aquarists are also constantly searching for unique species or morphs that are new to captivity. This has led to the creation of new markets for rare and exotic species or morphs. Some awesome stony corals that contain incredible pigment patterns and brilliant pigment intensities have been discovered. Sometimes an awesome pigmentation is apparent when a new coral colony >>

Submit your original photographs for a chance to win Blue Life prizes!

250 or 400 watt Metal Halide Bulb log on to see the 2nd and 3rd place prizes!

Would you like to contribute to Reef Hobbyist Magazine? Visit us at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com and find out how!

6

>> Awesome Stony Coral Series is imported, but at other times specific corals have developed incredible pigmentation only after being maintained within captive reefs for a period of time. Collector markets exist where stony aquarists either purchase known awesome corals or they conduct searches for ‘hidden gem’ corals

that are originally drab colored when imported or acquired. A true hidden gem coral will develop or intensify hidden pigments and can turn a “diamond in the rough” into an awesome living gem.

>>

The Awesome

Watermelon Corals The first Reef Building Stony Coral featured within this Awesome Stony Corals Series is one of the most incredibly pigmented LPS corals ever seen within captivity. The coral is called the ‘Watermelon’ coral (see image 1-A) and its brilliant fluorescing pigmentation patterns can quite literally make it the centerpiece of a captive reef display. The first true ‘Watermelon’ coral was acquired and maintained by Ron Johncola. Ron called the coral ‘Watermelon’ because it contained a brilliant fluorescing green colored edge, while its inner surface areas were colored bright fluorescing pink. The coral has also been called the ‘Watermelon Alien Eye’ coral. Ron traded some of his first Watermelon coral fragments to Hugo Zuniga (snipersps) who added the phrase ‘Alien Eye’ to the corals’ name. Hugo added the term ‘Alien Eye’

because this coral possessed the same brilliant green coral polyp pigments that are also contained within the original ‘Alien Eye’ Echinophyllia coral found by John Susbilla (Tubs). When the polyp mouths of these corals are open, they can develop a strange ‘Alien Eye’ appearance. The ‘Tubs Alien Eye’ coral also contains a bright green colored edge or growth rim. That coral can be seen on the left side of the ‘Three Alien Eye’ coral image (see image 1-B). A closeup of the original Watermelon coral is located on the far right side of that image. New coral species and morphs containing different color patterns similar to the original Watermelon pigmentation have recently been acquired or found by captive aquarists. continued pg 9

7

>>

Original Watermelon Coral (image 1-A)

Three Alien Eye Corals (image 1-B)

Image taken by Steve Tyree. This was Hugo Zuniga’s colony that was grown from a Ron Johncola original fragment. Note the thick fluorescing green growing edge pigmentation. The main body is primarily colored bright pink. The typical ‘Alien Eye’ look can be seen in the left green corallite which has its polyp mouth slightly opened.

Image taken by Steve Tyree from Hugo Zuniga’s reef. On the left is the original Tubs Alien Eye coral. It has a bright green edge and bright green corallite centers. The newer Red Watermelon coral is located in the center. The original Watermelon coral is located on the right side of this image.

Enter the Blue Life sponsored photo contest at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com and show off your photo skills!

Jayda’s Yellow Eyed Watermelon Coral (image 1-C)

Bazooka Joe Watermelon Coral (image 1-D)

Image taken by Steve Tyree. This rare Yellow Eyed Watermelon coral also contains the normal bright green leading growth edge along with some brilliant pink main body pigmentation. Greg Carroll named this coral after his daughter Jayda.

Image taken by John Dakan. This Watermelon coral has a pink and blue base pigmentation. Corallites also have well developed ridges or round mounds that surround each polyp. It can also develop an amazing number of corallites or alien eyes on its surface.

>> Awesome Watermelon Corals Hugo Zuniga discovered the ‘Red Watermelon Alien Eye’ coral, which has a bright red base pigmentation instead of the brilliant pink. This new ‘Red Watermelon’ morph can be seen in the center of the ‘Three Alien Eye’ image (see image 1-B). Another Watermelon morph has been discovered and developed by Greg Carroll. It is called the ‘Jayda’s Yellow Eyed Watermelon’ and its corallite centers or eyes contain yellow pigments (see image 1-C) which give the coral’s eyes a yellow coloration. This Watermelon-like colored species also has slightly elevated large round protrusions or ridges around the corallite eyes, while both the original Watermelon and the Red Watermelon corals lack large corallite ridges or protrusions. Another new morph of Watermelon coral was recently acquired by John Dakan. It is called the ‘Bazooka Joe Watermelon’ coral and its main base coloration is a mixture of pink and blue (see image 1-D). This new pink and blue Watermelon coral has very prominent large ridges or protrusions around the corallite centers. These large protruding corallite ridges along with an unusually high density of corallite eyes, help to give the Bazooka Joe Watermelon a very unique appearance. When the original Watermelon coral was imported into the U.S., its amazingly brilliant pigmentation was already apparent. A closeup examination of the green corallite centers and green growth edge of this coral also reveals amazing spots or dots of colorful pigmentation. The 9

Bazooka Joe Watermelon also arrived from nature with its brilliant pigmentation intact and fairly intense. Although the newer spectrum and higher wattage metal halide lamps have helped to maintain these original pigments, the Watermelon corals seem to prefer to be located near the bottom of brightly lighted reefs. Coral exporters have also become aware of the fact that brilliantly pigmented corals are highly desirable to collectors and farmers. Whole imported coral colonies containing awesome pigmentation patterns typically have very high wholesale prices. There are however less expensive ways to acquire awesome corals. Aquarists can purchase small captive grown fragments or they can try their luck at discovering a hidden gem. Both the Red Watermelon and the Jayda’s Watermelon corals discussed within this article were originally brownish colored when imported. They only possessed a faint hint of pink pigmentation. Both of these corals turned out to be hidden gems that were developed into living jewels within captive systems. In some cases hidden Watermelon gems may lack the green edge or green eyes, but still possess some base pink pigmentation. In other cases the corals can have the green corallite centers or eyes and will develop the pink base pigments and bright green fluorescing growth edge after being maintained within captivity. Aquarists should note that not all pinkish or green edged Echinophyllia-like corals have the ability to develop intense pink or red base pigments. Only true Watermelon corals will develop those awe inspiring pigmentation intensities.

Share your reef vidoes and browse our video collection at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com!

Deadly Beauty L

Zoanthids

By Norman Tom photo by Jeremy Hale

imu Make O Hana, the Deadly Seaweed of Hana, grew in a secret Hawaiian tide pool. Local warriors used the Limu Make to prepare their weapons for battle. Any spear tip, once brushed with the Limu Make, would bring instant death upon finding its mark. According to ancient legend, villagers discovered a shark god living in disguise amongst them. The creature had been preying upon the villagers and was found to be responsible for numerous mysterious disappearances. Once revealed, the shark god was torn to pieces and burned until nothing remained but ashes. The villagers threw the ashes into a nearby tide pool whereupon its seaweed became poisonous. This seaweed became known as Limu Make O Hana. We now know that this seaweed actually is not a plant, but a zoanthid of the species Palythoa toxica. Zoanthids, also known as button polyps and sea mat, are relatively hardy. With proper precaution, these corals are easily kept by the beginning reef hobbyist. Available in a myriad of colors and patterns and various combinations thereof, zoanthids can be used to form an attractive reef aquarium display all on their own or along with other reef invertebrates. They can be particularly striking when displayed in a desktop nano tank where one can appreciate their brightly colored details up close. Types of zoanthids commonly maintained in the home reef aquarium include those from the genera Zoanthus, Palythoa, Protopalythoa, and Parazoanthus. All of these are photosynthetic and contain symbiotic zooxanthellae. In general, polyps of the genus Zoanthus feed by absorption of dissolved nutrients, whereas Palythoa, Protopalythoa, and Parazoanthus actively take in particulate food material. Though tolerant of less than pristine water conditions, all benefit from regular water changes, good water quality, and good water circulation. Zoanthids do well under a variety of lighting systems, from power compacts to metal halides. The latter, though not required, do seem to enhance color depth and highlights. Recent years have seen an increasing interest in collecting and maintaining unique zoanthid morphs. Today’s zoanthid fans have their own websites and online forums dedicated to sharing all things zoanthid. Some coral vendors, taking note of zoanthid popularity among hobbyists, have chosen to specialize in providing exotic specimens to their customers. Each collector has his or her own favored zoanthid morphs that may be of an interesting color or pattern. Prized morphs may bear multiple bright colors, an eye catching metallic sheen, a sparkly stardust pattern, colorful striations, or some other unusual or uncommonly beautiful characteristic. Some hobbyists have become specialized

propagators of these corals in order to share and trade with others. Zoanthids, like any other marine animal, may harbor pests or be subject to disease. The reef aquarium hobbyist should inspect newly acquired zoanthid specimens for such things as predatory nudibranchs, zoanthid spiders, sundial snails, foramaniferans, asterinas, red planaria, fungus, and white “zoa pox”. These may be remedied by a variety of treatments including manual removal, fresh or salt water based dips of iodine, hydrogen peroxide, fluke/flatworm medications, or Furan-2, depending on the predator or ailment. Due to the possibility of palytoxin exposure, one should always wash one’s hands with hot soapy water after handling these animals. Be sure to avoid contact to eyes, cuts, mouth and/or abrasions when handling zoanthids. Palytoxin, the neurotoxin first isolated from Palythoa toxica, is said to be the most toxic organic substance known. A complex molecule with a chemical formula of C129H223N3O54, palytoxin has been estimated to be lethal to humans in dosages of as small as 4 micrograms. Note that a single crystal of table salt weighs approximately 65 micrograms! Palytoxin disrupts the ability of cell membranes to control ion flow. The heart muscle is particularly sensitive and poisoning results in constriction of the blood vessels of the heart and lungs. Additionally, the toxin causes rupture of red blood cells. Symptoms of palytoxin exposure include chest pains, breathing difficulties, racing pulse, and unstable blood pressure. Death can occur within minutes after poisoning. One recommended antidote is papverine injected directly into the heart. As potentially deadly as it may be, palytoxin may one day play an important role in saving human lives. Scientists frequently have turned to nature in searching for complex biological compounds that might prove useful to mankind. Zoanthid palytoxin has been found to have anti-tumor and anticancer effects. University of Hawaii cancer researchers recently have been experimenting with attaching palytoxin molecules to antibodies designed specifically to attack cancer cells. The diversity of our natural reefs provides much more to be appreciated than just eye candy to reef hobbyists.

Ask our advertisers questions about their products in our forum at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com!

10

A basic guide to clownfish care

photo by RHM

Clownin’ around: By Robin Bittner

L

Helping push the popularity of these fish is their nearly ubiquitous presence in the aquarium industry, as it is a very rare store that doesn’t have at least a handful of specimens from the roughly 2 dozen species of clowns commonly available. This popularity was further fueled by the release of the “Finding Nemo” movie a few years ago, which focused on the adventures of an Ocellaris (False Percula) clownfish off the coast of Australia. While aquarium purists still cringe whenever a child (or adult for that matter!) passes a tank of clownfish and squeals, “Oh look, NEMO!!!”, this movie helped increase the popularity of saltwater aquariums more than any other single event over the past few decades. Of course, as the star of the movie, “Nemo” (aka Percula and Ocellaris clownfish) also increased in popularity and became the desired pet of tens of thousands of >> budding aquarists.

11

Enter the Blue Life sponsored photo contest at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com and show off your photo skills!

photo by Greg Rothschild

ikely every marine aquarist considers at one time or another the addition of a clownfish to their aquatic menagerie. For some this results in just another colorful resident in their little slice of the ocean, while for others the attraction to this friendly little fish becomes so strong that a saltwater aquarium just wouldn’t seem complete without one (or a pair) of these characters. Part of the appealing nature of the clowns is their engaging behavior, but their generally hardy dispositions make many of them good candidates for the novice as well as the experienced aquarist.

>> Clownin’ Around

There’s More Than Just One To Choose From

photo by Greg Rothschild

photo by Greg Rothschild

Despite the relatively large number of clownfish species available, the clownfish family can be broken down into five general groupings — the clarkii, tomato, skunk, Percula, and maroon complexes. Each of these groups exhibits varying levels of behaviors and needs, but in general the tomato, clarkii, and maroon groups are the most aggressive while the Percula and skunk groups are smaller and more peaceful. However, this is not to say that the smaller fish cannot be quite aggressive also, as any owner of a Percula clownfish will agree if they’ve been nipped by an overprotective clown while cleaning the tank!

Typically the clowns seen most often in aquarium stores are the clarkii variants (brownish body and yellow belly with 2 white stripes), assorted tomato clowns (reddish body with a bare or single white stripe on the head), and the Percula/ocellaris clowns (orange body with 3 white stripes and varying levels of black). Although the tomato and clarkii clowns are very common, the ocellaris clown can arguably be crowned as the most popular clownfish due to its small size, relatively hardy nature, pleasant personality, and endearing “wiggle” as it dances above its favorite spot in the aquarium.

photo by Greg Rothschild

Where Do They All Come From?

13

With recent advances in marine breeding and rearing technology, all of the common clownfish species are now currently being captive bred and raised at commercial facilities in the U.S., Australia, England, and the Caribbean. Although these captive breeding efforts have contributed significantly to the supply of these highly desired fish, demand still is outstripping the captive supply such that wild caught clownfish remain one of the “bread and butter” staple imports of the aquarium trade. This high demand for clownfish has also led to the formation of a cottage industry of hobbyists who typically have 5-10 tanks dedicated to the breeding and raising of one or two species of clownfish. In our next article, we’ll take a closer look at one such hobbyist setup to better understand what it takes to experience the joy of raising these fun little fish.

Want your LFS to carry free copies of RHM? Visit us at www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com and email us your LFS’s information!